Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/156/03. The contractual start date was in April 2015. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Crane et al. This work was produced by Crane et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Crane et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report presents the findings of a major study in England of the delivery of primary health care to single people who were homeless. It included people sleeping on the streets or in other public places, squatting, staying in temporary accommodation such as hostels or bed-and-breakfast hotels, or staying temporarily with friends or relatives (sofa surfing). It did not include families or couples with dependent children who were homeless. The study, Health Evaluation About Reaching The Homeless (HEARTH), examined four models of primary health care provision at 10 Case Study Sites (CSSs), and included a mapping exercise across England of specialist primary health care services for single people who are homeless. To our knowledge, it is the first UK study to compare and evaluate different models of primary health care provision for this patient group.

Background

Since 2010, homelessness has increased substantially across England. Contributory factors include high housing costs and a shortage of affordable housing; the ending of assured shorthold tenancies in the private rented sector; welfare benefit changes and sanctions, including the capping and freezing of Local Housing Allowance; and cuts to social support budgets. 1 A 2018 report suggested that approximately 200,000 single people experience homelessness each year. 2 Many stay in hostels, bed-and-breakfast hostels or with friends or relatives, and move from place to place. Others ‘sleep rough’ on the streets, in vehicles or parks, or in other public places. The number of rough sleepers in London increased from 3673 in 2009/10 to 11,018 in 2020/21. 3,4 Of the 2020/21 number, 7531 were described as ‘new’ rough sleepers.

Physical health, mental health and substance misuse problems are common among people who are homeless. 5–7 Their health needs are greater than those of the general population, and many have multiple long-term conditions and die earlier. 8–10 People sleeping rough are exposed to damp and the elements, are at risk of exposure and hypothermia, and are susceptible to infestation. Chronic respiratory disorders and circulatory and gastrointestinal problems are common. Physical health problems are aggravated by alcohol use, drug use and malnutrition, and injuries from accidents and assaults are common. Homelessness is also associated with demoralisation and depression. Health problems among people who are homeless are exacerbated by their unsettled lifestyle and sometimes disorganised behaviour, which can reduce their engagement with treatment programmes. Many also face barriers to accessing health care, including inflexible services, negative attitudes from some staff, and the challenges of treating complex and multiple needs. 11 They make unusually high demands on emergency health services, such as accident and emergency (A&E) departments. 12 A 2010 Department of Health (DH: known as Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) since 2018) study estimated that this group consumes around four times more acute hospital services than the general population, costing at least £85M each year, and hospital stays are, on average, three times longer than those of the general population. 13

Since the 1980s, specialist primary health care services for homeless people have been established in several UK towns and cities. Their development took various forms, including dedicated ‘walk-in’ health centres and mobile health teams visiting hostels and day centres. 14 The National Health Service (Primary Care) Act 199715 provided the statutory framework for the development of Personal Medical Services (PMS). Through flexible contractual arrangements, health professionals were encouraged to deliver primary health care to underserved groups, including people who were homeless. According to Wright,16 this was ‘the most significant favourable piece of legislation for homeless people since the start of the NHS’. There have, however, been very few evaluations of these services, and their success in engaging people who are homeless in health care is unknown.

The 2010 DH study13 grouped specialist primary care provision for people who are homeless into four models: (1) mainstream general practices providing special services for people who are homeless, (2) outreach teams of specialist homelessness nurses, (3) full primary care specialist homelessness teams and (4) a fully co-ordinated primary and secondary care service. The analysis was unable, however, to demonstrate whether or not the provision was fully meeting the needs of people who were homeless. The study reported lack of systematic data on the use of health services and on costs, and lack of research evidence of the potential to improve primary care and health outcomes, and reduce secondary costs.

There are long-standing debates about whether primary health care for people who are homeless should be provided by mainstream or specialist services. Several researchers and clinicians believe that some targeted provision is necessary to reach people on the streets, but the aim should be integration into mainstream general practice services. 16–18 A survey of 86 people who were homeless found that 84% preferred specialist primary health care services. 19 A 1999 survey in England of managers of services for people who were homeless found that the majority favoured integration into mainstream primary health care services for their clients, believing that separate services were divisive. 20

Study proposal and aims

In 2013, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research Programme issued a call for studies on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of innovative and integrated health and care services for homeless people. In response to this call and to address the knowledge gap identified in the DH study,13 this research proposal was submitted and funded.

The overall aim of the HEARTH study was to evaluate the effectiveness and costs of different models of primary health care provision for people who are homeless, with special reference to their integration with other services, and how this affected a range of health, social and economic outcomes. The objectives were as follows.

-

To identify (1) the prevalence of specialist primary health care services for single people who are homeless and their geographical distribution, (2) types of models found in different NHS regions and key characteristics of these services and (3) areas with a homeless population but no specialist health care service.

-

To examine the characteristics and integration of different models of primary health care services for people who are homeless with dental, mental health, secondary health, substance misuse, homelessness sector, housing and social care services.

-

To examine the effectiveness of different models in (1) engaging people who are homeless in health screening; (2) responding to the physical health, mental health and social care needs of people who are homeless; and (3) providing continuity of care for health problems including long-term and complex conditions.

-

To evaluate the impact of different models over time on service users’ health and well-being, and their use of other health and social care services including dental, emergency and secondary care.

-

To investigate the resource implications and costs of delivering services for the various models.

-

To compare the various models across a range of outcomes, reflecting service user and NHS perspectives, using a cost–consequences framework.

-

To provide evidence to NHS commissioners and service providers regarding cost-effective organisation and delivery of primary health care to people who are homeless.

It was proposed that four Health Service Models would be evaluated, including a ‘usual care’ model for comparison.

-

Health centres specifically for homeless people, comparable to the DH’s full primary care specialist homelessness team, but located at a fixed site.

-

Mobile Teams that run sessions in homeless services such as hostels, comparable to the DH’s outreach team of specialist homelessness nurses.

-

Mainstream general practices that also provide specialist services for people who are homeless.

-

Mainstream general practices that provide ‘usual care’ services to the general population, which by default include people who are homeless. This type of provision was not included in the DH models, but is commonly used by people who are homeless if there are no local specialist services.

The research questions that the study would address were as follows.

-

Which models or service elements are more effective in engaging people who are homeless in health screening and health care?

-

Which models are more effective in providing continuity of care for long-term or complex health conditions?

-

What are the associations between integration of the models with other services and health outcomes for people who are homeless?

-

How satisfied are service users, primary health care staff and other agencies with the services?

Layout of this report

Chapter 2 presents literature reviews undertaken during the study, and Chapter 3 describes the study design and methodology. Chapter 4 summarises the findings of the mapping exercise. Chapters 5 and 6 set the scene, by describing the CSSs and the case study participants. Chapters 7–13 focus on primary and secondary outcomes. Chapter 14 examines ways in which contextual factors and mechanisms of health care delivery are likely to have had an influence on outcomes. Finally, the conclusions and implications for NHS commissioners and primary health care managers and practitioners are discussed in Chapter 15.

Chapter 2 Reviews of the literature

This chapter presents two literature reviews. The first focuses on the delivery of primary health care to people who are homeless, conducted during the early months of the study. The second examines the changing policy context in which primary health care services in England for people who are homeless have been developed, dating back to the 1990s. Its findings were summarised in the 2018 mapping report,21 and updated to November 2022.

Review A: primary health care for people who are homeless – evidence-based practice

This scoping review examined evidence-based practice of the delivery of primary health care to people who are homeless, focusing on models of provision and methods of delivering interventions. The inclusion criteria were single people aged 18 years and older who were homeless, but not homeless families or children. It involved the delivery of general medical services (GMS) by general practitioners (GPs), primary care physicians, practice and community nurses, and specialist primary health care teams. It did not include studies of the prevalence of health conditions or clinical features of illnesses, nor studies of specialist services that were not part of primary health care teams.

Methods

A comprehensive and systematic search was conducted of literature from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, published between January 2000 and July 2016. Twelve databases were searched: British Nursing Index, The Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Health Management Information Consortium, Global Health, Social Policy and Practice, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, SciVerse Scopus and Web of Science. Medical subject headings and subject terms were used to identify the homeless adult population and primary health care services (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 1). Only English-language literature was included.

Two researchers independently reviewed all titles and abstracts; full texts were obtained for relevant papers, and a data extraction form was completed for each paper. Decisions were reached about their inclusion, and any uncertainties were reviewed by a third researcher. In line with the methodology for scoping reviews,22,23 a systematic quality assessment of included studies was not conducted. Although a systematic review would have enabled quality assessment, the scoping review methodology allowed inclusion of a range of study designs and interventions. Of the 4096 references identified, 2565 were screened, data extraction was completed on 89 papers, and 38 included in the final review (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Figure 1). 24

The final papers reported on 30 studies (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 2). Thirty-three papers concerned studies conducted in the USA; two were conducted in Australia; and one each in Canada, Italy and the UK. The papers were grouped according to models of service provision, namely specialist health centres for people who are homeless, and primary health care within homelessness service settings. A third group covered studies comparing specialist and generic (sometimes referred to as mainstream or ‘usual care’) provision.

Specialist health centres for people who are homeless

Fifteen papers involved studies at specialist health centres for people who are homeless (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 2: A1–A15), including six at the Weingart Center, Los Angeles, CA, and two at the Boston Health Care for the Homeless (HCH), MA. Most papers pertained to health screening or vaccination programmes, or the management of health conditions. Common features of their approaches were case management, enhanced and tailored services, and multiagency working.

At Boston HCH, the effectiveness of a ‘chronic care’ model in engaging 82 women who were homeless and had an alcohol problem in treatment was evaluated. 25 An intervention group (n = 42) received screening from a primary care provider, followed by referral to substance misuse services and 6 months’ support from a care manager. The ‘usual care’ group (n = 40) received no support from a care manager and their primary care providers had no alcohol intervention training. Women in the intervention group accessed substance misuse services more frequently than the usual care group, but there were no significant differences between groups in reductions in drinking, housing stability or physical and mental health.

To increase the uptake of cervical screening, Boston HCH introduced an enhanced programme that included the availability of cervical screening during any clinical encounter, rather than only at specific times, and improved health maintenance forms. Over the next 5 years, cervical screening rates improved from 19% to 50%. 26 Examining the delivery of a combined hepatitis A and B vaccination over 6 months to 865 people who were homeless at the Weingart Center, improved completion of the course was linked to nurse case management, hepatitis education, financial incentives and client tracking. 27

Various strategies were implemented by the specialist health centres to retain patients in treatment programmes, including adapting electronic medical records to remind them of health appointments or to trace them if they failed to attend. A small study of 20 homeless veterans found that text reminders 2 and 5 days in advance reduced missed appointments by 19%, and cancelled appointments by 30%. 28 A study at the Weingart Center examined completion of treatment for latent tuberculosis (TB) infection among 520 homeless people allocated to either a nurse case management or a standard care programme. 29 The former received education sessions on reducing the risk of TB and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and coping and problem-solving, whereas the standard care group received a short briefing on TB and the importance of treatment. Both groups received incentives to complete treatment. Sixty-two per cent in the case management group, but only 39% in the other group, completed treatment.

Primary health care at homelessness services and on the streets

Sixteen papers examined the provision of basic health care at homelessness services or on the streets to engage with people who were homeless and not accessing health services (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 2: B16–B31). In New York City, NY, physicians from Montefiore Medical Center worked alongside outreach staff to deliver health care to people with HIV infection in single-room occupancy hotels. 30 This resulted in increased uptake of medical care and acceptance of antiretroviral medication. In Sacramento, CA, some residents in transitional housing received an on-site tailored service by a physician, nurse and social worker. There was increased uptake of cervical screening and reduced ED use, but little detectable impact on physical functioning or mental health. 31

The goal of outreach clinics is to encourage people who are homeless to use primary health care services. In Baltimore, MD, teams from the HCH clinic regularly visited people who were homeless and had HIV infection, persistent mental illness and substance misuse problems at soup kitchens, shelters and on the streets. Almost half (47.3%) contacted by the outreach team subsequently attended the HCH clinic. 32 Similarly, O’Toole et al. 33 tested whether or not an outreach intervention (health assessment and brief physical examination) at shelters and soup kitchens, immediately followed by a clinic orientation visit, would encourage veterans who were homeless to engage in health care. More than three-quarters (77.3%) who followed this pathway accessed primary health care in the following 4 weeks.

Four papers examined the benefits of providing health education and health promotion within homelessness services. 34–37 For example, a pharmacist and pharmacy student, who ran a fortnightly clinic at a women’s shelter in Arizona, delivered 10 health education sessions over 11 months to residents. 36 These covered urinary tract infection, menopause and diabetes, and 56 women attended at least one session. Attendees said their awareness of health issues had increased and that they would make changes to their health, and 70% would seek advice from a pharmacist in the future.

Lack of facilities may impede the delivery of health care on an outreach basis. Colorectal cancer screening rates among homeless and low-income domiciled patients aged 50 years and over who accessed health clinics at two New York City shelters were examined. Domiciled patients were significantly more likely than those who were homeless to have completed screening (41.3%, compared with 19.7%). 38 The authors concluded that lack of privacy in shelters made it difficult for residents to undertake faecal occult blood tests or prepare for a colonoscopy.

Specialist, compared with generic, health care provision

Seven papers contributed to debates about whether primary health care for people who are homeless should be provided by generic or specialist services (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 2: C32–C38). In Rhode Island, USA, comparisons were made between veterans who were homeless and attending general internal medicine clinics and those accessing a tailored primary care clinic. 39 The latter resulted in greater improvements in chronic disease management over 12 months for hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia, significantly more primary care visits during the first 6 months, and fewer medical admissions and inappropriate ED visits.

Some studies provided evidence of the benefits of integrating primary health care services with other provision. Another study in Rhode Island compared health service use among homeless and non-homeless veterans registered with Patient-Aligned Care Teams (PACTs). 40 The homeless group was registered with a specialist homeless PACT, which provided walk-in services, and was co-located with housing assistance, social work and vocational services. The non-homeless group was assigned a primary care provider with an appointment system and no co-located services. Those accessing the homeless PACT made significantly greater use of primary care, mental health and substance misuse services during the first 6 months, and had reduced ED usage. Similarly, McGuire et al. 41 found a primary care clinic in the same building as homelessness social services programmes and mental health services improved access to primary health care for homeless veterans with serious mental illness or substance abuse problems, and reduced their use of emergency services.

Summary of review A

This review examined the delivery of primary health care to people who are homeless. Most papers described various interventions used by health professionals to engage this population in health care and to address their needs. These included enhanced and tailored services, nurse case management, integrated care provision, targeted programmes, outreach and tracking, and adaptation of electronic patient medical records. Most had positive outcomes in terms of improving uptake of screening and vaccination programmes, encouraging the use of primary health care services, treating health conditions, engaging people in specialist care and reducing the number of ED visits. Most were conducted in the USA, however, and focused on one aspect of service delivery or a single intervention, rather than on a model or a service in its entirety. Several originated from just two specialist health centres.

Review B: health policy developments in England relating to people who are homeless

Several policy developments in England since the 1990s addressed the delivery of primary health care to people who are homeless. A Royal College of Physicians’ working party on homelessness and ill health in the 1990s17 recommended that the DH should introduce systematic monitoring of the health of people who are homeless and their use of health services, and that the government should fund special primary care practices for people who are homeless, and restructure deprivation payments to GPs. The National Health Service (Primary Care) Act 199715 enabled the development of PMS, which stimulated the development of primary health care services to people living in deprived communities, and to underserved and disadvantaged groups, including people who are homeless. Local Development Schemes were introduced by the DH in 1998, enabling additional payments for GPs and allied staff to provide services in deprived areas (later known as ‘enhanced services’). The extra funding incentivised GPs, for example, to register and provide medical care to people staying in hostels.

Underpinning these developments, Addressing Inequalities: Reaching the Hard-to-reach Groups was published by the DH in 2002 as a practical aid for primary care. 42 Among its recommendations were primary care trusts [replaced by Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in 2013] should encourage GPs and nurses to focus on hard-to-reach groups via PMS and/or Local Development Schemes. The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) produced a statement on homelessness and primary care in 2002, with recommendations for practices and primary care trusts. 43 In 2004, primary care organisations could commission new Alternative Provider Medical Services (APMS) to provide essential primary care services, additional services where GMS/PMS practices opted out, enhanced services and out-of-hours services. They could contract these services from providers, including commercial and not-for-profit agencies, and NHS foundation trusts. 44

Influential reports, such as Securing Good Health for the Whole Population45 and the 2010 Marmot Review,46 ensured that equalising health outcomes across society gained prominence within national policies. In 2010, the Social Exclusion Task Force launched Inclusion Health, a framework for driving improvements in health outcomes for socially excluded groups. A DH report published alongside Inclusion Health acknowledged that health care for people who were homeless may have been historically underfunded due to inaccurate population data. 13 A National Inclusion Health Board was established to lead the Inclusion Health agenda. Just 3 months later, however, there was a change of government and the Social Exclusion Task Force was disbanded.

The Health and Social Care Act 201247 transferred NHS commissioning responsibilities to CCGs prompting greater general practice control of service provision. Under the Act, CCGs were required to reduce health inequalities and provide integrated services. 48 Health and well-being boards were established by local authorities to act as forums whereby health and social care commissioners and providers could address the health and well-being of local populations and promote integrated services. 49 These boards were required, with CCGs, to produce a Joint Strategic Needs Assessment and a Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy for their local populations. Leng50 produced a guide to help local authorities improve health and well-being among people who are homeless, and reduce health inequalities. Healthwatch was developed in 2013 as a patient and service user champion at local and national levels. This has taken a role in monitoring some services for people who are homeless.

Public health responsibilities moved from primary care trusts to local authorities in April 2013, and Public Health England (PHE) was established. PHE brought together public health specialists into a single public health body responsible for protecting and improving the public’s health and reducing health inequalities. Its call for action in 2015, All Our Health: Personalised Care and Population Health,51 urged health care professionals to use their skills and relationships to maximise impact on avoidable illness and promote well-being and resilience. PHE produced a framework and issued guidance on homelessness, both of which were updated in 2019. 52,53 It recommended that health and well-being boards should ensure that homelessness is addressed in joint strategic needs assessments and health and well-being strategies, and that the relationship between health and homelessness is acknowledged in local housing authorities’ homelessness reviews. PHE also produced guidance on tackling TB, a disease disproportionately affecting people who are homeless. 54

In 2016/17, Sustainability and Transformation Plans were developed in 44 areas across England as a new planning process for health and, to some extent, social care. Renamed Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships, they required NHS organisations to develop plans for local health services, including working with local authorities and other partners. They represented an important shift in DH policy: although the Health and Social Care Act 201247 sought to stimulate competition within the health care system, NHS organisations were asked to collaborate, rather than compete, to plan and provide local services. 55 The Health and Care Act 2022 was passed in April 2022. This legislation required Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) to be established in England on a statutory basis from 1 July 2022. ICSs replaced Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships as outlined in the White Paper Integration and Innovation: Working Together to Improve Health and Social Care for All. 56 Forty-two ICSs have been established across England with a responsibility to plan and fund health and care services in their area. Each ICS is made up of an integrated care board (ICB) and an integrated care partnership (ICP). ICBs replaced CCGs and are responsible for planning NHS services, including ambulances, primary care, mental health care, hospital (acute services), community and specialist care, and are accountable to NHS England. A representative from ICBs is required to participate in local Health and Wellbeing Boards, in place of CCG members. ICPs cover public health, social care and wider subjects impacting the health and wellbeing of their local populations, and operate as a statutory committee between the ICBs, local authorities, and voluntary and community organisations. The establishment of ICSs represents the first large-scale structural change to the NHS since 2012 (NHS Confederation 2022). Further details are in Chapter 15.

Linked to such initiatives have been several policy moves to tackle homelessness. The Ministerial Working Group on Homelessness was formed in 2010, and 1 year later a ‘No Second Night Out’ scheme was launched to ensure that people who were sleeping rough received help quickly. 57 Around the same time, ‘Housing First’ pilots were introduced into the UK. This model originated in New York in 1992, with the premise that stable housing is key to tackling chronic homelessness, and should be secured before problems such as substance misuse and mental illness can be addressed. 58,59 Significant modifications to the model have, however, made it difficult to assess the influence of the model on programme outcomes. 60,61 Several researchers have concluded that Housing First provides improvements in housing stability, but, apart from the use of emergency health services, there is little evidence as yet to suggest that it produces better outcomes for physical health, mental health and substance misuse than treatment in the community. 62,63

The Homelessness Reduction Act 201764 placed many public authorities, such as emergency departments (EDs), urgent treatment centres and in-patient hospitals, under a duty to refer people at risk of homelessness to the local authority. The Act’s focus on prevention, as well as on developments of planned individual support, is arguably the most important policy development across the NHS and local authorities for people who are homeless or insecurely housed since the Housing (Homelessness Persons) Act 1977. 65 In 2018, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government published a new Rough Sleeping Strategy, with a commitment to halve rough sleeping by 2022 and end it by 2027. 66 In the first year, it allocated up to £2M to enable access to health and support services for people sleeping rough.

Published in 2019, the NHS Long Term Plan sets out new action the NHS will take to help tackle health inequalities, with £4.5B over the next 5 years. 67 Up to £30M is being invested into the needs of people sleeping rough, and ensuring areas most affected have better access to specialist NHS mental health support, integrated with existing outreach services. New primary care networks are intended to bring together general practices to work at scale together to focus on local patient care.

Although many of these developments reflect primary care services and their interface with local authorities, policy attention has also focused on improving services for people who are homeless and in hospital. Pathway, a charity founded in 2009, introduced the ‘Pathway’ model of integrated care to bridge the gap between primary and secondary care. This involves specialist primary health care services collaborating with secondary care services to improve care in hospital for people who are homeless. In 2020, The Royal College of Emergency Medicine produced a best-practice guide, Inclusion Health in the Emergency Department: Caring for Patients who are Homeless or Socially Excluded. 68 A 2021 evaluation concluded that specialist approaches to hospital discharge for people who are homeless are more effective and cost-effective than standard care involving discharge to the streets without support. 69

Over the decades, policy attention to the health of people who are homeless has been driven by organisations such as The Faculty for Homeless and Inclusion Health (supported by Pathway), a multidisciplinary network of health care workers and experts by experience. It produced a set of standards for commissioners and service providers in 2011 covering health care planning, commissioning and provision for people who are homeless (revised in 2013 and 2018). 48,70 The London Homeless Health Programme, formed in 2015 as part of the Healthy London Partnership, issued guidance in 2016 (updated in 2019) for London’s CCGs on improving health outcomes for people who are homeless. 71 It recommended there should be a Homeless Health Lead in every CCG to champion the homeless health agenda and engage with London’s homeless health clinical networks. In partnership with Healthwatch London and Groundswell (a charity supporting people who are homeless), it produced ‘my right to access healthcare’ cards to help people who are homeless register with a general practice. The Queen’s Nursing Institute has developed a Homeless and Inclusion Health Programme.

Efforts to improve health care for people who are homeless are continually advocated by voluntary sector homelessness organisations, including Centrepoint, Crisis, and St Mungo’s. In 2009–10, Homeless Link was funded by the DH Third Sector Investment Programme to pilot a Homeless Health Needs Audit Tool, to help health service commissioners and providers, and local authorities, gather data about the health needs of local people who are homeless and their use of health services. 11 An updated audit tool, with funding from PHE, reflected new local commissioning environments and other changes. 72

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NHS and English housing authorities implemented the ‘Everyone In’ initiative, to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on people experiencing homelessness. Under the initiative, £3.2M was made available to local authorities in March 2020 to accommodate people sleeping rough or in accommodation where it was difficult to self-isolate, such as night shelters. 73 By the end of November 2020, more than 33,000 people had been helped to find accommodation, and, according to the National Audit Office, COVID-19 infections and deaths among this population had been relatively low. 74 In November 2020, the ‘Protect Programme’ backed by £15M, was announced to ensure that vulnerable people, including those sleeping rough, were to be protected during the second period of national restrictions and throughout the winter. 73 In April 2020, NHS England and NHS Improvement also produced clinical advice and guidance on delivering health care to people who are homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic. A new National Institute for Health Protection has been formed with a focus on biosecurity and other elements of public health; the implications of this for homelessness policy and services will no doubt emerge. 75

Summary of review B

This second review summarises the many policy initiatives introduced in England since the 1990s to stimulate the development of primary health care services for people who are homeless. Yet, as the first review identified, there have been very few evaluations of such services in England, and little is known about their effectiveness in engaging this population in health care, their effectiveness in treating health conditions and their costs. The paucity of studies examining the effectiveness of generic primary health care services for people who are homeless is concerning, given that, in England, more than half of homelessness services rely on generic general practices to deliver primary health care to their clients. 21 The HEARTH study aimed to address these knowledge gaps. Its design and methodology are described in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3 Study design and methodology

This chapter describes the HEARTH study’s design and methodology. It summarises the study’s conceptual framework, primary and secondary outcomes, fieldwork accomplished, data analyses, and Patient and Public Involvement (PPI).

Theoretical and conceptual framework

It has long been recognised that those who are in most need of health care are least able to access services, a phenomenon termed the ‘inverse care law’. 76 In terms of people who are homeless, the belief was that their complex needs could not be met by mainstream GPs; therefore, specialist primary health care services were established in some areas (see Chapter 1). Some theorists associate the exclusion of people who are vulnerable with problems of discrimination and the ‘bureaucracy’ and regimes of formal services, which result in them being inadvertently or deliberately excluded. Merton77 associated the exclusion from mainstream society of people who are homeless with ‘retreatist’ behaviours, and an inability or unwillingness to comply with society’s norms and values.

Using a case study approach, the HEARTH study examined the effectiveness of different models of primary health care services for people who are homeless to determine what works, for whom and in what circumstances. This approach allows researchers to investigate a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, and enables multiple sources of evidence to be gathered. 78 The role of contextual factors and mechanisms in the delivery of health care to people who are homeless, and how these influence outcomes, were examined at CSSs. Contextual factors included the wider health and care system, financing, staff and physical resources, and the availability and accessibility of other relevant services. Mechanisms included strategies used by CSS staff to engage with people who were homeless and provide health screening and treatment (Table 1). The theoretical framework for this was informed by Andersen’s79 behavioural model of health service use by vulnerable populations, and applied by Gelberg et al. 80 to people who are homeless. The model has three domains: (1) population characteristics, such as demographics, personal and family resources, community and health services resources, and perceived health needs; (2) health behaviour, such as lifestyle factors and use of health services; and (3) outcomes, such as satisfaction with care, and the availability and accessibility of health services.

| Contextual factors | Mechanisms (service delivery factors) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Size and geographical spread of the local population that is homeless. Availability of resources (funding and staff) to enable CSSs to respond to the health needs of local people who are homeless. Availability of competing primary health care services. Availability of local health and social care agencies, their knowledge of the CSS and referral procedures, and their ability to provide services to CSS referrals. Local commissioning influences, for example catchment area, population to be served by CSS, exclusion groups. National policy influences relating to who is eligible/not eligible for NHS care. Local authority influences, for example the length of time homeless people can remain in a hostel in the locality. |

Staff understanding of homelessness, and their attitude towards working with people who are homeless. Composition of team and its clinical expertise in assessing and treating health problems of people who are homeless, and referring them to appropriate services. Staff knowledge of the local homeless population and of services to which this group can be referred. Flexibility and accessibility of the service. An environment that is welcoming and acceptable to people who are homeless. Person-centred approach to health care that encourages engagement and continuity of care. Holistic approach that responds to housing, social and welfare needs. Champions health promotion and health screening. Availability of protocols and ability of staff to manage difficult or challenging behavior. Integration with mental health, dental, substance misuse, social care services, homelessness and other services required by people who are homeless. |

Primary outcome: six indicators of engagement in health screening 1. BMI 2. Smoking 3. Hepatitis A 4. Mental health 5. Alcohol 6. TB Secondary outcomes: 1. Management of five SHCs: i. Hypertension ii. Chronic respiratory problems iii. Depression iv. Alcohol problems v. Drug problems 2. Oral health status and receipt of dental care. 3. Self-ratings of health status and well-being over time. 4. Use of health and social care services, including substitute primary care services (walk-in, A&E) and unplanned hospitalisations. 5. Patients’ satisfaction with the CSS. 6. CSS staff and local service providers’ satisfaction with the CSS. 7. Addressing the needs of local people who are homeless. |

Integration between each CSS and relevant services were measured, drawing on measures adopted by Browne et al. 81 and Joly et al. 82 Distinctions were made between (1) types of services, for example health, housing and social care; and (2) organisations involved at different stages of care such as hospital services, and those that provided complementary services. The ‘depth’ of integration between the CSS and each service was scored by staff, according to the extent to which they were involved with a service, and the extent to which they should be involved (see Chapter 11). Similar information was collected from external health and social care agencies.

Study approvals and management

The study started in April 2015. It received ethics approval from the London – Bloomsbury Research Ethics Committee on 5 October 2015 (reference number: 15/LO/1382) and study-wide governance approval from the lead Clinical Research Network (CRN) on 19 October 2015, and local NHS Research Governance approval was granted for each study site as they were recruited. As the study progressed, three substantial and seven non-substantial amendments were approved by the London – Bloomsbury Research Ethics Committee and the Health Research Authority, and four changes were made to the original research protocol. The non-substantial amendments concerned the addition of CSSs to the study, and the substantial amendments concerned changes to the research protocol (see following sections).

A Study Steering Committee (SSC) was formed; it met annually and guided the research team throughout the study.

Phase 1: mapping of specialist primary health care services

The mapping exercise aimed to (1) examine the prevalence, geographical distribution and characteristics of specialist primary health care services in England for single people who are homeless; (2) determine the extent to which temporary accommodation and day centres for single people who are homeless had access to specialist primary health care services; and (3) collect information from those not linked to specialist health services about accessing primary health care.

Using semistructured questionnaires, two complementary surveys were undertaken. The first collected information from specialist primary health care services about their service such as opening hours, staff composition and patient groups (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The second survey collected information from managers of hostels and day centres for single people who are homeless about their project, access to primary health care for clients and general practices used, clinics run by doctors or nurses at their project, and whether or not the primary health care needs of their clients were being met (see Report Supplementary Materials 3 and 4). Details of the methods are available,21 and summary findings reported in Chapter 4.

Phase 2: evaluation of models of primary health care provision

An evaluation of four models of primary health care provision for people who are homeless was undertaken:

-

Two specialist health centres primarily for people who were homeless (Dedicated Centres).

-

Two mobile homeless health teams that held clinics in hostels or day centres for people who are homeless (Mobile Teams).

-

Two general practices with special services for people who were homeless (Specialist GPs).

-

Four generic general practices providing ‘usual care’ services to the local population, including to people who were homeless (Usual Care GPs). The intention was to have two sites, but because of difficulties recruiting general practices and insufficient numbers of patients who were homeless at these sites, two additional practices were added.

Fieldwork ran from January 2016 to June 2019. Data were collected through interviews with CSS managers and staff, and local health, social care and welfare agencies. People with a current or recent history of homelessness and registered with the CSS were recruited as ‘case study participants’, and information was collected from them and from their medical records about their health and service use over 12 months.

Primary outcome: health screening of people who are homeless

The primary outcome was the extent of health screening among people who are homeless. Six Health Screening Indicators (HSIs) were selected: body mass index (BMI), mental health, alcohol use, TB, smoking and hepatitis A. The HSIs are a set of minimum standards or ‘markers’ from a clinical perspective, and extend beyond screening alone, as evidence of an intervention was sought if a problem was identified. Screening for BMI, mental health, alcohol use and TB covered the preceding 12 months, smoking covered the preceding 24 months and hepatitis A required that a vaccination programme was in progress or had been completed in the preceding 10 years. The HSIs were derived from existing guidelines,83–87 and from the expert opinion of Ford (retired GP), who consulted two generic GPs, two GPs specialising in homelessness and a hospital physician. The six HSIs were included in a list of health screening indicators for people who are homeless in the Faculty for Homeless and Inclusion Health’s standards for primary care. 48 They were selected for our study because smoking, mental health and alcohol problems are common among single people who are homeless (see Chapter 1), and their diets are often poor. 88 Moreover, compared with the general population, hepatitis A and active pulmonary TB are relatively common. 89–91

Data for the HSIs came solely from the participants’ medical records, which were accessed at the end of the study. A score of 1 was given to each HSI if there was evidence in the medical records of both screening having taken place and an intervention being offered, if applicable, thus giving a total range of 0–6. Further details are in Chapter 7.

Secondary outcomes

Outcome 1: management of Specific Health Conditions

Five heath conditions that might be difficult to manage because of the unsettled lifestyles of people who are homeless, or that may require integration with other services, were selected to assess the response of the CSS to the condition, and its effectiveness in providing care and treatment. The five Specific Health Conditions (SHCs) were (1) hypertension, (2) chronic respiratory problems, (3) depression, (4) alcohol problems and (5) drug problems. It was expected that most participants would have at least one of these conditions, given their prevalence rates in other studies of people who are homeless: chronic respiratory problems, 17–29%; depression, 30–43%; hypertension, 17–33%; alcohol problems, 27–50%; and drug problems, 39–54%. 11,92–98

Five outcomes examined the effectiveness of the CSS in providing health care for each SHC: outcomes 1 and 2 assessed processes of care by the CSS; outcomes 3 and 4 measured patient perceptions of the quality of care; and outcome 5 assessed control of, or change in, condition over the study period (see Chapter 8). The intention had been that CSS staff would also complete a short questionnaire at the end of the study about care provided for each SHC. After piloting, it was omitted because staff did not have the time to complete it, and the information needed was mostly in the medical records.

Outcome 2: oral health status and receipt of dental care

Poor oral health and dental problems are common among people who are homeless. Access to dental care is believed to have a beneficial impact on oral health outcomes, and on global and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), dental anxiety, satisfaction with dental care and positive health behaviours (oral hygiene practices, sugar consumption patterns and smoking). The impact of the CSSs on the receipt of dental care and on oral health status by people who are homeless was assessed over the study period. It was hypothesised that CSSs that had greater integration with primary care dental services would have higher rates of access to dental care and more positive oral health outcomes.

Instruments to measure the impact of the CSS on dental service use, dental anxiety and changes in self-reported oral health status and OHRQoL were administered, drawing from the Adult Dental Health Survey,99 the GP Patient Survey,100 the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 items (OHIP-14),101 the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS),102 Global Self-Rating of Oral Health103 and whether or not participants felt that they needed dental treatment. 104 Self-reported and OHRQoL measures have been validated for use with people who are homeless by the HEARTH study’s co-investigator (Daly). 105 Further details are in Chapter 10.

Outcome 3: health status and well-being over time

Changes over time in health status and well-being were examined, using the Short Form 8 Health Survey (SF-8) and the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS), which participants completed at baseline and at 8 months (see Chapter 9). Information on nutrition and smoking was collected at baseline and at 8 months to assess the impact over time of the CSS in improving health-related behaviours among people who are homeless.

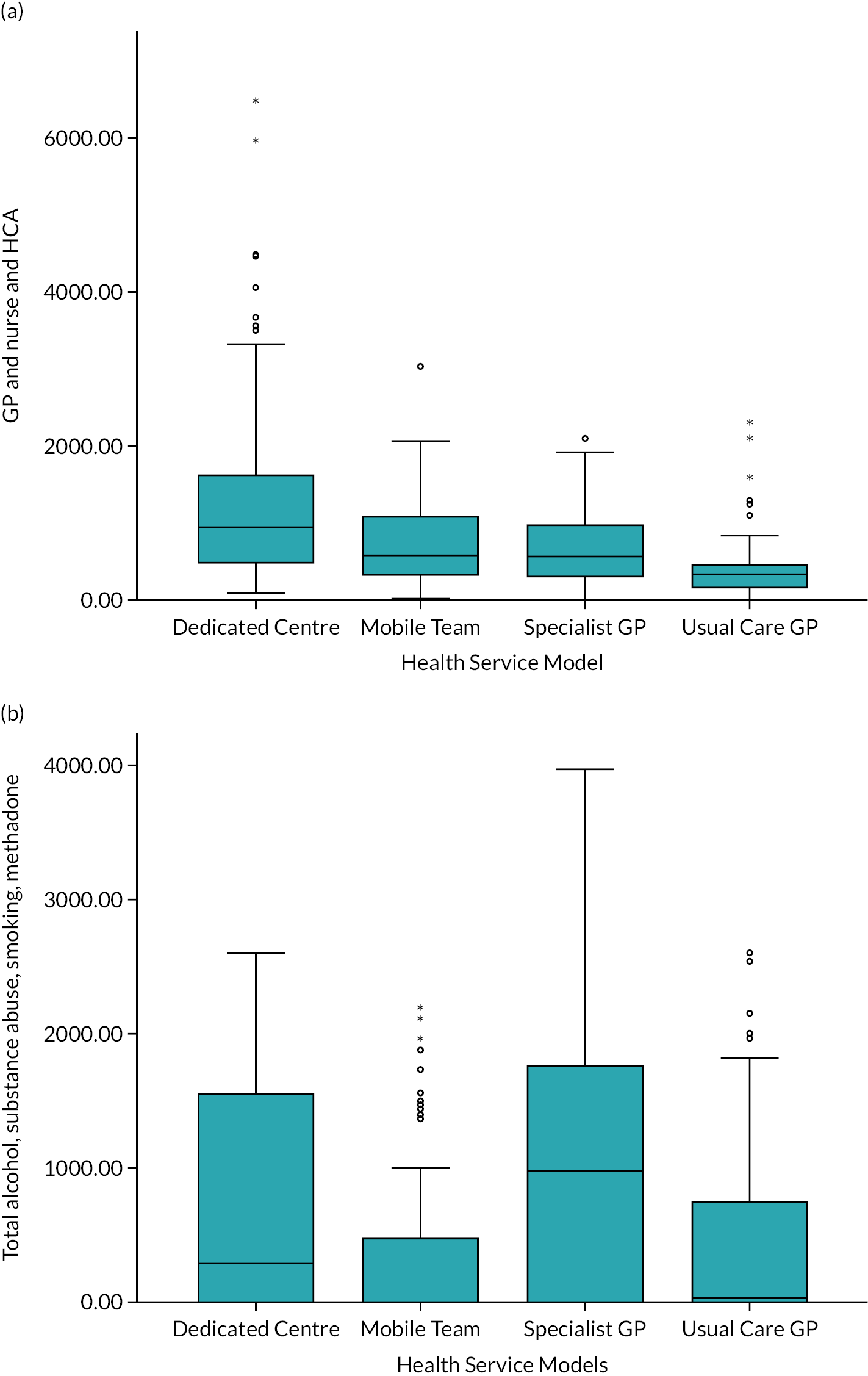

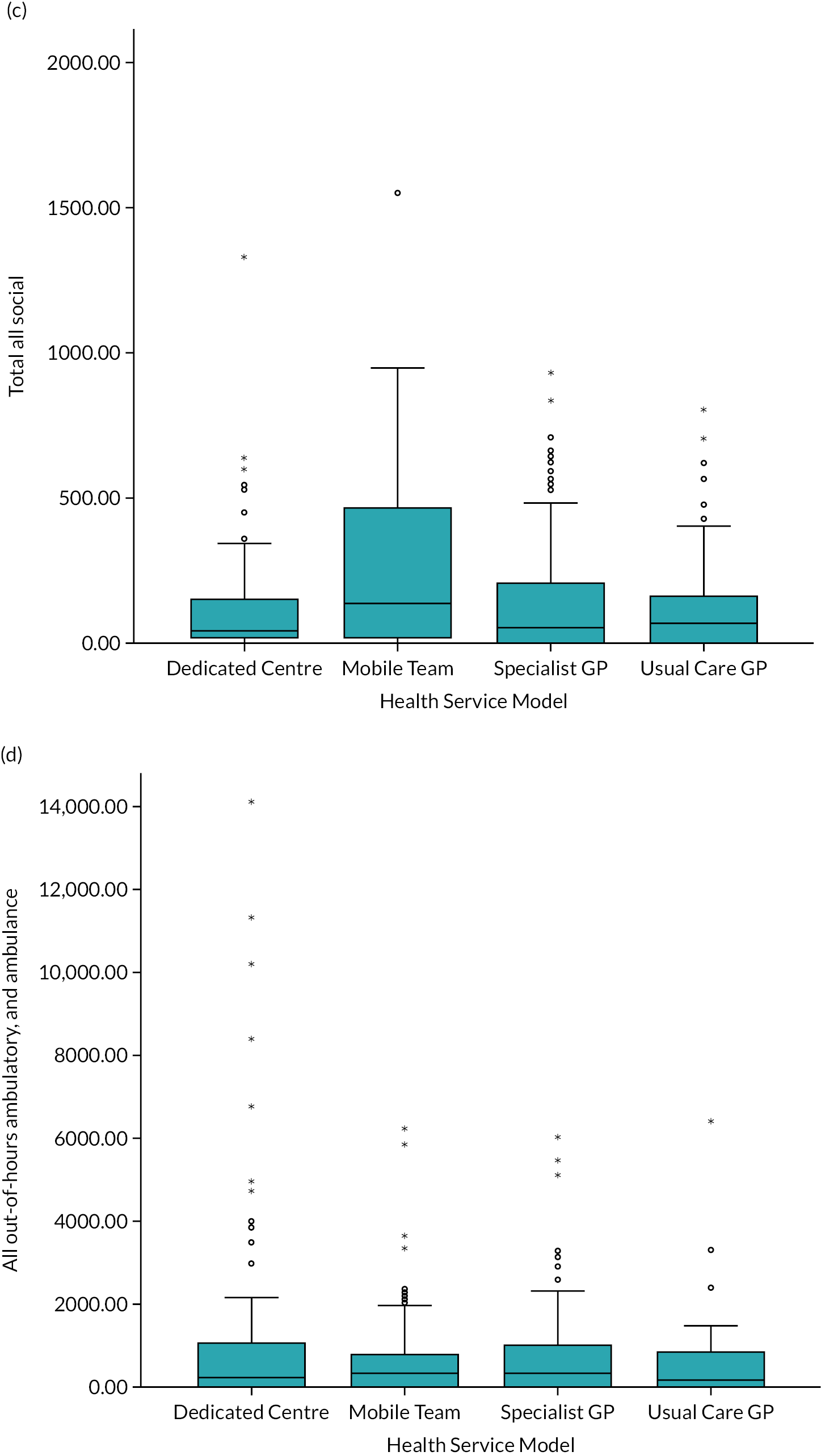

Outcome 4: use of health and social care services, and service use costs

Medical records of participants were accessed on completion of fieldwork at each site, and data relating to service use over the 12-month study period were extracted (contacts with general practices, community services, out-of-hours services, ambulances, hospital inpatient and outpatient care, tests and investigations). These data were supplemented with information provided by participants during interviews at baseline and at 4 and 8 months. Items taken from the Client Service Receipt Inventory106 were embedded in interview schedules asking participants to report on use of primary care, community, substance misuse and hospital services; social services (including local authority housing and welfare offices and for personal care); and support from the voluntary sector. Use of substitute primary care services (A&E, NHS walk-in/urgent care clinics, NHS 111, ambulance call-outs) was identified as possible indicators of the effectiveness of the CSS in providing an accessible service for people who are homeless, and in preventing avoidable hospital admissions or re-admissions. Service use data were converted to costs (Great British pounds, 2020) using nationally validated sources. 107

Outcome 5: satisfaction with the Case Study Site

Using questions from the GP Patient Survey and General Practice Assessment Questionnaire, participants’ views of the CSS and satisfaction with the service were obtained. Questions covered access, arranging appointments, waiting times, opening hours and quality of care. During interviews with CSS staff and local service providers, their perspectives of the CSS, and their integration and satisfaction with the CSS, were also sought.

Outcome 6: addressing the health needs of local people who are homeless

Through interviews with people who were homeless but not using the CSS, and with CSS staff and other agencies, information was gathered about the extent to which the CSS was addressing the health needs of the local population that was homeless and any unmet health needs.

Recruitment of Case Study Sites

Drawing on the mapping exercise, primary health care services working with people who were homeless were identified for the three specialist models. Their selection depended on whether or not they responded to the mapping exercise, the number of patients who were homeless, and staff resources or imminent changes to the service that affected their ability to participate.

Early on it became apparent that recruiting general practices for the Usual Care GP model would be exceptionally difficult. The mapping exercise revealed that many large hostels were linked to specialist primary health care services. Among those that were served by a mainstream general practice, some hostel managers declined involvement, and some agreed, but the general practices failed to respond or declined as they were too busy. General practices serving smaller hostels were therefore considered, although this meant fewer potential case study participants per site.

Substantial time and effort were spent liaising with general practices and primary care leads of CRNs to try and recruit Usual Care GPs. It was agreed with the SSC that, instead of two sites for this model, attempts would be made to recruit additional practices to reduce the number of participants required at each CSS. In collaboration with five CRNs, attempts were made to recruit a cluster of hostels and general practices in an area. This proved successful in two locations, and eventually four Usual Care GPs participated. Recruitment of participants at the final site did not commence until April 2018.

Case studies of health and service use over 12 months for people who are homeless

At each CSS, patients who were currently or recently homeless were recruited as case study participants and information was collected about their health and service use over 12 months.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged 18 years and over, (2) homeless currently or at some time during the previous 12 months, (3) registered with the CSS for at least 4 months and (4) had at least one consultation with a CSS doctor or nurse during the previous 4 months. Families or couples with dependent children who were homeless were not included. Homelessness was defined as sleeping on the streets or in other public places, squatting, staying in temporary accommodation such as hostels or bed-and-breakfast hotels, or staying temporarily with friends or relatives (sofa surfing). By focusing on those who had been homeless at some time during the preceding 12 months, this enabled people who frequently move in and out of homelessness to be included.

Sample size

The aim was to recruit 96 participants from each of the four models (total N = 384), divided evenly, as far as possible, between the CSSs in each model. It was estimated that the attrition rate would be 33% over the study period. Hence, it was expected that at least 80 people in each of the four models would be interviewed at 4 months, and 64 at 8 months (final N = 256).

The primary outcome variable was the six-item HSI tool, with a score of 0–6. Given the innovative nature of this tool, there were no previous data on its level of variation. Extensive simulations exhibited a maximum standard deviation (SD) of 2.0. An outcome variable with a SD of no more than 2.0 would necessitate a minimum required sample size of 64 in each of the four models to detect a difference of 1 point on the six-item tool between any two types of model, with size = 5% and power = 80%.

The possibility of small percentages of participants with a particular SHC meant that it might be possible to detect only relatively large differences in continuity of care for that SHC between the four models. For example, if only approximately 30% of participants in any group had a particular condition, it would be difficult to identify a difference between groups in continuity of care for that condition of less than 40%. Each SHC was assessed separately when numbers permitted.

Recruitment of case study participants

Recruitment of case study participants started in January 2016 and ended in August 2018. At most CSSs, recruitment lasted several months (and longer than planned) to reach the required number. For the three specialist Health Service Models, participants were recruited at the CSS, or at hostels and day centres where CSS staff held clinics. Recruitment was undertaken by the fieldwork research team (Joly, Cetrano, Coward and Crane), who spent weekly periods at a location until the required number was achieved. The study was explained briefly to consecutive patients by CSS staff, who handed them a participant information sheet about the study and what their involvement would entail, and those interested were introduced to the research team. The research team then explained the study in more detail, confirmed the patient’s eligibility regarding homelessness and checked with CSS staff their date of registration at the practice. Only those who gave informed, written consent to be interviewed and for the research team to have access to their medical records at the end of the study were included.

For Usual Care GPs, it was impractical to recruit at the CSSs as most patients were not homeless. Participants were therefore recruited at hostels and day centres, where the staff explained the study to people they believed were eligible, handed out participant information sheets and passed on the names of those who were interested. The research team then explained the study to them in more detail and determined their eligibility to participate. If necessary, written consent was obtained from potential participants to enable the research team to check the date of registration with the CSS and the date they were last seen by a doctor or nurse with CSS staff.

By August 2018, the target number of 96 had been reached at each of the specialist Health Service Models, but only 75 Usual Care GP participants had been recruited (Table 2). It was agreed with the SSC that recruitment should cease to enable time for follow-up interviews.

| Health Service Model | CSS (N = 10) | Case study participants (N = 363) |

|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Centre | DC1 | 48 |

| DC2 | 48 | |

| Mobile Team | MT1 | 47 |

| MT2 | 49 | |

| Specialist GP | SP1 | 51 |

| SP2 | 45 | |

| Usual Care GP | UC1 | 28 |

| UC2 | 30 | |

| UC3 | 15 | |

| UC4 | 2 |

Interviews

Using structured questionnaires, case study participants were interviewed at baseline and at 4 and 8 months, and were offered £10 for each interview as appreciation for their time and involvement (see Report Supplementary Materials 5–8). Information was gathered about their socioeconomic circumstances (housing, income, involvement in training or work, support from family and friends); health-related activities, such as smoking and nutrition; physical and mental health problems, and use of alcohol and drugs; dental health; use of health and other services in the preceding 4 months (resulting in 12 months’ data); and their views of the CSS. During the interviews at baseline and at 8 months, participants completed the SF-8 and the SWEMWBS concerning health status and well-being; they also completed validated instruments pertaining to depression and respiratory problems if a potential SHC was indicated (see Chapter 8). Quantitative and qualitative data were generated from these interviews.

Most interviews were conducted at the CSS or at hostels or day centres at a time and place convenient to participants. A few took place on the streets, in cafes or offices, or at a participant’s home. The interviews at baseline and at 8 months lasted approximately 45–60 minutes, and the interviews at 4 months lasted 30–40 minutes, as less information was needed. Whenever possible, the same researcher conducted all interviews to enable continuity. The interviews touched on sensitive and possibly upsetting topics, such as ill health and homelessness; therefore, participants were offered opportunities to have a break or stop the interview if they became distressed or anxious or found it hard to concentrate. All interviewers had substantial experience in interviewing people who were homeless or who had mental health problems. In most instances, participants welcomed the opportunity to talk about their experiences and needs and fill in self-completion instruments.

For some participants, several attempts were made to contact them and several appointments arranged before a follow-up interview was achieved. Drawing on the research team’s previous experience of longitudinal research with people who are homeless,108 various strategies were used to find and engage with some participants. These included contacting street outreach workers and other service providers, opportunistic visiting of day centres and hostels, leaving letters for participants with service providers and searching on the streets. Written consent was obtained from participants at baseline for the research team to contact CSS staff and other services when necessary. When possible, follow-up interviews were conducted with participants who left the CSS during the study and moved elsewhere.

Overall, 898 interviews were conducted, and all except three were face-to-face. At 4 months, 272 participants (74.9%) were interviewed, fewer than the target number (320). At 8 months, 263 (72.5%) participants were interviewed, slightly higher than the target number (256) after allowing for attrition, despite fewer people being recruited to the study. At 8 months, 30 participants were included who could not be interviewed at 4 months. There were no statistical differences by Health Service Model in the number of interviews achieved at each period (Table 3). The main reasons why participants could not be interviewed were because they were in prison or hospital, could not be found, or declined or did not respond to interview attempts (see Appendix 1, Table 45). At 8 months, 10.4% of Dedicated Centre participants were in prison, and 8.3% of Mobile Team participants were outside the UK. Five participants died during the study.

| Interviewed at | Case study participants, n (%) | Comparison test; p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 363) | Dedicated Centre (N = 96) | Mobile Team (N = 96) | Specialist GP (N = 96) | Usual Care GP (N = 75) | ||

| 4 months | 272 (74.9) | 68 (70.8) | 73 (76.0) | 67 (69.8) | 64 (85.3) | Chi-squared; 0.086 |

| 8 months | 263 (72.5) | 65 (67.7) | 70 (72.9) | 70 (72.9) | 58 (77.3) | Chi-squared; 0.573 |

| Baseline only | 61 (16.8) | 20 (20.8) | 15 (15.6) | 17 (17.7) | 9 (12.0) | Chi-squared; 0.474 |

| Breakdown of interviews at different intervals | ||||||

| 4, but not 8, months | 39 (10.7) | 11 (11.5) | 11 (11.5) | 9 (9.4) | 8 (10.7) | Chi-squared; 0.962 |

| 8, but not 4, months | 30 (8.3) | 8 (8.3) | 8 (8.3) | 12 (12.5) | 2 (2.7) | Chi-squared; 0.146 |

| Baseline and 4 and 8 months | 233 (64.2) | 57 (59.4) | 62 (64.6) | 58 (60.4) | 56 (74.7) | Chi-squared; 0.161 |

Interviews with Case Study Site staff and sessional workers

Face-to-face interviews were conducted by the fieldwork research team with 65 CSS staff and sessional workers, including practice managers, primary health care nurses, GPs, mental health nurses, drug and alcohol workers, case managers, health care assistants (HCAs) and receptionists. Using a template (see Report Supplementary Material 9), operational and performance data were collected from CSS managers about (1) the development of the CSS; (2) current operation, including staffing, client groups served, opening hours, registration, funding and types of services provided; (3) integration with local health, dental, welfare and social care services; and (4) involvement of the CSS in local strategy and service development.

Using an interview schedule adapted for different job roles (see Report Supplementary Material 10), interviews with CSS staff and sessional workers collected information about (1) length of time with the CSS, role within the team, qualifications and experience of working with people who are homeless; (2) services provided to people who are homeless, and strategies to encourage engagement; (3) collaboration with local agencies and services; and (4) perspectives of the CSS’s strengths and limitations. All consented for their interview to be recorded. They also rated their actual and expected levels of integration with other services (see Chapter 11). Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes. They were sent a participant information sheet prior to the interview explaining the study and their participation.

There were delays in arranging some interviews due to staff workload. Where sessional workers were employed by an organisation that was not the CSS, additional research and development approvals were required. Our intention had been to hold a focus group with CSS staff towards the end of the study to gather their reflections on their work as a team. However, owing to their work pressures, individual interviews were more appropriate.

Interviews with local service providers and stakeholders

To examine the wider context in which the CSS delivered care, interviews were also conducted with 81 local service providers and stakeholders. All except three were face-to-face, and all but two were recorded. Service providers included street outreach workers, hostel and day centre managers, and drug and alcohol workers who were not part of the CSS. Using an interview schedule (adapted for different job roles), information was gathered about (1) their work with people who are homeless, (2) their awareness of the CSS and referral procedures, (3) use of the CSS by their clients or reasons for non-use and (4) their perspectives of the CSS (see Report Supplementary Materials 11 and 12). Each person was asked to rate their actual and expected level of integration with the CSS. Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes. They also were sent participant information sheets prior to the interview.

Interviews with three local authority service commissioners and four Healthwatch directors collected information about local strategies and plans for health care delivery to people who are homeless, and the role of the CSS in local health provision. It was not possible to arrange interviews with some stakeholders.

Interviews with people who were homeless and not using the Case Study Sites

In eight CSS areas, 107 interviews were conducted with people who were homeless and not registered with the CSS. Using a short, structured questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 13), information was gathered about their awareness of the CSS, reasons for not using it, and their health needs and use of health care services. They were recruited at hostels and day centres, and were offered £5 as thanks for taking part. Staff at these sites handed out participant information sheets to potential participants, and those interested were introduced to the research team. The research team explained the study in more detail, checked the potential participant’s eligibility and obtained their written consent to participate. Peer interviewers conducted 49 of these interviews (described in Patient and Public Involvement).

Observations

Observations were undertaken of ways in which CSS staff engaged with people who were homeless, and worked with other agencies. This mainly involved observations in CSS reception areas and in day centres while trying to recruit or find participants for follow-up interviews. Observations focused on the ways in which people who were homeless presented to the CSS, their behaviour in the reception areas and how this was managed by the CSS staff, and whether they were seen by clinicians or left prematurely. It was not feasible to undertake observations in reception areas of Usual Care GPs, as it would not have been possible to identify whether patients were housed or homeless.

Observations were undertaken at day centres of the systems in place for service users to see a CSS nurse, and the ways in which nurses engaged with those who were reticent. Other opportunities to undertake observation work were sought. At one CSS, two researchers attended a multidisciplinary staff meeting. At another, a researcher accompanied a CSS staff member and outreach worker while they conducted street outreach work early in the morning. At a third site, research staff attended a drop-in service for rough sleepers run by CSS staff. Field notes were maintained of the various observations.

Data from medical records

After the interview at 8 months, printouts of all medical record data held by the CSS for the 12-month study period, including consultations, letters, reports and referrals, were requested for each participant. This included GP records that were shared with the Mobile Teams. Data were also requested dating back 2 years regarding smoking and dating back 10 years regarding hepatitis A (for scoring the HSIs). Organising data extraction and ensuring that complete data were obtained proved intricate and time-consuming. Each site identified a person responsible for data extraction and Joly (research team) instructed them accordingly. They were provided with the requirements for data extraction for each participant. The extraction process was undertaken by the CRN at one CSS, and elsewhere by CSS administrative staff. Data were then checked by Joly for completeness, and missing documents requested. At some sites, this process was repeated several times before complete data were obtained.

Medical records were obtained for 349 of the 363 participants. They were used to score the primary outcome and some SHC outcomes, and to provide service use data. Medical records were not obtained for 14 Usual Care GP participants, including both participants from one site (UC4). This was because participants were no longer registered with the CSS at the end of the study and the records were unavailable. As shown in Table 4, medical records for the entire study period (12 months) were available for most participants, with no statistically significant difference by Health Service Model.

| Length of time | Case study participants, n (%) | Comparison test: p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 349) | Dedicated Centre (N = 96) | Mobile Team (N = 96) | Specialist GP (N = 96) | Usual Care GP (N = 61) | ||

| 1–4 months | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | Kruskal–Wallis: 0.168 |

| > 4–6 months | 14 (4.0) | 3 (3.1) | 7 (7.3) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (4.9) | |

| > 6–8 months | 16 (4.6) | 5 (5.2) | 4 (4.2) | 5 (5.2) | 2 (3.3) | |

| > 8–10 months | 31 (8.9) | 8 (8.3) | 11 (11.5) | 9 (9.4) | 3 (4.9) | |

| > 10–12 months | 286 (81.9) | 80 (83.3) | 72 (75.0) | 81 (84.4) | 53 (86.9) | |

Although the research team checked with CSS staff that a person had been registered at least 4 months prior to recruitment, once medical records were obtained, it was found that 50 participants had been registered less than 4 months prior to recruitment. For 26 of these participants, it was possible to collect additional data from the medical records at the end of the study period to provide 12 months’ medical data on service use.

Data management

All data collected during the study were stored in locked filing cabinets in our department at King’s College London (KCL), which itself is locked. Only the KCL team had access to these filing cabinets, and to the database on the university server (which was password protected). Identifiable participant information was not disclosed beyond the KCL research team. Names were not entered into spreadsheets or databases created for the analyses.

The recorded interviews of CSS staff, service providers and stakeholders were transcribed by a professional company used by KCL. A confidentiality agreement was drawn up and audio files were transferred to the company using the KCL File Transfer Protocol system (a secure method of transferring data). Staff were informed of this on the participant information sheets and consent forms. Once interviews were transcribed, all personal identifiers were removed.

Data analyses

A descriptive picture of the context and mechanisms of each CSS was built from interviews with CSS staff and other agencies. Using the templates created by each CSS manager, information was entered into an IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) database about the service, including staffing, types of services provided and accessibility of the CSS. Similarities and differences between and within models were examined.

Information from the case study participants’ interviews was entered into an SPSS database, alongside data relating to (1) primary and secondary outcomes extracted from the medical records, (2) characteristics of the CSS and (3) service use over 12 months. Summary statistics relating to both the background characteristics of participants and quantitative outcomes were produced, along with histograms to enable assessment of normality so that appropriate statistical tests could be employed.

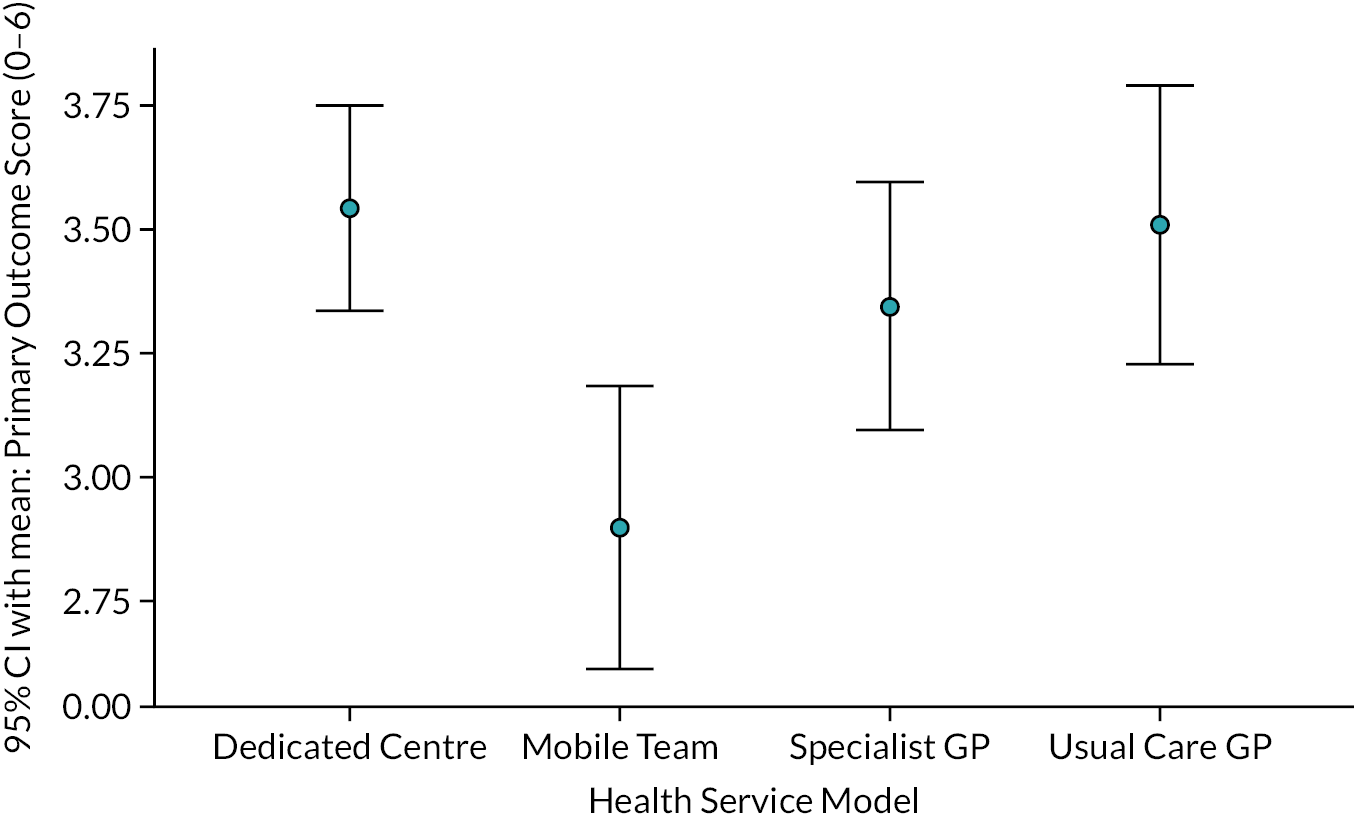

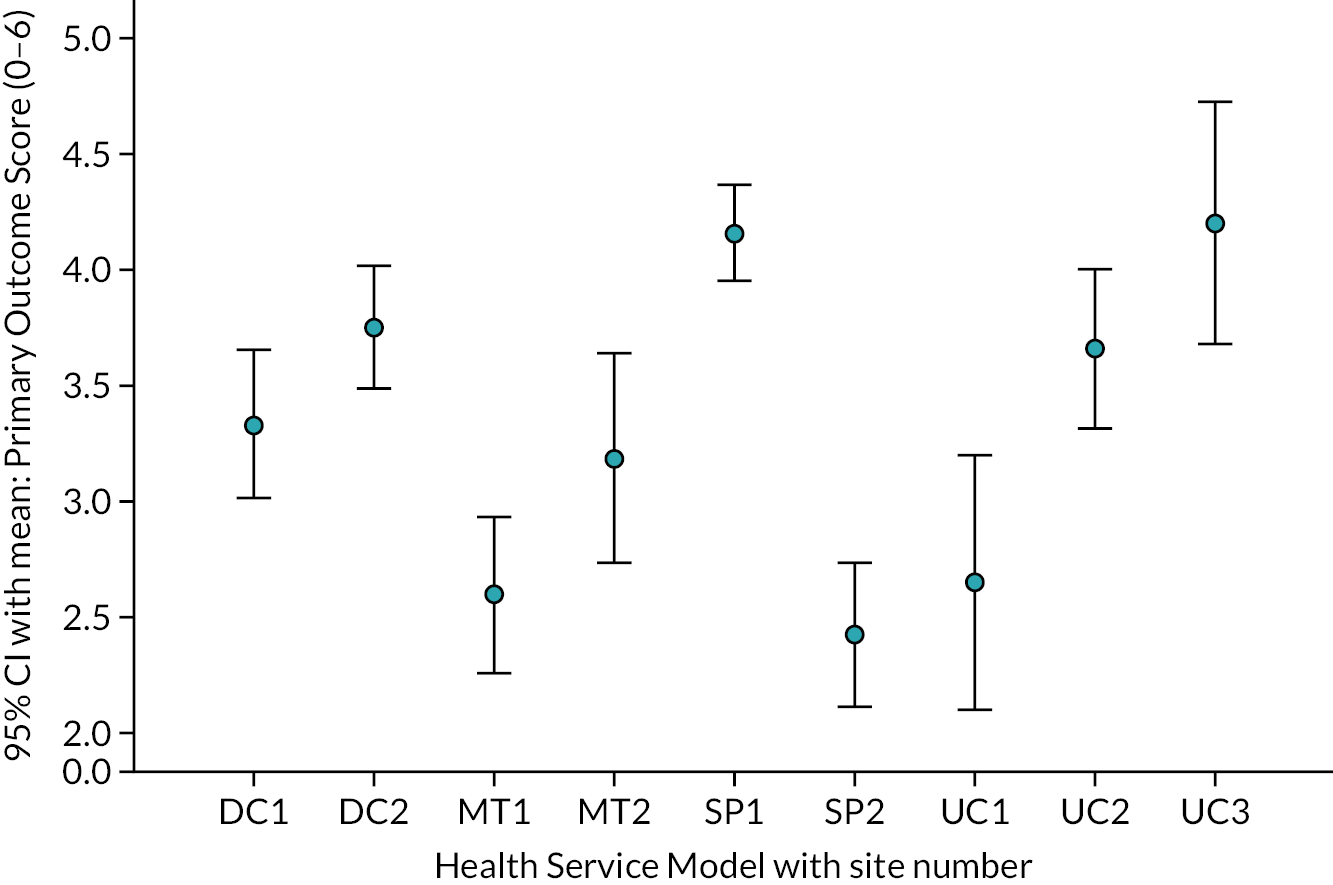

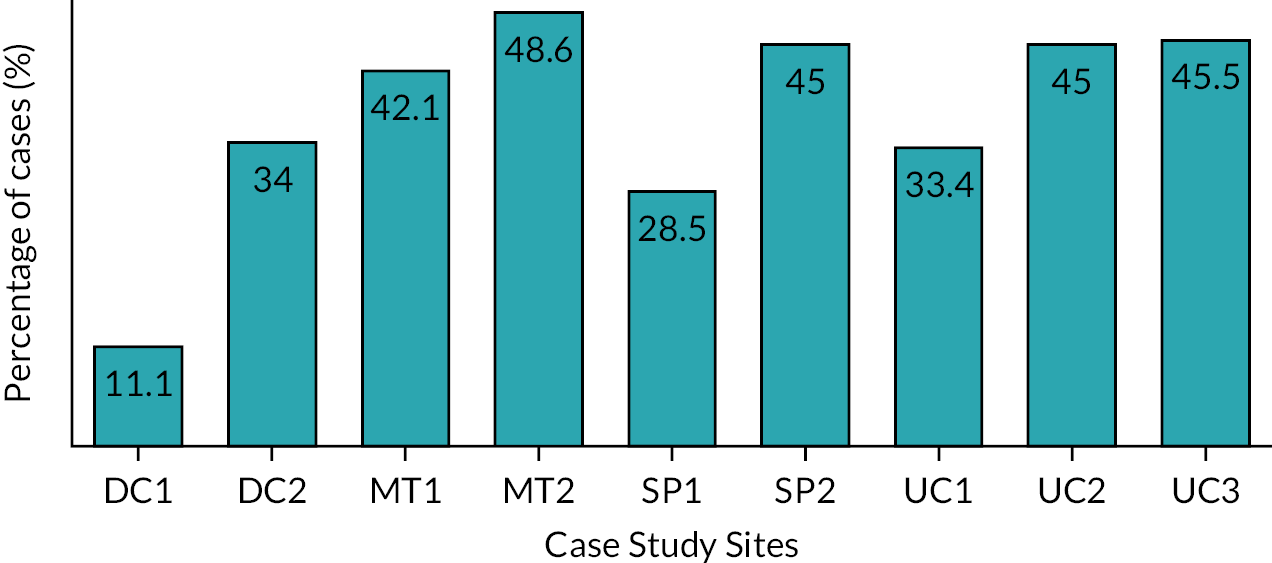

A range of indicators was used to measure the relative effectiveness of the four Health Service Models, and each indicator was analysed separately. First, the models were compared with respect to the primary outcome variable (the six-item HSI, score 0–6) using analysis of variance (ANOVA). An in-depth comparison was then performed using appropriate regression techniques to explore associations between the HSI and demographic, background and health profiles of participants. The model type was entered as a dummy variable. The four models were then compared for each of the secondary outcomes. The prevalence of each of the SHCs was compared across the models using the chi-squared test. The analysis of each SHC then proceeded using just the subgroup having the relevant condition. Each of the five dichotomous SHC outcomes within each SHC was compared across the four models using the chi-squared test.

Each of the continuous outcome variables [physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) of the SF-8, the SWEMWBS, and service user satisfaction with the CSS] was compared between the four models at baseline, and changes from baseline to 8 months were calculated and compared by model type. Stepwise linear regression modelling was performed to adjust for other factors (such as personal characteristics, length of time using the CSS and service features of the CSS) when comparing the four models. This was carried out initially at baseline to include as many service users as possible, and at 8 months using changes when available.

Differences in outcomes between models were investigated in relation to the contexts and mechanisms of care to seek understanding of the reasons underlying the patterns observed. Quantitative information was triangulated with data from qualitative interviews with case study participants and staff about accessing health and other services. Satisfaction of the case study participants with the CSS was compared with satisfaction of the general population with their GP, using data from the GP Patient Survey.

Comparisons were made between oral health status and receipt of dental care across the four models, and their extent of integration with primary dental care services. Comparisons were also made between access to dental care and impact on self-reported oral health status and OHRQoL, dental anxiety and satisfaction. Receipt of dental care by the four models was compared with local and national populations’ access to primary dental care, using national NHS statistics.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data from the interviews with case study participants, and with CSS staff and other agencies were entered as separate projects into NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK). For the case study participants, qualitative data were first transcribed from the completed interviews into templates using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Nodes were then created for each open-ended question at baseline and at 8 months covering participants’ views and experiences of the CSS. This information was examined in more detail, with reference to the mechanisms listed in the framework for this evaluation (see Table 1). Themes were identified; these are presented in Chapter 12. For CSS staff and other agencies, nodes were created for each of the context factors and mechanisms identified in the evaluation framework, and their interviews coded accordingly. Data were examined in detail; themes are presented in Chapter 11. The integration scores of CSS staff and other agencies were entered into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation) spreadsheets, and are also summarised in Chapter 11.

Economic analysis