Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR130588. The contractual start date was in November 2022. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cantrell et al. This work was produced by Cantrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Cantrell et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The term ‘winter pressures’ refers to ‘how hospitals cope with the challenges of maintaining regular service over the winter period’. 1 Although attention typically focuses on additional demands on accident and emergency (A&E) services, pressures are exerted in terms of increased demand across the entire health and social care system. Increased prevalence of respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses during the winter places severe demands upon systems that already face difficulties in matching service provision to demand. Better or earlier planning and/or increasing service provision across integrated care (IC) systems and related sectors, such as housing, constitute just two of the possible responses to increased demand.

The COVID-19 pandemic response illustrates many issues that need to be addressed in planning for hospital discharge when the health system faces specific expected or unexpected system pressure. While very large numbers were rapidly discharged to care home beds in the early months of the pandemic, the discharge process generated significant concerns about whether the associated risks to both the discharged patients and the care homes had been sufficiently considered in the discharge planning process. 2

Winter pressures are a familiar phenomenon within the National Health Service (NHS) and represent the most extreme of many regular demands placed on health service provision. The impact of winter pressures is pervasive and operates along a continuum from public health, in mitigation via immunisation campaigns, through to discharge into social care and the community. Interventions target multiple points along this continuum, as well as whole-system approaches.

This mapping review focuses on one stage of the pathway, considered particularly problematic, namely the discharge process from hospital. Studies of discharge interventions and transfers of care are plentiful and international initiatives are reviewed in a recent scoping review. 3 However, a considerable challenge lies in identifying interventions that specifically are articulated as an explicit response to ‘winter pressures’. There is strong rationale for focusing on the subgroup of winter pressure interventions because these may represent interventions implemented in response to particularly acute and severe system pressure. This contrasts to interventions that seek to improve discharge within a system in ‘steady state’. While commentators on the current context articulate that the system experiences ‘winter’ pressures all year round, until recently, responses have targeted the context of winter pressures. Potentially, this set of studies therefore represents a highly relevant evidence base on discharge related interventions to inform current NHS planning.

This mapping review aims to chart and document the evidence in relation to winter pressures in the United Kingdom, together with either discharge planning to increase discharge (both a reduction in patients waiting to be discharged and patients being discharged to the most appropriate place) and/or IC. For the purposes of this review, ‘integrated care’ involves partnerships of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined-up health and care services in NHS England.

Objective of the review

The primary objective of the mapping review is to address the question:

-

Which interventions in relation to discharge planning/IC have been suggested, tried or evaluated in seeking to address winter pressures in the United Kingdom?

The secondary review question is:

-

Which research or evaluation gaps exist in relation to service- or system-level interventions as a response to discharge planning/IC in the context of winter pressures?

In addressing this question the mapping review will seek:

-

to identify a potential winter pressures research agenda in relation to discharge planning/IC to inform commissioning of future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

We undertook a systematic mapping review to map the winter pressure literature, specifically in relation to discharge planning and IC, and to help to determine opportunities for further research. The mapping review explores the volume and characteristics of the available evidence in relation to discharge planning or IC in response to winter pressures.

The systematic mapping review closely adhered to published methods for a mapping review. The methodology described by James et al. 4 was used to guide the five stages of the review: setting the scope and inclusion criteria, searching for evidence, screening evidence, coding and database production, describing and visualising the findings.

Setting the scope and inclusion criteria

This mapping review focuses on interventions designed to reduce clinically unnecessary occupancy of hospital beds and demand on health services through discharge and transfer to social care or the community (e.g. ‘hospital at home’). Such interventions typically require improved linkages and communication between various health and social care services, captured in the concept of IC. Integrated care systems seek to capitalise on the benefits of such ‘joined-up’ systems.

Key to feasibility is the requirement for study authors to have linked their research or data explicitly to winter pressures. Numerous interventions have been proposed to handle discharge planning but not all have been explored within the context of a pressurised health or social care system. Insisting on this requirement helped in identifying interventions or mechanisms that offer promise within other pressurised care environments. Specifically, we based eligibility on the following aspects – population, exposure, comparative, outcome(s), study types:

-

users of UK health and/or social care systems (population)

-

winter pressures impacting on discharge, to social care and the community and IC (exposure)

-

other foreseeable, unusual or exceptional periods of demand (if appropriate) (comparison – may or may not be present)

-

increased smart discharge (both a reduction in patients waiting to be discharged and patients being discharged to the most appropriate place), system effects, health and health service outcomes, effects on patients, carers and staff (outcomes)

-

eligible types of study design: primary research study, evidence synthesis or research report (study types).

Searching for evidence

The mapping review took a two-pronged approach to identifying the evidence for this review. The first-stage search identified the interventions through explicit references to winter pressures. The second stage of further searching was undertaken of named interventions extending beyond winter pressures on Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) to find systematic reviews and guidance. More detail is provided below.

First-stage search

For the first stage, the literature search employed two separate methods according to the type of source being used. We searched databases that offer title and abstract search facilities using terminology relating to winter pressures. We examined retrieved items identified as initially relevant at full text to establish whether they contained data within the context of discharge planning or IC. We searched data sources that enabled full-text searching (e.g. Google Scholar) and other web searches by combining the winter pressure terms with the twin concepts of discharge planning and/or IC.

Search terms and languages

The literature search covered the period 2018–22 and was restricted to English only. This search cut-off date was determined by the need to optimise the relevance to the current context and ways of working. However, we have documented UK studies published before 2018 referenced in evidence syntheses or research reports as still being of contemporary relevance. International intervention in systematic reviews as mapped. We extracted findings from these studies for completeness.

-

Concept 1: winter pressure(s); winter plan(s)/planning; winter resilience; winter protection plan.

-

Concept 2: discharge plan(s)/planning; delayed transfer of care; discharge to assess (D2A); better care fund, increased smart discharge (both a reduction in patients waiting to be discharged and patients being discharged to the most appropriate place).

-

Concept 3: integrated care.

An initial search was conducted in October on MEDLINE and then translated to the other databases. The MEDLINE search strategy is provided in Appendix 1. The search used free-text terms for winter pressures and winter planning. We were unable to identify specific relevant thesaurus terms for winter pressures. To optimise sensitivity of the search, we did not use specific discharge/IC terminology in the search strategy but decided that judgements on discharge planning/IC context would be operationalised during title/abstract and full-text screening stages rather than relying on uneven application of database indexing.

Databases searched

-

MEDLINE Ovid Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions, 1946 to 11 October 2022.

-

HMIC Ovid: Health Management Information Consortium, 1979 to July 2022.

-

Social Care Online.

-

SSCI: Social Sciences Citation Index, 1900 to present.

-

King’s Fund Library.

Google Scholar was also searched through Harzing’s Publish or Perish software (www.harzing.com).

The following organisation websites were also searched to identify report about initiatives to improve discharge planning or IC process:

-

British Medical Association

-

Department of Health and Social Care

-

Health Foundation

-

King’s Fund digital archive

-

Nuffield Trust.

Searches on Google were also undertaken for winter pressures and discharge OR integrated care limited to .NHS, .GOV or .org sites.

Second-stage search

The second stage involved searches of Google Scholar for named candidate interventions from the literature and current practice. The searches were on Google Scholar for evidence broader than winter pressures. These searches were intended to retrieve reviews, ideally systematic reviews, and were limited to research published from 2012 to 2022. These searches helped with completing the intervention tables and identifying the evidence gaps.

Screening evidence

Study screening and selection was undertaken in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A team of three reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the 723 references from the searches. Articles meeting the inclusion criteria for titles and abstracts or items with insufficient detail on content relating to discharge planning or IC were reviewed at full text.

Study validity assessment

The primary purpose of the mapping review was to create a profile of the available evidence base and this was then used to identify potential evidence and synthesis gaps. We assessed individual studies at a study design level and not through individual critical appraisal. Initially identified items were categorised as primary research, evidence synthesis or research report. The last of these identified reports from organisations such as the Nuffield Trust, King’s Fund and Health Foundation that combine critical commentary, usually with primary data. Outputs from governmental or professional organisations were processed in a similar way. We identified research gaps from the distribution of primary studies and their research questions, summaries from evidence syntheses and recommendations from research reports. We then evaluated the authority and credibility of the research gaps accordingly.

Coding and database production

Metadata extraction and coding for studies were undertaken using Microsoft Excel. For mapping purposes, references were categorised at title and abstract stage according to study design, characteristics and broad thematic content. A data coding spreadsheet was used to code data for study type, population, intervention (if present), outcomes or findings and conclusion. Following granular coding, we then classified related studies within broader thematic categories that were be used to present study characteristics and to structure an accompanying narrative. Due to the time and resource constraints of the proposed work, missing or unclear information was not solicited from authors.

Describing and visualising the findings

Development of taxonomy

To classify into the broader thematic groups of interventions, we developed a taxonomy (see the Excel spreadsheet) documenting the candidate interventions together with other relevant supporting literature. Our team started from categories developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group for their systematic reviews of discharge planning cited by Parker et al. 2002. 5 These were further expanded using categories from a rapid review produced by the Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash University. 6

This process resulted in the following broad groupings: structural (S), changing staff behaviour (CSB), changing community provision (CCP), IC, and targeting carers (TC). The draft taxonomy was reviewed for parsimony (to minimise duplication of concepts) and comprehensiveness (to include all named interventions identified to date). However, published commentary has documented the non-exclusivity and lack of precision of existing labels. Following the production of the draft map using the taxonomy, we decided that it would be useful to split the taxonomy headings into the following categories: hospital avoidance, alternate delivery site, facilitated discharge and cross-cutting.

Producing the map

Once the taxonomy was developed, tested and agreed, we mapped candidate interventions to the taxonomy of intervention types to produce the draft map. Following changes to the taxonomy, we updated the draft map to produce the final map.

Stakeholder involvement

During the mapping review, we consulted with stakeholders at the Department of Health and Social Care and the National Institute for Health and Care Research, as well as with a standing advisory group of patients and carers. This ensured that the review of winter pressures was informed by the views and experiences of stakeholders. The aim of this consultation was to:

-

conceptualise the scope of the review

-

illuminate the practical and personal challenges experienced by those planning or using health services during times of exceptional demand

-

inform the second phase of our search strategies by identifying specific strategies, initiatives and interventions that target discharge planning and IC in the context of winter pressures

-

identify gaps in the literature with a view to compiling a future research agenda.

Patient and public involvement

A patient and public involvement (PPI) meeting with members of the Evidence Synthesis Centre standing public advisory group was conducted on 30 November 2022 to discuss the mapping review. The meeting aimed to ascertain the group’s thoughts and experiences around discharge planning and IC interventions to minimise winter pressures. To help bring out their thoughts and opinions, we developed five scenarios around interventions found in the literature and asked what they liked about each approach and what were the drawbacks or what might have been overlooked. The five interventions used in developing the scenarios were D2A, same-day emergency care (SDEC), hospital avoidance response team, Care & Repair and telecare. The scenarios are provided in Appendix 2.

The PPI group met on 30 November online and five members attended. The group’s thoughts and experiences about the different scenarios were helpful and are provided in more detail in Appendix 2. At the end of the meeting, the group voted on which intervention they thought it would be most useful to fund future research into. Three members of the group voted for telecare, believing that the delivery of healthcare is moving in this direction and that it is important to have research to ensure it can be used effectively and to determine what works for different people and in which circumstances. One group member voted for hospital avoidance response team, emphasising their belief in the importance of paramedics in helping to mitigate winter pressures. Within this member’s local area, paramedics have been specially trained and with the long waiting times for an ambulance to arrive or with patients at A&E departments waiting to be seen, the role of paramedics is becoming more important. The final group member chose not to vote.

Chapter 3 Results

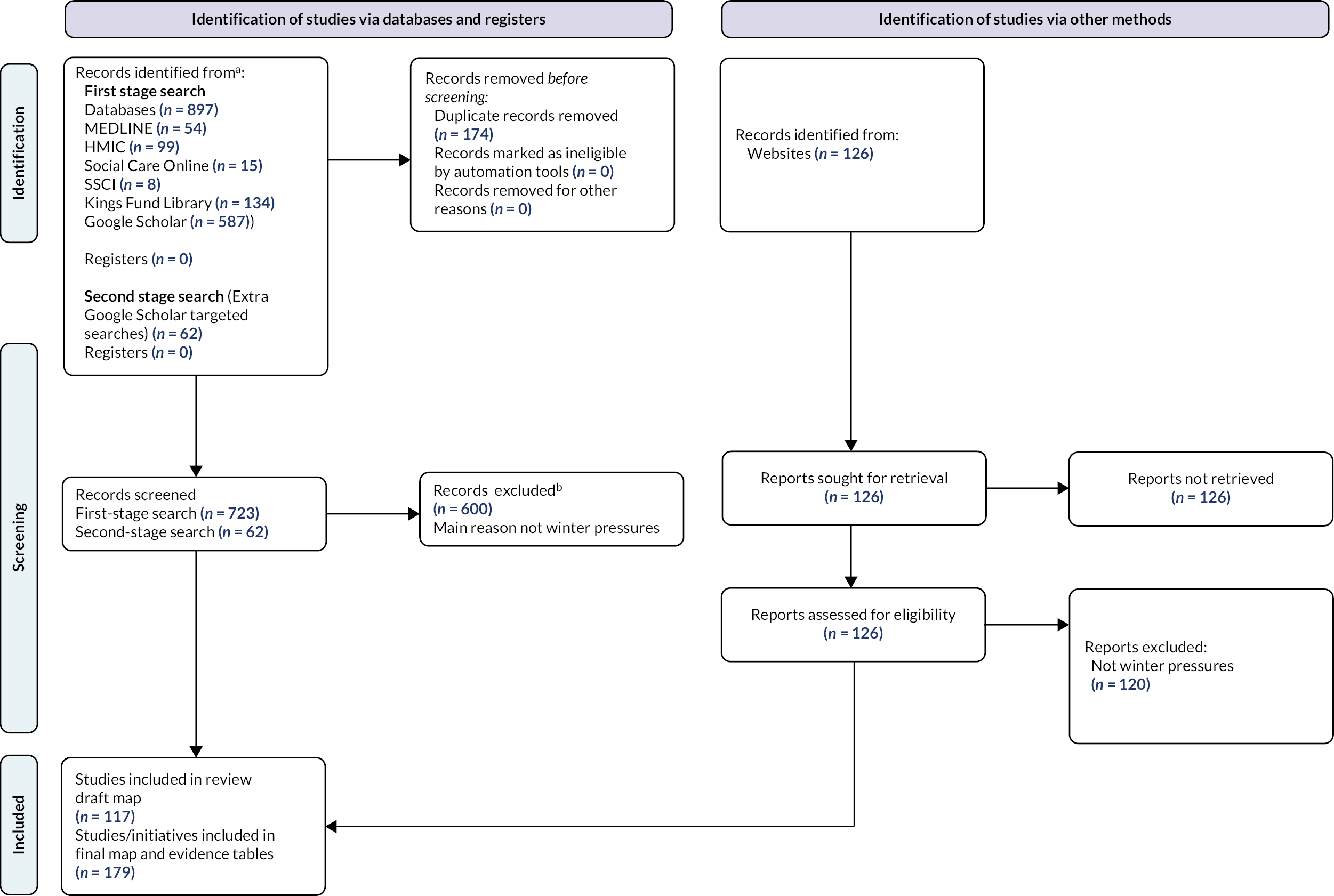

The initial ‘winter pressures’ search identified 723 items, of which 117 were judged to be relevant and used for the draft map. Subsequent targeted searches identified a further 62 items related to the different taxonomy headings, together with references to guidance and websites (see tables below). A modified Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram reflecting the searches and selection process in this review is provided in Appendix 3, Figure 2.

Findings: taxonomy

The final taxonomy is presented in Table 1. The taxonomy reflects the focus of the review on supporting early discharge where safe and appropriate, but also includes interventions aimed at avoiding hospital admission through rapid response or delivering care in other settings. The ‘cross-cutting’ category groups interventions that could be delivered at different stages of the patient pathway and/or different applications of a particular technology (e.g. digital and data).

| Hospital avoidance | Alternative delivery site | Facilitated discharge | Cross-cutting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Structural | Structural | Structural |

| S – same day services | S – specialist units | S – bed management | S – communication and teamwork |

| S – extra service delivery | S – same day services (see ‘hospital avoidance’) | S – discharge co-ordinators | S – digital and data |

| S – discharge to assess | S – extra service delivery (see ‘hospital avoidance’) | ||

| Changing community provision | Changing community provision | S – monitoring and review | S – prioritisation and triage |

| CCP – rapid response/see and treat | CCP – care homes | S – patient flow | S – governance |

| CCP – single point response | CCP – community teams | S – managed care approaches | |

| CCP – step-up facilities | CCP – home care | Changing community provision | S – policies |

| CCP – telecare | CCP – rehabilitation, recovery and reablement | S – seven-day services | |

| CCP – step-down beds | S – staff redeployment | ||

| CCP – other agencies | S – volunteers | ||

| CCP – private sector | |||

| CCP – social care | Changing staff behaviour | ||

| CCP – voluntary services | CSB – clinical audit | ||

| CSB – education of staff | |||

| CSB – protocols/guidelines | |||

| CSB – quality improvement programmes | |||

| CSB – quality management systems |

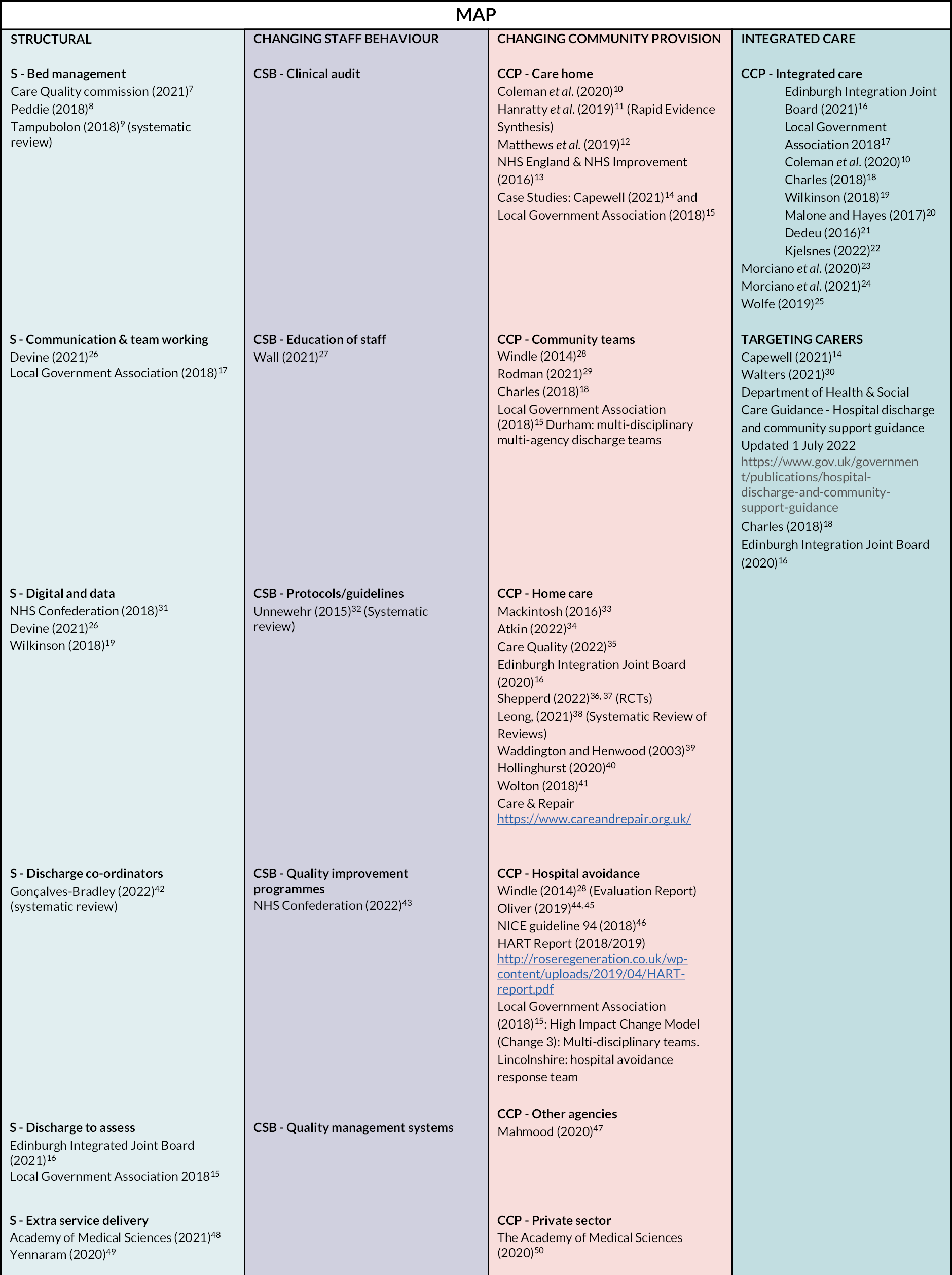

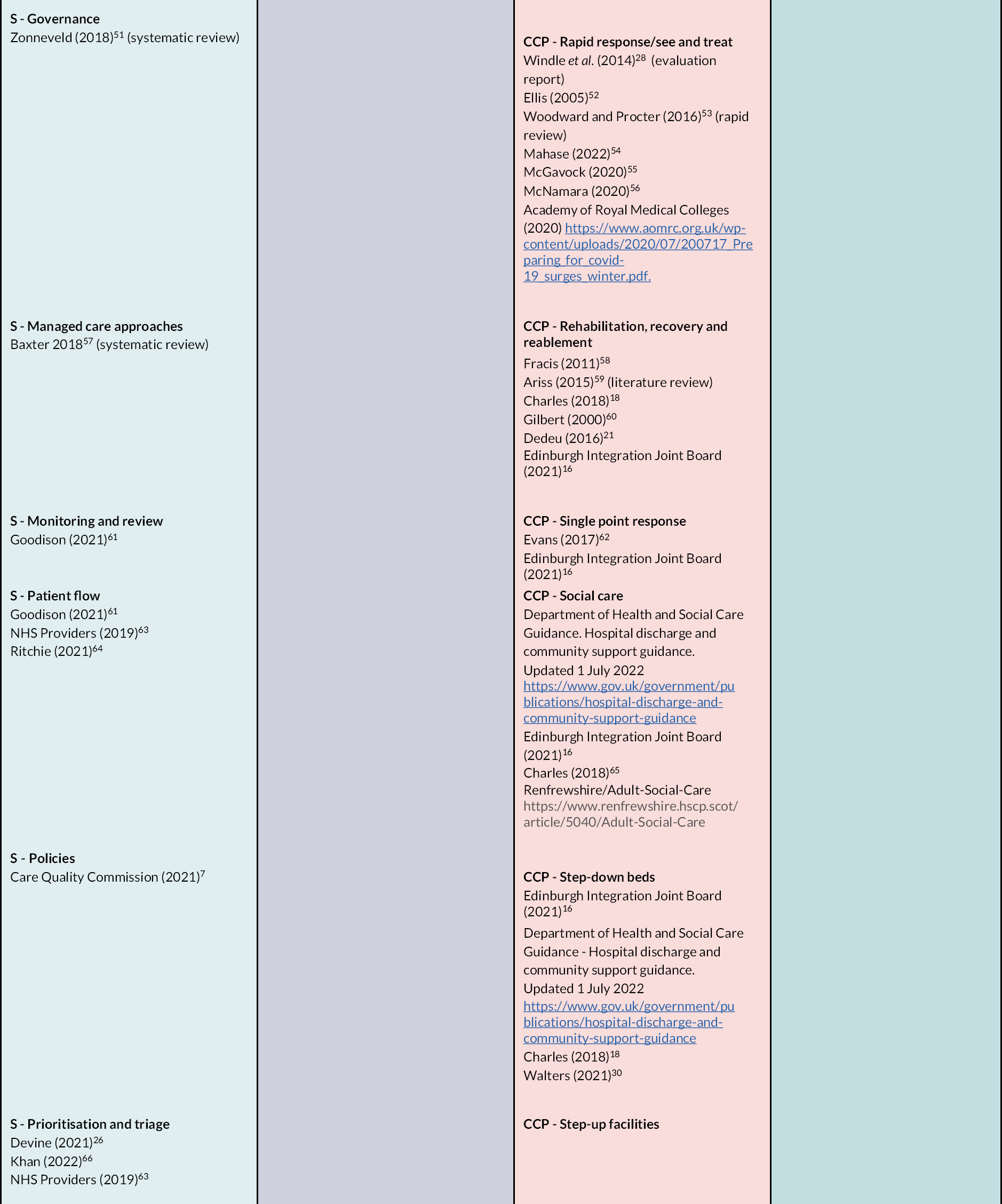

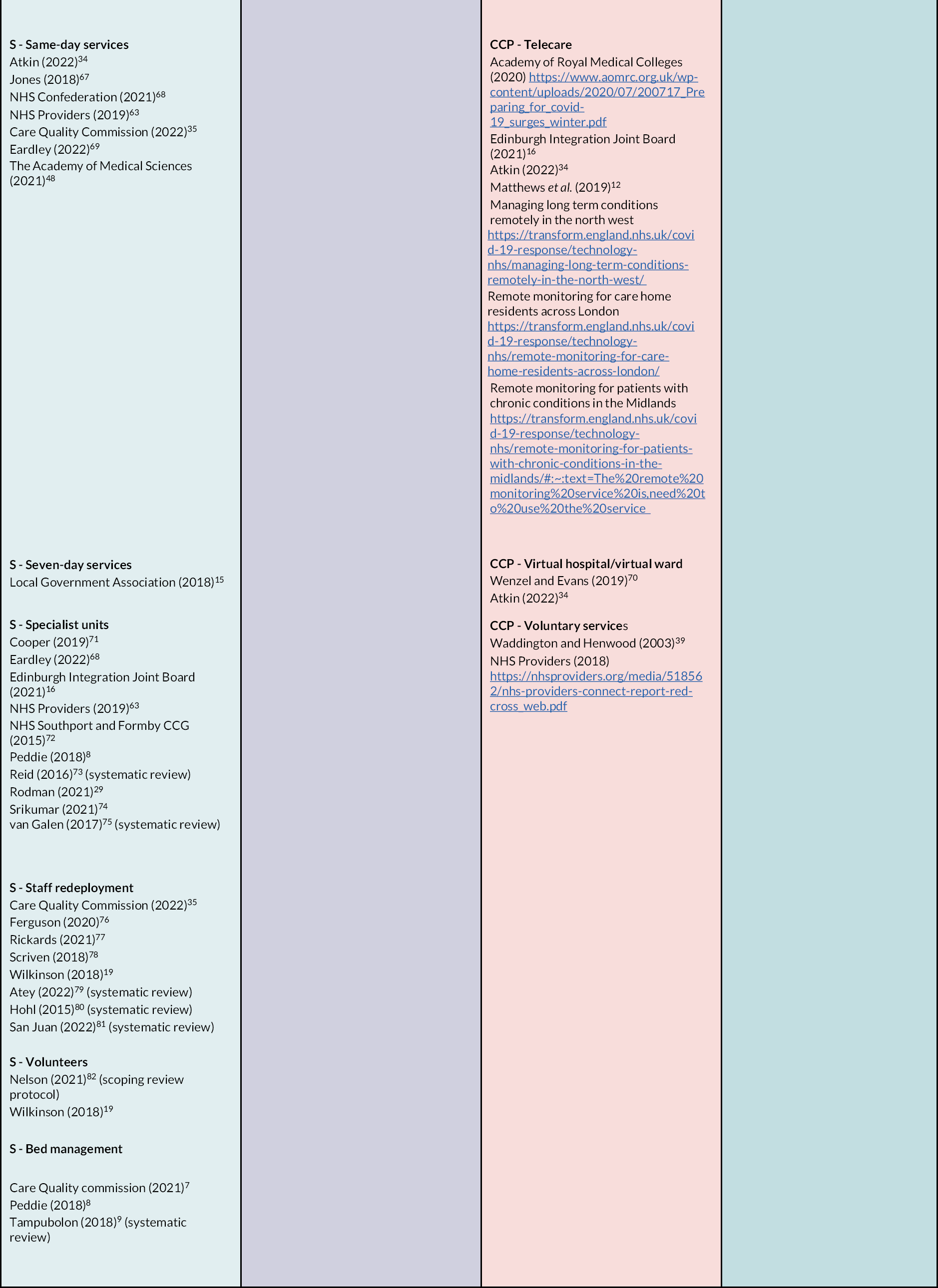

Findings: map

The final map (Figure 1) is provided below and is also available as an accompanying PDF. The map lists key evidence sources for candidate interventions and is colour coded under the headings of the taxonomy S, CSB, CCP, IC, and TC. Modelling and workforce planning were excluded from the scope. Interventions delivered at different stages of the patient pathway are not differentiated in the map but are identified in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Map of winter pressures research organised by taxonomy headings. Note: a list of references for the report is available in the supplementary material (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Findings: taxonomy headings/interventions

Findings are presented in the following tables following the order of the taxonomy presented in Table 1. Definitions and sample interventions are presented first, followed by a separate table of supporting evidence and identified research gaps under each taxonomy heading. For brevity within the report, the tables for the taxonomy headings with limited evidence are provided in the appendices.

Structural interventions

Findings for taxonomy headings classified as structural are summarised in the tables below. The tables are organised by the different stages of the patient pathway and first cover hospital avoidance then alternative delivery sites, followed by facilitated discharge and then Tables 18–34 cover cross-cutting headings. Detailed information can be found in the tables, with brief overviews before and after each group.

Hospital avoidance

The main taxonomy headings for hospital avoidance are same-day services (Tables 2 and 3); extra service delivery (see Appendix 4, Tables 53 and 54); see also 7-day services (see Appendix 4, Tables 61 and 62).

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – same-day services | Services provided the on the same day without need for hospital admission | Same-day services could help with winter pressures by reducing admissions |

| Example interventions: same-day emergency care (SDEC)/ambulatory emergency care/ambulatory care unit surgical hubs/elective surgical hubs/high-volume low-complexity surgical hubs | SDEC – provision of same-day emergency care for patients otherwise admitted to hospital. Patients that present with relevant conditions can be rapidly assessed, diagnosed and treated without needing to be admitted to a ward and if a clinician deems clinically safe they can go home the same day | SDEC aims to benefit patients and the healthcare system by reducing waiting times and hospital admissions where appropriate. Winter 2018/19 witnessed an increased use of ambulatory care units |

| Surgical hubs – located at existing hospital sites and provide common procedures performed relatively quickly and effectively in one place, with patients able to return home the same-day | Surgical hubs help to deal with the rise in healthcare provision needed over the winter by enabling surgeons to continue to treat patients for routine operations preventing waiting list backlogs |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstracts) |

|---|---|

| SDEC | We have identified four published evaluations since 2018 of SDEC. A short research article describes the moving the ambulatory care service to a new purpose-built ambulatory emergency care unit.88 Increased numbers of ambulatory care patients were seen in 2018 compared with same period in 2016/17 and in the number of same day discharges |

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Atkin et al. 202234 | |

| Care Quality Commission 202235 | |

| Jones 201867 | |

| NHS Confederation 202126 | |

| NHS Providers 201963 | New challenges are faced with the moving of the unit but changes have enabled patients to access ambulatory care and be seen in a more appropriate care setting. Another short research article describes a hospital running a 2-week pilot of an ambulatory care unit in December 2017. During the pilot calls attended by ambulatory care unit middle grade ranged from 12 to 20 each day. Phone advice to the referring general practitioner (GP) was required in approximately 25% of these calls, which potentially avoided attendance. Of about four patients seen each day by the unit there was a < 25% conversion rate to admission with most discharged directly or re-attended later that week. Patients admitted to ambulatory care unit were seen within 30 minutes of their arrival and had a management plan within 2–3 hours. Following the promising results of the pilot, a permanent unit was approved89 |

| Guidance | |

| NHS England 202182 | |

| NHS England 202183 | |

| Royal College of Emergency Medicine 201984 | |

| Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 201985 | |

| NHS England 201886 | |

| Published evaluations | A poster abstract describes the introduction of an ambulatory care service which helped increase the percentage of 0-day discharges to 15% and an improvement in A&E 4-hour target, exceeded to 5%90 |

| Pincombe et al. 202287 | |

| Ash 201988 | An economic evaluation from Australia of a medical ambulatory care service found that it was cost-effective for GPs and patients referred from wards but the impact for patients referred from the emergency department (ED) was less clear |

| Varrier 201989 | |

| Ali and Karmani 201890 | |

| Case studies | Evidence reveals multiple knowledge gaps in how best to structure SDEC services and identify appropriate patients, to gain maximum benefit for patients and for healthcare services. Additional services could help the delivery of SDEC (e.g. virtual wards) but the effect of running the additional services on current service delivery needs to be considered |

| Ambulatory Emergency Care Network 201991 | |

| Ambulatory Emergency Care. n.d.91 | |

| NHS Improving Quality n.d.65 | |

| Surgical hubs | No published evaluation on surgical hubs, NHS guidance on design and layout of elective hubs |

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Eardley 202268 | |

| Academy of Medical Sciences 202148 | The Royal College of Surgeons report on the case for surgical hubs gives the impact of winter and COVID-19 pressures as important drivers in developing surgical hubs. Three case studies demonstrating promising findings are provided in the case for surgical hubs report |

| Guidance | |

| Getting It Right First Time 202292 | |

| Published evaluations | |

| No published evaluations, NIHR call in February 2022. 22/26 HSDR Evaluating the high volume low complexity surgical hubs model: Commissioning brief. URL: www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/2226-hsdr-evaluating-the-high-volume-low-complexity-hvlc-surgical-hubs-model-commissioning-brief/29940 (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Case studies | |

| Royal College of Surgeons of England 202293 (includes case studies) | |

| Research gaps | |

| For SDEC: only small, low methodological quality evaluations and case studies. Guidance available from the NHS and relevant professional bodies. Need to further research the effectiveness of SDEC | |

| For surgical hubs: guidance on planning effective surgical hubs. No published evaluations; NIHR published a call to evaluate the surgical hubs model in February 2022, indicating a need for research in this area, which is in the process of being commissioned. The Royal College of Surgeons report on the case for surgical hubs includes three case studies | |

| Research priority | |

| Few UK initiatives (implementation and research gap) | |

Same-day services

Extra service delivery

The tables for the taxonomy heading extra service delivery are provided in Appendix 4. This heading includes a broad category of interventions, making it difficult to identify general research priorities.

Same-day services fall into two broad categories: SDEC followed by discharge without hospital admission, and routine surgery performed on a day-case basis, with patients returning home on the day of surgery. Both have been widely adopted and are supported by relevant guidance. However, a clear need remains for further research and evaluation (see Table 3).

Extra service delivery takes a variety of forms and some successes have been reported in both emergency and elective care (see Appendix 4, Table 54) but the evidence base remains limited.

Alternate delivery site

The heading ‘alternative delivery site’ covers a variety of specialist units delivering services outside general hospitals or in demarcated areas within them. Examples are acute medical units and short-stay units. More information and the evidence is provided in Tables 4 and 5.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – specialist units | Specialists units are units to deliver a particular service | Specialist units can provide services, separately from hospitals, which reduce admissions, reduce infection by keeping patient groups separate, and enable patients to receive the care they require |

| Surgical hubs/elective surgical hubs/high-volume, low-complexity surgical hubs | Surgical hubs are located at existing hospital sites and provide common procedures that can be performed relatively quickly and effectively in one place or high-volume, low-complexity surgeries. They will bring together staff with the required skills and expertise in one place | Surgical hubs help to deal with the rise in healthcare provision needed over the winter by enabling surgeons to continue to treat patients for routine operations preventing waiting list backlogs. They improve infection control by keeping these patients separate from the ED and other wards in the acute hospital. Reduce number of operation being cancellations at short notice when hospitals are full |

| Acute medicine urgent access clinic/acute medicine clinic | The clinic allows early outpatient review of symptoms and outstanding investigations. This means that clinicians can discharge patients sooner with an appointment to attend the clinic | Help doctors to discharge patients earlier from ED, acute medical units expedite discharge from post-take ward round and help to manage the increased healthcare usage during the winter months |

| Acute medical unit/acute assessment unit/medical assessment unit | Acute medical units provide rapid assessment investigating and treatment for acutely ill medical patients through referral by the ED, their GP or outpatient services. Patient can receive acute medical assessment in one unit staffed by specialist medical and nursing personnel with equipment required for the assessment. Patients can be admitted for a short hospital stay for ongoing assessment or discharged home the same-day | Reduces number of patients going to the ED during this busy time of year, which helps with patient flow throughout the hospital |

| CRT + and long-COVID-19 single point of access | To provide a triage point to allied health professional rehabilitation services for people recovering from COVID-19 | Provide triage for people recovering from COVID-19 without them disrupting flow within health and social care |

| Frail elderly short-stay unit | Short-stay unit that assesses frail older people as soon as they come into hospital to ensure that they get the best possible care and treatment when they are in hospital and are supported (e.g. through comprehensive geriatric assessment) to recover when they leave | Help with flow of frail older people through health and social care services, useful in winter when their healthcare usage could increase |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Acute medicine urgent access clinic | A recent survey of medical doctors at Warrington Hospital on the introduction of new acute medicine urgent access clinic found promising experiences. 93% of doctors believed that the introduction of the clinic allowed them to discharge patients earlier from the acute take, 77% believed that the clinic enabled quicker discharge from the ED, 79% of the doctors believed the clinic had sped up discharge from post-take ward round and 87% that it had sped up discharge from the acute medical unit. Further details of the introduction of the clinic at Warrington and Halton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust are provided in a case study in the RCP Chief Registrar Scheme 2017/18 year book. |

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Cooper 201970 | |

| Additional evidence | |

| Royal College of Physicians (RCP) 201894 | |

| Acute medical unit | Two reviews published after 2012 were retrieved on acute medical units. A literature review from van Galen et al.75 concluded that current literature demonstrates an overall beneficial effect after implementation. The systematic review by Reid et al.72 concluded that acute medical units were associated with reductions in hospital length of stay and less convincingly mortality when implemented in European and Australasian settings. |

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Peddie and Gordon 20188 | |

| Additional evidence | |

| Systematic reviews: | |

| van Galen et al. 201774 | |

| Reid et al. 201672 | A prospective cohort study8 found results that suggest the median length of stay for the patients moved ‘out of hours’ was significantly less than that of the patients moved ‘within’ hours group. This could be due to the higher number of ‘boarders’ in the ‘out of hours’ group (36/57 patients = 63.2%) when compared to the ‘within hours’ group (32/162 patients = 19.8%). Boarding while unacceptable still exists and it is not only related to winter months. |

| Guidance | |

| NICE 201895 | |

| Community resource team (CRT) + and long-COVID SPOA/post-COVID-19 assessment services | The Edinburgh Integration Joint Board’s evaluation of winter planning 2020/21 provides brief outcomes of funding project which includes the CRT+ and SPOA service. The CRT+ service received 23 referrals, of which 16 (70%) were considered at risk of hospital admission. The service was able to support 100% admission avoidance at 48 hours and 83% at 7 days. The SPOA service acted as a triage point to allied health professional rehabilitation services and 290 referrals were received during the period November 2020 to end of March 2021; 314 onward referrals were made, demonstrating the success of SPOA to rehabilitation services. |

| Winter pressure specific | No further evidence was found on these services. |

| Edinburgh Integration Joint Board 202116 | |

| Additional evidence | |

| None | |

| Frail elderly short-stay unit | Additional ‘winter funding’ from central government in September 2013 enabled the establishment of a frail elderly short-stay unit in November 2013, as part of NHS Southport and Formby CCG service developments to reduce admissions and length of stay for frail older people. |

| Winter pressure specific | |

| NHS Southport and Formby Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) 201572 | |

| Published evaluations | A conference abstract from 201496 details the outcomes of a 12-week pilot of a frail elderly short-stay unit. The average length of stay in the unit was 4.7 days and total length of stay (including subsequent inpatient care) was 6.5 days, which had a positive impact on the care of the elderly wards. |

| Michael and Ijaola 201496 (conference abstract) | |

| Ring-fenced arthroplasty unit | A conference abstract detailed the assessment of a ring-fenced arthroplasty unit performance during winter pressures and the pandemic (December–March 2018–9 and 2019–20).73 The unit performed 280 total hip and knee replacements in 2019–20 and the patients had a mean length of stay of 43 hours. This showed a reduction when compared with the length of stay in 2018–9 of 69 hours when 288 total hip and knee replacements were performed. Early discharge, defined as within 36 hours of surgery, occurred for 74% of patients in 2019–20 vs. 24% in 2018–9, which add up to 333 inpatient days saved. |

| Winter pressure specific | No further evidence was found on ring-fenced arthroplasty units. |

| Srikumar et al. 202173 (conference abstract) | |

| Additional evidence | |

| None | |

| Speciality review at rapid access clinics | The Edinburgh Integration Joint Board’s evaluation of winter planning 2020/21 details how NHS Lothian intended to use the additional funding for winter 2020/21, which including avoiding admission with services developed to provide certain initiatives including speciality review at rapid access clinics. |

| Winter pressure specific | No further evidence was found on speciality review at rapid access clinics. |

| Edinburgh Integration Joint Board 202116 | |

| Additional evidence | |

| None | |

| Research gaps | |

| Research in specialist units other than acute medical units could be helpful. | |

| Research priority | |

| Acute medical units, low – good-quality systematic review(s) and plentiful UK research studies (no gap). | |

| Other: high – few UK initiatives (implementation and research gap). | |

Specialist units

In summary, acute medical units have a good evidence base overall, with some research specific to winter pressure conditions. Frail elderly short-stay units have been supported by winter pressure funding but we found limited research on these and other types of specialist unit.

Facilitated discharge

Facilitated discharge is a key area for health and care services dealing with winter pressures. It includes interventions to optimise use of resources and minimise length of stay for patients in hospital, planning for discharge and discharge with support in place prior to a full assessment of health and care needs (D2A).

Bed management

There was limited evidence for bed management to reduce winter pressures (see Appendix 4, Tables 50 and 51). By ensuring optimum use of inpatient bed capacity, it could potentially reduce the number of patients occupying an inpatient bed that could be discharged safely. The lack of UK initiatives make bed management a high research priority.

Discharge co-ordinators

Discharge co-ordinators have responsibility for discharge planning and can contribute to facilitated/supported discharge and reduce delayed transfers of care freeing up beds for new patients. More information about discharge co-ordinators and the evidence base is provided in Tables 6 and 7.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – discharge co-ordinators | Individual with designated responsibility for discharge planning. Early discharge requires robust systems to be in place to develop plans for management and discharge, and to allow an expected date of discharge to be set within 48 hours (LGA 2018)17 | Contributes to various forms of facilitated/supported discharge. Could be a temporary role or given extra support to cover winter pressures |

| Example interventions: often part of complex multidisciplinary team (MDT) interventions (e.g. hospital at home; cited in Williams 202297), Oxfordshire Integrated Liaison Hub (LGA 2018)17 | Integrated liaison hub staffed by MDT including qualified nurses and therapists with expertise in discharge planning, discharge planners, administrators and staff from adult social care (in-reaching) | Reduces delayed transfers of care and hence frees up hospital beds for new patients |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Initiative: | |

| Oxfordshire Integrated Liaison Hub (LGA 2018)17 | The liaison hub has delivered a fully integrated service, which has resulted in a reduction in delays and the release of acute beds. Service users are cared for in a more appropriate environment and for some patients rehabilitation occurs earlier in their pathway |

| Systematic reviews (in reverse chronological order) | A structured discharge plan that is tailored to the individual probably brings about a small reduction in hospital length of stay and unscheduled readmission for older people with a medical condition. Discharge planning at an appropriate time in a hospital admission can facilitate the organisation and timely discharge of a patient from hospital and the organisation of post‐discharge services. Even a small reduction in length of stay can be important in freeing up capacity for subsequent admissions in a system during a shortage of acute hospital beds |

| Gonçalves-Bradley et al. 202242 | |

| Dimla et al. 202298 | Reviews role of social workers in discharge planning for older people. The most common support measures were assessment, education, care co-ordination, liaison and engagement with families and providers, conflict resolution, counselling and post-discharge follow-up. Barriers included medical complexity, lack of communication, time constraints, limited family support, availability of resources and patient safety |

| Doshmangir et al. 202299 | General review of interventions to manage use of hospital services. Discharge planning was found effective in reducing hospital length of stay |

| Williams et al. 202297 | Review found that providing early supported discharge (ESD) intervention for older adults admitted to hospital for acute medical reasons can significantly reduce the length of their acute hospital stay, without adversely affecting their mortality, function, health-related quality of life, hospital readmissions, long-term care admissions and cognition |

| Guidance | |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): transition between inpatient hospital settings and community or care home settings for adults with social care needs. 2016100 Age UK recommends appointment of a discharge co-ordinator when discharge is likely to be complex101 |

Recommends a designated discharge co-ordinator for all patients with care needs |

| Research gaps | |

| Focusing on discharging older adults from the acute hospital setting to home, Harris (2005)102 noted that further research was required to assess the cost-effectiveness of community-based interventions. Similarly, NICE recommended extending research to assess the effectiveness of home interventions post discharge.97,100 Impact of ESD interventions on stakeholders including patients, family carers and professionals97 | |

| Research priority | |

| Moderate – few UK research studies but plentiful UK initiatives and recent systematic reviews (research gap) | |

Discharge to assess

Discharge to assess aims to minimise unnecessary delays in hospital discharge. More information and the evidence base are provided in Tables 8 and 9.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – D2A | People who do not require an acute hospital bed but may still require care services are provided with short-term funded support to be discharged to their own home or another community setting, with subsequent assessment for longer-term care and support needs. No set model for D2A; it may work alongside time for recuperation and recovery, ongoing rehabilitation or reablement (Department of Health, Directors of Adult Social Services, NHS England. Quick Guide: Discharge to assess. London: NHS England; 2016. www.england.nhs.uk/blog/martin-vernon-3) | Minimises unnecessary delays in hospital discharge. Not specific to winter but frequently mentioned in winter planning documents |

| Example interventions: D2A, home first; safely home; step-down | D2A and home first (see above). Step-down beds provide short-term accommodation to bridge the gap between hospital and home (LGA 2018)17 | See above |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstracts) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Edinburgh Integrated Joint Board 2021 (Assistant Practitioners; Occupational therapy; Home First therapists)16 | Increased referrals in 2020/21 compared with previous winter. Assistant practitioners and Home First therapists contributed to skill mix |

| Local Government Association 201817 (D2A) | Five successful local initiatives described |

| Published evaluations | |

| Does a D2Aprogramme introduced in England meet the quadruple aim of service improvement? Jeffery et al. 2022103 | Aims appeared to be me |

| Gadsby et al. 2022104 | Service was difficult to implement and desired outcomes elusive |

| Offord et al. 2017105 | Reduction in length of stay from 5.5 to 1.2 days |

| Initiatives/case studies | |

| Pilarska J. Discharge to assess: an East Lothian experience. Physiotherapy 105(Suppl 1):E64–E64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2018.11.025 (accessed 23 November 2022) | Full text not available |

| NHS England. Discharge to assess: South Gloucestershire and Bristol. URL: https://bnssghealthiertogether.org.uk/staff-and-partners/discharge-to-assess/#:~:text=Discharge%20to%20Assess%20is%20our,can%20be%20supported%20to%20recover (accessed 23 November 2022) | Early pilot reported reduction in bed days and financial savings but also ongoing operational issues |

| Discharge to Assess with HomeLink Healthcare. Retaining the Positive Improvements from the Pandemic. URL: https://www.ihpn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Discharge-to-Assess-Case-Study-HomeLink-Healthcare.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | No outcome data |

| NICE Shared learning database: Supporting best patient outcomes through a joint Discharge to Assess, Home First service. URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/supporting-best-patient-outcomes-through-a-joint-discharge-to-access-home-first-service (accessed 23 November 2022) | Bristol/Gloucester/Somerset. No outcome data but detailed description of implementation |

| Edwards and Anwer 2019106 | Reports significant benefits on a Discharge to Assess process on improving patient flow and improving hospital performance in managing unscheduled care |

| Lawlor et al. 2019107 | Reports that rapid discharges can be facilitated which reduced length of stay and increased patient and family’s satisfaction with the discharge process |

| Bath: Home First/D2A. URL: https://www.local.gov.uk/case-studies/bath-home-firstd2a (accessed 23 November 2022) | Step-down apartments for people discharged but unable to return home. A previous review of the service found that the six units saved £561,762 for the NHS by enabling discharge of patients, and the Social Return on Investment was £6.21 for every £1 invested (where no reablement care package is required) |

| Orkney Health and Care. 2021. Integration Joint Board: Progress of Home First Service Pilot. URL: www.orkney.gov.uk/Files/Committees-and-Agendas/IJB/IJB2021/IJB30-06-2021/I17_Home_First_Service_Pilot-original.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | Evaluation of pilot recommended that winter planning funding be used to sustain the service |

| Other evidence | |

| Healthcare Improvement Scotland. 2021. Discharge to Assess. URL: https://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/evidence/rapid_response/rapid_response_02-21.aspx (accessed 23 November 2022) | Rapid review finds very limited evidence for D2A |

| Healthwatch Staffordshire. 2019. Report on Discharge to Assess (D2A) at Staffordshire Hospitals. URL: https://healthwatchstaffordshire.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Discharge-to-Assess-D2A-Healthwatch-Staffordshire-report-October-2019.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | Healthwatch reports provide ‘real-world’ data on patient experience |

| Health and Social Care Moray. Discharge to Assess. URL: https://hscmoray.co.uk/discharge-to-assess.html (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Healthwatch Coventry. 2019. Experiences of D2A pathways in Coventry summary report. URL: www.healthwatchcoventry.co.uk/sites/healthwatchcoventry.co.uk/files/HW_Coventry_Summary_Report_Discharge_to_assess_JUNE2019.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Healthwatch Suffolk. 2019. Discharge to Assess (D2A): a qualitative evaluation of patient experience (Ipswich Hospital) – Executive summary. URL: https://healthwatchsuffolk.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/D2A-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Systematic reviews (in reverse chronological order) | |

| Conneely et al. 2022108 | Umbrella review of ED-based discharge interventions. Review found that the evidence base for the effectiveness of ED interventions in reducing adverse outcomes is limited, due to the poor quality of the randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Higher quality intervention RCTs as well as a focus on intervention development with the engagement of stakeholders are required |

| Platzer et al. 2020109 | Based on nine studies, this review found that inter-professional or multi-professional interventions had no impact on mortality rate but either positive or neutral effects on physical health, psychosocial wellbeing and utilisation of healthcare services |

| Guidance | |

| Department of Health, Directors of Adult Social Services and NHS England. Quick Guide: Discharge to Assess. Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England. n.d. URL: www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/keogh-review/Documents/quick-guides/Quick-Guide-discharge-to-access.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Welsh Government. 2021. Home First: The Discharge to Recover then Assess model (Wales) | |

| Department of Health and Social Care. 2022. Hospital discharge and community support guidance. URL: www.gov.uk/government/publications/hospital-discharge-and-community-support-guidance/hospital-discharge-and-community-support-guidance#how-nhs-and-local-authorities-can-work-together-to-plan-and-implement-hospital-discharge-recovery-and-reablement-in-the-community (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| NHS England. Act Now – Getting People ‘Home First’. n.d. URL: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3-grab-guide-getting-people-home-first-v2.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| NHS England. Principle 5: Encourage a supported ‘home first’ approach. n.d. URL: www.england.nhs.uk/urgent-emergency-care/reducing-length-of-stay/reducing-long-term-stays/home-first (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Research gaps | |

| The evidence base comprises plentiful UK initiatives and case studies but few peer-reviewed research studies. The case studies vary in depth of reporting and the interventions described as D2A or Home First are highly diverse. Evaluations almost use a before/after approach to assess effectiveness, with no control group. However, given that D2A and Home First are already in wide use, it would seem appropriate for research to focus on how best to implement interventions and obtain optimum value for money. We identified no systematic reviews of D2A, although some broad reviews focus on related areas (see above). We identified a synthesis gap with available evidence suggesting that a review based on realist principles may be appropriate to support ongoing implementation of D2A/Home First | |

| Research priority | |

| Moderate – few UK research studies but many UK initiatives (research gap) | |

Monitoring and review

Monitoring and review are interventions to quickly identify patients suitable for discharge or transfer. There was limited evidence for monitoring and review; the tables can be found in Appendix 4, Tables 55 and 56.

Patient flow

Patient flow is a broad heading that covers a range of interventions to ensure that patients move through the health and care system as quickly and efficiently as possible while maintaining safety and patient focus. More information is provided in Tables 10 and 11.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – patient flow | Covers a range of interventions to ensure patients move through the health and care system as quickly and efficiently as possible while maintaining safety and patient focus | At periods of high demand, it is particularly important to minimise unnecessary contacts and use telephone or video appointments if appropriate to avoid patients choosing to attend the ED. Closely related to ‘monitoring and review’ and ‘prioritisation and triage’ |

| Example interventions: patient flow bundle; flow navigation centres | Flow navigation centres (hubs) receive referrals directly from NHS24 (Scotland). They offer rapid access to a senior clinical decision maker within the multidisciplinary team, via a telephone or video consultation where possible64 | Optimising patient flow at the point of entry into the system (prehospital) |

| The SAFER patient flow bundle is applicable to inpatient wards (excluding maternity). In highly specialist settings, daily review can identify patients who would benefit from transfer to a lower-intensity community setting63 | Optimising patient flow within hospitals |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| NHS Providers 2019 (SAFER patient flow bundle)63 | Rolled out by NHS during winter 2018/19 |

| Ritchie 2021. Flow navigation centres64 | The additional step of seeking immediate help for urgent problems via NHS24 (111 service) diverted to local flow navigation centres may add to the complexity and length of the care journey for some patients |

| Case studies/evaluations | |

| Yeovil District Hospital (Sethi 2020)110 | Interventions to improve inpatient flow also improved ED clinical quality indicators |

| Kent acute hospitals optimisation programme (LGA 2018)17 | 59% reduction in long-term residential placements and a 54% reduction in short-term beds |

| Kent Single Health Resilience Early Warning Database (SHREWD) (LGA 2018)17 | SHREWD indicators vital to identifying areas of pressure as they arise |

| Systematic review | |

| Åhlin et al. 2022111 | Review of barriers to patient flow in hospitals. Long lead times, inefficient capacity co-ordination and inefficient patient process transfer were identified as the main barriers. Barriers were caused by inadequate staffing, lack of standards and routines, insufficient operational planning and a lack in information technology functions. Review includes a framework for policy makers |

| Guidance | |

| NHS Improvement. Rapid improvement guide: the safer patient flow bundle. 2022 | |

| NHS Improvement. Good practice guide: focus on improving patient flow. 2017 | |

| URL: https://improvement.nhs.uk/uploads/documents/Patient_Flow_Guidance_Case_studies_13_July.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Research gaps | |

| We identified one UK research paper and a small number of initiatives related to patient flow as well as a recent systematic review. This relatively small body of evidence may overstate the size of the research gap as patient flow is difficult to disentangle from related areas such as bed management, discharge planning, monitoring and review, and prioritisation and triage | |

| Research priority | |

| Moderate – few UK initiatives (implementation and research gap) but one UK research study and a recent systematic review | |

We found that some aspects of facilitated discharge are relatively well researched, particularly D2A and similar interventions (e.g. Home First). Interventions with little UK evidence were sometimes supported by systematic reviews, although the quality of these reviews varied. Some taxonomy headings (e.g. ‘bed management’ and ‘discharge co-ordinators’) were often evaluated as part of a broader process of ‘discharge planning’.

Cross-cutting

The cross-cutting section of the taxonomy covers a diverse group of structural changes with broad applicability, including multidisciplinary and multiagency teams, use of digital technology and data, monitoring and accountability in the healthcare system, national and local policies, staff redeployment and the role of volunteers.

Communication and teamwork

Detailed information on communication and teamwork interventions is provided in Tables 12 and 13.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – communication and teamwork | Tackles barriers at the interface between disciplines and or agencies (e.g. NHS and local government, hospitals and care homes) | Such barriers may become more pronounced as a defensive reaction to periods of exceptional demand/pressure on staff |

| Example interventions: use of advice and guidance; MDTs/multiagency discharge teams | Generalists and specialists working together to avoid admission. Co-ordinated discharge planning based on joint assessment processes and protocols and on shared and agreed responsibilities | Unnecessary hospital admissions are avoided. More efficient discharge process |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Devine 2021 (better use of advice and guidance)26 | Identified as a key initiative but no further details provided |

| Local Government Association 2018 (MDTs/multiagency discharge teams)17 | Three local initiatives (Lincolnshire, Durham and Kent) described. Lincolnshire hospital avoidance response team supported 1553 people between December 2015 and August 2017; 303 admissions were avoided and indicative savings of between £1,094,000 and £1,362,000 were achieved |

| Systematic review | |

| Coffey et al. 2019112 | The most effective interventions to avoid inappropriate readmission to hospital and promote early discharge included integrated systems between hospital and community care, multidisciplinary service provision, individualisation of services, discharge planning initiated in hospital and specialist follow-up |

| Guidance | |

| NHS England. MDT Development: Working toward an effective multidisciplinary/multiagency team 2014. URL: https://diabetes-resources-production.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/diabetes-storage/migration/pdf/NHS%2520England%2520-%2520MDT%2520development%2520%28January%25202014%29.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Research gaps | |

| From the systematic review (high-quality but broad in scope): key elements for which evidence was identified and which merit further study include integrated systems spanning acute and home-based services; multidisciplinary care provision; person-centred services; and discharge initiated in acute care predischarge initiated with specialist follow-up | |

| Research priority | |

| Unclear – UK initiatives and good-quality broad systematic review but UK research studies unclear | |

Digital and data

Detailed information on digital and data interventions for discharge planning is provided in Tables 14 and 15.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – digital and data | Optimal use of digital technology and sharing of patient data to support decision-making | Data sharing potentially facilitates quicker and safer discharge (e.g. supplying all required prescriptions). Digital technology can enable monitoring of a patient’s condition at home or in a community setting after discharge |

| Example interventions: digital health centre; data sharing; prescription tracking | Digital health centre (Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust): community and care home teams provided with observation equipment. Hospital-based team of nurses provide clinical advice and, where appropriate, patient can be treated remotely.31 Effective management of treatment lists by sharing patient data (no further details supplied).26 Pharmacy prescription tracker (Luton and Dunstable University Hospital), including electronic prescribing during ward rounds19 | Aims to reduce ED attendances and associated admissions. Improves treatment pathway and saves time in treatment and discharge. Service can be quickly stepped up in response to demand, including extra prescribing pharmacists and a 7-day 12-hour service |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Digital health centre31 | Between March 2017 and May 2018, 46/47 local care homes signed up. Outcomes included 1263 ED attendances prevented; 400 GP interactions avoided; and 725 prescriptions issued without need for a face to face appointment |

| Management of treatment lists by data sharing19 | No data provided |

| Prescription tracking19 | No data provided |

| Systematic reviews | |

| Kattel et al. 2020113 | Delayed or insufficient transfer of discharge information between hospital-based providers and primary care remains common. Creation of electronic discharge summaries seems to improve timeliness and availability but does not consistently improve quality |

| Mehta et al. 2018114 | This review found a paucity of information on evidence of real-world use of big data analytics in health care |

| Guidance | |

| NHS England and NHS Improvement. Pharmacy and Medicines Optimisation: A Toolkit for Winter 2018 URL: www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/pharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-a-toolkit-for-winter-2018-19 (accessed 23 November 2022) | |

| Research gaps | |

| Systematic review identifies few examples of real-world impact using big data analytics Many initiatives in this and related sections but few comparative research studies |

|

| Research priority | |

| Moderate – few UK research studies but plentiful UK initiatives (research gap) | |

Governance

No UK research studies or initiatives were identified related to governance. The tables for this taxonomy heading are provided in Appendix 4, Tables 57 and 58.

Managed care approaches

Managed care is primarily a feature of insurance-funded health systems (particularly the United States) and evidence of its use to address winter pressures is unlikely to be relevant to the UK setting. Further details about this taxonomy heading can be found in Appendix 4, Table 52.

Policies

The tables for the policies taxonomy heading are provided in Appendix 4, Tables 59 and 60. No evidence was identified for this heading specifically. Most policies would cover one or more headings from elsewhere in the taxonomy.

Structural: seven-day services

The tables for the seven-day services taxonomy heading are provided in Appendix 4, Tables 61 and 62. Limited evidence was identified for this heading indicating a need to further research the effectiveness of seven-day services.

Prioritisation and triage

Information about prioritisation and triage interventions to avoid admissions is provided in Tables 16 and 17.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – prioritisation and triage | Prioritisation and triage (assigning patients to care based on the urgency of their needs) can take place at different levels of the healthcare system. In addition to triage in urgent and emergency care settings, times and/or sites can be allocated to more or less urgent procedures | Can help to avoid hospital admission when safe and appropriate. Reducing variation where possible for routine procedures may represent a more efficient use of resources at times of high demand. Closely related to ‘Patient flow’ (e.g. green/red day system linked to SAFER patient flow bundle) |

| Example interventions: green/red days; ‘hot’ (trauma) and ‘cold’ (elective) sites for orthopaedics; rapid assessment areas | Examples of separation by time (red days indicate when a patient is awaiting an intervention); degree of urgency; and prioritisation in the ED | See above |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Green/red days (NHS Providers 2019)63 | Widely recommended and implemented |

| Hot (trauma) and cold (elective) sites for orthopaedics (Khan 2022)66 | See case study case studies below |

| Nurse triage models in rapid assessment areas (Devine 2021)26 | No data presented |

| Case studies/evaluations | |

| Analysis of data from National Joint Registry for hospitals with different service structures (Khan et al. 2022)66 | Supports need to separate hot and cold sites |

| NHS England. United Lincolnshire Hospitals sees hot and cold orthopaedic success. 2019. URL: https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/united-lincolnshire-hospitals-see-hot-and-cold-orthopaedic-success (accessed 23 November 2022) | Since launching the pilot in August 2018, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust has seen on-the-day cancellation rates drop by more than one-third. Length of stay has also improved, with the average for orthopaedic procedures falling from 2.9 to 2.4 days |

| The Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust outpatient services transformation programme115 | Referrals to outpatient services are now triaged and streamed. The number of patients reviewed virtually on patient-initiated follow-up and seen closer to home has increased |

| Research gaps | |

| Prioritisation and triage is a broad area covering a wide range of possible interventions. Designation of green and red days for in-patients assists patient flow, which is relatively well researched (see above). Separation of different types of orthopaedic surgery on different sites (hot and cold) has some supportive evidence and is recommended as part of the Getting it Right First Time programme. Triage (primarily in emergency and urgent care settings) has an extensive evidence base but the intervention mentioned by Devine (2021)26 was not identified in a search of Google Scholar, suggesting a paucity of research in this area | |

| Research priority | |

| Moderate – few UK research studies but plentiful UK initiatives (research gap) | |

Staff redeployment

Staff redeployment can help improve patient flow by deployment of specialist staff to support other settings, which gives patients easy access to specialist staff. Systematic reviews exist for certain staff redeployment initiatives, the use of pharmacists in the ED and redeployment of staff to the intensive care unit. However, research gaps remain in other areas where the only evidence is unevaluated UK initiatives. Further information is provided in Appendix 4, Tables 63 and 64.

Volunteers

Volunteers can be used to support paid staff in times of high demand, which can help to increase access to advice or services. The detailed information is provided in Tables 18 and 19.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| S – volunteers | Use of volunteers to improve patient flow through the health and social care system | Help with patient flow through health and social care services; useful in winter when healthcare usage increases |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Wilkinson 201819 | Protocol for scoping review demonstrates the need for review of the evidence for volunteers supporting hospital to home transfers.81 The feature by Wilkinson on how pharmacists are helping to relieve winter pressures includes an initiative in the Wye valley, called Pharmacy Volunteers.19 Volunteers help the pharmacy team to deliver urgent medicines to ward and department in the County Hospital and volunteers have supported the pharmacy team to deliver 18,000 urgent medicines over 18 months and the scheme has won an award. Service analysis demonstrates that the average delivery time for urgent medicine is 5.4 minutes, meaning that per week, an estimated 35 hours has been saved. Volunteers deliver urgent medicines to mainly (40%), day-case surgery (10%) and the discharge lounge (8%) |

| Additional evidence | |

| Nelson et al. 202181 | A broad evidence review commissioned by the HelpForce fund in 2017 identified three areas of volunteering with roles to play and that can be effective: commissioned services, organisation (provider)-based services and social action.117 If well supported and enabled, volunteers can be effective in all these roles |

| Guidance | |

| NHS England. Recruiting and Managing Volunteers in NHS Providers 2017116 | |

| Published evaluations | |

| Boyle et al. 2017117 | |

| Ross et al. 2018118 | |

| Research gaps | |

| Evaluations of specific volunteer roles | |

| Research priority | |

| Few UK initiatives (implementation and research gap) | |

In summary, evidence support for initiatives in this group varied widely. The winter pressure search identified UK initiatives to support improved teamwork, together with associated guidance (see Table 19). Various initiatives have applied data sharing and digital technology, but we found a relative lack of research studies. Actions at the organisational level, (e.g. involving changes in governance or formulation and implementation of policy) play an important part in responding to winter pressures, but we found that this was not reflected in research. Further research studies are needed in the area of seven-day services, although promising case studies do exist. Staff redeployment has achieved successes within the pharmacy profession. Further research into staff redeployment would be useful. Volunteers have been used within the NHS in many different areas but there needs to be further evaluation of these initiatives in relation to winter pressures.

Changing staff behaviour

Findings for taxonomy headings classified as CSB are summarised in Appendix 5, Tables 65–74. The taxonomy headings were clinical audit, education of staff, protocols/guidelines, quality improvement programmes and quality management systems. Within this taxonomy section, we identified limited initiatives or research studies. CSB can take time and initiatives to minimise winter pressures are generally implemented rapidly without the time for thorough evaluation or to measure all potential outcomes. Initiatives to minimise winter pressures could potentially be too short to make changes to staff behaviour and they might not measure staff behaviour as an outcome. Further research studies could plan evaluations that consider a variety of outcomes including changes in staff behaviour, although it can be difficult to measure.

Changing community provision

In the first version of the taxonomy, as employed during the initial winter pressures mapping process, all CCP entries were subsumed under a single overarching heading. Subsequently, as we sought evidence on the specific intervention types, the review team decided to differentiate community provision within three subcategories. We believe that this is the first and most important step towards starting to think how different types of intervention attempt to respond to winter pressures in advance of a realistic focus on mechanisms. The three subcategories are therefore labelled as CCP – hospital avoidance, CCP – alternate delivery site, and CCP – facilitated discharge. Each is considered, together with specific interventions under each subcategory in the tables below.

Hospital avoidance

Findings for taxonomy headings classified as CCP are summarised in Tables 20–23 and Appendix 6, Tables 75–78. The taxonomy headings were rapid response/see and treat, single point response and step-up facilities.

| Taxonomy heading | Brief description/definition | Mechanism for minimising winter pressures |

|---|---|---|

| CCP – hospital avoidance | Provides active treatment by healthcare professionals outside hospital for a condition that otherwise would require admission | Offers treatment outside hospital as alternative to acute hospital inpatient admission |

| Example interventions: ‘Community Connect’ (Somerset) | Works alongside Home First discharge model using mix of voluntary, community and social enterprise and microprovider provision to provide rapid response away from hospital setting. Drew upon robust community infrastructure including village agents (people who link their local communities to services/information they need and at times deliver it themselves) countywide | Harnesses community resilience to allow people to receive care closer to their home, support admission avoidance and link to D2A model (home with therapy support and reablement beds) |

| Hospital avoidance response team | Provided to either prevent an avoidable A&E attendance or admission, or to speed up discharge from secondary care. Facilitates supported discharge and provides up to 72 hours of care and support to resettle a person at home offering ‘bridging the gap service’ for 72-hour period offering telecare unit, enabling access to responders 24/7 – assurance of support through the night if required and wellbeing service assessment with onward referral as appropriate | 72-hour period gives other domiciliary or reablement services opportunity to commence later in the pathway supporting the clinical assessment service to avoid hospital admission and/or attendance at A&E |

| Example interventions: Lincolnshire Independent Living Partnership: hospital avoidance response team. URL: www.local.gov.uk/case-studies/lincolnshire-independent-living-partnership-hospital-avoidance-response-team (accessed 23 November 2022) | Service delivered by Lincolnshire Independent Living Partnership, which takes referrals from secondary care discharge hubs, A&E in-reach teams, the ambulance service, primary care and community health providers | Provides appropriate support and referral bypassing formal presentation to hospital services |

| Example interventions: Talking Cafes (Somerset) | Village agents run talking cafes (face to face or online) to offer a point of contact and reassurance. Village agent service works with local authority and GPs to support the vulnerable, setting up food and equipment networks, and harnessing support from within communities | Increase community resilience by offering local events where people can get information, advice, support or even company |

| Supporting evidence | Results/findings/recommendations (from abstract) |

|---|---|

| Winter pressure specific | |

| Windle et al. 201428 [evaluation] | No demonstrable changes in monthly emergency admissions. Emergency bed days fell from (mean) 6.55 to 6.28 days. Significant increase in zero bed-nights. Short-term evaluation did not enable full cost-effectiveness evaluation; each intervention seemed to demonstrate value for money against cost of an acute admission |

| Systematic reviews | |

| Huntley et al. 2017119 | Concludes many available options are safe and appear to reduce resource use. However, cost analyses and patient preference data lacking |

| Gravelholt et al. 2014120 | Several interventions reduced hospital admissions and may represent important aspects of nursing home care to reduce hospital admissions. Quality of evidence low |

| Commentary on systematic reviews | |

| Oliver 2019a44 Oliver 2019b45 | Systematic reviews, &‘found no consistent evidence for interventions to reduce hospital attendance or admissions. Systematic review focusing on people over 65 with predicted high risk of admission also found no compelling evidence’. Cochrane reviews on Ha H, even for selected patient groups, showed mixed results |

| Published evaluations | |

| Rose Regeneration. Hospital Avoidance Response Team: Evaluation report 2019. URL: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/category/reports/page/3 (accessed 23 November 2022) | Service filled ‘distinctive gap in service provision and has made materially important contribution to the quality of life of its beneficiaries.’ Individuals supported by service almost universally positive. Supported around 120 hospital discharges and 25 admission avoidances per month. Review suggests that hospital avoidance response team contributed to supporting almost 25% of all individuals (2018/19). Over 6 months, 967 individuals accepted by service. £565,100 of savings (£245,100 net) delivered to NHS. In social value has delivered £8.43 per £1 invested |

| Local Government Association. High Impact Change Model (Change 3): Multidisciplinary teams. Lincolnshire: hospital avoidance response team 201815 | |

| Additional evidence | |

| NICE Guideline NG94 201846 | Covers organising/delivering emergency/acute medical care for people aged over 16 in community and in hospital. Aims to reduce need for hospital admissions by giving advanced training to paramedics and providing community alternatives to hospital care. Also promotes good-quality care in hospital and joint working between health and social services |

| Oliver 2019a44 Oliver 2019b45 | NHS plan ‘aims to reduce acute hospital bed use through roll-out of NHS 111 advice line/web service, GP-led urgent treatment centres, community multidisciplinary rapid response teams, and enhanced support for care home residents’. Problems: ‘exit block’ in patients who could technically leave, potential risks from admission, and patients whose problems might have been dealt with upstream/closer to home. Case mix of acute hospitals has grown older, more medically complex, and more acute despite success in sending more patients home within 24 hours or to ambulatory care. Patients often choose to attend hospital – often for reassurance |

| Research gaps | |