Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR135660 as part of a series of evidence syntheses under award NIHR130538. The contractual start date was in October 2022. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 de Bell et al. This work was produced by de Bell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 de Bell et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Globally, the population is ageing. By 2050, the proportion of people over the age of 60 years will have doubled. 1 Currently, this is occurring most rapidly in high-income countries; it is estimated that 22% of people in the UK will be aged over 65 years by 2023. 2 These shifting demographics have implications for the health and social care services, as both the type and number of health conditions that tend to develop as people age mean that older populations have different health and care needs. 3 Rates of non-communicable diseases are higher in older age groups,3 and older people are more likely to have multiple long-term health conditions. 1,4 In Wales, it is predicted that there will be a 38% increase in the number of older people with a long-term limiting illness by 2035, meaning another 120,000 people over the age of 65 years may need care and support. 5

Treatment for patients with multiple morbidities can be complex, often involving a number of health and social care services. 6 Providing the best possible care requires co-ordination and integration between health and social care organisations and professionals. 4 Integrated care can either be vertical, connecting generalists and specialists – for example, general practitioners (GPs) and hospital care – or horizontal, requiring broad-based collaboration such as between different community-based services, with both needed for whole system integration,7,8 enabling consistent and efficient delivery of care and services. The intended benefits of integrated care include improved clinical outcomes and patient and carer experience as well as cost-effectiveness. 8,9 Where barriers arise to integrated care, this may lead to inefficiencies in the provision of care, for example fragmentation of services10,11 or overlap;12 patients or their carers having to repeat their needs or stories to different professionals;9 intervention overload;13 and care ‘gaps’8 or missed opportunities, for example for co-ordinated care planning. 14

Additionally, it is important that care is tailored to the needs of older adults. 1 There has been an increasing focus on providing personalised care in the health and social services. 1,4 Yet older people often feel unheard when decisions are being made about their care and powerless in relation to health and social care professionals. 15 Older people’s autonomy needs to be respected and they should be involved in decision-making, with choice over treatment and place of care. 16

Integrating health and social care

The need for co-operation and co-ordination between health and social care has been recognised for a long time. In the UK, integrated working has been required by various pieces of legislation; these have included the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the Care Act 2014. 17 More recently, there has been a move to Integrated Care Systems,17 which are supported by the NHS Long Term Plan. 4 Different ways of joint working have been tested through pilot programmes, including the Integrated Care Pilots, launched in 2008; the Integrated Care and Support Pioneers, which began in 2013; and the 2015 New Care Model Vanguards. 8 Within these programmes, information technology and data-sharing have consistently been identified as issues. 8,11 Informational continuity – the availability of relevant data or information on a patient to any professional involved in their care – is essential for care co-ordination. 9 Failure to ensure informational continuity and care co-ordination ‘… is likely to result in inefficient use of resources and relies on people or their family or carers, to coordinate care themselves’. 18

Data-sharing between health and social care

Although data-sharing is an aspect of communication, it has its own specificities. Initiatives and interventions aiming to improve communication between health and social care professionals may not necessarily lead to improvement in data-sharing. Data-sharing always has interorganisational and interprofessional aspects: even when information is shared between individual professionals, specific conditions (e.g. policy, legal and ethical frameworks, inter-institutional agreements and professional beliefs) need to be in place to make the exchange of information acceptable and desirable. Data-sharing is also a complex process that involves collecting, coding, storing and updating information which is then shared with or retrieved by other stakeholders, who interpret and make use of it. Stakeholders in the system are informationally dependent in the sense that they require data generated by other stakeholders to complete specific tasks and co-ordinate activities. They may differ in terms of information needs (e.g. content, format, access) as well as usage and contribution to the system’s maintenance (e.g. collecting, uploading and updating information).

Data-sharing can take different forms19 depending on whether it:

-

is between two or multiple stakeholders (e.g. telephone call vs. multidisciplinary team meetings or shared electronic record systems)

-

involves direct synchronous communication (e.g. face to face, telephone calls, multidisciplinary team meetings) or happens indirectly/asynchronously (e.g. making data available to other users on a shared electronic record system)

-

is formal (e.g. multidisciplinary team meetings) or informal (e.g. ‘corridor’ conversations)

-

involves patients and their families (e.g. patient-held paper-based records, patient access to an electronic record system)

-

involves technology (e.g. telephone, fax, e-mail, electronic record systems)

Different methods of data-sharing are often used in complementary ways (e.g. multidisciplinary team meetings and phone calls). The effectiveness of the process is further mediated by policy context, institutional boundaries and cultures, professional relationships and technological developments.

The provision of information systems that support data-sharing across organisational and professional boundaries has been identified as a key element in providing integrated care10,16 and is a long-standing policy objective in the UK. 20 Advances in technology increasingly enable electronic data-sharing; the NHS is tasked with using data and technology to improve health outcomes and is aiming to introduce a digital patient record accessible to health and social care professionals. 19

However, there are a range of challenges in sharing data between health and social care, occurring at both interorganisational and interprofessional levels. 6 Legislation such as the General Data Protection Regulation means that governance agreements need to be in place to allow data-sharing and also leads to concerns about what type of data can be shared and who it can be shared with. 6,8 Patient information is often inaccessible as different professions may not have access to the same records, or because of inconsistent documentation across organisations and professional boundaries. 6,21 Additionally, professional hierarchies lead to power asymmetries which can form a barrier to effective data-sharing. 16

Theories underpinning data-sharing

Data-sharing between health and social care organisations is a broad and complex phenomenon with multiple inter-related social and technical elements. There are numerous theories relating to different aspects of data-sharing, and the judgement of their relevance to the current project is to some extent subjective, reflecting the authors’ background, experience and preferences as well as input from different stakeholders. Since data-sharing is an aspect of communication, we considered communication theories most pertinent to our investigation. There are a wide range of communication theories and models; some focus on communication at different levels, such as between individuals or institutions, others on communication in different contexts. Here we provide a brief summary of the set of theories and concepts that we used as a starting point to explore further the conceptual landscape of data-sharing as a sociotechnical phenomenon.

Schramm22 presents one of the earliest interaction models of communication where communication is conceptualised as an interaction between active participants who encode, decode and interpret information, drawing on their respective ‘fields of experience’. Successful communication (and data-sharing) depends on the overlap of such ‘fields’ which concern not only language but, more broadly, the social context in which communicators operate. If there is not sufficient overlap of the ‘fields of experience’ of health and social care professionals, interpretation of shared data might be difficult and additional communication (e.g. further explanation and clarification) might be required. Such differences could be overcome by developing a common language and building a shared vision of reality. Similarly, Waring et al. 23 describe how knowledge boundaries between organisations and occupations can be understood in terms of differences and dependencies, with differences being the different forms of knowledge held and needed by specific groups, while ‘dependency’ refers to whether, and how much, the knowledge of a different group is needed to solve a particular problem. Where differences are small, standardised knowledge exchange is possible, for example, because language is shared. When differences are large and dependencies variable, however, semantic meanings and beliefs need to be translated across boundaries.

These theories are related to social constructionist models of communication, which suggest that communication is not a simple exchange of information but a meaning-making activity where shared understanding is the aim. Communication between health and social care professionals, which data-sharing is part of, helps to create a shared vision of the care process and develop knowledge of others’ roles and needs, thus changing the social reality in which data-sharing takes place. 24 A related concept is that of ‘systems awareness’: the aim of data-sharing is to improve the system’s performance as a whole, and therefore being aware of how the system works and the informational needs of all stakeholders makes the process of data-sharing more effective; one knows what information is needed, by whom and why. 25

While this provides a broad framing for understanding, and improving, communication between health and social care, data-sharing is a specific facet of communication, often involving the use of technology. The literature on technological change emphasises the additional layer this adds to the change process, with the need for both technical and adaptive, or behaviour-based, change. 26 Sociotechnical systems theory conceptualise the inter-related nature of technological and social elements in the workplace. 27 It considers organisations to be complex systems with intersecting social and technical elements, themselves operating within a wider system. 27,28 Whether introducing a new technology or implementing a programme of change within an organisation, it recognises that both technical and social factors are critical to the success of interventions. 29

There have been various developments of sociotechnical systems theory since it was initially conceptualised around 60 years ago. Davis et al. 27 represent the inter-related elements forming an organisation as goals, people, technology, buildings and infrastructure, culture, and processes and procedures, with the external factors that might have an influence including stakeholders, regulatory frameworks and economic circumstances. This framework is intended to support analysis of the relationships between these different social and technical elements. Sociotechnical systems theory has been used previously to understand conditions that support innovations in the healthcare system30 and responses of healthcare staff to the NHS National Programme for Information Technology. 31

Why it is important to do this review

The overall topic and area of uncertainty that the review focuses on was identified as a priority within a James Lind Alliance research prioritisation project. The overarching topic of the research prioritisation exercise was: How can we best provide sustainable care and support to help older people live happier and more fulfilling lives? The third of the ‘Top 10’ research priorities, prioritised by care workers, carers and older people, was:

How can social care and health services, including the voluntary sector, work together more effectively to meet the needs of older people?

This was viewed as a priority in order to ensure:

-

care workers and health professionals know about all the care and support available in their area and can signpost older people and their families to services

-

assessments in health services lead to the provision of appropriate social care and someone takes responsibility to check that all needs are met

-

funding and resources are distributed across all sectors to avoid voluntary services being forced to provide social care ‘on the cheap’

-

social care workers are members of multidisciplinary teams caring for older people in hospital

-

voluntary sector services are valued and respected for the essential care they provide

-

health professionals and care workers co-ordinate their care successfully to provide the best possible care for the older person

-

health and social care services communicate with each other, refer older people to each other’s services and provide seamless care. 32

The researchers involved in the priority-setting project stated:

there is a large existing evidence base (and several evidence syntheses) on integrated working but it is hard for practitioners to make sense of it. The key question is how to mobilise existing knowledge about integrated working… not just amongst health and Local Authorities, but also social care providers. 32

Overall, the project concluded that:

A new evidence synthesis is also needed on the mechanisms/interventions that local areas implement to improve communication between health services, social care services and social care providers. 32

This review addresses this need. Initial scoping searches found a wide-ranging body of evidence regarding communication between health and social care, including strategies aimed at organisations and individual professionals. Consultation with key stakeholders was used to focus the review on a specific aspect of communication: data-sharing.

Chapter 2 Research question

What are the factors perceived as influencing effective data-sharing between health care and social care, including private and voluntary sector organisations, regarding the care of older people?

Our specific research objectives were to:

-

identify factors that could potentially influence effective data-sharing between health care and social care, including private and voluntary sector organisations, relating to the care of older people

-

identify factors that could potentially influence effective data-sharing between care professionals who work in health care, social care or other organisations providing care for older people

-

identify factors that affect the successful adoption or implementation of initiatives to improve data-sharing between healthcare and social care organisations and/or care professionals.

Chapter 3 Methods

A protocol detailing inclusion criteria and methods for the review was developed and registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023416621).

Inclusion criteria

The criteria for the inclusion of studies in the review are described below and summarised in Table 1. Further detail can be found in Appendix 1, Table 8.

| Include | Exclude | |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Qualitative studies or mixed-methods studies with a qualitative component. | Other study designs, including qualitative surveys. |

| Population | Older people, as defined by individual studies. Populations where it is reasonable to assume that the focus is on older people (e.g. people with dementia, people in residential care homes). Qualitative study participants could include both the service user population – older people – their family and carers, and health and social care professionals involved in their care. |

Studies focusing on other age groups or not reporting the results for older people separately. |

| Intervention | Data-sharing, defined as: information held by an organisation about an individual patient (e.g. an electronic patient record) which is transferred or made available between organisations or care professionals belonging to different organisations, where this is across the health and social care boundary. |

Studies investigating data-sharing within the same organisation, or which is not across the health and social care boundary. Informal data-sharing or sharing of aggregated and anonymised data. |

| Focus | Description or analysis of factors perceived as influencing effective data-sharing relating to the care of older people, including regarding the successful adoption or implementation of initiatives to improve data-sharing. | All other outcomes. |

Types of evidence

This review included qualitative studies designed to identify, explore and/or understand factors influencing effective data-sharing or the implementation of data-sharing improvement initiatives. Mixed-methods studies were included if the qualitative component was reported separately.

Type of service user population

We included studies where the service user population, the ultimate intended beneficiaries of the services and care organisations of interest, were older people. All studies that defined their service user population of focus as older people were included, regardless of the exact definition used. While we loosely defined an older person as someone over the age of 65 years, in line with NHS England’s ‘Improving care for older people’ guidance,33 this was used as a guiding principle when deciding on the inclusion or exclusion of studies where the service user population was not clearly defined as ‘older people’. Applying a strict definition was not always possible or desirable, as age does not necessarily relate to functional ability. 1,34

While there is no consensus on the key conditions associated with older age,35 studies were also included if it was reasonable to assume the majority of the population would be older people (e.g. people with dementia, multimorbidities, people in residential care homes). If the focus of a study was on a mixed population (i.e. of older and younger people), it was included if the results for older people were reported separately.

Type of study participant

As we were interested in data-sharing relating to the care of older people, we included studies where participants were health and social care professionals involved in the care of older people. Studies of older people and their families and carers were also included if they discussed data-sharing.

Types of intervention

Studies were included if they focused on data-sharing as related to the care of, or services for, older people. Data-sharing was defined as:

-

information held by an organisation about an individual patient or client (e.g. an electronic patient record or handwritten notes)

-

which is transferred or made available between organisations or care professionals belonging to different organisations, where this is across the health and social care boundary.

Studies were excluded if they investigated data-sharing within the same organisation, between different NHS or healthcare organisations (e.g. between primary and secondary care), or between different social care organisations (e.g. between social workers and care home staff). We also excluded studies focused on informal data-sharing, such as conversational sharing of knowledge about patients and their care, or the sharing of aggregated and anonymised data.

Focus of study

As the review includes qualitative studies, we included studies based on their focus rather than outcome measures. Studies were included if they contained:

-

description or analysis of factors perceived as influencing effective data-sharing relating to the care of older people

-

description or analysis of factors perceived as influencing the successful adoption or implementation of initiatives to improve data-sharing.

Types of location

Studies were limited geographically to those focusing on data-sharing between care organisations and care professionals in the UK. This was to ensure that the results from the review were relevant to improving data-sharing in the UK, and specifically for informing the policies and research of Health and Care Research Wales and Social Care Wales (who commissioned this work).

Types of setting

We included studies in any setting where data were shared between health and social care. This included secondary care, primary care and community settings such as the patient’s own home and care homes.

Search methods and sources

Electronic searches

The bibliographic database search strategies were developed using MEDLINE (via Ovid) by the information specialist (AB) in consultation with the rest of the review team. The search strategy combined search terms for data-sharing and qualitative research36 using both controlled vocabulary when available (e.g. Medical subject heading in MEDLINE) and free-text searching. A qualitative research filter informed our qualitative search terms. 37 To find studies conducted in the UK, a UK search filter,38,39 along with ‘United Kingdom’ and synonyms, was used as search terms in MEDLINE then adapted for the other databases (e.g. Web of Science, CINAHL), if required. The full search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

We searched the following bibliographic databases in March 2023:

-

CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost), 1937–present

-

EMBASE (Ovid), 1974–present

-

HMIC (Ovid), 1979–present

-

MEDLINE (Ovid), 1946–present

-

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (ProQuest), 1637–present

-

Social Policy and Practice (SPP) (Ovid), 1890–present

-

Web of Science (Clarivate):

-

Science Citation Index (1990–present)

-

Social Science Citation Index (1990–present)

-

Arts and Humanities Citation Index (1975–present)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (1990–present)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index–Social Science and Humanities (1990–present)

-

Emerging Sources Citation Index (2015–present) (Clarivate).

-

-

Google Scholar using Publish or Perish (a software program that retrieves and analyses academic citations40).

Searching other resources

We searched relevant websites for publications in May 2023. The following websites were searched using these websites’ own search functions using the key words ‘data’, ‘information’ and ‘sharing’:

-

Age UK (www.ageuk.org.uk/)

-

Age Cymru (www.ageuk.org.uk/cymru/)

-

Older People’s Commissioner for Wales (https://olderpeople.wales/)

-

British Association of Social Workers (www.basw.co.uk/)

-

Royal College of General Practitioners (www.rcgp.org.uk/)

-

British Medical Association (www.bma.org.uk/)

-

Health Foundation (www.health.org.uk/)

-

Nuffield Trust (www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/)

-

NHS Confederation (www.nhsconfed.org/)

-

Care Quality Commission (www.cqc.org.uk/)

-

Care Inspectorate Wales (www.careinspectorate.wales/)

-

Social Care Wales (https://socialcare.wales/)

-

NHS Wales (www.nhs.wales/)

-

NHS England (www.england.nhs.uk/)

-

Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (www.adass.org.uk/)

-

ADSS Cymru (www.adss.cymru)

-

Public Health Wales (https://phw.nhs.wales/)

-

IMPACT Centre (https://impact.bham.ac.uk/)

-

Skills for Care (www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Home.aspx)

Additionally, the term ‘older people’ was used in the search function on the websites of The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute (www.thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk/) and the Centre for Care (https://centreforcare.ac.uk/). We browsed the publication lists for NHS Professionals (www.nhsprofessionals.nhs.uk/).

Manual checking of reference lists and forward citation searching using Scopus and Web of Science were conducted on studies that met our inclusion criteria in June 2023.

Screening and study selection

Stage 1: title and abstract

Once the search results were obtained, members of the review team (SDB, ZZ, JTC) independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to a representative sample of citations (n = 100). Decisions were discussed in a group meeting, allowing clarification of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and definitions updated where necessary. This enabled consistent reviewer interpretation and judgement of the criteria.

Following the initial calibration exercise, two reviewers (SDB, ZZ) independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the title and abstract of each identified citation. Results from MEDLINE were screened first, then citations from all databases apart from EMBASE. Our experience from previous health evidence syntheses and research41,42 suggested that searching EMBASE was unlikely to retrieve any unique results, particularly as we were searching for qualitative research,43,44 while considerably increasing the number of titles to screen (in this case up to 2725). Therefore, instead of screening all EMBASE results, we decided to carry out a precise search of the EMBASE records in End note using ‘older’ or ‘data sharing’ or ‘United Kingdom’ as keywords in the title field. There were 112 citations, which were single-screened by SDB. This also meant we had more time for citation searching, which has been found to be a lucrative method to find qualitative research. 44

Stage 2: full text

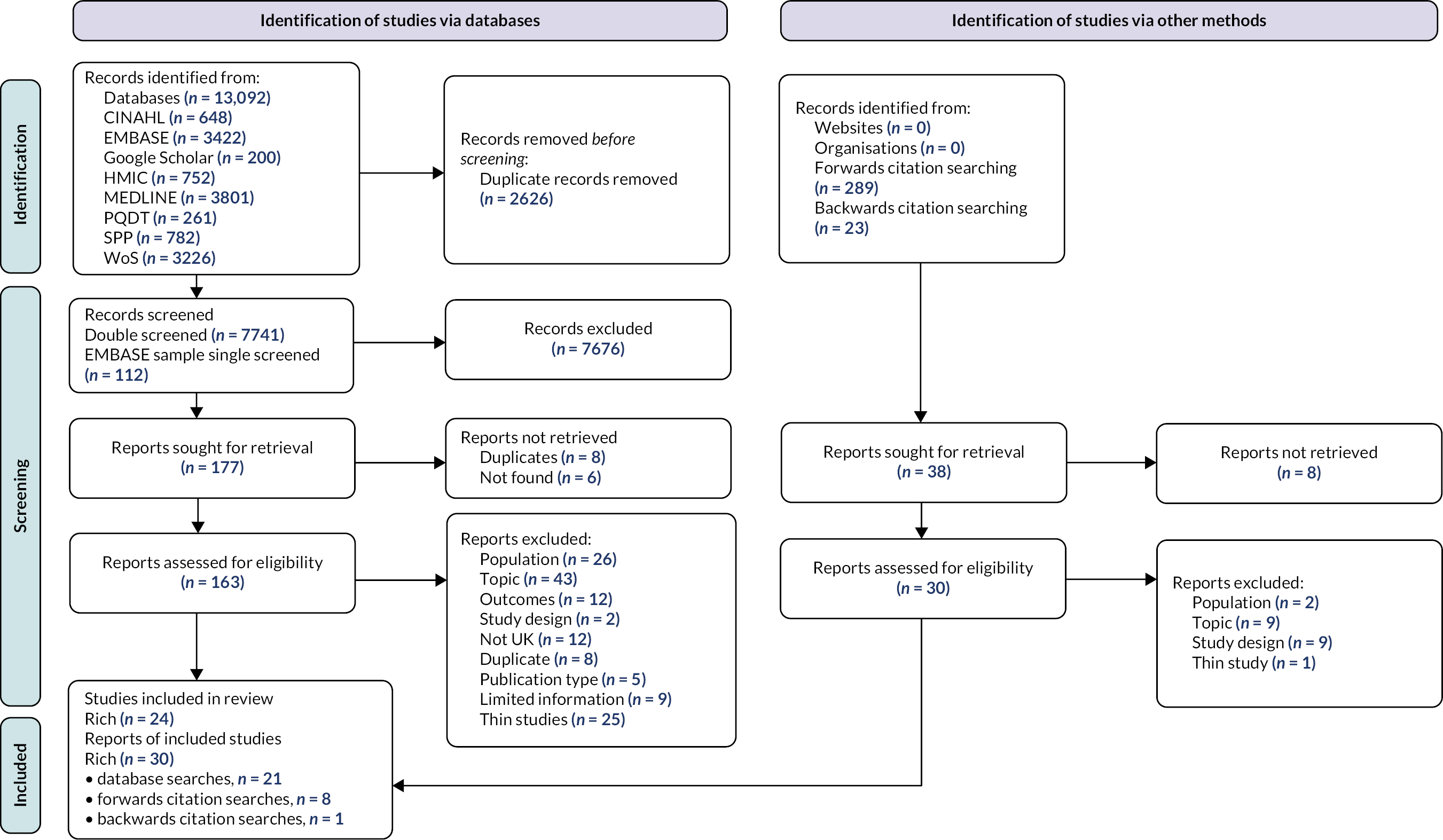

We obtained the full text of papers where either reviewer judged the title and abstract to meet the criteria. Two reviewers (SDB, ZZ) assessed the full-text publication of each record independently for inclusion, with disagreements settled through discussion and, where necessary, with the involvement of a third reviewer. The study selection process was detailed using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-style flow chart (Figure 1), with a reason reported for exclusion of each record assessed at full text. 45

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the screening process.

Data extraction and management

We considered multiple reports or publications which used the same data to be a single study. This meant that 49 studies met the inclusion criteria (reported in 54 papers, with 1 study reported in 6 papers and 1 study in 2 papers). In qualitative evidence syntheses, this poses a problem; unlike reviews of effectiveness, they do not aim for an exhaustive sample but to include variation in concepts. Also, a volume of qualitative data too large to allow familiarity with the content can reduce the quality of the synthesis. 46 We therefore used purposive sampling to identify the papers which would contain the most relevant data for the analysis. Consultation with stakeholders (as detailed in Stakeholder engagement) indicated their interest in data-sharing in a wide range of settings and populations, so we decided to use maximum variation sampling to ensure the broadest range of possible studies were included. 46 We began by mapping the included studies, identifying their aims and alignment with our review objectives, population of focus and the richness of the data in the study. 46,47 The richness of data was defined according to the scale developed by Ames et al. 47 where ‘thin’ studies had very little, and often only descriptive, qualitative data relating to our review objectives, while ‘rich’ studies had a large amount and depth of qualitative data relating to our objectives. Whether a study was ‘rich’ or ‘thin’ was decided independently by two reviewers (SDB, ZZ), with disagreements settled by discussion.

This exercise indicated that the majority of studies did not have aims which were closely aligned with our objectives and that over half the included studies had ‘thin’ data. We included all studies with ‘rich’ data (n = 24) in the analysis (and all studies with aims that corresponded more directly with the review objectives fell in this category). Studies with ‘thin’ data (n = 25) are reported in Appendix 3.

From the final sample, we extracted data on:

-

the characteristics of the study (e.g. study reference, aim, methods, service user population, study participants and findings)

To fully capture the characteristics of the included studies, we developed and piloted a data extraction form in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) based on templates developed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 48,49 This summarised contextual and methodological information as identified above and can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1.

-

themes identified by the study authors during the analysis (passages from the papers associated with the identified themes, including participants’ accounts and the authors’ interpretations, i.e. the Results, Discussion and Conclusions sections of the included studies)

Since the extraction of data related to the themes was part of the data analysis, we detail this in Data analysis. The full texts of all included studies were uploaded into NVivo v.12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), and all data extraction tasks related to specific themes were managed using this software.

One reviewer (SDB or ZZ) performed data extraction for each study, with their data checked by a second reviewer (ZZ or SDB). Disagreements were settled through discussion.

Quality assessment

Quality appraisal of included studies was performed by one reviewer (SDB or ZZ) and checked by a second (ZZ or SDB), with disagreements settled by discussion and, if required, a third reviewer (RA).

Studies were not excluded based on quality. However, the methodological quality of the included studies and the quality of reporting were considered in the interpretation of results. 50,51

Wallace criteria

The methodological strength and limitations of the included studies were assessed using the Wallace checklist,52 as adapted by Gwernan-Jones et al. 53 The latter included 14 questions which covered a range of domains, including research questions, context, data collection, data analysis, substantiation of findings, claims to generalisability, ethics and reflexivity. Each could be answered ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’. The checklist can be used to assess any qualitative research methodology, making it suitable for this review as studies came from a range of disciplines and used differing approaches. 54

In piloting the checklist, we found the following two questions difficult to interpret and apply consistently:

-

Is the theoretical or ideological perspective of the author explicit?

-

Has the theoretical or ideological perspective influenced the study design, methods or research findings?

To resolve the problem, we consulted the literature on methodological quality appraisal of qualitative studies and applied the questions to the included studies. After considerable deliberation in the team, we decided to exclude these questions from the final checklist. Our arguments are as follows:

-

It is not universally agreed that qualitative studies should be conducted from an explicit theoretical perspective; their logic could be purely inductive, aiming to develop a theory from the categories generated from the data. Whichever approach is taken, researchers’ particular understanding of the topic will always have a bearing on the way they investigate a specific research question. Such preconceptions need to be considered in relation to the design of the study and interpretation of results – which, within the Wallace checklist, is already covered by the question relating to reflexivity.

-

It is difficult to decide, in relation to our specific research question, what an ‘explicit ideological perspective’ means. All included papers start from the assumption, explicit or implicit, that health and social care interventions, data-sharing included, should result in better patient/client care; they also assume that such claims should be supported by research evidence rather than be taken for granted. These are core values in modern healthcare research in the UK and their explicit statement is usually unnecessary; not making them explicit does not constitute a failure of the authors to report their ideological perspective. As above, potential bias related to the authors’ endorsement of a specific policy or intervention (e.g. integrated care) should be dealt with in the reflexivity question and does not require a separate prompt.

As a result, the final checklist included 12 questions; we provide details of our interpretation of each question in Appendix 4, Table 9.

Data analysis

Framework analysis is a systematic method of analysing primary qualitative data. 55 This method has been developed for application in systematic reviews of qualitative evidence, where it is known as framework synthesis. 56 It is increasingly valued in the study of complex interventions and health systems,57 as it offers a highly structured but flexible approach to data analysis and can be used to map and compare the concepts under study, including identifying associations between themes. 56,58

Conducting framework synthesis involves five distinct stages:51

-

familiarisation with the topic

-

development of a ‘framework’ (i.e. initial set of themes)

-

indexing, where studies are screened and relevant data extracted using the initial framework

-

charting, where themes are revised according to data in the studies

-

mapping and interpretation

Developing the framework

In the first stages of the synthesis, we used a ‘best fit’ approach to develop an initial framework to analyse the data. 56,59 This involved identifying research detailing relevant theories and conceptual models in conjunction with searching for studies for inclusion in the review57 and consulting with stakeholders (as detailed in Stakeholder engagement).

The first iteration of the framework was based on sociotechnical systems theory. 27 This choice was informed by our initial scoping of the literature, which indicated that effective data-sharing between health and social care involves both social elements (e.g. trust in other professionals) and technical elements (e.g. interoperable IT systems). As described in the Introduction, sociotechnical systems theory considers organisations to be complex systems, with interacting social and technical elements. 27,28 The performance of the system as a whole depends on the ‘goodness of fit’ between the human and technical subsystems, which need to be treated as equally important and ‘jointly optimised’ in the iterative process of system design and redesign. Favouring one aspect of the system – for example, trying to get humans to adapt to a new technology without considering their specific requirements and needs – is likely to lead to undesired consequences and poor effectiveness. 28 Despite its origin in heavy industry, sociotechnical systems theory has gradually evolved and found a wide range of applications,28 including to support the design of large-scale IT projects for the NHS and social care. 60 Additionally, we consulted the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) core model; this is a key methodological framework used to evaluate the properties of health technologies and share information on their effects. 61 It contains nine domains which overlap with those of sociotechnical systems theory so indicated important factors to consider in the development of our framework, as well as extending our understanding by highlighting areas not specifically raised in sociotechnical systems theory, for example the legal context.

The six key domains of sociotechnical systems theory outlined by Davis et al. 27 formed the main themes in the framework. In Table 2, we describe our understanding of each theme, providing an indication of the subthemes we considered to fit within each. Specific subthemes (codes) were based on the HTA core model, as described above, and further scoping of the literature during the screening of the studies, which identified additional relevant theories and key points regarding data-sharing. For example, while screening, we considered the technology being used in studies, whether there were factors which were consistently mentioned related to technology, and discussed and agreed on factors (e.g. cybersecurity) that should be subthemes in the initial framework. Subthemes are not detailed further as the framework evolved rapidly during the process of indexing and charting, as described in the next section.

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| People | Various stakeholders are involved in the data-sharing process: health and social care professionals, care users and their informal carers. Their personal beliefs and attitudes, knowledge and skills, needs and relationships are likely to have a bearing on the data-sharing process. |

| Goals/metrics | Although the overarching goal of data-sharing is to improve care co-ordination leading to better patient outcomes, its focus will be slightly different in different settings; for example, to avoid undesirable medical procedures (e.g. cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and unnecessary hospital admissions in palliative care patients. |

| Processes/procedures | Successful data-sharing requires a complex set of inter-related processes and procedures, both internal to a care provider (e.g. data collection protocols and training) and external (e.g. policy context, legislation, funding, interagency agreements). |

| Technology | Technology is often involved in the process of data-sharing. In the past, paper records had to be copied and sent by mail or faxed. With the advent of new information and communication modalities, such as shared electronic record systems, the role of technology becomes crucial, impacting other aspects of the data-sharing process, for example interprofessional relationships. |

| Infrastructure | Infrastructure relates to the physical aspects of the data-sharing process. Examples of its impact include the physical implementation of information and communication technologies (e.g. interoperability of different systems) and the colocation of health and/or social care workers to facilitate collaboration and data-sharing. |

| Culture | Shared ideas, values and practices influence people’s behaviour and could act as a barrier or facilitator for effective data-sharing. An example is the often-observed asymmetry in data-sharing (e.g. care home staff should share information with GPs, while GPs may decide to share or not) underpinned by dominant ideas of professional hierarchy. |

Indexing and charting

After identifying and screening studies (as detailed in Search methods and sources and Screening and study selection), we moved to the indexing and charting stages of the synthesis. This involved coding the data from included studies (as defined in Data extraction and management) line by line using an iterative approach. 48 The initial framework served as a starting point for the coding process, with new codes generated to capture further details in the data not covered by the original framework. There was constant comparison of codes across studies,51 with the initial framework developed and changed to accommodate new data and evolving understanding of the phenomenon under study (data-sharing between care organisations and professionals).

The included studies were divided randomly between the reviewers, with half being coded first by SDB and the coding checked by ZZ, and the other half coded first by ZZ and checked by SDB. Data and themes were further explored and clarified through discussion with the wider review team. 62

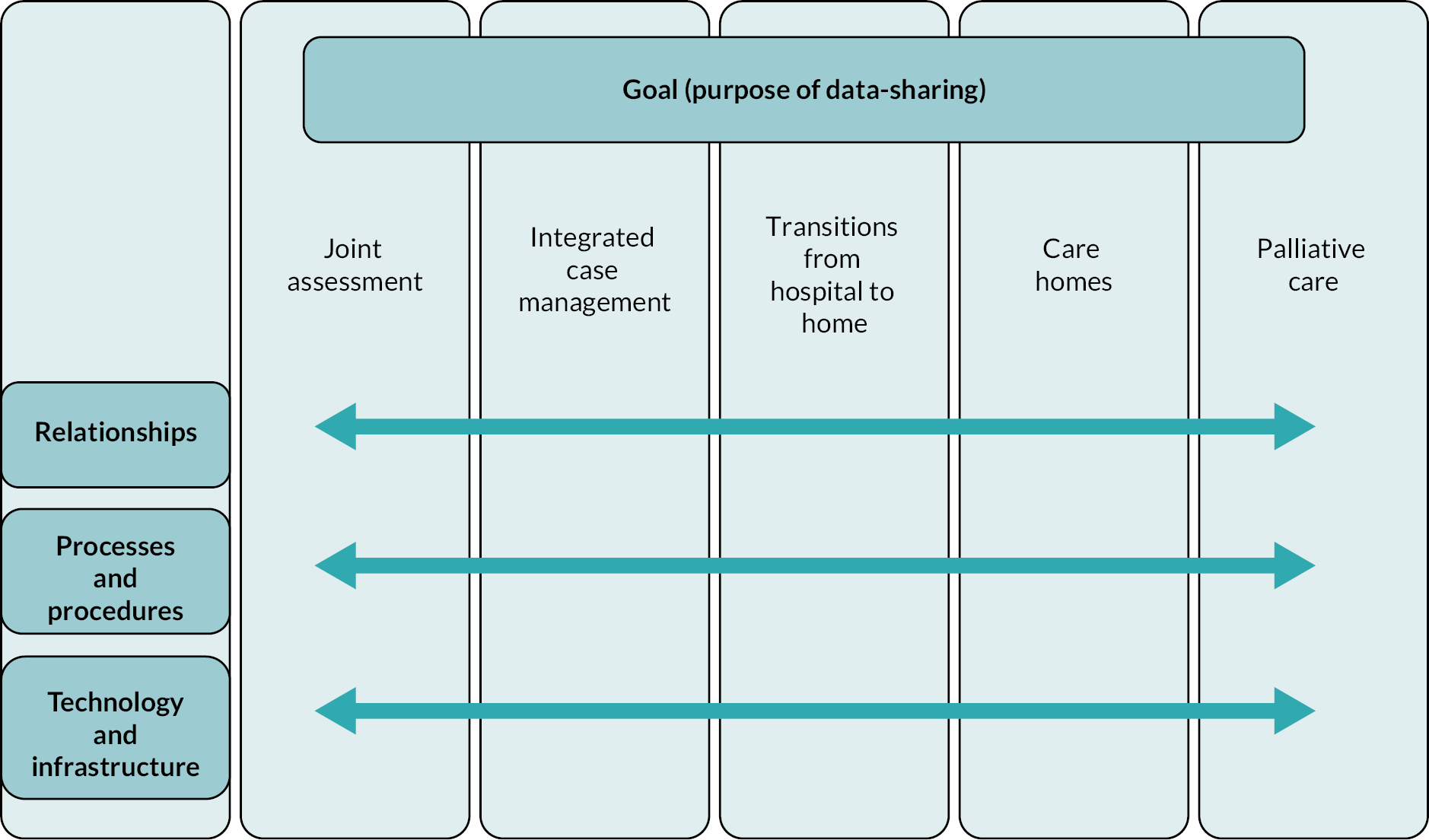

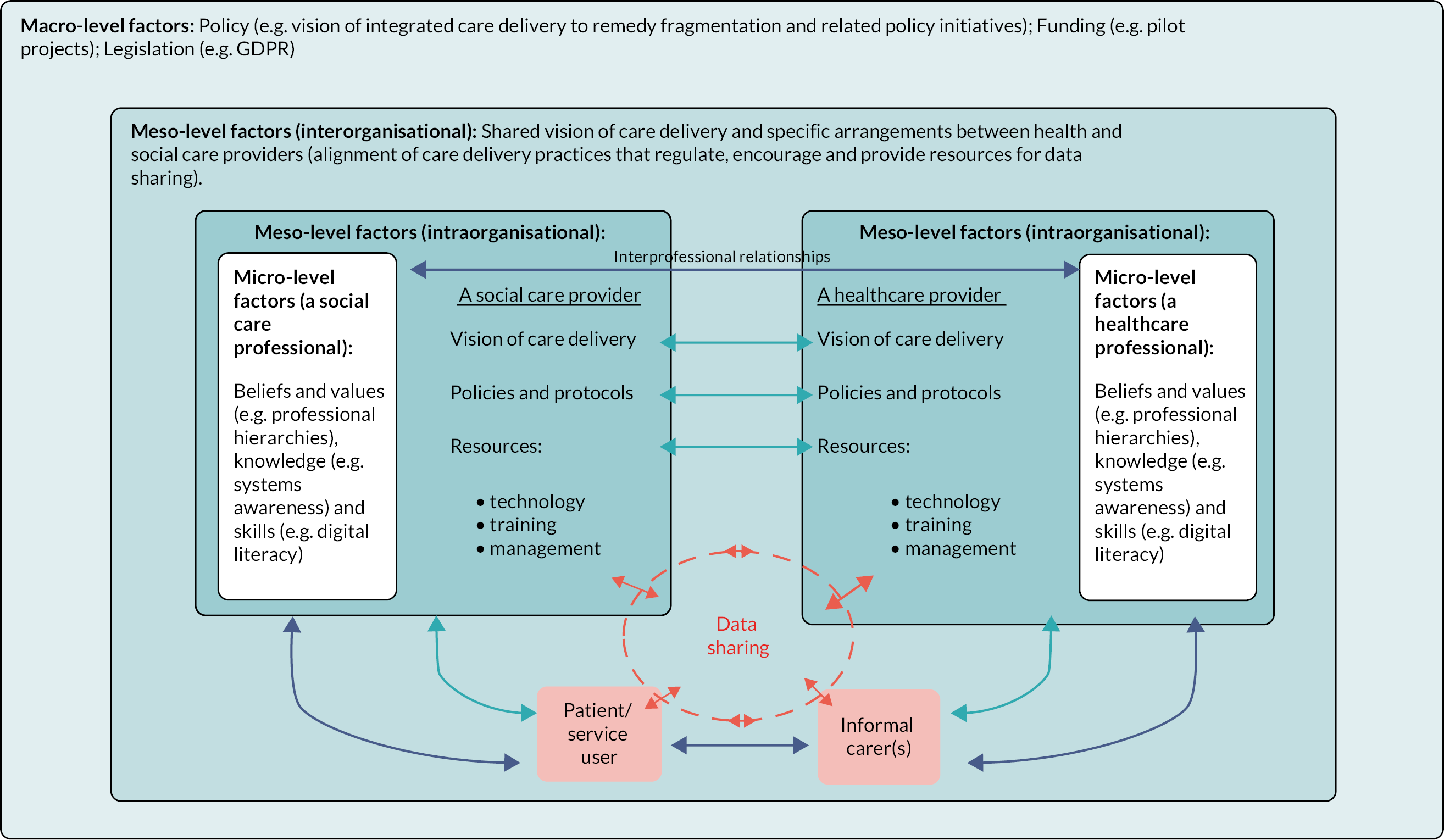

Mapping and interpretation

Finally, we mapped and interpreted the data and codes, synthesising these to derive a final set of themes from the data using the iterative process described above, and to develop a conceptual model of the phenomenon under study. There were four main themes in this final framework: Goals; Processes and procedures; Technology and infrastructure; and Relationships (encompassing People and Culture from the initial framework). The final framework was compared to the original framework, recognising where themes had been merged and new subthemes which had been identified from the data added, and examining relationships between them (Table 3). 62 As detailed in Chapter 4, Findings, the theme of Goals identified five purposes of data-sharing in the included studies; studies were grouped into five clusters based on these purposes of data-sharing for further analysis. We mapped the themes in the form of a chart for each cluster of studies to aid interpretation. 56 Drawing on the final framework, we developed a conceptual model (detailed in Conceptual model of data-sharing between health and social care) that links together the macro-, meso- and micro-level factors identified in the studies and aims to explain the effectiveness and acceptability of data-sharing and data-sharing interventions.

| Theme | Subtheme (with examples) |

|---|---|

| Goals | Purpose of data-sharing; for example, for transitions from hospital to home |

| Implications of data-sharing; for example, benefits of data-sharing or consequences of not sharing data | |

| Processes and procedures | Translation of policy into procedure; for example, formal agreements for information governance (IG) |

| Implementation of procedures; for example, embedding data-sharing in ways of working | |

| Guidance and training; for example, protocols for data-sharing | |

| Type of record/data | |

| Technology and infrastructure | Method of data-sharing; for example, shared electronic system |

| Data protection and cybersecurity | |

| Access and availability; for example, whether different professional groups could log in to the same electronic system | |

| Update and accuracy; for example, perceptions of the quality of data in an electronic system | |

| Relationships | Interorganisational relationships; for example, culture of mistrust between organisations |

| Interprofessional relationships; for example, professional hierarchies, trust and respect | |

| Attitudes and perceptions; for example, knowledge and understanding of other professional roles, patient perceptions of data-sharing |

External engagement

The focus of this review – data-sharing between health and social care organisations and professionals in relation to the services they provide to older people – is naturally fraught with tensions and controversies. This is evidenced by the long history of local and national initiatives targeting collaboration between health and social care organisations. The results from the current review are intended to be of value to and impact on the lives or professional practices of various stakeholder groups, including older people and their carers, health and social care professionals, voluntary organisations, healthcare commissioners, social care commissioners, and policy-makers.

To ensure we adequately understood the complexity, and sometimes the technical nature of the topic, and considered different perspectives and interests, the review team engaged with professional stakeholders and public and patient involvement and engagement (PPIE) representatives at different stages of the work.

Stakeholder engagement

As commissioners of the research, Health and Care Research Wales and Social Care Wales were key stakeholders, but we also consulted a Professional Stakeholders Advisory Group (PSAG). The PSAG (n = 12) included representatives of health (n = 5) and social care organisations (n = 7) (e.g. social workers, doctors, managers, commissioners), focusing on those operating in Wales. Members of the group were recruited through relevant contacts in Wales and England and had different professional backgrounds and experiences:

-

Social Care Wales, including representation from IG and Mental Health

-

Age Cymru

-

All Wales Heads of Adults’ Services Group (AWASH – comprises heads of adult services from all local authorities in Wales)

-

Social Services Directorate, Welsh government

-

South West Academic Health Science Network

-

NHS Wales Delivery Unit

-

Livewell Southwest

-

Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

The PSAG met online twice to discuss progress and provide input to the following:

-

an understanding of data-sharing between health and social care organisations in Wales and how the review could provide impact

-

the framework for analysis and results of the review

-

dissemination of results

Decisions made as a result of consultation with the PSAG are detailed in the relevant sections of the report, with the group informing the focus of the review (see Why it is important to do this review), purposive sampling of studies (see Quality assessment) and feedback on the findings (see Implications/recommendations for future research).

Public and patient involvement

It was important to engage with patients, social care users and/or their carers as part of this project both because they often experience the consequences of poor data-sharing and, more fundamentally, because the data being shared are about them, that is, their personal data. The PPIE group included representatives of the relevant service user population – older people and their families and carers. Members of the group were recruited through relevant contacts in Wales and England following advice and support from the ARC South West Peninsula Patient and Public Engagement Group (https://arc-swp.nihr.ac.uk/patient-public-involvement-engagement/). We recruited four representatives of the service user population (three women and one man), each with different backgrounds and experiences. Three representatives were interested in the topic due to their own experiences, one as a result of their experiences as carer for a family member.

The PPIE group met once, to provide input into the topics detailed above in Stakeholder engagement, as well as providing feedback on the Plain language summary. Changes as a result of consultation with the PPIE group are detailed in Public and patient involvement and engagement.

Departures from the protocol

After screening results from all other databases that had been searched, we decided to refine the EMBASE search. This was due to the high volume of references which would have needed to be screened and because EMBASE has rarely been found to retrieve unique results in previous health evidence syntheses. 41,42 Further detail is given in Screening and study selection.

Due to the large number of relevant full-text articles initially identified for inclusion, we decided to use a purposive sampling method to focus the analysis on a smaller number of the most relevant studies. This is described more fully in Data extraction and management.

Chapter 4 Results

Results of the search and studies included in the review

A summary of the search and screening process is provided in Figure 1. The bibliographic database searches retrieved 13,092 records, with another 312 records then identified through citation-chasing and searches of websites. Following deduplication, we double-screened 7853 records from database searches and 312 records from other sources at title and abstract. This identified 192 reports which were eligible to be assessed at full text. Of these, 49 studies met our inclusion criteria, reported in 54 papers, with 1 study reported in 6 papers and 1 study in 2 papers. After purposive sampling, 24 studies were included in the analysis. Studies that met the inclusion criteria but were not included in the analysis (‘thin studies’) are reported in Appendix 3.

Studies excluded after screening at full text are listed in Report Supplementary Material 2, along with reasons for exclusion. The primary reasons for exclusion at this stage were that the population of focus was not older people (n = 28) or that the topic was not data-sharing (n = 50).

Summary of included studies

Of the 24 studies included in the review, reported in 29 papers and one report, the main settings or contexts in which data-sharing took place were primary care (n = 4 studies),9,12,20,63 the community (n = 8),18,64–70 transitional care (n = 5),14,23,71–73 palliative care (n = 5)19,21,74–76 or care home settings (n = 2). 77,78 Few studies (n = 5)14,20,66,71,77 reported demographic details regarding the service user population that data-sharing was intended to benefit. Most defined their population of focus as older people with care needs (Table 4), although some were conducted in specific populations, for example, adults with dementia (n = 2). 66,68 More details on service user populations, where provided, are given in the descriptions of the study clusters below.

| First author and date | Aim | Service users | Main points relating to data-sharing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Badger 201274 | To evaluate the impact of a training programme to improve end-of-life care in nursing homes on collaboration between nursing home staff and other health practitioners. | Nursing home residents (end-of-life care) | Implementation of the GSF for care homes training programme led to perceived improvement of collaboration between care home staff and other healthcare professionals (GPs, palliative care), and increased their confidence in seeking contact and sharing information. While shared vision supported improvement (GP practices who have implemented the GSF were supportive of the GSF for care homes, while out-of-hours GPs often failed to engage), interprofessional relationships and attitudes were more important. |

| Bailey 202263 | To compare social work in integrated teams with social-work-only teams to evidence the extent to which integration delivers cost-effective and quality outcomes (focusing on prevention of hospital admissions). | Adults aged 65 and over with complex care needs | One of the mechanisms through which integrated care achieved effectiveness was by facilitating communication and data-sharing between social workers and healthcare professionals, in the context of shared understanding of each other’s roles, trust and appreciation, and shared knowledge and information. ‘Embedding’ (which implied colocation and multidisciplinary team meetings) made data-sharing easier as health and social care professionals could build relationships. |

| Bower 201864 | To explore the process of implementation of the Salford Integrated Care Programme and the impact on patient outcomes and costs. | Adults aged 65 and over with long-term conditions | Facilitators of integrated care (and the Salford Integrated Care Programme) included establishing protocols for information-sharing, creating the necessary infrastructure (e.g. multidisciplinary team meetings), and a shared integrated record (acknowledging legal and technical limitations). |

| Chester 202120 | To evaluate the implementation of a shared electronic record system between nursing and adult social care practitioners in separate agencies and locations to inform assessment of need. | Adults referred to the continuing healthcare service team for assessment | The electronic system led to more timely and efficient service delivery and better partnership working (although the quantitative surrogate outcomes were inconsistent). Health and social care workers appreciated the new system; involvement in the design was suggested to be important in its success. Another reason was the lack of options for direct, face-to-face communication. |

| Care Quality Commission 201618 | The aim of this review was to independently assess integrated care within the fieldwork areas and build on existing information to better understand older people’s experiences of integrated care. | Older people (predominantly people with complex needs and comorbidity) | Data-sharing between health and social care providers varied across regions, reflecting levels of integration. It was discussed in relation to the identification and assessment of older people at increased risk of hospital admission, transition from hospital to community (including to care homes) and care management (e.g. duplication of care plans between providers). Data-sharing arrangements were a key element of good practice examples. |

| Dickinson 200665 | The evaluation aimed to produce information about the implementation, operation and effectiveness of the SAP pilot in order to inform and guide further action. | Older people | The implementation of SAP and data-sharing between health and social care professionals was affected by multiple factors including contradictions at programme level (e.g. between person-centred care and standardised assessment); ‘hurried up’ implementation without proper training and groundwork; interprofessional relationships and failure to address these in the implementation process; different managerial styles and attitudes; success/failure to engage with the development of the assessment tools which had implications for their adequacy and adoption; logistics of information-sharing (paper-based tools that had to be copied and faxed ‘across the border’). |

| Ellis-Smith 201877 | To understand the mechanisms of action of a measure to support comprehensive assessment of people with dementia in care homes; and its acceptability, feasibility and implementation requirements. | People aged over 65 with dementia | Care home staff identified barriers to communicating with external healthcare professionals; for example, shift work, staff turnover, differing expectations and lack of shared documentation. The measure was thought to have potential to support communication, particularly with mental health professionals, but GPs were unlikely to have time to read it. The form was paper-based but participants suggested that touch-screen technology could improve usability. |

| Holloway 200666 | To develop and implement a Care Pathway framework for people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers, involving a simplified referral system and more effective communication across health and social care, to facilitate more integrated care. | People with Parkinson’s disease | Elements of the Care Pathway (e.g. the clinic summary and service record) were felt to have potential to support consistent transfer of information between health and social care professionals. The service record needed to be brief enough to be completed by busy professionals but contain enough information to be useful. However, there was little evidence of either being used by other service providers and confusion on the purpose of these forms among patients, who did not ask professionals to fill them in. |

| Kharicha 200512 | To investigate perceptions of joint working in social services and general practice, identifying strengths, weaknesses and good practice. | Older people | Data-sharing was influenced by differences in professional identity and status. Face-to-face contact was seen as a solution to some problems of joint working, but social workers emphasised that this should be formal where possible; for example, multidisciplinary team meetings, which would encourage understanding of their roles. Health professionals saw the implementation of shared records and the restructuring of social care as more important. |

| Lewis 201367 | To describe the care practice in three virtual ward sites in England and to explore how well each site had achieved meaningful integration. | People at high risk of unplanned hospital admission | Patients at high risk of admission were typically cared for by multiple professionals, leading to fragmentation and failures of communication and care. Integrative processes were important; for example, multidisciplinary team meetings helped foster shared values (even where attending professionals were not organisationally aligned). Data-sharing and information management were key in all case studies; for example, in two, all virtual ward members could write in GP electronic records. |

| MacInnes 20209 | To support and monitor improvements to the Over 75 Service, an initiative delivering integrated health and social care. | Adults aged 75 or older, with multiple health and social care needs, living at home | The importance of interprofessional relationships and trust in sharing information were emphasised. Primary care and social services were not geographically aligned, which was a barrier to data-sharing, as were IT systems due to factors such as lack of interoperability and lack of understanding about what could be shared. Another important finding was that care plans were rarely used for data-sharing between professionals as the information they contained was not relevant for everybody. |

| Mahmood-Yousuf 200875 | To investigate the extent to which the GSF for palliative care influences interprofessional relationships and communication, and to compare GPs’ and nurses’ experiences and whether its implementation led to a change in the doctor–nurse relationship. | People with palliative care needs | The GSF enabled timely sharing of information about patients with palliative care needs; for example, from GP to nurse. It strengthened professional relationships and made information-sharing easier; for example, nurses were more likely to seek informal contact with GPs. Multidisciplinary team meetings were valued for information-sharing and felt to increase professional confidence but could be difficult to organise. The extra GSF paperwork was seen as a negative by some. |

| Patterson 201919 | To explore whether access to, and quality of, patient information affects the care paramedics provide to patients nearing end of life, and their views on a shared electronic record as a means of accessing up-to-date patient information. | People receiving end-of-life care | Social care was mentioned only in relation to the new electronic system; paramedics expressed the view that such a system could include social care data which would be helpful when dealing with patients at the end of life. |

| Petrova 201876 | To critically analyse EPaCCS, present a framework for comparing their features, contexts and outcomes, and suggest ways forward. | People receiving end-of-life care | Clinical IT systems need development, for example for interoperability. While these are being developed, temporary solutions are being used, many of which have problems. For example, IT systems external to all users require separate log-ins and double data entry. IG does not address many key issues for EPaCCS; there are communication difficulties in their development, for example between IT experts and professionals, and time is required for training and education. EPaCCS need national support and clinical leadership and projects need to be framed appropriately. |

| Piercy 201868 | To evaluate a new integrated service for postdiagnostic dementia care, assessing how well the service provided support, and understanding the opportunities, benefits and challenges associated with the model. | People with dementia and their families/carers | Information-sharing was a specific problem – securing permissions was a barrier and meant Admiral Nurses had no access to medical records (they were reliant on information from the referral process which was often inadequate). This meant potential risks and duplications of information. |

| Redwood 202371 | The study aim was to understand why delays in discharge from hospital occur and identify obstacles that may be amenable to local solutions that could also have wider application across other health and care systems. | Older people living with frailty | Hospital professionals had less time to collect patient information than social care staff. Information was recorded on paper and electronically, but this was often haphazard and non-systematic, with professionals unable to access information collected by others. Data were shared face-to-face, for example in multidisciplinary team meetings, which were important settings for care co-ordination. Social care information was rarely included in discharge summaries. Difficulties in accessing information led to delays in discharge. |

| Rwathore 200769 | To understand social workers’ and district nurses’ views about information flow, interagency working and SAP. | Older people living at home | Barriers to and facilitators of data-sharing in the context of SAP were discussed, including cultural aspects (e.g. mistrust between organisations/professionals), concerns related to feasibility (e.g. more paperwork) and preference for some forms of data-sharing (e.g. multidisciplinary team meetings were seen as more effective and having other benefits, such as building interprofessional relationships that enabled data-sharing, and overcoming technical and feasibility problems). |

| Shaw 201772 | To examine how and why macro-, meso- and micro-level influences inter-relate in the implementation of integrated transitional care out of hospital in the NHS. | Older people | The focus of the study was integrated transitional care, with this creating conditions for successful [implementation of] data-sharing or the effects of successful collaboration, implicitly including data-sharing. |

| Shenkin 202278 | To inform the development of a care home ‘data platform’ between social care and health for care home residents by (1) identifying what data are routinely collected as part of resident care and (2) collating care home managers’ views and experiences of collecting, using and sharing data. | Care home residents | Two main themes were identified: (1) the rationale for collecting data, and (2) the reality of collecting and sharing data. There were a range of barriers to data-sharing, including variation in practice, lack of standards and lack of agreement about what data should be collected and why. Linked to this were lack of interoperability and other technical issues. The reality of data collection and maintenance would depend on dedicated staff time, which has implications for data-sharing; for example, if data are not up to date or are incorrect, this may have an impact on the wider system when accessed from outside. |

| Standing 2020,21 202079 | To explore attitudes towards the potential of an EPaCCS solution for improving interdisciplinary information-sharing and co-ordination in end-of-life care and facilitating the delivery of care that meets patient preferences, focusing specifically on professional and organisational factors that promote or inhibit the acceptability, usefulness and integration of collaborative care planning across health and social care into service delivery and everyday practice. | People in need of end-of-life care | Poor information-sharing is a barrier to effective end-of-life care and frustrating for patients. Paper-based acute care planning documentation does not appear to be effective; for example, documents are often unavailable and variable in quality. Patients welcomed the idea of an EPaCCS that facilitated sharing of their information between health and social care services, and they did not report the same concerns about data protection and security issues that concerned clinicians. Perceived barriers to an EPaCCS were the increased demand on time and the lack of infrastructure in place to support the system. Care must be taken to ensure that information contained within the EPaCCS does not become overwhelming, particularly for emergency services, such as paramedics, who work under extreme time pressures. |

| Sutton 201673 | To characterise challenges in a project to improve transitions for older people between hospital and care homes. | Older people during periods of acute illness | One intervention implemented in the study was a summary discharge sheet. However, this solution was not co-produced with care home staff, and they did not feel it contained adequate information; this contributed to a negative relationship between hospital and care home staff. |

| Waring 2014,80 2015,81 2016,82 2019,23 2020;83 Bishop 201984 | To explore various aspects of the process of hospital discharge, including professionals’ and patients’ perceptions of threats to safety, the role and experiences of patients, and communication and co-ordination across multiple occupational and organisational boundaries, including investigation of three widely used interventions (information communication technologies, discharge co-ordinator roles and multidisciplinary care planning meetings) in enabling interprofessional knowledge-sharing and learning. | Orthopaedic hip fracture and stroke patients | Information and communication technology (particularly well-co-ordinated and easily accessible patient records), discharge co-ordinators (professionals with dedicated roles who work across institutional boundaries), and multiple-professional group formats (e.g. multidisciplinary team meetings) can facilitate data-sharing during discharge. They are complementary and each has its own advantages and disadvantages. Technology was not used consistently and seemed to support intra- rather than interorganisational activities, with fragmentation and duplication across different sites. |

| Wilberforce 201714 | To evaluate the implementation and potential value of an electronic referral system to improve integrated discharge planning. | Older people with complex care needs | The design and implementation of the electronic system affected data-sharing (e.g. the system had limited usability and did not duplicate the paper-based system forms that staff were familiar with and seemed to like; other issues included the time it took to load and the lack of interoperability/connection between services). However, staff were positive about potential benefits; for example, reducing the need to chase referrals. |

| Wright 199570 | To elicit potential clients’ views of new client-held joint health and social care records. | Older people | Older people found it difficult to conceptualise a shared health and social care record (some saw theoretical advantages, e.g. in emergencies) and were unwilling to contemplate their needs for social care. There were concerns about confidentiality and security. |

In 11 studies, study participants were health and social care professionals,12,14,19,20,67–69,73–75,78 11 studies included patients and carers as well as professionals,9,18,21,23,63–66,71,72,77,79–84 in 1 study participants were not clearly reported,76 while 1 study was conducted solely with older people. 70 Sample sizes ranged from 2 to 220 participants. A total of 13 studies9,14,18,20,53,64,66,68,70,74,76–78 used a mixed-methods approach and 11 were solely qualitative. 12,19,21,23,65,67,69,71,72,73,75,79,80–83 Interviews were used to collect data in all studies, with most obtaining additional data using other methods such as focus groups9,21,23,63,68,70,77,79–84 and participant observation. 23,63,65,69,71–73,75,77,80–85 Eight studies conducted document analysis or audits, for example of care plans. 9,14,20,64,68,69,72,76

Data were shared through face-to-face communication (between two or more care professionals, including formal communication, such as multidisciplinary team meetings, and informal communication e.g. ‘corridor’ conversations), technology-assisted interpersonal communication (e.g. telephone, e-mail, fax) and shared electronic record systems. The former two methods often involved paper-based records. In five studies, all of these methods were used. 12,14,23,64,69,80–84 Two studies focused only on shared electronic systems,21,68,79 one on multidisciplinary team meetings,72 and in two, the data were stored on paper-based forms. 65,74 In all other studies, multiple (but not all) methods of data-sharing were used (Table 5). Both health and social care data were shared in most included studies. 9,12,14,18,20,21,23,65,68–71,74,76,79–84

| First author | Method of data-sharing | Healthcare professionals | Social care professionals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Badger 201274 | Paper |

|

|

| Bailey 202263 | IT system, face-to-face, multidisciplinary team meetings |

|

|

| Bower 201864 | All (apart from fax) |

|

|

| Chester 202120 | IT system |

|

|

| Care Quality Commission 201618 | Unspecified |

|

|

| Dickinson 200665 | Paper |

|

|

| Ellis-Smith 201877 | Paper, face-to-face |

|

|

| Holloway 200666 | Paper, face-to-face |

|

|

| Kharicha 200512 | All (apart from fax) |

|

|

| Lewis 201367 | E-mail, IT system, multidisciplinary team meetings |

|

|

| MacInnes 20209 | E-mail, IT system, multidisciplinary team meetings, phone, face-to-face | Over-75 team:

|

Wider service delivery team:

|

Wider service delivery team:

|

|||

| Mahmood-Yousuf 200875 | Paper, phone, face-to-face, multidisciplinary team meetings |

|

|

| Patterson 201919 | Paper, IT system, face-to-face |

|

|

| Petrova 201876 | IT system |

|

|

| Piercy 201868 | Paper, IT system |

|

|

| Redwood 202371 |

|

|

|

| Rwathore 200769 | Paper, phone, face-to-face, e-mail, IT system, multidisciplinary team meetings |

|

|

| Shaw 201772 | Multidisciplinary team meetings |

|

|

| Shenkin 202278 | Paper, face-to-face, IT system |

|

|

| Standing 2020,21 202079 | Paper, IT system | All professionals involved in end-of-life care | |

| Sutton 201673 | Paper, phone |

|

|

| Waring 2014,80 2015,81 2016,82 2019,23 2020;83 Bishop 201984 | All | Acute hospital:

|

|

Community and primary care

|

|||

| Administrative | |||

| Wilberforce 201714 | All |

|

|

| Wright 199570 | Paper | Not specified | |

There were 13 studies investigating current practice,9,12,18,19,21,63,67,69,71,72,75,76,78,79 while 11 studies evaluated the implementation of initiatives focused either solely on improving data-sharing or on improving care delivery, of which data-sharing was a part (Table 4). 14,20,23,64–66,68,70,73,74,77,80–84 A range of health and social care staff shared data in the included studies (Table 5). Social workers were the social care professionals most often involved in data-sharing, with other professionals including social care assessors, representatives from the voluntary sector (e.g. dementia advisers) and care home staff. From the healthcare sector, nurses (district, community and/or specialist) shared data in the majority of studies, while other professionals included doctors (GPs, geriatricians and other specialists), occupational therapists, physiotherapists, mental health practitioners, paramedics and pharmacists.

Quality of included studies

Wallace criteria

Table 6 shows the score of all studies for each item on the Wallace checklist. Overall, the methodological quality of the included studies was good. Only two studies scored ‘yes’ to all questions; however, 14 out of 24 studies scored ‘yes’ to 11 or more questions,12,19–21,23,63,66,68,69,71,73,74,77–79,81–84 and a further three scored ‘yes’ to 10 or more questions,9,64,75 indicating that most studies scored fairly highly. Of the remaining seven studies, three scored lower than the rest, with ‘yes’ for three or fewer questions. 18,67,76

| Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Total (Y, N, CT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badger 201274 | Y | Y | N | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | 9, 1, 2 |

| Bailey 202263 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10, 1, 1 |

| Bower 201864 | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8, 3, 1 |

| Chester 202120 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9, 3, 0 |

| Care Quality Commission 201618 | Y | Y | N | CT | N | CT | N | Y | N | CT | CT | N | 3, 5, 4 |

| Dickinson 200665 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | CT | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | 7, 3, 2 |

| Ellis-Smith 201877 | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10, 1, 1 |

| Holloway 200666 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 9, 3, 0 |

| Kharicha 200512 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11, 1, 0 |

| Lewis 201367 | Y | CT | N | CT | N | CT | N | CT | N | Y | Y | N | 3, 5, 4 |

| MacInnes 20209 | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | 8, 2, 2 |

| Mahmood-Yousuf 200875 | Y | Y | Y | CT | N | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8, 2, 2 |

| Patterson 201919 | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10, 1, 1 |

| Petrova 201876 | CT | CT | Y | CT | N | CT | N | CT | N | Y | N | N | 2, 5, 5 |

| Piercy 201868 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | 10, 2, 0 |

| Redwood 202371 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | 11, 0, 1 |

| Rwathore 200769 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12, 0, 0 |

| Shaw 201772 | Y | Y | Y | CT | N | CT | CT | Y | N | Y | N | N | 5, 4, 3 |

| Shenkin 202278 | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10, 1, 1 |

| Standing 2020,21 202079 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12, 0, 0 |

| Sutton 201673 | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | 9, 1, 2 |

| Waring 2014,80 2015,81 2016,82 2019,23 2020;83 Bishop 201984 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12, 0, 0 |

| Wilberforce 201714 | Y | Y | Y | CT | N | CT | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7, 3, 2 |

| Wright 199570 | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | CT | N | Y | N | N | 6, 4, 2 |

| Total (Y, N, CT) | 23, 0, 1 | 22, 0, 2 | 21, 3, 0 | 6, 4, 14 | 16, 7, 1 | 16, 0, 8 | 12, 10, 2 | 21, 0, 3 | 17, 6, 1 | 23, 0, 1 | 20, 3, 1 | 3,17, 4 |

There were some questions for which the majority of studies scored ‘yes’. All included studies apart from one76 had a clear research question, and most used a suitable research design, with only two studies scoring ‘can’t tell’ for this question. 67,76 For ‘Do any claims to generalisability follow logically and theoretically from the data?’, only one study scored ‘can’t tell’,18 with all other studies scoring ‘yes’. Similarly, the majority of studies considered ethical issues; of the 24 studies, 1 study scored ‘can’t tell’18 and 3 ‘no’ to this question. 70,72,76

The criteria which were not met, or where the reported information was insufficient to make a decision, varied across studies and it was therefore difficult to judge their implications for the validity of the overall conclusions of the review. However, there were three criteria for which a large proportion of studies (≥ 50%) failed to score highly; these are discussed further below.

Only six studies21,23,63,68,69,71,79,80–83 provided sufficient evidence that their samples were adequate to explore the full range of perspectives relevant to their research question. Of the remaining 18 studies, 14 studies9,14,18,19,64,67,70,72–78 failed to report sufficient details to judge the adequacy of the samples. Studies may have faced practical limitations, such as the difficulties of accessing specific groups of busy healthcare professionals. However, data-sharing was not the focus of many of the included studies, and more than half of the studies were mixed-methods studies with multiple objectives, so the low scores of studies in this domain may be partly due to their definition of adequate sample being different from ours, for example in terms of types of health professionals. It could also reflect narrow understanding of the data-sharing flow, with only the ‘main protagonists’ (with higher professional status) being included in the research, thus reflecting the impact of professional hierarchies on data-sharing, as discussed further in Chapter 4, Findings. Although this means that individual studies might have failed to include all relevant stakeholder groups and reported on a limited range of perspectives, this is less of a problem for the review as a whole, as we included studies focusing on a wide range of perspectives and highlighted instances where evidence was limited or completely missing.