Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128070. The contractual start date was in January 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Baker et al. This work was produced by Baker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Baker et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Safety within mental health services

Mental health services report high levels of safety incidents1,2 that involve both patients and staff. This is a key concern of the Care Quality Commission3 and an NHS priority. 4,5 According to UK government records for 2020–1, 300,703 incidents were reported to have occurred in a mental health service in England. 6 More detailed data from acute mental health wards show that the most frequently occurring incidents in this setting involve violence and self-harm. 7 On acute mental health wards, safety incidents are often associated with increased costs, including the costs of restraint, seclusion, rapid tranquilisation and increased one-to-one nursing and physical and psychological harm to the patient, which may increase length of stay and have a negative impact on their health-related quality of life. 8 In some cases, injuries to staff may occur, with associated costs of replacement staff and staff support. 9

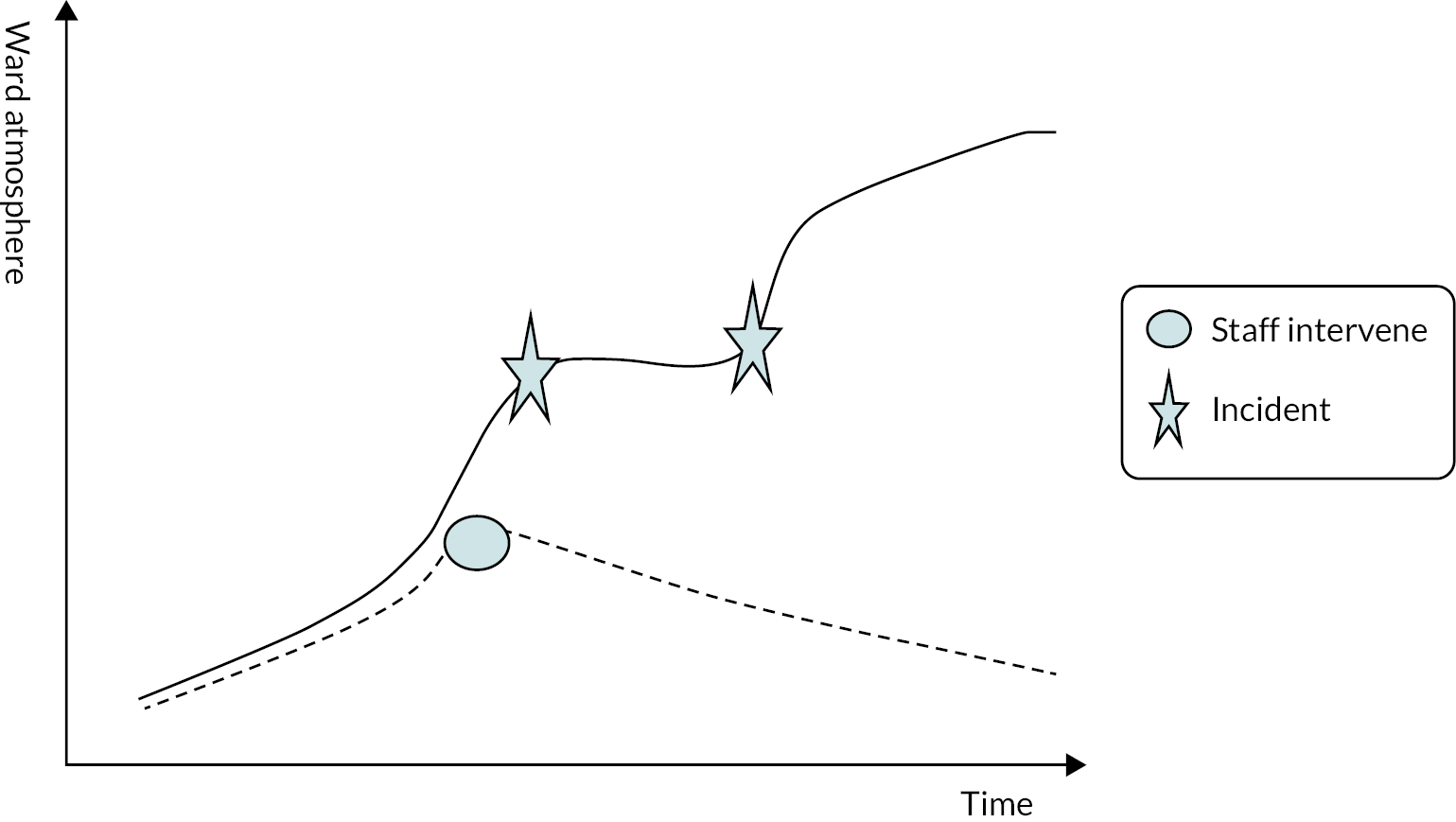

A further safety issue on acute mental health wards is that one incident may increase the probability of further incidents occurring, via a disturbed ward milieu and social contagion. 10 Social contagion is a mechanism by which an influence or idea spreads from person to person. For example, self-harming behaviours can spread among people on a mental health ward through behavioural contagion (a type of social contagion11–13),14,15 so successfully avoiding one incident may bring further positive benefits by reducing the probability of future incidents. 14–17

Previous work examining contributory factors to safety incidents in secondary care hospital settings produced the Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework (YCFF). 18 The YCFF describes 20 separate domains, such as team factors, supervision and leadership. In response to the recognition of patient safety as an under-researched but important aspect of mental health care, researchers19 adapted the YCFF to focus on contributory factors within a mental health setting. Further qualitative work exploring patient perspectives on safety highlighted wider issues than those currently captured via incident reporting systems; for example, factors such as ‘not being listened to’ or not feeling psychologically safe. 20

Discourses on safety

Patient discourses around safety in the mental health literature suggest that inpatient mental health settings perceived by patients to be safe are places where it is not dangerous to be vulnerable,21 patients have a sense of being recognised as a whole person22 and they have some feeling of control within an uncertain world. 23 However, the organisational perspective tends to dominate, and this prioritises identification and risk management of violence, aggression, self-harm or suicide by patients. 24–27 Furthermore, patient safety as an academic discipline has traditionally focused on acute physical health care settings, both empirically and theoretically. It is widely acknowledged that patient safety in mental health care contexts has been a neglected area of research. 28–30

Service-oriented perspectives tend to omit patients’ definitions of safety. 20,31,32 Consequently, incident reporting systems fail to capture the spectrum of patients’ safety concerns, for example, around bullying, intimidation, racism, aggression, drug and alcohol use, or theft of personal property. 33 This in turn obscures the extent and impact of physical and psychological harm caused by restrictive practices. 31,34,35 Psychological consequences for those involved directly or indirectly (e.g. as witnesses)36 can include anger, fear, anxiety and symptoms suggestive of post-traumatic stress disorder.

In addition, where organisations focus on the avoidance of risk, ward cultures can be characterised by defensive practices that are ineffective and potentially harmful. 32,37 Safety incidents can include iatrogenic harm even when procedures are correctly followed and best practice38,39 is observed. 31,34,35,40,41 Given their far-reaching impact, it could be argued that restrictive practices, which are intended to prevent harm,42 are simply sanctioned violence. 43

Various frameworks and sets of guidance for the appropriate use of restraint have been produced. 38,39,44–47 Nonetheless, ongoing abuses in mental health wards and other institutional settings have attracted media attention. 48–51 For instance, in 2022, an undercover journalist recorded evidence of harmful use of restrictive practices in a UK mental health unit,50 in a narrative that resonates with other witness accounts of abuse, for example, Reese (2021). 52

Behavioural contagion

Behavioural contagion is a type of social contagion. 11–13 The term refers to the tendency for people to repeat a behaviour after others have performed it,53 in a process similar to the transfer of emotions between staff and patients in a healthcare setting. 54 Behavioural contagion has been identified in studies of self-harm, aggression and assaults,14–16,55 and suicide and deliberate self-harming behaviour. 14,55,56 Parents and health professionals have expressed concerns that adolescents in mental health settings may acquire destructive behaviours in hospital, for example, self-harm and suicide. 57 Their perspectives are supported by the results of a study exploring the dynamics of violence on adult mental health wards, which found that patient aggression and self-harm incidents clustered temporally, both within a specific day and also in adjacent days, indicating that behavioural contagion was a factor. 15

Milieu

The milieu of a mental health ward is something in the environment or setting, beyond formal treatment, that is potentially beneficial to mental health inpatients. 58,59 It has been described as the interaction between the physical environment, social structures and social interactions. 60 Some research on mental health wards has linked the use of physical space61,62 or noise levels63–65 with agitation and aggression. According to Gunderson,66 a therapeutic milieu is one that reassures patients that they are physically safe and cared for; it makes ‘conscious efforts … to make people feel better and improve their self esteem’ (p. 329); has predictable and helpful structures (e.g. of routines, roles and activities), invites patients to be involved in the social environment and validates each individual. Conversely, a ward milieu that is less therapeutic may feature unstructured periods, denial of privileges, high noise and activity levels, threatening language and authoritarian, inflexible or confrontational staff. 67

Improving therapeutic milieu has been associated with reduction in violent incidents and restrictive practices (e.g. seclusion and mechanical restraint) and staff and patient injury. 67 The trend towards short inpatient stays, however, may prioritise achieving measurable safety targets over building community and therapeutic relationships;58 making it harder for patients to heal. 67 When short inpatient stays are the norm, potentially helpful and feasible factors include therapeutically minded nurses,58 thoughtful tolerance of risk68 and a move away from a coercive culture. 69 Therefore, ward milieu seems to be highly relevant to patient safety interventions development for acute mental health wards.

Patient perspectives on safety

Patient involvement is a priority for mental health research. 29 Indeed, the need to involve patients and their families in improving the quality and safety of health care is recognised as a cornerstone of policy and practice. 70 Previously, the Berwick report on how to improve services in the wake of care failures at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust had concluded that, ‘the patient voice should be heard and heeded at all times’ (p. 18);71 yet it has been argued that this report may not have had a clear impact72 and, in 2022, the British Broadcasting Corporation50 showed a poor mental health ward environment in which patients did not appear to have opportunities to offer feedback to service providers.

Patients and staff have been shown to have different perspectives on safety, and despite the policy focus, very few patient-reported safety data are collected in the health services. 73 Patients have pointed out that healthcare staff prioritise physical safety, often at the cost of psychological safety. 31 The commonly accepted World Health Organization definition of ‘the prevention of errors and adverse effects to patients associated with health care’74 could arguably be enhanced through the inclusion of patients’ perspectives on safety. 19,20,31,75 Furthermore, adverse incident reporting mechanisms in NHS hospitals may not effectively identify all such incidents. 76,77 The submission of organisational incident data to the National Reporting and Learning System is largely voluntary to encourage openness and continual increases, and should be seen as indicative rather than precisely accurate (p. 18). 78

Barriers to participation of experience experts (patients, service users, carers) in mental health research

Lay perspectives from experience experts (e.g. patients, carers, lived experience advisory groups, patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) groups and non-executive director roles) is a valuable and relevant component of mental health research. 20,79 It can be perceived to meet the requirements of the equality, diversity and inclusion agenda80 and in some contexts is a mandatory element of a research funding application. 81 However, these groups may have limited influence other than to help secure funding. 81 There are many structural and personal factors that discourage experience experts from participating in mental health research, whether or not they are currently patients (i.e. actively receiving care). They may feel too unwell to participate in research; alternatively, their opinion may be given less weight than that of other experts, because it is assumed that they have unreliable judgement. 20,82–85 Even when specifically invited to offer a perspective, a patient may have difficulty articulating their view, and/or may not be given a genuine opportunity to speak up. 86 Individuals may be deterred from participatory research roles because of feelings of shame (e.g. Femi-Ajao et al. 87; Roodt et al. 88) and hence, an ongoing fear of judgement. 89 Better training and preparation for health professionals can mitigate these barriers90 and can encourage lay experts to share their perspectives to improve health care and health research.

Patients and carers also struggle to raise safety concerns because of fear of repercussions from raising concerns and because the processes are onerous, particularly for someone experiencing poor mental health. 20 Therefore, staff may be unaware of the psychological harms occurring on wards, whether caused by staff behaviour, treatment or other patients. Patients may consequently experience harm while resident on acute mental health wards and also have difficulties raising concerns with staff. If patients were given the opportunity to report safety issues in real time, staff could potentially respond and intervene before situations escalate.

The need for more patient involvement in mental health safety research

Research studies in general hospital settings have found that patients can be a valuable source of safety information and that participating in such activities is both acceptable and feasible for patients. 20,91,92 Generally, there appears to be little empirical evidence concerning interventions that enable staff to use patient feedback about safety to improve service-level safety performance, although The Patient Reporting and Action for a Safe Environment (PRASE) intervention18,93 offers a theory and evidence-based approach to the systematic collection of hospital inpatient feedback about safety and a framework to help staff interpret and act on that feedback. Furthermore, research on the potential for ward staff to respond to patient feedback about safety is limited and appears to be restricted to secondary care hospital settings. Two studies found that ward staff required additional support to respond to patient feedback;75,94 other research found that real-time data support staff to respond proactively to safety issues. 95 A stronger research base in this field can inform how these findings might be applied to an acute mental health ward.

Proactive safety monitoring

Two emerging ideas within the literature on safety in health settings are the notion of safety ‘monitoring’ as opposed to solely ‘measurement’, alongside awareness that prospective clinical surveillance may have potential as a means of promoting safety within organisations. 96,97 Prospective clinical surveillance is particularly important within the acute mental health context, since there can be rapid fluctuations within the dynamic of the inpatient group and between patients, staff and the environment, such that individual patient needs create immediate knock-on effects for other patients, their quality of care and their safety.

In previous98 national level initiatives, such as the NHS Safety Thermometer,99 monthly data relating to mental health ward safety were collected from patients by staff; however, a recognised limitation of this measure was its ‘snapshot’ nature, which in this case was an opportunity sample of patients on one predetermined day per month. There are established strategies for measuring harms that have already occurred but approaches to understanding safety of care in real time are more limited. 100 Incident data are often reviewed retrospectively but this precludes the opportunity for anticipation and prevention; that is, data are ‘lagging’, rather than ‘leading’. 100

Alignment with the measurement and monitoring of safety framework

In 2014, Vincent et al. published the Measurement and Monitoring of Safety Framework (MMSF),100 a theoretical framework for the measurement and monitoring of safety in health care. This framework proposed a shift of focus from the measurement of past harm towards the prevention of future harm, through assessment of current safety. It involved co-design with service users and was evaluated in a range of healthcare services, including mental health services. The MMSF has five domains:

-

Past harm: has patient care been safe in the past?

-

Reliability: are our clinical systems and processes reliable?

-

Sensitivity to operations: is care safe today?

-

Anticipation and preparedness: will care be safe in the future?

-

Integration and learning: are we responding and improving?

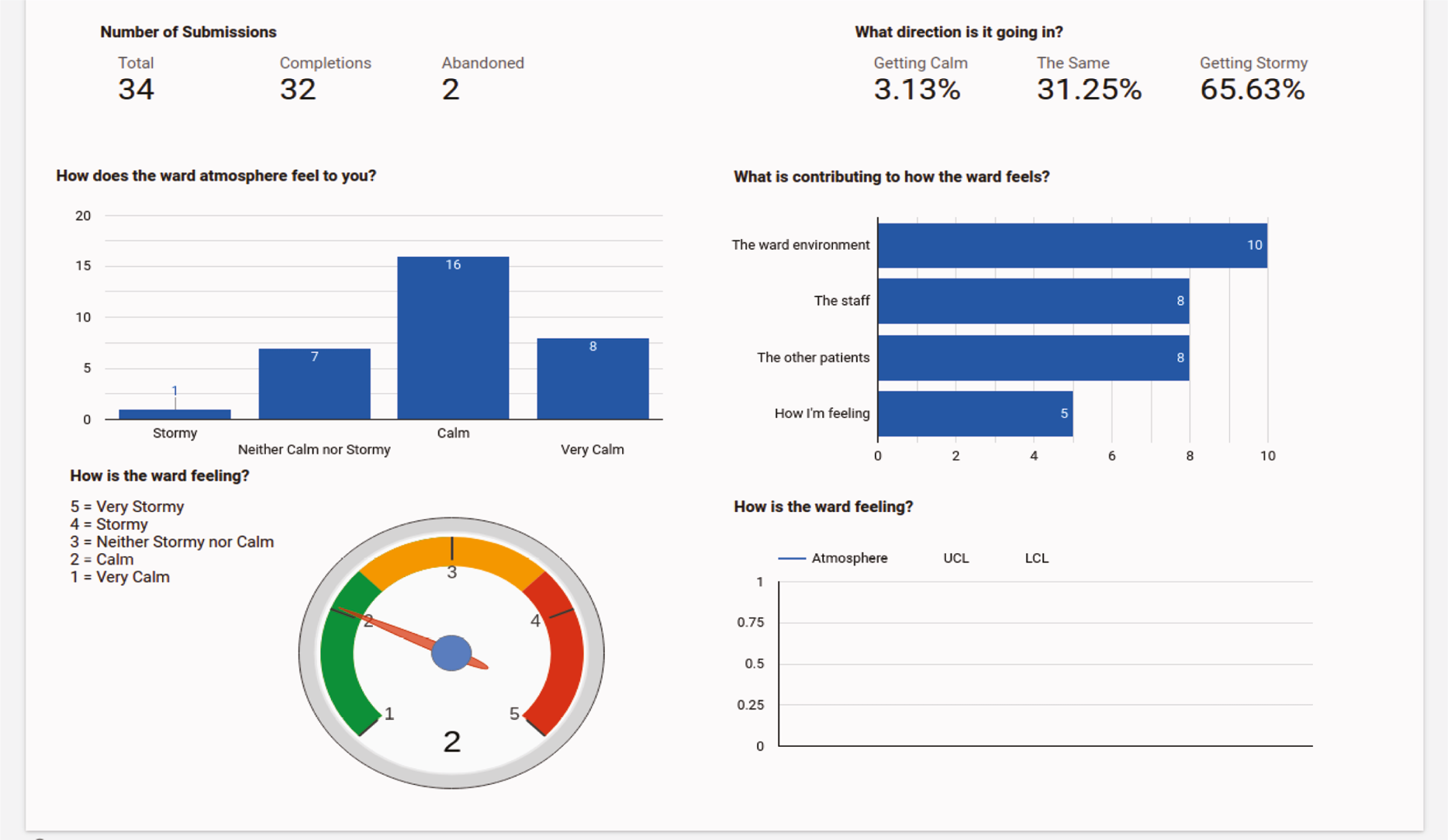

The current study is aligned with the MMSF100 domain ‘sensitivity to operations’. This domain highlights the crucial but often overlooked activity of monitoring the safety of care as it is delivered in real time, recognises patients and families as important sources of information, and highlights the need for staff to develop a collective awareness of the workings of the service and to be sensitive and responsive to subtle changes and disturbances. Proactive day-to-day monitoring of patient perspectives could potentially bring greater benefits than the traditional reactive approaches relying on retrospective review and could be part of a broader vision of how to improve ward safety.

Mechanisms for patient feedback

At present, there is no mechanism by which leading (i.e. moment to moment) safety data from patients on acute mental health wards can be captured and made available to staff in real time. There are different potential mechanisms for patient feedback about safety to be received and discussed by ward staff in an acute mental health ward. For example, in the PRASE intervention,92 feedback was collected over a 3- to 4-week period, and staff came together to consider the feedback report and produce action plans. 20,91,92

Routine shift handover meetings between outgoing and incoming staff can successfully be modified to incorporate standard items such as evidence. 101 Another option is ‘safety huddles’,102 which originated in secondary care as short daily meetings to brief staff on immediate safety issues. They were found to facilitate real-time identification of, and response to, safety concerns,103 and have been implemented successfully in a mental health setting. 102

Implementation of innovations in health settings

Innovations can meet resistance in acute mental health settings104,105 and implementation was carefully considered in the current study. Staff burnout is one contributing factor; its effect may be mitigated when staff can influence the change,103 leading to improvements in feasibility and acceptability. Leadership appears to be another moderating factor, since managers in acute mental health care have been found to be more positive than their ward staff about change. 101

Feasibility and acceptability are consistently identified as key concepts within implementation theory, although with varying relative importance. For instance, Allen et al. 106 groups feasibility, fidelity, acceptability, sustainability and adoption together as the principal determinants of implementation, whereas Hernan et al. 107 identifies feasibility as the overarching concept, with acceptability, fidelity, enablers, barriers, scalability and process of data collection as measurable components.

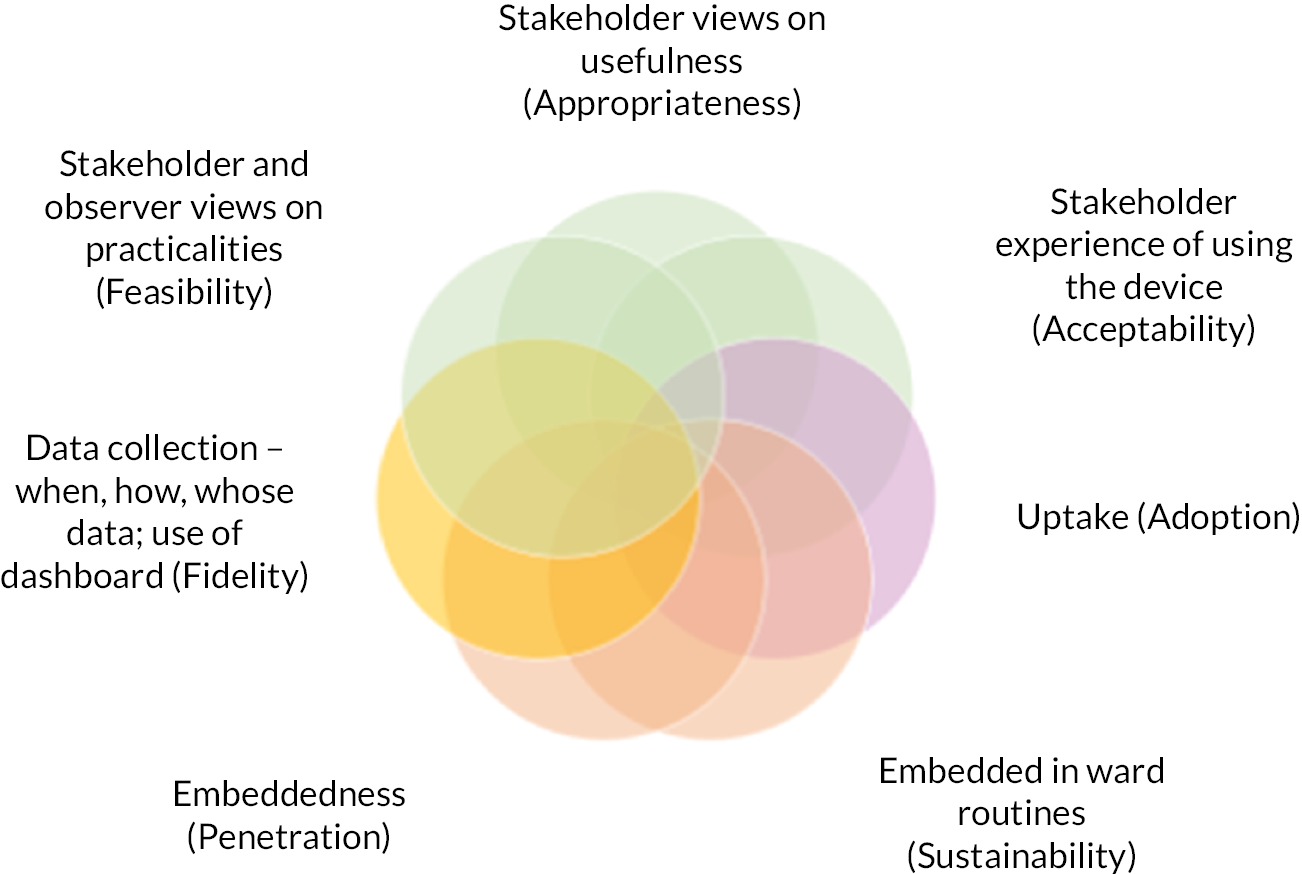

An implementation outcomes taxonomy produced by Proctor et al. 108 was a useful framework for thinking about implementation within the current study. It comprises eight primary influences on innovation implementation within a health setting (Table 1). In this model, implementation outcomes are seen as preconditions for successful service, system and clinical outcomes, and should be understood before progressing to a larger study.

| Implementation components | |

|---|---|

| Acceptability | Stakeholder perception of satisfactoriness |

| Adoption | Stakeholder willingness to adopt intervention |

| Appropriateness | Stakeholder perception of suitability and usefulness of intervention in the specific setting |

| Cost | The cost/effort of the intervention |

| Feasibility | The degree to which the innovation can be used or implemented successfully |

| Fidelity | The degree to which the intervention was implemented as intended |

| Penetration | The degree to which the intervention is embedded within the systems |

| Sustainability | The degree to which the intervention is normalised |

Focus of the current study

Using the MMSF100 as the theoretical foundation, the focus of the current study was to develop a monitoring tool for collecting and monitoring real-time data directly from patients on acute mental health wards using digital technology and to explore whether staff could use this information on a daily basis to anticipate and avoid developing incidents, thereby proactively managing safety in acute mental health settings. Our focus mapped closely to the vision for data on mental health inpatient settings recently published by the UK Department of Health and Social Care,109 ‘where the potential of data and evidence is fully exploited so that the healthcare system is able to ensure the highest standards of care in all mental health inpatient wards and pathways’ (p. 8).

Chapter 2 Design overview

This was a two-phase mixed-methods study. The design was theoretically informed by a triangulation approach, which employs multiple methods to understand a phenomenon. 110,111 Phase 1 focused on development and Phase 2 on evaluation. The study was characterised by iterative co-design, information gathering, review and reflection.

Although the structure of the current report may suggest a linear timeline, the research was essentially iterative. For example, PPIE activities were concurrent with, informed, and were informed, by other parts of the research.

Aims and objectives

The study had two principal aims:

-

To co-design a monitoring tool to improve patient safety on acute mental health wards, through the collection of daily data about the patients’ perceptions of safety, to support staff in monitoring and improving the safety of the clinical environment (Phase 1).

-

To implement the tool and explore its feasibility and acceptability (Phase 2).

The following objectives were identified:

-

To co-design with service users and staff a digital innovation that will allow real-time monitoring of safety on acute mental health wards.

-

To explore the feasibility and acceptability of capturing real-time feedback from service users about safety.

-

To explore how staff use this information when reported during daily handovers (or other mechanism).

-

To explore how the resulting data are related to quality and safety metrics.

-

To explore how these data can be used longitudinally to promote safety.

The study objectives and corresponding issues to explore are indicated in Table 2 and revisited in Chapter 10.

| Phase | Objective | Corresponding issues | Chapter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 1 | With service users and staff, co-design a digital intervention, to allow real-time monitoring of safety on acute mental health wards. It was envisaged that the intervention would involve use of a tablet computer device (hereafter referred to as a ‘tablet’ or ‘device’). | Does the intervention allow real-time monitoring of safety (i.e. how/when do staff circulate the tablet; do/how do patients engage with the tablet; do staff access data; what do staff do with the data; do they/how do they action it?) | 4–7 |

| Phase 2 | 2 | Explore the feasibility and acceptability of capturing real-time feedback from patients about safety | What are patient and staff attitudes/expectations? What practical issues come up in using the device? | 8–9 |

| 3 | Explore how staff use this information when reported during daily handovers (or other mechanism) | How do staff use the data in practice? | 8 | |

| 4 | Explore how the resulting data are related to quality and safety metrics | How do the resulting data relate to quality and safety metrics? | 9 | |

| 5 | Explore how these data can be used longitudinally to promote safety | How can these data be used longitudinally to promote safety (i.e. what conditions context and culture are needed to improve safety using the data?) | 8 | |

Design

This was a mixed-methods design in two phases, developed and refined to suit the context. The approach taken to reporting the study adhered to key principles of reporting guidance described in the literature. 112

Phase 1 design

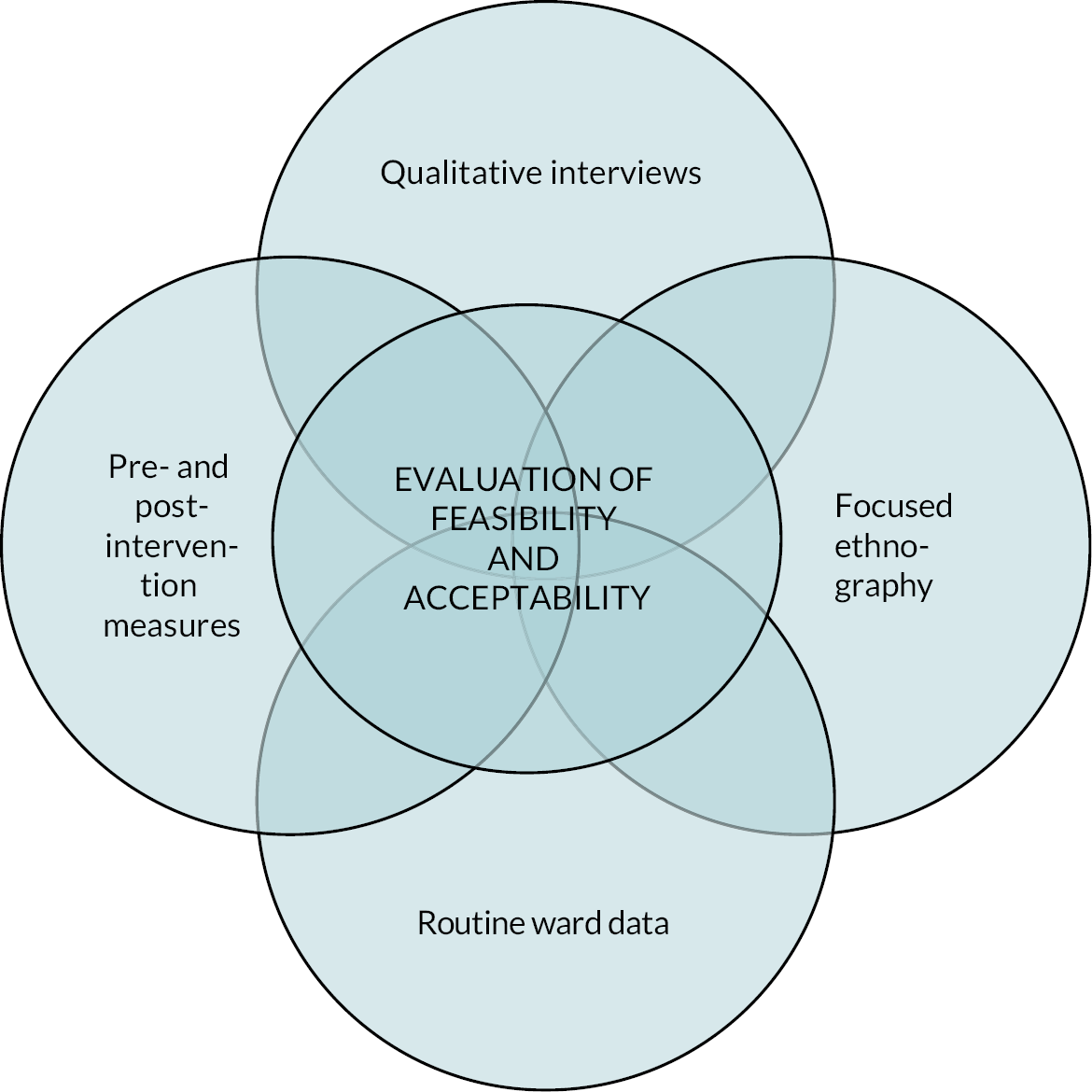

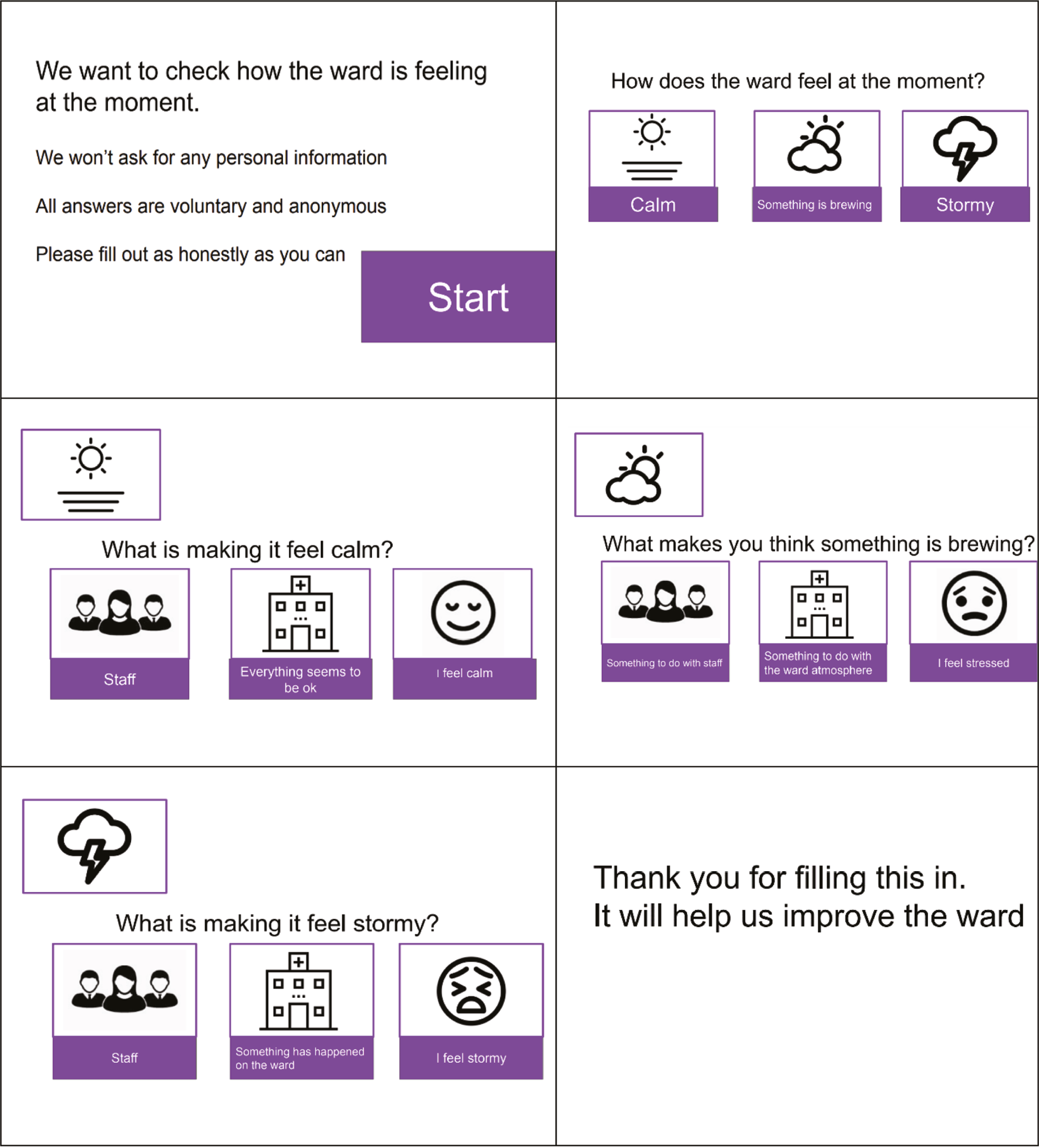

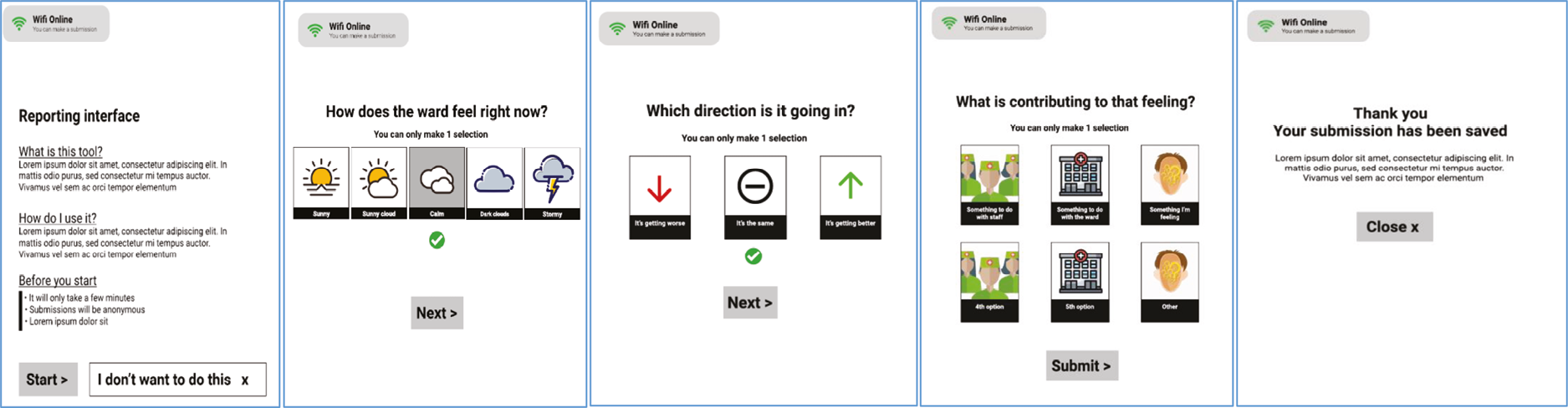

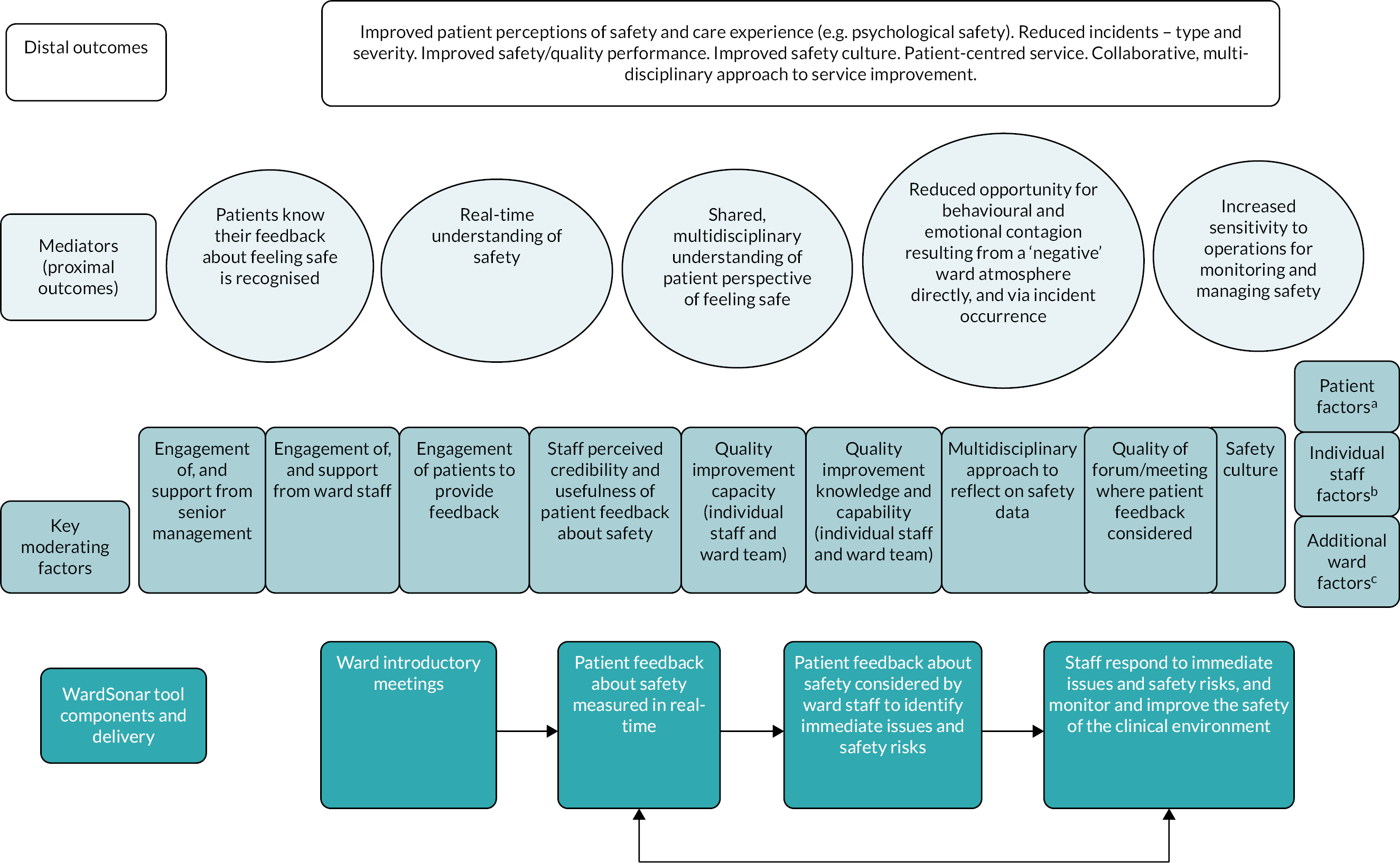

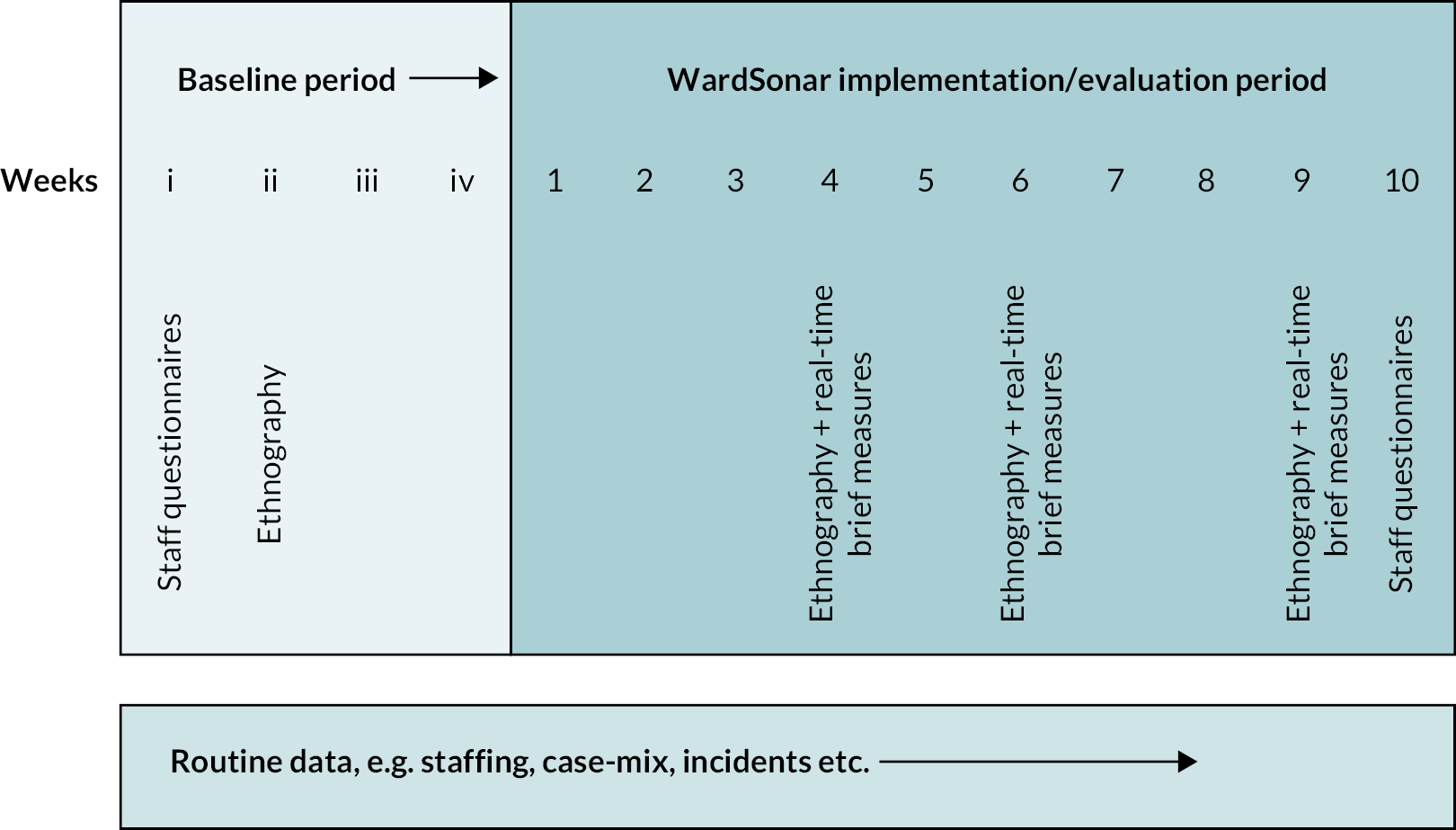

Phase 1 consisted of overlapping stages progressing towards conceptual clarification, as illustrated in Figure 1, followed by technical specification and delivery of a testable intervention. Key theoretical concepts underpinning the development of the tool were the MMSF domain ‘sensitivity to operations’, contagion and milieu. These were explored in the literature at an early stage in the study113 to aid conceptual clarity and inform the research design.

FIGURE 1.

Phase 2 data categories synthesised for evaluation of feasibility and acceptability.

Specific Phase 1 components were:

-

A co-design approach.

-

A series of consultations with patient advisory groups, current inpatients and health professional staff to explore possible conceptualisations of the intervention and refine prototypes.

-

A review of the literature on patient involvement in safety interventions in acute mental health care.

-

An evidence scan of the use of digital technology in mental health contexts.

-

Semistructured qualitative interviews with mental health patients and health professional staff, to elicit their views on ward safety.

-

Ongoing engagement with stakeholders to guide and inform concept development and refine technical iterations.

-

Development of a logic model and programme theory to act as a framework for organising and refining ideas about a safety monitoring tool.

-

Technical development of a testable tool that uses patient feedback for proactive safety monitoring.

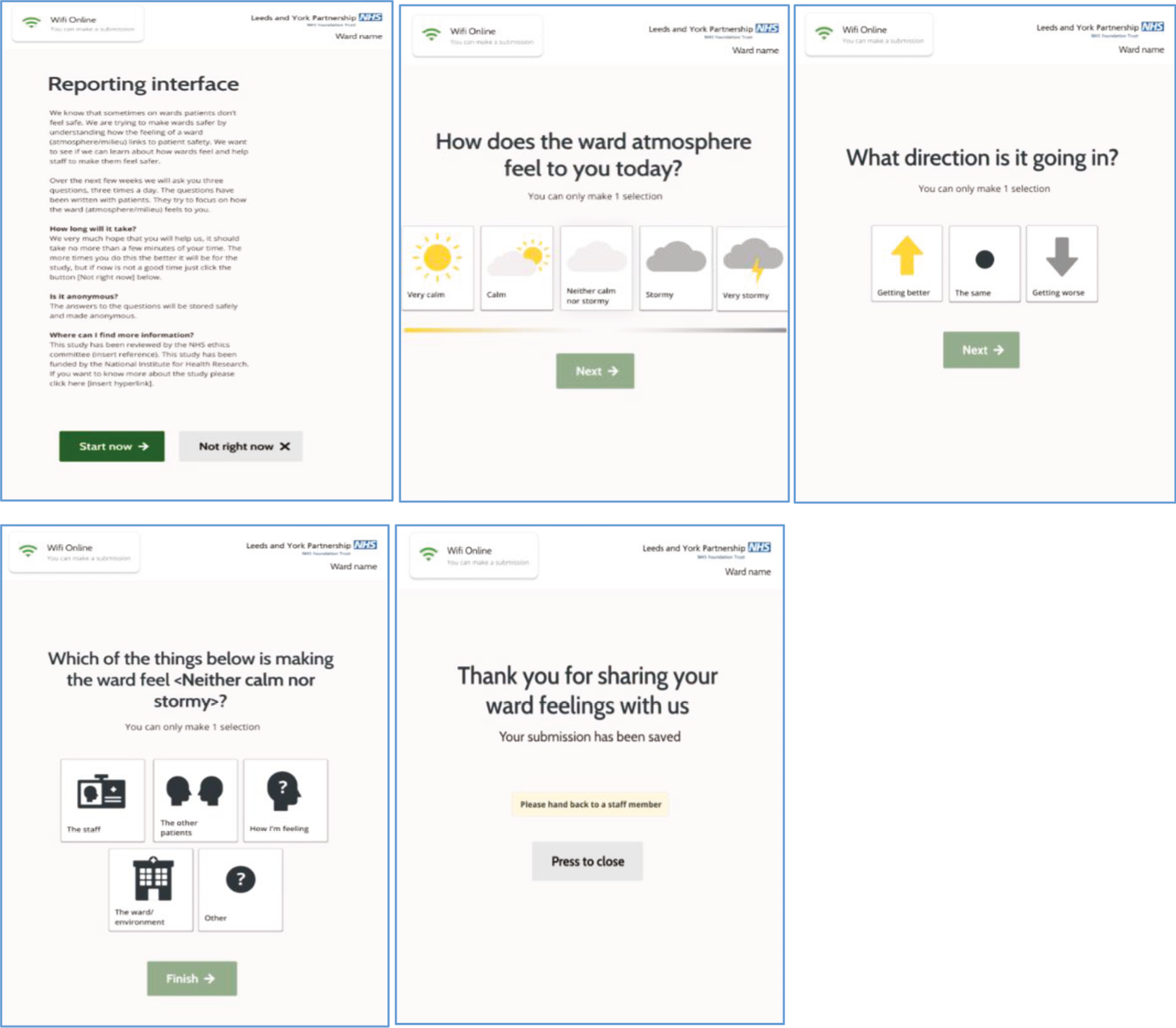

Phase 1 resulted in a testable monitoring tool that used a tablet computer device for real-time safety monitoring of patients’ perceptions of safety on the ward.

Phase 2 design

Phase 2 was a mixed-methods process evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of the monitoring tool via four categories of data (qualitative interviews, focused ethnography, pre- and post-intervention measures, real-time measures and routinely collected ward data; Figure 1).

Specifically, these categories were:

-

A focused ethnography to explore how staff communicate and use safety data; this included on-site observations by researchers.

-

Qualitative interviews with patients and staff (health professional staff).

-

Simultaneous collection of routine data (i.e. incidents, workforce and ward occupancy).

-

Pre- and post-intervention measures relating to staff perceptions of safety culture and ward atmosphere, together with real-time measures of these concepts.

-

Analysis of data from all the above.

Collaborating partners

The core research team worked with collaborating partners to deliver specific pieces of work. Two NHS mental health trusts in the UK supported the project throughout. One of these trusts was directly involved in the Phase 1 intervention development activities. Other collaborators were the co-design specialists ‘Thrive by Design’114 and the digital product developers ‘Ayup Digital’. 115

Promoting equality, diversity and inclusion through patient and public involvement and engagement activity

In the current study, the PPIE work reflected the research team’s intention to promote equality, diversity and inclusion. Patient and public involvement and engagement116 is key to effective and relevant health research82 and was integral to WardSonar. The whole project development was informed by stakeholder and lay input, specifically through discussions with patients and co-applicants with lived-experience expertise. The original PPIE strategy involved convening and engaging a lived experience advisory group. It was developed on principles of co-design and incorporated multiple face-to-face discussions with different groups, but necessary revisions were made to the original design to try to accommodate the original objectives (see Coronavirus disease 2019 amendments to project design below). The PPIE plan was revisited and replaced with an alternative stakeholder engagement plan that was feasible during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. A member of the core research team with experience expertise established links and facilitated a series of sessions with two pre-existing stakeholder groups hosted by a mental health trust in the north of England.

Technological co-design

The intervention technical development in this study was co-produced by Thrive by Design and Ayup Digital in consultation with service user networks, healthcare staff and wider stakeholders, using a collaborative, human-centred and sprint-based/agile approach. 117–119 Ayup Digital was involved in co-design, put the technical brief into operation and provided technical support during the implementation of the intervention. Cycles of co-design activities were led by Thrive by Design and included workshops and activities with patients and staff on two wards, in addition to more opportunistic in-person discussions with health professionals at one NHS trust.

Coronavirus disease 2019 amendments to project design

The project commenced in 2020 in the very early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This context had a considerable impact on plans for stakeholder engagement. The original intention behind convening a lived-experience advisory group was for the group to consider the emerging evidence from the early phases of the project and to contribute to deciding how the evidence should inform the development of the tool. Once there was broad agreement on what the monitoring tool would be, we intended to run a series of co-design discussions, with separate discussions for staff and patients (approximately 12 participants per discussion) on different sites and with different groups, facilitated by up to three co-design experts.

However, a significant amount of non-COVID-19 related research was paused, and it was not thought appropriate to advertise (e.g. via social media) to convene a new group. Various alternatives were considered. For example, at the co-design stage, a hybrid approach was suggested in which patients in stakeholder roles were gathered in a room on the ward, facilitated by staff, and the co-design team joined them remotely via video link. Difficulties relating to poor connectivity, limitations on physical space, and COVID-19 restrictions around patients mingling and going off the ward meant that this was not feasible. In brief, pragmatic adjustments were made to the co-design plan to produce a feasible alternative in which a single NHS trust permitted limited visits from a clinical collaborator familiar with the local protocols, who was able to gather ad hoc views and opinions from patients and staff passing through a communal space. The PPIE work is described in more detail in Chapter 5. In addition, following discussion with the funders, timescales were adjusted and a decision was made to remove a phase of small-scale testing.

Subsequent waves of COVID-19 infection had significant impact on the testing of the monitoring tool, particularly in the early months of 2022. These caused delays in accessing sites, unusual staff to patient ratios and considerable challenges to the researchers involved in observing the implementation of the monitoring tool.

The development of the WardSonar monitoring tool is describe in more detail in Chapter 5.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for Phase 1 was obtained in November 2020 from the University of Leeds, School of Healthcare Ethics Committee, reference HREC 19-028 (health professional arm of the study) and South Central – Berkshire B Research Ethics Committee, reference 20/SC/0360 (patient arm of the study).

Ethical approval for Phase 2 was obtained in November 2021 from East Midlands – Nottingham 2 Research Ethics Committee (IRAS project ID: 300833; REC reference: 21/EM/0247).

Chapter 3 Literature reviews

Objective

Patient safety in acute mental health care is a pressing concern48,120 and patient involvement in safety research is crucial to addressing the issue. 121 The development of a patient safety monitoring tool was informed by exploration of the literature around: (1) patient involvement in safety research in acute mental health care and (2) the application of digital technology in mental health contexts. The literature reviews aimed to provide background information to inform processes outlined in objective 1; that is:

-

With service users and staff, co-design a digital intervention, to allow real-time monitoring of safety on acute mental health wards.

Methods

The literature reviews comprised a scoping review of the literature on patient involvement in safety interventions and an evidence scan of the application of digital technology in mental health contexts.

Scoping review of the literature on patient involvement in safety interventions

The team conducted a scoping review of the literature on patient involvement in safety interventions in an acute mental health setting. The Smits ‘Involvement Matrix’122 was applied to classify and assess patient involvement in development, implementation and/or evaluation of relevant research and interventions. The following section contains a summary of the review. Further information is available in the published report in Appendix 1. 123

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

Systematic searches of academic databases (CINAHL, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and Scopus) and grey literature were designed using medical subject headings and the research question: ‘To what extent are patients involved in interventions to improve patient safety in acute mental health care?’ Searches (2000–20) were conducted during March–June 2020 (last academic database search 1 April 2020; last grey literature search 19 June 2020).

Grey literature was included because of the likelihood of finding unpublished research around safety in acute mental health conducted by clinical teams. Additionally, 14 mental health-specific sources (e.g. Centre for Global Mental Health) and 25 non-mental health-specific sources (e.g. Royal College of Nursing) were explored, together with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evidence database, ProQuest Thesis and Dissertations database, and three social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook, YouTube). Additional grey literature sources of interest identified by authors’ expertise and hand searching were screened. Review papers produced by the search were scanned for potentially relevant papers. Duplicates were identified and removed using EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) bibliographic software.

The same eligibility criteria applied to both academic and grey literature. Eligible studies involved patients in active research and/or patient or staff safety improvement role, as classified by the Involvement Matrix. 122 Eligible outcomes related to patient involvement in patient safety research or interventions. Eligible settings were inpatient mental health care contexts. All study designs were eligible for inclusion.

Search results were exported to Covidence (Melbourne, Australia) for screening at title, abstract and full text level by two researchers. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart124 is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow chart.

Data extraction used the Covidence online tool and was informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual. 125 Study quality was appraised using the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Methodology Tool (MMAT),126 which is suitable for assessing diverse study designs. Patient involvement was evaluated using Smits et al.’s Involvement Matrix. 122

Results summary

A total of 52 studies from the grey and published literature were included. They were conducted in the UK, United States, Canada, Finland, New Zealand and Europe. The majority (n = 33) focused on reducing staff use of restrictive practices. About half of the studies reported only limited patient participation in the research, and the involvement of patients as decision-makers was reported in only four studies.

Safety interventions ranged from system change at the organisational level, through operational decision-making at ward level to interventions for individuals, such as a smartphone application (app). Patients were involved mainly as co-thinkers, advisers and partners rather than decision-makers. The more extensive their involvement, the more likely they were to have active roles in the research. Research with high patient involvement tended to focus on forensic mental health and to be associated with reduction in restrictive practices. Low patient involvement tended to be associated with less reduction in restrictive practices.

Narrative synthesis of the included literature identified a possible association between studies with high levels of patient involvement and more effective safety interventions, but methodological quality of the surveyed papers was inconsistent. The review findings were incorporated into the ongoing synthesis of all data and learning from Phase 1.

Evidence scan of the application of digital technology in mental health contexts

Methods

To further inform the development of a safety monitoring tool, an evidence scan127–129 of the literature around digital technology in a mental health context, was conducted in November 2020, using the databases CINAHL, PsycINFO and Web of Science. The search terms and included studies detail can be found in Appendix 1.

Results

Research in the field of application of digital technology in mental health contexts appears to be concentrated primarily on therapeutic interventions, such as assessment of suicidal ideation or suicidal risk, and psychological support therapies, such as counselling. A limited body of research on telecare and the design of mental health apps for use in various other contexts was identified but digital technologies specifically related to mental health care are relatively new. Many digital technologies for health (mainly apps) have been designed within the tech industry, not always using mental health expertise. 130

Regarding technology design, there was an emphasis on usability and accessibility and some concerns around confidentiality. Poor digital literacy is seen as a barrier to utility and some degree of personalising technology to the user was seen as potentially helpful. Preferred design features included images and the use of colour. Other themes included the possibility of under- or over-reporting by patients and the impact of the technology on staff. Establishing a threshold for staff action and building it into the technology to trigger an appropriate response were considered important. The reviewed literature also indicated that patients’ cognitive abilities, health status and confidence in the technology affect their engagement and that, provided that the digital technology does not cause patients any harm, it is seen as potentially helpful and useful to them.

Factors that support successful technology implementation and staff engagement included connectivity (e.g. access to a reliable internet connection), training for people who may be using the technology, the provision of technical support, and ensuring effective communication about the technology so that its rationale is understood.

Conclusions to literature reviews

Interrogation of the literature clarified that there was an evidence gap regarding meaningful patient involvement in mental health safety research. It further indicated potential priorities for the development and design of digital mechanisms to improve ward safety from patient perspectives. These conclusions were incorporated into Phase 1 data synthesis.

Chapter 4 Phase 1: qualitative interviews

Objective

Phase 1: qualitative interviews relate to objective 1, that is:

-

With service users and staff, co-design a digital monitoring tool, to allow real-time monitoring of safety on acute mental health wards.

Semistructured interviews were conducted in Phase 1 to explore patient and staff perspectives on safety issues and how patients and health professionals can contribute towards the measurement and monitoring of ward safety in an acute mental health setting. Access to patients for interview was greatly affected by COVID-19 restrictions. Ultimately, 8 patients and 17 mental health professionals participated in interviews. The intention was to use learning from the interviews to inform overall data synthesis and hence intervention development.

Methods

Recruitment

Two NHS mental health trusts in the north of England (NHS trust 1 and NHS trust 2) supported the overall project and facilitated recruitment of patients. Patients were recruited via posters placed in NHS trust premises. Patients who were interested in taking part notified designated health professionals, who passed on contact details to the researchers. Health professionals were recruited via advertisements on social media (Twitter, now X, X Corp., San Fransisco, CA, USA) inviting them to contact the research team about the study. Potential interviewees were provided with further information and consent forms. Before commencing each interview, researchers explained the purpose and process of the interview to the participant, read the consent form out loud and recorded consent verbally. Interviews took place via the telephone/Microsoft (MS) Teams (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Patients who were interviewed received a £10 shopping voucher as a thank you for their time.

Data collection

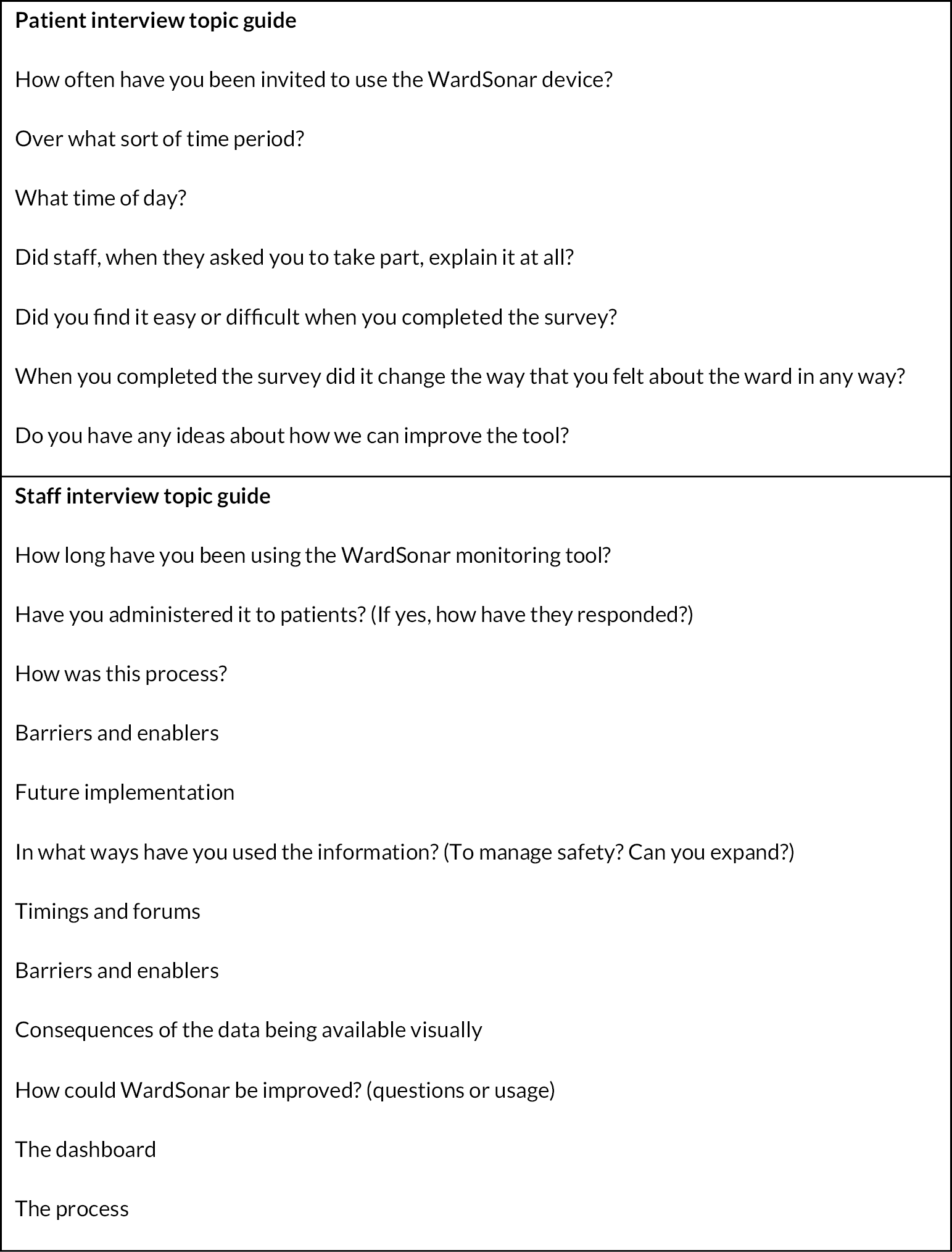

A topic guide was used to explore participants’ views about safety issues in acute adult mental health inpatient services and was adapted as interviews progressed so that pertinent topics were raised with subsequent participants. Appendix 2a contains the interview topic guide. Staff participants were asked to describe their job role and experience in acute adult inpatient mental health services. All interviewees (patients and staff) were prompted to discuss what they considered to be the features of safe and unsafe wards, their experience (or otherwise) of sensing that an incident had occurred or was about to occur, and their understanding of why safety incidents appeared to be temporally clustered. Interviews were audio recorded, anonymised and transcribed professionally.

Analysis

Members of the core research team coded the transcripts and jointly developed a coding framework based on inductive open coding of transcripts and deductive application of codes relating to the research questions and the topics covered in the interview. The constant comparison technique131 was used throughout, and analyses were conducted by hand and in Nvivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software. Thematic analysis informed by Braun et al. 132 identified themes that cut across the descriptive categories.

Results

Sample

A sample of 25 patients and mental health professionals participated in semistructured interviews via telephone or video link. Patient interviews were conducted between November 2020 and April 2021. Health professional interviews were conducted September–November 2020. Interview duration was driven by the interviewee and ranged between 15 and 71 minutes. The interview sample is summarised in Table 3.

| Patient | Health professional | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| Male | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Total | 8 | 17 | 25 |

A total of eight patients (female n = 2; male n = 6) over the age of 18 years with current or recent experience (during the past 2 years) of being an inpatient on an acute mental health ward were recruited for interview after responding to publicity material displayed in clinical areas. They made contact with the researcher and received further details about the study with a consent form. This sample was smaller than originally intended, with many fewer patients than staff. It is likely that the COVID-19 restrictions and the general social context influenced patients’ motivation to participate in interviews.

From health professionals, 17 (13 nurses, a psychologist, a psychiatrist, a speech and language therapist and a social worker) were recruited for interview. All had experience of working in UK inpatient psychiatric settings; 12 were based in one UK region and 11 were female; 8 were currently working in an acute mental health inpatient setting. Experience of working in mental health inpatient settings ranged from under 5 years to over 15 years.

Thematic data analysis133 explored aspects of contagion and milieu, highlighting the relationship between the milieu and contagion, and identifying themes of contagion via risk amplification, contagion via therapeutic depletion and contagion via increased exposure to safety incidents. Individual factors, the social and physical environments, and wider service factors (such as staffing levels) were considered as influences on safety.

The relationship between behavioural contagion and the milieu

Participant accounts of the physical, cultural and therapeutic space that constitutes a mental health ward described a complex, multilayered milieu in which attributes such as the social interactions of patients and staff and the wider service context were important influences. Their narratives suggested three mechanisms by which the milieu contributed to behavioural contagion: amplification of risk; a diminished therapeutic milieu; and increased exposure to safety incidents.

The extract below illustrates how different layers of the milieu and the interactions between them may be seen as facilitating, if not directly causing, perceived clusters of safety incidents.

When I enter a ward, I’m often told, you know, so-and-so has become distressed and then it’s set off someone else … I wonder whether, as professionals, we put that [interpretation] on the situation, because we’re trying to make sense of it ourselves, … You know, if someone becomes distressed, it then, kind of, ruminates with another person [and] they then feel upset. I think there might be a little bit of trauma stuff behind that, in terms of seeing someone be distressed is really upsetting … I also wonder whether there’s a relationship between that availability of staff. So, you know, if someone’s distressed because they haven’t been able to see the doctor, then it’s very likely that another person is going to get distressed, because they also can’t see the doctor. So I wonder whether there’s a more tangible reason why more than one person might be upset at that time.

Senior leadership team member

In this extract, the participant described being briefed about an incident (‘so-and-so has become distressed’) resulting in contagion (‘set off someone else’). She offered two explanations for contagion: (1) individuals’ characteristics (rumination, retraumatisation or increased sensitivity due to trauma, difficulty interpreting, regulating and expressing emotions); (2) the service context; specifically, that a diminished therapeutic milieu might frustrate patient attempts to access care (‘they haven’t been able to see the doctor’), leading to unmet needs and distress for that individual and potentially others.

Perspectives on safety

Participants referred to safety incidents that they said stemmed from patients and/or staff, and/or deficiencies within the service context. Aggression, violence, absconding, self-harm, suicidal behaviour, bullying, intimidation, substance use, property damage and use of restrictive practices were seen as safety issues.

Staff also referred to other events as having implications for safety, such as unexpected admissions or meetings, a chaotic patient, boredom, a fire alarm in the night, missed patient leave or staff being perceived (by patients) as acting unfairly. Many staff acknowledged that individual-level interpretations of service-level policy might vary between patients and staff or even different professions and that some incidents ‘never get recorded because it’s not recognised as an incident by a clinician’ (social worker, patient safety lead). This reflects differences in perspectives of patients, staff and organisational processes.

The quotation below illustrates how bullying by patients, staff behaviour and the wider service context combine to influence safety.

There was a lot of bullying. I felt really uneasy with some patients’ company, I spent a lot of my time in the activity room or in my own room, [or] on the occasions when I could get out, [in] the communal garden … Sometimes it was behind your back, if I was in the activity room but as soon as staff leave you could feel that uneasiness, you know what I mean, and there was one occasion when a member of staff went in and the panic alarm started but this female patient was always bullying people and the staff literally didn’t know how to handle her. It was so understaffed but the lack of staff, staff cannot be everywhere patrolling the wards, and they’re escorting patients and doing medication.

Patient 6, F

Patients drew on personal experience and gave examples indicating a broader range of the factors affecting physical and psychological safety. Other patients were a potential safety issue, as some were wary of the possibility of being attacked, without being protected by staff:

You get attacked in the hospital, by other patients and the staff don’t do nothing about it … I did get attacked in the hospital and they did nothing about it … I rung the police but the staff were saying he’s a liar.

Patient 3, M

Various norms and values around safety and risk were expressed, forming an impression of the cultural aspects of the milieu from reflections on policy, training, individual interpretations and staff–patient relations. Staff described shifts in attitudes to risk, safety and the use of restrictive practices (e.g. physical restraint, as-needed medication) had shifted over the past decade. They recalled feeling safe when ‘we could all restrain people and we had access to medications and that there were loads of staff’ (ward manager 1) and how the focus of post-incident reviews had shifted from explaining ‘why the incident occurred from our perspective’ (nurse 4) to considering patients’ psychological safety.

Staff also revealed how qualities they associated with a safe milieu could produce harm and clusters of behaviours they interpreted as ‘contagion’. For example, being ‘risk averse’ or performing well-intentioned efforts to prevent anticipated safety incidents could actually increase risk and safety incidents by imposing a culture perceived as oppressive: ‘the more restrictions we put on people, the more chance we’ve got of violence’ (ward manager 2). To add to the complexity of the context, it was possible that, if staff were out on the ward, visibly monitoring safety, patients could interpret this as a sign of disinterest in the patients:

I just think that they’re too busy, they’re moving around constantly, they’re not really putting the patients first.

Patient 5, M

Temporal clustering

One feature of social contagion is ‘temporal clustering’,134 where incidents of a behaviour are clustered together over a short period of time, like a ‘chain reaction’ (patient 2, M). Staff reported temporal clustering of incidents using terms such as ‘knock-on’ (ward manager 2) and ‘ripple’ (nurse 2). Arguably, this type of language represents a view that fails to consider contextual factors (such as staff shortages or subsequent COVID-19 restrictions).

Staff shared their perspectives on how patient aggression may be amplified and incidents of one type (violence, shouting) might have consequences (patient traumatisation, staff redeployment, patients need support, patients’ needs go unmet) that lead to incidents of another type (self-harm, leaving the ward without permission):

If a patient is very violent and aggressive on a ward, you may see a contagion for other violence and aggression … you may also see an incidence of increasing self-harm because people are distressed.

Social worker, patient safety lead

If you ever get a violent incident, you always end up with knock-on events … people requiring more one-to-one input [but] they can’t get it because the staff are redeployed somewhere else so that … it has a massive effect on the ward. And it’s traumatic, isn’t it, if you see something like that and people really struggle …

Ward manager 2

Information sharing between staff was seen as integral to constructing and maintaining a predictable, safe milieu, and indicative of a good team. Handovers between shifts provided an opportunity for outgoing staff to update incoming staff but could also ‘set off a chain of reaction with [staff]’ (nurse 6).

You get people going, oh you might as well go home, you’re going to have a terrible shift, it’s been a bloody horrible day, so-and-so’s been awful. You just think, for God’s sake, I don’t need this, this is not going to help me.

Ward manager 2

Although sharing patient information might help the team to feel prepared and safe, it could also lead staff to make negative assumptions, create anxiety and impact on how they interpret and respond to that patient.

Oh, Helen’s [name changed] been on this ward before and she’s really violent and then suddenly the next four people get this narrative of this person. And then […] maybe you’re scared or you’re unsure of what to do or your experiences inform how you interact with Helen.

Ward manager 1

Through their hypervigilance and information sharing, staff were primed to interpret cues based on their experience of previous instances that felt similar, information about patients, patients’ diagnoses and unconscious biases. Participants reflected that preparedness could be almost self-fulfilling: ‘when you’re expecting that situation, it can almost create that situation’ (social worker). They described how thinking about ‘scenarios that might arise, and how you’re going to manage them’ (nurse 4) generated feelings of tension and anxiety which affected relations with patients and also within the clinical team and could produce a ‘never-ending kind of spiral round of frustration, agitation and aggression’ (social worker, patient safety lead). Participants also described how they might arrive for a shift ‘already on the defensive’ (nurse 2) and full of ‘dread’ and this influenced how they processed information.

Staff interpretation of patient sensitivity

Health professionals observed that patients were ‘very perceptive as to what’s going on’ (nurse 8 manager) and inevitably affected by disruptions such as patient departures and arrivals and staff changeovers. Patients suggested that if other patients were ‘calm and settled’ (patient 4, M), this would help them to feel safe themselves. However, while staff saw their own hypervigilance as a marker of skill and expertise, they associated patients’ hypervigilance with hypersensitivity and impaired perceptions, judgements and abilities attributable to, for example, paranoia, poor emotional regulation, sensory issues and substance use.

Patients said that staff could misinterpret their behaviour, as these two examples show:

If you stay in your room they say you’re isolating or you could walk the corridors and take your chances but it’s a very violent environment … you couldn’t sit down and watch the telly or anything like that because if they got a telly the patients would smash it up. I couldn’t stay in my room because they said I was isolating myself.

Patient 8, M

I got a day release and I come home but then I got stuck in traffic so I phoned them up to say I was setting off back but it took me an hour and half because of the traffic and I got locked up for a week … I phoned up three times, I phoned from [city] in rush hour, stuck in traffic but the staff didn’t really tell that, and the doctor said lock him up. I was extremely pissed off.

Patient 1, M

Furthermore, whereas staff did not reflect on patients’ perceptions of how staff were feeling, this seemed to be important to patients.

If the staff are not warm and empathetic, that can really affect how you feel.

Patient 4, M

The importance of predictability

The belief that safety incidents are predictable and contagious was pervasive; for example, participants repeatedly demonstrated their conviction that a safe milieu was a predictable milieu: ‘you need to know what’s going on in order to have that safety and be able to practice safely’ (nurse 3). Participants proposed that structure, stability and predictability, ‘knowing what’s coming next’ (ward manager 1), were essential for staff and patients to feel safe.

Staff knowledge and experience of all aspects of the milieu at all three levels (service context, social and physical environment and individual) informed planning and preparedness for ‘what possible situations can arise’ (nurse 4), increasing incident predictability and therefore preventability. Staff were expected to know and understand many formal procedures and processes, policies and guidelines, to perform regular activities completing care plans, handovers, meetings, training in de-escalation and restraint, safety huddles,102 including structured risk assessments of patients to calculate ‘how risky they are to us, to our other patients’ (ward manager 2). They were expected to be familiar with patients’ triggers and ‘calm down methods’ (nurse 6), the whereabouts of ligature points and blind spots on the ward, be ‘trained in conflict and violence management’ (ward manager 2), de-escalation and ‘able to use physical restraint’ when necessary (nurse 7).

‘Ground level work’ (ward manager 2) was also required; that is, being with patients, meeting their needs and providing meaningful activities were thought to help build therapeutic relationships and, ultimately, safety: ‘you feel safe, they feel safe’ (social worker). There was a tension for staff between planning for anticipated risks and spending time with patients, however:

[Staff] feel like they’re going to get in trouble if they’ve not done a care plan, … But don’t realise that maybe if they’d sat out with the [patients] for a few hours that morning, you’ve probably managed about a million incidents … that are not going to happen because you’ve spent that time and had a cuppa with someone.

Ward manager 1

Staff claimed that ‘there’s always something like a precursor’ (nurse 4) and there were few safety incidents ‘we could never have predicted’ (psychologist). They interpreted safety incidents and other behaviours that occurred over the course of one or more days as causally related, ‘suddenly there’s three [incidents] in a day, that’s just not going to be chance’ (psychiatrist).

Staff described how their interpretation of what was expected in terms of safety led them to be in a constant state of ‘sensory awareness’ (SW, patient safety lead) or ‘hypervigilance’ (nurse 2) for anything that jarred with their notion of a safe, predictable milieu. There was a common belief that staff could sense ‘tension in the air’ (nurse 7) or ‘that feeling when you come on the ward’ (nurse 1), either from intuition or ‘micro-cues’.

I don’t really believe that it’s something that’s in the air. But it’s something about the situation that’s not the same and I suppose people who work in mental health, and people who have mental health issues, they’re more acutely attuned to those micro-changes in behaviour, in environment.

Nurse 1

These digressions were conceptualised as ‘disruptions’ in the milieu: something unexpected or out of the ordinary, ranging from shouting, alarms sounding or police presence to silence, an absent administrator or empty lounge. Disruptions were significant because participants interpreted them as cues: ‘it was like you knew something was going on’ (nurse 7). Claims about the ‘atmosphere’ or ‘vibe’ of the ward could be traced to disruptions in the physical or embodied milieu: visual and auditory ‘micro-cues’ (nurse 1), ‘subconscious stimuli’ or ‘environmental signals’ (nurse 2), such as changes in behaviour or body language, or the presence or absence of people. For example, one staff believed that patients ‘set the tone for the ward’ through their body language (relaxed or tense) and ‘what they’re saying, how they’re saying things, what they’re doing’ (nurse 9, practice development).

Patients said they did not think staff noticed everything. ‘Patients are more vigilant … got to look after themselves’ (patient 1, M). They emphasised how easily a small irritation can escalate:

Usually it builds up, you know? Starts with a disagreement over something or other, petty little thing and then escalates. For an example when I was in XXX, this lad … came in [to the TV room] to make himself a cup of tea … anyway he came in and went back out and then came in again and he says to me you pinched my phone. I said don’t talk daft I haven’t pinched your phone, look round for it … he found his phone and he didn’t apologise for that, so I just went in my room, I thought, the bastard just accused me, excuse my language, I were seething.

Patient 2, M

Impact of physical layout

Safety at the service-context level could be facilitated by the physical layout and visibility. Poor lines of sight and blind spots were considered ‘unnerving’ (nurse 9 practice development) by staff; patients tended to agree:

[Ward T] has four corridors that all join in the middle in the nurses’ office, I thought that were one of the best layouts. They can stand outside the office and turn 180 degree and see down all corridors, from that junction. They can keep an eye on people. First time I’ve come across that, other wards are corridors with little rooms coming off it where things could happen and people couldn’t see.

Patient 3, M

The milieu as a physical place brings patients who might ‘rub each other up the wrong way’ (psychologist) into proximity, whereby even one person ‘can completely change the dynamics of the ward’ (psychiatrist). Health professionals thought that, in some services, particular conditions (e.g. learning disability, personality disorder, autism) and patient mix affected safety by increasing the likelihood of ‘unpredictable’ behaviours.

When we have a lot of people with bipolar and everybody’s a little bit manic then what’s happening is everybody’s looking at somebody and saying are you having a go at me, are you looking at me. You’re looking at me strange. And being very high in their activity, more reactive to just normal cues or more reactive to other people being unwell. And getting involved in each other’s care.

Nurse 1

Although ‘patients really want to help each other out’, whether by ‘trying to soothe someone’ or ‘someone else is upset about something and they go, “oh yes and me”' (ward manager 2), this could lead them to become distressed or create additional challenges for staff. Although patient communities and friendships were beneficial, they could also facilitate the development of shared behaviours and goals.

If one [patient] would become difficult or challenging or if one would become upset for whatever reason, it would spread to the other two [patients], or the other two would be quite obstructive, or they would become quite difficult to engage.

Nurse 9, practice development

A physical layout that facilitated visibility made both intentional and inadvertent witnessing of incidents and staff and patient behaviours possible. Participants suggested that patients could be ‘distressed by witnessing’ (SW, patient safety lead) and/or hearing incidents. ‘I think when someone sees [an incident] it infuriates someone else’ (patient 4, M). This could reportedly facilitate the spread of fear, anxiety and distress, ‘like an infection’ (nurse 1).

[A patient] said he’d smash the ward up worse than the guy next door to me if you don’t let me out. It was then that ripple effect of he’d seen or heard what happened next door and thought well I want to leave, and maybe the only way I can leave is by doing what he’s done.

Nurse 7, staff nurse

Attempts to minimise the impact of witnessing an incident by dispersing patients could have their own negative implications. Staff suggested that patients encouraged to stay in their rooms may ‘feel more and more frustrated and concerned’ (nurse 8, manager), while one-to-one observation might be experienced by patients as ‘unhelpful’ (ward manager 2) or ‘unsafe’ (senior leadership team member). Similarly, the use of alarms to signal for assistance caused stress in both staff and patients across ‘the entire service’ (nurse 8, manager).

Patients described the impact on their mental health of the layout, cleanliness and general appeal of the physical environment.

Interviewer: Why did you not feel safe?

It was dirty … The cleaners were good and the morning clean was good, but it’s not enough. In my room there was snot on the walls, I had to clean it off myself … They cleaned in the morning but after that it were left, you know what I mean, it was constant, people making a mess, flooding toilets, staff saying ‘it’s not my job’.

Patient 1, M

One explained the significance of having their own room:

If you’re not feeling safe then go to your room and read a book or something. People have their own tellies and whatnot … their own private space so if you’re feeling a bit dodgy or irritated then go to your room.

Patient 2, M

Another patient was very clear about the importance of fresh air and space, in a dialogue that suggests these preferences were independent of the impact on wards of COVID-19.

Interviewer: What kind of things make you feel unsafe?

Patient: An unpleasant physical … environment, yeah. If there’re not enough windows and sort of fresh sunlight. Yeah, I’d say that.

Interviewer: Anything else about the kind of physical environment?

Patient: If it’s not spacious enough.

Interviewer: Right, so space and natural light, windows, that kind of thing?

Patient: Yeah.

Patient 4, M

As a physical space, the milieu could be said to bring similar individuals and similar behaviours together, creating the impression that patients’ behaviour is clustered because it occurs in broadly the same spatio-temporal context of the milieu. This phenomenon has been interpreted as the ‘convergence model of group influence’135 (p. 746), in which individuals within a group (e.g. patients on a ward) become more similar to each other as a result of the influence of group norms over time. Participants thought that this could increase the likelihood of patients upsetting each other and their vulnerability to contagion. Also, ward design with its emphasis on visibility intended to facilitate staff surveillance of patients in the pursuit of safety, and enabled patients to witness and be affected by the behaviour of staff and other patients, further facilitating contagion.

Contagion via therapeutic depletion

Therapeutic environments can become depleted when target-driven care models are prioritised over holistic philosophies of care. 136,137 Participants viewed the therapeutic potential of the milieu as another fundamental component of safety, suggesting that without it, ‘everything starts to fall to pieces’ (nurse 8, manager) and the ward becomes merely a ‘holding pen’ (senior leadership team member). Some pointed out that a depleted therapeutic milieu was harmful because ‘you’re leaving people just in their own distress or disturbance’ (ward manager 1) and creating an opportunity for aggression and unrest to develop.

They might sit for a couple of hours longer in the bedroom and then something that might have been quite easily resolved earlier on becomes another incident, whether it be self-harm or whether they go AWOL [absent without leave] or it could be anything.

Nurse 5

If you’re not allowing people to have access to leave, access to activities, access to things that make them feel well, you’re going to find that it’s going to be more unsafe because people are going to be more aggressive, people … there’s going to be a lot of unrest, people are going to be unsettled.

Ward manager 2

Furthermore, staff who looked disinterested or unhappy could influence the whole milieu:

[There should be something for staff] to remind themselves why they’re actually there, they’re there to help people, you know, to help those in need. Some having that negative, very down, low attitude, it’s going to translate into the team and translate into the patients.

Patient 5, M

It should be included in their training about showing empathy and compassion with patients no matter what their situation is because some of them can be really dismissive and just not interested … I think again it comes down to like, you know, more staff, attentive staff, staff that are not overworked to really sort of help dissipate these sorts of problems.

Patient 4, M

Patients were also sensitive to a ward milieu that made life difficult for staff.

A patient punched [a nurse] in a private area and all she did was go into the toilet and cry about it and then come back out and get on with her job … She should have reported. I mean if you’re a female in a hospital and you get touched inappropriately by a patient then you should report it. There were another female nurse that happened to, it were the same patient.

Patient 3, M

The topic of smoking was particularly highlighted, as restrictions on smoking could build up tension within the milieu without staff noticing.

This lad who kicked off, they wouldn’t let him have a smoke and that wound him up.

Patient 1, M

One of the examples of what staff don’t know about is smoking. In xxx you have to get an e-cig off one of the nurses and smoke it. I smoke myself and when I were in xxx I got fed up of asking for cigs so for a week I ended up on [nicotine] chewing gum, but that were the same, and every time I asked it were like ‘ten minutes’, ‘not now’, and it ended up they were like that with the chewing gum as well … I think that annoys people, not having a cigarette it affects people in different ways, some of those misunderstandings come from not having a cigarette.

Patient 2, M

Safety could be considered therapeutic in itself: ‘a vital thing for somebody to feel well’ (nurse 1). The therapeutic potential of the milieu could be diminished via exposure to an incident, or due to staff availability/unavailability, because of redeployment to an incident or retreat to their offices. Staff saw enormous potential for patients to feel ‘pissed off’ (nurse 8, manager), ‘rejected’ (nurse 7) and unsafe which may lead them to ‘self-harm or to try and abscond’ (nurse 7) or to try to elicit care, by using ‘verbal aggression’ (nurse 5) and ‘competing for volume’ (ward manager 2). These processes would damage trust: ‘it ruptures the patient–staff relationship hugely’ (psychologist).

Contagion via increased exposure to safety incidents

Potentially, exposure to safety incidents can create a norm whereby even in quiet periods, everyone within the milieu is anticipating the next incident, with resulting tensions contributing to the likelihood of it developing. When they do occur, the impact is widespread.

All the staff, kind of, run away into an office and say, are you alright, is everyone alright, and we’re all checking with each other. But we forget that we’ve got 20 guys either on the ward or in the bedrooms that are probably just as terrified or unsure of what’s happened, but we’ve left them to dwell in it. And then they don’t know what to do with it so then … we get that ripple effect of incidents.

Nurse 2

Finally, staff and patients shared concerns about the impact on patients of asking them to monitor their feelings of safety:

It is important to give feedback of any experiences, but … it is extra stress to be on the lookout for anything, you know, bad going on, having to report it and take the responsibility of reporting it, and everything.

Patient 4, M

One phenomenon in the data that can be interpreted as behavioural contagion was anxiety. Anxiety could be transmitted between staff and between patients and staff, leading to an overall increase in anxiety across the ward. The data presented here also included examples that did not qualify as contagion. For example, convergence, in which group norms lead to increased similarity, may be seen in the hypervigilance that stemmed from shared norms around the predictability of safety incidents.

Implications for development of the monitoring tool

The socioecological model (e.g. 138, 139) explains how levels of a setting interact to affect the development of an individual or organisation. In view of the staff interview data, it can be argued that the pervasive risk culture of the psychiatric milieu (context) primes staff attitudes, behaviours and interpretations of patients’ behaviours and safety incidents as contagious through a process of risk amplification which staff transmit between each other (priming).

Safety discourse in psychiatry often focuses on individual-level patient risk (e.g. reducing incidents of violence or self-harm) rather than on ward culture and staff characteristics and behaviours. 24,25,27 Risk culture drives staff to engage in practices that examine patient characteristics and past and recent incidents and individualise safety incidents such as risk assessment, care planning, debriefing and post-incident review. By shifting the focus to patients, this dominant conceptualisation of risk obscures the potential harm caused by associated risk management or safety promotion strategies. Risk culture also facilitates the anticipation and prevention of future incidents, encourages the retrospective attribution of linear cause and effect, and reinforces staff perceptions of incidents as predictable, preventable and contagious.

The harm caused by risk management strategies such as restraint and seclusion was acknowledged by staff, but the data presented here suggest that staff are also implicated in contagion (despite this usually being attributed to patient behaviour). Practices such as handovers between shifts or sharing information with other staff about patients could negatively prime staff’s expectations and interpretations of patients’ behaviour. Like staff, patients are tuned in to the atmosphere of the ward33,140 and value predictability and structure. 22,141 Seemingly innocuous staff practices such as the constant process of looking for and responding to disruptions in the milieu could therefore contribute to further disruption and provoke patients142,143 with potential implications for patients’ psychological safety and their perception of the milieu as a therapeutic space.

Thus, the milieu may act as a ‘depleting barrel’, not only eroding resources144 (p. 3), but also resulting in therapeutic depletion, and according to participants, therapeutic depletion could also contribute to contagion. By prioritising specific types of risk and safety staff are diverted away from therapeutic work, leading to unmet needs among patients. Yet patients’ conceptualisations of safety risks as including ‘not being listened to’, ‘not feeling psychologically safe’, understaffing and diminished therapeutic relationships19,20 suggest that therapeutic depletion is potentially harmful and may contribute to contagion. This was observed by Kang et al.,145 who reported that lack of support and emotional distress preceded ‘behaviours of concern’. A snapshot of the interim data (i.e. discussions around applying interview data to the development of the monitoring tool) is available in Appendix 2c.

Conclusion

The analysis of these interviews revealed dominant safety ideologies that shaped the perceptions and interpretations of individual staff, the consequences of which were played out in staff–patient relations, particularly in how staff interpreted and responded to patients’ characteristics and behaviours and how they sought to prevent and manage safety incidents. The data suggest that it is not only patients’ exposure to safety incidents that triggers further incidents. Instead, participants’ accounts indicate that any kind of disruption detected in the microsocial dynamics of the milieu could act as a cue for staff or patient behaviours that may subsequently be interpreted as a safety incident and/or contagion.

These findings illuminate the hitherto unexplored influence of staff and the psychiatric milieu on contagion via the proposed mechanisms of disruption, priming (risk amplification), involuntary convergence and therapeutic depletion. Kindermann and Skinner’s135 proposed criteria for identified contagion were limited by the lack of direction regarding how to define the attribute being transmitted, with clear implications for the over- or under-identification of contagion. In this study, identification of contagion must also be treated with caution. Although multiple examples of ‘contagion’ were identified by participants, their interpretation of disruptions in the milieu were informed by dominant cultural beliefs around the identifiability of risk, predictability of safety incidents and inevitability of contagion. Moreover, it is possible that contagion is also more likely to be identified in spatiotemporal contexts where individuals with shared characteristics and identities are gathered, subject to contextual confounds. 135 Previous studies of contagion among professionals have tended to focus on employee misconduct and ‘bad apples’,144,146 and even references to context such as the ‘corrupting barrel’ imply fault. 144,147,148 Analysis of staff views on ward safety, however, suggests that in their enactment of risk culture and the pursuit of safety and predictability, staff are capable of causing harm in their execution of care.

Chapter 5 Patient and public involvement and engagement in the development of the digital monitoring tool

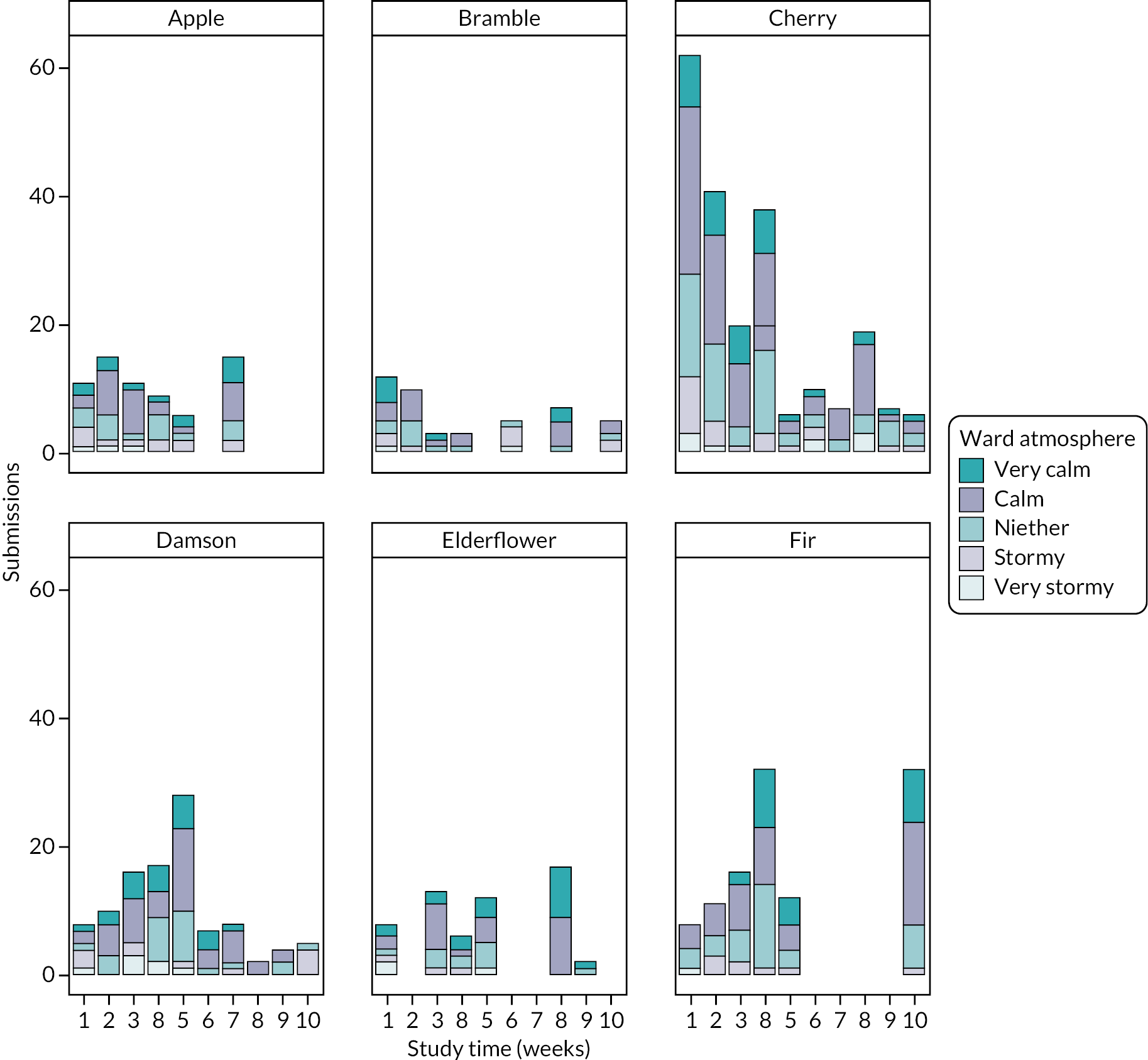

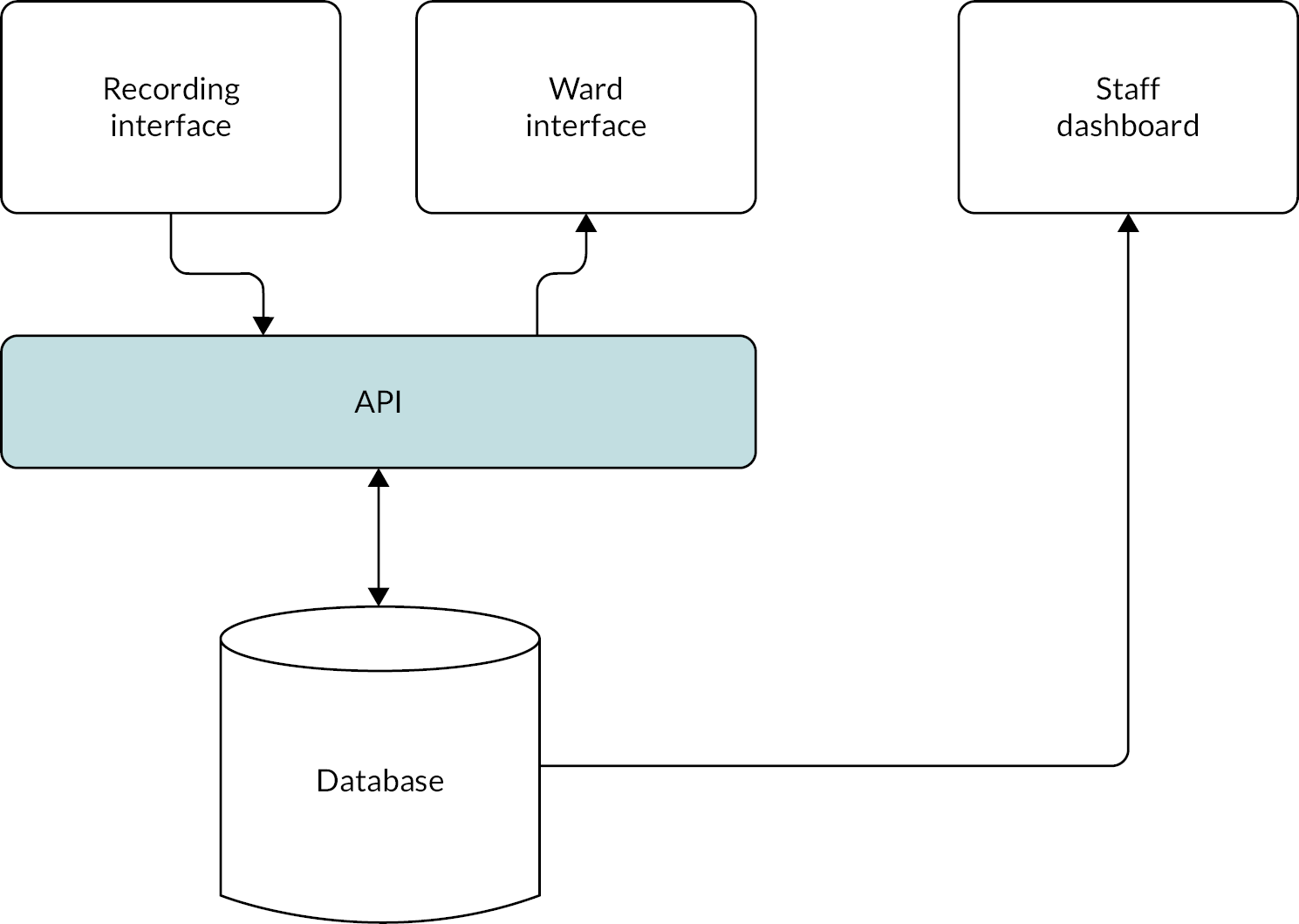

Patient and public involvement and engagement in the current study addressed the principles of equality, diversity and inclusion. It was not a discrete piece of work but integrated into all the development and design processes. However, the narrative has been structured for readability. This chapter focuses on stakeholder consultations and co-design activities.