Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/116/82. The contractual start date was in June 2018. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Morris et al. This work was produced by Morris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Morris et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Overview

Rare diseases affect many people, more than 3.5 million in the UK alone. Poor co-ordination of care is a problem faced by many people affected by rare diseases. In this introductory chapter we consider what care co-ordination means in the context of rare diseases, the problem addressed by this research and the aims and objectives of the research. In this report we use the terms ‘rare conditions’ and ‘rare diseases’ interchangeably to refer to rare, ultra-rare and undiagnosed diseases and conditions.

What does care co-ordination mean?

The focus of this study is the co-ordination of care for people affected by rare diseases. A systematic review conducted in 2007 reported no single agreed definition of co-ordinated care and proposed the following working definition:

Care co-ordination is the deliberate organisation of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services. Organising care involves the marshalling of personnel and other resources needed to carry out all required patient care activities and is often managed by the exchange of information among participants responsible for different aspects of care. 1

As part of our research, we sought to improve this definition in the context of rare diseases.

What is the problem being addressed by this research?

There are an estimated 6172 unique rare conditions. 2 Each rare disease affects fewer than 1 in 2000 of the population,3 but combined they affect a large number of people, approximately 3.5 million in the UK4 and 30 million in the European Union. 3 The problem being addressed by this research is the variation in how care is co-ordinated for people affected by rare diseases in the UK (and in many cases the complete lack of care co-ordination), depending on where they live and the disease they are affected by.

Rare diseases are often serious, chronic and complex in nature, affecting multiple systems of the body. As a result, several health-care professionals (HCPs) are often involved in patients’ care. Many people need access to a number of different NHS services to receive the care they need, including care by specialists and care nearer to home. Care by specialists may require travelling long distances and staying away from home, which can be inconvenient, costly and stressful. Care nearer to home may involve care by the local hospital or general practitioner (GP). Receiving care from a range of people, including specialists and local providers, can cause problems because co-ordination between the different professionals and services is often poor, care plans may not be in place or followed and some patients may have gaps in their care because they do not see the right professionals and, when they do, the information to facilitate appropriate care may not be to hand. Parents/carers of children with rare conditions often face a significant care burden, needing time off work to look after their children and take them to appointments. There can also be challenges in ensuring continuity of care when children transition from paediatric to adult services.

Why is this research needed?

There is evidence to suggest that care is poorly co-ordinated for people affected by rare diseases. In addition, improving care co-ordination for people affected by rare diseases has been raised as a major concern by policy-makers.

In January 2016, Rare Disease UK (London, UK) published results from a survey of more than 1200 people (patients and carers) affected by rare diseases, which found that information on test and procedure results and treatment was not shared effectively between services, meaning that patients may have received suboptimal treatment. 5 The survey also found that patients and families frequently had to attend multiple clinics and travel significant distances to reach them. For example, one in three respondents had to attend three or more clinics and 12% of respondents attended more than five different clinics. Respondents attended clinics monthly (23%), every 6–8 weeks (32%), quarterly (55%) or at least once a year (92%). 5

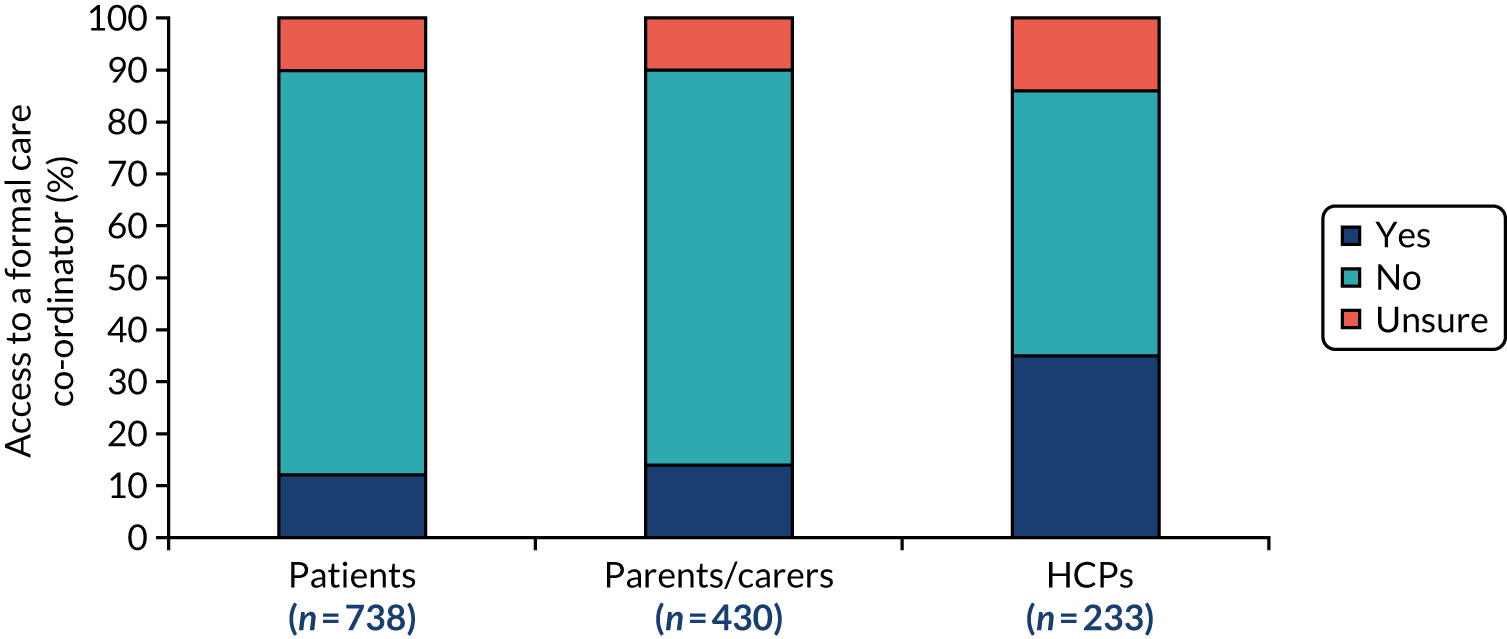

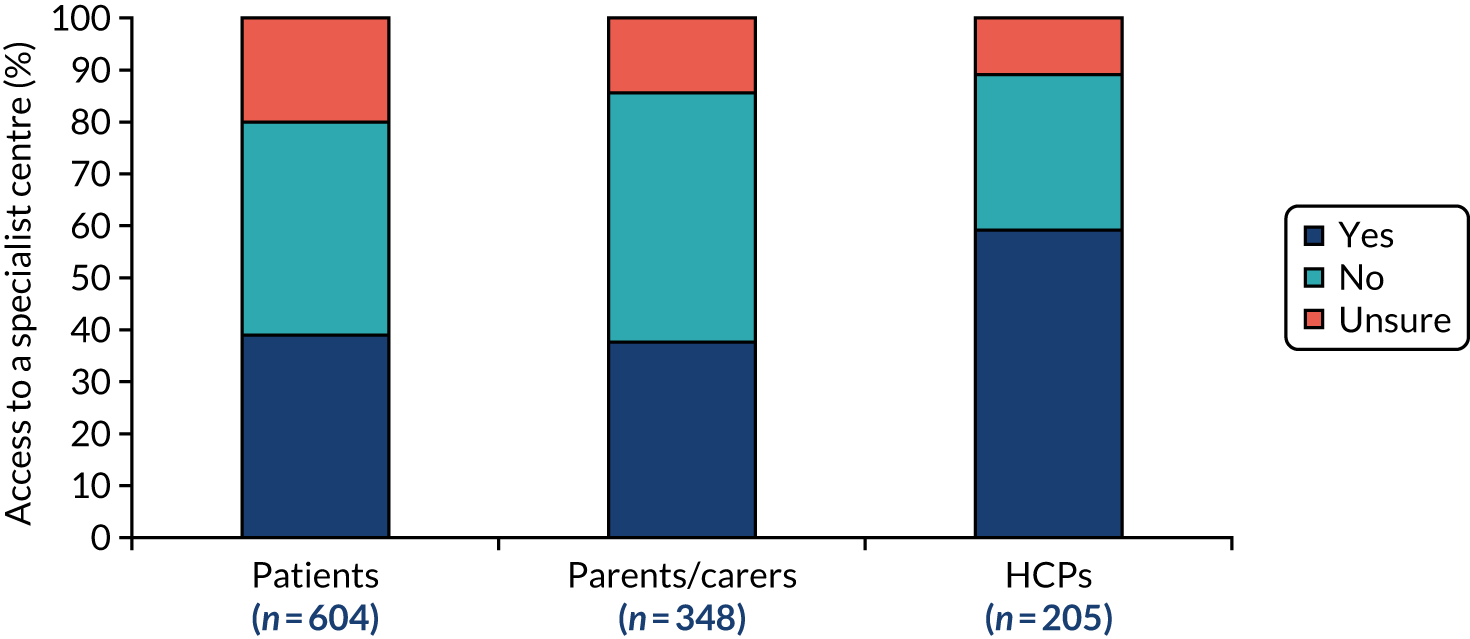

In addition, not only did patients have to frequently visit multiple clinics, but nearly half the survey respondents reported that they travelled for more than 1 hour to get to their furthest clinic, with 11% of respondents reporting that they had to travel for more than 3 hours. 5 The survey found that 81% of patients did not have a care co-ordinator or advisor, and a further 8% of patients were unsure whether or not they did. The survey also found that 40% of respondents did not know if there was a specialist centre for their condition. Of the patients who were aware of a specialist centre for their condition, only 66% used it. 5 These data illustrate the heavy burden that poor care co-ordination places on patients and families dealing with rare diseases, which could be improved by better co-ordination.

In September 2016, Genetic Alliance UK (London, UK) undertook a study to identify the hidden costs of rare diseases in the UK. 6 The aims of the study were to examine how services are co-ordinated for patients with rare diseases, what is known about the impact of the lack of co-ordinated care, what costs and outcomes are important to patients and families, and how these data might best be collected. The study involved interviews with patients, families and patient organisations. The main conclusions were that receiving co-ordinated care is important for patients with rare diseases, yet remains a challenge; the full costs and benefits associated with different models of care for patients with rare disease are unknown; patients and families face significant hidden costs, both financial and psychosocial, associated with the way their care is managed; and there are limitations associated with existing research and data sets for rare diseases.

The problem of poor co-ordination of care for patients with rare diseases has also been highlighted by the UK governments, although the evidence base is largely anecdotal. In 2013, the Department of Health and Social Care, Northern Ireland Executive, Scottish Government and the National Assembly for Wales published The UK Strategy for Rare Diseases,7 which said that it was essential to co-ordinate care for people with rare diseases. The strategy also stated that more needed to be done to improve co-ordination and that research was needed on how care for people with rare diseases should be co-ordinated. In the progress report from the All Party Parliamentary Group on rare, genetic and undiagnosed conditions it was noted that care continues to be badly co-ordinated. 8

More recently, the UK government, and patients and families, further highlighted the problem of co-ordinated care for people affected by rare diseases in The UK Rare Diseases Framework. 9 The UK Rare Diseases Framework9 restated that co-ordination of care was one of the top challenges facing people affected by rare diseases and better co-ordination was listed as one of the four top priorities. In addition, better co-ordination was also listed as one of the four major challenges facing the rare diseases community. In a ‘national conversation’ survey of 6293 members of the UK rare diseases community, conducted in 2019, co-ordination of care was identified as the top challenge by 16% of patients, 19% of families and carers, 11% of rare disease patient organisations and 18% of HCPs (Table 1). 9 We note that, although co-ordination of care was noted as a major challenge in its own right, any improvement in co-ordination is also likely to have a positive impact on the other challenges (e.g. by improving diagnosis, awareness and access).

| Challenge | Stakeholder group (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People living with a rare disease | Family members and carers | Rare disease patient organisations | HCPs | |

| Getting the right diagnosis | 30 | 17 | 29 | 18 |

| Awareness of the rare disease among HCPs | 19 | 17 | 14 | 14 |

| Access to specialist medical care and treatment | 17 | 14 | 16 | 11 |

| Co-ordination of care | 16 | 19 | 11 | 18 |

Unfortunately, although there are indications that care needs to be better co-ordinated for people affected by rare diseases, there is not good evidence as to how this should be achieved. A 2013 report by Rare Disease UK10 provided anecdotal evidence of the benefits of having a named care co-ordinator and concluded that there was a strong case for investment in care co-ordinator posts, although quantitative evidence was lacking. Van Groenendael et al. 11 analysed the national service for an ultra-rare disease (Alström syndrome) and compared outcome and cost of the service with standard care. 11 Van Groenendael et al. 11 found that organised multidisciplinary ‘one-stop’ clinics achieved better outcomes than standard care, at similar costs. Indicative of the lack of evidence about how to improve care co-ordination for people affected by rare diseases, The UK Strategy for Rare Diseases7 called for further research in this area, in particular around how care for people with rare diseases is co-ordinated and how best it ought to be co-ordinated. Our study aimed to address these gaps.

Aims and objectives

Aims

The aims of this study were to use quantitative and qualitative research methods to investigate (1) if, and how, care of people with rare diseases is co-ordinated in the UK and (2) if, and how, patients and families affected by rare diseases, and HCPs who treat rare diseases, would like care to be co-ordinated.

Objectives

-

To undertake a scoping review to identify what ‘co-ordinated care’ means, what the components of co-ordinated care are and to identify in what ways, and why, co-ordinated care for people with rare diseases might be similar to or different from co-ordinated care for people with other conditions.

-

To understand if and how care of people with rare diseases is co-ordinated in the UK.

-

To analyse preferences for different models of co-ordinated care by patients, families and HCPs.

-

To develop a taxonomy describing how care for people with rare diseases could be co-ordinated.

-

To calculate the costs of the models of co-ordinated care identified in the taxonomy.

-

To work closely with patients and families throughout the project and disseminate findings widely.

Research questions and overview of the research project

The research questions (RQs) we addressed to meet the aims and objectives were as follows.

Research question 1

What does ‘co-ordinated care’ mean, what are the components of co-ordinated care and in what ways, and why, may co-ordinated care for people with rare diseases be similar to or different from co-ordinated care for people with other conditions?

Research question 2

Is care for people with rare diseases in the UK co-ordinated and, if so, how?

Research question 3

What are the preferences of patients, families and HCPs in relation to how care for rare diseases is co-ordinated?

Research question 4

What are the different ways in which care for people with rare diseases might be co-ordinated?

Research question 5

How much do these options cost?

Our study was interested in exploring all spectrums of co-ordination (from a lack of co-ordination through to good co-ordination).

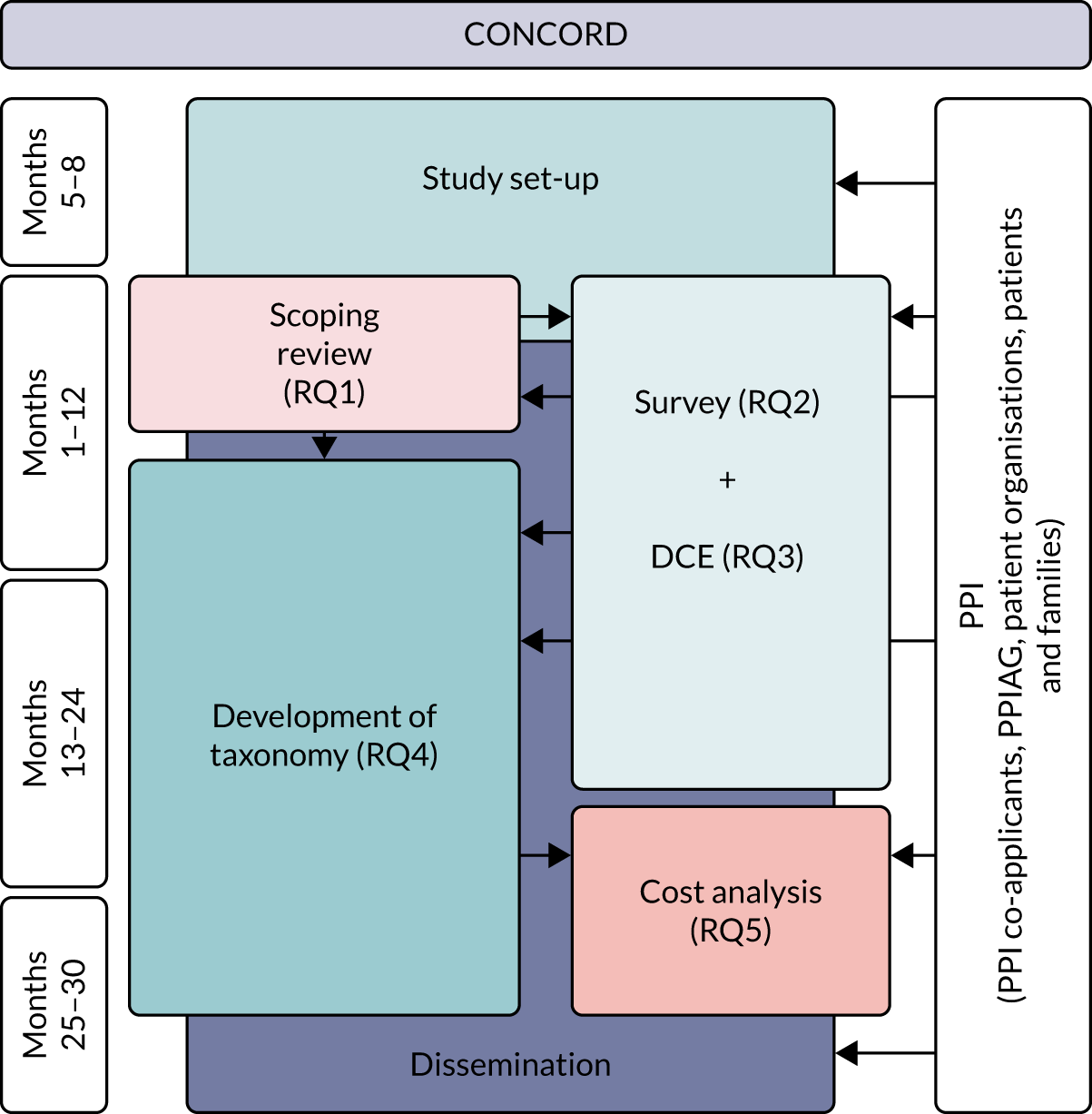

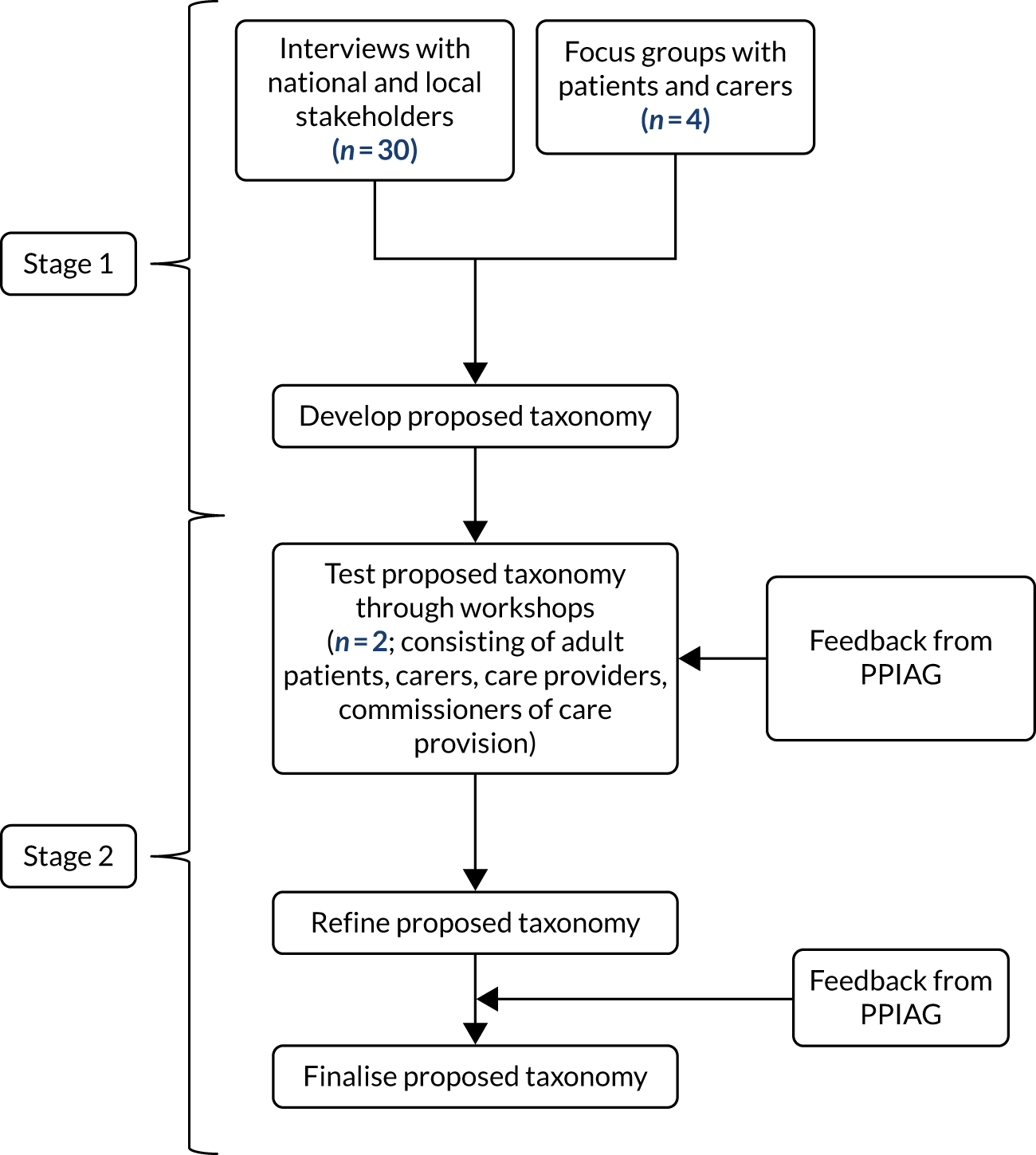

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme from June 2018 to February 2021. The CONCORD (Co-ordinated Care Of Rare Diseases) study timeline is summarised in Figure 1. For RQ1, we undertook a scoping review (not only in rare diseases) that focused on care co-ordination across organisational boundaries and interventions employed to support and improve this. For RQs 2 and 3, we created a questionnaire-based survey of current experiences and costs, incorporating a discrete choice experiment (DCE) of preferences for co-ordination. In addition, we undertook an exploratory qualitative interview study to understand the impact of a lack of co-ordinated care on patients and carers, and preferences for co-ordination. For RQ4, we drew on the findings of the scoping review and also carried out interviews, focus groups and workshops with a range of stakeholders to develop a taxonomy of co-ordinated care for rare diseases. For RQ5, we reviewed the costs of different components of co-ordinated care.

FIGURE 1.

The CONCORD study flow chart. PPI, patient and public involvement; PPIAG, Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group.

Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows.

Chapter 2 presents the overarching design of the study and provides an overview of the methods employed. (Detailed information on methods is presented within each of the findings chapters.)

Chapter 3 presents the methods and results of a scoping review to define co-ordinated care for people living with rare conditions. Chapter 3 extends previous research by providing an updated definition of co-ordinated care for rare conditions, and by identifying and categorising components of co-ordination according to their role within complex care processes.

Chapter 4 presents an exploratory qualitative interview study of patients affected by rare conditions and their carers, exploring how these groups are affected by whether or not care is co-ordinated, and the factors that might influence effective care co-ordination.

Chapter 5 presents the findings from a national cross-sectional survey of patients, parents/carers and HCPs about different aspects of care co-ordination for rare diseases, including the use of specialist centres, care co-ordinators and care plans.

Chapter 6 presents the findings of a DCE to evaluate preferences of patients, parents/carers and HCPs for characteristics of co-ordinated care.

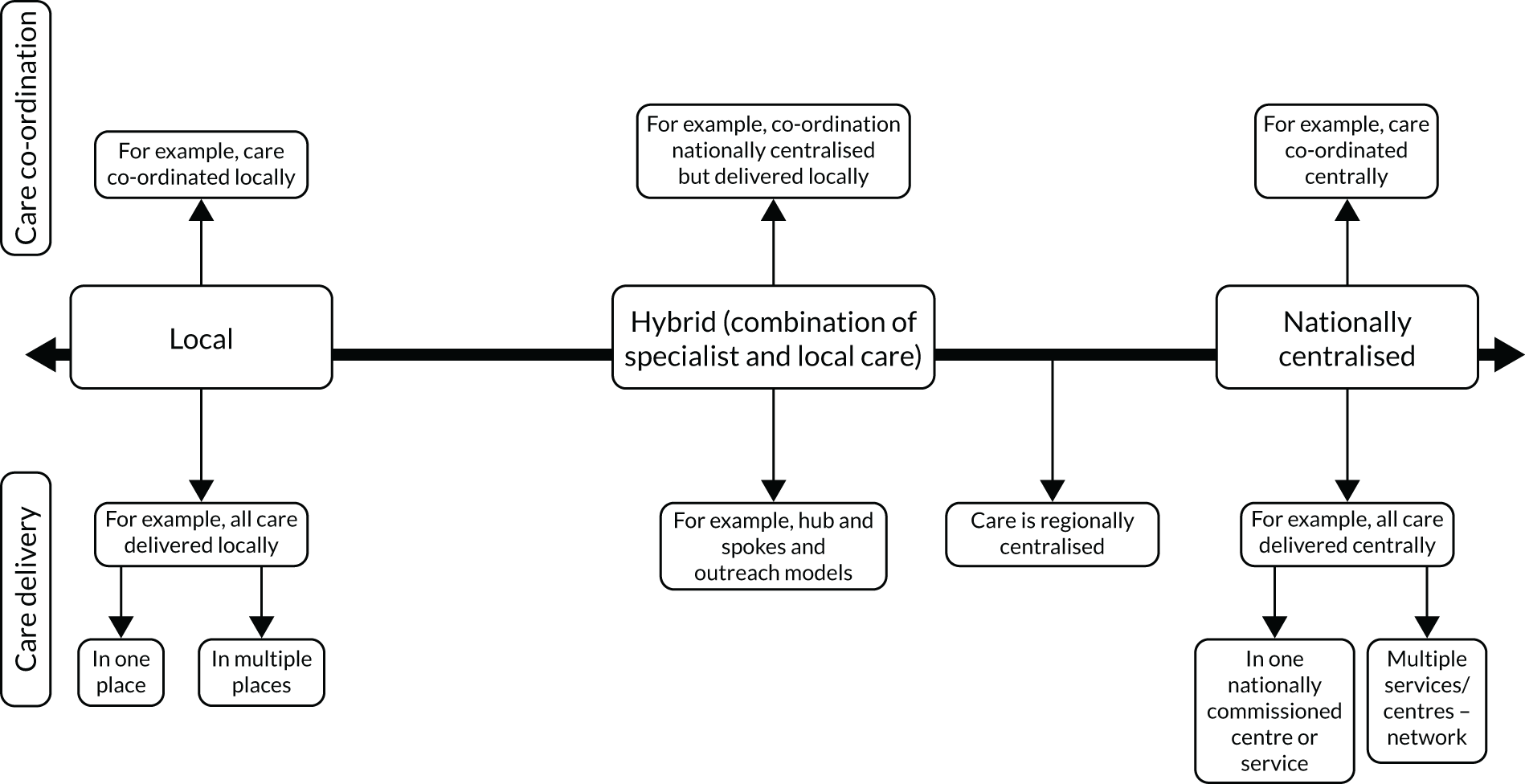

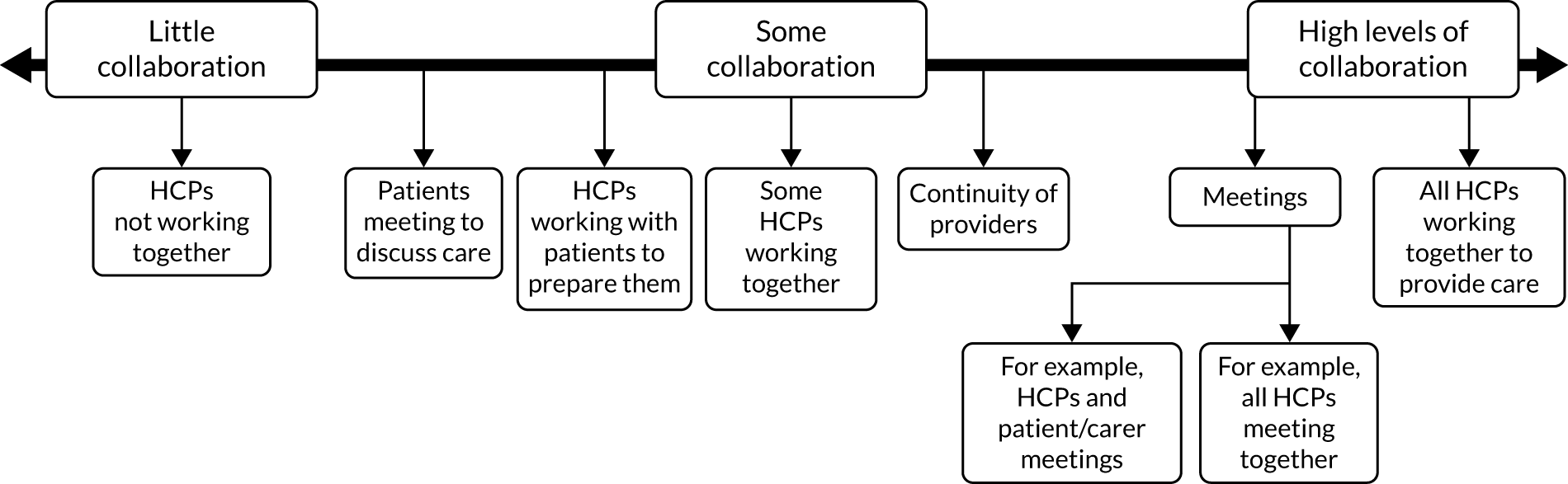

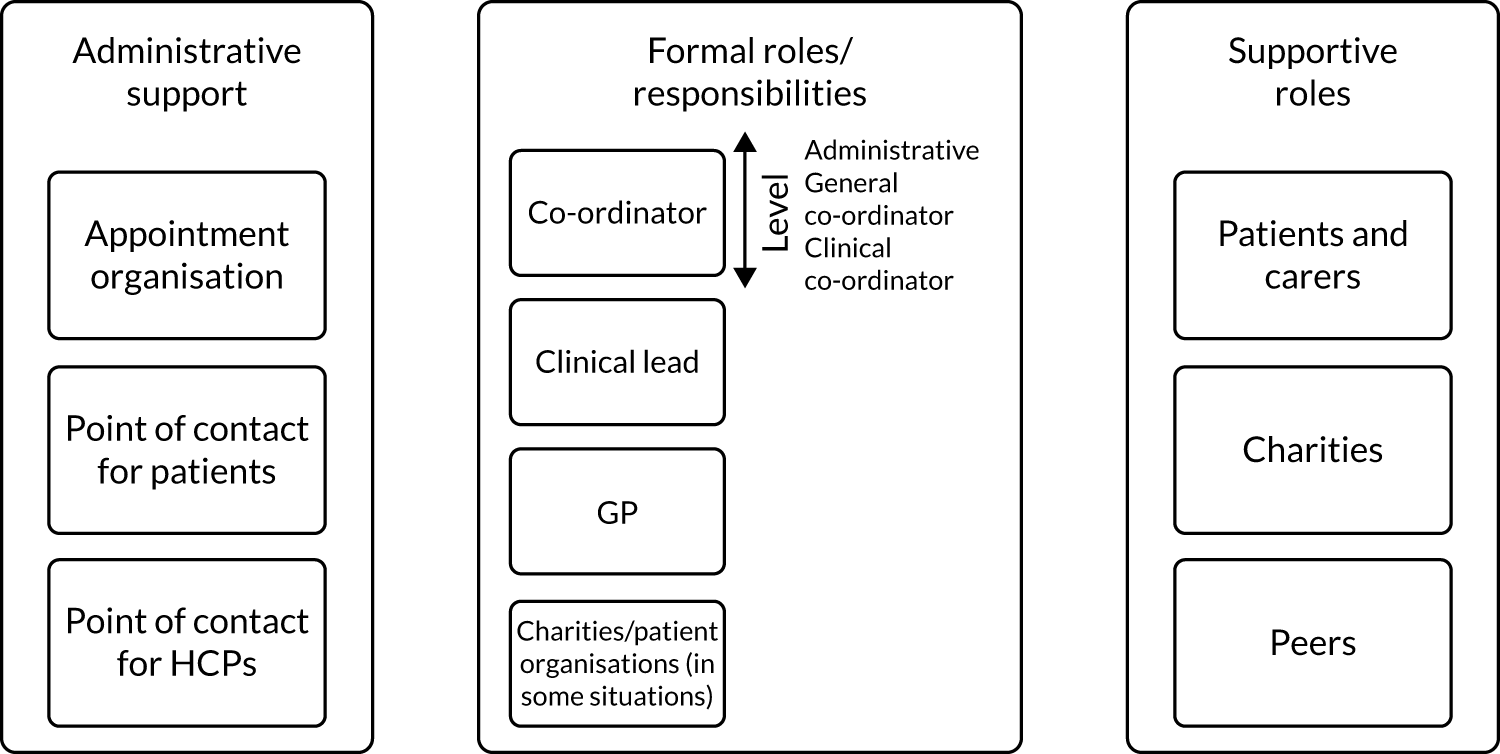

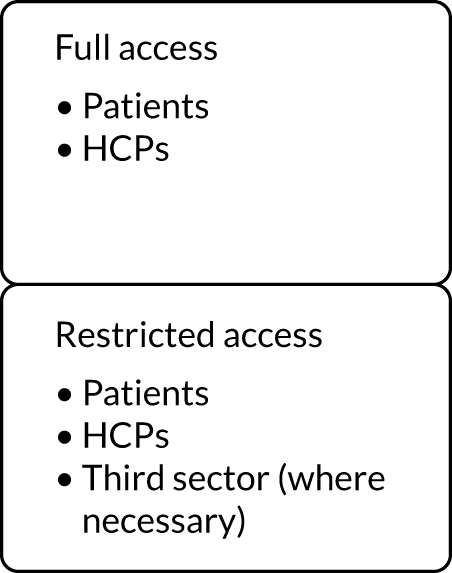

Chapter 7 outlines the development and refinement of a taxonomy of care co-ordination for people living with rare conditions. The taxonomy outlines the six domains involved in co-ordinating care for rare conditions.

Chapter 8 presents selected models of co-ordinated care from the taxonomy and illustrative costs of different components of co-ordinated care.

Chapter 9 presents a discussion of our findings linked to our RQs and the implications for health services and research.

Chapter 2 Research methods

Overview

In this chapter we provide an overview of the design and methods employed in the CONCORD study. We outline the qualitative and quantitative methods used. Further information on methods is presented within each of the chapters that follow.

Methods

Setting

This study is concerned with how people with rare conditions are cared for across organisational settings in the UK, including the NHS, the social care sector and the third sector. The primary focus for this study was NHS care, but we were also interested in providers that are gatekeepers to social care provision and third-sector care, as significant elements of co-ordination specifically relate to the integration between health care and these other sectors. To identify as many different models of co-ordination as possible, no limits were set on the rare conditions included or where people lived in the UK.

Overview of approaches

We used the following methods in our research:

-

a scoping review (not only in rare diseases) that focused on care co-ordination across organisational boundaries, and interventions employed to support and improve this

-

an exploratory qualitative interview study to understand the impact of a lack of co-ordinated care on patients and carers

-

a questionnaire-based survey of current experiences, incorporating a DCE of preferences for co-ordination

-

interviews, focus groups and workshops with a range of stakeholders to develop a taxonomy of co-ordinated care for rare diseases

-

a review of the costs of providing co-ordinated care.

There were numerous interdependencies between the different components of the study (see Figure 1). The scoping review provided the theoretical underpinnings for the taxonomy of co-ordinated care and informed the content of the survey, the DCE and what is known about the costs of co-ordinated care. The exploratory qualitative interviews informed the scoping review, the survey and the DCE. The survey and DCE helped to identify different models of care co-ordination, which were used to create the taxonomy. In addition, the survey and the DCE were also intended to provide data for the cost analysis of the different co-ordination models, which were, in turn, based on the taxonomy (which delineated the options to be costed).

Study participants

Study participants comprised patients (aged ≥ 18 years) affected by a rare condition, parents/carers (aged ≥ 18 years) of children or adults with rare conditions, HCPs (e.g. doctors, nurses and allied health professionals) involved in the care of people with rare conditions, national leads on specialist health-care commissioning, national patient groups and charities, and local providers and commissioners of co-ordinated care. More specifically, participants were involved in various elements of the research as follows:

-

To find out if the scoping review findings applied to rare conditions and to support the design of the survey and DCE, we undertook three focus groups. The focus groups were as follows:

-

one virtual focus group with seven patients and carers affected by rare diseases

-

one face-to-face focus group with six patients and carers affected by rare diseases

-

one face-to-face focus group with four HCPs.

-

-

To explore the impact of unco-ordinated care, and to support the design of the survey and DCE, we conducted interviews with 15 patients and carers affected by rare diseases [14 interviews were via telephone and one interview was via Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)].

-

To ensure that the survey was worded appropriately and contained appropriate questions, we undertook a pilot study of the survey and DCE questionnaire with 24 patients, carers and HCPs. The study comprised four think-aloud interviews and 20 interviews that provided written or verbal feedback.

-

For the survey and DCE, we obtained 1457 responses from 760 patients affected by rare diseases, 446 parents/carers and 251 HCPs.

-

To develop the taxonomy, we planned to undertake up to 30 national and local stakeholder interviews. These interviews included national leads on specialist health-care commissioning, national patient groups and charities, local providers of co-ordinated care (including health care, social care and the voluntary sector) and local commissioners of co-ordinated care.

-

To develop the taxonomy, we undertook 30 interviews with HCPs, charity representatives and commissioners, and four focus groups involving a total of 22 patients and carers affected by rare diseases.

-

To refine the taxonomy, we conducted two workshops with 15 attendees each. Workshop participants included adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) and carers of adult patients, carers of younger patients (aged < 18 years), care providers (including health care, social care and the voluntary sector) for adults with rare conditions, care providers (including health services, social services bridging health and social care and the voluntary sector) for children with rare conditions, and commissioners of co-ordinated care provision, including NHS England and local authorities.

Participants were accessed via patient and provider networks and organisations.

Patient and public involvement

To meet our aims, the study required substantial input from patients and families. The research team included representatives from a national charity that is an alliance of more than 180 patient organisations (Genetic Alliance UK) and from national patient organisations with direct experience of living with rare conditions. These representatives ensured that patients’ and families’ priorities and needs remained the focus of the study, and contributed to the design and management of the study, patient recruitment, data collection, interpretation of findings and dissemination. In addition, these representatives ran the study’s Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group (PPIAG), which involved managing and working with a group of six to eight patients and carers and meeting twice a year for the duration of the project. The PPIAG supported the development of resources and participant information, patient recruitment and dissemination of findings.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from University College London Research Ethics Committee (reference 8423/002) and the London–Surrey Borders Research Ethics Committee of the Health Research Authority (reference 19/LO/0250).

Overview of research methods

Scoping review

The scoping review was designed to help us understand what aspects of co-ordinated care could or should be provided for people with rare conditions, and help us build on what was already known about co-ordinated care in other contexts that might be used to enhance co-ordinated care for rare conditions. The scoping review had six stages. 12

Stage 1: defining the research questions

In stage 1, we developed three RQs.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

In stage 2, we conducted a review of reviews about care co-ordination for chronic conditions in general, not just rare conditions, to identify factors important to co-ordinated care. We searched for evidence from a range of different sources, including electronic databases, hand-searching of key journals and reference lists of retrieved studies. We limited the search to studies published after 2006 (as a comprehensive 2007 review1 included papers published up to 2006). Reviews published in peer-reviewed journals, as well as grey literature, were included.

Stage 3: study selection

In stage 3, selection criteria were developed iteratively and reviews were included if they focused on care co-ordination in some form, provided a definition of co-ordinated care, identified components of co-ordinated care and focused on patients with rare conditions, chronic conditions or long-term conditions. Identified studies were screened in three phases (i.e. title, abstract and full text) and a percentage were screened by a second researcher.

Stage 4: charting the data

In stage 4, we extracted data, including the characteristics of co-ordination, from the identified reviews.

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting results

In stage 5, we presented an overview of materials reviewed and a thematic analysis of their results.

Stage 6: stakeholder consultation

In stage 6, draft findings were shared with three focus groups and these were used to develop our analysis and interpretation of findings, including whether co-ordinated care for people with rare conditions is similar to or different from those in other contexts.

For further details about the methods employed, see Chapter 3, Methods.

Survey

We conducted a national survey to understand how care of people with rare conditions was co-ordinated in the UK. The questionnaire incorporated a DCE to quantify what aspects of care co-ordination participants preferred.

The content of the questionnaire was informed by 15 semistructured qualitative interviews with patients and carers to identify costs associated with living with rare conditions. These interviews were also used for the exploratory qualitative study to investigate the impact on patients and carers of having care that was not co-ordinated.

Survey participants were adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) affected by a rare condition, parents/carers (aged ≥ 18 years) of children or adults with rare conditions and HCPs (e.g. doctors, nurses and allied health professionals) involved in the care of people with rare conditions. The target number of responses for each of these three groups was at least 300, with an overall target sample size of 1500. Participants were required to live in the UK, but there were no restrictions in terms of rare condition, demographic factors or geographical location within the UK.

Participants were accessed through patient networks and organisations, and through care providers and regional genetics services.

We produced a draft of the questionnaire based on the outputs of the in-depth interviews and scoping review (including the focus groups). This was reviewed by the PPIAG and amended accordingly. We then piloted the survey and made amendments according to feedback received. The survey was then finalised in discussion with the PPIAG.

The questionnaire covered a variety of topics, including experience of diagnosis, rare condition, availability/role of care co-ordinators, content and use of care plans, availability/role of specialist centres, use of health services and perceived impact of care co-ordination on quality of care.

A survey company generated online, electronic and hard-copy versions of the questionnaire ready for circulation. Most respondents completed the questionnaire via a weblink to the online questionnaire, which was made available on a dedicated website. Participants were also given options to complete the survey by mailed hard copy, electronically by e-mail or by telephone.

Analyses of the data were descriptive. The results of the categorical, ordinal and interval questions were reported as frequencies and percentages, or means and medians, with corresponding measures of spread [e.g. confidence intervals (CIs) or interquartile ranges].

For further details about the methods employed, see Chapter 5, Methods.

Discrete choice experiment

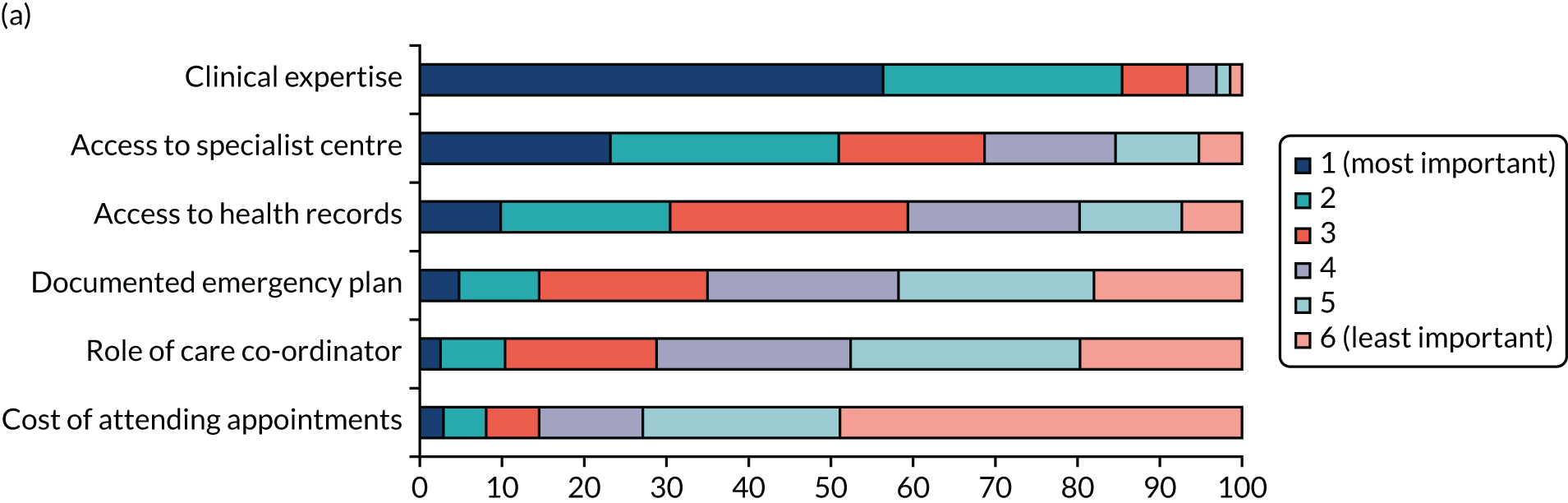

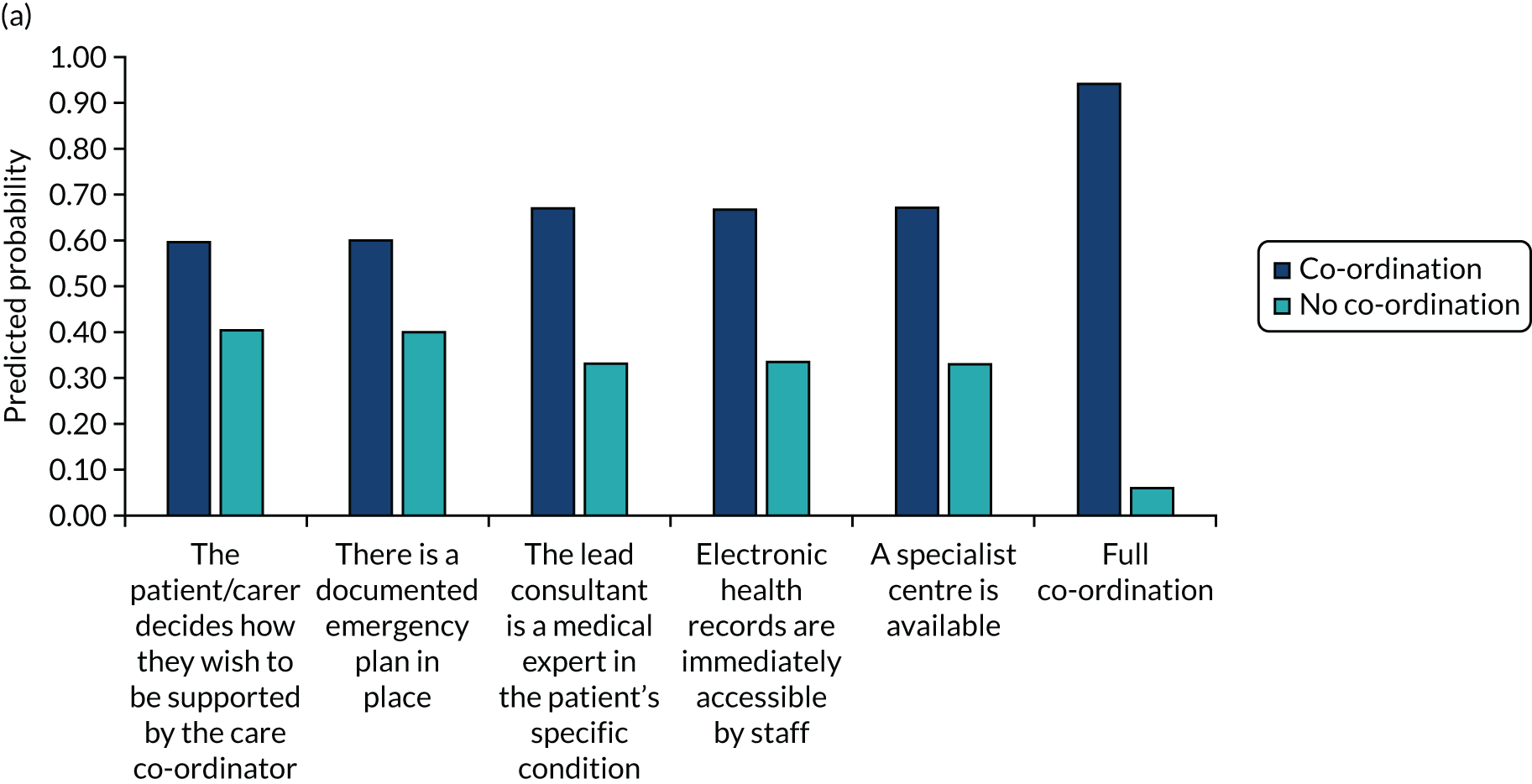

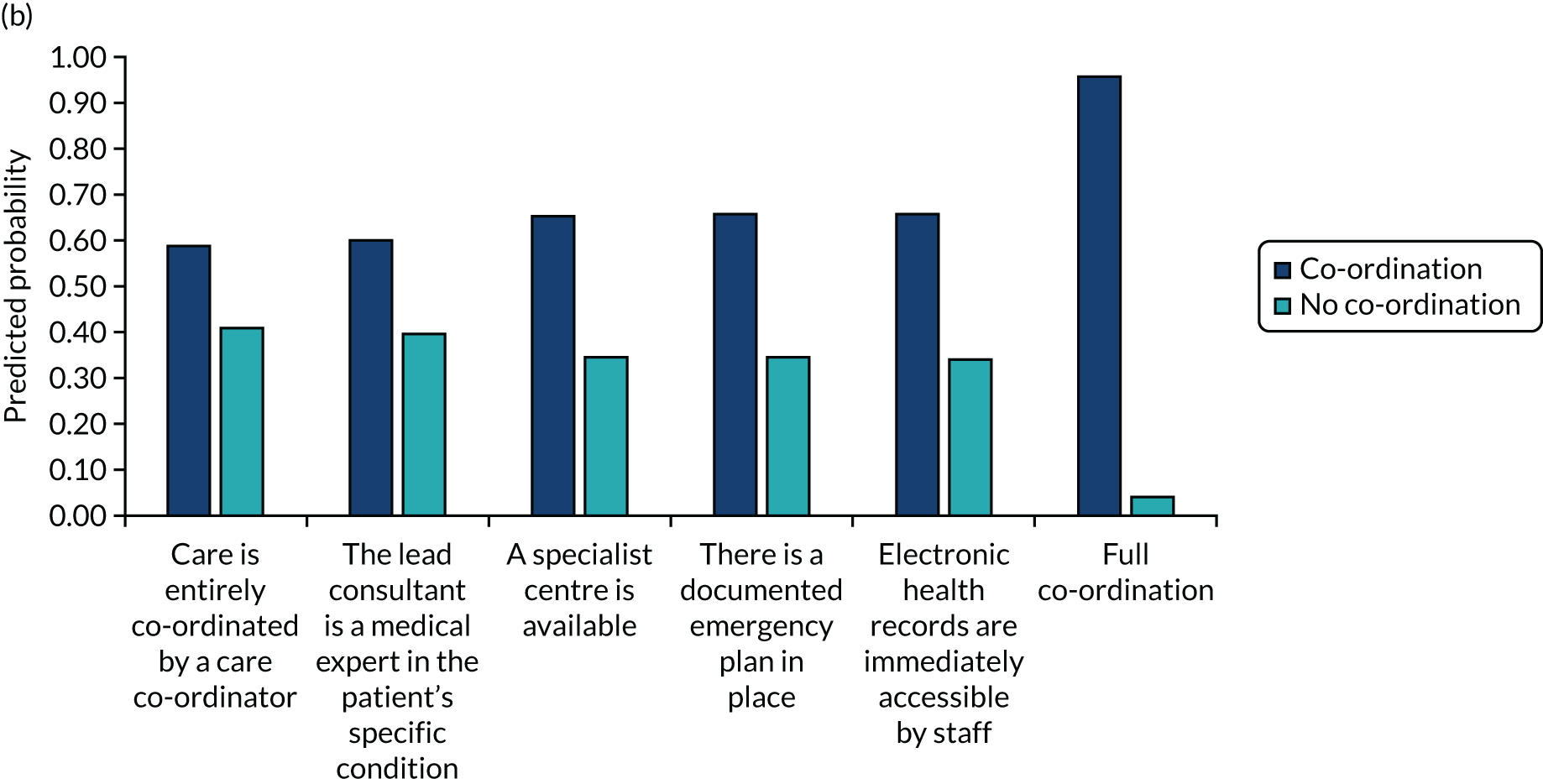

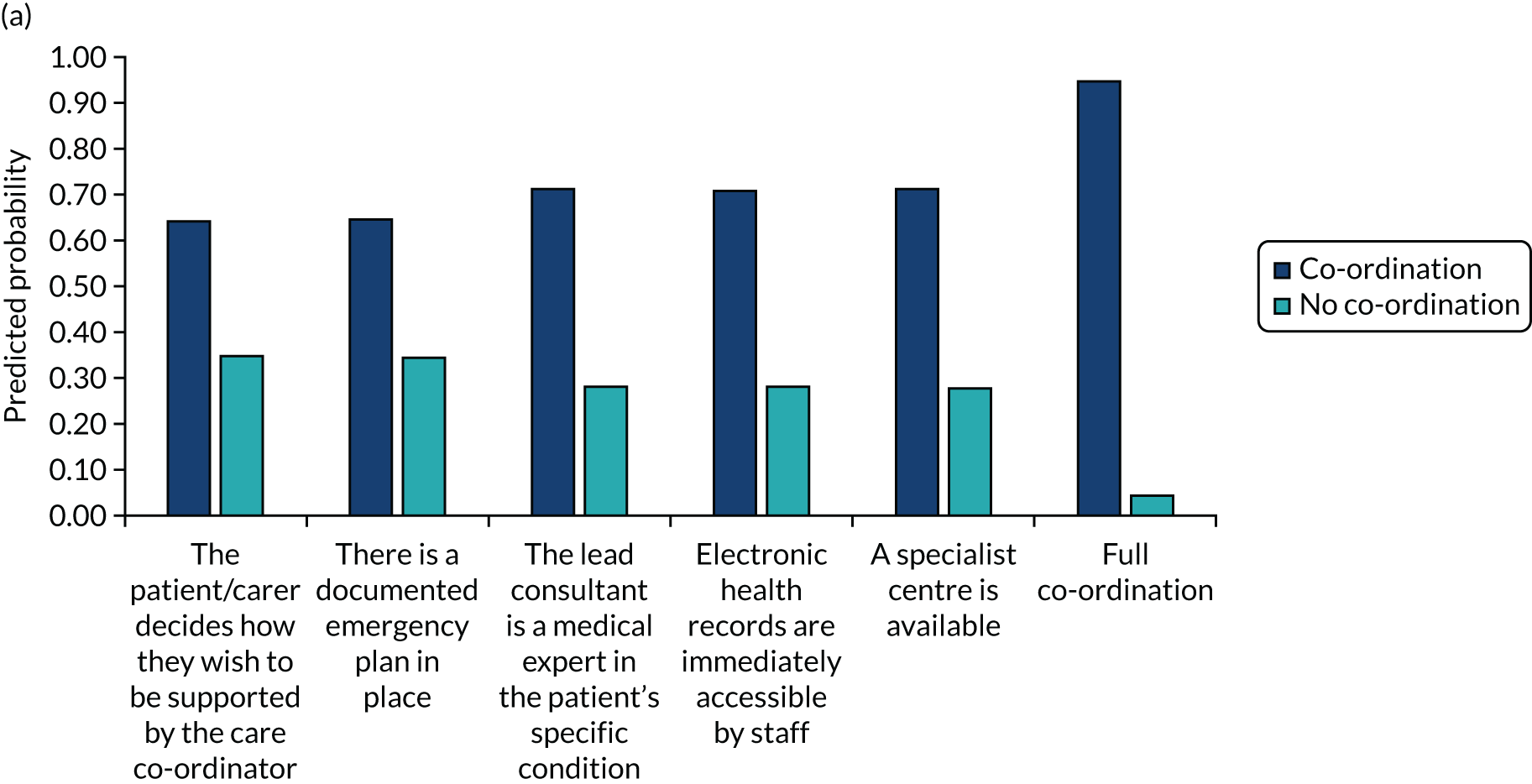

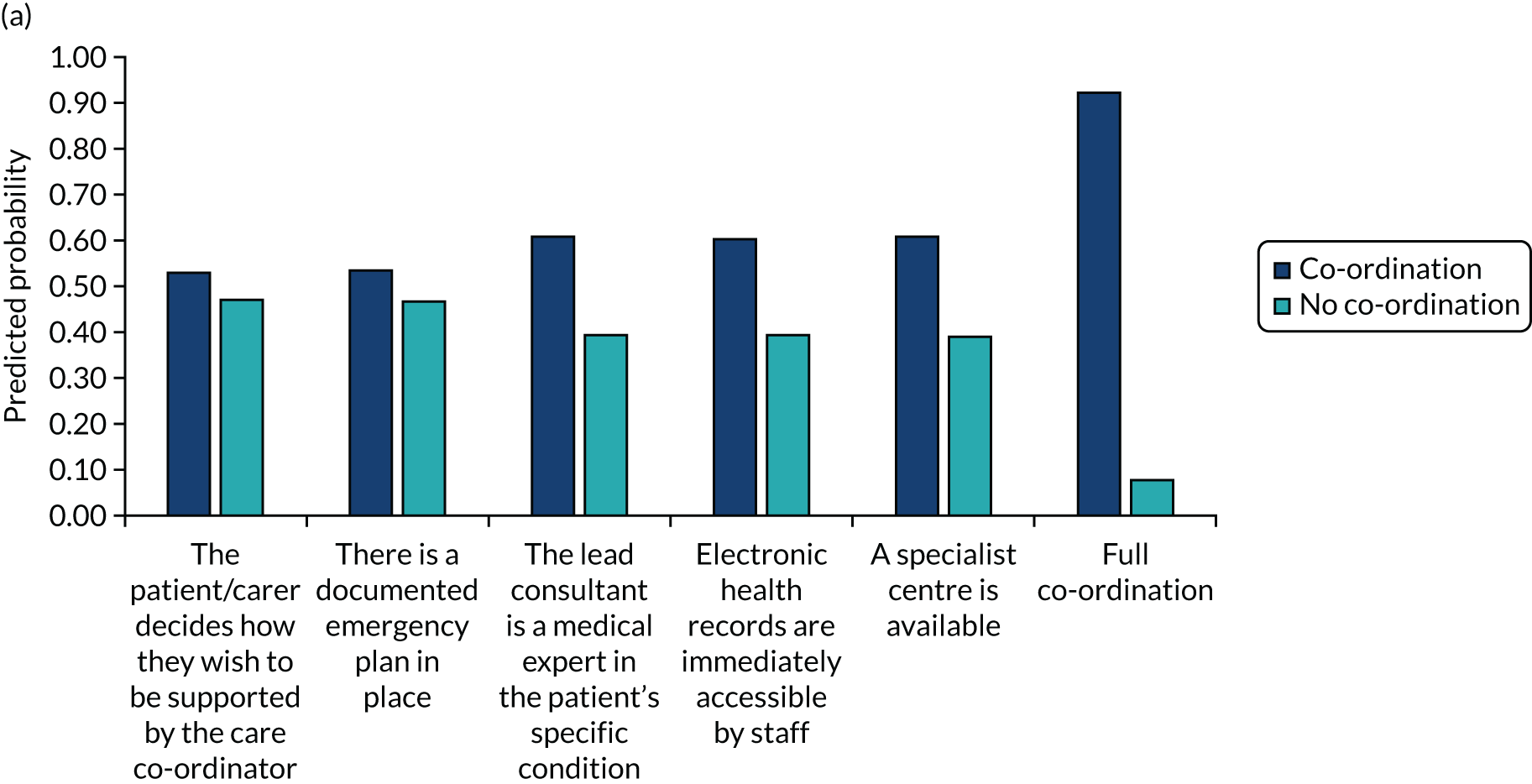

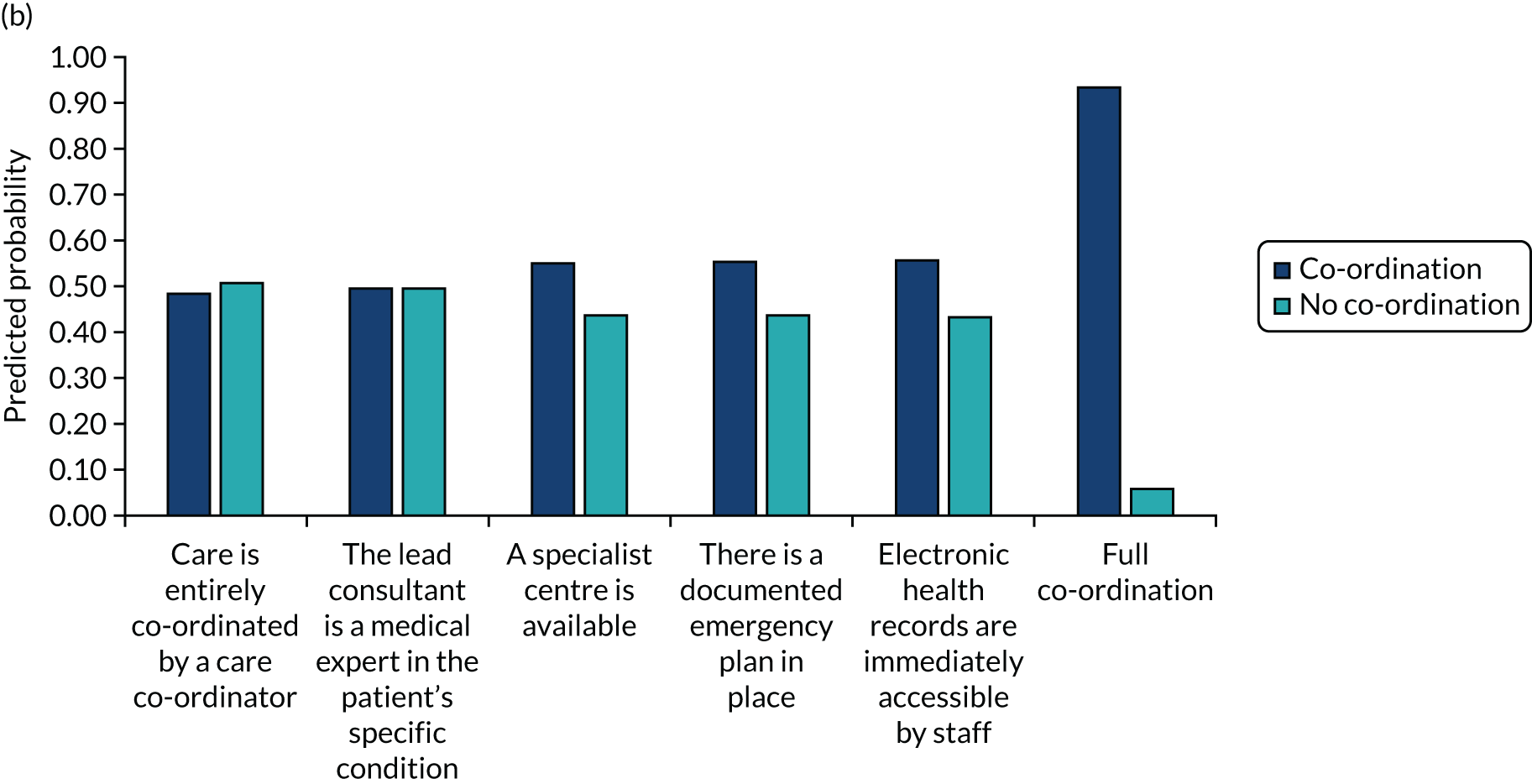

We undertook a DCE to investigate preferences for care co-ordination. 13 A DCE is a quantitative method used to elicit preferences from participants without directly asking them to state their preferred options. 14 The DCE formed one part of the survey questionnaire, eliciting preferences for the way in which care is co-ordinated for the three participant groups. A longlist of attributes was drawn from the scoping review and was shortened to six attributes based on feedback from the interviews, focus groups and the PPIAG. The levels of each of the attributes were based on feasible ranges derived from reviews of documentary evidence from the scoping review and feedback from the PPIAG and interviews. The DCE used a pairwise choice framework, describing combinations of levels and attributes of different models of co-ordinated care, including main effects only. We reduced the total number of feasible pairwise choice questions to 18, which were split into three blocks of six (i.e. each participant completed six choice questions). We also asked respondents to provide a simple ranking of the attributes according to importance.

The DCE data were analysed using conditional logit analyses. We selected this type of regression model given our focus on identifying which attributes significantly affect preferences, and which attributes are most and least important to respondents, conditional on the other attributes in the analysis. We tested for differences in preferences between responder groups. We calculated marginal rates of substitution (MRSs) with respect to costs, dividing the coefficient for each attribute by the coefficient for the cost attribute to calculate the ‘willingness to pay’ for each attribute. We also calculated the predicted probability that different combinations of the attribute levels would be selected, allowing us to rank different models of co-ordinated care in terms of their order of preference by the participants.

For further details about the methods employed, see Chapter 6, Methods.

Taxonomy of models of co-ordinated care

We developed and refined a taxonomy (classification) of different models describing how care for people with rare conditions could be co-ordinated. To do this, we conducted interviews and focus groups with stakeholders to derive a draft taxonomy. The sampling framework was designed to capture experience with different models of co-ordinated care. We aimed to conduct up to 30 interviews with national leads on specialist health-care commissioning, national patient groups and charities, and local providers and commissioners of co-ordinated care. We also conducted four focus groups with patients and carers. We then ran a series of workshops to discuss the draft taxonomy. We aimed to run up to five workshops, each with up to 20 attendees. Owing to COVID-19, we ended up amending the study to include two virtual workshops (with up to 15 attendees each), instead of five face-to-face workshops. To recruit for the interviews, focus groups and workshops, we used a range of methods, including e-mail invitation, social media, voluntary sector recruitment and recruitment via our partnerships with four NHS sites.

The interviews and focus groups used topic guides that focused on key aspects of care co-ordination, including use of specialist clinics, information-sharing between specialist and local services, transition from child to adult services, implications of co-ordination on clinic attendance and travel distances, and influential factors affecting the ability to provide co-ordinated care. The sessions were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Iterative and thematic analysis of all data were undertaken concurrently, accounting for outputs from the scoping review, the survey and the DCE. To develop the taxonomy, a combination of inductive and deductive thematic analysis was used (see Chapter 7 for more information).

The resulting draft taxonomy was tested in consensus-building workshops, which aimed to produce recommendations about the taxonomy (see Chapter 7 for more information). A final taxonomy was developed based on workshop feedback.

For further details about the methods employed, see Chapter 7, Methods.

Cost of co-ordinated care

We used the findings from the taxonomy to develop hypothetical models of co-ordinated care (see Chapter 8, Methods, for further details of the development process). These hypothetical models give an example of what co-ordinated care may need to look like in different situations. We aimed to calculate the costs of these models of co-ordinated care using data from both the national survey (see Chapter 5) and the workshops used to refine the taxonomy (see Chapter 7). Unfortunately, it was not possible to use either of these sources. In the case of the survey, most people did not experience co-ordinated care. In addition, it was not possible to attribute the hypothetical models that were developed to survey respondents. In the case of the workshops, the health service utilisation associated with each hypothetical model was unknown by workshop participants, primarily because this was likely to vary according to situation-specific factors. The result was that it was not possible to generate costs associated with each hypothetical model from the survey data or workshop data. Instead, we undertook a review of the costs of different components of co-ordinated care to illustrate indicative costs. For further details, see Chapter 8, Methods.

Chapter 3 Methods and results of a scoping review to define co-ordinated care for people living with rare conditions

Overview

This chapter draws on a paper by Walton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

What was already known?

-

Co-ordinating care may be beneficial to patients and carers, as it may ease treatment burden.

-

Many terms and definitions have previously been used to refer to co-ordination of care (mostly for common chronic conditions).

What this chapter adds

-

This chapter extends previous research by providing an updated definition of co-ordinated care for rare conditions.

-

This chapter extends previous research by identifying and categorising components of co-ordination according to their role within complex care processes.

-

This chapter highlights similarities and differences between co-ordination for common and rare conditions (i.e. many of the components apply to both common and rare conditions, but that there are additional components and context-specific issues that are relevant for rare conditions).

Background

To co-ordinate care more effectively for people living with rare conditions, we need to be able to define what co-ordination means. A clear definition could help researchers and stakeholders to understand care co-ordination for rare conditions and identify situations where services are not co-ordinated and may require improvement. Identifying key components of co-ordination could help researchers to (1) develop care co-ordination programmes and evaluate whether or not components are delivered in practice, (2) identify potential costs, (3) standardise delivery of care co-ordination programmes (where appropriate)16 and (4) identify components that are applicable to both common and rare conditions or that are most relevant to rare conditions. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no previous reviews that have focused on care co-ordination for rare conditions only6 and, therefore, it would not have been possible to focus this review on rare conditions alone. Many, if not most, rare conditions are chronic lifelong conditions. ‘Chronic disease’ is an umbrella term used to refer to a range of long-term conditions, including both common and rare conditions. Therefore, it seemed appropriate to focus this review of reviews on co-ordination for chronic conditions (including both common and rare chronic conditions). Some reviews have been conducted into care co-ordination for chronic conditions;1,17 however, there was a need to update these reviews to include new evidence, given that organisation and technological context for care is likely to have changed significantly since the previous reviews. Therefore, this review of reviews updates our understanding of care co-ordination for common and rare chronic conditions. This review will also extend previous research by supplementing review findings with stakeholder consultations with patients and HCPs who have experience of rare conditions. This will help us to understand if definitions and components of care co-ordination are shared across common and rare chronic conditions or if some are specific to rare conditions.

This review of reviews aimed to extend previous knowledge by providing, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first reviews of care co-ordination for rare conditions. We aimed to:

-

provide an updated definition of co-ordination of care for chronic conditions (both rare and common)

-

identify key components of care co-ordination for chronic conditions (both rare and common)

-

explore whether or not findings apply to rare conditions.

Methods

We followed a recommended systematic approach to our scoping review. We carried out the following six steps:12 (1) defined the RQs, (2) identified relevant studies, (3) selected reviews, (4) charted the data, (5) collated, summarised and reported the results and (6) consulted with stakeholders (Table 2). We followed reporting standards for scoping reviews. 27

| Scoping review stage | Description of our method |

|---|---|

| Defined RQ | All co-authors developed three RQs:

|

| Identified relevant studies | Information sources:

|

| Selected reviews |

|

| Charted data |

|

| Collated, summarised and reported results |

|

| Consultation with stakeholders | Sample:

|

A scoping review methodology was appropriate for this review, as defining co-ordinated care and identifying components of co-ordinated care for common and rare conditions is a broad topic that requires accumulation of evidence from a range of study designs. 12

Stages of the scoping review

We followed these six stages to complete the scoping review.

Stage 1: defined research questions

We developed three RQs (see Table 2).

Stage 2: identified relevant studies

We searched electronic databases, hand-searched key journals and reference lists of included reviews and asked experts to identify missing papers. Details of our search and inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table 2 (details of the search terms are provided in Appendix 1).

Stage 3: selected reviews

One reviewer conducted the search and reviewed titles, abstracts and then full texts against the exclusion criteria. A percentage of titles (40%), abstracts (30%) and full texts (5%) were independently screened by a second researcher. Researchers met to discuss discrepancies.

Stage 4: charted data

A data charting form was developed and used to chart data for all included reviews. Data included aims of the review, type of review, outcome measures and results in relation to definitions of co-ordinated care and components of co-ordinated care. We defined components as individual aspects of care that may be important for co-ordination. We extracted information on definitions and components of co-ordination from the whole review paper. We extracted all components reported in review papers (including those reported from individual studies within the review). Although we have research demonstrating the potential benefits of co-ordinated care (see Chapter 4), we do not yet know what effective co-ordination looks like. Therefore, we did not judge effectiveness of components. Instead, we aimed to identify components across the spectrum (e.g. from lack of co-ordination through to potentially good co-ordination). A second researcher extracted data from 10% of reviews. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

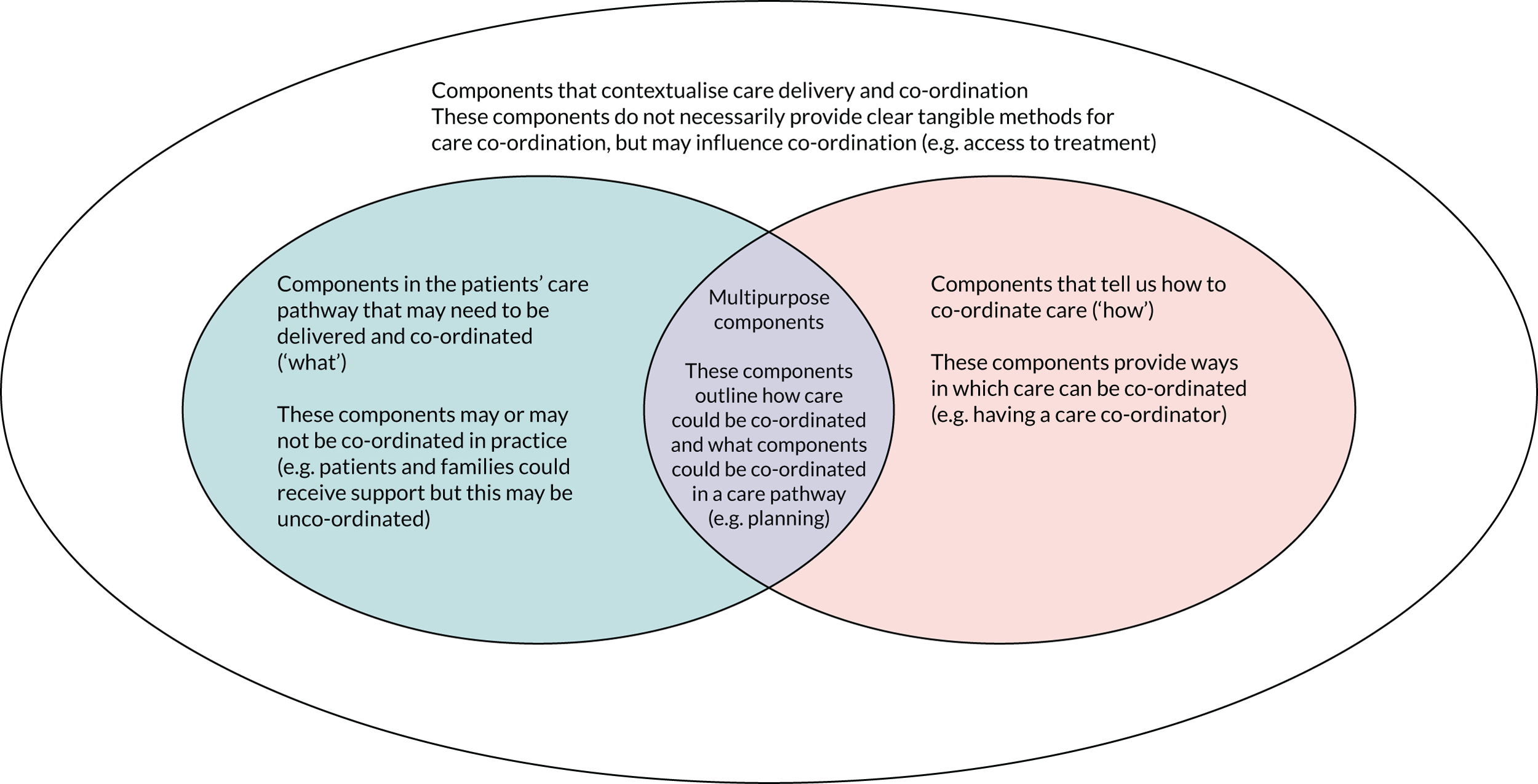

Stage 5: collated, summarised and reported results

Narrative synthesis was used28 to develop definitions and identify and group components. A second researcher grouped 10% of components independently. To develop a definition of co-ordinated care, we coded individual definitions inductively. Codes were grouped by one researcher and used to develop a preliminary definition, which was reviewed and amended by the wider research team. Components were coded and grouped by one researcher. Examples of groups included ‘planning’, ‘methods of co-ordination’ and ‘approaches of co-ordination’. A second researcher double-coded 10% of components into groups. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. Groups of components were developed into themes and subthemes, and the number of reviews that reported each theme, subtheme and component was recorded. The themes were (1) care pathway (i.e. components that related to the care pathway), (2) approaches (i.e. components relating to care/co-ordination approaches), (3) support (i.e. components relating to support), (4) features (i.e. components relating to features of care) and (5) wider environment. Each theme had a number of subthemes that each contained multiple components. Once themes and subthemes of components had been developed, individual components were then reviewed and categorised into four types of components (Figure 2). The wider research team also reviewed and agreed on the categorisation of components.

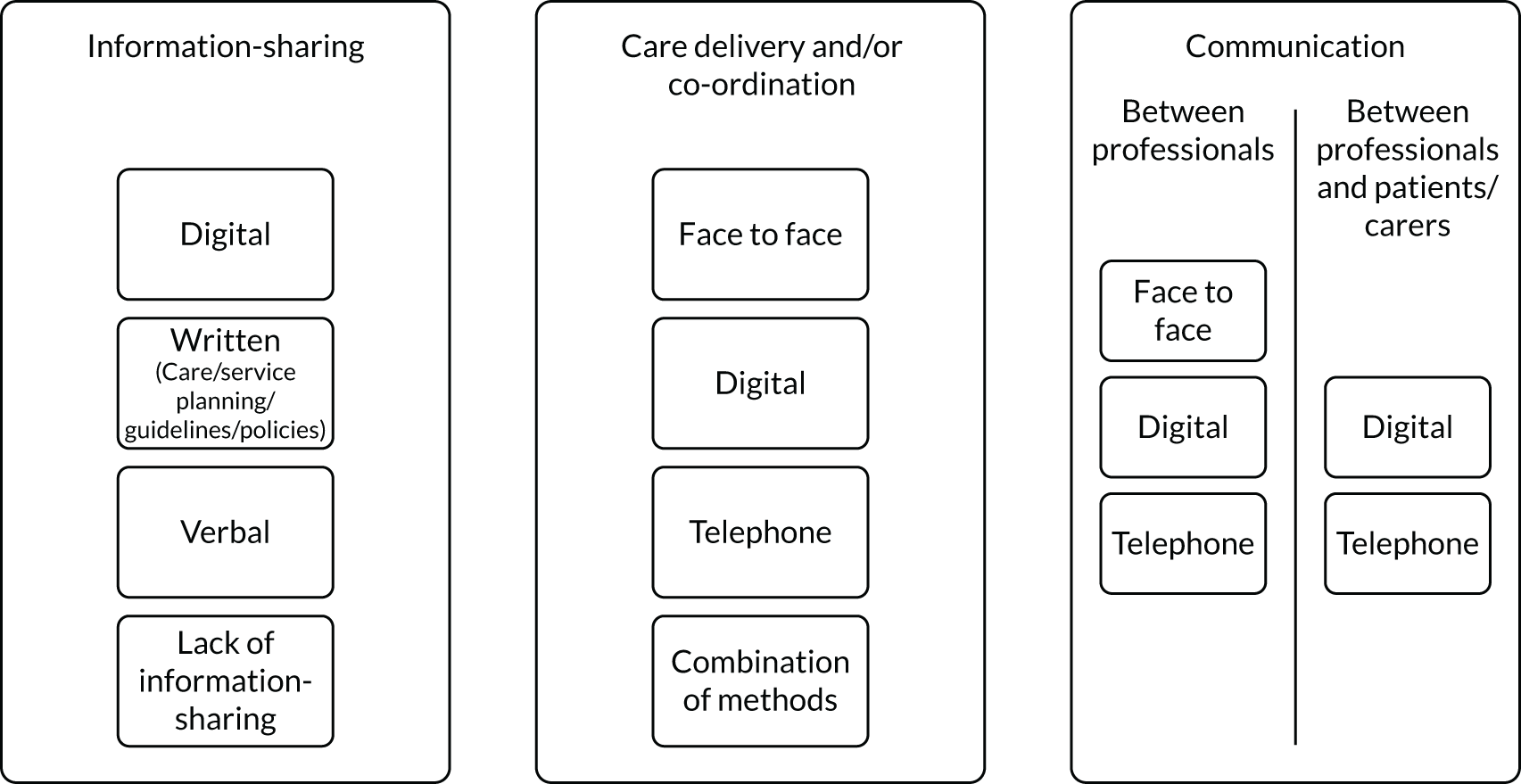

FIGURE 2.

Categorisation of components of co-ordinated care. This figure is adapted from Walton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Stage 6: consultation with stakeholders

Three focus groups were conducted with adults aged ≥ 18 years (two focus groups with patients and carers and one focus group with HCPs). Participants provided informed consent for participation. A structured topic guide was used to facilitate conversations (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The guide included participants’ background, thoughts on definitions of co-ordinated care, views on scoping review findings, relevance of findings to rare conditions, missing components and components that worked well or were difficult. Participants were asked to reflect on a summary of early findings, including definitions from review papers and examples of components, from the review at varying stages of the review process. The short summary included information on the purpose of the review, a summary of some of the definitions that had been found so far and a table with examples of components of co-ordination (i.e. individual aspects of care that may be important for co-ordination) that we had identified from the review. Participants were asked to read this summary before the focus group.

Focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed (by a professional transcription company), checked for accuracy and fully anonymised. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. Two researchers inductively coded the focus group transcripts. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data in relation to the three RQs. Findings were discussed with the research team and refined. Stakeholder consultation findings were used to identify the relevance of the definition and components identified from the scoping review in the context of rare diseases. The Results section in this chapter integrates both the scoping review findings and the stakeholder consultation findings to highlight aspects of stakeholder consultation findings that supported, refuted or extended scoping review findings.

Results

Review characteristics

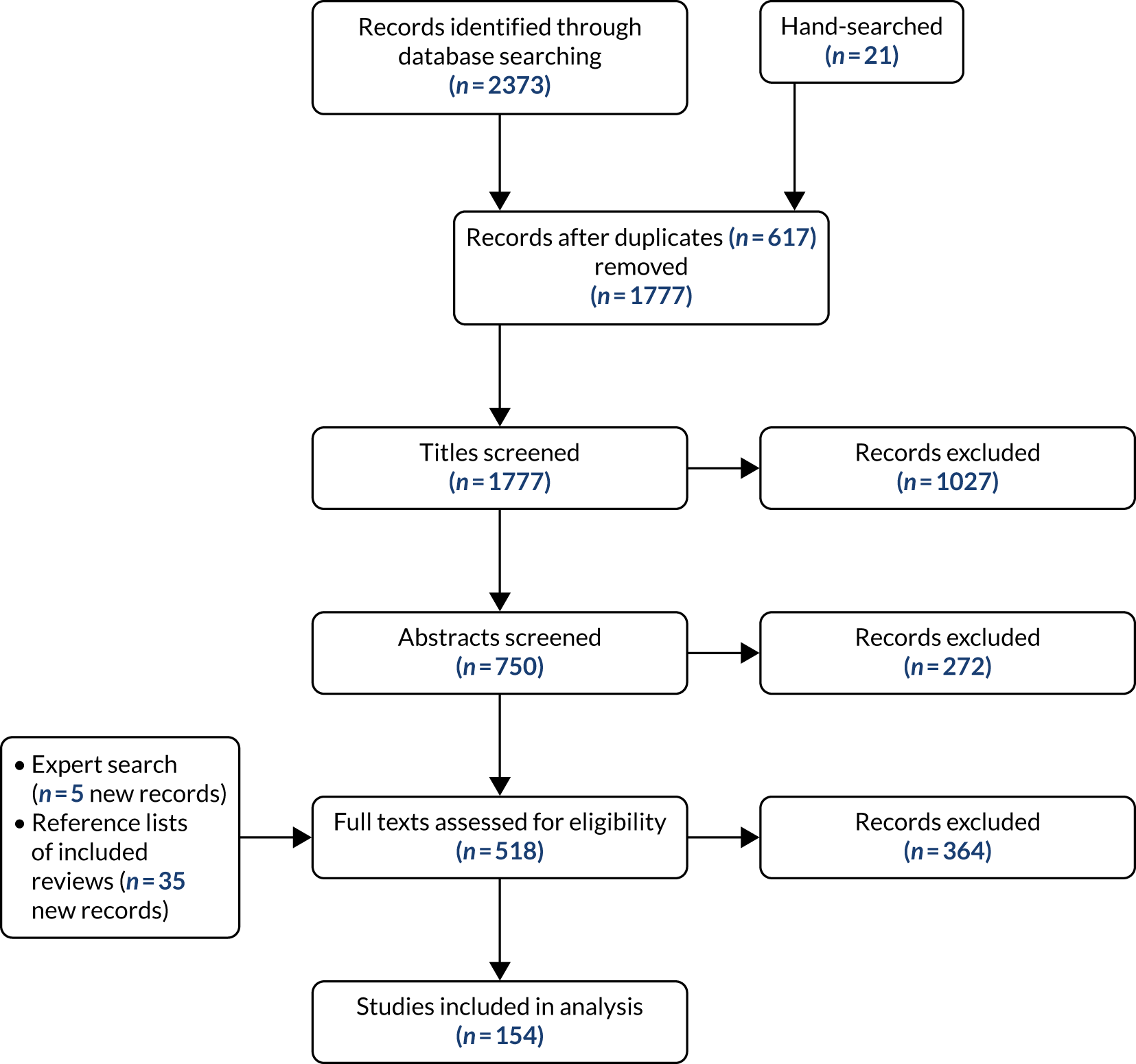

We included 154 review papers22,29–181 (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for characteristics). Figure 3 outlines the review selection process. Common chronic conditions were reviewed in 139 reviews. Only three reviews focused on a single rare condition and 12 reviews focused on both rare and common chronic conditions.

FIGURE 3.

The study selection process (based on Moher et al. 182). This figure is adapted from Walton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Stakeholder consultation characteristics

Stakeholder consultation participant characteristics are shown in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Focus group (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Mode of delivery | Virtual | Face to face | Face to face | |

| Number of participants | 7 | 4 | 6 | 17 |

| Type of participant | ||||

| Patients | 4 | N/A | 2 | 6 |

| Parents/carersa | 3 | N/A | 4 | 7 |

| HCPsb | N/A | 4 | N/A | 4 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Female | 6 | 4 | 3 | 13 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 29–59 | 6 | N/A | 3 | 9 |

| ≥ 60 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 3 |

| Not specified | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| One specific rare condition | 4 | N/A | 3 | 7 |

| Multiple chronic conditions (including at least one rare condition) | 2 | N/A | 3 | 5 |

| Undiagnosed | 1 | N/A | 0 | 1 |

| Number of regionsc represented | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

What does co-ordinated care mean for rare conditions?

Many terms and definitions were used to describe co-ordinated care (see Appendix 2 for the terms and definitions used). Stakeholder consultation findings indicated that terms and definitions were relevant for rare conditions, with some aspects emphasised [e.g. communication, expertise and multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)] or new aspects highlighted (e.g. the importance of care co-ordination being delivered equitably across geographical areas, individualisation, importance of the whole family and need to co-ordinate across a person’s whole lifetime).

From these findings, we developed a definition of co-ordinated care for rare conditions:

Co-ordination of care involves working together across multiple components and processes of care to enable everyone involved in a patient’s care (including a team of health care professionals, the patient and/or carer and their family) to avoid duplication and achieve shared outcomes, throughout a person’s whole life, across all parts of the health and care system, including: care from different health care services . . . care from different health care settings . . . care across multiple conditions or single conditions that affect multiple parts of the body, the movement from one service, or setting to another. Co-ordination of care should be family-centred, holistic (including a patient’s medical, psychosocial, educational and vocational needs), evidence-based, with equal access to co-ordinated care irrespective of diagnosis, patient circumstances and geographical location.

What are the components of co-ordinated care for rare conditions?

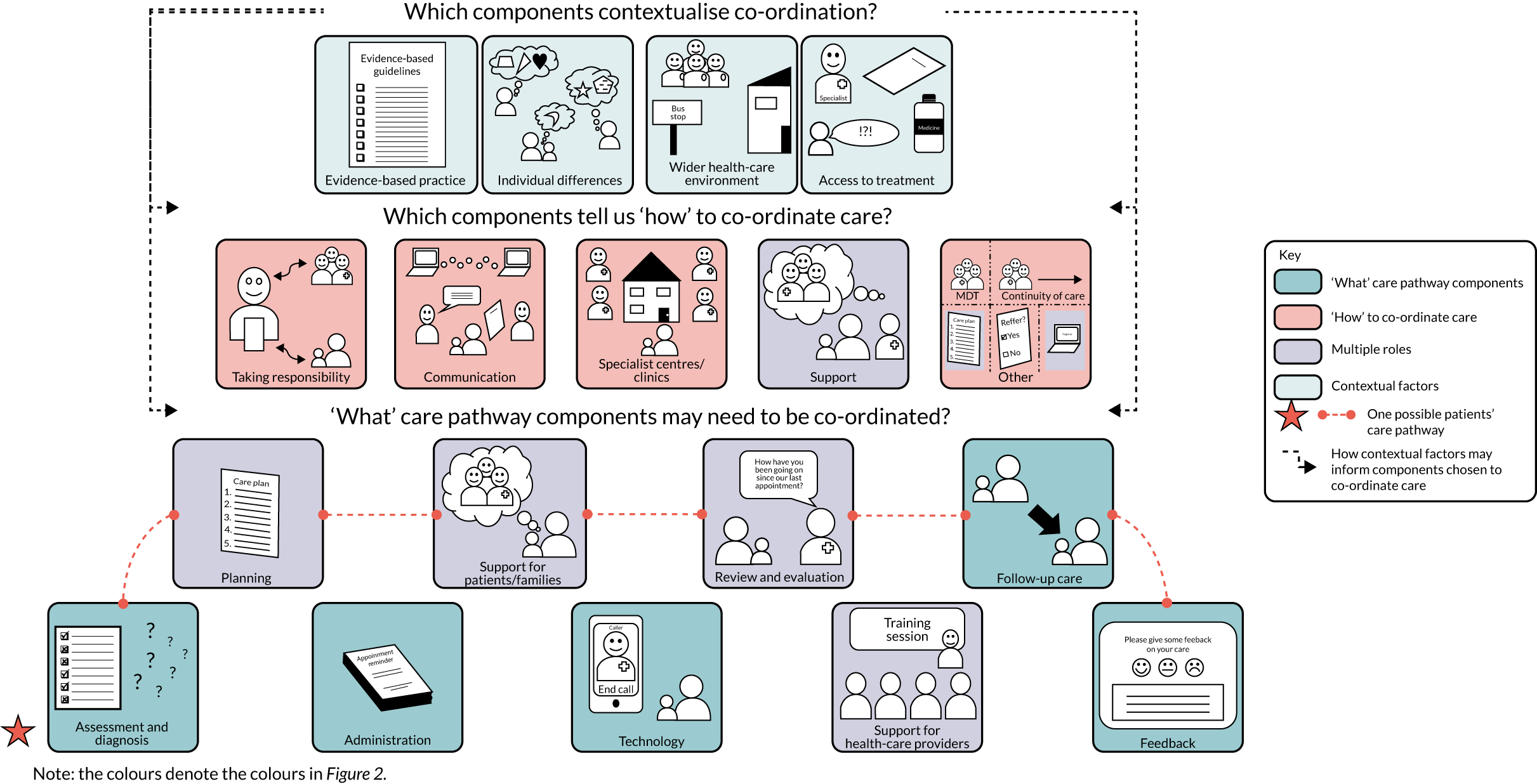

We identified many components of care co-ordination. Figure 4 provides a summary of components identified through the review and stakeholder consultation findings. Throughout Results, we give examples of components and the percentage of reviews (n = 154) that reported each component (see Appendix 3). We also present findings from the stakeholder consultation (see Appendix 4). In this chapter, we briefly describe the components in relation to the review findings and stakeholder consultation findings. For a more in-depth analysis of these components, please refer to the published manuscript. 15

FIGURE 4.

Summary of components of care co-ordination (from review and stakeholder consultation findings). This figure is adapted from Walton et al. 15 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Components indicating ‘what’ care pathway components need to be co-ordinated

Scoping review findings indicated that components relating to administration, assessment and diagnosis, planning, review and evaluation, feedback, follow-up care and technology were frequently reported (development of care plans, 61.7%; follow-up care, 52.6%; monitoring, 51.3%). Stakeholder consultation findings highlighted that although these components are important, patients and carers do not always receive these components in practice (e.g. a lack of care plans and regular reviews were identified):

I’m thinking of review and evaluation with the therapist and on in-community. So, for people with rare conditions, there’ll be a period of intervention, then all will go quiet, everything’s being managed well, and then some other problem will come up, but the way therapists work is that there’ll be a period of intervention, measured outcome, closed case, no contact kept until a crisis down the road and they come back, and when I was in that position, I always wanted to be able to keep that person under review [. . .] because you were then managing a situation before it became a crisis.

FG-HCP

Scoping review findings also highlighted many support components that need to be co-ordinated, including support for patients, carers and families (education/skills training for patients, 73.4%; self-management support, 54.6%) and support for HCPs (education, 32.5%; training, 31.2%). Stakeholder consultation findings highlighted that support for patients and families across a range of needs (including medical, psychological, practical, emotional and social) and from various people (including health-care providers, peers, schools and patient support groups) is important. Findings also highlighted that support for HCPs (to access specialist knowledge and to address fears and anxieties) is necessary when co-ordinating care for rare conditions. Despite the importance of support, patients reported a lack of support and information provision for rare and undiagnosed conditions.

Components indicating ‘how’ care can be co-ordinated

Five main groups of components that outline ‘how’ care can be co-ordinated were identified. There is potential overlap between some of these components, and they are not mutually exclusive.

Someone taking responsibility

Scoping review findings highlighted frequently reported components relating to HCPs, patients and/or carers taking responsibility (co-ordination, 70.8%; responsibility for co-ordination by one health-care provider, 70.8%; patients co-ordinating own treatment, 16.9%). Stakeholder consultation findings highlighted that responsibility is key for co-ordination for rare conditions. However, it was not clear who should take responsibility (e.g. HCPs vs. patient/carers). Some participants thought that patients and carers may be best placed to co-ordinate, whereas others did not want patients to co-ordinate care:

I think having a consultant who takes the lead has been the best thing for me, that’s been the most helpful because I ring his secretary for everything and he knows that it’s his responsibility and he took responsibility but just for himself, he didn’t do it because he’s being paid to do it he just recognises that we were really sinking.

FG-PC1

Some participants wanted to be seen as partners, with control over some aspects of co-ordination, but not everything. Administrative co-ordinators were also perceived to be valuable. Findings indicated that a model of co-ordination that suits the whole family’s needs and situation should be negotiated:

Well, very similar, I mean, when it comes to co-ordination I think it’s about, for me anyway, I’d like to be in partnership with somebody rather than me doing it all but also because these sorts of illnesses, disorders, whatever, there is very little I can control about them and this might be the only thing I can have some control over but, yeah.

FG-PC2

Specialist centres/clinics

For specialist centres and clinics, components included single visit approaches (40.3%), joint clinics or consultations (14.9%) and specialist or condition-specific clinics (22.7%). Stakeholder consultation findings indicated that these components are useful for co-ordination, although some potential barriers were identified (e.g. needing funding and clinics not being delivered to standard).

Communication

Scoping review findings outlined that many components related to verbal and written communication (communication between providers and patients, 57.1%; using and sharing documentation, 46.8%; team meetings to discuss co-ordination, 76.6%). Stakeholder consultation findings highlighted a lack of communication in practice for rare conditions (e.g. lack of shared documentation, resulting in patients sharing documents between providers, and a lack of communication between professionals, resulting in patients repeating information):

. . . you know, you should have access and all those people should speak to each other because it’s an interconnected condition and they don’t, in fact it’s quite hard to find a single person who knows.

FG-PC1

Forms of identification for rare conditions may facilitate co-ordination (e.g. pendants and health passports). Many components identified in the scoping review related to technology (electronic medical records, 22.1%; teleconferencing, 22.7%; reminders for professionals, 20.1%; reminders for patients, 7.1%). Stakeholder consultation findings highlighted that technology may improve communication and, therefore, co-ordination. The need for joined-up systems was highlighted as key for co-ordination; however, this is currently not happening in practice.

Support

Scoping review findings highlighted that care could be co-ordinated through different types of support for patients and families (education and skills training, 73.4%; general support for patients, 68.2%; opportunities to familiarise with services, 9.7%; support for carers, 26%) and for HCPs (training, 31.2%; education, 32.5%; supervision, 30.5%). Stakeholder consultations highlighted the importance of patient organisations and charities that support patients and carers to develop expertise to take control over their condition and co-ordinate care. Providing patients, carers and HCPs with the opportunity to familiarise themselves with services, and development of clear expectations around co-ordination and self-management support, may help develop patients’ and carers’ expertise to co-ordinate and self-manage their care. Stakeholder consultation findings also highlight the important role that schools play in co-ordination for patients with rare conditions.

Other methods

Other components included MDT approaches (76.6%), continuity of providers (14.9%) and development of care plans (61.7%). Stakeholder consultation findings highlighted a lack of care plans for rare conditions, despite their importance for co-ordinating care in both everyday situations and emergency situations.

Components that contextualise co-ordination

Scoping review findings show that evidence-based practice (guideline-based treatment, 37%; evidence-based treatment protocols, 35.1%), individual differences and the wider health-care environment (access to care, 31.2%) may influence co-ordination. Stakeholder findings concurred with scoping review findings, but highlighted a lack of care pathways and defined standards for rare conditions and emphasised that treatments are not delivered consistently (where standards are available):

. . . it’s, having those clear pathways . . . and having something that people can, you know, work towards which is really clear . . . Even though it’s very rare, it’s, like, ‘OK, this is the process now’, and that’s really important . . . And I think that makes the systems work a lot better if there is something like that in place. I think when it’s wishy-washy or it’s not clear, or there is no clear, kind of, guidance or pathways, and because some of the situations are quite, you know, specialised, I think it’s difficult, it’s very difficult to manage.

FG-HCP

Participants reported having to travel to access care and that they were happy to do so if it meant that they received expert care. One of the key issues preventing patients with rare conditions from accessing care was a perceived limited availability of HCPs with expertise in their condition. To take limited expertise in each condition into account, findings also indicated the need to succession plan by training more experts.

Can the definitions and components of care co-ordination from common chronic conditions be applied to rare conditions?

Stakeholder consultation findings indicated that components identified through the scoping review were comprehensive and relevant for rare conditions. Although our findings highlighted that the components identified in the scoping review are relevant when co-ordinating care for people with rare conditions, we found that patients experienced a lack of co-ordination (e.g. having to attend multiple appointments on different days, gaps and delays in information-sharing and disagreements between professionals). There were particular concerns around emergencies and the necessity for patients to take control themselves to mitigate worries:

But why are we living in a world where we have to pick one or two or three of these? Why can’t it be all of them?

FG-PC1, patient

Certain factors may make it more difficult to co-ordinate care for rare conditions (e.g. difficulties in diagnosing rare conditions due to a lack of knowledge and ability to recognise symptoms and limited condition-specific expertise due to small numbers of patients).

Participants expressed views that some components were missing or may need to be emphasised for rare conditions. These included having someone to take responsibility for co-ordination, genome-based medicine/genetic screening, social support needs, counselling, and antenatal and bereavement care. In addition, participants expressed views that more focus should be given to undiagnosed patients and families for many of the components.

Discussion

Key findings

Co-ordinated care for people affected by rare conditions requires working together across multiple components and processes of care to ensure that everyone involved achieves shared outcomes throughout a person’s whole life and different parts of the health and care system. Our definition encompasses the idea that for rare conditions co-ordinated care should be family centred, evidence based and equitable for all.

These findings suggest that many of the key components and issues for co-ordinated care apply to both rare and common chronic conditions. Stakeholder consultation findings revealed additional components and context-specific issues that are relevant in the context of rare conditions.

How findings relate to previous research

Our findings extend previous research1,117 by developing a definition of care co-ordination for rare conditions.

Previous research proposed that it is difficult to distinguish between aspects of care and co-ordination components. 17,183 Our findings extend previous research, as we have grouped components according to their roles, situating components within the wider health-care pathway and environment. Our four categories overlap with those outlined in previous research,1 but clarify how co-ordination components may be involved in complex care processes.

Our review highlights that little is currently known about co-ordination for rare conditions (as most of the reviews focused on common chronic conditions). Despite similarities in need, stakeholder findings suggest that co-ordination for rare conditions may be less consistent in practice,5,8 as many of the components identified were not delivered effectively or consistently for people with rare conditions, let alone co-ordinated. These differences may be attributed to complexities associated with rare conditions (e.g. that rare conditions affect multiple body parts, children, may be lifelong, need to be co-ordinated across multiple sectors and bring complexities of diagnosis due to limited expertise). These complexities suggest that more care co-ordination is needed in cases of greater system fragmentation, clinical complexity and decreased patient capacity. 1

Limitations

We used inclusive definitions for co-ordination and chronic conditions, and reviews covered a range of countries. We are unlikely to have captured every relevant review. To identify as many studies as possible, we conducted a comprehensive search, which included contacting experts and searching the reference lists of included reviews.

It is possible that the reviews that we included in this research may not have captured all evaluations of care co-ordination in practice. Therefore, publication bias may be present. However, we used many approaches to minimise this risk, including expert consultation and stakeholder consultations.

Components reported in published descriptions of interventions do not necessarily equate to the delivery of all components and, therefore, this review is limited to the components reported in the reviews. In addition, individual studies may be included in more than one of our included reviews. We based our analysis on the wording reported in the review papers and not individual studies.

This review focused on the identification of co-ordination components, rather than testing the effectiveness of co-ordination. The effectiveness of individual components, or combinations thereof, on relevant outcomes (e.g. reduced waiting times, better health-care outcomes and better experience) is not known.

Although the scoping review provides insight into the components that are involved in co-ordination, given the small number of stakeholders included in the scoping review, it was not always possible to provide further specifics regarding whether or not different components of co-ordination may be suitable for different conditions and situations (e.g. regarding the findings on who should take responsibility for co-ordination). However, this is something that is explored in our survey, DCE and taxonomy development work (see Chapters 5–7).

Implications

Our findings provide support for various international policy initiatives. 7,19,24 We identified many components within our review that are reported as necessary for co-ordination. 7 Our findings also show that delivering co-ordinated care is complex because there are many different options for co-ordinating care. Our findings emphasised the need for someone to take responsibility for co-ordination, as outlined in the NHS Implementation Plan,19 but highlight that there are many ways in which responsibility could be managed.

Researchers and clinicians could use the components to begin to develop and evaluate existing and new models of co-ordination for common and rare chronic conditions.

Future research

This review has highlighted different components of care co-ordination. Future research could test and evaluate the clinical effectiveness, implementation and cost-effectiveness of these components in practice. This could be achieved, for example, by identifying current use of these components and evaluating them empirically, either retrospectively or prospectively.

Summary

We have defined co-ordination as working together across multiple components and processes of care to ensure that everyone involved achieves shared outcomes across a person’s whole life and throughout different parts of the health and care system. There are lots of different components that may be delivered and co-ordinated as part of a care pathway, many different ways to co-ordinate care and many factors that contextualise co-ordination. Most of the key components for co-ordinated care apply to rare and common chronic conditions, with some additional components and context-specific issues that are relevant for rare conditions.

Chapter 4 Impact of the way in which care is co-ordinated on patients with rare diseases and their carers

Overview

This chapter draws on Simpson et al. 184 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

What was already known?

-

Care co-ordination is considered important for patients with rare conditions.

-

Research addressing the impact of care co-ordination on patients and carers with experience of rare diseases is limited.

What this chapter adds

-

This chapter explores how care co-ordination (or lack of) has an impact on patients and carers.

-

Unco-ordinated care results in delays and barriers to accessing care and places a burden on patients and carers, which, in turn, has negative effects on patients and carers in terms of physical health, financial and psychosocial impacts.

-

Approaches to co-ordination that improve access to care and lessen the time and burden placed on patients and carers may be particularly beneficial.

Background

Limited research suggests that there may be both financial and non-financial ‘hidden’ impacts for patients and their families affected by rare diseases, associated with how care is co-ordinated,6,185 including:

-

psychological and emotional challenges resulting from high turnover of HCPs and a lack of information and knowledge among professionals186

-

stress and financial concerns for parents due to the burden associated with planning and co-ordinating care to meet the unique needs of their children187

-

a substantial time burden for patients and carers, in part, because of co-ordinating their care. 18

However, the evidence base is weak. Given the paucity of data in this area, the aims of this study were to explore:

-

how rare disease patients and their carers are affected by how their care is, or is not, co-ordinated

-

the factors that might influence effective care co-ordination from the patients’ and carers’ perspective.

Methods

This was an exploratory qualitative interview study of patients affected by rare conditions (including undiagnosed conditions) and their carers. We recruited patients and carers (including parents of patients and spouses/partners of adult patients) affected by rare conditions in the UK. Participants were recruited from charity networks [Genetic Alliance UK, Rare Disease UK and Syndromes Without A Name (SWAN) UK (London, UK)] using a purposive sampling method. An advert inviting interested individuals to contact the research team was disseminated via e-mail (including newsletters and members’ updates), social media and charity websites. In October 2018, 15 participants were selected from 60 interested individuals. The sample was chosen to include patients and carers, those with and without a diagnosis and those with a range of co-ordination experiences (including those who had a professional co-ordinating their care and those who co-ordinated care themselves, and those who attended a specialist centre and those who did not). Participants were also selected to represent a range of ages and locations across the UK.

Interviews were semistructured and conducted by telephone or Skype. All participants received a participant information sheet and consent form via e-mail and were given the opportunity to discuss the study and ask the researcher questions before they agreed to take part. Verbal informed consent was taken and recorded at the start of the interviews. Fifteen interviews were conducted between October 2018 and January 2019 (telephone, n = 14; Skype, n = 1). Interviews were recorded using an encrypted dictaphone and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcribing company.

The interview included questions about how care was currently organised and how individuals would like it to be organised, what was important to them in relation to care co-ordination (and how this might change over time), and the costs and benefits associated with how care is co-ordinated.

A draft coding framework, including both anticipated and emergent codes, was developed based on previous studies6 and open-coding of two transcripts by two members of the research team. Three transcripts were then independently coded by two researchers, who met to share their coding. Any disagreements were discussed until a consensus was met. The revised coding frame was then applied to all remaining transcripts. To develop themes, a process of iterative categorisation188 was followed to systematically reduce, review and summarise the data.

Results

Participant characteristics were collected prior to interview for the 15 interviewees. Participants included patients affected by rare diseases (n = 7) and carers (n = 8). Carers were all informal carers [they were either the parent of a child with a rare disease (n = 6) or the spouse/partner of an adult with a rare disease (n = 2)]. Participants were a range of ages, from a range of geographical areas, some were affected by a diagnosed condition and some by an undiagnosed condition, and had a mix of experience in terms of access to a specialist centre.

Findings are grouped under the following three headings: (1) Experiences of unco-ordinated care for patients with rare conditions, (2) How unco-ordinated care impacts on patients and carers and (3) Examples of co-ordinated care and approaches to reduce the negative impacts of unco-ordinated care on patients and carers.

Experiences of unco-ordinated care for patients with rare conditions

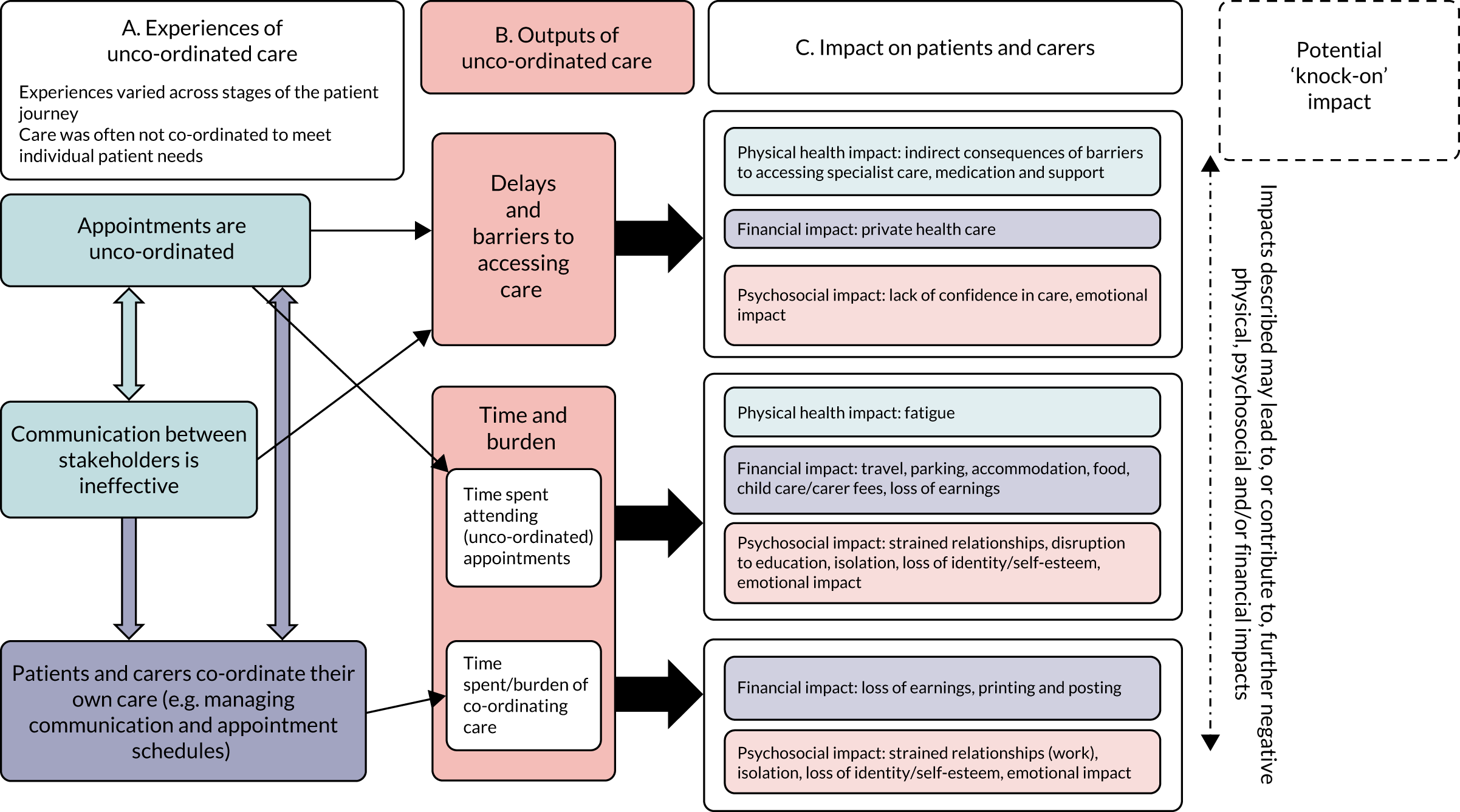

Participants described a range of experiences of unco-ordinated care (Figure 5, section A), which included the following:

-

unco-ordinated appointments [i.e. unnecessary frequent appointments to see different professionals/services across different NHS settings, some of which were located far from home (i.e. at specialist centres), lack of choice about when or where their appointments took place and appointments with one professional at a time (with little evidence of medical and non-medical services being offered in the same clinic)]

-

ineffective communication between professionals and between professionals and patients/carers [i.e. lack of communication/team approach across various care professionals (particularly between those in specialist centres and local teams), no point of contact to approach with queries, problems relating to information-sharing (particularly the timeliness of information-sharing) and limited use of care plans]

-

patients and carers co-ordinating their own care (i.e. patients and carers undertaking a number of tasks, including chasing services, holding information and facilitating information-sharing, with many reporting being the main co-ordinator of care).

Experiences of unco-ordinated care varied across individuals and stages of the patient journey. For example, there were challenges associated with emergencies or acute episodes (with a lack of awareness locally and difficulties accessing timely treatment), establishing care and support pre and post diagnosis, following discharge from hospital (and receiving the appropriate care within the community) and transitioning from paediatric to adult services.

FIGURE 5.

Patients’ and carers’ experiences of unco-ordinated care and its impact. This figure is reproduced from Simpson et al. 184 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

How unco-ordinated care impacts on patients and carers

Unco-ordinated care resulted in delays and barriers to accessing care and placed an additional burden on patients and carers (see Figure 5, section B). These delays and barriers, in turn, had several negative impacts for patients and carers (see Figure 5, section C).

How did unco-ordinated care influence patients’ access to care?

Interviewees reported that unco-ordinated appointments and ineffective communication between stakeholders had an impact on their ability to access care and access that care in a timely way. Seeing numerous professionals over several different appointments resulted in delays in decision-making about their care. Delays were also evident as a result of ineffective communication between professionals and information-sharing across different trusts/services. Interviewees reported wasting time during appointments due to updating professionals and/or waiting for professionals to chase results.

Initiatives that could facilitate communication between professionals (e.g. care plans or multidisciplinary meetings) were limited. Therefore, even for those patients who accessed specialist care (i.e. via a specialist centre), the location and accessibility of specialist care/advice combined with the lack of effective communication between local and specialist teams resulted in challenges, particularly in accessing local care during acute scenarios:

I would imagine a lot of people with rare diseases find this: that when they turn up at their local hospital whoever is on-shift generally has no idea what you’re talking about so you always have to go back to your consultant [and] there could be delays.

Parent of a child, diagnosed

More than one interviewee reported facing delays in accessing their medication, again as a result of ineffective communication between specialists and local services. Patients and carers reported that health and other sectors, such as social care, did not communicate with each other, sometimes preventing vital access to non-medical support:

. . . it’s terrible the co-ordination between the social work side of things and the health side of things. It took us 18 months actually to get a social worker, which seems crazy given that my son has a really profound disability.

Parent of a child, diagnosed

How did the challenges associated with access to care have a negative impact on patients and carers?

Barriers and delays were likely to have consequences for patients and carers. First, barriers and delays had a negative impact on a patient’s physical health, particularly if diagnosis or treatment was delayed. Second, barriers and delays had a financial impact on families, with participants reporting paying for private health care as a last resort as a result of delays or fighting for access to care. Third, barriers and delays had psychosocial impacts, with patients and carers reporting a significant emotional impact of having to fight for their care after experiencing a loss of confidence in the care they received:

Our main problem was obviously getting access to a doctor . . . who could do the appropriate tests . . . when [respondent’s son 1] developed that squint . . . which was kind of about a year before, he should have been referred to a neurologist at that point.

Parent of a child, diagnosed

It was also noted that impact on physical health was likely to have further ‘knock-on’ impacts for patients and carers. For example, poorer physical health could result in the need for more medical intervention, which, if unco-ordinated, could magnify many of the issues already faced, including increased challenges associated with daily activities, such as going to work (carrying further financial and psychosocial costs).

How did unco-ordinated care create additional burden on patients and carers?

Patients and carers described the time and burden placed on them to attend frequent and unco-ordinated appointments, with patients and carers spending significant time travelling to and attending various appointments. In addition, some patients and carers reported having to co-ordinate their own care, including supporting communication/information exchange and organising their vast appointment schedule. In the absence of care co-ordination (and tools, such as co-ordinators or care plans) families described having to adopt a proactive approach themselves to ensure that they received the right care. This involved spending significant amounts of time chasing services for results, appointments and advice:

I’m the one that chases appointments and makes sure that we’re where we’re supposed to be . . . a huge amount of work but how can that really be improved?

Parent of a child, diagnosed

A major task for families related to the management of information relating to the condition and the patient’s care. Participants suggested that the records kept by professionals were sometimes incomplete or inaccurate. As a result, patients and carers were often required to update or correct professionals at each appointment. Some kept detailed paper records at home, rather than relying on the records kept by professionals:

. . . If I ever got hit by a bus, we’d be screwed. Well, I wouldn’t be obviously, I’d be completely blissfully unaware, but he would be stuffed because all of this stuff is in my head.

Parent of a child, undiagnosed

The time and burden associated with attending appointments and managing a care schedule affected all patients to some extent (including those with positive experiences of co-ordinated care). However, interviewees reported that the costs were increased by (1) the unco-ordinated nature of appointments, that is they were required to travel far and frequently for services that could, in theory, be offered locally and/or in one visit rather than several, and (2) a lack of effective communication between the various professionals involved across specialties and locations.

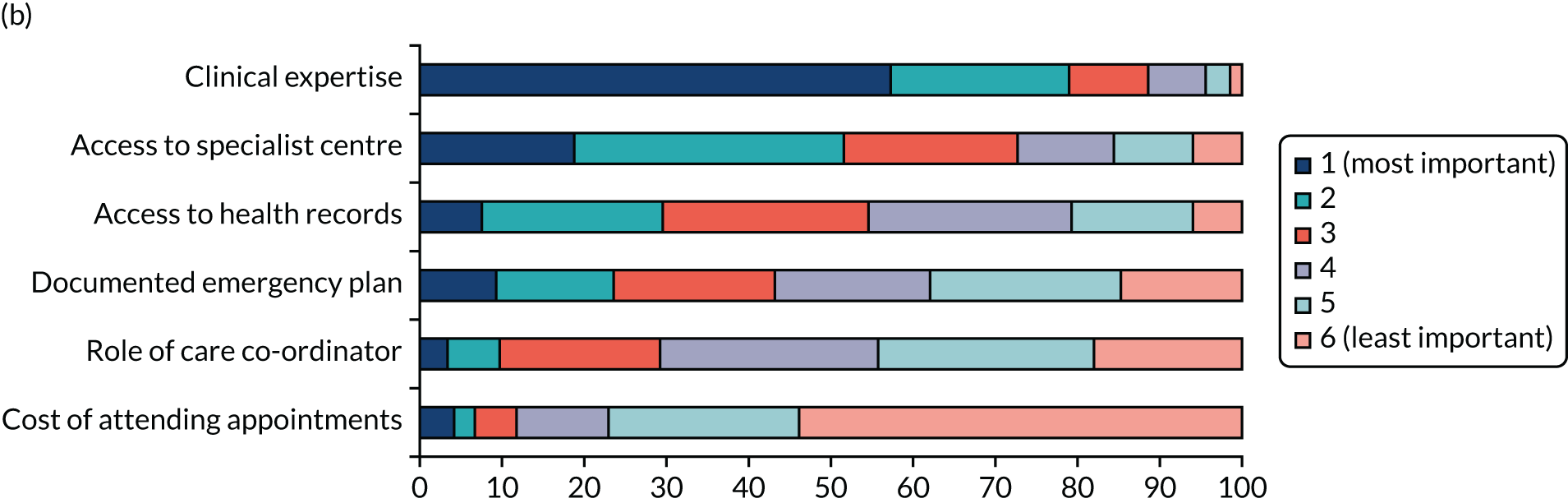

How did the additional burden have a negative impact on patients and carers?