Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/100/15. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Hannigan et al. This work was produced by Hannigan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Hannigan et al.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

In this project, we undertook a rigorous synthesis of research and other evidence in the area of end-of-life (EoL) care for people with severe mental illness (SMI), conducted according to internationally agreed quality standards. The project has been within the remit of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme in addressing quality, organisation and access in health services. In the context of calls for parity of esteem between mental health and physical health care,1 the health problem this project has addressed is a highly relevant but perhaps neglected one.

In preparing the original proposal supporting this project, an initial scoping review of literature was undertaken (with updated searches run in July 2018), and a targeted search was made for relevant policy documents across the four UK nations. A search of the database of NIHR projects was conducted to check for overlapping or related studies. Preliminary searches of four databases (combining ‘palliative care’, ‘mental health’ and ‘service provision’ terms) produced 4754 citations, within which were a number of relevant papers, including two previous literature reviews (from the UK and Canada, respectively), both now out of date, having been published over a decade ago. 2,3 Items discovered in this scoping search confirmed the timeliness and feasibility of a new, rigorous evidence synthesis, and particularly an EPPI (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information)-Centre-style review that is sensitive to the needs of stakeholders and that includes grey and non-research materials. 4 Items from this initial search, combined with general material addressing what is known about the burden of disease and the physical health of people living with mental health difficulties, have been used to inform this background and rationale (and subsequent) sections of this project report.

Burden of disease and costs

The overarching background for this project includes what is already known about the burden of SMI, cancer and end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure. Mental ill-health is a leading cause of years lived with disability around the world, with major depressive disorder the leading cause of years lived with disability in 56 countries and the second leading cause in a further 56. 5 Specific cancers, along with mental ill-health, neurological conditions, drug use disorders and specific organ diseases, all feature in the leading 20 causes of disability adjusted life-years in England for 2013. 6 The wider economic costs of mental illness in England were recently estimated at £105.2B each year. 7 This figure combines the direct costs of services, lost productivity at work and reduced quality of life, with the annual costs of the same in Wales estimated at £7.2B. 8

Meeting the physical health needs of people living with severe mental illness

The term ‘severe’ (or, often used interchangeably, ‘serious’, ‘serious and enduring’ or ‘serious and persistent’) mental illness, as used throughout this project, has longstanding currency in the fields of mental health policy, services and practice, dating back in the UK at least as far as the publication of Building Bridges: A Guide to Arrangements for Interagency Working for the Care and Protection of Severely Mentally Ill People. 9 It continues to be used in research10 and has currency with the NIHR Dissemination Centre, which published a themed review on SMI in 2018. 11 Building Bridges recognised the imprecision of the term ‘severe mental illness’ and endorsed a multidimensional framework definition encompassing five areas: safety, need for informal or formal care, disability, diagnosis and duration. Diagnosis is, therefore, an important, but not the only, dimension used in the identification of people with SMI and includes the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders, bipolar affective disorder, and disorders of adult personality and behaviour,12 along with similar Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, bipolar and related disorders, and major depressive disorder. 13

The particular focus in this project on EoL care can also be set in the context of people with SMI having high comorbidities2 and experiencing higher mortality rates and reduced life expectancy than the general population. 14 Higher mortality and morbidity rates for this group have been found across all age groups,15 with a 10- to 20-year reduction in life expectancy reported. 16 Inequities, not limited to care at the EoL specifically, can be explained with reference to individual- and system-level factors. People with SMI are less likely to attend health screenings and may respond to symptoms differently. 17 They may delay or avoid seeking help, and are more likely to exhibit disruptive behaviours or miss contacts with health professionals,3,18 putting them at risk of delayed disease detection. 2 Inadequate support systems are also common among those with SMI, affecting their ability to access appropriate clinical care and navigate complex health systems. 19 Other factors influencing variations in mortality and morbidity for people living with SMI include poor previous experiences of seeking help from health-care professionals (HCPs), care staff’s incorrect attribution of physical symptoms to psychiatric disorder and the lack of experience by mental health professionals in determining how and when to refer people onwards to other appropriate services. 3,20

End-of-life care for people with severe mental illness

In this study, following the definition used by the General Medical Council,21 EoL care is used to refer to the care of people who have diagnoses of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and are likely to die within the next 12 months. It includes care provided in hospitals, hospices and other institutional settings (e.g. care homes, prisons and hostels) and care provided in the home and via outreach to people who may also be homeless.

Beyond the inequities identified above, commitments to parity of esteem demand that EoL care for people with SMI should be as timely and as high quality as it is for others. However, early evidence gathered in support of this initial project proposal suggests that this group is poorly served, with England’s Cancer Strategy 2015–2022 recognising that people with SMI need to be the focus of improvements diagnosis and care. Although the incidence of cancer among people living with SMI is similar to that of the general population, mortality rates among those with SMI are double. 23,24 This disparity may be related in part to late presentation and reduced use of interventions such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. 25,26 The experience of SMI can delay detection and treatment of life-threatening physical disorders as people are less likely to seek treatment, to verbalise pain and to access timely health care. 27 Consequently, this patient cohort is more likely to present with more advanced cancers that are invariably more complex and costly to treat, with patients less likely to undergo invasive treatments and more likely to die. 28 Some cancers, other terminal conditions and/or related treatments may also compound mental illness and precipitate potential ‘problematic’ behaviours. 29 For many patients, therefore, palliative care is often the only meaningful treatment option available.

The original case for this evidence synthesis also built on the observation that, once people with SMI are in touch with EoL services, their symptoms may be poorly recognised and undertreated, with staff working in EoL services lacking knowledge, training and experience in this area. 30 Undetected and hence untreated mental illness can jeopardise treatment outcomes, reduce patient satisfaction and increase health-care costs. 31 Variable adherence can be a complicating factor,19 compounded by comorbid disorders, such as substance misuse, and social factors, such as homelessness, isolation or lack of transportation, all of which can exert an impact on planning for EoL care and treatment. 3,15 Assumptions about the capacity of people with SMI to make EoL decisions, and concerns that EoL discussions would be too distressing or would exacerbate mental health problems, may lead to inadequate consultation and advance care planning. 32 The case for this project included reference to the fact that people with SMI have a higher percentage of ‘do not resuscitate’ orders than other groups and are less likely to have had discussions about their explicit wishes for EoL care. 33

Palliative care

Although not all people at the EoL need palliative care, a review of the evidence34 confirmed inequities in palliative care provision for both cancer and non-cancer patient populations. In Wales, an estimated 24,000 of the 32,000 people who die per year would benefit from palliative care, but over one-quarter do not have access to it. 34,35 Access to palliative care services among people who die from cancer is 46%, compared with 5% among those dying from other conditions,36 including end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure.

The case for this project recognised that people with mental illness and advanced incurable cancer and/or lung, heart, renal or liver failure face inequities and discrimination35 and a lack of integrated care. 2 Some may be excluded from EoL care planning3, and even from hospitals or hospices entirely. 29 They may be referred back to mental health services, where staff are often inadequately prepared to provide appropriate EoL care. 3 Difficulties accessing appropriate services mean that for people with mental illness and a life-threatening disease palliative care may be the first line of treatment. 2 The specific provision of palliative care for people with SMI is known to be poorer than for the general population. People with SMI are approximately 50% less likely to access appropriate palliative care, including symptom control and pain relief. 3,20 Palliative care and hospice staff often feel unskilled,20 lacking confidence and training in conducting discussions about EoL care with people SMI. 32 Evidence gathered to inform the proposal for this synthesis also indicates that there is a lack of co-ordinated EoL care, and that access to appropriate psychosocial support is often limited. 2,3 Medical and nursing staff working in hospices have also been shown to be unprepared for working with people with SMI, basing their assessments on instinct rather than using evidence-based approaches. 37 In a survey of psychological services in hospices in the UK and the Republic of Ireland, only 30% of hospices had access to a psychiatrist, 41% had access to a clinical psychologist and 45% had neither. 38 Patient experience data underscore these observations, with England’s National Cancer Patient Experience Survey showing that people with a long-term mental health condition (2% of those surveyed; n = 1184) reported less positive experiences of cancer care. 39 In Wales, the most recent National Cancer Patient Experience Survey40 found that the lowest proportion of respondents reporting positive experiences of their cancer care were those identifying as also having mental health problems.

Evidence explaining why this research was needed

Research at the interface of physical and mental health care is recognised as a UK priority. 41 Against the background presented above, this project has created generalisable knowledge to improve EoL care and services for an underserved group. Policies from the four UK governments focus on improving EoL care, where diagnosis is immaterial. 42–50 These policies require the introduction of palliative and supportive care earlier in the illness trajectory, with patient surveys showing that this is rated very highly by those receiving it. 51 The charity Marie Curie (London, UK) identified triggers that should initiate palliative care for people with diagnoses other than cancer,52 but, apart from dementia, it does not mention those with pre-existing SMI. In national policy the needs of people with SMI who develop advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure are acknowledged poorly, or not at all. This group face the prospect of ‘disadvantaged dying’53,54 at a time when quality of care in the last months of life should be uniformly high for all groups.

Uniquely among the cancer, palliative and EoL strategies developed across the four countries of the UK, the Independent Cancer Taskforce’s Achieving World-class Cancer Outcomes: A Strategy for England 2015–202022 makes the specific recommendation that the NIHR commission research in the area of cancer care for people living with SMI. This project has responded to this call, and expanded it to also cover EoL care for people living with SMI and facing end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure. It has answered a question that is both timely and relevant: what evidence is there relating to the organisation, provision and receipt of care for people with SMI who have an additional diagnosis of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and who are likely to die within the next 12 months?

This rigorously conducted evidence synthesis has brought together reports of approaches to service organisation, processes and interventions shown to both facilitate and hinder the provision of high-quality, accessible, equitable and acceptable EoL care to people with SMI. The project team has also gathered research and other evidence reporting the views and experiences of service users, families, and health and social care staff. Outputs from the project are intended to have an impact on services and practice, and plans are in place to present findings in accessible ways to NHS and other managers, practitioners and educators. It is anticipated that findings will inform future National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, and thereby help shape the provision of services. Current relevant NICE guidance55–59 lacks standards or recommendations that particularly address EoL care for people with SMI.

A pre-project search of NIHR databases found studies that have investigated the physical health of people with SMI (e.g. Health Technology Assessment 12/28/0560), services for this group across organisations (e.g. HSDR 11/1023/1361) and care for people experiencing mental health difficulties after receiving cancer diagnosis (e.g. Health Technology Assessment 09/33/0262). As no research has been commissioned in the area addressed here, this project has effectively opened a new and important programme of work with value to the NHS and its partners. Having used a methodical, systematic and transparent approach, the MENLOC project team now plans to use this synthesis as the starting point for a programme of research that builds on what is already known, is designed with people who have experience of mental health difficulties and with people who have lived with cancer and have cared for family at the EoL, and generates new evidence of what works with value to the NHS and other relevant organisations.

Chapter 2 Working with stakeholders and defining parameters

In this chapter, the approach taken to working with stakeholders, including members of the public and people with personal experience of mental health and/or EoL care, is described. Reporting of this section is completed with reference to GRIPP2-SF standards. 63 The proposal for this evidence synthesis was shaped by people with experience of mental health problems, cancer and other long-term conditions, and by people with experience of caring. The original idea for the study arose following sustained and critical discussions between two co-investigators, Roger Pratt and Sally Anstey, who together identified that individuals with SMI are disadvantaged when diagnoses of advanced cancer or end-stage organ failure are made. Roger is a retired mental health social worker who lives with lymphoma (in long-term remission) and heart failure. He cared for his wife who died from advanced peritoneal cancer; she received specialist palliative care in the last year of her life and died in a hospice. This discussion observed that professional perceptions and misperceptions such as stigma and fear have an impact on management (e.g. pain control, supporting choice and place of care/death) in the case of people with SMI receiving EoL care. Alan Meudell later joined the project team as a mental health service user consultant and researcher. He has worked on two previous NIHR studies64,65 and one Health and Care Research Wales study66 and has led training for Health and Care Research Wales on involving service users in research. He is also interested in the physical health care of people living with mental health difficulties and in the provision of equitable services.

Throughout the project, building on these beginnings, the aim of public and patient involvement was to embed public and patient involvement perspectives into all aspects of the project, from the definition of search terms and parameters onwards to impact and dissemination. The role Alan Meudell played was equal partner in all stages of the research process except the literature search (which was led, uniquely, by Mala Mann as the team’s information services specialist). At his request, once the project had started, Roger contributed at stakeholder advisory group (SAG) meetings only, although both he and Alan Meudell participated in initial training that other investigators joined. They also contributed to the task of identifying carers and service users to join the project stakeholder group. Alan Meudell advised on the ongoing focus and direction of the study, and directly contributed to the screening of items for possible inclusion, the synthesis of materials and the accessible writing-up of this final report. In preparing an initial project proposal for submission to the HSDR programme, plans were also presented to the Patient Experience and Evaluation in Research (PEER) group at Swansea University (www.swansea.ac.uk/humanandhealthsciences/research-at-the-college-of-human-and-health/patientexperienceandevaluationinresearchpeergroup/; accessed 14 February 2020). The PEER group comprises people with experience of using health-care services and of caring and exists to provide a public and patient view of research proposals before they are submitted for funding. When the proposal was considered by the PEER group, members gave it a very positive response, stating that this was a much-needed project in an area that is largely ignored. People were particularly interested in plans for choosing members of the SAG and advised the project team to engage with charities such as Macmillan Cancer Support (London, UK), with hospices and with palliative care staff such as nurses. They also recognised the difficulty of actually recruiting SAG members from the target population but believed an attempt should be made to engage by offering opportunities for people with SMI and EoL diagnoses to participate in any way feasible for them. This advice was noted, and services in South Wales were approached to seek their agreement in principle to help put project team members in touch with service users and carers (as well as managers and practitioners) able to advise the study.

Populating the SAG was accomplished during the project set-up phase, with representatives drawn from the mental health and EoL fields. Members included professionals from a range of practitioner backgrounds based in NHS and charitable organisations, policy advisers and people with lived experience of mental health difficulties and of life-threatening disease. The full membership of the SAG is found in Appendix 1, and over the life of the study the combined project team and SAG met, in Cardiff, at three strategic time points. The first meeting was scheduled at the commencement of the project, with the focus on agreeing terms of reference (see Appendix 2) and then refining database search terms and wider search strategies, including the identification of online sources for the team to consult (see Appendix 3). The second meeting took place after the evidence searching and screening had been completed, which provided an opportunity to share work in progress (see Appendix 4). The final meeting was scheduled at the commencement of the whole-project synthesis and report-writing phase, with a focus on sharing preliminary findings and discussing plans for dissemination and maximising impact (see Appendix 5).

Defining the project’s parameters: ‘severe mental illness’ and ‘end of life’ (and related)

At the first, key, combined project team and SAG meeting, candidate database search strategies and search terms developed by the project team for both SMI (see Appendix 6) and EoL care (see Appendix 7) were distributed and discussed at length with the purpose of refinement.

Severe mental illness

Project team and SAG members recognised the imprecise nature of the phrase ‘severe mental illness’, but also the everyday currency of the term. It was recognised that the focus of this study was broadly on EoL care for adults over the age of 18 years who have used secondary, specialist, inpatient and/or community mental health services. At the meeting participants also discussed the inclusion of additional diagnoses [e.g. anorexia and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)] not listed in the MENLOC protocol. It was noted that diagnostic manuals are extensive, and that listing new individual diagnoses at this point would open the door to including all diagnoses, making for unmanageable searches. It was decided, therefore, not to include such terms.

An intense dialogue was held around the diagnosis of depression as a result of the large numbers of outputs initially retrieved via the scoping search reporting on depression as a consequence of receiving an EoL diagnosis, as opposed to preceding such a diagnosis. The continuum of depression was also noted, and the project team agreed that outputs concentrating on people with mild, commonly experienced depression (and, by extension, anxiety) should be excluded. A consensus was to remove ‘depression’ as a search term or MeSH (medical subject headings) term but instead use ‘depression’ in conjunction with other terms such as ‘psychosis’ or ‘pre-existing’ or ‘severe’. This meant, therefore, using adjacency searching to retrieve accurate results. Project information specialist Mala Mann confirmed that older terms such as ‘melancholia’ would not need to be searched for, because database indexing combines outputs using these phrases with outputs using more contemporary terminology.

Project members reported that not all initial EoL care outputs retrieved made clear whether or not the mental health problems experienced preceded EoL diagnosis. Some discussion also took place on whether or not a fourth arm should be added to the search strategy, capturing the use of secondary services, in recognition of the fact that people with SMI are overwhelmingly people who use secondary mental health services. It was noted that a four-arm search would be too narrow, and that citations containing such terms would already be identified using the existing three-arm search (see Chapter 3).

A decision was made not to search specifically for the search terms ‘suicide’, ‘assisted death’, ‘assisted suicide’ and ‘euthanasia’ (noting that euthanasia may be seen by some people using services as the only possible option when all else fails), as papers in these areas would be found through existing search strategies.

End-of-life care

Suggestions from SAG members for search terms related to the EoL were noted, including ‘thanatology’ (the study of the theory, philosophy and doctrine of death); ‘best supportive care’/’enhanced supportive care’ (these being relatively new terms currently in use); ‘end-stage’, as a term to represent dying with chronic conditions; and ‘conservative management’ or ‘conservative treatment’. A consensus was to exclude ‘self-poisoning’ or ‘self-inflicted injuries’, as the goal of treatment likely to be reported in outputs was to sustain life. A consensus was also not to add into the search strategies terms attempting to establish the reasons for EoL care, but to include terms reflecting the closing down of active treatments: ‘withdrawing active treatment’, ‘withdrawing’ or ‘refusing’ treatments such as dialysis and ‘moribund’. It was noted that the ‘expected last six months of life’ is a term used in the USA and should be included.

At this first combined project team and SAG meeting, participants identified a group of conditions not previously considered by the project team, covering (for example) conditions broadly referred to in the meeting as ‘brain failure’. It was noted that ‘brain failure’ outputs would be captured under the term ‘organ failure’, and that a separate funding proposal was being prepared to synthesise the evidence in the area of EoL care for people with neurodegenerative conditions.

Finding grey literature, including non-research material

Websites to search that had already been identified by the project team were circulated (see Appendix 8), and in this first, key, meeting SAG members were invited to identify additional online sites. Suggestions made in the meeting or received thereafter included a Hospice UK (London, UK) report (KC), deaths in custody (SP), palliative care in prisons (NP) and searches on institutional repositories.

Chapter 3 Methods and description of included materials

This chapter describes the methods used in this evidence synthesis, and the materials finally included. At the commencement of the project a protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO CRD42018108988). 67 The synthesis was conducted with the co-investigator involvement of an expert from the Cardiff Specialist Unit for Review Evidence (SURE). It followed guidance for undertaking reviews in health care published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination68 and in incorporating stakeholder views and non-research material used methods informed by the EPPI-Centre. 4 To ensure rigour, the review is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 69 Factors facilitating and hindering high-quality EoL care for people with SMI were identified, as was evidence relating to services, processes, interventions, views and experiences.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this project was to synthesise relevant research and other appropriate evidence relating to the organisation, provision and receipt of EoL care for people with SMI (including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychoses, major depression and personality disorder). Specifically, it answered the following question: what evidence is there relating to the organisation, provision and receipt of care for people with SMI who have an additional diagnosis of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and who are likely to die within the next 12 months?

The specific objectives were to:

-

use internationally recognised, transparent literature review approaches to locate, appraise and synthesise the relevant research evidence relating to the organisation, provision and receipt of care in the expected last year of life (LYoL) for people with SMI who have additional diagnoses of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and who are likely to die within the next 12 months

-

locate and synthesise policy, guidance, case reports and other grey and non-research literature relating to the organisation, provision and receipt of care in the expected LYoL for people with SMI who have additional diagnoses of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and who are likely to die within the next 12 months

-

produce outputs with clear implications for service commissioning, organisation and provision

-

make recommendations for future research designed to inform service improvements, guidance and policy.

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants

This evidence synthesis considered all relevant evidence specifically relating to adult participants (> 18 years of age) with SMI who have an additional diagnosis of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and who are likely to die within the next 12 months. SMI was defined as including but not limited to schizophrenia, schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, schizotypal and delusional disorders, bipolar affective disorder, bipolar and related disorders, major depressive disorder and disorders of adult personality and behaviour.

Types of intervention and phenomena of interest

All citations were considered that addressed service organisation and the provision and receipt of EoL care for people with SMI who have an additional diagnosis of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure and who are likely to die within the next 12 months. Citations reporting the views and experiences of service users, families and health and social care staff were also included.

Context

All citations were considered with regard to organisation, provision and receipt of EoL care provided in hospitals, hospices and other institutional settings (e.g. care homes, prisons and hostels) and care provided in the home and via outreach to people who may also be homeless.

Types of evidence

Types of evidence sought included quantitative research, qualitative research and non-research material (e.g. policies, guidelines, reports of practice initiatives and clinical case studies). Searches were conducted for UK-only grey literature, including policies, guidance and related information, in recognition of the fact that the primary audience of decision-makers interested in the study’s key findings and implications is likely to be UK based. Materials published in the English language since the inception of databases were considered.

Exclusion criteria

-

As confirmed in a first combined project team and SAG meeting, where reporting allowed the distinction to be made, evidence relating to mental health problems (e.g. depression) as a consequence of terminal illness (e.g. cancer or chronic organ failure).

-

Evidence relating to EoL care for people with mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use, except where these coexisted with SMI as specified above.

-

Evidence relating to EoL care for people with dementia or other neurodegenerative diseases, except where these coexisted with SMI as specified above.

-

Evidence from animal studies.

Developing the search strategy

The focus of the search strategy was to achieve high sensitivity and specificity for retrieving studies relevant to the review question. The search strategy was comprehensive and designed to ensure that all relevant literature was obtained, with the precise emphasis on concepts associated with the research question discussed in the first combined project team and SAG meeting, described in Chapter 2. Although some terminology remains equivocal in this area, the search strategy as it became finalised was designed to identify all relevant evidence relating to EoL care (i.e. in the LYoL) in those with SMI. Reflecting the importance of diagnosis in the framework definition of SMI,9 diagnostic terms included in the search strategy included schizophrenia, schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, schizotypal and delusional disorders, bipolar affective disorder, bipolar and related disorders, major depressive disorder and disorders of adult personality and behaviour. Reflecting prevailing definitions of SMI (e.g. as used by the NIHR Dissemination Centre11), searches were not made for studies into mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use or for studies into dementia or other neurodegenerative diseases, and items in these areas were not included in the review, except where participants’ diagnoses co-existed with the disorders included above.

Preliminary searching

Preliminary database searching using MEDLINE was carried out as part of initial scoping undertaken in preparation of the proposal for funding, with material from this drawn on in Chapter 1. The preliminary keywords that were used to inform these searches included the following:

Palliative care OR Hospice care OR Terminal care OR Terminally ill OR End of life care OR Last year of life

AND

Neoplasms OR Cancer OR heart failure, lung failure, liver failure or renal failure

AND

Mental health OR Depression OR Mental disorders OR Depressive disorder OR Personality disorders OR Bipolar disorder OR Schizophrenia OR Mental illness

An analysis of the text words contained in the titles and abstracts, and of the index terms used to describe each article, was undertaken. As a result of this, the search strategy was further developed, and in July 2018 the opportunity was undertaken to update and extend the preliminary scoping exercise across four databases. These were, on Ovid, MEDLINE® ALL, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, PsycInfo and EMBASE. The MEDLINE search can be found in Appendix 9.

Comprehensive searching

A comprehensive search strategy was developed by Mala Mann following discussion at the first combined project team and SAG meeting (see Chapter 2). This search strategy was initially developed for MEDLINE (see Appendix 10) and PsycInfo (see Appendix 11). As a means of testing and refining this search strategy before applying it across multiple databases, Deborah Edwards first screened the citations retrieved across MEDLINE and PsycInfo to ensure relevance and to assess that the strategy was neither too broad nor too narrow. Once the project team was satisfied with the search strategy, this was tailored to the remaining eight databases, with searches run from each database’s inception. Databases searched included:

-

on the Ovid platform – MEDLINE ALL, EMBASE, HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium), PsycInfo and AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database)

-

on the EBSCOhost platform – CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials)

-

on the ProQuest platform – ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts)

-

others – DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) and the Web of Science.

Supplementary searches were undertaken to identify additional papers, information on studies in progress, unpublished research, research reported in the grey literature and personal blogs. Members of the SAG advised the project team as to which relevant websites to search (see Chapter 2), and a full list of websites searched along with the search terms utilised can be found in Appendix 12. Members of the SAG were also asked to inform the research team of any other publications of which they were aware that they thought might be relevant to the review. The principal investigator (BH) and the project manager (DE) followed a number of key EoL and mental health authors and organisations on Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) to identify any material that could be potentially relevant to the evidence synthesis.

Searches were also conducted using Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), as described by Mahood et al. 70 The first 10 pages of each Google output were screened using the following terms:

-

“palliative care” and “mental illness”

-

“end of life” and “mental illness”

-

“end of life” and schizophrenia (searching the first five pages of output)

-

“end of life” and bipolar (searching the first five pages of output).

To identify published resources that had not yet been catalogued in electronic databases, recent editions of the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Cancer, Psycho-Oncology and BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care were hand searched. These journals were selected because a large number of outputs identified in database searches had been published in them. Reference lists of included studies were scanned and forward citation tracking was performed using the Web of Science.

Primary research citations retrieved from database searches

All citations retrieved from the 10 database searches were imported or entered manually into EndNote™ (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and duplicates were removed. The total numbers of hits retrieved for each database are displayed in Table 1.

| Database | Search interface | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| AMED | Ovid | 196 |

| ASSIA | ProQuest | 836 |

| CINAHL | EBSCOhost | 361 |

| CENTRAL | Wiley | 958 |

| DARE | CRD | 263 |

| EMBASE | Ovid | 7033 |

| HMIC | Ovid | 39 |

| MEDLINE alla | Ovid | 1302 |

| PsycINFO | Ovid | 663 |

| Web of Science | Clarivate Analytics | 125 |

| Total | 11,776 | |

Primary research citations identified from supplementary searching

All primary research citations identified as potentially relevant from across all supplementary sources (Table 2) were entered manually into EndNote. A total of 128 citations were identified.

| Source | Number of citations |

|---|---|

| Reference lists of included studies | 88 |

| Forward citation tracking of included studies | 15 |

| 4 | |

| 8 | |

| SAG | 2 |

| Trial registers | 0 |

| Hand-searching | 11 |

| Total | 128 |

Removing irrelevant citations

Once all of the primary research citations had been imported into EndNote, irrelevant citations were removed by searching for keywords in the title using the search feature of the EndNote software. The project team had previously agreed which keywords to use to identify papers that did not meet the review’s inclusion criteria. All hits for each keyword were screened by Deborah Edwards to ensure that they were, in fact, irrelevant before they were removed. The following keywords were used:

-

Abuse/substance

-

Adolescence/adolescent/youth

-

AIDS/HIV

-

Alcohol

-

Anxiety

-

Assessment

-

Bereav*

-

Bipolar diathermy/electrocautery

-

Book review

-

Child

-

Dementia/Alzheimer’s

-

Depression

-

Diabetes

-

Diagnos*

-

Fatigue

-

Grief

-

Incidence

-

Instrument/tool

-

Letter

-

Neonate/neonatal

-

Parent

-

Predict*

-

Prevalence

-

Prognosis/prognostic

-

Psychometric

-

Scale

-

Screen*

-

Sleep/insomnia

-

Smoking/tobacco

-

Spiritual/religious

-

Survival

-

Thesis

-

Validity/reliability/validation

-

Version.

At the end of this process, the remaining citations were exported as an XML file and then imported into the software package Covidence™ (Melbourne, VIC, Australia).

Title and abstract screening

All citations were independently assessed for relevance by two members of the review team using the information provided in the title and abstract using Covidence. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer, and, where needed for further clarity, the full text was retrieved to aid this discussion. Particular care was taken with citations referencing people experiencing depression. Depression is a commonly experienced mental health problem, but it is also one that can manifest as a severe mental health problem, requiring an urgent and potentially life-saving intervention. As our focus was on EoL care for people with pre-existing SMI, we excluded citations reporting on prior experiences of mild depression, and excluded items reporting on the identification of depression and its treatment among people who had experienced psychological distress subsequent to their EoL diagnosis. Only citations clearly reporting on EoL care for people who had pre-existing severe depression were included.

For citations that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, or in cases in which a definite decision could not be made based on the title and/or abstract alone, the full texts of all citations that appeared to meet the review’s inclusion criteria by title and abstract screening were retrieved.

Full-text screening

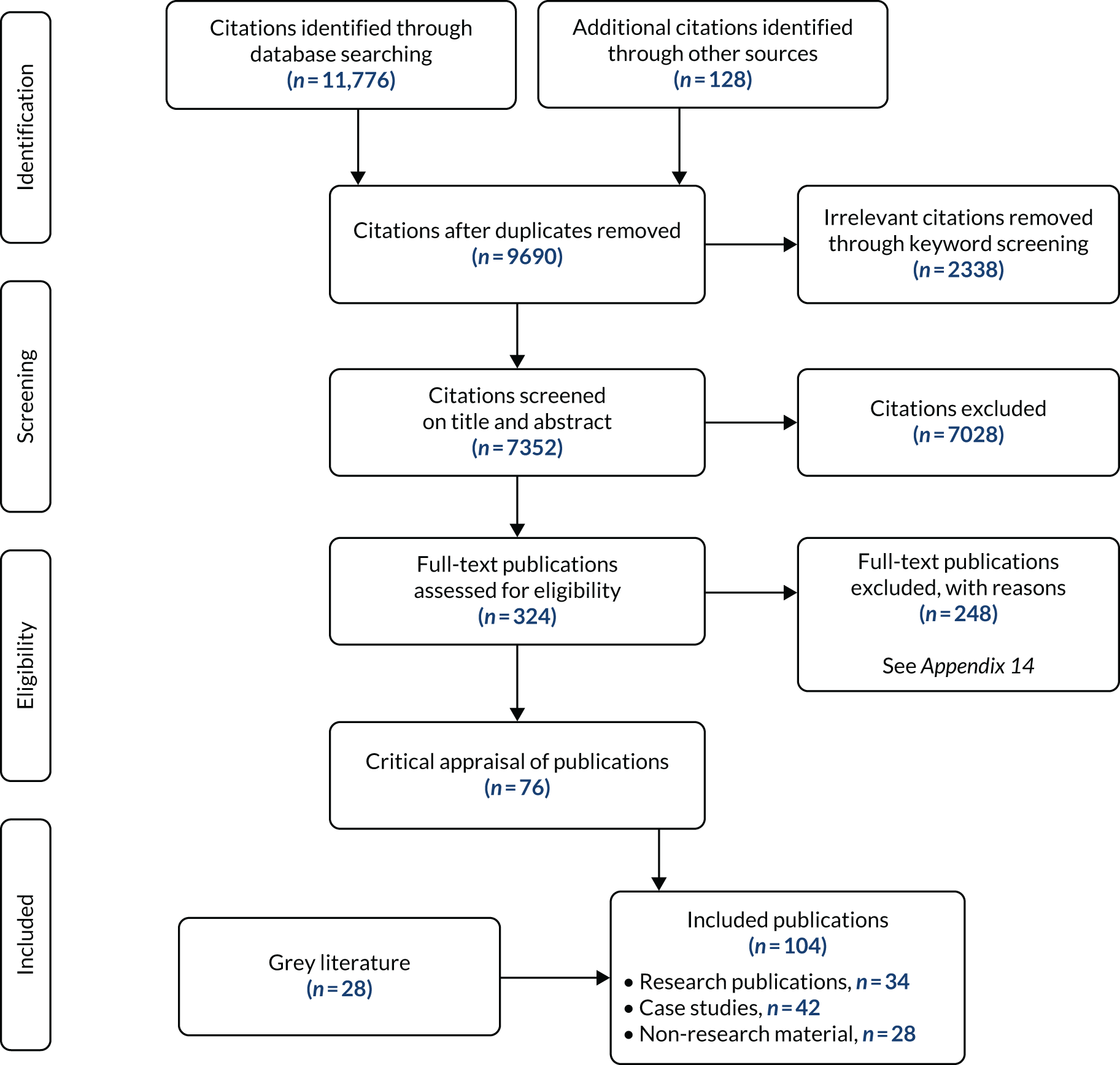

To achieve a high level of consistency, two reviewers screened each retrieved citation for inclusion using a purposely designed form (see Appendix 13). Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. All English-language items relating to the provision of EoL care to and the receipt of EoL care by people with SMI and an additional diagnosis of advanced incurable cancer and/or end-stage lung, heart, renal or liver failure were included at this stage. The flow of citations through each stage of the review process is displayed in the PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1. 69

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow chart. Reproduced with permission from Edwards et al. 71 © The Author(s) 2021 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Grey literature identified from supplementary searching

Sixty-eight grey literature citations were identified as potentially relevant from across all supplementary searches (Table 3), and these were all entered manually into EndNote. Policies and guidance, reports and other non-research materials found in the grey literature were also read by two members of the project team and considered against the topic inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved as above. Forty were excluded (see Appendix 15), leaving a total of 28 that were assessed as relevant to the review (see Appendix 16). A test search for relevant information in renal-specific documents produced no material suitable to be included in the review. The decision was therefore made by the project team not to search within (the large number of) disease-specific policy and guidance documents for material concerned with the management of EoL care for people also with SMI.

| Source | Number of citations |

|---|---|

| Organisation websites | 47 |

| SAG | 16 |

| 3 | |

| E-mail alert for HQIP | 1 |

| Reference lists of included studies | 1 |

| Total | 68 |

Materials included in evidence synthesis

One hundred and four publications were included in the evidence synthesis, which consisted of research publications (n = 34), case studies (n = 42) and non-research policy and guidance material (n = 28).

Terminology and language use

Language is important (and sometimes contentious), and, as described in Chapter 2, Defining the project’s parameters: ‘severe mental illness’ and ‘end of life’ (and related), the variety of terms used in the mental health and EoL fields and in the materials included in this synthesis were recurring items at combined project team and SAG meetings. Across the items located and included in the synthesis, no agreed definitions could be discerned relating to the precise meanings of SMI or the content of EoL care or palliative care. Specialist palliative care could refer, particularly in the UK context, to care provided in any setting (hospice, home, care home or hospital) by a dedicated specialist team with additional education and skills in palliative care that enables them to support those at the EoL with any diagnosis who have complex, high-level needs, whatever the cause. Palliative care, however, could refer to care provided by all HCPs to those who are at the EoL (across all care settings) and do not have the additional complex needs that require additional specialist support. This clinical distinction may be similar across many countries with similarly developed health systems (e.g. the USA, Australia and Canada), but, in each case, the project team, having finalised the materials to include, noted the existence of different funding and organisational arrangements and varying standards for eligibility to access services. Discussion also took place between project team and SAG members on the language to be used in this report to describe people with SMI at the EoL. In recognition of people’s receipt of (or need for) integrated care crossing mental health and palliative care system boundaries, a decision was made at the third combined project team and SAG meeting to use the word ‘patient’.

Quality appraisal

Following searching and screening, information from research and case study publications was assessed independently for methodological quality by two reviewers using one of a number of agreed appraisal checklists. Alternative tools, which reflected the specific design and methods used in individual research outputs, were used as necessary when suitable Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools were not available. Any disagreement on quality was resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. No research items were judged to have been fatally flawed, and all were included. The policy and guidance documents and non-research reports were not subject to quality appraisal.

For qualitative studies, the appropriate checklist available from CASP was used. 72 For cross-sectional designs, the Specialist Unit for Review Evidence 12-item checklist73 (with responses ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t tell’) was used and an overall score reflecting the number of items answered ‘yes’ was generated.

Retrospective cohort studies were appraised using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network’s Methodology Checklist 3: Cohort Studies. 74 This is a 14-item checklist (with responses ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t say’ and ‘does not apply’). Six items do not apply to this type of study design (statements 1.3, 1,4, 1,5, 1.6, 1.8 and 1.12). The overall assessment reflects how well a study has sought to minimise the risk of bias or confounders. The final rating is high quality (++), acceptable (+) or low quality (–). Reproduced from Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network with permission. 74 These guidelines are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence. This allows for the copy and redistribution of SIGN guidelines as long as SIGN is fully acknowledged and given credit. The material must not be remixed, transformed or built upon in any way. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

As retrospective designs are generally regarded as weaker, the authors of the checklist suggest that these should not receive a rating higher than ‘+’.

For case studies, the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for case reports was used. 75 This is an eight-item checklist (with responses ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’, ‘not applicable’) from which an overall score is generated reflecting the number of items answered ‘yes’.

Data extraction

All demographic data from the 76 research and case study publications were extracted directly into tables based on study design (see Appendices 17–20), following the format recommended by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 68 The work was allocated to a member of the research team who extracted the relevant data, and a second reviewer (DE) independently checked the data extraction forms for accuracy and completeness. A record of corrections was kept. Where multiple publications from the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as if from a single study.

Data analysis and synthesis

Following discussion at the second of the three combined project team and SAG group meetings, the decision was made to conduct a first analysis and synthesis for the combined research studies (n = 34) and policy and guidance documents (n = 28), and a second analysis and synthesis for the case studies (n = 42). The project protocol stated an intention to perform meta-analyses of data for included intervention studies. However, no intervention studies were found. All synthesised findings are therefore presented as narrative syntheses in Chapters 4 and 5.

All research papers were available in full-text form, and each was uploaded to a project created using the software package NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). All policy and guidance documents were available as electronic documents, and the content of each was searched using keywords relevant to the review (‘mental illness’ and ‘end of life’). Data retrieved in this way were extracted and entered verbatim into Microsoft Word (Microsoft 365 Apps for Enterprise; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents, one for each policy and guidance item. Microsoft Word files containing the extracted data were then uploaded to the same NVivo project as the research items in preparation for analysis. All case studies were available in full-text form and were uploaded to a second NVivo project.

A thematic approach was employed to analyse and synthesise both sets of data,76 with work on the combined research and policy data set led jointly by Ben Hannigan and Deborah Edwards and work on the case study data set led by Michael Coffey. Using NVivo, in both cases inductive data-driven codes were generated and attached to segments of material through the line-by-line reading of documents. To aid discussion and refinement, and to support a visual appreciation of the overall character of the developing research and policy synthesis, codes and their relationships to each other were also reproduced on large sheets of display paper. In both thematic syntheses, codes were grouped into meaningful candidate themes (and, in the case of the research and policy synthesis, subthemes) reflecting the material being synthesised and the overarching objectives of the project. 4 These were shared with all members of the project team for review and further refinement, with no major disagreements noted. Themes and subthemes were then tabled at the third combined project team and SAG meeting, where the overarching thematic structure of both syntheses was discussed and approved. Both syntheses aimed to bring together reports of approaches to service organisation, processes and interventions shown to both facilitate and hinder the provision of high-quality, accessible, equitable and acceptable EoL care to people with SMI. The reporting of the separate analysis and synthesis of the combined research, policy and guidance items is contained in Chapter 4, and the reporting of the analysis and synthesis of the case study items is contained in Chapter 5. Figure 6 in Chapter 6 provides a visual overview of both thematic syntheses as a whole.

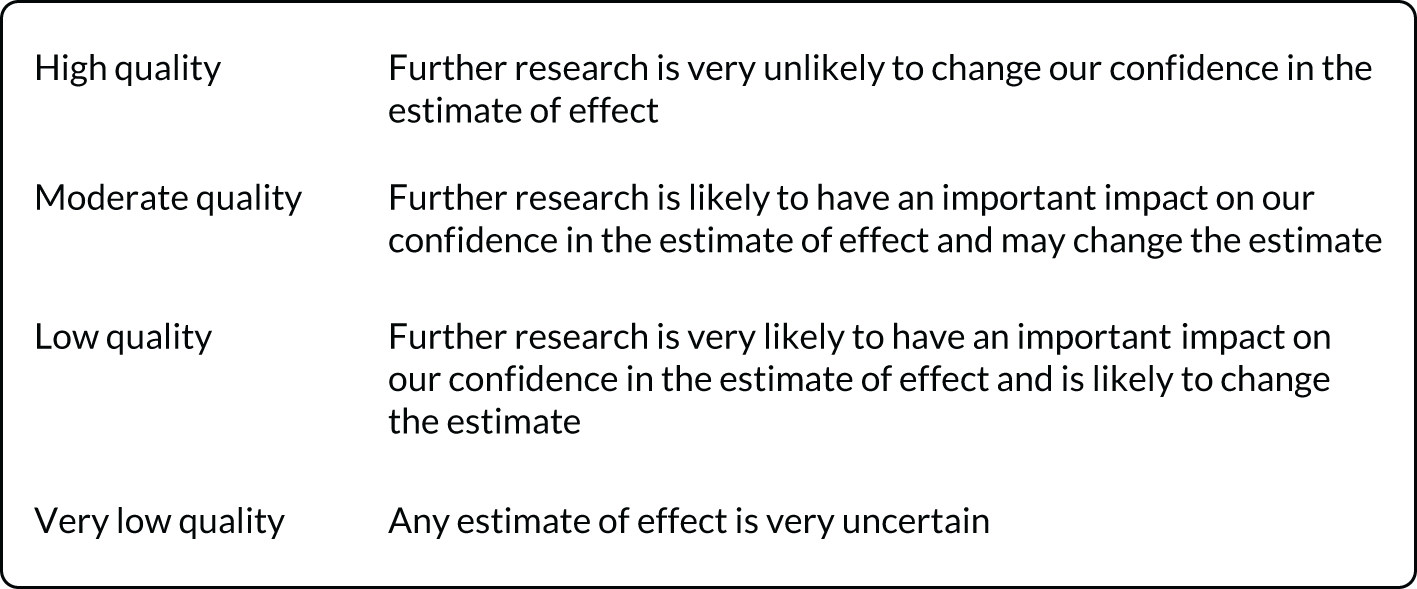

Assessing confidence

The assessment of the quality of evidence for retrospective cohort studies was conducted using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach,77 and was conducted by Deborah Edwards and checked by Ben Hannigan. This approach rates the quality of a body of evidence as ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’ or ‘very low’ (Figure 2). 77 Explicit criteria, including study design, risk of bias, impression, inconsistency, indirectiveness and magnitude of effect, are used. As the studies retrieved for this evidence synthesis were observational as opposed to interventional, the initial quality of the body of evidence overall started off as low. 78 When the evidence base was rated specifically on study design (in particular retrospective cohort studies), this led to the ratings for all evidence generated using material from these types of study being downgraded from ‘low quality’ to ‘very low quality’.

FIGURE 2.

The GRADE quality of evidence and definitions. Reproduced from GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. , volume 336, pp. 924–6, 2008, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 77

The strength of the synthesised qualitative and non-intervention findings was assessed using the CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) approach,79 and this was again led by Deborah Edwards and Ben Hannigan. The original CERQual approach was designed for qualitative findings, but in this project a process previously used by members of the research team in HSDR 11/1024/0880 and in HSDR 08/1704/21181 was used. This approach involved using CERQual for the additional purpose of assessing confidence in findings synthesised from surveys and other non-intervention quantitative studies. The confidence in individual synthesised review findings is based on the assessment of four components: coherence, methodological limitations, relevance and adequacy. Overall assessments of confidence are then described using four levels – high, moderate, low or very low – as summarised in Figure 3, which draws on and adapts material previously published. 82

FIGURE 3.

The CERQual: applying high, moderate, and low confidence to evidence. Reproduced with permission from Lewin et al. 82 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Description of research studies

Thirty-four publications covering 30 research studies were deemed suitable for inclusion in the review: 19 quantitative studies (reported across 21 publications), nine qualitative studies (reported across 11 publications) and two mixed-methods studies. Demographic information on the characteristics of included research studies is given in Appendices 17–20.

Country of research

Data were retrieved from 10 countries: the USA (n = 12, across 13 publications32,83–94), Canada (n = 4, across five publications95–99), New Zealand (n = 1100), Taiwan (Province of China) (n = 1101), Australia (n = 4, across six publications102–107), France (n = 1108), Belgium (n = 1109), the Netherlands (n = 2109–111), the UK (n = 337,112,113) and the Republic of Ireland (n = 1114).

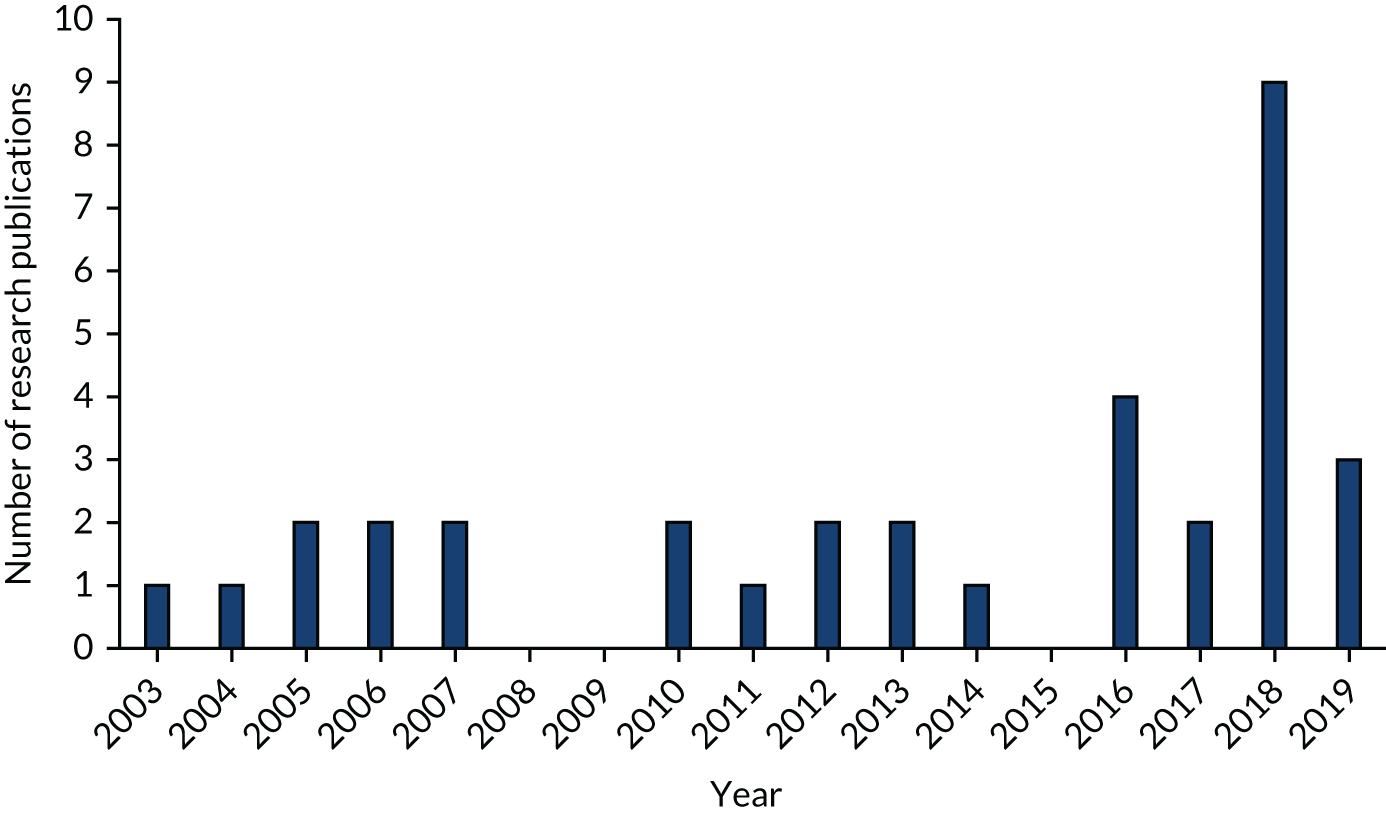

Year of publication

Figure 4 displays the year of publication of the 34 research study publications.

FIGURE 4.

Histogram of year of publication of research studies.

Study designs and methods

Among the quantitative studies, 12 studies (across 13 publications) were retrospective cohort studies,84,88–92,95,97,98,100,101,107,108 seven studies (across eight publications) were descriptive surveys83,85–87,93,94,96,111 and nine studies (across 11 publications) used a qualitative design. 32,37,99,102–106,109,112,113 Among the qualitative studies, five studies (across seven publications) were described as using a non-specific qualitative descriptive approach,102–106,112,113 two utilised grounded theory,37,109 one used ethnography99 and one used phenomenology. 32 Specific methods used to collect qualitative data included interviews (n = 6,32,37,102–106,109 across eight publications), focus groups (n = 1112), a combination of interviews and focus groups (n = 1113) and a combination of observation and interviews. 99 One mixed-methods study consisted of a retrospective review of patients’ medical records and a post-test evaluation of educational/training initiatives with HCPs, descriptive surveys and non-specific qualitative descriptive approaches using interviews. 110 The other mixed-methods study consisted of a descriptive survey and a qualitative descriptive approach using interviews. 114

Settings

The settings in which research studies were undertaken were described as follows: specialist palliative care services;100 palliative care consultation services;93 acute and psychiatric care;85,108 Veterans Administration medical centres/nursing homes;83,88,90 all medical care covered by one insurance company;101 acute care;91,92,96 all hospital and community based palliative care (n = 2 studies, across three publications);95,97,107 homeless/vulnerably housed;99,113 shelter-based hospice for the homeless;98 general practices and psychiatric practices;114 nursing/care homes;84,111 mental health and hospice/palliative care services32,94,112 including community, residential homes, supported accommodation and psychiatric hostels;106 mental health services (hospital and/or community based) (n = 5 studies, across eight publications);86,87,102–105,109,111 hospices;37 and not stated. 89

Participant characteristics

In 11 studies (across 12 publications) participants were decedents (people who had died) who were described as having had a diagnosis of severe and persistent mental illness,100 schizoaffective disorders,88,95,97,101,107,108 a pre-existing psychiatric illness,91 a mental health diagnosis,89 pre-cancer depression92 or PTSD. 90 One further study explored the views of family members of decedents who had PTSD. 83

Seven studies (across eight publications) directly involved patients and included:

-

residents in a nursing home with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychosis84

-

homeless patients admitted to a shelter-based hospice with a range of mental health diagnoses98

-

homeless or vulnerably housed individuals (inferred that some would have had a mental health diagnosis) who were on a palliative trajectory and their support workers and formal service providers99

-

current or previous homeless individuals (inferred that some would have had a mental health diagnosis) and their health and social care providers, hostel and outreach staff113

-

adults with schizophrenia or other psychosis, mood disorders (major depression and bipolar disorder), personality disorders or PTSD who were receiving community-based services86,87

-

patients with severe and persistent mental illness96 or schizophrenia109 who were not at the EoL, but the study focused on future care preferences.

The remaining 12 studies (across 14 publications) were conducted with HCPs who worked with patients with SMI at EoL32,37,85,93,94,102–106,110–112,114 and these included mental health HCPs,85,102–104 EoL HCPs,37 mental health and EoL HCPs,32,94,106,112 psychiatrists105,114 and general practitioners (GPs). 114

Terminal or chronic condition/s or cause of death

A large number of research studies (n = 16, across 19 publications32,37,83–87,93,94,99,100,102–105,109,111,112,114) explored the perspectives of HCPs who cared for those with SMI at EoL and as a result did not refer to any specific terminal or chronic condition. The remaining studies reported cause of death (n = 6 studies across seven publications88,95,97,98,101,108,110), terminal condition(s) (n = 689,90,92,96,106,113) or chronic condition(s) (n = 291,107) and included the following:

Description of case studies

Forty-two publications consisted of 51 case studies of individuals who had an existing mental illness diagnosis and who went on to develop an EoL condition (see Appendix 20). In four case studies the purpose of the paper was to show the application of a particular model of care, such as dynamic system analysis115 or stepwise psychosocial palliative care. 116,117 Most of the case studies were published in peer-reviewed research journals (n = 38), along with two conference abstracts,118,119 one that appeared in a report120 and one that was in a first-person-account blog. 121 The case studies ranged in depth from discursive papers with little direct detail about the individuals involved, to those that focused mainly on the patient’s or patients’ physical illness and a substantive number that discussed issues of mental capacity and the ability of the person to express their choice to accept, refuse or abandon treatments.

Country of research

The majority of case study papers were published in the USA (n = 2826,116,117,121–145); followed by the UK (n = 4120,146–148), Canada (n = 3149–151), Australia (n = 115), France (n = 1152), Israel (n = 1153), Mexico (n = 1119), the Netherlands (n = 1115) and Singapore (n = 1154), with one conference abstract not stating the country in which the case study was located. 118

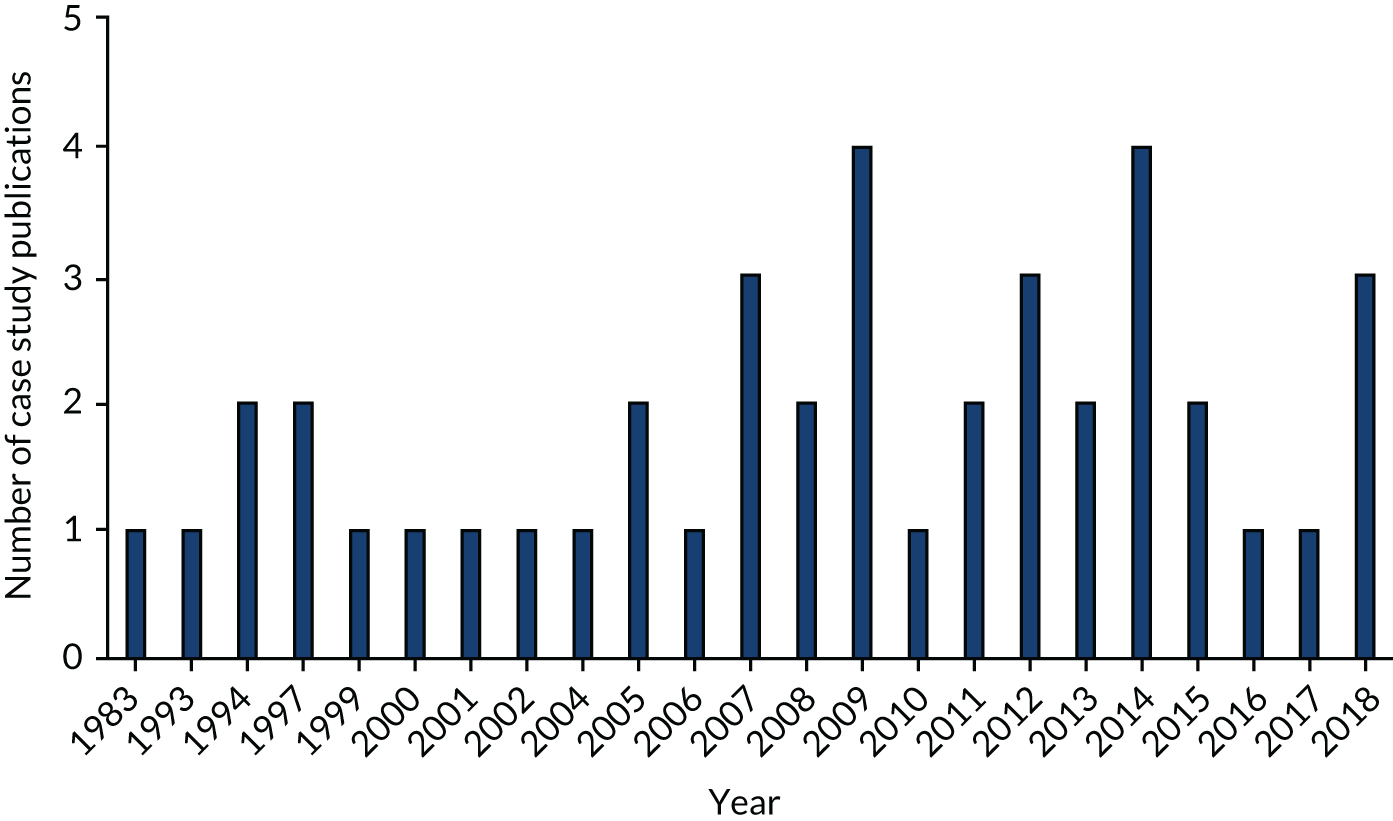

Year of publication

The earliest case study was published in 1983133 and outputs appeared regularly up until the end of the search period in 2019. 118,119,150 Figure 5 displays the year of publication of the 42 research study publications.

FIGURE 5.

Histogram of year of publication of case studies.

Attributes of service users

The case studies outlined, sometimes in very sparse detail, the individual attributes of the people with pre-existing mental health problems who were in the EoL trajectory. The age range across the case studies was 20–91 years (mean age 55 years) and was provided in all except two of the studies. 121,143 Women were the focus of 24 case studies. Diagnosis was reported for all case study individuals and included psychotic-type diagnoses (schizophrenia, psychosis, schizoaffective and bipolar conditions) (31 publications reporting 35 case studies15,26,115,118–121,124,127–130,132,133,135–147,149–154), personality disorder (five publications reporting five case studies122,123,125,131,132), PTSD (three publications reporting three case studies116,117,126) and anorexia nervosa (n = 2134,148). In the papers discussing the individuals with anorexia, the EoL condition was a direct result of that condition, leading to chronic fractures and organ failure. 134,148 These are then two outliers in that the EoL condition was a direct result of the mental health issue for those individuals. The vast majority of EoL conditions presented in the case study papers were cancer-related diagnoses, and organ failure [heart (n = 3 (across four publications115,126,129,130), liver (n = 1122) and kidney (n = 5131,139,146,150,154)] made up the remainder.

Results of quality appraisal

Critical appraisal scores for cohort studies

The methodological quality of each of the 12 cohort studies was judged against the relevant eight quality criteria derived from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network’s Methodology Checklist 3: Cohort Studies checklist,74 and each study is summarised in Table 4. All the studies were judged to be of acceptable quality, indicating that some flaws in the study design were present, with an associated risk of bias. Seven studies did not provide confidence intervals (CIs) as part of the statistical analysis. 88–91,98,100,107

| Study (authors and year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q7 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q13 | Q14 | Overall assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butler and O’Brien 2018100 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Acceptable |

| Chochinov et al. 2012;95 Martens et al. 201397 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Acceptable |

| Ganzini et al. 201088 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Acceptable |

| Huang et al. 201789 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Acceptable |

| Huang et al. 2018101 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Acceptable |

| Lavin et al. 201791 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Acceptable |

| McDermott et al. 201892 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Acceptable |

| Podymow et al. 200698 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Acceptable |

| Spilsbury et al. 2018107 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Acceptable |

| Fond et al. 2019108 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Acceptable |

| Cai et al. 201184 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Acceptable |

| Kelley-Cook et al. 201690 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Acceptable |

Critical appraisal scores for descriptive surveys

The methodological quality of seven descriptive studies and the survey component of two mixed methods studies110,114 were judged against the 12 quality criteria used in the SURE tool, and each study is summarised in Table 5. The authors of one study, reported in two companion papers,86,87 did not state the type of study that they had undertaken and were reporting on, but from the description of the methods this was classified as a quantitative descriptive project and, thus, was included in this section with other studies of this type. The quality of 9 of these 11 descriptive studies was high, with all nine meeting either 11 or all 12 criteria. The quality of the other two studies was significantly lower, with either the majority of quality criteria not being met or the account in the published paper being unclear. 85,94

| Study (authors and year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alici et al. 201083 | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Elie et al. 201896 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Evenblij et al. 2016110 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Evenblij et al. 2019111 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Foti 200385 | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Foti et al. 2005;87 Foti et al. 200586 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Patterson et al. 201493 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sheridan et al. 2018114 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Taylor et al. 201294 | Y | Y | N | N | U | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N |

Critical appraisal scores for qualitative studies

The methodological quality of each of the nine qualitative studies and the qualitative component of two mixed-methods studies110,114 were judged against the 10 quality criteria used in the CASP qualitative checklist,72 and each study is summarised in Table 6. In the case of two studies,106,113 the authors did not include a description of the type of study conducted, but from the description of the methods used these were classified as examples of qualitative descriptive studies. The quality of these 11 studies was high, with all bar one106 of the studies meeting at least 9 of the 10 quality criteria.

| Study (authors and year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evenblij et al. 2016110 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hackett and Gaitan 200737 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jerwood 2018112 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| McGrath and Forrester 2006;104 McGrath and Holewa 2004;102 McGrath and Jarrett 2007103 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| McKellar et al. 2015105 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| McNamara et al. 2018106 | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Morgan 201632 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sheridan et al. 2018114 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shulman et al. 2018113 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Stajduhar et al. 201999 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sweers et al. 2013109 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Critical appraisal scores for case studies

The methodological quality of each case study was judged against the eight quality criteria used in the Joanna Briggs Institute case report checklist,75 and each study is summarised in Table 7. As this shows, the quality of the studies varied overall. Twenty-five of the 42 case studies met either seven or all eight criteria; the single criterion missing from the majority of papers in this group related to the description of diagnostic tests or assessment methods and their results. Eight of the 42 studies met half or fewer of the eight quality criteria, but for the purposes of inclusivity all 42 studies were included in the subsequent narrative synthesis (see Chapter 5).

| Study (authors and year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ang et al. 2009154 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Badger and Ekham 2011122 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Bakker 2000115 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Boyd et al. 1997123 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Cabaret et al. 2002152 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Candilis and Foti 1999124 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Clements-Cortes 2004149 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 6/8 |

| Doron and Mendlovic 2008153 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Feely et al. 2013125 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Feldman and Petriyakoil 2006126 | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | 4/8 |

| Feldman et al. 2014116 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Feldman et al. 2017117 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Geppert et al. 2011127 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Gonzelez et al. 2009128 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Griffith 2007129 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Griffith 2007130 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Hill 2005131 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Irwin et al. 201426 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Kadri et al. 2018150 | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 5/8 |

| Kennedy et al. 2013120 | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Kunkel et al. 1997132 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Levin and Feldman 1983133 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Lopez et al. 2010134 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 6/8 |

| Maloney et al. 2014121 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Mason and Bowman 2018118 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| McCasland 2007135 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| McKenna et al. 1994136 | Y | N | U | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 4/8 |

| Mogg and Bartlett 2005146 | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | 2/8 |

| Moini and Levenson 2009137 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 5/8 |

| Monga et al. 2015138 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Muhtaseb et al. 2001147 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| O’Neill et al. 1994148 | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 2/8 |

| Picot et al. 201515 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Rice et al. 2012139 | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Rodriguez-Mayoral 2018119 | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 5/8 |

| Romm et al. 2009140 | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 3/8 |

| Shah et al. 2008141 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/8 |

| Stecker 1993142 | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 4/8 |

| Steves and Willliams 2016143 | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 4/8 |

| Terpstra et al. 2014144 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/8 |

| Thomson and Henry 2012145 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | 2/8 |

| Webber 2012151 | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 3/8 |

Chapter 4 Thematic synthesis of policy, guidance and research

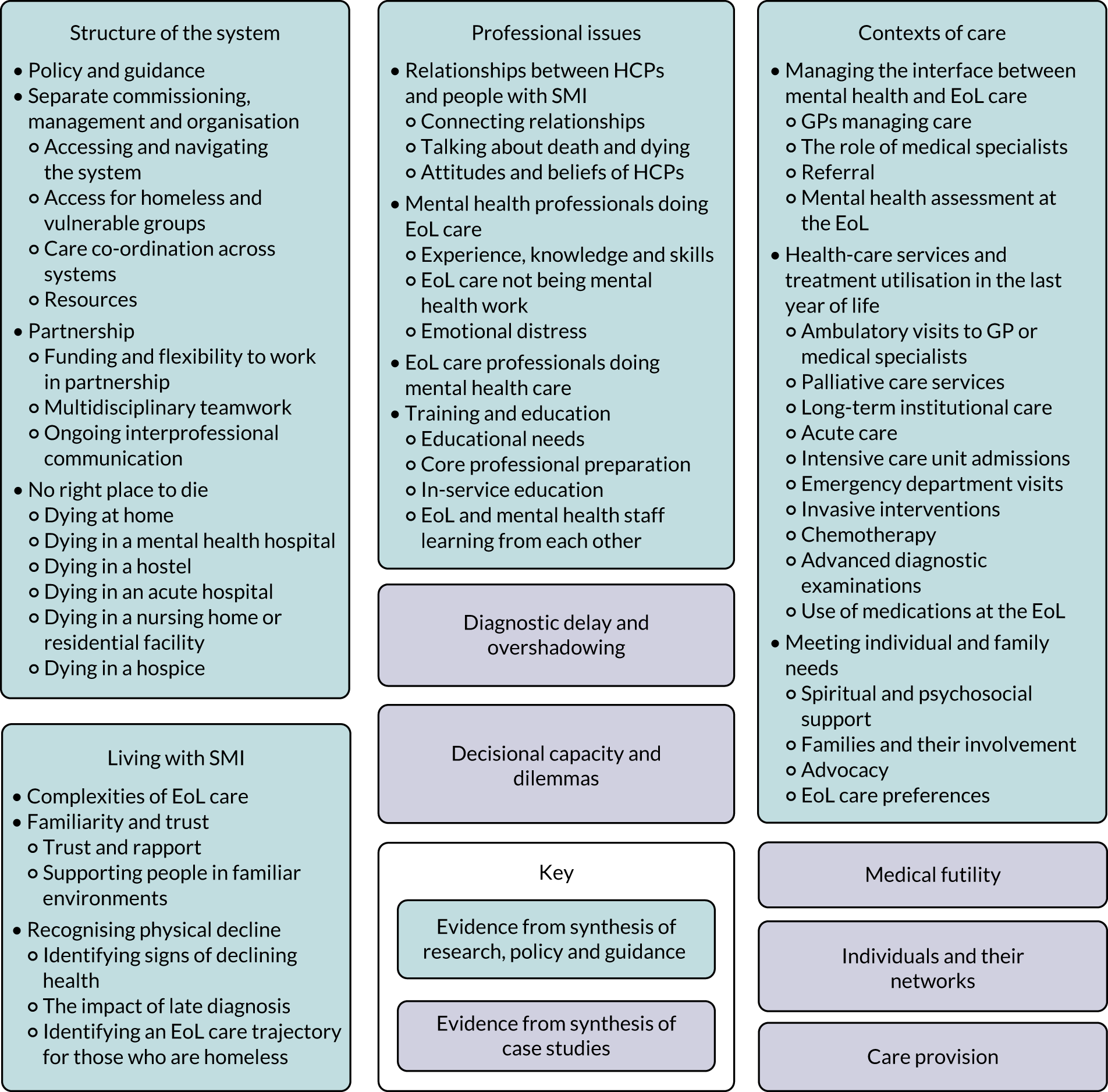

This chapter presents a synthesis of policy, guidance and research included in the overall review. Material from the research studies and policy and guidance documents has been synthesised into four themes: structure of the system, professional issues, contexts of care and characteristics of people with SMI.

Structure of the system

Twenty-six policy and guidance documents22,30,55,120,155–176 and 18 research outputs32,85,88,91–94,97–99,103,105,106,108,110,112–114 contribute to this theme, which addresses the broad shape and structure of the EoL and mental health care systems. Material is organised under four subthemes: policy and guidance; separate commissioning, management and organisation; partnership; and no right place to die.

Policy and guidance

Nineteen policy and guidance documents22,30,156–161,163–170,172,174,175 and one research output contribute to this subtheme. 112

People with SMI are recognised as a group needing particular attention in the provision of EoL care in multiple independent UK reports and consultations,22,156–158,161,163–165 with the Care Quality Commission158 suggesting that many health-care providers have focused efforts on reducing premature death among people with a mental health condition rather than properly considering EoL care needs.

There is a lack of national and local policy guidance in the UK that addresses the EoL care of people with SMI;112 however, isolated examples of local policy do exist. 170 Evidence166 also exists that a majority (62%) of mental health providers have produced action plans to promote improvement in EoL care. Where this is in place, 92% of mental health providers have also reported forwarding this to clinical teams, and three-quarters (75%) have reported forwarding this to the trust/university health board. In the context of a lack of specific national and local policy, both mental health and palliative care nurses report concern about their legislative responsibility. 112

Standards of care for people with mental health problems should be the same as those for people with physical health problems, and this ideal is strongly emphasised across generic UK health policies,160,167–169 national mental health-specific policies159,172,175 and independent reports and guidance documents. 157,164 By extension, EoL care for people with SMI should be as good as the EoL care provided to others. 30 Aspirations that high-quality EoL care should specifically apply to people with SMI are found in Scottish mental health policy,172 and in Wales the current mental health strategy175 refers to supporting recovery and enablement through to the EoL with recent whole-system policy referring to equitable services for people with mental health difficulties and specifically improving EoL care. 174 Northern Ireland’s mental health service has a standard that people with incurable conditions should be supported at the EoL and to die in their preferred place of care. 159 English strategy identifies that there is a need to improve the provision of EoL care information in unscheduled care settings,168 and targets additional resources at homeless people. 167

Separate commissioning, management and organisation

Eleven policy and guidance documents30,120,157,158,162,164,166,169,170,173,176 and 11 research outputs32,85,93,94,99,103,106,110,112–114 contribute to this subtheme.

Accessing and navigating the system

All national health-care systems have obligations to provide access to palliative care for people with disabilities, including those associated with existing mental health difficulties. 176 In relation to access to hospice care specifically, a specific aim of the UK charity Hospices UK to make their services more available to people with serious mental illness. 162 Data reported in the National Audit of Care at the End of Life report,166 however, show that only 10% of mental health service providers have their own specialist palliative care service, in comparison with 95% of English and Welsh acute care providers. A majority of mental health providers report having access to specialist palliative care beyond their own hospital, however, with 16% having access to at least one EoL care facilitator, of which 40% are contained within a specialist palliative care team. Availability of specialist palliative care HCPs to mental health providers include 60% having face-to-face access to nursing staff during usual working hours across the whole week, and 49% having the same access to doctors. Other means of access to specialist palliative care reported include telephone contact, with doctors available at any hour to 57% of mental health providers and nurses available at any hour to 42% of mental health providers. 166

The separate organisation of mental health and EoL services means that many people with existing mental health issues do not receive treatment that is appropriate for them when they are eventually admitted to hospital. 164 Treatment also becomes more complicated if patients are receiving analgesia and other EoL medication. 164 Evidence brought together by the Social Care Institute for Excellence 2013173 is that people with mental health needs remain one of the groups missing out on equal access to EoL care. The needs of people with SMI are not always considered by commissioners and service planners, who have been described as lacking awareness of the EoL needs of people with SMI. 157