Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR127709. The contractual start date was in September 2019. The final report began editorial review in October 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Clibbens et al. This work was produced by Clibbens et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Clibbens et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Mental health crises cause significant disruption to the lives of individuals and their families and can be life-threatening. 1,2 The need for community crisis care is driven by international deinstitutionalisation of mental health care,3 whereby hospitalisation is a last resort and community services are available to respond to mental health need, including in times of crisis. 4 Crisis resolution services originated in the USA5,6 and Australia7 and were later implemented in the United Kingdom (UK)4 and some other countries in the rest of Europe. 8,9

Since the implementation of statutory crisis services in 2000,4 UK crisis services have seen the development of a proliferation of community-based services for people experiencing acute crises embodied in a complex range of service providers, service designs, referral routes and interventions. The voluntary sector has grown significantly in response to gaps in statutory crisis services,10 but this growth has contributed to the confusing array of care pathways, which can be difficult to access and navigate. 11,12 Evaluation study data suggest that too many people are unable to access timely crisis support and are dissatisfied with the help they receive. 12–14

Previous research in this field has, for the most part, focused on evaluating and developing the fidelity of NHS Crisis Resolution Teams (CRTs),15–17 scoping the range of crisis services available nationally (including alternatives to hospital admission)18,19 and understanding the role of the voluntary sector in crisis care. 10,20 This collage of evidence leaves substantial gaps in our understanding about how or why these different crisis services work for people in different circumstances.

A mental health crisis can be defined in different ways,10 including as a relapse in a psychiatric condition, characterised by increased symptom severity (such as voice-hearing, suicidal thoughts and risky behaviours) and decreases in social functioning (including reduced self-care). 21,22 Irrespective of psychiatric diagnoses, a mental health crisis can also be defined as a reaction to adverse life events, leading to increasing disruption for the person and their family whereby their usual coping strategies have failed. 23 Being in a state of crisis can also be conceived as an opportunity for change and may enable people to develop new ways of coping. 24

Mental health crises are serious, are sometimes life-threatening and are often associated with increased risks to the safety and well-being of the person or others. 11,25 The nature of a crisis varies between individuals and has a complex aetiology linked to factors including general health; life stresses; treatment adherence; coping skills; and social situation, including family, work, income, social support and housing. 9,22 This can result in a complex array of health problems related to mental, physical and social well-being that can, if people are unsupported, lead to catastrophic outcomes, such as suicide. 25 Social stigma and a lack of public awareness about mental health contribute to delays in contacting services because of fear of being coerced into treatment or negatively labelled,26 and may influence how and from whom people seek help in a crisis. The complexity of service structures and referral routes may also present a barrier, resulting in people failing to access the most appropriate or timely crisis care for their needs. 12

The Crisis Care Concordat27 was a national response in England to a need for urgent improvement in mental health crisis care. A key part of this strategy has been the development of local plans that bring together multiple agencies through local implementation that is co-ordinated nationally. The Crisis Care Concordat has influenced improvement in crisis services, including more people being seen quickly, more people reporting being taken seriously and fewer people describing their care as poor or having their first contact with the police. 28 Our review of the Crisis Care Concordat27 web pages (www.crisiscareconcordat.org.uk/) identified that the information-sharing component had not been active since 2016 and that many of the data contained there were of poor quality or incomplete. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health,29 which followed the Crisis Care Concordat, sets out the broad mental health policy direction and highlights the importance of effective crisis services.

Crisis services across health, social care, local government and the voluntary sector are shaped by health priorities, including increasing community-based care that is close to home, available urgently 24/711,30 and situated in an appropriate safe place. 31 The involvement of people and their family members in decisions about crisis care2 and improved access for marginalised communities are also important. 11,30 Associated policy priorities include suicide prevention32 and reducing pressure in both hospital bed use and accident and emergency (A&E) attendances. 33

Mental health crisis care is delivered through two main commissioned care pathways: the acute mental health care pathway34 and the urgent care pathway. 35 In theory, CRTs play a central role in co-ordinating crisis care, often through a single point of access (SPA) service. 36 The function of CRTs has been summarised as follows:9

-

assess all patients being considered for acute psychiatric hospital admission and act as gatekeeper

-

initiate home treatment as an alternative to hospital admission until the crisis has been resolved

-

refer to other services for ongoing support

-

facilitate early discharge for those requiring a hospital admission.

In practice, implementation of CRTs appears to be highly variable. According to reports published between 2015 and 2018, less than half of CRTs in England provide 24/7 services,12 the number of referrals varies between 42 and 430 per 100,000 of the population across England,37 and some core CRT functions are inconsistently implemented. 11,38 CRTs have, however, been shown to reduce the cost of crisis care (although estimates vary between 17% and 30%39,40), and they work well for many people. 13,16 Despite this, areas where CRTs fall short of expectations include the lack of a consistent care worker; the timing, duration and frequency of visits; and the tendency for interventions to focus excessively on risks and medicine management. 41,42 A fundamental reason for this variability appears to be the lack of evidence for each of the specific interventions delivered by CRTs, or indeed consensus about what these, or any other crisis intervention, should comprise.

The voluntary sector has a long history of delivering crisis care services alongside statutory care and has gained recognition over the past decade as providing an alternative or an adjunct service, as well as occupying the gaps left by statutory services. 10 Voluntary sector crisis care was, initially, largely focused on providing alternatives to acute inpatient care;43 it has increasingly focused on community interventions such as crisis cafés, night-time drop-in services and services to improve access for marginalised communities. 44 Increasingly, community crisis care is jointly funded between local government, the NHS and voluntary sector organisations, as evidenced in the range of investment in crisis care via NHS non-recurrent funding. 45

Currently, in England, access to mental health crisis services is postcode dependent and a diverse array of different services are available, for example:

-

A&E departments

-

ambulance and paramedic services

-

crisis cafés

-

crisis drop-in services

-

crisis houses

-

CRTS

-

day treatment services

-

mental health liaison teams

-

NHS 111

-

NHS 999

-

out-of-hours teams

-

place of safety suites

-

police

-

specialist home treatment teams

-

street triage teams

-

telehealth

-

general practitioners (GPs).

It is unclear what each of these services offers (and how provision may vary in different contexts), or which mechanisms (such as safety, trust, community involvement) are most effective for whom and in which circumstances.

Study justification

Identified need

There is a drive in the UK to improve experiences of crisis care and to design services and interventions that are effective, timely and accessible to all those in need,30 including services that are able to respond with urgency that equals that of responses to physical health emergencies. 29 It is therefore vital to develop complex interventions from a theoretical understanding of the mechanisms that produce the desired outcomes and in which contexts these work best. The Crisis Care Concordat27 identified a need for crisis care to be developed across multiple agencies, including statutory and voluntary sectors; for crisis care to be largely community based; and for improved implementation across the UK, to avoid crisis care being postcode dependent. Attention has been focused on service providers and settings, but there is currently a lack of evidence about the mechanisms that underpin effective mental health crisis care and how these are activated to resolve crises across a range of contexts. A focus on underpinning theoretical development would enable commissioners to invest in a range of services designed to include the mechanisms that produce the best outcomes across service designs and providers.

Health services are under ongoing financial pressures, and inpatient care is not only undesirable in many cases, but is expensive37 and scarce. 33 Community-based crisis care presents an opportunity for cost-effectiveness, provided that interventions can successfully be developed, tested and implemented to enable improved prediction of outcomes. 46 The development of effective community crisis care may also help to alleviate pressure in the urgent care pathway, particularly in A&E departments.

Previous work

Prior to the commencement of the current study, the review group’s consultations with people who have accessed community crisis care [patient and public involvement (PPI)] showed that these services resemble a tangled web of overlapping services with complex referral routes and blurred functions. PPI participants endorsed a focus on community crisis services on the grounds that they are generally preferred; they provide the respite, information and support that people ask for; and they avoid the need to be away from home and family. These experiences echoed the published evidence in respect of mixed experiences of CRTs, and lent weight to the need to improve understanding of how services work to resolve crises. This could improve people’s ability to access the right care at the right time. 12

Aim

The aim of this study was to identify mechanisms to explain how, for whom and in what circumstances community crisis services for adults work to resolve crises, with a view to informing current and future intervention design and development.

Objectives

-

Use stakeholder expertise, current practice and research evidence to develop programme theories to explain how different crisis services work to produce the outcome of resolution of mental health crises.

-

Use a context, intervention, mechanism and outcome (CIMO) framework to construct a sampling frame to identify subsets of literature within which to test programme theories.

-

Iteratively consult with stakeholders via a series of consultations with an expert stakeholder group (ESG) and individual interviews with diverse stakeholders to test and refine programme theories.

-

Identify and create pen portraits of UK crisis services that provide exemplars of the programme theories to explain how mental health crisis interventions work to explore and explain contextual variation.

-

Synthesise, test and refine the programme theories, and, when possible, identify mid-range theory, to explain how crisis services work to produce the outcome of resolution of the crisis, and hence provide a framework for future empirical testing of theories in the pen portraits and for further intervention design and development.

-

Produce dissemination materials that communicate the most important mechanisms needed to trigger desired context-specific crisis care outcomes to inform current and future crisis care interventions and service designs.

Chapter 2 Review methodology and methods

Introduction to methodology and methods

This chapter outlines how the research team used stakeholder expertise, research evidence and current practice to develop programme theories to explain how, for whom and in what circumstances different community mental health crisis services for adults work to resolve crises. The chapter was developed as per the publication standards for Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES). 47 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline48 for reporting systematic reviews has been used to structure flow charts representing the process of identification and selection of included records.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

Prior to commencement of the study, members of the public, people with lived experience of crisis care, their carers and other stakeholders in statutory and voluntary sector services were consulted to help formulate the general aims and direction of the research. This was achieved through telephone consultations with key voluntary sector service managers, attendance at team meetings of CRTs and a focus group with people who had recently accessed crisis services for themselves or a family member. Visitors from two voluntary sector services involved in pre-protocol PPI consultation continued their involvement through membership of the ESG.

Ethics approval

Following favourable review by an NHS Research Ethics Committee, approval was granted on 8 January 2020 [Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) reference number: 261486; Research Ethics Committee reference number: 19/YH/0347]. Approvals were obtained for recruitment and consent of members to the ESG and individual interviews (see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/TWKK5110).

Study design and rationale

A four-phase realist evidence synthesis design was developed, comprising (1) identification of initial programme theories (IPTs); (2) iterative group and individual interviews to prioritise, test and refine programme theories; (3) focused reviews of prioritised IPT ; and (4) synthesis to mid-range theory. The focus of the realist synthesis was to develop programme theories to explain how different elements of crisis mental health care work provide appropriate and effective responses to mental health crises. Figure 1 summarises the study design.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of study design.

Realist synthesis

The synthesis design drew on realist expertise within the research team. Realist synthesis is a theory-driven approach for understanding existing diverse multiple sources of evidence relating to complex interventions. 47,49 A realist approach aims to understand the interaction between an intervention and its context, mechanisms and outcomes. 47 It draws on realist philosophical ideas to answer a generative causal question that, rather than asking ‘Does “A” lead to “B”?’, instead asks ‘What is it about “A” that results in “B” happening, for whom and in what circumstances?’,50 in other words, how the context (the situation around a person) affects any mechanism (the resources and human responses) to generate an outcome (intended or not). 47,51

How people respond to the resources offered by an intervention is conceptualised in realist syntheses as a ‘mechanism’. Realist programme theories are theories about what an intervention is expected to do and how it is expected to work. Realist synthesis uses both iterative and purposive sampling from a wide range of evidence to develop, refine and test theories about how an intervention works, for whom and in what circumstances. 52

Application of realist methods to explore complex interventions

The current study conceptualised crisis resolution services as heterogeneous, complex interventions, as defined by the Medical Research Council. 46 Complex interventions activate multiple human responses that interact in non-linear ways to produce highly context-dependent outcomes. 47 Realist review offers an optimal approach for exploring how and why complex programmes involving human actions and decisions, such as crisis mental health services, may or may not work, and to inform the theoretical development of intervention(s). 46,47

Theory testing

Outcomes of interventions are causally activated by multiple context-sensitive mechanisms. They happen not only because of what is done in an intervention, but also because of how people respond. 47,51,53 The realist approach offers a participatory method of synthesis that allows for, and indeed capitalises on, continual testing and refinement of emergent programme theories against empirical evidence, data from policy documents and primary data (e.g. from engagement with stakeholders). 49 The involvement of consumers of health care is central to this type of research. 54,55

A theory-driven approach strengthens the potential to inform commissioning, service design and delivery that are sensitive to context across diverse service designs and providers. 56 From the perspective of patients and the public, the theory testing provides a platform for future empirical testing of service designs, thereby improving access and experience of crisis care. This research aims to inform the ongoing development and evaluation of existing mental health community crisis services and interventions.

Programme and mid-range theories

Realist synthesis offers a lens through which a research team can make sense of what is occurring within a complex intervention, particularly in understanding the circumstances in which it is more or less likely to be effective through the identification and testing of programme theories. 47,49,57

‘Programme theory’ is conceived as a fairly concrete set of ideas and observations that explain how different elements of a specific intervention (or programme) interact to produce the intervention outcomes. In contrast, mid-range (or middle-range) theories represent intermediaries between programme theories and ‘all-inclusive speculations comprising a master conceptual scheme’. 56,58 Mid-range theory considers the theoretical and practical issues simultaneously, thus applying theory to practice. Mid-range theories are therefore useful frameworks to guide development of interventions and make generalisations about their application.

In the context of realist synthesis, these ‘minor working hypotheses’ are labelled ‘programme theories’ or explanations for how the programme or intervention works. Mid-range theories are often useful ‘as frameworks for understanding a problem or as guides to develop specific interventions’. 56 According to Pawson et al.,49 mid-range theories can be a product of the realist synthesis process. However, the world of health, social and behavioural research is so densely populated with mid-range theories that it is common to find confirmation of programme theory findings in existing mid-range theory. Although it has not yet proved possible to harvest these theories in a systematic way, realist synthesis harnesses theories identified via the expertise and knowledge of the review team and its experts, through theories referenced in included studies and through a body of theorisation published alongside included studies.

Study methods

Overview of methods

As realist research is essentially iterative,49 decisions about how to proceed are informed by emerging insights into how best to explore the research question. These methods do not readily fit with a linear narrative and so the following description of methods aims to provide a transparent and clear account of the study components, rather than a strict chronology.

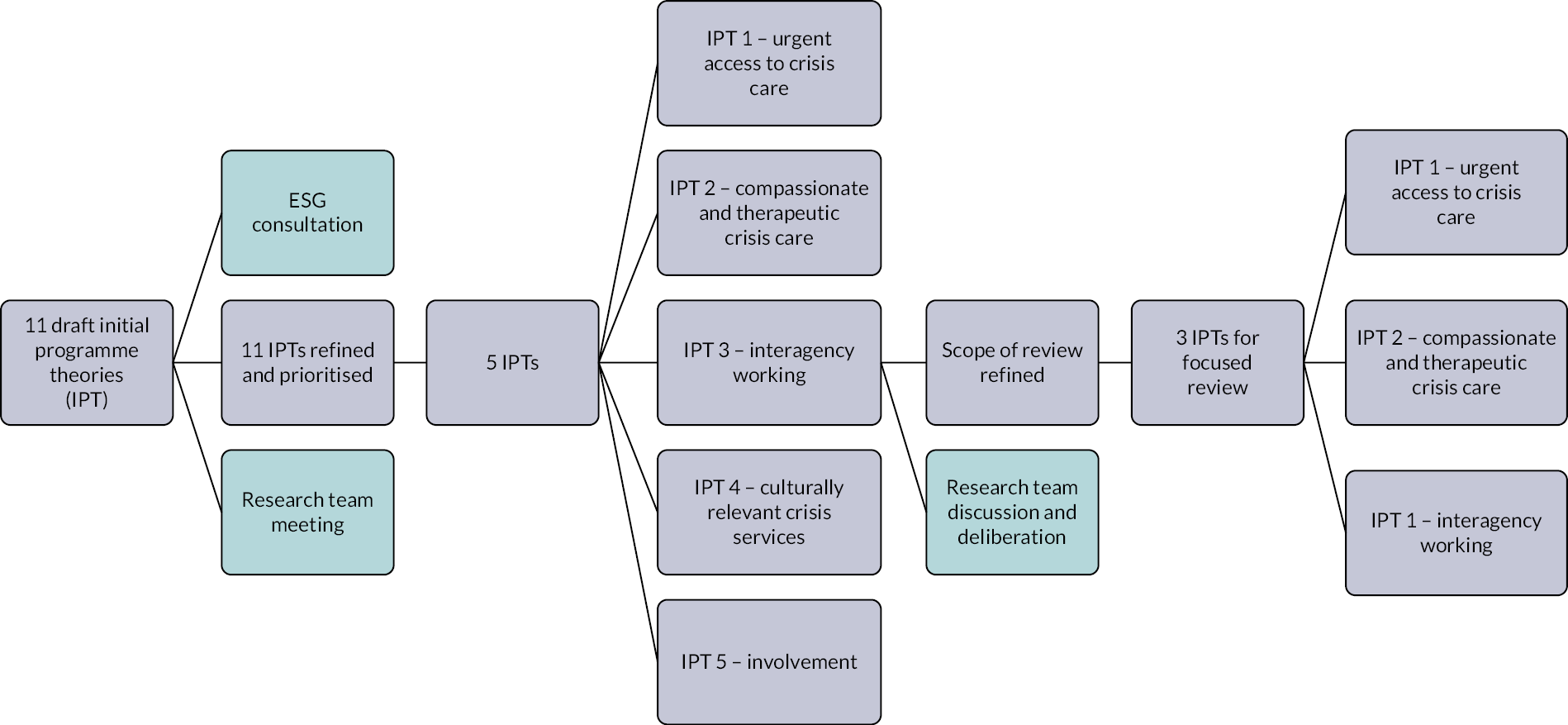

A preliminary search of the literature sought to identify IPTs about how UK crisis interventions and crisis services work. Expert stakeholders were consulted to refine the IPTs and to agree research priorities and the scope for the review. These processes resulted in three prioritised IPTs and were the focus for three focused reviews. Consultation with the ESG and individual interviews facilitated further sense-making, theory testing and refinement. A final search was undertaken to synthesise the programme theory components with mid-range theory. Pen portraits were used to formulate exemplars of service user journeys through the system, to convey generative causal logic, to connect the theory components with real-world experiences of stakeholders and to explain how mental health community crisis interventions work. Figure 2 illustrates the study process, highlighting how the focus contracted and expanded throughout the review.

FIGURE 2.

The scope and focus across the life of the synthesis.

Changes to the study plan, including in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

This research commenced in September 2019 and was largely conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic precipitated ongoing adjustments to the project milestones and timeline: delaying ethics approval, prolonging uncertainties about the feasibility of face-to-face meetings and interviews, limiting options for recruitment of participants, restricting access to practitioners and service users, challenging continued engagement of stakeholders and resulting in unexpected absences among the research team. Hence, these challenges were addressed in the context of national restrictions on accessing practice areas and delays in communication due to the reduced capacity of many organisations. For example, the ESG was established before the start of the government restrictions. They met face to face in February 2020. Subsequent delays, postponements or cancellations and a switch to video link may all have affected the ESG contribution.

The original plan to interview up to 50 experts in crisis care from across the UK was modified. After postponement of interview recruitment, it was planned to include 25 participants; finally, 19 participants were recruited to 20 interviews. In addition, issues related to gaining ethics approval during the COVID-19 pandemic restricted recruitment to three NHS health trusts and one NHS ambulance trust in England. The planned six pen portraits was reduced to three, linked to each of the three prioritised programme theories. The original plans to support the ESG members to produce a short animation to share the findings with a wide audience has not been achieved owing to delays earlier in the project delivery and funding limitations.

Focus of the review

The research team focused the review59 using the definitions of crisis stated in the Crisis Care Concordat,27 which highlights the architecture of crisis services, summarised as follows:

Access to support before crisis point . . .

Urgent and emergency access to crisis care . . .

Quality of treatment and care when in crisis . . .

Recovery and staying well . . ..

Crisis Care Concordat27

The review focused on ‘Urgent and emergency access to crisis care’ and ‘Quality of treatment and care when in crisis’, specifically on initial contact and access via the crisis aspect of services, thereby excluding home treatment and onward referral.

Expert stakeholder group engagement, recruitment and membership

Following ethics approval via IRAS/the Health Research Authority, expert stakeholders (n = 15) were recruited through NHS trusts, the voluntary sector and service user/carer networks. The ESG members included professional and user/carer expertise. Two research team members (JT and NC) maintained contact with two voluntary sector organisations following the pre-protocol PPI, which aided engagement and recruitment of those with lived experience to the ESG. Michael C Ashman led and co-ordinated the recruitment of all stakeholders and co-chaired the group with Jill Thompson.

The ESG membership comprised six people with lived experience of using crisis services, a carer, a peer support worker, a consultant psychiatrist, a mental health nurse, an NHS crisis service manager, a mental health social worker with approved mental health professional (AMHP) experience, a voluntary sector manager, a mental health services commissioner and a mental health policy specialist.

Membership of the ESG reflected diverse community crisis care services, recognising that no single individual or group holds all knowledge about crisis care. 60 All were based in England at the time of the consultation. Many participants described dual roles: the peer support worker had (of necessity) crisis service lived experience, but many others had acquired lived experience, either personally or through carer responsibilities. Membership of the ESG remained largely stable throughout the study, with the following exceptions: one service user dropped out, commissioner expertise was covered by two people, and a voluntary sector manager was replaced by their new manager. Table 1 charts the composition of the ESG.

| ESG rolea | Number of individuals |

|---|---|

| Carer | 1 |

| Commissioner | 2 |

| Consultant psychiatrist | 1 |

| Mental health nurse | 1 |

| Mental health policy specialist | 1 |

| Mental health social worker/AMHP | 1 |

| NHS crisis service manager | 1 |

| Peer support worker | 1 |

| Person with lived experience | Initially 6, reduced to 5 during course of project |

| Voluntary sector manager | 1 |

| Total number of individuals in ESG | 15 |

Expert stakeholder group consultations were held in February, September and December 2020 and April 2021. The first ESG meeting was face to face and was recorded through photographs and audio-recordings; subsequent meetings were via recorded video link.

The realist searches

The search followed the six principal procedures for a realist search61 (Box 1). Search strategy development was supported by expert guidance from an information specialist.

-

Formulate specific questions as lines of inquiry.

-

Ascertain previously published research, refining the research question as necessary.

-

Identify theories as hypothetical explanatory accounts of how an intervention works in order to identify programme theories.

-

Identify empirical evidence for context–mechanism–outcome configurations to test and refine the programme theories.

-

Respond to new information needs as they emerge during testing and refining of the IPT.

-

Explicit and transparent documentation of the search process.

Adapted from Booth et al. 61

Search for initial programme theories

The search for IPTs sought to find data to develop IPTs related to the architecture of crisis interventions and crisis services in the UK context. 61 During August and September 2019, an information specialist conducted the search using Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (see Appendix 3 and Report Supplementary Material 1). 47 As programme theories may be located in the title, abstract and sections other than the results,62 the search strategy was designed to identify programme theories by screening full texts.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusions

Literature was included if it related to people aged ≥ 16 years accessing adult mental health services for a crisis related to mental health, relevant to the UK context. Reports from the European Union, the USA, Canada and Australasia, with similar structures and a shared history of development, were also considered relevant. Settings included health services, voluntary sector, social care and police crisis services based in community settings. Published articles, reports, theses and book chapters were considered eligible if they were published in the English language. No date limits were used for the theory scoping searches, but focused reviews included documents published between 2000 and 2021.

Exclusions

General hospital inpatient care and acute inpatient mental health care, including acute mental health wards, psychiatric intensive care and short-stay acute wards, were excluded. Literature related to crises without a mental health focus and crisis services specifically commissioned for children and young people aged <16 years was outside the study scope and not eligible. Records that did not contain relevant theory were not eligible.

Search terms: initial programme theory identification

The research team identified 25 relevant terms relating to setting (Box 2). Each setting was combined with a filter for identifying logic models together with terms related to mental health and crisis care. Logic models are representations of programme theory that include a focus on steps in the explanatory causal chain including inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes. 52

-

NHS 111.

-

NHS Direct (Wales).

-

24 hours.

-

Helpline.

-

Crisis line.

-

Accident & emergency (A&E).

-

Hospital.

-

999 (telephone number for emergency services in the UK).

-

GP.

-

Liaison psychiatry service.

-

Local on-call mental health services.

-

Social services.

-

Local Community Mental Health Team.

-

Crisis houses.

-

Crisis teams (CRHT).

-

Café.

-

Drop in.

-

Day services.

-

Day treatment.

-

Police.

-

Street triage.

-

Crisis resolution teams (CRTs).

-

Community.

-

Decision.

-

CRHT, Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment Team.

The first 50 results for each of the 30 systematic searches carried out in Google Scholar were reviewed. When at least one potentially relevant result was found, a further 50 records were scanned; summary search terms are shown in Appendix 3 and full search terms are in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Initial programme theory identification

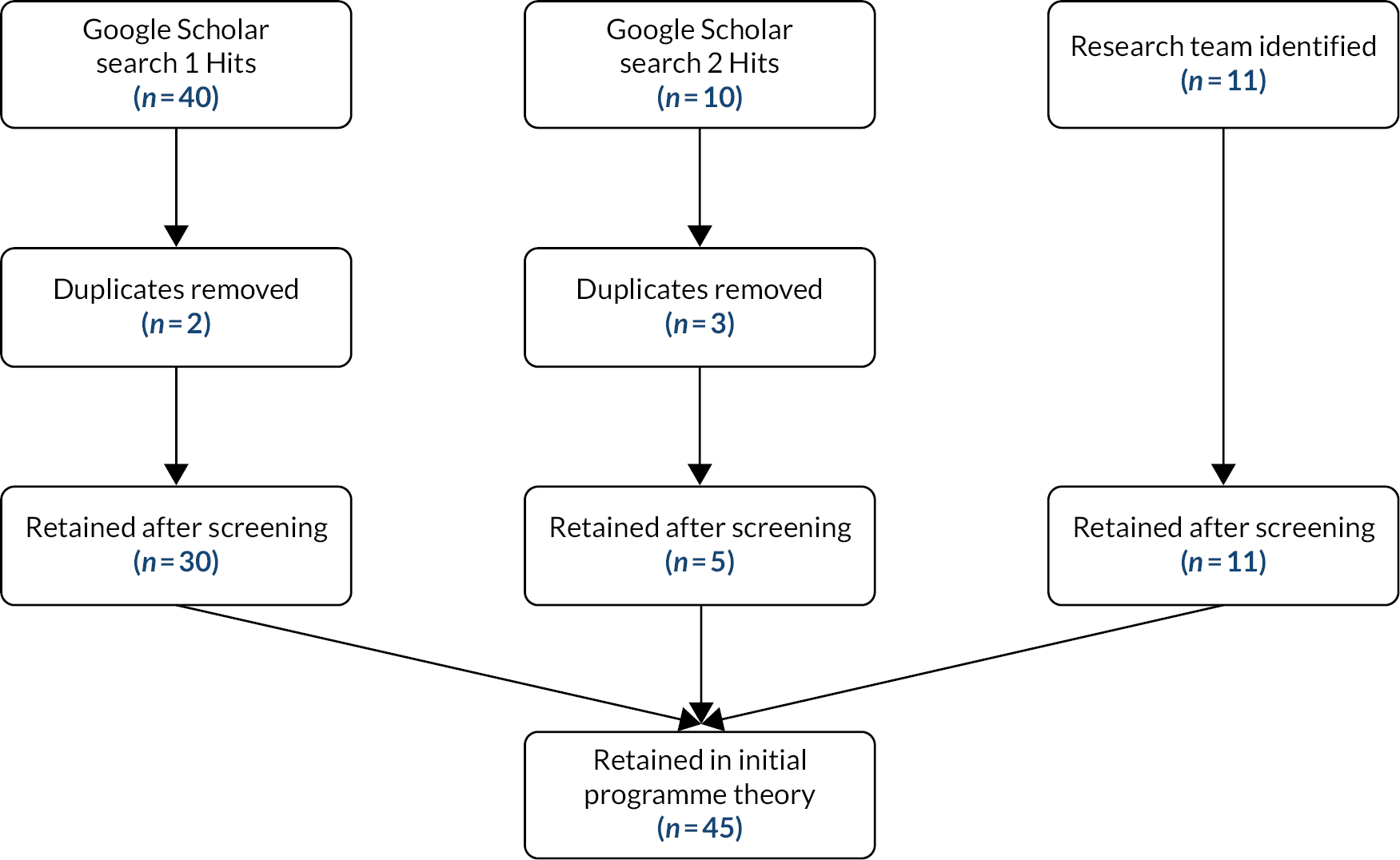

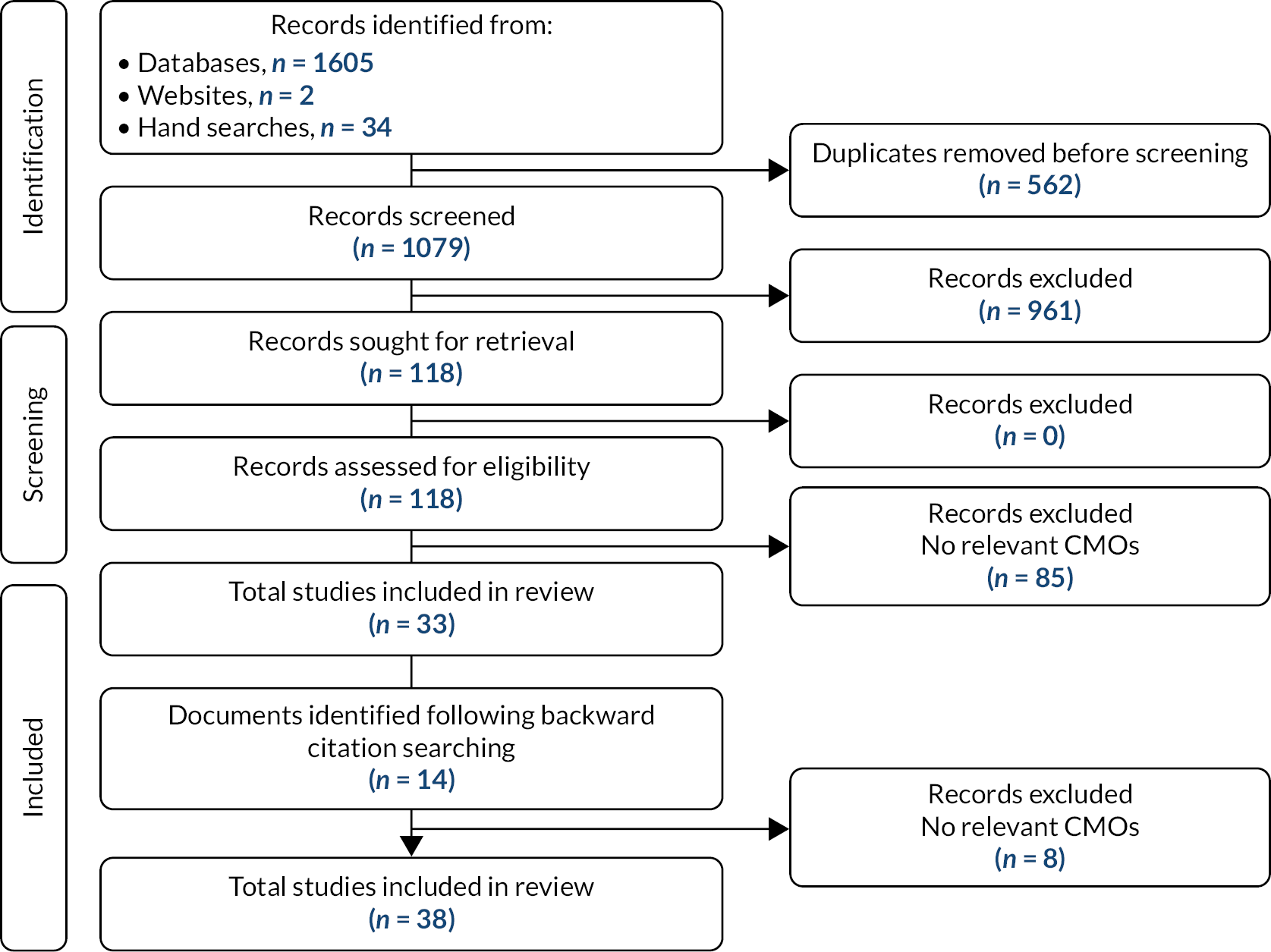

Selected records were used to construct a long list of IPTs. 61 All articles, reports, doctoral theses and book chapters identified by the information specialist (n = 55) were read in full by three researchers independently (KB, LS and NC). Disagreements were resolved through discussion and resulted in 10 records being excluded because they were out of the scope of the study (n = 5) or contained no relevant theory (n = 5). Data on CIMOs were extracted to a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet from 45 records (see Appendix 1). The results of the search for IPTs is shown in a flow chart in Figure 3. 48

FIGURE 3.

Results of search for IPTs.

Data extraction from 45 included documents to an Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (see Appendix 1) according to the CIMO framework resulted in a total of 247 incomplete lines of IPT. At this stage, not all aspects of the CIMO framework were complete in each line of theory. Members of the research team (NC, LS and KB) used a sense-making exercise to compare, contrast and synthesise the initial theories from the extracted data. The extraction and synthesis processes were supported by regular discussions with all members of the research team. Once the research team reached consensus on 11 embryonic IPT areas (see Box 3), these were discussed with the ESG.

-

A mature multi-agency approach and joint commissioning.

-

Urgency of response.

-

Compassionate care.

-

Involvement.

-

Access to crisis care and treatment.

-

Culturally relevant care and treatment.

-

Ability to meet the needs of vulnerable groups.

-

Service configuration.

-

Therapeutic intervention.

-

Sustaining professionals/staff.

-

Professional/staff skills and knowledge.

Involvement of the expert stakeholder group

The ESG worked in partnership with the research team to discuss, refine and test theories, and to prioritise topics for focused review. Subsequently, the ESG scrutinised the focused review outcomes and contributed to the overall synthesis. Four ESG consultation meetings took place. Engagement with stakeholders took place at key stages of the research to ensure that important, yet potentially hidden, subtle contextual conditions were not missed. 63

Expert stakeholder group involvement in agreeing on the focus and priorities

In the first meeting, held face to face in December 2019, ESG members were introduced to the project and methods, and were provided with information about taking part and the opportunity to ask questions before providing written consent. One lived experience participant declined involvement in the ESG, but requested to be invited to take part in an individual interview.

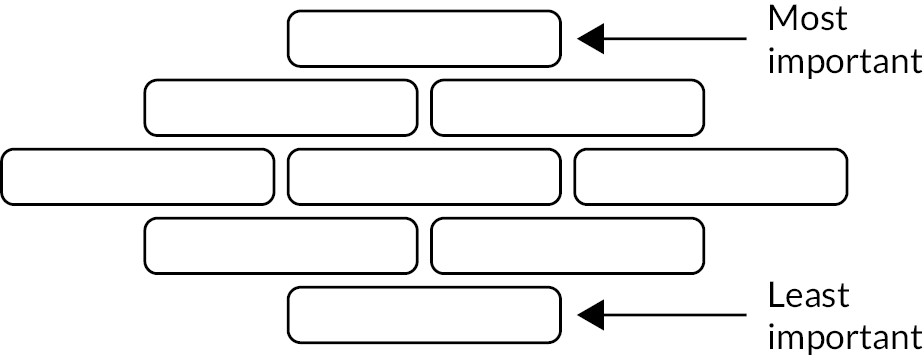

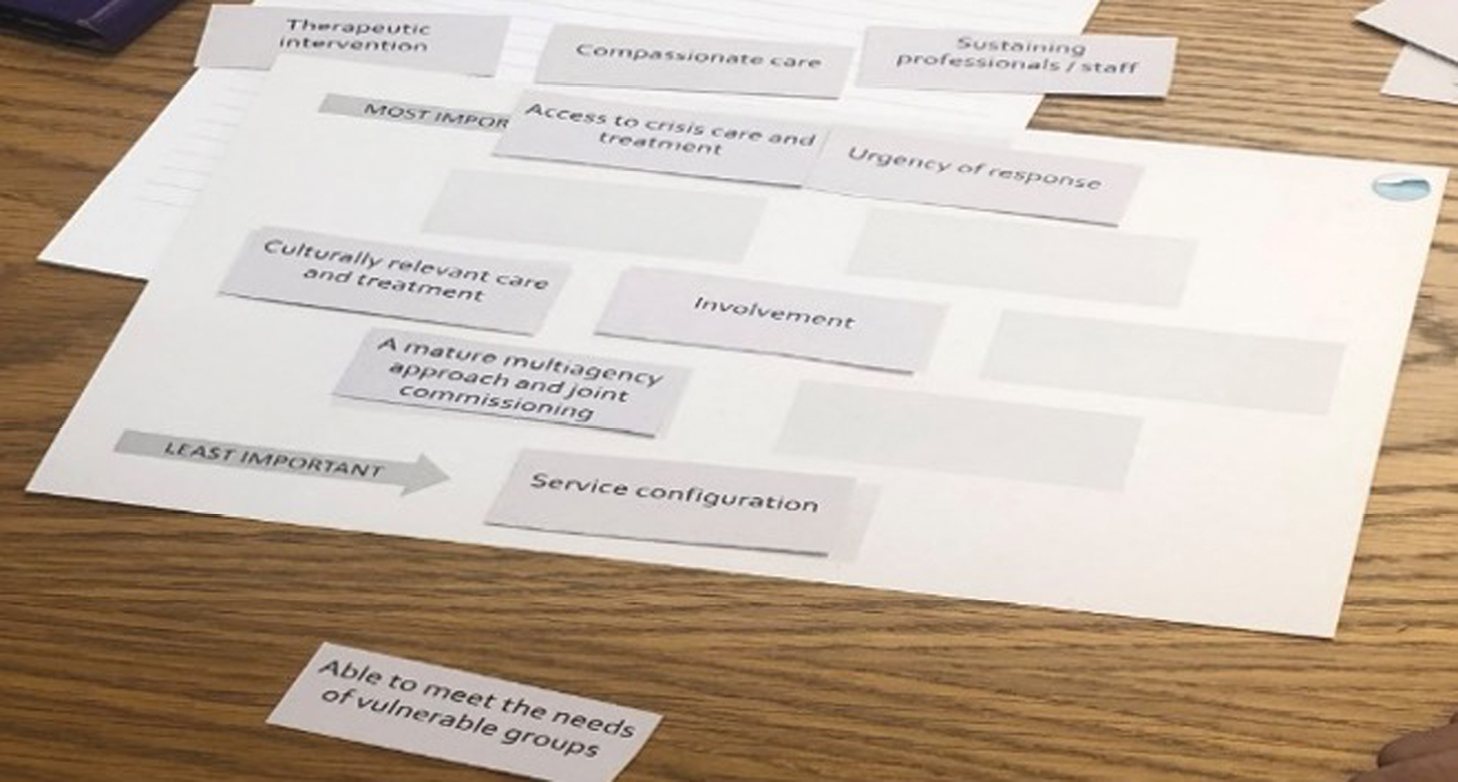

Expert stakeholder group members worked in small groups of mixed expertise to use their expertise to make sense of, debate and rank the importance of the 11 embryonic IPT areas (see Box 3). This was achieved using the Diamond-9 consensus and prioritisation approach, which encourages participants to work together, developing and exposing thinking. 64 A template used for the exercise is shown in Figure 4 and a photographic image of the ESG group deliberations shown in Figure 5. Each of the programme theory areas were printed onto individual cards along with blank cards to facilitate new ideas from the ESG deliberations. The stakeholders organised themselves into four groups so that they could prioritise, reject, or amalgamate any of the 11 embryonic programme theory areas using a card sort process. Each of the four groups included experts by lived and professional experience. Expert views and rankings were aggregated across the groups to generate overall agreement on refined and prioritised IPTs.

FIGURE 4.

Diamond-9 prioritisation template.

FIGURE 5.

Photograph of ESG members deliberating IPT using Diamond 9.

The results of the ESG discussions and Diamond-9 process showed that the most important priority for the ESG members was ‘urgency of response’. The pivotal role of urgency and easy access was highlighted by one ESG member:

. . . if that’s wrong, everything goes out of line because things aren’t happening at the right time with the right people.

The theories, ranked in descending order of importance following urgency of response, were compassionate care, access to crisis care and treatment, culturally relevant care and treatment, and involvement. Sustaining professionals/staff was identified as the least important.

The initial theories ‘service configuration’ and ‘mature multi-agency approach and joint commissioning’ were not prioritised by the ESG. However, after discussion between the research team and the ESG, the research team retained the ‘mature multi-agency approach and joint commissioning’, considering it integral to the architecture of crisis services and fundamental to the research focus. Through an iterative process of discussion and deliberation between the research team and ESG members, a reduced and refined set of five IPTs were agreed. These IPTs were developed from the data extracted and recorded in the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (see Appendix 1). These are outlined as a narrative summary in Table 2.

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| IPT 1: crisis services can be accessed urgently | ||

| When community crisis services are adequately resourced, work together across agencies, are known to people and are easy to access . . . | People are more satisfied with the service and are more motivated to engage . . . People believe that the service is ‘for them’ . . . |

Which results in people seeking help earlier in the crisis. People understand what is on offer and make informed choices about where to seek help. Expectations for timely support are met |

| Staff trust that they have the resources to respond | Staff use resources to provide timely responses according to need | |

| IPT 2: care in a crisis is compassionate and therapeutic | ||

| When community crisis services provide compassionate and therapeutic care that is non-judgemental, dignified and safe, and such care is provided by staff who have relevant therapeutic skills, knowledge and support . . . | People feel listened to and taken seriously, and trust staff . . . | Which results in reduced distress (and duration of distress) and in therapeutic engagement |

| Staff trust the organisation and their peers and believe that they have the skills and resources needed for compassionate care | Staff retain compassion, have confidence | |

| IPT 3: community crisis agencies work together | ||

| When community crisis services work effectively and seamlessly together across agencies and providers . . . | People have a sense of connection that prompts trust. People in crisis and the staff experience a sense of ownership and affiliation . . . Staff are prompted to have a wider systemic understanding and learn together . . . |

Which results in shared decision-making, improved communication between agencies, improved knowledge of services across the system Which results in reduced likelihood of traumatic repeat assessments Which results in transitions between services that are seamless and timely |

| IPT 4: community crisis services are culturally relevant | ||

| When community crisis services are culturally relevant, by employing people who share characteristics of the local population, and when they train staff in knowledge and appreciation of culture and ethnicity in relation to health and mental health . . . | People are less stigmatised and stereotyped, prompting trust and willingness to engage . . . | Which results in people seeking crisis support sooner and being less likely to require hospitalisation or involvement from the criminal justice services |

| Staff are confident, aware and sensitive to issues of culture and ethnicity | Staff have skills and knowledge that enable cultural sensitivity; they adapt interventions and refer appropriately across the crisis care system | |

| IPT 5: community crisis services are developed and delivered with involvement of service users | ||

| When there is meaningful involvement of people with lived experience of crises and their family and friends, that is recognised by those designing, leading and delivering services and is appropriately resourced . . . | People recognise the service as being for them; they trust services and believe that the service reflects their expectations . . . | Which results in increased engagement and community recognition and acceptance of the service |

| There is ownership and affiliation. Equalising of power is facilitated | People have an increased sense of personal control (agency) | |

Defining the scope for the focused review

Following the RAMESES guidance on defining and refining the study scope,47,53 the ESG and research team jointly discussed the scope of the review and the selection of IPTs for focused review. First, an overarching focus on the initial stages of a person in crisis seeking help and securing support and the quality of the support provided (key intervention points in the architecture of crisis services as identified in the Crisis Care Concordat27,28) was agreed. Although the term ‘multi-agency’ was initially adopted, it was replaced by ‘inter-agency’ in the course of the team discussions because of the perceived synergy between agencies that work together effectively in crisis care. The two terms can be interpreted as broadly synonymous. 65

Figure 6 illustrates the process used to refine the scope of the study and identify the IPTs for focused review: from 11 embryonic IPT areas (see Box 3) to five IPTs (see Table 2) and, finally, resulting in three IPTs retained for focused review. The deliberations between the ESG and the research team resulted in amalgamation of ‘urgency of response’ and ‘access to crisis care’ into IPT 1 (crisis services can be accessed urgently) as they were felt to be inherently linked. The ESG and research team also combined compassionate and therapeutic care into IPT 2: care in a crisis is compassionate and therapeutic. The third and final programme theory combined multi-agency working and joint commissioning, amalgamated to IPT 3: inter-agency working.

FIGURE 6.

Figurative illustration of the decision-making process to prioritise and refine the scope of the review.

IPT 4, culturally relevant care (although highly relevant), was acknowledged to require consideration beyond the scope of the current study. Our initial searches revealed little published evidence focused on culturally relevant crisis care at a level that was sufficiently granular to provide adequate explanation. It was decided that IPT 4 would benefit from a future primary realist evaluation to generate new explanatory evidence. Data pertaining to cultural relevance, when identified as relevant to causal explanations, have been included in IPTs 1–3. IPT 5, involvement, was felt to be cross-cutting and has been reported when causally linked to concepts in focused reviews for IPTs 1–3.

Pen portraits

At the fourth and final ESG meeting, a pen portrait method was used to support theory development. Pen portraits offer an analytic method to focus large volumes of qualitative data while maintaining richness. 66 In ESG meetings, brief vignettes (see example in Report Supplementary Material 2) were used to structure discussions. These vignettes enabled the ESG members to use their expertise to relate the evidence from the included documents to real-world experiences. Discussions took a realist perspective that sought to explain and identify causal links.

Pen portraits were developed once the focused reviews were more fully developed, and provided an illustration from a real-world perspective of the causal link between mechanism and outcomes. They were constructed using synthesised data to map components of crisis interventions structured around the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)67 (see Box 10 and Appendix 2), together with context, mechanisms and outcomes, and to inform future empirical testing of the programme theory. The use of vignettes and pen portraits facilitated discussions with ESG members throughout the research, enabling theory to be presented to stakeholders in an accessible way, and to test and refine the understanding of CIMO in crisis services.

Rather than a description of any individual experience, the pen portraits provide examples of people experiencing crises, their circumstances and the crisis responses. Three pen portraits were developed (i.e. one drawn primarily from each focused review) to illustrate real-world examples of the theories in action; they were subsequently refined following ESG consultation and through the process of synthesis across focused reviews and mid-range theory. The draft pen portraits were discussed between research team members to ensure that the stories effectively linked to IPTs 1–3 (see Table 2) and interventions described in TIDieR Lite (see Box 10 and Appendix 2) before presenting them to ESG members. At the fourth and final online meeting between the ESG and the research team, ESG members were asked to sense-check three draft pen portraits, by moving between three subgroups. Discussions were recorded and reviewed by members of the research team (NC, KB and LS) and used to refine the pen portraits.

The discussions told us that the pen portraits were recognisable to ESG members, who endorsed them as exemplars of good crisis care. Some found them somewhat idealistic and were not convinced that the system could respond as the pen portraits described. Discussion of the final pen portrait versions is included in the three focused review chapters: Chapter 3, IPT 1 pen portrait: urgent and accessible crisis services; Chapter 4, IPT 2 pen portrait: compassionate and therapeutic crisis services; and Chapter 5, IPT 3 pen portrait: community crisis agencies work together.

At this final meeting, ESG members were invited to complete an ESG evaluation; the template for feedback and a summary of the evaluation results are in Report Supplementary Material 2, with a blog providing a personal account of participating in the ESG.

Testing and refining the initial programme theory via focused review

Focused searches were conducted to identify literature to test the IPTs61 between January and July 2020 by an information specialist (Ruth Wong). Iterative cluster searching was carried out by the researcher in each focused review up to March 2021 (NC, KB, LS). Included documents were published between 2000, when community crisis services were first mandated by the UK government,9 and March 2021.

Sources for empirical testing

Ten academic databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science Core Collection (Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Abstracts and Indexes (A&I), and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC).

Search strategies combined mental health keywords with keywords for crisis and keywords for each programme theory, together with a highly sensitive and published geographical UK filter,68 using the AND Boolean operator. The filter was applied to all database searches except ASSIA, ProQuest Dissertations & Thesis A&I and HMIC. All searches were restricted to English-language studies. The search results were managed using EndNote (X9 version 3.3) [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] (see Appendix 3 for a summary of search strategies and see Report Supplementary Material 1 for the full search strategies).

Theory-orientated searches

Theory-orientated, focused review searches were conducted from February to March 2020, with supplementary searches conducted in July 2020. The intention was to sample, rather than to identify an exhaustive body of literature. 69 A Google Custom Search (Google Inc.) was created to facilitate supplementary searching of grey literature sources across 32 UK websites (January–April 2020), with particular attention paid to NHS England publications, the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Centre for Mental Health (see Appendix 3 for a summary of grey literature searches).

Cluster searching

The search strategy was developed iteratively and revisited at predetermined milestones, using different permutations and additional concepts. 69 As each focused review progressed, the lead author considered how each document contributed to the aims and objectives of the realist synthesis and to theory development. When relevant, lead authors deployed ‘cluster searching’, an innovative purposive sampling approach, to identify ‘clusters’ of related publications. This approach added to the conceptual richness and contextual thickness of the studies identified through topic-based searching. 69 Sibling (i.e. outputs directly linked to a single study) and kinship (i.e. papers sharing a common contextual/conceptual legacy) reports were sought to add richness while preserving rigour and relevance. 69 The research team pursued citation networks, using Google Scholar and Web of Science. The iterative approach enabled the research team to search for data beyond the literature particular to community crisis services, but also to test veracity in the context of UK community crisis interventions. The theory was continually tested and refined through expert consultation and individual interviews. The ESG also recommended records, based on its expertise. Searching continued until sufficient data were found (‘theoretical saturation’) to conclude that the programme theory components were coherent and plausible. 53,70

Screening

Retained records included primary research, reports, policy documents and expert opinion. Using EndNote (X9), retrieved records were screened for relevance by three members of the research team (LS, KB and NC). Full texts of the selected records were obtained and screened (see Figures 7–9). A list of the retained records from the searches for initial theory is provided in the Appendix 4.

Appraisal of relevance and rigour

A modified realist appraisal tool (Dr Justin Jagosh, director of the Centre for the Advancement of Realist Evaluation and Synthesis, visiting professor at the University of the West of England, Bristol, and a research fellow at the University of Surrey, personal communication, 2021) was used to appraise relevance and rigour across all the retained records (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Relevance was determined to be less substantial, medium or high. A document was considered highly relevant when the framing of the research and the research questions closely matched the review questions. Rigour was assessed by quality appraisal of the study methods, using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)71 (see Report Supplementary Material 3), in all documents where a methodology was available for assessment (J Jagosh, personal communication). 53

Data extraction

An analytical framework was created by the research team; the data extracted included the publication type, origin, type of service or intervention, and influencing factors (i.e. theoretical perspective). When it was possible to make inferences, the data extracted were attributed to context, mechanism or outcome. Data suggesting explanatory links between context and mechanism, between mechanism and outcome or between context and outcome were also extracted. Relevant data from the retained records were coded against the analytical framework (i.e. deductive coding) or by identifying new codes (i.e. inductive coding). 47,49,53 Data were extracted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (see Appendix 1) and coded in NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Individual realist interviews

The realist interviews were theory driven, and used conversation to explore participant views, with the specific aim of investigating ‘how, where when and why programmes are and are not effective’. 59 Ethics approval was obtained for individual interviews, as outlined in Study design and rationale (see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/TWKK5110).

Recruitment

Purposive strategies were used to identify mental health service users, carers and professionals from diverse organisations including the NHS, local authorities, universities and the voluntary sector. Expertise not represented in the research team or the ESG was prioritised. Representation was sought from urban and rural areas, as well as mental health trusts, ambulance trusts and the police force. Study information was distributed to potentially eligible participants, who could contact the research team if they wanted to participate.

Sample

Following revision of the size and scope of the sample frame, in view of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, study recruitment targeted an updated intended sample size of 25. The final sample comprised 20 interviews, with 19 expert interviewees (one participant took part in two interviews). Table 3 details the sample profile, along with the corresponding interviewee codes.

| Interviewee background | Interviewee context | Code | Participants (N = 19) (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 (where relevant) | |||

| Academic | Voluntary sector | KB4 | 1 | |

| Ambulance emergency care assistant | Ambulance trust | LS3, LS4, LS5 | 3 | |

| Carer | Paramedic | Carer accessing crisis care and ambulance trust | NC3 | 1 |

| Manager | CRT manager | KB6, LS1 | 2 | |

| Mental health nurse | SPA, CRT, A&E liaison | LS2, LS6, NC1, NC2 | 3 | |

| Paramedic | Ambulance trust | KB2, NC4 | 2 | |

| Police | Street triage | KB1 | 1 | |

| Policy expert | Social worker | CMHT, AMHP | KB3 | 1 |

| Psychiatrist | CRT | KB5, LS7 | 2 | |

| Service user | Crisis services | JT1, JT2, JT3 | 3 | |

Strategy for realist interviews

A bank of semistructured interview questions, formulated in accordance with a realist interviewing approach,72 was agreed within the research team (see Report Supplementary Material 4). Interview participants were asked to comment on the evidence and on how thinking in the research team was developing. Participants were selected for interview based on their expertise in one or more programme theories. All interviewers had access to all interview questions and could opt for relevant questions as the interview progressed (see Report Supplementary Material 4).

Participants were invited to take part via Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation), Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA)73 or telephone, and were provided with a participant information sheet and consent form in advance. Verbal consent was audio-recorded before the interview; interviews lasted up to 1 hour.

Four research team members conducted the interviews (NC, LS, KB and JT). Interviews were recorded and saved to a secure, password-locked server accessible by the research team. The interview recordings were reviewed, and detailed notes transcribed by each interviewer and shared with the research team. Following discussion between the research team members, a deductive coding process was used to connect interview data with the IPTs in the focused reviews. Interview data were used to test the veracity of the IPTs, particularly where there were gaps in the published evidence, but also to strengthen real-world understanding of the architecture of crisis services and causal links between context, mechanism and outcome. Excerpts from the interviews are reported throughout the focused review chapters in the form of discussion and direct quotations. After the completion of 20 interviews, it was agreed that there were sufficient data to inform the programme theories.

Data synthesis and theory refinement

Data from the focused review chapters, which included contributions from ESG and individual interviews, were synthesised to refine the programme theories. The synthesis enabled the team to identify important mechanisms that need to be ‘activated’ in a programme or intervention, together with links between the contexts and the key mechanisms. Synthesised context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations are presented in table in Appendix 5. Confidence in the synthesised findings was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation – Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual). 74 GRADE-CERQual assesses confidence at the level of findings in four domains: (1) methodological, informed by the MMAT;71 (2) relevance, supported by realist appraisal (J Jagosh, personal communication); (3) coherence, the extent to which the finding is grounded in the data; and (4) adequacy, the degree of richness and quantity of data. 74 Discussion about the relationship between intervention strategies and their underpinning mechanisms is provided in Chapter 6.

Developing a mid-range theory

A final search was undertaken to link the three programme theories with mid-range theory. 61 Mid-range theories were identified relating to inter-agency collaboration,75,76 feeling in control,77 breaking point,78 a strengths perspective,79 compassionate care80,81 and protection motivation theory. 82

Evidence sources

Sources of evidence for the study are summarised in Table 4.

| Source | Use |

|---|---|

| Literature (academic; grey, including websites and reports) | Background search for logic models and candidate programme theories |

| ESG consultation | Selection of broad theory areas for focused review; theory testing |

| Literature (academic; grey, including websites and reports) | Focused reviews to test programme theories for urgency and accessible care, compassionate and therapeutic care, and inter-agency working |

| Individual interviews with experts | Theory testing |

Summary

This chapter provides the rationale for undertaking the realist synthesis, documenting the search for IPTs, the procedures for scoping the literature and identifying the IPTs, the search for empirical evidence, and the strategy for finalisation and synthesis of the programme theories. 61 It supplies additional detail on how the expert stakeholders contributed through the collection and analysis of primary data and the use of pen portraits to connect the theories to real-world stakeholder experience, facilitating the assessment of quality and rigour,61 following RAMESES publication standards47 (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

Structure of review chapters

Chapters 3–5 report the three focused reviews to test and refine IPTs 1–3 (see Table 2): IPT 1, crisis services can be accessed urgently; IPT 2, care in a crisis is compassionate and therapeutic; and IPT 3, community crisis agencies work together.

Chapters 3–5 are structured to follow the realist CMO convention. The context is reported first, followed by outcomes and unintended consequences, and, finally, mechanisms and conclusions. The IPTs are explained from three circumstances: the person in crisis and their family, front-line staff and the crisis care system. Each chapter concludes with an ‘if – then – leading to’ statement and a pen portrait to illustrate the IPT from a real-world perspective. Synthesis across the findings from IPTs 1–3 and mid-range theory is discussed in Chapter 6.

Chapter 3 Focused review for initial programme theory 1: crisis services can be accessed urgently

Introduction

This chapter examines the first of the three IPTs (i.e. crisis services can be accessed urgently), identified from the initial searches outlined in Chapter 2.

If crisis services are adequately resourced, work together across providers, are known to people and use shared decision-making, then there is satisfaction with crisis care that meets expectations for urgency, people believe in the service and there is trust, leading to people accessing urgent help that is timely and appropriate to their individual needs.

This chapter first describes the characteristics of urgent and accessible services, including interventions and intervention components identified in the literature to enhance their development and delivery. The evidence base for urgent and accessible services, the outcomes of urgent and accessible services and the unintended consequences when key components are not in place or are not effective are described. Next, the chapter describes the mechanisms for urgent and accessible services, demonstrating how they may be facilitated at different points within mental health community crisis care. A narrative drawn from the literature is supported by contributions from the ESG discussions and interviews. The chapter concludes with an overview of how urgent and accessible services can enhance mental health crisis care, using the ‘if – then – leading to’ convention.

Context: urgent and accessible crisis care

The theory component ‘urgent and accessible care’ was prioritised through discussion between the research team and the ESG. Feedback from one breakout group of ESG members emphasised the primary importance of urgent access:

Without urgent access to services in a mental health crisis, nothing else will work.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and NHS England35 define ‘emergency’ and ‘urgent’ situations as follows:

An emergency is an unexpected, time-critical situation that may threaten the life, long-term health or safety of an individual or others and requires an immediate response. An urgent situation is serious, and an individual may require timely advice, attention or treatment, but it is not immediately life threatening.

NICE, the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and NHS England. 35Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Policy and published evidence state that crisis interventions should be ‘timely’ or ‘urgent’,35,83,84 yet this has been poorly defined in a mental health context. 83,84 The focus on waiting times excludes some agencies providing crisis care, contrary to the aspiration for multi-agency collaboration of the Crisis Care Concordat. 28,86 The risks to safety posed by a failure to respond in a timely way have driven the development of clinical decision tools. 86–88 Clinical approaches including decision tools are not, however, universally accepted by people using services or by all types of community crisis service. 10

Uncertainty as to what constitutes a mental health crisis, uncertainty as to the intervention required10,85,89,90 and the heterogeneity of the population seeking crisis support85,89 means that people access crisis services via a complex range of routes. 10,15,78,89,91–93 The route into crisis care is different for those known to mental health services than for people seeking crisis support for the first time. 89

Services have been developed to improve urgent access in a range of settings, including in A&E,94 with the police,92 with ambulance services95 and in voluntary organisations. 10 The UK government invested in the development of mental health crisis resolution services (i.e. CRTs) and a body of research has resulted in a service fidelity model. 16,17 There is a long history of telephone support in crisis services, and planned development of telehealth has been fast-tracked as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. 84 Shared decision-making, information-sharing and skilled front-line staff have been identified in studies of stakeholder perspectives as indicators of good crisis services. 83,96 Inter-agency working is important to providing urgent access and has been identified as an IPT explored in detail in Chapter 5. Box 4 lists contextually important intervention strategies that facilitate urgent access to community crisis mental health care.

The evidence

Approach to identification of studies for review

Three iterative database searches were conducted: the first used search terms related to urgency and access, the second search used terms related to waiting and delay and the third focused on mental health triage. The results of these searches were combined. After exclusions on the grounds of relevance to IPT 1, urgent and accessible crisis care, 33 records were retained [13 from academic databases, five from grey literature (websites and reports) and 15 from hand-searching]. Backward citation searching of 18 records identified in database and grey literature searches produced a further 14 records, of which five were retained. In total, 38 records were included. The flow chart in Figure 7 shows the process of identification of studies for this review. 48

FIGURE 7.

Search results of the focused review: IPT 1, urgent and accessible crisis services.

Retained records

Details of the 38 retained records for the urgency- and accessibility-focused review are provided in Appendix 4.

Settings

The research settings reported included all community mental health services,90,99,102,106,108–117 community crisis services,2,10,15,83,85,96–98,100 integrated services with the police,78,89,92 integrated services with paramedics,95 emergency departments93,94,103–105 and telehealth. 84,87,88,101,107

Focus

Included documents were focused on joint crisis planning,110–117 crisis response models,78,83,85,94,102 gatekeeping and referral processes,97,99,107 triage and decision-making,87,88,98,101,103 waiting times,103,105,106 service user perspectives of crisis services,2,10,15,78,96,100,104,109 carers’ experiences of mental health services,90 co-location models,78,89,95 interventions in rural areas,108,109 telehealth,84,87,88,107–109 experiences of black and minority ethnic groups accessing crisis services100 and the voluntary sector contribution to crisis services. 10 Companion documents containing findings from the same study focused on joint crisis planning112–114,117 and on telephone triage. 87,8

Appraisal of relevance and rigour

All included documents were appraised for relevance and richness using a modified realist appraisal tool (J Jagosh, personal communication) (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Documents containing primary research data were also appraised for rigour using the MMAT71 (see Report Supplementary Material 3). The combined appraisal of relevance and rigour identified that the evidence supporting IPT 1, urgent and accessible crisis services, is based on studies of mixed quality.

One mixed-methods multisite study of the voluntary sector contribution to crisis care was highly matched to the theory component, providing a rich description of context, mechanism and outcome. 10 This study was methodologically rigorous and highly relevant, and was included as a key document.

Included documents reporting randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were all focused on joint crisis plans (JCPs). 110,111,116,117 These studies provided context and outcome but provided less substantial theoretical relevance. One study of JCPs reported the economic data drawn from the RCT, but the small sample size and lack of quality-of-life measures limited the rigour of these findings. 110 All included RCTs reported methodological problems, including small sample sizes110 due to under-recruitment;111 a lack of reliability in the measures;116 and inadequate staff training, causing intervention implementation problems. 117

The included mixed-methods evaluations reported small samples, mostly limited to a single site; lacked comparators; and did not consistently synthesise across methods, but provided less substantial95,115 to moderate89,92,93,98,102 framing of context, mechanism and outcome.

The included qualitative studies were theoretically rich, despite problems of rigour related to small samples that lack variance. 78,88,104,112,113 Included qualitative studies with less substantial theoretical relevance were rigorous. 15,87,90,96,97,99,114 One qualitative study provided context, but lacked rigour. 108

A scoping review85 and a realist review91 provided less substantial relevance, and one systematic review provided moderate relevance, to the theory. 94 A case study design provided less substantial relevance and rigour, but was retained because of its specific focus on triage decisions. 101

Expert reports were not assessed for rigour. Appraisal of these documents for relevance found that documents moderately framed to the theory provided context and mechanism. 2,103 Documents with less substantial theoretical relevance provided context. 83,100,105 Three documents were retained because they provided specific contextual relevance from policy or services, but were less substantially relevant. 84,106,107

Outcomes

This section discusses outcomes relating to service users, staff and systems. Included studies often focused on service and organisational outcomes over outcomes at an individual level. The documents contained few outcome data, often based on studies with methodological limitations.

Service user outcomes

Urgency and timeliness of response

Service users want to be seen the same day. 15 From a service user perspective, rapid referral to a mental health intervention, a feature of CRTs,15 A&E liaison94 and NHS 111 services,107 is viewed as the most helpful feature of crisis services. 15 Rapid referral15,94 and co-response models such as street triage92 result in people reaching a mental health assessment more quickly, but may not improve urgent access to a mental health intervention. 10,94

Accessibility of crisis services

The timeliness of response of crisis services is linked to accessible service designs. An independent review of acute and crisis services concluded that people who experience a crisis are more willing to access crisis services in the future if they have a positive experience of initial access to crisis support. 2 Successfully navigating to appropriate crisis support led to people feeling believed and hopeful, which, in turn, enabled them to manage their distress. 104

When people lack information about mental health services83 or have physical health concerns, they are more likely to contact their GP78 or attend A&E. 91,93,102 Open access (including self-referral) is highly valued by service users and families15,98 and is a feature of voluntary sector services. 10 Open access to NHS crisis services is a policy aspiration;83,86,98 currently, open-access options are often available only to people already engaged in a mental health service. 89 Walk-in services, mostly available via A&E and some voluntary sector services, provide black men with an access route they prefer and are more likely to use,10 thus avoiding delays in seeking help because of stigma related to both racial stereotypes and mental ill health. 100

Service users valued co-response models providing joint assessments by mental health staff and other agencies such as police, ambulance staff or A&E staff, especially in situations where risk of violence or suicide were high. 78,92,95 Joint responses also helped avoid the stigma related to being taken into custody. 89 Although policy emphasises the need to provide services close to home, time away from the context of the crisis, in a community setting, allows some people to ‘take stock of the situation’10 and regain control of the crisis. 10,112

Accessibility of crisis care was linked to service users and family carers being involved in decisions through gatekeeping,97 the use of video-conferencing in rural areas109 and JCPs. 116 JCPs developed with the involvement of a patient advocate, when compared with those developed by clinical staff alone, were more comprehensively completed and specific about individual needs. 116 Shared decision-making facilitated by JCPs with people with personality disorder provided a greater sense of control and improved relationships with their care provider. 111 Despite RCTs findings that JCPs had no significant impact on treatment effects or cost, when compared with a control,110,117 a difference according to ethnicity was observed. This difference suggested a higher probability of cost-effectiveness with black (90%) service users than with white (30%) or Asian (10%) service users. 117 These findings suggest that JCPs may provide a sense of trust for black people, who often report experiencing higher levels of fear, stigma and marginalisation. 100,117

When people have personal resources, such as family support, they often seek support from them first (JT2, service user), but some people are concerned about being a burden to their family. 10 A less clinical approach, involving peer support, seems to act as a proxy for family and friends by providing support in comfortable environments and through an approach that:

. . . is not kind of saying ‘I’m making you better, it is my job to make you better’. There is something about ‘we’re in it together, you and I’.

Newbigging et al. 10

Access to peer support as part of joint crisis planning generated a sense of being understood. 113 In addition, people from black and minority ethnic communities reported that peer support enabled them to ‘learn about themselves and have a new perspective on their situation’. 10 This was linked to a distal outcome through their recognition of opportunities to volunteer, which gave meaning and hope. 10

Services were perceived as more approachable when front-line staff provide immediate interventions, including supportive counselling88 and active listening; this conveyed hope and encouragement, thus engendering a sense of relational safety. 10 Relational safety improved therapeutic relationships,110,117 thereby calming the crisis situation and enabling the person to deal with their crisis. 10,104 People with lived experience report that this leads to a distal outcome of being more likely to access the service again in the future. 2

Front-line staff outcomes

Urgency and timeliness of response

Outcomes related to the timing of crisis responses were highly theoretical. Front-line staff viewed urgency of response as important and linked this to response times stated in policies of between 1 and 24 hours, depending on assessed urgency of need. 15,86 Staff in CRTs value the role of gatekeepers, originally intended to reduce hospital admissions, but also viewed by staff as controlling workload by reducing inappropriate referrals,97 although their success in achieving these outcomes is unclear. Fears about being overwhelmed by referrals and about resource pressures made NHS front-line staff reticent about open-access service designs. 97

Accessibility of crisis services

Being able to access a crisis service required front-line staff to have skills to create a sense of trust and safety that facilitates the person being able to communicate their needs. 10 This was achieved when front-line staff had skills in supportive counselling that enabled them to be flexible and responsive to the individual needs of the person seeking help. 87 Compassionate staff were more collaborative, providing a sense of involvement that people in crisis value, thereby supporting the immediate stabilisation of the crisis,96,109 even by telephone. 88 A service user interviewee explained the important link between the interpersonal approach of staff and the development of trust:

Their approach is very person centred [and I have] more trust in that service. They might not be able to solve your problem, but sometimes it is just being able to speak to someone.

JT3, service user

Front-line staff deal with trauma, distress and decision-making in often pressured situations, putting them at risk of the ill effects of stress, including compassion fatigue and burnout. Access to clinical leaders and systems of support and supervision is linked to staff being less fearful of blame or competency issues, and being more likely to seek out support98 and to sustain compassionate engagement. 10 When staff are supported, decision-making improves98,101,109 and staff stress is decreased, including when support is provided via telephone or video conference. 87,92,109

System outcomes

Urgency and timeliness of response

Data related to clinically relevant waiting times in mental health crisis care are lacking. 85 The rationale for current waiting time standards is not understood by front-line staff:

. . . some of the standards recommend a time frame, ‘see people within 24 hours’, [the] new standard is 4 hours. I would like an explanation of where that target comes from, what is the clinical reason and evidence for that.

LS6, mental health nurse

The time people wait for a mental health assessment is linked to availability of resources,15,94 even when services are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. 89,92 Co-locating mental health practitioners in emergency control rooms improves the timeliness of responses because the most appropriate service can be despatched or issues can be dealt with using telehealth. 92,95 Co-location in emergency control rooms has been found to be cost-effective, and therefore sustainable in the longer term,92 but has not been fully evaluated.

Joint or parallel assessments improves collaboration between staff,94 and leads to more rapid responses92,94,95,104 and fewer people failing to reach a mental health intervention. 94 According to one interviewee, parallel assessments, as well as saving time, are more accurate and avoid the discomfort of multiple assessments for service users105 (NC1, mental health nurse).

A mental health triage tool, adapted for use in the UK, has been ‘subject to preliminary validity and reliability testing’. 87 Following front-line staff training, triage approaches have been linked to more timely and appropriate service responses88,98 and improved accuracy in identification of suicidality. 98 The outcomes of service thresholds on timely access to crisis care have not been fully evaluated. ESG members and an interviewee explained that how services manage access thresholds may have more impact on urgent access than assessment and triage processes:

I think once you get through to the triage element and the assessment, you’re kind of in. It’s . . . thresholds that I think is quite a barrier to people.

NC1, mental health nurse

Accessible crisis services