Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HSDR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/05/88. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in January 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Meader et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Epidemiology

General health risks associated with multiple risk behaviours

Health risk behaviours (e.g. smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, excess alcohol consumption and illicit drug use) are common in the UK and internationally. Smoking is the single largest directly avoidable cause of death in the UK, and a major cause of respiratory disease, cancer and cardiovascular disease. 1 Physical inactivity and unhealthy diet are strongly associated with weight gain, obesity, cancer, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. 2 Excessive alcohol consumption is also associated with greater risk for cancer, liver disease and cardiovascular disease. 3 Drug use is associated with greater risk of developing human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C and tuberculosis infections. 4

There is good evidence, both in the UK and internationally, that health risk behaviours cluster. 5 The majority of adults report engaging in two or more risk behaviours, and approximately one-quarter engage in three or more risk behaviours. 6 A 2017 Norwegian population-based cohort study7 of > 30,000 participants found a dose–response relationship between number of risk behaviours and all-cause mortality (i.e. increase in risk of all-cause mortality of 1.55-fold for two behaviours, 2.26-fold for three behaviours and 3.16-fold for four behaviours). There was a similar dose–response effect for risk of stroke in a large UK study of > 20,000 participants: the relative risks for people who engaged in four risk behaviours were 2.31 when compared with people who engaged in no risk behaviours, 2.18 when compared with people who engaged in one risk behaviour, 1.58 when compared with people who engaged in two risk behaviours and 1.15 when compared with people who engaged in three risk behaviours. 8 There is strong evidence that social and health inequalities are associated with engaging in multiple risk behaviours. People in the UK who do not complete secondary school or who have an unskilled occupation are three to five times more likely to engage in multiple risk behaviours. 9

Multiple risk behaviour interventions in general populations were associated with small reductions in smoking, unhealthy diet and physical inactivity, but there is currently insufficient evidence for reductions in alcohol and drug use. 10 In addition, small benefits were found in terms of reductions in weight, blood pressure and total cholesterol in the general population. 10

Health risk and inequalities in severe mental illness populations

Preventing long-term conditions has been a key policy priority for some time, and people with severe mental illness (SMI) constitute a particularly vulnerable subgroup of the population.

Risk of cardiovascular mortality is two to three times higher in people with SMI11 and life expectancy is 15–20 years lower than that of the general population. 12 This substantial risk is probably driven and sustained by complex interactions between social inequalities13, genetics, neurobiology, psychosocial impairment and symptoms associated with SMI,14 side effects of medication15,16 and a lack of access to physical and mental health interventions. 13

Smoking is the largest cause of premature mortality in the UK, and the biggest contributor to health inequalities among people with a mental health condition. 17 Therefore, it is particularly concerning that smoking is up to three times as prevalent in SMI populations than the general population, and even higher in certain subgroups (e.g. mental health inpatients). Although the prevalence of smoking in the general population has reduced by one-quarter in the past 25 years, the change in prevalence for smoking among people with a mental health condition in the same period is negligible. 1 This means that 42% of all cigarettes in the UK are now smoked by people with a mental health condition,1 who have been shown to lose, on average, 17 years of life as a result of tobacco smoking. 18

Similarly, people with schizophrenia are more likely to engage in an unhealthy diet, including lower fibre and fruit intake and higher saturated fat and calorie intake than the general population. 19 A study of people with SMI in psychiatric rehabilitation programmes found that only 4% met physical activity guidelines. 20 People with schizophrenia engaging in multiple risk behaviours are more likely to be overweight, to have high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, to have low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and to have increased fasting glucose levels. 19 Antipsychotic treatment, and other commonly prescribed medications, are associated with increased weight gain, particularly within the first years of psychosis. For example, a systematic review estimated an average 12-kg weight increase in the first 24 months of taking antipsychotics. 21 Similarly, Kahn et al. 22 found that people with first-episode psychosis experienced a 7% increase in body weight during the first year of treatment.

However, it should also be noted that, although antipsychotic use may increase risk of cardiovascular disease, there is also evidence that antipsychotic use overall may be associated with improvements in mortality in people with schizophrenia. 23

People with SMI are also substantially more likely to engage in substance use. A large US study of > 20,000 participants found that people with psychosis were four times more likely to engage in heavy alcohol use, cannabis use and use of other recreational drugs. 24 A UK study found that 30% of people with first-episode psychosis engaged in illicit drug use, 25% engaged in both alcohol misuse and illicit drug use and 10% engaged in excess alcohol consumption. 25

People with SMI are more likely to engage in multiple health risk behaviours. For example, in one study, on average, people with SMI were found to engage in five risk behaviours. 26 Therefore, an important question is whether to target these risk behaviours concurrently (i.e. multiple risk behaviour interventions) or to focus on a particular behaviour alone (i.e. single risk behaviour intervention).

Why this research is needed

Reducing risk behaviours in people with SMI is a clear priority for the NHS. These aims relate to wider initiatives such as the Mental Health Taskforce’s Five Year Forward View for Mental Health,27 which highlights the importance of integrating physical and mental health care. However, there are key evidence gaps that are important in informing practice:

-

Most people with SMI engage in multiple risk behaviours – a key question is whether interventions should target multiple risk behaviours in parallel or target single behaviours.

-

The importance of investigating factors that are likely to influence the clinical effectiveness of risk behaviour interventions in this population (e.g. intervention delivery, frequency) has been recognised.

Multiple compared with single risk behaviour interventions

There are several systematic reviews that have focused on the effectiveness of interventions among people with SMI for particular behaviours: smoking,28 unhealthy diet and/or physical activity. 29–31

Despite a relatively developed literature of primary studies in this area, to our knowledge, there are currently no systematic reviews specifically focused on multiple risk behaviour interventions in people with SMI. It is not possible from current systematic reviews to delineate the benefits of focusing on a particular risk behaviour, compared with targeting multiple behaviours concurrently, in a SMI population. Risk behaviours cluster; therefore, it is important to question whether services should seek to reduce risk behaviours in parallel or to target risk behaviours one at a time, as interventions to promote change in a health risk behaviour have important implications for engaging in other behaviours. For example, our systematic review of multiple risk behaviour interventions in general populations10 found that changes in diet were positively associated with changes in physical activity, and that both, in turn, were associated with increased weight loss. This is consistent with evidence from qualitative studies; for example, people with diabetes reported that improvements in physical activity acted as a ‘gateway’ to changes in diet. 32 Conversely, changing some risk behaviours may have negative consequences for engaging in others.

Identifying ‘active ingredients’ of risk behaviour interventions

Behaviour change interventions are typically complex with multiple interacting components. Therefore, behaviour change technique taxonomies (BCTTs) have been developed to help identify the effective components in these interventions to help inform future research [e.g. which behaviour change techniques (BCTs) should be included in future trials] and implementation in services. 33 We are unaware of any systematic reviews that have investigated the impact of intervention content using these methods in SMI populations.

Qualitative studies on barriers to and facilitators of change and experiences of risk behaviour interventions

There is an important need to synthesise qualitative data on the experiences of people with SMI to inform interpretation of the quantitative data and future trial design. For example, qualitative data are important for identifying barriers to and/or facilitators of behaviour change. This enables us to compare which barriers or facilitators were addressed in trials and to identify intervention content for future trials. Similarly, we can compare the extent to which the reported experiences of people with SMI in the qualitative data reflect findings from the quantitative data. As far as we are aware, this is the first systematic review to have synthesised this literature specifically focused on multiple risk behaviour interventions, especially in a SMI population.

Chapter 2 Methods of effectiveness review, meta-analysis and qualitative review

The systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018104724).

Objectives

We aimed to provide a comprehensive and objective summary of available primary research about the clinical effectiveness of health risk behaviour interventions in people with SMI.

More specifically, the objectives of the systematic review were to:

-

provide a descriptive overview of all the evidence for multiple health risk behaviour interventions on behaviour change (e.g. fat intake, smoking abstinence) targeted by the intervention, and change in outcomes affected by these behaviours [e.g. weight, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure]

-

examine the clinical effectiveness of multiple risk behaviour interventions, compared with single risk behaviour interventions, using network meta-analyses (NMAs), in terms of their impact on behavioural outcomes (e.g. smoking abstinence) and outcomes affected by changes in behaviour (e.g. weight, BMI).

-

examine the effect of study-level intervention content (e.g. using BCTTs) and participant characteristics (e.g. targeted by study for physical comorbidities) as moderators of effectiveness of risk behaviour interventions using meta-regression and component NMAs.

-

explore, through qualitative evidence, factors affecting the clinical effectiveness of risk behaviour interventions (including barriers and facilitators) for people with SMI.

Literature searches

Searches were carried out in October 2018 in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), MEDLINE, PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA) and Science Citation Index (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). The date range searched was inception to October 2018. The searches identified 27,795 records, which was reduced to 18,513 records after deduplication using EndNote (Clarivate Analytics) bibliographic software.

Updated searches were carried out in March 2020 in EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycInfo and the Science Citation Index; these identified a further 2822 records, which was reduced to 1433 records after deduplication. It was not possible to download records from CENTRAL owing to issues with the database at the time of the updated search (28 March 2020). We searched Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (date range inception to September 2020), and conducted an updated CENTRAL search in September 2020. The updated search of CENTRAL identified a further 1843 records, which was reduced to 1579 after deduplication. The search of ASSIA identified 658 records, which was reduced to 151 after deduplication.

The strategies used for both the original and updated searches are reproduced in Appendix 1.

Study selection

Population

Adults (aged ≥ 18 years) diagnosed with SMI (defined as schizophrenia or other psychoses, depression with psychotic features, or bipolar disorder) were included. Interventions aimed at people with SMI who were overweight or obese, had long-term conditions or risk factors for long-term conditions (e.g. high blood pressure, high cholesterol) were also included.

Interventions

Behavioural interventions were included with no restrictions on whether the focus of the intervention content was psychological, educational or environmental, nor were any restrictions applied based on setting.

For some health risk behaviours (e.g. smoking, excess alcohol consumption, opioid use), pharmacological treatment may be a component of standard care. When this was the case, behavioural interventions in combination with standard pharmacological interventions were included. However, studies were excluded if they primarily aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions.

Single health risk behaviour interventions were included if they aimed to change one of the following risk behaviours: smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, excess alcohol consumption or drug use. Multiple health risk behaviour interventions were included if they aimed to change two or more of these behaviours.

Comparators

-

No intervention.

-

Treatment as usual (TAU).

-

Treatment as usual with additional active control elements (e.g. attention control).

Outcomes

For quantitative studies, we included data on the following outcomes:

-

changes in behaviours directly targeted by the intervention (smoking, diet, physical activity, alcohol use, drug use)

-

anthropometric measures [weight (kg), BMI]

-

metabolic outcomes (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol)

-

quality of life

-

mental health symptoms.

Study designs

For the clinical effectiveness analyses, we included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

In addition, we included qualitative studies assessing the experiences of behaviour change in people with SMI (including barriers and facilitators).

Methods of effectiveness review and meta-analysis

Data extraction and screening

Data extraction, screening and risk-of-bias assessment were conducted by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer if necessary.

The data extraction form was piloted on a selection of studies by three reviewers to ensure consistency. Data from multiple publications of the same study (or data set) were extracted and reported as a single study. When there were data from multiple time points, we grouped these data into the following categories: end point, ≤ 6 months post intervention, 6–12 months post intervention, and ≥ 12 months post intervention.

Two reviewers extracted information about the content of each intervention and control, including which risk behaviours were targeted, whether the choice of risk behaviour was fixed or tailored to the individual, background/expertise of the intervention provider, mode of delivery (e.g. group or individual focused), intensity of intervention (duration of sessions, duration of intervention, etc.), setting (e.g. outpatient, inpatient), and adaptation of content for people with SMI. BCTs were categorised using the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 (BCTT v1). 33

The participant characteristics extracted included mental health diagnoses, whether or not the intervention was given at first initiation of antipsychotics, antipsychotic use (proportion of participants receiving antipsychotics, and which type of antipsychotic), physical health comorbidities, age, sex and ethnicity.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The risk of bias of the individual studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool version 2 for RCTs. 34 As per recommendations, we conducted separate risk-of-bias assessments for the key outcomes: the most widely reported behavioural outcomes (smoking abstinence) and the most widely reported outcomes affected by behaviour (weight and BMI).

Data analysis

All analyses were performed in a Bayesian framework with a random-effects model using WinBUGS (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK),35 taking into account the correlation between multiarm trials when appropriate. However, when there were sparse networks (and potentially insufficient data to reliably estimate between-study heterogeneity), we compared the goodness of fit of fixed-effect and random-effects models and used data from the better-fitting model. When both models fitted equally well, we selected the simpler model.

A binomial likelihood was used for dichotomous data and a normal likelihood for continuous data. We assumed a common between-study heterogeneity variance of the relative treatment effects for every treatment comparison. We used vague prior distributions for trial baselines, heterogeneity and relative treatment effects. For WinBUGS code (including prior distributions), see WinBUGS code for models (see the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library projects web page; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/170588/#/). Network geometry for NMAs was illustrated using network diagrams (see Appendix 7).

We assessed convergence of two chains based on visual inspection of history, Brooks–Gelman–Rubin and autocorrelation plots.

Network meta-analysis enables the estimation of indirect comparisons not addressed in the primary trials. 36 Such analyses assume consistency in the evidence network between indirect and direct evidence. Unfortunately, few trials compared single or multiple risk behaviour interventions directly; therefore, there were insufficient data to assess the consistency of direct and indirect evidence.

Intervention effects were estimated along with 95% credible intervals (CrIs). Continuous outcomes were usually pooled mean differences (MDs) on natural units such as number of cigarettes, weight (kg), BMI (kg/m2) and blood pressure (mmHg). Some outcomes, such as physical activity and alcohol use, were measured in various ways across studies, so we used standardised mean differences (SMDs) to analyse these data.

The analysis proceeded in three stages.

Model 1: intervention effects model

Across studies, interventions targeted a range of single (e.g. unhealthy diet alone, physical inactivity alone) or multiple health risk behaviours (e.g. unhealthy diet and physical inactivity). We used NMAs to assess the effectiveness of targeting these different combinations of risk behaviours.

Studies varied in terms of participant (e.g. targeting people with SMI who also had comorbid physical illness) and intervention characteristics (e.g. whether studies were primarily delivered to groups or individuals). Therefore, we extended the model to include covariates estimating the association between these participant and intervention characteristics and intervention effectiveness.

Model 1a: effectiveness of targeting different combinations of risk behaviours

-

Targeting any risk behaviour.

We used a random-effects NMA model to compare any health risk behaviour intervention with TAU. Studies with TAU with additional active components (hereafter referred to as TAU+) as a comparator were also included in the network to inform estimates.

-

Targeting combinations of risk behaviours. We used a similar random-effects NMA model, as model 1a:1, but, instead of comparing any intervention with TAU, we assessed the impact of targeting different health risk behaviours compared with TAU.

Model 1b: impact of intervention and participant characteristics

Second, we assessed the impact of intervention and participant characteristics on effectiveness estimates by adding the following covariates to model 1a:

-

participants selected for physical comorbidities (yes/no)

-

intervention delivered primarily to individuals (yes/no)

-

intervention setting (inpatient or not inpatient)

-

authors reported tailoring the intervention for people with SMI (yes/no).

We assessed the impact of these intervention and participant characteristics by assessing the magnitude of the covariate estimate, along with its 95% CrI. In addition, we conducted a more global assessment, comparing the goodness of fit of model 1b with covariates and model 1a without covariates in terms of deviance information criterion (DIC), total residual deviance and between-study standard deviation (SD).

Model 2: does targeting multiple risk behaviours lead to positive or negative synergies (interaction model)?

Model 1 gives some insight into the benefits of targeting different combinations of risk behaviours. But it does not directly assess whether or not targeting multiple risk behaviours leads to positive or negative synergies (e.g. does targeting diet and physical activity together result in greater or fewer benefits than expected from the sum of their effects?).

There were sufficient data to conduct interaction models for weight and BMI models only. We used a components NMA approach,37 where µj is the mean weight (kg) or BMI (kg/m2) for the TAU group bi in trial j. θjk is mean weight (kg) or BMI for any risk behaviour intervention k from trial j:

where

δjk represents the MD between TAU and any risk behaviour intervention k, compared with TAU bj, in trial j, with between-study SD τ; dk is the pooled estimate of the MD comparing any risk behaviour intervention with TAU.

Model 2 is an extension of model 1a:1, in which the MD dk was the MD comparing any intervention with TAU, which assumed that:

Model 2 allowed for each component to have its own independent impact on the MD. For example, targeting diet and physical activity together may each have contributed separately to reductions in weight or BMI. The model also allows components to interact with each other. For example, targeting diet and physical activity may lead to greater reductions (positive synergies) in weight or BMI than would be expected by the sum of these components. Model 2 also allowed for lesser reductions in weight or BMI than would be expected if the components were summed (negative synergies). We did not include targeting alcohol or smoking as separate effects as all interventions in the analyses targeting one of these behaviours also targeted diet and physical activity:

where PA = physical activity.

Model 3: effectiveness of behaviour change techniques

Risk behaviour interventions vary not only in terms of which behaviours are targeted, but also in terms of the BCTs included in these interventions.

We therefore fitted models that classified interventions in terms of BCTs (using the BCTT v1). 33 We fitted two models and compared them in terms of goodness of fit (total residual deviance, between-study SD and DIC). As above, there were sufficient data to conduct these analyses for only weight and BMI.

Model 3a: additive model (independent model)

Similar to model 2, we fitted a model that allowed each BCT to have an independent impact on the MD (dk) between any risk behaviour intervention compared with TAU. The BCTs included in the weight and BMI models were largely the same, but with slight variation, depending on what studies reported these outcomes.

For weight, the following BCTs were independent components contributing to the MD between any intervention and TAU:

For BMI, the following BCTs contributed to the MD between any intervention and TAU:

The models included a total of nine BCTs [BCTT v1: 1.1 goal-setting (‘goal’), 1.2 problem-solving (‘prob’), 1.4 action-planning (‘action’), 2.2 feedback on behaviour (‘feedback’), 2.3 self-monitoring of behaviour (‘mon’), 3.1 social support (unspecified) (‘soc_sup’), 4.1 instruction on how to perform a behaviour (‘inst’), 5.1 information about health consequences (‘info’) and 6.1 demonstration of the behaviour (‘demonst’)] that were used in at least five studies.

Model 3b: two-way interaction model (interaction model)

We extended model 3a to allow for pairs of BCTs to interact with one another. There was little overlap between BCTs used across studies, which limited the extent to which we could explore interactions.

For weight, the interaction model included only two further parameters in the model (studies that included BCTT v1 4.1 instruction in how to perform a behaviour and BCTT v1 1.2 problem-solving, and studies that included BCTT v1 4.1 instruction in how to perform a behaviour and BCTT v1 2.3 self-monitoring of outcomes):

For BMI, it was possible to include further interaction parameters in the model:

Methods of the qualitative review

Objective

The objective of the qualitative review was to address the following question (with consideration for methodological quality and certainty of evidence):

What are service user perspectives on the acceptability and feasibility of using risk behaviour interventions to change behaviour and improve physical health-related outcomes, with specific reference to intervention uptake, adherence and service experience?

Quality assessment

Established guidelines by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group [www.gradeworkinggroup.org (accessed 3 February 2020)] and the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group [cqim.cochrane.org (accessed 3 February 2020)] were followed, to implement the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual)38 approach to assess both the methodological limitations of individual studies and the coherence of our review findings.

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool [https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed 3 February 2020)] was used to assess limitations of the methods used in included studies, per GRADE–CERQual guidance.

The CASP tool is not a rating system, but facilitated transparent assessment across 10 prompts relating to the quality of the design and reporting of studies. Each prompt on the checklist was answered with a ‘no’, ‘yes’, or ‘cannot tell’. ‘Cannot tell’ was allocated when authors’ reporting did not allow reviewers to make a clear decision.

The CERQual approach is similar to GRADE in that both approaches aim to assess the certainty of (or confidence in) the evidence, and both also rate this certainty for each finding across studies, rather than for each individual study. Unlike GRADE, which is only relevant to evaluations of effectiveness, CERQual offered a framework to evaluate the certainty of evidence that addresses questions beyond effectiveness of interventions, such as acceptability. Coherence of the review was assessed by identifying patterns across the data contributed by each of the individual included studies, for example when findings are consistent across multiple settings or different subgroups of people with SMI. The certainty of evidence in each individual study was rated as being high, moderate or low, and ranked according to the methodological limitations and coherence of each finding of our review.

Data analysis

Papers were read in detail to identify core ideas for comparison across studies based on quotations from participants. Interpretations from authors of the included studies were not extracted unless required to contextualise an abbreviated quotation from a participant.

Drawing on guidance for qualitative syntheses to inform policy-making and research prioritisation, a narrative synthesis approach was used. 39 This approach gave a descriptive account that forms the basis of an interpretative synthesis. Published data were analysed using principles of thematic synthesis, as described by Thomas and Harden,40 to facilitate the identification of recurring and emergent themes. Themes within and between transcripts were categorised, with iterative classification, development and refining of categories. 41

Initial line-by-line coding of participant quotations was undertaken in NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) by one reviewer, and data extraction was a function of coding. The data could be used to support the development of different, but overlapping, themes. Initial coding was descriptive, remaining close to original reports and began without hierarchical structure. Translation of codings was iterative.

Analytical themes were developed through further refinement of coding, comparing primary data with developed themes. This process was repeated within themes to draw out subthemes. A second reviewer helped reduce repetition and overlap, thereby producing more focused themes.

Greater emphasis was placed on studies with in-depth examinations of user experience. Studies that lacked this detail were used to augment and contextualise the findings. The relative contribution of individual studies, the impact of methodological limitations and certainty on the findings were summarised narratively, in line with the CERQual approach.

Methods for integrating quantitative and qualitative data

There remains a lack of consensus on the most appropriate methods for integrating quantitative and qualitative data. Our approach used methods commonly used in systematic reviews that were also appropriate for the nature of our data. 42,43

The overall themes and subthemes identified in the synthesis of qualitative studies were used as the basis for examining whether or not the findings from the quantitative data approximated those found in the qualitative data. For example, when a particular factor was identified as a barrier or facilitator in the qualitative data, we examined whether or not intervention content seeking to address this barrier or facilitator affected the effectiveness estimates using meta-regression analyses (based on the magnitude of the covariate and precision of the 95% CrI). If these meta-regression analyses were unplanned, we conducted these analyses post hoc, when possible.

For each theme, we investigated whether or not we could identify an analogue of this theme in the included quantitative studies. We then categorised the relationship between findings from the qualitative and quantitative data according to four categories adapted from a recent study:44 silence (no overlap between quantitative and qualitative data), dissonance (conflicting findings), partial agreement (complementary findings, but limited overlap) and agreement (convergence in the data). However, when there was overlap in quantitative and qualitative findings, but the data were insufficiently precise to categorise, the finding was labelled inconclusive.

Methods for patient and public involvement

People with lived experience of SMI and carers contributed significantly to all stages of the project. Sophie Corlett (Director of External Relations, Mind) was a member of our advisory group that provided oversight on the progress of the project.

We also formed two patient and public involvement (PPI) groups that met throughout the course of the project. One group began meeting in York and consisted of four members. The group was chaired by a relative of a person with SMI (DS), and also included one peer researcher (CD) and a peer researcher who is also a carer (HK). One further group member (a carer) was no longer able to attend after the first meeting because of other commitments.

We also regularly met with two peer researchers (MS and GJ) who are members of the Lived Experience Research Collective hosted by the Mental Health Foundation.

All the members of our PPI groups were included as authors of the report, reflecting their substantial contribution to the project. The PPI groups decided on the name of the project (HEALTH study), provided extensive comments on the protocol, contributed to interpretations of the study results, played a key role in disseminating the findings of the project, participated in the webinar and provided feedback on an animation summarising the findings of this project. For further details, see Chapter 7.

Chapter 3 Search results

Flow of studies included

The original searches were carried out in October 2018 using CENTRAL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycInfo and the Science Citation Index. The date range searched was inception to October 2018. The searches identified 27,795 records, which reduced to 18,513 records after deduplication using EndNote bibliographic software.

Updated searches were carried out in March 2020 using EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycInfo and the Science Citation Index; these identified a further 2822 records, which reduced to 1433 after deduplication. An updated search of CENTRAL in September 2020 identified a further 1843 records, reduced to 1579 after deduplication. A search of ASSIA in September 2020 identified 658 records, reduced to 151 after deduplication (the date range searched was inception to September 2020). An additional record was located through reference-checking. Therefore, 21,677 titles and abstracts were screened in total.

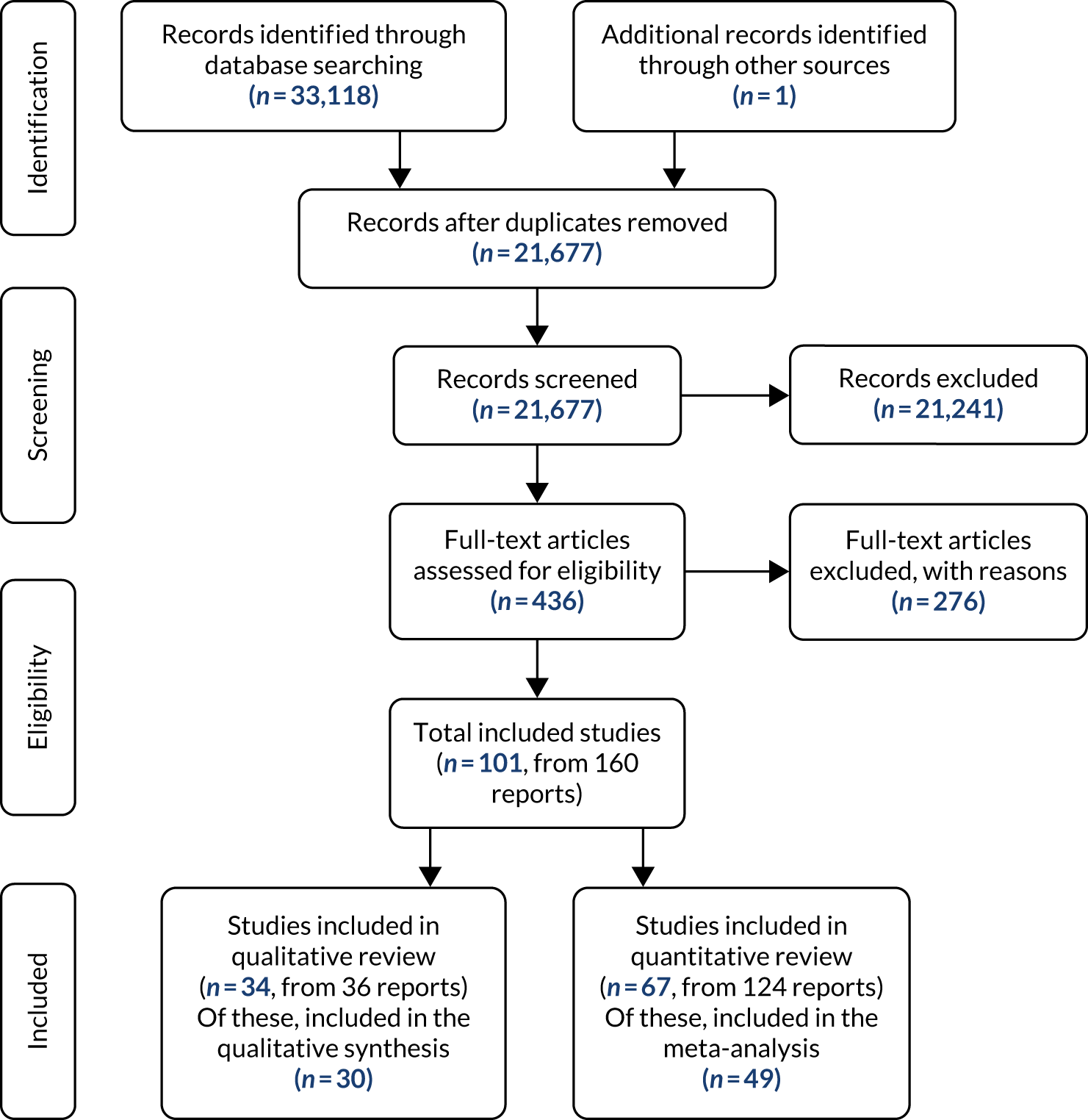

Of these, 436 full-text records were then double-screened, and 276 were subsequently excluded, as summarised in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Figure 1. A table of excluded studies with rationale for exclusion can be found in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram summarising the flow of studies.

Studies included

Overall, 101 studies were included. Of these, 67 were RCTs included in the effectiveness review,45–111 and 34 studies (reported in 36 records) using a qualitative study design were included in the review of qualitative studies. 112–147

Characteristics of the randomised controlled trials included

For detailed summaries of population characteristics of included RCTs, see Appendix 3; for detailed summaries of intervention characteristics, see Appendix 4. Descriptions of the interventions are provided in Appendix 5. The majority were conducted in the USA (n = 2250,51,54,55,57–59,61,65,68,72,77,81,83,84,89,95,96,103,105,108,111) and the UK (n = 1257,67,69,71,75,76,78,88,93,94,100,109), followed by other European countries [Italy (n = 548,52,87,92,99), Switzerland (n = 353,70,80), Denmark (n = 373,74,102), Spain (n = 263,86), Germany (n = 249,60), Sweden (n = 164), the Netherlands (n = 198), Greece (n = 179) and Croatia (n = 1101)], Asian countries [Thailand (n = 291,106), China (n = 1110), Japan (n = 1104), India (n = 166) and the Republic of Korea (n = 182)], then Australia (n = 446,47,62,107), Canada (n = 285,97), Israel (n = 190) and Brazil (n = 145).

Of the included trials, 43 investigated multiple health risk behaviour interventions, and 24 investigated single health risk behaviour interventions. Risk behaviours were mostly targeted in pairs (n = 33), with few studies targeting three or more risk behaviours (n = 10). The most commonly targeted risk behaviours were physical inactivity (n = 48 studies) and unhealthy diet (n = 41 studies), which were also commonly targeted in combination.

Across included studies, the most commonly reported BCTs were instruction on how to perform behaviours (BCTT v1: 4.1; n = 40), social support (unspecified) (BCTT v1: 3.1; n = 27), self-monitoring of behaviour (BCTT v1: 2.3; n = 23), problem-solving (BCTT v1: 1.2; n = 23), information about health consequences (BCTT v1: 5.1; n = 23), goal-setting (BCTT v1: 1.1; n = 21), action-planning (BCTT v1: 1.4; n = 15), feedback on behaviour (BCTT v1: 2.2; n = 14) and social support (emotional) (BCTT v1: 3.3; n = 10). The totals reported here are much greater than the number of included studies as most interventions used several BCTs. For details of all BCTs reported across studies, see Appendix 4.

Fifty-two RCTs were included in the meta-analysis (see Figure 1). 45–49,54–56,59–64,67–70,72–76,78–87,89–91,93,94,96–99,101,102,104–111

Characteristics of the qualitative studies included

The flow of studies can be seen in the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1. Thirty-four studies (from 36 reports) were included;112–147 three records were based on the same cohort and so represent one study,126–128 and four conference abstracts were also included in the systematic review, but not in the synthesis, owing to limited data. 112–115 Therefore, 30 studies were included in the synthesis. Included studies used qualitative designs such as interviews and focus groups, and applied qualitative data analysis techniques such as the interpretative phenomenological approach and thematic analysis. Further details on population characteristics and study designs can be found in Appendix 6.

Multiple risk behaviours were considered in 18 studies,116,117,121,122,126,132,133,135–137,139–141,143–147 and 12 considered single risk behaviours. 118–120,123–125,129–131,134,138,142 Multiple risk behaviours were most commonly considered in pairs (14/18 studies);116,117,122,126,132,133,135–137,140,141,145–147 the most common combination of risk behaviours was physical activity and diet (11 studies). 116,117,122,126,135,137,140,141,145–147 Two studies139,143 addressed risk behaviour outcomes in a way that did not appropriately fit with the risk behaviour targets of this review and, therefore, were classified as ‘other’. One considered health promotion (classified as a multiple risk intervention)143 and the other considered weight loss (also classified as a multiple risk behaviour intervention). 139 The most commonly addressed single risk behaviour was physical activity (6/11 studies). 118–120,124,125,134 See Appendix 6 for further details.

Chapter 4 Results of effectiveness review

Summary of network meta-analyses results

Model 1: intervention effects models

Network diagrams for all outcomes are provided in Appendix 7. Although most trials aimed to change behaviour, few studies directly reported behavioural data. Weight and BMI were, by far, the most commonly reported outcomes. Smoking-related outcomes (quit rates and number of cigarettes smoked) were the most common behavioural outcomes reported. However, these data were too heterogeneous to combine in NMAs, so we conducted narrative syntheses for smoking outcomes. There were insufficient data to conduct NMAs of multiple and single risk behaviour interventions (i.e. model 1a:2) for diet, physical activity, alcohol use and cannabis use outcomes.

Table 1 summarises the results of the NMAs (model 1a) where it was possible to assess the clinical effectiveness of multiple and single risk behaviour interventions. All models converged after 20,000 iterations. Effect estimates are based on a further 60,000 iterations after discarding earlier iterations.

| Risk behaviours targeted | Outcome, MD (95% CrI) | Quality of life (9 RCTs, n = 1853), SMD (95% CrI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) (30 RCTs, n = 2614) | BMI (kg/m2) (36 RCTs, n = 3308) | Blood pressure (mmHg) (SBP: 15 RCTs, n = 1790; DBP: 13 RCTs, n = 1489) | Cholesterol (mmol/l) (HDL: 15 RCTs, n = 2121; LDL: 9 RCTs, n = 1071; total cholesterol: 11 RCTs, n = 1727) | ||

| Any risk behaviour | –2.10 (–3.14 to –1.06) | –0.49 (–0.97 to –0.01) |

|

|

|

| Diet alone | –2.27 (–6.22 to 1.60) | –0.04 (–1.72 to 1.65) |

|

|

– |

| Physical activity alone | –1.40 (–6.00 to 2.99) | –1.23 (–2.63 to 0.20) |

|

|

– |

| Smoking alone | – | – | – | – |

|

| Diet + physical activity | –2.12 (–2.94 to –1.34) | –0.53 (–1.07 to 0.04) |

|

|

|

| Diet + physical activity + alcohol misuse + smoking | 1.27 (–1.46 to 3.42) | –0.02 (–1.05 to 0.98) |

|

|

|

Smoking

Smoking abstinence

Eight trials46,47,55,67–69,102,148 were included in the narrative synthesis for smoking abstinence.

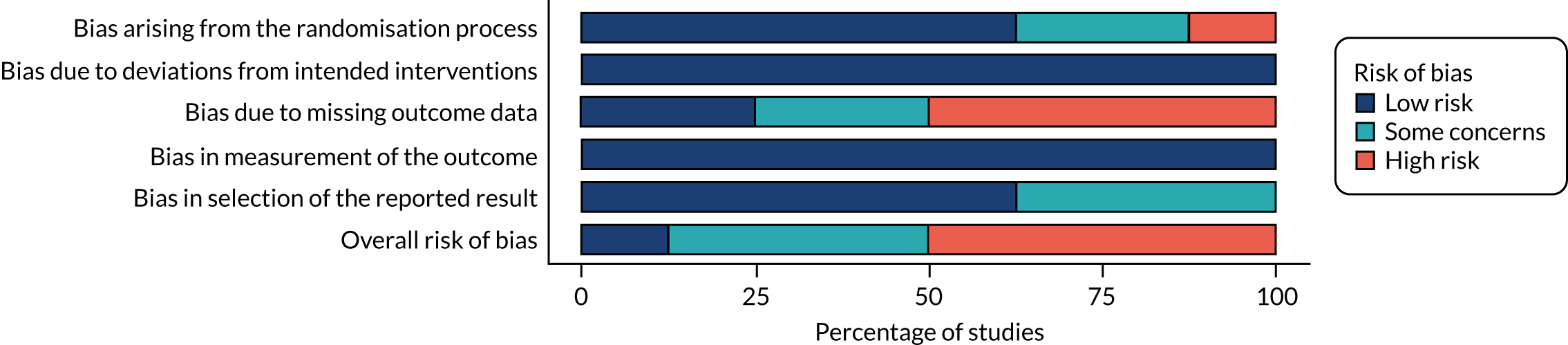

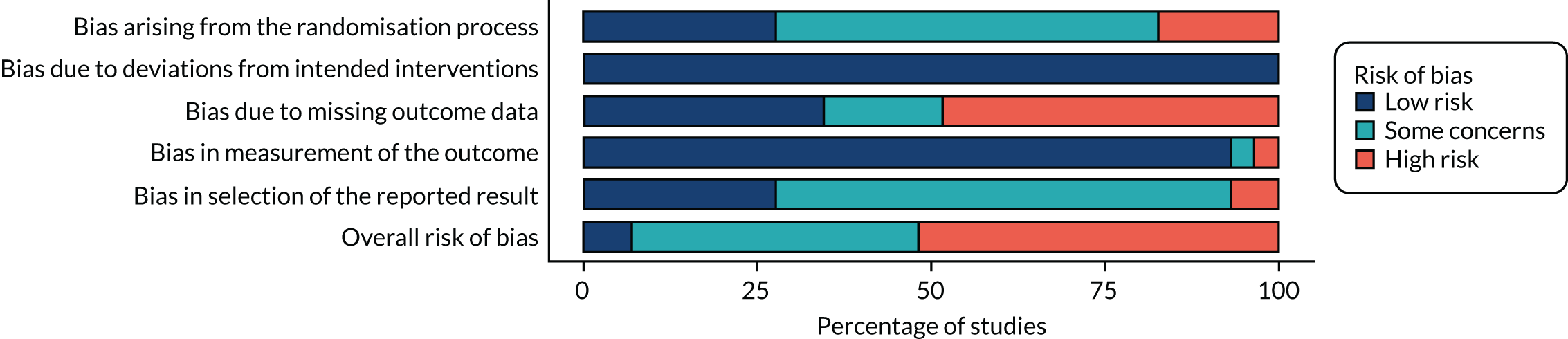

Figure 2 summarises the risk-of-bias judgements across studies measuring smoking abstinence. Just over half of included studies in the NMA were rated as having a high overall risk of bias. The most common reason for studies being judged to have a high risk of bias was missing outcome data (e.g. uncertainty over whether or not missing data depended on the outcome’s true value). Bias arising from the randomisation process was the next most common risk of bias (e.g. allocation concealment not reported and important baseline differences between groups).

FIGURE 2.

Summary of risk of bias across studies measuring smoking abstinence.

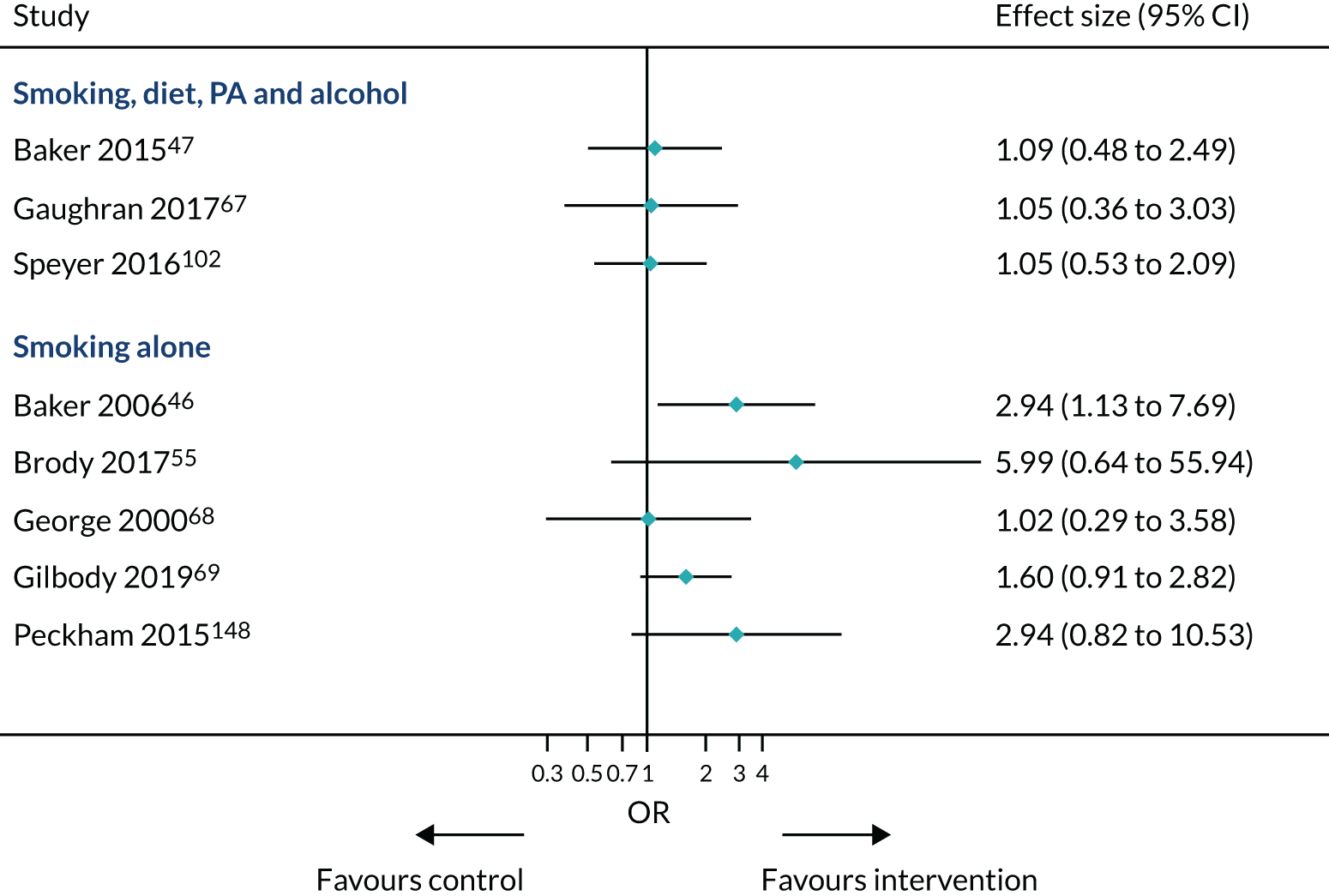

Given the diversity of the data, we conducted narrative syntheses rather than NMAs on smoking abstinence. Five trials targeted smoking alone. 46,55,68,69,148 Controls ranged from very low intensity46 and low intensity69,148 to high intensity. 55,68 Interventions in all five trials were high intensity.

Four of these trials found that interventions targeting smoking alone may be more effective than controls (Figure 3) in promoting smoking abstinence. 46,55,69,148 Odds ratios (ORs) for these studies ranged from 1.60 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.91 to 2.82]69 to 5.99 (95% CI 0.64 to 55.94),55 but effect estimates were imprecise for all studies. One trial68 targeting smoking alone did not favour the intervention over the control, although the CI was very wide (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.29 to 3.58). This trial included a high-intensity control, which may potentially explain different effects, compared with other included studies.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot comparing smoking abstinence in interventions targeting smoking either alone or in combination with other behaviours. PA, physical activity.

Three trials targeted smoking with other risk behaviours (including unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and excess alcohol consumption). 47,67,102 Controls ranged from very low intensity67,102 to medium intensity. 47 One intervention was of low intensity,67 one was of medium intensity102 and another was of high intensity. 47 The results were very similar in these three trials that targeted smoking in combination with other behaviours such as diet, physical activity and alcohol use. ORs ranged from 1.05 to 1.09, suggesting that there may be no difference between intervention and control in promoting smoking abstinence, although 95% CIs were consistent with both increased and reduced odds.

Number of cigarettes smoked

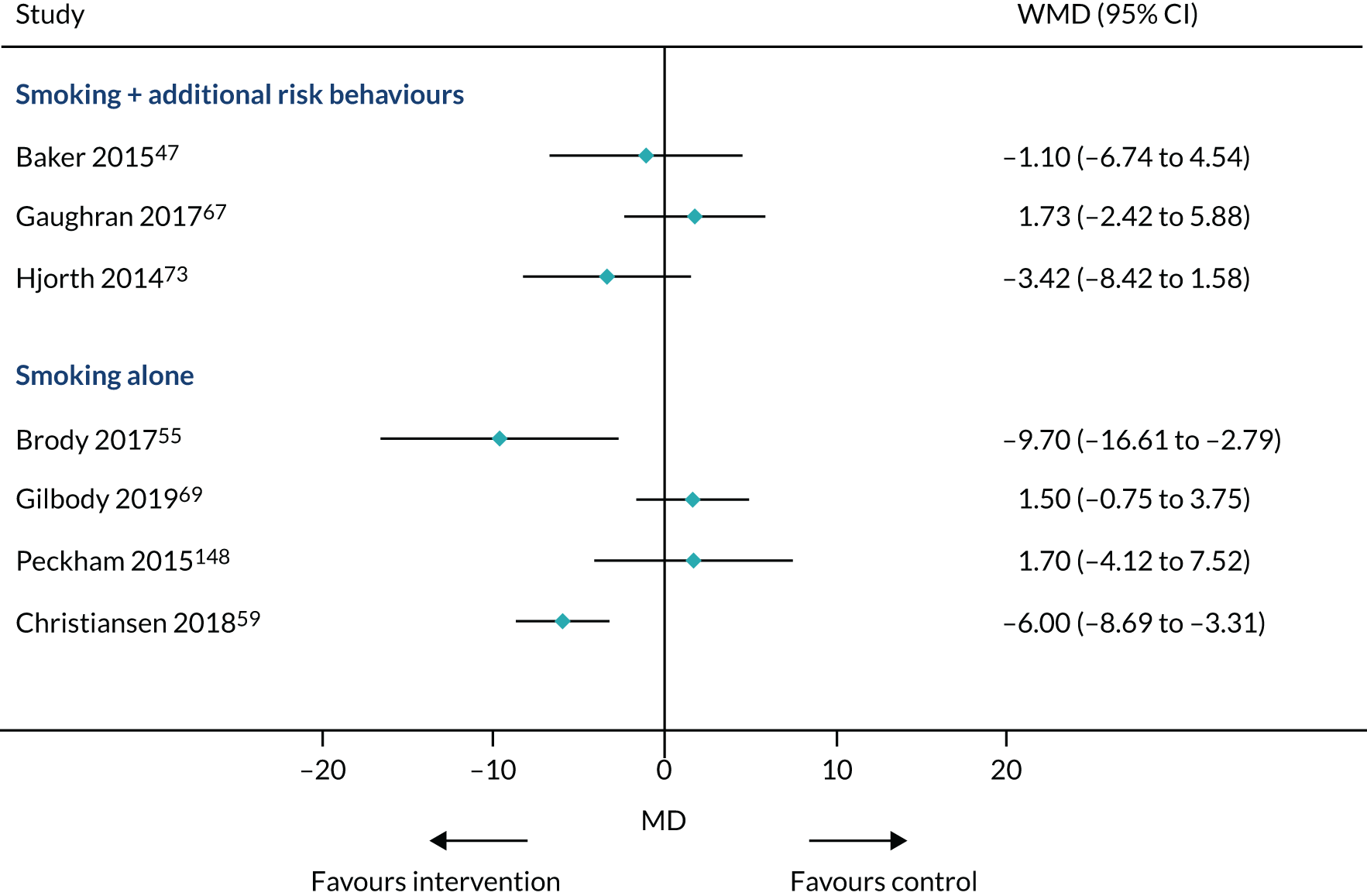

Seven trials47,55,59,67,69,73,148 were included in the narrative synthesis for assessing the number of cigarettes smoked.

There was a high level of variability between studies (Figure 4). Similar to Smoking abstinence, trials focusing on smoking along with other risk behaviours showed limited evidence of effectiveness in reducing the number of cigarettes smoked. Trials focusing on smoking alone found mixed evidence for reducing the number of cigarettes smoked. Two studies found evidence of effectiveness in reducing number of cigarettes,55,59 whereas two other studies did not. 69,148

FIGURE 4.

Summarising effect estimates of the number of cigarettes smoked at the end point for studies targeting smoking alone or with additional risk behaviours. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Cannabis

Four trials, with 716 participants providing data, were included in the NMA on cannabis use. 47,49,67,74

Each trial targeted a different combination of risk behaviours: alcohol, drugs or both;49 diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol;47 physical activity, smoking and alcohol;73 and smoking, diet, physical activity, alcohol, any drug use. 67

Therefore, there were sufficient data to only compare any intervention with TAU at the end point. Given the sparse nature of the network, we decided to use a fixed-effects model, as there were insufficient data to reliably estimate between-study heterogeneity.

Goodness of fit was acceptable for the model (total residual deviance was 3.14 data points, compared with 4 data points). There was no evidence that interventions reduced cannabis use (SMD –0.05, 95% CrI –0.25 to 0.15). However, CrIs were relatively wide, indicating uncertainty about this effect estimate.

Alcohol misuse

Five trials (731 participants) were included in the NMA on alcohol use. 47,49,67,73,78 Trials targeted a range of combinations of risk behaviours: alcohol alone;78 alcohol, drugs or both;49 diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use;47 physical activity, smoking and alcohol use;73 and smoking, diet, physical activity, alcohol use and drug use. 67

There were sufficient data to only compare any intervention with TAU at the end point. Goodness of fit was acceptable for the model (total residual deviance was 5.25 data points, compared with 5 data points) and the between-study SD was 0.36 (95% CrI 0.02 to 2.01, SMD scale). There was no evidence that interventions reduced alcohol misuse (SMD 0.14, 95% CrI –0.71 to 1.00). CrIs were very wide, indicating considerable uncertainty about this effect estimate.

Physical activity

Seven trials45,67,86,89,105,109,149 reported data on physical activity. Most of these trials measured total physical activity (including self-report measures, such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, and objective measures, such as an accelerometer).

Five trials45,75,86,89,105 targeted diet and physical activity; one trial targeted physical activity and sedentary behaviour;109 and one trial targeted diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol misuse and drug misuse. 67

Therefore, there were sufficient data to conduct only meta-analyses of any intervention and TAU. Goodness of fit for this model was acceptable [total residual deviance was 8.51 data points, compared with 7 data points and between-study SD was 0.23 (95% CrI 0.01 to 0.96)]. Evidence was very limited for the effect of any interventions compared with TAU for improving total physical activity (SMD 0.10, 95% CrI –0.25 to 0.49).

Diet

Six trials45,47,67,88,89,93 reported data on diet. Diet was measured using a diverse range of outcomes: calorie intake,89 fat intake45,67,93 and fruit and vegetable intake. 47,88 We considered these outcomes too diverse to combine in meta-analyses. Therefore, despite an unhealthy diet being one of the most commonly targeted health risk behaviours, it is difficult to conclude how effective interventions are at promoting a healthier diet.

Anthropometric outcomes

Weight (kg)

Thirty trials45,47,48,54,56,60–64,76,80,82,84,85,87,89,91,96,97,99,101,102,104,105,107,108,110,149,150 with data from 2614 participants were included in the NMA of weight outcomes at the end point.

Figure 5 summarises the risk-of-bias judgements across studies measuring weight loss. Just over half of the included studies in the NMA were rated as having a high overall risk of bias. The most common reason for studies being judged to have a high risk of bias was missing outcome data. Bias arising from the randomisation process was the next most common.

FIGURE 5.

Summary of risk of bias across studies measuring weight loss.

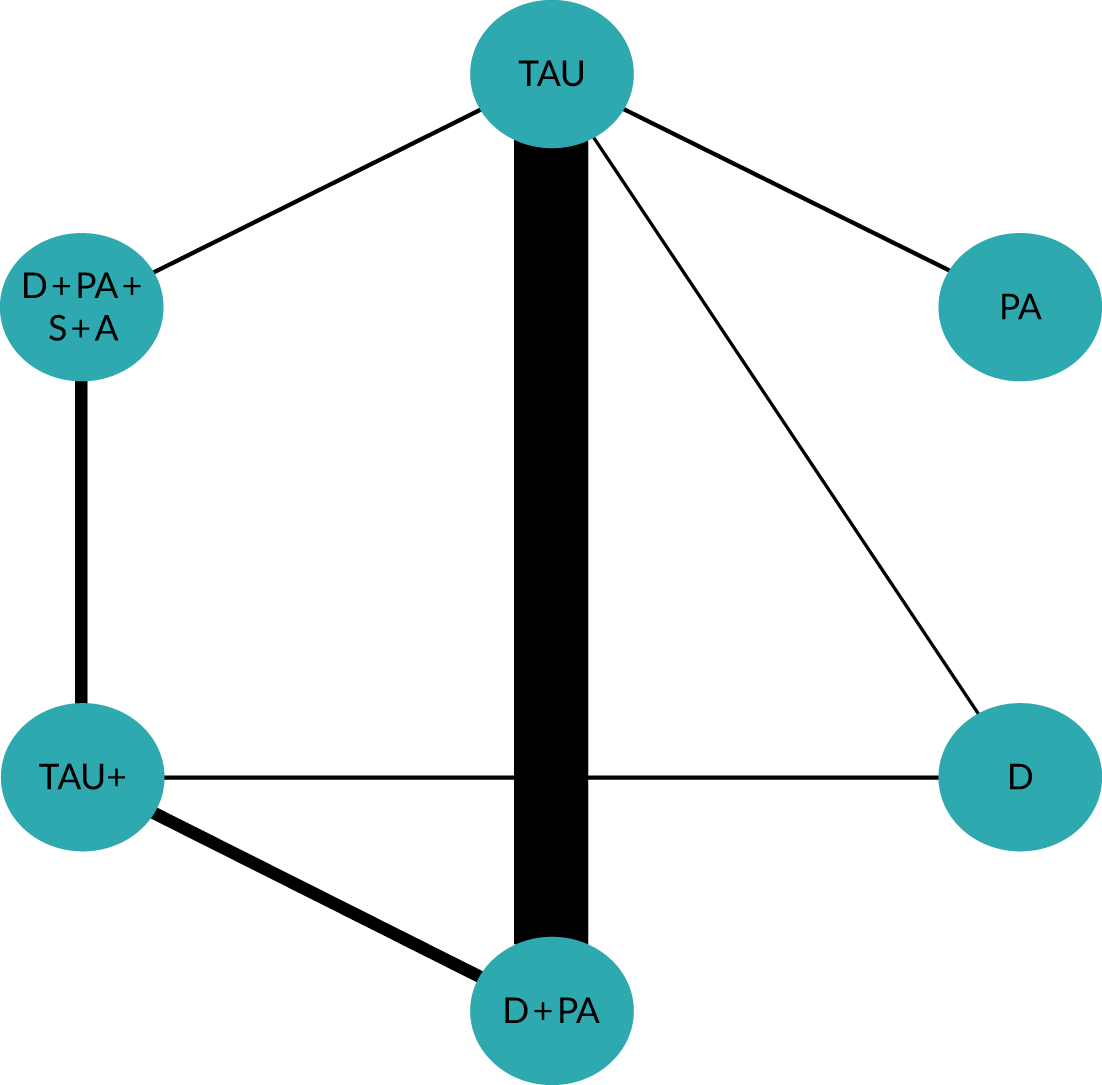

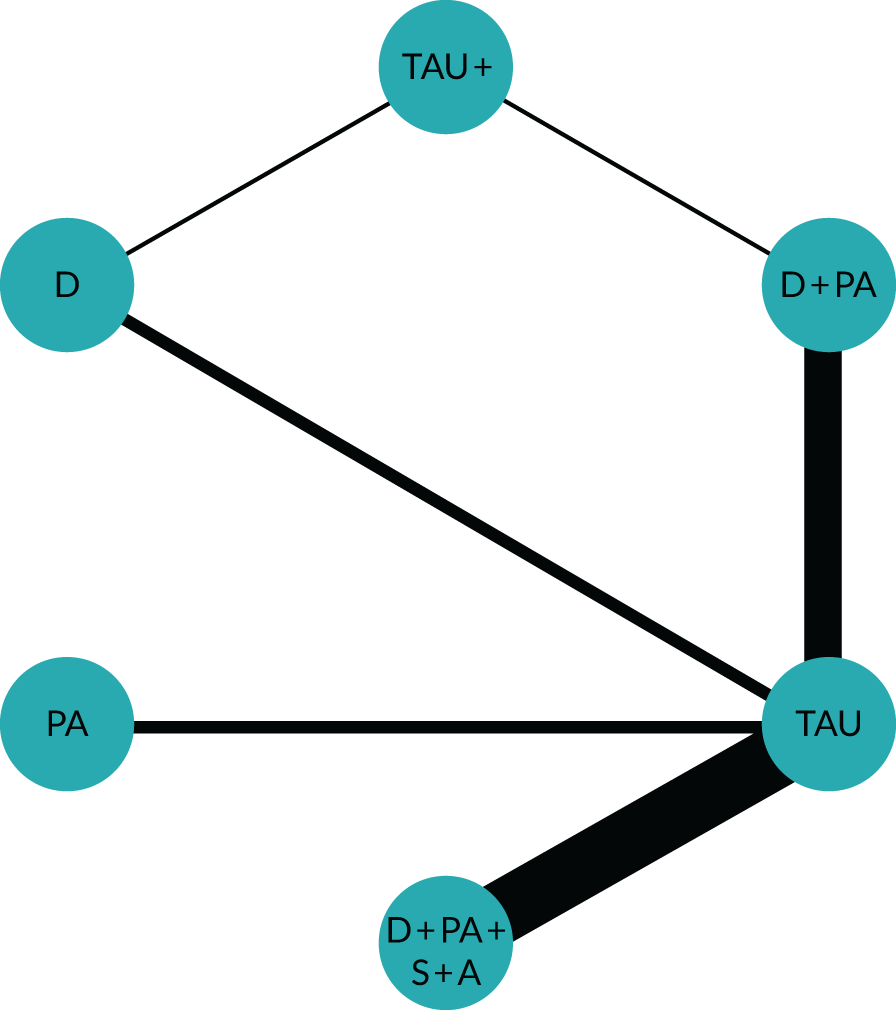

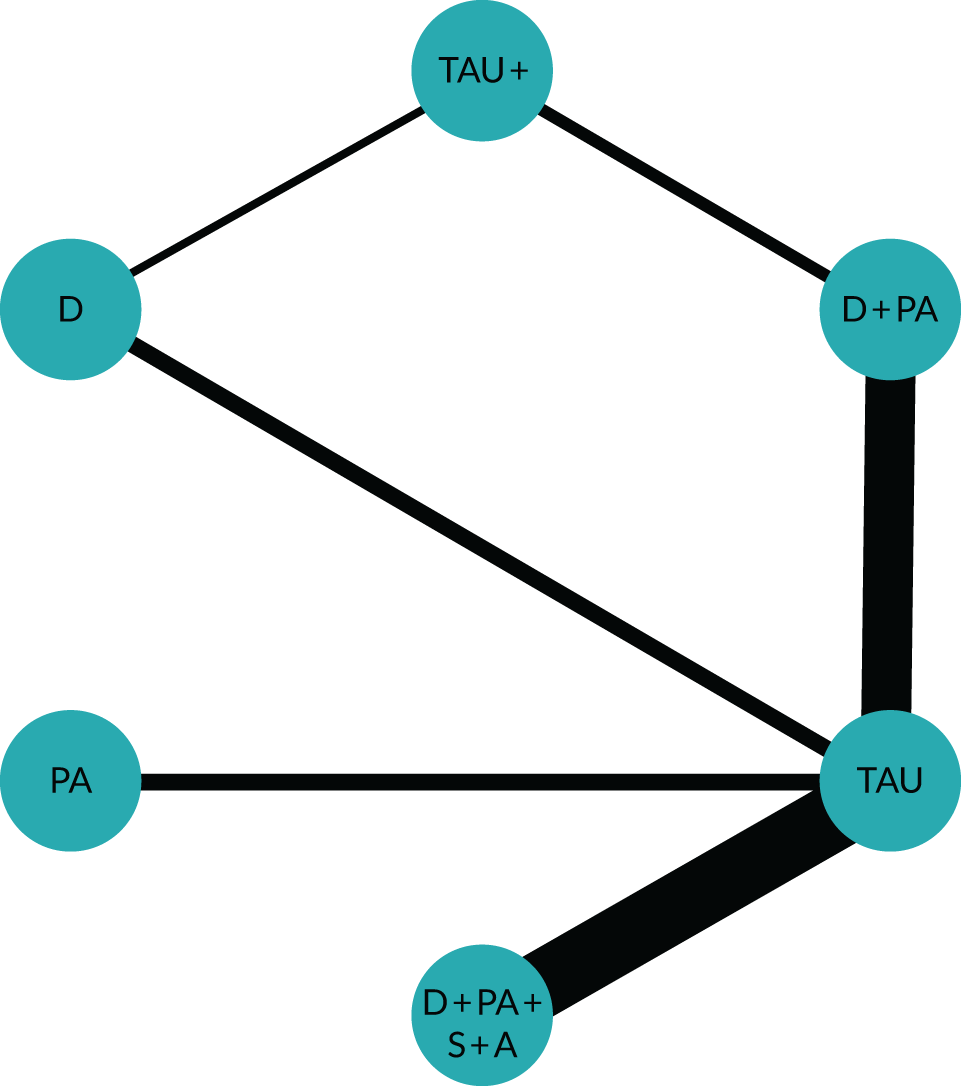

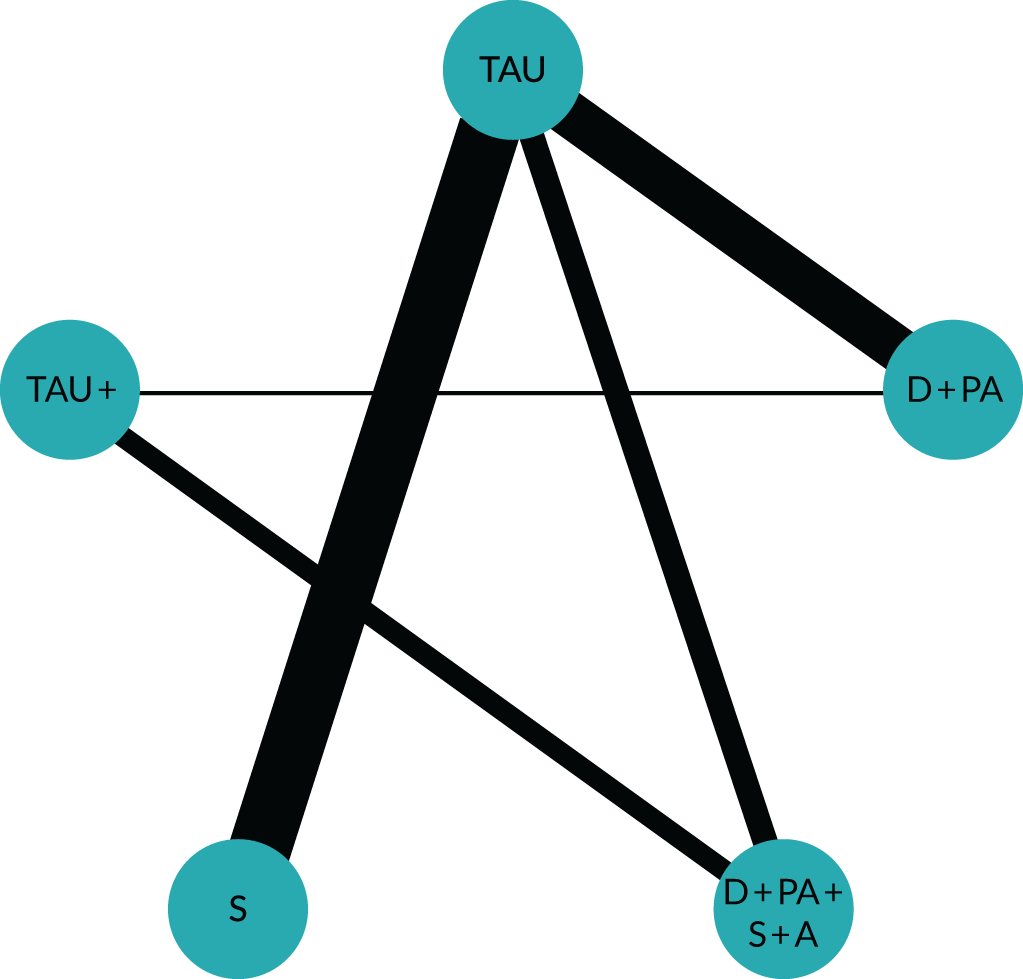

Figure 6 illustrates the different risk behaviours targeted by weight loss interventions and their comparators. By far the most commonly targeted risk behaviours for intervention were diet and physical activity compared with TAU (17 trials)45,54,56,60–62,70,75,76,84,87,91,96,104,105,107,108 or TAU+ (five trials). 64,80,82,89,110 Interventions targeted diet alone and TAU in two trials,99,104 and diet alone and TAU+ in one trial. 101 Three trials targeted physical activity alone and TAU,48,85,97 and none targeted physical activity alone and TAU+. Interventions targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use and TAU in two trials,63,102 and diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use and TAU+ in one trial. 47

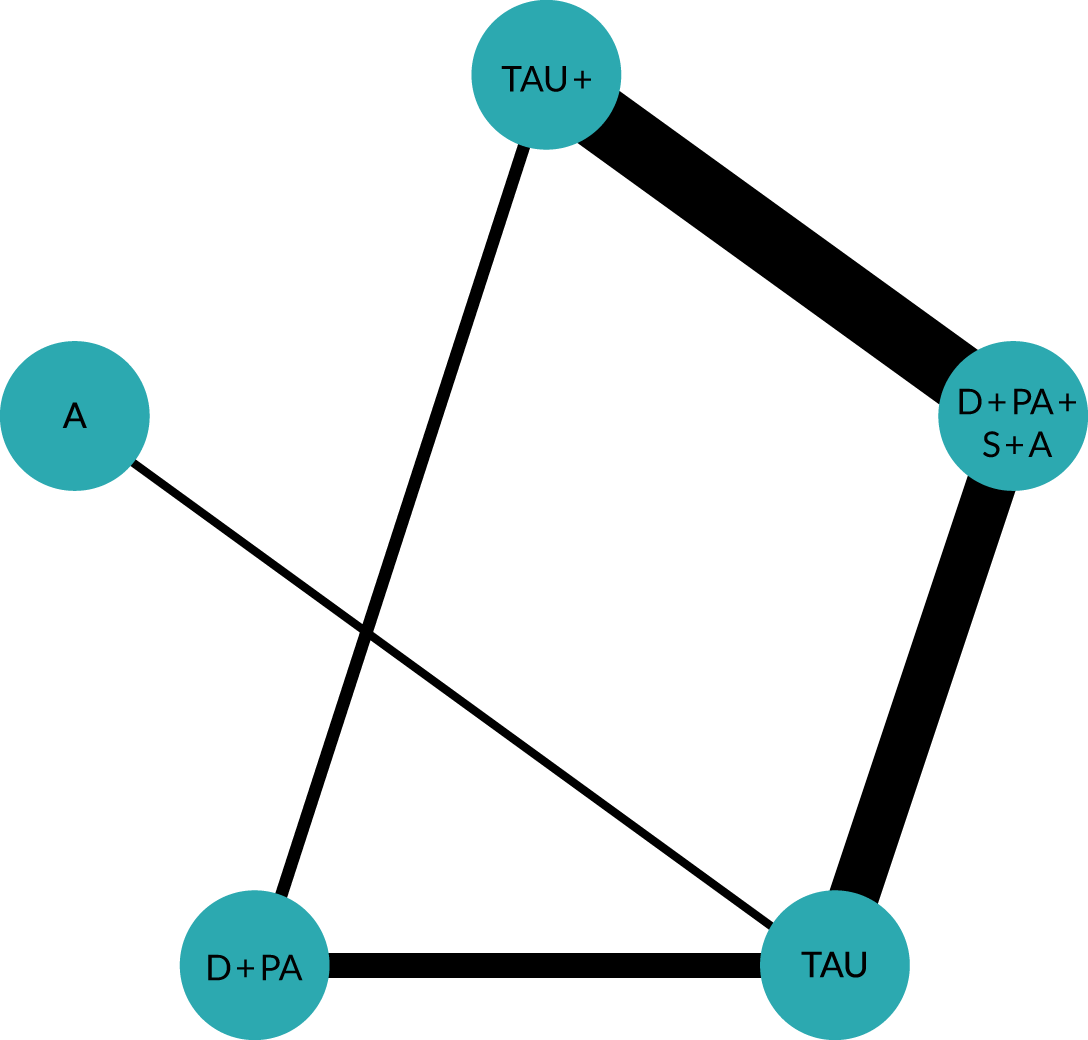

FIGURE 6.

Network diagram illustrating risk behaviours targeted in weight loss interventions (thickness of edge is weighted by sample size). A, alcohol use; D, diet; PA, physical activity; S, smoking.

Total residual deviance did not suggest problems with model fit (mean 59.5 data points, compared with 63 data points) and between-study SD was 0.71 [95% CrI 0.04 to 1.89, MD on weight (kg) scale].

Targeting diet alone was the most effective intervention, although it was not possible to rule out a lack of effectiveness or weight gain (MD –2.27 kg, 95% CrI –6.22 to 1.60 kg). Targeting both diet and physical activity was a little less effective at reducing weight than TAU (MD –2.12 kg, 95% CrI –2.94 to –1.34 kg). However, CrIs were narrower, as more studies directly compared these interventions with TAU. Targeting physical activity alone was the next most effective strategy for reducing weight, compared with TAU (MD –1.40 kg, 95% CrI –6.00 to 2.99 kg). Interventions targeting diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse were unlikely to be effective on weight loss, compared with TAU (MD 1.27 kg, 95% CrI –1.46 to 3.42 kg), and may potentially lead to a mild weight increase.

The effect estimate comparing any risk behaviour intervention with TAU was similar to that found for interventions targeting diet and physical activity (MD –2.10 kg, 95% CrI –3.14 to –1.06 kg). This is probably because interventions targeting these risk behaviours had most weight in the NMA (see Figure 6).

Follow-up data were relatively sparse; there were sufficient data to only assess effectiveness at ≤ 6 months’ follow-up. All six trials targeted diet and physical activity. 60,62,80,84,91,150 Effectiveness at ≤ 6 months post intervention was similar to that found at the end point (MD –2.88 kg, 95% CrI –7.09 to 0.42 kg).

Body mass index

The most common reported outcome in all included studies was BMI. The NMA included data from 36 trials and 3308 participants. 45,47,48,54,60–64,73,75,76,79,80,82–87,89–91,93,97–99,101,102,104,105,107,108,110,111,150

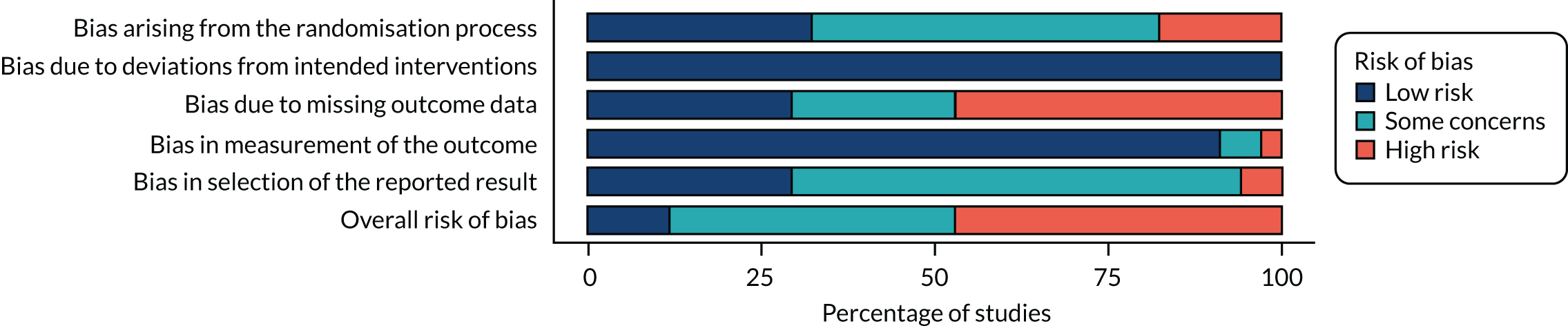

Figure 7 summarises the risk-of-bias judgements across studies measuring BMI. Just under half of the included studies in the NMA were rated as having a high overall risk of bias. The most common reason for studies being judged to have a high risk of bias was missing outcome data. Bias arising from the randomisation process was the next most common reason.

FIGURE 7.

Summary of risk of bias across studies measuring BMI.

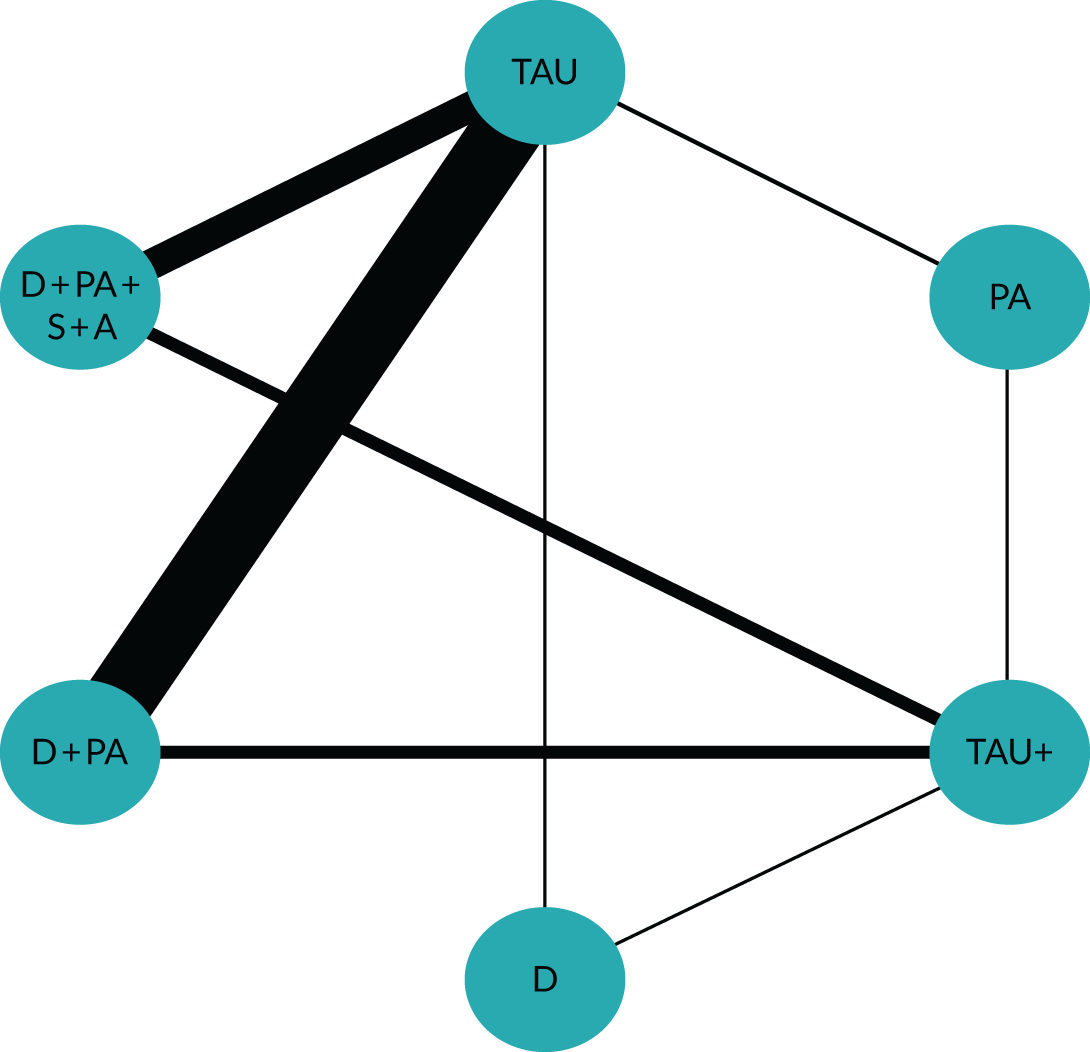

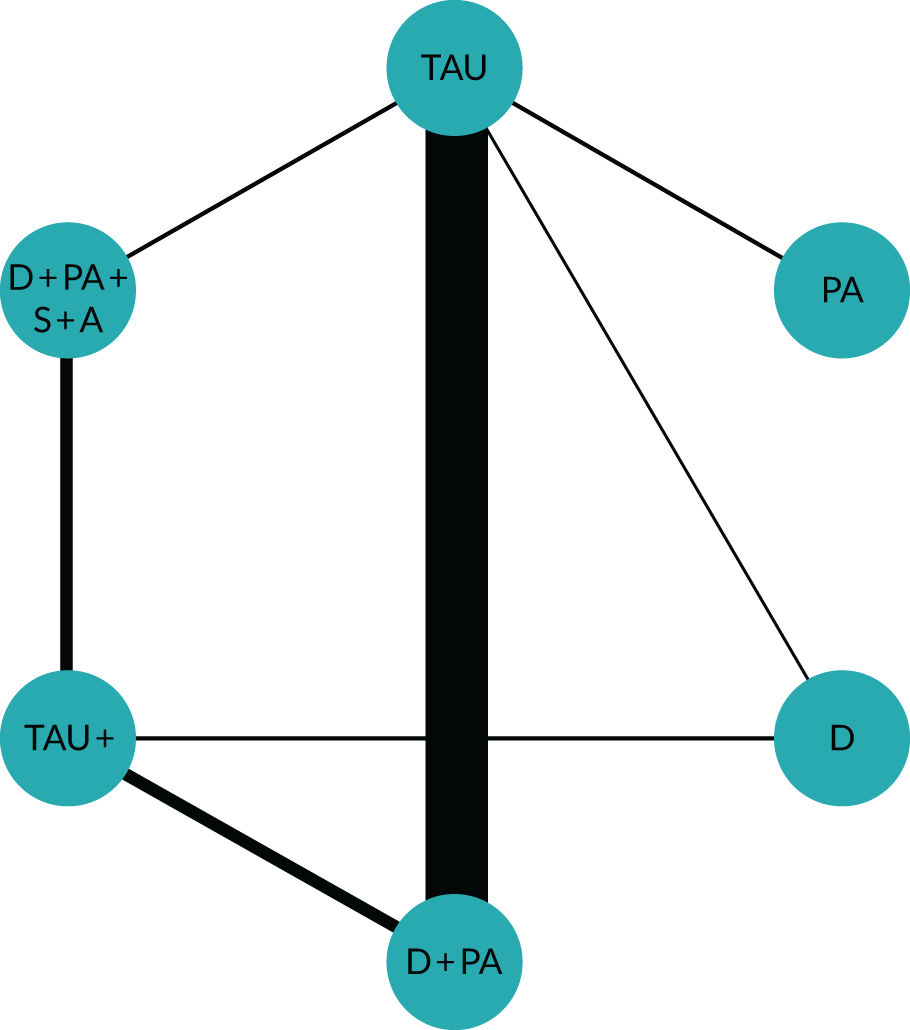

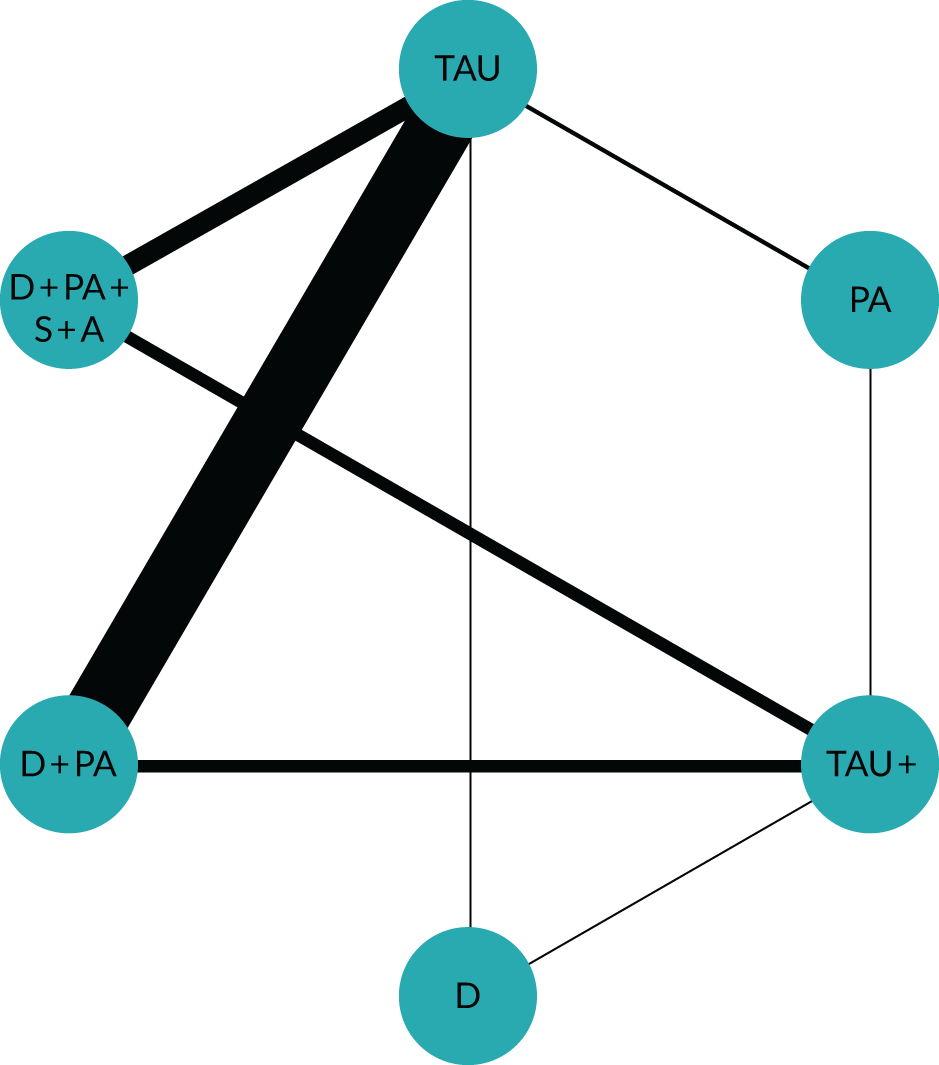

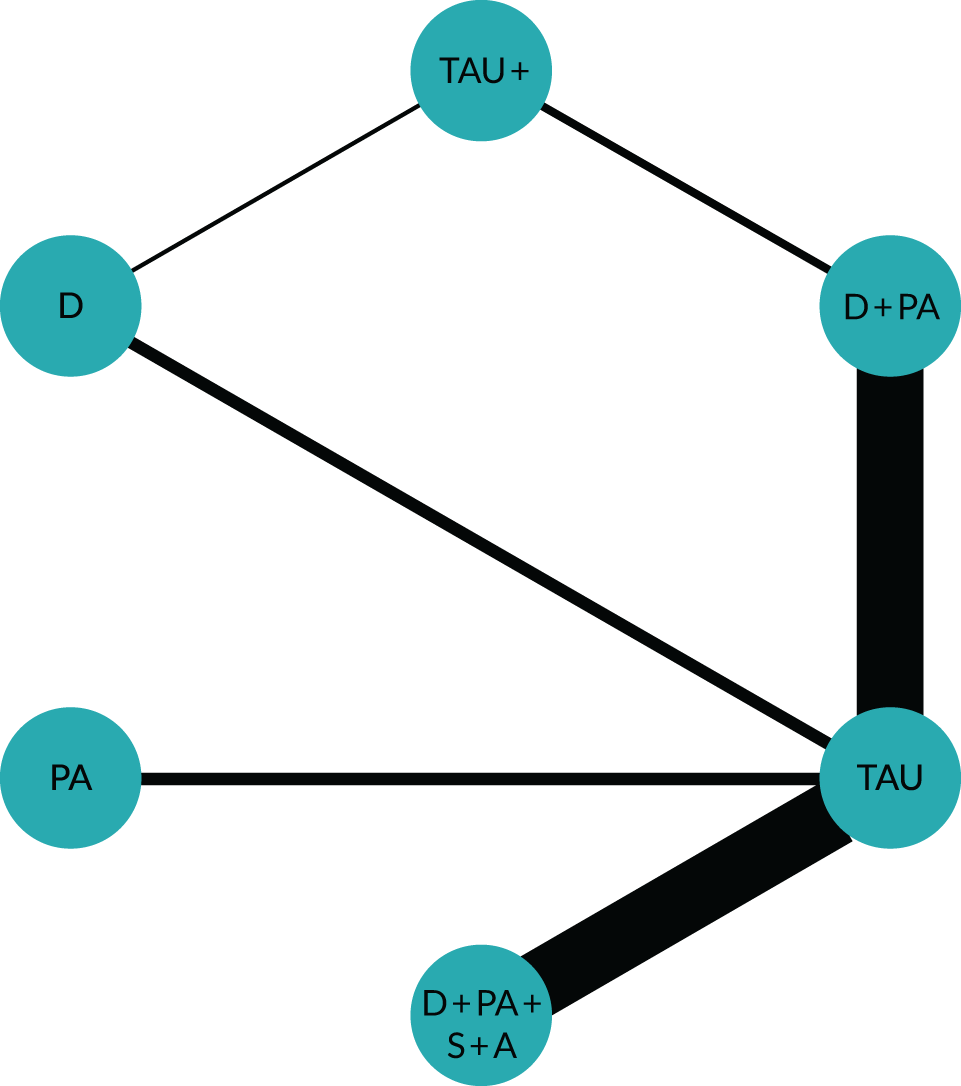

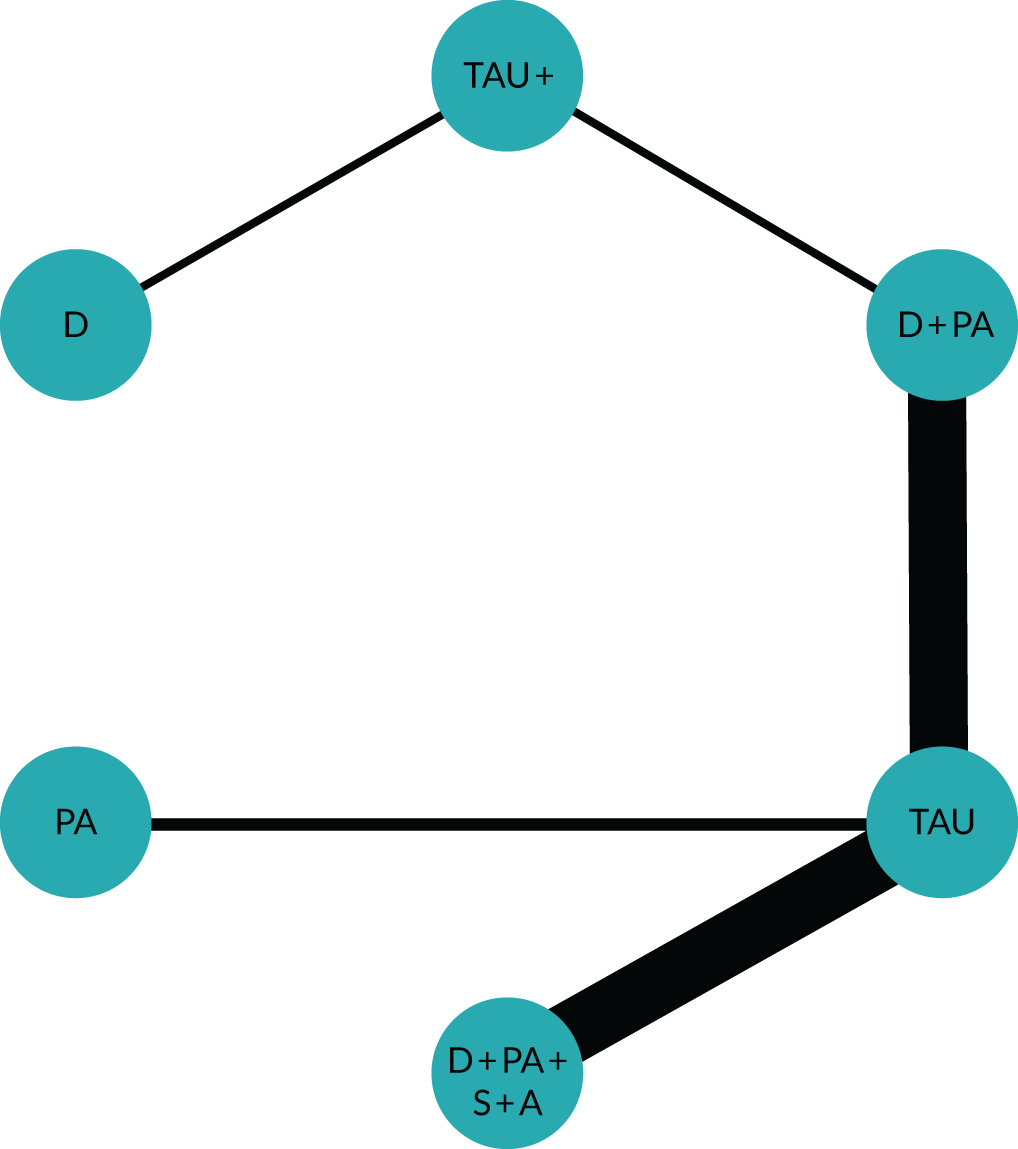

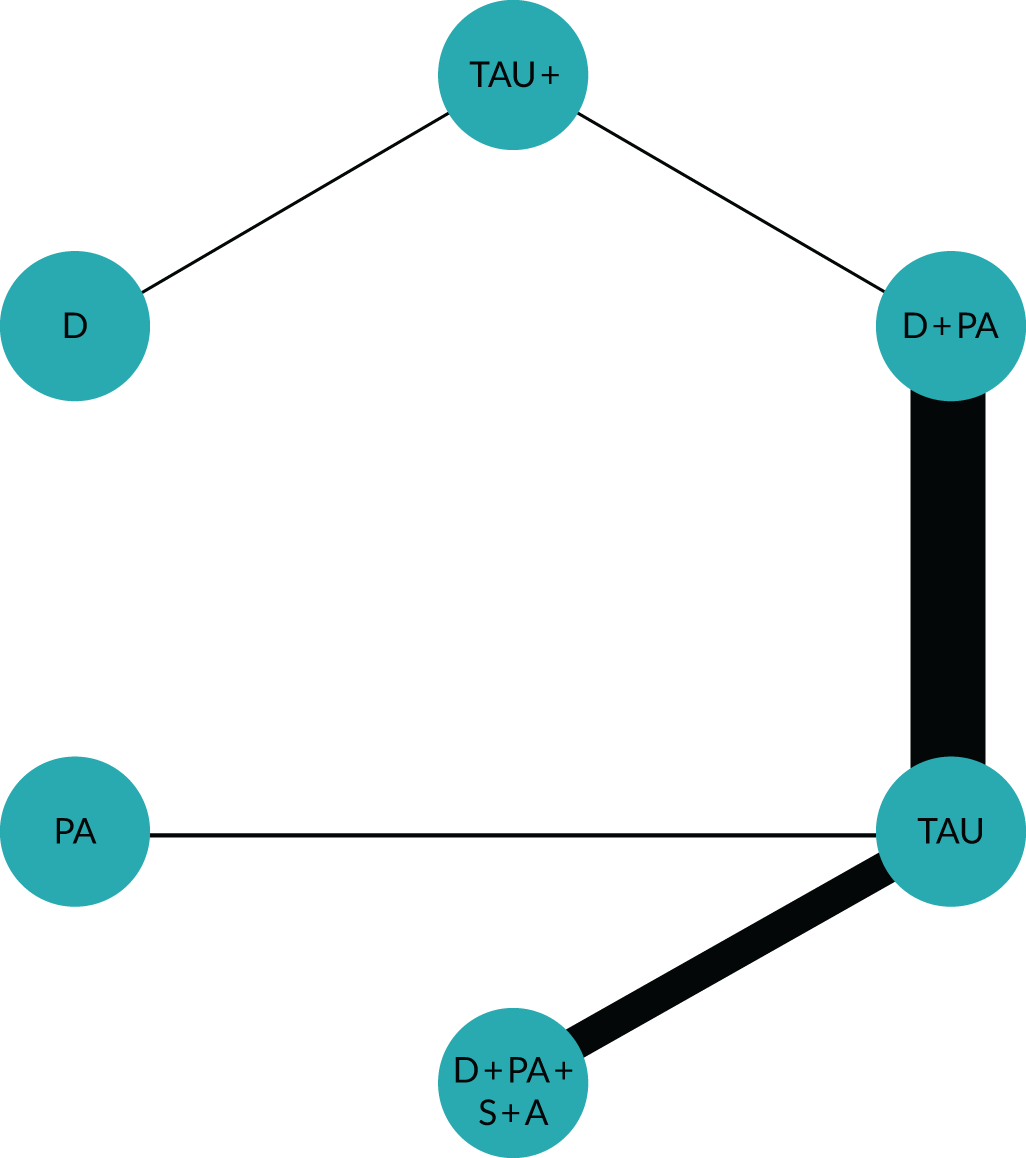

Figure 8 shows that most data were available for the comparison of interventions targeting diet and physical activity (17 trials) with TAU. 45,54,61,62,70,75,76,84,86,87,89,91,104,105,107,108,111 A further five RCTs compared diet and physical activity with TAU+. 64,80,82,90,110 Interventions targeting diet, physical activity, alcohol use and smoking were next most common (four trials compared such interventions with TAU60,63,73,102 and two trials compared them with TAU+47,102).

FIGURE 8.

Network diagram illustrating risk behaviours targeted in interventions to promote reduction in BMI (thickness of edge weighted by sample size). A, alcohol use; D, diet; PA, physical activity; S, smoking.

There were very limited data on interventions targeting physical activity alone (five trials48,79,83,85,97 compared such interventions with TAU and one trial101 compared them with TAU+) or diet (two trials99,104 compared such interventions with TAU and one trial101 compared them with TAU+).

The total residual deviance suggested that there were no problems with model fit (mean 71.77 data points, from 75 data points), and between-study SD was 0.89 (95% CrI 0.57 to 1.36; BMI scale).

Interventions targeting physical activity alone were most effective, compared with TAU, in reducing BMI (MD –1.23 kg/m2, 95% CrI –2.63 to 0.20 kg/m2). Interventions targeting diet and physical activity were the next most effective (MD –0.53 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.07 to 0.04 kg/m2), compared with TAU. There was no evidence that either targeting diet alone (MD –0.04 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.72 to 1.65 kg/m2) or targeting diet, physical activity, alcohol misuse and drug misuse concurrently (MD –0.02 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.05 to 0.98 kg/m2) were effective in reducing BMI.

Follow-up data were also scarce for BMI; there were sufficient data to only assess effectiveness at ≤ 6 months’ follow-up. Seven trials targeted diet and physical activity62,70,80,81,84,89,91 and two trials targeted a broader range of behaviours (including diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse). 60,93 Given the lack of diversity of risk behaviours targeted, we were able to conduct an analysis only on any intervention and TAU. Effectiveness at ≤ 6 months’ follow-up was similar to that found at the end point (MD –1.33 kg/m2, 95% CrI –2.65 to –0.10 kg/m2).

Cardiovascular-related outcomes

Systolic blood pressure

Fifteen trials45,47,54,61,63,64,83,89,93,97,98,101,102,104,150 with 1790 participants were included in the NMA.

Similar to anthropometric outcomes, trials targeting both diet and physical activity compared with TAU were most common (five trials); 45,54,61,70,104 two further trials compared interventions with TAU+. 64,89 Four trials targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use compared with TAU. 47,63,93,102 Only one trial targeted diet alone and TAU,104 and one trial targeted diet alone and TAU+. 101 Two trials targeted physical activity alone and TAU,83,97 and one trial targeted physical activity alone and TAU+. 98

Total residual deviance did not identify any problems with model fit (mean 29.54 data points, compared with 32 data points), and between-study SD was 1.45 (95% CrI 0.07 to 3.95; MD scale for systolic blood pressure).

In contrast to the risk behaviours and anthropometric outcomes, studies targeting multiple risk behaviours were more effective in reducing systolic blood pressure than those targeting single behaviours. The most effective interventions targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse concurrently (MD –2.17 mmHg, 95% CrI –5.46 to 0.87 mmHg), although the CrI did not rule out no benefit. Interventions targeting diet and physical activity were the next most effective (MD –1.56 mmHg, 95% CrI –4.42 to 0.98 mmHg), although the CrI did not rule out no effect. Substantially lower effect estimates and wide CrIs were found for studies targeting diet alone (MD 0.42 mmHg, 95% CrI –4.52 to 5.30 mmHg) or physical activity alone (MD –0.26 mmHg, 95% CrI –5.43 to 4.97 mmHg).

Diastolic blood pressure

Thirteen trials45,47,61,63,64,83,89,93,97,98,101,104,150 were included in the NMA, comprising data on 1489 participants.

Total residual deviance did not identify any problems with model fit (mean 26.78 data points, compared with 27 data points), and between-study SD was 1.78 (95% CrI 0.16 to 4.27; MD scale on diastolic blood pressure).

Credible intervals were wide for all comparisons, indicating uncertainty about their effectiveness. The most effective interventions in reducing diastolic blood pressure targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse (MD –2.04 mmHg, 95% CrI –5.76 to 1.23 mmHg). The next most effective intervention targeted diet alone (MD –1.60 mmHg, 95% CrI –6.37 to 2.94 mmHg), followed by interventions targeting diet and physical activity (MD –1.06 mmHg, 95% CrI –4.04 to 1.48 mmHg), and, finally, interventions targeting physical activity alone were not associated with any benefit (MD 0.34 mmHg, 95% CrI –3.80 to 4.25 mmHg).

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Fifteen trials45,61,63,64,67,83,89,93,97,98,101,102,104,149,150 were included in the NMA, with data from 2121 participants. Total residual deviance did not identify any problems with model fit (mean 33.95 data points, compared with 32 data points), and between-study SD was 1.75 (95% CrI 0.18 to 4.26).

Most trials targeted diet and physical activity together compared with TAU (five trials)45,61,70,75,104 or compared with TAU+ (two trials). 64,89 Four trials targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use compared with TAU,63,67,93,102 and one trial targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol compared with TAU+. 102 Interventions targeted diet alone and TAU in one trial,104 and diet alone and TAU+ in another trial. 101 Interventions targeted physical activity alone and TAU in two trials,83,97 and physical activity alone and TAU+ in one trial. 98

The most effective interventions for increasing HDL cholesterol targeted diet alone (MD 4.88 mg/dl, 95% CrI –0.02 to 9.66 mg/dl), although it was not possible to rule out no benefit. Physical activity alone (MD 2.99 mg/dl, 95% CrI –1.42 to 7.26 mg/dl) was the next most effective intervention, but the 95% CrI was wide. Targeting diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse was a little less effective (MD 2.59 mg/dl, 95% CrI –0.53 to 5.78 mg/dl). There was limited evidence for the benefits of targeting diet and physical activity (MD 0.15 mg/dl, 95% CrI –2.46 to 2.40 mg/dl).

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Nine trials45,61,67,83,89,93,97,101,150 were included in the NMA, comprising 1071 participants.

Given the sparse nature of the network, and concerns over whether or not there were sufficient data to estimate between-study heterogeneity, we compared the goodness of fit between a random-effects and fixed-effects model. The greater complexity of the random-effects model did not result in a better fit (random-effects model: DIC = 111.65, total residual deviance 17.24 data points; fixed-effects model: DIC = 110.62, total residual deviance 18.00 data points; compared with 18 data points); therefore, we used a fixed-effects model for the analysis of LDL cholesterol.

Data were imprecise for all interventions; therefore, it was not possible to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of reducing LDL cholesterol.

Total cholesterol

Eleven trials,45,61,67,83,86,89,93,97,101,149,150 with 1727 participants, were included in the NMA.

Both the fixed-effects and random-effects models were an acceptable fit (random-effects model: total residual deviance 21.09 data points; fixed-effects model: total residual deviance 22.36 data points; compared with 22 data points). But the greater complexity of the random-effects model meant that the fixed-effects model was preferred (random-effects model DIC = 138.95, fixed-effects model DIC = 137.99).

Data were imprecise for all interventions; therefore, it was not possible to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of reducing total cholesterol.

Quality of life

Quality-of-life data help to assess the overall self-reported benefits of interventions to physical health. In addition, these data help to assess if there are any self-reported benefits or deterioration to mental health-related quality of life.

Physical health

Nine trials,45–47,67,69,81,86,107,148 with 1853 participants, were included in the NMA.

Three trials targeted smoking alone and TAU; intensity of TAU was judged similar enough to be included in the NMA. Interventions targeted diet and physical activity and TAU in three trials, and diet and physical activity TAU+ in one trial. One trial targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use and TAU, and a further trial targeted these behaviours and TAU+.

Total residual deviance was low for the random-effects (6.21 data points, compared with 9 data points) and fixed-effects (5.72 data points, compared with 9 data points) models, possibly indicating overfitting. Because of the greater complexity of the random-effects model, we preferred the fixed-effects model, as there was no difference in goodness of fit (random-effects model DIC = –5.68, fixed-effects model DIC = –7.43).

Interventions targeting smoking alone improved physical health-related quality of life (SMD 0.19, 95% CrI 0.05 to 0.34). There appeared to be no difference between interventions targeting diet and physical activity and TAU in physical health-related quality of life (SMD 0.02, 95% CrI –0.14 to 0.18). Interventions targeting diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse may have led to a small reduction in physical health-related quality of life (SMD –0.21, 95% CrI –0.43 to 0.02).

Mental health

Nine trials45–47,67,69,81,86,107,148 were included in the NMA, with 1853 participants.

Total residual deviance was low for the random-effects (6.09 data points, compared with 9 data points) and fixed-effects (5.31 data points, compared with 9 data points) models, possibly indicating overfitting. Because of the greater complexity of the random-effects model, we preferred the fixed-effects model, as there was no difference in goodness of fit (random-effects model DIC = –5.72, fixed-effects model DIC = –7.74).

Three trials targeted smoking alone and TAU;46,69,148 the intensity of TAU (i.e. low to very low) was judged to be similar enough to be included in the NMA. Interventions targeted diet and physical activity and TAU in three trials,45,86,107 and diet and physical activity TAU+ in one trial. 81 One trial targeted diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use and TAU,67 and one trial targeted these behaviours and TAU+. 47

There was no evidence that either single (interventions targeting smoking alone: SMD 0.01, 95% CrI –0.14 to 0.16) or multiple risk behaviour (interventions targeting diet and physical activity: SMD –0.09, 95% CrI –0.25 to 0.07; diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse: SMD –0.09, 95% CrI –0.32 to 0.14) interventions led to a reduction in mental health-related quality of life. This is an important finding, given concerns that trying to promote physical health may lead to deterioration in mental health.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was the most commonly reported mental health outcome measure; it is designed to monitor symptom severity in people with schizophrenia. We used these data to assess whether or not risk behaviour interventions had adverse effects on mental health for people with SMI.

There were insufficient data to assess the impact of which behaviours were targeted; therefore, we assessed differences between any risk behaviour intervention and TAU on the PANSS. As there were only two comparisons in the network, this was equivalent to conducting a pairwise meta-analysis. In addition, only data on the PANSS total score51,54,60,67,79 were sufficiently reported to conduct meta-analyses.

Given that only five trials were included in the analysis, and concerns about whether or not there were sufficient data to estimate between-study heterogeneity, we compared the goodness of fit between a random-effects and a fixed-effects model. The greater complexity of the random-effects model did not result in a better fit with the data (random-effects model DIC = 56.91, total residual deviance = 10.25 data points; fixed-effects model DIC = 56.63, total residual deviance = 11.09 data points, compared with 10 data points); therefore, we used a fixed-effects model for the analysis of the PANSS total score.

There was no evidence on the PANSS total score (MD 0.03, 95% CrI –2.56 to 2.65) that any risk behaviour intervention had a harmful effect on mental health in people with schizophrenia, although the CrI was wide, suggesting uncertainty on estimating the true effect.

Model 1b: meta-regression analyses to investigate the impact of intervention and participants characteristics on effectiveness

There were only sufficient data to conduct meta-regression analyses for weight and BMI outcomes (Table 2).

| Covariate | Beta (95% CrI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Initiation of antipsychotic treatment | 0.36 (–2.69 to 3.37) | 0.34 (–1.27 to 2.12) |

| Targeting people with comorbid physical conditions | –0.74 (–11.61 to 10.18) | –0.39 (–2.34 to 1.61) |

| Individual-based intervention | –2.70 (–4.69 to –0.75) | –1.11 (–2.15 to –0.01) |

| Inpatient setting | 3.18 (0.21 to 6.12) | 0.45 (–1.29 to 2.23) |

| Tailoring for people with SMI | 1.31 (–0.66 to 3.32) | –0.16 (–1.32 to 0.98) |

Weight

We investigated the impact of including five study characteristic covariates to NMA model 1a: behaviour change intervention at initiation of antipsychotic treatment, if participants were targeted for specific comorbid conditions (e.g. diabetes), if the intervention was delivered to individuals, if the intervention was delivered in an inpatient setting and if the intervention was tailored for people with SMI. We then compared the goodness of fit of this covariate model with model 1 without covariates.

We compared model 1b (covariate model) with model 1a (model without covariates). Total residual deviance showed that goodness of fit was acceptable in both models (model 1b = 55.30 data points, model 1a = 60.00 data points, compared with 63 data points). The DIC did not substantially differ between models (model 1b = 279.52, model 1a = 282.17).

However, the inclusion of covariates in model 1b explained some of the heterogeneity, indicated by a reduction in the between-study SD (model 1b: SD 0.44, 95% CrI 0.02 to 1.54; model 1a: SD 0.69, 95% CrI 0.04 to 1.78).

Interventions delivered to individuals were more effective than those delivered to groups (beta –2.70, 95% CrI –4.69 to –0.75). In addition, interventions delivered in inpatient settings were less effective than interventions delivered in community settings (beta 3.18, 95% CrI 0.21 to 6.12). CrIs were very wide for all other covariates.

Body mass index

Differences in DIC values indicated that the covariate model (model 1b: DIC = 186.91) fitted the data better than the model without covariates (model 1a: DIC = 196.76), although the covariates included in the model reduced the between-study SD only a little (model 1b: SD 0.83, 95% CrI 0.46 to 1.40; model 1a: SD 0.88, 95% CrI 0.56 to 1.35).

Total residual deviance was acceptable for the covariate model (mean 68.53 data points, compared with 70 data points). Similar to weight outcomes, interventions delivered to individuals were more effective than those delivered to groups (beta –1.11, 95% CrI –2.15 to –0.01). All other covariates had very wide CrIs.

Model 2 (interaction model): does targeting multiple risk behaviours lead to positive or negative synergies?

The preceding analyses provide some insight on how targeting particular risk behaviours affects outcomes. A different way of exploring that question is to assess whether or not targeting risk behaviours together results in positive (i.e. larger benefits than would be expected from the sum of their effects alone) or negative synergies (i.e. less benefits than expected from the sum of their effects). There were sufficient data to explore these interactions on weight and BMI only (Table 3).

| Risk behaviours | Outcome (95% CrI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Diet | MD –2.56 (–6.34 to 1.35) | MD –0.01 (–1.65 to 1.67) |

| Physical activity | MD –1.61 (–6.09 to 2.67) | MD –1.08 (–2.28 to 0.13) |

| Diet and physical activity | MD 1.88 (–4.02 to 7.57) | MD 0.56 (–1.48 to 2.61) |

| Diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol misuse and drug misuse | MD 2.97 (1.03 to 4.84) | MD 0.66 (–0.43 to 1.68) |

| Total residual deviance | Mean 58.42 | Mean 71.78 |

| Between-study SD | 0.77 (0.05 to 1.73) | 0.86 (0.56 to 1.31) |

Weight

Model fit was acceptable (mean total residual deviance = 58.42 data points, compared with 63 data points). The findings were similar to those of model 1. We did not find evidence of positive interactions. There did not appear to be additional benefits of targeting diet and physical activity concurrently, compared with summing the effects of targeting each of these behaviours alone (MD 1.88 kg, 95% CrI –4.02 to 7.57 kg).

There was evidence of negative synergistic effects when targeting diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol misuse and drug misuse. Benefits on weight loss were less than would be expected if these behaviours were targeted alone (2.97 kg, 95% CrI 1.03 to 4.84 kg).

Body mass index

Model fit was acceptable (total residual deviance was 71.78 data points, compared with 75 data points). Targeting physical activity was associated with a small reduction in BMI (MD –1.08 kg/m2, 95% CrI –2.28 to 0.13 kg/m2). There was insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of targeting diet alone (MD –0.01 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.65 to 1.67 kg/m2).

There was no evidence of a positive interaction when targeting diet and physical activity concurrently (0.56 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.48 to 2.61 kg/m2). There was also no evidence of a positive interaction when targeting diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol misuse (MD 0.66 kg/m2, 95% CrI –0.43 to 1.68 kg/m2).

Model 3: effectiveness of behaviour change techniques

We fitted component NMA models to evaluate the effectiveness of BCTs in models assuming these BCTs affected outcomes independently of one another (independent model) and in models allowing for interaction effects between these BCTs (interaction model) (Table 4).

| BCTs (BCTT v1) | Model 3a: independent model (95% CrI) | Model 3b: interaction model (95% CrI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | |

| 1.1 Goal-setting (behaviour) | –2.22 (–4.54 to –0.44) | –0.61 (–1.53 to 0.28) | –2.26 (–4.68 to –0.25) | –1.85 (–2.91 to –0.69) |

| 1.2 Problem-solving | 3.61 (1.18 to 5.32) | 1.56 (0.61 to 2.36) | 3.82 (0.36 to 7.03) | 1.46 (0.11 to 2.67) |

| 1.4 Action-planning | – | –0.61 (–1.29 to 0.27) | – | –0.34 (–1.07 to 0.42) |

| 2.2 Feedback on behaviour | –0.83 (–2.70 to 1.77) | –0.58 (–1.43 to 0.28) | –0.67 (–2.73 to 1.97) | 0.02 (–0.78 to 0.84) |

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour | –0.12 (–1.91 to 1.78) | –0.35 (–0.96 to 0.40) | –0.96 (–3.55 to 1.38) | –0.70 (–1.42 to 0.07) |

| 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | 0.84 (–1.48 to 2.65) | –0.24 (–1.04 to 0.51) | 0.47 (–2.25 to 2.83) | –0.42 (–1.12 to 0.32) |

| 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | –2.10 (–3.42 to –0.45) | –0.59 (–1.10 to –0.02) | –2.50 (–4.40 to –0.34) | –1.19 (–1.85 to –0.55) |

| 5.1 Information about health consequences | –0.94 (–2.75 to 1.30) | 0.69 (–0.11 to 1.38) | –0.60 (–2.59 to 1.81) | 0.05 (–1.23 to 1.29) |

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour | –0.94 (–2.75 to 1.30) | – | –0.85 (–3.24 to 1.56) | – |

| 4.1 × 5.1 | – | – | – | 1.71 (0.44 to 3.00) |

| 4.1 × 1.2 | – | – | –1.43 (–5.54 to 2.31) | –0.84 (–2.10 to 0.45) |

| 4.1 × 2.3 | – | – | 2.10 (–1.06 to 5.53) | 0.93 (–0.05 to 1.96) |

| 5.1 × 2.3 | – | – | – | 0.07 (–1.23 to 1.38) |

| 1.1 × 2.3 | – | – | – | 1.11 (–0.54 to 2.51) |

| 1.2 × 2.3 | – | – | 0.75 (–0.52 to 2.12) | |

Weight

Goodness of fit was acceptable for both models (independent model: total residual deviance = 59.42 data points, interaction model: total residual deviance = 58.46 data points, compared with 63 data points).

The DIC values (independent model: DIC = 281.67, interaction model: DIC = 282.37) and between-study SDs were similar (independent model: SD 0.81, 95% CrI 0.03 to 2.22; interaction model: SD 0.91, 95% CrI 0.04 to 2.43). This may reflect that there were sufficient data for only two interactions to be included in the interaction model and that both covariates were very imprecise. Therefore, the summary of results will focus on the simpler independent model.

The strongest evidence was found for goal-setting (behaviour) (MD –2.22 kg, 95% CrI –4.54 to –0.44 kg) and instruction on how to perform the behaviour (MD –2.10 kg, 95% CrI –3.42 to –0.45 kg).

In addition, problem-solving was associated with weight gain (MD 3.61 kg, 95% CrI 1.18 to 5.32 kg).

Body mass index

Goodness of fit was acceptable for both models (independence model: total residual deviance = 77.86, interaction model: total residual deviance = 73.31).

The interaction model (DIC = 192.86) fitted the data better than the independent model (DIC = 198.84) and explained more of the heterogeneity [between-study SD: interaction model, 0.21 (95% CrI 0.01 to 0.74); independence model, 0.55 (95% CrI 0.12 to 1.07)]. Therefore, the summary will focus on results from the interaction model.

Similar to the weight NMA, the strongest evidence was found for goal-setting (behaviour) (MD –1.85 kg/m2, 95% CrI –2.91 to –0.69 kg/m2), instruction on how to perform a behaviour (MD –1.19 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.85 to –0.55 kg/m2) and self-monitoring of behaviour (MD –0.70 kg/m2, 95% CrI –1.42 to 0.07 kg/m2), although it was not possible to rule out negligible benefits for self-monitoring of behaviour.

As for weight, problem-solving was associated with a worsening of BMI outcomes (MD 1.46 kg/m2, 95% CrI 0.11 to 2.67 kg/m2).

Chapter 5 Results of the qualitative review

Quality of included studies

Methodological limitations of included studies were assessed using the CASP tool. Reporting was generally acceptable across studies, allowing for consideration of most, if not all, prompts in the CASP tool for each study. However, authors’ consideration of the relationship between researcher and participant (question 6) was consistently poorly addressed. Only 4 of the 25 included studies addressed this issue adequately.

One consideration that was addressed well was ethics issues (question 7), which require sufficient detail in gaining ethics approval and informed consent of participants. When this did not score ‘yes’, it was because of an apparent lack of reporting.

Results of the GRADE–CERQual assessment per subtheme can be found in Appendix 8. There was moderate to high confidence in the evidence presented by the subthemes reported here. The four components of CERQual also raised only very minor to moderate concerns. Methodological limitations (as assessed by the CASP tool) were not a general concern: coherence was largely assessed as a minor concern; adequacy was mostly assessed as a very minor to minor concern; and relevance was a slightly larger concern, predominantly assessed as being of minor to moderate concern.

Narrative synthesis

Here we are going to address the question: what are service user perspectives on the acceptability and feasibility of using risk behaviour interventions to change behaviour and improve physical health-related outcomes, with specific reference to intervention uptake, adherence and service user experience?

Data from primary studies organised around four higher-tier themes: interaction of physical and mental health, motivational contexts for change, barriers to behaviour change, and experiences of interventions.

Interaction between physical and mental health

Across the studies, data highlighted the reciprocal nature of physical and mental health. Participants reported the impact of mental health states on their engagement in healthy behaviours, and there was an emerging consensus that physical health risk behaviours had the potential to affect mental health negatively.

Healthy behaviours improving mental health and well-being

People with SMI reported that physical activity was helpful in changing mental health. But, overall, mental health and a sense of well-being were valued more than changes in activity.

When discussing physical activity, data gathered around two core ideas: physical activity to refresh the mind and physical activity for symptomatic relief. Engaging in activity was frequently reported to result in mental clarity:

. . . I’d notice, after I’d done the gym sessions, I felt really fresh. Like, afterwards, like my mind felt kind of washed, if you like.

Firth et al. ,119 single risk behaviour intervention (SRB), physical activity

Healthy behaviours were also used for immediate symptom relief in one study:

. . . when I feel like I’m just so angry, and stuff like that, I’ve gone training, I’ve done press-ups and stuff at home and it’s cleared my head, killed me anger . . .

Firth et al. ,119 SRB, physical activity

An overarching concept from this theme related to participants’ desire to find a suitable space to bring about positive mental change:

[The gym] gives me somewhere to go to vent out stress.