Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in June 2022. This article began editorial review in November 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 King et al. This work was produced by King et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 King et al.

Background

Health visiting services in the United Kingdom

Child health programmes (CHPs) in the UK offer every child and their family an evidence-based programme of screening tests, immunisations, developmental reviews, information and advice. Successive Health for All Children Reports have developed the evidence-based foundations for these programmes. 1–6 They place a clear emphasis on parenting support, public health priorities such as breastfeeding and obesity prevention, and integrated services with the health visitor as the lead. They adopt a model of progressive universalism, recognising there are different levels of need, with specific tailoring required to meet the needs of individual families. The overarching aim is to give every baby and child the best start in life to ensure they reach their full potential. 7

The early years are crucial for a baby’s future health and development. 8 Between conception and age 2 years, an individual’s cognitive, emotional and physical development will influence their life chances into adulthood. 9 Deprivation in childhood negatively impacts life chances. 10–16 Babies’ and young children’s health, development and safety are affected by a wide range of factors including caregiver interaction, diet, sleeping arrangements, home conditions, dental hygiene and opportunities for play. Too many babies also experience physical, sexual and psychological abuse, neglect, exposure to domestic violence, substance abuse, parental mental illness, loss of a parent and poor attachment relationships with parents or carers. Health visitors play an important role in identifying the support that a new family needs and are key to delivering CHPs for babies and pre-school children. They deliver a universal service, intended to take account of the different dynamics and needs of all families, and provide a suitable platform for enabling early intervention and reducing inequalities in health. Health visitors are specialist public health nurses who are qualified nurses or midwives who have undergone additional training. 17 They are the only professionals who proactively and systematically reach all families with babies and young children from the antenatal period up to school entry.

Difference in different United Kingdom countries

Political devolution in the UK has enabled devolved institutions to influence national policy for early child health and development. 18 The specific delivery of CHPs across the UK varies depending on each country’s policy and strategic frameworks. Key differences are summarised in Table 1. However, there is little detailed knowledge about how health visiting services are organised and delivered in the four countries. Within England, where a range of providers are commissioned by local authorities, data suggest significant variation in delivery/uptake of mandated contacts between local areas, and variation in who completes them. 19,20 A recent survey conducted in 2018,21 which attempted to map the variety of ways in which teams and caseloads are configured in different areas, garnered 584 responses from individual health visitor practitioners, but the majority of these (n = 531) were working in England. The survey found that health visiting teams and their caseloads are organised in a variety of ways across the UK, with various pros and cons of different caseload management approaches, and a mixed and complex picture.

| England | Northern Ireland | Scotland | Wales | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key legislation | Health and Social Care Act 2012 | Health and Social Care (Reform) Act (Northern Ireland) 2009 | Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 | Social Services and Wellbeing (Wales) Act 2014 |

| Child Health Policy | Healthy Child Programme 0–19 years (2009, 2016, 2018, 2021, 2023) | Health Child, Healthy Future Programme (2010) | Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) Policy (2010) and Universal Health Visiting Programme (2015) | Healthy Child Wales Programme 0–7 years (2016) |

| Over-arching model | ‘Universal in reach, personalised in response’ | UNOCINI Thresholds of Need Model22 | SHANARRI model of well-being23 | ‘All Wales approach’ |

| Who commissions CHP? (Purchaser) | One hundred and fifty-three upper-tier and unitary local authorities | Department of Health and executive agency Public Health Agency | No purchaser–provider split | No purchaser–provider split |

| Who delivers CHP? (Provider) | Range of providers including NHS bodies, local authorities, private healthcare providers, charities or community interest companies | Six Health and Social Care Trusts | Fourteen territorial NHS Boards, working with 32 local authorities via 30 integrated joint boards and one joint monitoring committee | Seven local health boards |

| Working and employment models | Health visitors expected to lead on mandated reviews, but can delegate any aspect of their work to other staff members, including community staff nurses and nursery nurses | Health visitors managed by Health and Social Care Trusts. Assessments led by health visitors, but opportunities for skill mix at local level encouraged24 | Health visitors employed by NHS, except in Highland (employed by Highland Council). All visits to be undertaken by health visitors in the home | Health visitors provide expert clinical leadership to a multidisciplinary team where skill mixing is used ‘as an enhancement’ to the professional role of health visitor |

| Scheduled assessments in universal service | 5 (+ 2 suggested) Antenatal: 1 Birth to 1 year: 3 (+ 2 suggested) 1–5 years: 1 |

7 Antenatal: 1 Birth to 1 year: 4 1–5 years: 2 |

11 Antenatal: 1 Birth to 1 year: 7 1–5 years: 3 |

8 Antenatal: 0 (unless targeted) Birth to 1 year: 5 1–5 years: 3 |

Health visiting in the United Kingdom during the pandemic

The UK Government’s Coronavirus Action Plan (March 2020) set out measures to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak and detailed the government’s four-stage strategy: contain, delay, research and mitigate. It also set out changes to legislation necessary for giving public bodies across the UK the tools and powers they need to carry out an effective response. Across the UK, initial lockdown restrictions from March 2020 saw all non-urgent healthcare services stopped and capacity focused on the COVID-19 response. 25,26 Providers of community services were generally requested to ‘release capacity’ to support the acute sector, and health visiting services in many areas were reduced to a partial service incorporating a significantly reduced number of contacts. 27 The timing, duration and stringency of COVID-19 responses across the four nations of the UK diverged, highlighting their autonomy and legislative powers as devolved nations. 28 These responses included school closures, movement and gathering restrictions, self-isolation and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Initially, very little consideration was given to the wider impacts of the pandemic on babies and young children, or the health visiting service that supports them. The Institute of Health Visiting reported that service leads and commissioners lacked information and guidance on issues such as redeployment, PPE and infection control, and acceptable adaptations of the health visiting service delivery model (iHV, personal communication).

While the precise guidance from governments differed across the UK, all NHS managers had to support prioritisation of the workforce as part of the resilience response, and health visitors everywhere had to think differently about the prioritisation of support to families. Guidance emphasised the importance of some home visits (e.g. the first postnatal assessment), but there was a general presumption that most contacts would be virtual, with face-to-face contacts (with PPE) only where an individual assessment identifies a compelling need. 29 Where aspects of services were paused, the rate at which they were reinstated varied considerably. 30 The increased workload and pressures of working during the COVID-19 pandemic had significant negative impacts on the mental and physical health and well-being of health visiting staff. 31–33

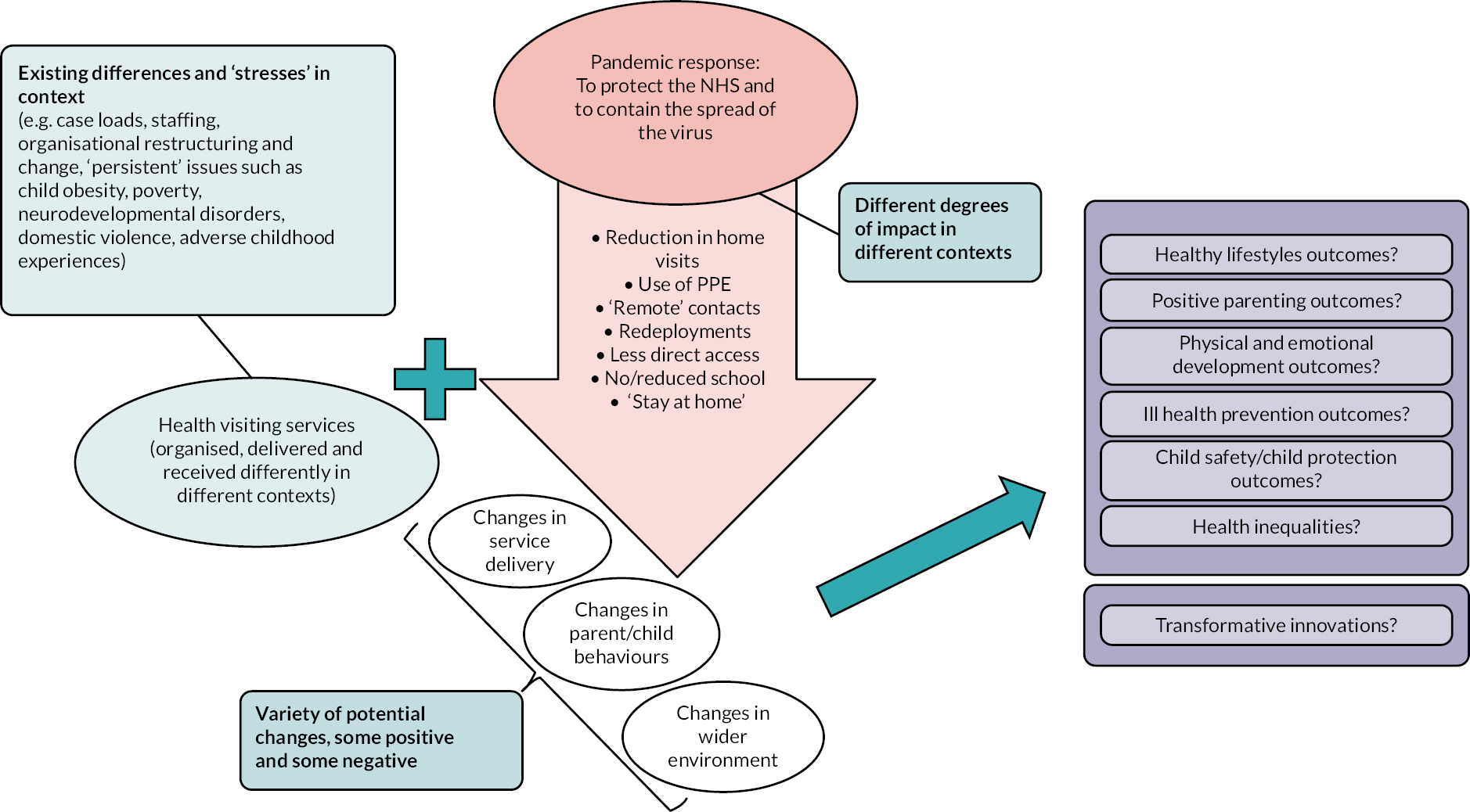

Throughout the pandemic response, practitioners expressed concerns about the impacts of reduced/differently delivered services on babies and families, particularly in relation to safeguarding and neglect, but also the impact of missed needs on the baby’s growth and development, parental mental health, breastfeeding and wider determinants of health exacerbated by COVID-19. 31–36 An estimated 1.4 million women would have experienced maternity and child health care between March 2020 and March 2022 under some level of COVID-19 restrictions. 25,37 Changes to maternity services, including restrictions on birth partners, reduced in-person appointments and increased virtual care provision, have led to increased stress, depression and anxiety among new mothers, which might have then impacted on health visitors’ caseloads. 38–41 Some restrictions continued beyond March 2022, such as limits to antenatal/postnatal hospital visits and some play and stay groups remaining closed. Reports of parents’ experiences show a mixed picture both in terms of different families’ ability to cope and the support they were given. Many parents felt unsupported, were cut off from family and community networks and with reduced access to formal services. 40,42–44 Existing inequalities were exacerbated for those in poorer, less educated and ethnic minority households and those facing issues of overcrowding, temporary housing, mental ill-health, lack of access to digital technologies or substance abuse within their families. 45–50 Prior to the start of the review we developed an initial programme theory (PT), drawing on this background literature (see Appendix 1, Figure 3).

Aim and objectives

The aim of the study was to identify and analyse literature related to health visiting, published since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic response, to better understand how the pandemic was experienced by health visiting services. As stated in our protocol, the study sought to answer the question: ‘How can the organisation and delivery of health visiting services in the UK be improved in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide equitable, effective and efficient services for young children and their families?’51 To be able to address this question, we identified four sub-questions:

-

What are the mechanisms that explain variation in and mitigation of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in different contexts?

-

What are the important contexts that influence whether the different mechanisms produce the outcomes that have been identified in the literature?

-

In what circumstances are the (positive and negative) impacts likely to be most (and least) profound?

-

What can we learn from the way health visiting services have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic to improve their organisation and delivery?

Objectives

-

To conduct a realist review of the literature to examine what the impacts (both positive and negative) of the COVID-19 pandemic have been on health visiting services in the UK, for whom, in different contexts.

-

To engage with key policy, practice and research stakeholders in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to understand important contextual differences across the UK in relation to the planning, organisation and delivery of health visiting services.

-

To identify recommendations for improving the organisation and delivery and ongoing post-pandemic recovery of health visiting services in different settings, for different groups. 51

Methods

Since March 2020, there has been a profusion of literature describing the experiences and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health services delivery. 42,52–55 This literature comes from a range of academic researchers, practitioners, advocacy organisations, policy-makers and other commentators, and is published not just in academic journals but also as reports, working papers, presentations and other documents. It contains important learning at a time when services, and the contexts in which they are delivered, were undergoing an unusual amount of change. Our review of this literature capitalises on the opportunity to learn new things about health visiting services and what works, for whom and in what circumstances. Given the complexity of health visiting as a programme of work and the variety of relevant literature and its sources, we chose to conduct a realist review. A realist review is a systematic and theory-driven approach to synthesising and analysing evidence. It focuses on understanding how complex interventions work in particular contexts by examining the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors. 56,57 The involvement of stakeholders in a realist review is crucial.

People with lived experience and stakeholder engagement

The engagement of professional stakeholders and people with lived experience of caring for babies during the pandemic in the design, conduct and dissemination of this study has ensured recommendations are meaningful and outputs are accessible to parents/carers, the wider public, commissioners, providers and policy-makers. Our patient and public involvement (PPI) lead (MB) has worked as a key member of the research team from inception to completion. We recruited a group of eight people with lived experienced of health visiting (who have had cause to access health visiting services during the pandemic period) to work alongside us. The group of eight comprised two people from each of the four UK countries, sampled to ensure diversity of the number of children and deprivation levels. The group met online four times during the study, facilitated by our PPI lead. Members also contributed additional feedback outside of meetings (by e-mailing or telephoning our PPI lead or researcher). This is described in more detail in our synopsis paper.

To form a separate professional stakeholder group, we invited 26 professionals (policy leads, commissioners, practitioners and policy advocates), with representatives from each of the four UK nations. In a change to our original protocol, stakeholders met five times throughout the study, rather than the planned six, and contributed additional feedback outside of meetings (by reviewing and commenting on documents). This was to make best use of their time and involvement.

Realist review methods

Our realist review methodology followed Pawson’s five iterative steps,58 and is described in more detail in our protocol. 60 This manuscript is reported following the RAMESES publication standards for realist synthesis. 59

The steps, and the involvement of our stakeholder group and people with lived experience group in each step, are summarised in Table 2.

| Step | Aim | Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: locate existing theories | To locate underlying programme theories for health visiting service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic | Early discussion and literature scoping to inform an initial PT Informal exploratory searching of published literature and current policy documents Further development of the PT with our stakeholder group |

| Step 2: search for evidence | To conduct a formal search of literature related to health visiting during the COVID-19 pandemic | Searches conducted in five databases (see Appendix 2) Grey literature identified from relevant websites Literature provided by stakeholders Citation chaining E-mail alerts of relevant material ongoing throughout Documents screened against inclusion/exclusion criteria |

| Step 3: article selection | To select full-text documents for inclusion in the review based on an assessment of relevance | Documents selected for inclusion when they contained data that could inform the PT A random sample of 10% independently assessed for relevance |

| Step 4: extracting and organising data | To organise and describe relevant documents To code data and make interpretations and judgements |

Characteristics of included studies extracted into an Excel spreadsheet Full texts of documents coded deductively, inductively and retroductively Theories and interpretations included in additional memos Initial interpretations and judgements discussed with team and with stakeholder and lived experience groups |

| Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions | To apply a realist logic to analyse the extracted data To construct propositions represented through CMOCs |

Propositions represented through CMOCsa with evidence for justification Draft set of CMOCs presented to full project team in January 2023 for discussion and refinement CMOCs presented to stakeholder and lived experience groups in February 2023. Groups helped provide a richer understanding of contexts and mechanisms in different localities Regular meetings between EG and EK to discuss and iteratively develop these CMOCs Extended project team meeting September 2023 to refine the themes found and discuss/develop the final PT. The CMOCs were mapped onto themes and then recommendations, which were presented to the stakeholder group, who suggested refinements and highlighted areas of uncertainty |

Our search strategy involved formal searches (in October 2022) of MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, HMIC and Google Scholar using combinations of free text and subject heading terms describing health visiting and relevant UK policies and programmes with terms describing the COVID-19 pandemic. The searches were limited to identifying literature published from 2020 onwards to capture material produced from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic response. This main search was augmented by searches for grey literature conducted in November and December 2022, to identify relevant reports, position papers, policy and programme documentation and other non-research material that was not identified in the main searches. This search focused on material available via relevant organisational websites identified by the project team, using a combination of searching and browsing to explore published material. Our strategy was further supplemented by forward and backward citation searching in May 2023, by a Google Scholar search alert active throughout the project, and by requests to our professional stakeholder group.

Documents were screened for inclusion by EK by title and abstract (where available), and then in full text (see published protocol for more detail60). At each stage, a 10% random sample of records was screened in duplicate by EG for quality control purposes. Eligibility criteria were applied as follows:

Inclusion

-

Type of intervention: health visiting

-

Study design: all study designs

-

Types of settings: any setting providing health visiting services

-

Types of participants: all families eligible for universal health visiting services

-

Outcome measures: all outcome measures related to health visiting services

Exclusion

-

Health visiting type models or programmes run in countries other than the UK

-

Specialist or targeted health visiting services for select populations only

As the project progressed, we made minor deviations and additions to our original protocol.

In step 1, we analysed the similarities and differences in health visiting services across the four UK nations. We created a table detailing CHPs across the different UK nations and shared it with our stakeholder group for feedback and refinement (summarised in Table 1).

In step 2, we conducted an additional search in April 2023 to address the limited data on responses to the COVID-19 pandemic at local management level. To avoid missing relevant material and potential pandemic-related insights, we devised a new search to uncover recently published content related to health visiting services, even if it did not explicitly mention the pandemic. We refined our search by removing COVID-19-related terms and repeated it in the same databases, focusing on material published from 2021 onwards. A relatively small number of included papers were found in this search. They predominantly referred to data collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic or with different or unclear populations (e.g. midwives). Although these papers were re-reviewed at a later stage in our iterative methods, none were found to contribute further to our PT.

We did not undertake the potential option of other purposive searching, for example looking at other countries, or at closely aligned services. Our original searches identified several articles from other countries, but they were deemed ineligible due to the unique nature of the health visitor role within the UK’s settings. The team felt there was sufficient data focusing on health visiting to refine the PT, without the need to look at other services such as social work.

In step 3, we selected documents for inclusion based on assessment of their relevance, in terms of their contribution to theory building and/or testing. However, we did not assess the methods used to generate the data. This is because most documents were either first-person accounts of health visiting or documents from organisations whose primary purpose is advocacy. We reflected on this advocacy/first-person perspective during our data analysis.

In step 4, we also used the KUMU software [Kumu, Kumu Relationship Mapping Software, 2023. URL: https://kumu.io (accessed 31 October 2023)] to visually draw links between different areas of interest, to add reflections from stakeholder and lived experience groups, and to visually present these at team and stakeholder meetings.

In step 5, themes from the data were presented as draft context, mechanism, outcome configurations (CMOCs) and discussed at a face-to-face team meeting. Through further discussion with the team, regular meetings between EK and EG, and the input of our lived experience and stakeholder groups these CMOCs were iteratively refined. We wrote narratives for the CMOCs based on themes and underlying propositions, checking for consistency against our data and uncovering gaps and overlaps. Finally, each CMOC was translated into a finding and draft recommendation, which was subsequently refined by our stakeholder group. During the stakeholder meeting, the attendees were also asked to indicate how ‘do-able’ they felt these recommendations would be to implement, with a group discussion on this.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

Our expression of interest form for recruiting the lived experience group included optional questions on ethnicity and postcode. From the postcodes, we calculated the relevant index of deprivation and attempted to achieve a spread of deprivation levels and geographical areas, albeit within a small group. Group meetings were held online to allow those from across the UK to attend without travel time. Group members discussed their own preferred time for meetings, to fit around child care and existing commitments.

We had little control over the diversity of our professional stakeholder group, who were recruited for the professional roles that they occupy. We did not collect any personal information from these members. All meetings were held online to reduce travel.

We did not receive any notifications about additional accessibility requirements from either group. A more thorough discussion of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) issues, particularly in relation to the data, is included in our accompanying synopsis paper.

Statistical analysis

There was no statistical analysis performed in this realist review.

Data sources (for systematic reviews)

Full details of search strategies and data sources are shown in Appendix 2.

Ethics

General University Ethics Panel approval was obtained from the University of Stirling (reference 7662).

Results

Documents included in the review

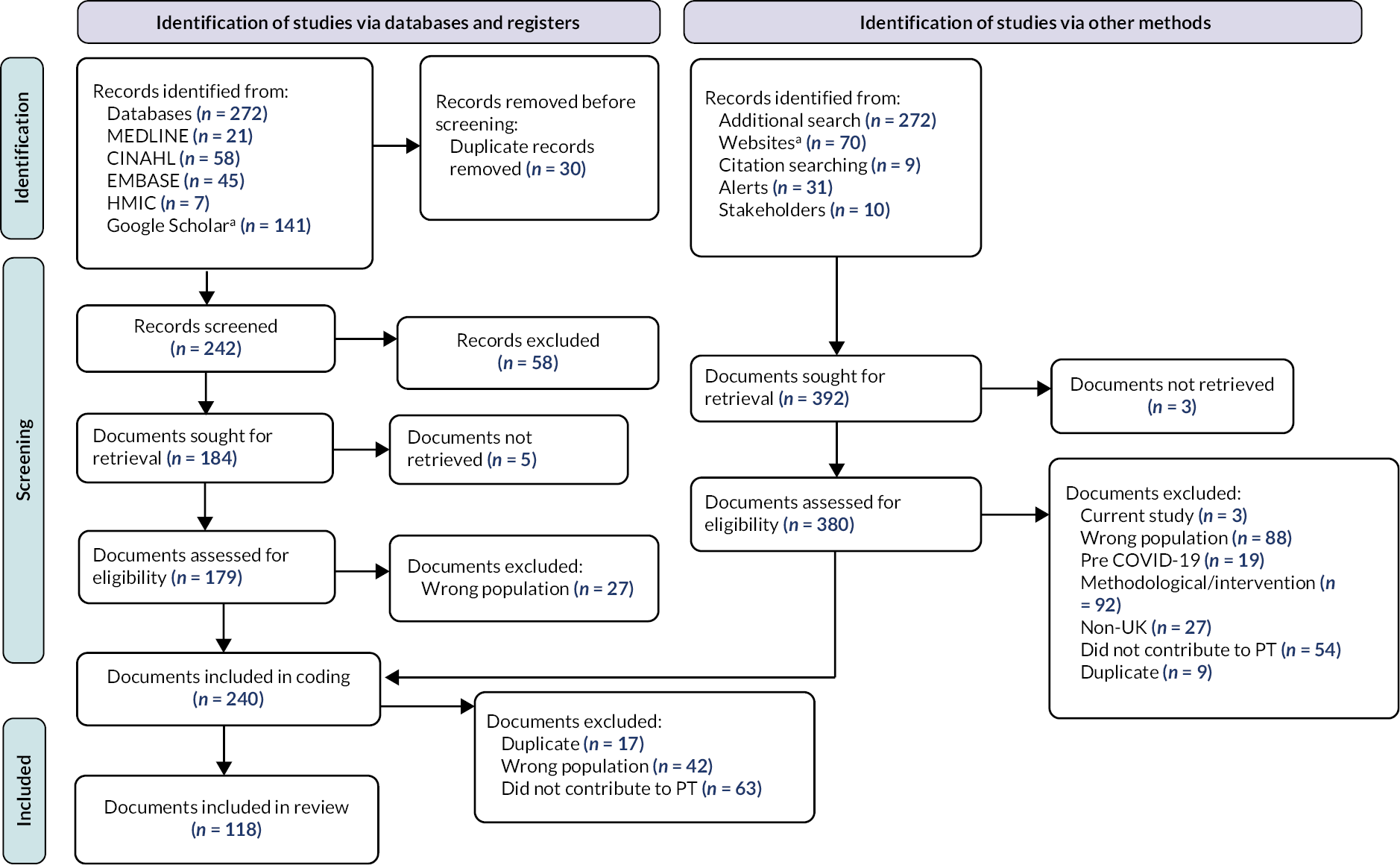

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram showing the identification, screening and inclusion of documents is provided in Figure 1. A total of 118 documents contributed data to the review, with full details shown in Table 3, Appendix 3.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses61 diagram showing the identification, screening and inclusion of documents. a, Google Scholar and website search results screened ‘on screen’; see Appendix 2 for details.

The majority of included documents were from either an advocacy perspective (33%) or the perspectives of practitioners (28%). Most documents were from England (n = 51) or the UK (n = 37), with very few specifically focused on Scotland (n = 4), Wales (n = 7) or Northern Ireland (n = 1). Our stakeholder group discussions sought to counter this English bias in the literature. A more detailed analysis and discussion of both the primary perspective and the country of focus for documents included in the review can be found in our synopsis paper.

Working definitions of terms

Various terminology is used across the devolved nations in relation to health visiting and the CHPs. Following guidance from stakeholders, we developed working definitions of terms which we use throughout the results and discussion. These can be found in the Glossary.

Review findings

Our findings are grouped into three categories: health visiting contacts, health visiting connections and the health visiting workforce. Tables of CMOCs with quotes are shown in Appendix 4. The full relationships between CMOCs, findings and recommendations are included in our synopsis paper.

Health visiting contacts

The practice of health visiting rests on the conduct of ongoing holistic assessments of family needs, conducted by experienced professionals, so that the families and practitioners can identify any support required for the baby/family to thrive. Our findings highlight the importance of these universal assessment reviews, particularly in terms of ensuring potential needs are not missed, and enabling the team to provide a proactive and personalised response to the changing needs of babies, young children and families. While a proportion of reviews was always missed prior to the pandemic (national data sets on this are poor but all highlight gaps), the COVID-19 pandemic meant many more were either missed or were conducted differently. Across our data, practitioners and families express concerns about potential needs not being identified in good time (CMOC01). An increased number of contacts were made remotely, for example, via telephone or with questionnaires sent by post, and using a wider staff skill mix. Our data suggest that such contacts can sometimes enable useful information to be gathered, and that this information can support an assessment of needs (CMOC02). However, face-to-face contacts play a crucial role since they can gather information through physical observations and interactions which might otherwise be missed (CMOC03). Our data highlighted practitioners’ concerns about not being able to assess a family properly remotely. This was recognised to have an impact on other parts of the healthcare system, for example, when issues were picked up later by other healthcare professionals.

Our findings also illustrate the role face-to-face universal assessment reviews play in building trusting relationships with families (CMOC08). From the health visitor’s perspective, these universal assessment reviews enable them to identify problems which parents might have missed, to intervene early, to tailor advice and support for each family and to have sensitive conversations with families. The need for this appeared to be heightened when more families were under considerable pressure (e.g. caused by the pandemic response and cost of living crisis).

From the parents’/carers’ perspective, our data suggest that families feel more supported when they have an opportunity to build a relationship through face-to-face contacts; such contacts facilitate a better understanding of the family context (CMOC09), and families are more likely to disclose their concerns. However, outside the universal assessment reviews, remote contacts can be useful for certain families at certain times. For example, when health visiting teams use remote contacts to proactively maintain open and responsive channels of communication, parents can feel supported (CMOC12). During the difficult times of the pandemic response, some families found a quick ‘check-in’ (e.g. by phone or video call) by the health visitor made them feel that somebody was interested in them, and had remembered them, even if they didn’t receive a longer face-to-face contact.

From the health visitors’ perspective, practitioners might successfully use remote connections to keep in touch with families on their caseloads, when it is appropriate to do so (CMOC11). With no travel time required, remote connections can allow practitioners to be in more regular contact with multiple families, for example using WhatsApp groups to disseminate information. Some families, however, do not have the resources or desire to engage meaningfully with remote consultations and the substitution of face-to-face contacts accentuates the disparities between individuals who struggle with non-face-to-face interactions, and those who are accustomed to and excel in an online environment. The needs of babies and young children are an important consideration in the choice of method of contact, since they are generally excluded from any remote form of interaction (CMOC10); in face-to-face contact, health visitors can directly observe mother–baby interaction, development, play and feeding.

During the pandemic, urgent and immediate needs took precedence, resulting in less time for providing families with holistic, preventive support. Our data highlight health visitors’ concerns around not being able to fulfil their health promotion and wider support role adequately, given demand and caseloads (CMOC04). The pandemic exacerbated issues already seen with high workloads. From the families’ perspective, regular contacts with the health visiting team enable the building of supportive relationships and increase opportunities to explore aspects of family/infant health and well-being, particularly as families’ needs change over time (CMOC05). With fewer face-to-face contacts, there were missed opportunities to provide tailored support that benefits from physical presence, for example, demonstrating or role-modelling activities. However, the pandemic experience also highlights that some forms of information, guidance and support can be usefully delivered by health visiting teams in a digital format (e.g. apps, videos, links to support groups) (CMOC06). Digital/remote provision is only useful for some support, for some people, some of the time. New digital resources were created during the pandemic, continuing a trend that had begun prior. While this gives health visiting teams useful new ways of delivering information and support, there is little evidence of evaluation of these resources, and there appears to be duplication across different local areas (CMOC07).

Health visiting connections

Health visitors are only able to support families in a holistic way by making connections to other services and to the wider community. This relies on a sound understanding of the communities they work in, an up-to-date knowledge of local services and good relationships with other professionals working in their communities. The COVID-19 pandemic response disrupted the continuity of care, with greater mobility of staff within and between health visiting teams, and redeployment of staff to more acute services. Community contexts were also disrupted, with many services closing, reducing capacity or becoming less accessible, for example by increasing their thresholds for support. Our findings highlight that when other services in the community close, or change their provision, then health visitors cannot perform a vital part of their role, signposting and referring families for additional help (CMOC13). Health visitors may assume additional responsibilities in situations where other forms of support are lacking. This may include managing cases that would previously have been handled by children’s social care, or assisting children who are awaiting a diagnosis for special educational needs or disability support. Furthermore, health visitors may go beyond their usual duties to help families with tasks such as translation, form filling and accessing food banks, which are typically supported by local charities (CMOC14).

Some aspects of the wider community provision could not be easily replaced during the pandemic, such as local peer support and socialising groups for babies. Our findings suggest that children and families missed out on opportunities to socialise and take part in different activities (particularly those that support learning and development), which potentially increased the risk of social isolation and stress on parents (CMOC15). From the families’ perspective, our data highlight the concerns of parents regarding children’s lack of contact with other people outside their close family, and particularly opportunities to socialise with children of their own age. Fun activities/groups also provide a useful structure to parents’ days, enabling them to venture out of the house, connect with other parents and experts and try new ideas for engaging their children.

During the pandemic response, informal contact was generally restricted between members of health visiting teams and others, such as clinicians. Our findings highlight that these connections are important for staff well-being and development. Data point to issues of workforce stress and isolation related to this lack of connection, and fewer opportunities for informal discussion, support and peer review, alongside formal clinical supervision and reflection (CMOC16). There are indications that the increased stress and isolation resulted in mental and physical health impacts for some health visitors, including reduced self-care, burnout and lack of compassion for families on their caseload (compassion fatigue).

Digital and remote technologies were increasingly used as a substitute for face-to-face interaction between staff. Our findings suggest that the use of such technologies can enable peer discussions, team meetings and delivery of some types of education, and can increase access to training and networks that may not be available locally. They can also be an efficient use of time when combined with more traditional communication and education routes (CMOC17).

The health visitor role depends on good interagency working, particularly with regard to safeguarding which relies on the appropriate sharing of information between professionals and agencies. Our data highlight the importance of the health visitor’s role in making connections with other agencies such as social services and general practitioner (GP) surgeries. During the pandemic response, many other agencies, schools and child-care settings were not seeing children face-to-face. Health visitors’ connections to other agencies were disrupted, at a time of increased concerns regarding parental mental health, domestic abuse and issues of child safeguarding. In some areas, due to redeployment and workforce shortages, there were not enough health visitors to meet the scale of need (CMOC18).

Health visiting workforce

Health visiting work relies on skilled practitioners, able to exercise professional judgement to identify and respond to needs in an appropriate and tailored way. Health visitors and other members of health visiting teams had varied experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to the guidance they were given, the procedures they were asked to follow and the restructuring of provision. There was also considerable variation in the extent to which health visiting team members were redeployed to support other parts of the healthcare system, and the extent to which health visiting teams were protected, or even enhanced, during the height of the pandemic. Across our data, being or feeling valued as a highly trained specialist is an important theme. Findings highlight that top-down guidance, updates and restructures often did not reflect the policy and professional commitments to babies, children, families and health visitors. When health visitors in some areas were seen as dispensable and able to be redeployed, they felt particularly devalued (CMOC19).

A related theme is the extent to which government policy focused on managing acute care during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a focus on babies and young children being largely absent. Much literature reflects that younger children were not considered a priority for policy and decision-makers during the pandemic response. The divergence in policy across the devolved nations, and across local authorities within England, also led to different models of support for parents with babies and young children (CMOC20). This situation exacerbated pre-existing workforce pressures, sometimes pushing health visiting services close to breaking point, with a range of negative consequences being reported within the literature for staff, families and children (CMOC21). Understaffing, redeployments, staff illness and health visitors leaving contributed to increased workload and work-related stress for remaining health visitors.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic rapidly and dramatically altered the context in which health visiting services are delivered. The impact of the pandemic on babies and families has been far-reaching, uneven and enduring. Health visiting staff rapidly adapted, finding new ways to ensure that babies and families continued to receive support in different contexts. However, the variation in practice and service delivery across the UK has been amplified, and there are important and ongoing implications of the pandemic response for future service delivery.

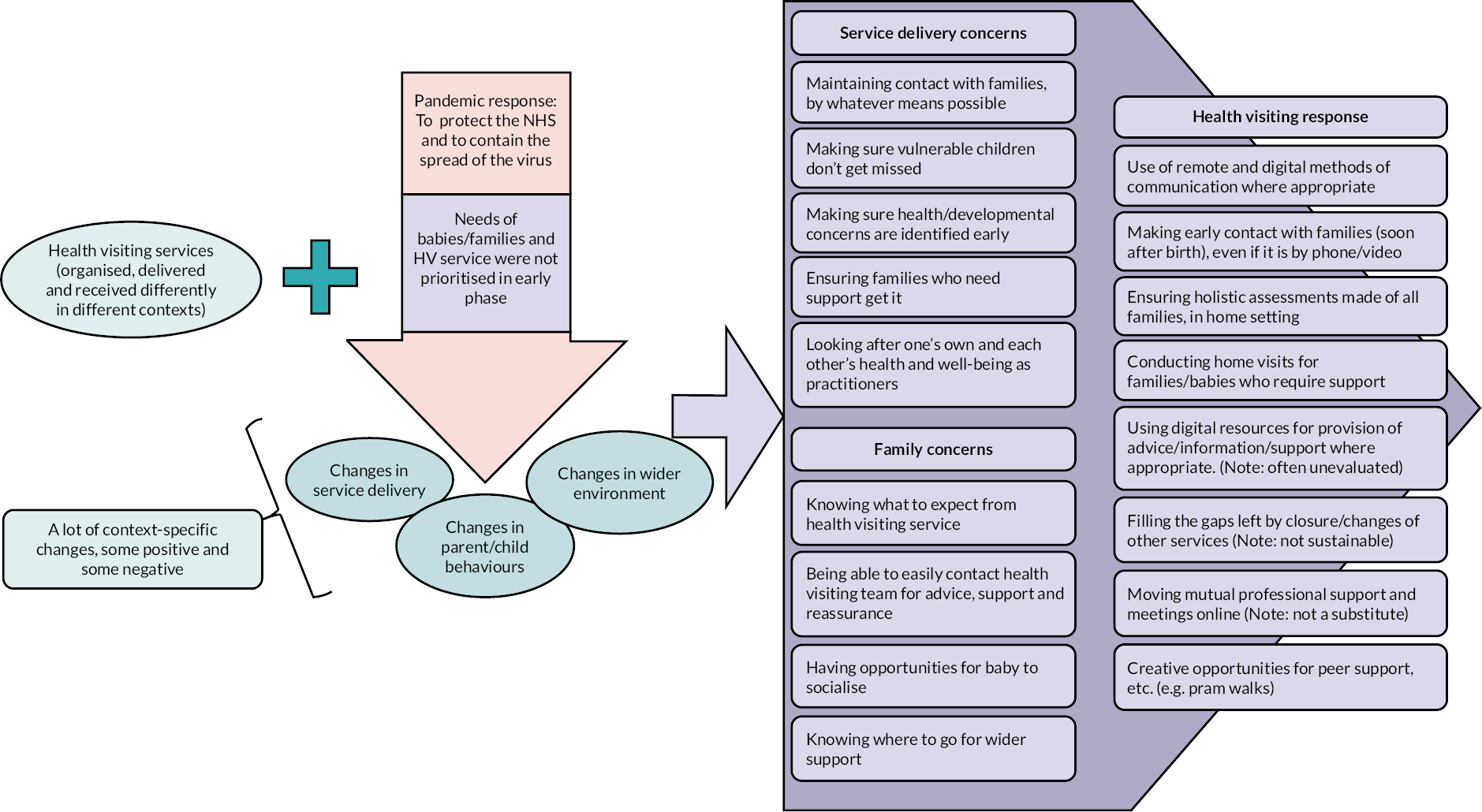

This study sought to answer the question: How can the organisation and delivery of health visiting services in the UK be improved in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide equitable, effective and efficient services for young children and their families? The 118 documents included in our study reported on aspects of changes made to services during the pandemic in different contexts. Our realist review of these documents, together with the input and guidance from our professional stakeholder and lived experience groups, has revealed a new understanding of the mechanisms by which health visiting outcomes occur. In terms of providing equitable, effective and efficient services, our findings highlight the importance of relationships (built via contacts) between health visitors and families, and holistic assessments for early intervention (facilitated by connections to other staff and support services). They also point to the variety of health visiting work and illustrate how, during a very challenging time, practitioners made adaptations in the way they practised, driven by core motivations: to maintain contact with families by whatever means possible; to make sure vulnerable children don’t get missed; to make sure health/developmental concerns are identified early; to ensure families who need support get it; and to look after one’s own and each other’s health and well-being as practitioners. These points (relationships, holistic assessments and health visiting work) are discussed further below.

In terms of improving the organisation and delivery of health visiting services in the UK, our study found very little evidence detailing disruptions at this managerial level, and consequently no new insights into how teams or caseloads might be organised, for example, for greater efficiency. However, findings suggest that the complexity and variety of health visiting work in different and constantly changing contexts call for requisite variety in turn, with skilled professionals (and their managers) having the flexibility and capacity to assess the appropriateness of their services for the environment they operate in. Such situations do not suit standardisation, but instead, they require good communication and information flow.

Our final PT diagram summarises our findings and is presented in Figure 2 below.

FIGURE 2.

Final PT.

Importance of relationships

The concerns of practitioners throughout the pandemic response highlighted the importance of relationships between health visitors and families. Practitioners recognised the need to build and maintain trusting relationships with families by any means possible, even when home visits were not advised. Research has consistently shown that establishing positive relationships between parents and health visitors is crucial for achieving desired outcomes in child health. 10,62 A good relationship allows a health visitor to assess the needs of an individual family and provide tailored support, and facilitates disclosure from family members, for example regarding domestic violence or mental health. 1 It is particularly important for enabling access to support for those families who might otherwise find such support hard to access. 10,63–65 During the pandemic response, many contacts between health visitors and families were stopped or were no longer face-to-face. While families missed the face-to-face contact for the mandated reviews, many were also positive about other methods of maintaining contact, such as WhatsApp messages or phone calls. When regular contact was maintained, families felt reassured that they had not been forgotten, encouraging them to reach out to their health visitors with queries. Our lived experience group shared mixed experiences of the health visiting service, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. One frustration was with health visitors who appeared to be focused on a tick-box exercise rather than building a real relationship with families. This, and our review findings, demonstrate that the skill of relationship building is the priority, whether the contact is face-to-face or online.

Holistic assessments for early intervention

Health, developmental and other problems within a family can be identified early and mitigated with the help of skilled practitioners. Our findings show that maintaining this role is a key concern for health visitors. It is important to conduct holistic assessments and identify needs soon after every baby is born. However, family situations and child vulnerability are dynamic. The assessment of needs by health visitors is articulated in other research as an ongoing process, with repeated iterations facilitated by the continuous provision of a comprehensive service that covers the period from pregnancy to starting school. 10 While face-to-face contact is critical for holistic assessments, remote contact can be a useful way of keeping in touch with families and making sure emerging needs are not missed. They can also help families keep in touch with the health visiting service and feel less isolated.

When the need for support is identified, practitioners are then concerned with ensuring that those needs are met. In a context that was rapidly changing, the importance of a health visitor’s role in signposting and making referrals was highlighted. 66,67 Where other services and/or informal support becomes less available or accessible, this presents additional challenges for health visiting teams. 68–70 Health visitors, as skilled public health practitioners and as a key part of a local child/family health and social care system, tailor their advice and support within a particular context. Some forms of support rely on face-to-face contact. However, the pandemic has shown that some support can be provided to some families using remote methods. Digital technologies, if evaluated, can provide a quick and acceptable mechanism for providing information to multiple families at once. Parent–peer support can also sometimes be facilitated in creative ways.

Health visiting work: varieties of human work

Our findings highlight the wide variation in health visiting service delivery and the range of ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic impacted health visiting work. A recent review of literature on health visitor workloads noted the complexity of health visitors’ work and the difficulties in capturing its diversity. 71 Reflecting on our own findings, particularly with our lived experience group, we uncovered significant disparities in the perception of how health visiting is practised and its actual implementation. Our understanding of the processes at work is drawn from Shorrock’s concept of ‘varieties of human work’, borrowed from psychology and ergonomics science literature. 72–74 This concept has been useful in other areas of UK health care to explain the influences of human and organisational characteristics. 75,76 It helps us to elaborate the distinction between work-as-imagined, work-as-prescribed, work-as-disclosed and work-as-done, each of which has areas of overlap and areas of difference.

The pandemic experience exposed a partial understanding of health visiting work-as-imagined by policy-makers and the public. It highlighted a disconnect between an imagined, abstract system and a lived, experienced one, where the envisioned work represented a strong perception of what should be happening in the health visiting service. Some decisions affecting health visiting work during the pandemic were made on the basis of an incomplete imagined view of the work. Moreover, the lack of clarity and communication with families regarding health visiting work means they often do not know what to expect. This can mean families’ expectations are not met.

We obtained some documents describing how the formalised work of health visitors (work-as-prescribed) was disrupted at a national level during the pandemic response. Our data and stakeholder group discussions revealed that work was also significantly disrupted at the subnational level, with local service managers adopting varying approaches to service organisation and delivery. However, there was a dearth of evidence describing these changes. Our findings highlight many of the problems with work-as-prescribed that are articulated by Shorrock: there are many ways in which the work of health visitors can be done; much health visiting work is impossible to capture in prescribed work; and the conditions of work (such as staffing levels and time) are not guaranteed and are usually suboptimal in practice.

Within the many documents we reviewed that discussed health visiting during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to observe how health visiting work is described and by whom. What was disclosed or explained in the data is not a complete expression of how work is really done. Some work-as-disclosed might be explicitly designed to reassure, in terms of demonstrating an alignment with work-as-prescribed. Other work-as-disclosed might amplify the differences between work-as-done and work-as-prescribed, perhaps as part of an advocacy agenda that is fighting to preserve or increase resources in a difficult financial climate. 77–79

Work-as-done is actual activity that takes place in an environment that is inevitably more complex and constrained than imagined. The pandemic introduced additional variety in work-as-done across different health visiting teams and within different families. It has been reported that variations in the interpretation of COVID-19 rules led to different local restrictions,80 resulting in greater variety in health visiting work. This variety reflects the degree of flexibility that health visitors need to tailor support for individual families and to meet the needs of different populations. 81 While it is impossible to fully describe work-as-done and how that changed during the pandemic, it is useful to draw attention to the motivations, expressed in the literature, for the adaptations that health visitors made during the pandemic.

Implications for policy and practice

In October 2023, we discussed draft recommendations, identified from our CMOCs, with our professional stakeholder group and separately with the lived experience group. Professional stakeholders present at that final meeting took part in a poll on the ‘do-ability’ of these recommendations. Stakeholders not able to attend sent responses separately via e-mail. This feedback led to refinements, particularly in terms of specificity, resulting in the implications for policy and practice listed below.

Health visiting contacts

-

Health visiting contacts are vital opportunities to gather information for an assessment of the needs of babies, children and their families. All families should know what to expect and what to receive as part of a prescribed schedule of universal reviews that are sufficient to identify their needs. Since assessment is a continuous process, some light-touch contact/check-ins are important between universal assessment reviews. All relevant forms of contact with families are useful, but the additional benefits of face-to-face contact over remote connections must be recognised.

-

Health visiting contacts provide an opportunity for preventive, holistic support. Health visiting teams must have sufficient capacity to provide this service, beyond responding to immediate needs.

-

Health visiting contacts are an opportunity to build relationships and provide reassurance. Universal assessment reviews should be conducted face-to-face by a qualified health visitor, with whom families can build a relationship over time.

-

Remote contacts can prove beneficial for some families during particular periods and can provide a means of establishing open communication channels and offering assistance or information when needed. However, practitioners must consider inclusivity in relation to remote service delivery, and the potential to disadvantage some families.

-

Digital resources can be a useful way of providing additional support; however, practitioners must be assured that such resources are of high quality. Furthermore, alternatives should be in place to meet the needs of families living with digital poverty, to avoid inadvertently widening inequalities in access and outcomes.

Health visiting connections

-

Connecting families with other services is an important part of the health visitor’s role. Health visitors should be supported to highlight where local service provision is missing and to advocate for additional local investment to strengthen the system of support for families across a range of health, education and social needs.

-

Connecting with other health visitors is important for staff well-being and development. Digital and remote technologies might be considered for certain staff training and team meetings, but these should be combined with more traditional communication and education routes.

-

Interagency work is an important part of the health visitor role. Health visiting and other services/agencies involved in safeguarding children must support each other and co-ordinate service delivery, to maintain the visibility of children during times of crisis.

Health visiting workforce

-

Health visiting should be appropriately valued for its impact on child and family health and for longer-term public health outcomes. Universal home visiting services, dedicated to new parents and children, are ‘vital services’ and should therefore be protected in any future emergency. The long-term repercussions of the pandemic response for certain children and for health visiting teams remain partially understood. Additional organisational support may be required to mitigate its impacts.

Future research

The RReHOPE study forms an important piece of a jigsaw of evidence, alongside several others funded by NIHR. 19,82–85 Completed and ongoing studies are bringing together additional evidence, which combines primary and administrative data, to examine the variations in health visiting organisation and delivery throughout England. These studies also aim to assess the resulting impacts on outcomes and experiences for babies, children and parents. This collective body of research will provide a much stronger evidence base for future policy and practice.

This realist review presents several areas for future research. First, it is imperative to explore how health visiting teams can optimise their use of limited resources and manage their workload to enhance their capacity to identify and tackle health needs within the community. This is consistent with another recent review that highlighted the urgent need to assess the complexity of health visitor workload activity and the quality of service provided. 71 Second, further research could explore differences and changes in health visiting service organisation at the local management level and the implications for both staff and service users. Case study research here might further explore how access, delivery and uptake of health visiting and related services vary across regions, and how and why different population groups are affected by changes in services. Third, it is necessary to enhance the theoretical understanding of how alterations in service organisation and delivery can influence outcomes, translating evidence into a plausible narrative that explains how changes can be implemented effectively in a specific locality. Such research might also consider how the measurement and collection of outcomes at the local level can be improved. Fourth, support is needed for national funding of large cohort studies of babies born since 2020 to look at the effect of health visiting input over time on outcomes for children. Fifth, this realist review highlighted the English-centric bias in the current health visiting literature and the need for future work to be focused on other UK nations. Finally, the current work with our lived experience group highlighted the value of their perspectives and input. Further research should explore how parents can actively participate in improving service delivery in their localities. A further step could be to identify health visiting as a James Lind Alliance topic area for prioritisation of specific domains of research, which will inform policy and practice over the next 5–10 years.

Strengths and limitations

Our realist review has looked across the four UK countries and has synthesised and analysed data from 118 documents that informed our PT of health visiting during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have incorporated the insights of people with lived experience, and professional stakeholders from across the UK, who have helped us to identify implications for policy and practice, with the aim of improving the organisation and delivery of health visiting services in the UK.

The review was limited by the lack of specific evidence from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. This limited our ability to analyse the evidence in a comparative way, and inevitably led to findings and conclusions that might be more significant for the English setting than for other countries. However, our stakeholder group helped us to consider the differences in context, policy and service delivery, and the impact of the pandemic across the four countries of the UK. They have also helped us to tailor our recommendations to different countries, which will be further reflected in additional country-specific outputs.

A further limitation was the lack of data focusing on pandemic-related changes at a local management level. Our extensive searching and communications with professional stakeholders suggest that such information was not formally recorded. This meant our review could not fully uncover local variability, for example in service organisation and workload/caseload management.

The number of mandated universal assessment reviews varies between each country, from 5 in England to 11 in Scotland. While the evidence in our review demonstrated the value of face-to-face universal assessment reviews, it did not enable us to comment further on the optimum number of reviews.

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, health visiting teams adapted service delivery in different contexts in order to continue providing support for families with babies, and to ensure families remained visible to them in very challenging circumstances. They prioritised the need to build and maintain trusting relationships with families and used a range of methods to communicate and interact with families. However, the lack of face-to-face contact and home visits posed a considerable threat to this important part of a health visitors’ role. Health visitors also prioritised holistic needs assessments; they placed considerable importance on the postnatal assessment review and used remote contacts to try to keep in touch with families’ changing needs within a dynamic context. The experience reinforced the importance of scheduled home-based assessment reviews, conducted by a health visitor in the home setting, throughout the baby’s first 3 years. These home visits must be long enough to enable the health visitor to build trusting relationships, and to offer proactive and holistic support. The pandemic experience also highlighted that a health visitor, in optimally fulfilling their role, depends significantly on their connections with other support services in the local community. As these were impacted by the pandemic, so too were health visitors.

Given the gaps in evidence highlighted above, there is still a great deal to learn about the equitable, effective and efficient organisation and delivery of health visiting services in the UK. However, this study has culminated in some important implications for policy and practice and will usefully inform future research.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Emma King (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3611-9647): Methodology, Project Administration, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Erica Gadsby (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4151-5911): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision and Writing – reviewing and editing.

Madeline Bell (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2846-7318): Conceptualisation, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Geoff Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5384-4157): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Sally Kendall (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2507-0350): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Claire Duddy, specialist librarian, for undertaking the formal searches, initial drafting of the PRISMA diagram and contribution of Appendix 2. With thanks also to Alison Morton, Institute of Health Visiting, and the people with lived experience and professional stakeholders involved in this study for their enthusiasm, commitment, guidance and input.

Data-sharing statement

This realist review uses secondary data and therefore the data generated are not suitable for sharing beyond that contained within the manuscript. Further information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Stirling, application reference RReHOPE 7662 on 26 April 2022.

Information governance statement

The University of Stirling is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679. Under the Data Protection legislation, the University of Stirling is the Data Controller, and you can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for our Data Protection Officer here: www.stir.ac.uk/about/professional-services/student-academic-and-corporate-services/policy-and-planning/legal-compliance/data-protectiongdpr/privacy-notices/

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/MYRT5921.

Primary conflicts of interest: Madeline Bell is an employee of an NIHR Local Clinical Research Network. Sally Kendall was a Trustee of the Institute of Health Visiting 2012–18. Geoff Wong was a member of the HTA Prioritisation Committee 2015–22, HTA Remit and Competitiveness Committee 2015–21, and HTA Post-Funding Committee 2018–21. No further disclosure of interests to declare.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practices and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Study registration details

This study is registered as PROSPERO CRD42022343117.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme as award number NIHR134986.

This article reports on one component of the research award Realist Review: Health visiting in light Of the COVID-19 Pandemic Experience (RReHOPE). For more information about this research please view the award page (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR134986).

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in June 2022. This article began editorial review in November 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 King et al. This work was produced by King et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

Glossary

- Face-to-face

- Health visitors or other practitioners seeing a child in person, in the child’s home, in a clinic, at a health visitor-led baby group, etc.

- Remote connections

- Synchronous or asynchronous connections made using a variety of technology, for example phone calls, text messages, phone-based helplines and WhatsApp. These are generally brief connections between service users and members of the health visiting team, who may or may not be a qualified health visitor. They may be initiated by either the health visiting team or the service user.

- Remote consultations

- Synchronous consultations using telephone, or internet-based voice or video calls, to relay specific information to service users. This may be a one-to-one call or a group call with other service users. This might include breastfeeding support, classes on baby massage, or other additional support from a health visitor. They are different from the universal assessment reviews. Delivery is by a member of the health visiting team, or appropriately qualified role outside the health visiting team.

- Remote outreach

- Asynchronous outreach by the health visiting team is designed to deliver non-personalised information to many people. Examples of methods used include blanket e-mails, photocopied letters and posts on social media. Examples of information shared include meningitis symptoms, who to contact if you need medical help, ideas for play and interaction with your child.

- Remote universal assessment review

- Synchronous telephone or internet-based voice or video consultation involving direct interaction between a service user and a health visitor or member of the health visiting team. It is a direct replacement for one or more of the universal assessment reviews set out in the Child Health Programme for that nation.

- Universal assessment reviews

- Reviews of child development set out in the Child Health Programme for each nation of the United Kingdom. Offered to all families and ideally carried out face-to-face by a qualified health visitor.

List of abbreviations

- CHP

- Child Health Programme

- CMOC

- context, mechanism, outcome configuration

- PPE

- personal protective equipment

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- PT

- programme theory

References

- Health for All Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989.

- Health for All Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- Health for All Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

- Health for All Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- Health for All Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Health for All Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019.

- Hackett A, Clarke K, Wilkinson J. Health Visiting: Specialist Community Public Health Nursing. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022.

- Rosenthal DM, Ucci M, Heys M, Hayward A, Lakhanpaul M. Impacts of COVID-19 on vulnerable children in temporary accommodation in the UK. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e241-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30080-3.

- HM Government . The Best Start for Life: A Vision for the 1,001 Critical Days. The Early Years Healthy Development Review Report CP419 (25 March 2021) 2021. www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-best-start-for-life-a-vision-for-the-1001-critical-days (accessed 10 November 2023).

- Cowley S, Whittaker K, Malone M, Donetto S, Grigulis A, Maben J. Why health visiting? Examining the potential public health benefits from health visiting practice within a universal service: a narrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:465-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.013.

- Wickham S, Anwar E, Barr B, Law C, Taylor-Robinson D. Poverty and child health in the UK: using evidence for action. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:759-66. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306746.

- Taylor-Robinson D, Lai ETC, Wickham S, Rose T, Norman P, Bambra C, et al. Assessing the impact of rising child poverty on the unprecedented rise in infant mortality in England, 2000–2017: time trend analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029424.

- Galster G, Marcotte DE, Mandell M, Wolman H, Augustine N. The influence of neighborhood poverty during childhood on fertility, education, and earnings outcomes. Hous Stud 2007;22:723-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030701474669.

- Featherstone B, Morris K, Daniel B, Bywaters P, Brady G, Bunting L, et al. Poverty, inequality, child abuse and neglect: changing the conversation across the UK in child protection?. Child Youth Serv Rev 2019;97:127-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.009.

- Cecil-Karb R, Grogan-Kaylor A. Childhood body mass index in community context: neighborhood safety, television viewing, and growth trajectories of BMI. Health Soc Work 2009;34:169-77. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/34.3.169.

- Bandyopadhyay A, Whiffen T, Fry R, Brophy S. How does the local area deprivation influence life chances for children in poverty in Wales: a record linkage cohort study. SSM Popul Health 2023;22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101370.

- Bryar RM, Cowley DS, Adams CM, Kendall S, Mathers N. Health visiting in primary care in England: a crisis waiting to happen?. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:102-3. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X689449.

- Black M, Barnes A, Baxter S, Beynon C, Clowes M, Dallat M, et al. Learning across the UK: a review of public health systems and policy approaches to early child development since political devolution. J Public Health (Oxf) 2019;42:224-38. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz012.

- Fraser C, Harron K, Woods G, Shand J, Kendall S, Woodman J. Variation in health visiting contacts for children in England: cross-sectional analysis of the 2–2½ year review using administrative data (Community Services Dataset, CSDS). BMJ Open 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053884.

- Woodman J, Harron K, Hancock D. Which children in England see the health visiting team and how often?. J Health Visit 2021;9:282-4. https://doi.org/10.12968/johv.2021.9.7.282.

- Whittaker K, Appleton JV, Peckover S, Adams C. Organising health visiting services in the UK: frontline perspectives. J Health Visit 2021;9:68-75. https://doi.org/10.12968/johv.2021.9.2.68.

- Department of Health . Thresholds of Need Model 2010. www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/thresholds-need-model (accessed 15 November 2023).

- Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills . Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC): Wellbeing (SHANARRI) n.d. www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/wellbeing-indicators-shanarri/ (accessed 13 November 2023).

- Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professional Directorate . Healthy Child, Healthy Future – A Framework for the Universal Child Health Promotion Programme in Northern Ireland 2010. www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/healthy-child-healthy-future (accessed 13 November 2023).

- Singh A, Shah N, Mbeledogu C, Garstang J. Child wellbeing in the United Kingdom following the COVID-19 lockdowns. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford) 2021;31:445-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2021.09.004.

- Jackson C, Brawner J, Ball M, Crossley K, Dickerson J, Dharni N, et al. Being pregnant and becoming a parent during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal qualitative study with women in the Born in Bradford COVID-19 research study. Res Sq 2023;23. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2317422/v1.

- Conti G, Dow A. Using FOI Data to Assess the State of Health Visiting Services in England Before and During COVID-19. London: UCL Department of Economics; 2021.

- Hale T, Angrist N, Goldszmidt R, Kira B, Petherick A, Phillips T, et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat Hum Behav 2021;5:529-38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8.

- Institute of Health Visiting . 24 March – Morning Update: COVID-19 2020. https://ihv.org.uk/news-and-views/news/24-march-morning-update-covid-19/ (accessed 16 November 2023).

- Morton A, Adams C. Health visiting in England: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nurs 2022;39:820-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13053.

- Conti G, Dow A. The Impacts of Covid-19 on Health Visiting in England: First Results. London: UCL Department of Economics; 2020.

- Institute of Health Visiting . State of Health Visiting in England: Are Babies and Their Families Being Adequately Supported in England in 2020 to Get the Best Start in Life? 2020.

- Barlow J, Bach-Mortensen A, Homonchuk O, Woodman J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Services from Pregnancy through Age 5 Years for Families Who Are High Risk of Poor Outcomes or Who Have Complex Social Needs 2020. www.ucl.ac.uk/children-policy-research/projects/impact-covid-19-pandemic-services-pregnancy-through-age-5-years (accessed 15 November 2023).

- Institute of Health Visiting . State of Health Visiting in England: ‘We Need More Health Visitors!’ 2021.

- The Child Safeguarding Review Panel . Annual Report 2020: Patterns in Practice, Key Messages and 2021 Work Programme 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/609945c78fa8f56a3e32f9a3/The_Child_Safeguarding_Annual_Report_2020.pdf (accessed 15 November 2023).

- The Child Safeguarding Review Panel . Child Protection in England: National Review into the Murders of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes and Star Hobson 2022. www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-review-into-the-murders-of-arthur-labinjo-hughes-and-star-hobson (accessed 15 November 2023).

- Office for National Statistics . How People Spent Their Time After Coronavirus Restrictions Were Lifted, UK: March 2022 2022. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/howpeoplespenttheirtimeaftercoronavirusrestrictionswerelifteduk/march2022 (accessed 20 March 2024).

- Irvine LC, Chisnall G, Vindrola-Padros C. The impact of maternity service restrictions related to COVID-19 on women’s experiences of giving birth in England: a qualitative study. Midwifery 2024;128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2023.103887.

- Kasaven LS, Raynaud I, Jalmbrant M, Joash K, Jones BP. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perinatal services and maternal mental health in the UK. BJPsych Open 2023;9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.632.

- Silverio SA, De Backer K, Easter A, von Dadelszen P, Magee LA, Sandall J. Women’s experiences of maternity service reconfiguration during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative investigation. Midwifery 2021;102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.103116.

- Sanders J, Blaylock R. Anxious and traumatised’: users’ experiences of maternity care in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Midwifery 2021;102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.103069.

- Saunders B, Hogg S. Babies in Lockdown: Listening to Parents to Build Back Better 2020. https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/our-work/campaigning/babies-in-lockdown/#fullreport (accessed 17 May 2022).

- McKinnell C. The Impact of Covid-19 on Maternity and Parental Leave: First Report of Session 2019–21: Report, Together with Formal Minutes Relating to the Report. London: House of Commons; 2020.

- UNICEF United Kingdom . Early Moments Matter: Guaranteeing the Best Start in Life for Every Baby and Toddler in England 2022. www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/EarlyMomentsMatter_UNICEFUK_2022_PolicyReport.pdf (accessed 15 November 2023).

- Holt L, Murray L. Children and Covid 19 in the UK. Child Geogr 2022;20:487-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1921699.

- Baker C, Hutton G, Christie L, Wright S. COVID-19 and the Digital Divide. UK Parliament; 2020.

- Lemkow-Tovías G, Lemkow L, Cash-Gibson L, Teixidó-Compañó E, Benach J. Impact of COVID-19 inequalities on children: an intersectional analysis. Sociol Health Illn 2023;45:145-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13557.

- Co-POWeR . Co-POWeR Animation Video 2022. https://mymedia.leeds.ac.uk/Mediasite/Play/49c3e27d80eb4ea6895c07ad90e00d7b1d (accessed 13 November 2023).

- Cattan S, Lloyd E, Montacute R, Shorthouse R. Early Years Inequalities in the Wake of the Pandemic. London: IFS; 2021.

- Watts G. COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e395-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2.

- King E, Gadsby E, Bell M, Duddy C, Kendall S, Wong G. Health visiting in the UK in light of the COVID-19 pandemic experience (RReHOPE): a realist review protocol. BMJ Open 2023;13. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/3/e068544 (accessed 21 November 2023).

- Gadsby EW, Christie-de Jong F, Bhopal S, Corlett H, Turner S. Qualitative analysis of the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic response on paediatric health services in North of Scotland and North of England. BMJ Open 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056628.

- Institute of Health Visiting . Making History: Health Visiting During Covid-19 2020. https://ihv.org.uk/news-and-views/news/spotlighting-the-vital-safety-net-that-health-visitors-have-provided-for-babies-and-young-children-during-the-current-pandemic/ (accessed 15 November 2023).

- Lewis R, Pereira P, Thorlby R, Warburton W. Understanding and Sustaining the Health Care Service Shifts Accelerated by COVID-19 2020. www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/understanding-and-sustaining-the-health-care-service-shifts-accelerated-by-COVID-19 (accessed 15 November 2023).

- Wilson H, Waddell S. COVID-10 and Early Intervention: Understanding the Impact, Preparing for Recovery. London: Action for Children; 2020.

- Pawson R. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2006.

- RAMESES . Realist Synthesis: RAMESES Training Materials 2013. www.ramesesproject.org/media/Realist_reviews_training_materials.pdf (accessed 20 March 2024).

- Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist Synthesis: An Introduction 2004.

- Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-21.