Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 18/01/06. The contractual start date was in April 2019. The final report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Dedication

This project was originally conceived and developed with the late Professor Scott Reeves, who died unexpectedly in May 2018. Scott, a global research leader, was first and foremost a sociologist and ethnographer. He brought his sociological lens to the study of challenging problems of health and social care professional relationships, in their learning and their work. His original ideas and considerable expertise in interprofessional health-care research were instrumental in the formation of this study and the research team dedicate this project to his memory.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Harris et al. This work was produced by Harris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Harris et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this report have been reproduced or adapted from Harris et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this report have been reproduced or adapted from Sims et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Rationale for the review

This chapter sets out the background and rationale for the study and explains our purpose in conducting a realist synthesis of leadership of integrated care teams and systems. It explains the history of integrated care and discusses the reasons for identifying the attributes that facilitate effective leadership of these systems. Our approach, which focuses on identifying and understanding the mechanisms through which leadership of integrated care works and the necessary contextual circumstances,3–5 is informed by the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) publication standards for realist syntheses,6 providing justification for utilising realist approaches in the study of a complex system and subject.

The organisation of health and social care in England is moving rapidly towards integrated models. NHS policy documents, such as the Five Year Forward View7 and the more recent Long Term Plan,8 have emphasised this shift, with the strategic intention of building upon existing cross-sector interdependence between the NHS, social care, local authorities, communities and employers. To ensure success in existing collaborations and integrated systems, a range of development needs has been identified, including leadership. 9 Leadership of integrated teams and systems is a complex, multifaceted concept, lacking a strong evidence base. In particular, there is little understanding of how effective leadership across integrated health and social care teams and systems may be enacted, the contexts in which this might take place and the subsequent implications for integrated care as a whole. 10

Our realist review of leadership of integrated care teams and systems responds to this first by comprehensively mapping the evidence base and, second, by applying realist principles in the interpretation of the literature to identify the key characteristics that comprise effective leadership practices. Realist synthesis is a particularly useful approach when exploring a concept as fluid as leadership, as the processes of theoretical reasoning that are required by the approach enable an interrogation of systems and policy to a depth not possible with more conventional or systematic evidence reviews.

Objectives and focus of review

This review developed and refined the programme theories of leadership of integrated care teams and systems in health and social care, exploring what works, for whom and in what circumstances. It has produced recommendations for policy-makers, health and social care leaders, managers and clinicians to help them design work systems and leadership development initiatives to support effective leadership of complex multisystem services.

Formal objectives for the review were as follows:

-

to investigate who are the leaders of integrated care teams and systems and what activities contribute to their leadership roles and responsibilities

-

to explore how leaders lead/manage integrated care teams and systems that span multiple organisations, agencies and sectors

-

to develop realist programme theories that explain successful leadership of integrated care teams and systems iteratively through stakeholder consultation and evidence review

-

to identify the development needs of the leaders of integrated care teams and systems

-

to provide recommendations about optimal organisational and interorganisational structures and processes that support effective leadership of integrated care teams and systems. 1

These objectives were designed to enable the analysis of established perspectives around integrated health and social care, leadership, and these elements in combination. The next section provides background on the development of integrated care, exploring how and why effective leadership is important.

Defining integrated care

The cross-cutting nature of integrated care suggests that a single definition is problematic. These systems serve a complex and diverse range of stakeholders. Expectations regarding the purpose and objective of integrated care are likely to differ, sometimes significantly, although there have been useful descriptions that enable the identification of a range of central characteristics that constitute an integrated care team and system.

In answer to the question ‘What is integrated care?’,11 a number of commonly used definitions have been presented. These include a health system-based definition, a definition from the perspective of health and social care managers and a social science definition. Although these emphasise a common need for co-ordination of people and services around a shared goal of improving health outcomes, the patient perspective seems both the most illustrative and the most important:

I can plan my care with people who work together to understand me and my carer(s), allow me control, and bring together services to achieve the outcomes important to me.

National Voices. 12

In addition, The NHS Long Term Plan8 explains the purpose of an integrated care system (ICS) as follows:

An ICS brings together local organisations to redesign care and improve population health, creating shared leadership and action.

They state that an ICS includes the integration of primary and specialist care, as well as social care and mental health services.

Historical development of integrated care systems

There are, in addition, universal factors that have been identified as driving the implementation of ICSs, including reduction of fragmentation, continuity of care beyond the hospital setting, patient centeredness and shared managerial vision. 13

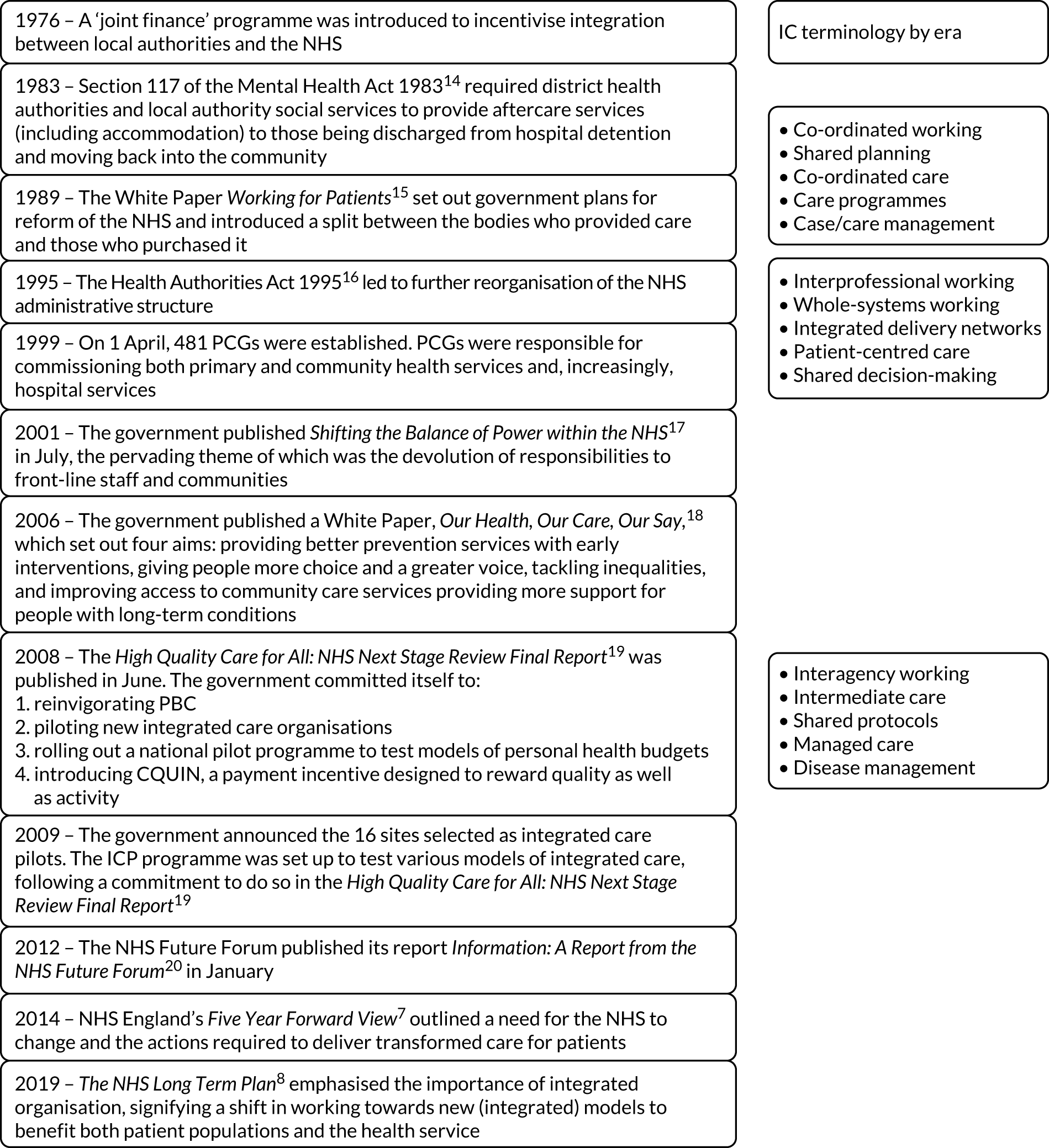

The initiatives included in Figure 1 broadly combine to lay the foundations for what is now known as integrated care in the UK context, suggesting a long held, gradually refined intention to integrate health and social care services across a range of disparate contexts. To further understand how integrated services have reached their most recent iterations, an exploration of the relevant policy developments may assist. It is possible to discern how the shift towards a recognition of the value of integrated working and systems has come about, and how integrated care has been adopted as a concept and goal across governments and periods of time. 21 Figure 1 provides a selected chronology of the main policy interventions that have prompted a move towards integrated systems of health and social care in England. In addition, the boxes on the right-hand side of Figure 1 offer examples of the terminological development of integrated care22 and how this type of working has been referred to across different periods of time.

FIGURE 1.

A selected chronology of policy interventions prompting integrated systems of health care. CQUIN, Commissioning for Quality and Innovation framework; ICP, integrated care pilot; PBC, practice-based commissioning; PCG, primary care group.

The emergence of integrated care in England can be viewed as a consolidation of the devolution of the NHS across the country accompanied, perhaps paradoxically, by greater centralisation in the form of NHS England. In addition, integration is seen as a means to protect resources through joint working and as a more effective method of delivering care to an ageing population with the associated rise in long-term conditions. 23 While the combination of these elements is important, there is also a distinction to be made between a universal recognition that integrated care is representative of progress and the complex realities that face sometimes radically different locations and patient/service user populations. Although this offers some insight into the development of integrated care, the difficulty around conceptual definition remains. The complex variation of health and care provision and populations across the country has been acknowledged and offers some explanation of why consensus has not and perhaps should not be reached. The following excerpt24 explores this complexity, while providing key principles that can be broadly applied to integrated care:

Integrated care takes many different forms. In some circumstances, integration may focus on primary and secondary care, and in others it may involve health and social care.

The King’s Fund. 24

The authors further state that:

A distinction can be drawn between real integration, in which organisations merge their services, and virtual integration, in which providers work together through networks and alliances.

The King’s Fund. 24

And conclude that:

The most complex forms of integrated care bring together responsibility for commissioning and provision. When this happens, clinicians and managers are able to use budgets either to provide more services directly or to commission these services from others.

The King’s Fund. 24

Achieving a combination of real and virtual integration, alongside delivery and commissioning, is a challenge for leadership. In this complex context, implications for leaders’ merit addressing. They must respond to the dynamic perceptions and realities of integrated care in their activities and behaviours. This highlights a need for a processual view of leadership to accommodate the complex and constantly changing relationships and circumstances inherent in integrated systems. The next section offers examples of leadership organisation in contemporary integrated care models.

Leadership of integrated care

Leadership is a complex concept, with many differing definitions, including those which seek to distinguish it from management. 25 Yet, despite these differences, there is a consensus that leadership involves the direction of a group towards shared goals, wider organisational values, a vision and objectives and the management of ongoing change. 26,27 Effective leadership is claimed to be a key element of well-co-ordinated and safe health and social care,28–31 and ineffective or absent leadership has been linked to reports of failures in care leading to patient/service user harm. 32 Existing research on leadership tends to be based on the premise that leaders provide guidance for single or uniprofessional teams33,34 and overlooks the complexity, intricacies and inevitable tensions that arrive in leading ICSs. These leaders do not influence just one organisation or professional group, but instead often work between several organisations across primary and secondary care, health and social care, publicly funded services, the not-for-profit sector and private businesses. Leaders of ICSs will, therefore, require different skills from their predecessors,24,35 yet there is currently little understanding of what these may be, what the mechanisms for effective leadership across integrated care teams and systems might be, the contexts that might influence it or the nature of the resulting outcomes. 10

The NHS Long Term Plan8 described the governance of ICSs as being inclusive of the following:23

-

a partnership board, drawn from and representing commissioners, trusts, primary care networks, local authorities, the voluntary and community sector and other partners

-

a non-executive chair

-

sufficient clinical and management capacity drawn from across constituent organisations

-

a named accountable Clinical Director of each primary care network

-

a greater emphasis by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) on partnership working and system-wide quality in its regulatory activity, so that providers are held to account for what they are doing to improve quality across their local area

-

NHS providers to take responsibility, with system partners, for wider objectives related to a) use of NHS resources and population health; and b) longer-term NHS contracts with all providers, including clear requirements to collaborate to support system objectives

-

clinical leadership aligned around ICSs creating clear accountability to the ICS.

Although this suggests that there are leadership structures in place, questions concerning how leaders can operate effectively in these structures are timely. Although The NHS Long Term Plan8 states that leadership should be aligned with ICS structure, the collective governance additionally described builds largely on existing leadership processes, providing adaptive reaction rather than a more directive development of leaders of and for integrated care. Thus, while there is evidence to suggest that strong and supportive leadership and joint governance are important to the successful implementation of integrated care programmes,36–38 we do not know the characteristics required to provide this strong and supportive leadership, how this may look and under what circumstances this can be most effectively enabled.

Chapter 2 Review methods

Study design and conceptual basis

As with all complex social interventions, it can be assumed that leadership might work for different stakeholders in various settings in different ways. We therefore adopted a realist synthesis methodology39,40 to enable the identification of the key contextual characteristics and mechanisms that contribute to effective leadership practice in integrated care. This methodology involved developing and iteratively refining initial programme theories through both stakeholder consultation and evidence review.

Realist synthesis was developed as a means of applying realist methods to the evaluation of evidence. 39 This may be of particular help when exploring a concept as fluid as leadership, where the processes of theoretical reasoning will enable an interrogation of systems and policy to a depth not possible with more conventional methods or systematic evidence reviews. 1 Indeed, it has been suggested41 that systematic review is inadequate when the intention is to develop a fresh perspective, reinforcing a need for an inherently iterative, non-linear approach that performs multiple literature searches and constantly refines the evidence-based programme theories. Judging the literature should, in addition, be guided by how well it ‘fits’ into the process, rather than using predetermined quality criteria. This method also allows for the plurality of leadership strategies, the success of which seem often dependent on the unique combination of specific contextual conditions and associated actions.

Research question, boundaries, and scope

The research question identified for the review was:

What aspects of leadership of integrated teams and systems in health and social care work, for whom and in what circumstances?

As no unifying definition of an ‘integrated care team’ had been identified in the literature, we agreed to adopt the following definition of an ‘integrated care team’:

Integrated care teams consist of two or more teams that span multiple organisations, agencies or sectors within health and/or social care and interface directly and interdependently to address individual patient/client goals.

Similarly, as no single definition of an ICS existed, we defined it as:

Integrated care systems consist of the executive boards and senior leadership teams of two more organisations, agencies or sectors within health and or/social care which enable integrated care teams to work efficiently and address their goals.

These definitions were presented to and agreed by the expert stakeholder group. Thus, to be identified as an integrated care team or system and to be included in the review, any team/system in the literature needed to span organisations, be it across health settings (e.g. acute and primary care) or across both health and social care organisations. Initially, literature not relating to health and social care settings (e.g. the business and management literature) was excluded, although this was referred to at a later stage in the synthesis (see Stage 1b). Furthermore, to be included in the review, literature needed to discuss how to lead integrated care or how to develop leaders of integrated care, as opposed to focusing on the process of integration or whether or not integration in itself ‘works’. No limits were placed on the geographical location of the teams or on the nature of their client/patient group.

Searching the literature

Following realist synthesis methodology,39 two distinct search phases were undertaken for this review; stage 1 and stage 2. Owing to the complexities in identifying relevant literature for this synthesis, stage 1 was also further expanded into stages 1a and 1b.

Stage 1

Research literature

In consultation with information services specialists at both King’s College London (London, UK) and Kingston University London (London, UK), the following search strategy was developed:

“Integrat*” OR “multi-team*” OR “multiteam*” OR “cross-bound*” OR “cross bound*” OR “cross-organisation*” OR “cross organisation*” OR “cross-sector*” OR “cross sector*” AND “leader*” (Limiter: English language only, where available).

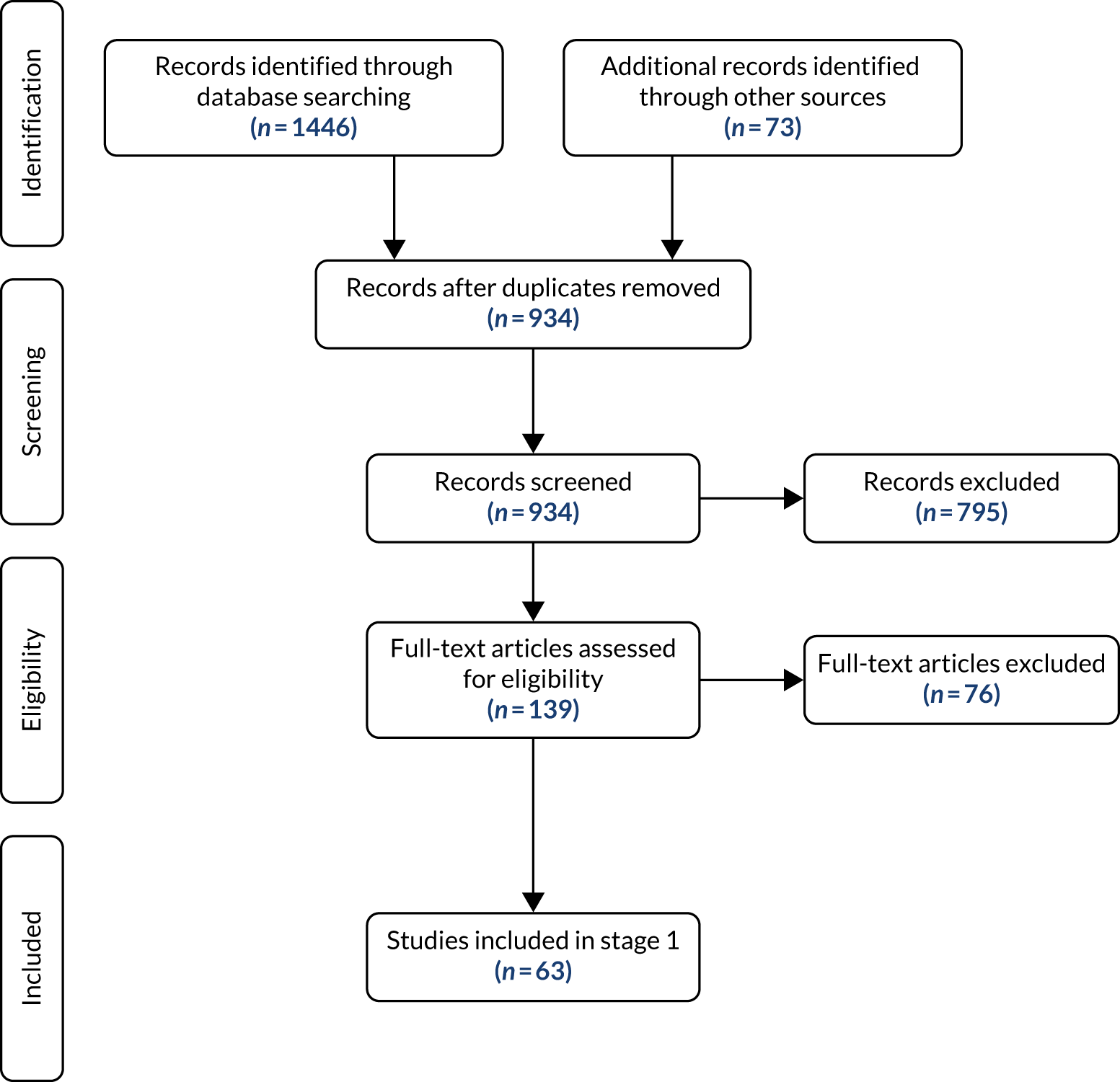

This search strategy was run in the following databases: EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Social Policy and Practice, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, International Bibliography of Social Sciences, PsycINFO and Education Research Complete. A total of 1446 empirical research papers were identified, of which 532 were duplicates and were removed, leaving a total of 914 papers for review. These papers were divided between two reviewers (SS and SF), who read only the abstract of each paper to determine whether or not it was relevant to the focus of the review. At this stage, 848 papers were deemed not relevant and, therefore, were excluded from the review, leaving a total of 66 papers. These papers were divided between the two reviewers and read in full, as a result of which 43 papers were excluded,25,42–83 leaving a total of 23 papers. 31,84–105

Grey literature

Grey literature relating to policy and organisational-based material was sought by searching Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), Google Scholar, government and other specialist websites [e.g. NHS Leadership Academy, Skills for Care, The King’s Fund, Advance HE (formerly known as the Higher Education Academy), The Institute of Healthcare Management, Social Care Online, NHS England and NHS Improvement]. Key words adapted from the main search strategy were used and included ‘leader’, ‘leadership’, ‘integrated care’ and ‘integrated system’. Enormous numbers of evidence sources were identified in the searches. Most were not relevant. Forty-one pieces of grey literature were identified and read in full by one reviewer (RH). This excluded 27 pieces of grey literature,8,9,106–130 leaving a total of 14. 10,131–143

Stage 1 analysis

Stage 1a

A total of 37 papers (23 empirical research, 14 grey literature) were included in the first phase of the stage 1 search. These papers were divided between the three reviewers (SF, SS and RH), who each independently compiled a list of mechanisms or preliminary programme theories based on the papers they had read [to ensure consistency of approach, a small number of papers (n = 4) were read by all the reviewers so that the team could compare their analyses]. The reviewers then met together regularly to discuss their coding of mechanisms and any queries they had until agreement was reached. The following preliminary mechanisms were identified and accepted by all the study team (a short description of these mechanisms can be found in Table 1):

-

supportive relationships and trust

-

team working/collaborative working

-

shared mission/vision/approach/purpose

-

shared responsibility/ownership

-

learning, development and innovation

-

communication

-

providing clarity

-

balancing needs

-

advocacy

-

external liaison/consensus building.

| Mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Supportive relationships and trust | Leading integrated care teams requires skill in building high-quality interpersonal relationships, creating significant connections and establishing trust among diverse individuals and groups. Presence, mindfulness, engagement, empathy, team spirit and ownership are key characteristics of compassionate leadership. Dissatisfaction is communicated through appropriate feedback mechanisms to mitigate any negative impact on the team. For ICSs to work effectively, relationships need to be credible and resilient, with clarity in their collective focus. Supportive relationships in teams help overcome the scepticism and protectionism found among professionals regarding collaborative work while reducing duplication of services and visits in the community |

| Team working/collaborative working | Leaders work collaboratively with staff, patients, service users, politicians and citizens. Effective leadership teams work in a collegiate way and have a clear sense of collegiate responsibility. Leaders encourage the participation of all professionals and prevent resistance behaviours, ensuring that co-operation, trust, openness and fairness are instilled into the fabric of the service. Voluntary collaboration between NHS and local authority leaders develops a shared, system-wide approach to strategy, planning and commissioning and financial and performance management, and drives integration of care and services |

| Shared mission/vision/approach/purpose | Leaders of integrated teams are committed to a shared philosophy and common mission/vision/purpose for integrated services. Integrated services involve cross-boundary working with a wide and varied group of organisations. Leaders of these teams need to have insight into the motivations and challenges of other organisations, work through challenges in partnerships to develop collective solutions and look beyond reactive problem solving to take a longer term strategic view. Leaders oversee the implementation of the shared vision, ensure the right resources are available and regularly review the outcomes achieved. Shared vison can be used as a mechanism to focus effort at times of conflict and disagreement |

| Shared responsibility/ownership | Leaders of integrated teams share responsibility for financial cost and quality targets. This is enabled through collective engagement with risk sharing protocols that concern finances, resources and commitments, in addition to measures that monitor and review achievements. Performance management and outcomes frameworks are also used by leaders in local partnerships. Chairpersons and Chief Executive Officers develop a shared vision of the future for their organisation, ensuring that individuals throughout the system understand and accept it as something worth achieving. Shared responsibility for financial cost and quality targets has been deemed important to implementing successful models of leadership |

| Learning, development and innovation | Leaders generate continuous organisational learning and innovation, building adaptable and responsive team cultures. Aiming to improve themselves and those around them, leaders are inspirational and act as role models to encourage continuous learning and build a learning culture, offering opportunities for team members to develop and stretch themselves. Leaders have an interest in innovation and embrace evidence-based practice. They are skilled at leading complex, large-scale change through excellent facilitation and influencing skills. They use performance measures and data to inform design and planning and are also ready to support staff if and when the innovation does not succeed. Leaders create active partners rather than passive employees and, if nurtured appropriately, can encourage and support the individual development of leadership skills within their team |

| Communication | Leaders of integrated care teams possess an ability to listen and consult, adapt communication styles to suit the needs of the situation and audience, manage difficult conversations and read ‘what is not being said’ in an interaction. Leaders can challenge the status quo, manage conflict and have the willingness to engage in robust, open and honest debate. They engage others and can frame and reframe issues to influence how people see them, focusing team members’ attention to bring clarity and agreement to complex situations. Leaders promote high levels of communication and feedback upwards, downwards and across an organisation. They support their own team members to communicate effectively, equipping them to manage conflict and maintain a healthy work environment free of toxic behaviours and relational issues |

| Providing clarity | Leaders ensure that governance arrangements are clear and create synergy and cohesion by ensuring that rules are formed and a system of checks and balances is in place. Leaders also ensure clarity of leadership among their team members. Leaders translate complexity, making sense of disparate policy drives, legislation, performance requirements, regulatory systems and funding mechanisms. Leaders ensure that staff have a clear mandate for decision-making, with documents explaining how decisions are made and who has the authority to make them. This transparency enables stakeholders to see who has authority over specific areas to prevent confusion and enables them to navigate organisations with multiple decision-making bodies |

| Advocacy | Leaders act as advocates for improvement for their patient/client group, demonstrating effective communication with diverse individuals, groups and communities and a strong commitment to achieving positive outcomes. Leaders are enthusiastic local ‘change agents’, demonstrating full, visible and sustained support for service integration. Leaders may need to advocate for greater involvement of some organisations where there is the perceived need to change the historical power balance, e.g. between care homes and the NHS |

| External liaison/consensus building | Leaders have a strong focus on outcomes and the end goal in mind. They focus on the ‘bigger picture’ across their local health and care economy and on broader outcomes, acknowledging the importance of making strategic connections with leaders in other parts of the system and all other staff. They represent their team externally, demonstrating their effectiveness through data collection and evaluation and developing networks and linkages to promote the work of the team. Leaders are good at ‘deliberate’ engagement techniques and can take people on a journey with them, enabling them to see that not everyone will win. They also ensure that their team has the necessary resources and understands its customers so that it can exploit new opportunities |

Given the complexity of this review, an important component of the methodology was the inclusion of contributions from key stakeholders throughout the process. This process is recommended in realist methods,144 as learning what stakeholders know about an intervention and its reason for implementation is essential to understanding it. In this study, consultation and discussion with the stakeholder group was a vital part of the review process. Throughout the report we refer to their contribution to developing knowledge about leadership of integrated care teams and systems. Patient/service user and carer representatives were members of this group and therefore patient and public involvement (PPI) was embedded in all stages of the review. To ground the review in the lived experiences of stakeholders, separate consultation meetings were held during the project period with three stakeholder groups: those leading or working within integrated care teams and systems, patients/service users and carers receiving care from integrated services (PPI) and researchers with expertise in integrated care or realist methods. Most members of the stakeholder group were identified by searching on the internet for leaders of integrated care teams and systems. We were keen to find people who were currently involved in leading care delivery and overall system leaders. It was a challenge, as little detail is provided on NHS and social care websites. Some members were known to the research team in their professional capacity or were suggested as relevant by people we invited. Thirty-three people were invited by e-mail; four did not reply to the invitation and follow-up e-mail, seven declined (no longer in the UK, n = 1; retiring, n = 1; too busy, n = 4; unavailable on planned meeting days, n = 1) and three accepted the invitation but were unable to join any meetings and did not contribute to the review of study documents/findings by e-mail. Nineteen geographically dispersed stakeholders agreed to participate in the group and contributed to at least one meeting, consisting of six individuals with expertise in integrated care, eight with direct experience in leading integrated care teams or systems, two researchers with methodological expertise and three patient/service user and carer (PPI) representatives. Several members of the stakeholder group also had experience of both working in integrated care and leading teams or systems. The first stakeholder meeting took place at stage 1a in the synthesis, when the group met in person to discuss the preliminary mechanisms highlighted in Table 1. An independent chairperson led whole-group and small-group discussions, during which stakeholders were asked to comment on the mechanisms, including which they felt were most pertinent, any that did not appear relevant and any important mechanisms that may have been missed.

Overall, stakeholders felt that, although some of the mechanisms or programme theories were valid and relevant to integrated care teams and systems (e.g. ‘providing clarity’), others (such as ‘communication’ and ‘supportive relationships and trust’) were too general, and had already been identified in the generic leadership literature. They felt that the review needed greater interrogation to identify the components of leadership that were specific to integrated care teams and systems. For example, one potential mechanism that stakeholders felt was missing from the synthesis was around the use of power dynamics in teams and the way that leaders negotiate these. They therefore suggested that we include ‘use of power’ as a potential new mechanism and specifically search for any discussion of this in the literature (for more information on how stakeholders contributed to the development of mechanisms see Chapter 3, Stakeholder perspectives). Stakeholders were asked to forward any relevant papers that we may have missed on to us for review. Stakeholders also agreed that we consider exploring literature outside of health and social care, to see whether or not any other fields had identified potential theories around leading integrated teams and systems that may be applicable to health and social care. A subsequent search stage (stage 1b) was therefore undertaken.

Stage 1b

Given the difficulties that we had experienced in identifying mechanisms of leading integrated teams and systems in the health and social care literature reviewed, the scope of the review was expanded to include material outside health and social care (e.g. business and disaster management). We returned to the papers previously identified but excluded because they were based outside health and social care and also identified any possible new papers from their reference lists. Twelve possible new papers were identified at this stage. 47,48,70,145–153 These papers were divided between two reviewers and read in full. Five of these papers were excluded and the remaining seven were included. 47,48,70,145,147,148,150 Five additional papers were also forwarded on to us by members of the stakeholder group who felt that they would be useful inclusions in the review. These were again divided between two reviewers (SS and SF) and read in full. All five papers were included in the review at this stage. 154–158

The additional 12 papers identified in stage 1b were divided between three researchers (SF, SS and RH) for review. Each reviewer independently compiled a list of mechanisms based on the papers they had read and also returned to their papers included in the stage 1a search and re-analysed these to look for any newly identified mechanisms. Thus, a total of 49 papers were included at this stage. The reviewers then met together again to compare their mechanisms and discuss their findings. In these discussions, they explored how their new mechanisms compared with those identified in stage 1a and explored ways in which the different mechanisms could be separated or merged to identify the components of leadership that were specific to integrated care teams and systems. The following 10 preliminary mechanisms were then agreed:

-

inspiring intent to work together (this merged components of the ‘supportive relationships and trust’ mechanism with the ‘communication’, ‘advocacy’ and ‘team working/collaborative working’ mechanisms as well as incorporating newly identified aspects identified in stage 1b)

-

enabling people to work together (this merged the ‘shared mission/vision/approach/purpose’ with newly identified aspects identified in stage 1b)

-

strategic networking/focusing on the bigger picture (this merged components of the ‘supportive relationships and trust’ mechanism with the ‘external liaison/consensus building’ mechanism as well as incorporating newly identified aspects identified in stage 1b)

-

commitment to learning and development (this mechanism remained similar to that identified in stage 1a but also incorporated feedback from the first stakeholder consultation group and searches conducted in stage 1b)

-

clarifying complex processes (this merged aspects of the ‘providing clarity’ mechanism with newly identified aspects identified in stage 1b)

-

creating balance between organisations and individuals/managing conflict (this merged components of the ‘balancing needs’ mechanism as well as incorporating newly identified aspects identified in stage 1b)

-

use of power (this merged components of the ‘shared responsibility/ownership’ mechanism as well as incorporating feedback from the first stakeholder group and searches conducted in stage 1b).

-

leader resilience (this was a newly identified mechanism, based on searches conducted in stage 1b)

-

flexibility of leadership styles (this was a newly identified mechanism, based on searches conducted in stage 1b)

-

use of public narratives (this was a newly identified mechanism, based on searches conducted in stage 1b).

These mechanisms were discussed and agreed by the study team. We then met with our international advisor to the study and expert on multiteam systems (MTS), Professor Stephen Zaccaro. The team discussed the process undertaken and the difficulties experienced by the reviewers in identifying specific mechanisms of leading integrated care teams and systems. Professor Zaccaro advised the team that ICSs could be conceived of as MTSs and suggested that the reviewers review the MTS literature for mechanisms of leadership of complex teams. The team, therefore, ran a search in Google Scholar for ‘leadership of multiteam systems’. Twenty potentially relevant papers were identified and read in full, as a result of which 14 papers were included159–172 and six were excluded. 173–178 These 14 papers were divided between two reviewers, who, again, searched for any context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations and for any mechanisms, contexts or outcomes that were not specifically linked in an explanatory way and added these into the preliminary mechanisms mentioned previously. Thus, a total of 63 papers were included in the stage 1 search (37 papers from stage 1a combined with 26 papers identified in stage 1b). All the included papers (and the mechanisms identified from them) are listed in Table 2.

| Paper | Inspiring intent to work together | Creating the conditions to work together | Taking a wider view | Commitment to learning and development | Clarifying complexity | Balancing multiple perspectives | Working with power | Fostering resilience | Adaptability of leadership styles | Planning and co-ordinating | General contexts | General outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aitken and von Treuer84 (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Aldridge139 (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| American Medical Association85 (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Amelung et al.134 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Appelbaum et al.148 (2007)** | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Baxter et al.135 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Baylis131 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Bienefeld and Grote145 (2014)** | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Bolden et al.157 (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Burstow138 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Charles132 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Charles133 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development156 (2012)** | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cooper47 (2016)** | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Covin147 (1997)** | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Crosby and Bryson149 (2010)** | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Croze86 (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Daub et al.87 (2016) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| DeChurch and Mathieu159 (2009) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| deGruy88 (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| De Vries et al.167 (2016)* | ✓ | |||||||||||

| de Stampa et al.89 (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Fillingham and Weir10 (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Ghate et al.158 (2013)** | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hartley154 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Horrigan90 (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Insightful Health Solutions141 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Johannessen et al.163 (2012)* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Jonassen169 (2015)* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Jones et al.162 (2019)* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Kelley-Patterson91 (2012) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Klinga et al.92 (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Kugler et al.168 (2016)* | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Lazzara et al.160 (2019)* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Leadership Centre155 (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Luciano et al.172 (2018)* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Moore93 (2018) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Morse150 (2010)** | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Murase et al.165 (2014)* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Nieuwboer et al.94 (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Outhwaite95 (2003) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Owen et al.161 (2013)* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Palazzo96 (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Panzer et al.97 (2000) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Payne et al.98 (2019) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Perks-Baker140 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Provider Voices143 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Rico et al.170 (2018)* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Robb and Gilbert99 (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Schipper164 (2017)* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Social Care Institute for Excellence136 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Shirey et al.100 (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Smith et al.31 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| South, Central and West Commissioning Support Unit142 (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Stakeholder group feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sun and Anderson70 (2012)** | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thomas and While101 (2007) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Touati et al.102 (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Wachel103 (1994) | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Weaver et al.171 (2014)* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| West137 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Wheatley et al.104 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Williams105 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Zaccaro and DeChurch166 (2012)* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

A list of preliminary mechanisms was sent out by e-mail to the stakeholder group for review and then presented in full at the second in-person stakeholder group meeting. The independent chairperson again led small-group and whole-group discussions around how the mechanisms should be amended or merged. Stakeholders were specifically asked to challenge the mechanisms and were given space for questions to help generate deeper exploration of the key issues. By the end of this meeting stakeholders were content that the following mechanisms (generated as a consequence of literature searching and whole-group discussions) were pertinent to leading integrated care teams and systems (a short description of these mechanisms can be found in Table 3):

-

inspiring intent to work together

-

taking a wider view

-

creating the conditions to work together

-

clarifying complexity

-

planning and co-ordinating

-

balancing multiple perspectives

-

working with power

-

commitment to learning and development

-

fostering resilience

-

adaptability of leadership style.

| Mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Inspiring intent to work together | Integrated care teams and systems have no statutory basis but depend on voluntary collaboration between NHS and local authority leaders to develop a shared, system-wide approach to strategy, planning and commissioning, and financial and performance management. Leaders are effective as advocates for integrated care and for inspiring intent to collaborate with staff across the system and outside it, at various levels. They have a supportive management style that promotes team cohesion, trust, respect, reciprocity and collaboration. Not only do leaders champion these values in their own conduct but they also promote them in their staff. They empower and inspire participation from all professionals, use ‘public narratives’ where appropriate and prevent resistance behaviours, ensuring that key values such as co-operation, openness and fairness are instilled into the fabric of the service |

| Taking a wider view | Integrated services involve cross-boundary working with a wide and varied group of organisations and people with a plurality of interests, goals, aspirations and values. Leaders of integrated teams and systems have experience and insight into the motivations and challenges of other organisations and focus on the bigger picture by acknowledging the importance of making strategic connections with leaders in other parts of the system. They use this knowledge to engage with other leaders, be convincing/persuasive in their communications with others, and work through challenges in partnership with other organisations by bridging language, thought-world and goal differences that may otherwise prove detrimental. This enables them to come up with collective solutions and to look beyond reactive problem solving by taking a longer-term strategic view. Their political astuteness is a necessary and beneficial set of skills that enable them to get things done for constructive ends. Consequently, the goals of the team are more likely to be achieved. However, political astuteness can also be used to pursue personal or sectional interests |

| Creating the conditions to work together | Different organisations, teams and individuals bring their own organisational, sectional or professional interests, ways of working and cultures. Leaders of integrated teams understand, are committed to and champion a shared philosophy, shared mental models and a common mission/vision/purpose for integrated services. Leadership is fundamentally more about participation and collectively creating a sense of direction than it is about control and exercising authority. They provide a clear narrative and direction for their team members to enable and encourage them to align their goals, have a shared focus and to engage in integrated working, rather than think about their own clinical teams, organisations or personal needs. They offer team members a sense of common ownership of the team and its reputation, are willing to delegate responsibilities and provide their colleagues with shared responsibility/accountability for financial, cost and quality targets. As a consequence, role defensiveness or ‘turf wars’ are limited, decision-making is assisted and effort becomes more focused during times of conflict and disagreement |

| Clarifying complexity | Many complex and challenging conditions are associated with integrated working, with unclear boundaries, structures and processes and different governance procedures and funding streams, but leaders can navigate the tension between certainty and uncertainty and translate this to their teams and/or systems. Leaders employ sensemaking strategies, in which they use a set of available artefacts to make the understanding of their message clear and internalised. They are successfully able to negotiate the narrow parameters between oversimplification and exclusionary detail, enabling team members to understand the complexity of disparate policy drivers, legislation, performance requirements, regulatory systems and funding mechanisms to ease working arrangements for the team. They do this by developing policies and initiatives that are easily communicated and understood, with documents explaining how decisions are made and who has the authority to make them. This prevents confusion and enables team members to navigate organisations with multiple decision-making bodies |

| Planning and co-ordinating | Leaders co-ordinate, strategise and serve as a liaison and boundary spanner between their team and the other teams in the system. They actively plan and synchronise the teams within the system, aiding the teams with their timing and executions of plans and helping them to organise intrateam processes with interteam processes and decision-making. When component teams struggle to perform their tasks because of high workloads, leaders can provide backup behaviours by prompting other component teams to provide help, shifting workloads to other teams or proactively offering to help with specific tasks. They employ smooth co-ordination processes that provide the necessary capacity to the whole system to move nimbly and synchronously. This strategising and co-ordination improves both team processes and system performance. However, system leaders must also be mindful of changing and competing demands and be able to switch quickly from the routine to the non-routine. Thus, leaders of systems devote time to ensuring system flexibility. If unexpected changes occur and contingency plans no longer seem appropriate, leaders decide whether to reconsider, abandon or adjust the original plan |

| Balancing multiple perspectives | There are historic power imbalances between health and social care (e.g. between care homes and the NHS) and between professional disciplines. Leaders ensure that there is balance between the organisational cultures, social mission and business aims of the organisations owing to having several specialist areas of knowledge and a good understanding of a broad range of topics. They are enthusiastic ‘change agents’ and demonstrate full, visible and sustained support for service integration. They advocate for those organisations that need greater power and are willing to have difficult conversations with colleagues across different organisations and specialisms and to deal with the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent in complex adaptive systems. This enables greater collaborative and equal working across organisations. Leaders are also able to create balance between professional hierarchies in the team and manage conflict between team members appropriately, working with, and negotiating with, many different stakeholders who have divergent values, goals, ideologies and interests. Leaders recognise tension and work through it with staff to develop a condition in which it is safe to challenge and discussion becomes healthy. A productive balance between harmony and healthy debate is maintained and a coalition is created, with a degree of actionable shared purpose |

| Working with power | Leaders have an awareness of power dynamics and know that the appropriate use of power within and across teams and organisations can be critical during times of uncertainty. Leaders are aware that power dynamics should be skilfully and intelligently negotiated and recognise that colleagues in other parts of the system are sometimes in a better position to lead on certain initiatives than themselves. In such circumstances, they are willing to shift power, migrate authority and relinquish control where appropriate, i.e. if better outcomes can be achieved. When leaders are unwilling to relinquish control, progress can stall. Leaders step aside, showing interest but not interfering or steering. They are also aware that tactics for reducing resistance to change based on threats, manipulation, or misinformation are likely to backfire. Leaders use referent power to bring their teams together (i.e. a charisma that makes others feel comfortable in their presence). This leads to higher team satisfaction during the process of change. Because referent power generally takes time to develop, this finding may highlight the importance of placing individuals who are known, liked and respected by employees in transition-related positions |

| Commitment to learning and development | Leaders have a strategic commitment to access external support and rapid learning with other like-minded systems. They are committed to reflecting on and personally learning from a variety of sources, through formal and informal networks, and to act as a role model for team members, encouraging them to also learn and improve. Leaders establish communities of practice for team learning and the pooling of knowledge. Although managers apply proven solutions to known problems, leaders are exposed to situations in which groups need to learn their way out of problems that could not have been predicted. Leaders recognise that training initiatives can increase component team members’ awareness and understanding of their knowledge structures, as well as their ability to regulate then improve the effective co-ordination of the whole system under dynamic circumstances. They have an interest in innovation and creativity, inviting feedback and embracing change and evidence-based practice for continuous improvement. They encourage team members to generate ideas and explore possibilities but also have a tolerance for things not working and learn how to fail ‘well’ |

| Fostering resilience | Those providing public services need to deal with increased demand, higher expectations from the public about service standards, hostility and psychological projections from the public and the media, often in the context of declining resources for public services. The pace can be relentless and the physical, intellectual and emotional demands very high. Successful leaders of integrated systems have both the personality and learned skills that foster high resilience, perseverance and an awareness of the importance of remaining empathic to the public while also resilient in terms of their own well-being. They put in place social support systems (both in and outside work) and attend appropriate training and personal development programmes to strengthen resilience. Leader stress is therefore reduced |

| Adaptability of leadership style | Leading an integrated team or system is difficult, given the complexities of moulding two or more organisations into one and the sense of loss or uncertainty that employees may experience as part of this. Collaborative leaders are able to adapt their actions based on the circumstances that they confront. They acknowledge that particular situations call for particular leadership skills and behaviours. Leaders align their styles according to the situation at hand, combining or switching approaches as necessary, changing strategy towards flexibility and the use of their tacit knowledge. This generates co-operation, cohesiveness and improved communication among group members |

Although some mechanisms (e.g. ‘inspiring intent to work together’, ‘creating the conditions to work together’ and ‘clarifying complexity’) were felt to be more relevant than others (e.g. ‘planning and co-ordinating’, ‘fostering resilience’ and ‘adaptability of leadership style’), the stakeholders and research team agreed that all 10 mechanisms should be explored in greater detail in stage 2 of the study.

The stage 1a and 1b search processes are shown in the flow chart in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of stage 1a and 1b searches.

Stage 2

After the preliminary mechanisms were identified in stage 1, a second stage search was undertaken to look specifically for any empirical evidence of these mechanisms. This second search comprised a search of the following databases: Social Policy and Practice, Education Research Complete, Social Care Online, Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, EMBASE, HMIC, PsycINFO and PubMed, using the following search strategy:

“Integrat*” OR “multi-team*” OR “multiteam*” OR “cross-bound*” OR “cross bound*” OR “cross-organisation*” OR “cross organisation*” OR “cross-sector*” OR “cross sector*” OR “Interorganisation*” OR “Inter-organisation*” AND “leader*” AND “Health” [Limiter: English language only].

Hand-searching of key journals identified by the study team and stakeholders (Journal of Interprofessional Care, Journal of Integrated Care and International Journal of Integrated Care) was also carried out by searching for the term ‘leadership’ in the online version of the journal. A total of 5673 papers were therefore identified at this stage, and all abstracts were read by two reviewers (SS and SF). A total of 5253 papers were excluded either because they were duplicates or because they were deemed not relevant, leaving 420 remaining papers. A further eight papers were also sent to us by the stakeholder group at this stage and added to the pool of documents for review, along with two papers that were picked up in the stage 1 searches but not stage 2; the 14 MTS papers identified in the stage 1 search; 11 papers identified through searching reference lists of relevant papers; and three papers recommended by the study co-applicants. This initially resulted in 458 possible papers, although 16 of these were inaccessible through library resources179–194 and not available through the British Library, which meant that 442 papers were divided between two reviewers and read in full. For this stage in the search, we were seeking only empirical research based in health and/or social care settings and a data extraction form was created and completed for each paper read. In line with realist synthesis methodology, conventional approaches to quality appraisal were not used. 41 Rather, each study’s ‘fitness for purpose’ was assessed by considering its relevance and rigour.

Of the 442 papers read in full, 32 papers were included. 84,92,98,102,105,195–221 The remaining 410 papers were excluded. 10,25,42,44,47,48,51,53,54,59–62,65,75,78,89,91,94,95,97,100,101,104,106,107,110,129,149,150,153,159–172,174,222–585 Around this time, Professor Zaccaro informed us that he had recently completed a comprehensive review of all MTS papers and this had been published. 586 To ensure that no key MTS papers had been missed in the stage 1 search, we searched the full reference list of this review for any empirical research exploring MTS in health or social care. No new papers were found.

To ensure consistency of approach, a third reviewer (RH) read all 32 papers included in the review to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Any CMOs identified from these papers were discussed with the third reviewer to ensure that there was agreement in decision-making. The third reviewer also read and reviewed a sample of the excluded papers to ensure that there was agreement around their exclusion. 310,321,330,347,359,373,431,483,547,583 After team discussion, it was agreed that one originally excluded paper should be included in the review. 583 Thus, at this stage, 33 papers from the original 442 papers were included in the review and 409 papers were excluded. The study team and stakeholders were informed of the number of papers included in the review at this stage and were asked for further advice on how to identify any additional papers. It was suggested that we search the Nuffield Trust website (nuffieldtrust.org.uk). After typing the word ‘leadership’ into the search box (filtered for ‘research’ only), three additional relevant papers were identified. 22,587,588 Thus, a total of 36 papers were included at stage 2 of the synthesis. 22,84,92,98,102,105,195–221,583,587,588 At this point, members of the wider study team were consulted, and they suggested that literature searching stopped, as the process had been comprehensive.

The evidence collected from these 36 papers was synthesised by drawing together all information on CMOs and comparing similarities and differences to build a comprehensive description of each mechanism and its role in the leadership of integrated care teams and systems. This was an iterative process throughout, identifying where mechanisms were triggered (or not), the context that enabled or hindered this and the resulting outcomes. Specific explanations of how CMOs were linked and recurrent patterns of CMO configurations within and across the papers were sought and recorded. These theoretically derived explanations were tested and refined using the findings of these empirical studies. All 36 included papers (and the mechanisms identified within each of them) are highlighted in Table 4.

| Paper | Inspiring intent to work together | Creating the conditions to work together | Taking a wider view | Commitment to learning and development | Clarifying complexity | Balancing multiple perspectives | Working with power | Fostering resilience | General contexts | General outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aitken and von Treuer84 (2014) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Alexander et al.208 (2001) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Asakawa et al.209 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Atkinson et al.207 (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Axelsson and Axelsson210 (2009) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Balasubramanian and Spurgeon211 (2012) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Benzer et al.212 (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Best213 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Brouselle et al.214 (2010) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Carroll et al.215 (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Choi et al.216 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Chreim et al.217 (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cohen et al.218 (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Cramm and Nieboer219 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Dayan and Heenan587 (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dickinson et al.220 (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Grenier583 (2011) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Karam et al.195 (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kharicha et al.196 (2005) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Klinga et al.92 (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Ling et al.197 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Lunts198 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Nicholson et al.199 (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Payne et al.98 (2019) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Rees et al.200 (2004) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Roberts et al.201 (2018) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Rosen et al.588 (2011) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Scragg221 (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Shand and Turner202 (2019) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Shaw and Levenson (2011)22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Stuart203 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Touati et al.102 (2006) | ✓ | |||||||||

| van Eyk and Baum204 (2002) | ✓ | |||||||||

| Williams105 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Williams205 (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Willumsen206 (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

These descriptions were then, again, e-mailed to the stakeholder group for review and discussed in detail at the third and final stakeholder meeting. Owing to restrictions in place as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a face-to-face stakeholder meeting was replaced by the online video conferencing software Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA). A member of the team led whole-group discussions, where stakeholders were presented with the evidence found for each mechanism and asked to help develop and refine these descriptions and explanations further, using their own lived, research or practice experiences. For more information on how the views of the stakeholder group were incorporated into the review during this final stage of the evidence synthesis, see Chapter 3, Stakeholder perspectives.

Figure 3 provides a flow chart detailing the stage 2 search processes.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of stage 2 searches.

Chapter 3 Results

The 36 research papers included in this synthesis identified empirical evidence for seven mechanisms: ‘inspiring intent to work together’; ‘creating the conditions to work together; ‘balancing multiple perspectives’; ‘working with power’; ‘taking a wider view’; ‘a commitment to learning and development’; and ‘clarifying complexity’. There was insufficient evidence to identify two of the mechanisms (‘adaptability of leadership style’ and ‘planning and co-ordinating’) as discrete mechanisms in themselves and, therefore, these were incorporated into the other mechanisms. No evidence was found for the mechanism ‘fostering resilience’.

For clarity, findings for each mechanism were divided into two sections – those components of the mechanism that were identified at a systems leadership level and those that were identified at a team level. Although we acknowledge that a systems leader may also lead a specific senior leadership team, in this study, we focused on the role of the overall systems leader of an organisation. However, we acknowledge the added layer of complexity that these different levels of leadership bring. In some cases, the same components were identified as important for leaders at both levels, and this information is recorded in an ‘overarching leadership qualities’ section for each mechanism. On occasion, it was difficult to determine what level of leadership (i.e. team or system) was being directly referred to. Where this was the case, these findings were also incorporated into the ‘overarching leadership qualities’ section for that mechanism. Furthermore, the terms ‘manager’ and ‘leader’ were used interchangeably across the included papers, often with little or no description of what these terms meant. For the purposes of this report, managers and leaders are all described as ‘leaders’, although the research papers themselves may have used either of these terms. Examples of specific CMO configurations identified in the research papers are presented in text boxes.

Mechanism 1: inspiring intent to work together (n = 22)

The original definition of this mechanism developed in stage 1 was ‘integrated care teams and systems have no statutory basis but depend on voluntary collaboration between NHS and local authority leaders to develop a shared, system-wide approach to strategy, planning and commissioning, financial and performance management. Leaders are effective as advocates for integrated care and for inspiring intent to collaborate with staff across the system and outside it, at various levels. They have a supportive management style that promotes team cohesion, trust, respect, reciprocity and collaboration. Not only do leaders champion these values in their own conduct but they also promote them in their staff. They empower and inspire participation from all professionals, use “public narratives” where appropriate and prevent resistance behaviours, ensuring that key values such as co-operation, openness and fairness are instilled into the fabric of the service.’

In stage 2, we found a total of 22 empirical research papers that discussed this mechanism. 22,84,98,105,197–199,203,205–210,213,214,216,217,219–221,588

Overarching ‘inspiring’ leadership qualities

Certain components of the ‘inspiring intent to work together’ mechanism were identified as important at both the systems and team level. This included leaders having a clear vision for collaboration and being able to articulate this vision to others with passion. 22,84,207,208,588 This vision acted as the criterion against which leaders judged the suitability of a proposed course of action, ensuring that they focused on what was central and enduring to integrated working. 208 It was important that leaders lead change according to this vision rather than being ‘swept along’ by external events. 22 Other overriding components of ‘inspiring’ leaders included being visible,213,588 being strongly committed to integration and implementing lasting change,84,197,588 being able to gain the trust and respect of others,198,210,217,588 being a good communicator22,84,208,209,219,588 and being able to develop strong interpersonal relationships with colleagues. 22,198,217 It was considered important for leaders at both levels to have the skills to build and sustain a culture of interdependency, reciprocity and collaboration and to instil key values such as co-operation, openness and fairness among their colleagues. 84,105 As a sense of ‘being in it together’ developed, there was evidence in one study of a reduction in ‘gaming’ between organisations, which made negotiations and collaboration more straightforward. 22

Despite the numerous competing demands on their time and energy, having leaders at all levels who demonstrated good listening skills was identified as important to develop a deep understanding of other organisations and individuals. 208 Being listened to by leaders made people feel as though their input was valued and helped increase motivation and engagement. 208 Similarly, leaders who openly recognised the time, effort and skills that others contributed to integrated working made staff feel respected, appreciated and motivated to contribute more. 208 Conveying genuine respect for the views of all staff, regardless of affiliation or power, reinforced principles of inclusion and elevated members’ respect for leadership. 208 At both systems and team levels, the importance of leader credibility and legitimacy was also identified. 22,105,208,217,588 Credibility was gained through having knowledge of both health and social care through direct experience of working in both fields – for example, a nurse leader who had previously worked in local authority social services;105 through being associated with previously successful developments;588 or through one’s personality, skills and the dynamics of one’s relationships with others. 22 Credibility was lost when leaders appeared to listen to the contribution of others but never incorporated their input substantively. 208

System-level leadership

Important components of the ‘inspiring intent to work together’ mechanism at a system level included having good communication skills, particularly around communicating the vision of an integrated care partnership to the partnering organisations22,207,208 and in maintaining an open, honest and consistent message. 22,220 Successful systems leaders were immersed in developing a clear vision of integrated working and spent considerable time and energy encouraging other executives to share this vision. 22 A study of community health partnerships in the USA208 found that partners valued systems leaders who were forthright and direct in their communications and willing to address issues ‘head on’ rather than trying to minimise or deny them. The authors stated that, because system-level leaders could not rely on formal structures and authorities that facilitated action in organisations, they relied heavily on their own interpersonal skills and effective communication skills to assure a wide and multidirectional diffusion of information. There was also evidence that system-level leaders needed to demonstrate adaptability in their communication style, for example, demonstrating the ability to communicate with individuals across several organisations in multiple directions – both up and down but also horizontally and even diagonally. 208 Traditional leadership styles may have required communicating with a limited number of leaders, but leaders of integrated care systems needed to respect and allow for the diverse needs of a variety of organisations and communities, each of which had different expectations of the timing, extent and channel of communication. Systems leaders were, therefore, required to tailor their style of communication and the language or jargon employed to bridge cultural gaps between organisations and communities. 22,208

A UK-based action research study exploring the aspirations and achievements of a newly formed Mental Health NHS and Social Care Trust220 highlighted the importance of systems leaders in inspiring staff during the early phases of integration. In this study, the formation of a new Care Trust (integrating the local Mental Health NHS Trust and the mental health and learning disability services provided by the local authority social services department) was seen as an innovative move by many of the staff involved, although there were complexities around staff expectations for the ‘culture’ of the new trust. Staff wished to retain several characteristics of their ‘old’ health and social care cultures (e.g. localness, relationships) while simultaneously recognising the need for a new, integrated, culture. This aspiration was acknowledged by the Chief Executive during the consultation process when she stated that the culture of the Care Trust would ‘keep the best of both’ previous organisations in the development of the new one. This key role of the systems leader was, therefore, seen to influence the subsequent culture of the Care Trust and helped to reassure staff that the new integrated systems would contain positive aspects from both the health and social care settings (Box 1). Furthermore, the authors reported that this positive early experience of integration at a system level formed a foundation for the importance of partnership working between health and social services, which became one of the core values of team-level leaders within the Care Trust. 220 Other authors have highlighted the importance of systems leaders creating opportunities for staff to talk about their successes and ensuring that local ‘wins’ are celebrated and communicated to the wider group. 217

Staff within a newly integrated Mental Health NHS and Social Care Trust in the UK were conflicted around their expectations for the culture of the new trust – they wanted to retain characteristics of their old health and social care cultures while also recognising the need for a new culture. This aspiration was acknowledged by the Chief Executive, who assured staff that the culture of the new Care Trust would maintain the best components of the previous organisations. This positive early experience of integration at a system level formed a foundation for the importance of partnership working between health and social services, which became one of the core values of team-level leaders in the Care Trust.

The process of integrating services into a new Mental Health NHS and Social Care Trust means that staff feel conflicted in their expectations for the culture of the new trust (C) → the Chief Executive openly acknowledges and addresses any concerns that staff members have, including clarifying that the culture of the Care Trust will maintain the best components of their previous organisations (M+, resource) and staff are reassured by this (M+, reasoning) → the positive experience of integration at a system level forms a foundation for the importance of partnership working between health and social services (O+) and becomes one of the core values of team-level leaders within the Care Trust (O+).

A facilitating context for this mechanism was that team members could trust their system-level leaders. Team-level leaders said that their ability to ‘sell’ their message about integration to their teams depended on whether or not they trusted that the arrangements in place at a system level would improve care or allow for the detection of deteriorating quality. 588 However, in an investigation of four international case studies of integration,588 building trust was identified as requiring time, and in some cases, work to strengthen integration was founded on a decade of prior work, through which trusting relationships had slowly grown. Many physicians in these sites said that they were only willing to participate in integrated working because they had trust in their systems leaders and their belief in the mission (Box 2).

An investigation of four international case studies of integration found that trust in systems leadership was a key ingredient for integration. However, building trust was identified as requiring time, and in some cases, work to strengthen integration was founded on a decade of prior work, through which trusting relationships had slowly grown. Many physicians in these sites said that they were only willing to participate in integrated working because they had trust in their systems leaders and their belief in the mission.

A decade of prior work had been undertaken to develop trusting relationships (C) → leaders have a strong vision of integration which they attempt to ‘sell’ to their team (M+, resource) and physicians trust in their leaders and their belief in the mission (M+, reasoning) → physicians demonstrate willingness to participate in integrated working even when this is not specifically required of them (O+).

Instances were also provided where the ‘inspiring intent to work together’ mechanism was absent in system-level leadership. For example, an Australian case study199 provided two contrasting contexts of health governance for integrated care and found leadership to be significantly lacking at both board and executive levels. The study found that, although interorganisational relationships between boards and chief executive officers were crucial to effective system-level working, they were often absent and instead replaced by an adversarial culture typified by a ‘master–servant relationship’ between organisations. A Scottish study198 described the implementation of a project to develop and test models of integrated working within a health board. Team leaders were asked what helped and hindered them in the delivery of change in this integration project and identified the lack of ‘buy-in’ from senior-level leaders as a key hindrance. Not having a clear steer or support from senior leaders meant that these team leaders felt that they lacked permission to ‘act’ and this resulted in role confusion among the team. A Swedish study comparing two cases of clinical integration efforts following a hospital merger further highlighted the absence of the ‘inspiring intent’ mechanism at a system level. At one case study site, team members described system-level leaders undertaking the process of integration without consulting staff at a team level or including them in decisions (Box 3). Team members felt that these decisions had been made hastily and in secret and so refused to be involved with the merger decision or adapt their ways of working. 216