Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR135618. The contractual start date was in May 2022. The final report began editorial review in March 2023 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Sidhu et al. This work was produced by Sidhu et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Sidhu et al.

BRACE: The NIHR Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Rapid Evaluation Centre

The NIHR BRACE Rapid Evaluation Centre (National Institute for Health and Care Research Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation Centre) is a collaboration between the Health Services Management Centre at the University of Birmingham, the independent research organisation RAND Europe, the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge and National Voices. BRACE carries out rapid evaluations of innovations in the organisation and delivery of health and care services. Its work is guided by three overarching principles:

-

Responsiveness. Ready to scope, design, undertake and disseminate evaluation research in a manner that is timely and appropriately rapid, pushing at the boundaries of typical research timescales and approaches, and enabling innovation in evaluative practice.

-

Relevance. Working closely with patients, managers, clinicians and health-care professionals, and others from health and care, in the identification, prioritisation, design, delivery and dissemination of evaluation research in a co-produced and iterative manner.

-

Rigour. All evaluation undertaken by the team is theoretically and methodologically sound, producing highly credible and timely evidence to support planning, action and practice.

Chapter 1 Background, context and objectives

Summary of key points

-

The phase 2 rapid evaluation reported here follows up outstanding issues set out at the end of the report of phase 1 and addresses gaps in the literature on vertical integration in the context of the National Health Service (NHS) in England: understanding the extent of vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices that has already taken place throughout the NHS in England; the impact on outcomes from the use of secondary care services, how service delivery has changed or is expected to change and the patient experience of vertical integration, with a particular focus on whether patients with multiple long-term conditions are affected differently from other patients.

-

Patient demand on general practices and patient dissatisfaction with general practitioner (GP; primary care physician) services are both growing.

-

Practices are merging and horizontally integrating in line with NHS primary care network (PCN) policy. The number of general practices is falling and the numbers of patients per practice is increasing nationally.

-

Policy focuses on horizontal rather than vertical integration. Vertical integration has not yet been part of government or NHS policy in England, although early in 2022 there was ministerial reference to it.

-

There is growing concern in policy discussions about meeting the particular requirements of patients with multiple long-term conditions, who are likely to be frequent users of health care and may particularly benefit from improved integration of health care.

Overview and scope

This report presents the second phase of a two-phase rapid evaluation of arrangements whereby NHS organisations operating acute hospitals have additionally taken over the running of general practices in locations in the NHS in the UK. This is a form of vertical integration: where one organisation provides care at different stages along the patient pathway. 1 We focus on cases where providers of secondary care in acute hospitals merge with providers of primary care (general practices). The setting of the rapid evaluation reported in the following pages is the NHS in England, but its findings are likely to be of interest internationally as forms of vertical integration have also occurred or could be introduced in other health-care systems.

The scope of the phase 2 rapid evaluation of vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices starts from that of the phase 1 study, which is described and explained in full in chapter 2 of Sidhu et al. 20222,3 and is not repeated here. The phase 1 rapid evaluation was a qualitative study undertaken in 2019 and early 2020, which focused on the rationale, implementation and early impact of the vertical integration of acute hospitals with general practices in England and Wales. Prior to that study,2,3 there had been little systematic information on the rationale for, or desired impact of, vertical integration in a UK NHS setting, or on why it is being introduced in some places despite not being an explicit part of NHS policy. The phase 2 rapid evaluation reported here combines quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods to understand the extent of vertical integration in the NHS in England, its impact on patients’ use of hospital care, how service delivery has changed (or is expected to change) and the patient experience of vertical integration.

In the NHS in England, secondary health care is provided by organisations known as ‘trusts’. Some trusts provide acute hospital services, some provide community-based secondary care services, some provide mental health and/or learning disability services. Some trusts provide combinations of these types of services. For the purposes of the research reported here, we have grouped trusts into those that we refer to from here on as ‘acute trusts’ and those that we label ‘community trusts’. Any trust that provides acute hospital services we categorise as an ‘acute trust’, regardless of any further services that the trust may also provide. Other trusts that have taken on the running of general practices but do not provide acute hospital services we label for brevity as ‘community trusts’, although two trusts we label in this way are providers only of mental health and learning disability care. As in the phase 1 evaluation, we concentrate in this study on vertical integration of general practices with organisations that run acute hospitals, but we include reference to vertical integration of general practices with organisations providing other secondary care where that clarifies the analysis.

A novel aspect of the second phase evaluation reported in the following pages is that we have specifically analysed whether patients with multiple long-term conditions are affected by vertical integration differently from other patients. The rationale for this part of the present study is that changes in the organisational structure of primary care and its integration with secondary care may be expected to particularly affect those patients presenting with more than one single chronic condition. 4,5 These patients access care more frequently than others, are more complex in their needs and will often require access to and coordination of many different health-care providers not all operating from the same site. As far as we are aware, there has not yet been an evaluation of whether and how vertical integration affects people with multiple long-term conditions differently from other patients.

Throughout the phase 2 study we have attempted to allow for the disruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken to combat it. The pandemic began in the UK in February 2020 and had a large initial impact on the volume of primary and secondary care activity. It has gone on to have a fundamental effect on how primary care is delivered. In particular there was an initial, large, step-change increase in the proportion of primary consultations conducted remotely (via digital or telephone consultations) rather than in person, although the remote proportion has dropped back to some extent more recently. 6 The quantitative analyses presented in the following chapters use data up to April 2021 to identify all locations in England where NHS hospitals are running general practices and the dates at which that first happened, and activity data up to February 2020 to estimate the impact of vertical integration on patients’ use of secondary care services and experience of primary care. Thus, for the analysis of secondary care usage we avoid the period when the pandemic affected hospital activity. The qualitative analysis is based on fieldwork conducted during the summer and autumn of 2022 and so is unavoidably affected by the changes to primary and secondary care brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the rest of this chapter, we summarise the institutional and policy context relevant to vertical integration in the NHS in England, which has three major aspects: (1) the challenges being faced by GP care in recent years; (2) the continuing attempts to better integrate health-care services; and (3) the particular needs of people with multiple (rather than single) long-term conditions. We then summarise what is known about vertical integration from the existing literature, including the main findings and conclusions of the phase 1 evaluation. 2,3 We finish the chapter by stating the aims of the phase 2 rapid evaluation reported here and the specific research questions, and by outlining the structure of the rest of the report.

Institutional background

Within the NHS, acute hospitals do not usually run general practices (nor other primary care services provided in community settings by dentists, pharmacists and opticians). GPs are contracted by the NHS to provide primary care medical services to the patients who register with them. Box 1 summarises the types of GP contract in use.

The general medical services (GMS) contract is agreed nationally. The contract is held (in perpetuity) by the practice, not by individual GPs. It provides the contracting general practice with an income stream to pay for the staff, premises and other costs of providing a menu of compulsory ‘essential’ services. Under the GMS contract, a practice may also voluntarily provide and be paid for ‘additional services’ and ‘enhanced services’. Around 70% of general practices operate under GMS contracts.

Personal medical servicesPersonal medical services (PMS) contracts are negotiated locally [formally with the local clinical commissioning group (CCG), now with the local integrated care board (ICB)]. These contracts are held by individual GPs rather than practices. They are held in perpetuity but can be terminated by the commissioner with six months’ notice. GPs contracted via PMS contracts are paid to provide a defined service as agreed locally. Around 25% of general practices operate under PMS contracts with their GPs.

Alternative provider medical servicesAlternative provider medical services (APMS) contracts are locally agreed and can be let to private sector – both commercial and voluntary – organisations as well as to traditional general practices. They are, unlike GMS and PMS contracts, time limited. This type of contract tends to be used in areas where it is difficult to recruit and retain GPs. Just 2% of general practices hold APMS contracts.

GPs also act as ‘gatekeepers’, referring patients to other, specialist (i.e. secondary care) NHS services, including those provided by acute hospitals. Despite these roles, the large majority of GPs are not employees of the NHS but instead are either contractors to the NHS or are salaried employees of organisations that are (e.g. partnerships of GPs who hold a contract with the NHS or private companies that do so). Practices employ not only GPs but also nurses and other health-care professionals, together with managers, administrative and reception staff. Many practices operate out of a single location, but some work from two or more sites. At the end of September 2022, there were 37,026 full-time equivalent (FTE) GPs (including trainees) in 6456 general practices in the NHS in England. 9 The number of general practices in England has been decreasing as individual practices merge with one another or close (the consequence of which is that their patients are then distributed across the remaining practices). In the 3 years to September 2022, the number of general practices in England fell 6.0% (from 6867 to 6456) and average practice list sizes rose 9.8% (from 8737 registered patients per practice in September 2019 to 9596 in September 2022).

Acute hospital trusts are providers of hospital-based, emergency and/or elective specialist health care. In England, acute hospitals are run by publicly owned organisations, which are either ‘NHS foundation trusts’ or ‘NHS trusts’ (hereafter referred to collectively as trusts). In September 2022, there were 142 acute hospital trusts in England. The services of acute hospitals are contracted for by both national and local NHS commissioners of care. In England, the commissioning organisations were, until 1 July 2022, NHS England (nationally) and 106 local clinical commissioning groups (England) (CCGs). Since July 2022, commissioning of health care for their resident populations has become the responsibility of 42 integrated care boards (ICBs), which have in effect absorbed the CCGs.

Some acute trusts in England now run general practices. Such vertical integration is a relatively new phenomenon in the NHS, occurring over the period since 2015, and rising over time. This kind of integration is distinct from horizontal integration, whereby organisations at similar stages along the patient pathway integrate or even formally merge with one another, such as when one acute hospital trust integrates or merges with another or when one general practice integrates or merges with another. There are many types of horizontal integration between general practices10 but this is not the main focus of the evaluation reported here. Nevertheless, each vertically integrated organisation that includes more than one general practice does necessarily also include a degree of horizontal integration between the practices that are owned by the same trust. Furthermore, we have found, as explained later in the report, that it sometimes happens that general practices are merged together (horizontally) at the time they are vertically integrated with a trust or subsequently. Consequently, any impacts of vertical integration may be seen as the combined result of both vertical integration between a trust and the practices it runs and horizontal integration between the practices that are run by the same trust.

As is explained in the report of our phase 1 evaluation,2 the concept and term ‘vertical integration’ is familiar to economists, although perhaps less so to health-care audiences. In the economics literature (e.g. Joskow et al. 200511 and, as applied to the health-care sector, Laugesen and France 201412) vertical integration is seen as having three main rationales: (1) as a way of increasing market power relative to other providers; (2) enabling better management of some risks (e.g. concerning the level of demand for an organisation’s services); and (3) to reduce transactions costs via better information sharing, monitoring and decision-making. In the health-care context, vertical integration has been defined as being along any or all of six types: organisational, functional, service, clinical, normative, systemic. 13 The examples of vertical integration studied in our phase 1 evaluation and now in the phase 2 evaluation mainly concern organisational and functional integration, together with some elements of service, clinical and normative integration. Interest in vertical integration is not limited to the UK NHS, other countries which have adopted this approach include Denmark, Spain and the United States. 14–17

Policy context

The phase 1 study2,3 highlighted (1) sustaining primary care in locations where practices were likely to close, and (2) better integration of care, as the two main drivers of vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices in the NHS in England and Wales. The overall NHS context is one of persistently increasing demand and activity both in secondary care and primary care settings (about which we say more below). Indeed, our phase 1 study found that part of the motivation for hospital trusts to take on the running of general practices was the desire of trust management to maintain some control over the flows of patients to secondary care, especially accident and emergency department (A&E) attendances and emergency admissions. 2,3

Vertical integration in one of the two case study sites in England in the phase 1 evaluation had stemmed from an innovation in service provision aimed at people with multiple long-term conditions who were consequently frequent users of primary and secondary health-care services. Better meeting the needs of people with multiple conditions is an area of increasing policy concern. 18–20 The following paragraphs summarise the policy context in England with respect to the challenges for general practice-based care, integration of primary and secondary health care, and service provision for people with multiple long-term conditions.

Challenges for general practitioner primary care

The sustainability of primary care has for several years been the subject of increasing concern and debate for policy makers in England, as well as for health-care professionals, service managers and commissioners. In essence, demand for primary care is growing inexorably and the supply of GPs is not keeping pace with that demand. 19,21–25 GP FTEs in England grew by 6.6% in the 3 years to September 2022: from 34,729 in September 2019 to 37,026 in September 2022. This was a combination of a small decline in FTEs of fully qualified GPs (down 626 over that period from 28,182 to 27,556) and a large increase in GPs in training (up 44.6% over the same period from 6547 to 9470). 9 Over the same period, the total number of appointments at general practices increased by a similar amount: up 7.1% over the same 3-year period from 26,420,000 in September 2019 to 28,300,000 in September 2022. 26,27 The similarity between the two growth rates is perhaps unsurprising in a supply-constrained system (i.e. where potential demand exceeds available supply) given that the number of GP appointments is necessarily constrained by the number of FTE GPs available for patients to consult with. But it also suggests that employment in primary care practices of health-care professionals other than GPs did not greatly add to capacity for patient consultations over that period. 28

There has also been a rise in the number of patients with multiple long-term conditions, higher costs, developments in the consulting technology and tightening workforce constraints as result of GP recruitment and retention difficulties. 25,27,29,30 The gatekeeping role of GPs means that increasing difficulty with meeting patient demand in a primary care setting can lead to growing pressure on acute hospital emergency services. A desire on the part of managers at acute trusts to keep some control over the flow of patients to their hospitals was evident in our phase 1 evaluation. 2

The policy response has focused on increasing the numbers of GPs in training, as evidenced by the rapid growth in numbers of trainees mentioned earlier; on providing funding for new staff roles in general practice and on merging and integrating primary care practices horizontally with one another in the hope of increased efficiency (more and/or better patient services delivered per primary care staff member). 2,19,22,31 Nevertheless, patient experience and patient satisfaction with general practice services in England is falling, as summarised in the House of Commons Health and Social Care Select Committee report in October 2022 (quote taken from paragraph 25 of that report):25

Over several years the GP Patient Survey has shown declining access standards, albeit with satisfaction rates remaining high: from 2018 to 2020 the proportion of people who reported having a good overall experience of making an appointment fell slightly from 68.6% to 65.5%, but the proportion of people rating their care as good overall remained 81.8% in 2020. In the latest GP Patient Survey, however, the results are significantly worse and show the level of difficulty patients now face when trying to access general practice: the proportion of people who had a good experience of making an appointment has fallen sharply to 56.2% and the proportion of people rating their overall experience as good has also fallen significantly to 72.4%. 23,25 (Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2022. This material is reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence v3.0, which is published at: https://www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/open-parliament-licence)

Integrating health care

NHS policy has, over the past 10 years, repeatedly stressed an objective of more integrated patient care across primary health care, secondary health care and social care settings. 19,21–23 The policy focus on care integration led to the development of several recommendations in the 2014 NHS ‘five-year forward view’. 21 Among them was to seek stronger integration between primary and secondary care, in what were termed primary and acute care systems (PACS). Some piloting of PACS was funded as a result. The 2016 General Practice Forward View announced increased funding for GP services and plans for developing them further. 22 The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan19 set out the intention that all general practices in England should come together to deliver services as part of primary care networks (PCNs). This is a form of horizontal integration designed to cover populations of 30–50,000 patients per network. Since July 2019, all but a tiny number of practices have become horizontally integrated in that way with other practices, while remaining separate legal entities with separate contracts. Findings from a recent rapid evaluation of PCNs show that there have been a number of facilitators and challenges to horizontal integration to help achieve sustainable primary care, address growing workload issues and improve the availability and coordination of local primary care services. 10

Since 2015, a number of local initiatives have led to trusts running general practices but this was not in response to any particular policy stimulus. Apparently explicit policy-maker interest in NHS trusts running general practices emerged in early 2022. 32,33 The expectation was reported as being that functions, activities and organisations that provide different levels of patient care might be brought together under a single management and result in cost savings in secondary care, as had been reported at one vertical integration site by Yu and colleagues. 2,3,34 This policy-maker interest was despite the findings from our phase 1 evaluation that vertical integration in a health-care system worked when driven by local initiative (rather than central direction) and that many GPs evidently did not wish to become vertically integrated with trusts. 2,3

A subsequent ‘stocktake’ commissioned by NHS England of the state of integration in primary care and published in May 2022 made no mention of vertical integration as such. Instead, it focused on ‘building integrated teams’ at the level of PCNs but broadened the concept to:

teams from across primary care networks (PCNs), wider primary care providers, secondary care teams, social care teams, and domiciliary and care staff [working] together to share resources and information and form multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) dedicated to improving the health and wellbeing of a local community and tackling health inequalities. (Source: NHS England 2022, p. 6)31

Caring for people with multiple long-term conditions

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defines multimorbidity as ‘the presence of two or more long-term health conditions, which can include:

-

defined physical and mental health conditions such as diabetes or schizophrenia

-

ongoing conditions such as learning disability

-

symptom complexes such as frailty or chronic pain

-

sensory impairment such as sight or hearing loss

-

alcohol and substance misuse.’35

The prevalence of people with two or more such long-term conditions has recently been estimated at 53% of the adult population in England. 36 People with multiple long-term conditions are higher users of NHS services than other members of the population and would particularly benefit from services focused around the individual patient rather than an individual condition. 24 The World Health Organization describes people with multimorbidity, compared with other members of the population, as facing:

more frequent and complex interactions with health-care services leading to greater susceptibility to failures of care delivery and coordination; the need for clear communication and patient-centred care due to complex patient needs; demanding self-management regimens and competing priorities; more vulnerability to safety issues … (p. 4)37

Multimorbidity is now a high-profile issue for consideration in NHS policy and practice. It is a major theme in the NHS Long Term Plan18 and the Academic Health Science Network, National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and NHS England report on priorities for innovation and research. 18 In July 2019, the Academy of Medical Sciences, NIHR, Department of Health and Social Care, Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust jointly declared that: ‘Multimorbidity is recognised as an important priority across all our organisations and we all take a special interest in it’. 38

Evidence for vertical integration

It remains the case that relatively little evidence is available to inform policy makers about vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices. Yu and colleagues34 found in a statistical study at one location, Wolverhampton in the West Midlands of England, using data from the period April 2015 to March 2019, that vertical integration between an acute hospital and 10 general practices was associated with a statistically significant, reduction in the rate of unplanned hospital admissions and readmissions, but not of A&E attendances. They estimated that this would imply an annual cost saving to the hospital of around £1.7 million. 34 We include in Chapter 4 a comparison of Yu and colleagues’ findings with our analysis for the same vertically integrated practices in Wolverhampton.

Our qualitative, phase 1 rapid evaluation of vertical integration at two locations in England and one in Wales revealed several noteworthy findings. It showed that key to achieving vertical integration is better clinical integration (coordination of treatment services for a patient) and functional integration (strengthening key support functions, such as financial management, human resources and strategic planning). Trust managers at case study sites anticipated that vertical integration would enable better management of patient demand for secondary care services, a view consistent with the findings of Yu and colleagues. 34 Vertical integration can lead to alterations in contractual arrangements and accountability, workforce recruitment, premises and care pathways, which in turn have the potential to create better care and outcomes for the patient. The phase 1 study also found potential downsides to vertical integration, including fears among GPs of loss of autonomy and having to interact with more bureaucratic and slower back-office processes in trusts (finance, procurement, human resources, estate management). It is certainly the case that even in locations where some general practices are integrated with an acute trust, many other general practices choose to remain outside any such arrangement. 2

Aims and research questions

In 2019–20, the phase 1 rapid evaluation of vertical integration investigated the implementation of acute hospitals managing general practices, as well as addressing questions relevant to scaling-up this model of integration in an NHS setting. That qualitative evaluation focused on understanding the rationale for, and the implementation and early impact of, vertical integration. It included the development of a theory of change, identifying what outcomes this model of vertical integration is expected to achieve in the short-, medium- and long-terms, and under what circumstances.

Phase 2 of the study of vertical integration, reported here, starts from the institutional and policy contexts described earlier and aims to address outstanding issues identified in phase 1. 2 These include: understanding the extent of vertical integration which has already taken place throughout the NHS in England; the impact on outcomes form the use of secondary care services; how service delivery has changed or is expected to change; and the patient experience of vertical integration, with a particular focus on whether patients with multiple long-term conditions are affected differently from other patients. To address these aims, the phase 2 rapid evaluation focuses on attempting to answer the following research questions:

-

How many general practices have already vertically integrated with NHS organisations running acute hospitals in England; when did the integration between general practices and acute hospitals take place, and what are the characteristics (in terms of geographical location, patient demographics and practice size/workforce) of those practices where vertical integration has taken place?

-

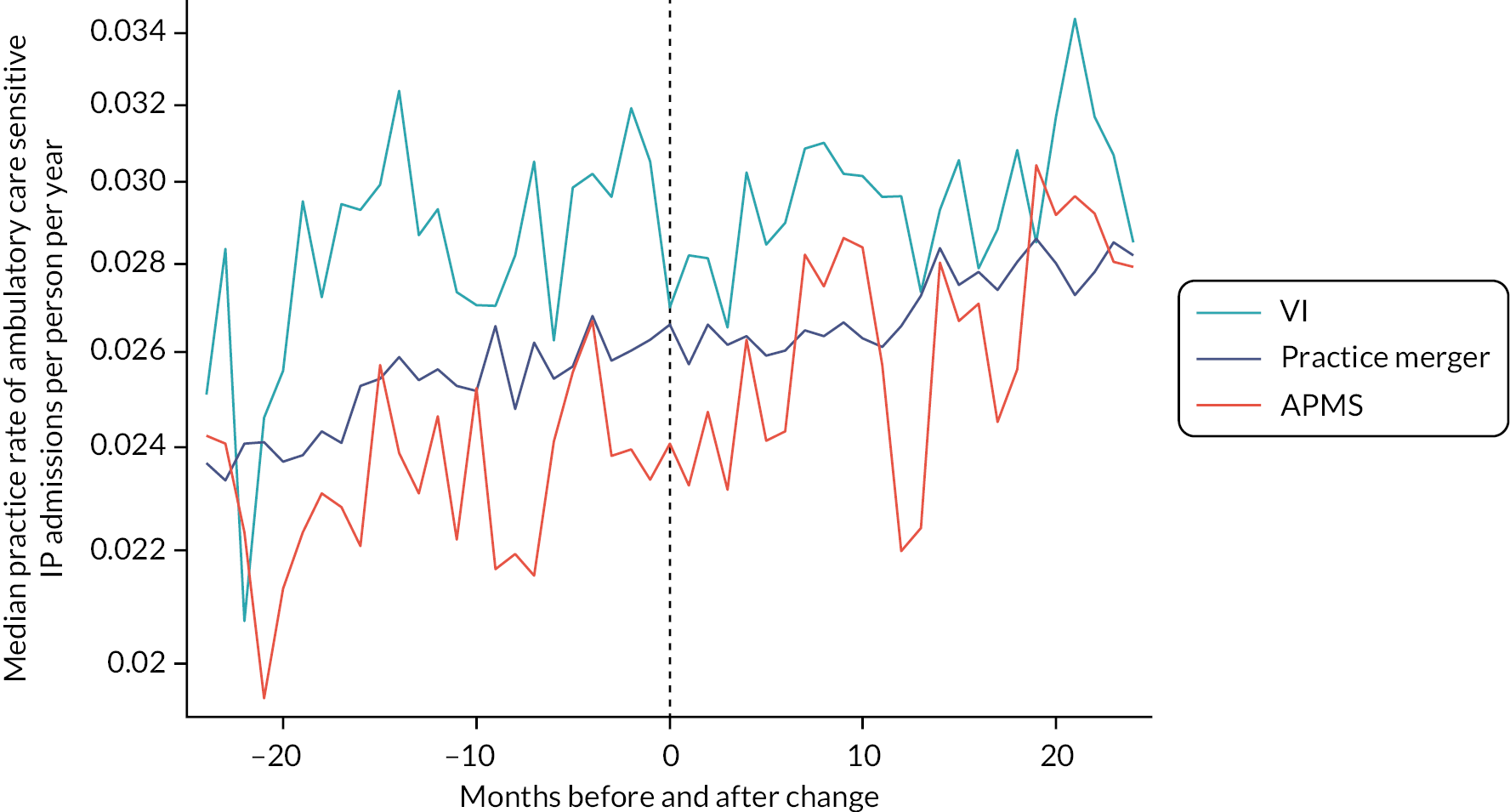

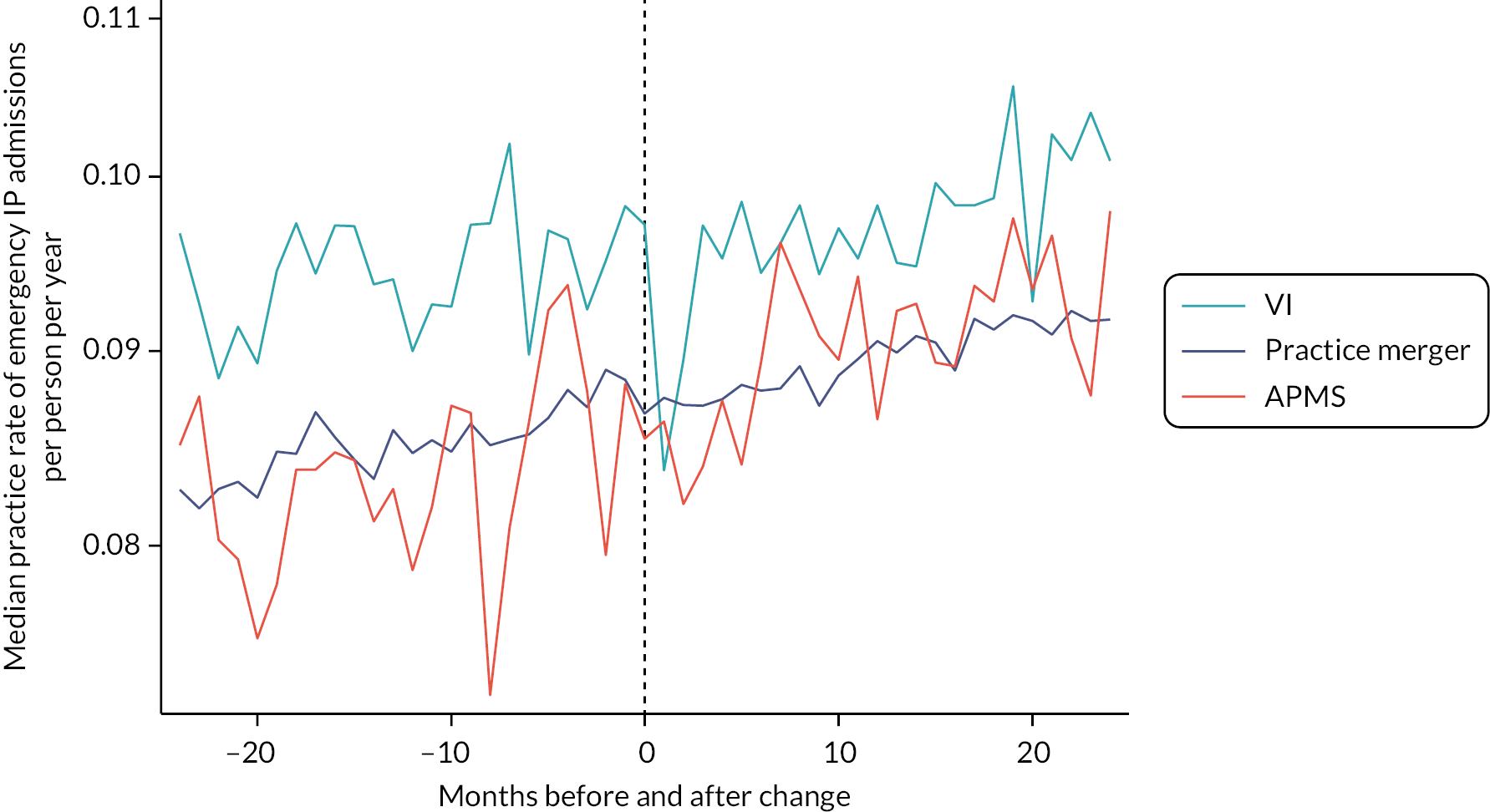

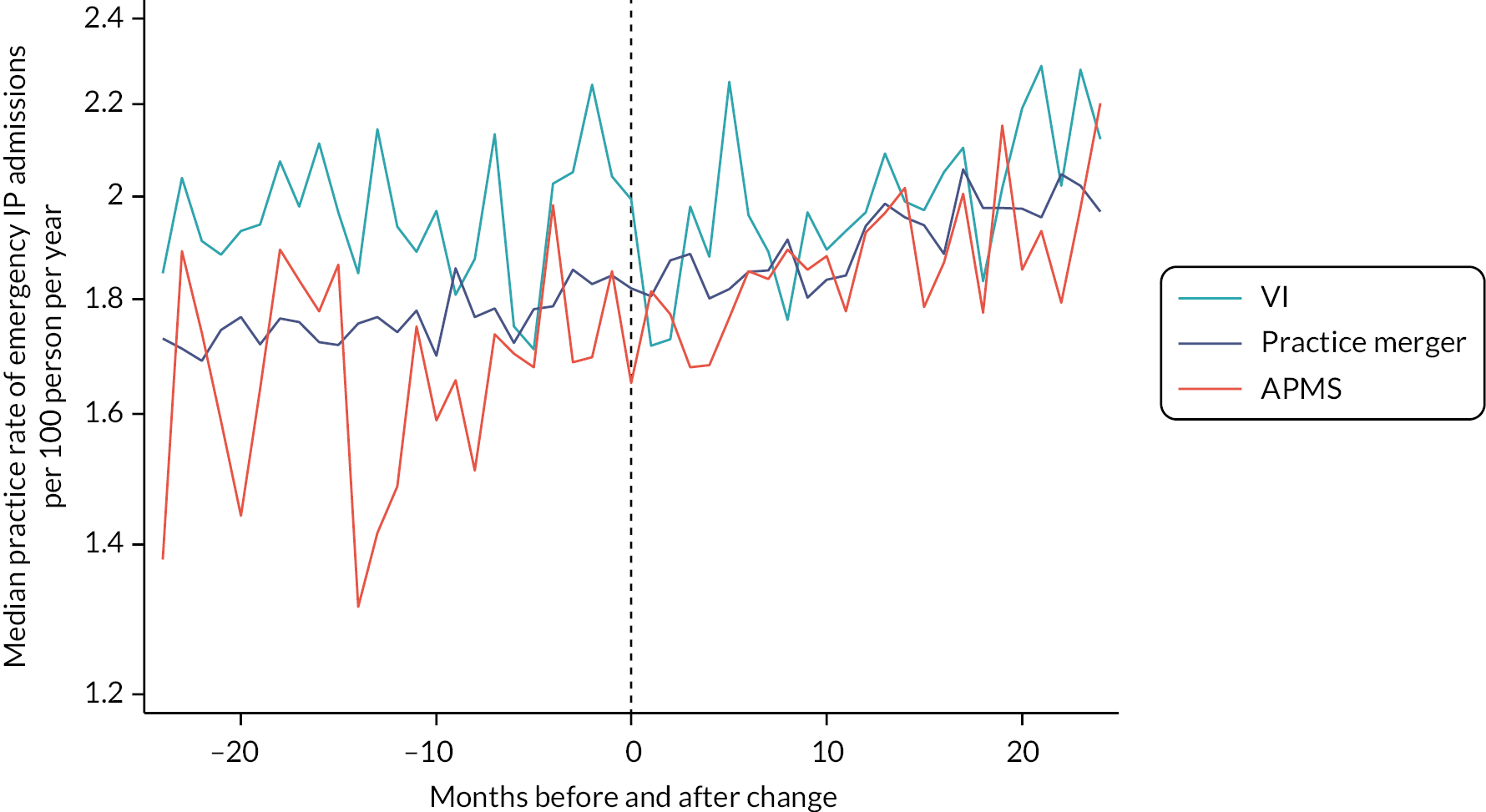

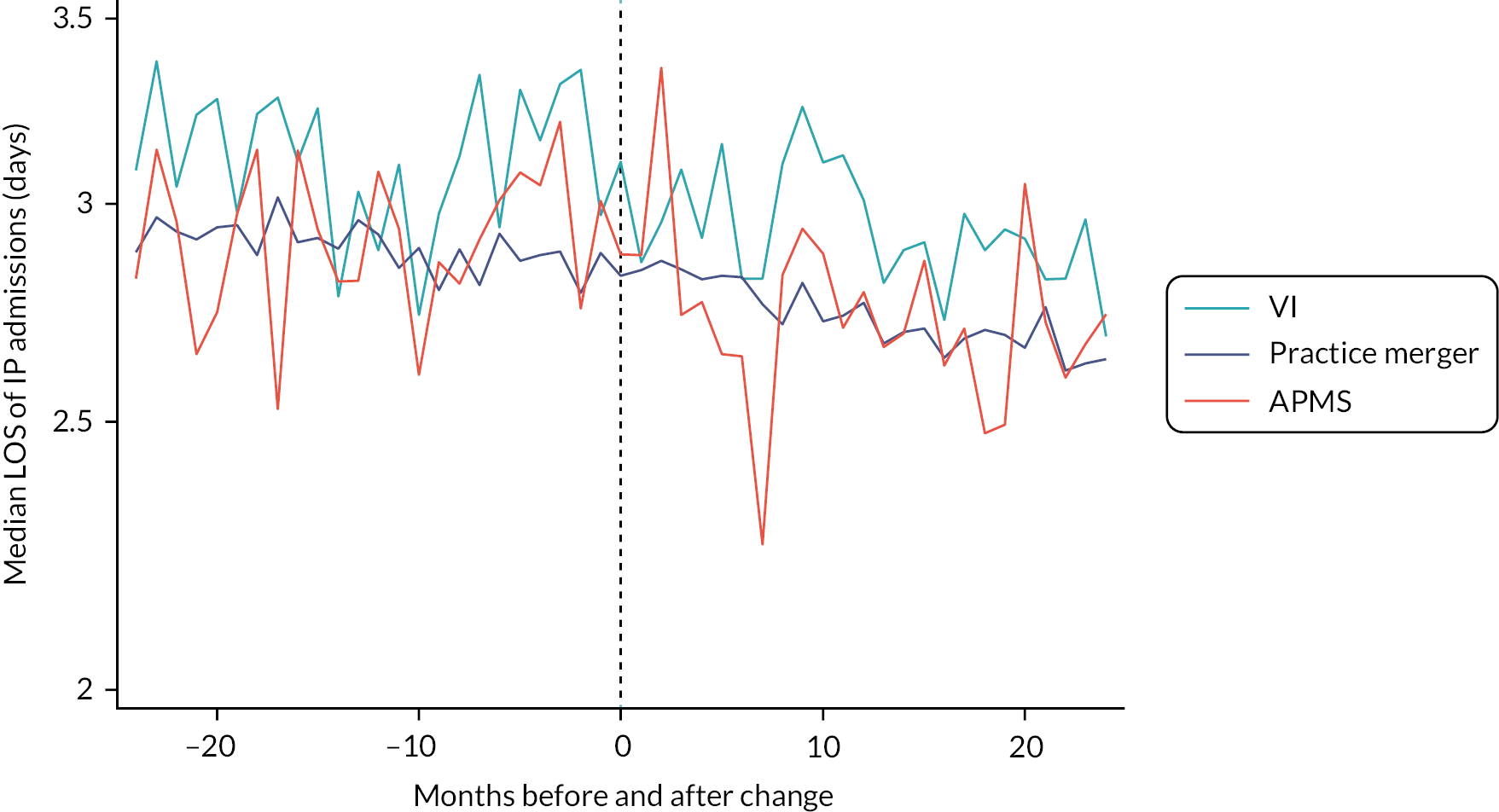

What impact is vertical integration having on the use of secondary care services [outpatient attendances, A&E attendances, all inpatient admissions, emergency inpatient admissions, inpatient admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC), bed days, readmission within 30 days of discharge]? Does this impact differ for people with multiple long-term conditions compared with other patients without long-term conditions or living with a single condition?

-

What impact is vertical integration having on the patient journey with regard to access to and overall experience of care? How does the experience differ for people with multiple long-term conditions compared with those living with no or one long-term condition?

An overview of the methods used for the phase 2 evaluation is given in Chapter 2. The subsequent chapters then set out in turn the findings of work package (WP) 1, on the current extent of vertical integration in England; WPs 2 and 3, quantitative analyses of the impact of vertical integration on patient experience of primary care and utilisation of secondary care; and WP4, qualitative exploration of the patient journey and experience of care in three vertical integration case studies. These findings chapters are followed by a discussion and conclusions.

Chapter 2 An overview of the methods used in the evaluation

Summary of key points

-

Our phase 1 study in 2019 and early 2020 answered some of the pertinent questions about the introduction of vertical integration. However, it did not go so far as to investigate the impact on the use of secondary care services and patient experiences of vertical integration.

-

The research questions for the currently proposed project (phase 2) were designed to update and validate our theory of change for vertical integration.

-

We completed a mixed methods evaluation comprised of four WPs:

-

WP1: desk-based review of NHS trust annual reports, relevant literature and identified data sets, to understand the scale of vertical integration of general practices with acute NHS hospitals and other secondary care providers that has taken place across England.

-

WP2: development of the statistical analysis approach.

-

WP3: quantitative analysis of national data to explore the impact of vertical integration on hospital care and the financial implications of that, and on the patient experience of GP care as measured by a national survey of patients. The quantitative analysis investigated if there is any differential impact for people with multiple long-term conditions.

-

WP4: qualitative data collection and analysis with key stakeholders and patients across three case study sites in England to explore the impact of vertical integration on patient experience of care, particularly focusing on patients with multiple long-term conditions.

-

Protocol sign-off

An initial short pro forma outlining the study aims, methods and outcomes was submitted in December 2021 and was approved by NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR). It was used as the basis for the full evaluation protocol, which drew on relevant literature and an online workshop with our user involvement group. The protocol was approved by NIHR HSDR in May 2022.

General approach

Our general approach to meeting the aims and answering the research questions was a cross-comparative case study mixed-methods evaluation comprising four WPs. The WPs were designed to overlap and thus inform each other to support analysis and triangulation between the quantitative and qualitative data. The study began with a desk-based review of NHS trust annual reports, relevant literature and identified data sets, to understand the scale of vertical integration of primary care practices with acute NHS hospitals that has taken place across England. Then, the study team completed a quantitative analysis of national hospital activity data to explore the impact of vertical integration on the use of secondary care services and the financial implications of that, and on the patient experience of GP care as measured by a national survey of patients. The quantitative analysis investigated if there is any differential impact on secondary care for people with multiple long-term conditions. We completed qualitative data collection and analysis with key stakeholders and patients across three case study sites to explore qualitatively the impact of vertical integration on patient experience of care, particularly focusing on patients with multiple long-term conditions. These four WPs are summarised in Table 1.

| WP | Description | Research questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Understanding the current scale of vertical integration | Establish the extent of vertical integration in England through a desk-based analysis of secondary care statutory financial reporting and primary care GP workforce data | 1 |

| 2. Development of the statistical analysis approach | Identifying the appropriate counterfactual or control sites and the appropriate approach to coding multiple long-term conditions | 1, 2 |

| 3. The impact of vertical integration on use of secondary care | Assess the impact of vertical integration overall and for patients with multiple long-term conditions for secondary care services for identified outcomes, for vertically integrated and control practices before and after vertical integration was introduced; and for patient experience of GP care as measured by a national survey of patients. Also report the financial implications based on the secondary care resource use data for vertical integrated and non-vertically integrated practices | 2, 3 |

| 4. Impact on the patient journey regarding access to and overall experience of care | Interviews and focus groups at each case study site, to which we invited key service managers and clinicians from the acute hospital, community care, and general practices. Primary qualitative research via interviews, capturing the views of patients from integrated general practices, to understand their experiences of the following where vertical integration models are present: what impact is vertical integration having on the patient journey with regard to access to and overall experience of care? How do models of vertical integration support patient transitions from primary care to acute care? How do patients experience services, more commonly found in secondary care, within a vertically integrated general practice setting? How does the experience differ for people with multiple long-term conditions compared with other patients? | 3 |

Learning from the BRACE phase 1 evaluation of acute hospitals managing general practices and the need for a follow-on phase 2 evaluation

In 2019/20, Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation Centre (BRACE) carried out a phase 1 rapid evaluation of arrangements in three case study areas where the NHS organisations operating acute hospitals had taken over the running of general practices at scale in England and Wales (i.e. a fully integrated model of vertical integration). 2 The aims of the phase 1 evaluation were to understand the early impact of vertical integration, namely: its objectives; how it is being implemented; whether and how vertical integration can underpin and drive the redesigning of care pathways; whether and how services offered in primary care settings change as a result; and the impact on the general practice and hospital workforces. The study team developed a theory of change for vertical integration, identifying the outcomes it is expected to achieve in the short, medium and long-term, and under what circumstances (see Figure 1). They found the single most important driver of vertical integration to be the maintenance of primary care local to where patients live. Vertical integration of general practices with organisations running acute hospitals has been adopted in some locations in England and Wales to address the staffing, workload and financial difficulties faced by some general practices. This phase 1 study answered some of the pertinent questions about the introduction of vertical integration. However, it did not go so far as to investigate the impact on secondary care and patient experiences of vertical integration. These interests are reflected in the research questions for the phase 2 project reported here.

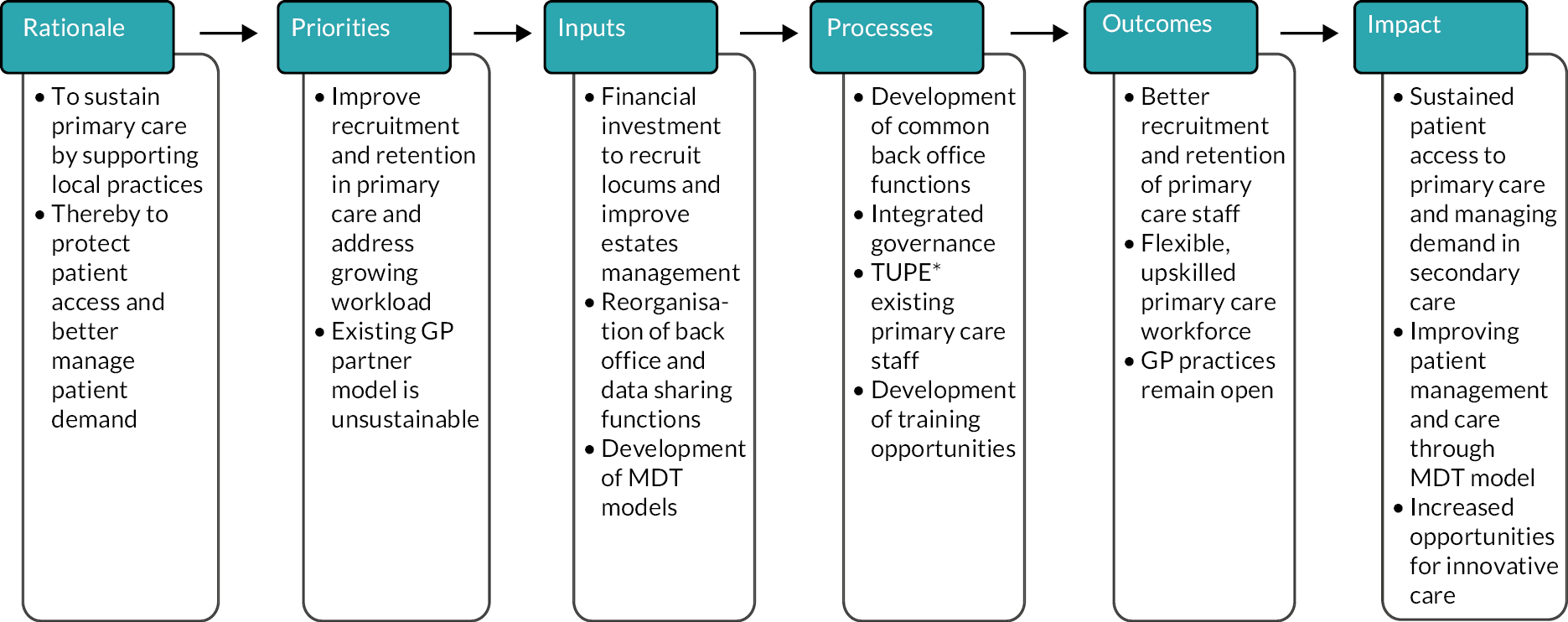

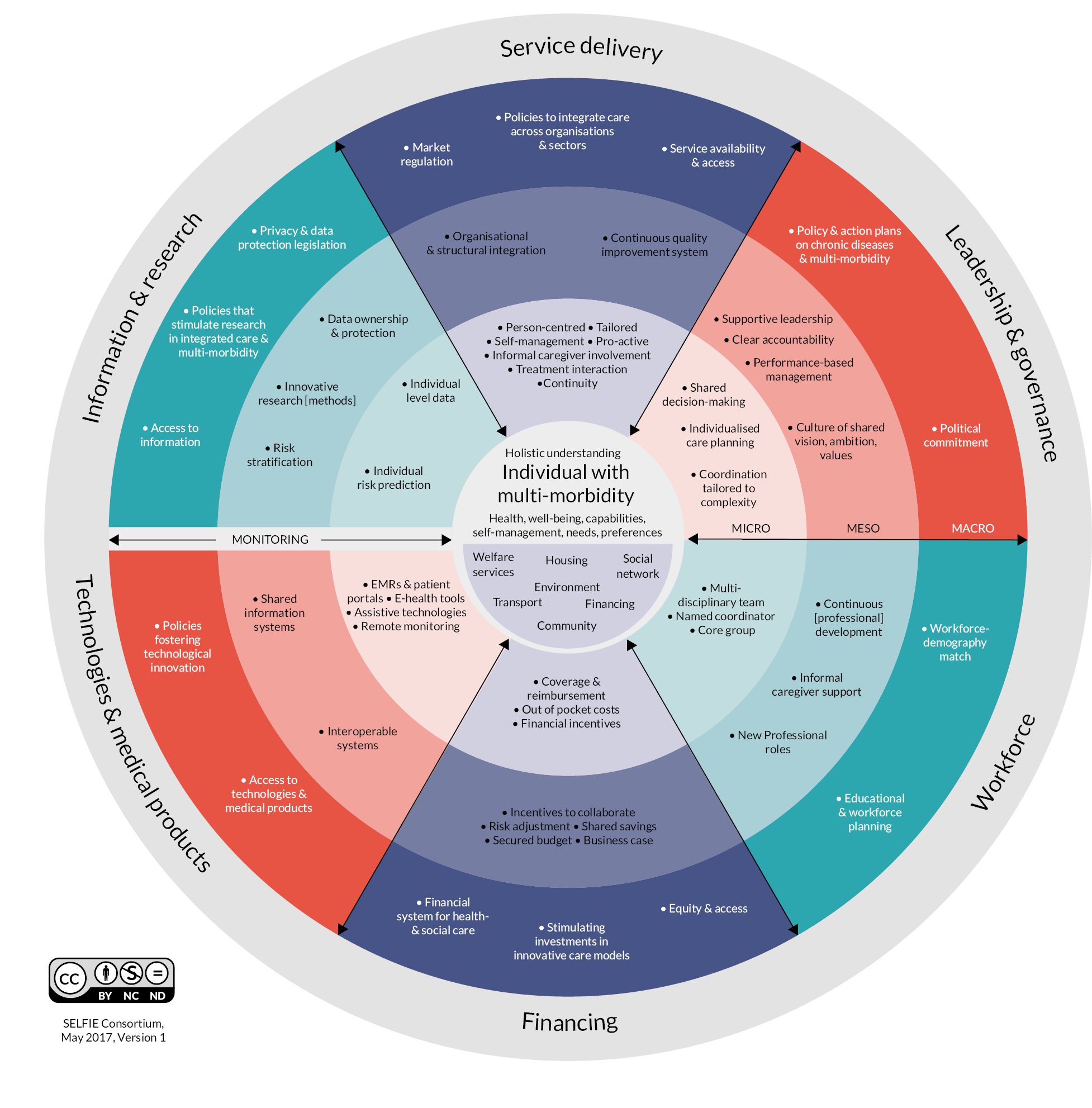

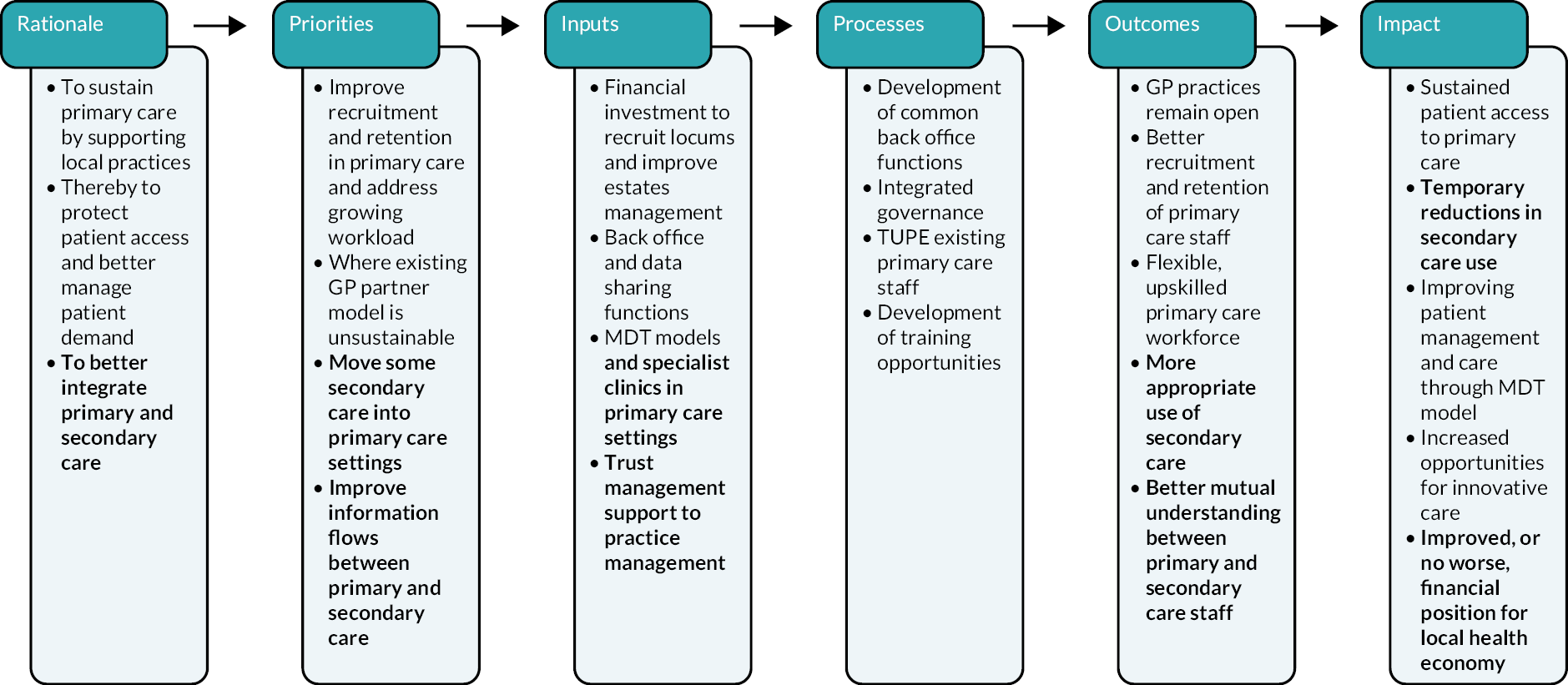

FIGURE 1.

Overall vertical integration theory of change developed from the BRACE phase 1 rapid evaluation. 2 *TUPE, transfer of undertakings (protection of employment) – A ‘TUPE transfer’ happens when an organisation, or part of it, is transferred from one employer to another; a service is transferred to a new provider, for example when another company takes over the contract.

Co-designing the study approach and research questions with members from the BRACE patient and public involvement panel

Members of the study team met with the BRACE patient and public involvement (PPI) panel and discussed the ‘what’ questions (what is important to find out/know about) and the ‘how’ questions (how best to gather this information). Members of the PPI panel took part in two workshops across the duration of the study. A structured agenda was prepared in advance of each workshop and included time for presentation of findings, as well as time for discussion and feedback when sharing learning from data collected. As part of the first workshop (May 2022) members commented on our research questions, choice of methods and recruitment strategies, and participant facing study documentation. A second workshop (November 2022) was held to discuss preliminary findings whereby feedback fed into interpretation of data and supported synthesis of learning across data sets.

Overview of methods by work package

Work package 1: understanding the current scale of vertical integration in England

WP1 details the extent of vertical integration in England through a desk-based analysis of secondary care statutory financial reporting and primary care GP workforce data. There is triangulation of practices where vertical integration has been identified. Statistics that describe the characteristics of the vertically integrated practices are presented: number of acute hospital trusts managing general practices; the number of general practices managed by the acute hospital trust; practice sizes in terms of patient population, patient demographics and workforce descriptors.

Work package 2: development of a statistical analysis plan

As part of WP2, the study team identified appropriate control sites and an appropriate approach to coding multiple long-term conditions as part of a detailed plan of analysis. In addition, this WP addresses several methodological questions, for example how to deal analytically with general practices that have merged with other practices during the study time frame, and how to allow for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the analyses of how patients use secondary care.

Work package 3: quantitative analysis of the impact of vertical integration on the use of secondary care services

As part of WP3, we assessed the impact of vertical integration on patients’ use of secondary care services both overall and more specifically for people with multiple long-term conditions. We examined the following outcomes: outpatient attendances, A&E attendances, all inpatient admissions, emergency inpatient admissions, inpatient admissions for ACSC, bed days, readmission within 30 days of discharge; for the identified practices and their controls before and after the identified practices were vertically integrated. We then discuss the financial implications in terms of an overall cost difference for secondary care use between vertically integrated and not vertically integrated practices. We additionally analysed the results of the GPPS questions relating to patient experience of primary care, comparing replies for vertically integrated practices with those for control practices.

Work package 4: staff and patient experiences of care delivery and provision across three purposively selected case study sites

We completed focus groups and interviews across three case study sites in England with key service managers and clinicians from the acute hospital, community care and general practices; and primary qualitative research via interviews, capturing the views of patients from integrated general practices, to understand their experiences of accessing services in areas where models of vertical integration are present.

We present more detailed methods and our findings in the next three chapters. Chapter 3 provides a description of the scale of vertical integration of primary care practices with acute and community trusts that has taken place across England. The subsequent chapter (Chapter 4) presents a quantitative analysis of national routine data to explore the impact of vertical integration on patient satisfaction and use of health-care services. Chapter 5 sets out an analysis of interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders and patients across three case study sites to explore qualitatively the impact of vertical integration on patient experience of care, particularly focusing on patients with multiple long-term conditions.

Chapter 3 Work package 1: understanding the current scale of vertical integration in the NHS in England

Summary of key points

-

We have compiled the first comprehensive list of trusts and general practices in England that are vertically integrated.

-

The process of identification of vertical integration is not straightforward and (at the time of writing this report February 2022) there is no organisation that holds information about the scale of vertical integration in England.

-

As part of WP1, we describe the characteristics of the vertically integrated practices including: number of acute hospital trusts managing general practices; the number of general practices managed by acute hospital trusts; practice sizes in terms of patient population, patient demographics and workforce descriptors.

-

As of March 2021, we identified 26 trusts in vertically integrated organisations, running a total of 85 general practices (i.e. with unique practice codes) across a total of 116 general practice sites (as some practices work from two or more locations). Vertically integrated practices do not appear to be ‘typical’ general practices but rather tend to be: poorer performing, located in more deprived areas and often with smaller patient numbers and fewer staff.

Methods

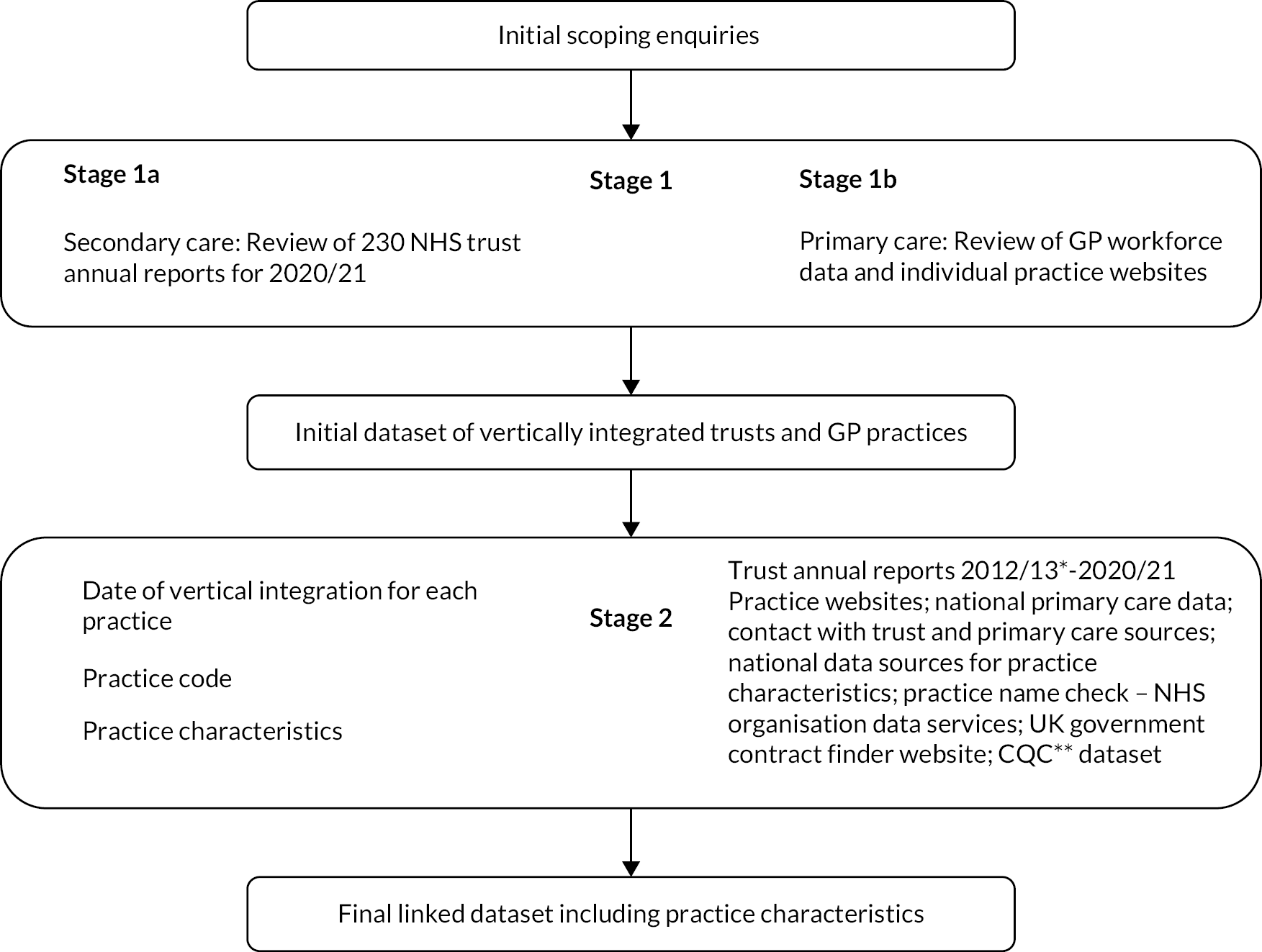

At the start of the phase 2 rapid evaluation, we undertook preliminary scoping work to assess the availability of data on trusts and general practices in vertically integrated arrangements. In addition to online searching, including the NHS Digital website, we contacted representatives of the British Medical Association, the Royal College of General Practitioners, NHS England and NHS Improvement. We found that none of these organisations holds such information systematically or comprehensively. The research team therefore compiled these data in the following way, which is represented schematically in Figure 2. In essence, we used trust annual reports as the main data source and then checked the robustness of that information by comparing with GP workforce data, general practice websites and other sources as listed in Figure 2 and described below.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of WP1 search process. *Using CQC data. 39 **Although vertical integration generally took place from 2015/16 onwards, we checked back to 2012/13 to allow for any earlier models of vertical integration which might have taken place.

Stage 1a: secondary care statutory financial reporting

The principal source of information on vertical integration where trusts run general practices, was trusts’ annual reports. We hand searched the annual reports of all 230 NHS trusts listed on the nhs.uk website. 40 Each NHS foundation and non-foundation trust must publish annual reports and accounts to allow scrutiny of the year’s operations and outcomes. Trust annual reports are typically published in a PDF format on the trust’s website. 41 We first searched the reports from 2020/21 (the most recent available) and then backed this up by searching the reports from 2019/20, which revealed several additional vertical arrangements not evident from the later year’s reports.

One member of the research team (FO) used the ‘find and retrieve’ search option for the terms ‘general practitioner’, ‘GP’ ‘general practice’ and ‘primary care’ within each annual report and determined from the corresponding text whether the trust had reported a financial/ownership relationship with a provider of GP services, and thus would be considered vertically integrated with that practice or practices. For trusts with no vertically integrated practices, our expectation was that we would find less frequent use of the search terms in the report. We found that the search terms were frequently mentioned in the pension reporting sections but with no reference anywhere else in the report in question that indicated that the trust owned or managed any general practices. These were, consequently, not instances of vertical integration. The researcher (FO) was otherwise independent of the study and had no prior knowledge of vertically integrated practices, which helped to ensure an unbiased assessment of where vertical integration was present. All trust reports with identified vertically integrated general practices were then reviewed for a second time by another member of the research team. A further 20% of trusts identified by the first reviewer as not having vertically integrated practices were also second-reviewed as a control. The second review confirmed that these trusts were not integrated with general practices.

We checked the websites of practices identified by this process to confirm their connections with NHS trusts. We additionally searched via Google for press mentions of trusts taking over the running of general practices. Finally, we cross-checked the findings of the blinded reviews against study team knowledge of areas where vertical integration is occurring and found that all instances of vertical integration previously known to members of the research team had been identified, plus some further instances.

Stage 1b: validation via primary care general practitioner workforce data and practice websites

A key finding from our phase 1 evaluation2 was that vertical integration was a way of sustaining local primary care, and one form of vertical integration was for a trust to employ GP staff directly. We therefore inspected the GP workforce data published by NHS Digital at 31 March 2021,42 which reports all types of GP employment contracts. Our focus for searching was on GPs categorised as ‘other’ (i.e. not salaried GPs, GP partners, trainees or locum practitioners). A preliminary review of these data identified 243 practices where one or more ‘other’ GPs were employed. We then searched on the practice names to find and review the corresponding individual practice websites for further indications of possible vertical integration with a trust. Practice names were cross-checked against information provided by NHS Digital. 43

Further robustness checks were provided by reviewing all general practices with alternative provider medical services (APMS) contracts on the UK government contract finder website to identify those where acute or community trusts hold the contract. 44 This revealed no further examples of vertical integration for our analysis. We also cross-checked our findings of vertically integrated practices with the Care Quality Commission register of general practices39 filtered by ‘location primary inspection category’ and ‘provider type/sector’.

Stage 2: finalisation of linked dataset

The second main stage in the identification process was to return to the annual reports of those trusts that had been found to be running general practices, to enable identification of practice level details including the individual practice code (the ‘organisation code’ which identifies any NHS organisation uniquely). The practice code is required to be able to link the study outcomes (described in Chapter 4) with the vertically integrated practices. We also needed to identify the practice name and the date that it became vertically integrated into a trust. Practices entering a vertical integration arrangement with a trust are undergoing an organisational change and may consequently have a change in their practice code. We found that there were sometimes practice mergers occurring around the time that practices became part of vertically integrated organisations. To help us track which preintegration practices had merged into which post-integration practices and when that happened, we took note of information about the sites (geographical locations) from which vertically integrated practices were working. A site becoming a location for a practice with a different practice code than previously, is an indication that the practice working from that site has merged with another. All this information gathering entailed hand-searching the annual reports of each of the vertically integrated trusts, starting with the 2020/21 annual report in each case and then working backwards preceding year by preceding year, noting all mentions of general practices and/or practice sites being vertically integrated (and whether they were merged at any point or left the vertically integrated organisation at any date) until the date of the first vertical integration event (the first general practice whose management was taken over by the trust).

Details on models of integration at the practice or trust level are not always stated clearly in trust annual reports, specifically the date when the change happens and what happens to the practice codes at that date. Where practice code, name and date of integration were not mentioned or were otherwise unclear in trust annual reports, the following detailed search process was followed in hierarchical order:

-

Visited individual practice websites and carried out online searching for date of entry into vertical integration; we then visited local and national media sources.

-

Used NHS Digital ‘GP and general practice related data’ sources for two separate years (2022 and 2016; 2022 was chosen as the first year to identify practice codes as it was the most up-to-date version available. We also used an archived version from 2016 as being around the start of vertical integration and would enable us to identify any practice codes which might since have changed due to mergers, closures and so on) to identify the practice code using the data files for both GP practices (epraccur) and branch surgeries (ebranchs). 43,45–47 The datasets include all general practices active in that year. We searched on practice name to match to practice code. Where there was uncertainty, practice address was used for confirmation of a match.

-

Contacted trust or practice contacts, where research team members had those, to ask for practice code and date of entry into vertical integration.

During our preliminary work we identified that horizontal integration (where general practices join with one or more practices) would be a methodological challenge for the quantitative analysis in our study. We therefore undertook a two-step approach to identifying where horizontal general practice mergers had taken place.

In step 1, we used person-level outpatient data from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), held under the BRACE data sharing agreement. We used data from the financial year April 2013/14 to the financial year April 2019/20 (i.e. April 2013–March 2020). In each year, we selected practices with at least 1000 patients and then identified practices in the following financial year where over 50% of patients from the previous financial year were now registered. For example, if 100 individual patients with the same practice code in the HES data for 1 year are again treated in hospital the following year but more than 50 of those patients all now have the same practice code, that is different from the practice code they had the previous year, then we may reasonably assume that the first practice has been merged into the second. We also looked in the data set from April 2018/19 for practices where the majority of patients were registered previously and cross-checked the practice codes from the two approaches.

In the second step, we used practice-level data on branch surgeries listed by the NHS Organisation Data Service via NHS Digital40 and matched current practice codes for branch surgeries with historic practice codes for practices at the same postcode (where a postcode was unique by practice) but which no longer had registered patients. This would indicate that a surgery that was previously the base for one practice has become a branch surgery for a practice based elsewhere and thus is likely to have merged with that practice.

Once we had identified the general practice codes before and after vertical integration of all practices integrated vertically with trusts, whether acute or community trusts (by our definition, as described in Chapter 1) we retrieved data on practice characteristics from general practice level data sources provided by NHS Digital at the national level. Further details are provided in the following ‘data and sources’ section. The datasets were extracted as raw CSV files from the primary source and imported into STATA® Se version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The required variables from each of the data sources were then merged, matching on the practice code. The dataset we had created detailing vertically integrated trusts and their general practices was then merged into the practice characteristics dataset, again using the practice code as the identifier.

Data and sources

We constructed a cross-sectional dataset for March 2021 for all general practices in England and with all the relevant characteristics of the sites from which the vertically integrated practices operate, as follows.

-

Practice code – an organisation code that uniquely identifies each general practice in England.

-

VI – a binary variable which has a value of 1 if it is a vertically integrated NHS trust or general practice. Identified from the search process described earlier.

-

NHS trust type – NHS trusts are publicly owned organisations providing health care to NHS patients and are either NHS foundation trusts or NHS trusts. For the purposes of our work, we refer to them collectively as ‘trusts’. Trusts can take different forms: acute, community, mental health – and any combinations of those – or ambulance trusts. For the purposes of our study, we define an acute hospital trust is one providing acute hospital-based secondary health care, whether solely that or in combination with community and/or mental health services. An acute trust can have more than one acute hospital site within it. In March 2021, there were 230 trusts in England, with 144 of them being acute hospital trusts. 41 For our analysis, we split the trust type into a binary variable with a value of 1 if an acute hospital trust or a combined trust including acute hospital services, and a value of 0 if any other type of trust. For brevity we label this second category as ‘community trusts’, as explained in Chapter 1.

-

Date of vertical integration – This is the date that the first general practice was integrated with that trust. This is retrieved from the primary data source: the trust annual report or the general practice website.

-

Practice list size – This is defined as the number of patients who are registered at a general practice on the first day of each month. These data are nationally available at the practice level via the NHS Digital website. 48 For the purpose of this analysis, the list size data are retrieved for March 2021.

-

Contract type – general practice services are contracted by NHS commissioners (until July 2022, these bodies were known as CCGs; since July 2022, NHS commissioners are ICBs) following national guidelines for the practice to provide general medical services for the population registering with them, who are typically resident locally to the general practice’s premises. Most practices are run by at least two, and usually more, GPs alongside other health-care professionals such as practice nurses and physiotherapists who work within the same building. One or more of the GPs may own a stake in the practice business, although practices can also be owned by companies and via other ownership models. 8 Each practice holds an NHS contract to run the practice, of which there are three different types as described in Box 1 in Chapter 1: general medical services (GMS), personal medical services (PMS) and APMS. We obtained the contract type for each practice from NHS Digital ‘NHS Payments to General Practice’ for 2021/22. 49

-

GP workforce – We obtained the number of FTE GPs at the general practice level using NHS Digital data on GP workforce. 42 We also retrieved data on the number of GPs funded by ‘other’ as defined by NHS Digital (i.e. those GPs who are neither salaried, nor partners, trainees or locum practitioners). We did this in case GPs employed by trusts would be recorded in this category.

-

Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) score – Quality and outcomes indicators are agreed as part of the NHS GP contract negotiations every year. These indicators have points attached that are awarded according to how well general practices do against them, and so the QOF score is a proxy measure for the quality of the practice. We retrieved data on practice level QOF scores from NHS Digital,50 and specifically whether each practice achieved a QOF score within 25% of the total quality points achievable.

-

Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) code – The IMD is the official measure of relative deprivation for small areas in England based on seven different domains to produce an overall relative measure of deprivation. 51 It provides a rank from 1, which is the most deprived area to 32,844, the least deprived area. Using the ranks, decile 1 represents the most deprived 10% of areas nationally and at the other end of the scale, decile 10 represents the least deprived 10% of areas nationally. We report the percentage of practices in the most deprived decile as of March 2021. We obtain IMD codes for the postcode of each general practice in our dataset using the ‘English indices of deprivation’ 2019 online tool. 51

-

Rural or urban classification – We distinguish rural and urban areas, where the classification defines areas as rural if they fall outside of settlements with more than 10,000 resident population. 52 We retrieved data on the rural or urban classifier through the NHS Digital, ‘NHS Payments to General Practice for England dataset 2019/2020’,49 which we then linked to our practice level dataset using the practice code.

Findings

Number of vertically integrated general (medical) practitioner practices

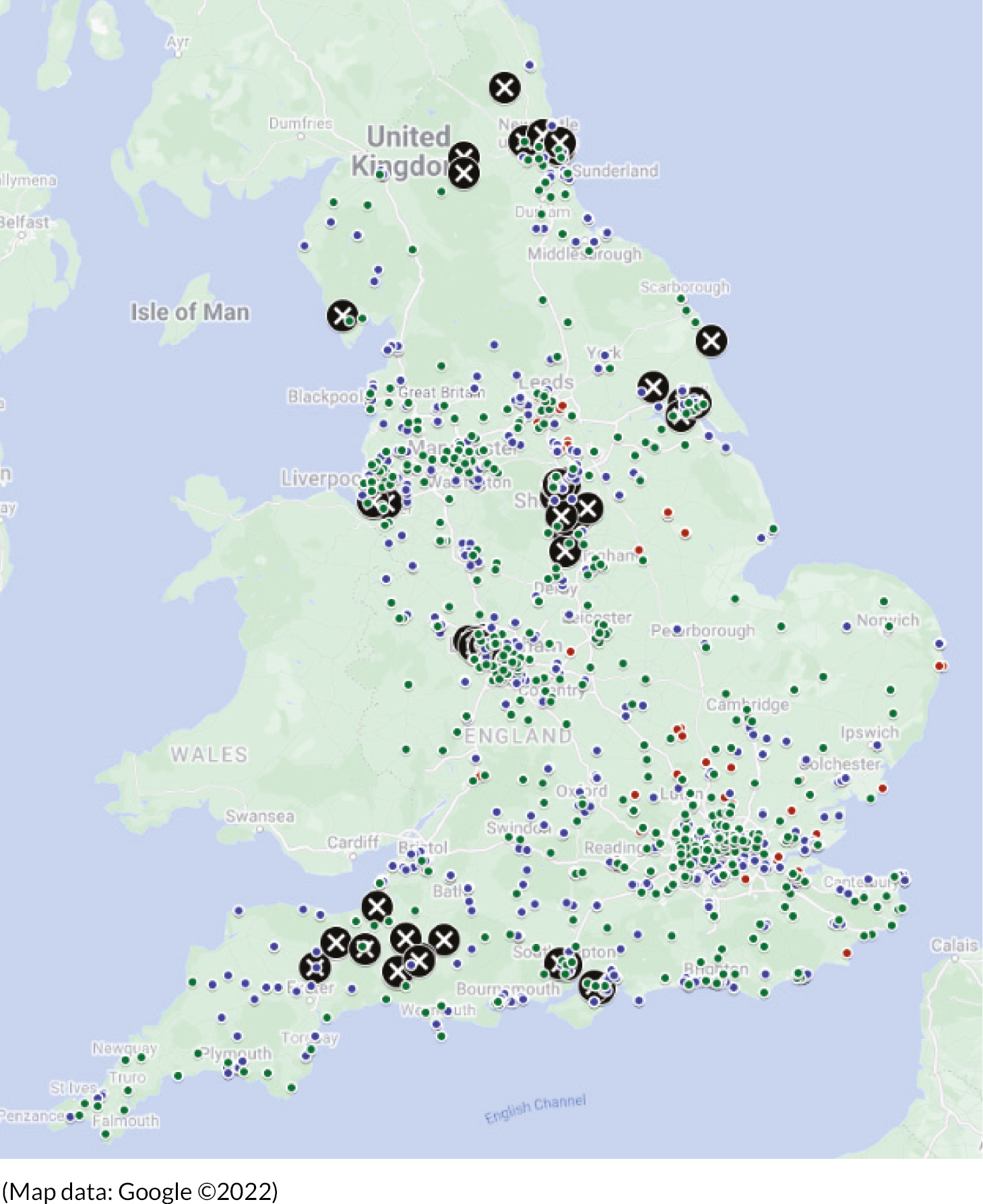

As of March 2021, we identified 26 trusts in vertically integrated organisations, running a total of 85 general practices (i.e. with unique practice codes) across a total of 116 general practice sites (as some practices work from two or more locations). The locations of these vertically integrated practices are scattered across England (see Figure 3). There are concentrations of vertically integrated practices in several locations, but with no particular geographical pattern, although we note that there are few instances in London.

FIGURE 3.

Locations of vertically integrated general practices in England, March 2021.

We initially identified 26 vertically integrated trusts from financial year 2020/21 trust annual reports and a further 7 from the 2019/20 reports. Further in-depth checking of these 33 annual reports by a second researcher, confirmed that 7 of the total number of apparently vertically identified trusts from this search process were not in fact cases of vertical integration. The reasons why these trusts were incorrectly identified was most commonly because the trust was either in a joint working arrangement with a general practice or was using primary care premises for some trust activity. The final total number of vertically integrated trusts identified from the annual reports identified in Stage 1a of our analysis was thus 26.

Stage 1b confirmed many of the instances of vertical integration that we found by inspecting trust annual reports and did not reveal any additional instances. The resulting list of vertically integrated trusts and general practices included all of those that had been known to the members of the research team (which includes two researchers who had taken major roles in the phase 1 evaluation of vertical integration) prior to the analysis. This triangulation encourages confidence that the list of 26 vertically integrated trusts with 85 practices operating from 116 sites obtained from the search of trust annual reports is robust and reliable.

During the search process, it became evident that there is not a single criterion for identifying vertically integrated general practices, and that identification can prove complex, for example:

-

One general practice we identified is co-owned by both an acute and a community trust and is included in our dataset as owned by the acute trust only.

-

Five practices owned by acute hospitals and identified in this process were serving populations of homeless people or provided services for patients who are otherwise unable to access primary care and had been running in a similar structure for over 20 years. These practices are excluded from the analysis in this chapter.

There is also heterogeneity in the ownership arrangements for practices who become vertically integrated; for example, practices may undergo vertical integration at the same time as the acute or community trusts takes on the APMS contract. For some practices within a vertically integrated model, their GMS contracts are retained, although for some they are not. Ownership of practices can be taken on directly by the trusts or in some cases the trust sets up a wholly owned subsidiary company, which then owns the vertically integrated practices within the trust. However, the biggest challenge was in identifying the practice codes and the date of which the vertical integration of a practice took place (as detailed in the methods section).

Our preliminary scoping work revealed that general practices may undergo several stages of reorganisation as part of the vertical integration process, for example initially becoming a vertically integrated practice, and then undergoing horizontal mergers with other vertically integrated practices within the same trust. Although horizontal mergers have been a feature of primary care nationally, it has become evident that they are also a particular feature of vertically integrated general practices. The fact that practice codes within vertically integrated practices are particularly susceptible to change has meant that being able to reliably identify horizontal integration as well as vertical integration of primary care is an important methodological step for this evaluation (Appendix 1 provides further details of the process of identifying horizontal integration and the application to vertical integration of general practices into NHS trusts).

Linking to general practitioner practice characteristics

The next stage in constructing the dataset was to link it to data on general practice characteristics using NHS Digital GP primary care data sources as described in Chapter 2. Appendix 2, Table 23 provides a tabular overview of the linkage process in more detail.

The data set of vertically integrated practices initially contained 119 unique practice codes, 66 of these practices were run by acute hospital trusts and 53 were by community hospital trusts. Just 5 of the 119 practices were identified as homelessness practices or provided services for patients who are otherwise unable to access primary care. These practices were excluded from the analysis for WP1 because some had been established more than 20 years ago and all had been created specifically to serve those special populations. For the analysis in this chapter, we have used a cut off time point of March 2021. Thus, three further practices were excluded from the analysis in this WP, as their date of vertical integration took place after March 2021. Finally, a further 28 practices were excluded as they had either closed or merged with another practice before the cut-off point of end-March 2021 (2 of these 28 practices were homeless practices and thus had already been excluded). This gave us dataset of 85 general practices still operating as of March 2021 (see Table 2).

| Trusts/general practices | Trusts | General practices |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 230 | 6576 |

| Of which vertically integrated, n (% of total) | 26 (11) | 85 (1) |

| Of which: | ||

| Acute hospital, n (% of all vertically integrated) | 15 (58) | 52 (61) |

| Community, n (% of all vertically integrated) | 11 (42) | 33 (39) |

The mean number of practices run by each trust was 3.3 (median 2.5; range 1–12) with community trusts (mean 3.0; median 2.0; range 1–8) running slightly fewer practices on average than acute trusts (mean 3.5; median 2; range 1–12). The largest group of practices was run by an acute trust, Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, which has a wholly owned subsidiary company called Symphony Healthcare that is responsible for running 12 general practices across the south-west of England. The second largest group of practices was also run by an acute trust: the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, which manages 10 practices as part of the trust. By contrast, 11 of the vertically integrated trusts were each only running one practice (see Table 3).

| Trust | Practice sitesa | Unique practice codes (April 2021)a | Date first practice joinedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute hospital trusts | |||

| Chesterfield Royal NHS Foundation Trust | 7 | 3 | May 2015 |

| Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 | 1 | October 2019 |

| Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust | 4 | 4 | January 2021 |

| Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 2 | November 2019 |

| Imperial College Health NHS Trust | 1 | 1 | July 2016 |

| Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 9 | 8 | April 2015 |

| Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 1 | January 2018 |

| Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust | 7 | 3 | May 2019 |

| Somerset Foundation NHS Trust | 3 | 3 | September 2016 |

| St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | 1 | 1 | April 2020 |

| The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust | 11 | 10 | June 2016 |

| University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 1 | July 2020 |

| University Hospitals of Morecombe Bay NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 1 | October 2016 |

| West Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust | 1 | 1 | June 2020 |

| Yeovil district hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 16 | 12 | April 2016 |

| Community trusts | |||

| Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust | 4 | 3 | July 2015 |

| Derbyshire Community Health Services NHS Foundation Trust | 5 | 3 | May 2016 |

| Dudley Integrated Health and Care NHS Trust | 1 | 1 | April 2020 |

| East London NHS Foundation Trust | 5 | 2 | May 2013 |

| Humber Teaching NHS Foundation Trust | 9 | 8 | June 2015 |

| Lincolnshire Community Health Services NHS Trust | 3 | 2 | April 2019 |

| North Staffordshire Combined Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 1 | June 2018 |

| Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust | 6 | 4 | June 2015 |

| Solent NHS Trust | 4 | 1 | October 2017 |

| Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust | 4 | 1 | April 2017 |

| Sussex Community NHS Trust | 7 | 7 | March 2019 |

| Totals (26 trusts) | 116 | 85 | |

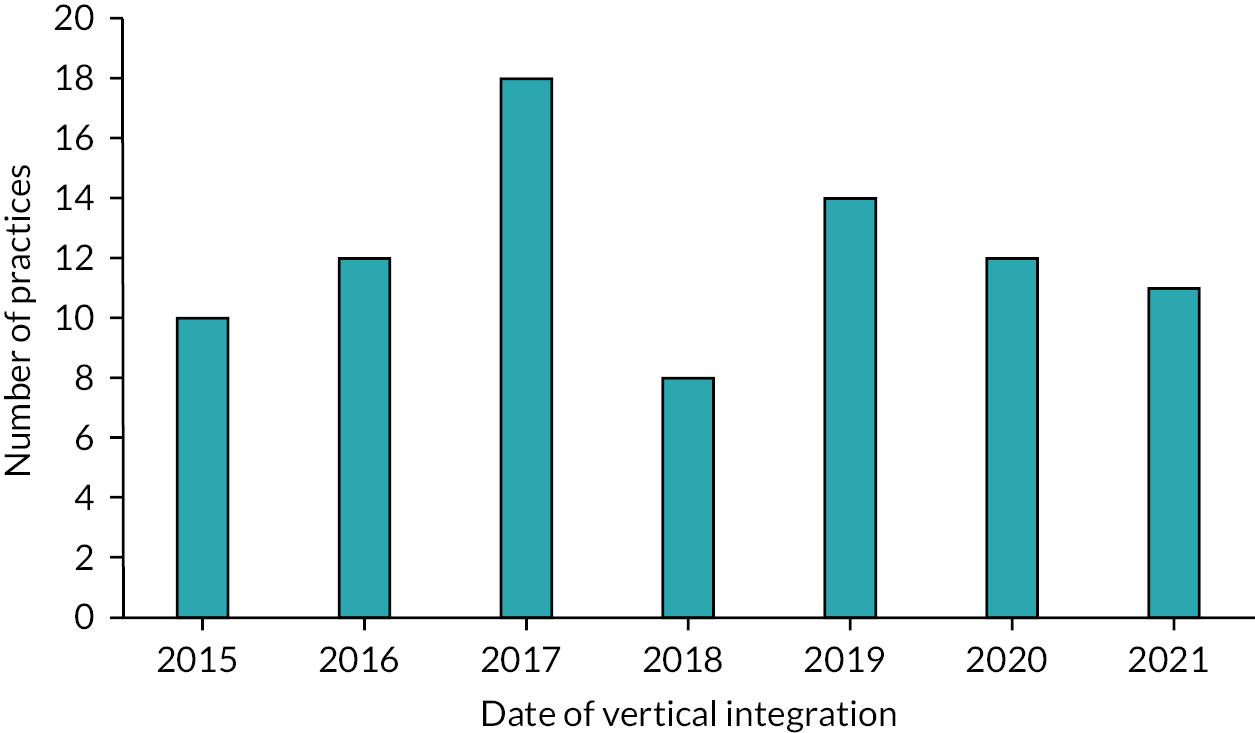

Figure 4 plots the number of general practices by the date when they became vertically integrated. It shows that the first case of vertical integration between a trust and a general practice recorded in our dataset occurred in 2015.

FIGURE 4.

Date of vertical integration by number of general practices.

Table 4 reports descriptive statistics (as of March 2021) comparing vertically integrated with other general practices and disaggregating vertically integrated practices according to whether they are integrated with an acute or community trust. Overall, vertically integrated general practices are smaller than other practices on average, with a median list size of 6794 patients (mean 8902) at vertically integrated practices against a median list size of 8028 patients (mean 9245) at other practices. There is not much difference in size between practices integrated with acute trusts and those integrated with community trusts, although the latter are on average slightly larger in terms of median patient list sizes as of March 2021. The phase 1 study2 found that one reason (though by no means universal) for a general practice to become vertically integrated with an acute trust was due to a practice with one or two remaining GP partners (i.e. probably a smaller than average practice) finding it difficult to recruit new GPs when the existing GP(s) were contemplating retirement. This rationale is consistent with finding that vertically integrated practices are smaller than other practices on average.

| General practice characteristics | Category | Vertically integrated | Not vertically integrated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Acute | Community | |||

| List size, median (IQR) | 6794 (5177–10,273) | 6647 (5390–10,430) | 6927 (4406–9,507) | 8028 (5195–11,734) | |

| IMD, n (% in most deprived decile)a | 16.4 | 11.5 | 24.2 | 15.2 | |

| Contract type, n (%)b | APMS | 12 (14.1) | 6 (11.5) | 6 (18.2) | 150 (2.3) |

| GMS | 50 (58.8) | 33 (63.5) | 17 (51.5) | 4567 (70.5) | |

| PMS | 23 (27.1) | 13 (25) | 10 (30.3) | 1763 (27.2) | |

| Rural/urban, n (%)c | Rural | 22 (27.5) | 18 (34.6) | 4 (14.3) | 1052 (16.6) |

| Urban | 58 (72.5) | 34 (65.4) | 24 (85.6) | 5302 (83.4) | |

| QOF (% achieving top 25% score)d | 58.90 | 63.50 | 51.59 | 75.80 | |

| GP FTEs, median (IQR)e | 3.6 (2–6) | 3.4 (2–5.5) | 3.8 (2–6.1) | 4.3 (2.3–7.2) | |

| GP FTEs employed in the practice on an ‘other’ contractf (%) | 21 | 25.40 | 15 | 2.50 | |

| Practices that have undergone a merger between 2013 and 2021 (%) | 24.4 | 20.7 | 30.3 | 23.1 | |

Table 4 shows that, in terms of social deprivation levels where they are located, vertically integrated practices are very slightly more likely to be in the most deprived decile when compared with non-vertically integrated practices (16–15% respectively). Disaggregating the vertically integrated practices further by acute and community trusts reveals that those located in community trusts are far more likely to be in deprived areas (24% compared with 11% for acute trusts).

Vertically integrated practices are more likely to have GMS than PMS or APMS contracts (see Box 1 in Chapter 1), but this pattern is weaker than among other practices. Vertically integrated practices are considerably more likely to be on APMS contracts than are other practices: only 2% of other practices have APMS contracts but 14% vertically integrated practices do. Practices integrated with community trusts are rather less likely to hold GMS contracts than do practices integrated with acute trusts.

A higher proportion of vertically integrated practices are in rural areas (26%) than is the case for other practices (16%) and this difference is entirely due to those practices that are integrated with acute trusts. This result is skewed by the vertically integrated trust with by far the most general practices being located in a rural area (Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, which ran 12 general practices by April 2021).

Three-quarters (75%) of practices that are not vertically integrated achieved a QOF score within 25% of the total quality points achievable. The performance of vertically integrated practices, as measured by QOF scores, was weaker: only 59% of the vertically integrated practices achieved QOF scores of at least 75% of the possible maximum. This result is further emphasised for practices that are integrated with community trusts, of which only 52% are achieving a QOF score within 25% of the maximum possible score. These findings are suggestive of practices with greater performance issues being more likely to be vertically integrated. The direction of causation is not known, but the phase 1 study2 noted that a rationale for practices to vertically integrate with an acute hospital was because the practice was struggling to keep going on its own.

In line with the finding that vertically integrated practices have, on average, smaller patient list sizes than other practices, Table 4 shows that vertically integrated practices also employ fewer GPs on average: a median of 3.6 compared with 4.3 in other practices. Average list size per FTE GP is similar in vertically integrated as compared with other practices. The numbers for acute and community trusts’ practices are very similar. We note that practices that are not vertically integrated employ just 2.5% of their GPs on ‘other’ arrangements (i.e. other than being salaried, partners, trainees or locum practitioners) but this proportion is considerably higher, at 21%, among vertically integrated practices. We made use of this difference when checking the robustness of our initial search for vertically integrated trusts and practices (see Stage 1b: validation via primary care GP workforce data and practice websites).

In summary, this is, to our knowledge, the first time that the extent of vertical integration of NHS trusts running general practices in England has been determined. We have developed and tested a robust and comprehensive method using a two-stage process. In doing so, we have identified that as of March 2021 there were 26 NHS trusts, running 85 general practices with 116 sites. We have been able to provide summary statistics about these practices, revealing that practices in vertically integrated organisations with NHS trusts are, compared with other practices in England: on average smaller with fewer GPs and fewer patients; less likely to be on GMS contracts; more likely than other practices to be on APMS contracts; and to have a higher proportion of their GPs on ‘other’ terms of employment than being partners, salaried, trainees or locum GPs.

Chapter 4 Work packages 2 and 3: quantitative analysis of the impact vertical integration has on primary care patient experience and use of secondary care services

Summary of key points

-

In this chapter, we present the methods and results for the quantitative part of the impact evaluation of vertical integration providing evidence to answer research questions 2 (What impact is vertical integration having on secondary care utilisation) and 3 (What impact is vertical integration having on the patient journey), also considering specifically the experiences of people living with multiple long-term conditions.

-

We contrast this impact with the impact of horizontal mergers between general practices and with the impact of switching to APMS contracts not associated with vertical integration.

-

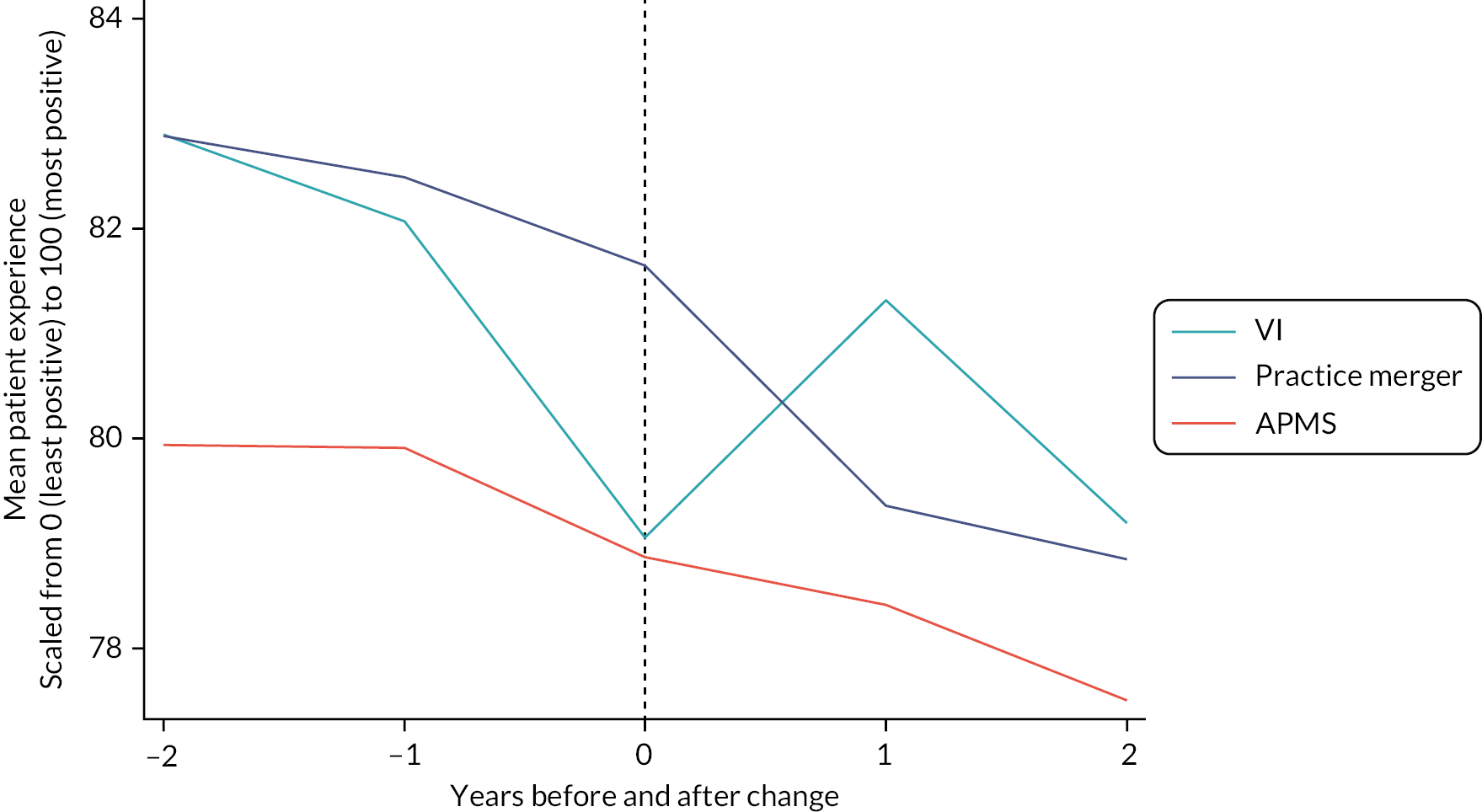

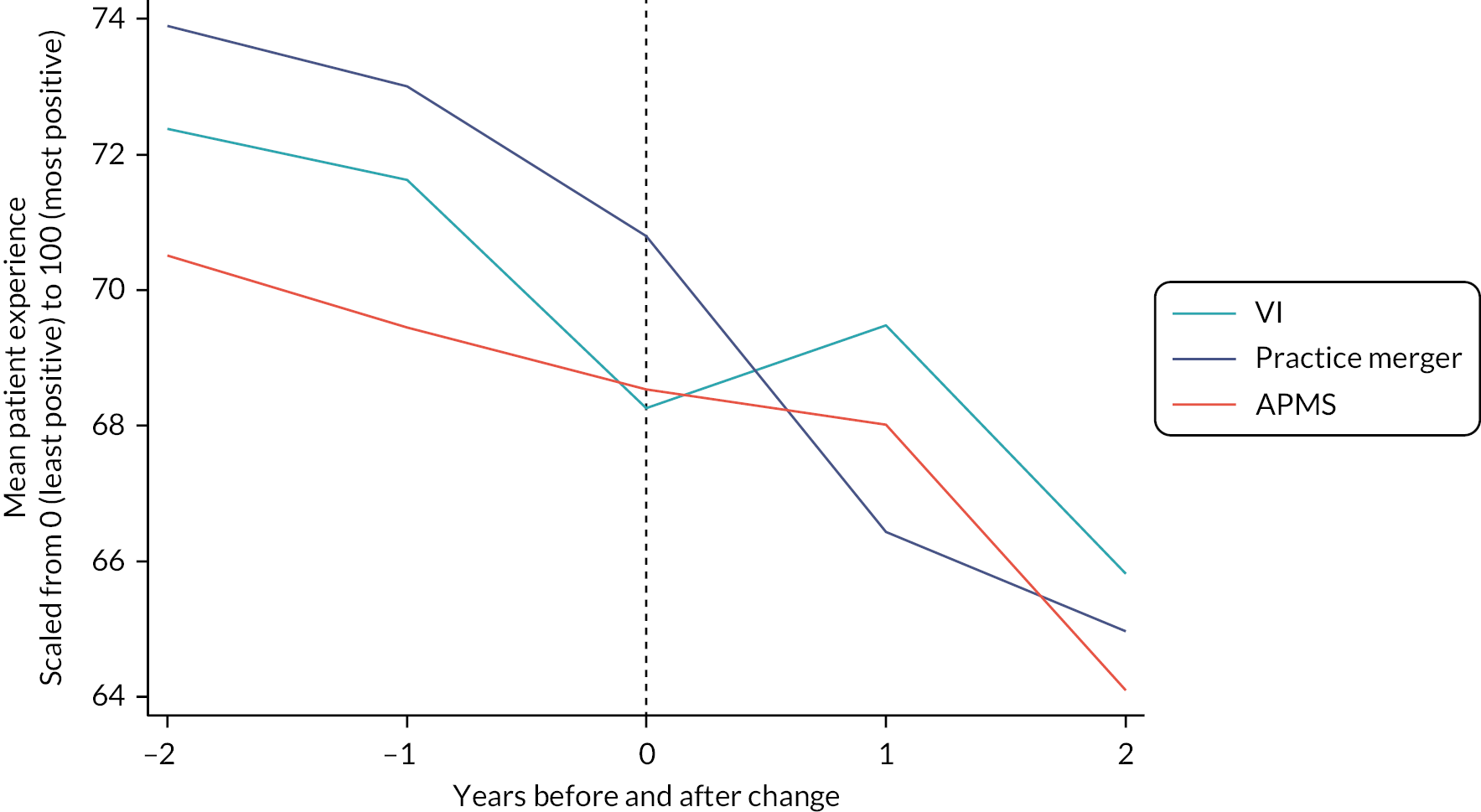

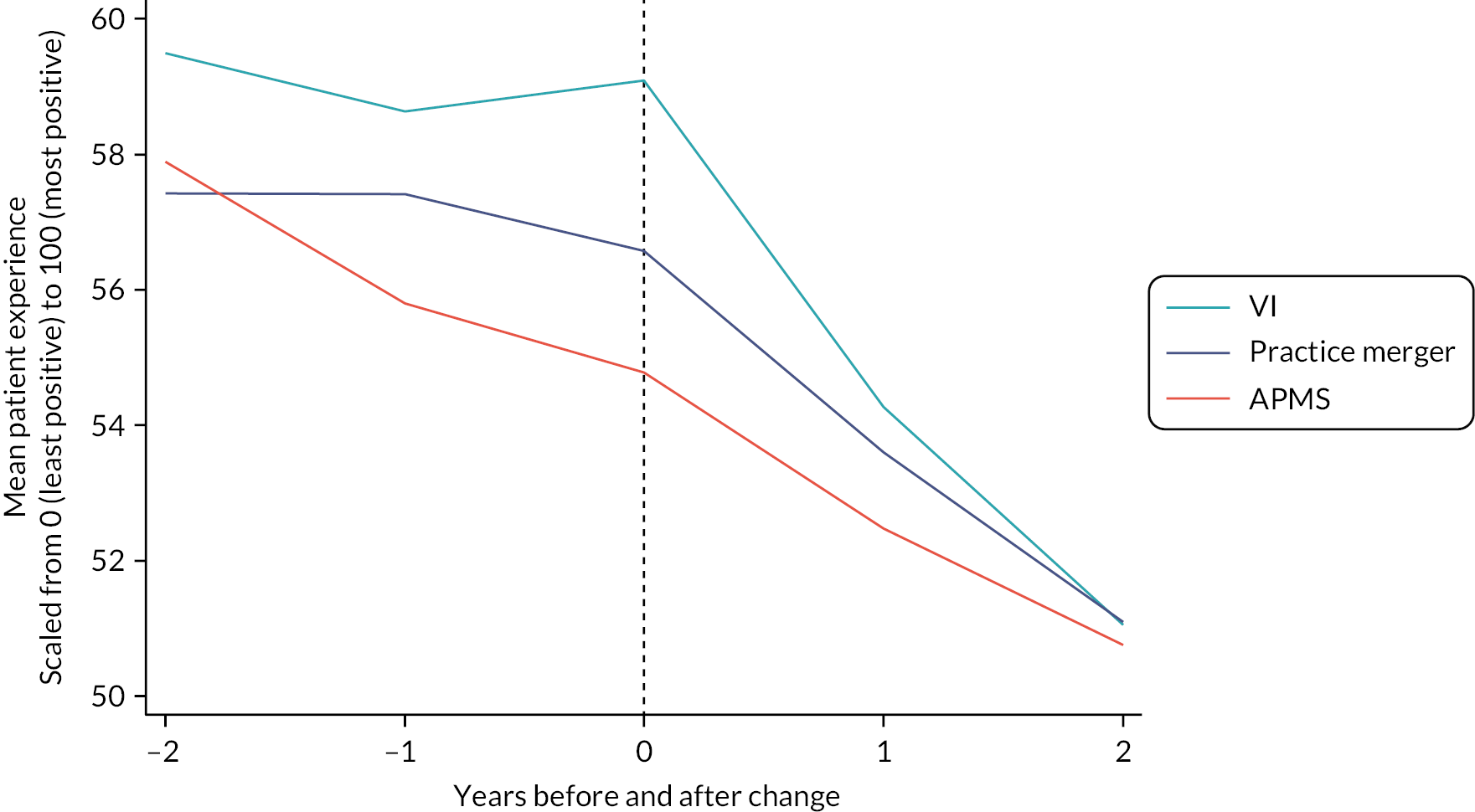

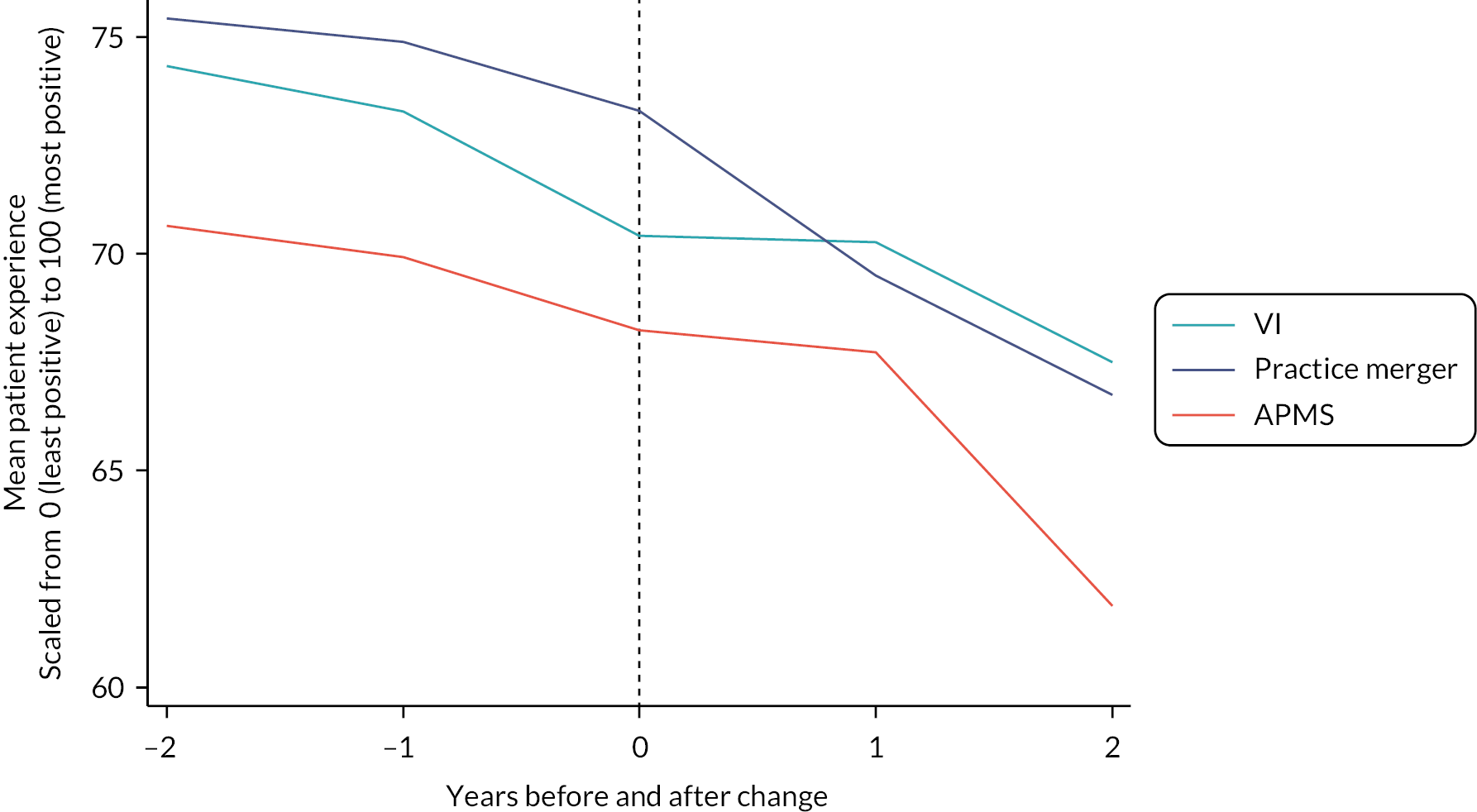

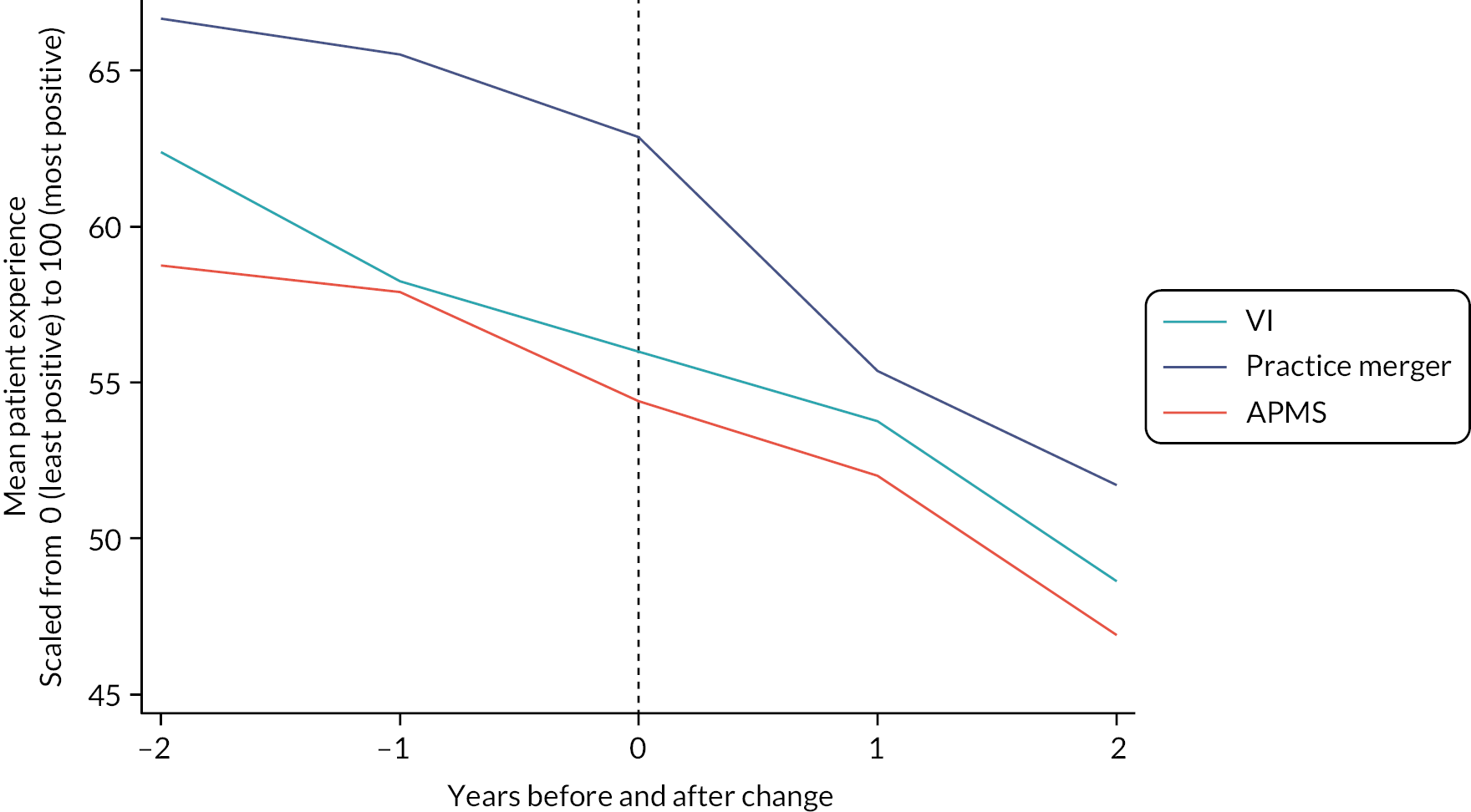

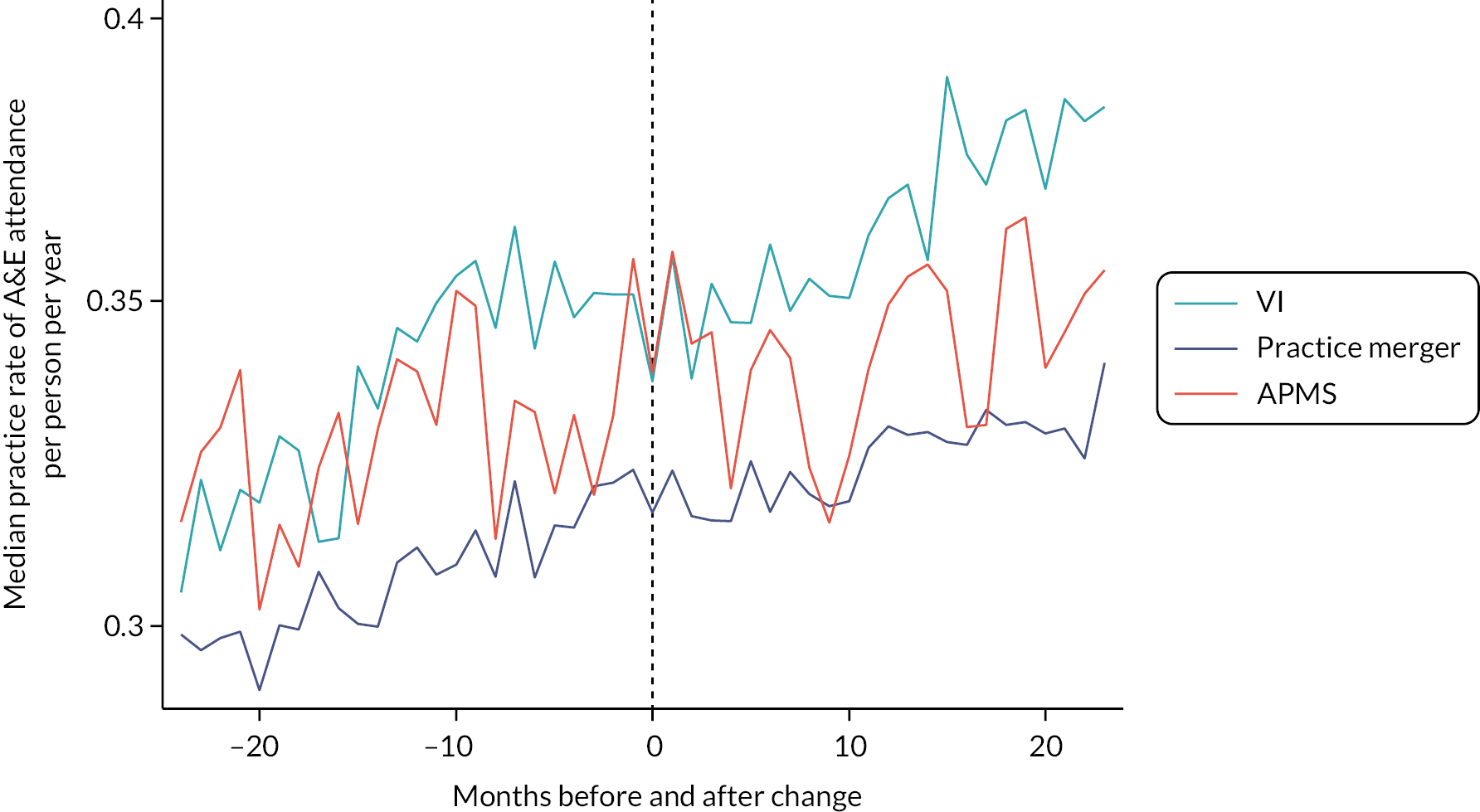

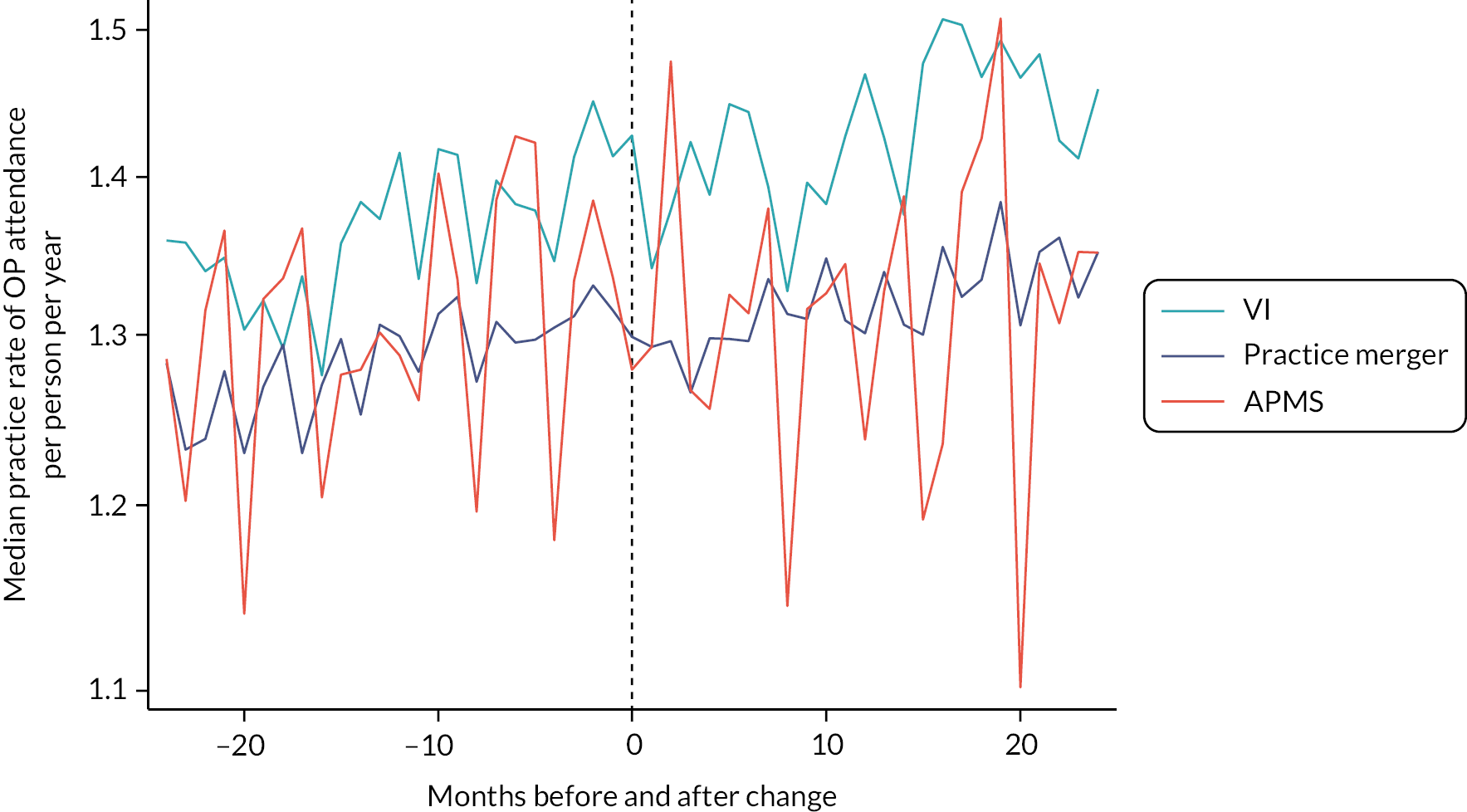

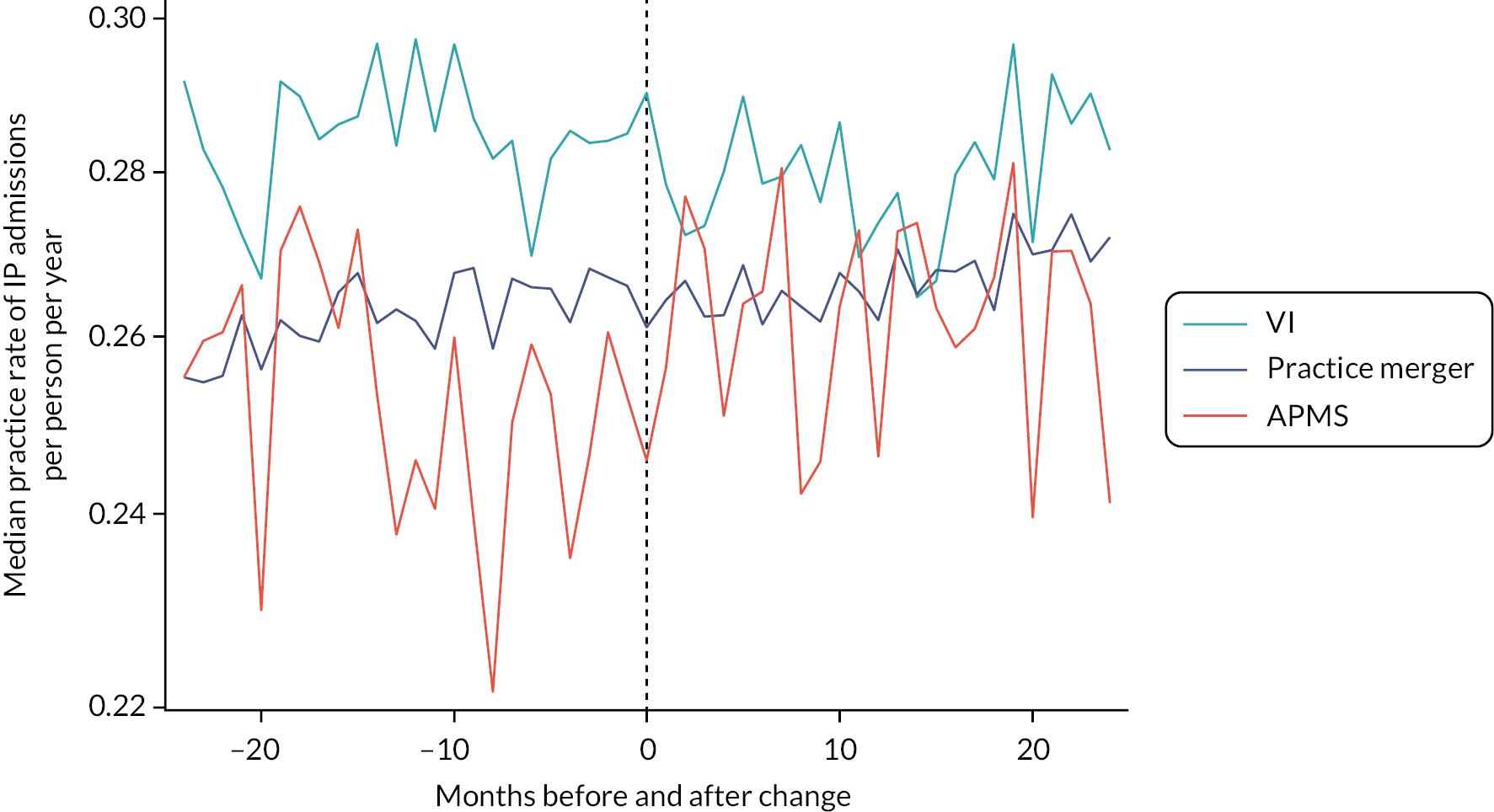

We find that the impact of vertical integration on patient experience is small, with the exception of the effect on continuity. Horizontal mergers have minimal impact on patient experience while switching to an APMS contract is associated with slightly worsening patient experience for continuity, access and satisfaction.

-