Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/136/67. The contractual start date was in November 2017. The final report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in November 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. This report has been published following a shortened production process and, therefore, did not undergo the usual number of proof stages and opportunities for correction. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Featherstone et al. This work was produced by Featherstone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Authors et al.

Chapter 1 Context

There is increasing recognition that action is required to improve the experience and outcomes of people living with dementia (PLWD) admitted to hospital for an additional acute condition. 1–5 The Alzheimer’s Society (Plymouth, UK) has identified widespread poor care for PLWD in the acute setting, with the quality of care received varying widely. 6 This variation means that PLWD are ‘likely to experience poor care at some point along their care pathway’. 7

Prevalence of people with dementia in the acute setting

The acute hospital setting has become a key site of care for PLWD, with the Department of Health and Social Care recognising that between 25% and 50% of all acute hospital admissions are of people who are also living with dementia,6,8–12 representing high levels of unscheduled and emergency admissions (77%). 13 A diagnosis of dementia is associated with increased risk of hospitalisation,14 with potentially preventable conditions, such as pneumonia, sepsis, urinary system disorders and leg fractures,10,15 often the principal cause of admission.

Estimates are likely to be low because of under-reporting or late diagnosis of dementia in this population. 2 Previous screening studies suggest that, in the acute setting, approximately 50% of patients affected by dementia remain undetected and undiagnosed16 and do not yet have a formal diagnosis in their medical records;10,17,18 however, more recent figures suggest that this rises to two-thirds19,20 or even three-quarters12,21,22 of older people (i.e. patients aged > 65 years) during an acute hospital admission. A high prevalence of delirium (15.5%), undiagnosed delirium (72%)23 and comorbid mental health disorders among17 this patient population, as well as comorbid chronic conditions, such as diabetes,18 also potentially has an impact on cognitive function during an admission.

Impact on patient outcomes

People living with dementia are a highly vulnerable group, and their hospitalisation is associated with increased risk of deterioration,14,17 functional decline and a range of adverse outcomes,22,24 including delayed discharge25 and institutionalisation. 26 PLWD also have a markedly higher short-term mortality9,26–28 than similar patients without a dementia diagnosis.

Acute hospitals have been called ‘challenging’28 and ‘dangerous’29 places for older people and PLWD. Health-care-related harm and adverse events experienced by PLWD are typically associated with falls, delirium, incontinence and functional decline. 30 Associated iatrogenic impacts31 of an admission include incontinence,32 reduced mobility,33–35 increased agitation,36 delirium,37–40 longer admissions41 and distress. 42–46 These adverse events can result in further dependency, institutionalisation and, potentially, death during an acute admission. 31

Calls for transformation

In response to this evidence, there has also been recognition by policy-makers of the urgent need to improve care for PLWD in hospitals, particularly for admission to general hospitals for an unrelated condition. 28 A ‘transformation of dementia services’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0) has been called for in the Department of Health and Social Care national Living Well with Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy4 and by the Dementia Action Alliance. 47 In partnership with the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (Coventry, UK), a key objective within the Dementia Action Alliance’s call to action47 is to design services around the person with dementia through the creation of dementia-friendly hospitals. These objectives are supported and reinforced by a wide range of policy recommendations. The Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia48 renewed the focus on dementia-friendly health and care, with the goal of every person with dementia obtaining the safest and best care in acute hospitals.

However, although acute hospitals have an increasing range of initiatives,8 even in institutions where high-quality acute care is identified, this is limited to specific wards, failing to reach across an organisation. 8 Overall, it is acknowledged that hospitals struggle to respond to the needs of an ageing population, with increasing hospital admissions among this group. 49

The social organisation and interactional context of care

Research draws attention to the social and organisational context of care in influencing front-line delivery in acute wards, with much research focused on the care of older people and PLWD. Meta-ethnography50 identifies that, despite nurses’ aspirations for a high standard of psychosocial care, a high standard of psychosocial care was largely dependent on ward-level social and organisational conditions.

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) studies report strong associations between ward cultures and care quality. Patterson et al. 51 found that positive patient and carer assessments of acute care for older patients were associated with higher staff ratings of a positive climate for care, which was mirrored in a second NIHR study that found that experiences of working in wards directly influenced patient experiences. 52 The impact of different shifts on work goals and priorities,53 a culture of reactivity,54 and austere ward environments and cultures that emphasise routines with few opportunities for communication restricted both patients and staff, and were associated with staff moral distress and burnout. 53,55,56 A systematic review of qualitative studies highlighted the importance of relational work in delivering high-quality care in acute wards57 and the importance of the nursing role in identifying and promoting dignity for older people with dementia. 56 However, given the increasing delegation of ‘hands-on’ care to health-care assistants (HCAs), an important focus needs to be this less-privileged58 and marginalised group, and how this group can influence how care is organised and delivered. 58,59

Despite PLWD representing a significant population in the acute setting, ward cultures can mean that delivering care appropriate to their needs is often viewed as ‘a disruption to core business’,60 as PLWD can be viewed as a group of patients who do not belong in the acute setting61 and should be transferred to other services. 62 Older people and family carers recognise that developing good relationships with staff powerfully informs and shapes their experience of a hospital admission. 63 Acute ward staff can fail to promote the identity and well-being of PLWD in their care, and may not recognise or respond to opportunities to deliver the recommended person-centred care,64 with patients who are viewed as ‘complex’ or ‘demanding’ receiving less personalised care. 56 As a result, the acute setting remains a potentially harmful location for this patient group.

Continence care: body work and ‘dirty work’ of the ward

Continence care is part of everyday intimate care to support PLWD, and has been described variously as ‘dirty work’, ‘elimination work’, ‘body work’ and ‘body labour’. These forms of paid work carried out on the bodies of others65 and their waste products are habitually regarded as low status, bordering on the polluted,66 and are often gendered. 66 This work poses a serious threat to formal caregivers’ sense of self and status, with higher-status workers distancing themselves from body work. 66–68 It is also invisible work,67 with body workers hiding ‘dirty work’ from others (e.g. by drawing screens around the bed,69 protecting the dignity of both the patient and the worker). Supporting patients to use the toilet supports the maintenance of dignity, as well as well-being and quality of life (QoL), which is a core nursing role. 70 Despite this, continence care is often described as ‘basic’, rather than ‘essential’, care. 71

Dementia, incontinence and stigma

A diagnosis of dementia is associated with significant levels of stigma and powerfully impacts on opportunities for social inclusion. 72 Incontinence is also powerfully stigmatising, particularly in care settings,73,74 discrediting an individual’s social identity and eliciting fear, stereotyping and social control. 75,76

The continued stigma, shame, social isolation and loss of integrity experienced by people living with incontinence is linked to a cultural disgust with urine and faeces. 77 Incontinence in older people can be viewed as a loss of control, a sign of incompetence that is incompatible with adulthood, putting them on the path to becoming a ‘non-person’. 78 Therefore, loss of continence has consequences that go far beyond the physical impairment, including casting strong doubt on a person’s social competence79 and disrupting privacy, as incontinence ‘threatens to expose the incompetence of the body to others’. 7

This stigma is further impacted by intersections of gender, race and ethnicity. 80,81 For example, older women with dementia are exposed to a ‘triple jeopardy’73 of age, sex and condition. Reviews examining the experiences of older women with incontinence identified microaggressions from others (e.g. subtle and insidious acts of aggression, such as impatience, intended to make the individual feel inferior), leading to social isolation. 80

Continence and dementia in the hospital setting

Urinary incontinence is one of the most commonly reported symptoms experienced in the last year of life, experienced by an estimated 72% of PLWD at this stage. 82 Key predictors of incontinence are the severity of cognitive impairment and degree of immobility. 83 Therefore, incontinence is typically a feature of the moderately severe and advanced stages of dementia. 84 Importantly, this does not reflect the continence status of the majority of PLWD admitted to acute wards, generally in the early and moderate stages of the disease, when incontinence should not be a typical feature of their dementia. However, in the acute setting, a UK national audit found that 71% of patients aged > 65 years (33% of whom had a diagnosis of dementia and 44% of whom had impaired mobility) were classified as incontinent of urine. 85 Similarly, a screening study of emergency admissions of patients aged > 70 years with cognitive decline found that 47% of patients were classified as incontinent,14 with 86% of patients identified as requiring supervision and assistance with toileting. 84

In the acute setting, PLWD are at high risk of ‘functional incontinence’, that is when their cognitive impairment, mobility problems or medication (associated with their admitting condition) means that they cannot reach the toilet in time84,86 as a result of their environment, rather than their dementia. 87 A small number88–90 of international audits in acute settings have identified that PLWD who are continent at admission are at significant risk of developing incontinence during admission, with this becoming permanent at discharge. An estimated 17%90 to 36%88 of previously continent PLWD will be clinically incontinent following an acute hospital admission. Carers report high dissatisfaction (60%) with continence care for PLWD during an acute admission, with hospital-acquired incontinence frequently reported as the key long-term post-discharge impact. 10

These high rates of hospital-acquired incontinence are associated with a number of hospital organisation and treatment factors. A primary provisional diagnosis of delirium, dementia or cognitive impairment is the most significant risk factor,89 more than doubling the risk of hospital-acquired incontinence. 91 Increased length of stay,88 advanced age (i.e. aged ≥ 85 years),89,91 gender (i.e. women identified as more at risk)91 and reduced mobility and physical functioning92 also increase risk. The use of continence pads, urinary catheters90 and chair restraints,91 and symptoms of drowsiness, daily pain and sleep problems,91 have all been associated with an increased risk of acquired incontinence following discharge. However, continence care, including new-onset incontinence among older adults and PLWD during their hospitalisation, is a significant and understudied phenomenon.

Continence care for PLWD in acute hospital wards is a continued concern for policy-makers,93 families and carers. 10,94–96 The systemic failure in the NHS to provide older and vulnerable patients with dignified continence care is widely highlighted in service reviews and inquiries. 94,95,97–99 Lack of dignity and privacy was a recurrent theme. 93,97,98

Dementia guidelines emphasise that incontinence is often treatable. 100 However, the small number of qualitative studies examining continence care for older patients in the acute setting identify containment (e.g. use of disposable pads and catheterisation) as key strategies,101,102 corroborated by national audits. 103

Incontinence is highly discrediting7,75 and can increase stigma and attack social status when combined with dementia. 74,104 A disparity exists between policy recommendations to improve care and actual implementation. Although incontinence care plans are common (83%) in care homes, only 37% of trusts have an integrated incontinence care pathway103 and only 18% of trusts have a continence nurse specialist,51 with low levels of continence training for ward staff. 49,102 Despite the growing population of PLWD and the significance of continence care in the acute setting,105 little is known about the appropriate management, organisation and interactional strategies for PLWD admitted to hospital. 8

The current paucity of evidence85 fails to support this population’s continence needs in this key site of care. 105 This presents a significant NHS challenge8 and new approaches are needed. Therefore, our research question is ‘how do ward staff respond to the continence care needs of PLWD being cared for in acute hospital wards, and what are the experiences of continence care from the perspectives of patients, their carers and families?’

Chapter 2 Research objectives

This in-depth ethnographic study aims to establish an empirically based conceptual and theoretical foundation to inform the development of innovative interventions in service organisation, delivery and training that will improve clinical care for PLWD, a large and growing, but often overlooked, population in acute hospital wards. This study focuses on an important, but poorly understood, feature of everyday care for PLWD, that is continence care.

Specific objectives are as follows:

-

To provide a detailed understanding and directly observed examples of the organisational and interactional processes that influence how acute hospital staff respond to continence management and the toileting needs of PLWD –

-

What are staff doing and why?

-

What caring practices are observable when interacting with this patient group?

-

How do staff respond to and manage continence needs?

-

What informs these approaches?

-

-

To provide a detailed understanding and concrete examples of the ward routines that have an impact on continence care for this group, specifically to examine the assessment, classification and management of patient toileting needs and their place in ward handovers, routines and schedules.

-

To examine and describe the experiences of incontinence, toileting and catheterisation care in the ward from the perspectives of PLWD and their carers.

-

To explore the relationship between continence needs and patient dignity to add to understandings of how continence care has an impact on person-centred care, patient dignity, the potential for dehumanisation, family experiences and staff morale.

-

To identify factors associated with the improved care of this patient population that are actionable, specifically what clinical care needs to look like to improve the quality and humanity of continence care for PLWD and their carers in acute hospital settings. This may include enhanced awareness of the risk of incontinence interventions and clinical management options.

-

To identify low-cost factors at the organisation level (e.g. staff training, ward practices and routines) that can lead to actionable change, and to explore barriers to and facilitators of implementing changes.

-

To provide a detailed foundation of knowledge to inform a longer-term programme to develop and evaluate interventions providing new or enhanced approaches to delivery of continence care to PLWD.

-

To transfer new knowledge to front-line providers of acute hospital care, including managers, service commissioners and the research community.

To the best of our knowledge, little empirical research has examined continence care for PLWD to inform practice in the acute setting. A systematic review85 has found a lack of evidence-based nursing interventions to manage continence care for PLWD. In addition, it cannot be assumed that interventions from long-term care can be transferred unproblematically to the acute setting. Therefore, we conducted a mixed-methods systematic review and thematic synthesis of the literature, alongside ethnographic fieldwork, to establish an empirical foundation from which interventions in acute care settings can be established.

Chapter 3 Methodology

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Featherstone et al. 106 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Featherstone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

This study utilised an ethnographic approach, alongside a mixed-methods review. It focused on the routine work of continence care for PLWD admitted to acute hospital settings in the wider context of the everyday care carried out by nurses and HCAs. We provide a detailed understanding of social and institutional forces shaping and influencing continence care. Our ethnographic approach enabled us to understand how staff respond to the continence care needs of PLWD and to follow the consequences of their actions. We examined how staff account for and make sense of the needs of PLWD in these contexts. 107

Ethnography provides a sophisticated toolkit for exploring the complexities of the everyday, forging better understandings of daily meaning-making92 in organisational structures and settings. Ethnography delivers detailed understandings of organisational culture, organisational change and the inter-relationships between different elements of an organisation. In health-care settings, ethnography allows researchers to take into account perspectives across the clinical experience, exploring the perceptions of patients and carers; medical, nursing and care teams; and wider auxiliary, administrative and managerial staff. 108,109 It is particularly useful to examine research questions that aim to access the unspoken and tacitly understood, as well as complex and highly sensitive, topics that are not easy or appropriate to measure. 110

Our approach to ethnography is informed by the symbolic interactionist tradition, which aims to provide an interpretive understanding of the social world. This places an emphasis on interaction, understanding how action and meaning are constructed in a specific setting, and acknowledging the mutual creation of knowledge by both the researcher and those researched. 111 The study aimed to deliver understandings of everyday continence care for PLWD in the acute hospital setting, focusing on how the wide range of social actors in these settings (i.e. the large number of ward staff that patients will come into contact with during an admission) respond to continence care needs of PLWD and to follow the consequences of their actions. Ethnography allows us to examine these elements and, importantly, the interplay between them. Ethnography examines ‘up close and in person how work is organized and how the organizing organizes people’. 92

Ethnography, at its core, is the in-depth study of a small number of cases. By exploring people’s actions and accounts in their natural everyday settings, ethnographers can collect relatively unstructured data from a range of sources, including observation, informal interviews and documentary evidence. 112 Ethnographers ‘hold that an appreciation of the extraordinary-in-the-ordinary may help to understand the ambiguities and obscurities of social life’. 92 This approach provides a depth of understanding and theory generation. 113 There is long tradition of ethnography in health-care settings,111 and there are many examples of ethnographic studies that have had a significant impact on policy and practice. 114–117

Our aim in utilising ethnography was to explore the otherwise unnoticed details of everyday life, in other words what is tacitly acknowledged, but rarely discussed, around ordinary and, in the case of continence care, hidden activities. Starr118 notes the importance of examining organisational infrastructure and the ‘hidden mechanisms’ constructed and embedded in the technical and procedural work carried out within it. 118 The articulation work of people in organisational and institutional settings was examined (i.e. how people in organisational and institutional settings account for and make sense of their actions). An ethnographic approach allowed us to explore both the front-stage performance and also the backstage work practices,119 while always maintaining the dignity and privacy of both patients and staff.

In any organisation, there are groups of people whose everyday work is unrecognised formally, often unnoticed and invisible. 118 In the hospital setting, such groups include carers, nurses, HCAs and auxiliary staff, for example those working in domestic services. In the context of our research questions, ethnography can examine how social and institutional forces shape and influence the work of health-care providers (HCPs)120 and the everyday routine behaviours of individuals, both within and across multidisciplinary teams. 121

This study focuses on the routine work of continence care for PLWD admitted to acute hospital settings. This study considers the wider context of the everyday care carried out by nurses and HCAs, and provides a detailed understanding of the social and institutional forces that shape and influence continence care. Our ethnographic approach enables us to (1) understand how staff respond to the continence care needs of PLWD and (2) follow the consequences of their actions. We examine how staff make sense of the needs of PLWD in these contexts. 107 In presenting our findings, utilisation of ethnographic ‘thick description’ enables the reader to connect concepts, policies and practice to detailed empirical examples. 122 This approach allows the reader to develop not only a strong connection to the social world of these wards, but also an understanding of the complex social relations within them; the personal impacts of continence care on patient, carers and ward staff; and how this connects with wider issues in the organisation and delivery of care in these institutional settings. 122

Prior to data collection, in January 2018, Deborah Edwards and Jane Harden carried out a mixed-methods systematic review and thematic synthesis of the literature to identify successful strategies in care settings that could inform innovations in continence care for PLWD in the acute hospital setting. This approach bridged the gap between research, policy and practice123 and was useful in examining the complexities of health service settings. The generated synthesis was used to refine our approach to fieldwork and analysis, and to inform the development and feasibility of the interventions.

Chapter 4 Data sources

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Featherstone et al. 106 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Featherstone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK. In addition, parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Featherstone and Northcott124 under licence CC-BY-ND-4.0.

Ethnographic fieldwork

Multiple sites were used in this ethnography as an exercise in ‘mapping terrain’. The goal was not ‘representation’ or ‘comparison’, but ‘identification’ to reveal the social processes surrounding continence care for PLWD in the acute setting. Therefore, it was important to observe interaction and performance, how continence care work was organised and delivered, and how it was communicated between different actors. This moves beyond the traditional examination of verbal communication to exploring tacit and non-verbal interaction, that is the multiple, complex and nuanced, but everyday, interactions and strategies that occur around continence care, which often ‘communicat[e] many messages at once, even of subverting on one level what it appears to be “saying” on another’. 125 In these hospital settings, many such interactions are concealed and are part of backstage talk, veiled language, euphemism and informal conversations. Our approach remedies a common weakness in many qualitative studies, that is that what people say in interviews may differ from what they do or their private justifications to others, an issue that is exacerbated when the topic under discussion is taboo or concealed from everyday, public life. 126 Our approach allowed us to respond to this and to examine the impacts of the organisation and delivery of continence care on PLWD and those caring for them over time.

This ethnography was carried out in six wards in three hospitals across England and Wales. These wards were purposefully selected to represent a range of hospitals types, geographies and socioeconomic catchments. Across these sites, 180 days of observational ethnographic fieldwork were conducted in areas of acute hospital care known to admit large numbers of PLWD, including general medical wards (e.g. acute wards for older people) and medical admissions units (or variants thereof). Approximately 500,000 words of observational fieldnotes were collected, written up, transcribed, cleaned and anonymised by the ethnographers (KF and AN). To provide a detailed contextual analysis of the events observed, the expertise involved and the wider conditions of patient care, we also carried out ethnographic (during observation) interviews with ward staff (n = 562) on multiple occasions. Case study participants who were living with dementia (n = 10) and their family members and carers (n = 20) also took part in ethnographic interviews (n = 30) during their admission and, in some cases, following discharge. Given the scope of our data set, in this report, we focus on presenting our analysis of the observational data, examining key features of continence care in these wards, including the use of continence ‘pads’ in everyday bedside care, the impact of the use of the continence ‘pads’ on PLWD and ward staff, and the influence of continence ‘pads’ on shaping ward cultures. To fully present the analysis of other aspects of continence care (e.g. catheter care) and of other data sets (i.e. staff interviews and case studies following PLWD and their families), these will be published separately.

Multisited ethnography defines the object of study via a number of techniques or tracking strategies. In the fieldwork, we recognised the importance of focusing on the ‘busy intersections’127 and of seeking out sites of tension where a large number of interests and identities are expressed. It is at these points that identity and culture become articulated, enacted and constructed. We aimed to provide a detailed understanding of the clinical and interactional work and processes that influence ward teams, their response to the pressing continence needs of patients living with dementia and the organisation of continence care for multiple patients within and across shifts. We also explored the work of other clinical staff (e.g. specialist registrars, consultants, allied health professionals and staff with managerial responsibilities) and auxiliary staff (e.g. domestic services) involved in the care of PLWD and their continence. We observed their actions and accounts to explore how individuals, teams and institutions prepare for, respond to, communicate and organise continence care in these settings, and the cultures that are both produced and maintained by these approaches.

At each hospital (n = 3), we conducted 30 days of observation in each ward (n = 2) over a period of 8 weeks of detailed fieldwork. Care was observed during day and night shifts, on weekdays, weekends and, where possible, public holidays. Observation periods ranged in duration from 2 to 6 hours and were reactive to events in the wards during observation. These periods of observation were followed by a further 8 weeks of follow-up data collection (including case study interviews and additional observation) so that, where possible, we could examine the implications of continence care practices for discharge and long-term care trajectories. Fieldwork always preserved patient dignity (as this study did not need to go ‘behind the screen’ to observe intimate care) and the goal of our observational strategy was to provide an in-depth evidence-based analysis of the management and context of continence care in these wards:

-

The fieldwork used non-participant observation and concentrated on the visible work of nurses and HCAs who are responsible for continence care. Other health-care staff were also included, as they are involved in wider continence assessment and decision-making for this patient group.

-

The fieldwork focused on ward routines where continence care took place or was prompted, including observation rounds, personal care routines, medication rounds and mealtimes.

-

The fieldwork observed responses to personal alarms, calls for assistance and decisions to prioritise or defer to examine the classification, urgency and management of patient continence care needs when it disrupted ward routines and schedules.

-

Communication and language around continence care were examined, including everyday interactions and strategies used in the wards, communication between staff, and communication with PLWD and their families.

-

The fieldwork focused on ward practices of assessment and management of continence care for PLWD by ward staff (i.e. nurses and HCAs), the medical teams and other staff when they were involved in continence care, assessment and decision-making.

-

Shift handovers were observed to examine everyday ward classification practices of continence and incontinence, and explore how these classification practices informed the organisation and planning of patient care during shifts and how these classifications entered risk assessment and discharge planning.

-

The technical and procedural work around continence care management (e.g. types and use of pads), assessment and recording was examined.

-

The fieldwork focused on observing conversations with carers as opportunities for sharing information about continence and how these conversations might best be managed with regard to decisions about discharge and place of discharge.

-

The study collected routine ward data, providing a context and an understanding of the workload around both everyday care routines and continence care in these wards.

This in-depth evidence-based analysis enabled us to provide detailed understandings of organisational and interactional care processes that were having an impact on the responses to and the management and delivery of continence care for this patient group.

Working in acute wards required the researchers to adopt a range of observational practices and strategies. Observation time was spent standing, rarely sitting, reflecting the pace of work of the teams and the widespread hospital staff in them. Our practice was to stand in the corridor, usually close to an alcove, sink, trolley or equipment that was already blocking part of the walkway, where there was space to stand out of the way of the team, but we could still view areas of the ward and the events taking place there. We also shadowed and walked with individual members of staff and teams as they worked in the ward. The built environment of the observed wards was highly variable: some wards consisted of a central hub with satellite bays, whereas other wards took the form of a long corridor either with or without windows onto bays and rooms. In all wards the researchers positioned themselves appropriately in the corridors to maximise visibility while minimising obstruction.

Our strategy was comprehensive note-taking, with notes written up as more detailed accounts. The researchers wrote extensively during these periods of observation, using A4 spiral-bound notepads. Writing was typically carried out with the notebook in hand, writing as we were standing or walking. The fieldnotes recorded took the form of a running record of events and incidents and included details and near-verbatim text of conversations and interactions. The opposite side of the notebook remained clear of fieldnotes and was used to insert thoughts and any additional points or queries to follow-up on or expand later. Note-taking was clearly visible to all staff and patients in the wards, and both staff and patients had natural opportunities (and were offered opportunities by the team) to ask questions about our notes. Staff were granted access to look at the fieldnotes if they requested this.

Ethnographic interviews with ward staff

To provide a detailed understanding of the influences on HCPs’ response to continence care, ethnographic (during observation) interviews focused on and were predominantly carried out with nurses (across all grades), HCAs from a range of disciplines (e.g. clinical staff, foundation year doctors, junior doctors, registrars, consultants, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists and specialist dementia teams), staff with co-ordinating responsibilities (e.g. ward clerk and discharge co-ordinators) and auxiliary staff (e.g. domestic services) where appropriate. These interviews (n = 562) with ward staff were carried out over multiple occasions and during and across shifts as staff cared for PLWD in each ward. These interviews had a broad focus on the organisation and delivery of everyday care and continence care, and allowed us to question routine practices, rationales and decision-making to understand what staff were doing and why:

-

What was the articulation work in acute ward settings and how did staff account for and make sense of their actions?

-

For staff working with PLWD and providing continence care, what were their experiences, what training was provide for this type of care and what informed their practices?

-

What aspects of caring were defined as difficult, demanding or rewarding, and were staff confident in caring for this patient group?

-

What were the barriers to and enablers of supporting PLWD?

-

What were the recognition and rewards from patients, relatives, colleagues and managers for providing care for this group?

Case studies

A number (n = 10) of patients were recruited for case studies. We aimed to follow individuals living with dementia and their family carers from initial admission to the acute ward through to being discharged home or to long-term care and to follow their short-term care pathways. However, we were not able to seamlessly identify and follow people through an admission. The organisation of hospital admissions, with patients admitted, transferred and discharged on these wards 24 hours per day, meant that identifying and tracing a patient was not always possible, requiring the availability of the nurse in charge of the ward to access systems on behalf of the researcher. These obstacles meant that we recruited 10 patients for case studies rather than 12, which was our objective, but these patients represented a range of diagnostic, prognostic and sociodemographic factors, including patients with a range of continence care needs, reflecting our aims of including people with diverse experiences.

The goal of our study was to support PLWD and their families, and to share their experiences of an acute hospital admission. However, the case studies provided limited data that specifically related to continence care. Nevertheless, these data contribute to our wider understandings of the experiences and perspectives of an acute admission and its consequences for PLWD and their families. To fully represent the experiences PLWD, and their families, a separate analysis will be published.

Sampling

Sampling in ethnography requires a flexible, pragmatic approach that involves using evidence from available literature and a range of variables that may influence the phenomena under observation. Probability sampling is inappropriate and, therefore, non-probability sampling was used to provide analytically, rather than statistically, generalisable findings. 128,129 Using this approach, the number of sites and participants in the sample was judged not on the basis of size, but by the nature and scope of the study aims, the findings of our syntheses, the quality and appropriateness of the sample, and the achievement of theoretical saturation of data. 129

Sampling of hospitals and ward sites

Hospital settings are well suited to an ethnographic approach. 130,131 We identified a range of variables that may influence the phenomena under observation using purposive and maximum variation sampling to include three sites that represented a range of hospital types, geographical location, expertise, interventions and quality. In these hospitals, we included sites of care (e.g. assessment units and general medical wards) that received a large number of patients living with dementia, with a wide range of continence care needs and who required acute medical attention. Detailed descriptions of these hospital sites and profiles of the participating wards can be found in Appendix 1.

Sampling in each acute hospital site

Although our sites (i.e. acute hospitals and wards) were standardised, with sequential and systematic data collection, there was some variation between sites. We applied theoretical sampling in sites to achieve robust analytic concepts in the analysis. Informed by grounded theory, sensitising concepts from the ongoing analysis fed into each stage of data collection, expanding the research process to capture emerging relevant aspects in the ongoing analysis. The focus was on ‘discovery’, ensuring the grounding of emerging concepts in data and the reality of the settings. 132

Sampling and recruitment of staff for observation and interviews

We followed the routine and everyday work of nurses and HCAs. We used purposive sampling to include a wide range of clinical grades and roles across the ward settings. In addition, we included other clinical staff, staff with co-ordinating responsibilities and auxiliary staff who were also involved in the care of PLWD and in continence care.

Sampling and recruitment of patients for observation

It was not possible to predict the type of patients who would be present in acute hospital wards during the fieldwork period. However, we were confident from our previous research106 that PLWD would constitute a significant population in these wards. Details of the populations in these wards are found in Appendix 1.

Ethics approvals

Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval for the study was granted by the NHS Research Ethics Service via the Wales REC 3 on 19 April 2018 (reference 18/WA/0033), with approval from the Health Research Authority (London, UK) and Health and Care Research Wales (Cardiff, UK) granted on 5 September 2018 [Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) 239618/protocol 4804]. The research project was approved for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act 2005,133 confirming that it met the requirements of section 31 of the Act in relation to research carried out as part of this project on or in relation to a person who lacks capacity to consent to taking part in the project. Recruitment for the study was managed and recorded through the Central Portfolio Management System, beginning on 11 October 2018 and ending on 31 October 2019. A total of 108 participants were recruited to the study.

The safety of all participants was a key priority at each stage of the study. Before commencement, the ethics of observing care and of reporting, where necessary, what was observed was frequently discussed with the hospital sites and our carers group. In meetings with the REC that approved this study, it was clarified that, although neither of the researchers (KF and AN) had a clinical duty of care (i.e. being academics without clinical qualifications or professional affiliation), they would be bound to safeguard any patient participants observed during the project.

Prior to commencement, both researchers, experienced in both hospital ethnography and conducting research with PLWD, renewed their Good Clinical Practice certification and upgraded their existing Protection of Vulnerable Adults level 1 certification by completing Safeguarding Vulnerable Adults levels 1–3. The researchers were made aware of safeguarding and whistleblowing procedures at each site and had a named member of staff (i.e. the site principal investigator or a senior nurse on shift) to contact if malpractice or behaviour that put vulnerable patients at risk was observed. Both researchers underwent full occupational health checks, held honorary contracts with the NHS health boards and trusts, and had up-to-date Disclosure & Barring Service certification and NHS research passports.

Several months in advance of the period of observation at each ward, the research team visited the wards to introduce the study to the ward staff and to discuss the study aims with relevant staff. These meetings were repeated 24 hours before observations started, in handover meetings in week 1 of observations and to individuals throughout the study to ensure that ward staff were aware of the study, to answer questions and to recruit staff to the study.

Over the course of the observations, the researchers saw many aspects of everyday practice that would not be considered ‘best practice’ or in the interests of the individual patient. The examples of practice presented in this report were not isolated and formed part of systemic and established everyday routine practice in every ward at each hospital site. We never observed individual malicious behaviour or isolated incidents of deviance that placed a vulnerable adult at risk. Instead, we observed how the everyday routine organisation and delivery of continence care itself often placed the vulnerable person living with dementia at risk, as a part of the routine practices and established cultures of these hospitals and the wards within them. At no point did the researchers feel that any individual or ward team was acting in a way that necessitated escalating or whistleblowing.

The researchers did, however, frequently intervene to support PLWD and their families and carers, where necessary, to protect the comfort of the patient. PLWD would frequently tell the researchers that they wanted to go to the bathroom or that they were in pain, or share concerns about, for example, home, family or pets, or how to pay for their care. In response to disclosures, the researcher (with permission from the patient) would inform ward staff and ensure that this was attended to by the ward team.

The researchers were sometimes the only member of ‘staff’ spending uninterrupted time in a specific area of a ward and so would regularly ask patients if they needed anything. Sometimes, when ward staff were absent or could not be called quickly to a bay, the researchers provided immediate support. For example, were a patient at immediate risk of physical danger, the researchers would call staff and, if necessary, intervene. Similarly, the researchers would fetch cups of tea, pour glasses of water and carry out other simple tasks in these wards when requested and when permitted. Although the researchers accept that this may have, on occasion, contaminated the purity of their data, the welfare of those in the field of observation was always the priority.

Between sites, the emergent analysis was regularly presented to the research team, including nurses, clinicians, trust leads, PLWD and family carers, and, although it was agreed that the care observed could be detrimental or distressing to a person living with dementia, it was also recognised as routine and recognisable as the everyday practice of acute ward staff.

Although, in isolation, some of the descriptions of continence care presented in this report may appear to breach patients’ rights, we hope to have demonstrated in our analysis that these were not isolated incidents, but rather the everyday reality of the care delivery that each person living with dementia will experience during admission to acute hospital care. The results presented in this report also show that nurses and HCAs, likewise, experience distress, with little organisational support or recognition of the care required to respond to the continence needs of PLWD in ways other than those outlined here. The cultures of these wards prioritised risk reduction and timetabled routines over the comfort or preferences of PLWD. The actions of nurses and HCAs in response to continence needs presented in this report were carried out in good faith, attempting to protect the patient and the ward, and to respond to the policies and perceived expectations of the wider institution. We hope that the evidence presented here highlights the challenges faced by ward staff as they deliver care in the acute environment, and the need to better support both patients living with dementia and staff in this setting.

Chapter 5 Modes of analysis/interpretation

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Featherstone et al. 106 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Featherstone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Data collection (in situ observations and interviews) and analysis was informed by the analytical tradition of grounded theory,132 which is a flexible approach for ethnographic research. 126 This approach utilises theoretical sampling and the constant comparative method, in which data collection and analysis are inter-related134,135 and conducted concurrently. 134,136 The flexibility and responsiveness of this approach were of particular significance, enabling us to increase the ‘analytic incisiveness’126 of the study. Preliminary analysis of data continued in parallel with data collection at later sites, informing the focus of further stages of data collection and subsequent concurrent analysis. The constant comparative method means that the coding of data into categories was a recurrent process. Data were examined in the context of previous fieldwork and analysis, which informed further strategies of data collection in subsequent sites, producing more focused stages of analysis. 126 The analytical concepts emerging were then further tested and refined to develop robust analytical concepts that transcend the local contexts of individual wards and sites, and identify broader structural conditions137 that influence continence care for PLWD in the acute setting.

Findings from our mixed-methods review informed the ethnography in various ways, with a focus on initiating the process of early thinking and theorising during data collection and analysis. The review aimed to increase our theoretical sensitivity to key areas of importance to explore during data collection, including communication, language and the importance of non-verbal cues. The review was conducted alongside data collection at the first site, with data at this site analysed as they were collected. The review and its findings were used to stimulate questions during the ongoing iterative analytical process. This affirmed our focus on issues of continence-related communication, language, privacy and dignity, combined with known routines and strategies of bedside care.

Corbin and Strauss135 caution that, in grounded theory, literature should not impede ‘discovery’, emphasising the importance of using it actively to identify potential areas to inform theoretical sampling. Therefore, we explicitly sought opportunities to identify examples of individualised care, planning and assessments, with the goal of improving the continence of PLWD during an acute admission and the use of promoted strategies, such as ‘prompting’ and other continence routines and schedules, identified in the review.

Grounded theory strengthens the ethnographic aims of achieving theoretical interpretation of data, whereas the ethnographic approach prevents a mechanistic and rigid application of grounded theory. 126 Ethnography can treat everything in a setting as data, leading to the ethnographer collecting large numbers of unconnected data and a heavily descriptive analysis. 129 Our approach provides a middle ground in which the ethnographer uses grounded theory to provide a systematic approach to data collection, with the analytic goal of developing theory to address the interpretive realities of the range of actors in these ward settings. 126 Data collection strategies explicitly supported ‘theoretical saturation’132 (i.e. where further data collection was no longer adding to the development of analytic concepts).

Analysis involved the development and testing of analytic concepts and categories. The strategies we used for the development of concepts and categories included careful reading of the data; looking for patterns and relationships; and noting surprises, inconsistencies and contradictions across the range of perspectives gathered. Line-by-line coding is inappropriate for field notes and, therefore, coding was selective, involving whole events or scenarios. 117 Initially, this produced a collection of ‘sensitizing concepts’138 and analytic memos that informed the later development of more refined and stable analytic concepts. At this stage, Katie Featherstone and Andy Northcott re-examined the raw data informed by the subsequent phases of analysis (re-coding where necessary), looking for examples and events to test the analysis. Emerging analytic concepts were tested and refined to develop (in collaboration with the wider research team) stable concepts that identified broader structural conditions135 influencing continence care.

Throughout this process, we drew on multiple perspectives (e.g. sociological, policy, clinical, patient and carer) to inform our analysis. This included the use of our mixed-methods systematic review, with the narrative syntheses generated (see Chapter 6) informing data collection strategies and the analysis. Credibility checks included presenting emergent analysis to ward staff (in participating sites) and to PLWD and carers (see Chapter 9) for discussion throughout this process.

Field notes of observation and near-verbatim text were hand-written and then transferred into Microsoft Word files (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) following data collection. 139,140 All audio-recordings of observations and interviews (i.e. ethnographic and in-depth) were written up in Word files or transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. All sites and individuals, and the data collected, were anonymised and sorted in line with the UK General Data Protection Regulations as part of the Data Protection Act 2018. 141 Storage of the data was managed by the Information Security Framework of Cardiff University (Cardiff, UK).

Chapter 6 Findings from mixed-methods review and thematic synthesis

This chapter focuses on the mixed-methods systematic review and thematic synthesis. Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Edwards et al. 142 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methods

This systematic review uses methods informed by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre). 143,144 A scoping exercise in January 2018 was followed by a targeted and in-depth review and synthesis. The protocol has been registered as PROSPERO CRD42018119495.

Scoping exercise

The scoping exercise asked ‘what is known about the management and practices of continence care (i.e. continence care, incontinence care, toileting and catheter care) for PLWD in acute, long-term and community health-care settings and home settings?’ Two databases (MEDLINE and PsycInfo®) were searched from inception to January 2018 for citations that focused on or contained an element relating to each of the following inclusion criteria:

-

PLWD, Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive impairment

-

acute, long-term and community health-care and home settings

-

urinary or faecal continence/incontinence, or toileting issues

-

conservative management or care practices (defined as any continence care practice that does not require medical or surgical intervention, including catheterisation145).

After title and abstract screening, 114 of the 1348 citations retrieved remained. After standard screening processes by two reviewers (DE and JH), 87 papers were included, including studies (n = 40, across 48 publications), discussion/opinion papers (n = 17), reviews (n = 13, across 17 publications), audits (n = 2), guidelines (n = 2) and a documentary analysis (n = 1). Studies or reviews published multiple times were treated as one and, therefore, the final number of included papers was 75.

In keeping with the EPPI-Centre approach, findings were presented to stakeholders to ascertain their views on the priority areas for the second phase of searching. All stakeholders (see Appendix 2), as part of this process, were asked to complete a priority-setting exercise, facilitated by answering the question ‘What do you think are five of the most important ways that continence could be managed for PLWD when they are in hospital?’. Responses were collated, coded and grouped together to generate a list of methods for managing continence in the hospital setting.

Descriptive maps of the findings from the scoping exercise and a summary of the consultation with the stakeholders were presented to the collaborative research/project team of co-applicants. Across both groups, the top two priority areas identified as most salient to informing and improving continence care in the acute setting were (1) ‘communication’ and (2) ‘individualised care planning’. This exercise informed the research question taken forward to the mixed-methods systematic review, that is ‘what is known about the management and practices of continence care in relation to communication and individualised care planning for PLWD in acute, long-term and community health-care settings and home settings?’

Mixed-methods systematic review

Objectives

The review aimed to:

-

explore carers’, family members’ and HCPs’ perceptions and experiences of communication and individualised care planning for PLWD with regard to toileting and continence

-

identify the communication strategies and the use of individualised care planning employed by carers, family members and HCPs to manage toileting and continence for PLWD.

Eligibility criteria

We used the PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design)/PICO (population, intervention, control/comparison, outcome) framework to guide the inclusion criteria for participants, intervention/phenomenon of interest, comparators, outcome, study design and context (see Appendix 3).

Searching

Eight databases were searched from inception to June 2018 (updated August 2020), including MEDLINE, PsycInfo, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Education Resources Information Center, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, British Nursing Index and Open Grey (see Appendix 4). Relevant organisational websites were searched for UK policy and guidance, and key journals were hand-searched (see Appendix 5). Reference lists of included studies were scanned, experts contacted and forward citation tracking performed using Web of Science.

Screening

All citations retrieved were imported into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicate references were removed. Two reviewers (DE and JH) conducted all screening processes, with disagreements resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Multiple articles by the same authors reporting the same study were linked to help inform decisions on which studies to include.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal of the research material was conducted by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through discussion with a third reviewer using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2011. 146–148 Each study was assigned a score based on the number of criteria met (with 25% representing one criterion met and 100% representing all criteria met). Studies were excluded if they scored < 50% for quality (i.e. a maximum score of two out of four criteria). 146 Non-research evidence (e.g. policies and reports) were not subjected to quality appraisal.

Data extraction

Demographic data from the included primary research studies were extracted and entered into a series of electronic tables (see Appendix 6, Tables 4–6, and Appendix 7, Tables 7 and 8). Study findings for the primary research studies for the purposes of this review were all considered to be text labelled as results or findings. All such results were extracted and entered verbatim into Microsoft Word. Data for non-research material were extracted and entered directly into an electronic table (see Appendix 8). All non-research material was available as electronic documents, searched using keywords relevant to the priority areas (e.g. ‘communication’, ‘tailored’ and ‘individual’). These data were then considered to be findings and were extracted and entered verbatim into Microsoft Word. Data extraction was independently checked for accuracy and completeness by a second researcher (DE or JH), with any disagreements noted and resolved by consensus.

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis was employed to bring together data from both qualitative and quantitative primary research studies and non-research material. 149

Assessing the certainty and confidence of the evidence

The confidence of the overarching synthesised findings derived from descriptive quantitative research (that had undergone qualitisation) and qualitative research were assessed using the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual) approach,150 and the findings from quantitative experimental research were assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. 151

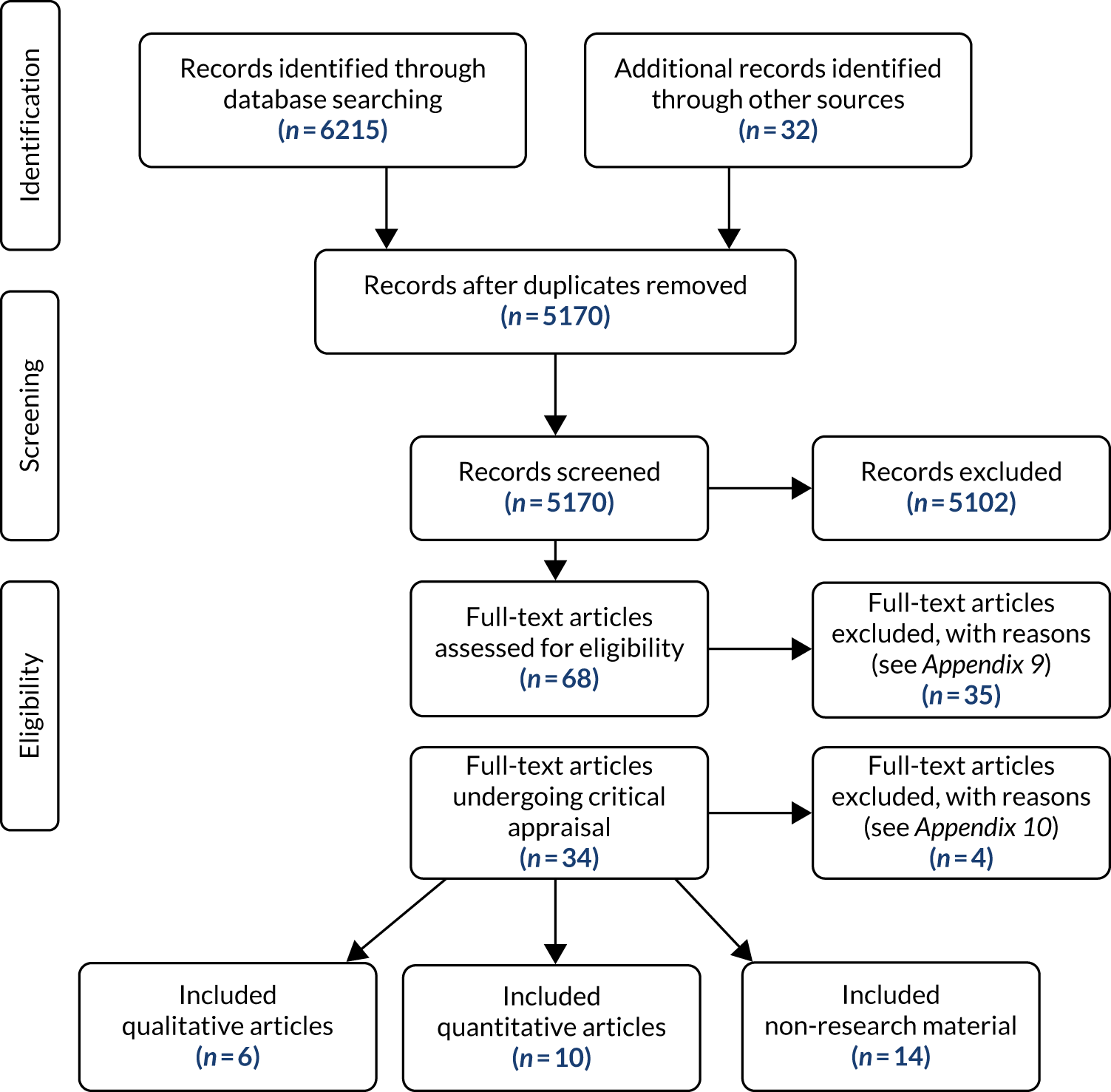

Flow of studies through the review

The database searches yielded a total of 5170 citations after removing duplicates (Figure 1). 149

FIGURE 1.

Flow of citations through the systematic review.

Characteristics of the included studies

The 30 included publications included quantitative research studies, qualitative research studies and non-research material studies and non-research material (Table 1).

| Study design | Number of studies and citation |

|---|---|

| Case series with non-concurrent multiple baselines | 2152,153 |

| Randomised controlled trial | 1154 |

| Pre test/post test | 1155 |

| Prospective cohort | 1156 |

| Post-intervention descriptive surveys | 2157,158 |

| Cross sectional survey | 2159,160 |

| Adapted three-stage Delphi consultation study | 1161 |

| Qualitative | 5 (across six publications)162–167 |

| Web pages/web booklets | 5168–172 |

| Guidelines | 21,87 |

| Reports | 2173,174 |

| Guidelines/guidance | 2175,176 |

| Framework | 1177 |

| Model | 1178 |

| Information sheets | 1179 |

The 15 research studies were conducted in seven countries (Table 2). Four publications of non-research material were published outside the UK: one European guideline,87 one international guideline,175 and a framework and model published by the same author from Australia. 177,178

| Country | Number of studies and citation |

|---|---|

| USA | 8 (across nine publications)152–154,157,158,162–164,166 |

| Australia | 2159,165 |

| UK | 1161 |

| Japan | 1155 |

| Taiwan (Province of China) | 1160 |

| Sweden | 1156 |

| Malta | 1167 |

The research studies were conducted across a variety of settings (Table 3).

| Setting | Number of studies and citations |

|---|---|

| Home care/community | 5154,157,158,161,162 |

| Nursing home | 2155,165 |

| Residential care facility | 1156 |

| Alzheimer’s disease rehabilitation centre | 2152,153 |

| Secondary care setting | 3160,166,167 |

| Alzheimer’s disease-specific day centre and home care setting | 1163 |

| Hostel care for ambulant people with dementia, aged care complex with hostel and nursing home facilities, and an acute hospital ward | 1159 |

| Day centre and long-term care facility | 1160 |

Methodological quality

The methodological quality is reported in Appendix 11.

Thematic synthesis

The findings from the quantitative and qualitative research, and from the included policy and guidance materials, were synthesised separately for each objective

Objective 1

The first objective was to explore carers’, family members’ and HCPs’ perceptions and experiences of communication, and the use of individualised care planning for PLWD with regard to toileting and continence. The objective comprised eight subthemes.

Communicating in a dignified way

The importance of protecting personal and social dignity163,165,166 during continence care was significant, and HCPs reported a belief that PLWD and their caregivers prefer not to talk about incontinence because it is a highly embarrassing165,166 and distressing issue. 178 HCPs believed that the provision of quality continence care for PLWD includes measures and approaches that conceal incontinence by creating situations that allow PLWD to go to the toilet in private and avoid communication that reveal their issues around incontinence or care dependence, which could cause them to feel embarrassed, ashamed or humiliated. 165

Respecting PLWDs’ right to privacy was also considered important. 163,165,178 To relieve PLWDs’ perceived embarrassment of accepting assistance,163,165 HCPs stressed the importance of building rapport and trust, using humour178 and ‘acting natural’163 when supporting continence needs. HCPs also felt that they should have the appropriate knowledge and skills to communicate with PLWD in ways that would minimise any emotional impact. 165 Other strategies to enhance privacy included whispering to the client about toileting issues165 and keeping these issues secret. 163 However, HCPs acknowledged that PLWD may have difficulties in recognising and communicating their continence needs, and PLWD not being verbally able to request toileting assistance was viewed as a barrier to protecting dignity. 165 Closely overlapping with this theme of communication is the issue of HCPs’ attitudes towards continence care.

The attitudes of health-care providers towards continence and continence care

The language used in a care environment is important with regard to continence care. 173,177 The language used was not always respectful;173 however, in situations in which staff had good knowledge of the people they cared for, staff were respectful and built good relationships with PLWD. 173 Ostaszkiewicz,177 discussing coercive continence care practices, described these practices as including ‘the use of verbal or physical force to wash a person, to accept wearing continence pads or other forms of incontinence containment and to accept continence checks’. 177 Ostaszkiewicz177 also suggested that chastising a person for being incontinent could be said to be a form of verbal abuse. Although some ward staff promote continence, this does not appear to happen consistently in acute settings. 167 Relatives expressed concern that, although PLWD would be happy to go to the toilet if assistance was provided, staff often encouraged them to ‘do it in the nappy’. 167 In addition, at times, for example when staff members were busy or appeared uncomfortable with or uninterested in providing support, routine toileting was avoided and cues ignored. 163,167 Ostaszkiewicz177 recognised that ‘[c]ommunicating therapeutically about incontinence with any person, including people with dementia, involves the demonstration of warmth, compassion and humanity’. 177 This requires both clinical knowledge and interpersonal and communication skills, which should all be included in education programmes. 178 Both formal caregivers and family carers would benefit from such programmes, which would also enable the development of ‘empathetic understanding’177 of the emotions that a person living with dementia has in response to incontinence and its care. 177

Presence of people living with dementia during outpatient consultations

There is no consensus as to whether or not PLWD should be present with their caregivers during outpatient consultations. 162,164,166 HCPs believed that care recipients should be present when discussing continence problems during consultations;166 however, caregivers expressed mixed opinions. 162,164 Caregivers who favour this approach view the HCP as an authority in this subject, with the result that they believe the PLWD would be more likely to co-operate with management strategies because they had been involved in the discussion. 162 By contrast, caregivers who opposed this reported that they did not want to upset or make their care recipient anxious by discussing a problem that the PLWD might not fully understand or be able to control. 162 Caregivers who were daughters felt the need to be sensitive to their parent’s privacy and feelings, preferring to discuss incontinence in greater depth with their HCPs, but this was not the case for caregiver spouses. However, time constraints or inability to meet alone with the HCPs prevented in-depth discussions from taking place. 164 Some caregivers suggested that HCPs could explain the problem and management options in simple terms when the care recipient was present in outpatient settings and then speak separately to the caregiver, providing more details. 162

Initiating conversations during outpatient consultations

There was a lack of consensus with regard to who caregivers thought should be responsible for initiating conversations about incontinence during dementia-related consultations in outpatient settings. 162,164,166 Caregivers believed that it is the responsibility of HCPs to initiate conversations about incontinence during both initial consultations and follow-up appointments. 162 However, there were differences depending on whether the care recipient was a parent or a spouse. Caregivers who were daughters or daughters-in-law would discuss incontinence with HCPs only when it became problematic to manage at home, whereas husbands tended to communicate their wives’ problems much sooner. 164 By contrast, HCPs thought that conversations about incontinence should be initiated by the caregiver. 162 However, when HCPs did initiate conversations about incontinence, they reported that this was appreciated by the caregiver, who was receptive and engaging in discussion around the topic. 166 However, in secondary care, not all HCPs saw addressing incontinence as a priority and many thought that the topic should be dealt with by the patient’s primary care providers, rather than during a specialist secondary care referral. 166

Extended family and friends who were caregivers reported that HCPs do not always ask about incontinence during consultations. 164 A lack of awareness of available resources and concerns about frightening patients/caregivers about potential problems before they occurred were suggested as possible explanations as to why HCPs do not routinely discuss incontinence and fail to initiate conversations about incontinence. 166 Time was the most common barrier to discussing incontinence reported by HCPs, as HCPs believed that a considerable amount of information needed to be covered during appointments and discussing incontinence issues needed more time than was typically allocated. 166 Possible solutions suggested by HCPs were for the patient/caregiver to have a follow-up appointment to discuss incontinence or to offer referrals to a nurse in continence care. 166

The language of incontinence during outpatient consultations

Caregivers prefer ‘straight talk’ from HCPs about incontinence and its management in relation to PLWD. 162 In a US study, Hispanic caregivers stressed that it is essential for providers to discuss incontinence using language that those with English as a second language can understand. These caregivers strongly supported having materials written in Spanish about incontinence in PLWD and the treatment plans available. 164 During outpatient consultations, caregivers rarely used the term incontinence and, instead, use terms such as having accidents, leaking, losing control, wetting or messing their pants, having a urine/bowel problem, urgency, diarrhoea, loose bowels, being unable to hold it and not getting there in time, difficulty in getting to the bathroom, and leaking and soiling themselves. 162,166 HCPs also tended to adopt these terms when discussing incontinence with family caregivers or patients. 166 Caregivers, when questioned, said that they did not know the right terms and did not want to be disrespectful to their care recipients. However, once caregivers were made aware of the term incontinence they were happy to use it. 162

Caregivers and HCPs suggested a number of different types of written information resources that could be provided to caregivers attending outpatient consultations,162,164,166 for example:

-

a guide to talking to a HCP about these problems, including definitions of common clinical terms162

-

a pre-visit checklist or written materials of some type to enable patients/caregivers to indicate whether or not incontinence is present, as this could then prompt the HCP to start a discussion during the consultation166

-

readily available handouts that would offer more detailed explanations of what had been covered during the appointment166

-

short and focused handouts that could stand alone and address a single concern. 166

The importance of non-verbal cues

People living with dementia are not always able to recognise and communicate that they need to go to the toilet or indicate that they need assistance. 87,152,153,157–159,162,163,165,166,171–173 Therefore, it is important to recognise the non-verbal signals, body language, facial expressions, behaviours and any signs that the PLWD use to communicate in such instances163,171–173 so that their wishes can be acknowledged. 173 Listening carefully to the words or phrases that PLWD use for describing the toilet,1,159,170,172,173 as well as being able to recognise familiar gestures,1,159,173 is seen as important. New staff should be trained to recognise the importance of toileting and on how to understand individual behaviours and non-verbal cues in relation to toileting. 163

A range of different non-verbal cues indicating need to go to the toilet have been observed or reported, include pulling/taking off clothing;87,160,171,179 making particular sounds, such as moaning or grunting;160,163,171 assuming a different posture;87 looking around;163 fidgeting;87,163,170,179 getting up and walking around or pacing;163,169,170,179 restlessness; 87,160 holding the crotch or stomach;87,163,170 various facial expressions, such as worry87 or sorrow;160 and going to the corner of the room. 170

Hutchinson et al. 163 also reported a number of affective cues, which included anger, profanity and acting in a frustrated and irritable manner. One study160 that investigated common behaviours when PLWD experience either bowel movement or urination needs found that anxiety, restlessness and taking off/putting on clothes inappropriately were exhibited by more than 30% of patients. 160

Finding the appropriate words and symbols to describe the toilet

Wilkinson et al. 159 sought to evaluate the comparative suitability of a range of words or symbols used to label toilets for PLWD. Among the 24 institutions surveyed, 16 used the label ‘toilet’ and x used the words ‘male/female’. Four institutions used no labelling. Only four institutions used symbols; one used the international symbols, one used a toilet symbols, one used yellow wrapping over the door and one used a ceramic plaque on which the word ‘toilet’ was written (n = 1). A further survey, among PLWD, found that the preferred word and symbol for toilet varied significantly (p < 0.05) according to mental status (assessed using the Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam and classified as normal, mild, moderate and advanced). The labels ‘Ladies’ and ‘Gents’ were preferred by those with no cognitive impairment and ‘toilet’ by those with moderate dementia. The international symbols was preferred by people with no cognitive impairment or mild dementia, whereas the toilet symbol was preferred by those with more advanced dementia. 159

The importance of individualised continence care

Targeted and individualised/person-centred continence care87,168,172,174,175,178 that is established after a thorough clinical assessment has taken place87,175,177,179 is seen as important, including the use of a bladder diary. 87 Individualised continence care means care that is best for the individual,87,172 avoiding harm87 and about promoting autonomy and independent living. 87

Objective 2

The second objective was to identify the communication strategies and the use of individualised care planning that carers, family members and HCPs have employed to manage toileting and continence for PLWD. This objective comprised five subthemes.

Strategies for improving communication

To reduce anxiety, fear and embarrassment, it is important to check HCPs’ awareness of good communication techniques when working with PLWD. 161 HCPs should consider:

-

getting to know the person with dementia, such as their previous routines, habits and lifestyle170–172 and how they communicate172

-

introducing themselves and seeking PLWD approval before performing tasks165

-

asking the person with dementia how they can help them manage their continence170

-

communicating with the family to determine usual behaviour patterns163

-