Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HSDR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR135075. The contractual start date was in June 2021. The final report began editorial review in October 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Coelho et al. This work was produced by Coelho et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Coelho et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Mental health conditions are common in the UK, and increasingly prevalent in young people. National surveys1 of children and young people in England show that rates of probable mental health disorders increased considerably between 2017 and 2020, from approximately one in nine (11.6%) to one in six (17.4%) 6- to 16-year-olds, and from 1 in 10 to 1 in 6 of those aged 17–19 years. The same survey1 found that children aged 6–16 years who had a probable mental health disorder were twice as likely to have missed > 15 days of school as those without a probable mental health disorder. The 2020 survey data also showed that white children were twice as likely (20.1%) as children from an ethnic minority (9.7%) to have a probable mental disorder; however, this difference was lower for 17- to 19-year-olds (17.8% vs. 15.9%, respectively), and the survey was conducted during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic so may reflect atypical mental health stresses and lower mental health service availability than before the pandemic. 1

Health care, including mental health care, is not equally utilised by all ethnic groups in the UK. 2 The 2019 report on mental health equality by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health3 also highlighted some stark ethnic inequalities in access to care and responsiveness to treatments. For example, citing a mix of other national sources, ethnic minorities were at an increased risk of involuntary detention, had lower recovery rates following psychological therapies and experienced greater deterioration rates than white mental health service users. 3 In addition to levels of service use, stakeholders consulted as part of the process of developing this guidance3 for the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health also highlighted that people from ethnic minorities accessed care via different pathways; for instance, they were more likely than their white counterparts to access acute mental health care via the criminal justice system. In 2018, the independent review of the 1983 Mental Health Act4 specifically aimed to address some of these ethnic inequalities, as they were related to the compulsory detention of those experiencing acute mental distress.

Health inequalities arise when, after accounting for rates of ill health and health preferences, there is a disproportional unmet need in one group compared with another. For example, a systematic review5 of British population- and clinic-based studies evaluating both prevalence of child mental health conditions and associated service use among different ethnic groups in the UK suggested a potential unmet need for mental health care among Pakistani and Bangladeshi children. In addition, a more recent systematic review6 found ethnic inequalities in the incidence of diagnosis of severe mental illness in England, with the risk of diagnosis of psychosis being higher for all minority ethnic groups, but particularly black ethnic groups, than those from a white background.

The routes through which children and young people from non-white British ethnic backgrounds obtain mental health support may also differ from those used by white British children or other ethnic groups (with those from non-white British backgrounds being more likely to seek support from informal services, community/voluntary organisations, family and friends). For example, a study by Vostanis et al. 7 conducted in England found that, even when accounting for lower level of need, adolescents aged 13–15 years of Indian ethnicity were less likely than their white peers to use children and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), but more likely to obtain mental health support from siblings, other non-parental family members, teachers and primary care providers.

Among children and young people who do use CAMHS, referral pathways (both referral sources and destinations) may differ according to ethnicity. Routine data collected from across the UK indicated that children and young people from non-white British backgrounds are more likely than white British children and young people to be referred to CAMHS through education, social services, child health services or the criminal justice system rather than through primary care. 8,9 More recently, a study10 analysing data from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust found that 12- to 17-year-olds of black African ethnicity and 18- to 29-year-olds of black African, black British and Asian ethnicity were more likely than white British children and young people to be referred from secondary care, as opposed to primary care, and that all ethnic minority groups were more likely than their white British peers to be referred via the criminal justice system. There is also evidence that, compared with white British children and young people, those from non-white British backgrounds are more likely to be referred to inpatient and emergency services rather than outpatient or non-emergency services,10 or involuntarily rather than voluntarily. 11 This evidence implies that, for these groups, these mental health needs may not be being met through usual health service routes. This has potential cost implications for the individuals, their families and wider communities, and for public services if there is greater use of ‘crisis’ services or involvement of criminal justice.

The picture is clearly complex. When considering all aspects of mental health need (i.e. rates of mental health difficulties, rates of formal and informal service use, different referral pathways, and the care and support preferences of children and young people of different ethnicities), it appears that non-white British children and young people may differ from white British children with regard to the extent and type of unmet mental health care and support needs. The reasons why these needs might be unmet are likely to differ according to ethnic group. A systematic review12 of both quantitative and qualitative studies of the barriers to and facilitators of children and adolescents accessing psychological treatments reported that there were perceived cultural and language barriers or facilitators among people from ethnic minority groups. However, this review was not specific to non-white British children and young people, was not UK specific and was limited to studies evaluating parents’ perceptions.

It remains unclear how much qualitative evidence exists on the factors influencing access to and ongoing engagement with mental health care and support in the UK for non-white British children and young people. This rapid scoping review seeks to address this by documenting the nature and scope of the qualitative evidence in this area, and will focus on identifying studies reporting the experiences, views and perceptions of non-white British children and young people in the UK; their parents, guardians, carers or other family members; their health or social care workers and other professionals who provide referrals or care/support; and commissioners of mental health services.

This scoping review and report was commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme to inform the work of the Department of Health and Social Care’s (DHSC’s) mental health research initiative. In particular, it aims to help identify and prioritise research towards achieving goal 4 and target 4A of the NIHR/Medical Research Council’s (MRC’s) mental health research goals for the UK for 2020–3013 (Box 1). This built on the DHSC’s 2017 framework for mental health research. 14

[Conduct r]esearch to improve choice of, and access to, mental health care, treatment and support in hospital and community settings.

RationaleThere has been a failure to reach all the people who need care and support them to access timely and evidence-based treatment and support.

Target 4AResearch to understand the barriers to help-seeking and service access, and to delivery of mental health services and other support in diverse settings and across different communities, including BAME and LGBT+, to address stigma, discrimination and social exclusion.

BAME, black, Asian and minority ethnic; LGBT+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender +.

Source: Mental Health Research Goals 2020 to 2030. 13

Chapter 2 Objectives

We aimed to undertake a rapid scoping review to describe the nature and scope of the qualitative research in this area and to summarise the main findings as expressed by study authors. The following research questions were to be answered:

-

What is the nature and scope of the qualitative evidence on the experiences, views and perceptions of children and young people from non-white British backgrounds and their parents/carers in accessing and engaging with mental health care and support?

-

What is the nature and scope of the qualitative evidence on the experiences, views and perceptions of those who refer to, provide and commission mental health care and support regarding how children and young people from non-white British backgrounds access and engage with mental health care and support?

Scoping reviews are a type of systematic review that aim to examine the extent, nature and scope of research within a topic area. 15,16 They also typically identify gaps in research and may also summarise and disseminate research findings. 17,18

Therefore, a third objective was:

-

To summarise findings from within studies that relate to the two research questions (i.e. focused on seeking, accessing or engaging with mental health care and support), including providing illustrative quotations from study participants.

Chapter 3 Methods

The following methods were developed in collaboration with our policy contacts within the DHSC, and agreed and published as a protocol before the searching and screening stages were completed. The review protocol is available for download as a project within the Open Science Framework. 19

Inclusion criteria

The full final inclusion criteria are described in Appendix 1.

Phenomenon/outcomes of interest

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they described the included groups’ perceptions, views and experiences of access to or ongoing retention/engagement with mental health care and support (with a view to explaining the factors affecting this). Any type of experience, as described by the participants, was considered valid and eligible for inclusion.

Population

To be included in the review, studies had to be focused on non-white British children and/or young people (aged 10–24 years) who required, were seeking or were receiving mental health care or support. The lower age bound of 10 years was directly suggested by the policy customers of this review.

Non-white British ethnic groups included British ethnic minority groups as determined by 2011 Census Office for National Statistics categories. 20 Studies that focused on travelling communities (including Roma, Gypsy and Irish Traveller communities), or on refugees, people seeking asylum or those who are stateless were also included. In addition, studies reporting data on any non-white British group(s) alongside data from white British groups were included (so long as the white British participants constituted less than half of all study participants).

Eligible studies could report the views, perceptions and experiences of:

-

non-white British children and/or young people requiring, seeking or receiving mental health care and support, or provided the study’s main focus was on access/engagement of non-white British children or young people (aged 10–24 years) to mental health care and support

-

parents, guardians, carers or other relatives of such children or young people

-

health and social care professionals that refer, or provide, care and support to such children or young people

-

other referrers and providers such as teachers, charity/voluntary-sector staff or staff working within the criminal justice system

-

commissioners of mental health care and support for this population group.

Health problem

A broad definition of ‘mental health’ was used, and encompassed the following mental health issues/conditions: anxiety disorders [including obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related mental health issues], depressive disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, conduct disorders, eating disorders, disorders of addiction and misuse, disorders of sleep, somatoform disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), gender dysphoria, self-harming behaviours, general stress and mental/psychological well-being. Studies focused on conditions sometimes assessed or treated by services outside CAMHS or adult mental health services (e.g. autism, social communication disorders, ADHD and/or learning disabilities) were included when the primary focus of the study was mental health rather than the non-mental health aspects of these conditions (such as initial diagnosis).

Setting

Eligible studies were conducted in the UK. Studies that focused on access to and/or engagement with any service, care or support that had a mental health focus or a clear mental health component were eligible for inclusion. This included, but was not limited to, CAMHS, other secondary or tertiary care-based mental health services (including specialist and highly specialist mental health services), charities’/third-sector mental health projects and services, and community-based voluntary services (formal or informal, such as those provided by community associations or religious organisations). A broad and inclusive definition of mental health care and support was used, and, particularly in the case of charity projects and voluntary community-based services, studies including mental health support and care offered as part of a holistic well-being package were eligible for inclusion.

Comparison groups

Studies of single groups or cohorts with no aim to compare experiences between groups (i.e. no comparator group) were eligible for inclusion. Comparison groups may have been included and could have involved comparison with white British populations or between ethnic minority groups. Comparison may also have been made between people involved in children and young people’s mental health care and support (e.g. comparison of perceptions and experiences of children and young people with those of their parents/caregivers, or between parents and health professionals).

Study designs

Any qualitative study design was eligible for inclusion. The decision to focus on qualitative studies was suggested by the review team given the policy customer’s main stated goal of understanding the causes of variations in access to mental health care and support in these groups.

Commentaries, letters and opinion pieces were excluded. Systematic reviews of qualitative studies were included if most of the included studies were relevant to this review. Quantitative studies and policy and guidance documents not describing the perceptions, views or experiences of the study population were excluded.

Other limits

Only studies published in the last decade (between 2012 and the search date) were included so that the evidence was as relevant as possible to current service configurations. Our policy customers thought that evidence from before 2010 would be too far back and much less relevant, and the Health and Social Care Act21 and No Health Without Mental Health22 strategy were introduced in England in 2012 and 2011, respectively. In addition, at national level, the biggest changes in the last decade were the funding as part of the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (for NHS England, published in 2016)23 and then the NHS Long Term Plan (2019 onwards). 24

We included both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed papers or reports (i.e. ‘grey literature’).

Stakeholder engagement

To inform our methods and description of findings, we engaged with two clinical/service topic experts (by e-mail). One (Professor Kam Bhui) was a psychiatrist and academic researcher with experience and interest in sociocultural risk and protective factors to prevent and reduce inequalities in population mental health and suicide, including understanding ethnicity as a driver of inequalities. The other expert advisor (Professor Julian Edbrooke-Childs) was a chartered research psychologist and academic researcher whose research focuses on empowering young people to actively manage their mental health and mental health care, with a particular focus on social inequalities.

Both advisors provided comments on the review protocol before it was finalised and provided valuable comments on a draft of the review’s report and findings before the discussion and conclusions had been written. The policy customers of this report, who were members of the DHSC’s mental health policy team, also had an opportunity to comment on a draft of the report (which contained the findings, draft discussion and draft conclusions).

Patient and public involvement

There was little time to recruit and involve young people from ethnic minorities early in the process of this rapid scoping review. However, through an intermediary organisation [Healthy Teen Minds (London, UK)], and using a relevant online network/e-mail list, we recruited three young black people (aged 21, 22 and 23 years, all identifying as male and with lived experience of accessing mental health support) to comment on our findings (see Scientific summary) and help us craft our Plain English summary.

Search methods

Bibliographic database searches were designed by an information specialist (SR) in consultation with the review team. Searches were carried out on 23 June 2021 in Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts [(ASSIA) ProQuest], Cumulative Index in Nursing and Allied Health Literature [(CINAHL) EBSCOhost], Health Management Information Consortium [(HMIC) Ovid], MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycInfo (Ovid), Social Policy and Practice (Ovid) and Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics).

Terms for the mental health conditions (as determined by the team) were combined with terms for the Office for National Statistics ethnic minority group categories (as defined for the 2011 national census). 25 These were further combined with terms for children and young people, and for the UK setting. 26 A qualitative study filter was added27 and studies were limited to those published from 2010 onwards. The full MEDLINE search strategy is shown in Appendix 2.

A later decision was made to limit to studies published from 2012 onwards and this was done during screening; see below. Reference lists for the final included studies were checked and forward citation chasing was carried out in Scopus (Elsevier).

Screening and study selection

As an initial calibration exercise of inclusion judgements, two reviewers applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to a subsample of search results (n = 50) and discussed the screening decisions. The calibration exercise was used to refine the clarity of the inclusion criteria to enable more consistent reviewer interpretation and judgement. This helped refine subtle boundaries/rules in applying the criteria and did not change the inclusion criteria themselves. For example, it clarified whether or not study abstracts needed to indicate if there were young people from ethnic minorities in the sample or subsample (our rule: yes, unless there was no information at all about the population characteristics, in which case investigate at full-text stage).

Following the calibration exercise, titles and abstracts of bibliographic database search results were independently screened by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Full-text articles were retrieved and independently screened by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through discussion (in consultation with a third reviewer when needed). When studies contained a subset of eligible participants, these were included when the majority of participants reflected the target population, or when data from eligible participants were reported separately. Papers excluded at the full-text stage are reported in Appendix 3.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction

A standardised data extraction template was developed in Microsoft Excel® (Excel 2013, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and piloted by two reviewers on a selection of included studies. Data were extracted separately for each study (i.e. same sample and analysis), even if the study was reported in more than one publication. For each study included at the full-text stage, information was extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second, with disagreements resolved through discussion (in consultation with a third reviewer when needed). For an overview of data extracted from studies, see Appendix 4.

Quality appraisal

The quality of each paper was assessed using the 13 criteria in the Wallace checklist,28 which is widely used to assess the quality of conduct and reporting of qualitative research. Compared with alternative tools for assessing the quality of qualitative research, our team has found the Wallace checklist to be clearer and more applicable to a wide range of types of qualitative research. The criteria cover assessment of the clarity and coherence of a study in relation to its question, theoretical perspective, study design, context, sampling, data collection methods, data analysis methods, reflexivity, generalisability and ethics. The criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by another. The quality appraisal was conducted primarily to inform methodological research recommendations, but also so that readers interested in particular studies or groups of studies could consider their independently assessed quality/reliability alongside the summarised findings.

Data presentation

The extracted data were used to categorise studies according to institutional setting or population group, or mental health needs, and aimed to describe the number of studies available for different ethnic or other groups, types of services and mental health needs. Tables were used to simplify and summarise the nature and types of studies found. The findings/themes and compelling illustrative quotations that seemed most relevant to our review objectives (i.e. about care-seeking, or accessing services or support for mental health problems) were summarised or presented.

Departures from protocol

There were two differences between the methods we used and those planned and published in our review protocol. First, we had intended to hand-search the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews identified in our searches, but we did not. Second, we had originally planned to present our findings according to the different ethnic minorities in studies, but could not, as most were based on samples of young people from many different ethnic backgrounds, including some studies with participants from both white British and ethnic minority backgrounds (see Table 1).

Chapter 4 Findings

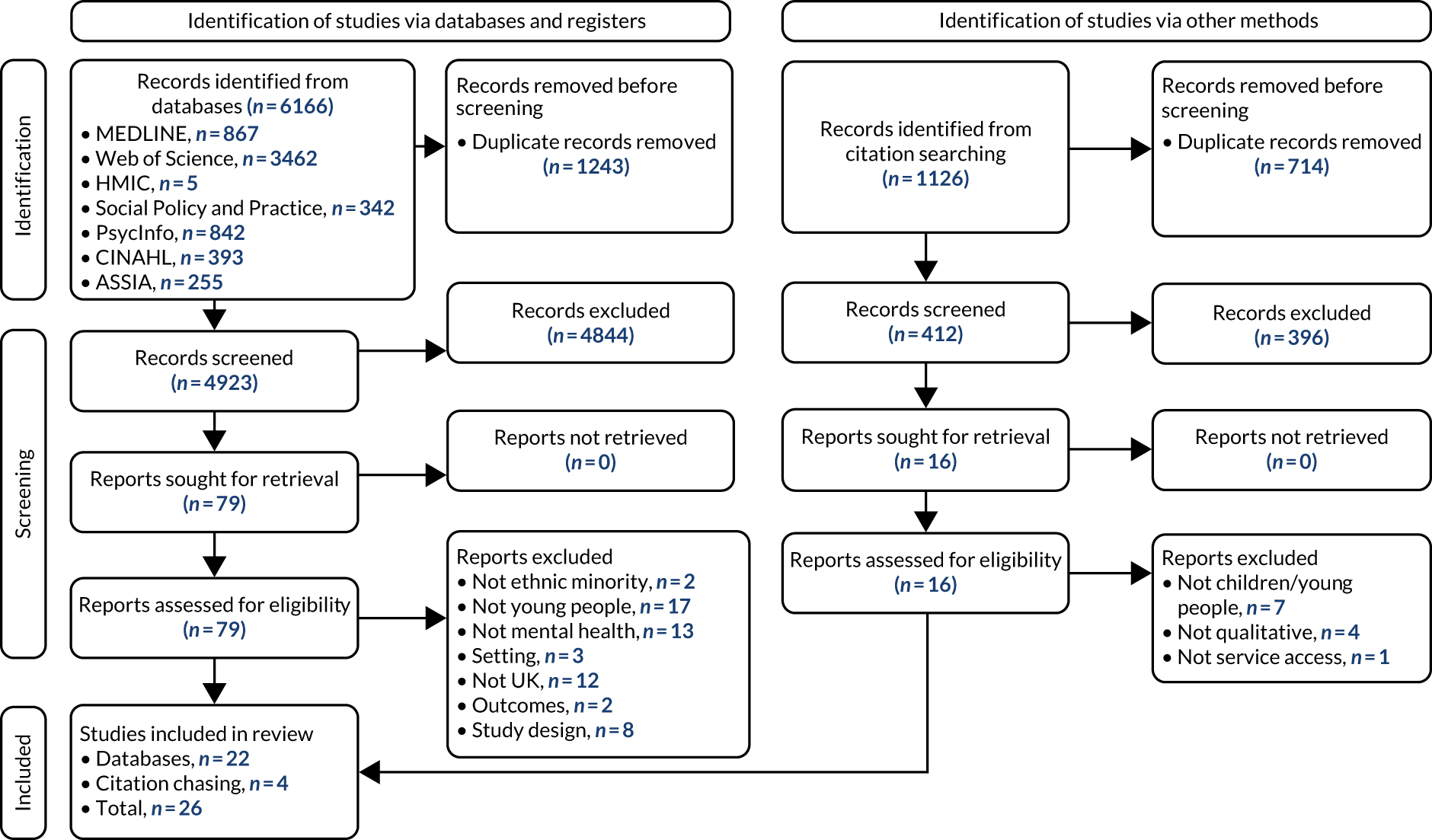

Figure 1 provides an overview of results of the searches and how the final number of included papers and studies were found from them. In total, 5335 records from searches were screened, with 26 papers/publications, reporting 22 studies, included in the final scoping review.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 flow diagram of the searches and screening process. 29

Overview of included studies

Included studies were highly heterogeneous in terms of the type of mental health need, service setting, and ethnicity and age of the young people (Table 1). Table 2 provides a fuller description of the key characteristics of all included studies.

| Ethnic group(s) in study sample | Type of mental health need | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Various or non-specific mental health difficulties | Specific needs or conditions | Receiving specific treatments | |

| Multiple ethnic groups (including some white British) |

The Children’s Society30 Birch et al. 31 |

Cadge et al. 32 (schizophrenia) Channa et al. 33 (bulimia nervosa) Klineberg34 (self-harm) |

Bunting et al.35 (multisystemic therapy) |

| Multiple ethnic groups (all non-white British) |

Fazel36 Fazel et al. 37 (stress of refugee status) Hurn and Barron38 King and Said39 |

Islam et al. 40 (psychosis) Chowbey et al. 41 (eating disorders) Kolvenbach et al. 42 (OCD) |

Gurpinar-Morgan et al.43 (CBT) |

| Single or few ethnic groups in sample |

Davies Hayon and Oates44 (most from Afghanistan) Majumder et al. 45–48 (most from Afghanistan) Olaniyan49 (black British and South Asian British) Rowland50 (Orthodox Jewish young people) Sancho and Michael51 (black African, mixed or black Caribbean young people) |

Edge and Grey52 (schizophrenia in African Caribbean and black African young people) Wales et al. 53 (eating disorders in South Asian young people) Gleeson et al. 54 (drug/crime interventions in black and Asian young people) Gray and Ralphs55 (substance abuse interventions in Pakistani and Bangladeshi young people) |

|

| First author, year; city/region | Population of interest | Health/well-being needs or services | Study aims | Methods | Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity or country of origin | Age (years) | Other population characteristics | Needs or difficulties | Services | ||||

| Birch,31 2020; Sheffield | White, Romania, Kurdistan, Islamic Republic of Iran, Sudan, Pakistan, Persian | 17–27 | Some asylum seekers | Various/not specified | (Proximity to) nature | Explore the value of urban nature for the mental health and well-being of young people | Interviews and creative art workshops | 24 young people |

| Bunting,35 2021; London | Samoa, the Netherlands, Sudan/Kenya, Georgia, Nigeria, Morocco, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq | 14–18 | Parents’ religous group: Muslim, Christian, Pentecostal, Jehovah’s Witness | Not specified, (MST is for antisocial behaviour for young people and study reports number of convictions) | MST | Explore minority ethnic young people’s experiences of MST, focusing on their understanding of their presenting difficulties and aspects of the intervention that facilitated or hindered engagement and change | Semistructured interviews | 7 young people (female, n = 4; male, n = 3) |

| Cadge,32 2019; Birmingham | Britain, Pakistan, India, African Caribbean, dual white British and African Caribbean | 18–22 | University students | Schizophrenia | Various | Explore perceptions and understanding of schizophrenia in university students | Semistructured interviews and thematic analysis | 20 university students |

| Channa,33 2019; West Midlands | British Indian | Early twenties | Within 5 years of diagnosis with eating disorder | Bulimia nervosa | Eating disorder service | Explore the experiences of a young British Indian woman with bulimia nervosa | Case study based on a single semistructured interview reanalysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis | 1 young British Indian woman |

| The Children’s Society,30 2020; London, Midlands, North East England | 9 were white, 18 were from black and other ethnic minority backgrounds | 11–21 | Two were autistic, three had learning disabilities, two were transgender | Various, including self-harm | NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Service (Tier 3/specialist service) | To answer the question: how many people really know what it is like for children and young people who are trying to get support for their mental health? | Interviews | 27 young people |

| Chowbey,41 2012; Sheffield | Pakistan, Bangladesh, Somalia, Yemen and India | 18–24 | Similar number of young men and young women | Eating disorders | SYEDA | To understand whether the use of SYEDA’s services by solely white British clients reflected a low level of need among other ethnic groups or whether there might be other factors acting as barriers to diagnosis and service access | Interviews and focus groups | 42 relatives of those with eating disorders, ‘key informants’ and community members |

| Davies Hayon,44 2019; UK | Most from Afghanistan | Various – difference-in-difference studies (literature review) | Refugees/asylum seekers (mostly unaccompanied) | Primarily PTSD, depression and anxiety | Schools and community centres | Suggesting how to enhance practice and improve outcomes for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in the UK | Systematic review | 303 young people across all studies |

| Edge,52 2018; North West England | African Caribbean | ≥ 18 | No other characteristics described | Schizophrenia | Community locations and NHS mental health services | To determine whether or not members of the African Caribbean community would be willing to partner with health-care professionals and academics to co-produce a culturally appropriate and acceptable version of an extant evidence-based, cognitive behavioural model of FI | Four focus groups | 10 service users, 14 family members/advocates, 7 health-care professionals, 11 mixture of above groups |

| Fazel,36 2015; Oxford, Glasgow, Cardiff | 20 countries | 15–24 |

Refugees (13 unaccompanied) Median time in the UK: 2.5 years 29 male, 11 female |

Various/not specified | School-based mental health service set up specifically for refugee children | Describe the role of schools in supporting the overall development of refugee children and the importance of peer interactions | In-depth semistructured interviews | 40 former users of the school-based mental health service |

| Fazel,37 2016; Oxford, Glasgow, Cardiff | Various (from 20 countries) | 15–24 |

Refugees/asylum seekers Median time in the UK: 2.5 years 29 male, 11 female |

Focus on the stresses associated with refugee status | School based | To determine the experiences of adolescents directly seen in school-based mental health services | In-depth semistructured interviews | 40 former users of the school-based mental health service |

| Gleeson,54 2019; London, the Midlands and North East England | Black and Asian | 16–24 | Recipients of youth justice and substance abuse interventions | Drug/crime interventions | Drug interventions and criminal/youth justice systems | To establish how young people from diverse ethnic backgrounds interact with drug interventions and youth/criminal justice systems in the UK | 19 individual interviews and one focus group | 25 service providers |

| Gray,55 2019; North West England | Pakistan, Bangladesh | Range unclear | Substance users | Substance use | Substance use services | Reasons for the under-representation of British South Asian people in substance use services. This paper contributes to the debate around how substance use services can best engage with young British Pakistani and Bangladeshi substance users | Interviews | 18 young people, 18 stakeholders, 6 staff members |

| Gurpinar-Morgan,43 2014; North West England | ‘Self-identified as being from a black or minority ethnic group’ | 16–18 | One male, four female | CBT users for mental health problems | CBT | This study aimed to examine BME adolescent service users’ perceptions of how ethnicity featured in the therapeutic relationship and its relevance to their presenting difficulties | Interpretative phenomenological analysis was used to explore the experiences of five young people using an adolescent mental health service | Five young people who had been accessing CBT for 4–12 months |

| Hurn,38 2018; West Yorkshire | Syria, one from Libya | 6–11.9 | Refugees/asylum seekers | Trauma, one participant had ADHD | ‘CHUMS’: mental health and emotional well-being service | To investigate whether a particular therapy would be valuable for child refugees whose trauma symptoms failed to reach CAMHS thresholds. In addition, the project aimed to identify cultural hurdles that may hinder access to Western psychological approaches | SUDS, child rating scale, therapists’ reports and interpreter focus group | Eight children, two therapists, four Arabic interpreters |

| Islam,40 2015; Birmingham | Pakistan, the Caribbean, Bengali, Africa | 18–35 | 50% female/50% male | Psychosis | EI for Psychosis Services | Examine the cultural appropriateness, accessibility and acceptability of the EI for Psychosis Services in improving the experience of care and outcomes for black and ethnic minority patients | Focus groups | 56 service users, carers, community and third-sector organisations, service commissioners, EI professionals and spiritual care representatives |

| King,39 2019; city/region not stated | Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia | 14–17 | UASC | Various/not specified | Group discussion sessions supported by the NHS | This paper outlines a psychological skills group for unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people, with a focus on cultural adaptations in the context of a UK mental health service | Interviews and session rating scales | 14 young people |

| Klineberg,34 2013; Hackney, Newham | White British, Asian, black | 15–16 | 24 female, 6 male | Self-harm (10 participants had never self-harmed, 9 had self-harmed on one occasion and 11 had self-harmed repeatedly) | Schools | To increase understanding of how adolescents in the community speak about self-harm, exploring their attitudes towards and experiences of disclosure and help-seeking | Interviews | 30 young people |

| Kolvenbach,42 2018; London | 10 from white backgrounds and 10 from ethnic minority backgrounds | 13–17 | 60% female | OCD | National specialist OCD, BDD and related disorders clinic for young people | Identify and compare barriers that parents from different ethnic groups face when accessing specialist services for OCD for their children | Interviews | 20 young people and parents |

| Majumder,45 2015; central England | Mostly Afghanistan, also Islamic Republic of Iran, Somalia and Eritrea | 15–18 | Unaccompanied refugee minors | Predominantly PTSD, depression and self-harm | CAMHS, among others | To appreciate the views and perceptions that unaccompanied minors hold of mental health and services | Semi-structured interviews | 15 young people and carers |

| Majumder,46 2016; central England | Mostly Afghanistan, also Islamic Republic of Iran, Somalia and Eritrea | 15–18 | Unaccompanied refugee minors. Mostly male. English as a second language | Depression, self-harm, PTSD, anxiety, adjustment reaction, substance misuse, impaired sleep | CAMHS | What are the perceived resilience factors that can lead to better psychological coping and mental health outcomes in unaccompanied refugee minors? | Interviews and thematic analysis | 15 young people and carers |

| Majumder,48 2019; central England | Mostly Afghanistan, also Islamic Republic of Iran, Somalia and Eritrea | 15–18 | Unaccompanied refugee minors. Mostly male. English as a second language | Depression, self-harm, PTSD, anxiety, adjustment reaction, substance misuse, impaired sleep | CAMHS | To explore unaccompanied refugee children’s experiences, perceptions and beliefs of mental illness, focusing on stigma | Interviews and thematic analysis | 15 young people and carers |

| Majumder,47 2019; central England | Mostly Afghanistan, also Islamic Republic of Iran, Somalia and Eritrea | 15–18 | Unaccompanied refugee minors. Mostly male. English as a second language | Depression, self-harm, PTSD, anxiety, adjustment reaction, substance misuse, impaired sleep | CAMHS | Research questions: ‘what are the perceptions of unaccompanied refugee minors of their treatment and practitioner and what does that teach us about engagement?’ | Interviews and thematic analysis | 15 young people and carers |

| Olaniyan,49 2021; West Midlands | Black British, South Asian British | Unclear | University students from two universities: one with low and one with high REM participation | Various | University mental health services | To examine the influence of the university environment on the mental health and help-seeking attitudes of REM undergraduate students, evaluating their experiences at a Russell Group university with low REM participation and a neighbouring non-Russell Group university with high REM participation | Interviews | 48 young people |

| Rowland,50 2016; Hackney | Orthodox Jewish | Children and young people aged 1–22 | From families of between one and five children | Unspecified/various | Tier 2 NHS mental health services | Consider the experiences of Orthodox Jewish parents who have accessed CAMHS to seek help for their families. Consider whether there are barriers that have to be overcome to access services from outside the Orthodox community and how these are experienced. Whether or not there may be particular concerns about accessing a mental health service for children | Semistructured interviews and thematic analysis | 9 parents |

| Sancho,51 2020; Birmingham | Black African, mixed or black Caribbean heritage | 18–25 | Undergraduate students, lived in the UK for a minimum of 5 years. Majority were psychology students | Various/not specified | Not specified | Understand the barriers and facilitators that African Caribbean undergraduates perceive to accessing mental health services in the UK | Focus groups (critical incident technique) | 17 young people |

| Wales,53 2017; Leicester | South Asian | < 25 (another focus group was for those aged 25–65) | University students | Eating disorders | Specialised eating disorder clinic | Identify barriers to help-seeking for eating disorders among those from a South-Asian background | Focus groups | 28 young people and 16 clinicians |

Note that the labels and categories used in the table (e.g. to describe the ethnicity of the samples) are those used in the original studies. By today’s conventions, we acknowledge that some of these labels [such as the acronym BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic)] may no longer be seen as appropriate, that they may not reflect people’s self-perceived ethnic background and cultural identity, and that they may be a poor reflection of the true diversity among young people from different minority ethnic backgrounds.

Seven studies36–43 included a mixture of young people from different non-white British ethnic minority backgrounds, and six others30–35 had a mixture of young people from different ethnic minorities that also included some white British young people. Other studies were conducted in more specific, selected ethnic groups (black and Asian young people,54 Orthodox Jewish young people,50 South Asian young people,53 Pakistani and Bangladeshi young people,55 black British and South Asian British students,49 and mainly Afghan refugees45–48).

The populations of interest varied and included unaccompanied teenage refugees (typically from a wide range of Middle Eastern or North African countries), university students, school students and the general population of young people from different ethnic groups and with different mental health needs. Most studies were local to a particular British city or region, although four studies30,36,37,44,54 had study participants from several cities or regions across the UK. There was no evidence that any studies had been conducted among young people living in the south-west of England, or the south-east of England outside London, and only one study36,37 included some participants from Wales (Cardiff) or Scotland (Glasgow).

Correspondingly, given these different service contexts and populations of interest, the age range of the young people in the study samples also varied. In six studies31–33,40,41,51 the young people were all or mostly aged ≥ 18 years, and in seven studies34,35,38,39,42,43,45–48 they were all or mostly aged < 18 years. In six studies30,36,37,50,53,54 there was a wider age range, including children (aged < 16 years), older teenagers and those in their twenties.

The included studies have primarily been summarised in four overlapping groups:

-

studies of young people in particular circumstances or institutional settings (e.g. university students, refugees/asylum seekers) (n = 9)

-

studies among people with specific mental health needs (e.g. schizophrenia or psychosis, eating disorders, self-harm) (n = 14)

-

studies among people receiving specific treatments (e.g. CBT, multisystemic therapy) (n = 3)

-

other studies not already covered in the first three groups (n = 1).

It should be noted that the above four groups of studies are not mutually exclusive. For an outline of which studies are covered in which findings section of this report, see Table 3. For example, of the four studies about access to mental health care among university students, one32 was about experiences of living with schizophrenia while at university, and another53 was about barriers to help-seeking for eating disorders among South Asian students. As social stigma was a recurring factor affecting care-seeking and access to mental health services and support across a number of need groups and settings, there is a section summarising the relevant findings from across studies in which this was a key factor affecting service use or engagement.

| First author, year | Paper title(s) | Report section | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refugees/asylum seekers | University students | Studies among people with specific mental health needs | Studies about accessing and engaging with specific interventions | Stigma as a barrier to accessing or seeking help | Studies on access to other resources or support | ||

| Davies Hayon,44 2019 | The mental health service needs and experiences of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in the UK: a literature review | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Fazel,36 2015 | A moment of change: facilitating refugee children’s mental health in UK schools | ✓ | |||||

| Fazel,37 2016 | The right location? Experiences of refugee adolescents seen by school-based mental health services | ✓ | |||||

| Hurn,38 2018 | The EMDR integrative group treatment protocol in a psychosocial program for refugee children: a qualitative pilot study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| King,39 2019 | Working with unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people: cultural considerations and acceptability of a cognitive behavioural group approach | ✓ | |||||

| Majumder,45 2015 | ‘This doctor, I not trust him, I’m not safe’: the perceptions of mental health and services by unaccompanied refugee adolescents | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Majumder,46 2016 | ‘Inoculated in pain’: examining resilience in refugee children in an attempt to elicit possible underlying psychological and ecological drivers of migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Majumder,48 2019 | Exploring stigma and its effect on access to mental health services in unaccompanied refugee children | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Majumder,47 2019 | Potential barriers in the therapeutic relationship in unaccompanied refugee minors in mental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Cadge,32 2019 | University students’ understanding and perceptions of schizophrenia in the UK: a qualitative study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Olaniyan,49 2021 | Paying the widening participation penalty: racial and ethnic minority students and mental health in British universities | ✓ | |||||

| Sancho,51 2020 | ‘We need to slowly break down this barrier’: understanding the barriers and facilitators that African Caribbean undergraduates perceive towards accessing mental health services in the UK | ✓ | |||||

| Wales,53 2017 | Exploring barriers to South Asian help-seeking for eating disorders | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Edge,52 2018 | An assets-based approach to co-producing a Culturally Adapted Family Intervention (CaFI) with African Caribbeans diagnosed with schizophrenia and their families | ✓ | |||||

| Islam,40 2015 | Black and minority ethnic groups’ perception and experience of early intervention in psychosis services in the United Kingdom | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| The Children’s Society,30 2020 | Waiting in line: stories of young people accessing mental health support | ✓ | |||||

| Klineberg,34 2013 | How do adolescents talk about self-harm: a qualitative study of disclosure in an ethnically diverse urban population in England | ✓ | |||||

| Chowbey,41 2021 | Influences on diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders among minority ethnic people in the UK | ✓ | |||||

| Channa,33 2019 | Overlaps and disjunctures: a cultural case study of a British Indian young woman’s experiences of bulimia nervosa | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Gleeson,54 2019 | Challenges to providing culturally sensitive drug interventions for BAME groups within UK youth justice systems | ✓ | |||||

| Gray,55 2019 | Confidentiality and cultural competence? The realities of engaging young British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis into substance use services | ✓ | |||||

| Kolvenbach,42 2018 | Perceived treatment barriers and experiences in the use of services for obsessive–compulsive disorder across different ethnic groups: a thematic analysis | ✓ | |||||

| Bunting,35 2021 | Considerations for minority ethnic young people in multi-systemic therapy | ✓ | |||||

| Gurpinar Morgan,43 2014 | Ethnicity and the therapeutic relationship: views of young people accessing cognitive behavioural therapy | ✓ | |||||

| Rowland,50 2016 | How do parents within the orthodox Jewish community experience accessing a community child and adolescent mental health service? | ✓ | |||||

| Birch,31 2020 | Nature does not judge you – how urban nature supports young people’s mental health and wellbeing in a diverse UK city | ✓ | |||||

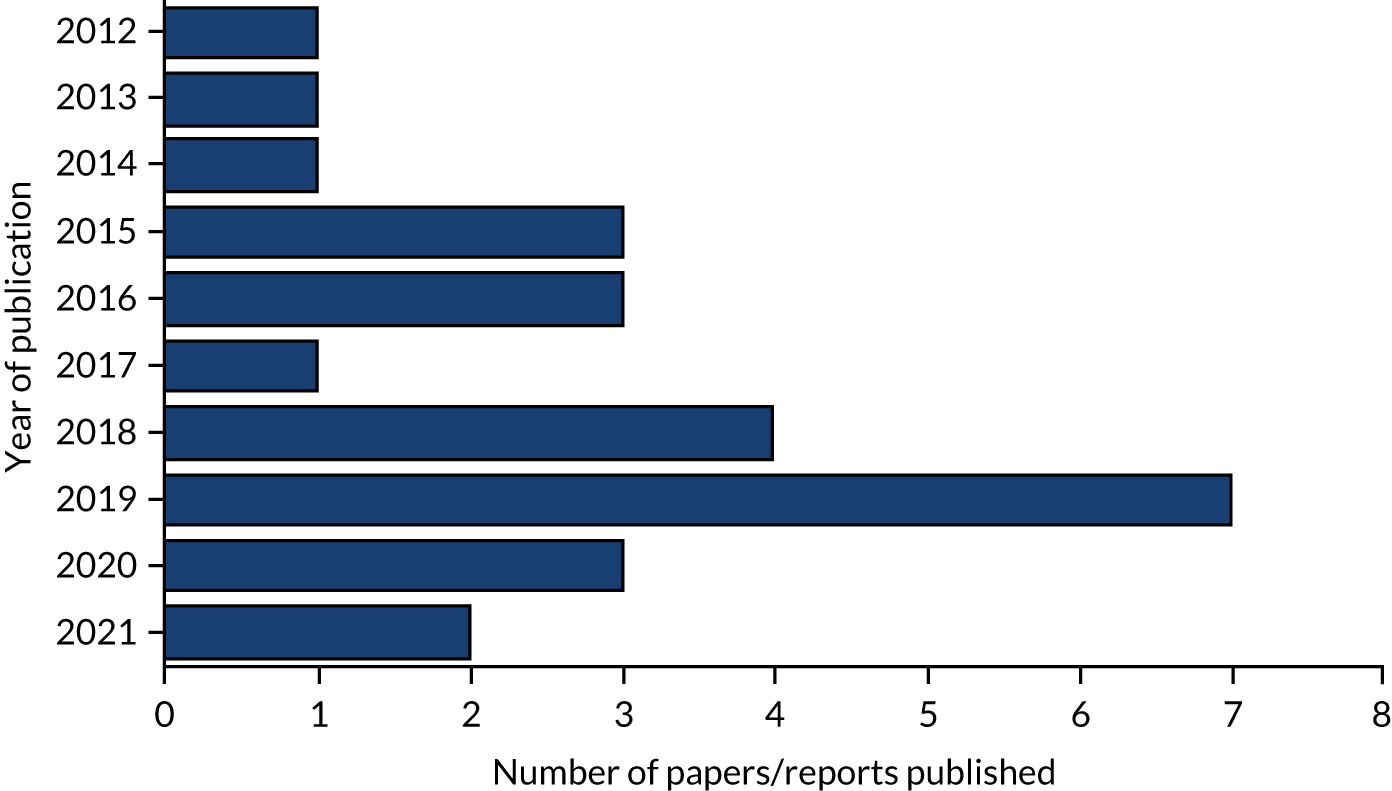

Figure 2 shows that the majority of the papers or reports found were published quite recently within the 10-year period, with 16 published from 2018 onwards and five published in 2020 or 2021. 30,31,35,49,51 However, this may not reflect the years in which the studies were actually conducted (for example, the four papers by Majumder45–48 – published in 2015, 2016 and 2019 – were based on analyses of mental health service use in 2010 and 2011).

FIGURE 2.

Number of papers by year of publication.

Quality of included papers

The quality assessment of the included papers is shown in Table 4. We assessed the quality of each included paper or report (rather than each study) because many of the quality criteria in the Wallace checklist relate to how well studies describe and justify what they did and what they found, and this may vary between papers and analyses conducted for different purposes. 28

| First author, year | 1. Question | 2. Theoretical perspective | 3. Study design | 4. Context | 5. Sampling | 6. Data collection | 7. Data analysis | 8. Reflexivity | 9. Generalisability | 10. Ethics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the research question clear? | Is the theoretical or ideological perspective of the author (or funder) explicit? | Has this influenced the study design, methods or research findings? | Is the study design appropriate to answer the question? | Is the context or setting adequately described? | Is the sample adequate to explore the range of subjects and settings, and has it been drawn from an appropriate population? | Was the data collection adequately described? | Was data collection rigorously conducted to ensure confidence in the findings? | Was there evidence that the data analysis was rigorously conducted to ensure confidence in the findings? | Are the findings substantiated by the data? | Has consideration been given to any limitations of the methods or data that may have affected the results? | Do any claims to generalisability follow logically and theoretically from the data? | Have ethical issues been addressed and confidentiality respected? | |

| Birch,31 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bunting,35 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cadge 201932 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Channa,33 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| The Children’s30 Society, 2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | |

| Chowbey,41 2012 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Davies Hayon,44 2019 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | |

| Edge,52 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Fazel,36 2015 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | |

| Fazel,37 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Gleeson,54 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Gray,55 2019 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | |

| Gurpinar-Morgan,43 2014 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Hurn,38 2018 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Islam,40 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes |

| King,39 2019 | No | No | Cannot tell | No | Yes | No | Cannot tell | No | Cannot tell | No | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Klineberg,34 2013 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Kolvenbach,42 2018 | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell |

| Majumder,45 2015 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Majumder,46 2016 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Majumder,48 2019 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Majumder,47 2019 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Olaniyan,49 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rowland,50 2016 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Sancho,51 2020 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | |

| Wales,53 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

Overall, the majority of papers were of good quality and were sufficiently well reported to identify information about the aims, methods of data collection, and approaches to data analysis and interpretation. Seventeen of the 26 papers addressed > 10 of the 13 quality questions. The nine lower-quality papers, meeting < 10 of the 13 criteria, were those by Bunting et al. ,35 The Children’s Society,30 Chowbey et al. ,41 Davies Hayon and Oates,44 Fazel et al. ,36,37 Gleeson et al. ,54 Gray and Ralphs,55 and King and Said. 39

The most poorly reported aspect of studies was whether or not any claims to generalisability followed logically and theoretically from the data: in the papers by Bunting et al. 35 and Channa et al. ,33 the claims did not appear to clearly follow the data, and in a further 1730,34,36–41,43–47,51,52,54,55 of the 26 papers there was insufficient evidence to judge this. Other quality criteria frequently not met were making explicit the theoretical or ideological perspective of the author (or funder) (not met by 15 papers30,32,36,38,39,41,43–48,50,51,55) and giving consideration to any limitations of the methods or data that may have affected the results (not met by eight papers30,33,36,39,41,45,52,54). The methods of data collection were also judged not to be adequately described in nine of the papers. 35–37,39–41,49,54,55

Refugees/asylum seekers

Five studies focused on the mental health experiences of, and support or service use by asylum seekers and refugees; these were reported in nine papers, four of which were based on the same data set from the same lead author, Majumder, and two were on the same data set from Fazel et al. (Fazel,36 Fazel et al. ,37 King and Said,39 Davies Hayon and Oates,44 Hurn and Barron,38 Majumder45–48) (Table 5). In addition, Birch et al. 31 included some limited data from refugees; however, these are reported separately in Studies on access to other resources or support, as they focused on exposure to nature as a determinant of mental well-being, rather than access to formal mental health services.

| First author, year; city/region | Population of interest | Health/well-being needs/services | Study aims | Methods | Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Age (years) | Other population characteristics | Needs | Services | ||||

| Davies Hayon,44 2019; UK | Most from Afghanistan | Various (literature review) | Refugees/asylum seekers (mostly unaccompanied) | Primarily PTSD, depression and anxiety | Schools and community centres | Suggesting how to enhance practice and improve outcomes for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in the UK | Systematic review | 303 young people across all studies |

| Fazel,36,37 2015 and 2016 Oxford, Glasgow, Cardiff | Various (from 20 countries) | 15–24 |

Refugees (13 unaccompanied) Median time in the UK: 2.5 years |

Various/not specified Focus on the stresses associated with refugee status37 |

School-based mental health service set up specifically for refugee children |

Describe the role of schools in supporting the overall development of refugee children and the importance of peer interactions36 To determine the experiences of adolescents directly seen in school-based mental health services37 |

Semistructured interviews | 40 former service users |

| Hurn,38 2018 West Yorkshire | Syrian, one Libyan | 6–11.1 | Refugees/asylum seekers | Trauma, one participant had ADHD | CHUMS: mental health and emotional well-being service | To investigate whether a particular therapy would be valuable for child refugees whose trauma symptoms failed to reach CAMHS thresholds. In addition, the project aimed to identify cultural hurdles that may hinder access to Western psychological approaches | SUDS, child rating scale, therapists’ reports and interpreter focus group | Eight children, two therapists and four Arabic interpreters |

| King,39 2019; city/region not stated | Afghan, Ethiopian, Sudanese, Somalian | 14–17 | UASC | Various/not specified | Group discussion sessions supported by the NHS | This paper outlines a psychological skills group for unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people, with a focus on cultural adaptations in the context of a UK mental health service | Interviews and session rating scales | 14 young people |

| Majumder,45–48 2015, 2016, 2019 and 2019; central England | Mostly Afghan, also Iranian, Somalian and Eritrean | 15–18 | Unaccompanied refugee minors | Predominantly PTSD, depression and self-harm | CAMHS, among others |

The aim of this research is to appreciate the views and perceptions that unaccompanied minors hold about mental health and services45 What are the perceived resilience factors that can lead to better psychological coping and mental health outcomes in unaccompanied refugee minors?46 To explore unaccompanied refugee children’s experiences, perceptions and beliefs of mental illness, focusing on stigma48 Research questions ‘what are the perceptions of unaccompanied refugee minors of their treatment and practitioner and what does that teach us about engagement?’47 |

Semistructured interviews | 15 young people and carers |

The studies carried out among refugees and asylum seekers included some specific factors that suppressed acknowledgement of mental illness. Some extreme negative associations were expressed about mental ill health, raising concerns among young people that they would be treated with prejudice and rejection by friends and family if they were labelled as having a mental health issue:48

. . . For them it was mad, they are mad. So they should be put in mad asylums.

Carer48

. . . So sometime my friends don’t wants to be with me because I’ve got this problem.

Young person48

These fears could be compounded by mistrust of mental health services, the origin of which was attributed by some to their experiences in their home country and their experiences as a refugee:45

. . . didn’t say to anything about my problem, I didn’t tell it to anybody, you know, because I don’t trust anybody.

Type of participant not given45

In some cases, it was implied that this mistrust was associated with a fear of incarceration in a mental health facility:48

I say no I don’t want to go hospital to be with the mentals or that kind of people.

Type of participant not given48

Davies Hayon and Oates44 recognised the role that nurses can play in overcoming this mistrust among young refugees. However, to be in contact with mental health nurses, young people must already be engaged with the service. Breaking down negative perceptions could therefore be key to overcoming this initial barrier to access.

Some interviewee comments indicated that refugee minors may access mental health services via non-traditional routes, more frequently going through local authorities and teachers than following visits to a general practitioner (GP):44

When I joined the high school yeah . . . I tell my the teacher . . . I have this problem which can make me not concentrate . . . and she advised me to see X.

Type of participant not given44

The location of services may also be important in ensuring that refugees feel comfortable making contact. For example, Fazel et al. 37 found that two-thirds of participants preferred to be seen at school. However, experiences reported at school were varied, with some participants avoiding telling their teachers about their background as an asylum seeker for fear that they would be treated differently:

Just some of them, not all of them, just some of the teachers . . . they are like racist or . . . yeah and or like some of them would be really nice . . . We do want them to be nice, we want them to treat us like other students.

Brother37

Similarly, Davies Hayon and Oates44 highlighted the importance of being able to access mental health support via facilities commonly used by the population in question, including community centres.

In addition, the content of services could be improved through being tailored to suit the communication needs of refugees (e.g. accounting for culture, language, age and experiences). One example is that the Arabic-speaking service users involved in Hurn and Barron’s38 study preferred oral communication to paper-based assessment (perhaps relating to other general fears among refugees around filling and signing forms). They also preferred to have direct instructions rather than a more flexible approach.

Another theme seen in the predominantly Afghan population of Majumder’s45 study was a preference for medication over talking therapies. This was attributed to the participants preferring to look forward, and seeing being positive as a better alternative to reliving traumatic experiences in their home country:

That doesn’t helps me . . . that makes me more hard because um the all the time I was talking about the past . . . so every time I went there . . . reminding me after I went home again . . . same depression and same problems.

Type of participant not given45

Language and culture were also commonly cited as barriers to effective engagement once services had been accessed. In some cases, service users reported trusting English-speaking facilitators; however, they felt better understood when they could communicate in their native language. 47 Facilitators mentioned that the use of an interpreter could make it more difficult for them to control sessions, as interpreters occasionally went beyond what was actually said. 38 This was reported as a particular challenge to overcome in ensuring that facilitators can effectively treat young people while making them feel as comfortable as possible.

The background of mental health service facilitators was another aspect that was discussed. 47 Some of the participants mentioned a lack of trust in Asian practitioners in particular, although the reason for this was not explored. In addition, some reported being more likely to open up about their issues with a male practitioner47 (although it was not stated whether it was male or female service users who felt this). This was attributed by the authors to the cultural attitudes of study participants, in which it may be important to protect females from stressors:

To S [young person], women need to be protected, women need to just see the soft side of things and don’t have to suffer, and if there is any burden of suffering, it is good for the man to carry this burden and not for a woman . . .

Carer47

King and Said39 reported on a service that was successful with unaccompanied asylum seekers in a group cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) setting:

Before I came to the group I felt very sad and worried, since coming here I have opened up and I feel relaxed.

Male, 17, Somalian39

Participants valued both the content of the sessions and the opportunity to meet peers in similar positions to themselves. In addition, they appreciated that the group was kept flexible to cater for their needs and that the group setting helped normalise the process:39

I come here and saw everyone that has problems just like me. Everyone is working together to help each other.

Male, 17, Somalian39

This was a seen as a successful programme for these asylum seekers, which saw good rates of repeat attendance, overcoming a significant obstacle to service provision. One further possibility for improving access to services, considered by Hurn and Barron38 was providing rewards for attendance at mental health appointments. One example given was an educational reward, as education is often highly regarded by refugees; in this case a family trip to the Yorkshire Dales was added as a fourth and more activity-based education session.

University students

Four studies included a focus on understanding the mental health care-seeking experiences of undergraduate students from ethnic minority backgrounds. 32,49,51,53 These four papers focused on the experiences of African Caribbean students in accessing mental health services,51 the mental health and help-seeking experiences of black British and South Asian British students at two universities,49 South Asian students with eating disorders53 and students of various ethnicities living with schizophrenia. 32

The main features of these studies are summarised in Table 6, below.

| First author, year; city/region | Population of interest | Health/well-being needs/services | Study aims | Methods | Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Age (years) | Other population characteristics | Needs | Services | ||||

| Cadge,32 2019; Birmingham | British, Pakistani, Indian, African Caribbean, dual white British and African Caribbean | 18–22 | University students | Schizophrenia | Various | Explore perceptions and understanding of schizophrenia in university students | Semistructured interviews and thematic analysis | 20 university students |

| Sancho,51 2020; Birmingham | Black African, mixed or black Caribbean heritage | 18–25 | Undergraduate students who had lived in the UK for a minimum of five years. Majority were psychology students | Various/not specified | Not specified | Understand the barriers and facilitators that African Caribbean undergraduates perceive to accessing mental health services in the UK | Focus groups (critical incident technique) | 17 young people |

| Olaniyan,49 2021; city not named | Black British and South Asian British | Unclear | University students from two universities: one with low and one with high REM participation | Various | University mental health services | To examine the influence of the university environment on the mental health and help-seeking attitudes of REM undergraduate students, evaluating their experiences at a Russell Group university with low REM participation and a neighbouring non-Russell Group university with high REM participation | Interviews | 48 young people |

| Wales,53 2017; Leicester | South Asian | < 25 | University students | Eating disorders | Specialised eating disorder clinic | Identify barriers to help-seeking for eating disorders among those from a South Asian background | Focus groups | 28 young people and 16 clinicians |

In three of the studies,32,51,53 interviewees reported a lack of knowledge and understanding of the relevant mental health issue, although this theme was more prominent in the studies of Cadge et al. 32 and Wales et al. ,53 which focused on specific mental health conditions. In contrast, the study51 focusing on experiences of African Caribbean students identified a lack of trust in the services to which the students had access. Misdiagnosis was raised as an issue, with some (services or professionals) missing the signs of the mental health problem. When interviewees recognised a mental health issue themselves, there was an indication that they may not seek help owing to underappreciating the severity or seriousness of the issue:

I just think [. . .] eating disorders they’re easily fixed so why go seek help if you can do it yourself?

Male, < 25 years53

A similar quotation was found in Cadge et al. ’s32 paper, which focused on schizophrenia:

It’s all well saying I’d probably seek help but I honestly don’t think I would . . . you think you’re strong enough to probably get over it yourself.

Keshini (pseudonym), Indian32

This illustrates that, for some problems, the perceived expectation that young people can just ‘get over it’ (implicitly, on their own) is itself a barrier to help-seeking and may stem from views within their communities. This may be particularly the case for male participants:

Where I am from, men need to be in control, we are head of the home. I’m the first boy and in my culture that’s a big deal.

Type of participant not given49

Indeed, the perceived need to deal with issues alone, combined with a lack of knowledge around conditions and lack of available support, may be linked with internal conflict between interviewees’ Western beliefs and those of their religion and community:

I think I’m quite Western in the way I think about this but I know there’s a spiritual aspect to these things too.

Type of participant not given49

A related theme that emerged through these papers was stigma, although this was not exclusive to university students (see later section on the stigma findings, Stigma as a barrier to accessing or seeking help, for more details). For example, the study by Sancho and Michael,51 which included African Caribbean students, found that students, particularly those identifying as male, felt that they have to conform to certain ideals, and that having a mental health issue would depart from this. More generally, having a mental health issue may be less commonly discussed in some ethnic minority groups

In my community . . . they’re like this doesn’t exist . . . it’s a white person thing.

Waqas (pseudonym), Pakistani32

For some, religious beliefs might either deter care-seeking or provide an additional source of support and advice. In the study exploring the experiences of African Caribbean students,51 religion appeared to add to the stigma of mental health issues. In contrast, in the study by Wales et al.,53 which included South Asian students with schizophrenia, it was highlighted that religion or the religious community and leaders might be the first point of access to mental health support (before accessing formal or professional support).

If ethnic minority students feel that they are misdiagnosed, or that health professionals and services miss signs of mental health issues and that they are on their own dealing with these issues, then it is clear that ethnic minority students will need as much information and help as possible to understand what services are available to them. Students in the Wales et al. 53 and Sancho and Michael51 studies also suggested that the promotion of available support services is inadequate. Students in both studies highlighted the importance of publicity, and of ensuring that campaigns reach ethnic minority students by placing leaflets and posters in areas around the university most frequently accessed by students from these communities. 49

Studies among people with specific mental health needs

There were 13 studies, published in 16 papers,32–34,38,40–42,44–48,52–55 about seeking or accessing care for specific mental health needs. These studies related to young people with PTSD or trauma (n = 3, already described as part of Refugees/asylum seekers), schizophrenia or psychosis (n = 3), risk/experiences of self-harm (n = 2), eating disorders (n = 3), substance abuse problems (n = 2) and OCD (n = 1).

Post-traumatic stress disorder/trauma

There were three studies in which PTSD or past trauma was the main area of mental health need, reported in six publications, four of which were from the same data set and had the same lead author. 45–48 The other two studies focused on the needs and barriers to care of asylum-seeking children from war-affected countries (Afghanistan,44 and Syria and Libya38).

Key findings and insights from these studies have already been summarised in the section on refugees and asylum seekers as a distinct population group (see Refugees/asylum seekers).

Schizophrenia or psychosis

In three studies, published in three papers, participants were young people with schizophrenia or psychosis. 32,40,52 The key characteristics of these three studies are summarised in Table 7. People with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia can be especially stigmatised, and findings related to stigma from these studies are presented in Stigma as a barrier to accessing or seeking help.

| First author, year; city/region | Population of interest | Health/well-being needs/services | Study aims | Methods | Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Age (years) | Other population characteristics | Needs or difficulties | Services | ||||

| Cadge,32 2019; Birmingham | British, Pakistani, Indian, African Caribbean, dual white British and African Caribbean | 18–22 | University students | Schizophrenia | Various | Explore perceptions and understanding of schizophrenia in university students | Semistructured interviews and a thematic analysis | 20 university students |

| Edge,52 2018; North West England | African Caribbean | ≥ 18 | No other characteristics described | Schizophrenia | Community locations and NHS mental health services | To determine whether or not members of the African Caribbean community would be willing to partner with health-care professionals and academics to co-produce a culturally appropriate and acceptable version of an extant evidence-based, cognitive–behavioural model of FI | Four focus groups | 31 service users, family members, professionals, advocates |

| Islam,40 2015; Birmingham | Pakistani, Caribbean, Bengali, African | 18–35 | 50% female/50% male | Psychosis | EI for psychosis services | Examine the cultural appropriateness, accessibility and acceptability of the EI for Psychosis Services in improving the experience of care and outcomes for black and ethnic minority patients | Focus groups | 56 service users, carers, community and third-sector organisations, service commissioner, EI professionals and spiritual care representatives |

These studies highlighted how a lack of cultural adaptation to services can act as a barrier to accessing mental health care or engaging in treatment. For example, in the Edge and Grey52 study, young people from African Caribbean backgrounds suggested that their inclusion in talking therapies could be increased through the use of story-telling, pictures and other non-literary formats of communication. In the Cadge et al. 32 study, care-seeking was also affected by perceptions of the causes being uncontrollable (e.g. genetic) or beyond health care (e.g. spiritual causes). Indeed, in the Islam et al. 40 study, service users suggested that they would be more likely to seek spiritual/religious and/or cultural explanations of symptoms in the first instance. However, when service users recognised severe mental illness, they feared accessing services owing to associations with punishment and being compulsorily detained (‘sectioned’).

Access to formal mental health services might be further hindered by misconceptions about the scope of the care provided by GPs:32

With something that’s a mental illness there has to be some therapy from like experts.

Waqas (pseudonym), Pakistani32

The Islam et al. 40 study echoed the reluctance to see GPs about such problems, but, in this study, this was because parents/carers felt that they would not be listened to and understood.

Self-harm

Two studies, reported in two papers,30,34 specifically focused on self-harm in young people, who were mostly from non-white ethnic backgrounds. Both studies were based on interviews with small samples and included white British young people as well as those from ethnic minority backgrounds. The Klineberg study34 was carried out in younger people who were still at school, including some who had never self-harmed, and The Children’s Society study30 was also not exclusively carried out in those who had self-harmed.

Among young people in both studies, there was a perceived lack of understanding of the help that was available for those self-harming, and a fear of what family or friends might say if they knew. However, in the case of some participants in the study by Klineberg,34 the self-harm was described as a means to alert others of a deteriorating mental state:

I wasn’t a good talker, like, back then, so . . . that’s why I knew that they would kind of help me in some way.

Male, 15 years, Asian, repeated self-harm34

Parents/carers were seen by some young people as more useful and easier to talk to than a mental health service. This view came through even more strongly in The Children’s Society study,30 which also reported that boys find it more challenging to seek help than girls. Teachers were not often approached owing to fears of non-confidentiality, and some participants did not consider self-harm a big enough concern to seek help.

The views of young people who had never experienced self-harm may create shame among those experiencing this mental health issue and, therefore, a barrier to help-seeking. One participant in the Klineberg study34 who had never self-harmed said:

I don’t like people who purposefully like try and attention seeking and like who go to hospital and waste doctors’ time . . . I think if you’re going to do it, yeah, do it properly, yeah? If you really want to hurt yourself, die or whatever, then just do it, yeah?

Female, 15 years, mixed ethnicity34

Eating disorders

Three studies, published in three papers,33,41,53 specifically focused on help-seeking and access to care for young people with eating disorders. One of these studies53 was among South Asian university students and another41 among young people from a range of ethnic minority backgrounds (including those from Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Somali, Yemeni and Indian backgrounds). The third study33 was a qualitative case study mainly based on qualitative re-analysis of an interview with one young British Indian woman with bulimia nervosa.

The study by Chowbey et al. 41 was aimed at understanding barriers to accessing a specialist eating disorder service in Sheffield, and based on interviews with relatives of those with eating disorders, ‘key informants’ (not further elaborated) and community members. The primary challenge identified in the study was a lack of awareness of the problem of eating disorders:

Parents are not aware of eating disorders. I have noticed tell-tale signs in some youngsters but parents are not worried.

Type of participant not given41