Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HSDR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/138/31. The contractual start date was in March 2021. The final report began editorial review in October 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Sidhu et al. This work was produced by Sidhu et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Sidhu et al.

Chapter 1 Background, context and objectives

The key points of Chapter 1 are summarised in Box 1.

-

There are over 15,000 care homes in England, with an estimated combined capacity of approximately 450,000 beds and an average of slightly under 30 residents per home. Care homes in England employ an estimated 600,000 staff.

-

The majority of the care home resident population are older adults who have multiple long-term health conditions, and approximately 40% of the total care home population receive specialist dementia care. Care homes also provide accommodation and care for people with physical or learning disabilities of all ages.

-

During the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency procedures were introduced to free up bed capacity in NHS secondary care, including discharging some patients into care homes.

-

The NHS has included support for care homes in The NHS Long Term Plan,1 and this has been accompanied by development of the EHCH model. The EHCH model stipulates that all care homes should be aligned with a named PCN.

-

Although pulse oximeters may have been previously available in some nursing homes, there is evidence that increased and wider use of pulse oximetry in care home settings has been prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

We carried out a mixed-methods evaluation, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, to understand the current level of use of pulse oximetry in the care home sector and the associated support provided to care homes.

EHCH, enhanced health in care homes; PCN, primary care network.

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced with permission from the following sources:

-

The King’s Fund. 2 [This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.]

-

Care Provider Alliance. 3 [This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text where cited.]

-

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). 4

-

Wessex Academic Health Science Network. 5

-

Keith et al. 6 [This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.]

-

The Health Foundation. 7

The study reported here is an extension to a concurrent evaluation of remote home monitoring models during the COVID-19 pandemic in England (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Box A). We begin the report by providing a short overview of adult social care and the care home sector in England.

Adult social care and the care home sector in England

According to The King’s Fund,2 adult social care covers a wide range of activities to support individuals who are older and frail, and living with a physical or mental impairment, to live independent lives. The King’s Fund2 states that adult social care includes ‘personal care’ (e.g. washing, dressing, social engagement) and ‘social care’ to allow people to live independently in their own homes, which may include sharing information and advice, as well as additional support for family carers. Social care can be both ‘short term’ (encouraging independence with limited need for ongoing support) and ‘long term’ (ongoing support in the form of nursing of community-embedded help), and is provided by local authorities using a range of health professionals.

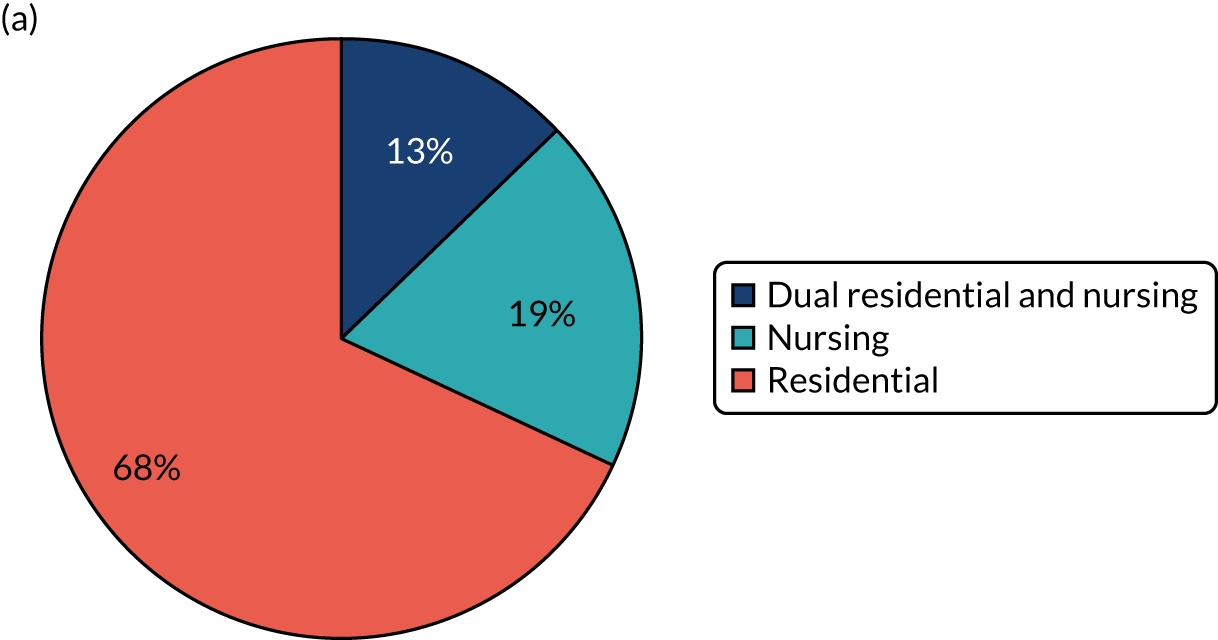

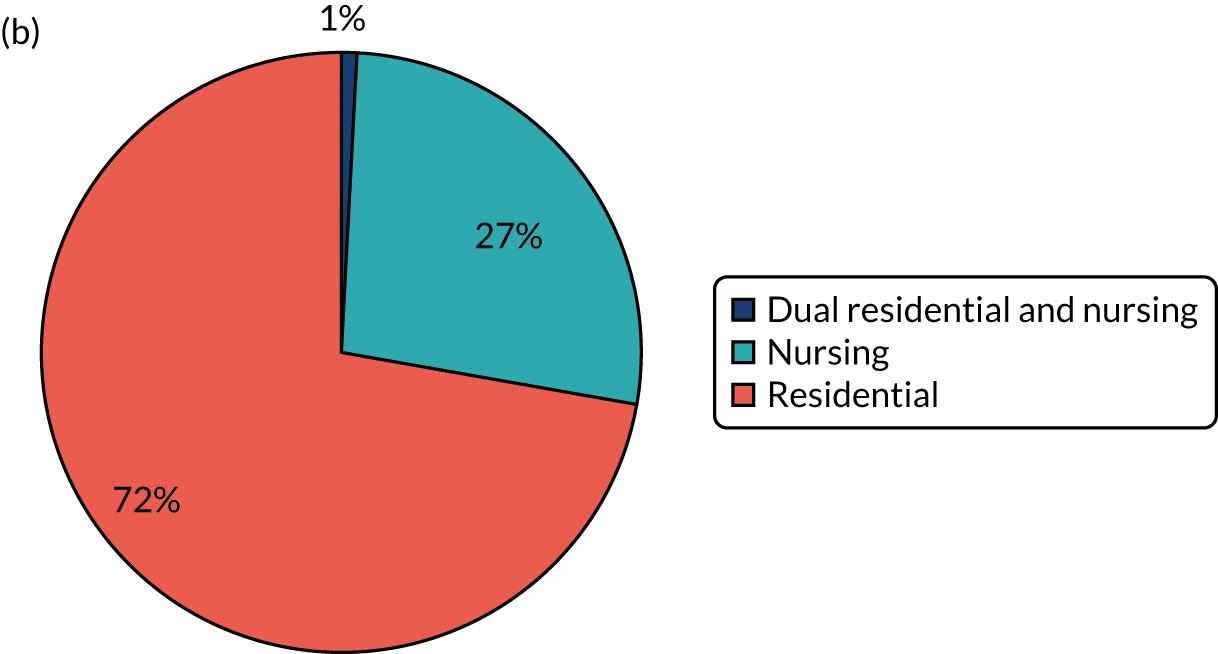

Most publicly funded social care in England is available only to people with the highest needs and lowest assets (currently under review by the UK government). People with assets worth more than £23,250 are normally ineligible (in the case of residential care, this figure includes the value of a person’s property if they have one). 2 Local authorities are responsible for assessing people’s needs for publicly funded social care, which may also involve weekly top-up fees. Everyone else (i.e. people who do not qualify for publicly funded social care) must fund their own care, including places in care homes. In addition, housing-based services (e.g. extra care housing) in the form direct payments are a funding choice in personal budgets. Direct payments allow individuals to purchase their own care and support services, with the aim of maximising their involvement and control over how their needs are met. 8,9 Most social care services are delivered by independent domiciliary care and residential care providers, which are mainly for-profit companies, but also include some not-for-profit, voluntary sector organisations. In England, on 18 May 2021, there were 15,362 care homes registered with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) (London, UK). [The CQC registration data are live data, and they are available from the CQC website (URL: www.cqc.org.uk/about-us/transparency/using-cqc-data). The numbers reported here are from data downloaded on the 18 May 2021.] Just over one-quarter (27%) of these care homes are nursing homes, meaning that they have qualified nursing staff on site at all times. Seventy-two per cent of care homes are residential homes (i.e. without nursing staff) and 1% of care homes are dual residential and nursing. The total bed capacity of these care homes is approximately 450,000, implying an average capacity of just under 30 beds per home. Many care homes are parts of chains that have multiple individual sites. The six largest care home providers combined account for 11% of all UK care homes and 17% of UK care home beds. 10 Yet, despite the growth of care home chains, one-third of providers are businesses of one or two care homes, and almost 10% of the care home population in England are wholly funded by the NHS as continuing care recipients. 11 Long-term conditions, many of which linked to ageing, are all prevalent in the resident population of care homes, including arthritis, cancer, chronic heart disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, hypertension, respiratory disorders, stroke, cognitive impairment (not dementia) and hearing and vision loss. 12 At present, only 40% of long-term care providers offer specialist dementia care, despite 70% of older care home residents having cognitive loss/dementia. 12 Hence, the population living in care homes in England has a unique set of needs, and this directly affects who is responsible for assessment and how residents’ needs are recognised, communicated and documented.

English residential care homes facilities employ approximately 600,000 staff, of whom 85% are women. 13 The estimated annual turnover of directly employed staff working in the adult social care sector (which is broader than care home staff alone, but includes care home staff) is high. In 2019/20, the estimated annual turnover rate was 30.4%, meaning that at the end of the financial year nearly one-third of the staff had moved on from the employer they were with at the start of the financial year. Staff vacancy rates are also considerable, and it was estimated that in 2019/20 a total of 7.3% of roles in adult social care were vacant. 13

Providers of care homes are inevitably subject to financial pressures. Since 2015, the CQC has overseen the financial sustainability of around 65 difficult-to-replace care providers, representing around 30% of the overall care market by number of beds. 14 In addition, some providers with a sizeable regional or local presence may not be subject to the CQC’s oversight, but their failure would have a significant impact on the number of care home places available. In 2017, the Competition and Markets Authority (London, UK) concluded that care homes primarily accepting local authority-funded residents were unlikely to be sustainable at the rates local authorities paid. 11 Considering that 46% of care home residents in independent care homes were estimated to have received some form of state funding in 2018, this is a significant proportion of the sector. 10,11 Furthermore, the CQC’s State of Care 2019/20 report15 noted that many care homes were relying on higher prices for self-funders to remain viable (i.e. self-funders were subsidising publicly funded residents). 16

Challenges experienced by care homes in England during the COVID-19 pandemic

A survey of 9000 care homes in England found that 56% of the care homes had experienced at least one case of COVID-19 by July 2020. 17 Coronavirus was mentioned on the death certificate of 19,286 care home residents who died between mid-March and mid-June 2020. During the second wave of the pandemic (i.e. between 31 October 2020 and 5 February 2021), there were 16,355 COVID-19-related deaths registered among people in care homes. 18 Overall, during the first two waves of the pandemic in England, there was evidence to report that one-third of residents and one-quarter of care home staff had a COVID-19 infection. 19

The care homes sector also reported an increased demand for hospital discharge beds to support COVID-19 patients with high levels of dependence and acuity who, under other circumstances, would have been discharged to their own homes, following National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines. 20 Notably, patient discharge from acute hospitals to care homes during the pandemic came under scrutiny. Many patients were discharged without having been tested for COVID-19 or having tested positive, or care homes were not notified of test results. 21 As a result, after negative reactions from the care home sector, residents’ families and some clinicians, official guidance from Public Health England (London, UK), NHS England (London, UK) and the Department of Health and Social Care (London, UK), in April 2020, abandoned the previous approach of rapid discharge of hospital patients to care homes without waiting for test results. 22

A survey of nearly 300 social care staff carried out in July 2020 found that staff felt that their job had left them feeling ‘tense, uneasy or worried’ more often since the onset of COVID-19. 12 In addition, a Queen’s Nursing Institute (2020) survey found that care home staff felt that their workload had risen since the onset of the pandemic, mainly as a result of covering for colleagues who had to self-isolate or having to train new volunteers. Staff turnover in 2020 was 29.6% in residential care and 36.8% in nursing facilities, indicating significant workforce pressures in both residential care contexts. 23

A report by Healthwatch with care homes in Barnet, north London, found that most care home managers reported that they had coped well during the first wave of the pandemic, although many care home managers noted that it had been an exceptionally stressful and challenging time for staff. 24 Many managers reflected that this was, to some extent, exacerbated by personal protective equipment coming 4 or 5 weeks too late, along with frustrations with accessing COVID-19 testing for staff and residents. The extra costs of personal protective equipment, a reduction in new admissions to care homes and the cost of COVID-19-related staff absences were all identified as key obstacles when dealing with the effects of the pandemic. In addition, care home staff had to accommodate the transition of routine health care for their residents to being predominantly provided digitally, with face-to-face consultations being carried out only if clinically necessary. Despite considerable nuanced learning coming from the Healthwatch report,24 such learning may be specific to the health system and care home network in Barnet, and may not be generalisable to other care home setting across England. Nevertheless, challenges remain, particularly the staffing shortfall in care homes across England (largely as a result of a post-Brexit economy) and the requirement for all care home workers to be fully vaccinated against coronavirus. The King’s Fund’s (2021)25 response to the Health and Social Care Committee report on workforce burnout and resilience in the NHS and social care stated that:

. . . the added pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic has left many staff physically and emotionally drained, but health and care services have been dogged by staff burnout and workforce shortages for many years.

As a result, the pandemic and years of funding shortfalls in social care have left the front-line workforce depleted, demoralised and feeling unvalued. These challenges can, at times, be exacerbated by how fragmented adult social care is, and how complex it is to try to deliver adult social care across many different providers working with NHS partners in different sectors of the economy. According to Skills for Care, an estimated 21,200 organisations (across 41,000 establishments) were involved in providing or organising adult social care in England, ranging from large national employers, large charities and local authority adult social services departments to small independent care services. 13 During the pandemic, policy-makers may have interpreted the term ‘care homes’ generically and not taken full account of local organisational NHS and non-NHS structures.

COVID-19 brought rapid change in hospital discharge, with ongoing concern about its immediate and longer-term consequences. Emergency procedures were introduced to free up beds in secondary care within days, and many patients were discharged to care homes without first being tested for COVID-19. The Public Accounts Committee reported that 25,000 people were discharged from hospital to care homes before the introduction of routine pre-discharge testing in mid-April 2020. 26

The NHS Five Year Forward View stated that the NHS in England was prioritising support for frail older people living in care homes,27 including a commitment to identify what changes were needed, as well as detailed prototyping of new care models of in-reach support (e.g. medical reviews, medication reviews and rehabilitation services). The NHS Long Term Plan1 built on this ambition by recommending that the NHS strengthen its support for the people who live in, and work in and around, care homes, using the enhanced health in care homes (EHCH) model. 3 The model was designed to be equally applicable to homes for people with learning disabilities and/or mental health needs as to care homes for frail older people. The EHCH model incorporates best practice with regard to moving away from reactive models of care delivery towards proactive individualised care. Key features of the EHCH model are described in Box 2.

-

Every care home is aligned to a named PCN.

-

Every care home has a named clinical lead.

-

A weekly ‘home round’ or ‘check-in’ with residents by an appropriate member of care home staff.

-

Within 7 days of re-admission/admission to a care home, a resident should have a person-centred holistic health assessment.

-

Within 7 days of re-admission/admission to a care home, a resident should have in place personalised care and support plan(s).

-

A requirement to prioritise care home residents who would benefit from a structured medication review.

To bring the EHCH service into being, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have played a key role in aligning each eligible care home to an individual PCN. 3 PCNs built on the new ‘vanguard’ models of integrated health care that had been developed as a result of the Five Year Forward View. 27 Smith et al. 4 state that those vanguard models of care entailed pilots of significant integration of general practice and community health services; hospital, mental health, community and primary care; general practice and social care (particularly in providing support to residential care homes); and services focused on particular clinical conditions such as cancer.

In addition, the NHS in England is attempting to train and equip care home staff with necessary tools and skills to monitor the health of residents and to educate staff of when to escalate care. For instance, Recognise early soft signs, Take observations, Respond, Escalate (RESTORE2) is a physical deterioration and escalation tool for residential care/nursing homes based on nationally recognised methodologies. 5 The RESTORE2 tool is designed to support care home staff and health professionals to (1) identify those at risk of physical deterioration, (2) act in accordance with the resident’s care plan, (3) take the necessary physical observations to inform escalation, (4) communicate in a timely manner with health professionals and (5) provide a history of the resident’s escalation history so that they can make appropriate health-care decisions.

Stocker et al. ,28 in a qualitative study, explored the use of a National Early Warning Score (NEWS) intervention in care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that the NEWS tool improved the response of care home staff and health-care professionals to deterioration in residents’ health and that staff felt empowered by the NEWS tool, which provided a common clinical language that they could use to communicate concerns with external services, acting as an adjunct to staff intuition of resident deterioration. In addition, the British Geriatrics Society has emphasised the importance of care home staff having the skills, training and equipment to identify deterioration in residents. 29 However, embedding assessment technology in care homes and enabling care home staff to adequately engage to better identify residents who are deteriorating requires support from the wider health-care system to support scale-up. It remains important for care home staff to have access to trusted NHS professionals who can provide training on how to pick up on ‘soft signs’ (e.g. residents presenting reduced appetite), which, when combined with assessment technology, can lead to more robust decisions regarding escalating care. 30

The application of pulse oximetry during the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes

There is emerging evidence that using pulse oximetry, that is a non-invasive and painless test that measures a person’s blood oxygen saturation level, in community settings can accurately predict outcomes for individuals who have tested positive for COVID-19 with regard to mortality and intensive care unit admission. 28 Risk of severe disease and death from COVID-19 is known to be higher in people who are older and in those with certain underlying health conditions. 31

For nursing homes, pulse oximeters are part of a suite of standard clinical measurements that nursing staff have at their disposal. 32,33 Pulse oximeter usage is not mandated, and the decision to take the measurement is at the discretion of the clinician [e.g. general practitioner (GP) or nurse]. Information about the extent to which pulse oximeters are used in care homes is sparse. Therefore, the project team underwent a scoping process of mapping relevant literature and interviews with key experts to understand the extent of pulse oximetry use in care homes.

Identification of gaps in the literature

Although pulse oximeters may have previously been available in nursing homes, there is evidence that increased and wider use of pulse oximetry in care home settings has been prompted by the pandemic. Yet little is known about the introduction of pulse oximetry in other care home settings (specifically, residential care homes) that cater for a range of residents living with long-term health conditions, including dementia and learning disabilities. Furthermore, there is a paucity of evidence regarding support that the NHS has provided to care homes to administer pulse oximetry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, we carried out a mixed-methods evaluation, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, to understand the current level of use of pulse oximetry in the care home sector and the associated support provided to care homes (Box 3).

-

Oxygen is carried around in your red blood cells by a molecule called haemoglobin. Pulse oximetry measures how much oxygen the haemoglobin in your blood is carrying, and this is called the oxygen saturation and is a percentage (scored out of 100). A pulse oximeter is a small medical device that is put on the tip of the finger to check someone’s oxygen levels.

-

Pulse oximeters are provided to patients as part of the NHS response to COVID-19. The NHS supports people at home and in care homes who have been diagnosed with coronavirus and are most at risk of becoming seriously unwell.

-

Advantages of pulse oximetry include that it is non-invasive and simple and can be used to evaluate trends.

-

Pulse oximetry can help with earlier detection of silent hypoxia, low oxygen levels in the absence of significant shortness of breath, and this can help ensure more timely hospital treatment if required.

-

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, pulse oximetry was used across a range of health-care settings to treat a number of health conditions.

-

During the first wave of the pandemic (between March and September 2020) there were over 30,500 excess deaths of care home residents. A total of 4500 additional deaths of domiciliary care users were also reported, a greater proportional increase in deaths than in care homes (225% vs. 208%).

-

The ability of social care services to deal with the crisis was affected by a severe staff shortage, a care system that is fragmented within complex national and local arrangements and a lack of good-quality data on what is happening in the sector.

Research questions

Following our mapping of the literature and scoping interviews with key experts, the research questions were identified as follows:

-

When and how is pulse oximetry being employed in care homes for managing the health care of residents with COVID-19 and other health conditions?

-

Which care home staff are involved in the set-up, delivery and monitoring of pulse oximetry in care homes?

-

What support are care homes receiving from primary, community and secondary care NHS teams with regard to the use of pulse oximetry, and is that support appropriate? Are there any weaknesses in providing that support that can be rectified?

-

-

What are the perceived benefits to residents (e.g. health-related outcomes, satisfaction with care received, hospital admission avoidance, impact on perceived anxiety) of using pulse oximetry in their care home?

-

What are the experiences of staff using oximetry in care homes, including barriers and enablers, and lessons learnt?

-

What training have care home staff received to deliver pulse oximetry in a range of care home settings?

-

What impact has the use of pulse of oximetry had on the well-being and confidence of care home staff?

-

What are the challenges faced by care home staff in delivering pulse oximetry and associated monitoring?

-

-

What are the views of senior care home staff and managers on the guidance and resource necessary to support and sustain the use of pulse oximetry in care homes?

-

What are the experiences of the primary, community and secondary care health-care staff involved in supporting the use of pulse oximetry in care homes, including, where relevant, as part of the national COVID Oximetry @home (CO@h) service?

The methods adopted for the rapid evaluation are described in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2 Design

The key points of Chapter 2 are summarised in Box 4.

-

We conducted a mixed-methods evaluation, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. The evaluation comprised the following WPs:

-

scoping interviews and engaging with relevant literature, as well as co-designing the study approach and research questions with members from a User Involvement Group (WP1)

-

a national online survey that examines the application of pulse oximetry in care homes (WP2)

-

in-depth interviews at six case study sites (WP3)

-

synthesis, reporting and dissemination of study findings (WP4).

-

-

A survey was distributed to registered managers across 15,362 care homes (i.e. the total number of care homes in England registered with the CQC) to understand current practices regarding the use of pulse oximeters in patients with COVID-19 and other conditions.

-

We carried out semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of stakeholders in six selected (care home) sites. The sites were selected based on the principles of maximum variation and convenience sampling. Our analysis was guided by theoretical frameworks to understand staff engagement and adoption of pulse oximetry in care homes across England.

-

Our analysis was informed by CFIR and the Gale et al. 35 framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multidisciplinary health research. The Gale et al. 35 framework method is a systematic method of categorising and organising data while continuing to make analytical and interpretive choices transparent and auditable.

-

We adopted the ‘following a thread’ approach put forward by O’Cathain et al. ,36,37 whereby synthesis of data takes place at the data analysis stage to identify key themes and data that warrant further analysis.

CFIR, Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research; WP, work package.

Aims of the evaluation

The study was conducted by the Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation Centre (BRACE) and the Rapid Service Evaluation Team (RSET). Both BRACE and RSET have received funding from the NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme for a 5-year research programme that aims to rapidly evaluate health and care service innovations to produce timely findings of national relevance and immediate use to decision-makers. The topic of this report was identified through discussions between the NIHR HSDR programme and NHS England and NHS Improvement’s (NHSE&I’s) (London, UK) CO@h workstream. NHSE&I established a working group, which acted as a Project Steering Group to the evaluation (see Report Supplementary Material 2), to investigate the potential role of using pulse oximetry to support residents in care homes throughout the pandemic.

The rapid evaluation had two distinct aims:

-

To understand how pulse oximetry is used in care homes by care home staff and health-care professionals (including, but not limited to, through remote monitoring services run by NHS), and for which conditions and in which circumstances. The source of pulse oximeters, the nature of staff involved and their experience of using pulse oximeters, the level of training received by care home staff to deliver pulse oximetry and remote monitoring, the recording and storing of data, pathways for monitoring and escalation, and the level of support from primary, secondary and community NHS health-care teams were also considered.

-

To develop an understanding of how the use of pulse oximetry in care homes might be optimised, including an understanding of resources, approaches and activities necessary to sustain the use of pulse oximetry in care homes (e.g. support from national and regional bodies, such as CCGs, NHS trusts and local authorities).

We have carried out a mixed-methods evaluation, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, to understand the current level of use of pulse oximetry in the care home sector and how that use might be optimised and supported in the future. The rapid evaluation comprised the following main steps: (1) scoping and designing the rapid evaluation by carrying out scoping interviews, engaging with the relevant literature and co-designing the study approach and research questions with members from a User Involvement Group (completed as part of a workshop delivered in February 2021); (2) a national, online survey sent to all registered care home managers in England, examining the application of pulse oximetry in care homes; (3) in-depth interviews with managers, staff and primary, community and secondary care providers at six purposively selected case study sites, plus interviews with national policy leads, alongside analysis of data and testing findings with members from a User Involvement Group (completed as part of a workshop delivered in May 2021); and (4) synthesising and reporting the findings and disseminating them to policy-makers, experts, academics and other key stakeholder groups to enable them to share and discuss the findings. These four work packages (WPs) are summarised in Table 1.

| WP | Description and activity | Research question |

|---|---|---|

| WP1: scoping interviews and engaging with the relevant literature, as well as co-designing the study approach and research questions with members of a User Involvement Group (as described in Chapter 1) |

To obtain an overview of the existing evidence on the use of pulse oximetry and remote monitoring in the care home sector and to inform the propositions to be tested through the national survey and interviews Interviews with key NHS leaders, care association directors and care home managers, mapping and engaging with relevant literature, and co-designing the study approach and research questions with a User Involvement Group (online workshop) |

1 (1.1 and 1.2) |

| WP2: a national online survey that examines the application of pulse oximetry in care homes |

A national online survey of care homes exploring the various aspects of pulse oximetry and remote monitoring use in care homes, including analysis of data and testing of findings with members from a User Involvement Group (online workshop) An online survey of all care homes in England on the use of pulse oximetry |

2, 3 (3.1, 3.2 and 3.3) |

| WP3: in-depth interviews at six case study sites | A series of interviews with managers and staff and at six purposively selected care homes, as well as with the NHS staff supporting them, exploring in depth the use of pulse oximetry and remote monitoring. WP3 includes further interviews with national policy experts, alongside analysis of data and testing of findings with members from a User Involvement Group (online workshop) | 2, 3 (3.1, 3.2 and 3.3), 4 and 5 |

| WP4: synthesising and reporting findings and disseminating them to policy-makers, practitioners, managers, academics and other key stakeholder groups to enable them to share and discuss findings |

To share and discuss findings generated from data collection from WP2 and WP3 and to develop recommendations for care homes, commissioners, health-care providers and policy-makers Workshops with NHSE&I’s CO@h and People Receiving Social Care groups |

5 |

We have used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to guide and structure the rapid evaluation. 6 The CFIR is a conceptual framework that was developed to guide systematic assessment of multilevel implementation contexts to identify factors that might influence intervention implementation and effectiveness. The CFIR is well suited to guide rapid evaluation of the implementation of complex health-care delivery interventions because it provides a comprehensive framework to systematically identify factors that may emerge in various multilevel contexts to influence implementation. The five major domains of CFIR are presented in Box 5. The framework was used as a theoretical tool to provide a thread to synthesise, integrate and interpret data, and to present our key learning and findings. 6

-

Intervention characteristics, which are the features of an intervention that might influence implementation. Eight constructs are included in the domain of intervention characteristics (e.g. stakeholders’ perceptions about the relative advantage of implementing the intervention, complexity).

-

Inner setting, which includes features of the implementing organisation that might influence implementation. Twelve constructs are included in inner setting (e.g. implementation climate and leadership engagement).

-

Outer setting, which includes the features of the external context or environment that might influence implementation. Four constructs are included in the outer setting (e.g. external policy and incentives).

-

Characteristics of individuals involved in implementation that might influence implementation. Five constructs are related to characteristics of individuals (e.g. knowledge and beliefs about the intervention).

-

Implementation process, which includes strategies or tactics that might influence implementation. Eight constructs are related to implementation process (e.g. engaging appropriate individuals in the implementation and use of the intervention, reflecting and evaluating).

Reproduced with permission from Keith et al. 6 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Protocol sign-off

The study topic was identified and prioritised for rapid evaluation, with NIHR HSDR senior colleagues working with NHSE&I as part of a call to undertake a rapid evaluation. An initial short pro forma outlining the study aims, methods and outcomes was submitted (January 2021) and, once approved, was used as the basis for writing the full research protocol (February 2021), which drew on scoping interviews with key experts, relevant literature and an online workshop with our User Involvement Group (WP1).

Ethics approval

An application for ethics review to the University of Birmingham’s Research Ethics Committee was made by the project team and approval was gained in March 2021 (reference ERN_13-1085AP40). The project team received confirmation from the Head of Research Governance and Integrity, University of Birmingham, that this study was to be categorised as a service evaluation and, therefore, approval by the Health Research Authority or an NHS Research Ethics Committee was not required. At each of our six case study sites, we approached relevant research and development personnel/care home managers to confirm that all were content for the evaluation to proceed in their care home.

Method

The methods used in each of the evaluation WPs are described below. WPs 1–3 all included working with a User Involvement Group.

Co-designing the study approach and research questions with members from a User Involvement Group

Members of the study team met with a specially convened User Involvement Group. The User Involvement Group consisted of three members who were co-researchers who have either worked on previous care home sector-related studies and/or are currently supporting close family members in a care home (n = 2) and a member of the BRACE Patient and Public Involvement Group (n = 1). The User Involvement Group discussed the ‘what’ questions (e.g. what is important to find out/know about) and the ‘how’ questions (e.g. how best to gather this information). All members of the User Involvement Group took part in two workshops and two members attended a third workshop. 6 A structured agenda was prepared in advance of each workshop and included time for presentation of findings from the review of relevant literature and scoping interviews, as well as time for discussion and feedback when sharing learning from data collected. As part of the first workshop (February 2021), members of the User Involvement Group commented on our research questions, our choice of methods and recruitment strategies and the study’s participant-facing documentation. A second workshop (May 2021) was held to discuss preliminary findings whereby feedback fed into remaining data collection. A third workshop (June 2021) was held to refine interpretation of data and support synthesis of learning across data sets.

Work package 1: scoping interviews and engaging with relevant literature, as well as co-designing the study approach and research questions with members of our User Involvement Group

Members of the study team carried out seven telephone interviews, using a semistructured topic guide informed by the literature and revised iteratively following preliminary interviews with key stakeholders, including key NHS leaders, representatives of national care associations and senior care home managers. The interviews had two purposes: (1) to gather stakeholders’ initial insights and views on the use of pulse oximetry and remote monitoring in care homes and (2) to help define the scope of the work regarding the maturity of the use of pulse oximetry in care homes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the review of the literature (see Description of review strategy for grey literature search and summary of findings from scoping work) and the initial scoping interviews, the research team held a workshop with the Project Steering Group, which comprised members from NHSE&I and from the Care Provider Alliance (which represents most care homes in England). In addition, the research team held a separate event with the User Involvement Group. Both groups suggested that further investigation was required on the feasibility of including residents in the rapid evaluation. During initial evidence searching for this further investigation, a systematic review from 2016 was identified and further engagement with more recent relevant literature was guided by key experts. 38 Concurrently, members of the study team completed telephone/online interviews, again, using a structured topic guide, with a range of key experts (n = 5) with vast experience of working in and/or carrying out research with residents in care facility settings. A summary of key themes and messages from our scoping work can be found in Boxes 6 and 7.

To scope the evaluation, we captured learning from BRACE and RSET’s rapid systematic review in 2021 of remote home monitoring models set up during the COVID-19 pandemic38 and performed an additional evidence review of grey literature identified in the 12 months between January 2020 and January 2021, following principles outlined by Munn et al. 39 Grey literature is non-academic literature that is published in sources such as reports and/or working papers from policy groups or committees. 38,40,41 The full details of the evidence mapping are given in the following sections and Boxes 6 and 7.

As part of the scoping phase of the project, the study team engaged with relevant literature to:

-

collate published literature, including grey literature (i.e. research that is either unpublished or has been published in non-academic form), using a selective systematic approach to searching on the use of pulse oximetry and remote monitoring in care homes in the England

-

provide a descriptive summary of our findings

-

inform our study design, research questions and methods.

Description of review strategy for grey literature search and summary of findings from scoping work

The evidence review strategy included grey literature identified in the 12 months between January 2020 and January 2021, using the search terms ‘remote monitoring’ OR ‘oximetry’ AND ‘Covid-19’ (including synonyms) AND ‘Care home’ (including synonyms).

The search was performed by the HSMC Knowledge and Evidence Service at the University of Birmingham on 21 January 2021. The search used the Health Management and Policy database, from the Healthcare Management Information Consortium, and Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The search was re-run on 27 January 2022 to identify any new literature (identifying one additional publication).

Material was considered eligible if it detailed the use of oximetry and/or remote monitoring in a care home setting during the COVID-19 pandemic or in the 12 months prior. Seventy-nine sources were identified (excluding three duplicate sources), of which 63 items were reviewed. These sources were all reviewed by one member of the research team (JRT), with learning shared during weekly team meetings, allowing input from all authors. Sources included a variety of media, including newspapers, guidance, evaluation plans and product videos focusing on care homes for older adults, with none sources mentioning other types of care homes, such as homes for people with sensory or learning disabilities. In addition, the search identified a variety of supportive guidance from NHSE&I, NHS Digital (Leeds, UK), NHSX (London, UK), Public Health England, the Local Government Association (London, UK) and the British Geriatric Society (London, UK). Data from sources were extracted using a thematic framework, which was shaped by early evaluation research questions and was iteratively updated alongside learning captured from scoping interviews completed as part of WP1. A subteam of authors (JRT, JB, IL and MS) came together as part of an online meeting to identify cross-cutting themes from both scoping interviews (n = 7) and mapping of the relevant literature and agreed final themes.

Box 6 summarises what we found from the scoping work.

-

Variation in the care home sector, with nursing and residential homes having different skill sets in the use and interpretation of pulse oximetry.

-

Localised variation in IT infrastructure and networks of relationships with the NHS (across primary, secondary and community care).

-

Workload changes as a result of the pandemic and also due to pulse oximetry accompanying other elements of service change, such as new IT systems, which were likely to have an impact on staff perception of pulse oximetry as a tool generally.

-

Some expert interviewees felt that the CO@h programme was well advertised to the care home sector; however, some interviewees from the care sector remained unaware.

-

The comfort and understanding of residents with pulse oximetry was variable and dependent on pre-existing conditions, such as dementia and familiarity with health technology.

-

IT, information technology.

Inner and outer settings: considerations for care homes when introducing pulse oximetry

Interviews with key experts indicated that there was a great deal of variation in the care home sector, with nursing and residential homes having different skill sets in the use and interpretation of pulse oximetry, with care home staff varying in their familiarity with administering pulse oximetry to a range of residents living with long-term conditions, including dementia. Within care homes, staff undertaking routine measurements were likely to be senior, but pulse oximetry was perceived as a form of monitoring accessible by any member of staff. The issue of localised variation in information technology (IT) infrastructure and networks of relationships between care homes and the NHS (across primary, secondary and community care) was raised, and many of the staff interviewed felt that there should be a better and more nuanced understanding of how care homes operate across different regions in England. Notably, information on care home relationships with local general practices, PCNs, CCGs and acute hospital trusts was limited; however, there was mention of tools to support appropriate escalation by interviewees for care home residents [e.g. National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) and RESTORE241]. In addition, one study mentioned that decisions by central government can result in resource constraints and additional work and, consequently, sometimes impair the ability of care home staff and managers to make decisions regarding the care of their residents. 42

Characteristics of individuals involved in the administration of pulse oximetry

Admissions to hospital of care home residents decreased substantially during the pandemic, with 11,800 fewer admissions during March and April in 2020 than in previous years. In addition, there were numerous reports of a reluctance among GP, ambulance and hospital staff to accept care home residents as patients during the pandemic. 7 Expert interviewees highlighted workload changes as a result of the pandemic and the introduction of pulse oximetry accompanying other elements of service change, such as new IT systems. These factors were likely to have an impact on staff perception of pulse oximetry as a tool generally. Concern for staff working across care home settings throughout the pandemic was voiced by a number of staff interviewed, and it was clear that the ability of care home staff to engage with programmes like CO@h was likely to be compromised as a result of increased workload and pressure, especially during the first wave of the pandemic.

The implementation process, relative advantages and sustainability of remote monitoring and pulse oximetry in care homes

Remote monitoring was mediated in a variety of ways, including via online platforms, paper-based systems with telephone calls or (less frequently) through wearable sensors. Remote monitoring models based on telephone calls were considered more inclusive than paper-based systems alone. 38

Which care home staff members took readings and how they were submitted to NHS contacts varied between systems and care home type, as did the type of training available for staff using pulse oximetry with residents. Some care home staff were described as having low skill and confidence levels and were, therefore, nervous of using new devices. Developing these skills was identified as key to utilising new technologies to reduce infection transmission risk. 20 Some expert interviewees felt that the CO@h programme was well advertised to the care home sector and was being locally adapted to account for differing clinical pathways for residents; however, some interviewees from the care sector remained unaware. Some care homes may be benefiting from the programme, but associate the programme with wider support services from their GP, PCN, CCG or initiatives derived from the EHCH programme, rather than knowing it as the CO@h programme.

Some interviewees mentioned the benefits of using pulse oximetry to manage conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or to manage frail patients near the end of life. Expert interviewees also highlighted that the level of care home residents’ comfort with, and understanding of, pulse oximetry was variable and dependent on pre-existing conditions, such as dementia, and on familiarity with health technology.

Exploration of including data collection with care home residents

Following a review of relevant literature and interviews with experts, the project team found that research with care home residents would require significant support from care home staff, social workers and/or family members to help the resident understand the purpose of the research and to help make clear to the researcher what might be meant by the resident (i.e. communicating resident experiences as the resident intends as best as possible), as well as requiring informed consent. It would have been time-consuming and problematic to obtain such support during the pandemic. Box 7 summarises the key challenges and issues in collecting data from care home residents.

-

The use of pulse oximeters is often accompanied by the use of other physiological monitoring methods. Therefore, separating the use of pulse oximeters specifically from the wider experience of care home resident monitoring may miss the wider context of care in these unique environments.

-

Residents’ capacity to share their views and recall their experiences may be a challenge across some groups of residents who encounter greater difficulty around memory and recall, as well as capacity to consent.

-

Residents’ capacity to be involved and provide consent could vary from day to day. In addition, many residents have sensory impairments (visual/hearing) and and/or speech impairments that would make it difficult to collect data remotely.

-

Among residents with cognitive issues, periods of lucidity can be irregular and, therefore, flexibility and more elapsed time needs to be built into the research process. 43

-

In the COVID-19 era, care homes require all visitors, including researchers, to be fully vaccinated and tested. In addition, each participating home needs to invest significant time in encouraging resident participation.

-

Interviews would be possible, but could be subject to significant bias if family members and care home staff were facilitating conversations or answering questions on behalf of their relative/resident without first relaying questions.

It was agreed by the project team and the Project Steering Group (see Work package 1: scoping interviews and engaging with relevant literature, as well as co-designing the study approach and research questions with members of our User Involvement Group) that a rapid evaluation could not address the main knowledge gaps with regard to capturing the experience of care home residents.

In addition, members of the study team established a Project Steering Group. This was made up of senior policy leads at NHSE&I, policy directors from two national care associations (part of the Care Provider Alliance) who have supported the identification of research evidence, and key experts related to the use of pulse oximetry and remote monitoring in care homes. A descriptive summary of the findings was provided to the Project Steering Group for comment and discussion. In addition, the project team set up a workshop with the project-specific User Involvement Group (see Co-designing the study approach and research questions with members from a User Involvement Group). The workshop was held in March 2021, and at this workshop it was agreed that further scoping on the involvement of residents in the evaluation of pulse oximetry in care homes was required.

Work package 2: national survey of care homes

The main objective of the survey was to understand current practices relating to the use of pulse oximeters in care homes to monitor COVID-19 and other conditions, and the extent to which care homes were receiving support and guidance from the NHS about the use of pulse oximeters. Therefore, the survey was designed to understand the potential impacts of the use of pulse oximeters, and the associated support, on (1) outcomes for care home residents, such as the extent to which residents appear to be reassured; (2) the delivery of health and social care services in care homes; (3) the organisational workflow and workforce capacity of care home staff; and (4) residents’ use of health-care services, including emergency department attendance and hospital admission.

Specifically, the survey explored the following:

-

the conditions for which pulse oximetry are used (e.g. management of COVID-19 and other conditions)

-

the procedures and processes involved in the use of pulse oximetry (e.g. implementation, monitoring and escalation) and if and how procedures and processes differ by type of care home setting and characteristics of residents

-

the experiences of staff delivering pulse oximetry and their perspectives on residents receiving pulse oximetry (e.g. deciding which patients should receive pulse oximetry, taking readings, monitoring residents, deciding when to escalate residents to acute care, and working with NHS staff if appropriate).

-

the competencies (skills) and training needs of care home staff in the use of pulse oximetry in care homes, and staff capacity to deliver pulse oximetry

-

staff knowledge and engagement with the NHS CO@h service in care home settings

-

the expected impact on residents’ attendance at hospital emergency departments, admission to hospital or other use of health-care resources

-

the expected impact on residents’ health outcomes.

The survey questionnaire was designed collaboratively with the Project Steering Group, informed by scoping interviews with key experts and feedback received from members of the User Involvement Group during a workshop in March 2021. To reduce burden and to improve response rates, the online survey was designed so that it would take no longer than 20 minutes to complete.

Based on discussion with representatives from the Care Provider Alliance, managers of care homes were considered the most relevant survey respondents. Each care home has an assigned registered manager who has overall knowledge of all of the processes and procedures implemented in the care home that they manage. The CQC agreed to advertise, and provide a link to, the survey in its fortnightly online bulletin that is sent to all registered care home managers in England.

The survey was disseminated using the online platform SmartSurvey (SmartSurvey Ltd, Tewkesbury, UK) and was piloted between 23 and 26 February 2021 with a small number (n = 6) of key stakeholders identified by the research team. The survey questionnaire was revised slightly based on feedback from the pilots.

Key organisations were contacted by the research team to support survey distribution and to encourage care home managers to respond. Several organisations supported the online survey throughout March and April 2021:

-

The CQC distributed the survey via its fortnightly electronic bulletin to all 15,362 registered care homes in England. A message inviting care home managers to take part in the survey was included in two CQC bulletins (11 March 2021 and 25 March 2021).

-

The Care Provider Alliance supported survey dissemination by means of separate e-mail communications to its members, which includes associations representing the majority of care homes in England.

-

NHSX included a message about the survey in its March 2021 newsletter.

-

The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services included information about the survey in its March newsletter.

The study team monitored the survey response rate frequently. As the survey response rate was low, the study team implemented additional methods of reaching out to registered home managers. A variety of additional stakeholders were approached and asked to support the survey link distribution:

-

The study team contacted all members of the Skills for Care Registered Manager Network whose e-mail addresses were listed on that organisation’s website, asking them in turn to share the survey link with their contacts in care homes.

-

In April, the NIHR Applied Research Collaborations circulated a survey link by e-mail among members of the care home researcher network.

-

The NIHR ENRICH (Enabling Research in Care Homes) Research Ready Care Home Network shared the survey link with its members.

-

My Home Life England sent the survey link to its members.

-

NHS England and Improvement sent the survey to stakeholder associations.

Participants were able to access the survey between 8 March 2021 and 30 April 2021 (inclusive). The original plan had been to close access to the survey on the 6 April; however, given the low participation rate, the survey data collection phase was extended to the end of April 2021. Despite the extended survey period, and the considerable assistance of several organisations (as described above), the response rate finally achieved was only 1.5% (i.e. 232 out of 15,362 care homes). The demands on care home managers were very high throughout the survey period as a result of the roll-out of the COVID vaccination programme, exacerbation of staff shortages due to the pandemic and continued restrictions on visits from residents’ families. Responding to our survey is likely to have been a low priority for many care home managers in the circumstances. The survey provided useful insights into how care homes (with a wide variety of different residents) were using pulse oximeters. The survey also provided useful information regarding care home managers’ experiences of using pulse oximeters. However, the low response rate means that the survey results cannot be assumed to be representative of all care homes.

In early May 2021, the survey data were downloaded from the survey website and were cleaned before being analysed. The research team developed an analysis plan describing how to best analyse and present the information emerging from the survey to answer the research questions. The analysis was carried out in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which was adequate in relation to the number of respondents.

Analysis included descriptive statistics and identification of patterns and trends in the data. The analysis was conducted in two stages. First, the team performed descriptive analysis (i.e. frequency distributions) of each question individually. Second, cross-tabulations for group analysis were carried out to compare similarities and differences in experiences in the use of pulse oximetry by different groups (i.e. frequency distributions of the grouped variables). 44 These analyses were conducted for the following groups:

-

type of care home (residential, nursing or dual residential and nursing).

-

size of care home (by number of beds)

-

length of use of pulse oximeters (< 12 or ≥ 12 months).

Work package 3: in-depth case studies of staff experience based on interviews

The aim of this workstream was to explore the use of pulse oximetry in care homes, using the experiences of a range of stakeholders involved in delivering this technology in care homes; the factors influencing this delivery, including the communication to care homes about use of pulse oximetry and the level of support offered by NHSE&I and by local primary and secondary care providers; the range of conditions for which pulse oximetry is considered a beneficial component of a resident’s care (including residents who have tested positive for COVID-19); any variation the use of pulse oximetry across different care home settings (e.g. nursing or residential, size, location); perceptions of residents’ experience; and, finally, the potential to optimise the use of pulse oximetry and other remote monitoring approaches in the longer term.

Data collection followed a rapid qualitative research design, involving teams of field researchers and iterative data collection and analysis. 45 Three researchers (JRT, IL and MS) with a background in the social sciences and public health, and with a record of undertaking qualitative data collection with a range of stakeholders, carried out semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of stakeholders in six selected (care home) sites, with the aim of ensuring an appropriate variety of sites and giving opportunity to complete a significant number of interviews to achieve a depth of understanding to answer our evaluation questions. 46

Care home sites were selected purposively based on the principles of maximum variation (i.e. sampling for heterogeneity by selecting a small number of case study sites to understand a phenomenon from the perspective of a range of stakeholders in different settings relevant to our research questions) and convenience sampling, taking a pragmatic approach with the aim of selecting care homes that are, taken together, able to address many of the following criteria in combination: nursing, residential and learning disability care homes, funding model, size, geographic location (with regard to socioeconomic deprivation) and mechanism [e.g. application (app), paper based or both] for remote monitoring7 (Table 2). We did not have prior data on how long pulse oximeters had been used across care homes and, therefore, this was not taken into account when sampling for case study sites, but we did account for CQC ratings. Recruitment of case study sites was aided by NIHR-funded ENRICH facilitators, who approached care homes across their clinical research network on the study team’s behalf. In addition, the NHSE&I Project Steering Group supported the identification of care homes administering pulse oximetry with the support of the NHS CO@h programme’s primary and secondary teams. In all, seven care homes were identified (five care homes by ENRICH and two care homes with the support of the NHSE&I Project Steering Group). One care home was excluded, as another care home from the same care home group was already included in our study sample. An overview of our case study sites is presented in Chapter 3.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| User group |

Without dementia or learning disability With dementia With learning disability |

| Type of care home |

Nursing Residential |

| Organisation size | Number of places |

| Mechanism for patient monitoring |

Paper based App |

| Geographic location |

Urban Rural |

Interviewees comprised a purposive sample of study participants, who were selected in relation to the sampling framework outlined in Box 8 using snowball/convenience sampling. 47 We aimed to carry out interviews with five staff members with various levels of responsibility and experience (managers, care assistants, employees involved in the set-up, implementation and/or delivery of care using pulse oximeters, etc.) at each site.

Senior managers from care home associations (e.g. Care England, National Care Association, Nursing Homes Association, National Care Forum).

Care home manager.

Staff using the service with nursing or clinical training.

Staff using the service with no nursing or clinical training (including staff working day and/or night shifts).

Where relevant, NHS staff (primary, community or secondary care) supporting the care home’s use of oximetry.

To achieve this, the evaluation team planned to carry out 37 interviews across the six care homes (with a minimum of four per care home) or until data saturation (meaning that, once data were triangulated, no new emerging information was being discovered during data analysis, only data that confirmed existing themes and conclusions). 9 We interviewed a range of care home staff and senior managers in the care home sector and related care associations, plus NHS health-care professionals across primary, community and secondary care who are currently working with care homes, as well as senior national policy leads. Data collection was carried out between March and May 2021. The point of saturation was agreed by all members of the qualitative subteam (MS, IL and JRT), along with the co-principal investigators (JS and RM). Fieldwork, with regard to interviews, was carried out in some care homes sooner than others owing to difficulties in arranging interviews in some homes. Ian Litchfield was responsible for communicating with three care homes, Jamie-Rae Tanner was responsible for communicating with two care homes and Manbinder Sidhu was responsible for communicating with the final care home.

Individuals participated in a semistructured interview with one member of the study team (JRT, IL or MS). Interviews were carried out at a time convenient to the individual (e.g. during or outside working hours) via telephone, Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) or Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Each participant was provided with a participant information sheet at least 48 hours in advance of the interview to enable them to make an informed decision regarding whether or not to participate. Interviewees had the opportunity to ask questions about the study and/or wider BRACE-related work. Participants signed a consent form prior to participating in the interview. This also required them to say whether or not they consented to the recording of the interview. Participants were informed that they were entitled to withdraw from the study at any time and were given information about how to find out more about the study and how to raise any concerns about its conduct. In total, the study team approached 42 potential interviewees across the six sites, and 34 agreed to participate. Those who chose not to participate cited other, more important, commitments as the reason for doing so. Salient characteristics of stakeholders interviewed across our six case study sites are provided Table 3.

| Type of care home/participant | Generic description of role | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Senior managers from national care associations and national policy leads | Senior managers from care home associations (e.g. Care England, the National Care Association, the Nursing Homes Association, the National Care Forum) | 3 |

| Nursing | Care home manager | 3 |

| Staff using the service – with nursing or medical training | 4 | |

| Staff using the service – with no nursing or clinical training (including those working day and/or night shifts) | 4 | |

| NHS staff (primary, community or secondary care) supporting the care home’s use of oximetry | 1 | |

| Residential | Care home manager | 5 |

| Staff using the service – with nursing or medical training | 0 | |

| Staff using the service – with no nursing or clinical training (including those working day and/or night shifts) | 13 | |

| NHS staff (primary, community or secondary care) supporting the care home’s use of oximetry | 1 | |

| Total | 34 |

An interview guide was piloted at a workshop with our User Involvement Group and with two scoping interviewees to determine whether or not the guide was designed appropriately to answer the evaluation questions. The guide was used by researchers as an aide memoire during the interviews.

The interviews lasted approximately 30–60 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded (subject to consent being given), transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service, anonymised and kept in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation 2018 and Data Protection Act 2018. 48

Given the short time frame of this rapid evaluation, the study team adopted a pragmatic approach to the comprehensive analysis of the data, with a shorter timescale than traditional qualitative analysis, undertaken in two stages. First, data collection and analysis of interview data were carried out in parallel and facilitated through the use of rapid assessment procedure (RAP) sheets, as explained in Vindrola-Padros et al. 49 RAP sheets were developed for each case study site to facilitate cross-case comparisons and per population (i.e. to make comparisons between subgroups). The categories used in the RAP sheets were structured in accordance with the interview topic guide, maintaining flexibility to add categories as the data collection proceeded. The interviewers (JRT, IL and MS) completed site-specific RAP sheets following each interview, noting key points from the data under the agreed categories. The researchers (JRT, IL and MS) held weekly 1-hour meetings to discuss emerging learning and relayed this learning to other members of the study team during weekly team meetings throughout the duration of the study. A virtual workshop meeting was held in May 2021 and was attended by all researchers. The meeting aimed to develop and establish themes drawn from the data (both survey and interviews) and to ensure that all research questions had been addressed.

Following the virtual workshop, the second stage of analysis began with further interrogation of interview data by Jamie-Rae Tanner, Ian Litchfield and Manbinder Sidhu. The analysis was informed by the CFIR and the Gale et al. 35 framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multidisciplinary health research. The Gale et al. 35 framework is a systematic method of categorising and organising data while continuing to make analytical and interpretive choices transparent and auditable. Specifically, the Gale et al. 35 framework facilitated constant comparison across the six case studies. There are seven stages to the analysis:

-

transcription of interviews

-

familiarisation with the interview/observation/documentary material

-

coding

-

developing a working analytical framework

-

applying the analytical framework

-

charting data in a framework matrix

-

interpreting the data.

Stage 1: transcription

All interviews across the six case study sites were transcribed verbatim through a professional, outsourced transcribing company. A single organisation, specialising in transcribing health-related qualitative interviews, was used for all interviews. The quality of transcriptions was checked by having one of member of the research team (MS) check one transcript against the audio-recording.

Stage 2: familiarisation with the material

Three members of the project team (JRT, IL and MS) established familiarity with the data by each reading four transcripts from across the six case study sites (based on type of stakeholder interviewed) and by holding weekly data analysis meetings while data collection was still ongoing/near completion (May to June 2021). During each meeting, team members were able to reflectively discuss and share thoughts and impressions of early findings.

Stages 3 and 4: coding and developing a working analytical framework

Stages 3 and 4 of the analysis took place in tandem. The study team applied an inductive approach, having developed predefined codes that focus on specific areas of interest identified from our interview topic guide, RAP sheet and CFIR. The codes were reviewed, refined and added to. One interview transcript was independently coded, with a further 11 interview transcripts coded by all three project team members (JRT, IL and MS). The remaining 22 transcripts were read to ensure that no emerging learning was missed, to identify deviant cases, to draw out relevant quotes to support conclusions and to ensure that no important aspects of the data were missed. NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used for coding. After the first data analysis workshop meeting (May 2021) and the independent coding of one transcript, an analytical coding framework was agreed (see Report Supplementary Material 3). The codes were categorised under the following broad themes of the CFIR framework (i.e. the five overarching domains). Note that not all 39 constructs of the framework emerged from our data. Each domain, with its existing construct (with definition) and emerging issues, is summarised in turn and illustrated by exemplar quotes under thematic headings. The analytical coding framework was reviewed at subsequent data analysis meetings between Jamie-Rae Tanner, Ian Litchfield and Manbinder Sidhu, as well as with the wider study team.

Stage 5: applying the analytical framework

The working analytical framework was then applied by indexing by Jamie-Rae Tanner, Ian Litchfield and Manbinder Sidhu across a sample of 12 interview transcripts [i.e. the systematic generation of codes (n = 37)].

Stage 6: charting codes

The project team took a novel, rapid approach to charting codes, by developing a matrix based on summaries of each code and using the CFIR (once the analytical framework had been applied to the 12 transcripts). This process was led by a single researcher within the project team (IL), with input from the other team members (JRT and MS). The matrix was structured according to research questions and how best to develop integrative themes. As a result, summarised codes were merged together to support the development of themes with respect to overarching CFIR domains under newly devised thematic headings.

Stage 7: interpreting the data

The project team held a final weekly meeting in July 2021 to finalise the development of themes. Key to this meeting was to understand the characteristics of the implementation of pulse oximetry in care homes across the six case study sites and the differences across qualitative and survey data, interrogating theoretical concepts relational to our research questions, and mapping connections across our themes. In September 2021, the research team circulated a summary of findings (via a digital slide deck) to each case study site, and gave them the opportunity to provide comments (i.e. member validation). In addition, emerging data were shared in an online workshop with key stakeholders and the Project Steering Group (including members of NHSE&I, care provider associations and of the User Involvement Group).

Work package 4: synthesising findings from qualitative and quantitative components of the evaluation

A virtual workshop meeting of the research team was held in July 2021. Jon Sussex, Barbara Janta, Giulia Maistrello, Ian Litchfield and Manbinder Sidhu attended the meeting to discuss how to thematically synthesise findings across survey and qualitative interviews, guided by the CFIR framework. The ‘following a thread’ approach put forward by O’Cathain et al. 36,37 was adopted, whereby synthesis of data takes place at the data analysis stage to identify key themes and data that warrant further analysis. 36,37 Hence, following the identification of key themes within each data set, the researchers used the CFIR’s five overarching domains to create a ‘thread’ to organise the findings. As part of the workshop, colleagues took an iterative approach, going back and forth across both sets of themes (for survey and interview data) to draw out key messages that were consistent with answering research questions and also most pertinent within the data. For example, during the workshops, members of the team would begin with findings from the survey, identify corresponding learning that supported and/or deviated from the data, and then iteratively return to the relevant literature, both policy and theoretical, to identify key learning from both sets of data. In addition, the team presented findings and recommendations to the User Involvement Group (May and October 2021), at the NHSE&I CO@h – Evaluation Workshop (September 2021) and to the NHSE&I People Receiving Social Care Group (May, July and October 2021). The accumulated outputs of these workshops will lead to a slide deck of findings, which will be disseminated across the NHS and into the public domain.

In summary, we followed an adapted rapid qualitative analysis approach, including the use of RAP sheets, interrogation of transcripts, application of a theoretical lens, using a framework approach, including repeated discussion across the whole research team and calling on additional national experts, in the development of our findings. We used a COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) checklist to add rigour to our reporting. Throughout this chapter, we have detailed processes for protocol sign-off and ethics approval, and described the nature of our scoping work (both with literature and key experts) and the methods used with regard to how we collected data using an online survey and interviews.

We present our synthesised findings for both the survey and interview study in the next two chapters (Chapters 3 and 4). The first of these chapters (Chapter 3) covers domains I, II and III of the CFIR, that is, the characteristics of the intervention we are evaluating and the outer and inner settings into which the intervention is introduced. Therefore, Chapter 3 provides a description of the use of pulse oximetry in care homes, including a description of the care homes included in our sample, the application of pulse oximetry in care homes and how the use of pulse oximetry relates to routine practice and care pathways. The subsequent chapter (Chapter 4) covers domains IV and V of the CFIR, looking at staff experiences of pulse oximetry and staff views on the impact on residents of implementing pulse oximetry in care homes.

Chapter 3 The use of pulse oximetry and the care pathways associated with its delivery in care homes

The key points of Chapter 3 are summarised in Box 9.

-

There are more than 15,000 care homes operating in England. Following repeated reminders that were distributed to all care homes, and with the assistance of the CQC, the Care Provider Alliance and other organisations in contact with care homes, we received survey responses from 232 (1.5%) care homes.

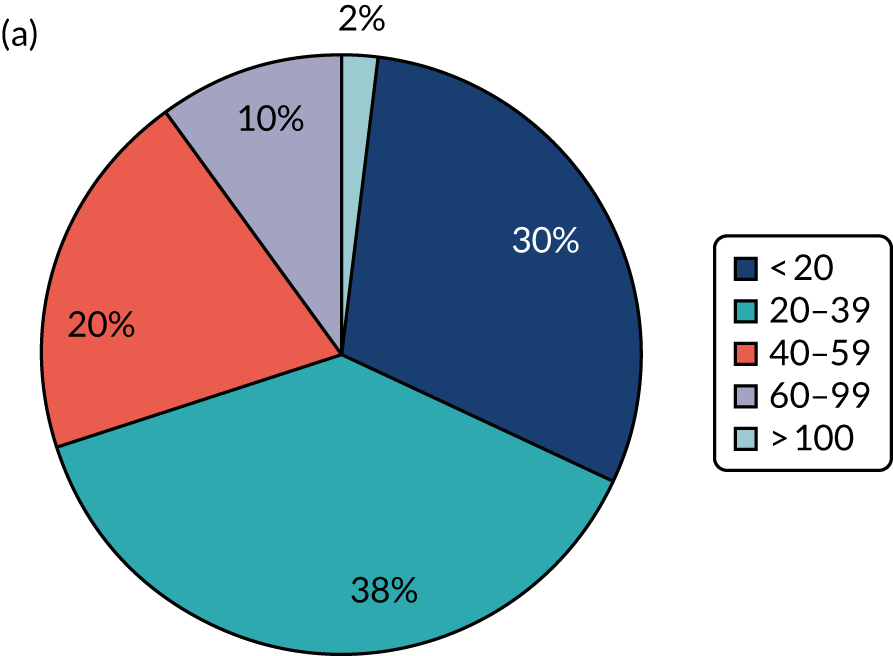

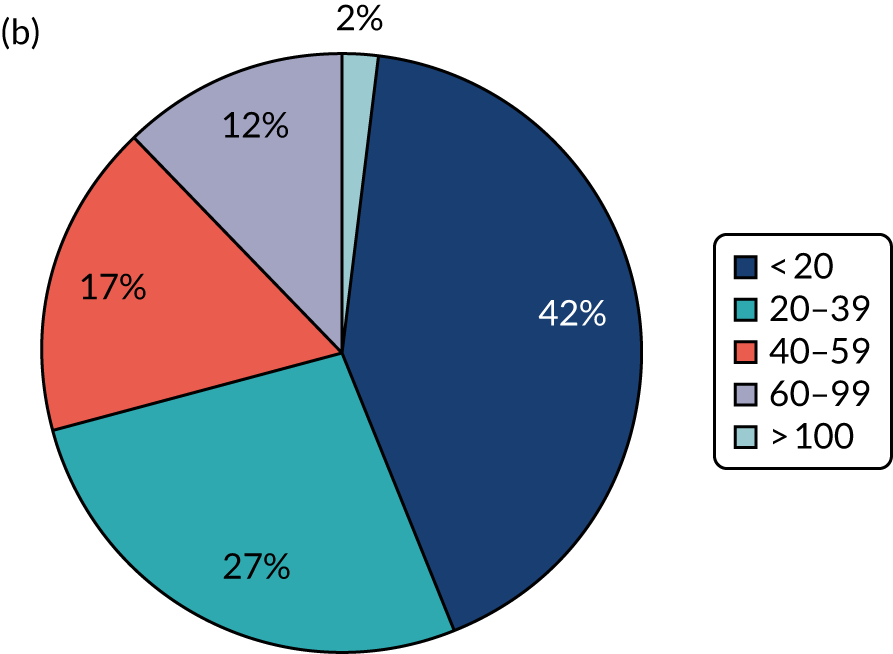

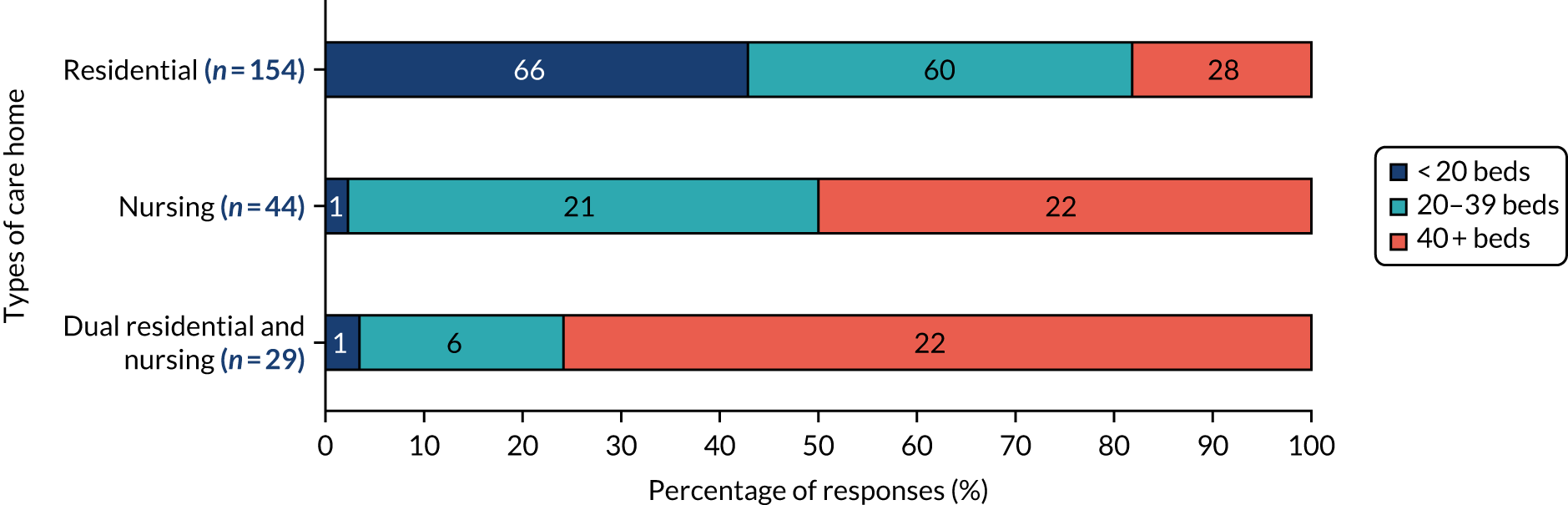

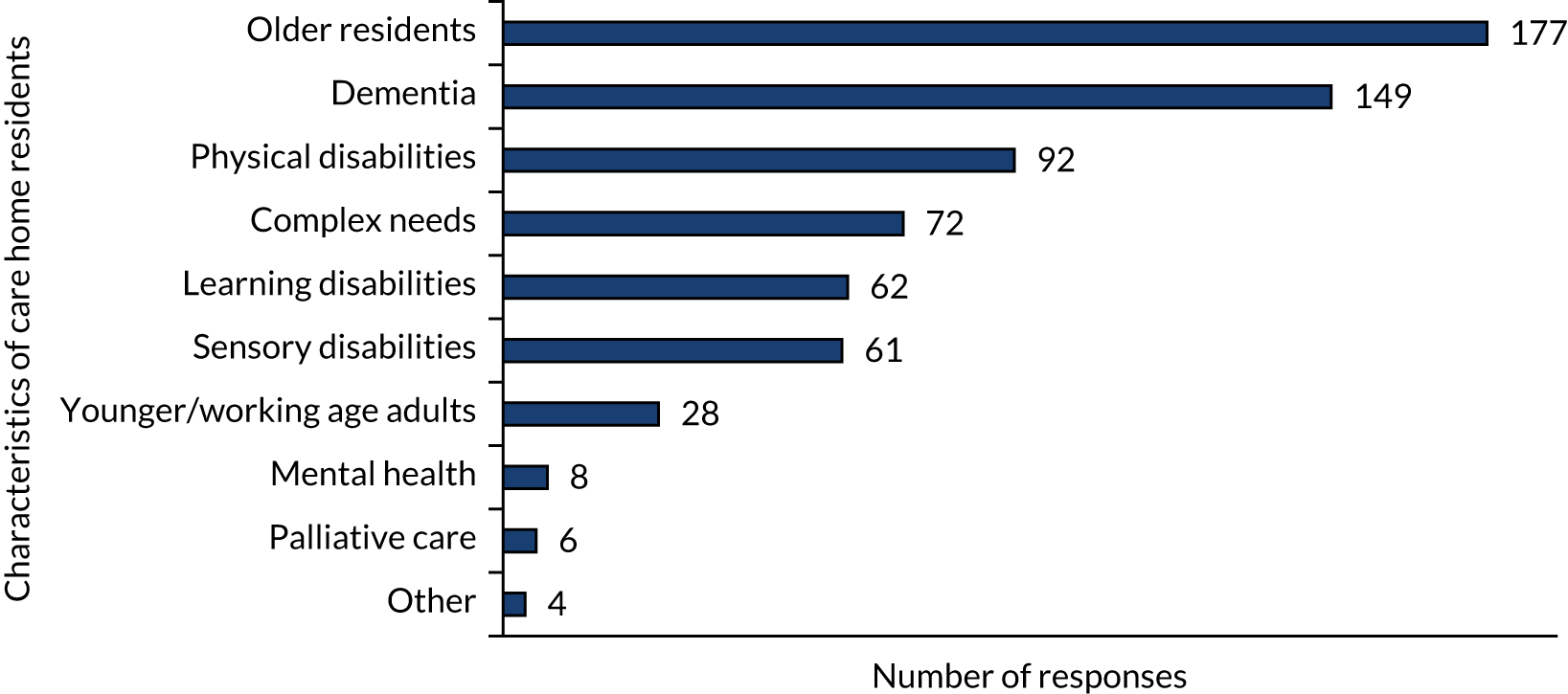

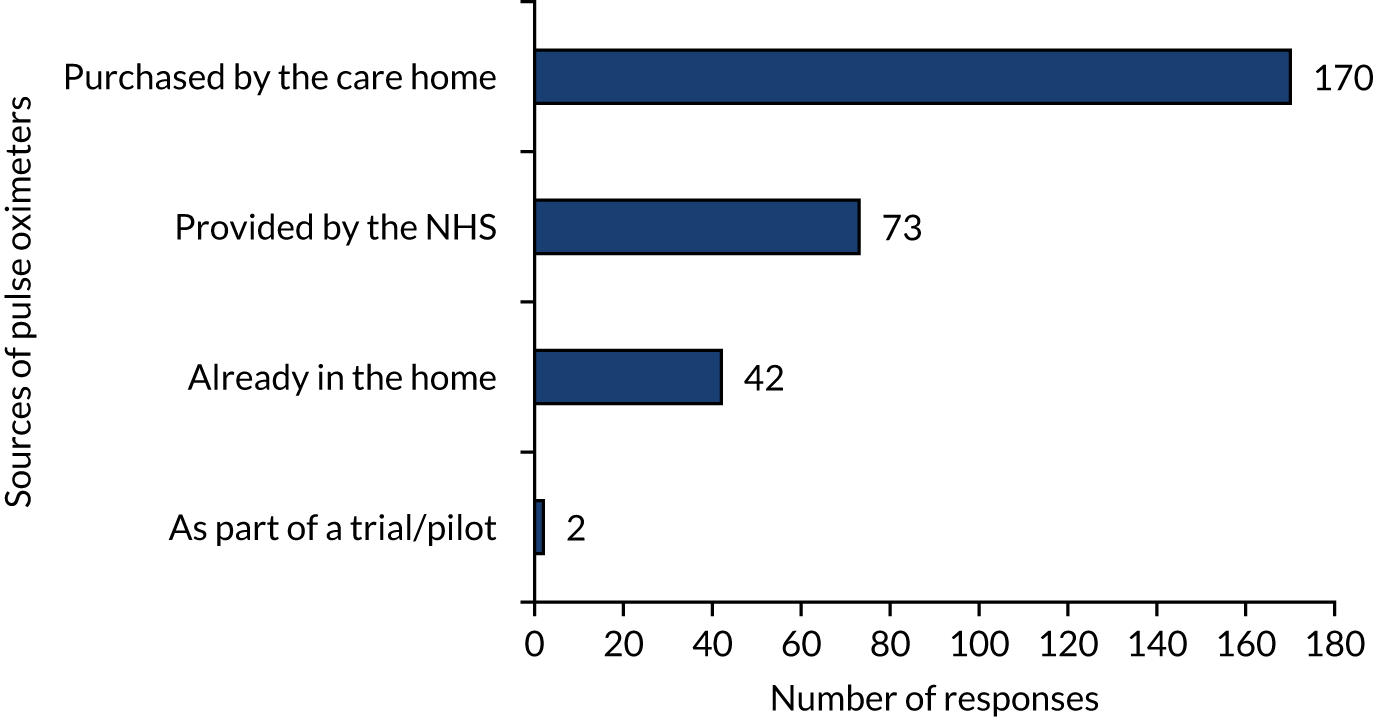

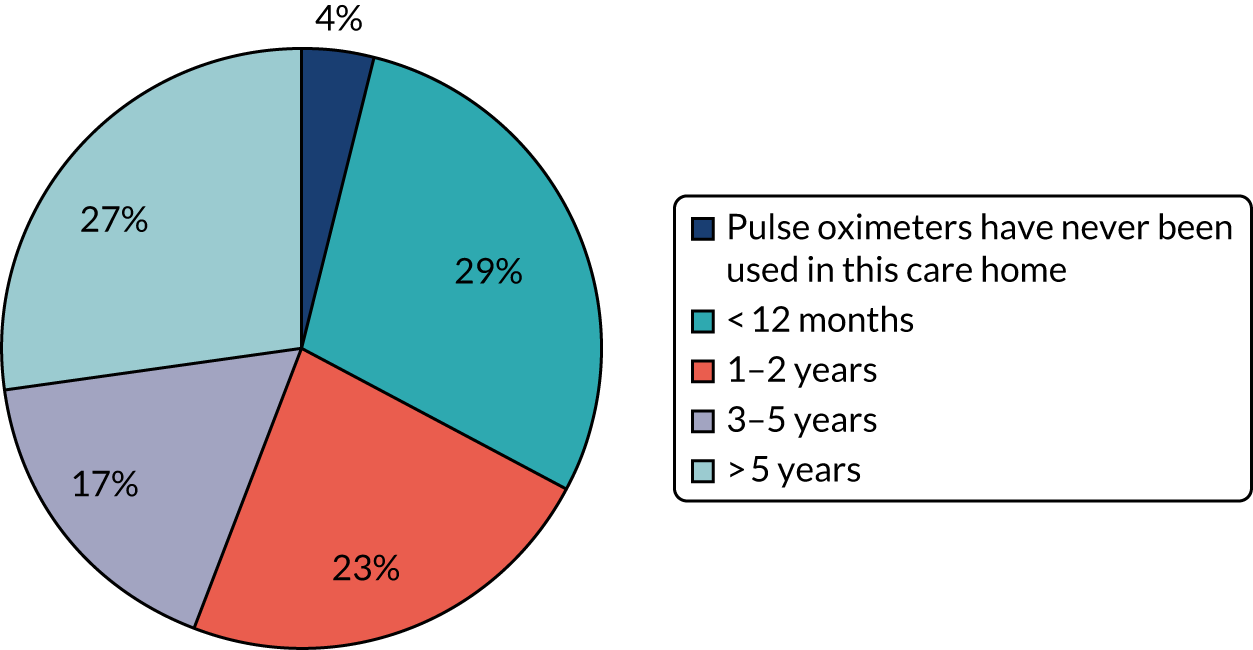

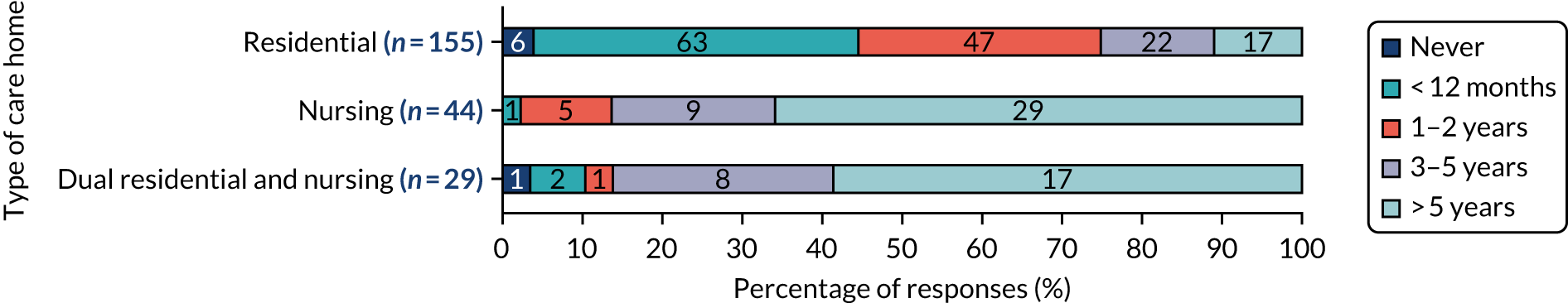

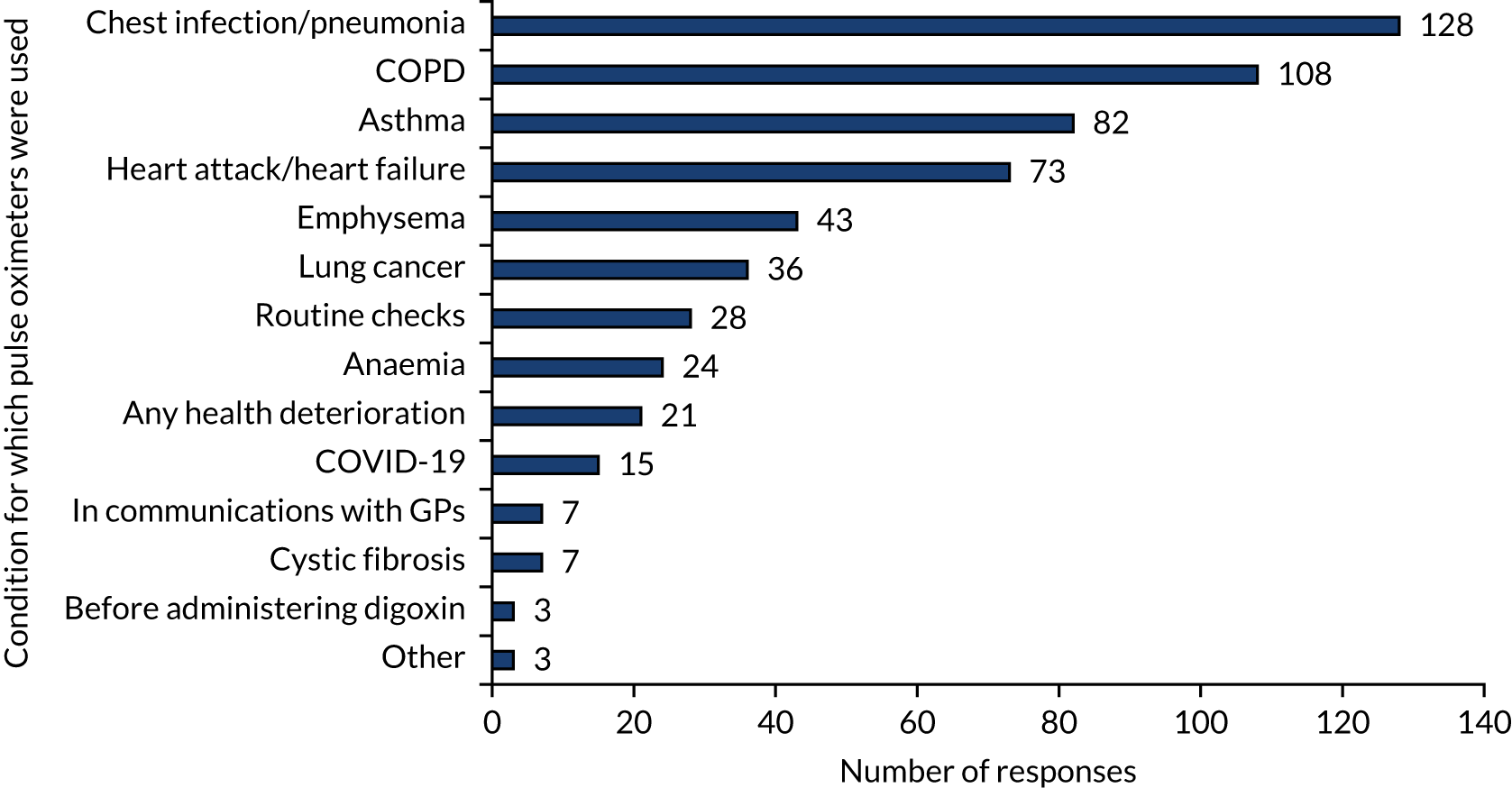

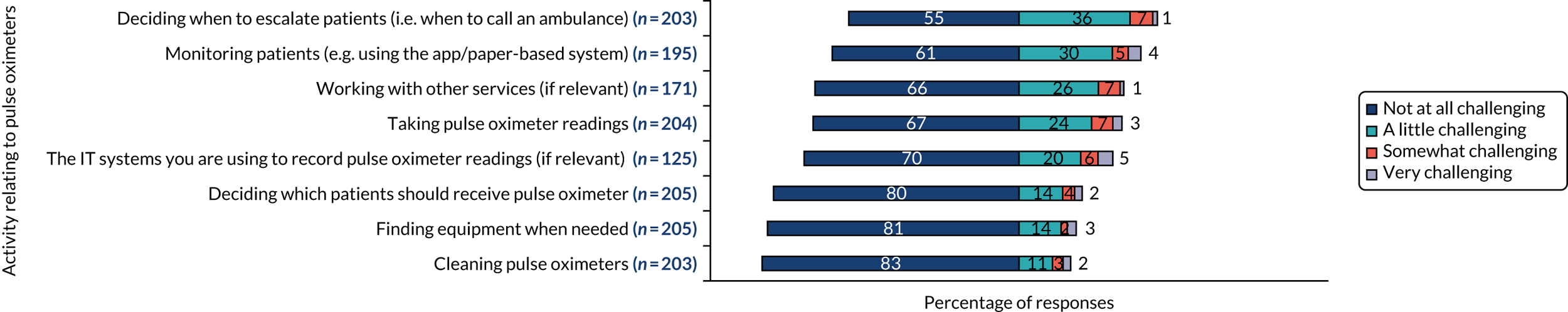

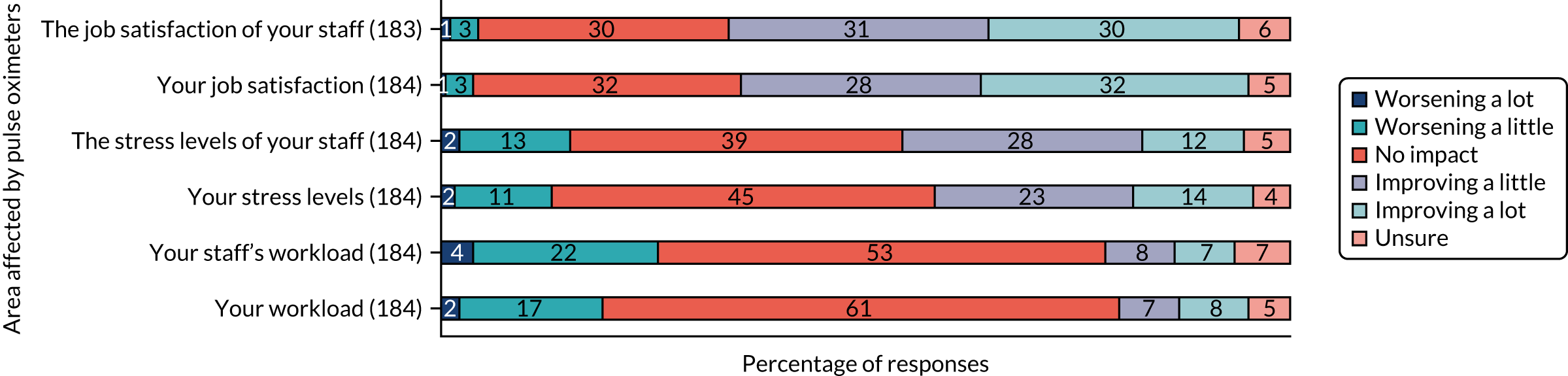

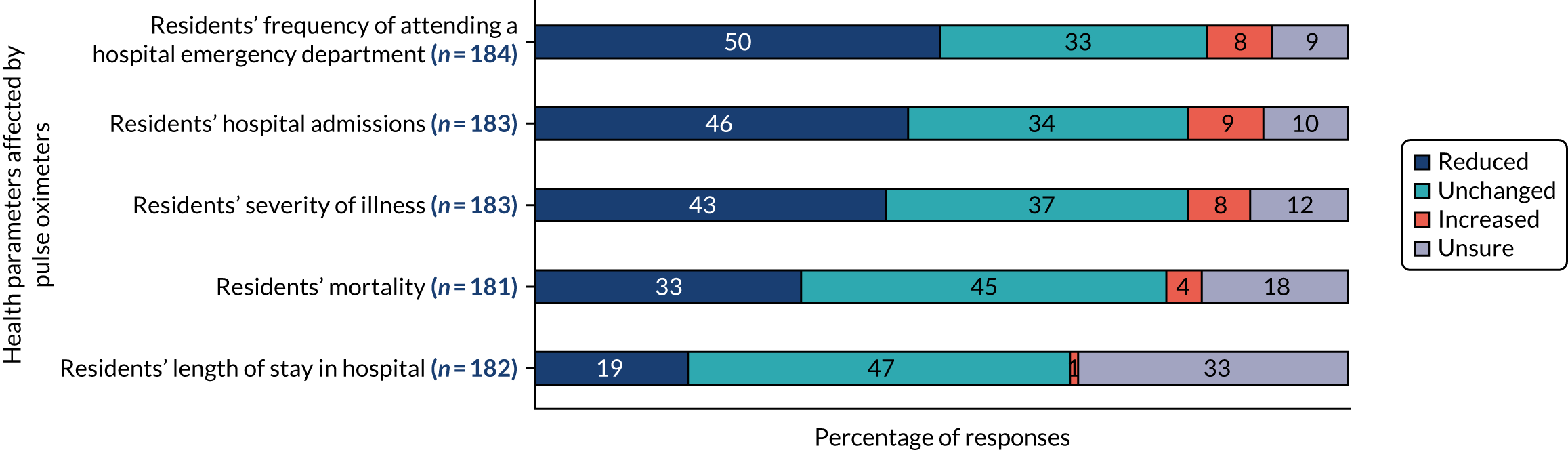

-