Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128616. The contractual start date was in April 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Ryan et al. This work was produced by Ryan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Ryan et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

The importance and value of the co-production of public services have been increasingly recognised since the 1980s, in terms of providing more efficient and effective services and through improving active citizenship. 1 Qualitative research into experiences of patients, social care service users and providers can provide insights into how services might be improved, but too often these insights are not followed through into changes in practice. 2 Even when improvements are achieved, practitioners may doubt whether the lessons are transferable to other settings within the same sector. The challenge of knowledge transfer is recognised in health, where there is a substantial body of work exploring how patient experience and feedback can be captured and used to improve the quality of health care. 3,4 However, it is arguably a greater challenge in social care, where the routes for incorporating evidence into practice are less well established and supported, and where the settings in which social care happens are diffuse, sometimes unknown and often unbounded. For example, social care services can be delivered in people’s homes, public places, residential homes, community centres or even schools. Cost-effective ways to integrate the perspectives and experiences of social care service users into the design of prevention, care and support initiatives led by local authorities and their partners are needed.

Experience-based co-design (EBCD)5 is a participatory action research (PAR) approach to co-designing healthcare improvements, which draws on the co-production and design science literature. PAR is a partnership approach which has its roots in community development; EBCD sought to bring these participatory principles to health care. It has been used nationally and internationally in a range of settings, including mental health, but as far as we are aware, this study is the first to apply it as a specific structured approach in social care. A distinguishing feature of EBCD has been its emphasis on rigorously collected and analysed narrative interviews with patients and staff and observations of care as the basis for subsequent co-design work. The importance of people’s experiences, knowledge and expertise is at the centre of this approach. This helps to ensure the co-design phase is solidly based on a range of real-life perspectives and builds an effective partnership between users and staff. In this project, we explored whether an ‘accelerated’ version of EBCD, evaluated positively in the NHS,6 could offer a way to design improvements in social care, and what adaptations it may require to be practical and acceptable in this setting. Loneliness was selected as the topic of focus. We first wanted to understand what the experience of loneliness is like from the perspective of people who are or have been lonely, and how it affects all aspects of their lives, relationships and well-being. We then drew on these experiences to work, in one local authority, with people who experience loneliness and use local loneliness support services, and with local authority staff, to find better ways to address people’s needs. Through this process, we evaluated the use of accelerated experience-based co-design (AEBCD) in social care and identified recommendations for adaptations.

Challenges for social care

Adult social care in England is distinct from health care and encompasses care and support arrangements for people with (generally) long-term needs and a wide range of characteristics and circumstances. Social care also has different aims of care which are much more aligned to supporting individual well-being, independence and safeguarding, with activities focusing on personal care, domestic routines and supporting people to live full lives.

Care is needs- and means-tested with the underlying core objectives of promoting independence; encouraging and enabling choice, control, and ‘personalisation’; safeguarding; and supporting people to contribute to society. Older people comprise the largest user group and account for a high proportion of social care expenditure, though important groups in terms of incidence, needs and spending include people with physical, learning or sensory disabilities and those with mental ill health. Social care is delivered by many individuals and providers. Skills for Care estimates 17,900 organisations were involved in providing or organising adult social care in England as at 2021–2. Those services were delivered in an estimated 39,0007,8 establishments providing, or involved in organising, adult social care in England, with a somewhat dynamic picture of for-profit private sector providers dominating service markets. Social care is also heavily dependent on family and other unpaid carers, with about 5.4 million in the UK. Its structure is distinct from that of health care and less familiar to the public and those working outside of local authorities or with direct responsibility for commissioned services.

Despite recent cuts, commissioning of care by the public sector remains considerable. There were almost 2 million requests for adult social care support from nearly 1.4 million new service users to local authorities in 2021–2. However, the number of people receiving long-term care has decreased slightly to 818,000. 9 Eligible people receive local council funding for their social care but typically also pay a means-tested contribution. The council funding is either paid directly by the council to the care provider or it can be paid to the person needing care as a budget called a direct payment. Direct payments can be used in a variety of approved ways to meet care needs. If people are not eligible for local council funding, they pay for their care and support themselves and are known as self-funders.

In 2021–2 around 220,000 adults, older people and carers received direct payments, and the total number of direct payment recipients employing staff remained stable (at around 70,000) between 2014–5 and 2021–2. 7,8 However, estimates of a rapidly growing self-funded care sector who are often hidden from view and under-researched are less established, although we do know that self-funders find accessing and arranging social care difficult and emotional. 10,11 The Office for National Statistics estimates that 47% of residents in care homes for older people are self-funding. 7 Copayments (user charges) are common for many public services. Monitoring care quality is possible through contracting, and regulation is the responsibility of the Care Quality Commission.

Need for social care is growing rapidly with population ageing. If today’s care and funding arrangements continue unchanged, public and private expenditure on social care for older people will rise by 162% by 2035. 8 The need to address early identification and prevention agendas to avoid escalation of need is important and urgent in both health and social care contexts. Achieving this effectively would facilitate swifter and better-managed transitions of care and better support the growing self-funder population to access care and manage their resources.

Co-production and experience-based co-design

Co-production is widely held to be an important approach to improving the design and delivery of public sector services, by making them more inclusive and responsive and increasing individual and collective well-being. It involves professionals and members of the public working together; while an evolving concept,12 one definition is: ‘the provision of services through regular, long-term relationships between professionalized service providers (in any sector) and service users or other members of the community, where all parties make substantial resource contributions.’13

Co-production requires things to be done differently to deliver the aims of efficiency, patient or service user empowerment and accountability. 14 It involves a ‘reimagining of traditional health systems and practice trajectories’15 and reflects a political agenda to address inequalities and promote democracy. 16 Co-production has a key place in the values underpinning social care and is enshrined within the statutory guidance supporting the 2014 Care Act.

Co-production can operate at individual, group and collective levels, with the latter viewed as having the most potential to lead to wider, systematic change. 1 Different layers of public value have been identified: user value; value to groups; and social, environmental and political values. 17 In exploring why professionals (in this case hospitals) support co-production, Vennik et al. 18 found a belief that increased and improved patient involvement would improve the quality of care provided, that it helped to maintain the hospital position in a competitive healthcare market and that the approach was aligned to an adherence to organisational goals and ethos.

Osborne et al. 19 argue that co-production in public services may be unintentional and may simply arise from any interaction between professionals and users that shapes the service provided. They therefore use the term co-design to signify a more intentional, active process of working together to improve services.

Experience-based co-design is a well-established co-production approach used in health care. EBCD adopts PAR methods to involve patients and healthcare professionals as equal partners in redesigning services. 20 PAR approaches are underpinned by a collective commitment to investigate and resolve social problems with the building of alliances between researchers and those with direct experience of the issue being considered. 21 EBCD also draws on user-centred design, which again involves a collaborative approach to co-designing solutions to problem areas, and uses learning theory with a focus on reflective practice and narrative-based approaches to change. 5 There are a set of six clearly defined stages to EBCD that have been described in full elsewhere. 6,22 We briefly summarise these in Table 1.

| Stage | Activity |

|---|---|

| 1 | The clarification and organisation of governance and project management arrangements. |

| 2 | Interviews with staff working in the relevant area to explore their experiences of working within the service, and observations. Staff participants are brought together in a facilitated workshop to discuss themes emerging from the data analysis and produce a list of priorities for service improvement. |

| 3 | Video- or audio-recorded in-depth interviews with patients and family carers explore their experiences of the health service. Touch points – that is, defining moments of good or poor interaction between people using the service – are identified from the data analysis. A short film is produced using interview extracts to illustrate these points and shown to patient and family carer participants in a facilitated workshop. The group identifies a set of priorities for service improvement. |

| 4 | Staff, patients and family carers come together for the first time in a third workshop and watch the film. The two priority lists are shared, and the group decides what areas they want to work on. |

| 5 | ‘Co-design working groups’ work together on these areas over the next few months. |

| 6 | The working groups reconvene in a celebration event to share progress in implementing service change ideas and decide what the next steps are. |

A review of the international spread of EBCD 10 years after its development found more than 80 projects in 6 countries (UK, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Canada and Netherlands). 20 The authors note that many positive evaluations have been undertaken which report not only specific changes to services or care pathway redesign but also changes in staff attitude and morale. However, they note several challenges, particularly the time involved in an average EBCD cycle (1 year) and the cost of conducting interviews and observations. These issues have led to often informal and untested adaptations to the method. Only half the studies included in the review used observations, and only just over half filmed interviews with users. These adaptations may reflect not just resource issues but also concerns about anonymity, privacy and unequal power relations. In one inpatient mental health unit, for example, filming was retained but the process of recruiting participants and interviewing was led by a user group with existing relationships within the unit. Rather than a single interview, a repeated cycle of interviewing with an art therapist was adopted, giving people time to prepare and reconstruct the story of their experiences in their own way. 23,24 Mulvale et al. 25 introduced novel elicitation methods with experience maps and co-designing visual ‘prototype’ solutions, alongside the catalyst film.

A case study synthesis of six EBCD projects in Australia covering different areas of health care found that there was a need for guidance on capability development and preparedness for all participants in the project, not only for the project leads. 26 The authors found that the variability in implementation of the approach made it difficult to identify which component parts were essential for sustained service improvement. An evaluation of EBCD in a cancer centre in two large NHS trusts in London found that the engagement in the setting and proactive involvement of key clinical leaders alongside ‘particularly skilled staff who were committed to the philosophy of the approach’ were key ingredients to its successful ‘implementation’. 27 Locock et al. further describe ‘push and pull’ factors:

[T]he ‘push’ of active support and ‘opinion’ leadership at a high level of an organisation; the ‘pull’ of active quality improvement teams on the ‘look out’ for new approaches; and the mediating effects of ‘outward-reaching’ quality improvement leaders to build potential relationships. 6

Ramos et al. 28 explored the barriers and facilitators to the approach through a literature review and small-scale qualitative interview study with EBCD project facilitators. While EBCD has commonly been focused on staff in direct care roles, the authors conclude that active management participation in the process facilitates the implementation of service improvement, and underlines the importance of the project facilitation role, full organisation support, and the relationship between the service and patients. More recently, the use of the approach has been extended in different settings including forensic services29 and domestic violence and abuse services. 30

The importance of the adaptability and flexibility of this approach to different contexts while retaining its core philosophy has been emphasised,6,27 and we now turn to a key adaptation.

Accelerated experience-based co-design

‘Accelerated’ EBCD was developed by Locock et al. ,6 who sought to examine whether efficiencies could be gained by using existing filmed interviews to create a catalyst film, rather than collecting new user interviews locally. The project drew on a secondary analysis of interview data from an existing University of Oxford archive of interviews from studies of people’s experiences of illnesses or health topics. Evaluation suggested this approach led to a similar number and type of changes compared to standard EBCD but at lower cost and time, and the same catalyst film could be used in numerous settings. This model has since been used in different settings, including a hospital-at-home service for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and for advanced care planning in later life. 4,31,32

Experience-based co-design and its accelerated form are now well-established techniques for service improvement in healthcare settings but have so far not been widely used in social care or to improve care support for people whose lives are affected by social rather than health-related issues. In this study, we produced a data set of nationally conducted interviews focusing on loneliness to explore the use of AEBCD in one local authority, Doncaster. The findings of the interview study and the catalyst film will be published on Socialcaretalk.org and available for use nationally under licence.

Thinking critically about co-production

Co-production is not without criticism, and Steen et al. 33 describe the tendency of researchers towards optimism without engaging with the ‘dark side’ of this approach. Steen et al. highlight the optimism surrounding the approach and an often-presented idealised view by scholars and others, which they argue masks a set of potential problems. Attention should be paid to the potential relinquishing of responsibility by government, local authorities and other public sector bodies. Co-production can lead to a lack of clear responsibility, with boundaries blurred between public, private and voluntary sectors. There is little evidence of sustained change, with innovations often remaining precarious and small,34 and it is important to recognise the costs associated with the approach. 35 Co-production can be dominated by people who are wealthy and well educated, leading to further exclusionary practices and a professionalisation of involvement. 36 There can also be co-destruction rather than co-production if the process is done poorly or as a tick-box exercise; it can cause conflict and lead to misunderstandings, opportunities to change services may be missed, and the approach is open to misuse and manipulation by government. This is not only a waste of resources; it can also generate mistrust. 11,35 While it is important to note that Williams et al. 37 have pointed out flaws in some of these concerns, we agree critical questions should be asked about how situated practices of co-designing, facilitating or participating in co-produced activities can reflect or disrupt power relations at a local level. 14 Tools are available to help navigate this complex terrain. Leach,38 for example, presents a normative framework to assess the efficacy of co-production which involves consideration of inclusiveness, representativeness, impartiality, transparency, deliberativeness, lawfulness and empowerment. Thinking specifically about EBCD, Donetto et al. 39 draw on Bradwell and Marr’s40 working definition of co-design process to frame how the EBCD approach is operationalised. Bradwell and Marr’s framework sets out four key dimensions of co-design process: participation (a collaborative process); development (an evolving, maturing process); ownership and power (a transforming process); and outcomes and intent (a process with practical intent in which unplanned processes and transformations are also likely). Bradwell and Marr acknowledged, as did Leach,38 that such frameworks of principles for co-production or co-design represent ideals which are difficult to achieve fully in practice but can act as a guide to key aspects deserving attention. We return to Bradwell and Marr’s40 framework when reporting on the current study in Chapter 6.

Loneliness

There is an unprecedented rise in loneliness globally, with around a third of people affected by what has been referred to as the ‘widespread disorder of our times’. 41,42 Loneliness is viewed as a serious issue associated with a range of negative health outcomes comparable to smoking and obesity. 43 In 2016, the Local Government Association, Age UK and the Campaign to End Loneliness produced a guide for local authorities on key research about, and practical steps to help tackle, loneliness. 44 This guide was updated in 2018 with additional sections on public health and preventing loneliness. 45 The report advised, among other things, that council leaders should understand local levels of loneliness and set out plans for action. In 2020, loneliness was announced as a government priority in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and government-enforced lockdown conditions. A new public campaign, #LetsTalkLoneliness, was launched alongside a £750 million charity funding package. Despite this focus, the definition of loneliness remains elusive largely because it is a subjective experience. As Fried et al. suggest: ‘We believe loneliness can be defined as a subjective negative experience that results from inadequate meaningful connections, but neither definitions nor assessments of loneliness have achieved wide-scale consensus.’46

Three main theoretical or conceptual frameworks have been offered to understand the phenomenon: existential, social and cognitive/emotional perspectives. 47 Common ground across these approaches is that loneliness is an emotionally negative experience that increases the risk of adverse effects on physical and mental health. The existential perspective conceives loneliness as a natural and necessary component of human existence,48 which involves the perception of being disconnected from others, and emotional aspects which include emptiness and feeling abandoned. 49 The social perspective focuses on the absence of needed relationships, feelings of disconnection, vulnerability, powerlessness and lack of interpersonal affirmation, with roots in attachment theory and childhood. 50 This perspective is commonly used in research, with 70% of studies in a recent review following this approach. 47 The cognitive or emotional perspective describes loneliness as a negative and involuntary experience that arises from the perceived discrepancy between desired and emotional and/or social relationships. 51 Different types of loneliness are distinguished based on chronicity. While transient loneliness may arise due to circumstances (e.g. moving house or retirement) and people tend to adjust to an unfamiliar environment or life situation, chronic loneliness alludes to feelings that last for more than 2 years and are hard to change, or to an intense feeling that is hard to endure. 52

There is controversy around the use of the term ‘chronic’, which suggests a pathologisation of loneliness and has been challenged in favour of terms like ‘persistent’ or ‘prolonged’ loneliness. 53 Research is often framed as though loneliness needs curing or management through health and social care services rather than being a relational and emotional state that can affect us all. A recent report by the Campaign to End Loneliness,54 however, underlined the importance of focusing on chronic loneliness, which affects around 2.6 million people in the UK (around the same number that experienced chronic loneliness pre COVID-19). The authors highlight how chronic loneliness is more likely to be experienced by people with poor health, disabled people, family carers and those receiving care, people living in poverty, and people from minority groups, as well as intersections of these factors. The lack of detail and focus on inequalities in research evidence about loneliness was also highlighted in the evidence synthesis by Mansfield et al. 47

A further limitation of research in this area is that it focuses on generating a quantifiable definition of the term to measure its antecedents and consequences. The prevalence of loneliness in later life, however, has not changed despite considerable attention to this area and a host of interventions across decades. 55 In a paper based on the findings of the first stage of this project (see Chapter 3), we suggest that more qualitative and conceptual/theoretical work is needed to better understand the phenomenon and develop appropriate resources. 56 Studies tend to explore deficits in interpersonal relationships, emphasising individual characteristics such as personality, social skills and physical mobility. Less research explores the role of communities and societal relationships that contribute to loneliness. 57 The word ‘loneliness’ is often used interchangeably with ‘social isolation’, which is measurable and considered an objective state. Unlike loneliness, which can be experienced in the presence of other people, it is more about the lack of ‘meaningful’ relationships than the size of a person’s social network. 58 While a lack of social contact can lead to loneliness, it is possible to live a solitary life and not feel lonely. 59 Indeed, solitude can be connected to feelings of freedom and a sense of comfort with one’s life. 47

There is recent interest in younger people and loneliness,19 in part fuelled by COVID-19, and we need to explore the concept beyond the constraints of age. Advanced age and ageing are often equated with becoming lonely, although a recent synthesis of qualitative studies exploring loneliness indicated there was a fall in the number of studies focusing on ageing to less than half the studies included in the review. 47 Victor et al. 60 found that 14% of older people who were lonely had experienced loneliness in five life stages from childhood to older age. Other qualitative studies explore loneliness in relation to groups such as disabled people or people with mental ill health and identify explicit contextual and person-related factors that contribute to feeling lonely. 61,62

Loneliness interventions

Reviews of intervention studies, for example the work of Victor et al. ,53 draw attention to insufficient separation of related concepts, such as loneliness and isolation, for underpinning the persistent difficulty in establishing ‘what works’ in tackling loneliness, for whom and in what circumstances. Fried et al. highlight how the evidence base for interventions ‘is characterised by poorly constructed trials with small samples, a lack of theoretical frameworks, undefined target groups, heterogeneous measures of loneliness, and short follow-up periods.’46

Although loneliness matters for a prevention agenda, a review of interventions among older people found that mechanisms for reducing social isolation and loneliness differed and the quality of evidence was generally weak. 63 However, local authorities continue to introduce interventions without consideration of the very little existing evidence and few robust evaluations.

Interventions often use ‘asset-based’ approaches focused on maximising personal and social network resources. 64 Asset-based approaches have gained traction in social care, where many people fund their own care and cutbacks contribute to growing unmet need, and have been enthusiastically embraced in preventative agendas around tackling loneliness and isolation within the context of the Care Act 2014, which orientates local authorities to a duty to prevent or delay the need for care.

While many reviews and evaluations have concentrated on the findings from quantitative studies of interventions, qualitative study findings have helped understand some of the nuances of complexity, pointing to why certain interventions may be experienced as more effective. For example, Gardiner et al. 63 found three characteristics common among effective interventions: attention to local context, participants doing productive activities and involving local users in design and implementation of interventions. McMullin1 compared co-production initiatives aimed at older people experiencing loneliness in England and France and identified the importance of how the social problem is framed in terms of values. The Ageing Better programme based in England explicitly linked loneliness to individual problems, while the Monalisa initiative in France was linked to wider social and political values which motivated the selection of activities which are more geared towards successful co-production. Other reviews similarly suggested factors associated with successful interventions, including adaptability, community involvement in the design and development of the intervention, and active rather than passive client engagement. 65–67 Some of the sociodemographic factors considered important when tailoring interventions included age, poverty, and being a carer, as well as aspects of the social environment such as access to transport and driving status. 68 Interventions based on social loneliness and a focus on social connections and community integration are unlikely to work. 47

Where interventions were delivered by multidisciplinary partnerships, colocation of professionals involved was shown to be beneficial, by acting as a reminder to those delivering the intervention of the availability of support from others. 69 Finally, the importance of identifying triggers or events where loneliness and/or social isolation may change – for example, life-course transitions such as retirement, and relationship and health changes – was also shown to be key. 70

The reviews reported fewer factors that hindered the effectiveness of interventions. Of those reported, most concerned digital technologies. Specifically, these were the attitudes of older people towards the required technologies and lack of interest in learning new technological skills; the cost of technology; access to technology (including digital literacy and access to devices, especially in care homes); and concerns over privacy and online safety. 67,71,72 Other non-technological factors hindering the effectiveness of interventions were the workload and lack of interest of those involved in delivery65 and difficulties that carers of people living with dementia had with relaxing at joint events due to concerns about how the person with dementia would react. 73

In general, the reviews report a lack of sufficient evidence on ‘what works’ to guide practice. Reviews note that this is not to deny that some people experience beneficial impacts from interventions intended to help address loneliness or social isolation. Rather, evidence remains weak owing to the complex nature of interventions and research quality issues, which included little theoretical exploration of how interventions can mitigate loneliness and/or social isolation and a lack of methodological rigour in their evaluation. In summary, reviews are increasingly calling for providers to move away from standard, ‘one-size-fits-all’ interventions to more tailored offers and for future research about the effectiveness of interventions to be able to discern what works for whom, how and in what context.

COVID-19 and loneliness

The impact of COVID-19 and associated government policies around social distancing have led to considerable research on loneliness in the last 2 years. This evidence is contradictory in places. Some research suggests the experience of loneliness has remained stable despite social distancing rules74 while other findings suggest the pandemic has resulted in more loneliness. 75,76 It is clear, however, that pandemic-related conditions have had an uneven impact, with some people more affected than others. A recent report from the Campaign to End Loneliness, drawing on data from the Office for National Statistics, showed an additional million people experienced loneliness during the pandemic, and this impacted more heavily on people who already experience disadvantage: ‘[T]he fallout from COVID-19 could further embed economic and health inequalities, with disadvantaged people more likely to be out of work and in ill health, increasing their risk of chronic loneliness.’77

While concerns have been raised about the impact of COVID-19-related responses on older people, with a request for more nuanced and less ageist responses,78 people over the age of 60 years had a greater resilience to loneliness and mental ill health, possibly because older people have more experience of being alone and of dealing with potentially life-threatening medical situations. 79 The pandemic has brought into focus the impact of loneliness on children, young people and people with mental ill health. 80–82 Consideration around women is raised in some studies, although again it is not clear whether this is a continuation of pre-pandemic patterns. 81,83

In summary, tackling loneliness remains a key priority for health and social care services in the UK because the health and well-being impacts of loneliness can be substantial for those experiencing it. The costs to the health and social care sectors of increased health problems can also be considerable. Mansfield et al. suggest that co-production methods would enhance research around loneliness, concluding that: ‘[w]e need to comprehend more clearly who feels lonely, when where and in what context.’47

Why Doncaster?

Doncaster has a high concentration of neighbourhoods at elevated risk of loneliness (Age UK Loneliness Map),84 including several wards (e.g. Mexborough) in the top percentile of risk nationally. Local consultations have highlighted the loss of many social spaces linked to the decline of manufacturing and mining (e.g. community centres, working men’s clubs), and concern that loneliness is worsening (Doncaster Talks). Doncaster’s local authority and public health stakeholders have determined that addressing loneliness and social isolation is a key strategic priority, recognised in the local Health and Wellbeing Board priorities for 2018–21. The Doncaster Cabinet founded a third sector-led Social Isolation and Loneliness Alliance to substantially reduce loneliness in Doncaster.

The local authority and its Alliance have been highly committed to supporting our research. Given the challenges that social care research faces in engaging practice and the time it can take to build and sustain links with local authorities, it is important to have a willing organisation that is interested in research and has a clear commitment to the topic area. Doncaster is also part of the Curiosity Partnership, a 4-year Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR)-funded research capacity-building network which is further developing the use and production of research at the level of local authorities.

In addition to Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council acting as co-applicants to the research, planning discussions were held with the Head of Strategy and Performance, Head of Programme Delivery, the Assistant Director for Communities, and the Director of Public Health as well as the co-ordinator of the council’s work with the voluntary, community and faith (VCF) sector. They remained particularly interested in engaging with the video-based presentation of qualitative research as a means for enabling evidence to feed into service development and action planning.

The rationale for this project

Research, and more generally the use of data, should play a leading role in supporting commissioning and practice in social care. However, there is a weaker research culture and a lack of quality improvement architecture in the social care sector compared to health, with implications for the involvement of decision-makers, practice and service users. At present, local authorities collect some routine outcomes data but lack (even) the data-analytic capacity of health services. Qualitative data are a more natural format for experiential information, and robustly undertaken, could be more amenable to translation into service improvement. Moreover, narrative forms of data would be more accessible to local communities seeking to engage in service improvements. There is a slight caveat here, in that loneliness as the exemplar sits in local authority prevention work and is in the orbit of public health, which is more research orientated.

Social care policy is set nationally but interpreted, shaped and implemented in 152 locally elected councils. The result is wider variation in social care practice than in health care. There are very few public sector providers, making it harder to get research messages heard or acted upon, and most of the care workforce have no research experience or training. Those who provide services are typically in highly competitive markets and operate with low profit margins.

Staff turnover is high and even those seen as ‘qualified’ social care professionals (e.g. social workers, occupational therapists) receive less research training and continuous professional development than most of their equivalents in health. They are rarely exposed to research evidence, and indeed many do not have access to online research resources during their working hours. Few social care researchers simultaneously combine academic and practice responsibilities.

In short, models of working and the organisation, funding, commissioning and delivery of social care, as well as the research landscape, are quite different from health care, and the generalisability of innovation from health to social care is unlikely to be straightforward or comfortable. This makes it vital to ensure that what seem like promising interventions that support evidence-informed practice (e.g. the work of improvement scientists in the NHS) are tested in social care contexts. We know that there is considerable room for improvement in the provision of social care support in the UK and that innovative and cost-effective approaches are needed both to help prevent the need for social care and to guide the best use of current resources.

Study aim and objectives

Aim

Our aim was to assess whether an effective and efficient co-design approach, AECBD, could be translated from health to social care, using experiences of ‘loneliness’ as an exemplar.

Objectives

-

To understand how loneliness is (1) characterised and experienced by people who are in receipt of social care in England and (2) characterised by social care staff and the voluntary sector.

-

To identify how services might be changed to help tackle the problem of loneliness experienced by users of social care.

-

To explore, with one local authority, whether an approach to service improvement, known to be effective in health care, could be adapted for use in social care.

-

To disseminate all study outputs and publish resources on a newly established Socialcaretalk.org platform for public, family carers, service users, voluntary organisations, researchers, teachers, policy-makers and providers.

Outline of this report

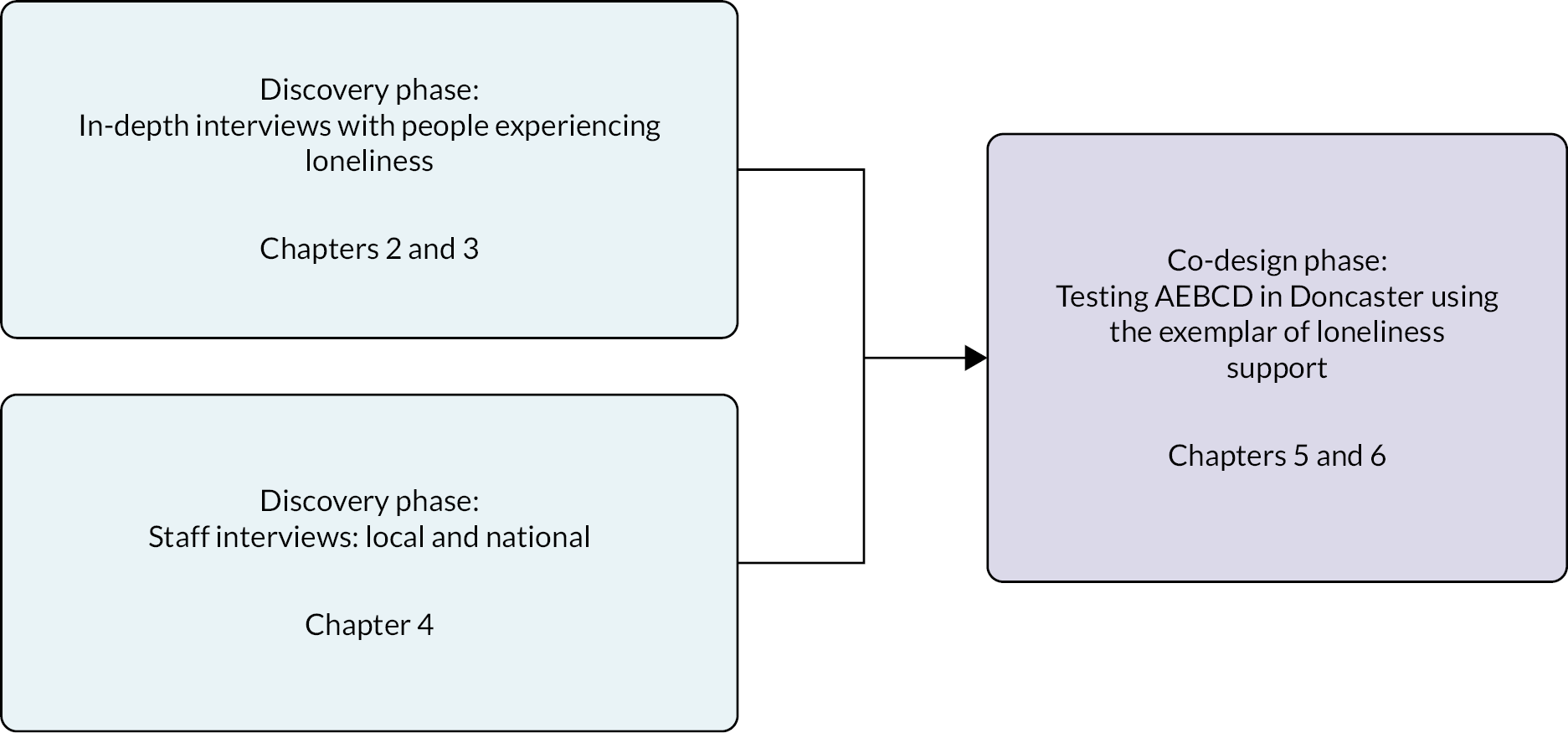

We have structured Chapters 2–6 of this report in line with the two chronological phases of AEBCD: discovery and co-design. We first present the methods and findings of the discovery phase. This phase comprises two elements. First, an in-depth interview study with members of the public who experience loneliness, required to create the film to use in the co-design phase to test the accelerated form of EBCD. This work is presented in Chapters 2 and 3. Second, interviews with staff working in loneliness support. Most of the staff interviewed worked in Doncaster, with themes from the findings used in the co-design phase. A small number of staff working elsewhere were also interviewed, to explore generalisability of the local findings. The methods and findings from this work are presented in Chapter 4. Figure 1 summarises the flow of reporting the discovery and co-design phases in Chapters 2–6 of the report.

FIGURE 1.

Chapters reporting the discovery and co-design phases of the study.

Chapters 5 and 6 present the methods and findings of the co-design phase, which was exploring whether the AEBCD intervention worked in Doncaster, along with the parallel evaluation. In Chapter 7, we outline how members of the public were involved in the project. Chapter 8 brings both stages of the project together, and we present our conclusions and recommendations for how AEBCD could be used effectively in social care settings.

Chapter 2 Discovery phase: study design, methods and public interviews

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Malli et al. 56 This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

This phase of the study involved a separate, preliminary stage of qualitative research to produce a nationally generated data set based on in-depth narrative interviews with people who experience or have experienced loneliness. While we were using an accelerated EBCD approach, we had to create this initial national data set to draw on in the co-design work. By contrast, the test of AEBCD in health care used by Locock et al. 6 was able to draw on the extensive existing Oxford national archive of qualitative interviews published on Healthtalk.org (https://healthtalk.org). This archive has over 4500 interviews conducted since 2000 and covers over 120 health conditions including experiences of mental ill health, pregnancy, long-term conditions, cancers and, more recently, COVID-19. The research question underpinning these projects is ‘what are the health, information, and support needs of people with experience of the condition?’ We replicated this approach85 to create the data set from people with experience of loneliness, which has created two new resources; video, audio and text extracts from these data were used to produce a new section on loneliness and a catalyst film, both published on Socialcaretalk.org (https://socialcaretalk.org).

The Healthtalk approach

Each Healthtalk project aims to generate a diverse sample in terms of demographic characteristics and types of experiences, which means the number of participants is typically large for a qualitative study. An expert advisory panel made up of patients, third-sector representatives, health professionals and academics offers suggestions about condition-specific experiences to guide the researcher in recruitment and other aspects of the research. Participants are interviewed in depth about their experiences and asked to give permission for their interviews to be used in research, teaching, publication, broadcasting and to form part of the new online resource. They can select whether they would like data extracts to be used in text, audio, or film versions. While Healthtalk.org was originally created to provide support and information for patients and carers going through similar health issues, it has become widely used in medical and health education and the project findings are used to inform health policy, for example, in the development of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines. 86

While the aim of the current project is to assess whether AEBCD can be translated from health to social care, in this chapter, we present the methods designed to achieve the first part of objective 1, namely, to understand how loneliness is (1) characterised and experienced by people who are in receipt of social care in England and (2) characterised by social care staff and the voluntary sector.

Field review

A brief field review on the topic of experiences of loneliness was conducted to inform the interview topic guides. This review guided the selection of study participants and highlighted issues for inclusion in the interviews. It further helped the team to recognise the limitations of previous studies and find innovative ways to avoid them.

We developed the search through an iterative process, using combinations of keywords and synonyms for loneliness and social care: loneliness; social isolation; social networks; intervention; review; public health; support; lonely; alone; isolated. We searched a range of social care, health, and social science databases, including Social Care Online, Social Science Abstracts, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Social Science Citation Index. We also screened reference lists of relevant papers. Literature on improvement science was included to identify individuals who write about this area and communities who could be relevant in terms of engagement and dissemination. A literature topic alert was set up for the project’s duration and on the advice of our Study Steering Committee (SSC), the literature review was updated in October 2021 to include studies focused on COVID-19 and loneliness.

The initial field review was completed during months 1–3 of the study by researchers Malli (Oxford) and Maddison (York) when the start of the fieldwork was delayed by COVID-19. From the starting point of the latest synthesis of qualitative studies across the adult life course (144 studies published up to 2018), Malli identified an additional 30 recent articles. Of these 174 studies, 98 focused on loneliness in relation to elderly people and in developed countries.

Maddison examined published research reviews of interventions designed to reduce loneliness and/or social isolation. The purpose was to explore what types of interventions are effective and why. The search was limited to English-language peer-reviewed papers published since 2000, identified via the Cochrane Library or the Social Policy and Practice database. A total of 36 papers were identified, dating from 2003 to 2022; a further 8 were identified by cross-checking the list against a key ‘grey’ report prepared for the Cabinet Office in 2018. 60 The body of research reviewing ‘what works’ in relation to interventions to reduce loneliness and/or social isolation appears recent but is growing rapidly: almost half (18/44) of the reviews identified were published in 2020 or later. The findings of the review are included in Chapter 1.

Method

An interpretative approach to knowledge production was used to understand how people make sense of their experiences, particularly loneliness. Narrative interviews were used in line with the EBCD approach. 87–90 Narrative interviews allow participants to convey stories that are meaningful to them and articulate the impact of loneliness on their lives and the lives of those around them, as well as the strategies and routes they may have used to help alleviate loneliness. 91 We were interested in understanding how participants construct and negotiate the meaning of their experiences of loneliness. 92 Our aim was to generate a deeper understanding of the experiences and meaning of loneliness through the analysis of accounts of being lonely. Blumer believed that research methods should be faithful to the empirical world under investigation, so we did not provide participants with a definition of loneliness, allowing space for subjective constructions of loneliness to emerge which could enhance our understanding of the phenomenon. Participants actively engaged in meaning-making during the process of the interviews as they were encouraged to explore and consider their experiences through careful probing and questioning.

The national, qualitative research study involved in-depth interviews with 37 people who self-identified as being lonely, conducted between October 2020 and January 2021. Participants were aged 18–71 years, with 23 identifying as female, 13 identifying as male and 1 as non-binary. A further two people were interviewed and later withdrew.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the interviews were conducted online (n = 30) using videoconference or by telephone (n = 7) depending upon participants’ preferences. A purposive maximum variation sampling approach was used to capture a wide range of perspectives and understand variations in people’s experiences. 93

We particularly wanted to capture the experiences of marginalised people as our review highlighted that this group could be more susceptible to experiencing loneliness. Our sample included participants with multiple intersecting identities, as outlined in detail in Table 2, which states the number of participants that identified with these marginalised identities.

| Identitiesa | Number of participants (n = 37) |

|---|---|

| Physically disabled people | 3 |

| People with mental ill health | 21 |

| People with learning disabilities | 2 |

| Autistic people | 4 |

| Bereaved people | 4 |

| LGBTQ community | 5 |

| Migrants | 6 |

| Substance users | 4 |

| People living with HIV | 4 |

| Domestic violence and abuse survivors | 4 |

| Family carers | 2 |

| People from ethnic minorities | 3 |

| People that have experienced homelessness | 3 |

Recruitment

Participants were recruited using a range of strategies including mental health charity advertisements, local authority newsletters, personal contacts through previous research and the involvement of colleagues, snowballing through existing contacts and social media platforms. More specifically, Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), which has been identified as a useful tool in approaching seldom-heard populations,94, 95 was used. Flyers for the study were posted on relevant public Facebook pages and closed support groups. Due to the latter’s strict access conditions, the study was only advertised after permission was granted by the administrator through private messages providing details of the research. More than 30 closed Facebook groups were approached relating to mental illness, disabilities, drug and alcohol dependencies and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) issues, of which 3 declined to advertise the study. Participants had to be 18 years old or over and to have experienced loneliness. Although some studies have avoided using the term ‘loneliness’ during recruitment due to negative connotations of the word,96 it was clearly stated in our flyers so as not to mislead potential participants about the topic of our study. Originally, we intended to include only people who used social care services; however, it transpired that people were often not aware of whether groups or services they had interacted with were included, and we widened our sample criteria to people who experienced loneliness.

All participants received a £30 voucher in recognition of their time and contribution to the research.

Interviews

The narrative interviews were conducted by Malli, an experienced qualitative researcher. A ‘warm-up’ discussion preceded the interview to make the participants feel at ease. This is especially pertinent to sensitive topics, such as loneliness. The interview was divided into two sections. An open question (‘Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and how loneliness came into your life?’) was used at the start of the interview to allow participants to highlight what was important to them, their values, meanings, priorities and experiences. The second part of the interview was based on the topic guide grounded in the field review and feedback from our project advisory panel. It covered loneliness and support, identity, loneliness, and the media (see Report Supplementary Material 1). To bridge the two parts of the interview, the researcher started with questions about topics raised by the participant in their primary narrative and then asked the additional questions to understand participants’ experiences of their wider lives including relationships and employment, social care services and other sources of support. We also explored how services could be improved. The interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 2 hours and were audio- and video-recorded with participants’ permission.

Transcript checking

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by professional transcribers, checked for accuracy against the recording, and deidentified. Time codes were added throughout. The transcripts were returned to participants to give them the opportunity to read and remove any sections they would not like disseminated or used in research. At that stage, they were asked to sign a form giving the copyright for their interview to the University of Oxford to enable their interview to be used in online resource production, including a resource to be published on Socialcaretalk.org and the catalyst film. The transcripts were also deposited in a University of Oxford data archive available to other bona fide research teams for secondary analysis under licence.

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted alongside the fieldwork until ‘data saturation’ was reached. We defined this as a point where new data repeated that of previous interviews without bringing new contributions to the understanding of the phenomenon. 97 A multistage inductive thematic analysis was carried out as a systematic method of generating themes and patterns within the data following the Braun and Clarke98 guidelines and using the organisational support of NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). A deviation from the study protocol included the use of grounded theory; this approach was felt to be more flexible, allowing us to analyse the data within the time constraints we were facing due to a delay in gaining ethics approval.

Initially, the data were read carefully by Malli in a process of familiarisation before being coded in NVivo to maintain participants’ meaning as far as possible. Malli and Ryan independently coded the first three interviews and met to discuss the different codes generated. The codes were then reordered into a more formal tree structure allowing the identification of broader categories. Malli continued to code the remaining transcripts. The descriptive codes were organised into categories and these categories were analysed conceptually in what Braun and Clarke98 describe as a process of ‘latent analysis’ to examine underlying ideas, assumptions, connections and links within the data. From this analytic stage, themes were identified, and the data were systematically reviewed to ensure that a name and clear definition for each theme were produced and that these themes worked in relation to the coded extracts. We returned to the original recordings as appropriate to aid this stage of analysis. To increase the integrity and trustworthiness of the study, the first author kept a reflective diary during the interviews, transcription and analysis phase.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee (REC), after the submission was moved from Social Care REC, on 2 October 2020 (ethics reference: 20/WM/0223). COVID-19 necessitated further planning to minimise face-to-face interaction with research participants where possible. New operating procedures were introduced for the capture of data suitable for dissemination on a web platform which specifies methods to optimise video and audio quality while adhering to data security policy.

Producing a catalyst film

A core output for the co-design phase was to produce a ‘catalyst’ film using film, audio and text extracts. A ‘touch point’ coding report was produced during the analysis process detailed above. Malli selected extracts of data which highlighted key points illustrating excellent or particularly poor support. These extracts were shared with full team members and advisory panel members before meeting to discuss the content further. The planned workshop to finalise the content of the film was unable to go ahead because of COVID-19 limitations. Locock separately arranged a meeting with the Doncaster team, the evaluator, and the workshop facilitator to talk through AEBCD and the film’s use in the co-design phase of the project. The content of the catalyst film was further revised in individual discussions with public advisory panel members. Extracts included participants’ discussions of what good loneliness support looked like and what had not worked for them in terms of social care and privately provided interventions.

The DIPEx charity produced a draft version of the 20-minute film using the video and audio extracts, and the link was shared with the full team and advisory panel members by e-mail. Comments were invited and incorporated into the film. A final discussion about the film was held at an advisory panel meeting in January 2022. Feedback included concern about the quality of the sound, which led to the addition of subtitles, and the organisation of the content which has the following sections:

-

What is loneliness?

-

What does loneliness feel like?

-

What has made loneliness worse?

-

Why are people hesitant to access support in relation to loneliness?

-

What hasn’t worked for you in relation to loneliness support?

-

What does good loneliness support look like?

The film was used in the co-design workshops (see Chapters 5 and 6) and is published on Socialcaretalk.org (https://socialcaretalk.org/introduction/loneliness/).

Developing a Socialcaretalk section

The second output from this stage was the production and publication of a new section on experiences of loneliness on Socialcaretalk.org. In producing the section, the aim was to include a representation of the full data set, and this was achieved by identifying what mattered to participants and reflecting a diverse range of perspectives around loneliness in a balanced manner. From the identified categories and themes, we developed a series of lay summaries on the issues that were most important to people who self-identify as lonely (https://socialcaretalk.org/introduction/loneliness/). The summaries include contextual, evidence-based information and links to other sources of information and materials.

To ensure quality, balance and comprehensiveness, each summary was prepared by Malli, with Ryan independently mind-mapping the coding reports on which the summaries were based and adding any aspects that had been overlooked. When each summary was drafted and checked by Ryan, it was reviewed by members of the project advisory panel before final editing and publication.

Example feedback from advisory panel members included these comments:

I think they are really interesting, and the text is an excellent summary of the themes, the childhood one was so sad it brought tears to my eyes.

I think they would be brilliant to use in teaching about loneliness and really make it clear that it is much more than not having people around you but is often more of an internal state of feeling.

Chapter 3 Discovery phase: public interview findings

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Malli et al. 56 This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

An early finding from this research was the ambiguity relating to the relationship between participants and social care services. Unlike healthcare services, where people typically enter a healthcare setting or contact at a clearly defined contact point, there was a lack of clarity around the meaning or scope of social care and whether it is seen as an extension to community-based preventative activity such as loneliness support. Some participants used social care services such as support workers, and some used local services that may have been funded by the local authority.

Our analysis led to the identification of six key themes. Four of these – loneliness as lacking, loneliness as abandonment, lingering loneliness and the unspoken and trivialised experience of loneliness – have been published. 56 In addition to the findings reported in the paper, two additional themes were identified: the double-edged sword of social media and inevitably, though unplanned for in the initial project design, reappraising connections as an outcome of COVID-19. The section below is a summary of the published paper and the two additional themes.

Loneliness as lacking

Loneliness was linked to the loss of important close relationships and the absence of close relationships with people who could genuinely understand participants, empathise with them and affirm their value as an individual.

Loneliness as loss

Loss and bereavement strongly featured in participants’ narratives, and these deaths were often unanticipated and accompanied by additional emotional trauma. Participants were deprived of the company and affection of the person and an envisioned future together. P29, who lost her partner abruptly in her late 30s, explained:

I know this woman who lost her husband, but she was in her seventies or eighties. And I always say, ‘You lost a lot of past, but not so much future. I lost a lot of future and not so much past.’ It’s very different to be on your own when you’re, let’s say, in your seventies and maybe you are a grandparent, and you have a completely different role in life than when you are just a young person who had their whole life to go.

P29

Participants described irreplaceable bonds that could not be substituted, which worsened loneliness. P1 talked about the loss she felt after the death of her mother, whom she relied on in different ways:

I think that had a huge impact on how I interact with other people now I just, I don’t feel as connected any more. So she was always kind of like she had, she was a friend, she was a sister, she was a carer as well like, you know, she’d always sort of check up on me and she had so many roles and when that went it just left this huge hole in my life, so I think that, yeah, it sort of affected me quite badly.

P1

The unanticipated loss brought an additional layer of loneliness as participants discussed how they struggled to approach the grief of premature death. There was a lack of the comforting and supportive responses that bereaved people commonly receive. As P40 said in relation to her brother’s death:

When your 27-year-old brother dies from a heroin overdose it’s like there’s no [card company] card for that . . . people also don’t wanna talk about it because it’s a bit like ‘oh, do we bring it up?’ whereas people seem more comfortable bringing it up sort of if a parent or grandparent’s died.

P40

Loneliness as absence

For many participants, loneliness was marked by the absence of a meaningful person to turn to, a relationship that they never experienced. Many wanted a connection with someone they could talk to and confide in. The following extracts capture this absence:

I have no-one to share my life with . . . I don’t have someone to turn to, to tell my problems to, or anything like that.

P37

There’s moments when I’d like to sort of really connect with someone or when I’m feeling low, I want to sort of, because I don’t really have [um] many friends and [um] I think that’s when it does appear like [um] I feel that intense loneliness when I feel quite isolated.

P1

Even participants who perceived themselves as sociable and surrounded by casual friendships missed an intimacy and affection which was absent from their life. For P2: ‘I suppose I would really like my friendship to be like quite close, friendships should be quite close, so I want to feel like, like family’.

For P22 and many participants, the intensity of a friendship rather than the quantity of the social circle combated loneliness: ‘it no longer mattered whether I had other friends because I found another really, person who I could be really close with’.

Loneliness as abandonment

Loneliness could begin with strained family relationships and feelings of invisibility and abandonment from childhood. Others described feeling abandoned by society because of insufficient care and cuts in funding.

Being overlooked during childhood

Loneliness was discussed in relation to participants’ family and childhood experiences, including stressful environments, the emotional unavailability of close family members, and other adverse experiences such as abuse and neglect. Looking back at their childhoods, they described how loneliness was about the need to be listened to, believed, supported and protected. The impact of this abandonment could be extreme, as P32 describes, talking about her relationship with her father:

It took years for me to realise that I actually felt annihilated in his presence. I was so unacknowledged, um, that I almost felt like there was nobody reflecting me back and my grasp on my own existence was tenuous. I realised when I was very much an adult, um, that just being in his presence was enough to make me feel suicidal because I felt so unacknowledged, like somebody had rendered me invisible.

P32

The illness of his younger brother, who subsequently died, led P12 to feel neglected by his mother, while P35 felt her parents gave her brother all the attention when he was born 8 years after her:

I was an only child for eight years and then my brother came along. […] So my parents favoured him over me pretty much from the get-go, so I kind of, because everyone was always all over my brother I kind of retreated [um] and just kind of spent a lot of time in my room by myself [um] not really socialising and isolating myself I suppose.

P35

For some participants, loneliness came from keeping experiences of abuse secret. Fear of the consequences of disclosing this and perceptions of self-blame emotionally isolated participants and made them feel that they could not reach out and ask for support. P11 described how:

I was being sexually abused from the age of 9 and, and it was quite a secret thing, [um] it was something I was keeping to myself . . . think it was quite lonely because I suppose it’s a lot to deal with and at the time, I didn’t really have anyone to talk to about it.

P11

The need to keep domestic violence as a private family matter that could not be disclosed and discussed with people outside the household left P37 feeling lonelier:

I was like locked inside of the prison, you know, I couldn’t say a word I couldn’t look for help I literally felt like I’m like decaying inside, like the living dead. You know we are forbidden to talk about this to anyone and it does make you feel lonely.

P37

Being abandoned by society and those who could have helped

For many participants, loneliness was a result of being deprived of community and social care resources due to austerity cuts. Financial cuts were seen as a source of social alienation that made people feel invisible. Social clubs and support groups which for many were an important resource for active networking with ‘similar others’ were closed. P19 talked about the impact of two social clubs closing:

They lost their funding, which was hard because I was enjoying it. I was enjoying the activities they were doing. They were doing like games, cooking in one of them. All different types of stuff . . . It was hard because I was enjoying it. I enjoyed seeing people.

P19

P18 described feeling isolated and abandoned after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. He described getting ‘a whole bunch of pamphlets thrown at you and told you have MS, and told we’ll see you in six months for a check-up’.

Other participants discussed not being heard within the mental healthcare services. They described a process of dehumanisation and objectification from healthcare professionals that induced loneliness and social isolation. In relation to mental health care, P6 described:

If I could at least [have] told them about my experiences and what I was going through, I wouldn’t necessarily have wanted an answer, but I’d have wanted someone to listen and if someone’s listening to me, they see me, I’m not lonely any more.

P6

Finally, some participants felt that their social identity was invalidated and undervalued, which made them feel lonely. P3 reflected on her unpaid carer role:

When I’m being sort of selfish, I think maybe I made a mistake and I should have just kept my career because they certainly don’t look after carers, they’re on their own . . . Because people seem to forget that the productivity coming from unpaid carers in this country saves the state about a £132 billion every year so, you know, it’s a bit of a sore point when people say you didn’t go to work.

P3

Lingering loneliness

For many participants, loneliness was something that accompanied them throughout their life. It was perceived as an innate part of their identity that stemmed from a sense of otherness, and its presence lingered even in the company of others. Participants also described feeling trapped in a cycle of loneliness, which intensified personal isolation.

Loneliness and identity

For many participants, a sense of loneliness came from feeling ‘different’ and was inevitably ingrained in their identity. For example, P1 said ‘I think [um] being autistic [um] I feel lonely quite a lot of the time [um] so I think it’s always there, I think it’s never not a part of who I am’.

For some, being ‘different’ affected their sense of integration and belonging, and emotions were tied to loneliness. P33 said, in relation to mental illness:

I kind of always, I guess, had this like longing to belong or like be a part of other people’s lives where I wasn’t really. Um, so I spent kind of like most of my teen years extremely lonely.

P33

Being ‘different’ sometimes meant being stigmatised and fearing or experiencing rejection. In relation to her mental illness, P39 said:

It’s like damaged goods you don’t ever, nobody ever prioritises damaged goods, you look for an apple you look for a perfect one in the supermarket you don’t look for one that has got lumps and bumps.

P39

A common point was loneliness that stemmed from not being understood by people. Participants seemed to experience a profound sense of loneliness through trying to convey how they felt to people who could not relate to them. In relation to psychosis, P15 commented:

There’s a sense of loneliness that people can’t experience the same things that I’m experiencing, and people say to me, if I’m talking to somebody [um] that other people can’t see, it can be quite frustrating when people are saying, ‘But I can’t see that,’ when it’s very real to me. And that makes you feel lonely because people aren’t experiencing the same world that you’re experiencing.

P15

The absence of people with similar experiences, who could provide emotional support and validation of their identity, creates what Stein99 terms ‘experiential loneliness’:

You feel very much alone and you’re very much aware that the experiences you’re having and the feelings you’re having aren’t the same as the people around you. And as much as they try and are as supportive as they can be, I don’t think that they will ever be able to fully understand. You kind of feel like if you’re trying to communicate something to them about like, something difficult about being like gay or non-binary, they can try to understand but they won’t fully know, and I think that is a form of loneliness.

P33

Loneliness despite the presence of others

For many participants, loneliness persisted even in the presence of others. They felt the experience of emotional isolation amid a group of people, within their family or even their intimate relationship. Togetherness in some cases could make loneliness worse:

I’ve been with people and felt lonelier than when I was on my own. I don’t really know why. I guess, if you can’t relate to people, or like you don’t really feel a part of their group, then it can definitely feel lonelier to be around people.

P25

Loneliness was also experienced in absence of shared understanding, as P8 describes:

Going to the pub and being around people I still felt very isolated because of my HIV. And that people, there weren’t people who got where I was at, and understood [um] the position I was in, and what was going on in my mind. I felt very isolated. Even though I was surrounded by people.

P8

Some participants described an ‘internal’ type of loneliness, that kept them separated from the world and made them feel like an outsider. P37 describes this when referring to the relationship with her then partner:

I used different things in those times to cover over it [loneliness] and deal with it in a different way. But eventually it would come to the surface as the relationship developed [um] . . . but no, I’ve never not felt this crushing emptiness and loneliness.

P37

The vicious cycle of loneliness

Many participants reported feeling trapped in a cycle of loneliness in which the lonelier they became, the more isolated they felt from society. 100 They recognised how they should act to reduce this, while feeling that loneliness had become an integral part of their life in which they felt secure. P32 described the paradox of wanting to ease feelings of loneliness while feeling unwilling to step outside the comfort zone loneliness had become:

That might sound a bit peculiar, but I’ve begun to recognise that when I have the opportunity to socialise it’s almost as though I’ve turned in so much on myself, that [sighs] it’s becoming hard to turn outwards and meet other people again.

P32

It was apparent that loneliness can create a tendency in people to dwell in self-pity, be more sensitive to rejection, withdraw and be less trusting of the people around them. This in turn created worsening feelings of loneliness. The fear of experiencing loneliness in the future could further obstruct the enjoyment of the present.

The unspoken and trivialised experience of loneliness

Most participants discussed the difficulties of disclosing their experiences of loneliness due to the associated shame and stigma. The experience in their view was a taboo subject and silenced or associated with the public discourse of old age and failing health. On the rare occasions when loneliness was discussed, it was approached with a veneer of light-heartedness and easy-fix solutions and interventions recommended by people who did not understand their experiences.

The silencing of loneliness

A pivotal subtheme here was the notion of stigma, shame and self-blame which restricted any constructive discussion about loneliness. Many participants discussed the ‘archetype of the loner’ who is depicted as socially ‘defective’, inept and incapable of forming key relationships to combat isolation and loneliness. P39 highlighted: ‘If you’re a loner there’s something wrong with you . . . It is not a positive word to put on someone . . . there must be something, because why would someone choose to be alone?

This stereotype, which carries negative and derogatory connotations, views the person through a lens of personal and social failing and intrinsic character flaw. Subsequently loneliness is pathologised and viewed as an experience outside the boundaries of what is considered to be normal.

I think there was a lack of talking about loneliness as a thing that can happen to just normal people. It was always this person visibly has no social skills and you know is really profoundly like struggling in society, not this is another well-adjusted person who has got some confidence issues and is struggling to make friends in a new context.

P22

The ‘tyranny of positive attitude’, which is saturated with the view that we must think positive thoughts and block out negative emotions and avoid any difficult but nevertheless authentic emotions, further contributes to the silencing of the discussion of loneliness. P10 expressed ‘We’re meant to be these very successful, bubbly, happy-go-lucky people who do these great things every weekend and you know, are never stressed, are never behind at work, you know, are never struggling’.

Indeed, the stereotype and trope of the lonely elderly prevail in the collective consciousness, leaving little room for other populations to share their experiences of loneliness. By being excluded from the loneliness discourse, many participants resorted to self-blame for failing wider expectations:

They always say it’s the older people that feel lonely . . . They never talk about the younger generation. I think because society expects people at that age to be married, have children, and have their lives sorted so to speak, so they don’t think about people that might be gay, they don’t think about people that might be single, they don’t think about people that might be trans-sexual, they just think about the mainstream. And then sometimes that makes me feel guilty about being lonely or feel weird about being lonely, because I think I shouldn’t be lonely at my age, I should have lots of friends, I should have a partner. And then I think ‘what’s wrong with me? Why do I not have these things?’

P17

The stigma attached to loneliness dissuaded many participants from seeking support from services. Indeed, the intolerance towards individuals who experience loneliness acted as a barrier to help-seeking. In reference to accessing help for loneliness, P5 mentioned: ‘I would have really benefited from it at the time [support] I don’t know if I would have accepted it if anybody had said it because I also think there’s that kind of, you don’t wanna be stigmatised.'

The trivialisation of loneliness

Many participants said that the seriousness of loneliness can be diminished through a process of trivialisation. The consequences it might have for quality of life and mental health are downplayed and the reality, nuances and causes of the experience are oversimplified and even ignored. Moreover, the legitimacy and severity of loneliness are questioned and there is an implication that it may be the person’s fault. People are blamed for not being proactive, for not taking steps to make positive changes. Thus, individual agency was presented to participants as an effective approach to managing loneliness. For example: