Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/197/44. The contractual start date was in February 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in November 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Butler et al. This work was produced by Butler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Butler et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Context

Hospice and palliative care services in England

The UK is world-leading in hospice and palliative care (H&PC) services, which care for people with life-limiting health conditions and those approaching the end of their lives. 1 These services are small or extremely small players operating in a complex system of health and social care that people approaching the end of life must use and navigate. Hospice services in the UK historically began in the charitable sector, and most of the funding for H&PC services continues to be derived from charitable sources. H&PC organisations are also in receipt of NHS funding (on average, the NHS contributes 32% of total funding to hospices in England2) and are subject to NHS commissioning processes. These factors, together with their small size, provide a range of challenges for H&PC organisations in terms of funding and sustainability.

Individual H&PC services have developed in localities as a result of voluntary activity led by key local people. There is a strong sense of ownership in communities of their ‘local hospice’, which continues to be vital for fundraising activities and generates a large supply of willing volunteers. The reputation of the hospice, both as a worthy, local charity and for excellence in care, is held very dear for all of these reasons . The public’s sense of identification with its local hospice tends to focus on the bricks and mortar building, and there is often less awareness or understanding of palliative care community services, including hospice at home (HAH) services.

National strategic direction

National strategy in England sets further context in terms of the drive towards encouraging choice about where people receive care and increasing the opportunities to be cared for and to die at home (moving away from the acute hospital sector). 3 This would seem to be in step with public preferences; evidence suggests that the majority of people would wish to die at home,4 and also indicates that the number of people expressing this wish is increasing. 5,6 Identifying how care can be delivered and maintained at home was a top research priority in a public consultation by the James Lind Alliance in 2015. 7 However, in 2019, only 24.4% of all deaths in England occurred at home (not including care home deaths)8 and it seems that, overall, health and social care services are not well equipped to meet this demand. 9

Another direction of national strategy that provides context for this study is that towards the integration of health and social care. H&PC services lend themselves naturally to this integration because holistic care, recognising the physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of people’s needs, has long been a basic precept of good palliative care. H&PC services routinely employ social care professionals, counsellors and spiritual care staff in addition to health-care professionals (HCPs).

Broader cultural and societal issues

Although H&PC services are prized and respected, as described previously, the reality of talking about and accepting death and dying in contemporary health care is more of a challenge. The public increasingly demands more and better acute, interventional health care into older and older age, staving off the inevitability of the ending of life. In this context, HCPs may lack the skills or confidence to open discussions about curtailing interventional medical care when it can no longer offer benefit and about planning for death and dying. H&PC services, which are so explicitly geared to death and dying, may therefore struggle to be accepted and to attract referrals of people who could benefit from their care. This issue may have even more impact in some cultural or faith communities or among those with diseases other than cancer, which are not as clearly identified with dying.

In addition to these influences, caring for and enabling people to die at home is affected by significant societal changes that have been under way over many decades. It can no longer be assumed that families will live nearby or have the resources to provide unpaid care. Home-based care of any description is heavily dependent on family/informal care, and those without such support have a more limited range of options.

Hospice at home services and the evolution of this project

Hospice at home services sit within this web of factors as a subset of H&PC services, often, but not always, linked to a local hospice organisation and building. Most of these services explicitly aim to support care and dying at home when this is the preferred place of death (PPOD).

In 2007, Pilgrims Hospices in East Kent decided to increase community palliative care provision to enable more patients to die in their own homes. To ensure that these service changes were in line with the best available evidence, a literature review of the evidence for HAH services was commissioned from the University of Kent. The literature review10 indicated that the evidence base for the efficacy of such services was weak, with few controlled studies, although many qualitative studies indicated that such services were appreciated by patients and families. The characteristics of services that appeared to produce the most favourable outcomes included care given by palliative care specialists, out-of-hours (OOH) availability, crisis intervention and rapid-response capability. Based on the findings from the literature review, the hospice designed and implemented a new HAH service.

A successful application to the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit funding stream was made to evaluate the impact of the new service. The evaluation used a quasi-experimental cluster design and the results have been published. 11,12 This new service did not improve patients’ chances of dying in their preferred place (> 60% of patients died in their preferred place in both the intervention and the control groups), although patients in areas where the HAH service was operating had a significantly higher rate of a preference to die at home.

From the results of this study, a number of questions remained unanswered:

-

Is there a better service configuration than the one examined here that would allow more patients to die where they prefer and to have a good quality of death?

-

One of the gaps in this service was difficulty accessing medications, which was, in part, due to challenges in working with other community providers – how can we improve this with our partners in the community?

-

What would be the highest level of achievement of PPOD we could hope to reach, that is what is a realistic gold standard and what services are able to deliver this?

Our collaboration with the National Association for Hospice at Home (NAHH) for this current study confirmed that these questions, and the overall question of ‘what does an optimal HAH service look like?’, were commonly debated across the sector.

An updated literature review confirmed that the published evidence for HAH services continued to demonstrate wide variation in HAH service provision and the settings in which such services operated around England. Services that had been evaluated often demonstrated positive benefits for patients, such as increased choice and dying at home. 13,14 However, the published studies reported such a range of different outcome measures that there was no opportunity to synthesise the data or to make useful comparisons. It was also unclear what elements of HAH services delivered which outcomes and to what extent such outcomes were delivered in conjunction with other services that formed part of the whole system of care. This lack of clarity about what aspects of services produce the desired outcomes for patients (and their families/informal carers) makes sharing good practice between HAH services difficult and limits efficient service development.

Aim and objectives

Parts of this section have been reproduced from Butler et al. 15 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of the organisation, delivery and settings of different models of HAH on patient and carer outcomes and experiences of end-of-life care (EOLC) in England. Given the complexity of the whole system of care used by patients at the end of life, the range and variation of HAH services themselves, and the many different settings in which they operate, a realist evaluation methodology was chosen. 16,17 This theory-driven methodology uses iterative, qualitative data analysis, supplemented in this study by quantitative data, to identify the underlying generative mechanisms that produce outcomes in complex systems. In addition, the study looked at the financial cost of care in the different services and settings.

The overarching research question that the study addressed was as follows: what are the features of HAH models that work, for whom and in what circumstances?

The detailed study objectives were as follows:

-

phase 1

-

identify the range and variation of HAH services operating across England

-

categorise the HAH services into models according to key features and setting

-

-

phase 215

-

assess the impact of each model on patient and carer outcomes

-

investigate the resource implications and costs of patient care in each model

-

explore the experiences of patients, family carers, and providers and commissioners of the different HAH models

-

identify the enablers of and barriers to embedding HAH models as part of service delivery.

-

Report structure

Chapter 2 describes the published literature about evaluations of HAH services in England. As a spin-off from this study, a realist-informed review of the literature was also undertaken and was utilised in the qualitative analysis. 18 Chapter 3 includes information about realist methods, descriptions of the three-phase study design with diagrammatic illustrations and details about the mixed-methods data analysis. Chapter 4 describes the development, management and contribution of patient and public involvement (PPI) in the study. Chapters 5–7 present the results: Chapter 5 presents the results of the survey undertaken in phase 1, Chapter 6 presents the quantitative data and the health economics results and Chapter 7 presents the results of the qualitative data analysis. The synthesis of the overall mixed-methods data set is addressed in Chapter 8, alongside the discussion. Chapter 9 presents the study conclusions, implications for health care, limitations and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Review of the literature

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Butler et al. 15 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

This chapter reports the review of the literature to understand existing models of HAH services in the UK and their evaluation.

Background

Providing patients with choice about where they receive their care at the end of life remains central to UK policy3 and HAH services have been introduced to support patient choice if their wish is to die at home. The number of patients wishing to die at home has been increasing. 5,6 Home palliative care increases the chance of dying at home and reduces patient symptom burden and grief for family carers post death. 19

Stosz10 conducted a literature review in 2008 to establish the evidence base for HAH services. The characteristics identified and the terms describing the services operating included the following: a palliative care service provided in the home environment, OOH, hospital at home, community specialist palliative care, crisis intervention and rapid-response teams. The recommendations from that review were that a successful intervention should include the following:

-

a service operating in addition to existing community services that is available throughout the course of the end stages of illness (particularly in the last few weeks of life when crises may occur)

-

rapid access to specialist input at all hours

-

providing access to medication and equipment

-

viewing the informal carer as integral to the care team and recognising carer burden.

Based on the findings and recommendations of the Stosz10 literature review, Pilgrims Hospices in East Kent developed a new HAH ‘rapid-response’ service caring for adults in the last 72 hours of life. 20 Evaluation of this service was conducted through a pragmatic quasi-controlled trial. 11 Although the new service was cost neutral and enabled more people to die at home, it did not improve hospice patients’ chances of achieving PPOD (primary outcome).

In 2012, the NAHH and Help the Hospices (now Hospice UK; London, UK) collaborated to conduct a multiservice survey (across 76 services in England), which started to describe the landscape of HAH services across the country (Heather Richardson and Andrew Thomson, Hospice UK, 2014, personal communication). The conclusions from this work were that HAH services were not homogeneous and that there were at least two models of care, despite the shared name of HAH. A clear distinction was found between one set of services, delivering high numbers of completed episodes of care (> 50 episodes of care per service per month), and the other set, providing significantly fewer completed episodes of care (< 50 per month). In addition, there were notable differences relating to reasons for referral, episode duration, who was involved in care, and knowledge regarding preferences and PPOD. The recommendations from this survey acknowledged that there was a need to further increase understanding of HAH. There was lack of clarity about what was the best model of care, for example there was uncertainty about skill mix and to what degree teams should incorporate senior staff alongside more junior nurses and social carers (Heather Richardson and Andrew Thomson, personal communication).

The NAHH also published recommendations in the form of national standards for HAH services, which they developed through workshops with HAH service professionals in May 2011, November 2011 and May 2012. These resulted in six agreed core standards, with examples of structural, process and outcome criteria underpinning them:21

-

The HAH service has a workforce management, education and development strategy that ensures the competence and confidence in practice of its employees to deliver and support high-quality clinical services.

-

The HAH service is integrated into the local EOLC service provision and involved in providing co-ordinated care for patients and families.

-

The HAH service clearly defines and communicates referral criteria and pathways to all referrers, key stakeholders and other partners.

-

The HAH service ensures that patients, and their families and carers, receive the service information required to enable them to make informed choices in relation to their preferred place of care and support, including at the end of life.

-

The HAH team’s care and support service, in partnership with other agencies, meets the assessed needs of patients, carers and families.

-

The HAH service has systems and processes to ensure pre-and post-bereavement support for patients (when appropriate), carers and families. 15

The findings from these projects indicated that there was value in HAH as a concept, but led to the broader question of what would be the most successful and cost-effective model of HAH that could improve the outcomes for an even higher proportion of patients whose preference was to die at home, in their area. This prompted a further review of the existing literature, to understand what different HAH models existed in the UK and their value, that is whether or not any comparative data or assessment of optimum HAH service model delivery existed. This review of the literature, initially conducted in 2014, and updated in 2017, 2019 and 2020, is described in the following sections.

Search strategy for hospice at home models, comparators and outcomes

The search sought to identify any type of literature or study that aimed to describe or evaluate a HAH model in the health and social care setting of the UK that was providing care to adults with a life-limiting illness who wished to die at home. The service could be described as a HAH service by name or could potentially be a community service under a different name. Therefore, the search strategy included concepts that could identify these services in the literature. The search concepts were chosen based on the previous literature review. 15

The criteria for selection of articles were as follows:

-

HAH service

-

community service under a different name with clear HAH characteristics:

-

rapid response

-

crisis management

-

24-hour coverage

-

staff in service were palliative care specialists who were hospice trained.

-

-

UK based.

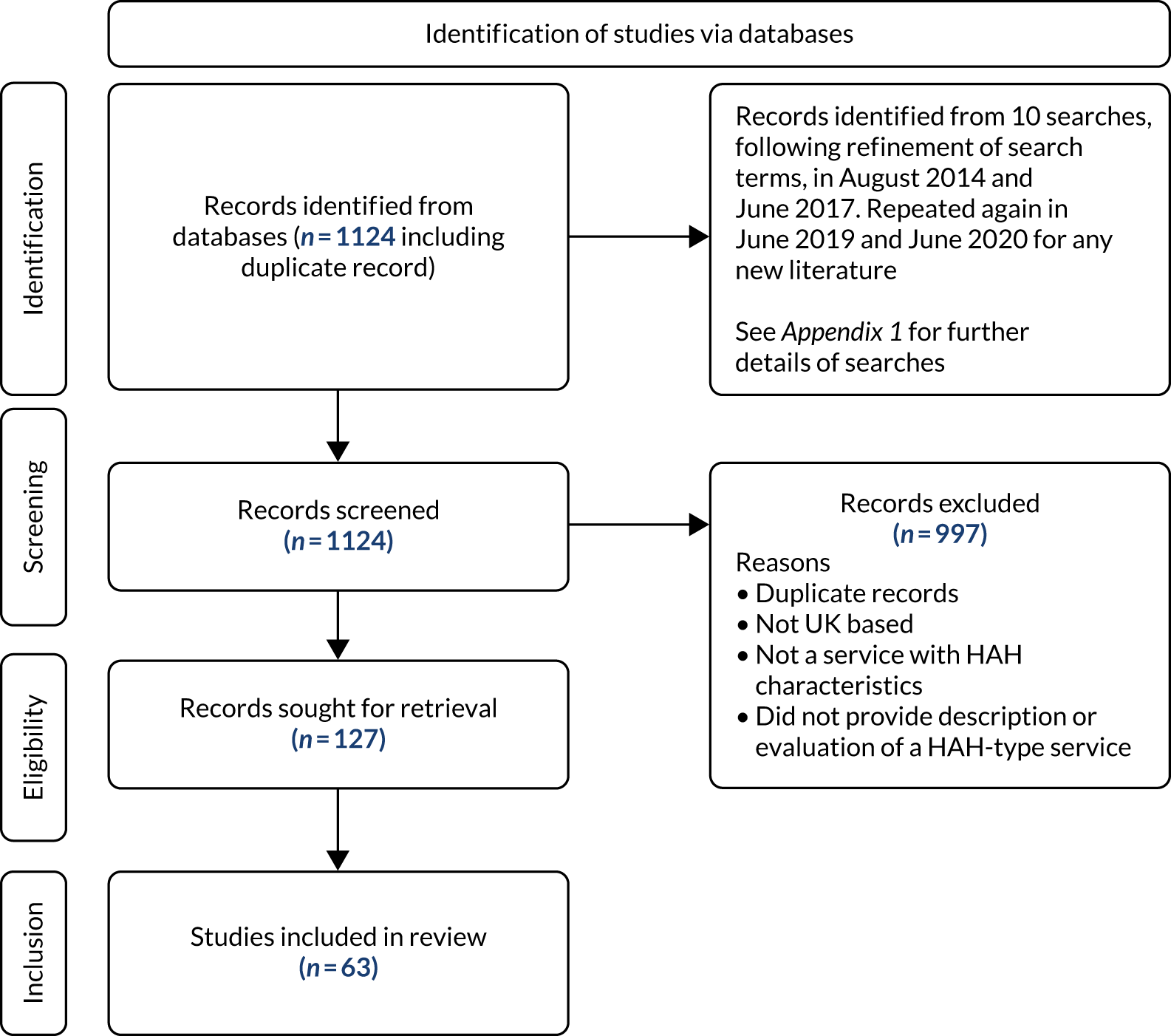

A set of searches was carried out on several databases of academic publications, grey literature and current research (Figure 1; also see Appendix 1, including Tables 19–21, for further details).

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram.

Scoping the literature on service models and evaluations

Sixty-three papers/grey literature sources were identified from the searches. The articles were analysed by recording key information from each article relating to (1) study design and (2) service description (Table 1). This provided information to scope what types of services existed and what work had been undertaken to evaluate them. Any identified barriers to and facilitators of accessing the service, or the service achieving its aims, were also included.

| 1. Study design | 2. Service description |

|---|---|

| Aim of study | Location |

| Population | Description |

| Methods | Aim of service |

| Primary outcome(s) | Rapid-response service? |

| Cost analysis? | Target group |

| Main findings | Definition of HAH provided? |

| Limitations | Barriers |

| Future research suggestions | Facilitators |

Many articles included were evaluations or descriptions of one service model in one locality. However, 13 articles (involving 11 studies) looked at several models of care. Two of these were multiservice surveys to understand and scope HAH models: the NAHH/Help the Hospices survey mentioned previously (Heather Richardson and Andrew Thomson, personal communication) and the survey conducted as phase 1 of the OPtimum hospice at home services for End of Life care (OPEL) study. 22 Eight were literature reviews or syntheses. 5,10,18,23–27 Hashem et al. 18 applied a realist logic of analysis to their review of HAH. Taylor et al. 23 conducted a literature review of the international evidence for models of care supporting effectiveness in reducing inappropriate/non-beneficial hospital bed-days for people nearing the end of life; they concluded that such evidence was generally limited or absent. HAH was one type of care described in the review. 23

The criteria for ‘home palliative care’ services were much broader than the definition used for HAH in some of the reviews, and looked at literature beyond the UK. 5,24,25 Sarmento et al. 25 undertook a review of qualitative evidence to understand patients’ and family caregivers’ experiences, and the key components of care that shaped the experiences of service users. Shepperd et al. 5 undertook systematic reviews of the trial and controlled study literature on home-based EOLC. Bainbridge et al. 24 identified components of home-based programmes: a total of 30 unique components were identified by a content analysis of the literature. Efficacious programmes included multiple components; the most common were linkage with acute care, multidisciplinary nature, end-of-life expertise and training, holistic care, pain and symptom management, and professional psychosocial support. Luckett et al. 26 looked to understand elements of effective palliative care models in a range of settings, not just home care. They identified essential attributes of effective palliative care models to be communication and co-ordination between providers, rapid response to individuals’ changing needs and preferences over time, skill enhancement and specialist expertise. Another study looking at care models provided a set of criteria to define and compare models of UK specialist palliative care, which distinguished home-based care from other forms of care as one criterion, with several other cross-cutting criteria. 28 Another looked at a number of models of care, but only within a primary care setting. 29,30

A smaller number of articles (seven) identified in the review looked at variations of the same service model: the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care at Home Service31–33 and the Marie Curie Delivering Choice Programme;34–37 realist evaluation principles were used in one evaluation of each service model. 32,37 The Marie Curie programme was implemented across two counties, and included co-ordination centres, a telephone advice line, ‘discharge in reach’ nurses, a specialist community personal care team and nurse educators. The importance of having ‘highly skilled’ palliative professionals with ‘dedicated and sufficient time’ to support informal carers in navigating the system was noted. The whole-system approach of the Delivering Choice Programme underpinned its success, which relied on the collective effort of senior and front-line professionals across hospices, the NHS and social care services. In contrast, Johnston et al. 32 found variation in the implementation of the Macmillan service across its six sites. Overall, they concluded that users of the service were more likely to die at home, and identified the importance of rapid response, early referral, good leadership, flexible working and the added value of health-care assistants (HCAs) and volunteer roles within the service, in particular for psychosocial support. These studies assessing specialist palliative care models highlighted the variation in the components of HAH or home-based palliative care services.

Description of services

The majority of HAH services offered service provision that had long periods of involvement (i.e. not just for the last days or weeks of life) and did not provide a crisis management element or a 24-hours-per-day, 7-days-per-week (24/7), rapid-response service.

Common service characteristics identified in the literature were as follows:

-

enabling patients to be cared for and to die in their place of choice, namely home

-

specialist staff [whether HCA or registered nurse (RN) core staff] with high levels of palliative care expertise

-

ability to provide more staff time with a patient

-

some HAH named services offered ‘sitting’ services or assisted discharge from hospital.

A diverse range of multifaceted services was described in the literature based on locally perceived need, for example population/geography, which tended to complement other existing services. However, some inequality of access was observed, for example:

-

Association between greater deprivation/lower socioeconomic status and lower rates of access to HAH. 38,39

-

Inequality in referral practices in primary care – difficulties in prognosis and identifying terminal phase of non-malignant diseases. The majority of patients seen by HAH were cancer patients. 39,40

Some publications described the process of service development20,41,42 through learning from the evidence base, listening to their local stakeholders and service users or by replicating service models that seemed to work elsewhere. An example of sharing of lessons learned for service development was published by a service in north-west England, which provided its own 10 steps to develop an effective HAH service: preparation, being clear on what it can offer, clinical leadership, staff have community or palliative care experience, comprehensive induction with the hospice, support for staff, good lines of communication with primary care teams, reassurance to other health professionals (e.g. about not ‘taking over’), clear referral criteria agreed by all stakeholders and publicity among the public. 43 The provision of services was often still evolving, and services were being evaluated in the light of the need to secure further funding to continue. 44,45

Evaluations of services

The majority of evaluations of single HAH services were descriptive, capturing views of service users and/or the service staff. 13,14,43,45–47 They did not have a control group and had small sample sizes. Tyrer and Exley40 focused on the demographics of the service users, referrals and service use.

Some evaluations captured the views of bereaved carers. 12,20,48–50 Grande et al. 51 looked at the impact of HAH on carer bereavement. Other studies included views of referrers to the service, such as community nurses/district nurses (DNs) and general practitioners (GPs). 52–56 These descriptive studies tended to use surveys or qualitative methods such as focus groups and interviews.

Buck et al. 39,44 evaluated services by reviewing case notes, and Koffman et al. 47 measured clinical and psychological changes at the time of referral to HAH and after receiving the service, for patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome using the support team assessment schedule. 47 Others reviewed their current service provision by how well they had met key performance indicators or other objectives of their services, or patient outcomes. 42,57,58

Some evaluations assessed the extension of already established HAH services. These included the introduction of additional OOH support,59,60 a respite service61 and combining existing services to enable cross-working between multidisciplinary teams. 62 Strategic changes played a key part in the success of one service. 60

The difficulty of trial designs in palliative care was acknowledged in the literature, and only two of the evaluations reported were trial designs. One of these was in east Kent, where a pragmatic, quasi-experiential, controlled trial to evaluate a rapid-response HAH service was undertaken. 11,20 The second trial was of a ‘hospital at home’ service in the Cambridgeshire area in the late 1990s. 38,63–65 The latter service was more focused on the provision of respite care, rather than rapid response, and was not a ‘specialist’ service as is characteristic of the more recent HAH services. There were two retrospective cohort studies in which patients were not randomised: one observed outcomes of patients who accessed the service43 and the other compared the outcomes of patients who accessed the service with those of patients who did not. 36 One evaluation did attempt a before-and-after study, but had to abandon it because of small numbers. 41

Only four evaluations included a health economic component to try to assess the cost-effectiveness of their service. 53,66,67 The Spiro et al. 67 pilot study suggested a model that could offer an economic propostion, but concluded that assessing the cost of EOLC was complex. 67 Gage et al. 66 and Addicott and Dewar68 found the services they were evaluating to be cost neutral, but offered an increased likelihood of achieving death at home. Grady and Travers53 were not able to draw firm conclusions because of the limited number of data.

Place of death was a common outcome measure for evaluations to assess what proportion died at home and prevention of admission to hospital/hospice. Otherwise, outcomes were weaker and looked at ‘impact’ or ‘strengths and weaknesses’ in line with the descriptive nature of the majority of studies.

Themes identified in the literature

The following themes were identified as features of HAH services that work well, but there were also challenges:

-

Staff offered specialist knowledge and something over and above other service provision at home. A particular feature was that HAH services were able to spend time with the patient that other services visiting the home could not provide. Good communication was also key.

-

A minority were rapid-response/24-hour services; only seven offered rapid response. 40,42,43,45,48,53,69,70 Services providing rapid response reported effectiveness in enabling patients to remain at home.

-

Eight services in the literature offered 24/7 OOH provision. Some provided full service, whereas others offered a reduced service OOH, for example a telephone advice line or voluntary staff. OOH provision was seen as desirable for many services that were not offering it. However, difficulties continued to be identified, even for those that were offering 24/7 services, for example access to medication, fewer staff and less medical support OOH.

-

Instead of 24/7 rapid response, services tended to offer ‘sitting’ respite, appointment-based services or assisted discharge from inpatient units to allow a patient to be at home.

-

The role of the carer was key: HAH services helped to provide physical, emotional and social support to relieve carer burden, and also provided bereavement support in some cases.

-

Working with primary care teams (GPs and DNs). Patients remained under the care of the primary care teams, so HAH services complemented this. Communication was key to reassure them that the HAH service was not ‘taking over’.

-

Issues of timeliness in receiving equipment into, and removing it from, the home.

Conclusions of the review of the literature

Hospice at home is an umbrella term with no clear service specification. Many hospices have adapted and used elements of what could be described as HAH, resulting in many different models of HAH being implemented in practice.

This literature review set out to identify the literature that described HAH service models in the health and social care setting of the UK, or community models under a different name that had HAH ‘characteristics’ in terms of rapid response, crisis management, 24-hour coverage and palliative care specialist staff who were hospice trained. A limited number of studies of services, described as HAH, met all these characteristics. Most often, HAH services shared the objective of enabling a patient to die at home if that was their place of choice, but they were less likely to provide the service on a 24/7 basis that offered rapid-response crisis management. Other elements that these services did provide were appointment-based services such as ‘sitting’ respite-type services or assisted discharge from inpatient units to allow a patient to be at home. A theme present through all the service models was staff with high levels of palliative care experience. The additional time they were able to spend with patients, which other services visiting the home could not provide, was a highly regarded element of HAH service provision, whether the core staff were RNs or HCAs.

The literature supported the proposition that HAH services at the end of life are valuable and complement existing service provision, but much of the literature was limited and the evidence was relatively weak.

Summary

The literature endorsed the value of HAH services in supporting patients to remain at home to receive their care at the end of life. However, the review of the literature posed important outstanding questions and highlighted continuing gaps in evidence about the most successful and cost-effective service configuration and activity. These questions cover the following topics: staffing profile, working patterns, communication and co-ordination with other local services, and support for carers. The review informed the funding application to Health and Social Care Delivery Research for the development of the OPEL study to identify optimum HAH services at the end of life. 15

Chapter 3 Methodology

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Butler et al. 15 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Hospice at home is a complex intervention operating within the wider system of health and social care delivery. Hence, research methods were required that could capture the complexity of the intervention and the impact of the implementation of different HAH models on the organisation, delivery and experience of EOLC from the perspective of service users (patients) and their family carers, and service providers and commissioners.

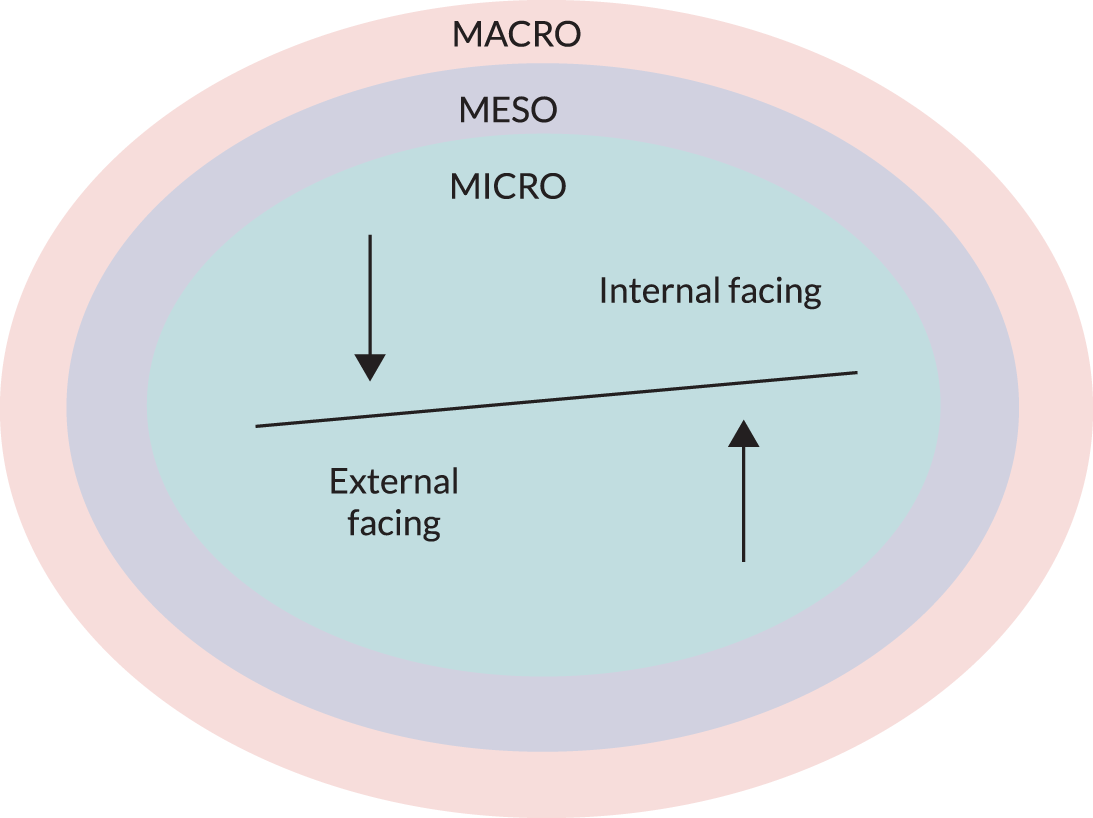

The research design was informed by realist evaluation,17 a theory-driven methodology increasingly used to evaluate complex interventions,71 including services for EOLC. 37 Realism provides the philosophical foundation for realistic evaluation. At the core of realism is the notion of ‘generative mechanisms’. A generative mechanism is a causal link, the ‘black box’ that leads from A to B and creates an ‘effect’. 72 Realist evaluation attempts to theorise what the mechanisms are, even though they are not necessarily ‘measurable’ in an empirical sense, and it seeks to find evidence of their existence. The relationships between mechanisms, the contexts in which they are operating and the effects they produce are represented through propositions that take on a basic formula: context + mechanism = outcome. Thus, the aim of empirical research is to identify patterns to support an explanatory theory about what mechanisms are working (or not) in a given situation. 73 A pluralist approach to data collection suits a realist evaluation.

Realist evaluation analysis in mixed-methods research

Realist evaluation analysis aims to understand both what is happening and how it is happening in an intervention. Understanding how contextual factors influence health interventions, such as HAH, is central to this methodology. It is acknowledged that an intervention and its outcome are dependent on contextual factors, and understanding how, why, for whom and when an intervention works16 is core to the approach. The context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configuration is central to the analysis, which is intended to be pragmatic in that findings can be transferable across settings. 74 The idea that it is people and their responses to interventions that create change is also important.

In realist evaluation, data analysis takes a ‘retroductive’ approach. 75 This means that those factors that lie behind observed patterns are identified with the aim of understanding causation. Retroduction is the idea that we can explore the underlying social and psychological drivers that influence intervention outcomes by looking behind observable patterns to understand what produces them. Multiple data sources are typically required for realist evaluation. 75 Both quantitative and qualitative data can be used to generate evidence to support and refine the CMO configurations.

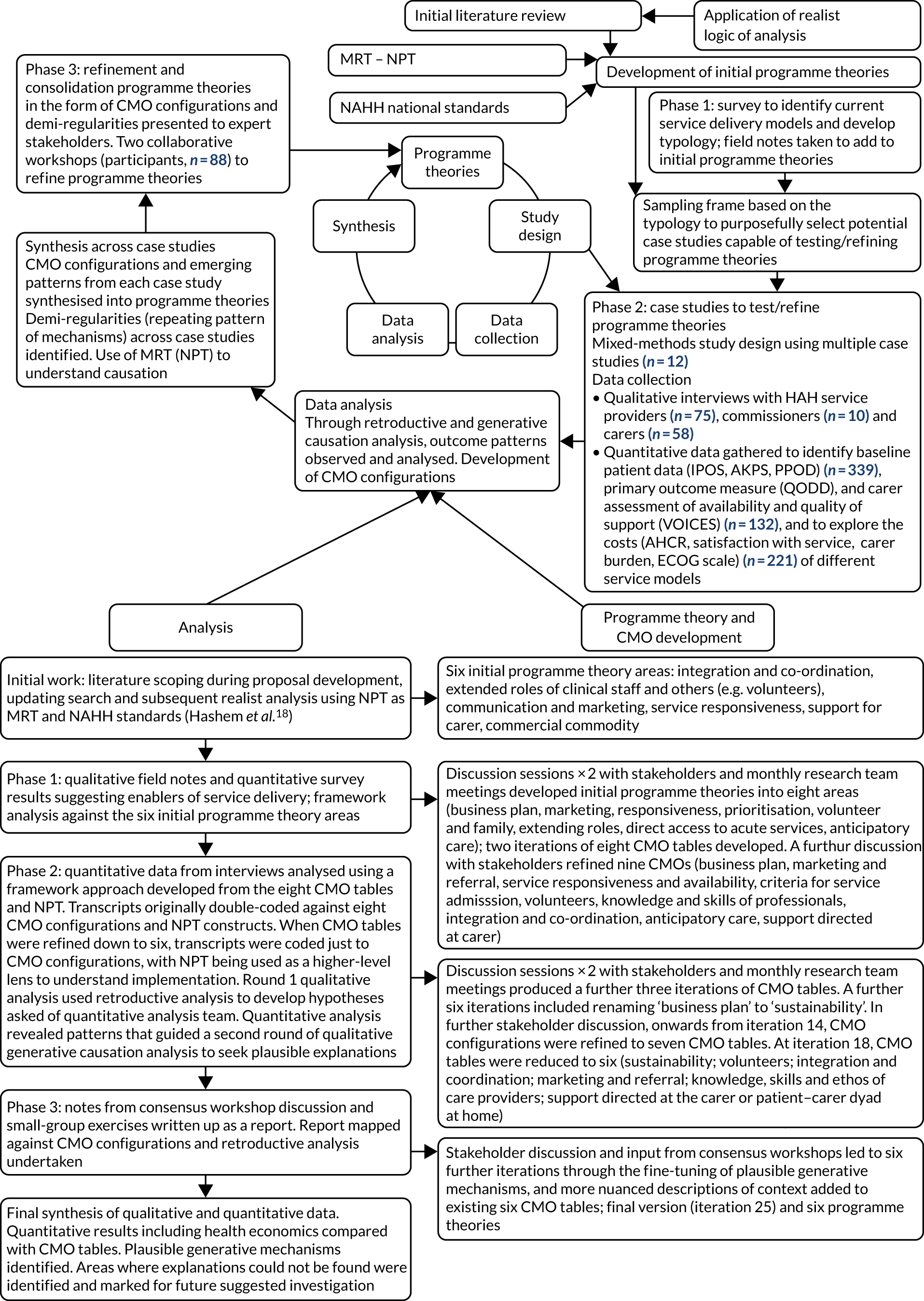

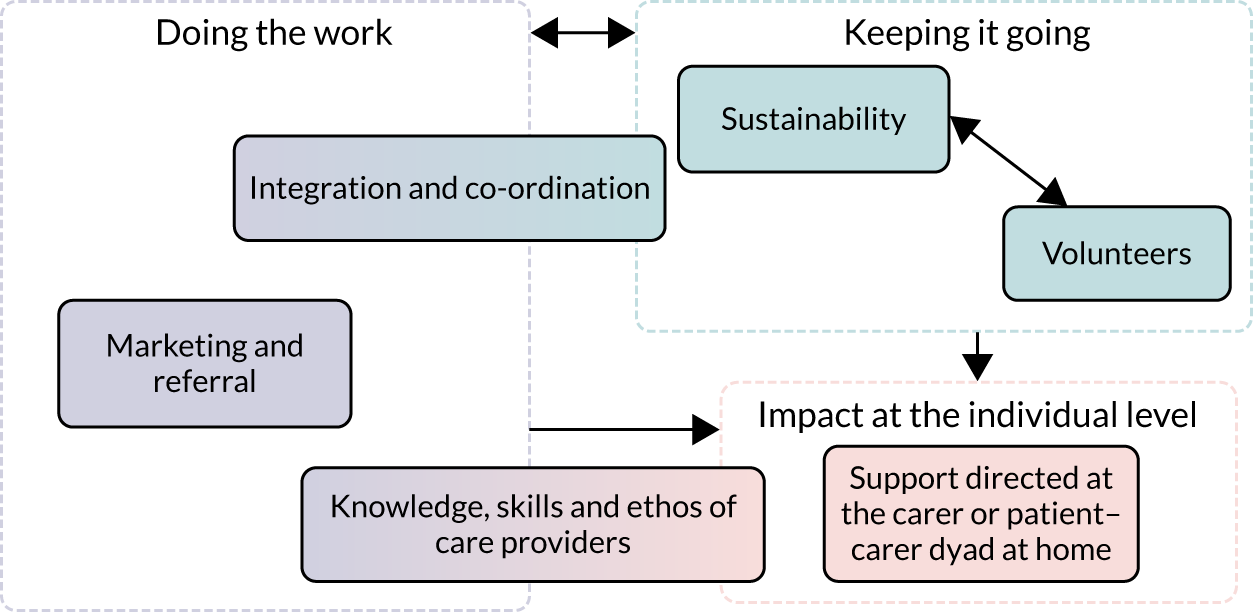

Overall design and development of context–mechanism–outcome configurations

The OPEL HAH study employed a mixed-methods design, using realist evaluation methodology and incorporating an economic analysis. The design of the study comprised three phases, alongside which programme theories and CMO configurations were developed (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Study design, analysis and CMO configuration development. AHCR, Ambulatory and Home Care Record; AKPS, Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPOS, Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale; MRT, middle-range theory; NPT, normalisation process theory; QODD, Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire; VOICES, Views of Informal Carers – Evaluation of Services.

The first stage of a realist evaluation is to develop initial programme theories. These were elicited through a variety of sources. 76 First, the NAHH standards21 were taken as indicative of an overall programme theory (how HAH should work). Second, an initial review of the literature (undertaken during proposal development and subsequently updated) was synthesised through a realist logic of analysis. 18,77 Finally, as a theory-driven methodology, concepts from abstract theories were sought to inform the initial programme theories. Normalisation process theory (NPT)78 was identified as a suitable candidate theory. NPT is increasingly being used in combination with realist evaluation to understand what needs to be in place for the implementation of complex interventions,79 and it was anticipated that it would aid understanding of how HAH may become embedded as part of a local health-care economy. Data collection then occurred, based on these initial theories. CMO configurations emerging from the programme theories were identified and coded within the qualitative data. 80 During analysis, CMO configurations were synthesised in an iterative process to refine and evolve the understanding. Quantitative data were analysed in tandem, with qualitative data reinterrogated to seek plausible explanations of quantitative findings.

Stakeholder involvement is integral to the whole process and is a key feature of realist studies; by engaging lay or content experts, evidence is built to support theories on the basis of coherence and plausibility. 81 Stakeholder involvement was operationalised through PPI activities (see Chapter 4); 6-monthly meetings with the Project Oversight Group, which included lay and content experts; and two national consensus workshops.

Patterns within the data were used to refine and justify the emerging theory. The resulting CMO configurations describe common patterns (‘demi-regularities’)75 that can be applied to different settings and, in particular, the generative mechanisms at work.

Detailed design of each phase

Phase 1: national telephone survey

Hospice at home services serving adult palliative care patients in England were surveyed.

The survey aims were to (1) develop an understanding of the range of services and operations and (2) identify categories (types) of services from the survey information to use as a sampling framework for recruiting case study services in phase 2 of the study.

A total of 128 HAH services in England and the appropriate contact (e.g. service lead) were identified from the NAHH and Hospice UK directories of services and approached to take part in a telephone survey. Each service contact was posted an information letter, a survey and opt-out slip. An interview to collect the data over the telephone was proposed. Contacts were followed up 2 weeks later to arrange the interview if they had not already responded or opted out.

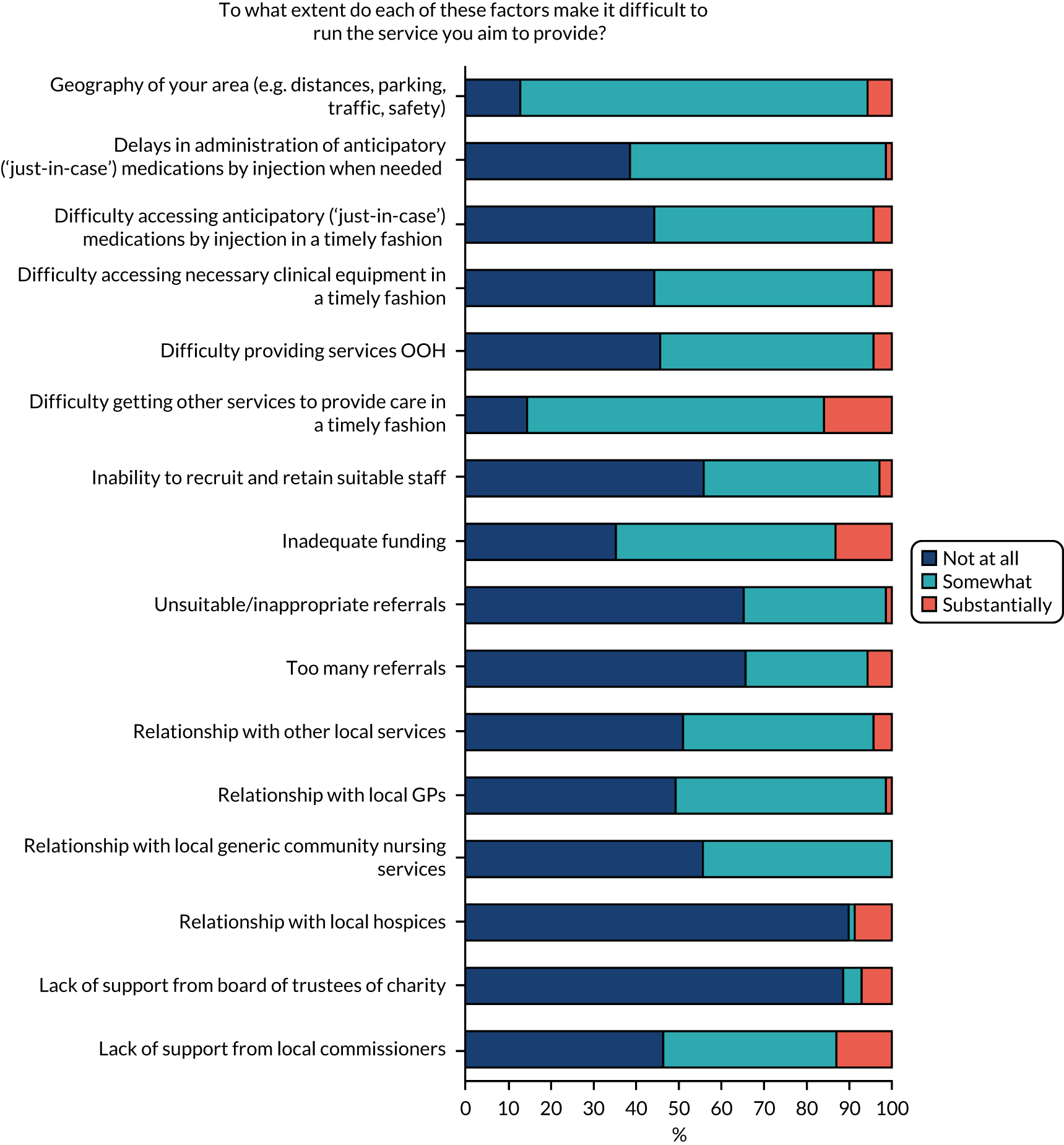

Telephone survey calls were conducted by a nurse with palliative care experience to facilitate understanding of the services. The survey was semistructured, comprising a selection of closed and open questions. Respondents were asked to provide details of the population characteristics in the catchment area; other relevant local services and access to palliative care beds; and HAH activity levels, staffing, facilities, equipment, processes, budget, and barriers to and facilitators of operating (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for the full questionnaire). HAH services were asked to provide supporting documents and to indicate willingness (or not) to consider becoming a case study site in phase 2.

Phase 2: case studies

Case study methods are a well-established approach to conducting research in ‘real-life’ health-care settings. 82 The approach employs mixed methods to gain an in-depth understanding of the impact of service models, resource implications and the experiences of all stakeholders, including service users, providers and commissioners. Yin83 describes case study design as orientated towards a realist perspective The design allows methodological flexibility to generate theoretical insights from the findings,84 which is a key requirement for realist evaluative design. 17 We adopted Yin’s83 approach to defining a case as an individual organisation. Although each case needed to be bounded, there was also some need to maintain flexibility, and each case was defined as what the site described as their HAH service.

Plan of investigation for case study sites

When HAH services had agreed to take part, full training on the study and the informed consent process was provided to site staff (research nurses, clinical staff, managers, etc.) by the members of the research team. The training was delivered in person at site initiation visits and follow-up training was also provided on site and remotely, as needed.

Recruitment and informed consent

Patient and informal carer dyads

Participants at each site were invited to take part in the research at the time they were admitted to the HAH services. A patient-directed flyer was made available at HAH sites to raise awareness about the study (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

patient admitted to HAH service

-

patient had a lay informal/family carer who also agreed to take part in the study (defined as someone who provided care and support at home on a daily basis)

-

ability to obtain informed consent from patient and carer.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

patients without a suitable informal carer

-

inability to obtain consent from the participants

-

participants unable to complete questionnaires in English

-

patients in a care home at the time of admission to the HAH service.

Hospice at home service staff introduced the study to the patient and their carer. Information sheets (see Report Supplementary Material 3) were given to the participants and they were allowed time to read the information and ask any questions; if needed, the information sheet was read out.

Patients were asked to consent to taking part in data collection at one time point (on admission to the study or as soon as possible thereafter). They were also asked to agree to the collection of information on their use of health and social care services from 2 weeks prior to joining the study until death. The carers were asked for their consent to be contacted to complete a post-bereavement questionnaire, and informed that the option of taking part in an in-depth interview post bereavement would also be offered.

Service staff took consent from the patient and carer, using the study consent forms (see Report Supplementary Material 4), and both were given a copy of their information sheets and consent forms. Copies of the consent forms were filed in the study site file; a copy of the patient consent form was also filed in the patient’s medical notes. The carer was asked to provide contact details and to indicate the best time of day for the research team to call to collect data.

Owing to the nature of the patient population, some of the potential participants lacked capacity and were unable to provide informed consent. For this reason, a variable consenting process, involving consultee assent, was used. The local HAH team made the decision to proceed using one of the following options:

-

If the patient was deemed to have capacity by the local team, then consent was sought from the patient in the normal manner.

-

If the patient was deemed not to have capacity, then a personal consultee (i.e. someone who has a role in caring for the person who lacks capacity or is interested in that person’s welfare but is not doing so for remuneration or acting in a professional capacity) was approached for advice regarding the patient entering the study. The personal consultee could be a relative or friend of the person, in practice often the informal carer. 15

-

If the main carer or personal consultee was not available, a nominated consultee was approached for advice regarding the patient entering the study. The nominated consultee was a clinically qualified member of the patient’s care team who was not involved in patient consent or in study procedures such as data collection.

When a personal or nominated consultee was used, they were given an information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 3) about being a consultee and the patient information sheet. They were given time to read the information and the opportunity to ask questions about the study and asked if, in their opinion, the patient would object to taking part in the study. The local staff member then gained a declaration from the consultee, using the study consultee declaration form (see Report Supplementary Material 4), as to whether or not they agreed that the patient would be willing to participate in the study.

Service providers and commissioners

The managers of HAH services identified a range of staff from their organisations for interview, to give a detailed picture of each organisation and its operations. These included clinical staff, the HAH service manager, charity trustees, fundraising staff and volunteers. Relevant commissioners from the local area were identified by HAH service providers for interview . Potential participants were invited by e-mail or by telephone by the research team and an information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 4) were sent by e-mail or post. If they agreed, interviews were arranged (either by telephone or in person) at a time and location convenient for the interviewee. Prior to the interview, the participant was asked to complete a consent form.

Data collection

Baseline patient data

After consent, a member of the participant’s clinical care team assessed the patient using the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS) (staff version),85,86 the Phase of Illness87,88 and the Australian modified Karnofsky Performance Status. 87,89 These instruments are recommended measures reflecting the key domains of palliative care, and have been validated for use in research. Patients were also asked if they had a PPOD (i.e. home, hospice, hospital).

Service use data

After consent, a member of the research team contacted the carer by telephone as soon as possible to collect health service use data retrospectively for the patient for the 2 weeks prior to recruitment. Data were collected using the Ambulatory and Home Care Record90 (AHCR), an instrument designed for capturing the use of health, social and voluntary services and informal caring for palliative care patients based at home. Items relate to services received both inside and outside the home [e.g. hospital appointments, accident and emergency (A&E) visits, inpatient stays]. The AHCR was customised for use in this study following piloting with a hospice population in England. 91 Carers were sent an optional ‘home care diary’ to assist with tracking service use.

Completion of each AHCR included three additional questions: satisfaction with services (scaled as follows: 1, exceeded expectations; 2, just met expectations; 3, fell short of expectations), carer burden [Short Form Zarit Burden Interview: six items relating to stress, strain, relationships, health, control and time for self, each scored on a 5-point scale, leading to a total score ranging from 0 (best) to 24 (worst)]92 and the patient’s health status [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale, range: 0 (fully active) to 4 (completely disabled)]. 93 The last satisfaction and carer burden responses prior to death were used as measures of the performance of services.

After the collection of retrospective service use data, contact was made with the carer by telephone every 2 weeks to request completion of another AHCR covering the intervening 2-week period. In this way, a continuous record of services used by the patient could be collected. Researchers were assigned to data collection in specific case study sites to enable continuity with carers. Each telephone call lasted approximately 15 minutes.

Post-bereavement data collection from carers

Post bereavement, a follow-up letter was sent to carers to remind them that the research team would be in touch to collect further data. This letter included information sheets about the questionnaire and about the optional in-depth interview. Participants were given a choice about how to complete the questionnaire: by telephone, using an online survey tool or by post. The original protocol stated that the invitation to complete the Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire (QODD) would be offered either when hospice bereavement services made contact with the carer (usually around 6 weeks post death) or at 4 months [replicating the design of the Views of Informal Carers – Evaluation of Services (VOICES) survey94]. The researchers, who were already in contact with the participants to collect AHCR data, found that some participants expressed that they would prefer to compete the QODD earlier; a study amendment was approved to enable this.

The questionnaire contained the primary outcome measure, namely the QODD (English, 7-day recall, version 1), a validated 30-item instrument95–97 (note that we removed a question on euthanasia not relevant for use in the UK). Two short questions about the overall care received were also included in this questionnaire. The first asked if the carer and family had received as much support as they needed when caring for the patient (five-point scale, from ‘as much as needed’ to ‘no help at all’); the second was a rating of the quality of care received (five-point scale, from ‘outstanding’ to ‘poor’). These questions were taken from the VOICES questionnaire, a national survey of bereaved people conducted by the Office for National Statistics and commissioned by NHS England, based on research by Addington-Hall and McCarthy. 94

Three attempts were made to contact carers by telephone; if these were not successful, a paper copy of the QODD and VOICES questions was posted to the carer for completion (on one occasion only). This was accompanied by a cover letter to explain that the research team had been unable to contact them and if they would prefer to self-complete the questionnaire at home they could do so. A stamped addressed envelope was provided for return of the questionnaire.

Optional interview, bereaved carers

An in-depth interview was completed by a subset of participants; we aimed for up to 20 interviews per service model type, with a stopping criterion of three interviews if no new themes were coded, to achieve data saturation. 98 If the QODD was completed by telephone, the researcher asked the participant if they would be willing to participate in an optional in-depth interview by telephone or in person to understand more about the HAH service received. If the QODD was completed in the postal or online formats, carers could indicate at the end of the questionnaire if they would be happy to take part in an optional interview. If the postal or online QODD was not completed within 1–2 months, a final follow-up letter was sent to invite carers to take part in the optional interview only. Interviews were semistructured, following a topic guide (see Report Supplementary Material 5), and explored the experience of the HAH service and the EOLC the patient received.

Interviews with service providers and commissioners

The research team conducted interviews with 5–10 managers, health-care staff and commissioners per case study site. Interview schedules were designed for both staff and commissioners (see Report Supplementary Material 5) and were semistructured; they included questions to explore the service history, logic, rationale, funding, processes and contextual features facilitating or inhibiting service delivery, as well as enablers of and barriers to providing HAH services.

Withdrawal criteria

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time. Patients and carers were made aware in the information sheet that withdrawal would not affect the care they would receive. If a participant withdrew from the study, they were asked, if possible, if the data collected to date may still be used in the final analysis. If they did not wish for their data to be used in this way, all data collected from the participant were destroyed. If it was not possible to consult the participant on this, data collected up to the point of withdrawal were utilised according to the original consent.

Distress

A distress protocol was designed and made available to all case study sites (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

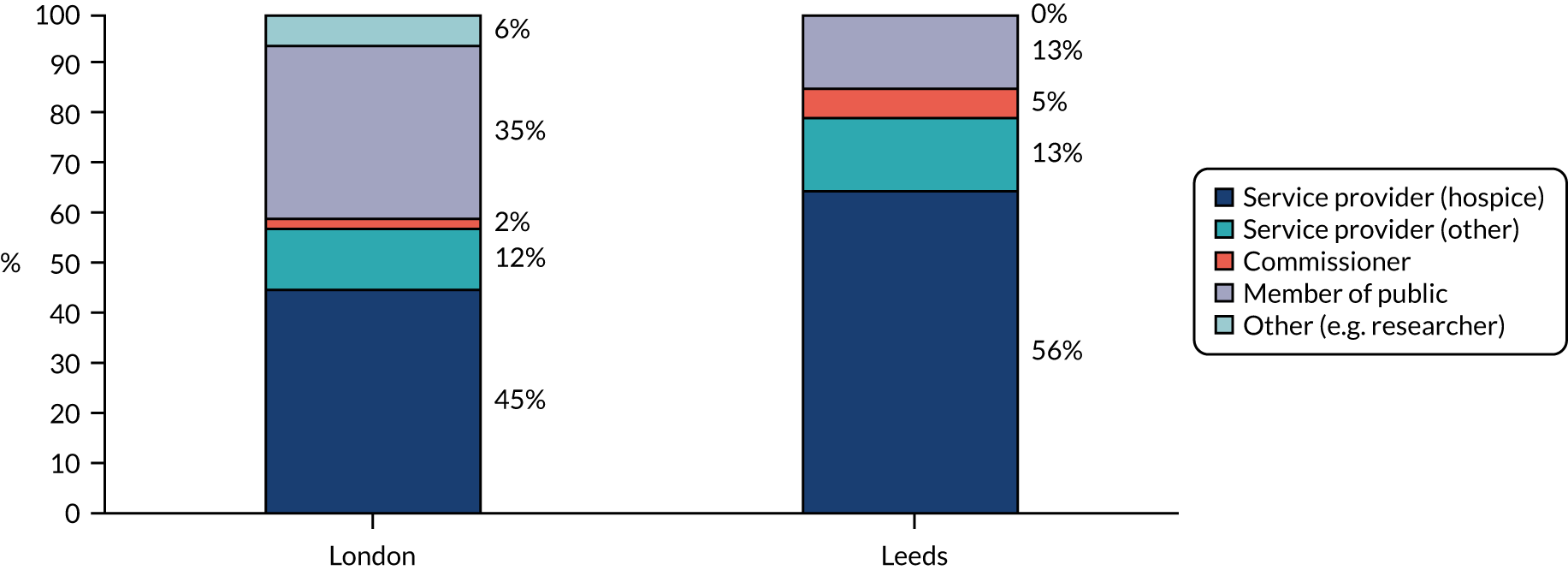

Phase 3: stakeholder consensus

Two national consensus workshops, with up to 60 participants each, were held. To maximise potential attendance from stakeholders, one workshop was held in London and one in Leeds. Each event took place over 1 whole day at a conference venue, facilitated by the project research team, including PPI members. HAH services that had participated in the phase 1 survey were offered a £50 bursary to support attendance at a workshop. Additional invitees were identified through the NAHH, study co-applicants’ networks and the Project Steering Group. Other organisations also advertised the events: Clinical Research Networks, Applied Research Collaborations, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), Healthwatch and other national charities and groups (e.g. Marie Curie). Stakeholders included service providers, commissioners, researchers, members of the public and service users. The purposes of the workshops were to fine-tune the CMO configurations developed in phase 2 of the study and to provide a more nuanced understanding of the features of HAH models that work, for whom and under what circumstances.

Emerging findings and relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes were presented to stakeholders using a mix of formats and approaches, including lecture-style, small-group work and poster presentations (see Report Supplementary Material 7). Consensus workshop methods were used99 to facilitate discussion. Consensus event delegates also contributed to planning the methods of communicating the study findings, in particular advising on the presentation of information relevant and accessible to the public, service providers and commissioners of HAH services. After the events, participants were sent a workshop report.

Analysis

Phase 1

A descriptive analysis of survey responses was undertaken using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software, version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), to gain an understanding of the range of HAH services. The analysis also sought to enable the identification of types of HAH service models for phase 2. Findings were presented in tables. Categorical variables [e.g. urban/rural setting, presence of hospice building(s), yes/no] were cross-tabulated with each other to identify underlying associations. Associations were explored between all variables. These results were used to identify any natural groupings of service features that could be defined as service models or types. Based on prior survey work from the NAHH21/Hospice UK (Heather Richardson and Andrew Thomson, personal communication), it was projected that approximately four high-level types of the model would be distinguished.

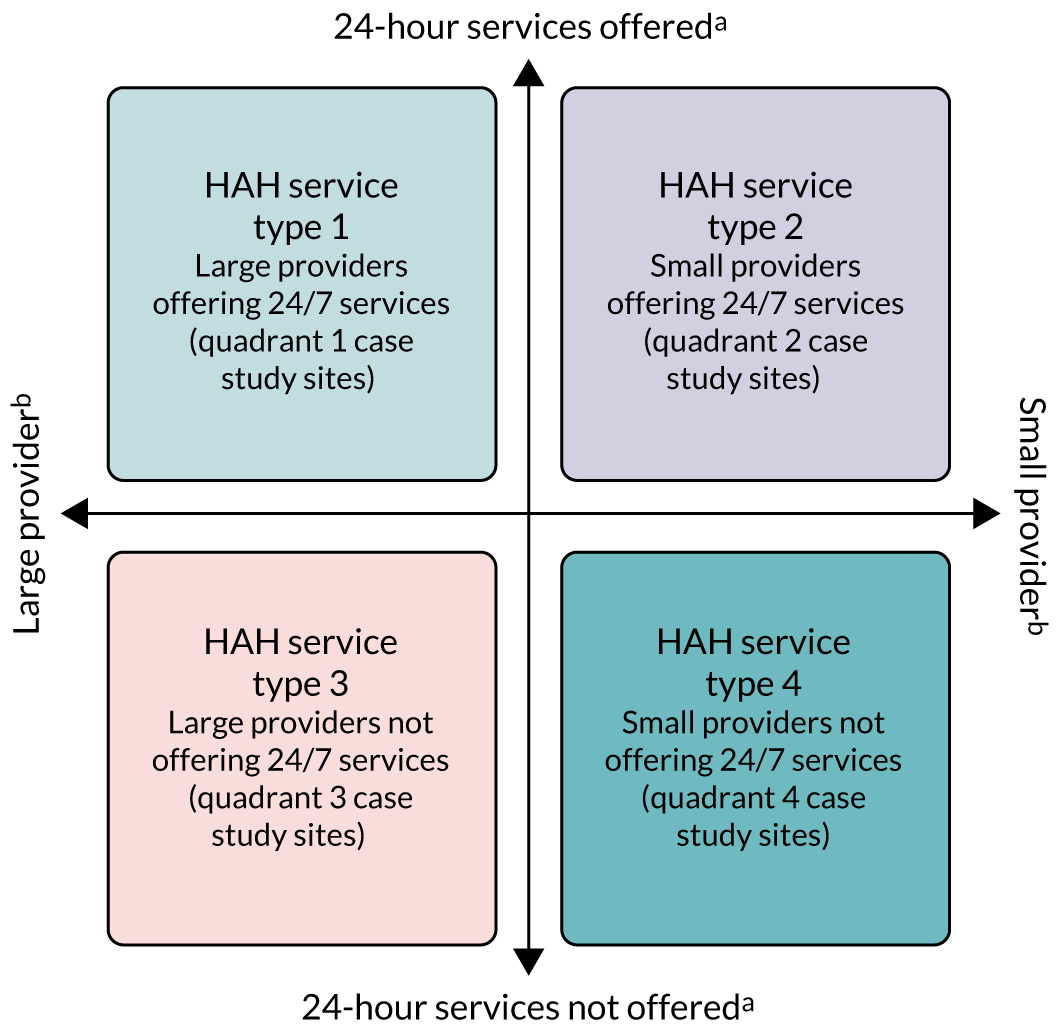

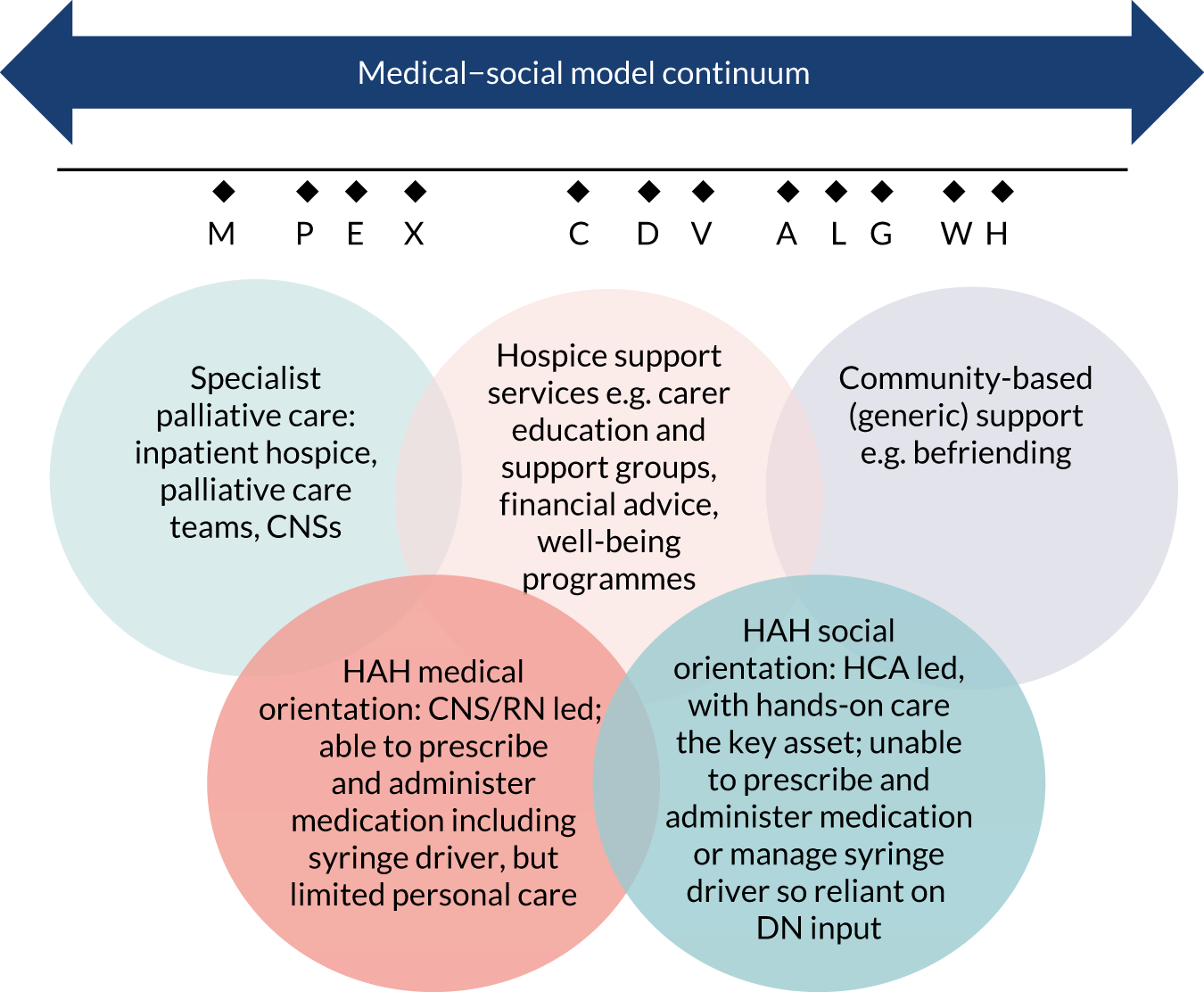

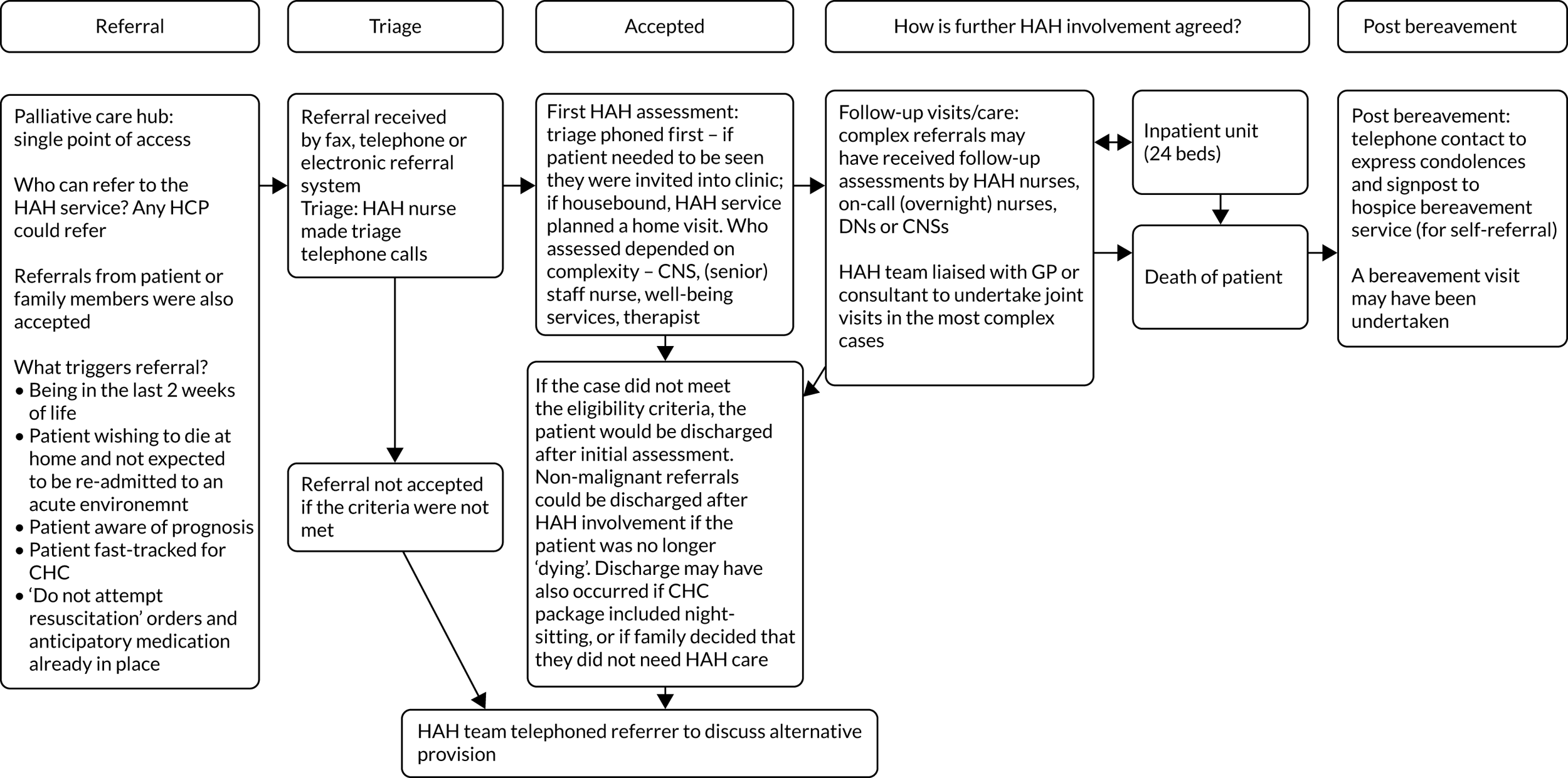

Qualitative field notes collected during the survey data collection were typed up and analysed inductively to identify relevant factors for the development of the typology. These were combined with the output from quantitative analysis and discussed at a meeting of the full team, resulting in agreement on a typology that could provide a framework for the recruitment of services as case studies for phase 2 (Figure 3).

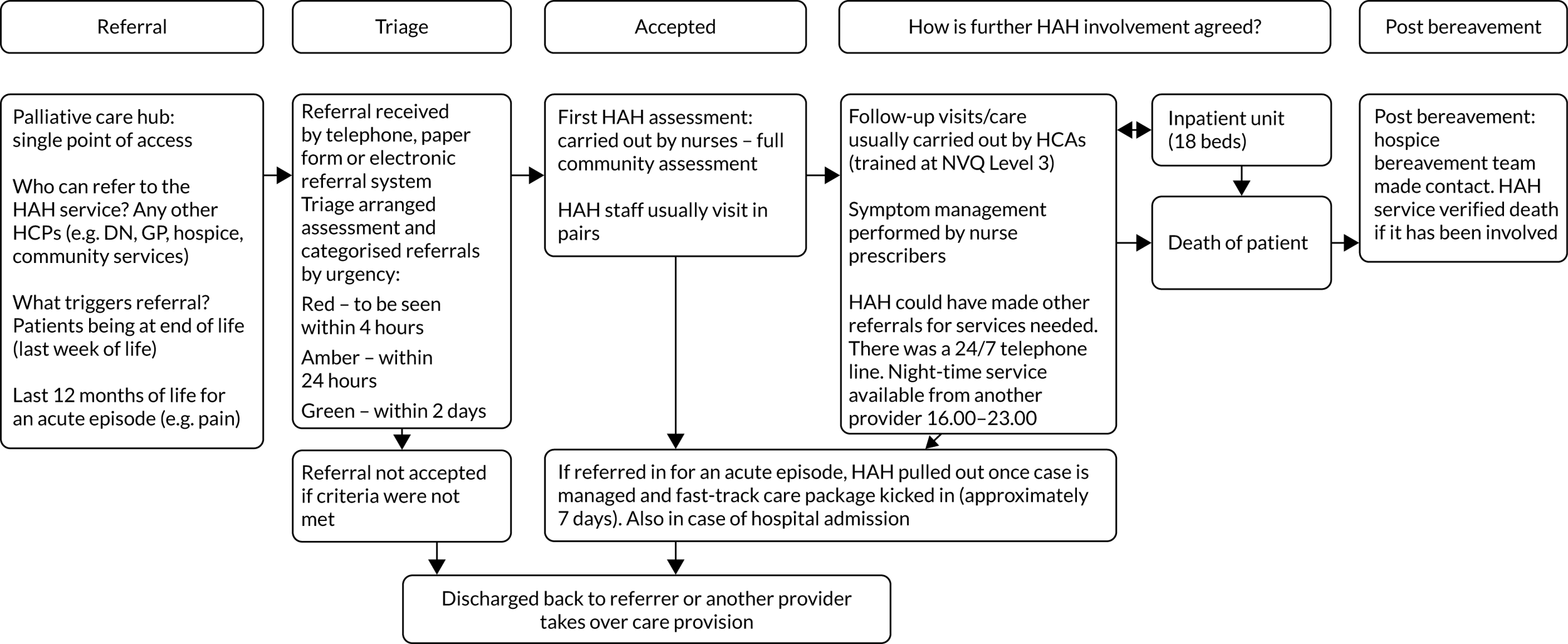

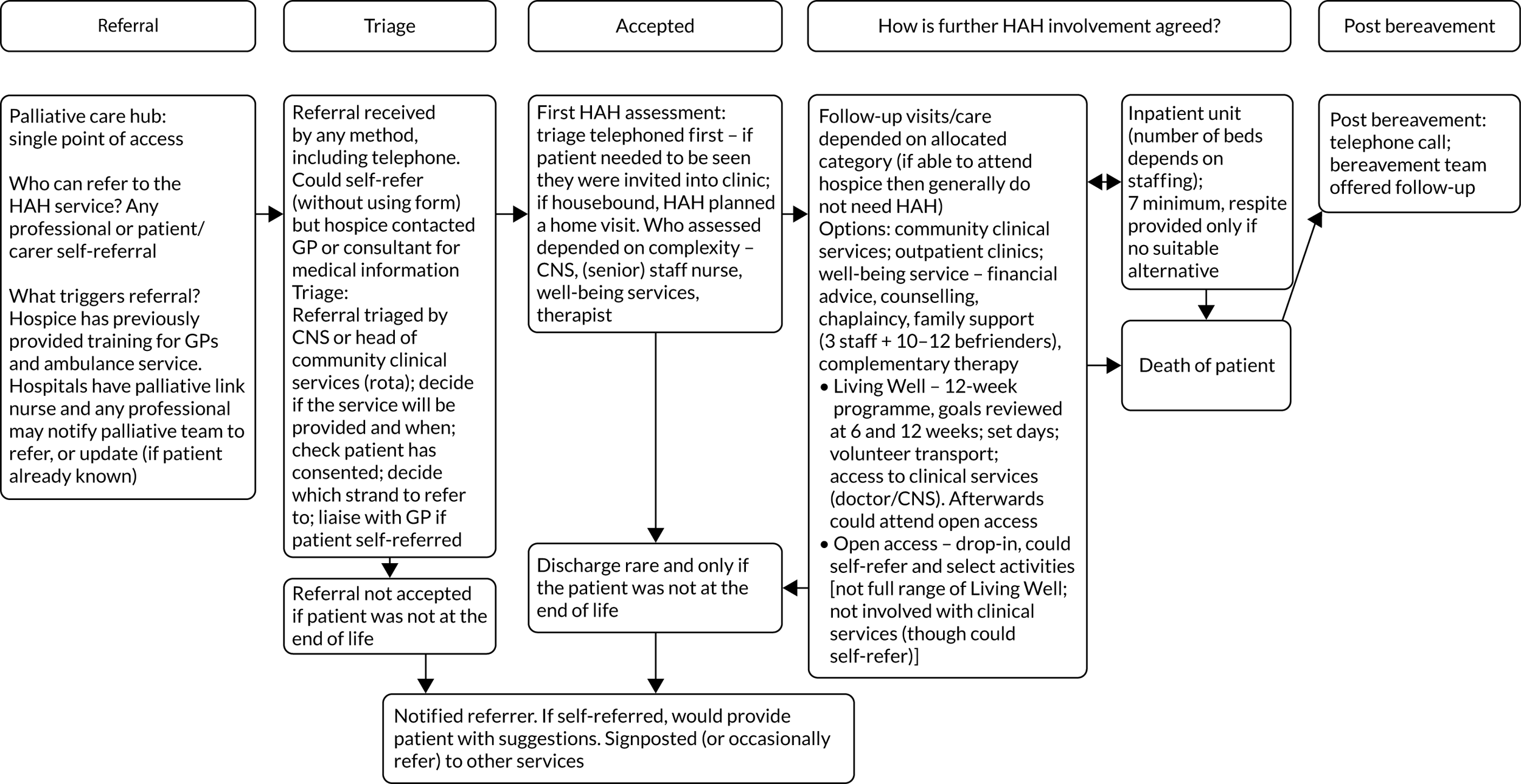

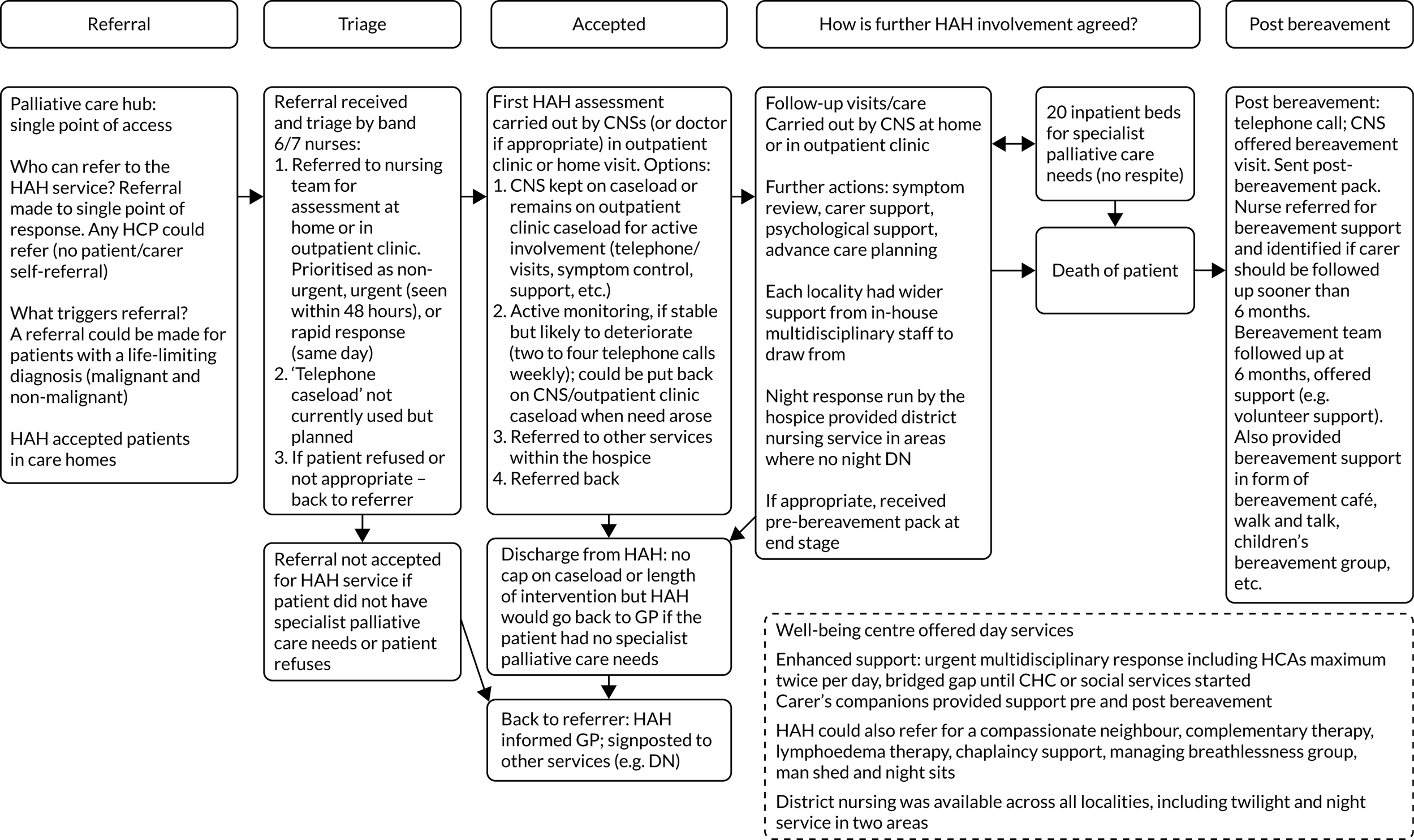

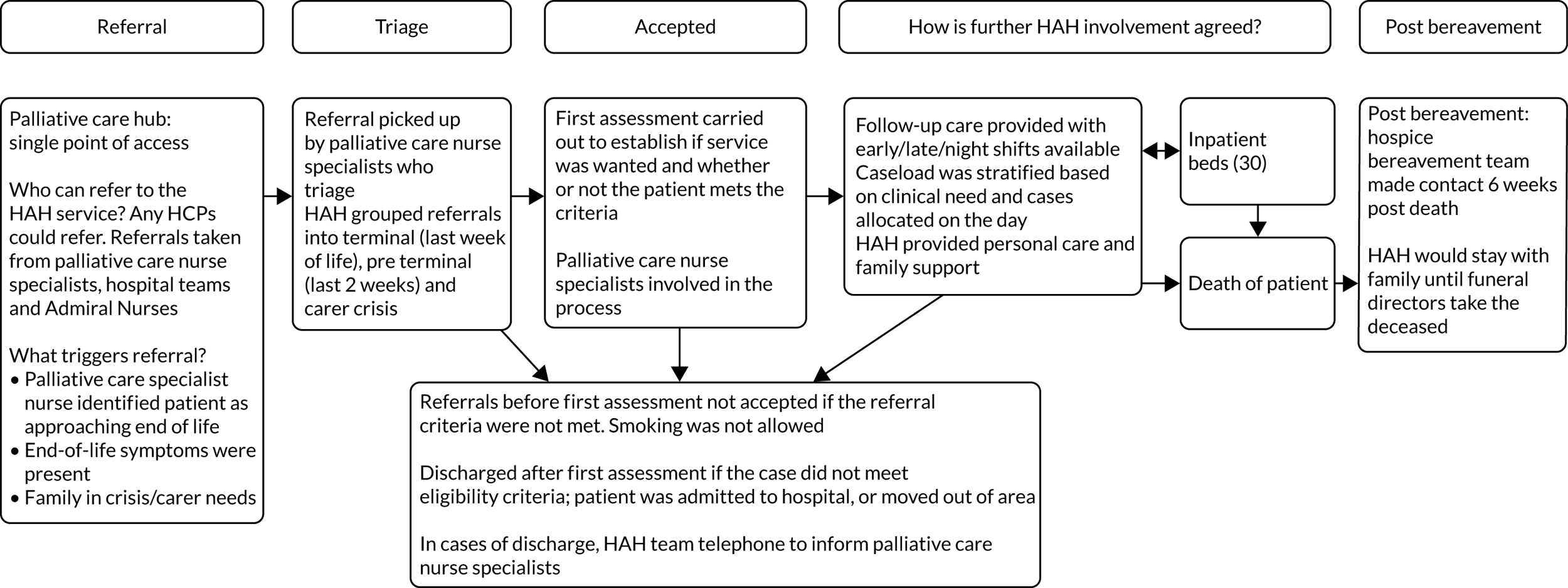

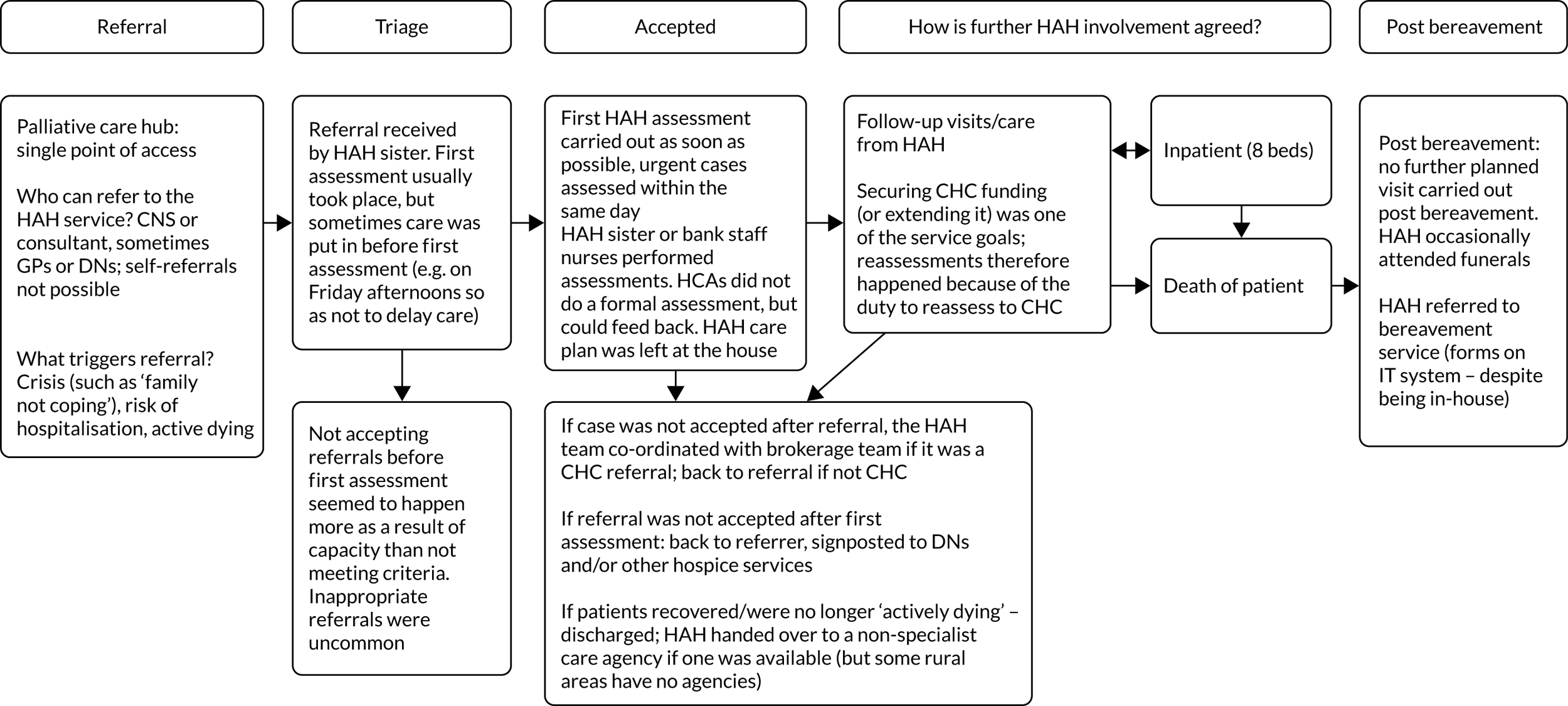

FIGURE 3.

Service model typology. a, A 24-hour service provision is defined as two or all of the following: 24-hour hands-on care, 24-hour symptom assessment and management or fast response time (< 4 hours); b, provider size is based on having either more or fewer than 365 referrals per annum (one per day).

Based on survey responses, hospices that had indicated willingness to consider becoming a case study site were then approached to represent the identified service types as case study sites. We purposively sought diversity in geographical spread, socioeconomic profile, staffing mix and funding sources. Services were approached initially by e-mail; further queries and negotiation were managed by e-mail and telephone follow-up.

Phase 2

Sample size

The total score for the primary outcome measure, the QODD, ranges from 0 to 100 (a higher score indicates better quality). Hales et al. 100 identified scores of 30 and 70 as cut-off points for distinguishing terrible/poor (< 30), intermediate (30–70) and good/almost perfect (> 70) quality of death. 15 Hence, on the basis of a difference of 10 representing a meaningful change, and using a standard deviation (SD) of 16.41,101 at least 44 participants in each model would be required for comparisons between any pair of models. To allow for a participant non-completion rate of 33%, a sample size of 66 patients per model type (up to four models) was proposed. The non-completion rate was based on the 55.4% response rate obtained when the 24-item intensive care unit QODD was mailed to carers 4–6 months post death;102 a higher response rate was expected in this study because telephone interviews were being used.

Based on estimated HAH service size and annual throughput of patients, it was anticipated that recruitment of 66 patients per model type was achievable, for medium and large units in particular. The national minimum data set 2013/14 by the National Council for Palliative Care103 grouped HAH services by size into roughly three equal groups: small, < 191 patients per annum; medium, 191–310 patients per annum; and large, > 310 patients per annum. If small sites were recruited, it was agreed by the steering group to recruit two case study sites of the same model type to reach an overall sample size of 66. In the final regression modelling process (outlined below), a dummy variable would be used to distinguish between providers if comparisons were necessary.

Statistical analysis

Availability of data from the various sources [background/baseline, AHCRs, date of death (DOD) from hospice services or carer, post-bereavement interview for QODD and VOICES] was examined and patient–carer dyads were broken down into four categories according to the data they provided (with categories 3 and 4 merged for analysis purposes because no post-bereavement interview was possible):

-

date of patient death known and occurred before the end of the study period

-

patient/carer withdrew from the study before the end of the study period; data were available for analysis up until withdrawal unless the participant requested otherwise

-

patient still alive at the end of the study period

-

patient died at unknown date after the end of the study period.

The baseline sociodemographic characteristics of patients and carers, and the clinical status of patients in the different service models, were summarised using relevant descriptive statistics (proportions, medians, ranges, means, SDs, 95% confidence intervals, etc.) before being compared on the basis of each patient sociodemographic, clinical and carer feature using the appropriate bivariate test [including one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), chi-squared tests and Kruskal–Wallis tests, depending on the nature of the variable]. The time between recruitment to the study and death was calculated and compared across models.

A minimum of six responses [from the total of 30 items (20%)] were required for the calculation of the total QODD score (as 10 × mean of all non-missing responses) from each carer. Several questions were not always applicable (e.g. spend time with pets), so a response rate of 100% was unlikely in most instances. The frequency of responses and summary statistics for total QODD score, and for the dichotomised form of the total QODD score (≤ 70 vs. > 70, the latter indicating a good/almost perfect death), were calculated, as recommended by Hales et al. 100

The secondary outcomes VOICES 1 (five-point scale relating to the sufficiency of the help and support from health and social care services that had been received) and VOICES 2 (a five-point quality rating of that help and support) were presented as frequency tables, given their ordinal nature. Achievement of PPOD was calculated for each patient for whom both the preferred and actual places of death were known; these values were presented by place of death as numbers and percentages. Means and SDs were calculated for the final secondary outcomes derived from the AHCRs: carer burden in last 28 days and service satisfaction in last 28 days. For each AHCR, the six-item carer burden (Zarit Burden Interview) total score92 was calculated [sum of six responses, 0 = never to 4 = nearly always, range 0 (best) to 24 (maximum worst burden)]. The mean of non-missing responses was assigned to missing items. For each AHCR, the service satisfaction was coded as ‘exceeded expectations’ = 1 (best outcome), ‘just met expectations’ = 2 and ‘fell short of expectations’ = 3 (worst outcome). A ‘last 28 days’ carer burden or service satisfaction score was included only if the final AHCR was conducted no earlier than 28 days before the patient died; any patient alive at the end of the study period, or with no known DOD, was therefore counted as missing.

All outcomes were compared between models using appropriate statistical tests. Because three of the four models included multiple HAH services, summary statistics were also generated at the HAH service level. Bivariate associations were explored between the QODD primary outcome score (total QODD score) and a set of covariates that were agreed as important by the research team. These included sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patient at baseline; place of death; how long before death the patient was aware that they were dying (from the QODD); number of days the carer had seen the patient in the last 7 days before death (from the QODD); how long the patient was in the study, and hence receiving hospice services (between recruitment and death); and time between death and when the carer completed the QODD. Appropriate statistical tests were used, depending on the nature of the variables.

Linear regression was used to model total QODD score, VOICES 1 and 2, carer burden in the last 28 days and service satisfaction in the last 28 days; logistic regression modelling was used for the dichotomised total QODD score and achieved PPOD. All outcomes were modelled (using forward stepwise selection) against predictors agreed on as important by the research team, with results including 95% confidence intervals for fitted parameters and goodness-of-fit statistics for the overall model. Service model was always included as a predictor, such that the fitted parameters in the final models indicate if service type is associated with differences in QODD scores. The characteristics of service types that result in better QODD outcomes were identified from descriptive data collected at each site as part of the realist evaluation.

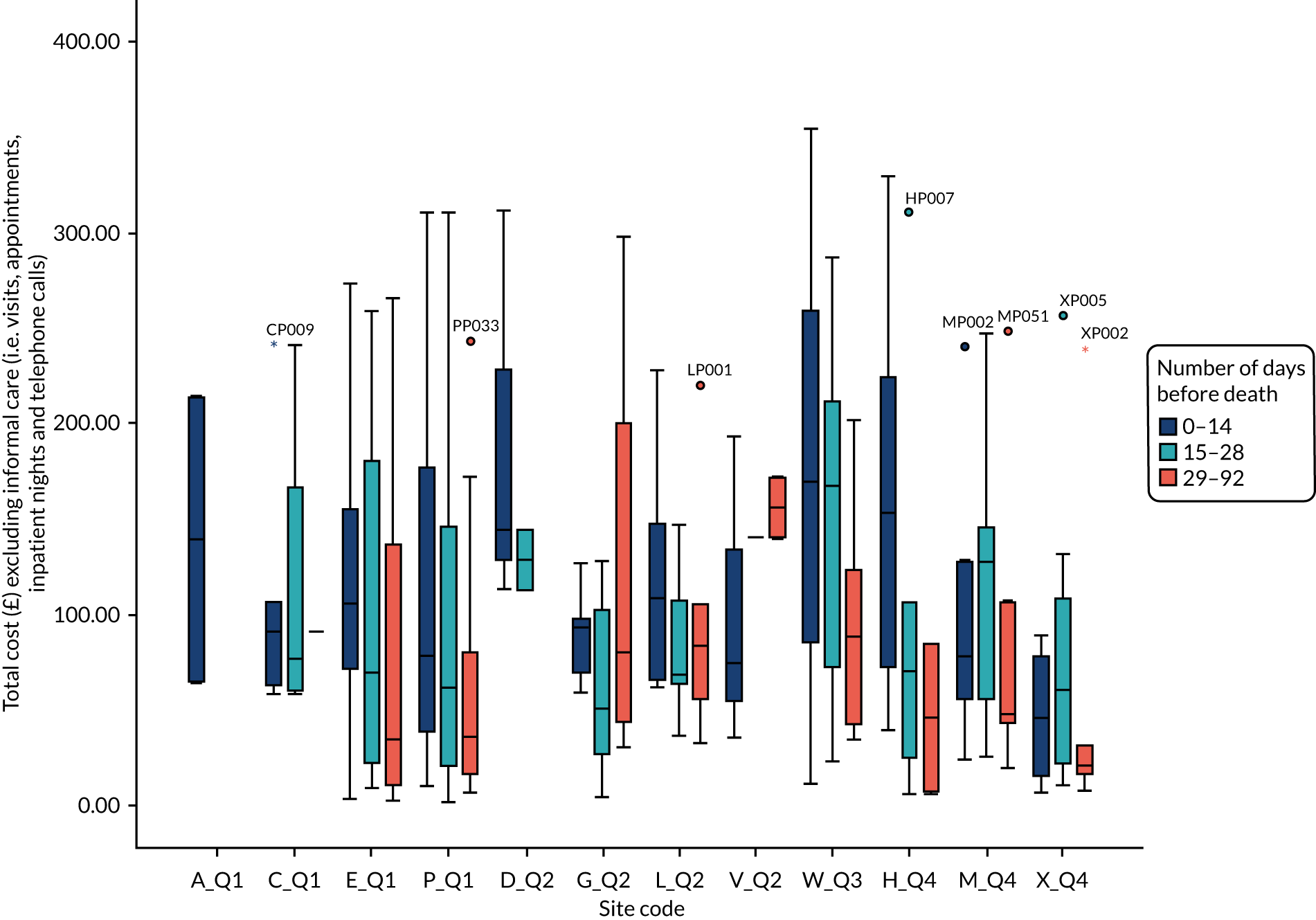

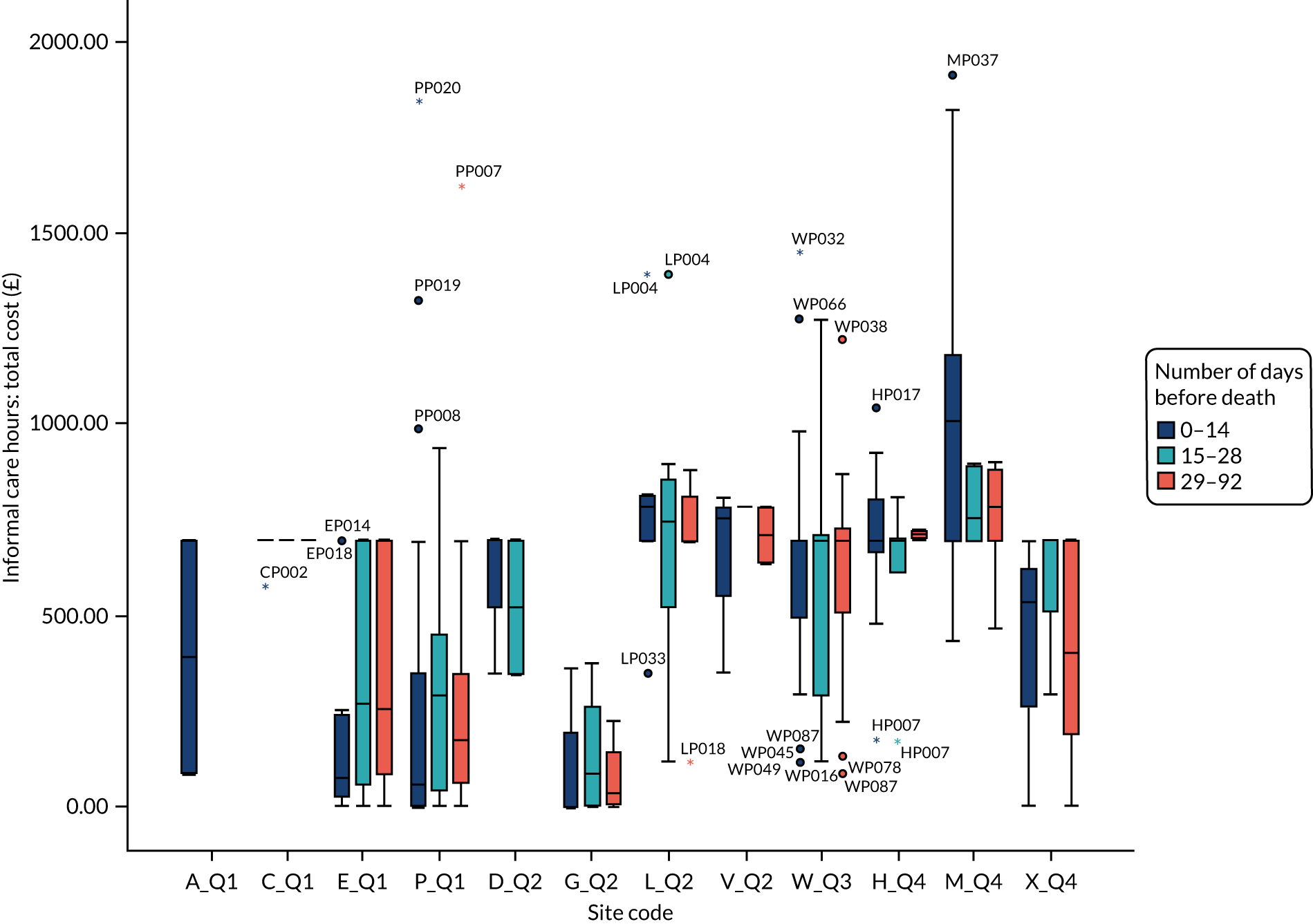

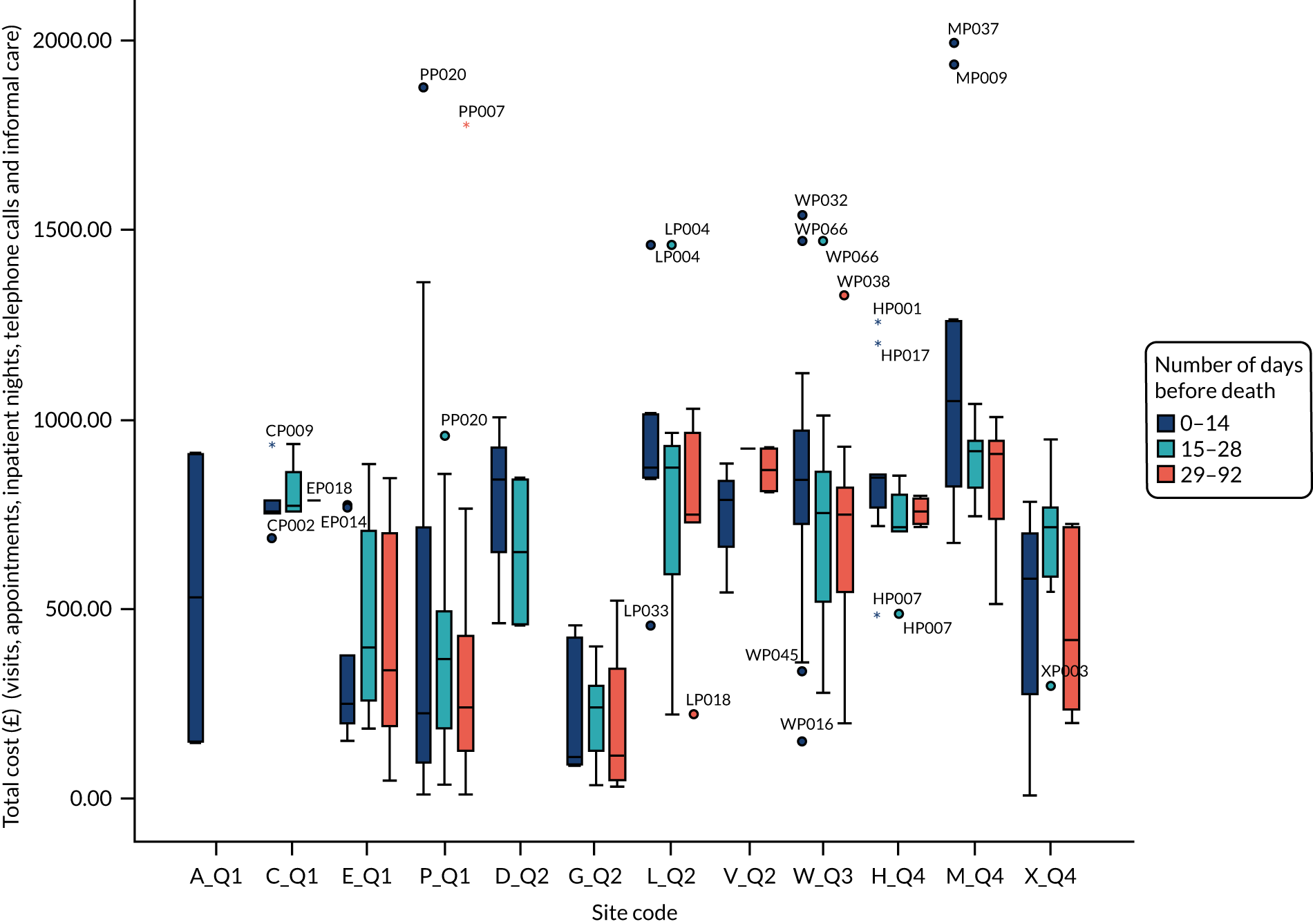

Economic analysis

The economic analysis was planned at two levels. First, a descriptive analysis of the resources and costs of running each case study HAH service, covering staff; service facilities, inpatient beds, equipment, overheads; transport for home care; and other sundry items associated with care delivery. These data were requested during the interviews with service managers, together with information on activity rates and financing, so that costs per patient receiving the HAH service could be calculated and compared between case studies.

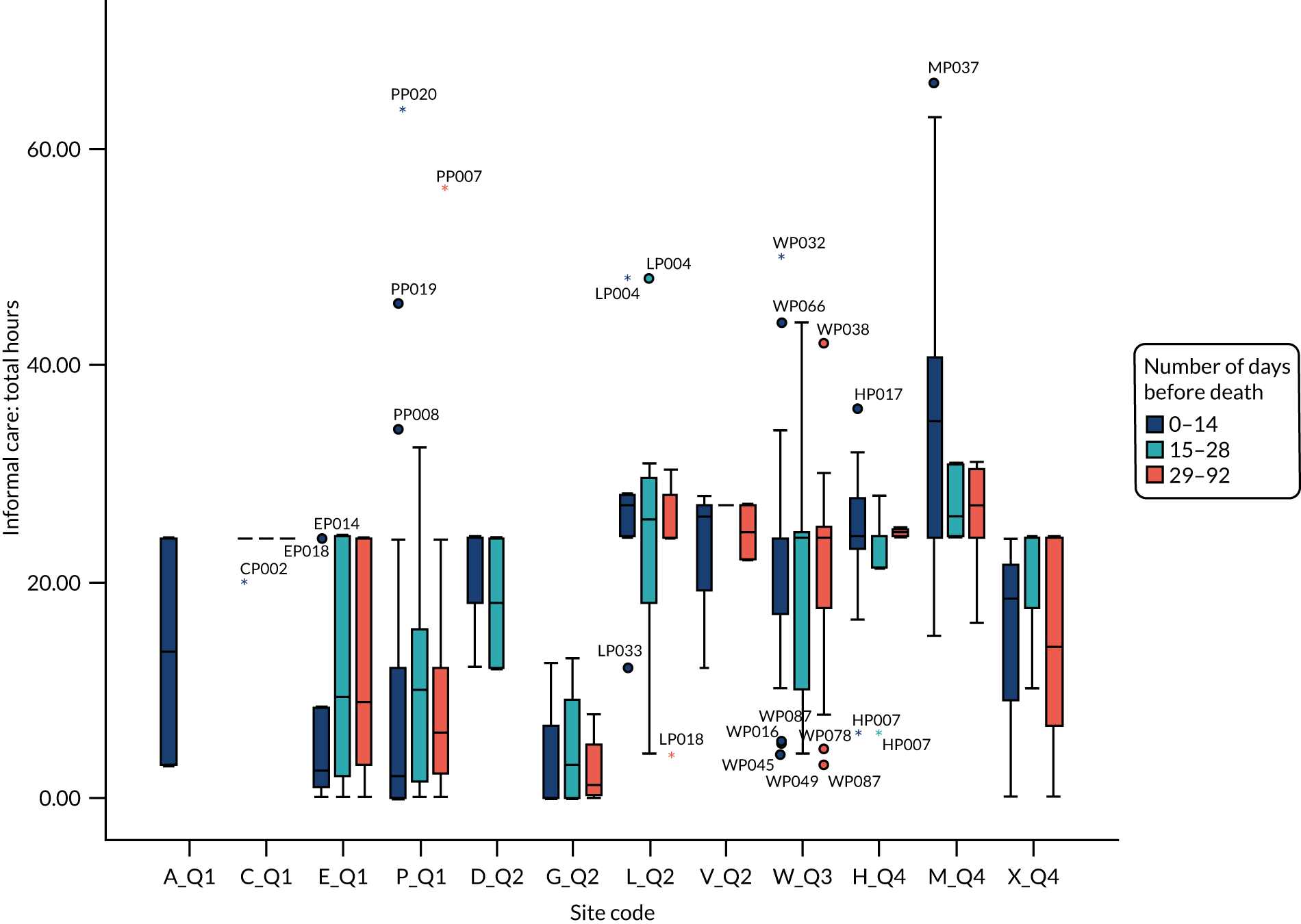

Second, a patient-level analysis was undertaken. Owing to the nature of this study, patients recruited were likely to have short and variable life expectancy, leading to an inconsistent time horizon for the individual patient-level data captured. This lack of a normalised time-integrated measure of health outcome (such as a quality-adjusted life-year) or cost, makes a traditional comparative cost-effectiveness analysis problematic. Hence, the economic analysis was limited to a descriptive analysis of service use and cost for the different HAH models. Whole-system resource use (provided by the hospice; local NHS primary, community and hospital services; and the voluntary sector) in EOLC was captured prospectively from the point of recruitment to the study for each patient. A customised version of the AHCR,91 which included informal care, was used for this purpose, as described in Service use data. At their first interview, participants were asked to report retrospectively, via recall, service use for the 2 weeks prior to recruitment.

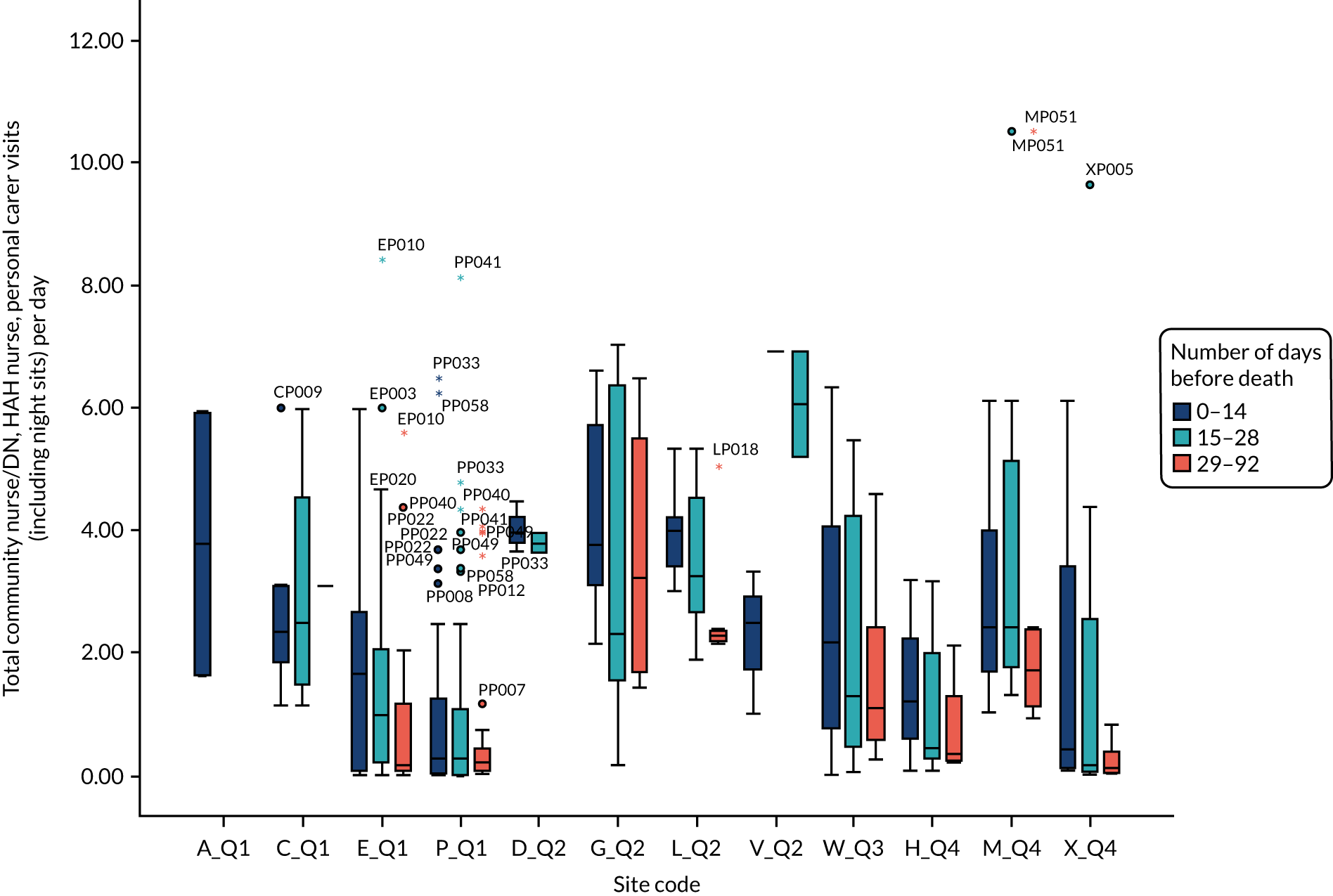

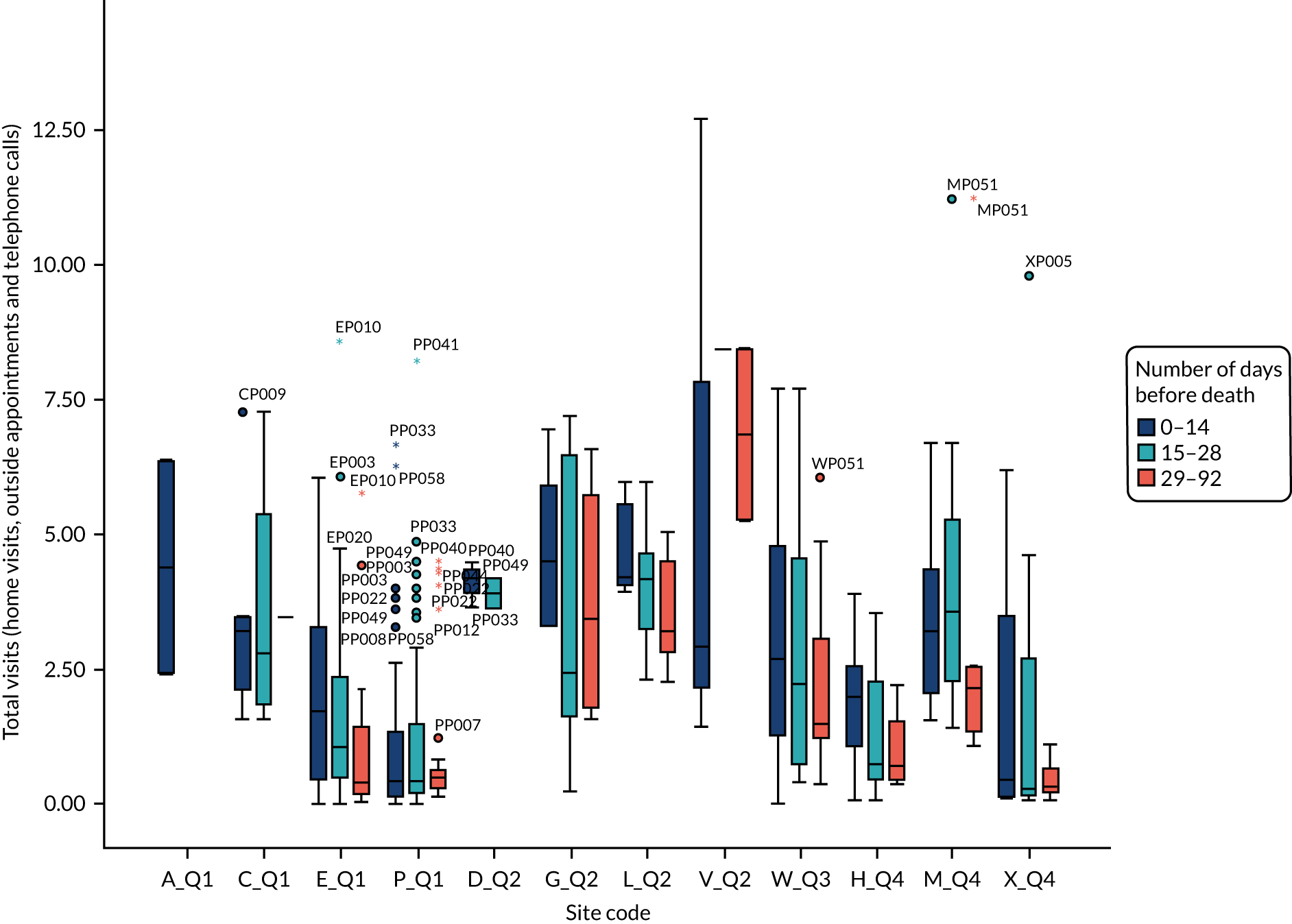

Service use data, once captured, were grouped into time periods of approximately equal sample sizes, delimited by survival time following the start of the service use data collection. The cut-off points were determined by the distribution of the data. The methodology explaining how service use data were allocated to time periods, and how missing AHCR data were dealt with, is given in Appendix 2. Resource use was converted to costs [in 2019 Great British pounds (GBP)] using national tariffs. 104 Informal care was valued using replacement cost methods (see Appendix 3).

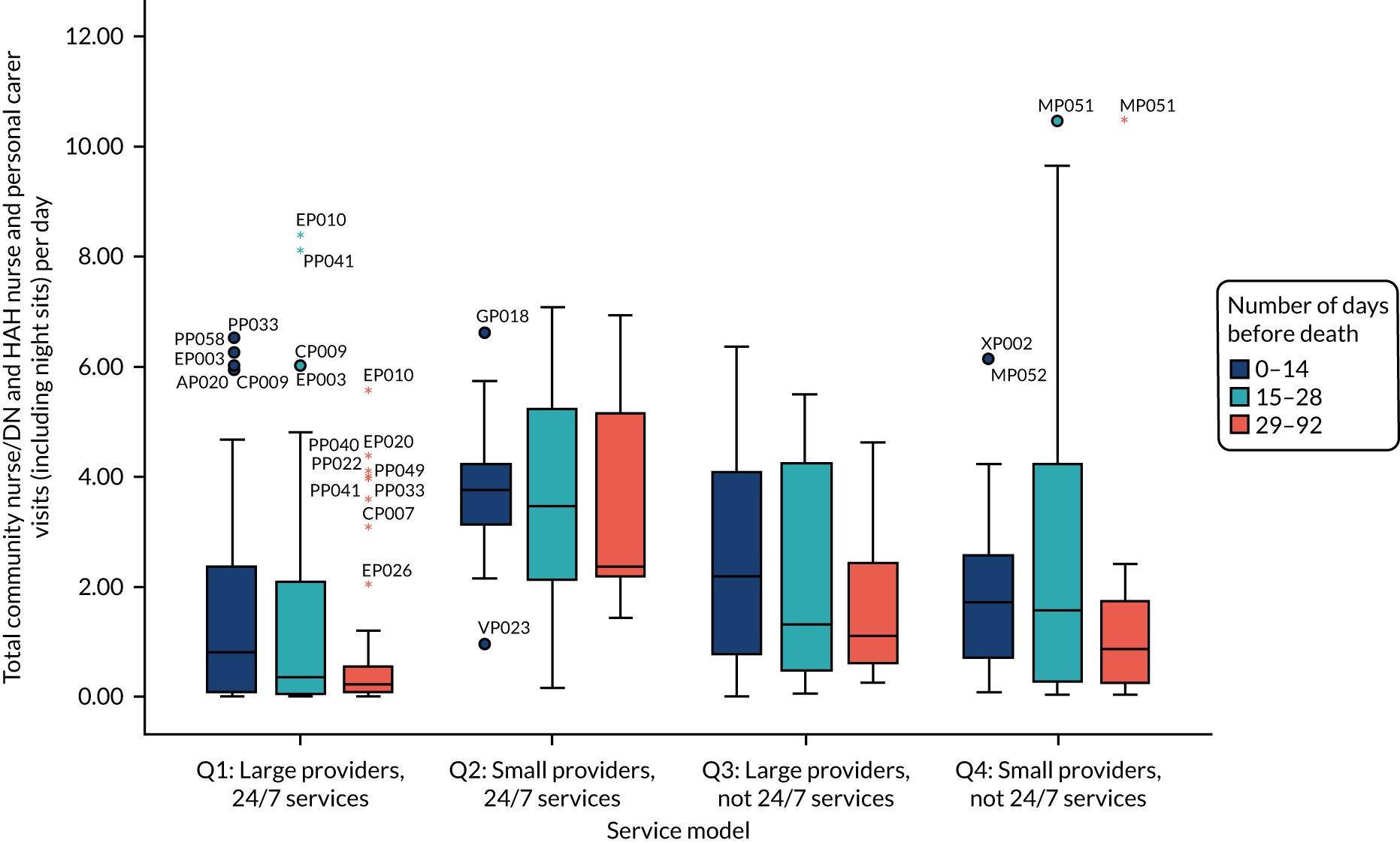

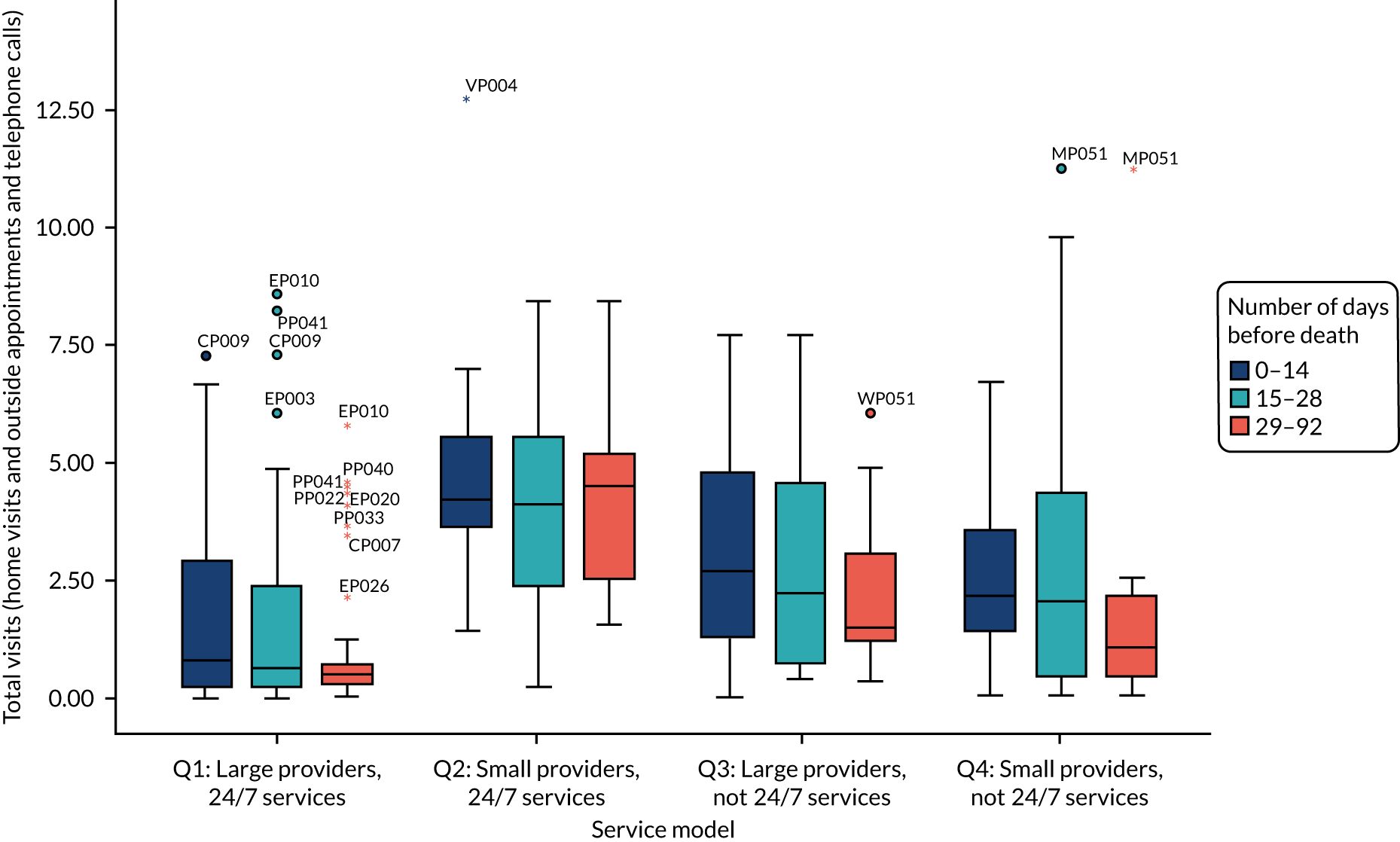

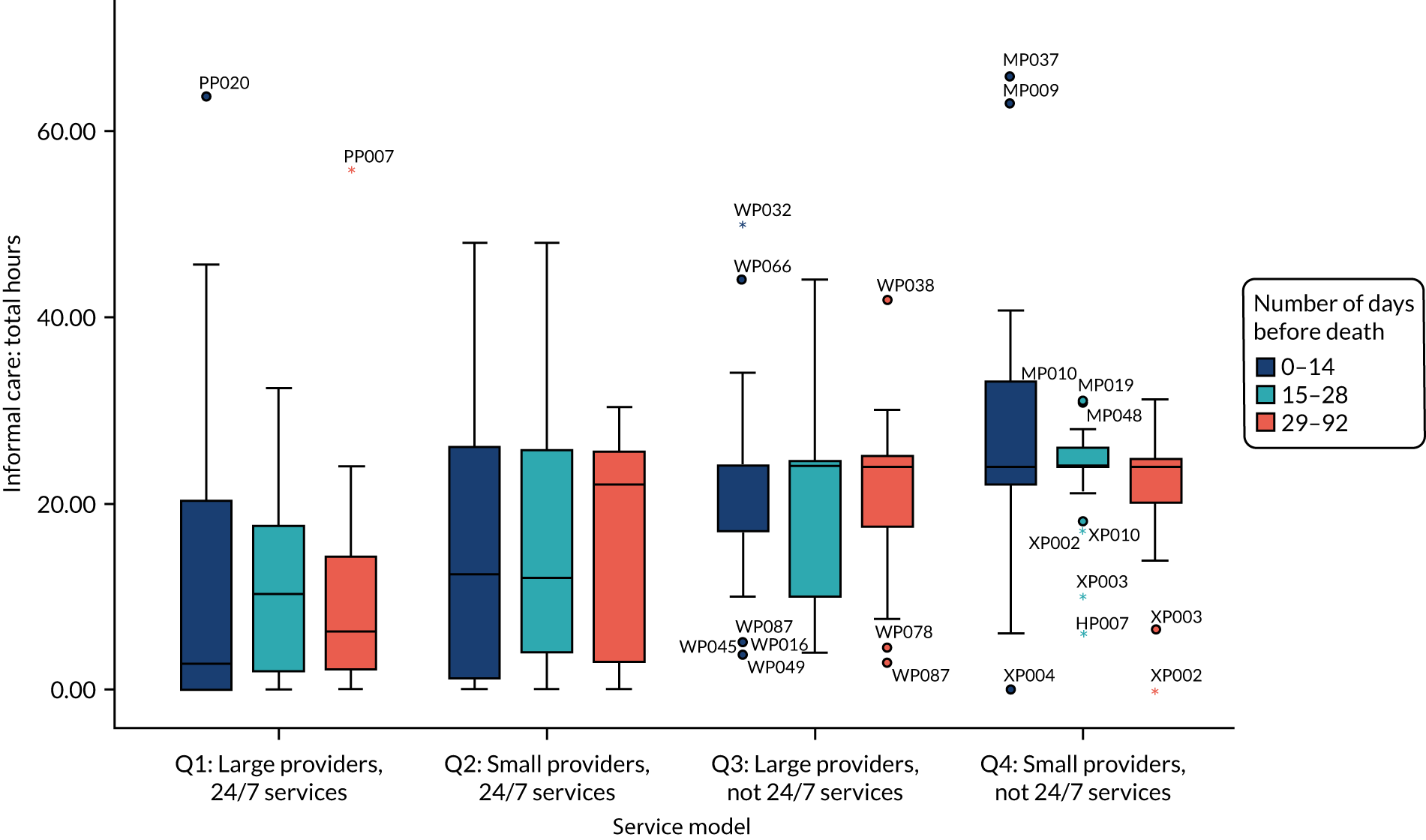

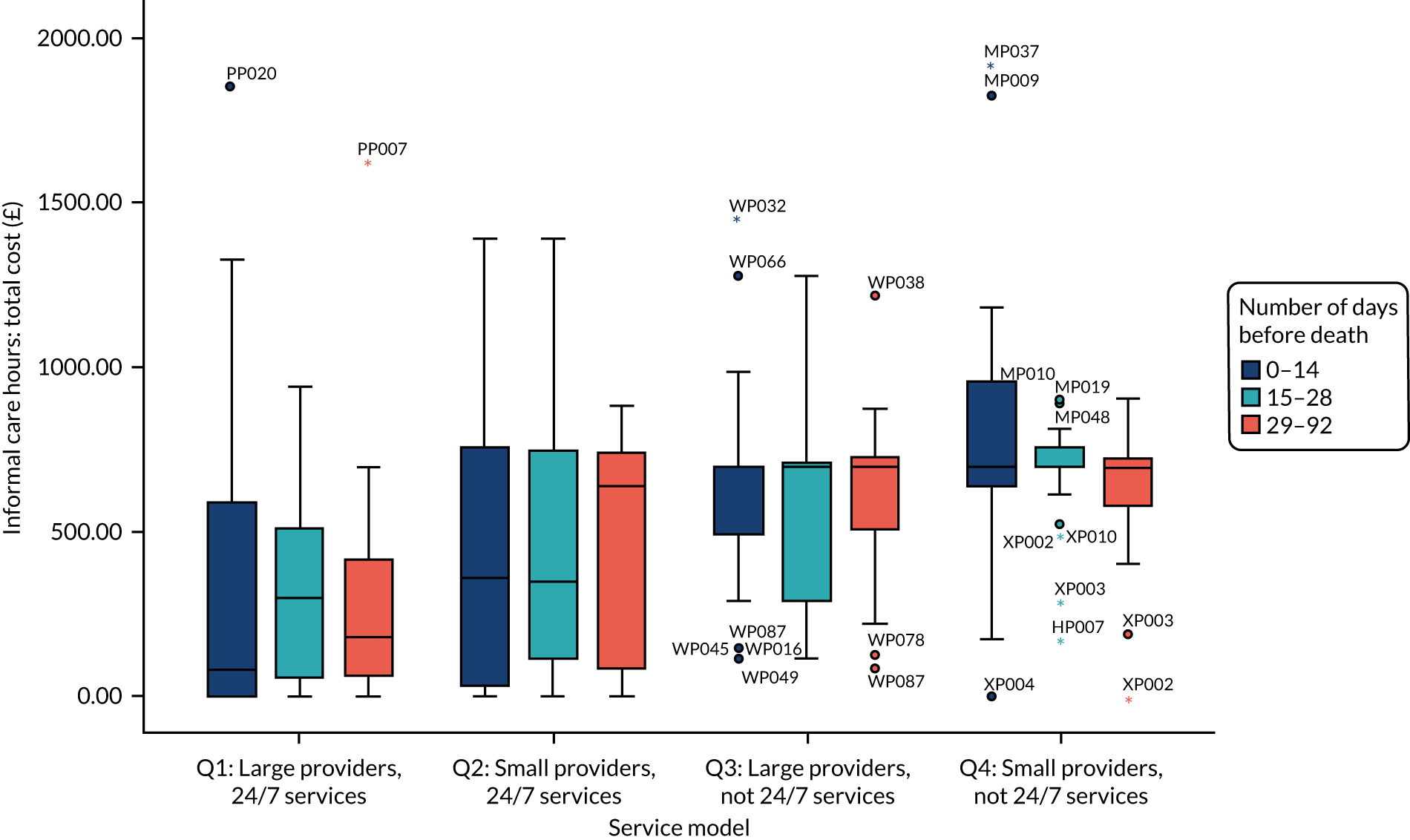

For each of the models of HAH service provision, an average cost per day of treatment was estimated for each time period. This provided descriptive cost data, independent of expected survival time, that can be compared between HAH models. Costs are presented as means and medians, given the typical skew in the distribution of costs. Comparisons of costs between each pair of HAH models were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test and are presented as box plots showing medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Analysis was also broken down by individual HAH services within models to illustrate variability. Costs were considered in relation to outcomes from different models in a cost–consequences framework.

Qualitative data analysis of phases 2 and 3

A four-stage framework approach98,105 was undertaken, using retroductive analysis of the data. Retroduction demands counterfactual thinking based on knowledge and experience, analysing why expected phenomena anticipated in initial programme theories (such as volunteering) may or may not be present, and identifying what conditions are needed for them to be in place. 106 Consequentially, qualitative data analysis throughout the project was characterised by monthly team meetings to discuss what the data were suggesting could be happening, regular sounding-out with lay and content expert stakeholders and testing out these hypotheses in subsequent batches of data.

Stage 1, familiarisation, involved the research team reading the detailed written field notes taken during the telephone survey in phase 1, alongside phase 1 quantitative results suggestive of enablers of HAH services. In addition to monthly research team meetings, two discussion sessions with project stakeholders were conducted; from these, eight initial CMO configuration tables were developed (see Report Supplementary Material 8). These CMO configuration tables and the four core constructs of NPT78 (i.e. coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring) were used in stage 2, constructing an initial thematic framework. This framework was uploaded to qualitative data software (NVivo 12; QSR International, Warrington, UK). Interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded in NVivo. During monthly meetings, the research team reviewed a set of six to eight transcripts that were independently coded and then compared, discussed emerging themes and ensured a shared understanding of the coding framework. Stage 3, reviewing data extracts, was conducted during these regular meetings. Over 18 months, interviews from all participants and sites were reviewed by the research team. This involved organising data into more coherent groupings. 98 CMO configuration tables were refined down to six after further stakeholder discussions and it was noted that coding to CMO configuration tables and to NPT core constructs was not adding to interpretation at this level, but that NPT was useful as a lens for the next stage. Stage 4, mapping and interpretation, involved further refinement of CMO configuration tables before presenting them at phase 3 consensus workshops. Feedback from small-group exercises and group discussions was recorded by facilitators (research team members, including lay co-applicants) and compiled into a detailed report (see Appendix 4, including Table 26, Boxes 9–17 and Figures 18–22). The report was mapped against the CMO configuration tables and further refinements were made. NPT was used as a higher level of interpretation and to check that implementation of HAH could be explained through the generative mechanisms identified. Quantitative questions were derived from qualitative data and used for quantitative analysis (see Appendix 5). One example of this was that carers’ qualitatively described the perception of staff having time to provide extensive hands-on care and develop a relationship with the family. Quantitative data were then tested for staff grade (it being hypothesised that lower bands of staff were more likely to be providing hands-on care), number of visits per day, duration of visits and the relationship with the QODD scores. Once quantitative data analysis was completed, suggested statistical associations were used as a guide to further interrogate the qualitative data for plausible generative mechanisms. For example, quantitative data suggested that smaller service models had more positive outcomes, and the qualitative data were analysed for possible explanations.

In total, 25 iterations of CMO configuration tables were developed. These were based on the qualitative data findings (what was working and why), literature (what, in theory, should be working but is not present, and why) and outcome patterns suggested by quantitative data.

Ethics

Patients approaching the end of their lives are entitled to evidence-based care as much as any other NHS service user, and research is required to develop high-quality palliative care. There are, however, important considerations and vulnerabilities to be taken into account when planning research in this context and safeguards need to be put in place. The family/informal carers of dying patients are also experiencing a key life event and their vulnerability must be taken into account in study design. 107

Key areas of concern were as follows.

-

Emotional distress exacerbated by the demands of the research. A number of strategies were put in place to deal with this concern:

-

A leaflet was made available in all case study sites to advertise the research, so that potential participants might already be prepared to be approached when referred to HAH.

-

The study required written consent from both patient (or consultee) and carer, supported by full information about the study procedures. There was also a strength in the patient–carer dyad recruitment – because study subjects (patients and their carers) were recruited together as a pair, they were mutually supportive of the research and processes.

-

The majority of the data were collected by telephone, with support from researchers [there was a distress protocol for researchers to follow if a carer became distressed during data collection (see Report Supplementary Material 6)].

-

Participants were made aware of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, without providing a reason or jeopardising their clinical care.

-

-

Patients lacking capacity at recruitment or losing capacity as the study proceeded. For this reason, we had a variable consent process (see Patients lacking capacity) and we did not collect data directly from patients; instead, we used staff or carer proxy data collection methods.

-

Gate-keeping by staff as a result of patient vulnerability. We offered training and support to all staff involved in recruitment to address this concern and additional training and support resources were deployed when staff voiced concerns about this issue or when recruitment did not proceed as expected.

Summary

This chapter summarises the methods used in this study, which used mixed methods with an overarching realist evaluation approach. 108 The study was in three phases. Phase 1 was a survey of HAH services in England, to understand the range of contexts and operations and to develop a broad typology of services for further investigation. Literature reviewing, stakeholder insight and phase 1 of the study all contributed to the development of initial programme theories and candidate CMO configurations. Phase 2 involved quantitative, qualitative and health economics data collection from case study sites across England, to assess the impact of each model on patient and carer outcomes; to investigate the resource implications and costs of patient care in each model; to explore the experiences of patients, family carers, providers and commissioners of the different HAH models; and to identify the enablers of and barriers to embedding HAH models as part of service delivery. As the qualitative data were collected, the CMO configurations were iteratively tested and refined. Reciprocal reviews of CMO configurations and qualitative interview data were undertaken with quantitative and health economics data to synthesise the findings. In phase 3, through stakeholder consensus workshops, the data and explanatory CMO configurations were presented, further refined and validated.

Chapter 4 Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public whose care is the subject of research are well placed to work with researchers to design and deliver the best possible research. Although PPI is becoming more widely accepted in palliative care research, challenges remain with involvement being sought from a vulnerable population, and a potential lack of confidence among researchers to undertake it. 109,110 However, we integrated PPI in this study from development through to dissemination, incorporating co-production in some elements of the project. This chapter explains the work undertaken and highlights the important role that PPI played in the project.

The aim of patient and public involvement in this study

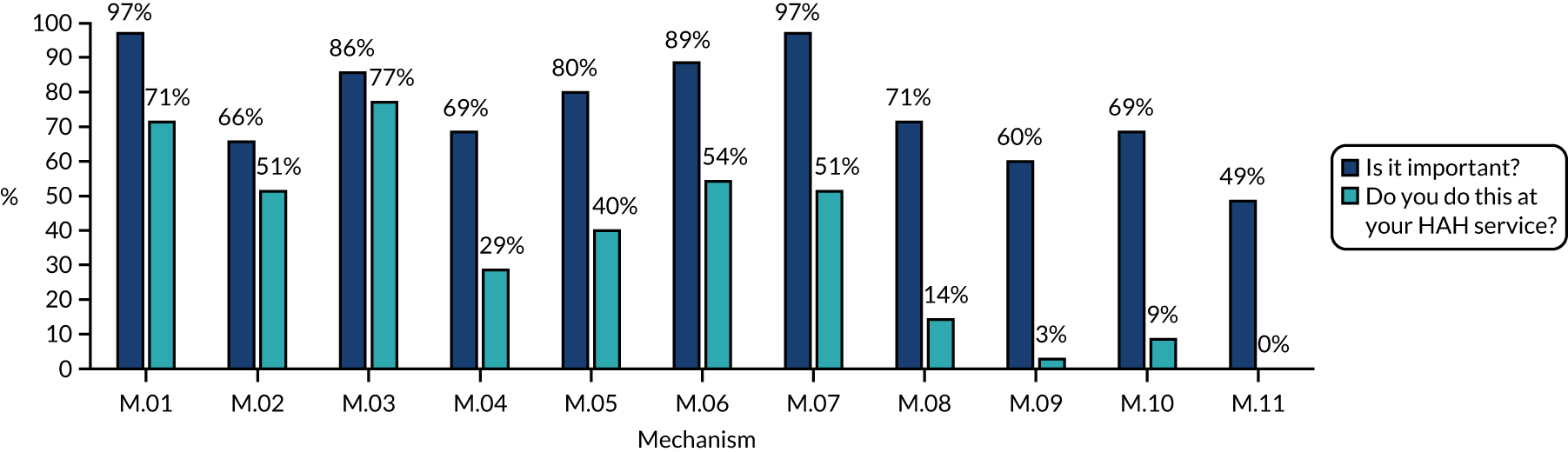

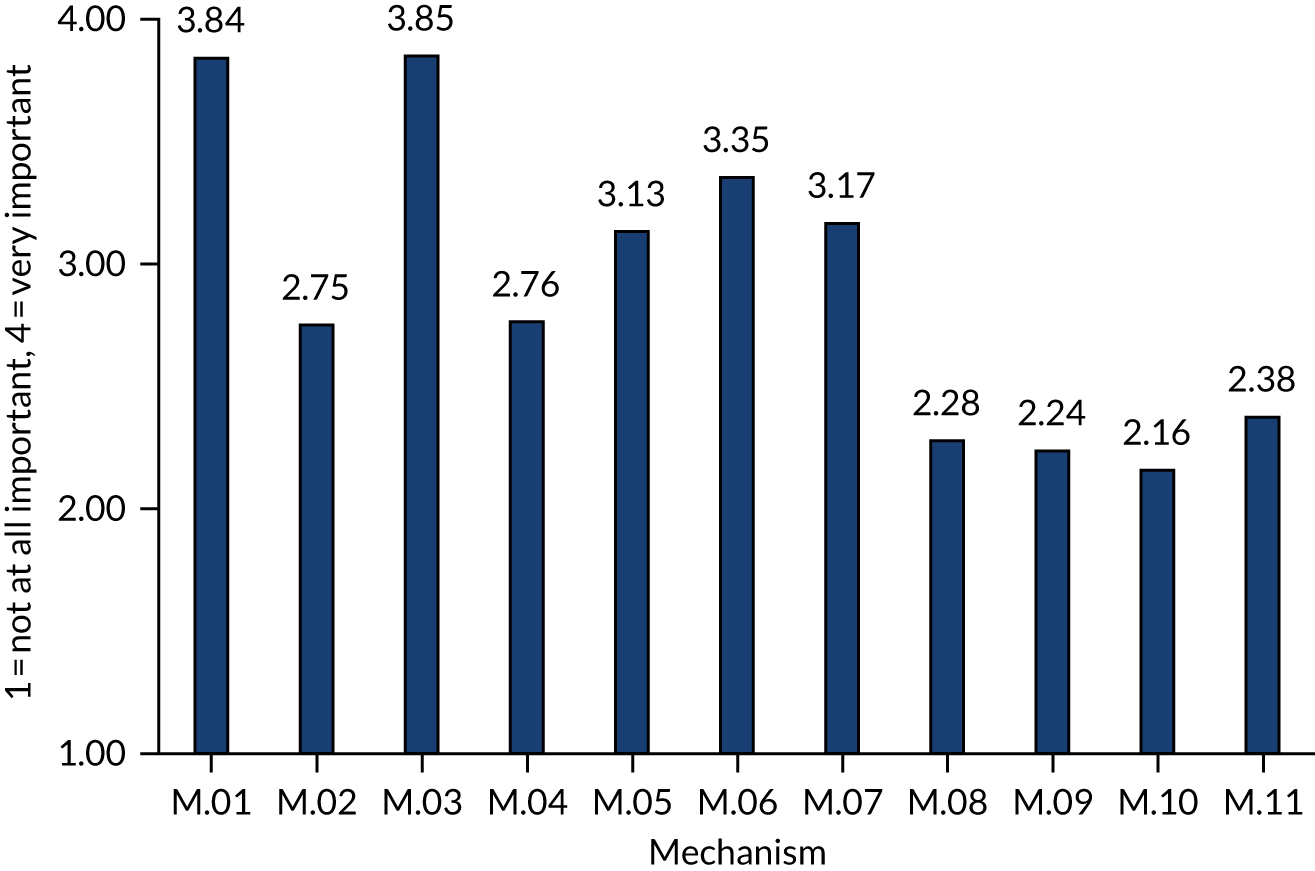

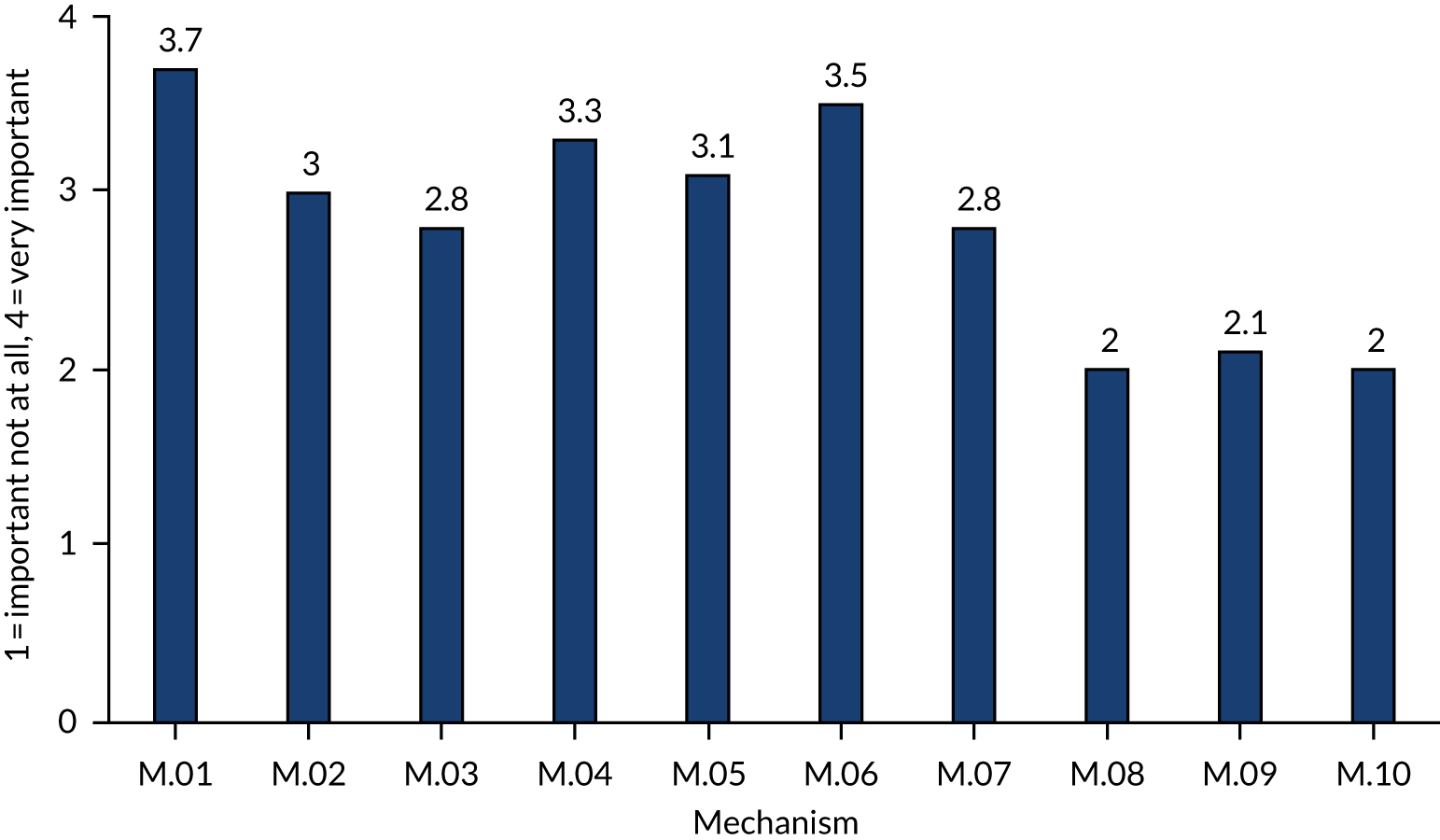

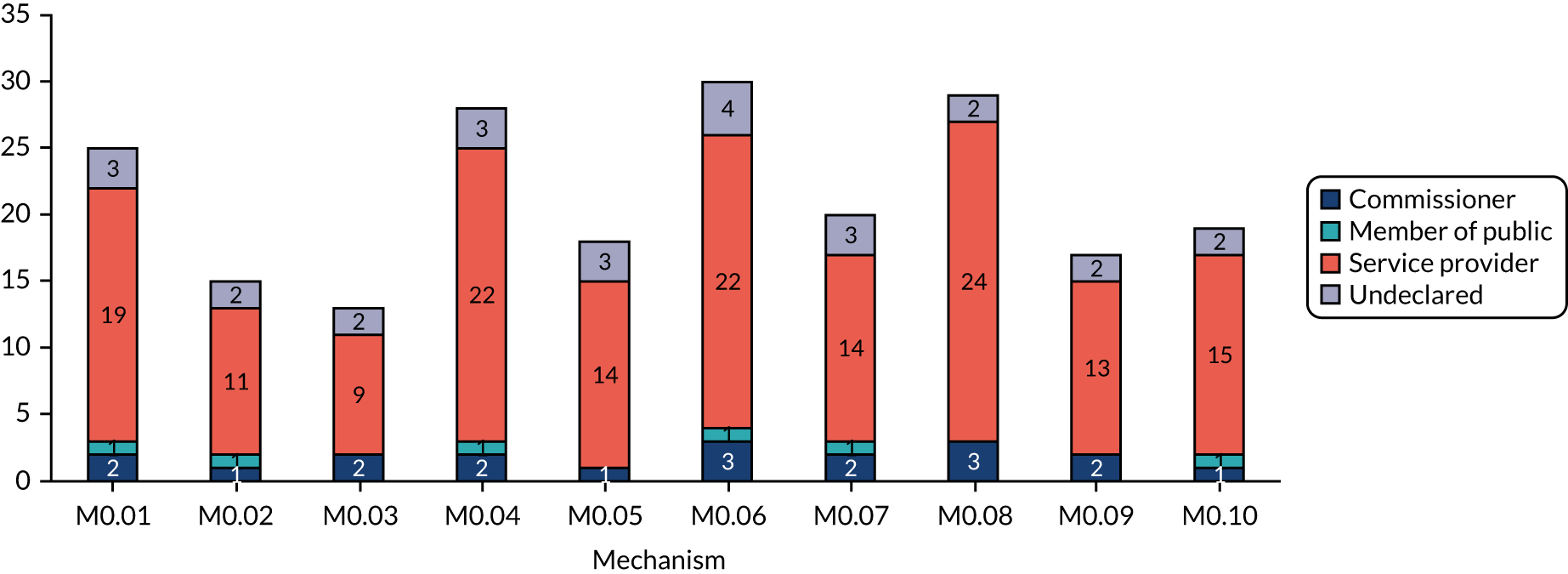

Parts of this section have been reproduced from Butler et al. 15 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.