Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HSDR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR133541. The contractual start date was in November 2020. The final report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Chambers et al. This work was produced by Chambers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Chambers et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Cognitive impairment is an overarching term that refers to deficits in one or more of the areas of memory, problems with communication, attention, thinking and judgement. Impairment can range from mild to severe. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is defined as objective cognitive symptoms (e.g. memory problems) in the absence of dementia. 1 MCI is common in older people, affecting 20% of those aged > 65 years. 1 Subjective cognitive decline (SCD), in which people report problems but perform normally on cognitive tests, affects half of those aged > 65 years.

Although most people with MCI do not go on to develop dementia, the condition is associated with increased dementia risk, and this may lead people with MCI (or SCD) to seek help from health services. People with MCI may also be identified as a result of treatment for other conditions in a range of settings.

In the UK, the 2009 National Dementia Strategy2 and associated Prime Minister’s challenge3 emphasised the importance of prevention and prompt diagnosis, both of which involve a focus on people with MCI and other memory problems. The responsibility for prevention of dementia and support for people with the condition is divided between public health, the NHS and social care, although recent policy increasingly favours the integration of health and social care. Health and social care are devolved matters, with some differences between the nations of the UK.

Access to services for people with MCI is a complex issue. Lifestyle changes can reduce modifiable risk factors for dementia, including cardiometabolic dysfunction (i.e. diabetes and cardiovascular risks), physical inactivity, social isolation, hearing loss, mental illness, alcohol and smoking. 1 Although there are numerous interventions aimed at modifying lifestyle, there appear to be no evidence-based interventions aimed specifically at preventing dementia and suitable for delivery on a large scale. Responsibility for preventing dementia also falls into a grey area between public health (i.e. the responsibility of local authorities) and the NHS. A review of policies and strategies for dementia prevention in England found limited evidence for their implementation at the clinical level. 4 NHS memory services are limited to people with a diagnosis of dementia and are unable to help those with MCI beyond ‘signposting’ to other services. 1 Although early identification of people with MCI may facilitate monitoring, those who do not meet criteria for referral to memory services may remain on their general practitioner (GP)’s books without access to specialist services.

The current configuration of services leads some health professionals to question the value of identifying people with MCI. These health professionals argue that a ‘label’ of MCI may worsen anxiety or other mental health problems without offering access to effective treatments that are not otherwise available. On the other hand, prevention of dementia is a high priority for those directly affected and society as a whole.

In 2017, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme issued a call for research into cognitive impairment. The response to this call was limited. The HSDR programme team requested that the Sheffield HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre review the current evidence base, taking different perspectives into account, to identify key implications for research and service delivery.

An initial scoping search of the MEDLINE database (November 2020) identified some potentially relevant papers. In particular, a consensus meeting held in Manchester in 2019 led to the publication of a clinical guideline on MCI in November 2020. 5 The authors stated that the guideline covers ‘the use of neuroimaging, fluid biomarkers, cognitive testing, follow-up and diagnostic terminology’ in MCI. 5 Although clearly important for UK practice, this guideline does not cover the full range of topics of interest to the HSDR programme. Indeed, one of the authors’ key recommendations is that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) should produce guidance on MCI. In the absence of such guidance, a targeted evidence review may be of value to both research commissioners and decision-makers in health and social care.

Chapter 2 Overview of methods

Patient and public involvement

The Sheffield HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre’s strategic Public Advisory Group were involved from the outset of the review. The group commented on the review scope, including whether or not the research questions were the right ones, what they thought were the most important outcomes, if there was anything else they thought should be covered and what might be the priority areas for the public, before the protocol was finalised. A topic-specific patient and public involvement group was set up with the assistance of members of the Strategic Advisory Group. This group provided further input on their experience of services for people with MCI and the advantages and disadvantages of MCI as a diagnostic label. Near the end of the review, there was a second meeting where the patient and public involvement group commented on the review findings and were involved in writing the Plain English summary. A further meeting was held to discuss dissemination of the review findings to patients and the public. Approximately 15 members of the public were involved, including people with MCI, carers and those without direct experience of the condition.

Review questions

This report addresses the following questions:

-

What is the evidence base around the assessment and management pathway of older adults with MCI in acute hospital wards, community/primary care and residential settings? In particular –

-

How are older adults presenting with memory problems investigated to understand the underlying cause of impairment?

-

What are the advantages and disadvantages of a ‘diagnosis’ of MCI? (We will aim to address both patient and health/social care provider perspectives.)

-

What is known about the experience of health and care services from the perspective of people with memory problems and their support networks (e.g. family, friends and other carers)?

-

The report comprises two separate evidence reviews: (1) a descriptive review with narrative synthesis, focusing on diagnosis, service provision and patient experience; and (2) a critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) of evidence on the advantages and disadvantages of MCI as a diagnostic label. The first subquestion is addressed in Chapters 7 and 8, the second subquestion is introduced in Chapter 6 and is the main focus of review 2 (see Chapters 11–13) and the third subquestion is covered in Chapter 9 and review 2.

Identification of evidence

A broad literature search was developed to identify research on the assessment and management pathways of older adults with MCI. The search strategy developed by the information specialist combined thesaurus and free-text terms and relevant synonyms for the population (e.g. older adults with memory problems with or without a diagnosis of MCI), intervention (e.g. screening and assessment tools, management pathways and service modules) and uses. The search terms were then combined using Boolean operators appropriately.

The search strategy was developed on MEDLINE and then translated to the other major medical and health-related bibliographic databases. The MEDLINE search strategy is presented in Appendix 1.

The search was limited to research published in English between 2010 and 2020. The date range was chosen to reflect the introduction of the UK National Dementia Strategy in 2009. 2 Earlier publications were incorporated by including relevant literature and systematic reviews. A search filter for UK studies was applied to the search to ensure that retrieved studies were relevant to the UK context. In addition, editorials, comments and letters were excluded where database functionality allowed.

The search was conducted in January 2021 on the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo®, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, The Cochrane Library (i.e. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index.

In addition, grey literature searches were performed to retrieve clinical guidelines, policy documents and reports related to MCI from relevant websites. A full list of the websites searched is provided in Appendix 2. Reference and citation searching of included studies and relevant existing reviews were conducted for areas where more evidence was needed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Participants were older adults (likely to be aged ≥ 60 years or ≥ 65 years) with memory problems, with or without a diagnosis of MCI, and relevant health and social care professionals, family caregivers and volunteers.

Interventions

Interventions included screening and assessment tools (including staff training), management pathways and service models for people with MCI.

Comparator

The most relevant comparator was no treatment/standard care. Quantitative studies with and without a control/comparator group were included when they met other criteria.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest included quality of life, mental health and other patient/carer outcomes, as well as health system outcomes (e.g. measures of costs/resource use).

Study designs

Study designs that were included were quantitative research studies of any design; qualitative research involving, for example, interviews and focus groups; mixed-methods studies; service evaluations (from the UK only); UK-relevant guidelines; policy documents and grey literature; and systematic and narrative literature reviews.

Context/setting

Studies with a health and social care context/setting, including acute hospital wards, community/primary care and residential settings, were included. Although the main focus was the UK, studies from other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries were included to address gaps in the UK evidence base.

Other criteria

Other criteria included studies published after 2010 and grey literature from the UK.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies in which people had a formal diagnosis of dementia.

-

Lifestyle interventions intended to reduce the risk of developing dementia.

-

Editorials, commentaries, news and discussion articles, unless they provided full details of a service or pathway.

-

Books and book chapters, theses, articles in professional magazines and conference abstracts.

Study selection

Search results were downloaded to a reference management system (EndNote X9.2, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicates removed. Unique references were imported into EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK) systematic review software for screening and analysis. Titles/abstracts of imported references were screened against the inclusion criteria by four members of the review team, with any queries resolved by discussion among the review team. A 10% sample of excluded references were checked by one of the reviewers to ensure consistency and guard against premature exclusion. References that appeared potentially relevant were screened as full-text documents for a final decision on inclusion or exclusion, with any uncertainties resolved by discussion among the review team.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Key data were extracted and tabulated from the included studies, including study type, area of study, population, setting, study methods, findings, conclusions and key limitations. For the CIS, data extraction included positioning in argument, cited affiliations, study methods and CIS themes. Data extraction was undertaken using the coding and reporting functions of EPPI-Reviewer 4. Data extraction was performed by the four reviewers (DC, AB, AC and KS) and a 20% sample of each other’s work was checked.

Quality (risk-of-bias) assessment was undertaken for all studies that used a recognised design for which an appropriate quality assessment tool is available. Quality assessment tools used in this review included the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for quasi-experimental studies, the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) tool for qualitative studies, AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) for systematic reviews, the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment tool to assess methodological limitations of qualitative evidence synthesis, and risk of bias for cohort/cross-sectional studies and diagnostic studies from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) and Cochrane Collaboration, respectively. Quality assessment was performed by the four reviewers (DC, AB, KS and AC), who also checked a 20% sample of each other’s work. Assessment of the overall strength (quality and relevance) of evidence for each research question formed part of the narrative synthesis.

Synthesis of evidence

A narrative synthesis of the evidence was undertaken based on the predefined research questions and includes textual and tabular summary and critique of the included studies. Quantitative and qualitative evidence will be synthesised using methods based on the principles of CIS. 6 Briefly, CIS is a synthesis approach designed to analyse a broad range of relevant sources and use analytical outputs to develop a conceptual framework. We planned to use a variant that mobilises the literature to construct two alternative conceptual frameworks (i.e. one that assumes a pivotal role for the establishment of a definitive diagnosis of MCI and one that progresses a management pathway in the absence of a definitive diagnosis).

We have chosen a CIS methodology given its acknowledged strengths as a form of systematic review that draws on both traditions of qualitative research inquiry and systematic review methodology. A CIS is best suited to study a phenomenon that emerges over time and that constitutes a challenge to define, as is the case for MCI. In contrast to conventional systematic reviews, in which a precise question is tightly focused, CIS methodology offers the flexibility to draw from diverse relevant sources. Furthermore, CIS is not constrained to include only prespecified designs or quality of documents. Documents are selected according to relevance and their capacity to address the research question. Starting from an initial compass question relating to the assessment and management of older adults with MCI, two alternative management pathways were created and iteratively modified and defined as the synthesis progressed. In particular, we explored the extent to which assignment of a defining diagnosis or label determined the management pathway and eventual outcome. Quantitative and qualitative empirical studies was classified by the extent to which they supported each management pathway or to which they shared a common ground between the alternative pathways. The effect of contextual factors and their influence on the likelihood that individuals will progress down one or the other pathway was also explored.

Chapter 3 Review 1: definition, diagnosis and patient experience – introduction and results of literature search

Review 1 was a descriptive systematic review, incorporating evidence from primary studies and supplemented by systematic reviews. Included studies were allocated to one or more of the following groups for a narrative synthesis: conceptual studies, screening and diagnosis, services and pathways, and patient/carer experience. Of the 29 studies included in review 2 (see Chapters 11–13), 24 were included in review 1.

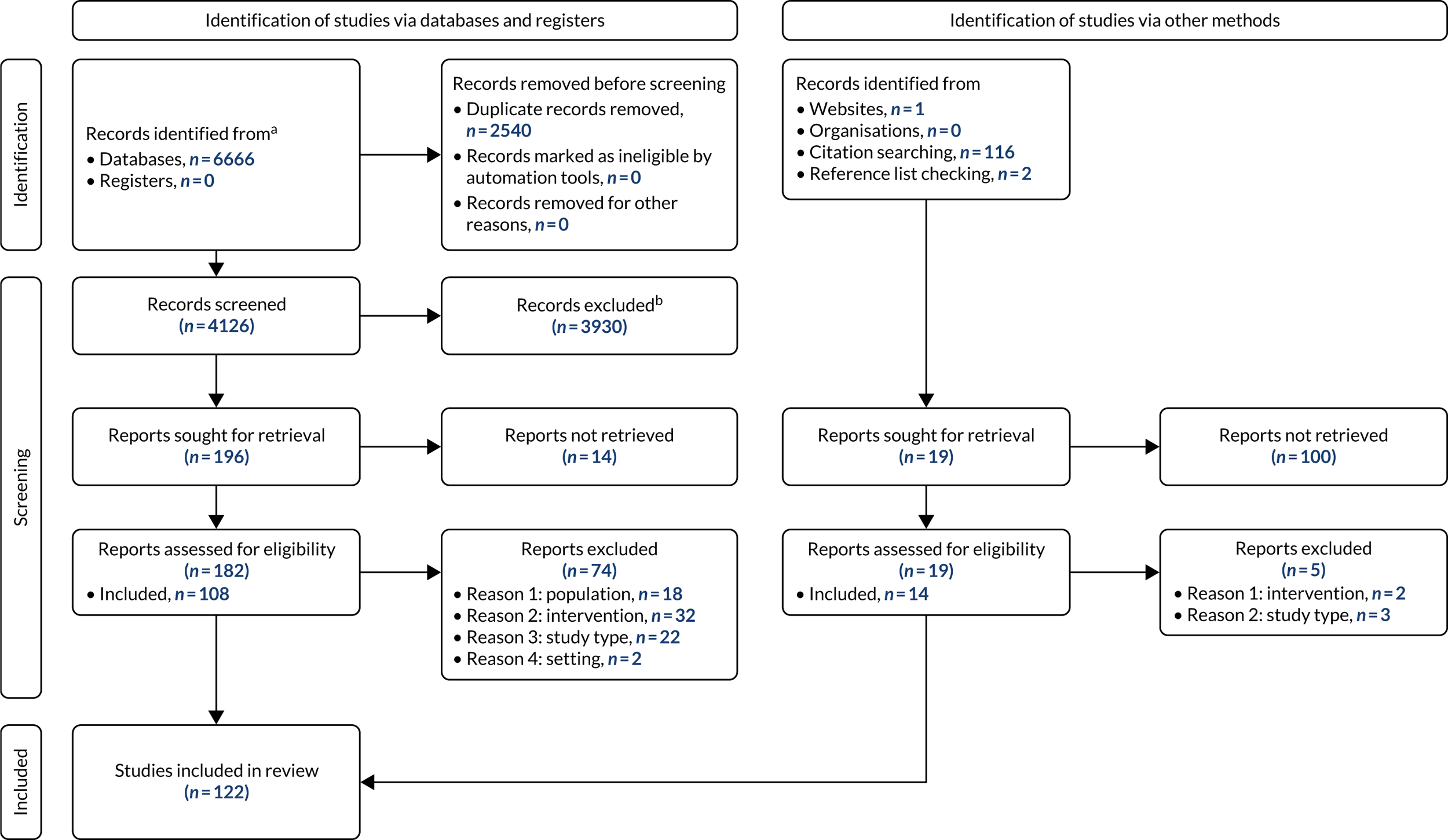

From a database of 4126 citations, we included 108 studies, with a further 14 studies identified by other methods, primarily citation searching. Figure 1 is a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram illustrating the process of study selection and inclusion.

FIGURE 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram. 7 a, Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers); b, if automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

Chapter 4 Summary of included study characteristics

Table 1 summarises the study designs of papers included in review 1. The most common study types were quantitative, systematic review and narrative review, with a predominance of qualitative studies for patient/carer experience. Most quantitative studies had a cohort or cross-sectional design, but a small number of cluster-randomised trials were also included. Study participants were most commonly recruited from populations of community-living older adults or those who had sought medical help for memory problems.

| Study design | Screening/diagnosis (n) | Services/pathways (n) | Patient/carer experience (n) | Conceptual (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 34 | 12 | 3 | 3 |

| Qualitative | 9 | 7 | 17 | 2 |

| Mixed methods | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Conceptual/historical | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Systematic review | 17 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Narrative review | 15 | 8 | 2 | 5 |

| Commentary | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Other | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

Summary tables of study characteristics are presented as part of the narrative synthesis in Chapters 6–9.

Chapter 5 Quality (risk-of-bias) assessment

For a summary of the risk-of-bias assessment, see Appendix 3, Tables 19–23. The wide range of study designs included in the review required us to use numerous different checklists. In general, systematic reviews and qualitative studies were rated as being of reasonable quality, with limitations being most commonly related to reporting of conflicts of interest (systematic reviews) and consideration of relationships between participants and researchers (qualitative studies). The quality of the cross-sectional and cohort studies varied widely, with common issues being small samples, lack of blinded outcome assessment and adjustment for confounders. Each of the other study designs (e.g. diagnostic, qualitative evidence synthesis, cluster-randomised trials, quasi-experimental and economic evaluations) were used in just a few studies. The review also included studies, such as service evaluations and audits, that were relevant to the review question, not designed as research studies and difficult to assess for risk of bias.

Chapter 6 Conceptual studies

This review included a category of publications to offer a conceptual overview of MCI. This group of publications aimed to identify key conceptual features of MCI over time in the context of UK services. The category of publications included conceptual (non-empirical) papers or reviews and empirical papers containing conceptual elements. Publications explored diagnostic definitions and causes of MCI, the application of diagnostic concepts, the concept of MCI as it relates to services and the patient experiential conceptualisation of MCI.

Features of included papers

There were various types of included publications from the 13 publications8–20 identified. Conceptual overview papers were identified as a result of searches. Ball et al. 8 explored underlying disorders in relation to functional cognitive disorder. Forlenza et al. 9 critically reviewed existing knowledge on the conceptual limits and clinical usefulness of the diagnosis of MCI and the neuropsychological assessment (including short- and long-term prognosis). Stewart10 presented a narrative review of literature relevant to the presentation and detection of MCI in primary care. Stephan et al. 11 conducted a systematic review of the neuropathological profile of MCI, synthesising 162 clinical studies. Blackburn et al. 12 compared MCI, SCD and functional memory disorder (FMD). Brayne and Kelly13 explored the desirability of early diagnosis. The discussion paper by Swallow et al. 20 explored the process of negotiating risk in constructing classification boundaries in the memory clinic.

Other sources contained conceptual explanations for MCI as part of their objectives. One type was an evidence briefing by the British Psychological Society (Leicester, UK). 14 Such publications distil current narratives around MCI, which influence practice. The authors note that MCI is not a simple entity and the foremost narrative is the complexity of the conceptual understanding that is required. 14 There is a continued need to provide an overview of the current evidence for MCI. Evidence is framed as the support that may be needed by those for whom problems are detected before a dementia may be diagnosed.

The remainder of the studies were empirical. Swallow et al. ’s qualitative study20 examined practitioners’ accounts of the complexity associated with constructing the boundaries around MCI, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and age in the clinic. Pierce et al. 15 presented a qualitative discourse analysis study of seven people with MCI. A service evaluation conducted by Jenkins et al. 16 consisted of an e-mail-based questionnaire, containing a vignette of an individual presenting with subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), distributed to 112 memory clinics. Stephan et al. 17 conducted a quantitative study of the suitability of forms of diagnostic tests based on criteria for MCI to predict dementia risk in the clinic. Data were from the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. 21 The study by Guzman et al. 18 consisted of a cross-sectional study of 34 participants with MCI (47% female and 53% male, with a mean age of 76.4 years) and evaluated the relationships between cognitive impairment, illness perceptions and cognitive fusion and their effects on levels of distress and quality of life. Rodda et al. 19 conducted a survey of clinicians on the Royal College of Psychiatrist’s (London, UK) Old Age Psychiatry Register about their perspectives on MCI.

The concept of mild cognitive impairment over time

Forlenza et al. 9 described the emergence of the MCI concept in the USA from the first use of the term in New York University (New York, NY, USA) (Reisburg et al. 1988 cited in Forlenza et al. 9) to the work carried out at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) in the 1990s to suggest additional criteria (Petersen 1999, Petersen 2001 and Winblad 2004 cited in Forlenza et al. 9). Following this work, the US National Institute on Aging (Bethesda, MD, USA) and the Alzheimer’s Association (Chicago, IL, USA) placed emphasis on biomarkers for early diagnosis.

The study by Stephan et al. 11 was conducted prior to standardisation of the definition of MCI and reporting of pathology and, therefore, barriers existed to the creation of an integrated picture of the clinical and neuropathological profile of MCI.

Blackburn et al. 12 explored memory loss and dementia. The authors12 identified considerable confusion about the most appropriate diagnostic labels for people with memory problems at this point in time.

Issues remain in defining MCI, most prominently the conceptualisation of MCI as a stage on a pathway to dementia lacking diagnostic specificity. 8,14 MCI is described within the context of dementia, whereby an asymptomatic phase is followed by an early symptomatic phase with subjective memory complaints or MCI. 13

Definitions of mild cognitive impairment and causes of impairment

Ball et al. 8 explored underlying disorders in relation to functional cognitive disorder. Current research, such as this, has identified that some MCI cases are due to non-neurodegenerative processes and Ball et al. 8 point out the weaknesses in conceptualising MCI as a stage on a pathway to dementia lacking diagnostic specificity. In addition, Ball et al. 8 emphasise that MCI is an aetiology-neutral description and includes patients with a wide range of underlying causes. Cognitive disorder was a way of defining MCI for some time. Forlenza et al. 9 defined the criteria for the MCI concept as a ‘[s]ubjective complaint of cognitive impairment with objective cognitive impairment adjusted for age. Normal general intellectual function. Intact basic and instrumental activities of daily living’. 9

Recommendations from the British Psychological Society evidence briefing14 also identified shifting definitions of MCI. One of the central diagnostic definitions surrounds the existence of a prodromal stage of dementia. The authors14 stressed that this does not necessarily imply that everything between normal ageing and dementia (currently labelled as MCI) should be considered prodromal dementia. A key principle that emerged is the distinct pathway of MCI because it is recognised that many people labelled with MCI do not go on to develop dementia.

The same briefing paper14 provided another example of the way that a more sophisticated understanding of MCI has developed through recognition of the flaws in accepted criteria for MCI (specifically the measurement of cognitive impairment tests and the inclusion of memory impairment, which many do not experience). The authors argued that MCI should not be defined by performance below a cut-off point, but by evidence of decline from previous performance. It was suggested that subjective memory complaints are not necessarily a precursor of MCI and may reflect other conditions, such as low mood. The final areas of concern in the criteria are the possible impact of MCI symptoms on daily living and potential difficulties in defining significant impact. 14

Mild cognitive impairment has been underpinned conceptually with reference to memory loss and dementia, leading to challenges in understanding MCI at a conceptual and diagnostic level. 12 Blackburn et al. 12 pointed out that there is considerable confusion about the most appropriate diagnostic labels for people with memory problems. Despite a defined MCI label, it is widely misunderstood. Blackburn et al. 12 focused on concepts of MCI, SCD and FMD and, therefore, locating MCI within the suite of memory complaints conditions. The findings of Blackburn et al. 12 suggest that more work is required to help clinicians differentiate between non-progressive subjective memory dysfunction and the early stages of progressive memory disorders, such as AD.

The construct of SCI has been linked to MCI, although also emerging in its own right. Jenkins et al. 16 argued that SCI may be a risk factor for both MCI and dementia. Variable responses to a questionnaire containing a vignette to describe the presentation of a patient with SCI suggested a lack of a clear concept of SCI and how to manage the condition. Jenkins et al. 16 provided an insight into the relative increased clarity for MCI:

What is also clear is that several years ago the concept of MCI was the topic of similar debate to that surrounding SCI today and that MCI is now a widely recognized clinical diagnosis.

Jenkins et al. 16

The neuropathological profile of MCI was presented by Stephan et al. 11 Findings from included studies indicated that MCI is neuropathologically complex and cannot be understood within a single framework. The pathological changes identified included plaque and tangle formation, vascular pathologies, neurochemical deficits, cellular injury, inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial changes, changes in genomic activity, synaptic dysfunction, disturbed protein metabolism and disrupted metabolic homeostasis. Therefore, determining causation is problematic (i.e. which factors primarily drive neurodegeneration and dementia and which are secondary features of disease progression).

The application of mild cognitive impairment diagnostic concepts

Stewart10 wrote a review paper on the challenge of real-world detection and diagnosis. The paper’s central focus is the construct of MCI and controversy surrounding the way it was defined (i.e. Stewart10 echoed the point made by the British Psychological Association14 about diagnostic cut-off points for measuring cognitive decline). Stewart10 stated that MCI is both a relatively simple and an important construct. Its importance depends on the assumption that early diagnosis and intervention are likely to be beneficial. The MCI construct is controversial because it ‘involves the imposition of categorical entities on what is essentially a continuous and mostly gradual process of decline in people who do develop dementia, not to mention incorporating the heterogeneity of cognitive changes in people who do not have underlying neurodegeneration’. 10 Stewart10 discussed the diagnostic process as likely to be based on subjective memory complaints under current definitions, rather than screening at a population level (which is unlikely to be feasible or acceptable). Yet, subjective memory complaints are heterogeneous in their aetiology, poorly predict medium-term dementia risk and are unlikely to be reported to GPs. In the process of diagnosis, the review raised the issue of distinguishing MCI from dementia and the challenges of identifying declines in functional activities of patients. The paper10 highlighted the subjectivity of the judgement in aspects such as cultural expectations for functional activity levels, individuals with increased support who may have higher function as a result and individuals with existing physical conditions that can have an impact on function. Findings10 relating to identifying MCI in clinical practice stress the importance of understanding health-seeking behaviours.

Previous concepts have focused on areas such as clinical characteristics and predictors of dementia9 and identification of dementia risk through identification of MCI. 17 Forlenza et al. ’s9 critical review of the limits of the diagnostic concept for MCI argued that the diagnostic criteria are complex, requiring sophisticated assessments:

Thus, there is a need for development of assessment strategies that are cost-effective, easy to administer and that generate results that are easy to interpret, while maintaining good sensitivity and specificity to identify MCI cases.

Forlenza et al. 9

The study by Stephan et al. 17 showed that definitions are not suitable for identifying people with MCI and at high risk of dementia in the general population. However, the definitions were able to identify people at elevated risk (possibly suitable for ‘watchful waiting’), as well as those considered to be not at risk. According to Stephan et al. ,17 identification could be achieved by using a simple test, such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and more complex MCI criteria were not required.

Narratives questioning the desirability of the diagnosis have gained increasing traction. The desirability of early diagnosis was addressed by Brayne and Kelly. 13 Brayne and Kelly13 set the concept of early diagnosis in a UK policy context and the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia. 3 Although the paper by Brayne and Kelly13 focused on dementia, it has relevancy for the exploration of the concept of early diagnosis and framed MCI in the context of dementia. Brayne and Kelly13 described a process of an asymptomatic phase followed by an early symptomatic phase with subjective memory complaints or MCI. Crucially, the authors point out that this challenge called for improved dementia diagnosis rates and is based on assumptions of benefit to individuals and those who care for them. In addition, the paper13 questions what is meant by ‘early’. Dictionary definitions include ‘in good time’, ‘before the usual time’ and ‘prematurely’. ‘In good time’ suggests a time that is appropriate for an individual, ‘before the usual time’ suggests a process that may be beneficial or harmful and ‘prematurely’ suggests the possibility of harm. 13 This concept of timely diagnosis means disclosure of the diagnosis at the ‘right time for the individual with consideration of their preferences and unique circumstances’ (Watson et al. 2019 cited in Brayne and Kelly13). This interpretation surrounds help-seeking at the point of noticing symptoms and referral to specialist secondary care assessment, such as memory clinics. Therefore, a timely diagnosis is delivered at the point people are ready for and will benefit from it. However, this has to coincide with adequate services to account for benefits costs and harms.

Mild cognitive impairment concept relating to services

In a study by Rodda et al. ,19 almost all respondents (99%) were moderately or extremely familiar with MCI. One hundred and ten (24%) respondents thought that the concept was more useful for doctors, 47 (10%) felt that it was more useful for patients and 292 (65%) rated it as the same for both. Findings from the Rodda et al. study19 indicated that psychiatrists thought that it would be helpful for patients to have a name for their symptoms. However, the study demonstrated the contentiousness of the diagnosis construction and related practices at the time among this group of professionals. For example, some respondents did not consider MCI a helpful concept and a few wrote in the free-response section that they did not consider it to be a diagnosis.

The discussion paper by Swallow et al. 20 explored the process of negotiating risk in constructing classification boundaries in the memory clinic. Swallow et al. 20 framed the process of constituting the diagnostic boundaries of disease in the clinic as interpretive and relational. In addition to diagnosis as a process to sort the ‘real from the imagined’ (Jutel 2009 cited in Swallow et al. 20), it was also a space for contestation (Bowker and Star 2000, Jutel 2009 and 2015, Jutel and Nettleton 2011, and Rosenberg 2002, 2003 and 2006 cited in Swallow et al. 20). Swallow et al. 20 pointed to the complications of the diagnostic conceptualisation that categorises pathology at earlier stages and in which there is a blurring of boundaries. According to a sociology of diagnosis perspective, the discussion highlighted the way that the grey area of the diagnosis is a liminal and ‘ “uncomfortable” space for patients and practitioners, favouring more conventional categories’. 20 The ‘functionality’ of diagnosis (Jutel 2015 and Timmermans and Buchbinder 2010 cited in Swallow et al. 20) is, therefore, called into question if underpinned by uncertainty [including potential positive aspects, such as uncertainty serving to return the act of decision-making to the clinic (Latimer 2013 and Reed et al. 2016 cited in Swallow et al. 20)]. Swallow et al. 20 also incorporated wider themes, such as ageing and differing positive or negative sociocultural constructions of ageing, and loss of self and related conditions, such as AD or MCI (Beard and Neary 2013, Latimer 2018, and Swallow and Hillman 2018 cited in Swallow et al. 20). Swallow et al. 20 argued that these constructions may exist at some level within the practices of the memory clinic.

Stewart et al. 10 pointed out that most research in this area has focused on the applicability of cognitive assessments in primary care. However, in general, the detection of MCI in primary care is low and, therefore, detection may need to be expanded. The authors10 suggested the use of routine clinical data and nurse practitioner involvement.

Experience-related aspects of the mild cognitive impairment concept

Psychosocial adjustment is a conceptual term emphasised by Guzman et al. 18 and their cross-sectional study of standardised measures for cognitive assessment, illness perceptions, cognitive fusion, depression, anxiety and quality of life. Guzman et al. 18 outlined the features of a MCI diagnosis. Receiving a MCI diagnosis can evoke a broad range of emotional responses in people diagnosed with MCI, including worry, ambivalence or relief. 22,23 MCI is a vague term and makes the person confused as to whether or not they will go on to develop dementia. Some researchers argued that a MCI diagnosis merely causes undue distress for individuals and their caregivers about what may be part of a ‘normal’ ageing process. 24,25 Among their findings,24,25 the researchers showed that illness perceptions were a stronger predictor of depression and quality of life than cognitive impairment. However, limited research has focused on individual experiences of receiving this diagnosis. Recommendations24,25 include multiple treatment targets to help people adjust and accept a diagnosis, which is a factor in secondary conditions, such as depression, and in improving quality of life.

Discourses of patients with a MCI diagnosis were explored by Pierce et al. 15 A central narrative was ‘[k]nowingly not wanting to know’15 about the possibility MCI would develop into dementia. Another MCI discourse was characterised as not knowing about MCI. In addition, Pierce et al. 15 explained a third discourse: ‘[i]n the absence of a coherent discourse [of MCI], around a diagnosis given to them by experts in a memory clinic, participants turned to a more familiar discourse to help them ascertain their positioning – that of ambivalent ageing and certainty of death’. 15 Therefore, the conclusions of the study suggest that the conceptualisation of MCI by patients should be considered by clinicians in terms of how information is presented to people about MCI and, in particular, how MCI is positioned in respect to normal ageing and dementia.

Summary

The conceptual landscape of MCI has changed significantly over time, gaining its own diagnostic label. However, conceptual features of MCI remain challenging for diagnosis and patient acceptance. A conceptual understanding of MCI as purely a pre-dementia condition persists, with a reliance on categorical cut-off points to distinguish between normal ageing and MCI. In addition, conceptualisations include both those who go on to develop dementia as well as those with a wide range of cognitive problems but no underlying neurodegenerative decline. This produces a level of conceptual complexity in a single framework that locates MCI definitions in the context of dementia, leading to understandings that incorporate an absence of diagnostic boundaries with the neuropathological complexity of the condition. In practice, this means that diagnosis is subjective and there is a reliance on assessment of function and memory. Clinicians call for a more sophisticated assessment of function relative to the individual.

Chapter 7 Screening/diagnosis

We included 82 studies in the screening/diagnosis group. This group includes strategies to identify people with ‘memory problems’ in broader population samples to distinguish those with MCI from those with related conditions [e.g. SCD and functional cognitive decline (FCD)] and to identify the underlying problem in people with the MCI label. The group overlaps with, but does not fully cover, the larger topic of diagnosis of dementia, given the specific focus of the review on MCI. Primary research studies were supplemented by evidence from reviews and clinical guidelines (Table 2). The group also includes help-seeking, which is an essential requirement for memory problems to be identified in routine practice.

| Study | Type of study | Study aims/objectives | Study sample/population | Setting | Findings: screening/diagnosis | Study limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunne et al.5 |

Narrative review Expert consensus guideline with narrative literature review |

To describe the scope of use of MCI as a diagnostic category, determine its utility and explore the implications of its continued use in research and clinical practice To create a clear problem statement as a framework for future national guidance on minimum standards in diagnosis and management of MCI |

Not applicable (literature review/guideline) Clinical/health service perspective |

Guideline focuses on UK clinical and research settings | Clinical benefits of accurate diagnosis may include resolution of uncertainty for patient and clinician, discharge from regular clinic visits, referral to more appropriate specialties, advance care planning, access to clinical trials, advice on current and future treatments, and counselling, support and education. Decisions about investigations should be made on an individual basis | Expert guideline with no apparent patient or carer involvement |

| Langa and Levine26 | Narrative review | To present evidence on the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of MCI and to provide physicians with an evidence-based framework for caring for older patients with MCI and their caregivers | Review focuses on people with MCI | General review with no specific setting | The prevalence of MCI in adults aged ≥ 65 years is 10–20%. Risk increases with age and appears to be higher in men. Substantial variation in (dementia) risk estimates (from < 5% to 20% annual conversion rates). A suggested approach to diagnosis based on history, physical/neurological examination, laboratory testing and cognitive testing is presented | Narrative review with an apparent US focus |

In the context of MCI, screening refers to administration of cognitive tests, often in primary care settings, to identify people who may need specialist investigation. A secondary use of the term relates to cognitive testing of older adults as part of research studies. Screening of older adults without symptoms of cognitive decline is not recommended by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care27 or the US Preventive Services Task Force because of lack of evidence of benefit. 28,29

Help-seeking

We identified three studies30–32 of barriers to and facilitators of help-seeking for memory problems and two UK studies33,34 of interventions aimed at encouraging people with concerns to consult their GP (Table 3). A 2018 systematic review30 found that there is often a long delay between noticing symptoms and seeking help and that help-seeking is often precipitated by a ‘pivotal event’. In the absence of such an event, people may discount their symptoms as normal, reserve judgement about them or misattribute them. In a small study31 of Irish adults, facilitators of help-seeking were family, friends and peers, alongside well-informed health professionals. Barriers to seeking help were a lack of knowledge, fear, loss, stigma and inaccessible services. 31 Ethnic minority groups may encounter specific barriers to help-seeking. A qualitative study32 of South Asian people identified barriers, including not knowing what help is available, a perception of lack of time in GP consultations and a belief that ‘good families’ care for people with dementia themselves. Barriers to accessing early/timely diagnosis at the level of the health system are discussed below (see Recognition and recording in primary care).

| Study | Type of study | Study aims/objectives | Study sample/population | Setting | Findings: screening/diagnosis | Study limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan et al.33 | Quantitative pilot study | To determine if a leaflet campaign by the Alzheimer’s Society to raise awareness of memory problems increases the number of people presenting to their GP with memory problems |

Intervention practices combined population: 88,924 Control practices combined population: 53,863 |

Fourteen UK general practices. Seven general practices in neighbouring locality acted as a control. The intervention and control locality referred to the same specialist service | Just under 40% of people presented with memory problems had a blood test in control and intervention localities. Referral to secondary care occurred in approximately 80% of people presenting with memory problems and was more likely in the intervention group. Patients were more likely to be referred than to have investigations or be prescribed antidepressants | Authors noted that the study demonstrated the strengths and weaknesses of routinely collected data |

| Devoy and Simpson31 | Mixed methods | To identify factors that may increase intentions to seek help for an early dementia diagnosis among people experiencing memory problems |

People aged 50–69 years living in Dublin or Kildare, Ireland (n = 22 for focus groups and n = 95 for survey) Patient/public perspective |

Community groups serving older people | Content analysis revealed that participants had knowledge of the symptoms of dementia but not about available interventions. Facilitators of help-seeking were family, friends and peers, alongside well-informed health professionals. Barriers to seeking help were a lack of knowledge, fear, loss, stigma and inaccessible services. The main predictors of help-seeking were knowledge of dementia and subjective norm, accounting for 6% and 8% of the variance, respectively | Limitations to TPB; some participants considered survey too long/repetitive. Irish population and so may not generalise to UK |

| Livingston et al.34 | Quantitative | To assess whether a GP’s personal letter with an evidence-based leaflet about overcoming barriers to accessing help for memory problems increases timely dementia diagnosis and patient presentation to general practice | Patients aged ≥ 70 years without a diagnosis of dementia and living in their own homes (n = 6387 in 11 intervention practices and n = 8171 in control practices). Health service/GP perspective | Twenty-two general practices and 13 corresponding secondary care memory services in London, Hertfordshire and Essex, UK | There was no between-group difference in cognitive severity (MMSE score) at diagnosis. GP consultations with patients with suspected memory disorders increased in the intervention group compared with the control group (odds ratio 1.41, 95% confidence interval 1.28 to 1.54). There was no between-group difference in the proportion of patients referred to memory clinics | It is not known if the additional patients presenting to GPs had objective as well as subjective memory problems and, therefore, should have been referred. In addition, the intervention aimed to empower patients but did not do anything to change GP practice |

| Mukadam et al.32 | Qualitative | To determine barriers to timely help-seeking for dementia among people from South Asian backgrounds and what the features of an intervention to overcome them would be | Purposively recruited 53 English- or Bengali-speaking South Asian adults without a known diagnosis of dementia through community centres and snowballing. (Number of adults with dementia or MCI unknown) | Community settings in and around Greater London | Health-care system. Not knowing what help is available. Perception that GPs do not have enough time in consultations. Perception of good families look after people with dementia themselves | Study is not necessarily representative of that whole community. Reliability of a hypothetical case (i.e. opinions could change in reality) |

| Perry-Young et al.30 | Systematic review | The aim of this review was to systematically search, critically appraise and present a synthesis of the literature on the social dynamics of help-seeking for dementia | A total of 249 participants were represented, including 32 people with dementia and 217 carers (171 spouses, 39 children, sons- or daughters-in-law and one sibling). (Searches include MCI, but this number of participants is not given) | Three of the studies were conducted in Canada, two in the USA, two in the UK, one in the Netherlands and one in Sweden | Delays due to services (e.g. immigrant caregivers faced particular difficulties in accessing resources). Participants experienced active reflection and seeking of further evidence about memory problems (leads to the redefinition of the situation). Person with dementia’s denial and refusal to seek help causes a moral dilemma for the significant other, who may feel that seeking medical help or consulting lay networks would be a betrayal | Limitations of representativeness of third-order interpretations. Findings may not account for all complexities involved in the interpersonal aspects of decision-making. Recollection and hindsight may have affected data accuracy. Carer reflection may have been self-censored to avoid hurting the feelings of the person with dementia/MCI |

Chan et al. 33 and Livingston et al. 34 reported on interventions in the English NHS to encourage people with memory concerns to consult their GP. Both studies33,34 involved distribution of information to patients at the level of the general practice. Chan et al. 33 found that recording and management of memory problems improved during the period of the study, but there was a greater improvement in a control area where no additional information was distributed. In the study by Livingston et al. ,34 consultations about memory problems increased in intervention practices compared with control practices. However, there was no increase in diagnoses or referrals to memory clinics. This limited evidence suggests that provision of information to patients may not be sufficient to overcome barriers to help-seeking and obtaining help for memory problems.

Recognition and recording in primary care

We included six reviews10,35–39 and 12 primary studies40–51 in this section.

As noted above, identification and investigation of memory problems generally begins when patients or family members are concerned about a person’s symptoms, leading to a consultation with the patient’s GP. The objective of the investigations is often presented as ‘early diagnosis’ of the underlying cause of the memory problems (i.e. dementia or other). 10 Brooker et al. 35 have developed the concept of a ‘timely diagnosis’ (of dementia), stating that ‘citizens should have access to accurate diagnosis at a time in the disease process when it can be of most benefit to them’. 35 The concept of timely diagnosis is discussed further in review 2 (see Chapter 11).

Two included studies40,41 identified barriers to early diagnosis in general or for disadvantaged groups. A survey of primary and secondary care physicians (n = 1365) found that barriers included patients seeing cognitive decline as a normal part of ageing and not disclosing symptoms, long waiting lists, and a lack of treatment options and definitive biomarker tests. 40 Although a relatively large sample, this survey reflected the perceptions of a self-selected group of physicians only. A mixed-methods study of homeless older people living in hostels reported that the memory assessment service (MAS) was difficult to access and not patient centred. 41

People who report memory concerns to their GP are likely to be assessed using ‘pencil and paper’ cognitive tests in the first instance (see Cognitive tests). Six included studies36,42–46 assessed recognition and recording of memory problems by GPs in the UK and the Netherlands. A meta-analysis from 201136 found that GPs have considerable difficulty identifying people with MCI or mild dementia using clinical judgement, and diagnoses are poorly recorded in medical records. 36 For MCI, GPs recognised 44.7% of cases and the diagnostic label was recorded for only 10.9%. This review was published in 2011 and so may not reflect current practice. 36

Given the limitations of clinical judgement, efforts have been made to promote the use of cognitive screening tests in primary care. In the UK, these include guidance from NICE and the Social Care Institute for Excellence and the National Dementia Strategy, published in 2006 and 2009, respectively. 2,42 A comparison of GP referrals to memory clinics before and after the launch of this guidance found that the number of referrals increased, but the rate of dementia diagnoses decreased and the use of cognitive screening tools did not change. 42 This suggests an absence of evidence for the effects of the guidance in promoting screening, at least in the short term. As an alternative or complement to screening, Olazarán et al. 43 investigated the role of data routinely collected by GPs in identifying MCI and predicting its course (i.e. progression to dementia or reversion to normal cognition). For example, old age, source of information about symptoms (informant or primary care physician), short duration and low education were associated with MCI or dementia at baseline.

The implications of failing to diagnose or record cases of MCI or dementia in primary care have been investigated in more recent research (three included studies44–46). A recent UK study,44 which used linked records, found that 34% of participants with known dementia had a primary care diagnosis in 2008–11 and 44% had a primary care diagnosis in 2011–13. In both periods, a further 21% of participants had a record of a concern or a referral, but no diagnosis. There was a lack of relationship between severity of non-memory symptoms and diagnosis, suggesting possible low awareness of such symptoms. In a study in the Netherlands,45 GPs showed variable awareness of the presence of cognitive impairment in their older patients (i.e. those aged ≥ 65 years) without a firm diagnosis of dementia. Lack of awareness of a problem was highest for the older age groups. Training GPs to diagnose MCI and dementia, followed by case finding, resulted in a non-significant increase in new MCI diagnoses when compared with control practices. 46

Although the common model in the UK is for people with memory problems to be identified in primary care and referred to a memory clinic for more detailed assessment, primary care-led services are available in some areas. Three included studies47–49 focused on screening and diagnosis, and the topic of different service models is discussed in more detail below (see Chapter 8). An evaluation of primary care-led services in Bristol found that, in practice, GPs rarely made independent diagnoses of dementia. 48 A need for specialist support with diagnosis was also identified in a study aimed at developing a multidisciplinary memory clinic in south-western Sydney, NSW, Australia. 49 Eye clinics have been suggested as an alternative setting for screening,47 but this approach does not appear to have been tested.

Finally, two scoping reviews37,38 have examined the potential use of telehealth technologies to support diagnosis of memory problems, especially in remote areas, as well as highlighting limitations of the available evidence. Two overlapping articles50,51 by the same author reviewed the role of mobile applications, but the review focused on features of the applications rather than evidence of their accuracy or value for diagnosis. A review39 of the international literature, included for completeness, provided few new data, but emphasised the lack of evidence from low- and middle-income countries, especially the former.

Screening in hospital settings

We identified only one study52 of screening for memory problems in a hospital setting. A Commissioning for Quality and Innovation payment led to improvements in practice, as demonstrated by audit of case notes in three wards at a large university teaching hospital in England. This study53 involved hospital inpatients aged > 75 years who were admitted as emergencies. The study was subsequently withdrawn.

Diagnostic terminology

Conceptual studies of MCI are summarised in Chapter 6 and the advantages and disadvantages of MCI as a ‘diagnostic label’ are the focus of review 2 (i.e. the CIS). We found evidence from two included studies (surveys)19,54 that indicated that clinicians regard MCI as a valuable diagnostic label, suggesting that any change to the labelling of patients may be difficult to achieve. A survey of UK psychiatrists (n = 453) found that only 4.4% of clinicians did not view MCI as a useful concept, although they showed less uniformity in their diagnostic practices. 19 The authors reported that psychiatrists saw MCI as a transitional stage between normal ageing and dementia. A more recent survey of members of the European Academy of Neurology (Vienna, Austria) and the European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium (EADC) (Mannheim, Germany) (n = 102) reported that 92% of respondents used MCI as a diagnostic label in clinical practice. 54 A majority (68%) of respondents also used the labels prodromal AD or MCI due to AD. Over 70% of respondents thought that these labels had additional value compared with a label of MCI and influenced decisions about treatment, as well as communication with patients.

Patient/carer experience of diagnosis

This section deals specifically with experience of the process of diagnosis and labelling of memory problems. The broader topic of patient and carer experience of services is covered below (see Chapter 9), although some overlap is inevitable. This section is based on evidence from four reviews22,55–57 and six primary (mainly qualitative) studies. 1,15,24,58–60

An early scoping review55 of consent for the investigation and diagnosis of memory problems noted that early discovery of AD biomarkers in research or clinical settings is problematic because it requires patients to consent to disclosure of findings that indicate an uncertain risk of developing AD in the future. The authors of the review55 argue that expectation of future decline may lead to stigma, isolation and discrimination, but offer no solutions beyond the need for more nuanced analysis of the ethics issues involved. Closely linked to consent is the question of how patients and carers understand and describe the concept of MCI. Two studies15,58 specifically addressed this question. Roberts and Clare58 used a qualitative methodology (interpretive phenomenological analysis) to analyse transcripts of interviews with 25 people with a clinical diagnosis of MCI who had been informed of their diagnosis. Four higher-order themes were identified, but participants did not use the term MCI, suggesting that the term was not meaningful for them, although they did want a clear explanation for their memory problems. Pierce et al. 15 applied ‘discourse analysis’ to interviews with seven people diagnosed with MCI. One of the discourses identified was ‘not knowing’ about MCI. This was accompanied by ‘knowing about aging and death’ and ‘not wanting to know about dementia’. These two complementary studies set the scene for difficulties in patient experience of diagnosis and labelling.

Three included systematic reviews22,56,57 cover experience of the diagnostic pathway from diagnosis of MCI22 to investigation in memory clinics56 and diagnosis of dementia. 57 Dean and Wilcock22 noted a lack of studies on the effect of disclosing a diagnosis of MCI on patients and carers. Patients and carers receiving a diagnosis of MCI produced a range of negative and positive emotional responses, but there were no studies of experience of the diagnostic process. The review by Robinson et al. 56 included experiences of the diagnosis of both MCI and dementia, with similar findings to those of Dean and Wilcock. 22 Specifically, for MCI, a diagnosis could lead to feelings of exclusion, but could also reinforce a shared identity with others. Participants wished to be proactive in their response to a MCI diagnosis. 56 Bunn et al. 57 identified more concrete information on experience of the diagnostic process. Bunn et al. 57 reported that patients and carers perceived that, in some cases, doctors were slow to recognise symptoms or reluctant to give a diagnosis, and that even when people were referred to memory services the process could be slow, with long periods of waiting. 57

The four primary qualitative studies1,24,59,60 (Table 4) provided more detailed and richer data than those that were available from the reviews. The topic is discussed in more detail below (see Chapter 9) because the studies also include patient experience of services. Overall, the studies identified substantial difficulties with the diagnostic/labelling process from the viewpoint of patients and carers. These are well summarised by the titles of the studies, which refer to ‘making sense of nonsense’,24 ‘falling through the cracks’1 and ‘negotiating a labyrinth’. 60

| Study | Type of study | Study aims/objectives | Study sample/population | Setting | Findings: screening/diagnosis | Study limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beard and Neary24 | Qualitative | The purpose of the study (a subset analysis) was to examine the specific experiences of memory loss for individuals diagnosed with MCI | All participants had sought cognitive evaluation following memory problems and had been given a diagnosis of amnestic MCI within the previous 3 years. All were community dwelling | Study participants were recruited from a research registry at an AD centre in a large Midwestern US city | MCI is undergoing a medicalisation process and narrative accounts of the condition do not support this (despite advances in diagnostic criteria). Authors suggest that the MCI label is used inconsistently by clinicians and researchers. Understanding of MCI following diagnosis: location on a continuum of age-associated cognitive challenges causes confusion | None provided |

| Manthorpe et al.59 | Qualitative | To increase understanding of the experiences of people developing dementia, and of their carers, to inform practice and decision-making |

Participants had early dementia or MCI (and carers) Fifty-three participants in total (27 individuals with memory problems and 26 carers; 20 were matched pairs) |

Memory clinics situated in London (n = 1), the north-west of England (n = 1) and the north-east of England (n = 2) | Few participants experienced the process of memory assessment as patient centred. Where assessment processes were lengthy and drawn out, participants experienced considerable uncertainty. Many participants experienced tests and assessments as distressing, sometimes in settings that were perceived as alarming or potentially stigmatising by association. Information provision and communication were variable and practitioners were not always thought to help people to make sense of their experiences | Interpretative nature of qualitative research |

| Poppe et al.1 | Qualitative | To investigate how services respond to people with memory concerns and how a future effective and inclusive dementia prevention intervention might be structured | Eighteen people aged ≥ 60 years with subjective or objective memory problems, six family members, 10 health and social care professionals and 11 third-sector workers. Mixed perspective | NHS and third-sector organisations supporting older people | Diagnosis of MCI seen as entering a transitional state between health and dementia. Patients perceived that MCI was a medical problem, but responsibility for preventing dementia and seeking help if symptoms worsened was placed on them | Diverse sample of health professionals but authors note that the patient sample was primarily people who had recently sought help for memory problems and so may not be representative |

| Samsi et al.60 | Qualitative | This study explores the experience of the assessment and diagnostic pathway for people with cognitive impairment and their family carers |

Twenty-seven people with cognitive impairment and 26 carers (20 dyads). Most participants with cognitive impairment were recruited and interviewed once when first referred to the memory service. Purposeful sampling and a variable sample matrix applied Inclusion criteria were people who: |

London (one site), north-west England (one site) and north-east England (two sites). In site 2, assessments were conducted at home and diagnosis communicated in the memory clinic. However, by the end of the study, staff in site 2 were conducting all assessments in the memory clinic |

(1) Initial service encounters: primary care seen as gateway (2) Assessment processes (2a) Confusing referral process. Lack of clarity on when and who referral was about (2b) Entering the labyrinth: patient confusion, tests included ‘X-rays of the head’, general scans, MRI, electrocardiography and blood and cholesterol tests (2c) Waiting times. Time from the first consultation in primary care to the point of diagnosis ranged from 3 to 9 months. Diagnosis communicated in a way patients thought it enhanced shock (3b) Lack of information (3c) Relationship with practitioners. Everyone who had been assessed and diagnosed in their own homes reported a positive experience (4a) Memory retraining. One memory service held ‘classes’ on practical strategies for managing memory problems. Independence was a key priority (4b) Planning. Advice welcomed (4c) Dashed expectations. Long waiting times also had the added disadvantage of raising expectations, which were then dashed at diagnosis |

Generalisability of context: community-dwelling older people excluded those living in care homes. The study excluded people with severe communication difficulties and those unable to speak English. Finally, there was an absence of professional perspectives |

Cognitive tests

Cognitive tests are the main tools available to GPs and other primary care clinicians to supplement clinical judgement in assessing people with memory problems. There is an extensive literature on the diagnostic accuracy of such tests, but this review focused on the role of cognitive tests in aiding decisions about further investigations and referral or treatment pathways.

Evidence from systematic reviews indicate that a number of comprehensive screening tests, such as the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination – Revised, the Cambridge Cognitive Examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease, have > 80% sensitivity for distinguishing people with MCI from healthy volunteers. 61 However, the time and expertise required to administer some tests may limit access to them in primary care settings. 5 An international survey of physicians (n = 1365, 63% specialists) found that most reported using cognitive tests for early detection of MCI or dementia, with the MMSE being the most commonly used tool. 62

We included two systematic reviews63,64 and three primary studies65–67 of specific tests or types of test (Table 5). A 2018 systematic review63 of automated tests included 16 studies of 11 tools, but none was suitable for monitoring disease progression or response to treatment. A systematic review64 of the Ascertain Dementia 8 questionnaire concluded that that this was a suitable tool for use in busy primary care settings because, on average, it took < 3 minutes to administer.

| Study | Type of study | Study aims/objectives | Study sample/population | Setting | Findings: screening/diagnosis | Study limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslam et al.63 | Systematic review | To determine whether or not automated computerised tests accurately identify patients with progressive cognitive impairment and, if so, to investigate their role in monitoring disease progression and/or response to treatment | People with MCI or early dementia | Various countries and settings (e.g. primary care, memory clinic) | Sixteen studies assessing 11 diagnostic tools were included. No studies were eligible for inclusion in the review of tools for monitoring progressive disease and response to treatment | The wide range of tests assessed and non-standardised reporting of diagnostic accuracy outcomes meant that statistical analysis was not possible |

| Chen et al.64 | Systematic review | To assess the diagnostic accuracy of the AD8 questionnaire for cognitive impairment | Population appears to be people with cognitive impairment (i.e. MCI or dementia). Seven studies with 3728 participants were included | Primary care (i.e. community, clinic or hospital) | Studies were classified into two subgroups according to the severity of cognitive impairment (MCI/dementia vs. normal cognition, and dementia vs. non-dementia). The overall sensitivity across the subgroups MCI/dementia vs. normal cognition, and dementia vs. non-dementia, respectively (0.72, 0.91), was superior to specificity (0.67, 0.78). The pooled negative likelihood ratio (0.17, 0.13) was better than the positive likelihood ratio (2.52, 3.94). The areas under the summary receiver operating characteristic curve were 0.83 and 0.92, respectively. Meta-regression indicated that location (community vs. non-community) may be a source of heterogeneity. The average administration time was < 3 minutes | Only seven studies included and three did not include MCI. There were diverse populations and settings |

| Ehrensperger et al.65 | Quantitative | To describe the development and test the feasibility and validity of a newly developed case-finding tool (BrainCheck) for cognitive decline |

Feasibility study: 52 GPs rated the feasibility and acceptance of the patient-directed tool Validation study: an independent group of 288 memory clinic patients with diagnoses of MCI (n = 80), probable AD (n = 185) or major depression (n = 23) and 126 demographically matched cognitively healthy controls Medical/health service perspective |

Memory clinics in Switzerland |

Feasibility study: GPs rated the patient-directed tool as highly feasible and acceptable Validation study: a classification and regression tree analysis generated an algorithm to categorise patient-directed data, which resulted in a correct classification rate of 81.2% (sensitivity = 83.0%, specificity = 79.4%). The correct classification rate of the combined patient- and informant-directed instruments (BrainCheck) was 89.4% (sensitivity = 97.4%, specificity = 81.6%) |

Memory clinic patients may not be representative of those seen in primary care |

| Hancock and Larner66 | Quantitative | To investigate the diagnostic utility of the TYM as an independent test to differentiate patients with and without dementia in memory clinics |

Consecutive patients (n = 224; 58% male, 35% meeting clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia) attending two memory clinics in the UK Clinical/health service perspective |

A memory clinic based in a psychiatric hospital and a cognitive function clinic based in a regional neuroscience centre | TYM was easy to use and acceptable to patients. Downwards adjustment of the TYM test cut-off point to ≤ 30/50 (vs. ≤ 42/50, which was used in the index study) was necessary to maximise test accuracy and specificity. Using this revised cut-off point, TYM showed comparable diagnostic utility (sensitivity = 0.73, specificity = 0.88, positive predictive value = 0.77, negative predictive value = 0.86, area under receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.89) to the MMSE and the ACE-R for the differentiation of dementia from non-dementia | Further work is needed to assess test performance in other settings and effect of factors like age and education |

| O’Malley et al.67 | Quantitative | To evaluate a fully automated system (CognoSpeak), which enables risk stratification at the primary–secondary care interface and ongoing monitoring of patients with memory concerns | Fifteen participants in each of four groups: AD, MCI, FCD and healthy controls. Groups were 40–67% male, with a mean age ranging from 55 to 68 years. Clinician/health service perspective | Memory clinic and community (i.e. controls) in Sheffield, UK | CognoSpeak distinguished between participants in the AD or MCI groups and those in the FCD or healthy control groups with a sensitivity of 86.7%. Patients with MCI were identified with a sensitivity of 80% | Initial evaluation with a relatively small sample |

Tests evaluated in single studies were ‘BrainCheck’, TYM (Test your Memory) and ‘CognoSpeak’ (a fully automated screening tool). Ehrensperger et al. 65 developed and evaluated ‘BrainCheck’, which was a brief screening instrument for use in primary care and combined different sources of data. ‘BrainCheck’ was rated highly feasible and acceptable by GPs and correctly classified 89.4% of cases (including MCI, probable AD, depression and healthy controls). The TYM test, which was designed to be self-administered under medical supervision, was evaluated in a memory clinic population. 66 TYM was considered easy to use and acceptable to patients (n = 224, 35% meeting criteria for dementia). Using a revised cut-off point, the TYM showed comparable diagnostic utility to the MMSE and the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination – Revised for the differentiation of people with and without dementia. The authors66 suggested that self-administered tests, such as TYM, may be particularly useful where clinicians’ time is limited. In a pilot study involving 15 people with MCI, people with other conditions and healthy controls, the automated system achieved levels of accuracy comparable to those of current manually administered screening tools. 67 This suggests potential to improve the efficiency of screening processes in the future.

An important point about cognitive tests is that the prevalence of the condition of interest (e.g. MCI or dementia) depends on the test used and the selected cut-off point. In an early study involving people aged 70–90 years without dementia (n = 981), Kochan et al. 68 found that the prevalence of MCI ranged from 4% to 70%, depending on the criteria used. Klekociuk et al. 69 noted that existing MCI diagnostic criteria resulted in an unacceptably high rate of false-positive diagnoses of MCI. The authors69 reported that a combination of measures of complex sustained attention, semantic memory, working memory, episodic memory and selective attention correctly classified the outcome in > 80% of cases. The rate of false-positive diagnoses (5.93%) was lower than that reported in previously published MCI studies. The issue of ‘false-positive’ labelling of MCI (i.e. reversion to normal cognition) is discussed below. In practice, sophisticated combinations of tests, such as those used by Klekociuk et al. ,69 are unlikely to be available in normal clinical practice.

NHS London Clinical Networks guidance recommends the use of a validated brief screening test, such as MoCA, for the detection of MCI,70 but this appears to be in the context of a memory service assessment rather than in primary care.

Two papers by Sabbagh et al. 71,72 focus on early detection of MCI in different settings. The review,71 which was focused on primary care, identifies barriers to effective screening in primary care related to time constraints and test validation. Tests delivered in ≤ 10 minutes are unlikely to fully evaluate all dimensions of cognition. In addition, tests developed and tested on highly homogeneous and well-educated populations may perform less well in routine practice with more diverse populations. Factors such as level of education and proficiency in English may affect test performance, potentially reducing test scores and resulting in people being wrongly labelled with MCI.

A further paper72 by the same group of authors deals with early detection of MCI at home. The time constraints of primary care are less of an issue in this setting and a range of digital technologies are available as supplements or alternatives to conventional ‘pencil and paper’ tests. These technologies are less well validated than tests in clinical settings and other barriers include costs and concerns about reliability of the technology. However, the authors conclude that ‘passive’ technologies that work by monitoring user behaviour could ultimately provide a low-effort, easy-to-use solution for widespread cognitive performance monitoring. 72

We identified one economic evaluation73 of cognitive testing for MCI and dementia in primary care. The authors73 examined three cognitive tests and concluded that any of them could be considered cost-effective compared with unassisted clinical judgement by GPs. The most cost-effective option in the base case was the GP assessment of cognition. It should be noted that benefits from testing were due to early access to medication for dementia.

In summary, the time and expertise needed to administer cognitive tests is variable. Although much research has focused on diagnostic accuracy, quick tests suitable for use in primary care may effectively identify people who need further investigation for cognitive impairment.

Imaging

We included two narrative reviews and a systematic review, giving a broad overview of imaging (scanning) in the investigation of MCI and dementia, together with a study of service variation and a cost study (which also included biomarkers). Two included studies (one a systematic review) reported on the effects of amyloid imaging on diagnosis and treatment, whereas a further systematic review focused on the impact of disclosing amyloid imaging results to people without dementia. The Manchester consensus guidance5 also covers imaging and is more recent than the general reviews.