Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/117/03. The contractual start date was in June 2018. The final report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Hughes et al. This work was produced by Hughes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Hughes et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Sexual assault referral centres (SARCs) are a single point of access for the treatment of people who have experienced sexual assault. They bring together criminal justice and health services to address the multiple needs of someone reporting a sexual assault as a recent or non-recent event. SARCs are commissioned by NHS England and provision includes forensic medical examinations (to collect evidence for a prosecution), physical and mental health assessment, safeguarding and risk assessment, and psychosocial support. SARCs also refer to other agencies in the local area should a need be identified.

Mental health problems are common in people who attend SARCs. In the Netherlands,1 the United States2 and England,3 approximately 40% of SARC attendees have been estimated to have a mental health problem. In a recent audit of Thames Valley SARCs, Brooker and Tocque4 found that 69% of attendees could be defined as experiencing a mental health problem, 20% had a history of admission to a psychiatric unit, 32% were drinking at ‘hazardous’ levels and 45% had previously self-harmed. In a secondary analysis of data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, Brooker and Tocque4 found that there was a consistent relationship between risk of mental health and substance use problems and the level of sexual violence experienced. While the national service specification for SARCs5 acknowledges that mental health issues are common among people attending SARCs, it states only that SARCs should ensure the provision of appropriate psychosocial support according to need, and where this exceeds what NHS talking therapies can support, then people will be referred to secondary mental health services.

In the first national survey of SARCs, Brooker and Durmaz6 reported that only half of the SARCs routinely assessed mental health needs of attendees and, where it was assessed, it was completed by a forensic medical examiner (FME). Substance misuse issues were not always included. Almost two-thirds of SARC services reported problems in referring on to mental health services for a variety of reasons. The paper argued that more research was needed in this important area, and that NHS England should fully describe the skills required to undertake a mental health risk assessment when someone has been the victim of rape or sexual assault.

Rationale

Despite the elevated levels of mental health and substance use needs of those who attend SARCs, there is limited evidence regarding the specific needs of people who attend SARCs, what works for whom, in what context, and where resources could be allocated to obtain maximum benefit. To do this, there is a need to identify models of identifying and assessing mental health and/or substance use problems; what subsequent referral pathways are available for a range of people; the views and preferences of people who use SARCs; the workforce needs, not only for SARC staff but for the network of agencies that work with survivors (including mental health, third sector counselling and substance use services); and the costs and benefits of different models of service provision.

The aim of the Mixed Methods of SARCs study (MiMoS) study was to generate evidence related to how SARCs identify and address mental health and substance use issues, through the following questions:

-

What programmes are identified in published and grey literature to inform how mental health and substance use can be best addressed in SARCs?

-

What models can be identified across the SARC services in terms of addressing mental health and substance use?

-

What is the prevalence and nature of mental health and substance use among people who attend SARCs?

-

What types of services are accessed by people with a range of needs following attendance at a SARC, and how satisfied are they with those services?

-

What are the barriers and facilitators to accessing the right support at the right time for people who have attended a SARC?

-

How do outcomes differ between a bespoke psychological therapies service at a SARC and mainstream mental health?

Research objectives

-

To undertake an evidence review of global SARC provision for health outcomes (including mental health and substance use) – work package (WP) 1.

-

To identify what models of SARCs currently exist in England (WP2).

-

To identify the mental health and substance use needs of attendees of SARCs in England (WP3).

-

To identify what services are available in SARCs in England and to explore satisfaction with care, barriers to access and gaps in provision (WPs 2, 3 and 4).

-

To understand, from the perspective of the SARC workforce, their current practice, skills and training needs in terms of recognition of, and referral for, mental health and substance use issues (WP4).

-

To obtain the survivors’ views on how they felt their emotional well-being was addressed by the SARC, as well as by external services (WP4).

-

To compare health outcomes for people who experience sexual assault and access bespoke SARC psychological therapies provision compared with those who experience sexual assault and are in mainstream mental health services (WP5).

-

To produce a range of lay and academic outputs that will aim to identify and share good practice in SARC services related to substance use and mental health to have an impact on care delivery.

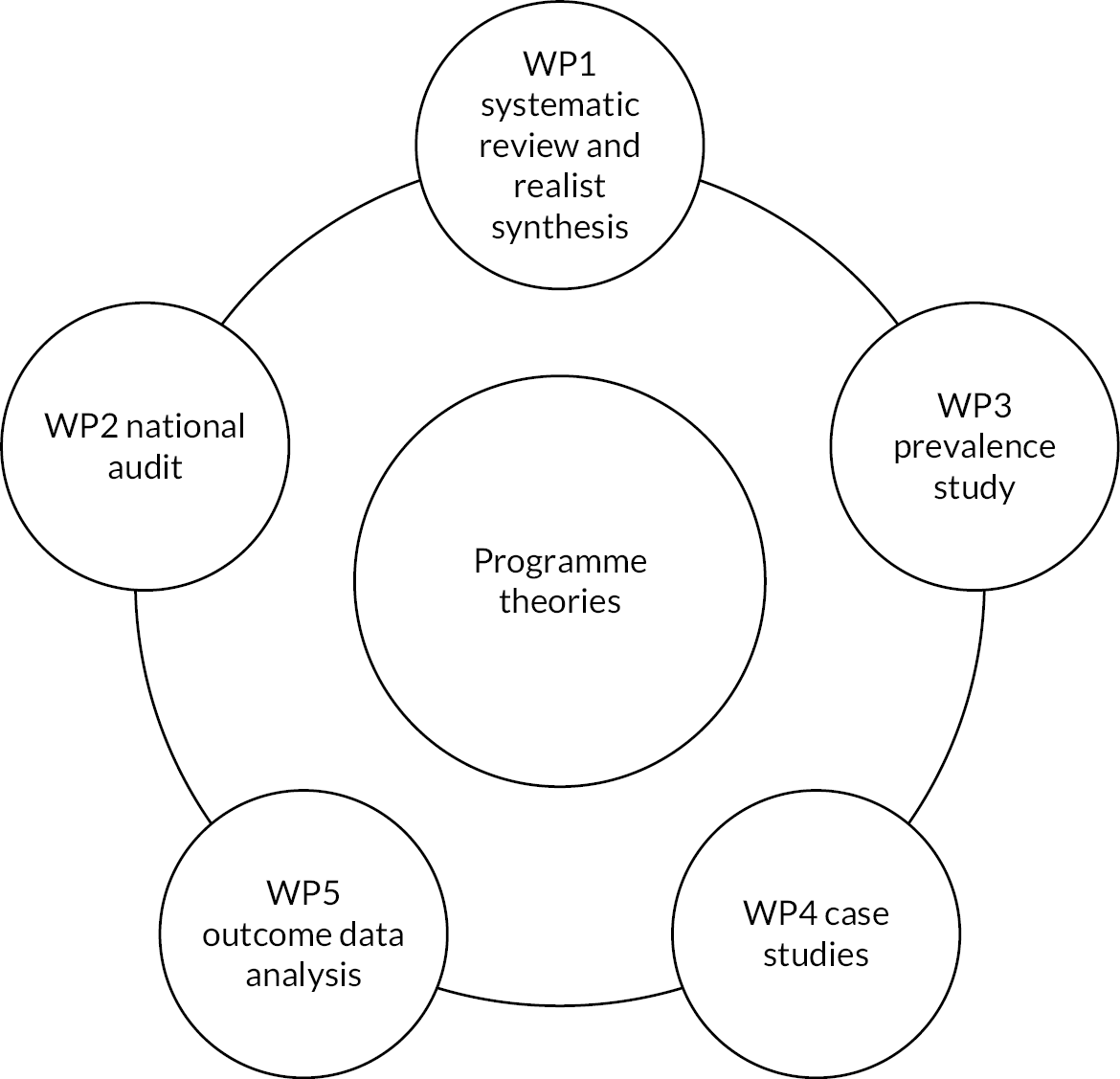

To address these questions and objectives, a three-year multimethod study was undertaken, comprising five WPs of research and an additional WP (WP6) for co-production of outputs with key stakeholders and dissemination (Figure 1). The first WP was a systematic review of the literature7 to identify models of good practice in working with mental health and substance use (WP1). An additional realist synthesis was conducted to identify initial programme theories, which would be refined in subsequent WPs.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

WP2 was a national survey of SARCs to identify the ways in which they are recognising and addressing mental health and substance use. This was completed as an audit and the findings were used to undertake a cluster analysis to identify a typology of SARCs (three typology clusters were identified). This typology was then used as a sampling framework for six case studies using the SARC as the case ensuring we had examples of all three clusters.

WP3 was intended to be a prospective study of mental health and substance use needs of people attending SARCs across the range of typologies, where informed consent was obtained then participants completed a set of screening tools in the immediate period after attending a SARC (more than one week up to six weeks post SARC attendance). WP3 was modified because of the pause to research in 2020 resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing impact of social restrictions.

In WP4, two activities were undertaken: a realist analysis of local documentation,8 which provided contextual information to inform theory development and refinement through group and individual interviews. Three main groups of informants were interviewed: staff who worked in the SARC; people who attended the SARC to report a sexual assault (survivors) and respondents from ‘partner agencies’ consisting of key informants from local primary and secondary mental health providers; rape counselling agencies and drug and alcohol treatment services.

In WP5, analysis of anonymised datasets: (1) South London and Maudsley Foundation NHS Trust Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) dataset comparing outcomes of people with and without a reported sexual assault who accessed mainstream mental health services for specific psychological treatments; (2) a SARC clinical dataset comparing outcomes of SARC clients who received different forms of therapeutic support via in-house SARC therapeutic pathways.

Through a process of iteration, synthesis and consultation with key stakeholders, data from the WPs were used to develop and refine programme theories and provide evidence about; how services work for certain groups of people, what are the contexts that influence outcomes and the mechanisms by which outcomes are realised. Findings include recommendations for policy, practice and further research in relation to mental health and substance use needs. The findings were presented in online consultation events with survivors and practitioner advisors and the recommendations further refined as a result.

Patient and public involvement

The survivor voice and perspective is especially important to the MiMoS study. From WP1, it was noted how little survivor-focused research existed. We worked in partnership with survivors for all aspects of the study and we had a person who led this aspect as the lead coordinator (Dr Sarah Kendal). Fay Maxted (FM) is one of the MiMoS study co-investigators and she is chief executive of the Survivors Trust. She is a high-profile activist for the rights of survivors of abuse. Fay has been an active member of the project group and offers the survivor perspective to all aspects of the study including the interpretation of data and developing recommendations for the report and other outputs. In addition to FM, a lived-experience advisory group (LEAG) was convened. Advertisements for group members were placed in SARC services and on the project website, and some individuals were introduced to the group via contacts of the project team. Four group members were young people (age range 18–25 years).

The LEAG worked closely with the researcher(s) on all aspects of the study – planning and data collection, and were part of the analysis phases. A flexible and individualised approach was undertaken to meet the needs and comfort of the individuals. This involved having options to contribute including face-to-face meetings (prior to COVID-19 restrictions), telephone calls, Skype/Microsoft Teams® video calls and email. The involvement of survivors was influenced by the Survivors Voices Charter ‘Turning Pain into Power: A Charter for Organizations Engaging Abuse Survivors in Projects, Research and Service Development’. 9 Concetta Perot from Survivor’s Voices was a key contributor and advisor to the research study and provided training on working with survivors of abuse to the research team prior to recruitment and data collection. Concetta Perot facilitated a training session on working with survivors as part of our researcher training in July 2019 as well as attending some of the study steering groups.

Limited personal information was collected from the members around their demographics, and it is summarised in Table 1.

| Route into group | Adult men | Adult women | Young people |

|---|---|---|---|

| Via project team contact | 1 | 1 | |

| Via project team contact | 1 | ||

| Via project team contact | 1 | ||

| Via project team contact | 1 | 1 | |

| Via project team contact | 1 | ||

| Responded to advert | 1 | ||

| Responded to advert | 1 | 1 | |

| Responded to advert | 1 | 1 | |

| Responded to advert | 1 | ||

| Introduced by LEAG member | 1 | ||

| Total | 2 | 8 | 4 |

In May 2019, a LEAG meeting took place in Huddersfield to scrutinise draft study protocol documents prior to NHS ethics application. Three LEAG members were able to attend in person and provided comprehensive input into the plans to recruit and collect data including safety issues. Two more members were able to provide detailed written feedback by email.

In June 2020, a virtual LEAG meeting to respond to documents produced by WP3. Comments were also received via email from three further LEAG members. Owing to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the LEAG members have been less responsive; however, a small core group remains in contact with us. A survivor-focused meeting was planned for September 2021 to present the initial findings as part of the stakeholder involvement but it was cancelled as no one signed up. This was despite widely circulating the invitation to many survivor groups around the UK and promotion on social media.

Research ethics and governance

Ethical approval process

Recruiting people who have recently experienced violence and abuse to research studies needs to be conducted sensitively and in conjunction with those with lived experience. While there is a risk of adding an additional burden during a difficult time, there is also evidence to suggest that survivors of abuse find participating in research helpful. Survivors Voices produced a charter ‘Pain into Power’, which aims to promote the engagement of survivors in research and this survivor-led document provides a useful framework to inform the design and implementation of research. 9

There were three main risks to the MiMoS study. The LEAG was mostly concerned with protecting anonymity of participants and the risks that could be posed to participants if they lived with their perpetrator. The LEAG stressed the importance of using a range of methods of communication according to the preference of each potential participant. We also implemented a code-word scheme so that if during a phone or online conversation a participant gave us the code word we would know that they were no longer able to have a private conversation. The LEAG felt that it would be helpful to have information that signposted all participants and potential participants to a range of relevant helplines and resources. This information was on a page of our study website as well as on participant information sheets. We additionally identified that participation may exacerbate emotional distress and there may be disclosures of self-harm or suicidality. To mitigate these risks, we were very clear in our written and verbal communication exactly what the study was about and the nature of the participation. We excluded anyone who was already in acute distress (as evidenced by admission to a mental health unit and/or having been in contact with mental health crisis team). All researchers underwent training prior to data collection and this was facilitated by Concetta Perot from Survivors Voices regarding how to work with people who experience trauma and we had a robust standard operating procedure (SOP), which included detailed protocol for handling any issues that arose during recruitment and data collection (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

WP3, 4 and 5 required NHS ethical and Health Research Authority (HRA) approval. We co-produced the recruitment strategy and data collection methods with the LEAG. NHS Ethics Committee Favourable opinion was obtained on 6 December 2019 (IRAS 238440 REC reference 19/NW/0663).

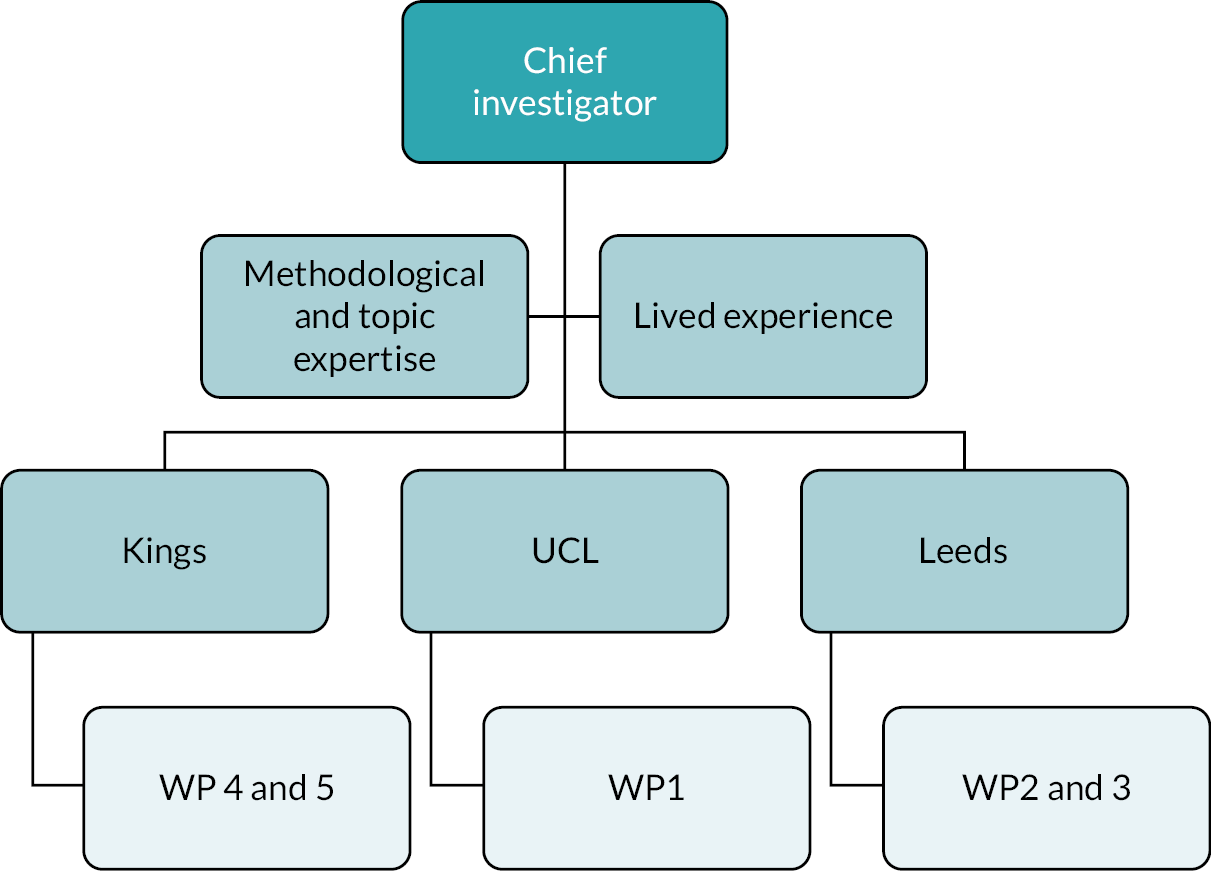

Project governance

The chief investigator, Professor Elizabeth Hughes, had overall responsibility for the delivery of the study. Each WP had a named academic lead. There were three main centres with an associated lead academic and researchers . In addition, we had additional senior academics and a lay co-investigator who brought topic and methodological expertise to the project team.

The core project team met weekly throughout the project, which was operationally focused and discussed progress of WPs against milestones. In addition to these meetings, we had steering group meetings; these groups had a wider membership, including members of the LEAG and external stakeholders, including SARC managers, forensic medical experts and psychologists (Figure 2). The purpose of the steering group was more strategic and included stakeholder input into the development of the study phases and reflecting on the implications of emerging findings. We also had an independent oversight group, which met once per year to review progress and provide independent advice about any issues that emerged including the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

FIGURE 2.

Project management structure.

Impact of COVID-19

The study was greatly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in a number of ways:

-

The prevalence study had to be halted in March 2020 just as we were starting to recruit actively. There was a national pause to NHS research that was not COVID-19 related. The research was restarted in stages in the summer of 2020 using remote methods to collect data. We moved to WP4 staff focus groups ahead of WP3 (survivors) first then recommenced WP3 in autumn 2020, but not all SARCs were able to support this particular WP, because of new ways of working, as indicated in point 2. By early 2021, it was clear that we would not be reaching our target of 360 people recruited for the baseline and we made the difficult decision to remove the six-month follow-up and concentrate on maximising the responses for the baseline screening questionnaires. This was done in agreement with National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the independent oversight group. The other issue this impacted was recruitment to survivor interviews in WP4, as WP3 was a route to recruit people for that aspect of the study. We also found that many survivors did not wish to participate in our study due to feeling the challenges of the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns.

-

SARCs changed their mode of delivery. The SARCs in our case study sites moved to remote working, apart from the forensic examinations. This impacted on the staff capacity to support research when it restarted, as they were working in difficult circumstances themselves, such as working from home, home schooling and staff sickness. The SARCs also reported that there was a drop in footfall at the SARCs and this was possibly due to under-reporting due to lockdown and the ban on social mixing. This reduced the population from which to recruit.

-

The MiMoS team moved to working remotely. The whole team worked from home during the pandemic and all meetings, recruitment and data collection occurred using telephone and video meetings (Microsoft Teams). Some of the researchers lived alone and we recognised that the team missed the peer support from being in an office with colleagues, as well as support from their line managers. Undertaking research into interpersonal violence can have an impact on a person’s well-being. To address this issue as much as possible, there was a senior member of the team ‘on call’ during data collection and researchers could call the person after an interview for advice and support even if there was no safeguarding issue to be addressed. We had weekly meetings for all the researchers and welfare was always on the agenda. In order to support the team, the chief investigator sought permission from the NIHR to use some of the underspend in the budget (unused travel and subsistence) to have a weekly group yoga session online. At the end of the six sessions, the researchers gave feedback and here is a summary:

-

‘The sessions offered me a much-needed diversion/break from the lockdown routine of sitting on my desk working. As it was my first time, I must say I was surprised how the sessions were a good form of exercise’.

-

‘The sessions helped me to relax and not think of anything else during that moment, so much that afterwards I could switch back to my usual routine feeling refreshed’.

-

‘I have recently taken up running, but needed something else to go with it, and as the swimming pools are currently closed (still so in my area!) yoga is a good alternative. It’s something I need to build into my “self-care” routine and continue as a good habit for the rest of my life’.

-

‘Thanks so much for offering these yoga sessions. It was great to be able to have these regularly as it really helps to acknowledge the impact of this work on us’.

-

‘I particularly liked the sessions where we moved more (as opposed to the more yin-style ones). I think this is because I spend so much time sitting at my desk! Therefore, it felt really good to move around and get my body in different positions’.

-

‘For me, there was something important about having a shared experience with the team all together where we were not “talking shop” and getting out of our heads and into our bodies and being in the moment. Scheduling in a session in the middle of the day was a reminder how important it is to be able to take breaks from sitting, thinking and feeling usual level of stress that comes as part of the job’.

-

‘These yoga sessions were a good opportunity to move and have a break from sitting at my desk and staring at a screen. I very much enjoyed the more dynamic sessions and thought it was a fun way for the team to bond over a non-work related activity’.

-

Chapter 2 Systematic literature review (work package 1)

Systematic review aims

A systematic review7 was conducted to identify the evidence informing the identification and treatment of mental health and substance misuse in UK SARCs and equivalent services internationally. For the purposes of the review, SARCs and (equivalent services internationally) were defined as specialist services providing both health care and the collection of forensic evidence within a single service. The review addressed the following three questions:

-

What are the approaches to identification and treatment of mental health and substance misuse problems in different SARC service models?

-

What models of care in SARCs are effective regarding service users’ mental health and substance misuse outcomes?

-

What are stakeholders’ views and policy recommendations about how SARCs should address the mental health and substance misuse needs of service users?

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review examining mental health and substance misuse provision in SARCs.

Methodology

The systematic review protocol was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42018119706) and the review followed guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination on undertaking reviews in health care and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 10

Eligibility criteria

There were three subsearches within the review and each one related to the main questions and as such had specific inclusion criteria. Some papers had information that addressed more than one review question.

Inclusion criteria

-

Question 1: Any service description with information about mental health and drug and/or alcohol conditions (journal articles, doctoral theses, conference proceedings and book chapters were eligible for inclusion).

-

Question 2: Comparison studies; SARC service users; mental health and drug and/or alcohol conditions outcomes (compared SARCs with standard care; different SARC service models; or two different interventions/packages of care within a SARC).

-

Question 3: Qualitative interviews, focus groups or surveys of sexual assault service stakeholders.

Search strategy

The review team searched for relevant studies through four electronic databases (PsycINFO, MEDLINE, the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), conference proceedings, government websites and Google Scholar. The search was restricted to humans and to records published from 1975 onwards. This is because the first one-stop service for sexual assault (SANE: sexual assault nurse examiner) model was introduced in the mid-1970s. The last search was conducted in August 2018, and was refreshed for the realist review in 2020. The paper relating to the initial systematic review has been published. 7

Data were extracted from studies relevant to each research question. A narrative synthesis was conducted according to economic and social care research guidelines. 11 Members of the review team extracted the data using a data extraction schedule designed and piloted for the purposed of this review. Ten per cent of the data extraction was checked by another team member to control for selection bias.

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool12 was applied to assess the quality of the included studies for review questions 2 and 3. The quality assessment was undertaken by members of the review team. Papers were not excluded because of low-quality scores but quality scores were reported and considered in the narrative synthesis.

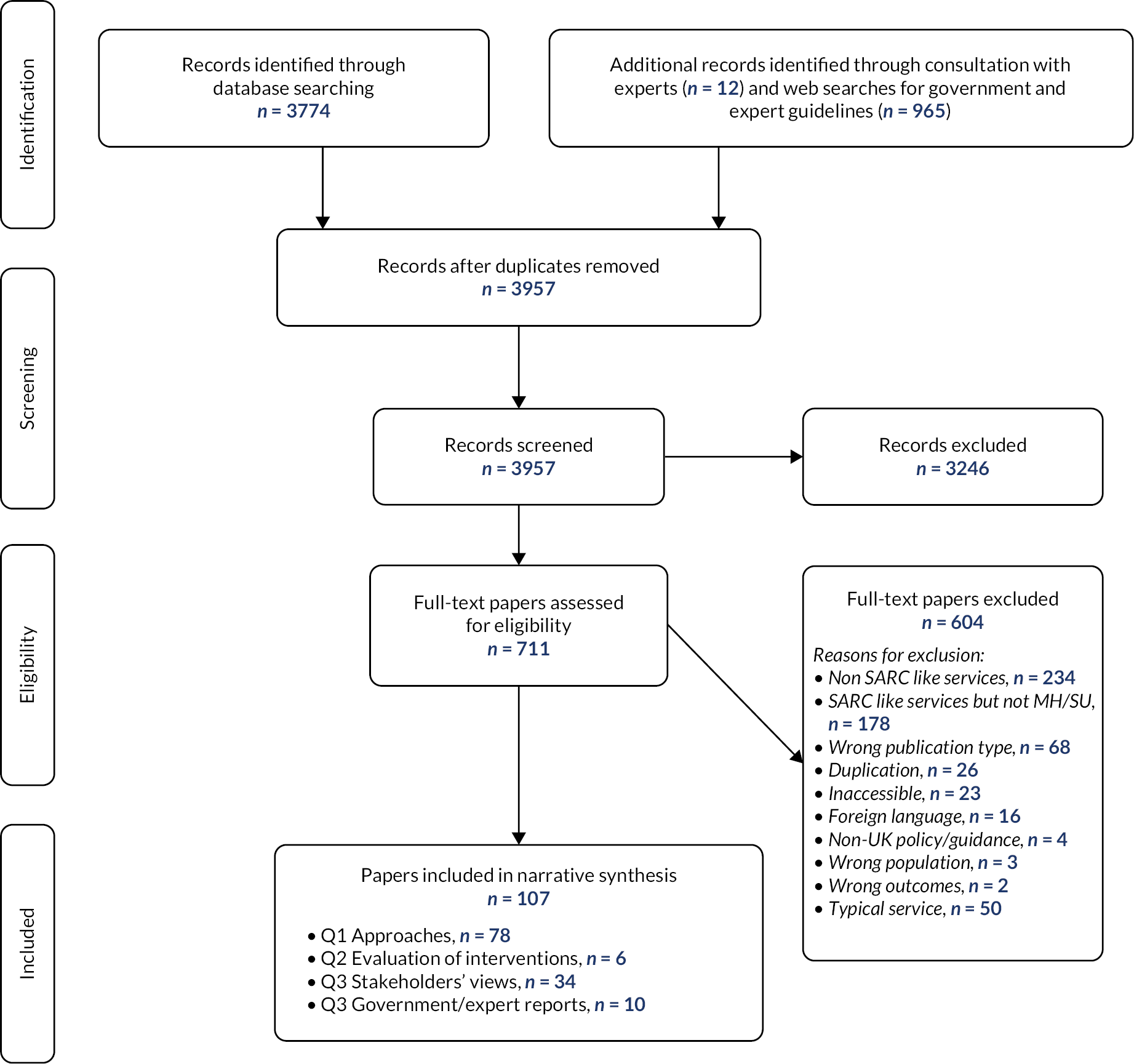

Findings

A total of 107 papers were included in the review. The PRISMA diagram (Figure 3) illustrates study screening and selection.

FIGURE 3.

PRISMA diagram.

The included papers were published between 1979 and 2019 and covered services around the world. Some of the papers were relevant to more than one research question.

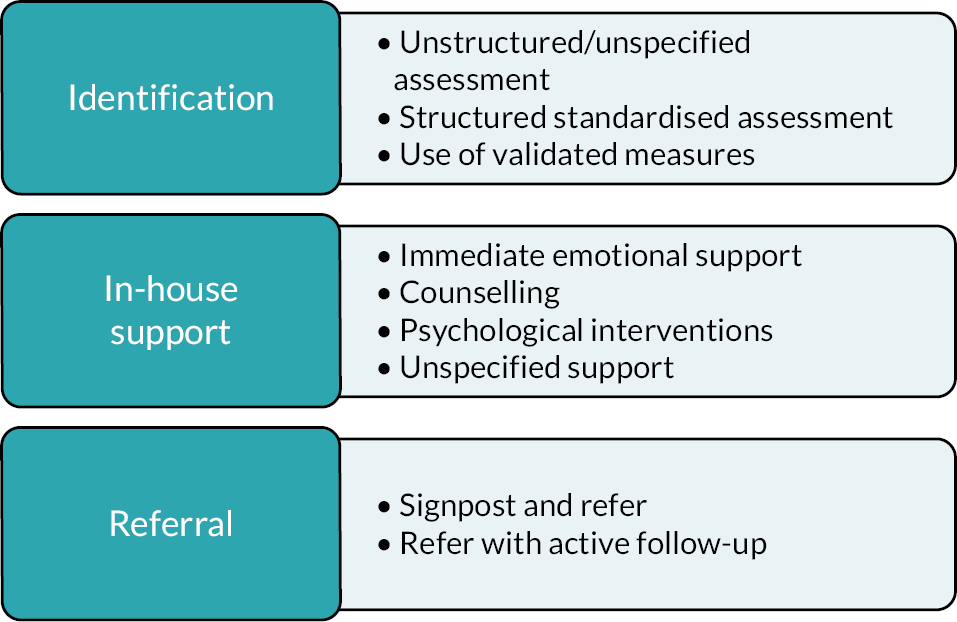

Question 1: approaches to mental health and substance misuse

We found 78 papers that provided information on how SARCs identify and treat mental health/substance misuse problems. These were published between 1979 and 2019, with 64 being journal articles and 14 retrieved through searches of grey literature. Based on extracted data from these 78 papers, we developed a provisional service typology for three domains of service provision as shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Approaches to mental health and substance use.

The most common approach to identification was unstructured assessment, which included professional judgement, casual observation, medical history-taking, self-reported disclosure and one-off questions about mental health. Unstructured approaches to identification were the most reported across all service models, and especially in UK SARCs, and the equivalent model in the United States. The most common approach to in-house support was the provision of supportive or unspecified counselling. That included any type of counselling provided from the sexual assault team that was not specified as a structured psychological therapy; for example, crisis counselling, supportive counselling and unspecified counselling. Finally, referral to other services was most reported to involve signposting and/or referral without active follow-up. Overall, there was a wide variation in mental health and substance misuse service provision in SARCs. The included papers had minimal information on how drug and/or alcohol was identified or addressed.

Question 2: evaluation of interventions

The review identified five studies evaluating psychological interventions for people attending SARCs. The studies were all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published between 2003 and 2017, and set in the United States and the UK. Four of these studies evaluated brief psychoeducational video interventions compared with standard care and one study evaluated a brief six-session ‘cognitive processing therapy’ compared with standard care. The assessed outcomes were substance use and abuse, anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Video interventions were shown before or after the forensic medical examination. They included information on what would happen during the examination, as well as psycho-educational material about self-management to prevent post-assault distress and substance misuse. These RCTs provided mixed evidence of moderate quality. They had significant methodological shortcomings, including small sample sizes and high attrition rates. In summary, there is a lack of robust empirical evidence to guide interventions for mental health and drug and/or alcohol conditions provision in SARCs.

Question 3: stakeholder views and policy recommendations

The review identified 34 papers (relating to 32 studies) that reported stakeholder views on how SARCs should identify and respond to mental health/substance use for people following sexual assault. Of these, 25 were peer-reviewed publications and 9 were identified from grey literature searches. They were published between 1980 and 2018; 11 studies included staff from sexual assault services as participants, 5 included service users, 2 included carers, 1 included staff from partner agencies working closely with sexual assault services, and 13 included a mix of stakeholders. The included studies consisted of surveys, interviews and quantitative questionnaires. Of the total, 13 studies were set in the United States, 12 in the UK, 4 in Canada, 2 in South Africa and 1 in each of 7 European countries.

The main recommendations included (Table 2):

-

accessibility, flexibility and continuity of care

-

SARCs to systematically assess for mental health and drug/alcohol needs

-

provision of in-house counselling/psychological support for both adult and child service users

-

clear referral pathways and closer links with mental health/substance misuse services

-

SARC staff to facilitate and encourage the take-up of follow-up services

-

SARC staff to receive training in assessing and managing mental health and drug/alcohol needs; how to support people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ+) plus pansexual, asexual, non-binary, and intersex LGBTQ+ and people with learning difficulties.

| Included papers, N (dates) | Main recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders’ views | 34 (1980–2018) | Systematic assessment of mental health/SM In-house counselling/psychological support Clear referral pathways Refer with active follow-up SARC staff trained in mental health/substance misuse; LGBT and learning difficulties training |

| Policy documents | 10 (2004–18) | Some assessment of mental health/substance misuse Refer when needs are greater than IAPT level 3 support Absence of guidance about substance misuse Cognitive behavioural therapy for clients with PTSD Specialist support for LGBT people Counselling to friends and family |

A total of 10 policy documents from government and expert bodies published between 2004 and 2018 were retrieved, including 6 UK government documents, 3 European policy documents reporting on the European Union-funded Comparing Sexual Assault Interventions (COSAI) project, and 1 research project commissioned by the UK Home Office. 7 The main recommendation that consistently emerged from the synthesis of the policy documents was that there was a need to assess for mental health and substance use issues at the SARC. Older guidance suggested this should be in the form of a comprehensive assessment; however, more recent guidance recommended assessing risk of self-harm and vulnerability but did not specify how this should be done.

In the UK, there is a stepped approach to the provision of psychological treatment. NHS talking therapy services offer steps 2 and 3 of the stepped model of care, in which step 1 is delivered in primary care. Step 2 comprises low-intensity interventions for mild to moderate depression and anxiety delivered by psychological well-being practitioners, and step 3 comprises high-intensity interventions delivered by specialist therapists. Step 4 is treatment for severe and recurrent anxiety and depression, and is delivered by senior therapists. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance13 recommends that people with a diagnosis of PTSD should receive step 3 therapy within one month of the traumatic event and does not recommend low-intensity interventions due to the lack of evidence that they are effective. People with more complex and multiple mental health needs above NHS talking therapies level 3 should be referred to community mental health teams (CMHT) or acute mental health services. The role that SARCs play in providing support for survivors with mental health needs at or below this severity threshold is not specified. From the review of the policy documents, it was noted that there was a lack of guidance about how to address the drug and alcohol needs of people who attend SARCs.

European Union COSAI guidance recommendations were broadly similar to the UK SARC specifications but they included more specific guidance in directing SARCs to aim to actively engage people with mental health problems, ensuring provision of cognitive behaviour therapies (CBTs) to treat clients with symptoms of PTSD, advocating the provision of counselling support for families and close friends of the SARC client where needed, as well as access to specialist counselling support for people who identify as LGBTQ+.

Limitations of the review

Many of the included papers did not focus specifically on mental health and drug and/or alcohol conditions and so may lack detail in terms of these issues. Moreover, many of the studies had small sample sizes and high attrition rates and therefore risk being underpowered to detect differences, so their findings are not reliable. It was interesting to note that most of the qualitative studies reported staff views only, and there was a distinct lack of the survivor perspective regarding care and treatment related to mental health and alcohol/drug needs. Finally, while policy guidance was identified to inform SARC service provision, such guidance lacked specific detail on how this should be done, and this may reflect the lack of evidence.

Conclusions

The issues related to mental health and drug/alcohol use issues for those who attend a sexual assault centre have received little research or policy attention. There is a limited evidence base on interventions to address mental health needs within sexual assault services, and significant variation in how sexual assault services identify and assess mental health and substance misuse service needs. The review7 highlights the urgent need for high-quality evidence to inform service development.

The subsequent chapters report on the research conducted in UK SARC services from 2019 to 2021. Chapter 3 reports on a national survey conducted to establish the ways in which SARCs address mental health and substance use (WP2).

Chapter 3 National sexual assault referral centre survey (work package 2)

Design and setting

This was a service-level audit that aimed to describe how SARCs across England identified, assessed and responded to mental health and alcohol/drug use in people who attended their services.

Procedure

The MiMoS team joined with the other NIHR commissioned study (NIHR 16/117/04) to undertake a single survey that addressed both project aims. A set of questions were developed in Qualtrics (Qualtrics XM, London, UK) online survey platform and were piloted by a sample of SARC stakeholders prior to distribution. The survey met the HRA criteria for a ‘service evaluation/audit’ and therefore did not require NHS ethics approval but did receive an internal ethics review at Coventry University.

The survey was completed by a SARC manager and aimed to collect information in relation to SARCs themselves, their workforce and service delivery. For the purposes of meeting the aims of the MiMoS study, data were collected on mental health interventions [nature of mental health/substance misuse screening, provision of any mental health service on site (e.g. counselling, trauma focused), any special requirements for mental health/substance misuse]; mental health/substance misuse pathways (formally commissioned, locally negotiated, local data on numbers referred and outcome, nature of inequality data routinely obtained); and mechanisms for local victim–survivor engagement (satisfaction questionnaires, involvement in managing the service, recruiting/training staff; a copy of the survey is available as a project upload).

SARC managers across England were contacted via email distribution lists. The email explained the purpose of the survey and provided a link to the electronic survey. Responses were monitored and reminder emails were sent out to SARCs who had not responded. The data collection period remained open between March and April 2019.

Analysis

The data were exported to Microsoft Excel® and analysed using IMB SPSS Statistics v25 and summarised using descriptive statistics. For the cluster analysis, usable data for the five variables selected for the cluster analysis were used. The ‘best fit’ natural grouping revealed by a two-step cluster analysis was three clusters. As validation, this cluster solution was compared with all cluster solutions derived from hierarchical and K–means methods and reruns of the two-step method for forced solutions with two to five clusters and was accepted as the optimal solution by the research team. The three-cluster solution was then presented to a stakeholder group of SARC staff to check that these had face validity.

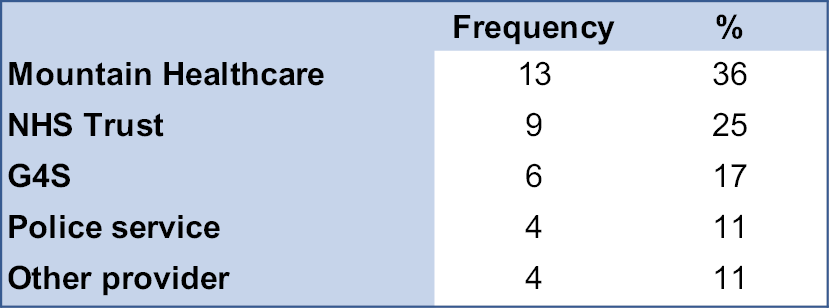

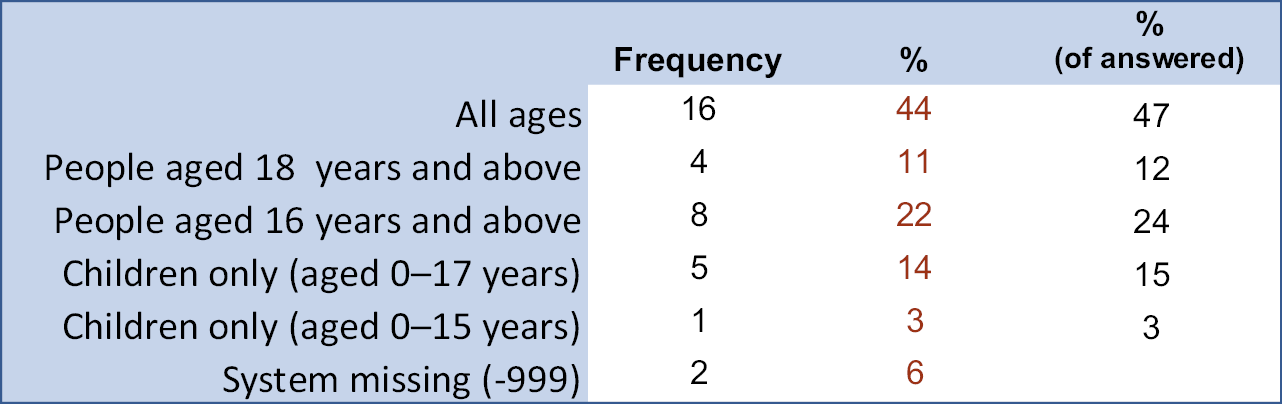

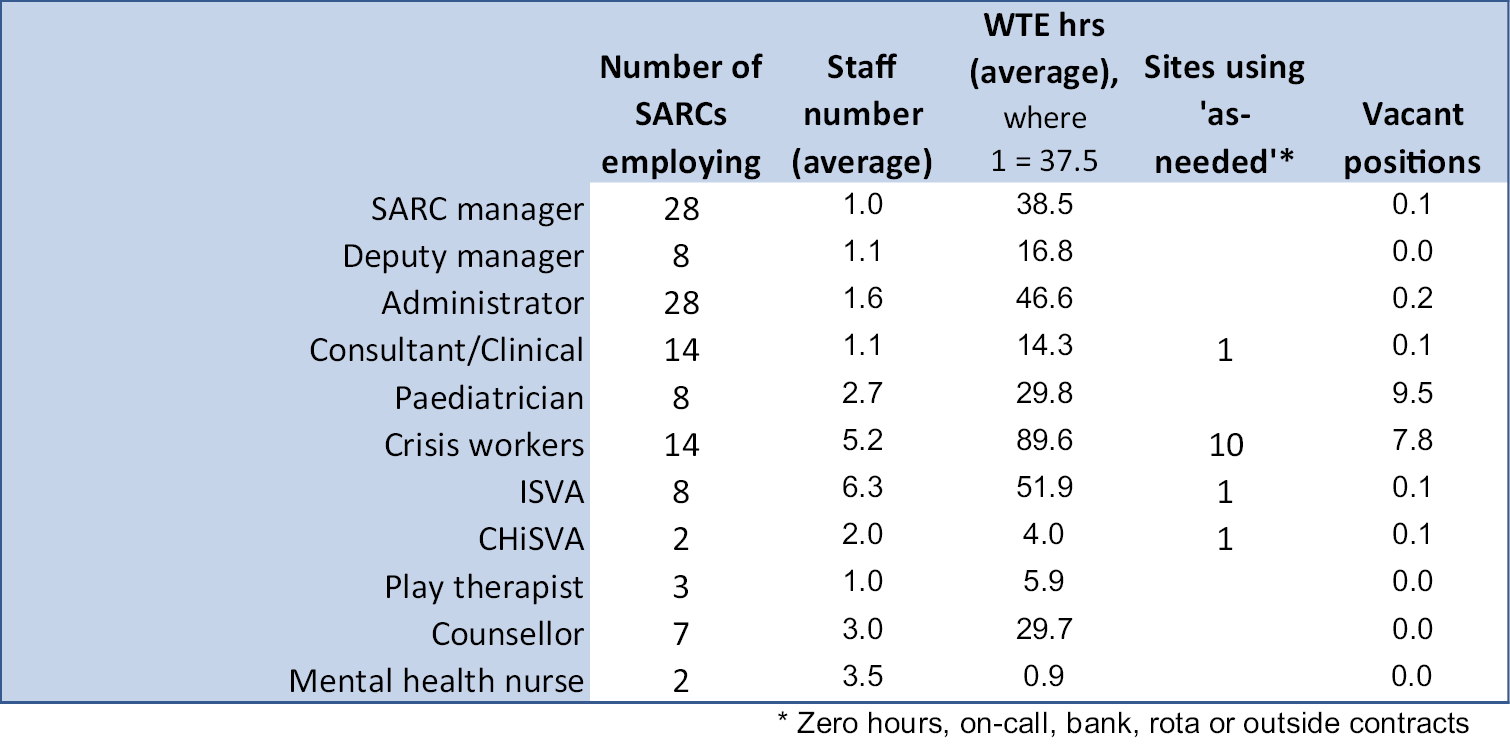

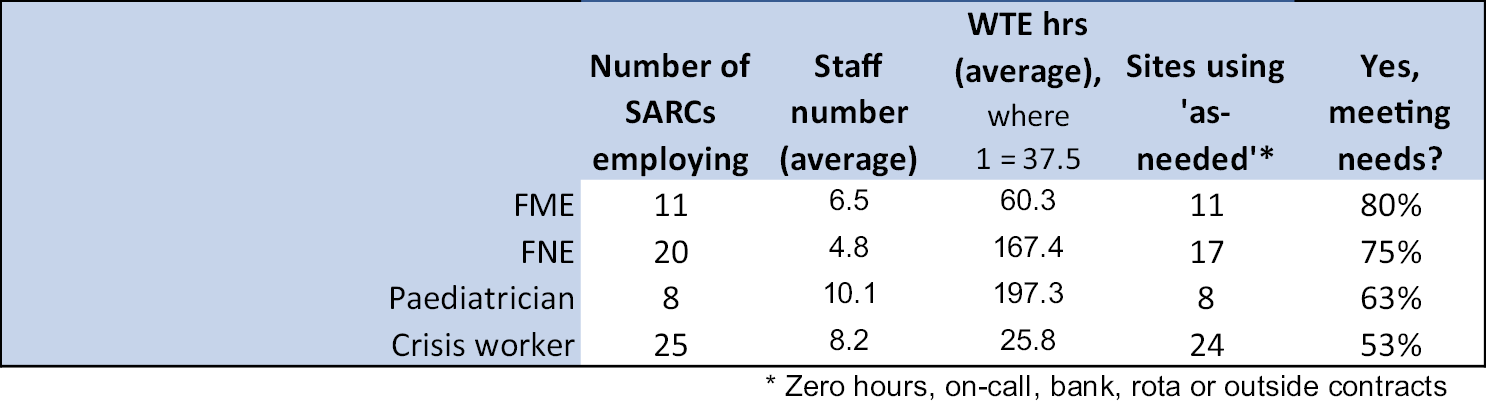

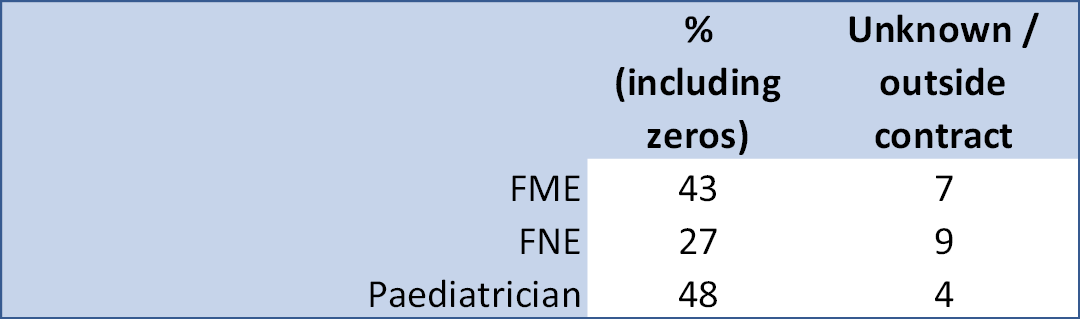

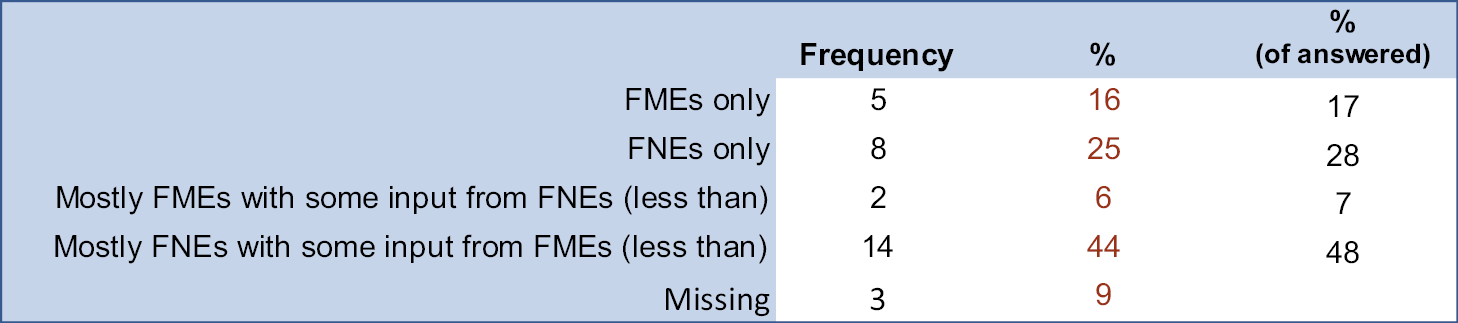

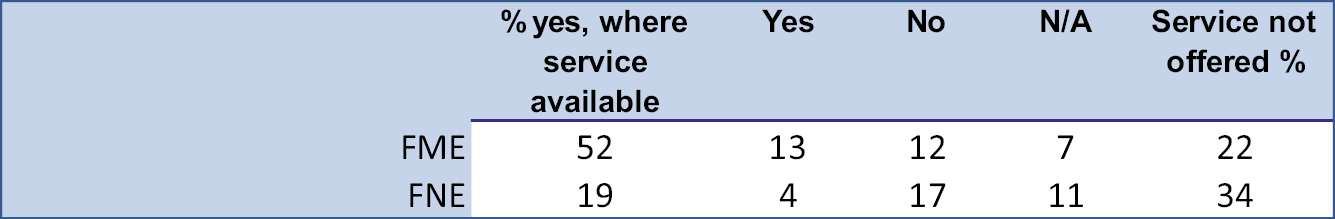

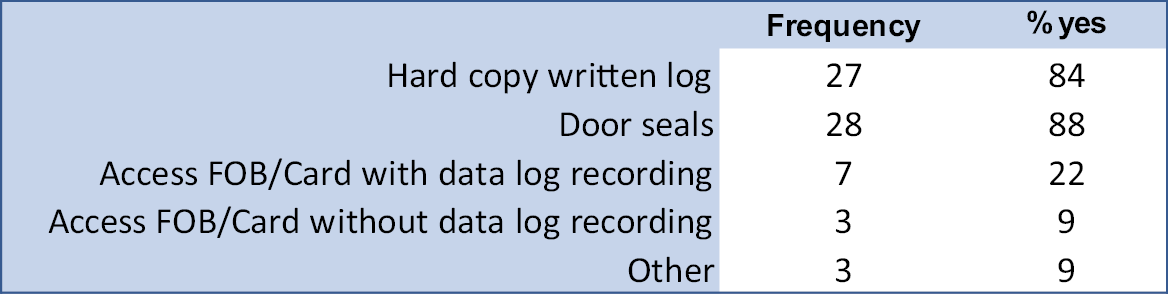

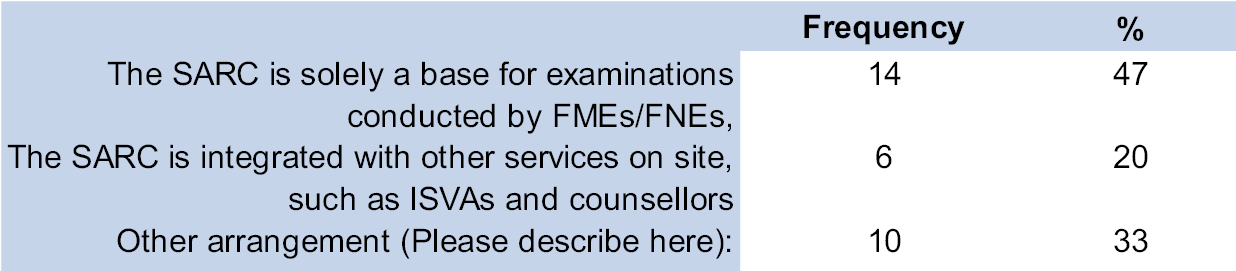

In summary, there was an overall response rate of 77% (36 of a possible 47 SARCs). The responses to each item within the survey was variable within the respondents so the denominator is the total number of responders to that item rather than the overall response of N = 36. As previously reported, this survey was done in conjunction with the other commissioned research study (NIHR 16/117/04 MESARCH) and for the purposes of addressing the MiMoS study aim, only the variables relating to mental health and substance use will be reported here.

Findings

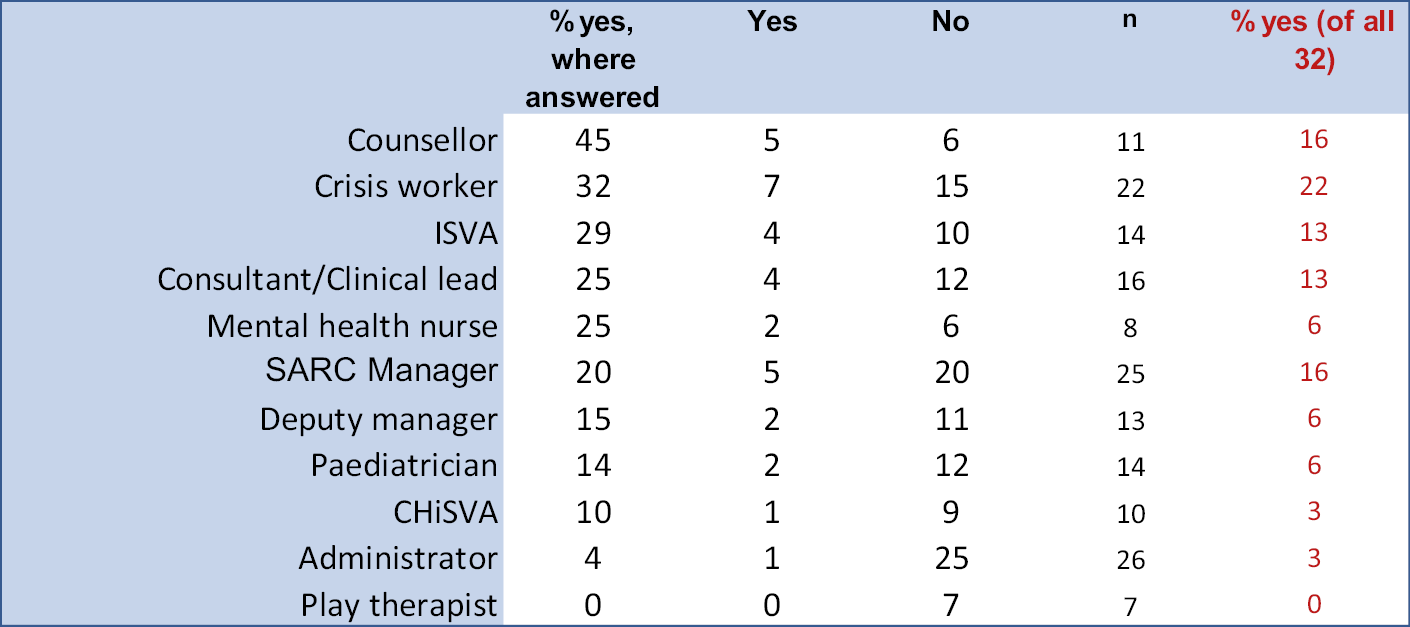

Mental health background of sexual assault referral centre staff

A full set of descriptive statistics can be found in Appendix 1. The responses indicated that there is overall limited mental health experience in the core SARC skill mix. It is interesting to note that just under half reported that the counsellor had a mental health background or qualification. As seen in Table 3, this question was left blank by some respondents. It is therefore difficult to know whether a non-response indicates no mental health staff in that SARC or that those roles are not present in that SARC. The table presents the percentage ‘yes’ of those who responded to the question but also the percentage ‘yes’ of the total respondents to the survey.

| Yes, where answered (%) | Yes (n) | No (n) | Staff (N) | Yes, of all 32 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counsellor | 45 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 16 |

| Crisis worker | 32 | 7 | 15 | 22 | 22 |

| ISVA | 29 | 4 | 10 | 14 | 13 |

| Consultant/clinical lead | 25 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 13 |

| SARC manager | 20 | 5 | 20 | 25 | 16 |

| Deputy manager | 15 | 2 | 11 | 13 | 6 |

| Paediatrician | 14 | 2 | 12 | 14 | 6 |

| Children’s ISVA | 10 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 3 |

| Administrator | 4 | 1 | 25 | 26 | 3 |

| Play therapist | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

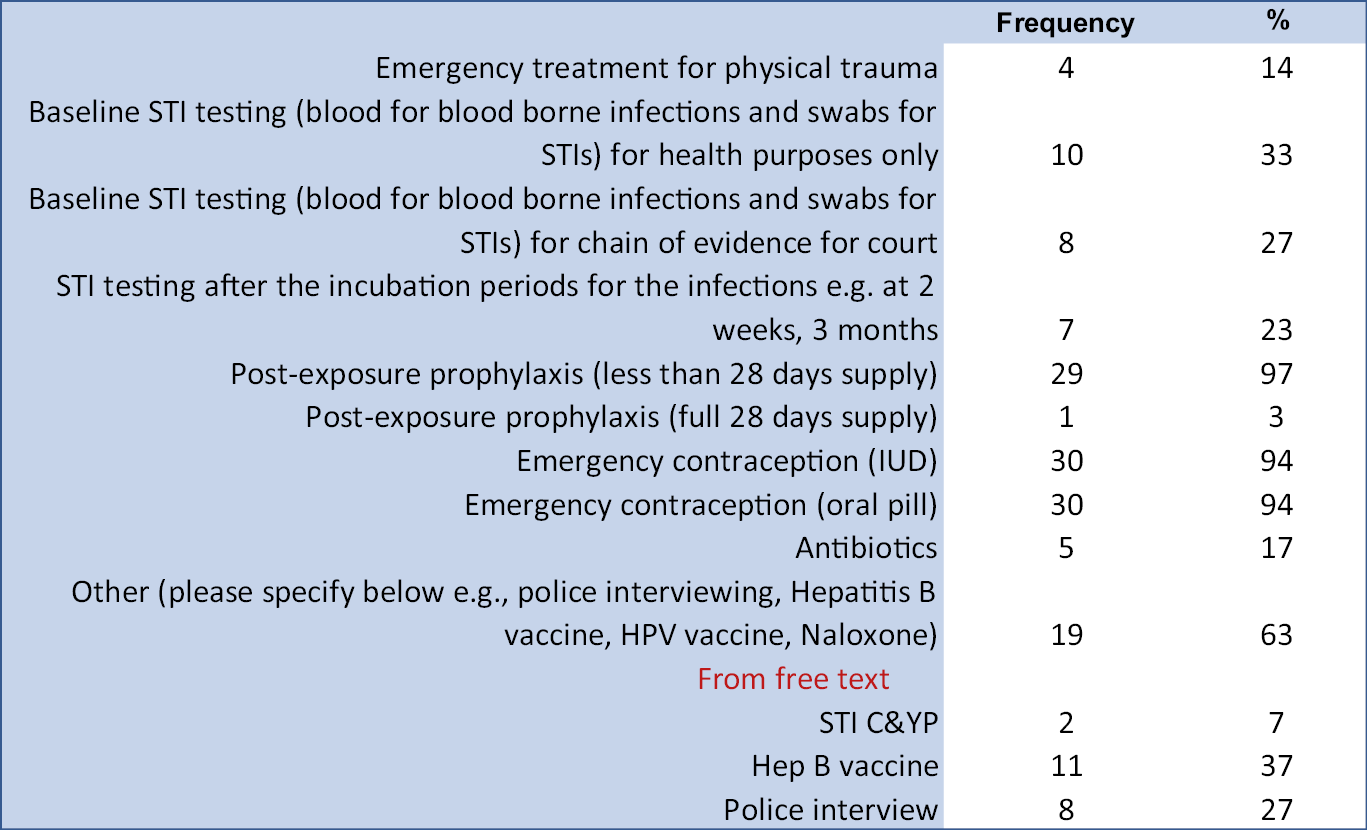

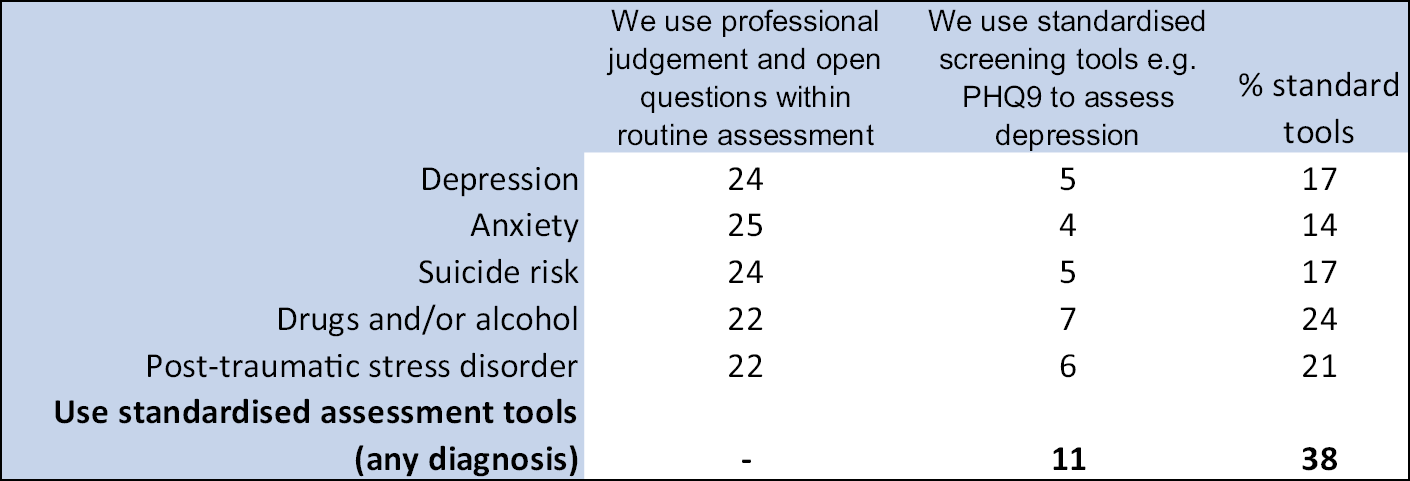

Assessment of mental health and substance use needs

The respondents were asked to indicate the method (e.g. professional judgement, standardised screening tools) used to assess a set of common additional needs that survivors may present with including depression, anxiety, suicide, drugs and/or alcohol and PTSD. From Table 4, it is noted that just over one-third of SARCs reported using standardised tools for any diagnosis (38%) and this seemed to be mainly for screening for drugs and or alcohol use (24%) and PTSD (21%).

| We use professional judgement and open questions within routine assessment (N) | We use standardised screening tools e.g. PHQ-9 to assess depression (N) | SARCs using screening tools (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 24 | 5 | 17 |

| Anxiety | 25 | 4 | 14 |

| Suicide risk | 24 | 5 | 17 |

| Drugs and/or alcohol | 22 | 7 | 24 |

| PTSD | 22 | 6 | 21 |

| Use standardised tools (any diagnosis) | – | 11 | 38 |

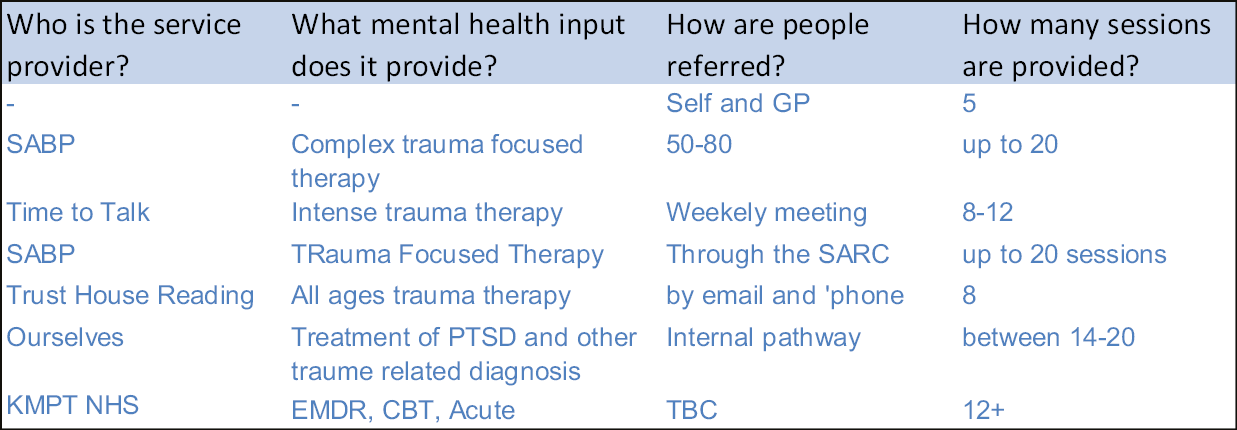

Mental healthcare provision

Only 7% (2/28) of SARCs stated that a talking therapy service was provided or co-located within the SARC (even if the provider was a different organisation). One-fifth of respondents (21%, N = 6 of 29) reported that they had access to a clinical psychologist, either in-house or co-located within the SARC (even if the provider was a different organisation) and half (46%, n = 13 of 28) reported that they had a counselling service provided within or co-located at the SARC (even if provided externally). Only 10% (n = 3) indicated that they had some form of in-house or co-located substance use service provided by an external organisation. Only one SARC stated that they had an ‘other mental health or substance misuse service’ provided or co-located within the SARC (even if the provider was a different organisation). This was indicated to be a ‘mental health nurse on an 18-hour per week contract’ and their role was to undertake assessments, manage and follow up referrals.

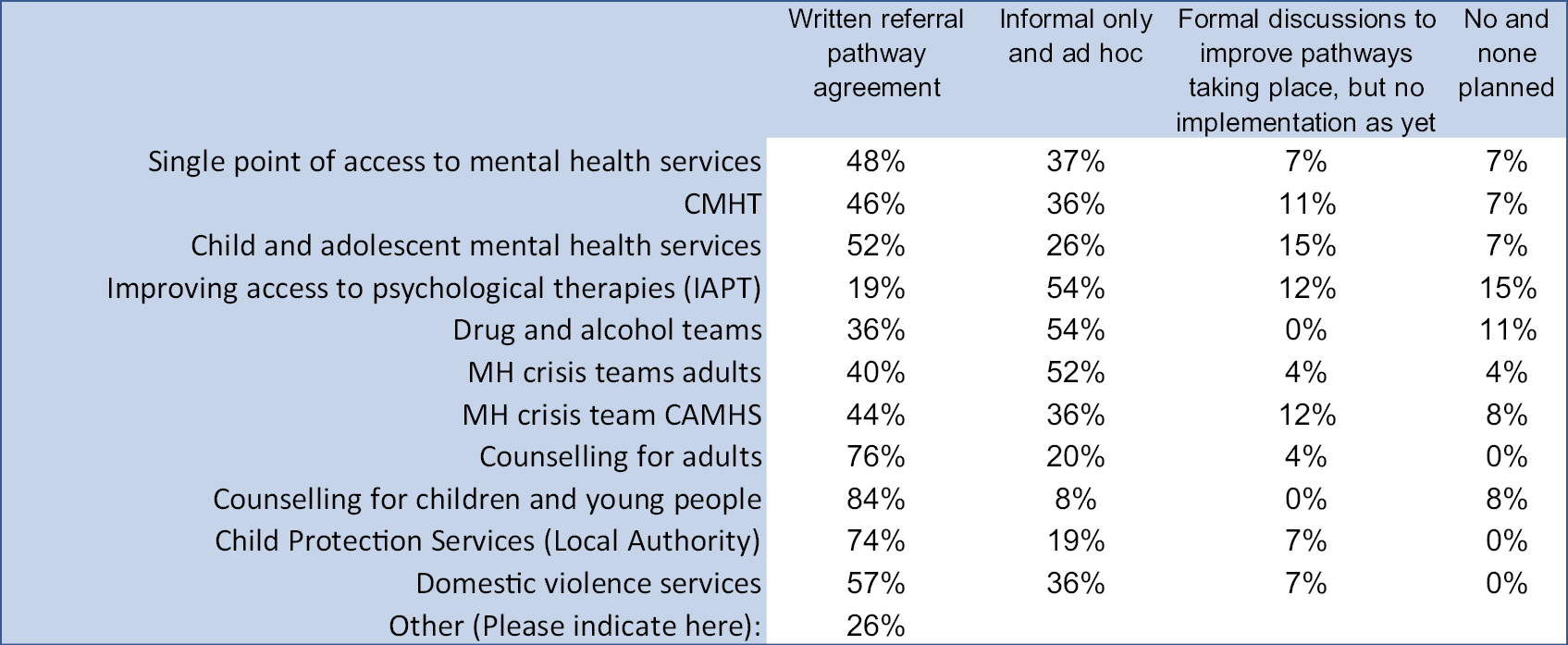

One question asked respondents to consider a range of follow-up services that would likely to be involved in mental health and substance use care and indicate whether there was a pathway agreement in place, whether it was informal and ad hoc, whether there were discussions in place but not yet implemented, and finally if none and no plans for formalised onward referral (Table 5). The majority of SARCs reported that they had formal pathways to child protection and counselling for children and young people, but for adults it appears to be less formalised and variable between SARCs. Just under half of the respondents indicated that they had a written referral pathway agreed to single point of access (48%) and community mental health services (48%), and only 40% to the local mental health crisis teams. Only 36% had a formal pathway to drug and/or alcohol teams and 19% had a formal pathway to talking therapy services.

| Written referral pathway agreement (%) | Informal and ad hoc only (%) | Formal discussions to improve pathways taking place, but no implementation as yet (%) | No, and none planned (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single point of access to mental health services | 48 | 37 | 7 | 7 |

| CMHTs | 46 | 36 | 11 | 7 |

| Child and adolescent mental health services | 52 | 26 | 15 | 7 |

| IAPT service | 19 | 54 | 12 | 15 |

| Drug and alcohol teams | 36 | 54 | 0 | 11 |

| Mental health crisis teams (adult) | 40 | 52 | 4 | 4 |

| Mental health crisis team (CAMHS) | 44 | 36 | 12 | 8 |

| Counselling for adults | 76 | 20 | 4 | 0 |

| Counselling for children | 84 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Child protection services | 74 | 19 | 7 | 0 |

| Domestic violence services | 57 | 36 | 7 | 0 |

| Other | 26 |

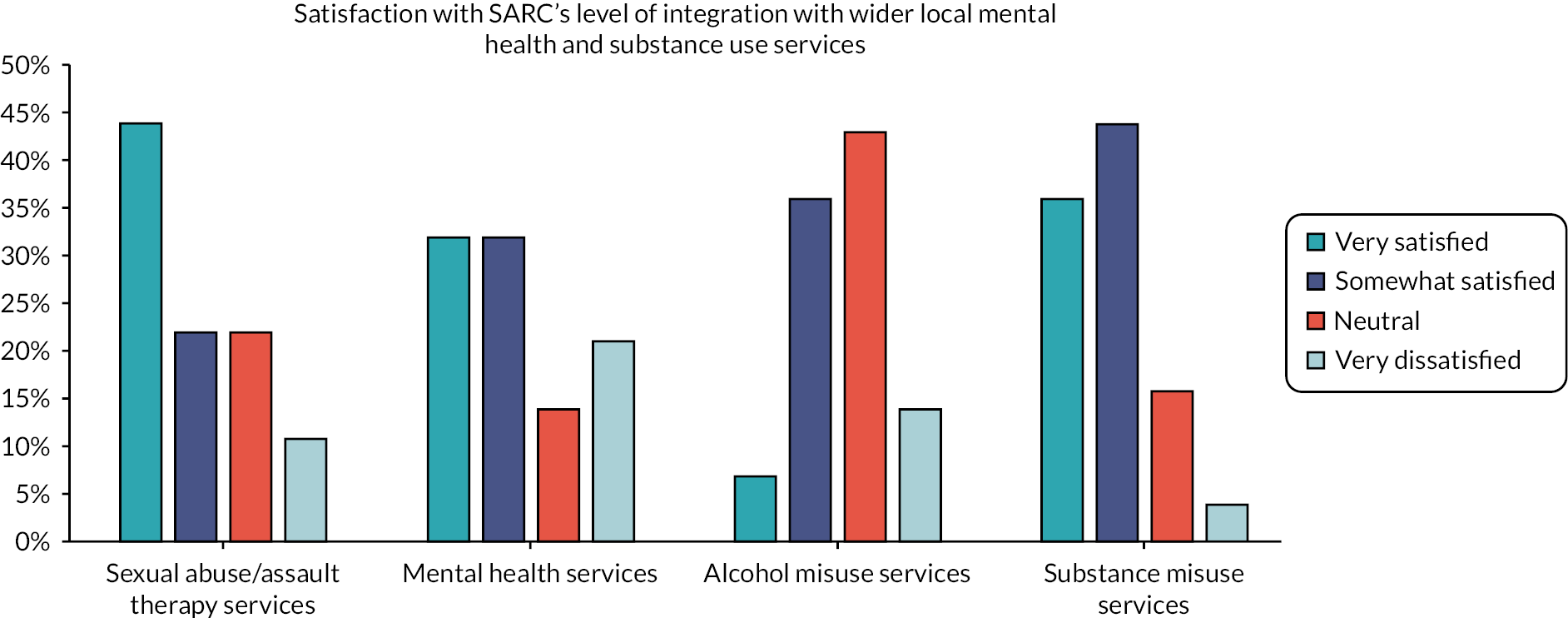

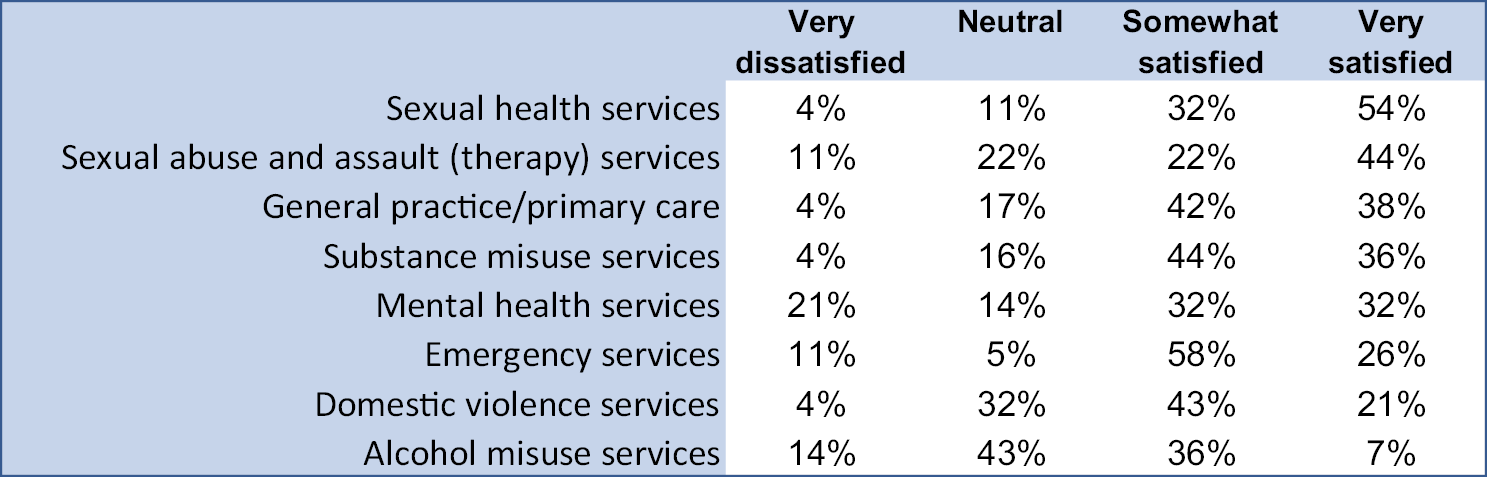

Sexual assault referral centre respondents were asked to rate how satisfied they were with the level of integration with external agencies. Figure 5 indicates that SARCs are most satisfied with integration with external sexual abuse/assault therapy services, and 64% were very satisfied/somewhat satisfied with mental health services. However, satisfaction was most positive in relation to substance use services with 80% of respondents indicating very satisfied/somewhat satisfied with integration.

FIGURE 5.

Satisfaction with level of integration.

At the end of the survey, a free-text question asked respondents to make suggestions about what could improve integrated mental health support. The free-text responses were grouped thematically as follows (with the number of related responses in brackets):

-

SARCs having more ‘resource’ (n = 5).

-

Additional training and development occurring in SARCs (n = 6).

-

Additional training and development occurring together with external mental health services (n = 7).

-

Improved pathways when making referrals to external agencies (n = 10).

-

Improved responses when making referrals to external agencies (n = 12).

-

Provision of specialist mental health services on SARC sites (n = 17).

Cluster analysis

There were usable data for the five variables selected for the cluster analysis from 28 SARCs (just under 60% of the total number of SARCs). The ‘best fit’ natural grouping revealed by a two-step cluster analysis was three clusters. As validation, this cluster solution was compared with all cluster solutions derived from hierarchical and K–means methods and reruns of the two-step method for forced solutions with two to five clusters and was accepted as the optimal solution by the research team (Table 6).

| Cluster | SARCs (N) | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | 8 | Some support, not integrated | No written pathways to mental health services No drug and alcohol support Variable staffing, use of structured assessment and provision of in-house counselling |

| Type 2 | 8 | Clinicians and pathways | All have mental health staff All have written referral pathways to mental health services Least likely to offer in-house counselling |

| Type 3 | 12 | Integrated and holistic | All have written referral pathways to mental health services Nearly all provide structured assessment and drug and alcohol support Most likely to provide in-house counselling |

We then presented the three-cluster solution to a stakeholder group to sense check that these clusters and their characteristics had face validity. The cluster analysis identified three broad types of service models and ways of working in relation to mental health. Cluster 1 ‘some support, not integrated’ were SARCs that had limited mental health staffing, no formal care pathways to mental health services and variable methods of assessment. Cluster 2 ‘clinicians and pathways’ tended to have staff with a mental health background in the team, written referral pathways to other relevant external agencies but did not provide in house counselling. Cluster 3 SARCs provided an integrated mental health and alcohol/drug offer among their other work. All three clusters had referral pathways, structured assessment and were most likely to offer in-house counselling.

Conclusion

The survey was useful in that it provided a national snapshot of how SARCs addressed mental health and alcohol/drug use. However, there are several limitations to the data. First, the surveys were completed by one person at each SARC (typically the SARC manager) who may not have all the information about what happens within various parts of the service. Second, not all SARCs participated in the study so there is a risk that this does not represent all the mental health and drug/alcohol approaches. However, the response rate was reasonable and there was a range of providers and geographical spread in the responding SARCs.

The findings broadly concur with the systematic review in that there was a lack of structured tools for assessing mental health and substance use; there was limited evidence that there were any psychological therapies provided in-house in SARCs and mostly informal or ad hoc referral pathways to external or partner agencies for mental health and alcohol/drug issues. Using the variables, a cluster analysis was performed, which identified three clusters into which the SARCs who responded fitted. However, the cluster analysis was limited by the quality of the responses to the survey and the fact that not all SARCs provided data. The analysis also demonstrated that while there was some clustering of variables into three types, there was considerable variability between SARCs. The clusters were presented to a group of SARC staff stakeholders, who verified that the clusters have some face validity. However, it was helpful as a rudimentary guide to inform the sampling of SARCs across the range of types of provision for the subsequent case studies.

Chapter 4 Prevalence study (work package 3)

The aim of this study was to collect data on mental health and substance use needs to the be able to estimate the prevalence of mental health and substance use difficulties of people attending SARCs. It was a cross-sectional design.

Setting and sample

The setting was participating SARCs at six sites across England, which were selected with examples from each of the three clusters identified in WP2. The target sample was adults over the age of 18 years who attend SARCs and who consent to participate. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

aged 18 years or older

-

able to read and understand English (or there are suitable confidential translation services available).

The exclusion criteria are as follows:

-

lack of capacity to provide informed consent

-

participation was deemed to significantly increase risk to self or others (e.g. being in an acute mental health crisis as evidenced by being admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit at the time of recruitment)

-

attendee of a SARC that was not participating in the study.

A priori sample size calculation

The sample size of n = 360 across the six sites were calculated based on the following: an estimated population of 4000 across six sites per year and 40–60 referrals per site, per month. Based on a previous audit of mental health needs at a single SARC in England, the SARC staff obtained consent and collected data on 42% of attendees and 38% declined to participate (with limited support to recruit). It should, therefore, have been feasible to obtain consent from 50% of attendees to participate, which meant 20–30 per site, per month. However, because of the impact of COVID-19, several factors impeded recruitment and the target sample was not achieved.

Measures

The measures were selected as they have good reliability and validity and are appropriate for the setting and sample:

-

demographics questionnaire designed for the study which covered gender, sexuality ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status (by post code) previous contact with mental health services and pre-existing self-reported mental health and drug/alcohol issues (see Report Supplementary Material 1)

-

Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation 10 (CORE-10) covering anxiety, depression, trauma, physical problems, functioning and risk to self14

-

alcohol screening tool: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)15

-

the PC-PTSC-516

-

Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL): a quality-of-life measure developed specifically for those with mental health conditions17

-

drug use screening tool: Drug Abuse Screen Tool (DAST)18

-

Structured Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): a brief screening tool for personality disorder. 19

Information on each outcome measure cut-off scores is provided in Appendix 2.

Data management

The information provided by participants was treated as confidential and, in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018 and General Data Protection Regulations, any personal data (identifiable details) were stored separately from the research data (i.e. answers given during on the questionnaire). Research data were anonymised using a study number. The only exception to this confidentiality was if the research team had concerns about current or future risk of serious harm to the participant or to anybody else. Similarly, confidentiality was broken if participants disclosed details of intention to commit a crime or if participants shared details of a crime for which they had not been convicted. If that happened, the research team followed SOPs, which covered things like informing the participant’s GP or other relevant services (on a need-to-know basis only). Researchers always tried to discuss this with participants first where possible.

A data management plan (MiMoS_23240_Data Management Plan_v1_16.08.2019) was developed for WP3, 4 and 5 to complement this protocol.

Recruitment and enrolment

The recruitment strategy was informed by a trauma-informed approach aiming to empower participants to have control over decisions to participate in research. 9 The research team worked with the LEAG group to develop a range of options for people to opt to engage with the study and they designed our recruitment materials and participant information sheet.

Sexual assault referral centre staff mentioned the study to people during their attendance at the SARC. Because of the pandemic, some of this contact was via telephone so the staff emailed PDF versions of the leaflet and obtained consent to be contacted by the research team. More details of this procedure can be found in the study protocol. Participants could also refer themselves to the study via the study website. Once consent to be contacted was received, the MiMoS researcher made contact via the potential participant’s preferred contact method. A total of five attempts at contact were made, after which the potential participant was not contacted again. If the researchers were able to make contact, they would then provide the information necessary for the participant to make a fully informed decision to participate or not. Participants were given at least 24 hours (or longer if needed or requested) to consider the information before deciding whether to take part. Once consent was obtained, the baseline study questionnaire was sent via a link emailed to the participant using the University of Leeds online survey (Online Survey). There was also an option to complete a paper version of the questionnaire. A further option for completing the questionnaires was over the phone with a researcher. In this instance, the researcher completed the online consent form and questionnaire over the phone with the participant, obtaining text or email confirmation of consent.

The participants received a £10 e-voucher for participation in the prevalence study.

Welfare checks and safeguarding

The MiMoS researcher was able to log into the Online Survey and review the responses. If any of the responses indicated risk to self/others, a welfare call would be undertaken as per the SOP. All MiMoS researchers had access to an on-call senior team member (EH, ML, BLE) if they required advice about risk and action to be taken. All action was documented using identity numbers to protect anonymity recorded in the secure shared Microsoft Teams folder.

The demographics of our prevalence study sample, both non-recent and recent cases, was initially compared with routine data collected from the six sites over the course of the national survey (WP2) to assess the representativeness of our sample. The final dataset was then weighted for demographics (e.g. age, sex, deprivation).

Analysis

A direct estimate of the prevalence of mental health within SARC attendees was determined from the sample and weighted estimates produced for the SARC sites. Additionally, a further weighted national estimate was produced (if demographic data could be obtained for all 47 SARC sites; see Appendix 3). Analysis of other health, well-being and behavioural measures followed the same principle to produce direct (and site-specific and national weighted) estimates. Prior to producing these estimates, the dataset was analysed to determine how or whether demographics, site or method of data collection influenced prevalence measures.

Findings

WP3 was an aspect of the MiMoS study that was most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The target sample of 360 was not achieved due to challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Recruitment started in the spring of 2020 and was almost immediately suspended due to the first lockdown in March 2020 (all NHS research was suspended at that time unless it was COVID-19-related) and restarted in September 2020). Once the study was able to restart data collection, it continued to be affected by the continuing pandemic during the autumn, winter and to the spring of 2021, with to the third wave and second national lockdown. For this reason, the study remained open to recruitment from September 2020 to the end of May 2021, extending the original six-month recruitment window. A decision was made to end recruitment rather than extend it further as there was no indication in the spring that it was going to be possible to recruit anywhere near our target in a reasonable period of time. Even with extending the recruitment window there was no sign that recruitment was picking up to the expected pre-COVID-19 estimated pace. It is also important to note that of the original six SARCs, recruitment only occurred from four of the services due to changes to services during the COVID-19 pandemic at some of the SARCs, which made additional recruitment difficult. In addition, some SARCs saw a dramatic drop in attendees during the lockdown periods. The decision to end recruitment was agreed by an independent study oversight group and with the funder. The decision to remove the planned six-month follow-up was also approved and the amendment made to the NHS ethics protocol.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from four of the six case study sites. A total of 236 consents to contact were received from people who had recently attended a SARC, of which 157 (67%) were contacted by a member of the MiMoS team. Of those contacted, 78 (50%) gave informed consent to participate and completed the online screening (Figure 6). Two were excluded from the analysis as they were under 18 years of age, leaving 76 to be included in the analysis.

FIGURE 6.

Participant flow.

Sample characteristics

The sample was recruited mostly from the London SARC. However, on comparing sample characteristics from London and non-London, there were very few demographic differences except that in London:

-

there were slightly fewer people who identified as white

-

participants had slightly higher educational attainment, were more employed and fewer were living in temporary accommodation

-

slightly lower mental health needs were identified and lower prescription of medication for mental health and alcohol/drug treatment.

Most of these differences were not statistically significant except for those living outside London who were more likely to state that they were prescribed medication for mental health or substance use difficulties (64%) than participants living in London (36%) (Pearson Chi-square p ≤ 0.05). Therefore, the sample was not disaggregated by London/not-London.

London and the south were less affected by the impact of autumn local area lockdowns compared with the north of England, and this is one of the reasons why recruitment was more successful in these areas. Most of the sample (80%) were in the 18–24 years and 25–34 years age groups. The vast majority were women (91%), with 6% identifying as male and 3% identified as trans/non-binary. In terms of sexuality, most (73%) identified as straight; 8% as gay/lesbian and 19% as bisexual. Most (65%) of the sample identified as white; 13% as Asian/Asian British and 13% as Black Caribbean, African, British.

The survey demographics were compared with national data from the 2018–19 Sexual Assault Referral Centre Indicators of Performance (SARCIP) returns. This showed that the survey was broadly representative of the overall SARC population in 2018–19, with a slightly lower proportion of people identifying as white due to the dominance of participants from London and slightly more participants aged 25–34 years.

Prevalence of mental health, alcohol and drug needs

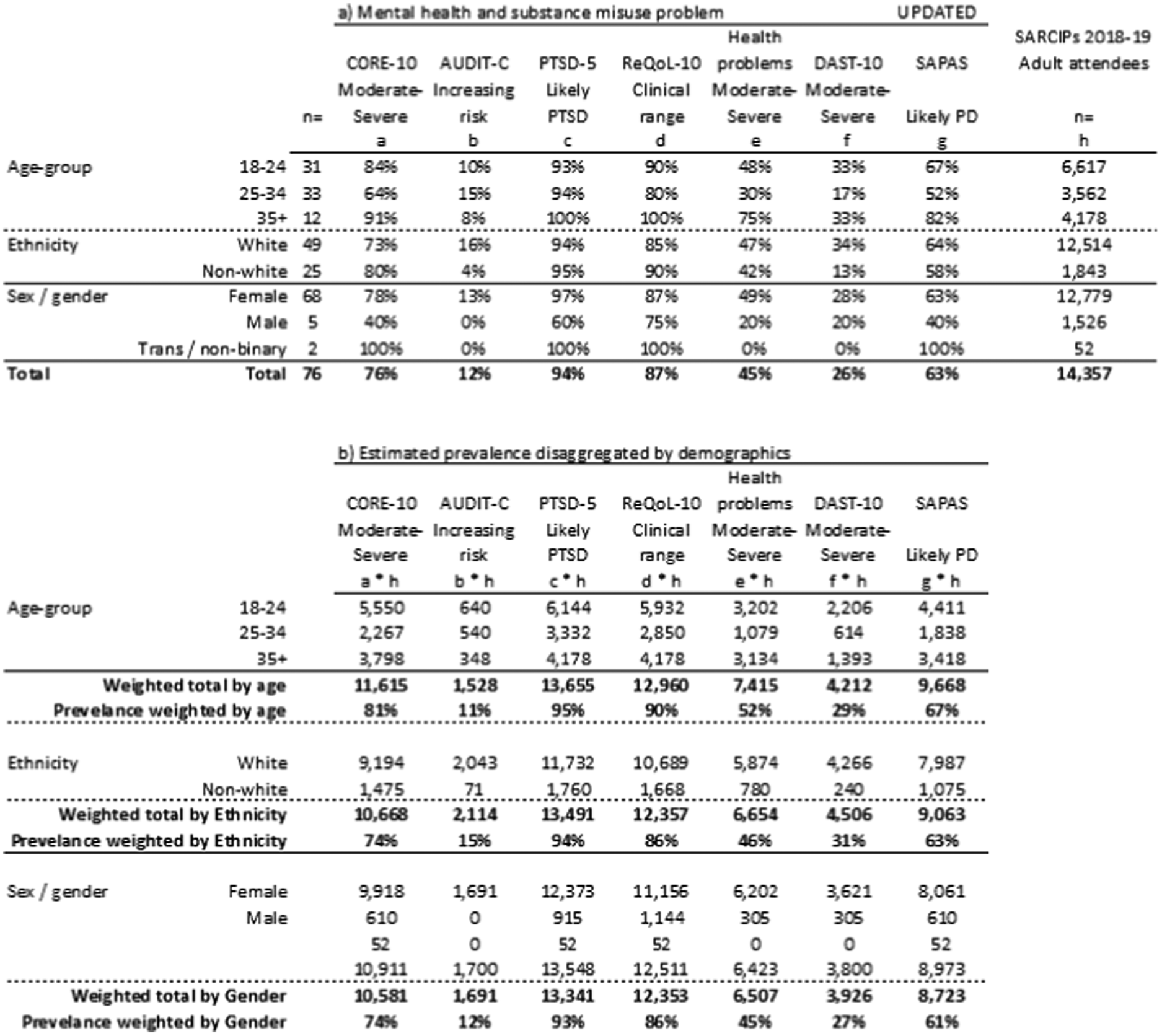

A series of standardised screening tools were used to measure mental health, well-being and substance use needs. The moderate to severe cut-off score for the CORE-10 is above 2 and the clinical cut-off (indicating those in need of psychological therapy compared to a non-clinical population is 1). We are deliberately reporting the percentage of those scoring in the higher severity range and therefore likely to be experiencing an elevated level of psychological distress requiring specialist mental health assessment and support (Table 7).

| n | CORE-10 | AUDIT-C | PTSD-5 | ReQoL-10 | Health problems | DAST-10 | SAPAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate – severe (%) | Increasing risk (%) | Likely PTSD (%) | Clinical range (%) | Moderate – severe (%) | Moderate – severe (%) | Likely PD (%) | |||

| Age-group (years) | 18–24 | 31 | 84 | 10 | 93 | 90 | 48 | 33 | 67 |

| 25–34 | 33 | 64 | 15 | 94 | 80 | 30 | 17 | 52 | |

| 35+ | 12 | 91 | 8 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 33 | 82 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 49 | 73 | 16 | 94 | 85 | 47 | 34 | 64 |

| Non-white | 25 | 80 | 4 | 95 | 90 | 42 | 13 | 58 | |

| Sexa | Female | 68 | 78 | 13 | 97 | 87 | 49 | 28 | 63 |

| Male | 5 | 40 | 0 | 60 | 75 | 20 | 20 | 40 | |

| Total | 76 | 76 | 12 | 94 | 87 | 45 | 26 | 63 | |

| 95% CI | 65% to 85% | 6% to 21% | 86% to 98% | 77% to 94% | 33% to 57% | 17% to 39% | 50% to 74% | ||

These results showed an overall prevalence (95% CI) of:

-

76% (65–85%) with moderate–severe psychological distress (CORE-10)

-

12% (6–21%) scored between 8–15, indicating ‘increasing risk of alcohol problems’ (AUDIT-C)

-

94% (86–98%) PTSD (PC-PTSC-5)

-

87% (77–94%) were in the clinical range for low quality of life (Re-QoL-10)

-

45% (33–57%) moderate to severe health problems (Re-QoL)

-

26% (17–39%) moderate to severe drug problems (DAST)

-

63% (50–74%) personality disorder (SAPAS).

In 2018–19, 14,357 adults (aged 18 years or over) attended SARCs across England. By applying the unadjusted prevalence of mental health or substance use conditions to this total (Table 8) we estimate that, of these 14,357:

-

10,911 had moderate–severe psychological distress

-

1700 had increasing alcohol risk

-

13,548 had likely PTSD

-

12,511 had clinically low quality of life

-

6423 had moderate to severe health problems

-

3800 had moderate to severe drug problems

-

8973 had a probable personality disorder.

| CORE-10 moderate to severe (n) | AUDIT-C increasing risk (n) | PTSD – possible PTSD (n) | ReQoL-10 clinical range (n) | ReQoL health problems – moderate to severe (n) | DAST 10 – moderate to severe (n) | SAPAS –possible PD (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted from survey | 10,911 | 1700 | 13,548 | 12,511 | 6423 | 3800 | 8973 |

| Weighted by age | 11,615 | 1528 | 13,655 | 12,960 | 7415 | 4212 | 9668 |

| Weighted by ethnicity | 10,668 | 2114 | 13,491 | 12,357 | 6654 | 4506 | 9063 |

| Weighted by gender | 10,581 | 1691 | 13,341 | 12,353 | 6507 | 3926 | 8723 |

The prevalence of each mental health condition or substance misuse varied slightly by various demographics (age, ethnicity, sex/gender) – but disaggregated sample sizes were relatively small. When applying the disaggregated prevalence to the disaggregated national SARC population for 2018–19 (see Appendix 3), the weighted estimates show broadly similar numbers of SARC attendees with identified mental health issues, alcohol and/or drug use.

Although sample sizes are small, a cross-tabulation between outcomes shows that there is some tendency for dual diagnosis of mental health and substance misuse (Table 9). These differences were statistically significant only for 72% of individuals with moderate to severe drug misuse who also had health problems (compared with 38% of those with no/low drug misuse).

| CORE-10 | AUDIT-C | PTSD-5 | ReQoL-10 | Health problems | DAST-10 | SAPAS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | Moderate – severe | Increasing risk | Likely PTSD | Clinical range | Moderate – severe | Moderate – severe | Likely PD | ||

| DAST-10 | Moderate – severe | 18 | 83% | 11% | 94% | 78% | 72% | 89% | |

| No/low risk | 50 | 76% | 14% | 86% | 82% | 38% | 48% | ||

| Pearson chi-squared test of association | p = 0.52 | p = 0.76 | p = 0.89 | p = 0.42 | p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 | |||

| AUDIT-C | Increasing risk | 9 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 33% | 22% | 50% | |

| Lower risk | 66 | 73% | 89% | 79% | 47% | 24% | 62% | ||

| Pearson chi-squared test of association | p = 0.72 | p = 0.46 | p = 0.22 | p = 0.46 | p = 0.76 | p = 0.44 | |||

Summary

The analysis indicated consistently elevated levels of psychological distress across the sample recruited. All participants completed the scales in the immediate period after visiting a SARC but at least one week was allowed prior to data collection to allow the initial and acute reaction to trauma to subside. Elevated levels of PTSD were also identified. These results are not surprising considering the recent sexual assault experience but illustrate the importance of using standardised screening tools to identify need and inform what sort of follow-up and access to trauma-specific psychological therapy may be needed. There was some tendency for substance use concerns to co-occur with psychological distress. A larger sample could explore this trend with more certainty; however, accessing effective treatment for co-occurring mental health and substance use can be a challenge, especially psychological therapies (which can exclude those who have active alcohol or drug issues). There are limits to this study because the sample size required was not reached due to impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the sample is representative of people who attend SARCs as well as the rates broadly concur with previous prevalence studies of mental health of SARC attendees. 1,3

Realist synthesis of literature review

Realist methodology

The mixed-methods study was informed by an iterative programme of realist inquiry, which used realist evaluation20,21 and realist synthesis approaches22 to develop and refine programme theories and provide an increasingly evidence-informed theoretical framework to understand emerging findings.

The initial programme theories explained how the SARCs, and related services are intended or expected to achieve specific outcome patterns. As the project proceeded, further theories were developed and refined to encapsulate the diversity of experiences and explain what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why. The programme theories were developed and refined iteratively using tools such as logic models, if–then statements and context, mechanism and outcome configurations (CMOCs) and supported by data from a range of sources including WPs 1–5.

While each WP produced its own discreet outputs, an iterative approach was taken; each stage was informed by the findings of the previous stages, as well as within each stage (e.g. qualitative interview schedules were modified as patterns were identified, and theories were developed which were tested at the subsequent interviews).

We used a comparative realist evaluation approach comprising detailed investigation of the relationship between organisational processes and contexts,23 which generated a holistic understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. 24 Using this methodology, the study sought to explain and understand current SARC service provision by considering how variations in service provision and processes interplay with important aspects of individual service users, thereby influencing how mechanisms work and produce different outcome patterns. 21 This was achieved by developing, refining and testing hypotheses (programme theories) that described how various outcome patterns (O) were observed depending on whether the contexts (C) allowed specific mechanisms (M) to operate. These hypotheses are called CMOCs. A simple example could be the following:

-

Mechanism (resource) – identification of need and referral to external mental health services.

-

Context – previous positive/negative experience of mental health services.

-

Mechanism (response) – service-user decision to take up the referral.

-

Outcome patterns – attending/not attending mental health services, which influences longer-term expected outcomes such as improved wellbeing and reduced risk of further assault.

A CMOC incorporating these elements could be constructed as follows. It is expected that identifying a mental health need and subsequent referral to external mental health services (M) will result in improved wellbeing (O). However, if the service user has had previous adverse or unsatisfactory experiences of these services (C) and as a result decides not to take-up the referral (M) then the anticipated desirable mechanism (decision to take-up the referral) will fail to ‘fire’. Not only will the anticipated benefits of attending these services not be realised (O), but the service user might experience adverse outcomes such as despair or lack of hope (O), thereby potentially leading to worsening of psychological state and higher risk of further assault.

In this CMOC, the key elements that influence outcome patterns (O) are the referral process mechanisms (M) and whether they operate as expected, which is dependent on the context (C) of previous experiences of referral to these (or similar) services.

Realist review

To generate initial programme theories that would then be refined and tested in the case studies and other WPs, a realist review was undertaken. This used outputs identified in the WP1 systematic review. In line with realist methodology,20 the review aimed to create an initial framework for understanding how SARCs respond to mental health/substance misuse while identifying gaps in knowledge and key areas of interest. The review aimed to address the following question:

-

What are the theoretical explanations relating immediate and longer-term outcomes to the identification and treatment of mental health and substance misuse problems in SARCs?

The review was based on international literature. However, the findings were prioritised for relevance to the UK sexual assault service models.

Methodology

The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020182808) and the review follows the RAMESES publication standards for realist reviews. 22

The realist review included papers from the systematic review and built on its searches. 7 We updated the search in the PsycINFO and MEDLINE databases (20 March 2020) using broad search terms and synonyms for SARCs. The search was limited to humans but there were no language restrictions. We also consulted experts in the field to identify additional key papers. The purpose of the review was to develop a theoretical framework and initial programme theories that were specific to the SARC setting, which would then be further refined through the research activities of the other work streams. 25 Therefore, a single comprehensive search, specifically focused on SARCS, rather than iteratively developing additional theoretically driven searches was considered appropriate for the purposes of the programme as a whole.

All retrieved records were independently screened for relevance by two reviewers in a web-based review management system (Covidence, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and, where necessary, after discussions with a third researcher. A data extraction schedule was drafted, piloted and further developed. We extracted data using Microsoft Excel®.

A separate row was used for each theory, whether this was a complete theory or fragment, rather than for each paper. This approach ensured that theory-rich papers did not result in theory-dense outputs and allowed more precise categorisation and comparison of theories. Data were extracted in the form of form of context (C), mechanisms (M) and outcomes (O), and included ‘if–then, leading to’ statements. This approach ensured that relevant details were extracted for theory development and the relationships between C, M and O were articulated. Training sessions and workshops were held for the team to develop skills and knowledge in realist synthesis. However, where members of the data extraction team were less comfortable with describing theoretical relationships, the ‘if–then’ statement column was completed later, by more experienced members of the team using the extracted data and with reference to the original sources.

Extracted information also included theory description, position in pathway, intervention, expected outcomes, for whom, in what setting; generalisability for UK SARCs, usefulness, plausibility, relevance and trustworthiness of the theory. We extracted data for all included papers, found both from the original and the updated search. Most members of the review team extracted data and were involved in discussions around theory generation.

Microsoft Word® was used to collate extracted data according to their position in the pathway. The extracts were then compiled into themes and subthemes that were relevant to these pathway positions. These documents were then reviewed and the contents synthesised into further refined ‘if–then’ statements and CMOCs. Regular discussions among the review team facilitated theory generation. During this process, consideration was given to associations with existing mid-range theories or the development of bespoke theories.

An example of the development of synthesised CMOCs is provided below. This example is positioned at the ‘pre-SARC’ point in the process pathway.

Initial ‘if–then’ statements

The following ‘if–then’ statements were constructed directly from the literature by extracting CMOCs from the source documents and then formulating the relationships between these elements in the extraction form.

49: If sexual assault service staff members (i.e. forensic nurses) are educated and trained appropriately, then they can carry out public health/preventative activities, resulting in a safer community. 26

87: If someone attends a SARC they will benefit from the multi-agency model because of the joined up approach between bureaucratic systems. If they do not trust statutory services however then they may be wary of the SARC because of its perceived links with the police and health system. 27

126: if the services and structures around sexual assault support and the legal system are perceived as fair and supportive, then a higher proportion of assaults would probably be reported. 28

144: If survivors are unaware of SARCs or don’t think they fit the criteria, then they will either not present at all or may present outside the forensic window. This may be because e.g. they think their injuries aren’t serious enough, they are too traumatised to help-seek, or they have internalised rape myths. Therefore, SARCS should aim info strategies specifically at those at risk and should ensure it’s clear who is eligible for support. 29

Extracts and synthesised statements retained their extracted theory ID number at every stage, to allow referral back to the extraction form and source documents. This ensured that important meaning was not lost and allowed clarification of details. Table 10 demonstrates how this specific information extracted from the source documents was synthesised. This stage of the process produced less detailed, yet generally applicable key principles, which could be used to guide the other work streams and potentially be tailored for implementation in any SARC setting.

| Position in pathway | Theme | Subtheme | Context | Mechanism | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-SARC | Role of the SARC in supporting engagement | SARC role in raising awareness about their service | If SARCs raise awareness about their service and provide outreach to the community | Survivors will know about the SARC and understand why, how and when to access it | More survivors will access the service in a timely manner, thus providing an opportunity to improve mental health outcomes | 49, 87, 126, 144, 171, 221, 247 |

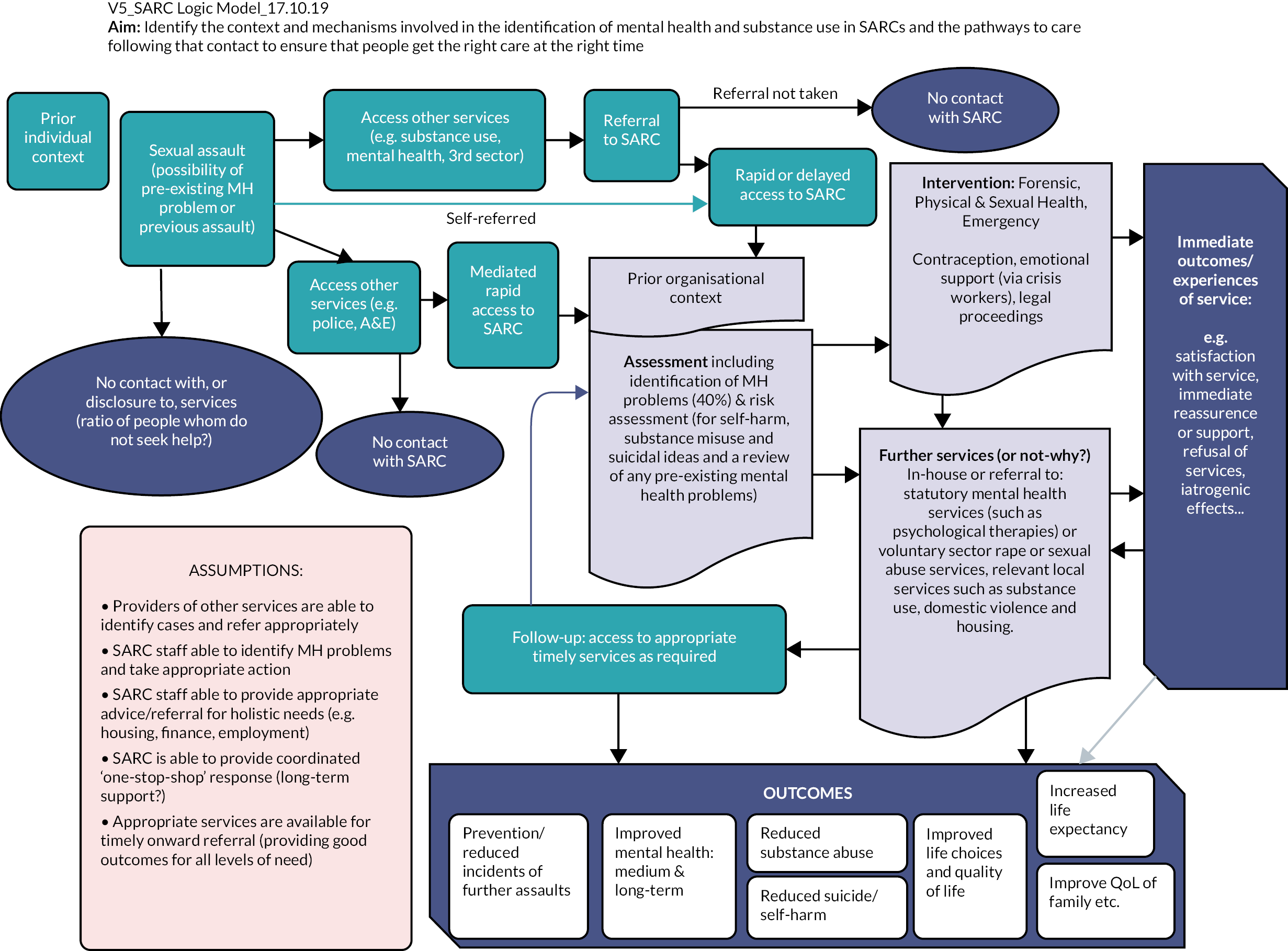

Findings

The initial programme theories were developed from the study proposal and discussions with the study team. For instance, the prevalence of unmet needs indicated problems with the start of the pathway, such as access, referral, and case-finding issues. Rates of mental health service-use, PTSD and substance use are also known to be high in users of SARC services. However, it was not clear how well these needs were being assessed or met during first contact or subsequently (e.g. through referral pathways or follow-up). A process/logic model was developed, which included assumptions about what good-quality care would look like, possible decisions at key points in the pathway and important questions for the study to answer.

Initial hypotheses were developed, which assumed that attending a SARC would be a good thing for those with mental health and/or alcohol/drug use needs. In theory, attending a SARC means that:

-

Survivors can have their mental health and/or alcohol/drug needs assessed; can be referred to talking therapies or drug and alcohol services where needed; can be supported to access other services to have their healthcare needs met, which might otherwise cause stress; that is, SARC attendance provides a point from which formal support services can be accessed.

and

-

In the immediate aftermath of assault, survivors can gain reassurance that they will be believed; they can have negative appraisals about blame challenged by SARC staff; can regain a sense of control and safety. That is, SARC attendance might reduce risk for developing/exacerbating MH/SU difficulties through informal (trauma-informed) ways that survivors are treated, which increase sense of safety.

These two processes may also interact – survivors are more likely to disclose difficulties and take up services where they have experienced trauma-informed care. The synthesis aimed to develop initial programme theories that begin to describe how these formal and informal processes impact on outcomes for people with histories of mental health problems and substance use.