Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in August 2021. This article began editorial review in March 2024 and was accepted for publication in June 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Tierney et al. This work was produced by Tierney et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Tierney et al.

Background

Patients attending general practice often present with health problems (physical and/or mental) that stem from, or are aggravated by, non-medical issues (e.g. inadequate housing, financial problems, bereavement, loneliness). 1 There is a tradition in general practice of working with local communities to access non-medical support for health issues. Recently, this has become formalised within the UK, as in other countries,2 through the delivery of social prescribing. Social prescribing has seen the introduction of a new role – link workers (other terms may be used – e.g. community connectors or social prescribers), who help people with their non-medical issues. Link workers are expected to connect patients to community organisations, groups or services, which tend to be based in the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector.

In England, social prescribing forms part of the NHS Comprehensive Model for Personalised Care. 3 Personalised care centres on choice and control and what matters to patients, drawing on their strengths and needs. 4 It relates to the concept of person-centred care (PCC): ‘treating patients as individuals and as equal partners in the business of healing …’ and taking into consideration their medical, social, psychological, financial and spiritual circumstances. 5,6 There is some evidence that PCC can enhance relationships between patients and practitioners,7 increasing the latter’s job satisfaction8–10 and the former’s satisfaction with care. 11–13 Delivering PCC in practice – at both patient and professional level – remains a challenge; social prescribing and the associated link worker role is recognised as one approach to help. 4

Link workers are expected to deliver support that reflects PCC. 14,15 Doing so can foster buy-in to social prescribing, a key concept from a previous realist review we conducted. 16 Buy-in relates to the acceptance and legitimation of social prescribing as an additional means of assisting patients, and a willingness to work with link workers. This review noted how connections (relationships) between patients, link workers, primary care staff (especially general practitioners – GPs) and the VCSE sector are central to such buy-in. Another review, by Husk and colleagues,17 highlighted how enrolment to social prescribing is shaped by a patient’s belief that this will help them, while engagement relates to patients perceiving that activities or resources proposed by link workers are accessible. These previous reviews were broad in nature and did not provide empirical analysis of how patients buy-in to social prescribing and the link worker role. This is a focus of the current paper.

Aim and objectives

The analysis undertaken for this paper focused on data collected from a larger realist evaluation18–20 that set out to understand and explain how link workers become part of primary care delivery. In this paper, we centre on data collected from patients to understand their experiences of social prescribing. We use these data to explain how patients’ interactions with a link worker (1) shaped their buy-in to this role and (2) relate to PCC. We are aware that link workers can be situated outside of primary care, and people receiving social prescribing may be referred to as clients or service users. However, we use the term ‘patients’ in this paper because the focus of our study was on the link worker role in primary care, and because participants used this term during data collection.

Methods

Design

Our realist evaluation addressed the question: when implementing link workers in primary care to sustain outcomes – what works, for whom, why and in what circumstances? The starting point for this study was the programme theory developed from our previous realist review. 16 A programme theory is a proposition that provides ‘a plausible and sensible model of how a program [in our case, the link worker role in primary care] is supposed to work’. 21 We published a protocol for the study on Research Registry (www.researchregistry.com) before starting data collection. Approval for the study was provided by East of England – Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 21/EE/0118). We followed RAMESES quality and reporting guidelines. 22

Sample

We focused data collection around seven link workers (our cases), purposively selected for variation in terms of where in the country they were located, the socioeconomic status of where they worked, how their link worker service was run (who employed them, whether they served one or more practices), and their length of time in this role (Table 1 for details).

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Link worker time in role (in months) at start of data collection | 24 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 31 | 38 |

| Deprivation in area serveda | Medium | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | High | High |

| Location of site in England | South | Midlands | South | Midlands | South West | North | North |

| Employment of link workers | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded, contracted and managed by primary care | Funded, contracted and managed by primary care | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded, contracted and managed by primary care |

| Who set up the link worker service | VCSE, GP and link worker | GP | VCSE and link worker | Mainly link worker | Practice manager and link worker | VCSE and link workers | Link workers |

| How many general practices the link worker served | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

Data collection

We carried out focused ethnographies between November 2021 and November 2022 around the link workers (our cases). We spent 3 weeks with each of them, observing their interactions with others (with patients, healthcare staff, VCSE organisations), and talking to them at the end of each day about what they had done. In addition, we conducted interviews with these link workers, with other link workers in their team, with primary care staff, with VCSE representatives and with patients they supported. Interviews were conducted in-person or remotely (via Microsoft Teams or telephone) and lasted between 20 and 65 minutes. We re-interviewed patients and link workers 9–12 months later. These interviews, which took place between December 2022 and August 2023, allowed us to explore (1) sustainability in terms of longer-term outcomes and patients’ reflections on their experience of seeing a link worker, and (2) any changes made to the social prescribing service during this time. These follow-up interviews were conducted via telephone or Microsoft Teams and lasted between 10 and 50 minutes. In this paper, we focus on data collection involving patients and on what patients told us during interviews (both first interview and follow-up), alongside observations of their meetings with a link worker.

Analysis

Researchers coded data within the qualitative data management software NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Coding was based on previous concepts from our realist review but also allowed for the inductive development of new codes. Codes were discussed among the research team at regular analysis meetings. They were used to consider contexts, and mechanisms required to ‘trigger’ outcomes associated with the link worker role – resulting in the development of context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs). Some CMOCs were drawn from our previous review, with primary data used to test (confirm, refute and, where appropriate, refine) these or to develop new CMOCs.

Patient and public involvement

We formed a study patient and public involvement (PPI) group composed of six people. They met with us seven times and also commented on documents (e.g. plain English summaries, participant information sheets) in between meetings. They helped us to think about issues related to patient readiness to engage in social prescribing and interactions between link workers and people they were supporting. We also discussed with them the VCSE sector’s role in social prescribing.

Results

We interviewed 61 patients (Table 2 for details), 41 of whom took part in a follow-up interview. We also observed 35 patients meeting with a link worker. In this paper, we explore the meaning of enrolment and engagement for patients. We add to this the idea of patient readiness, which was clear within the data we collected; it relates to our previous review16 and the concept of buy-in. Hence, the concepts covered in this paper, around which CMCOs were built, are: Enrolment, Engagement (covering interpersonal skills, knowledge sharing and being an anchor point) and Patient Readiness.

| Involvement in the study (n = 84) | Observation only | 23 |

| Interview only | 49 | |

| Interview and observation | 12 | |

| Ethnicity | White British | 62 |

| White (non-British) | 6 | |

| Asian (including British Asian and Indian) | 5 | |

| African Caribbean/Black British | 5 | |

| Mixed ethnic groups | 3 | |

| Other | 3 | |

| Gender | Female | 55 |

| Male | 29 | |

| Age | Range | 19–86 years |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 49.3 years (SD 19.5) |

Enrolment into social prescribing: seeking hope and support

Most interviewees were referred to a link worker by their GP. Table 3 outlines the range of issues patients recalled presenting to social prescribing with; they were often experiencing more than one of these issues when first meeting with a link worker. In particular, mental health problems (anxiety/stress and low mood) were common.

| Mental health | Living with anxiety, stress, low mood, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress, lack of confidence |

| Somatic | Living with body dysmorphia, menopause, finding it hard to be active due to ill health, seeking support with non-medical pain management or weight, struggling to sleep |

| Social | Seeking asylum status, loneliness/isolation (loss of connections), housing issues, problems with neighbours |

| Personal relationships | Family difficulties (including domestic violence), feeling overwhelmed with caring responsibilities, bereavement |

| Financial | Struggles with employment, concerns about buying food, assistance with applying for benefits or a blue badge for parking (if they had a disability) |

Patients’ narratives suggested they were in search of a way forward when social prescribing was first raised with them, although almost all had been unaware of the link worker role at this point; few had seen it advertised within their GP practice. This meant that patients could be nervous about agreeing to a referral. They also mentioned feeling unable to go on alone and, thus, being willing to take a ‘step into the unknown’ by meeting with a link worker.

… you’ve tried everything else that’s not worked, and you’ve placed your vulnerability in this person’s hands in the hope that they’re gonna give you something that you haven’t yet got … It takes a huge amount of bravery.

Site2P03 (follow-up)

Referral via a GP fostered initial trust in the link worker. This could be augmented when a link worker contacted the patient to offer a first (in-person or remote) meeting. The manner in which any opening conversation was undertaken, and clarity provided by the link worker about their role, was an important step in patients taking up the offer of a referral.

… she explained the first time she phoned me, she said, to make you aware I’m not a doctor, I’m not a therapist, I’m not any of this, I’m solely here to offer guidance and things, I’m not forcing you to come here, if you don’t like what I’m telling you, you don’t have to take any of it on board.

Site2P01

Engagement: connection with a supportive, knowledgeable and consistent link worker

This section outlines the qualities and abilities that patients we interviewed attributed to their link worker – their interpersonal skills, how they shared their knowledge, and their ability to act as an anchor point (a consistent and stable source of support) – and shaped their willingness to engage in social prescribing.

Interpersonal skills

Patients differed in how much time it took them to develop a rapport with and open up to a link worker. Some felt an instant connection; for others, this connection took longer to establish.

I think for the first two or three, maybe even four sessions I didn’t really tell her anything and it was just, I’d tell her like the base level stuff that I felt comfortable with and then as we built the relationship, I felt able to share with her more openly and then I think because of that she was able to help me better.

Site4P08 (follow-up)

The way link workers engaged with patients was crucial; listening, not rushing, showing empathy, being relatable by adopting an informal conversation style or using local dialect were mentioned within interviews. As the following quotations from interviewees illustrate, link workers’ communication style gave patients the sense of being cared for, made them feel they were not alone and put their needs centre stage.

She was … really kind and there was no stress or rush … she was asking me what kind of things do you want to achieve? How can we help you achieve what you want to achieve and how do we start, where should we start?

Site2P07

I’ve never had any love in my life or laughter or you know, kindness. So when somebody just like how they speak to you as well, it’s just so comforting. You know somebody’s there to reassure you and help you not to be afraid …. They’ve given me strength, they’ve given me courage, they’ve given me comfort.

Site5P06

… she was so sympathetic and understanding and she actually listened. It’s nice for somebody to listen and not give their side of things ….

Site6P05

Some patients recalled becoming upset and crying at their first meeting with a link worker as they disclosed the difficulties they were experiencing in their life. A non-judgmental and caring approach was essential from the link worker to encourage patients to continue engaging. The link worker’s communication style gave patients space and support to think more clearly. It also gave them permission to ‘offload’ with someone who showed an interest in their life but was not a close part of it (unlike a family member).

… sometimes I think if you’re offloading to say like friends and family, it becomes a bit much for them sometimes, it’s sometimes better to have someone outside to make things slightly clearer.

Site3P08 (follow-up)

Patients said they enjoyed and looked forward to conversations with a link worker because they found these interactions uplifting and comforting, giving them a sense of ‘hope for the future’ (Site7P10).

Talking to her … made me see that everything is brighter, that there was stuff waiting for me in various social settings if I wanted to and had the time to do it … rather than everything feeling a bit bleak ….

Site4P05

Knowledge sharing

Patients described how link workers gave them options by informing them about various resources and providing them with contact details of different organisations or services. This knowledge was seen as a key part of the link worker role. However, it was important that link workers were not overly directive; decisions needed to be a joint endeavour, enabling patients to feel some ownership in the steps they took to improve their situation.

I think having someone to actually work through that with you … collaboratively with you makes a massive difference … I did actually feel genuinely comfortable talking to her and telling her these things, maybe it was partly because she felt like more of an equal than having this power imbalance.

Site4P08 (follow-up)

… she helped me talk about some of the things I was dealing with and look at what some of the options were … all the other things that might help me … things I didn’t even know I needed, you know, were being brought to the forefront ….

Site7P07

For patients requiring financial support, assistance from link workers with accessing benefits eased the pressure they were encountering in their life.

I was struggling financially and they just … got all the contacts …. They gave the contacts … That took a lot of stress away from me.

Site5P03 (follow-up)

Yet knowing about local provision may not be enough; how information was presented by a link worker needed to be considered. For example, one interviewee talked about being resistant to using a foodbank after a link worker made this suggestion: ‘I don’t want to go and say I want some food. No, I’m not going there’ (Site1P06).

Link workers’ knowledge extended to supporting patients to develop coping strategies, which included talking to other people, engaging in social activities, taking exercise, writing things down and undertaking mindfulness practices.

… rather than saying, sometimes going to a therapist or a doctor – here’s medication, here’s that, off you go …. She was like, right, go for a walk, speak to somebody, write things down … and we’ll go over what you’ve written about – how you’re feeling … it was very simple sort of steps that seemed to help a lot.

Site2P01 (follow-up)

Anchor point

A feeling of being overwhelmed, when first referred to a link worker, was present in patients’ narratives. Hence, patients required space and support, initially, to think clearly and decide how they wanted to move forward. Link workers were described as providing perspective, helping patients to make sense of their situation.

… it was just being able to sort of look at things a bit more objectively and reasonably I guess because it’s very easy to get all … it’s all terrible, nothing can change … but to … take a step back and say, okay, it feels like that but that’s not necessarily the case and I can deal with little bits at a time to make the small changes. I think having someone like a social prescriber to talk it through with just helps.

Site4P03 (follow-up)

Link workers were described as reliable – someone who would do what they said (e.g. ringing people back, looking for different sources of support) – as a ‘cheerleader … she was on my side’ (Site3P02), as ‘backup …’ (Site5P03) and as a ‘safety net’ (Site1P10). In certain cases, the link worker undertook an advocacy role, by contacting other professionals or organisations

… she sent me numerous bits of information to try and help me out, particularly when I was in … temporary accommodation …. She certainly fought my corner there a little bit for me … making herself available if I needed letters or anything like that.

Site5P04 (follow-up)

Like in the other flat where I used to live, they were smoking weed and there were a lot of drugs, [link worker] fought and fought, and she did eventually, she put me on right track …. She gave me advice, she got me a grant from the council because my cooker had blown up.

Site6P11

This advisory role could include helping patients to make an appointment to see a GP when necessary. However, patients noted how having a link worker available meant they were less likely to contact their GP.

… I don’t see my GP as much now because I know I’ve got someone else to talk to, so I’m therefore saving the NHS time for other people … do you know what I mean? So it helps the whole system.

Site3P14

I can basically phone the GP if I need her for anything and make an appointment but apart from like reviews on my pain meds and stuff, I mainly just deal with [link worker] … it’s not very often I see her [GP] now, it’s all in [link worker’s] corner so to speak.

Site6P07

… normally you’ve got to ring the doctors at 8 o’clock …. You can never get through, there’s no emergency appointments left. As soon as [link worker] got involved with us, because of the problems that me and my son are going through … she’s able to expedite, she can say, ‘Right I can organise a doctor’s appointment for you next week’.

Site7P06

Ending a relationship with the link worker had to be managed carefully. Some patients talked about their link worker phasing out contact with them over time, but others felt this could have been better managed.

I had six sessions … it was spread out … roughly about three months of sessions sort of spread out … then it just ended and I was never offered sort of like any follow-up … I feel it would have been really beneficial for me just if there had been like a follow-up at the end of this year or like six months down the line asking ‘how are you getting on?’

Site2P01 (follow-up)

Several patients were reassured by knowing they could return to see the link worker if requiring additional support in the future. However, not everyone was clear about this, which could cause anxiety about meetings with a link worker ending.

After we’ve spoken, I always say ‘Thank you ever so much, you’ve made me feel a lot better’, which she has …. It’ll be sad when it ends because I know she’s not going to be able to be with me forever …. You’ve got to grab it while you can and cherish it.

Site6P11

Sensitivity to patients’ willingness and capacity for readiness to change: connection to external support

Patients discussed how link workers, while not pushing them to take specific actions, encouraged them to think about trying new things. This was seen as important by some interviewees.

… you also need someone to prepare you to get ready. You might not be ready but someone will be there you know, to motivate you in getting ready. And once you are motivated you are ready to move on.

Site1P11 (follow-up)

I think most people need someone to … encourage them … someone like to steer them … to give them support and … make them see how good it would be for them to go out and meet people.

Site3P012 (follow-up)

However, patients were not always at a point whereby they were receptive to such suggestions, and being too directive could be counterproductive. Hence, link workers had to show sensitivity to where a patient was in their life – dealing with their prime concerns first then, if relevant, identifying and working with other psychosocial problems requiring attention.

… in the middle of all of the stuff that was going wrong with me it wouldn’t have been appropriate then ’cause I didn’t have the headspace to want to do any of the stuff that she might have recommended to me. It was only when I was starting to come out of, let’s say, my darkness.

Site4P05 (follow-up)

… I think when you’re feeling the way I’ve been feeling, I don’t think putting pressure on you or me would have been any good. I probably would have just left it and not had another appointment.

Site5P05

Patients described how link workers invested time into personalising resources proposed, making some feel accountable to take steps to access external support. For patients able to engage in social groups, they identified how this led to them leaving their house more, increased their social connections, and enabled them to experience a sense of purpose by having things to look forward to.

I feel very joyful. I feel like I’m making the best of my time, the best of myself.

Site3P02 (follow-up)

I locked myself away and I’ve lost a lot of friends. That’s painful. That hurts but it’s nobody else’s fault but mine … I was the one that locked myself away but now I’m becoming more confident. Yes. Now I’m starting to enjoy going out, I’m starting to be with company, people, conversations. I didn’t realise just how lonely I was.

Site5P02 (follow-up)

It should be noted that some patients were uncomfortable about attending group activities, concerned about how they would be regarded by others. Link workers, therefore, had to be responsive to each person’s preferences; yet observations conducted for the study suggested that not all patients were asked by link workers about their views of joining a group. Being part of a group could be a particular issue if someone was not fluent in speaking English, or had experienced mental health problems, or if members of the group were perceived to have different concerns. A few interviewees talked about preferring to draw support from those they were close to, which could be easier to do after meeting with the link worker because this interaction helped to improve their relationship with a partner, children or friends.

I’ve opened up a little bit more to friends … talking about how I feel, meeting up and stuff.

Site2P06 (follow-up)

… [link worker] definitely encouraged me to talk, especially to my husband, about how I was feeling and the pressure that I felt under and I think we do talk more now and he’s more understanding.

Site4P03 (follow-up)

Some patients found meeting with a link worker transformative; having this space and support allowed them to engage in self-reflection or re-evaluation. This was referred to as a changed mindset: seeing life more positively and being receptive to trying things, to asking for support from others, to adopting health behaviours. Sometimes, this involved making goals with a link worker, which encouraged patients to move forward by achieving small, manageable objectives.

… overcoming that hurdle changed my mindset as well because it was like well, you did it and you didn’t want to do it …. Like now having that mindset of it all being goal driven, I do loads of stuff which is goal driven now because it really, really helps me.

Site4P08 (follow-up)

There seemed to be a difference between a willingness to make life changes and having capacity to do so. For example, some patients were unable to attend activities or groups due to difficulties associated with public transport. Others mentioned how caring responsibilities (e.g. for children or older parents) prevented them from accessing external support.

… my dilemma has always been that I have [child] with me 24/7 and I am a carer for my mother, so that limits me quite a bit on what I can actually get to and feel relaxed without feeling I’m stretching myself and getting stressed.

Site3P03 (follow-up)

In follow-up interviews, several patients mentioned a decline in their physical health; this could have a negative impact on how they were feeling and their mood, which might stop them from accessing external support.

… they’ve [link worker] texted me so many phone numbers, associations, people that I can – when I’m ready, I can reach out and get in contact with … but I’m not quite there just yet … they’re there and just waiting for me to find the confidence to contact somebody.

Site5P03 (follow-up)

It was noted by some interviewees that although they did not take up any suggestions from their link worker, speaking with this person gave them the impetus to look for alternative support or provided hope that there were solutions available.

… when people realise they have choice and they have options, that tends to lift a lot of the weight off of them, the anxiety … there is a way out of this ….

Site3P13

So she suggested some things which as I say, I couldn’t actually manage but then that made me carry on looking for other things.

Site4P05 (follow-up)

Programme theory: buy-in to social prescribing through connection

We developed a series of CMOCs related to the key concepts outlined above. These CMOCs are presented in Table 4.

| CMOCs on enrolment | Uncertainty about how a link worker can help (C) may make patients reluctant to engage with this person (O) because they are unsure of what to expect (M). |

| A patient’s difficult life circumstances (C) leads them to urgently seek solutions (M) so they agree to see a link worker (O). | |

| Reaching out to a link worker, an unknown source of support (C), calls for a leap of faith from patients (O) because they do not feel there are other choices in terms of help (M). | |

| Being referred through a GP (C) provides credibility to the link worker role (M), which means the patient is more likely to take up a referral (O). | |

| CMOCs on link workers’ interpersonal skills | When a link worker gives patients space to discuss their life and shows active listening skills (C), patients feel valued and respected (M), which encourages them to open up about their needs (O). |

| Link workers use of informal language/local dialect (C) levels out any power imbalance between them and patients (M), making patients more receptive to what link workers propose (O). | |

| Social prescribing offers patients space to be listened to and offload (C), which helps them to feel less alone and less stressed (M) so they feel more able to cope (O). | |

| When patients are able to offload their troubles to a link worker (C), they enjoy meeting with this person (O) because they feel less burdened (M). | |

| When patients feel a connection with a link worker during their meetings (C) they are uplifted (O) because the conversation makes them feel valued and worthy of attention (M). | |

| CMOCs on link workers’ knowledge sharing | When link workers have good knowledge of a range of local support and resources so they can propose different options (C), patients are reassured that there are solutions to their problems (M), making them hopeful that they can improve their situation (O). |

| Together, the patient and link worker develop a personalised plan of action (C), which makes the patient feel more in control of their life (O), as they start to see a clearer way forward (M). | |

| Link workers present potential solutions to patients in a sensitive manner (C), which patients are then willing to try (O) because they feel they are an acceptable means of support (M). | |

| Assistance with financial matters through a link worker (C) reduces the daily pressure encountered by patients (M), making them feel less stressed/anxious (O). | |

| When link workers share their knowledge about coping strategies (C) they arm patients with a means to cope (M) so patients feel better able to manage their day-to-day life (O). | |

| CMOCs on the link worker as an anchor point | Having a link worker who is regarded as responsive and reliable (C) makes patients feel comforted that they are not alone (M), easing their stress and anxiety (O). |

| When link workers are willing to advocate for patients when needed (C), it helps patients to feel less alone in their struggles (O) because they sense that someone else cares about them (M). | |

| Link workers’ advocacy role (C) could include helping patients to make an appointment with their GP (O) because link workers have access to primary care staff (M). | |

| Having access to a link worker (C) means that patients are less likely to contact their GP (O) because they have an alternative and trusted source of support (M). | |

| Tapering off contact with a link worker gradually (C) helps the patient to prepare to move forward alone (M) so they do not feel they have been abandoned (O). | |

| If a patient is informed that they can be re-referred to the link worker (C) it is reassuring (M), which allows them to end their contact with this person (O). | |

| CMOCs on readiness | When link workers tailor support to match individual values and state of readiness (C), patients are more open to suggestions (O) because they feel seen and understood (M). |

| Hearing about options available in the community from a link worker (C) opens the patient’s mind to possibilities (M), which encourages them to start seeking out their own sources of external support (O). | |

| Being supported by a link worker to access community groups or activities (C) enables patients to feel more connected to others (M), reducing their sense of being alone in their struggles (O) and making them feel fulfilled (O) and less stressed (O). | |

| Receiving information and support from a link worker they have built a relationship with (C) prompts patients to take steps towards changing (O) because they do not want to let this person down (M). | |

| Connecting with local support (C) improves patients’ relationships with their friends and family (O), because they feel less alone or overwhelmed by their circumstances (M). | |

| When patients are able to develop realistic goals with a link worker (C) it helps them feel a sense of achievement (M), increasing their self-confidence (O). |

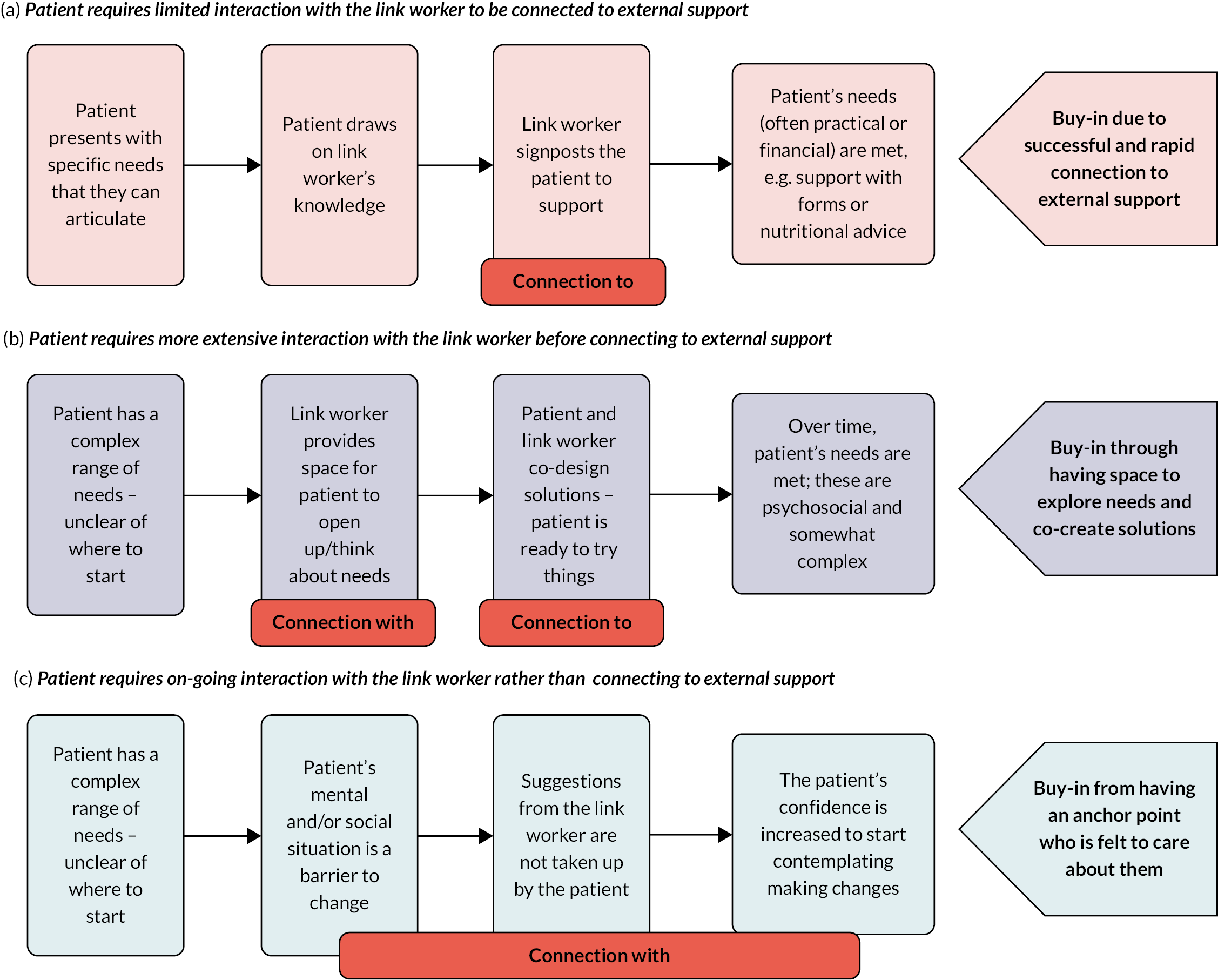

The CMOCs in Table 4 were used to help with developing Figure 1; it provides a visual representation of how patients buy-in to social prescribing through connections. We acknowledge that this figure simplifies the myriad of needs and situations that link workers attend to, but believe it provides a succinct overview of key ways in which patients buy-in to social prescribing through connections (with link workers and/or external sources). We found that some patients only required a small amount of anchoring from a link worker (e.g. encouragement to join a gym, to make healthier food choices, to access information about services for a child with learning difficulties). These individuals experienced relatively rapid connections to external support through the link worker (see Figure 1a). However, it was common for the people we interviewed to require more intensive interactions with a link worker before having the clarity, confidence and motivation to make changes or to access external support. Experiencing the link worker as an anchor point allowed these patients to develop personal resilience and an internal capacity to consider options, and time to develop clarity regarding their situation before connecting to external resources (see Figure 1b). For a third group of patients, external pressures meant that having motivation was not the same as having the capacity to act; for some individuals, internal (e.g. low mood) and external (e.g. caring responsibilities) circumstances meant they were unable to connect to other support or services. Yet they still valued the assistance they received through connecting with a link worker and, at a later stage, might connect to other services (see Figure 1c).

FIGURE 1.

Types of buy-in to a link worker role through different forms of connections (connection ‘with’ the link worker or ‘to’ external support/services).

Connection with: our data highlighted the importance for patients of connecting with a link worker, starting when they first spoke to this person, a conversation that some patients entered into with trepidation. Connecting with a link worker was facilitated through their communication skills – being relatable, reliable, warm and empathic. This made patients feel they mattered and that someone was on their side, prompting them to buy-in to the idea of social prescribing. Data also indicated that link workers gave patients hope by providing them with ideas and options. This increased people’s confidence by engendering a sense of control and optimism. The link worker’s knowledge helped patients to identify a potential pathway to resolve their difficulties. This was facilitated through connecting with a link worker who was encouraging during interactions and, in some cases, supported patients to set goals without removing their agency by exerting pressure on them to access external sources of support.

Connection to: alongside developing a connection with patients, another important part of the link worker role, according to our interviewees, involved connecting people to external support. This called for link workers to know what was available locally (which may be limited depending on where they were based), but also to know when to encourage someone to step outside their comfort zone and when to hold back from such direction. Anchoring helped the patient to start to find some equilibrium which, for many of those we interviewed, living with uncertainty, in challenging circumstances, was crucial. Focusing on solutions was difficult without an ability to experience some sense of stability or safety; this could be achieved through meetings with a link worker, whose ability to be an anchor point reassured patients.

Discussion

Data collected from patients emphasised the complexity of the link worker role and highlighted the range of skills and flexibility called for from these employees. The programme theory (see Figure 1) drew out the importance of connecting with patients, alongside connecting them to external support. It highlighted how buy-in to the role involved a mixture of the link worker’s interpersonal skills, knowledge of external resources, and their ability to be an anchor when required. Link workers have to be sensitive to an individual, their needs, the speed with which they are able to open up and their capacity to access external resources. This has implications in terms of person-centred care (PCC).

Person-centred care

Person-centred care places a focus on the unique characteristics, circumstances and preferences of individuals. 24 Effective communication is a key element, calling for staff who demonstrate respect and empathy, make patients feel part of decision-making, and have time to enable individuals to express their needs. 24,25 Our data showed that link workers employed a PCC approach through their interpersonal skills and knowledge, as well as their sensitivity around when to be an anchor point and to modify support offered to match someone’s readiness to act. This chimes with The Health Foundation’s26 depiction of PCC as tailoring support to meet individual needs through expressing dignity, compassion and respect, providing personalised assistance and promoting people’s strengths and abilities.

In terms of PCC, link workers acted as a constant, reliable source of support – an anchor point. This consistency was offered by GPs previously. However, shortage of such professionals and changes to how primary care services are delivered means this part of their job is being lost for GPs. 27,28 GPs’ limited capacity to deal with patients’ non-medical issues (due to time constraints and lack of knowledge of local support) has been reported in previous research. 29,30 There is a risk of deskilling GPs when patients’ non-medical needs are ‘outsourced’ to link workers, separating the biomedical from the psychosocial. However, this could work well when GPs and link workers act as a team, whereby the former takes responsibility for assessing and diagnosing problems and determining with the patient if biomedical input is required. For patients who remain uncertain about whether de-medicalising their health issue is appropriate, a ‘trial and learn’ approach through engagement with a link worker may be part of the support needed to achieve connection with, and so connection to. In this case, the roles of GPs and link workers are distinct but complementary. An effective feedback system is essential to this, whereby link workers can inform GPs about patients’ progress and ongoing non-medical needs. Using shared electronic health records can facilitate this communication. 31

Person-centred care from the link worker perspective is not just about offering consistent support; it also entails having good knowledge of the local area and provision. In our realist review, we identified this as a key component of the link worker role. 16 The context within which they work may allow link workers to accrue knowledge of the range of local connections required to deliver PCC, but if greater emphasis is placed on number of patients seen, this part of the job may be diluted or removed completely. Our broader realist evaluation suggested this is an issue. 32 Furthermore, there is a danger that if link workers face mounting pressure to have more but shorter consultations, they will be unable to establish the connection with patients that was key to our interviewees’ experiences of social prescribing.

Therapeutic alliance

Quality of relationship with a link worker (described in our programme theory as ‘connection with’) was crucial to many interviewees’ ability to move forward and, where relevant and possible, to their connecting to community support. In this sense, a type of therapeutic alliance is forged:33 a collaborative relationship between a practitioner and patient, and mutual agreement to work towards specific treatment goals. 34,35 A therapeutic alliance is fostered through a practitioner using the right sort of communication and giving people space to open up in their own time, in a setting that feels safe and contained. 36 This was something that patients we interviewed identified as critical to the link worker role.

This notion of the therapeutic alliance brings into question the purpose of the link worker role and how far it is there to develop social capital (through connecting people to resources), something that was part of the original programme theory from our realist review. 16 Data we collected from our interviewees showed that patients valued link workers connecting with them, to build their confidence and ability to think about taking steps towards change. For some patients, this connection, or therapeutic alliance, with the link worker was the key benefit they took from social prescribing, especially if they were experiencing structural factors that made change or connecting to external sources difficult. As a non-clinical role, the therapeutic alliance that link workers develop with patients may not have been anticipated by policy-makers. We have expanded on this topic in another paper focused on the concept of ‘holding’. 20

Social determinants of health

‘Connection to’, which formed part of the programme theory illustrated in Figure 1, although depicted as a key element of the link worker role,31 may not be easy to achieve. Our data showed it is simplistic to state that individuals are responsible for their own lifestyle or that having knowledge, on its own, is enough to support people to move forward. Link workers have limited control over the availability of community resources or the ability to address more structural factors affecting people’s well-being (e.g. housing or unemployment). They need to be sensitive to people’s capacity to act, forging an in-depth understanding of the lives people encounter, shaped by their personal situation and social positions (e.g. financial, caring responsibilities). This is why simple signposting may not be enough for many people37 because it lacks the depth of connection with an individual, or an understanding of their preferences and current circumstances. It is important to consider if some parts of the population are experiencing exclusionary processes that act as a barrier to social prescribing due to social determinants of health. 38

Practice and policy implications

It is inevitable that people referred to social prescribing through general practice will present with a range of issues. This was indicated in our data. Link workers have to accommodate diversity in patients they support and understand their needs. In order to cope with this complexity, link workers require access to appropriate support and a suitable infrastructure, which allows for the development of requisite skills and knowledge. Existing literature suggests that not all link workers receive the support that would enable them to do their role effectively and safely. 39–42 It highlights the need for link workers to be in an environment that understands the role, with colleagues who appreciate how they can help patients. 43

Our research raises issues around sustainability of the link worker role, especially given the expanding scope of work-related tasks they may be expected to take on and lack of training and supervision provided. 32 Finding people with the right skills and disposition to carry out this role can be difficult. 44 Hence, those delivering and/or managing link worker services need to consider if there is a system in place that (1) allows link workers to receive necessary training; (2) provides link workers with supervision and peer support; (3) enables link workers to tailor support for patients – this includes having the opportunity to find out about VCSE resources to meet the range of issues patients face; and (4) provides patients with clear information about the link worker role so they enter social prescribing with realistic expectations. 45

Well-planned introductions and endings as part of social prescribing can help with fostering a therapeutic alliance. Tools exist to assess how far this type of connection has been developed,46,47 which link workers may wish to employ to gauge whether they should alter their working style with an individual patient. A flourishing therapeutic alliance is partly based on a patient’s openness, but a therapist’s characteristics and approach may be more important. 48 This implies that professional development/training in connecting with patients is appropriate for link workers.

Future research

More research is warranted around the example in Figure 1c (patients connecting with a link worker but not necessarily to external support), to explore how far this reflects individuals experiencing health inequalities (e.g. due to finances but also due to circumstances such as caring responsibilities or not being able to converse in English comfortably). In particular, future research could explore how gender as well as socioeconomic status correlate with specific forms of interaction with a link worker (as outlined in Figure 1). Furthermore, studies that strive to capture the views of patients who have had a negative social prescribing experience would be worthwhile, although we acknowledge it is difficult to identify/engage these cases for research. It might also be valuable to undertake some longitudinal work, following up patients more regularly to further understand how their circumstances were influenced by connecting with a link worker.

Exploration of the therapeutic alliance in social prescribing could identify the significance of this component of the link worker role and training required around it. This might include understanding optimum ways to introduce the idea of social prescribing to patients to ensure they are receptive to meeting with a link worker. Likewise, studying whether PCC improves patients’ satisfaction with social prescribing and increases link worker job satisfaction is a topic for further research.

A study on link worker retention is currently under way by some authors of this paper. 49 However, future research is needed to critically examine how their role relates to other professionals who support person-centred approaches to health (e.g. health and well-being coaches). Our realist evaluation surfaced mechanisms needed for PCC. This work could be extended to these other roles to describe a new theory of community provision of PCC (non-medical), which outlines workforce skills, attributes and training required.

Equity, diversity and inclusion

We involved patients who ranged in age, gender and ethnicity (see Table 2). We included sites that varied in terms of deprivation (see Table 1). However, we know that social prescribing is not necessarily as broad an offer as it could be, and future research should examine the extent to which some groups are over- or under-represented. 50 Our PPI group supported us to ensure that language used in information for recruitment purposes was clear and understandable. Our study team consisted of men and women, and people from different ethnic backgrounds. It included researchers with a disability and individuals who varied in their research experience – from early career to senior academics.

Strengths and limitations

We collected observational alongside interview data. This enabled us to understand in depth the interaction processes encountered between patients and link workers. We did not hear from patients who had not taken up the offer of social prescribing; those we interviewed had a neutral or often positive view of link workers. This could reflect the fact that we relied on link workers to invite patients to be interviewed. The main criticisms coming from interviewees included wanting more time with a link worker, or link workers not having expertise in lifestyle (e.g. diet) or specific disabilities (e.g. autism).

Conclusion

This paper explored how buy-in to the link worker role was established for patients through their connection to this individual (who instils them with a sense of hope and provides an anchor) and their connection to external resources (which provides them with direction and ongoing assistance or support by building their social capital). Link workers’ positive interaction style prompted patients to enrol and engage in social prescribing; their knowledge and ability to be an anchor point when required were important to patients’ continued engagement. Link workers had to be sensitive to patients’ readiness to engage – knowing when to gently encourage people to move forward and when to hold back from doing so. This called for an understanding of patients’ specific circumstances. Focusing on potential solutions was difficult for some patients who were experiencing significant challenges; they needed to encounter stability or safety, which they gained through meeting with a link worker. The research highlights that the link worker role is person-centred, and allows for the development of a therapeutic alliance, while also emphasising how structural barriers can impede social prescribing’s capacity to address people’s difficult life circumstances.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Stephanie Tierney (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2155-2440): Conceptualisation (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (lead); Writing original draft (lead); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Geoffrey Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5384-4157): Conceptualisation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Debra Westlake (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6927-5040): Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Amadea Turk (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5139-0016): Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Steven Markham (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0564-3158): Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Jordan Gorenberg (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2723-8786): Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Joanne Reeve (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3184-7955): Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Caroline Mitchell (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4790-0095): Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Kerryn Husk (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5674-8673): Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Sabi Redwood (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2159-1482): Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Tony Meacock: Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Catherine Pope (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8935-6702): Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Beccy Baird (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9976-5446): Conceptualisation (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Kamal R Mahtani (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7791-8552): Conceptualisation (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Editing and reviewing (equal).

Data-sharing statement

Due to the consent process for data collection with participants, no data can be shared except for quotations in reports, journal articles and presentations. All data requests should be sent to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was secured from East of England – Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 21/EE/0118). This was provided on 4 May 2021.

Information governance statement

The University of Oxford is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and UK General Data Protection Regulation. This is specified in the University’s data protection policy (https://compliance.admin.ox.ac.uk/data-protection-policy#collapse1102266) and in the research protocol. The University of Oxford, as sponsor of this research, is the data controller. You can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights, and can access the contact details for the University of Oxford Data Protection Officer here: https://compliance.admin.ox.ac.uk/individual-rights.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/ETND8254.

Primary conflicts of interest: Stephanie Tierney: Part of the Academic Partnership for the National Academy for Social Prescribing. Geoffrey Wong: HTA Prioritisation Committee A (Out of hospital) 1 January 2015–31 March 2022; HTA Remit and Competitiveness Group 1 January 2015–31 January 2021; HTA Prioritisation Committee A Methods Group 21 November 2018–31 April 2021; HTA Post-Funding Committee teleconference (POC members to attend) 1 January 2015–31 March 2021. Caroline Mitchell: Chair of NIHR in Practice Fellowship Award 2023; HTA Prioritisation Committee A (Out of hospital) 2022–2026. Kerryn Husk: HS&DR Researcher-led – Panel Members 1 December 2018–30 June 2020; HS&DR Funding Committee (Bevan) 1 July 2020–30 June 2022. Part of the of the Academic Partnership for the National Academy for Social Prescribing. Catherine Pope: NIHR HS&DR Researcher-led panel member 1 July 2017–31 July 2021; HS&DR Funding committee (Bevan) member 1 November 2020–31 July 2021; Academy panel 2019–present. Kamal R Mahtani: NIHR HTA Prioritisation Committee A (Out of hospital) 1 March 2018–31 March 2023; NIHR Remit and Competitiveness Group 1 March 2018–31 March 2023; NIHR HTA Prioritisation Committee A Methods Group 1 March 2018–31 March 2023; NIHR HTA Funding Committee Policy Group (formerly CSG) 1 March 2018–31 March 2023; NIHR HTA Programme Oversight Committee 1 March 2018–31 March 2023.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this publication are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Study registration

The study is registered at Research Registry in 2021 (www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/registrationdetails/5fff2bec0e3589001b829a6b/).

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme as award number NIHR130247.

This article reports on one component of the research award Understanding the implementation of link workers in primary care: A realist evaluation to inform current and future policy. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR130247).

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in August 2021. This article began editorial review in March 2024 and was accepted for publication in June 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Tierney et al. This work was produced by Tierney et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

List of abbreviations

- CMOC

- context–mechanism–outcome configuration

- GP

- general practitioner

- PCC

- person-centred care

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- VCSE

- voluntary, community and social enterprise

References

- Citizens Advice . A Very General Practice: How Much Time Do GPs Spend on Issues Other Than Health? 2015. www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Public%20services%20publications/CitizensAdvice_AVeryGeneralPractice_May2015.pdf (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Morse DF, Sandhu S, Mulligan K, Tierney S, Polley M, Chiva Giurca B, et al. Global developments in social prescribing. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7.

- NHS England . Comprehensive Model of Personalised Care 2018. www.england.nhs.uk/publication/comprehensive-model-of-personalised-care/ (accessed 4 February 2024).

- NHS England . NHS Long Term Plan 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Coulter A, Oldman J. Person-centred care: what is it and how do we get there?. Fut Hosp J 2016;3:114-6.

- Ekman I. Practising the ethics of person‐centred care balancing ethical conviction and moral obligations. Nurs Philos 2022;23.

- Hamovitch EK, Choy-Brown M, Stanhope V. Person-centered care and the therapeutic alliance. Commun Ment Health J 2018;54:951-8.

- The King’s Fund . Leadership and Engagement for Improvement in the NHS: Together We Can 2012.

- van der Meer L, Nieboer AP, Finkenflugel H, Cramm JM. The importance of person-centred care and co-creation of care for the well-being and job satisfaction of professionals working with people with intellectual disabilities. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:76-81.

- van Diepen C, Fors A, Ekman I, Hensing G. Association between person-centred care and healthcare providers’ job satisfaction and work-related health: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2020;10.

- Olsson LE, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, Ekman I. Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials – a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:456-65.

- Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev: MCRR 2013;70:351-79.

- Rossiter C, Levett-Jones T, Pich J. The impact of person-centred care on patient safety: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;109.

- NHS England . Personalised Care Operating Model 2021. www.england.nhs.uk/publication/personalised-care-operating-model/ (accessed 4 February 2024).

- NHS England . Workforce Development Framework: Social Prescribing Link Workers 2023. www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/workforce-development-framework-social-prescribing-link-workers/ (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Tierney S, Wong G, Roberts N, Boylan AM, Park S, Abrams R, et al. Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: a realist review. BMC Med 2020;18.

- Husk K, Blockley K, Lovell R, Bethel A, Lang I, Byng R, et al. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health Soc Care Commun 2020;28:309-24.

- Tierney S, Westlake D, Wong G, Markham S, Turk A, Gorenberg J, et al. Fitting in or belonging: emerging findings from a realist evaluation of social prescribing link workers in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2023;73.

- Westlake D, Tierney S, Mahtani KR. Understanding the Implementation of Link Workers in Primary Care: A Realist Evaluation to Inform Current and Future Policy 2021. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/understanding-the-implementation-of-link-workers-in-primary-care-a-realist-evaluation-to-inform-current-and-future-policy (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Westlake D, Wong G, Markham S, Turk A, Gorenberg J, Pope C, et al. Health Soc Care Commun. 2024.

- Bickman L. Using Program Theory in Evaluation. London: SAGE; 1987.

- Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, Greenhalgh J, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med 2016;14.

- Westlake D, Tierney S, Turk A, Markham S, Husk K. Metrics and Measures: What Are the Best Ways to Characterise Our Study Sites? 2023. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/metrics-and-measures-what-are-the-best-ways-to-characterise-our-study-sites (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Ahmed A, van den Muijsenbergh METC, Vrijhoef HJM. Person-centred care in primary care: what works for whom, how and in what circumstances?. Health Soc Care Commun 2022;30:e3328-41.

- Michielsen L, Bischoff EWMA, Schermer T, Laurant M. Primary healthcare competencies needed in the management of person-centred integrated care for chronic illness and multimorbidity: results of a scoping review. BMC Prim Care 2023;24.

- The Health Foundation . Person-Centred Care Made Simple: What Everyone Should Know about Person-Centred Care 2016.

- Fraser C, Clarke G. Measuring Continuity of Care in General Practice 2023. www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/measuring-continuity-of-care-in-general-practice (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Hull SA, Williams C, Schofield P, Boomla K, Ashworth M. Measuring continuity of care in general practice: a comparison of two methods using routinely collected data. Br J Gen Pract 2023;72:BJGP.2022.0043-e779.

- Aughterson H, Baxter L, Fancourt D. Social prescribing for individuals with mental health problems: a qualitative study of barriers and enablers experienced by general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 2020;21.

- White C, Bell J, Reid M, Dyson J. More than signposting: findings from an evaluation of a social prescribing service. Health Soc Care Community 2022;30:e5105-14.

- NHS England . Social Prescribing: Reference Guide and Technical Annex for Primary Care Networks 2023. www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/social-prescribing-reference-guide-and-technical-annex-for-primary-care-networks/ (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Tierney S, Westlake D, Wong G, Turk A, Markham S, Gorenberg J, et al. Understanding and explaining the consequences of micro-discretions and boundaries in the social prescribing link worker role in England. Health Soc Care Deliv Res 2024;12. https://doi.org/10.3310/JSQY9840.

- Bordin ES. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychother: Theory Res Pract 1979;16:252-60.

- Baier AL, Kline AC, Feeny NC. Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: a systematic review and evaluation of research. Clin Psychol Rev 2020;82.

- Powell A. Therapeutic alliance and its potential application to physical activity interventions for older adults: a narrative review. J Aging Phys Act 2022;30:739-43.

- Sondena P, Dalusio-King G, Hebron C. Concep-tualisation of the therapeutic alliance in physiotherapy: is it adequate?. Musculosk Sci Pract 2020;46.

- British Red Cross . Fulfilling the Promise: How Social Prescribing Can Most Effectively Tackle Loneliness 2019. www.redcross.org.uk/-/media/documents/about-us/research-publications/health-and-social-care/fulfilling-the-promise-social-prescribing-and-loneliness.pdf (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Commentary: structure or agency? The importance of both for addressing social inequalities in health. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:378-9.

- Frostick C, Bertotti M. The frontline of social prescribing: how do we ensure that link workers can work safely and effectively within primary care?. Chronic Illn 2021;17:404-15.

- Moore C, Unwin P, Evans N, Howie F. ‘Winging it’: an exploration of the self-perceived professional identity of social prescribing link workers. Health Soc Care Commun 2023;2023:1-8.

- Rhodes J, Bell S. ‘It sounded a lot simpler on the job description’: a qualitative study exploring the role of social prescribing link workers and their training and support needs. Health Soc Care Commun 2021;29:e338-47.

- National Association of Link Workers . Care for the Carer: Social Prescribing Link Workers Views, Perspectives, and Experiences of Clinical Supervision and Wellbeing Support 2020. www.nalw.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NALW_Care-for-the-Carer_-Report_8th-July-2020-Final.pdf (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Baird B, Lamming L, Bhatt R, Beech J, Dale V. Integrating Additional Roles into Primary Care Networks 2022. https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/1404655eb2/integrating_additional_roles_general_practice_2022.pdf (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Fixsen A, Barrett S, Shimonovich M. Weathering the storm: a qualitative study of social prescribing in urban and rural Scotland during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Med 2021;9.

- Westlake D, Ekman I, Britten N, Lloyd H. Terms of engagement for working with patients in a person-centred partnership: a secondary analysis of qualitative data. Health Soc Care Commun 2022;30:330-40.

- Fenton LR, Cecero JJ, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Perspective is everything: the predictive validity of six working alliance instruments. J Psychother Pract Res 2001;10:262-8.

- Gutierrez-Sanchez D, Perez-Cruzado D, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Systematic review of therapeutic alliance measurement instruments in physiotherapy. Physiother Canada 2021;73:212-7.

- Del Re AC, Fluckiger C, Horvath AO, Symonds D, Wampold BE. Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance–outcome relationship: a restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:642-9.

- Tierney S. Embarking on Research to Explore Issues Related to Retention of Social Prescribing Link Workers in Their Role 2023. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/embarking-on-research-to-explore-issues-related-to-retention-of-social-prescribing-link-workers-in-their-role (accessed 4 February 2024).

- Tierney S, Cartwright L, Akinyemi O, Carder-Gilbert H, Burns L, Dayson C, et al. What Does the Evidence Tell Us about Accessibility of Social Prescribing Schemes in England to People from Black and Ethnic Minority Backgrounds?. London: National Academy for Social Prescribing; 2022.