Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR131316. The contractual start date was in May 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Slowther et al. This work was produced by Slowther et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Slowther et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and study rationale

Anticipatory treatment plans

When a person develops a life-threatening condition or has a sudden deterioration in an existing illness, rapid treatment decisions may be needed. Often, the person is unable to be involved in the decision at the time, and there is limited clinical information or information about what their treatment preferences might be in this situation. Anticipatory treatment decisions and recommendations can improve this decision-making process and help to guide healthcare professionals while ensuring the person’s values and preferences are respected in the future. Anticipatory treatment plans can take several forms. A person may decide to make an advance decision to refuse treatment and specify particular treatments that should not be given to them should they be unable to speak for themselves. 1 More commonly an advance care plan (ACP) may be made between a person, their family and those caring them to document their future priorities of care more broadly, including preference for place of death. 2–4 ACP is mainly advocated in the context of end-of-life care, although an international consensus definition of ACP states that: ‘Advance care planning is a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals and preferences regarding future medical care’. 5

Emergency care treatment plans (ECTPs), sometimes called treatment escalation plans, focus specifically on treatment decisions in emergency or acute illness situations. Their aim is to make treatment recommendations that reflect the person’s preferences and values, and they are reached in discussion with the person or their family. However, the specific recommendations are made by the healthcare professional and are intended to guide future treating clinicians. 6 An important distinction between ACPs and ECTPs is that, whereas the ultimate focus of ACPs is on end-of-life care preferences, ECTPs focus on steps to be taken in the event of an acute pathophysiological deterioration in which recovery is possible, although it may be unlikely. 7 Prior to 2016, stand-alone do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) recommendations were the most commonly used form of emergency care treatment planning document in acute NHS hospitals (72% of hospitals). 8 However, concerns existed about their use, including lack of discussion with patients and/or their family, failure to consider cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) recommendations before a patient deteriorates, and lack of transferability of forms between primary and secondary care and ambulance services. 9,10 A particular concern was that a focus on CPR leads to lack of consideration of other treatments that may or may not be appropriate. 11–13 Responding to these concerns, some hospitals and health networks developed ECTPs to provide a more holistic approach to anticipatory medical decision-making. 14–16 In 2016, the Resuscitation Council United Kingdom (RCUK) led development of a national standardised approach to support conversations about goals of care and to provide guidance to clinicians about treatments to be recommended in an urgent situation when the patient lacks capacity to decide for themselves: Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT). 6

The ReSPECT process

ReSPECT is both a process and a form documenting the process (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for copy of ReSPECT form, versions 2 and 3). As described on the RCUK website, the ReSPECT process creates a summary of personalised recommendations for a person’s clinical care in a future emergency in which they do not have capacity to make or express choices. The process takes into account both patient preferences and clinical judgement and records ‘agreed realistic clinical recommendations’ including a recommendation whether or not CPR should be attempted if the person’s heart or breathing stop. Implementation of ReSPECT in NHS acute trusts began in December 2016 and within 3 years it was used in 22% of trusts. While other forms of ECTPs were used in some trusts, ReSPECT accounted for 60% of the observed move away from stand-alone DNACPR forms to ECTPs during this time. 17 Since its initiation the ReSPECT form has been modified in response to feedback from clinicians and patients (in 2023 both versions 2 and 3 were in use).

Although ReSPECT implementation occurred first in acute trusts, it was always envisaged that this process would cross the primary and secondary care interface. Indeed, it was developed as a patient held form rather than a clinical record. An evaluation of ReSPECT in early-adopter trusts found that many clinicians thought that the ReSPECT conversation and documentation of recommendations fitted better into a primary-care setting. 18 Patients may have an established relationship with their general practitioner (GP), conversations can occur over an extended period, patients are often less sick and more able to engage in discussion, and conversations can be placed in a wider context of ACP. However, there are also potential difficulties in moving ReSPECT conversations to primary care; patients and families may be less ready to think about these things until a crisis emerges, GPs may be uncertain about hospital-based interventions, and both may have concerns about the effect of a conversation on the patient–doctor relationship. Another challenge to the use of ReSPECT across the primary and secondary care interface is that hospital doctors and GPs use the process in different ways and recommendations do not always translate to different settings. 19

Emergency care treatment plans and person-centred care

There is an ethical and professional obligation to balance benefits and burdens of treatment from the patient’s perspective. 20 Current NHS policy and professional guidance emphasises a model of personalised care and shared decision-making. 21 ECTPs can facilitate person-centred shared decision-making in the acute situation by summarising earlier considered assessments of the potential benefits and burdens of a range of future treatments, taking into account what is important to the patient.

People with a learning disability might particularly benefit from emergency care treatment planning as their needs and wishes are often not met in acute situations. 22 Health outcomes are often poor for people with a learning disability because health professionals do not understand their needs. 22–24 Obstacles include lack of education and training among health professionals, communication challenges and/or a perception that individuals lack capacity because of their disability. 25,26 Anticipatory care planning with people with a learning disability is minimal due to a lack of confidence and awareness among medical staff. 27–29 This further disadvantages people with a learning disability by denying them input into decisions about future treatment.

The impact of COVID-19 on emergency care treatment planning

The COVID-19 pandemic generated increased interest in the use of ECTPs in general and ReSPECT in particular. High mortality, particularly among older frail people and those with specific medical conditions, few effective treatments and restrictions on hospital visiting, all had a potential impact on decisions about whether a person would benefit from or would want hospital admission or treatment if they developed COVID-19. GPs and hospital doctors admitting acutely ill patients were encouraged to have these conversations with patients early and to document the resulting treatment recommendations. In a UK teaching hospital, completion of treatment escalation plans more than doubled during COVID-19 from 20% of inpatients to 50%, and the scope of the recommendations was broader than before COVID-19. 30 This renewed emphasis on anticipatory decision-making during COVID-19 was seen as supporting best practice in person-centred care. A paper reporting a retrospective analysis of a multicentre cohort study of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 also found more nuanced decision-making around life-sustaining treatments, such as CPR. Participating clinicians explained that the use of the ReSPECT process allowed more nuanced treatment recommendations to be made compared with using DNACPR forms. 31 It was also an opportunity to embed the principles and practice of ACP and emergency care treatment planning into clinical practice more generally. 32 However, there were concerns that the impetus to complete ECTPs early, and the restrictions on communicating with patients and their families in person, might lead to inappropriate use of ECTPs and result in poor patient care, leading to guidance being issued by professional and regulatory organisations. 33,34 The Care Quality Commission’s report into its review of DNACPR recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic recommended that decisions about DNACPR should be made as part of a wider conversation about ACP, and that people and their representatives should be supported in having these conversations. The report suggested that ReSPECT was a good example of an ACP process that enabled these conversations to occur. 35 The Royal College of General Practitioners and British Medical Association recognised the specific challenges for GPs in having these conversations during a pandemic and provided guidance to its members reiterating the requirement for individualised conversations about future treatment decisions. 36,37 It is not clear to what extent practice around emergency care treatment planning has changed since the pandemic.

Evaluating the use of emergency care treatment plans in the United Kingdom

We identified six UK evaluation studies of locally developed ECTPs published between 2010 and 2017. 14,15,38–41 All reported that the ECTP improved communication and documentation of treatment escalation decisions. Three studies reported perceived improvement in appropriate decision-making around treatment escalation and resuscitation, although appropriate was not defined. ECTPs were positively evaluated by staff. Two studies demonstrated a significant reduction in patient harms associated with the use of the ECTP compared with patients who had a standalone DNACPR form documented in their notes. 40,41 Since the introduction of ReSPECT, the focus of published evaluation studies has been on this model of ECTP. An evaluation of the first ReSPECT pilot in Scotland, which included 200 ReSPECT forms completed in a range of settings (hospital, hospice and community), found that patients with a ReSPECT form were more likely to die in their preferred place of care and had a reduced chance of readmission within 3 months of hospital discharge. Patients and staff were generally positive about the process. Challenges included time pressures, staff reluctance to initiate a conversation or lack of confidence to do so. 42 A multicentre evaluation of the use of ReSPECT in early adopter sites involving six acute NHS trusts in England took place between 2017 and 2019. It found that ReSPECT conversations were mainly initiated with patients nearing the end of their life or at imminent risk of deterioration and focused on CPR decisions. However, a move towards a more holistic approach in terms of treatment recommendations and conversations with patients and their families was observed. 8 Doctors’ uncertainty about a patient’s prognosis, constraints of time and external environment, and the need to minimise patient distress, influenced both the prioritisation and content of conversations. 18 An interview study with GPs and care home staff in the West of England found a generally positive attitude to the use of ReSPECT but noted that its use was complex and there were challenges in incorporating patients’ preferences into decision-making. The authors recommended a multidisciplinary approach that engaged care staff more in the process. 43 There has been no large study of the use of ReSPECT or other ECTP in the community setting.

Chapter 2 Overview of study design

Here, we outline the study aims and objectives, and corresponding work packages (WPs), describe the theoretical approach underpinning the research and the ethical considerations raised by the research. Finally, we explain changes made to the original protocol in response to challenges encountered during the research process.

Study aims and objectives

Our overall aim was to evaluate the ReSPECT process for adults in primary care to determine how, when and why it is used, and what effect it has on patient treatment and care.

Our objectives were:

-

To understand how ReSPECT is currently used in primary care from the perspective of patients, their families, clinicians and care home staff

-

To describe the views of patients, the public, primary and community healthcare professionals, and home care workers on ECTPs in general and ReSPECT in particular

-

To identify enablers and obstacles to embedding ReSPECT in primary care practice

-

To explore the impact of ReSPECT on patient treatment decisions

-

To understand how health and social care professionals can optimally engage people with a learning disability in the ReSPECT process and co-produce relevant support materials

-

To develop a consensus on how ReSPECT should be used in primary care.

Study design

Work package 1

A qualitative study exploring the experience of ReSPECT in primary care and community settings drawing on interviews with GPs, patients and their families/carers and staff in care homes, and conversations with other members of staff in the participating GP practices (see Chapters 4, 5 and 6).

Work package 2

Focus groups and interviews with healthcare professionals, home care workers, members of the public and faith leaders to explore their views on the principles and practice of ReSPECT and other forms of anticipatory decision-making; two national surveys, one of the public’s attitudes to ECTPs and one of GPs’ experiences and views of anticipatory decision-making (see Chapters 3 and 4).

Work package 3

Quality assessment of ReSPECT form completion in the GP practice sites involved in WP1 (see Chapter 4).

Work package 4

Co-production workshops with adults with a learning disability to explore their understanding of and views on emergency care treatment planning and to co-create resources to support the engagement of people with a learning disability with ReSPECT; focus groups and interviews with relatives of people with a learning disability to capture their views and experiences of emergency care treatment planning. This WP was added to the original protocol following a successful application to NIHR for additional funding in response to a call for proposals to be submitted by current NIHR award holders for additional research related to social care, to be completed within their current award time frame (see Chapter 7).

Work package 5

An initial synthesis of findings across the WPs informed the content of a stakeholder meeting with participants from professional and patient organisations and implementers of ReSPECT across the UK; final synthesis of all findings (see Chapter 8).

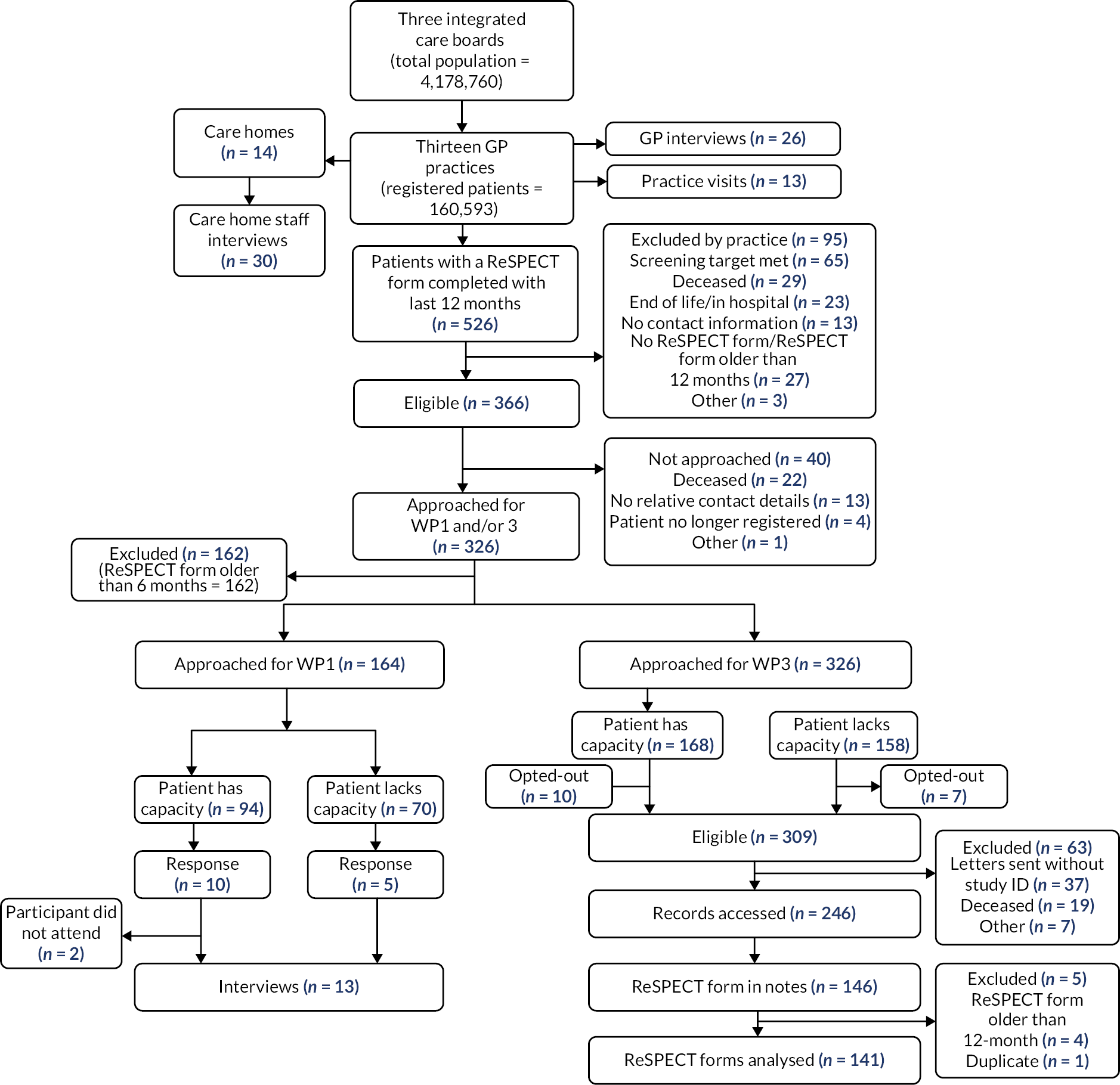

See Report Supplementary Material 2 for study flow-chart.

Theoretical framework

Our overarching theoretical framework for analysis was normalisation process theory (NPT). 44,45 We wished to investigate to what extent ReSPECT is embedded in routine primary care practice and how it is perceived and enacted by health and care professionals and patients. NPT characterises a set of mechanisms (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring) that influence the embedding of new interventions or processes into clinical practice.

Data from WPs 1, 2 and 3 primarily informed our NPT analysis. In this analysis, we asked how do clinicians, care home staff, patients and their families:

-

conceptualise ReSPECT (coherence)

-

initiate or engage with the process (cognitive participation)

-

use the process and the documentation (collective action)

-

evaluate the impact of ReSPECT and how it changes behaviour (reflexive monitoring).

Data from the focus groups with members of the public and the public attitudes survey (WP2) provided a broader societal perspective to provide context for ReSPECT implementation.

Localities

Three Clinical Research Networks (CRNs) recruited practices across three diverse Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) areas in England. To maintain participant confidentiality, we are not reporting which CCG areas were involved.

Ethics and regulatory approvals

We gained NHS/Health Research Authority (HRA) ethics approval (21/LO/0455) and Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) approvals (21/CAG/0089) for the study. A summary table of the approvals, including amendments, is presented in Report Supplementary Material 3. The sponsor was the University of Warwick.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues for this study included recruitment and conduct of interviews on a sensitive and emotive topic; responding to distress of participants during interviews and focus groups; verbal consent for conversations with practice staff; responding to concerns raised regarding safeguarding or unprofessional conduct; accessing medical records without explicit consent; and involvement of people with a learning disability in co-production workshops. We describe how we addressed these in Appendix 1. Access to patient records and ReSPECT forms by study researchers was approved by the HRA Confidentiality Advisory Group under Section 251 of the NHS Act. Our justification for CAG approval is in Report Supplementary Material 4.

Changes to the protocol

Changes to recruitment of care homes

In our original protocol, we aimed to recruit two care homes associated with each GP practice site. Planned care home involvement included interviews with senior care home staff, involving care homes in recruitment of patients and their relatives, and identification of ReSPECT forms. Of 23 care homes identified by our GP practices, only 11 agreed to participate and, of those, 8 agreed to take part in the interview element only. Service delivery pressures related to COVID-19 and its consequences and frequent changes in senior staff contributed to the challenge of recruitment. To ensure that we captured the full range of care home experience, we expanded our recruitment through care home networks to include care home staff not linked to our GP sites.

Changes to recruitment approach for patient and relative interviews

Recruitment of patients and relatives of patients who lacked capacity was low. In response, we simplified our recruitment approach by removing the link between interview (WP1) and access to patient records (WP3) in the invitation letter. We also sought to advertise the interview study directly through care home networks.

Decision to stop data collection for congruence

We originally planned a retrospective analysis of patient records and ReSPECT forms to measure congruence between ReSPECT recommendations and clinical decision-making at the time of an acute event for people with a ReSPECT form completed in the previous 6 months. The estimated sample size for this analysis was 413 ReSPECT forms, assuming that the acute clinical event rate within 6 months of a ReSPECT form completion was 70%. Across our first 6 practice sites, we identified 233 patients with a record of a ReSPECT form completed in the previous 12 months, of whom 169 were eligible to participate. Of eligible patients, we were only able to identify and extract data from 65 ReSPECT forms. We had anticipated that GP practices may not always have a copy of a patient’s ReSPECT form as they are designed as patient held forms. However, we had expected that we would be able to identify additional ReSPECT forms through the care homes recruited to the study. As noted above, recruitment of care homes to this element of the study was extremely challenging and so this method of data collection was not possible. Additionally, analysis of the clinical records of patients with a ReSPECT form found an acute event rate of 24%. Following discussion between the study team, the study independent steering committee and the funder, it was agreed that it would not be possible to achieve the required sample size within the parameters of the current study. Therefore, data extraction from clinical records was discontinued for the remaining sites but collection of data from anonymised ReSPECT forms continued to enable a quality analysis of form completion.

We then obtained the relevant approvals to conduct a feasibility study to explore whether a different study design, using care home records only, could answer this research question. We encountered several challenges in recruitment of care homes and recruited two from a target of three homes. We found that 17/75 (22.7%) of residents had both a ReSPECT form and an acute event in a 6-month period. We estimate that we would need to work with 50–60 care homes to complete a congruence analysis (see Appendix 2 for a more detailed report). This finding and our findings on the quality of recorded recommendations in our review of ReSPECT forms in general practices lead us to conclude that at present a congruence analysis as originally conceived is not feasible.

Patient and public involvement

The main aim of ECTPs is to create personalised recommendations for clinical care and treatment in emergency situations where someone cannot make decisions for themselves. Key to this is involving the person, or someone close to them if the person lacks capacity, in conversations about what is important to them so that their preference can inform the clinical recommendations. This aim is set out on the RCUK ReSPECT web pages. As we sought to evaluate how such an explicitly patient-focused process is used in primary care and community settings, we recognised the importance of patient and public involvement (PPI) and engagement at every stage and embedded PPI in our project governance structure.

Scope of patient and public involvement

Project design

Before submission of the application for funding, we held two meetings with the lay advisory group that had contributed to our previous study evaluating ReSPECT in acute NHS trusts. The group was originally recruited through Warwick University’s University/User Teaching and Research Active Partnership and members had lived experience of health conditions or being a carer. During the first meeting, we presented findings from the initial ReSPECT study evaluating its use in secondary care. The group discussed the identified lack of evidence of how the ReSPECT process works in primary care and the difference in how it is viewed between primary and secondary care. We discussed the proposed aim of this research, the suggested research questions and study methods. The group was asked for their views particularly about how to conduct the research in a way that was sensitive to patients and their families, and how to engage with the wider public, including hard to reach groups, to ascertain their opinions on ReSPECT and emergency care treatment planning. At the second meeting, the group considered feedback from our outline application and commented on our proposed responses to reviewers’ comments.

The group agreed that this research was important. They noted that it was crucial for patients and their families to have their preferences about future treatment decisions taken into account and that the process for supporting this needs to be robust and properly evaluated. The group discussed the importance of including the perspectives of marginalised and hard to reach groups and offered suggestions on recruitment from these groups for WP1 and 2. They also gave advice on the approach and conduct of interviews with patients and their families. Our lay advisors also reviewed and contributed to our application for additional funding to include a WP that focused on the experiences and perspectives of people with learning disability with regard to ReSPECT (WP4, see Chapter 7).

Investigator team

The study investigator team included a PPI member (CB) who was involved from inception in the design and development of the project and was also a member of the lay advisory group to support linkage across the project. He provided guidance on the acceptability of proposed methods, attended lay advisory group meetings, commented on all patient and family information materials and contributed to the writing and editing of reports from the different WPs. A PPI lead from the main study team (JH) also ensured linkage, communicated with the advisory group between scheduled meetings regarding project progress and any matters arising.

Advisory group

Our lay advisory group of five members had between them a range of lived experience of health care. The group met at 6-monthly intervals during the project to discuss project progress and develop and review fieldwork instruments and study documentation. They commented on draft questions for the survey of members of the public with their suggestions being incorporated into the final version. They also reviewed and commented on interim analyses of qualitative data to help interpret patient and relative experiences, and the stakeholder meeting report to help shape key messages. The group also advised on approaches and audiences for dissemination of the study findings to the public.

An integral part of WP4 (perspectives of people with a learning disability) was the inclusion of a reference group for this WP. The reference group was recruited through CHANGE (Leeds, UK) a national advocacy group for people with a learning disability, and all members had a lived experience of learning disability. This group worked closely with the study researcher and CHANGE to develop the format and content of the study workshops and pilot activities to be used in the workshops. They also contributed to the development of the resources that were created as part of this WP (see Chapter 7).

Stakeholder meeting

We invited delegates from a range of patient and public support organisations to the stakeholder meeting in addition to our lay advisory group members. Delegates participated in group discussions to develop recommendations on issues to consider in the future development of ReSPECT in community settings. Two members of the learning disability reference group presented findings from their WP at the stakeholder meeting, and examples of the materials produced and used by people with a learning disability during the workshops were displayed for delegates to view throughout the day.

Summary

The importance of PPI was recognised at an early stage of development of the project and was integral to its development, conduct, delivery and successful completion. Embedding the lived experience of people with a learning disability in development and outputs for WP4 was particularly important and enriched the overall study findings. The presence of PPI throughout the project also helped to ensure that the work retained its focus on the person at the heart of the ReSPECT process, and that language and communication was consistently clear and accessible.

Chapter 3 Attitudes and experiences of the public around emergency care treatment planning

Introduction

The development of ReSPECT involved a public consultation but beyond that, there is little information on public perceptions of emergency care treatment planning in the UK. 46 There is some literature on the attitudes and experiences of patients and their families regarding DNACPR decision-making. 10,47 A YouGov survey of the public commissioned by Compassion in Dying in 2020 found that most people did not understand why a DNACPR decision is made, or what treatment and care will be given if a doctor decides they are ‘not for CPR’. 48 Attitudes to ACP, which may include emergency care treatment preferences, have been investigated although, as with DNACPR studies, they have tended to focus on patients rather than the general public. 49–51 A study of public attitudes to ACP in Northern Ireland found that ACP was recognised as important despite limited awareness, lack of knowledge and misperceptions. 52

To situate our qualitative evaluation of ReSPECT in primary care in the wider public context we carried out focus groups and a national survey to answer the research question: What does the wider public think about the concept and use of ECTPs? Additionally, we sought to interview faith leaders to explore how faith perspectives might influence public attitudes to ReSPECT.

Focus groups with members of the public and interviews with faith leaders

Methods

Recruitment

We sought expressions of interest for focus group participation from members of the public with an interest in health through local Health Watch, community and patient organisations and patient groups linked to our participating general practices in each of our three study areas. 53 We asked our PPI advisory group for suggestions of relevant networks to approach and carried out desktop research to identify local patient and carer organisations in each area, including those representing minority groups. We provided a poster about the study, an invitation e-mail and brief information leaflet. Most expressions of interest came from advertising through local Health Watch organisations. Potential participants contacted the study team directly and were provided with further information and offered a range of dates for planned focus groups. If they agreed to participate, they were given details of how to join their focus group. Online participants had unique links to a Zoom™ (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) meeting. One participant unable to attend a focus group was interviewed separately. Prior to data collection, participants were sent a copy of the ReSPECT form and a consent form. We obtained written consent at the start of the in-person group. Online, we went through the consent form with each participant and recorded their consent.

We advertised the study to faith leaders through community faith groups, local councils, university chaplaincy and NHS trust chaplaincy services in our three study areas and followed up expressions of interest as above.

Data collection

We developed topic guides with input from our lay advisory group. Focus groups were facilitated by researchers JH, SR or CM. Online and face-to-face focus groups and the individual interview followed the same process. After introducing the purpose and format of the discussion, and the ReSPECT process, facilitators used a topic guide to guide the discussion (see Report Supplementary Material 5). They prompted participants to consider potential benefits and disadvantages of emergency care treatment planning for patients, relatives, the health service and wider public, and consider aspects of implementation, including how and when ReSPECT conversations should be initiated, any potential challenges in using the forms, and if, and when ReSPECT forms should be reviewed.

Interviews with faith leaders followed the topic guide for the focus groups with additional prompts on how the values embedded in ReSPECT interact with key values in their faith.

Participants received a shopping voucher as a thank you for participation. We ran four focus groups; one of which was in person. Interviews were online apart from one faith leader interview. Focus groups lasted between 53 and 66 minutes; interviews with faith leaders lasted 56 and 62 minutes, respectively. All focus groups and interviews were recorded with consent, professionally transcribed and checked by the study team.

Analysis

We analysed the data as one data set using framework analysis. 54 Four study team members (FG, AS, JH, SR) initially each read a transcript from study area one, discussed the data and identified potential themes for public survey questions. JH read and coded all transcripts from area one using the topic guide as a framework, identifying themes from which we confirmed topics for the survey questions. Two researchers (CB and CM) then independently coded one focus group transcript to check for consistency and themes were discussed with JH. CM then further developed and refined the coding framework to analyse the remaining focus group and interview transcripts. Finally, AS read all transcripts and confirmed final themes with CM.

Results

We recruited 21 public participants to 4 focus groups, mostly in area one (3 focus groups 16 participants) and 1 individual interview. Recruitment in areas two and three was extremely challenging. We conducted two faith leader interviews; both participants were from Christian faiths. We identified four themes.

ReSPECT could help normalise discussion about emergency care

Participants across the focus groups acknowledged that death and planning for the end of one’s life were sensitive topics, and many people resist having these conversations. They agreed that ReSPECT could offer a way for individuals, families, and clinicians to begin the conversation.

It’s a really helpful tool, a kind of lever to, to have a conversation about end of life and about dying with people, and I think that’s a conversation that people find very hard to have, but it’s a really important conversation to have and I think having a document that acts as a stimulus to a conversation about end of life is really useful and really important and we don’t do enough of it, so I think it’s a good thing to have.

Public focus group 2

Participants initially discussed ReSPECT conversations as important for people approaching the end of life or with a progressive or life-limiting condition. This progressed to a discussion of relevance of ReSPECT for a much wider range of people, as emergencies could occur at any age, and that everyone inevitably would have deteriorating health. Early conversations and records of a person’s wishes could help families make difficult decisions.

I think you’re focusing more, aren’t you, on the elderly people, but you talk, it’s got the word ‘emergency’ in the title, and you could be in a car accident at 25, you know, there’s all sorts of reasons when it could be brought in.

Public focus group 2

I think life is a terminal illness. You know, … we’re all gonna get there. And I think it’s important to think about these things while you’re able to, you know, whatever your circumstances are, because it, it takes so much pressure off your family.

Public focus group 4

Good communication during the ReSPECT conversation between patient, relatives and health professional was seen as important to ensure good understanding of the purpose of the plan and the potential future scenarios and treatments. Participants were clear that the health professional needed to be skilled in having these conversations and thought that conversations would work best when the person had an established relationship with the health professional, although they recognised that this was not always possible: ‘I think it, it’s, it’s the person you have the best relationship with, not everybody has a good relationship with their doctor’ (public focus group 1).

Some participants suggested that increased public awareness of ReSPECT, for example through the media, would encourage more people to have these conversations. They suggested ideally it should become normalised ‘like the organ donor card’ (public focus group 2). The person should be at the centre of the process

A key theme across focus groups was that the ReSPECT process should focus on the individual, recording a plan that reflected their wishes and preferences about their future treatment. Some participants thought the ReSPECT plan was an excellent means for a person to communicate their wishes.

… I think they seem like a very useful tool so that you can, kind of, convey your wishes before being in that situation, if ever. At least you’ve laid out a sort of plan and your, your wishes can be respected.

Public focus group 4

However, some participants expressed concern that the ReSPECT process was insufficiently focused on the person. The form seemed medically orientated rather than person orientated. In one focus group where participants were mainly care home residents’ relatives, several compared the ReSPECT form to an ACP that they had completed for their relative on entering the home. They felt the ReSPECT plan, with its focus on emergency treatments, did not capture their relative’s reality which was more of a slow decline rather than sudden emergencies.

the one we filled in here for when my mother came in, I thought was wonderful, it was about how she wanted to be treated, you know, and it was very reassuring. I look at this and think it’s not really relevant to her, … it’s not really suitable, ’cause it’s so difficult to answer the questions. Whereas the, the form we filled in here was very warm … and personal and this is very bleak.

Public focus group 3

Participants were concerned that the person may not understand what was being discussed in a ReSPECT conversation, particularly if conversations were initiated at a late stage in a person’s illness trajectory. They commented on the potential complexity of treatment options discussed and the uncertainty of prognoses or potential future events. One participant expressed a feeling of disempowerment when considering completing a ReSPECT plan at a time of deteriorating health.

But actually, in a, a real-life scenario I think I would feel quite disempowered, that other people hold the power about things to do with my life. And I really, you know, in my most vulnerable state I don’t even know what my options are.

Public focus group 1

One faith leader suggested that it could be helpful for some people to include a faith leader in their discussions about life-sustaining treatment.

All participants across the focus groups felt strongly that the plan needed to be reviewed regularly to reflect changes in the persons health status and wishes over time.

… your views definitely change … I think it should be re-evaluated, as I say, I think to a certain degree you like to put it in the back of your mind, but sometimes I think when you’ve had more time to think about it, your views might have changed. So, I do think there should be a follow-up on it, definitely.

Public focus group 3

Yeah, that already then is a flaw in the system to me. Because what I might wish to do today may change due to experience, different circumstances. Your health might, you know, you, you, you might think your health is A today, and in two years’ time something else happens.

Public focus group 4

ReSPECT and the patient’s family

There were mixed views across the focus groups about the extent to which families should be involved in the ReSPECT process. Many thought it was important that the person’s family was involved in or aware of the ReSPECT plan to ensure that the person’s wishes were followed and take pressure off the family.

If you’ve got that understanding, there’s no fear …, you’re then at, at, at peace internally, you know, you’re at peace with what is happening to your other, to your other half, rather than not knowing what that person wants.

Faith leader 2

This will help your relatives make a difficult decision in a time when you’re not there to advise.

Faith leader 1

The ReSPECT process could also reduce conflict between family members when decisions needed to be made when the person was very unwell.

I think it helps promote clarity between the, … patient and, and their relatives about what might be wanted … It’s not necessarily going to fix all of the misapprehensions that people have, but it’s, it is a clear way of having that conversation and, and, you know, flushing out whether there are agreements or disagreement, it’s a really important thing.

Public focus group 2

[I]t, it really needs to, to be a, an open discussion which is not just linked to the immediate close person in your life. I think it has to, it has to be wider. And then the, because it’s, it will be for, for everyone it would be a very, very emotional situation to deal with.

Public interview 1

However, other participants noted that not everyone wanted their families to be involved in or know about their healthcare decisions.

And, you know, in, in some cases perhaps somebody doesn’t want this to be discussed with the whole of the family, because it is their treatment, and there are issues about confidentiality, even within the family.

Public focus group 1

Participants recognised that it was often difficult for clinicians when faced with families who wanted them to intervene for their sick relative, even when there was a form specifying that this was not what the patient wanted.

Scepticism about use of the plan in an emergency

While many participants talked about the benefits of having a ReSPECT plan, they were not confident it would be followed in the situations it was designed for.

I’m not entirely confident that having … an emergency care treatment plan will necessarily produce the result that the person was expecting, because I think there are all sorts of things that could get in the way of what somebody wants actually being implemented.

Public focus group 2

Participants identified several obstacles to effective use. They discussed practical problems in ensuring the plan was available when needed. Someone living at home may forget where the form is kept or be too sick to tell the health professional, usually a paramedic, who is attending. A potential solution would be a centrally held form or record of the plan that was accessible to clinicians at the time. Participants were generally sceptical of the ability of current NHS electronic systems to provide reliable access to these plans. Participants were not confident the recommendations on the plan would be followed. Examples were given of paramedics noting plans but then taking a different course of action because of their clinical judgement.

And both of those people had the ambulance service come, both of them showed the ambulance service the documentation, and both of them were told that they would not take that action, they were there to save life. And that upset both families very much.

Public focus group 4

Ambiguity in the plan recommendations could result in actions that were inconsistent with the plan’s intention. For example, a recommendation about not being admitted to hospital without specifying the relevant circumstances may lead to someone being admitted/not admitted inappropriately. Participants recognised that it was impossible to specify every circumstance and provide detailed management recommendations. They recognised that recommendations would need to be read quickly in an emergency so should be quite brief, but that this created a tension with communicating detailed person specific instructions about a person’s care.

You do need something that’s fairly quick to refer to, because you can’t give a, a long kind of detailed set of instructions if it’s going to be read by paramedics and, and that sort of thing in an emergency situation.

Public focus group 2

Some participants commented that it was important to think of the recommendations as guidance but that the attending clinician would need to ultimately make the treatment decision, and people would need to trust that the clinician would act in their best interests.

I’m still convinced that the doctor makes the decision at the end of the day.

For me the form is a way to help people think about these things, express an opinion, but it’s not obligatory, as it says on the form…it’s useful for clinicians who don’t know that patient. To have something there, as guidance, and know that there has been a discussion, particularly in an emergency.

Public focus group 1

Lack of resources could result in recommendations not being fulfilled. For example, if treatment at home rather than hospital was recommended this might require urgent nursing or other support.

Reflecting on these challenges to effective use of ReSPECT plans, some participants questioned how person centred the plan was: ‘it seems to me control is taken away from you and that’s what’s so frustrating and tiring and bureaucratic’ (public focus group 3). However, even if the plan was not available or could not be followed precisely, some participants still regarded the process as helpful to ensure the person’s wishes were taken into account.

I’m a realist though and I perfectly understand that come the day when I get unplanned admission to hospital nobody is actually gonna dig through my file in the GP practice, and dig this out from seven years ago, and respect my wishes. But at least my daughters might remember something that was said.

Public focus group 1

Survey of attitudes of the British public to emergency care treatment plans

Parts of this section are reproduced with permission from Underwood et al. 55 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. To understand the views and attitudes of the public on the concept and use of emergency care treatment planning, we carried out a national survey. Here, we describe the survey and its findings.

Methods

Questionnaire development

To ensure a high-quality nationally representative population sample, we commissioned the National Centre for Social Research to include our questions in the annual British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey. 56 The BSA is the UK’s longest-running survey of public opinion. It provides a high-quality nationally representative attitudinal survey with a stratified sample based on postcode and includes face-to-face data collection using computer-assisted personal interviewing and self-completion. Question development was a collaborative process between the study team and the BSA team. Firstly, members of the study team (AS, FG, SR, JH) developed a draft set of questions, drawing on data from focus groups. Following feedback from our co-investigators and lay advisory group the questions were further refined. Next, the study team met with the BSA team and, through an iterative process, the final set of questions to be included in the BSA annual survey were agreed. We aimed to determine the willingness of members of the public to complete an ECTP for themselves or someone close to them, under what circumstances they would consider completing one and who they would prefer to complete the plan with. We also sought their views on potential benefits or harms of having an ECTP. A sample of the questions were then tested by the BSA team in cognitive interviews with 10 people, and the full set of finalised questions was piloted with a sample of 56 participants recruited from the BSA panel database and using telephone interviews. Results of the cognitive interviews and pilot were discussed with the study team and minor modifications made to question wording (see Report Supplementary Material 6 for final questions).

Data collection

Data collection was carried out in accordance with the National Centre for Social Research’s protocol for delivery of the BSA survey. Invitations to participate in the survey, with the option of online or telephone interview completion, are sent to a stratified sample of households in the UK identified from the postcode address file with up to two adults in each household able to participate. Two online access codes are provided to each household. If selected households do not wish to complete the survey online, they are able to call a freephone number and arrange to complete the survey by telephone with a specialist telephone interviewer. To maximise response up to three invitation mailings are made. Respondents are offered a conditional £10 incentive to participate. Fieldwork took place between 9 September and 30 October 2022. The target sample for administration of our question set was 1000.

Analysis

In addition to descriptive statistics for each question, we present logistic regression analyses investigating the variables associated with the three dichotomised dependent variables: (1) being in favour of anyone being able to have an ECTP (strongly and somewhat in favour vs. the other categories); (2) whether they would like an emergency care and treatment plan at present (definitely and probably would like vs. the other categories) and (3) (for those who did not already have an a emergency care and treatment plan) how comfortable (very and fairly comfortable vs. the other categories) they would feel about making such a plan for themselves. For each analysis, the independent variables were age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, having an illness lasting more than 12 months, caring for someone ill or with a disability and being close to someone with a condition that could shorten their life. These were chosen after discussion within the study team to identify ‘a priori’ the most important possible independent variables. Using the statistical software R Core Team (2023; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for each dependent variable, both fully adjusted model and non-adjusted models were fitted at the 5% significance level. With very few missing data, the logistic regression models for binary data fit well.

Results

All data used in these analyses have come from the National Centre for Social Research British Social Attitudes Survey 2023 © National Centre for Social Research September 2023.

Of the 6699 respondents to the BSA survey 1135 completed our module. Overall, they were sociodemographically representative of the UK although minority ethnic groups were slightly under-represented against age standardised values (see Appendix 3, Table 10). Seventeen respondents (1.5%) currently had an ECTP. Among these respondents, the most common trigger for ECTP completion was a diagnosis of a life-threatening illness (7/17) or long-term condition (6/17) (see Appendix 3, Table 11). Eight respondents with a completed ECTP were aged under 45 years and 7 aged 45 years or over. Most plans (10/17, 59%) were completed by the respondent’s GP (6/17) or another doctor who knew them well (4/17; see Appendix 3, Table 12). Of respondents with an ECTP, most were very comfortable (9/17) or comfortable (5/17) with the discussion. However, one respondent was fairly uncomfortable and one very uncomfortable with the discussion.

Attitudes to emergency care treatment plans

A large majority of respondents were in favour of people being able to have an ECTP if they so wished, with 908/1135 (80%) at least somewhat in favour (see Appendix 3, Table 13). Females were slightly more likely to be in favour than males [82% vs. 77%; odds ratio (OR) 1.45; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.06 to 1.97; p = 0.02]. When compared with those with no qualifications, people with degrees were significantly (p = 0.002) more likely to be in favour (70% vs. 84%; OR 2.68, 95% CI 1.42 to 5.07). However, the absolute difference is modest and there is not a clear trend for more people with a higher educational level to be more in favour of ECTPs. Overall, ethnicity did not appear to affect people’s views, although the numbers in each group were small. However, people of Asian ethnicity might be less likely than those identifying as white British to be in favour of everyone being able to have an ECTP 67% versus 82% (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.84, p = 0.012) (Table 1).

| Are you in favour or against anyone being able to have an emergency care and treatment plan if they wish?a N = 1135 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In favour | p-value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| (n/N) | (%) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 380/493 | 77 | 1 | |

| Female | 510/619 | 82 | 0.02 | 1.45 (1.06 to 1.97) |

| Other | 7/8 | 88 | 0.382 | 2.62 (0.3 to 22.69) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 51/66 | 77 | – | 1 |

| 25–34 | 137/173 | 79 | 0.922 | 1.04 (0.51 to 2.11) |

| 35–44 | 138/172 | 80 | 0.748 | 1.12 (0.55 to 2.3) |

| 45–54 | 160/205 | 78 | 0.955 | 1.02 (0.51 to 2.04) |

| 55–59 | 85/99 | 86 | 0.14 | 1.89 (0.81 to 4.4) |

| 60–64 | 86/107 | 80 | 0.598 | 1.24 (0.56 to 2.73) |

| 65–69 | 82/107 | 77 | 0.992 | 1 (0.47 to 2.17) |

| 70 + | 168/205 | 82 | 0.295 | 1.48 (0.71 to 3.07) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 820/1005 | 82 | – | 1 |

| Black | 10/14 | 71 | 0.285 | 0.52 (0.15 to 1.73) |

| Mixed | 30/44 | 68 | 0.115 | 0.57 (0.29 to 1.15) |

| Asian | 37/55 | 67 | 0.012 | 0.45 (0.25 to 0.84) |

| Qualifications | ||||

| No qualifications | 43/61 | 70 | – | 1 |

| Qualifications less than A level | 138/183 | 75 | 0.358 | 1.37 (0.7 to 2.66) |

| A-levels/SCE Highers | 127/158 | 80 | 0.048 | 2.05 (1.01 to 4.17) |

| Other Higher Education | 129/170 | 76 | 0.346 | 1.38 (0.7 to 2.72) |

| Degree or equivalent | 446/528 | 84 | 0.002 | 2.68 (1.42 to 5.07) |

| Do you have any physical or mental conditions or illnesses lasting or expected to last 12 months or more? | ||||

| No | 624/777 | 80 | – | 1 |

| Yes, but does not reduce activity | 82/99 | 83 | 0.704 | 1.12 (0.63 to 1.98) |

| Yes, and reduces activity | 198/254 | 78 | 0.528 | 0.89 (0.61 to 1.29) |

| Is there anyone who you look after or give special help to, for example, someone who is sick, has a long-term physical or mental disability or is elderly? | ||||

| No | 670/829 | 81 | 1 | |

| Yes | 195/246 | 79 | 0.431 | 0.86 (0.58 to 1.26) |

| Yes, but only in a professional capacity as part of my job | 43/60 | 72 | 0.12 | 0.61 (0.33 to 1.14) |

| Do you or does someone close to you have a condition or illness that you think is likely to shorten life? | ||||

| No | 647/817 | 79 | 1 | |

| Yes | 261/318 | 82 | 0.298 | 1.22 (0.84 to 1.76) |

Of respondents who did not currently have an ECTP, 698/1112 (63%) felt they would be at least fairly comfortable making an ECTP, with only 49/1112 (4%) saying they would be very uncomfortable having an ECTP discussion (see Appendix 3, Table 14). Compared with those with no qualifications, people with degrees were more likely to feel comfortable having an ECTP (70% vs. 49%; OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.40 to 4.39; p = 0.002; Table 2). Comfort with completing an ECTP was not significantly associated with age, gender, or experience of caring for someone with a long-term health condition. Of those respondents who said they would like to have an ECTP for themselves, half (316/618, 51%) would want their GP to complete this with them while one-quarter (161/618, 26%) would want a doctor or nurse who did not know them but was trained in making ECTPs to do this (see Appendix 3, Table 12).

| How comfortable or uncomfortable do you feel about making an emergency care and treatment plan yourself with a doctor or nurse?a (N = 1112)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfortable | p-value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| (n/N) | (%) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 309/482 | 64 | – | 1 |

| Female | 380/609 | 62 | 0.647 | 0.94 (0.72 to 1.22) |

| Other | 2/7 | 29 | 0.118 | 0.25 (0.05 to 1.41) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 40/62 | 65 | – | 1 |

| 25–34 | 116/168 | 69 | 0.977 | 1.01 (0.53 to 1.92) |

| 35–44 | 100/168 | 60 | 0.197 | 0.66 (0.35 to 1.24) |

| 45–54 | 117/204 | 57 | 0.141 | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.17) |

| 55–59 | 66/98 | 67 | 0.822 | 1.08 (0.53 to 2.21) |

| 60–64 | 73/107 | 68 | 0.885 | 1.05 (0.52 to 2.13) |

| 65–69 | 65/104 | 63 | 0.487 | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.56) |

| 70 + | 121/200 | 61 | 0.359 | 0.74 (0.39 to 1.41) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 633/987 | 64 | – | 1 |

| Black | 6/13 | 46 | 0.092 | 0.38 (0.12 to 1.17) |

| Mixed | 22/43 | 51 | 0.097 | 0.58 (0.30 to 1.11) |

| Asian | 32/54 | 59 | 0.354 | 0.76 (0.42 to 1.36) |

| Educational level | ||||

| No qualifications | 29/59 | 49 | – | 1 |

| Qualification less than A level | 91/179 | 51 | 0.792 | 1.08 (0.59 to 1.99) |

| A-levels/SCE Highers | 94/153 | 61 | 0.064 | 1.82 (0.97 to 3.44) |

| Other Higher Education | 100/166 | 60 | 0.273 | 1.65 (0.68 to 4.02) |

| Degree or equivalent | 365/521 | 70 | 0.002 | 2.48 (1.4 to 4.40) |

| Do you have any physical or mental conditions or illnesses lasting or expected to last 12 months or more? | ||||

| No | 479/765 | 63 | – | 1 |

| Yes, but does not reduce activity | 74/97 | 59 | 0.013 | 1.91 (1.14 to 3.19) |

| Yes, and reduces activity | 144/245 | 59 | 0.452 | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.21) |

| Is there anyone who you look after or give special help to, for example, someone who is sick, has a long-term physical or mental disability or is elderly? | ||||

| No | 512/816 | 63 | ||

| Yes | 154/238 | 65 | 0.57 | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.53) |

| Yes, but only in a professional capacity as part of my job | 32/58 | 58 | 0.31 | 0.74 (0.42 to 1.32) |

| Do you or does someone close to you have a condition or illness that you think is likely to shorten life? | ||||

| No | 494/805 | 61 | ||

| Yes | 204/307 | 66 | 0.193 | 1.23 (0.90 to 1.67) |

Who would like an emergency care treatment plan for themselves and when would they want to have it in place?

Half of respondents without an ECTP (620/1112; 56%) would want one at present (see Appendix 3, Table 15). Overall, fewer people in older age groups would want an ECTP at present; however, the difference was only statistically significant for one comparison; 63% in those aged 18–24 years compared with 47% for those aged 65–69 years (p = 0.045, OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.98; Table 3). People with a chronic physical or mental health condition that reduces their activity were more likely to want a plan at present compared with those in good health (64% vs. 52%; OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.45; p < 0.001; see Table 3). Knowing or caring for someone with a long-term physical or mental health condition did not affect whether they would want an ECTP for themselves (see Table 3). In answer to a more specific question of when you would want an ECTP in place for yourself, 152/1112 (14%) would want one ‘now’ with just 36/1112 (3%) saying that they would never want one. Developing a long-term condition or becoming disabled would lead 467/1112 (42%) and 481/1112 (43%) respondents respectively to want an ECTP. Even more 534/1112 (57%) would want a plan if they developed a life-threatening condition (see Appendix 3, Table 16). Of the 441 people who said they would want an ECTP when they were older, the peak decades identified were their 60s and 70s with 270/441 (61%) wanting an ECTP in place by the time they were aged 70 years (see Appendix 3, Table 17). When asked if they would like to be involved in completing an ECTP for a close family member if they were not able to do this for themselves, 930/1135 (82%) said that they definitely or probably would (see Appendix 3, Table 14).

| Would you or would you not like to have an emergency care and treatment plan for yourself at present?a (N = 1112)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing | p-value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| (n/N) | (%) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 260/482 | 54 | ||

| Female | 349/609 | 57 | 0.321 | 1.14 (0.88 to 1.46) |

| Other | 2/7 | 29 | 0.18 | 0.3 (0.05 to 1.73) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 39/62 | 63 | – | 1 |

| 25–34 | 109/168 | 65 | 0.912 | 1.04 (0.55 to 1.94) |

| 35–44 | 90/168 | 54 | 0.164 | 0.64 (0.35 to 1.20) |

| 45–54 | 106/204 | 52 | 0.089 | 0.59 (0.32 to 1.08) |

| 55–59 | 56/98 | 57 | 0.366 | 0.73 (0.37 to 1.44) |

| 60–64 | 61/107 | 57 | 0.275 | 0.69 (0.35 to 1.35) |

| 65–69 | 49/104 | 47 | 0.045 | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.98) |

| 70 + | 108/200 | 54 | 0.195 | 0.66 (0.35 to 1.24) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 544/987 | 55 | – | 1 |

| Black | 10/13 | 77 | 0.117 | 2.91 (0.76 to 11.06) |

| Mixed | 23/43 | 53 | 0.595 | 0.84 (0.44 to 1.60) |

| Asian | 33/54 | 61 | 0.461 | 1.25 (0.69 to 2.25) |

| Educational level | ||||

| No qualifications | 33/59 | 56 | – | 1 |

| Qualification less than A level | 95/179 | 53 | 0.699 | 0.89 (0.48 to 1.63) |

| A-levels/SCE Highers | 74/153 | 48 | 0.285 | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.33) |

| Other Higher Education | 93/166 | 56 | 0.681 | 1.13 (0.64 to 1.99) |

| Degree or equivalent | 310/521 | 60 | 0.681 | 1.13 (0.64 to 1.99) |

| Do you have any physical or mental conditions or illnesses lasting or expected to last 12 months or more? | ||||

| No | 400/765 | 52 | – | 1 |

| Yes, but does not reduce activity | 56/97 | 58 | 0.159 | 1.37 (0.88 to 2.14) |

| Yes, and reduces activity | 158/245 | 64 | < 0.001 | 1.78 (1.30 to 2.45) |

| Is there anyone who you look after or give special help to, for example, someone who is sick, has a long-term physical or mental disability or is elderly? | ||||

| No | 461/816 | 56 | ||

| Yes | 130/238 | 55 | 0.481 | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.23) |

| Yes, but only in a professional capacity as part of my job | 27/58 | 47 | 0.054 | 0.57 (0.32 to 1.01) |

| Do you or does someone close to you have a condition or illness that you think is likely to shorten life? | ||||

| No | 437/805 | 54 | ||

| Yes | 181/307 | 59 | 0.348 | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.55) |

Perceived potential benefits and harms of emergency care treatment plans

To explore how responders felt about potential benefits and harms of ECTPs, they were asked whether they agreed to a series of statements in relation to ECTPs. Predominately, 938/1135 (83%) respondents agreed or strongly agreed that ECTPs would help avoid their family needing to make difficult decisions on their behalf, and that a plan would ensure doctors and nurses knew their wishes (Table 4). Nevertheless, a small majority 628/1135 (55%) agreed that there is a serious risk that a plan could be out of date and so not reflect their current views or health condition, and a substantial minority 330/1135 (29%) agreed that in having a plan they might not get a treatment that would save their life (see Table 4).

| Please say how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about having an emergency care and treatment plan (N = 1135) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I might not get the treatment that could save my life, n (%) | Having a plan can avoid my family having to make difficult decisions for me, n (%) | There is a serious risk that the plan could be out of date and not reflect my current views or my current health condition, n (%) | Having a plan ensures that doctors and nurses know my wishes, n (%) | |

| Strongly agree | 66 (6) | 302 (27) | 90 (8) | 227 (20) |

| Agree | 264 (23) | 636 (56) | 538 (47) | 712 (63) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 445 (39) | 143 (13) | 346 (30) | 142 (13) |

| Disagree | 256 (23) | 20 (2) | 124 (11) | 29 (3) |

| Strongly disagree | 89 (8) | 22 (2) | 23 (2) | 13 (1) |

| Don’t know/refused | 15 (1) | 12 (1) | 14 (1) | 12 (1) |

For each of our regression models, the results of our univariable analyses were not materially different from our multivariable analyses (see Appendix 3, Tables 18–20).

Summary

Overall, participants in the focus groups and faith leader interviews were supportive of the concept of ReSPECT or emergency care treatment planning. They thought it could be an important tool in precipitating and facilitating important conversations about end-of-life care. However, they thought the process and form needed to be more person centred. They emphasised the importance of in-depth conversations to understand the person’s preferences and to be confident that the person understood the future options being discussed. Involving the family was seen as important but the level of involvement needs to be determined by the person whose plan it is. Several concerns were raised about whether the plans would be available or followed in an emergency.

From our survey, we found that members of the public across the UK are overwhelmingly supportive of anyone being able to have an ECTP if they wished, and half of those without a plan would want one for themselves. However, very few respondents currently have an ECTP in place. Most respondents would also like to be involved in completing a plan for a close family member if the person was unable to do so for themselves. Respondents with a chronic physical or mental condition that reduces daily activity were more likely to want an ECTP than those in good health. Unexpectedly, younger participants, were more likely to want a plan for themselves than older participants. Potential triggers for completing an ECTP were a change in health status with a diagnosis of a chronic disabling or life-threatening condition or increasing age. Respondents recognised benefits of ECTPs including ensuring their wishes about treatment are known and easing decision-making burdens on their family. However, they also recognised potential risks of ECTP recommendation becoming out of date and a potential risk that they may not receive a life-saving treatment. Respondents would prefer to complete an ECTP with their GP or a doctor or nurse trained in ECTP conversations, reflecting views expressed in our qualitative data about the importance of the relationship and quality of the conversation.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, we have completed the first community survey of the UK public’s views and attitudes to the completion of ECTPs. The use of the annual BSA survey to collect these data means that we can be confident that our sample is nationally representative and that the data quality is good. However, this approach will exclude many for whom ECTPs are most relevant, that is frail older people and those with cognitive impairment. The slight under-representation for people from minority ethnic groups is typical of push surveys of this nature but is not large enough to affect our overall conclusions. The rigorous process for developing our questions, including preparatory qualitative work, and their piloting by the BSA survey team minimises question ambiguity. Nevertheless, it is still possible that some respondents misunderstood the purpose of each question. Some caution is needed when interpreting statistical significance because of the large number of analyses done.

Despite contacting a wide range of community and faith groups, several of whom supported advertising the study, we received very few expressions of interest for focus group participation. Feedback suggested that many groups had insufficient resources to support recruitment. GP patient groups had often stopped during the COVID-19 pandemic. We were unable to purposively select participants for demographic variability because of lack of interest in two study areas. The small number of faith leader participants meant that it was not possible to achieve our aim of exploring the impact of different faith values on how people might view or engage with ReSPECT. All participants had a particular interest in, or experience of ReSPECT or ACP so may not have reflected the views of the general public. However, because of their interest and experience, our participants were able to provide in depth reflection on the topic.

Chapter 4 How ReSPECT is used in primary and community care, experiences of health and social care professionals

In this chapter, we focus on how ReSPECT is used and experienced in practice in a community setting. First, we report our survey documenting how GPs from across England view and use ReSPECT. Then using our qualitative data, we explore how GPs and their staff conceptualise ReSPECT, initiate and carry out the ReSPECT conversation and complete the plan. We explore their views and experiences of how they negotiate challenges, what happens after the ReSPECT plan is complete and any monitoring of the ReSPECT process within their practice. Similarly, we report the views and experiences of ReSPECT among senior staff in care homes and other health and social care staff who encounter the ReSPECT process and ReSPECT plans completed in the community. We then report on the content of ReSPECT forms stored in general practice medical records.

General practitioner survey

Parts of this section are reproduced with permission from Underwood et al. 57 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Methods

Obtaining good response rates to surveys of GPs’ views is challenging; return rates of ˂ 30% are common. 58–60 There are substantial operational challenges in sourcing up-to date contact details of groups of GPs that can provide national representation, and that include the range of professional roles (partners, salaried non-principals, locums and trainees). For these reasons, we commissioned a market research company, medeConnect, to include our questions in their monthly online survey of 1000, regionally representative, UK GPs (GP Omnibus). 61

Questionnaire development

Drawing on initial analysis of our interviews with GPs, and reflecting the questions in our public attitudes survey, members of the study team (AS, FG, JH, CB) developed a draft set of questions. We aimed to measure experience of using ECTPs compared with standalone DNACPR forms, views on the use of ECTPs in primary care, and how likely they were to complete a plan for their patients. During question development, we identified that knowing which factors might predict how comfortable GPs were at having an emergency care treatment planning consultation with a patient, or family member, as a key questions of interest, and likely to reflect how likely a GP was to complete a plan with their patients. We originally planned to use 11-point numerical rating scales to assess GPs’ attitudes to aspects of emergency care treatment planning. Input from our qualitative work and the work we did refining the questions led us to conclude that five-point Likert scales were more likely to be satisfactorily completed and the findings would be easier to interpret; that is, ‘very comfortable’ to ‘very uncomfortable’ for our main outcomes of interest.

Following feedback from our lay advisory group and GP co-applicants, a revised set of questions was further refined through cognitive, think-aloud interviews with a small number of GPs not involved in the study. The final set of questions were piloted within the format of the online survey (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

Data collection

The market research company, medeConnect, draw their sample from GPs who are registered with Doctors.net.uk and who have been active on this online platform. Opportunity to take part in the monthly survey is posted on the home page of all GPs who have been active on the site within the previous 90 days and an e-mail is sent inviting participation to all GPs who have given consent to be approached to take part in research. Each GP can only participate once. Doctors.net.uk undertakes weekly automated checks of its membership base against the publicly available licensed status of practising doctors in the UK as published and maintained by the General Medical Council. Before a survey starts, the questions are tested by the internal research team, the sponsor (in this case the research team based at Warwick) and a small sample of the target group (Miles N, personal communication, medeConnect, Abingdon, 16 February 2023).

Analysis

For a binary outcome on our key question of interest (very comfortable or comfortable completing a plan vs. all other responses) a sample size of 1000 would, if 50% were ‘comfortable’, provide precision of 6.2%, or if 80% were comfortable a precision of 5%. This is the size of the medeConnect monthly survey and hence our original sample size. However, this includes UK GPs based outside England who were not covered by our research ethics approval. Thus, a smaller number of responses was expected. We present descriptive statistics for each question. For the outcome of how comfortable GPs are in having emergency care and treatment plan discussions, with patients or with someone close to the patient, using the statistical software R Core Team (2023), we first did univariable logistic regression analyses at the 5% significance level with gender, GP role, NHS region, type of area (major conurbation, large town/city, medium town/city, small town/city, hamlet) years since completion of GP training, and use of ReSPECT form versus DNACPR/Other as explanatory variables. We then constructed a fully adjusted logistic regression model. We repeated this using a backward elimination approach to select the most statistically significant variables.

Results

The survey ran from 4 November to 27 November 2022. We received 841 valid responses, all fully completed. Our respondents’ demographic characteristics are largely representative of the whole population of English GPs (see Appendix 4, Table 21). Half (426/841, 51%) of respondents reported that their practice used standalone DNACPR forms. ReSPECT forms were used by 41% (345/842) and 7% (55/841) used other locally developed ECTPs with 2% (15/841 reporting no ECTP or no knowledge of ECTP use) (Table 5). There were substantial regional differences in the forms used; ReSPECT was the predominant form used in the East Midlands (49/62, 79%) and West Midlands (74/92, 80%) whereas a DNACPR form was most commonly used in London (87/114, 76%), the North East (33/44, 75%) and the North West (88/115, 77%) (see Appendix 4, Table 22).

| Totals and percentages for the emergency care and treatment planning form completion | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total, n (N = 841) | % (CI) | |

| What form of emergency care and treatment plans does your practice use? | ||

| ReSPECT | 345 | 41 (0.38 to 0.44) |

| DNACPR | 426 | 51 (0.47 to 0.54) |

| Other ECTP | 55 | 7 (0.05 to 0.08) |

| None/don’t know | 15 | 2 (0.01 to 0129) |

| Who completes emergency care and treatment plans within your practice? | ||

| GP | 780 | 93 (0.91 to 0.94) |

| GP trainee | 0 | – |

| Practice nurse | 79 | 9 (0.07 to 0.11) |

| Advanced nurse practitioner | 234 | 28 (0.25 to 0.31) |

| Specialist nurse practitioner for elderly care | 140 | 17 (0.14 to 0.19) |

| Who do you think should be able to complete ECTPs in a GP practice? | ||

| GP | 797 | 95 (0.93 to 0.96) |

| GP trainee | 522 | 62 (0.59 to 0.65) |

| Practice nurse | 350 | 42 (0.38 to 0.45) |

| Advanced nurse practitioner | 648 | 77 (0.74 to 0.80) |

| Specialist nurse practitioner for elderly care | 663 | 79 (0.76 to 0.82) |

| Emergency care practitioner | 550 | 65 (0.62 to 0.69) |

| Who do you think should be able to complete ECTPs in the community? | ||

| Specialist nurse practitioner for palliative care | 802 | 95 (0.94 to 0.97) |

| Other specialist nurse practitioner | 691 | 82 (0.80 to 0.85) |

| Community matron/senior nurse practitioner for community care | 690 | 82 (0.79 to 0.85) |

| District nurse | 467 | 56 (0.52 to 0.59) |

| Senior care home staff | 207 | 25 (0.22 to 0.28) |

| Senior nurses in nursing home | 430 | 51 (0.48 to 0.55) |

| When would you consider completing an emergency care and treatment plan for a patient? | ||

| When a patient reaches a certain age | 199 | 24 (0.21 to 0.27) |

| When a patient is diagnosed with a life-threatening condition | 722 | 86 (0.83 to 0.88) |

| When a patient is diagnosed with a chronic long-term condition | 509 | 61 (0.57 to 0.64) |

| When a patient is severely disabled | 497 | 59 (0.56 to 0.62) |

| When you think a patient is likely to die within 12 months | 813 | 97 (0.95 to 0.98) |

| When a patient is admitted to a care home | 596 | 71 (0.68 to 0.74) |

| When do you review an emergency care and treatment plan for a patient? | ||

| When a patient requests it | 477 | 57 (0.53 to 0.60) |

| When a patient is discharged from hospital with an ECTP | 389 | 46 (0.43 to 0.50) |

| Annually | 309 | 37 (0.33 to 0.40) |

| 6-monthly | 104 | 12 (0.10 to 0.15) |

| Annually or 6-monthly, or a > 75 years health check | 486 | 58 (0.54 to 061) |

| During or following the annual health check for patients aged 75 years or over | 238 | 28 (0.25 to 0.31) |

| When you think the patient’s health has changed | 595 | 71 (0.68 to 0.74) |

| My practice does not have a system for reviewing ECTP forms | 169 | 20 (0.17 to 0.23) |