Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR132541. The contractual start date was in November 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Fitzpatrick et al. This work was produced by Fitzpatrick et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Fitzpatrick et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from a study protocol paper published by the authors in 2021. 3 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This mixed-methods study was designed to explore and understand the real-life experiences of social distancing and isolation in care homes (CHs) for older people in England from the perspective of multiple stakeholders and to develop a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources for health and care delivery. This chapter describes the context to this study and the structure of the report.

Context

Around 15,375 CHs in England provide care for older adults – 11,025 residential CHs and 4350 with nursing. 4 In the UK, CHs are part of the adult social care sector, typically known as social care. Both residential and nursing CHs provide personal care for residents. In addition, nursing CHs employ registered nurses (RNs) to provide nursing care. The CH sector is diverse and complex in its configuration, for example ownership (with CHs run by private companies, voluntary or charity organisations and some by local councils), provision size and residents’ funding arrangements. The CH sector in England employs approximately 670,000 people, caring for just under 400,000 older people. 5 Many older people living in CHs have complex health and social care needs,6,7 with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease being the most common conditions for those in England and Wales. 8 These older people are at high risk of poor health outcomes and mortality if they contract coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 9

COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 202010 and in the UK the first national lockdown was announced by the Prime Minister on 23 March 2020, with people being ordered to ‘stay at home’ and ‘save lives’. 11 Shortly after that restrictions to CH visiting were issued,12 and on 15 April 2020 an action plan for social care in England was introduced by government that adopted a four-pillar approach to control the spread of infection; support the workforce; support independence, support people at the end of their lives and respond to individual needs; and support local authorities (LAs) and providers of care. 13 Plans for the other three countries of the UK occurred around the same time; the decision-making and policy response of the devolved administrations of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland is, however, beyond the scope of this study.

For 22 countries worldwide, 41% of all COVID-19 deaths were CH residents. 14 The Office for National Statistics for England and Wales reported that since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, of an estimated 274,063 CH resident deaths, 16.7% (45,632) were attributable to COVID-19. 8 At the peak of the first wave (defined by the authors as starting on 1 February 2020 and lasting until 31 August 2020), an observational study of 4.3 million adults over 65 years living in CHs in England reported that the risk of mortality among women increased by 115% and among men by 147%. 15 This contrasted with 30% for women and 47% for men living in private homes. 15 COVID-19 was the second leading cause of death for women in CHs in England in the first and second waves and the leading cause of death for men living in CHs in England during wave one. 8

Early evidence indicated that the CH sector was overlooked in the initial planning of how to contain COVID-19,16 with reports of CHs caring for older people facing significant challenges. 17,18 Challenges included inadequate support to manage infection prevention and control (IPC) effectively; decision-making at speed in a vacuum of evidence-informed guidance to care safely for residents, families, friends and staff; sourcing and funding of personal protective equipment (PPE); concerns about testing; and guidance related to the discharge of older people from hospitals to CHs. 19,20

Care homes implemented various measures to help protect residents from contracting COVID-19, including social distancing and isolation as per government guidance, which is the focus of our study. We use the terms social distancing and isolation as set out in the UK government document, ‘Admission and care of residents in a CH during COVID-19’. 21 The guidance stated that CHs ‘should be stringent in following social distancing measures for everyone in the care home and supporting those in clinically extremely vulnerable groups to follow shielding guidance’ (p23). Further, residents should be isolated in their own bedroom for 14 days following discharge from hospital or interim care facilities or when moving into a CH from a private home. Likewise, symptomatic residents, and residents without symptoms but who had been exposed to a person with possible or confirmed COVID-19, should be isolated for 14 days in their own bedroom from the onset of symptoms or a positive test result or after the last exposure. The evidence base to support the delivery of social distancing and isolation in CHs was lacking. 9 Care homes reported that implementing these measures when caring for residents was challenging,22 with regard to social distancing and isolation for residents living with dementia who may ‘walk with purpose, often called wandering’. 9

The NIHR commissioned research to better understand and manage the health and social care consequences of the global COVID-19 pandemic beyond the acute phase. Our study provides a unique contribution to helping protect older people living in CHs from COVID-19 now and for any future outbreak. It identified the real-life challenges and consequences of providing safe care incorporating social distancing and isolation measures within a CH setting while balancing potentially negative consequences for residents’ psychological, emotional, cognitive and physical well-being, and importantly it is informed by the perspective of residents, families and friends, CH staff, and external health and social care stakeholders. The study culminates in a co-designed toolkit comprising evidence-informed guidance and resources to support CHs, their staff, residents and families/friends during this and for any future outbreak.

Why this research is important

Research is needed to explore and understand the challenges experienced by CHs endeavouring to implement these measures in a person-centred way so that CHs do not become institutions of confinement. It is critical to capture the expert ways in which CHs are implementing social distancing and isolation requirements in this challenging environment and mitigating adverse consequences. For older residents, negative consequences of isolation reported included loneliness, low mood, loss of cognitive function23 and loss of physical function,9 and for those living with dementia, a worsening of both cognitive and psychological symptoms. 24 Possible adverse consequences for families and friends included loss and grief25 and for CH staff, moral distress, fear and fatigue. 26,27 Our study will complement this early research and make an important contribution to a growing body of national and international evidence in the field.

Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows:

-

Chapter 2 reports the study aims and objectives and the methodological approach used to address these.

-

Chapter 3 describes the first phase of the study, the rapid review of the evidence on measures used to prevent or control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in CHs for older people.

-

Chapter 4 describes social distancing and isolation policies and protocols and routinely collected CH data for the six case study sites in phase 2.

-

Chapter 5 explores CH staff perspectives of social distancing and isolation measures implemented in CHs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Chapter 6 explores the perspectives of residents and their families of social distancing and isolation measures implemented in CHs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Chapter 7 explores the perspectives of senior health and care leaders on social distancing and isolation measures implemented in CHs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Chapter 8 presents phase 3 of the study, the development of a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources for health and care delivery, now and for any future outbreaks.

-

Chapter 9 discusses the key findings from the study, reviews the approach and methods used, provides suggestions for future research and presents the implications of findings for policy and practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from a study protocol paper published by the authors in 2021. 3 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter reports the study’s aim and objectives and the methodological approach used to address these. Also reported is the patient and public involvement (PPI).

Aim and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to explore and understand the real-life experiences of social distancing and isolation in CHs for older people from the perspective of multiple stakeholders, and to develop a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources for health and care delivery now and for future outbreaks of the coronavirus. The study objectives were as follows:

-

(1) To investigate the mechanisms and measures used by CHs to socially distance and isolate older people to control the spread of COVID-19 and other infectious and contagious diseases [e.g. other acute respiratory infections, Clostridium difficile and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) etc.].

-

(2) To examine the experiences of residents and families/friends of social distancing and isolation measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, including how these measures impacted their well-being and how they adapted to change.

-

(3) To explore how RNs and CH staff adapted to and managed the delivery of personal, social and psychological care for residents with different needs while maintaining social distancing and isolation measures.

-

(4) To identify how CH managers, owners and external stakeholders developed, managed and adapted policies, procedures and protocols to implement social distancing and isolation measures including workforce organisation, training and support, use of communal spaces, visiting and working with external health and social care professionals.

-

(5) To use the findings to develop a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources and a mosaic film, detailing which interventions and strategies for social distancing and isolation for residents work well and which do not work in specific situations and contexts to support decision-making about health and care delivery in CHs and to facilitate resilience-building for future planning.

Study design and conceptual basis

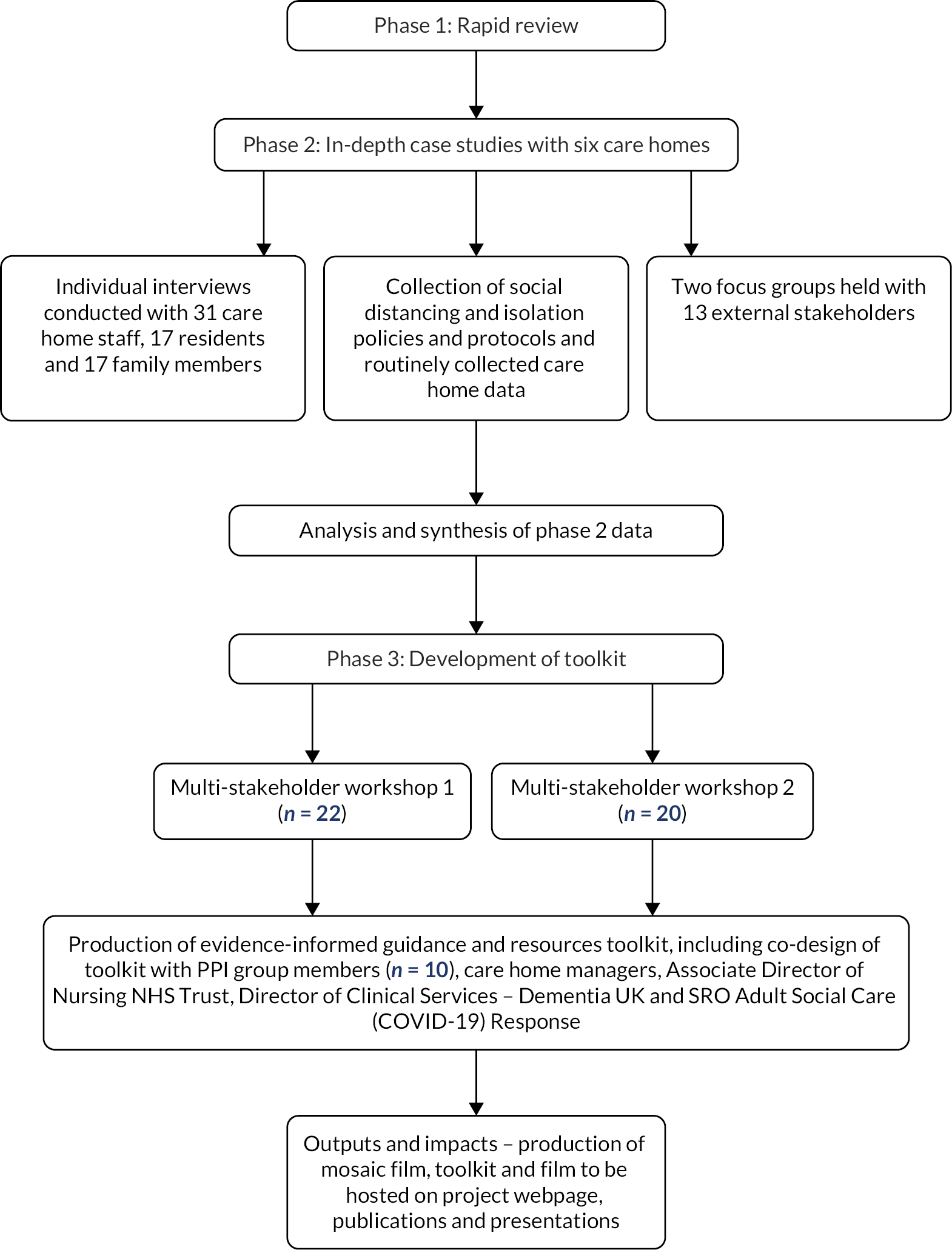

A mixed-methods, phased design was undertaken to identify the challenges, consequences and solutions to implementing social distancing and isolation measures in CHs for older adults to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19. The study was conducted in three phases: (1) a rapid evidence review of measures used to prevent or control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in CHs for older people, (2) in-depth case studies of six CHs in England involving individual interviews with CH staff, managers, residents and families (see NIHR project page for interview guides); focus groups with CH owners and external stakeholders (see NIHR project page for focus group topic guide); and the collection of social distancing and isolation policies/protocols, and routinely collected CH data (see NIHR project page) and (3) the development of a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources, and a mosaic film, for CHs for older people. A protocol was developed to manage any disclosure of poor practice or participants’ distress during data collection (see NIHR project page for this protocol). Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram. We have used reporting guidance for qualitative research. 2

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram.

Phase 1: Investigating the mechanisms and measures used by care homes to socially distance and isolate older people to control the spread of COVID-19 and other infectious and contagious diseases (Objective 1)

Method

Review design and conceptual basis

A rapid review of published literature on measures used to prevent or control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious and contagious diseases in CHs for older people was undertaken (PROSPERO registration: CRD42021226734). This methodology was selected due to the time-critical nature of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The process for study selection and data extraction followed the evidence-informed guidance for conducting rapid reviews. 1

Research questions, boundaries and scope

This research aimed to identify and assess the previously and currently used strategies by CHs to prevent and control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious and contagious diseases. Specific review questions were as follows:

-

(1) What mechanisms and measures have been used to implement social distancing and isolation for residents and staff?

-

(2) How are they implemented? What are the challenges and facilitators to implementation?

-

(3) What is the impact of the implemented measures and mechanisms?

-

(a) What are the psychosocial and physical consequences for older people?

-

(b) What are the consequences for family members, significant others, staff and organisations?

-

(c) What is the evidence of measures and mechanisms that work for different types of CHs, different resident needs and various ways of organising care delivery?

-

(d) What recommendations have been made after the implementation of these measures?

-

Inclusion criteria: to be included in the review, literature needed to address COVID-19 or other infectious and contagious diseases [e.g. C. diff, diarrhoea and vomiting, MRSA, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)] in older people (aged 65 years and over) living in CHs, nursing homes, long-term facilities or residential CHs. Literature discussing adults under the age of 65 years or those living outside of long-term care facilities were excluded from the review. No limits were placed on the geographical location or timeframe of the research, but only English-language articles were included because of the resources available. Empirical research studies were included, along with literature reviews and grey literature, such as best practice guidance and expert opinion.

Exclusion criteria: non-English-language outputs.

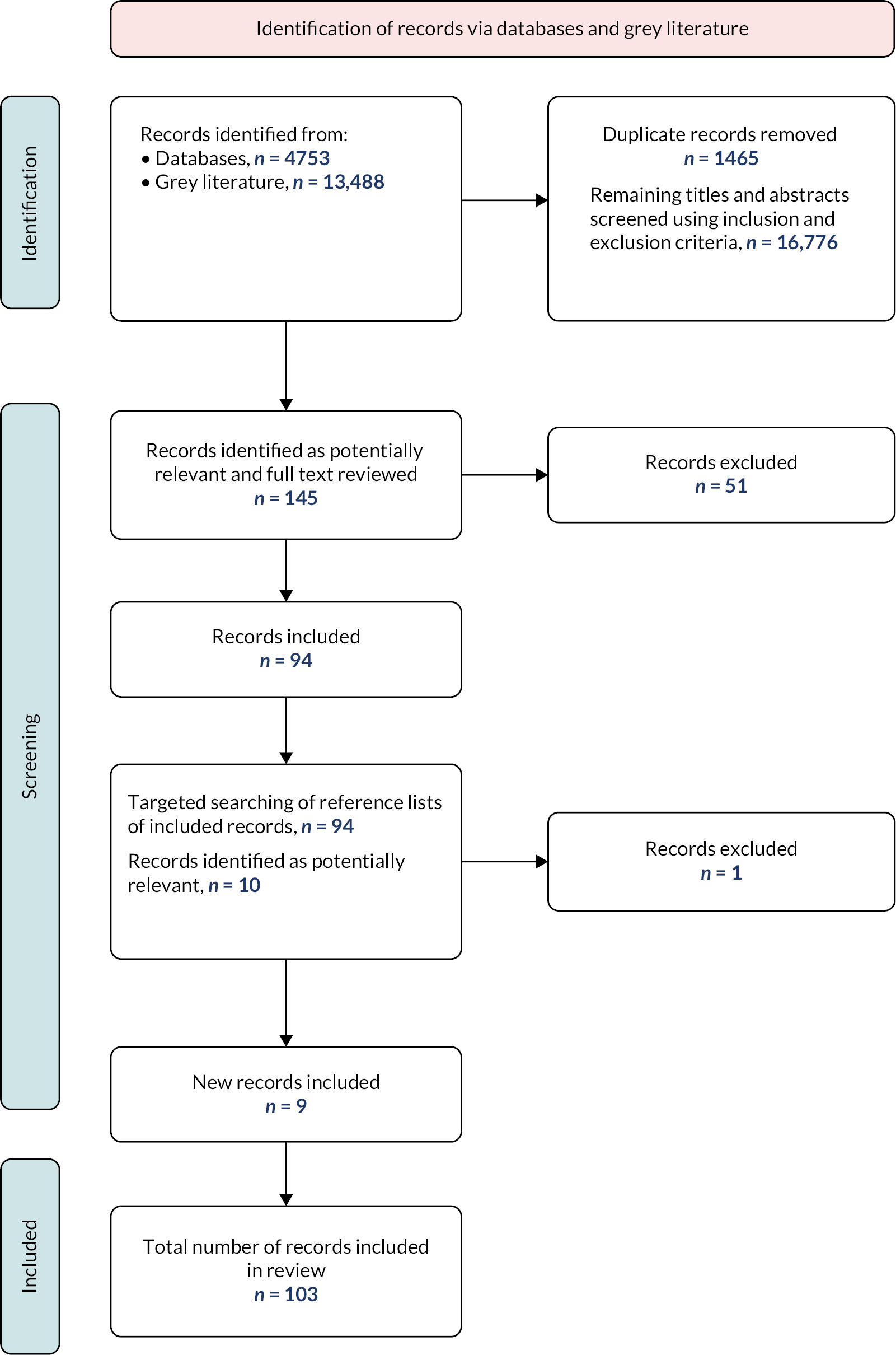

Findings from the 103 papers included in the review were synthesised using tables and a narrative summary organised around the review questions. Full details of the search strategy, screening and selection, flow chart of the review process, summary table of 103 records, and findings are presented in Appendix 1.

Phase 2: Examining experiences, consequences and solutions of social distancing and isolation measures (Objectives 2, 3, 4)

Introduction

For the second phase of the study, in-depth case studies were undertaken to examine how social distancing and isolation of residents were being implemented in CHs for older people. This involved individual interviews with CH staff, residents and family members, and the collection of social distancing and isolation policies and protocols and routinely collected CH data. When interviewing staff members, we asked about their experiences of social distancing and isolation and their understanding of resident experiences, based upon what residents had reported to them and their own observations during the pandemic. When interviewing residents and family members, we asked about their own specific experiences of social distancing and isolation. We also conducted focus groups with senior health and care leaders in England and national-level stakeholders to understand their experiences of developing and applying policy for CHs, and how they responded to the resulting challenges.

Individual interviews: method

Research team

The interviews were carried out by four members of the research team: SP, SS, AD and JF. All interviewers are established academic researchers with experience in qualitative interviewing and a background in health and/or social care research. The interviewer and participant had no relationship before the interview, as all recruitment was carried out by the CH manager or project champion at the participating case study sites.

Recruitment

Six CHs in England were recruited for the study. Care homes were invited purposively, using a sampling frame designed to maximise variability in terms of size of the CH, geographical location, Care Quality Commission (CQC) rating, registration (nursing, residential or dual registration), ownership and incidence of COVID-19. The pandemic experience for the CH sector has impacted on CHs being research ready; the team worked hard over a prolonged period to recruit two case study sites with a ‘requires improvement’ CQC; this was not successful. We also managed a key issue around recruitment of participants from black and minority ethnic (BAME) groups. At meetings of the Study Steering Committee and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee, we discussed these challenges and there was agreement that we should prioritise diversity of participants and not focus on recruiting CHs with a CQC rating of requires improvement. This revised plan was shared with NIHR and we were granted permission to proceed with this revised plan.

Recruiting CHs began with an initial meeting with interested provider organisation representatives, who had been sent the study information via existing contacts and networks of the research team. Following this meeting, the provider representative nominated a CH that met the criteria and would have the capacity to participate in the study. A further meeting(s) took place between the manager of the nominated CH and the researchers to provide additional details about the research and involvement of the CH. All meetings took place remotely using Microsoft Teams.

Care home managers were asked to nominate a ‘project champion’ to be the point of contact within each home to help facilitate the research, which was conducted entirely remotely due to COVID-19 restrictions on visiting care facilities. The project champion was required to be a member of staff who knew staff and residents well, and who had the capacity in their role to help with the recruitment and interview process. It was undertaken by staff members with different roles in each home, including the CH manager, deputy manager, well-being co-ordinator, activity co-ordinator and administrator. The project champions were briefed about the study and guided by research team members throughout the process; this included us working closely with CHs to try and increase diversity of participants. Potential interview participants were nominated by the CH manager in collaboration with a member of the research team and invited to participate by the project champion, using the paper copies of the study information sheets and consent forms sent to the home by the research team. The information sheets and consent forms were tailored to each participant group; resident and relative documents were produced in an easy-read format, following guidance from the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) and feedback from our PPI group members.

The purposive sample of participants required from each home included staff (n = 5), residents (n = 3) and relatives or friends of residents (n = 3). For CHs with nursing or dual registration, the staff sample consisted of the manager/deputy (n = 1), RNs (n = 2) and care staff (n = 2). For the CHs without nursing (residential), the sample included the manager/deputy (n = 1) and senior care workers or care workers (n = 4). Inclusion criteria for staff included being permanent staff (i.e. not agency) and having worked at the home during the pandemic. Staff were purposively recruited to ensure a range of age, gender, ethnicity and time in service. Resident participants were also recruited purposively, to ensure a range of genders, ethnicities and different health and care needs. Inclusion criteria were that residents must be over 65 years old and have the capacity to consent. Residents were asked during the consent process if they would like to nominate a friend or family member to participate in the research. If they or the invited family member declined or there was no nomination, the CH manager/project champion was asked to recruit a family member or friend of a non-participating resident. The project champion was responsible for collecting informed consent from participants and sending scanned copies of the completed forms to the researchers ahead of the interview. All participants were given the option to have a phone or video call with the researcher before giving signed consent, to ask any questions or talk through the research process; however, none chose to do so.

As part of the consent process, participants were asked if they were happy for the interview to be video-recorded so that excerpts from interviews could be used to create a short film as part of an evidence-based resource for CHs. The information sheet explained that a television production company technician would be present for the remote interview to ensure that there were no issues with recording. The technician could be asked to leave the call at any point should the participant wish. The option for being video-recorded was voluntary. If a person declined, they were asked whether the interview could be audio-recorded or, if preferred, only written notes to be taken. Participants were also given the option to have their face pixelated in the final video if they were happy to be video-recorded but wanted to maintain anonymity. In total, 12 participants (5 staff, 4 residents and 3 family members) chose to be audio-recorded but not video-recorded, and none opted for written notes only. The remaining participants all agreed to be video-recorded.

Setting

All resident and staff interviews took place at the CH, using an iPad sent to the home by the research team. Interviews were carried out in either the resident’s room or a quiet place in the CH such as the manager’s office, visitors’ room or hair salon when not in use. Relatives were given the option of doing their interview in their own home using their own device (e.g. smartphone, laptop, tablet, telephone). One family member chose to be interviewed at home and all others were carried out at the CH, complying with requirements for visitors.

The iPad was set up for each interview by the project champion and positioned so that the participant could see the researcher on the screen. Interviews that were being video-recorded were carried out using VMix, a secure video-call service hosted online and accessed by the technical team at KMTV. KMTV were responsible for making both the audio- and video-recordings for those participants who were video-recorded and for forwarding the audio files to the research team. Interviews that were audio-recorded only took place on Microsoft Teams. All participants were asked if they would like the project champion to be present during their interview and 17 participants (7 staff, 5 residents and 5 family members) chose to have the project champion present.

Data collection

Interviews at CHs were conducted non-simultaneously, and interviews at one CH were generally completed before interviews at another CH began. This approach to data collection meant that data were collected at different times for different CHs. These time periods were as follows: Care Home 1, February and March 2021; Care Home 2, March and April 2021; Care Home 3, April and May 2021; Care Home 4, June and July 2021; Care Home 5, August and September 2021; Care Home 6, October to December 2021. Interviews were semistructured, with a separate schedule of questions for each participant type. Interview schedules were developed by the research team and reviewed by the PPI group, and by a CH manager and resident from a non-participating CH.

Additional prompts were added to the schedules following the initial interviews of each participant type in the first CH and were agreed upon by the research team. The schedule of questions was shared with each participant at the point of recruitment to the study. Immediately before the interview began, the researcher checked consent, reminded that participation was voluntary and that the interview could be paused or stopped at any time, and gave the participant the opportunity to ask any questions. A demographic form was also completed before the recording began. For resident participants, these were collected with permission from residents and the care manager (e.g. about their primary health needs, length of time living in the CH, age group, gender, ethnic group). For families/friends participating in the study, demographic data included the nature of their relationship to residents, age group, gender and ethnicity. Staff participants were asked for their role title, length of time in the current role, length of time working in the CH sector, age group, gender and ethnic group. Once started, interviews lasted between 20 minutes and an hour. Following each interview, the researcher made field notes about the engagement of participants, any key points that had arisen, and whether there had been any technical issues, such as problems with Wi-Fi.

Data analysis

The interview audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a transcribing company approved by King’s College London (KCL) and were quality assured by a researcher. The interviews for each participant group were assigned to one researcher (staff interviews – SS, resident interviews – AD and family interviews – JF). We adopted an inductive orientation to thematic analysis – analysis was located within, and coding and theme development were driven by the data content. 28 At the beginning of the analysis process, a sample of staff, residents and family/friend transcripts were each read and coded independently by five researchers (JF, AD, SS, RH, SH). The researchers met and discussed their coding and, as a team, compiled a specific coding index for each participant group. The themes identified in the rapid review (phase 1) were used as deductively derived main themes in the coding indexes, and subthemes and any additional themes were inductively derived from the transcripts. AD and other team members began developing a coding framework for resident interviews based on the themes from the review and initial readings of the transcripts. However, it quickly became apparent that the elliptical nature in which many residents spoke in response to questions meant that using a framework was a blunt and, therefore, not particularly useful way of analysing this data set. AD read and reread resident transcripts and generated key themes of resident discussion (loosely described as ‘codes’) and compared how these themes were expressed across the interview data set. Researchers each analysed transcripts from their assigned participant group, but SS, AD and JF met regularly to discuss and compare their findings and modify their indexes accordingly. JF also read and analysed a subsection of transcripts coded by SS and AD for quality assurance.

Focus groups: method

Recruitment

For the second component of phase 2, we recruited and conducted two focus groups (FG1, FG2) with a purposive sample of external key informants (n = 13) beyond the CH sites. Participant characteristics (role or type of organisation worked for) are given in Chapter 7, ‘Introduction’. Potential participants were identified through study team discussions and through contact with people known to the study team. Potential participants were emailed to gauge their initial interest and then were invited to one of two focus group sessions. Focus group participants were given a participant information sheet and asked to complete a consent form and demographic information sheet. These participants had macro-level knowledge and experience relevant to the pandemic for the CH sector and included clinical leads, CH providers, organisations representing CH providers, the regulator, LA commissioning leads, Public Health England, Skills for Care, Social Care Institute for England, organisations representing residents and relatives, and Trade Union representation.

Data collection

The focus groups were conducted remotely using Microsoft Teams on 17 August 2021 (FG1) and 31 August 2021 (FG2), respectively, and each lasted 120 minutes. Each focus group was facilitated by a member or members of the study team; FG1 was facilitated by RA and AMR; SH facilitated FG2. Areas of discussion were agreed upon among members of the study team in advance. The focus group discussions centred on these areas principally, with facilitator discretion to explore themes and ideas as they emerged from the participants themselves. Facilitators ensured each participant was allowed the opportunity to contribute. The focus groups were audio-recorded with permission and transcribed. Notes were made by a designated note-maker from the research team.

Data analysis

Initial impressions of the focus groups were discussed at study team meetings. Data from the focus groups were woven into the initial informal processes of analysis and discussion alongside emerging findings from the study sites. SH and AMR read the transcripts and thematically analysed them, employing a method of familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, and mapping and interpreting the data. 28 The themes were discussed with the broader study team and further refined.

Social distancing and isolation policies/protocols and routinely collected care home data: method

Data collection

For each CH, the CH manager or designate was asked to collate and share with the researchers all documents relevant to social distancing and isolation policies and protocols (e.g. for managing new and returning residents, zoning and cohorting of residents, visiting, staff training and education, education for residents and families/friends, support for residents, families/friends and staff, and testing of residents and staff). They were also provided with a proforma to complete, which asked for routinely collected CH data (e.g. number of beds; resident occupancy pre- and during the pandemic; staffing data including absence, redeployment, employment of agency and bank staff; COVID-19 incidence rates; testing and vaccination rates (see NIHR project page for the proforma). The proforma was developed in collaboration with CH provider representatives and an expert social care researcher, with insight into the type of data regularly collected by CHs. All six CHs provided their social distancing and isolation policies to the research team. All six CHs also completed the proforma for routinely collected data, though a small number of questions remained incomplete for some CHs.

Data analysis

Analysis of the CH policy and protocol documents was undertaken to understand the requirements and guidance provided to staff to prevent and control the spread of infectious diseases and COVID-19. 29 Documents were read and reread by RH, and information collated around the key themes of social distancing, isolation, cohorting, zoning and other restrictions. The data were carefully considered and distilled focusing on similarities, differences, usefulness and completeness of the available guidance. Routinely collected CH data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and descriptive summary statistics were used to describe quantitative data. Concurrent data collection and analysis informed decision-making about the need for further data and from which sources. Strategies to promote quality were embedded within our data analysis strategy. 30 This included engaging with stakeholders to check emerging findings and researcher interpretation.

Phase 3: Developing a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources for care homes (Objective 5)

Development of the toolkit (workshops)

Drawing on the findings of phases 1 and 2 and in collaboration with a broad sample of stakeholders (service users and public representatives, CH managers, nurses and carers, and leaders working in health and social care services and research), the research team developed a toolkit of evidence-informed guidance and resources to support social distancing and isolation for CH residents.

Workshop 1: 17 January 2022

The aim of Workshop 1 was for participants to discuss the study findings with reference to several trigger questions (see Appendix 2). Several documents were shared in advance with participants, including the workshop agenda; a summary of findings for interviews with residents, families and staff, and the focus groups with external stakeholders; questions to consider; and the draft paper on the findings of the study review. At the workshop, participants listened to presentations on the findings of interviews with residents (AD), families (JF) and CH staff (SS) and the findings of the focus groups with external stakeholders (SH). In two mixed breakout groups, participants were facilitated to reflect on and discuss the findings to gain a consensus on priority areas for the toolkit and how CHs could use the toolkit. In both workshops, the breakout groups were facilitated by a research team member and co-facilitated by a senior CH sector representative and coinvestigator (Breakout Group 1, Facilitators – RH, RA, Note-Maker – SS; Breakout Group 2, Facilitators – AD, LR, Note-Maker – JF). The whole workshops were audio-recorded. Participants were also invited to post any further questions and comments in the meeting chat. A synthesis of the Workshop 1 discussions is presented in Chapter 8.

For Workshop 1 these data sources informed the development of draft content that was organised around six priority areas: supporting the well-being of residents when social distancing; supporting the well-being of residents when they are isolating; supporting residents and their families and friends to communicate when visiting is not permitted; supporting visits from families and friends when visiting is allowed but with restrictions; supporting CH staff; supporting CH managers. For each priority area, ‘consequences’ and ‘actions to consider’ were presented with illustrative data extracts and case studies. This draft content was the focus of Workshop 2.

Workshop 2: 31 January 2022

The purpose of Workshop 2 was to discuss and develop further the draft toolkit content. The workshop began with an overview of the draft toolkit by JF, including its purpose, and proposed content underpinned by the study findings and informed by Workshop 1 discussions. Documents shared in advance with participants were a workshop agenda; draft toolkit content; questions to consider; a summary sheet of the research findings (for participants who were unable to attend Workshop 1); preliminary findings presented at Workshop 1 (for participants who were unable to participate in Workshop 1). Two mixed breakout groups were facilitated to work through the discussion points in Appendix 3 (Breakout Group 1, Facilitators – RH, RA, Note-Maker – SH; Breakout Group 2, Facilitators – AD, LR, Note-Maker – JF). A synthesis of the Workshop 2 discussions is presented in Chapter 8.

Final co-design activity

A third and final co-design activity involved sharing a further version of the draft content of the toolkit with stakeholders drawn from Workshops 1 and 2 (PPI group members × 10, CH managers × 2, Associate Director of Nursing × 1, Director of Clinical Services (Dementia UK) × 1, project team members × 8).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was an integral part of all stages of this study. Its design was guided by the Service User and Carer Research Expert Group from the Centre for Public Engagement in the Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education at Kingston University. This group has considerable experience of contributing to research proposals from a patient and public perspective and it is facilitated by Sally Brearley who is the PPI lead for this project and a coinvestigator. This group comprises mostly of older people, many of whom have extensive personal experience of health and care services, and several are or have been (informal) carers. We established a dedicated study PPI group comprised of 10 members, 2 of whom were also members of the Study Steering Committee. The study’s PPI lead and coinvestigator, Sally Brearley, recruited the service user and public contributors and worked with them to develop support and training needs. PPI contributions to the study included reviewing all participant-facing paperwork for submission to the Research Ethics Committee (e.g. plain language summary, project flyer, participant information sheets, consent forms and interview guides). The PPI group and project team met via Microsoft Teams in May 2021. Nine of the 10 members joined this meeting for an update on study progress, challenges along the way, findings of the rapid review, progress with the case studies and opportunities to ask questions, challenge and discuss. The Chief Investigator (CI) engaged with PPI group members throughout the study to keep them abreast of progress. PPI group members also participated in online workshops in January 2022 to contribute to co-designing the toolkit for CHs of evidence-informed guidance and resources.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Coventry and Warwick Research Ethics Committee [20/WM/0318] on 6 January 2021. Permission to access the CHs was obtained as per local procedures. Informed consent was obtained for all participants, and all participants were informed that they were free to refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: rapid review (Objective 1)

Introduction

Some text in this chapter and Appendix 1 has been reproduced from a review paper published by the authors in 2022. 31 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter describes the first phase of the study: the rapid review of evidence on measures used to prevent or control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in CHs for older people. Recommendations from papers exploring COVID-19 interventions and from papers exploring other infectious disease interventions are presented. The method for the review is presented in Chapter 2, with full details of the search strategy, screening and selection, flow chart of the review process, summary table of 103 records and findings presented in Appendix 1.

Included papers

A total of 103 records were included in this review. 9,22,24,25,32–130 Of the 103 records included in the review, 10 were empirical research studies, 7 were literature/rapid reviews and 86 were policy documents/grey literature. Of the 10 empirical studies, 8 explored COVID-19 and 2 explored other infectious diseases. Three studies were conducted in the UK; four were conducted in Europe, two in Asia and one in North America. Two empirical studies mentioned social distancing measures, nine mentioned isolation interventions, eight mentioned restrictions and two mentioned zoning or cohorting. The quality of these studies varied greatly (e.g. one was pre-print and not peer-reviewed) and methodologies included a randomised control trial, a pilot survey study and a retrospective cohort study. However, the risk of bias of each study was assessed by two researchers, using an appropriate quality assessment tool131–134 and there was an agreement to include all 10 studies in the review. Also included in this review were 85 policy documents/grey literature, which came from around the world and included policy documents highlighting different countries’ responses to the pandemic, guidelines/guidance for CHs, briefing documents, discussions and commentaries. The seven literature/rapid reviews were also of varying quality (again, some were pre-printed and not peer-reviewed) and five were related to COVID-19 and two related to other infectious diseases.

Recommendations from papers exploring COVID-19 interventions

A wide range of recommendations was made by papers exploring strategies used by CHs to prevent and control the transmission of COVID-19. These recommendations included the following:

-

Governments (internationally but also specifically those in the UK, New Zealand and Finland) must work collaboratively with acute and community sectors to develop guidance for the safe discharge of people with COVID-19 from hospitals to CHs82,112 and provide more extensive and detailed guidance on how CHs should operate in future pandemics. 69 They must acknowledge that a ‘blanket approach’ to guidance is inadequate and ensure that the individual needs of older people are at the heart of policy-making. 91,94,112 Particular attention should be paid to the clarity and feasibility of guidelines to ensure that CH providers can implement them successfully within their facilities. 69

-

Long-standing problems in social care systems, including inadequate funding and staffing, lack of integration between health and social care, lack of recognition and regard for care staff and other workforce pressures, must be addressed by governments. 22,56,66,77,85,116

-

A balance should be sought between the implementation of IPC measures and the need to ensure residents’ quality of life, dignity and well-being33,52,80,113 to ‘explore creative ways of providing care during COVID-19 that makes life worth living’84 (p28).

-

There is a requirement for consistent records to be maintained by CHs worldwide to enhance research into COVID-19 in these settings. 24,37,56 This includes the need for openly accessible and comprehensive records on COVID-19 cases and fatalities identified within CHs37 and a minimum dementia data set to enhance understanding of people living with dementia in CHs. 24

-

All CH residents should be provided with recovery and rehabilitation opportunities to address the periods of reduced activity and social isolation they have experienced. 94,112 Trauma and grief counselling services may also need to be provided for family members and CH staff. 84,94

-

Care homes must review their visiting policies for future outbreaks, including exploring how family members, including children, may be enabled to visit safely. 48,56,82,91,113 Blanket visitor bans should not be used to prevent future outbreaks. 91,113 Care homes should also receive additional government funding and support to enable them to implement safe visiting practices. 91

-

Clear, proactive communication between CHs and family members must be maintained during periods of restriction, making use of technology where possible. 95,110

-

Staff members should consider, where possible, confining themselves to CHs to protect the facility from an outbreak of COVID-19. 39

-

More research is required in a variety of areas, including the exploration of new models of planning and design to develop CH structures and layouts that better address IPC measures;33,91,112,119 an evaluation of which measures of IPC have proved successful in COVID-19;38 an investigation of the long-term effects of the COVID-19 lockdown;84 and an exploration of innovative ways of mitigating loneliness for CH residents, especially those with cognitive impairment. 24,25,103

Recommendations from papers exploring other infectious disease interventions

A limited number of recommendations were made by papers exploring strategies used by CHs to prevent and control the transmission of non-COVID-19-related infectious diseases. These recommendations were the following:

-

Develop sound, evidence-based guidelines for isolation in CHs during infectious disease outbreaks. 72

-

Further research is required on a range of topics, including how to maintain quality of life within CHs during outbreaks of infectious diseases;88 and around the concerns, experiences and perceptions of CH staff around delivering IPC interventions. 65

Concluding remarks

The material presented here is the first-ever review of strategies previously and currently used by CHs worldwide to prevent and control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious and contagious diseases. We learnt that there is a lack of empirical evidence and only limited policy documentation around social distancing and isolation measures in CHs. Evaluative research on these interventions is needed urgently. In the following chapters, we present findings from the empirical phase of the study. We explore the real-life experiences, challenges, facilitators and impacts of implementing social distancing and isolation interventions within the CH setting, informing best practice guidance and resources, thus adding to, but also complicating, the picture presented by the review.

Chapter 4 Phase 2: care home case studies: routinely collected CH data and social distancing and isolation policies and protocols (Objective 4)

Introduction

This chapter describes the routinely collected CH data and the internal layouts of the six CHs. It also presents the local policy and protocol documents that guided the implementation of social distancing and isolation measures in the participating CHs.

Routinely collected care home data

All CHs completed the study proforma (though some CHs did not answer a small number of questions), providing us with their routinely collected data. This included data on the number of beds in the CH and across the organisation; resident occupancy pre- and during the pandemic; CH staffing data including absence, redeployment, employment of agency and bank staff; COVID-19 incidence rates; testing and vaccination rates.

The participating CHs were geographically spread across England, and all had a CQC rating of either ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’. All CHs were part of larger organisations (ranging from 7 to 114 CHs per organisation and between 767 and 5875 beds per organisation). Four of the participating CHs were part of privately run organisations, and two were part of voluntary/not-for-profit organisations. One CH had a ‘Dual’ CQC registration, three had a ‘Nursing’ registration and two were registered as ‘Without Nursing’. All provided services for adults over the age of 65 years, though three also provided a service for adults under the age of 65 years. Most also provided some specialist care, such as care for dementia, learning disabilities, physical health problems and mental health problems. Five CHs had a range of funding sources, including LA, National Health Service (NHS), Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and self-funded, while one was self-funded only.

The number of beds offered by the participating CHs ranged between 37 and 73. Some CHs saw no impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bed occupancy rates. However, some reported a significant reduction in the number of occupied beds, particularly during the first wave of the pandemic, for example a CH closed one floor to be able to isolate floors and staff in the event of an outbreak. Care homes varied greatly on the number of positive COVID-19 cases that had been identified within the home, with one reporting only one case of COVID-19 between March 2020 and February 2021, while another reported 27 cases within November 2020 alone. Most CHs had few or no residents transferred from a hospital or home with COVID-19 throughout the pandemic, though one CH had opened a specially allocated ‘COVID-ward’. They, therefore, received 125 residents with COVID-19 between March 2000 and February 2021. Only two CHs had to transfer any residents from the home to hospital with suspected COVID-19: one had only transferred one patient to hospital between March 2000 and February 2021, but one had transferred nine patients to hospital in March 2020 alone. In one CH, no residents had died within 28 days of a positive COVID-19 test, while 10 residents had died in another home.

A COVID-19 vaccination programme started for residents within participating CHs between December 2020 and March 2021 and all residents had been fully vaccinated in three of the six case study sites. A staff vaccination programme also started in participating CHs between December 2020 and March 2021 and the percentage of vaccinated staff varied between case study sites, from 85% to 100% of staff. All participating CHs said they had taken measures to avoid front-line staff moving between CHs. Half of the homes had employed agency staff during the pandemic, but all those who had said this was within limits (e.g. agency staff could only work at one CH, or only staff from a single agency were used). The number of staff unable to work during the pandemic due to having COVID-19 symptoms varied widely between CHs and from month to month. The maximum number of staff reported being off work with COVID-19 symptoms in any one month was 16. Further information on the routinely collected data for each participating CH is provided in Appendix 4.

Internal layouts of care homes

Care home 1

Care home 1 has 64 en suite bedrooms spread over three floors. Each floor contained resident bedrooms and at least one additional bathroom. The ground and first floors also each had two resident lounges and a treatment room. Other spaces on the ground floor included a kitchen, dining room, nurses’ station and break room, senior nurse manager’s office, administration office and hair salon, while the first floor had an additional activity room.

Care home 2

Care home 2 has 37 beds spread over three floors. The ground floor contained resident en suite bedrooms, bathrooms, three lounges, a kitchen, dining room, office, reception area and staff room. The first floor had resident bedrooms, bathrooms and a nurses’ station, while the second floor contained resident bedrooms, bathrooms, a hair salon and a staff room.

Care home 3

Care home 3 has 45 en suite bedrooms spread over two floors. The ground floor contained resident bedrooms, two lounges, a kitchen, dining room, visitors’ room, hair salon, nurses’ station, break room and manager’s office. The first floor comprised a further three bedrooms, bathroom, kitchen and lounge.

Care home 4

Care home 4 has 72 en suite bedrooms allocated to specific ‘households’ and 18 self-contained apartments. All households and apartments were spread over three floors. The ground floor contained a large bistro and kitchen area, reception desk, administrator office and general manager’s office. It also had two households, each having the same layout with 12 bedrooms, living/dining room, communal bathroom and household kitchen. A further six self-contained apartments were also on the ground floor. The first floor comprised an additional two households and six apartments, a function room, internet café, exercise studio/gym and salon. The second floor contained two more households and six more apartments, alongside other meeting rooms and offices.

Care home 5

Care home 5 has 64 en suite bedrooms spread over four floors. All four floors contained resident bedrooms, a bathroom, at least one kitchen area and two dining rooms. The first three floors also had staff offices and staff rooms.

Care home 6

Care home 6 has 48 en suite bedrooms spread over two floors. The ground floor contained resident bedrooms, three lounges, a kitchen and a dining room, while the first floor comprised of resident bedrooms and a multiroom.

Social distancing and isolation policies and protocols

All six CHs sent local policy documents that guided the implementation of social distancing and isolation measures in their home. Fifty-four documents were received in total. Twelve documents were excluded as they did not address local policies about social distancing or isolation measures. These were excluded for the following reasons:

-

one was a policy about permanent closure of a CH

-

two were documents containing links to national policy guidelines on the www.gov.uk website

-

one was a protocol for cleaning processes

-

one was a protocol about staff returning to work after shielding during COVID-19

-

two were protocols for COVID-19 vaccination – one for residents, one for staff

-

one was a protocol for assessing signs of COVID-19

-

one was a protocol for staff uniform laundering

-

one was policy about dependency levels and safe staffing

-

one was a policy about test and trace service

-

one was a protocol for risk assessment for BAME employees during COVID-19.

Document characteristics

There was variation in the number of documents received from each home and in the level of detail provided about the policies and actions recommended. A summary of documents received is provided in Table 1.

| Care home | No. of policy documents received | No. of policy documents included | Size of documents (range) (no. of pages) | No. of embedded links to online government and company guidelines | Infection control measures included in documents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social distancing | Isolation | Zoning | Cohorting | Restrictions | |||||

| 1 | 32 | 23 | 1 to 8 | 0 to 5 | P | P | P | P | P |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 60 | 6 | P | P | x | P | P |

| 3 | 11 | 9 | 2 to 9 | 0 to 10 | P | x | x | x | P |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 to 11 | 0 to 3 | P | P | P | P | P |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 67 to 69 | 11 to 24 | P | P | x | P | P |

| 6 | 3 | 2 | 7 to 23 | 7 to 24 | P | P | x | P | P |

Some CHs had a more significant number of policies each of which addressed one aspect of service provision, whereas others had a smaller number of lengthy documents that included guidance on all aspects of managing service provision during COVID-19. There was evidence that policy documents had been updated as the trajectory of COVID-19 progressed, and national government guidelines had changed. Some CHs had multiple versions of documents, whereas one CH updated the original policy document and highlighted the new changes as guidelines were revised. Either way, the content of the documents was repetitive at times and potentially challenging to navigate for busy CH staff. Some of the documents had links to embedded documents or online government guidance, which considerably increased the volume of material to read. There was considerable variation in the detail of the guidance provided by each CH with some providing very comprehensive, lengthy guidance and others much shorter guidance that gave a broad overview.

Findings

Social distancing

Social distancing was addressed by all CHs in at least one of their policy documents, although there was considerable variation in the detail of the guidance provided. One CH directed that social distance requirements should be followed but gave no further details. The other five CHs stipulated that 2 m was the required social distance to maintain between residents, staff and visitors at all times, for all activities and in all areas of the home including resident communal areas, dining areas, residents’ rooms, offices and gardens. There were a few exceptions, for example where residents were receiving essential care delivered by staff. For these activities, where maintaining the required social distance was not possible, staff were required to wear PPE including face masks. Policies for two homes discussed the different requirements of PPE depending on the activities being undertaken and whether it was possible to maintain the required social distance of 2 m. Residents were required to socially distance from other residents in all communal areas including the garden and two homes included the need for residents to be advised of this in one of their policy documents. However, one acknowledged that some residents might have difficulty in understanding and following this advice.

There was more guidance in the policy documents about managing social distancing during visits by external visitors, for example residents’ family members, health professionals, maintenance staff, entertainers and senior CH company staff. There was variation in the level of detail of guidance provided and in what aspects of the organisation of visits this guidance covered. For example, one CH gave very detailed guidance about arrangements for visiting entertainers including considering where they would be positioned to ensure at least 2 m social distance from residents, allowing additional space for singers as evidence suggests water droplets from breath carry further during singing. Generally, policies required that visitor access to the CH be carefully managed and supervised to minimise entry to resident communal areas, ensure social distancing and wear a face mask if this was not possible. Most visitors were required to do a lateral flow test (LFT) at the home before entry and policies in some homes stipulated that they must maintain social distancing while waiting for their result.

When family members of residents were allowed to visit, CH policies emphasised the requirement for social distancing. The policy for one home stated that visitors should be asked to verbally consent to abide by the terms and conditions of social distancing while in the home and grounds. The staff were required to set up the home environment to reinforce and maintain social distancing. For example, one home included detailed criteria for the internal visiting room including that it should have an external door, so the visitor did not have to walk through the communal areas of the CH to access it, a separate entrance for the resident, if possible, a substantial floor to ceiling Perspex screen and a hands-free wireless intercom system or mobile phone to facilitate communication during the visit. Other CH policies stated that for internal visits (in the designated visiting room or bedroom visits when allowed) chairs and tables should be positioned to maintain social distance with a screen in place; one home specified that this was also required for exceptional end-of-life (EoL) visits. One CH allowed relatives to remove their masks to aid communication if they remained behind the screen but encouraged them not to raise their voices. There were some differences in the policies about physical contact between resident and their relatives. Most CHs clearly stated that social distance must be always maintained, for example one home specified that relatives must not go behind the screen to touch, hug or kiss the resident. Another CH acknowledged that this would be difficult when visiting policies were revised to allow indoor visiting. Any initial breach of close contact between a resident and their family member should be gently pointed out and advised against. However, one CH guided that close contact should be kept to a minimum with hand-holding being acceptable, but hugging should be avoided and that this must be explained to the visitor. Another CH had a policy that relatives would be supported with physical contact such as hugging with the resident as long as IPC measures were in use.

Some CHs had policies that guided the actions of CH staff when travelling to work. Car sharing among staff was not recommended and alternative arrangements should be made if possible. If there is no alternative, one CH policy stated that 2 m social distance should be adhered to, that staff should car-share with the same colleagues for as short a journey as possible with no physical contact and the windows open for ventilation. They should consider the seating arrangements and try and face away from other passengers. One CH included that CH staff should maintain social distancing as per government guidance when not at work, for example in shops or on public transport.

Isolation

Isolation was addressed in at least one policy document for five of the six CHs. There was more consistency in the requirements for isolation among the CHs, although there was variation in the level of detail provided. Five CHs provided guidance about measures for resident isolation and four provided guidance for staff isolation.

One CH included guidance on how to prepare the CH to implement isolation measures including ensuring each resident bedroom could be used as an isolation room with access to PPE and handwashing facilities. Interestingly, a policy document provided by another home gave details of advising that, at the beginning of the pandemic, all residents needed to stay in their rooms to complete 14 days of isolation keeping away from other residents.

When residents were required to self-isolate all five CHs stipulated that this should be for 14 days (or longer if still symptomatic) and that residents should isolate in single bedrooms with en suite facilities or a designated commode. One home advised that if single room accommodation was not available, then residents should isolate in well-ventilated multioccupancy rooms with designated toilet facilities. The range of reasons stated for the need to self-isolate included the following:

-

any residents who were symptomatic or tested positive for COVID-19

-

residents who were newly admitted or transferred back to the CH from a hospital or A&E visit (unless treated in a designated COVID-19-free zone)

-

residents who had been in contact with someone with possible/confirmed COVID-19

-

clinically extremely vulnerable residents, assessed on a case-by-case basis as needing to shield.

One home provided details of updated guidance of isolation exemptions where many required conditions were met. This included a more detailed risk assessment of newly admitted residents who were transferring from another care facility or planned discharge from hospitals. These new residents who were fully vaccinated and had had no contact with someone COVID-19 positive could take part in an enhanced testing regimen including polymerase chain reaction test (PCR) and LFTs to determine the need to self-isolate. However, following emergency care, residents discharged from hospital were still required to self-isolate for 14 days. A resident who had tested positive for COVID-19 in the last 90 days, had completed their required period of isolation and had no new symptoms was not required to undergo testing. If a resident who was planned to be discharged from the hospital back to the CH or who was a new admission who had tested positive for COVID-19, the CH policy proposed careful consideration of whether there were sufficient staffing levels and availability of a single room before accepting the transfer. Where a resident was identified as a close contact with someone who had tested positive and was fully vaccinated, they did not need to self-isolate.

Where residents were required to self-isolate, one home specified the need to ensure that the resident was kept informed of the rationale for isolation, given the opportunity to ask questions and had an individualised care plan in place. This particular home provided detailed guidance on how to support the resident during isolation including updating the resident’s relatives daily, ensuring that they understand that visits were not recommended and could only happen in exceptional circumstances and authorised by managers, maintaining awareness of the resident’s mental health as they may become anxious and withdrawn and the need to seek further advice from managers and infection control teams if the resident was displaying behaviours that make isolation impossible, for example dementia and non-compliance. Additional support interventions included support from a companionship team (interactions limited to 15 minutes) who would provide an isolation box and support the resident to maintain contact with relatives via video calls. Where a resident refused to comply with isolation and endangered themselves or others, guidance required mental health or safeguarding assessment. If the resident had full capacity and continued to refuse to comply with isolation requirements, the CH manager could discharge the resident from the home. The guidance provided by other CHs was not so detailed but included some important additional activities, for example clearly marking the bedroom doors of residents, updating all heads of department within the home about which residents were isolating so all staff are aware and establishing a safe area for a resident with dementia who walks with purpose when keeping them in their bedrooms would not be possible even if that meant repurposing a communal area.

One CH had sheltered apartments located within the CH and guidance was that tenants must not enter the communal areas of the home site or village and staff were also required to contact them twice a day to check their well-being. Five of the CHs had policies that guided the need for staff to self-isolate. Staff were required to stay off work and self-isolate for 10 days if they had symptoms of COVID-19, a positive test, declined to test, contacted by track and trace, were required to quarantine after returning from a red list country (or amber list country if not vaccinated) or had a breach of PPE when providing personal care for asymptomatic or COVID-19-positive residents.

Restrictions

Restrictions were addressed in at least one policy document for all six homes. There was consistency in the guidance provided by homes although the detail varied considerably. Some of the documents submitted were older documents and the guidance about restrictions had subsequently been updated. Other documents had been updated but still included the older guidance, which reduced the clarity in places.

Resident restrictions

All CHs submitted guidance that restricted residents in some way. As discussed above, residents often had less freedom to move within the home, may have to move rooms if cohorting required this, had fewer visits from family and friends (discussed below), were unable to go to the hospital for routine appointments, their discharge home from the hospital if admitted may be delayed and new residents may experience delays in moving in. Strategies for staff to support residents to maintain regular communication with family and friends via telephone and virtual calls were provided in the policies of some CHs. Restrictions reduced as the pandemic progressed and vaccinations had been given.

Restrictions for families and friends

Most of the guidance in the documents concerned restrictions in visiting for families and friends. EoL visits were restricted in all homes, for example limited to 60 min, one or two immediate family members at a time, no children, wearing PPE and asymptomatic (visit not allowed if the visitor had symptoms). Four CHs included guidance about different types of visits including window, garden and drive-through visits before indoor visits were allowed in government guidelines and visits in designated visiting rooms/suites when indoor visits were allowed followed by visits in resident’s bedrooms when restrictions relaxed further. Two homes provided exceptionally detailed guidance about the different visits including, for example, ensuring residents had sufficient shade in the garden and wore sunscreen on warm days and advising visitors to avoid public transport on their journey. There were consistent requirements for visitors in all CHs even as restrictions began to be relaxed. These included the following:

-

all visitors were required to be asymptomatic and have a negative LFT taken at the home before their visit

-

all visits were time and frequency limited and had to be booked in advance

-

there were a limited number of nominated visitors (initially one or two, to visit one at a time)

-

no or little physical contact with their family member was allowed

-

gifts had to be given to a member of staff to be wiped down

-

visitors were not offered refreshments or able to use toilet facilities.

Although visitor restrictions relaxed in line with government guidelines, some CH policies continued to emphasise the need to risk-assess visits and rules varied according to this assessment. For example, although from July 2019 there were no national limits on the number of nominated visitors or how many can visit each day, the number of visits available in some of the CHs was dependent on how many could be accommodated each day with the time needed to support visitor testing and in some cases supervising the visit, the layout of the CH, length of visit and the need to ensure equity in visiting for all residents.

One CH provided guidance about residents leaving the home. Where these visits were considered high risk, for example emergency admissions to hospital, the resident should self-isolate on their return to the CH. However, other low-risk visits were supported without the need to isolate on return, for example spending time with family and friends, overnight stays in the family home, participating in community groups and volunteering and routine hospital appointments. During these visits, COVID-19 precautions, that is social distancing, handwashing and face masks, should be followed. All CHs had a policy that emphasised that in the event of an outbreak of COVID-19, that is two or more residents or staff testing positive then restrictions would increase.

Restrictions for care home staff

Restrictions for CH staff were addressed by at least one policy document for most CHs. Although the guidance was not comprehensive, it was clear that CH staff had considerably adapted the way they worked to provide care for residents and to implement and support the restrictions (and the effect of the restrictions) for residents and all visitors. For example, guidelines of several homes described the role of staff to reassure visitors, provide advice about communicating with masks on and, where assessed necessary, to supervise the visit. One home suggested that staff should advise visitors to dress and style their hair to help the resident recognise them and prepare the resident for a visit by showing them photographs of the person who is due to visit and talking to them about their relationship. The role of housekeepers had also altered because of changes to cleaning and hygiene protocols and the increased frequency of cleaning required including between visits. One home suggested the nomination of a COVID-19 co-ordinator for each shift to ensure adherence to infection control and COVID-19 policies, which should be discussed in staff supervision.

One home required that vulnerable staff should not provide care for symptomatic residents and should discuss redeployment or furlough with their line manager. Furthermore, this home required that staff adhere to PPE protocols and national lockdown guidance outside work. Failure to do so may result in disciplinary action or referral to safeguarding. Staff were required to participate in routine COVID-19 testing at the home, and the guidance in one home stipulated that the CH manager should ask to see the result for verification. All staff with a positive test or who were symptomatic were immediately sent home and required to do a PCR test. The use of agency staff was not recommended unless necessary and approved by the regional manager in one home.

Restrictions for healthcare professionals and other visitors

Restrictions for healthcare professionals and other visitors were addressed in at least one policy document in each CH, although with varying degrees of detail. All visits to each home were required to be booked in advance and approved by the home manager and visitors were required to complete a visitor questionnaire. In one home, the only unannounced visitors who would be allowed to enter were CQC inspectors and the police. All visitors were required to be asymptomatic and have evidence of a negative COVID-19 test when these were available. Multi-site CH staff, NHS and CQC staff take part in routine testing but are still required to show evidence of a negative test to be allowed to enter the home. Homes gave guidance for essential and non-essential visitors. Essential visitors included healthcare professionals providing urgent or emergency assessment and treatment, for example general practitioners (GPs), allied health professionals (AHPs), district nurses and property maintenance staff for emergency repairs. These occur as required even during an outbreak. Non-urgent GP and AHP consultations were required to be agreed at the local level by some homes, although they could be undertaken by audio or video-link if preferred. Two homes had a policy where a member of CH staff substituted for a visiting professional to perform an activity in situations where it was considered safer for the professional not to visit or when the professional was unable to visit. For example, a RN member of CH staff could provide care as part of the district nurse’s ongoing treatment plan when they had the required skill and when this was agreed with the district nurse and the CH manager. Similarly, another home had a policy where non-medical care staff could verify the expected death of a resident where the GP and home manager agreed on an approach of how to manage this.

Some routine visits by multisite centre home employees, and operational and support staff were supported to continue in some policy documents on the instruction from heads of department, although they could only visit one home in a day. One home specified the use of Microsoft Teams to support oversight of governance and management with some additional in-person visits at least every 3 months or more frequently if needed. Where onsite visits were undertaken, staff were required to change into uniform/alternative clothing on arrival and leave these clothes at the CH to be laundered (or, if necessary, taken home in an alginate bag and put in a washing machine immediately without removing them from the bag). However, if there was an outbreak during that time, one home had a policy that required these staff members to work exclusively at that home for 14 days until the outbreak was fully resolved. Property maintenance staff who work across several homes were required to wear full PPE and disposable overalls and have no contact with residents unless emergency work was required, and risk assessed by the home manager and facilities manager.

Non-essential visitors included hairdressers, entertainers and prospective customers/family show-rounds. These visits did not occur early on during the pandemic, although as restrictions relaxed, they were allowed to start with strict policies of COVID-19 testing, PPE and social distancing measures. In some CH policies, some visitors still have no access, for example community groups such as rotary clubs, schools and nurseries and other social groups.

Zoning and cohorting