Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the Health and Social Care Delivery Research Programme and managed by the Evidence Synthesis Programme as project number NIHR131593. The contractual start date was in June 2020. The final report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Al-Khudairy et al. This work was produced by Al-Khudairy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Al-Khudairy et al.

Chapter 1 Background

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) supported the introduction of social prescribing (SP) for people with long-term conditions, poor mental health and complex social needs. 1,2 SP in this context encourages health-care professionals to refer patients to a link worker, who will develop a personalised plan for each individual. Plans can include activities such as arts, gardening and physical activity, with the aim of improving an individual’s health and well-being. Referral to link workers can occur from:

. . . a wide range of local agencies, including general practice, pharmacies, multi-disciplinary teams, hospital discharge teams, allied health professionals, the fire service, police, job centres, social care services, housing associations and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations. Self-referral is also encouraged.

There are several modes of SP, including signposting, direct referrals, the link worker model and the holistic model. 3 The Social Prescribing Network defines the link worker SP model as a facility that allows health-care professionals to refer a person to a link worker. A non-clinical social prescription is then co-designed by both the link worker and person referred. 4 NHS England (NHSE) defines SP as:

. . . a way for local agencies to refer people to a link worker. Link workers give people time, focusing on ‘what matters to me’ and taking a holistic approach to people’s health and wellbeing. They connect people to community groups and statutory services for practical and emotional support.

Link workers can support existing community groups, collaborate with local partners and support people to start new groups. 5 SP falls under the umbrella of NHS Universal Personalised Care,6 and the NHS Long Term Plan7 outlines proposals for a major expansion in the numbers of people referred to SP schemes. To support this, the 2019 general practitioner (GP) contract made provisions for all Primary Care Networks (PCNs) in England to employ one SP link worker from an allocated budget of £891M. This is a substantial investment in SP. 8

Description of the service under assessment

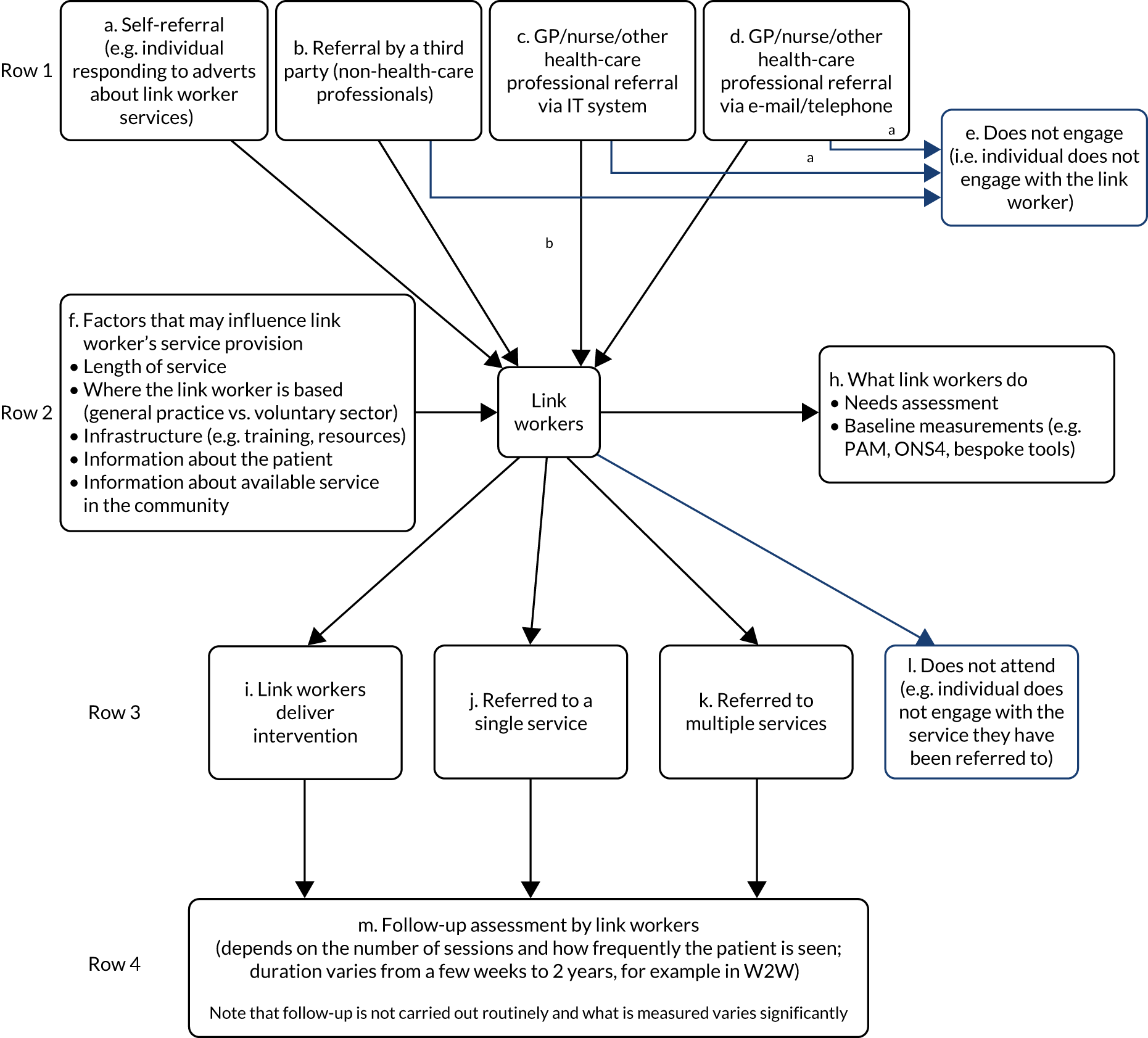

NHS England, in partnership with stakeholders, developed a standard model of SP, which is presented as Figure 1. NHSE worked with a range of stakeholders to develop its Social Prescribing Common Outcomes Framework to encourage consistent data gathering and measurement of the impact of SP because they were aware that locally driven approaches had emerged across England. The consensus reached was that the impact on the person, the impact on the health and care system and the impact on community groups should be measured. 5 In 2020/21, NHSE aimed to increase the number of link workers to build significant capacity to deal with higher uptake of the service (up to 900,000 referrals by 2023/24). 1 The DHSC wished to explore whether or not an evaluation of the link worker model of SP is possible. The Warwick Evidence Technology Assessment Review Team was commissioned to complete a feasibility analysis to understand what would be required and what is possible in a future impact evaluation study. The findings of our feasibility analysis are presented in this report.

FIGURE 1.

NHS England’s model elements of SP. Reproduced with permission from NHSE. 1 Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Research questions

To complete the feasibility analysis the following research questions were proposed in the commissioning brief:

-

What are the most important evaluation questions that an impact study could investigate?

-

What data are already available at a local or national level and what else would be needed?

-

Are there sites delivering at a large enough scale and in a position to take part in an impact study?

-

How could the known challenges to evaluation (e.g. information governance and identifying a control group) be addressed?

Research objectives

To answer the four research questions, we developed the following objectives:

-

Undertake a rapid systematic review to better understand current models of SP, previous evaluations and evaluation questions that an impact study could investigate (research question 1).

-

Undertake qualitative interviews with those working in SP to identify:

-

data already collected at local and national levels and gaps in data availability (in particular outcomes data) to inform likely data availability for future evaluation (research question 2)

-

delivery sites, scale and processes of current service delivery and the number of sites available for future service evaluation (research question 3)

-

known challenges to evaluating the SP link worker model (e.g. information governance and identification of a control group) (research question 4)

-

-

Draw together findings and make recommendations for a future national evaluation of the SP link worker model (including feasibility, strengths and limitations) and how known challenges can be addressed.

Chapter 2 Methods

Evidence synthesis

We conducted a rapid systematic review9–12 to better understand the literature on previous evaluations and evaluation questions that an impact study could investigate and to inform the development and structure of our data collection. We searched MEDLINE® (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA) ALL [via Ovid® (Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands)] from inception to 14 February 2019 (see Appendix 1) and the first 100 hits of a Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) search. We searched key studies for additional evidence. One reviewer screened potentially eligible studies and discussed with a second reviewer when in doubt. Studies were included if they included ‘social prescription’, ‘social prescribing’ or ‘social prescriber’. We included all study designs and study outcomes. Only studies published in the English language from 2015 were eligible. Two reviewers assessed studies for eligibility and data were extracted by two reviewers into summary tables. Key extracted data included study design, setting, definition of the link worker and outcomes reported. The evidence synthesis was analysed using a narrative approach and evidence summaries are provided in summary tables. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was conducted.

Qualitative interviews

To capture the perspectives of people involved in the planning and delivery of SP, as well as those of patients, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews that were informed by the rapid systematic review, questions set out in the project commissioning brief, and the study protocol. The protocol was generated in collaboration with the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and NHSE, and included the perspectives of other stakeholders including service experts, patient and public representatives and other relevant parties during the protocol planning phase of this study. We sought and received feedback, guidance and recommendations regarding the qualitative elements of our planned work during project stakeholder meetings and webinars. These were attended by a range of organisations and interested parties, including NHSE, voluntary sector organisations, link workers and other social prescribers, academics and members of the public. The supplementary information from the webinars was essential for facilitating discussions around the research gaps and potential areas for future work. A COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was carried out.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Warwick Biomedical and Scientific Research Ethics Committee (reference number BSREC 93/19-20). We did not deviate from the planned protocol.

Participants

Eligible interview participants were purposively sampled through the NHSE network and contacts of staff members at the University of Warwick (Coventry, UK). Subsequent participants were snowball sampled from these initial participants. We adopted an iterative approach, progressing to the next participants if information was not available from our primary target source. All participants were approached via e-mail by members of the research team (LAK, JH or IG). Targeted participants included (1) national SP leads identified through NHSE, (2) Social Prescribing Network regional leads (for East of England, London, North East, North West, South East, South West, West Midlands and Yorkshire and The Humber) and (3) sites delivering SP, both those with an established/mature link worker social prescribing model scheme and those that did not yet have a mature scheme.

In addition, we interviewed voluntary sector organisations involved in SP to understand what happens after people have been referred to voluntary sector service providers. We contacted people from five voluntary organisations and three people participated. In addition, we contacted project stakeholders, topic experts and academic colleagues to capture opinions and feedback regarding ongoing and completed SP evaluations. In total, we contacted 41 people (plus three academic researchers), of whom 28 participated in interviews (participants, n = 25; academics, n = 3; 68% participation rate).

Data collection

Qualitative data were collected using a semistructured interview topic guide that was informed by our rapid systematic review synthesis, questions set out in the project commissioning brief, and the study protocol (in collaboration with the NIHR and NHSE). The semistructured approach allowed for systematic data collection across participants and sites while ensuring flexibility in structuring the discussion.

The interview guide was peer reviewed by NHSE and colleagues at Warwick Medical School (University of Warwick) and piloted on one participant. Any questions that were not clear were amended as appropriate. Key areas of the interview topic guide included:

-

the nature of the service in terms of structure, models implemented, organisations involved and health domains covered

-

patient journey throughout the service

-

any measured outcomes

-

data collection methods and human resources

-

volume of service uptake

-

type of service utilisation (highest vs. lowest)

-

nature and length of follow-up

-

potential strengths and limitations of the current service

-

major enablers of and challenges to developing and implementing SP service

-

costs and savings when recruiting for and implementing SP service (for both PCNs and other organisations involved)

-

non-attendance data (e.g. resulting from people who do not take up their SP referral)

-

the make-up of people taking up SP (e.g. how they compare to the overall practice population and availability of social class data).

In addition, during the interviews we asked interviewees to comment on how the COVID-19 pandemic was affecting the implementation, provision and uptake of SP.

Interviews were conducted by four members of the research team (LAK, IG, JH or EM; three women and one man; 78% were conducted by IG). Two are senior research fellows, one is a research assistant and one a is medical student; all have previous experience or training in qualitative research methods. Most of the interviews were conducted on Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and only two were conducted over the telephone. Interviewers did not have a previously established relationship with interviewees at study commencement. A project brief was provided to each potential participant (either via e-mail or verbally) ahead of the interview, which described the research aims and objectives.

Interviews were audio-recorded with the interviewees’ consent, all audio-recorded data were manually transcribed and interview notes were generated by the interviewers. Interviews lasted for a mean of 51 minutes (range 31–147 minutes).

Virtual workshops

Two virtual workshops with researchers, people involved in delivering SP services, and patients and people with lived experience of SP services were undertaken to contribute to the specification and the focus of the recommendations for a future evaluation. The workshop attendees were grouped into two: nine experts focused on process evaluation and eight experts focused on impact evaluation. The workshops also considered the implications of COVID-19 for a future evaluation of SP.

Analysis

Of the 28 interviews that were conducted, 25 [which comprised interviews with link workers, social prescribers and voluntary community and social enterprise (VCSE) workers] were included in the main qualitative data analysis. The remaining three were academic colleagues, two of whom provided descriptions of their research projects to give us further insight into their work and experience in SP evaluations. Data from the academic participants do not follow the main topic guide and are discussed separately in Chapter 3, Ongoing studies of social prescribing: lessons learned from researchers. One academic colleague interview was excluded because their work was not appropriate to the research commissioning brief.

Interview data from the 25 non-academic participants were analysed using a pragmatic framework approach,13,14 using the interview guide as a framework to code and summarise the data into the key areas of interest. The framework was applied to and further developed as the subsequent transcripts were coded, and data were charted and summarised into the framework. Data manipulation and management were supported by NVivo 13 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software and the framework was constructed in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation). Analysis was performed by three members of the research team (AA, EM and IG). The immaturity of the data prevented any theoretical development and identification of reasons for the emergence of phenomena, beyond presentation of summary data in tables and example quotations.

Chapter 3 Results

Evidence synthesis

In this review we set out to identify evaluation questions, understand the nature of the existing evidence, identify outcome measures used in research and practice, and inform qualitative data collection. We screened 124 papers, of which 42 were assessed as relevant. Of these, 15 were excluded (seven protocols and eight editorials or clinical update reports). A total of 27 papers were included in the full-text review [see Appendix 1 for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram]. 15 Primary studies included one randomised controlled trial (RCT),16 one trial within a cohort study,17 two cohort studies,18,19 two before-and-after studies,20–22 five mixed-methods studies,23–27 and six qualitative studies. 28–33

We identified various forms of secondary studies, including four systematic reviews,34–37 a realist review,38 a rapid review,39 two scoping reviews40,41 and two literature reviews. 42,43 The studies are described in detail below by study design and the key outcomes of studies are presented in Appendix 2. Included studies used a range of well-being measures, including the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS), the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12), the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL), the Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information Project/World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practice/Family Physicians (COOP/WONCA) and the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale (RCFS).

In our summary we focus on the primary studies and briefly highlight the reviews (detailed study characteristics are available in Appendix 2). The classification of outcomes reported in studies is available in Appendix 3.

Randomised controlled trials

We identified one SP-intervention RCT. 16 The study was an evaluation of a smartphone application (app)-based well-being intervention involving 582 participants (54.2% of all selected participants) from Sheffield, UK. The app aimed to encourage appreciation of nature and was intended to be a potential social prescription. Primary outcome measures were the ReQoL and Inclusion of Nature with Self Scale. Secondary outcome measures were the Types of Positive Affect Scale (TPAS), Nature Relatedness Scale and Engaging with Nature Beauty Scale. The study participants were randomised to two different versions of the app, either intervention (green space) (n = 414, 70%) or control (built space) (n = 168, 30%). A total of 322 (55.1%) participants completed baseline measures and 164 (27.4%) completed the 1-month follow-up evaluation. The study reported an improvement in ReQoL score from baseline to follow-up for patients in the intervention group [mean score: baseline, 29.19 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) 28.53 to 29.85 points; follow-up, 32.05 points, 95% CI 30.93 to 33.18 points] but not in the control group (mean score: baseline, 28.67 points, 95% CI 27.69 to 29.65 points; follow-up, 30.69 points, 95% CI 28.90 to 32.47 points). Multivariate analysis showed no significant effect of condition (green vs. built space) [F(7, 118) = 0.964; p = 0.461; ηp2 = 0.054]. In summary, no overall clear benefit of the app was identified. The study was poorly designed because the discrepancy in group sizes (70% randomised to the intervention group and 30% to the control group) meant that the power of the study to detect differences was compromised. The minimum clinically important difference for the ReQoL is described as at least 5 points,44 which is larger than the differences that were observed in the paper reported. In addition, the study failed to recruit enough patients with common mental health problems (referred by a GP), had a high attrition rate for follow-up (the rate of retention from post intervention to follow-up was 27.36%) and reported that the app was only ‘moderately engaging’ to subjects.

Trials within cohorts studies

There was one study with a trials within cohorts (TWiCs) design. 17 The study evaluated telephone-based ‘health coaching’ among a cohort of 1306 older people with multimorbidity, of whom 504 were offered the health coaching intervention (intervention group) and the remaining 802 were not offered health coaching (the usual care group). This study measured patient-reported outcomes including patient activation, quality of life, depression, health-care utilisation and self-care. A cost-effectiveness analysis was also performed. There was no statistically significant improvement in patient activation, quality of life, depression and self-care in the intervention group compared with usual care. Use of planned services and overall costs increased and use of emergency care decreased in the intervention group. The incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) was £8049, and the probability that this intervention would be cost-effective at a cost-per-QALY threshold of £20,000–30,000 was 70–79%. The authors reported that the lack of significant improvement in primary outcomes may be due to the low level of uptake among those selected. The intention-to-treat study design included all patients who were offered health coaching in the intervention group regardless of whether or not they declined; therefore, the study estimates the effect of an ‘offer of treatment’ rather than the effect of receiving the treatment. Because only 41% of those selected consented to the intervention, 59% of participants in the intervention group did not receive health coaching, which substantially diluted the treatment effect.

Cohort studies

We identified two relevant cohort studies. 18,19 Munford et al. 18 assessed whether or not community assets participation is associated with better quality of life or lower costs of care among 4377 people aged ≥ 65 years with long-term conditions in Salford, UK. Outcomes assessed included QALYs, health-care costs and net benefits. Starting to participate in community assets was associated with a gain in QALYs of 0.056 (95% CI 0.017 to 0.094) at 18 months’ follow-up. The cumulative effect on care costs was –£453 (95% CI –£1366 to £461), for a net benefit of £1956 (95% CI £209 to £3703) per participant at 18 months. Stopping participation led to a change in QALYs of –0.102 (95% CI –0.173 to –0.031) and an increase in costs of £1335.33 (95% CI £112.85 to £2557.81) at 18 months. Overall, the study suggests that community assets participation was associated with improved quality of life and reduced costs of care. The study’s strengths include its longitudinal cohort design, use of statistical matching to address potential confounding and use of objective administrative data to collect health-care costs. However, it was conducted entirely in Salford, where significant investment in community groups has occurred, so results may not be generalisable to other regions. Furthermore, the study examined community assets participation (which may or may not be associated with SP schemes) rather than SP itself.

Sumner et al. 19 assessed factors associated with attendance, programme engagement and well-being change among 1297 patients with the ‘arts on prescription’ scheme in the south west of England. Higher baseline well-being was associated with successful attendance [odds ratio (OR) 1.030, 95% CI 1.006 to 1.054; p = 0.012] and increased likelihood of being engaged with the programme (OR 1.032, 95% CI 1.007 to 1.057; p = 0.012). However, higher baseline well-being also decreased the likelihood of improved well-being following the intervention (OR 0.961, 95% CI 0.933 to 0.989; p = 0.007). Considering deprivation level, participants in the medium deprivation quintile of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) reported more successful attendance (OR 2.080, 95% CI 1.092 to 3.963; p = 0.026) than participants of the lowest deprivation quintile of the IMD. Although the study had a large sample size, there was no control group, and the homogeneous socioeconomic status of participants reduced generalisability to other populations.

Before-and-after studies

There were two before-and-after studies. 20–22 Pescheny et al. 20,21 assessed change in mental well-being levels for 63 participants in the Luton SP programme, which involves link workers. Well-being, measured using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS), improved statistically significantly from baseline to post intervention by 2.78 points (95% CI 1.68 to 3.88 points; p < 0.001). However, the study authors noted that the mean difference in scores was less than the minimal clinically significant difference of 3 points. The study assessed mental well-being outcomes by working status, sex and age. It used skew-normal regression, which is better aligned with the data than a paired t-test. However, problems included large loss to follow-up, a short follow-up period and lack of a control group. Elston et al. 22 evaluated the impact of ‘holistic’ link workers on 86 older adults with complex health needs. They assessed well-being, activation and frailty, and use of health and social care services and associated costs. Well-being, measured using the WEMWBS and Well-being Star,52 increased significantly, by 7.9 points (95% CI 6.1 to 9.7 points; p < 0.001) and 13.3 points (95% CI 10.6 to 15.9 points; p < 0.001), respectively. The total costs increased at the end of the study by £4212 (p < 0.001). Elston et al. 22 reported that 59% of this increase was attributable to 13 users with high costs due to morbidity and frailty. The study had high follow-up rates and comprehensive data collection, but with a lack of a control group it is difficult to confidently attribute the changes observed to the intervention.

Mixed-methods approaches

Five studies used a mixed-methods approach. 23–27 Four of these23–26 used patient outcomes and other service-related outcome measures such as service-related outcomes, barriers and facilitators, training needs, potential wider impact and programme effectiveness. Bird et al. 26 performed an evaluation of a community-based, 12-week physical activity programme for inactive adults with (or at risk of) long-term conditions. A total of 326 participants attended at least one 30-minute activity session, which accounted for 30.2% (1080) of the target population. The study reported a significant improvement in WEMWBS scores from baseline to 12-month follow-up (9.09 points, 95% CI 5.65 to 12.53 points; p < 0.001) and weekly physical activity increased from baseline to 12-month follow-up by an average of 158.60 minutes per week (95% CI 103.11 to 214.10 minutes per week; p < 0.001). Strengths of this study are its Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) study approach,45,46 which allows for transparent understanding and reporting of intervention planning, evaluation and outcomes, and multiple quantitative/qualitative measures to assess a broad range of outcomes that are relevant to SP. However, missing data for long-term follow-up (6.8% of participants completed 12 months’ follow-up), self-reported data and lack of a proper control group are the main drawbacks of the study.

Bowden et al. 25 evaluated the effects of asthma control therapy (the BreathStar Project) among children with breathing difficulties and the associated lifestyle and wider community consequences. The study recruited 7- to 12-year-old children from deprived and highly polluted communities. There were no statistically significant improvements in asthma control. However, interviews with four subjects reported improvements in self-esteem, enjoyment of participating in a choir and the importance of a family-centred approach. Lack of GP and NHS involvement, a small sample size (four children at baseline and the end of the study), local cultural factors and difficulties generalising the study findings to other SP settings are problems in this study. A pilot study evaluated the effectiveness of a structured 6-week nature-based intervention (NBI) in improving mental health (anxiety and/or depression) of 16 individuals. 24 The pilot study documented significant improvements in mental well-being (mean WEMWBS score: pre intervention, 37 points, post intervention, 41 points; p-value = 0.009). However, again the small homogeneous sociodemographic study sample limits the generalisability of the findings.

Woodal et al. 23 evaluated the service outcome and the process of delivery of SP provided by ‘well-being coordinators’ in the north of England. 23 The data summarised change in well-being, mental and physical health, loneliness and ability to manage long-term conditions among 342 participants. Well-being scores significantly improved by an average of 3.98 points (95% CI 3.41 to 4.55 points; p < 0.001). The role of well-being coordinators, who directed patients to community groups and services, was considered the key element of SP. Limitations included lack of a control group, the cross-sectional design and the presence of the service manager during interview data collection.

Agaku et al. 27 explored barriers and facilitators related to the delivery and scale-up of the Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange (5As) smoking cessation intervention programme. They used semistructured interviews with 21 programme directors and a quantitative survey of 120 clinic staff members. Barriers included time constraints, difficulty engaging patients and documentation challenges. Community referral resources were considered as a facilitator. Staff confidence in discussing treatment options (29%) and supporting relapsed patients was low (30%). Study limitations included the small number of participants, preventing intervention stratification by provider type; possible misclassification of clinics into 5As training status; and self-reported data from clinic staff, leading to misreporting.

Qualitative studies

We identified six qualitative studies. 28–33 Batt-Rawden and Anderson28 reported that singing in a choir can affect social inclusion and women’s perceptions of their own health and well-being. The researchers interviewed 19 female choir members in Norway and found that choir singing can support health and well-being in four ways: choir members can experience (1) joy when singing, (2) singing as essential for survival, (3) group singing as a route to social connection and (4) increased social inclusion. Participation in the study was via self-selection and, therefore, subject to selection bias. With the lack of follow-up, it is not possible to attribute improvement in well-being to taking part in the choir. In addition, men were not included and participants came from only two locations, which limits the generalisability of the findings. In a similar study, Redmond et al. 31 analysed open-ended survey responses from 1297 participants in a longitudinal study of an arts referral programme in general practices in the south-west of England. The study reported benefits across the thematic domains of ‘being with others’, ‘being on my own’, ‘doing something for me’, ‘losing oneself’ and ‘threshold’ (i.e. threshold opportunities to recognise personal growth). The study had a large sample size but generalisability to SP is limited because of the lack of attention to health outcomes.

Wildman et al. 33 conducted semistructured interviews to explore experiences of SP among people with long-term conditions 1–2 years after their initial engagement with a link worker. The study included 24 participants aged 40–74 years living in a socioeconomically deprived area of north-east England. Participants reported less social isolation and improved health-related behaviours and condition management. Barriers to SP were lack of onward referral options, unsuitable location or scheduling of activities, and language and cultural barriers. The authors suggested that an evaluation of SP requires longitudinal data collection because of the range of improvements and their episodic nature.

The remaining three qualitative studies explored organisational experiences of SP among small samples of participants conducted in single sites. 29,30,32 Payne et al. 30 focused on the mechanisms of SP. 30 They recruited 17 participants from a multiactivity SP organisation in Sheffield, UK, and identified five themes: (1) receiving professional support, (2) engaging with other participants, (3) developing new skills, (4) changing perceptions and becoming open to new futures and (5) developing a positive outlook on the present while moving forward. The study reported limitations related to participant recruitment and data coding for qualitative analysis. Bertotti et al. 29 conducted an interview-based realist evaluation of a SP pilot in London, UK, in the boroughs of Hackney and City of London. They aimed to explore the contextual factors and mechanisms that underpin the pathway linking primary care with the voluntary sector, especially via the SP coordinator. The authors subdivided the pathway into three stages: the GP referral process, consultation with the SP coordinator and interaction with the community/statutory organisations. Several challenges relating to the pathway were highlighted. This included ‘buy-in’ from some GPs, branding and funding for third-sector organisations. White et al. 32 interviewed 18 health-care professionals and 15 third-sector organisation workers involved in SP to explore the quality of the relationships with participants. The authors reported different representations of ‘health’ between the two groups, ‘mistrust of unknown third sector organisations’ by health-care professionals and the ‘lack of effective networks connecting the two groups’. The transferability of the study findings is limited by the single organisational recruitment, ‘socially desirable’ self-perceived response and the small number of GPs.

Reviews

We identified four relevant systematic reviews. 34–37 One of these reviews35 aimed to assess the outcomes of SP programmes based on primary care and involving navigators for service users. The review identified 16 studies of variable quality and reported that qualitative studies reported improved health and well-being outcomes but that quantitative studies reported mixed results. The authors suggested there is a need for more high-quality evaluations to accurately assess SP. Bickerdike et al. 37 reviewed 15 studies and reported that most of the studies were small in scale and assessed as being at high risk of bias. A review by Pescheny36 explored the barriers to and facilitators of the implementation and delivery of SP. This review included eight studies and identified barriers and facilitators related to legal agreements, leadership, stakeholder engagement and local infrastructure. The authors reported a lack of high-quality studies relevant to the review. The fourth systematic review sought to measure health and economic outcomes of SP for frail, elderly adults living in the community, but no papers met the selection criteria. 34 Other literature reviews (i.e. non-systematic)38–43 also highlighted the need for more high-quality studies.

Summary

In this rapid systematic review we have identified and summarised the growing literature surrounding SP. We screened 124 papers and included 27 in the final review. We identified various primary and secondary studies that used a range of research designs and methods. In summary, the key findings identified from the included systematic reviews are:

-

SP is a clinical priority and a key to the future provision of community care.

-

The available evidence reported mixed results; some evidence suggests improvement in well-being and health-related behaviour and some evidence does not.

-

The available evidence comes from small-scale studies that are mostly poor in design.

-

There is a lack of standardised and validated tools to measure the outcomes.

-

Studies have included short follow-up durations and high levels of missing data.

-

Service-related barriers include implementation approach, legal agreement, staff engagement, communication between partners and stakeholders, and local infrastructure.

Our review helped to identify appropriate evaluation questions for the evaluation of SP and to inform our qualitative data collection. It fed into the structure and content of the topic guide. Our review also helped the systematic assessment of anticipated and reported outcomes captured in the data collection section (see Qualitative interviews). In addition, the review highlighted a number of research challenges such as the low uptake of SP interventions, relatively small study sample sizes, frequent lack of a control group, heterogeneity of interventions and programmes and geographical variation of the evidence that limits generalisability.

Qualitative interviews

Findings from 25 interviews of people directly involved in SP (link workers, social prescribers and VCSE workers) are presented here. The findings are presented in line with the 12 categories that formed the framework developed in the data analysis. The framework was informed by the interview topic guide and project stakeholders during the protocol phase of the study. The 12 categories are provided, with a brief summary of each. For additional example quotations, see Appendix 4. The 12 categories were:

-

the nature of the service in terms of structure, models implemented, organisations involved and health domains covered

-

patient journey throughout the service

-

any measured outcomes

-

data collection methods and human resources

-

volume of service uptake

-

type of service utilisation (highest vs. lowest)

-

nature and length of follow-up

-

potential strengths and limitations of current service

-

major enablers of and challenges to developing and implementing SP service

-

costs and savings when recruiting for and implementing the SP service (for both PCNs and other organisations involved)

-

non-attendance data (for instance resulting from people who do not take up their SP referral)

-

the make-up of people taking up SP (e.g. how different are they to the overall practice population, availability of social class data).

In the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, during the interviews we asked participants to share their experiences of how the pandemic was affecting each of these areas.

Characteristics of study participants

A total of 25 participants (18 women and seven men) were included in the main analysis; descriptions of ongoing studies from the two academic researchers are provided in Ongoing studies of social prescribing: lessons learned from researchers. Participants’ roles covered several regions in England: the North East (n = 5), South West (n = 5), West Midlands (n = 4), South East (n = 3), North West (n = 2), East of England (n = 2), London (n = 2) and Yorkshire and The Humber (n = 1). One participant had a national role. Participants’ length of experience in SP-related roles at the time of the interview ranged from 4 months to 20 years.

The most common roles were social prescribers/link workers (n = 8), regional leads (n = 5) and learning coordinators (n = 3). The remaining participants covered a range of roles, and included one commissioner, one head of community well-being services, one community-linking project development manager, one chief executive, one operations director and one manager. Three VCSE workers were interviewed, one of whom was a programme manager for the VCSE who had a background as a health trainer and in a ‘health trainers in GP surgeries’ scheme from 2009. The programme manager worked in an organisation that had a link worker structure and served as an ‘umbrella organisation’ for several services, and sometimes supported patients directly or referred patients to an appropriate service. The remaining two VCSE interviewees were from organisations that deliver specific services (i.e. arts on prescription and mental well-being services). They are mainly dependent on volunteers and have their own policies in place in terms of referral acceptance from the link worker, self-referral or directly from general practices. One of them had worked as a freelance director of a voluntary organisation for 4 years and had previously worked as an artist. The other was managing a new service that provided telephone support, risk assessment and secondary referrals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The organisations were all located in the West Midlands. Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

| Role in organisation | Length of practice in SP | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Lead | 14 years | South West |

| Stakeholder | 3 years | National |

| Lead | 20 years | South West |

| Lead | 5 years | London |

| Lead | ≥ 6 years | East of England |

| Link worker | > 1 year | South West |

| Link worker | < 1 year | South West |

| Stakeholder | 9 years | North East |

| Stakeholder | 5 years | North East |

| Stakeholder | 2 years | North East |

| Stakeholder | 9 years | Yorkshire and The Humber |

| Lead | 2 years | North West |

| Lead | 20 years | London |

| Stakeholder | 7 years | West Midlands |

| Link worker | 1.5 years | South East |

| Link worker | 4 months | North East |

| Link worker | 4 months | South East |

| Link worker | 5 months | South East |

| Stakeholder | 10 years | North East |

| Link worker | 2 years | East of England |

| Stakeholder | 10 months | North West |

| Link worker | 11 months | South West |

| Programme manager (voluntary sector) | 11 years | West Midlands |

| Freelance director (voluntary sector) | 4 years | West Midlands |

| Unknown role (voluntary sector) | 6 months | West Midlands |

Categories

In this section we provide a summary description of each of the 12 categories, with supporting example quotations from interview data.

1. The nature of the service in terms of structure, models implemented, organisations involved and health domains covered

Duration of services

Across the sample, the time since initiation of SP service operations ranged from 2 to 9 years. Some participants reported SP commencing in 2011; others (e.g. Gateshead) reported that it commenced 5 years previously; one clarified that a pilot started in 2015. Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) commissioned pilot community well-being services in 2017 but these services were not referred to as SP. SP commenced in 2018 in south Cambridgeshire, and seven participants (from Durham City, Kent, Berkley and Watton, Guildford and Waverly, Lewes and Ringmer, Barnstaple, and Yorkshire and The Humber) reported SP commencing in their area in 2019.

Types of services used (services patients are signposted to)

Participants reported a vast number of services that they could refer to according to patients’ needs. This included Citizens Advice (London, UK), well-being centres, gardening, walking groups, fishing groups and food banks. As reported by one participant:

We currently have a directory of over 3000 countywide . . . In terms of what is likely to be signposted to, it is varied as how many people we have on our books. And we try to offer a unique prescription to [suit the] needs [of the] person.

Stakeholder, 7 years, West Midlands

2. Patient journey throughout the service

Generally, GPs or nurses discussed SP with patients and obtained their consent for referral to link workers. The referral can be through clinical information technology (IT) platforms [such as EMIS (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK)], paper, e-mail or telephone. Our respondents reported that anyone can refer a patient and that self-referrals are made. Once a referral is received, the link worker contacts the patient, obtains a full assessment of their needs and completes any baseline questionnaires. Some participants reported that they prefer the initial contact with patients to be face to face, with initial meetings in the surgery for safety reasons (and subsequent sessions may be wherever the patient prefers). Other link workers hold the session in the patient’s home to facilitate a friendlier environment/insight into the patient’s living conditions.

During the initial assessment, the link worker works with the patient to highlight issues that are most important to them. Based on the patient’s goals, the link workers identify services to which to signpost the patient. Sometimes the link workers do not need to signpost patients to further services if the link worker is able to meet the patient’s goals themselves (e.g. help with completing forms). The length of time the link worker is engaged with patients and the number of sessions appeared to depend on the link workers’ assessments of the needs of the patient and their ongoing support requirements. A participant described the need to ‘move people’ on:

. . . people kind of click with you and people can’t move on. I am not good at managing expectations.

Link worker, > 1 year, South West

Communications received by voluntary community and social enterprises from link workers

The nature of communication between link workers and VCSEs varied. One organisation employed its own link workers embedded in general practices but also received external referrals. However, the participant noted that their organisation received more information about patients when referred by their own link workers than through external referrals. Link workers may communicate safety concerns to the organisation if, for example, a patient was at risk of suicide. Another organisation reported building positive communication with link workers at the time of referral and also after patients have made contact with the volunteer service activities (e.g. discussing concerns around individual patients). It appears that the nature and amount of information received from link workers may be influenced by the relationship between the link workers and the VCSE organisation.

Communications received by link workers/practices from voluntary community and social enterprises

The data feedback system varied among the services. One of the VCSE interviewees stated that they do not provide feedback to the link worker or GP, whereas others did. Generally, feedback included data such as patient attendance, referral made, referral accepted, referral declined and non-attended. Impact/outcomes data were not usually reported back to GPs.

3 and 4. Any measured outcomes, data collection methods and human resources

We found differences regarding data availability. Data collection was performed using a wide range of tools. There was inconsistency in the collection of outcome data, as can be seen in Table 2. Assessments were often made at the initial contact and sometimes repeated at the end of the process, but it was not always possible to capture the follow-up data and, therefore, it may not be possible to make an assessment about whether or not patients benefit from attending the service. Each locality appeared to have their own minimum data requirements and, whereas some localities reported collecting ‘standard outcome data’, some did not collect any outcome data.

| Variable | Additional comments |

|---|---|

| Name | – |

| Age | – |

| Sex | – |

| Marital status | – |

| Religion | – |

| Employment status | – |

| Long-term condition | – |

| Disability | – |

| Whether or not they have a carer | – |

| Whether or not they live alone | – |

| Contact details | – |

| General practice they are registered with | – |

| Contact with general practices | To see if consultation rates have been affected |

| Reason for referral | Includes various categories such as loneliness; social isolation; emotional well-being; being a carer; for exercise; to improve social skills and smoking and drug/alcohol problems; fire safety advice; and welfare benefits advice |

| Attendance/non-attendance | – |

| Number of contacts made | – |

| Time spent with patient/client | – |

| Number/type of goals | – |

| Number/type of sign postings | – |

| How long people are in the service | – |

Many participants (especially those based in general practices) recorded information about patients on clinical IT software, for example SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership Ltd, Leeds, UK) or EMIS Health (Leeds, UK) software, which is accessible to the GP. The link worker was able to liaise directly with the GP in the event of issues or change of circumstances. Access to the clinical IT software meant that the link workers did not need to gather their own ad hoc data (e.g. patient demographics, contact details). Some participants reported using Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) codes, although one participant pointed out that the SNOMED codes need to be reviewed, as the current codes do not fully capture what is being done in the service. Some participants reported using an Elemental Software (Liverpool, UK) system that has been developed for SP, while others developed their own systems.

Outcomes data collected included psychosocial health and well-being measures using questionnaires such as the Office for National Statistics four (ONS4) subjective well-being questions;47 WEMWBS;48 SWEMWBS;49 Patient Activation Measure (PAM);50 University of California, Los Angeles, Loneliness Scale;51 Well-being Star;52 and Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCaW). 53 The ONS4 and PAM were the most frequently used among our interviewees. However, participants suggested that evaluation instruments were not necessarily relevant for patients. For example, the PAM is focused on patients with long-term conditions and not other, social, issues patients may have:

The trouble with PAM is [that it has] really very little relation to the sorts of issues that we would normally be discussing with the clients. It is a very health-based model. That isn’t the kind of issue that comes up for us with our clients, most of the time.

Link worker, 1.5 years, South East

Tools that examine aspects of an individual’s well-being, such as housing and income, were thought to be more relevant. Some services had developed their own data collection tools, perhaps because of the lack of content and face validity of existing tools. VCSE participants reported similar issues, finding that the assessment tools did not always capture outcomes that are relevant to patients:

The issue is there are so many patients who access social prescribing programmes who don’t have things like long-term conditions. And so you’re taking patients through an extra set of questions . . . not only interrupts the flow of what the service, what the person needs in their urgency on the delivery end, but also you end up with data which doesn’t really tell us a good picture.

Voluntary sector interviewee 1

To overcome these problems, bespoke data collection and patient assessment tools have been created, such as the How Are You? (HAY) tool. HAY covers aspects such as housing, relationships, finances and physical health and was designed with consideration of accessibility to potentially marginalised groups, for example those with literacy problems:

It’s a very simple chart to be used for those who may have literacy problems as well, and started as a good tool to start a conversation with a new referral. . . . It also helps the patient prioritise what’s important at that point in time.

Stakeholder, 2 years, North East

A problem with the outcomes measures and data collection methods was the wide range of services that patients are referred to. This makes it difficult to attribute individual outcomes to specific services. Some VCSEs seemed to have a structured approach using validated instruments whereas others did not. Follow-up data in VCSEs were mostly related to health, well-being and lifestyle outcomes in order to identify areas for possible improvement (using tools such as the ONS4, PAM and Well-being Star). One VCSE interviewee mentioned that they completed the WEMWBS at the beginning and end of the intervention and noted other relevant and predominant issues in their case notes:

And now when we get, when people register with us, we ask if they will have this, or having to consent to WEMWBS self-report measure. And then we review that [at] 2-week intervals. Up until when the client finishes working with us. On our case management system, we have a classification code, so that we can attach presenting issues.

Voluntary sector interviewee 3

Social prescribers often stated that these measures and methods do not capture patient health information, such as body mass index (BMI) and levels of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), as these are variables that are recorded by medical staff, but were available to view as required. Participants pointed out that the direct medical outcomes are not the focus of SP. One participant mentioned that collecting health information is not an ideal approach for SP because:

. . . it’s not a health relationship. Although it’s impacting on health, it’s about being person centred and we know about the barriers that can build it. The first couple of meetings, someone weighing you and taking your blood pressure, it’s, it’s largely not the approach social prescribing schemes want to take.

Stakeholder, 10 months, North West

However, some onward referral services may capture this health information, for example if a person is referred to a weight management programme. Interviewees pointed out that, since SP programmes are often patient led, there could be discrepancies in what GPs refer the patients for and what the patient decides to focus on when they have their consultation and perform goal-setting with the social prescriber.

Some link workers focus on progress through the action plan as an outcome measure, describing using case studies to assess the overall impact of the social prescription. One participant stated:

We’re usually just based around the action plans. Where the people are making progress or whether they change . . . direction . . . Progress on the action plan is the measure.

Stakeholder, 9 years, North East

There was variation in reports of the health-care service data collection by social prescribers, for example GP consultations, social care service used/currently being used and accident and emergency department attendance. Many social prescribers reported that they do not systematically collect data on service uptake (user compliance and adherence); however, others do collect data, such as how many sessions were attended and reasons for stopping. Many participants stated that ‘failed encounters’ (non-compliance) often remained uncollected (e.g. if they unsuccessfully tried to contact a patient over the phone). However, one participant stated that the terms ‘adherence’ and ‘compliance’ are not appropriate for SP. Another emphasised that adherence and compliance are not straightforward because the service aims to help patients achieve what they want to achieve, and this may change from time to time. One participant stated:

So if someone comes to you and says I’m really struggling with my violent partner, then you have to say, ‘Well, what do you want to do about it? How can I help you with that?’. They may want to leave them, they may not want to leave them, they may say they want to leave them and 1 week later they’re back with them. We want to stick with people . . . as opposed to, whether they comply or not. We’re not there to judge them, we’re not there to decide what’s best for them.

Stakeholder, 10 years, North East

When asked about frequency of outcome measurement, participants reported information collection for individual patient outcomes (e.g. contacts, referrals and case study data), whereas others reported service-level outcomes; for example, one participant stated that they report to the PCN monthly, whereas others conducted quarterly reports with an annual overview (and one reported weekly during the COVID-19 lockdown). One participant reported that Ways to Wellness (W2W) (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) contacts clients for follow-up data collection every 6 months for a period of 2 years. Social prescribers would generally capture some data for individuals every time they met the client, but the data captured may not necessarily be individual outcome data. For example, one participant stated:

Data is captured at the beginning and ideally the end. Every time we have contact with a client we would record what happened within that contact and what was exchanged with the client on our case-recording system, but in terms of sort of measuring well-being, or measuring ongoing outcomes, then no, not really.

Link worker, 1.5 years, South East

There is also a considerable variability among VCSE organisations in how often outcomes are measured, depending on a patient’s needs and how often the patient is contacted. For example, one participant reported:

There are a lot of patients [that] need support prior to 4 months [i.e. the initial data collection point], so there’ll be ongoing appointments made with that patient depending on their need. We’ve allowed the patient and the link worker in their appointment to set their frequency for whatever the patient needs.

Voluntary sector interviewee 1

Difficulties in data collection have increased during the pandemic because there are increased challenges for patients (e.g. with literacy barriers) when link workers invite them to complete questionnaires remotely.

5. Volume of service and uptake

Mapping services

No standard system was used to map available onward referral services or their uptake. Some link workers created a database of available services that they shared with colleagues. Creating such databases is resource intensive, and such databases need to be constantly updated. Others used local directories from local authorities. However, local authority databases are not always comprehensive. Some link workers worked closely with VCSEs and had information on smaller local voluntary services (such as OurGateshead, Herts Direct and Connect Well). Others are based within voluntary organisations and, therefore, have the advantage of having access to information on available services. Link workers themselves have to map provisions in their area to identify what services are available and where they are located, and understand what they offer, for whom they are appropriate and which to refer to. This could involve Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) searches; WhatsApp (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) groups; physically visiting community centres; e-mailing or visiting other organisations; having conversations with services regarding referral processes, policy and safeguarding; and collecting information leaflets. Some services (especially small groups such as knitting groups or tea groups) are extremely local, do not have an adequate online presence and are difficult to locate.

Across all databases there were concerns about information going out of date. One of the participants pointed out that link workers cannot rely on directories:

[Link workers] can’t just rely on directories. They have to have confidence in services [to refer] their clients to, and therefore they have to actually get to know the organisations. Referring clients to an organisation that you have no knowledge of [is risky]. [Link workers] need to have a much closer understanding of the organisations.

Lead, 20 years, London

Voluntary community and social enterprise organisations reported engaging in active efforts to disseminate information about their services to link workers and general practices. For example, one participant said that they organise meetings with all the general practices to tell them about their services. Another reported that information about service activities is available in a database that could be shared with link workers. However, they did acknowledge that it is challenging for the link workers to signpost clients appropriately to the services available. For example, one interviewee stated that:

. . . [it’s] time-consuming to try and assess [services] on behalf of the client. Which of these range of services that seems to be offering the same service would be most appropriate we don’t know – how good they are – how professional they are. We, you know, we don’t necessarily have that information.

Interviewee 3

Capturing uptake

Link workers often have records of how many people have been referred to them and how many contacts they have had with each patient. One participant stated that they ask onward referral services to fill in attendance sheets, which they collect from the individual services. Link workers record this information on spreadsheets or upload it to clinical systems such as an EMIS Health system. The challenge faced by link workers was capturing uptake data beyond the point of referral, because uptake varies according to the person’s action plan and the type of service they are referred to. As a result, referral data may not be useful in an assessment of impact. A participant highlighted that referral and uptake outcomes are not comparable across different services:

And we certainly don’t do anything across the region to compare different types of interventions, because every intervention is slightly different, and every individual is different. But they would keep records of how outcomes are improving or otherwise at a global level, at a locality level.

Lead, 2 years, North West

Many link workers do not capture data beyond the point of referral. One participant stated that one of the reasons that data are not captured in the voluntary sector is the lack of incentive to capture uptake data: it may not be a priority for the organisation because it may not be linked to funding. The participant stated:

[Data are] rarely captured at the community level . . . because in most cases the community sector does not get paid for it. So they don’t have much incentive to capture the data. And if it’s captured, it is captured by those people who deliver the sessions, who manage the sessions.

Lead, 5 years, London

6. Type of service utilisation (highest versus lowest)

The most common referral services reported by link workers were services to help with social isolation, finance, housing, increasing physical activity, healthier living and weight management. Organisations included Citizens Advice (especially for benefits and housing), Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) (London, UK) and People Potential Possibilities (P3) (Ilkestone, UK). Informal groups included gardening groups, craft groups, lunch groups, working groups and coffee morning groups. Other types of organisations included bereavement counselling group therapy, art prescription and exercise on prescription. Some activities were also delivered on an individual basis such as telephone befriending. Some groups provide support for carers of people with specific conditions such as dementia, Alzheimer’s and cancer care. Participants reported changes in service use due to the COVID-19 pandemic, during which there were few face-to-face services available, reduced resources and increased social isolation.

7. Nature and length of follow-up

The nature and length of follow-up depended on a wide range of factors such as patient need, level of intervention implemented, goals to achieve, types of approaches to address needs, and local commissioning variation. One VCSE interviewee stated that clients were followed up by the link worker who had made the initial referral. Another stated that patients are generally not followed up by their GPs. The open-ended nature of many services means that establishing a discrete period of intervention with follow-up can be challenging. Participants highlighted this in their responses:

. . . we can move on with that person long term, we don’t have a time limit, in terms of how long we support somebody, so we don’t necessarily see a cut-off point.

Stakeholder, 2 years, North East

One participant described the development of a bespoke system to generate outcome data and report them to the GP. In these more formal arrangements, the link workers did an initial assessment and engaged for an active intervention period of one to six sessions for a maximum of 6–12 weeks. Follow-up sessions were described as follows:

We are funded to follow up for [the] long term. . . . Follow-ups are face to face in [the] first 6 months and come to 12 months depending on patient’s need.

Stakeholder, 5 years, North East

The two most reported challenges to follow-up and data collection were lack of communication and time:

Often, [it’s] not possible to always find out what’s happened. And, you know, communications may be difficult, they may be difficult to get hold of that person again.

Lead, 20 years, London

Across the VCSE organisations, follow-up generally included measurements of patient well-being. One interviewee reported that they also requested feedback on the service from the patients during follow-up, with this often being done remotely and taking a less formal approach (e.g. no specific structure or data collection tools used).

8. Potential strengths and limitations of current service

One strength mentioned by participants is that link workers give more time to patients (appointments of up to 1 hour) than is possible from GPs. Participants said that SP targets what is important to the patient and focuses on empowering individuals to achieve their health and well-being goals holistically:

We’ve got time to speak to the patients, [we] identify things that wouldn’t necessarily have come up in a 10-minute GP appointment. . . . We’re in a really unique position to actually talk to patients and see what matters to them and make a difference to those things that aren’t necessarily the medical and clinical.

Link worker, 2 years, East of England

One participant reported that SP has the potential to reduce GP workload and potentially save costs for the NHS:

The best value is that it will essentially save the NHS funding in the future. Also reduce the demands and dependence, and also reliance on GPs, it’s very person centred. So they have a voice, they’re empowered to make choices, and it works.

Link worker, 11 months, South West

Participants stated that SP has the ability to unite communities, identify community needs and grow and develop the voluntary sector in the community:

[SP] has the ability to bring communities together, and grow and develop the voluntary sector if done well, so that communities are thriving and there’s much more activity happening on the ground, much more opportunity for people to come together and take part in activities which we know improve health and well-being, because we know the opposite of that is isolation and loneliness, which is detrimental to health and well-being.

Stakeholder, 10 months, North West

Social prescribing also provides a bridge between the health-care and social care systems:

There is a divide between those and they’re almost two separate worlds [health care and social care] and I think social prescribing is a method to enable the coming together of those two things. We know that 90% of the factors that affect people’s health are rooted within communities. But, we give all the energy to the system, which only deals with a small portion of that.

Stakeholder, 10 months, North West

Participants suggested that being embedded in the primary-care team is of great benefit, particularly if they have access to referral systems that are easy to use. One participant was located in a Healthy Living Centre where there are four general practices and also a large community charity with 80 skilled and experienced staff. The link workers were able to be a part of both the GP team and the voluntary organisations delivering the service. Acceptance by voluntary organisations and community areas and link worker support peer networks were viewed as important strengths:

We have [a SP] steering group which has membership from all 10 localities, and enables us to share best practice. Find out what’s going on in different areas. People talk to each other and share information across the 10 localities, which I think is very good.

Lead, 2 years, North West

9. Major enablers and challenges to developing and implementing social prescribing service

Social prescribing is a relatively new concept, and sometimes patients do not want to engage with the service. Consequently, one of the main challenges highlighted was the acceptability of the non-clinical model that forms the basis of SP. Interviewees suggested that more communication around SP to increase awareness of the service would be beneficial. They also suggested that clear definition of the role of link workers in relation to other types of roles in the health-care system is important. One participant recommended that co-facilitation and co-delivery be maximised through linking with experts, patients and patient participation groups. Connecting directly to clinical IT platforms (such as EMIS systems) is also an important enabler. This allows the GPs to see what social prescribers are doing and, in the process, they can learn more about the role of a social prescriber.

During the interviews there was incongruence between models designed to improve well-being and those that were health related. Some participants mentioned that a lot of health-care professionals and patients still do not understand SP. For example, one participant reported as follows:

The challenge is convincing the health service and other referrers of the value and the worth in the community sector and the weight of that, actually going into a singing group is as powerful to health outcomes as medicine. I think it’s our chance to really change things and root people’s health in communities, and that medicine and structured health is something that fewer people need and rely on. But we need everyone to buy into that and that needs to be the first point of call if we’re going to crack this.

Stakeholder, 10 months, North West

Often a lack of GP engagement was reported, especially in cases where workers were not based in general practices. It was reported that practice managers do not always understand issues relating to caseload management and so difficulty was reported around the social prescriber being understood and having the support in place to be able to do their job effectively. As a result of the lack of acceptance, practice staff and charity staff are also sometimes hostile towards link workers, as described by two participants:

GPs just aren’t particularly interested in SP and unless the link workers are based in the surgery running clinics and actually interacting with GP colleagues and attending MDT [multidisciplinary team] meetings and practice meetings, then it’s very easy for the service to be pretty much sidelined.

Link worker, 1.5 years, South East

The charity become anxious the link worker may take some of their jobs. Those charities that provide one-to-one support become hostile and concerned that you are here to do their job, and patients don’t know how engagement with the link worker could be worth their time.

Link worker, 4 months, North East

Participants reported role boundary problems and difficulty getting other professional groups to understand exactly what a link worker does. For example, participants reported the need to define the difference between a link worker and a social worker and described the misleading nature of the term:

It’s a very unfortunate term because people think they’re going to be prescribed something, they need to tell them something they could do or something they can have. When in fact it’s not that at all, it’s much more coaching model.

Link worker, 1.5 years, South East

There were reported challenges relating to funding SP, such as high workloads, the need for increased numbers of link workers and the problem of short-term-funded and underfunded VCSEs for onward referral. This led to challenges in locating appropriate services to signpost patients to. There was a reported lack of adequate training for social prescribers and those addressing the needs of the community in VCSEs. A link worker and a national stakeholder describe the issues below:

When you look at NHSE guidelines for what a link worker is expected to do without any training except a 3-hour online course from Health Education England, its frankly ludicrous. The model tends to talk about coaching and motivational interviewing. . . . Well, that’s all very well and good, but people are trained for years to be able to do that. And I certainly haven’t had any training on it. I don’t think most of my colleagues have either.

Link worker, 1.5 years, South East

My view is that Health Education England regionally being commissioned to provide the training packages, leaning on the support of the organisations and the voluntary sector organisations and NALW [National Association of Link Workers] to understand what that training looks like. So there needs to be more collaborative approach between the experts in the sector . . . to develop what that package should look like.

Stakeholder, 3 years, National

One participant described the problem of conflicting salaries for workers recruited by the voluntary sector and those recruited by the NHSE:

We found that the introduction of NHS SP destabilised the local market because they were offering salaries far in excess of the current rate locally for that level of job. Most experienced staff have moved to those roles as they are paying higher rates. At that time the commissioners, local authorities, do not have money to pay that value loss of experienced staff and have to build that back again.

Stakeholder, 9 years, North East

The organisation of the link worker model potentially increases link workers’ isolation and lack of peer support. This may make their work challenging and may be detrimental to their own well-being:

The model that the NHS adopted was to assign one link worker per Primary Care Network. It means that link workers can be very isolated. They have no contact with other link workers, they’re not able to share practice and learn from others. And they have no peers to talk to. . . . Feeling not supported, or not having access to the support that they need.

Lead, 20 years, London

To minimise isolation, offering peer support was seen as helpful. Some participants described online forums where link workers can talk to others and receive peer support. One participant suggested that link workers should be employed as teams:

They have team meetings together, they have team training and learning opportunities together, they are able to contact each other. And therefore they feel supported, they’re able to grow and develop together. And they’re able to help each other, you know, when they come across a patient who’s got a problem that they’ve never come across before.

Lead, 20 years, London

One of the participants summarised the enablers of the link worker model using relationships, resources and research:

You need to get the relationships right, right within the GP practices, and the Primary Care Networks. . . . You need that relationship with patient. The public or the person that the service user needed the relationship certainly with the local health professionals, whether they are GP and GPs, are crucial to it. But you also need the relationship with the volunteer community sector to manage that. You also needed the resources, in terms of money and people. And you need the resources out there in the sector. And then, finally, you needed the research, in order to demonstrate the work to get social prescribing implemented, but you also needed some research as to what effect it has got because you were asking systems to make very difficult decisions with limited money.

Stakeholder, 9 years, Yorkshire and The Humber

10. Costs and savings when recruiting for and implementing the social prescribing service (both to Primary Care Networks and to other organisations involved)

Participants reported that SP funding was limited to funding direct employment costs and that there were different elements of the service that were not costed or were undercosted. One larger organisation reported having a link worker’s salary reimbursed by the NHS (i.e. PCN). However, many participants raised concerns about lack of support for overheads, management, training, coordination of link workers and costs on the voluntary sector. A participant from a VCSE infrastructure organisation reported as follows:

That was a big problem when it first started because all the money covered the direct employment costs. It didn’t cover all the costs of employing people, so there was a massive issue around management costs and overhead costs. It didn’t include training. So we had to beg, steal and borrow for training. They need some sort of management structure in place. That wasn’t covered.

Stakeholder, 9 years, Yorkshire and The Humber

Some link workers reported having no office or administrative support because of a lack of funding for overheads and service management. Some link workers reported having no access to a computer or telephone. One of the participants said that the salary provided by the PCN for social prescribers was not acceptable, so they paid their SP more than the PCN recommended:

The problem is, that’s not quite enough to fund a good standard of social prescribing link worker. So we’ve paid our social prescriber a bit more than the PCN allow, so we’re paying a little bit over what they give money for.

Lead, 20 years, South West

The limited funding for SP was similar in the VCSEs, where funding is often short term and limited (by value or time). One of the interviewees reported receiving funding from the local council for up to 2 years, but others reported struggling to get further funding as they do not have robust case data. This causes problems for SP if ongoing referral services are limited:

If the NHS are giving funding for social prescription workers, that’s pointless if there’s no funding for community groups.

Interviewee 2

Some VCSE organisations reported receiving COVID-19 response funding until the end of December 2020.

11. Non-attendance data (for people who do not take up their social prescribing referral)