Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/49/70. The contractual start date was in March 2019. The final report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Gillard et al. This work was produced by Gillard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Gillard et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Mental health crisis care

People living with challenges to their mental health can experience an acute mental health crisis while living in the community. This can include intense feelings of depression, anxiety or paranoia, including feeling suicidal, and can result in the individual and/or their family and loved ones feeling that they are unable to cope without urgent, professional support. In England, people who are already using secondary mental health services in the NHS might be able to contact their care coordinator, an out-of-hours service or mental health crisis line, and be referred directly to crisis care services. For example, they might receive regular visits from a crisis resolution and home treatment (CRHT) team for a short period until the immediate crisis has passed or be admitted to psychiatric inpatient care for a period of assessment and/or treatment. People who are not already in contact with mental health services, or who are unable to wait to be referred to specialist care, will often present at hospital emergency departments (ED). People who self-harm or attempt suicide as a result of their distress can self-present at, or be transported to, an ED by emergency services. In ED, people will first be triaged by a member of the ED team and if a mental health need is identified – and once any immediate medical need (e.g. resulting from self-injury) is resolved – be seen by a member of the liaison psychiatry, assessed, and follow-up care arranged (including, if deemed necessary, a psychiatric inpatient admission).

Mental health crisis care, as described above, is under intense pressure in the UK1 and in equivalent systems internationally. 2–6 Visits to EDs for mental health issues are increasing while the number of available psychiatric inpatient beds is decreasing, resulting in challenges to the ED system7 and lengthy waits in ED for people in mental health crisis. 8 In England, the ED system has been described as near breaking point. 9 Approximately two in three of all people with multiple attendances at ED have been in contact with specialist mental health services or have had a previous acute psychiatric admission,10 with frequent attenders at greater risk of psychiatric inpatient admissions. 11 People presenting with a mental health issue are over six times more likely than people presenting with a physical concern to wait more than 4 hours at the ED12 (in England breaches of a 4-hour wait are a key performance indicator for EDs). Mental disorders are estimated to account for around 5% of ED attendances in the UK and almost 30% of acute inpatient bed occupancy and acute readmissions. 13 Poor experiences and low levels of satisfaction with mental health care all point to the ED as not being a far from ideal environment for support and treatment for mental health crisis. 12,14

Psychiatric inpatient stays can be costly,15 in some cases detrimental to mental health,16 disproportionately harmful to people from some minority ethnic groups,17 and reportedly unnecessary for as many as 17% of referred individuals. 18 Admissions following an acute crisis can be brief (often < 5 days), yet the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and outcomes of short stays on psychiatric wards followed by early discharge is unclear. 19 Bed occupancy in inpatient psychiatric facilities is well above recommended levels with 91% of wards operating above the recommended occupancy rate. 13

The emergence of liaison psychiatry services has enabled mental health NHS trusts to provide responsive mental health assessment, advice and onward referral within emergency care settings, but wide variations in service provision20 remain and there are ongoing challenges to sustainability. 21 The introduction of CRHT teams22,23 and triage wards24 has offered little benefit in reducing contact with acute services, inpatient admissions or costs across the wider inpatient system compared with standard models of care, with ongoing staff concerns over the accuracy of triage decisions for mental health presentations in ED. 25,26 To address these growing challenges, policy in England has called for the development and evaluation of new, more effective models of crisis care as collaborations between health, mental health, social care, third sector and emergency service providers locally. 27,28 Alongside new street triage services,29 crisis houses30 and crisis cafes,31 some delivered in the third sector,32 psychiatric decision units (PDUs) have emerged as just one of a number of responses.

The psychiatric decision unit

Psychiatric decision units – also known in England as mental health decision units, crisis assessment units or assessment suites, among similar terms – have been set up in response to policy and the need to manage demand, to reduce unhelpful admissions to acute inpatient care, especially avoidable short admissions and expensive out-of-area or private admissions, and reduce mental health presentations at ED. International counterparts to the PDU fulfil a similar function,33 can be known as a psychiatric emergency service (PES), crisis stabilisation units or behavioural assessment units, and have become increasingly critical to the delivery of mental health crisis care. 34–36 This is particularly true for the USA where a third of hospitals are estimated to provide these emergency units,37 but they are also present in, for example, France,38 Singapore39 and Australia. 40

There is no single service specification for PDUs in England but rather a shared set of characteristics. PDU are short-stay facilities, based either on psychiatric or general hospital sites, for people in acute mental health crisis, offering time-limited care (typically up to 24–72 hours) including overnight stay. Units target people who experience repeat, often extended stays in ED, frequent use of other services such as the police and ambulance services, and have complex and frequent crisis-related needs but who might not benefit from a psychiatric inpatient stay. The focus of the units is on providing a comprehensive assessment in a calm, safe environment, offering therapeutic input as appropriate, and onward signposting and referral to a range of community-based care, both within and outside the NHS, hopefully breaking the cycle of repeat ED presentation and/or unhelpful acute admission. PDUs are distinguishable from triage or assessment wards; short-stay wards which typically accept all patients likely to require assessment or treatment in an inpatient setting. 41 Additionally, PDUs typically only accept informal patients (i.e. people not admitted assessment or treatment sections of the Mental Health Act), whereas triage wards will admit people formally under the Mental Health Act. Furthermore, as admission to PDU is not a formal inpatient admission, PDU staff are not required to complete inpatient treatment plans or the clustering tool for admission as they would on a ward, freeing up more time for individual face to face contact. Staff-to-patient ratio – at around 1 : 2 – is also typically higher than in an inpatient ward (typically around 1 : 4). 42 PDUs are often nurse led, supported by healthcare assistants (HCAs), with consulting input from psychiatry and other mental health professionals. PDUs can be co-located and share staffing with a Section 136 Place of Safety. Overnight accommodation is single sex, sometimes with flexible partitioning to enable the unit to respond to different numbers of male and female visitors, generally comprising reclining seating rather than beds. Units tend to be small with a capacity of around six to eight.

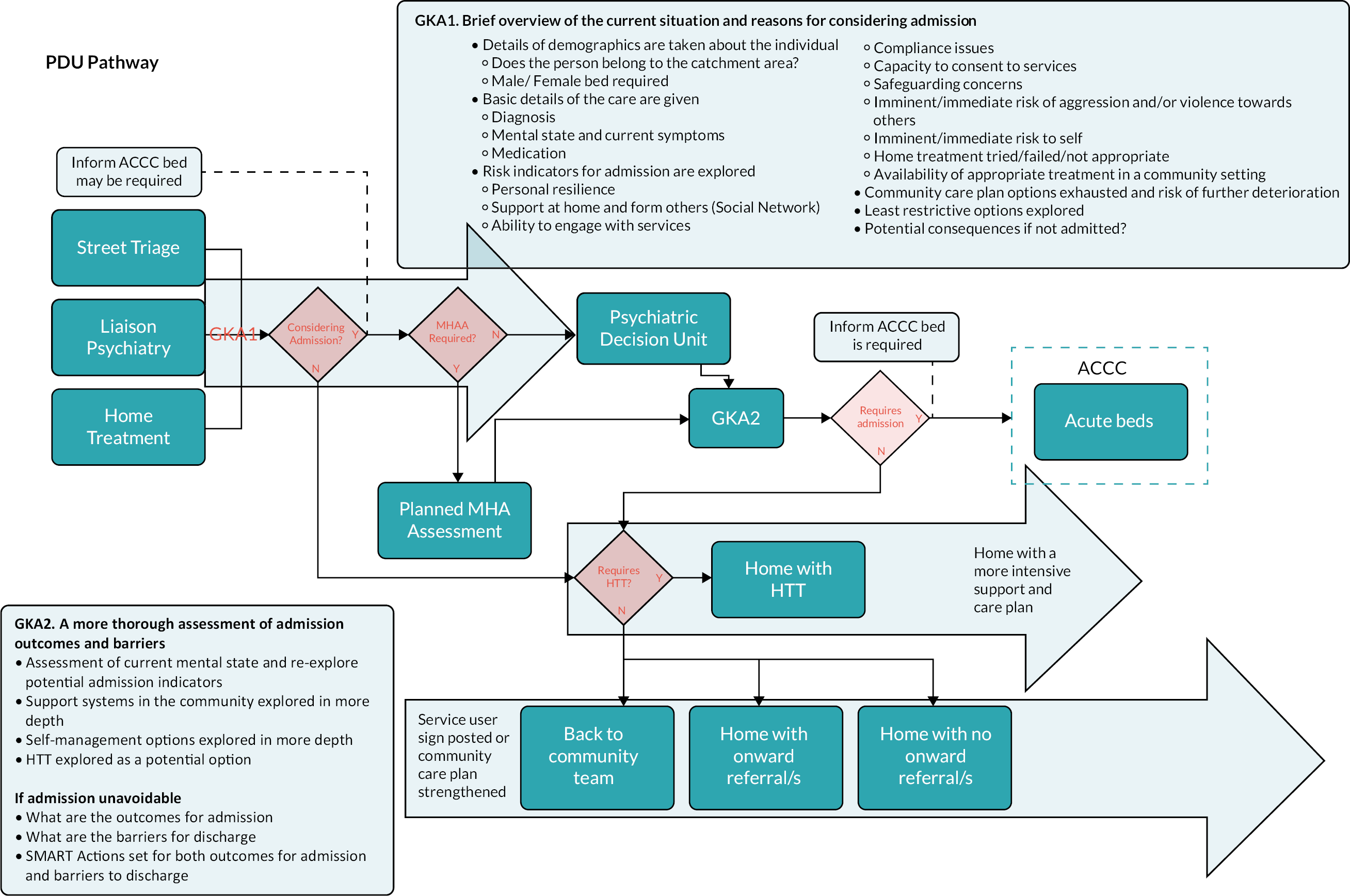

Efforts have been made to establish PDUs as an integrated part of the crisis care pathway. 43 PDUs accept referrals directly from liaison psychiatry teams based in ED, other mental health crisis services (e.g. CRHT and street triage teams), and sometimes community mental health services, primary care or third sector services – but do not generally accept self-referrals – with formal gatekeeping procedures in place. An example of the location of a PDU in the crisis care pathway in one of our sites can be seen in Figure 1, with the PDU playing a gatekeeping (assessment and referral) role for people identified by crisis services as having a higher level of need than might be met by intensive home treatment yet not in need of a Mental Health Act assessment, and from where a decision can be made about either subsequent inpatient admission or a return home with an appropriate support plan.

FIGURE 1.

Crisis care pathway map.

Aims and objectives

Although formal evaluations of recently developed PDUs in the USA and Australia have suggested that PDU-type units might reduce length of stay (LOS) in EDs and inpatient psychiatric admissions among people experiencing mental health crisis,37,40 evidence regarding the characteristics and effectiveness of PDUs in England is restricted to informal local evaluations. 44,45 While these reports suggest PDUs have potential to reduce demand on ED and psychiatric admissions, key data have not been reported (e.g. LOS in the ED) and study designs have not adequately accounted for variables that might confound comparison. In addition, PDUs in England have been developed organically, in response to policy and the pressure on services rather than the evidence base. There is a need for a clear description of the PDU model, including identification of key variables in unit configuration and function, and an understanding of how PDUs fit alongside other services in the crisis care pathway. It is possible PDUs introduce further fragmentation to the system, and, if not effective, may waste critical resources. As such, a formal evaluation of these services is urgently required to describe the model of care and generate much-needed knowledge about impacts, quality, and cost benefits.

The aim of the study is to ascertain the structure and activities of operational PDUs in England and to provide an evidence base for their effectiveness, costs and benefits, and optimal configuration. The study aim is addressed through the following research questions:

-

What is the range of hospital-based, short stay interventions internationally designed to reduce admissions to acute psychiatric inpatient care and what is their effectiveness?

-

What is the scope and prevalence of PDUs nationally and how are they configured?

-

How has the introduction of PDUs impacted on psychiatric inpatient admissions and ED psychiatric episodes/breaches?

-

What are the care pathways before and following an admission to the PDU?

-

What is the impact of the introduction of PDUs on inequalities of access to acute mental health services?

-

How do service users experience PDUs, as well as crisis care pathways before and after admission to PDU?

-

How are decisions made about referral and admission to PDU, and assessment and onward signposting and referral?

-

How do the economic costs and impacts of PDUs compare with areas without PDUs?

-

How do the costs for individual service users post PDU implementation compare with their costs prior to the introduction of PDUs to crisis care pathways?

Chapter 2 Methods

A mixed-methods approach

This is a mixed-methods study in six work packages (WP): WP1 – systematic review and service mapping; WP2 – interrupted time series (ITS) analysis; WP3 – synthetic control study; WP4 – cohort study; WP5 – qualitative interview study; WP6 – health economic analysis. A mixed-methods approach is taken to address the range of research objectives identified in Chapter 1, incorporating a number of different types and sources of data necessary to answer a broad set of research questions. 46 The underlining framework is a multilevel organisational research approach proposing that findings at an individual level cannot be assumed to apply at a higher (e.g. population) level or vice versa, because the ‘nested complexity of organisational life’ impacts on the phenomena we are trying to understand or measure. 47 Drawing on Goffman’s multilevel frame analysis,36 it is necessary to ‘frame’ our enquiry at macro, meso and micro levels ‘to understand the pace, direction and impact of organisational innovation and change’37 as well as the interconnection between levels. This involves specifying, at each level, the construct we wish to test, how we will measure that construct, what our sample or data source will be, and what analytical approaches we will use. Best available data are used from a range of sources at each level to produce utilisable knowledge,35 informing the further development and implementation of PDUs nationally. We conceptualise our levels of enquiry as:

-

Macro – national: how do policy, clinical guidance and other trends at a national level impact on the effectiveness and cost benefits of PDUs?

-

Meso – organisational: how does the configuration of crisis care pathways (including the provision of other crisis care services) and the structure of PDUs at site level impact on the effectiveness and cost benefits of PDUs?

-

Micro – individual: how do individual service user experiences of crisis care (including the PDU) and individual clinical staff decision-making processes along the pathway impact on the effectiveness and cost benefits of PDUs?

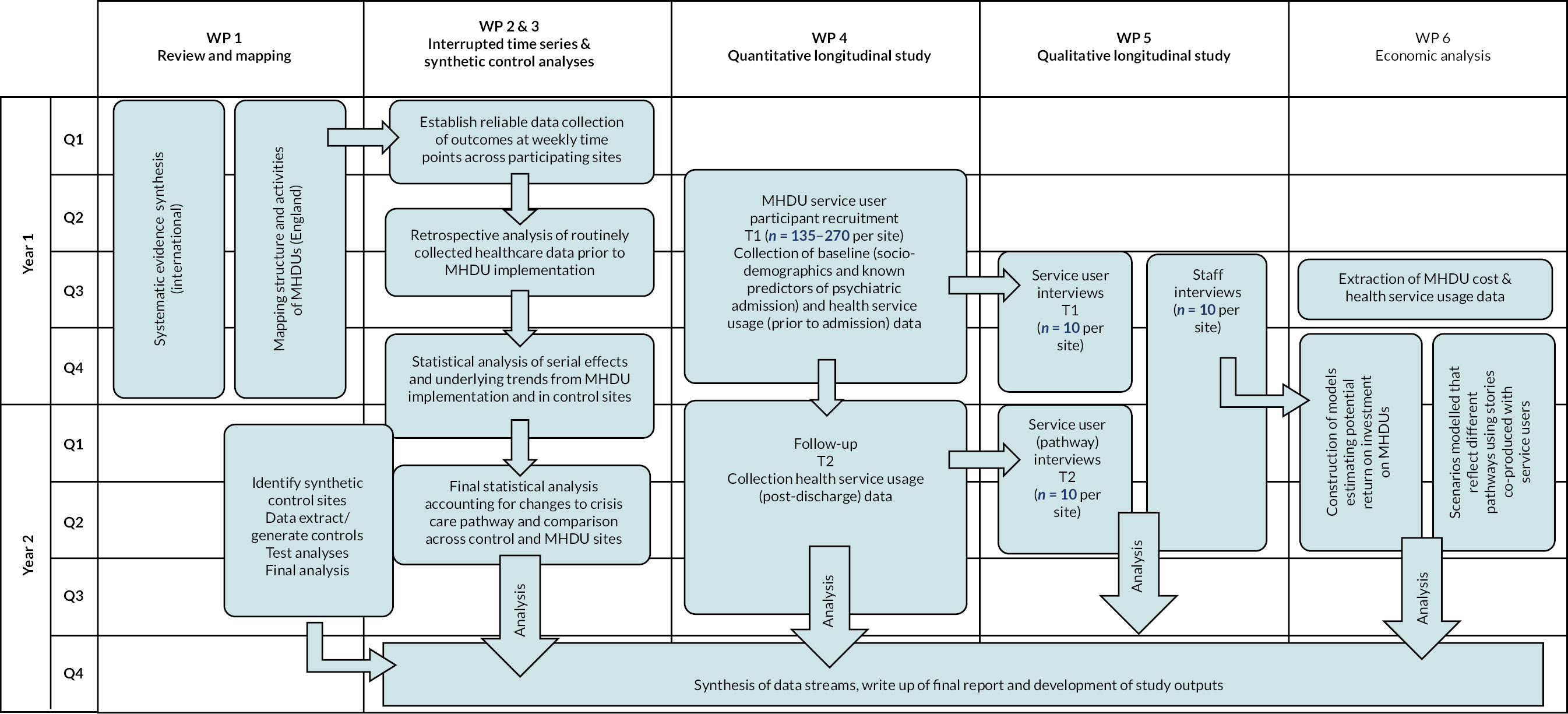

The specific way in which we frame research questions at each level and identify data sources and research methods for each of the six WPs is detailed in Table 1. Note that some questions (3 and 9) are broken down further with subquestions (a and b) and that on question, 3a is addressed in three different WPs (2–4), each using a different data set and, in some cases, covering different time periods. The challenges of this for data synthesis are addressed in Chapter 9. A diagram indicating how WPs are sequenced is given in Figure 2.

| WP | Question | Method | Level | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP 1 – review and mapping | 1) What is the range of hospital-based, short-stay interventions internationally designed to reduce standard admissions to acute psychiatric inpatient care and what is their effectiveness? | Systematic review | Macro | Peer-reviewed literature |

| 2) What is the scope and prevalence of PDUs nationally and how are they configured? | Service mapping | Macro | Telephone interviews, MHT strategic leads | |

| WP 2 – ITS | 3a) How has the introduction of PDUs impacted on psychiatric inpatient admissions and ED psychiatric episodes/breaches? | ITS analysis; qualitative interview study | Meso | Routinely collected, aggregate data from MHTs and EDs at hospital NHS trusts |

| 3b) What is the impact of policy changes at local and national level? | ||||

| Macro | Semistructured interviews with MHT and ED strategic leads and commissioners | |||

| WP 3 – SC study | 3a) How has the introduction of PDUs impacted on psychiatric inpatient admissions and ED psychiatric episodes/breaches? | Synthetic control study | Macro | Comparison of NHS Digital data between study sites and comparator sites |

| WP 4 – cohort study | 3a) How has the introduction of PDUs impacted on psychiatric inpatient admissions and ED psychiatric episodes/breaches? 4) What are the care pathways before and following an admission to the PDU? 5) What is the impact of the introduction of PDUs on inequalities of access to acute mental health services? |

Cohort study | Meso | Routinely collected, individual data of mental health and ED service use (new admissions to PDU) Participant characteristics (sociodemographic, psychiatric history etc.) |

| WP 5 – qualitative study | 6) How do service users experience PDUs, as well as crisis care pathways before and after admission to PDU? | Qualitative interview study | Micro | Semistructured interviews with service users admitted to PDU |

| 7) How are decisions made about referral and admission to PDU, and assessment and onward signposting and referral? | Semistructured interviews with ED, MHT crisis services and PDU staff | |||

| WP 6 – economic analysis | 8) How do the economic costs and impacts of PDUs compare with areas without PDUs? 9a) How do the costs for individual service users post PDU implementation compare with their costs prior to the introduction of PDUs to crisis care pathways, as well as in areas without PDUs? |

ITS; synthetic control study; cohort study | Meso and macro | Economic analysis of aggregate and individual-level MHT and ED service use data Appropriate unit cost data attached to services Liaison with PDU service providers and use of administrative data to determine resources used to deliver PDU services |

| 9b) What are the potential cost impacts of: i) alternative configuration of PDU pathways or access by specific populations, and ii) roll out and scale up of PDUs nationally? | All | Macro | As above, plus qualitative pathway stories, referral source and participant characteristics data |

FIGURE 2.

Sequencing of work programmes.

Patient and public involvement in the project

A co-production approach to research has underpinned this project. The team leading the research has a strong track record in methodological development, support and evaluation of coproduction throughout a research project. In previous National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded research we developed a set of characteristics of co-produced research:

-

High-value research decision-making roles distributed across the research team (including team members with lived experience of using mental health services and/or mental distress, as well as clinical and university researchers).

-

Different interpretations of data within the research team owned and understood in terms of who offered the interpretation.

-

Consideration given to whether all members of the team are involved in the production of knowledge and the impact of this on the knowledge produced.

-

Methodological flexibility in the research process (where the scientific conventions of how research is usually might constrain the input of team members with lived experience).

-

Rigorous and critical reflection on how the research was done and the impact of this on findings.

-

Research outputs that report critically on how knowledge was produced. 48

Lived experience in the research team in this project comprised:

-

co-investigator (KT): a qualitative researcher with many years’ experience of working from a lived experience perspective in mental health research

-

three researchers explicitly employed to work from a lived-experience perspective (KA, LG, JL)

-

Peer Expertise in Education and Research (PEER) group (a lived-experience research reference group at the lead site)

-

Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP): a group of eight people recruited nationally with lived experience of mental health distress, crisis and attending a PDU and or experience as an informal carer of someone with those experiences

-

lived-experience representation on the project steering group.

We used lived experience in developing the project as follows:

-

Two workshops with the PEER group discussing the study as a whole and the importance of employing a non-randomised study design in the context of crisis care, the ethics of use of routinely collected patient data in the cohort study, and identifying specific questions to be explored in qualitative interviews.

-

Co-investigator KT contributed to developing the proposal from a lived-experience perspective, playing a key role in developing the co-produced approach to interpreting qualitative data sets,48 extended here to our data synthesis approach.

Using lived-experience during the research:

-

A third workshop was held with the PEER group to support the application for NHS ethical approval for the study, including development of participant information sheets and informed consent procedures.

-

The two researchers working from lived experience focused on development and delivery of WP5 data collection, analysis and write-up, as well as shaping and carrying out the WP1 mapping exercise and systematic review.

-

The LEAP was facilitated by the two researchers working from lived experience with co-investigator KT’s support; the group met eight times during the study. The LEAP provided input into conduct of the study as it progressed, with input into material and application for ethical approval and the development of qualitative interview schedules.

-

The LEAP also played an active role in the analysis of qualitative research data with members involved in the preliminary coding of interview data and in interpretive workshops.

-

A second interpretive workshop involving the LEAP was held to ensure that lived experience informed the synthesis process bringing together data from all WPs to develop our final report.

-

A final session of the LEAP was held to plan and design an applied output for the study (not reported here) aimed at helping people in crisis better negotiate the crisis care pathway.

-

The lived-experience researchers on the team provided training to LEAP members as necessary, including around data analysis processes.

-

Co-investigator KT oversaw patient and public involvement on the project and provided support to the lived experience researchers on the team, including facilitating a regular lived experience reflective space.

-

There was lived experience on the study’s independent steering committee, brought by two committee members with who had made use of mental health crisis care, one of whom had also worked on a PDU in a support worker capacity.

We reflect on the impacts of patient and public involvement and our approach to coproduction in the study in the section on the Impact of patient and public involvement on the research.

Setting

With the exception of WP1, the study took place in four sites; sites were MHTs that had an operational PDU and the EDs at NHS hospitals in the same locality as the MHT that referred to the PDU. Key characteristics of study sites, including configuration of the PDU and other crisis care services available locally, are given in Table 2. Any changes in PDU or other crisis care provision during the time frame of the research, including those resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, are indicated in parentheses.

| PDU | Referring ED(s) | Geography | Date opened | Location | Maximum LOS (hours) | Capacity (n) | Referral route | Staffing | Staff : patient ratioa | Other crisis services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lotus Assessment Suite, SWLSTG MHT | SWLSTG; KHFT | Urban | November 2016 | Psychiatric hospital | 48 | 5 (increased to 7 during COVID-19 pandemic) | ED, CRHT, street triage | Mental health nurse, HCA, psychiatrist | 1 : 1 | Crisis house, crisis rather (x 2), (mental health ED opened during COVID-19) |

| Decision Unit, STHFT | STHFT | Urban | March 2019 | Psychiatric unit on a general hospital site | 48 (decreased to 24 during COVID-19 pandemic) | 5 | ED, CRHT, street triage, CMHT | Mental health nurse, support worker, psychiatrist | 4 : 5 | Crisis house |

| Psychiatric Clinical Decisions Unit, LPFT | ULHFT | Rural | January 2018 | Psychiatric hospital | 24 | 6 | ED, CRHT, street triage (16 months after PDU opens), AMHPs | Mental health nurse, HCA, psychiatrist (plus CMHT during COVID-19) | 1 : 2 | Triage ward, crisis house |

| PDU – BSMHFT MHTs | SWBHFT; UHBFT | Urban | November 2014 | Psychiatric hospital | Target 24 (72 maximum, reducing to 12 from 2019) | 8 (decreased to 5 during COVID-19 pandemic) | ED, CRHT, street triage | Mental health nurse, HCA, psychiatrist | 1 : 4 | Triage ward (16 months only), acute day unit, crisis café, crisis house (post-WPs 2 & 3) |

Service mapping

Design

We conducted a survey of PDUs in England, establishing their prevalence, structure and how they complement other NHS crisis care locally. A PDU was defined as a specific location where individuals in mental health crisis and using emergency care may be assessed and treatment plans formulated. The specific location should be distinct from the ED and psychiatric wards. We used a formal freedom of information (FOI) request to reduce nonresponses, as government organisations are legally compelled to answer under UK legislation. 49

Participants

NHS FOI and mental health service staff were the participants. Respondent role was noted.

Measures

An iterative cycle of questionnaire development, considering information about PDUs in study sites, was undertaken to establish how to define PDUs for the survey. A 29-item questionnaire was developed to determine whether mental health NHS trusts had a PDU and the operational structure of PDUs (e.g. capacity, maximum LOS, referral sources, staffing). We also asked about existence of alternative assessment provision (e.g. triage ward) and other crisis care (e.g. street triage team). Short open questions inquired about the purpose of the PDU.

Procedures

We used a publicly available list of mental health NHS trusts’ FOI e-mail addresses49 to send the survey for completion using LimeSurvey (LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), a secure web survey system; trusts were given the option to complete the survey on paper. Reminders were sent if trusts failed to acknowledge the FOI request within 7 days or respond to the survey within 20 working days. For precision, data were checked against responses from a recent survey of crisis care50 and incomplete or contradictory responses checked using information on trust websites or direct contact by e-mail or telephone. Follow-up questions were asked about PDUs identified in the survey as planned or closed to determine the reasons for launching or discontinuation. The survey ran between September and December 2019.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present quantitative data. Qualitative data were analysed using narrative synthesis.

Systematic review

Search strategy

We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception until 01 March 2021. Reference list and forwards citation checking of included studies was used to identify additional sources.

Eligibility

Inclusion

-

Studies of adults (over 18 years) experiencing a mental health or behavioural crisis.

-

Any mental health assessment intervention that: (1) is hospital-based; (2) permits overnight stay; (3) specifies a maximum LOS < 1 week; (4) has as its primary aim assessment and/or stabilisation, with the purposes of reducing the need or LOS of standard acute care admission, and/or reducing presentation or length of waiting time at an ED.

-

Measurement of standard acute admissions to psychiatric inpatient care (including number, type and duration of admission), and/or mental health presentations at EDs (including number of presentations and length of wait in ED) and other related outcomes.

Exclusion

-

Children; non-human subjects; all individuals detained under Mental Health Act section (or equivalent in country of study); all individuals who are forensic patients.

-

Community (i.e. no overnight stay is possible) or non-hospital, residential-based assessment or crisis units.

-

No measure of psychiatric inpatient service use or ED attendance.

Eligible study designs

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or studies incorporating a control or comparison group (e.g. a control group for between group comparisons or a pre-intervention period for a within-group study) including single-, double- or triple-blinded trials, ITS, quasi-experimental, observational, before-and-after or retrospective studies. We excluded studies with no comparison group or that were entirely qualitative.

Selection of studies

Electronic database search results were uploaded to CADIMA (Julius Kühn-Institut Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants, Quedlinburg, Germany)51 and duplicates removed using the CADIMA de-duplication process. To identify papers that potentially met eligibility criteria, 20% of abstracts and titles of retrieved studies were screened independently by two researchers (KA, JL). Inter-rater reliability (IRR) scores were recorded and exceeded the target of a moderate level of IRR (0.41). The remaining study titles and abstracts were screened singly by the two researchers.

Full texts of all papers included at the screening stage were reviewed by two researchers (KA, JL) to confirm eligibility. Disagreements, or where both researchers were uncertain of eligibility, were resolved through discussion with a third researcher (SG).

Data extraction

A standardised, pre-piloted form in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to extract data from included studies for quality assessment and evidence synthesis. Key information for extraction included:

-

characteristics of included study (e.g. study design; number and type of groups)

-

participants (e.g. country, eligibility criteria, recruitment method, number of participants in each group, demographics)

-

intervention groups (maximum LOS, purpose of unit, admission criteria, referral pathway and staffing, theoretical basis for the intervention, resource requirements etc.)

-

comparison groups (description, resource requirements, co-interventions)

-

all outcomes with a comparison group and associated statistics

-

data for risk of bias, assessed as described below.

Two researchers (KA and JL) independently extracted data on items 1–4 above from included studies, and two researchers (KA and LG) on items 5 and 6. Data extraction was cross-checked, with discrepancies resolved through discussion with the wider team.

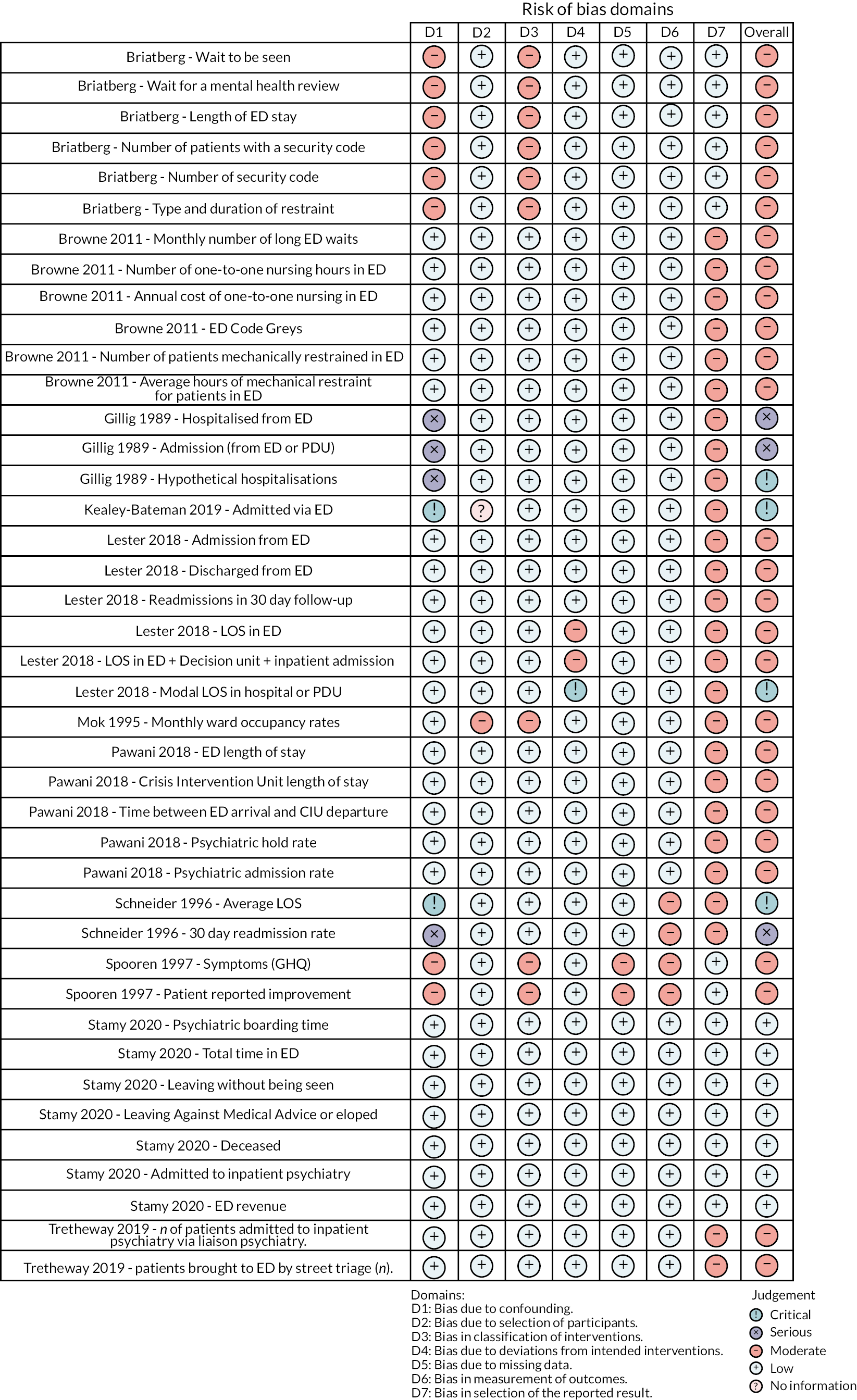

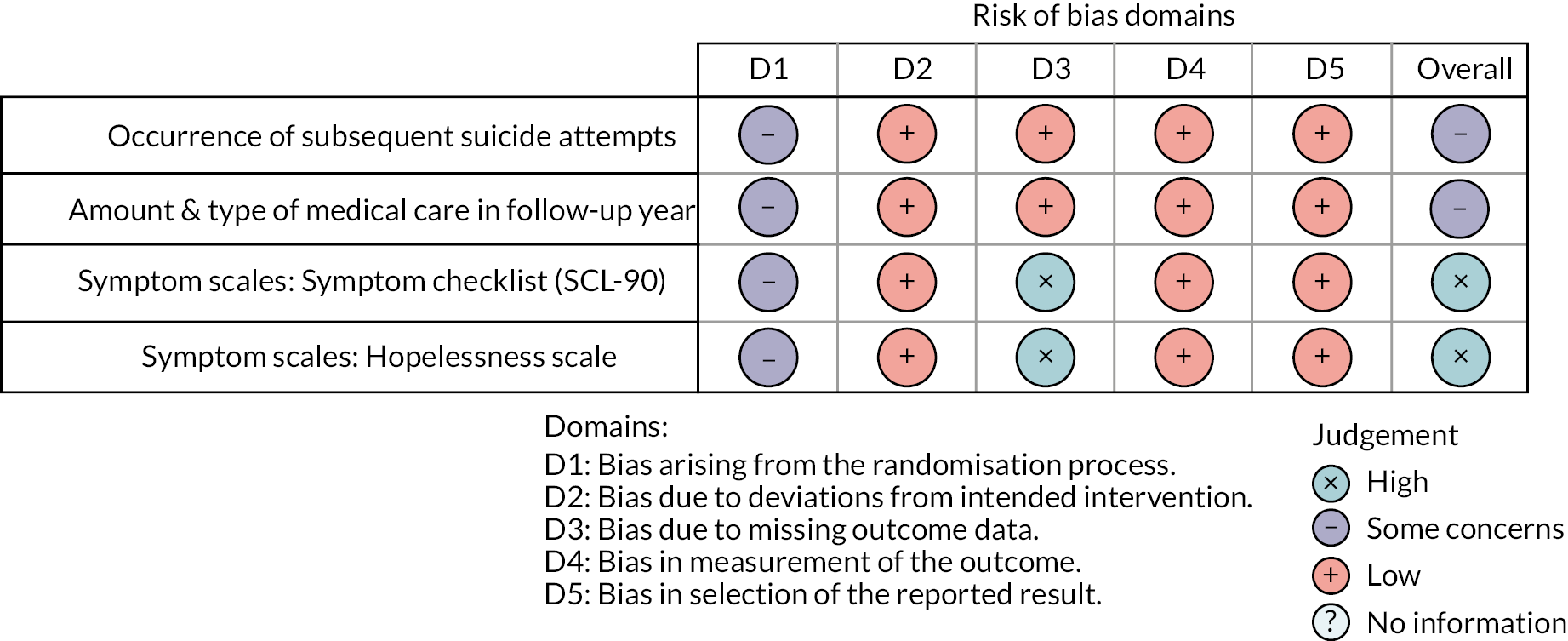

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

For RCTs, the Cochrane Collaboration’s revised risk of bias tool RoB 2 was used. 52 This is a widely used tool to assess bias using a judgement (high, some or low concern) in five domains (randomisation process, deviation from intervention protocol, missing outcome data, measurement of outcome and selection in the reporting of outcomes), as well as overall. For nonrandomised studies, the Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool53 was used. This tool is structured in seven sequential domains (pre intervention, at intervention and post intervention) and the assessment of domain-level and overall risk of bias judgement classified as low, moderate, serious or critical risk of bias. Risk of bias plots were created for all outcomes using the robvis application. 54

Quality was assessed independently by two researchers (KA and LG), with discrepancies resolved through discussion and taken to a third researcher (SG) if unresolved. Studies assessed as being at high risk of bias were included in primary analyses but removed from a secondary, sensitivity analysis (see below). Each meta-analysis was rated for the certainty of the evidence using Cochrane’s Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework. 55 The certainty of the evidence was discussed for all reported outcomes.

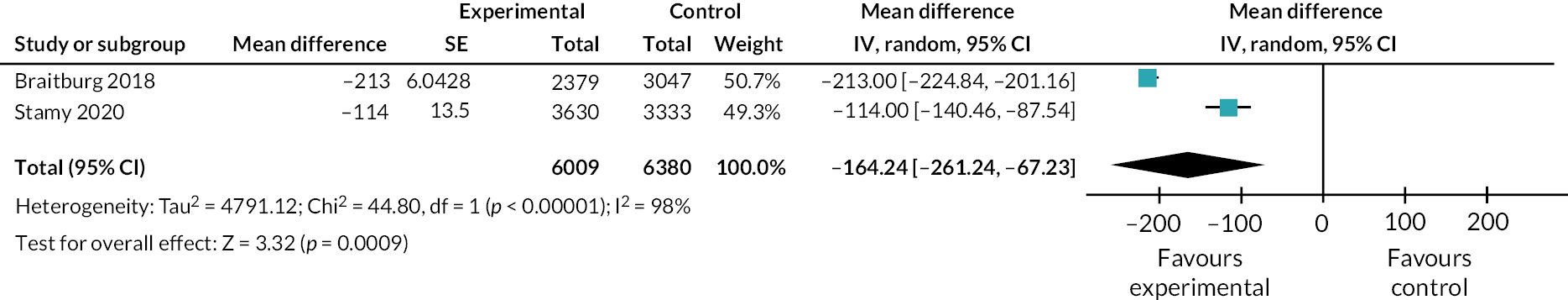

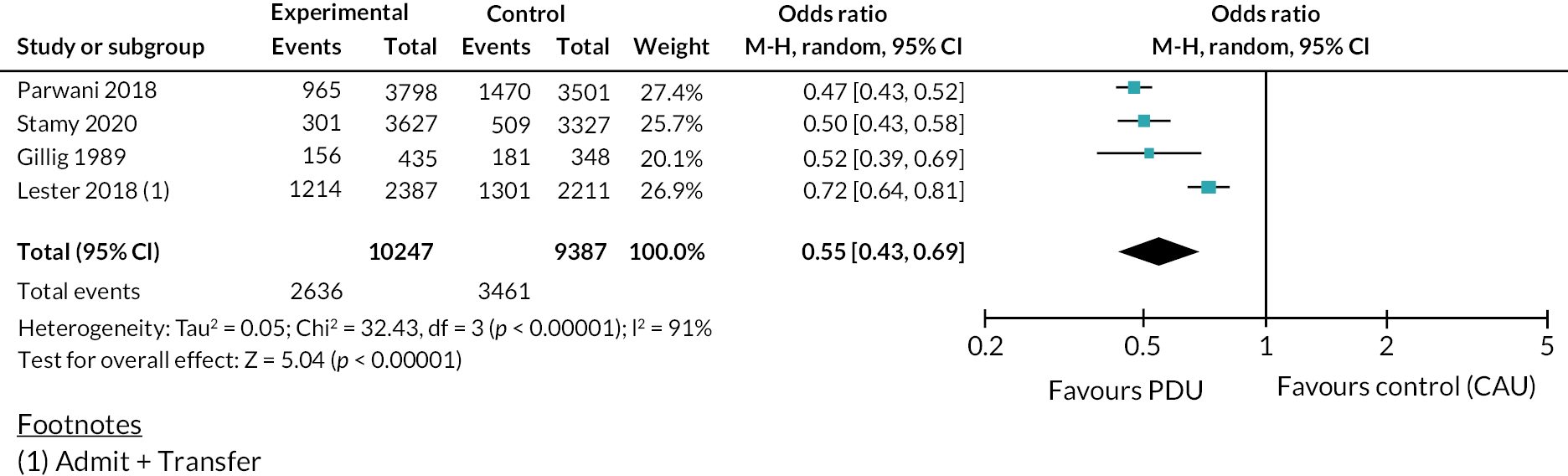

Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis of all included studies was undertaken, including a brief narrative description of risk of bias. Where sufficient studies reporting an outcome of interest were identified for statistical pooling, meta-analyses were performed. We considered standard acute admissions to psychiatric inpatient care (including number, type – formal or informal – and duration of admission), mental health presentations at EDs (including number of presentations and length of wait) and other related outcomes.

For the meta-analyses, we computed relative risk to estimate the effect of interventions on categorical outcomes where events were rare, and random-effects odds ratios (ORs)56 with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for events that were relatively common (e.g. inpatient admissions) to make the association clearer. We calculated Hedges’ g (an unbiased estimate of the standardised mean difference) for estimates of effect on continuous outcomes (where different ways of measuring the outcome were used). Where the same way of measuring the outcome was used (e.g. minutes), we used a mean difference model. We employed random-effects estimation (which provides estimates of intervention effects assuming heterogeneity) and 95% CIs to calculate the overall effect for interventions.

Analyses were performed using an intention-to-treat approach, with adjustments made for the effect of clustering in relevant trials. 57 Between-study variation in effect sizes was assessed using the I² statistic, a measure that describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, with the power to detect heterogeneity even when the number of studies is small. 58

We planned to assess publication bias qualitatively using funnel plots and then statistically, according to study design, by the Egger test, with Harbord modification in the case of categorical outcomes,59 where there were sufficient number of studies for these tests to be meaningful. Subgroup analyses, for example of specific sociodemographic groups, would be carried out, data permitting.

Interrupted times series

Study design

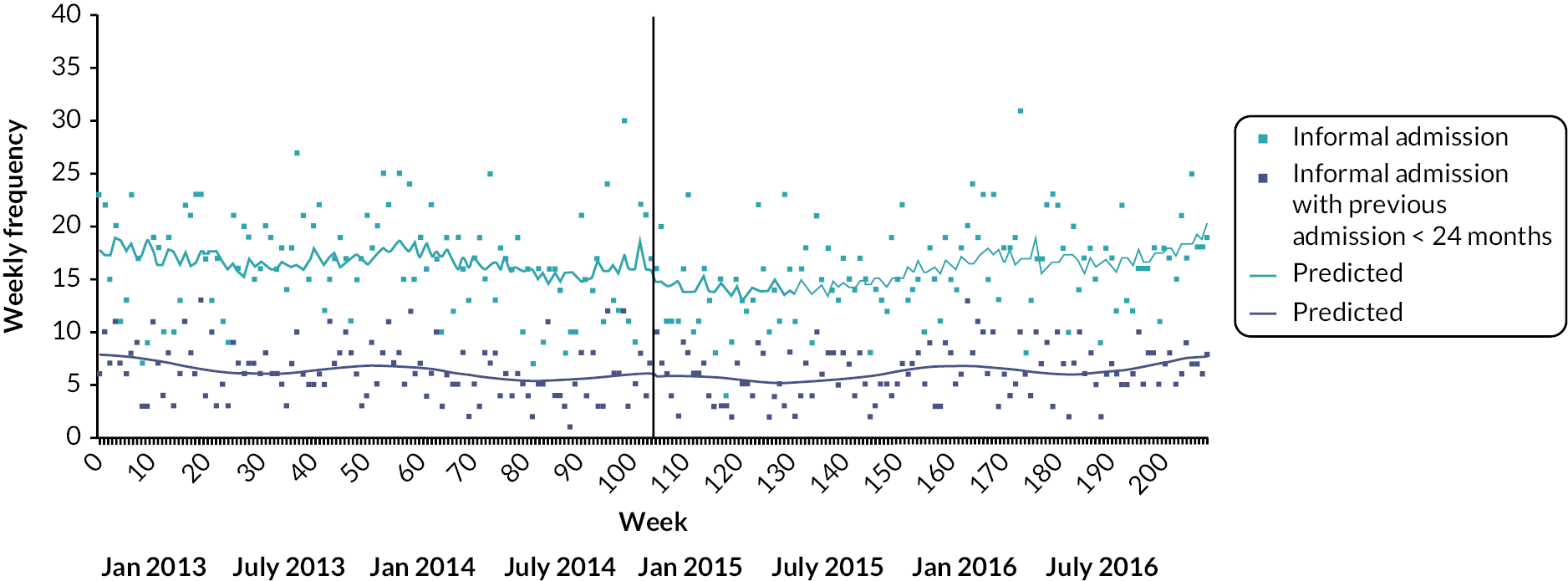

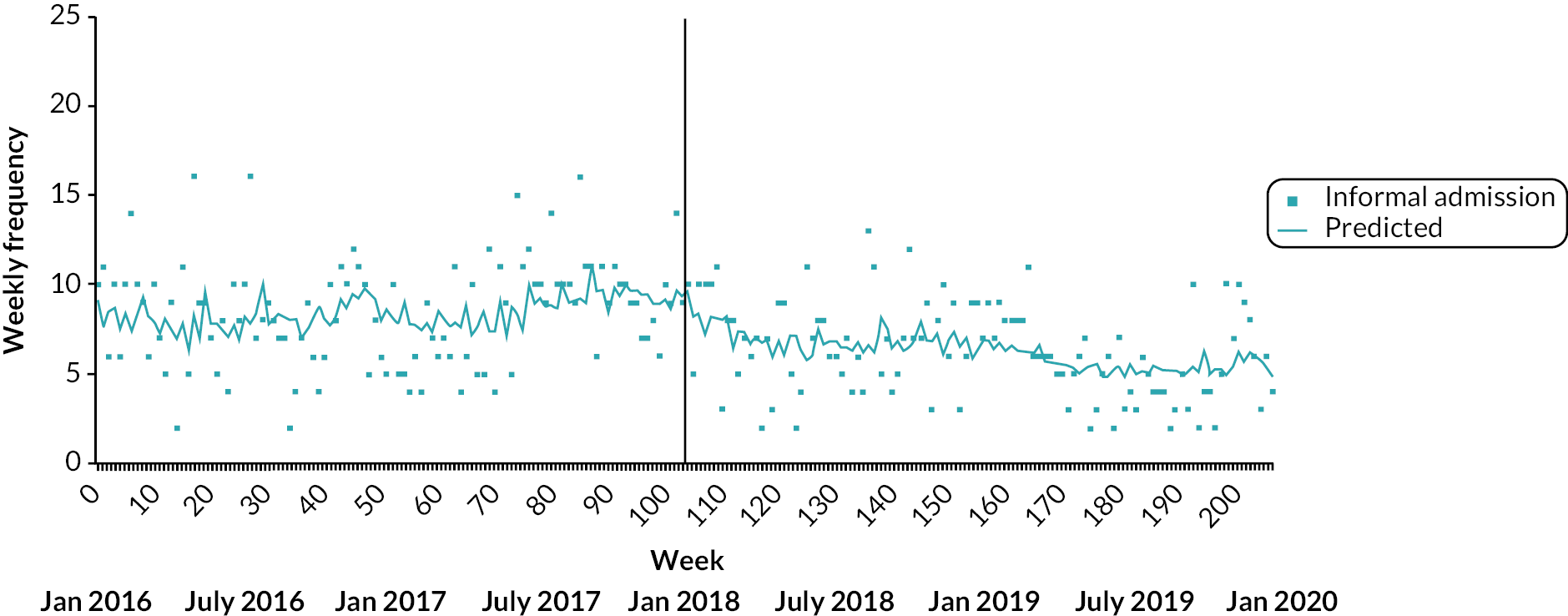

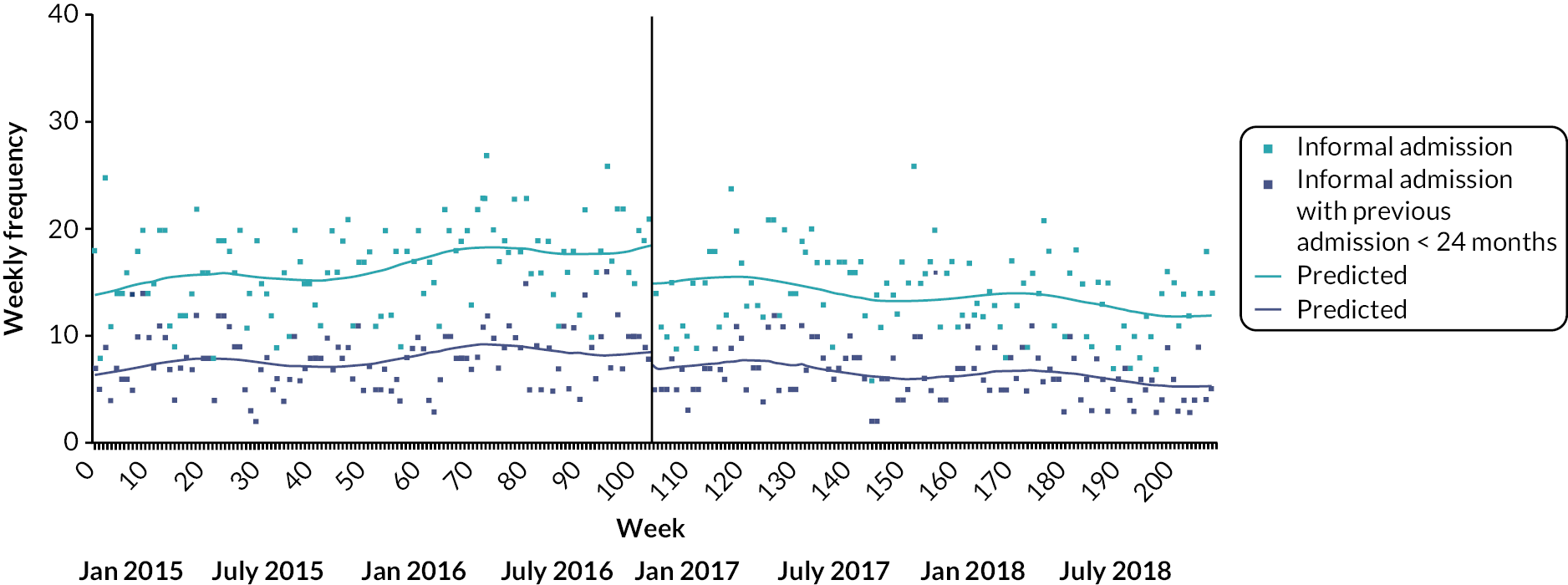

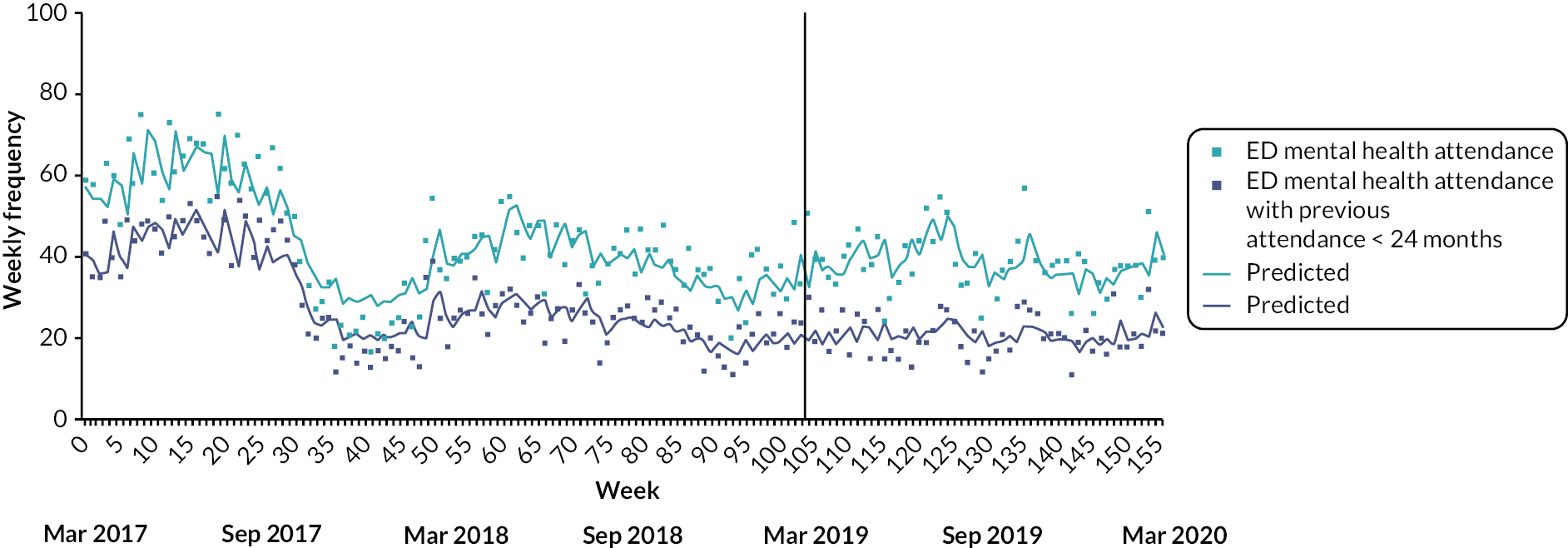

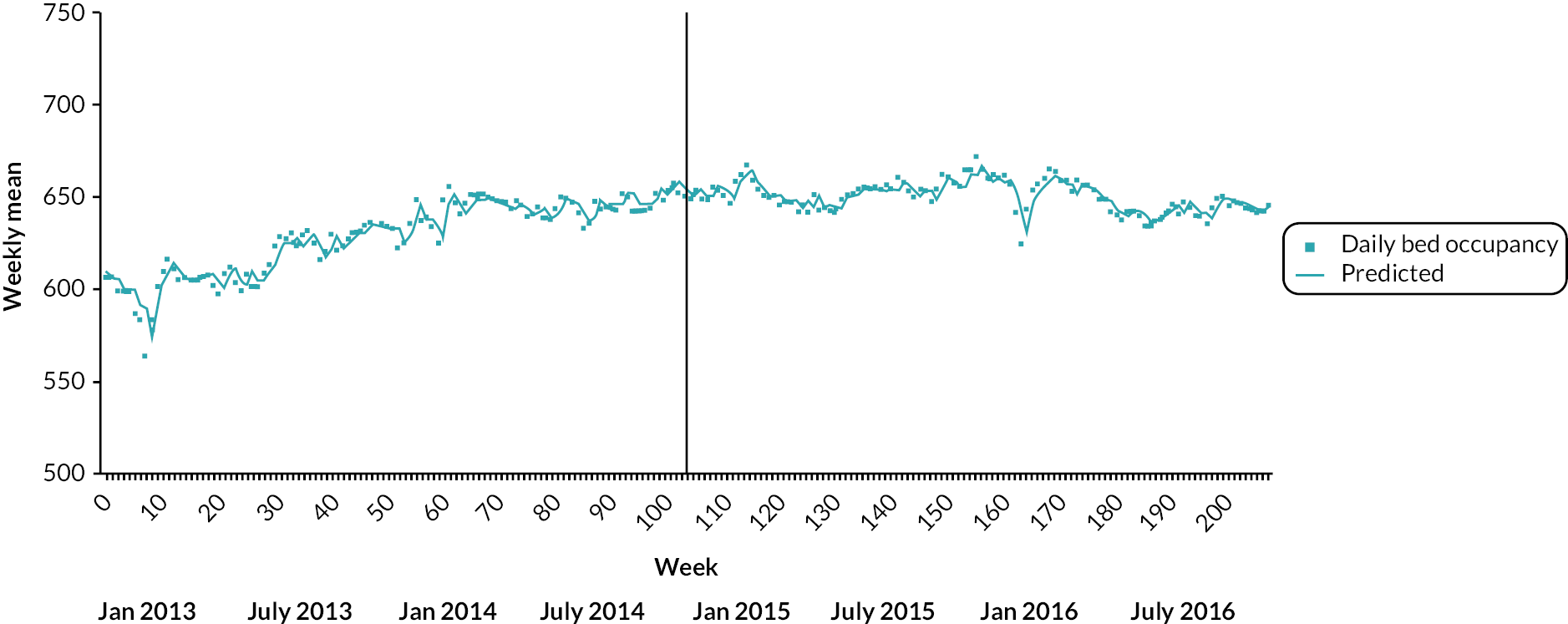

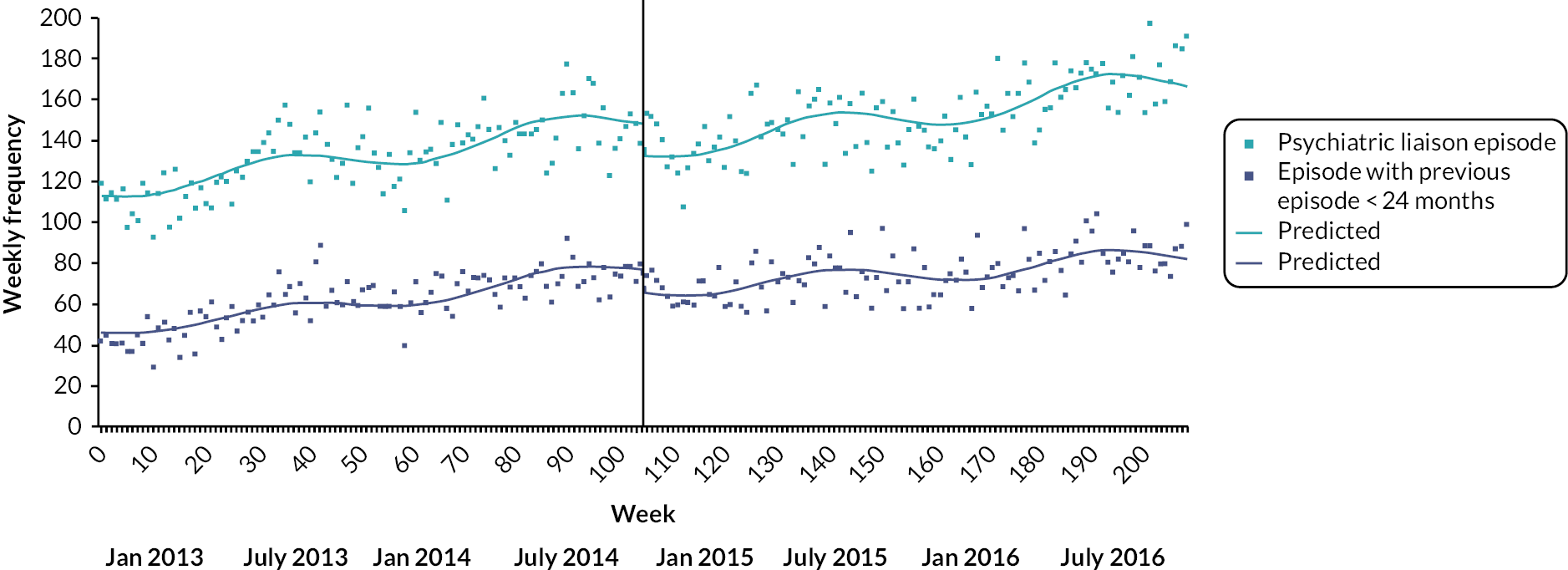

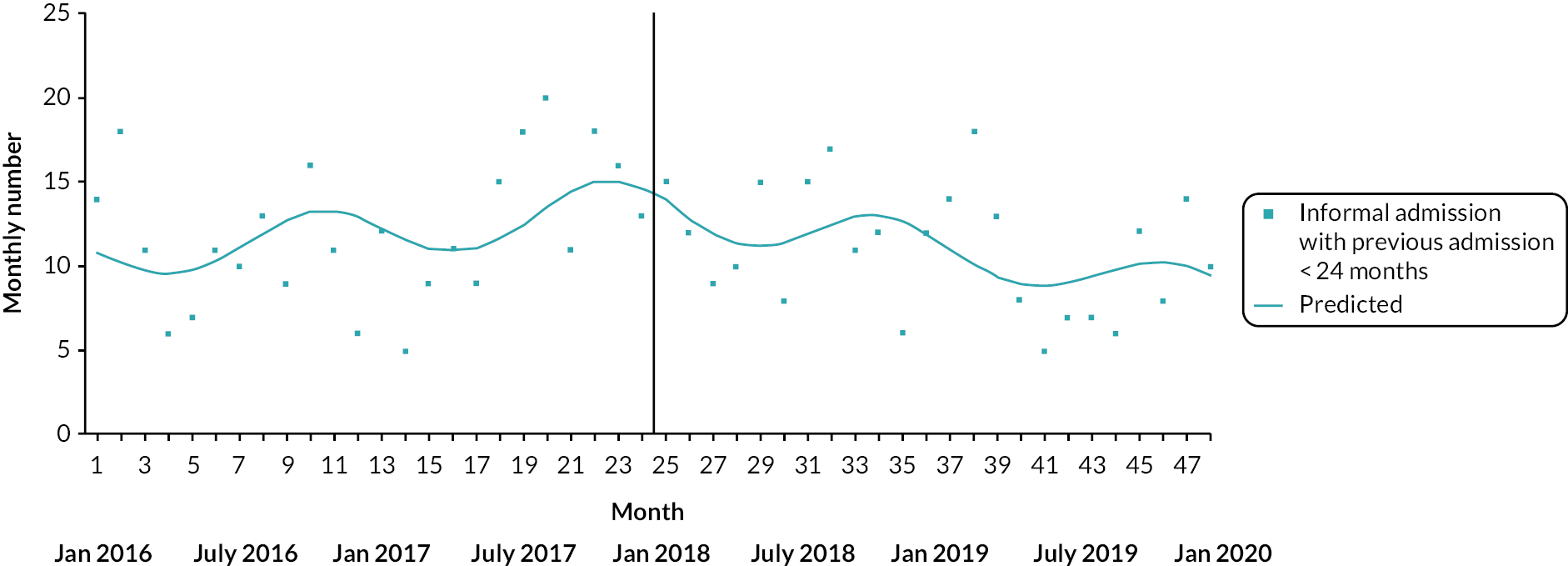

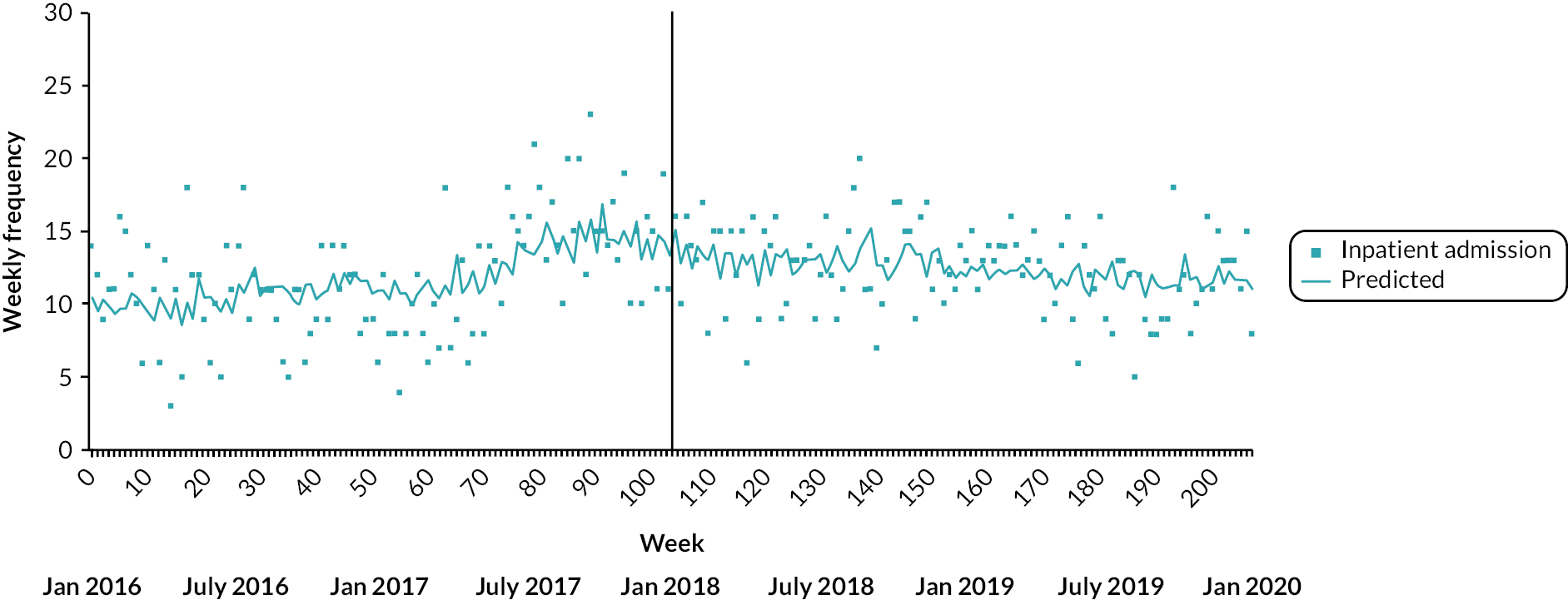

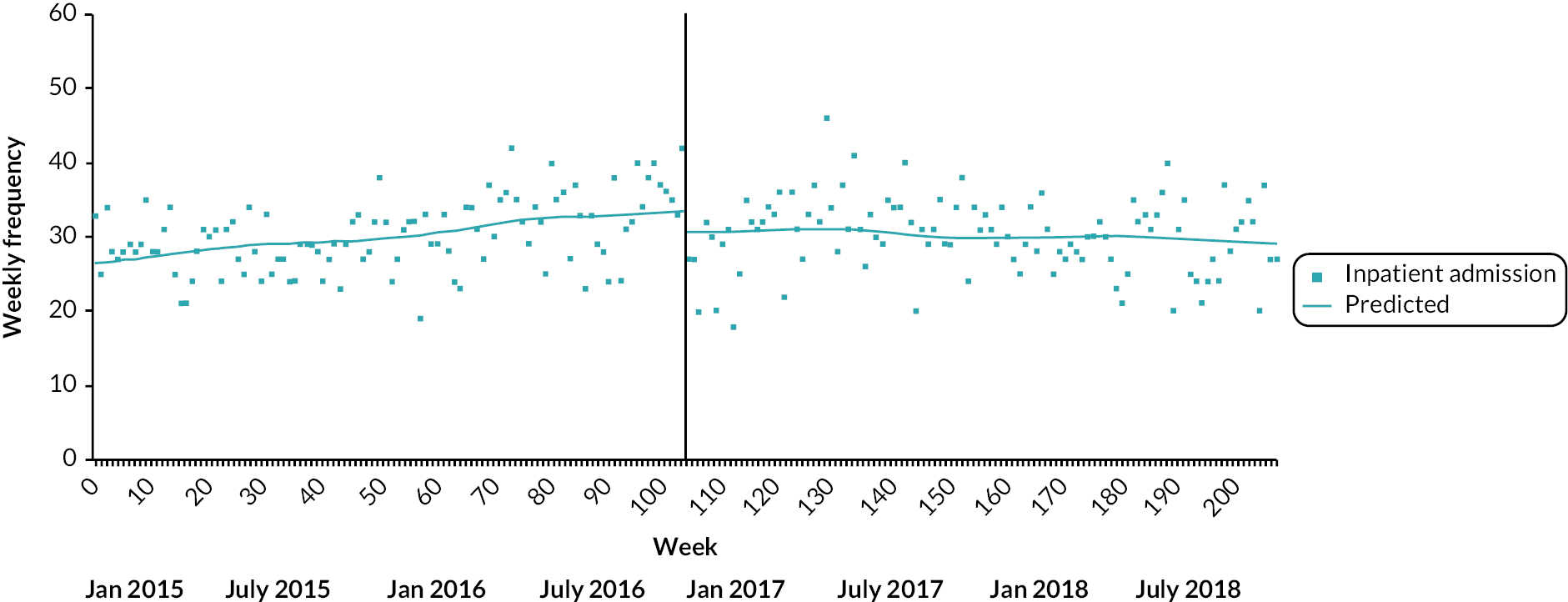

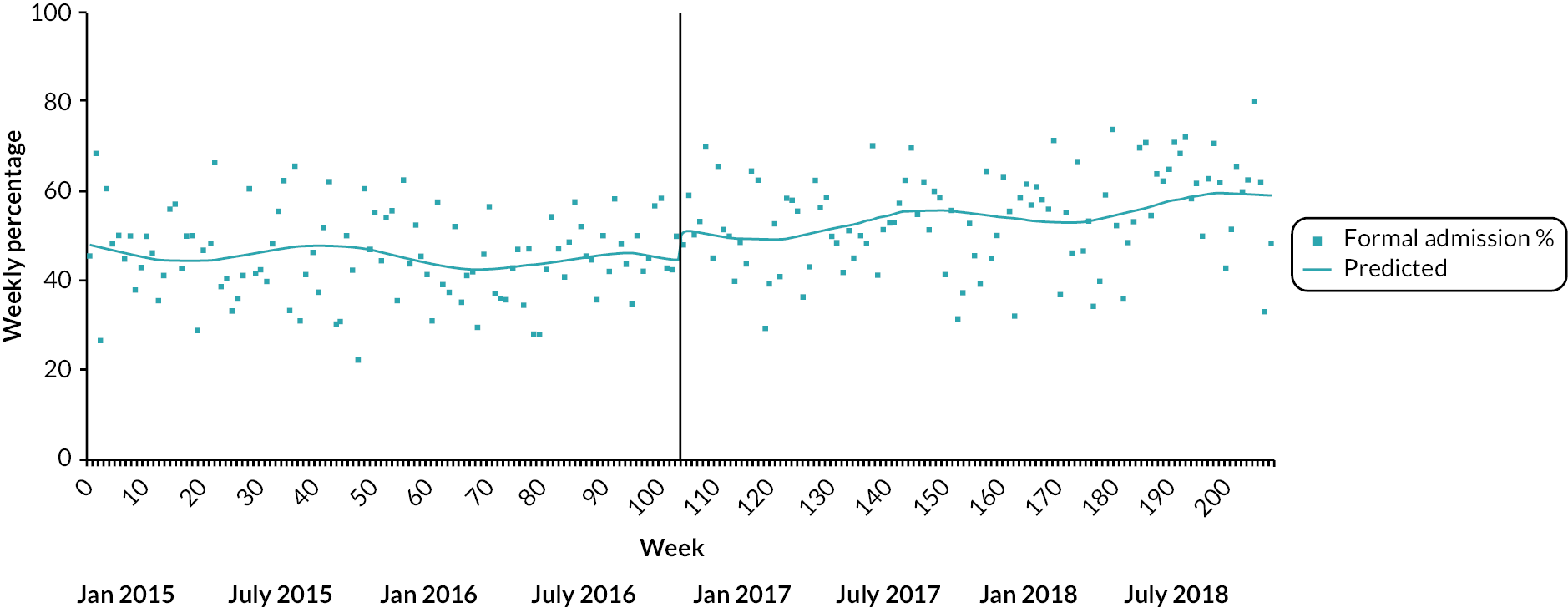

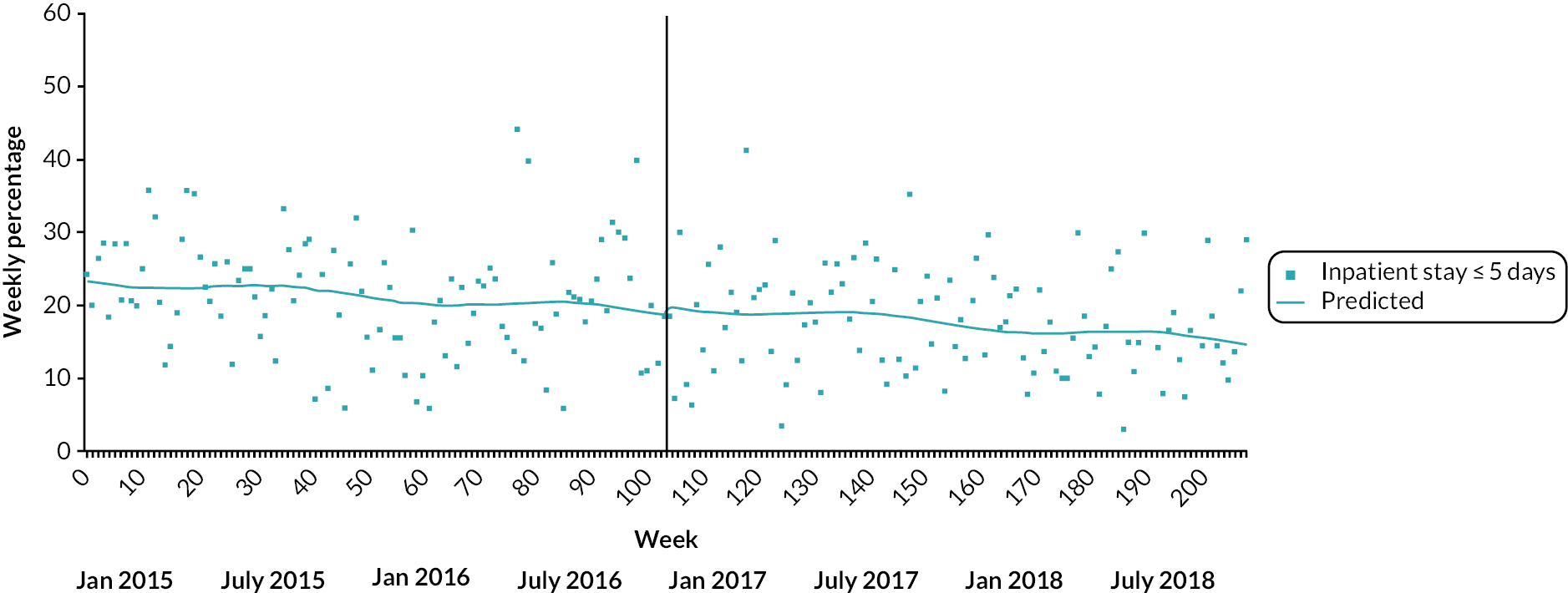

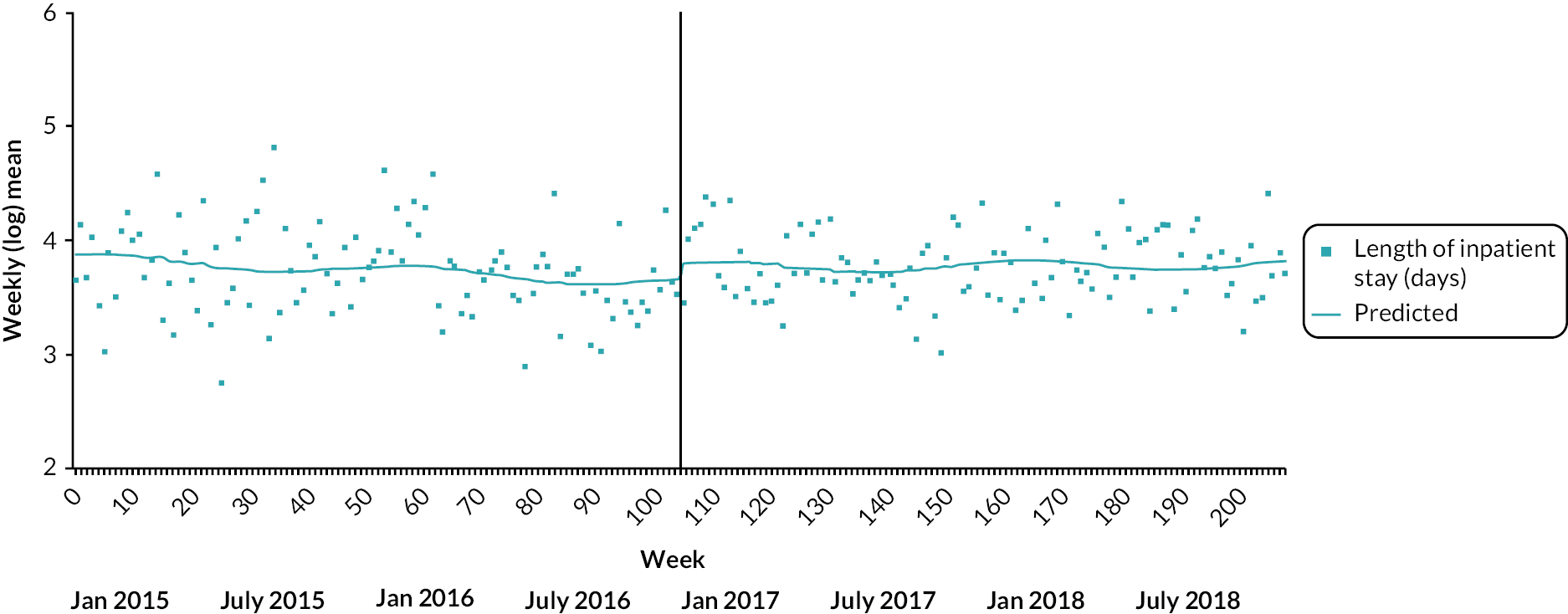

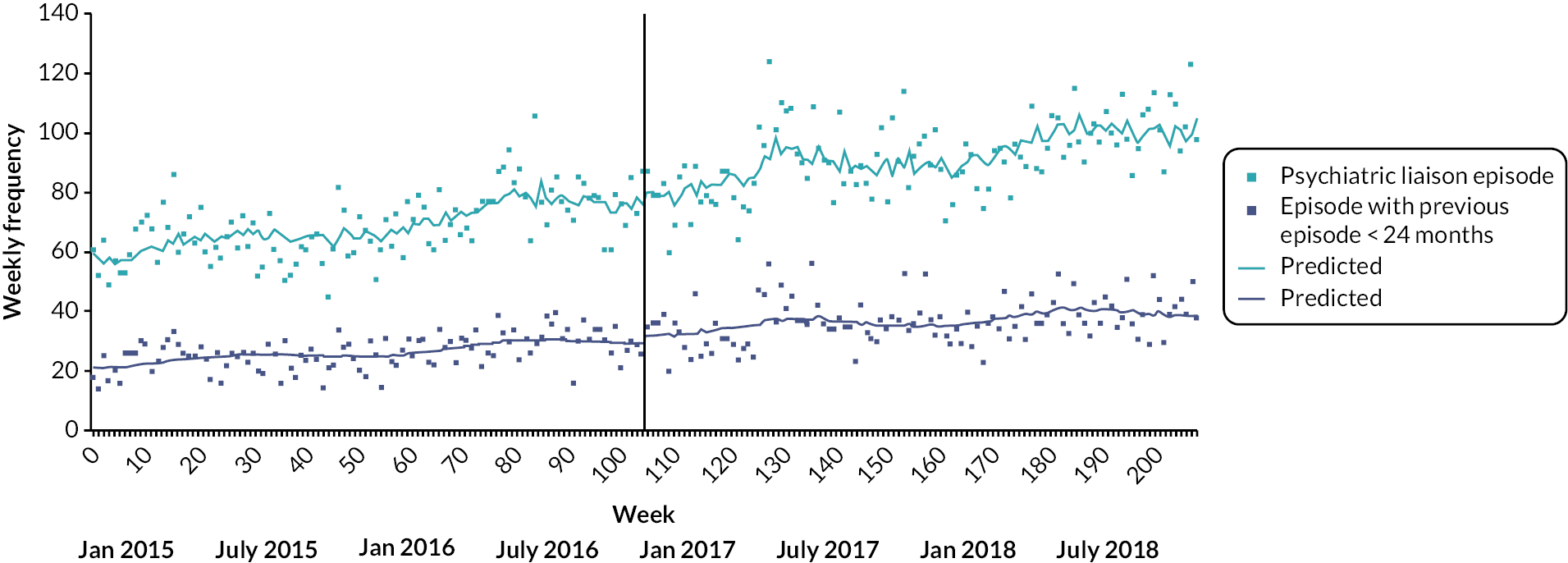

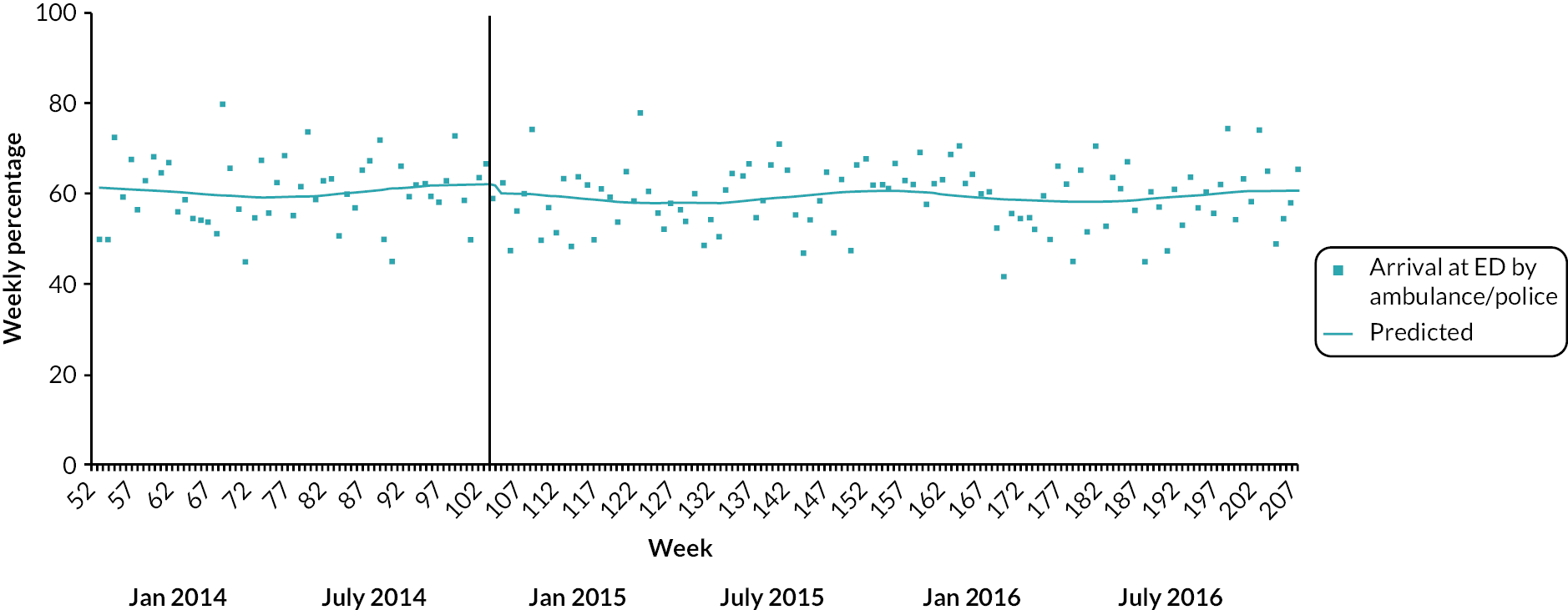

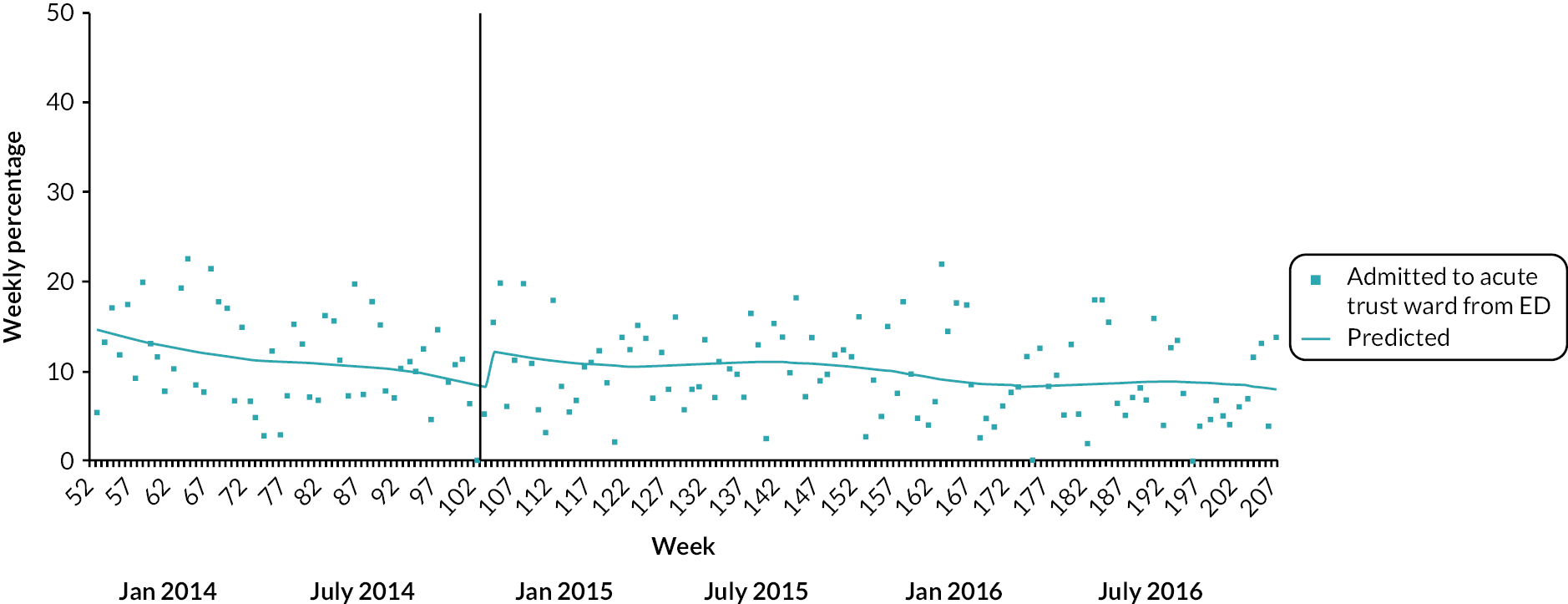

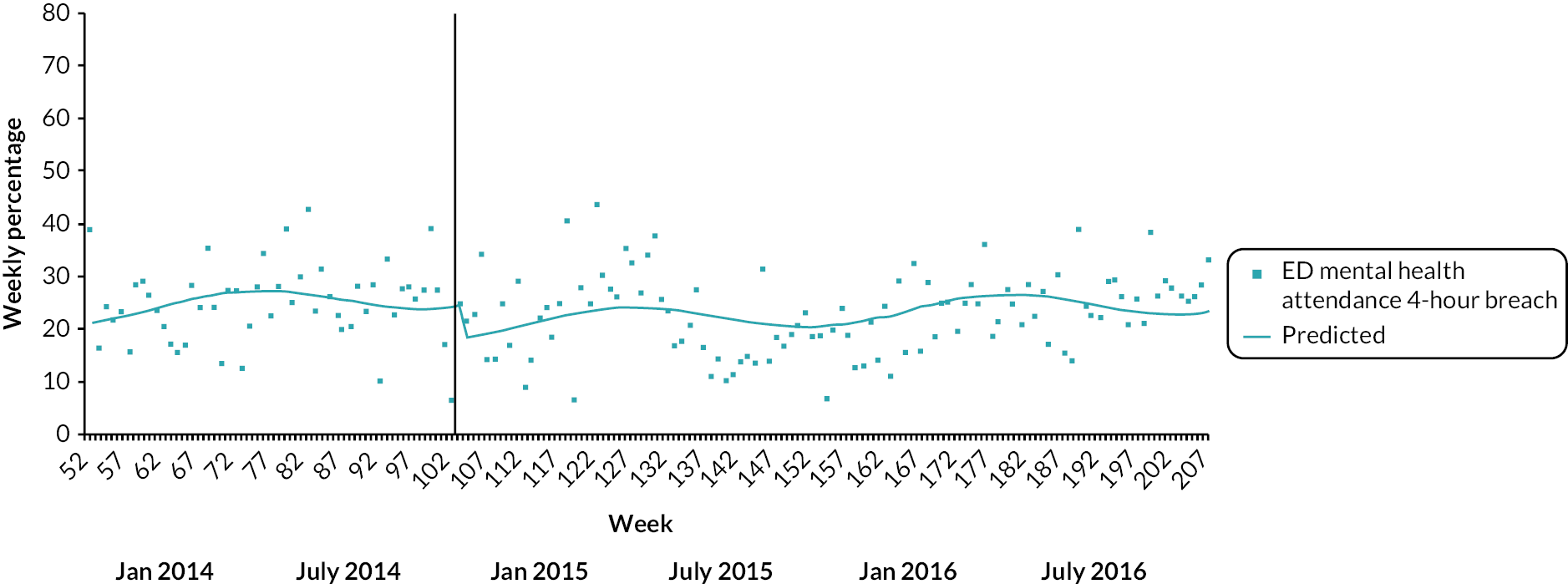

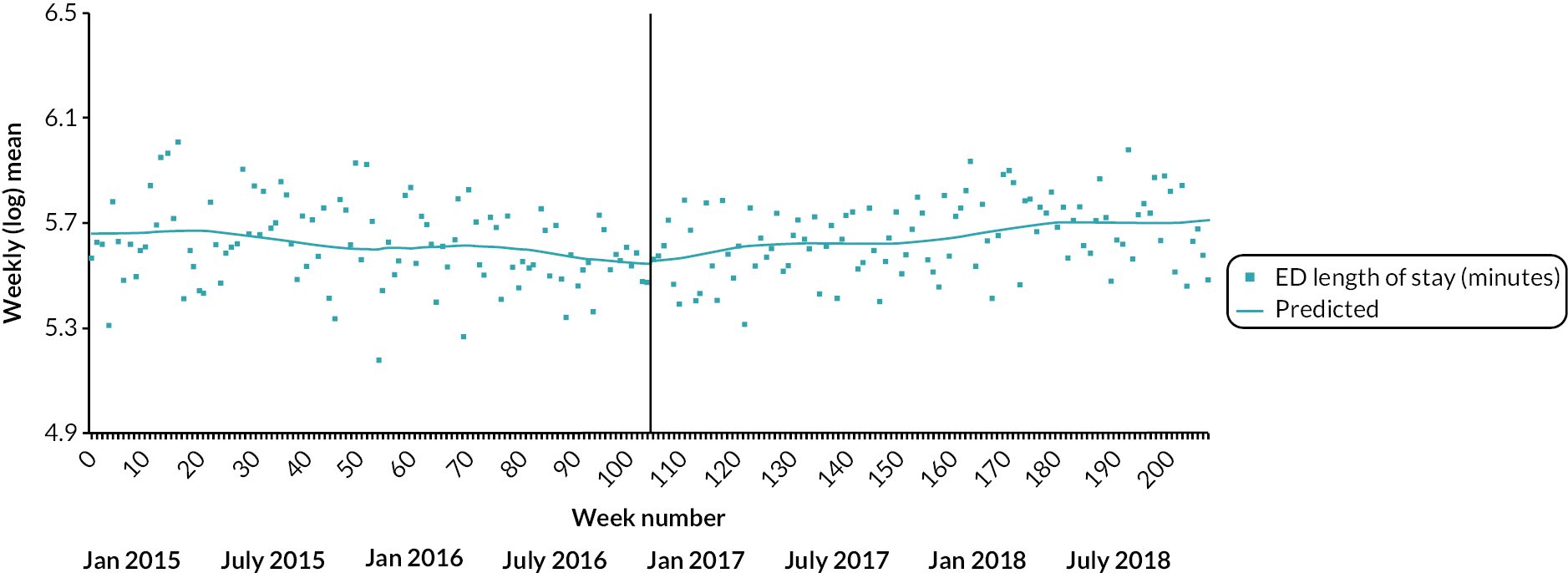

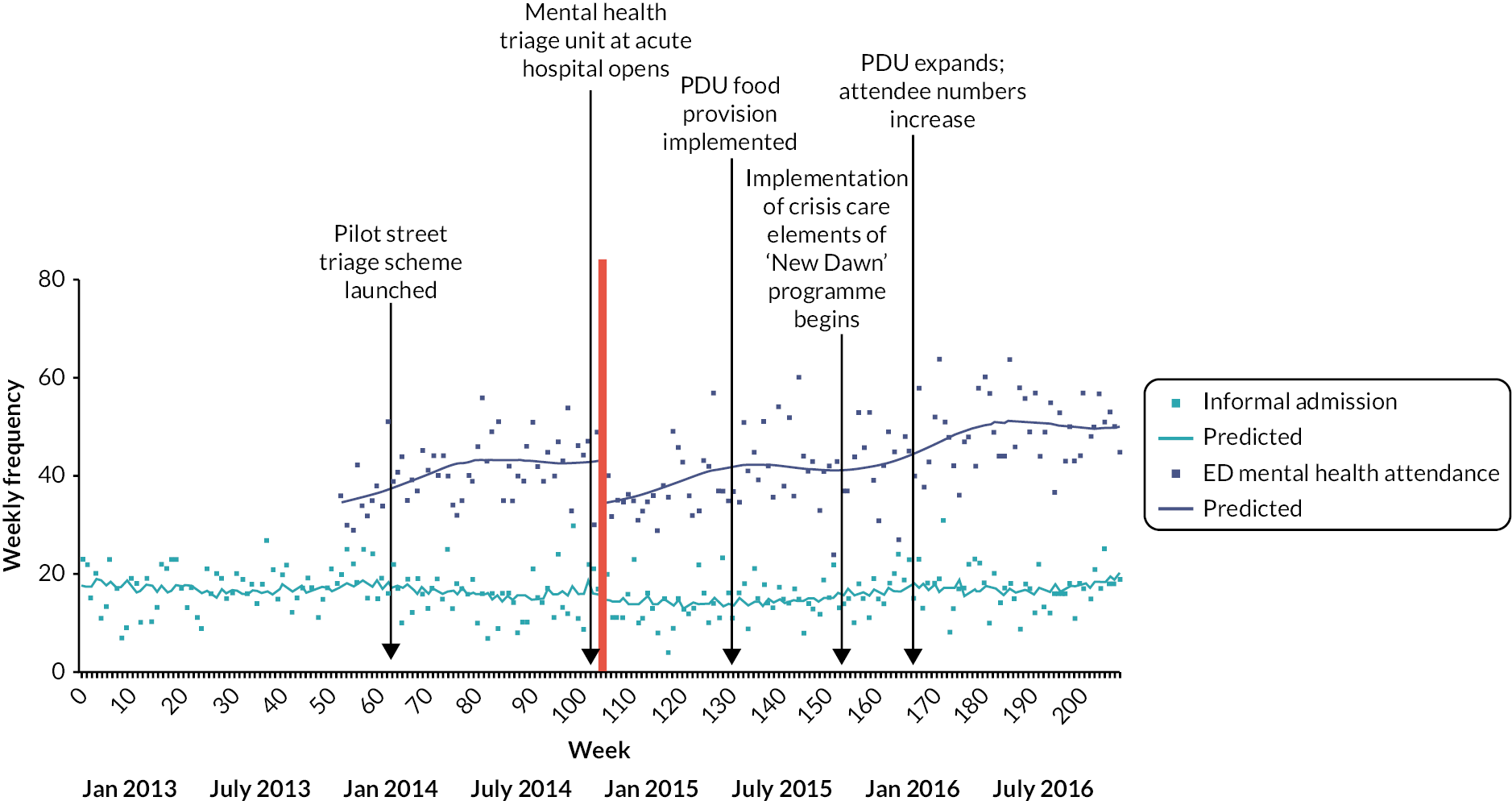

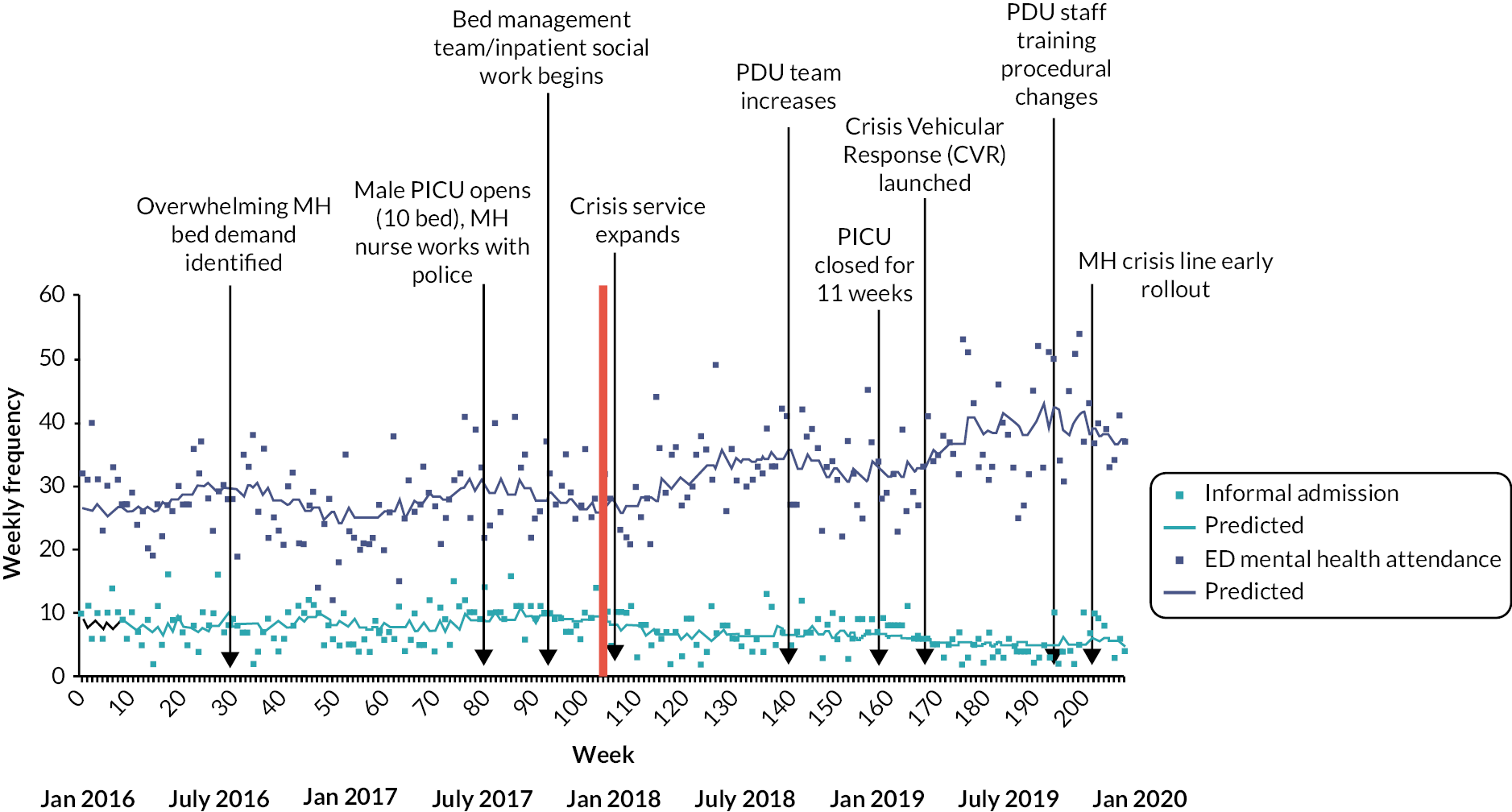

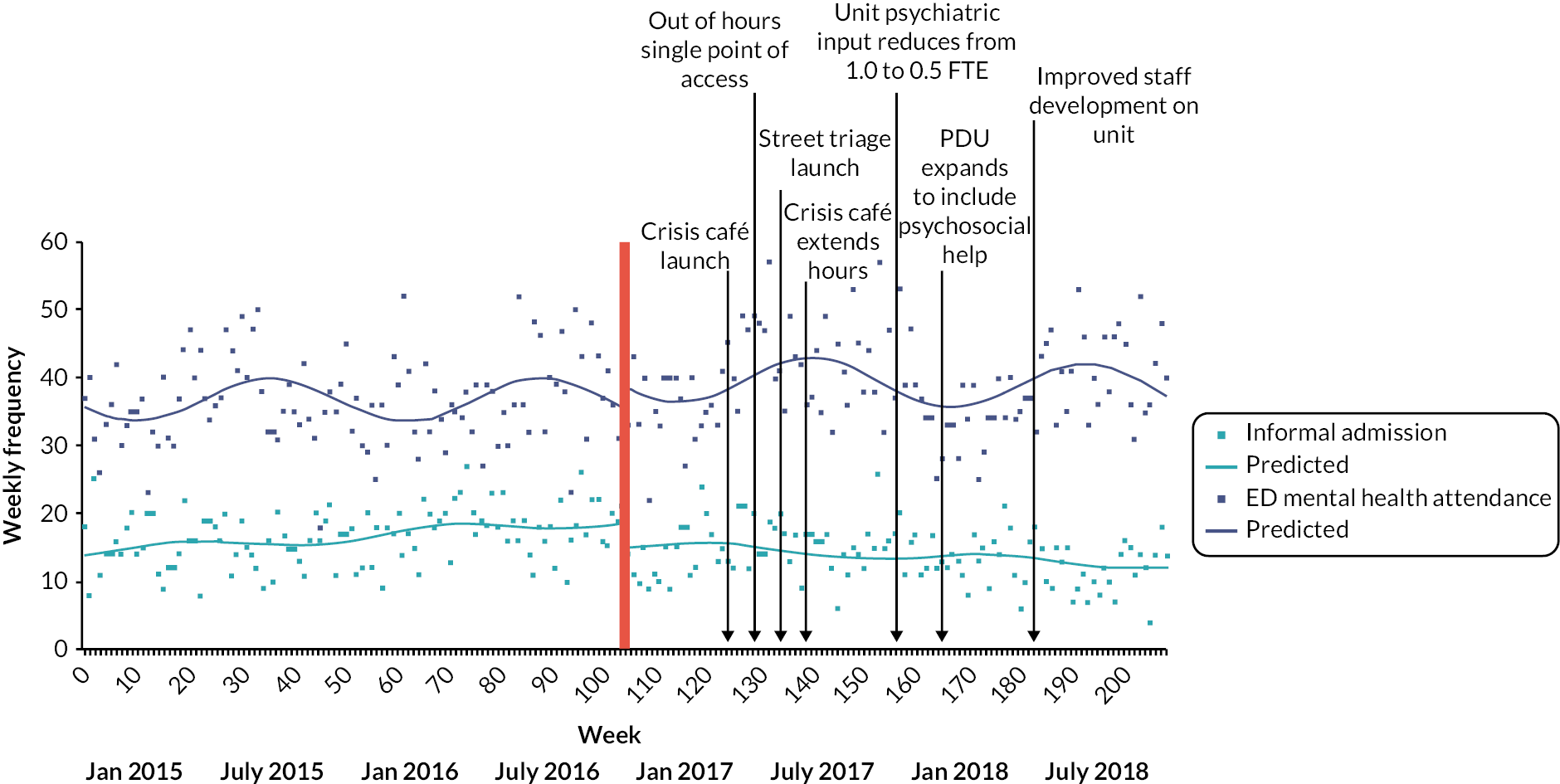

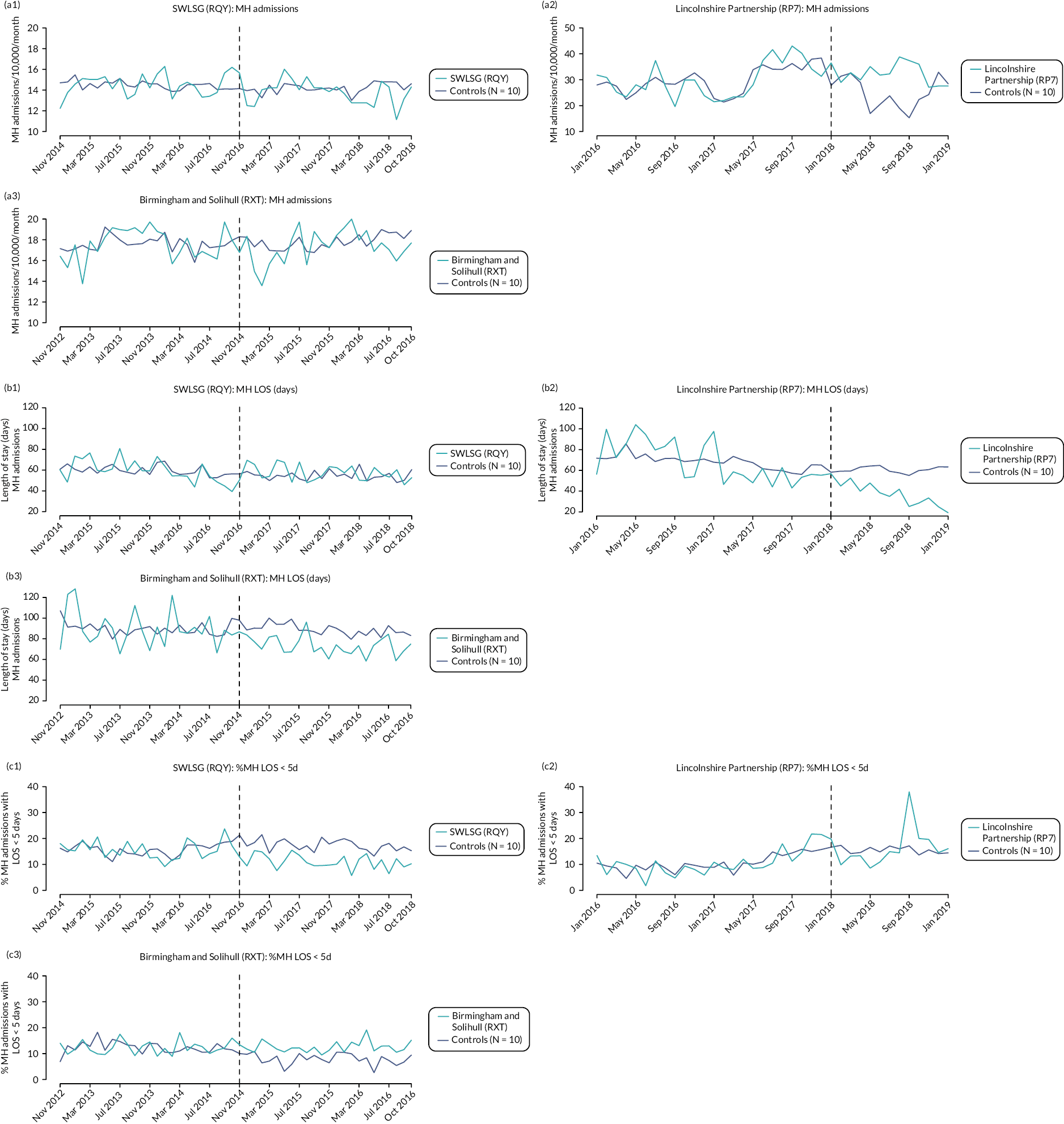

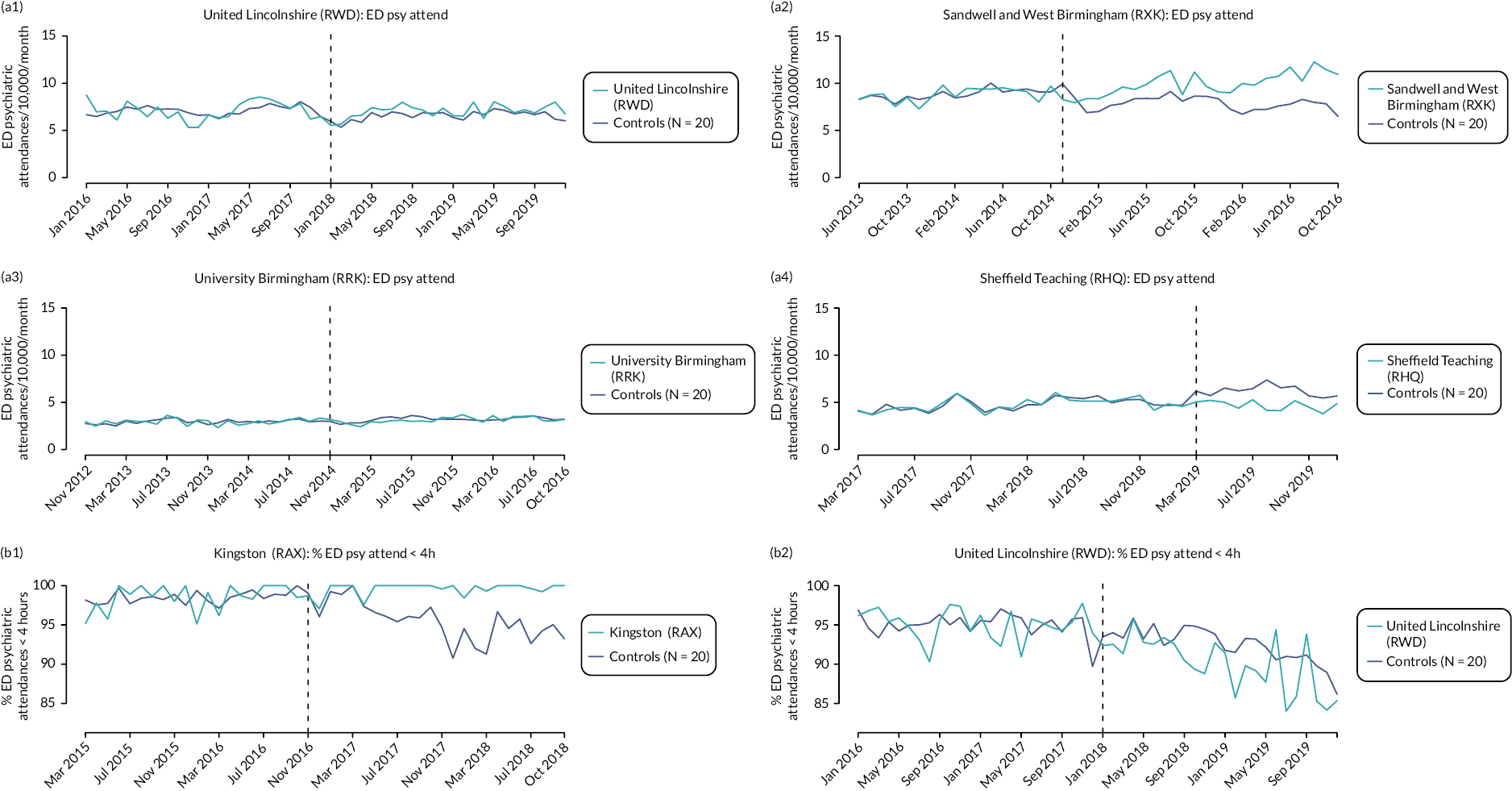

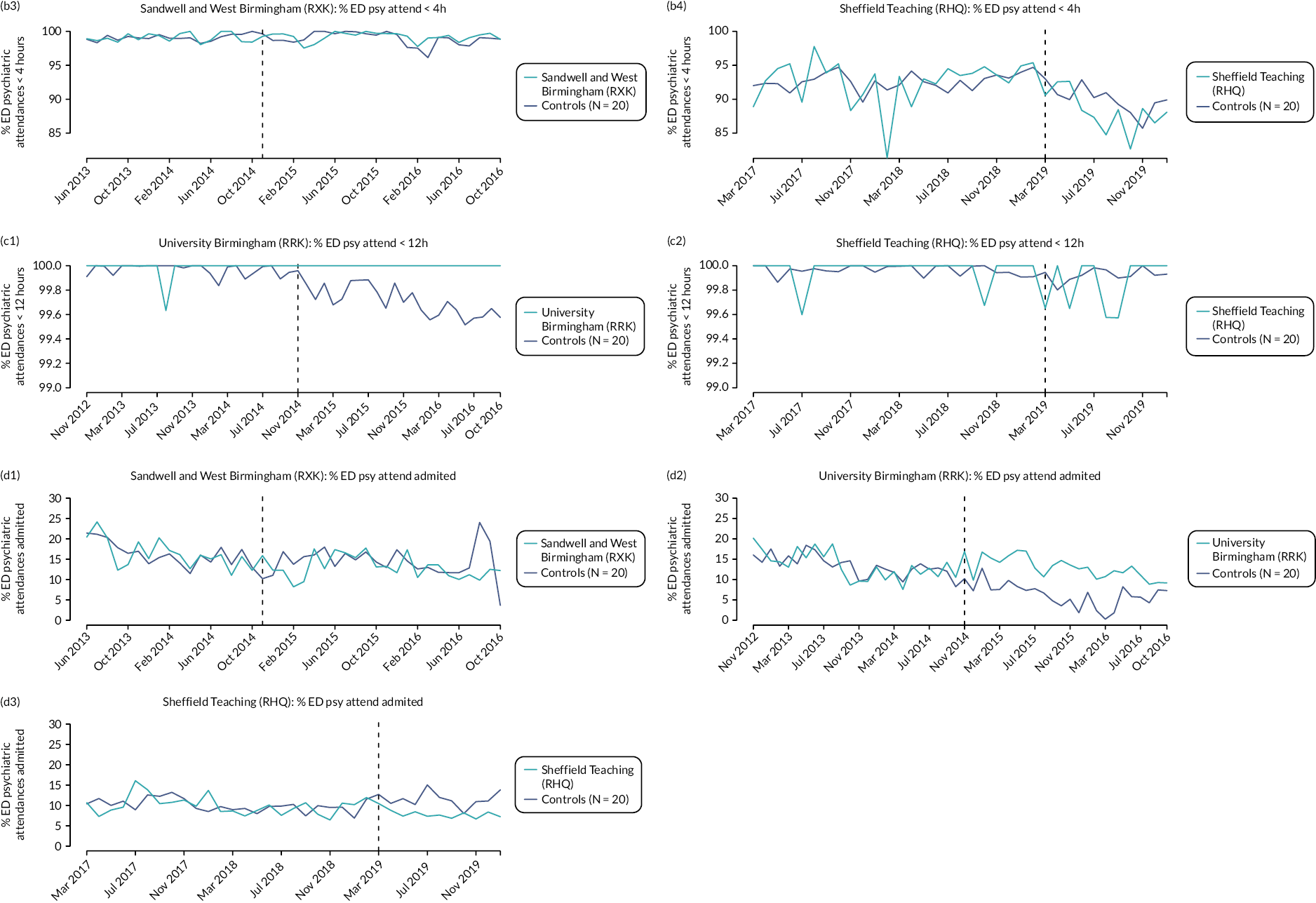

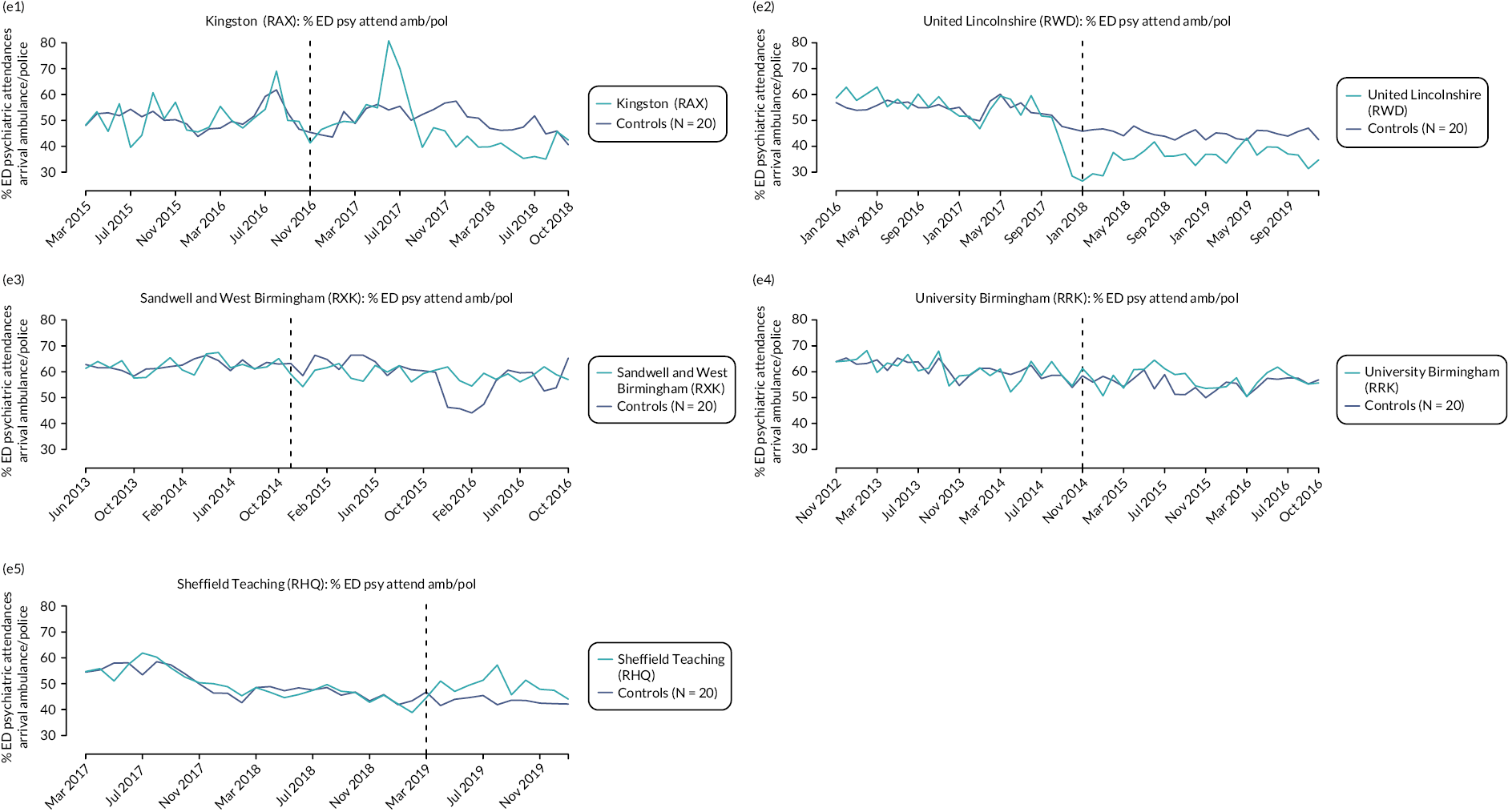

Changes in acute and psychiatric hospital activity following the introduction of PDUs in four sites were assessed via a retrospective, secular trend analysis using an ITS design considering routinely collected healthcare data. The exposure of interest was the implementation of the PDU. Acute adult psychiatric inpatient ward and mental health-related ED attendances in the 24 months prior to PDU implementation were considered unexposed, while those in the 24 months following PDU implementation were exposed. Detailed methodology of the ITS study has previously been described. 60

Setting and data set

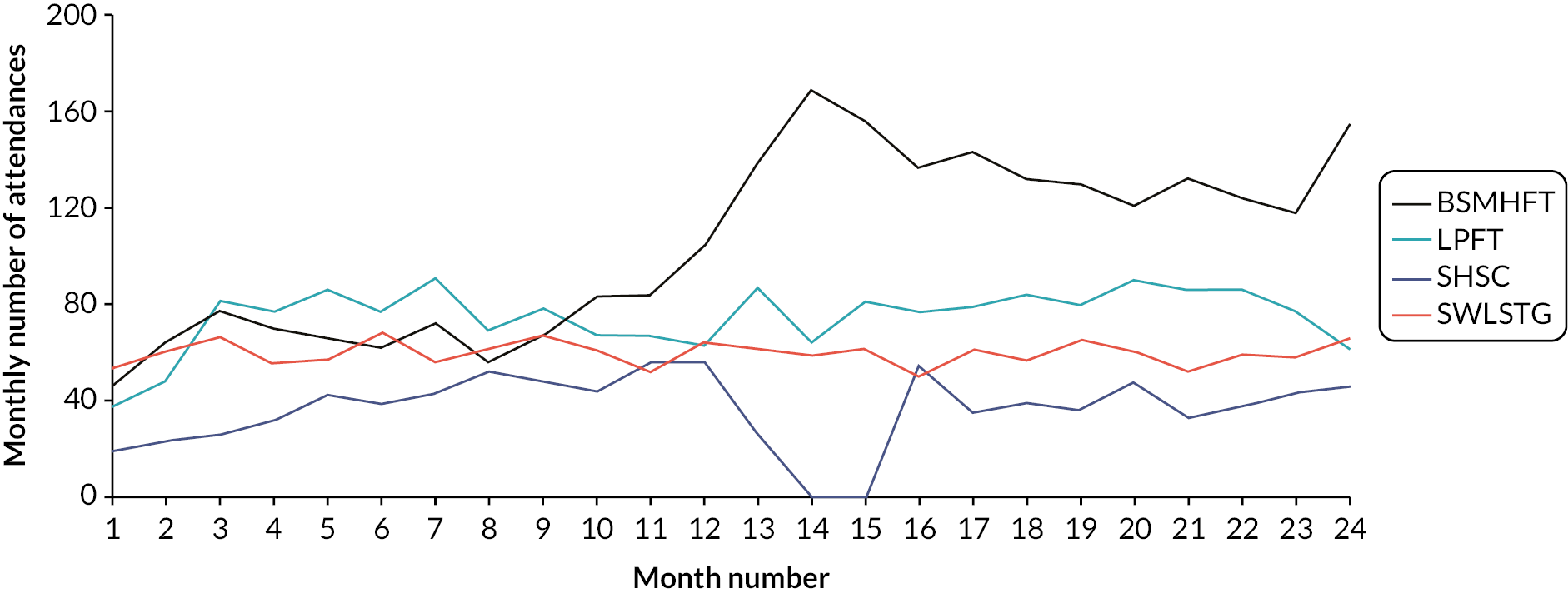

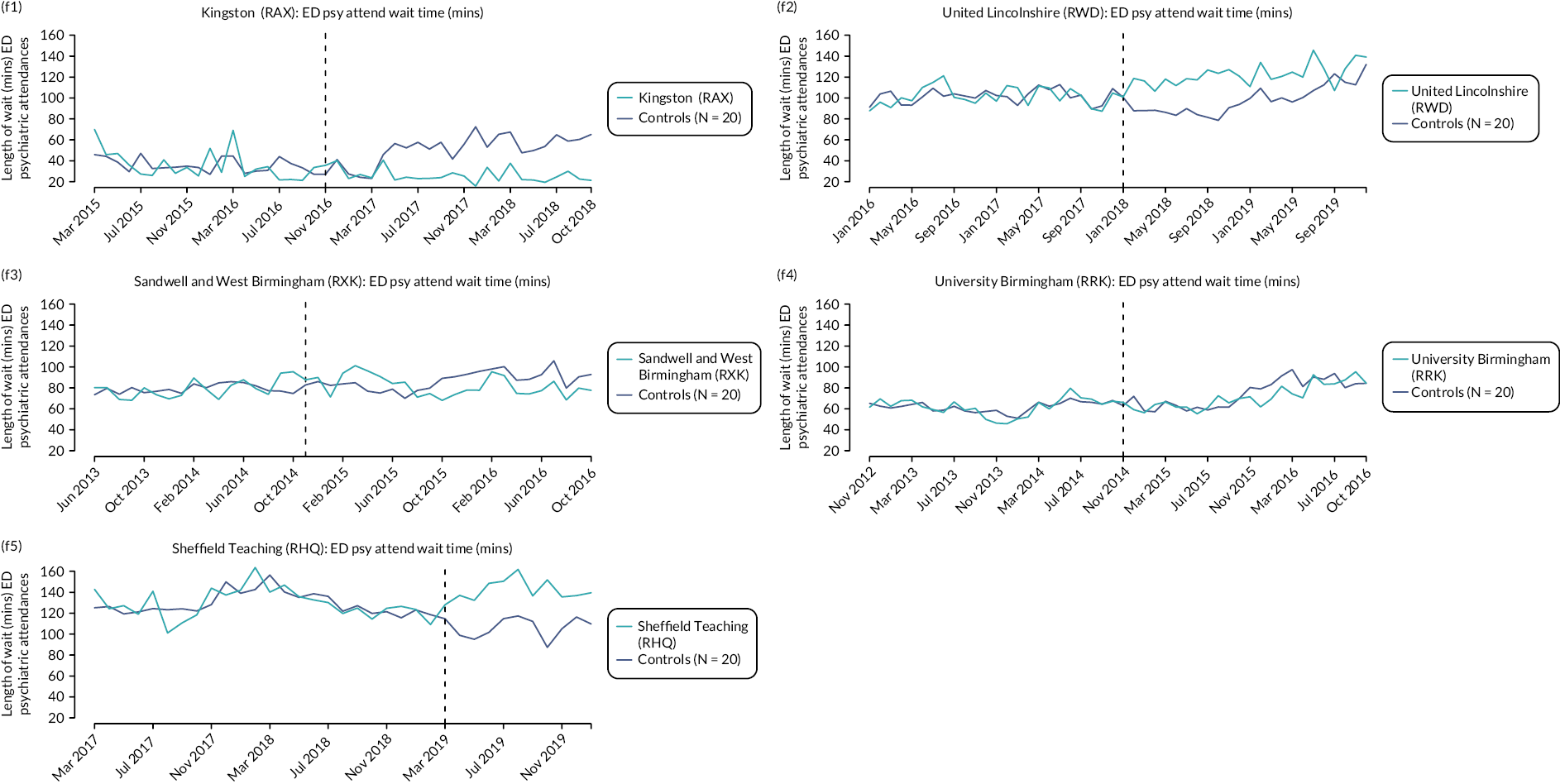

Service use data over a 4-year period were directly sourced from MHTs and the EDs (acute hospital trusts) of participating PDU sites. The periods under study therefore differed across participating sites according to the timing of the relevant PDU implementation. The MHTs (and time periods) under study were Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (BSMHFT; November 2012 to November 2016), Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (LPFT; January 2016 to December 2019), Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust (SHSCFT; March 2017 to March 2021) and South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust (SWLSTG; November 2014 to November 2018). The acute trusts under study were Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (SWBHFT; November 2012 to November 2016), Sheffield Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (STHFT; March 2017 to March 2021), St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (SGUHFT; November 2014 to November 2018) and United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (ULHFT; January 2016 to December 2019).

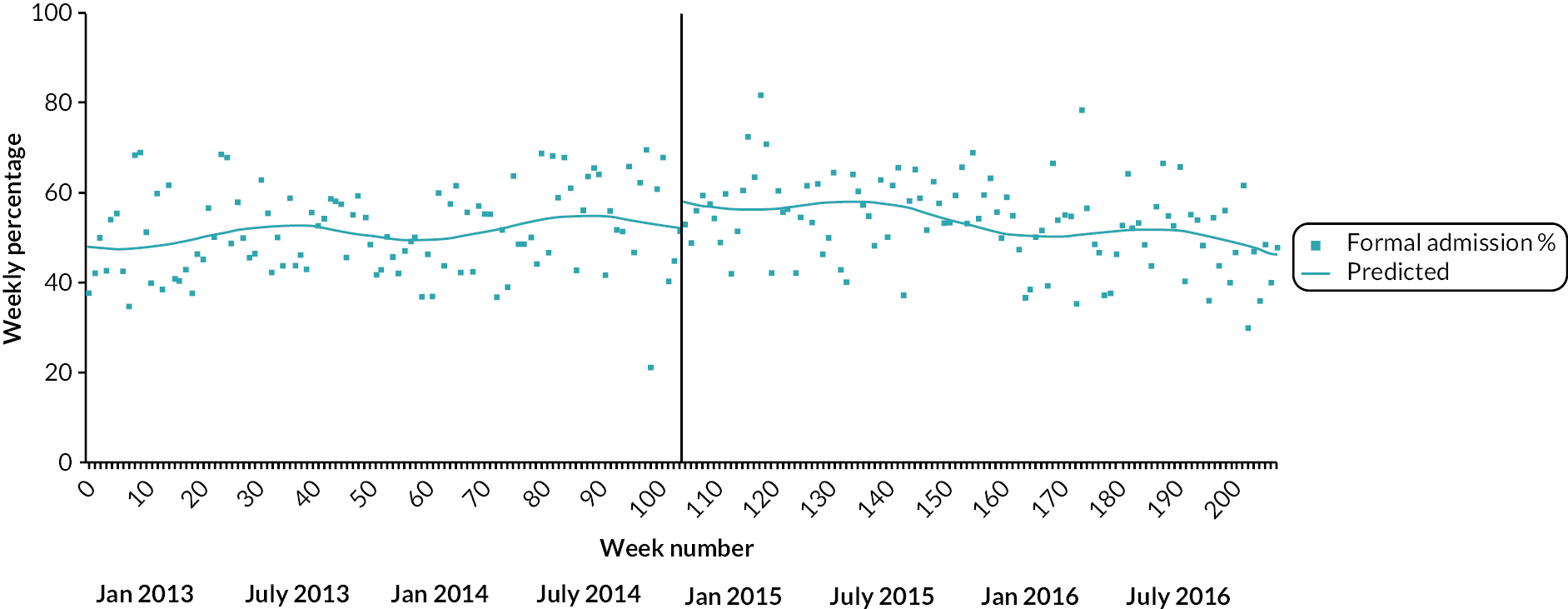

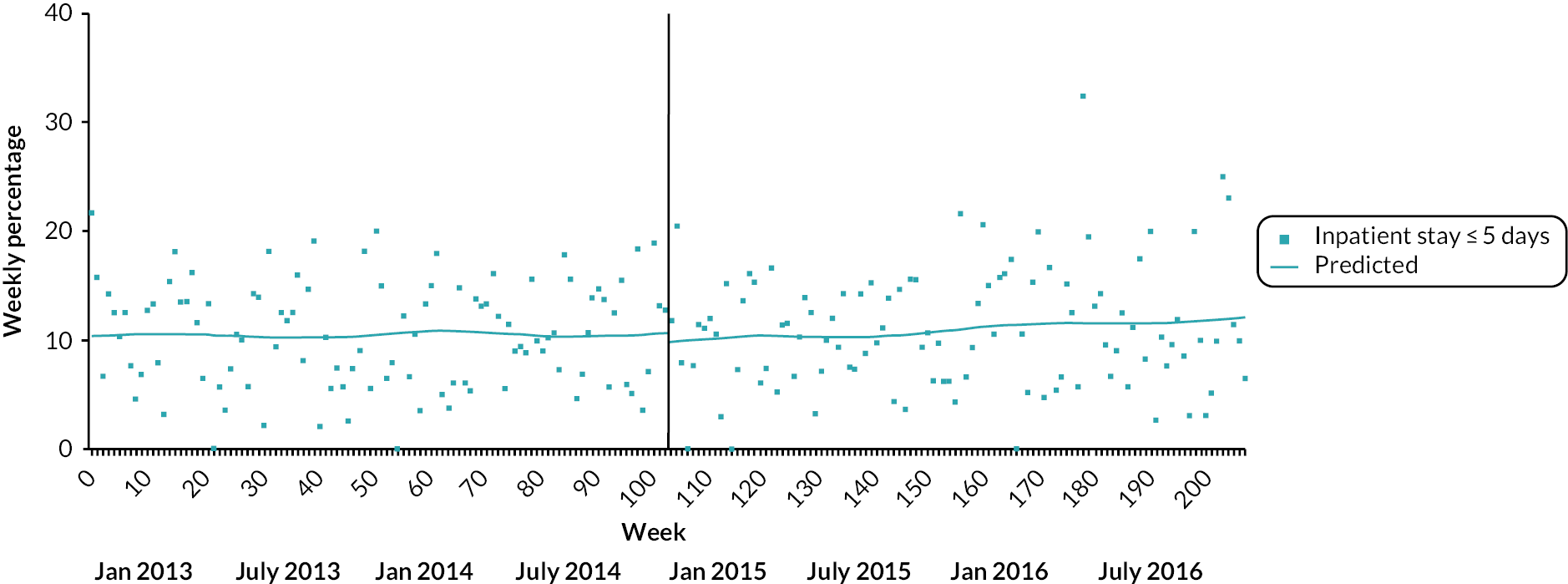

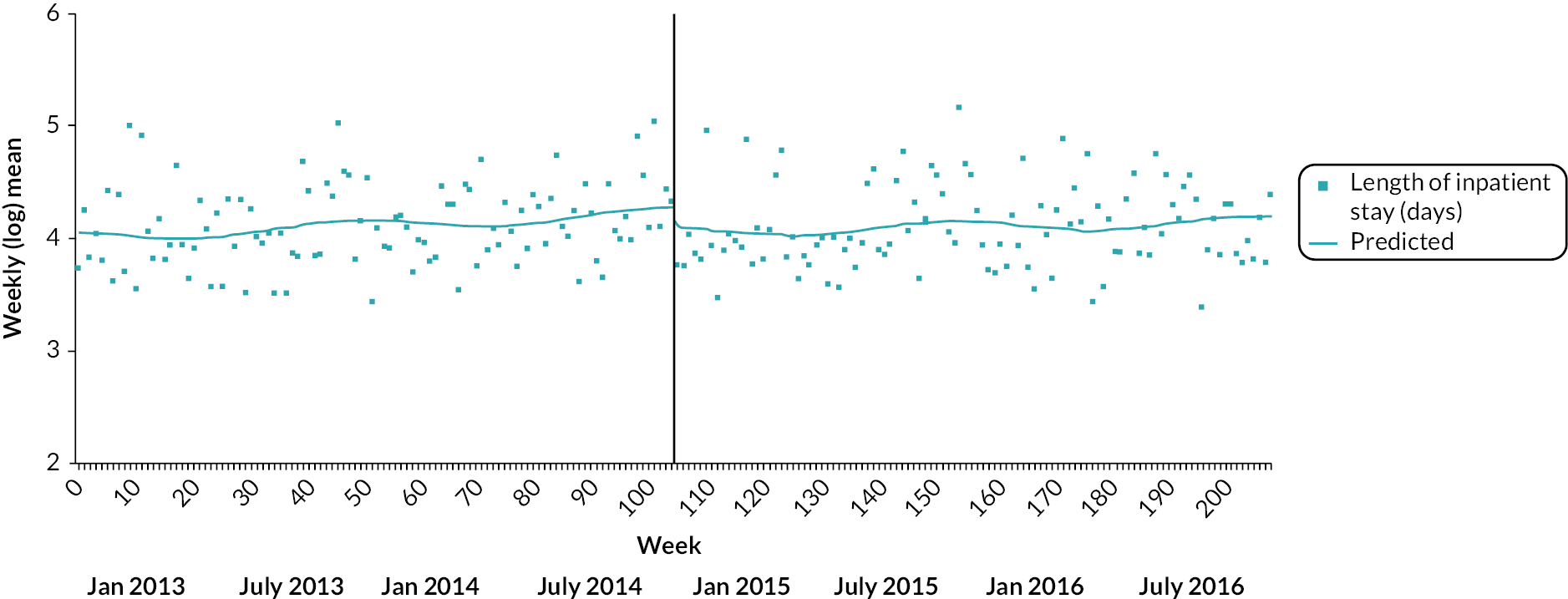

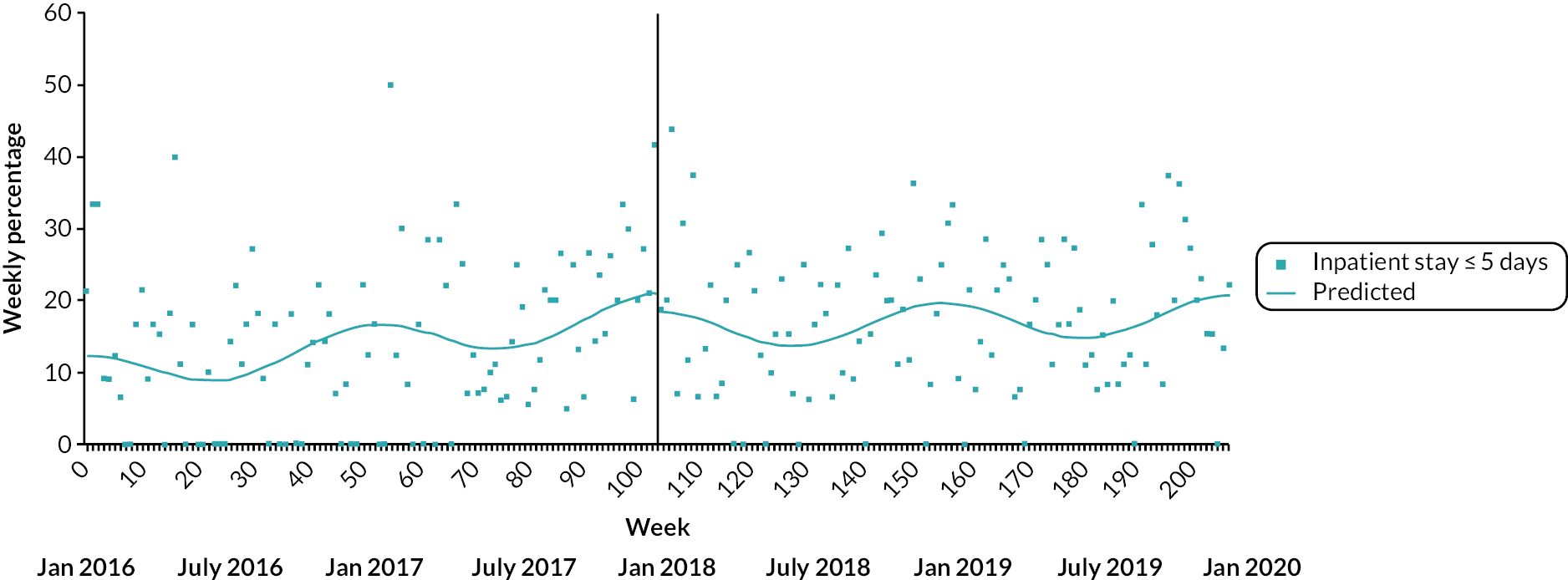

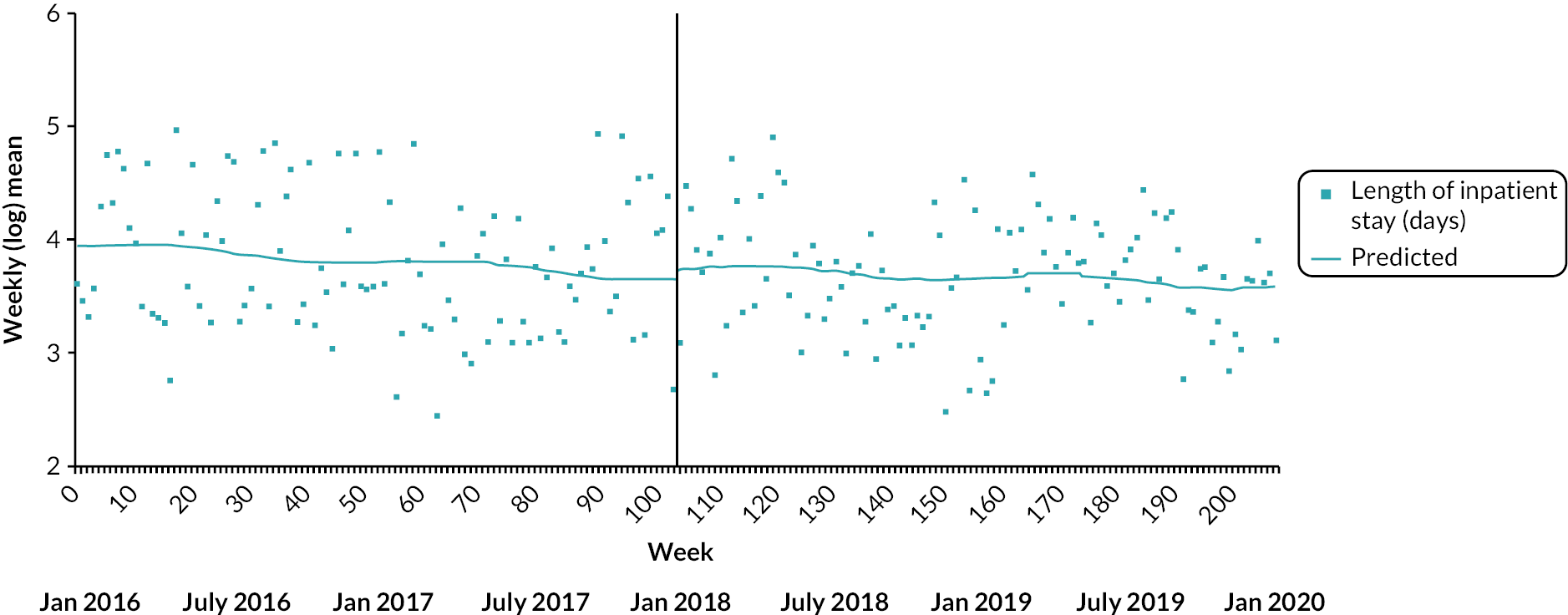

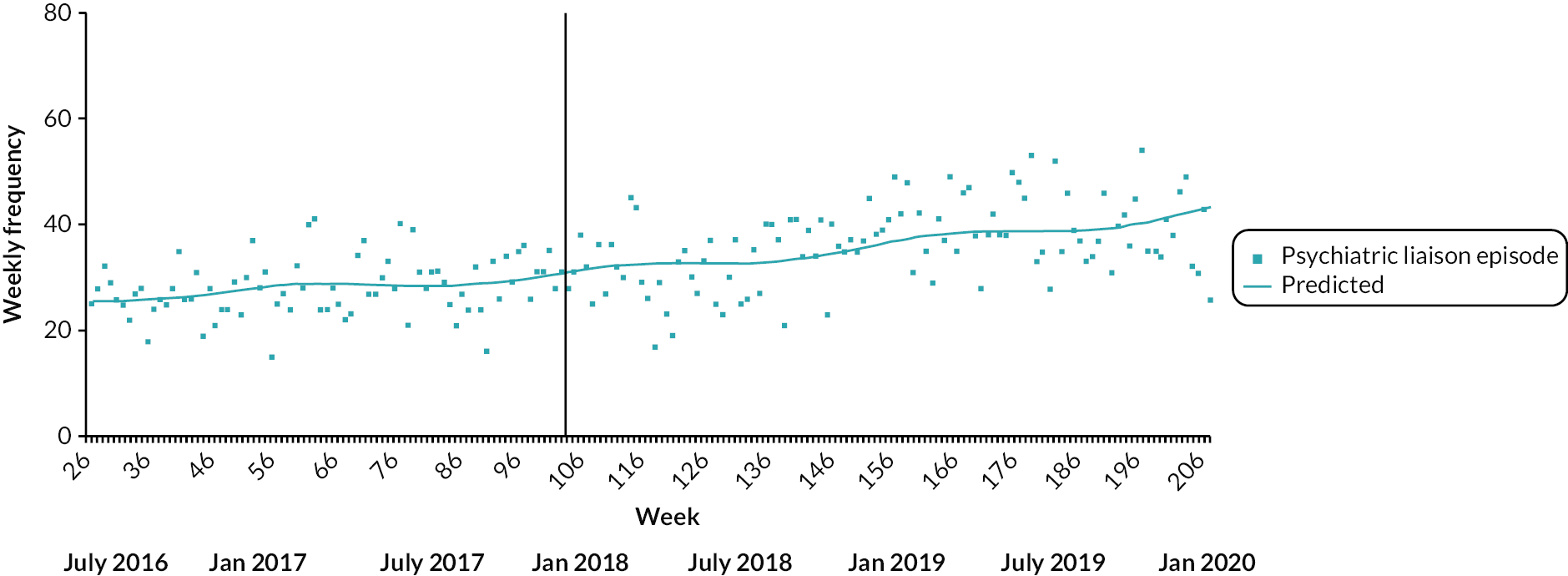

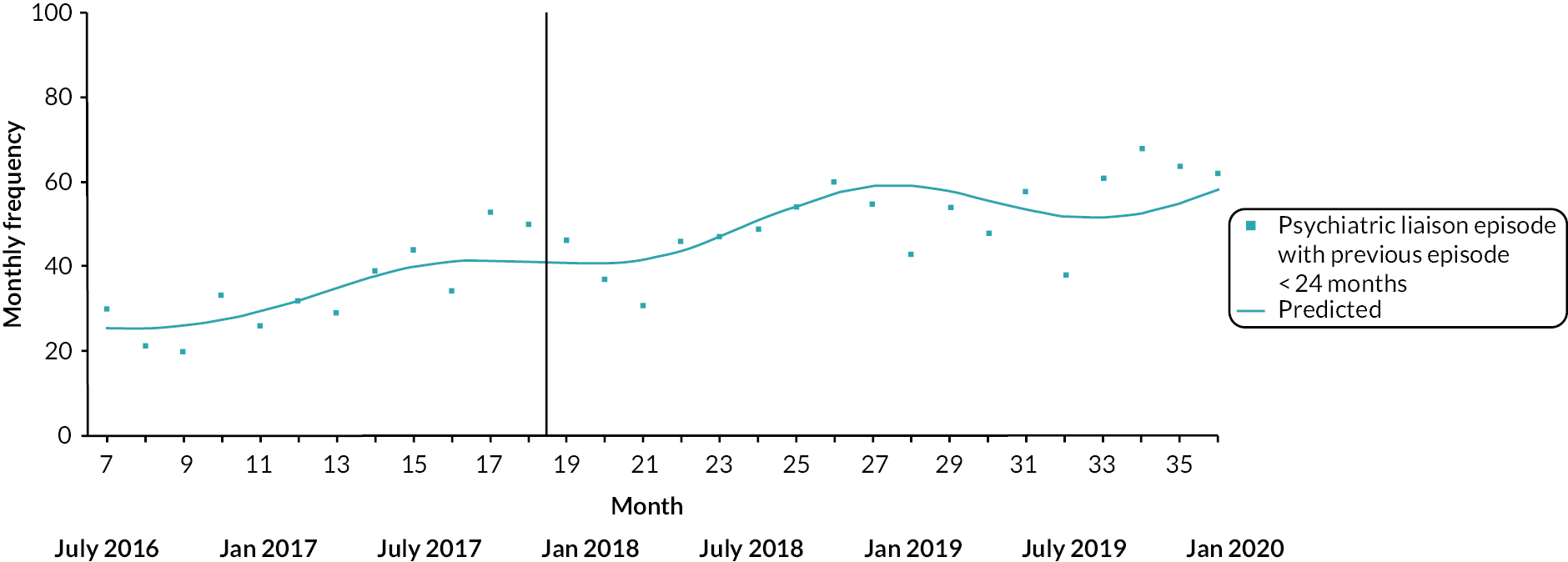

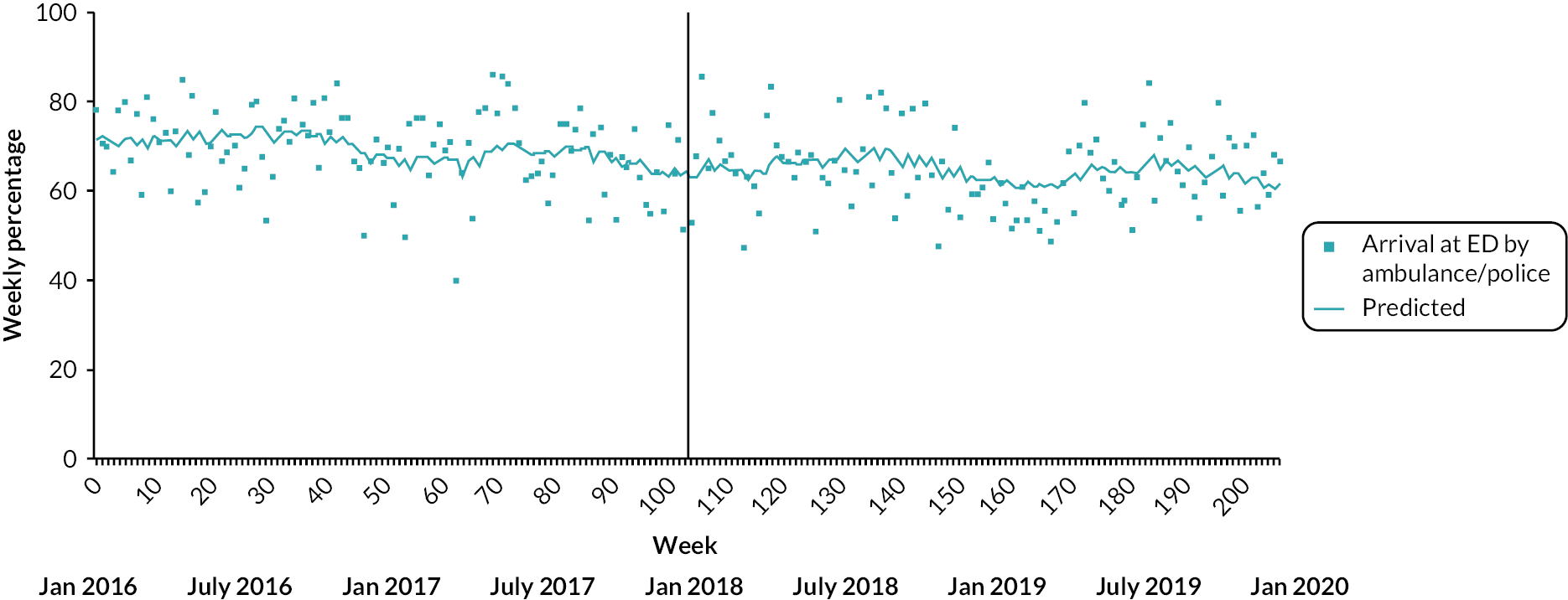

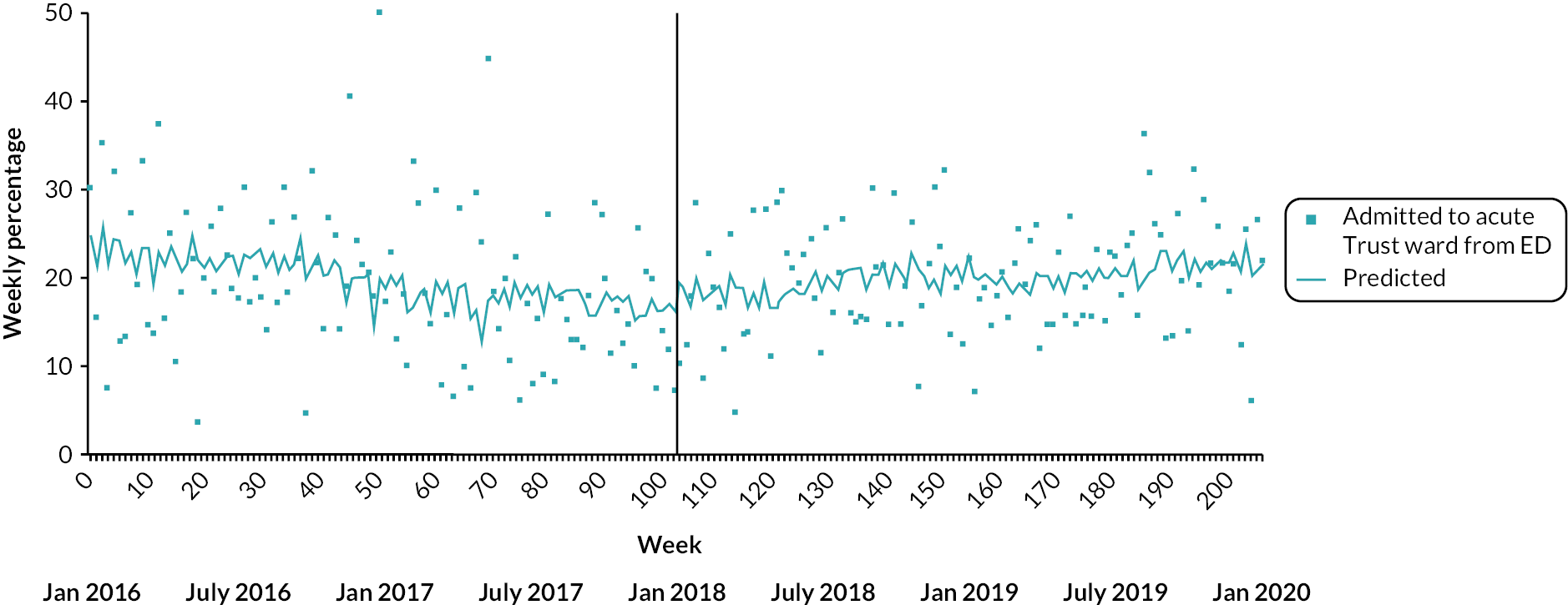

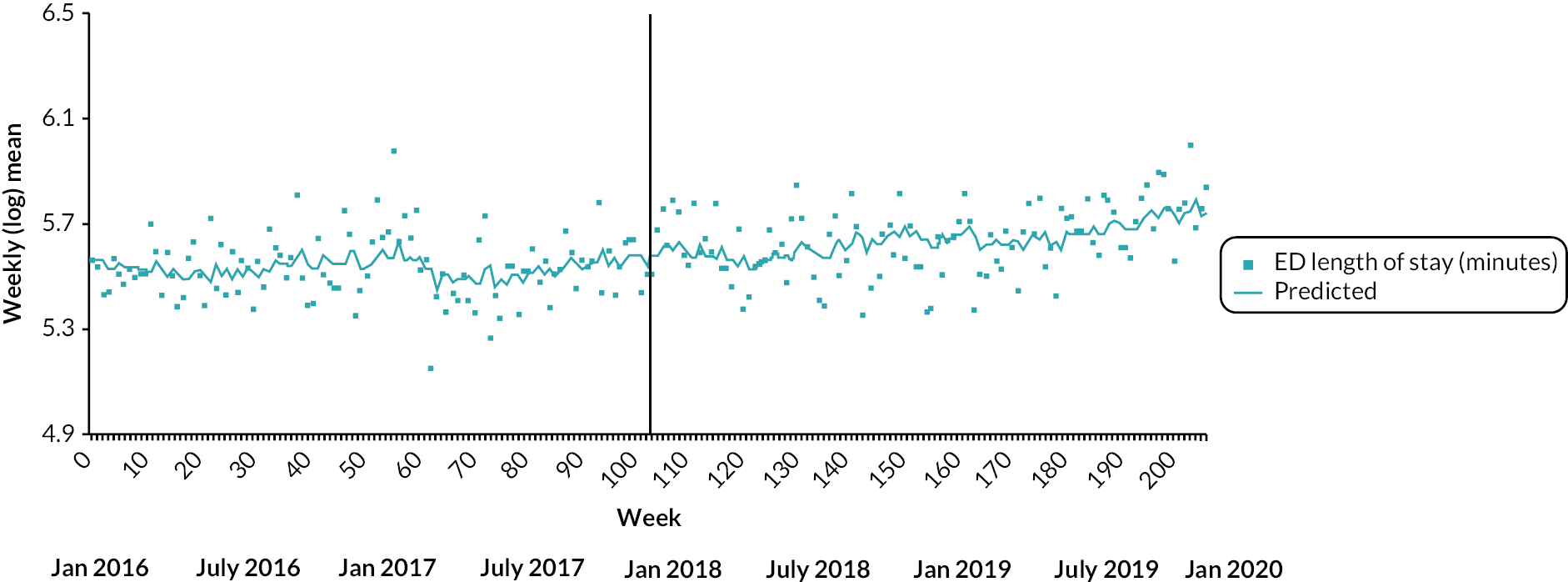

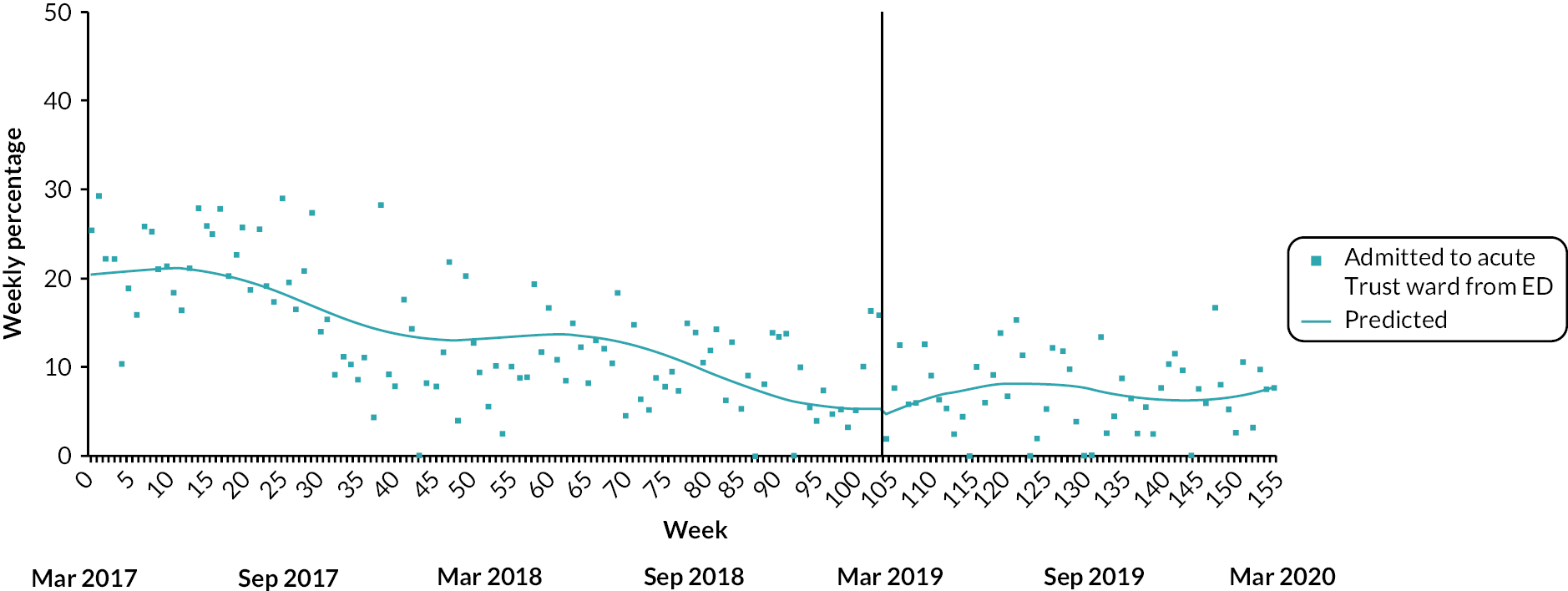

Interrupted time series outcome measures

Primary and secondary outcome measures concerning mental health crisis care service use in mental health and acute trusts are shown in Table 3. MHT data centred on patterns of activity in acute adult inpatient wards over the relevant period, including admission frequency and type (formal or informal), length of inpatient stay and frequency of ED-referred psychiatric liaison episodes (PLEs). ED-based hospital activity outcomes focused on psychiatric presentation frequency, arrival method (e.g. ambulance) and length of ED stay. Specifically, psychiatric presentations included adult attendances at a hospital ED where the presenting complaint reflected a mental or behavioural health issue and/or the primary diagnostic code was consistent with a diagnosis of either one or more mental and behavioural disorders [F01–F79 of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, (ICD-10)] or self-harm (X60–X84). Count data were adjusted in ITS analyses for size of catchment population. Details of data extraction and considerations are provided in Appendix 2.

| MHT | Acute trust |

|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |

| Voluntary acute adult psychiatric inpatient admissions | ED psychiatric presentations |

| Secondary outcomes | |

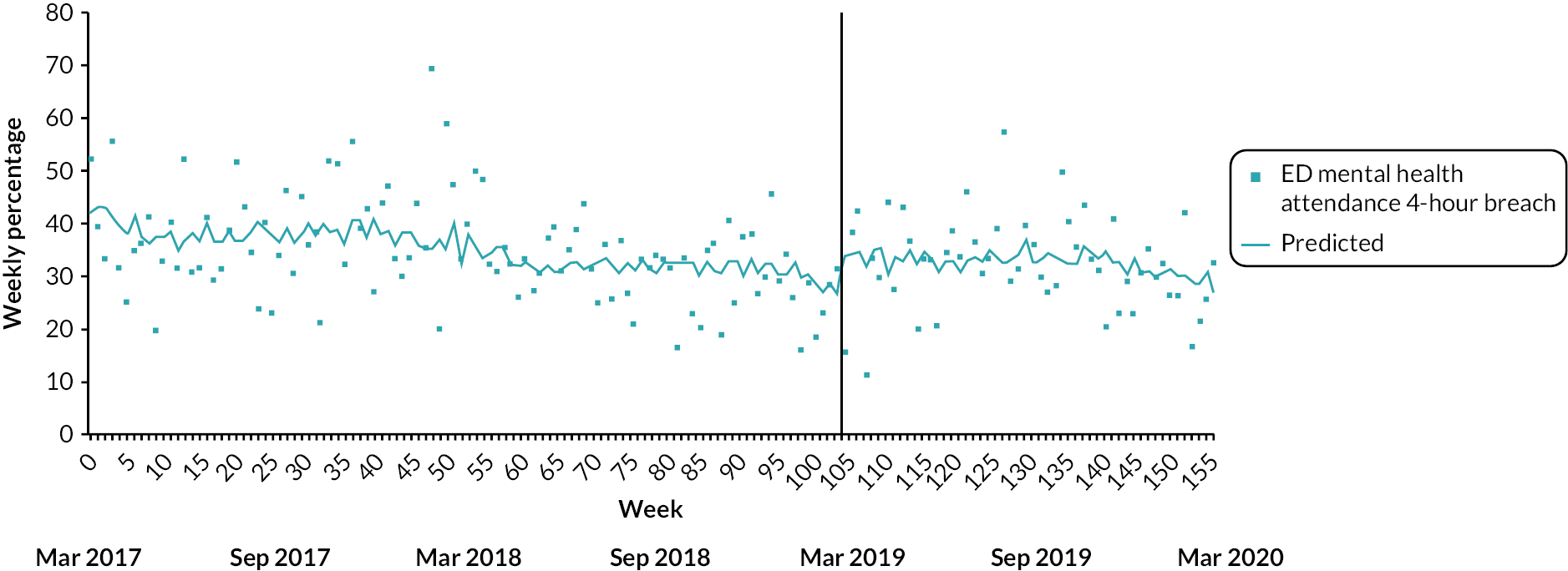

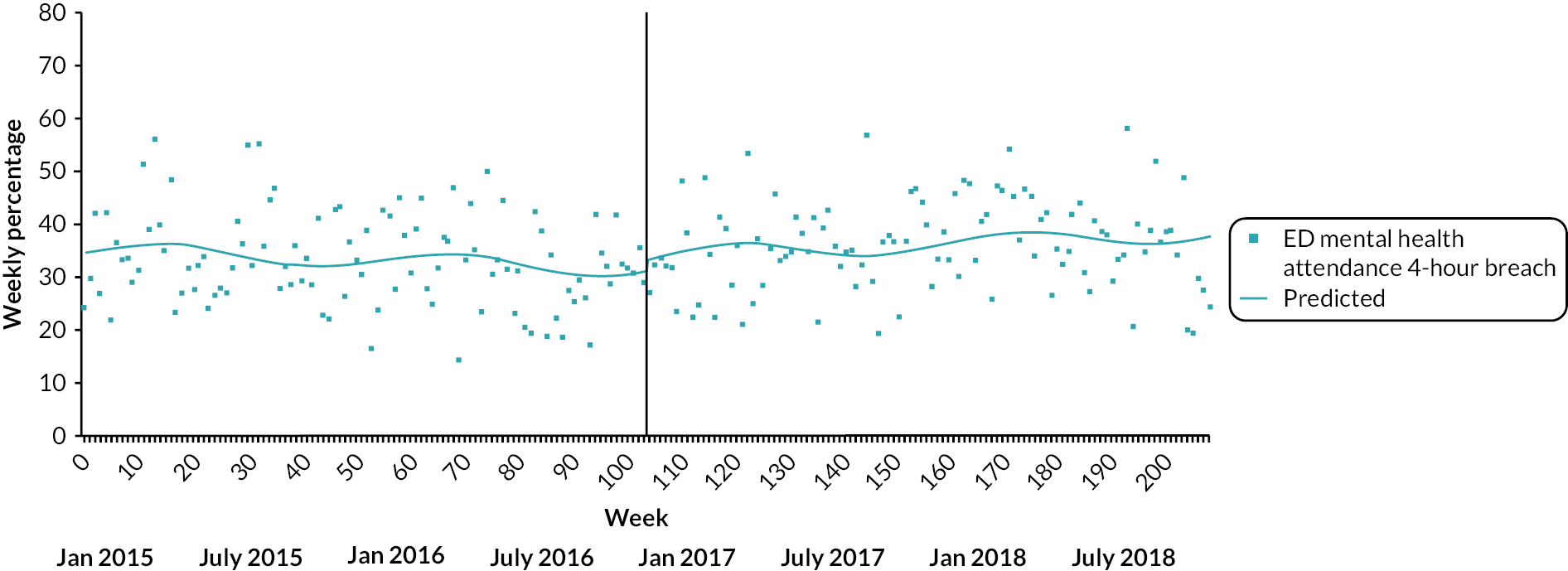

| Total acute adult psychiatric inpatient admissions | Proportion of ED psychiatric presentations with 4-hour breach |

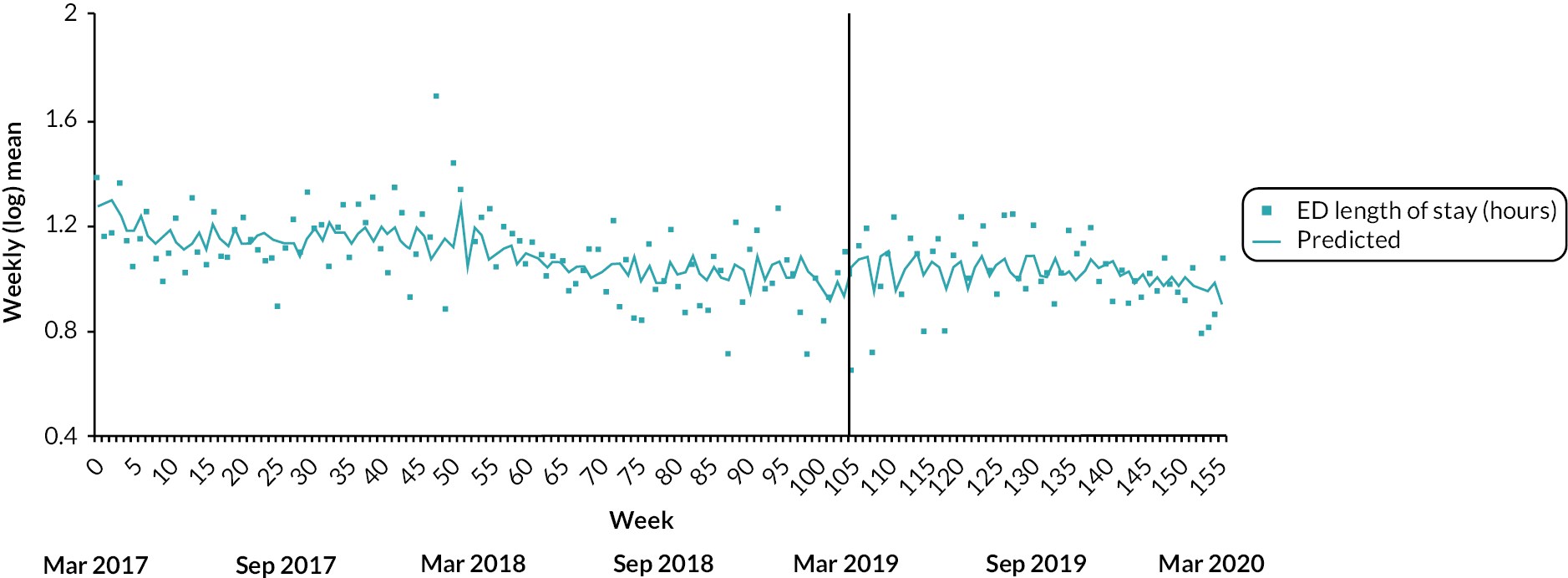

| Proportion of acute adult psychiatric inpatient admissions with stay of ≤ 5 days | Average length of psychiatric ED wait |

| Average length of acute adult psychiatric inpatient stay (bed days) | Proportion of ED psychiatric presentations with 12-hour trolley wait |

| Proportion of acute adult psychiatric inpatient admissions that were compulsory | Proportion of ED psychiatric presentations with admission to an acute trust ward bed |

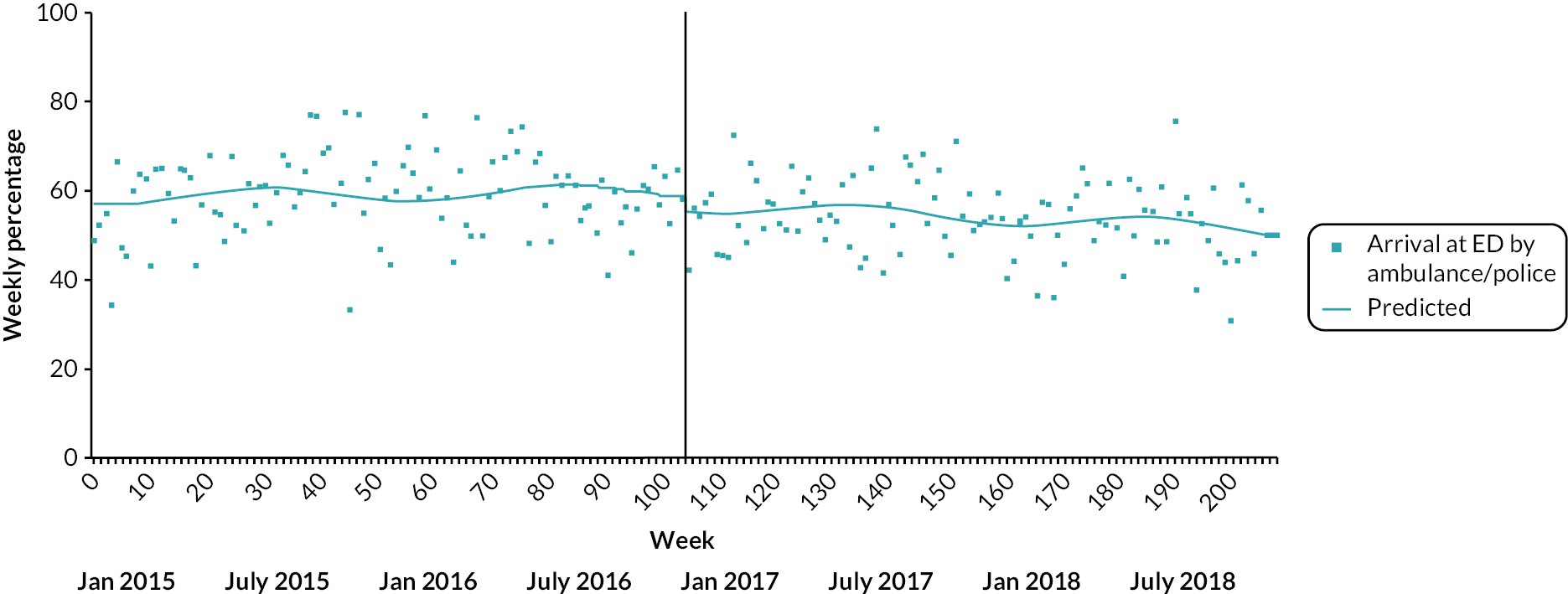

| PLEs referred from ED | Proportion of ED psychiatric presentations with arrival by ambulance/police |

| Mean daily occupied bed-days | |

| Out-of-area admissions (from the site trust to other trust/private provider) | |

Psychiatric decision unit data and pathway reconfiguration/change in model of care

PDU data (e.g. number of visits, LOS) pertaining to the first 2 years of operation for each site was also collected. Additionally, a small number of semistructured interviews were conducted with strategic managers in each site to identify other changes to the crisis care pathway (e.g. introduction or withdrawal of relevant services).

Statistical analyses

Service use parameters, including demographic characteristics of service users, were descriptively summarised for PDUs, psychiatric inpatient and ED mental health attendance activity in each trust. Outcomes were initially assessed for each site via pairwise comparisons of pre and post PDU implementation periods for each variable using chi-squared, t-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests.

Subsequently, outcome data were collated as time series over a (maximum) 48-month period for each site, aggregated to a single observation at weekly or monthly units depending on the variable under study. Segmented generalised linear model (GLM) regression analyses (with log or identity link) were employed to evaluate whether there was a change in healthcare use outcomes following PDU implementation. This method allowed the calculation of three regression coefficients to quantify the impact of service-level change: underlying trend prior to PDU introduction (b1), level change immediately following PDU introduction (b2) and slope change from pre-to-post PDU introduction (b3). The post PDU implementation trend (b1_b3) was calculated separately in analyses that considered only data from the post PDU period. Subsequently, to estimate overall effects, parameter estimates of PDU effect were pooled across sites in a meta-analytical model.

Additional ITS analyses were conducted for counts of inpatient admissions, ED mental health attendances and PLEs considering only those people who, in the preceding 24 months, had been discharged from psychiatric inpatient services, had attended the ED and been referred to liaison psychiatry, respectively. Secondary analyses of primary outcome measures in ITS were also performed with a view to attempt to account for the impact of any other service reconfigurations relevant to outcome measures by introducing a second break point in ITS models, subject to reconfigurations being sufficiently distant in time from PDU implementation to distinguish any impact.

A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. Analyses were administered using Stata® 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions), version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A full description of methods of ITS analyses with sample size considerations is provided in Appendix 2.

Synthetic control study

Data sources

Patient-level service use data were obtained from Hospital Episode Statistics admitted patient care (HES-APC) and emergency care datasets61 from November 2011 to December 2020. Data relating to the key characteristics of all NHS hospital trusts for the financial year 2018–19 were obtained from the NHS Trust Peer Finder Tool. 62 Further covariate data relating to the key characteristics of NHS acute hospital trusts from 2011 to 2018 were obtained from Public Health England. 63

Treated and control trusts

The treated trusts comprise the four MHTs with PDUs and their six referring acute trusts (see Table 4). One of the treated MHTs, SHSCFT, was excluded as it did not contribute any data to HES during the study period; 38 other MHTs in England and 136 other adult acute NHS trusts in England that contributed data to HES during our study period were included as potential controls. This was excluding four MHTs (in Coventry, Sussex, Leeds and Lancashire) that have active or decommissioned PDUs and their nine referring acute trusts. See Appendix 2 for full details.

| MHT | NHS trust code | PDU open date | MHT study perioda | Referring acute trust | NHS trust code | Referring acute trust study perioda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLSG | RQY | November 2016 | November 2014–October 2018 | SGUHFT | RJ7 | Excluded – sparse data |

| KHFT | RAX | March 2015–October 2018 | ||||

| LPFT | RP7 | January 2018 | January 2016–December 2018 | ULHFT | RWD | January 2016–December 2019 |

| BSMHFT | RXT | November 2014 | November 2012–October 2016 | SWBHFT | RXK | June 2013–October 2016 |

| UHBFT | RRK | November 2012–October 2016 | ||||

| SHSCFT | TAH | March 2019 | Excluded – no data | STHFT | RHQ | March 2017–January 2020* |

Patients

Admissions to a mental health trust adult inpatient ward

HES-APC includes all admissions to an English NHS hospital and English NHS-commissioned admissions in the independent sector. The unit of activity in HES is a finished consultant episode (FCE). Each FCE describes a period of care for a patient under a single consultant at a single hospital. Here, we linked FCEs to describe a continuous spell for a patient in a single hospital. Our analysis is at the spell level, which we hereinafter refer to as an admission. We proxied admissions to a MHT adult inpatient ward using the main specialty of the consultant (= 710, 722 : 726) or treatment function of the episode (= 710, 722–726) or, where these codes were not supplied, using the primary or secondary diagnosis code64 for the patient in the ICD-10 code in F03.0–F69.0, R44.0–R46.9). This approach has been verified for accuracy by comparison with data on NHS beds available and occupied (KH03) returns,65 but in more recent periods HES-APC may understate the true number of admissions to MHT inpatient wards. 1

Emergency department psychiatric attendances

Hospital Episode Statistics emergency care includes all ED attendance at English NHS hospitals. We proxied ED psychiatric attendances using the psychiatric ED diagnosis code (= 35) or patient group (= 30), arrivals by ambulance using the ED arrival mode (= 1), referrals to the ED by police by source of referral (= 6) and admissions to an acute trust inpatient ward at the same healthcare provider by ED attendance disposal (= 1). Referral to liaison psychiatry services could not reliably be determined from HES. 66

Outcomes

Admissions to a mental health trust inpatient ward

The primary outcome for MHTs was the rate of admissions to a MHT inpatient ward per 10,000 patients in the trust catchment population. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of these admissions with a LOS of less than 5 days and the average LOS.

Emergency department psychiatric attendances

The primary outcome for acute trusts was rate of ED psychiatric attendances per 10,000 patients in the trust catchment population. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of these attendances that breached 4/12 hours, where the patient was admitted to an acute bed at the same provider, arrived by ambulance or were referred by police, or were referred to liaison psychiatry; and the average length of wait.

Statistical analysis

Selecting similar controls

To ensure that we compared treated trusts with similar trusts elsewhere in the country, we used data and methods described in the NHS Trust Peer Finder Tool62 to identify each treated trust’s closest peers from the pool of potential controls based on a list of variables capturing key trust patient and operating characteristics. The closest peers are the control trusts with smallest Euclidean distance to the treated trust based upon standardised values of the variables. The closest 10 peers for MHT outcomes and 20 peers for acute trust outcomes, according to annual data available for 2018–19, were used as the control pool for each trust in the main analysis. We used a smaller pool for MHT outcomes as there were only 34 potential control MHTs compared with 127 potential control acute trusts. Chi-square tests for no difference between the distribution of key characteristics in the treated trust and the aggregated pool of controls were performed, allowing for a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

The generalised synthetic control

We used the generalised synthetic control (GSC) method67 to estimate the impact of the PDU on each outcome separately at each treated trust. Estimates were risk-adjusted to control for the size of the trust catchment population and other variables that reflect changes over time in the characteristics of the population at risk. Significance was assessed by a parametric bootstrap procedure. 67 Estimated standard errors were used in a random-effects meta-analysis to generate a pooled estimate across studies. Standard diagnostic checks were performed to test the validity of method assumptions. 68

Cohort study

Study design

The cohort study was conducted at all four participating MHTs. Participants were all individuals experiencing their first visit to a PDU over a 5-month period from 1 October 2019. The study was prospective, registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (53431343) on 11 February 2020, before entry to the cohort closed on 29 February 2020. Routine service use data were analysed for periods of 9 months both preceding and following the first visit to a PDU, extracted from electronic patient records by business intelligence teams at each site, pseudonymised, securely transferred to the study team, cleaned and analysed. The COVID-19 pandemic in the UK and subsequent restrictions to movement and social distancing measures overlapped with the follow-up period for the cohort study. The study was adapted to include a retrospective cohort at each site to identify whether the pandemic created issues for the generalisability of the follow-up period and to check the validity of the results. The retrospective cohort consisted of people who visited a PDU for the first time at one of the four sites during a 5-month period exactly 1 year prior to the prospectively designed cohort.

Measures

As PDUs are designed to ease the pressure on both ED and inpatient psychiatric wards, there were two primary outcomes. For inpatient wards, we examined whether there was a change in informal admissions during the study. For the ED, we examined whether there were changes in mental health presentations at ED, measured as liaison psychiatry episodes (referral to psychiatry within the ED). We examined a range of secondary outcomes that enabled us to identify additional changes to service use. These included total inpatient admissions, short-stay (0- to 5-day) admissions, average length of inpatient stays, compulsory admissions, use of Community Mental Health (CMHT) and CRHT teams and other community-based MHT services.

Statistical analysis

The population was summarised using descriptive statistics to understand who uses PDU services. Pre and post PDU visit periods were compared in the primary cohort to illuminate changes in service use following a service user’s first stay on a PDU. The post-PDU periods in primary and retrospective cohorts at each site were compared to check for changes to service use due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pre-PDU first visit periods at each site were compared to indicate whether significant differences in the two post periods might be found just through random chance due to repeated testing. We used paired t-tests bootstrapped with 2000 replications for continuous data69 or McNemar’s χ2 tests for binary paired data. 70

For the equalities impact assessment, we compared the demographics of those individuals in the primary cohort accessing the PDU to the general population of service users (calculated over a recent 1-year period) at that site. Z-tests were used to compare the proportions of each demographic where the numbers were sufficient. Z-tests were used as a valid way of comparing a subgroup drawn from a population to a wider population; correction for the overlap was not conducted as each subgroup represented far less than 10% of the whole population. 71

Qualitative interview study

This WP combined a cross-sectional qualitative interview study with PDU staff and crisis care pathway staff referring to PDUs, with a longitudinal interview study with first-time visitors (service user) of PDUs.

Participants

Psychiatric decision unit visitors

Participants were first-time admissions to PDUs, recruited within 1 month of discharge from the PDU, able to give informed consent to participate in research. A sampling framework was considered to ensure that the study included participants with a range of service use histories and sociodemographics, but in practice it was not possible to do so because of challenges in identifying and recruiting sufficient numbers of eligible participants. Our target recruitment was 10 participants at each of three study sites (South West London, Lincolnshire and Sheffield), increased to 12 participants to allow for loss of follow-up and 6 in Birmingham.

Members of the research team or site clinical studies staff visited PDUs in person or made enquiries by telephone on a weekly basis, asking unit staff to identify eligible unit visitors, including any new admissions. Potential participants were given with study information and, if interested, given an opportunity to ask questions about the study, invited to give informed consent to participate and an interview arranged. At the Birmingham site consent could also be taken verbally, by telephone and digitally recorded following ethical approval for amendments to procedures resulting from COVID-19.

Clinical staff

Participants were either working on PDUs or referring to them as part of the crisis care pathway. At each site we aimed to recruit between 10 and 12 staff participants (6 in Birmingham) including 4 members of the PDU team (unit manager, nurse, HCA and psychiatrist consulting to the unit) and 6–8 referring staff (member of the ED-based liaison psychiatry team; ED nurse and/or manager; referring clinicians from CRHT, street triage and other services directly referring to PDU as appropriate locally). A member of the research team contacted the local principal investigator, PDU manager and/or consultant to identify potential participants. Interested individuals were followed up with study information, given an opportunity to ask questions about the study and invited to give informed consent to participate.

Data collection

Psychiatric decision unit visitors

Baseline interviews were conducted either face to face on the unit, at another service, at the participant’s home or by telephone or video-conferencing application and were digitally, audio-recorded. Interviews lasted between 15–98 minutes. At about 8 months post-discharge from the PDU participants in the SWL, Lincolnshire and Sheffield sites were contacted by a member of the research team using their preferred contact details and, if interested, a follow-up interview arranged (between 8 and 10 months post-discharge). Follow-up interviews were conducted by telephone or video-conferencing application and were digitally, audio-recorded.

Interviews were semistructured and at baseline explored participants’ experiences of referral to the PDU, assessment, unit environment and therapeutic input on the PDU, and any immediate referral or signposting to post-discharge care. At follow-up, interviews explored participants’ experience of crisis and community care post-discharge from the unit, any differences in care pathway in the year before and after their stay on the unit, and any impacts of COVID-19 on care received post-discharge. Two workshops with the PEER group identified a number of issues important to explore in interviews. Final interview schedules were coproduced in a workshop conducted by service user researchers and our LEAP (see Appendix 3).

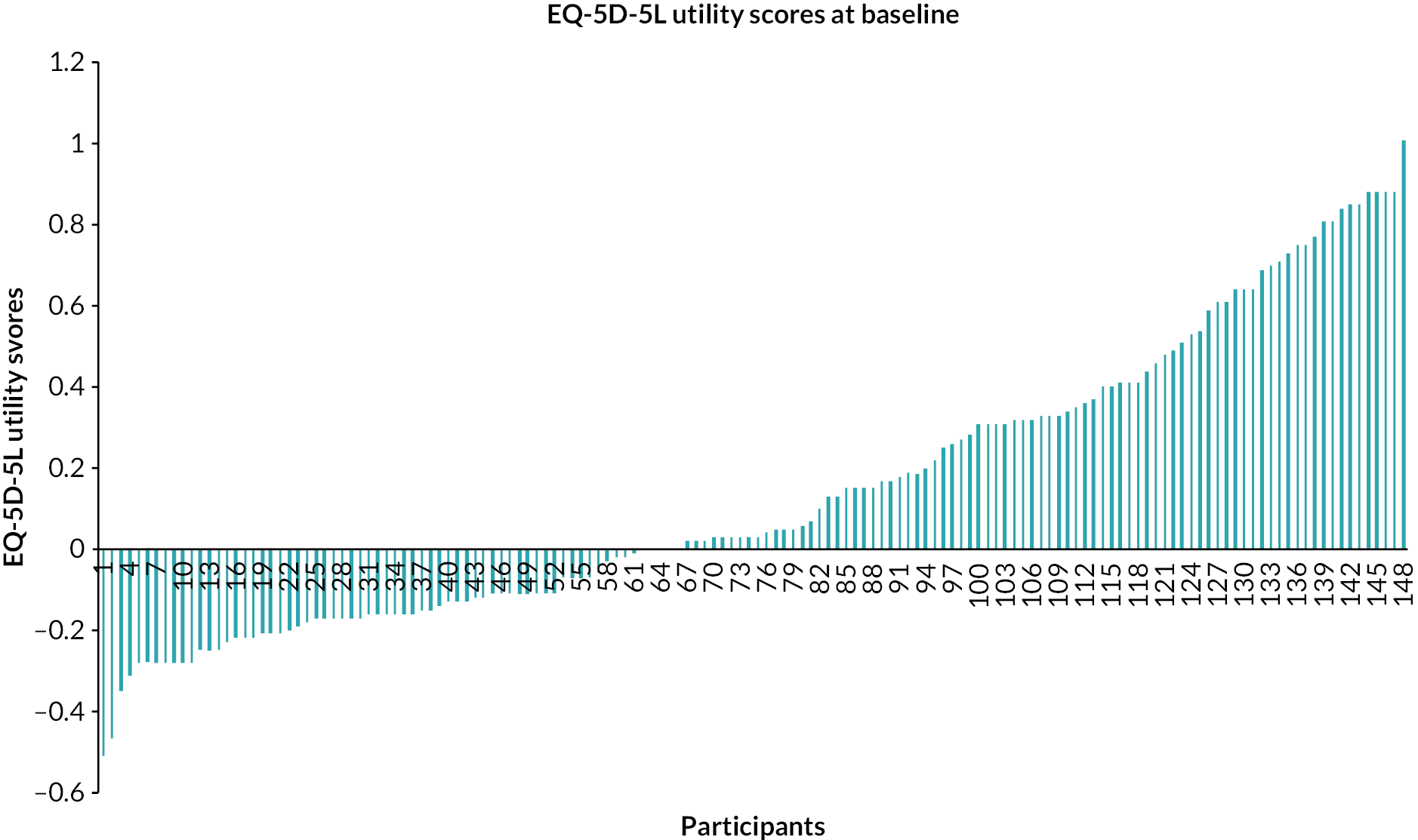

Additional interview questions were developed in collaboration with the health economics team (DMcD, A-LP) to inform economic modelling work in WP6. Participants were asked to complete the EQ5D quality-of-life measure72 at the end of their baseline and follow-up interview.

Clinical staff

Semistructured interviews with crisis care pathway staff explored their experiences and understandings of acute mental health crisis, expectations of the purpose and function of PDUs, the decision-making process and reasons for referral to PDU, who they refer to PDU and why, and their view on the impact PDUs. Interviews with PDU staff explored staff perceptions of the purpose and function of PDUs, appropriateness of referrals from other services, how referrals were assessed and the unit gate kept, experiences of working on the unit, balance of assessment/therapeutic intervention, how supported they felt in their role, decision-making around discharge and onward referral and signposting to other services, and their view on the impact of PDUs. Both clinical and PDU staff were asked about changes to crisis care due to COVID-19. Interview schedules were coproduced in another workshop with service user researchers and the LEAP (see Appendix 3).

Data analysis

Data were analysed thematically73 using a hybrid inductive and deductive approach to integrate both ‘theory-driven’ codes (i.e. a sensitivity to those phenomena that we might expect) and data-driven codes that articulate the idiosyncratic and unexpected in our data). 74 Output from qualitative analyses will be both descriptive, providing a detailed account of the crisis care pathway and PDU, and explanatory, seeking to understand the expectations and experiences of different groups of service users and staff, and the potential impact of differences on the functioning and outcomes of units.

We adopted an approach to coproducing our analysis, developed by the team in previous NIHR-funded research,48 to ensure that service users’ priorities and concerns were integrated alongside those of clinicians and other academic researchers. In the first stage of the process, service-user researchers on the team undertook preliminary thematic analyses of a small number of baseline service user interviews, presenting emerging thematic areas at an interpretive workshop involving the full research team. Emerging themes were discussed and refined by the team and a provisional coding framework produced. A second round took place remotely using virtual meeting software involving members of the LEAP taking a wider participatory approach to interpreting qualitative data, an approach developed by the team in research exploring mental health and experiences of the COVID-19. 75–77 Following training, members of the LEAP undertook preliminary analyses of staff and service-user follow-up interviews, as did service-user researchers and other members of the team. At a second interpretive workshop, including the LEAP, emerging themes from these additional data sets were discussed, expanding and refining the coding framework. Care was taken not to ‘fit’ data from one set of interviews into codes developed from other interviews, and inductive space was retained in the process so that idiosyncratic data were not discounted. The revised coding framework was used to code the entire qualitative data set using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative analysis software. In the final, writing stage of the analysis process76,77 themes were amalgamated and refined further through discussion by members of the team (KA, HJ, SG).

Health economic analysis

The potential improved outcomes for mental health service users that may be associated with the creation of PDUs as an alternative option to traditional care pathways also have direct implications for resource use and costs. This is both for service users referred to PDUs, as well as broader impacts on local health economies, if there are spill-over benefits associated with implementation. Some previous analyses have indeed suggested that use of PDUs will lead to a reduction in both the number and length of inpatient admissions, as well as reduced attendance at ED, and therefore lead to a reduction in resource use and costs to healthcare systems. 78–81

The overall objective of the economic analysis was therefore to bring together findings from across WPs to identify potential impacts on the local health economy in each study area following the introduction of PDUs. The analysis draws on both the results of the ITS reported in Chapter 4 and the synthetic control study in Chapter 5 for site-specific decision model parameters on changes in area-level acute hospital ED attendances as well as area-level psychiatric hospital admissions (both informal and informal) at a (clinical) population-level following the introduction of PDUs.

As noted in the section on service mapping (see Chapter 3), the ITS provides data on service use over a 4-year period (spanning 2 years prior to and 2 years post PDU implementation) in MHTs and acute hospital EDs in three of the four sites. The synthetic control study (see the section on the systematic review) sought to match and compare mental health admissions and LOS, as well as ED attendances for the mental health and acute trusts in our four study areas with trusts with similar characteristics in areas of England where PDUs have not been implemented.

In addition to ED attendance and psychiatric inpatient admissions, contact with PDUs might be expected to have an impact on the use of community mental health services. Longitudinal cohort data have been used to explore these impacts. The section on the ITS sets out methods used for the cohort analysis undertaken and Chapter 6 describes how, in each of the four study areas, data have been collected on patterns of service contact and utilisation in the 9 months before and after an initial visit to a PDU. We have then estimated changes in resource use and costs to the NHS in the 9 months following a PDU visit for each of the four sites. To inform scenario modelling, regression analyses have been used to identify potential explanatory factors for differences in levels of cost. Selected service user subgroup analyses for costs also reflect different sociodemographic characteristics or factors associated with the use of mental health services.

The primary function of mental services is to improve health outcomes and not just impact on resource use and costs. Although we did not intend to directly look at changes in clinical outcomes, such as levels of mental distress, it has been possible to collect some self-report data on quality-of-life scores, using the EuroQOL EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version) quality-of-life instrument for 148 participants referred to PDUs in two of the study areas, Lincoln and Sheffield. These data have been used to inform scenario modelling to help indicate the potential scope for improving quality of life of PDU service users. This can be useful, given that quality of life is the primary outcome measure used in economic analysis to inform decision-making in England, where judgements are typically concerned with assessing whether the additional costs incurred by a service are justified by quality-of-life gains.

Using these different sources of data chapter describes economic impact and the return on investment (RoI), from an NHS perspective, in each of the different study site areas. This compares the costs associated with PDU implementation with any subsequent cost offsets as well as additional costs incurred. Our service mapping review (see Chapter 3), where the resources required to implement PDUs in the different areas have been collected,82 has been used to estimate the costs of providing PDU services in each site; this review can also be used to explore the budgetary cost of expanding provision in England. In addition, we also look at impacts an individual service user level, scenarios that reflect the experiences of service users in qualitative analysis (see Chapter 7) have also been used to describe some potential individual journeys along service use pathways.

For all analyses costs are reported in 2019–20 prices, with costs for acute hospital-based contacts and specialists CMHTs taken from national reference cost. 83 Costs for psychiatric inpatient stays, as well as hourly costs for some additional community and hospital-based staff costs, are taken from the annual Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. 84 These staff costs estimate hourly costs using mean full-time equivalent basic salary for Agenda for Change (AfC) bands 4–9 of the April 2019 to March 2020 NHS staff earnings estimates. These estimates include salary overheads and other oncosts, including training, office, travel/transport, general supplies and utilities such as water, gas and electricity, as well as a share of capital overheads. The costs associated with PDUs have been estimated by applying these national salary costs to information provided by participating site area trust on the configuration of their PDU services, as well as previous publications that have estimated the costs of PDU (or similar) service provision. Discounting is not applied in this analysis, as only costs for up to 12 months are included.

Data synthesis

Synthesis of data from across WPs and across sites was conducted to critically appraise findings from the separate WPs, to provide insight into optimal configuration of PDUs in relation to the wider crisis care pathway and to inform potential future upscale and roll out of PDUs nationally. Data synthesis adopted a critical interpretive synthesis approach, as has been widely applied to the synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence in systematic reviews85 and the development of evidence-based practice. 86,87 In this approach, ‘constructs’ are derived from the various analyses (i.e. from descriptive analysis or hypothesis testing of quantitative data and thematic analysis of qualitative data) and mapped to an integrative grid that explores how those analyses interface. This enables the development of ‘synthesising arguments’ (analytical narrative) that offer explanatory insight into findings and inform applied learning from the research. An interpretive workshop involving members of the research team and LEAP was held to ensure that service user views and experiences informed this process alongside clinical and academic perspectives.

Following the workshop, a provisional set of constructs was specified, derived from preliminary findings from WP2–5. These constructs were further refined through discussion in the investigator team as we completed our analyses. The final data synthesis is presented in Chapter 9 and, together with our health economic analysis, provides the basis of our implications for policy and practice.

Changes from the proposal

The impact of COVID-19

As described for the cohort study above, follow-up to the WP4 cohort study began as lockdown measures were introduced, with many mental health services either closed or provided remotely during this period. 88 Recruitment of a retrospective pre-pandemic cohort to enable us to consider the impact of COVID-19 on crisis care is specified above. In addition, we were unable to access data on participant service use for the WP4 cohort study using the clinical record interactive system system at two of our sites, as site business intelligence staff were diverted to COVID-related work and the system was not updated as a result. Instead, we obtained pseudonymised data from all first-time attendees at PDUs directly from patient record at all sites.

Finally, working with our LEAP, we added questions specific to the impact of COVID-19 to WP5 qualitative interview schedules for both service user follow-up and staff interviews. Note that the 2-year period following the opening of the PDU had been completed prior to lockdown beginning in March 2020 for three of our four sites (Sheffield was the exception), so we did not change the design of the WP2 ITS or WP3 synthetic control studies. Amendments to NHS ethical approval were obtained for all changes detailed above.

Qualitative interviews at the Birmingham site

Birmingham was added as a fourth site at the funding stage of the research process in those WPs that involved routinely collected data only so as not to impact on the feasibility of undertaking the research within the proposed cost envelope. As such the original protocol did not include Birmingham in the WP5 qualitative interview study. It became apparent that the Birmingham PDU had a shorter typical LOS than our other sites. As we had identified LOS as a key variable in PDU configuration, we felt that we needed to include Birmingham in WP5 to better understand how the model worked and was experienced. An extension to the study was funded, and amendment of NHS ethical approval obtained that allowed us to collect a data set of staff and service user interviews at one time point.

Access to data

There were a small number of deviations from the methods described in the published protocol,60 primarily arising from the use of reduced datasets where availability was limited in WPs 2 and 3 (ITS and SC study). This resulted in a reduced set of outcomes in some sites in some WPs. Details are given within WPs and limitations on the study as a whole considered in the section on strengths and limitations.

Chapter 3 Service mapping and systematic review

Service mapping

A copy of the survey questionnaire has been published elsewhere. 82 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution licence 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. The text and Tables 5 and 6 below include minor additions and formatting changes to the original. Survey responses were obtained from 50 of 53 NHS trusts with a relevant remit (94% response rate). The survey was completed by FOI officers, acute care pathway leads, service directors and lead nurses.

| Theme | PDU characteristic | n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PDU setting | Psychiatric hospital | 6/6 (100) |

| Acute hospital | 1/6 (17)a | |

| Co-located with place of safety (section 136 suite)b | 5/6 (83) | |

| Trust-wide aim of service | Reduce presentations at ED | 4/6 (67) |

| Reduce ED breaches | 3/6 (50) | |

| Reduce inpatient admissions | 3/6 (50) | |

| Reduce out-of-area beds | 1/6 (17) | |

| Improve patient experience | 1/6 (17) | |

| Two or more aims | 5/6 (83) | |

| PDU environment | Overnight stays | 6/6 (100) |

| Recliners rather than beds | 6/6 (100) | |

| Partitioned areas | 6/6 (100) | |

| Maximum hours of stay | 12 hours | 2/6 (33) |

| 23 hours | 1/6 (17) | |

| 2 days | 2/6 (33) | |

| 3 days | 1/6 (17) | |

| Referral/entry to unit | Voluntary admissions only | 6/6 (100) |

| Liaison psychiatry | 6/6 (100) | |

| CRHT team | 5/6 (83) | |

| Street triage | 5/6 (83) | |

| CMHT | 2/6 (33) | |

| GP | 1/6 (17) | |

| Third or voluntary sector services | 1/6 (17) | |

| Police | 1/6 (17) | |

| Self-referral | 0/6 (0) | |

| Self-referral if included in crisis care plan (also known as joint crisis plan), a plan developed between service users and their clinical teams, typically for service users who experience crisis frequently. | 1/6 (17) | |

| Approved mental health professional | 1/6 (17) | |

| Activity on unit | Primarily assessment | 1/6 (17) |

| Primarily therapeutic input | 1/6 (17) | |

| Both assessment and therapeutic input | 4/6 (67) | |

| Capacity and duration of stay | Mean (SD), range (N) | |

| Capacity | 5.6 (1.4), 4–8 (6) | |

| Average LOS on unit (hours) | 25.3 (18.4), 8–48 (6) |

| Role (NHS pay band) | Sites including role in staff team |

|---|---|

| Nurse (band 6), n (%) | 6 (100) |

| Nurse (band 5), n (%) | 1 (17) |

| Healthcare assistant (band 3), n (%) | 4 (67) |

| Healthcare assistant (band 2), n (%) | 1 (17) |

| Administrative support (band 4), n (%) | 3 (50) |

| Administrative support (band 3), n (%) | 1 (17) |

| Psychiatrist; part time, n (%) | 6 (100) |

| Staff on shift; nurses and healthcare assistants: | |

| Day shift, mean (SD), range | 1.7 (0.31), 1–3 |

| Night shift, mean (SD), range | 1.7 (0.31), 1–3 |

| Staff : patient ratio; nurses and healthcare assistants: | |

| Day shift, ratio (SD), range | 1 : 21 (1.2), 1 : 1 to 1 : 4 |

| Night shift, ratio (SD), range | 1 : 2.3 (1.2), 1 : 1 to 1 : 4 |

PDUs were present in a relatively small number of trusts, six (12% of trusts), with a further two planned but yet to open. 82 The locations of the trusts that had a PDU were Sheffield, Lincolnshire, Birmingham, Coventry and Warwickshire, South West London and Sussex. Of the PDUs planned, one would be in Nottinghamshire and one serving Rotherham, Doncaster and South Humber. Four decommissioned PDUs were identified – one in Leeds and three in Lancashire. Of the decommissioned PDUs, the unit in Leeds had operated with ward status and so staff had been unable to refer patients onward for inpatient care. This meant a protracted LOS for some in what was designed to be a short-stay unit with communal sleeping areas. Of the Lancashire units, one received an unfavourable quality report due to lengthy patient stays and dissatisfaction with unit layout and sleeping arrangements. 89 The Lancashire trust repurposed units as crisis assessment spaces without overnight stays.

All six PDUs were located on the mental health NHS trust site (see Table 5), although one of those was in a shared site by the MHT and the acute hospital. In five of six sites, the PDU was co-located with the trust’s place of safety (Section 136 facility). The majority of units were designed to reduce pressure on EDs, and half were designed to reduce inpatient admissions. Two PDUs had addition aims to reduce out-of-area placements and improve the patient experience. All PDUs facilitated overnight stays, with partitioned areas for sleeping in recliners rather than beds, and had a capacity of four to eight service users. All units only accepted voluntary patients. The majority of PDUs aimed to deliver both assessment and therapeutic input (four of six). All PDUs accepted referrals from liaison psychiatry, with the majority accepting referrals from CRHT teams and street triage (an outreach service run by the police and mental health services). However, substantial heterogeneity of pathways was also identified: referrals from third or voluntary sector services, police, general practitioner, approved mental health professional or self-referral when included in crisis care plan, were each only available at one trust. 82

PDUs had a high staff-to-patient ratio. In the day, the mean staff-to-patient ratio for nurses and HCAs combined was 1 : 2.1 [standard deviation (SD = 1.2)], rising at night to a mean of 1 : 2.3 (SD = 1.2). Staffing includes some allocated staff time from psychiatry (see Table 6). Although all units have a high staff-to-patient ratio, a sizeable difference was observed; units ranged from 1 : 1 staffing to 1 : 4 staffing. 83

Survey findings indicate that trusts with a PDU were approximately twice as likely than trusts without a PDU to have several crisis services, including crisis houses, crisis cafes or crisis drop-in services and acute day units (see Table 7). About half of trusts have hospital-based assessment services without overnight stays, and this is the same whether a trust has a PDU or not. The percentage of trusts with short-stay assessment wards was similar across trusts which have and do not have a PDU. 82

| Components of crisis care pathway | Trusts nationally, n/N (%) | Trusts with PDU, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PDU | 6/50 (12) | – |

| Community-based assessment servicea | 50/50 (100) | 6/6 (100) |

| Hospital-based assessment service without overnight staysb | 23/50 (46) | 3/6 (50) |

| Street triage servicec | 29/50 (58) | 5/6 (83) |

| Sanctuary/crisis caféd/crisis drop-in service | 18/50 (36) | 4/6 (66) |

| Crisis house(s)e | 17/50 (34) | 4/6 (66) |

| Acute day unit | 7/50 (14) | 2/6 (33) |

| Crisis family placements | 1/50 (2) | 0/6 (0) |

| Short-stay assessment wards | ||

| Triage or short-stay assessment ward | 13/50 (26) | 1/6 (17) |

| Maximum length of stay on triage or short-stay assessment ward | ||

| 1–7 days | 4/13 (31) | – |

| > 7 days | 9/13 (69) | – |

| Number of triage/short-stay assessment wards at trust | ||

| 1 | 7/13 (54) | – |

| 2 | 5/13 (38) | – |

| 3 | 1/13 (8) | – |

| Number of triage/short-stay assessment beds at trust | ||

| < 10 | 3/13 (23) | – |

| 10–19 | 5/13 (38) | – |

| ≥ 20 | 5/13 (38) | – |

Systematic review

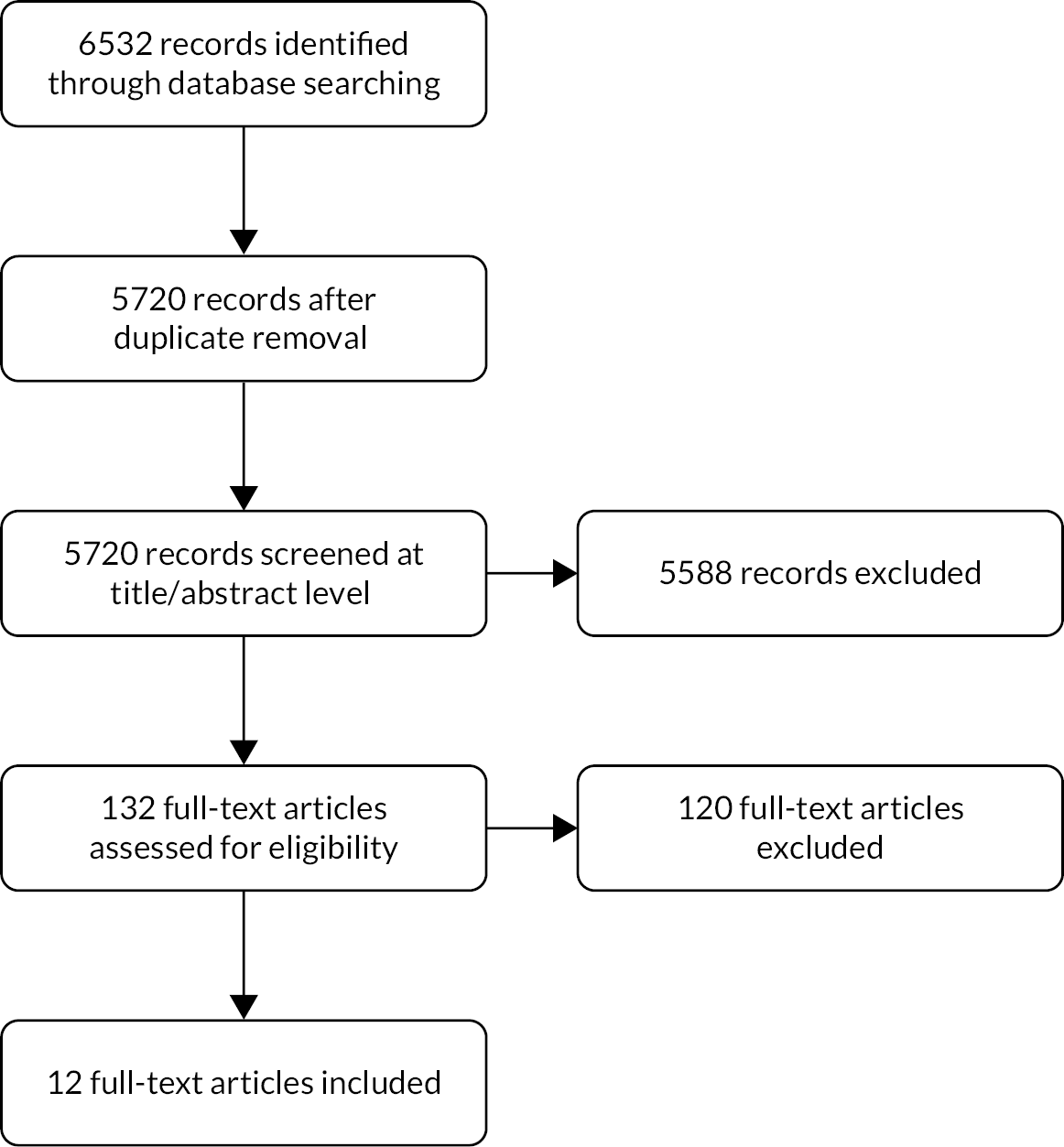

Twelve studies were included in the review. Figure 3 depicts the flow of information through the review. Study characteristics and further information regarding units evaluated in included studies can be seen in Table 8 and in Appendix 1, Table 33.

FIGURE 3.

Selection of studies for inclusion in systematic review.

| Study reference | Service description | Study design and duration | Setting | Participants | Outcomesa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Comparison | N (alternative n/comparison n) | |||||

| Braitberg et al.40 | 24-hour BAU | Pre/post study; 2-year comparison period | Australia, Royal Melbourne Hospital; 72,000 ED presentations per annum | Adults admitted to the BAU; no patients with a medical diagnosis | Adults aged 16+ years ED presentations with LOS 3–24 hours, diagnosis coded as MH issue, psychosocial crisis or related to intoxication | n = 5426 (2379/3047) | ED LOS; time to ED clinician; time to EMH clinician; ED security (‘code grey’) rates; ED restrictive intervention rates |

| Browne et al.91 | 48-hour PAPU | Pre/post study; multiple comparison periods | Australia, Royal Melbourne Hospital | All ED patients; no transfers from other EDs or other psychiatric catchment areas | All ED patients; no transfers from other EDs or other psychiatric catchment areas | Not reported | ED LOS Long waits in ED; ED security (‘code grey’) rates; ED mechanical restraint rates; ED 1 : 1 nursing time; ED 1 : 1 nursing cost |

| Gillig et al.92 | 24-hour extended evaluation unit | Comparison study; 2.5-week (intervention)/4-week comparison period; 30-day follow-up for intervention | Louisville, Ohio (intervention); Cincinnati, Ohio (comparison). Ohio Valley urban area, 600 patient visits per month | Adults aged 18+ years attending the PES | Adults aged 18+ years attending the PES | n = 783 (435/348) | Hospitalisation rates from ED; inpatient admissions (from ED & unit); hypothetical hospitalisations |

| Kealey-Bateman et al.93 | 72-hour joint SSU and Missenden assessment | Comparison study; 18-month (intervention)/unknown comparison period | Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, inner-city Sydney | Patients admitted to the SSU via ED | Patients admitted to a PECC | Not reported | Admission to unit via ED |

| Lester et al.94 | 48-hour CALM service | Pre/post study; 1-year comparison period; 30-day follow-up | USA, Ohio; 72,000 annual ED visits, ~7% for behavioural health complaints | ED patients who received a psychiatric consult | ED patients who received a psychiatric consult | n = 4598 (2387/2211) | ED LOS; hospital LOS; psychiatric hospitalisation rate; admission to unit via ED; discharged from ED; 30-day readmission rate; unit LOS |

| Mok and Walker95 | 3-day SSU | Comparison study; 8-month comparison period | Canada, metro Halifax | Patients admitted to the regular-stay unit | Patients admitted to regular-stay unit | n = not reported (124/not reported) | Ward occupancy rates |