Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR127590. The contractual start date was in September 2019. The final report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Turnbull et al. This work was produced by Turnbull et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Turnbull et al.

Findings

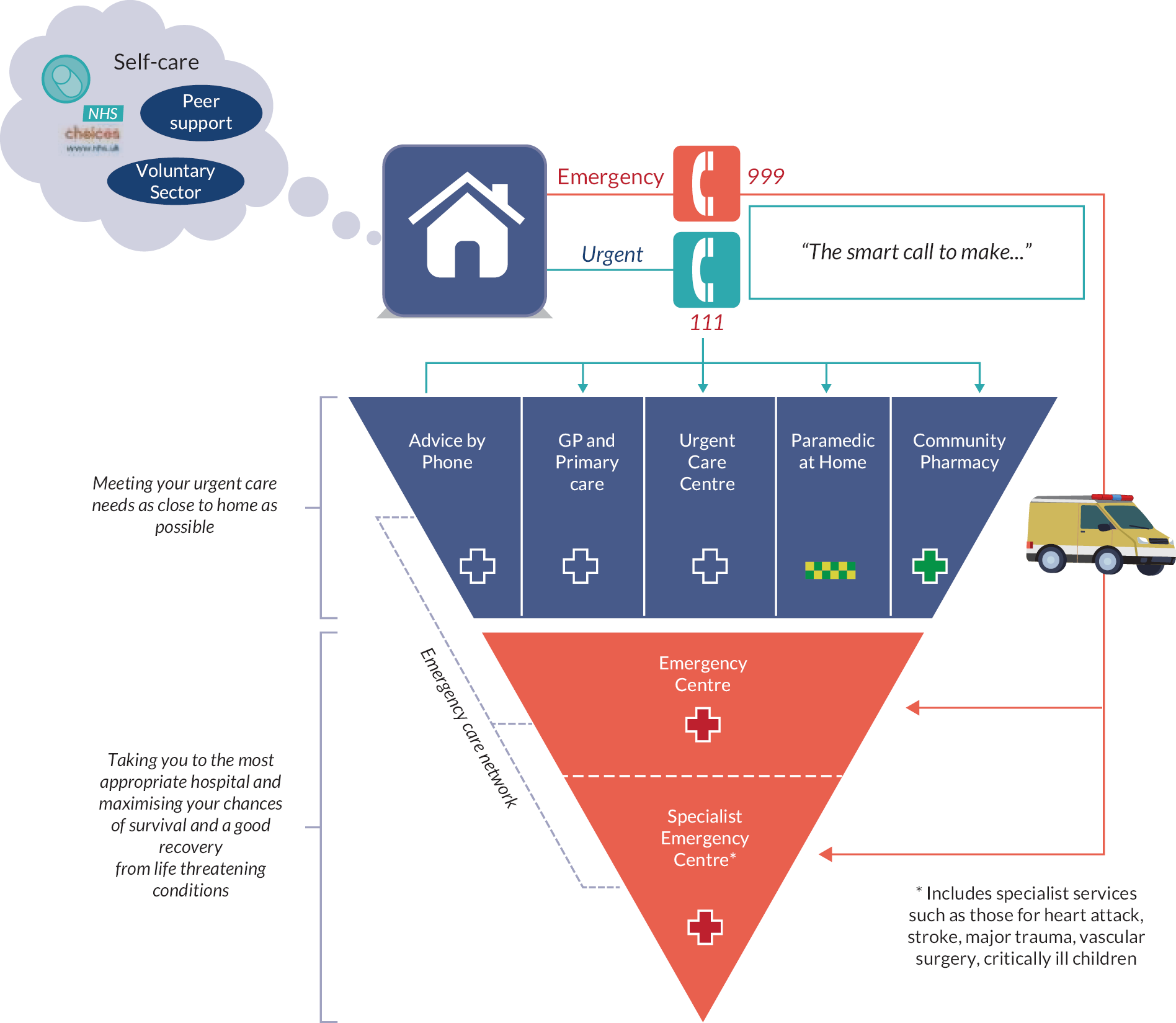

Pathways to care

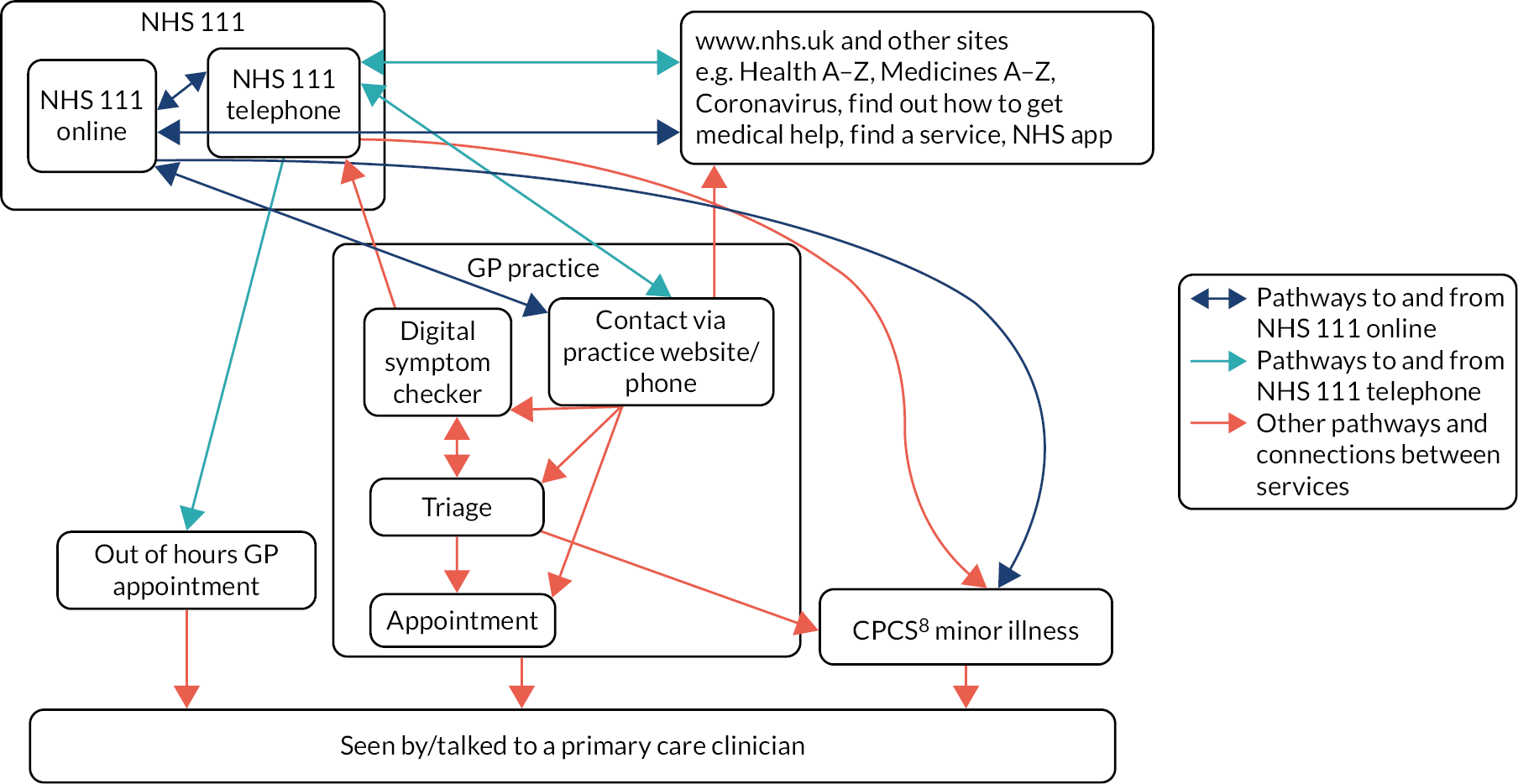

NHS 111 online has low visibility in the primary, urgent and emergency health and care system, and it is obscured by the presence of a number of other digital technologies, including online triage and assessment tools, notably in primary care. There were suggestions that awareness of the NHS 111 online service had increased in the pandemic and was beginning to be seen as helpful by some. We have corroborated the findings of the Sheffield study (NIHR127655) that NHS 111 online has added another access point for urgent and emergency care in the NHS and the result is that pathways to care are confusing and difficult to navigate.

Workforce and impacts on work in the wider health system

The workforce potentially associated with NHS 111 online services not only includes staff in primary, urgent and emergency care but also encompasses staff in dental services and a range of charity and non-NHS organisations who serve vulnerable population groups. Some staff and stakeholders perceived that NHS 111 services generate additional tasks or demand, although it was not clear that they attributed this extra work to NHS 111 online per se. Similar issues were raised by interviewees associated with the Healthdirect virtual triage services (where there was also a problem of low awareness by the public and professionals about these services). Dental services did not perceive that they received extra work as a result of NHS 111 online. In some areas, there was a direct emergency dentist booking facility via the NHS 111 telephone service, which was seen as meeting patient needs. There appears to be an opportunity to direct users of NHS 111 online who require emergency dental care to dental services, but this would require closer integration of these services than at the present time.

Comparison of NHS 111 with Healthdirect

A small team comprising service managers/operational leads, developers and a small number of clinical staff members develop and manage NHS 111 online. The Australian Symptom Checker has a similarly small team within Healthdirect. Outside these organisations, a wider network of care providers are implicated in, potentially provide services to or have contact with users of these online advice, triage and assessment technologies. Our interviews with staff and stakeholders associated with Healthdirect identified similar concerns to those voiced in English primary, urgent and emergency care interviews about the lack of integration between virtual triage and other parts of the health system. There was also a similar lack of awareness or understanding of the Symptom Checker in the wider network surrounding Healthdirect’s online provision. There was less evidence from the Australian interviews that staff and stakeholders perceived that Healthdirect’s virtual triage created additional work for their services. While there was a suggestion that Healthdirect’s virtual triage services inflated demand for emergency care, this was tempered by the suggestion that the users of its services may be augmenting other care/help seeking and, particularly for the Symptom Checker, that these were less serious presentations. We conclude from this that any additional work associated with assessment, re-assessment and navigating the health system is borne by patients and users, rather than the healthcare workforce in these settings.

Patient preferences (scenarios where patients want to use NHS 111 online)

A third of survey respondents had not used NHS 111 online or telephone services. The survey found differences in the types of symptoms for which people said they would use NHS 111 online. Those who had previously used the service were more likely to use it for each symptom scenario offered. These differences were significant for ‘an itchy bite or sting’, ‘a young child with a temperature and crying’, ‘a scalded hand’ and ‘pain when urinating’. A sizable proportion of respondents reported that they would be likely to use NHS 111 online for a young child with a temperature and persistent crying, and for severe pain in the chest that goes away after a few minutes. Those who had used NHS 111 online reported having used a wider range of urgent care services than those who had not used NHS 111 online. They also had higher cumulative use of a range of other NHS health services than those who had not used NHS 111 online.

eHealth Literacy among users and non-users of NHS 111 online

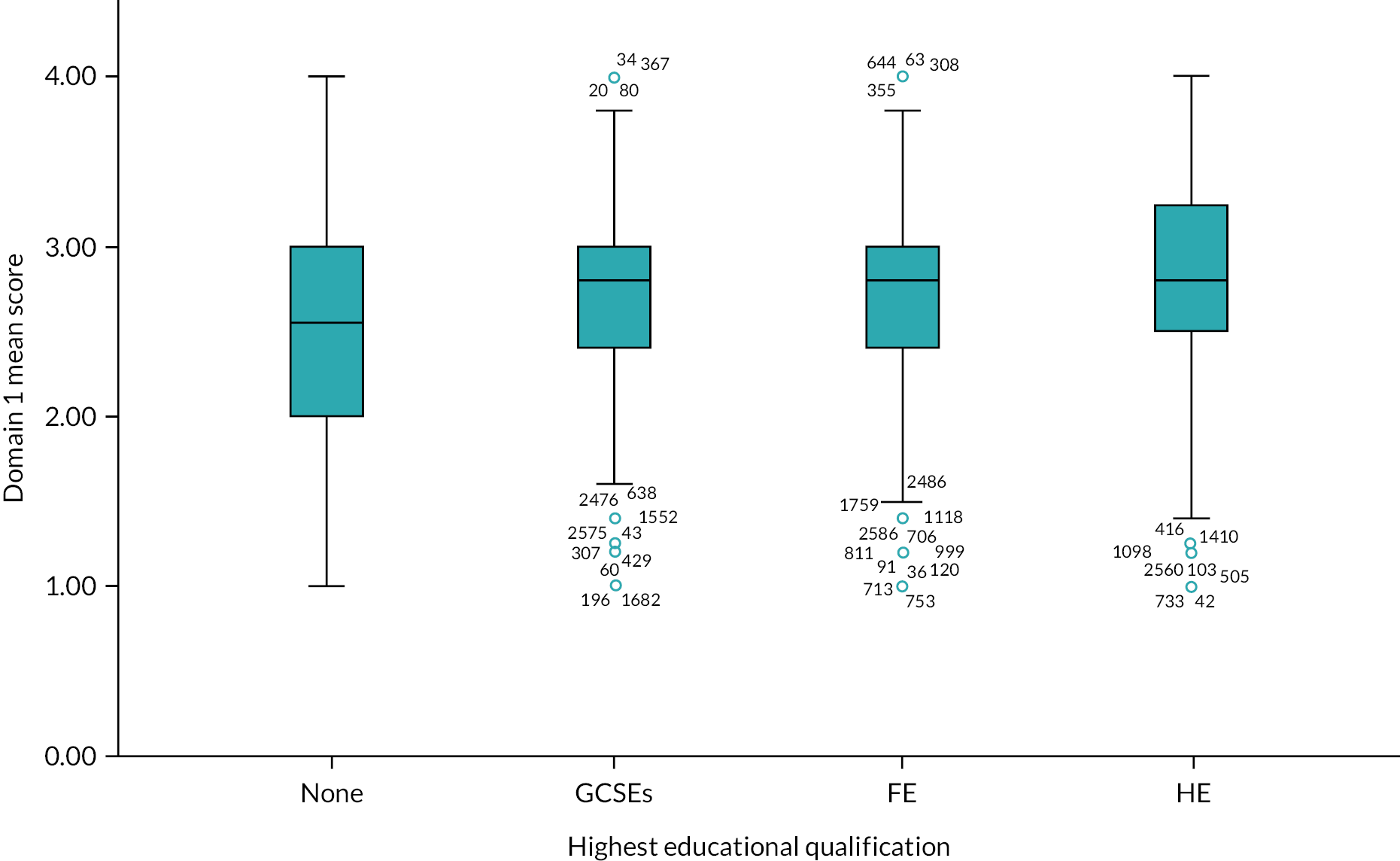

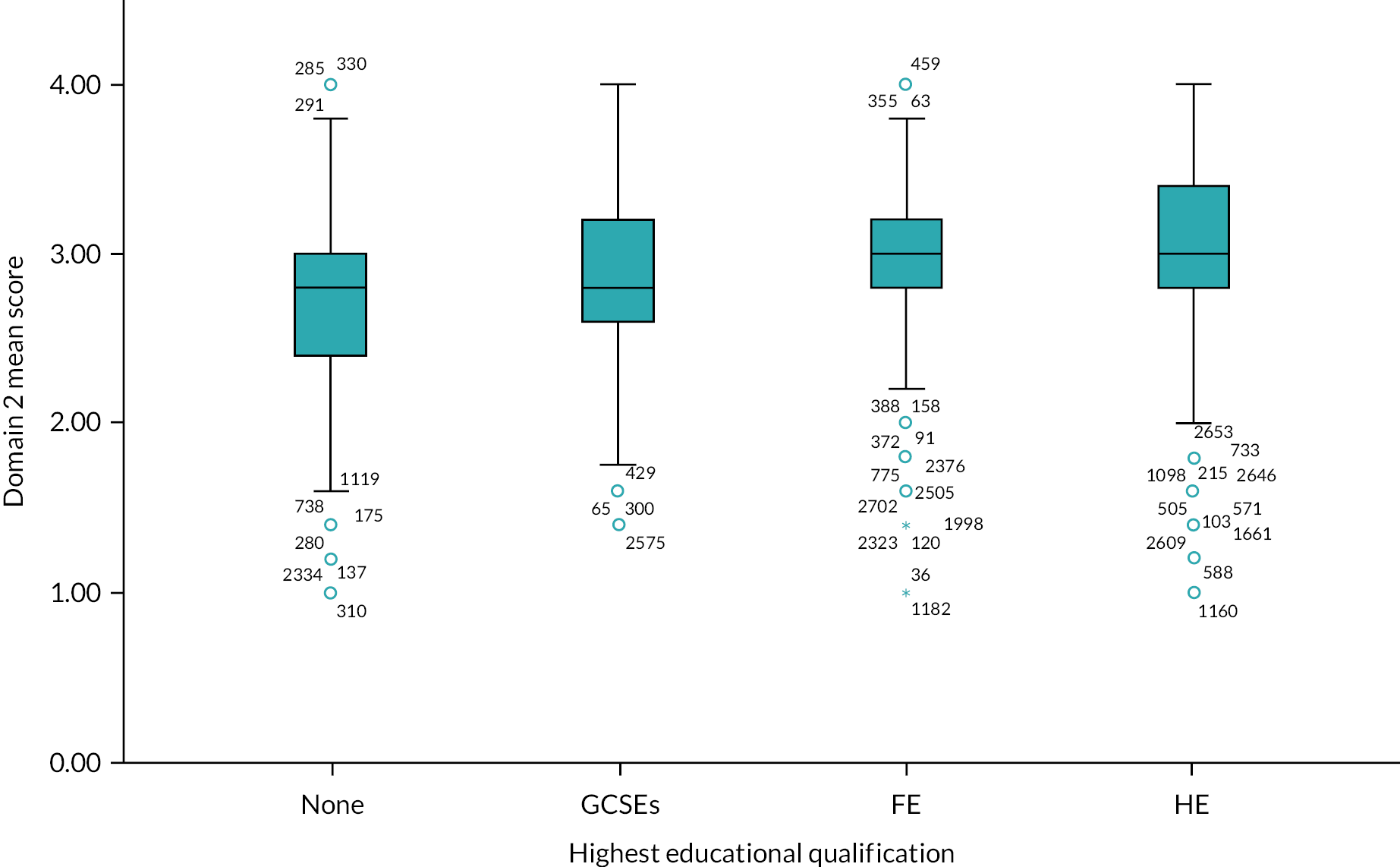

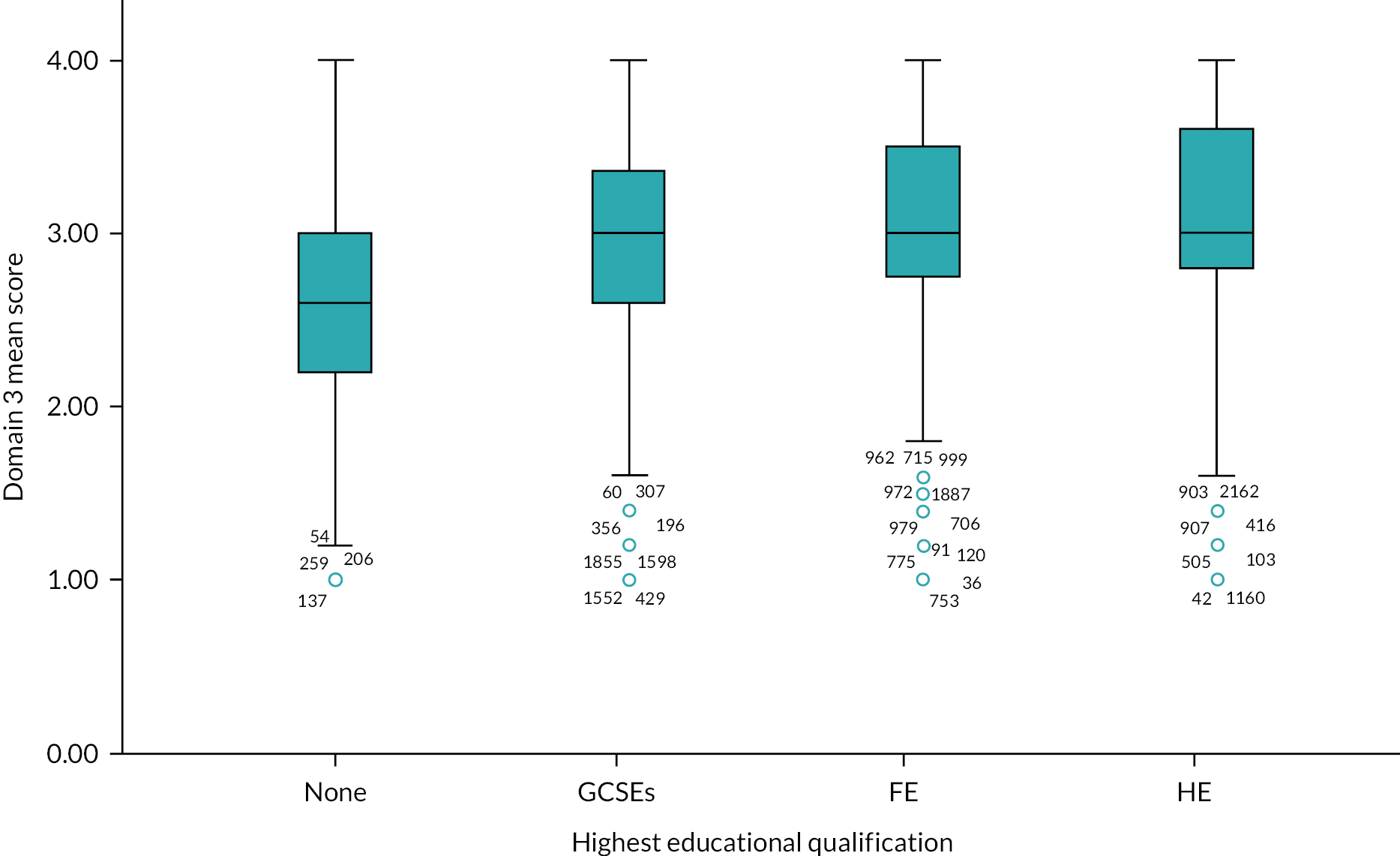

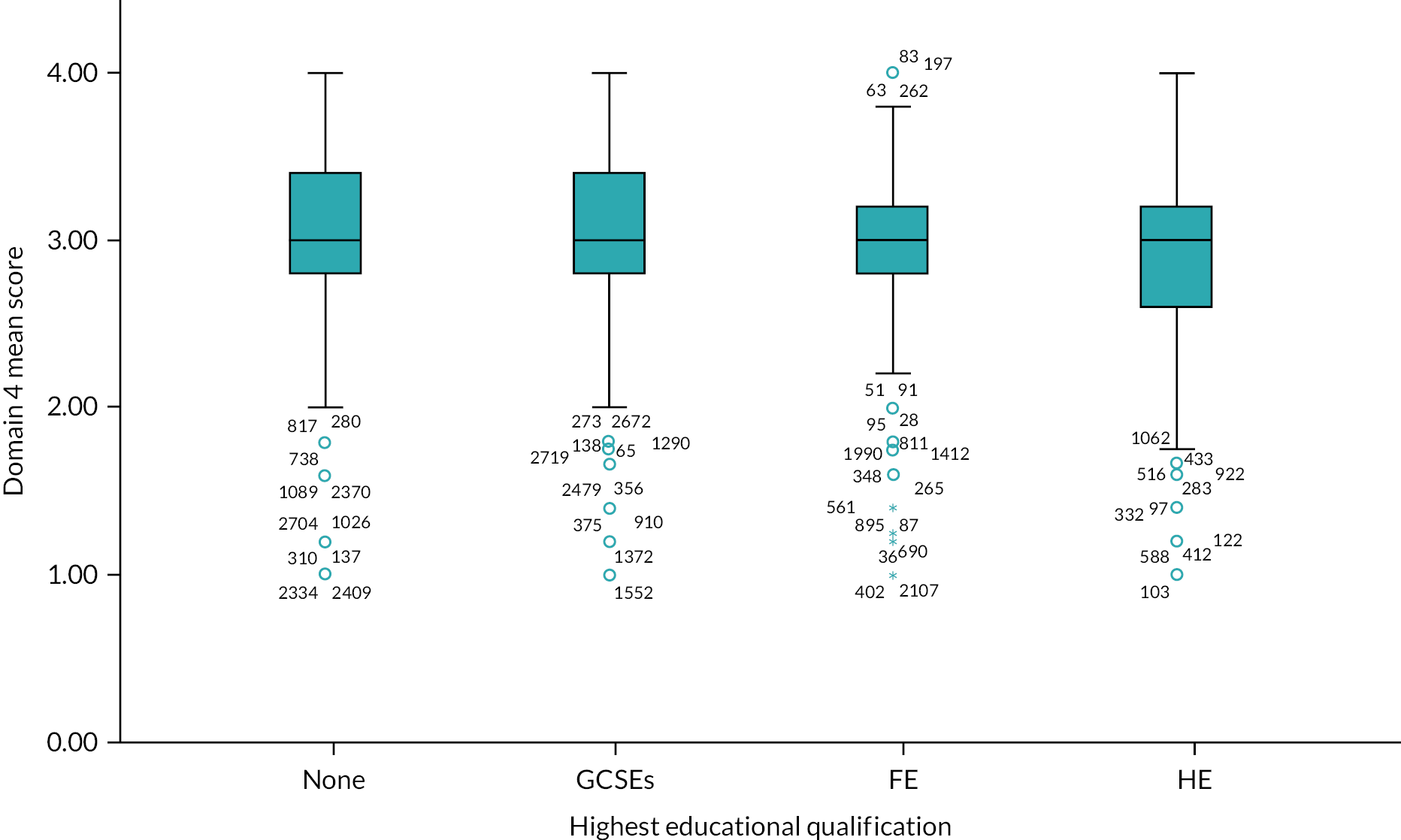

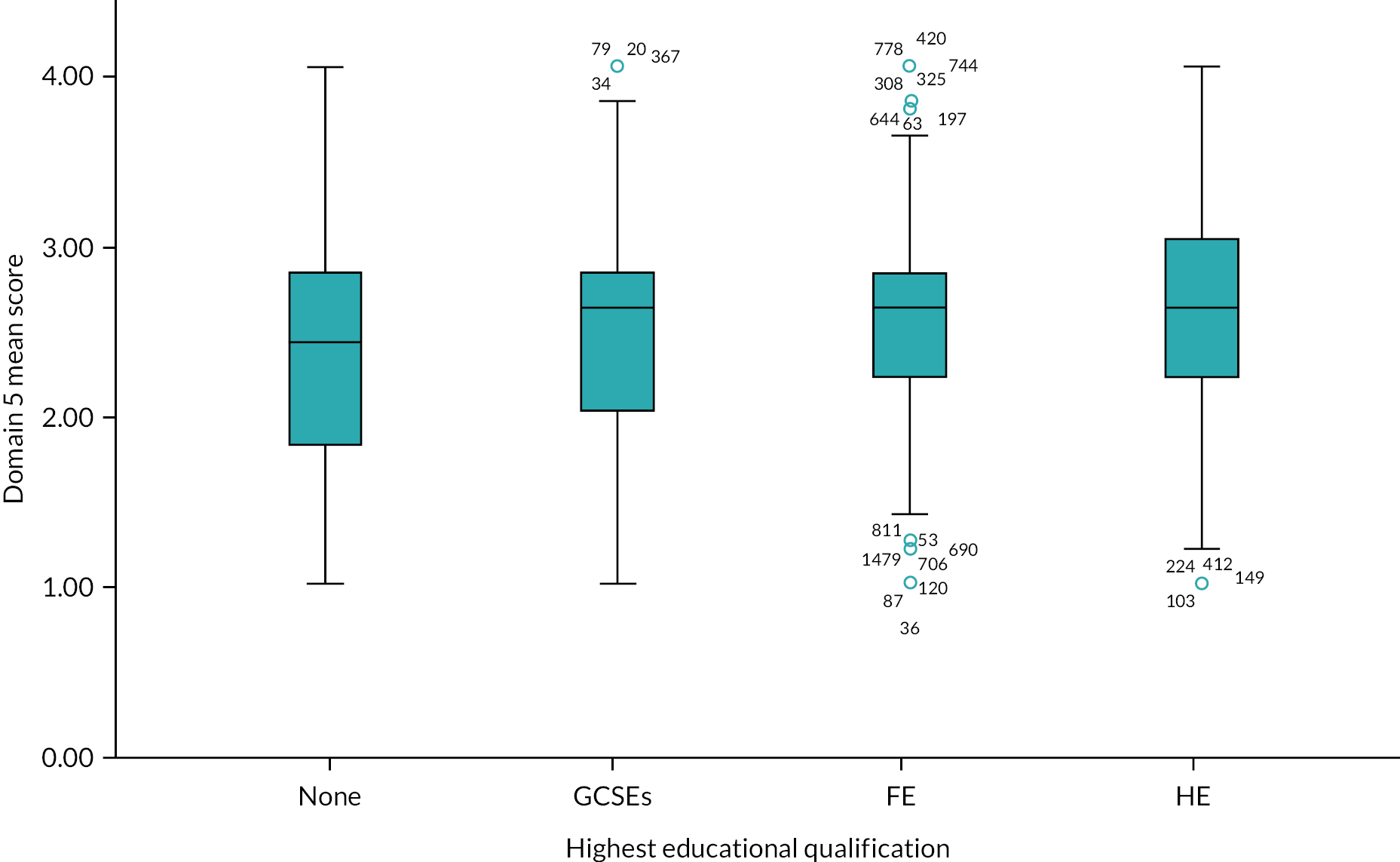

Our survey found evidence of differential use of NHS 111 online across key demographic characteristics: use was associated with younger age groups and those who had some more formal educational qualifications. Those who reported previously using NHS 111 online had higher levels of self-reported eHealth literacy across 5 of the 7 eHLQ domains. People with long-term conditions (LTCs) had lower eHLQ scores but were more likely to have used NHS 111 online.

Limitations

This research took place before and during the pandemic 2020–2021 and findings may change as the NHS and 111 services adjust further coming out of the pandemic.

NHS 111 online has been rolled out in the United Kingdom (UK) so it is not possible to conduct randomised trial research. Restricted working during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the scope of some of the planned qualitative work, removing the ethnographic research in healthcare settings which could have provided more detailed evidence about the workforce, work arrangements and impacts of NHS 111 online. Nonetheless we were able to complete 80 interviews in the UK and 41 interviews in Australia, providing robust sample sizes to support our thematic analyses.

Changes to our research timetable reduced the opportunities to integrate data collection and analyses with the Sheffield study also looking at NHS 111 online, but we have identified areas where our work augments and/or confirms their findings in the discussion.

Data collection was digitally-based, with interviews and surveys conducted online. Some surveys were completed on a computer tablet with help from a research nurse in face to face clinical settings. Despite this shift to online working we met our minimum sample size for the qualitative interviews, and we were able to adapt the design of our survey to substantially increase the sample size. The changes to the survey have resulted in the first and largest analysis of eHealth literacy among people who have sought help or advice from urgent care services. It is important to acknowledge that the use of digital methods of survey data collection mean that there is a bias towards some level of digital literacy in our sample. Some groups, such as older people, are less well represented. However, this means that our finding that there is differential use of NHS 111 online may under-estimate the digital divide. Digital exclusion may be greater than suggested in our analysis as people with very poor or no literacy, those without sufficient written English language comprehension or digital skills, and people with no access to digital technologies were unlikely to have taken part in the survey.

Conclusions

NHS 111 online is not clearly differentiated from the NHS 111 telephone service. It lacks visibility to staff and stakeholders in the primary, urgent and emergency care system and it is obscured by other digital technologies and other urgent and emergency care services. Pathways to care are confusing and difficult to navigate. There are opportunities to better integrate NHS 111 online with other services and digital platforms in ways to better support help seeking and access to care. Generic NHS 111 services are perceived as making more work for other parts of the NHS; notably by increasing administrative work, encouraging staff to duplicate triage and assessment and creating ‘inappropriate’ demand for Emergency Department (EDs) services. There are differences in eHealth literacy between those who have and those who have not used NHS 111 online and alternative pathways to advice and care are needed to ensure that provision does not increase health inequalities and exclusion. NHS 111 online users were more likely to have used other NHS urgent and emergency care services, and had higher cumulative use of health services compared to those who had not used NHS 111 online. This suggests NHS 111 is additional to and not substituting for other healthcare services.

Research recommendations

The research reported here is one of just two studies that have looked at NHS 111 online in the period just before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The service has rapidly grown, in scope (adding COVID-19 symptom assessment and advice) and use. New functionality has been added, notably the 111 First initiative allowing the service to triage and book arrivals to EDs. Further research will be necessary to support the ongoing development and integration of the urgent and emergency care system and the development of NHS 111 services, including NHS 111 online, within this. Future work indicated by this study includes:

-

Further investigation of access to digital services including NHS 111 and eConsultation systems by those with LTCs and people in vulnerable and marginalised groups to address concerns about digital exclusion.

-

Evaluation of different online advice, triage and assessment systems to understand the affordances and cost–benefits of different systems for users and healthcare providers.

-

Examination of patient, public and professional trust in computer-assisted and patient self-completed online assessments and consideration of how to reduce the burden of re-assessment and duplication for patients and healthcare staff.

-

Examination of multiple use of different entry points to the health system and adherence to the triage outcome(s), possibly with statistical analysis/modelling of linked data to explore health outcomes.

-

Further qualitative study of the additional work created by NHS 111 services for the wider network of services urgent and emergency care system, augmented with costings to support cost consequence analysis.

-

Further development and use of other measures of eHealth literacy to explore the impact of ‘digital first’ policies in health and other service settings.

-

Opportunities for further international comparative research and shared learning from other similar online triage and assessment systems.

Study registration

This study is registered at the Research Registry (UIN 5392).

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Programme grant number 127590 and will be published in full in Health Services and Delivery Research; Vol. 11, No. 5. See the NIHR Journals Library website for further project information.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

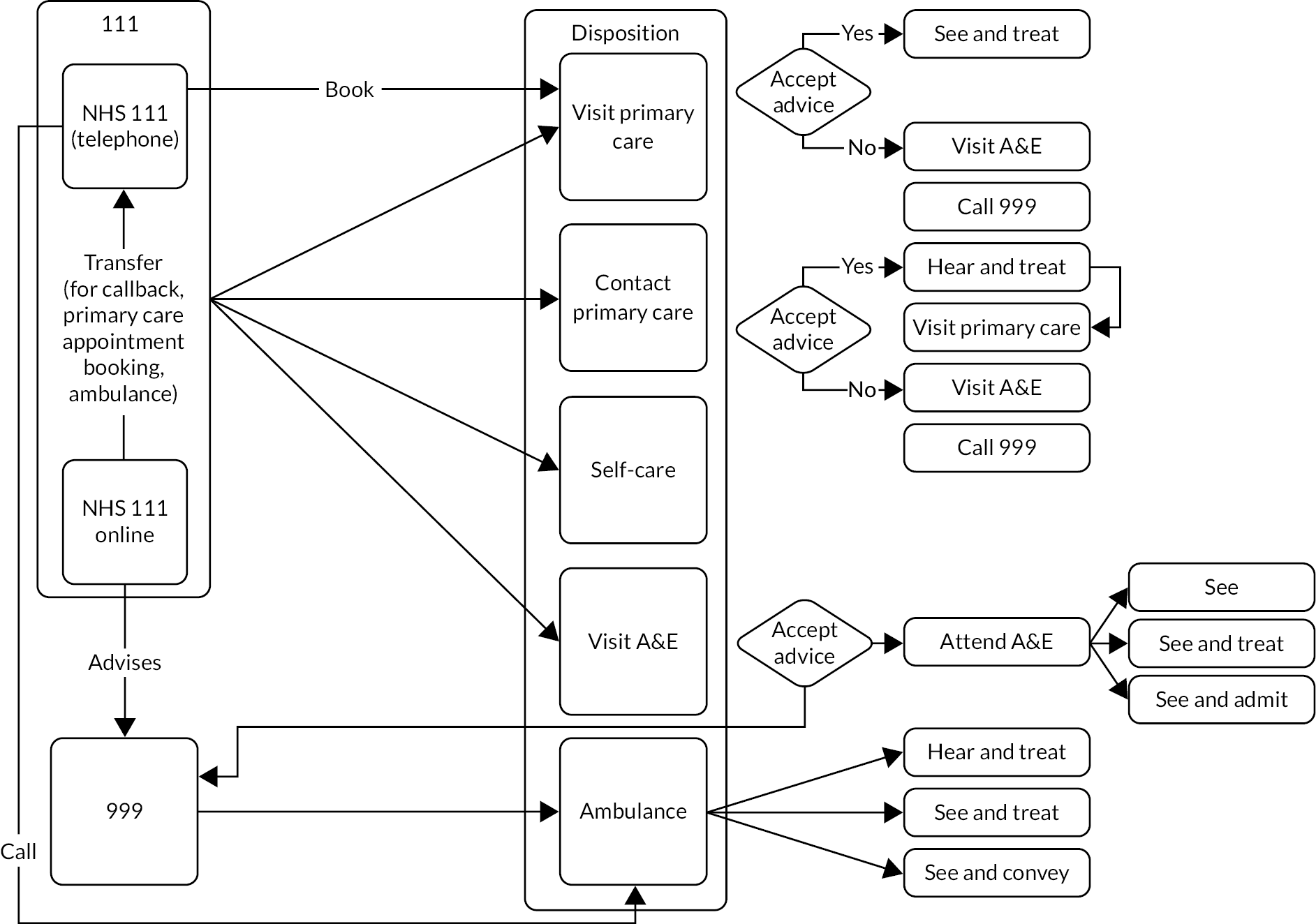

The NHS has provided urgent care telephone services underpinned by decision support tools for over 20 years, beginning with the nurse-led telephone advice service NHS Direct (1998–2014) and then NHS 111. The NHS 111 telephone service uses call handlers who are supported by a computer decision support software (CDSS) system called NHS Pathways. The NHS 111 telephone service is free to access, is available 24 hours per day, is aimed at people with urgent (non-emergency) care needs and offers clinical assessment/triage to direct callers to appropriate services or provides self-care advice. The telephone service can be used for babies and children as well as adults, but people concerned about the health of babies under 6 months of age are advised that it is harder for the call handler/clinician to assess very young babies over the telephone. The majority of NHS 111 telephone call handlers are not clinically trained; however, they can transfer callers to a clinician for more detailed assessment and advice when necessary and can book direct appointments with (some) primary and urgent care services. Use of the NHS 111 telephone service has steadily increased since its inception and there are approximately 48,000 calls to the service per day. 1

In 2017, NHS England sought to augment its telephone service with NHS 111 online (https://111.nhs.uk/). This was launched in four pilot areas, initially trialling different triage decision support systems, three included commercial products, and one was based on the NHS Pathways software (already in use for the NHS 111 telephone service and some 999 ambulance services). Following the pilot, NHS 111 online was rolled out by NHS England, using a version of the NHS Pathways software. NHS 111 online allows people to access web-based assessment and triage using a smartphone, tablet or computer, and is classed as a medical device. The service is intended for people aged ≥5 years and, as with the NHS 111 telephone service, it is free to access (subject to internet charges). NHS 111 online users follow a tailored algorithm and answer questions about symptoms or health concerns, which results in dispositions that direct users to appropriate services or provide self-care advice. Where indicated, a call back from a health-care professional may be offered and recently facilities for booking arrival at an emergency department (ED) [also referred to as accident and emergency (A&E)] have been added as part of the 111 first initiative. In May 2019, it was reported that NHS 111 online had been used over 1 million times. 2

NHS 111 services and COVID-19

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, NHS England issued guidance that the public should call NHS 111 if they had symptoms of COVID-19 or a suspected contact with a confirmed case of the virus. In March 2020, calls to NHS 111 doubled to nearly 96,000 calls per day. A dedicated NHS 111 online coronavirus service (111.nhs.uk/COVID-19), with a tailored NHS Pathways module, was launched on 26 February 2020; 35,000 people used the site in its first weekend of operation. At the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the UK, the online service was used 950,000 times per day. 2 Throughout the pandemic, the NHS 111 online COVID-19 service continued to evolve, with additions to the algorithm to include questions about overseas travel, updated symptom profiles, advice about recommended treatments and options for onward referrals, as well as adaptations to the URL and search engine optimisation to make the online service easier to find. In June 2020, questions about coronavirus were incorporated into the core NHS 111 online service. In the Autumn of 2020, NHS 111 online began trials of a new online booking facility that allowed patients who were directed to attend an ED to select an arrival time. In December 2020, as a way to reduce ED overcrowding, the ‘111 First’ or ‘call-before-you-walk’ scheme was introduced, initially in London and Portsmouth, which required patients to call NHS 111 before attending the ED. Some EDs have a facility that allows walk-in (ambulatory) attenders to use NHS 111 online on a computer tablet in the reception area of the ED before being seen. In November 2021,3 the NHS England’s national medical director launched the ‘Help Us, Help You’ campaign, which urged people to use NHS 111 online for urgent but not life-threatening medical issues to allow the NHS to care for more seriously ill people in EDs.

The wider digital care landscape

NHS 111 online sits within an urgent and primary care landscape in which digital technologies are increasingly being enrolled in health-care delivery, ranging from electronic health records and e-consultations to decision support systems for triage and assessment. However, evidence addressing key questions about how online systems are used, their effectiveness and their impact on wider health service demand is limited. Evidence regarding accuracy of assessments using symptom checkers is also contradictory (see Bisson et al.,4 Sole et al.,5 Powley et al. 6 and Anhang Price et al. 7), Typically, small-scale studies have evaluated symptom checkers and the results are mixed, with some noting that they may encourage users to seek care from health services when self-care is reasonable. 8,9 A more recent systematic review of online symptom checkers found little evidence of harm, but noted the paucity of large studies and longer-term follow-up data. 10 Although there is potential for these systems to support self-management, there is a widespread concern that they may drive demand towards consultations ‘with a doctor’ and/or to emergency services. 6,11 Research has also identified that some patients experience difficulties using symptom checkers: they may be confused,12 lack confidence or simply struggle to navigate software systems. 13,14 Alongside these barriers to use, there is a concern that web-based sources of health information can heighten anxiety and that the quality of online health information is variable. 15,16 These findings sit within the context of a wider literature that has raised concerns about accessibility of digital technologies and about inequalities of access and use of information and communication technologies (ICT). 17–20

Demand for urgent and emergency care services

The demand for urgent and emergency services has continually risen each year despite various initiatives that have attempted to manage and reduce demand. Between 2018 and 2019, ED attendances rose by 4% to 24.8 million attendances,21 and then reached 25 million attendances in 2019–20. This represented a 17% increase since 2010–11 and there were no signs that this upwards trajectory would change. However, in March 2020 there was an approximate 30% reduction in ED attendances, which was attributed, in part, to the COVID-19 pandemic (people were heavily discouraged from attending face-to-face services, and remote primary and secondary services were made available). 22 In March 2021, there were 1,691,000 attendances at EDs, representing a 14.5% increase from the same month in 2019, confirming that the reduction in demand was temporary. 23 Alongside EDs, the NHS offers a range of urgent care services, including urgent care centres (UCCs), minor injury units, walk-in centres and GP out of hours. These services have seen similar increases in demand. NHS England estimates that there are 110 million urgent same-day patient contacts, of which some 85 million are urgent GP appointments per year. 22

Both NHS 111 online and the telephone 111 service are seen as services that can ‘empower people to manage their own health and care’. There is some expectation that this could also help reduce demand for face-to-face urgent and emergency care services or at the very least halt the upwards trend in service use. 24 NHS 111 services form a key plank in the NHS Next Steps Forward View,25 which was designed to improve access to (appropriate) services under the banner ‘right person, right place, right time’. NHS 111 online in particular is seen as an important potential ‘channel shift’ away from face-to-face care delivery and as a way to reduce demand for the telephone 111 service by offering ‘a fast and convenient alternative’. 21 Earlier evaluations of the impact of NHS Direct services on ED attendances did not demonstrate that these services reduced demand, and an analysis of the impact of the NHS 111 telephone pilots found no evidence that these changed urgent and emergency service use. 26,27 There have been claims that the NHS 111 telephone service is too risk averse and is more likely to dispatch an ambulance or advise people to attend the ED. 28,29 Recent analysis of patient compliance suggests that many patients do not follow the advice given by the 111 telephone service and that non-clinical advisors may direct more patients to the ED. 30

Rationale for this project

This research project was designed in response to the NIHR Highlight Notice 18/77 and call for research to evaluate NHS 111 online, specifically addressing knowledge gaps regarding the impact and sustainability of this new service. It builds on our previous projects about the NHS 111 telephone service (HSDR 10/1008/10), the NHS Pathways software (SDO 08/1819/217) and on urgent care sense-making (HSDR 14/19/16). We also draw on our previous theoretical and empirical studies of web technologies and seek to contribute to the wider literature on digital health-care technologies. 31,32

There are a small number of studies on the experience of using NHS 111 telephone services. These suggest that the telephone service is acceptable30 and that users are largely satisfied with the service. 33,34 Media coverage about the service and the views of some other stakeholders, notably general practitioners and paramedics, have been less positive. 35,36 Knowles et al. 37 showed that, although there was good awareness of the NHS 111 telephone service, some groups, notably older people, men and those without longstanding illness or disability, were less likely to use the service. Given that NHS 111 online is a relatively new addition to NHS urgent and emergency care provision, there is an even more limited evidence base about this service. Because NHS 111 online service is used directly by patients and the public, without a call handler or clinical intermediary, this raises additional concerns about digital and health literacy and equity of access. The concept of health literacy considers whether or not and how people are able to understand and use health-care information and services to support their health decisions. The concept of eHealth literacy adds a digital dimension to consider whether or not and how people are able to use digital health information and services. We know that there is a strong link between health literacy and eHealth literacy. In addition, we know that people with lower health literacy and lower eHealth literacy are less likely to use online sources of health advice and care. We were, therefore, keen to examine eHealth literacy in relation to NHS 111 online.

A recent systematic review10 concluded that there was ‘a high level of uncertainty about the impact of 111 digital on the urgent care system and the wider healthcare system’. 10 This called for investigations of the pathways followed by patients using the service, and also of the barriers to the use of online symptom checkers by people who are less familiar with digital technology. Our project looks at where NHS 111 online fits in patient pathways to care and within the wider urgent and emergency care system, and provides the first large-scale examination of eHealth literacy, addressing these two areas of research need.

How this study builds on our previous work and other related studies

Our previous work has looked at the use of a computerised decision support system (CDSS) to support triage and assessment in urgent and emergency care. A study by Pope et al.,38 which was completed in 2010, examined the use of NHS pathways and the NHS CDSS used by 999 ambulance and out-of-hours urgent care services to understand how call handlers triaged and managed patients seeking help. A follow-on project, HSDR 10/1008/10,39 which was completed in 2012, investigated the work and workforce implications of NHS 111 and was able to look at the telephone service itself, the technologies used and the wider network of urgent care provided in primary care. HSDR 14/19/16,40 which was completed in 2018, looked beyond NHS 111 services to explore sense-making strategies and help-seeking behaviours associated with the use and provision of urgent care services.

The project reported here was funded alongside a ‘sister’ project (conducted by the University of Sheffield and led by Janette Turner, NIHR127655/ISRCTN5180111241), which explored the impact of NHS 111 online on the NHS 111 telephone service and on the wider urgent care system. The Sheffield project provided an updated evidence review, a time series analysis of the impact of the online service on the NHS 111 telephone service, a survey of service users and a cost–consequences analysis. The Sheffield team also interviewed 16 NHS staff across four NHS 111 sites to explore the impact of NHS 111 online on their workload and their views about how the service was implemented, used and could be developed. Our study augments this aspect of the Sheffield study, providing a larger qualitative interview study of a range of NHS staff and other stakeholders to understand the workforce impacts of NHS 111 online.

This report seeks to fill the gaps in the evidence base about NHS 111 online to inform the future development of NHS 111 services and to meet some of the research needs identified by NHS England for the evaluation of this digital service.

Study design, aims and objectives

Our multimethod study collected and analysed survey and qualitative interview data.

Work package 1 (patient pathways and eHealth literacy) describes the pathways of care and services used by patients who access NHS 111 online and explores eHealth literacy. The research questions were as follows:

-

Research question (RQ) 1. What is the impact of NHS 111 online on patient pathways of care?

-

RQ 2. Is there evidence for differential access and use of NHS 111 online?

Work package 2 (workforce implications) reports the analysis of English and Australian interviews and addresses RQs 3–6:

-

RQ 3. What are the workforce implications of introducing NHS 111 online?

-

RQ 4. How do work arrangements (e.g. staffing, skillsets, task allocation) vary within different types of NHS 111 online services?

-

RQ 5. How do variations in these work arrangements impact on the wider health and social care system?

-

RQ 6. How does UK NHS online workforce compare with Australian Healthdirect service?).

The aim of the project was to examine patient pathways and workforce implications of NHS 111 online. The objectives were to:

-

describe the pathways of care and services used by patients who access NHS 111 online

-

describe the extent of differential access to and use of NHS 111 online

-

describe the workforce for NHS 111 online and assess the impact of different work arrangements on the urgent and emergency health-care system

-

compare the workforce implications of NHS 111 online with Healthdirect in Australia.

Outline of this report

Chapter 2: study design and methods

Chapter 2 gives an overview of the study design, including the key changes that extended the study timeline, such as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We discuss the challenges of carrying out research in areas of high health need and engaging less research active sites. We also present our data collection and analysis methods, as well as details of our embedded PPI activities throughout the study.

Chapter 3: pathways to care

Chapter 3 looks at where NHS 111 online sits in the landscape of service provision and at patient pathways to care involving use of NHS 111 online. We report our analysis of the telephone interviews in England with health-care practitioners in primary and urgent care, emergency departments and dental services, and with charity organisations representing vulnerable people. We also draw on a range of policy documents and diagrams detailing pathways into urgent care and use these to build on and inform the draft pathway diagram included in our original research proposal and to reflect on what we have learnt about NHS 111 online and pathways to care.

Chapter 4: work, workforce and impacts on the wider health system – interviews in England and Australia

Chapter 4 looks at the work and workforce arrangements and impacts on the wider health system associated with NHS 111 online in English primary, urgent and emergency care services. It also reports data from interviews in Australia about Healthdirect and our comparison of this service (including the online symptom checker) with NHS 111.

Chapter 5: is there evidence for differential access to and use of NHS 111 online?

Chapter 5 presents the findings of a survey designed to address the research question ‘Is there evidence for differential access and use of NHS 111 online?’ and asked two main questions:

-

What are the demographic characteristics and preferences of users of NHS 111 online compared with those who have not used the NHS 111 online service?

-

What is the relationship between eHealth literacy and the use of NHS 111 online?

Chapter 6: discussion and conclusions

This chapter summarises the key findings, discusses these findings in the context of the wider literature and examines the implications of this work. This chapter also includes consideration of the limitations of this research study.

Chapter 2 Overview of the study

Research design and conceptual framing

We used a multimethod design, employing quantitative survey methods and semistructured interview methods, to explore patient pathways and workforce implications of the use of NHS 111 online. The study had two interconnected work packages. The first work package focused on patient pathways and eHealth literacy and looked at the impact of NHS 111 online on patients’ health-care journeys and navigation of the health-care system, and whether or not there was evidence for inequalities or differential access and use of NHS 111 online. The second work package explored the workforce implications of the introduction of NHS 111 online to understand how health-care work and workforce arrangements varied with the use of NHS 111 online and the impact of these arrangements on the wider health-care system. To broaden the scope of the study, we extended this second work package to include a comparative study of the Australian Healthdirect services staff and stakeholders. This allowed us to compare the work and workforce impacts of similar services in different health-care systems providing opportunities for shared learning.

Changes from the original proposal

A key change was the study timetable. Although designed initially as an 18-month study, the start date was moved to accommodate the relocation of the PI to the University of Oxford and the study was then affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. We experienced a series of COVID-19 pandemic research pauses, which meant that ethics, contracting and governance processes and data collection were stopped and had to be restarted, and the study duration had to be extended (with the agreement of the funder). In addition, COVID-19 risk management and changes to ways of working in research and in the NHS meant that we had to rethink some key elements of our research design.

The original study was conceived as an ethnographic case study, and we planned to combine the survey of eHealth literacy with substantial qualitative observation and interviews focused on case studies across eight different geographical locations. The COVID-19 pauses to data collection and the shift to remote data collection meant that we had to rethink this case study design and adapt data collection while trying to keep the study moving forward.

We discussed design changes with the Study Steering Group and worked with potential study sites to ensure that our study was feasible and would deliver on the core aim and objectives. We also worked to ensure that we protected the research team, patients and health-care workers, and minimised the need for additional work by parts of the urgent and emergency health-care system that were experiencing considerable demand and workload during the pandemic.

The key changes to the design concern the survey and the case studies, and are documented in Table 1.

| Component | Proposal | Changes (justification for this) |

|---|---|---|

| Survey of eHealth literacy skills of those who have used NHS 111 online and those who have not (WP1/RQ2 Objective 2) | Target sample size: 314 urgent and emergency care service users. Approx. 50 surveys per site. To be recruited via GP surgeries, NHS 111, Urgent Care services, Emergency Departments in the 8 case sites. Sample power calculation based on estimating the mean eHealth literacy scores in the general population of service users of urgent and emergency care services to a desired level of precision, as determined by the width of the 95% confidence interval for this mean. The aim was to estimate the mean to within +/–0.07; based on Kayser et al.42 who reported a baseline standard deviation of 0.63. We planned to offer electronic (web-based) survey or paper based survey. |

Actual sample recruited: 2754. Recruited from 23 primary care sites, seven Emergency Departments or Urgent Care Centres, 1 charity organisation and via NHS 111 online. Move to digital data collection via Web-link, self-completion or completion on a computer tablet assisted by research nurse in the recruitment setting. (COVID-19 infection control measures meant that paper surveys were not permitted.) Rebalanced the project in the light of restricted qualitative data collection and increased target sample size. (This counters possible biases created by shift to all electronic data capture and oversampling allows us to report analyses with greater precision and explore more explanatory and subgroup analysis.) These changes were agreed by the SSG following discussion with a statistical expert at University of Southampton. We discussed this revised plan with the NIHR commissioning manager and agreed to complete this work within the contracted funding envelope. |

| Case studies (WP2/RQ4 RQ5 Objective 3) | Data collection in 8 case study sites to include observation of work practice for a minimum of two weeks at each site. Interviews with commissioners, system developers, corporate and operational managers, healthcare professionals, charity workers and support staff to be conducted formally in person or by phone, or informally while observing (at least 10 people per site, 80 minimum). Collect copies of relevant policy documents, system specifications and updates, and organisational materials. | No qualitative observation, shifted to telephone interview data collection (COVID-19 infection control measures meant site visits were not permitted, this design complied with remote working guidance). The shift to remote working removed the practical and cost barriers to collecting data across the whole of England and allowed us to approach more than 8 sites. We defined three ‘service type’ categories 1) Primary care, 2) Urgent and Emergency care and 3) Other services and organisations (this included community NHS services, charity and peer support services targeted at vulnerable and disadvantaged groups). We purposively sampled respondents within each of these service types, until the planned minimum of 80 interviews was achieved. We were also able to use interim analyses to inform further sampling, to include services implicated in work associated with NHS 111 online that we had not previously considered (e.g. dentists). Sampling followed our original intention to deliberately seek out research participants from organisations that were less research active, and to understand the use of NHS 111 online in areas of high health need/or where there was significant socio-economic disadvantage or inequality. |

The extended timeline also led to some changes to the research team. Among the co-applicants, Lucie Lleshi left the study in 2021 following her change of job and the merger of the Southampton and Hampshire Clinical Commissioning Groups. Emily Petter joined in her place to provide the perspective of a policy decision-maker and health service commissioner to the study. (Emily is senior commissioning manager – Urgent & Emergency Care, South West Hampshire; NHS Hampshire, Southampton and Isle of Wight CCG.) Within the UK study team, Jennifer MacLellan was seconded for 8 weeks to a COVID-19 research study during one of the study data collection pauses. Kate Churruca and Louise A Ellis joined co-applicant Jeffrey Braithwaite to support the data collection and analysis for the Australian component part of the study.

Research in areas of high health need and engaging less research active sites.

In the original proposal, we outlined that our purposive sampling of cases would include sites in which the NHS 111 online service was established and sites in which the service was relatively new. This included the original pilot sites, sites that had been studied in a parallel research study led by the University of Sheffield and some sites that had only recently commissioned the service. At the time of writing the proposal, some areas were ‘beta-testing’ the system or favouring ‘soft’ roll out, whereas others saw the service as a core part of service provision. We were also mindful that people who live in regions of the UK in which the burden of need is greatest are often under-served by research, and we wanted to support NIHR’s goal of bringing applied research closer to these communities. 43 We, therefore, made particular efforts to recruit sites that we had not previously worked with. Our site selection was informed by area deprivation scores and sociodemographic characteristics of the population, including age profiles and the presence of ethnic minority groups.

Selecting research sites

We wanted to ensure that our study included sites reflecting deprivation and high health need. Rai et al. 44 explored how research sites are selected for multicentre randomised trials and showed that chief investigators (CIs) and teams tended to select research active sites with established governance processes and research delivery support infrastructure that enable recruitment targets to be met within tight study time frames. However, they also found that CIs who ‘broke the mould’ and actively identified and nurtured new sites reported as much success as those returning to familiar, highly research active sites. Inspired by this work, we mapped areas of socioeconomic deprivation, high diversity, low literacy and high health need, and targeted these areas for our recruitment.

We used the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) to map areas of greatest deprivation in England owing to their known association with high health need. 45 We also made particular efforts to engage with general practices, district hospitals and community trusts that were less research active, and those serving more ethnically diverse populations. We used literacy scores from the National Literacy Trust as a proxy indicator of potential barriers to the use of and access to digital health technologies. Together these scores and indicators helped us to target our site selection to primary and secondary care services in North West Coast, Yorkshire and Humber, West Midlands and South Midlands, Eastern Counties, Kent Surrey and Sussex, London, Wessex and Thames Valley.

The role of the Clinical Research Networks

The study was adopted on to the NIHR CRN portfolio and some CRNs were helpful in brokering connections with new sites, notably in identifying practices or services in their area that had little or no track record of engagement with research. Some CRNs worked with us to identify sites in areas of high health need with intersectional characteristics of interest (e.g. particular ethnic minority groups or areas with significant socioeconomic deprivation). However, several CRNs were unable to support the study once it became clear that the work involved required local intelligence about the population demographics and health need, or when they learned that we wanted to reach organisations that were not acute trusts or general practices and/or sites that were less research active. Several CRNs had well-established support for acute hospital-based research and randomised controlled trial recruitment but were not as well placed to support recruitment of sites and participants from community and dental services or services for vulnerable groups such as homeless people. Liaising with the CRN to approach less research active general practices in areas of high deprivation or with diverse populations took longer as most CRNs had stronger links with research active practices that tended to be those with white/less-deprived patients. Once sites were identified, contacting key personnel through the CRN was often straightforward; however, the link between the CRN and local-level governance was often patchy, and this added to the time and input required from the research team to obtain the necessary approvals for data collection.

Table 2 shows the timeline from initial approach to study approval by month across the 22 regional services that we approached to take part in the study. In this section, we refer to the services using alphabetical identifiers. We use the term ‘site’ to refer to specific general practices, EDs/UCCs and NHS 111 where we administered the survey or conducted interviews; please note that some of the services in Table 2 are associated with more than one site of data collection.

| Service ID | Service and regional location | September 2020 | October 2020 | November 2020 | December 2020 | January 2021 | February 2021 | March 2021 | April 2021 | May 2021 | June 2021 | Recruitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Primary care, south-east England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| K | Primary care, south England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| M | Primary care, north-west England | ✓ | Over target | |||||||||

| N | Primary care, south England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| P | Primary care, south England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| T | Primary care, London | ✓ | Over target | |||||||||

| U | Primary care, Midlands | ✓ | Below target | |||||||||

| V | Primary care, north England | ✓ | Over target | |||||||||

| A | Major trauma centre, east England | ✓ | Target | |||||||||

| B | Local trauma unit, north England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| C | Local trauma unit, south England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| D | Local trauma unit, south England | ✓ | Over target | |||||||||

| E | Major trauma centre, north England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| G | Major trauma centre, London | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| H | Major trauma centre, London | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| I | Local trauma unit, east England | ✓ | Over Target | |||||||||

| J | Local trauma centre, south England | ✓ | Target | |||||||||

| L | Urgent care centre, Midlands | ✓ | Over Target | |||||||||

| O | Major trauma centre, south England | ✗ | N/A | |||||||||

| Q | Local trauma centre, south England | ✓ | Target | |||||||||

| R | Urgent care centre, Midlands | ✓ | Over target | |||||||||

| S | Major trauma centre, south England | ✗ | N/A |

Less well-developed research infrastructure hindered recruitment of less research active sites in secondary care: this included a basic website without governance team contact details (service I), unsupported or unavailable governance staff (J, Q), and a lack of available research staff to support the study (B, E). Even in services that appeared to have a good research infrastructure, governance was often protracted and delayed (D, J, N, Q, U). Three shut down non-COVID-19 research during the national lockdowns to prioritise COVID-related studies (D, J, Q) and two declined to participate because of a heavy research workload (G, O, S). Out of 14 secondary care services, five were approached through networks of the research team (four did not proceed), one was ‘cold called’ (and did not proceed) and eight were approached through the CRN (and two did not proceed). Time from contact to starting recruitment ranged from 1 to 10 months. The longest delays (L, Q, T) were in part attributed to suspension of governance procedures for non-COVID-19 studies during the lockdowns, but also reflect significant governance delays, poor communication and the high workload of the CRN research nurse teams. Smaller secondary care services appeared more flexible in set-up and were faster in moving from contact to green light for recruitment. Unfortunately, in these services there were often fewer CRN-funded research nurses (as this is linked to recruitment accrual numbers) to deliver the study. Two EDs could not open to the study because there was no research nurse support (COVID-19 working restrictions meant that the central research team were not permitted to travel to these sites, relying on research teams in situ to deliver the patient survey at these sites).

In primary care, the CRN was responsible for reviewing study permissions before general practices could be approached and this sometimes delayed site recruitment. One CRN accepted all the HRA governance documents and sent out an expression of interest to sites within a few days (T). They also used their network of GP champions to commence recruitment and to cascade the study out to colleagues in areas of high health need. However, in the majority of cases, the CRN primary care team reviewed all the HRA-approved documents over 4–10 months (average of 7 months and 3 weeks) before granting permission for the CRN delivery team to contact local services for participation (D, J, N, Q, U, V). This extra layer of governance negatively impacted on the timeline of the study, despite the swift lifting of restrictions and restart of non-COVID-19 research. Access to primary care sites was highly dependent on the activity of the CRN link person. In one case, no practices expressed an interest to join the study after two newsletter advertisements (F) and the CRN could not identify other engagement strategies and did not have a research champion to assist with this work. In another large CRN, the research team were sent a Google search list of addresses of practices/services and were told to contact these directly because the CRN did not have any established links to any relevant sites (U). Out of eight primary care CRNs contacted for participation in the study, four proceeded to green light and recruitment over a period of 1 to 6 months.

Techniques used to support recruitment and site engagement

Two CRNs were highly responsive and efficient, and supported survey recruitment by working with general practices who were already linked with CRN research champions and by cascading information from these to other practices. One CRN invited research staff to attend local network meetings to raise awareness of the study and engage sites; this proved helpful in identifying key contacts who then helped with local governance processes and recruitment.

Some participating sites were innovative in their use of resources to maximise recruitment. Examples included temporarily moving staff from other departments to support the study, the use of newsletters and communication bulletins, locating spare laptops and promoting the use of QR codes for the survey. We reported weekly survey recruitment figures to facilitate accrual uploads and motivate further recruitment. For the qualitative interview component we found that offering flexibility in staff interview format and timing allowed clinical interviewees to balance participation with their clinical workload. We sent personal thanks to the research lead, governance manager and CRN for the research nurses working with our sites to encourage continued engagement.

It took significantly more time and effort to identify and set up this study in less research active sites and to sample sites in areas with diverse demographic profiles and high health need. Some of the delays encountered were probably exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, periods of lockdown and the prioritisation of COVID-19-related research and service activity. However, some appear to be related to CRN ways of working and gaps in infrastructure support for non-RCT and non-hospital-based research and studies attempting to access less research active sites. Despite the delays noted here and some of the structural barriers highlighted, the study was able to recruit sites from different geographical areas that included diverse populations, and we had some success working with general practices and services that had previously been less research active.

Qualitative interviews: England

We conducted telephone semistructured interviews to explore the workforce implications and work associated with NHS 111 online. This addressed objective 3, to describe the workforce for NHS 111 online (RQ3) and assess the impact of different work arrangements on the urgent and emergency health-care system (RQ4 and RQ5). Given that the parallel study led by Janette Turner at the University of Sheffield had undertaken interviews to examine the impact of the online service on the NHS 111 telephone service, looking at changes to casemix, workload and staff morale and retention,41 we focused our English interviews on the ways that NHS 111 online impacted on the work of other (i.e. non-NHS 111) services.

We developed an interview topic guide using open-ended questions and prompts to ask about experiences of the interface between NHS 111 online and other services, as well as the work undertaken because of or associated with NHS 111 online. We were interested to know about work arrangements, everyday processes and work content; for example, whether or not GP receptionists recommended NHS 111 online to patients, how they managed patients ‘referred’ by the service and any new tasks they undertook because of NHS 111 online. The topic guide asked some introductory questions about the interviewee’s professional role, the service provided, general awareness and knowledge of NHS 111 online and experience using or receiving/seeing patients/service users who had used NHS 111 online. Subsequent questions asked about the impact on work and workforce, including the skills, time and other resources linked to the use of NHS 111 online. The interview guide closed with consideration of broader benefits/challenges of the 111 services and asked the interviewee to reflect on how the service was developing and the longer-term implications for their work and workforce.

Selection and recruitment of interview participants: England

Interviewees were purposively sampled from primary, urgent and emergency health-care services and organisations. Site selection was informed by discussion with our steering group, the CCG and NHS England/NHS Digital stakeholders, and with input from the NIHR CRNs. Initial site contact was typically made by telephone calls/e-mails to relevant service managers to identify potential interviewees and negotiate access.

We sampled a range of health-care professionals and support staff, including commissioners, operational and strategic service managers, clinicians and administrative staff. Informed by pathways mapping in WP1 and earlier interviews, we broadened recruitment to include staff from community NHS organisations, NHS dentistry and third sector/charity organisations identified as having some links to or working with service users who were likely to use NHS 111 online. We took care to target areas of health need and a spread of geographical areas with diverse and disadvantaged populations.

Interview participants were invited to take part by e-mail, provided with an information leaflet and asked to sign a consent form or give audio-recorded consent. Our aim was to achieve a maximum variation sample to capture a range of views and experiences that offer a detailed and nuanced understanding, but not to enable statistical representativeness or prediction. Interviews took place between October 2020 and July 2021 and were conducted by experienced qualitative researchers (MacLellan, Pope and Turnbull). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim or as near-verbatim summaries.

A total of 80 interviews were conducted: 33 with staff in primary care (Table 3), 27 from urgent and emergency care (Table 4), nine dental service providers (Table 5), and 11 representatives of charities and non-NHS services representing vulnerable and disadvantaged groups, such as the homeless, refugees, people with mental illness and people who struggle with literacy (Table 6).

| ID | Site | Role | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC01 | London | Paramedic | Male |

| PC02 | London | Pharmacist | Male |

| PC03 | London | GP | Female |

| PC04 | London | GP | Male |

| PC05 | London | Pharmacist | Male |

| PC06 | London | GP | Female |

| PC07 | London | GP | Male |

| PC08 | London | Care navigator | Female |

| PC09 | London | Care navigator | Female |

| PC10 | North west coast urban | Nurse | Female |

| PC11 | North west coast urban | Nurse | Female |

| PC12 | North west coast urban | Care navigator | Female |

| PC13 | North west coast semi-rural | GP | Male |

| PC14 | North west coast semi-rural | GP | Male |

| PC15 | North west coast semi-rural | Pharmacist | Female |

| PC16 | North west coast semi-rural | Receptionist | Female |

| PC17 | North west coast semi-rural | Nurse | Female |

| PC18 | North west coast rural | GP | Female |

| PC19 | North west coast rural | Nurse | Female |

| PC20 | North west coast rural | Quality lead/manager | Female |

| PC21 | North west coast semi-rural | Reception manager | Female |

| PC22 | North west coast urban | Reception manager | Female |

| PC23 | North west coast semi-rural | Care navigator | Female |

| PC24 | North west coast urban | Care navigator | Female |

| PC25 | North west coast urban | Care navigator managera | Female |

| PC26 | North west coast urban | GPa | Female |

| PC27 | North west coast urban | Nursea | Female |

| PC28 | North west coast urban | Care navigatora | Female |

| PC29 | North west coast urban | Receptionista | Female |

| PC30 | North west coast urban | Paramedica | Female |

| PC31 | West Midlands urban | GPb | Male |

| PC32 | Yorkshire rural | GP | Male |

| PC33 | Yorkshire urban | GP | Female |

| ID | Site | Role | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED01 | Major trauma centre, east England | ED nurse | Male |

| ED02 | Major trauma centre, east England | Receptionist | Female |

| ED03 | Major trauma centre, east England | Pharmacist | Female |

| ED04 | Major trauma centre, east England | ED nurse | Male |

| ED05 | Major trauma centre, east England | ED doctor | Male |

| ED06 | Major trauma centre, east England | Senior manager | Male |

| ED07 | Local trauma unit 1, south-east England | GP in ED | Female |

| ED08 | Local trauma unit 1, south-east England | ED nurse | Female |

| ED09 | Local trauma unit 1, south-east England | GP in ED | Female |

| ED10 | Major trauma centre, south England | Urgent care quality lead | Female |

| ED11 | Major trauma centre, east England | Senior manager | Male |

| ED12 | Local trauma unit 2, east England | ED nurse | Female |

| ED13 | Local trauma unit 2, east England | ED doctor | Female |

| ED14 | Local trauma unit 2, east England | ED doctor | Male |

| ED15 | Local trauma unit 2, east England | ED doctor | Female |

| ED16 | Local trauma unit 2, east England | ED doctor | Male |

| ED17 | Local trauma unit 2, east England | ED nurse | Male |

| ED18 | Local trauma unit 3, south-east England | ED nurse | Male |

| ED19 | Local trauma unit 3, south-east England | ED nurse | Female |

| ED20 | Local trauma unit 3, south-east England | Receptionist | Female |

| ED21 | Urgent care centre, Midlands | UCC nurse | Female |

| ED22 | Urgent care centre, Midlands | UCC nurse | Female |

| ED23 | Local trauma unit 4, south-east England | ED doctor (trainee) | Female |

| ED24 | Local trauma unit 4, south-east England | ED doctor (trainee) | Male |

| ED25 | Urgent care service, Midlands | MIU receptionist | Female |

| ED26 | Urgent care service, Midlands | MIU receptionist | Female |

| ED27 | Urgent care service, Midlands | MIU nurse | Female |

| ID | Site | Role | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| D01 | London | Dentist | Female |

| D02 | West Midlands | Emergency dentist | Female |

| D03 | North-east England | Dentist | Female |

| D04 | North-east England | Associate dentist | Male |

| D05 | Yorkshire | Associate dentist | Female |

| D06 | South-east England | Dentist | Female |

| D07 | North England | Emergency dentist | Male |

| D08 | West Yorkshire | Dentist | Female |

| D09 | North-east England | Dentist | Female |

| ID | Charity organisation | Role | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH01 | Homeless charity | National policy-maker | Female |

| CH02 | Homeless charity | National policy-maker | Female |

| CH03 | Homeless charity | National policy-maker | Female |

| CH04 | Mental health charity | Service providera | Male |

| CH05 | Literacy charity | National policy-makera | Female |

| CH06 | Refugee charity | National policy-makerb | Female |

| CH07 | Homeless charity | Peer support worker | Female |

| CH08 | Homeless charity | Peer support worker | Female |

| CH09 | Homeless charity | Peer support worker | Male |

| CH10 | Homeless charity | Peer support worker | Male |

| CH11 | Homeless charity | Peer support worker | Male |

Qualitative interviews: Australia

A qualitative interview study was conducted with Healthdirect staff and external stakeholders to explore the work of this service and perspectives on the role of Healthdirect in the Australian health-care system. These interviews addressed objective 4 to compare the workforce experience of NHS 111 online with the Australian Healthdirect service, with the aim of learning from their experience of introducing similar virtual triage and assessment services.

Selection and recruitment of interview participants: Australia

The Australian interviews sought perspectives from stakeholders involved in, interacting with or affected by Healthdirect’s triaging system. Interviewees included Healthdirect staff, national policy-makers, representatives of primary health networks (PHNs), ED clinicians, GPs, service users and representatives of other organisations linked to Healthdirect. Recruitment was enabled in four ways: (1) facilitation by Healthdirect leadership; (2) contacting organisations (e.g. PHNs, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) to request they distribute information about the study to relevant members/employees; (3) e-mailing professional contacts of the research team; and (4) snowballing, where interviewees and contacts forwarded details to other potential participants.

Data collection took place in July and August 2021, with semistructured interviews conducted via video-conferencing platforms. Using a semistructured interview schedule, participants responded to open-ended questions about their current role and organisation, their level of knowledge and involvement with Healthdirect, their views on how its triage services are being used and by whom, the impact of Healthdirect on the broader health system, and their knowledge of NHS 111 services, if any, and how these compare with Healthdirect. In these discussions, the interviewer (Churruca or Ellis) paid particular attention to comments relating to the online services offered by Healthdirect and specifically the use of the online symptom checker. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

A total of 37 interviews were conducted with 41 participants (some interviews were conducted in small groups of two or three individuals). The primary role for each participant is summarised in Table 7; however, this categorisation does not capture overlapping roles. Several interviewees working within Healthdirect, in policy or in PHNs had a clinical background, and likewise several interviewees from policy and PHNs reported using Healthdirect triage services.

| Participant code | Role | Sex |

|---|---|---|

| HD01 | Healthdirect operational staff | Male |

| HD02 | Healthdirect operational staff | Female |

| HD03 | Healthdirect senior leadership | Female |

| HD04 | Healthdirect senior leadership | Female |

| HD05 | Consumer and patient representative | Female |

| HD06 | Healthdirect operational staff | Male |

| HD07 | Healthdirect operational staff | Female |

| HD08 | Healthdirect senior leadership | Male |

| HD09 | Healthdirect operational staff | Male |

| HD10 | Healthdirect operational staff | Female |

| HD11 | Healthdirect senior leadership | Female |

| HD12 | Healthdirect operational staff | Male |

| HD13 | Healthdirect operational staff | Male |

| HD14 | Healthdirect operational staff | Female |

| HD15 | Consumer and patient representative | Female |

| HD16 | GP | Female |

| HD17 | GP | Female |

| HD18 | ED doctor | Male |

| HD19 | GP | Female |

| HD20 | ED nurse | Female |

| HD21 | ED nurse | Male |

| HD22 | Paediatrician | Male |

| HD23 | Mental health professional | Male |

| HD24 | Policymaker | Female |

| HD25 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD26 | PHN representative | Male |

| HD27 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD28 | Policymaker | Male |

| HD29 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD30 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD31 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD32 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD33 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD34 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD35 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD36 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD37 | Policy-maker/clinician | Female |

| HD38 | Policy-maker | Male |

| HD39 | Policy-maker | Female |

| HD40 | PHN representative | Female |

| HD41 | Policy-maker | Female |

Interview data analysis

All transcribed interviews were de-identified prior to analysis, removing individual- and organisational-level identities and names. The English and Australian data sets were initially analysed by teams based in each country before opening up discussion to the wider analysis team meetings. Transcripts were read and re-read for familiarisation and imported into NVivo46 and coded using a draft coding framework developed in consultation with the wider research team. Revisions to the coding framework were made to capture ideas and data of interest, for example the lack of awareness of NHS 111 online in the English interviews and contextual aspects relevant to Healthdirect’s triage system, such as regional–remote Australian health service provision. Codes were discussed by the respective English and Australian interview teams and then by the larger analytical team comprising the MacLellan, Pope, Turnbull, Prichard, Churruca, Ellis and Braithwaite. Themes were developed by grouping related codes together and exploring comparisons using matrices/charts and mind maps to facilitate theme development. PPI members and the Study Steering Group were asked to comment on and consider the veracity and credibility of themes and interpretations, and were provided with de-identified data examples for this purpose.

Survey of eHealth literacy and user scenario preferences

We used a cross-sectional survey to address the research question ‘Is there evidence for differential access and use of NHS 111 online?’. The survey was first used to understand the demographic characteristics and preferences of users of NHS 111 online compared with people who had not used the service. Second, the survey was designed to understand the relationship between eHealth literacy and the use of NHS 111 online.

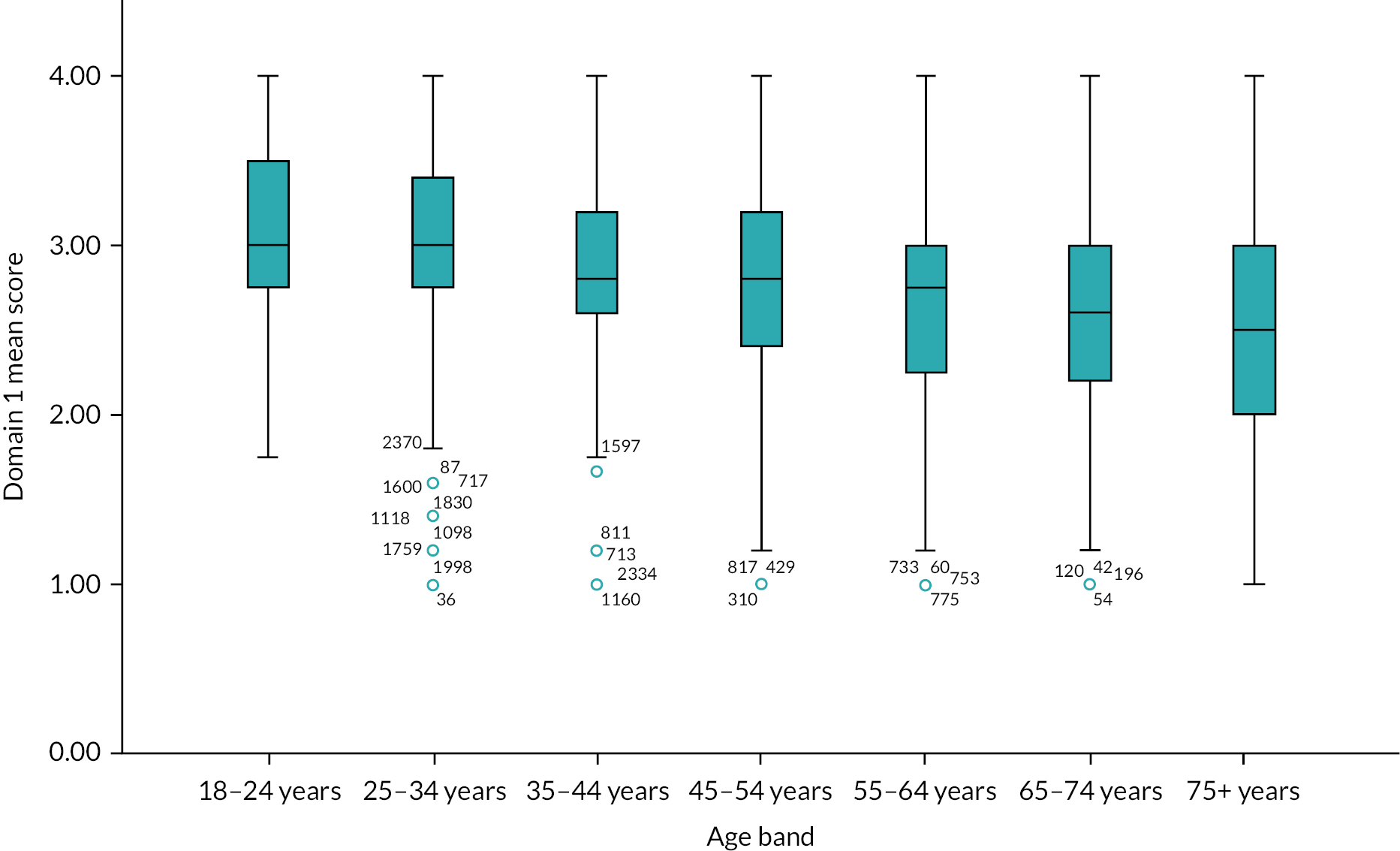

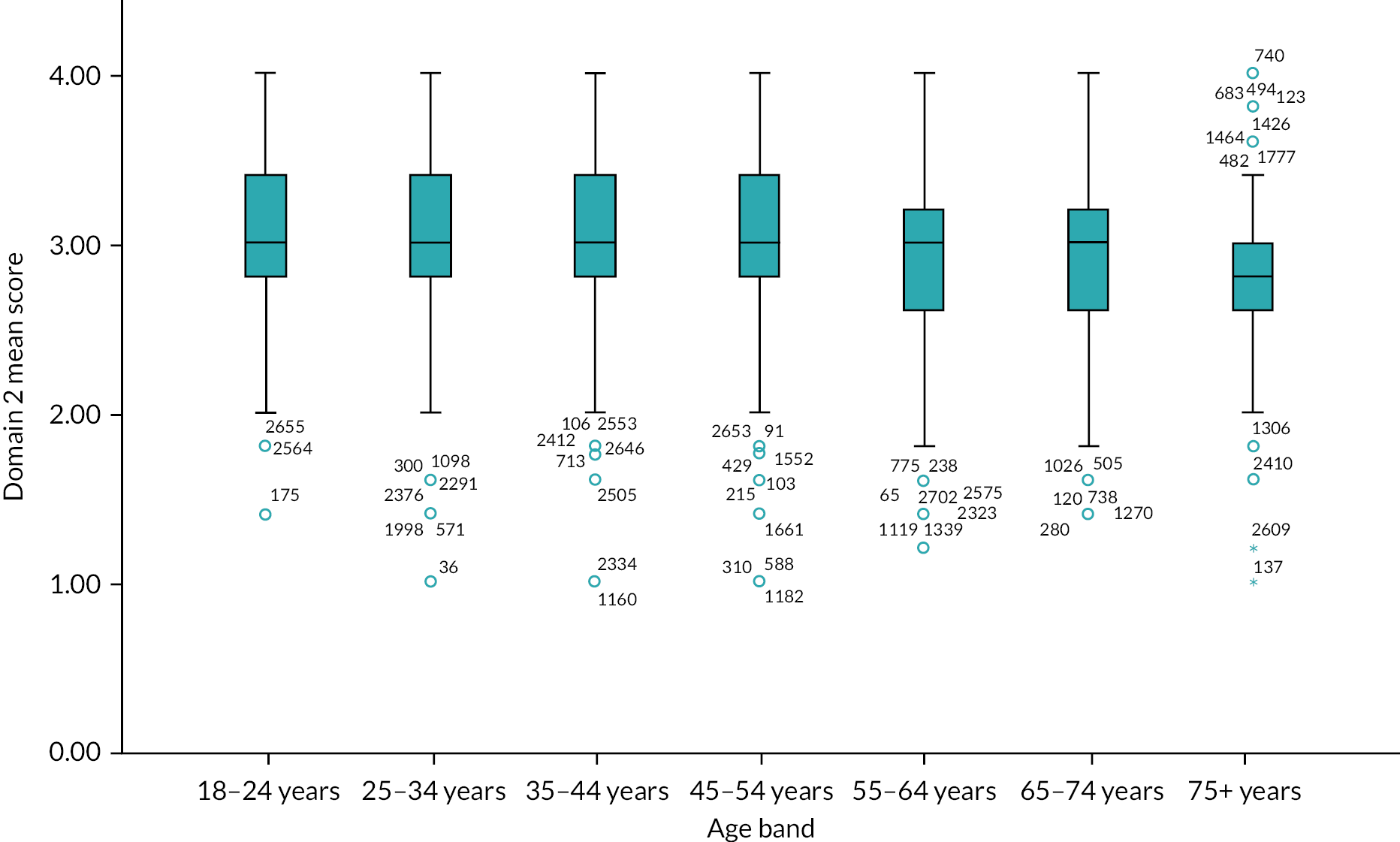

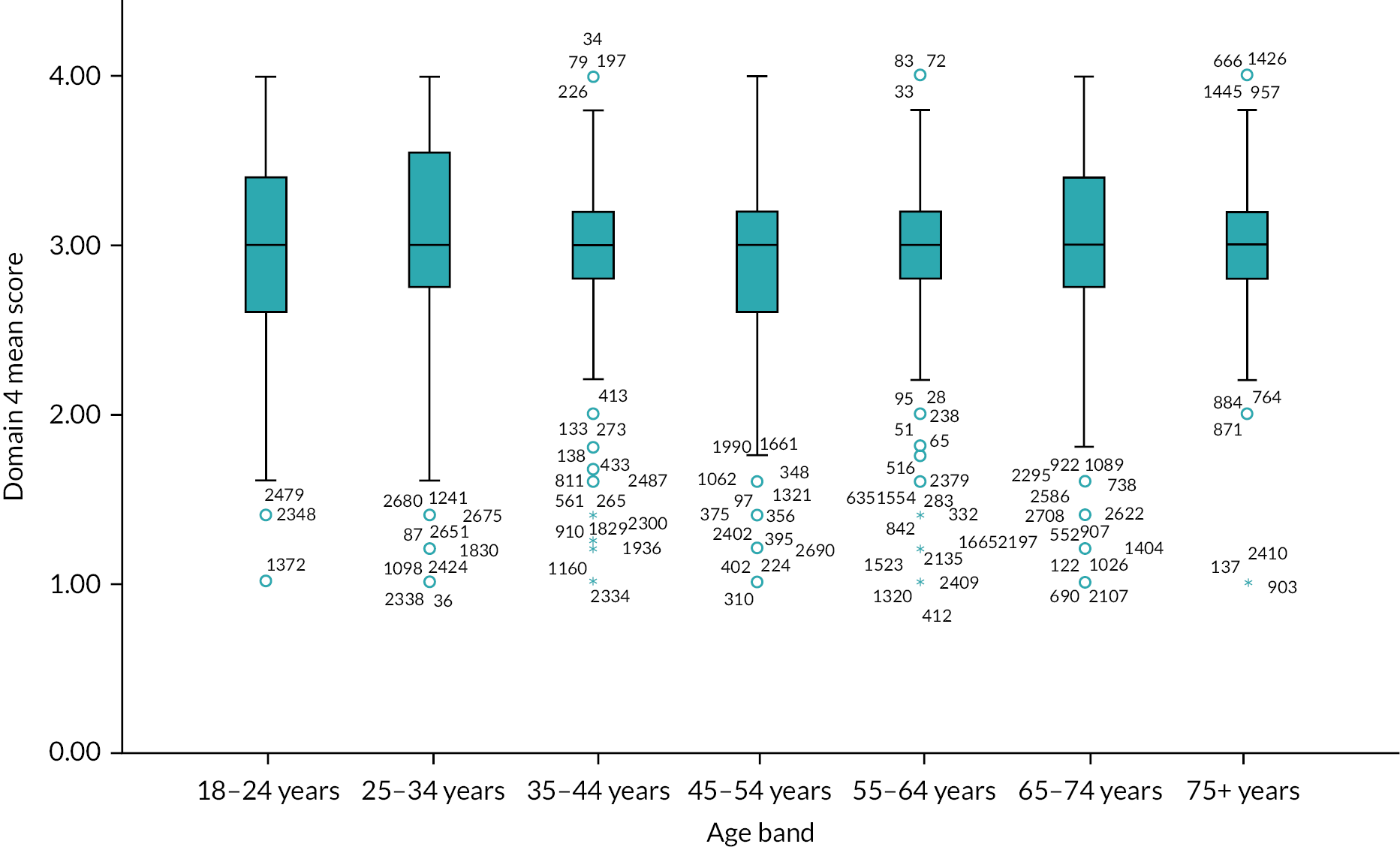

To capture those who used NHS 111 online compared with those who had not used it, the survey asked questions about age group (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, ≥ 75 years), sex (female, male, non-binary, prefer not to say), educational level (two levels were coded for the logistic regression analysis: no formal qualifications, one GCSE or higher) and employment status (employed/self-employed, unemployed/unable to work, retired, student, homemaker, other). Respondents were also asked if they had a long-term or chronic condition (yes/no). The survey consisted of sociodemographic and socioeconomic questions, which previous research has indicated are associated with influencing levels of eHealth literacy. 47,48 This literature is explored further in Chapter 5. We also asked respondents to indicate whether or not they had used other urgent and emergency care services previously (yes/no) and these included NHS 111 telephone service, GP out of hours, urgent care or walk in centre, ED and/or 999.

In addition to these questions, we also included a set of 10 scenarios that described common presenting conditions or urgent care needs, designed to explore awareness of the online service and preferences for online/call handling for different types of symptoms from less to more serious. Different health-care needs might motivate service use regardless of previous experience or literacy. In considering who uses NHS 111 online it is important to consider the different reasons that people seek online help because use might be driven by purpose in addition to demographic characteristics. These scenarios were developed in consultation with the NHS Digital/NHS 111 online team, including their PPI lead, and were informed by data from our previous research and the literature. They were designed to represent common urgent care and online symptom checker presentations, as well as some potentially more serious symptom sets. Because the scenarios were designed to be presented in a survey (rather than a qualitative interview), the scenarios were brief (Table 8) and respondents were asked ‘In the following scenarios, how likely are you to use NHS 111 online?’. Each scenario was rated on a five-point Likert scale from ‘very likely’ to ‘very unlikely’.

| Summary of scenario | Description |

|---|---|

| Minor injury: itchy bite or sting | Imagine you went for a walk in the countryside. Afterwards you develop a red, swollen lump on your arm. The skin around the insect bite or sting is itchy and painful |

| Child with high temperature or cough | Imagine your child aged 6 years (or child in your care) has had a high temperature for 2 days and has been crying in the last 24 hours. The child does not seem to be getting worse but has not improved |

| Minor illness: cough, cold, sore throat | Imagine you have had a cold, cough and sore throat for 3 days. You have a mild headache and your muscles ache. You have been taking over-the-counter medicines |

| Minor illness: diarrhoea and vomiting | Imagine you are on holiday in England and you have had diarrhoea and vomiting for 2 days |

| Minor injury: scald to hand | Imagine you have scalded your hand with boiling water from the kettle. The scald is about the size of a 10 pence piece and your skin has blistered |

| Minor illness but uncertainty about severity | You have had a headache for several hours. It is quite severe, and painkillers have not helped |

| Minor illness but uncertainty about cause of symptoms: painful when urinating | Imagine it is about 8 o’clock in the evening. It is painful when you pee. You have pain low down in your stomach |

| Dental problem: toothache | Imagine you have had toothache for 24 hours. You have tried painkillers, but you are still experiencing some pain |

| Mental health problem: unhappy and tearful | Imagine you have felt unhappy for several weeks. You have lost interest in things you used to enjoy and often feel very tearful. You are also not sleeping very well |

| Potentially serious symptom but ambiguous presentation | Imagine you are 55 years old. You are generally in good health, but you experience a sudden pain in the chest. The pain is severe, and you are also short of breath and sweating. After a few minutes you start to feel a bit better |

The research set out to understand if there was a digital divide in abilities that might prevent some service users accessing the online platform or result in them using it in unexpected ways. We set out to understand the relationship between eHealth literacy and the use of NHS 111 online to understand if eHealth literacy and sociodemographic characteristics are associated with the use of NHS 111 online. The eHealth Literacy Questionnaire (eHLQ), a validated 35-item 7-scale questionnaire,42 was used to examine this.

Two main eHealth literacy scales have been developed. First, the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) was developed by Norman and Skinner49 to assess people’s ability to engage with eHealth, with the purpose of informing clinical decisions and health promotion planning. Although the scale has been widely used in eHealth literacy studies, recent validation studies have cast doubts on the tool’s dimensionality. 50–52 Furthermore, the eHealth and digital landscape has evolved substantially since 2006, and use and acceptance of digital health technologies have changed. Norgaard et al. 45 developed the eHealth Literacy Framework, which led to the development of the eHealth Literacy Questionnaire (eHLQ). 42,53

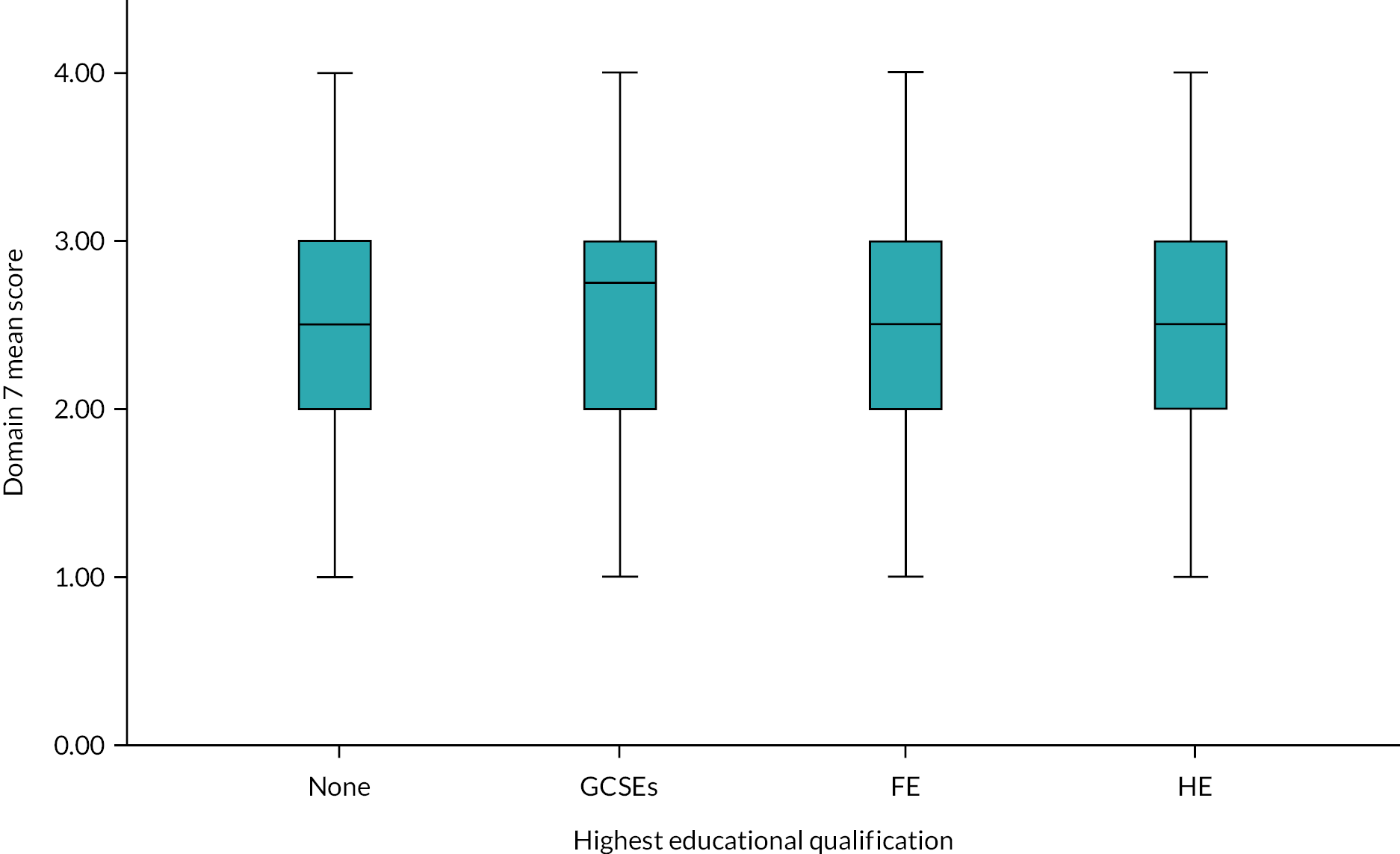

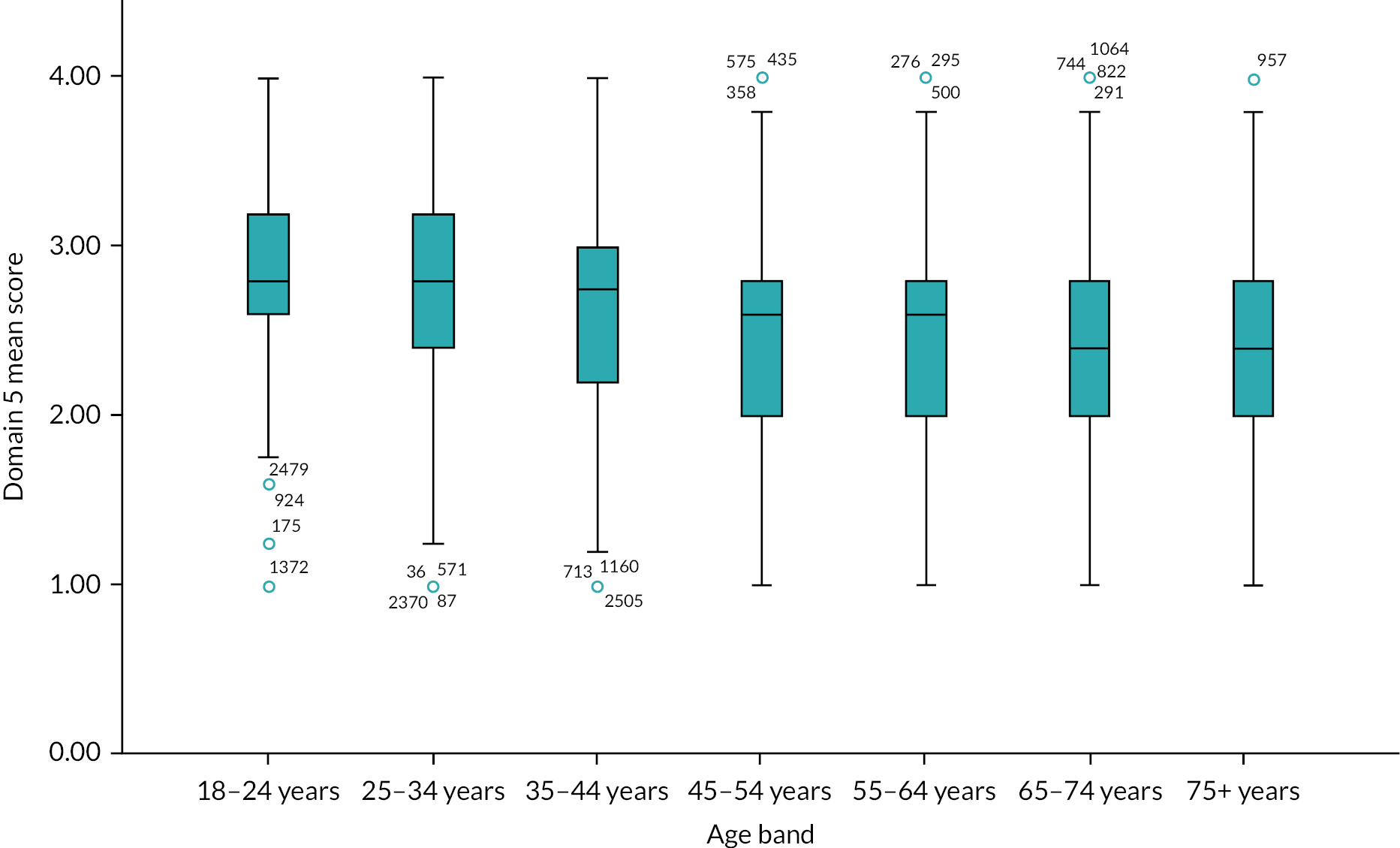

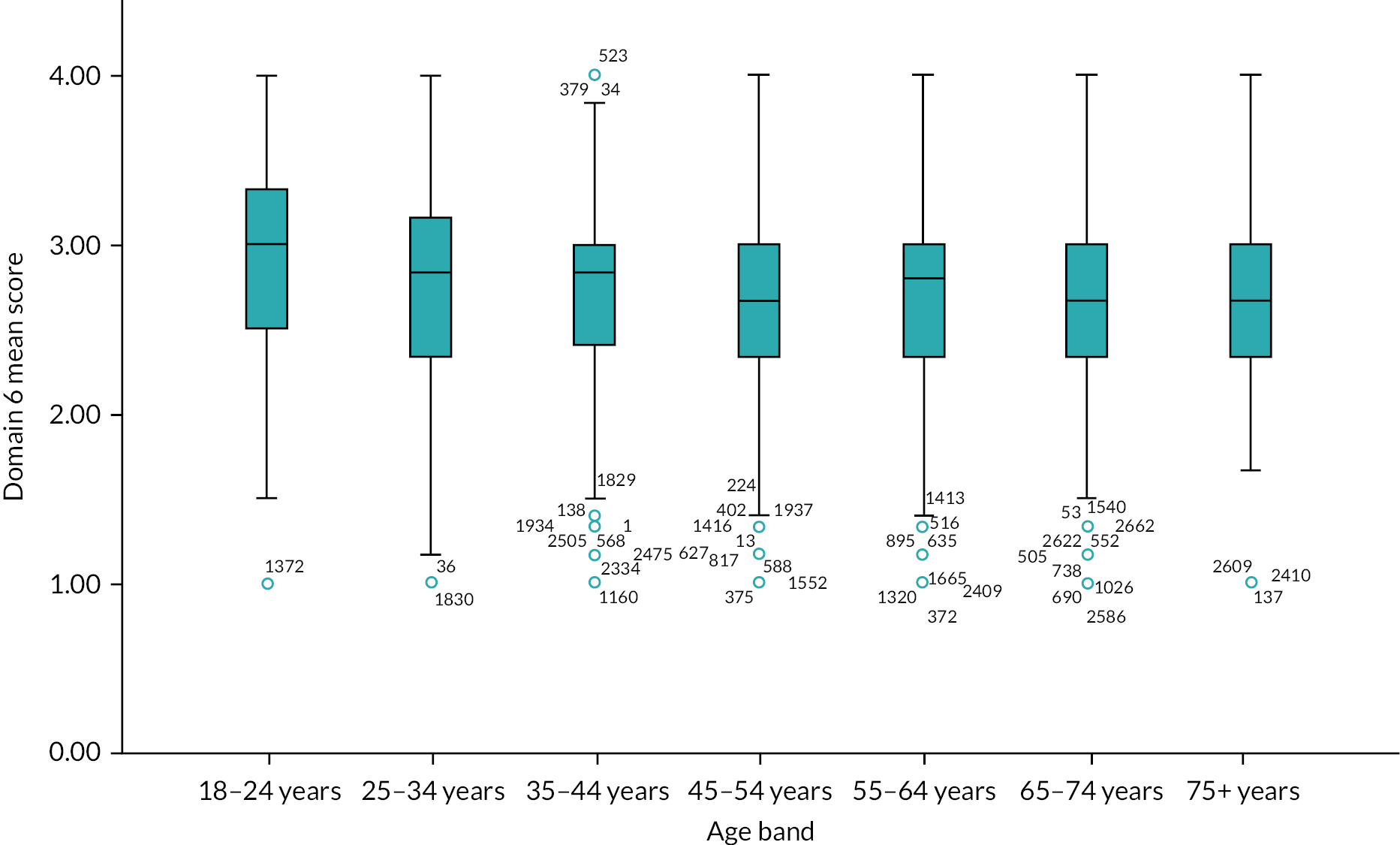

The eHLQ combines digital and health literacy and considers both individuals’ competences and individuals’ experiences and interactions with technologies and services. It consists of 35 items grouped into seven domains measuring different aspects of eHealth literacy, including the use of technology to process health information; understanding of health concepts and language; the ability to actively engage with digital services; feeling safe and in control in using online services; motivation to engage with digital services; access to digital services that work; and access to digital services that suit individual needs (Table 9). Each item on the eHLQ was scored using a 4-point ordinal scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Each domain contains between four and six items, and an average score was calculated for each domain. The eHLQ is not designed to produce a single measure score across the instrument but is a measure with seven different domains of digital literacy, and these are designed to be reported separately.

| 1.Using technology to process health information |

| 2.Understanding of health concepts and language |

| 3.Ability to actively engage with digital services |

| 4.Feel safe and in control |

| 5.Motivated to engage with digital services |

| 6.Access to digital services that work |

| 7.Digital services that suit individual needs |

The survey was administered via primary, urgent and emergency care settings and the NHS 111 online service. This was carried out in three ways:

-

The survey was made available through a mail out SMS link sent to eligible participants in participating general practices. Eligible participants were all people aged over 18 years who had consented to receive SMS messages from the general practice.

-

The survey was administered in participating emergency departments and urgent care centre sites through public display of the survey QR code on posters in waiting room areas, and in one case by e-mail to recent attenders. A hyperlink to the study survey was provided on the study web page hosted by the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences website to support this. To aid survey completion in these urgent and emergency care settings, a research nurse was available to support people wishing to access and answer the survey, using a computer tablet provided by the study team or the site.

-

The survey was distributed nationally following an NHS 111 online consult via a dedicated hyperlink. All survey responses were assigned a reference number that encoded the administrating organisation so that we could group responses by location; no personal identifying medical information was recorded. Having piloted the survey with the Southampton Consult and Challenge Group, we estimated that the survey would take approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Survey sampling and recruitment

Non-probability sequential convenience sampling was chosen as a pragmatic solution to access a range of people who had or had not used NHS 111 online. Recruitment was via primary, urgent and emergency care services, including general practices, emergency departments, urgent care centres, minor injury units and via NHS community trust, and third sector/charity organisations who were participating in the qualitative interview study. Potential survey respondents (aged 18 years or over) were identified by administrative or clinical staff at participating sites/organisations (e.g. by reception staff at emergency departments or general practices).

General practices were asked to select 100 random patients on their practice list who had consented to SMS mail outs. The research team fed back the recruitment response to the practice on a weekly basis. Some practices chose to sample a further random sample of patients to expand the mail out and increase recruitment. Recruitment across practices ranged from 4 to 185 people, with an average of 69 recruits per practice.

Emergency department and urgent care centres invited attendees to their services to take part by either using an online link or offering the opportunity to complete the survey on a tablet in the waiting room (assisted by a research nurse), which was cleaned between respondents. Sequential patients were offered a survey until a minimum of 50 participants had been recruited at each site. Recruitment ranged from 50 to 203 people, with an average of 89 recruits per site.

In addition, NHS 111 online invited patients in England who had completed the NHS 111 online algorithm via a tailored hyperlink. Consent was obtained for all respondents via a tick box at the beginning of the survey.

An administrative fee was paid to participating sites to contribute to the costs of administering and collecting the surveys.

In total, 32 sites recruited for the survey (23 primary care organisations, one charity, seven urgent or emergency care settings and the NHS 111 online website). For the purposes of analysis, we have combined the small number of respondents from the charity with primary care.

It is important to acknowledge that restrictions due to the pandemic meant that data collection was primarily digitally based. For this reason, respondents taking part in the survey will reflect a more digitally literate population and may not accurately represent some groups (e.g. more deprived populations, older populations for whom evidence suggests may be less likely to use digital technologies; see Chapter 4).

Survey data analysis

Survey responses were uploaded immediately at the end of the survey. Online surveys were hosted at the University of Oxford and data were downloaded and stored on password-protected servers for analysis by Turnbull, Prichard, Pope, and MacLellan. The data from each site were combined into a single SPSS54 file for the analysis.

The analysis was designed to address the overarching question, ‘Is there evidence for differential access and use of NHS 111 online?’. To this end, we first explored the demographic characteristics and preferences of users of NHS 111 online compared with people who had not used NHS 111 online to answer the question ‘Who uses NHS 111 online and why’?. The survey analysis of this component focused on understanding the demographic characteristics and preferences of users of NHS 111 online compared with people who had not used NHS 111 online. To understand if there was differential use of NHS 111 online, we grouped respondents into previous ‘users’ compared with people who had not used NHS 111 online, who are henceforth referred to as ‘non-users’. Non-users are respondents who had not previously used NHS 111 online. Respondents were allocated to each group based on whether they were recruited via NHS 111 online or reported that they had used the service previously. This grouping forms the basis of the comparison in Chapter 5. In total, 1137 (41.3%) respondents had used NHS 111 online previously.