Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/05/96. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The final report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Conroy et al. This work was produced by Conroy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Conroy et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Sections of the scientific summary have been reproduced from Conroy 20191 under licence CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Urgent and emergency care (UEC) is a major international issue. Older people with UEC needs and living with frailty are especially vulnerable to harms and delays that can arise in this system and the first hours have a powerful influence over the remaining UEC episode. 2–5 For example, the failure to identify delirium (new-onset confusion, often with a significant underlying medical cause) can lead to reduced attention, poor oral intake and reduced mobility, resulting in harms from the very first hours of the patient journey (e.g. dehydration, pressure sores). 6,7

It is not only the admitted population of older people who are at risk; those discharged from emergency departments (EDs) are also at risk of significant functional decline in the months following their attendance. 8,9 There is a need to improve the management of both patient groups to optimise their time in the UEC system, reduce complications and avoid unnecessary investigations and admission to hospital. This might involve a move away from ‘one problem, one solution’ approaches, which historically typifies emergency care, towards a more nuanced approach that takes account of multiple comorbidities, initial evaluations of which appear to show some promise in emergency care settings.

Demand for UEC is rising annually, especially in older people, who form one-fifth of attendees at EDs. 10 Analysis of 1.3 million attendances at 18 EDs in Yorkshire and Humber (YH) has shown that two-thirds of patients over the age of 75 years arrive by ambulance, patients over 75 years spend significantly longer in the ED and are referred for admission over half of the time. 11 We also found significant variation in admission rates by hospital studied (18–73%) in older people, which could not be fully explained by case mix. Understanding the range of variation in practice that leads to different admission rates and how this can be reduced would be timely and beneficial to health services.

The implementation of novel approaches to caring for older people living with frailty needs to be seen within the context of the complex array of different services models offered for UEC. It is therefore important that any new approaches are based on robust research evidence and their implementation is evaluated in terms of clinical and cost-effectiveness as well as understanding the impact for organisations and patients themselves. Such assessment needs to make the most of available data flows and modern approaches to understanding how patients move through care systems and the impact on effectiveness and efficiency. This proposal made use of existing data, modelling, qualitative enquiry and patient participation to describe the essential elements of a complex intervention, in keeping with Medical Research Council guidance. 12

Aims, objectives and research questions

We aimed to identify promising care models and produce guidance on implementation that addresses the needs of older people accessing UEC services. We conducted an evidence synthesis, stakeholder interviews, analysed patient pathways and outcomes in health-care data reflecting a range of models of care and used the information to conduct system dynamics modelling of the implications of changing pathways.

Work package 1: identifying best practice

-

WP1.1 – review of reviews of UEC interventions for older people, their outcomes and costs and any implementation factors identified

-

Research question (RQ) 1.1.1 – what is the evidence base for UEC interventions for older people, the outcomes of these interventions and the costs associated with these interventions?

-

RQ 1.1.2 – what factors have been described in the evidence base to date that influence implementation of UEC interventions for older people?

-

Output 1.1 – a taxonomy of UEC interventions with outcome effect sizes (where available) and descriptors of costs and implementation factors.

-

-

WP1.2 – patient and carer preferences.

-

RQ 1.2.1 – what elements of care are most important to older people and their carers with UEC needs?

-

RQ 1.2.2 – how could UEC interventions be configured to best meet the needs of older people?

-

Output 1.2 – description of patient and carer priorities for UEC.

-

-

WP1.3 – staff perspectives.

-

RQ 1.3.1 – what other interventions, not yet reported in the literature, offer promising models for improving outcomes for older people in the UEC pathway?

-

Output 1.3 – staff perspectives on the ‘state of the art’ and factors that will facilitate implementation.

-

Work package 2: qualitative study of delivery of exemplar urgent and emergency care pathways

-

RQ 2.1 – what aspects of interventions, context and approaches to implementation facilitate and hinder delivery of UEC interventions for older people?

-

Output 2.1 – context-, implementation- and intervention-related influences on delivery of interventions for older people in UEC settings.

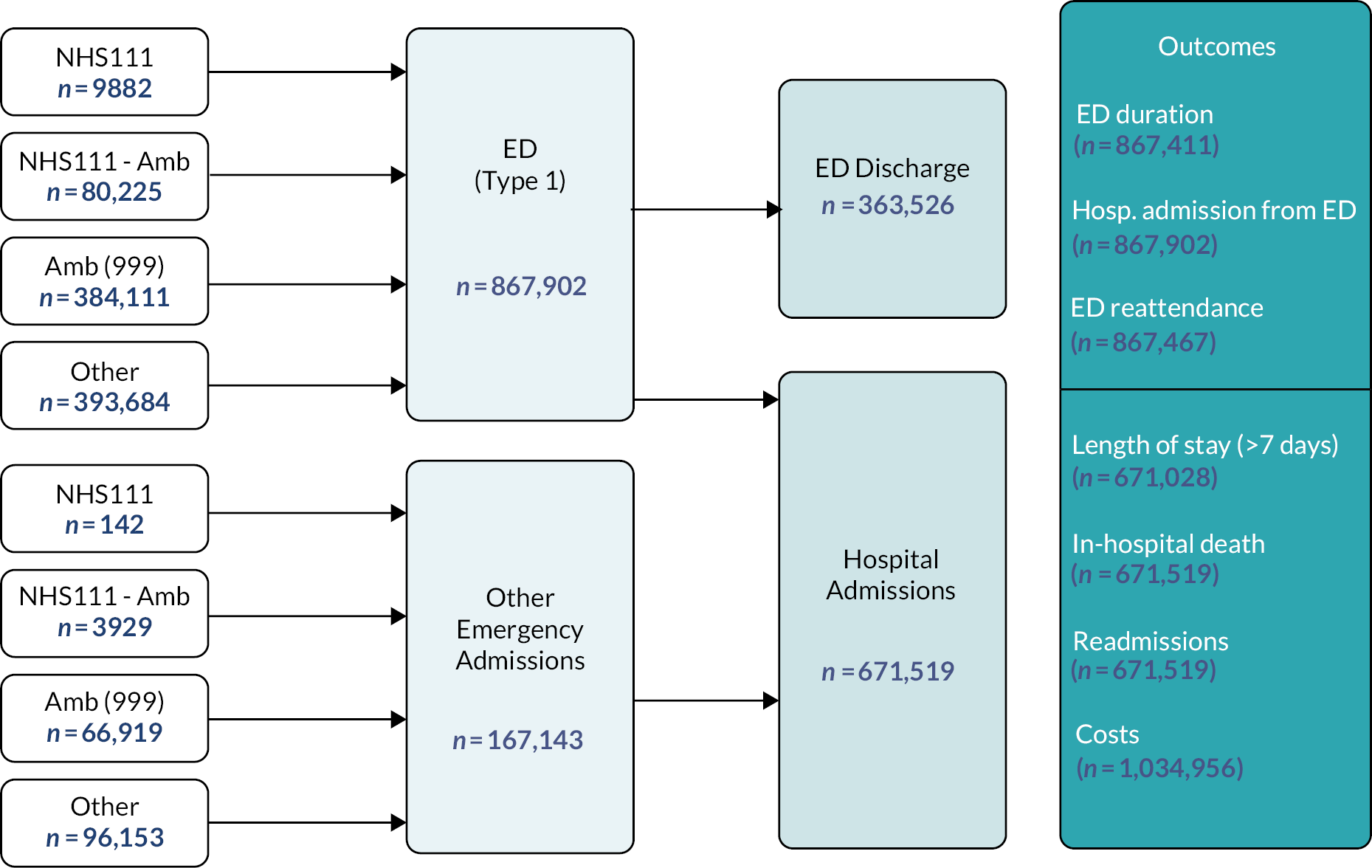

Work package 3: routine patient-level data analysis

-

RQ 3.1 – are some UEC pathways associated with better patient outcomes than others?

-

RQ 3.2 – have UEC pathways improved or got worse over time?

-

RQ 3.3 – over and above the UEC pathway, what patient characteristics, demand and supply factors explain differences in outcomes from place to place and over time?

-

RQ 3.4 – what is the relationship between outcomes and the costs of the UEC pathway and are some pathways more cost-effective than others?

-

Output 3.1 – estimates of what drives better outcomes and lower costs for older people with UEC needs.

Work package 4: improving emergency care pathways

-

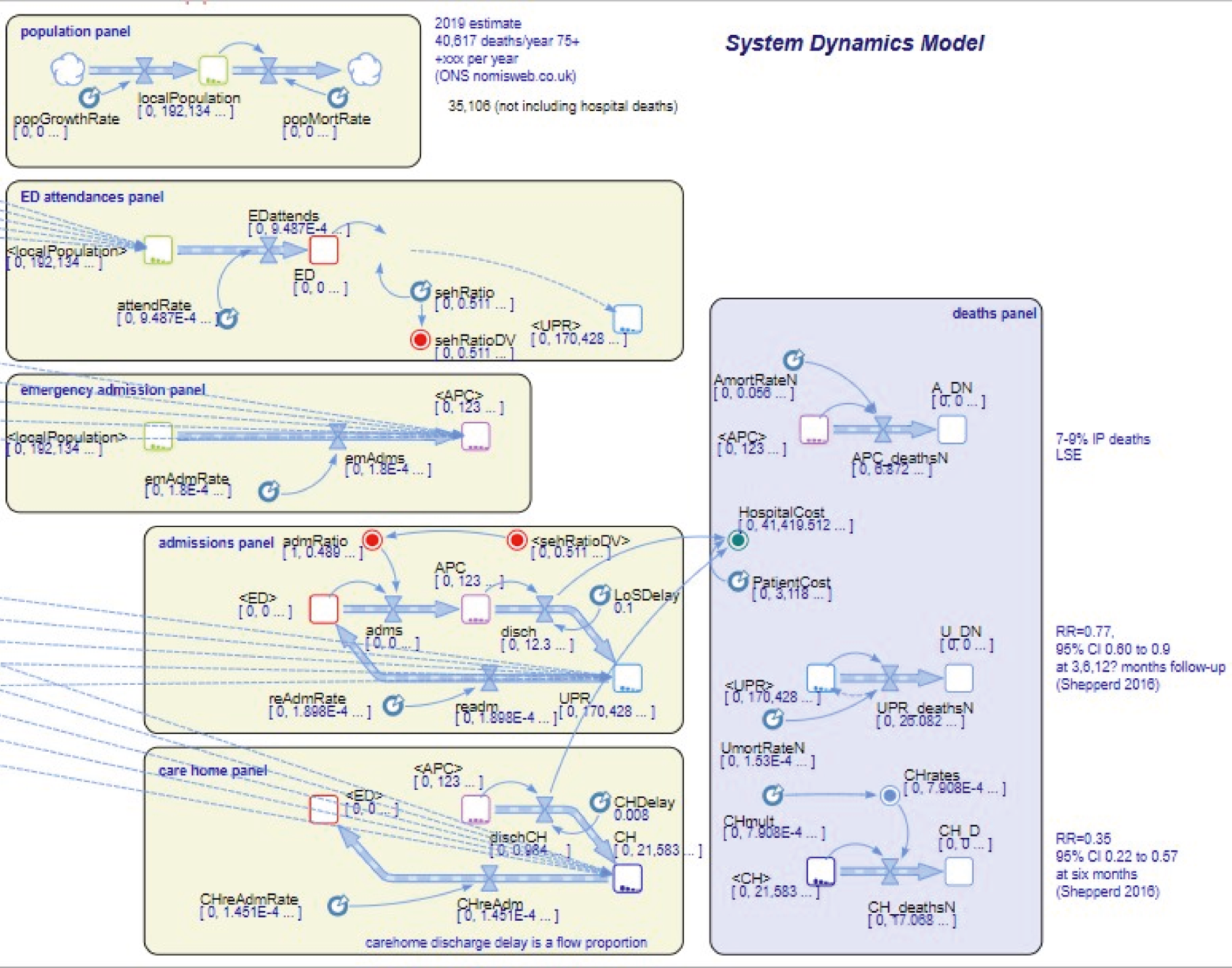

WP4.1 – baseline simulation model development.

-

RQ 4.1 – what is the best way to build an ‘archetypal’ or baseline model of patient flow into and out of one specific UEC pathway, ensuring that the model is valid and captures all the relevant factors?

-

Output 4.1 – a validated quantitative (stock-flow) system dynamics model of patient flow, describing the status quo situation in one specific setting.

-

-

WP4.2 – ‘what if’ analyses.

-

RQ 4.2 – what changes can be made to existing UEC pathways that will lead to greatest improvements, and what might the consequences of such changes be for the wider health-care system?

-

Output 4.2 – a family of system dynamics models based on output 4.1 describing the whole-system impact of evidence based, patient centred interventions applied to UEC pathways.

-

Chapter 2 Review of reviews

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Preston et al.,13 with permission.

Introduction

There is a large, but methodologically limited evidence base for interventions for older people in the ED. 14 Accordingly, we chose to undertake a review of reviews to answer two key RQs:

-

What is the evidence base for ED interventions for older people, the outcomes of these interventions and the costs associated with these interventions?

-

What factors have been described in the evidence base to date that influence implementation of ED interventions for older people?

In addition, the review was to inform the development of a taxonomy of models of care and any associated intervention effects to populate the system dynamics model (Chapter 7).

Methods

Reviews of reviews offer benefits in that they ‘enable broader evidence synthesis questions to be addressed … and in a faster timeframe’. 15 A review of reviews captures ‘the effects of different interventions for the same condition or population’ in this case, older people attending EDs. The protocol was published on PROSPERO in October 2018 (CRD42018111461).

Search methods for identification of reviews

Stage 1: database search

The line-by-line search strategy combined terms for UEC with terms for older people, limited by publication type (reviews), language (English language studies only) and date (2000 to current date) and was based on a previous strategy. 14 The search strategy was developed for Medline via Ovid SP (see Appendix 1) and was adapted for Embase via OVID SP, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCO Information Services, the Cochrane Library (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) via Wiley Interscience, Web of Science Core Collection via Clarivate, Scopus via Elsevier and AgeINFO (via the Centre for Policy on Ageing: http://www.cpa.org.uk). The database search was undertaken in Autumn 2018 and an update search (Medline via Ovid SP only). References were downloaded in Endnote version 9 and then version 20 with duplicates removed.

Stage 2: search of review sources

We searched key review sources: JBI Evidence Synthesis from the Joanna Briggs Institute (https://journals.lww.com/jbisrir/Pages/default.aspx), the Campbell Collaboration (https://campbellcollaboration.org), Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org) and PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/), using an adapted database search strategy.

Stage 3: other strategies

We undertook a cited reference search using Google Scholar and screened the results for inclusion. We also scrutinised the reference lists of included reviews and consulted with topic experts via the study executive management team (EMT). References from all sources across the three stages were downloaded in Endnote version 9 and duplicates were removed prior to screening.

Criteria for selecting reviews for inclusion

Screening of references at title and abstract level was done by one reviewer (LP or JvO), with 50% also screened by SA. All reviews that met the title and abstract screening criteria (Table 1) were screened at full text by LP and SC. Any reviews that were excluded at title stage were listed and reasons given for their exclusion. Agreement between reviewers was assessed using kappa scores.

| Criteria | Details |

|---|---|

| Publication details | Reviews published from 2000 onwards (ensuring reviews had at least 50% of their primary studies published after 2000). Peer-reviewed journal articles. Published in English. |

| Population | We included reviews with a population of whom at least 50% were people aged over 65 years or older people with living with frailty as defined by a recognised (published) frailty scale or clinical judgement. |

| Setting | Type 1 hospital-based EDs defined as ‘consultant-led, multispecialty 24-hour services with full resuscitation facilities and designated accommodation for the reception of ED patients.’ |

| Interventions | Any intervention or model of care delivered to an included population in an included setting, either initiated or wholly delivered within the ED. |

| Outcomes | Any patient, health service or staff outcome. |

| Study type | Evidence reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, qualitative reviews and mixed-method reviews. |

| Model of care | Any care or model of care delivered to the population in the ED. We did not include reviews focusing solely on methods for identification of frail or high-risk older people, although where studies focusing on identification were included as part of a larger review, the review was included but data relating to these studies was not included. |

| Comparator | Usual care, no intervention, other interventions. |

| Follow up | We did not include/exclude studies based on presence or length of follow-up. |

Application of reporting standard criteria

As part of the screening process, reviews were identified which were relevant (by inclusion criteria; Table 2) but did not meet the methodological standards for a systematic review. In the protocol, we stated that we would assess reviews according to A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews version 2 (AMSTAR2) to assess systematic reviews. However, we adapted this approach and added an additional stage where we screened reviews to assess their methods and reporting prior to the use of AMSTAR2. This prior assessment allowed the exclusion of evidence described as a review but where data extraction and quality assessment were not possible. The reporting standards criteria developed were based on the Cochrane Handbook definition of a systematic review and criteria developed by Brunton. 16 Reviews were included in the review of reviews if they met three or more of the criteria. Conference abstracts were not assessed according to these criteria.

| Criteria | Definition |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | Review needed to report inclusion and exclusion criteria developed a priori and included primary studies needed to be screened against these criteria. |

| Search | The review needed to include a systematic search, which was described in sufficient detail to identify studies that would have met the inclusion criteria. |

| Quality assessment | An assessment of bias or reporting standards using a named tool. |

| Included studies | A list of included studies in the review, linked to findings of the review and summary statements. |

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were single extracted by one reviewer (LP, SA or JvO). The full data extraction tables are included in Appendix 2. These tables were all checked by LP and a random sample of 10% were also checked by SA. Data were extracted on review description, review methods, description of included studies, all reported outcomes (including whether they had been synthesised or reported as individual studies) and a headline message/conclusion.

Assessment of the evidence base

For the review of reviews, we used two different tools: AMSTAR2 (for reviews reporting interventions) and the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (for non-intervention papers). AMSTAR2 was chosen because it allows the appraisal of reviews that include non-randomised studies of interventions, not just randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 17 We undertook a narrative assessment of the applicability of the results to the UK setting.

Size and scope of the evidence base

To examine the overall evidence base, a citation matrix18 was drawn up using EndNote 9 and Microsoft Word, mapping primary studies against the reviews in which they were cited.

Taxonomy development and validation

One of the review objectives was to develop a taxonomy of models of care delivery to older people in the ED; however, the evidence was not organised according to models of care. Three alternative frameworks (McCusker et al. 2018,53 American College of Emergency Physicians and the original framework described in the project protocol), were tested on three selected reviews by SC, JvO and LP. A process of discussion and consensus led to the choice of the Elder-Friendly Emergency Department Quality Assessment Tool. 19 This tool was used to identify whether the reviews included in our review of reviews included evidence of interventions related to any of the 13 subscales, which are as follows:

-

two‐step screening

-

standardised assessment tools

-

clinical care protocols

-

geriatric team

-

multidisciplinary staff

-

discharge planning

-

family‐centred discharge

-

linkages between ed and homecare services

-

physical environment and design

-

furniture and equipment

-

educational sessions

-

quality improvement

-

administrative data monitoring.

Again, three reviewers classified the reviews and then we discussed and agreed via consensus which of the subscales were represented in the reviews.

Results

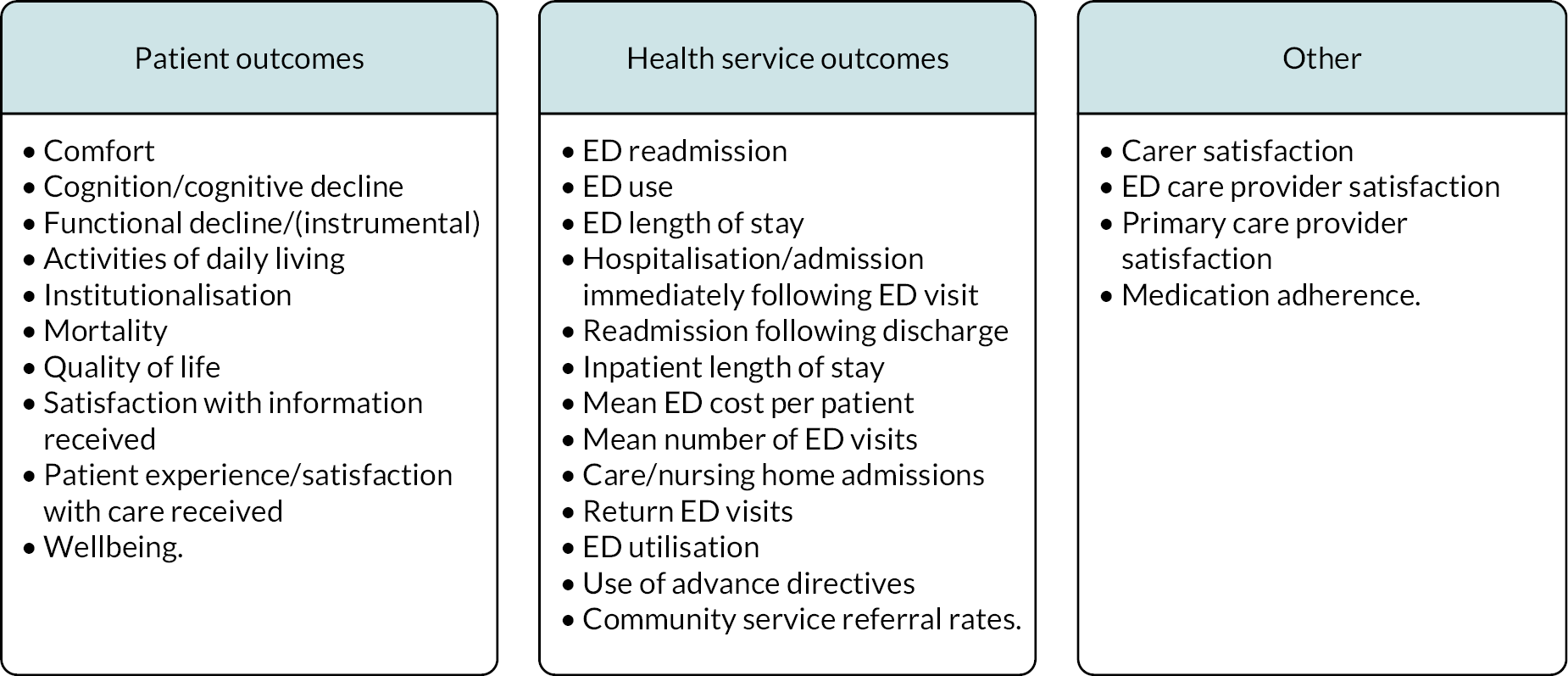

The searching and screening in 2018 resulted in the inclusion of 18 reviews and 3 conference abstracts (Figure 1). A list of reviews excluded (and reasons) at full text are available but not included in this report. The 2021 searching and screening identified an additional 151 reviews, of which 6 were relevant, and are described below.

FIGURE 1.

Modified preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Of the 735 references originally identified in the database searches, LP screened 368 and JvO screened 367. To check the screening consistency of the two single reviewers, a third reviewer (SA) screened 50% of each of these two sets. There was moderate agreement between SA and JvO (κ 0.6, 95% confidence interval, CI, 0.48 to 0.71) and LP and SA (κ 0.6, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.76). An additional reviewer (SC) checked all references where there was disagreement or uncertainty. For the 2021 searches, LP screened titles, and LP, JvO and SC all screened any articles that had passed title screening.

Characteristics of included reviews

A total of 18 reviews and three conference abstracts were included in the review of reviews. The date range was 2004 to 2019, with primary papers included in the reviews dating from 1984 to 2018. None of the reviews limited the papers by geographical setting. Not all the papers in all the reviews were included; where evidence related to screening for frailty or frailty related syndromes, these papers were excluded. The range of (relevant) papers included in reviews was 2–28 and there were 128 unique papers included in the 18 reviews. None of the conference abstracts reported bibliographic details of included studies.

Six supplementary reviews were identified in the 2021 searches.

Methods

The methods adopted by the review authors are shown in Table 3. Shaded reviews used meta-analysis. Three reviews undertook qualitative meta-synthesis. 20–22

| Author | Description of method | Method of synthesis of primary studies | Study types included in the review |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Burkett et al.)23 | Systematic review | Narrative/tabular synthesis | All study types |

| (Conroy et al.)24 | Systematic review | Quantitative synthesis including meta-analysis | RCTs |

| (Fan et al.)25 | Literature review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | Any experimental or observational |

| Fealy et al.)26 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | Clinical trials, before-and-after designs and descriptive-evaluative studies |

| (Graf et al.)27 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | Re CGA: RCTs or matched controlled trials |

| (Hastings and Heflin)28 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | RCTs, non-RCTs and observational studies |

| (Hoon et al.)20 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative results. | All study types |

| (Hughes et al.)29 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis and meta-analysis | Randomised or quasi-experimental study types. |

| (Jay et al.)30 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | RCTs, non-RCTs, and observational studies |

| (Karam et al.)31 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | Only included studies which used a comparison group |

| (Lowthian et al.)32 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Quantitative synthesis of quantitative data including meta-analysis | RCTs, quantitative studies |

| (Malik et al.)33 | Systematic review | Quantitative synthesis of quantitative data including meta-analysis | RCTs, multicentre and observational studies |

| (McCusker and Verdon)34 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | RCTs, non-RCTs, before and after studies and cross-sectional studies. |

| (Parke et al.)35 | Scoping review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | Systematic review, meta-analysis, clinical trial, cohort study, evaluation study |

| (Pearce et al.)21 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data and meta synthesis of qualitative data | Quantitative research study designs as well as narrative opinion and text |

| (Schnitker et al.)36 | Systematic literature review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | ‘Research based literature’ |

| (Shankar et al.)22 | Systematic review | Meta ethnography | Survey, questionnaire, focus groups or individual interviews |

| (Sinha et al.)37 | Systematic review | Narrative synthesis of quantitative data | RCT, non-RCTs, observational studies. |

Overview of included reviews

Population

The age threshold for older people adopted by the reviews tended to be aged 65 years and older, although Fealy et al. 26 and McCusker and Verdon34 included papers with age 60 years and older. Some reviews did not report a specific age but rather reported interventions for participants who were ‘older’ or ‘elderly’. Most reviews reported ED care for a general population of older people, not stratified by condition or severity. However, Schnitker et al. 36) and Parke et al. 35 both reported evidence on interventions for older people with cognitive impairment. Lowthian et al. 32 described the population of their review as ‘high risk’. This may indicate that there was some prior screening of patients before they were included in the intervention. Graf et al. 27 compared screening with intervention against intervention alone; however, this former group of papers were not included as the screening process meant that the intervention was targeted.

Interventions

Ten reviews focused on specific interventions, including discharge focused interventions19,24,28,31,32 and interventions led by specific staff. 21,26,27,30,33 Four reviews looked at measuring and classifying ED care for older people by identifying and assessing indicators for quality care23 and by describing core components of successful interventions. 25,29,37 Two reviews reported the views of older people about what constituted quality emergency care22 and the experiences of older people of the care they received. 20 Finally, two reviews looked at a variety of ED and non-ED interventions and outcomes for a specific population group (older people with cognitive impairment). 35,36

Most reviews reported interventions delivered by ED consultants, consultant geriatricians working within the ED and nurses (with or without an advanced role). There was also evidence of wider multidisciplinary team-led interventions, which included occupational/physical therapists, discharge co-ordinators, social workers, physiotherapists, and health visitors.

The review of reviews inclusion criteria stated that for interventions to be included in the review, they needed to be either initiated or wholly delivered within the ED. The discharge interventions reported in this review tended to include follow-up of patients after discharge, by ED or community/primary care professionals, although these were often reported incompletely. Only 5 of the 18 reviews reported interventions delivered exclusively within the ED.

Overview of included conference abstracts

Three conference abstracts were included in this review. Cherian et al. 39 reported interventions to enhance EDs to be more suitable for older patients. Gupta et al. 40 described a review of geriatric trauma protocols and interventions. Tran et al. 41 examined interventions for patients at high risk following discharge from the ED.

Synthesis

There was a high degree of heterogeneity in the review methods and reporting across the 18 reviews included in the review of reviews, so meta-analysis was not possible. Instead, data were reported as:

-

summary tables, reporting intervention descriptions and outcomes reported (where a statistically significant positive effect was measured)

-

narratively within evidence clusters designed to gather evidence by intervention type.

Summary tables

These tables report intervention descriptions (by review) and any statistically significant outcomes reported in the review, with the number of studies in which the outcome occurs. Table 4 contains data from reviews where results were reported narratively for patient outcomes. Table 5 contains from reviews where results were reported narratively for health service outcomes and Table 6 contains data from reviews where meta-analysis was undertaken. It is important to note that this table does not account for overlap across the reviews in terms of the primary studies included.

| Intervention description | Review | Outcome (positive +, negative –. mixed, no effect) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced functional decline | Reduced dependence in IADLs | Increased satisfaction with information received | Reduced cognitive decline | Patient satisfaction | Increased medication adherence | Increased wellbeing | Mortality | Advanced directives | Caregiver satisfaction | ||

| CGA (nurse-led) | Graf et al.27 | + (4 studies) | |||||||||

| Discharge interventions | Hastings and Heflin28 | + (2 studies) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | |||

| Sinha et al.37 | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | |||

| General interventions | Hughes et al.29 | + (4 studies) | |||||||||

| Intervention description | Review | Outcome (positive +, negative –. Mixed, no effect or unreported N/A) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced admission rates | Reduced LoS | Reduced readmission rates | Reduced ED revisits | ED use | Reduced nursing home admissions | Service use | Community service referral rates | Costs | ED care provider satisfaction | Primary care provider satisfaction | ||

| CGA (consultant led) | Jay et al.30 | + (5 studies) | ||||||||||

| CGA (nurse-led) | Graf et al.27 | + (3 studies) | + (1 study) | |||||||||

| Discharge intervention | Karam et al.2 | + (5 studies) | + (2 studies) | |||||||||

| Hastings and Heflin28 | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | ||||||||||

| Sinha et al.37 | + (1 study) | + (1 stud)y | +(5 studies) | + (1 study) | + (4 studies) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | + (1 study) | |||

| Various (to reduce ED revisits) | McCusker and Verdon34 | |||||||||||

| Intervention description | Review | Outcome (positive +, negative –. Mixed, no effect or unreported N/A) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced admission rates/hospitalisation | Reduced LoS | Reduced readmission rates | Reduced ED revisits | Reduced functional decline | Reduced Nursing home admissions | Reduced Institutionalisation | Reduced Mortality | Improved quality of life | Improved cognition | ||

| Discharge interventions | Conroy et al.24 | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | ||||

| Lowthian32 | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | ||||||||

| CGA (nurse-led) | Malik et al.33 | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (2 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | No effect (5 studies) | ||||||

| CGA (nurse-led) with primary care links | Malik et al.33 | No effect (2 studies) | + (2 studies) | ||||||||

Table 4 shows that reduced functional decline was the most frequently reported outcome, although in Table 5 it appears that most of the positive intervention effects were for health service outcomes.

Reviews which undertook meta-analysis24,32,33 reported on a variety of patient and health service outcomes but did not identify any statistically significant effects on outcomes as a result of interventions with the exception of Malik et al.,33 who reported reduced readmission rates.

Narrative synthesis

Table 7 describes the five evidence clusters that were developed from the review findings. These were developed iteratively and grouped thematically;42 they are presented narratively, and are summarised according to their reported effectiveness. This does not reflect the primary studies but on the strength of the findings as reported at review level.

| Cluster | Topic | Papers included |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staff-led interventions | Pearce et al.,21 Fealy et al.,26 Graf et al.,27 Jay et al.,30 Malik et al.,33 |

| 2 | Discharge-focused interventions | Conroy et al.,24 Hastings et al.,28 Karam et al.,31 Lothian et al.,32 McCusker et al.34 |

| 3 | Population-focused interventions | Parker et al.,35 Schnitker et al.36 |

| 4 | Patient views on ED care | Hoon et al.,20 Shankar et al.22 |

| 5 | Reviews reporting components/characteristics of successful interventions and indicators of quality care for older people in the ED | Burkett et al.,23 Fan et al.,25 Hughes et al.,29 Sinha et al.37 |

Reviews reporting interventions delivered by specific staff

Four reviews examined interventions delivered by nurses for older people within the ED21,23,26,27 and one review examined interventions delivered by consultant geriatricians. 30 For the nursing interventions, the range of included studies in reviews was 2–11 and there was a total of 15 studies from which findings were generated (7 studies were reported in more than 1 review). Graf et al. 27 also included studies reporting ED screening tools that were not part of an intervention, and these were excluded from this review. Fealy et al., Graf et al. and Pearce et al. 21,26,27 narratively summarised quantitative data, whereas Malik et al. 33 undertook narrative synthesis and meta-analysis of nine included studies across four outcomes (hospitalisation, readmissions, length of hospital stay and ED revisits).

Jay et al. 30 undertook narrative synthesis, as a meta-analysis was considered inappropriate due to heterogeneity of study design, population and interventions.

For the nurse-led interventions, Fealy et al. 26 described 11 interventions with nurse assessment, post discharge referral, patient education and follow-up. Graf et al. 27 described eight nurse-led CGA interventions, including follow up. Malik et al. 33 reported three different types of nurse intervention assessment using risk screening, CGA and nurse-led case/discharge management. The interventions reported by Pearce et al. 21 were limited to nurse-led interventions to enhance patient comfort in the ED, mainly relating to equipment.

The narrative summary of primary studies in the systematic review by Fealy et al. 26 reported reduction in service use across five studies and functional improvements across three studies; three studies found no effect. There was evidence of reduced service use in the ED being associated with increases in primary care use. The suggested characteristics of effective interventions included preintervention screening and better links with home care (as opposed to stimulating health service demand via primary care).

Graf et al. 27 reported that nurse-led CGA was effective in functional improvements. There was varying evidence on ED readmissions (both reduced and increased admissions) and potentially also nursing home admissions. Three studies found no effect. These negative findings were attributed partly to study design limitations.

The meta-analysis by Malik et al. 33 of nine studies across four outcomes found that nursing interventions did not have a significant statistical impact on any of the four domains (hospitalisation, readmissions, length of hospital stay and ED revisits). This study did not examine functional decline. Malik et al. 33 contrasted these findings with previous reviews, which are also reported in this review of reviews26,28,31 and which demonstrated both reduced service use as a result of these interventions, and also that ED risk screening led to reduced hospitalisation and nursing home admissions. These inconsistencies are attributed to methodological weaknesses in study designs, supporting an agenda for additional research on interventions which extend from the ED to the community.

Pearce et al. 21 identified only two studies which looked at patient focused outcomes. These indicated that both warming blankets and seating position had a positive impact on patient comfort and wellbeing. They noted the paucity of research around patient-centred outcomes such as nutrition, hydration and communication from a nursing perspective.

Jay et al. 30 reported statistically significant findings in terms of reduced admissions rates (which ranged between 2.6% and 9.7%). The evidence for length of stay and readmission rates was mixed. Several their included studies also reported changes in admissions rates for the control groups, indicating that CGA may have altered culture and practices around the risks of admission versus discharge.

In summary, there is contradictory evidence around the benefits of nurse-led interventions for older people in the ED. Some reviews report improved outcomes in terms of reduced service use and reduced functional decline (although there is also evidence of increased service). The strongest evidence, in the form of meta-analysis, found no effect from nurse-led interventions. In terms of consultant led CGA interventions, there was evidence of lowered admission rates. There is a common theme of methodological limitations reported across studies which limit the conclusions drawn.

Reviews reporting interventions delivered at specific points in the patient emergency department episode (and beyond)

This cluster contains five reviews. 19,24,28,31,32 These contained a range of 5–14 primary studies with 25 primary papers included, 9 of which appeared in more than 1 review and 1 of which appeared in all 5 reviews. 43 Publication dates ranged from 2004 to 2015, including primary studies from 1996 to 2013. The reviews by Conroy et al.,24 Hastings and Heflin28 and Lowthian et al. 32 were focused on the ED, whereas a subset of papers from the reviews by Karam et al. 31 and McCusker et al. 19 are reported here (as they also reported interventions initiated or delivered outside the ED).

Conroy et al. 24 focused on interventions delivered within 72 hours of ED attendance. These were CGA interventions delivered either by nurses or geriatricians and were targeted at older people with living with frailty. The review by Hastings and Heflin28 looked at evidence for interventions to improve outcomes for older people discharged from the ED; 14 of the studies reported by Hastings and Heflin28 were of interventions either initiated or concluded in the ED. A wide variety of interventions were reported, from CGA to single screening and assessment interventions, delivered by single practitioners or multidisciplinary teams. Karam et al. 31 limited inclusion criteria to interventions delivered within the ED and including CGA and other intervention types. Lowthian et al. 32 reported on discharge interventions in the form of community transition strategies (CTS) from the ED. All the CTS included geriatric assessment but this was undertaken by a variety of different staff (nurses, allied health professionals or health visitors). Follow-up interventions consisted of referral to community services or direct linkages, including telephone/general practitioner (GP) follow-up. In the review of interventions to reduce ED visits by McCusker and Verdon,34 9 of the 18 primary studies included were delivered in the ED. All these interventions had an ED and post-discharge component.

Outcomes were reported using meta-analysis24,32 and narrative synthesis. 28,31,34 Conroy et al. 24 found no clear evidence of benefit for CGA discharge interventions across all outcomes included in the review. Hastings and Heflin28 reported findings at the level of individual studies only across a wide variety of outcomes. Karam et al. 31 developed themes for intervention types (referral, follow-up, integrated model of care) and identification of study participants (risk screening or no risk screening). They found that the most effective interventions extended beyond referral and used a clinical risk prediction tool to identify those who would most benefit from the intervention. In the review by Lowthian et al.,32 four of the nine studies were included in a meta-analysis, which found no benefit of interventions in terms of ED reattendance, mortality and emergency hospitalisation. Individual studies were effective in reducing ED reattendance and nursing home admissions; Lowthian et al. 32 attributed this potentially to the methods of telephone follow up of discharged patients. The review by McCusker and Verdon34 found that there was limited evidence of benefit of discharge interventions (two studies of borderline statistical significance) on ED visits, with evidence of short-term increases in ED visits.

In summary, discharge interventions vary in their components but tend to employ improved linkages between the ED and the community, either through direct linkage or referral interventions. CGA is frequently used and is delivered by a variety of staff. There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions; two meta-analyses found no benefit and narrative synthesis demonstrated an increase in ED readmissions in patients who had received these interventions in the short term.

Reviews reporting interventions for patients with specific conditions

This cluster contained two reviews,35,36 both of which looked at interventions and best practice for older people with cognitive impairment in the ED. Findings were generated from a total of 27 primary studies. Four papers were included in both reviews. Schnitker et al. 36 also included evidence on the management of older people with cognitive impairment in acute care settings but these have been excluded from this summary. Both reviews undertook a narrative synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Schnitker et al. 36 generated themes from the evidence base. Neither review presented results in a format that could be extracted for the summary table of interventions and outcomes.

The interventions reported were around identification and management programmes dealing with the specific needs of older people with cognitive impairment. Parke et al. 35 also reported staffing interventions (team and individual changes to service delivery and staff training). Neither review reported patient or health service outcomes. Both reviews describe intervention characteristics that report positive outcomes but do not report the outcomes themselves. Both reviews summarised that interventions are not well represented or described within the ED literature but that there is more evidence from acute care, although transferability of these interventions to the ED is not well understood.

In summary, there was limited evidence which could not be synthesised. No conclusion was possible around ED interventions for older people with cognitive impairment.

Reviews reporting patient views and experiences of their care in the emergency department

This cluster contained two papers findings were generated from 28 papers. All the five papers in the review by Hoon et al. 20 were also included in the Shankar et al. 22 review. This review had a wider scope, including preferences and views of emergency care as well as patient experiences, to which the review by Hoon et al. 20 was limited. Hoon et al. undertook their review according to the methods of the Joanna Briggs Institute. Neither of the reviews presented results in a format that could be extracted for the summary table of interventions and outcomes.

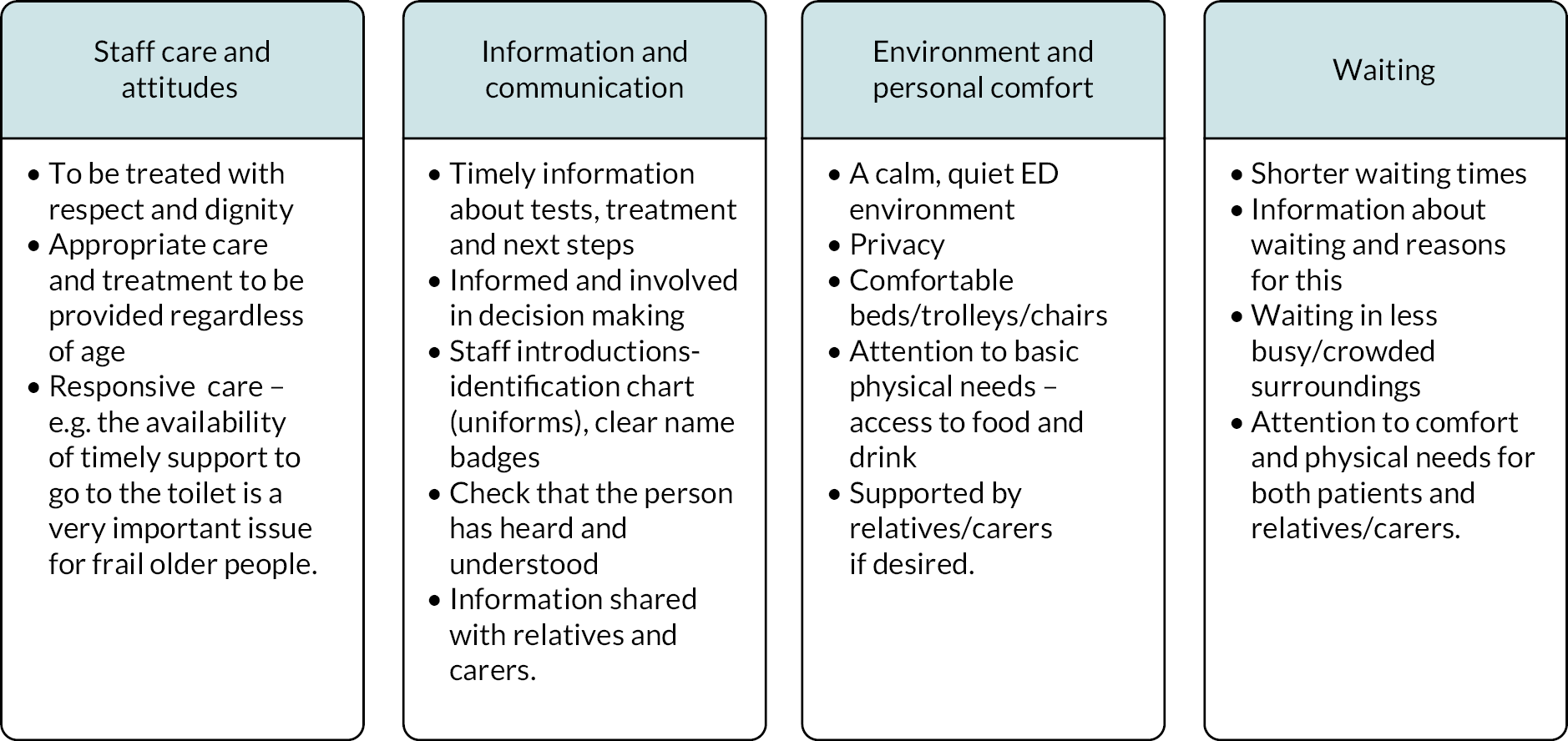

Both reviews undertook qualitative synthesis to generate themes/findings. There was some commonality between these findings. Both reviews reported on the negative experience of long waiting times for older people and on the physical care needs of this population, especially in relation to pain management. The content of communication and information received by older people was also important for patient experiences and quality patient care. The review by Hoon et al. 20 commented that health-care professionals should be more aware of the positive attitude of older people to the care that they are receiving and made recommendations on changes to the physical environment that might help. Shankar et al. 22 also reported that simple changes to physical infrastructure can make a big difference to pain and physical comfort. Another important quality indicator for older people was the leadership role that health-care professionals play in ensuring quality care. 22

Summary – the total overlap between the papers in these two reviews has generated a consistent evidence base regarding patient views of their care and what represents quality care for older patients. Repeating messages are around waiting times, patient-provider-family communication, and physical adaptations to better meet the needs of older patients.

Reviews reporting components/characteristics of successful interventions and indicators of quality care for older people in the ED

The reviews by Burkett et al.; Fan et al.; Hughes et al.; Sinha et al. 23,25,29,37 all took a broader view of the care of older people within the ED. Although in some reviews25,29,37 the effectiveness of interventions was reported, this evidence was enhanced by a consideration of the key components or elements of effective interventions as follows:

-

core operational components of interventions and the role of these components in the success of interventions37

-

key elements of effective interventions25

-

the methodological quality of quality indicators of ED care23

-

intervention components and intervention strategies adopted. 29

Fan et al.,25 Hughes et al. 29 and Sinha et al. 37 included a range of 15–20 papers in their reviews. The primary studies in the review by Fan et al. 25 also related to community interventions and wider hospital interventions, so a subset of papers was reported. There were 38 papers included in these 3 reviews, with 13 of these 38 included in 2 or all the 3 reviews.

In terms of intervention effectiveness, the case management interventions reported by Sinha et al. 37 were reported as having positive effects (not statistically significant) on satisfaction levels, reductions in ED reattendances, reductions in admissions (immediate and longer term), decreases in inpatient and nursing home admissions. Fan et al. 25 and Sinha et al. 37 found negative results in terms of a small but significant negative effect on ED reattendances37 and higher ED use. 25 There was a statistically significant outcome of lowering ED use or length of stay in 5 of 20 studies examined by Fan et al. 25 Hughes et al. 29 found a small positive effect of ED interventions on functional status.

Burkett et al. 23 included 61 sources of evidence for quality indicators, of which 20 were included in peer reviewed journal articles. The 50 indicators of quality care identified related to ED processes rather than outcomes and were cross cutting. Quality, as measured using a bespoke assessment tool ranged from 39% to 67% according to specific tools.

Table 8 reports the key intervention components/elements and strategies derived from the three reviews, associated with interventions that the reviews had found to be effective (shading indicating overlap across the three reviews).

| Fan et al., 201525 | Sinha et al., 201137 | Hughes et al., 201929 |

|---|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary team and gerontological expertise | Interprofessional and capacity building work practices | |

| Integrated social and medical care | Multi strategy interventions | |

| Risk screening and geriatric assessment | High risk screening Focussed geriatric assessment |

Assessment |

| Care planning and management | Case management | |

| Discharge planning and referral coordination | Initiation of care and disposition planning in the ED | ‘Bridge’ interventions (contact before and after discharge) |

| Follow up and regular group visits | Post ED discharge follow-up with patients | Referral plus follow-up |

| Evidence based practice model | Establishment of evaluation and monitoring processes | |

| Nursing clinical delivery involvement or leadership |

In summary, there was considerable agreement across three reviews of the components of successful interventions, which should (1) integrate strategies for social and medical care involvement (2) Include screening and assessment (3) initiate care in the ED and bridge this with follow up (4) monitor and evidence successful interventions. Indicators for quality care tend to focus on care processes rather than structures or outcomes and are lacking in evidence and limited in testing.

Conference abstracts

Cherian et al. 39 looked at evidence for the implementation of a geriatric ED model and found eight different components that were related to outcomes, namely structural enhancements, operational enhancements, provider education, quality improvement, coordination of hospital resources, coordination of community resources, staffing and patient satisfaction. The review by Tran et al. 41 reported interventions to prevent ED return visits following discharge. Six interventions were identified which reported ED returns as outcomes. Limited reporting described these interventions as bundles of care (screening within the ED, home visits and referrals); one study found improved outcomes because of the intervention, while five of the six studies did not report any reduction in ED return visits. The final abstract40 reported a review of trauma protocols for geriatric patients in the ED and found that geriatric assessment within the first 24 hours of presentation was critical for patient outcomes. They reported improved outcomes (length of stay, readmission, and functional status) associated with appropriate pain management, assessment of cognition, assessment of function and assessment of psychosocial issues.

Additional reviews identified in September 2021

Gettel et al. reviewed 17 ED care transition intervention studies. 44 They found that common care transition interventions included coordination efforts, CGAs, discharge planning, and telephone or in-person follow-up.

Elliott et al. 45 identified 25 trials (13 RCTs and 12 quasi-experimental) assessing interventions supporting discharge of older people to their home from the ED. They reported a trend to reducing ED reattendances associated with ‘focussed elder discharge health interventions’.

Leaker et al. 46 reviewed the impact of geriatric emergency management nurses on the care of older people living with frailty in the ED. The main finding was a reduction in ED reattendances.

Berning et al. 47 reviewed interventions to improve older people’s experience in the ED. Department-wide interventions, including geriatric EDs and frailty units, focused care coordination with discharge planning and referral for community services, were associated with improved patient experience. Providing an assistive listening device to those with hearing loss and having a pharmacist reviewing the medication list showed an improved patient perception of quality of care provided.

van Oppen et al. 48 reported upon what older people want from emergency care, concluding that capturing individuals’ preferred outcomes could improve person-centred care.

Hughes et al. 29 reviewed ED interventions for older people, concluding that studies assessing two or more intervention strategies may be associated with the greatest effects on clinical and service outcomes.

Overall, these more recent reviews did not materially impact upon our initial findings; there were no additional empirical data that could be used in the system dynamics model.

Study assessment

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews, Version 2

The methodological quality of the reviews reporting either randomised or non-randomised studies of interventions was assessed for 15 of the 18 included reviews using AMSTAR2 (see Appendix 3).

Joanna Briggs Institute tool for systematic reviews

The methodological quality of the reviews reporting non-interventional papers was assessed for 320,22,23 of the 18 included reviews using the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for systematic reviews. Of these three reviews, two had generally good quality assessment, which the third was lacking. There was limited evidence that any of the reviews had considered publication bias in their assessments.

Applicability of evidence to the UK setting

Although much of the primary research summarised in the reviews emanated from North America, it is likely that the review findings will apply to UK settings. Older patients with urgent care needs will present similarly in North America compared with the UK (e.g. high prevalence of non-specific presentations). The interventions were broadly holistic in nature, consistent with the international literature supporting CGA as an intervention to improve outcomes in older people with acute care needs. Finally, the outcomes described as important are consistent with the outcomes valued by older people in the UK, as well as the service outcomes being valued by providers and commissioners of care and consistent with the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement report. 38 It is therefore likely that the review findings will be relevant to the delivery of urgent care for older people in the UK.

Taxonomy

To address the research objective of developing a taxonomy of models of care, as reported in the introduction, the McCusker et al. 19 Elder Friendly Emergency Department Quality Assessment Tool was used to identify whether the reviews included in our review of reviews included evidence of interventions related to any of the 13 subscales of the tool. Use of this tool to classify the evidence allows us to describe which areas are more likely to have interventions relating to them (Table 9). The most frequently occurring subscales were interventions relating to multidisciplinary staff, with standardised assessment tools, two‐step screening, geriatric team, discharge planning and linkages between ED and homecare services also occurring in either 11 or 12 reviews. The remaining subscales were mentioned in few of the reviews, although there was often mention of issues relating to these in the background or discussion sections of reviews as being important, particularly to patients.

| McCusker subscales, in order of frequency in reviews | Total number of reviews in which subscale reported |

|---|---|

| Administrative data monitoring | 0 |

| Furniture and equipment | 1 |

| Quality improvement | 1 |

| Family‐centred discharge | 2 |

| Physical environment and design | 2 |

| Clinical care protocols | 3 |

| Educational sessions | 3 |

| Standardized assessment tools | 11 |

| Two‐step screening | 12 |

| Geriatric team | 12 |

| Discharge planning | 12 |

| Linkages between ED and homecare services | 12 |

| Multidisciplinary staff | 14 |

Discussion

The 18 reviews and 3 conference abstracts that met our inclusion criteria have demonstrated a diverse range of interventions, with varied outcomes, measured across different time periods and focussing on both individual patient and wider health service outcomes.

The evidence base is broad, with 128 primary studies being included across the 18 reviews, with the vast majority being included in only one review, but with a substantial number being included across multiple reviews, despite the review topics and titles not indicating substantial overlap. This overlap demonstrates the diverse ways in which interventions can be reported: by the health-care professional who is delivering the intervention, the type of intervention, when in the patient journey the intervention is being delivered and whether the intervention links multiple services, professionals or settings together.

As a result of the inconsistent reporting across reviews, the clusters that we have developed have significant overlap, for example an RCT of CGA with a multidisciplinary team follow-up post ED visit was reported in ten reviews across four of the seven clusters, indicating overlap between the reviews themselves and the evidence-based clusters that we developed.

The evidence base in terms of primary studies and reviews is extensive. The interventions developed and evaluated for this population in the ED setting are numerous. However, the evidence for their effectiveness is unconvincing and the messages around further research using experimental study designs is consistent.

In terms of effectiveness, the four reviews that undertook numerical synthesis of primary studies24,29,32,33 all found no or little evidence for the effectiveness of interventions across a broad range of patient and health service outcomes. The review by Malik et al. 33 was limited to nursing interventions; the other three reviews were more general, although Conroy et al. 24 and Lowthian et al. 32 focused on discharge interventions. Across these reviews, there was overlap in the 14 included studies – 2 primary studies were included in all 4 reviews and a further 3 primary studies were included in 2 or more reviews.

The remaining 11 reviews of interventions were similarly equivocal in their findings with reviews reporting mixed findings on the effects of interventions, demonstrating seemingly negative effects such as increased service use, alongside evidence of no effect and evidence of effectiveness, with either clinical or statistical significance. The systematic and narrative reviews did report evidence of the effectiveness of interventions on some outcomes. Fealy et al. 26 found evidence in terms of reduced service use and reduced functional decline from nursing interventions and Jay found consultant led CGA (which was variously implemented) did reduce admission rates. 30 Looking at a wider range of ED interventions, Graf et al. 27 found evidence for CGA in reducing functional decline and ED readmissions. Hastings and Heflin28 found mixed results with some evidence for reduced functional decline and health service use.

There was no synthesis of cost data, although reviews did include evidence from three studies that looked at the costs and cost effectiveness of interventions, so analysis would have been possible.

There was limited evidence for factors that influence the implementation of these interventions. The nature of the type and urgency of care delivered within the ED is a theme that runs throughout the included reviews as a challenge to developing and measuring interventions, but this is common to all the interventions that are either delivered or initiated within the ED. Evidence on implementation may more readily be extracted from the primary studies included in these reviews.

Additional evidence was reported from the four reviews23,25,29,37 which sought to develop overarching descriptions of effective interventions. Across these reviews, there were several areas of commonality that demonstrate where interventions may best be focused. However, as this list of descriptions of interventions demonstrates, most of them encompass delivery of care both within an outside the ED and care delivery in the acute setting is not limited to ED staff only:

-

interprofessional work practices/teams

-

integrating social and medical care

-

geriatric assessment including screening

-

case management

-

discharge planning with contact after discharge

-

post discharge referrals or follow ups

-

evaluation and monitoring/evidence-based practice.

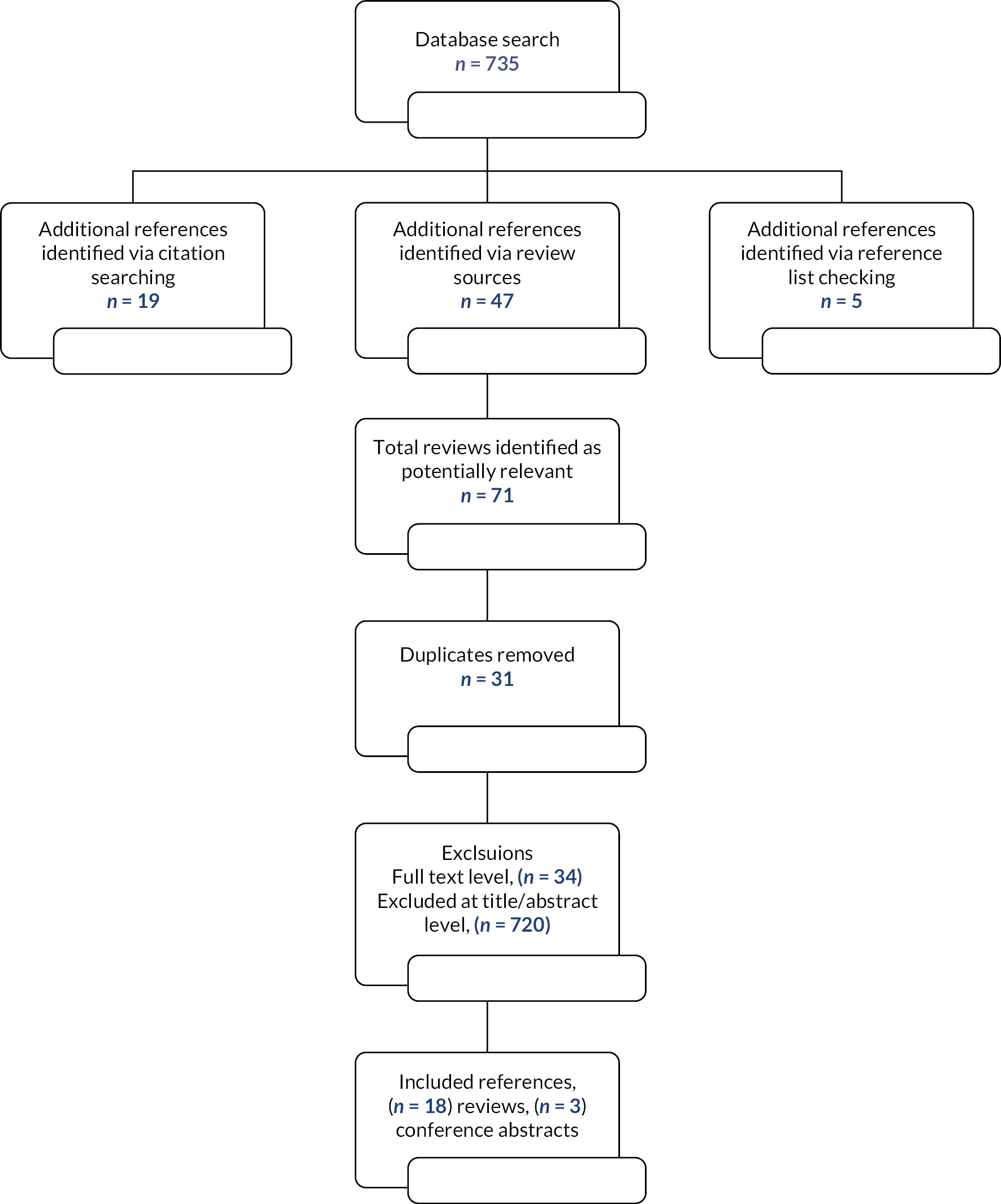

The list of 26 outcomes reported across the 18 papers included in our review of reviews was broadly in line with the core outcome measures as reported in the review by Hastings and Heflin. 37 This agreement indicates that our included reviews measured a wide variety of outcomes, as reported in the primary studies, rather than restricting reporting to specific outcome measures.

The McCusker et al. 19 tool has allowed us to look at the interventions and consider their relative importance in terms of which types of interventions have been tested. This process highlights the findings within our reviews on CGA (screening and assessment interventions), discharge planning and follow-up and the importance of the staff delivering care.

Adopting a review of reviews methodology necessitates that the unit of analysis is each review, rather than the primary studies that are contained within that review. Therefore, the confidence that we can take from review findings depends upon authors’ interpretations of the evidence. Within some of the included systematic reviews, primary studies were organised by intervention type or by outcome, whereas other reviews reported studies sequentially, which makes analysis and reporting of the overall review unit challenging.

There is little consistency in how individual studies have been classified; for example, the same study appears in reviews both reporting discharge interventions and staff interventions. This is a limitation of the reviews and a limitation of the way in which we have chosen to organise the data.

The summary tables of outcomes and interventions are limited. It is not possible to map the primary studies to the outcomes reported. We are also reliant on the review authors to have determined whether an intervention is statistically significant. There was little reporting of clinical significance, so this has not been included in these tables.

The literature reported here is predominantly US focused. This is not unusual but does present challenges in terms of our interpretation of the evidence; for example, the promising McCusker et al. 19 tool, which reports elements of interventions, includes reference to linking together services that are not delivered by a single provider, such as the NHS.

Conclusion

This review of reviews found a diverse but overlapping evidence base supporting a range of interventions. We have sought to develop typologies of effective interventions to guide implementation of interventions to improve the care of older people in the ED and after discharge from the ED. However, there was no consistent typology found in the literature that served this purpose. There was evidence that interventions initiated within the ED and continued into the community or primary care setting had better outcomes than those delivered in the ED alone. However, this does not represent a model of care or care pathway as described in our review protocol.

A wide range of tested interventions were identified across the 18 reviewed reviews. There was inconsistency in how these were reported whether by the clinician delivering the intervention or the point in the patient journey where it was being delivered. The evidence on outcomes of these interventions was inconclusive.

Using the review as a unit of analysis limits the extent to which conclusions can be drawn on the effectiveness and outcomes of specific interventions. Perhaps the most useful outcome from this work is the classification of existing interventions using the McCusker et al. 19 framework, which has allowed a summary of the strengths and weakness of the evidence base. This has also highlighted the importance of multifaceted and holistic assessments, but also the important absence of evidence for patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) being fed-back into the system.

Chapter 3 Patient and carer preferences

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Phelps et al. 49 with permission.

The aim of this interview study was to create an understanding of what ‘good looks like’, adding a strong patient perspective to the literature described in Chapter 2, which contained relatively little on patient priorities and outcomes. The patient perspectives were also used to inform the implementation toolkit (Chapter 5) and the modelling exercise detailed in Chapters 6 and 7.

We report patient experience and patient outcomes or preferences separately, although the data were ascertained using the same methods and participants. We understand that there is a significant overlap between experience and outcomes, particularly in older people living with severe frailty. 38 These individuals are typically in the last year or two of life, during which period, the experience of health care – being treated with dignity, comfort, and respect – can be as important if not more so that outcomes such as mortality or improving function. Indeed, previous authors have combined outcomes and experience in PROMs designed for older people. 50 However, for ease of reading, we have presented patients’ experiences in this section and outcomes in Patient reported outcomes below.

Patient experience

Introduction

Little is known about the experiences and preferences of older people for emergency care, even less for older people living with frailty. Reviews of existing evidence highlight waiting times, physical and psychological support alongside good communication and information provision in shaping the experiences of older patients in the ED. 20,22,48 Although existing studies included people with stereotypical markers of frailty, none used a validated frailty assessment. As such there is currently limited evidence about whether or how the presence of frailty impacts upon older people’s experiences and preferences for emergency care. 48 These needs must be understood and addressed to provide person-centred care.

Methods

Sampling and recruitment

Older people (≥ 75 years) and/or their carers with experience of emergency care were recruited from three EDs in England between January and June 2019. Recruitment was undertaken by experienced research nurses (sites 1 and 2) and clinical staff (site 3) using a purposive recruitment strategy which tried to reflect the population of interest according to: frailty, age, sex, ethnicity, cognitive impairment, place of residence, mode of arrival (ambulance or independent), whether seen in ‘majors’ or ‘minors’, different days of the week and different times of day as summarised below. Participants were included if they were at least mildly frail [≥ 5 on the clinical frailty scale (CFS)]. 51 Informed consent was taken by staff who recruited participants within 72 hours of patients’ entry to ED, with the majority being recruited on the day of their ED attendance.

Data collection

Data were collected via semistructured in-depth interviews using a topic guide informed by Chapter 213 and designed in collaboration with lay co-researchers. Interviews explored patients’ views on their recent experience of emergency care, their priorities and preferred outcomes. Where desired and possible, carers/relatives were also interviewed, alongside or separate from patients according to individual preferences.

In most cases, interviews (conducted by ER or KP) took place within 30 days of the patient’s ED attendance. Most took place in the patient/carer’s usual place of residence, typically their own home, but sometimes the family home, sheltered accommodation or care home. Four interviews, all with carers, took place via telephone at their request. Interviews were audio recorded and lasted approximately 60 minutes each.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service and analysed in NVivo (Lumivero, Denver CO) using the framework approach. 52 After reading the first transcripts, initially identified themes were used to generate a coding framework; transcripts were coded by two qualitative researchers (ER or KP). Themes generated during the analysis process were discussed and validated by wider members of the research team (SC and/or JvO) and our lay collaborators on a regular basis. Data collection and analysis were concurrent, with early findings directing further enquiries in interviews.

Patient and public involvement

The study was supported by the involvement of two lay collaborators (PR and JL) who provided advice on recruitment and helped in the design of topic guides and in the analysis. In addition, study updates were shared with the wider Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Ageing Patient and Public Involvement Research Forum on a quarterly basis, where useful feedback was provided.

Ethical approvals

The study was submitted to the London South East Research Ethics Committee for review which classified it as service evaluation. Accordingly ethical approval was granted by the University of Leicester’s Sub Committee for Medicine and Biological Sciences.

Results

Participants

In total, 40 participants were interviewed: 24 patients and 16 carers who, between them, described ED attendances for 28 patients across the 3 sites. Over two-thirds of patients (68%) were female; 43% were aged 75–84 years and 57% were aged over 85 years, including three aged over 95 years. The majority were white British; 12 had CFS scores of 5, 12 had CFS 6 and 4 had CFS 7. Table 10 shows demographic and ED attendance details for the patients whose ED experiences are described in the study.

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||||

| Male | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Female | 7 | 9 | 3 | 19 |

| Age (years): | ||||

| 75–84 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 12 |

| ≥ 85 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 16 |

| CFS frailty score: | ||||

| 5–6 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 24 |

| 7 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Ethnicity: | ||||

| White British | 7 | 11 | 8 | 26 |

| White other | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ED attendance: | ||||

| Majors | 8 | 11 | 7 | 26 |

| Minors | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Accommodation: | ||||

| Own home | 6 | 9 | 7 | 22 |

| With family | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Care home | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Travel to hospital: | ||||

| Ambulance | 8 | 11 | 7 | 26 |

| Independently/with family | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cognitive impairment: | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| No | 7 | 11 | 5 | 23 |

| Attendance at ED: | ||||

| Weekday | 4 | 12 | 4 | 20 |

| Weekend | 4 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| In hours (9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mon-Fri) | 2 | 10 | 3 | 15 |

| Out of hours | 6 | 2 | 5 | 13 |

Over one-third of patients had fallen; other common conditions included breathing difficulties, heart problems, confusion and stomach or back pain.

Reluctance to attend the emergency department

Most participants were reluctant to be taken to ED. Reasons for this reluctance included previous poor experiences in hospital, only recently having come out of hospital and therefore not wanting to go back in, fear of ‘never coming home again’, fear of a specific hospital, fear of ‘picking up a bug’ and the belief that it would be a ‘waste of time’:

M I resisted it. Told them [the ambulance crew] that I’d gone through the same thing before. Anyway, I went in and my treatment there exactly duplicated the previous time.

I … So you said you resisted that.

M Not physically.

I But you just made it –

M Yeah, I made it clear that I didn’t want to go …

I … And why is it that you didn’t want to go in …?

M Because the last time I went in, they wasted so much time.

In the face of pain, distress and anxiety, initial feelings of reluctance and resistance about being taken to ED gave way to feelings of resignation in most cases. In this context, the ‘decision’ to take participants to ED cannot really be seen as a decision at all, certainly not one in which participants could engage in any meaningful way. Ultimately, most accepted the decision recommended by paramedics who were seen as ‘knowing best’. Family members had, in several cases, played a role in persuading patients that they needed to be taken to ED:

F So we had to convince my Mom that taking to the hospital.

I Why did she not want to go?

F At first she didn’t want to but then when she, when we mentioned that was as soon as the treatment is finished we can bring you back home.

I Right.

F Everything will be fine and she trusts us of course, so I went into hospital with her in the ambulance. [S2 08C]

Staff care and attitudes

Participants emphasised attitudes, manner and responsiveness, rather than technical competence, when reflecting on the staff they had encountered in ED. Overall, participants were very positive about ED staff who were seen as being very caring, reassuring and pleasant in their manner:

F1 I didn’t doubt for one minute they cared.

I Why did you not doubt it?

F1 I don’t know. They kept saying ‘You’ll be all right [name] in a little while’ and they were gently caring. They weren’t sort of saying ‘Well, right…’ and talking amongst themselves as much to say, ‘Well right’ you know ‘here comes another one through the machine sort of thing.’ But they weren’t. They were genuinely caring. [S1 07PC]

The importance of being treated with respect, particularly in the context of older age, was highlighted. Comments made by some indicate that they had not expected a positive experience (fearing that they would be treated negatively because of their age) but this had not been the case:

F1 I refer to older people, to my age group, normally I’d be the first to say ‘Her age. They haven’t got the patience.’ But having been in the last time, well four times, I can’t fault it. [S1 07PC]

A small number of participants, however, did feel that they had been treated negatively because of their age, describing what they saw as a lack of input or intervention during their time in ED/hospital:

I Right. Okay. It doesn’t sound like much happened whilst you were there?

F No. It didn’t. To be quite frank with you. They don’t want to know us old ones.

I Is that how you feel?

F That’s how I feel…

F Did you feel the same in every single part of the hospital that you went in?

F Yeah. They didn’t. If you were over 80 they didn’t want to know. [S2 06P]

A key concern related to staff being unresponsive when patients called for their attention. This was a particular issue for patients who needed assistance with toileting. While highlighted by a small number of patients, this issue had a significantly negative impact upon their ED experience, relating as it does to personal comfort and dignity. One patient described how upon requesting assistance to go to the toilet she was effectively told it was acceptable for her to soil herself as she was wearing incontinence protection:

M You get the impression because you were wearing counter measures

F Oh –

M Yeah, proper pants –

I Incontinence –

M It’s basically – it’s all right, we’ll sort it out later. Which isn’t very good for dignity.

I No, it’s not –

F And I was told 2 or 3 times, when I say I don’t like getting wet underneath – I was told 2 or 3 times oh it doesn’t matter, that’s what the nurses are for.

I Really?

F I was more or less told it’s quite alright if you do it in your pants.

Information and communication

The provision of information and effective communication between staff and patients were highlighted as crucial by patients and relatives during their time in ED. Being kept informed of what was happening (tests and treatment), what was likely to happen (i.e. admission, transfer or discharge) and some indication of what was wrong was absolutely key. Experiences, however, varied significantly. Some patients reflected positively: staff had kept them informed, explaining pending tests and procedures using a clear and friendly communication style. On the other hand, some participants described negative experiences concerning the provision of information and communication which had caused frustration and bewilderment, as they were left with little sense of what was going on:

I Did you feel that they were communicating with you what tests had been done and did you get any results back or -?

M Erm … no, I think it’s just that waiting thing that kills it. So my wife and daughter went off and then at eleven o’clock, two ambulance guys turn up ‘can you get your kit, we’re off to [name of another hospital].’

I At what point did you know you were going to be admitted, taken to the [name of other hospital], was that decided quite quickly or did that take quite a while?

M I think the system knew but I didn’t really…the information really doesn’t go to the patient until it’s happening I think, you know, […] the system seems to know what’s happening, but sometimes the patient doesn’t. [S2 01P]

Linked to the provision of information, some patients commented on the extent to which they had been involved in discussions and decision making about their care. Again, experiences were mixed. Some patients reported that they felt listened to and had participated in decision-making; others, however, had not felt involved in important decisions about their care:

I When did you know that you were going to be moved on to a ward?

F Not till the stretcher come. I said, ‘Where am I going?’ They said, ‘You’re going on a ward.’ I said, ‘What for?’ ‘Oh, we don’t know whether you broke your leg or not.’ Well if they didn’t know if I broke my leg or not who did know?

I So you had had an x ray?

F Yeah. But nobody ever says, ‘Oh your x ray is fine’ or this that and the other. No. Very badly done.

I So nobody asked you whether or not you wanted to go onto a ward?

F No.

I It was just kind of done without asking you?

F Without asking me. As though I’m an idiot. I know I’m 82 years but I’ve still got it all up here. [S2 06P]

Together with the provision of information, the way ED staff communicated and the language they used were important to patients and relatives while in ED. Some patients had been impressed by the way in which staff had introduced themselves and explained what they did. Others, however, were not always clear on these details and this was seen as an impediment to communication; patients were often unclear as to whom they had seen and should speak to with queries. A few patients commented that the various coloured uniforms on display in ED (with no explanation as to what these represented) added to the confusion:

I Yeah. So you’re in the A&E bit. How many different doctors did you see, do you know?

F I think I saw two different ones. And some nurses, you don’t know who’s who, to be honest, even when I was in hospital, I said to my husband ‘do you know, there’s so many different colours, you know –

I Uniforms you mean?

M Yeah.

F - one’s got green, one’s got blue and one’s got light blue, one’s got white, one’s got pink’ and so in the end I never knew who really was the Sister and who wasn’t, you know. [S3 05PC]

A few participants commented on the language and communication style used by ED staff; again, painting a mixed picture. Some had appreciated the clear, candid and honest language employed by staff when discussing their cases. Others, in contrast, stated that they could not always hear or understand what they were being told or that things were not always explained properly. Staff, they found, did not always take time to speak slowly and clearly to ensure that information was received and understood.

Environment and personal comfort

The ED environment created a significant impression upon participants’ experiences of emergency care. Several patients at one site drew attention to what they described as an overcrowded, noisy, and sometimes rather ‘chaotic’ ED environment:

F Yeah. And it was, you know, chaotic I thought.

I Just because of the number of people there or -?

F Yes, it was a huge amount of people there, seemed to be, you know, and there was somebody calling out ‘I want some biscuits, can you get me some biscuits I want some biscuits!’ and then she turned round and started to sing! And I thought I’ve landed in a mental home! [Laughs]

F You know, it sort of went on like that for quite a while. And there was no music, nothing to listen to, except these chaotic things that were happening around me and I thought for crying out loud, you know, it would be nice if somebody turned on some music or if you could watch a screen and, you know –

I But there was nothing at all.

F No. [S1 08P]

In contrast, patients at another site, which had recently been refurbished and used glass, rather than curtained cubicles, generally talked about the ED environment in overwhelmingly positive terms. The resulting modern, calm, and quieter atmosphere had in turn made them feel calmer as they experienced less rushed and ‘smoother’ care: