Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR129483. The contractual start date was in March 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Johnson et al. This work was produced by Johnson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Johnson et al.

Chapter 1 Background

About this report

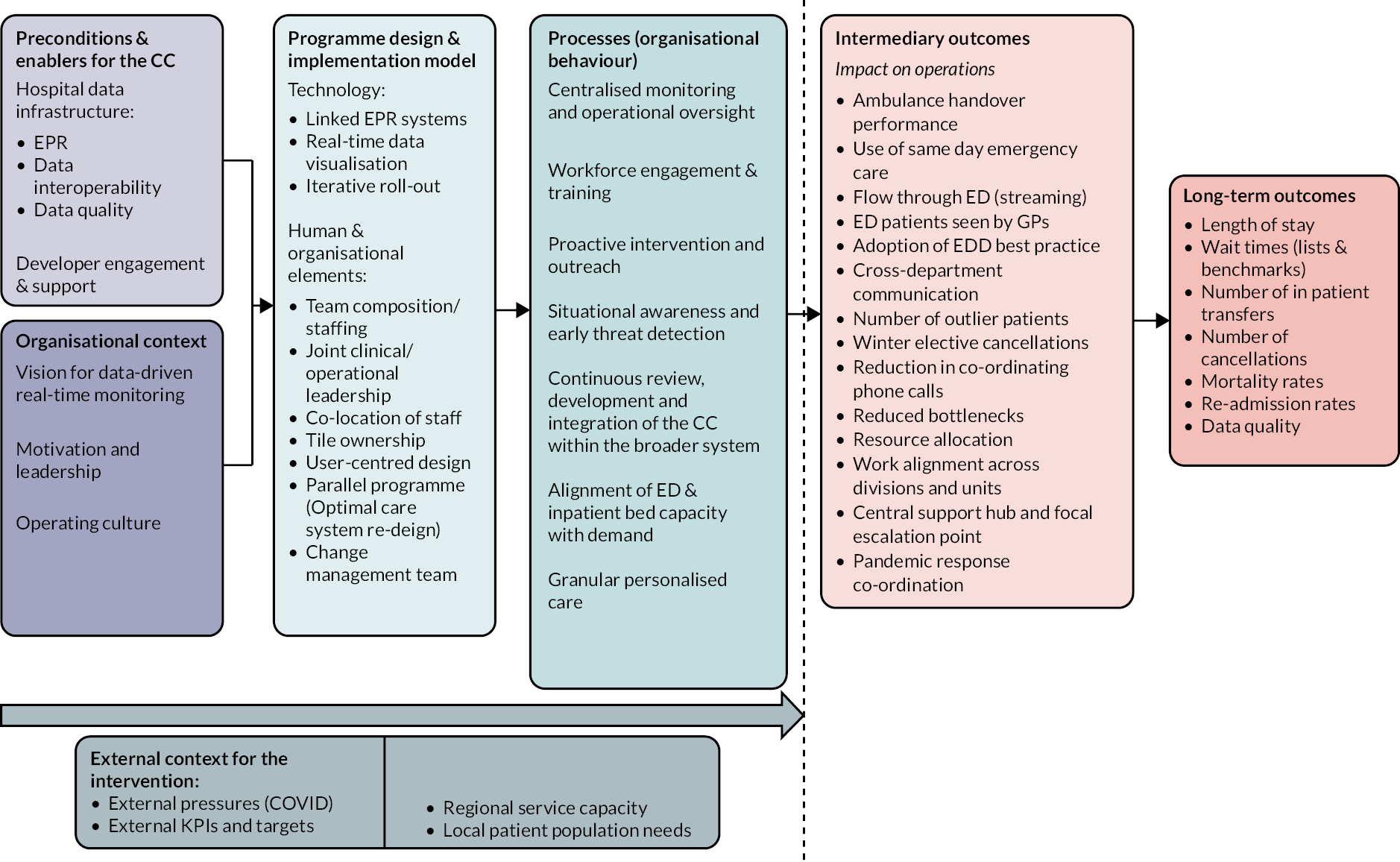

This report presents the results from research investigating the potential for adopting a command centre (CC) approach and related technology for hospitals in the UK NHS. We adopted a mixed-methods approach drawing on patient perspectives, relevant literature, qualitative research at a study and a control site and quantitative analysis of data drawn from the two sites. This chapter summarises the background and context to situate the research and its aims. Chapter 2 presents the overall methodology, including details of the methodology adopted for each sub-project. The results of our research are presented in Chapters 3–6. Chapter 3 summarises results from our patient and public engagement, Chapter 4 presents a detailed discussion of the literature on command and control approaches from our cross-industry review. Chapter 5 presents a case description of the CC implemented at the study site and comparisons with the control site. Chapter 6 presents the results of our data analysis from the two sites. We discuss the results from the different research methods and draw conclusions in Chapter 7.

The methods that we have adopted in this research may be useful to other researchers interested in evaluating CC approaches in hospitals in the UK NHS and more broadly and may be of general interest to researchers using mixed methods to evaluate complex sociotechnical implementations of digital health. Our results should be of interest to policy-makers and healthcare managers and practitioners keen to understand how technology can enable transformation in the management of complex healthcare service delivery.

Policy context

The introduction of electronic health record (EHR) has improved the patient care delivery process and quality of care, mainly through the easy access to comprehensive and rich patient data as well as minimising errors. 1 However, co-ordination of activities and sharing of real-time data from each department within hospitals are largely missing. 2 In fact, in most UK NHS hospitals, health service delivery is fragmented across multiple departments and services, with major implications for patient safety, efficiency and good patient care. Better use of digital technologies is a key feature of the NHS Long-Term Plan (2019), which sets out the basis in which ‘digitally enabled care will go mainstream across the NHS’ (chapter 9, page 91 onwards) and includes an emphasis on improving clinical efficiency and safety.

The 2019 plan set out a milestone that ‘By 2024, secondary care providers in England, including acute, community and mental healthcare settings, will be fully digitised, including clinical and operational processes across all settings, locations and departments’. While funds, leadership and national infrastructure have been provided to help achieve this, individual acute hospitals and their associated NHS trust organisations have been left to navigate their own path through the landscape of competing vendors, technologies, legacies and integration challenges. The result is that many acute hospitals continue to operate fragmented digital and semi-digital services even within different parts of the same hospital.

The fragmentation of the healthcare services is neither cost-effective nor safe for the delivery of patient care. 3,4 Such fragmentation can, however, be minimised by using health information management systems that consolidate data from disparate systems and disparate organisations. 5,6 One such technology that has attracted recent interest is the concept of a ‘command centre’ where data flow from various departments and services within a hospital are consolidated on centrally located digital displays in a room that is staffed with decision-makers able to co-ordinate the effective day-to-day operation of the hospital.

Hospitals in Canada, China, the UK, the USA and Saudi Arabia have reported implementing the command-centre approach using technology from a number of vendors in the last 6 years, but, to date, there has been limited empirical evidence to understand their impact and evaluate claims of success. The coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic has increased pressure on NHS hospitals to consider how best they can use digital technologies to provide faster, safer care with limited resources. It is becoming increasingly important to understand whether the CC approach should be adopted much more widely. Our research develops a detailed understanding of CC approaches to assist policy-makers in this vital area.

The concept of a ‘command centre’

Although the core transferable concepts of ‘command centres’, as they originate in non-healthcare domains, are the subject of a cross-industry review included in Chapter 4 of this report, it is useful to provide some background and context for the concept at this stage prior to describing the specific implementation of the CC at Bradford that forms the subject of our evaluation.

The modern concept of a CC was pioneered by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for the purpose of managing space flights six decades ago. 7 The iconic image is of ranks of technical staff each managing vital components of the space flight mission organised in a sloping amphitheatre and facing a wall of visual images including live video of the space flight and real-time streaming data. Earlier forms of CC can be found throughout military history where generals in a central (safe) location typically gathered around a map of the campaign that was updated with information about the disposition of troops as it became available. The rationale for the approach is that locating the decision-makers in a central place enables them to all be updated with the same information at the same time and to work together as a team to co-ordinate the command and control (C2) of the various resources they are responsible for.

In the information-system literature, Holwell and Checkland8 provide a detailed analysis of the ingredients necessary for CCs in their chapter on ‘An Information System Won the War’ through a case study on the British Royal Air Force national network of CCs used to good effect during the Second World War. 8 With digital technology, information can be gathered, integrated, analysed and acted on at increasingly close to real-time speed and with fewer human actors needed. There is also the intriguing possibility that artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to make decisions faster and more efficiently than human actors, paralleled with concerns that such automation creates new moral, ethical and safety concerns.

Command centres can take many other names, including ‘command systems’, ‘control rooms’, ‘mission controls’, ‘security control’, ‘operation centres’, ‘command control’, ‘mission command’ and ‘dashboard monitoring’. However, in general, CCs can be defined as places (or departments) where information is centralised to improve communication and situational awareness within an organisation. 9,10 More generally the concept of ‘command and control’ is used to describe an approach to managing organisations and complexity drawn from military approaches to management. 11 The modern study of C2 is multidisciplinary, multidomain and has given rise to an extensive volume of scholarly literature encompassing conceptual commentary, case studies and empirical research. In our research, we define a Command Centre (capitalised) as a physical room or location that plays a central role in a C2 approach to organisational management but recognising that other interpretations and definitions exist. We describe a CC approach (not capitalised) as an organisational approach to management that includes a physical CC as its central feature. Our cross-industry review of C2 detailed in Chapter 4 provides a structured review of the relevant literature and subject-matter expertise in this area, including discussion of conceptual definitions, with a focus on translation for health care.

Different versions of the CC approach have been widely adopted in retail industries, finance and banking, automotive, manufacturing and transport industries. Health care has been a slow adopter of the CC approach with the notable exception of ambulance services. Even in the ambulance service where the real time co-ordination of ambulances is a matter of life and death there have been notable failures in the implementation of CC technology – a new CC system for the London Ambulance Service in 1992 resulted in days of chaos until the new system was decommissioned and the project has become a textbook case of information-system implementation failure. 12

There is a paradox here: digital technologies now enable information to be communicated instantaneously and everywhere yet the centralisation of decision-makers within a physical space may still be an essential ingredient in the shared experience of this information and mediate how it is interpreted, acted on and used to augment collective human and organisational intelligence. The concept of a CC would still appear to be relevant to many organisations despite digital technologies and, indeed, may be more relevant than ever with increasing amounts of big data and the data science and artificial intelligence tools to automate alerts and distil and represent patterns that emerge from complex data. In applications such as health care where operational decisions can have complex social, ethical and safety implications it may be increasingly important to have human-in-the-loop decision-makers.

Command centres in health care

Although the CC in the acute care setting that forms the focus of the present evaluation is of one specific model, it is useful to consider the range of models that have been implemented in health care:13 (1) Incidence responses – are activated when they are needed in the case of emergencies, for example, mass casualty events and pandemics; (2) security operations centres – perform surveillance as well as integrate services around threat detection and alarm management response; (3) facility operating centres – asset management systems, which can include real-time location systems and guided vehicles to deliver medication, linens, and meals to patients and (4) capacity management/care progression centres – which aim to improve allocation of resources and patient outcomes, boosting hospital financials and maximising organisational efficiency.

In the UK NHS the ‘Gold, Silver and Bronze’ model of major incident response command was well established before the COVID-19 pandemic and played a major role in the way that the health service organised its response and was supported by data dashboards such as QualDash. 14 The UK public became used to hearing references to ‘Gold Command’ in media reports of the government’s and NHS’s responses to the pandemic.

Many hospitals in the USA, UK and other countries appear to be using the ‘Capacity Management’ CC type. However, there appear to be variations in the designs and scale of the command-centres across these facilities (see Chapter 4 for more details and Appendix 1 for examples). To illustrate the variation, the UK Imperial College Healthcare Trust was reported as having one large video wall screen monitored by a single person,15 and the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Trust16 and The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust17 report that they have multiple PC screens with video wall screens in front that are monitored by more than three people at a time. In the USA, AdventHealth18 and CHI Franciscan19 command-centres create one ‘common space’ by bringing data and staff from multiple hospitals; others such as the Bradford Command Centre represent only one hospital. 20

The use of command-centres in health care is a relatively new concept and its impact on patient care and safety has not been widely studied. However, preliminary reports suggest that command-centres have a positive impact on patient care and healthcare delivery process. 19,21–23 In this report we aim to generate a better understanding of the strengths and weaknesses and the opportunities and challenges inherent to the CC approach through in-depth evaluation of a recent implementation in a UK NHS hospital.

The Bradford Command Centre

In the UK, we identified at least four NHS hospital trusts who are piloting ‘command centres’, with others in early stages of planning. Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (BTHFT) was an early adopter with the introduction, in 2019, of the ‘Command Centre’ at their Bradford Royal Infirmary (BRI) hospital. 20 The CC technology was provided by GE Healthcare based on adapting successful implementations in the USA. The software is based on a three-tier architecture comprising (1) an integration engine which draws data from hospital information systems, most notably the Trust’s Cerner Millennium EHR; (2) an application layer that implements rule-based algorithms to consolidate and interpret data in real time, including raising warnings and alerts; and (3) a presentation layer that presents information on display screens (also known as ‘tiles’) that provide real-time information on emergency and inpatient hospital services: overall hospital capacity, emergency department (ED) status, patient transfers, discharge tasks, care progression and patient deterioration. Information entered into the EHR and other hospital information systems flows through the integration engine to be interpreted and displayed on the screens in the Bradford Command Centre room. Tile usability is continually assessed, and iterations are made to content, alerts and displays in response to user feedback.

The business case for the Bradford Command Centre was to provide faster and safer care by providing decision-makers with up-to-date information that would allow them to address, anticipate and avoid bottlenecks in care delivery before they cause problems and so reduce unnecessary waiting. Patient flow through the hospital should be faster and patient safety should be improved. Through a proactive campaign of addressing ‘false alarms’ through root-cause analysis and correcting data on the source systems it was also believed that overall data quality would improve. The Trust embarked on the CC project with realistic expectations that service transformation would take time, hard work and strong leadership.

The introduction of the Bradford Command Centre occurred in four phases (Table 1). The first phase was the commencement of a broad change-management programme to emphasise the importance of patient flow in preparation for the technology implementation. The second phase was to incrementally develop and deliver CC ‘tiles’ populated with data from the hospital’s IT systems to gather feedback and refine the design of the system. The third phase commenced with the go-live of the CC complemented by a programme of hospital-wide engagement and training. The CC was in place and operational for several months before the global COVID-19 pandemic started to have an impact on UK NHS hospitals, at which point major rethinks in the operation and priorities of the hospital became a regular necessity as healthcare providers continued to adapt to meet the pressures of the pandemic. The final phase was the post-COVID-19 resumption of hospital-wide engagement, and training recommenced 14 months later.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1 July 2018 | Onset broad patient flow programme |

| 1 May 2019 | Command Centre tile roll-in |

| 1 December 2019 | Command Centre goes live and hospital-wide engagement and training commences |

| 1 May 2021 | Post-COVID-19 resumption of hospital-wide engagement and training |

The CC remains fully operational at BRI and is internally viewed as a successful intervention that played a significant role in the hospital’s response to the pandemic. There is less clarity on the extent to which it has met its original aims given the major impact of the pandemic shortly after its ‘Go Live’.

Why is this research needed now?

The Bradford Command Centre was styled as ‘the first of its kind in Europe’ by GE Healthcare, the supplier, and has received significant press and NHS attention. As an early adopter of the capacity management/care progression CC approach it merits detailed investigation to understand what it is, how it works and to evaluate its actual and potential contribution to improving the operation of NHS hospitals. We hypothesise that the implementation of an integrated and centralised hospital CC such as the example at Bradford can improve patient safety, patient flow and data quality. This report presents the results of our investigation.

Study aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to understand how the AI CC at Bradford impacts on the quality, safety and organisation of BRI to generate findings that can be applied to other hospitals in the UK. The objectives of the project were:

-

to evaluate the impact of the CC on patient safety, patient flow and data quality (quantitative evaluation and ethnographic study)

-

to understand the process of implementation and integration of the CC within the primary study site (qualitative process evaluation)

-

to elicit cross-industry perspectives on hospital C2 technologies to contextualise the findings (cross-industry review)

-

to synthesise findings into practical outputs to engage service stakeholders and inform future investment and practice.

About this study

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme through award NIHR129483; https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2036192. The project commenced on 1 March 2021 for 18 months with a 3-month extension to allow for contracts and staff recruitment; it ended on 31 November 2022. The research team are all co-authors on this report. The study protocol was published as McInerney et al. 24

The proposed protocol was planned prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused substantial changes to the structures and processes used in healthcare systems, including those at the study and control sites. The pandemic also affected members of the research team and the ability to conduct effective research within UK health care. However, it also created opportunities to evaluate the ability of the health service teams to adapt and respond to the pandemic and specific opportunities to understand how the CC was used to support pandemic responses at the study site. Our research attempted to provide quantification of the influence of the CC implementation, but this report recognised that we were limited in our ability to distinguish the impact of the technology from impacts resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the health service responses.

Our mixed-method approach and involvement from our international study steering group helped to define the context of this turbulent period and to describe the processes of change in the hospitals studied. Under the epistemic constraints of our pre-COVID, funder-approved protocol, we have interpreted our research through these contextual descriptions.

Chapter 2 presents the methodology for the study as planned in the published protocol and as revised based on adapting to the opportunities and constraints experienced during the study period.

Chapter 2 Method

This chapter presents the methodology for the study including details of each of the substudies conducted as part of the research project. The original protocol was developed and agreed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and we necessarily adapted the approach to reflect the challenges and opportunities that this presented during the study period.

This study evaluates the implementation of the Bradford Command Centre as an exemplar of a real-time, centralised hospital CC. Our starting point was to recognise that the Bradford Command Centre represents a complex intervention within a complex adaptive system. We conducted a longitudinal mixed-method evaluation that was informed by public and patient involvement and engagement. We selected Huddersfield Royal Infirmary as a control site on the basis that it was broadly similar to the hospital in Bradford in terms of its geographic proximity, size, population demographics and in the maturity of its digital health systems. The pandemic affected all hospitals in the UK and the pressures felt by both the study site and control site can be broadly assumed to be similar.

Our mixed-method approach included interactions between the qualitative and quantitative workstreams through a number of iterations. Qualitative work combined ethnographic observations, qualitative process evaluation and quasi-experimental methods to study the evolving sociotechnical nature of the systems and processes within hospitals. Interviews and ethnographic observations informed iterations of quantitative data analysis that, in turn, helped to sensitise further qualitative work. Quantitative work identified relevant outcome measures from both the literature and pragmatically from data sets of routinely collected EHRs.

Our protocol was theoretically informed by contemporary safety-science theory concerning system resilience, human factors models of situational awareness and command and control in high-reliability organisations. The study protocol was approved by the NHS Health Research Authority (IRAS No.: 285933) on 1 April 2021. The study protocol was published as McInerney et al. 24 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. We have therefore reproduced much of the detail of this protocol here.

It was not possible to complete some parts of the protocol due to the impact of the pandemic on (1) the study sites, participants and study team and (2) consequential resource constraints at the end of the project. We describe the impact of the pandemic on the study and what parts of the protocol were not completed at the end of the chapter.

Our mixed-methods study design

System implementations such the Bradford Command Centre are complex interventions into complex adaptive systems that could provide improvements but might also result in emergent unforeseen consequences. 25,26 We conducted a longitudinal mixed-method evaluation informed by a multidisciplinary co-investigator team and public and patient involvement and engagement. A mixed-method approach is well suited to study complex interventions and the complex adaptive systems to which they are applied. Mixed-method approaches have been used to study information flow and organisational networks,27 integration of organisational interventions,28–30 effectiveness of service models30 and how health information technology affects communication,31 patient monitoring,32–34 care provision35 and clinical decision-making. 36

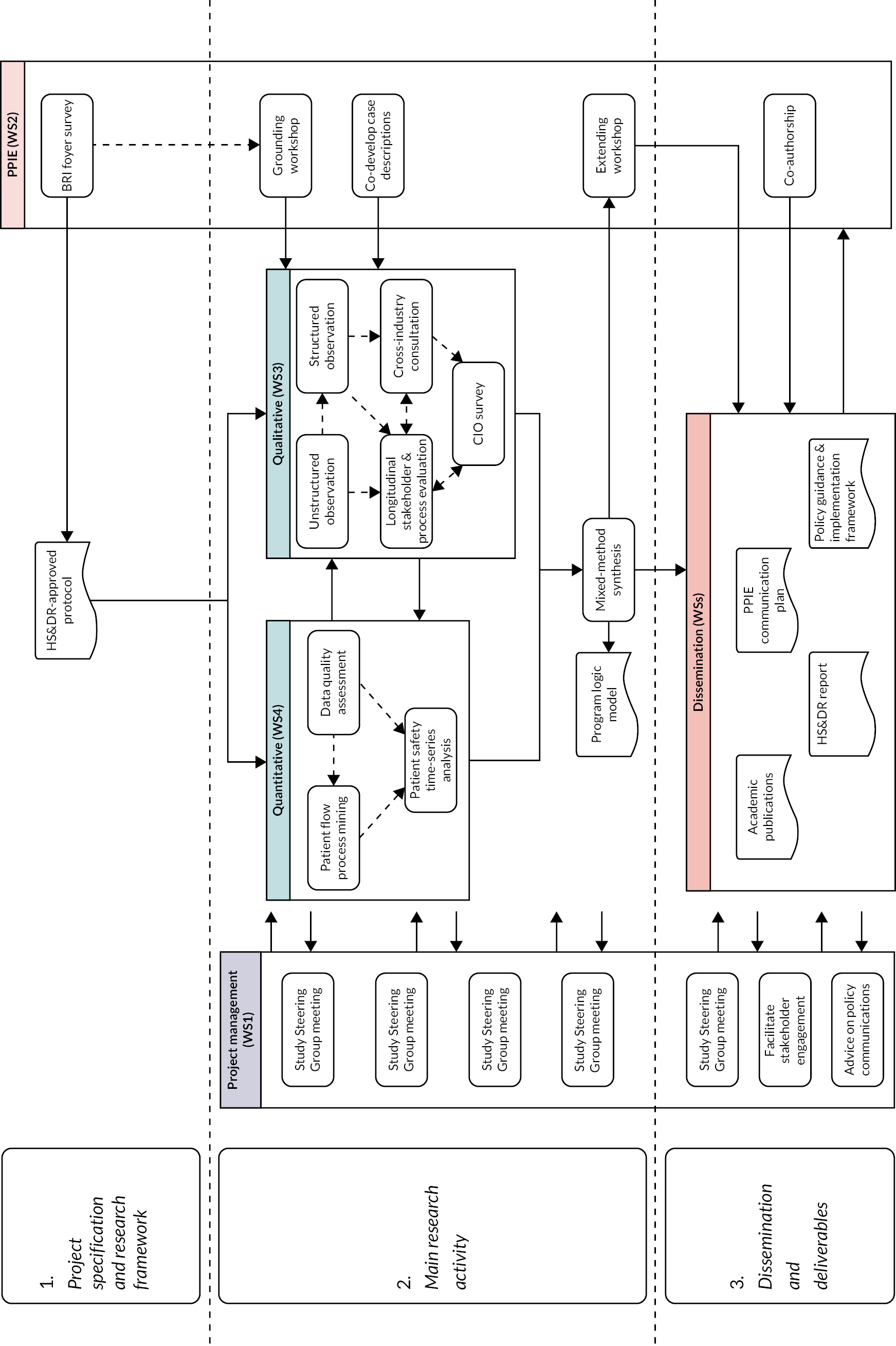

The study comprised five substudies across five workstreams (Figure 1). The five substudies were conducted by the qualitative and quantitative workstreams (WS3 and WS4). These workstreams mutually informed each other as part of an iterative synthesis of findings, rather than solely a summative synthesis. The main research activity was guided by the project’s Study Steering Group (see WS1) and by patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE; see WS2). Our Study Steering Group was an independent body ensuring the project is conducted to the rigorous standards set out in the Department of Health’s Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. 37 The Study Steering Group also facilitated stakeholder engagement in research and dissemination and advised on policy communications. Membership of our Study Steering Group includes clinical, technical, commercial and academic healthcare representatives from the UK, Canada, USA, China and Australia.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview of the research project’s components. CIO, chief information officer; HS&DR, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Service and Deliver Research funding programme; PPIE, patient and public involvement and engagement; WS, workstream.

Data sources

The mixed-method evaluation used multiple data sources, including EHRs, qualitative interviews, ethnographic field notes and documentary evidence. All data were managed according to a Data Management Plan approved by the University of Leeds and published as part of the study protocol.

Electronic health record data

The quantitative work was based on the analysis of routinely collected healthcare record data de-identified and processed by the hospitals’ data teams and accessed via Connected Bradford – a regional integration of health care and other data available for research purposes. 38

We conducted a retrospective cohort population-based study using EHR data from the systems at the study and control sites. Participants of the study were patients who visited accident and emergency (A&E) and inpatient departments of BRI hospital and in-patient departments of Calderdale & Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust (CHFT) between 1 January 2018 and 31 August 2021. We used complete sampling of EHRs within relevant periods. The duration of relevant periods was informed by the initial case description and unstructured observations in the qualitative work, which sensitised us to the information handled by the CC. De-identified UK NHS Digital Secondary Use Services (SUS) data were used. The SUS data are patient-level NHS England data made available to support national tariff policy and secondary analysis. Construction of the SUS data was conducted by Connected Bradford, located at the Bradford Institute for Health Research (BIHR) in Bradford. 39 The team uploaded the SUS data into a secure Trusted Research Environment on the Google Cloud Platform where relevant data were processed before final outputs were extracted. The Connected Bradford data service had worked with data from BRI for several years and had only recently gained similar access to data from CHFT; there were therefore occasions where more detailed data were available for the study site than for the control site.

Ethnographic data collection

The qualitative workstream conducted an ethnographic study comprising non-participant observations (including opportunistic interviews) with staff at the study site working in and around the CC and related organisational processes, document analysis and formal interviews with key stakeholders. Data collection took place between July 2021 and August 2022. Methods included ethnographic observations, document analysis and qualitative research interviews. In total 78 hours of observations were conducted involving 36 staff members that included 22 opportunistic conversations with CC staff and compilation of 100 pages of field notes between July 2021 and March 2022. A total of 19 interviews involving 16 members of key staff relevant to the initiative (15 at study site and 4 at control site) took place between May 2021 and August 2022 and ranged in length from 14 to 71 minutes, with a median length of 38 minutes (9.5 hours).

Following delays in gaining access to the study control site, interviews with staff in comparable roles to those conducted in the study site took place between 8 June 2022 and 11 August 2022. Four participants were interviewed in total, in senior management positions responsible for patient flow (two matrons and two senior clinical managers). In addition, we reviewed 64 documents relevant to the CC programme at the primary study site.

We recruited relevant staff at the CC and control site in key roles. NHS staff working in and around the CC were asked to take part in ethnographic observations. Sampling was in accordance with qualitative research practices to maximise variation in stakeholder perspectives. Potential participants were identified through clinical leads and early observations. Participants were told that they did not have to take part in the research if they wished and that they could withdraw up to the point that their data were anonymised (< 2 weeks following research interviews; < 1 week following survey).

In the following sections, we describe how these data were managed and used and the study design for each of the five substudies.

Substudy 1: data quality

This substudy contributed to Objectives 1 (‘Impact Evaluation’) and 2 (‘Process Evaluation’) based on the hypothesis that the introduction of the CC will affect the awareness of, recording of and processing of electronic healthcare data, which are inextricably related to data infrastructure, operational efficiency, and organisational processes. We applied Weiskopf et al.’s 3 × 3 matrix to assess the quality of healthcare data. 40 This framework maps Patient, Variables and Time data items in terms of Completeness, Correctness and Currency (in other words, presence, accuracy and timeliness). Further detail on how to implement the 3 × 3 matrix is available in appendix B of Weiskopf et al. 40 Our initial identification of variables was informed by our qualitative substudies, and additional clinical input informed the expected attributes of the data, for example plausible ranges, regularity, expected completeness. We used a root cause analysis to trace potential data quality issues back to underlying systems to understand how data quality issues arose and how they were addressed or mitigated.

Although this substudy had planned to examine data quality of the hospital systems, we found that the majority of data quality issues resulted from the data quality issues in the ‘provenance chain’ of research data extraction and management rather than in the source data. Our research team traced multiple data quality issues through our own data management pipelines to the source at Connected Bradford and from there to the extraction services that they had used. This included discussions with the on-site data management team and clinical representatives within the two hospitals involved. Although the work to address data quality issues was substantial, we decided to subsume our investigation of data quality within the main qualitative and quantitative work areas and discontinue this substudy area. The methods for assessing data quality changes over time were developed within Substudy 3 (Patient Safety) and the discussions with staff on data quality are included within Substudy 4 (Ethnographic and Qualitative Interviews).

Substudy 2: patient flow

Approach

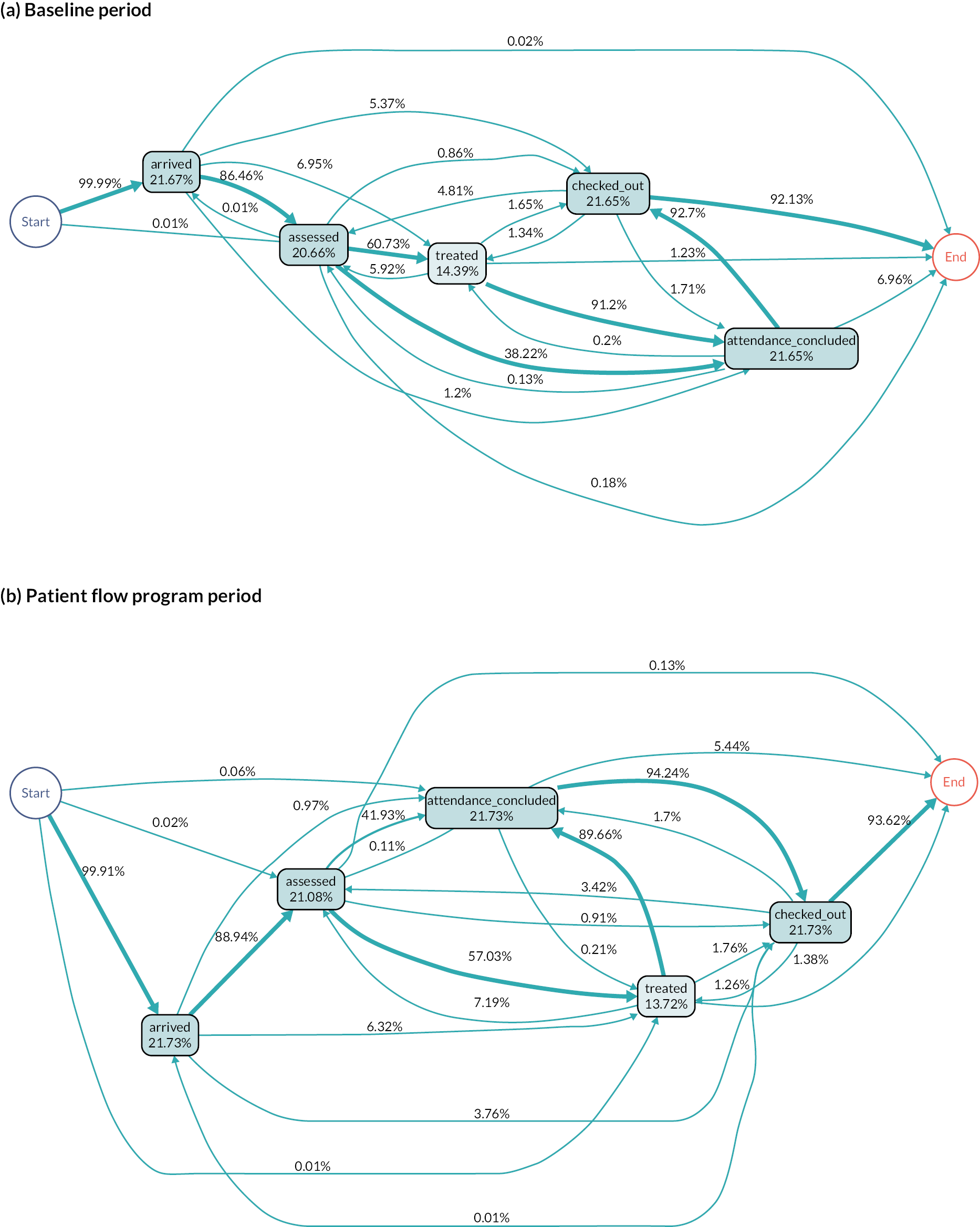

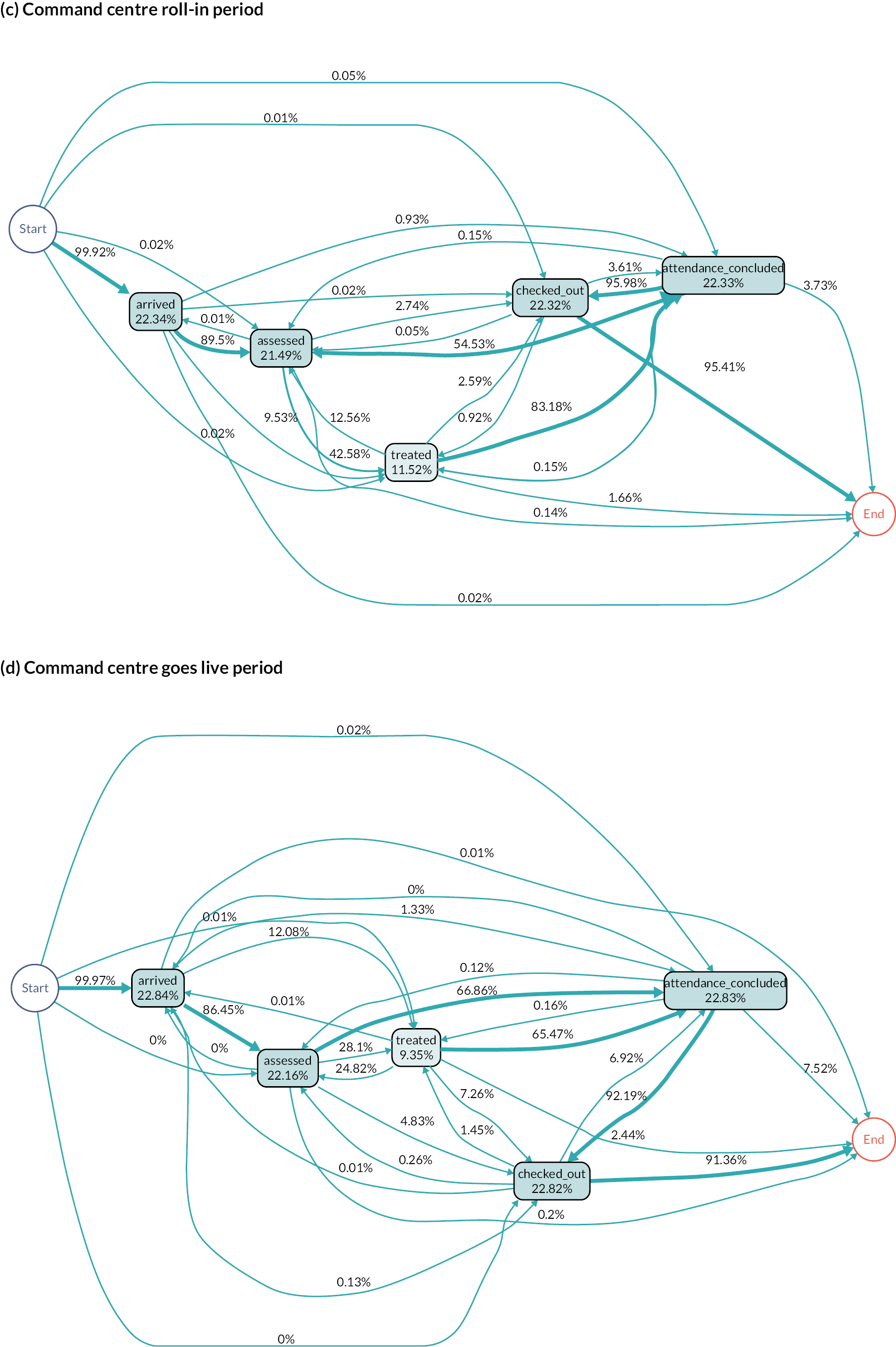

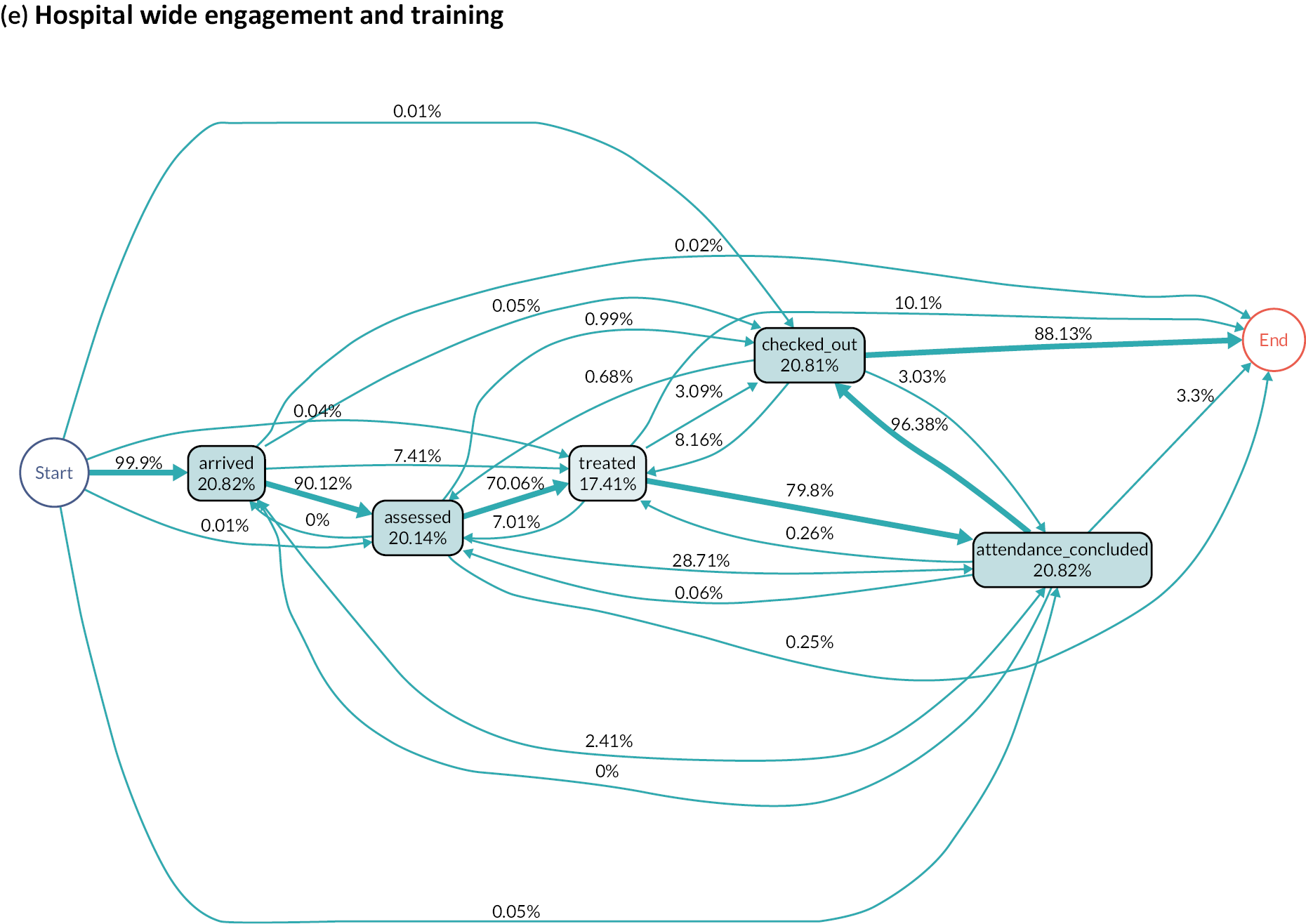

This substudy contributed to Objectives 1 (‘Impact Evaluation’) and 2 (‘Process Evaluation’) based on the hypothesis that operational efficiency, organisational processes and patient safety are affected by the flow of patients through the hospital. To study patient flow, we used process-mining methods41 to describe patients’ journeys through their hospital care. 42 Time-stamped data related to clinical events in individual patient journeys were extracted from the Connected Bradford data service and formatted to create event logs for patient cohorts of interest. An event log consists of a de-identified patient or hospital admission number, a date/time stamp showing the data and time an event occurred and an event or activity name. Typically, there are many events of potential interest within hospital systems and we worked iteratively with clinical domain experts to identify key events that ‘told the story’ of particular pathways of interest for patients at the two study sites.

Process mining

We constructed process models to represent patients’ log of clinical events (see Appendix 3) following a methodology our team had developed previously in dentistry,43 oncology,44 sepsis45 and primary care. 46 We evaluated these models by comparing their performance when constructed using various process-mining algorithms. The performance of the models was measured by:47

-

replay fitness, a measure of how many traces from the log can be reproduced in the process model, with penalties for skips and insertions; range 0–1

-

precision, a measure of how ‘lean’ the model is at representing traces from the log. Lower values indicate superfluous structure in the model; range 0–1

-

generalisation, a measure of generalisability as indicated by the redundancy of nodes in the model. The more redundant the nodes, the more variety of possible traces that can be represented; range 0–1.

We calculated conformance to a process model using the metrics defined in Fernandez-Llatas et al. 41 based on comparison between a normative model developed and agreed with domain experts and the actual events as found in the event log data. Conformance is measured as the proportion of moves-on-model and moves-on-log that ‘conform to’ the normative model against those that do not. One hundred per cent conformance suggests that all event logs fully comply with the normative model while 0% conformance suggests that the model is invalid in that none of the events follow the model. Our experience from previous work has been that few healthcare processes achieve 100% conformance due to the very individualised and personalised nature of patient care. We hypothesised that the CC should improve conformance to normative process models.

We identified process metrics of interest including process length and process conformance and calculated these for each month of the study to produce a time-series analysis to understand changes to process flow overtime. Patient flow as defined by the best-performing process model was described using the multilevel approach of Kurniati et al. ,48 which includes activity, trace and model measures. Where possible we conducted the same analysis between the study and control sites. Finally, we reviewed the results from our process flow investigation against the results from other parts of the study and reviewed these with clinical domain experts. The time-series results from our process mining are reported alongside the time-series data on Patient Safety (Substudy 3).

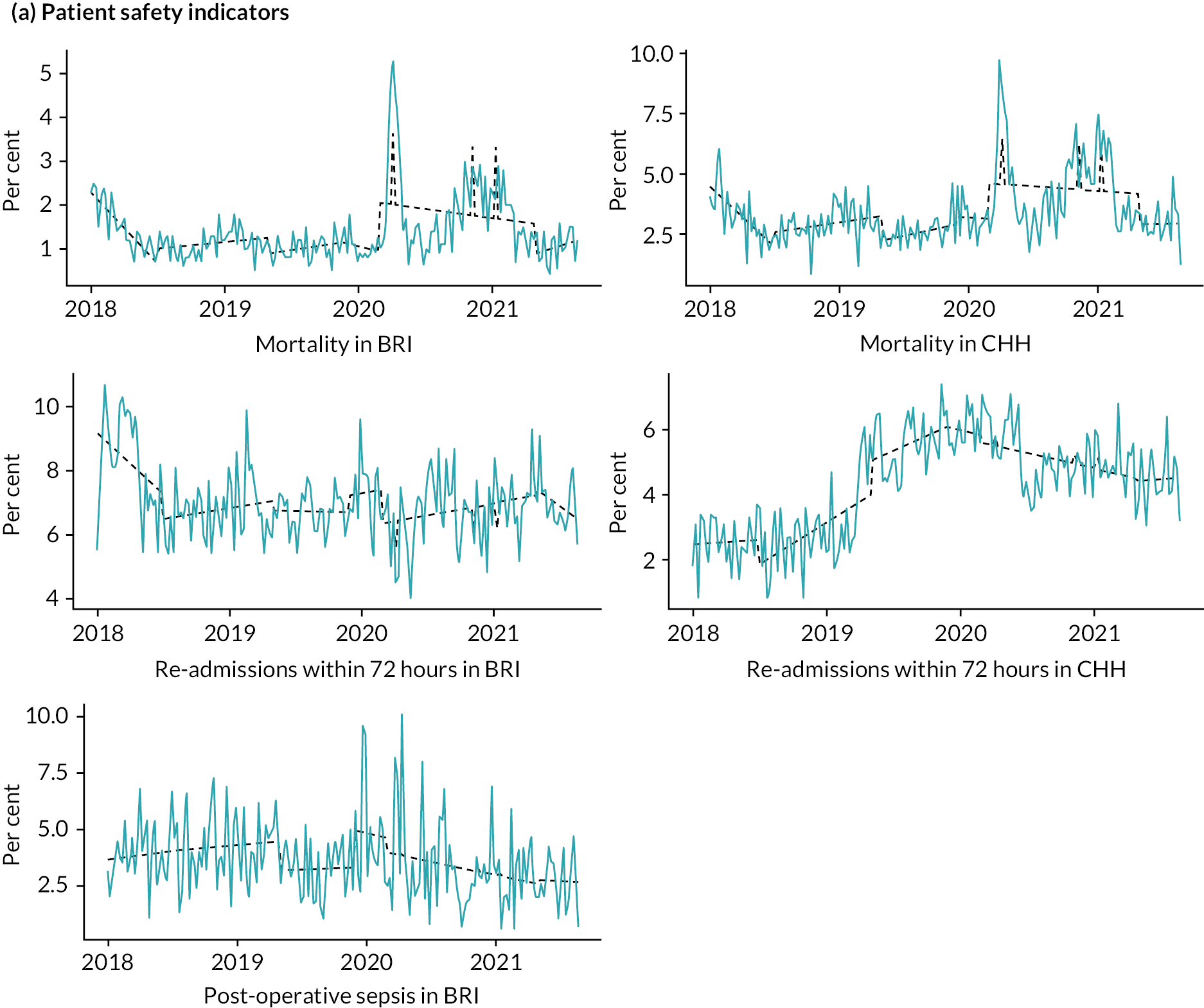

Substudy 3: patient safety

Approach

This substudy contributed to Objectives 1 (‘Impact Evaluation’) and 2 (‘Process Evaluation’) by directly evaluating the differences in patient safety outcomes before and after the implementation of the CC. The evaluation used longitudinal data analysis methods, for example including interrupted time-series analysis and latent growth modelling. We modelled trends in behaviour before, during and after the implementation of the CC, with consideration for the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We approached the analysis in a responsive manner, revising the interruptions in response to discussions with the qualitative workstream as they identified key events from their discussions with the study site staff. We identified candidate variables of interest that included the Patient Safety Indicators from the Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality, for example pressure ulcer rate, in-hospital fall with hip fracture rate, postoperative sepsis rate. 49 We supplemented these with variables of interest identified by the qualitative research team and feedback from early PPIE workshops where patients identified measures that they considered important.

We assume that patient safety is influenced by the flow of patients and the quality of information (as encoded in EHRs) and therefore link data quality and patient flow metrics to those clinical outcomes logically related to patient safety.

In our protocol we had planned to handle unobserved confounders by comparison with the control site given that the control site was from the same geographical region, used the same EHR system, but did not have a CC. This was less successful than hoped as the pandemic response led to multiple changes in management style and approach at both study and control sites. Indeed, the control site reported that, part way through the pandemic, they had implemented a CC approach of their own using dashboard technology and insights from the study sight. Our longitudinal analysis considers those indicators that can be extracted from study and control sites that may provide insights into variations in data quality, patient flow and patient safety outcomes over time.

Metrics for patient safety, patient flow and data quality

We assume that patient safety is influenced by the flow of patients and the quality of information (as encoded in EHRs) and therefore link data quality and patient flow metrics to those clinical outcomes logically related to patient safety. Table 2 presents the initial list of proposed variables for analysis as published in our study protocol. 24

| Variable | Patient flow | Patient safety | Data quality | Study site | Control site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulance diversion rates | X | ||||

| Ambulance handover rates | X | ||||

| Completeness | X | X | X | ||

| Correctness | X | X | |||

| COVID bed availability | X | ||||

| Currency | X | X | |||

| Diagnostic process time | X | X | X | ||

| Early discharges | X | X | X | ||

| Falls in hospital | X | ||||

| Hospital-acquired infections | X | ||||

| In-hospital transfers | X | X | |||

| Intensive care unit bed usage | X | X | |||

| Left without being seen rates | X | X | |||

| Length of stay | X | X | |||

| Marked ‘hospital discharge’ | X | X | X | ||

| Mortality in hospital | X | X | X | ||

| Mortuary crowding | X | ||||

| Number of patients awaiting surgery (inpatients and at home) | X | ||||

| Postoperative sepsis rate | X | X | |||

| Pressure sores in hospital | X | ||||

| Re-admission rates for same condition within 48 or 72 hours | X | X | X | ||

| Time to admission | X | X | X | ||

| Time to be seen | X | X | |||

| Time to discharge | X | X | X | ||

| Time to treat stroke patients | X | ||||

| Waiting time benchmarks (e.g. 4 hours A&E) | X | X |

Data constraints

Our longitudinal analysis considers those indicators that can be extracted from study and control site that may provide insights into variations in data quality, patient flow and patient safety outcomes over time. Patient safety, patient flow and data quality are not directly measurable. Hence, indicator variables were used as proxy measures for these outcomes. We identified a ‘long list’ of candidate indicators based on stakeholder discussion and relevant literature and shortened this to a ‘short list’ of what was feasible given data availability.

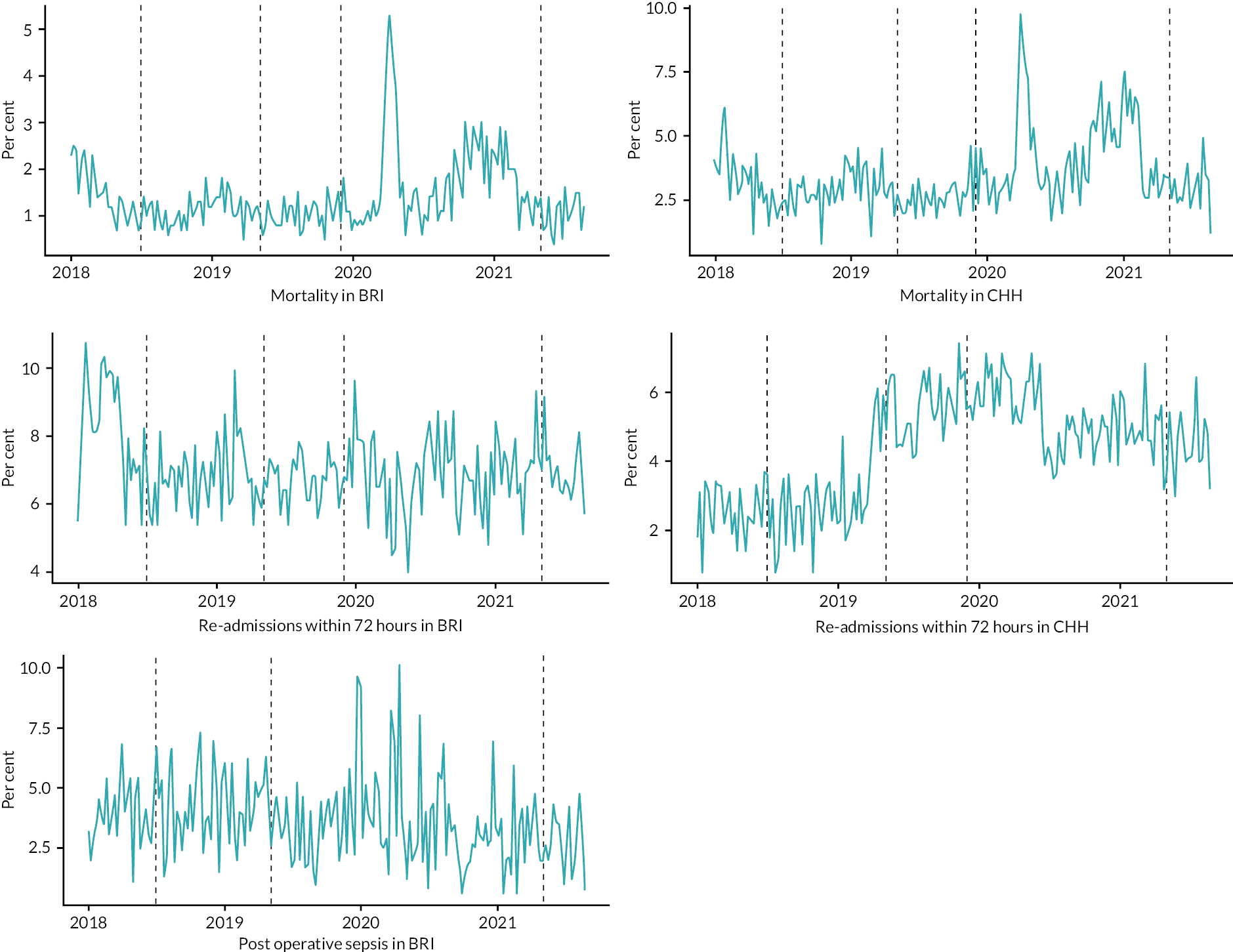

Indicators for patient safety

Three indicators from the BRI hospital, the study site (mortality, re-admissions within 72 hours and postoperative sepsis), and two indicators (mortality and re-admissions within 72 hours) from the CHFT hospital, the control site, have been used. The proportions of mortality and re-admissions in hospital were calculated as the total deaths and re-admissions, respectively, divided by the total number of emergency admissions. Postoperative sepsis was calculated by dividing the weekly count of patients with sepsis diagnostic codes in their records by the total count of surgical operations conducted in that week. The surgical operation codes were extracted from the UK Health Security Agency list of operation codes published document. 50 Postoperative sepsis occurrences were identified using T814 ICD10 code. 51

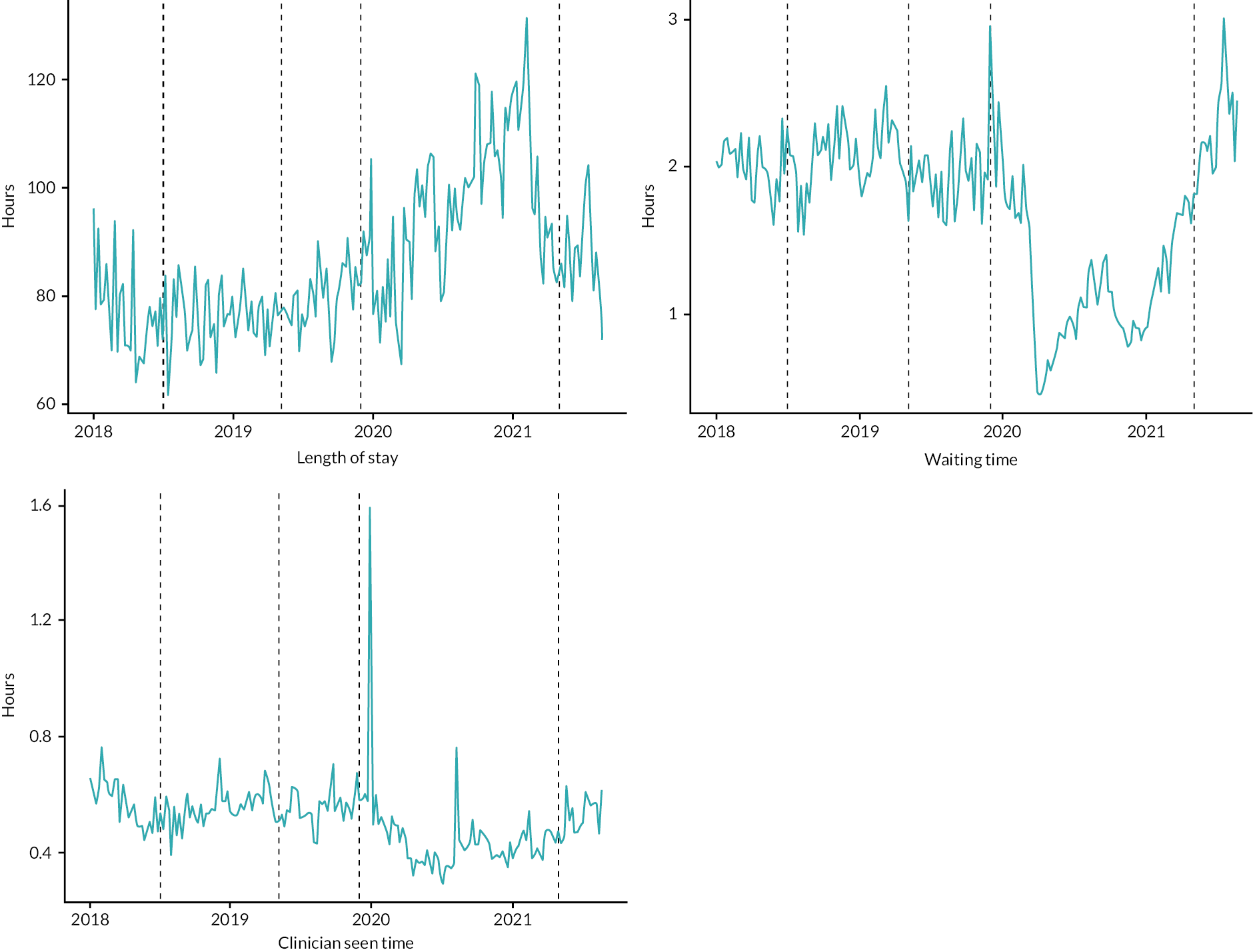

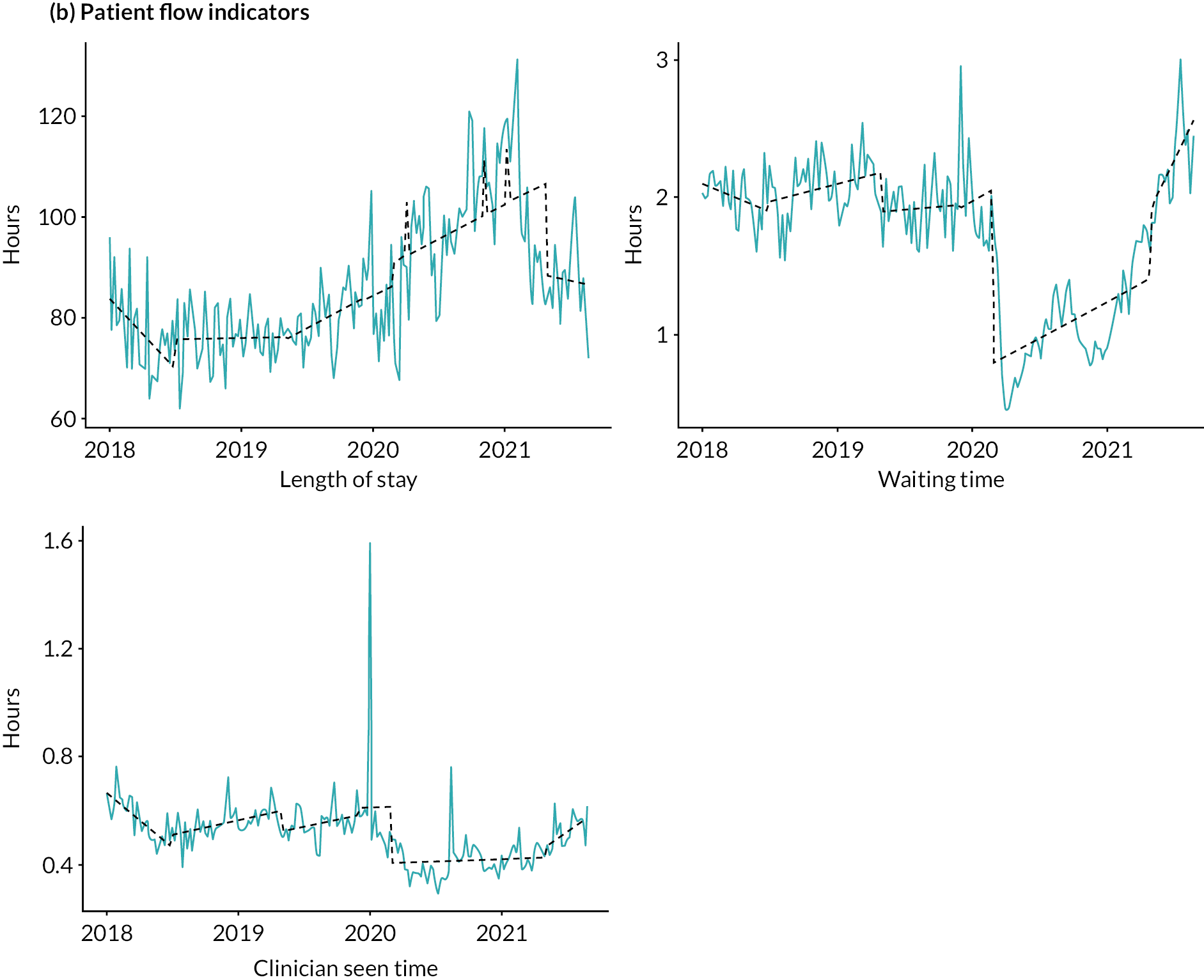

Indicators for patient flow

Four indicators of patient flow (length of stay, clinician seen time, waiting time and average transition time) were used and were only available from BRI hospital, the study site. Inpatient length of stay in emergency admissions (defined as the duration between date and time of admission and discharge), ‘clinician seen time’ (the duration between A&E date and time of arrival and seen by a clinician) and A&E waiting time (the duration between A&E date and time of arrival and treatment) were used as indicators for weekly patient flow patterns throughout the study period. In addition, average times taken between A&E transitions (arrival, assessment, treatment, visit conclusion and check-out) were used as indicators for patient flow patterns during the same period.

These indicators were subsequently supplemented by the inclusion of patient flow metrics derived from process mining of the data (Substudy 2) to produce a multidimensional perspective on patient flow.

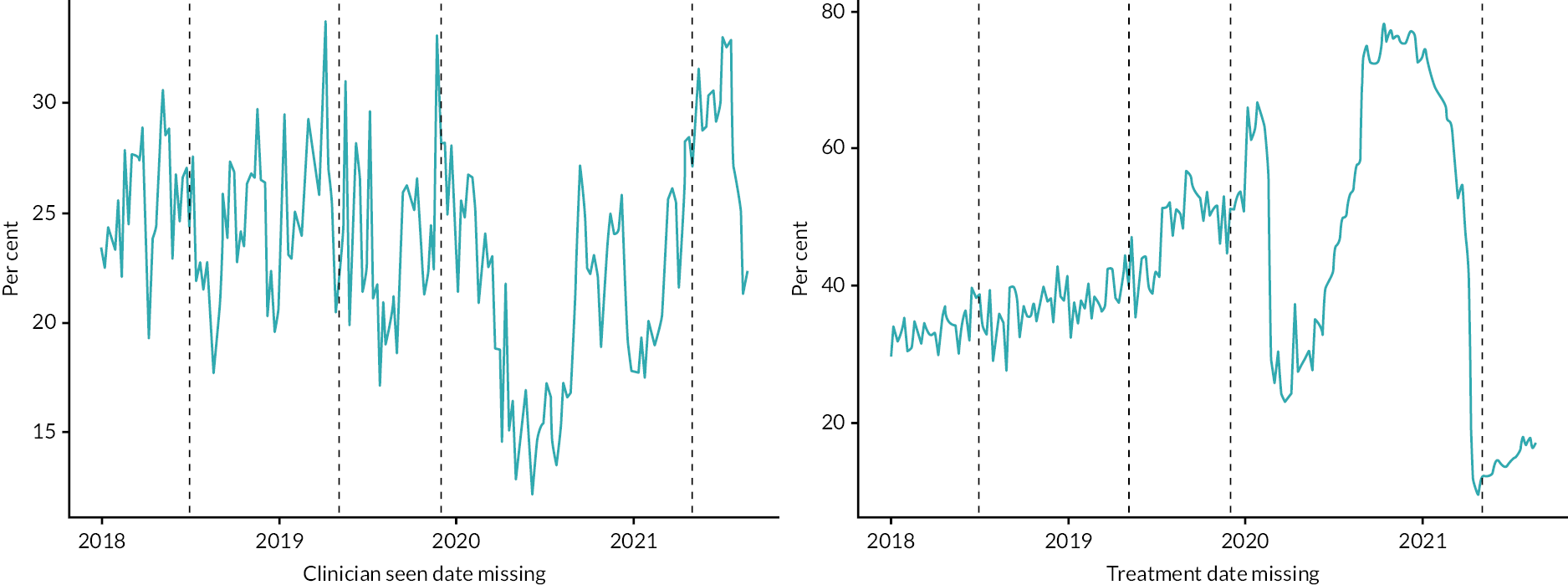

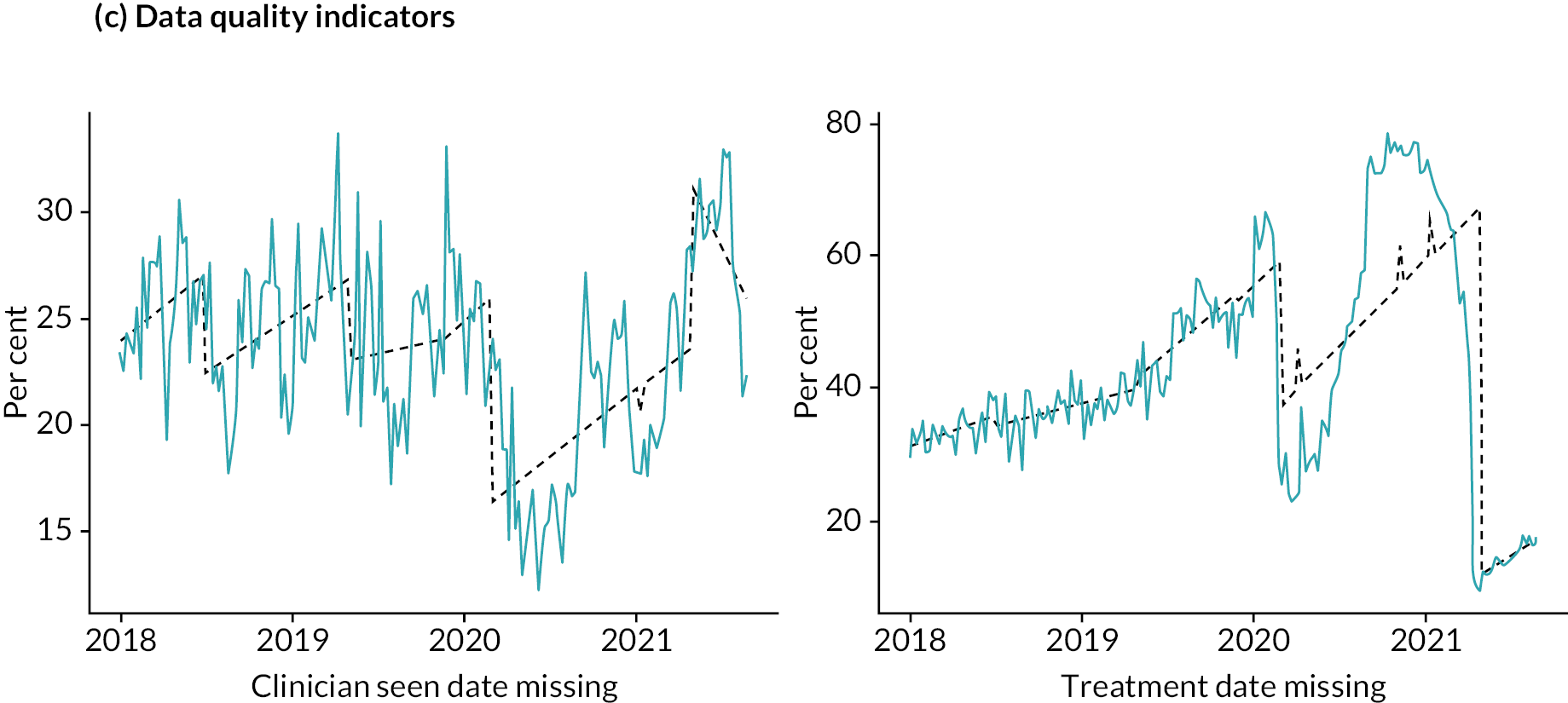

Indicators for data quality

Four indicators of data quality were available from the BRI hospital data. The proportion of missing dates of treatment and clinician’s assessment, and proportion of records showing valid transition (arrival → assessment → treatment → visit conclusion → check-out) and ‘left-shift’ (arrival ← assessment ← treatment ← visit conclusion ← check-out) of patients in A&E care were used.

Other variables for quantitative analysis

Dummy variables were created for each of the intervention components (‘broad patient flow programme’, ‘command centre tile roll-in’, ‘command centre goes live’ and ‘hospital-wide engagement and training’), COVID-19 pandemic and spikes of COVID-19 pandemic. The components of the intervention were given a value of ‘1’ starting from the date of its introduction until the introduction of the next component or phase, then a value of ‘0’ for the rest of the period. ‘COVID-19 pandemic’ was given a value of ‘0’ through February 2020 and a value of ‘1’, thereafter. A spike dummy variable was also added by setting ‘1’ for the COVID-19 spike periods based on the UK data52 and ‘0’ throughout.

The intervention and baseline phases were also modelled using five continuous time variables. At the date that phases started, a covariate was encoded with ‘1’ and increased by one unit for every time step for the duration of the phase; the covariate was encoded as ‘0’, otherwise. For example, the ‘Command Centre tile roll-in’ phase is defined between 1 May 2019 and 1 December 2019. Each week from 1 May 2019 was encoded 1, 2, 3, …, 29, 30 until the week commencing 29 November 2019, and encoded as 0, 0, 0, … from then on. In addition, seasonality was modelled by including dummy variables for the number of weeks in a year.

Quantitative analysis methods

Two types of models were explored: ‘simple tech’ and ‘complex’ models. For the ‘simple tech’ models, a three-phase, interrupted time-series model was used that consisted of a pre-intervention (first phase), ‘Command centre tile roll-in’ component (second phase) and ‘Command centre goes live’ component (third phase). For the ‘complex’ model, a five-phase, interrupted time-series model was used that consisted of pre-intervention (first phase), ‘onset broad patient flow programme’ component (second phase), ‘command centre tile roll-in’ component (third phase), ‘command centre goes live’ component (fourth phase) and ‘hospital-wide engagement and training’ component (fifth phase).

Interrupted times-series linear regression analysis was used to assess the impact of the Command Centre on the patient safety, patient flow and data quality. First, linear time-series models were fitted to the data. Tests for serial autocorrelation of residuals were conducted and all tests were statistically non-significant. Hence, regression models with autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) errors were not sought. The Akaike information criterion53 and the Bayesian information criterion54 were used in selecting the models best fitting to the data.

To estimate the average transition time between different stages of A&E care, and to map the destinations of A&E patients, a number of process-mining techniques were used. 55

A five-phase interrupted time-series was used for the main analyses. To explore if the technology alone would have had an impact on outcomes, three-phase interrupted time-series models were used as sensitivity analyses. The ‘broad patient flow programme’ and ‘hospital-wide engagement and training’ were assumed as independent events of the Command Centre and adjusted as independent dummy variables in the sensitivity analyses models. Five per cent significance level and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were adopted throughout. Analyses were implemented in R (Version 4.0.2).

Substudy 4: ethnography and qualitative interviews

Rationale for the ethnographic approach

With a complex system like the Bradford Command Centre implementation, it is important that the researchers develop an understanding of behaviour in context including the meaning of those behaviours and interactions within the immediate operating culture that has developed within the system. Ethnographic enquiry was selected in order to facilitate deep understanding of the technology in its broader social and organisational context, including human experience, engagement and interaction. 56,57 Ethnographic methods are widely used for understanding situated practices with technology. 58–62

Context for the ethnography

Bradford Royal Infirmary implemented their CC based on a centralised location that brings together operators with varying functional roles, each with access to their own real-time data feeds. The main purpose of bringing the roles together is that they have access to shared data visualisation that represents the real-time hospital state for the broader system that they are trying to control. The CC is connected to the broader system so that staff operating within can affect inputs into the system and respond to intelligence that is developed within the CC.

Participation and consent during fieldwork

All hospital staff involved in the organisation and/or delivery of patient care relative to the CC were eligible to participate in the study. Site access was made possible through a local collaborator and the Medical Director of the CC. Prior to data collection, the study was introduced to key staff relative to the CC through a series of face-to-face briefings across multiple shifts delivered by two of the authors, JB and CM. In addition, the Clinical Lead for the CC circulated information about the study to all staff working in the Centre. Written informed consent was obtained from staff observed in the Centre and those involved in early qualitative interviews. Later interviews were conducted online where the consent process was recorded verbally.

Ethnographic observations

Phase 1: unstructured observations

As an initial step in developing the case study and in order to immerse and sensitise the research team to the context of hospital operational C2, the first phase of our work involved unstructured ethnographic observation within pre-specified observation periods, and system mapping. Observations comprised non-participant observation (documented as researcher field notes) and opportunistic conversations with staff in the CC, guided by a study-specific field note template informed by the literature on ethnographic methods in acute care settings and more broadly in healthcare and safety-critical industries. 58,59,61–65 The purpose of this approach was to capture contextual information and a chronological account of critical events, actions and researcher reflections as they took place in order to understand events and actions as they unfold from the actor’s perspective (and the meaning that CC users attach to them) drawing upon the Critical Incident Technique. 66 Researchers also recorded incidents of observer effects (e.g. staff asking ‘What are you writing?’) to allow analysis of whether participants’ awareness of the researchers’ presence changed over time. 67 Researcher field notes were generated both during and shortly after each observation period drawing upon substantive, reflective and analytic concepts. 68

Phase 2: structured observations

Following our initial observation period, ethnographic data collection moved to a more structured approach in order to explore the impact of the CC beyond the operations room and at all levels of the organisation, including micro-level (front-line clinical workflow in specific specialties), meso-level operational planning (e.g. bed management) and macro-level strategic planning (e.g. use of data in quality and safety governance). Our approach to structured observation drew upon engineering ‘use case’ methodology to understand usability of the system in context. 69 The approach taken was twofold: (1) followed key information through the system from modules in the CC visual displays (i.e. understanding the impact of the CC on certain ‘tracer issues’ at hospital level, such as detection and escalation for the deteriorating patient) and (2) formal shadowing of key professional roles, such as Clinical Site Matrons and operational leads as they utilised, acted upon and made decisions based upon CC data and intelligence. We produced six use cases (or vignettes) of specific tracer issues/professional roles that emerged from inductive analysis of data collected earlier in the study that represent interaction with CC processes and outputs.

Sampling

Sampling of observation periods was based on opportunistic access provided by key personnel and as agreed with CC Leads so as not to overburden staff. Observations took the form of approximately 4-hour windows with sampling of observations periods stratified in order to ensure representation of varied days of the week (including weekends), time of day and CC conditions (e.g. team handovers). As the study progressed, we used theoretical sampling for the ethnography to produce tracer issues and also for the interview participants to follow up emergent lines of enquiry. Initial observations were carried out by Carolyn McCrorie (CM) and Jonathan Benn (JB), and subsequently by CM, at different times of the day and on different days of the week. Researchers were situated within the CC room, usually towards the back of the room where there was available space (and to adhere to rules on social distancing required during the pandemic). As the study progressed, CM identified opportunistic moments within the staff workflow to carry out conversations with staff to check understanding and to explore what had been observed in more depth. CM and Josh Granger (JG) also observed the role of the CC in supporting operational planning meetings (silver tactical meetings) that took place at fixed times over the day.

Documentary analysis

We reviewed emerging hospital policies and guidance related to the CC (content reported in the original business case and CC set-up, reported impact on key performance indicators, activation programmes and training material for hospital-wide roll-out, iterations to the tiles and CC staff role descriptions) where practicable as an alternative to data collection involving staff to capture the ongoing implementation and monitoring process. A sampling framework to guide collection of documents (key documents and dates) was informed through earlier qualitative interviews with key members of staff and observations within and around the CC.

Qualitative research interviews

To complement our observational work, we conducted qualitative research interviews with key members of staff at multiple time points within the CC programme. Sampling was theoretically driven, based upon emerging insights from the observations and earlier interviews to include CC programme leads, key roles working in the CC, clinical leads in front-line areas interacting with the CC and organisational-level stakeholders representing operational strategy and clinical governance. We utilised the use cases (which emerged from observations within and around the CC) as a probe to compare operational planning, control and decision-making in specific priority areas, with and without the support of a centralised CC function, in order to enrich our understanding of how a CC operates within a health service context. An interview topic schedule with domains relevant to research aims was developed for use with programme leads and staff relative to hospital operational planning and patient flow and iterated throughout the study [including additional questions in light of feedback from patient and public (PPIE) representatives who attended our first patient-facing workshop and ongoing engagement with our PPIE co-applicant to ensure that the interviews covered topics relevant to patients]. Interviews were conducted by CM and JB either in person or online, audio-recorded, and professionally transcribed.

Data analysis

Data were anonymised and entered into the qualitative data analysis tool NVivo (Version 12.0) (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to facilitate data management. The analysis was an iterative and reflexive process and proceeded in parallel with data collection. Thematic analysis was undertaken on interview and ethnographic data, drawing upon concepts from Grounded Theory. 70,71

The coding frameworks were developed by the qualitative workstream research team (CM, JB, JG and RR) and included a framework for the interviews and a separate, complementary framework for the ethnographic data. Preliminary coding of sample ethnographic field notes was reviewed in research team meetings with feedback provided by RR and JB to the primary coder (CM). A process of open coding on the first four interview transcripts by CM and discussion of emerging concepts with the research team provided an initial inductive analysis framework. A second researcher (JG) independently coded the same four transcripts. Informal comparison of code patterns, using the constant comparative method for category and theme refinement, supported the development of conceptual code definitions and interpretations, which was discussed collectively in a series of researcher workshops (CM, JG and JB) and PPIE workshops (CM, JG and NS) and refined for consistency and focus by the workstream research team.

Six tracer issues were identified through frequency of referral to concepts during ethnographic observations, during interviews and in discussion within the research team. Theoretical sampling (analysis in parallel to sampling) informed subsequent data collection in order to build a comprehensive picture as to how intelligence is used to support operational planning, situational awareness and decision-making.

Data extracted from documents were analysed through an inductive process to capture key developments in design and functioning of the CC. The data were analysed in parallel to observation and interview data and informed lines of questioning for subsequent interviews (e.g. analyse the ‘official’ story vs. what happens in practice).

Through the coding and discussions regarding links and distinctions across transcripts, field notes and relevant documents and emerging themes mapped to the research aims, the later stages of our analysis followed the reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) process described by Braun and Clarke72,73 to produce a final inductive coding framework with a smaller number of selective codes.

Our PPIE co-applicant (NS) supported with qualitative data analysis for WS3, informed through reported best practice and discussion with colleagues within the CC on their recent experiences of related work. Involvement included a range of activities: (1) a training workshop on qualitative analysis (held in March 2022) based on an excerpt from one interview transcript collected eaconduct 40 interviews in totalrly in the evaluation Workshop 1; (2) a data analysis workshop (held in May 2022) based on the developing coding framework and exemplar quotes from interviews conducted at different phases of the process evaluation Workshop 2 and (3) an extended workshop (held in July 2022) to discuss data interpretation further from a lay perspective.

Data saturation

The value of data saturation as a guiding principle in RTA has been questioned;73 however, we did find the concept useful in guiding when we moved the focus of our enquiry between stages, for example from unstructured to structured observations and in terms of the main timepoints for the qualitative interviews.

The number of interviews and the scope for observation were significantly constrained by the restrictions imposed during the pandemic. We had planned to conduct 40 interviews in total, but the restrictions of the pandemic increased the time and complexity of organising and conducting interviews, leading to only 19 interviews in total. We would have like to conduct more than 15 interviews at the study site; specifically, we would have liked to do more follow-up interviews to discuss some of the findings, for example from the qualitative work. We would also have liked to have interviewed more than four people at the control site but even these four interviews had taken over 6 months to organise at the height of the pandemic. Limited access to the control site reduced our ability to investigate the comparisons between sites, which is disappointing as we surfaced interesting insights into how the control site had found different ways to meet the challenges of the pandemic but were unable to investigate these in detail.

We were allowed only one researcher to do ethnographic observation on site. They conducted 78 hours of observations at times and on days when we expected working patterns to vary as well as observing changing practice over time. This led to what we believe to be a comprehensive picture, but it would not be appropriate to claim data saturation given the complexity of the subject and its changing nature over time. Specifically, it would have been helpful to have more members of the study team involved in the observation to gain a range of perspectives, enable the team members to discuss the observations from their own direct observation and improve the depth of understanding across the research team.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the NHS Health Research Authority (IRAS: 285933) on 1 April 2021. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research template was used to support complete, transparent reporting of qualitative research. 74

Substudy 5: cross-industry review

Rationale

With the increasing investment in, and implementation of, C2 centres in health care there is a need to develop a better understanding of the applicability of C2 principles to acute health care. Models of C2 were originally developed outside of health care, most notably in the military domain, and have long been the focus of research and development within these domains. C2 in health care, however, is a relatively new concept and as such there is a small but growing body of research in the area. Given this, there is a need to understand how acute health care can learn lessons from these mature safety-critical domains and how their C2 concepts and implementations can best be translated into the acute care environment. To understand this better, we planned and conducted a systematic scoping review supported by expert panel consultations to synthesise knowledge from across a range of non-acute healthcare domains to help inform the design and integration of C2 centres in hospital settings.

Review aims and objectives

The aim is to understand the principles of effective C2 as they have been developed in mature safety-critical industries and academic fields of enquiry, in order to synthesise and apply this knowledge in the development of hospital CCs in the acute healthcare setting. In doing so we scope and understand centralised C2 processes in safety-critical industries, including health care, and the key principles and contextual factors that may influence the applicability and transferability of C2 models and processes to a hospital setting. This review will help contextualise the findings from our qualitative and quantitative work.

Specific research objectives include the following:

-

To identify key principles/theories of effective C2 based upon expertise developed in mature, non-hospital safety-critical industries, including models of C2 implementations or theories of effective C2 processes

-

To describe and synthesise any available evidence for the efficacy of CC implementations in healthcare/high-risk industry

-

To develop transferable principles and recommendations for health care.

Study design

This systematic scoping review was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. 75 A scoping review methodology was deemed suitable as the research aimed to map the key concepts underpinning centralised C2, technologies, implementations and evaluations across a heterogeneous collection of peer-reviewed and grey literature. The synthesis of knowledge gained from the scoping review was guided by a series of interviews with members of an expert panel on C2 in safety-critical operations.

Search strategy

We conducted formal database searches for any peer-reviewed articles that discussed or evaluated centralised C2 and one or more of the identified domains (Table 3). We conducted an initial scoping review on 9 April 2021 using five databases (EMBASE, Global Health, HMIC, MEDLINE and Transport) which found 7310 records of which 147 were considered potentially relevant. Key papers were shared among team members and helped the researchers to prepare for and contextualise the work, notably in Substudy 4.

| Domain | Categories covered |

|---|---|

| Defence | British Ministry of Defence Air defence Navy Ground Aerospace |

| Industry | Utility organisations Nuclear power Health and safety assurance in safety-critical installations (e.g. offshore; petrochemical) Logistics |

| Transport | Air traffic services Rail Road traffic |

| Emergency services | Ambulance Fire and rescue Police |

The search strategies were developed iteratively and comprised multiple search terms for centralised C2 and the domain respectively. The centralised C2 search terms were adapted from the Franklin et al. terms for CCs. 76 The domain search terms were developed with the research team, encompassing key terms within the domain identified through discussion, review of exemplar papers and review of preliminary search results for sensitivity and specificity. Four additional search strategies were used: to capture articles that more broadly review concepts of centralised C2, and to capture articles that cover any existing implementations of centralised C2 in a hospital or inpatient setting, to capture articles that cover centralised C2 and related concepts (e.g. high reliability or situational awareness) and to capture articles that cover centralised C2 and operations management.

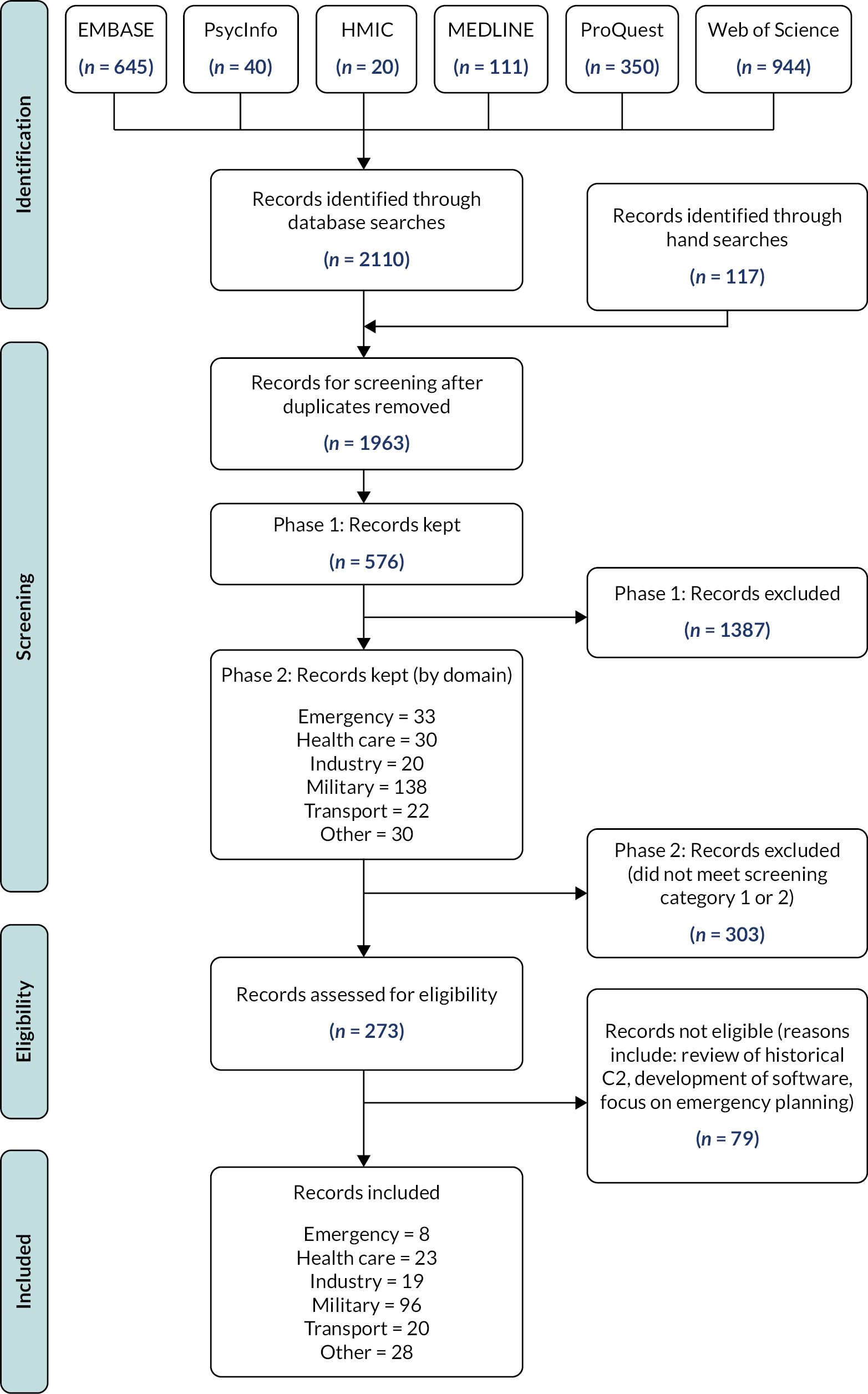

The search strategy from the cross-industry review is reproduced in Appendix 2 and is summarised in a PRISMA diagram in Figure 2. Six databases were searched: EMBASE, PsycInfo, HMIC, MEDLINE, ProQuest and Web of Science. Informal searches were also conducted to obtain grey literature (e.g. white papers and guidelines) and other relevant articles outside of the searched databases. All searches were limited to English and published between 1 January 2000 and the day of the search in order to cover contemporary research and processes. The last search was conducted on 14 June 2022. Search outputs were downloaded to EndNote for management and screening. Supplementary information and references were also gathered from expert panel interviews in which subject-matter experts were interviewed about their understanding and experiences of centralised C2. The additional article/resource recommendations from the interviews were added to EndNote for data extraction.

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for cross-industry review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The target literature and subject-matter expertise for the scoping review was theoretical articles and commentary, empirical studies and evaluations of C2 implementations, domain-specific grey literature, and reported descriptive case studies across multiple safety-critical domains, including health care.

Two screening categories were defined in relation to the research aims and used to both categorise and screen the search results. These categories were defined as:

-

Reported cases and evaluations of operations CC implementations in safety-critical domains: any article that focuses on the design and/or implementation of a specific/named command/control centre (for operations in the target safety-critical domains) or operational control processes linked to a specific/named command/control centre in the target domain.

Excluded:

-

Instances of reported control centres the purpose of which is not for control of ‘operational activity’ within the domain (e.g. cancer control centres, control centres for remote monitoring of patient data, poison control centre).

-

Non-safety-critical operations (e.g. automated vehicle-fleet management, manufacturing supply networks or supply-chain control centres).

-

General literature, reviews, studies and theory about effective C2 in safety-critical domains: any article that focuses on C2 or related concepts as a topic within the target domains (either by referring to design, processes, related theory, research or reports of studies not linked to specific implementations).

Excluded:

-

Articles with a focus on more general concepts not specific to C2 systems or processes (e.g. leadership, general communication, role assignment, preparedness or focus on cost-effectiveness).

-

Reports on the development of methodology for studying or evaluating C2, without reporting evaluative criteria (i.e. don’t convey information about effective C2).

-

Research that focuses on a non-safety-critical domain such as urban management or animal health emergencies or has a specific focus on team performance that does not directly relate to C2 (e.g. focus on a single role).

-

The development, proposal or implementation of digital software/systems for information management or display/monitoring, or virtual CCs.

-

The published protocol related to this research.

Study screening and selection

An initial phase of screening was conducted using EndNote and assessed the titles of each record found across the searches (n = 1963). Records were excluded if they were clearly not relevant to the study; the eligibility criteria were used to inform this decision. A sample of the initial body of records was reviewed and discussed among three researchers for clarity and understanding through which a high level of agreement was achieved. The remaining volume was screened by one researcher. The records marked for retention (n = 576) were exported to an Excel spreadsheet for further screening.

A second phase of screening assessed both title and abstract against the eligibility criteria. Two researchers independently reviewed a sample of 50 records. These decisions were then compared and discussed, resulting in an agreed understanding and interpretation of the eligibility criteria with no significant disagreements. One researcher conducted screening on the remaining volume; any queries were marked and discussed with the other researchers. During this process, records marked for retention (n = 273) were also classified for article type and their domain (e.g. military) (see Figure 2). Any records without abstracts present were carried forward to be reviewed for eligibility.

The remaining volume (n = 273) were then assessed for eligibility against the research aims. This led to the exclusion of articles that met the screening categories but were not relevant to the research aims (e.g. reviews of historical C2 in naval warfare). The eligible volume (n = 194) was separated and retained for data extraction.

Data extraction

A subset of exemplar articles was identified from the included literature set and subjected to full text analysis to draw out the main themes in response to the research objectives. This was done using principles from a thematic analysis methodology. 72 The remaining articles were analysed for relevant information that could be applied to the established themes.

Expert interviews

In order to support the findings from the scoping review literature, subject-matter experts were invited to informal interviews. The experts were identified through preliminary reviews of the literature conducted prior to the formal database searches and through dialogue with members of our steering group representing expertise in human factors and safety science. Invites were sent out to seven individuals of whom three agreed to interview. One additional interview was conducted where the expert was identified through snowball sampling. All interviews were conducted remotely via Microsoft Teams and recorded with the verbal consent of the expert. The recordings were transcribed and input into NVivo for analysis.

Data analysis and synthesis

Using the themes elicited through the data extraction method described above, the data were analysed to answer the research aims. More specifically this was done to highlight prevailing definitions and models of C2 and then discuss how C2 features and is researched in each domain. The articles classified as ‘screening category 2’ were used to discuss specific implementations of CCs and create a table of researched implementations featured in our data set. These discussions resulted in the further highlighting of three broad themes that featured across C2 in all domains. These themes were then discussed by drawing on a wide range of information in a cross-domain synthesis. The healthcare literature was analysed and discussed separately. The cross-domain synthesis and healthcare literature analysis were ultimately brought together in the final discussion to support recommendations.

Revisions to the methodology during the study period

Our study protocol was planned prior to the COVID-19 pandemic but this study period coincided almost exactly with the pandemic. The impact of the pandemic necessitated changes to our methodology as a direct effect on the study team, for example in staff recruitment and working practices, and on the study itself as both the study site and control site reacted to the events and pressures of the pandemic as best they could. Specifically, we were unable to:

-

explore data-quality issues to the extent originally planned (Substudy 1)

-

conduct the survey of chief information officers (CIOs) attitudes to CCs

-

disseminate the outputs of the research as widely as planned within the timeline of the original planned study.

We describe the impact of the pandemic on the project and the reasons for not being able to complete these three aspects of the protocol in the following sections.

Impact of the coronavirus-19 pandemic on the project

The CC had only been live at Bradford a number of weeks prior to the pandemic impacting on UK NHS hospitals. We therefore followed the emerging use of the CC as it supported Bradford’s response, including the addition of new ‘tiles’ for COVID management and the swift reconfiguration of services and hospital rooms. Our substudies on data quality, patient flow and patient safety were intended to provide quantification of the influence of the CC implementation but will be limited in their ability to distinguish such contributions from those motivated by the response to COVID-19. Our mixed-method approach and involvement from our international Study Steering Group has helped to define the context of this turbulent period and to describe the processes of change in the hospitals studied. Under the epistemic constraints of our pre-COVID, funder-approved protocol, we interpret our research through these contextual descriptions.

The pandemic also affected the study team. We were fortunate in being allowed to continue observations throughout the study but with social distancing and associated restrictions. Despite this, we were able to conduct the planned interviews at the study site, using a combination of face-to-face and online interviews. Access to the control site was, however, significantly delayed and when the research team did gain access late in the project timeline, this limited the extent of interviewees that could be recruited and we therefore prioritised key operational roles. Patient group meetings largely took place online.

The study sites, patients, the clinical professionals and all involved in the study went through an extremely challenging time. We consider ourselves fortunate that the majority of the study has been completed successfully and largely within planned timescales. We were unable to complete:

-

Exploring data-quality issues to the extent originally planned (Substudy 1). Data quality proved significantly more complex to measure. Our approach was to construct a ‘long list’ of candidate data-quality metrics and reduce this to a ‘short list’ of those that our clinical advisers felt were most appropriate and our data scientist confirmed would be achievable. Our original plan had been to investigate a wider range of data-quality issues through root-cause analysis based on on-site interviews with the informatics team and front-line staff. We were unable to get clearance for on-site access for more of our team and it was agreed that the people we needed to meet with had higher priorities.

-

Conducting the survey of CIOs attitudes to CCs. This survey would have provided important insights. During the pandemic, we were advised that CIOs would find our survey an unhelpful distraction from important work dealing with the pandemic. With some staff ill or isolating and additional challenges of getting access to hospitals and healthcare workers, we deferred this task until later in the project. The resource scheduled to design and implement the survey was successful in gaining a new role and left the project. We did not have sufficient time to recruit a new resource with the underspent budget before the project completed. We are proposing a follow-on project to disseminate the results, including to CIOs and hope to include this survey in that dissemination.

-

Disseminating the outputs of the research as widely as planned within the timeline of the original planned study. Our approach through the pandemic was to prioritise the gathering of information on the use of the CC. This was a challenging time for the research team, the study and control sites and the wider NHS and society and the work took longer and took more resource than originally planned as a result. Dissemination activity scheduled at the end of the project had to be condensed in order to complete the project on time.

What was achieved despite the coronavirus-19 pandemic

Despite the pandemic, we have produced a set of results which provides a unique insight into the potential use of CCs in the UK NHS that will help inform future investments in the approach. The results are presented in the following chapters in terms of patient and PPIE (see Chapter 3), a cross-industry review of the literature on C2 concepts supplemented by interviews with a panel of subject-matter experts (see Chapter 4), the results from extensive ethnographic observation at the study site and a process evaluation based upon staff interviews at both the study and control sites (see Chapter 5), the results of a quasi-experimental analysis of hospital data against control for the study period (see Chapter 6) and synthesis of findings to construct intervention logic to support future CC implementations and research evaluation, along with reflection on the study limitations including the implications of the changes detailed above (see Chapter 7). The project has a significant underspend which we are hoping to still use for dissemination and, if approved, this would include the planned CIO survey and our plans for PPIE communication.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement and engagement

This chapter provides details of our PPIE.

Integrating patient and public involvement and engagement within our research

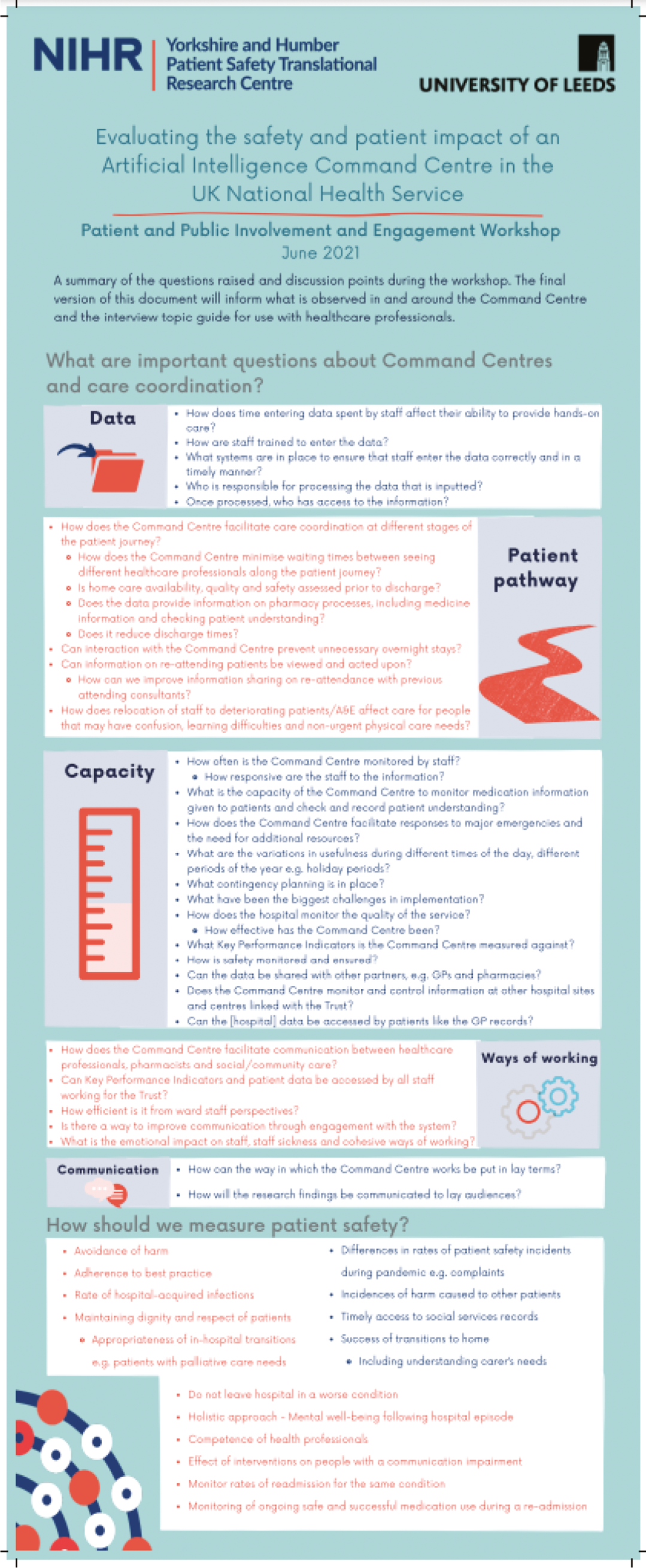

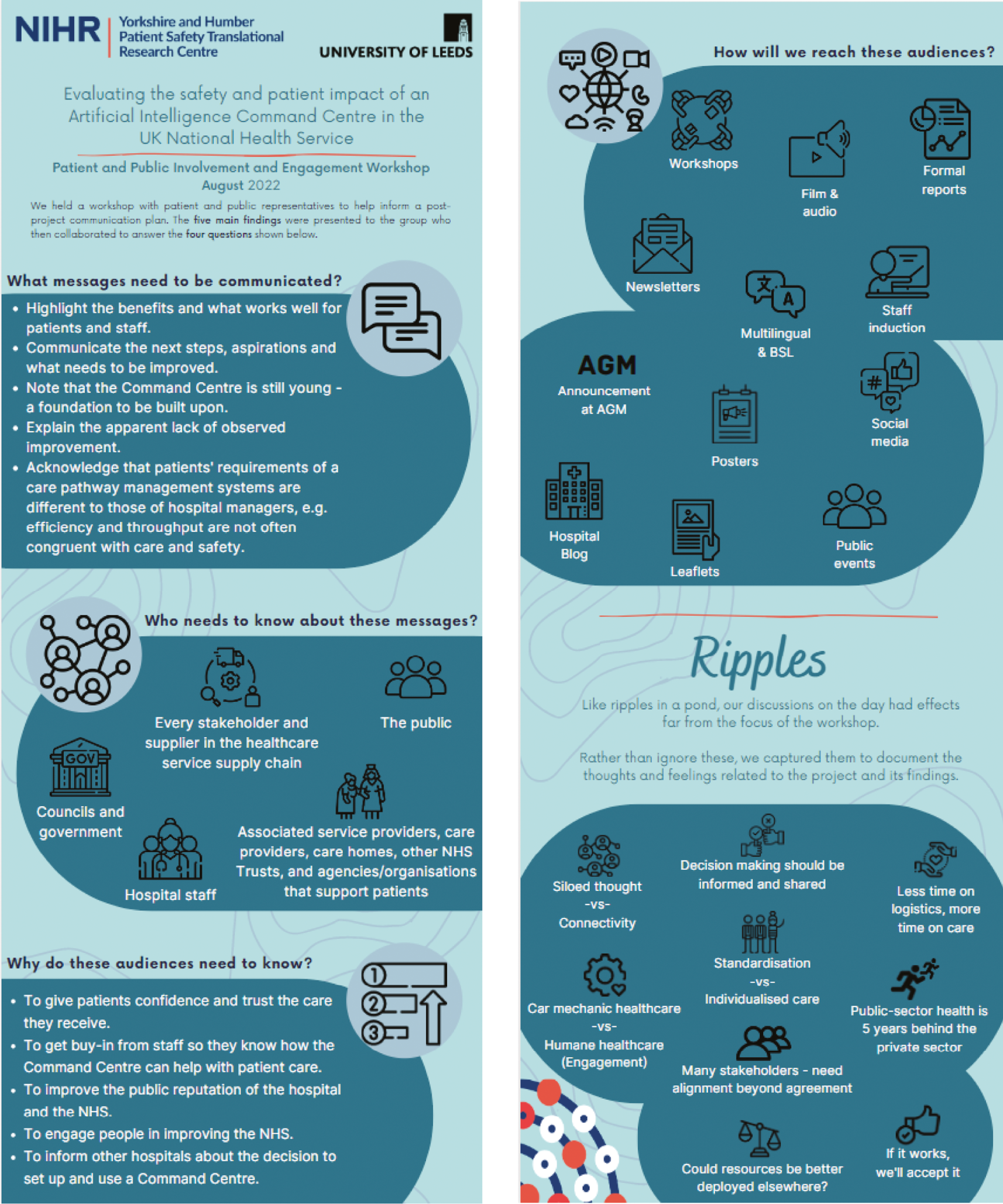

Integration of PPIE was an integral part of the study design, delivery and dissemination. Figure 1 shows how the PPIE workstream was engaged throughout all phases of the project.

Prior to commencement of the study our PPIE activity included working with a patient and public representative as co-applicant (NS), input on research design by the PPIE Research Fellow at the NIHR Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre, and an informal survey of visitors to the hospital in which the CC was implemented. Our PPIE co-applicant was involved and engaged from the early stage of the development of the funding proposal and made key contributions to help develop and contribute to the design of the interview schedule and inform analysis of ethnographic data. NS also shared and advised the rest of the research team based on his experiences as a patient, including the analysis of the transition of changes to care practice and how effective change was cascaded in practice to the benefit of patients.