Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR131606. The contractual start date was in October 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in December 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Aunger et al. This work was produced by Aunger et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Aunger et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some text in Chapters 1 and 2 has been reproduced with permission from Maben et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In 2019, we sought funding to better understand the unprofessional behaviours (UB) of healthcare staff towards each other; it is important to note the broader context in which this work took place. 1 While we knew there was a problem, the extent was not yet prevalent in public discourse and in the mainstream media. In 2023, as we write, this has significantly changed. Multiple investigations have revealed that UB appears rife in many public-sector workplaces. The Casey report revealed misogyny, racism and homophobia in the Metropolitan Police,2 a parliamentary report in 2021 found that two-thirds of women in the armed forces have experienced bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination during their career,3 and the Fire and Rescue Inspectorate has found that every fire brigade in England is plagued by bullying and harassment claims. 4 During our study, society has also started to pay greater attention to misogyny and racism. The #MeToo and #BLM movements have become global rallying cries to change societies throughout the world.

| Stakeholder feedback summary – capturing wider context |

| Stakeholders highlighted ongoing societal contexts throughout our review, including #BLM, #MeToo and the bullying and harassment scandals occurring at the highest levels of UK government. These can normalise bullying and harassment and fail to set a good example for healthcare organisations implementing initiatives to address UB.5 While identified literature for our review did not refer to these societal shifts, we have sought to place our review within this broader societal and historical context, as noted above. |

| We ran a specific stakeholder spotlight session that helped us hone our language when discussing staff with protected characteristics throughout this review. This session highlighted that different people prefer different terms: there was no single consensus. Some people found the use of the term ethnic minorities problematic, whereas others found the term ‘minoritised groups’ problematic. As a result, we are as specific as possible when we are referring to particular groups throughout this report. |

Healthcare organisations have also been under significant scrutiny during this period: a series of reports have highlighted the prevalence of staff-on-staff UB, creating cultures that do not allow staff to thrive at work. The Ockendon report into maternity services at the Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust6 found a culture of bullying and lack of psychological safety in the workplace. The Kirkup report7 – also into maternity services, this time at East Kent hospitals – found ‘unprofessional behaviours by some consultant obstetricians were not tackled’ and that ‘bullying, harassment, and discrimination were endemic at East Kent’, with the culture described as ‘“horrible” and “sickening”’. The systems that might have supported psychological safety, enabling staff to voice concerns, were weak or absent. Staff feared retaliation yet were ‘perversely blamed for their lack of courage’. 7 In 2023, Professor Bewick’s investigation into the clinical safety at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust8 ‘heard repeated reports of a longstanding “bullying and toxic” environment’ (p. 10) with negative impacts on patient care.

We have used the term UB to encompass a range of specific behaviours such as incivility, transgressions, disruptive behaviour, physical and verbal aggression and bullying. 9,10 According to one definition, UBs cover a wide spectrum of behaviours that can subtly interfere with team functioning, such as poor communication, passive aggression, lack of responsiveness, public criticism of colleagues and humour at others’ expense. These behaviours can be either casual and generalised or highly targeted with the intention to cause harm. In modern, inclusive healthcare settings, UBs are increasingly recognised as unacceptable because they negatively affect the work and psychological well-being of others. 11

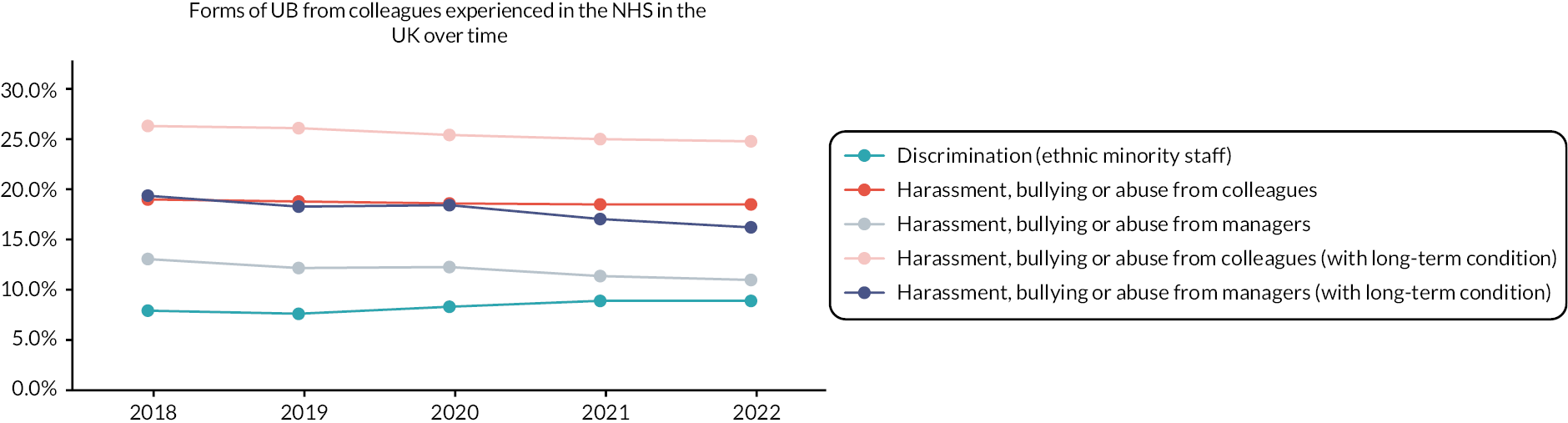

As the reports above suggest, UB – and specifically bullying and harassment – is, unfortunately, still prevalent in the United Kingdom’s (UK) National Health Service (NHS). Figures from the 2022 NHS Staff Survey indicate that 18.7% of staff experienced harassment, bullying or abuse from colleagues that year while 11.1% experienced the same from managers. Additionally, 9% of staff from ethnic minority backgrounds reported experiencing discrimination at work from managers or colleagues. According to Workforce Race Equality Standard data from 2022, the percentage of staff experiencing harassment, bullying or abuse from colleagues in the NHS was 22.5% for white respondents and 27.6% for ethnic minority respondents. The difference was much starker in corresponding groups at management levels, with 6.8% for white staff yet 17.0% for ethnic minority staff. 12 For those with a long-term health condition or illness, data show another significant increase in reports of UB compared to those without (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Forms of UB from colleagues experienced in the NHS in the UK over time. Data adapted from NHS Staff Surveys 2018–22. 16

Unprofessional behaviours are not just present in the UK: they are a widespread problem in healthcare systems around the world and have negative impacts on the psychological well-being of staff, patient safety and organisational costs. 13,14 Data from Australia across seven hospitals indicate that the problem is widespread, with 38.8% of 5178 respondents reporting experiencing UB on a frequent (weekly or more) basis during the past year and with 14.5% even experiencing extreme events such as physical assault. 15 Therefore, this study is unfortunately very timely; there is still much work to be done to mitigate, manage and prevent this global and pressing issue.

Unprofessional behaviour can negatively impact people targeted by it, as well as witnesses, patients, organisations in which it occurs and, by extension, society. 17–19 For targets and witnesses of UB, it can lead to mental problems such as burnout and depression and, in extreme cases, can lead to suicidal ideation. 20 Physical problems such as sleep disturbance, headaches and gastrointestinal symptoms are also common and both these physical and mental consequences can result in staff taking sick leave. 21 This results in organisations experiencing elevated staff turnover, which can have large economic consequences. 22 For patients, studies have shown that the presence of UB can lead to staff being less likely to follow safety procedures23 and more prone to making errors and being distracted. 14,24 Furthermore, patients whose surgeons behave more unprofessionally have been found to have worse outcomes. 25 A conservative estimate of the cost of UB to the NHS (due to sickness absence, employee turnover, reduced productivity, compensation and litigation costs) suggests damages from bullying alone were approximately £2.28 billion per annum or 1.52% of the NHS budget for 2019/20. 1,26 In the United States of America (USA), sources report the cost of replacing each nurse at between $2200 and $64,000 (USD). 27

The global COVID-19 pandemic and resulting healthcare workforce crisis has made the retention of healthcare staff critical in most healthcare systems. Tackling UB – a problem that contributes to staff turnover and losses of organisational reputation – could go some way to helping address workforce recruitment and retention. 7 Bullying and harassment have been cited as one of the primary reasons that NHS staff are quitting for other opportunities, with a recent report suggesting 49% of healthcare staff who have experienced UB are seeking another job as soon as possible. 28,29

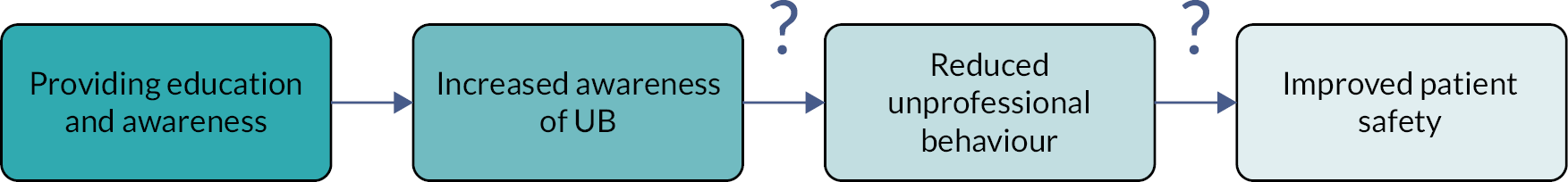

Previous studies have sought to collate and understand interventions to reduce UB both within21 and outside of health care. 30 However, either these have focused on bullying alone21 or their applicability to acute healthcare settings may be limited. 31 Existing contributions to the literature have noted that interventions to reduce UB in general ‘are underpinned by the assumption that workplace mistreatment will be lessened if more people know about it, know how to recognise it and be more assertive in their responses to it. This is a flawed assumption’. 31 Whether this ‘flawed’ approach is also dominant in health care is important to investigate, in order to improve future intervention efficacy.

A realist approach is ideal for investigating causes of UB in health care and interventions to reduce them because interventions in this area are heterogeneous, not well articulated, and complex in nature. This study builds directly on previous work, including the 2013 National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Illing et al. review21 to address the following aims and objectives.

Review aims and objectives

Our focus is on interpersonal (i.e. directed toward others or occurs in the presence of others32) UBs that are intended to cause harm between staff (not staff towards patients or vice versa).

Aim

To improve context-specific understanding of how, why and in what circumstances UBs between staff in acute healthcare settings occur and evidence of strategies implemented to mitigate, manage and prevent them.

Objectives

This review seeks to:

-

conceptualise and refine terminology: by mapping behaviours defined as unprofessional to understand differences and similarities between terms referring to UBs (e.g. incivility, bullying, microaggressions, etc.) and how these terms are used by different professional groups in acute healthcare settings;

-

develop and refine context, mechanism and outcome configurations (CMOCs): to understand the causes and contexts of UBs, the mechanisms that trigger different behaviours, and the outcomes on staff, patients and wider system of health care;

-

identify strategies designed to mitigate, manage and prevent UBs and explore how, why and in what circumstances these work and whom they benefit;

-

produce recommendations and comprehensive resources that support the tailoring, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of contextually sensitive strategies to tackle UBs and their impacts.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Rationale for and use of realist methods

This study uses realist review methodology. Realist reviews are driven by theories that seek to explain how and why certain strategies may or may not work in different contexts. 33 They focus on understanding the mechanisms by which strategies do or do not work, and seek to understand contextual influences on if, why, how and for whom these might work. In a realist framework, contexts can be either observable features that can facilitate or hinder an intervention or they can be dynamic and relational factors that shape the mechanisms through which an intervention operates. 34 Mechanisms, in turn, are seen as changes in participants’ reasoning in response to the resources introduced by the intervention. 35 These contexts, mechanisms and outcomes are combined into programme theories (i.e. a mapping of taken-for-granted assumptions) represented by a heuristic known as a CMOC to depict what is expected to happen when an intervention is delivered in a certain contextual environment. 36 The revised Medical Research Council (MRC) Complex Interventions Framework identified the important role of theory-based research perspectives such as realism within the iterative development, feasibility, evaluation and implementation phases of action-oriented research to address practice and policy issues. 37

Adopting a realist approach enables an examination of the mechanisms underlying both the UBs and the interventions designed to address them, which is particularly useful when context is likely to influence the effectiveness (or otherwise) of an intervention. This allows for the identification of direct links between the interventions and the environmental factors that contribute to, for example, UBs. In realist reviews, included evidence spans beyond academic literature to non-empirical studies, commentaries and grey literature from government and voluntary organisations. This illuminates the topic from multiple viewpoints, making it valuable for studying complex issues such as UBs in that it enables a more comprehensive understanding of the problem and its potential solutions.

The realist approach to data collection and analysis is based on retroduction – a form of logical inference beginning with empirical observations and seeking to explain them by identifying the underlying mechanisms that are capable of producing them. 38 This approach is indispensable when considering UBs within the healthcare workforce as it allows, for example, the examination of differences and similarities between staff groups based on factors such as speciality, professional group, setting and seniority. By examining these contextual factors and working practices using realist review methodology, it is possible to determine how context might influence the presence of UBs among healthcare staff working in acute settings.

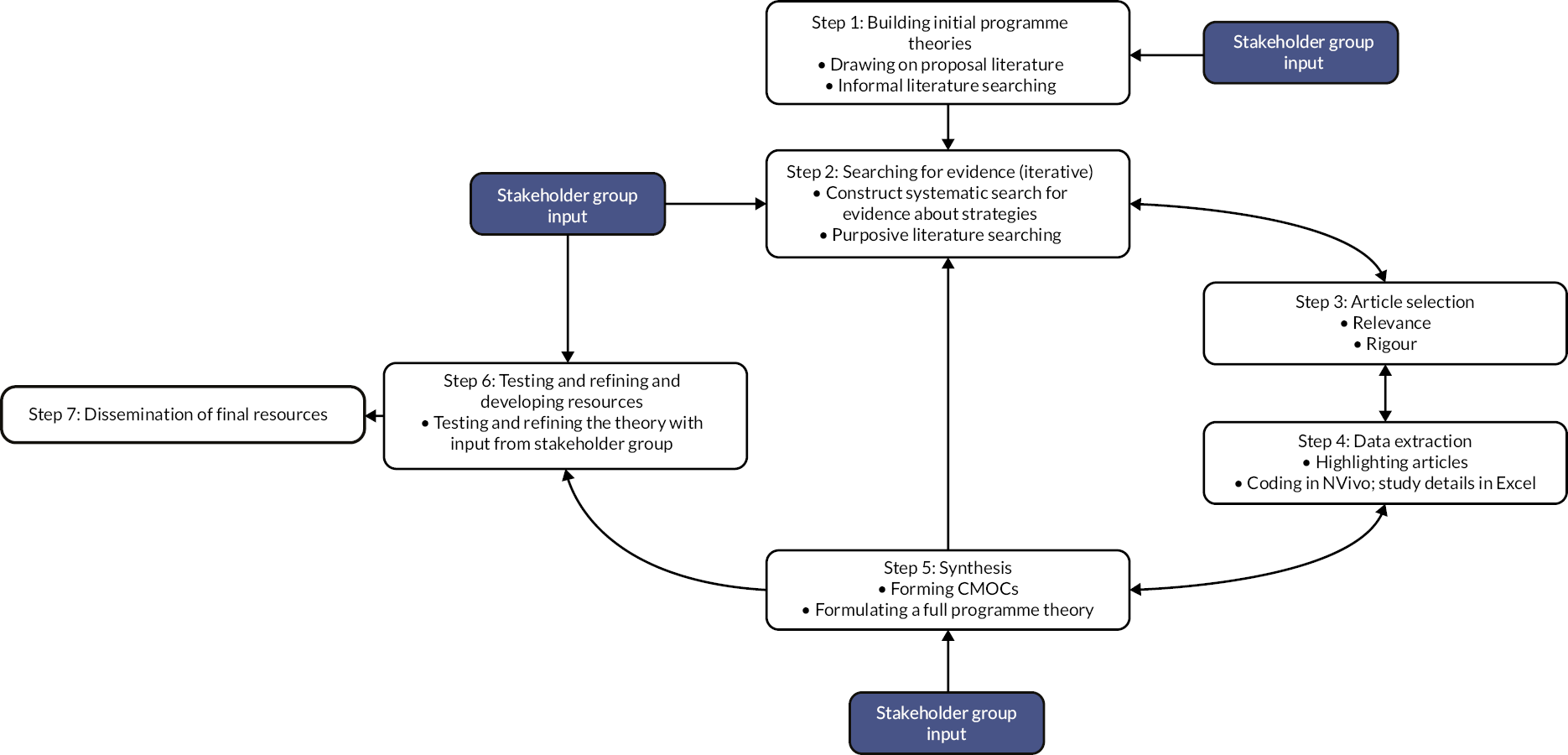

This review and report followed the Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) guidelines on quality and reporting. 39 The RAMESES checklist is reported in Report Supplementary Material 1. There have been no further protocol changes since NIHR protocol version 4.0_120822. An overview of the review process is shown in Figure 2, with the steps we took to achieve our objectives explained in the following sections.

FIGURE 2.

Review process flow diagram.

Step 1: Identifying existing theories and scoping the literature

Initial informal screening of the literature sensitised the team to the breadth and depth of published and unpublished literature on UBs within health care. By investigating the theoretical underpinnings of interventions, we mapped the conceptual and theoretical landscapes of UB causes and outcomes, as well as how any identified strategies and interventions are theorised to work in acute healthcare settings. This step helped identify the mechanisms at individual, group and professional levels by which strategies prevent or reduce the impact of these behaviours across and within healthcare staff groups. This process (of identifying existing theories) informed the construction of our initial programme theories. To do this, we iteratively:

-

drew on preliminary discussions within the project team, with the healthcare workforce, patients and the public

-

consulted with our multidisciplinary stakeholder and advisory groups (as outlined above)

-

examined healthcare literature known to the research team (papers, reviews and reports identified in our initial scoping review that informed the funding proposal were independently screened by JAA and RA)

-

sought additional literature to form theories across strategies and causes. Informal searches were conducted on relevant websites [e.g. The King’s Fund, NHS Employers, NHS England, the British Medical Association (BMA) and Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC)] from 19 October 2021 to 11 November 2021; search terms included ‘Bullying’, ‘Unprofessional’, ‘Incivility’, ‘Violence’ and ‘Harassment’, using built-in filters where possible to limit search results to relevant topics such as bullying, gender equality, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual and more (LGBTQ+) and whistleblowing.

Data from this step were imported and coded into NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). In this early phase, we were interested in identifying how contributing factors lead to UB, as well as how strategies work in different contexts. As part of this process, we developed ‘if, then, because’ statements, as well as a visual map/typology. These documents were then discussed by team members and presented to stakeholders for refinement. This step also helped to identify directions for future analysis, with further literature searches in step 2. Our initial programme theories for different portions of the analysis are presented in Appendix 1, Tables 22–24.

Step 2: Searching for evidence

Of the three realist synthesis search models identified by Booth et al., our approach follows the ‘Exclusive (Realist-only) searches’ model. 40 Therefore, step 2 was the formal stage at which we undertook systematic searches for evidence.

Search strategy

In step 2, we identified studies addressing strategies to reduce UBs among staff in acute healthcare settings by:

-

Systematically searching academic databases Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost), EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (Ovid) 1947 to 11 February 2022, and Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to 11 February 2022 on 14 and 15 February 2022. Search strategies comprised search terms, synonyms and index terms for: Acute care AND Healthcare staff AND UBs. Searches from existing similar reviews such as Illing et al. (2013) were consulted to aid identifying relevant search terms. 41 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) OECD geographic search filters were used in MEDLINE and EMBASE to exclude studies based in non-OECD countries since these were deemed not relevant to the UK NHS acute care setting and UK workplace culture. 42 The OECD filter was adapted for use in CINAHL. Limits for language and publication date were not used; however, animal, child and elder abuse studies were removed from the search.

-

Conducting similar searches for trade, policy and grey literature on Google Scholar (via Harzing’s Publish or Perish software), Google, HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium) (Ovid) 1979 to November 2021, NICE Evidence Search (www.evidence.nhs.uk/), Patient Safety Network (https://psnet.ahrq.gov/) and websites, including NHS Employers and NHS Health Education England.

See Report Supplementary Material 2 for the full search strategies used across these databases and grey literature sources. The range of databases and sources was chosen to identify relevant health research and policy reports in peer-reviewed journals, trade journals and organisation reports. For example, we sourced opinion pieces likely to discuss how and why UB interventions work in trade journals (e.g. AACN Bold Voices, Nursing Times, ED Management) via CINAHL and HMIC databases. Search strategies were peer-reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies method. 43 All search results were saved in EndNote X9 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] software and duplicates removed using University of Leeds Academic Unit of Health Economics (AUHE) guidance. 44

Step 3: Selection and appraisal of documents

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included peer-reviewed and grey literature that helped explain how and why strategies to reduce UBs in acute care settings work and whom they benefit. The inclusion criteria shown in Table 1 were used. 1

| Category | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Study design | Any (including non-empirical papers/reports) |

| Study setting | Acute healthcare settings – acute, critical, emergency and, potentially wider (see relevance criteria below) |

| Types of UB | All as exhibited and experienced by healthcare staff (not patients nor patient-to-staff) |

| Types of participants | Employed staff groups including students on placements |

| Types of interventions/strategies | Individual, team, organisational and policy-level interventions. Cyber-bullying and other forms of online staff-to-staff UB |

| Causes of UBs | All |

| Outcomes | Included but not limited to a focus on one or more of: staff well-being (stress, burnout, resilience), staff turnover, absenteeism, malpractice claims, patient complaints, magnet hospital/recruitment, patient safety (avoidable harm, errors, speaking-up rates, safety incidents, improved listening/response), cost |

| Language | English only |

Screening, relevancy and rigour

Screening of search results was primarily undertaken by JAA, but RA independently screened a 10% random sub-sample for quality control at title and abstract, full text and relevancy stages. An additional 50% of November 2021 Google Scholar searches were double-screened. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between JA, RA and JM (see below). The remaining 90% of decisions at these stages were made by JAA. Title and abstract screening was performed using Rayyan.ai software (www.rayyan.ai/) and full texts were screened using Mendeley (Mendeley Ltd.). 45

Decisions regarding sources were based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (above) and a combination of relevance (based on both the major/minor criteria below and the ability to inform programme theories, i.e. conceptual richness and depth of sources) and rigour (whether the methods used to generate the relevant data are credible and trustworthy). Assessment of rigour focused on the extent to which sources provided a detailed description of their methods and how generalisable and trustworthy their findings were based on those methods. 36

Our formal criteria for classifying the potential relevancy of sources included assessing for:

-

major contribution for sources that:

-

contributed to the study aims and are conducted in an NHS context in acute care; or

-

contributed to the study aims and are conducted in an NHS context; or

-

contributed to the study aims and are conducted in contexts with similarities to the NHS (e.g. universal, publicly funded healthcare systems); and

-

-

minor contribution for sources that:

-

were conducted in non-UK healthcare systems that are markedly different from the NHS (e.g. fee-for-service, private insurance scheme systems) but where the mechanisms causing or moderating UBs could plausibly operate in the context of those working in the NHS; or

-

contributed to the study aims and can clearly help to identify mechanisms that could plausibly operate in the context of the NHS (e.g. law, police, military).

-

We prioritised the sources of major relevance in relation to the above criteria. The criteria that are italicised reflect those criteria we adopted in our final review. We did not seek studies beyond health care because we reached theoretical saturation. These sources were then sorted into the above categories and assessed for their ability to inform the refinement of programme theories (theoretical relevancy and conceptual richness). Where a scarcity of ‘major contribution’ sources meant that we were unable to develop and refine aspects of the programme theory, we drew on literature from the minor relevancy criteria. In addition, we also classified documents according to their conceptual richness (thickness vs. thinness) using adapted criteria from Pearson et al. 46 These criteria reflected the usefulness of each document to the realist analysis so that we could judiciously draw on a wide range of sources in a timely manner.

The criteria for appraising conceptual richness are defined in Table 2, with examples.

| Element | Conceptually thick | Conceptually thin |

|---|---|---|

| Description | Possessing rich description of how causes of UB may increase UB or how strategies to reduce UB may work | Little or no useful description of how causes of UB or strategies to reduce UB work |

| Context | Consideration of context in which UB develops/intervention is implemented | Little or no description of context |

| Implementation | Description of how implementation of strategies deviated from expectations or presenting multiple theories for how causes may lead to UB | No description of how implementation of strategies deviated from expectations. Limited, single, surface-level explanation for how causes may lead to UB |

| Qualitative vs. quantitative | Exploration of the qualitative aspects of phenomena | Limited description, focus on quantitative aspects, for example associations between variables, prevalence of UB, etc., without further detail on the how or why |

| Example extract and explanation | ‘For example, it is now noted that some methods of delivering interventions to staff may induce feelings of being “targeted”, “at fault” and perhaps being bullied themselves, if content is “aimed” at certain negative behaviours, say “anger management”, or staff groups, say “the doctors”’.47 This example is rich because it provides evidence regarding in what context an intervention may have unintended consequences |

‘The Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Alert outlined the need for institutions to develop the following educational programme to address bullying in the nursing workforce: (a) skills-based training and coaching; (b) ongoing, nonconfrontational surveillance; (c) a system for assessing staff perceptions of the seriousness and extent of unprofessional behaviors; and (d) policies that support early reporting’.48 This example is thin because it simply lists the content of a proposed intervention without any explanation as to how it may work |

Results of searching and screening

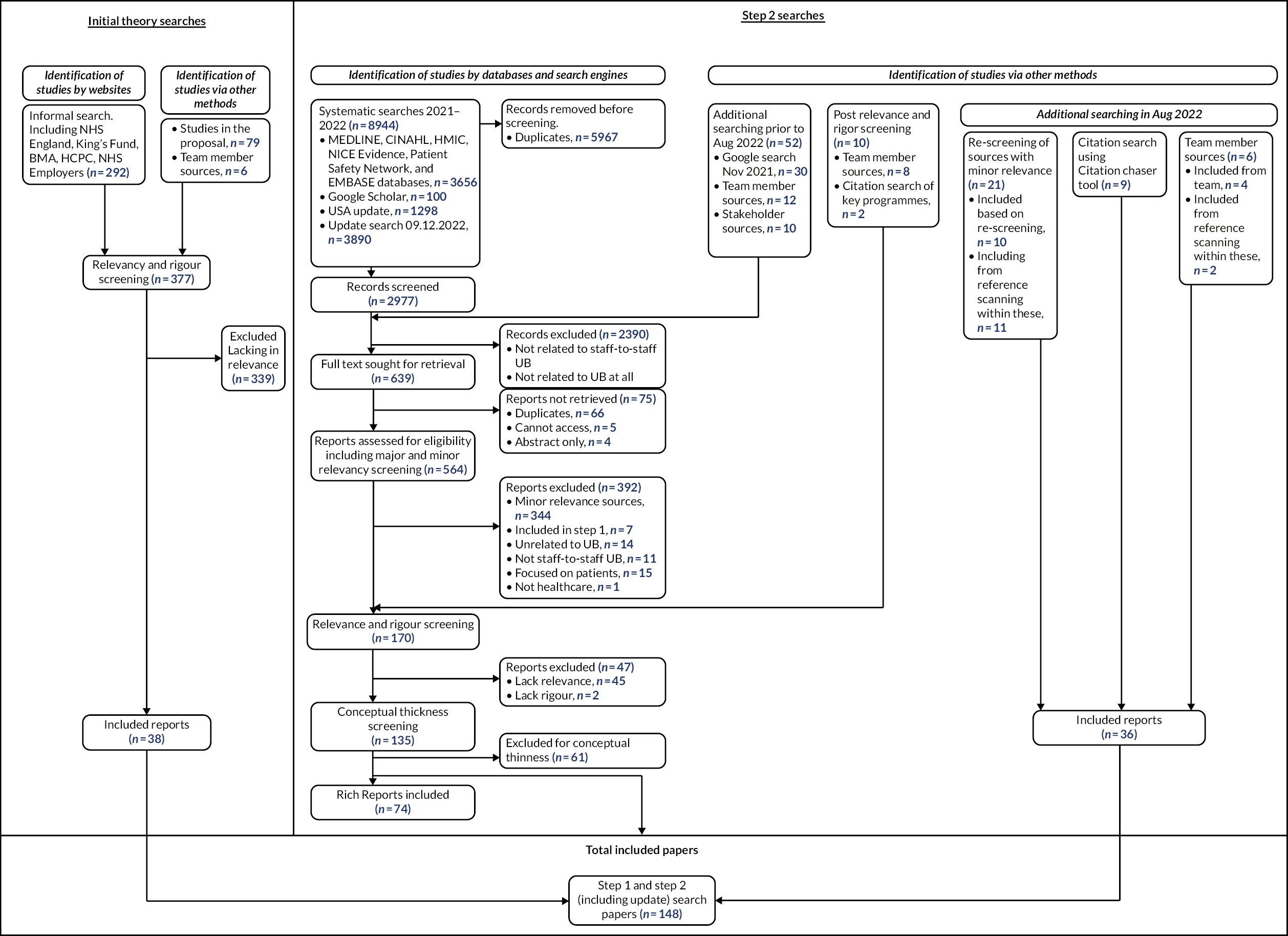

The following results are in chronological order and reflect multiple cycles of searches, screening and relevance/rigour assessments. Figure 3, however, displays the process of searching, screening and inclusion in a non-chronological order, that is, all cycles of search results are incorporated with the initial search results in the diagram. This demonstrates more clearly how many studies were found, included and excluded, at Step 1 versus Step 2 of the review.

FIGURE 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) style diagram outlining our search processes and results.

Step 1 (November 2021): Identifying existing theories and scoping the literature

We included 38 documents in the initial theory-generation step, comprising 30 identified from the proposal, five from informal searches and three from the team.

Step 2 (November 2021–February 2022): Searching for evidence

The initial systematic search identified 2629 records after 99 Google Scholar search results after cross-database deduplication. Initial independent pilot screening of 54 (of 2629) records resulted in 16 papers included for full-text screening with 100% agreement. Independent screening by two reviewers (JAA and RA) of 267 (10% of 2629) records led to 72 being included for the next step. Disagreement occurred on 40 items (15%) and was resolved through discussion between JAA and RA. The remaining 2308 papers were screened by JAA against the inclusion/exclusion criteria: of these, 400 papers were selected for full-text screening.

Google and Google Scholar searches (November 2021)

Two searches were performed on Google Scholar via use of Harzing’s Publish or Perish software (each was limited to the 50 most relevant results). This was to ensure we captured relevant grey or academic literature identified by Google’s algorithms. Search strategies are presented in Report Supplementary Material 2. After duplicate removal, 99 papers remained for title and abstract screening. Papers were excluded largely because they were not related to UBs between staff (Figure 4). Sixty-three papers were selected for full-text screening and then combined with the systematic search results at the full-text screening stage. An additional 52 sources were identified through searches on Google (30) in 2021, from the project team (12) and from stakeholders (10) during 2022 (see Additional searching). In total, 603 papers were selected for full-text screening. After cross-deduplication of these various sources of literature, 537 full-text papers were eligible for screening.

FIGURE 4.

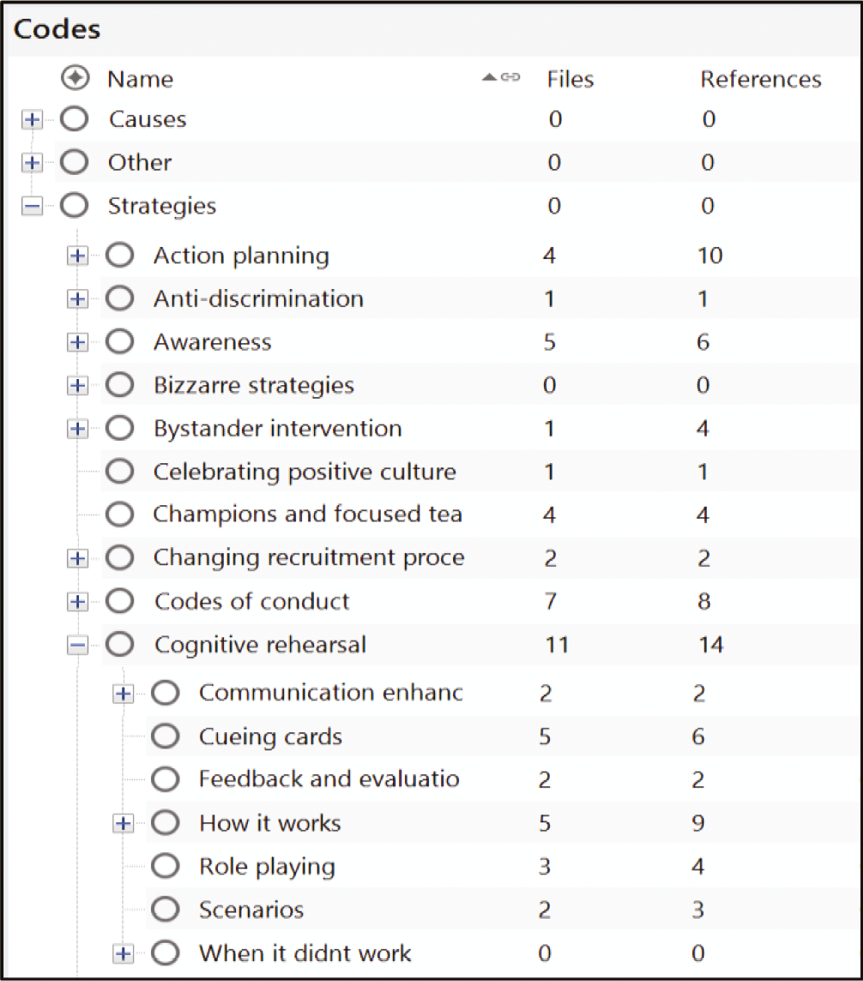

Example NVivo 12 coding structure for strategies.

Full-text screening

Following application of major/minor screening criteria to the 537 potentially relevant papers, 193 papers were determined to have major relevance and 352 were excluded for having minor relevance. In addition, 34 (10%) of those papers excluded at this stage were selected for independent screening (JAA and RA). From these, two decisions were found to be in conflict. These two discrepancies were resolved through discussion and remained excluded. The 193 papers were then screened against inclusion criteria and conceptual richness and 148 papers were included.

Relevance and rigour

The remaining 148 papers were screened for relevance according to the realist method, meaning papers had to include passages suitable for theory gleaning, testing or refining with respect to either causes or strategies. 49 Studies that lacked such passages were, therefore, screened out (n = 45), resulting in 103 papers. An additional six studies from the team and two studies from citation-tracking key intervention papers were added at this stage; thus, 111 documents were included for conceptual-thickness screening.

Conceptual-thickness screening

As a result of conceptual-thickness screening as outlined in Table 2, 47 sources were excluded at this stage for lacking conceptual thickness. This meant that 64 rich sources were included at this stage.

Additional searching and evidence gathering (August–November 2022)

Search update to expand relevancy criteria to US intervention studies (August 2022)

The team decided to include US-based literature because we wanted to include wider interventional literature, and exploratory searches indicated a significant amount of literature available from the USA. We reran the same searches for Step 2 but limited results to the USA (excluding HMIC due to its predominance of UK content, and NHS Evidence, which was withdrawn in April 2022). This identified 1298 records, which reduced to 57 once duplicates and previously screened records were removed. These 57 records were screened but none were included because no interventions were identified. However, we did re-include 10 USA studies from our Step 2 search, which had previously been excluded due to country.

A further nine relevant studies were identified by citation searching (forwards and backwards) from nine key further US studies using the CitationChaser Shiny App. 50 Four studies were identified by the team. Reference scanning of the 10 included US studies and the four identified by the team found a further eleven and two, resulting in a total of 36 additional papers from August 2022 searches. A total of 138 papers were included (Steps 1 and 2) prior to final update searches.

Searches for behavioural and organisational psychology theories (November 2022)

Members of the advisory group indicated that literature from behavioural or organisational psychology may provide useful evidence, so we searched for anti-bullying interventions that use behavioural science theory in ABI/INFORM® Collection (ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), Business Source Premier [EBSCOhost (Elton B. Stephens Company)] and Google Scholar. The lack of relevant search results prompted a further search [in ABI/INFORM Collection (ProQuest) and Google Scholar]. Due to low relevance of results during screening, papers found in this search were not utilised.

Search update (December 2022)

The above searches were repeated on 9 December 2022 (except for NICE Evidence, which was withdrawn in April 2022) to ensure our review remained up to date. The search strategies were reviewed before running the final update searches and no changes made. This identified 3890 records, which reduced to 192 records when we removed duplicates and previously identified records. After title and abstract screening, 36 papers were retained for full-text screening. Included from this update were eight papers and an additional two studies from the team (10 in total).

Total included literature (March 2023)

One hundred and forty-eight total papers were included. This included 38 papers from Step 1, 100 papers from Step 2, and 10 from our updated December 2022 search. Full search results are depicted in Figure 3.

Step 4: Data extraction

To aid in data extraction, sources were first categorised in Mendeley according to country and healthcare setting (e.g. acute care) and whether they described an intervention. To further organise our data, relevant sections of texts were coded and organised in NVivo 12 software (QSR International) (see Figure 4). This coding was both inductive (codes created to categorise data reported in included sources) and deductive (codes created in advance of data extraction and analysis as informed by the initial programme theory). Each new element of relevant data was used to test and refine aspects of the programme theory. A realist review aims to reach theoretical saturation in relation to the objectives, rather than to aggregate every relevant study.

Descriptive study information was extracted into an Excel spreadsheet. Sources reporting on interventions were explored in greater depth with samples, duration of interventions, behaviour-change strategies used, study design, theoretical frameworks, outcome measures and findings extracted and tabulated for each study.

Step 5: Synthesising evidence, refining initial theories and drawing conclusions

Realist analysis

During the review, we moved iteratively between analysis of examples from the literature, refinement of programme theory and further iterative searching to test particular programme theories as required (see Figure 2). We also used the strategies listed in Table 3 to make sense of the data. 46,51 This type of analysis enabled us to understand how the most relevant and important mechanisms work in different contexts, allowing us to build more transferable CMOCs.

| Strategies for synthesising evidence |

|---|

| Comparing and contrasting sources of evidence: e.g. where evidence about interventions or its mechanisms in one source allowed insights into evidence about outcomes in another paper |

| Reconciling of sources of evidence: where results differed in apparently similar circumstances, further investigation to find explanations as to why these different results occurred |

| Adjudication of sources of evidence: made the synthesis more manageable, i.e. dividing papers that make ‘major’ or ‘minor’ contributions to our research questions46 |

| Consolidation of sources of evidence: where outcomes differed in particular contexts, an explanation was constructed as to how and why these outcomes occurred differently |

These strategies found in Table 3 were also drawn upon in the theory-refinement process. In this process, we compared initial theories with novel data from Step 2 literature. Novel data were compared with initial theories to see if they affirmed, refuted or altered the existing initial theory and, in these cases, the above comparison strategies were drawn upon to make a decision regarding how theories were to be refined. Where novel data leading to candidate theories were identified that did not match with any initial theory from Step 1, we formulated novel theories and tested them further using literature from within Step 2 onwards.

Descriptive analyses

To ensure that the same information is not referred to in different ways in the report, our categories of contributors and strategies – developed based on underlying common realist mechanism (i.e. how and why they work) – were also used to organise the descriptive analysis. These categories were developed in an inductive way and discussed with the team and stakeholder group to ensure rigour. Additional codes were created in NVivo 12 for data relevant to the descriptive analysis, including the experience of particular professional groups of the contributors of UB (such as nurses and doctors) and for those from minoritised communities. In Chapter 5, we report on some basic statistics, such as mean or median sample sizes for included studies. These statistics were computed in Microsoft Excel using in-built formulae.

Categorising and collapsing contributors and strategies

When developing our programme theories to underpin individual contributors and strategies, the theories became too numerous and complex; we needed to collapse these to be more manageable and reportable. We accomplished this by forming categories according to common mechanisms underpinning how contributors lead to UB, as well as how strategies may mitigate or reduce UB. These categories were initially formed by JAA before refinement through intensive discussion with RA and JM, and input from the wider team and stakeholder groups.

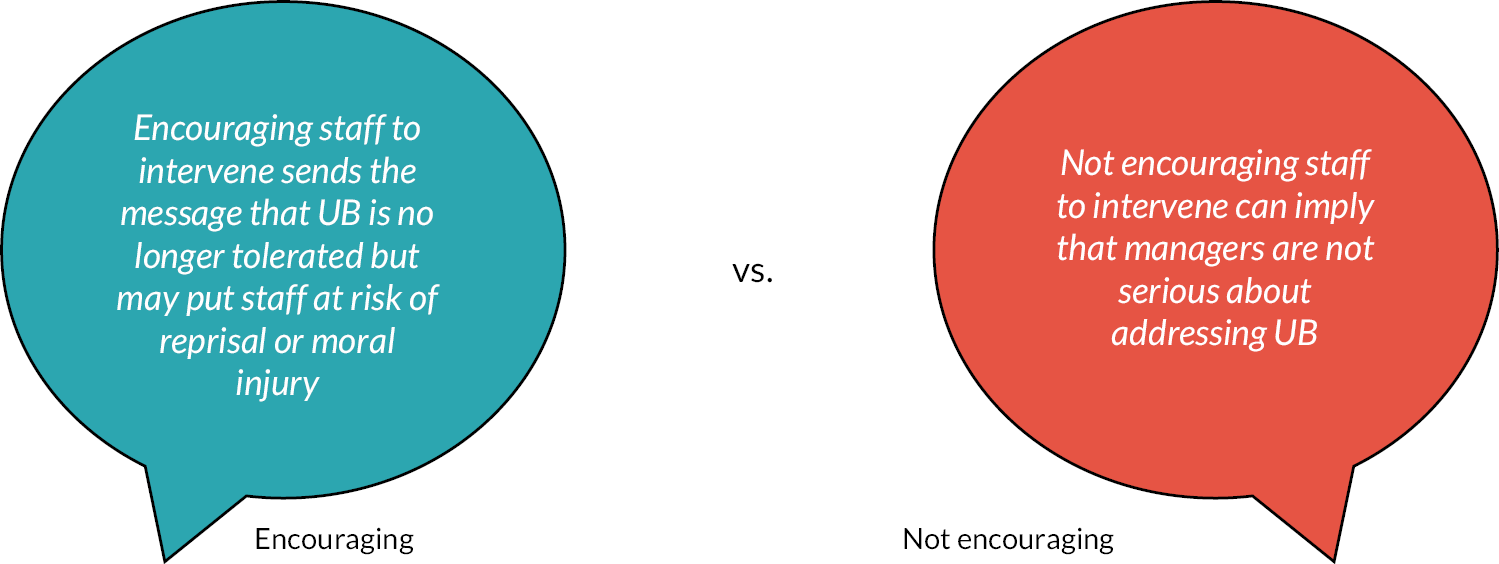

Identification of key dynamics

We operationalised many of the demi-regularities (or ‘semi-predictable patterns or pathways of programme functioning’ across studies) identified across studies as ‘key dynamics’36 and ‘implementation principles’ (see Chapters 7 and 8). Key dynamics were defined as contradictions within, considerations for or frequent unintended consequences of interventions/strategies. These dynamics and principles were iteratively discussed within the team before they were presented to our stakeholders to be sense-checked against their expertise. Our intention was to surface these often-implicit contradictions, which should be actively managed by those involved in implementing interventions in organisational settings.

Formatting of context, mechanism and outcome configuration in this report

Throughout this report, CMOCs are most commonly formatted as ‘if, then, because’ statements for simplicity: meaning ‘if [context], then O [outcome], because [mechanism]’. In Chapter 6, where particular strategies are discussed, we formulated the CMOCs using a method outlined by Dalkin et al. 35 This format is as follows: R (Resources introduced by the intervention) + C (Context) → M (Change in participant reasoning) = O (Outcome).

The purpose of the differing CMOC formulation in Chapter 6 is to make a greater distinction between the resource offered by the intervention (i.e. the strategy) and the context in which that strategy is delivered.

Step 6: Testing, refining and developing resources with stakeholders

Informed by the ‘Evidence Integration Triangle’ (EIT)52 and stakeholder involvement in March 2023, we used our realist review findings to produce actionable evidence to support NHS managers/leaders to better understand how work environments may help or hinder UBs and identify what strategies work where. Further detail on patient and public involvement (PPI) is in Chapter 9, Discussion.

Chapter 3 Characterising unprofessional behaviours

Introduction

This chapter outlines the characteristics of our included sources and explores the terminology used to describe UBs among staff in acute healthcare settings. We also propose a definition of staff-to-staff UB and outline the middle-range theories (MRTs) drawn upon in this report, which added depth to our analysis. Full detail on MRTs is given in Appendix 2.

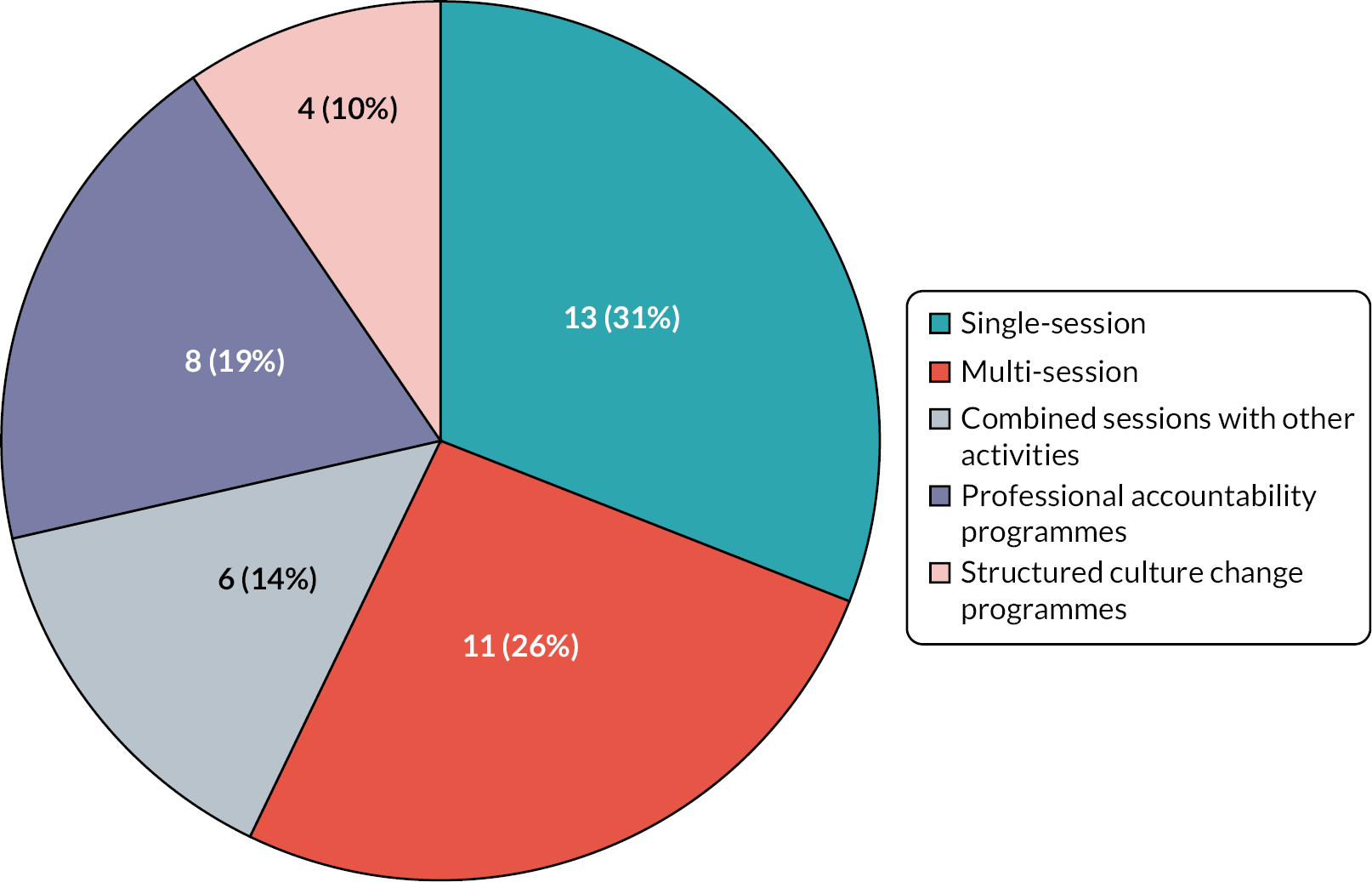

Document characteristics

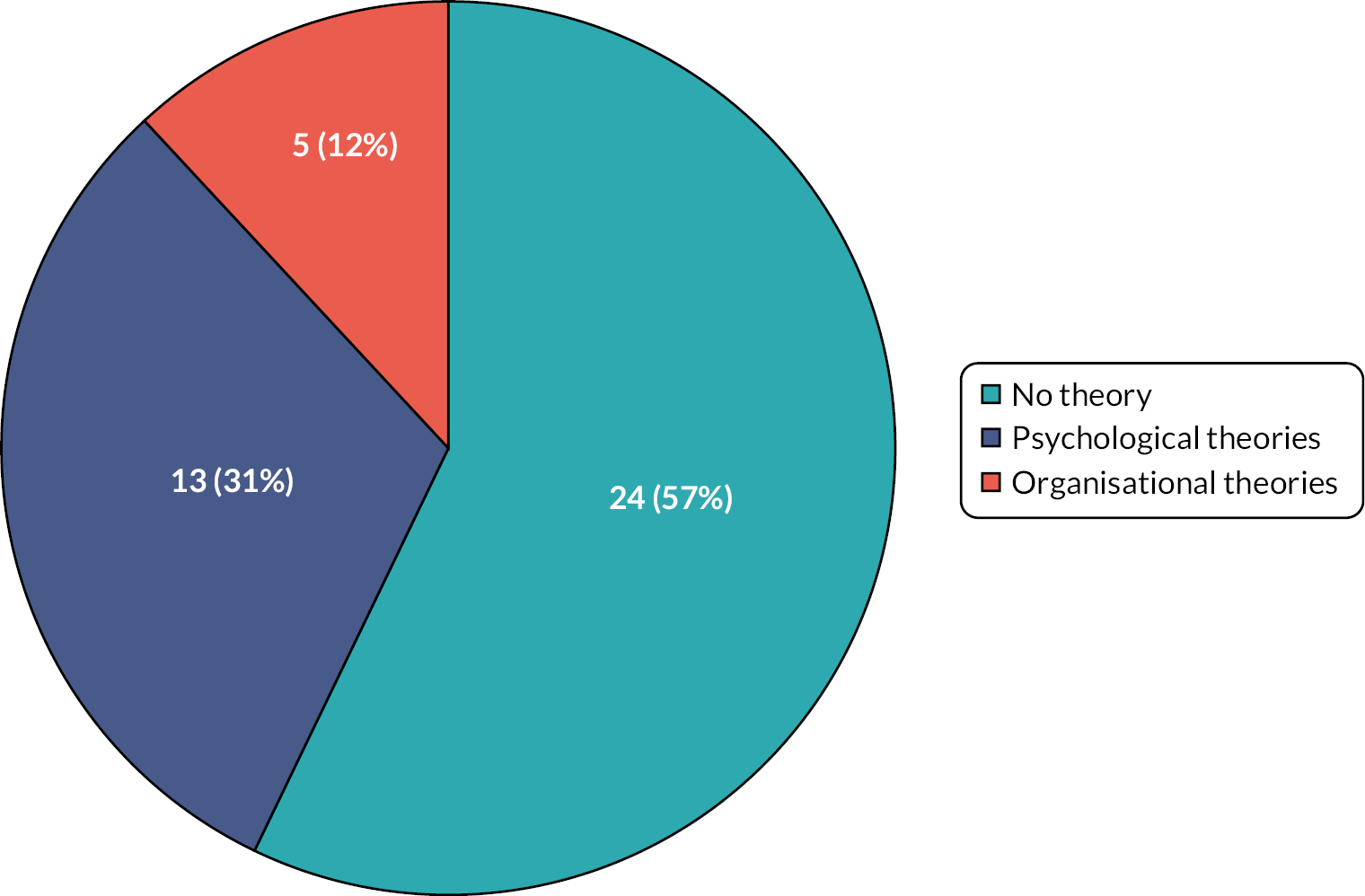

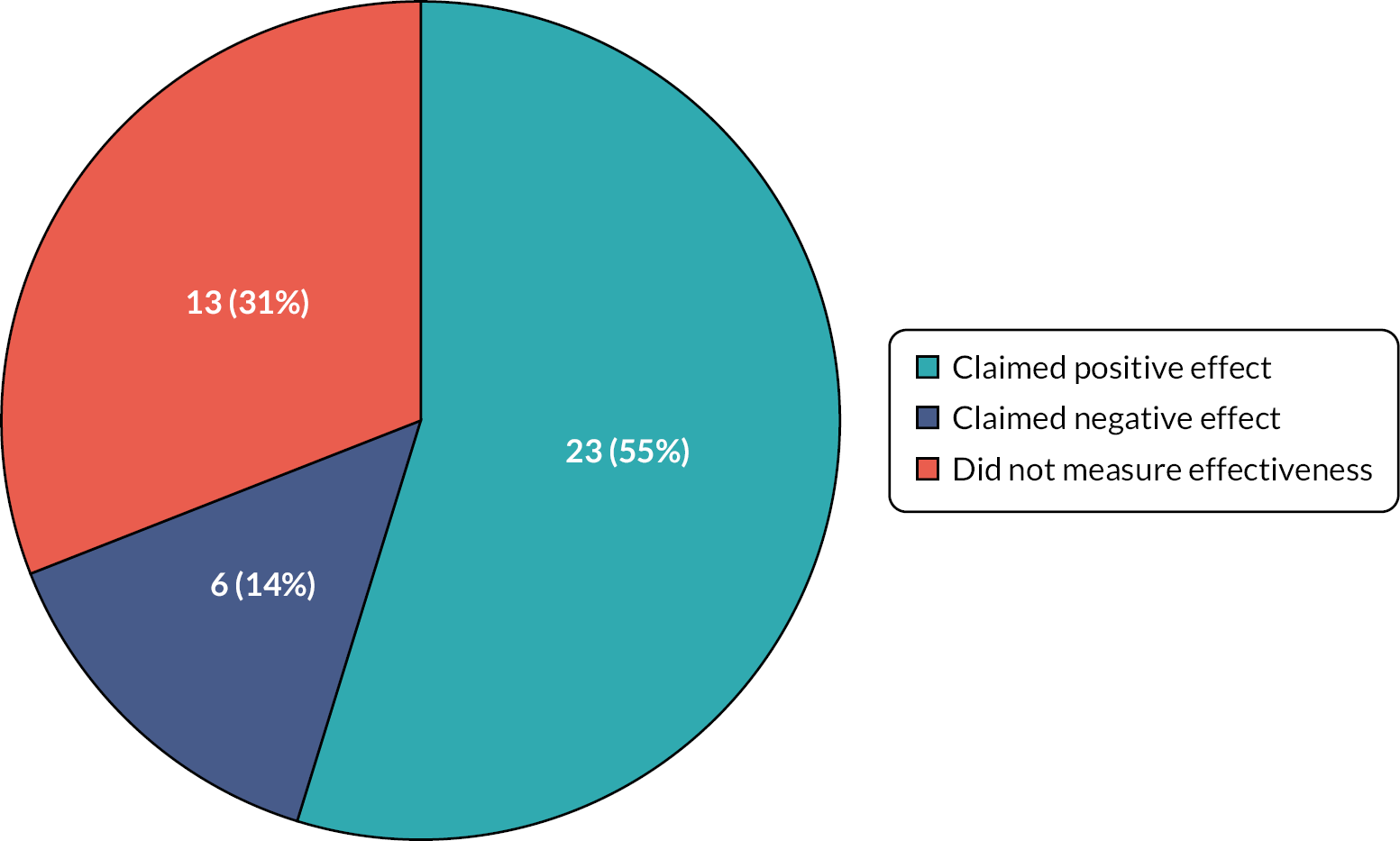

Source types

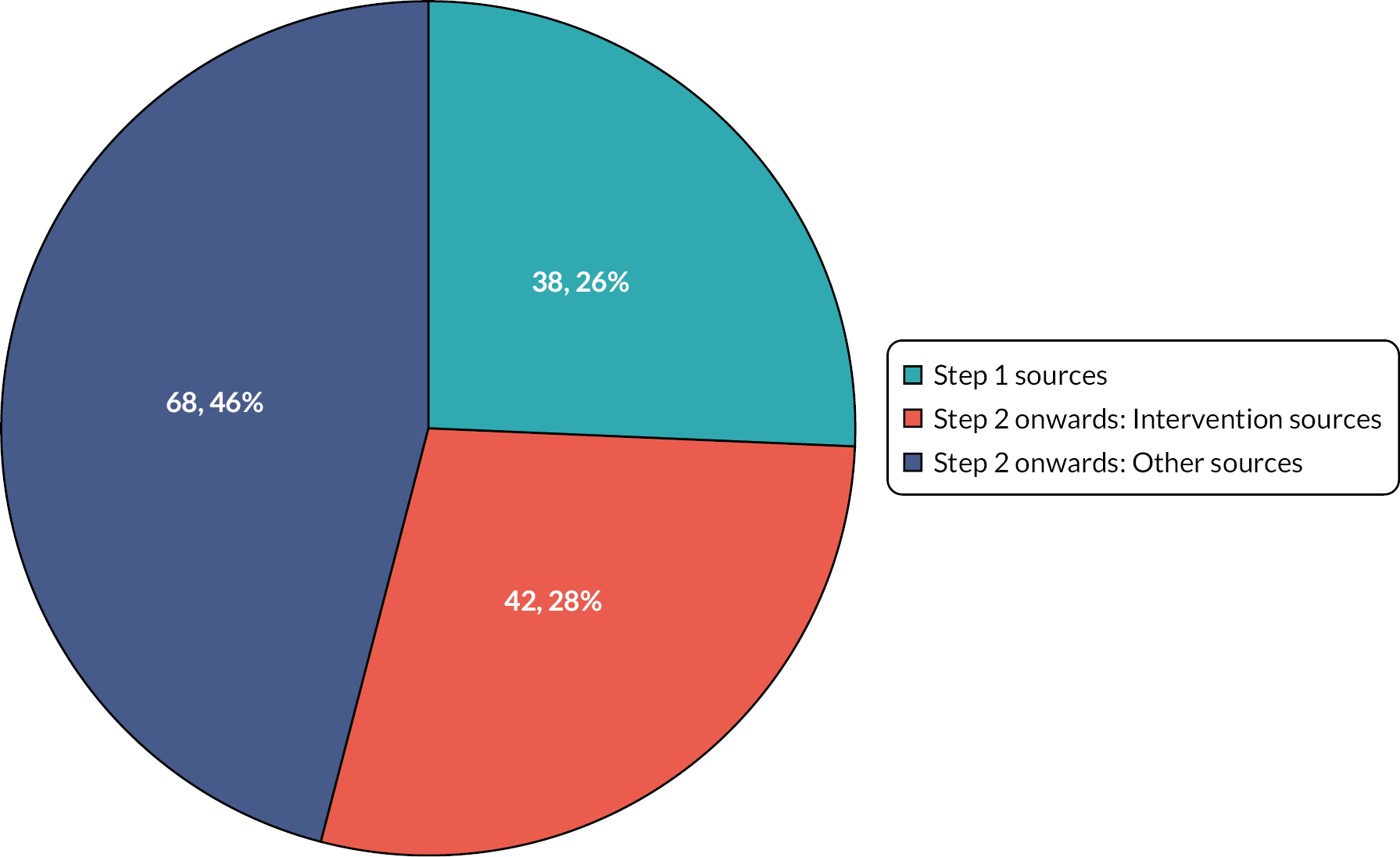

The 148 included sources encompassed 113 empirical and 45 non-empirical sources (Table 4). The largest source type was acute care intervention papers (n = 42) (Figure 5), all identified in Step 2 onwards. These interventions, the characteristics of their evaluations and their components are discussed in Chapter 5. Full details on all 148 included sources – including country, healthcare setting, samples, etc. – can be found in Appendix 3, Table 25.

| Study type | Step 1 | Step 2 and updates | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical (total n = 113) | |||

| Systematic review | 8 | 5 | 13 (8.8) |

| Narrative review | 3 | 8 | 11 (7.4) |

| Cross-sectional/case studies | 5 | 17 | 22 (14.9) |

| Intervention | 1 | 42 | 43 (29.1) |

| Report | 6 | 8 | 14 (9.5) |

| Simulation study | 3 | 1 | 4 (2.7) |

| Theoretical/modelling | 1 | 5 | 6 (4.1) |

| Non-empirical (n = 45) | |||

| Web page | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.4) |

| Opinion article | 3 | 0 | 3 (2.0) |

| News article | 1 | 1 | 2 (1.4) |

| Editorial | 5 | 23 | 28 (18.9) |

| Total | 38 | 110 | 148 (100) |

FIGURE 5.

Pie chart depicting distribution of included literature and to which step of the project it corresponds.

Healthcare settings

Included sources focus predominantly on acute healthcare settings, as per our protocol, comprising 37% of included sources (Table 5). We also included ambiguous healthcare settings (e.g. sources that referred to simply ‘bullying in health care’) or sources that encompassed multiple healthcare settings (general healthcare settings, 38.5%). We also included several sources focusing on a setting with medical professionals who were still in education or training. These comprised 5.4% of sources.

| Healthcare setting | Step 1 | Step 2 and updates | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specified health care | 28 | 29 | 57 (38.5) |

| Acute healthcare settings | 3 | 52 | 55 (37.2) |

| Speciality care (e.g. surgery, neonatal, obstetrics, military, mental health) | 5 | 9 | 14 (9.5) |

| Emergency | 1 | 12 | 13 (8.8) |

| Medical education | 0 | 8 | 8 (5.4) |

| Non-health care | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Total | 38 | 110 | 148 (100) |

Countries of focus

We collated information regarding the country on which the source content focused, not the country in which the source was published. Our included sources were predominantly focused on the USA or UK, together comprising over 52% of sources. A further 24.3% had a focus in no specific geographical region (Table 6).

| Country | Step 1 | Step 2 and updates | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 7 | 32 | 39 (26.4) |

| UK | 16 | 23 | 39 (26.4) |

| Australia and New Zealand | 1 | 14 | 15 (10.1) |

| Canada | 0 | 6 | 6 (4.1) |

| Turkey | 0 | 3 | 3 (2.0) |

| Ireland | 0 | 2 | 2 (1.4) |

| South Korea | 0 | 2 | 2 (1.4) |

| Iran | 1 | 1 | 2 (1.4) |

| Sweden | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.7) |

| Spain | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.7) |

| Jordan | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.7) |

| EU-wide | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| No focus | 12 | 24 | 36 (24.3) |

| Total | 38 | 110 | 148 (100) |

Terminology used to understand unprofessional behaviours

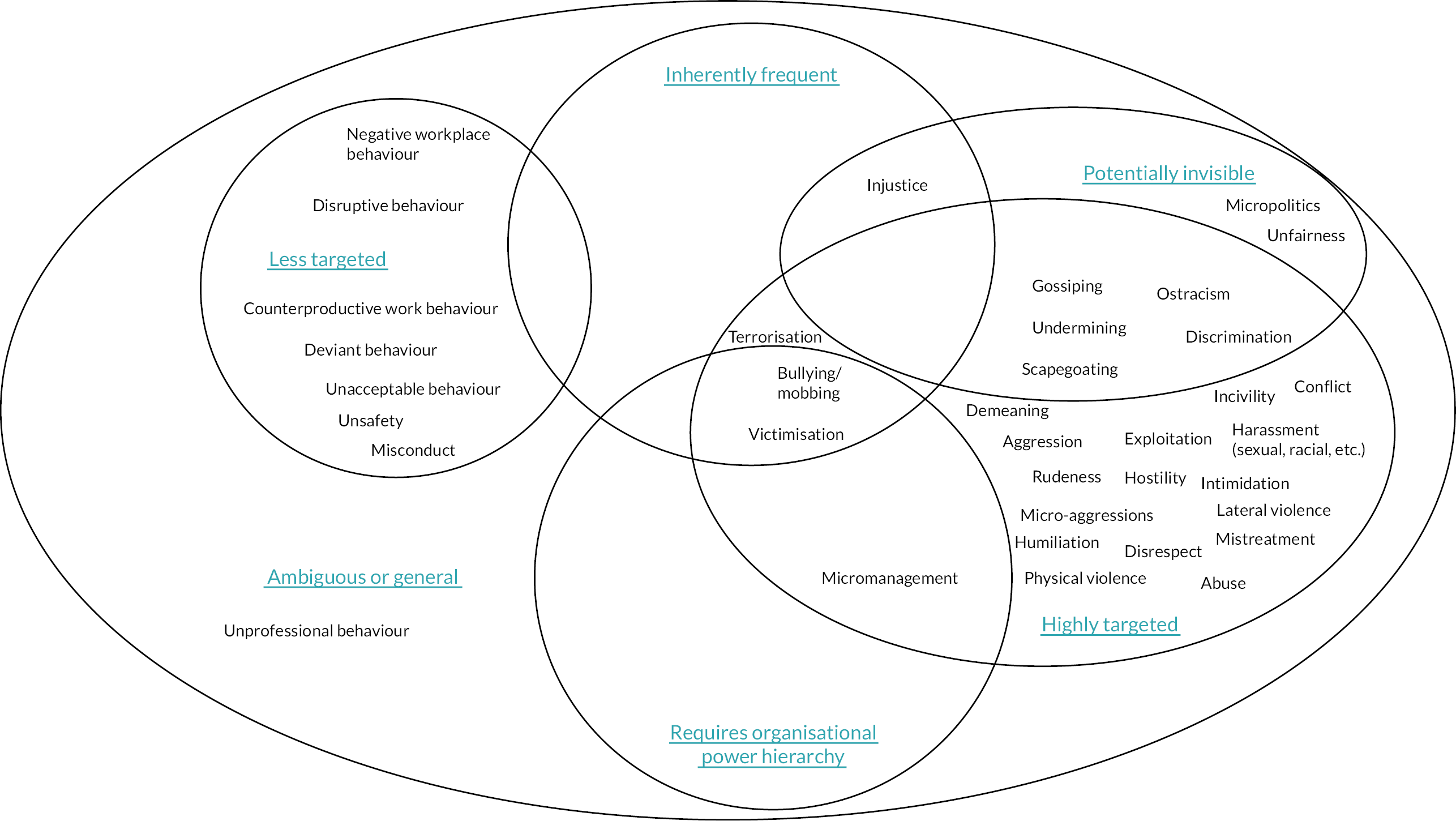

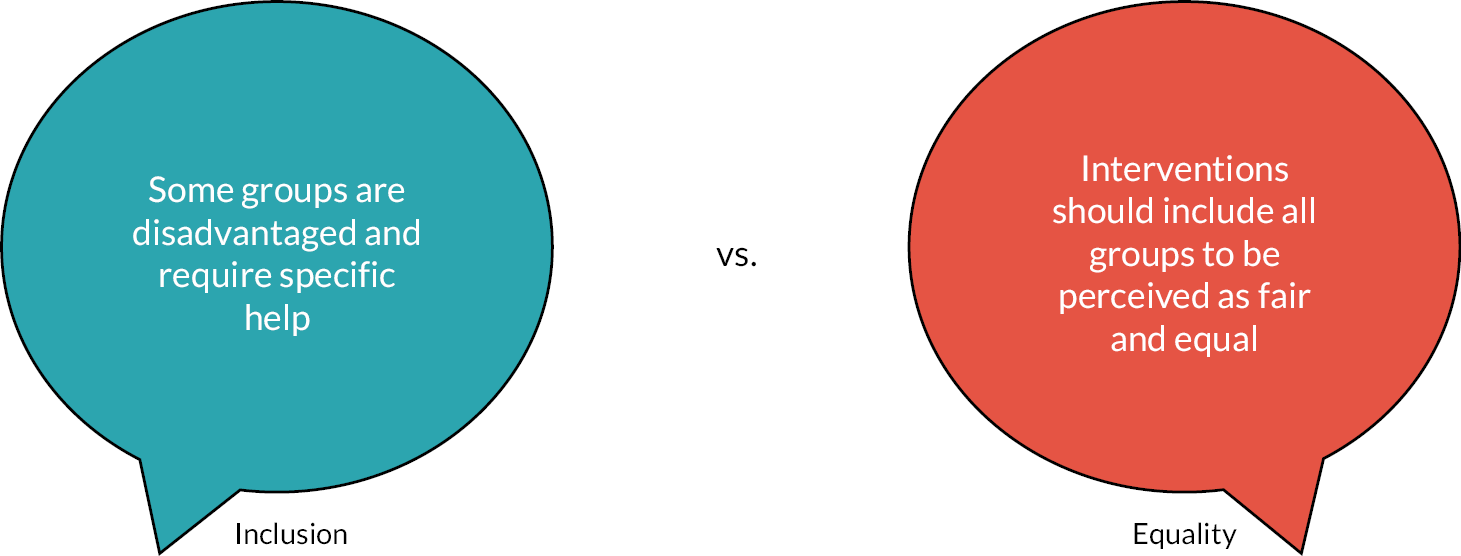

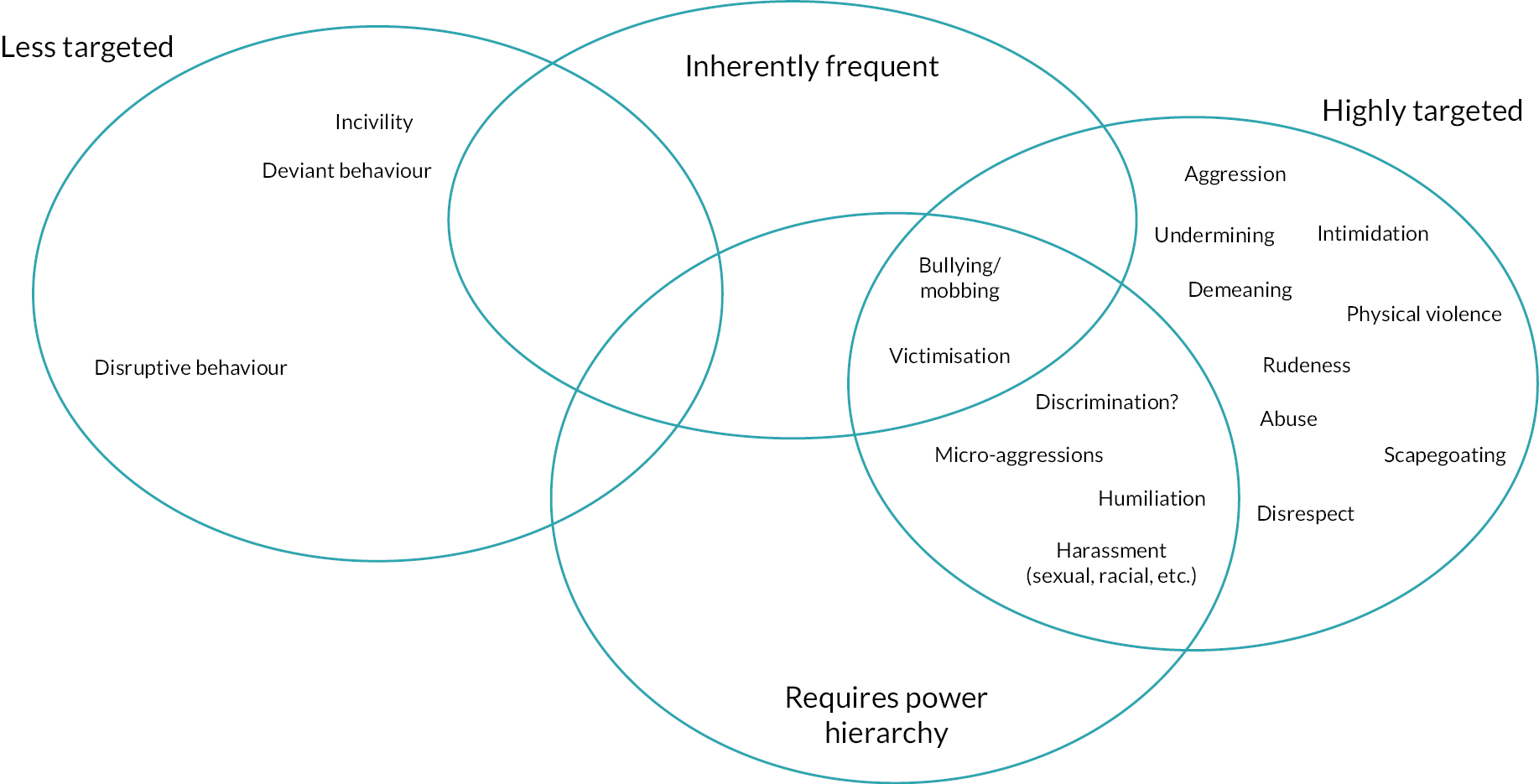

In this review, we focused on interpersonal forms of UB between staff – that is, those who can be targeted – as outlined in Figure 6. We did not examine counterproductive workplace behaviours such as laziness or lateness. UBs have been defined as ‘a wide spectrum that includes conduct that more subtly interferes with team functioning, such as poor or ambiguous communication, passive aggression, lack of responsiveness, public criticism of colleagues and humour at others’ expense’. 1 UBs can, therefore, be casual and generalised or highly targeted with the intention to cause distress or harm. The operational definition for UBs developed by the team, with stakeholder input, for use in this study is: ‘Any interpersonal behaviour by staff that causes distress or harm to other staff in the healthcare workplace’. We also acknowledge that UB can have many dimensions, and so also developed the following ‘extended’ definition: ‘Any interpersonal behaviour by staff that acutely or frequently undermines, humiliates, intimidates, or causes distress or harm to other staff, in the healthcare workplace’.

FIGURE 6.

Typology of UB terms and their dimensions.

| Stakeholder feedback summary – definition of UB |

| At our stakeholder group meeting in March 2023, we presented two definitions to the stakeholders – one simplified and one with more detail. The stakeholders were split as to which definition they preferred. They emphasised the importance of capturing the impact on bystanders of UB, as well as discussing whether ‘harm’ or ‘distress’ was a more appropriate term. Consequently, we made refinements to the definitions and included both. |

While some sources discussed more than one term to describe UBs, we synthesised terms that were used as the primary focus of each study. In so doing, we identified 21 different types of UB across our included documents (Table 7). Results show that over 50% of sources were focused on bullying, incivility and horizontal or lateral violence. Ten sources focused on more specific forms of UB that affect particular groups such as microaggressions, racism or sexual harassment. Twelve sources also focused on an issue adjacent to UB, such as organisational climate or communication issues between staff, and these were included where sufficiently rich to inform our analysis. It is also important to note that these terms are also a product of the focus of our search and may not be representative of proportions of such terms prevalent in the wider literature.

| UB type | Number of sources (%) |

|---|---|

| Bullying | 47 (31.8) |

| Incivility | 18 (12.2) |

| Horizontal/lateral violence | 16 (10.8) |

| Other (e.g. organisational climate, interpersonal collaboration, communication issues, discouraging environment) | 12 (8.1) |

| Unprofessional behaviour | 9 (6.1) |

| Positive environment (e.g. civility, professionalism, respect) | 8 (5.4) |

| Disruptive behaviour | 5 (3.4) |

| Microaggressions | 4 (2.7) |

| Undermining | 4 (2.7) |

| Racism | 3 (2.0) |

| Conflict | 3 (2.0) |

| Negative workplace behaviour | 3 (2.0) |

| Unacceptable behaviour | 2 (1.4) |

| Rudeness | 2 (1.4) |

| Hostility | 2 (1.4) |

| Mobbing | 2 (1.4) |

| Sexual harassment | 2 (1.4) |

| Harassment | 1 (0.7) |

| Misconduct | 1 (0.7) |

| Aggression | 1 (0.7) |

| Disrespect | 1 (0.7) |

| Mistreatment | 1 (0.7) |

| Discrimination | 1 (0.7) |

We also collated and mapped definitions and behaviours inherent to 33 different UB-related terms, including those in Table 7 (see Appendix 4, Table 26). Our findings indicate that literature generally refers to terms that encompass a wide set of behaviours, such as bullying, incivility, harassment and lateral violence.

Dimensions of terminology

Some terms – such as ‘unprofessional behaviour’ – are used in more ambiguous ways and can include ‘poor or disrespectful communication, irresponsible behavior, inappropriate care, and lack of professional integrity’. 53 As such, this term encompasses all behaviours that compromise a professional environment, from more ‘active’ behaviours (e.g. being rude to a co-worker) to those that can be considered more passive (e.g. being late to work). Disruptive behaviour is another similar term that was used by included sources but typically focuses more on those behaviours that compromise patient safety.

As well as terms that encompass more passive types of behaviour, there are also those that are more ‘active’, targeted and intended to cause distress or harm. These include bullying, harassment, disrespect, rudeness, conflict, and those that are actively harmful. Lateral violence is one example; it has been defined as ‘any repetitive behaviour among peers that is considered offensive, abusive, or intimidating by the target’. 54 This suggests that lateral violence typically occurs between individuals in the same group (e.g. frontline nurses) and highlights another dimension of included UB terms: whether or not they are targeted.

While lateral violence involves staff on the same hierarchical level, other forms of UB may require a vertical hierarchy. This is typical for bullying, for example. Included articles suggested that bullying was an interpersonal form of UB that was repeated and often from a person higher in an organisational hierarchy towards a person lower in the hierarchy: ‘bullying encompassed a range of disruptive, repetitive, and ineffective behaviors, such as criticism and humiliation, negative acts perpetrated by an individual in a position of power intended to cause fear in a targeted individual’. 55 This adds two further dimensions to UBs: frequency and requirement of a hierarchy.

Unprofessional behaviours can also be more insidious and invisible. While such behaviours are difficult to target or measure, they can also be highly targeted in nature. Such behaviours can include undermining, which is defined as ‘conduct that subverts, weakens or wears away a person’s confidence, and may occur when one practitioner intentionally or unintentionally erodes another practitioner’s reputation or intentionally seeks to turn others against them’. 56 As such, the behaviour may be invisible from the target’s perspective and can be difficult to identify from an organisation’s perspective. This adds the dimension of visibility to UBs.

Mapping dimensions of unprofessional behaviours

The above results identified that UBs can: be general or more specific in nature, be more or less targeted, require an organisational hierarchy or not, inherently be frequent (i.e. must occur more than once) as per its definition, and be more or less visible to both the organisation and the target. Figure 6 outlines our typology of UB terms and their location within the various dimensions. Terms such as ‘deviant’, ‘disruptive’ and ‘unacceptable behaviour’, which include non-targeted passive behaviours, sit at the top-left of Figure 6 and none are inherently frequent by definition (i.e. they can all be one-off events). Inherently frequent behaviours include bullying/mobbing, terrorisation, victimisation and injustice. Some of these behaviours – such as bullying – also require an organisational power hierarchy (according to most definitions), whereas micromanagement also requires a hierarchy but does not need to be frequent.

Most behaviours on which we focus in this review are targeted interpersonal behaviours, such as incivility, conflict, harassment, aggression, rudeness, microaggressions and disrespect. Some are also specifically targeted towards a person or entire group but are less visible. Such behaviours include discrimination, scapegoating and ostracism (see Figure 6). We considered a dimension of severity but these were fraught with complexity and are likely to be subjective, related to recipients’ perceptions. However, we acknowledge that some types of UB are broadly considered to be more ‘severe’ than others, that is, physical assault is worse than rudeness.

| Stakeholder feedback summary – typology |

| When we presented this typology to our stakeholders in January 2022, they pointed out that some behaviours were not classified correctly, e.g. discrimination is always highly targeted and does not necessarily require a hierarchy. They also provided us with the dimension that some behaviours may be ‘hidden’ or potentially invisible as our final typology reflects. We adjusted our typology accordingly. |

Conflicting definitions

Included sources often used terms in conflicting ways. Bullying, it seems, is often used as a catch-all term for UBs of all kinds – perhaps because it has been in use in the literature for a longer period. However, ‘there is no single, universal definition of workplace bullying either nationally or internationally’. 57 While many definitions suggested a hierarchy or power imbalance was essential for bullying, others did not. One definition stated that ‘[bullying has] been used to explain aggression between colleagues who are on the same level within the organizational hierarchy and who, because of their (supposed) low personal self-esteem and poor group identity, direct abusive behaviour toward each other’. 58 Evidently, this definition does not suggest that a hierarchy must be present. For the purposes of our review – and since most definitions state that bullying occurs within a hierarchy – we have included it in the part of our typology that requires hierarchy. Without the hierarchy component, it is not clear how the definitions of bullying and harassment differ as both are frequent forms of persistent UB.

Similarly, while it might be expected that ‘lateral violence’ occurs at the same level, there was disagreement on this in the literature. One included source suggested that: ‘Terms such as horizontal violence and lateral violence suggest the perpetrator is a nurse colleague of equal status, but this is not always the case. It might be a person in a higher position – or it might not even be a nurse’. 59 Table 8 depicts examples of selected terms where conflicting definitions were identified.

| Term | Definition 1 | Definition 2 | Key discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying | ‘a form of harassment which involves persistent, intimidating behaviour, usually by a supervisor toward an employee’60 | ‘repeated exposure to person‐, work‐, and intimidation‐related negative acts such as abuse, teasing, ridicule, and social exclusion over a period of time in the workplace’61 | Definition 1 suggests a hierarchy must be present but definition 2 does not |

| Lateral violence | ‘Lateral violence (LV) is described as behavior demonstrated by nurses who overtly or covertly direct dissatisfaction toward those less powerful than themselves and each other’62 | ‘LATERAL VIOLENCE is any repetitive behavior among peers that is considered offensive, abusive, or intimidating by the target’54 | Definition 1 suggests lateral violence can be towards those lower on the hierarchy, whereas hierarchy is not mentioned in definition 2 and suggests incivility must be frequent |

| Incivility | ‘subtle behaviors not intended to harm anyone but contrary to workplace standards’55 | ‘… repeated offensive, abusive, intimidating, or insulting behavior, abuse of power, or unfair sanctions that make recipients upset and feel humiliated, vulnerable, or threatened, creating stress and undermining their self-confidence’63 | Definition 1 suggests that incivility encompasses more subtle behaviours but definition 2 suggests they are not at all subtle |

| Disruptive behaviour | ‘The American Medical Association’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs defines disruptive behavior as behavior that ‘tends to cause distress among other staff and affect overall morale within the work environment, undermining productivity and possibly leading to high staff turnover or even resulting in ineffective or substandard care’64 | ‘… we define disruptive behaviour as constituting the following three criteria: (a) interpersonal (i.e. directed toward others or occurs in the presence of others); (b) results in a perceived threat to victims and/or witnesses; (c) violates a reasonable person’s standard of respectful behaviour’32 | Definition 1 suggests disruptive behaviour includes passive-type behaviours that undermine productivity, whereas definition 2 suggests it must be targeted |

How conflicting terminology impacts staff in practice

Included sources emphasised the importance of terminology and that staff understanding forms of UB such as bullying, microaggressions etc. – including their definitions and appearance – is essential to staff understanding their experience of UB in the workplace and for being able to interpret when it is appropriate to speak up. 65–67 One source stated ‘the absence of a comprehensive descriptive framework capturing and cataloguing those behaviours make identification, seeking assistance and intervention difficult’. 68 Included literature highlighted that the lack of uniform definitions can result in different interpretations of UB by staff members and from different perspectives (e.g. individual vs. organisational), which creates an atmosphere of confusion and inhibits speaking up.

Lack of uniform definitions also impacts the ability to assess prevalence of UB or identify where and how it is occurring, which can make implementing strategies more difficult. For example, differing definitions of what constitutes UB could impact ability to understand its prevalence, reduce the likelihood of speaking up and impact ability to intervene effectively. One study showed a lack of a uniform definition and clarity regarding bullying in the nursing profession meant that: ‘those who are exposed to such behaviour, including new graduate nurses, senior nurses, and nurse unit managers would have reported based upon their own understanding of these behaviours’. 58

Evolution of literature focus

One general trend noted in the literature over time was the articulation of more specific forms of UB, indicating that greater attention was paid to the experiences of minoritised communities – through the study of microaggressions or racism, for instance. All sources (n = 7) discussing microaggressions and racism more broadly were published from 2019 onwards, which is reflective of the more recent societal focus on racism and discrimination. 69–75 The same can also be said for literature relating to sexism (n = 9), which begins in 201362 and is more prevalent from 2016 onwards. 11,32,62,76–80

No such trends were observed for more widespread and generally used terms such as ‘bullying’ or ‘harassment’, as these have always been used frequently. While the greater focus on issues affecting groups with protected characteristics is encouraging, much more needs to be done to help address the greater burden these groups face from the impact of UB in the workplace.

Terms not included: ‘professionalism’, ‘civility’ and ‘other behaviours’

We also wanted to highlight the many adjacent behaviours that are not included in our review. These include those behaviours that may be the ‘inverse’ of UB, including behaviours and terms such as ‘civility’ and ‘professionalism’. It is important to highlight that professionalism may be more than the simple absence of UB, such as maintaining appropriate appearance, upholding patient confidentiality, applying clinical skills according to standards, and interacting honestly with patients. 81 On the other hand, some behaviours may be unprofessional from the perspective of an organisation – but not from that of colleagues. One example is the use of workarounds employed by healthcare staff that may deviate from organisational procedures perceived as barriers (and hence may be unprofessional from the perspective of the organisation) but that can improve patient safety. 82 Such nuanced cases are beyond the remit of this review; only interpersonal forms of UB are included.

Key concepts, middle-range theories and wider context for this review

Throughout this report, we draw on a number of MRTs to better interpret and add depth to various elements of our analysis, outlined in Table 9. Additionally, we want to highlight the influence of wider context on organisations – including societal events and transitions, such as COVID-19, #MeToo and #BLM – that form the wider, cultural and historical backdrop within which our review takes place. A full description of these MRTs can be found in Appendix 2.

| Middle-range theory | Description |

|---|---|

| Psychological safety | Psychological safety refers to staff perceptions of consequences of the risks of speaking up in the workplace83 and is defined as ‘a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking’84 |

| Moral injury | Moral injury in a healthcare context has been defined as ‘perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations’85 which may leave ‘long-lasting emotionally, psychologically, behaviourally and spiritually harmful impacts’86 |

| The JDR | Many included sources drew upon the JDR model as a contributor to bullying, explaining a lack of organisational resources could worsen UB.87 Originally used as a model to better understand burnout, it sets out the range of job demands that can contribute to exhaustion, as well as job resources that, if lacking, can lead to disengagement87 |

| FAE | The FAE is a phenomenon from social psychology whereby people tend to attribute a person’s behaviour solely to their personality – rather than acknowledging that, often, behaviour is a combination of a person’s personality and their environment.88 This applies mostly to other people’s negative actionss89 |

| Trust | Our report frequently discusses trust in management by staff, which is easily lost when UB is not addressed. Trust is defined by Robinson (1996) as ‘one’s expectations, assumptions or beliefs about the likelihood that another’s future actions will be beneficial or at least not detrimental to one’s interests’.90 Inherent to our understanding is the importance of managers’ roles in trust and UB; staff interests lie in managers providing a safe organisational environment free from UB |

Key findings and summary

In total, 148 sources are included in this review. We mapped different types of UB according to several main dimensions, including whether UB is more or less targeted, visible to organisations and their targets, and required an organisational hierarchy. Definitions of UB were found to have little agreement, making synthesis difficult and likely to sow confusion in practice. This review draws on the following MRTs: (1) theory of psychological safety, (2) moral injury, (3) the job demands and resources model (JDR) model to shed light on organisational processes that can contribute to UB, (4) the fundamental attribution error (FAE) and (5) trust, particularly in management. The literature does not yet sufficiently represent these wider societal events such as COVID-19 and movements such as #MeToo or #BLM and resultant changes in societal views.

Chapter 4 Contributors to and outcomes of unprofessional behaviour between staff in acute healthcare settings

Introduction

This chapter identifies and describes the contributors to and contexts of UB. It explains the ways interpersonal UBs are defined, developed and experienced across professional staff groups in acute healthcare settings according to the literature. We use the term ‘contributors’ to reflect the range of antecedents involved in how UBs manifest themselves and are discussed within current literature.

Results

This initial section sets out the lens with which we have viewed contributors to UB, as shaped by our analysis of the literature and discussions with our stakeholder group. Then, we discuss the four identified categories of contributors to UB. These categories include: (1) workplace disempowerment, (2) organisational confusion, uncertainty and stress, (3) job and organisational design that inhibits social connection and (4) harmful work cultures. Within these categories, we also elaborate a range of more specific contributors (e.g. shift working, leadership behaviours, etc.). Use of these categories allowed us to identify similar or shared mechanisms and explore how these categories and sub-contributors broadly work.

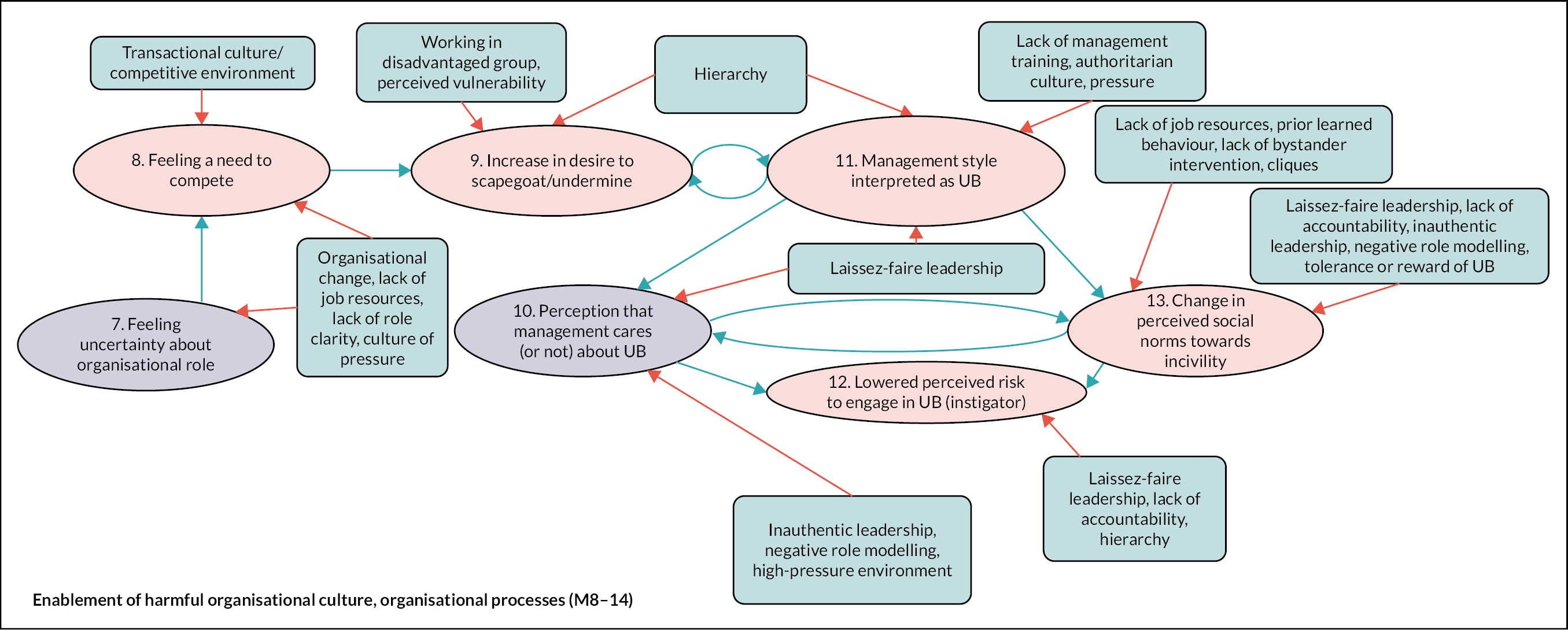

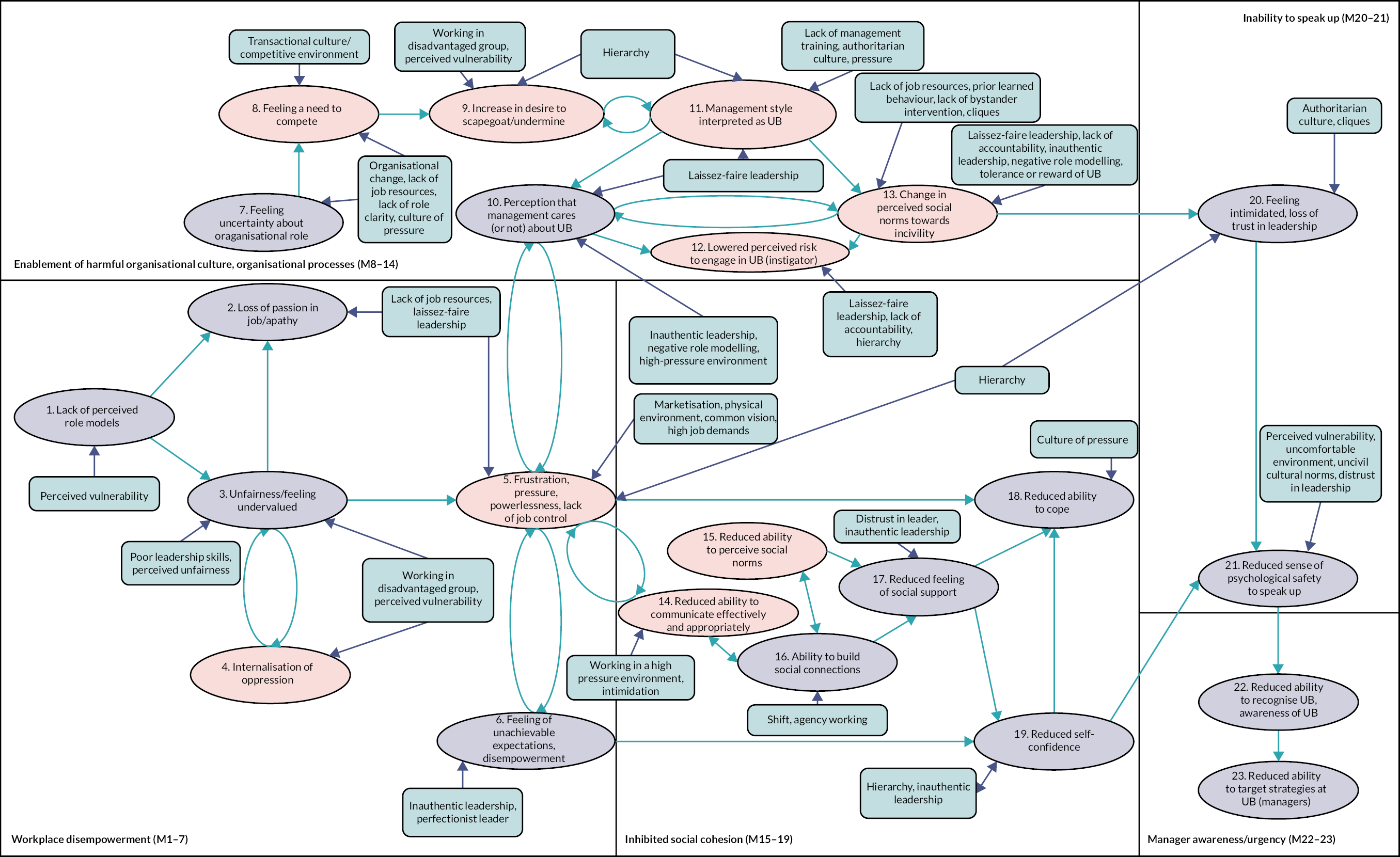

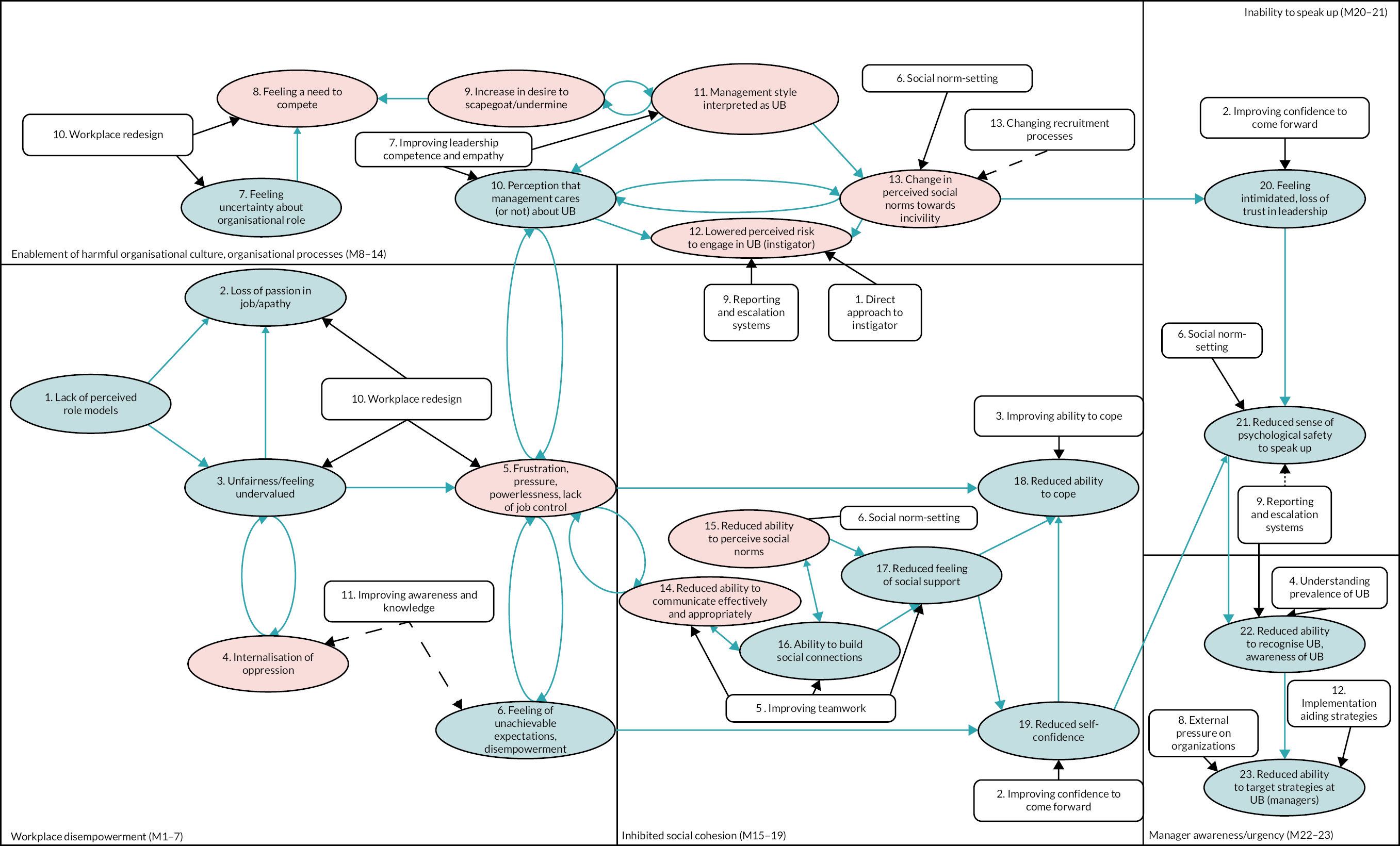

To elucidate how contributors lead to a worsening of UB, throughout this chapter we draw on a selection of CMOCs. In each section, we present a partial programme theory diagram (Figures 7–9). In these diagrams, mechanisms are depicted in ellipses; the contributors are in green boxes. Connections between these are indicated by arrows. Those mechanisms that can directly lead to an increase in UB are depicted by orange ellipses, while the blue ones simply connect to other aspects as indicated in the fully assembled programme theory (Figure 11). When CMOCs are depicted in the text, the mechanisms will be numbered. These numbers will correspond with the numbers in the partial programme theory diagrams to help locate where a CMOC lies in the causal chain. It is important to note that these diagrams may depict more information than there is capacity to discuss in the text because the emerging causal chain became increasingly complex with multiple and overlapping mechanisms and outcomes. The headings in each section explore the main sub-contributors identified in the literature.

FIGURE 7.

How CMOCs underpinning workplace disempowerment interact.

FIGURE 8.

How CMOCs underpinning poor social cohesion interact.

FIGURE 9.

How CMOCs underpinning enablement of harmful cultures, and battling organisational processes, interact.

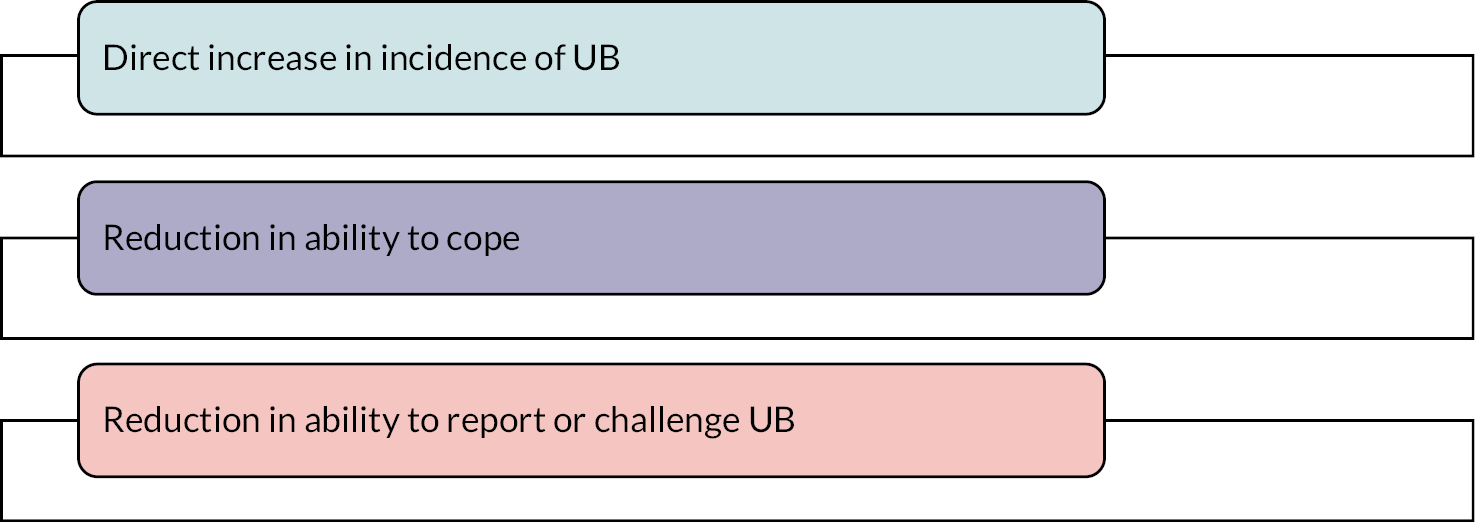

FIGURE 10.

Key outcomes from contributors to UB.

At the end of this section, in Figure 11, we present our fully assembled programme theory to depict the connections between the categories of UB. Consistent numbering of mechanisms across the partial programme and full programme theory diagrams allow the CMOCs to be cross-referenced with the full programme theory diagram. Our CMOCs are further tabulated (see Appendix 5, Table 27) with additional quotes from the literature, further explaining some of the dynamics explored in this chapter. At the end of the chapter, we explore the outcomes of both these contributors and UB, as well as the impact on different groups.

FIGURE 11.

Revised programme theory depicting interactions of different contributors and underlying mechanisms. Green squares are contributors and ellipses are mechanisms. Orange mechanisms are those that can directly increase proclivity to engage in UB.

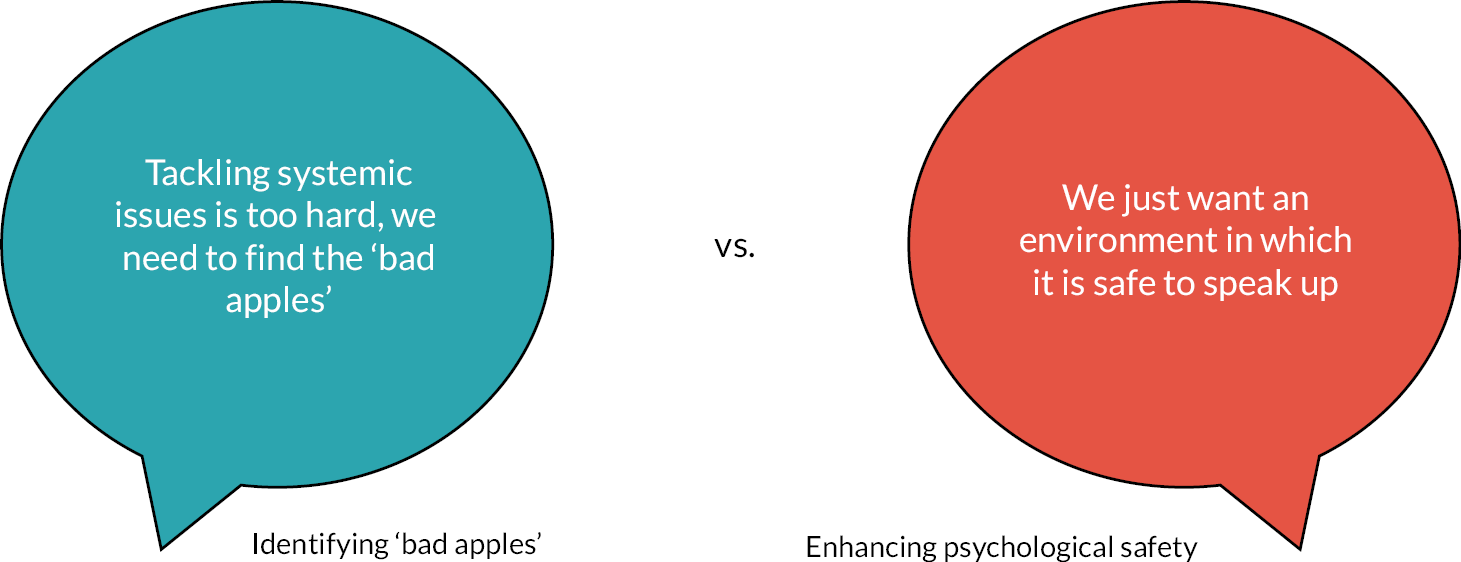

The ‘bad apple’ approach

We noted a focus in the literature on individual and personal characteristics as contributors to UBs. One source, for example, discussed ‘maladaptive personality traits’ – such as being ‘paranoid, narcissistic, passive-aggressive and borderline types’ – as well as describing instigators of UB as having ‘poorly controlled anger’ and experiencing a ‘spillover of home problems’. 91 These individuals are determined by the literature as having a greater proclivity to engage in UB than others and are often referred to as ‘bad apples’. 92 The organisational response to such individuals is often to weed them out and try to discipline them. Over time, the hope is that this may lead to culture change, as a critical mass of instigators have their behaviour addressed.

However, other literature in our review argued that a focus on individual characteristics is often used by organisations as a ‘get out of jail free’ card that enables abrogation of responsibility and accountability to implement wider cultural change or strategies targeting UB. 61,93,94 Moreover, evidence regarding individual-level contributors – such as personality types, gender or professional group – is often very mixed. For example, in terms of professional group, some sources find surgeons to be more frequent instigators of UB towards nurses because of inherent power dynamics, whereas other sources find nurses more frequently uncivil towards one another as a result of negative self-esteem, competition and fear. 32 Additionally, possessing certain personality traits does not guarantee that someone will behave poorly, which makes the effectiveness of understanding such contributors questionable. 95

Therefore, it may be more productive for organisations to focus on modifiable factors that are targetable by interventions in order to reduce UB. This can include improving working conditions, improving climate and culture, fostering a psychologically safe culture and eliminating barriers to providing high-quality care. 96 In this manner, an organisation can create an environment that is least enabling of UB, regardless of the individual staff working at their organisation. Mannion et al. referred to this as addressing problems at the level of bad cellars (organisations), bad barrels (health systems) and bad orchards (professions), rather than bad apples. 92 Professional accountability programmes such as Ethos in Australia and Vanderbilt in the USA show promise in fostering this kind of culture change. 97,98 As such, this report and chapter will focus on factors that can be modified by interventions and not focus on what makes someone a ‘bad apple’ or a less resilient target.

| Stakeholder feedback summary – contributors |

| We presented an early understanding of contributors to our stakeholders in January and May 2022. We received feedback that some of our understanding was too focused on the individual. This shaped our direction for the refined analysis in Step 2 of the project going forward, in which we focused on aspects that were within an organisation’s control to change. For example, in our initial theory of ‘causes’ of UB, we had many factors considered as individual-level, including professional or personal backgrounds, job demands and ability to cope. However, in our refined understanding, we now acknowledge that many of these factors are a function of the organisational environment rather than resulting from individual differences. |

| The stakeholder group also helped shape our language, moving from an understanding of ‘causes of UB’ – which was too deterministic – to ‘contributors to UB’. |

Category 1: Workplace disempowerment

Workplace disempowerment can be caused by (1) organisational hierarchies, (2) physical environment and (3) unfairness. 70,99–101 How these elements contribute to UB will be explained further, aided by presentation of CMOCs throughout this section.

Organisational hierarchies

The NHS and healthcare systems worldwide are known to be hierarchical; clinical professionals working across different grades and there are a range of disciplines, alongside non-clinical and/or support staff. As identified in the literature, working in a hierarchy was a key structure through which staff were disempowered. These hierarchies can exist both within and between professions and are often exemplified by the relationship between doctors and nurses, whereby doctors are often considered to be in a position of power relative to nurses. 101,102 Hierarchy can either be a result of the design of the system in which organisations operate68 or a result of a socially constructed environment whereby certain groups or individuals are perceived to have more power than others. As such, hierarchies also interact with existing societal power dynamics – with hierarchies having generational, cultural, professional and gender-based roots. 78

Hierarchies can contribute to UB because those lower in the hierarchy have less power – which, as well as making them an easy target, also makes them feel less safe to speak up. One source provides an example of creating an environment in which it is unsafe to speak up in which vertical hierarchies can lead to a culture of blame and intimidation:

There appeared to be a style of management within nursing at this hospital that was based on fear rather than respect. There was an impression that nurses were tolerated rather than valued, that they should keep their heads down and not threaten those above them by disagreeing with them. 103

This is highlighted in CMOC 1.

CMOC 1. If staff work in a disempowered position, such as at the bottom of an organisational or professional hierarchy (C), then this can inhibit willingness to speak up (M21/O1) and reduce ability to communicate (M14/O2) because a sense of intimidation and reduced psychological safety is experienced (M20).

With hierarchy as a ‘direct’ contributor to UB, the following quote from a patient support staff member from a qualitative study in Australia highlights the dynamic whereby a vertical hierarchy combined with a high-pressure environment creates more opportunity for ‘bullying down’:

If the surgeon is really anxious and tense, it flows down … they bully the anaesthetist, they bully the scrub nurse and scout nurses, and the techs cop it from everyone. 93

This dynamic is depicted in CMOC 2.

CMOC 2. If staff work in a disempowered position, such as at the bottom of a hierarchy (C), then this can increase likelihood of experiencing and being impacted by UB (O) because it can make staff an easier target (M12).

Literature also reported that UB may manifest itself within flattened structures or between peer groups where there can be powerlessness. For example:

Frustration with their powerlessness often turns to internal hostility, known as ‘horizontal violence’, because of negative self-esteem and fear of the oppressor. 104

Certain minority or disadvantaged groups can also be negatively affected and feel powerless (CMOC 3).

CMOC 3. If staff work in a disadvantaged group (C), then this can lead to displacement of aggression onto others (O1) and a feeling of being undervalued (O2) because of internalisation of oppression (M4).

Physical environment

Working in a physically uncomfortable environment (which is common in healthcare workplaces), for example where it is too hot or crowded or in close proximity to disease (such as during the COVID-19 pandemic), can increase a sense of pressure and frustration and reduce ability to cope (see Figure 7). 21 Sources highlighted that certain environments could become associated with past traumatic experiences, causing regular and repeated post-traumatic triggers such as flashbacks, which further reduces ability to cope. 77 See CMOC 4 (below).

Unfairness

Working in a lower position in a hierarchy can make staff feel they are disempowered and that organisational processes are unfair or unjust. Unfair processes – such as ‘bestowing apparent favours on some doctors in training by giving them access to resources, such as study leave or training opportunities, while denying these to others’105 and similar treatment – can be considered discrimination, ostracisation or undermining in themselves. Over time, this can lead to a sense of annoyance, frustration or anger that can eventually lead to conflict. 21 This is highlighted in CMOC 4.

CMOC 4. If staff work in a disempowered position where there does not seem to be a level playing field (C1) or work in a physically uncomfortable environment (C2), then this can cause them to externalise these frustrations – increasing proclivity to engage in UB (O2) because staff feel like they are being treated unfairly (M3), experience frustration (M5) and have a reduced ability to cope (M18/O1).

Depicting the processes of disempowerment

Figure 7 depicts how the contributors underpinning workplace disempowerment interact. You will notice that other factors, such as inauthentic leadership, are also depicted in this diagram; these will be discussed in the harmful work cultures section.

Category 2: Organisational confusion, uncertainty and stress

When staff experience organisational confusion, uncertainty and stress, these factors contribute to increased instances and experiences of UB. The following four headings demonstrate how this happens, showing that when staff experience a lack of control in their day-to-day work, they encounter challenges in building relationships that, in turn, increase conflict: (1) organisational change, (2) a lack of resources and high job demands, (3) a culture of pressure and (4) a lack of role clarity.

Organisational change

The literature and stakeholders suggested that whether or not organisational change increases UB often depends on the pre-existing culture and how change is managed. The primary evidence regarding how changes may contribute to UB is through an increase in uncertainty about one’s organisational role and a further increase in workload, as well as potential job insecurity,76 which may result in an increase in competitive attitudes that can set employees against each other. For example:

In competitive environments, organizational re-structure or periods of rapid change may create opportunities for individuals to engage in the misuse of legitimate authority for furthering self-interest or career opportunities. 58

This increase in competitive attitudes can further reduce the ability to engage in teamwork and generate conflict and UB in an organisation. This can also interact with hierarchy, whereby the power dynamic can be enhanced by the threat of organisational change and managers can seek to scapegoat employees beneath them to entrench their position. 21

CMOC 5. If staff experience a period of organisational uncertainty, such as organisational change (C), or they experience a lack of job resources (C2), then this can lead to conflict and UB (O) because staff perceive their job to be at risk; an increase in competitive attitudes ensues (M8).

Demanding work environments and lack of resources

Demanding work environments with high job demands and lack of resources were also identified as contributors to UB through reduced achievements, leading to reduced ability to communicate effectively with colleagues. For example, one source highlighted the ED as a highly demanding work environment, due to:

acuity and complexity of patient presentations, the lack of predictability of workflow and the need to attend to patients in a timely manner. 106

Such demands can impact staff in several ways, including reducing the quality of communication, which may increase the chance of it being perceived as UB. For example, one source highlighted that: