Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128107. The contractual start date was in December 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Sheaff et al. This work was produced by Sheaff et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Sheaff et al.

Chapter 1 Policy and research setting

Third sector organisations contribute substantially to the English health and care systems. This study examined how the NHS and local authorities (LAs) have commissioned voluntary, community and social enterprises (VCSEs); some of the outcomes for commissioners, VCSEs and the health and care systems; and which contexts facilitate or impede the production of these outcomes. Our aim was to examine which factors strengthen collaboration between commissioners and VSCEs in commissioning all kinds of health and care activities, as a contribution to making publicly funded services more responsive to patients’ and carers’ needs.

Health and care

Defining the sector and issue

This section summarises some definitional debates about health and care, the healthcare sector and commissioning, and positions the study vis-à-vis earlier studies of commissioning and of VCSEs, and situates its analytic framework against other conceptualisations.

A standard definition takes health as the ‘absence of disease’, as opposed to a ‘complete sense of well-being’, reflecting a tension between medical and social models of health, respectively. This report adopts the social model as it offers a more holistic picture and acknowledges the social determinants of health (SDoH), and therefore enables a broader assessment of agencies’ roles and contributions. For commissioning is concerned not solely with service delivery (‘health care’) but also with health improvement (including addressing health inequalities). 1 Furthermore, the three tracers (concrete examples used to trace causal relationships through a complex system) that we deploy in this study – social prescribing, end-of-life care and learning disability support – span activities which do not fall neatly into the category of healthcare provision. We take ‘health and care’ to include health care and social care. 2

In the UK there is a tendency to conflate healthcare funding and provision with the NHS, but a key purpose of the 1991 reforms was to separate them. While the NHS provides 85% of health spending in the UK,3,4 there is now increasingly diverse provision. The NHS itself continues to provide the bulk of services, but the independent sector plays key roles especially in some specialties, notably mental health and elective surgery. The independent sector includes for-profit businesses (corporations), not-for-profit organisations, social enterprises, and voluntary and community interest companies (CICs). LAs are responsible for the provision of adult and children’s social care (as well as other key public services such as social housing and public health). Social care funding consists of local authority (LA) funding and user payments.

Notwithstanding the NHS England (NHSE) role in commissioning tertiary and national services, LAs also commission services from the statutory and independent sectors, something especially relevant to the tracers that this report follows. Inevitably, there are some inconsistencies whereby commissioning arrangements at different geographical and organisational scales conflict. For example, regarding obesity, weight management services have traditionally been commissioned locally whereas bariatric surgery has been commissioned centrally. The idea of subsidiarity is that ‘a higher authority should not accredit itself with responsibilities which could otherwise be carried out by a lower authority or at a more local level’. 5 Likewise, debates about co-terminosity have assumed that contiguous boundaries of NHS commissioners and LAs foster interorganisational collaboration,6 but such benefits are not always realised.

The 2012 reforms had two impacts relevant for this analysis: increasingly complex accountabilities and greater fragmentation. The increased complexity arose from the dense pattern of accountabilities of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), which in turn arose from the proliferation of other NHS organisations involved in health system governance at local level. 7–9 This was not simply the tension between accountability upwards to the centre (through performance management) and accountability downwards (to local stakeholders including communities and public), with accountability upwards arguably predominating;8 the commissioning of primary medical care by CCGs created a (potential) conflict of interest, since CCGs were membership bodies whose members were mostly general practitioners (GPs), who would therefore be commissioning themselves to provide a service.

A second impact was greater fragmentation within the statutory sector and among other agencies (including VCSEs). While such fragmentation had been a consequence of the quasi-market since 1991, the 2012 reforms exacerbated it, with consequences for patient outcomes and for workarounds by commissioners to ‘knit back together pre-existing systems of service planning and delivery’. 9,10 The response of NHSE in the Five Year Forward View was therefore that ‘Increasingly we [the NHS] need to manage systems – networks of care – not just organisations’ and that ‘services need to be integrated around the patient’. 11 It proposed five new models of care (oriented towards primary and ‘out of hospital’ care) including multispecialty community providers, primary and acute care systems (vertically integrating hospitals and general practices), and urgent and emergency care networks. These models were intended to contain the growth of demand, and therefore waiting times and costs, in NHS hospitals.

The most recent step in that direction was the introduction of Integrated Care Systems (ICSs). Each ICS will contain an Integrated Care Board (ICB), primarily an NHS body and responsible for planning and delivering NHS services in the ICS area. Alongside, an Integrated Care Partnership – a committee jointly formed between LAs in the ICS, the ICB, and relevant wider partners – is responsible for creating a strategy stating how the health and care needs of the local population will be met by the ICB, LAs and NHSE. 12 The ICSs face the tasks of trying to make progress on local or longer-term priorities such as increasing healthy life expectancy and reducing avoidable ill health while also addressing the national policy focus on shorter-term challenges such as the elective care backlogs and accident and emergency (A&E) waiting times. Another unresolved issue remained ICB relationships with non-NHS providers, both corporate and third sector, which were outside the collaborative commissioning framework. This issue was connected with that of how different strategic, planning and commissioning roles will be allocated between the ICSs and ‘Place’-level entities within them. Initially, at least, VCSEs (among others such as ambulance trusts, education sector, police) appear to be involved for particular projects rather than as core members of the Place-based partnership. 13

Commissioning and the commissioning cycle

In the 1990s the original rationale for commissioning was to separate funding and provision, enabling more diverse provision, and separating the ‘rowing’ (operational) and ‘steering’ (strategic) functions of public agencies. 14–16 Commissioning has thus been applied to health and social care, besides education, social housing, transport and so on. However, there was an apparent asymmetry as originally (in 1991) health authorities were the NHS commissioners, but at the same time GP fundholding offered an alternative form of commissioning. For many years there was limited engagement between these commissioners, or between them and local government, which commissioned social care and many VCSEs. The introduction of primary care groups did secure a LA representative on the boards of these NHS commissioners17 but the multiple commissioners’ objectives and interests rarely aligned because, as Checkland et al. argue, ‘commissioners and providers struggled with the more fundamental ideas underpinning commissioning, suggesting that shared understanding is far from the norm’. 18 Other rationales for commissioning included:

increasing choice, devolving decision-making to local areas, increasing public services efficiency while making them more accountable, transparent and opening services to a wider set of providers… increasing value for money, encouraging increased joint working and information sharing, as well as creating shared and pooled budgets. 19

Across different LAs there developed different combinations of outsourcing services, spinning LA services off into independent but still publicly owned enterprises, and keeping services in-house. Earlier and more widely than the NHS in many cases, LAs also developed commissioning relationships with VCSEs. 20,21 Because VCSEs were somewhat tangential to commissioning activities and budgets focused especially on NHS secondary, curative care, NHS commissioners have had a more partial understanding of VCSEs’ capacities and resources, with less embedded relationality, perhaps displaced or fractured by staff turnover (with loss of organisational memory), and shifting information systems and performance metrics.

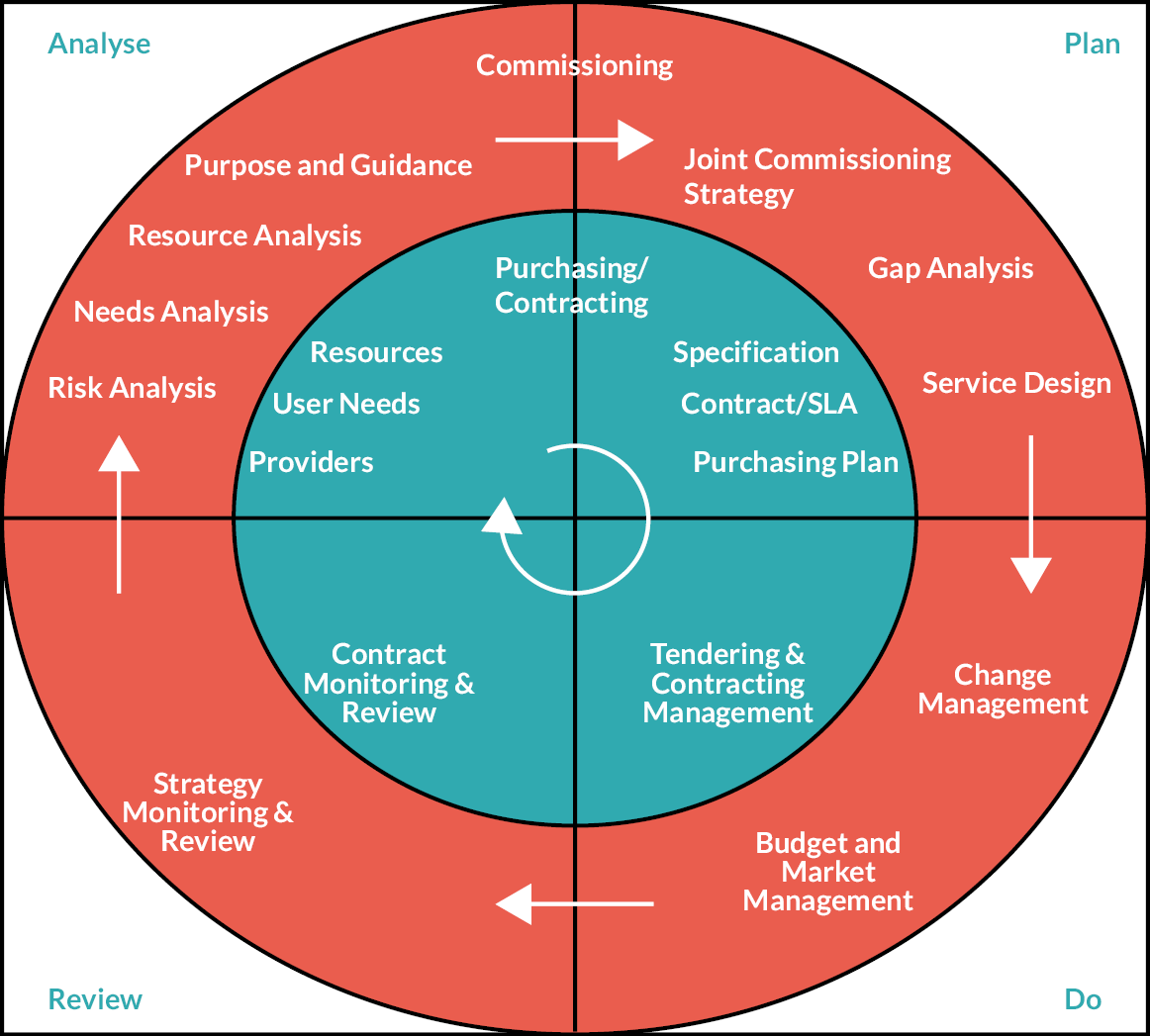

Commissioning is a cyclical activity. As Figure 1 shows, the commissioning cycle has resonances with strategic planning tools also employing a somewhat normative model comprising: health and care needs assessment, goal-setting and planning, procurement and contracting, monitoring performance, and revision subject to performance. 22,23 The Cabinet Office defined it as ‘a cycle of assessing the needs of people in an area, designing and then securing an appropriate service’. 24 Figure 1 shows how the commissioning cycle can be implemented through a ‘purchasing/contracting’, that is a procurement, cycle.

FIGURE 1.

Commissioning and procurement cycle. SLA, service level agreement. Source: Blackpool JNSA. 25

This model is as much normative as descriptive. In practice, commissioning may often be closer to that of managers searching the ‘garbage can’ of already available ideas, methods and resources for any they might apply to their current tasks or problems. 26 The complexity of commissioning is perhaps explained by the relationality (importance of connectedness and relationships) in the quasi-market and the social and institutional embeddedness (persistent multiple connections) of the actors in it. Granovetter argued that ‘[C]ontinuing economic exchanges become overlaid with social content that carries strong expectations of trust’. 27 The result is ‘relational contracting’, in which contractual obligations are heavily supplemented, and attenuated, by non-contractual relationships between the parties. 28–30 Multiple relations – social as much as economic – between commissioners and providers are then likely to develop, especially between those organisations with the most resource dependency on each other. 31,32 (Indeed, one study found up to 85% of commissioner budget was spent with ‘local’ providers. 33) Consequences of this are profound. Commissioners lacking detailed knowledge of providers may rely more on social relations (including trust and reputation33) to influence the providers. They may fear that removal of resource (however small) from one provider may precipitate undermining other services (especially if there is an element of cross-subsidy). Over time, individual commissioners may build strong relationships and develop relational contracts with individual providers, possibly in the VCSE sector.

Co-commissioning

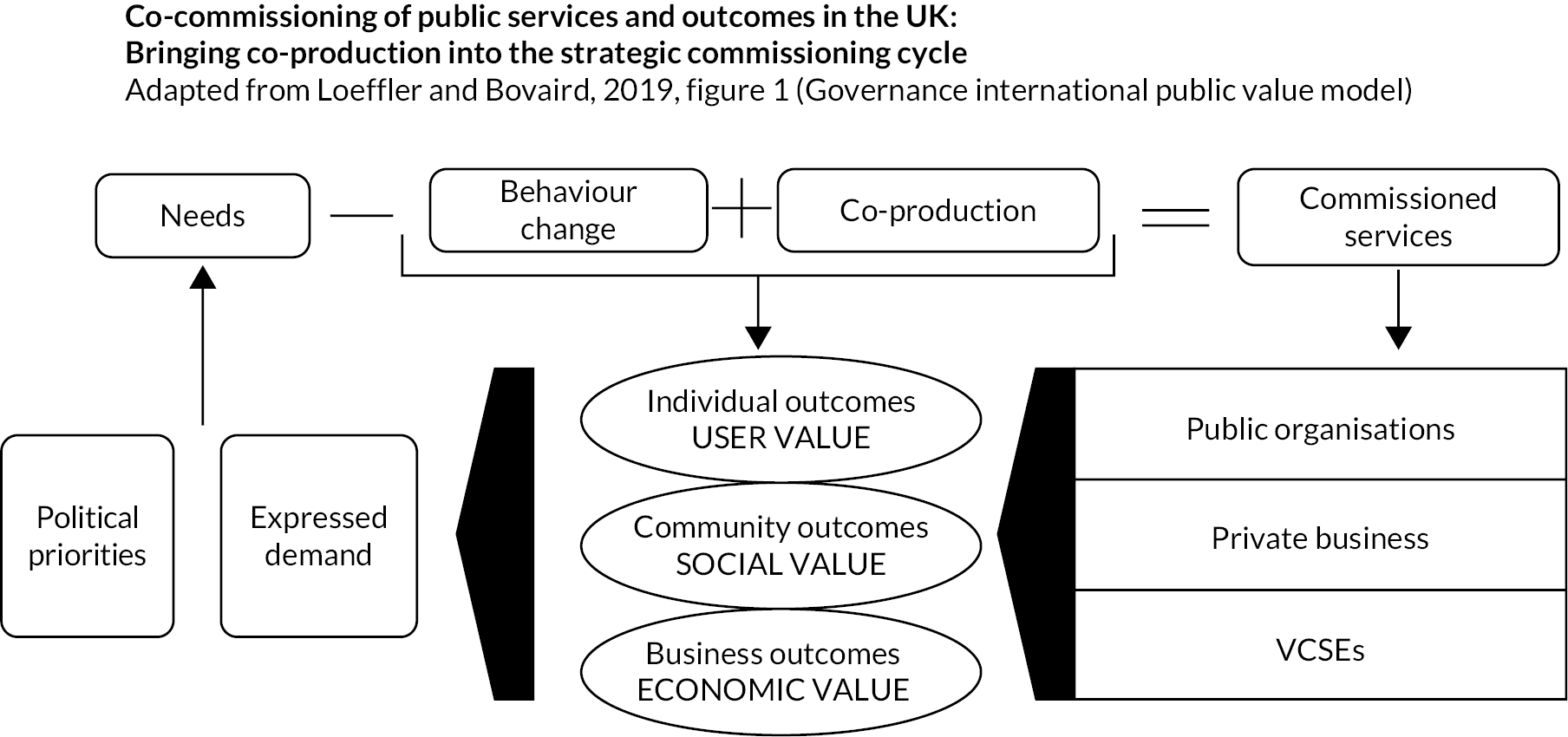

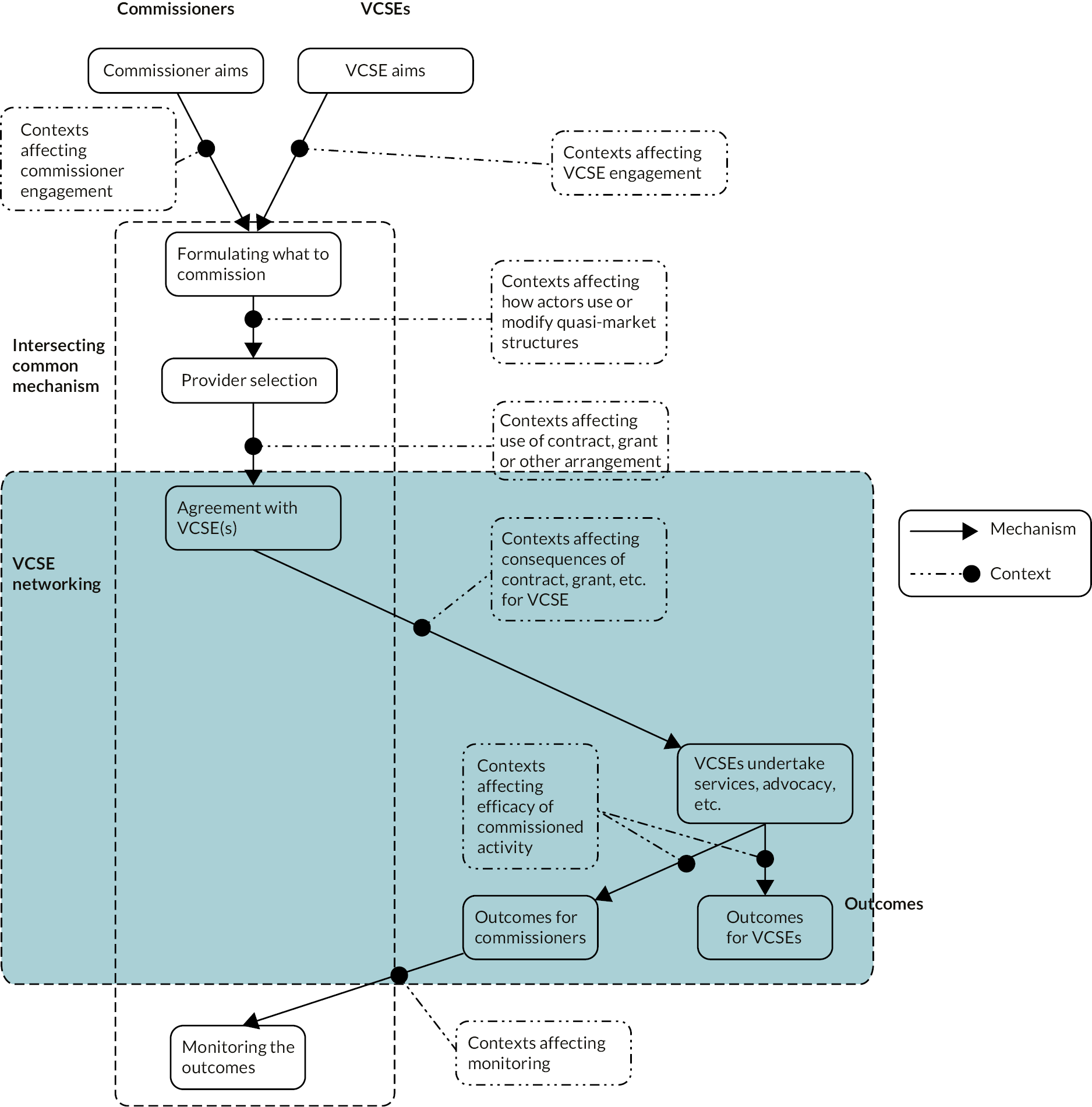

There has been growing interest in the co-production of public services with users and communities;34 that is, in ‘professionals and citizens making better use of each other’s assets, resources and contributions to achieve better outcomes and/or improved efficiency’. 35 Co-production is not simply closer collaboration between agencies but crucially with users, citizens and communities, often undertaken through and with VCSEs36 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Co-commissioning.

Loeffler and Bovaird distinguish four types of co-production: co-commissioning, co-design, co-delivery and co-assessment. 37 At minimum, commissioning might simply secure services in response to observed need, but through co-production, improved outcomes are likely. However, commissioners have traditionally been weak at co-production and, more specifically, co-commissioning. Through the mechanism of ‘citizen voice’, co-commissioning might comprise:

-

‘service users and community representatives on commissioning boards and procurement panels,

-

participatory budgeting to prioritise public policies or budgets,

-

personalisation – micro-commissioning and

-

crowdfunding’37

Practically, this might entail ‘co-deciding priority outcomes and services’, ‘joint monitoring of in-house services and external contracts’, ‘revising commissioning strategy’, and ‘joint analysis’.

Co-commissioning has been applied somewhat differently in various settings (e.g. mental health). 38 For example, in primary care, where it is relatively new, its first iteration followed the Five Year Forward View11 which announced enhanced powers for CCGs including greater involvement in primary care decision-making, joint commissioning and delegated commissioning arrangements. 39 Petsoulas et al. saw policy documents as making two main arguments for this shift: commissioning could be a ‘sticky plaster or solution to a problem’ or an ‘opportunity to develop place-based commissioning’. 40 Furthermore, co-commissioning can also be applied at an individual level such as through personalised budgets whereby ‘individuals are active participants in the planning and purchasing of their support’. 34 Yet while co-commissioning in this setting is an ‘iterative learning process’, it is also riven with power asymmetries and competing notions of expertise. There has been limited evidence of co-commissioning with VCSEs despite the call in the Civil Society Strategy41 for ‘a renewed focus on collaborative commissioning arrangements’. 19 Empirical studies of the health-related commissioning of VCSEs remain sparse.

Conceptual perspectives: commissioning as governance

Commissioning is among other things a form of governance which applies when, having relinquished line management control over other organisations, governments attempt to ‘steer’ and control in less direct ways the activities and independent organisations that they fund. Thus commissioning ‘remains the dominant process by which England’s state and third sector (and arguably NHS providers) financial relationships are managed’. 19 Governance (control without line management) through commissioning uses six main media of power:23

-

Managerial techniques, including those of the new public management, are extended from use purely within an organisation to the monitoring, and even management, of external organisations. 42–44 One way to do so is through a stable interorganisational network with the commissioner as its coordinating centre:45 a quasi-hierarchy. 42

-

Negotiated order: separate organisations may come to agree (perhaps only implicitly) a division of labour46 through which they coordinate resources in pursuit of shared activities or aims.

-

Discursive control by means of persuasion, whether scientific or ideological. That requires a shared discourse across the separate organisations, hence that each organisation has the ACAP to learn and use the common discourse.

-

Resource dependency and financial incentives: a commissioner stipulates the conditions under which it will purchase services,47 or pay more, thereby setting up financial incentives.

-

Provider competition: a commissioner can threaten to replace a non-compliant provider with another, whether only in principle (‘contestability’: the quasi-market is always open to new entrants48) or in practice if alternate providers already exist. 49–52

-

Juridical control: application of law, regulations or official inspections, or enforcement of the terms of a contract. 31,53

Different selections of media of power come to the fore at different stages in the commissioning cycle (e.g. competition, during provider selection). Similarly, commissioners select and hybridise these media of control according to local history and geography,54 provider ownership (public, corporate, practitioner-owned, third sector, etc.),55 the type of service being commissioned, and of course their own policy aims. 56

Commissioning reforms are seldom implemented entirely as intended. 57,58 As ‘street-level bureaucrats’, local commissioners have a degree of discretion. 59 Irrespective of national directives or guidelines, commissioners usually have some leeway in how they respond to local pressures and opportunities. 19 Commissioners must therefore engage in the ‘communicative and adaptive work’ of ‘street-level diplomacy’. 60 Bossert argued that the impact of decentralisation needed to be viewed in response to three dimensions:

-

‘the amount of choice that is transferred from central institutions to institutions at the periphery of health systems

-

what choices local officials make with their increased discretion (which may entail innovation, no change or directed change) and

-

what effect these choices have on the performance of the health system’. 61

In addition, commissioners are constrained ‘horizontally’ by having to collaborate with other local agencies, including other commissioners. The decision space framework (DSF) represents this intersection between vertical (central–local) and horizontal (local–local) constraints as the space for autonomy or ‘room for manoeuvre’62 that local agents have in making decisions about matters such as finance or human resources; Exworthy distinguished between inputs, process and outcomes. 63 Hence, local agents may have some discretion in certain aspects of their responsibility but not others. This can, of course, create tensions and ambiguities with higher-level agents. Moreover, the DSF highlights commissioners’ interdependencies, crucially, with other local agencies and organisations: for this study, VCSEs and LAs especially.

While the DSF aids understanding in the dimensions of autonomy for a local agency such as a commissioning organisation, it says little about how such autonomy is exercised in practice. Autonomy also needs to be understood in terms of the willingness and ability to exercise such autonomy,64 which a combination of factors might affect, including:

-

ongoing effects of centralisation (through behaviours and actions)

-

risk aversion, especially in financial matters

-

fragile managerial capacity and capability

-

concerns in adverse consequences of decisions for other local organisations.

The combination of willingness and ability to exercise their autonomy creates four possible scenarios for an agency:64

-

able but unwilling: unused or underused powers

-

unable but willing: frustration and disempowerment

-

unable and unwilling: acceptance of centralisation

-

able and willing: genuine local freedom.

Decision space does not remain fixed but is shaped by exigencies such as the dynamics of local politics, local agents’ capacity and capability and the central authorities’ demands, inter alia. Hence, the character of local (social and professional) networks has a strong bearing on how commissioning is conducted. 65,66 Moreover, it is likely that organisations will adopt workarounds to cope with and accommodate any perceived discrepancies between national policy and local networks. 67 These workarounds are likely to reinforce the local social and institutional embeddedness of commissioners and those whom they commission. 7

Voluntary, community and social enterprises in health and care

Defining the third sector

Next arises the question of what the third sector – a contested term – is. Alternatives include ‘voluntary sector’, ‘voluntary and community sector’, ‘social sector’ and ‘voluntary, community and social enterprises’ (VCSEs: the term we standardise on here). The wider concept of ‘civil society’ denotes all the non-state and non-market public spheres where citizens can express their different viewpoints and negotiate a sense of their common interests. 68 At any rate, the third sector is neither the state nor the market nor the family or entire community. Salamon and Anheier defined it as comprising all organisations that have all the following characteristics:69

-

institutionalised to some extent, either by being formally constituted or by having regular meetings, procedures, etc.

-

institutionally separate from government

-

not profit-distributing, reinvesting any profits internally

-

self-governing with their own internal governance procedures without external control

-

resourced to a meaningful degree by voluntary participation,70 whether in their activities or management

Besides noting characteristics which are not unique to VCSEs, such as having multiple stakeholders, revenue sources and activities, and complex accountabilities and tensions between senior staff and boards, many writers add that VCSEs are distinguished by the centrality of such aims (‘values’, ‘mission’) as empowerment and social justice. 71–73 Their functions correspondingly range across service delivery, self-help, mutual aid, capacity-building, campaigning and advocacy. In recent years, the boundaries between VCSEs and the public and private sectors have frequently become blurred and organisational hybrids more common,74 for instance the social enterprises encouraged by successive governments, including some in health and care. 75

Voluntary, community and social enterprises are very diverse, ranging from large household-name charities operating across the country to small organisations with few or no paid staff. VCSEs vary, firstly, in legal terms; contrary to popular belief, a charity is in England a legal status not a kind of organisation. VCSEs also differ by who controls them, having varying degrees of trustee, member and service user involvement in their governance. Some are democratically controlled by their working members (not just the trustees), beneficiaries or users,76 giving these VCSEs correspondingly distinct aims and motivations. 72,73

Voluntary, community and social enterprises and the policy setting

Many VCSEs originated in response to the failure both of markets and of the state to supply specific services or cater for particular care groups,77 although, conversely, much of the state welfare system including the NHS in turn arose in response to failures in VCSE coverage. 78 Governments have fairly consistently expanded the VCSE role of the sector in public service provision since the late 1970s, although their reasons have differed. 79 In the 1990s LAs predominated as the commissioners of VCSEs. Labour’s ‘Third Way’ emphasised partnership between sectors and mainstreaming VCSEs,80 and saw some substantial public investment in that. A ‘compact’81 between the government and VCSEs in England set out commitments for both sides to improve their collaboration. Several large capacity-building programmes were funded, including Futurebuilders which aimed to help VCSEs bid for public sector contracts and ChangeUp, designed to improve the sector’s infrastructure. NHS staff and other employees were encouraged to leave the public sector and create new VCSEs, usually social enterprises or mutuals. 15 Later initiatives paid more attention to the commissioning system itself and to public sector commissioners, in order to address some of the issues and challenges experienced by the third sector when contracting for public services. 20

David Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ agenda in 2010 promoted a changed relationship between citizens and the state, including new opportunities and spaces for voluntary action. One was opening public services to greater competition from charities and social enterprises, moving away from the partnership model of the Labour government. 82 However, the coalition government’s austerity policies radically changed the setting and terms of commissioning. Constrained public spending at both national and local levels put additional pressures on commissioners to procure services that provided value for money, while VCSEs faced growing demand for their services.

In 2018 the government highlighted the need to ‘reform commissioning in favour of charities and social enterprises’ in its Civil Society Strategy,41 supporting alternative commissioning models such as collaborative commissioning, flexible contracting (including Innovation Partnership projects) and Social Impact Bonds83 and, concomitantly, more extensive NHS commissioning of VCSEs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many commissioners adapted by giving VCSEs unprecedented levels of flexibility in delivering public sector contracts to respond to local needs. Commissioning relationships became viewed as less transactional and more collaborative. 84 Macmillan suggests that in the pre-pandemic decade much of the sector’s infrastructure was dismantled, which fragmented the provider landscape, but also that recent events have stimulated collaboration between national infrastructure bodies, greater recognition of their role, more spaces for dialogue and greater coordination. 85

Commissioning voluntary, community and social enterprises

Voluntary, community and social enterprise commissioning: size and scope

Government funding for VCSEs has largely mirrored wider policy. It grew substantially during 2000–10, fell during the period of public spending austerity, and then plateaued. In 2019–20 VCSEs comprised almost 166,000 organisations with a total income of £58.7B;86 26% of their income (£15.4B) was from government sources. Not all VCSEs were involved in public service delivery or received public funds. Approximately 38,000 VCSEs were active in health and in social services with a combined income of £19.7B (£6.4B and £13.3B, respectively), 34% of it from government sources. More recent Charity Commission (CC) data show a large increase in the percentage of VCSEs receiving government funding in 2020–1 due to the COVID-19 pandemic support packages. However VCSEs’ loss of income because of the pandemic was far bigger than in the 2008–9 recession and the period of austerity which followed. Public sector procurement data show that between March 2016 and April 2020, 3140 VCSEs were named on 7330 published public sector contracts together worth £17B,87 but these were only 5% of the total value and volume of contracts awarded. Local government awarded substantially more contracts to VCSEs by value (£8.9B) and number (4871 distinct contracts) than did central government and the NHS. Nevertheless, the value of NHS contracts awarded to VCSEs increased annually after 2017–8 and in 2018–9 equalled the value of contracts awarded by local government. Of the VCSEs named on a published public sector contract, 56% had only 1 contract, 41% had between 2 and 10 contracts, and 3% had more than 10.

Health and care was by far the largest activity by total value of VCSE contracts, with £11.6B awarded between 2016 and 2020, representing 24% of the total value of contracts awarded in health and care, although other activities saw higher proportions of the total number of contracts awarded to VCSEs, particularly those concerned with domestic violence and sexual abuse (66%) and homelessness (69%).

Kinds of activities and work-processes undertaken by voluntary, community and social enterprises

Voluntary, community and social enterprises’ health and care work is hugely varied, falling into four main categories: service provision; advice to commissioners, planners and funders; medical research; and policy and campaigns. 88 Their services range from specialist clinical provision (e.g. hospices) to community-based support (e.g. day care and home-based support), condition-specific and general wellness support and advocacy; and accommodation services (e.g. residential and nursing care). 88,89 Many VCSEs act as advocates in order to influence and shape practice and policy, including local commissioning priorities and co-design initiatives for specific care groups. Some focus explicitly on prevention and promoting healthy lifestyles, others on social prescribing activities which support the health and well-being of patients with complex health conditions and needs. 90 Some VCSEs, usually the larger ones, co-fund services with public commissioners through contracts for specific care groups and personal budgets or grants for individuals; and some contribute to financing medical research. However, many other VCSEs fund their own evaluations to assess the effectiveness and impact of their services, and so inform their advocacy work. Table 1 distinguishes the level of support that VCSEs provide for local health systems.

| Level of support | Activity | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Direct treatment and support | Health and care treatment/support delivered directly to people (including wider non-medical support) |

| Engaging people in keeping healthy, prevention | Activities designed to reduce the likelihood of people becoming unwell, including behaviour change campaigns, information services, outreach work with specific at-risk communities | |

| Supporting self-management | Activities designed to help manage an existing condition, information services, signposting to available support, health coaching | |

| Involving families and carers | Services providing support and information to families and carers to improve or work towards integration of families and carers into treatment processes and decisions | |

| System | Integrating and coordinating care | Coordinating care through statutory actors and organisations (e.g. relaying information along the patient pathway, research) and through patients (e.g. giving them knowledge and advice about services) |

| System redesign | Activities to inform how services and care pathways are designed and delivered (research, pilots and relaying the views of beneficiaries to commissioners and policy-makers) | |

| Support for health and care professionals | Training health professionals in specific areas, bringing them together with patients and other interested actors, providing relief capacity |

Dayson and Wells suggest that VCSEs’ comparative advantage lies in how VCSEs carry out their work, who they work and engage with, and the role they play within their communities. 92 They are trusted intermediaries and can act as a conduit for people’s views and engagement, and can access and reach communities which statutory providers can find difficult to reach. They also bring additional resources to the health and care system, including charitable funds and volunteers. 91

Who undertakes the activities within voluntary, community and social enterprises?

While charities, community groups, social enterprises, mutuals and cooperatives have all been commissioned by the NHS, there is no comprehensive overview of their level of involvement, by type of VCSE, in health and care. Procurement data for 2020 indicate that two-thirds of the income (£6.2B) from government contracts was secured by VCSEs with incomes above £10M, a group of just over 500 providers. 93 Especially for smaller VCSEs, the hidden transaction costs of contracting – especially those of tendering, process and of fulfilling information and monitoring requirements once the contract is let – can deter involvement. 94 Smaller organisations are often ill-equipped to navigate the complexities of commissioning and procurement systems and compete with better resourced VCSEs and corporations. 95

Voluntary, community and social enterprise services and activities can be undertaken by paid employees or volunteers or a mix. Although not all VCSEs involve them, volunteers are integral to the value of VCSEs because of their proximity to service users and connections within local communities. Volunteer labour can also be seen as a way of saving money. VCSE approaches to involving service users vary greatly according to each VCSE’s organisational form, interests and governance arrangements. 96 With co-production and co-commissioning rising on the commissioners’ agenda, the role of user-led VCSEs has come to the fore. In these organisations the boundaries between staff, users, members and volunteers are often blurred, with people having multiple and overlapping roles. 97

Voluntary, community and social enterprise relationship to public and corporate sectors

Voluntary, community and social enterprises are motivated to engage with commissioners for a range of reasons depending on their purpose and activities. For service delivery organisations, winning a public sector contract gains funding which helps them pursue their mission and goals, and diversifies their income stream in an increasingly challenging environment. As additional motivations, many VCSEs work with commissioners because they believe their experience, expertise and importantly, their relationships with users, members and communities put them in good stead to deliver public services and respond to users’ and communities’ needs. In England the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 required commissioners to consider the wider social, economic and environmental benefit of contracting, an attempt to acknowledge the social value that VCSEs generate and so make it easier for them to compete for contracts. However, ongoing debates as to how social value should be defined and measured have made its implementation challenging.

Finally, some VCSEs engage with commissioners as ‘strategic partners’, not to deliver services themselves but at a more strategic level, whether local or national, by seeking to shape public services, influence commissioning priorities, address health inequalities and change the relationship between the commissioners and VCSEs.

Consequences of entering a relationship with commissioners

Some studies have argued that being commissioned has led to the increased professionalisation of VCSE management, but also bureaucratisation98 and loss of internal democracy, even ‘managerial capture’. 99 A ‘degeneration’ theory suggests that a result has been VCSEs becoming assimilated to corporate and public sector organisations, losing the features that make them distinctive. 100 Similarly, the theory of institutional isomorphism101 suggests similar transformations occur as VCSEs mimic private and public sector managerial practices such as audit, performance management and outcomes measurement. 102–104 Other studies report risks to VCSEs’ independence, mission, finances and reputation, and that ‘co-optive’ relationships develop between the VCSEs and the statutory sector. 105 A literature review20 noted such adverse impacts as:

-

compromised independence, challenging VCSE advocacy and campaigning capacity106,107

-

mission drift away from VCSEs’ original core purpose,108 for example as VCSEs seek income to finance service changes that commissioners insist upon109

-

contract requirements diminishing VCSEs’ innovativeness and flexibility to respond to changing user needs

-

insecure employment terms and conditions, creating problems of staff retention and morale; or a shift from volunteer to paid labour110

-

more competitive relationships between VCSEs

-

stratification between VCSEs that deliver public services and those that do not

Yet the evidence is mixed, including VCSEs’ own views about whether their independence has been compromised or whether their mission has drifted. In some VCSEs public commissioning has led to more formalised volunteer management practices, especially the adoption of a work-based model of volunteer management with more developed training opportunities for volunteers and more emphasis on volunteering outcomes for service users and the volunteers themselves, alongside organisational culture changes as VCSEs have become more bureaucratic and business-like, placing additional pressures on volunteers. 111

This pattern of findings suggests that VCSEs’ experiences are context-dependent. While VCSEs are often portrayed as rather passive players in the commissioning landscape and facing multiple challenges, such accounts tend to underestimate how VCSEs’ strategies, practices and experiences vary, and underestimate VCSEs’ own active role. 36

Interfaces and interaction

Publicly funded services are often, even typically, provided under contract by corporatised112 but still publicly owned organisations or completely independent providers, including VCSEs. 113 Commissioning these providers is, among other things, a way for governments to exercise governance over these policy subjects in the absence of direct hierarchical control108,114–116 (see Chapter 1, Health and care). To that extent, commissioning relationships can be conceptualised as the application of different forms and combinations of media of control over the providers,23,117 through which governments attempt to implement their current policies for the sector (see Chapter 1, Health and care). In practice, governance through commissioning has had varying degrees of success. Alongside instances of policy subjects implementing a policy up to118 or even beyond119 policy-makers’ expectations are reports of implementation failures. 120 In other cases, policy subjects have tried to delay the implementation of policies which they expected to harm them,121 or implement them selectively,122 or resist them. 123 Either party may try to influence, even ‘capture’,124 their counterpart organisations, for instance by managing their access to information. 125,126

Realist evaluation,127 an established method for explaining such differences, makes six main assumptions about policy and its implementation:

-

Policy-making is understood agentially as stemming from the intentions and actions of policy-makers in particular, among the many actors involved.

-

Every policy is implicitly a theory:128,129 in the present case, a programme theory that specific ways of commissioning VCSEs will lead them to help produce the policy outcomes which the policy-makers first intended (see Chapter 1, Health and care).

-

To induce the policy subjects to implement a policy, the policy-makers apply or create implementation mechanisms which bring resources,130 persuasion, payment and the possibility of coercion to bear upon the policy subjects.

-

Achieving these outcomes also depends on the contexts in which these ways of commissioning are implemented. 131–133

-

Depending on the contexts, the resulting policy and organisational outcomes may approximate to the policy-makers’ original intentions but may also include perverse, unforeseen and emergent outcomes.

-

The programme theory and its implementation can therefore be evaluated instrumentally, in the policy’s own terms; that is, how far the observed outcomes satisfied the policy intentions which motivated it.

Items 1–5 together constitute a context–mechanism–outcome configuration (CMOC), which is defined relative to a focal agent. When evaluating attempts at policy implementation, the decision- or policy-maker is the focal agent. The policy subjects’ reactions may be a mechanism or outcome, depending on the case. The policy subjects and any other actors involved are parts of the implementation context. The latter influences how far the mechanism had the effects which the focal agent expected, including any intended effects on the policy subjects’ behaviour.

Whether the mechanisms for implementing a policy produce the outcomes that the policy-makers intended therefore depends critically upon how the policy subjects react. As Chapter 4, Voluntary, community and social enterprises aims outlines in respect of VCSEs, the policy subjects also bring their aims, assumptions and resources into the policy implementation mechanisms. Therefore the ways in which VCSEs engage in commissioning, and its consequences for them, can be explained – hence researched – by a reasoning symmetrical to the realist evaluation of the commissioners’ commissioning practice but in reverse, now taking VCSEs rather than commissioners as the focal actor.

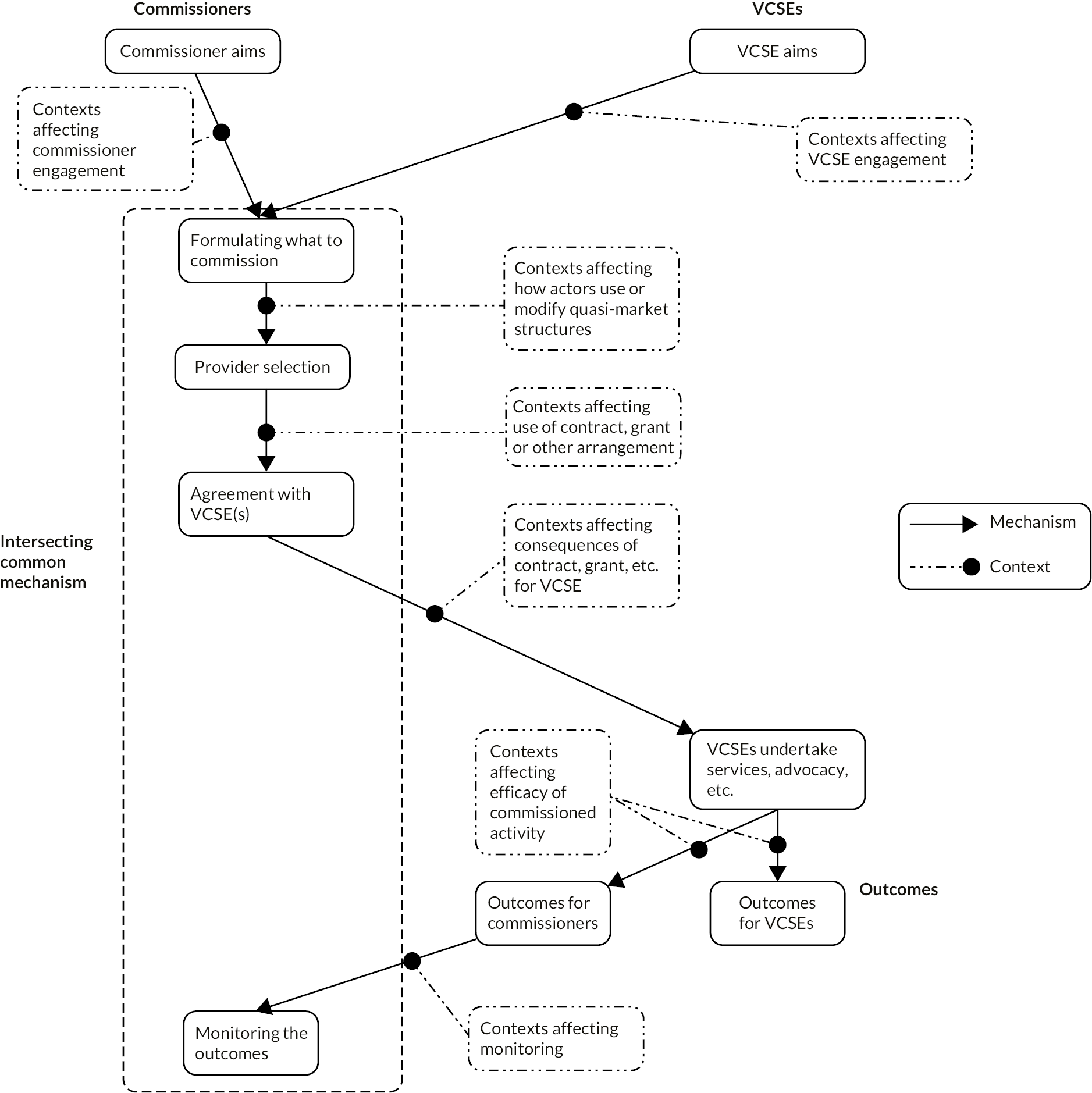

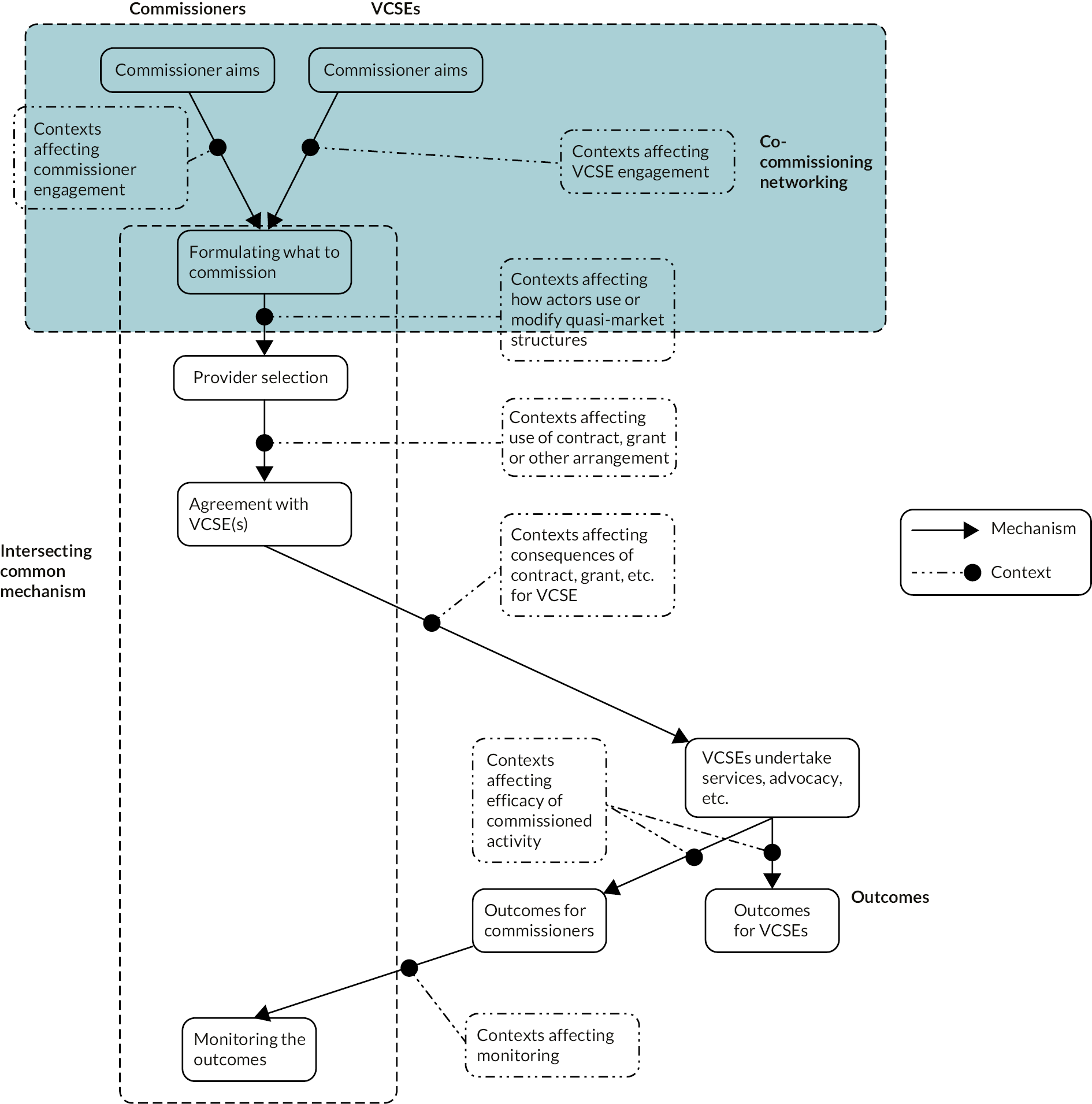

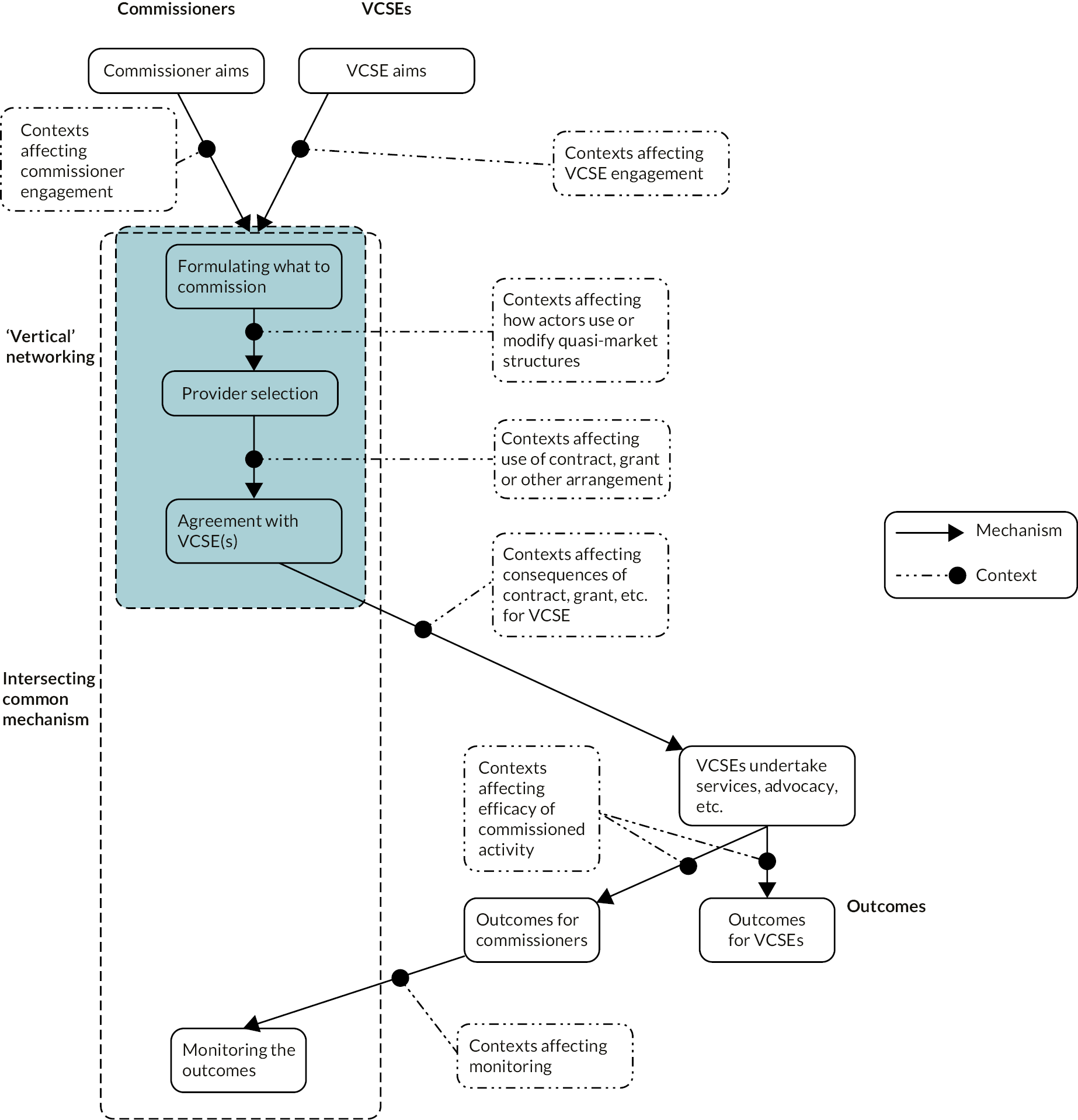

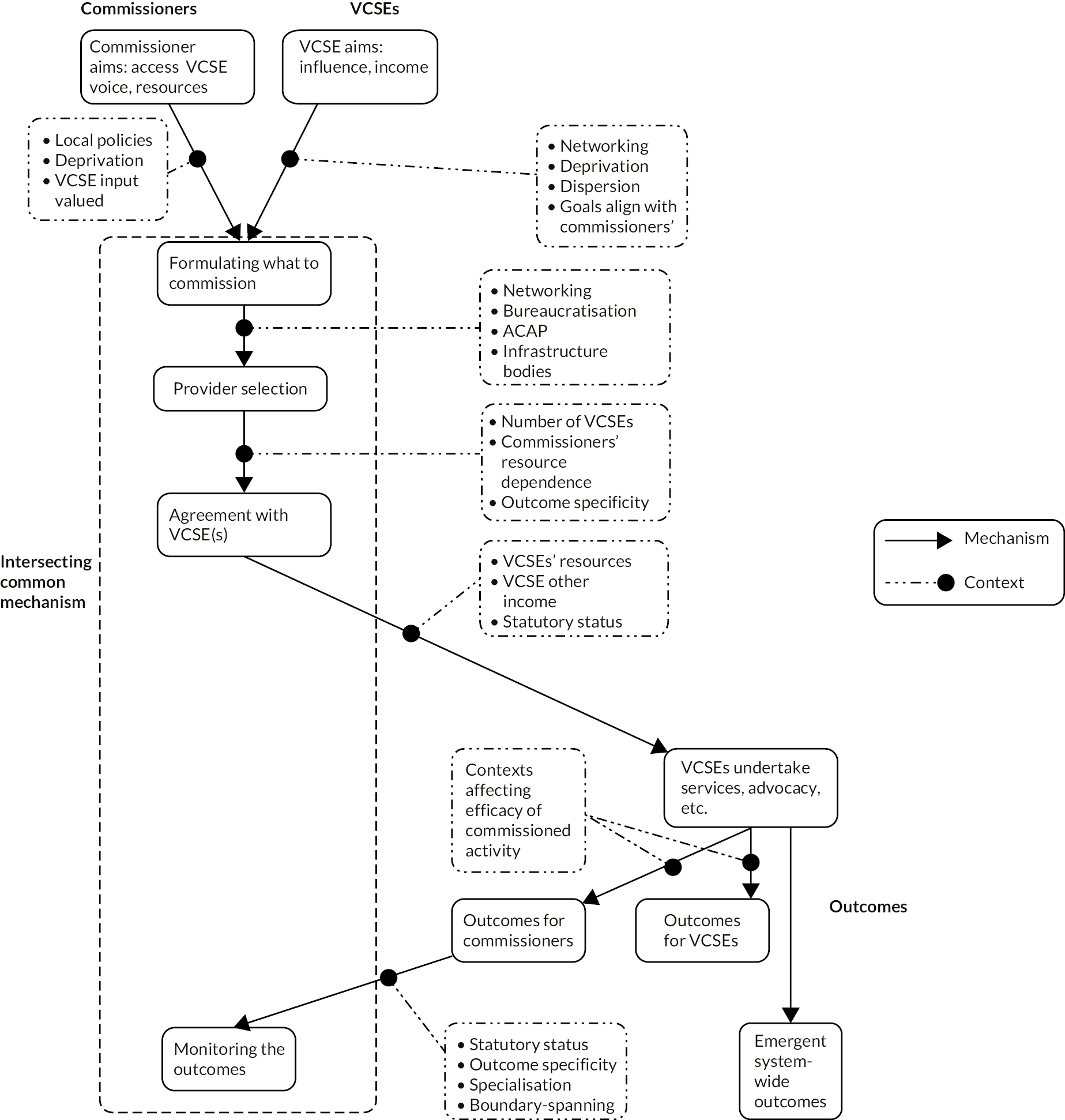

The policy outcomes and other consequences of commissioning VCSEs can therefore be understood as resulting from two interacting sets of mechanisms at the interfaces between commissioners and VCSEs: those that the commissioners use in commissioning VCSEs, and those that VCSEs use when engaging with commissioning. In one CMOC, commissioners are the focal actor. In commissioning VCSEs, they apply programme resources (e.g. finance, legitimation, influence) as mechanisms134 which, if VCSEs respond as the commissioners expect, will realise the commissioners’ current commissioning and policy aims. The ways in which VCSEs participate in the workings of those mechanisms by contributing resources and ideas over time are thus contexts133 which affect what outcomes the commissioning mechanisms produce. However, the ways in which the VCSEs engage with commissioning, and the outcomes for them, can be explained in a symmetrical fashion but with the roles reversed. In a second CMOC, VCSEs are conversely the focal actor, commissioning being (also) a mechanism through which they pursue their aims. How commissioners respond to VCSEs’ attempts to become commissioned are for the VCSEs a context which affects what outcomes commissioning mechanisms produce for the VCSEs. NHS commissioning of VCSEs can thus be understood as working of these two CMOCs which intersect where the commissioners and VCSEs interact, each party using the available governance structures as a means through which to secure and negotiate a contract, then letting the contract or making some alternative payment arrangement (e.g. a grant), and finally either ceasing, revising or repeating the experience. Figure 3 shows diagrammatically the two mechanisms and their points of intersection (surrounded by a dotted line). (For clarity,Figure 3 omits the feedback loops from monitoring to the possible revision of the commissioners’ and VCSEs’ respective aims in light of the outcomes achieved.)

FIGURE 3.

Commissioners and VCSEs: dual CMOC, common mechanism.

The area of intersection in Figure 3 thus contains the commissioning cycle (see Figure 1).

The outcome of an attempt to implement policy, in this case through commissioning, will therefore depend on what knowledge commissioners and VCSEs absorb about each other’s respective policy objectives or mission, intended mechanisms for achieving these objectives, assumptions about the likely consequences, and any side-effects of doing so (e.g. how their interaction will affect their other concurrent objectives). Such assumptions about mechanisms (the programme theories) underlie their respective ways of practising, or engaging with, commissioning. An important context for the mechanisms shown in Figure 3 would therefore appear to be what commissioners and VCSEs believe about each other’s intentions and likely behaviour, which results from how they learn these things; that is, their respective organisations’ capacity to access and apply knowledge from external sources135–137 – in short, their ACAP. ACAP consists of knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation in sequence. 138 Of the media of power, ACAP especially potentiates negotiated order (because ACAP both arises from and promotes relationality and organisations’ embeddedness in their local health economy) and discursive control.

By analogy with small and medium enterprises (in existing research, the nearest parallel to VCSEs in terms of organisational size and local embeddedness), one would expect ACAP in the present setting to develop, at least partly, out of networking between the organisations involved,138,139 with networking giving VCSEs a cheap and easy way to expand their knowledge; and in turn, to reinforce such networking138 in a virtuous circle. ACAP thus develops cumulatively in two senses. First, the knowledge acquisition phase is a precondition for assimilation, assimilation for translation, and translation for exploitation. Secondly, ACAP develops by building upon prior knowledge, and hence tends to be more fully developed in older organisations. 138,140

Absorptive capacity development thus has successive phases and multiple dimensions. It requires multiple organisational capabilities. These include combinative capability: the organisation’s socialisation processes141 (organisational eultures,142,143 internal dialogue,144–146 ‘mental models’ receptive to knowledge acquisition), its systems capabilities (formal policies, managerial support, training) and coordination capabilities (internal networking,147 access to expertise). Hence ACAP development is not a unilinear increase in just one characteristic but involves multiple linked changes in the profile of an organisation’s knowledge-absorption activities across the four phases (acquisition, assimilation, translation, exploitation) and in the profile of capabilities noted above. Which capabilities are most relevant to an organisation depends on whether its tasks and environment are stable (systems capability is most relevant), fragmented and diverse (socialisation capability) or dynamic (coordination capability). 139,148

First applied to corporations,135,140,149 then small and medium-sized enterprises (the German Mittelstand),150 and later CCGs,141 the concept of ACAP has yet to be adapted for or applied to the commissioning of VCSEs. A priori, all four phases of knowledge absorption appear likely to assist a more accurate translation of commissioner and VCSE aims and knowledge into needs assessments during co-commissioning, and enable VCSEs as prospective providers to attune their proposals or bids more closely to the needs assessments. Insofar as ACAP did develop among commissioners, among VCSEs and between commissioners and VCSEs, these organisations’ acquisition of knowledge would focus on each other’s aims, resources, and assumptions about the needs of their focal care groups in their localities, and knowledge of technical developments in the field. What matter here are the actors’ actual beliefs, not the a priori normative accounts of ‘rationality’ that microeconomics and game theory start from. Assimilation of this knowledge would involve translation between the different discourses by which commissioners and VCSEs formulate their aims and describe their organisations and activities. 108 Transforming the assimilated knowledge would firstly involve each organisation comparing, even reconciling, the other party’s with their own factual assumptions (e.g. about population needs, what costs are considered). Depending on how fully aligned the different organisations’ aims were, it might secondly involve reframing the acquired knowledge from a focus on the other party’s or parties’ aims (e.g. commissioners’ data structured around performance indicators) towards one’s own practical perspective (e.g. a VCSE demonstrating unmet service needs). Exploitation would consist of finding either new ways of delivering services and other activities, or new ways of performing the commissioning cycle, or both. Assimilation and transformation are more internal activities, although external expertise might contribute (indeed, be sought). Exploitation again involves external networking with commissioners, but also engagement, even co-production, with service users themselves. Greater capacity to acquire, assimilate and transform knowledge together appear likely to make provider selection better informed, help the negotiation of agreements between commissioners and VCSEs contribute to meeting the aims of both, and make the monitoring of VCSEs’ commissioned activity more accurate and informative. However, all these claims require empirical testing. In the NHS, both commissioners141 and VCSEs151 have often lacked sufficient skills and resources.

The preceding two sections suggest where our existing knowledge of the interactions shown in Figure 3 is incomplete, especially in the present changing setting. In summary, previous studies show that commissioners tend to find different combinations of methods (i.e. different ‘modes of commissioning’) effective in influencing different kinds of providers (NHS-owned, corporate, VCSE, etc.), rather than how the effective combinations of methods might differ for VCSEs, or indeed different kinds of VCSE. Neither is it known whether or how commissioning works differently when VSCEs contribute to their local commissioners’ priority-setting (i.e. to co-commissioning) besides, or instead of, as providers. At present (early 2024) there is little published evidence about how VSCEs will engage with the new ICSs. On the VCSE side, existing studies tend to focus on the risks, or potential risks, of commissioning to VCSEs rather than on how VCSEs try to engage with commissioners in pursuit of their own missions. We also lack knowledge of what specifically the contexts are which affect the working of the intersecting mechanisms in Figure 3.

These gaps in existing research, and the two-sided conception of commissioning practice outlined above, motivate our research questions.

Chapter 2 Aims and research questions

Research aims and objectives

This study therefore aimed to produce knowledge about which factors strengthen (or weaken) collaboration between health and care commissioners and VSCEs in commissioning all kinds of health and care providers, and make commissioning relationships between the NHS and VCSEs more productive for both, and so contribute to making publicly funded services more responsive to patients’ and carers’ needs. That is, to:

-

strengthen the evidence base for guidance to commissioners on how:

-

VSCE contributions can strengthen health and care commissioning

-

Commissioners and VCSEs can gain knowledge of each other’s needs

-

VCSEs can use research to inform their activities, to encourage and enable them to produce evidence in their own cause.

-

-

Produce evidence about how, and under what conditions, health and care commissioning of VCSEs and co-commissioning with them tends to produce the consequences which are positive or negative in the above terms: specifically, to evaluate empirically the two-sided programme theory outlined in Chapter 1, Interfaces and interaction and Figure 3.

-

extend the earlier typology of commissioning methods23 to commissioning VCSE providers and co-commissioning with VCSEs.

Additional study aims are to help develop:

-

commissioners’ capacity for co-commissioning with VCSEs, and the training and knowledge mobilisation methods required.

-

practice guides on the commissioning of VCSEs, for both VCSEs and commissioners.

Research questions

The earlier findings, explanations and frameworks which Chapter 1, Health and care and Voluntary, community and social enterprises in health and care summarised suggest making VCSE–commissioner interactions the focus of this research and a route towards mobilising the resulting knowledge. However, many of the relationships and contexts shown in Figure 3 have still to be researched. We therefore addressed four research questions. RQ1 concerns what the organisations commissioning VCSEs bring to, and take from, those interactions; that is, why commissioners try to commission VCSEs and how far the outcomes of that activity satisfy the commissioners’ aims. RQ2 addresses the same issues from the standpoint of the VCSEs who are commissioned, and RQ3 in regard to co-commissioning.

-

RQ1. How do healthcare commissioners address the task of commissioning VCSEs as service providers, and what barriers do they face?

-

RQ2. What are the consequences for VCSEs of the public bodies commissioning services from them?

-

RQ3. How are VCSEs involved in CCG, LA and other (e.g. ICS, NHSE) commissioning decisions?

-

RQ4. What ACAPs do healthcare commissioners and VCSEs, respectively, need for enabling VCSEs to be commissioned and for co-commissioning?

In this report, we conceptualise commissioning as an essentially quasi-market activity, not just as a synonym for planning or paying for health and care, even when quasi-markets are hybridised with other structures. ‘Healthcare commissioners’ are defined as all such publicly funded organisations, taking NHS commissioners and LAs together unless explicitly separated and, unless otherwise stated, as referring to commissioning organisations not individual employees. ‘Co-commissioning’ means the involvement of VCSEs as advisers, advocates or consultees to identify health and care needs and prioritise activities or services to commission. The term ‘media of power’ refers to governance through commissioning (see Chapter 1, Health and care), but on the VCSE side the media of power through which VCSEs pursue their own missions. We define ‘resources’ widely to include real-side inputs (staff, equipment, consumables, energy, help-in-kind, practical collaboration, etc.)152 and information, but also money, legitimation153 and status. Among ‘outcomes’ we include any unintended, unforeseen, emergent or perverse consequences of commissioning VCSEs.

Each research question corresponds to specific elements in the dual CMOC schema (see Figure 3), as Table 2 shows.

| Research question | Dual CMOC element(s) |

|---|---|

| RQ1: How do healthcare commissioners address the task of commissioning VCSEs as service providers, and what barriers do they face? | Commissioners’ and VCSEs’ aims, and their compatibility Intersecting common mechanisms (‘How do… providers’) Missing, ineffectual or conflicting mechanisms or parts of mechanism (‘barriers’) Favourable and unfavourable contexts (‘barriers’) |

| RQ2: What are the consequences for VCSEs of the public bodies commissioning services from them? | VCSE aims Outcomes for VCSEs |

| RQ3: How are VCSEs involved in CCG, LA and other (e.g. ICS, NHSE) commissioning decisions? | Intersecting common mechanisms Missing, ineffectual or conflicting mechanisms or parts thereof Favourable and unfavourable contexts |

| RQ4. What ACAPs do healthcare commissioners and VCSEs, respectively, need for enabling VSCEs to be commissioned and for co-commissioning? | Context: ACAP |

Chapter 3 Methods

Study design and its theoretical framework

Our research design was based on realist evaluation, since the latter has been developed specifically for explaining policy implementation (in this case, commissioning health-related VCSEs), its consequences and facilitating contexts. Whether implementing that policy had the outcomes that the policy-makers intended depends upon how the VCSEs reacted (see Chapter 1, Interfaces and interaction). As the mechanism for achieving their aims, commissioners use some selection and variants of the commissioning methods listed in Chapter 1, Health and care (and see Chapter 4, Commissioner and voluntary, community and social enterprise aims). From the VCSEs’ standpoint, becoming commissioned is a mechanism for achieving the outcomes that they seek (see Chapter 1, Voluntary, community and social enterprises in health and care and Chapter 4, Commissioner and voluntary, community and social enterprise aims), for which VCSEs will use their own distinctive working practices, governance structures, and external relationships. However, these two CMOCs intersect, as Figure 3 shows. Commissioners’ and VCSEs’ interactions during the commissioning cycle constitute a common mechanism that both parties use. We therefore require a study design that will identify separately the respective aims (intended outcomes) of either party; the common, intersecting mechanisms (both intraorganisational and interorganisational) which both parties think will achieve them and therefore use; how each party uses these mechanisms; the actual effects for each party separately; and what contexts these effects depend upon. Similar reasoning applies to co-commissioning. How each organisation acts and reacts depends on its ACAP, so the study design also required methods for describing ACAP, its development and effects. This reasoning implies making the relationship and interactions between VCSE and commissioner the research focus and the unit of analysis or ‘case’ when explaining the commissioning of VCSEs.

Because multiple components and methods were required to research these complex relationships, the study contained five work packages:

-

Preliminary scoping work with national-level NHS and VCSEs to identify important current developments in this domain and likely data sources (late 2019 to mid 2020).

-

A cross-sectional profile of CCG spending on VCSEs, both as a sampling frame for the three following work packages and as a source of data about patterns of VCSE commissioning (late 2019 to mid 2020).

-

Using findings from the preceding work packages, we drew a maximum-variety sample of places primarily in terms of the proportion of CCG spending of VCSEs [secondary sampling criteria are reported below (see Chapter 3, Sampling strategy: site selection criteria and methods)], and systematically compared case studies of VCSE–commissioner collaboration in formulating local commissioning strategies across all providers (‘co-commissioning’) in them (late 2020 to summer 2022). The aims of their commissioning activities, and the corresponding outcomes, were examined separately for the commissioners and the VCSEs. The structures and activities through which they interacted were examined in common.

-

A systematic comparison of case studies of the co-commissioning of VCSEs (late 2020 to summer 2022).

-

A group of action learning interventions (late 2020 to early 2023) and a survey of ACAP.

The third and fourth of these were analytically distinct and addressed different research questions but used the same research design, study sites and methods. Table 3 shows which work packages contributed to answering which research question.

| Research question | Work package(s) |

|---|---|

| RQ1: How do healthcare commissioners address the task of commissioning VCSEs as service providers, and what barriers do they face? |

|

| RQ2: What are the consequences for VCSEs, of the public bodies commissioning services from them? |

|

| RQ3: How are VCSEs involved in CCG, LA and other (e.g. ICS, NHSE) commissioning decisions? |

|

| RQ4. What ACAPs do healthcare commissioners and VCSEs, respectively, need for enabling VSCEs to be commissioned and for co-commissioning? |

|

In combination, these mixed methods were synergistic. Our methods for synthesising them (see Chapter 3, Synthesising the findings) yielded a systematic overview of the commissioning of VCSEs as a whole (see Figure 3).

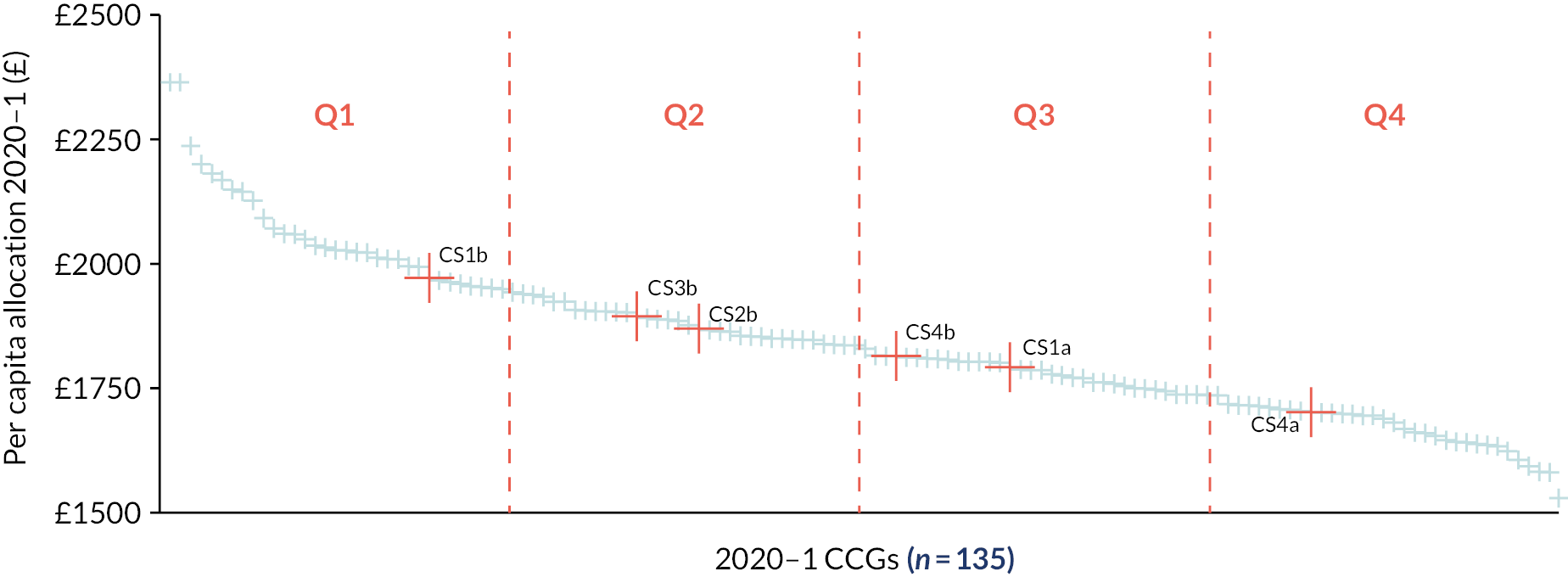

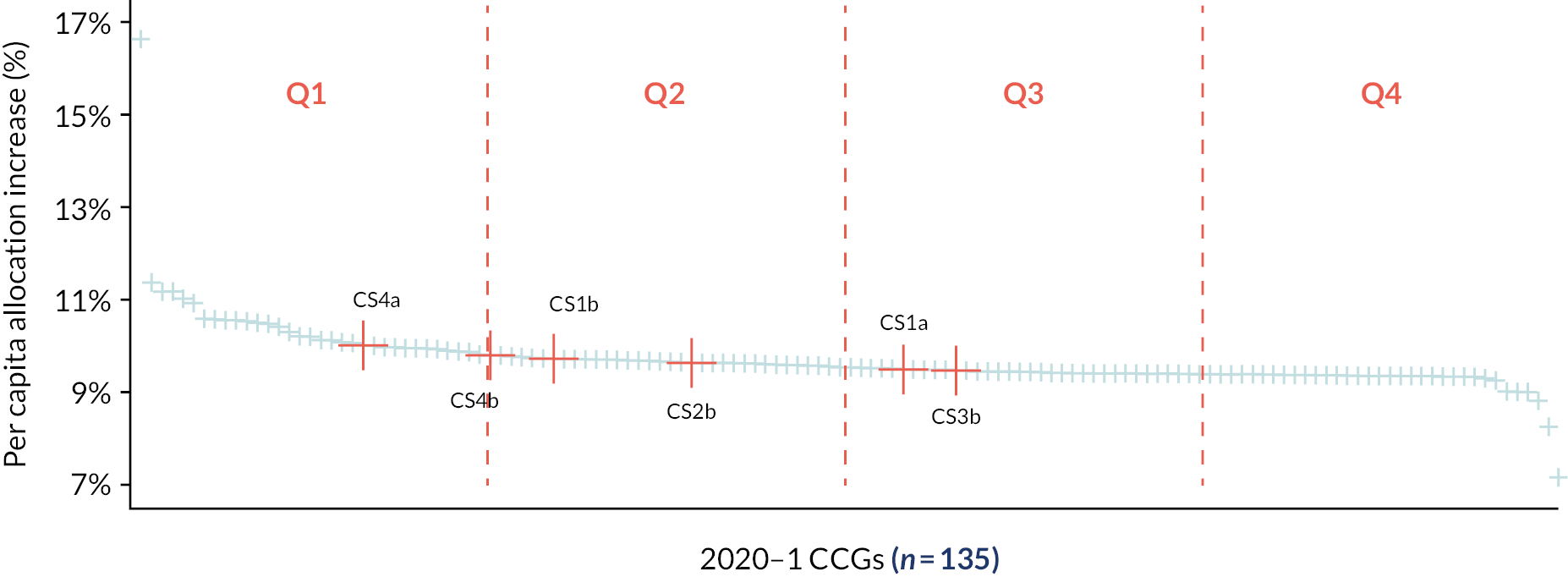

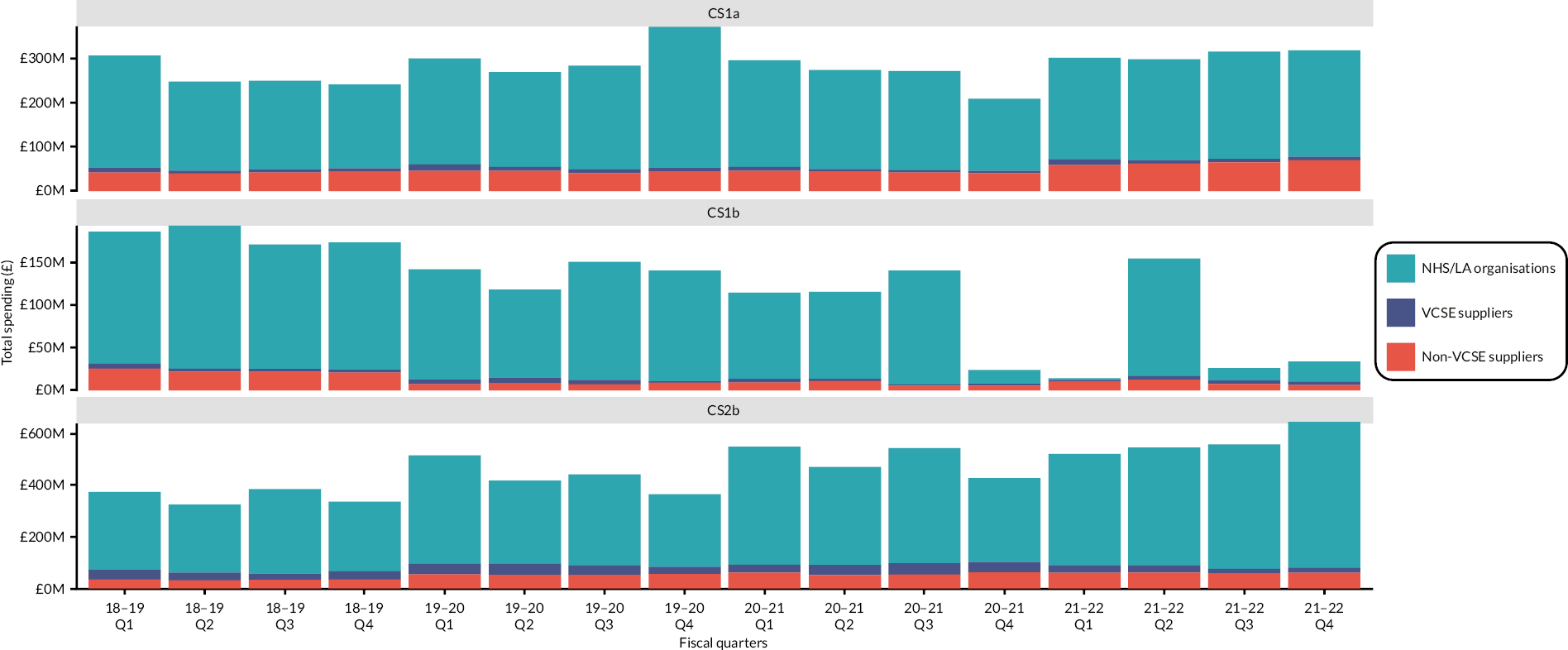

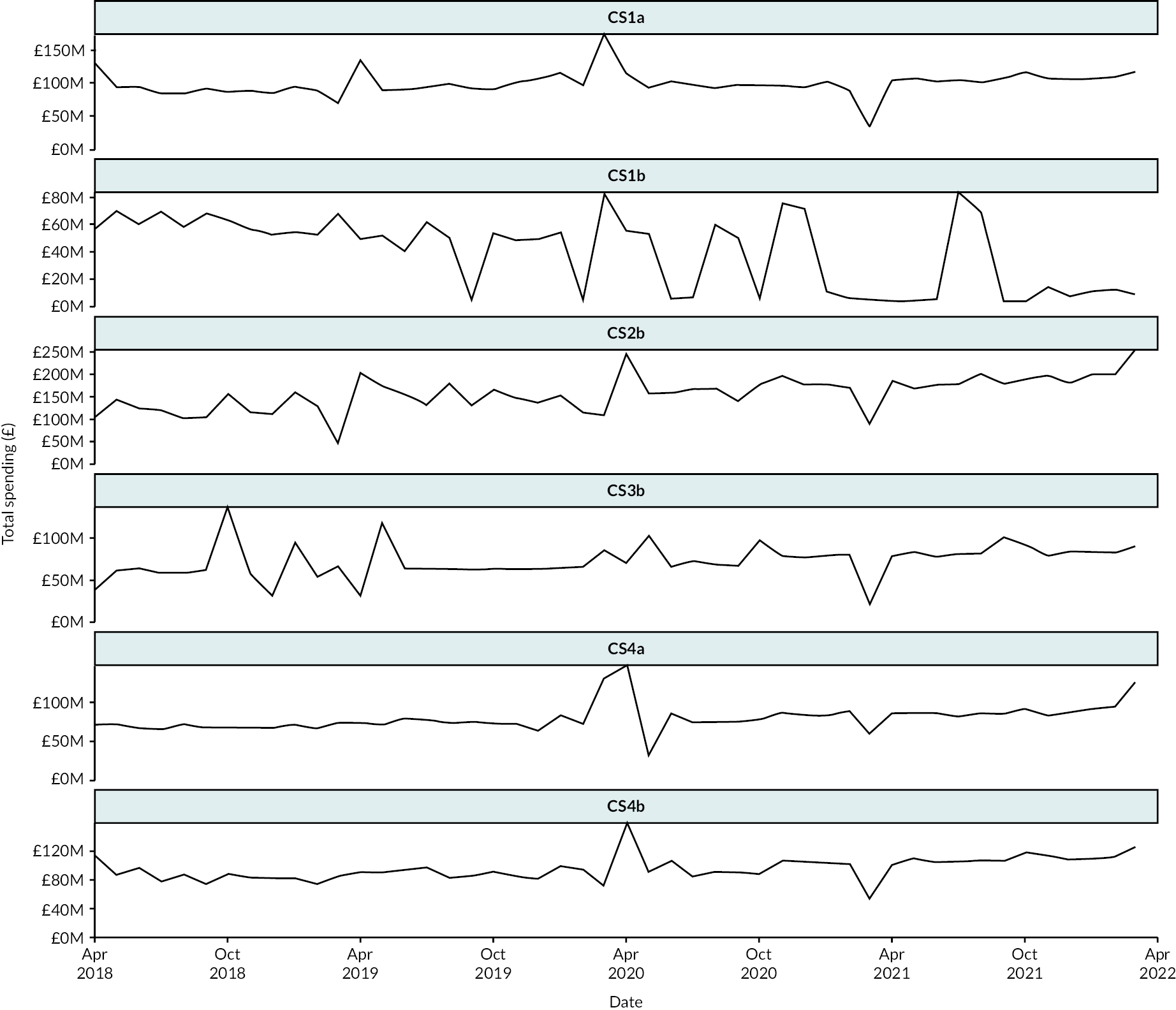

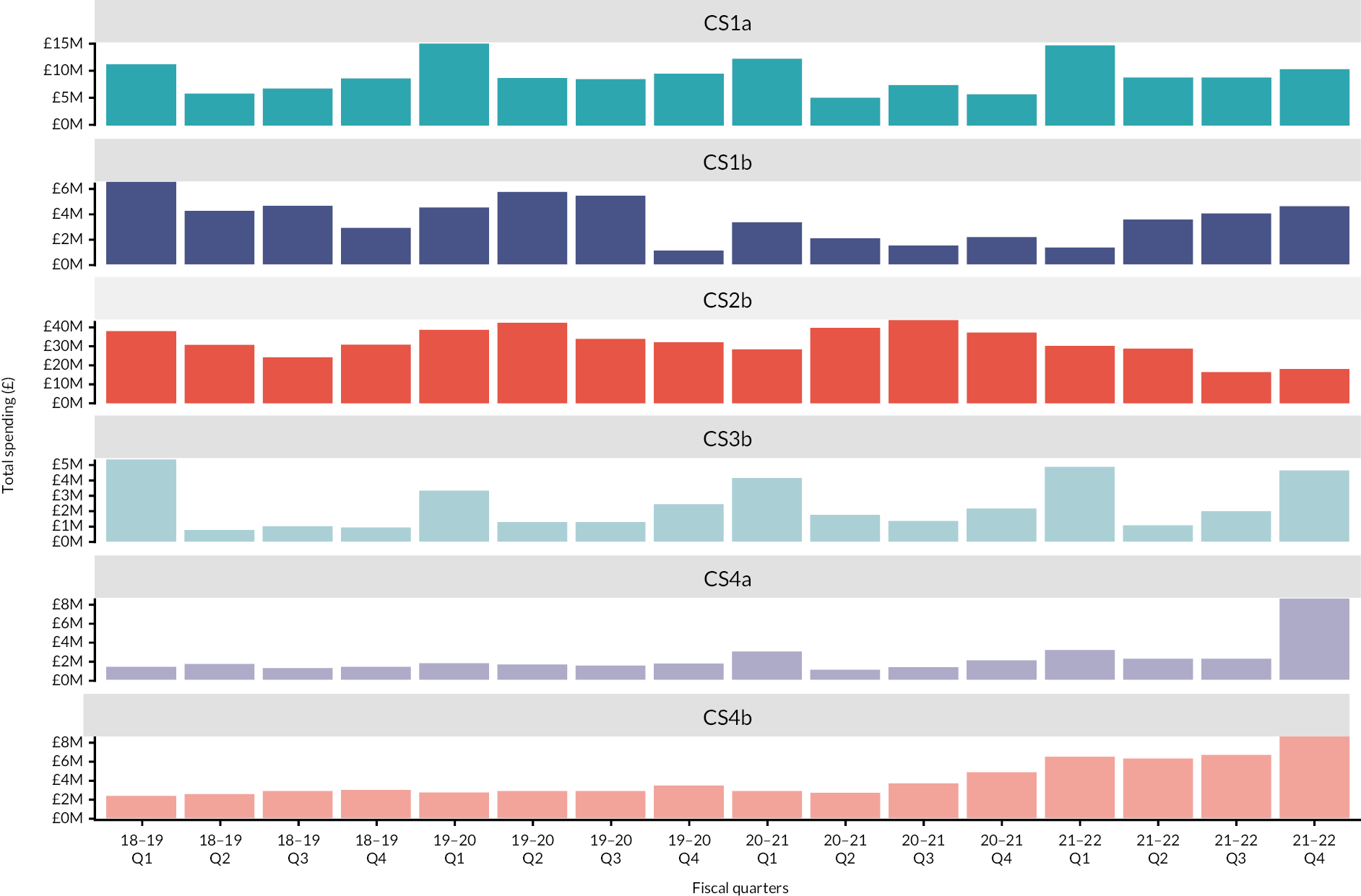

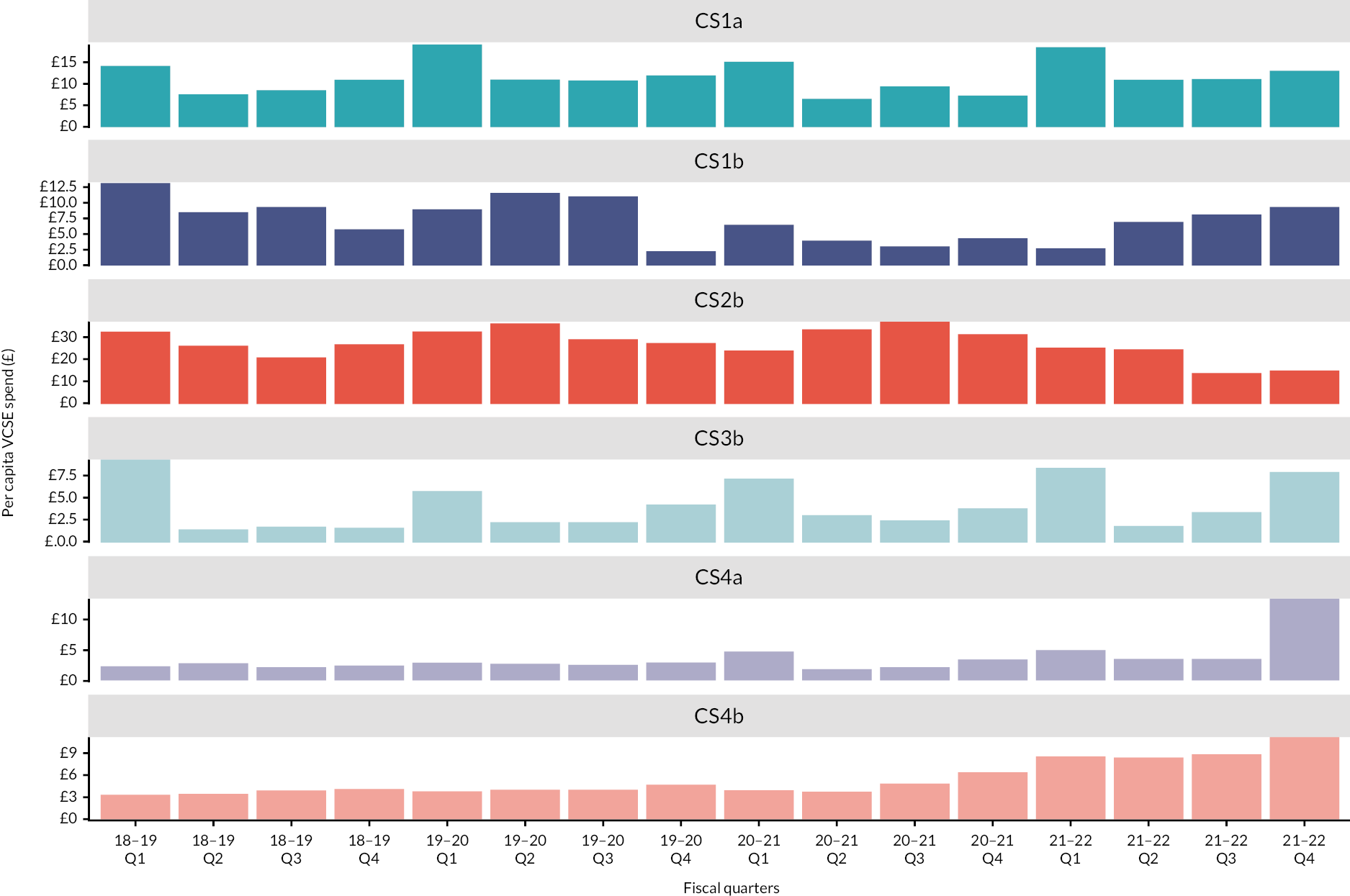

The sampling method (explained below), the cross-sectional spending profile and the national-level components of the action learning research work package provide means of checking the generalisability of findings. As Figures 9 and 10 in Chapter 5, Fiscal constraints show, these sites were well distributed across the range of levels of CCG funding and across the range of sizes of budget increases.

Preliminary scoping

Scoping work yielded a preliminary classification of the kinds of VCSE commissioning and co-commissioning relationships likely to be found in the wider study. Following Project Oversight Group (POG; see Chapter 3, Patient and public involvement and engagement) advice, we identified and interviewed 16 key informants from VCSEs, VCSE networks and national health and care bodies in late 2019 and early 2020, and consulted published policy statements and guidance, position papers (e.g. Carers Support Centre, NHS Choices provider lists, National Council for Voluntary Organisations), and rapportage (see Table 5). The interviews used a semistructured interview schedule (see Appendix 1) whose open questions included a final question asking what other relevant topics, if any, the interview had not so far covered. We piloted the interview schedule with two VCSE members. The interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. Later, the transcript contents were coded into the framework described below (see Chapter 3, Synthesising the findings) to enable automated searching in common with the other data sets when we synthesised findings across the work packages. Meantime we analysed the contents thematically (inductively)154 in order to identify the main ways and locations in which commissioners and VCSEs interacted, what objectives each pursued, and what issues and problems arose; and so produce some categorisations and initial middle-range theories about variations in the commissioning of VCSEs.

As explained below, later work packages used the findings to:

-

indicate criteria for selecting a maximum-variety sample of sites for the case studies and action learning

-

contribute to developing the project’s analytic frameworks

-

contribute to the final data synthesis

Cross-sectional profile of Clinical Commissioning Group spending on voluntary, community and social enterprises

Design

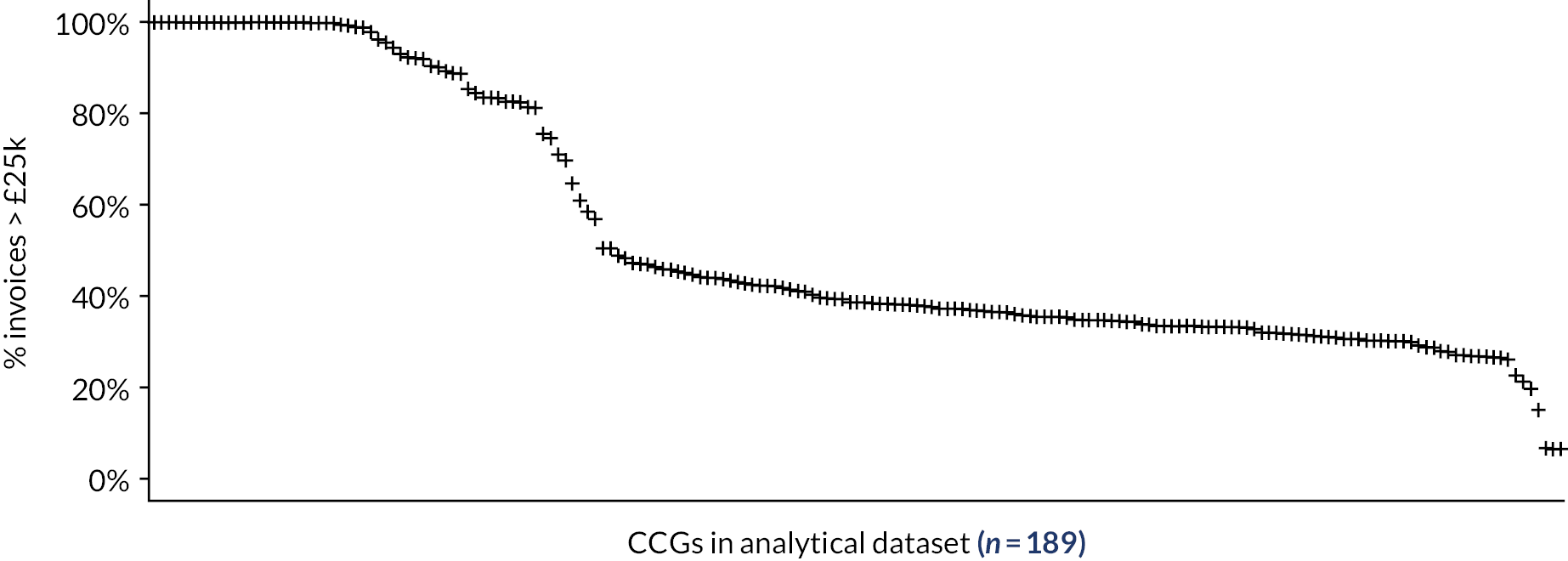

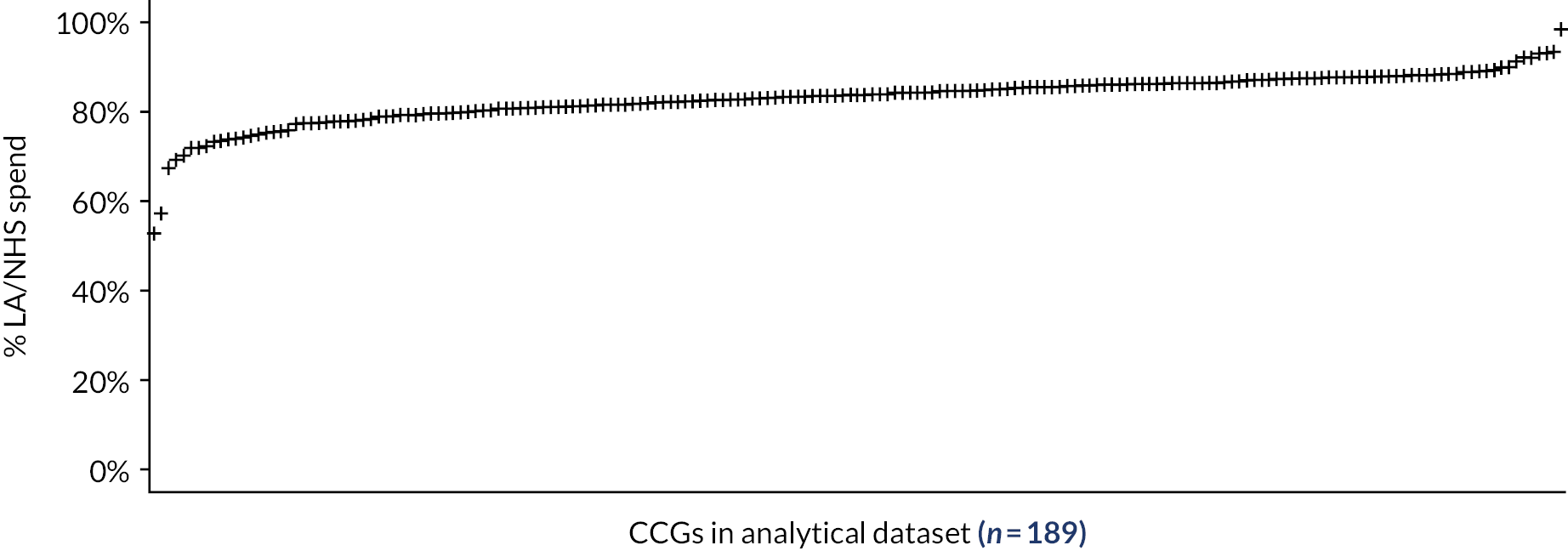

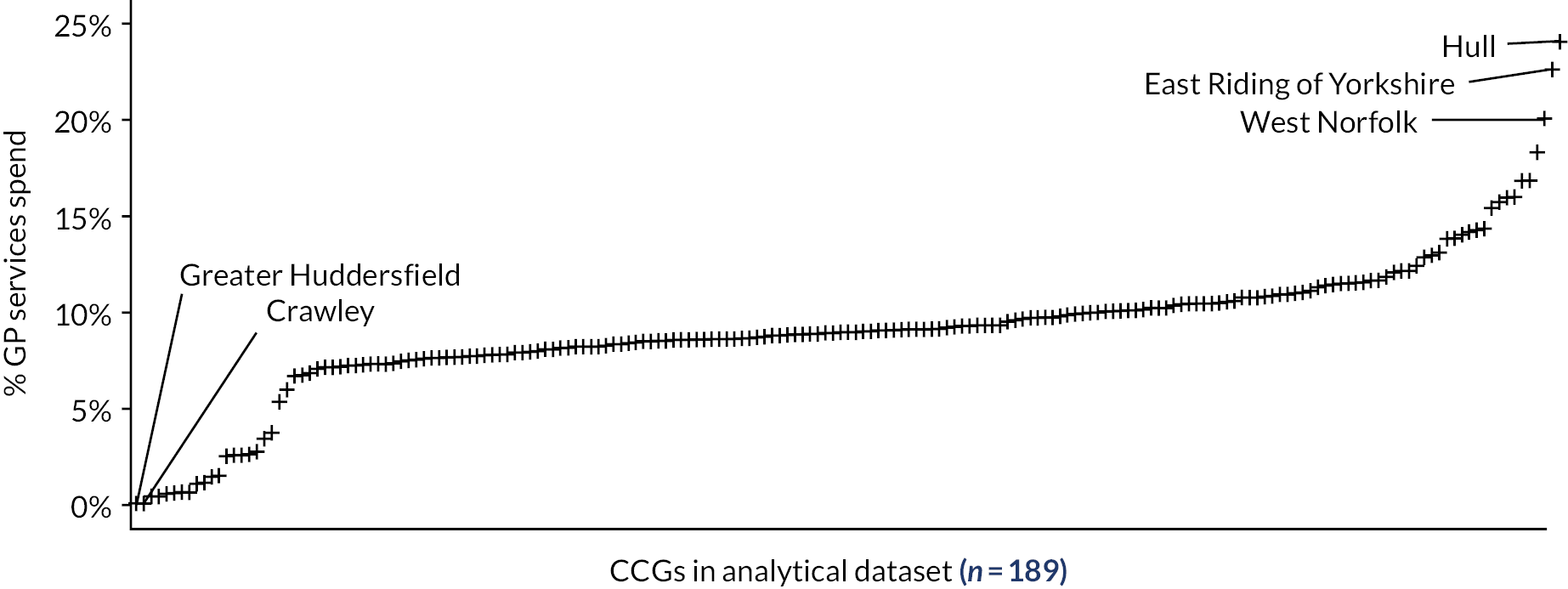

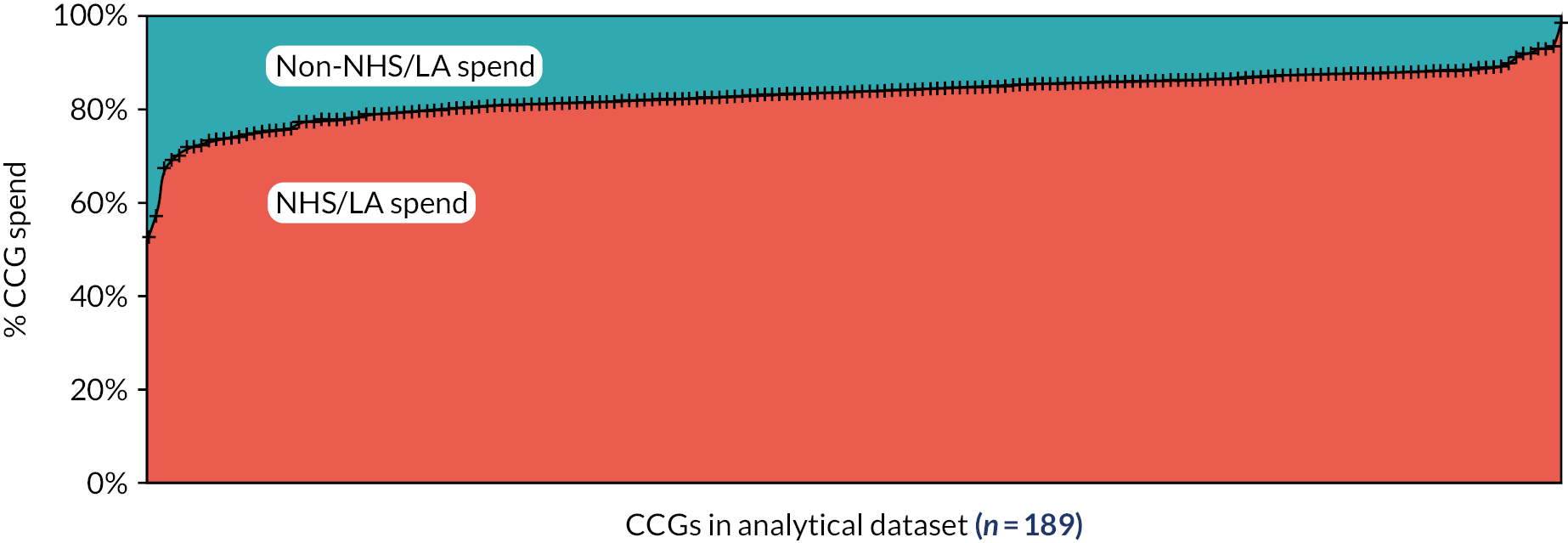

This cross-sectional census of CCG spending on VCSEs proceeded in four steps (further details in Appendix 5, data in the project’s GitHub data repository155):

-

Extract data from CCG ‘Expenditure over threshold’ accounts We harvested 689,536 records from 189 of the 195 CCGs extant in 2018–9. Data for four CCGs could not be obtained or made machine-readable. Data for two further CCGs appeared unreliable. Following HM Treasury guidance156 the accounts all included details on: (1) CCG name, (2) expense area, (3) expense type, (4) provider name and (5) amount. Treasury guidance required public bodies to report all transactions over £25k, although many accounts include invoices for smaller amounts. To ensure comparability between CCGs, only invoices ≥ £25k were used.

-

Obtain information about providers The ‘expense type’ field often referred to ‘voluntary’, ‘not-for-profit’ and other categorisations, but this was neither comprehensive nor reliable. For information on providers it was thus necessary to link provider names with Companies House (CH) and CC registers, and search their public-facing websites. Care Quality Commission (CQC) active and inactive registers157 and the NHS Payments to General Practice, England, 2018/19 data set158 were also used to obtain information on care homes and GPs respectively. The search of CH and CC databases was largely automated, using ‘fuzzy matching’ techniques to deal with the variation of names used in the accounts (trading names, acronyms and contractions, misspellings, etc.) but the search for, and of, provider websites was entirely manual.

-

Classify providers as VCSE, NHS/LA organisations or other NHS and LA providers were identified on the basis of name (n = 538 and 212, respectively), as were government and service providers (e.g. police and fire and rescue services). The legal status of providers given in the CH and CC registers was then used to classify non-NHS/LA providers as VCSE or otherwise. Additional information was obtained from providers’ own websites.

-

Quantifying VCSE activity at CCG level VCSE activity can be expressed in a number of ways (VCSEs’ share of invoices, providers or spend, or per capita VCSE spending in different CCGs), although to ensure comparability across all CCGs, all methods must include only spending > £25k. The denominator can most usefully be defined using:

-

all invoices except redacted personal health budgets, or

-

all invoices except personal health budget and NHS/LA spending.

-

The design was limited by difficulties linking providers as named in the accounts with those in the CH/CC registers. It is inevitable that automated fuzzy matching and subsequent manual follow-up will have missed, or indeed misidentified, some providers on the registers. Moreover, the approach cannot capture:

-

VCSE activity subcontracted via other providers (which our fieldwork suggested does occur)

-

NHS money reaching VCSEs via LAs (probably a larger amount).

Data collection

The www.data.gov.uk website and all CCG websites were searched and the relevant accounts were downloaded. Despite the 2013 guidance, freedom of information (FoI) requests then had to be sent to 106 of the 195 CCGs: 12 because no accounts were publicly available, 11 because one or more of the monthly accounts were missing, corrupted or referred to the wrong CCG, and 83 because the data, contrary to the guidance, were in the .pdf (portable document format) file format and could not be reliably converted into machine-readable numeric data. Mostly the FoI process was straightforward, but 17 requests were rejected and a formal follow-up was needed. By March 2020 four CCGs had still not provided useable data. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, we stopped pursuing our FoI requests, leaving us with data for 191 of the 195 CCGs (see Appendix 5, Table 11).

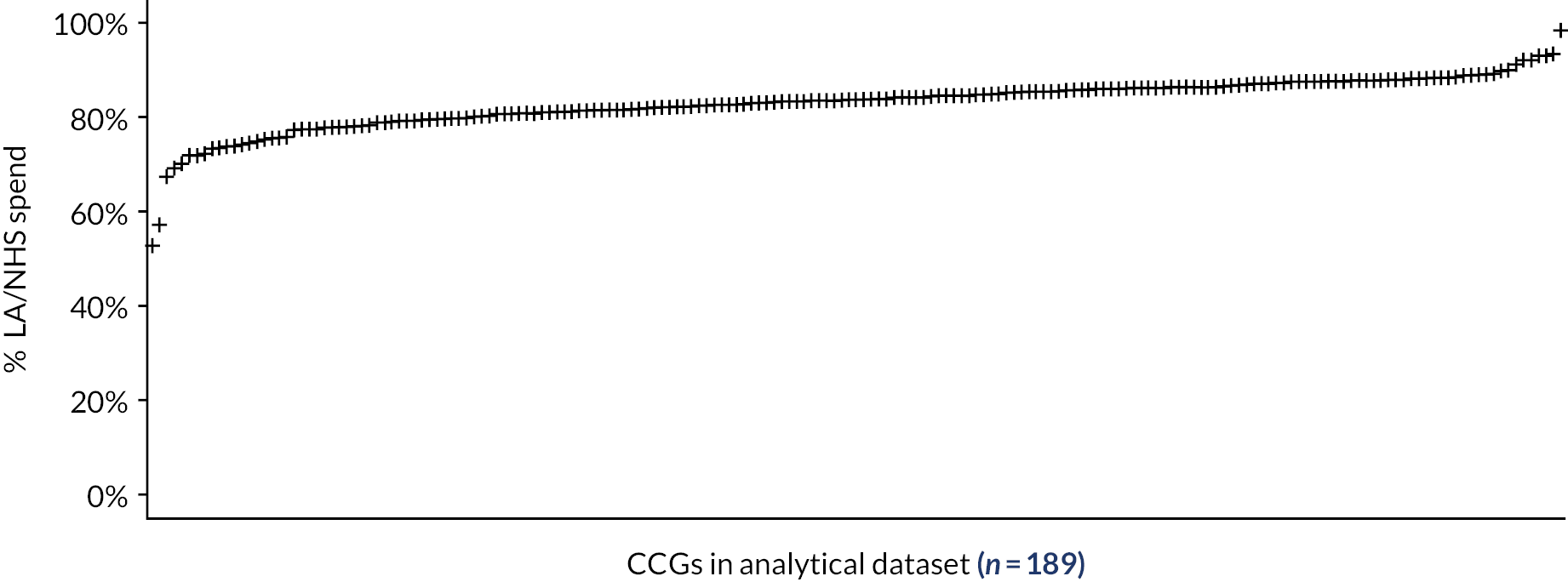

Preliminary data cleaning resulted in the exclusion of one CCG whose accounts were badly out of line with the most recent available NHSE CCG consolidated accounts,159 respectively, covering only 20.8% and 47.5% of total spending.

Using PowerShell® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and R Statistics (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), we amalgamated and aggregated the monthly accounts for the final set of 189 CCGs, extracted all invoices > £25k, and identified unique providers. The resulting data set comprised 226,138 invoices capturing £70.525B (representing 97.7% of all spending recorded in the accounts) and listing 10,930 named, and around 10,592 unique, providers.

Providers not categorised as NHS organisations, LAs or government organisations were then used to seed automated ‘fuzzy matching’ algorithms to search the CH register (using its application programming interface) and downloaded CC databases. Any providers not yet identified were then subject to a manual search for public-facing websites. In some cases this revealed CH/CC registration numbers, which were then followed up. In other cases explicit statements were found to the effect that they were ‘not-for-profit’, ‘social enterprise’ or ‘volunteer-led’ organisations. Only 188 (1.8%) providers [receiving just £189.361M (0.3%) of CCG spending] could not be linked to organisational websites or entries in the CC/CH registers. Some 6416 non-NHS/LA organisations could not be found in the CC/CH registers (60.7% of all providers), although these accounted for only 8.6% of total CCG expenditure > £25k.

Data on all invoices and providers, R analytical scripts and outputs are available on our project GitHub,155 with some summary analyses of patterns in Appendix 5, Figures 21–28.

Analysis

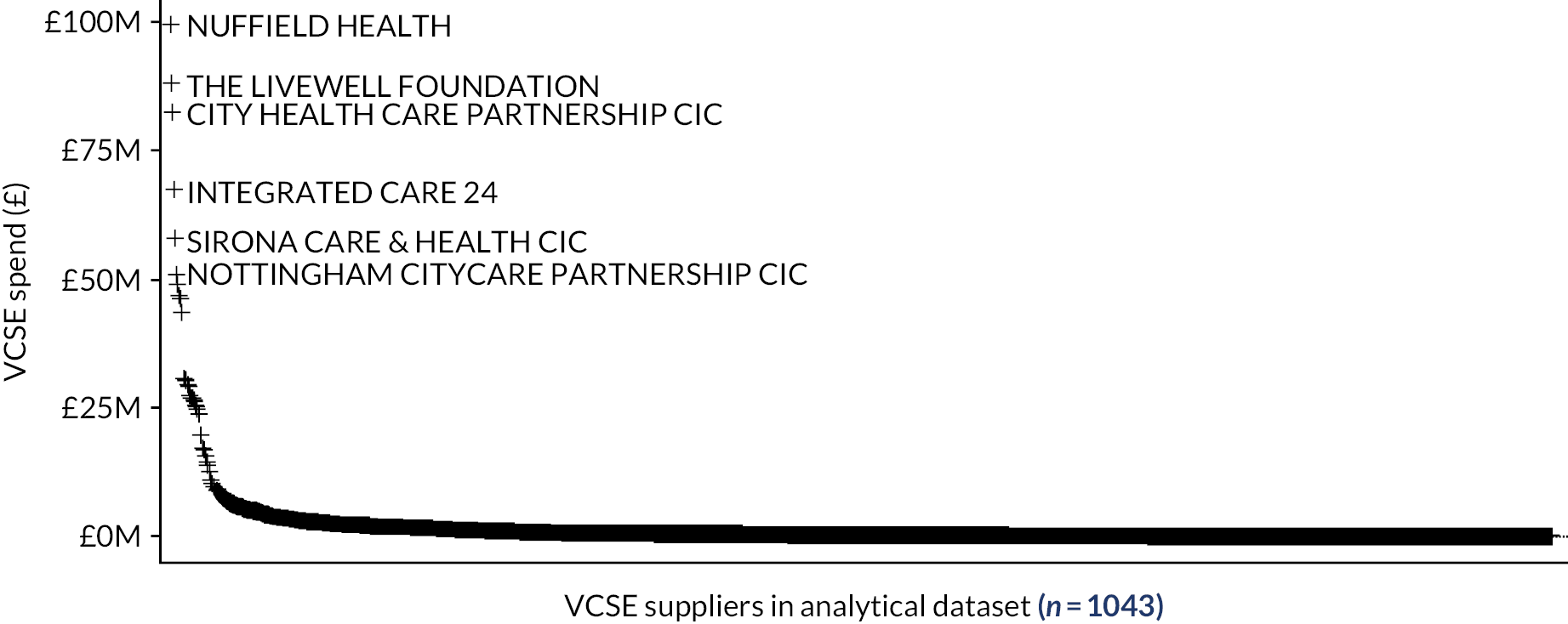

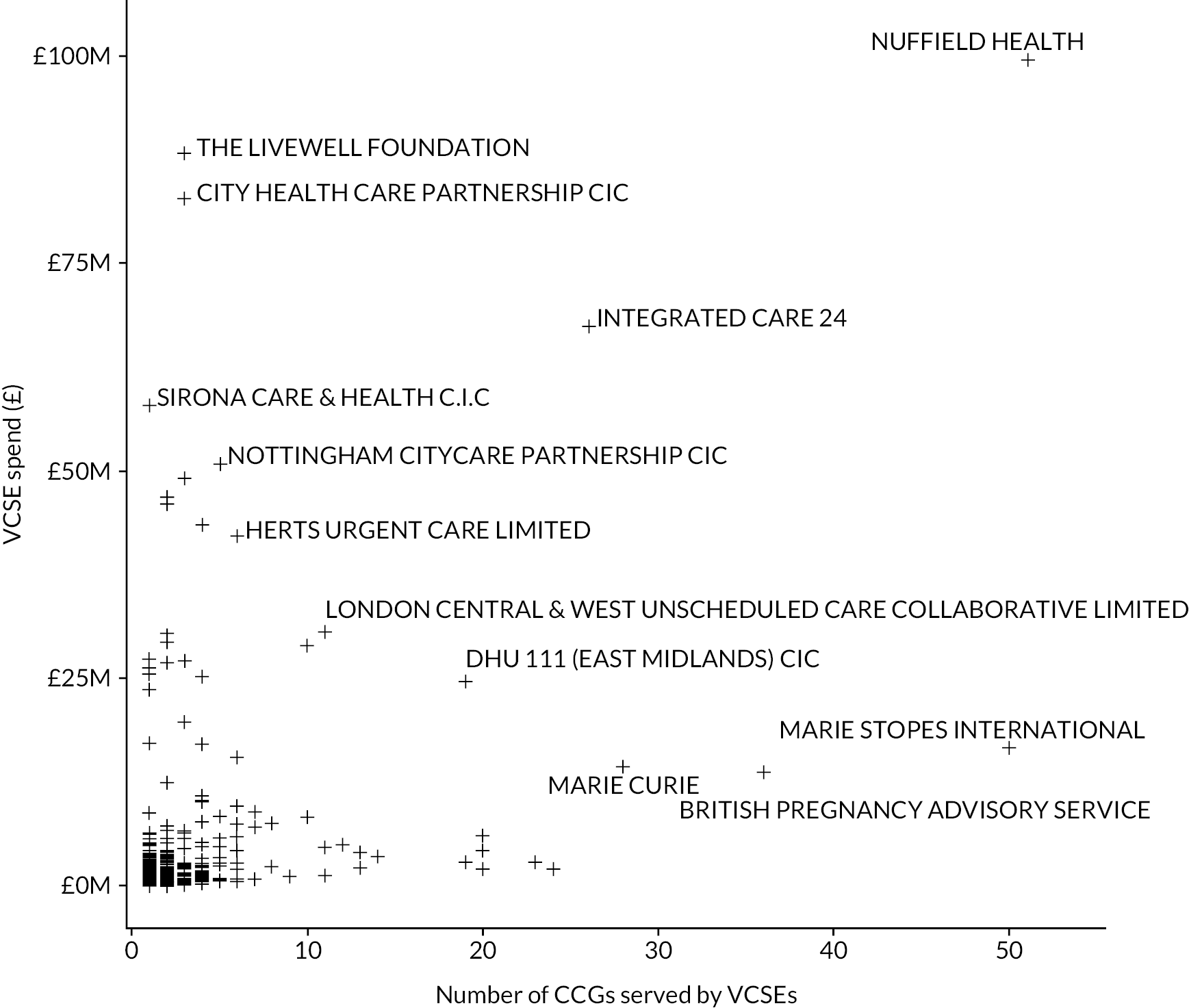

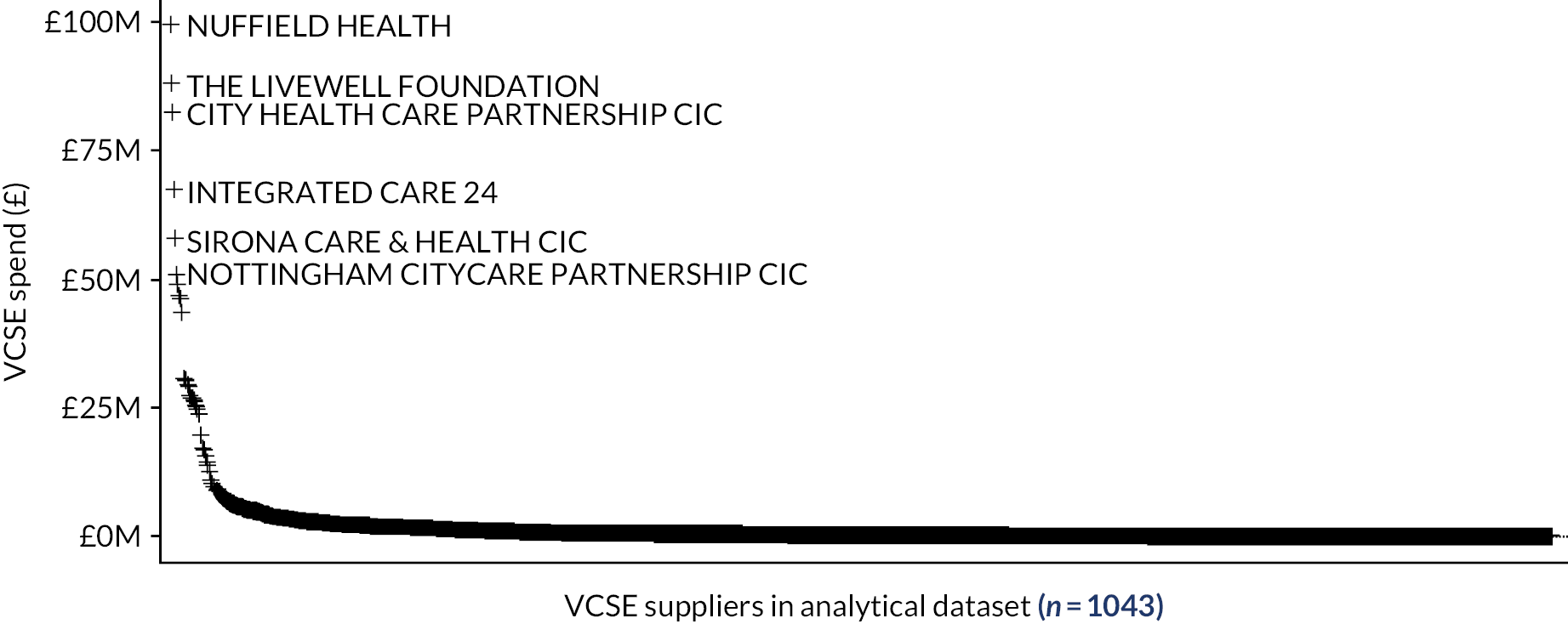

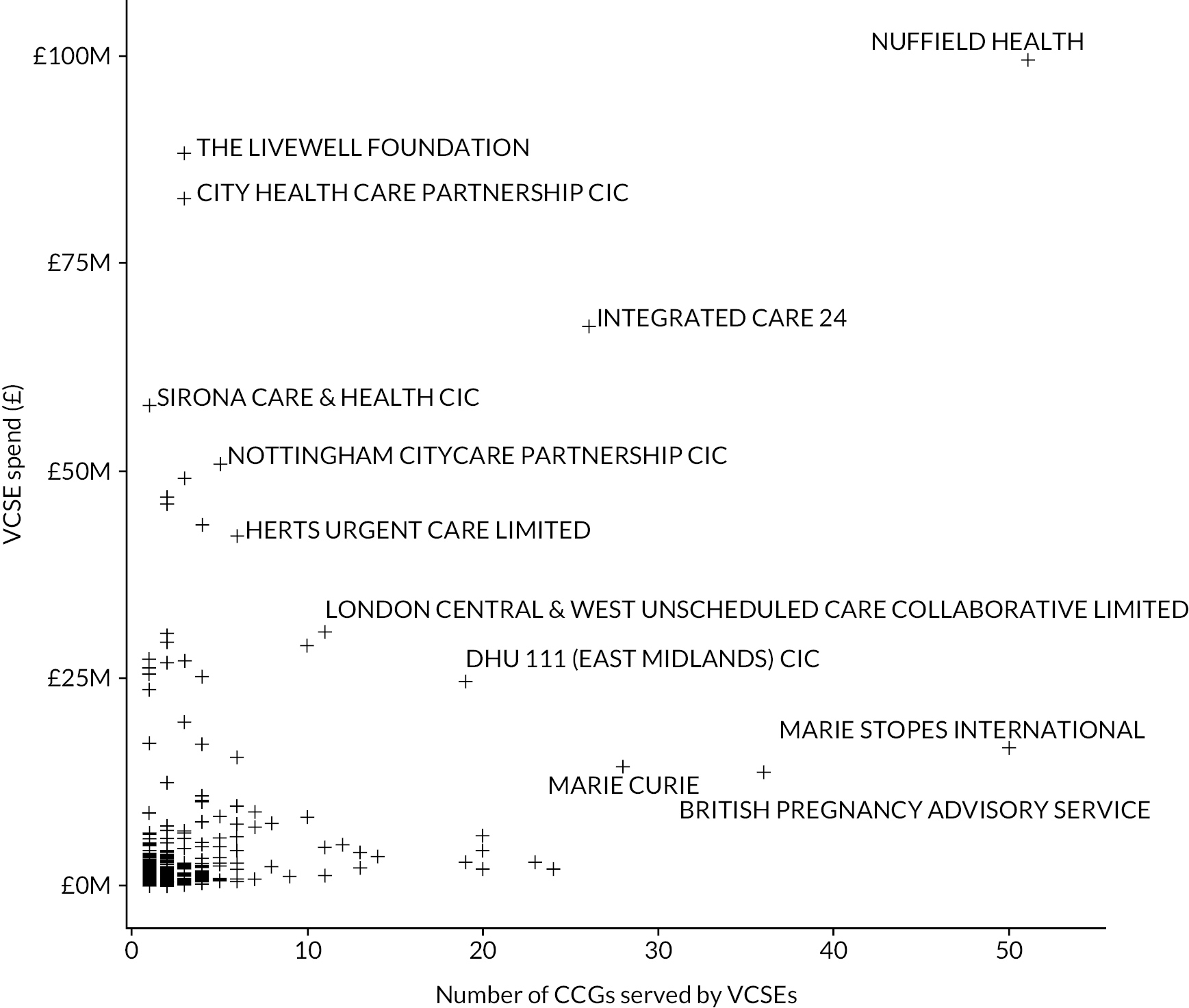

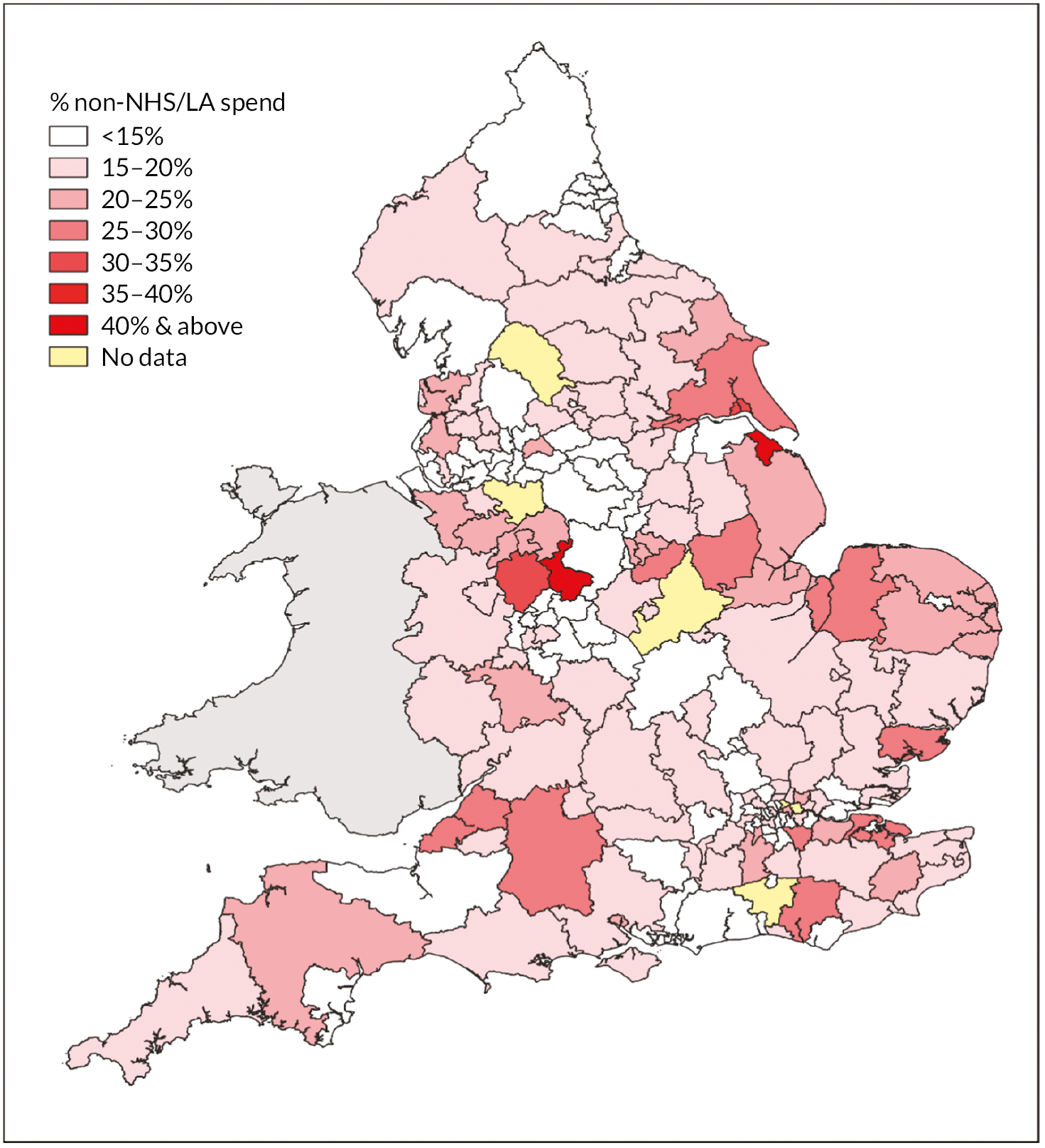

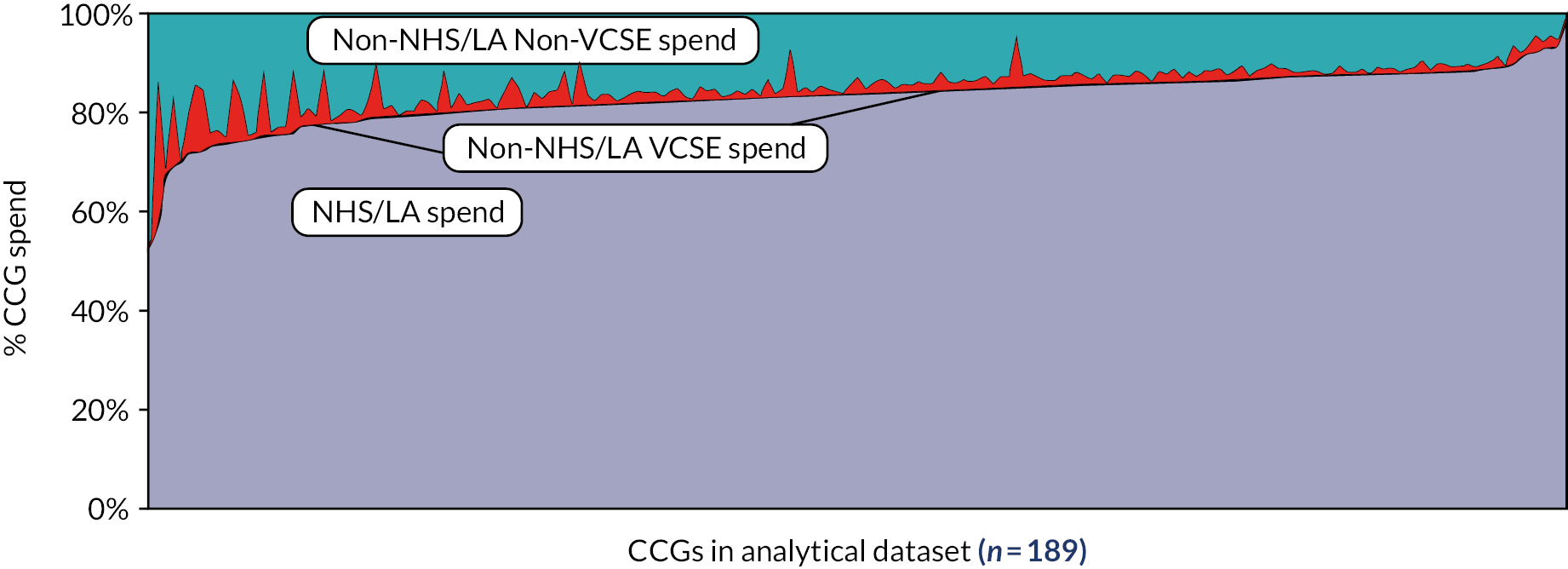

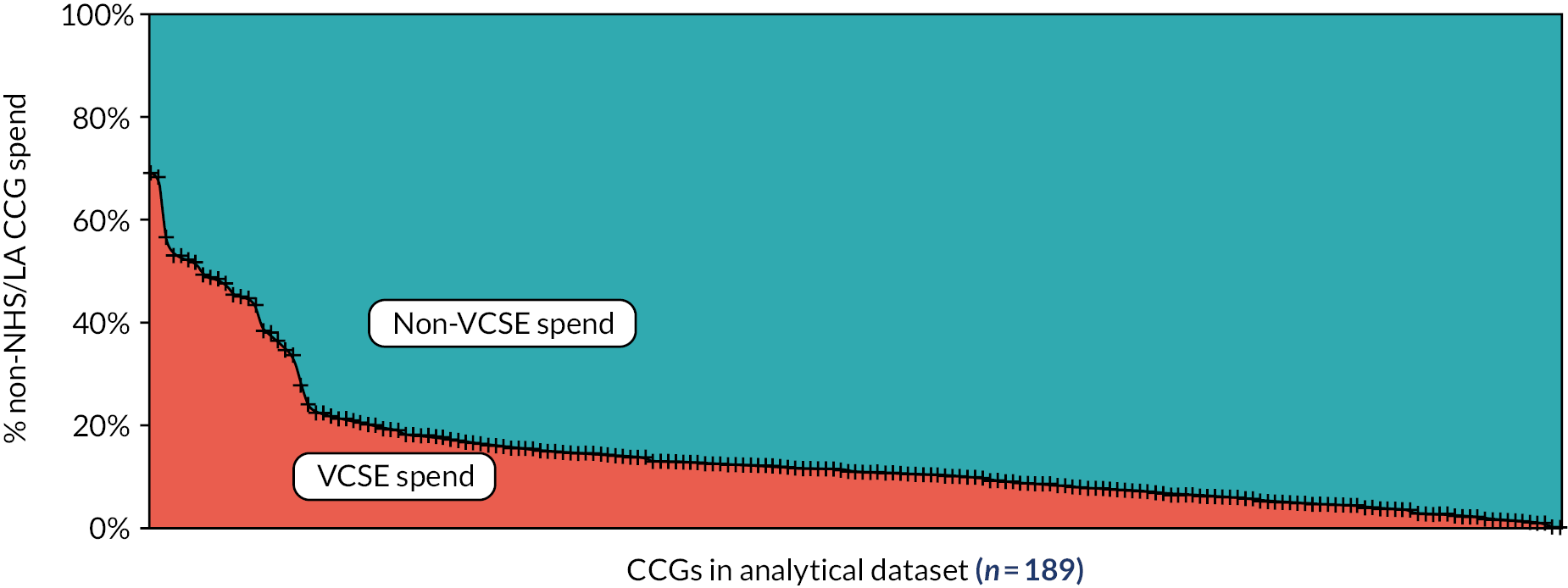

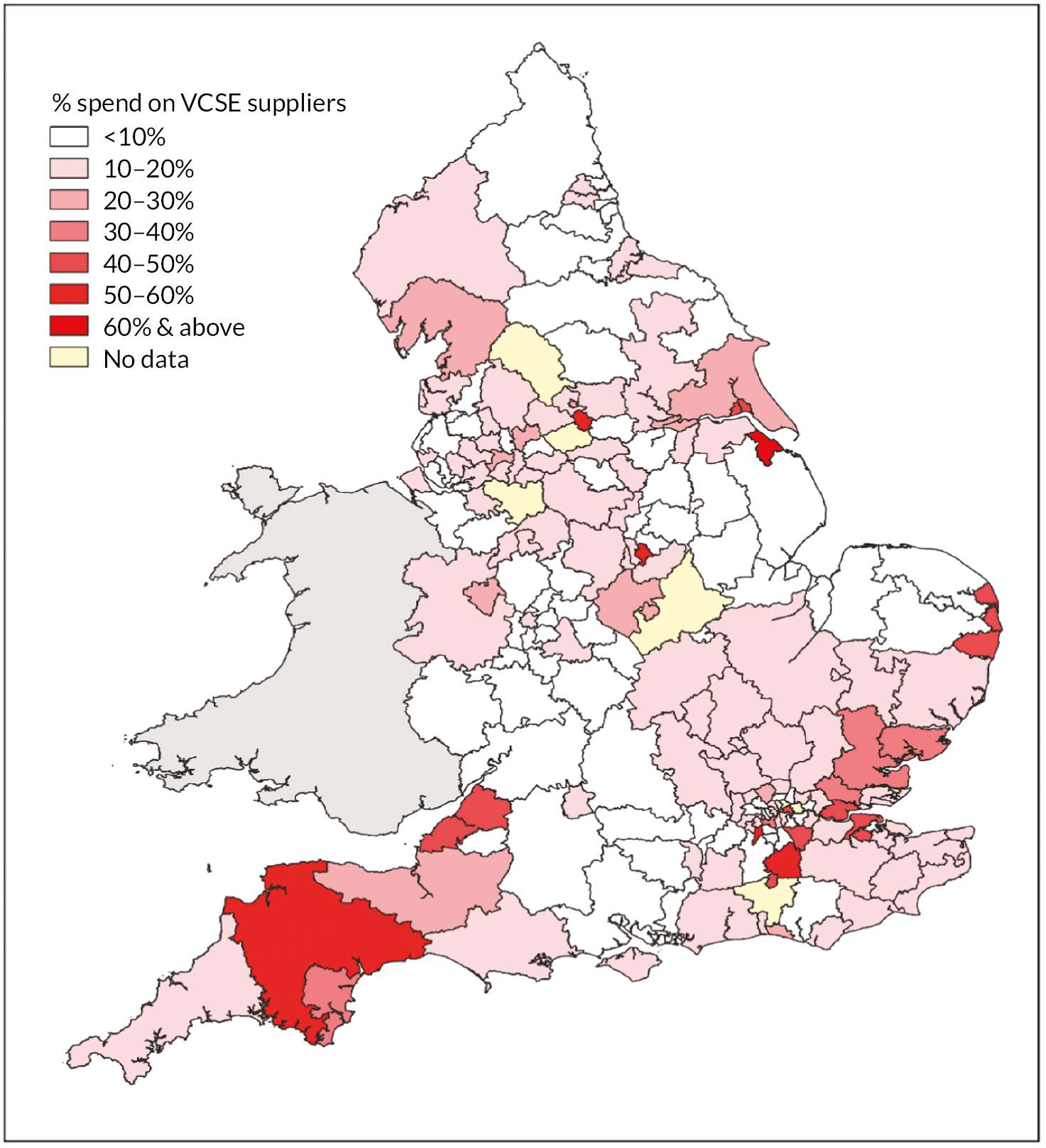

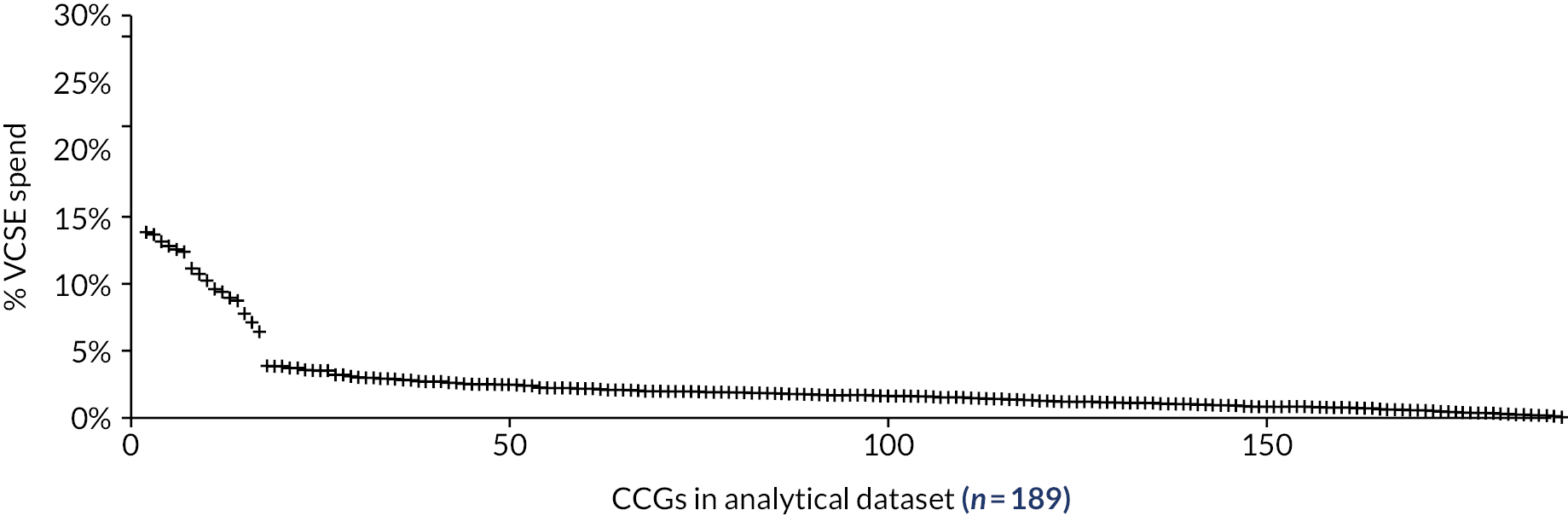

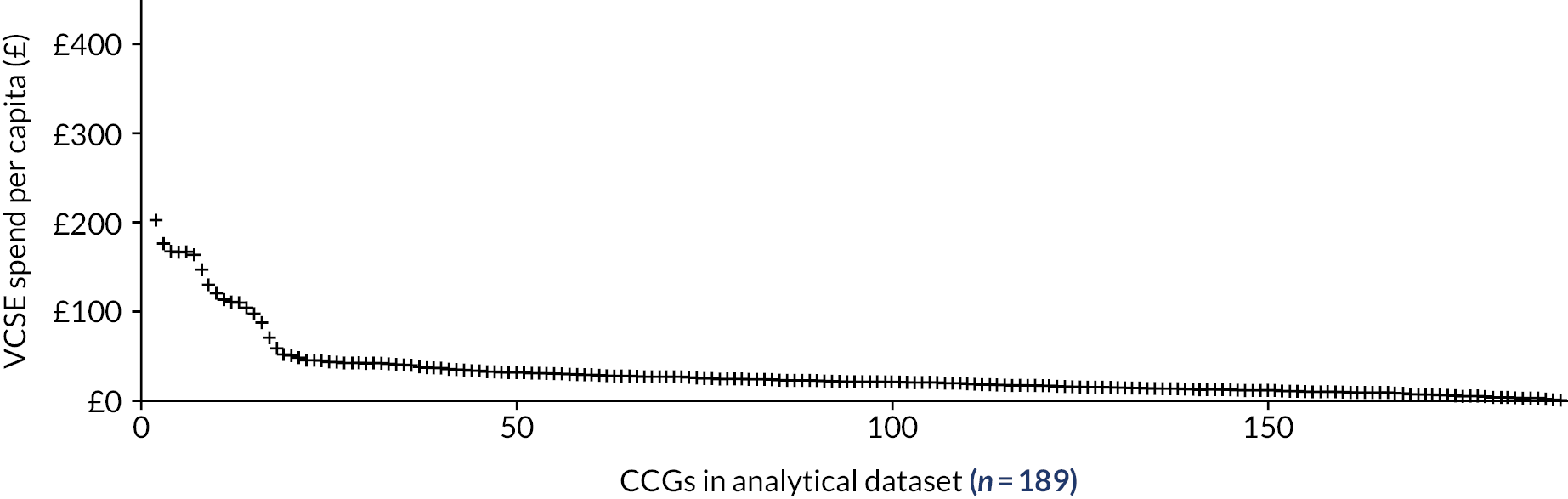

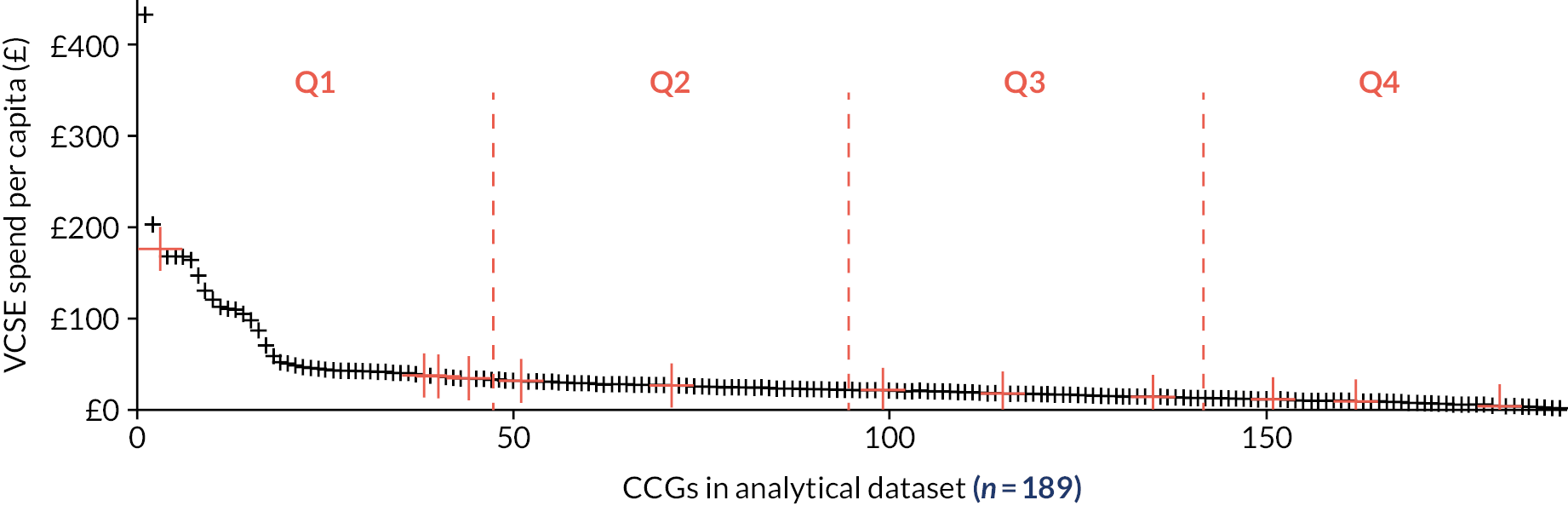

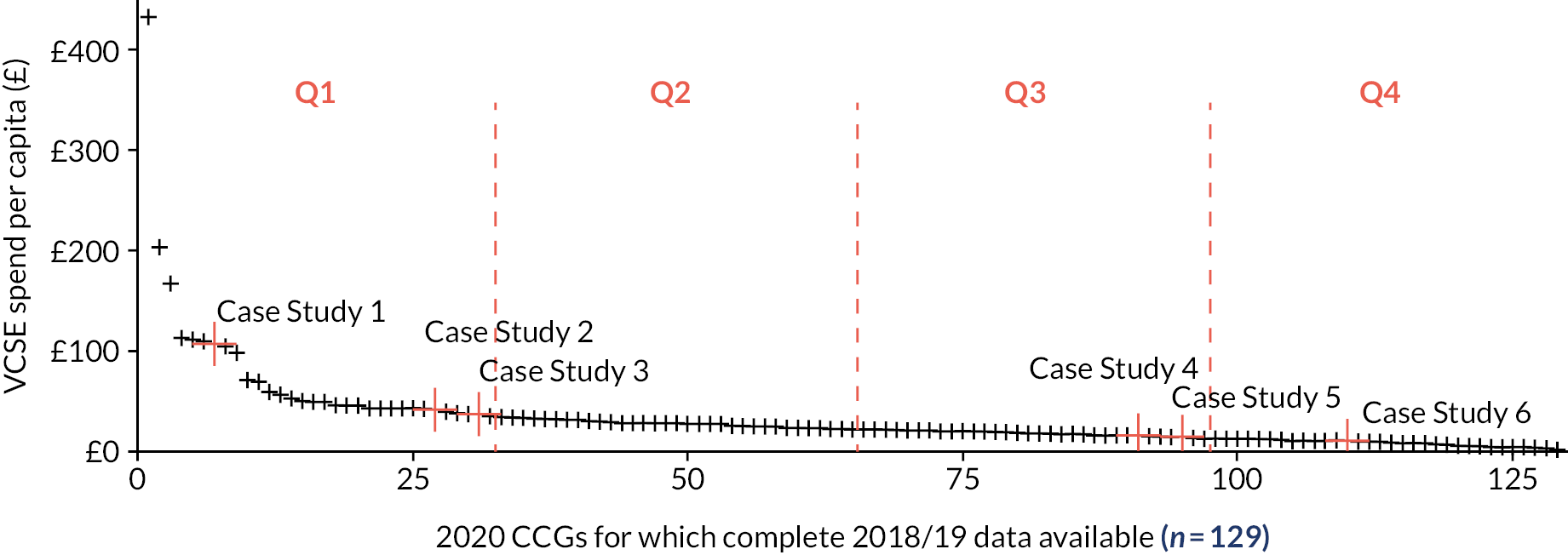

From these data we estimated, for each of the 187 CCGs, the proportion of expenditure on contracts worth > £25k on VCSEs during 2018–9. We ranked the CCGs in descending order by this proportion and divided the resulting list into quartiles. This created the sampling frame for study site selection (see Appendix 5, Figures 33 and 34). We also interrogated this list, and the data, to elicit the patterns of CCG use of and spending upon VCSEs, and the patterns of VCSEs contracts reported in Chapter 6, On mission or mission drift?.

Systematic comparison of case studies of co-commissioning and the commissioning of voluntary, community and social enterprises

These work packages used the same study sites, data and analytic frameworks, so we report their common methods together.

Sampling strategy: site selection criteria and methods

Since the research questions and theoretical framing of the study suggest making the relationship and interactions between VCSE and commissioner the research focus and unit of analysis or ‘case’, our sampling strategy was to select case study sites which, together, seemed likely to provide a maximum variety of commissioner–VCSE relationships. In theoretical terms, such a sample was the most likely to show a range of modes of commissioning VCSEs, commissioning contexts and outcomes.

The scoping work suggested that the dimensions of variation in commissioning relationships included:

-

The proportion of VCSE-provided services in each site. The larger that proportion, the greater the likely extent, complexity, variety and sophistication of commissioning relationships between commissioners and VCSEs.

-

The size of VCSEs involved, ranging through national VCSEs with local branches, large single local VCSEs (e.g. some hospices), and VCSEs which struggle to win contracts at all. One would expect all these VCSEs to differ in bargaining power and resources, especially access to specialised bidding expertise, and ACAP.

-

How long-standing the commissioning relationships are, because mutual trust and working relationships, and the concomitant skills, take time to develop.

-

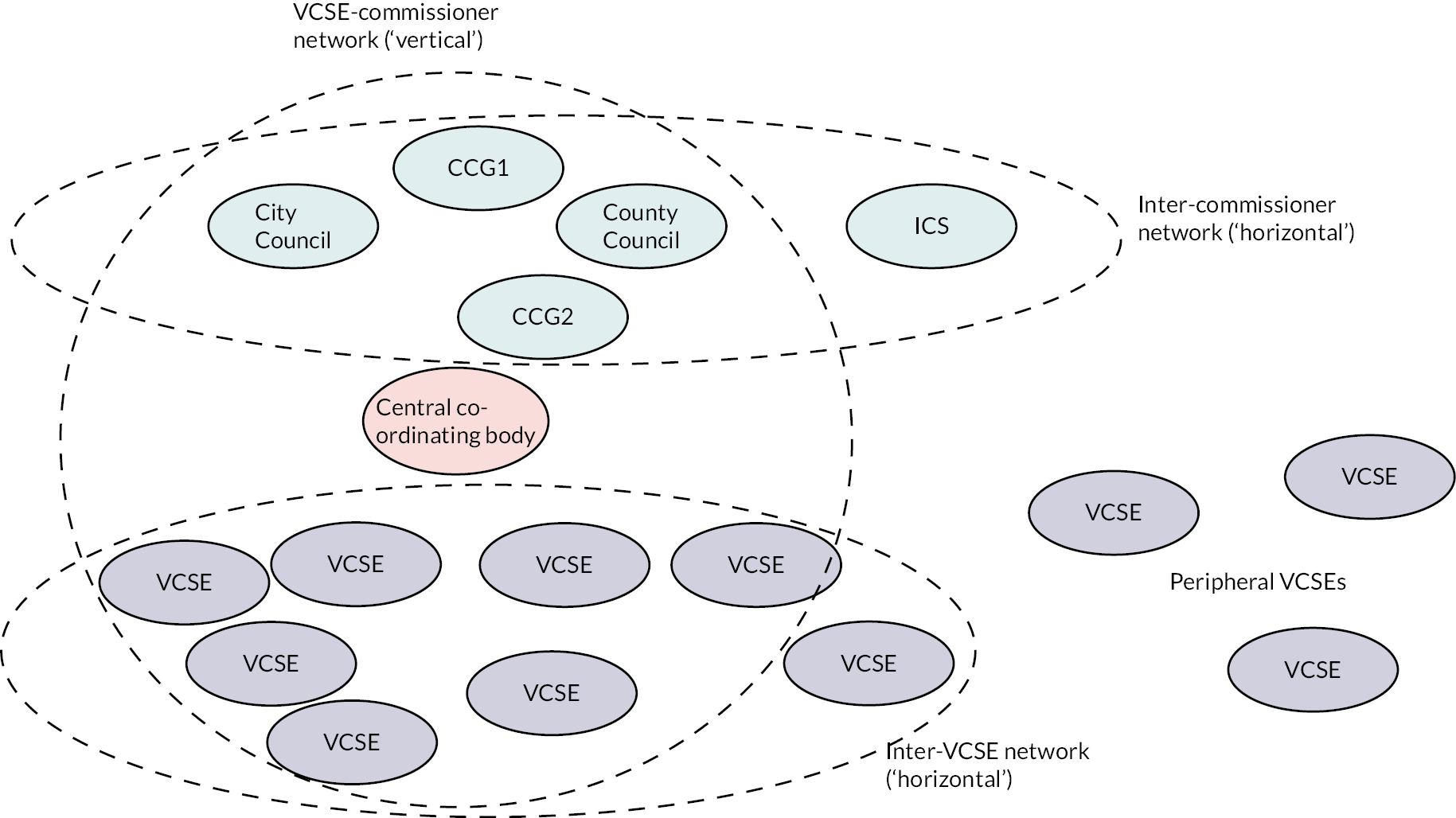

Which organisations were involved in commissioning, and which ones interacted with which. The scoping work suggested that the main patterns were:

-

One commissioner commissions one VCSE, for example when a CCG or an NHS Trust subcontracts a VCSE: a simple bilateral relationship.

-

Multiple commissioners collaboratively commission a VCSE, for example an NHS body transfers a budget to a LA (perhaps its public health department) which then commissions a VCSE.

-

One commissioner commissions an intermediary which then subcontracts or makes grants to further VCSEs.

-

Multiple commissioners collaboratively commission an intermediary which then coordinates further VCSEs.

-

Key local VCSEs advise or are consulted by one or more commissioners. The VCSEs involved may or may not then be commissioned by the commissioner(s) which consulted them.

-

Our sampling therefore proceeded through three stages. First we selected tracer activities likely to show maximum variety in types of VCSE activity, in case such differences affected how VCSEs were commissioned, and the consequences. Since it was impractical to study the entire range of VCSE activities (see Chapter 1, Voluntary, community and social enterprises in health and care), we took three tracer care groups as a maximum-variety sample of these differences, on the following assumptions:

-

Social prescribing This is a tracer with many fragmented, diverse, often small VCSEs, largely providing preventive activities usually requiring only modest resources and considerable self-help. Only relatively recently (post 2010) has the NHS commissioned such activities on a substantial scale (although many of these VCSEs and their activities pre-dated that). We therefore assumed that these VCSEs may be less accomplished than older, larger VCSEs in commissioning-related monitoring, evaluation and research.

-

End-of-life care, especially hospices This tracer covers larger-scale, more medicalised, intense and often inpatient care, and care provision rather than self-help. Its small range of specialist VCSEs are publicly commissioned, predominantly but not exclusively by the NHS, but have substantial other sources of funding.

-

Services for people with learning disability This tracer contains public, proprietary and corporate providers besides VCSEs. The latter are predominantly but not exclusively LA commissioned, although joint commissioning is also common. They serve a mixture of home, residential care and inpatient care settings.

These tracers thus provided opportunities to contrast VSCEs of different sizes, ages, and health system functions (prevention, self-management, formal care); and different mixes of contracts and funding sources, hence different degrees of dependence on commissioners. Some organisations and services (e.g. for learning disability, hospices) which cater for children and young people among others were likely to be included, but not those which exclusively served children or young people.

Next, as a proxy for how large a proportion of services VCSEs provided in each site, we selected a sample of study sites with maximum variety in size of expenditure on commissioning VCSE activity (see Appendix 5, Figure 7), on the assumption that such a selection was likely to reveal wide variety in commissioner–VCSE relationships and interactions. When this study started, CCGs were the main NHS commissioners of VCSEs. As explained (see Chapter 3, Cross-sectional profile of Clinical Commissioning Group spending on voluntary, community and social enterprises: Analysis), we ranked CCGs by their spending (on invoices > £25k) on voluntary and not-for-profit providers during 2018–9 as a percentage by value of all their spending on transactions of £25k or more (see Appendix 5, Figure 31). We divided the list into quartiles and invited the POG – whose membership consisted of experts in the field, VCSE and NHSE representatives – to produce for each quartile a shortlist of sites most likely to have the variety of commissioning relationships suitable for the study. Table 4 (sites anonymised) shows how, for the shortlist of sites that the POG suggested, this distribution across quartiles was sensitive to how ‘scale of CCG commissioning of VCSEs’ is defined.

| CCG | Total VCSE expenditure | Per transaction VCSE expenditure | % of transactions with VCSEs | % of transaction value (£) with VCSEs | Number of VCSE providers | % of providers that are VCSEs | % of value of transactions > £25k with VCSEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| B | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| C | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Da | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4a |

| E | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Fb | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2b |

| Ga | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1a |

| H | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Ia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1a |

| J | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Ka | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3a |

| L | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mb | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3b |

| Na | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2a |

| Oa | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4a |

We selected sites by the criterion of total value of transactions rather than percentage or number of VCSE providers. Most CCGs commissioned many VCSEs but only a few NHS Trusts and, in some cases, corporations, so non-VCSE providers would make up only a small proportion of the number of providers, and one unlikely to vary much across CCGs. Having decided to select by value of activity, not numbers of VCSEs commissioned, we selected by the criterion ‘% of value of transactions > £25k that are VCSEs’ on the assumption that a percentage would differentiate sites where the weight of VCSEs within overall commissioning varied, abstracting from the absolute size of expenditure of VCSEs.

On this basis, we selected two sites (see Table 4) from each quartile, checking the resulting sample with the POG for balance in terms of geographic spread, inner-city, suburban and rural sites, ethnic variation, population size, socioeconomic diversity (characteristics likely to affect the availability, size, range and character of VCSEs160,161), party political control of the LA, and the availability of volunteers. We also checked that the sites covered the range of commissioning relationships found in the preliminary scoping work. For two sites, CCG mergers occurred as we were selecting our sample. There, we continued with the new CCG containing the originally selected site. A final, practical consideration was site access. One site in the second quartile was in London. As other researchers have found, the volume of their day-to-day work and organisational ‘churn’ (reorganisations; staff turnover), and then the COVID-19 pandemic, made it practically impossible during 2020–1 to gain research access there. The other site was a large provincial city which, while its CCGs were being restructured, lacked a working research governance body. This left us with an accessible sample of one site per quartile plus one more in the upper and one more in the lower quartile, making six sites in all.