Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/08/25. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The final report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in November 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 McDermott et al. This work was produced by McDermott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 McDermott et al.

Chapter 1 Background and literature

Introduction

This chapter explores both the policy background and what is known from the literature about skill mix change in primary care. First, we explore the policy context in the UK at present, setting out the policy drivers at work and the assumptions underlying the policy solutions proposed. Second, we conducted a scoping literature review to explore what we know from the international literature about these assumptions and the implementation and impact of skill mix.

The workforce crisis in general practice in England

The current workforce crisis in general practice has been described in terms of a shortage of general practitioners (GPs), which is creating unsustainable GP workload pressures. It is claimed that heavy workloads for a limited supply of GPs are exacerbated by increasing complexity of patient caseloads due to frailty amongst an ageing population, population growth and declining NHS investment. In addition, a desire among new GPs for a better work–life balance, reticence about business risks associated with the partnership model and pension caps can further deplete the workforce through decisions to reduce time commitments and retire early.

Alternative approaches to managing demand in primary care range from self-care and team-based care to online consultations and the use of artificial intelligence to improve problem-screening, diagnosis, treatment and monitoring. 1–5 In recent years, attention has also focused on changing the skills and occupational mix of the general practice workforce through the employment of practitioners from a wide range of health-care disciplines to assist limited numbers of GPs in keeping pace with population growth and the changing health-care needs of an ageing population. 6

It has been observed that what has been framed as a shortage of doctors is a demand–capacity mismatch, which needs to be addressed by increasing the supply of staff able to deliver primary care. 6 However, it has been estimated that current strategies to increase GP recruitment will fall short of government targets and will not be sufficient to address demand. 7–9 Therefore, this recruitment and retention difficulty raises concern that primary care services could reach saturation point unless additional workers are employed to undertake some of the work that is traditionally carried out by GPs.

A national vision for a transformed NHS based on new models of care was set out in the NHS Five Year Forward View in 201410 and refreshed in 2017. 11 Both the NHS Five Year Forward View and the Primary Care Workforce Commission report12 [i.e. a report by an independent commission established by Health Education England (HEE) in 2014] recommended that primary care services be redesigned to support the development of multidisciplinary teams of highly skilled health-care staff. 10–12 The details are set out in the General Practice Forward View (GPFV), which was published in April 2016. 13 The GPFV proposed the creation of a minimum of 5000 new non-medical roles in general practices in England where ‘wider members of the practice-based team will play an increasing role in providing day-to-day coordination and delivery of care’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 13 This model is further endorsed in a report by the House of Lords Select Committee on the long-term sustainability of the NHS in 2017. 14

These recommendations are reflected in ‘skill mix’ changes in primary care, as the proportion of non-GPs to GPs in the workforce has been increasing in recent years. 15 Understanding the effects of these workforce changes requires clarity on what it means to change skill mix in general practice, what factors affect the uptake of skill mix and the impact of skill mix on health outcomes and costs.

Definition of skill mix and a framework of possibilities

There are variations in the meaning attributed to the term ‘skill mix’. Skill mix has been used in the literature to refer to the range of competencies possessed by an individual health-care worker, the senior (supervisory) staff to junior (supervised) staff ratio within a particular discipline or the mix of different types of staff in a team/health-care setting. 16

Conceptualising skill mix can be difficult because it cannot be considered in isolation from the broader organisational and health-care system contexts in which people work, or from other concurrent policy initiatives and organisational developments. 17 Therefore, there is a need to consider contextual factors that influence skill mix, which are often neglected in the literature. 17–20

Using skill mix change to address a demand–capacity imbalance would require tasks to be reallocated from GPs to non-GPs. Task reallocation refers to ‘a broad spectrum of shifting tasks and responsibilities, ranging from minimal delegation to complete substitution and also the introduction of complementary care’. 21 Therefore, skill mix changes can be seen to be occurring at both the role level and the service interface level and, as such, have been described as involving enhancement, substitution, delegation and/or innovation. 16 Two studies (a recent review of skill mix change and a qualitative comparison of three 'new' non-medical roles, which features skill mix change) have enabled further clarification and refinement of these categories of skill mix changes. 22,23 These studies suggest an overlap and a mixing of objectives in the four changes mentioned above (i.e. enhancement, substitution, delegation and/or innovation). Instead, it is suggested that enhancement and innovation should be seen as expressing different aspects of change from those related to delegation and substitution. Likewise, it is suggested that substitution is also discussed in relation to supplementation.

Of the four changes identified above, enhancement and innovation most clearly delineate the means through which skill mix can change. For example, nurses may extend their skills and lead clinics (i.e. enhancement). At the same time, the introduction of physiotherapists trained to deliver first-contact physiotherapy in general practices is an example of skill mix change through innovation. Likewise, delegation and substitution most accurately describe how skill mix change has led to task transfers between occupational groups. For example, nurses act as non-medical prescribers, enabling this core GP task to be transferred to nurse prescribers without supervision (i.e. substitution). Tasks can also be transferred to those who require supervision (i.e. delegation); for example, GPs may transfer tasks to physician associates (PAs) or health-care assistants (HCAs). Last, it is necessary to make a distinction between substitution and supplementation. Substitution implies explicit full substitution of a GP by an alternative (non-GP) practitioner, whereas studies indicate that general practices often aim at supplementing GPs to extend the range of services to patients. 24

The next section indicates how skill mix has changed over time in general practice, thereby contextualising the most recent workforce changes.

Skill mix changes in general practice in the UK

Since the introduction of the NHS in 1948, GPs have been contractually committed to providing primary and personal medical care for every patient on their registered list. Traditionally, many GPs worked in small or single-handed community-based practices, in contrast to consultant physicians and surgeons working in hospitals. They were seen as ‘gatekeepers’ because they select which patients to refer to specialist services available through hospitals or other health and social care services.

In 1966, doctors’ dissatisfaction over pay and conditions in the NHS led to a revised GP contract whereby GPs could be reimbursed for 70% of the cost of employing ancillary staff. 25 This led to the first skill mix change through innovation, that is, the rapid employment of practice nurses to carry out basic nursing tasks, such as recording health screening measurements, dressing wounds and administering injections. 26

General practitioner contract changes in 1990 and 2004 led to enhanced roles for general practice nurses in managing long-term conditions, such as diabetes, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as health promotion. 27 Although general practice has remained predominantly staffed by doctors and nurses, subsequent enhancement of nursing roles has enabled the transfer of tasks through a mixture of delegation and substitution. General practice nurses are now involved in broader aspects of patient care, such as minor surgical procedures, the treatment of minor injuries, health screenings, family planning, giving lifestyle advice and running vaccination programmes. 28 In addition, some nurses have undertaken training in the diagnosis and management of undifferentiated cases, developments now recognised in the role of advanced nurse practitioners (ANPs). 29 The employment of HCAs in general practice has also enabled the transfer of former nursing tasks through delegation. 30 HCAs are usually locally trained staff, with no standard training programme or agreed scope of practice. HCAs are not regulated and they perform their roles under the supervision of registered professionals.

Policy context underpinning skill mix changes in general practice in England

Although changes to skill mix in UK primary care have been happening gradually for some time, it is only in the past 5 years that policy has explicitly addressed this issue. Understanding how skill mix is perceived and implemented is vital to understanding the policy-drivers and mechanisms being put in place to realise the policy. To do this, we analysed the GPFV and the Network Contract Directed Enhanced Services (DES). 13,31 This analysis identified both the mechanisms that have been put in place and the outcomes expected from the implementation of employing additional roles in general practice.

The GPFV (published in April 2016) commits to an extra investment of £2.4B a year by 2020/21 to support general practice workforce expansion, moving from the two traditional occupational groups (i.e. GPs and nurses) to a more diverse and multidisciplinary workforce. 13 The programme also proposes investment to support a minimum of 5000 other staff working in general practice by 2020/21. In 2018, the government announced additional funding of £20.5B by 2023/24, and The NHS Long Term Plan (published in January 2019) sets out key ambitions for the next 10 years. 32 The ‘plan’ proposed a new service model with £4.5B of new investment to fund expanded community multidisciplinary teams aligned with primary care networks (PCNs). The PCNs were to be formed by general practices working together to deliver ‘fully integrated community-based healthcare’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0) for 30,000–50,000 people. 32 The implementation plan for this is set out in the Interim NHS People Plan (published in June 2019)33 and the subsequent We are the NHS: People Plan for 2020/21 (published in July 2020). 34

Although a gradual increase in the employment of non-GPs by general practices has preceded the formation of PCNs, these networks have become important as one of several mechanisms to increase skill mix and improve the recruitment and retention of doctors and nurses by the employment of additional primary care staff through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS) (with the investment of £891M). Through the Network Contract DES, which is an add-on contract to the existing General Medical Services (GMS) contract, network member practices are contracted to deliver seven national service specifications and are expected to achieve locally agreed schemes. 35 Five roles were initially selected: (1) clinical pharmacists (CPs), (2) PAs, (3) paramedics, (4) physiotherapists and (5) social prescribers. The focus on these five roles was based on the availability of practitioners, on the strength of practice demand and on confidence that these newer roles can reduce GP workload and create additional capacity.

Based on the historical ‘success’ of a 70% reimbursement of staff costs model in establishing roles for nurses and receptionists under the Charter for General Practice in 1965,25 a similar model was initially proposed under the ARRS for PCNs (i.e. 70% reimbursement to support staff employed in newer roles). From April 2020, the reimbursement has increased to 100% and a further six roles have been added: (1) pharmacy technicians, (2) care co-ordinators, (3) health and well-being coaches, (4) dieticians, (5) podiatrists and (6) occupational therapists. 36

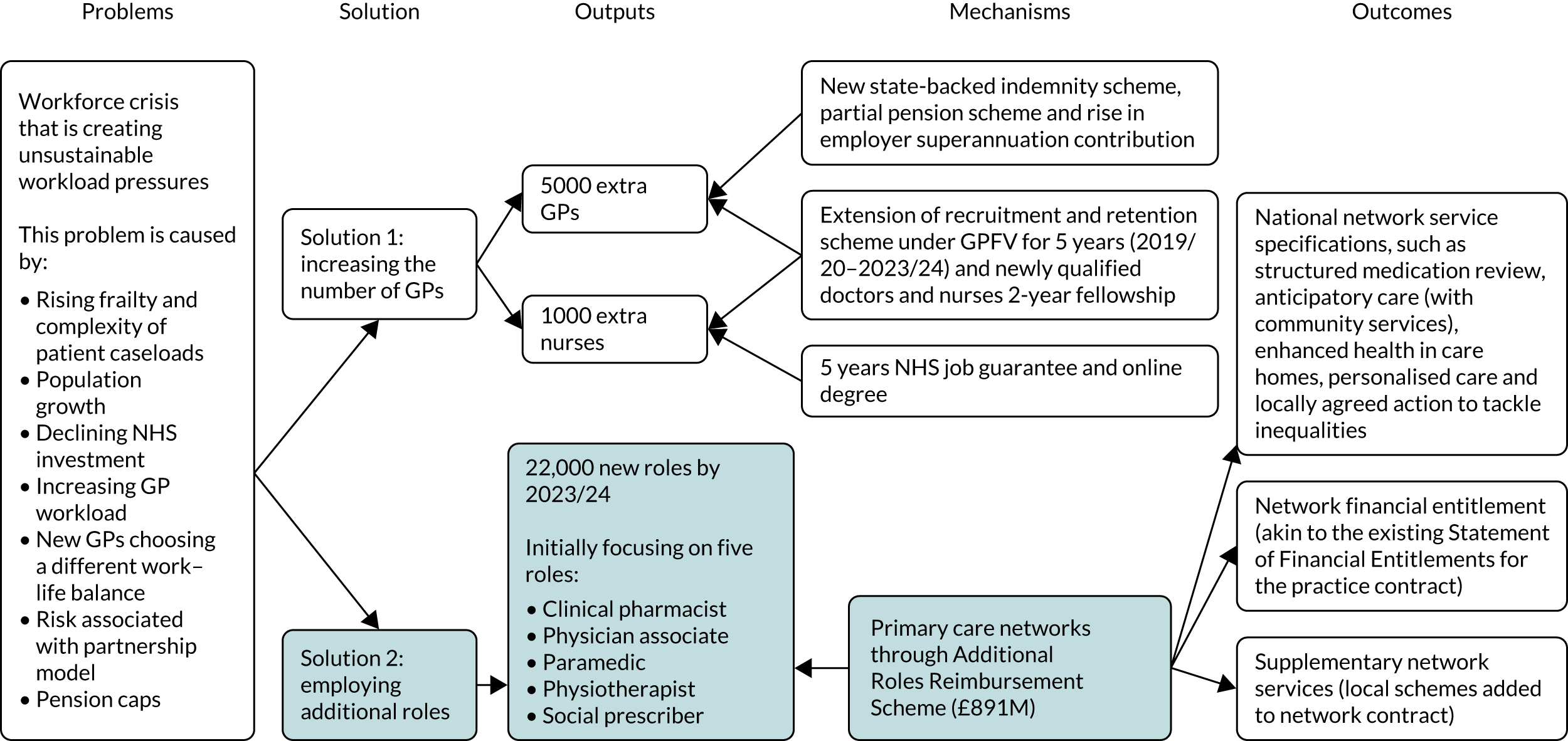

The policy intention is that workers in these newer roles become part of general practice teams rather than provide supporting services. The ARRS, therefore, adds impetus to increasing skill mix employment in primary care. However, because there is currently limited evidence about how changing the workforce composition works, this research provides evidence to fill that gap. In this context, a study of the scale and nature of the expansion of multidisciplinary work in general practice and the impact of these changes on outcomes are particularly important, and both are discussed below. Our summary of the current policy context, including the mechanisms that have been put in place and the anticipated outcomes, is set out in Figure 1. The relevant immediate context for this study is highlighted.

FIGURE 1.

Skill mix policy context.

Rationale for employing newer roles

The rationale for employing newer roles, as set out in policy documents and research evaluations, is influenced by perceptions of what practitioners in these roles can contribute, the time taken to embed newer roles and costs associated with implementing new ways of working. The contribution of newer roles is more evident for some roles than for others. For example, CPs can deal with medication-related tasks, such as medication reviews, repeat prescribing and monitoring safe or financially incentivised prescribing practices. 9,37–39 On the other hand, PAs have been described as being able to safely attend to ‘less complex’ patients. 40

In addition to perceptions about the contributions made by practitioners in newer roles, financial incentives have been shown to influence GPs’ willingness to adopt skill mix. For example, in Germany, GPs were willing to delegate home visit-related tasks to PAs if reimbursed by health insurers. In addition, in France, GPs were willing to delegate tasks to nurses when they shared a lower proportion of the cost of employing them. 41,42

Research has shown that the expansion of nursing in primary care has primarily been driven by a need to transfer work to manage GP workload. 43 Similarly, the introduction of CPs into English general practice has been done to reduce the burden on existing staff. 44 In the case of ANPs, variation in how ANPs were trained and supported has been shown to influence their ability to deal with acute ‘same-day’ care to manage high patient demand while complex patients are seen by GPs. 45

Multidisciplinary working

Team-based care has been shown to enable doctors to work more collaboratively and reflexively. 46 Evidence suggests that team-based care could improve continuity of care, with patients more likely to get the care they need. 47,48 However, the contexts in which multidisciplinary teams operate are important and facilitating factors include co-location; a stable organisational structure; clearly defined roles and workflow; good communication through ‘huddles’, team meetings and informal ‘handoffs’ of patients; shared goals; and mutual respect and trust. 23,49–54

Trust in non-GPs’ abilities has been shown to be key for acceptance by both GPs and patients. 21,55 For GPs, trust in non-GPs can be gained over time and influenced by the doctors’ belief that non-GP colleagues know when to seek help. 21,49,55–59 Established trust also facilitates the expansion of jurisdictional boundaries and reduced supervision. 56

Much of the evidence about skill mix changes in practice derives from secondary care contexts where established hierarchies and organisational structures support a structured approach to task-shifting and delegation. In UK primary care, by contrast, GPs act as both lead clinicians and organisational owner/employers. 60,61 In this context, the renegotiation of boundaries between professionals working together in a multidisciplinary team may be complicated by the fact that one professional is the employer of the other and, therefore, holds overarching responsibility and liability for what happens within the practice.

Research has long highlighted the issue of interprofessional competition and professionals’ attempts to protect occupational jurisdiction in their work, and many of these issues are pertinent when considering skill mix in primary care. 62–65 Studies have also revealed tensions between staff relating to authority, legitimacy, expertise and efforts made to gain professional recognition. 43,66–68

Within primary care, we know that when doctors’ expectations of a new role are not met (e.g. an expectation that non-GP autonomous practitioners, such as PAs, would reduce their workload), then they are less inclined to accept other professionals as part of the primary care team. 24,67 Others have noted that the concept of PAs as substitutes for GPs affect acceptance of such staff. 24 It has also been highlighted elsewhere that there is a need for a ‘paradigm shift’ among staff to accept CPs extending their role beyond dispensing. 56,69

Impact on outcomes

Most studies of increased skill mix employment have found no reductions in costs. In some cases, skill mix employment has resulted in lower productivity and adverse consequences for practitioners, such as increased workload for those taking on new tasks and lowered staff morale. 70 Some studies have reported cost reductions only when practitioners’ skill levels are appropriately matched to the severity of patients’ conditions, whereas other studies have reported mixed findings on the impact of skill mix on costs. 58,71–73 A few studies have reported cost reductions as a result of implementing skill mix changes. 71,74,75 However, when GPs are replaced by less expensive workers, estimations of cost should consider whether the same tasks take significantly longer to carry out, as this might explain why expected cost savings are not achieved. 70,76 It is also possible that ‘new’ roles may extend the scope of general practice (i.e. widening the health-care offering and meeting an unmet need). In doing so, the costs of additional work may not be fully compensated. 77

Patient outcomes, such as the safety and quality of care, are not consistently defined across the literature. Studies58,71–77 on the outcome of skill mix on patients have mainly focused on how patterns of care and service utilisation have been affected by the availability of newer types of practitioners in primary care, alongside an investigation of patient attitudes to particular service innovations and consultations with individual practitioner types.

Research indicated that changing skill mix increased patients’ ability to get an appointment, which led to increased acceptability of skill mix and positive experiences. 55,59,73,75,78,79 However, accommodating patient choice of practitioner is essential, and evidence suggests that patients’ overall evaluation of their care, as well as their trust and confidence, decrease if they do not have access to the practitioner of their choice (e.g. for those who want to see a GP but see a nurse instead). 80 Furthermore, the trust of patients in non-GP roles was influenced by factors such as the severity of their condition and desire for continuity of care, with increased severity associated with a preference for more highly qualified health-care professionals. 40,81 Generally, patients can find it more challenging to understand and navigate access to care when confronted with extensive and diverse primary care teams. 82

Why is this research needed now?

Several factors make it imperative to research the current skill mix changes in general practice.

First, changes in skill mix are occurring at a rapid pace, but have undergone limited evaluation. Therefore, it is vital that early evaluation of the operationalisation of skill mix policy and the impact of skill mix change on outcomes, costs and experiences of health care in England are undertaken. The complexity of the policy environment, variation in how general practices make and implement local managerial decisions, a wide range of clinically active professionals and the vital interests of patients experiencing health care mean that a multidisciplinary research approach is needed to gather coherent and useful information [work package (WP) 1].

Second, improvements in data collection [e.g. NHS Digital, Workforce Minimum Data Set (wMDS)] mean that data are now available for a detailed analysis of changes in workforce composition. This provides a platform to estimate staff costs and look for associations between skill mix changes and multiple outcomes (WP1).

Third, there is a lack of evidence about factors motivating changes in skill mix. General practices have traditionally been independently owned and operated businesses. The manner in which practices deliver services in accordance with the terms of their NHS contract is scrutinised by the Care Quality Commission, but management styles and structures are not standardised. 83,84 Moreover, organisational arrangements are transforming in many areas with the emergence of new models of care. 10 Given this diversity and the current period of change, it is crucial to explore GPs’ and practice managers’ motivations for employing different practitioners, as well as what these practitioners can bring to primary care and the financial viability of skill mix implementation for GPs as business owners (WP2 and WP3).

Fourth, there can be ambiguity about which practitioners perform which roles in general practice. The MUNROS (iMpact on practice, oUtcomes and costs of New roles for health pROfeSsionals) study85 observed that lack of clarity about practitioner roles and variation in the scope of practice of individuals within the same practitioner type could impede the smooth transfer of work and add confusion for patients seeking care. 10 This is, therefore, an area in which this research can reduce ambiguity and potentially increase acceptance and operational efficiency (WP2 and WP3).

Finally, the expansion of skill mix in primary care is gaining impetus with developing the PCN ARRS. 31 Under this scheme, practitioners are expected to work across networks, as opposed to being situated in single practices. As these roles are rapidly rolled out, it is imperative that we understand the factors that affect the successful integration of newer roles into practice teams because this knowledge can inform the design and operation of the scheme. Understanding the factors that support smooth team working and the requirements for supervision will support PCNs in supporting and managing newer practitioners.

In summary, we know that the implementation of skill mix change is not unproblematic and there may be unintended adverse consequences, such as increased workload for practitioners taking on new tasks, higher costs, lower staff morale and productivity, and concern about continuity of care for patients. 15,56,70,86–88 Variation in approaches to skill mix change across primary care providers and in what different types of practitioner contribute in general practice settings can now be evaluated using more detailed national- and practice-level data. These data, about the scale of skill mix deployment, its effectiveness and impact on costs, and about quality and patterns of care, are urgently needed to inform future workforce and resource planning. Furthermore, as access to timely and safe health care is vital for patients, the evidence from this research is needed to provide patients with practical and locally relevant guidance about making the best use of the options available, and to provide practices and PCNs with information about the factors most likely to support the successful integration of newer types of workers into general practice.

Aims and objectives

This study aims to investigate evolving patterns of skill mix in primary care, examine how and why skill mix changes are implemented, explore practitioner and patient experiences of these changes, and estimate the overall impact on outcomes and costs associated with a broader spectrum of practitioner types.

We identified three research questions and related WPs to address these aims.

Research question 1 (work package 1): what is the scale and distribution of skill mix changes in primary care and how is skill mix change associated with outcomes and costs?

-

How has the workforce changed and where has any change occurred?

-

How are compositional changes to the workforce associated with later changes in a range of outcomes, including patient and practitioner satisfaction?

-

How are workforce changes associated with later changes in costs and practice efficiency?

Research question 2 (work packages 2 and 3): what motivations drive skill mix deployment at the practice level and what is delivered by the deployment of different practitioner types?

-

What motivates practices to choose/not choose increased skill mix deployment? (WP2.)

-

Which aspects of health care are undertaken by different practitioner types? (WP3.)

Research question 3 (work package 3): how do skill mix changes affect the experiences of employers, practitioners and patients?

-

How are new ways of working being negotiated in general practices where skill mix changes have occurred?

-

How is the implementation of change in skill mix associated with the achievement of organisational objectives at practice level?

-

How does increased skill mix affect patients’ experiences when accessing primary care services? (WP1 and WP3.)

Work package 4 drew together data from all WPs to develop a comprehensive understanding of the implementation of skill mix changes in general practices and the consequences of these changes.

Summary

This chapter has set out the policy context underlying current skill mix changes in general practice in England and briefly summarised the relevant literature. In the rest of this report, we describe our methods and set out our findings. This was a complex project, and the organisation of our results chapters seeks to lead the reader through the study, considering, in turn, what is happening to skill mix in practice, why practices are opting to change the skill mix of their practice teams, how they are operationalising such changes and what the outcomes associated with skill mix change might be. Therefore, Chapter 3 addresses the first part of research question 1, providing the first in-depth quantitative exploration of the scale of skill mix changes in England. Chapter 4 addresses the first part of research question 2, exploring the motivations for employing a wider range of practitioners as reported by practice managers. Chapter 5 addresses the second part of research question 2 and research question 3, exploring how practices have accommodated newer types of workers and examining patient-reported experiences. Chapter 6 addresses the second part of research question 1, considering the outcomes associated with skill mix change in practices. Chapter 7 looks across the WPs to triangulate our findings. Finally, Chapter 8 provides an overall discussion and conclusions.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The study adopts a multimethod strategy to understand the breadth and depth of changes affecting general practice in England. Quantitative analysis of national data sets on workforce and other aspects of care quality and experience (WP1) is used to capture the extent and impact of skill mix changes. A large-scale survey of general practice managers (WP2) was designed to explore motivations for the employment of non-GPs across general practice in England. In parallel, exploration of issues such as definitional ambiguity in roles, variation in how the same role is implemented in different settings and variation in how work is experienced requires a methodological approach that interrogates roles and settings in depth and in situ. Here, the study employs a complementary comparative case study approach (WP3) to examine conduct and practice using in-depth qualitative methods in a way that is sensitive to important differences in context.

NHS Digital data (work package 1)

We used data about the range of practitioners employed in practices across England, which were available from NHS Digital. Using panel data regression techniques, we estimated practice-level associations between changes in patterns of skill mix and changes in costs and outcomes measured using national data sets.

Growth in the number and range of different workforce professionals employed by practices in recent years has facilitated new ways to deliver services for patients and offered the potential to lower costs and improve outcomes. 89 As practices are primarily small, employee-owned enterprises, they are likely able to respond to these changes more rapidly than larger organisations, such as hospitals, to contain costs and prioritise specific outcomes.

Details of data sources and a full account of our analysis are described in Chapters 3 and 6. In broad terms, we created and analysed a longitudinal practice-level workforce data set using the practice-level wMDS available from NHS Digital for 2015–19. The resulting workforce composition data were analysed against selected outcome data sets to look for associations between workforce composition and outcomes, including overall costs.

In addition to examining workforce changes by geographical region and over time, we looked for indications of potential substitution between the staff groups. Modelling was used to generate scenarios about potential variation in outcomes produced by changes in the number of practitioners employed.

Practice manager survey (work package 2)

We conducted an online survey with practice managers in general practices in England between August and December 2019. We targeted practice managers because it is typically their responsibility to report workforce data to NHS England, and they are generally involved in implementing decisions about staff employment.

Our initial plan was to conduct a postal survey to be sent to all general practices in England using publicly available practice addresses, but negotiated an agreement to conduct an online survey for the following reasons.

First, by using an online platform, we were able to use data that practices had previously supplied to NHS Digital to prepopulate the survey with practice-specific workforce data for managers to confirm or correct according to their current workforce. This allowed us to adapt survey questions so that they were appropriate for each general practice and to avoid duplication or unnecessary questions. For example, we asked participants to indicate the reasons for employing the types of practitioners in their current workforce.

Second, it became evident that local clinical research networks (LCRNs) were interested in supporting us in distributing the survey. The online version was seen as the most effective and appropriate way to reach practice managers.

Third, the use of an online survey was a more cost-effective way of gathering and extracting data for analysis.

We developed and pilot-tested an online questionnaire to be completed by practice managers. In addition to facilitating a check for accuracy of the NHS Digital wMDS, managers were asked about motivations for hiring staff from selected practitioner groups, their future workforce plans and their ideal workforce.

Survey administration

We worked with 15 LCRNs to e-mail the survey link to practice managers in England. Practices that had not opted out of receiving research invitations from their LCRNs were invited to participate in the study, receiving three e-mail invitations/reminders to participate in the study. We requested assistance from the Practice Management Network and used social media to publicise the survey to reach additional practices.

Practice managers were asked to enter a practice identification (ID) (Figure 2), which prevented duplication and allowed the survey software to automatically assign numerical IDs based on the order in which the respondent had started to complete the questionnaire. We did not store the response data with the practice IDs and the key was stored separately. All data were stored on our secured servers. The practice’s identity was needed to ensure that we presented the practice with appropriate questions related to their current staff and provided information for LCRN records about responding practices.

FIGURE 2.

Practice manager survey front page.

The online questionnaire was created using Lighthouse Studio (version 9.7.2; Sawtooth Software Inc., Provo, UT, USA) and was hosted on University of Manchester (Manchester, UK) servers. Data analysis was conducted using Stata® 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Survey content

The study focused on six practitioners (ANPs, specialist nurses, HCAs, PAs, paramedics and CPs) because they represented a mix of:

-

staff whose employment in practices largely predates the new GP contract (e.g. HCAs and advanced nurses)

-

staff whose employment has often been linked to financial incentives (e.g. CPs)

-

staff whose employment can be used to offer additional services (e.g. specialist nurses and CPs)

-

additional roles that can also be funded through PCNs (e.g. PAs and paramedics).

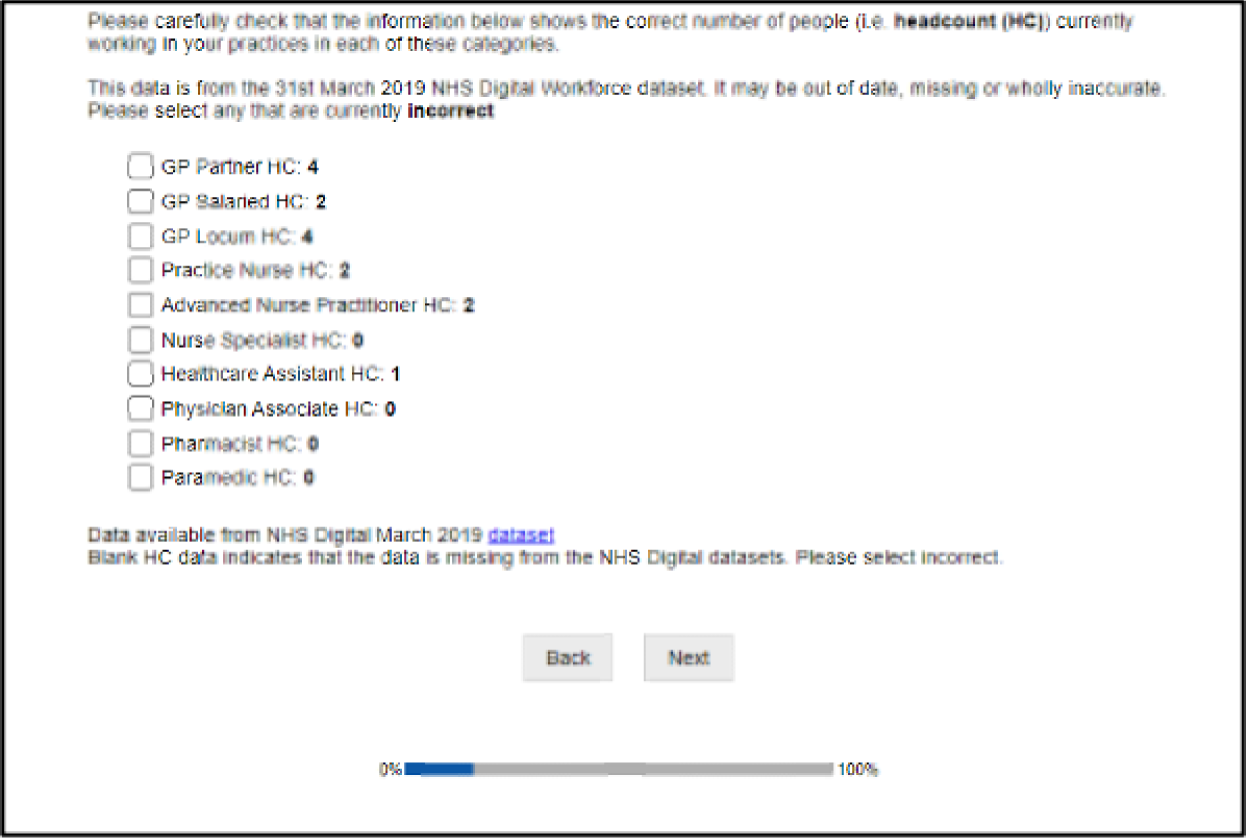

The questionnaire consisted of three sets of questions. The first set of questions focused on verifying publicly available practice workforce data. Practice managers were shown the workforce data [both headcount and full-time equivalent (FTE)] that NHS Digital released for their practice, as of 31 March 2019. This question is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Practice manager questionnaire: is the data correct?

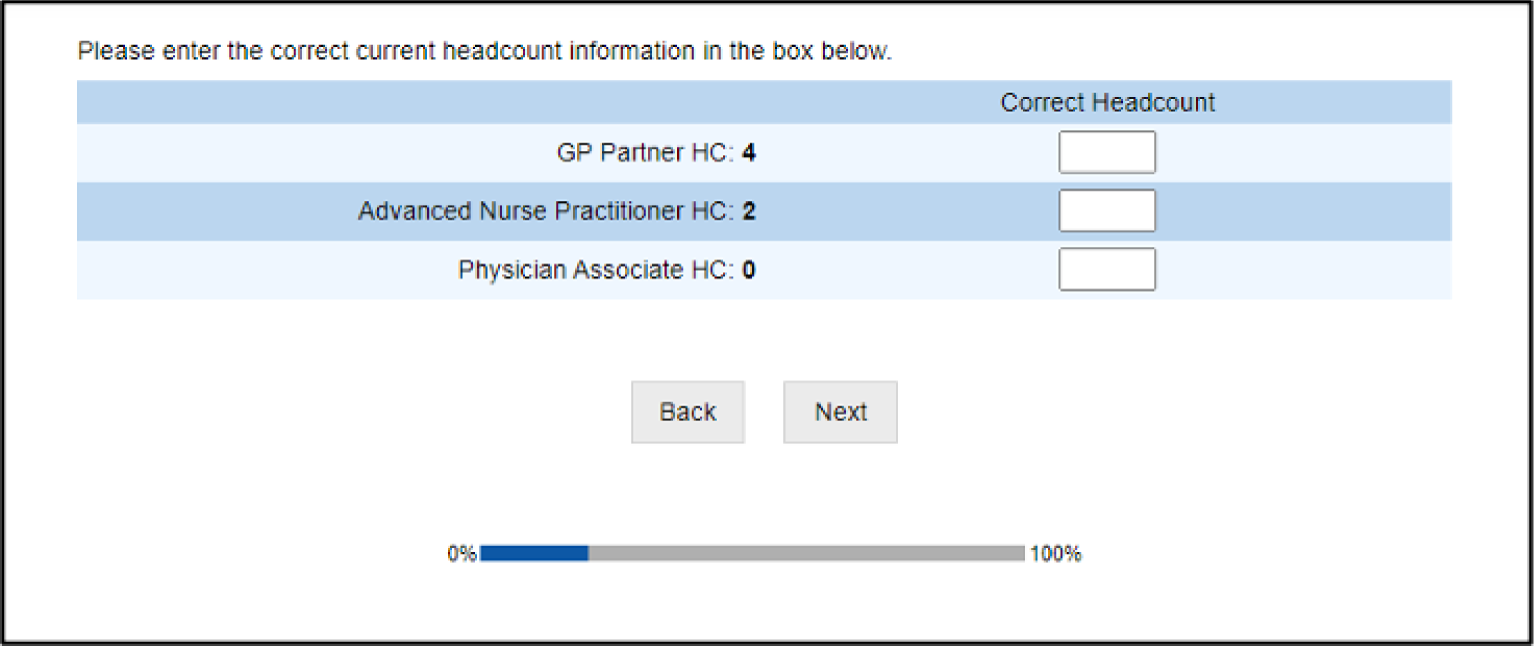

Practice managers were then asked to enter the correct current headcount or FTE figures for any incorrect practitioner groups (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Practice manager questionnaire: entering correct data.

The second set of questions asked those who employed staff in one of the six roles of interest what factors influenced their decision to employ staff in that role. Respondents were presented with a list of 12 predefined factors, the selection of which was informed by our knowledge of the literature and previous workforce research. Respondents were also permitted to add factors not captured in the list using free text. They were asked to select all factors that applied to their decision for each type of worker. They were then asked if any additional funding was explicitly supplied to support the employment of these staff, from which funding organisation and whether or not they were still receiving funding.

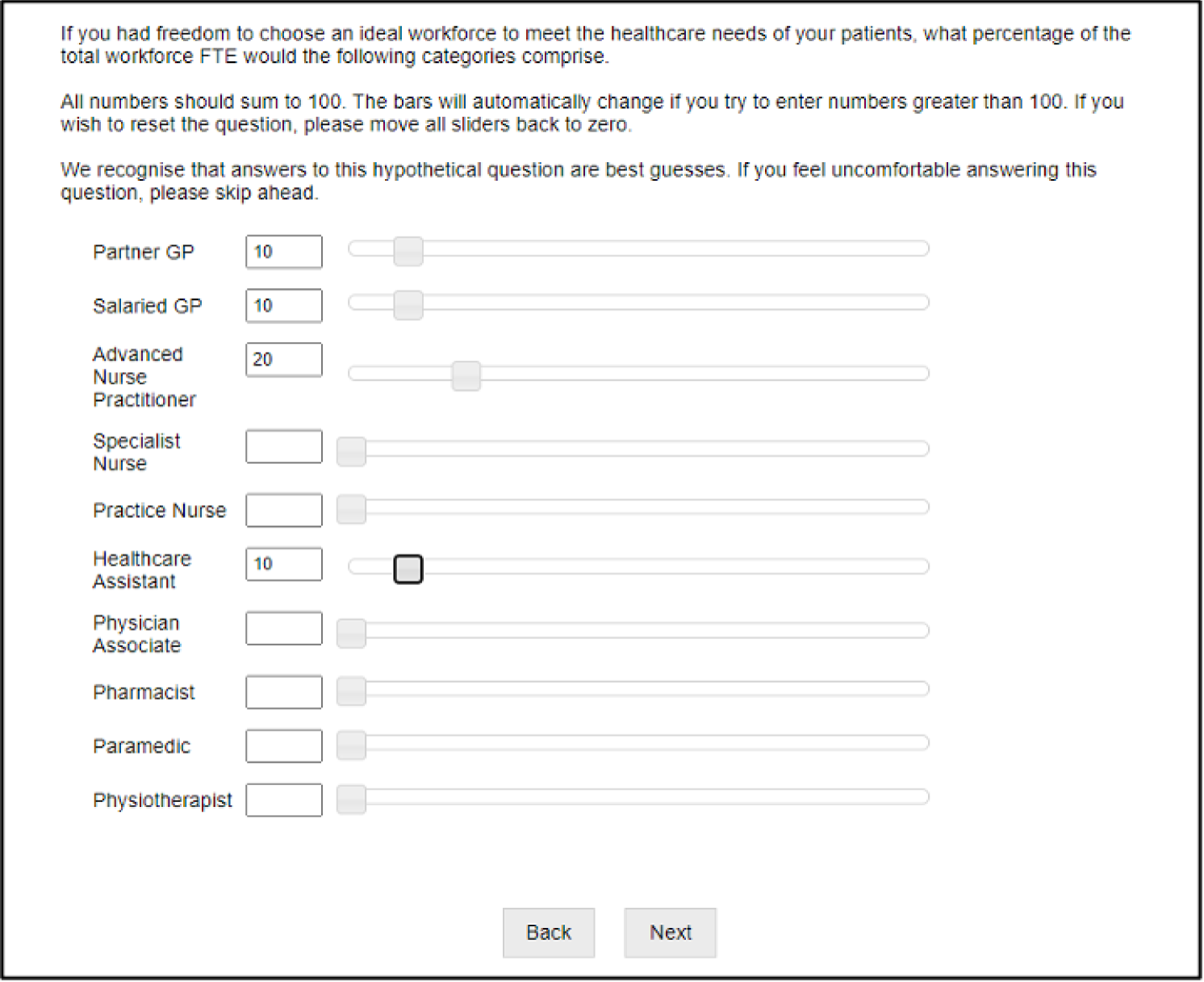

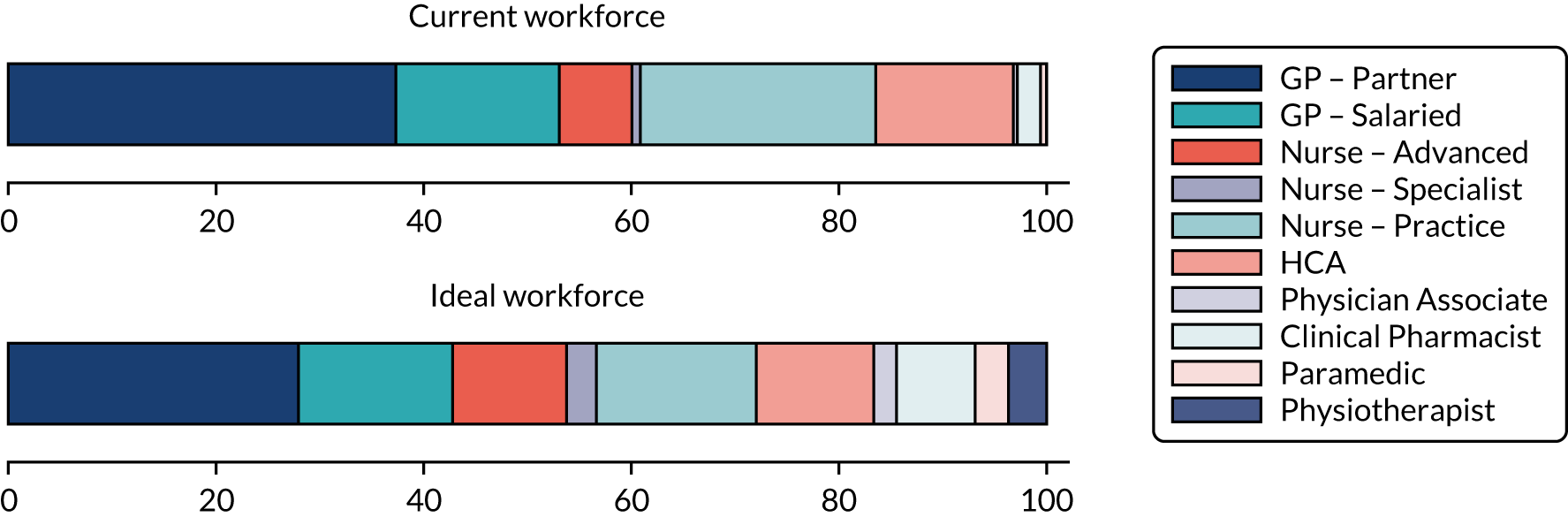

Regardless of their current workforce composition, the final set of questions asked all participants whether or not they would wish to employ additional staff from a list of roles in the future and, if so, whether they would prefer them to be directly employed by the practice or through a PCN. Finally, participants were asked to indicate their ideal workforce composition by selecting the percentage of their total clinical workforce made up of each of the listed roles. GPs were included in the list of roles for this question. Respondents were required to use slider bars to indicate the percentages for each worker group (Figure 5). These bars were programmed so that total percentages were automatically adjusted to 100%.

FIGURE 5.

Practice manager questionnaire: ideal workforce slider bars.

Case study (work package 3)

Multiple case studies

Aware of the need to generate rich research findings in their practical context, we used Yin’s multiple case study approach. 90 This enabled us to understand issues where there is limited prior knowledge and/or complex organisational conditions. Our claims to generalisability from the case studies rest on theoretical generalisation rather than on representativeness. In other words, our use of theory to structure both site selection and data collection allowed us to further refine and develop theory in this area, providing the opportunity for generalisation beyond the cases studied. 91

We conducted in-depth case studies of five purposively selected general practices using an appropriate mix of qualitative methods, including interviews with staff members and observations of consultations with GP and non-GPs. In case study research, the decision as to how many cases to include represents a balance of breadth (i.e. the need to recruit enough cases to make sure that there is the requisite variety between sites to capture the phenomenon of interest) and depth (i.e. the need to limit the number of sites to be able to collect data in sufficient depth to ensure a full understanding of each case site). Our experience of similar studies suggests that five case studies represent a broad enough sample to capture variation across the key dimensions of interest, while at the same time ensuring that we can undertake the requisite data collection to gain an in-depth understanding of the detailed local context and experiences of the full range of relevant staff, as well as patients. 92–94

Two primary considerations guided the selection of general practice sites for the case studies. First, we were interested in comparing the experiences of practices with a wide range of practitioner types with practices with a narrower range. Second, we were interested in comparing practices that have had a long experience of skill mix diversity with practices that have only recently become more diverse.

Selection of case studies

Sampling was informed by data from WP1 (i.e. data on employment of different practitioner types based on NHS Digital 2018 submission and insights from Expert Advisory Group members). Practices were chosen based on the following criteria:

-

Diversity of practitioners employed. This refers to the number of different types of practitioners in a general practice. From NHS Digital data, we were able to identify practices employing each of the individually listed practitioner types. This allowed us to select practices with more diverse teams (i.e. a larger number of different roles) and those with fewer roles other than GP and practice nurse. In addition, analysis of the scale of employment of specific types of practitioner allowed us to select those sufficiently prevalent in national data sets to be associated with having greater influence on workload or working practices. As a result, we selectively recruited practices based on their diversity of practitioners whose skills are likely to have greater operational impact.

-

Duration/maturity of skill mix implementation. This refers to the period during which a practice has been engaged in implementation of skill mix. We categorised general practices as being early adopters or late adopters. Early adopters refers to practices that have adopted skill mix in or before 2016 and late adopters refers to practices that have adopted skill mix since 2018. These dates were determined by availability of data (as a result of changes in NHS Digital data collection and publication).

-

Whether a practice has a large or small number of practitioners employed within a role. We selected this based on headcount rather than FTE. We focused on how practitioners work rather than the level of work that the practitioner undertakes.

-

Whether a practice has increased or reduced the number of practitioners employed within a role.

Data collection

Case study data were collected between August and December 2019. We initially planned to conduct case studies in six general practices, but, in early 2020, a sixth site withdrew to focus on another initiative. Our recruitment of an alternative site was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, realising that we had a rich and extensive data set, we followed the advice of the Study Steering Committee to abandon this plan and focus on data already gathered. Moreover, following a review of the qualitative data collected, we concluded that we had reached data saturation.

We conducted observations of GP and non-GP consultations at each site and face-to-face interviews with practice staff, focus groups and patient surveys. We conducted a total of 38 interviews and 27 observations (totalling 1620 minutes). Observational field notes provided insight into discrepancies between what people do and say, which pointed to tensions and new areas of interest that we explored in subsequent interviews.

We conducted focus groups with Patient Participation Group (PPG) members (n = 29) in four out of five sites. One of the sites (i.e. site C) did not have an active PPG and we were not able to recruit patients for a focus group at that site. We contacted all patients who indicated in the patient survey that they were willing to participate in a focus group. However, only patients at site D agreed to participate.

Survey sheets were distributed to patients as they attended the practices during site visits. Most survey sheets were distributed by our researchers and a total of 125 patient surveys were collected across five sites. The survey asked patients about which practitioner they had seen and how satisfied they were with how the consultation was conducted. Patients were also asked to provide their contact details (e.g. name, telephone number and/or e-mail address) if they were willing to participate in a focus group. For those patients who gave their contact details, these details were physically separated from the survey sheet and assigned study IDs to maintain anonymity.

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim by a transcriber approved by the University of Manchester.

To add information about how skill mix changes have been affected by, or facilitated, responses to COVID-19, we carried out follow-up telephone interviews with GP partners and/or practice managers at all general practices in our case study sites between September 2020 and January 2021.

Data analysis

Initial thematic codes identified by Imelda McDermott from reviews of the literature and research questions were reviewed, adapted and refined by the research team following initial data collection and a series of team discussions. For patient surveys, Elizabeth Dalgarno identified thematic codes based on literature reviews, research questions and free coding. Data from patient surveys and focus groups were compared across sites, and findings were reviewed with public contributors who were members of our Expert Advisory Group.

Anonymity

All participants were anonymised using study IDs, pseudonyms and/or vague job titles. Research sites were also anonymised and contextual details that might identify sites were disguised. All personal data that potential patient participants shared with us were stored in the University of Manchester’s Research Data Storage Service, which provides robust, managed and secure replicated storage and is accessible by members of the research team only. The pseudonymisation key was held separately and securely in the Research Data Storage Service (password protected) and was accessible to Sharon Spooner [study principal investigator (PI)] and Imelda McDermott.

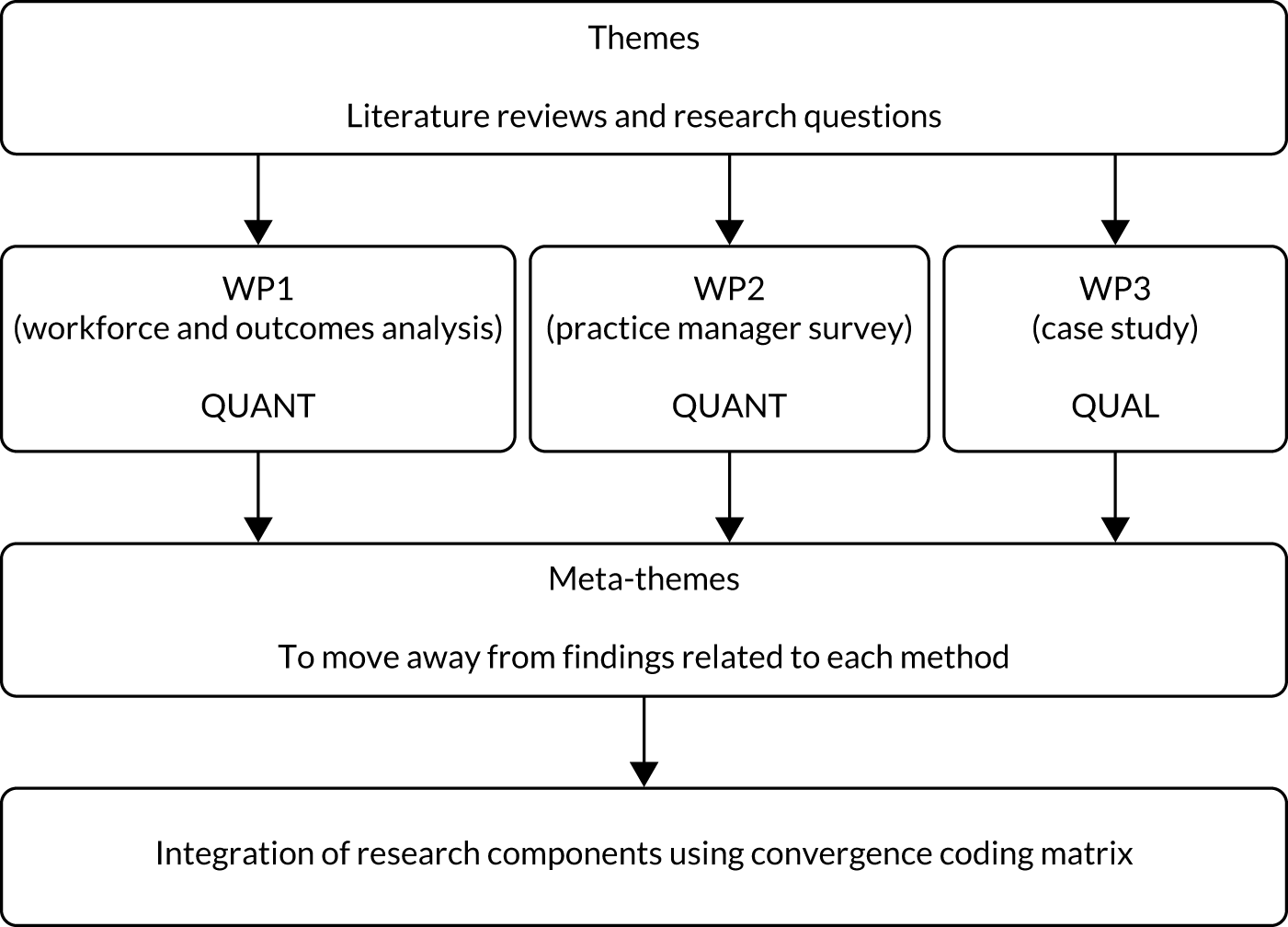

Triangulation (work package 4)

Our methodological approaches have been combined using the principle of ‘triangulation’. 95,96 In this context, the term triangulation describes a process that employs mixed methods to gain a complete picture of a problem. 97 Qualitative and quantitative data are not only used to cross-corroborate findings (i.e. to confirm descriptions of how particular roles are implemented); qualitative findings are also used to complement the quantitative analysis. For example, qualitative elements of the research are used to inform the measurements or analyses undertaken in the quantitative research, providing context to assist interpretation while at the same time inductively generating insights into the way in which phenomena are related in practice. 96 In this way, qualitative and qualitative research work together to facilitate a richer understanding of the phenomenon, generating a multifaceted portrayal of a complex social situation with breadth and depth. 98

Although the WPs (i.e. WP1, WP2 and WP3) were analysed separately, ongoing engagement between researchers on each WP was maintained during ad hoc conversations and monthly team meetings throughout the project to ensure that findings were integrated as specified in WP4. For example, insights from study sites and clinical members of the research team helped shape analysis and interpretation of how the employment of CPs may influence prescribing patterns.

As more structured support for this engagement, one researcher (IM) produced thematic codes based on a review of literature and the research questions. Themes were used to help structure an iterative dialogue between members of the research team, with regular meetings held to share findings as they emerged in each of the WPs. The thematic codes were grouped into meta-themes that cut across findings from different methods and integrated using a ‘convergence coding matrix’. 99 Meta-themes were considered for agreement and disagreement based on convergence (i.e. where findings directly agree), complementarity (i.e. where findings offer complementary information on the same issue), dissonance (i.e. where findings appear to contradict one another) and silence (i.e. where themes arise from one component study but not others). 100 Figure 6 depicts the triangulation process.

FIGURE 6.

Triangulation process.

Patient and public involvement

Members of Primary Care Research in Manchester Engagement Resource (PRIMER) (Manchester, UK) and a PPG that liaises with their practice team on matters related to GP services provided comments on our proposal. In addition, these members contributed to the research design, including case studies and the patient survey, in terms of patient experiences of care navigation, choice, confidence and understanding practitioner roles.

Two PRIMER representatives were members of the Expert Advisory Group to bring patient and public involvement perspectives to all aspects of research activity. The representatives contributed to the development of patient surveys and focus group topic guides and provided feedback on patient survey findings. Anne McBride supported PRIMER representatives to be fully involved throughout the research project. We are continuing to work through ideas for resources that may improve patients’ understanding of what less familiar practitioners do in general practice settings.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained following review by NHS Health Research Authority and North West- Greater Manager South Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/NW/0650).

Reimbursement

Following discussions and advice from the Greater Manchester Clinical Research Network, we obtained funder agreement to provide incentives to encourage participation in WP2 (i.e. the Practice Manager Survey) and WP3 (i.e. the case studies).

For WP2, general practices that completed and returned the survey were entered into a prize draw in which five winners of £50 were randomly selected. An ID key was used to identify the winning practices, which were then contacted to arrange for the prize to be sent to them (addressed to the practice manager). We were informed that some LCRNs offered supplementary funding to practices to cover the costs of completing the survey. The prize was payable to the practice to be spent on staff development.

For WP3, we reimbursed general practices for staff time that was diverted due to participation in interviews and observations.

Project management and governance

The project was managed by the PI with a project manager from the National Institute for Health and Care Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. However, owing to employment changes, the project manager left the project in month 13 of the project and a replacement administrator was appointed in month 16. Team meetings were conducted monthly, chaired by the PI and attended by the project manager/administrator and the research team. Minutes recorded in discussions and progress with key activities are listed in the timetable [see the NIHR Journals Library. URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/170825/#/ (accessed 31 January 2022)]. Project risks were discussed, and actions agreed to optimise smooth running and coordination of the project.

Issues arising in WP1 included delays due to unanticipated difficulties with data access. This was discussed with our Study Steering Committee and the National Institute for Health and Care Research Health and Social Care Delivery Research project manager, who confirmed continuing support for our proposed plans to accommodate these difficulties. Specifically, we experienced the following unanticipated problems in gaining access to routinely collected data sets.

Workforce data

As a result of changes made by NHS Digital to their collection, analysis and publication of the wMDS, our analysis was delayed while NHS Digital revised statistics from the earlier period of analysis.

GP Patient Survey

Changes in access requirements prevented access to the most detailed level of the most recent GP Patient Survey. We were, however, able to analyse data suitable for addressing our original research questions.

Hospital Episode Statistics

Delays in the processes necessary to obtain access to Hospital Episode Statistics after 2016–17 have not been resolvable within the study period. Nonetheless, our analysis of these data makes a useful contribution to our proposed overall analysis of outcomes.

Adjustments in WP2 to change from a postal to online survey, as described above, gained momentum following initial contact with the lead Clinical Research Network. Imelda McDermott set up contacts with LCRNs. Jon Gibson managed the running of the Practice Manager Survey and responded to queries from the LCRNs.

For WP3, the team involved in this WP (i.e. IM, SS, MG, KC, AM and DH) met fortnightly during the data analysis period and shared nuanced findings across the remaining members of the research team.

Meetings of the Study Steering Committee were arranged at the intended 6-monthly intervals. Full attendance was achieved on each occasion using virtual platforms, and minutes were produced and agreed.

Expert Advisory Group meetings were similarly arranged at 6-monthly intervals, but it proved challenging to maintain attendance by individuals from different practitioner groups. However, those who attended these meetings made valuable contributions and our patient and public involvement representatives remained engaged with the project throughout.

Chapter 3 Understanding the patterns of skill mix in England

In Chapter 1 we have seen that the strong policy push towards diversifying the skill mix of general practice in England is primarily driven by an ongoing workforce crisis and also underpinned by an aspiration to provide more comprehensive services for an ageing population. In this chapter, we explore how far those policy aspirations are reflected in the workforce’s current (up to 2019) composition.

To do this, we analysed national data on the workforce employed by general practices in England, particularly focusing on trends in the employment of different health-care professionals. Findings on the regional distribution of the workforce were published in the British Journal of General Practice in January 2020. 101 In this section, we expand upon these findings to examine how the workforce has changed over time, which provides insight into whether or not other worker groups have diminished in numbers as the variety of workforce groups has increased. The analysis was directed to answer research question 1(i) with regard to how the workforce has changed and where any change has occurred.

Data

We obtained data from NHS Digital on the range of practitioners employed in practices across England. We created a longitudinal practice-level workforce data set using the practice-level general practice workforce data sets (completed by practices as part of their wMDS obligations). These data contain both headcounts and numbers of FTEs for 38 categories of staff [GP categories, n = 5; nurse categories, n = 8; direct patient care (DPC) categories, n = 16; administration categories, n = 9]. For the purpose of this analysis, we focus on categories of staff who are responsible for directly providing health care to patients. These categories of staff are reported in three groups: (1) the GP group, including GP partners, salaried GPs and locum GPs, (2) the nurse’s group, including practice nurses, ANPs and specialist nurses, and (3) the DPC group, including HCAs, PAs, CPs, physiotherapists, paramedics and other allied health professionals.

We used data from 2015 to 2019. The most recent data we report is from the quarterly update that reports data to September 2019.

This is an evolving data collection, with different staff members being added at different times and a dedicated payment now offered to recognise the costs involved in reporting the data. 102 We worked closely with NHS Digital to understand the properties of the data. In data from September 2019, there were usable data for 6296 practices out of the 6867 practices for whom workforce data were made available.

Methods

To describe the practice workforce and its changing nature, we summarised workforce composition by year, by practice size and by region. We used data from the General Practice Workforce data sets from NHS Digital between September 2015 and September 2019. In addition to plotting the geographical distribution of the workforce, we estimated regression models to further examine the association between workforce and practice characteristics. We estimated separate equations for GP, nurse and DPC FTE per 1000 patients (PTP). However, workforce decisions relating to these groups are likely to be associated with practice workforce decisions for the other groups. Therefore, the equation error terms are likely correlated and any cross-equation hypothesis testing will be biased. To account for this correlation, we estimated the models as a seemingly unrelated regression system that has contemporaneous cross-equation error correlation. 103 We estimated the models using the sureg command in Stata 15.1.

Research question 1(i): how has the workforce changed and where has any change occurred?

Composition of the practice workforce

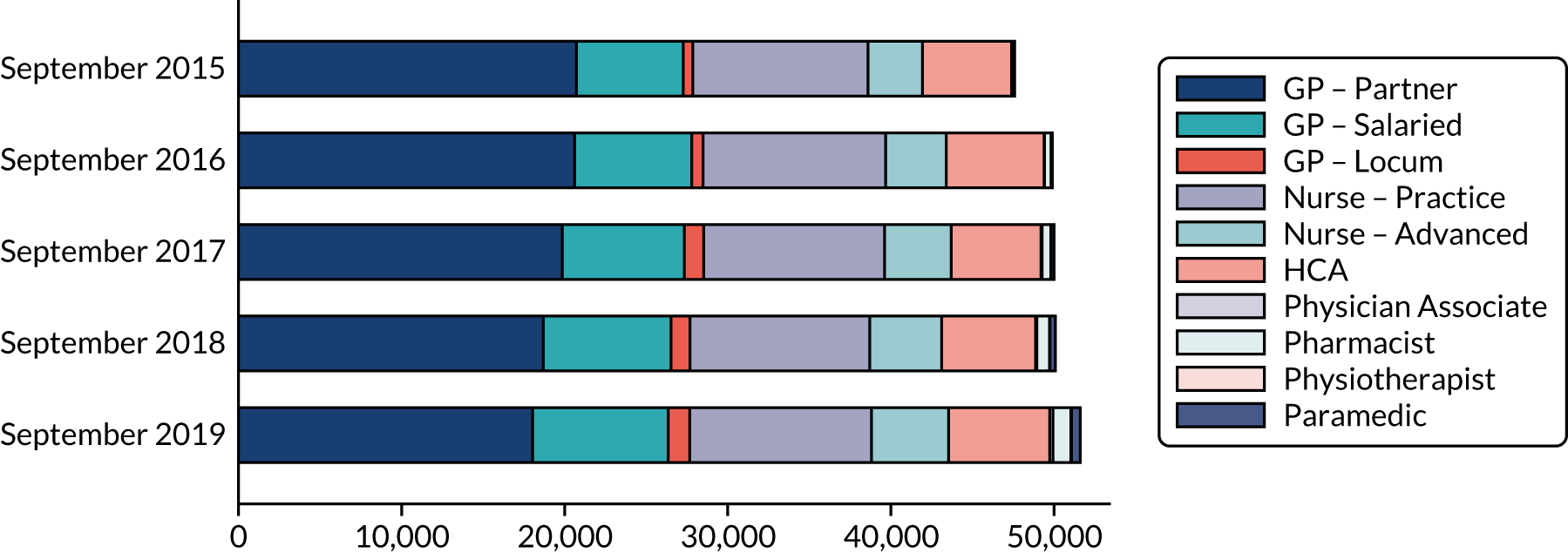

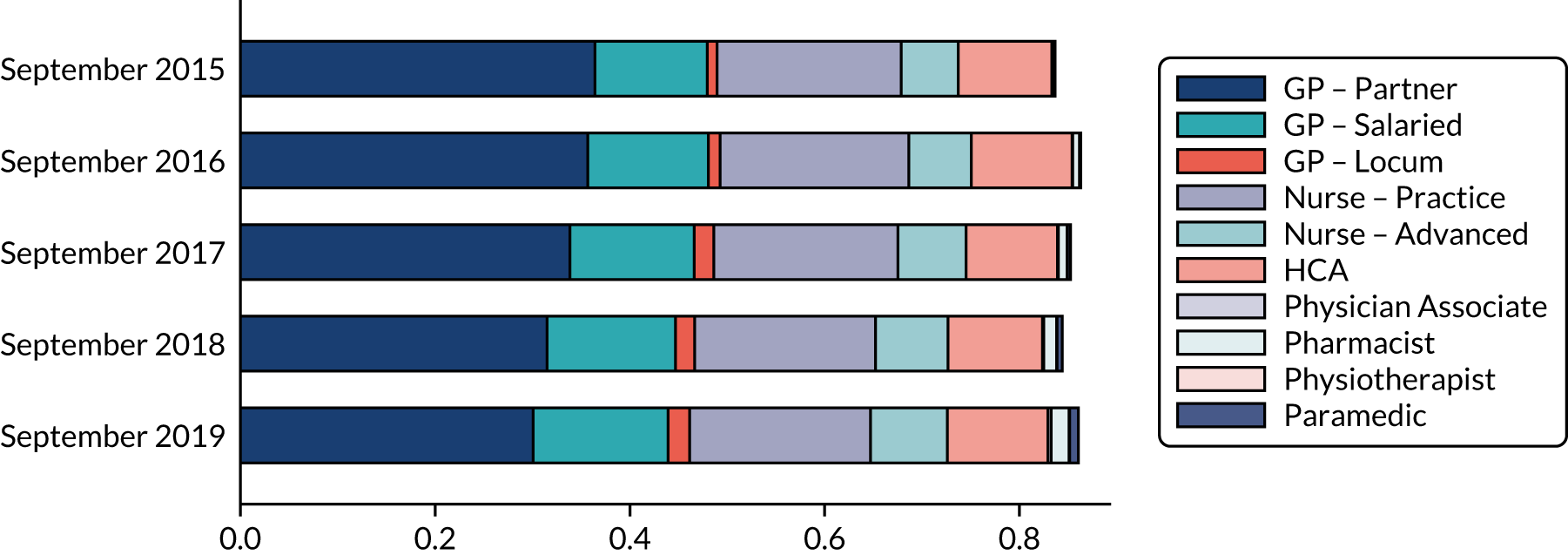

Since September 2015, for the sample practices with usable data, there has been an increase in total workforce FTE from around 47,600 to 51,600 (Table 1). Within that increase in workforce FTE, there has been a decline in the FTE of partner GPs and an increase in the FTE of advanced nurse roles and newer DPC roles, such as CPs and PAs. Table 1 also presents figures for workforce FTE PTP. These figures highlight workforce change in relation to the number of registered patients to whom the workforce are delivering health care, with implications for the capacity of the workforce to deal with changing levels of workload. For example, where an unchanging workforce has to serve an increasing number of patients, then this potentially reduces the practitioner time that can be focused on the needs of each patient. Table 1 shows that, although the number of FTEs in these workforce roles has increased by 8.44%, FTEs PTP have increased by 2.87% after accounting for the growing number of patients. These figures show the same pattern as the raw workforce figures. The number of GP partner FTEs PTP are declining, whereas salaried GPs and locum FTEs are increasing. The number of practice nurse FTEs PTP remains roughly constant, whereas the number of ANP FTEs PTP is increasing. This confirms a gradual shift in the overall workforce composition during this period. Graphical representations of this analysis can be found in Appendix 1, Figures 28–30.

| Date | Measure | Staff type | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP: partner | GP: salaried | GP: locum | Nurse: practice | Nurse: advanced | HCA | PA | Pharmacist | Physiotherapist | Paramedic | Total | ||

| September 2015 | FTE | 20,719 | 6554 | 578 | 10,745 | 3336 | 5463 | 12 | 165 | 19 | No data | 47,591 |

| September 2016 | FTE | 20,621 | 7168 | 693 | 11,204 | 3705 | 5995 | 35 | 396 | 21 | 57 | 49,895 |

| September 2017 | FTE | 19,849 | 7479 | 1187 | 11,086 | 4103 | 5508 | 49 | 534 | 23 | 184 | 50,002 |

| September 2018 | FTE | 18,692 | 7829 | 1154 | 11,026 | 4409 | 5758 | 81 | 777 | 22 | 335 | 50,083 |

| September 2019 | FTE | 18,028 | 8319 | 1321 | 11,136 | 4737 | 6194 | 207 | 1097 | 41 | 529 | 51,609 |

| % change in total FTE between 2015 and 2019 | 8.44% | |||||||||||

| September 2015 | FTE PTP | 0.3642 | 0.1152 | 0.0102 | 0.1889 | 0.0586 | 0.0960 | 0.0002 | 0.0029 | 0.0003 | No data | 0.8365 |

| September 2016 | FTE PTP | 0.3566 | 0.1240 | 0.0120 | 0.1938 | 0.0641 | 0.1037 | 0.0006 | 0.0068 | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | 0.8630 |

| September 2017 | FTE PTP | 0.3384 | 0.1275 | 0.0202 | 0.1890 | 0.0700 | 0.0939 | 0.0008 | 0.0091 | 0.0004 | 0.0031 | 0.8524 |

| September 2018 | FTE PTP | 0.3150 | 0.1319 | 0.0194 | 0.1858 | 0.0743 | 0.0970 | 0.0014 | 0.0131 | 0.0004 | 0.0056 | 0.8439 |

| September 2019 | FTE PTP | 0.3005 | 0.1387 | 0.0220 | 0.1857 | 0.0790 | 0.1033 | 0.0035 | 0.0183 | 0.0007 | 0.0088 | 0.8605 |

| % change in total FTE PTP between 2015 and 2019 | 2.87% | |||||||||||

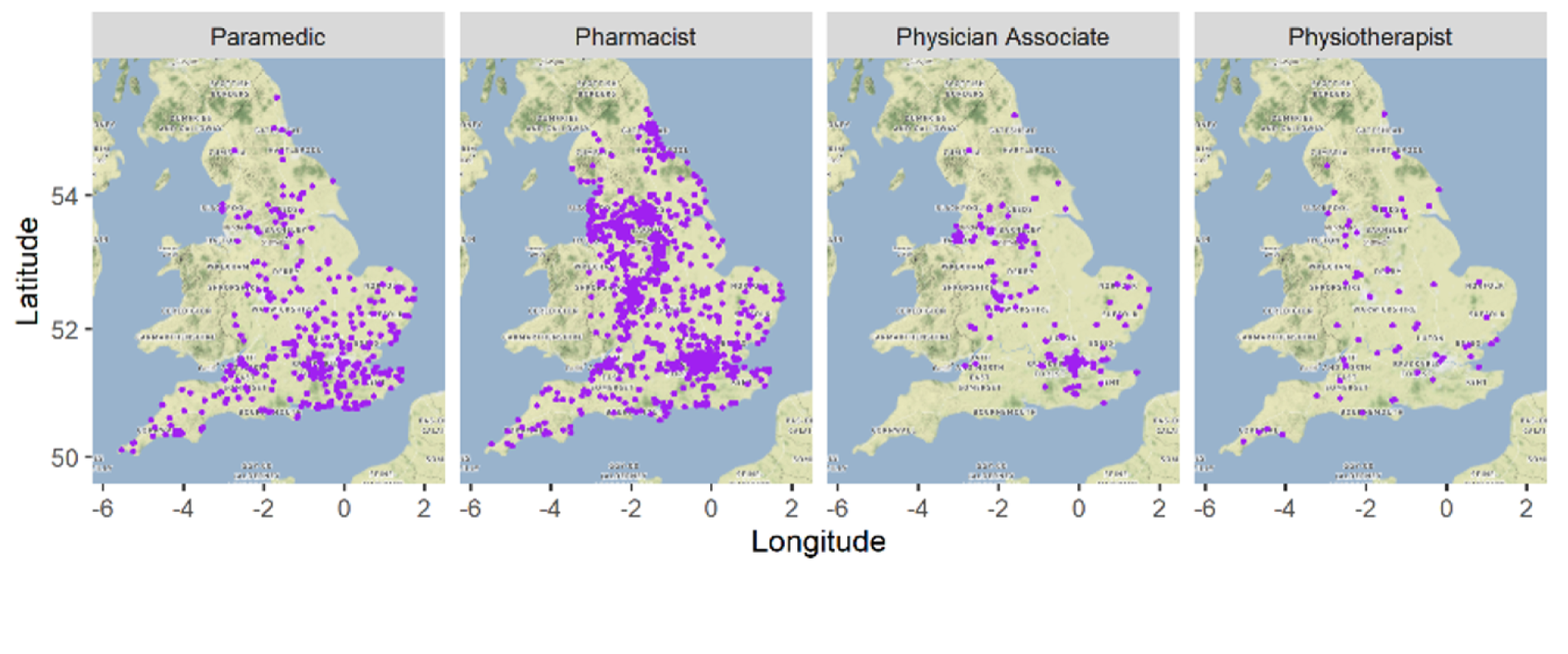

There has been an expansion of skill mix in a greater proportion of practices in some regions than in others. Table 2 shows the proportion of practices in each region with at least some FTE of the workforce roles. This demonstrates that, for instance, paramedics have been hired predominantly by practices in the south of England, whereas CPs are more evenly geographically distributed but have the highest uptake by practices in the east of England, North East and Yorkshire and the Midlands. ANPs are employed by 57% of practices in the east of England, but are employed by only 23% of practices in London. Paramedics are employed by 12% of practices in the south-east of England, but are employed by only 1% of practices in the north of England. These results highlight the variation in workforce composition across England.

| Region of England | Staff type (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP: partner | GP: salaried | GP: locum | Nurse: practice | Nurse: advanced | HCA | PA | Pharmacist | Physiotherapist | Paramedic | |

| East | 93 | 67 | 30 | 95 | 57 | 79 | 4 | 20 | 1 | 11 |

| London | 93 | 67 | 23 | 89 | 23 | 56 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 1 |

| Midlands | 94 | 64 | 30 | 94 | 50 | 77 | 3 | 20 | 1 | 4 |

| Midlands and east | 93 | 60 | 15 | 93 | 46 | 73 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 2 |

| North-east and Yorkshire | 92 | 67 | 23 | 95 | 58 | 85 | 3 | 22 | 1 | 3 |

| North-west | 85 | 63 | 25 | 92 | 43 | 65 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 2 |

| North | 89 | 60 | 10 | 91 | 43 | 71 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 1 |

| South-east | 94 | 73 | 18 | 95 | 45 | 57 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| South-west | 95 | 77 | 19 | 98 | 52 | 85 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 9 |

Figure 7 presents a map of England, highlighting practices that employ the different workforce roles. In addition to the pattern of paramedic and CP employment described above, Figure 7 shows that the practices employing PAs are located in the main population centres (i.e. London, the Midlands and the north-west of England) and, also, that there are a very small number of practices currently employing physiotherapists.

FIGURE 7.

Maps of England highlighting practices that employ different workforce roles. Map data ©2021 Google.

Modelling workforce

In addition to plotting the geographical distribution of the workforce, we estimated regression models to further examine the association between workforce and practice characteristics.

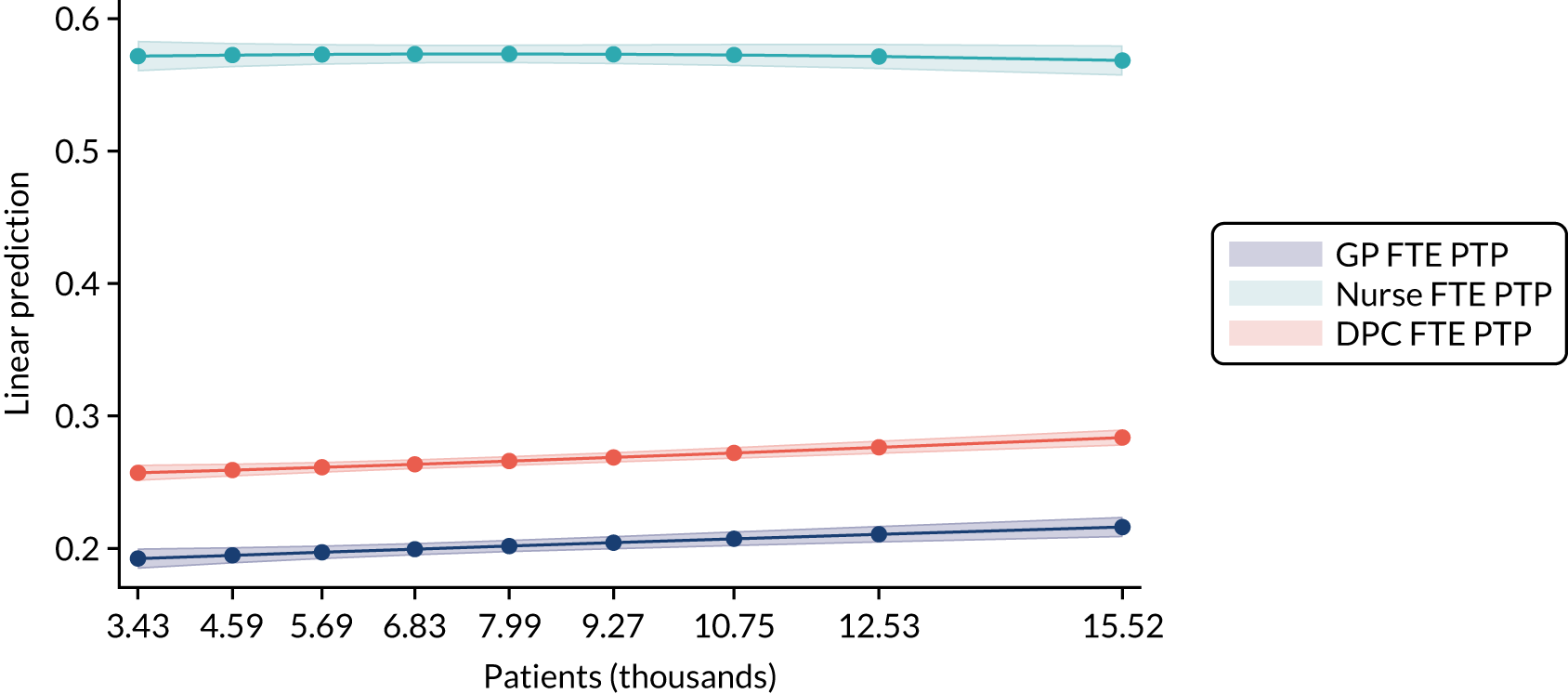

Our statistical analyses were based on a sample of 6287 general practices. Despite not being able to analyse data for all practices in England, our core sample was highly representative and allowed us to confidently extrapolate our results to the situation of English primary care more broadly. The characteristics of the typical practice in our sample are described in Table 3, which indicates that the mean number of GP FTE PTP is 0.57, whereas the mean numbers of nurse and other DPC (i.e. pharmacists, paramedics, PAs and physiotherapists) FTE PTPs are 0.27 and 0.20 respectively. The mean distance to the nearest hospital for a practice was 8.57 km and 17% of the practices in our sample were in rural areas. Moreover, 16% of practices in the sample were dispensing practices and 72% were on a GMS contract. The mean percentage of patients aged ≥ 65 years in the sample was 17.73%.

| Variable | Observed, n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP FTE PTP | 6287 | 0.57 | 0.27 |

| Nurse FTE PTP | 6287 | 0.27 | 0.15 |

| DPC FTE PTP | 6287 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| Patients (thousands) | 6287 | 9.08 | 5.82 |

| Distance to nearest hospital (km) | 6287 | 8.57 | 8.38 |

| Distance to nearest medical school (km) | 6287 | 19.67 | 16.32 |

| Proportion (%) of patients aged ≥ 65 years | 6287 | 17.73 | 6.95 |

| MPIG per patient | 6287 | 0.66 | 2.17 |

| Rural (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 6287 | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Market forces factor | 6287 | 1.18 | 0.11 |

| Income deprivation | 6287 | 0.14 | 0.07 |

| GMS (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 6287 | 0.72 | 0.45 |

| Dispensing practice (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 6287 | 0.16 | 0.37 |

| Extended hours payments (per patients) | 6287 | 1.21 | 1.19 |

To study the association between staffing and practice-level characteristics, we estimated a seemingly unrelated regressions model. We opted for a seemingly unrelated regressions model instead of a set of independent standard linear regressions because the employment decisions for the three workforce groups are likely to be connected. For instance, employing extra GPs is likely to reduce the workforce budget for employing staff from the other groups. In this case, the three separate models will likely have a correlated error term. The seemingly unrelated regressions model accounts for this contemporaneous correlation. 103 The Breusch–Pagan test is a test for independence of residual vectors between the model equations. As shown in Table 3, the null hypothesis of independence of residuals is rejected and, therefore, our model choice is justified.

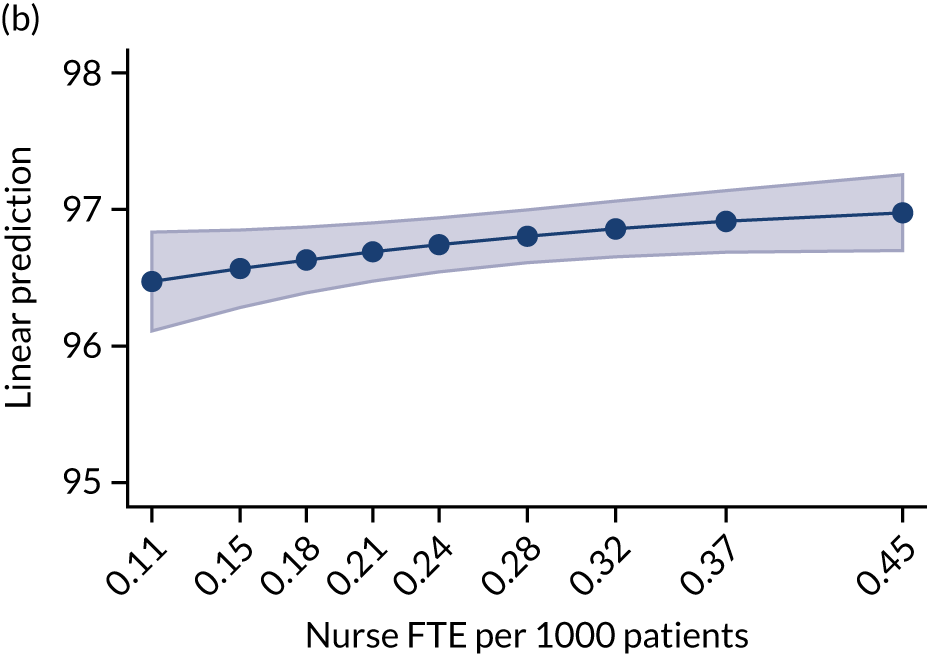

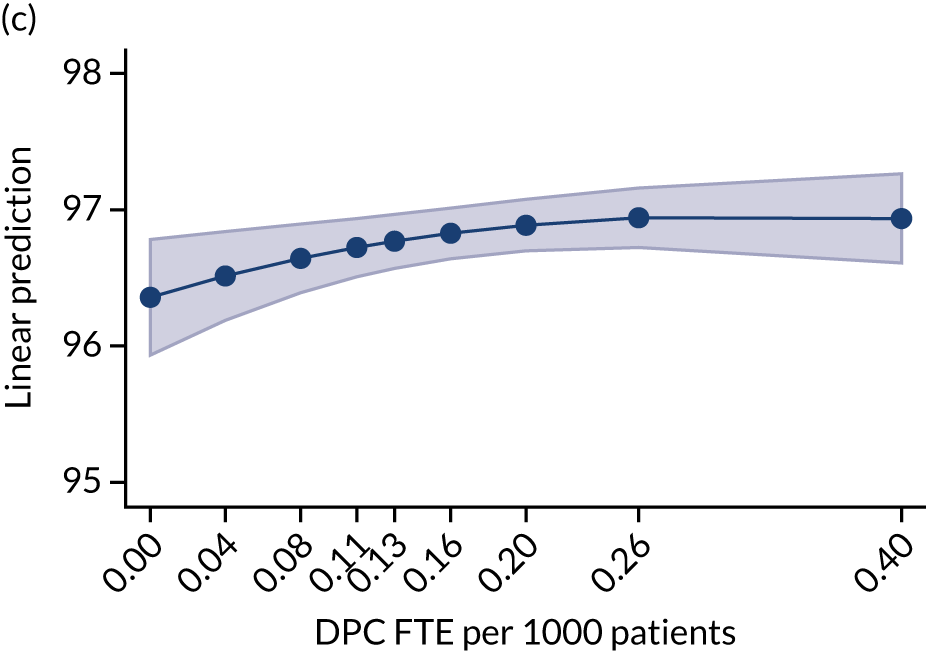

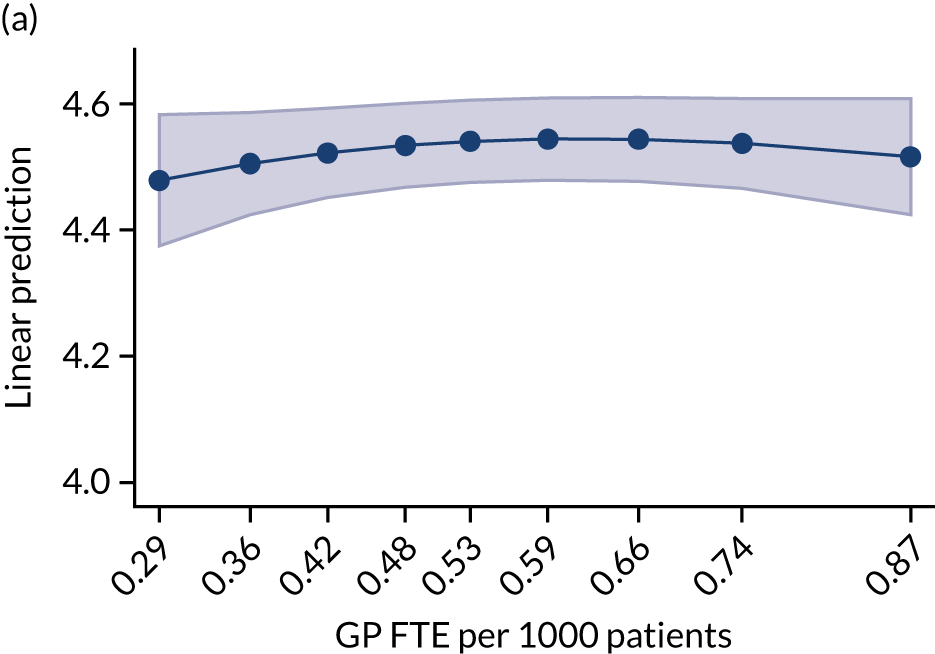

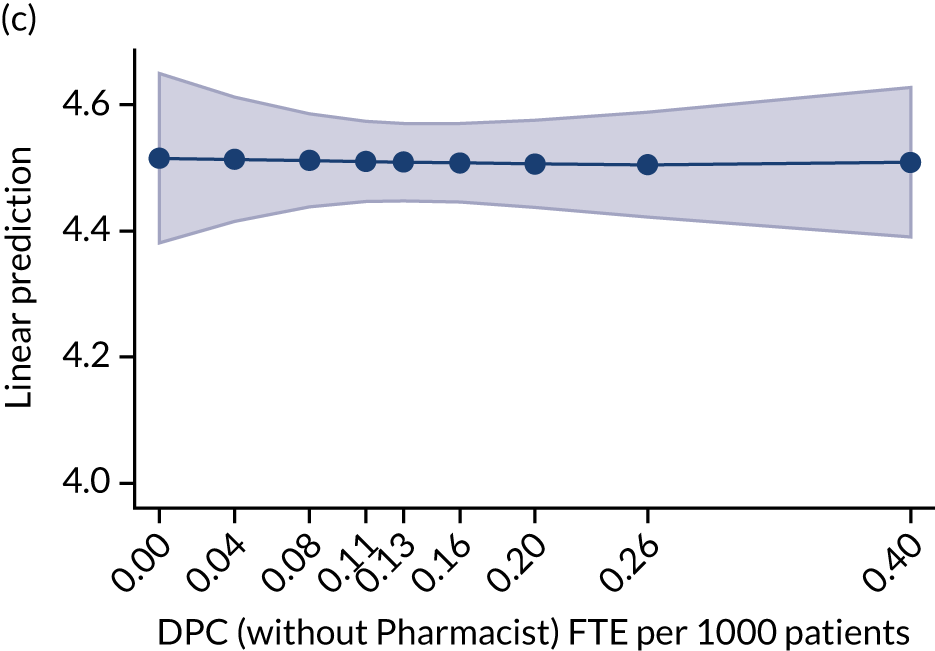

Patient list size enters these models in several ways. First, the outcome variables are workforce FTE PTP to ensure comparability across practices with different catchment populations. Second, patient list size is included as covariates as a cubic function to capture non-linearities in the effect of patient population on staffing (e.g. if the contribution to the practice drops or jumps above a certain patient number for certain roles). The parameter estimates, shown in Table 4, suggest that the number of patients is not significantly associated with workforce PTP. This relationship is presented differently in Figure 8, which shows that the level of staff PTP is stable across different patient population sizes.

| Outcome variable | Practice workforce FTE PTP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GP | Nurse | DPC | |

| Number of patients (thousands) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002 (0.001) |

| Number of patients (thousands)2 | –0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | –0.000 (0.000) |

| Number of patients (thousands)3 | 0.000 (0.000) | –0.000 (0.000) | –0.000 (0.000) |

| Distance to nearest hospital (km) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.001*** (0.000) | 0.002*** (0.000) |

| Distance to nearest medical school (km) | –0.001*** (0.000) | 0.001*** (0.000) | 0.001*** (0.000) |

| Proportion (%) of patients aged ≥ 65 years | 0.008*** (0.001) | 0.003*** (0.000) | 0.003*** (0.000) |

| MPIG per patient | 0.007*** (0.002) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.003*** (0.001) |

| Rural (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.033*** (0.012) | 0.014** (0.006) | 0.094*** (0.008) |

| Market forces factor | 0.061 (0.039) | –0.346*** (0.021) | –0.122*** (0.026) |

| Income deprivation | 0.117* (0.063) | 0.304*** (0.034) | 0.329*** (0.042) |

| GMS (1 = yes; 0 = no) | –0.006 (0.008) | –0.024*** (0.004) | –0.022*** (0.005) |

| Dispensing practice (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.055*** (0.012) | 0.016*** (0.006) | 0.238*** (0.008) |

| Extended hours payments (per patients) | 0.010*** (0.003) | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.003 (0.002) |

| Constant | 0.325*** (0.059) | 0.546*** (0.032) | 0.161*** (0.040) |

| Observations | 6287 | 6287 | 6287 |

| R 2 | 0.065 | 0.198 | 0.369 |

| Breusch–Pagan test of independence | χ2(6) = 884.098 | p < 0.001 | |

FIGURE 8.

Workforce predictive margins of patient list size.

Table 4 also shows that distance to the nearest hospital and medical school (in kilometres) are both positively associated with nurse and DPC FTE PTP, whereas distance to nearest medical school (in kilometres) is negatively associated with GP workforce. Distance to nearest medical school is potentially a supply effect where newly qualified GPs are more likely to locate near to where they have trained, whereas the distance to nearest hospital is a measure of the availability of secondary care. Practices that are located further away from a hospital have more nursing and DPC staff employed.

The proportion of patients aged ≥ 65 years, the amount of payments received through the minimum practice income guarantee (MPIG), rurality, patient income deprivation, the payments for extended hours access and being a dispensing practice are positively associated with workforce groups. These factors indicate that patient demand factors and income payments are positively associated with staff employment.

The market forces factor, which measures the unavoidable cost differences between geographical locations, is negatively associated with nurse and DPC workforce, but is not significantly different from zero for GPs. This is potentially a supply factor where staff on lower salaries (e.g. DPC/nurses) are unable to locate to more expensive areas. Alternatively, there could be a greater demand for GP services in more expensive locations and less demand for appointments with DPC and nursing staff.

Summary

Skill mix change in general practice has been expanding since 2015 to include roles such as CPs and paramedics. However, these roles still represent a small proportion of the workforce. The roll-out of these roles in general practice has not been uniform across the country, with paramedics mainly employed by practices in the south of England and PAs employed by practices in the larger cities. A more detailed workforce analysis shows a range of demand and supply factors associated with the practice workforce. These factors range from geographical factors (e.g. distance to the nearest hospital that may provide initial training for health professionals), supply factors (e.g. the market forces factor, which may affect the affordability of living near the practice for lower-paid workers) and demand factors (e.g. the proportion of patients aged ≥ 65 years whose health-care needs are likely to increase). These contextual differences are an important step in understanding the motivating factors behind the expansion of skill mix and, therefore, any subsequent analysis of the impact on service delivery.

Chapter 4 Practice manager survey

The main objectives of this WP were to investigate practice preferences for different workforce practitioner groups and to ascertain the accuracy of the workforce data collected by NHS Digital through the National Workforce Reporting System, focusing on practice-level data.

In our protocol, we stated that we would also explore ‘Which aspects of healthcare are undertaken by different practitioner types?’ Following reflection on previous work in this area (e.g. the MUNROS study85), we decided that this research question was too nuanced for an online survey and these issues were instead explored using qualitative methods in WP3. Therefore, in this chapter, we address research question 2(i) with regard to what motivates practices to choose/not choose increased skill mix deployment.

In workforce planning, and in appraising the effectiveness of workforce policies, it is vital to have accurate practice-level workforce data as submitted by practices to fulfil their contractual requirements and populate the wMDS. The wMDS was established in 2011 by the then Department of Health (now the Department of Health and Social Care) to support workforce planning and the commissioning of education and training.

Survey questionnaire

The first set of questions presented practices with data about their workforce composition that were retrieved from the wMDS. Respondents were asked to confirm or correct these data.

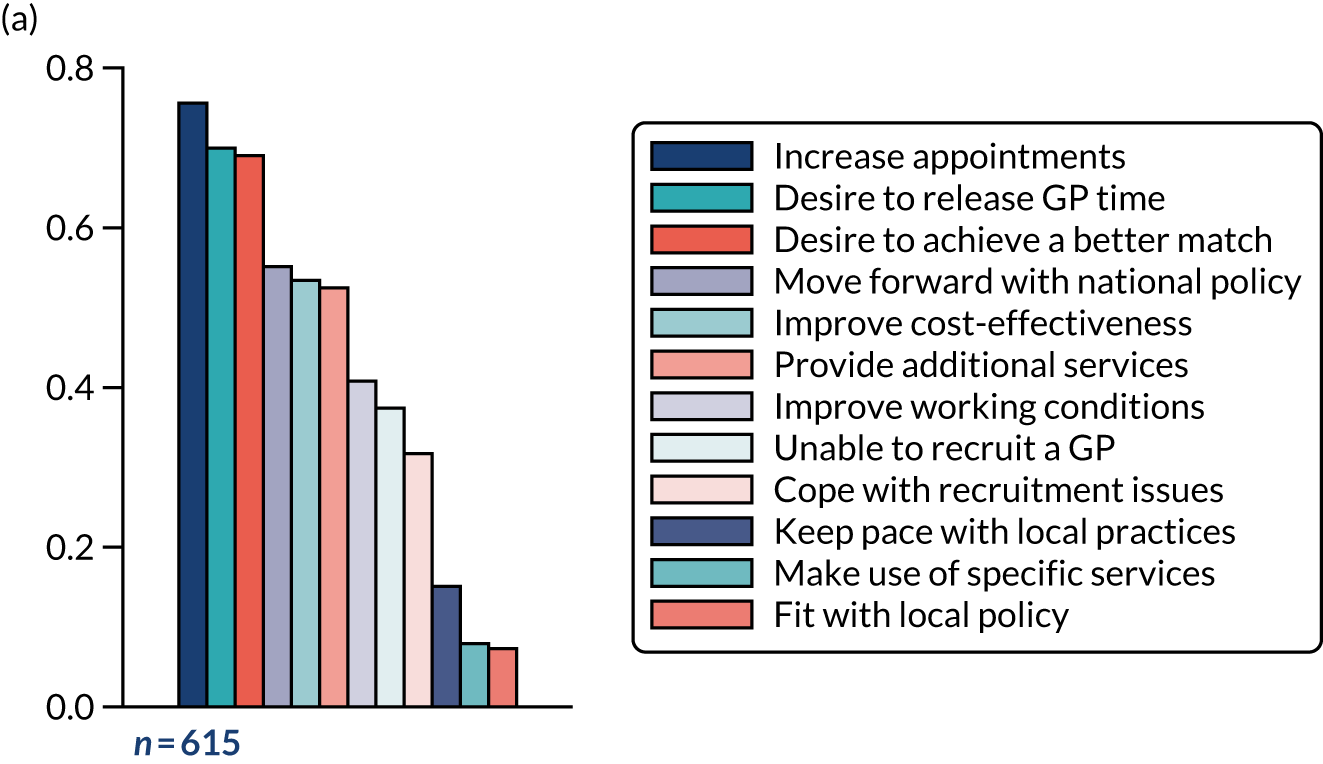

The second set of questions selectively asked practices about factors influencing their decision to employ staff in specific roles that they had just confirmed. Questions focused on six practitioner categories: (1) ANP, (2) specialist nurse, (3) HCA, (4) PA, (5) paramedic and (6) CP. As indicated in Chapter 2, these categories were chosen to include established practitioner types, employment supported by financial incentives, staff providing additional services and staff available through PCN funding. Respondents were presented with a list of 12 predefined motivating factors drawn from our knowledge of workforce policy and literature and insights from GP members of the research team. Respondents were permitted to add additional factors not captured in the list. Practices were asked to select all that applied to their decision. Those practices that employed staff in one of the six roles of interest were then asked if they had received external funding to support staff employment in that role and, if so, from which organisation and if they were still receiving funding.

The third set of questions was posed to all practices regardless of the workforce they currently employed. Practices were asked if they wanted to employ additional staff from a list of roles in the future and, if so, if they wished for them to be directly employed by the practice or through a PCN.

Finally, practices were asked to select their ideal workforce by selecting the percentage of their workforce that should be made up of different roles. Respondents used slider bars to indicate the percentage for each worker group. Bars were programmed to adjust to 100% total.

For the second and third sets of questions, we presented statistics for the variables of interest. These statistics were the percentage or proportion of practices selecting each option. For continuous variables, we presented a standard deviation (SD). Factors that affected the likelihood of the practice responding to the questionnaire could introduce bias if the characteristics and responses of the responding practices were systematically different from non-responding practices. Therefore, we used inverse probability weighting (see Mansournia and Altma104) to reduce this potential for bias. 64 To calculate these weights, we estimated a logistic regression model for the binary variable of whether or not a practice responded, using the workforce, region and registered population characteristics as explanatory variables. We predicted the probability of responding for each practice using this regression model and took the reciprocal of this fitted value as a weight.

Response and sample

Survey responses were submitted by 1261 practice managers. Workforce data from NHS Digital contained records for 7012 practices, as of December 2019. Our sample accounted for around 17% of this total population of general practices.

After exclusions due to missing data both in the submission and in the NHS Digital data (from responders and non-responders), responses from 1205 (i.e. 96% of 1261) practices were used for this analysis. The sample contained at least one respondent from 174 of 191 (91%) Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs).

Practices in the sample were larger than non-responding practices in terms of both workforce and patient list size. Mean GP FTE for the sample practices was 5.94 FTE compared with a mean of 4.84 FTE for non-responding practices (i.e. a difference of 1.1 FTE). Sample practices also employed more FTEs across the other three workforce groups (i.e. nurses, DPC and administration). Sample practices had, on average, larger patient list sizes than the total population, with a mean of 10,219 patients compared with a mean of 8702 patients (i.e. a difference of 1517 patients). The results from the logistic regression are presented in Table 5.

| Response (1 = yes, 0 = no) | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practice GP FTE | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 to 0.07 |

| Practice DPC FTE | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 to 0.08 |

| Income deprivation | –2.34 | 0.56 | –3.45 to –1.24 |

| Region | |||

| London | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.17 to 0.63 |

| Midlands | –0.59 | 0.13 | –0.84 to –0.34 |

| North East and Yorkshire | –0.17 | 0.13 | –0.41 to 0.08 |

| North West | –0.42 | 0.14 | –0.69 to –0.15 |

| South east of England | –0.58 | 0.13 | –0.84 to –0.31 |

| South west of England | –0.08 | 0.14 | –0.34 to 0.19 |

| Constant | –1.36 | 0.12 | –1.60 to –1.12 |

| n | 6447 | ||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.04 | ||

| Log-likelihood | –2991.24 | ||

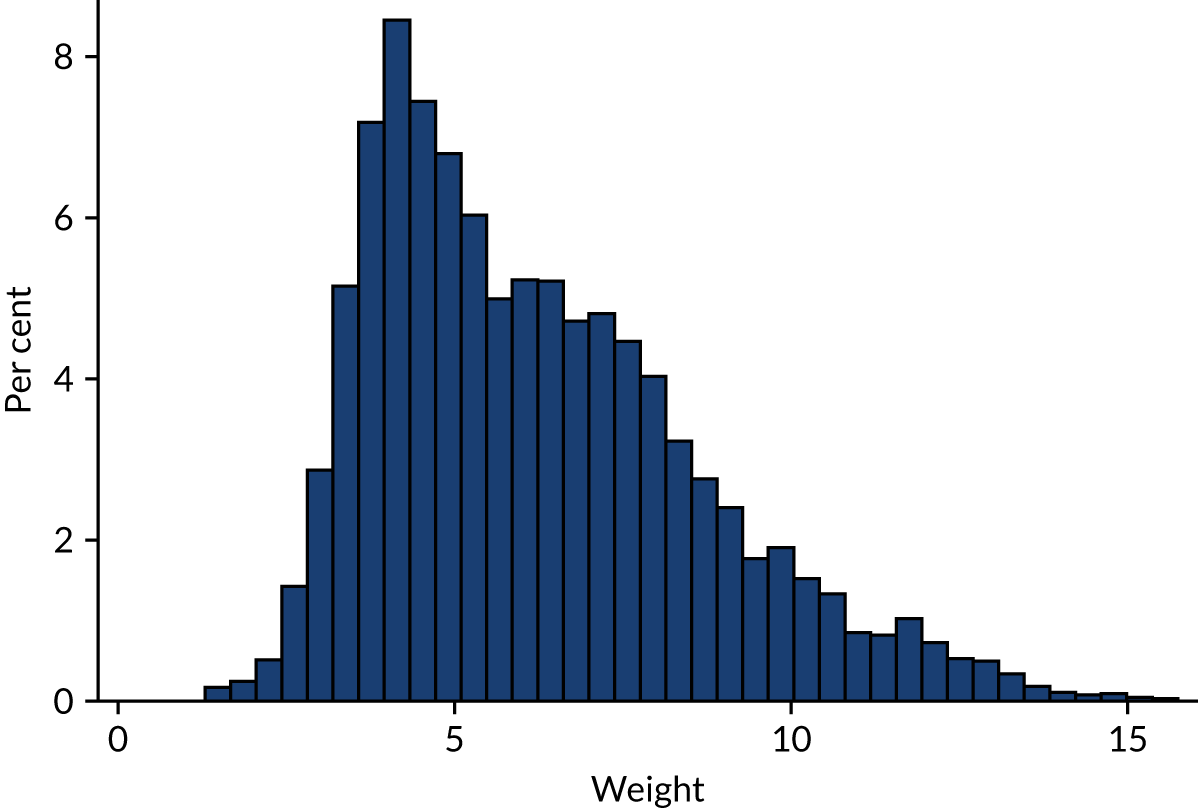

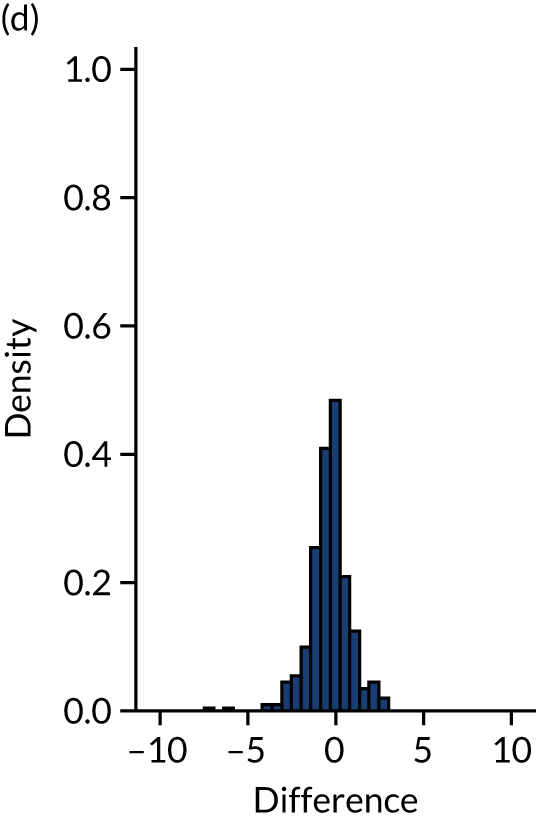

The distribution of the resulting weights is shown in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9.

Histogram of inverse probability weights.

Workforce data

Table 6 shows the number of practices that indicated that workforce data from NHS Digital were incorrect for the different staff groups. Around 30% of practices indicated that the FTE data were incorrect for the GP partner, GP salaried, practice nurse and HCA categories. Nurse specialists, PAs and paramedics had the lowest rates of data labelled as incorrect.

| Category | Practices, n | Practices selected incorrect, n | % incorrect |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP partner | 1247 | 394 | 31.6 |

| GP salaried | 1247 | 409 | 32.8 |

| GP locum | 1247 | 189 | 15.2 |

| Practice nurse | 1232 | 363 | 29.5 |

| Nurse advanced | 1232 | 291 | 23.6 |

| Nurse specialist | 1232 | 56 | 4.5 |

| HCA | 1218 | 374 | 30.7 |

| PA | 1218 | 34 | 2.8 |

| CP | 1218 | 247 | 20.3 |

| Paramedic | 1218 | 67 | 5.5 |

The practitioner categories with the largest percentage of incorrect data, such as GP, practice nurse and HCA, were the most commonly employed practitioners. Therefore, there was more chance of the FTE being incorrect relative to some of the other categories, such as paramedic or PA, where the vast majority of practices did not employ any FTE. Table 7 separated practices that employed some staff from the group (i.e. FTE > 0) and practices that did not (i.e. FTE = 0)

| Category | FTE | NHS Digital, n (%) | Indicated incorrect, n (%) | NHS Digital | Corrected | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n (%) | Mean | SD | ||||

| GP partner | FTE = 0 | 83 (6.7) | 19 (22.9) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 76 (6.0) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FTE > 0 | 1164 (93.3) | 375 (32.2) | 3.39 | 2.28 | 1181 (94.0) | 3.29 | 2.17 | |

| All | 1247 (100.0) | 394 (31.6) | 3.16 | 2.36 | 1257 (100.0) | 3.09 | 2.24 | |

| GP salaried | FTE = 0 | 337 (27.0) | 60 (17.8) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 303 (24.1) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FTE > 0 | 910 (73.0) | 349 (38.4) | 1.96 | 1.82 | 952 (75.9) | 2.01 | 1.83 | |

| All | 1247 (100.0) | 409 (32.8) | 1.43 | 1.78 | 1255 (100.0) | 1.52 | 1.81 | |

| GP locum | FTE = 0 | 884 (70.9) | 107 (12.1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 852 (68.2) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FTE > 0 | 363 (29.1) | 82 (22.6) | 0.64 | 0.78 | 397 (31.8) | 0.69 | 0.75 | |

| All | 1247 (100.0) | 189 (15.2) | 0.19 | 0.51 | 1249 (100.0) | 0.22 | 0.53 | |

| Practice nurse | FTE = 0 | 64 (5.2) | 21 (32.8) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 52 (4.2) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FTE > 0 | 1168 (94.8) | 342 (29.3) | 2.03 | 1.69 | 1196 (95.8) | 2.13 | 1.99 | |

| All | 1232 (100.0) | 363 (29.5) | 1.92 | 1.71 | 1248 (100.0) | 2.04 | 2 | |

| Nurse advanced | FTE = 0 | 713 (57.9) | 117 (16.4) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 632 (51.2) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FTE > 0 | 519 (42.1) | 174 (33.5) | 1.36 | 0.96 | 603 (48.8) | 1.59 | 2.39 | |

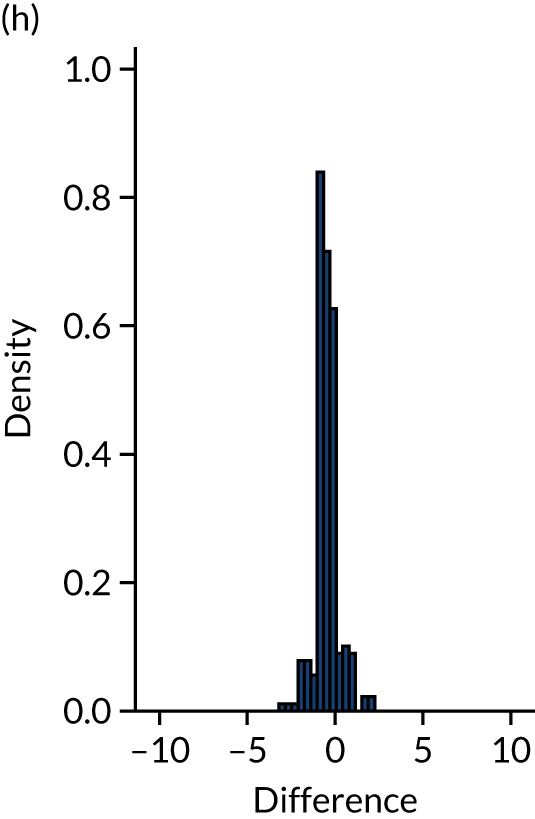

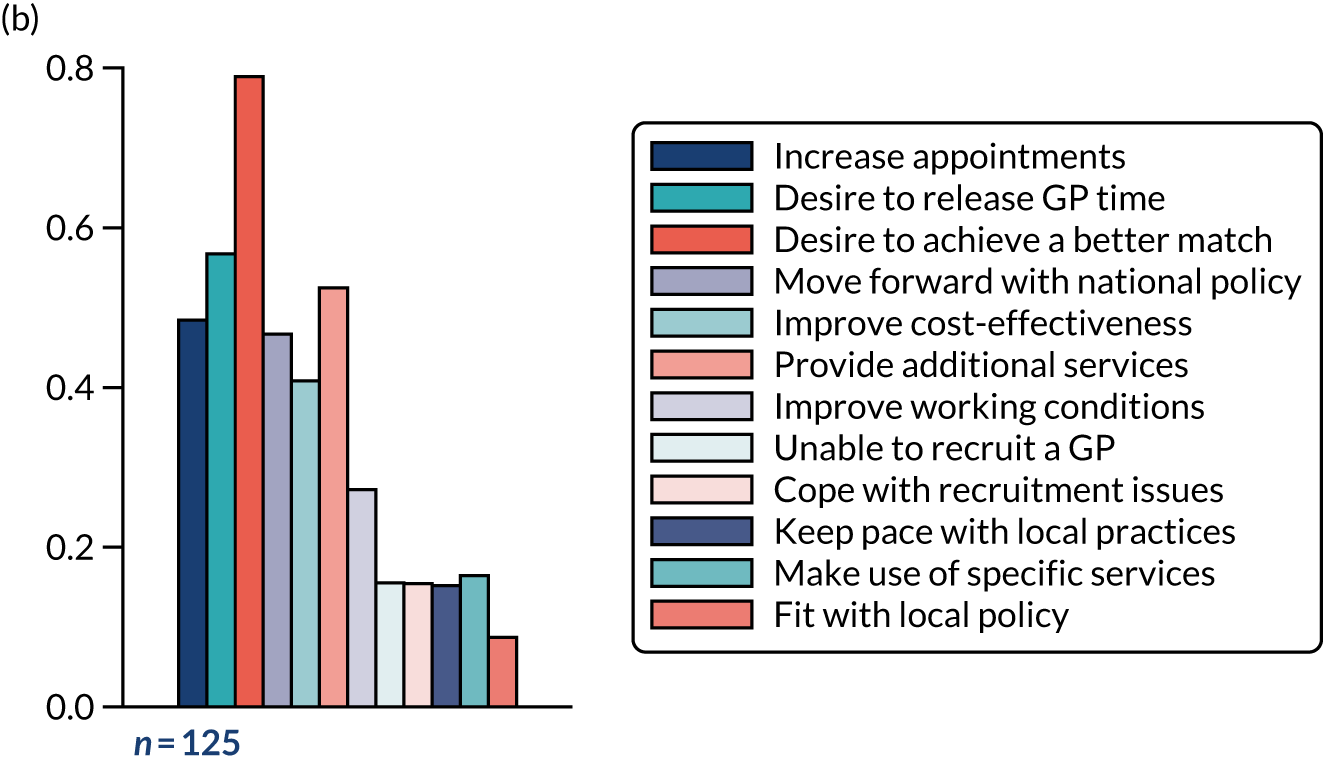

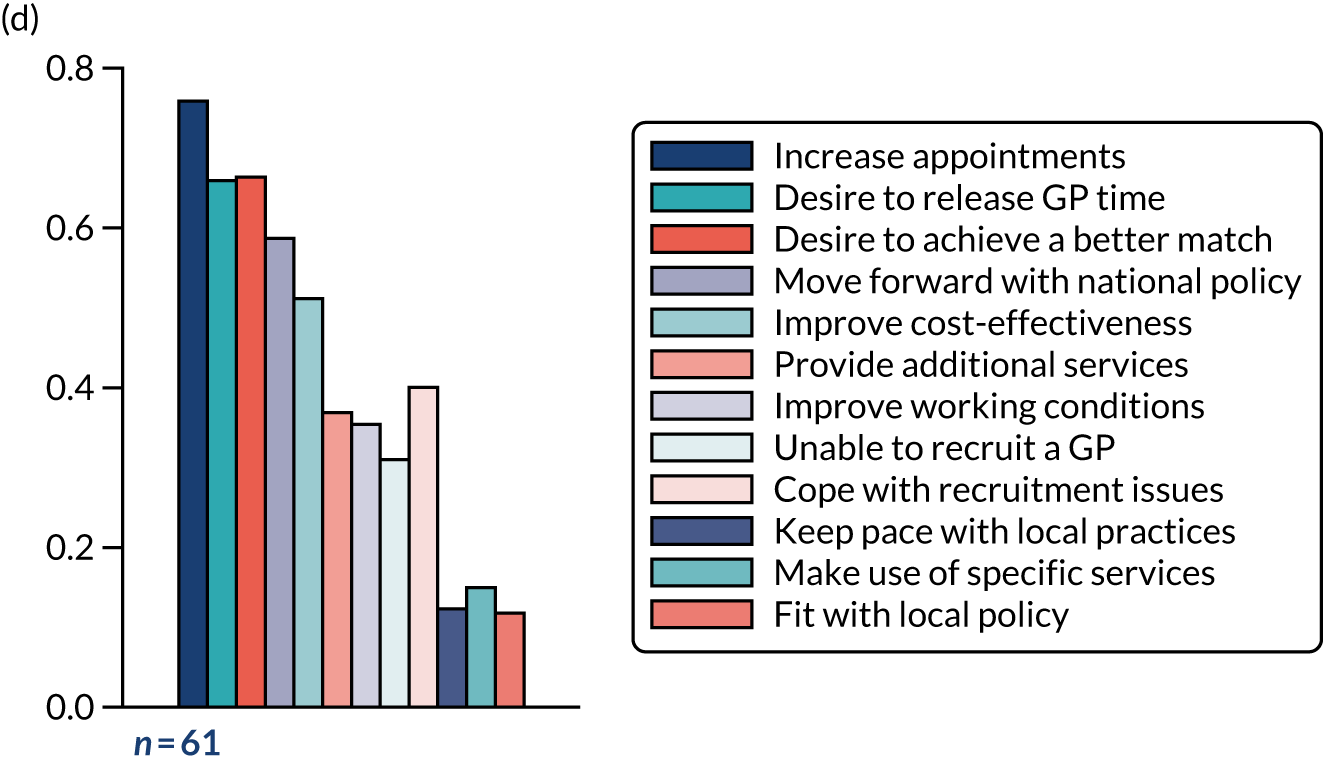

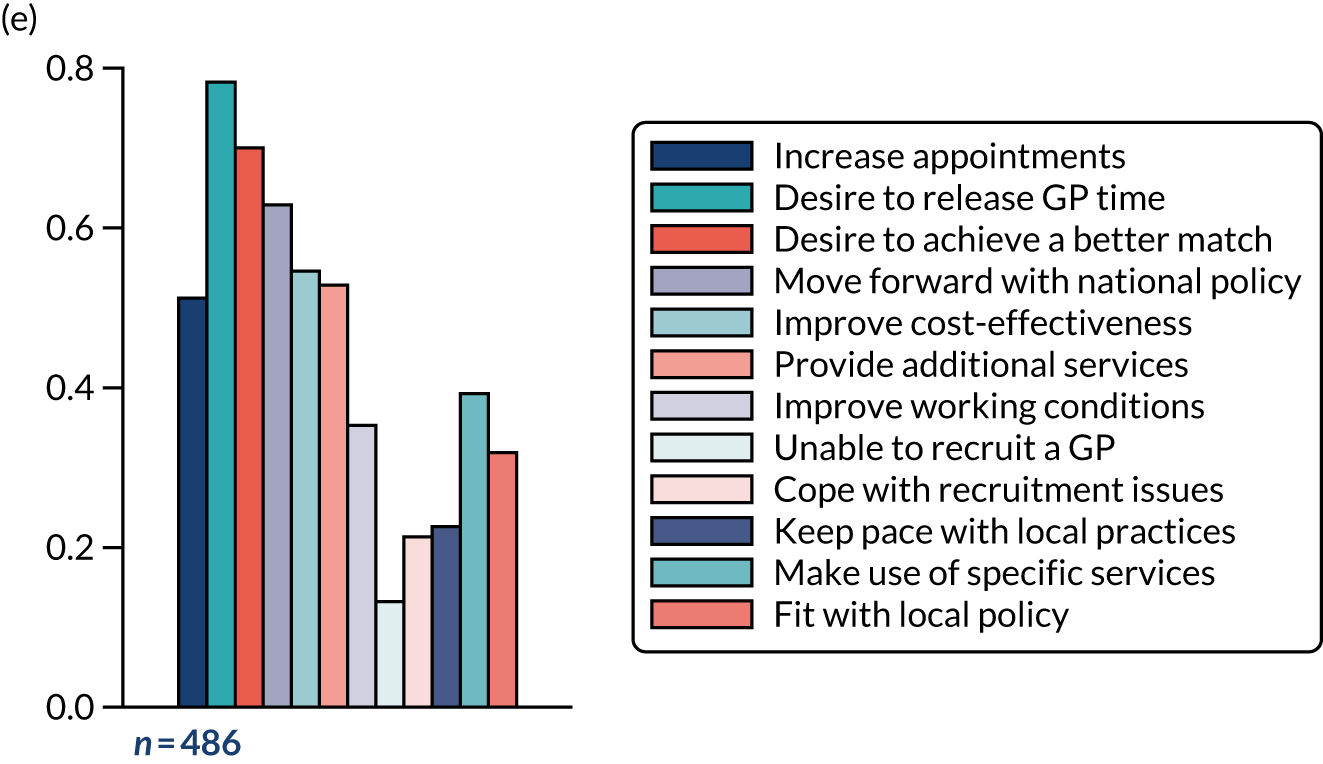

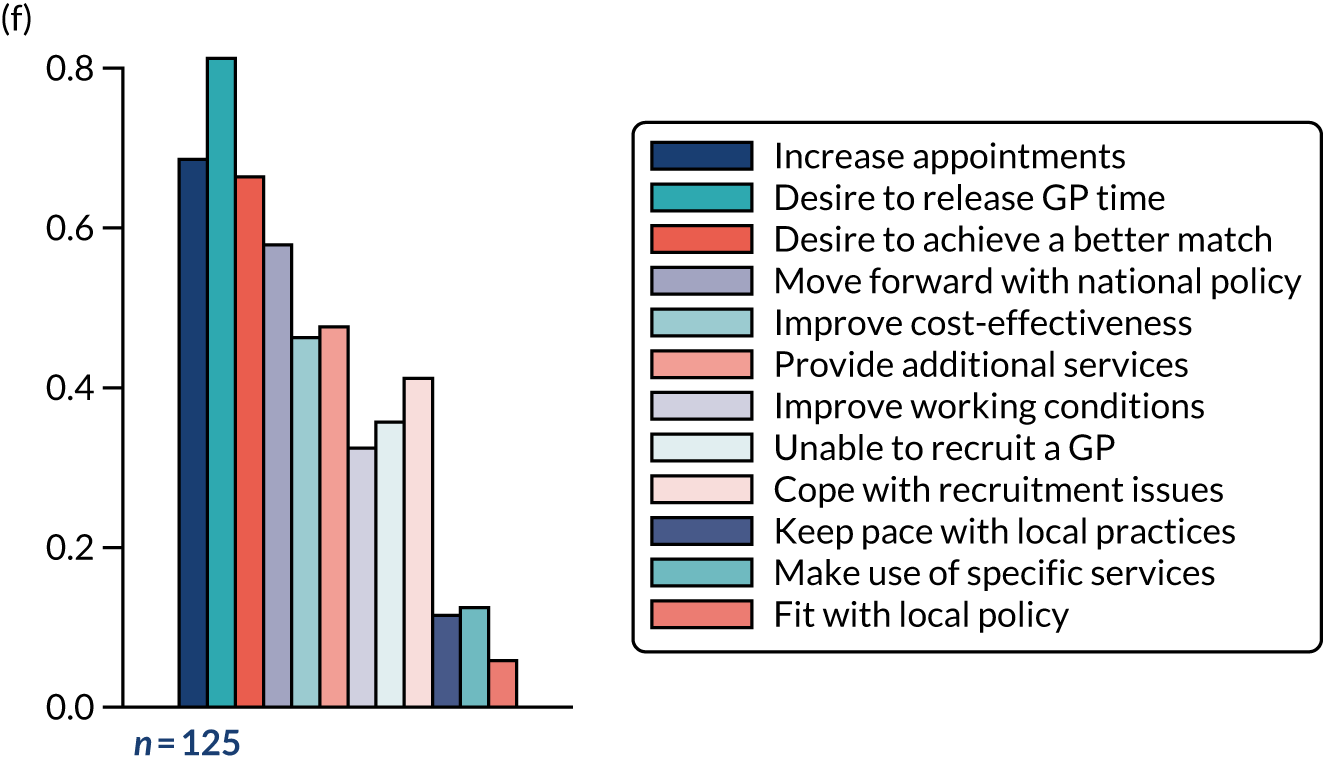

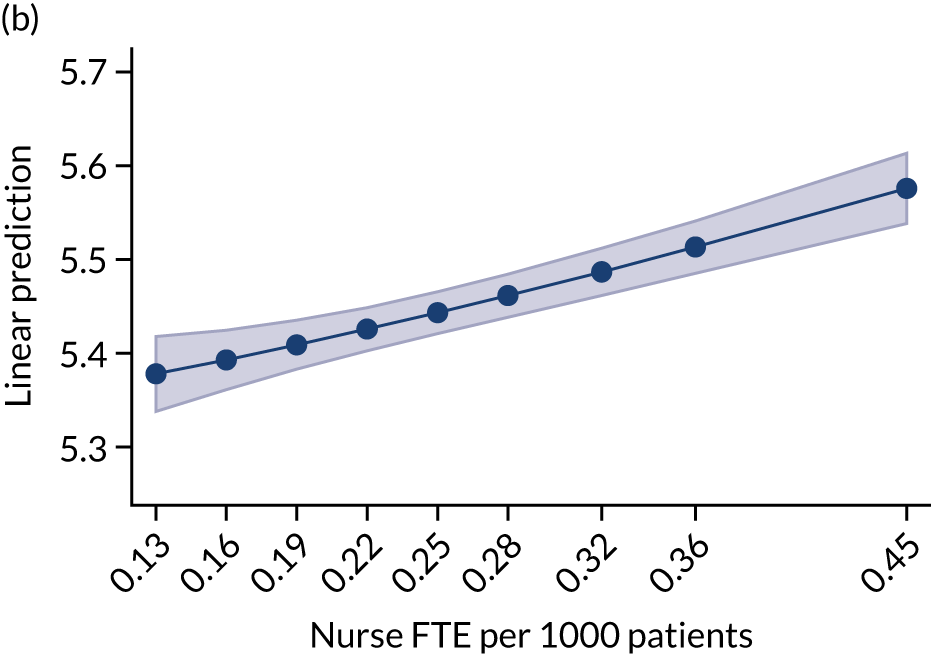

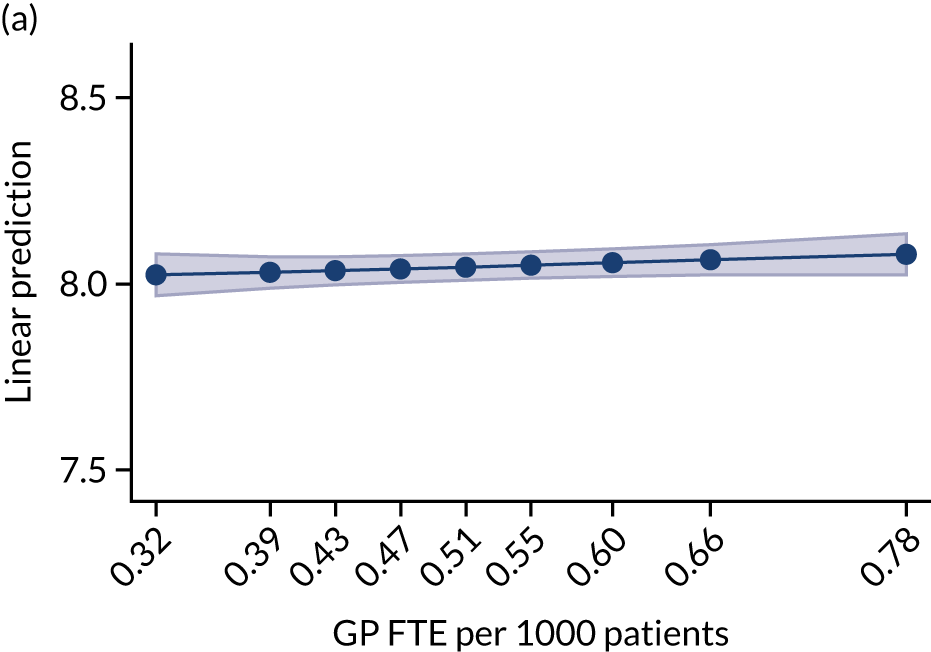

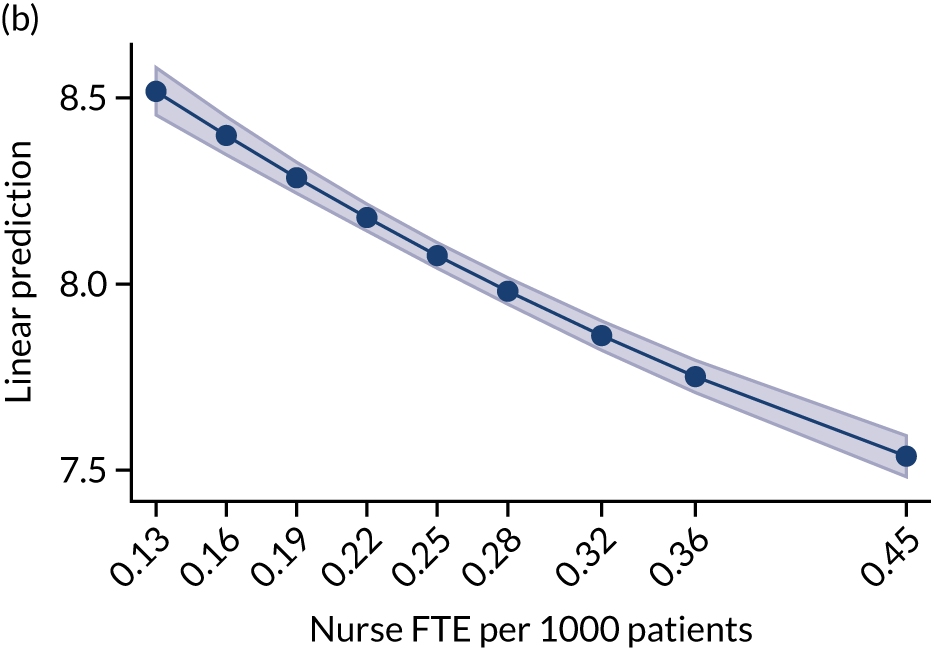

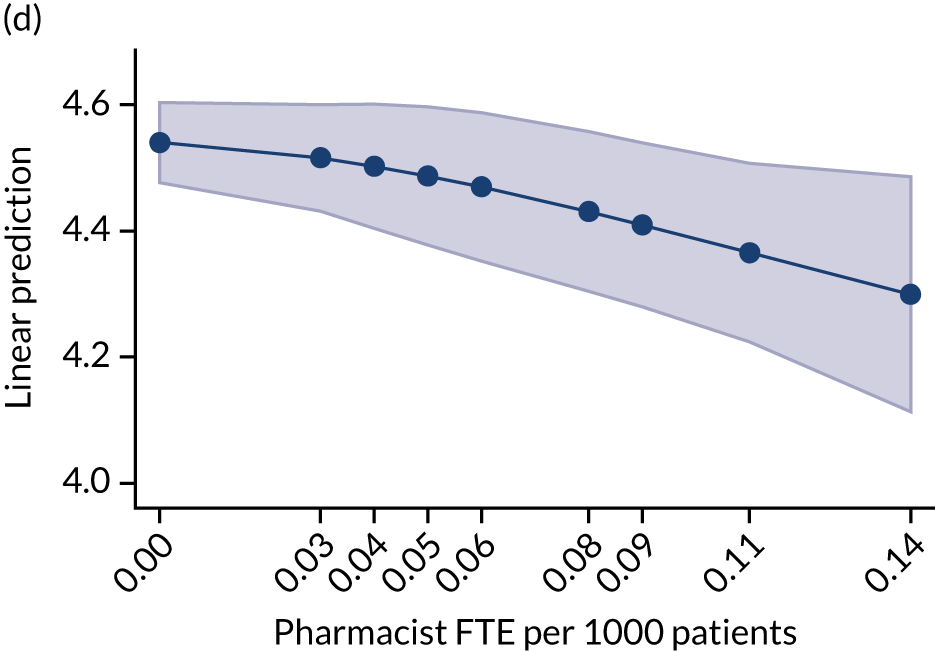

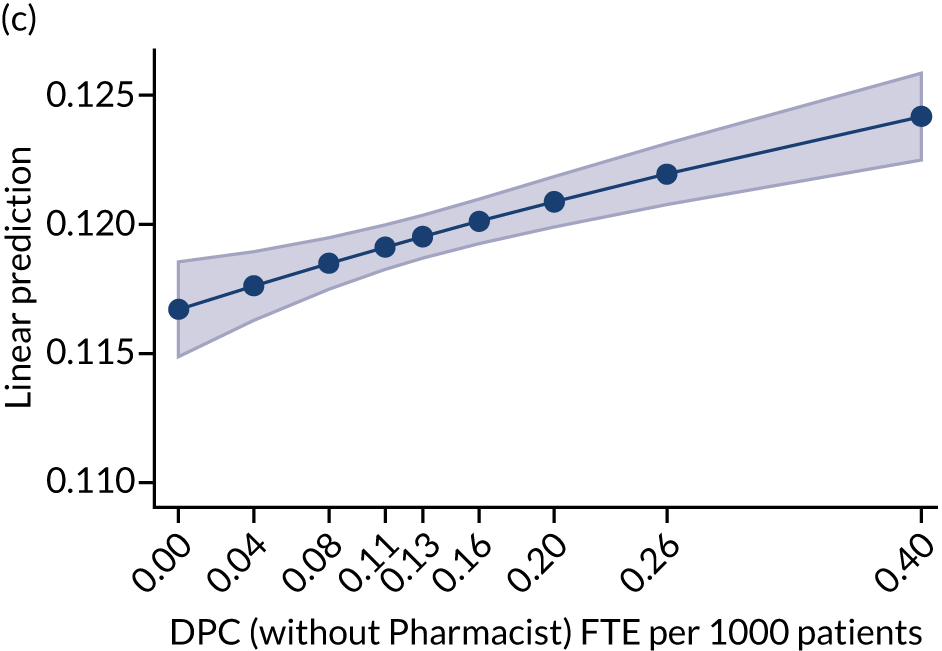

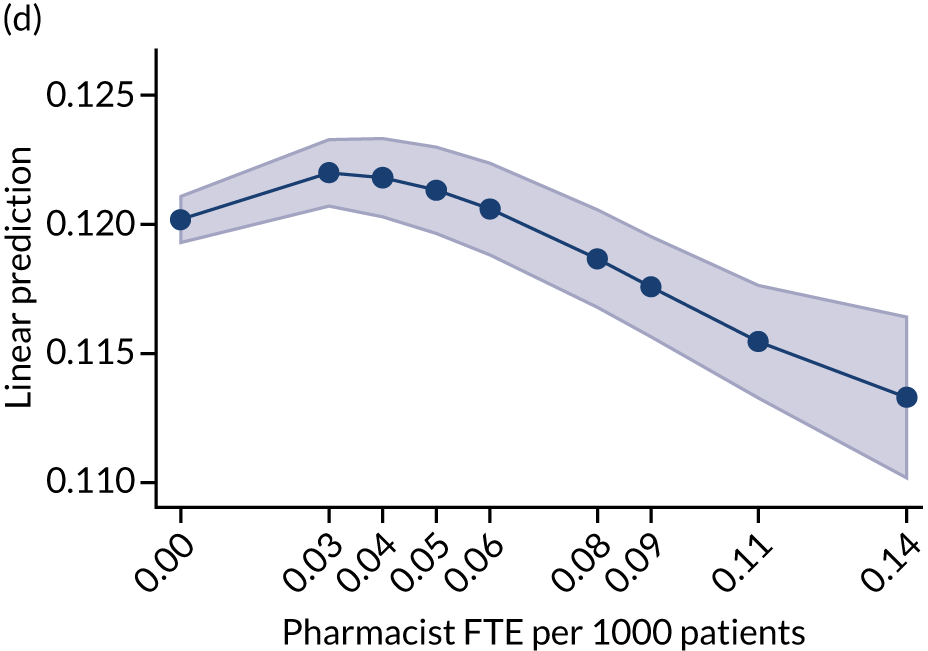

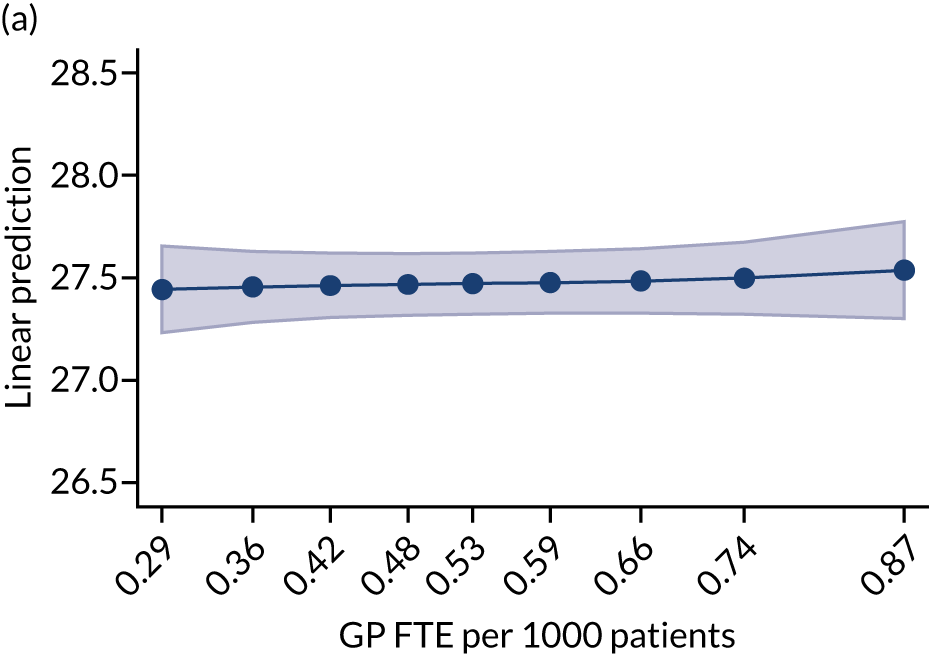

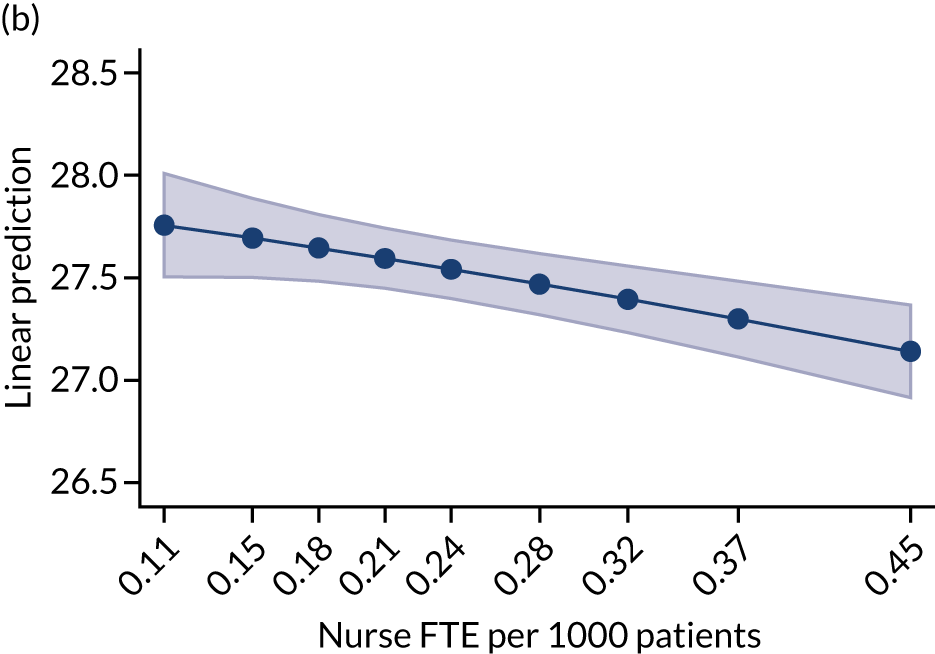

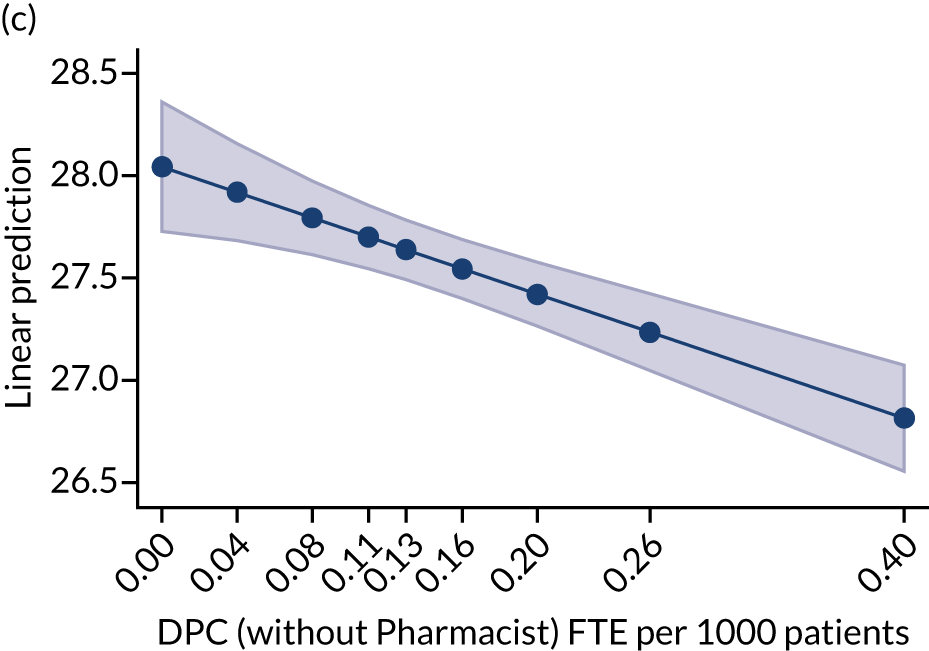

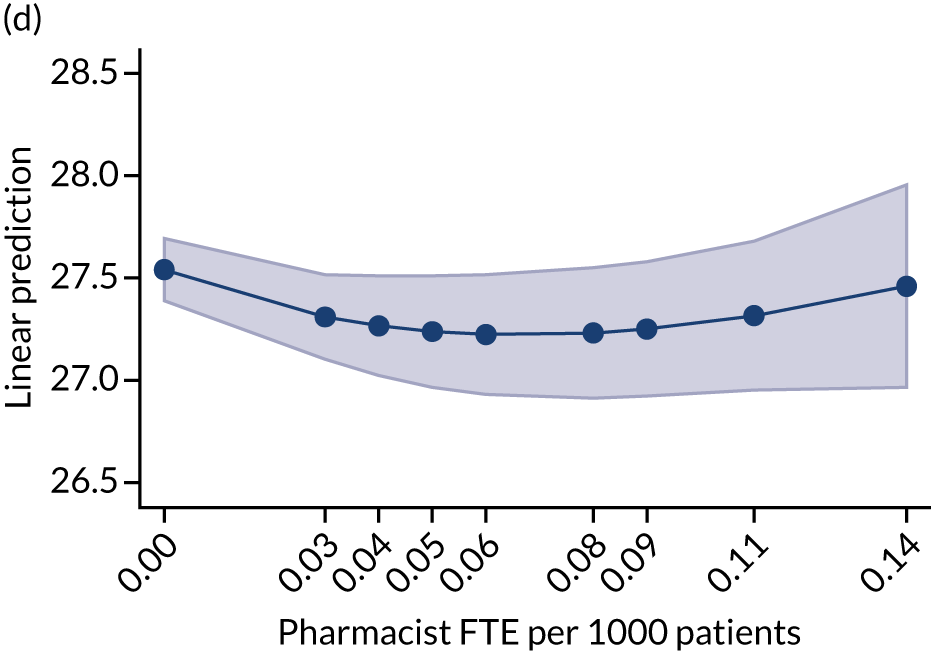

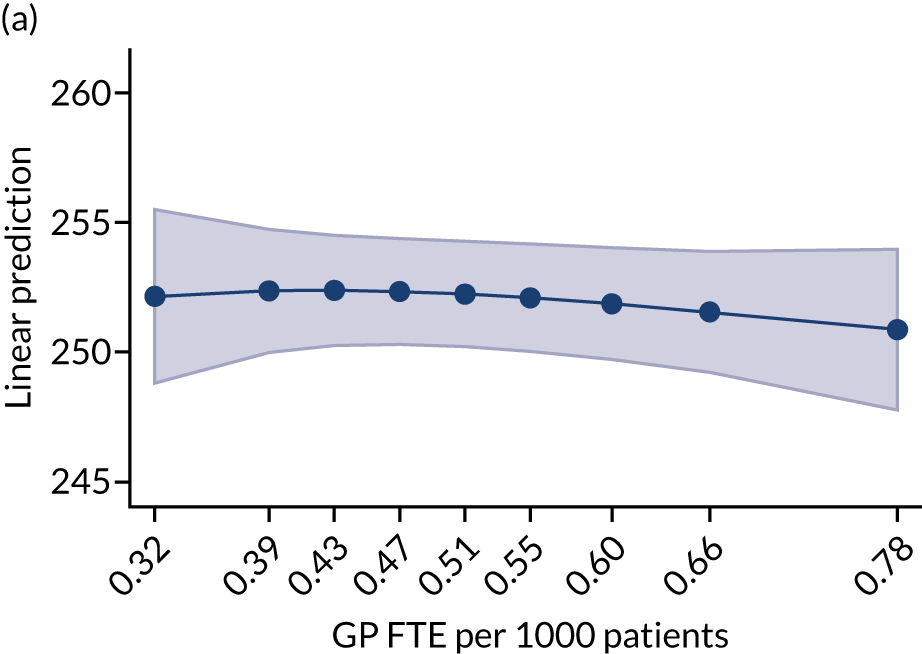

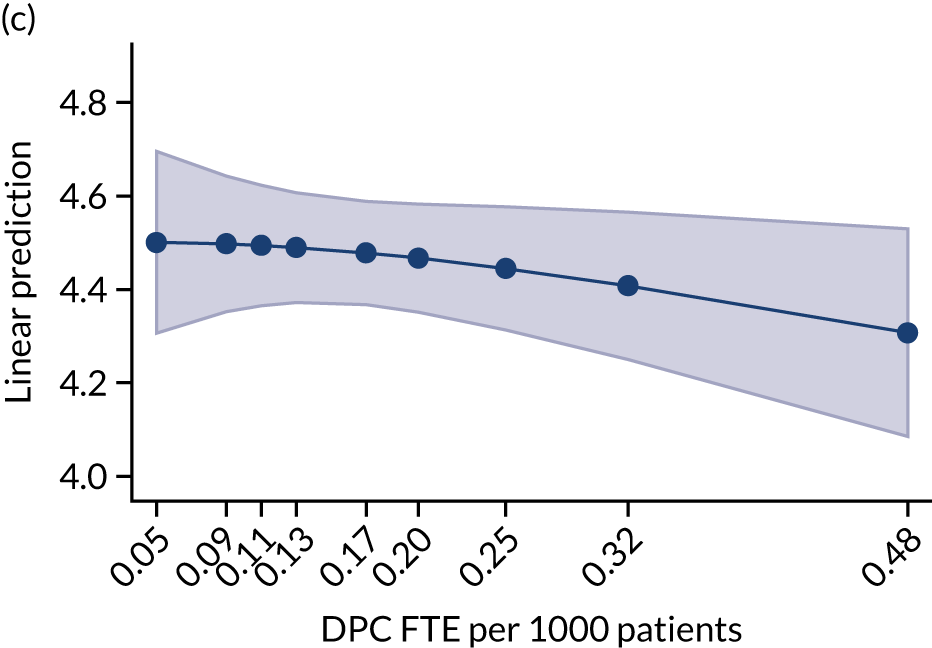

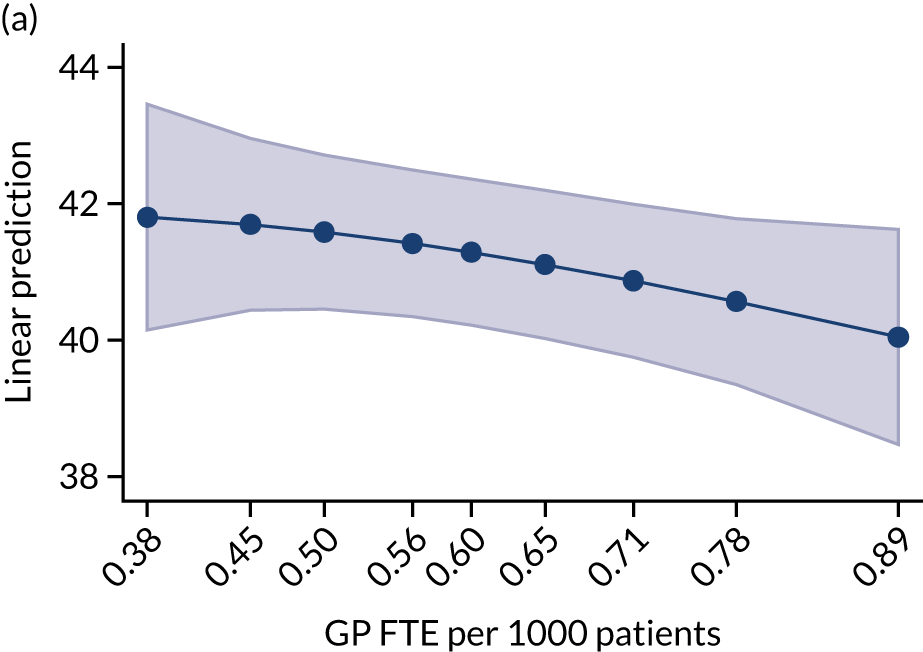

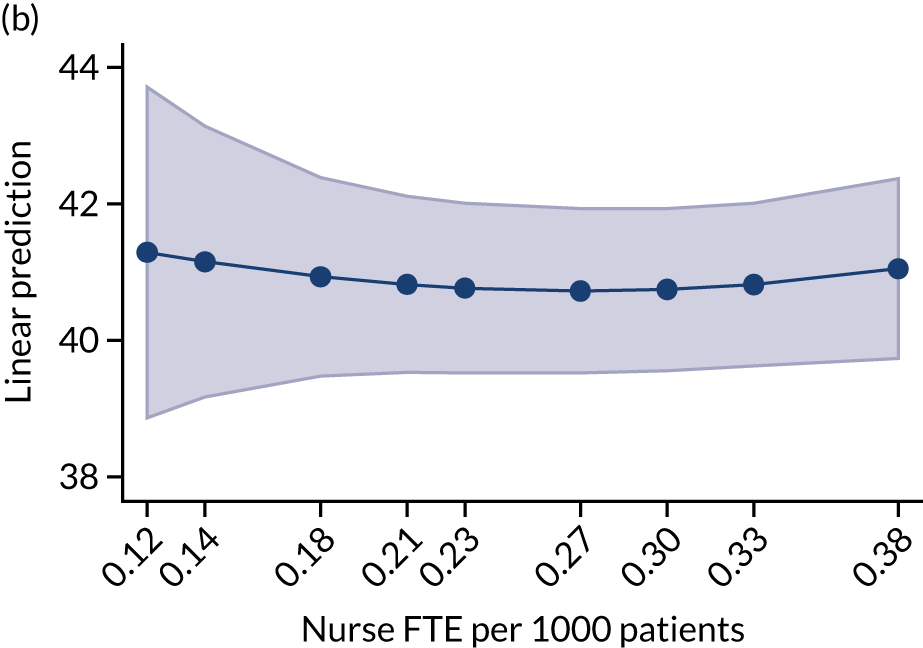

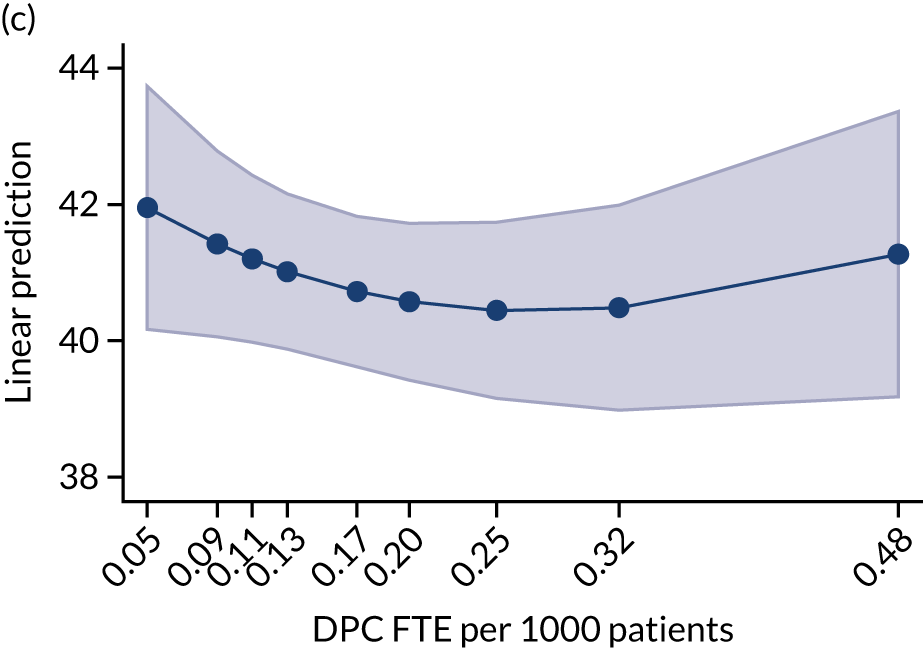

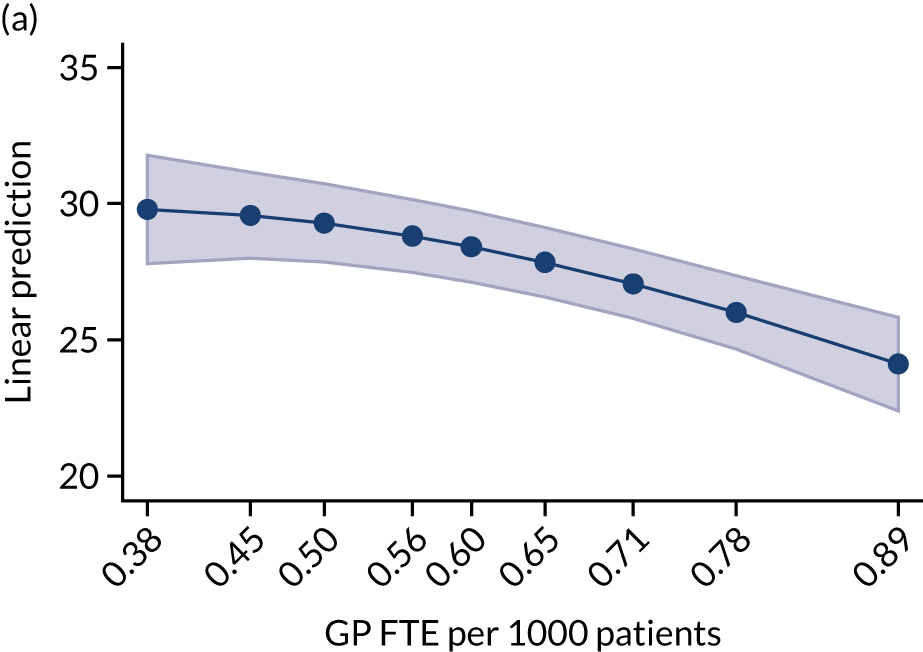

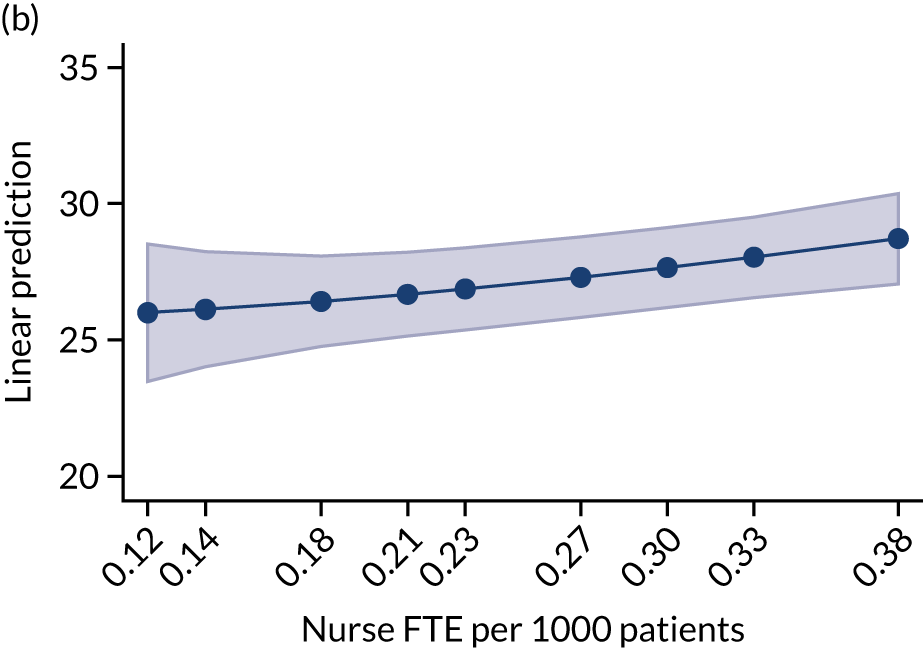

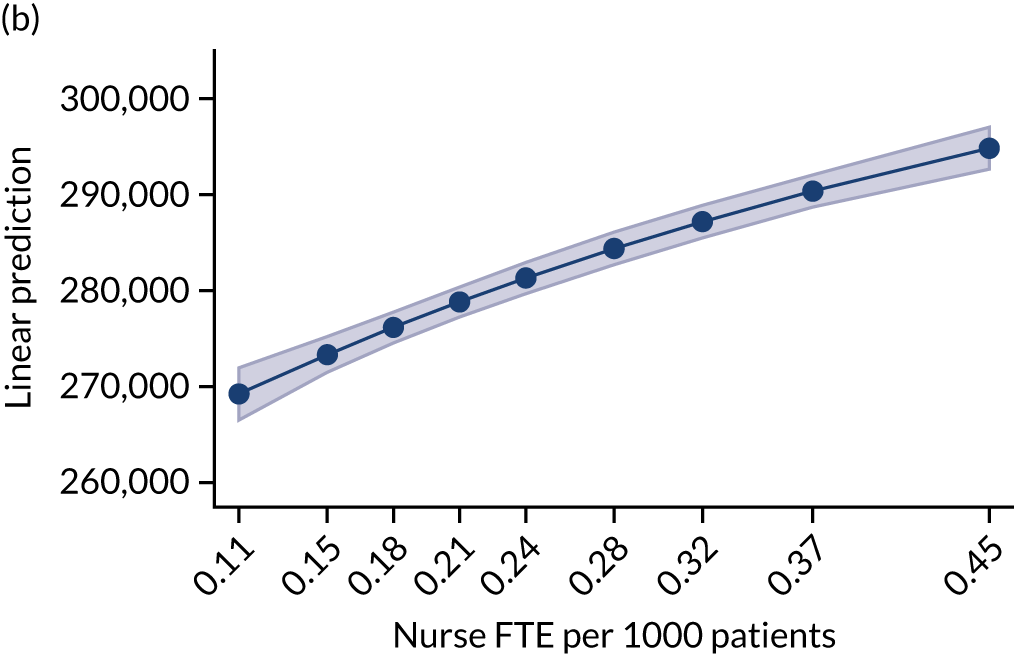

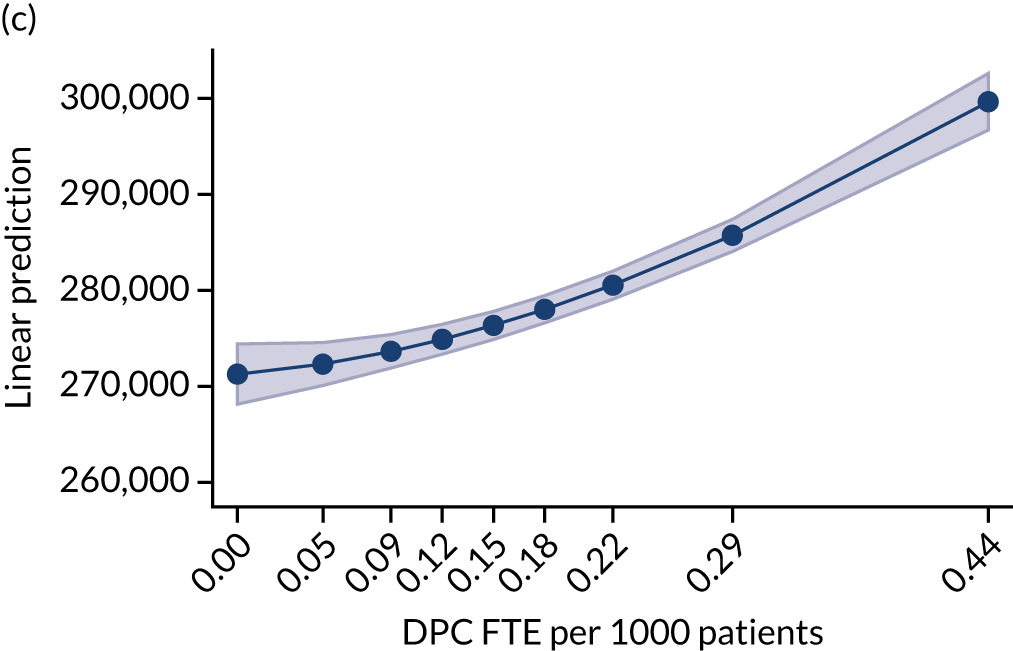

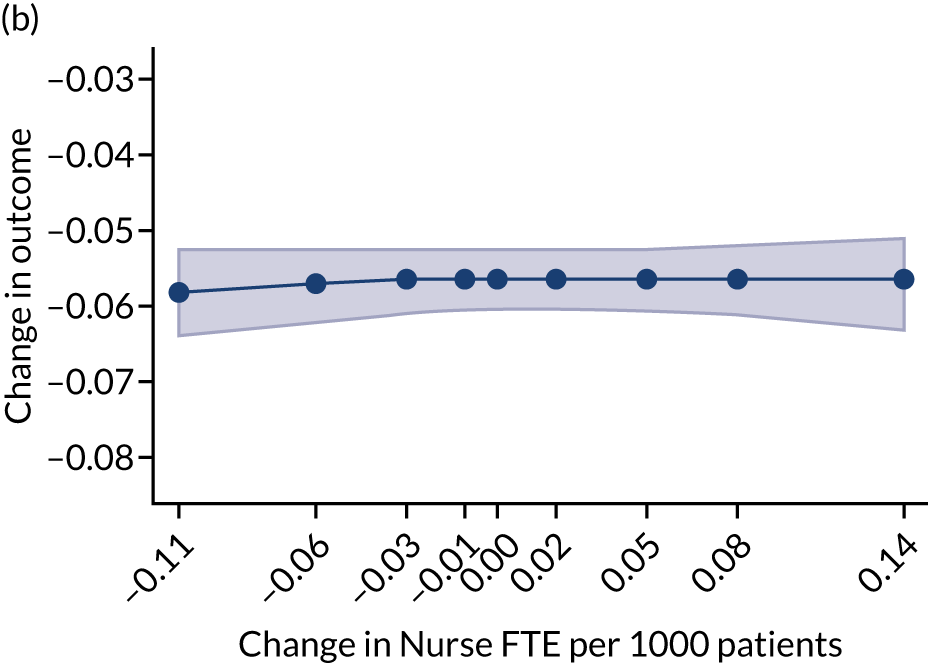

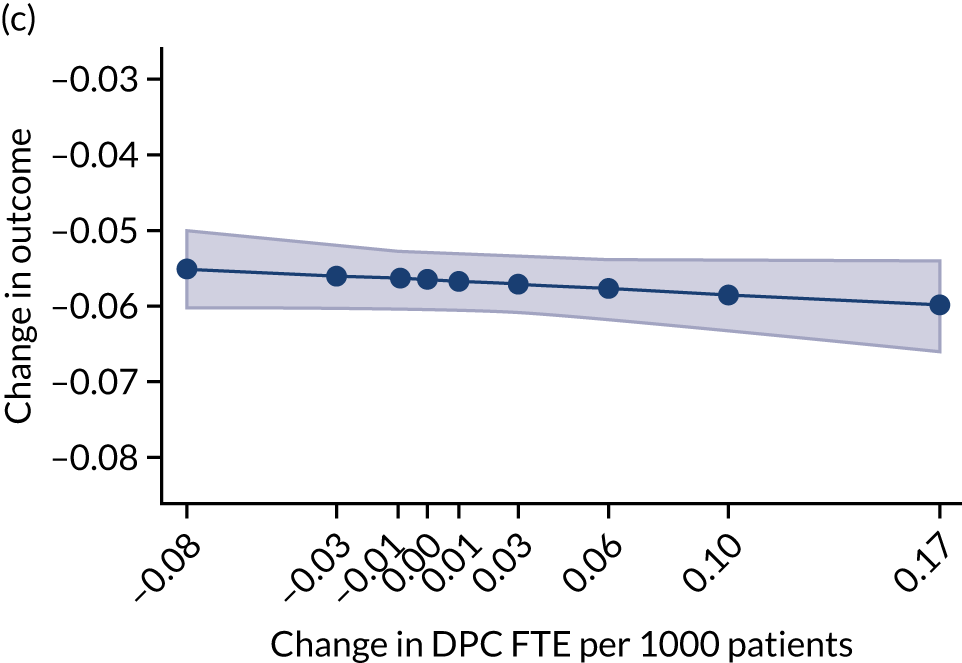

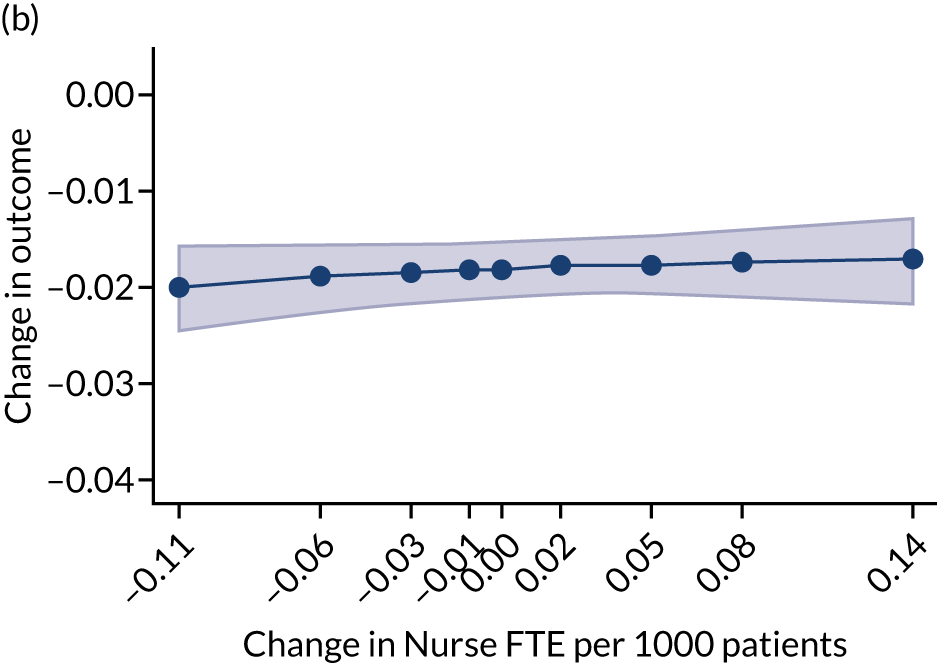

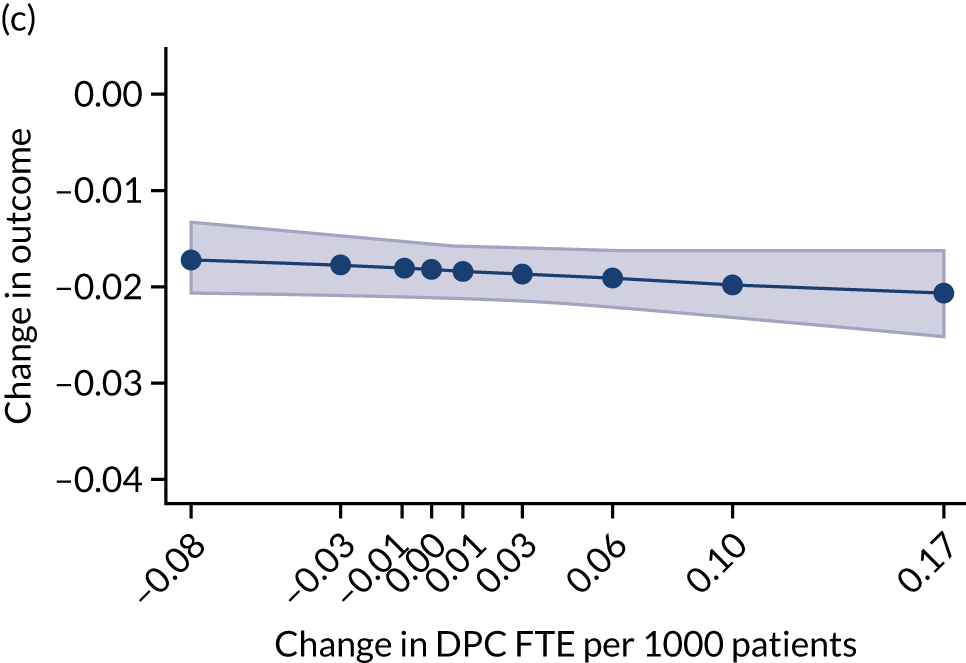

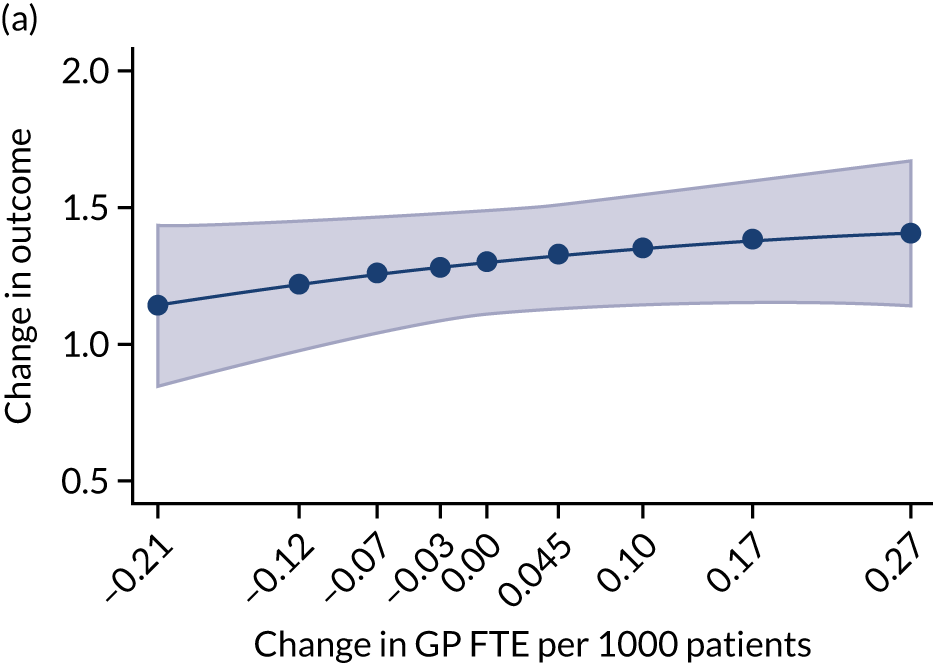

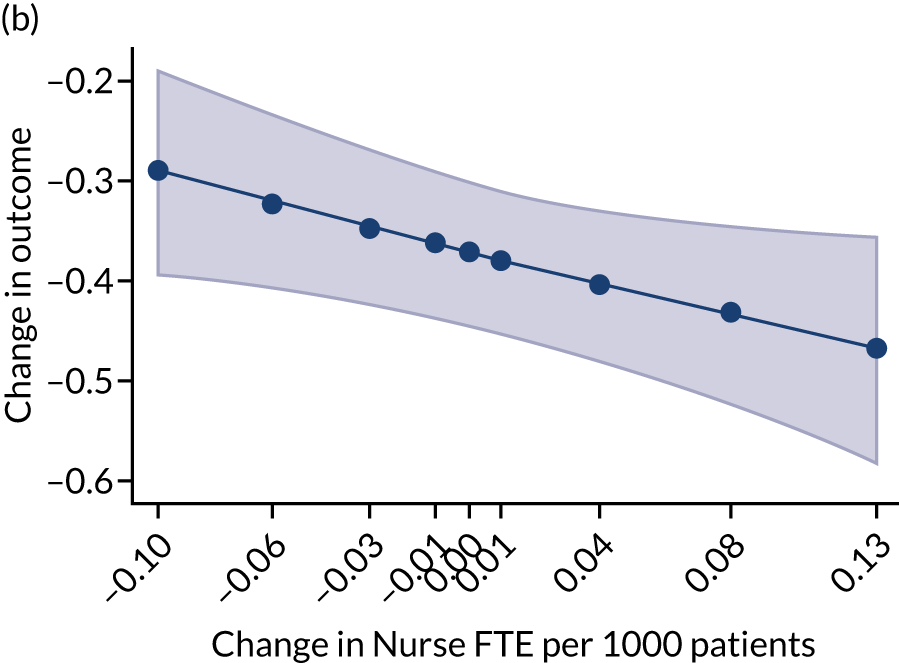

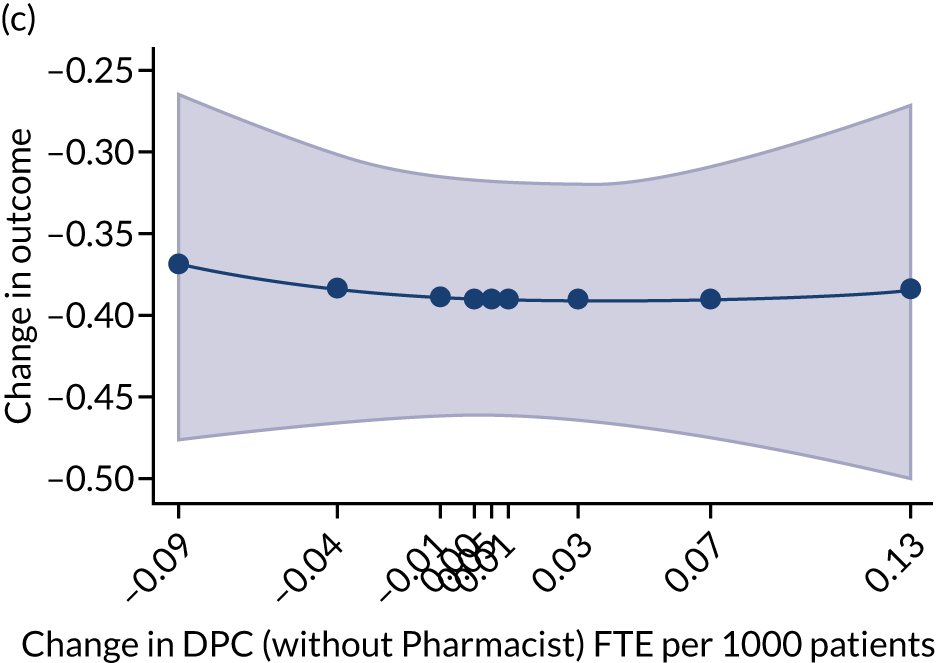

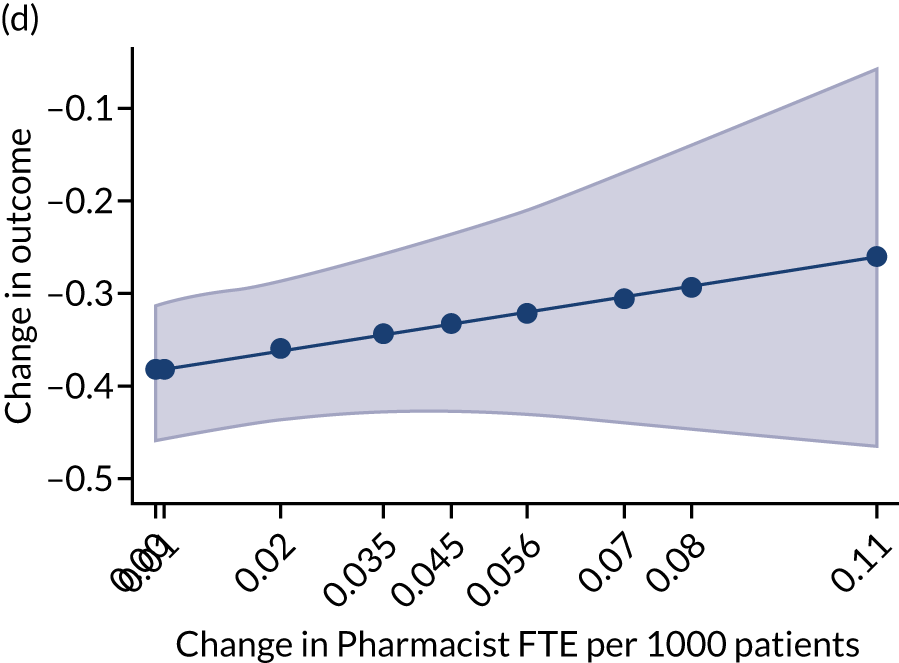

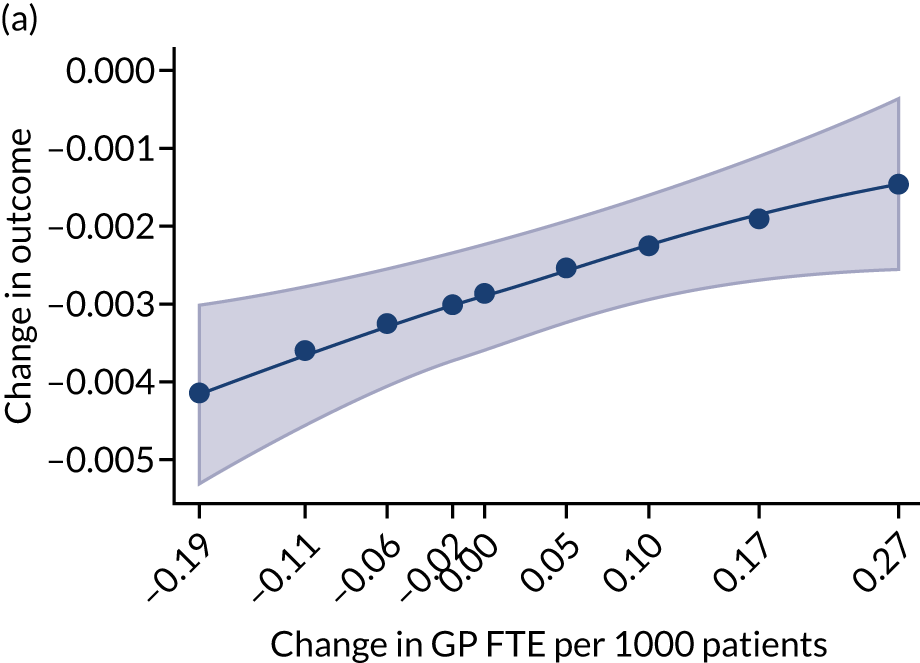

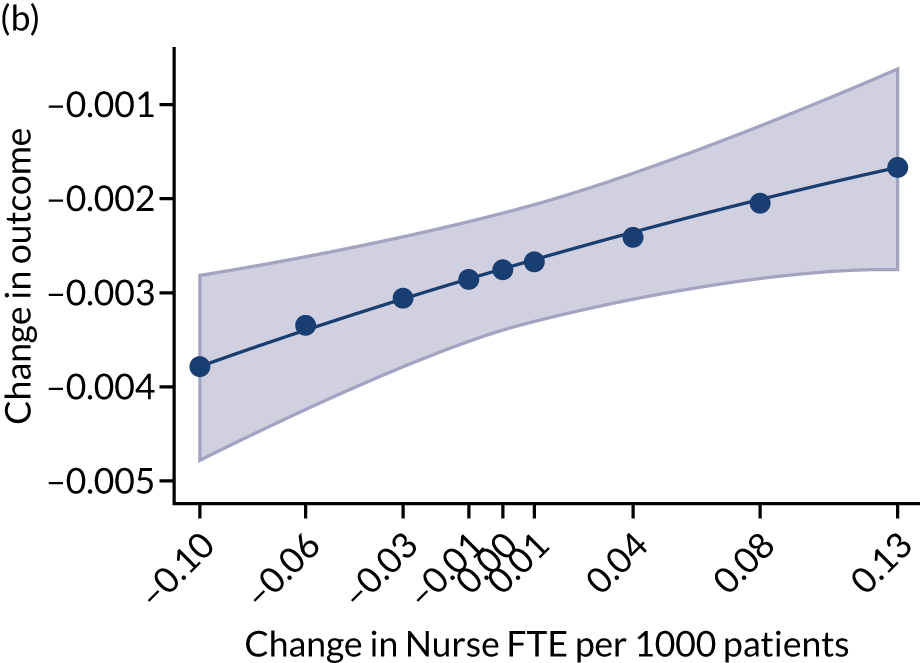

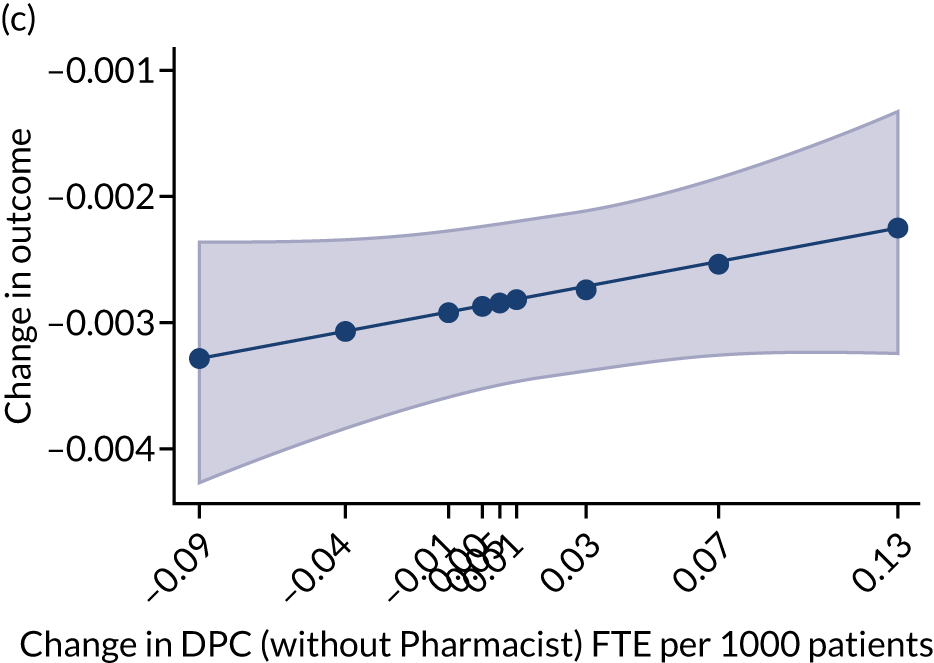

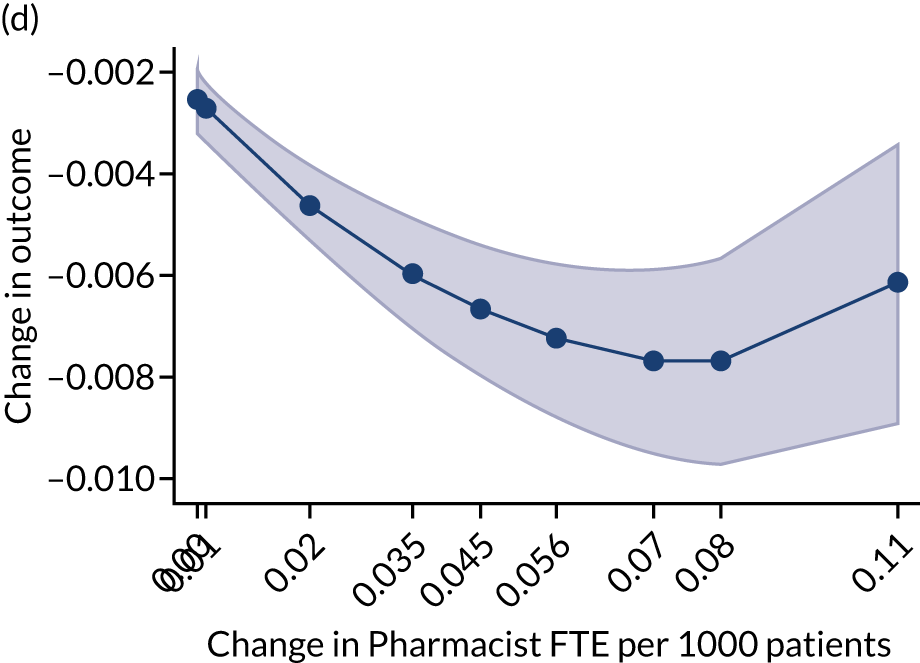

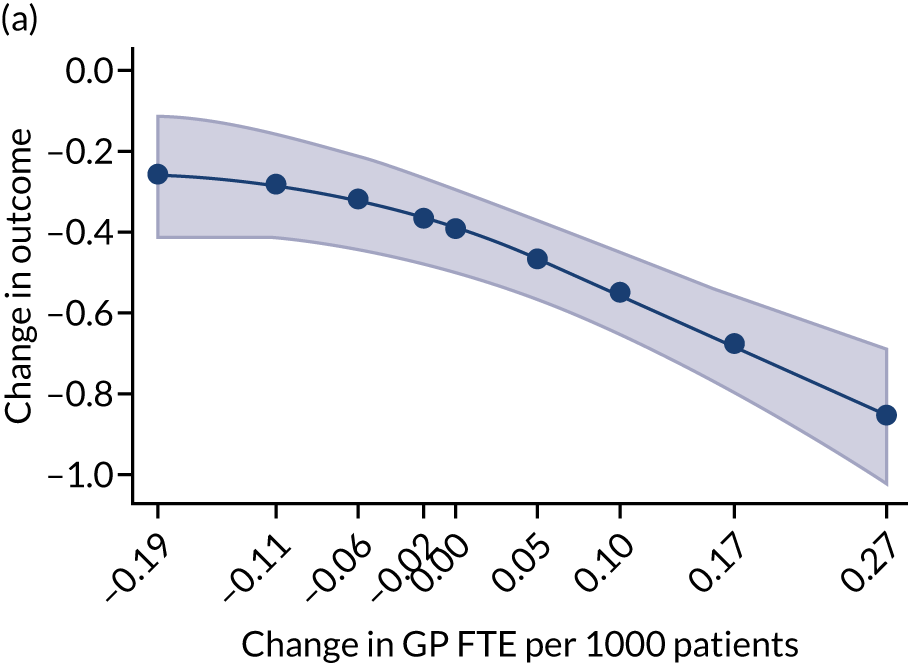

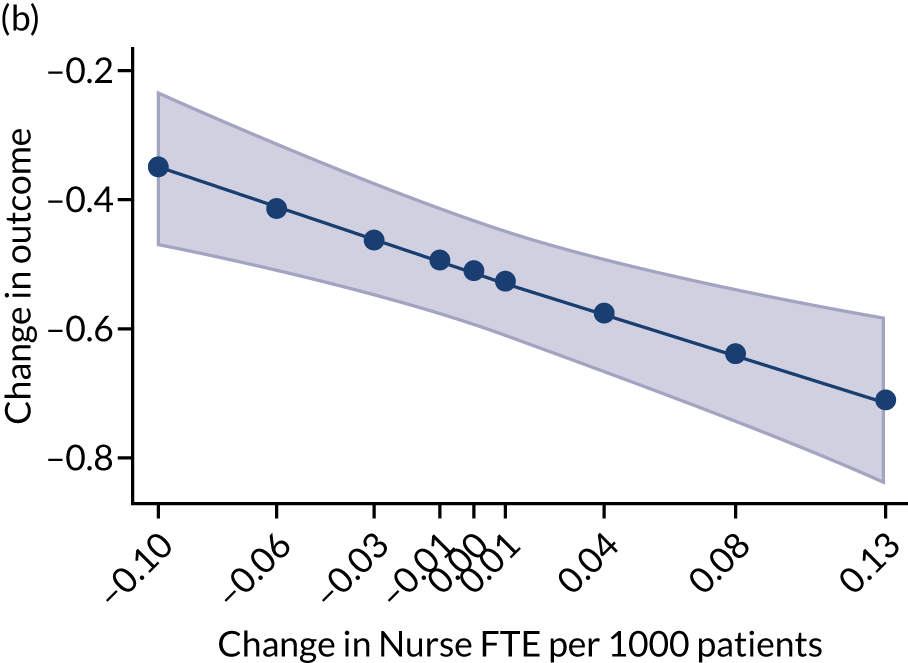

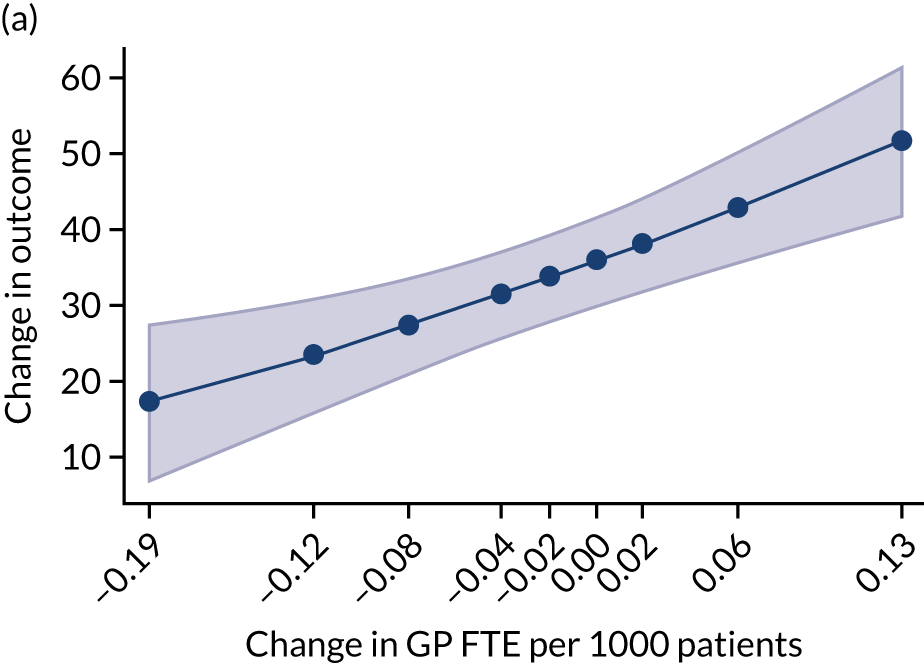

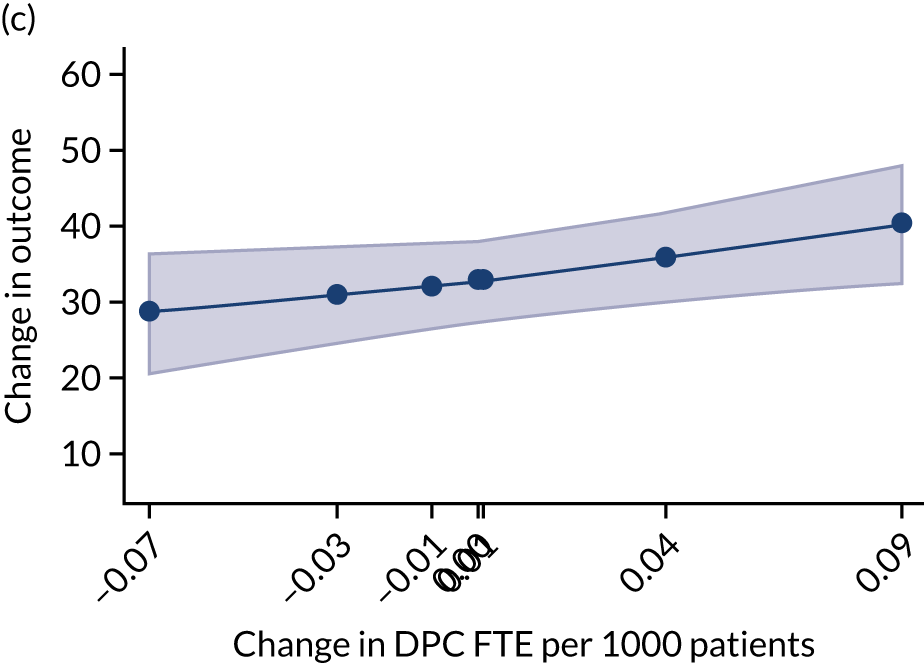

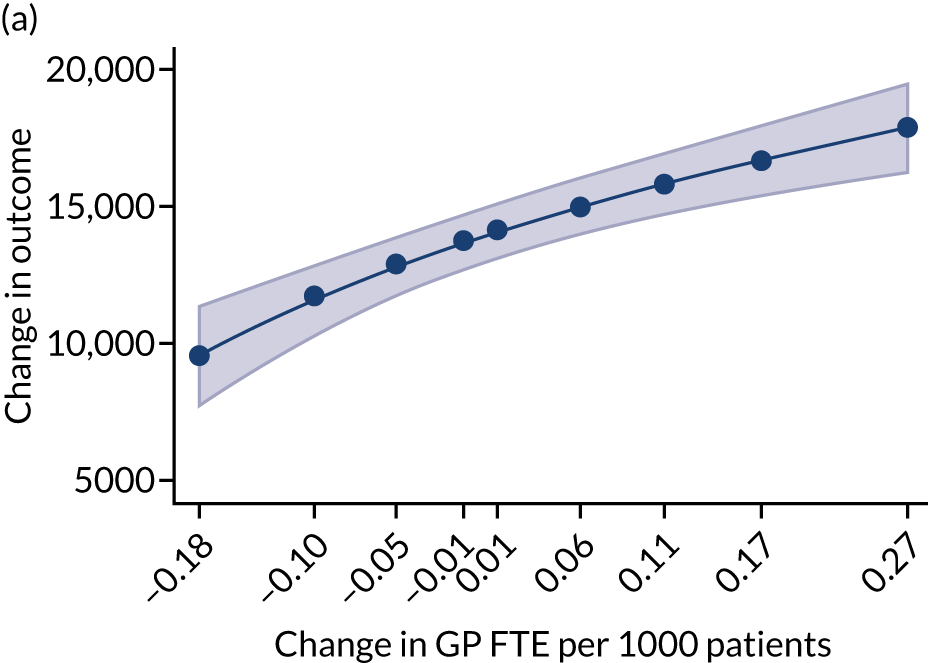

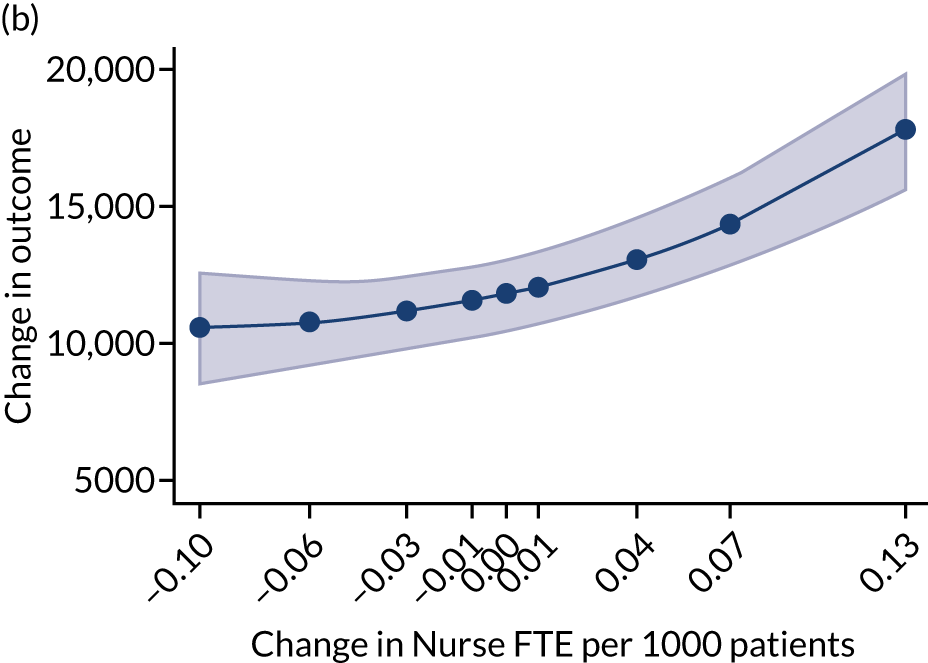

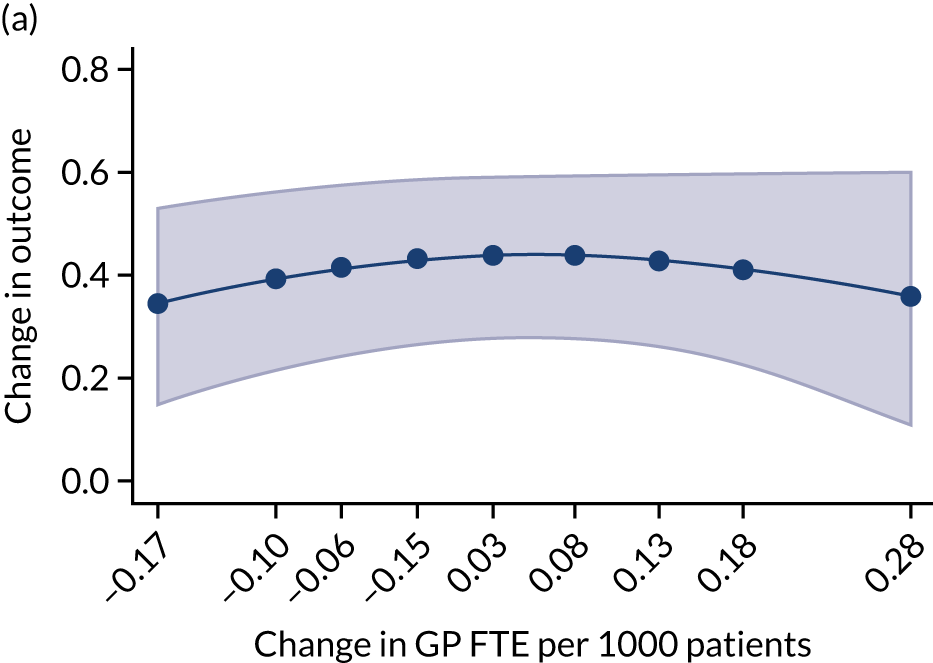

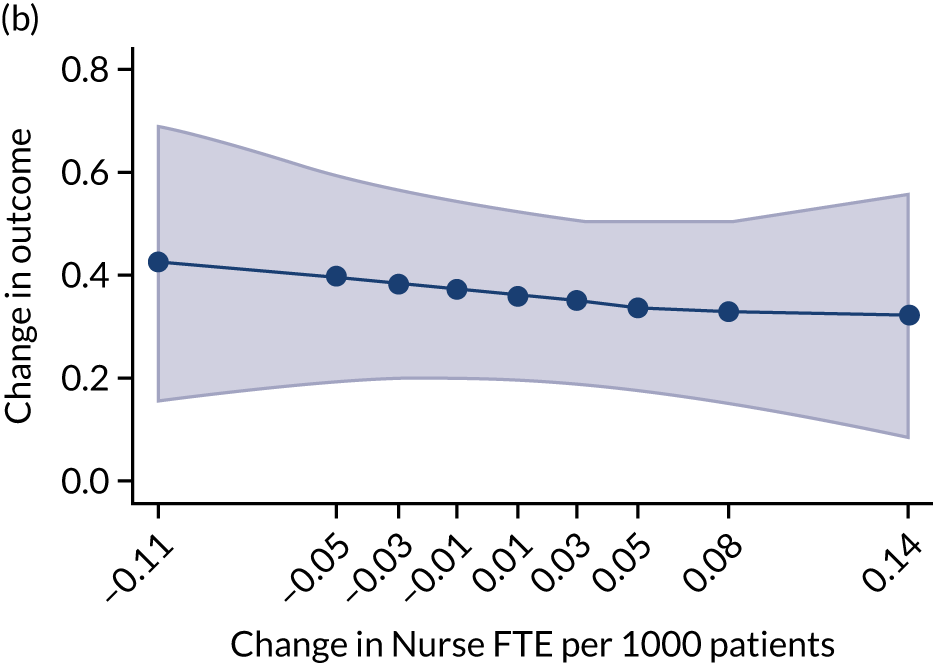

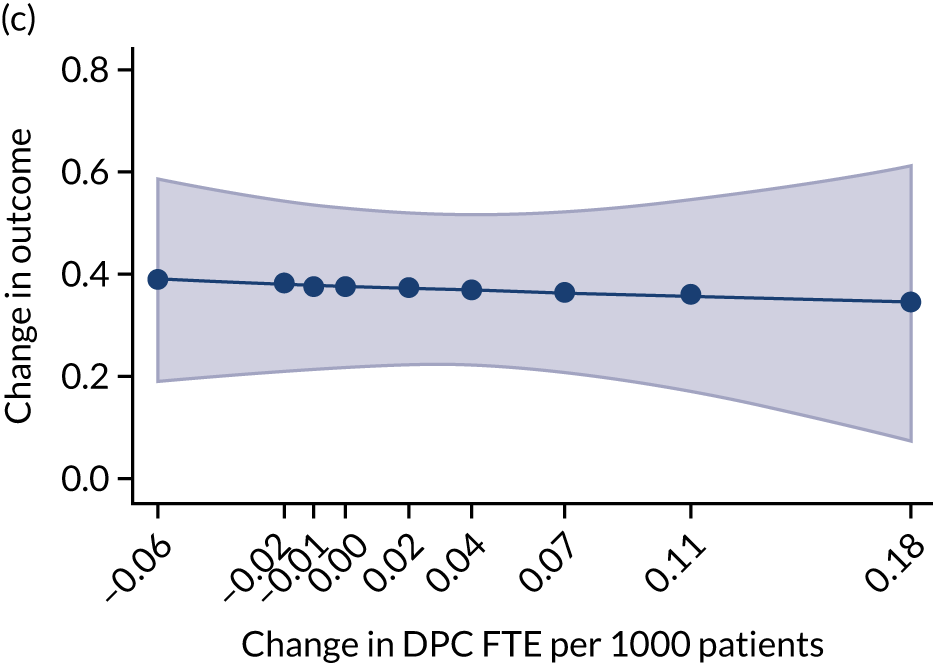

| All | 1232 (100.0) | 291 (23.6) | 0.57 | 0.92 | 1235 (100.0) | 0.77 | 1.85 | |