Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR129528. The contractual start date was in September 2020. The final report began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Maben et al. This work was produced by Maben et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Maben et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has rightly focused public attention on the extreme challenges of health-care work and the often-consequent psychological ill-health that can ensue. Yet, while the pandemic provided an intense and risky working environment, psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics has been a considerable problem worldwide for many decades, but while considered important to address, it has not been given a high priority. One rare benefit of the pandemic is that it shone a light on the critical significance of the psychological well-being of healthcare staff, particularly those working on the front line, and the importance of supporting staff to care well.

The National Health Service (NHS) is the biggest employer in Europe and the world’s largest employer of highly skilled professionals with 1.6 million people, three-quarters of whom are women. 1 The NHS needs healthy, motivated staff to provide high-quality patient care; however, in recent years increasing workload due to workforce shortages and societal demand for healthcare services, combined with budget restraints and increasing external scrutiny of their work, has taken its toll on staff as well as patients. 1,2 Pre-pandemic, commentators described staff as ‘running on empty’ (Pearson Commission 2018, personal communication) and the ‘shock absorbers in a system lacking (the) resources to meet rising demands’2 and the COVID-19 pandemic has only added further to those pressures.

The most recent (2021) NHS staff survey reports 47% of staff have felt unwell because of work-related stress in the last 12 months (this figure has increased for four consecutive years, now more than 8% higher than in 2017). In addition, 55% of staff have gone into work in the last 3 months despite not feeling well enough to perform their duties (presenteeism). Overall, 34% of staff said they feel burnt out because of their work, with paramedics (51%) and registered nurses and midwives (41%) the highest across all professions. Organisational factors (service architecture) are likely causes, with only 43% of staff reporting being able to meet all the conflicting demands on their time at work (at a 5-year low), with 76.5% saying that they often have unrealistic time pressures and 73% that there are not enough staff at their organisation to enable them to do their job properly (a significant increase from 62% in 2020). Only 68% are happy with the standard of care provided by their organisation, a decrease of more than 6% from 2020 (74.2%). 3

Psychological ill-health is a major healthcare issue, leading to presenteeism, absenteeism and loss of staff from the workforce. 1,4,5 Multiple government and industry reports have highlighted the need to reduce stress and improve psychological health in NHS staff. 1,6–8 A recent report examining NHS staff and learner’s well-being highlights the high financial and personal costs of psychological ill-health and recognises that working and learning in the healthcare sector is like no other employment environment. Every day, staff are confronted with the extremes of joy, sadness and despair, with clinical staff retaining a collection of curated traumatic memories9, p. 13. A rapid evidence review and economic analysis of NHS staff well-being and mental health10 estimated that the cost of psychological ill-health to the NHS is at least £12.1 billion a year and that, by tackling this and reducing staff attrition, the NHS could save up to £1 billion.

High levels of stress and burnout among NHS staff can affect their ability to provide high-quality care. 11,12 Stress among healthcare staff is greater than in the general working population and explains more than 25% of staff absence;13 while depression, anxiety, and a loss of idealism and empathy are also reported by nurses. 14–16 It also has a significant impact on staff retention creating a vicious cycle of staff shortages potentially leading to more stress and burnout.

A word on ‘mental ill-health’ terminology

When we wrote the proposal for this study we used the term ‘mental ill-health’ to build on the work of care under pressure 1 (CUP-1)17 (the term they used) and also to distinguish from the broader term ‘well-being’, which has become ubiquitous and something of a catch-all term. We used a stakeholder meeting to discuss terminology with members noting the importance of language. Members suggested there was the possibility of ‘well-being’ becoming a less powerful term, with some ‘well-being washing’ seen in some organisations (a term that describes a superficial well-being strategy, which is ‘all talk and no action’,18 one size fits all and superficial). One paramedic stakeholder felt that ‘mental health’ (used colloquially to mean mental ill-health) was stigmatising and was felt to be more about patients with clinical diagnoses of mental illness, whereas many staff did not associate what they were experiencing with these diagnoses; another agreed that the term mental ill-health/mental health may be excluding those that do not relate to it. Burnout, for example, is recognised as an occupational hazard, rather than a form of mental illness, yet these forms of psychological distress are very serious for individuals and the broader healthcare system but may be missed if we framed our work as interventions to address mental ill-health. It was also felt that this risked attributing the distress to factors specific to the individual, rather than attributing a causal role to the broader context.

Others suggested well-being was very firmly embedded in the NHS architecture and was therefore useful and that ‘psychological well-being’ would make a useful distinction from physical well-being. Others preferred ‘psychological distress’ and ‘vicarious trauma’. What became clear from the literature and the stakeholder group discussions was that there are pros and cons to any choice of terminology in this area. 19,20 After this discussion and much consideration, we have chosen to use the terms ‘psychological ill-health’ and ‘psychological wellness’ throughout this report to distinguish between the broader well-being term that may also encapsulate physical health (important and inter-related though that is) and to distinguish from any pathologising of mental ill-health, and to remove any perceived stigma to appeal to as broad an audience of staff as possible.

Why nurses, midwives and paramedics?

Nurses, midwives and paramedics are the largest collective group of clinical staff in the NHS.

In 2020, nurses and midwives (n = 365,034) made up 27.9% of the NHS workforce and paramedics (n = 18,000) made up 1.4%. Therefore, in total nurses, midwives and paramedics comprise 29.3% of the total NHS workforce and over 56% of the clinical workforce. 4

Specific issues that may impact on psychological ill-health for these three professions include, for example, issues of power and autonomy for nurses; fear of significant litigation for midwives; and physical isolation for paramedics, community nurses and midwives. These professions may also have prolonged exposure to patients over long periods of time, and regular exposure to traumatic incidents; shift work; and heavy workloads. 21 Paramedic stakeholders told us they are exposed to unpredictable high stress caused by traumatic incidents, which create potential flashpoints, and prolonged exposure can compromise psychological health with staff going through a rollercoaster of emotions in every shift. Unique challenges (not faced in other countries) include the strict response targets in a climate with increasing demands and efficiency drives as well as unpredictable finish times, long hours of driving and unpredictable breaks (also affecting many nurses and midwives). 22

All three groups may be subject to verbal or physical assault, dealing with cognitively altered members of the public and patients with mental illness, which confers significant risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 21 Nurses are reported to be reluctant to report aggressive and violent incidents and emergency nurses considered violence to be part of their normal working day. 23 Amongst health professionals, the suicide rate is 24% higher than the national average, largely explained by the increased risk of suicide in female nurses (four times the national average) and in male paramedics. 24 Colleagues affected by suicide are at greater risk of psychological ill-health and suicide ideation. Significant stigma around disclosing psychological ill-health is known to exist in nurses, midwives and paramedics18,25 and in the paramedics’ culture in particular there is a narrative that once you’re damaged, you’re out, resulting in a culture of not disclosing mental health difficulties.

Nurses, midwives and paramedics faced with psychological ill-health are likely to either come to work when ill because they feel that they have to continue caring for patients in spite of their own difficulties (presenteeism); take sick leave (absenteeism), resulting in gaps in service and experience and leaving staff feeling guilty about the increased burden this places on colleagues; or leave the profession altogether (workforce attrition), either temporarily or permanently, creating more staff shortages. Nurses, midwives and paramedics have high rates of illness and sickness absence. 26–28

Discussions with individual nurses, midwives and paramedics suggested it is difficult to take breaks with little access to facilities, toilets, and places for food and drink; that work can be lonely and isolating and, as autonomous workers, midwives fear litigation.

In terms of support, nurses, midwives and paramedics have the same access to NHS Trusts’ HR and occupational health (OH) services as doctors, but they do not have access to the national ‘Practitioner Health Programme’ (a confidential self-referral service for doctors and dentists who are experiencing psychological ill-health or substance use difficulties). Participants at the Wounded Healer Conference (2018) noted ‘as bad as support is for doctors, it’s far worse for nurses, they are not allowed time off for treatment, not encouraged to seek help and don’t have the means to seek private help. ’29 Paramedics we spoke to echoed this with the provision of care for paramedics reported as poor with no consistency or support for paramedics with psychological ill-health. Some nurses felt they had no ‘voice’ and did not feel they could speak up if something was wrong. Finally, a nurse ward manager told us that the most important need was for proper psychological health training for managers and clear guidelines for what to do when a staff member reports mental health difficulty, a step-by-step guide that they can easily implement. Our study aims to develop and provide these resources.

Current interventions and evidence gaps

There is a large body of literature on interventions that offer prevention, support or treatment to nurses, midwives and paramedics experiencing psychological ill-health. 25,30,31 This literature tends to be discipline-specific and focuses on individual interventions placing responsibility for good psychological health with nurses, midwives and paramedics themselves. 25,32–34 Addressing the wider professional, organisational and structural contexts that ‘affect nurses’, ‘midwives’ and ‘paramedics’ psychological ill-health is less prevalent. 22,25,35,36 Therefore, there is a need for research approaches that are sensitive to the complexities and causes of psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics, identifying what is unique within and between each profession and context.

This study builds directly on previous work: care under pressure (1): a realist review of interventions to tackle doctors’ mental ill-health and its impacts on the clinical workforce and patient care17 sharing research team members (KM; DC; SB) across CUP-1 and care under pressure 2 (CUP-2) to address the following aims, objectives and research questions.

Methods

Project overall aim

To improve understanding of how, why and in what contexts nurses, midwives and paramedics experience work-related psychological ill-health; and determine which high-quality interventions can be implemented to minimise psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics.

Our specific aims are to

-

A1. Understand when and why nurses, midwives, and paramedics develop psychological ill-health at work, and provide examples of where and how it is most experienced;

-

A2. Identify which strategies/interventions to reduce psychological ill-health work best for these staff groups, find out how they work and in what circumstances these are most helpful;

-

A3. Design and develop resources for NHS managers/leaders so that they can understand how work affects the psychological health of nurses, midwives and paramedics; and what they can do to improve their psychological health in the workplace.

Objectives

We will undertake a realist review to test and refine programme theories to meet A1 and A2 above to identify the following:

-

O1. How and why work has a positive or negative effect on the psychological health of nurses, midwives and paramedics and in what contexts these are most experienced and have impacted;

-

O2. The mechanisms at individual, group and professional levels by which strategies and interventions prevent or reduce the impact of work on the psychological ill-health of nurses, midwives and paramedics; and explain why, for whom and in which contexts these are most beneficial for these staff.

Using evidence from O1 to O2 above and informed by evidence-based implementation theory and stakeholder involvement we will

-

O3. Develop a range of resources to support NHS managers/leaders to understand better how work affects the psychological health of nurses, midwives and paramedics and identify what they can do to improve their psychological wellness in the workplace.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Introduction to realist synthesis

This study used realist synthesis methodology37–39 to scrutinise literature on workplace psychological ill-health for nurses, midwives and paramedics. Realist synthesis prioritises the development of explanatory theories postulating how, for whom and in which contexts interventions work to produce outcomes. The methodology is based in a realist philosophy of science, which acknowledges that ‘there is a (social) reality that cannot be measured directly (because it is processed through our brains, language, culture and so on), but can be known indirectly. ’40

Using realist synthesis methodology this investigation goes beyond simple lines of questioning, such as ‘do interventions to minimise psychological ill-health of nurses, midwives and paramedics work?’ Rather, we sought to understand how efforts to mitigate psychological ill-health work, for which staff, which organisations, and in what circumstances. We also sought to achieve this depth of analysis in relation to understanding causes of psychological ill-health. The analysis recognises the interwoven variables that operate at different levels in organisations. The realist approach to data collection in this study was driven by retroductive theorising, which is the ‘activity of uncovering underpinning mechanisms’. 41 Retroduction entails a logic of inference, which starts with that which is empirically observable and explains outcomes and events through identifying the underlying mechanisms which can produce them. 42

The literature retrieved in this synthesis (CUP-2) is based on theoretical prioritisation, in line with realist synthesis guidelines37,40 to further strengthen the context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMOc) framework used in the analysis. A key component of the starting point for this theoretical prioritisation was the programme theory from CUP-1. 43 The search for papers for theoretical understanding has been inclusive of both primary and secondary empirical research papers as well as theory discussion and editorial publications, key reports on NHS staff well-being (particularly those that have focused on nurses, midwives and/or paramedics) that have been published in the last few years, and other non-traditional forms of data for realist synthesis. This is in line with realist synthesis methodology promoting the use of diverse forms of data to build ontologically deep insights into the analysis. 44 Middle-range theory documents were collected as an ongoing activity identified by team members and our own networks, through consultation with stakeholder group members, and citations in included papers.

The realist approach has assisted in synthesising evidence on organisational and structural contexts (e.g. community or hospital work) and profession-specific working practices (e.g. types of shift work, team or lone working) within each of these three professional groups, but also differences and similarities between the groups (e.g. by speciality, setting). By illuminating differences in context and working practices, we anticipated how they might influence the development of psychological ill-health and the uptake and success, or otherwise, of interventions aimed at supporting psychological wellness within and between these staff groups. This feature of the approach is particularly appealing because the causes and solutions to workplace psychological ill-health are complex and multifactorial. Realist methodology is also pragmatically focused on developing and testing programme theories that have more potential to be effective.

The CMOc39,45 is the central heuristic used in realist analysis and has been used in this review. The realist approach suggests that to infer a causal outcome (O) between two events (X and Y), one needs to understand the underlying mechanism (M) that connects them and the context (C) in which the relationship occurs. 45 These are usually represented as Context (C) + Mechanism (M) = Outcome (O). For example, to evaluate whether an intervention improves psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and/or paramedics (O), we identified underlying mechanisms M (e.g. the resources offered by the intervention and how these might effect changes in participants through reasoning/response), and its contiguous contexts C (e.g. are there local skill shortages impacting on access to the intervention?). We draw on the work of Dalkin et al. 46 who discuss the importance of conceptualising mechanisms on an activation continuum, rather than a binary trigger (on/off switch). Theoretical explanations developed through realist review are referred to as ‘middle-range theories’, which ‘...involve abstraction... but (are) close enough to observed data to be incorporated in propositions that permit empirical testing’47 (cited in40). Table 1 provides a definition of terms of context, mechanism and outcome.

| Category | Definitiona |

|---|---|

| Context | Context includes elements of the background environment that impact whether mechanisms in interventions are enabled to produce outcomes. These operate at different ‘layers’ including individual, interpersonal, organisational and intrastructural (e.g. the prevailing NHS culture). |

| Mechanism | Mechanisms are usually hidden, sensitive to variations in context, and generate outcomes. They are a combination of (1) the resources offered interventions and (2) the reasoning and responses from people to these resources, which lead to outcomes. |

| Outcomes | Outcomes are any intended or unintended changes in individuals, teams or organisational culture generated by context-mechanism interactions. |

Study design

The design of CUP-2 builds upon similar prior work in CUP-1 with doctors only17,43 and adheres to our published protocol except minor deviations, which are described in Appendix 1, Table 13. An overview of the design is presented in Table 2, though note this was not a linear process as suggested by the table, with several different searches being folded into final analysis, as described further in the text.

| Review stage (as per project protocol) | Strategy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1a: Locate existing theories | Searching for middle-range theories and frameworks in key papers and reports. | Searching key papers and reports to extract relevant middle-range theories and frameworks. Examining outputs from CUP-1 to explore transferable lessons and possible reusable conceptual platform. |

| Step 1b: Understanding key contextual features that may impact on psychological ill-health | Systematic and comprehensive synthesis of NHS workforce data. | Comparative NHS workforce data for nurses, midwives, paramedics and doctors (in order to compare to CUP-1) in relation to demographics, service architecture, and well-being data. |

| Step 2: Searching for evidence | ||

| 2.1 Database searches and screening | Searches of bibliographic databases and Reverse Chronology Quota (RCQ) screening. | Establishing the number of papers to be retained in the round of screening; starting with the most recent publications, working in reverse chronology applying a screening tool until the established quota is met. |

| 2.2 Supplementary searching | Hand searching key journals when RCQ has not been met during database searching. | Consulting key journals (e.g. British Paramedic Journal) to retrieve relevant papers that may have been missed by the database searching due to journals not being indexed. |

| 2.3 Literature reviews and COVID-19 | Inclusion of literature reviews and electronic database searches for COVID-19 insights. | Literature reviews obtained in initial search were screened by two team members for inclusion and ten from each profession were retained (n = 30); COVID-19 database searches were conducted separately for the three professions: 50 most recent results were screened and ranked according to relevance, with the top ten retained in each profession (n = 30). |

| 2.4 Expert input | Inviting stakeholders and project team to suggest key papers/reports. | Project team, stakeholder and advisory group members (including patient and public representatives) supplemented database searching by suggesting key papers and reports that may be missed using key word searching in the databases. |

| Step 3: Assessing papers for inclusion | ||

| Developing and applying exclusion criteria, including two-person inter-rater scoring | Selection criteria development and application by two team members. | Selection criteria developed based on protocol and early theory sensitisation; two team members scored all papers using the selection criteria and agreement compared; disagreements arbitrated by a third member of the team. |

| Step 4: Extracting and organising data | ||

| 4.1 Descriptive extraction and analysis | Understanding article contents. | Capturing the type of papers (e.g. non-empirical/empirical, methodology used; description of causes and interventions architecture). |

| 4.2 Realist appraisal | Appraisal journaling. | Creation of journal entries for each paper that addresses (a) the important insights described or inspired from the document in relation to the overall analysis and (b) team member journal-on-journaling to build coproductive analysis. |

| 4.3 Realist data extraction | Data extraction. | Selection of key data that demonstrate causal insights mapped to the research questions. |

| Step 5: Synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions | ||

| 5.1 Analysing the literature in stages | Realist analysis. | Building ontologically deep analysis from appraisal journal content; rereading papers and developing CMO configurations to produce the synthesis. |

| 5.2 Stakeholder group contributions to analysis | Emergent analysis shared and discussed with stakeholders. | Over the course of four meetings, findings were shared and discussed with stakeholders to check for relevance and importance. |

Step 1a: locating existing theories

The goal of this step was to identify theories that explain how and why work has a positive or negative effect on the psychological health of nurses, midwives and paramedics and in what contexts these are most experienced and have impacted most significantly. Also, to identify the theories explaining how and why interventions prevent or reduce psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics; and explain why, for whom and in which contexts these are most beneficial.

For interventions to be successful in moderating the impact of psychological ill-health it is necessary to understand the relationship between the development of psychological ill-health at work for nurses, midwives and paramedics (the [causal] underpinning theory or theories), so that the interventions can be selected that may ‘intervene’ and minimise psychological ill-health. In realist terms, these are the programmes. Programmes are ‘theories incarnate’ (not always explicit or visible) – that is, underpinning the design of programmes or interventions, and include assumptions about why certain components are required and how they might work. These theories are often implicit; the designers of interventions have put them together in a certain way based on what needs to be done to get one or more desired outcomes. The realist researcher aims to make these more explicit and visible where possible.

The team began by building on the CUP-117,43 final programme theory as the initial programme theory for this study, and then took a specialised, inductive approach to go beyond what was already known (reviews of individual interventions) and determine a path through the potentially vast literature (see below). We also wanted to learn from and draw upon the knowledge and expertise of our stakeholder group.

Thus, an initial theory sensitisation stage consisted of the following activities. Members of the CUP-2 team

-

examined the CMO configurations and theories generated by our co-applicants (KM, DC, SB) in CUP-1. 17 Members of that project team (KM (principal investigator [PI] of CUP-1), DC and SB) are also co-investigators in CUP-2. When drawing on their findings in early discussions we identified some of the similarities and differences across professions. These led to the identification, extraction and comparison of nationally available data for demographics, service architecture (ways of working) and well-being outcomes for doctors, nurses, midwives and paramedics to underpin this work,4 see Step 1b below;

-

drew upon PI (JM) previous HS&DR funded study exploring patients’ experiences of care and the influence of staff motivation, affect and well-being (HS&DR-08/1819/213) and extended our understanding of psychological ill-health at work and the impact of staff psychological ill-health on patient care;

-

drew on PI’s (JM/CT) realist expertise from their previous HS&DR funded longitudinal evaluation of Schwartz Center Rounds as an intervention for enhancing compassion in relationships between staff and patients (HS&DR-13/07/49) – considering its findings in the context of other interventions for the improvement of psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics;

-

consulted with experts representing multidisciplinary perspectives in our Stakeholder group (including our nurses, midwives, paramedics and patient and public involvement and engagement [PPIE] representatives);

-

considered findings from NIHR HTA project – facilitating return to work of NHS staff with common mental health disorders: a feasibility study (HTA-15/107/02) about the role of OH in supporting staff with psychological ill-health;

-

drew on key reports published by advisory and steering group members: Michael West’s King’s Fund report30 and Gail Kinman and Kevin Teoh Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) report25; along with additional informal searching to identify causal explanations about how the programmes’ impact on staff mental health/well-being. Contextual factors (at different levels, for example, individual, organisational, economic, social) related to risk of psychological ill-health were extracted and synthesised, and preliminary CMOcs developed (see Appendix 2, Table 14 for an example).

This early activity allowed the team to explore the possible theoretical underpinnings, including structural features of work (which we called ‘service architecture’), on which programmes are based, in order to map out the conceptual and theoretical landscape of psychological ill-health causes and intervention outcomes and how they are supposed to work, for nurses, midwives and paramedics. This informal searching differs from the more formal searching process in Steps 1b and 2 in that it is more exploratory and aimed at quickly identifying the range of possible explanatory theories that may be relevant.

Step 1b: understanding key contextual features that may impact on psychological ill-health

The research team brainstormed key contextual features (important contributors to psychological ill-health for nurses, midwives and paramedics) and compared these to each other and to doctors, based on our own expertise and knowledge. We shared drafts of these demographic, service architecture and well-being features with our stakeholder group on two occasions requesting comments on their importance and to identify any omissions. Feedback suggested that the features we identified provided a useful summary of key statistics that could inform attempts to improve workforce well-being.

To understand the service architecture better, we next searched for whole NHS workforce data (focusing on hospital and community health services staff) where possible using NHS Digital NHS workforce statistics) and/or NHS England-related sources based on the whole NHS hospital or community services workforce in England. We prioritised the sources where data could be separated by the three professions of interest and compared with doctors. This was important because our review builds on CUP-1,17 which focused on doctors. We found limited data for the primary care workforce, so focused only on hospital and community health service settings in England. Sources were rated for their strength/accuracy of evidence, and comparability across professions and a summary of the key demographic, service architecture (structural features of work) and well-being indicators were produced. 4 See Chapter 4 and Report Supplementary Material 1 for full publication.

Step 2: searching for evidence

This step involved searching bibliographic databases, supplementary searching in profession-specific United Kingdom (UK) journals and input from stakeholder and team member experts.

Database screening

Reverse chronology quota sampling (RCQ) was applied to database screening by starting from the most recent date of publication and working backwards chronologically, applying a screening tool until a certain quota of papers had been met. Note: this strategy was used in conjunction with capturing literature by expert input through the stakeholder group and research team experts. RCQ was used in this study for several reasons:

-

to create roughly equal quotas (n ~ 30) in the initial database search for each of the professions and thereby a similar size body of evidence for each profession, thus not giving undue weight to one profession over another. This allowed us to capture the most up-to-date evidence, theories and frameworks with cross-comparisons across the professions and prevented nursing literature dominating over the smaller research fields in midwifery and paramedic science. We decided to limit the initial search to ~90 papers to allow adequate time for data immersion, knowing that more papers would be searched in subsequent rounds (see Initial database searching). The quota strategy aimed to retain ~30 papers in each of the professions as an approximation only. The final number of papers was determined by the combination of RCQ, eliminations of papers not relevant after full-text read, and the inclusion of additional papers through expert solicitation and purposive sampling at later stages of the analysis. The final number of papers and breakdown are presented in Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (see Chapter 3).

-

to capture the most recent literature and thereby ensure that the most recent aspects of context were analysed (realist methodology prioritises a context-sensitive understanding of evidence). Thus, outdated aspects of NHS context in literature undertaken in the last 10 years were eliminated. This review also sought to collect and analyse a diverse array of intervention architectures related to workplace psychological ill-health (i.e. organisational, team-based and individual-level interventions). Taking the most recent papers meant locating the latest innovations given the proliferation of psychological ill-health interventions and the rapidly changing context (e.g. COVID-19 pandemic) in the current context of health service delivery. However, older seminal papers/reports were included through supplementary searching, and team and stakeholder expert input.

-

initial pilot searching revealed that the literature on psychological ill-health in healthcare staff, especially in the nursing literature is vast. Given the large scope of the research design and finite timeframe, screening a large volume of papers would have been extraordinarily time-consuming and inefficient. Reviewers of this grant proposal previously observed that ‘the research is very ambitious in its scope and the amount of work required seems to be considerable for a 20 month project’ and we responded that we would ‘take a pragmatic approach to the scope of data included in our review. As realist reviews can include a multitude of different data sources, deciding when we have “enough” data will be of critical importance’. Setting limits on the number of papers to be selected in iterative rounds of searching brought clarity on the boundaries of the review, and shortened the time needed during screening, which allowed for more time for data immersion and analysis.

Initial database searching

The CUP-2 database searches were managed and executed by our information specialist (SB). Three rounds of searching were conducted during the review. This included (1) a search across all three professions; (2) an expanded paramedic search due to a dearth in the initial search of all professions; and (3) a COVID-19-specific search. CUP-2 was funded pre-pandemic and so the additional contextual factors caused by the pandemic in relation to causes and interventions were not considered within our protocol. While we recognised the limitations of focusing ‘only’ on the COVID-19 literature (e.g. in terms of extraordinary contexts, and poor quality of evidence) we felt it important to include this literature as an additional component. The methods are therefore explained in this chapter, but findings presented in the Appendices (see Appendix 3, Box 3).

The search terms and method for searches (2) and (3) are described later (see Second round of database searching and selection: literature reviews and COVID-19).

For search (1), across all professions, initial search terms describing psychological ill-health and outcomes of psychological ill-health were taken from CUP-1. 17,43 Additional search terms were added to retrieve papers relevant to nursing, midwifery and paramedic practice. Three databases were searched: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online Database (MEDLINE) ALL (via Ovid, which includes MEDLINE In-Process), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature database (CINAHL) (via EBSCO) and Health Management Information Consortium Database (HMIC) (via Ovid). These three databases were selected because they covered the core health science literature (MEDLINE ALL), nursing and allied health professional literature (CINAHL) and grey literature (HMIC). The search strategies included terms for the populations of interest (nurses, midwives and paramedics), common psychological ill-health problems (e.g. stress, anxiety, depression) and outcomes of psychological ill-health (e.g. sick leave and burnout). Anticipating a large volume of returns (especially in nursing) and to maintain the study’s relevance to the UK’s NHS context, we limited our initial search to UK-based literature. To accomplish this, a published UK geographic search filter was added to the MEDLINE search. 49 CINAHL did not have a UK filter option; however, a function within the database was used to limit studies to the UK geographic region. This is accessed via the Refine Results menu on the left-hand panel within CINAHL, under the subheading ‘Geography’, and allows the searcher to limit results to studies pertaining to pre-specified geographic regions, including ‘UK and Ireland’. The HMIC database, which is published by the UK Department of Health, the Nuffield Institute for Health (Leeds) and the King’s Fund Library50 has a mainly UK focus. With filters applied where they could be, three searches were conducted for each profession, and these were exported to Endnote X9 reference management libraries for screening. No date limits were applied to searches. The exclusion criteria we applied to literature captured in this initial search are presented in Table 3.

| Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Healthcare staff physical health (i.e. not about psychological health) |

Papers reporting exclusively on the physical ill-health of healthcare staff is beyond the remit of this review |

| Undergraduate student context | Papers reporting predominantly on the undergraduate experience of healthcare trainees is outside review scope |

| Not UK context | Papers reporting research outside the UK context may lack relevance to the specific realities of working in the NHS; definition of midwife and paramedic varies worldwide |

| Papers reporting COVID-19 (excluded from the initial search) | Papers reporting on the psychological health of staff during the COVID-19 pandemic were initially excluded as it was assumed such papers would overwhelm the RCQ process, particularly in nursing, and the included set may contain only papers on COVID-19. A separate second search for COVID-19 papers was completed later (see Second round of database searching and selection: literature reviews and COVID-19) |

| Patient well-being (not health professional) | Papers reporting exclusively patient psychological ill-health were outside the scope of this review |

| Literature reviews | Literature reviews were set aside to be revisited at a later stage (see Second round of database searching and selection: literature reviews and COVID-19) |

| Publication date older than 2010 OR papers beyond the 30 most recent relevant papers (whichever comes first) | Older papers will begin to lack relevance to the most recent developments in the UK healthcare setting |

The initial searches were run in MEDLINE and CINAHL on 12 February 2021 and in HMIC on 26 February 2021. Appendix 4 describes the search process and results in detail (see also Appendix 4, Tables 17–20).

After screening, the initial database search for paramedic papers yielded a dearth of studies (n = 7). For this reason we ran an additional search with more sensitive search terms, informed by paramedic stakeholders and research experts and a published search filter for the paramedic field. 51 The revised search included a wider selection of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and free-text terminology than the initial search, including terms such as ‘first responder’ and ‘emergency personnel’. Using these modifications, the second search for paramedic literature was undertaken in all three databases on 31 March 2021. Results from those searches are presented in Appendix 4, Tables 17–20.

Titles and abstracts for the total number of papers retrieved through the database searches were as follows: 1304 for nursing, 88 for midwifery and 79 for paramedics. These were exported to word files and filtered through a screening and selection process described in Step 3.

Supplementary searching

The initial database search was exhausted before we achieved the rough quota (n ~ 30) for midwifery and paramedics. Therefore, to meet the quota estimate, an additional 11 papers in midwifery and 23 papers in paramedics were identified through supplementary hand searching in relevant profession-specific UK journals. We selected this search method as it became apparent from contact with stakeholders that the database searches had not retrieved several papers that met our inclusion criteria, which were all published in a small number of midwifery and paramedic journals. There were a few possible explanations for this, including that (1) the CINAHL UK geographic filter erroneously excluded them, (2) the ‘outcomes of psychological ill-health’ terms did not pick them up; and (3) several of the papers did not have abstracts (e.g. commentaries, opinion pieces) which makes them harder to retrieve; (4) several may not have been indexed in the databases. After pilot testing the approach, we considered that the most efficient way of identifying relevant papers was to hand search the back issues of these journals. Starting from the most recent edition and using the same exclusion criteria, we searched the British Midwifery Journal, the Journal of Paramedic Practice, and the British Paramedic Journal. The PRISMA flowchart (see Chapter 3) presents the numbers of identified papers (see also Appendix 4). Two team members (JJ) and (CT) independently screened all papers for inclusion, with disagreements arbitrated by a third team member (JM).

Second round of database searching and selection: literature reviews and COVID-19

Literature reviews

Thirty of the most recent literature reviews identified (but set aside) in the initial database searches were included in this second round. Team members (CT) and (JM) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of each review and rated their inclusion based on a judgement of relevance to contribute to the emergent programme theory, and based on their knowledge of the literature and the potential for additional insights. Given the rich data found in the initial sample of papers, an additional 30 literature reviews were considered adequate to supplement the existing dataset (particularly as some key reports also contained recent systematic reviews or summaries of such reviews). The number of literature reviews in the quota was deliberately small, because secondary analysis in the included literature reviews contained fewer rich insights (thin data) for realist analysis in contrast to data found in the included primary literature, and most of the literature reviews were international (some not including any UK primary evidence), perhaps impacting relevance.

COVID-19

A second round of database searching was conducted on 7 December 2021, to supplement the ongoing work in building the synthesis with papers focused on COVID-19 and psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics. The initial screening and selection of ~90 papers excluded papers on COVID-19 because we anticipated that the number of COVID-19 papers in the last 2 years might have ‘overwhelmed’ the RCQ screening, particularly in nursing. We also anticipated that COVID-19 papers might not contain the range or depth of service architecture insights related to the causes and solutions to workplace psychological ill-health, which have been in existence for many years prior to the pandemic.

Once a first draft of the analysis of the initial sample of included papers was complete (see below), the information specialist (SB) ran a second search for COVID-19 papers across three databases (MEDLINE ALL, CINAHL and HMIC), separately for the three professions. This search used the same professional and psychological ill-health terminology as the initial search, but replaced search terms for the outcomes of psychological ill-health with COVID-19 search terms developed by the UK Health Security Agency library services team (https://ukhsalibrary.koha-ptfs.co.uk/coronavirusinformation/). We applied a UK filter to the MEDLINE search but not to the CINAHL search, in view of shortcomings identified in the initial searches (see above, where some UK papers were missed by the CINAHL UK filter); however, we did prioritise inclusion of papers from the UK through the ranking system used for selection (explained below).

COVID-19 two-step identification stage inclusion/exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for the COVID-19 papers are presented in Table 4. The COVID papers were appraised differently given the aim to draw out COVID-19-specific causes rather than just exacerbation of known existing causes; and/or novel interventions and innovations. The search strategies used for each database are presented in Appendix 4.

| Step one exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Healthcare staff physical health (i.e. not about psychological ill-health) |

Papers reporting exclusively on the physical ill-health of healthcare staff is beyond the remit of this review |

| Undergraduate student context | Papers reporting exclusively on the undergraduate experience of healthcare trainees is outside review scope |

| Patient, not professional psychological ill-health | Papers reporting on patient psychological ill-health during COVID-19 pandemic is outside review scope |

| Papers beyond the 50 most recent relevant papers | In the first stage, we retained 50 COVID papers for each of the professions |

| Step two exclusion criteria: ranking for inclusion | |

| 5 points | Paper cites a middle-range theory important for our analysis |

| 4 points | Paper is about COVID-19, UK-based, shows potential to make an important contribution to our current analysis regarding service architecture innovations (*only interested in papers ranked 4 and above unless there are less than ten 4 point papers, in which case the 3 point papers were rereviewed and the best selected) |

| 3 points | Paper is about COVID-19 but descriptive (about how bad circumstances are), lacks insight in service architecture, but UK-based or is about an underrepresented profession |

| 2 points | Paper is about COVID-19 but descriptive, lacks insight, not UK-based, not profession-specific |

The search for COVID-19 papers involved a two-step process. The initial step searched the 50 most recent COVID-19 papers in each of the professions to capture relevant information on the impact of the pandemic on psychological ill-health. The second step was a ranking process to select the top 10 papers in each of the professions for a total of 30 papers. As we anticipated, many COVID-19 papers reported only the acute negative state of psychological ill-health descriptively, rather than insight into the solutions developed in the context of the pandemic. The two-step selection process is described in Table 4.

Step 3: assessing papers for inclusion

As outlined above (and shown in Appendix 4), the database searches yielded a large literature for nursing and a smaller pool in midwifery and paramedic literatures. RCQ screening was applied to the sample, which meant that the most recent literature was prioritised over older literature.

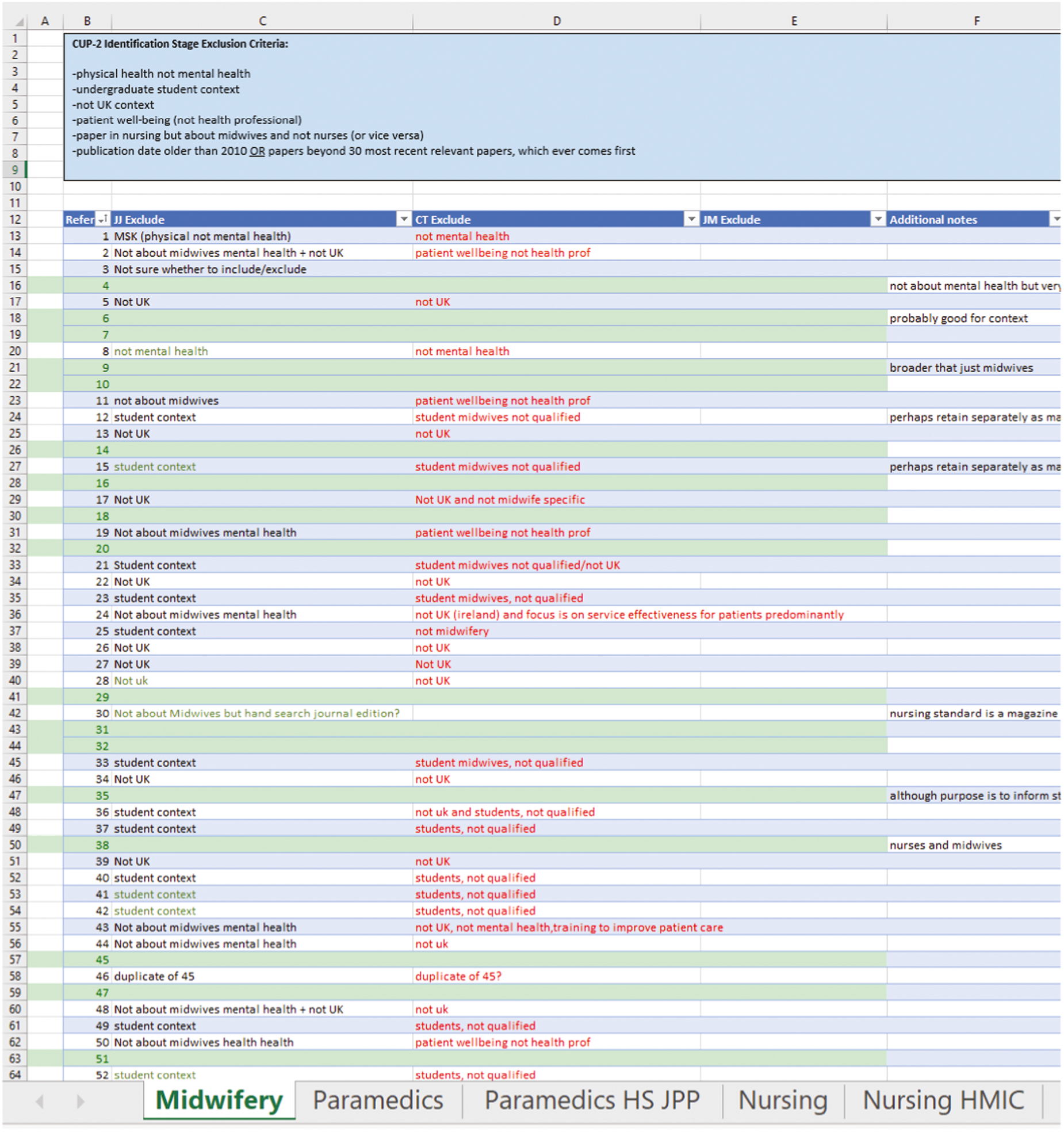

Two members of the team (JJ) and (CT) used Excel spreadsheets to record their independent judgments about the inclusion/exclusion of all papers/articles and these decisions were compared. In almost all cases, discrepancies between JJ and CT were easily resolved; on three occasions, a third team member (JM) arbitrated on final inclusion. Appendix 5 provides a sample of the Excel sheet used with the inter-rater scoring process exemplified.

Step 4: extracting and organising data

Descriptive extraction and analysis

In a realist review, due to the ontological depth it seeks to reach – aiming to go beyond simply empirical observations and insights45 – the whole paper counts as ‘data’, including, for example, the introduction and discussion. As such, all included papers provided evidence of causes and potential interventions because in a paper focused on describing or evaluating intervention(s), the authors are likely to argue for the need for the intervention(s) by describing the problem (causes of psychological ill-health) that the intervention aims to mitigate; and in a paper identifying, describing and/or measuring causes, the authors are likely to discuss potential ‘solutions’ or interventions.

Included literature for description of causes

In relation to causes, the existing evidence base, based upon numerous general or profession-specific reports of psychological ill-health in NHS professionals, has predominantly focused on quantitative survey-based measures of sources of job stress (thereby limited to what can be ‘measured’ empirically). The theoretical insights that we aim to achieve with a realist synthesis places equal importance on qualitative and grey literature (such as commentaries and editorials) and, as such, may offer different and/or expanded insights to the current evidence base. We, therefore, used all included literature except COVID-19 literature, which is presented separately (see Appendix 3, Tables 15 and 16).

Included literature for description of interventions

While most of the included literature mentioned interventions/solutions to psychological ill-health (even if the predominant focus of the paper was to describe/explain causes), this descriptive exercise focused on including those sources most likely to inform our understanding of interventions that may have benefit, and thereby included the following:

-

papers from the initial search cycle where either the purpose was to evaluate an intervention (n = 10/75) or was an editorial or commentary that aimed to discuss what was needed to mitigate psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and/or paramedics (n = 29/75). This thereby excluded 36 papers from the initial search that (1) solely or primarily focused on assessment or description of causes of psychological ill-health, or experiences of work (n = 27); or (2) ‘other’ types of papers, including discussion articles that did not include a specific focus on solutions/interventions (n = 352–54); conference abstracts (n = 255,56); study protocols (n = 157); continuous professional development/education resources (n = 258); and presentations (n = 159).

-

key reports (n = 7) and literature reviews (n = 24), excluding five that did not include interventions. 21,23,60–62

Data extraction

All included papers and reports (as described above) were read in full and any mention of causes and/or interventions was extracted to a study-specific spreadsheet that captured the type of paper, key focus of the paper (causes, interventions, or both), and for empirical papers, the methodological approach, method/design (including sampling), and overall results; and for interventions, the description of the interventions(s).

Descriptive analysis

Causes were described firstly using categories/language from the source paper and were also coded against the relevant domain(s) of the HSE Management Standards (https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/standards/index.htm): demands, control, support, relationships, role and change. The HSE Management Standards were chosen as a framework for categorising the data due to their robust evidence base, being derived from syntheses of features of work relating to psychological ill-health across many occupations, including health care. 63 In addition to using this framework, data that contributed to an understanding of ‘who’ was most at risk of psychological ill-health (particularly focusing on work environment/role factors, rather than simply demographics), and ‘when’ psychological ill-health was most likely to develop was extracted, to plug the gap in the identified limitations of previous reviews. Following this first layer of categorical analysis, the causes were read and reread, and a coding framework was developed to thematically group the specific causes described in each paper. The data on causes were coded independently by two members of the team (NK and CT), going back to full manuscripts to supplement the data extraction where coding was uncertain or differed. The data on risk factors (‘who’ is at risk and ‘when’) were similarly collated thematically. This analysis was not intended to systematically extract every instance of a ‘cause’ in each paper but focused on gaining a nuanced understanding of causes and providing data to compare and contrast within and between the three professions. For example, we acknowledge that most papers included mention of the high demand, low control/support being causes, as already known in the pre-existing evidence base, but have only cited exemplar sources for this.

Interventions were categorised according to the following:

-

their aim/focus: following the methods for categorisation used by previous reports25,30 and in line with intervention theory such as the ‘Hierarchy of Controls’,64,65 interventions were categorised as primary, secondary, tertiary (or multifocal where they straddled two or more of these levels). The Hierarchy of Controls purports that the further upstream the interventions are, the more effective they will be at both preventing exposure and thereby disease. So, while secondary and tertiary level interventions are also needed, primary interventions will be the most effective at tackling psychological ill-health. Primary interventions aim to eliminate or reduce risk of psychological ill-health by intervening at the source of the risk and thereby target the healthcare work environment, often at a structural level. Such interventions usually target whole organisational, employer (e.g. NHS-wide) or wider societal levels. Secondary interventions aim to delay or reverse the harmful impact that exposure to ‘risky’ work environment factors may have by modifying how staff respond when exposed (e.g. mindfulness training), manage their work environment (e.g. time management training) or develop competence/confidence in specific aspects of their job. The target of these interventions is usually the individual worker. Tertiary interventions aim to intervene once harm has been identified to reduce or minimise the impact and allow the worker to return to normal functioning. As well as including psychological interventions such as counselling and therapy, this category also includes initiatives such as return to work programmes. Interventions that straddled more than one category (e.g. primary and secondary) were labelled as multifocal interventions.

-

Whether the interventions were single discrete interventions or were multiple combined interventions (e.g. a programme).

-

Whether the intervention(s) was formal or informal (or mixed). We defined formal interventions as those with a defined structure or plan, often designed for replication and evaluated, whereas informal interventions were those without formal structure or definition, nor necessarily aimed for replication/evaluation, often staff-led and ad hoc. We acknowledge that for some interventions there is a fine line between formal and informal, and that some informal interventions could easily be ‘formalised’, but felt it was important to capture the interventions that are being recommended/stated to be required/beneficial, even if they did not have a specific formalised structure or description.

Once causes and interventions had been categorised as described above, analysis according to type of paper (empirical vs. non-empirical) and across the three professions (nurses, midwives and paramedics) was conducted to understand the similarities and differences according to type of data source/paper, and profession; and also conducted a preliminary analysis of ‘fit’ between causes and interventions.

Realist appraisal and appraisal journaling

An initial analysis, including CMO configurations, was drafted from a subsample of retained papers (n = 49) and reviewed by all team members. Papers were folded into the analysis in stages. All papers were read, and details entered into an appraisal journal (see below) by the team. On occasion, a paper was eliminated (or moved to a different part of the project, e.g. literature reviews or COVID-19) after reading the full-text, due to not meeting inclusion criteria that were applied at screening. This occurred when we screened papers without abstracts and had to read the full-text paper to know whether the paper met our inclusion criteria.

Realist synthesis appraisal involves an assessment of relevance and rigour of included evidence in the synthesis. 37 Pawson suggests that relevance in realist appraisal means adjudicating content of articles to determine how and in what ways they are relevant to the research questions and theoretical framing of the inquiry. An included primary study in a realist synthesis need not be appraised in its entirety, but rather the specific parts of the paper should be subject to scrutiny. 37 Therefore, we searched articles for causal insights that could be retrieved anywhere in the publication. These insights were extracted to the appraisal journal and reviewed by the whole team. Appraisal journaling was introduced to the team by coauthor (JJ) for this study as a step to be conducted before the full analysis involving CMOcs. A general process for the appraisal journaling included the following steps:

-

the full paper was first read and annotated

-

a new MS Word document was created for the journaling exercise. Title and abstracts for papers were imported into that document

-

using a free-write approach, one member summarised any important insights from the paper along with additional thoughts in a reflexive manner after reading the full text

-

the wider team then added their own free-thinking insights, expertise and NHS experience, providing challenge and counterarguments. This second-layer ‘journaling-on-journaling’ became an ongoing written dialogue amongst team members and served to build the analytic process, including notes to link theory and ideas from papers. An example of a journal entry is found in Appendix 6

-

subsequently, parts of the journaling were progressed to an analysis document, including key direct quotes from papers, and from there, CMO configurations were drafted. Links across papers were made at this stage, with a specific focus on building ideas around tensions in the healthcare delivery architecture (see below)

-

after journaling, full-text papers were revisited as needed, to investigate whether insights were fully captured and to test developing analysis against new or different insights.

Data extraction

Extraction of important insights began in the journaling, which informed our analytical thinking alongside journaling content. The first draft of the synthesis was based on a small sample of the papers (n = 15, five for each profession) and included CMO configurations built from data extractions and insights from the journaling process. Subsequent papers were journaled in batches and then folded into the existing analysis. Team members (JJ and CT) read and reread papers in tandem with the emerging analysis to ensure that papers containing causal insights were not missed on the first read. Second and third reading of papers was beneficial over the course of building the synthesis to identify and sometimes fill gaps, in particular in looking across the three professions.

Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

The literature synthesis began in the journaling stage (as described above). The journal entries were incorporated into the analysis document by the following: (1) editing the free writing to improve quality; (2) removing extraneous text; (3) incorporating important journaling insights from multidisciplinary team members; and (4) revisiting primary literature for further reflection, and possible data extraction. Through team discussions, coproduced appraisal journaling and expertise in psychological ill-health and realist methodology, the team agreed to look for ‘tensions’ in the healthcare service architecture to understand the causes and solutions to workplace psychological ill-health.

This idea was then advanced from initial insights drawn from the papers (key findings, possible interpretations of findings and rival explanations), triggering further team contributions leading to confirmation, challenge and new rival theories. We then studied all papers to reveal the (sometimes hidden, sometimes explicit) tensions in the health service architecture associated with healthcare staff psychological ill-health and extracted all instances in which a tension was identified. This helped reach an ontologically deep understanding of the causes and, thereby, solutions to workplace psychological ill-health and meet the expectations of a realist synthesis to go beyond a surface view of the evidence.

We continued to build, revise, and at times consolidate CMO configurations, using this theoretical framing to provide analytical clarity on the complex evidence in the dataset. At our third key stakeholder meeting in January 2022, we introduced a sample of these ‘tensions’ to receive expert feedback and to test the face validity of the emergent findings. Key stakeholders provided endorsement and expressed enthusiasm for the approach. Refined and revised tensions were then shared at the fourth stakeholder meeting in May 2022, where feedback from group members was that these were important and resonated with their experiences.

Analysing the literature in stages

After the initial set of papers had been synthesised from the database search, subsequent journaling and analysis of reports (n = 7), literature reviews (n = 29) and middle-range theories (n = 14) was undertaken. As more content from papers was added to the analysis, the headings were reorganised and CMO configurations expanded and modified to account for the full range of data entered into the analysis.

The COVID-19 papers were also journaled using the appraisal journal technique and drafted into a separate analysis (see Appendix 3). The aim of this work was to extract key insights in relation to the abrupt changes brought on by the 2020 global pandemic. In terms of the health service architecture, the COVID-19 analysis reflects considerable changes in service architecture, such as the sudden surge in intensity of healthcare delivery, sharp changes in resources and protocols, and new interventions to improve conditions for nurses, midwives and paramedics given the difficulties of pandemic-era health service delivery.

Stakeholder group contributions to analysis

Four stakeholder meetings were held during the review (December 2020, June 2021, January 2022 and May 2022). All meetings were held virtually (using Zoom) and included some core research team members (at minimum CT and JM) and Diana Bass, a psychotherapist whose role in the study was to provide psychological support to stakeholders should it be needed. Overall, these meetings provided confirmation that our developing analysis was resonating with stakeholders and provided suggestions regarding important areas to extend or improve our emerging analysis. Some alternative theories and challenges were also shared, which aided our thinking. All meetings (except the first where personal stories were shared) were recorded (with permission from all attendees), and meeting conversations and entries into the ‘chat’ function and on online whiteboards (Padlet, enabling anonymous contribution) were transcribed and reviewed in relation to the analysis to enrich and provide further support or challenge to the analysis. All stakeholders provided permission for their contributions to be used in this way, and contributions have been paraphrased and included anonymously in this report. Stakeholder meetings comprised a mix of presentation from the work-in-progress analysis as well as participants sharing stories and insights from their personal experience (see Table 5).

| Meeting #, (Date) | Number of attendees | Composition, N = nurse; M = midwife; P = paramedic | Activity relevant to data collection and/or analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Dec 2020) |

20 | Stakeholders: 20 - 10 staff by experience (5N, 3M, 2P) - 1 lay member - 9 other (e.g. Royal Colleges, Regulators) + Diana Bass |

Three of the stakeholders (a nurse, midwife and paramedic) shared their own particular poignant and traumatic experience story about ‘The day I questioned why I had chosen my profession.’ The rest of the group shared their reflections on the stories including common themes that they felt linked them in relation to causes of poor psychological ill-health and any specific issues related to the individual professional groups. This included the following: unpredictable/unexpected events; lone working; and wearing a professional ‘mask’ to protect self. |

| 2 (June 2021) |

24 | Stakeholders: 24 - 10 staff by experience (5N, 3M, 2P) - 1 lay member - 13 other + Diana Bass |

Subsequent to providing a progress update, including feedback and analysis of the stakeholder group contributions from meeting 1, the emerging ‘tensions’ were presented to the group for discussion. We also discussed the emerging findings about the existence of both ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ interventions and asked stakeholders to think about and tell us what has worked for you and why and how? In relation to well-being support. |

| 3 (Jan 2022) |

19 | Stakeholders: 19 - 7 staff by experience (3N, 1M, 3P) - 1 lay member - 11 other + Diana Bass |

Subsequent to providing a progress update, a short reminder regarding realist methodology was provided followed by an updated revised analysis of the ‘tensions’ presented as five key dilemmas – including draft C-M-O’s. Attendees also asked to help us with diversity in our group (age, gender, ethnicity, disability etc.). |

| 4 (May 2022) |

17 | Stakeholders: 17 - 9 staff by experience (3N, 2M, 4P) - 1 lay member - 7 other + Diana Bass |

Discussion on (a) the importance of terminology regarding psychological ill-health of healthcare staff; (b) key findings to date including a focus on three of the key tensions, including discussing the lack of intersectionality present in the literature, including menopause. Support for resonance and importance of uncovering the tensions; (c) comment on ideas for translating findings into recommendations and resources. Ideas were presented and discussed. |

Developing outputs

Our study outputs are in development, but we have developed recommendations for research, practice and policy (see Chapter 7). We worked with our stakeholder and advisory groups to turn our findings into recommendations and turn recommendations into practical guidance. This work is ongoing and due to be reported in Spring 2023. We held two advisory groups during the study (September 2021 and August 2022), and members provided academic input, lived experience and project oversight and governance. At our final advisory group in August 2022, we built on the responses from our stakeholder group in May 2022 to our suggested resources and presented refined ideas for comment and critique, which aided further refinement (see Chapter 7). We have also used the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR)66–68 to identify and attempt to mitigate implementation challenges in relation to the resources.

Ensuring rigour

Analytical rigour was supported by a number of strategies within the review process. This included the following:

-

the inclusion of empirical papers, grey literature, editorials and commentaries, reports and stakeholder as data sources to triangulate findings and create a robust analysis;

-

use of the realist and meta-narrative evidence syntheses: evolving standards (RAMESES) reporting guidelines (checklist uploaded to project webpage) to ensure rigour in the conduct and reporting of this realist synthesis;

-

whole-team appraisal engagement in reading papers, journaling-on-journaling that identified and confirmed the most important insights regarding tensions in the healthcare architecture to inform data analysis; and built on healthcare psychological ill-health knowledge and expertise in the group, resulting in the incorporation of wider relevant literature and middle-range theory;

-

a rigorous audit of the analysis conducted by team members (JM) and (CT) to ensure transparency from original source documents to the emergent tensions, including cross-checking consistency of key messages with the quotations/extracts used to inform analysis and CMO configurations, and searching across nurse, midwife and paramedic sources to ensure analysis was supported within the included literature;

-

consulting with the CUP-2 advisory and stakeholder groups on the relevance and richness of the analysis and receiving strong consistent messages from these groups that the analysis was relevant, important and provided new and needed insights.

Summary

Realist methodology was used to search, identify, appraise and synthesise the literature in relation to our aims to reach an ontologically deep understanding of causes and interventions to mitigate psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics. Due to the broad mandate of this review, and the potential for locating insights across a diversity of literature in nursing, midwifery and paramedic professions, we used reverse chronology quota screening for the first round of database searching followed by more specific supplementary searching strategies, including hand searching journals and inviting expert solicitation of key papers. This was supplemented by literature reviews, and separate searches focused on COVID-19. The appraisal journaling technique permitted the multidisciplinary team to extract key insights, build on existing knowledge of literature and the NHS, and use these insights to formulate CMO configurations. Multiple rounds of analysis in consultation with stakeholders generated insights into a wide range of tensions facing nurses, midwives and paramedics and a range of interventions that might support their workplace psychological ill-health and wellness.

Chapter 3 Results: characteristics of included literature sources

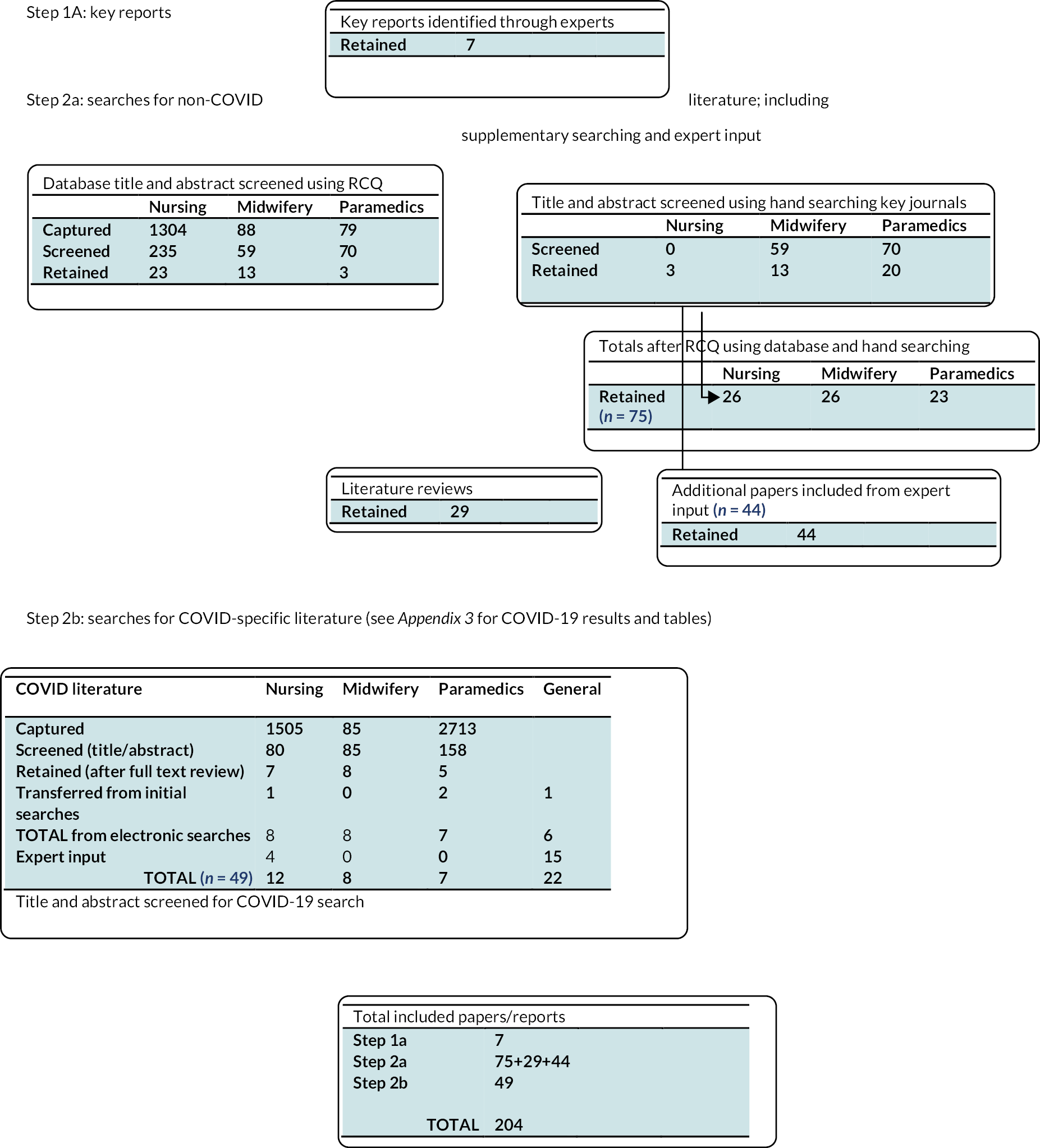

The searches described in Chapter 2 resulted in inclusion of a total of 204 papers through cycles of searching and synthesis, as described in the Methods chapter and illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram for CUP-2 screening and selection of papers.

This included 75 papers in the first cycle of electronic database searches: 26 nursing; 26 midwifery and 23 paramedic; 7 key reports; and 29 literature reviews (see Appendix 7, Tables 21–25) and 49 COVID-19 focused papers, reports and literature reviews (see Appendix 3, Tables 15 and 16).

Of the 75 papers included in the first cycle of searches, 35 were empirical papers (18 nursing, 10 midwifery and 7 paramedic) and 40 non-empirical (e.g. editorials, commentaries and other types of papers and grey literature) (8 nursing, 16 midwifery, and 16 paramedic).

Across all 75 papers, 15 focused predominantly on causes (6 nursing, 4 midwifery, 5 paramedic); 38 on interventions (12 nursing, 16 midwifery, 10 paramedic); and the remaining 22 papers focused on both causes and interventions (8 nursing, 6 midwifery, 8 paramedic).

The included literature reviews were a range of different types of review, including systematic, narrative, integrative and scoping reviews (see Appendix 7).

Chapter 4 What are the causes of psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics? A descriptive analysis

Introduction

This chapter reports on the ‘causes’ of poor mental health in nurses, midwives and paramedics, based upon descriptive analyses of the included literature. The overarching aim of our study was to understand ‘when’ and ‘why’ nurses, midwives and paramedics develop psychological ill-health at work and identify which nurses, midwives and paramedics are particularly affected (‘who’) in which specific contexts. This chapter is intended to provide descriptive analyses of the causes evidenced in our included literature to provide context for the realist synthesis of the included literature (see Chapter 6).

Our approach to understanding the causes of psychological ill-health is bio-psycho-social-cultural. We acknowledge that work-specific causes are only one part of the explanation for the development of psychological ill-health, but they are the focus of this project due to their potential power in explaining the excess levels of psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics compared to the general population.

Decades of occupational stress research has confirmed the relevance of demand, control and support at work, as well as relationships, role clarity and how organisations manage change. 63,69,70 These features of work predict job stress in many different occupational settings, cross-culturally and internationally, and in turn job stress is a strong risk factor for psychological ill-health at work. The strong evidence supporting the relationship between these features of work and psychological ill-health led to them underpinning the UK HSE Management Standards on stress, which provides resources for risk-assessing and reducing work stress. 71 It is therefore not surprising that, in the literature about causes of psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics, there is much discussion of these features. To advance our understanding still further and account for contextual differences, including within and between the different health professions, various authors have highlighted the need for research that takes different working environments into account. 25 In this chapter we have attempted to address the limitations of previous systematic reviews and reports to

-

describe the differences in demographic, structural features of work (service architecture), and well-being indicators between nurses, midwives and paramedics, and also compare to doctors to build on previous work (CUP-117);

-

provide a more detailed and nuanced understanding of why psychological ill-health develops in nurses, midwives and paramedics;

-

examine the literature to understand better ‘who’ is at risk and ‘when’, including identifying the differences within and between our three professions of nurses, midwives and paramedics, going beyond demographic and individual characteristics to also consider the impact of different work environments.

Please see Chapter 2, Descriptive analysis for the methods.

Results

Aim (a) to describe the differences in demographic, structural features of work (service architecture), and well-being indicators between nurses, midwives and paramedics, and also compare to doctors

We extracted and compared key demographic, service architecture (structural features of work) and well-being indicators for nurses, midwives and paramedics, as well as doctors. See Chapter 2, Step 1B for methods of the critical review we undertook, and Report Supplementary Material 1 for the full publication. 4 The comparison with doctors was important since this review built on CUP-1,17 which focused on doctors. Key differences that we found between the professions, that may be important to fully understand causes and interventions to mitigate psychological ill-health include the following:

-

Demographic

-

Gender: nursing and midwifery are female-dominated, whereas doctors and paramedics are more balanced. Various social and economic factors (e.g. being more likely to take on caring roles, live in poverty and experience domestic abuse) can put women at greater risk of psychological ill-health.

-

Age: nursing, midwifery and paramedic science have ageing populations – this ‘demographic timebomb’72 means many experienced professionals will be leaving the profession in the coming years.

-

Ethnicity: there is greater diversity among doctors and nurses than midwives and paramedics. Those with lower diversity have higher vacancy rates.

-

-

Service architecture

-

Turnover and retention remain problematic in all professions.

-

Nearly half of doctors were consultants, but much smaller proportions of staff held high-grade/band roles in nursing, midwifery and paramedic science.

-

Salaries were higher for doctors. There are significant gender and ethnicity pay-gaps across all professions.

-

-

Well-being

-

All reported high job stress, particularly midwives and paramedics.

-

Sickness absence rates for nurses, midwives and paramedics were three times those of doctors, and presenteeism nearly double.

-