Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/25/20. The contractual start date was in December 2016. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Papoutsi et al. This work was produced by Papoutsi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Papoutsi et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout this report has been reproduced from Papoutsi et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text throughout includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background and context

Diabetes represents one of the most significant global public health challenges of our time. 2 The global prevalence of diabetes has nearly doubled since 1980, with an estimated 8.5% of the global adult population living with the condition in 2014. 3 In the UK, recent figures place the number of adults living with diabetes at 3.9 million, of whom approximately 90% have type 2 diabetes (T2D) and 8% have type 1 diabetes (T1D). 4 It has been found5 that the prevalence of T1D and T2D has increased significantly in children and adolescents, and that these increases (particularly relating to early presentation in T2D) disproportionately affect people in ethnic minority groups. In the UK, the rising prevalence of diabetes has raised the cost of diabetes care to 10% of the annual NHS budget and has highlighted an urgent need to investigate different ways of delivering diabetes prevention and care. 6,7

In England and Wales, more than 30,000 children and young people with diabetes receive care in paediatric diabetes units. 8 Young people with diabetes constitute an important group, as the early adoption of good self-management practices at a young age can significantly reduce the risk of lifetime complications, prevent early mortality and lower costs for the health service. 9,10 An estimated 642 million people will be living with diabetes worldwide in 2040. 2 Yet, in 2018/19 only 36% of children and young people with T1D in England and Wales achieved recommended blood glucose control [haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels of < 58 mmol/mol as per the National Diabetes Audit target],11 and a similarly low proportion received all recommended care processes, with high variability between care providers. 8 These audit data are reinforced by research12 showing that mortality among young adults with diabetes in the UK is worse than in other European countries and that it rose significantly between 1990 and 2010. Diabetes is also known to have serious consequences in those diagnosed in childhood: diabetes-related complications (such as kidney and eye disease) were seen in one in three of those with T1D, and in three in four with T2D in their early 20s, within 8 years of diagnosis. 13,14 People diagnosed with T1D before the age of 10 years (compared with those of older ages) have been shown in one study to have a 30-fold greater risk of future cardiovascular disease. 15 In recent years, there has been a considerable increase in young women entering pregnancy with pre-existing diabetes,16 and this is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (to mother and child) that are exacerbated by suboptimal glycaemic control and the absence of pregnancy planning.

Barriers to accessing health care for younger people include a lack of equitable access to services, a lack of developmentally appropriate consultations, a fear of being judged and stigmatised, and diabetes-related distress. 17 Young adults report the worst NHS experience of any age group, and their health-care needs and priorities are distinct from those of other age groups. 18,19 This may be even more important for young people from socioeconomically deprived areas, who achieve worse blood glucose control and present with more complications and unplanned pregnancies than those from more affluent areas,20 and for those in ethnic minority groups who are disproportionately affected by T2D. 21

Why is research on group clinics needed?

Current practice of diabetes care and who/what it fails to reach

The research described in this report is important for people who have diabetes and for the NHS for a number of reasons. First, after the transfer (or ‘transition’) of care from paediatric to adult care, young adults (usually defined as people aged 16–25 years) frequently exhibit a deterioration in glycaemic control. Loss to follow-up is common22,23 and attendance rates are low. 24 Many young adults with diabetes report poor experiences of, and dissatisfaction with, the care that they receive and challenges navigating health-care systems. 25 High diabetes distress and poor self-care have also been widely recognised in young people with diabetes. 26 A well-conducted multicentre trial27 found that enhanced transition care, including close support from a transition co-ordinator, had only short-term benefits for young people with T1D, and there is little trial evidence for T2D care during transition and young adulthood. These issues have been recognised internationally in a consensus statement by the American Diabetes Association28 and by the NHS, which has designed service specifications to support transition and young adult care for people with diabetes. 29 As described above, diabetes outcomes are disproportionately poorer among children and young adults from ethnic minority backgrounds and living in deprivation than among those who are not. 21 These findings highlight a need to look beyond traditional models of diabetes care, currently based on one-to-one clinic appointments with health professionals, to try to improve engagement with care, quality and experiences of care, and diabetes-related outcomes.

The focus on young adults living with diabetes reflects a key point in an individual’s life course at which effective intervention has the potential to lead to major improvements in long-term health outcomes and could potentially have an impact on lifelong health behaviours and engagement with care.

Improving care design and delivery through participatory involvement

Recent quality improvement work within the NHS30 has built on accumulating patient experiences that suggest that current care models do not adequately support individuals to take control of their health or work with their care providers to achieve their desired outcomes and experiences. The concept of person-centred care is central to these quality improvement programmes and has been widely adopted by organisations designing, delivering and evaluating complex care models, such as the NHS, The Health Foundation and The King’s Fund. 30 A number of different approaches to developing person-centred care have been proposed, including collaborative care models and experience-based co-design (EBCD). 31 Person-centred approaches have been shown to engage diverse and underserved communities32 and young people,33 particularly in mental health-care settings.

Collaboration and co-design in health care are increasingly built into health services research and intervention development, with a relevant example in T1D structured education. 34 EBCD offers an approach to examine, test, review and refine the new care model it designs in an iterative evaluation process, valuably applied to health-care implementation research.

Could group clinics enhance the care of people with diabetes?

Group clinic-based care (also known as ‘shared medical appointments’) for people with diabetes has been used and evaluated before in specific contexts. 35 Group-based education, in models such as Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE), is already used widely in diabetes treatment, but is typically a single, time-limited intervention based on education to support a limited range of diabetes self-management practices. There is little evidence to support group-based models that incorporate a broader scope of care in health services. A study36 of Italian adults with diabetes who underwent group-based care, which focused on lifestyle interventions, found that those who underwent group-based care maintained better glycaemic control and required less clinician time than those receiving standard one-to-one care. This trial identified that group care requires the ‘reallocation of tasks, roles, and resources and a change in providers’ attitudes from the traditional prescriptive approach to a more empathic role of facilitator’,36 highlighting the need for innovation away from standard models of care in the delivery of such an intervention. Other evidence37 suggests that shared medical appointments can yield measurable improvements in patient trust, patient perception of quality of care and quality of life. Some studies suggest38 that shared medical appointments offer a route to better support and engagement in health care for underserved racial and ethnic minorities. With specific relevance to young adults, recent advances39 in neuroscience and psychology highlight that peer influences are likely to be particularly important for controlling risk behaviour and that this may have a significant impact in adolescence and young adulthood. The development of group clinics has exploited the potential for peer support to improve health-related behaviour, for example in the successful introduction of a group clinic for young adults following renal transplant, which led to a significant reduction in the incidence of graft loss. 40

To our knowledge, no studies have incorporated or evaluated group clinics designed with extensive participation of service users, have been designed to meet a wide range of health and social care needs or have been evaluated extensively in young adults with diabetes. Furthermore, recent systematic reviews have found that group clinics often had a positive effect on clinician- and patient-reported outcomes but have not undertaken detailed work on their mechanisms of action and context in which they work,41 and this is vitally important if group clinics are to be implemented within a health system, such as the NHS.

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) identified a need to generate an evidence base for the use of group clinics in chronic conditions, and supported a commissioned systematic review in 2015,41 followed by a commissioned funding call for primary studies, of which this is one. The systematic review identified previously published mixed-methods research, including 22 randomised controlled trials, of group-based clinics, the majority of which had been aimed at delivering care to people with diabetes. Their review concluded that, although group clinics seemed to have consistent and promising evidence of benefit on some biomedical outcomes, there remained significant uncertainty as to their potential benefit within the NHS and whether or not they would meet the needs of people from ethnic minority groups. The review41 also identified the need for greater understanding of the context in which group clinics might offer an appropriate alternative to individual consultations, and the conditions in which they would be less appropriate.

Research objectives

Aims

-

To explore the scope, feasibility, impact and potential scalability of group clinics for young adults with diabetes.

-

To contribute to NHS service redesign and improve care for people from underserved groups with long-term conditions.

Research questions

-

How and to what extent might an innovative, co-designed, group clinic-based care model meet the complex health and social needs of young people with diabetes?

-

Could a group approach help support diabetes self-management? If so, what can the experiences of participants, the functioning of the group and the wider context in which the new model takes place tell us about its mechanisms of action?

-

What is the feasibility, acceptability, cost and impact on outcomes of introducing group clinics for their users and stakeholders? What is the organisational impact of this model to the NHS and other stakeholders?

-

What would be the optimal size and study design of a cluster-randomised controlled study to evaluate the clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of offering group clinics to young adults with diabetes? What other factors should be considered when planning such a randomised controlled trial (e.g. factors relating to patient characteristics, existing models of service delivery, acceptability and mechanisms of action of group clinics on clinical outcomes)?

Chapter 2 Evidence synthesis (realist review)

Our evidence synthesis of group clinics for young adults with diabetes was underpinned by a theory-driven realist methodology. Realist reviews consider the mechanisms by which a programme (in this case, group clinics) works (or not) and the contexts in which these mechanisms are triggered to produce certain outcomes. Realist reviews (and evaluations) have been extensively applied in health services research.

A realist review was performed to synthesise findings from existing literature to understand how group clinics may work for young adults with diabetes and other complex needs. This detailed evidence synthesis followed the approach and standards of the NIHR-funded Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) project to understand ‘what works, for whom, under what circumstances’ in group clinics for young adults with diabetes. 42,43 The review synthesised existing qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies relevant to this topic area. The findings of this evidence synthesis supported the empirical research undertaken subsequently, including the co-design and context-sensitive development of a group clinic model and its implementation and evaluation within the NHS.

The realist review is presented as a published paper and includes a detailed description of its methodology and results. 44 Its findings highlighted four main principles that should be taken forward in the contextualisation and design of group clinics to support engagement from young people:

-

emphasis on self-management as practical knowledge

-

development of a sense of affinity between patients

-

provision of safe, developmentally appropriate care

-

the need to balance group and individual needs.

The realist review highlighted that the implementation of group clinics within health systems was rarely, if ever, straightforward. Numerous adjustments were needed to existing operational and clinical processes to deliver high-quality care through group clinics, and there was substantial ‘hidden’ work (i.e. work that was not recognised, measured or rewarded, and which was often carried out by relatively low-status staff in their own time) involved in doing so. Finally, it was noted that group clinics worked best alongside individual care and there was no evidence to suggest that they offer a means to replace it.

Chapter 3 Methods

Study design overview

The study, which built on the findings of the realist review described in Chapter 2,44 was conducted in three phases and embedded in a continuous process of participatory and dissemination activities; it is summarised in Figure 1. First, we undertook a scoping exercise, combining questionnaire data with NHS audit data, to generate a descriptive understanding of existing group-based care and the current state of diabetes care for young adults. Second, we carried out in-depth participatory co-design activities to develop a model of group clinic-based care that was then implemented in two NHS diabetes services (‘group clinic sites’). Third, we evaluated this group clinic model using mixed, qualitative and quantitative methods, and a cost analysis, with a further two NHS diabetes services used as ‘control sites’. Our evaluation assessed both the impact of the group clinics on young adults and the potential impact of group clinics within the NHS. Our quantitative evaluation of group clinics was not designed to provide a definitive estimate of differences in outcomes; rather, it was intended to contextualise the qualitative evaluation and, in combination with the cost analysis, to guide the feasibility of a future at-scale evaluation.

FIGURE 1.

Study design overview.

Our study design and methods have been published in a protocol paper. 1

Changes to the original protocol

There were three changes from our original (published) protocol, highlighted below.

Revised aims of National Diabetes Audit analyses

We had intended to perform unit-level (i.e. per clinical service) comparisons of the care delivered to all patients at our group clinic and control sites, using the NHS Digital National Diabetes Audit to provide a descriptive background and a comparison with national data. However, after data access had been granted by NHS Digital, it became apparent that complete unit-level data from our research sites were not available because the required data sets were not complete and, at one research site, could not be disaggregated at unit level from within a larger hospital trust provider. We, therefore, undertook an alternative analysis by using data collected at the individual level from our recruited research participants and comparing this with national-level data from the National Diabetes Audit (NDA). 45

Inclusion of an additional research site for group clinics

During the course of recruitment to our group clinic care model at Newham University Hospital, it became apparent that we would not meet our recruitment target because of a recent reduction in the total clinic population (owing to recent local service changes), as well as incomplete uptake. We, therefore, made a proactive decision to open a new research site at the Central Middlesex Hospital to run the group clinics. Central Middlesex serves a comparable multiethnic, deprived, urban population to Newham University Hospital. The inclusion of this new site had both advantages and disadvantages to the research process. The advantages were that we could evaluate the delivery of group clinics in an NHS setting with different staff, care processes and organisational structures, and we were able to study the group clinic model at a more advanced stage of its development following its co-design and implementation at Newham. This provided new insights and richness to the evaluation of implementation, and contributes to the generalisability of the research findings. There were fewer disadvantages: the variation in delivery of the care model made the direct comparison of quantitative data between Newham and Central Middlesex challenging, and, therefore, data from both sites have not been aggregated.

Comparative quantitative analyses

We had planned to undertake an intention-to-treat analysis, in which we would compare participants at the intervention sites who had been offered and agreed to participate in the group clinics with those who had not been offered group clinics. However, owing to the challenges of recruitment at the group clinic sites, and the variable attendance at group clinics of the recruited participants, we instead offered the group clinic to all young adults at each clinic site and compared those who did with those who did not attend (DNA). As planned, we then compared characteristics and trajectories of all participants at intervention sites with participants at control sites (intention-to-treat analysis).

Theoretical approach

Our work was underpinned by a set of theoretical ideas that influenced intervention development and implementation, and informed qualitative data analysis and interpretation; a more detailed theoretical analysis will be included in upcoming publications. Our approach to intervention development and implementation was underpinned by complexity theory, primarily drawing on an understanding of complex systems as characterised by uncertainty, unpredictability and emergence. 46,47 This means that we treated the introduction of group clinics as a complex change process in which mechanistic replication and standardisation were not sufficient, and attention to the dynamic properties of context and the ongoing tensions raised was necessary. 46,48 Following previous work,46,49 the principles driving our implementation effort can be summarised thus: acknowledging unpredictability, harnessing the capacity of implementation teams to self-organise differently in the different settings, facilitating interdependencies between clinical and operational processes, and encouraging sense-making and experimentation with different group clinic delivery formats. In addition, we focused on developing adaptive capability in staff so that they could make good judgements on how best to introduce this new model of care, attending to human relationships that would make this complex change feasible (e.g. through goodwill and reciprocity), and, finally, harnessing conflict productively to contribute to positive solutions. 46 Following a complexity-informed approach, our evaluation also produced a nuanced account of how change came about by drawing on different data collection methods and through developing close relationships with the field sites.

By drawing on ecological theories,50,51 we viewed patient self-management and self-care not as activities carried out in isolation, but as activities nested in multiple, proximal and distal contexts (e.g. family, education, employment, social life) that afforded particular opportunities and constraints, especially so in the context of socioeconomic deprivation. This was acknowledged not only in terms of how group clinic interactions attempted to influence self-care, but also in terms of how the evaluation elicited an understanding of how group clinics worked (or not) for young people.

The evaluation delved further into social theory to make sense of the way that group clinics worked and theoretically substantiate an understanding of their change mechanisms. We drew from ideas on practices of solidarity as theorised by Prainsack and Buyx,52 who conceptualise solidarity as enacted, embodied and contextual, based on a view of personhood as relational (i.e. in which people are dependent on and open to their environments). Our analysis draws not only on instances of solidarity at an interpersonal level (i.e. manifestations of willingness to carry costs to assist others with whom a person recognises similarity in at least one relevant respect), but also on instances of solidarity at a group level, through shared commitment to engage together with others in diabetes care, including through a sense of a joint purpose. 52

In contrast to individual appointments, group clinics put relational aspects of self-care to the fore, with the focus on interactions between patients rather than just patient–clinician relationships. This introduced new types of ethics relations between patients and projected new ways of enacting patienthood. We explored what it meant for clinical care to be harnessing experiential knowledge directly through active patient participation in service provision. This included an understanding of how a balance was achieved between biomedical knowledge and practical experiential knowledge in group clinics. Following Pols,53 we examined how embodied patient knowledge becomes transferable and useful in the context of group-based care. 54 We asked the following question: what kinds of knowledge are shaped in group clinics and what are the conditions for doing so? This was supplemented by burden of treatment theory, which focuses on how self-management work and responsibility become delegated to patients and the demands that these place on them. 55

Finally, another theoretical perspective that informed our analysis of group clinic implementation related to articulation work as the hidden, invisible adjustments and alignments necessary to successfully carry out tasks in sociocultural settings. 56 We were specifically influenced by the three different types of articulation work proposed by Allen:56 (1) temporal articulation, with health professionals acting proactively to facilitate care processes or reactively to address unexpected developments; (2) material articulation, referring to how tools and other artefacts become mobilised and embedded in care pathways to maintain their stability; and (3) integrative articulation, which covers relational aspects of receiving input and managing co-ordination and coherence in care, including working with contradictions.

National context

Existing use of group clinics in the NHS

To investigate the existing and potential use of group clinics in diabetes management and treatment, a scoping survey was set up for interested health-care professionals in May 2017. An online questionnaire tool was disseminated to clinical networks and professionals via e-mail and social media.

National Diabetes Audit

The NDA is a large audit managed by NHS Digital. It contains individual- and service-level data on diabetes care processes and outcomes from NHS trusts in England, benchmarked against quality standards (e.g. guidance from NICE). 57 We planned to use NDA data to provide a national context to our research and make unit-level comparisons with our research sites. We used the standard NDA audit reporting of eight routine care processes [HbA1c levels, blood pressure (BP), cholesterol, renal function, urinary albumin, foot examination, body mass index (BMI) and smoking review, recorded in the previous year] and three treatment targets (HbA1c levels of ≤ 48 mmol/mol, BP of ≤ 140/80 mmHg and total cholesterol of ≤ 4 mmol/l in the previous year).

As planned, an application was submitted to the NHS Digital Data Access Request service on 22 May 2017 for service-level data on patients aged 16–25 years in the NDA. However, there were a number of changes to the process for accessing NDA data over the study period, which caused a long delay in receiving these data. Our data application (DARS-NIC-228637-P6N0L) was not approved until 14 August 2019, and at this point we were given access to 2016/17 and 2017/18 data.

During the course of this application, a number of unexpected issues arose. First, it became apparent that we would not be able to obtain unit-level data disaggregated by our research sites to compare with data from other units or national-level data. This is because the NDA is designed predominantly for analysis by general practices and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) rather than hospital services. In addition, data from all patients at Newham University Hospital (NUH) (a group clinic site) and Mile End Hospital (MEH) (a control site) were aggregated and reported by the overseeing NHS trust provider [Barts Health NHS Trust (BH)] in 2017/18. Data were not available from Central Middlesex Hospital (CMH), which is part of the larger London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust. Second, the data extraction process changed to a new system in 2017/18 and we were advised that national comparison would not be possible between 2016/17 and 2017/18. Finally, we were given access only to data with small numbers suppressed. For this reason, statistical analysis of unit-level data was often inappropriate owing to the relatively small sample size.

Within these limitations, we had to change our intended aim of using NDA data to make unit-level comparisons between our group clinic sites and national data, and instead we used the data to make more general descriptive comparisons, as follows:

-

describe sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of young people (aged 16–25 years) under the care of adult diabetes services in England

-

study performance on the three treatment targets and eight care processes for young people (aged 16–25 years) under the care of adult diabetes services in England

-

compare descriptive characteristics of young people (aged 16–25 years) at our research sites with young people and older people (> 26 years) nationally.

We studied NDA data from England cross-sectionally from 2017/18 audit submissions. Data were aggregated by type of diabetes; however, owing to small numbers, rare types of diabetes defined by NDA as ‘other’ (e.g. cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and monogenic diabetes) were included with the T2D data. The aggregation of rare types of diabetes with T2D is unlikely to distort the findings because they are a small fraction of the whole, especially outside tertiary specialist centres (which were not included in our research sites). We obtained national data (from all England sites submitting to the NDA) as well as data from BH (which included our group clinic site NUH and our control site MEH, in addition to two other clinical services). NDA data were not available from CMH. We made descriptive comparisons between young adults (aged 16–25 years) at our research sites and national data on the same age group, as well as people aged ≥ 26 years.

Setting

We included four research sites based at clinical services delivering young adult diabetes care (Table 1). These included two sites (NUH and CMH) that would deliver group clinics, and two sites [MEH and Whittington Hospital (WH)] that would act as comparator (control) sites.

| Characteristic | Group clinic sites | Control sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUH | CMH | MEH | WH | |

| Setting | ||||

| Borough | London Borough of Newham | London Borough of Brent | London Borough of Tower Hamlets | London Boroughs of Islington and Haringey |

| Ethnic minorities (%) | 72 | 65 | 69 | 32 and 38, respectively |

| Childhood poverty rate (%) | 52 | 43 | 57 | 47 and 40, respectively |

| Clinic | ||||

| Approximate size of the young adult clinic | 200 young adults aged 16–25 years | 75 young adults aged 16–25 years | 150 young adults aged 16–25 years | |

| Percentage of young adults with T2D | ≈ 30 | ≈ 15 | ≈ 15 | ≈ 15 |

| Clinic organisation | Monthly multidisciplinary clinic and weekly nurse clinic with virtual option and mobile telephone access | Multidisciplinary clinic twice per month, with daily walk-in clinics and mobile telephone access to a named diabetes specialist nurse | Bimonthly multidisciplinary clinic. Diabetes specialist nurse input offered as required by telephone/e-mail | Multidisciplinary clinic runs twice per month and incorporates transition clinic. Diabetes specialist nurse is available daily |

| Staffing | Consultant diabetologist, diabetes specialist nurse, dietitian, psychologist and youth worker. Close work with the paediatric team post transition | Consultant diabetologist, diabetes specialist nurse, dietitian, with input from a psychologist as required | Consultant diabetologist, diabetes specialist nurse, dietitian, psychologist | Consultant diabetologists from both adult and paediatric services and a diabetes specialist nurse. Dietitians and a psychologist contribute to the clinic when available |

| Other notable features | Recent service improvement work, e.g. offering peer support groups | Recent service improvements including delivery of a new structured education programme (TEAM T1) tailored specifically for young adults | Peer support offered to type 1 patients, but not specific to young adults | |

Research participants

We recruited young adults (aged 16–25 years) living with diabetes (of any type) and receiving care at the four research sites, with the aim of recruiting 80–100 participants across all sites. There were no exclusion criteria. Young adults recruited at the ‘group clinic sites’ were invited to join group clinics co-designed and implemented during the course of this research. Young adults recruited at ‘control sites’ were involved in data collection only.

When the study was designed, we did not anticipate that we would invite all young adults (if eligible) under each service to join the study. However, after observing the high patient turnover in the clinics and low attendance rates, we revised this plan and instead attempted to recruit all young adults under each service.

Potential participants were identified by usual-care teams, and were approached by the research team (which included usual-care team members), and were given invitation letters and patient information sheets. Informed consent was then sought from interested individuals. An example of all patient-facing documents (i.e. invitation letter, patient information sheet and consent form) is given in Report Supplementary Material 1. The research was given a branding and logo and named ‘Together Study’, which was used across all patient-facing documents.

Co-design

Methodological approach

Our research drew on key theoretical and practical approaches to participatory research that allow researchers, practitioners and service users to learn together for the benefit of service redesign. 58,59 The group clinic interventions were co-designed using a participatory approach to ensure cultural, developmental and practical relevance; enhance recruitment and retention; and attempt to instigate system change and support sustainability. 59 Co-design focuses on improving patient and staff experiences, with equal importance being given to each perspective. Participants in co-design, whether patients, staff or other stakeholders,60 are seen as being ‘expert through experience’, and this experience is utilised in co-design to identify opportunities for improvement and adaptations to service design, focused on the functionality (usability) for patients and staff. In co-design approaches, patients and staff work alongside each other to identify problems that can be practically overcome and to develop a jointly negotiated outcome. Co-design with young people may require special facilitation skills and adaptation to be developmentally and age appropriate. The role of the facilitator is key in building trust,61 but there are also considerations around the special challenges of engaging young people to take part and in ensuring informed consent.

We used The King’s Fund Experience-based Co-design Toolkit. 31,61–63 This approach was chosen because research64 suggests that co-designed services can lead to service improvement. The EBCD process provides a template for co-designing service development, drawing on the expertise of patients and staff, with regular review and iteration. EBCD gives a detailed insight into the experiences of all participants, including both patients and staff. When EBCD is conducted, patients and staff work separately at first and are then brought together for joint work. This careful approach supports participation from patients and staff (including wider stakeholders), in prioritising aspects of existing care to build on, as well as areas for improvement and change.

We planned a co-design process that would evolve and adapt as the project developed, and would fit around availability of participants, practical constraints and hospital procedures. Previous work65 indicates that there are particular challenges of engaging young people in co-production work, especially if they are also coping with a long-term condition as well as the day-to-day challenges of education and/or work.

We made adaptations to the full EBCD process, which ordinarily includes the production of a series of films that help to share perspectives between the groups. We omitted this step because it was decided that this aspect would be too time-consuming and might be a disincentive to young adults and staff engaging with the process. Instead of filming, we relied on audio-recording and verbal feedback at meetings. These changes are consistent with reports from other users and researchers of co-design who have also streamlined these EBCD processes. 64

Co-design processes

We undertook co-design in two phases.

Phase 1

In year 1, co-design was used to develop and build the new group clinic-based model of care and involved the following:

-

Group and individual sessions – group co-design sessions were formed for young people and staff/stakeholders separately, and were complemented by additional one-to-one interviews.

-

Analysis of the main themes arising from the interviews.

-

A joint patient and staff/stakeholder event to bring perspectives together.

-

Further analysis of emerging themes.

-

Follow-up interviews with additional participants as necessary.

-

Feedback to participants.

Phase 2

In year 2, the second phase of co-design supported iterative development of the group clinic model, refining its design and delivery after the clinics had already been implemented for 1 year. This involved the following:

-

Group sessions – further group sessions involving both patients and staff took place across both research sites.

-

Individual interviews with both staff and patients at both research sites.

Continuous co-design processes

Ongoing co-design was built in alongside the implementation of the group clinics, using discussion and feedback after each session and facilitated by the clinician and researcher in residence. This supported wider participation from young adults beyond the discrete co-design sessions outlined above, allowing iterative adaptation.

Consent/information procedures

Patient participants for co-design were recruited from the clinical settings in which we planned to deliver group clinics. In addition, staff and stakeholder participants were also selected as representatives from organisations (e.g. CCGs) with responsibility for the care of young adults with diabetes. Formal informed consent procedures were used for all co-design participants.

Conducting the co-design sessions

Co-design workshops took place in community and clinical facilities linked to NUH and CMH. Co-design was led by the Association for Young People’s Health (AYPH) (London, UK), an external and third-sector organisation with particular expertise in participation work with young people and health professionals. The clinical teams delivering diabetes care to young adults at NUH and CMH also contributed to the delivery of the co-design process, as did the research team.

The facilitation of co-design sessions was led by experienced staff from the AYPH. Sessions were audiotaped and transcribed. The following principles and approaches were used:

-

Young people living with diabetes. Each individual was encouraged to tell their own story, recalling their own voice and experiences and communicating their own personal ‘truths’. The facilitator had prepared a workshop of questions and workshop activities to defuse any anxiety or embarrassment and provide a way to encourage sharing. However, the issues raised mainly came from the participants, and discussions followed the line that they wanted to take. Sessions lasted no longer than 2 hours and opened and ended with a ‘check-in’ to raise any emotional anxieties and to ensure that young people left the process in a safe state of mind, feeling supported and listened to. Young people were also given an outline of the next steps in the work and details about how to find further information.

-

Health-care professionals. It was important to allow staff the same freedom as the patients to share their perspective. Participants included a wide range of professionals and stakeholders, including dietitians, specialist nursing staff, a CCG commissioner, representatives from primary care, representatives from the voluntary sector (Diabetes UK, London, UK), consultant diabetologists and reception staff.

-

Joint discussions. To focus and support discussions, all those attending the joint sessions (patients and staff/stakeholders) were asked to prepare in advance three issues to present to the group, instead of collating and sharing issues during the group session. This supported the effective use of the time available and provided a valuable structure for discussions.

Discussion topics introduced in the co-design

We drew on the findings from our realist review to identify the following areas of discussion during co-design:

-

Group composition and continuity. At the time of our study, to our knowledge, there was little certainty in the literature around the ‘ideal’ composition of group clinics, and we considered the possible importance of age-related developmental stages, sex and disease type in the co-design of our group clinic model. We also discussed the possible importance of factors such as independence (e.g. living at home, away at university), time from diagnosis, family circumstances and general life experiences. Our realist review highlighted the importance of continuity within the group (participants and/or staff) to support relationship building, cohesion and the sharing of stories.

-

Role of parents. The realist review identified parents as possible active participants in a group clinic model for young adults, and that their involvement could have both positive and negative effects.

-

Individual versus collective experiences. We identified the need to manage group discussions in such a way that they would support both individual and shared experiences.

-

Content and approach specific to young people. Our review suggested that many young people prioritised fitting in with their peers as more appealing than closely following diabetes self-management advice, and that this challenge was a potentially fruitful area of focus in the group clinics.

-

Logistical considerations. We identified a number of logistical considerations important to the design of group clinics, including the time of day they should be scheduled and the location they should be held in.

-

Clinical aspects. Previous literature44 highlighted a range of strategic considerations relating to the clinical care delivered in group clinics, including whether group clinics should replace existing care appointments or run in parallel to them (i.e. offer additional care), how the group should be led and facilitated and by whom, how frequently they should be held and how the safety of participants could be ensured through setting ground rules.

Evaluation of the group clinic model

Qualitative methods

Embedded research

A ‘researcher in residence’ model was adopted as a practical manifestation of a participatory approach to research and evaluation. The researcher was an integral member of the front-line implementation team, contributed theoretical and practical insights based on research findings, and helped to navigate different bodies of expertise within the study. The embedded researcher worked towards bridging the qualitative and quantitative evaluations, helping to include practitioner and patient views into the design and feeding back early findings to stakeholders. We followed previous experience with how the researcher-in-residence model was applied in a number of different settings. 66

Ethnographic observation

The researcher in residence (CP) worked closely with the clinical teams throughout the project and carried out ethnographic observation in the two hospitals. This primarily included three types of observations, involving different degrees of participation depending on the encounters observed:

-

Group clinics. The researcher was involved in different aspects of the group clinics programme, including planning and setting up, co-ordination between the clinical teams, and de-briefing and discussing ongoing adjustments to the model of care. She carried out ethnographic observation in most group clinics organised in the two hospitals, had informal discussions with patients ahead of the clinic, participated in icebreakers and generally helped with delivery where needed. To support the ongoing co-design of this new model of care, at the end of each clinic the researcher held brief feedback discussions with patients to understand what had worked well and what they thought should change next time (when the researcher was absent this was led by the diabetes specialist nurse or the youth worker). The researcher introduced herself to the group as a researcher from the university interested in finding out how group clinics work for young people, and she worked towards building rapport. Especially with some of the frequent attenders, she managed to build a good relationship and understand people’s experiences not just as a one-off interaction but longitudinally over the course of the group clinics programme. A significant amount of field notes was collected from ethnographic engagement. These notes included information on clinic characteristics, such as session content, context, group dynamics and facilitation style. The majority of group clinics were also audio-recorded with participant consent and transcribed for analysis.

-

Individual appointments. To gain a wider understanding of standard diabetes care and to be able to draw comparisons with group clinics, the researcher also conducted ethnographic observations in 15 individual appointments in young adult clinics. These were sampled to achieve maximum variation between different consultants and nurses in the two hospitals. Some of these appointments were with patients taking part in group clinics, which allowed a broader understanding of their engagement with care as part of different interactions. It was striking how some patients presented themselves differently in the one-to-one appointments and in the group clinics.

-

Other interactions. The qualitative researcher also collected field notes from ethnographic observations in co-ordination meetings; facilitation trainings; and other informal interactions with clinical teams in the context of setting up, managing and delivering group-based care alongside standard clinical practice.

Qualitative interviews

Between February 2018 and October 2019, the researcher in residence carried out 31 semistructured interviews with patients, group facilitators and other clinical and non-clinical staff (see Appendix 1 for further details). Interviews lasted 30–110 minutes and followed a semistructured format (see Appendix 2 for interview guides with indicative questions). One staff participant was interviewed twice to reflect on the development of group-based care over time. Another interview involved two siblings who were interviewed jointly about their experiences living with diabetes and attending group care. Most patient interviews took place in hospital settings or other mutually convenient locations either before or after the group clinics, although five patients preferred to be interviewed on the telephone. Staff interviews were conducted in offices or other hospital settings; two took place on the telephone. Interviews formed only part of the encounters with participants in the context of a broader relationship developed with the qualitative researcher during the project (e.g. through ethnographic observations in clinics or informal discussions during clinic set-up). The purpose of the interviews was, therefore, to continue conversations that had already been taking place over the course of the project and to consolidate some of the learning from patient and staff perspectives. The researcher took contemporaneous field notes to contextualize interactions and encounters with research participants, bringing together data from different formal and informal discussions throughout the 2 years of fieldwork. Most interviews were audio-recorded with consent and professionally transcribed; in two of the telephone interviews it was more practical to keep field notes.

-

Patient interviewees (n = 19). We recruited 19 young people in interviews, nine female and 10 male, who were between 18 and 25 years of age and from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. Four patients had attended 7–10 clinics, nine had attended three to six clinics and six had attended zero to two clinics (one of whom withdrew from the research study after one clinic and another consented but never attended). Most interviewees were living with T1D (of whom two were also using an insulin pump) and two had T2D. This was representative of the broader composition of participants in group clinics, which predominantly included patients with T1D in both hospitals. Interviews addressed experiences of being diagnosed and living with diabetes as a young person; experiences of receiving diabetes care; and experiences of participating in group clinics, including encounters with health professionals and other young people. Guided by clinicians’ knowledge of patients and the relationships with the researcher as part of the ethnographic engagement, we recruited patients with varied clinical background, time since diagnosis and experiences of diabetes care. Despite our efforts, we were only able to recruit one young person who had not attended any of the clinics; most of those who did not engage with group-based care also declined participation in interview.

-

Staff interviewees (n = 11). We recruited three diabetes consultants, three diabetes specialist nurses, one youth worker, one research nurse, one dietitian, one psychologist and one sexual health advisor who delivered sessions and/or supported the group clinic programme. Discussions covered clinicians’ experiences of providing care for young people with diabetes and their views on how diabetes health services could better meet the needs of this population, as well as their experiences of setting up and delivering group-based care in the two hospitals involved. We focused our sampling on clinical and non-clinical staff who had been involved in the group clinic programme (as group facilitators or in other roles) to understand their views and experiences.

Documents

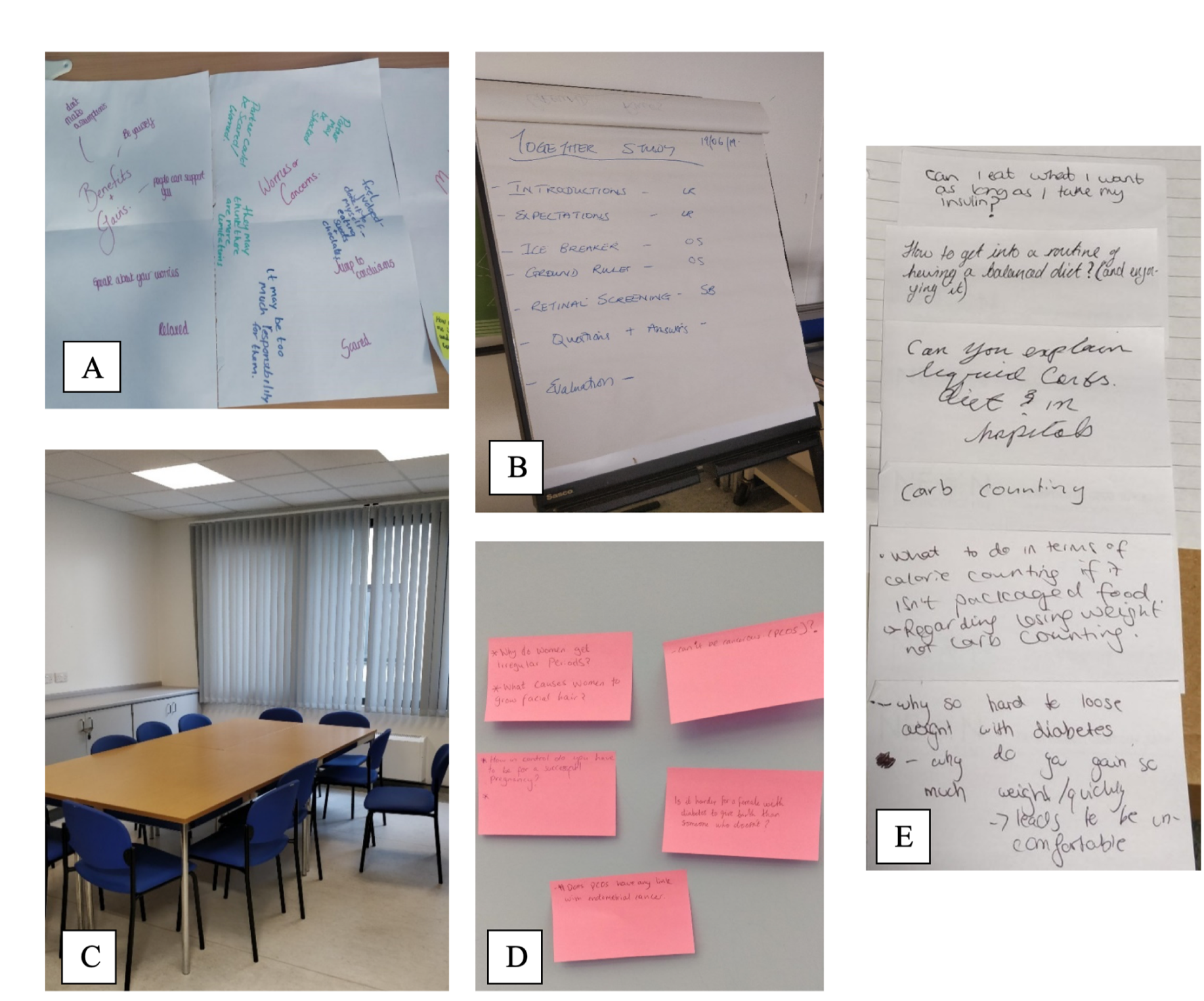

We collected all documentation produced in co-design sessions, project and steering group meetings, facilitation training and other interactions. Other materials collected as part of our ethnographic fieldwork in group clinics included outputs of group activities using flip charts, icebreaker materials, sick-day rules diagrams and other artefacts used in the group context (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Photographs illustrating the group clinic materials and room set-up (photographs A and D from NUH; and B, C and E from CMH).

Qualitative data analysis

Owing to the iterative nature of the research, the researcher in residence carried out analysis in parallel to data collection throughout the project, with emerging findings presented and discussed in team meetings and used to adapt the model of care. The analysis drew on different theoretical lenses (see Theoretical approach), such as complexity approaches in health services research47,49 and frameworks on invisible, hidden work,56,67 as well as burden of treatment and patient work theory,55 solidarity practices52 and critical perspectives on patient expertise. 53 We moved between an inductive and a deductive approach to our analysis, paying attention to emergent themes and using substantive theory as a sensitising device to drive further interrogation of the data. We also drew on the programme theory developed as part of our realist review in earlier stages of the project (see Chapter 2) and refined its different components based on further analysis of our empirical data. We continuously developed the overall narrative emerging from our analysis and iteratively added to the coding framework. A second researcher (AF), with a background in psychology and complex intervention development, was involved in later stages of the analysis of the group clinic transcripts, independently verifying the coding framework and developing consensus on emergent themes. Interim analysis was also driven by pragmatic requirements to inform implementation, as well as to ensure that no safety issues were raised by participants.

NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents were used to support management and analysis of qualitative data, which included anonymised interview and group clinic transcripts, ethnographic field notes, e-mail communications and other documents. An example NVivo analysis is presented in Appendix 3.

Quantitative methods

Data collection

Members of the research team at each site (both group clinic and control sites) collected sociodemographic and questionnaire data through face-to-face or telephone interviews with recruited study participants. We were unable to collect data on participants who did not wish to be recruited, but collated brief information on their reasons behind that decision. Clinical data were accessed through each site’s clinical record system. Data were then collated on a standard template [see the NIHR project web page; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/NKCR8246) using the study number of each participant as the only unique identifier. No identifiable information was recorded on this template.

Baseline data were collected at entry to the study. Follow-up data were collected approximately 1 year later (a window of 9–15 months was used to allow co-ordination with clinic visits, university holidays and other practical considerations).

The following data were collected at baseline:

-

Sociodemographic characteristics – age, sex, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintile, ethnicity, English as first language (yes/no), education and employment status (education/employment, both/neither).

-

Clinical characteristics (including health-care activity) – type of diabetes (1/2/other), most recent HbA1C mmol/mol level, reported frequency of blood glucose monitoring per day, age at diagnosis, use of technology within the last year and previous attendance at any group education for diabetes. In addition, we captured the percentages of planned diabetes appointments, emergency department (ED) attendances (diabetes related), inpatient admissions (diabetes related) and primary care consultations, all within the previous year.

-

Patient-reported instruments – the Problem Areas In Diabetes Score and Patient Enablement Instrument were used. 68,69 Relevant information about these instruments is presented in Table 2; for example questionnaires see the NIHR project web page (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/NKCR8246).

At the follow-up visit, all of these variables were again collected and recorded in the study template, with the exception of age, sex, IMD quintile, ethnicity, first language being English and type of diabetes, for which duplicate information was not necessary.

Quantitative data analysis

Four main sets of quantitative analyses were performed to compare the following:

-

baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all participants, with comparisons made among sites, and among those at group clinic sites who did and did not choose to attend group clinics

-

trajectories of participants who did and did not choose to attend group clinics (‘difference in difference’ analysis)

-

differences in trajectories of participants attending group clinics according to the number of group clinics attended (‘dose response’ analysis).

All groups were compared using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables with normal distribution. Trajectories were analysed by subtracting the follow-up from the baseline values to derive a new set of variables that reflected change over time.

In addition, linear regression models were used to investigate the association between clinic attendance and trajectories among participants at group clinic sites. Initially, the independent variable was entered as a binary variable (attended any vs. attended no group clinics) and each derived trajectory variable was entered in turn as the dependent variable. These models were then repeated, adjusting for the participants’ diabetes type, age, sex, ethnicity, age at diagnosis and deprivation. Unadjusted and adjusted models were then performed in which attendance was entered as a categorical variable (attended zero, one, two or three or more clinics), with zero clinics used as the reference category.

p-values of > 0.05 were not considered to be significant. Values below this level are highlighted but are interpreted with caution. It is recognised that we are making multiple comparisons and some values of < 0.05 owing to chance would be expected.

Quantitative methods: health economics

An NHS perspective was adopted, spanning primary and secondary health-care sectors. Economic evaluation methods followed the Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal 2013,70 which provides guidance on how to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of new and established technologies in the NHS.

Microcosting of the group clinic intervention

Microcosting was used as a means to estimate the economic cost of the group clinic intervention to the health system (the NHS) using Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) 2018 costs. 71,72 Microcosting is particularly applied to the costing of new interventions; including the large variability across providers of the group clinics for young people with diabetes we also included a bottom-up construction of the costs associated with co-design and delivering the intervention.

The cost of co-design included time spent preparing workshop materials, recruiting participants, running and recording the workshops, transcribing records and analysing transcripts.

The clinic running costs included staff costs of running the clinics, preparing the room and materials, arranging appointments, chasing non-attenders, booking the venue, arranging refreshments and making patient notes. Data on resources associated with designing and delivering clinics were collected prospectively using purposely designed questionnaires; staff completing these questionnaires were encouraged to report all staff work and time commitments, including that of ‘hidden’ work. Staff time was costed using the NHS pay scales 2018–19. 73

Cost of intervention per clinic and per participant

The estimated cost of the intervention was based on the number of clinics and the number of patients who attended the clinics using PSSRU costs. 72 The average cost per participant for each centre was derived by dividing the total cost of running clinics by the number of attenders (per-protocol analysis). Sensitivity analyses were conducted, varying the number of clinics and the number of participants for both CMH and NUH.

Use of health-care resources

Data on the use of primary and secondary health-care services (usual care) for a 12-month pre-intervention period was extracted from clinical records. These data included the number of contacts with a diabetologist, diabetes specialist nurse, dietitian or psychologist (planned and attended); unplanned contacts with a GP, practice nurse or diabetes specialist nurse; accident and emergency (A&E) attendances; and hospital admissions. Individual-level resource use data were combined with unit costs to calculate the total cost of health services use for each participant. Primary care consultations and referrals to community care were costed using the National Schedule of Reference Costs 2017–18. 74 The list of unit costs used for costing health care services are included (see Appendix 4). Data analyses were conducted in Microsoft Excel® 2016.

Summary of data sources

A summary of the data sources used in this project is given in Table 2.

| Characteristic | Scoping | Co-design data | Qualitative data | Quantitative data | Health economic data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | National | Group clinic sitesa | Group clinic sitesa | Group clinic sitesa and control sitesb | Group clinic sitesa and control sitesb |

| Data source | Survey and NDA (2017–18) | Group co-design session and individual interviews | Individual interviews, ethnographic observation and documentary evidence | Questionnaires (including Patient Enablement Instrument and Problem Areas in Diabetes) and clinical record data | Health economics usual-care costing template completed by usual-care team |

| Purpose | Contextual data on existing use of group clinics and care quality for young adults with diabetes in the NHS | Design and implementation of the group clinic model | Evaluation of the group clinic model. Experience of those engaging with it, and its organisational impact | Descriptive data to inform qualitative analysis and help design of future at-scale research | Estimate use of resources and cost of the group clinics |

| Analysis | Descriptive | Descriptive | Qualitative (thematic) analysis | Quantitative (thematic) analysis | Microcosting |

Project management and governance

The study received ethics approval from the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI) on 23 February 2017 (reference 17/NI/0019) and is registered on the UK National Research Register as ISRCTN 27989430.

Standard rules applied for data security, confidentiality and information governance. Informed consent was sought for ethnographic observations during group clinics and interviews, and for accessing routinely collected NHS data on participants. Confidentiality and safety among group clinic participants was a priority, and all participants who attended were asked to agree to a code of conduct and confidentiality to ensure that all clinic discussions were kept within the group.

The study was led by Sarah Finer, with co-leadership from Dougal Hargreaves. Owing to Sarah Finer taking maternity leave, Trish Greenhalgh temporarily led the study, with Dougal Hargreaves, from April 2019 to January 2020. The study was delivered and managed by a core working group (SF, DH, CP, SV, MK, AH and GC) and supported by 6-monthly independent steering group meetings, along with ad hoc communication with steering group members when necessary. Monthly research management meetings were held throughout the lifetime of the project, which focused on progress towards short- and long-term milestones, administrative tasks and general project management. These were attended by the core team identified above and often supported by others, such as clinical teams, depending on the focus of the meeting. Action points and minutes circulated after all meetings enabled team members to keep track of study progress and ensured steady progression towards milestones and early identification of potential challenges.

A routine internal audit was carried out by the study sponsor on 10 September 2018. No critical or major findings were identified, and following action of nine minor findings the audit was closed and a certificate was issued on 5 December 2018.

Project steering group

Project steering group meetings were held every 6 months, starting on 6 November 2017 and finishing with a final wrap-up meeting on 20 April 2020. Group members included representatives from Diabetes UK and their young adult panel, along with expert lay people, clinicians, external academics and team members. Support from this group with a wide range of experiences and perspectives was invaluable to the development of the work, and the external, critical viewpoint has been very helpful in raising and highlighting areas that have benefited from further development. In particular, the group has helped the project to maintain a wide perspective so that findings and dissemination could be accessible to a variety of audiences, including commissioners, stakeholders and service users, as well as an academic audience.

Dissemination and patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI), and wider dissemination to the academic and practitioner community, were both built into our research from the outset and followed INVOLVE guidance. 75 We built on research priorities identified through the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnerships for type 1 and 2 diabetes,76,77 which identified the need to research approaches to the patient-centred management and delivery of social support for people living with diabetes. Our PPI approach was also built on the foundations set by the participatory co-design of the group clinic model.

Key patient and public involvement elements

The main planned elements of PPI in our research were led by our voluntary sector partner, the AYPH, in partnership with the main project delivery team and academic partners.

The overall intention of the PPI and dissemination activities was to share learning about the challenges and achievements of the group clinic model as it was implemented across the sites, so that others could understand and, potentially, replicate the model. As the project unfolded, dissemination was focused on sharing the results of the realist review, the co-designed new care model, its evaluation and messages for generalising findings to a wider context. We also focused on disseminating specific outputs related to co-design, so that others could learn from our successes and failures and apply these to their own service improvement work.

Patient and public involvement processes can bring challenges relating to the relationships of power between patients and public services,62 and we were mindful of this in our PPI and dissemination activities, for example involving a young person in the design and delivery of stakeholder events.

Patient and public involvement methodology

The main methods employed for involving patients and the public, local and national stakeholders and the wider dissemination list included the following:

-

Co-design. A co-design approach to developing the group clinic model supported involvement from young people, clinicians, commissioners and others from the outset.

-

Management of the research. An external steering/advisory group was convened and worked alongside the research team throughout the duration of the research, and included a patient representative from Diabetes UK with lived experience of T1D as a young adult.

-

Developing participant information resources. Patient representatives and stakeholders were involved in reviewing all patient-facing documents (e.g. information sheets and consent forms).

-

Dissemination of research findings. We planned to produce a range of events and outputs, including stakeholder engagement events, briefing papers and summaries, and these are discussed in Chapter 9. Our intended target audiences included young adults with diabetes (‘patients’) and stakeholders with roles in service use, service delivery, policy-making and health service design. In addition to this, we used social media engagement though our website and project-specific Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) account.

Dissemination networks

We built wide networks for dissemination, drawing on the contacts of the main project partners. This included the following:

-

local clinical and academic networks –

-

institution based: Queen Mary University of London, University College London, University of East London, BH, Newham CCG and Newham Borough Council

-

Local Transforming Services Together Programme

-

NHS England London Region Children and Young People’s Programme

-

Improvement Science London

-

NIHR Clinical Research Networks North Thames.

-

-

clinical and patient networks –

-

Diabetes UK.

-

-

strategic and national networks –

-

national children and young adult working groups chaired by the national leads for children and teenage and young adults

-

royal colleges, including the Royal Colleges of Physicians, General Practice and Paediatrics and Child Health.

-

-

national policy forums –

Chapter 4 National context

Scoping survey

We had 42 respondents to our survey from across the UK (including Scotland and Northern Ireland); these included hospital diabetologists (56%), dietitians (33%), diabetes specialist nurses (8%) and diabetes educators (3%). There were no respondents from paediatric services.

Although the majority of respondents reported delivering group-based education programmes (e.g. DAFNE), only 16 out of 42 respondents reported that actual group clinics or shared medical appointments were offered in their services, and these were delivered to young adults in only half of these instances. Group clinics were predominantly delivered by specialist nurses and dietitians, rarely doctors, and they were mostly situated in hospital. The content of existing group clinics was predominantly lifestyle management and peer support.

The majority view towards group clinics was positive, and reasons given were that they would offer a means to provide more peer support, be a more efficient use of resources and potentially provide more holistic care. However, 8 out of 42 respondents felt that group clinics were not a good idea, listing lack of proven benefit, lack of suitable staff or environment and potential detriment to patient–professional relationship as reasons.

The sample size of this scoping survey is small and, therefore, its findings are limited. However, the illustrative findings give some indication that adopting group clinics might be acceptable to NHS clinicians, given that the scene for group-based processes is already set by group education.

National Diabetes Audit data

Young people with diabetes at two study sites, Barts Health NHS Trust and the Whittington Health NHS Trusts, were more ethnically diverse (higher proportion of people from ethnic minority groups) than both older patients at the same trust and young people nationally. This was seen particularly in young adults with T2D, with 75.0% at BH and 100% at Whittington Hospital being from ethnic minority groups, compared with 41.4% and 33.3% with T1D, respectively (see Table 3). Nationally, young adults with T2D were predominantly female (males represented 25.8% of the total) and, compared with those with T1D, were more likely to come from an ethnic minority group (20.3% vs. 11.2%; Table 3).

| Data source | Age band (years) | Type of diabetesa | n (%) | Male (%) | Whiteb (%) | Ethnic minority groupb (%) | Ethnicity not knownb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BH | 16–25 | T1D | 145 (78) | 41.4 | 55.2 | 41.4 | 3.4 |

| T2_other | 40 (22) | 37.5 | 12.5 | 75.0 | 0.0 | ||

| All, N | 185 | 40.5 | 45.9 | 48.6 | 2.7 | ||

| ≥ 26 | T1D | 625 (49) | 53.6 | 75.2 | 24.8 | 0.8 | |

| T2_other | 640 (51) | 56.3 | 33.6 | 66.4 | 0.8 | ||

| All, N | 1265 | 54.9 | 54.2 | 45.8 | 0.8 | ||

| Whittington Trust | 16–25 | T1D | 90 (86) | 61.1 | 55.6 | 33.3 | 11.1 |

| T2_other | 15 (14) | 33.3 | 33.3 | 100.0 | 33.3 | ||

| All, N | 105 | 57.1 | 52.4 | 42.9 | 14.3 | ||

| ≥ 26 | T1D | 510 (31) | 55.9 | 81.4 | 16.7 | 2.0 | |

| T2_other | 1110 (69) | 54.1 | 44.1 | 55.0 | 1.4 | ||

| All, N | 1620 | 54.6 | 55.9 | 42.9 | 1.5 | ||

| National data | 16–25 | T1D | 14,020 (81) | 52.0 | 84.4 | 11.2 | 4.4 |

| T2_other | 3320 (19) | 25.8 | 65.4 | 20.3 | 14.5 | ||

| All, N | 17,340 | 47.0 | 80.7 | 13.0 | 6.3 | ||

| ≥ 26 | T1D | 67,885 (28) | 53.3 | 89.2 | 7.8 | 3.0 | |

| T2_other | 172,685 (72) | 53.0 | 73.2 | 21.0 | 5.8 | ||

| All, N | 240,570 | 53.1 | 77.7 | 17.3 | 5.0 |

Young adults with diabetes (of all types) were less likely than patients aged ≥ 26 years to receive all eight care process checks (i.e. assessment of HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, serum creatinine, urine albumin, foot surveillance, body mass index and smoking status) at all sites and nationally. These differences were not apparent in the small number of young adults with T2D at Whittington Hospital (Table 4). Nationally, there was a striking age difference in the proportion of people with T2D receiving all eight care processes, with 19.1% of 16- to 25-year-olds versus 52.2% of those aged ≥ 26 years receiving all recommended checks. Irrespective of age, measurement of urinary albumin was the least likely of all of the eight care proceses to be carried out among patients with diabetes, and it has been hypothesised that this is because of the practical difficulties of giving urine samples, as well as the fact that it is not promoted in the NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework. 80

| Data source | Age band (years) | Type of diabetesa | n (%) | All eight care processes received (%) | All three treatment targets met (%) | Structured education offered (%) | Structured education attended (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BH | 16–25 | T1D | 145 (78) | 31.0 | 22.2 | 58.6 | 13.8 |

| T2_other | 40 (22) | 50.0 | 20.0 | 62.5 | 25.0 | ||

| All, N | 185 | 35.1 | 21.7 | 59.5 | 16.2 | ||

| ≥ 26 | T1D | 625 (49) | 35.2 | 22.2 | 71.2 | 17.6 | |

| T2_other | 640 (51) | 58.6 | 16.1 | 74.2 | 23.4 | ||

| All, N | 1265 | 47.0 | 18.9 | 72.7 | 20.6 | ||

| Whittington Hospital | 16–25 | T1D | 90 (86) | 44.4 | 28.6 | 27.8 | 5.6 |

| T2_other | 15 (14) | 66.7 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 0.0 | ||

| All, N | 105 | 47.6 | 29.4 | 33.3 | 4.8 | ||

| ≥ 26 | T1D | 510 (31) | 46.1 | 27.4 | 24.5 | 2.0 | |

| T2_other | 1110 (69) | 54.5 | 20.6 | 25.2 | 2.7 | ||

| All, N | 1620 | 51.9 | 22.7 | 25.0 | 2.5 | ||

| National data | 16–25 | T1D | 14,020 (81) | 39.1 | 15.8 | 32.5 | 10.1 |

| T2_other | 3320 (19) | 19.1 | 25.1 | 26.5 | 2.7 | ||

| All, N | 17,340 | 35.3 | 16.8 | 31.3 | 8.7 | ||

| ≥ 26 | T1D | 67,885 (28) | 52.9 | 16.5 | 30.4 | 15.1 | |

| T2_other | 172,685 (72) | 52.2 | 27.1 | 34.7 | 7.1 | ||

| All, N | 240,570 | 52.4 | 23.9 | 33.5 | 9.4 |

The proportion of people living with diabetes reaching all three treatment targets (i.e. HbA1c levels of ≤ 48 mmol/mol, blood pressure of < 140/80 mmHg and total cholesterol levels of< 4 mmol/l) was low across all groups: nationally only 16.8% of young adults with diabetes met these targets, compared with 23.9% of people aged ≥ 26 years (see Table 4). Attainment of all three treatment targets was lower for young adults with T2D receiving care at Barts Health Trust than for those receiving care at Whittington Hospital and nationally (20.0%, 33.3% and 25.1%, respectively). Data per individual treatment targets are presented in Appendix 5. In national and local figures, the differences in attainment of treatment targets varied by type of diabetes, with young adults with T2D more likely to attain HbA1c targets than those in any other group, probably because they were early in the course of a progressive disease. Only 6.2% of young adults with T1D in England attained the HbA1c target. Attainment of the total cholesterol target was lower for all young adults in England (16.8%) than for older adults (23.9%), with comparable effects seen in local data.

The proportion of people living with diabetes attending structured education was also low across all groups (see Table 4). Nationally, only 8.7% of 16- to 25-year-olds and 9.4% of those aged ≥ 26 years attended structured education, with rates slightly higher for people with T1D than for people with T2D. This reflects, in part, the fact that structured education is offered to only about one-third of people living with diabetes. Compared with national data, offers of and attendance at structured education was higher at BH for all people with diabetes, irrespective of age and type of diabetes (e.g. 59.5% of young adults had been offered structured education, but only 16.2% of young adults had received it). The low conversion (approximately 30%) from an offer of structured education to uptake of it was seen across all groups; this is an important area to address further.

These data indicate significant areas for improvement in delivering diabetes care, and disproportionately poor uptake of care process checks and attainment of treatment targets in young adults compared with older adults living with diabetes. We also identify variation between two hospitals delivering diabetes care and national data that could result from differences in care quality or patient factors. The low uptake of care process checks and attainment of treatment targets is likely to translate to higher future risk of diabetes complications and poor outcomes.

Chapter 5 The group clinic model: co-design and delivery

Co-design: phase 1

Attendance at phase 1 co-design sessions

The composition of the co-design sessions that took place were as follows:

-

Patient sessions. Six sessions were planned and four took place, and these comprised a single young adult with diabetes with a facilitator. The young adults comprised two females aged 18 years, one female aged 20 years and one male aged 24 years, and between them represented people living with T1D and T2D of varying duration.

-

Staff sessions. Two staff sessions took place at NUH, one with 6 and one with 10 participants. Participants comprised a range of professionals and stakeholders, including dietitians, specialist nursing staff, a CCG commissioner, representatives from primary care, representatives from the voluntary sector (Diabetes UK), consultant diabetologists and reception staff.

-