Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128671. The contractual start date was in August 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Silveira Bianchim et al. This work was produced by Silveira Bianchim et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Silveira Bianchim et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Chronic pain in childhood is widespread: UK figures indicate that 8% of primary care consultations by 3 to 17 year olds are for musculoskeletal chronic pain alone;1 at least 4–14% of children worldwide are estimated to have chronic pain, but the prevalence could be as high as 24–88%, dependent on the type of pain. 2 Frequent severe chronic pain of all types affects 8% of children, according to a Dutch survey. 3 A global survey found that around 44% of adolescents reported chronic weekly pain. 4

Definition

The eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) defines chronic pain as ‘pain that persists or recurs for more than three months’. 5 Chronic pain is recognised as a condition in its own right but it is also a key feature of conditions, such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Size and impact of the problem

Chronic pain has considerable negative impacts on children’s health and quality of life; for instance, UK surveys have shown that the majority of adolescents with chronic pain experience disability in physical, psychological, social, familial and developmental domains. 6,7 Chronic pain is associated with increased use of healthcare services and medication,8 adversely affects social and family relationships9,10 and results in poorer school attendance. 11 For treating adolescent pain alone, the cost to the NHS is estimated at 4 billion pounds a year. 12 UK parents pay £900 out-of-pocket expenses a year supporting their adolescent’s chronic pain and have work absences of 7–37 days costing on average £750 per family each year; some parents give up work entirely to care for their adolescent child. 13 Moreover, longitudinal research indicates a high risk of childhood chronic pain continuing into adulthood14 with further individual, NHS and societal costs. For example adult back pain alone costs the UK economy £11 billion with a direct healthcare cost of £1 billion. 15

Current service provision and clinical guidelines

Despite the high prevalence and serious impacts of childhood chronic pain, UK provision of and access to specialist children’s chronic pain services and multidisciplinary chronic pain management is very limited8 and services are considered to be inadequate. 16,17 The most recent National Pain Audit in England and Wales in 2011–217 found that services were ‘of inconsistent standard and quality and not always available for those who need them. This is particularly true for centres specialising in treating children with chronic pain’17 (p.4). The 2021 Lancet Commission ‘Delivering transformative action on paediatric pain’ recognised that children’s pain is often undertreated. 18

There is also a lack of high-quality trials evidence to inform clinical guidelines, and thus guide children’s chronic pain management. 8,15,18–24 This lack has been identified in the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline,8 the 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) guideline19 and its supporting systematic review,20 and Cochrane reviews of treatment effectiveness trials for children’s chronic non-cancer pain. 22–28 The 2021 National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE),29 NICE chronic pain guideline does not include children under 16 years of age due to the lack of robust trials evidence. 29

Furthermore, the 2018 SIGN guideline on the management of children’s chronic pain indicated that UK-based healthcare professionals require more training in managing chronic pain in children. 8 For instance, there is no inpatient clinic for children with chronic pain in Scotland; children with severe chronic pain, that is not manageable within an outpatient setting, are sometimes referred to national specialist services in Bath, Oxford or London for intensive pain management programmes because of a lack of local expertise and/or programmes. 18,21 Research also indicates that healthcare professional training in pain management in the UK and across Europe is insufficient. 30,31 Hence, there is an urgent need for the NHS to improve how it supports children with chronic pain and their families, using high-quality evidence to inform design and delivery of services and treatments.

Evidence uncertainties and why this research is needed now

The SIGN guideline8 concerning the management of pain in children, recent Cochrane reviews on treatment effectiveness for children’s chronic pain,22–28 and the Lancet Commission on children’s chronic pain18 identified a dearth of research to inform chronic pain management. Several Cochrane reviews on the effectiveness of different pharmacological treatments of children’s chronic non-cancer pain also identified that we do not know which outcomes are important to children with chronic pain and their families. 22–25 Identifying these outcomes can guide design of services and treatments and inform future research.

The WHO children’s chronic pain management guideline indicated that research is needed in many areas including large multicentre trials and qualitative and mixed-method studies to understand how and why interventions are effective. 19 The guideline also specified that a biopsychosocial approach, which takes into account the whole range of biological, psychological and social influences on pain, is required. The guideline highlighted that there are inadequate data on interventions for chronic pain in children across all age groups and a wide range of subpopulations, particularly children under 10 years of age, those with intellectual or developmental disabilities, family members including siblings and caregivers. Without high-quality evidence, children will not receive evidence-based good-quality pain management, resulting in poor short-term and long-term outcomes in terms of pain and pain-related disability.

The Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care (PaPaS) group prioritised research into children’s chronic pain in 201832 and the International Association for the Study of Pain set its global theme for 2019 as ‘the year against pain in the most vulnerable’ – a group which includes children – in order to raise awareness and improve pain assessment and management. 33 The NIHR also recognised the urgent need for research on chronic pain management with its themed call for research in this field. The 2021 Lancet Commission ‘Delivering Transformative action in children’s chronic pain’18 called for research to ‘make pain better’.

It is crucial that we understand how children and their families experience, understand and live with chronic pain of different kinds; which treatment outcomes are meaningful to them; and their views and experiences of health and social care services in relation to their pain management in order to design and deliver services and interventions which meet their needs and inform further research including trials and the outcomes they measure. Qualitative research is ideally suited to addressing these urgent and important issues.

Rationale for the research

Our preparatory work and scoping searches indicated existing relevant qualitative research to inform these issues,34–38 but there were no existing or planned syntheses of this qualitative evidence, indicating a gap in the research. These conclusions were based on our searches of PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (in May 2019); bibliographic databases MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online), PsycInfo (American Psychological Association’s online database) and PubMed; and Google Scholar using keywords (pain/chronic pain, children/paediatric); the Cochrane library; our team’s reference databases; and reference lists in policy documents and Cochrane reviews. We also consulted experts in the field and checked Zetoc alerts (journal article monitoring and search service) of all newly published qualitative evidence syntheses.

To date, there has been inadequate use of qualitative research evidence about children and their families’ experiences of chronic pain in the form of qualitative evidence syntheses to inform design of trials and the outcomes they measure, services and treatments. Prior to commencing our qualitative evidence synthesis, we identified existing published qualitative evidence syntheses, which were limited in focus. Two syntheses looked at specific childhood chronic pain populations and topics – the experience of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis39 and the impact of pain on adolescents’ social relationships. 9 Tong et al. 39 found that children and young people (CYP) felt different, misunderstood and stigmatised and juvenile idiopathic arthritis restricted their social participation. Jordan et al. 9 found mainly negative impacts of chronic pain on relationships, although some relationships became stronger in the face of challenges.

In addition, three review authors (EF, JN, MSB) conducted a qualitative evidence synthesis for WHO40 in January–September 2020 (conceived after we had submitted a funding proposal for the research reported here), to inform the revised 2020 guidelines for children’s chronic pain management. 19 The WHO synthesis took a global perspective on the management of children’s chronic pain, with a particular focus on research conducted in low- and middle-income countries. It incorporated the perceptions and experiences of healthcare professionals, in addition to those of children with chronic pain and their families. It focused solely on the views, perceptions and experiences of the risks, benefits and acceptability of three types of intervention: pharmacological, psychological and physical therapies. Our current qualitative evidence synthesis was intended to take a broader perspective on chronic pain and its management than the three existing syntheses, including how children and their families conceptualise and live with chronic pain of different kinds and to consider any kind of intervention or service. We did not set out to explore the views of healthcare professionals (which were explored in the WHO synthesis) and have focused mainly on the UK (including evidence from similar high-income contexts).

Furthermore, none of the above three syntheses developed a theory to inform a comprehensive pain management approach. There appears to be no comprehensive theory of children’s chronic pain, which covers how children and families conceptualise pain, experiences of living with pain and of pain management services and views of ‘good’ pain management and services. Most existing theories have been developed within a specific field, which might narrow our understanding of how children experience chronic pain. For instance, psychological theories tend to focus only on specific aspects of the pain, such as what causes pain, or they adopt a child development approach to explaining children’s understanding of their chronic pain. 41 Biopsychosocial theories of chronic illness, which specify the inter-relatedness of biological, psychological and social aspects of illness, better reflect our theoretical approach to chronic pain. 42 However, there do not appear to be any comprehensive biopsychosocial theories about children’s experiences of chronic pain and its management, for instance, one biopsychosocial theory focused only on clinical assessment and management of children’s chronic pain. 43

Meta-ethnography is ideally suited to synthesising qualitative evidence on the complex issues related to children’s chronic pain in order to develop new conceptual insights and theories to inform service and intervention implementation. 44,45 Therefore, we conducted a rigorous qualitative evidence synthesis using meta-ethnography44 to investigate the diverse experiences and perceptions of children up to age 18 years with chronic non-cancer pain and their families (children with cancer-related chronic pain have different care pathways) and generate theory to inform health and social care. We refer to the meta-ethnography reported here by the acronym ‘CHAMPION’ (Children And young people’s Meta-ethnography on Pain).

The meta-ethnography was also conceived as a Cochrane review intended to extend the findings of existing relevant Cochrane reviews on the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions,22–26,46,47 psychological interventions,27,48,49 dietary interventions;50 and physical activity interventions28 for children’s chronic pain. Integrating our qualitative findings with quantitative evidence of effect22–26 should inform the design and implementation of future interventions, and their evaluation and synthesis by highlighting key outcomes that need to be addressed and generating hypotheses that can be tested out. Data integration with Cochrane reviews of intervention effectiveness for children’s chronic non-cancer pain also contributes to developing more relevant, acceptable and effective interventions through greater understanding of the pain experience from the perspective of children, parents and wider family members.

While we were conducting our meta-ethnography, core outcomes for clinical trials were published which identified outcomes of importance to a narrow sample of children with chronic pain in the USA. 51 This core outcome set was developed from a study that recruited mainly female patients, all aged over 12 years, from tertiary pain and gastroenterology services, and drew on limited qualitative data from open-ended survey questions. Our meta-ethnography could further enhance the outcome set by potentially confirming, disconfirming and/or supplementing their outcomes with data from a wider range of participants.

The meta-ethnography could change healthcare delivery and policy, inform treatments and indicate gaps in knowledge and hence new directions for chronic pain research. 52 Because chronic pain is an aspect of many health conditions, our findings should have wide reach and transferability to similar settings across paediatric patient groups, while recognising the heterogeneity of children’s chronic pain. 23

Research plan

Research aim

To conduct a meta-ethnography on the experiences and perceptions of children with chronic pain, and their families, of living with chronic pain, treatments and services to inform the design and delivery of health and social care services, interventions and future research.

Review questions

-

How do children with chronic pain and their families conceptualise chronic pain?

-

How do children with chronic pain and their families live with chronic pain?

-

What do children with chronic pain and their families think of how health and social care services respond to and manage their/their child’s chronic pain?

-

What do children with chronic pain and their families conceptualise as ‘good’ chronic pain management and what do they want to achieve from chronic pain management interventions and services?

Objectives

-

Conduct comprehensive searches to identify qualitative research literature on the experiences and perceptions of children with chronic pain and their families to address review questions 1–4.

-

Select relevant studies and synthesise them using meta-ethnography.

-

To ensure salience of findings via involvement of children with chronic pain and their families in study design, analysis and interpretation.

-

Assess how much confidence can be placed in our synthesised findings using GRADE-CERQual (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation-confidence in the evidence from reviews of qualitative research)53 in order to facilitate use of our findings for NHS decision-making.

-

Identify research gaps regarding review questions 1–4 in order to inform future research directions.

-

Integrate our findings with existing relevant Cochrane treatment effectiveness reviews22–28,46–50,54,55 in order to determine if programme theories and outcomes of interventions match children and their families’ views and preferences.

-

Inform the selection and design of patient-reported outcome measures for use in chronic pain studies and interventions and care provision to children and their families.

-

Disseminate findings to academic, clinical, lay and policy audiences to influence childhood chronic pain policy and practice.

Summary

Children’s chronic pain is a widespread public health problem. We will report our analysis and synthesis of qualitative evidence to reach new interpretations and generate explanatory theory, increasing our understanding of families’ experiences and perceptions of chronic pain, pain treatment and services.

See Chapter 2 for details of the methodology including meta-ethnography.

Chapter 2 Meta-ethnography methods

Introduction

In this chapter, we provide a detailed account of the methods used to conduct our meta-ethnography.

Research design

We conducted a meta-ethnography44 following the methods of Noblit and Hare,44 Cochrane Qualitative Implementation Methods Group (QIMG) guidance56 and the eMERGe meta-ethnography reporting guidance45,57,58 and its associated methodological publications59,60 to facilitate the production of a high-quality meta-ethnography. We registered our review protocol on PROSPERO (reference: CRD42019161455) and published an a priori protocol with the PaPaS group (review number 623). 61

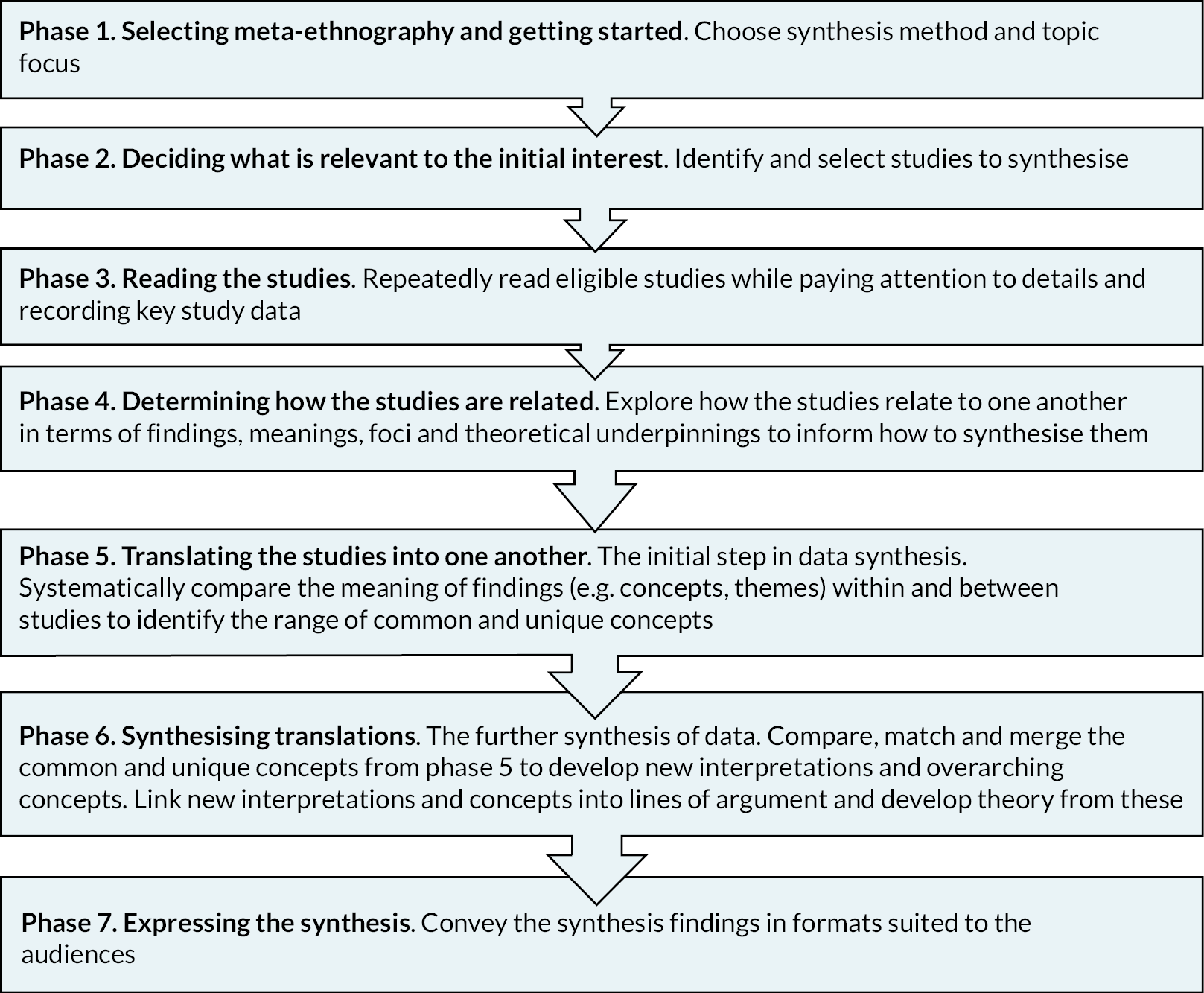

Meta-ethnography has a unique analytic synthesis method; this involves systematically comparing the meaning of concepts from primary studies, identifying new overarching concepts and linking these into one or more ‘line of argument’ syntheses leading to novel conceptual insights and theory development. 45,52 Meta-ethnography does not involve simply aggregating findings. 44,45 It is a rigorous, inductive methodology which takes into account the contexts and meanings of the original primary studies,44 making it ideal for synthesising the diverse contexts of children’s chronic pain research. The seven phases of meta-ethnography44,45,57,59,60 are described (Figure 1); although presented linearly, some phases run in parallel, and the process is iterative.

This meta-ethnography was conceptualised as a Cochrane review. 61,62 It is a Cochrane requirement that qualitative evidence syntheses, such as meta-ethnography, are used to supplement reviews of intervention effects to further understanding of the development and implementation of interventions. Therefore, the meta-ethnography findings were integrated with existing relevant Cochrane reviews of intervention effects.

In delivering this meta-ethnography, the review team worked in partnership with children living with chronic pain and their families and other stakeholders collaborating on all aspects of the meta-ethnography conduct. They influenced the aim and review questions during proposal development, the final search strategy (when finalising the protocol) and study sampling decisions and interpretation of data during conduct of the meta-ethnography. For a detailed description of patient and public involvement (PPI), see Chapter 3.

Phase 1: Selecting meta-ethnography and getting started

Meta-ethnography is ideally suited to developing new understandings, insights and theory about the experiences of children with chronic pain and their families to inform service and intervention implementation and identification of outcomes of value to children and families. Preliminary searches indicated that no meta-ethnography existed in this area, and that a reasonable-sized and conceptually rich (in-depth explanatory/interpretive) evidence base existed, suitable for meta-ethnographic synthesis, to address our review questions. Meta-ethnography involves reinterpretation of the findings in primary studies, taking into account the contexts and meanings of the original studies;44 it therefore requires in-depth explanatory or ‘conceptually rich’ data with accompanying detailed or ‘thick’ data on the study context.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Topic of interest

Our topic focus was refined through discussion with health consumers (professionals and patients, see Chapter 3 for more details), examining relevant Cochrane intervention reviews and scoping searches of the available literature. We included studies that focused on the views and experiences of children with chronic non-cancer pain and their families towards chronic pain, health services and treatments. We excluded chronic cancer pain following common practice in chronic pain research, including Cochrane intervention effects reviews on children’s chronic pain, which focuses on cancer pain separately due to the very different care pathway and causes of the pain. 22–26 End-of-life chronic pain in the last weeks and months of life was excluded for similar reasons; children have a distinct care pathway accessing different kinds of services, for example hospices, and their pain management has different aims and considerations, for example addiction to analgesics is less of a concern. We defined a ‘child’ as a person under 18 years of age, according to the UN Convention of the Rights of a Child.

Inclusion criteria

-

Peer-reviewed journal articles, published reports, book chapters, books, PhD theses.

-

Contained qualitative research data on chronic pain, that is, pain lasting for 12 weeks or more, relevant to the review questions.

-

Reported the views of children with chronic non-cancer pain from 3 months up to age 18 years or their family members (e.g. parents/guardians, grandparents, siblings).

-

Qualitative primary research studies of any design (e.g. ethnography, phenomenology, case studies, grounded theory studies) including mixed-methods studies if it was possible to extract data that were collected and analysed using qualitative methods.

-

Used recognisable qualitative methods of data collection (e.g. focus group discussions, individual interviews, observation, diaries, document analysis, open-ended survey questions) and analysis (e.g. thematic analysis, framework analysis, grounded theory).

-

In any language.

-

Any publication date.

Exclusion criteria

-

Acute pain, that is, pain lasting for < 12 weeks, such as that caused by medical procedures.

-

Cancer pain.

-

Pain in neonates and babies < 3 months old.

-

Focused on end-of-life pain management (in the last weeks and months of life).

-

Non-empirical article, for example editorial, commentary, study protocol.

-

Findings did not differentiate between children with acute and chronic pain.

-

Findings did not differentiate between adult and child participants.

-

Studies did not use qualitative methods for data collection and/or analysis (e.g. studies which analysed qualitative data quantitatively).

-

Literature reviews.

The inclusion criteria were discussed and subsequently agreed with our PPI group (see Chapter 3).

Search strategy

Phase 2: Deciding what is relevant to the initial interest

A rigorous search for studies was conducted via bibliographic databases and supplementary searches, as outlined below. RT led the design and conduct of literature searches assisted by the research fellow (MSB) and Cochrane PaPaS. Initial literature searches of all information sources were conducted between August and September 2020. Bibliographic database searches were updated in September 2022 to bring the review up to date prior to publication. Studies were selected according to the methods outlined in Selection of studies. Our PPI group discussions informed which websites to search and which experts to approach for study suggestions (see Chapter 3).

Bibliographic database searches

We searched 12 bibliographic databases selected for their good coverage of qualitative research and spectrum of relevant disciplines (Table 1).

| Discipline/type of literature | Databases |

|---|---|

| Health and social care | CINAHL EMBASE MEDLINE (including MEDLINE in Process and ePub ahead of print) Social Care Online (Science Citation Index Expanded) |

| Psychological | PsycInfo |

| Sociological | Social Sciences Citation Index |

| Education | British Education Index |

| Multidisciplinary | Scopus |

| Grey literature and theses | HMIC OpenGrey EThOS |

| CYP | Child Development and Adolescent Studies |

See Appendix 1 for the database search strategy for MEDLINE. The search strategy combined three key search concepts: (A) qualitative study designs; (B) population – children and their families; and (C) phenomenon of interest – chronic pain. The MEDLINE strategy was then adapted to the remaining bibliographic databases listed in Appendix 1. All databases were searched from their inception.

Supplementary searches

Supplementary searches12 for studies were conducted between 1 August 2020 and 17 December 2020 via:

-

Searches of key websites, as outlined below.

-

Hand-searching 24 months, from 1 December 2018 to 31 December 2020, of key journals relevant to our review questions and/or qualitative health research:

-

BMC Pediatrics

-

Clinical Journal of Pain

-

European Journal of Pain

-

Journal of Pediatric Psychology

-

Qualitative Health Research

-

Social Science and Medicine

-

Sociology of Health and Illness

-

-

Contacting experts in the field for recommended studies, including ongoing research.

-

Checking reference lists of included papers and relevant literature reviews for any further relevant studies.

Grey literature was identified by searching:

-

Three bibliographic databases [Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), OpenGrey and Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) – see Table 1].

-

Websites of key organisations representing chronic pain health conditions including British Pain Society, Department of Health, NIHR Library, Sickle Cell Society, Versus Arthritis, CRPS UK, Fibromyalgia Action UK, Crohn’s and Colitis UK, Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association, European League Against Rheumatism network, European Pain Federation, Pain Relief Foundation, Children’s Health Scotland, children’s hospitals, Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association supporting the CRPS community, Children’s Health Scotland, The Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, Sick Kids Hospital, NHS Lothian and Evalina Hospital in London.

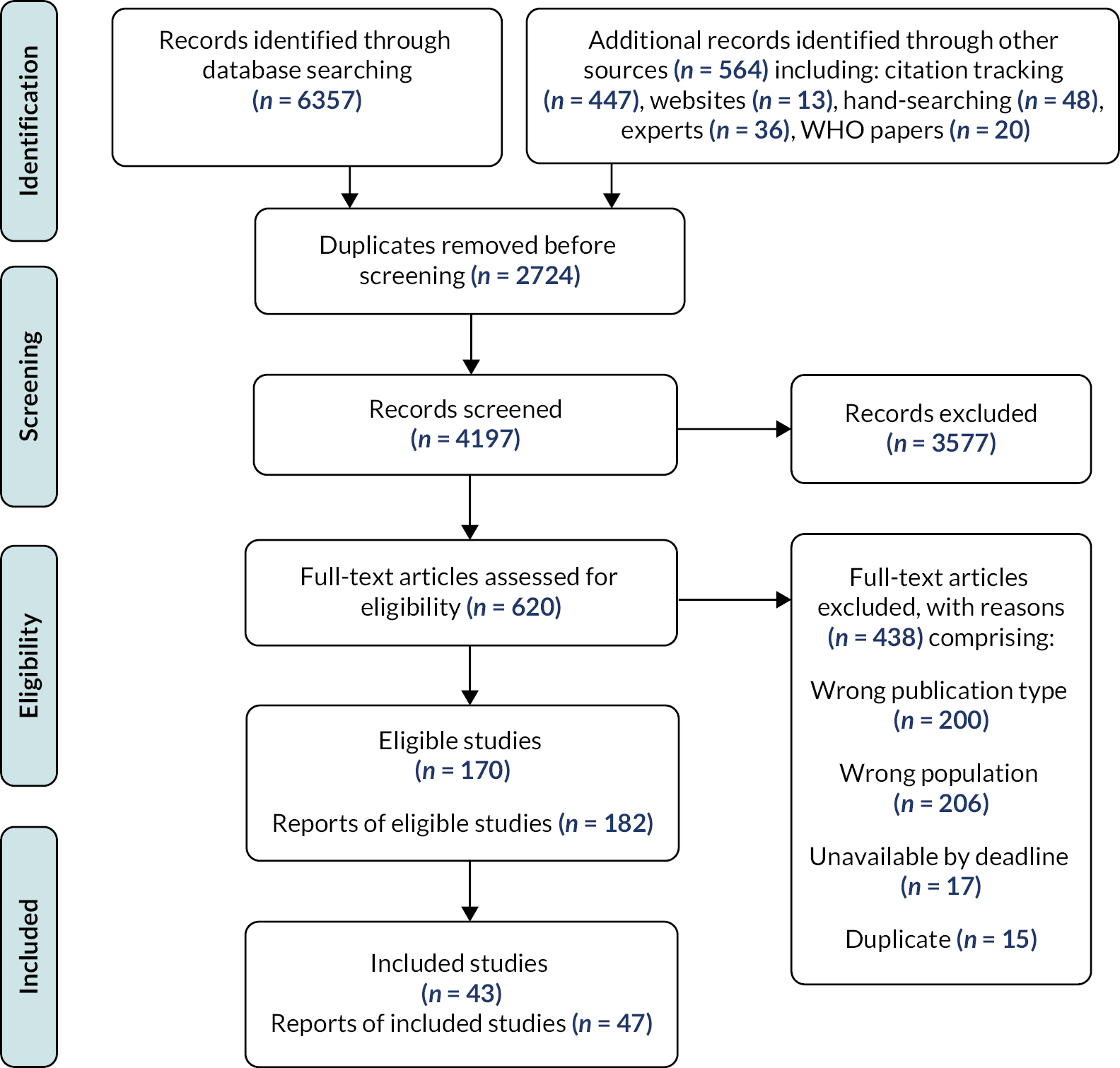

Supplementary searches were not updated in 2022 due to resource limitations, with the exception of asking experts to suggest potentially relevant new studies. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was used to record search results and the results of study screening for inclusion (Figure 2). Characteristics of the excluded studies can be seen in Report Supplementary Material 1.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Selection of studies

Literature screening and selection

Search results were exported to EndNote and duplicates removed. Then one reviewer (MSB) screened titles to remove off-topic records that were clearly not about children’s chronic pain, which was checked by a second, independent reviewer (RT). All remaining references were uploaded to Covidence systematic review management software. 63 First, titles and abstracts were screened, and clearly ineligible records were excluded. Then, the full text of all remaining studies was screened against our full inclusion criteria. At both stages, records were screened in duplicate by two independent reviewers (MSB, RT, EF, IU, LF, AJ, JN and/or KT). Disagreements were resolved through discussion and referred to a third reviewer, if necessary. Ten randomly chosen studies were used to pilot and standardise screening practices between reviewers.

Language translation

The review team are proficient in English, Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and French. Any titles, abstracts and full texts published in any other language were initially translated through Google Translate to determine eligibility.

Sampling

Our final set of included studies was purposively sampled from all studies meeting our eligibility criteria. We used published guidance from The QIMG64–66 and input from our PPI group and Project Advisory Group (PAG) (see Chapter 3) to develop a strategy for sampling studies summarised below and in Box 1. In short, our sampling approach prioritised ‘conceptually rich’ and ‘thick’ UK studies with explanatory/interpretive findings and detailed contextual data, and then filled gaps in the data with less rich/thick UK studies and both rich/thick and less rich/thick non-UK studies. Our rationale for this is described below.

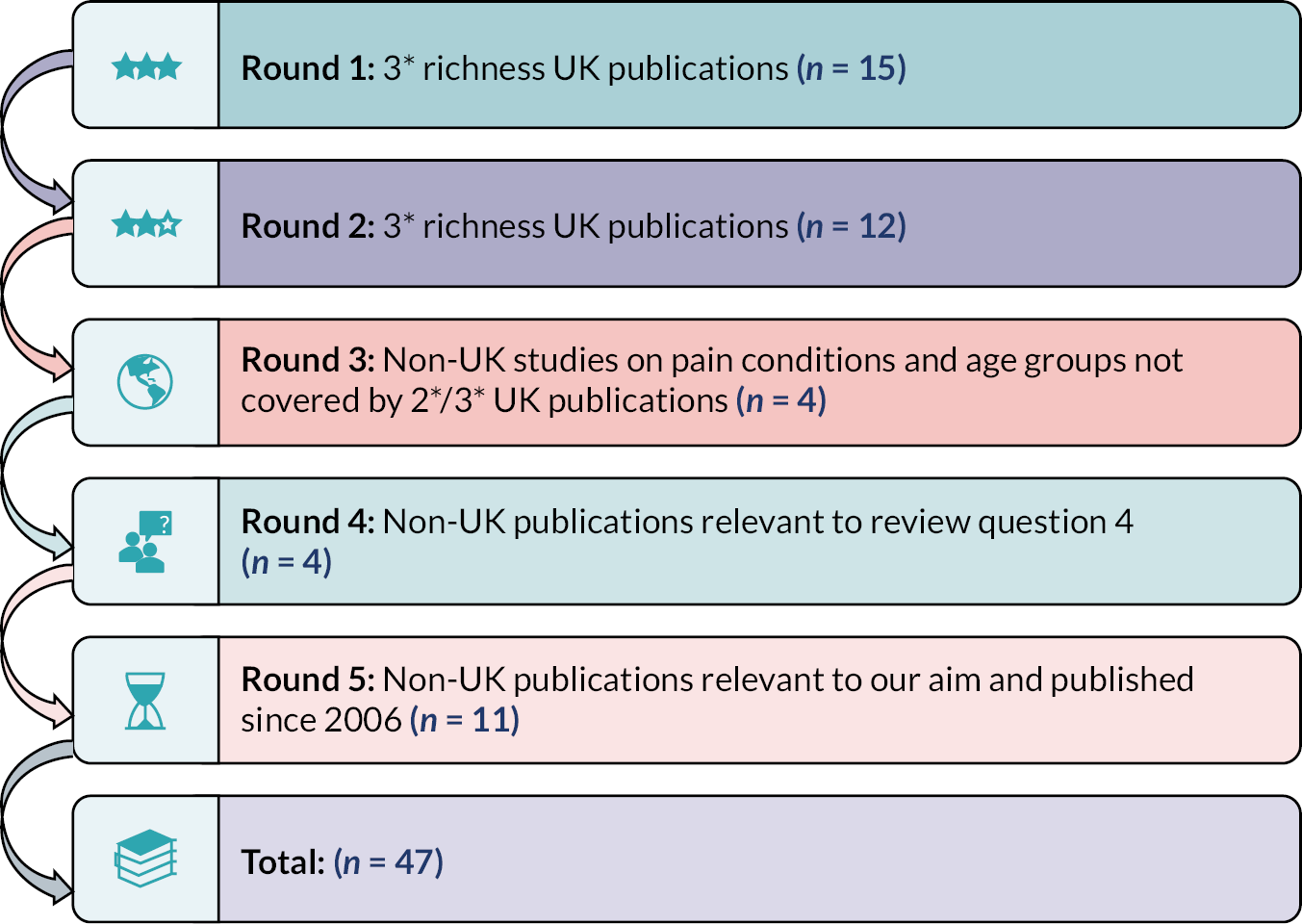

Round 1 – We included all publications reporting UK studies (‘UK publications’) assessed as 3* for richness.

Round 2 – We included all UK publications assessed as 2* for richness.

Round 3 – We included non-UK publications focusing on pain conditions, palliative care and/or types and ages of participants (e.g. children under 5 years old) not well represented in the sampled UK publications.

Round 4 – We included non-UK publications from high-income contexts similar to the UK NHS and relevant to review question 4 (assessed by checking the aims and abstracts).

Round 5 – We included non-UK publications whose aims were most closely related to our aim and review questions (assessed by their abstract), which had been published after 2006.

A meta-ethnography warrants studies with a good or fair amount of rich qualitative data and moderate to fair depth or ‘thickness’ of context and setting descriptions. 59 We assessed the conceptual richness of findings (i.e. whether the findings were explanatory/interpretive) and the thickness of contextual detail (how in-depth the context, intentions and meanings underlying the findings were) in UK studies selecting rich and thick studies for synthesis. This ensured that we were including studies that were the most adequate to address our review questions that were developed for a UK context. We adapted Ames, Glenton65 existing scale in assessing data richness, developed for qualitative evidence synthesis using thematic analysis, into a 3-point scale to suit meta-ethnography to focus on conceptual richness and contextual ‘thickness’, drawing on Popay et al. 67 and Cochrane QIMG guidance. 68 The scale and user guidance were drafted, piloted and revised by the research team. Table 2 presents our final richness scale (in which we used only the terms ‘thick’ and ‘thin’, whereas we would now also use the terms ‘rich’ and ‘poor’).

| Richness Score | Measure | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1* | Thin or fairly thin qualitative data (findings) presented that relate to the synthesis objectives. Little or no context and setting descriptions | For example a mixed-methods study using open-ended survey questions, a more detailed qualitative study where only part of the data relates to the synthesis objectives, or a limited number of qualitative findings from a quant-qual mixed-methods or qualitative study |

| 2* | Fairly thick qualitative data (findings) that relate to the synthesis objectives. Some/moderate amount of context and setting descriptions | For example a typical qualitative research article in a journal with a smaller word limit and often using simple thematic analysis |

| 3* | Thick or very thick qualitative data (findings) that relate to the synthesis objectives. Fairly detailed or detailed/fairly large or large amount of context and setting descriptions | For example data from a detailed ethnography or a published qualitative article with the same objectives as the synthesis that includes more in-depth context and setting descriptions and an in-depth presentation of the findings |

We first selected all the 3* UK publications for inclusion. We then explored any potential gaps in the data provided by these studies. We extracted basic information such as age and type of participants, pain condition, aims, setting and which of our review questions were addressed by their findings. These 3* UK publications only covered a limited range of pain conditions, and few provided information on review question 4, which indicated that the UK publications might not provide sufficient data to answer all our review questions.

Further sampling decisions were made in collaboration with our PPI group and PAG, to ensure that the synthesis addressed what is of greatest importance to children and their families and considered the views of other key stakeholders including healthcare professionals. The PPI members supported our preferred option not to include poor UK studies (rated 1* for richness) but felt we should include 2* as well as 3* UK studies. We therefore continued with a meta-ethnography rather than conduct a thematic synthesis, which could have incorporated less rich 1* findings. PAG members, including PPI representatives, agreed it was important to include non-UK studies (i.e. studies not conducted in the UK), as long as they fitted our aim and review questions, to try to represent a wider range of pain conditions and of participants. We completed richness assessments only for those non-UK studies which met our sampling criteria. Only those non-UK studies that were rated as 2* or 3* for richness (fairly or very rich data on our review questions) were included. We repeated the sampling process following the update of our literature searches in September 2022.

We referred to the PROGRESS-plus criteria (place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status and social capital) when judging whether relevant populations were represented in the sample. 69 We used the four GRADE-CERQual domains (methodological limitations, adequacy, coherence, relevance) to guide the sampling process in order to develop the strongest findings for decision-making (see Assessing confidence in synthesised findings).

Assessing methodological limitations of included studies

In addition to assessing the conceptual richness of studies, as described above, we also assessed the methodological limitations of the included studies. Two independent reviewers (EF, MSB, IU, LF and/or three volunteer research assistants) assessed methodological limitations of the included studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)70 qualitative tool using the following domains:

-

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

-

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

-

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

-

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

-

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

-

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

-

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

-

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

-

Is there a clear statement of findings?

Studies which were limited by poor methodological reporting were not excluded. No studies were judged to be fatally flawed (e.g. methodologically unsound); fatally flawed studies would have been excluded because there is a distinction between quality of methodological reporting and quality of study design (with only the latter being detrimental to the quality of the findings). We resolved any potential disagreements by discussion, and when necessary, a third review author was consulted. Where a review team member was the author of an included study, they were not involved in the assessment to ensure an unbiased appraisal. The end point of assessment was an overall judgement of methodological concern for each individual study (no or minor concerns, moderate concerns or serious concerns). We transparently recorded all decision-making in Microsoft Excel. Assessments of methodological limitations subsequently informed GRADE-CERQual judgements of how much confidence can be placed in our synthesised findings (see Chapter 4).

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis: meta-ethnography phases 3–6

Phase 3: Reading the studies and data extraction

Studies were repeatedly read in full by at least two team members. We recorded study characteristics of all eligible studies (e.g. aim; country; number and type of participants, e.g. gender, age, diagnosis/type of chronic pain, patients, parents or other family members) in Microsoft Excel. Further characteristics were recorded for the final included studies such as study design, recruitment setting, sampling method, methods of data collection and analysis, ethnicity, conflicts of interest, funders. We referred to the PROGRESS-Plus criteria, described above, when extracting data on participant characteristics. 69

Full-text PDFs of the included studies were uploaded into NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 71 Each study was added as an individual ‘node’ and all of its conceptual findings were extracted as ‘subnodes’. (A ‘node’ is a container, given a specific label, into which data are gathered.) Each conceptual finding or theme was ‘extracted’ or coded, regardless of whether it appeared in the ‘findings’ or ‘discussion and conclusions’ sections, and labelled with the author, study identification number and the concept/theme name (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Authors’ recommendations and ‘interventions that worked’ were also extracted as subnodes for each paper. In total, we extracted data into 529 nodes. Some studies did not contain conceptual-level data but instead contained, for example descriptive themes or rich descriptions. For these studies, where possible, we interpreted the findings to develop new concepts and coded them at a new node. For studies identified in the updated searches, we compared the findings of included studies directly with our synthesis findings rather than extracting data in NVivo.

Phase 4: Determining how studies are related – grouping studies

In deciding our approach to grouping studies for synthesis, we considered grouping studies by type of participant (children, parents or siblings), or age of the children focused on (e.g. 0–5 years, 6–8 years), or type of pain/pain condition. We concluded that we could not classify studies into groups according to the type of participant or the children’s age group because many studies included the views of children and parents and/or focused on a wide age range. Grouping by the type of pain or pain condition seemed to be a more feasible and logical approach. Therefore, we then looked at existing systematic reviews of intervention effectiveness and qualitative evidence syntheses on children’s chronic pain to see how they had grouped studies by conditions and consulted our healthcare professional PAG and team members to agree the groupings (see Chapter 3).

We found only two Cochrane effectiveness reviews on children’s chronic pain which had grouped trials into headache versus non-headache chronic pain (all other pain conditions) for subgroup analyses; the decision was based only on the numbers of trials. 54,55 Separate Cochrane reviews had been conducted specifically for recurrent abdominal pain and for sickle cell disease pain in children. We planned to integrate our findings with existing Cochrane effectiveness reviews so separate groupings on sickle cell disease, headache and recurrent abdominal pain seemed appropriate. A WHO review 20 had categorised trials by pain condition, according to the ICD-11 classification. Most of our included studies provided a poor level of detail on pain conditions so we could not use ICD-11 to classify and group them. The only two qualitative evidence syntheses in the field at the time9,39 did not group studies by condition since one focused solely on juvenile idiopathic arthritis39 and the other included only eight studies. 9

After seeking advice from the healthcare professionals in the PAG (see Chapter 3) and team members, we grouped included studies by health condition, which resulted in a total of 11 groups:

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

-

Abdominal pain

-

CRPS

-

Sickle cell disease

-

Headache

-

Neurological conditions

-

Musculoskeletal conditions

-

Skin conditions (epidermolysis bullosa)

-

Dysmenorrhoea

-

Mixed conditions

-

Unspecified types of chronic pain

We consulted high-quality relevant systematic reviews and qualitative evidence syntheses to inform our subgroup analysis. 52,72–74

Phase 5: Translating the studies into one another

The conceptual data/findings from all NVivo nodes were interpreted in chronological order from the earliest publication date using NVivo memos. This process consisted of interpreting and capturing the key meaning of each conceptual finding while taking account of relevant contextual data. These interpretive memos were labelled with the condition, author’s name, study identification number and concept/theme name (see Report Supplementary Material 3). For the first three studies, each node was interpreted independently by two reviewers (EF and MSB). The two reviewers then discussed their interpretations and, if possible, agreed a joint interpretation recorded in one memo or recorded their alternative interpretations. For the remaining studies, one reviewer interpreted the data (EF or/and MSB) from each node and recorded this in a memo; a second reviewer (EF and MSB, IU, RT, LC and/or AJ) read the data coded at the node, then read the first reviewer’s interpretive memo and challenged, confirmed and/or added to the interpretation of the first reviewer. All authors kept an ‘analysis journal’ in a memo in NVivo to record any reflections, thoughts, issues or questions during the analysis.

Informed by our PPI group and based on previous meta-ethnographies,52 we initially analysed data in each grouping of studies separately before bringing them all together in phase 6, as we describe below. In total, 346 memos were created. In phase 5, we used the data in the memos to compare concepts systematically, study by study for each of the 11 condition groupings to identify both common and unique concepts. The translation and interpretation were completed using an inductive approach, guided by data and focused on meaning and context. At least three reviewers analysed (translated) the concepts to try to reach a new level of interpretation.

In the study-by-study translation for each grouping, all memos were downloaded from NVivo as .docx files and combined into one Word document. Then, we read the interpretive memos for each study in chronological order by publication date. We took the earliest publication first and read the memos for each concept, we compared the meaning of each with the memos for the second study looking for similar and contradictory concepts, we then compared these with the third study and so on, until we had identified the full range of concepts including common and unique concepts. To help juxtapose the concepts, we used tables in a MS Word document, one for each grouping, described below (Table 3). For groupings with only one publication, we looked for and identified any overarching concepts where possible. One reviewer (EF or MSB) carried out the initial translation for each grouping. A second and third reviewer (EF, MSB, IU, AJ, RT, LF, LC and/or JN) then read and challenged, confirmed and/or added to the translation. Common and unique concepts were identified within each grouping.

| Author’s name_#studyID_name of the construct | Author’s name_#studyID_name of the construct | Our interpretations/common and unique constructs |

|---|---|---|

| Brodwall75#5239_Desire for a specific diagnosis and discussion with a professional | Smart76#3799_Interactions with doctors | Importance of diagnosis for parents (Brodwall,75 Smart76) |

| The outcome most wanted by parents after examinations were detection of a somatic disease with a well-defined treatment. (…) Parents described as extremely sad and frustrating regarding the lack of diagnosis that could potentially led to a treatment. Focusing on the pain could drive the family and the doctor into a vicious cycle of hunting for undetected causes instead of focusing on pain management. The anxiety that something dangerous may be overlooked may make the parents crave further examinations. (…) They wanted their child to have further medical examinations, and that this should happen quickly in case it is ‘something very serious’. |

Mothers (n = 22) visit doctors to establish whether a child was malingering (3 cases); to exclude a physical disease so that they could manage the pain themselves (13 cases); and to seek help in managing the pain (6 cases). Mothers (22) reported consulting doctors to establish whether a child was ‘malingering’ (3 cases) (mothers); to exclude a physical disease so self-manage the condition (13 cases); and to seek help with pain management (6 cases). Mothers’ view the interaction as satisfactory when they had been given a simple explanation for the pain as this acknowledged that the child was indeed genuinely ill and their concerns for their child were thus legitimate which removed any charge against their competence. Mothers perceived interactions with doctors to be satisfactory when a simple explanation for the child’s pain had been offered. Such an explanation provided validation of (1) parental concerns, (2) legitimacy of the child’s illness and alleviated any potential charges against maternal competence. |

Parents wished for a diagnosis that would enable treatment, were sad and frustrated with the lack of diagnosis and anxious it is ‘something very serious’. Focusing on finding a diagnosis could be at the expense of pain management. Diagnosis legitimised and validated the pain. |

One PhD thesis77 was also published in two other included publications38,78 and contained similar data/findings, which were analysed together and considered as one publication. Britton (2002)79 and Britton (2002)80 reported different participants’ perspectives from the same study sample, so findings were also analysed as separate publications. Renedo (2020)81 and Renedo (2019)82 also used the same cohort for their studies and presented similar findings, and therefore were analysed as one publication.

Phase 6: Translation and synthesis within condition groupings

After the process of comparing concepts and looking for common and unique concepts in phase 5, we matched, merged and developed overarching third-order constructs. These third-order constructs expressed a new interpretation of the data which went beyond the findings of the original studies; we achieved this for some of the conditions for which there were sufficient in-depth data. Report Supplementary Material 4 and Appendix 2 show, for each pain condition grouping, how we progressed from included study findings to third-order constructs, illustrating the outcomes of our translation and synthesis of translations. We produced a textual synthesis in a narrative format for each of the concepts, and where possible, we also created diagrams showing how the new constructs linked to each other. We also referred to any theory or model produced by the original authors of the studies to check we had taken account of the original meanings.

All phase 5 translation and phase 6 synthesised translation information for each grouping was summarised in a table (example in Table 3) which included the author’s name and study identification number; a list of all the author’s themes or concepts labels (second-order constructs); where relevant, a list of our constructs (new second-order constructs) created for descriptive studies; a list of common and unique constructs across all studies (created from study-by-study translation); and a list of any overarching third-order constructs (our new interpretations).

Britten et al. 83 coined the term ‘third-order constructs’, thus further developing Schutz’s84 notion of ‘first-order constructs’ – lay understandings – and ‘second-order constructs’ – the researchers’ interpretations of the first-order constructs. The translation and synthesis process resulted in a total of 39 third-order constructs and 169 second-order constructs across all the groupings.

Translation and synthesis across condition groupings

To translate and synthesise data across condition groupings, we conducted a series of four research team meetings including one hybrid in-person/online and three synchronous online meetings. Prior to meeting, data from all groupings were organised into one document, which included all the narratives (the textual syntheses) created from the translation process, and data that were used to create new second- and third-order constructs. Labels (like Post-it® notes) for each construct including the condition, the name of the construct, the contributing studies and a brief description of the construct were used during the meeting. Labels were colour-coded according to the condition and whether they were second- or third-order constructs. Six members of the team then organised the labels through a thematic analysis into distinct themes and then into broader ‘analytic categories’ (thematic headings) according to shared meaning. Four members attended in person (EF, IU, LF and MSB) and two members online (RT and AJ). Members participating online were able to follow the analysis process using a Padlet85 (a real-time collaborative web platform used to share and organise content – see Report Supplementary Material 5).

Following the hybrid analysis and synthesis meeting, the narrative document (containing all themes/constructs across all groups) was reorganised according to the new ‘analytic categories’. A further three online team meetings using Google Jamboard86 (a digital interactive whiteboard) focused on analysing the findings using all the different perspectives and expertise from the whole research team (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

Once all data were organised into analytic categories (five categories were created), we finished updating the textual synthesis, and used Microsoft Teams87 whiteboard to create diagrams to express and understand how themes/constructs and analytic categories were related (see Report Supplementary Material 7). We used the diagrams created in Microsoft Teams whiteboard to discuss the findings/analysis virtually with the research team; subsequently, we produced short descriptions for each analytic category based on the diagrams. These descriptions were developed into detailed textual syntheses.

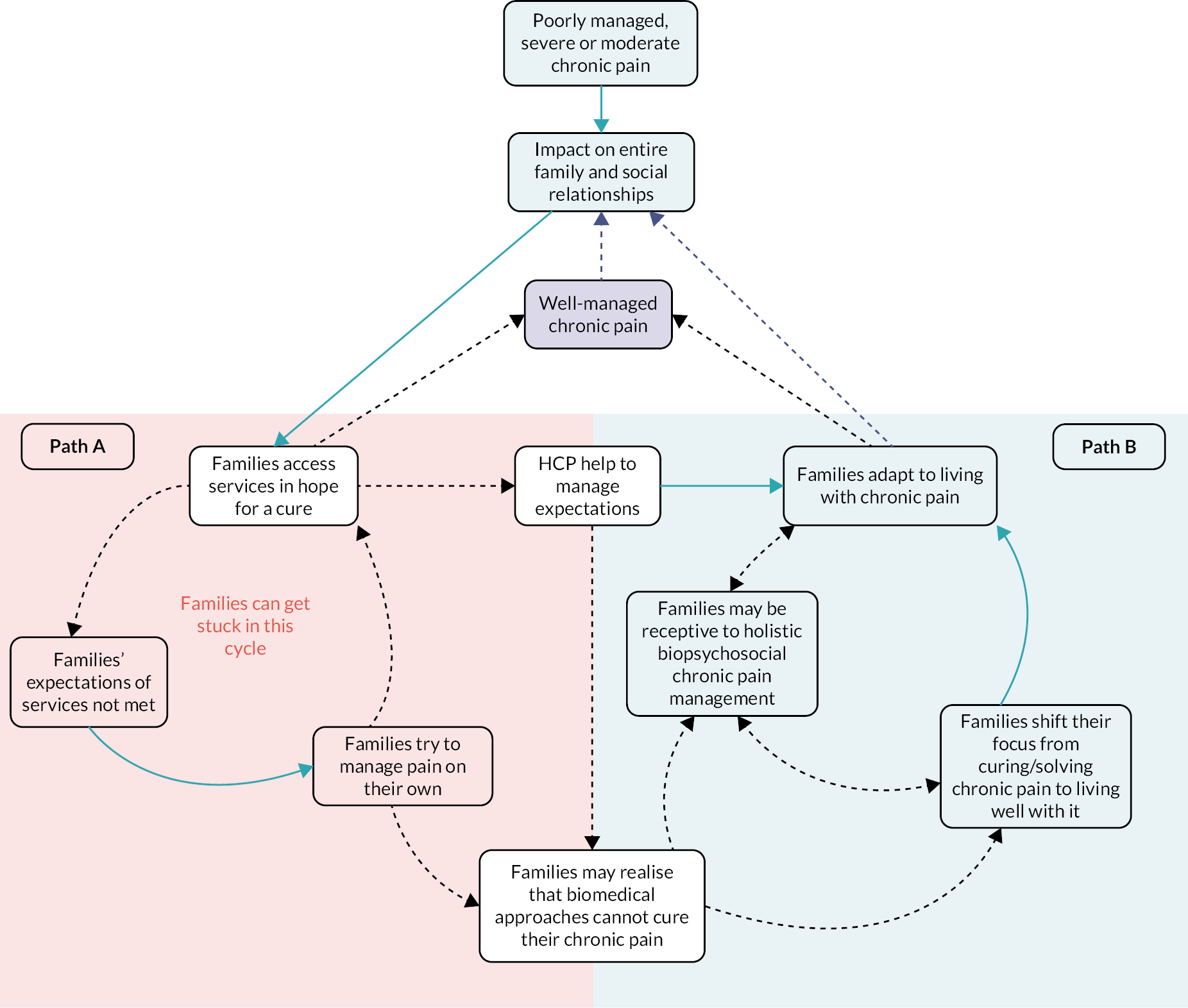

We continually further developed and refined our analysis and synthesis. In order to clarify our terminology, where we had been able to reach the level of new interpretation, the analytic categories were renamed as ‘third-order constructs’, for example ‘Pain organises the family system and the social realm’, most comprise ‘second-order constructs’, for example ‘adapted parenting’, which we had previously called ‘themes’. We developed lines of argument – the ‘overarching storylines’ – to explain how all the final constructs linked together with the help of diagrams in Whiteboard and team discussion. These lines of argument together enabled us to develop our theory of children’s chronic pain. We discussed and clarified ambiguous or unclear findings with our PPI and PAG groups (see Chapter 3).

Assessing confidence in synthesised findings

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation-confidence in the evidence from reviews of qualitative research assessments of how much confidence can be placed in individual qualitative evidence synthesis findings help decision-makers in the NHS and policy-makers use the findings to inform policy and practice; assessments indicate how well each finding represents the phenomenon of interest. 53 We applied the GRADE-CERQual approach to our meta-ethnography findings,53 using the online iSoQ (interactive summary of qualitative findings) software tool. We used CERQual to evaluate the overall confidence in the synthesised evidence for each review finding according to its adequacy of data, coherence, relevance and the methodological limitations in the primary studies contributing to a synthesised finding. 53 Adequacy refers to the overall richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding. 88 Coherence refers to the fit between the data from the primary studies and a review finding. 89 Relevance is how applicable the data supporting a review finding are to the context (e.g. population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the review question. 90 Methodological limitations refer to concerns about the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed to a review finding. 91

Integration of synthesised qualitative findings with Cochrane intervention reviews

It is important for decision-making to develop an overall understanding of intervention effect, feasibility, acceptability and factors that create the context for barriers and facilitators to successful implementation. We therefore integrated our synthesised qualitative findings with the results of recent Cochrane intervention effectiveness reviews22–28,46–50,54,55 using quantitative/qualitative data integration methods from Cochrane QIMG92 to determine if the programme theories (i.e. how a complex intervention is thought to work93) and outcomes of interventions match families’ views and expectations. We created a matrix in Microsoft Excel94 to juxtapose key outcomes and aspects of interventions that are important to children and families with the outcomes and focus of the reviews. We extracted the programme theories for all reviews and two reviewers (EF, KT) assessed whether these matched families’ views, experiences and expectations and whether they adopted a biopsychosocial perspective. A programme theory is simply the theory of how the intervention works and does not imply a realist methodology.

Integration mechanisms for quantitative results and qualitative findings

There were various points in overall meta-ethnography production at which integration occurred. 92,95 We have integrated quantitative and qualitative perspectives during review question formulation and synthesis.

Qualitative and quantitative review team membership and communication

Members of our qualitative evidence synthesis review team (JN, EF and LC) had close contact and communication (during both this meta-ethnography and previous reviews for WHO) with key reviewers who conducted and/or were the managing editor for the quantitative intervention effect reviews. For instance, we wrote funding applications with some of the quantitative reviewers, shared search strategies and outputs for the WHO reviews, had joint meetings and consulted regularly to obtain early sight of the quantitative outcomes. This meta-ethnography is also registered with Cochrane PaPas for publication in the Cochrane Library. The managing editor and quantitative intervention effect review authors also shared resources with our meta-ethnography team, such as draft intervention effects reviews, the new core outcome set and the Lancet Commission Report, which were used during quantitative/qualitative review data integration. Because of this close collaboration and the way that the meta-ethnography has been designed to ‘speak’ to the Cochrane intervention effects reviews, facilitated the subsequent quantitative/qualitative integration. This enabled us to establish a high level of coherence between the qualitative and quantitative evidence.

Question formulation

The meta-ethnography review questions were formulated to address known gaps in Cochrane intervention effectiveness reviews.

Additional synthesis to integrate qualitative findings and quantitative results

We used a matrix approach adapted from one used previously in several Cochrane reviews (see, for example Munabi-Babigumira et al. 96). Our matrix explored whether potential implementation factors (patient values, preferences and desired outcomes, acceptability, feasibility, etc.) identified in our meta-ethnography were acknowledged or addressed in the intervention programme theories in the Cochrane reviews of intervention effectiveness.

Deviations from the protocol

The original literature search of all sources (including bibliographic databases, reference list checking of included studies, website searches and contacting experts) was completed in September 2020. To bring the literature search up to date prior to publication, we reran the bibliographic database searches and contacted our expert panel for new and ongoing studies in September 2022. The update searches did not follow the full protocol. Due to time constraints, we did not rerun the website searches or check the reference lists of the newly included studies identified from our updated search. Furthermore, the ‘OpenGrey’ database was discontinued in 2020 so the update search could not be rerun.

In the protocol, we had planned to perform ‘cluster searches’, which involve identifying ‘clusters’ of related study reports to reconstruct the study context97 if a relevant study lacked contextual information. Due to the large volume of studies and lack of resource, we did not perform cluster searching, although we did record which included studies we felt needed more information about the study context as part of our richness assessments. In the protocol, we had planned to search the Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts bibliographic database but could not because of lack of institutional access.

Summary

We conducted a meta-ethnography, which adopted a rigorous, systematic approach to analysis and synthesis of data to reach new interpretations of data. We assessed our confidence in our synthesised findings using GRADE-CERQual. We used established methods to integrate our findings with results from Cochrane intervention effects reviews. For details of our PPI, see Chapter 3, and for details of the meta-ethnography results, see Chapter 4.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement and stakeholder engagement

Introduction

INVOLVE98 defines PPI as ‘research being carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them’98 (p.1) (emphasis in the source reference). The involvement of patients and members of the public helps to protect and promote their interests and create research that is more relevant, with clearer outcomes and impact. PPI played a central role across all stages of the meta-ethnography, from inception through to dissemination. PPI contributed to tasks such as helping with the development of the grant funding proposal; finalising the study design; deciding the study name and logo; deciding which studies to include and how to organise them for synthesis; sharing their experiences in order to clarify, confirm or disconfirm findings; identifying important areas missing from existing research; and participating in dissemination.

The study included both PPI and engagement. Public engagement is not synonymous with public involvement, and in the UK, the former refers to sharing research information and knowledge with the public. 99 We had a core PPI group who provided detailed feedback and helped with important decisions and data analysis and interpretation. We also sought views from the wider population of CYP with chronic pain and their parents/guardians. We also had a PAG of stakeholders, including medical experts, academic experts, third-sector organisations and children with chronic pain and their families, who contributed at key time points. Aspects of the PAG role included both involvement and engagement. The PAG was tasked with providing strategic advice to the research team on four key areas: (1) methodological issues, (2) clinical and lived experience of chronic pain, (3) study conduct and (4) dissemination.

We were guided by the UK Standards for Public Involvement100 and used the ACTIVE framework to guide our reporting. 101 PPI and PAG members decided their level of involvement or engagement throughout the duration of the study. In this chapter, we describe the PPI and PAG involvement and engagement and their impacts.

Recruitment

Patient and public involvement group

Patient and public involvement recruitment was conducted in three main stages. These comprised:

-

During development of the meta-ethnography research grant proposal in 2019, we involved 10 lay people including 3 CYP with chronic pain (1 was also a patient representative for a third-sector organisation), 4 parents, 2 adult patient representatives from the third sector and 2 adult members – 1 with chronic pain and 1 with a chronic illness from a university PPI Research Partnership Group (designed to assist with developing research relevant and useful to patients, carers, family members and healthcare professionals).

-

In 2020, we recruited a core PPI group of children aged 8–18 years, and parents or/and informal carers (i.e. not healthcare professionals) of children with chronic pain aged 3 months to 18 years. Additional prospective recruitment during the meta-ethnography was carried out as needed (e.g. to fill the gaps in terms of experiences with specific contexts/conditions).

-

In 2019–20, healthcare professionals, representatives of third-sector organisations and academics with relevant experience were recruited to join our PAG.

We advertised for PPI members via national pain services, social media (Facebook and Twitter) and third-sector organisations (charities) including the Sickle Cell Society, Fibromyalgia Action UK, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Pain UK, The Brain charity, CCAA kids with Arthritis, Pain Relief Foundation, Action on Pain, Coeliac UK, Guts Charity, Dystonia UK, Endometriosis UK, Sick Children Trust, Action for ME, A way with Pain, MS Trust, Diabetes UK, Fibro Awareness UK, Pain Concern and Independent Nurse. We tried to recruit a diverse core PPI group with any type of chronic pain, except for pain associated with cancer – whether primary (e.g. fibromyalgia) or secondary pain conditions (e.g. arthritis) – with a variety of experiences, ages, ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses. Other stakeholders were approached directly via e-mail.

Participants

Patient and public involvement group

We successfully recruited 12 children (10 females, 1 male and 1 non-binary from 8 to 20 years old) and 8 parents (all female). The young people had chronic pain conditions including Ehlers–Danlos, fibromyalgia, migraines, general chronic pain and chronic lumbar paravertebral muscle spasm, chronic headaches and CRPS. Parents and/or informal carers in the group were all mothers of children with pain from cystic fibrosis, CRPS or Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. All members lived in the UK, specifically in England, Scotland and Wales and were white. All PPI members were invited to join the PAG group.

Project Advisory Group

The PAG, which also facilitated some PPI involvement, comprised 27 members including 10 children with chronic pain and 7 mothers of children with chronic pain (also part of the PPI group), 6 healthcare professionals and 7 other stakeholders. The healthcare professionals/academic healthcare professionals included a consultant in paediatric anaesthesia and pain medicine who was a senior clinician and research lead at a specialist pain service; a clinical academic and consultant in pain medicine who was national lead clinician for chronic pain for the Scottish Government and vice chair of the National Advisory Committee on Chronic Pain; a clinical academic who was Chair of Pain Medicine, Honorary Consultant in Anaesthesia and Pain Medicine, and chair of the 2018 SIGN guideline development group for children’s chronic pain; one general practitioner and two physiotherapists. There were two patient representatives from the third sector including from Pain Concern and Children’s Health Scotland, a representative from Healthcare Improvement Scotland (Scottish Government), and an academic expert in qualitative evidence synthesis. We were unsuccessful in recruiting representatives of NICE or the UK government.

Involvement and engagement methods

Strategies to involve PPI were flexible and inclusive to allow everyone to participate individually or in a group. We provided preparatory training to meet the needs of PPI members, for example how to use the video-conferencing software, understanding the research. Engagement with members of the PAG was focused on specific tasks. We used a combination of online workshops and interim online communication (e-mail, teleconference calls, social media, e.g. Facebook and Twitter pages, online surveys) throughout the research. No face-to-face interaction was possible because of the COVID-19 pandemic. PPI members were paid for their time in vouchers.

Project Advisory Group and PPI members received plain language meeting materials in advance. PPI members were offered an online briefing in advance of the meeting, individual follow-up debrief calls after meetings/workshops, and given a list of support organisations. All meetings and workshops were designed to be engaging and to appeal to young people including a fun activity or ‘ice breaker’, multiple rest breaks and co-created ground rules to help create a safe space. The PAG workshops were chaired by two skilled chairs independent from the research team and their institutions: Bernie Carter, a professor with expertise in children’s chronic pain at Edge Hill, and Professor Richard Hain, clinical consultant and lead clinician in paediatric palliative medicine at Ty Hafan children’s hospice. PPI workshops were facilitated by two team members (EF, MSB). See Table 4 for a description of the different stages of the meta-ethnography in which PPI and PAG members were involved.

| Phase | Involvement activity | Number of PPI involved | Number of PAG members involved | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning of proposal and phase 1 | Feedback on study aims, objectives, review questions, lay summary and dissemination strategy | 10 | 0 | |

| Phases 1 and 2 | Finalise the study protocol, for example the literature search strategy | 8 | 0 | |

| Phase 2 | Finalise inclusion/exclusion criteria, for example the types of chronic pain included and the characteristics of the population we will include. Sample studies for synthesis | 8 | 17 | Separate online workshops for PPI (1 April 2021) and PAG (6 May 2021) |

| Phases 3 and 4 | Decide how studies were organised/grouped for analytic synthesis, for example grouping them by type of chronic pain, age of participants | 0 | 11 | |

| Phases 5 and 6 | Analyse and interpret primary study findings, for example to check if our interpretation of the study findings is different from or the same as children and families’ interpretations, check if their experiences are similar or different to those of the people in the studies, if important areas are missing from research | 5 | 6 | Separate online workshops for PPI (9 December 2021) and PAG (28 April 2022) |

| Phase 7 | Producing outputs, dissemination. We invited members to copresent a conference paper and the group to codevelop lay, patient and policy outputs. The group is helping ensure the development of lay dissemination materials for children and families is appropriate and relevant |

1 PPI conference presentation | 0 | E-mail and online meetings |

Patient and public involvement in the review focus and questions

Methods

Initial PPI engagement during grant development involved sending PPI volunteers materials via e-mail about the topic and our rationale for the focus of the review and draft review questions.

Impact/outcome

Respondents confirmed the importance of the topic and review questions.

Patient and public involvement in the literature search strategy

Methods

We finalised aspects of the literature search strategy in collaboration with our core PPI group in September 2020. Specifically, we e-mailed them materials explaining the search terms, sources in plain and simple language and asked them to suggest sources, key studies or experts (see Report Supplementary Material 8).

Impact/outcome

The PPI group suggested seven additional sources, which were included in the search strategy (see Chapter 2, section Supplementary searches). They agreed our final study inclusion criteria.

Sampling decisions

Methods

Our PPI and PAG groups informed sampling of studies. Eight PPI members (four children with chronic pain and four parents/guardians) contributed to decisions – six took part in a 1-hour online workshop on 1 April 2021 and a further two members took part via an online survey. The team presented gaps identified in the UK data and asked five questions (see Appendix 3) related to the sampling of studies in terms of their conceptual richness, study setting and pain conditions. We also asked if we should continue with a meta-ethnography or instead use an alternative synthesis methodology (e.g. thematic synthesis) which would allow inclusion of a wider range of studies, not just conceptually rich ones.

We then asked our PAG how we should sample non-UK studies. Twenty-three people attended an online workshop on 6 May 2021, including six research team members, four parents and four CYP with chronic pain, and nine healthcare professionals, academics or other professionals. We presented the gaps in populations and pain conditions covered by the conceptually rich UK studies.

Impact/outcome

The PPI members indicated that we should not include studies rated 1* for richness, but we should include richer 2* as well as 3* studies; and therefore, we should continue with a meta-ethnography rather than conduct a thematic synthesis. The PPI group also agreed that some studies conducted outside the UK should be included. Subsequently, most PAG members agreed we should include non-UK studies regardless of the country in which the study was conducted, studies for a wider range of pain conditions, and a broad range of participants, as long as studies fitted well with our meta-ethnography aim and review questions.

Patient and public involvement and Project Advisory Group involvement in deciding how to group studies for synthesis

Methods

We e-mailed PPI and PAG members in June 2021 to ask how we should group studies for preliminary analysis by subgroup, prior to synthesising the whole sample of studies and received 16 responses. Subsequently, we e-mailed 11 clinicians and pain experts to ask about their views and suggestions on the preliminary groups of health conditions (see Report Supplementary Material 9 and Chapter 2, Phase 4: Determining how studies are related – grouping studies).

Impact/outcome

Patient and public involvement and PAG responses contributed to the decision to group the included studies into a total of 11 groups of health conditions: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, abdominal pain, CRPS, sickle cell disease, headache, neurological conditions, musculoskeletal conditions, skin conditions (epidermolysis bullosa), dysmenorrhoea, mixed conditions and unspecified type of chronic pain.

Patient and public involvement in data analysis and interpretation

Methods

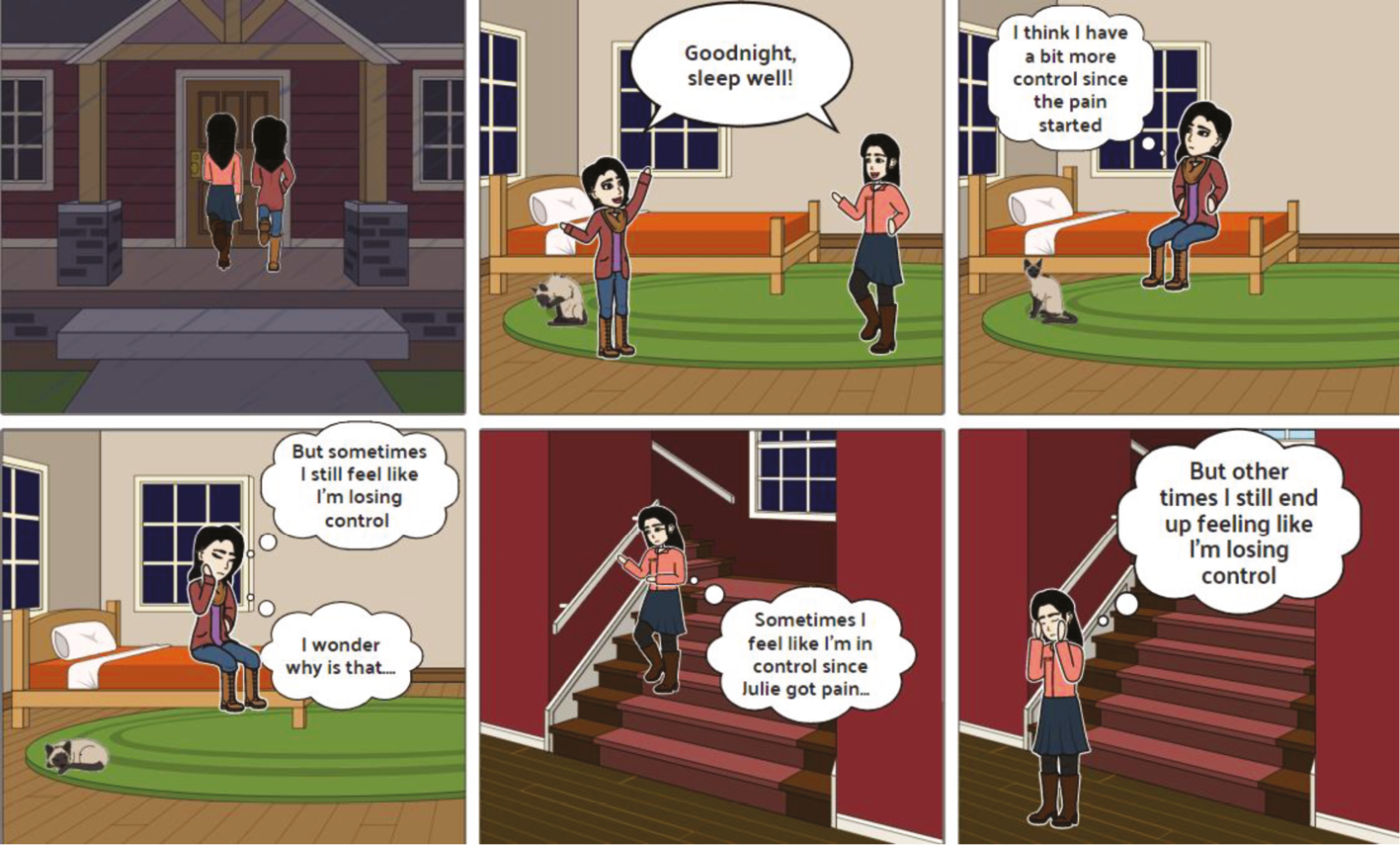

A 2-hour PPI workshop with two parents and three young people was held in December 2021 to discuss, clarify and interpret preliminary findings from primary studies. We used the software StoryboardThat (www.storyboardthat.com) to create cartoons and accompanying scenarios (e.g. Figures 3 and 4) to convey these findings to prompt discussion. Cartoons included people of different ethnicities and genders. We formulated the dialogue in speech bubbles using the language and terminology from children’s and parents’ quotations in the included studies and ensured it was suitable for a minimum reading age of 8–9 years of age. Members of the team approved all dialogues prior to the workshop. All PPI members received the cartoons and an infographic (see Report Supplementary Material 10) explaining the study findings a week prior the workshop.

FIGURE 3.

Example of cartoon used during PPI analysis workshop.

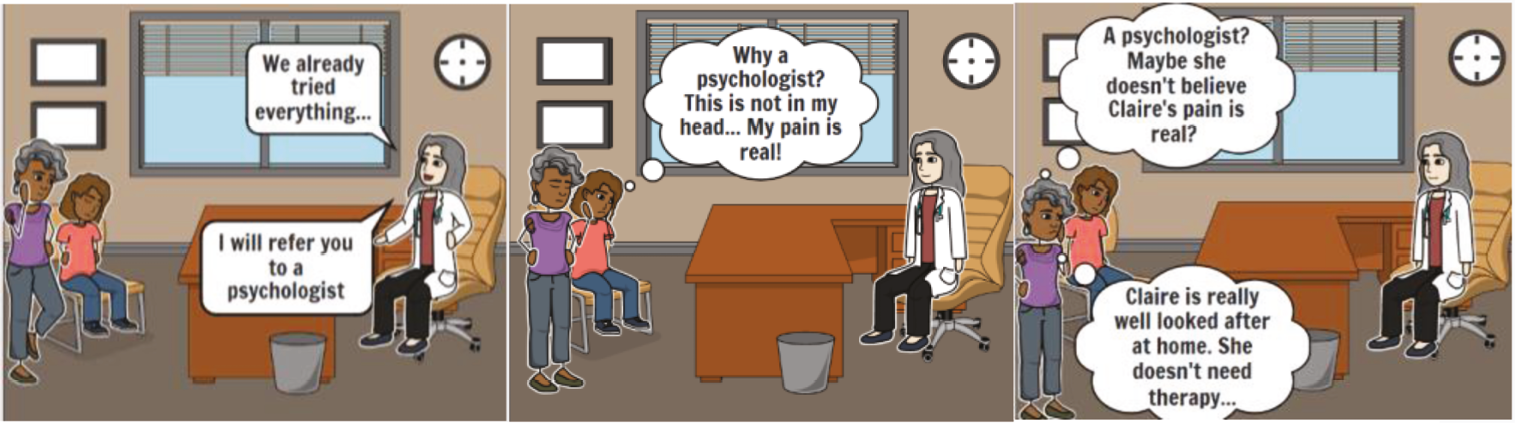

FIGURE 4.

Example of cartoon used during PAG analysis workshop.

Cartoon title: Mixed Feelings

Cartoon scenario: Claire brings her daughter Julie home after a busy day. They are getting ready to go to sleep, but both have a lot on their minds.

The findings discussed were: (1) why children might not communicate pain verbally, (2) why it is important for children and parents to be acknowledged and understood by healthcare professionals, friends and family, (3) what families want from treatment and services, (4) differences between accepting versus being resigned to pain, often referred to as ‘coping’ in included studies, (5) the meaning of ‘control’ in relation to pain (Figure 3) and whether ‘coping’ strategies are used to achieve control over the pain condition. After showing each cartoon, we asked a series of open-ended questions, for example:

-

In your experience, what do you think is going on here?

-

Have you ever had a similar experience?

-

Can you tell us why do you think this is happening?

-

Any other comments?

These questions were intended to provide clarity to, and/or address gaps in, the primary study findings. Data from the workshop were recorded in notes.

Impact/outcome

Patient and public involvement provided a different perspective on and/or interpretation of some of the findings discussed. For instance, PPI feedback added nuance and clarification to the idea of ‘control’ found in primary studies and helped the team to reach the following perspectives:

-

The idea of ‘control’ had been used in included studies often without clear definitions and without adequate consideration of what it means to parents and CYP with chronic pain.

-

The perspective of control might vary, for example for a parent it could mean something quite different than for a young person.

-

Overall, parents and CYP perceived the term ‘control’ in relation to chronic pain negatively, for example it implied that CYP could control their pain and its impacts.

New data and insights were incorporated into our analysis and synthesis and helped us to further develop and refine the following second-order constructs:

-

– Pain organises the family system (see Third-order construct 1: pain organises the family system and the social realm).

-

– Pain’s adverse psychosocial impacts on the whole family (see Third-order construct 1: pain organises the family system and the social realm).

-

– Pain forces adjustment and adaptation (see Third-order construct 1: pain organises the family system and the social realm).

-

– Families’ striving for diagnosis and a cure (see Third-order construct 2: families struggling to navigate health services).

-

– Importance of being listened to and believed by healthcare professionals (see Third-order construct 2: families struggling to navigate health services).

The core PPI group also helped fill gaps in the data, for example around disengagement with NHS health services, and brought experiences of pain conditions not represented in the included studies, such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and cystic fibrosis.

Project Advisory Group involvement in data analysis and interpretation

Methods

In a 2-hour online PAG meeting in April 2022, attended by four parents and two young people, we discussed four further findings from included studies. No healthcare professionals or other stakeholders attended this meeting despite being invited. We also used cartoons to facilitate the discussion (e.g. shown in Figures 3 and 4). All members received the cartoons and an infographic (see Report Supplementary Material 9) explaining the study findings in advance of the workshop.

Cartoon title: Attitudes to being offered psychological treatment

Cartoon scenario: Many families don’t know why they are being offered psychological help and get offended by it.

The findings related to pain management and included (1) how families and doctors/healthcare professionals think about pain and treatments, (2) stigma associated with psychological approaches to managing pain (Figure 4), (3) discrimination and prejudice in health services and (4) the lack of a clinical pathway for chronic pain management. After each cartoon, we asked a series of open-ended questions, for example:

-

How do these findings reflect your experiences, if at all?

-

Anything else you would like to add about what we discussed?

Data from the meetings were recorded in notes and new data were incorporated into our analysis and synthesis.

Impact/outcome