Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR127281. The contractual start date was in July 2019. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Baker et al. This work was produced by Baker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Baker et al.

Chapter 1 Background

This chapter sets out the study context, explaining why it is important to enhance knowledge about restrictive practices in children and young people’s (CYP’s) institutional settings, and how the behavior change technique (BCT) taxonomy can contribute to the development and understanding of interventions.

Restrictive practices in children and young people’s institutional settings

There are approximately 80,000 CYP living in state and privately run institutions in England alone;1 such institutions include residential children’s homes, residential schools, young offender institutions, secure training centres, secure children’s homes and immigration detention centres, in addition to NHS inpatient settings through Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (approximately 1140 beds). 2 The CYP in these disparate institutional settings share some characteristics: many have experienced trauma, abuse and loss;3–8 some present serious risks of harm to themselves and/or others;9,10 and some exhibit behavioural and/or psychological difficulties. The health and safety of these CYP and the staff who work with them hinges on the safe and effective avoidance and management of incidents involving violence, aggression and self-harm.

Definition of restrictive practices, rates of use

Staff responses to incidents involving violence, aggression or self-harm may involve the use of potentially harmful restrictive practices (defined by the Department of Health and Social Care as ‘deliberate acts on the part of other person(s) that restrict an individual’s movement, liberty and/or freedom to act independently in order to: take immediate control of a dangerous situation where there is a real possibility of harm to the person or others if no action is undertaken’11,12). Restrictive practices, such as restraint, seclusion and (in health settings) the use of forced medication, are a common occurrence. Rates of use are similar in psychiatric and criminal justice settings. One study calculated that one-quarter of CYP treated in psychiatric settings have had at least one seclusion episode and 29% have had at least one restraint episode,13 whereas the level is estimated at 28% (in 2014) in custodial settings. The rate is estimated to be higher in learning disability services, with more than half of CYP experiencing seclusion, restraint or a harmful incident. 14

Prevalence data are not available from other settings, although individual cases have attracted media attention. 15 Some studies have found that approximately 60–70% of all reported seclusions or restraints in CAMHS can be accounted for by a small minority (7–15%) of all hospitalised CYP. 16,17 Recent UK figures revealed that 17% of girls in CAMHS facilities had been physically restrained, compared with 13% of boys. 18 Face-down restraint was more commonly used on individuals < 18 years old, with > 2500 occurrences in 2014/15, and, again, in particular with girls (> 2300 occurrences), often repeatedly with the same girls. 18

Risks and costs: physical, psychological, financial

Restrictive practices carry high risks of physical and psychological harm. In the UK, 45 CYP died in restraint-related circumstances in inpatient psychiatric facilities in the period 1993–200313,19,20 and two have died in youth custody in the past 15 years. 21,22 In 2015 alone, there were 429 injuries to children resulting from restraint in youth custody. 23

Research has described the negative impact of experiencing restrictive practices in adult service users but little is known about CYP’s experiences. 21,22 It is thought that, as with adults, such practices can have a profoundly detrimental effect on therapeutic relationships between care staff and CYP24 and they are particularly counter-therapeutic for CYP with an abuse history. 25 The subsequent costs of restrictive practices to the NHS are substantial [estimated by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) at £20.5M per year for damage and injury, £88M per year for observations and £6.1M for restraint]. 26 Evidence-based interventions to reduce the use of restrictive practices clearly have the potential to result in significant cost savings.

Concerns regarding overuse

The problem of overuse of restrictive practices within UK state-provided children’s services has become a matter for serious concern. The United Nations raised specific concerns regarding the use of restrictive practices with CYP who have psychosocial disorders, and at the end of 2017 called again for the UK to end all use of restraint in the context of disability, segregation and isolation practices, and any practices that might be considered to be torture or degrading treatment (Section 73a). 27 Voluntary organisations such as Mind (London, UK),24 Article 39 (Nottingham, UK)1 and Agenda (London, UK)18 have ongoing campaigns on the issue.

Legislative frameworks for the use of restrictive practices

Legal provision for restrictive practices varies across these settings. For example, in the UK, pain-inducing restraint techniques remain lawful in Ministry of Justice settings but have been made unlawful by the Departments of Education and Health. Nevertheless, the UK government has sought to reduce restrictive practices across all settings. The Ministry of Justice implemented the Minimising and Managing Physical Restraint (MMPR) programme, although this has been criticised on the grounds that the restraint techniques it authorises are life-threatening. 28 In 2014, the Department of Health and Social Care launched the Positive and Pro-active Care guidance,12 aimed at phasing out face-down restraint and deeming restrictive interventions a ‘last resort’ across health and social care provider organisations. Since then, services’ use of restraint has been subject to inspection by the Care Quality Commission. 29

More recently, in its publication Reducing the Need for Restraint and Restrictive Intervention with Children and Young People with Learning Disabilities, Autistic Spectrum Disorder and Mental Health Difficulties,30 the Department of Health and Social Care and Department for Education has set out core principles for the use of restraint: it should be used only where necessary to prevent risk of serious harm, and not as punishment; with the minimum force necessary; by appropriately trained staff; and should be documented, monitored and reviewed. 30 In 2018, The Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Bill31 – which sought to manage the use of force in mental health services in England and Wales, requiring commitment to a reduction in the use of force and reporting on its use – became law.

Strategies to address reduction of restrictive practices

There is a growing body of research into the reduction of restrictive practices. In the UK, initiatives to reduce restrictive practices in mental health care such as ‘Safewards’,32 ‘Six Core Strategies’33 (6CS) and ‘No Force First’34 have been promoted and adopted by some mental health trusts, including in CAMHS; some of these initiatives have been evaluated and reported in the literature. 32,35 There has been similar research carried out seeking to reduce the use of restraint with people with learning disabilities. 36,37 These have typically aimed to reduce violent and aggressive behaviour by changing staff behaviour to encourage use of de-escalation techniques, supported by various policy and procedural changes.

There is some evidence of interventions that are effective in reducing the use of restrictive measures specifically with CYP in mental health services; however, empirical data are limited13,19,38–41 and often primarily use case studies of single-facility initiatives. 19,42 Although the outcomes of some of these interventions have been the subject of systematic reviews,32 their specific content has not been examined in detail and the causal mechanisms through which they might change behaviour are not fully understood. It remains unclear which components of these interventions have contributed to their effectiveness. Furthermore, it is not known to what extent those interventions that have resulted in reductions in the use of restrictive practices (or other outcomes such as increased staff confidence) have features in common.

The research context for the current study

The existing literature on restrictive practices repeatedly calls for guidance to be based on robust, transparent studies,43,44 and for interventions to be better described and better evaluated. Livingston et al. 45 reviewed training interventions to reduce restrictive practices and highlighted the difficulty of reaching conclusions, as the evaluated interventions comprised ‘different types of aggression management programs, which contain a variety of approaches’ and ‘the focus, curriculum, and duration of the training vary substantially from one program to another’. 45 The NICE guideline on violence and aggression46 calls for research to be carried out into the content and nature of effective de-escalation techniques, together with the most effective and efficient approaches to training professionals in their use. 46 According to the guideline, research is needed that will apply a systematic approach to the description and reporting of de-escalation techniques currently in use. 46 With specific reference to CYP, it notes the ‘lack of research on the nature and efficacy of verbal and non-verbal de-escalation of seriously agitated children and young people with mental health problems’ and recommends research to ‘systematically describe expert practice in adults, develop and test those techniques in aroused children and young people with mental health problems, and develop and test different methods of training staff’46 (NICE. Violence and Aggression: Short-term Management in Mental Health, Health and Community Settings. London: NICE; 2015. © NICE 2015 Violence and Aggression: Short-term Management in Mental Health, Health and Community Settings. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of Rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication).

The current study is one of a pair addressing NICE’s recommendation to systematically describe restrictive practices with adults and children. The research team’s original study, COMPARE (HSDR 16/53/17),47 fulfilled the first part of NICE’s recommendation by systematically describing practice with adults in mental health inpatient settings. The current review, CONTRAST, is a companion study that took the same approach but reviewed the evidence for interventions to reduce staff use of restrictive practices in child and adolescent institutional settings, including, but not limited to, mental health contexts. It was anticipated that the features of an intervention (its content and delivery) were likely to interact with the delivery context (the target population and setting) and with the features of the target behaviour. 48 Although the target behaviour (use of restrictive practices) was the same as the original study, the context shifted to a range of institutions caring for children and adolescents with different physical, psychological and developmental abilities, employing a wide range of professions, and in which the legality and guidelines for the use of restrictive practices vary. The intention was to compare interventions across these settings to permit exploration of the relationship between intervention features (content and delivery) and context (target population and setting), together with the identification of differences in content, influences on delivery and potential implications for effectiveness.

Addressing the limitations of the evidence base using the behavior change technique taxonomy

The reporting of non-pharmacological trials is challenging because of the absence of a common language with which to describe their components. 49,50 A review51 found that only 39% of interventions were ‘adequately’ described when published. In response to this lack of consensus, the Medical Research Council (MRC) supported the development of a taxonomy of BCTs that can be used across all theory-based interventions aimed at patients or professionals,52 both prospectively in their design and/or to synthesise evidence restrospectively. 52,53 A BCT is defined as ‘an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of a programme designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behaviour’. 52 All interventions to reduce restrictive practices use BCTs. For example, role-playing verbal de-escalation strategies could be coded as rehearsal of relevant skills involving social comparison (BCT 6.2), monitoring of emotional consequences (BCT 5.4) and feedback on behaviour (BCT 2.2). Delivery of information by an expert about risks of restraint could involve information about health consequences delivered by a credible source (BCT 5.1). The taxonomy therefore enables reliable, precise and transparent reporting, replication and comparison of interventions,54 along with more successful implementation with proven effectiveness. 52 It is increasingly used internationally to report interventions,55 synthesise evidence56,57 and reanalyse existing interventions to explore their components. 58 It is also influencing intervention design48 and contributing to the identification of potentially effective BCTs. 52

Chapter 2 Aim and objectives

Aim

The study aim was to identify, standardise and report the effectiveness of components of interventions that seek to reduce restrictive practices in CYP’s institutional settings using the behaviour change taxonomy.

Objectives

The study objectives were to:

-

provide an overview of interventions aimed at reducing restrictive practices with CYP

-

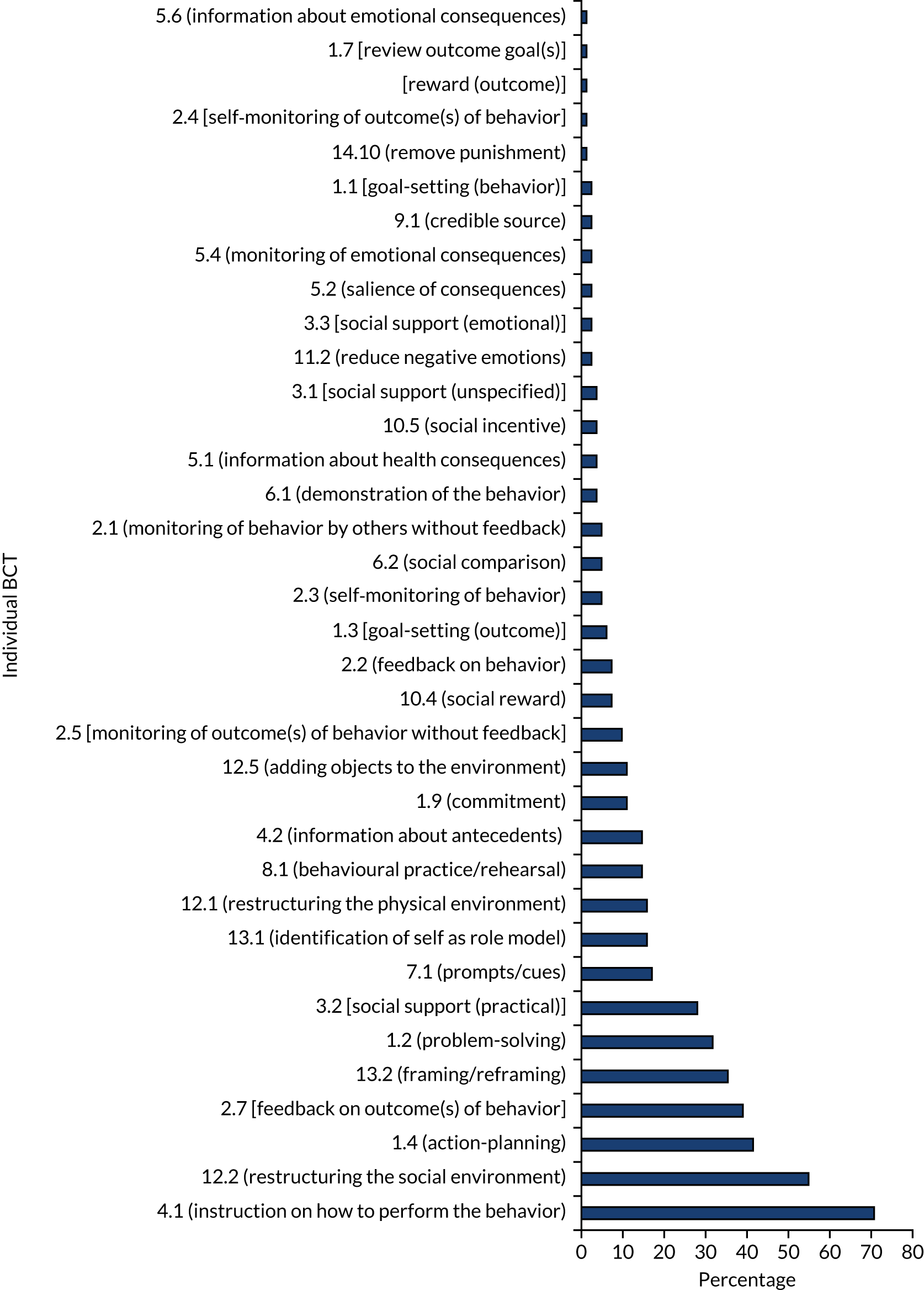

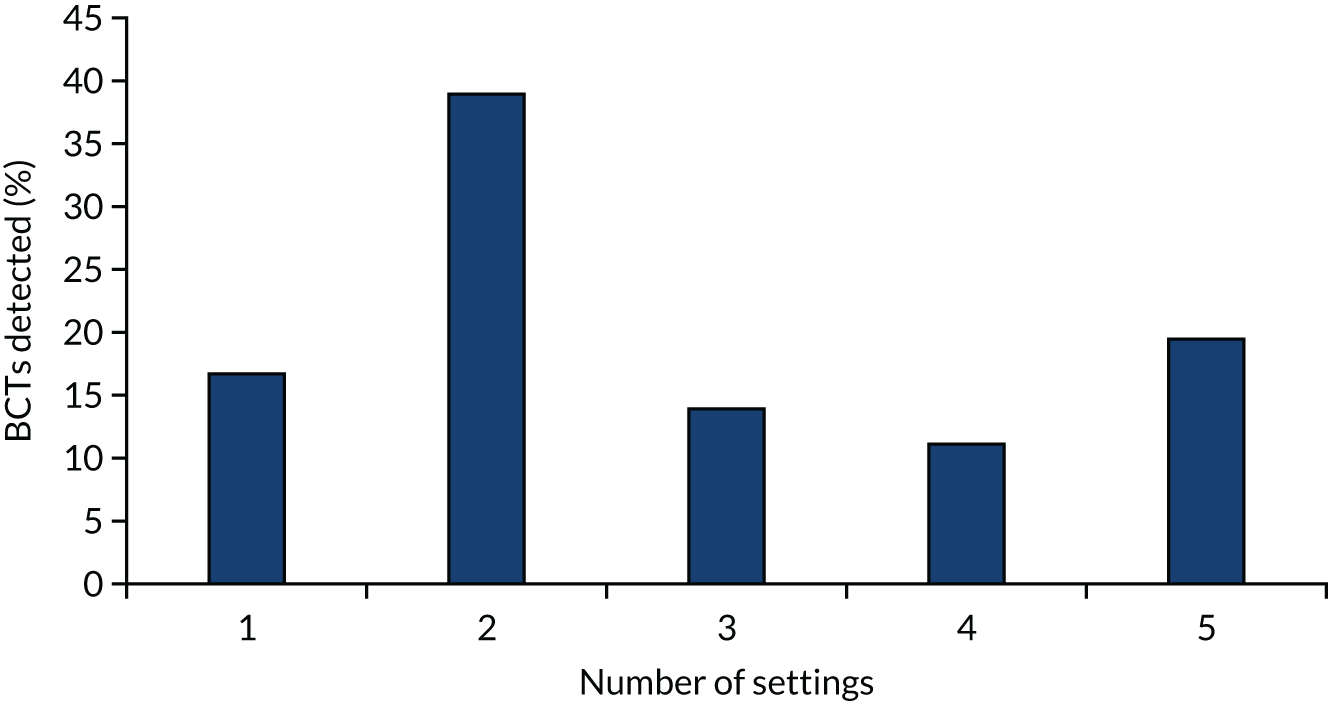

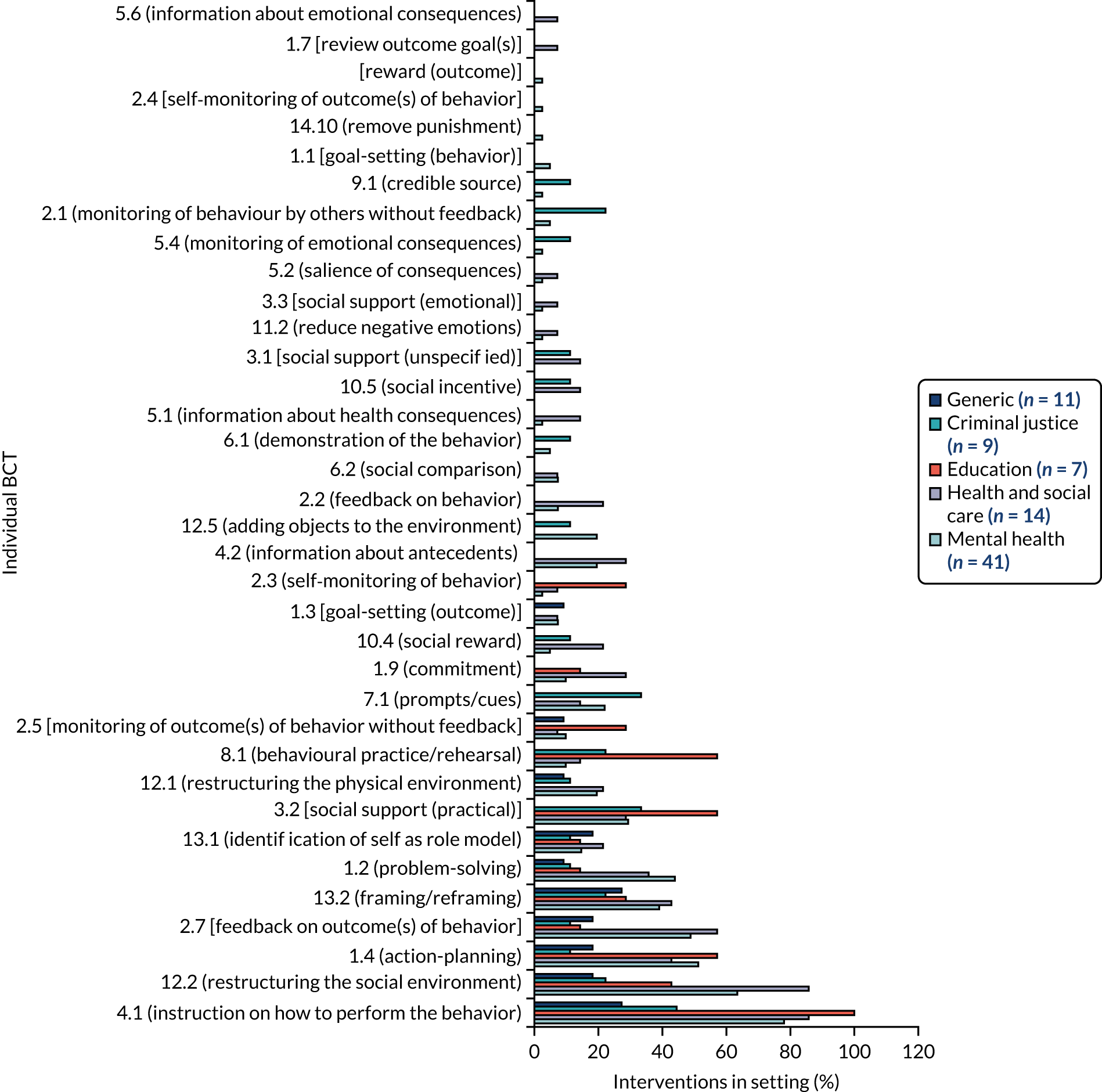

classify components of those interventions in terms of BCTs and determine their frequency of use

-

identify the role of process elements in intervention delivery

-

explore the evidence of effectiveness by examining BCTs and intervention outcomes, where possible

-

compare the components of interventions in CYP’s settings with those in adult psychiatric inpatient settings47 and identify potential explanations for any differences

-

identify and prioritise BCTs that show the most promise of effectiveness and that require testing in future high-quality evaluations.

Chapter 3 Methods

This chapter describes the study design, including approaches to the literature search, data extraction and analysis.

Design overview

Design and conceptual framework

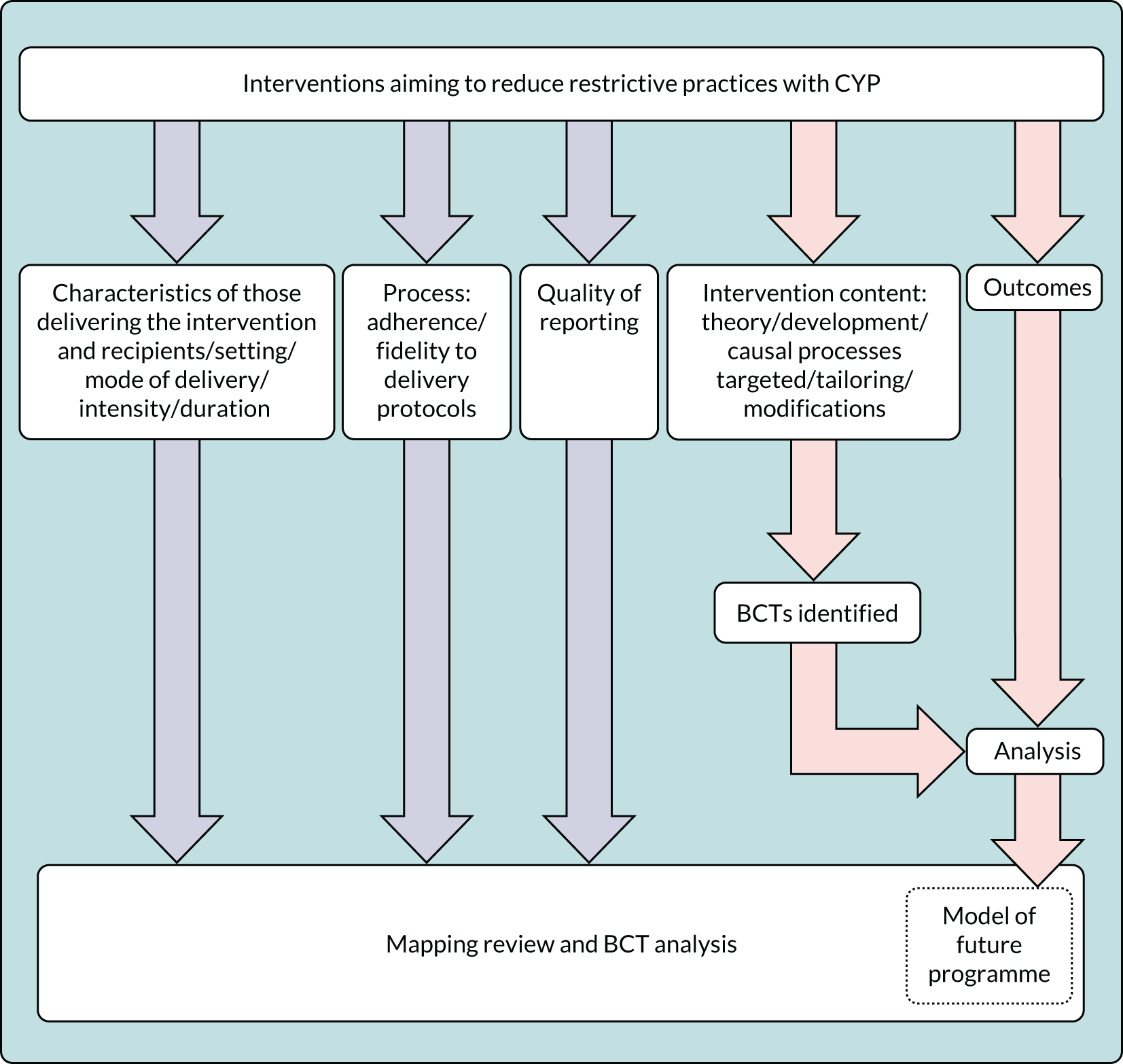

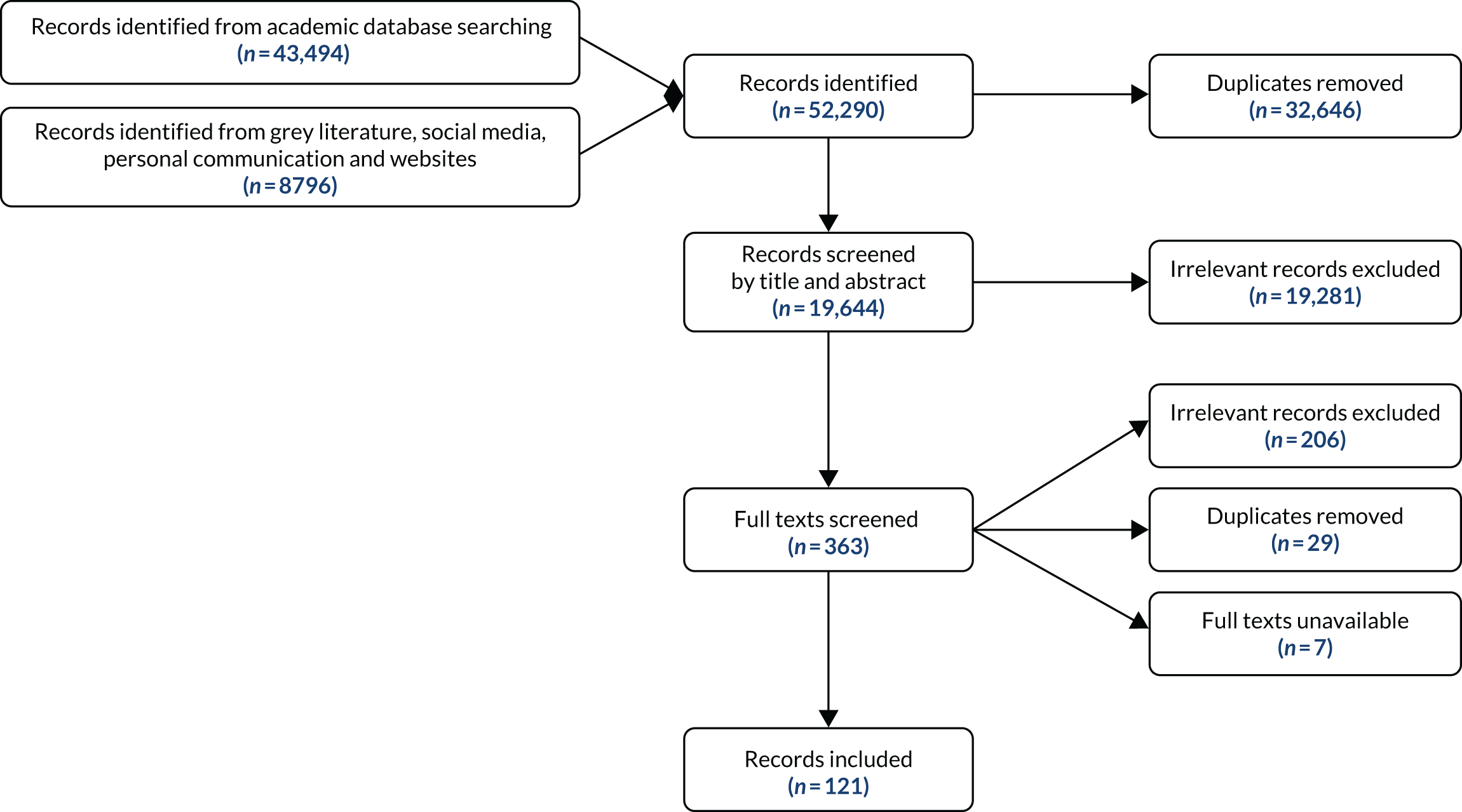

The study approach was a systematic mapping review. An ‘intervention’ was any documented approach that sought to reduce the use of restrictive practices through BCTs. The literature review focused on ascertaining the range and characteristics of interventions, irrespective of evidence of effectiveness, which involved systematically searching and reviewing all reports of interventions seeking to reduce the use of restrictive practices (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Design of systematic mapping review.

The study design comprised the following six objectives.

Environmental scan involving a systematic search of all English-language reports of interventions to reduce restrictive practices in children and young people’s institutional settings (objective 1)

The search strategy approach drew on the increasingly used method of mapping59–64 to inform the purpose and output of the review, but differed from the method described by Bradbury-Jones et al. 59 with respect to the broad scope of the search and inclusion of interventions in the current study. It was known that, in addition to a small number of well-known interventions reported in the academic literature, there were numerous small-scale, stand-alone initiatives available for implementation in services. Not all of these would appear in a search restricted to the published research literature, as they could be reported in unpublished literature or relevant sources that are not reporting research. Furthermore, the current study required the documentation from the interventions (e.g. training programmes) themselves, offering full descriptions of the interventions in addition to research studies evaluating the intervention.

Therefore, an environmental scanning approach was applied. Environmental scanning methods were developed to identify broader information about an area than that which is retrievable solely from published literature. They allow flexibility in the approach to obtaining materials. Environmental scans have been used for identifying and evaluating online resources or training and for reviews of training programmes. 65–67 In health-care settings, this method has been used to inform future-planning, to document evidence of current practice and to raise awareness of an issue. 68

Application of the method can take a ‘passive’ approach in which existing data, both published and unpublished, are collected and analysed, or an ‘active’ approach in which additional knowledge is generated through primary data collection. 68 This study used passive environmental scanning methods to collect available descriptive or evaluative information about interventions that aim to reduce staff use of restrictive practices.

This approach fitted well with the need to search using internet search engines and social media, plus a large number and wide variety of websites, to identify training programme materials. Hence, it was an appropriate choice for expanding the scope of the search strategy.

Synthesis of the features of interventions, alongside a critical appraisal of all retrieved records (objectives 2, 4 and 6)

The study design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Examples included delivery to groups or individuals, the person delivering the intervention, and the setting, timing and frequency of the interventions. 49 These were recorded using WIDER (Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research),69 a checklist that prompts detailed recording of interventions based on the questions ‘why, what, who, how, where, when and how much?’. WIDER serves as an extension to both CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) and SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials). 51

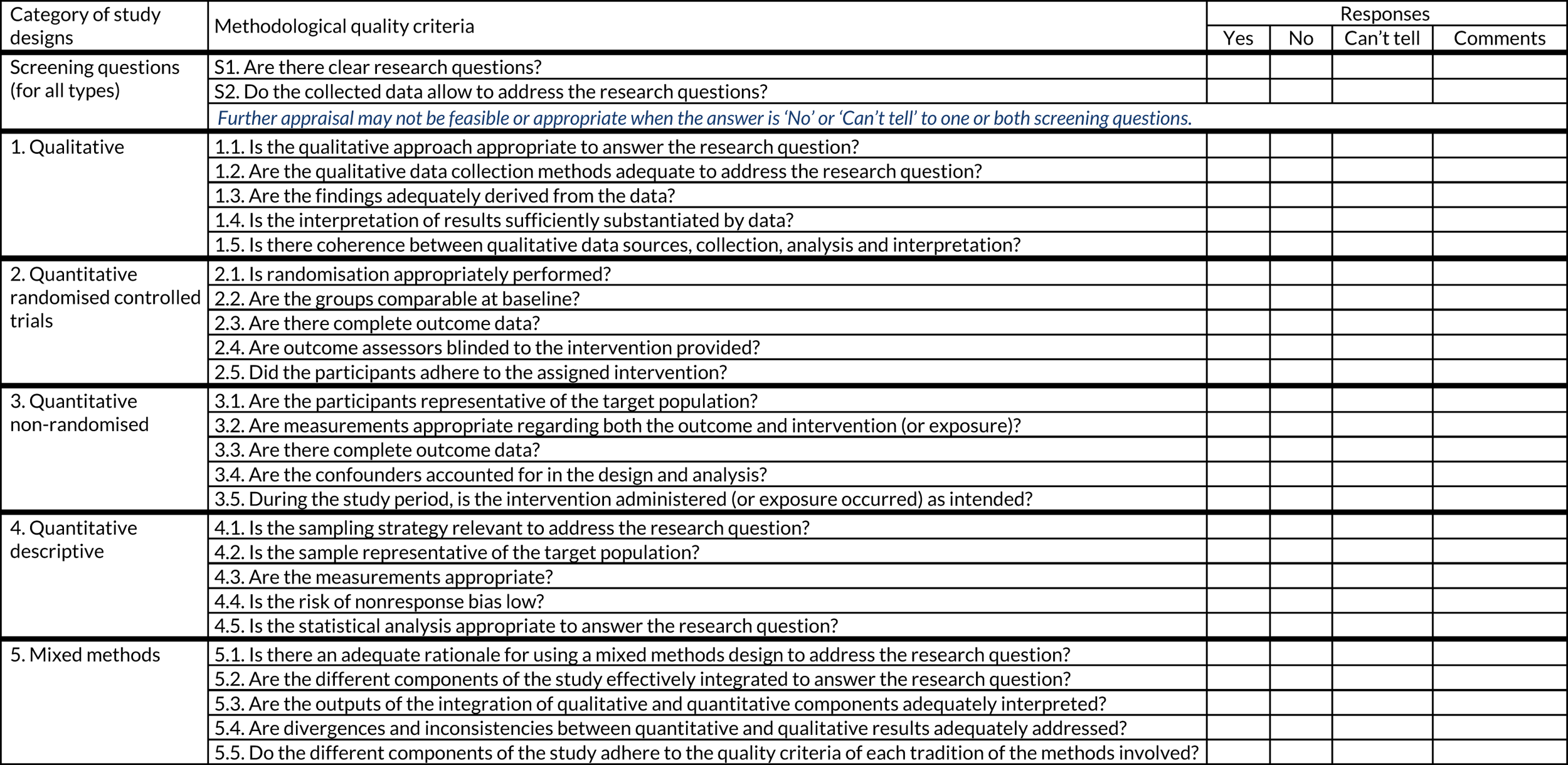

Critical appraisal was informed by the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), which is an appraisal tool specifically designed for mixed-methods reviews. 70,71

The Behaviour Change Wheel

To support the synthesis of the context of the interventions, the Behaviour Change Wheel was used. This was produced from a synthesis of frameworks of behaviour change research literature. 72 It is based on a model of behaviour called the COM-B, which attempts to describe how Capability, Opportunity and Motivation can change Behaviour. The Behaviour Change Wheel contains the higher-order categories of BCTs at its hub (e.g. ‘social’ or ‘reflective’). The next level includes intervention functions such as ‘training’ or ‘incentivisation’, and the third, outer, level contains policy categories such as ‘legislation’ or ‘regulation’.

The initial data extraction included the categories from the Behaviour Change Wheel. The subsequent, more detailed, BCT coding of interventions was therefore an extension to this process, focusing on the detail of the study in which it was reported, and relating it back to intervention function in the Behaviour Change Wheel. For example, providing information on consequences of restrictive practices would relate to the intervention functions of ‘education’ and ‘persuasion’. Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel in this way facilitated reporting of all interventions in different levels of detail.

Extraction of intervention content for analysis using a validated, structured taxonomy (the behavior change technique taxonomy) to identify the content of the interventions, when possible (objective 2)

The behavior change technique taxonomy

When possible, content of the interventions was extracted using the BCT taxonomy, which is supported by the MRC. 73 The MRC BCT taxonomy consists of 93 items, each one an individual BCT, for example BCT 6.2 (social comparison) or BCT 1.2 (problem-solving). Individual BCTs are also grouped into clusters, for example cluster 1 (goals and planning). The taxonomy provides examples of these items, often related to patient behaviour, although recent studies have provided examples of health-care professionals’ behaviour to inform studies such as this that seek to code health-care professionals’ behaviours. 73

The BCT taxonomy is a reliable method for extracting data regarding the content of interventions. 52 All materials available for each intervention (e.g. manuals, evaluation reports) were coded by trained coders using the taxonomy. This process identified the individual BCTs detected in each intervention and their frequency of use.

Where possible, extraction of the outcomes of coded interventions and relating of them to the behavior change technique taxonomy (objectives 3 and 4)

When an intervention was coded for BCTs, available outcome data were then extracted.

Comparison of components of interventions in children and young people’s settings with those in adult psychiatric inpatient settings (objective 5)

The two settings were compared to address questions about the comparability and transferability of interventions to reduce restrictive practices and their specific BCT components, such as:

-

Do interventions aimed at staff of different professions working in children’s services take account of the significant differences in population?

-

Are the BCT components of interventions aimed at staff in children’s settings different from those in adult settings, and should they be?

It was possible that interventions in adult settings might comprise particular BCTs that were not found in interventions in children’s settings. If identified as effective, these BCTs could be considered to be worth testing in children’s settings (and vice versa).

Analysis of potential relationships between reduction of restrictive practices and behaviour change techniques (objective 6)

Analysis of potential relationships between reduction of restrictive practices and BCTs was carried out with the aim of generating hypotheses for future testing and developing potential causal models for future trials.

Literature search strategy

Search strategy

The approach to searching and screening was guided by the mapping and scoping literature59–64 and provided an initial draft search. This draft search went through several iterations before a final search was conducted. The reviewers screened some sample search results to consider the relevance of the studies. Research literature, policies and grey literature, including training manuals, were identified using comprehensive search strategies developed in collaboration with the information specialist and from consulting the known literature and database thesauri (e.g. medical subject heading).

Searches were developed for the following concepts: child or child behaviours; restraint practices or named programmes; and a variety of institutional, health-care and educational settings. The search was limited to material after 1989 because of changes in attitudes to children’s rights, as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) 198974 and, in the UK, the 1989 Children Act,75 which introduced comprehensive reforms to the law in terms of the care and protection of children.

Restraint studies relating to road safety or traffic incidents were excluded. Subject headings and free-text words were identified for use in the search concepts by the information specialist and project team members. Further terms were identified and tested from known relevant papers.

All searches were peer reviewed by an information specialist. Search strategies were adapted with the aim of producing fewer and more relevant results without missing relevant studies. Additional studies were identified via bibliographies of reviews and retrieved articles, targeted author searches, contacting international experts and forward citation searching. The project management group was asked for details of any known interventions, and authors of current and recently completed research projects were contacted directly.

In June 2019, academic databases were searched for studies looking at child restraint in a variety of settings. The searches were updated in January 2020 in all but the Education Abstracts and Scopus databases. Analysis of the studies selected for inclusion from the 2019 searches showed that none had come exclusively from these two databases. Table 1 indicates the databases that were searched within the stated dates.

| Database | Date range searched |

|---|---|

| ASSIA (ProQuest) | 1987 to 24 January 2020 |

| British Nursing Index (HDAS) | 1992 to 24 January 2020 |

| CINAHL (EBSCOhost) | 1981 to 30 January 2020 |

| Child Development and Adolescent Studies (EBSCOhost) | 1927 to 24 January 2020 |

| Criminal Justice Abstracts (EBSCOhost) | 1830 to 30 January 2020 |

| Education Abstracts (H. W. Wilson) (EBSCOhost) | 1983 to present, updated 14 June 2019 |

| EMBASE Classic and EMBASE (Ovid) | 1947 to 21 January 2020 |

| ERIC (EBSCOhost) | 1966 to 30 January 2020 |

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily | 1946 to 20 January 2020 |

| PsycInfo (Ovid) | 1806 to week 2 January 2020 |

| Scopus (Elsevier B. V.) | 1823 to 13 June 2019 |

Grey literature searches were conducted in August 2019 and updated in January 2020 in the websites and databases in Box 1. See Appendix 1 for full details of all searches.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

AGENDA: Alliance for Women & Girls At Risk.

Article 39.

Barnardo’s.

British Association of Social Workers.

British Institute of Learning Disabilities.

British Society of Criminology.

Challenging Behaviour Foundation.

Children Society.

Crisis Prevention Institute.

Foundation for Professionals in Services to Adolescents.

Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA).

HM Inspector of Constabulary and HM Inspector of Fire & Rescue Services.

HM Inspectorate of Prisons for England and Wales.

HM Inspectorate of Probation.

Howard League.

INQUEST.

MENCAP.

National Children’s Bureau.

National Police Library.

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

National Youth Work.

Prison Reform Trust.

Prisons and Probation Ombudsman.

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I (ProQuest) 1743 to 24 January 2020.

Restraint Reduction Network.

SAFE Crisis Management.

SCIE.

Secure Children’s Homes/Secure Accommodation Network.

Social Care Online (SCIE) 1980 to 28 January 2020.

Twitter (www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA).

Young Minds.

Youth Justice Board for England and Wales.

Eligibility

In keeping with objective 1 (to provide an overview of interventions aimed at reducing restrictive practices in children’s settings), the search criteria targeted diverse reports of non-pharmacological interventions aimed at changing the behaviour of service staff to reduce restrictive practices. The scope of the searches was necessarily broad to include all records of an intervention, whether it was an evaluation or a descriptive report. To include as many interventions as possible within the scope of the search, no quality threshold was imposed either indirectly (by restricting the search to high-impact journals) or directly via the search criteria or by screening. Inclusion was not restricted by study design. Interventions that solely involved policy change and those that aimed to reduce the use of one type of restrictive practice by replacing it with another were not eligible for inclusion. 59–64,68,70,71

In addition to interventions intended to reduce or eliminate restrictive practices, reports of interventions designed to improve quality or reduce or manage violence were included if their procedures and/or outcome measures addressed restrictive practices. The search for relevant interventions records was informed by the ‘environmental scanning’ approach68 described above. Eligibility criteria are shown in Table 2. See Appendix 1 for full details of all searches.

| Criterion | Include | Exclude |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Staff working in state and privately operated CYP’s institutional settings [including children’s homes; residential schools; boarding schools; young offender institutions; secure training centres; immigration detention centres; and inpatient child and adolescent mental health, child and adolescent hospitals (non-mental health) and learning disability services] | Interventions to reduce staff use of restrictive practices with adults (only > 18 years) |

| Date | Dated 1989 to date | Pre-1989 |

| Interventions | Intervention: documented interventions aimed at reducing staff use of restrictive practices with CYP in institutional settings |

Pharmacological only intervention Non-English-language interventions |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: reduction of restrictive practices | |

| Language | English |

Data management and review

All potentially eligible records were stored and managed in the reference management software EndNote™ version X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Two reviewers screened titles. When both reviewers agreed to exclude an article, the reason for exclusion was recorded. When there was disagreement, the full text of the articles was reviewed and any unresolved disagreement was subject to third-party review. When there was agreement between the two reviewers on inclusion, the full-text article was retrieved and independently assessed against the inclusion criteria by the two reviewers and, again, any disagreement was subject to third-party review.

Quality appraisal using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

Because the inclusive search criteria identified very diverse record formats, quality appraisals were used not to exclude papers but to inform the synthesis by identifying study designs and, hence, evaluations. Study quality was assessed using the MMAT. This tool is suitable for appraising studies with diverse designs. 70,71 The characteristics of the MMAT70,71 make it the most suitable tool with which to judge study quality in the context of wide-ranging research methods.

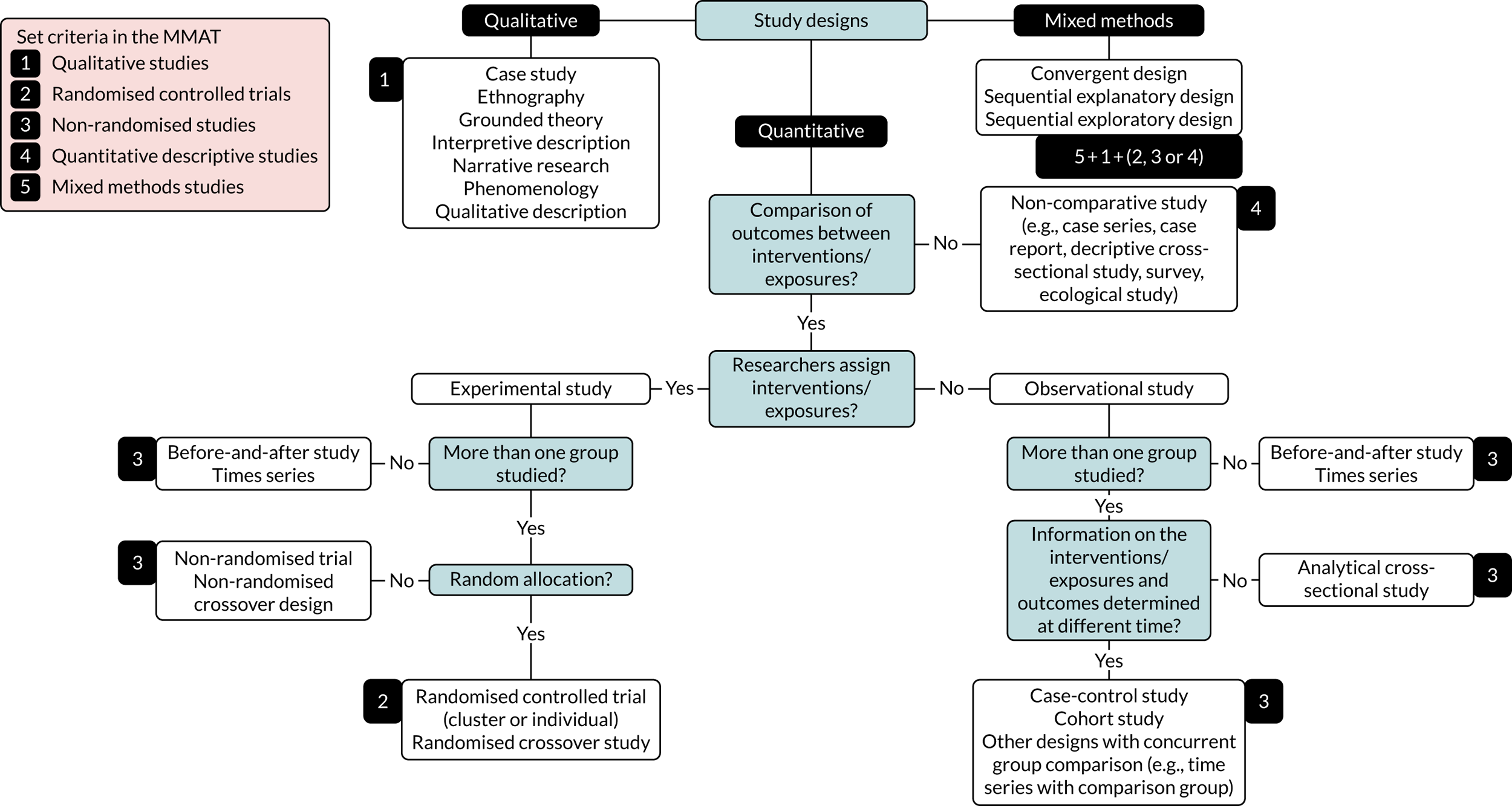

The MMAT was developed for use in complex systematic literature reviews that include quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies (Figure 2). It was developed from theory and a literature review and has been found to have good validity. 76 The MMAT algorithm for selecting study categories is illustrated in Figure 3. Using the MMAT algorithm, reports of milieu change and case studies were categorised as qualitative studies if reporting suggested a primarily qualitative approach.

FIGURE 2.

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, version 2018. Adapted from Hong Qn, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. 70 Registration of Copyright (#1148552) Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

FIGURE 3.

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool algorithm for selecting study categories. Adapted with permission from Hong Qn, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. 70 Registration of Copyright (#1148552) Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

Using the MMAT, quantitative and qualitative studies are judged against four criteria and mixed-methods studies are judged against three. The quantitative domain is split into three subdomains: randomised controlled, non-randomised and descriptive. As applied in the current study, surveys, case reports, descriptive cross-sectional studies and ecological studies were categorised as ‘quantitative descriptive’ if reporting suggested a primarily quantitative approach. The mixed-methods category included reports of milieu change with substantial quantitative analysis.

Therefore, the tool was used at two levels: (1) to identify records of interventions that had been evaluated to get a sense of the quality of the evidence using the two initial screening questions, and (2) to assess the quality of the evaluation reports. The application of the MMAT to screen and categorise all the records informed the narrative accounts provided in Chapters 4 and 5.

Documented interventions were identified. Data extraction was governed by a pro forma that allowed systematic collection of data relating to the interventions. Analysis of the features of interventions revealed the context of how interventions were delivered (e.g. delivery to groups or individuals; the person delivering the intervention; and the setting, timing and frequency of the interventions). 49 When available, these details were recorded using the WIDER69 checklist. WIDER is a tool for assessing reporting quality. It contains a number of relevant categories that facilitated this process.

Content extraction

The content of interventions was extracted to allow their components to be coded using the BCT taxonomy. Extraction was carried out by two reviewers and any discrepancies were subject to third-party review. Extraction categories were developed from the WIDER69 checklist. Data were extracted about the characteristics of each intervention, including participants, setting, intervention type, outcome measures, fidelity, acceptability, recommendations and quality. When information was available, associated costs were described in terms of training materials, delivery and staff time.

Intervention coding

The researchers were fully trained in the application of the BCT taxonomy. Using the taxonomy and supporting examples, the researchers independently coded the selected interventions. Interventions that were coded for BCT components had information about their outcomes extracted to examine the efficacy of these techniques.

Coding was carried out by importing all intervention materials (published papers, manuals, slides, handbooks) into NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), a flexible qualitative software package that facilitates the coding of multimedia materials for analysis. Each of the 93 items of the BCT taxonomy was turned into a code within NVivo and considered for each intervention. The codes were applied when there was evidence of the BCT being used; for example, when a professional received information about the potentially harmful effects of restraint during a training session, this was coded as BCT 5.1 (information about health consequences). Any assumptions made by the coder were recorded, also within NVivo, in order that discrepancies could be discussed. Once the coding was complete, NVivo was used to generate individual study reports that revealed discrepancies between coders. Each discrepancy was discussed and resolved by the coders and, if necessary, further discussion took place with other expert members of the team to achieve resolution. This discussion consisted of the coder explaining their reasoning as to why they had assigned the code. The individual study reports were compiled to produce a summary of how many of the possible 93 BCTs were found in interventions, how often they occurred and whether or not they were from particular clusters. Study outcome data were extracted and used to explore whether or not there were potential relationships between study outcomes and particular BCTs.

Data synthesis

The approach to data synthesis was designed to suit the diverse set of included records. It was not relevant to apply stringent academic appraisal techniques in a conventional way because the data set included some records that were neither academic publications nor formal reports. For example, a key source of information about the 6CS intervention was a set of workshop slides. 77

Meeting the objectives set out in this chapter involved exploring and categorising the records, identifying intervention evaluations and then conducting a detailed analysis of the available information about the interventions. The purpose of this was to identify BCTs to produce a synthesis of intervention characteristics, components in terms of BCTs, process elements, effectiveness evidence in terms of BCTs and intervention outcomes, and also to compare the results with the results of the companion COMPARE study47 focusing on adult acute mental health settings.

Therefore, data were synthesised by a process of close scrutiny of the included records, and tailored application of the MMAT and WIDER recommendations to understand the scope and quality of the materials and meet the study objectives.

Following extraction, the records were organised into groups according to the intervention or interventions they described. This allowed for a primary focus on the evidence for each intervention, rather than the overall evidence (objectives 4 and 6) in parallel with the classification and analysis of intervention components (objective 2).

Narrative synthesis

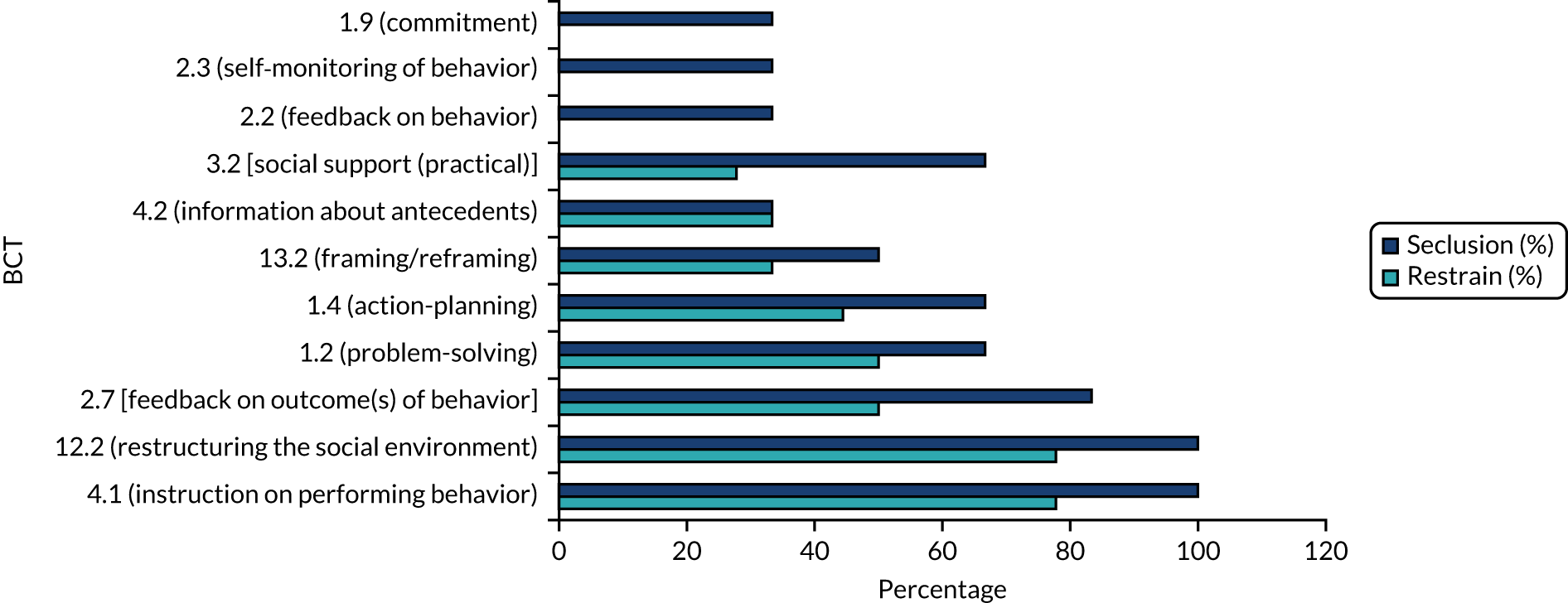

Interventions were placed in subgroups according to the setting and type of restrictive practice that they seek to reduce [e.g. p.r.n. (pro re nata) medication, physical and seclusion]. A narrative synthesis across and within each subgroup was carried out exploring and describing the features of the interventions including their theoretical basis, population, outcomes and conclusions. The content of the types of intervention was described in terms of the types and frequency of BCTs that could be identified [e.g. social support, skills practice and modelling (Table 3)]. The outcome data from the interventions were presented in relation to the BCTs present, and hypotheses were formulated around whether specific types of BCTs appeared more frequently, or not at all, in studies reporting certain outcomes.

| Type of BCT | Example of how this BCT has been used in a model reducing restrictive practices |

|---|---|

| Health consequences | Information given about the potential risks of asphyxiation or cardiac events during restraint33 |

Chapter 4 Results of literature search

Introduction

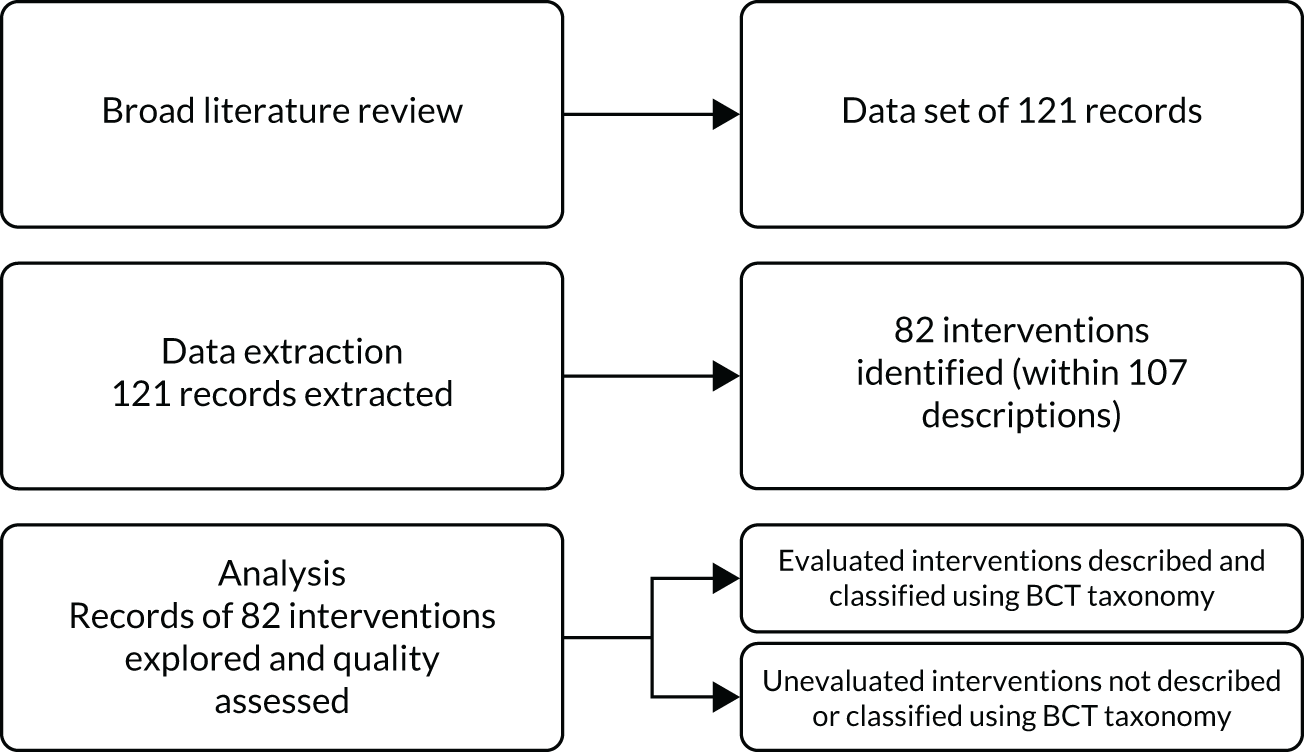

The chapter provides an overview of the literature search results, including a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) figure to indicate the extraction process. The included records are listed in Appendix 2. In this chapter, the results are described in detail and key characteristics of the data set are highlighted. As per objective 1 and in keeping with the mapping approach, a narrative overview of interventions aimed at reducing restrictive practices with CYP is then provided. It describes the characteristics of the interventions identified within the data set of records, including their scope and common features. The description of the evaluations is informed by WIDER reporting recommendations. Figure 4 summarises the study processes.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of study processes.

Search results

As illustrated in the PRISMA figure (Figure 5), the search of academic databases identified 43,494 records and these, as well as 8796 records found in the grey literature (including social media), were entered into Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) for further analysis. After the removal of duplicates, and accounting for records that were not available, 19,644 records were subjected to title and abstract screening. The final data set consisted of 121 records for extraction. Further details of the search strategy and results are available in Appendices 1 and 2.

FIGURE 5.

The PRISMA figure. Grey literature: non-academic databases and websites, social media and ‘other’ records. ‘Other’ records: discovered using forward citation searches and contact with authors. Excluded because not relevant: records excluded because they report not an intervention but, for instance, a generic policy change or replacement of one restrictive practice with another.

Responses to requests for intervention materials

In addition to the processes described above, attempts were made to request further information about interventions to supplement information found in the 121 included records. This involved sending e-mails to authors and co-authors, and, when appropriate, to organisations, using contact details provided in or otherwise gleaned from the records. Seventy-one e-mail requests were sent (see Appendix 3), resulting in new information about six of the interventions: Six Core Strategies for Reducing Seclusion and Restraint Use,33 Trauma Affect Regulation,78 Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics,79 Milieu Nurse Shift Assignments,80 Crisis Intervention81 and Checklist for Assessing Your Organisation’s Readiness. 82

Study screening

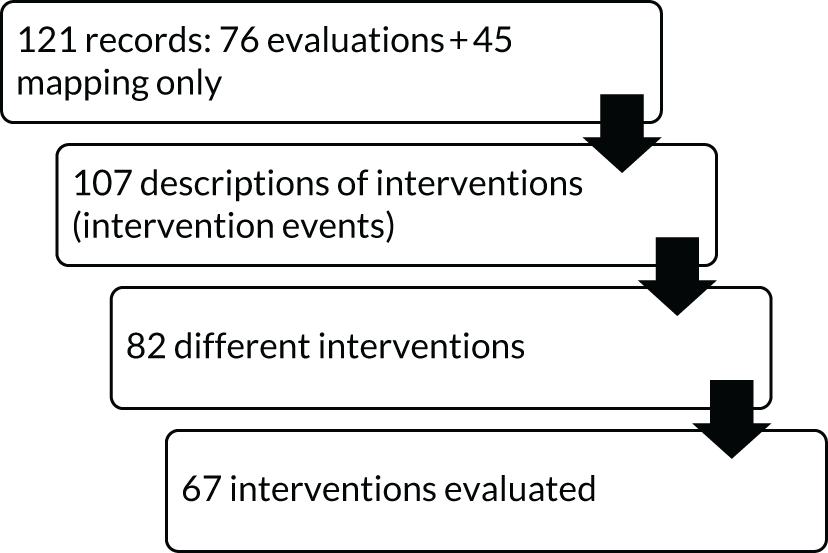

The records were diverse in terms of format and reporting quality. The first two questions of the MMAT70 were applied to screen the 121 records to identify those that were evaluations. In all, there were 76 records that were evaluations and 45 records that were descriptive only and did not contain evaluations. These 45 were used for mapping only and consisted of training resources, blogs, websites and almost all of the reports (e.g. reports to organisations).

Categorising the studies

Some interventions occurred in more than one record, some records reported more than one intervention and some reports were mentioned in more than one record. Overall, the data set contained 107 descriptions of interventions, referring to 82 interventions in total, of which 67 interventions had been evaluated. The data set is summarised in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Summary of the data set.

Categorisation of study (evaluation) design

In view of the widely ranging literature retrieved from the searches, the MMAT was used to categorise all 121 records by study design. As reported above, 76 records were classified as evaluations; the remainder were descriptive only. The 76 evaluations were allocated, where possible, to one of the five MMAT categories:70 qualitative description, randomised controlled trial (RCT), non-randomised trial, quantitative description or mixed-methods study. As summarised in Table 4, the majority of the 76 records of evaluations reported non-randomised designs. Thirty-two evaluation records lacked sufficient detail for categorisation by study design with the MMAT. None was categorised as a RCT. Only 15 of the 45 mapping records provided detail of study design; however, as indicated above, not all mapping records were research reports. Based on the MMAT screening questions, intervention study design was as follows: non randomised, n = 41; quantitative, n = 21; mixed methods, n = 5; qualitative, n = 5; no study design reported, n = 2.

| Study design | Evaluation records (n = 76) | Mapping records (n = 45) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-randomised trial | 41 | 3 | 44 |

| Quantitative description | 23 | 7 | 30 |

| Qualitative description | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Mixed-methods study | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Insufficient detail | 2 | 30 | 32 |

| Total | 76 | 45 | 121 |

Consistency and comprehensiveness of intervention reporting

Overall, reporting about interventions lacked consistency and comprehensiveness. The WIDER tool69 that was used to develop the data extraction strategy also informed the appraisal of reporting quality and identified a great deal of missing information about key aspects of interventions. Within the evaluation records, intervention recipient and setting were well reported, but intervention aims and by whom the intervention was delivered were not consistently reported. Most evaluation records did not report on intervention dose, fidelity to the intervention protocol, whether or not modifications were made to the intervention, whether or not intervention protocols were used and whether or not service users were involved in the development of the intervention. Within the mapping records, reporting was weak across the WIDER categories. The detail is presented in Table 5. Evaluation and mapping records are reported separately because of the differing overall characteristics of each subset. The detail provided in Table 5 reflects information as reported directly in the records, rather than inferred or extrapolated.

| Reporting | WIDER recommendation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detailed description of interventions | Assumed change process and design principles | Access to manuals/protocols | |||||||||||

| By whom delivered | Recipient | Setting | Mode of delivery in implementationa | Dose | Modification | Fidelity | Theory informedb | Developmentc | Materials | ||||

| Duration | Intensity | ||||||||||||

| Evaluation records (N = 76) | |||||||||||||

| R | n | 42 | 72 | 76 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 3 | 12 | 43 | 10 | 10 | |

| % | 55.26 | 94.73 | 100 | 28.95 | 28.95 | 19.74 | 3.95 | 15.79 | 56.58 | 13.16 | 13.16 | ||

| NR | n | 34 | 4 | 0 | 54 | 54 | 60 | 64 | 64 | 33 | 66 | 66 | |

| % | 44.74 | 5.26 | 0 | 71.05 | 71.05 | 78.95 | 84.21 | 84.21 | 43.42 | 86.84 | 86.84 | ||

| N/A | n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.32 | 11.84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mapping records (N = 45) | |||||||||||||

| R | n | 8 | 11 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| % | 17.78 | 24.44 | 13.33 | 8.89 | 0 | 4.44 | 4.44 | 4.44 | 2.22 | 8.89 | |||

| NR | n | 7 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 11 | ||

| % | 15.56 | 8.89 | 0 | 24.44 | 33.33 | 28.89 | 28.89 | 28.89 | 31.1 | 24.44 | |||

| N/A | n | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | ||

| % | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 66.67 | |||

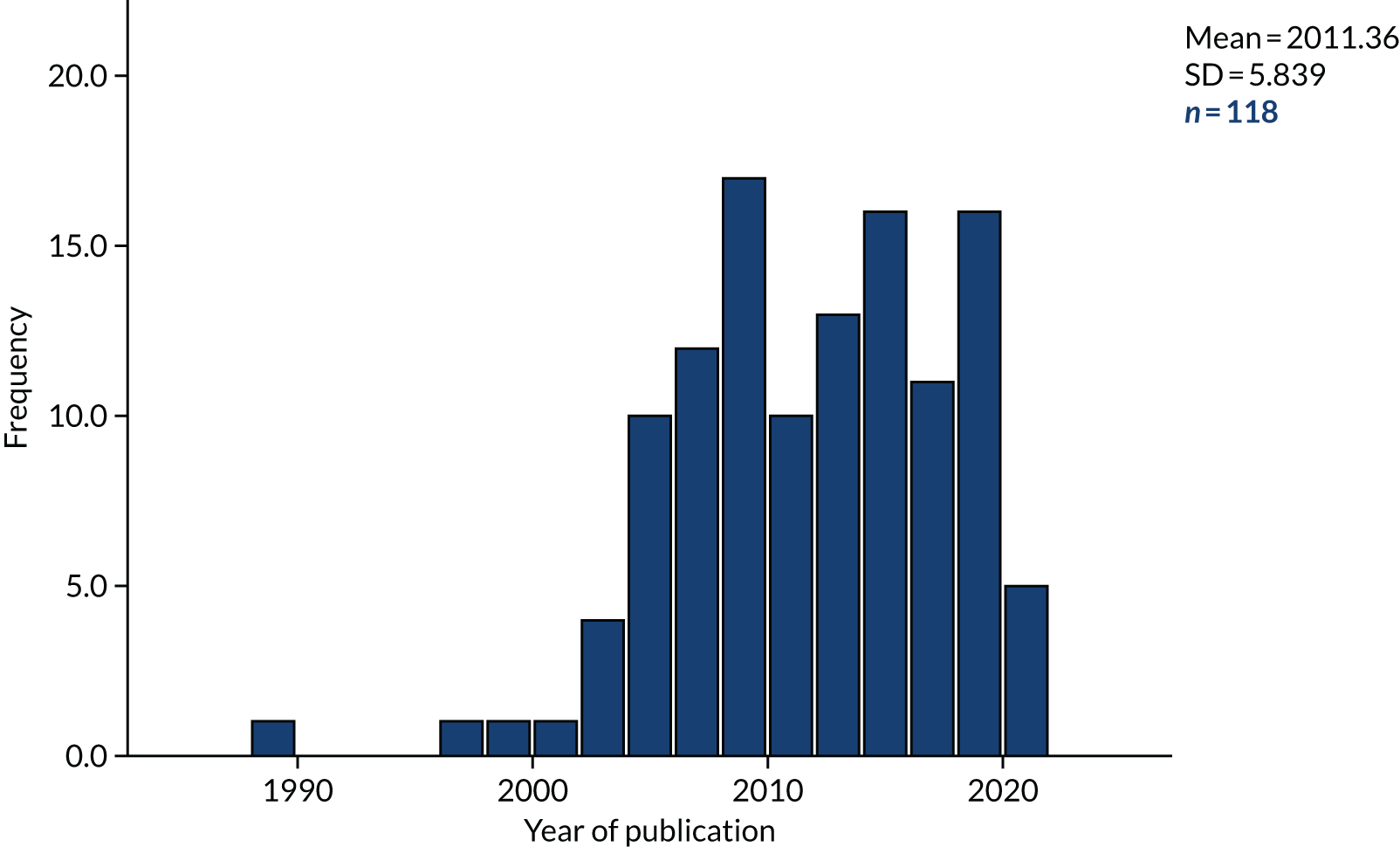

Publication date and format

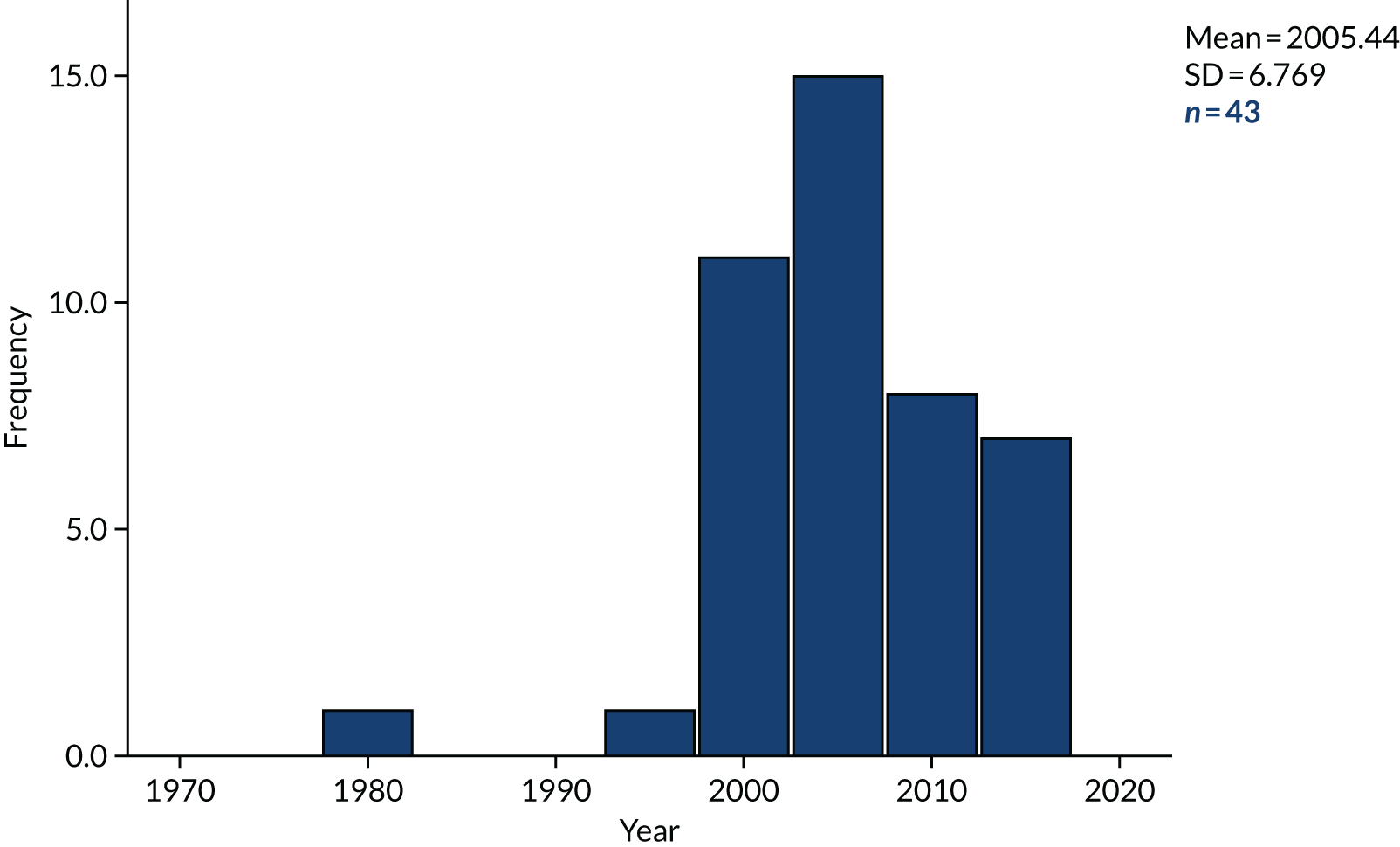

Figure 7 illustrates the pattern of publication dates of 118 of the records. Three records were undated training resources in which the context and content indicated that they fell within the inclusion criteria. The figure shows that there was a brief increase in publications in the late 1980s and a sharp increase from the mid-2000s. The latter increase coincides with a US-wide policy response83,84 to a series of newspaper reports published in 1998 in the Hartford Courant newspaper, highlighting deaths related to the use of restraint in mental health and learning disability facilities across the USA. 33,83,84

FIGURE 7.

Publication dates.

Characteristics of records

The 121 records were organised by format type. Study designs of evaluations and mapping records are summarised in Table 6. Over half of the records were published in academic journals (n = 61). Eighty (66.1%) of the 121 records were peer reviewed. The additional peer-reviewed sources included book chapters (n = 3),85–87 dissertations (n = 11)88–98 and conference proceedings (n = 5). 99–103 The other records comprised training resources (n = 12); newsletters (n = 6); professional magazines (n = 4); presentation slides (n = 4); websites (n = 3) and blogs (n = 2); and reports (n = 10), of which seven were for government departments (UK, Wales, USA), two were for training organisations and one was for a US health-care service provider. 104

| Record type | Number of records (N = 121), n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Peer reviewed | ||

| Academic journals | 61 | 50.4 |

| Book chapters | 3 | 2.5 |

| Dissertations | 11 | 9.1 |

| Conference proceedings | 5 | 4.1 |

| Other | ||

| Training resources | 12 | 9.9 |

| Newsletters | 6 | 5.0 |

| Professional magazines | 4 | 3.3 |

| Presentation slides | 4 | 3.3 |

| Websites | 3 | 2.5 |

| Blogs | 2 | 1.7 |

| Reports | 10 | 8.3 |

| Total | 121 | 100.0 |

Peer-reviewed sources

The 11 peer-reviewed sources that featured more than once appear in Table 7. The most frequently occurring single source was the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing.

| Peer-reviewed source | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing | 9 |

| Psychiatric Services | 7 |

| Residential Group Care Quarterly | 6 |

| Residential Treatment for Children & Youth | 6 |

| Dissertation Abstracts International | 5 |

| Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry | 4 |

| Chapters from same book | 3 |

| Dissertation unpublished/other | 3 |

| Journal of Family Violence | 2 |

| Journal of Psychiatric Practice | 2 |

| Research on Social Work Practice | 2 |

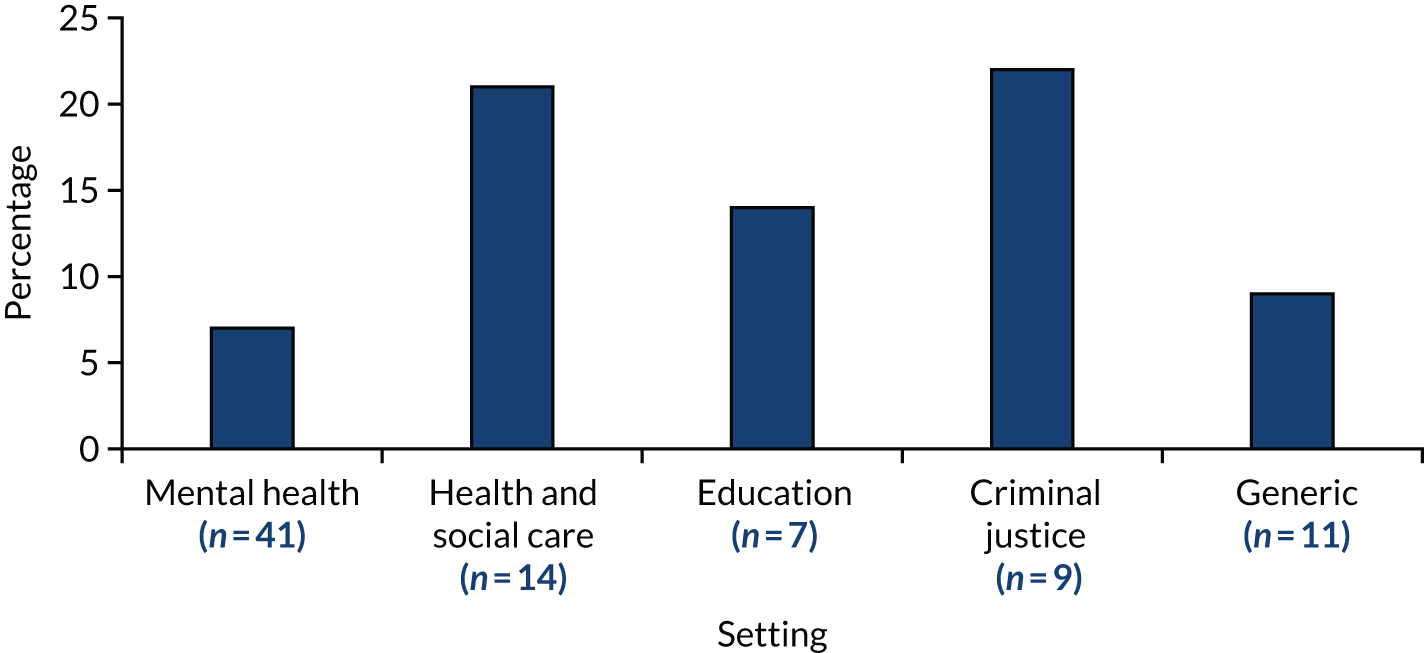

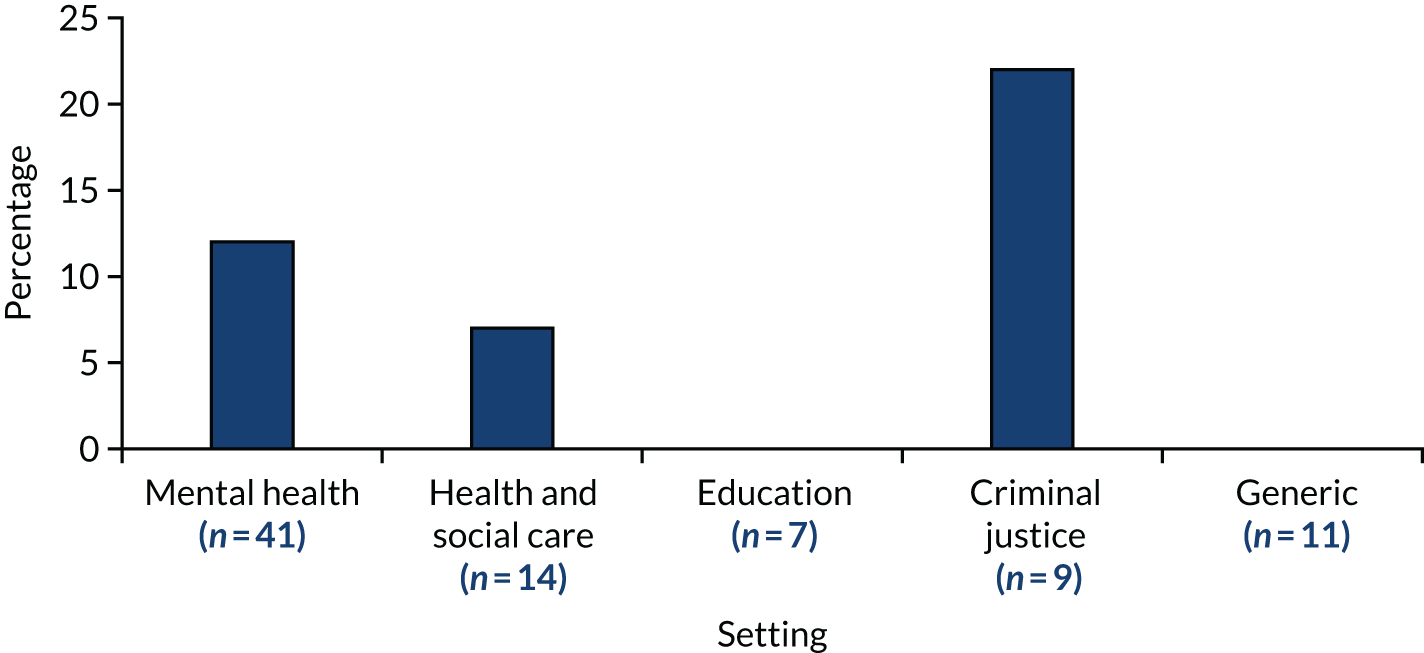

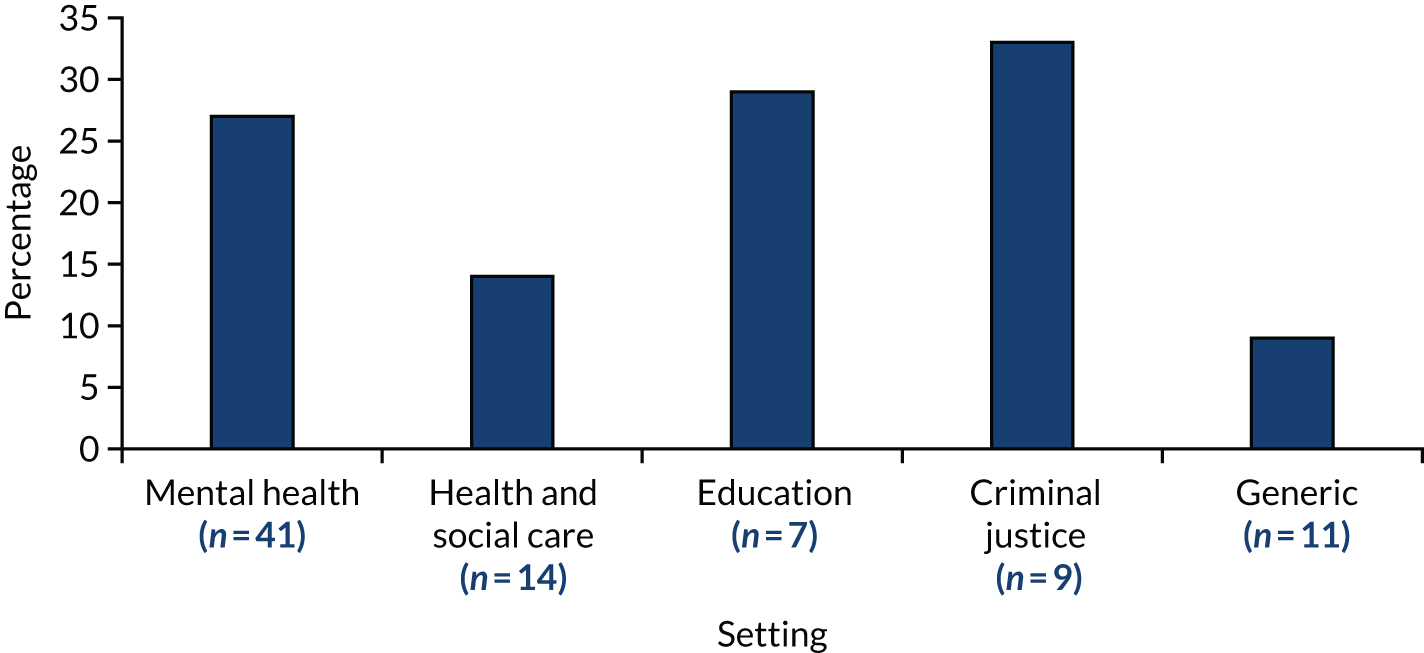

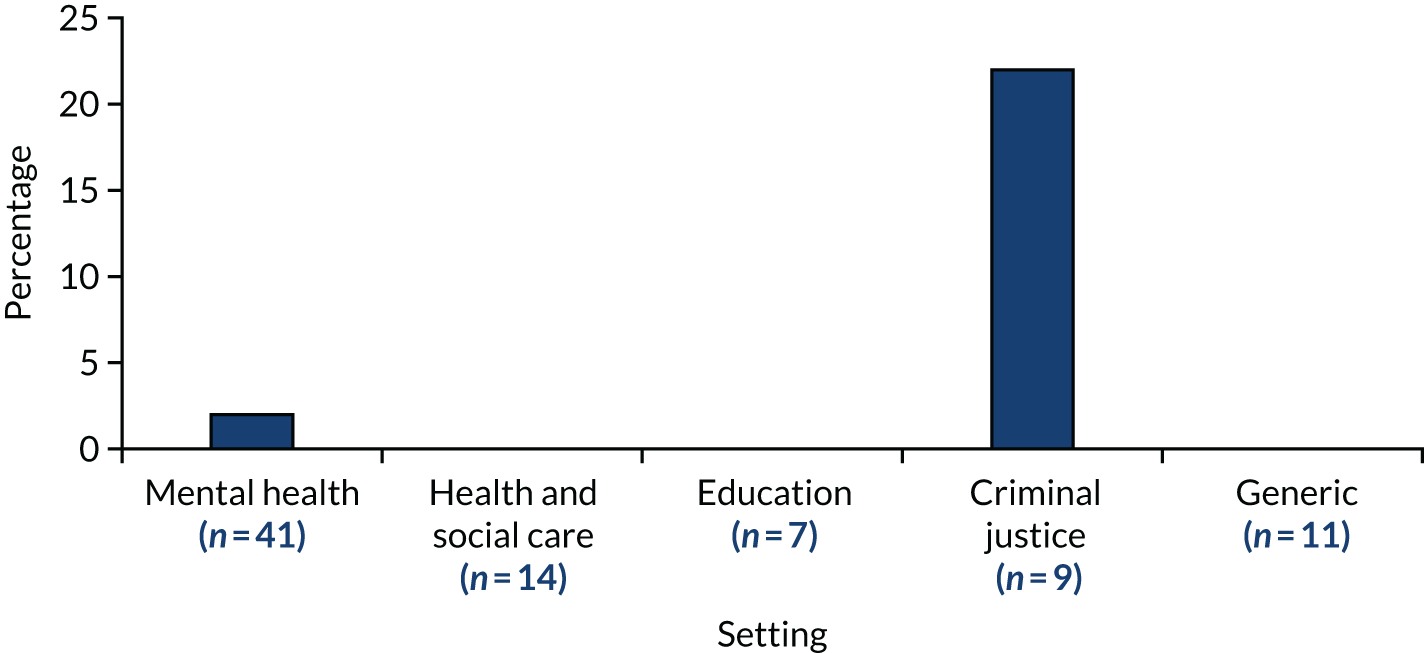

Service setting

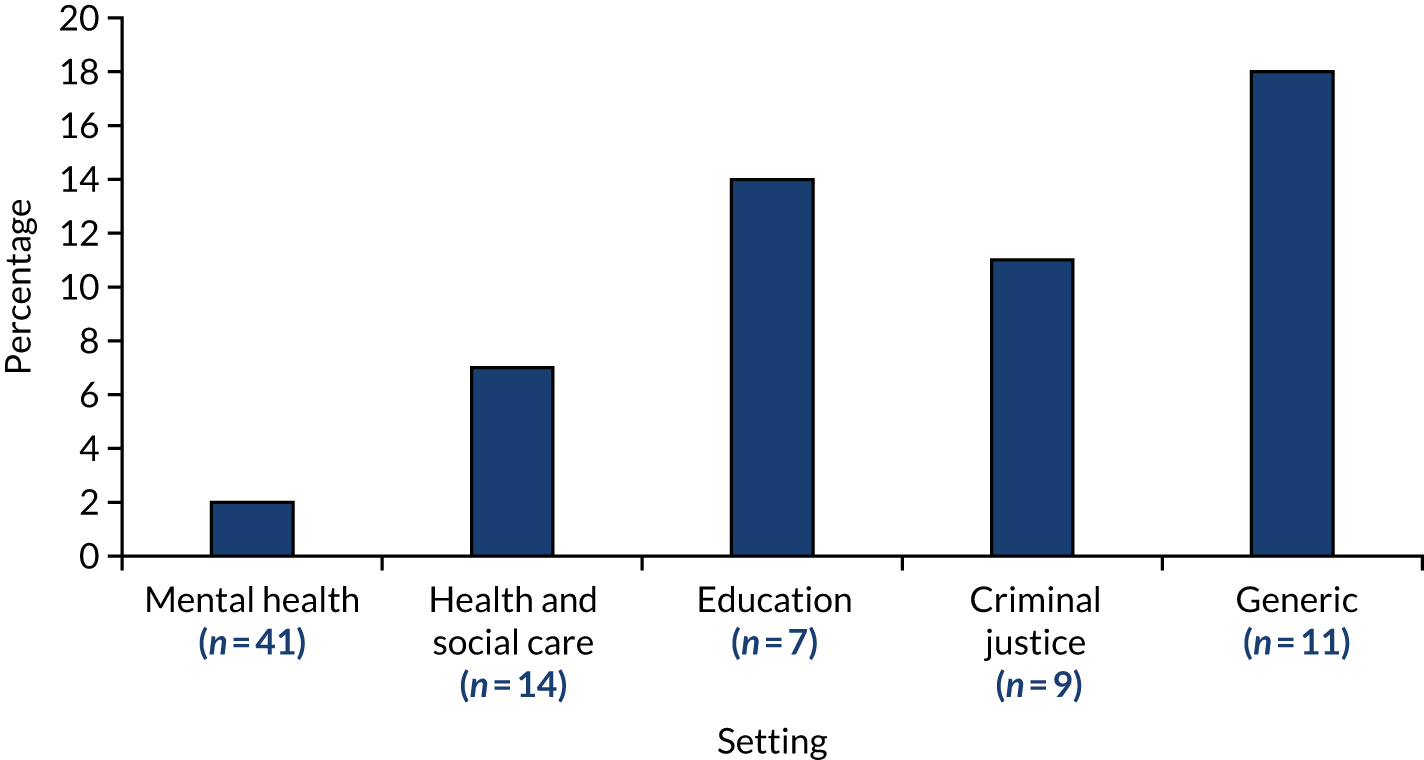

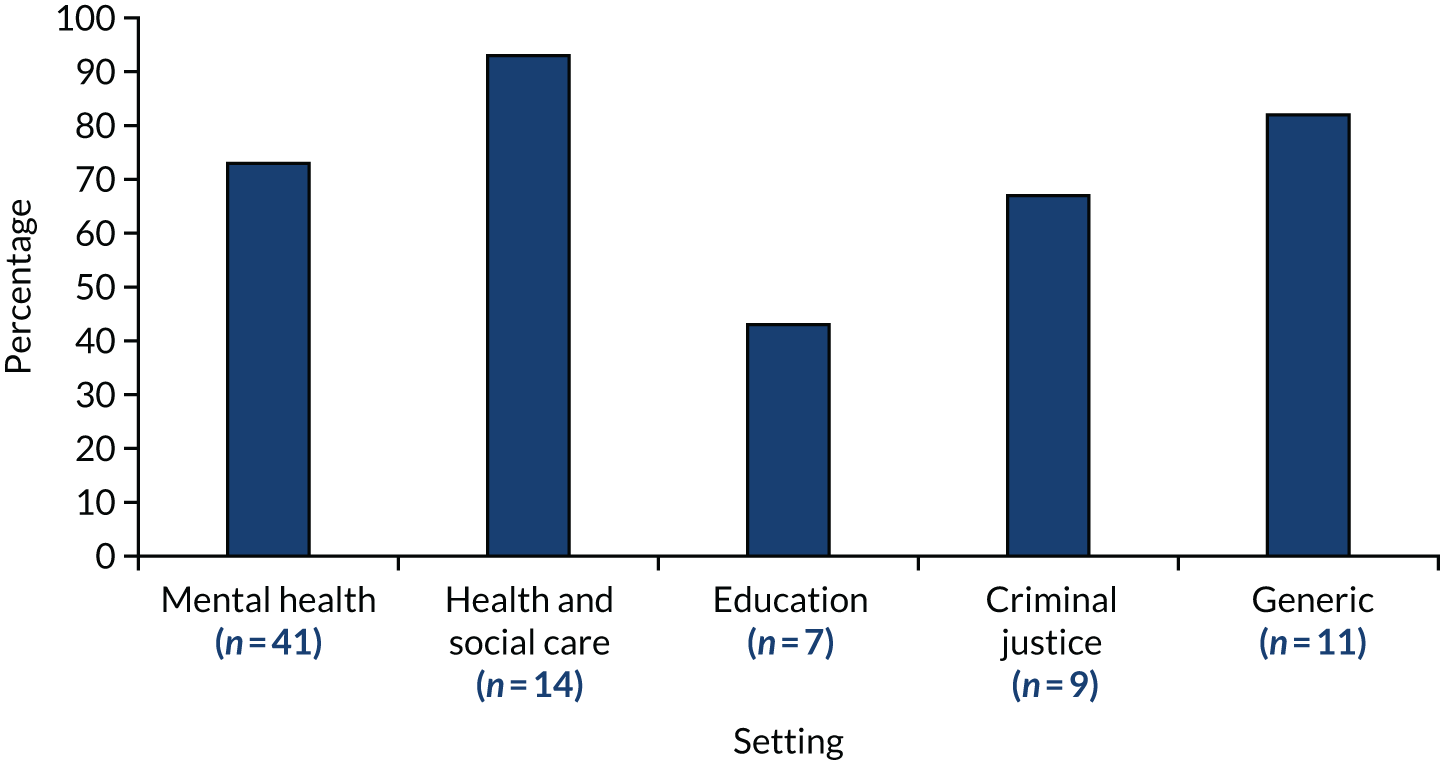

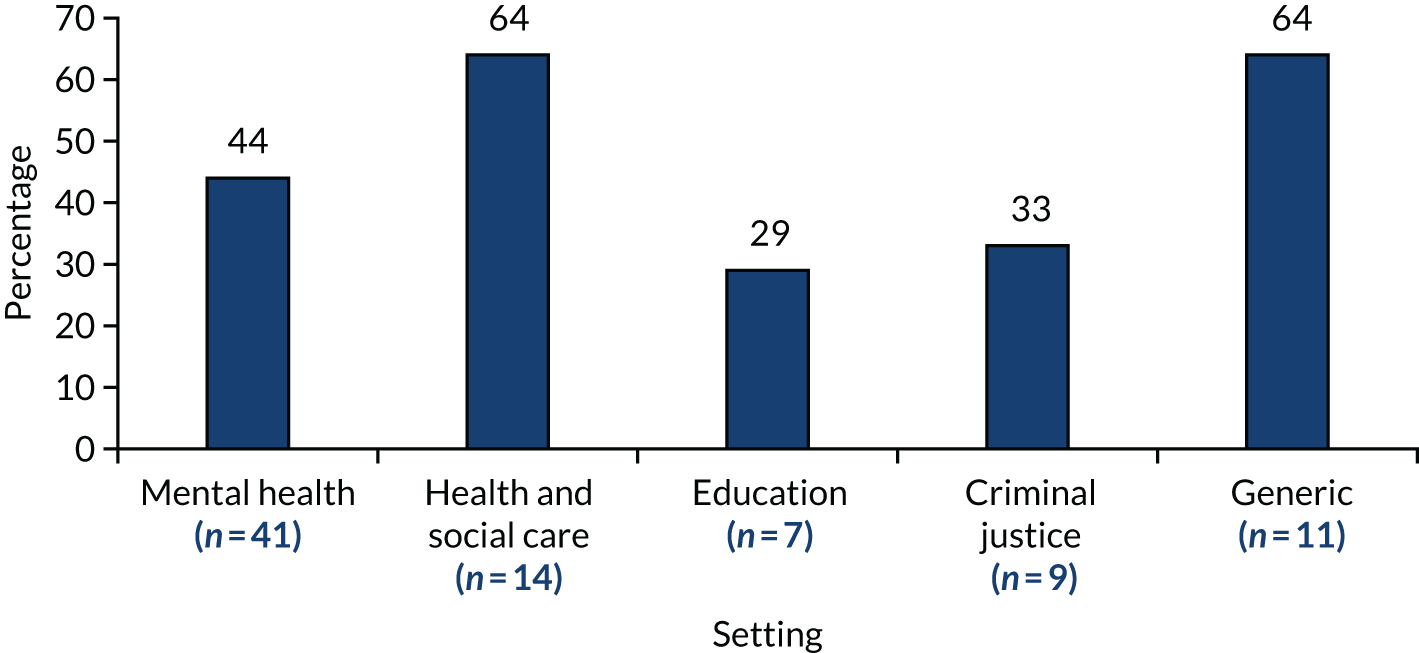

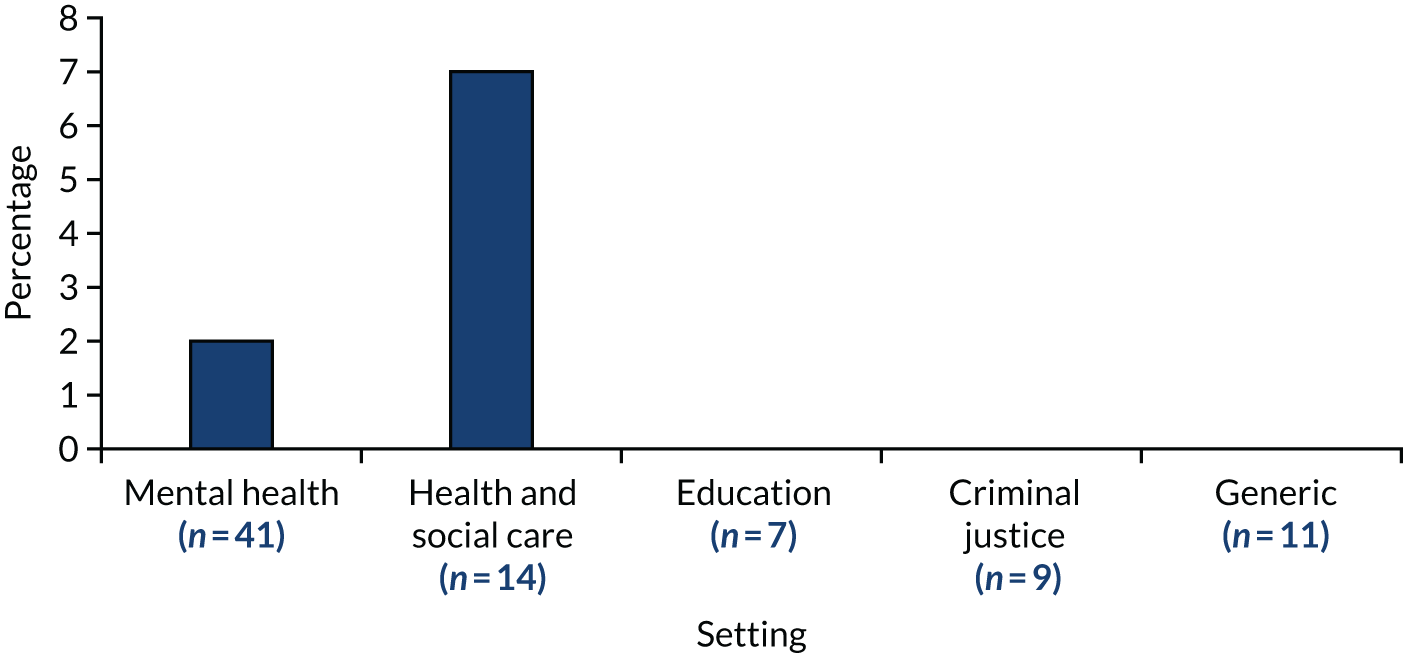

Just under half of the records (60/121) came from mental health settings. The other service settings were health and social care, criminal justice and education. Three evaluation records and 14 mapping records reported more than one setting within a single service and were categorised as ‘generic’ (Table 8).

| Setting | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health | 60 | 49.6 |

| Health and social care | 23 | 19.0 |

| Generica | 17 | 14.0 |

| Criminal justice | 11 | 9.1 |

| Education | 10 | 8.3 |

| Total | 121 | 100.0 |

Records and interventions by geographical setting

Records by geographical setting

The majority of records (87/121) reported evaluations or projects conducted in the USA. A further 21 were conducted in Europe and the remainder were conducted in Canada, Australia, Singapore or in more than one country. Three records did not report a location. The spread of geographical settings by record is detailed in Table 9.

| Country | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 87 | 71.9 |

| UK | 18 | 14.9 |

| Canada | 4 | 3.3 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 0.8 |

| Australia | 3 | 2.5 |

| Finland | 1 | 0.8 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 0.8 |

| France | 1 | 0.8 |

| Singapore | 1 | 0.8 |

| International | 1 | 0.8 |

| Total | 118 | 97.5 |

| Missing | 3 | 2.5 |

| Total | 121 | 100.0 |

Interventions by geographical setting

Only 2 of the 82 interventions had been applied in more than one country: Therapeutic Crisis Intervention (TCI) [UK, USA and one other intervention event (i.e. separate occurrences of the specific intervention) with an unreported location] and Modified Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (M-PBIS) (UK, Wales and USA). All other interventions that were applied more than once were implemented in the USA. These were the 6CS (n = 11 events), Collaborative Problem-Solving (CPS) (n = 7 events), comfort versus control (n = 2 events), the Grafton program (n = 2 events), Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET) (n = 2 events), and Devereux’s Safe and Positive Approach (SPA) (n = 2 events).

There were 74 ‘stand-alone’ interventions (i.e. were applied in a single event). They were often developed within and for a specific setting and were not necessarily given a name. Of these, 51 were delivered in the USA, seven in the UK, three in Canada, three in Wales (UK), three in Australia, two in international projects and one each in Finland, New Zealand, Singapore, the Netherlands and France. Therefore, in both range and quantity, the vast majority of interventions were applied in the USA.

Reporting of interventions

An ‘intervention event’ indicates an occasion on which an intervention was implemented. For example, an intervention implemented on two separate occasions generated two ‘intervention events’. The same intervention implemented on a single occasion generated one ‘intervention event’, regardless of the number of records reporting it.

Two records seemed to pertain to an ongoing programme,38,105 but there were no other follow-up or replication studies. Several interventions were reported in more than one record, for example Craig88 and Canady,106 including some instances in which the same intervention evaluation was reported in different formats, such as a dissertation and a published paper (e.g. CPS89,107 and the Grafton program88,108).

The intervention for which the most records were identified was the 6CS [n = 12 records, including five evaluations (journal articles) and seven mapping records, comprising one journal article, one magazine, one training resource, one set of presentation slides, two blogs and one implementation tool]. The next largest group of records (n = 9) pertained to CPS. This group consisted of evaluations only, and comprised four dissertations,90–93 one publication from a dissertation107 and four journal articles. 109–112

The eight remaining interventions were comfort versus control (two events), TCI (three events), the Grafton program (two events), CPS (seven events), M-PBIS (three events), TARGET (two events) and SPA (two events). Those interventions that featured more than once are shown in Table 10. All records of interventions in evaluation studies and mapping studies are listed by author in Appendix 4, and further details are given in Appendix 5.

| Intervention | Intervention events (n) | Where delivered | Evaluation records (n) | Mapping records (n) | Number of records |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6CS | 12 | USA | 538,77,104,113,114 | 733,105,115–119 | 12 |

| CPS | 9 | USA | 989,91–93,107,109–112 | 0 | 9 |

| Comfort vs. control | 2 | USA | 288,120 | 0 | 2 |

| TCI | 3 | UK, USA | 181 | 4121–124 | 5 |

| Grafton program | 2 | USA | 288,108 | 0 | 2 |

| M-PBIS | 3 | UK, USA | 2100,125 | 2126,127 | 4 |

| TARGET | 2 | USA | 2128,129 | 1130 | 3 |

| SPA | 2 | USA | 1131 | 1132 | 2 |

| Total | 32 |

Intervention aims

All interventions aimed to reduce restrictive practices, and most focused on achieving that by changing staff behaviour.

Intervention recipient

When the recipient was reported, all interventions were delivered to staff, with some also aimed at service users and/or introduced within a wider organisation or as milieu change. Seventy-nine intervention events targeted staff only, 13 targeted staff and service users, and two included staff and/or service users in the context of change in milieu (Table 11).

| Delivered to | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Staff | 79 | 73.8 |

| Staff and service users | 13 | 12.1 |

| Staff, service users and milieu | 1 | 0.9 |

| Staff and milieu | 1 | 0.9 |

| Total (excluding missing data) | 94 | 87.9 |

| Missing data (i.e. not reported) | 13 | 12.1 |

| Total | 107 | 100.0 |

Outcomes reporting

The 82 interventions described in the records reported a total of 228 outcome measures, with the number of measures described per record ranging from 0 to 11. The number of occasions when restraint was used was reported in 63 of the records, and the number of times seclusion was used was reported in 36 of the records. Other outcomes were reported in ≤ 11 records. Outcome measures are listed in Table 12.

| Outcome category | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Staff development and activity | Number of interventions |

| Intervention duration | |

| Number of behaviour plans in place | |

| Staff trained | |

| Staff knowledge/perceptions/attitude | |

| Use of restrictive methods | Mechanical restraint |

| Documentation of restraint | |

| Use of force | |

| Resource implications (financial and human) | Worker compensation |

| Injuries to all | |

| Patient progression and satisfaction | Patient satisfaction |

| Recidivism | |

| Number of elopements | |

| Client goal mastery | |

| Frequency of rule violation |

Outcomes categories

Outcomes reported were in four broad categories: staff development and activity, use of restrictive methods, resource implications, and patient progression and satisfaction (see Table 12).

Use of standardised outcomes measures

The reporting of standardised measures is shown in Tables 13 and 14. The range of measures reported per record was 0 to 7. In 106 of the records, no standardised measures were reported. One record129 reported the use of seven standardised measures to evaluate an intervention. In total, 22 different standardised outcome measures were reported across the 121 records.

| Number of standardised measures reported per record | Number of records |

|---|---|

| 0 | 106 |

| 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 |

| Measure | Number of times used in 121 records |

|---|---|

| CAFAS133 | 3 |

| CBCL134 | 2 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning135 | 2 |

| ADR92 | 1 |

| BASC-2136 | 1 |

| UCLA PTSD Reaction Index137 | 2 |

| CECI138 | 1 |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale139 | 1 |

| CAPE140 | 1 |

| Devereux Scales of Mental Disorder Manual141 | 1 |

| Freemantle Acute Arousal Scale142 | 1 |

| MAYSI-2143 | 1 |

| MFQ143,144 | 1 |

| Perceived Stress Scale145 | 1 |

| QOC measure146 | 1 |

| Self-report BDI147 | 1 |

| Self-report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders148 | 1 |

| Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire149 | 1 |

| The Generalised Expectancies for Negative Mood Regulation150 | 1 |

| The Ohio Scales151 | 1 |

| Toronto Mindfulness Scale152 | 1 |

| Trauma Events Screening Inventory153 | 1 |

Assumed change process and design principles

Fifty-two records reported mandatory participation in the interventions, including 31 records that described interventions involving a whole system, either across a whole organisation (e.g. a hospital) or in a self-contained unit (e.g. a section of a residential school). Nine records reported voluntary engagement in interventions, and in the remaining 60 records it was unclear whether engagement in the intervention was mandatory or voluntary.

Many studies lacked internal congruence, in that the relationships between the aims, intervention, mechanisms of change and reported outcomes were not necessarily clear. For example, reductions in restraint data occurring after a staff education intervention might be interpreted as an effect of the intervention, with little attention to potential confounding factors or fidelity. This point is noted in the literature. 40,112

Mandatory changes

Mandatory changes to services were reported in 50 out of 107 (47%) records of interventions, and a permanent change was described in 40 out of 107 (38%) (e.g. revised policies or protocols, changes to the care approach or changes to the physical environment). This was consistent with the tendency for records to report on changes to practice that were made and evaluated within a particular organisation, in contrast to introducing an intervention specifically to test it.

Reference to theory

There was some indication of the theory informing the intervention in 44 out of 107 records of interventions (41%), but without further details about what the intervention was, how it had been developed and how it was tested and refined. Many of the ‘quality improvement’ interventions used a ‘plan, do, study, act’ cycle, a mechanism to repeat and adjust interventions until they achieve the desired effect.

Some interventions made explicit reference to programme-level theories that had informed their intervention procedures, such as sensory modulation or trauma-informed care. Other programme-level theories cited sought to explain staff behaviour, service user behaviour, therapeutic relationships and organisational change. These studies often sought to test or modify not the actual theory, but rather the impact of using interventions based on the theories in relation to the reduction of restrictive practices.

The most frequently cited theory related to staff behaviour was social learning theory, used to support training interventions that sought to improve the self-efficacy of individual staff and staff teams.

Mode of delivery: intervention procedures

The intervention procedures are set out by theme in Table 15. The most common procedures focused on staff training. Other procedures related to guideline or policy change, risk assessment tools, data review, milieu changes and changes to therapeutic approach (e.g. introducing trauma-informed care, and staff involvement in intervention development).

| Theme | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Staff training | 16 | 57.1 |

| Guidelines or policy change | 3 | 10.7 |

| Risk assessment tools | 3 | 10.7 |

| Data review | 3 | 10.7 |

| Milieu changes | 1 | 3.6 |

| Changed approach (TCI) | 1 | 3.6 |

| Staff involvement | 1 | 3.6 |

| Total | 28 | 100.0 |

Staff-focused procedures

Staff-focused procedures were those that were aimed at and undertaken solely by staff, with a view to influencing staff use of restrictive practices. One dominant procedure was training, which could cover, among other topics, the use of a newly introduced resource (e.g. the ‘feelings thermometer’,154 aromatherapy155 or a sensory modulation room156); a strategy or therapy such as ‘restraint reduction meetings’,157 ‘deactivation therapy’158 or ‘milieu therapy’;159 or skills such as verbal communication. 160 Another staff-focused procedure was role modelling, which could involve supervision or mentoring (e.g. Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg104), and was seen in complex interventions that were encouraging changes to the culture, structure and/or values of a setting (e.g. Verret et al. ,161 Eblin162 and Dean et al. 163).

Alternative approaches

Compared with the companion review focused on adult mental health settings,47 there were more interventions involving non-medical or psychological approaches to reducing restrictive practices. These included sensory modulation via the installation of sensory or comfort rooms,156,164,165 aromatherapy155 and activities. 166,167

Incident-focused procedures

Other procedures were incident-focused, that is they were responses to incidents of restrictive practices. 89,105 These included incident review procedures, in which organisations (staff and managers) collected and monitored their incident data to establish baseline and progress rates to identify patterns for targeted intervention or to conduct retrospective audits. 23,115,117,168,169 In contrast to this whole-system review, debriefing was conducted immediately or soon after an incident (e.g. Magnowski and Cleveland80 and Leitch94).

Organisation-focused procedures

In addition, several organisation-focused procedures were identified. These were system-wide structural and cultural changes including making changes to staffing levels85,109,132,170 or the way staffing was organised. 80 Another procedure involved changing therapeutic approaches (e.g. to a trauma-informed approach78,171,172). This theme also included improvements to communication (e.g. Ercole-Fricke et al. 89 and Kalogjera et al. 173), community meetings102 and de-escalation. 161 Further procedures focused on policy change115,174 and leadership, in which senior management tended to be directly involved in meetings and made statements of commitment. 38,78,175

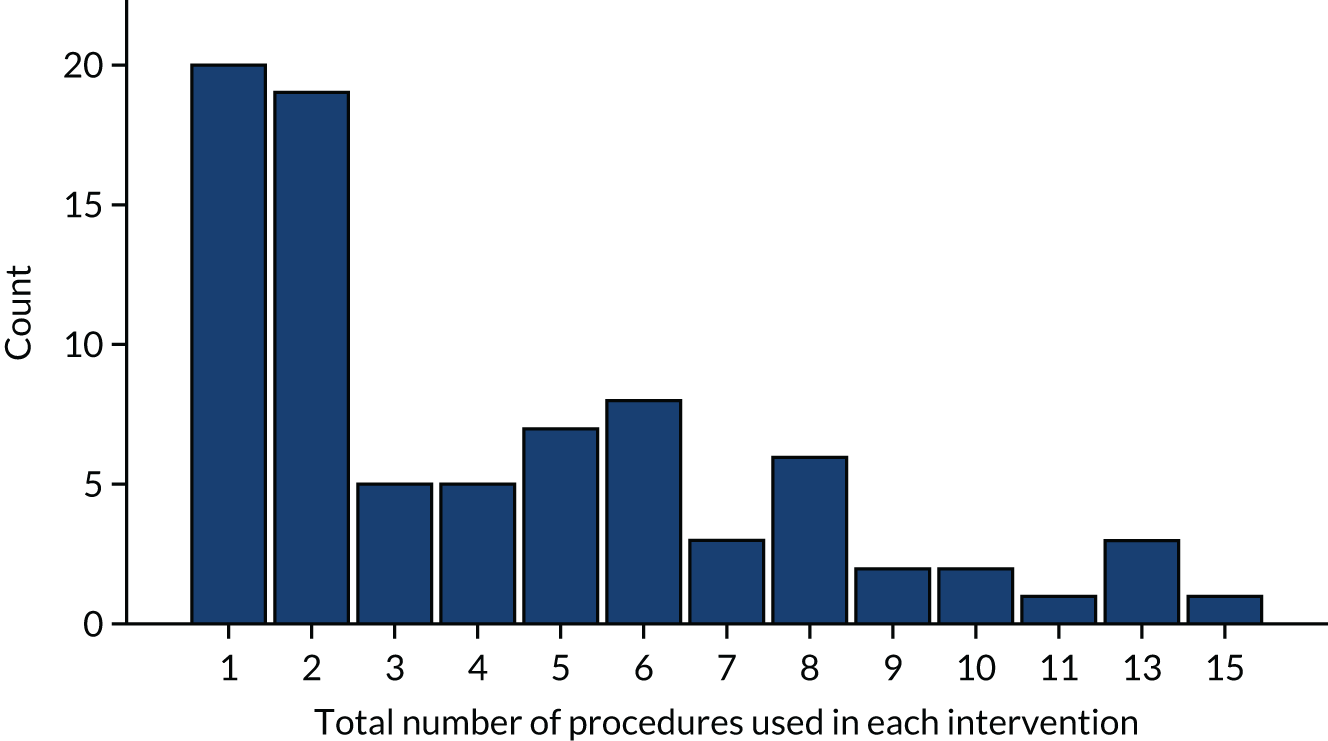

The extraction process highlighted the procedures used by each intervention to address restrictive practices. The maximum number of procedures found in a single intervention was 15. A total of 16 unique procedures were identified from the analyses (Figure 8). The average number of unique procedures reported per record was 4.28 (mean) and 3 (median).

FIGURE 8.

Count of unique procedures per intervention. Unique procedures across interventions, n = 16. Maximum number of unique procedures per intervention, n = 15.

Twenty interventions (24%) used a single procedure only, and the most common single procedure was staff training (Table 16). However, many interventions (n = 62) used more than one procedure.

| Procedure | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Training | 88 | 19.3 |

| Changed approach (e.g. TIC) | 58 | 12.7 |

| Guidelines or policy change | 44 | 9.6 |

| Data review | 36 | 7.9 |

| Care planning changes | 33 | 7.2 |

| Debriefing | 33 | 7.2 |

| Enhanced leadership | 30 | 6.6 |

| Risk assessment tools | 21 | 4.6 |

| Milieu changes | 20 | 4.4 |

| Environmental changes | 17 | 3.7 |

| Staff involvement | 17 | 3.7 |

| CYP involvement | 15 | 3.3 |

| Family involvement | 14 | 3.1 |

| Enhanced staffing | 13 | 2.9 |

| Activities | 9 | 2.0 |

| Sensory approaches | 8 | 1.8 |

| Total procedures reported | 456 | 100.0 |

Procedures used in interventions

The reporting on the procedures used in interventions was inconsistent and at times limited.

Reporting on procedures

Staff training was the most widely reported procedure, although reporting of details could be brief. In 84 out of 107 records of interventions, the total hours of training were not reported. Few reported the content, mode of delivery or training provider in any detail.

Staff training occurred in 88 procedures, making it the most frequently used intervention procedure across all interventions (including those using a single procedure and those using multiple procedures). The least often used procedures were activities (n = 9) and sensory approaches (n = 8). One intervention incorporated visits to other units. 94

Delivery of training

Where training was used it was delivered in house in 40 interventions (37%). Training providers were not reported in 58 of the records. Although 23 records reported that it was delivered by an external provider, there was little further detail. It appeared that where an intervention was a commercially available or copyrighted product, such as the 6CS, training was likely to be brought in as part of the package.

Table 17 illustrates the total number of hours of training provided. This varied widely, from 1 to 35 hours.

| Hours of training reported | Number of records reporting training time | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 2.0 | 2 | 1.9 |

| 3.0 | 4 | 3.7 |

| 4.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 7.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 8.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 15.0 | 2 | 1.9 |

| 16.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 19.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 21.0 | 2 | 1.9 |

| 24.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 28.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 30.0 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 35.0 | 3 | 2.8 |

| Total reported | 23 | 21.5 |

| Not reported | 84 | 78.5 |

| Total | 107 | 100.0 |

Service user involvement in interventions

Service user involvement in interventions development is recommended in the literature, but involvement was reported in only 16 records, and CYP’s involvement was reported in only 15 records. Service user involvement in interventions development was reported in only 9 of the 107 evaluation records. Across the records, this aspect of the intervention reporting lacked detail and so it was unclear as to the type and extent of the involvement (Table 18).

| Involvement | Number of records | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Involvement reported | 9 | 8.4 |

| Involvement not reported | 98 | 91.6 |

| Total | 107 | 100.0 |

Service user or family involvement was reported as an intervention component in the 6CS,38,105 and several stand-alone interventions, for example HM Government,30 Fralick176 and Nunno et al. 177

Intervention dose, duration and intensity

Many evaluations did not report details about the duration and intensity of the intervention. Partial details (e.g. overall duration of the intervention or of an individual component, usually training) were sometimes, but not always, provided. Often, the evaluation period and the duration of intervention implementation were not distinguishable. Similarly, the duration of individual intervention components was often not reported. With this proviso, interventions ranged in length from 3 months98,129 to 13 years. 120 Some interventions described providing stand-alone training sessions, whereas others were conducted over a short period of time (e.g. 1 week) or longer (e.g. several months). Some evaluations, for example that by Fralick,176 described ongoing training including refresher sessions or supervision.

Intervention materials

Interventions reported using various materials in the implementation of the intervention, including training materials, guidelines, multimedia resources, tools, posters, slides, and policies. Some referred to materials that are publicly available on the internet, such as:

-

Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS)

-

Cognitive milieu therapy

-

Modified Positive Behavioral Intervention Support (M-PBIS)

-

Six Core Strategies © (6Cs)

-

Therapeutic Crisis Intervention (TCI)

-

Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET)

-

Trauma Systems Therapy (TST).

Intervention evaluation

Evaluations were identified by scrutinising each report using the screening questions of the MMAT to ascertain whether or not a research question was described and whether or not the data required to answer the question had been collected. Those reports that passed the screening were then appraised, again using the MMAT. The MMAT prompts an appraisal of if qualitative methods are appropriate; if the data collection methods are adequate, and the findings and their subsequent interpretations are sufficiently reported; and if the study has overall coherence. Evaluations are detailed in Appendix 5.

As seen in Appendix 5, there are more evaluation data about the 6CS and CPS than about any of the other interventions reported or described in the 121 retrieved records. Although the 6CS is more frequently reported, only 5 of the 12 6CS records are evaluations, as defined by the WIDER criteria. In comparison, there are nine separate implementations of CPS, all evaluated. The 6CS evaluations span 10 years, from 2007 to 2017, and the CPS evaluations span 8 years, from 2008 to 2016. Therefore, over a similar timespan, 6CS has been used more but evaluated less than CPS. This suggests that intervention use is not routinely generating evaluation data, and that intervention choice may not be informed by evaluation data.

Reporting on the design of evaluation studies

Evaluation design was often not described, and when it was reported a variety of terms were used. Accordingly, design had to be inferred from other study details in some cases. When study design was described, no RCTs were identified, and only around one-third of the records (36/121) reported quantitative data. Details of evaluation study design are provided in Appendix 6.

As reported in Table 7 and Appendix 6, most evaluations were non-randomised studies. Only eight were controlled. Twenty-two generated quantitative data only, and five generated both quantitative and qualitative data. The great majority of the quantitative studies compared counts or rates of restrictive practices before and after a period of intervention implementation.

All evaluations were considered to have recruited participants who were representative of the target population and used suitable outcome measures. Several were not considered to have reported complete outcome data and few discussed confounders, with some exceptions that were principally reflections on the challenges of evaluating complex interventions, for example the evaluation by LeBel et al. 40 There was very little reporting of modifications and fidelity to the intervention protocol, with only 12 evaluations reporting this.

Twenty-one quantitative studies were identified. There were several evaluations of cultural or organisational change that took a systems approach and presented qualitative data. Some of these focused on process (e.g. Fralick176 and Elwyn et al. 178) and others focused on outcomes (e.g. Eblin162). A number of stand-alone interventions incorporating system change were presented as case studies (e.g. Thompson et al. 87 and Fralick176).

A common approach to evaluation was to compare counts or rates of restrictive practices before and after an intervention (e.g. Huckshorn77). However, causal links were rarely explored in the reports despite the prevalence of multicomponent interventions.

Reporting on setting size and sample size

There were two main approaches to describing the size of the setting in which the intervention was conducted. Some reported setting size in terms of the number of beds (n = 25) and others in terms of the size of the service user population (n = 15). The size of the setting varied greatly in both cases, from 7 to 925 beds (mean 65.32) and from 27 to 5600 service users (mean 475.53).

Likewise, sample size was reported in diverse ways, including numbers of service users, patient-days, admissions, beds and staff. Number of service users was the most common (n = 30) way to report sample size, and service user-days (n = 2) and beds (for health settings) (n = 2) were the least common (Table 19).

| Basis of sample size calculation | Number of studies | Sample size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | ||

| Patient-days | 2 | 279 | 1000 | 639.50 |

| Admissions | 5 | 65 | 1485 | 621.20 |

| Beds | 2 | 23 | 52 | 37.50 |

| Staff | 10 | 13 | 340 | 93.20 |

| Service user-days | 30 | 3 | 6361 | 486.97 |

Year of evaluation

As seen in Figure 9, starting in the mid-1990s, the number of evaluations that were commenced suddenly increased compared with the previous decade. Evaluations published prior to 1989 were not eligible for inclusion in the review. The commencement of evaluations appeared to then decrease steadily from the mid-2000s.

FIGURE 9.

Year evaluation commenced.

Outcome measures in evaluations

Seventy-one outcome measures were reported (mean 3, range 0–9 outcome measures). The most common outcome measure was the number of restraints, followed by duration of restraint, number and duration of seclusions, number of injuries, number of incidents and length of stay. Injuries to staff was an outcome measure in three evaluations and injuries to all was an outcome measure in eight. No evaluation specifically used injuries to service users as an outcome measure, although two counted the service users involved in an incident (Table 20). For standardised outcome measures identified in the evaluation, see Table 14.

| Outcome measure | Number of studies | Percentage | Percentage of studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of staff trained | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Patient satisfaction | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Number of care plans in place | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Service user goal mastery | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Staff compensation | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Rule violation | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Use of force | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Number of observations | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Use of sensory room | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Discharge of placement | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Quality of restraint | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Number of accidents | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Number of errors | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Staff sick leave | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Security use | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Service user mood | 1 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Staff knowledge | 2 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Use of mechanical restraint | 2 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Duration of interventions | 2 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Number of service users involved in incident | 2 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Staff turnover | 2 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Number of interventions | 3 | 1.8 | 4.7 |

| Staff injury | 3 | 1.8 | 4.7 |

| Culture change | 3 | 1.8 | 4.7 |

| p.r.n. | 4 | 2.5 | 6.3 |

| Length of stay | 6 | 3.7 | 9.4 |

| Duration of seclusion | 7 | 4.3 | 10.9 |

| Injuries all | 8 | 4.9 | 12.5 |

| Incidents | 9 | 5.5 | 14.1 |

| Duration of restraints | 10 | 6.1 | 15.6 |

| Number of seclusions | 30 | 18.4 | 46.9 |

| Number of restraints | 53 | 32.5 | 82.8 |

| Total | 163 | 100.0 | 254.7 |

Several interventions used existing routinely collected data for their evaluations, such as archived data and incident reports. Some evaluations developed measures for the purposes of their evaluation, whereas others developed or adapted tools to collect data.

Reporting on use of measures in interventions

Standardised outcome measures were reported to have been used in 14 interventions, with a minimum of one and maximum of seven per evaluation (details are provided in Table 15). The measures used more than once were the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale133 and Global Assessment of Functioning. 135

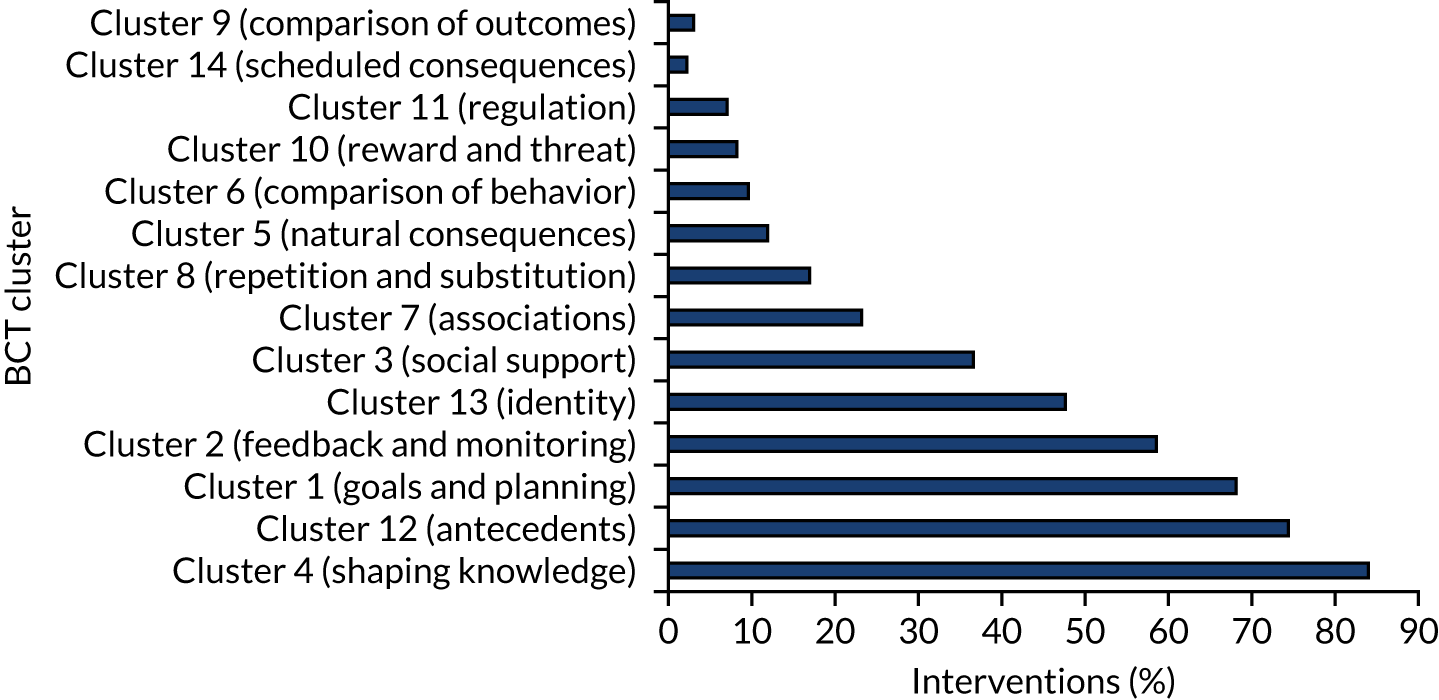

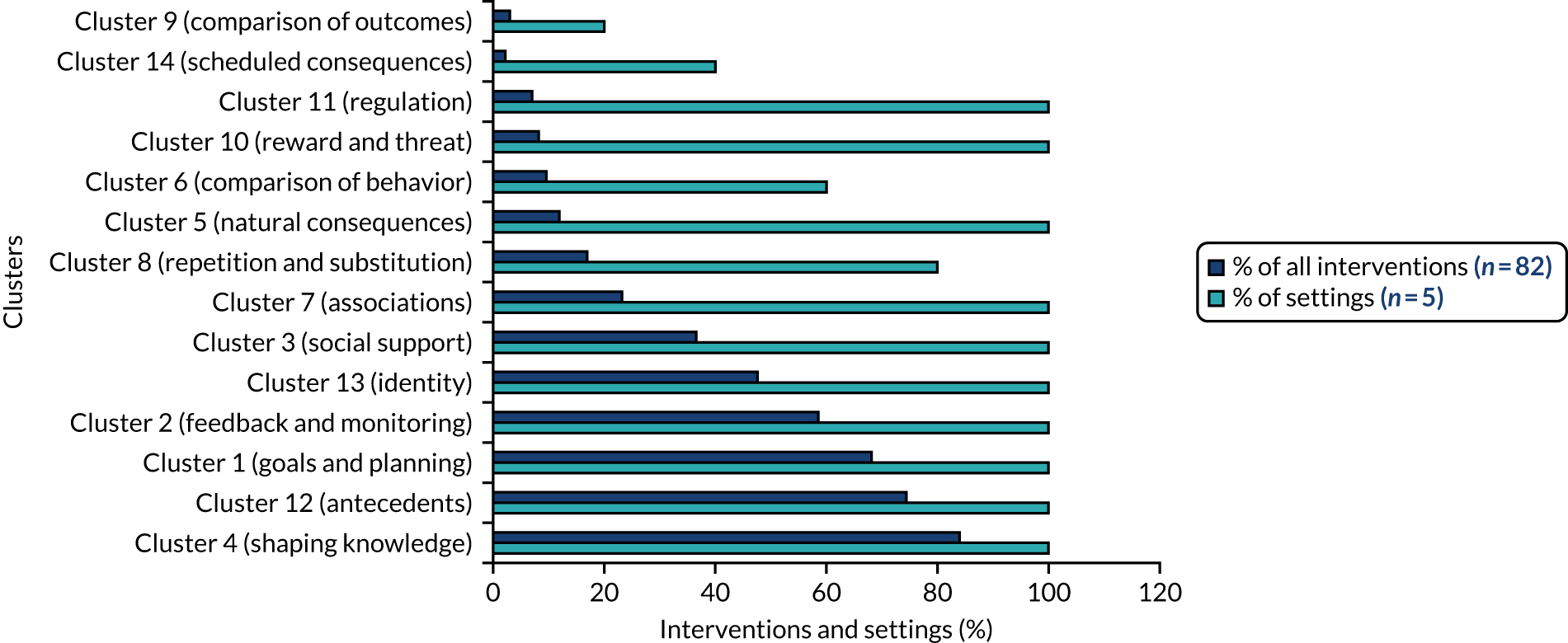

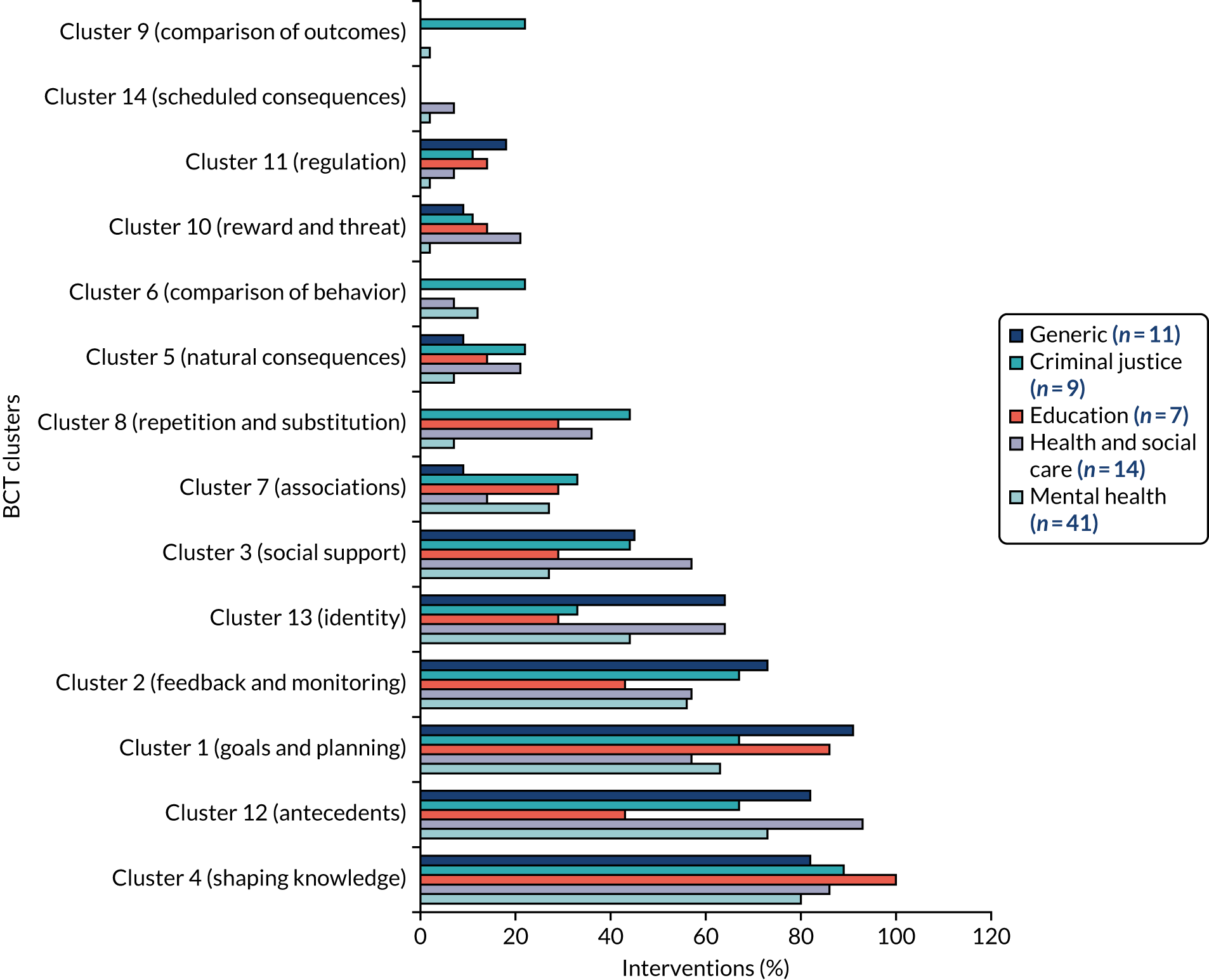

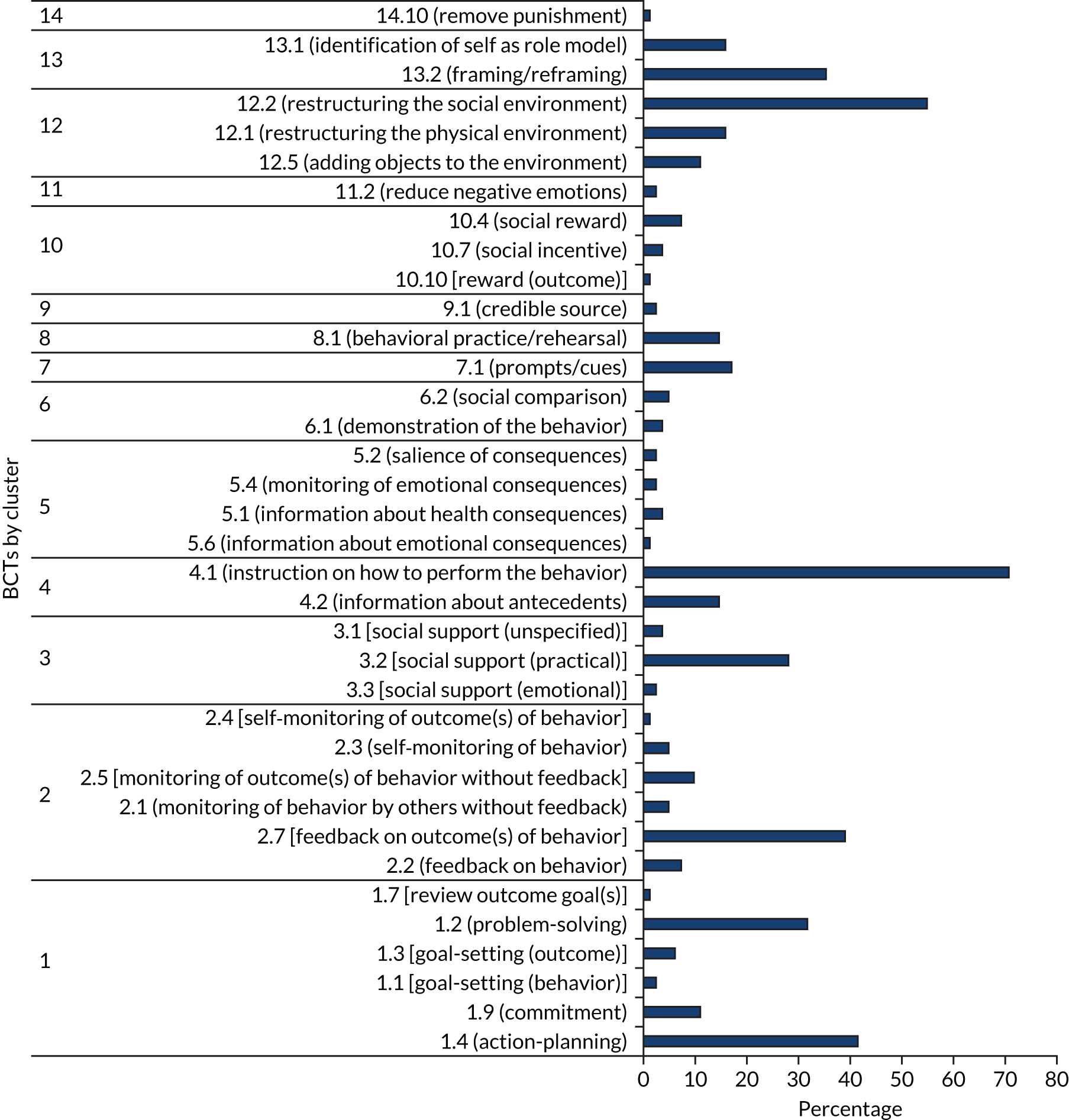

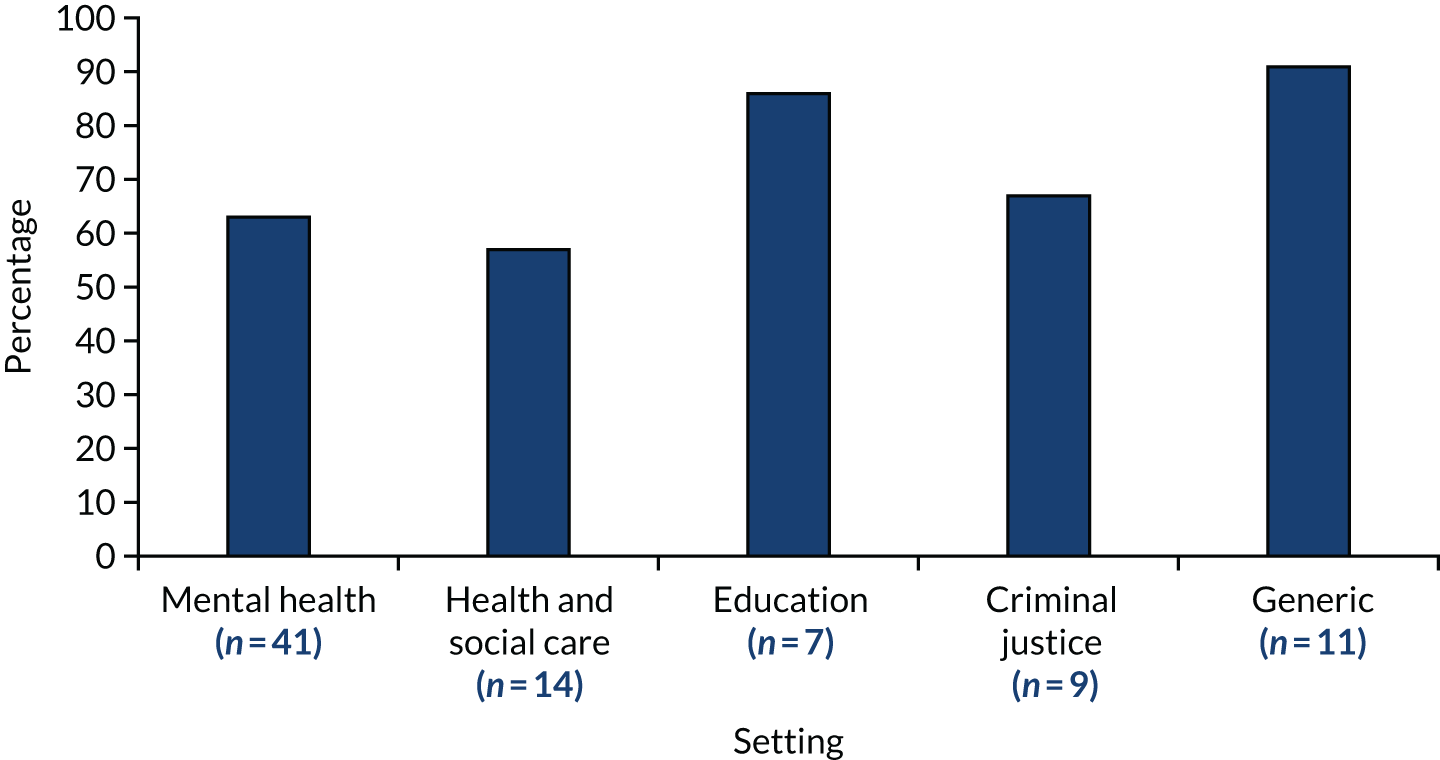

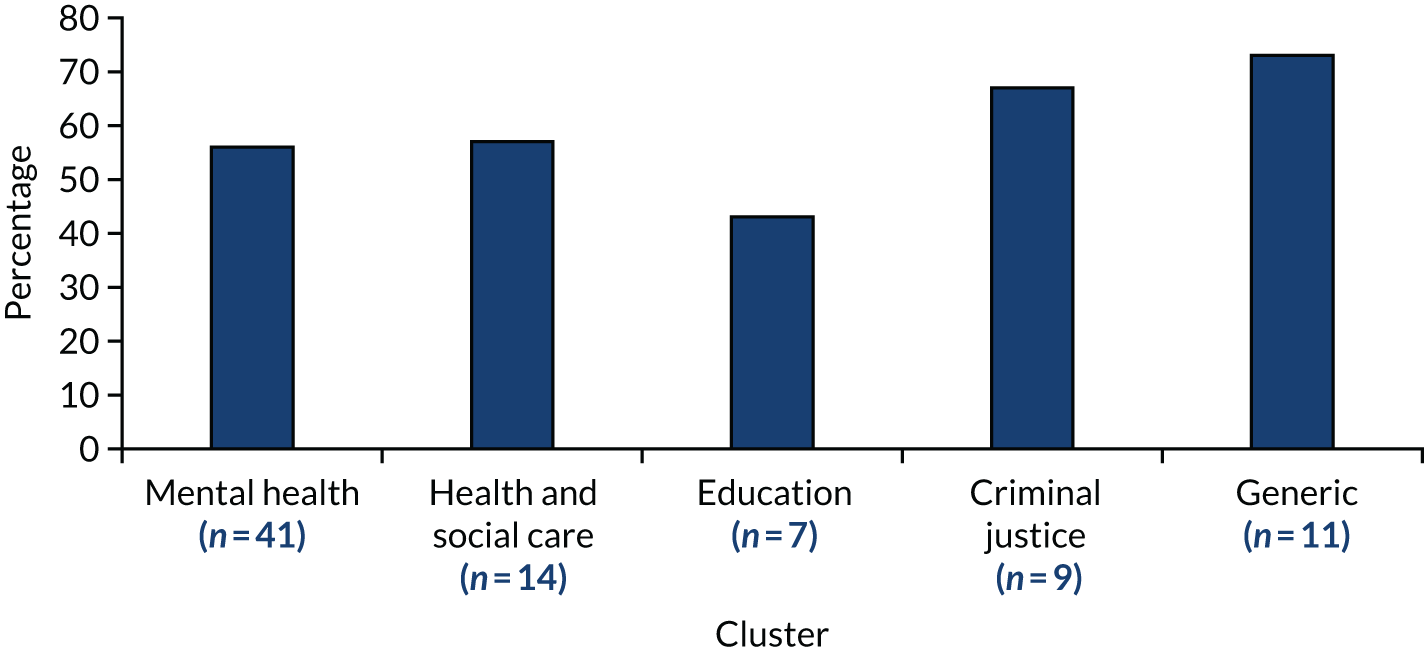

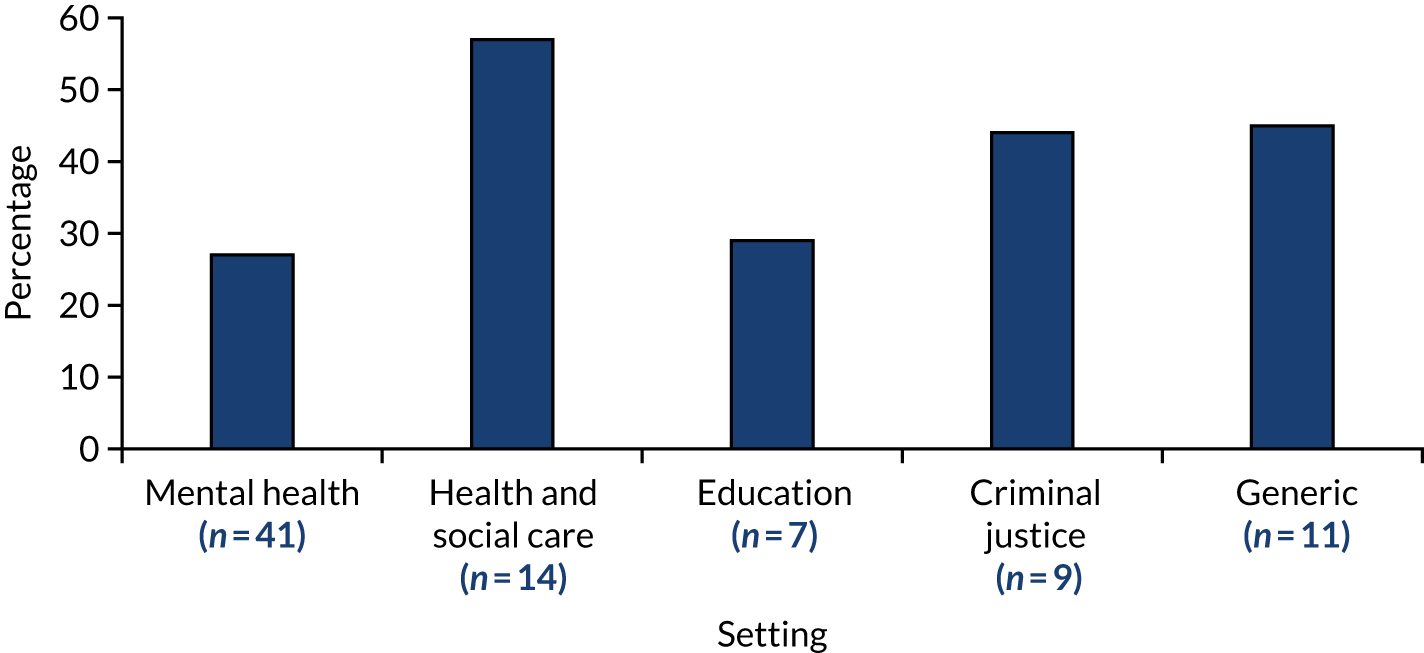

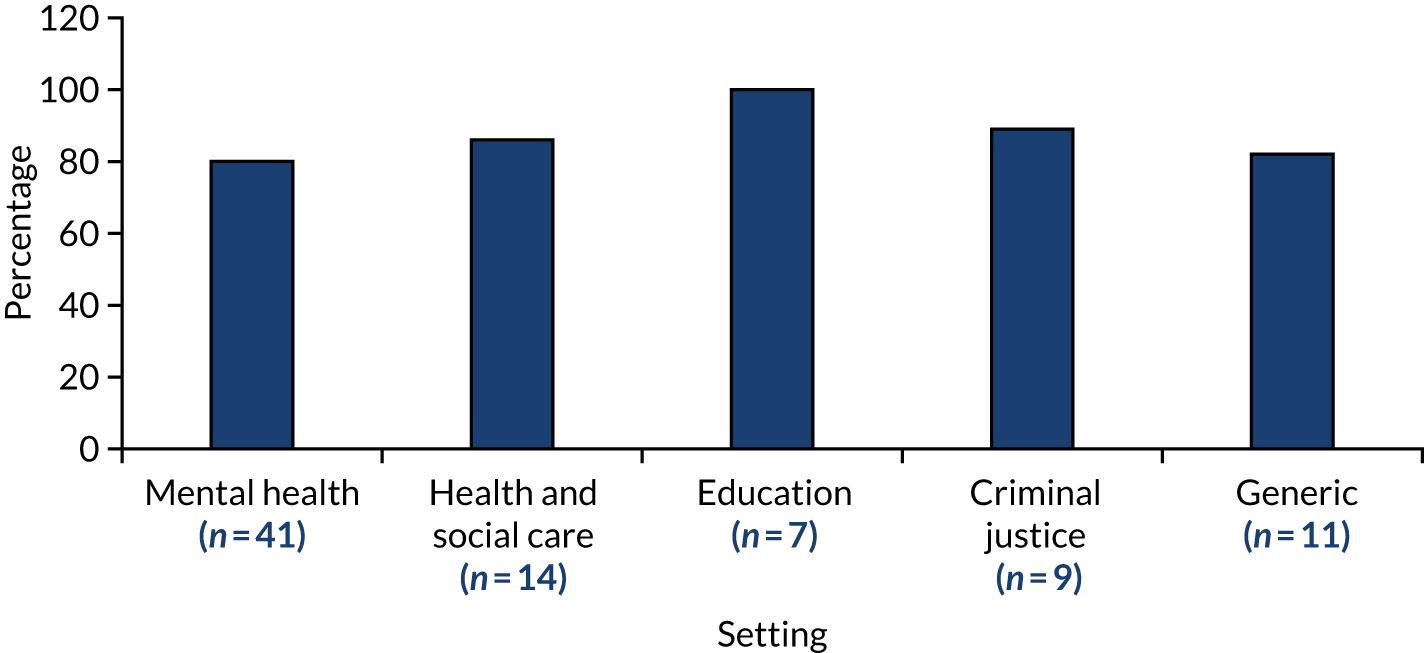

Reporting on evaluation findings