Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 10/135/02. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft manuscript began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Sackley et al. This work was produced by Sackley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Sackley et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease

Epidemiology

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder affecting around 6.1 million people worldwide in 2016. 1 PD is more common in men (1.4 : 1.0) and mostly affects people aged over 50, with peak incidence between 85 and 89 years old. The reported prevalence of PD has increased substantially over the 20 years up to 2015, making it the fastest-growing neurological disorder worldwide. 2

Risk factors/causes

Most cases of PD are sporadic and likely to be caused by a mixture of genetic and environmental risk factors. Rarely, single gene mutations can cause PD predominantly in younger onset patients. 3

Over 60 environmental risk factors have been studied for their proposed association with PD including smoking, biomarkers, physical activity, drugs, exposure to environmental toxins and head-injury. Some risk factors such as smoking and physical activity have shown significant protective effects in larger studies. 4

Symptoms/disease progression and prognosis

Symptoms of PD are classified as motor or non-motor. The initial diagnostic motor symptoms are unilateral tremor, slowness, stiffness and mild imbalance. However, as the condition progresses, more severe motor decline occurs with imbalance leading to falls and unpredictable freezing episodes, all of which are unresponsive to medication.

There is a high prevalence of non-motor symptoms in PD, the most severe of which concern mental health. 5,6 Dementia occurs in around 40%, leading to a fluctuating state of confusion with visual hallucinations. There is a similar frequency of depression and anxiety. Sleep disturbances which include rapid eye movement sleep disorder (RBD), where people act out their dreams, are also common. Autonomic problems include orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure on standing) which can lead to falls, and constipation requiring regular laxatives.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive condition with severe motor decline and dementia leading to death over 15–20 years. Symptoms of PD and their progression can have an impact on the person with PD and their family and friends. However, there may be different types of PD with varying prognoses:7 A predominantly tremulous form of the condition may have a more benign outcome, compared with those with little tremor and early balance problems who develop dementia early and have a shorter life expectancy.

Treatments

At present, there are no disease-modifying therapies for PD;8 all therapies are symptomatic. First-line symptomatic treatment for the motor symptoms is pharmacological therapy with levodopa, the precursor of the neurotransmitter dopamine. 9 With disease progression, the dose of levodopa tends to be capped to avoid severe involuntary movements (dyskinesia), so in younger non-dementing patients adjuvant drugs are added to levodopa. These include dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) inhibitors and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors. The N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist amantadine is used to treat more severe dyskinesias if they occur.

A minority of younger mentally healthy PD patients may need more interventional therapies for severe disease once maximal oral therapies have been tried. 10 Continuous infusion of the dopamine agonist apomorphine can help smooth out gaps in ‘on’ time due to wearing off of oral medication. Surgical implantation of electrodes into the subthalamic nucleus can also provide a smoother response, but at the expense of potential postoperative complications of depression, speech disturbance, stroke and death.

Non-motor symptoms in PD are treated symptomatically as suggested in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. 10

Speech and voice problems experienced by people with Parkinson's disease and their families

Impact of speech problems

Speech impairments are common among people with PD, with a reported prevalence of 68% for patient-perceived problems and 71% for listener-rated speech impairment. 11 In a study of 125 people with PD,12 38% placed speech among their top four concerns and, in another study, 29% of participants reported speech problems to be among their greatest present difficulties. 13 Changes in communication led to increased physical and mental demands during conversation, an increased reliance on family members and/or carers and an increased likelihood of social withdrawal. 14

Speech or voice problems experienced by people with PD are typically related to motor disorders of the muscles required to produce speech, known as dysarthria. Dysarthric speech is often perceived as imprecise, creating a social barrier to communication. 15 Difficulty in successfully conveying emotions is also experienced by people with PD and their listeners. 15,16 A qualitative study involving 24 people living with PD identified problems with speaking as an activity. The interviewees reported having to think more about speaking; weighing up the value versus the effort of speaking; having negative feelings about speaking; finding that speaking is influenced by different people and places; and having to adjust to the effect of speaking with the disease progression and their medication. 17 Overall, impairments of speech have been recognised to reduce the quality of life of people with PD. 15,18,19

Speech and language interventions

Speech and language therapy (SLT) in the UK aims to deliver interventions that improve communication for people with PD-related dysarthria and their families. Some interventions prescribe exercises to improve motor skills, others support the communication interaction and partnership between the person with PD and their communication partner, while others aim to augment, or provide alternative means of communication. SLT varies not only by intervention approach, content, materials and procedures but also by the component(s) of speech and voice targeted by the intervention(s) in addition to the therapy regimen [intensity, total hours of therapy (dosage), frequency and overall duration of the intervention] and tailoring to the individual (by functional needs and by level of difficulty).

The Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT) is an approach to SLT, which consists of protocol that can be personalised. 20 The commercial developers have licenced the intervention as LSVT LOUD® for use by certified clinicians or certified and supervised assistants and students who undertake initial training and updates every 2 years. The most detailed description of the intervention is in the LSVT LOUD training manual. In contrasting LSVT LOUD with other interventions, the following components are highlighted as distinct to LSVT LOUD:

-

standardised intensity (of dosage or regimen);

-

number of task repetitions and perceived effort);

-

a simple focus on LOUD;

-

three daily tasks (maximum sustained movements; directional movements;

-

functional movements);

-

a hierarchy of tasks to use from day one to move learning from daily tasks into context specific and variable speaking activities;

-

use of modelling with minimal cognitive load to shape healthy vocal loudness;

-

and sensory calibration through focusing attention on what ‘LOUD’ feels and sounds like (and training this through carryover activities and homework practice).

Surveys can help build a picture of reported practice. A 2016 survey of SLT practice for PD in Australia21 found that education and support components were commonly used and for direct intervention, motor speech was the main therapy target. The components of SLT offered included two LSVT packages (LSVT LOUD and LSVT LOUD-X) as well as developing individualised self-monitoring and prompting cues; aided augmentative and alternative communication (AAC); traditional dysarthria exercises; a pacing or alphabet board to slow speech rate; and expiratory muscle strength training which are common in NHS SLT. Loud therapy, increasing client’s insight to changes and speech tasks with increased cognitive load were also offered components common in both LSVT and NHS SLT.

Based on 2011 data, SLT provision for PD in the UK22 frequently targeted breathing control, voice quality and intelligibility. Methods of addressing these targets overlap considerably and include LSVT, breathing exercises, pacing, relaxation, articulation, and loudness and voice exercises. Use of AAC, language and psychosocial components were reported less frequently. Due to service constraints, not all therapists report delivering LSVT to the specified intensity or in the form prescribed by its developers.

Parkinson’s disease was the most common patient group reported in the 2012 UK survey of SLT treatment practices among people with progressive dysarthria. 23 The three most commonly reported SLT components for PD were general rate, volume and prosody work, functional communication and speech subsystems work.

For people with dysarthria as a consequence of PD in Australia in 201621 most sessions were individual and, for both individuals and groups, once-weekly therapy was usual. Similarly, therapy duration was most frequently reported to last 4 weeks or 6 weeks. Session length for individuals was varied from 30 to 60 minutes. Of the LSVT LOUD certified therapists, 90% reported delivery issues due to service factors including allocated time, caseload sizes and the number of therapists working part-time. 21

In 2011 in the UK, more than 50% of therapists saw PD patients as outpatients, with a third of patients needing hospital transport to participate. 22 A median of six sessions was offered over a median period of 42 days with each lasting a median of 45 minutes. Therapists reported expecting to spend 60% of their time face to face with the patient. An advice and review pattern of service delivery was dominant, and a lack of understanding of the evidence24 for motor learning principles such as regular intensive practice was also reported.

In the USA25 the most commonly recommended dosage for home education programmes by occupational therapists in the community for those with neurological injuries was 16–30 minutes a day. The content was focused on preparatory activities rather than being used directly to achieve a client’s goal. Most home practice was communicated through handouts and demonstration, with video rarely used.

Capability of and access to technology is growing rapidly, offering new opportunities for self-management and service delivery. The LSVT training manual26 describes using devices to measure time, volume, pitch and voice quality. These can be low tech (e.g. a stopwatch/Sound Level Meter/pitch pipe/tape recorder) or high tech (e.g. smartphone apps, Companion Software).

Clinical guideline recommendations

Many countries have national guidelines for PD and speech problems. 27,28

The NICE clinical guidelines10 for PD state that clinicians should consider referring people who are in the early stages of PD for assessment, education and advice from a speech and language therapist with experience of treating people with PD.

The guidelines state that people with PD who are experiencing problems with communication should be offered SLT, which should include strategies to improve speech and communication, such as attention-to-effort therapies.

Evidence base for speech and language therapy for speech problems in Parkinson‘s disease

Two previous Cochrane reviews have been published in this field (Herd et al. 29, 30). Herd et al. 29 evaluated the effectiveness of SLT interventions with placebo or no intervention. They concluded that there while there was some clinical improvement in vocal loudness (for reading and speaking), but overall, there was insufficient evidence based on three small trials (63 participants). In a linked synthesis, Herd et al. 30 compared the benefits of different types of SLT interventions. They identified six trials (159 participants) that used a variety of different restorative and compensatory approaches, but again concluded that while there were improvements in speech, there was insufficient evidence to support the selection of one SLT intervention over another.

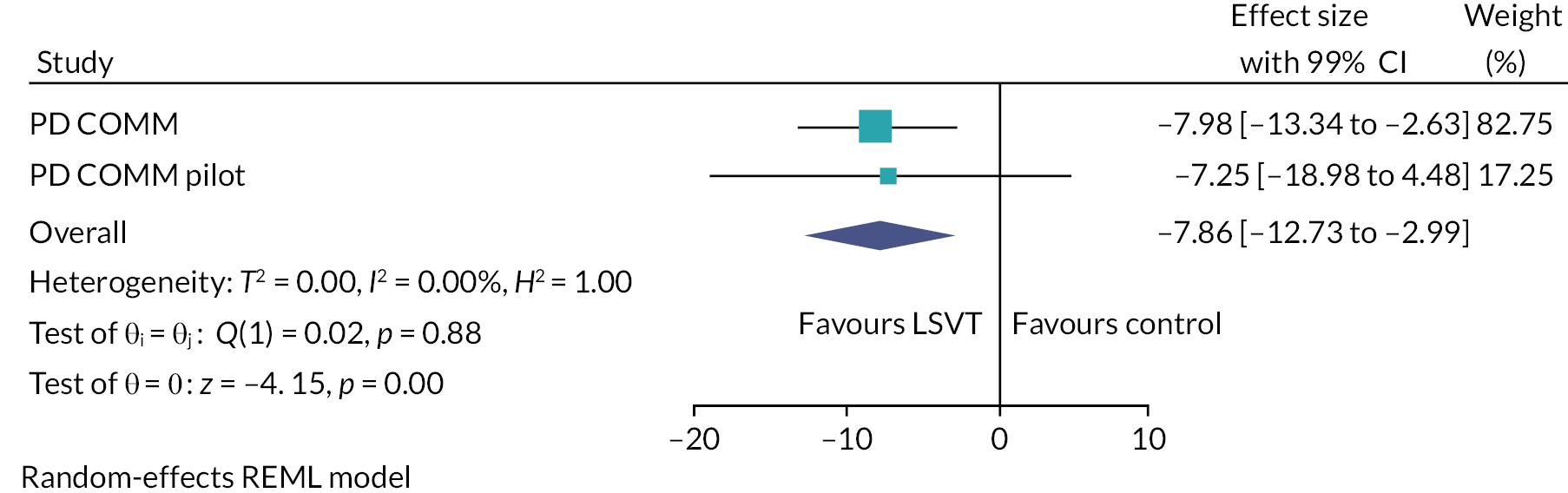

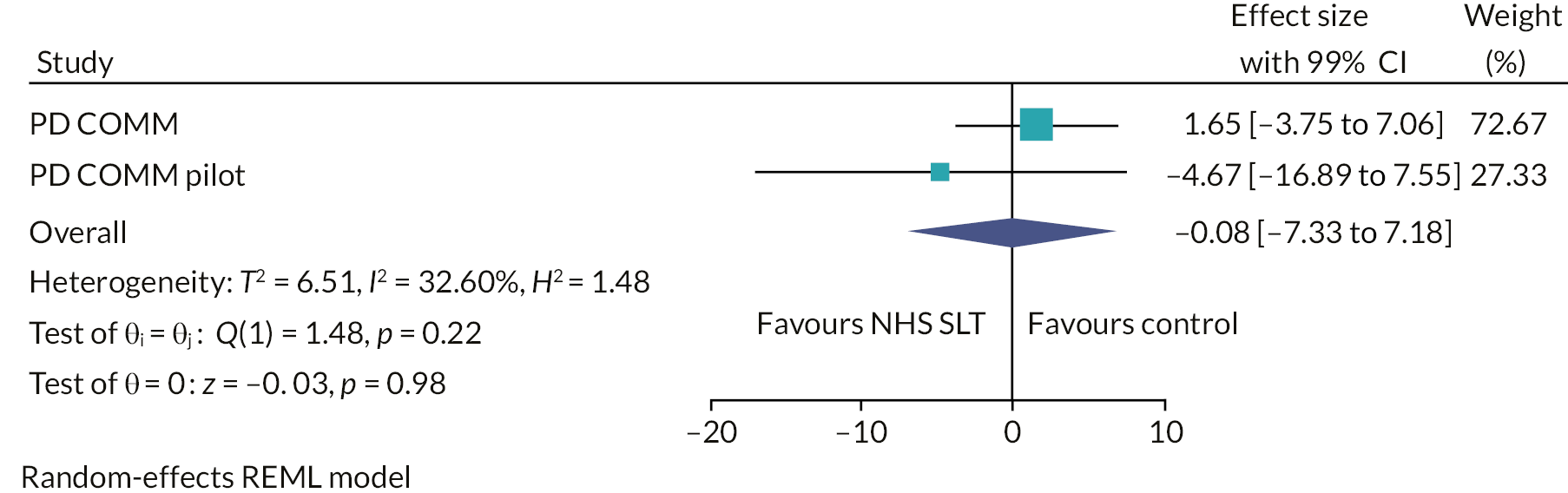

An updated Cochrane systematic review (date of last searches 3 October 2022) builds on the two previously published Cochrane reviews. 29,30 Quasi-RCT studies were excluded and a further 20 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified and published since the previous reviews were conducted. For the RCTs excluding this (the PD COMM) trial, despite no high-to-certainty evidence supporting the use of SLT interventions being identified, the review provided further confidence in the evidence of benefit for SLT interventions for the communication outcome, and vocal loudness while reading or speaking a monologue. This was a consistent finding across all three comparisons: no intervention, placebo control and when compared with another SLT intervention (where data were available). All three Cochrane reviews were in agreement regarding the need for standardisation of outcome measures (P Campbell, Glasgow Caledonian University, 2022, personal communication). Other relevant systematic reviews and evidence syntheses were identified. 31–35 Two recently published meta-analyses evaluated the effectiveness of LSVT with no intervention or another speech intervention in people with PD. 32,35 Yuan 2020 identified nine studies for inclusion (date of last search March 2020); Pu 2021 identified ten (quasi-RCTs and RCTs) studies for inclusion (date of last search December 2021). Both reviews reported that LSVT was effective in increasing vocal loudness and functional communication. Reviews have also demonstrated that there is a lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of different SLT techniques compared with no SLT.

Rationale and the need for the PD COMM trial

Rationale for trial

From 2009, several National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) commissioned calls were issued to assess methods of SLT for improving speech intelligibility and effectiveness of communication in people with Parkinson’s disease.

The call from which the PD COMM trial was successfully funded, called for a pragmatic RCT in people with PD to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of NHS SLT compared with no treatment. The specifications included a follow-up of at least 1 year and the trial should follow a pilot phase. This recommendation was based on several factors:

-

dysarthria is common in PD and increases in severity and prevalence as the disease progresses;

-

quality of life is negatively affected by speech problems;

-

speech and language therapy being offered by the NHS was variable;

-

the lack of definitive studies investigating SLT for PD-related dysarthria.

Trial design

Driven by the HTA commissioned calls, the feasibility and acceptability of a large-scale SLT trial in people with PD were assessed and found to be acceptable in the PD COMM pilot trial36 funded by The Dunhill Medical Trust (grant R192/0511). The data from this pilot trial informed the design of the definitive RCT (PD COMM) to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of these SLT interventions. The pilot trial assessed eligibility, recruitment and retention, participant acceptability and treatment compliance. It also provided data to help inform the sample size calculations and to refine the choice of outcome measures including those used for the economic evaluation.

The 2017 NICE guideline10 for PD states that SLT should be offered to people with PD who have communication problems. The optimum treatment regimen including delivery method and theoretical basis were not and continue to remain unclear. 35 To progress the understanding of how SLT interventions are delivered and the mechanism of action, the PD COMM trial included a process evaluation.

Rationale for choice of interventions

Before the trial, guidance on SLT best practice for people with PD-related dysarthria as a result of PD could be found in two historical resources from the Royal College of Speech and language therapists. 37,38 Two Cochrane systematic reviews29,30 of the evidence published in 2012 were also available but could not provide clear, evidence-based recommendations for practice. These sources of evidence were not robust enough to be clear about the optimum treatment approach for PD-related dysarthria. The choice of treatments for the PD COMM trial was taken based on testing two commonly chosen treatment options in the UK in direct response to the HTA commissioned call.

Stakeholder involvement

This trial was supported by the Parkinson’s UK, The Dunhill Medical Trust and the Local Clinical Research Network, Division 4: Neurology.

Chapter 2 Methods

Material in this chapter has been adapted from the PD COMM trial protocol by Sackley et al. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7251680/). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

The trial was reported using the following reporting guidelines: CONSORT and extension for non-pharma trials, extension for three-arm trials and abstracts, GRIPP2, CHEERS and Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidelines.

Objectives

The primary objective of the PD COMM trial was to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of two approaches to SLT (LSVT LOUD and NHS SLT) compared with no SLT treatment in people with PD.

An additional objective was to evaluate and compare the clinical and cost-effectiveness of two types of SLT (LSVT LOUD vs. NHS SLT) in people with PD.

The primary comparisons were:

-

Lee Silverman Voice Treatment LOUD versus no SLT (control)

-

National Health Service SLT versus no SLT (control).

An additional comparison was:

-

Lee Silverman Voice Treatment LOUD versus NHS SLT.

Research questions

-

Do people with PD-related speech or voice problems who are treated with NHS SLT report less voice handicap than those who have no SLT treatment at 3 months after randomisation?

-

Do people with PD-related speech or voice problems who are treated with LSVT LOUD treatment report less voice handicap than those who have no SLT treatment at 3 months after randomisation?

-

Do people with PD-related speech problems who are treated with LSVT LOUD report less voice handicap than those who are treated with NHS SLT treatment at 3 months after randomisation?

Trial design

The PD COMM trial was a pragmatic UK, multicentre, three-arm parallel group, unblinded, superiority, RCT with a 12-month follow-up. Participants were randomised at the level of the individual to receive either: LSVT LOUD, NHS SLT or no SLT (control) in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio. There were two nested studies within this trial: a process evaluation and an economic evaluation. Participants randomised to the no SLT (control) group could be referred for SLT at the end of trial or, if it became medically necessary, during the trial. The type and dose of SLT for those in the control group for whom treatment became necessary were determined by the local therapists responsible for the care plan of the participant. Non-compliance with trial treatment did not constitute the participant’s withdrawal from the trial.

The trial received ethical approval on 7 December 2015 by the West Midlands NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) (15/WM/0443). Version 4.0 (14 November 2018) of the protocol is currently in effect. Sponsored by the University of Birmingham (Research Governance Team, University of Birmingham, Birmingham), participating centres each obtained local research and development approval.

Participants

People were eligible to be included in the trial if the following criteria were met:

-

diagnosis of idiopathic PD as defined by the 1988 UK PDS Brain Bank Criteria39

-

the person with PD or their carer report problems with the person with PD’s speech or voice.

People were excluded from the trial if they met any of the following criteria:

-

dementia, usually defined clinically by the person with PD’s clinician

-

evidence of laryngeal pathology including vocal nodules or a history of vocal strain or previous laryngeal surgery as LSVT may not be appropriate in such contexts40

-

received SLT for PD speech or voice-related problems in the previous 2 years as there is some evidence that benefits of LSVT may persist for 24 months. 41

Setting

Recruitment took place at 41 sites throughout the UK, except Northern Ireland. Distribution of sites across the UK was not uniform as attempts to recruit trial sites in the whole of Northern Ireland were not successful and were only minimally successful in the southeast of England. The main reason for not joining given by potential sites contacted was a lack of capacity in their SLT service.

Participants were recruited from their routine outpatient appointments. These appointments took place in geriatric/elderly care, neurology or SLT secondary care settings.

The interventions were provided through secondary care outpatient community-based SLT departments. For some participants who had specific needs, or as a service delivery choice, the intervention was provided at home.

Interventions

Participants were encouraged to be fully compliant with their randomised treatment allocation. We anticipated that it was possible that some may have received SLT as arranged by other health or social care providers not associated with the trial. As any access to SLT for their dysarthria could dilute the intervention effect, at each assessment participants in the no SLT (control) group were asked whether they had received any SLT.

Participants randomised to either of the SLT treatment arms completed brief home-based therapy diaries to determine the level of home-based practice prescribed and undertaken by participants outside of the therapy sessions.

In order to monitor intervention delivery, therapists providing the SLT interventions completed a SLT Initial Interview Log including the abbreviated mental test42 and after each SLT session delivered, the therapists completed a treatment record form (TRF). These forms were used to monitor participant adherence (including missed or cancelled appointments), and therapist adherence to these programme protocols. In addition, for the NHS SLT intervention, the forms were used to further explore what SLT delivered within the NHS entailed.

We maintained a supportive environment to encourage therapists to make and maintain a distinction between the two SLT intervention approaches throughout the trial, including continuing professional development opportunities such as therapists’ days and an online network, and a proactive approach to encouraging queries.

Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD)

The focus of LSVT LOUD is to ‘think loud’, improving phonation and vocal loudness through better vocal fold adduction. 40 The intervention aimed to replicate the dose and content recommended by the originators and delivered in clinical practice and previous ‘standard’ LSVT trials. The LSVT LOUD intervention consisted of four face-to-face or remote 50-minute sessions per week delivered over 4 weeks. 40 Remote sessions were provided through the LSVT Companion software and could support remote intervention delivery for up to 8 of 16 sessions. Each session follows a similar structure which can be personalised for each patient: 25 minutes of repeated and intensive maximum effort drills, and 25 minutes of high-effort speech production tasks. 40 Participants were also prescribed 5 to 10 minutes of home-based practice tasks on treatment days, and up to 30 minutes of home-based practice tasks on non-treatment days. 43 The content of the intervention consisted of repeated repetitions of sustained ‘ah’ phonation, maximum fundamental frequency range high and low pitch glides, and functional sentence repetition for the first half of each session, and exercises using speech production hierarchy that progresses throughout the duration of the treatment programme (single word, phrases, sentences, paragraph reading, conversation) during the second half of the sessions. 43 Throughout all of the sessions, the focus of the intervention was to ‘think loud’, maintaining the vocal loudness produced during vowel phonation throughout all other tasks during the treatment. 40 Delivery of LSVT LOUD in the trial was as typical within an NHS setting.

National Health Service speech and language therapy

The content, intensity and dose of NHS SLT for people with PD-related voice or speech problems are poorly defined within the published literature. For this reason, the NHS SLT group took a pragmatic approach to the intervention and encompassed all local standard NHS SLT practices and techniques with the exception of LSVT (as per the LSVT LOUD Protocol). Therapists were free to tailor therapy to individual participant’s needs. NHS SLT could potentially include interventions targeted at rehabilitation of the underlying movement disorder functions that resulted in dysarthria, behavioural or compensatory strategies and AAC strategies to improve communicative function and participation. 44 The therapist involved participant’s family members or carer(s) as appropriate.

Treatments targeted at impairments of the underlying speech production movements may include exercises focused on improving capacity, control and co-ordination of respiration, techniques for improving phonation intensity and co-ordination with respiration (but not LSVT), and exercises to improve the range, strength and speed of the articulatory muscles. 45,46 Behavioural therapy includes interventions that target the reduction of prosodic abnormality47,48 such as exercises targeting pitch, intonation, stress patterns and volume variation,45–49 and techniques to address the overall rate of speech45,46 including the use of therapeutic devices such as pacing boards. 50,51 AAC strategies such as topic and alphabet supplementation through communication books and boards may be employed,44 along with AAC devices such as voice amplifiers, delayed auditory feedback systems and masking devices. 52–54

Pitch limiting voice treatment55 may also be utilised within the NHS SLT intervention. The above NHS SLT approaches may include techniques that are also used in LSVT LOUD (e.g. vocal intensity exercises) but will be distinct from that intervention as it was anticipated, based on the available literature, that they would be delivered in combination with other SLT strategies and at a different intensity and dose. Though dose and frequency were to be determined by the local therapist in response to participants’ individual needs, it was anticipated that it would reflect the median dose as reported in a survey of current UK SLT practice for PD by Miller et al. ,22 of six sessions delivered over 42 days. The PD COMM Pilot trial36 also found the median NHS SLT intervention dose to be six sessions (range 1–14) over an average of 9.6 weeks (standard deviation 6.1 weeks).

Control no speech and language therapy group

Participants were randomly allocated to the no SLT (control) arm for PD-related speech or voice problems for 12 months participation in the PD COMM trial. Participants may still receive SLT for swallowing problems (dysphagia). Since there is insufficient evidence to prove or disprove the benefit of SLT in PD, equipoise still exists. Therefore, it is ethical to randomise between SLT and no SLT. Investigators, however, remained vigilant throughout the 12-month trial follow-up period for participants randomised to the no SLT (control) group, who deteriorated to the point of needing therapy urgently for their speech or voice problems received SLT without delay via the usual local NHS services. At the end of the trial after their 12 months of patient and clinical assessments, participants in the control arm could be referred for SLT for their dysarthria by their usual care specialist through local NHS referral pathways.

Adherence to the interventions

As this was a pragmatic trial of two existing interventions in the NHS, our approach to fidelity was multidimensional. 56 The PD COMM pilot established that dosage was a key differentiating factor. For the practical purposes of statistical analysis, LSVT LOUD treatment adherence was defined as participants randomised to the LSVT LOUD arm receiving at least 14 out of the 16 prescribed LSVT LOUD sessions and having completed these sessions within 3 months of randomisation. A session was considered an LSVT LOUD session if at least 30 minutes of time was attributed to LSVT LOUD on the SLT treatment log (supervised or unsupervised). As a secondary assessment of LSVT adherence, we only included those who received all 16 sessions of LSVT within 3 months of randomisation. The first measure of adherence used a pragmatic approach, for example, a participant may have missed one session due to taking a holiday, whereas the second measure of adherence is strictly looking at those participants who received the intervention as prescribed.

As NHS SLT is not a prescriptive intervention, participants were considered adherent if they completed their SLT sessions within 3 months of randomisation that is they had their last session within 3 months of randomisation. These sessions should also not have any time attributed to LSVT LOUD. The NHS SLT was deemed to have been completed for a participant when a returned SLT log has been answered as ‘Yes’ to this being the last treatment session of the therapy course.

Adherence to the no SLT (control) arm was monitored through the resource usage form where participants could record whether they had received any SLT. If a participant in the no SLT (control) arm reported receiving SLT over the course of the 12-month follow-up, then they were considered non-adherent. The only exception to this was if SLT had been prescribed for the treatment of dysphagia only.

Training requirements

Prior to commencing recruitment, all site staff involved with the trial had to complete good clinical practice training. Key members of the site research team were required to attend either a meeting or a teleconference covering aspects of the trial design, protocol procedures, adverse event reporting, collection and reporting of data and record keeping. All therapists who took part were registered with UK regulatory body, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), which sets standards for education, training and practice.

Only speech and language therapists or therapist assistants trained in LSVT LOUD, which includes a detailed manual and 2-year updates, could deliver the LSVT LOUD intervention. Therapists were provided with LSVT LOUD training through the trial by LSVT Global20 for free if they had not done this training or needed it to reregister as an LSVT therapist.

Ideally every therapist delivering LSVT therapy should have conducted at least three treatment sessions before delivering the intervention to trial participants; however, this was at the discretion of the trial sites.

Three workshops were held early into the trial, which brought together site speech and language therapists, research nurses and the research team to explore the PD COMM interventions. The workshop participants explored what was considered ‘core’ and ‘peripheral’ for each intervention and the barriers and challenges of delivering the interventions. The workshops helped to ensure that the trial ran smoothly.

Outcomes

In the pilot trial, extensive vocal assessments were carried out alongside the participant-reported outcomes. We decided not to undertake vocal assessments within the PD COMM trial as:

-

the additional time involved was prohibitive;

-

there was concern that since one of the trial interventions (LSVT LOUD) specifically focussed on vocal loudness that the results might be skewed in favour of this intervention;

-

the focus of the trial was on the participants’ self-perception of functional communication rather than vocal loudness.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was the patient-reported Voice Handicap Index (VHI)57 total score at 3 months. The VHI comprises of 30 questions divided into emotional, functional and physical subscales. 57 It aims to assess the psychosocial consequences of voice disorders, and can be used to gain an overall perception of effectiveness of voice-related communication. The VHI total score ranges from 0 to 120 (with 0 being the best score and 120 the worst score) and the subscales range from 0 to 40.

Many previous trials have used vocal loudness as their primary outcome. It has been used as an outcome measure in an extended LSVT trial for PD16 and was also collected in the PD COMM Pilot trial. 36 The VHI was chosen as it was a patient-reported outcome that took little time to complete, was well-completed in our pilot trial36 and better reflected the focus of the PD COMM trial objectives.

Secondary outcomes

Patient-reported measures were used to assess the participant’s perception of how their voice impacted on daily activities and their quality of life, and to complement the primary outcome. The secondary outcome measures were:

Quality of life was measured using the PDQ-39. 59 This is a validated, health-related quality-of-life measure specific to PD,59 and was the most widely used disease-specific quality-of-life rating scale for PD completed by the participant. It comprises of 39 questions divided into the following dimensions: mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, stigma, social support, cognition, communication and bodily discomfort. The PDQ-39 summary index and each of the individual dimensions provide a score that can be converted into a 0–100 metric where 0 = no problem at all and 100 = worst or maximum level of problem.

-

Questionnaire on Acquired Speech Disorders (QASD)60

Participation restriction related to speech and communication were assessed using the self-reported QASD. 60 The QASD questionnaire comprises of 30 questions which are scored 0–3 giving a total score that ranges from 0 to 90, where lower scores were better.

-

EuroQol5D (5-level version). 61

The EQ-5D-5L61,62 is a well-established standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome. It provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. It is completed by the participant, and comprises of the following five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension can take one of five responses: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems or extreme problems. There is also a 100-point visual analogue scale. It is often used together with resource utilisation questionnaires (see below) to provide data to inform the cost-effectiveness analysis.

-

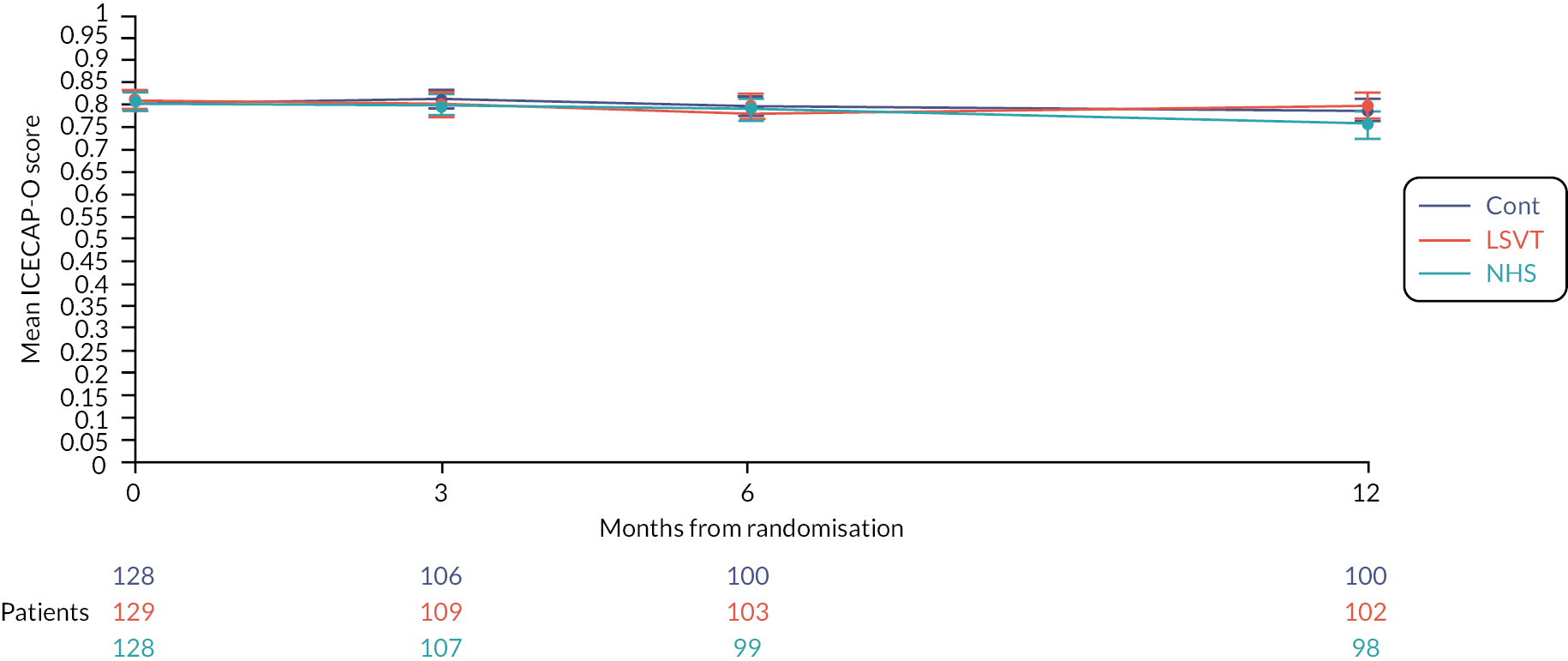

ICEpop Capabilities Measure for Older Adults (ICECAP-O).

The ICECAP-O63 is a measure of capability in older people for use in economic evaluations. Unlike most profile measures used in economic evaluations, the ICECAP-O focuses on well-being defined in a broader sense, rather than health. The measure covers attributes of well-being that were found to be important to older people in the UK and is completed by the participant. It comprises of five attributes: attachment (love and friendship); security (thinking about the future without concern); role (doing things that make you feel valued); enjoyment (enjoyment and pleasure) and control (independence).

-

Adverse events (AEs) (see Chapter 2, Safety reporting).

-

Hoehn and Yahr stage.

The Hoehn and Yahr stage64 is a clinician-rated measure of disease severity in PD. It is a standard staging scale for PD that is required to document the severity of PD in the participant population.

-

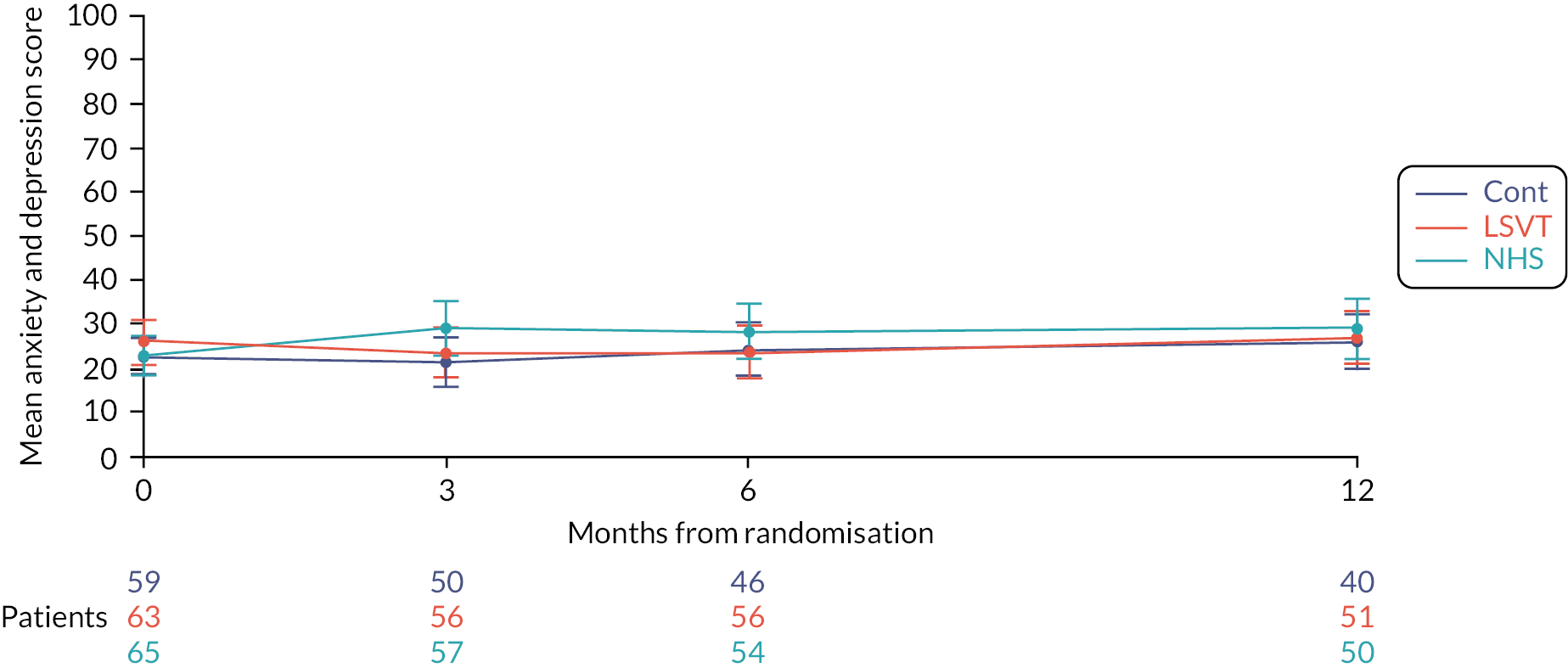

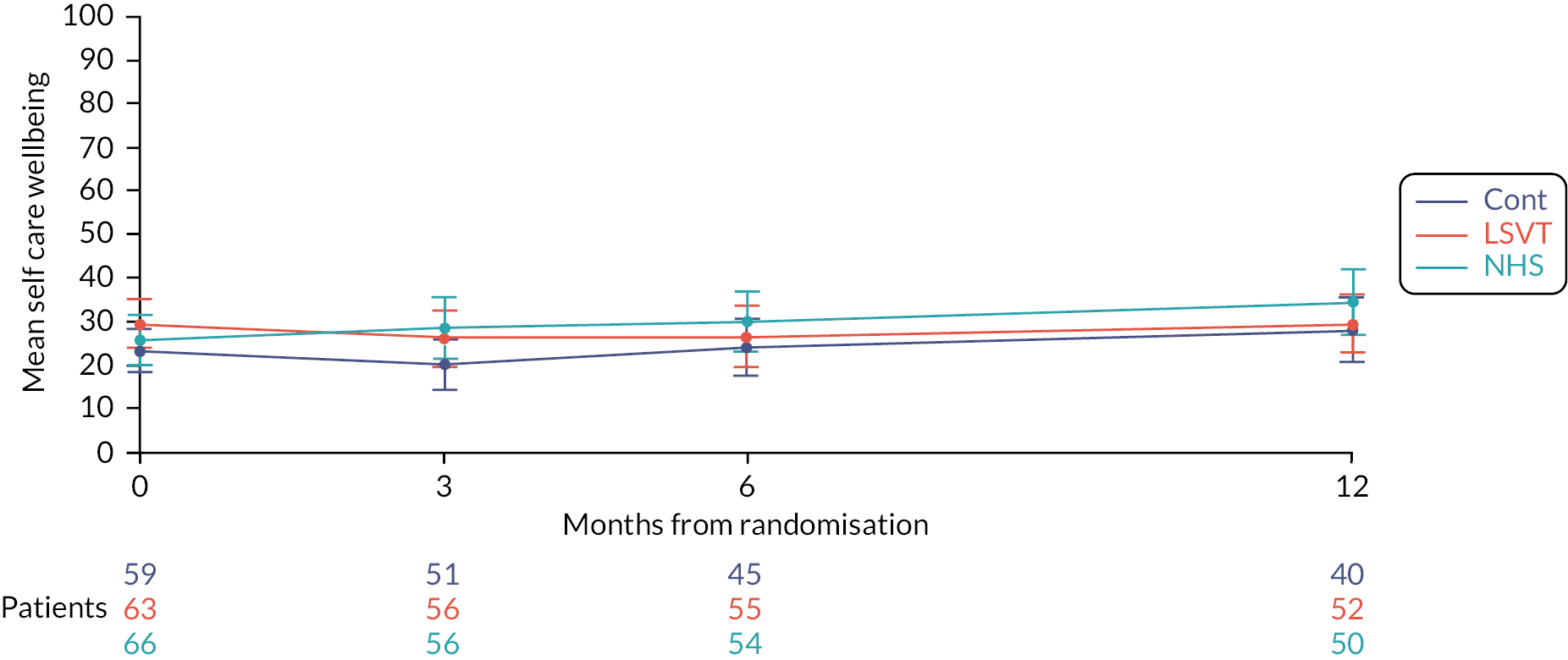

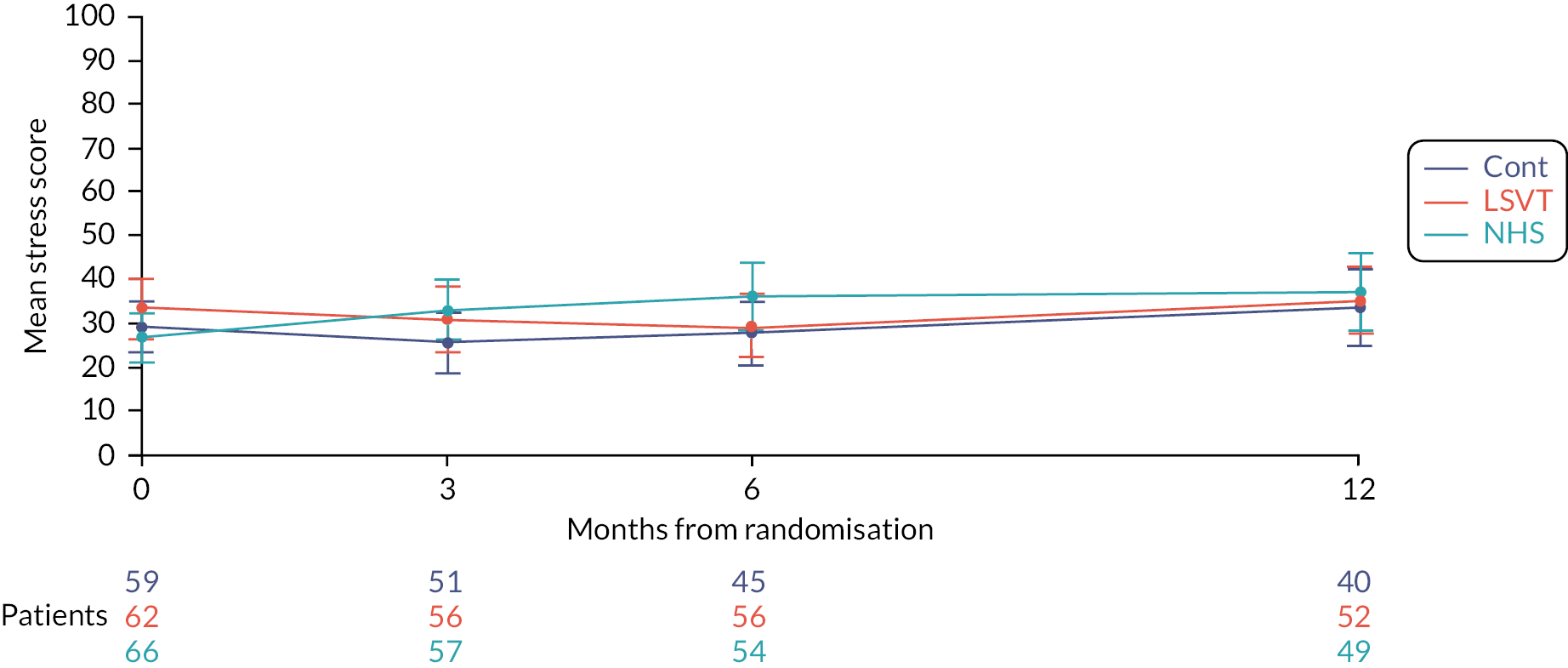

Carer quality of life (Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire – Carers).

Carer quality of life will be measured using the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire – Carer. 65 This is the first disease-specific measure of quality of life for carers of people with PD and is a validated and reliable tool. It is completed by the carer and comprises of 29 questions with 5 responses (Never/Occasionally/Sometimes/Often/Always). It is made up of four discrete scales: social and personal activities (12 items), anxiety and depression (6 items), self-care (5 items) and stress (6 items). The raw score of each scale can be calculated and converted to a 0–100 metric where 0 = no problem at all and 100 = worst or maximum level of problem. The sum of the scale scores can provide a single figure used to assess the overall quality of life of the individual questioned.

-

Resource utilisation (collected for the Health Economic Evaluation).

Developed for use in the PD COMM Pilot, a disease-specific Resource Usage questionnaire was used to collect information on participant resource usage data. The questionnaire included items on primary care and secondary care healthcare utilisation, including the use of therapy services, and outpatient appointments. Further questions related to use of social services, including provision of meals and formal care. Finally, information was collected on time off work, participants’ out-of-pocket costs (e.g. travel, medication) and costs incurred by informal carers, to inform analysis from a societal perspective.

Outcome assessment time points

Assessments were made following informed consent, and prior to randomisation (baseline assessment), and then at 3 months (i.e. after treatment if in the SLT arms), 6 and 12 months after randomisation ([ee the trial record forms at (URL: www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/bctu/trials/pd/pd-comm/investigators/documentation)]. Assessments completed by the participants at 3, 6 and 12 months were returned to the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU) by post. The participants had clinical assessments at baseline and then again at 12 months after randomisation (Table 1).

| Measure | Completed by | Assessment time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||

| Randomisation form | Clinician | ✓ | ||||

| Clinical data entry: Entry form or 12-month CRF | Education and living arrangements | Clinician | ✓ | |||

| Height | Clinician | ✓ | ||||

| Weight | Clinician | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| PD Medication | Clinician | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | Clinician | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| VHI | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PDQ-39 | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| QASD | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| EQ-5D-5L | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ICECAP-O | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Resource usage questionnaire | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Transition item | Participant and carer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| PDQ-Carer | Carer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Adverse event log | Clinician | ✓a | ||||

| Initial Interview Log (first session only) and treatment record form (all seasons). | Speech and language therapist | ✓b | ||||

| Home-based therapy diary | Participant | ✓c | ||||

Sample size

The primary outcome was the mean difference in the VHI total score at 3 months across the three comparisons: LSVT LOUD versus no SLT (control); NHS SLT versus no SLT (control); and LSVT LOUD versus standard NHS SLT. Data from the PD COMM Pilot trial were used to inform the sample size calculations for this trial as the minimal clinically important differences (MCID) for the VHI had not been established in PD patients. In the PD COMM Pilot trial,36 a difference of around 10 points in VHI total score was observed at 3 months between SLT and no SLT (control) for both types of SLT (NHS SLT and LSVT LOUD). To detect a 10-point difference in VHI total score between arms at 3 months (using a two-sided t-test and the upper standard deviation of 26.27 obtained from the VHI baseline data from the pilot trial; effect size 0.38), with 80% power and α = 0.01, we needed to recruit 163 participants included per arm. Allowing for 10% dropout this increased to 182 participants per arm, meaning the trial had a planned sample size of 546 participants.

Global rating scale (transition item)

The transition item is a single question asked at the 3-month time point to the participant and carer: ‘Compared to 3 months ago (when you joined the trial), has your ability to communicate using speech changed?’ with seven levels of response ranging from ‘much worse’ to ‘much better’ or ‘Compared to 3 months ago (when your partner/family member/friend joined the trial), has his/her ability to communicate using speech changed’ is used for the participant and carer respectively. It measures whether the participant or carer has noticed any change in communication by voice or speech since the participant (with PD) entered the trial. The transition item was used to calculate the MCID for the VHI.

Randomisation

Sequence generation and allocation concealment

Following informed consent and completion of all baseline data collection, the participant could be randomised into the trial. Participants were randomised at the level of the individual via a central, secure, web-based computer-generated randomisation system developed and controlled by the BCTU, thus ensuring concealment of next treatment allocation. To randomise a patient into the trial, staff delegated the task of randomising patients into the trial either logged onto the trial database or rang the BCTU randomisation telephone line. The randomisation process used a minimisation procedure. The following minimisation variables were used:

-

age (≤ 59, 60–70, > 70 years);

-

disease severity measured using the Hoehn and Yahr staging64 (1.0–2.5, 3.0–5.0); and

-

severity of speech measured using the VHI57 total score (≤ 33, mild 34–44, moderate 45–61, severe > 61).

To avoid any possibility of the treatment allocation becoming predictable, a random element was included within the randomisation process. Once the participant was randomised into the trial, they were given a unique trial identifier and the treatment allocation was confirmed by e-mail to the site.

Recruitment and selection

The trial was designed to reflect routine care, thus minimising the burden for people with PD and difficulties with movement and fatigue. Participants were usually identified during routine clinic appointments with their specialist clinician or PD specialist nurse. The healthcare professional then informed potentially eligible patients of the trial and provided a copy of the participant information sheet (PIS). Patients were given time to review the PIS and/or go through it with a member of the team, typically the research nurse, and given the opportunity to ask questions. Given the low-risk nature of the trial, and the mobility limitations of the population, potential participants could join the trial on the same day that they had discussed the trial and received the PIS or they could come back at a later date if they preferred.

Prior to randomisation, the availability of speech and language therapists at the site was checked. Availability of SLT interventions locally was investigated before randomisation in order to reduce delays between randomisation and the start of treatment. Once randomised into the trial, the aim was to start providing the NHS SLT intervention within 4 weeks and the LSVT LOUD intervention within 7 weeks of randomisation, thereby allowing for potential Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) referrals prior to starting the intervention, and enabling the intervention to be completed prior to the primary analysis time point (at 3 months post randomisation). Randomisation could be deferred if the SLT intervention could not be initiated within the set time frames (e.g. if the therapist was on leave, or there was no service capacity to engage in LSVT LOUD at that time). However, the participant’s baseline questionnaire had to be completed within 2 weeks prior to randomisation, so this was factored into any planned delay of a patient’s randomisation. Provision of treatment at a location different to the randomisation location was permitted within the trial, depending on local practice. Participant’s General Practitioner was informed of their patient’s randomisation into the trial.

Typically, the research nurse obtained informed consent and enrolled the participant into the trial including randomising the participant via the BCTU web-based system or by telephoning BCTU telephone randomisation service. They also liaised with the local speech and language therapists to ensure that SLT, should they be randomised to therapy, started within the required time frame (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Intended trial participant flow.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention, the trial was not blinded; participants, trial assessors or treatment providers were all aware of the intervention group to which the participant had been randomised.

Statistical methods

The primary comparisons within the PD COMM trial compared (1) those randomised to receive LSVT LOUD compared to no SLT (control) and (2) those randomised to receive NHS SLT compared to those randomised to no SLT (control). A third comparison compared those randomised to LSVT LOUD to those randomised to NHS SLT. All primary analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, with participants analysed in the treatment groups to which they were randomised.

For all tests, summary statistics (e.g. mean differences) are reported along with 99% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values from two-sided tests. A p-value of < 0.01 was considered statistically significant, as per the sample size calculations to take into account the multiple treatment comparisons being undertaken. For the primary comparisons, the no SLT (control) group was the reference group. In the secondary comparison, the NHS SLT group was the reference group. All analyses were undertaken using SAS®, version 9.4 [SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA (SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration)], or Stata®, version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

The primary outcome measure was the VHI total score at 3 months. A linear regression model was used to estimate differences in the VHI total score at 3 months between the two arms of interest, with the VHI baseline score and the minimisation variables: age and severity of PD (Hoehn and Yahr) included in the model as covariates. Statistical significance of the treatment estimate was evaluated using the corresponding p-value in the model. Three per-protocol analyses were performed on the primary outcome only. These were:

-

analysing those who were adherent (see Adherence to interventions for adherence definition) to randomised intervention and those who completed the 3-month assessment form inside the assessment window (± 1 month)

-

analysing only those who were adherent

-

analysing only those who completed the 3-month assessment form within the assessment window.

Sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of missing data were also restricted to the primary outcome and included assuming worst score and best score in place of missing responses, with different combinations by intervention group; assuming mean score of domain in place of missing response; and multiple imputation using important prognostic variables (e.g. treatment allocation; baseline value) to predict the missing response.

The majority of the secondary outcome measures (e.g. PDQ-39) are continuous measures and were analysed in the same way as for the primary outcome: a linear regression analysis adjusting for relevant baseline score and all of the minimisation variables (baseline VHI, age and severity of PD). Mean differences were reported alongside 99% CIs. The primary analysis of the secondary outcomes was at 3 months as per the primary outcome.

Participant-completed questionnaires were also completed at 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Secondary analyses assessed these data at both 6 and 12 months using linear regression analysis adjusting for relevant baseline score and minimisation variables as per the primary analysis. Continuous outcomes were also analysed using repeated measures models using all available data. Baseline value of the measure and time were included in the model along with the minimisation variables as fixed effects. Time was assumed to be a categorical (fixed) variable. To allow for a varying treatment effect over time, a time-by-treatment interaction parameter was included in the model. If the p-value of this interaction was significant, then mean differences between the groups were reported from this model, else the interaction term was removed before reporting mean differences. A general ‘unstructured’ covariance structure was assumed.

Adverse events and safety data were summarised descriptively by treatment arm and the number of events and percentage of participants experiencing any AE reported.

Subgroup analyses were performed for the primary outcome only to assess whether there were differences in the treatment effect by the minimisation variables: VHI total score (≤ 33; mild 34–44; moderate 45–61; severe > 61); age (≤ 59; 60–70; > 70 years); and PD severity as measured by Hoehn and Yahr staging (1–2.5; 3–5). The trial was not powered to detect for differences in treatment effect in these subgroups and, therefore, these analyses were to be treated as purely hypothesis generating.

Oversight and monitoring

Interim data analyses of the primary outcome and AE were supplied in confidence to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), which gave advice on whether the accumulated data from the trial, together with the results from other relevant research, justified the continuing recruitment of further participants. The DMC could recommend discontinuation of the trial if the recruitment rate or data quality were unacceptable, or if any issues were identified which may compromise participant safety. The trial would have stopped early if interim analyses or new evidence emerged showing differences between treatments that were deemed to be convincing to the clinical community.

The DMC was able to advise the chair of the trial steering committee (TSC) if, in their view, any of the randomised comparisons in the trial had provided both (1) ‘proof beyond reasonable doubt’66 that for all, or for some, types of patient one particular treatment is definitely indicated or definitely contraindicated in terms of a net difference in the major end points, and (2) evidence that might reasonably be expected to influence the patient management of many clinicians who are already aware of the other main trial results. The TSC would then have had to decide whether to close or modify any part of the trial. Unless this happened, however, the Trial Management Group (TMG), TSC, the investigators and all the central administrative staff (except the statisticians who supply the confidential analyses) remained unaware of the interim results.

Safety reporting

A risk assessment of the PD COMM trial was performed with the SLT interventions considered to be of low risk. From the literature, the only reported AE associated with the interventions was a small increased risk of vocal strain or abuse; however, none were reported in the PD COMM pilot trial. This risk was minimised as speech and language therapists are trained to identify and rehabilitate vocal strain. No other risks were expected to arise from taking part in the trial and therefore it was reasonable to collect only targeted AEs.

For participants in either treatment arm, any vocal strain or abuse believed to be associated with treatment was identified by the therapists at the participants’ SLT session and reported in the AE log. In all trial arms, the participant-reported resource usage form was checked to ensure that no vocal strain or abuse occurred following participants reporting outpatient appointments with ENT specialists. At the 12-month clinical visit, the medical professional also checked whether any AEs occurred since entering the trial.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) are events that cause death, are life-threatening, require or extend an existing hospitalisation, result in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; birth defect or congenital abnormality; or are otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator. SAEs that are not related to vocal strain or abuse were excluded from expedited notification during the course of the trial and were collected in the resource usage and 12-month clinical case report form (CRF).

Treatment-related AEs associated with vocal strain or abuse will be documented and reported from the date of commencement of protocol-defined SLT treatment until 30 days after the administration of the last treatment. AEs associated with vocal strain or abuse that are not considered treatment related [i.e. AEs experienced on the no SLT (control) arm] were reported from randomisation until 12 months post randomisation via the resource usage questionnaire.

Summary of any changes to the trial protocol

The following amendments and/or administrative changes were made to this study since the implementation of the first approved protocol. 67

Original application was submitted with version 1.0 of the protocol. Substantial changes to the protocol and participant CRFs were made to satisfy requirements from the REC.

Resubmitted to REC as version 1.1 and the protocol was approved subject to minor changes. This version was released to trial sites at the start of recruitment of the trial.

Version 2 of the protocol added an exclusion criterion that the investigator had to be certain that the participant would not require SLT in the 12-month trial period. A note was also added which stated that should it become medically necessary, participants in the ‘no treatment’ control group could be given SLT treatment. The severity measure H&Y was removed from 3- and 6-month data collection and height and weight were removed from the 6-month data collection. The CRFs were removed from the clinician-reported outcome measures.

Version 3 was not approved and so was not an active version of the trial protocol.

Version 4 added that participants could be contacted by letter or phone by a member of the clinical team to inform them of the trial prior to them attending clinic or afterwards should this be more practical or appropriate. The need for participants to explicitly consent to members of the research team and or members and representatives of the sponsors to be given direct access to their medical records was added. The protocol was also amended to confirm that a participant’s GP was only informed of the participant’s involvement in the trial, if they had given their consent for this to happen.

The ability to defer randomisation due to SLT service availability was added. The baseline questionnaire had to be completed within 2 weeks prior to randomisation and consent was reconfirmed if the delay was longer than 3 weeks.

For the qualitative interviews, the timeframe of interview was changed to between 3 and 6 months assessments and the length of the interviews was amended to 30 minutes from 30 minutes to 1 hour. Providing a participant information sheet for the process evaluation was amended from optional to mandatory.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

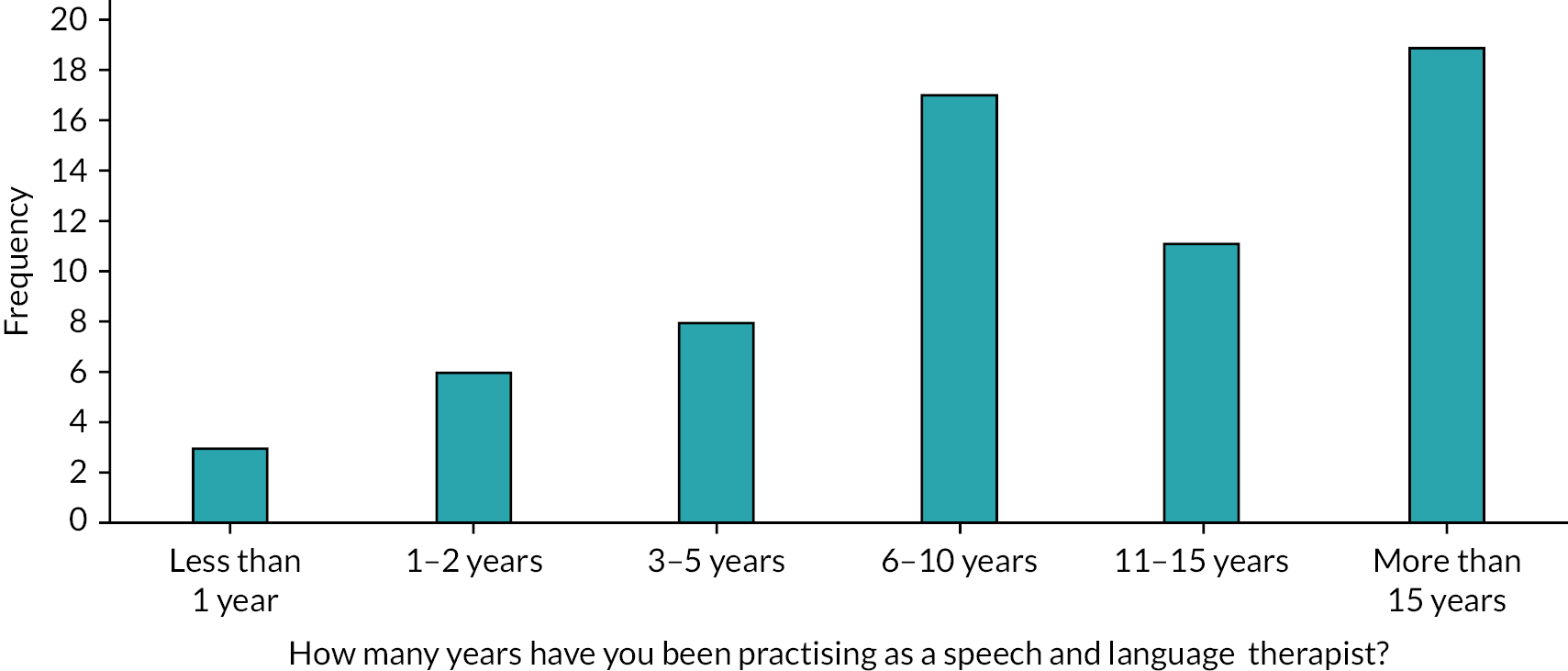

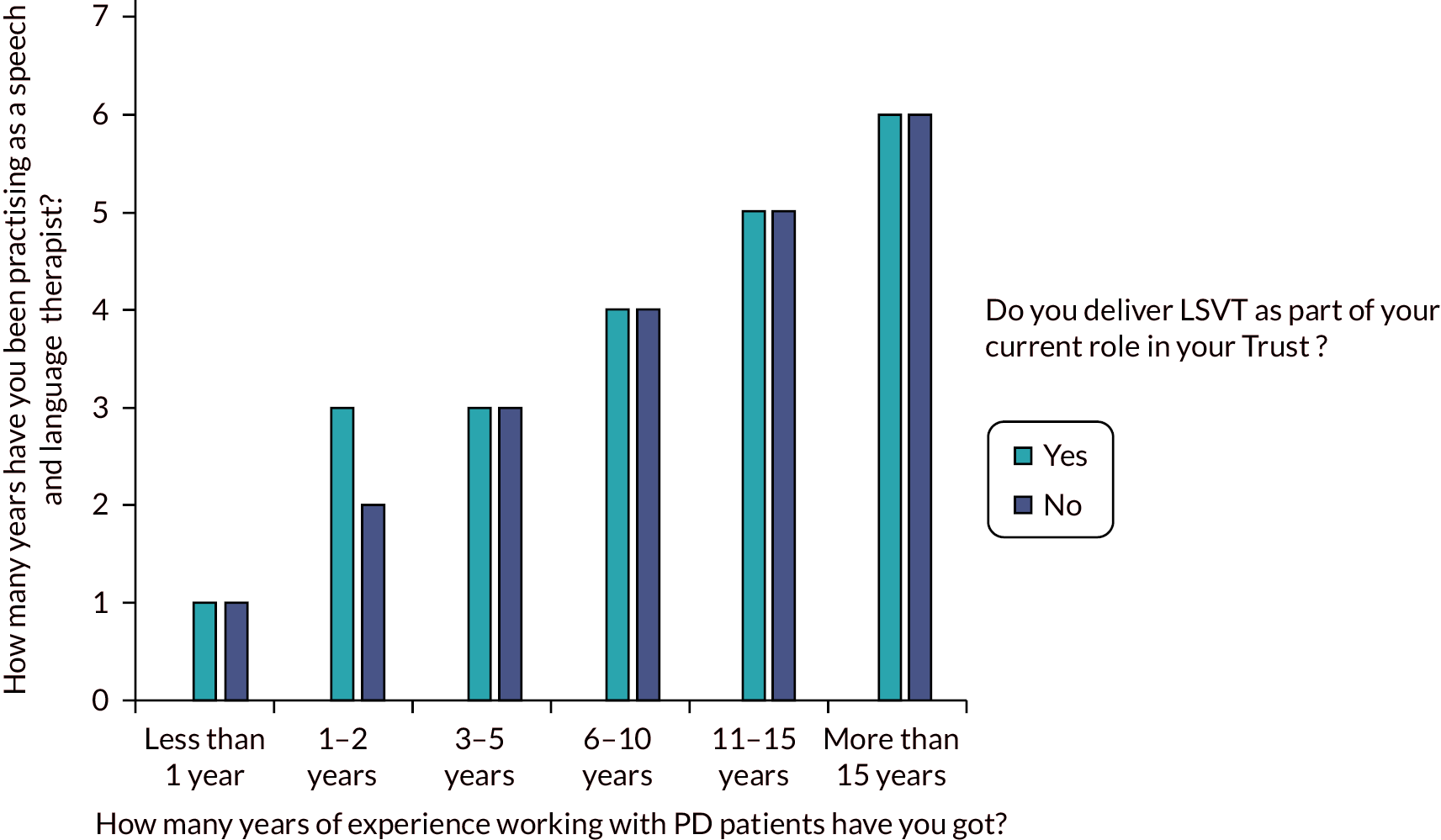

The PD COMM trial opened to recruitment on 26 September 2016 and was suspended on 16 March 2020, before the recruitment target of 546 participants was achieved, due to the impact of the coronavirus disease discovered in 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (see Appendix 1, Figure 31). Following discussions among the coinvestigator group and then with the TSC and the funder, it was decided that the COVID-19 pandemic meant that recruitment to the trial and delivering the trial interventions in the same way as pre-pandemic would have been difficult. The decision was made to not reopen the trial and recruitment closed in November 2020 without reaching this target. As of 16 March 2020, 388 participants were recruited to the trial; 130 participants were all allocated to LSVT LOUD, 129 participants were allocated to NHS SLT and 129 participants were allocated to no SLT (control).

There were 42 centres across England, Scotland and Wales opened to recruitment, of which 41 recruited at least one participant. The centres were a diverse range of secondary care facilities and SLT services based in hospitals in large urban centres to small centres serving rural communities. The numbers of participants recruited at each centre were skewed (see Appendix 1, Figure 32) with a few centres recruiting a large number of participants and the majority of centres recruiting low numbers. The highest recruiting centres were in large urban centres in Scotland. The median number of participants recruited at each centre was 8 (range 2–32).

Participant flow

The participants were randomised to treatment and progressed through the trial (Figure 2) to complete a 12-month follow-up appointment; the two active SLT intervention arms had to complete the therapy within the 3 months from randomisation. Of the 388 participants randomised, a total of 31 did not start an active trial intervention (see Appendix 1, Table 20) for a range of different reasons. None of the reasons were recorded for more than two participants. Of those that started active treatment or no SLT (control), 7 participants (2%) died during the trial, 30 participants (8%) withdrew from the trial, 2 participants were lost to follow-up and 10 participants (3%) partially withdrew from the trial: 7 (2%) of these provided clinical data only and 3 (1%) provided participant completed data only.

FIGURE 2.

Flow of participants.

Baseline data

The mean age of participants in PD COMM was approximately 70 years old, and 74% were male (286/388) (Table 2). The mean duration of Parkinson’s was between 5 and 6 years, with a broad range from newly diagnosed to over 30 years, and the majority (61%) were in Hoehn and Yahr stage of 2 or less (< 5% were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 4 or more). The participants mostly lived with a significant other (83%) or lived alone (14%). The levodopa equivalency (see Table 6) of the medication the participants were taking at baseline was similar in the two SLT intervention groups (551.4 and 557.2 mg/day) but was slightly higher (597.6 mg/day) in the no SLT (control) group.

| LSVT | NHS SLT | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients randomised | 130 | 129 | 129 | |

| Number of randomisation notepads available | 130 | 129 | 129 | |

| Number of entry forms available | 130 | 129 | 127 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | N | 130/130 | 129/129 | 129/129 |

| Mean (SD) | 69.9 (8.4) | 69.7 (9.4) | 70.2 (8.1) | |

| Range | 40.6–93.1 | 37.8–90.8 | 47.6–86.6 | |

| Age group (years) | N | 130/130 | 129/129 | 129/129 |

| < 60 (%) | 16 (12) | 17 (13) | 14 (11) | |

| 60–69 (%) | 42 (32) | 42 (33) | 43 (33) | |

| 70–79 (%) | 59 (46) | 52 (40) | 61 (47) | |

| ≥ 80 (%) | 13 (10) | 18 (14) | 11 (9) | |

| Gender | N | 130/130 | 129/129 | 129/129 |

| Male (N, %) | 91 (70) | 100 (78) | 95 (74) | |

| Weight (kg) | N | 129/130 | 128/129 | 126/127 |

| Mean (SD) | 75.4 (15.5) | 77.5 (14.3) | 76.6 (14.1) | |

| Range | 39.9–118.8 | 25.3–120.7 | 41.8–114.3 | |

| Height (m) | N | 128/130 | 129/129 | 123/127 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.71 (0.10) | 1.72 (0.09) | 1.70 (0.11) | |

| Range | 1.45–1.93 | 1.47–1.90 | 1.31–1.96 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | N | 128/130 | 128/129 | 123/127 |

| Mean (SD) | 25.6 (4.4) | 26.2 (4.5) | 26.6 (4.7) | |

| Range | 15.6–41.0 | 11.5–38.4 | 18.4–44.0 | |

| Stage of Parkinson’s disease | ||||

| Duration of PD (years) | N | 130/130 | 129/129 | 127/127 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (5.8) | 5.1 (4.6) | 6.1 (6.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.9 (1.5–8.9) | 3.7 (1.4–7.5) | 4.1 (1.7–8.7) | |

| Range | 0.008–32.7 | 0.1–21.3 | 0.04–29.8 | |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | N | 130/130 | 129/129 | 129/129 |

| ≤ 2.0 (%) | 78 (60) | 83 (64) | 73 (57) | |

| 2.5 (%) | 17 (13) | 10 (8) | 22 (17) | |

| 3.0 (%) | 29 (22) | 31 (24) | 33 (25) | |

| ≥ 4.0 (%) | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | |

Data completeness

Data returns and data completeness were good throughout the trial (see Appendix 1, Tables 21 and 22). The participant completed VHI, PDQ-39 and QASD had response rates of over 85% at each time point. As did the quality-of-life questionnaire completed by the carer (PDQ-Carer). The clinician-completed forms had a response rate of over 90% (99% at baseline; 94% at 12 months).

Adherence to treatment

Of the 130 participants randomised to LSVT LOUD, 109 (84%) started LSVT LOUD and of these 105 completed LSVT LOUD. Twenty-one participants did not start LSVT LOUD for a variety of reasons (see Appendix 1, Table 20). Of the 129 participants randomised to NHS SLT, 119 (92%) started NHS SLT, with 118 participants considered to have completed their NHS SLT. Ten participants did not start NHS SLT, again for a variety of different reasons. In the no SLT (control) group, 120 (93%) participants received no SLT, with 9 participants receiving SLT (1 LSVT LOUD, 8 NHS SLT) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

| LSVT LOUD | NHS SLT | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised to SLT | 130 | 129 | 129 |

| Number completed intervention | 105 | 118 | – |

| Adherent (%)a | 77 (73) | 70 (59) | 120 (93) |

| Non-adherent (%) | 28 (27) | 48 (41) | 9 (7) |

| Number not completed interventionb | 25 | 11 | – |

| Crossover to control | 8 (32%) | 0 (–) | – |

| Died | 1 (4%) | 0 (–) | – |

| No confirmation of treatment completion | 2 (8%) | 0 (–) | – |

| No intervention | 10 (40%) | 8 (73%) | – |

| No treatment data available | 1 (4%) | 2 (18%) | – |

| Withdrew | 3 (12%) | 1 (9%) | – |

In the LSVT LOUD group, 28 of the 105 participants who completed the treatment were considered non-adherent (27%) as they did not complete 14 or more sessions of LSVT LOUD within 3 months of randomisation. Of the participants in the LSVT LOUD group who did not complete the intervention, most had no intervention (18/25, 72%); the rest either withdrew from treatment (3/25, 12%), did not have confirmation of treatment completion (2/25, 2%) or had no treatment data in their trial records (1/25, 4%) or died (1/25, 4%). For the NHS SLT group, 48 of 118 participants (41%) were considered non-adherent as they did not have a final session confirmed by their treating therapist within 3 months of randomisation. For those who did not finish the NHS SLT intervention, the most common reason was that they did not receive the intervention (8/11, 73%). There was no treatment information available for two participants and one withdrew from treatment (see Table 3) (see Appendix 1, Table 20).

Interventions as given

The provision of the two active speech and language therapies used for this trial was monitored and recorded to provide information about the interventions as delivered (Table 4). For greater detail on the content of the interventions as delivered, see Chapter 6.

| LSVT | NHS SLT | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants randomised | 130 | 129 | |

| No. of participants with log data | 107 | 118 | |

| No. of participants had last session | 105 | 118 | |

| N | 107 | 118 | |

| Number of sessions | Median (IQR) | 16 (16–17) | 5 (4–7) |

| Range | 1–22 | 1–15 | |

| N | 107 | – | |

| Number of sessions of LSVT LOUD | Median (IQR) | 16 (14–16) | – |

| Range | 0–18 | – | |

| N | 107 | 118 | |

| Total time (mins) | Mean (SD) | 1216.3 (453.6) | 404.1 (233.5) |

| Range | 70–2080 | 50–1331 | |

| N | 107 | 118 | |

| SLT contenta time | Mean (SD) | 962.9 (330.4) | 298.2 (171.2) |

| Range | 45–1670 | 40–1065 | |

| SLT activities by type | N = 107 | N = 118 | |

| Assessment and review time (mins)b | Mean (SD) | 132.9 (86.1) | 84.3 (51.1) |

| Range | 0–415 | 0–295 | |

| Goal setting (mins)b | Mean (SD) | 25.8 (33.2) | 25.3 (26.0) |

| Range | 0–125 | 0–130 | |

| Information provision and advice (mins)b | Mean (SD) | 36.1 (44.3) | 38.8 (32.1) |

| Range | 0–315 | 0–175 | |

| Therapy~ (mins)b | Mean (SD) | 15.0 (45.0) | 148.9 (112.7) |

| Range | 0–300 | 0–550 | |

| LSVT (mins)b | Mean (SD) | 751.8 (287.3) | – |

| Range | 0–1105 | – | |

| Indirect contact (mins)c | Mean (SD) | 5.4 (26.3) | 1.3 (6.0) |

| Range | 0–195 | 0–40 | |

| Liaison/onward referral (mins)c | Mean (SD) | 4.6 (14.0) | 5.7 (17.9) |

| Range | 0–105 | 0–130 | |

| Other for example, writing notes, phone calls (mins)c | Mean (SD) | 243.4 (184.8) | 98.8 (76.9) |

| Range | 0–710 | 0 - 380 | |

| Time per session (minutes) | N | 107 | 118 |

| Mean (SD) | 79.7 (15.9) | 74.2 (21.1) | |

| Range | 46.3–127.5 | 40.0–165.0 | |

| SLT contentd time per session | N | 107 | 118 |

| Mean (SD) | 62.7 (9.5) | 55.0 (15.6) | |

| Range | 30.9–91.7 | 23.7–100.0 | |

| LSVT LOUD time per session (minutes) | N | 98e | – |

| Mean (SD) | 54.3 (7.1) | – | |

| Range | 34.1–69.3 | – | |

| Treatment duration (weeks)f | N | 107 | 118 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.6 (6.5) | 11.4 (11.4) | |

| Range | 0–54 | 0–69 |

LSVT LOUD

Lee Silverman Voice Treatment LOUD was delivered over a median of 16 sessions and a mean of 6.6 (SD 6.5) weeks. The dose of the treatment was 1216 (SD 454) minutes, which consisted of 963 (SD 330) minutes of SLT content [mean SLT content per session: 63 (SD 10) minutes], with 752 (SD 287) minutes dedicated to LSVT LOUD [mean LSVT LOUD content per session: 54 (SD 7) minutes]. Participants were encouraged to continue with home-based practice and completed homework diaries. Ninety-six participants completed at least 1 week of the home-practice diary. Diary completion was high with a median completion of 4 weeks.

National Health Service speech and language therapy

National Health Service SLT was delivered over a median of five sessions over a mean of 11.4 (SD 11.4) weeks. The duration of NHS SLT was shorter than LSVT LOUD, totalling a mean of 404 (SD 234) minutes, with 298 (SD 171) minutes dedicated to SLT content. Mean active therapy time for NHS SLT was 149 (SD 113) minutes. The mean individual session length was similar to that of LSVT LOUD at a mean of 55 (SD 16) minutes. Therapy assistants provided a small number of treatment sessions across interventions and a few participants received the course of therapy in a group setting.

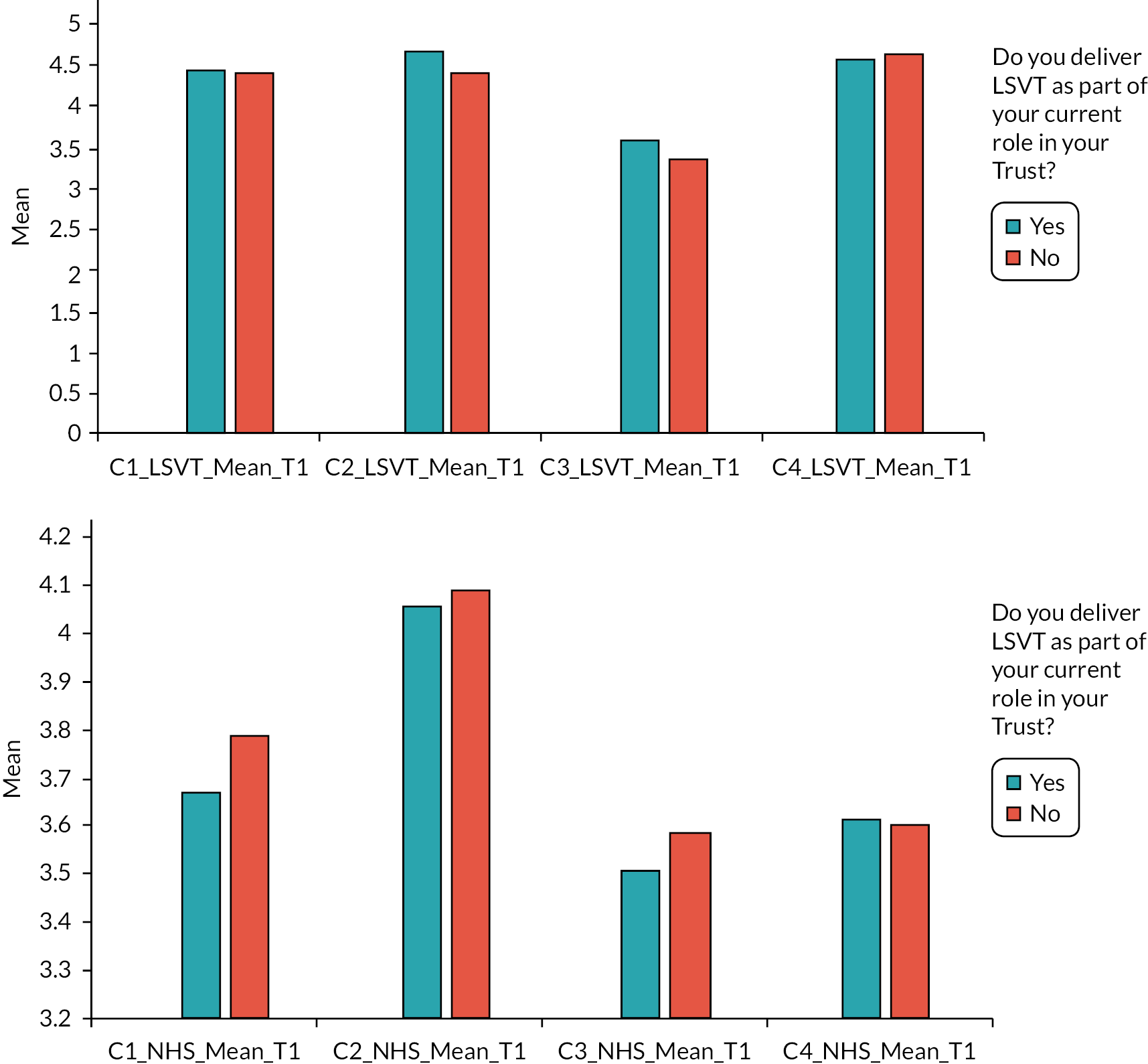

Effectiveness of speech and language therapies for Parkinson’s disease-related speech and voice problems (dysarthria) after 3 months (primary outcome)

Primary analysis

The impact of the speech or voice problems at baseline across the three randomised groups was similar: a mean of 44.6 (SD 21.9, n = 130) in the LSVT LOUD group, 46.2 (SD 24.8, n = 129) in the NHS SLT group and 44.3 (SD 22.3, n = 129) in the no SLT (control) group. At 3 months all three group’s voice impact scores were lower compared with baseline, indicating less impact from speech or voice problems: the LSVT LOUD group had a mean score of 35.0 points (SD 20.1, n = 106), the NHS SLT group had a mean score of 44.4 points (SD 24.8, n = 102) and the no SLT (control) group had a mean score of 40.5 points (SD 21.5, n = 98) (Table 5).

| Mean (SD, n) | Mean difference (99% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSVT | NHS SLT | Control | LSVT vs. control | NHS SLT vs. Control | LSVT vs. NHS SLT | |

| N = 130 | N = 129 | N = 129 | ||||

| Baselinea | 44.6 (21.9, 130) | 46.2 (24.8, 129) | 44.3 (22.3, 129) | – | – | – |

| Baselineb | 45.4 (22.4, 106) | 45.3 (24.2, 102) | 42.3 (21.5, 98) | – | – | – |

| 3 monthsc | 35.0 (20.1, 106) | 44.4 (24.8, 102) | 40.5 (21.5, 98) | −8.0 (−13.3 to −2.6); p = 0.0001 | 1.7 (−3.8 to 7.1); p = 0.4 | −9.6 (−14.9, −4.4); p < 0.0001 |

The interventions were compared against each other for relative impact of speech or voice problems at 3 months by calculating the mean difference in VHI total score between groups. At 3 months, the VHI total score for the LSVT LOUD group was 8 points lower than for the no SLT (control) group [−8.0, 99% CI (−13.3 to −2.6); p = 0.0001]. For NHS SLT, at 3 months, the VHI total score was 1.7 points higher than the no SLT (control) group [1.7, 99% CI (−3.8 to 7.1); p = 0.4]. In the third comparison, the LSVT LOUD group was 9.6 points lower than the NHS SLT group [−9.6, 99% CI (−14.9 to −4.4); p < 0.0001] (see Table 5).

Per-protocol analyses

The main per-protocol analysis population included only those participants who both adhered to treatment and completed the 3-month VHI outcome assessment within the 1-month time window. This analysis gave similar results to the main ITT analysis: LSVT LOUD versus no SLT: −9.7, 99% CI (−16.0 to −3.4); NHS SLT versus no SLT: 1.1, 99% CI (−5.6 to 7.8); and LSVT LOUD versus NHS SLT: −10.8, 99% CI (−17.8 to −3.8). Similar results were also seen for the two other per-protocol analyses (see Appendix 1, Table 23).

Sensitivity analyses to assess impact of missing data

Various sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the impact of missing data. Different assumptions were made about the reasons for missing data to investigate the impact, if any, to our analysis of the primary outcome. All these analyses gave results that were in agreement with the primary ITT analysis (see Appendix 1, Table 24). For example, the sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation gave the following results: LSVT LOUD versus no SLT: −6.9, 99% CI (−10.9 to −2.9); NHS SLT versus no SLT: 1.8, 99% CI (−2.3 to 5.9); and LSVT LOUD versus NHS SLT: −8.7, 99% CI (−12.7 to −4.7).

Exploration of the impact of potential confounders on the impact of voice problems at 3 months

Subgroup analyses were pre-specified and performed on the minimisation variables: VHI category (≤ 33 negligible; mild 34–44; moderate 45–61; severe > 61); Age category (≤ 59; 60–70; > 70 years) and Hoehn and Yahr (1–2.5; 3–5) to assess whether one particular subgroup may benefit more (or less) from the SLT interventions. There was no evidence that the effect of the interventions differed according to age (test for interaction, p = 0.7) or Hoehn and Yahr stage (test for interaction, p = 0.7) (see Appendix 1, Table 25). There was, however, evidence that the intervention effect may differ depending on the baseline VHI score (test for interaction, p = 0.007). Across all three comparisons, the treatment effect generally increased as the baseline VHI increased; for example, for LSVT LOUD greater benefits were observed in those with more severe VHI scores at baseline. A post hoc analysis excluding participants who recorded the 3-month VHI score after the start of COVID restrictions was also performed (see Appendix 1, Table 26).

Effectiveness of speech and language therapies on the impact of voice problems over 12 months

The effectiveness of the trial interventions was monitored over 12 months. The VHI total score was assessed at 6 and 12 months separately as well as over the whole 12 months using a repeated measures analysis. These were secondary analyses for the trial. LSVT LOUD scores were lower (i.e. better) than no SLT (control) and there was no evidence of a difference between NHS SLT and no SLT (control) across these time points. LSVT LOUD also had lower VHI scores (i.e. better) than NHS SLT (see Figure 3 and Appendix 1, Table 27).

FIGURE 3.

Mean VHI total score profile plot over 12 months by intervention.

Effectiveness of speech and language therapies on the emotional, functional and physical impacts of voice problems (secondary outcome)

The VHI outcome measure comprises of three different subscales: emotional, functional and physical, which were assessed separately as secondary outcomes with the aim building a detailed picture of which particular voice-related impacts were improved.

Emotional subscale

At 3 months, the LSVT LOUD group had a lower score (i.e. better) than the no SLT (control) group [−3.0 (−5.1, −0.9); p = 0.0003], while there was no difference for standard NHS SLT compared to no SLT (control) [0.2 (−1.9, 2.4); p = 0.8]. LSVT LOUD resulted in a lower (i.e. better) emotional subscale score compared to standard NHS SLT [−3.2 (−5.3, −1.1); p < 0.0001] at 3 months. Similar results were seen for the comparisons at 6 and 12 months, and over the whole 12-month trial follow-up period (see Figure 4 and Appendix 1, Table 28).

FIGURE 4.

Mean VHI emotional subscale score profile plot with error bars over 12 months by intervention.

Functional subscale

At 3 months, the LSVT LOUD group had a lower score (i.e. better) than the no SLT (control) group [−2.9 (−4.8, −1.1); p < 0.0001], while there was no difference for NHS SLT compared to no SLT (control) [−0.0 (−1.9, 1.9); p = 1.0]. LSVT LOUD resulted in a lower (i.e. better) functional subscale score compared to NHS SLT [−2.9 (−4.7, −1.1); p < 0.0001] at 3 months. Similar results were seen for the comparisons at 6 and 12 months, and over the whole 12-month trial follow-up period (see Figure 5 and Appendix 1, Table 28).

FIGURE 5.

Mean VHI functional subscale score profile plot with error bars over 12 months by intervention.

Physical subscale

Only LSVT LOUD resulted in a lower (i.e. better) physical subscale score compared to NHS SLT [−2.2 (−4.1, −0.3); p = 0.003] at 3 months. Similar results were seen for the comparisons at 6 and 12 months, and over the whole 12-month trial follow-up period (see Figure 6 and Appendix 1, Table 28).

FIGURE 6.

Mean VHI physical subscale score profile plot with error bars over 12 months by intervention.

Effect of the interventions on participant’s dysarthria-specific quality of life (secondary outcome)

To assess what impact the interventions may have on quality of life particularly associated with dysarthria (voice or speech problems), the QASD was used. At 3 months, the QASD scores were lower (i.e. better) in the LSVT LOUD group when compared to both the no SLT (control) [−5.4 (−9.8, −1.0); p = 0.002] and the NHS SLT [−4.3 (−8.7, 0.1); p = 0.01] groups. There was no evidence of a difference in the scores for NHS SLT compared to no SLT (control) at 3 months. Similar results were seen for the comparisons at 6 and 12 months, and over the whole 12-month trial follow-up period (see Figure 7 and Appendix 1, Table 29).

FIGURE 7.

Mean QASD profile plot over 12 months with error bars by intervention.

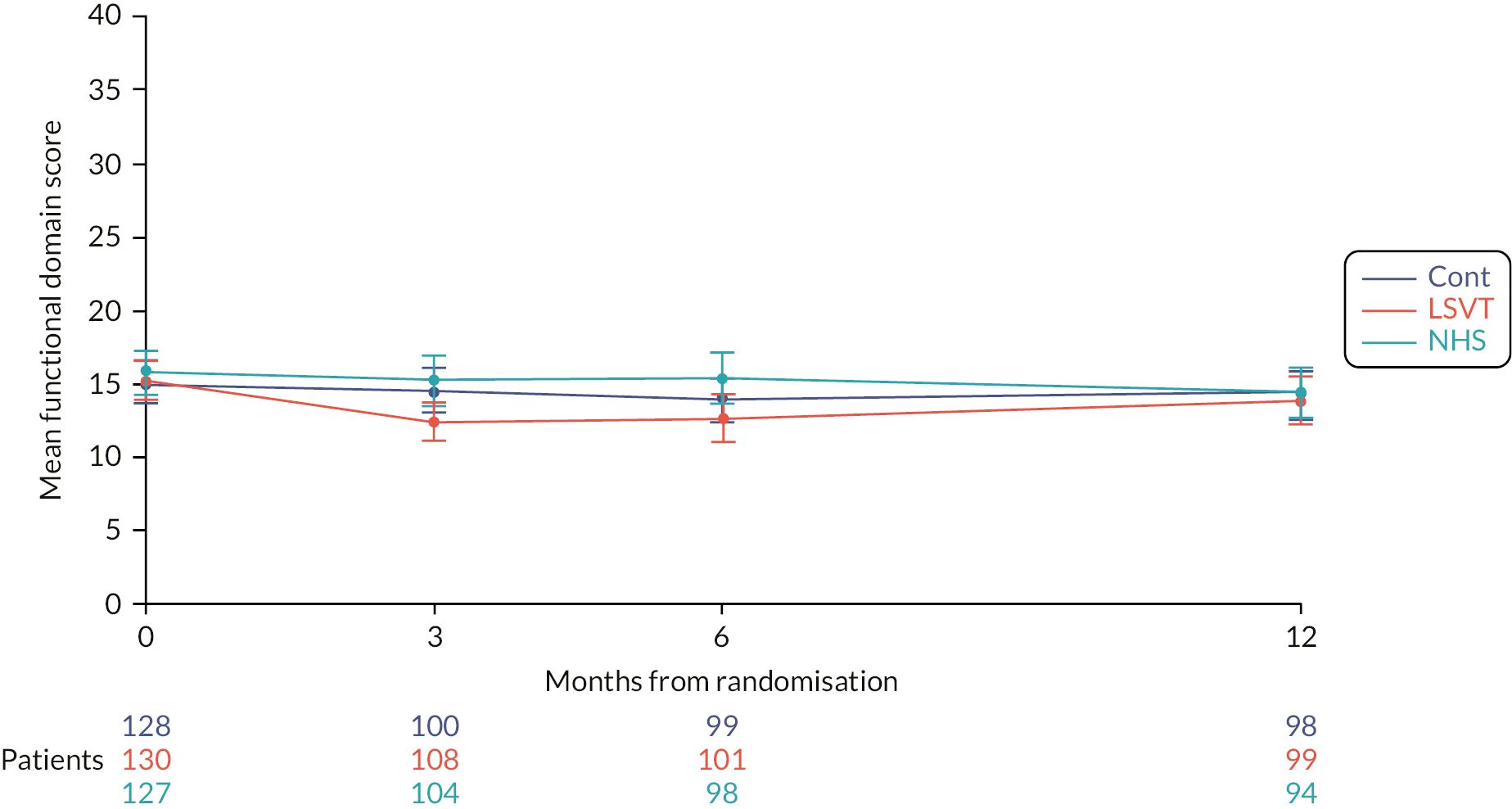

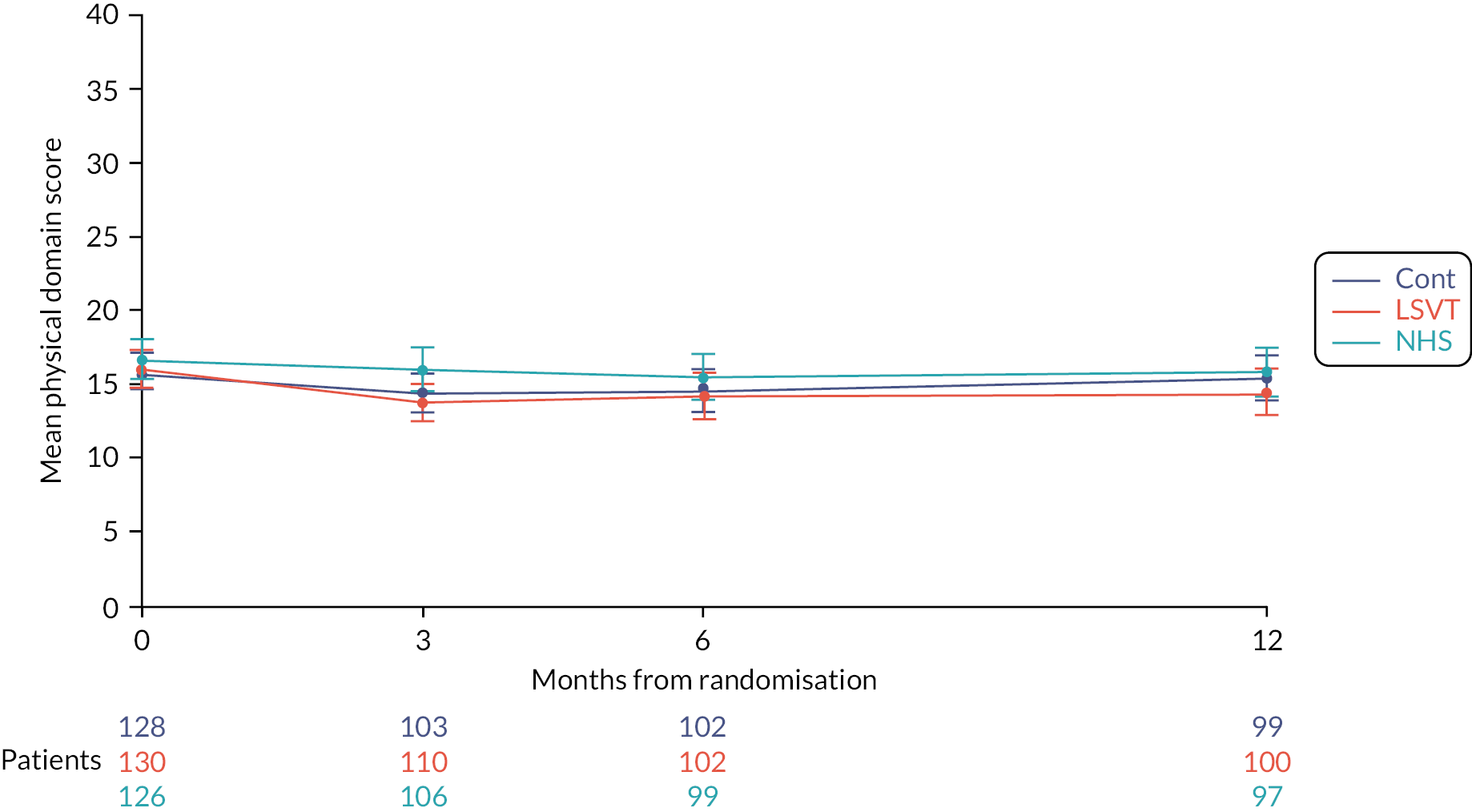

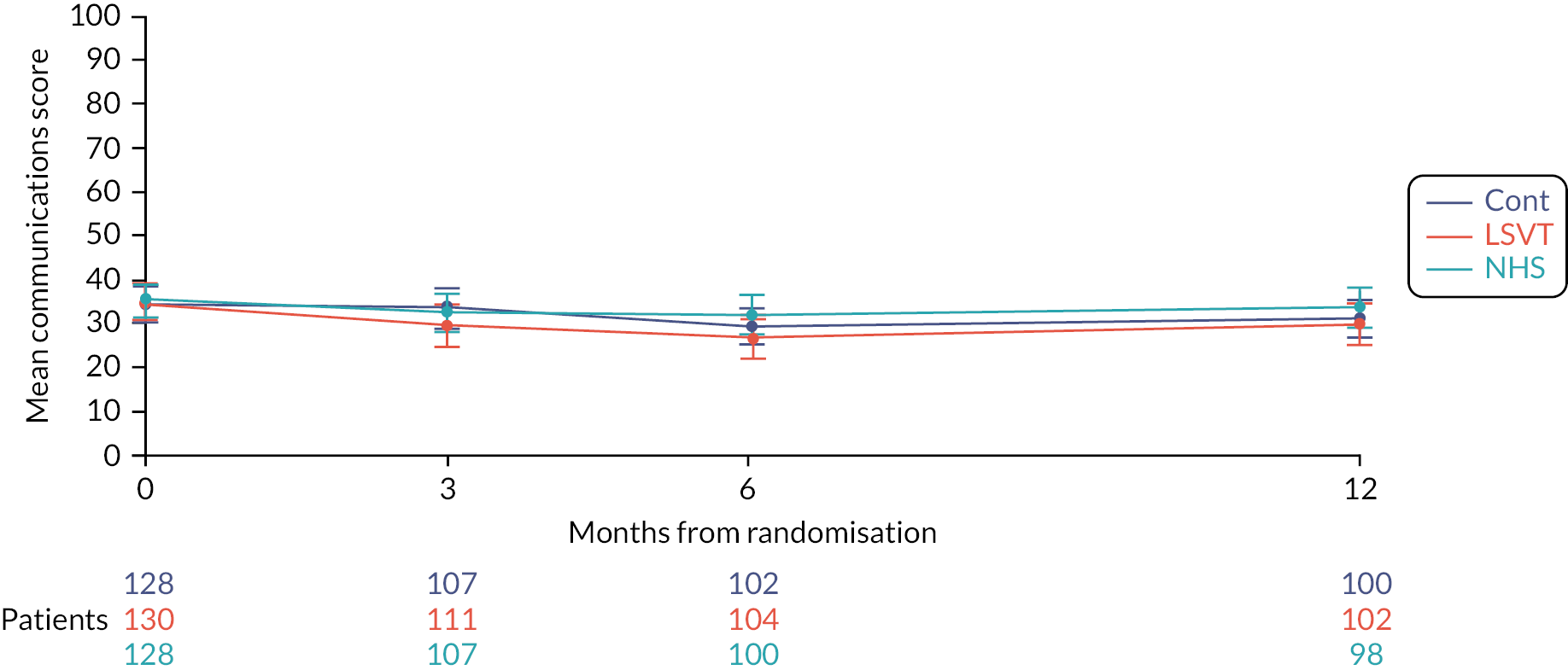

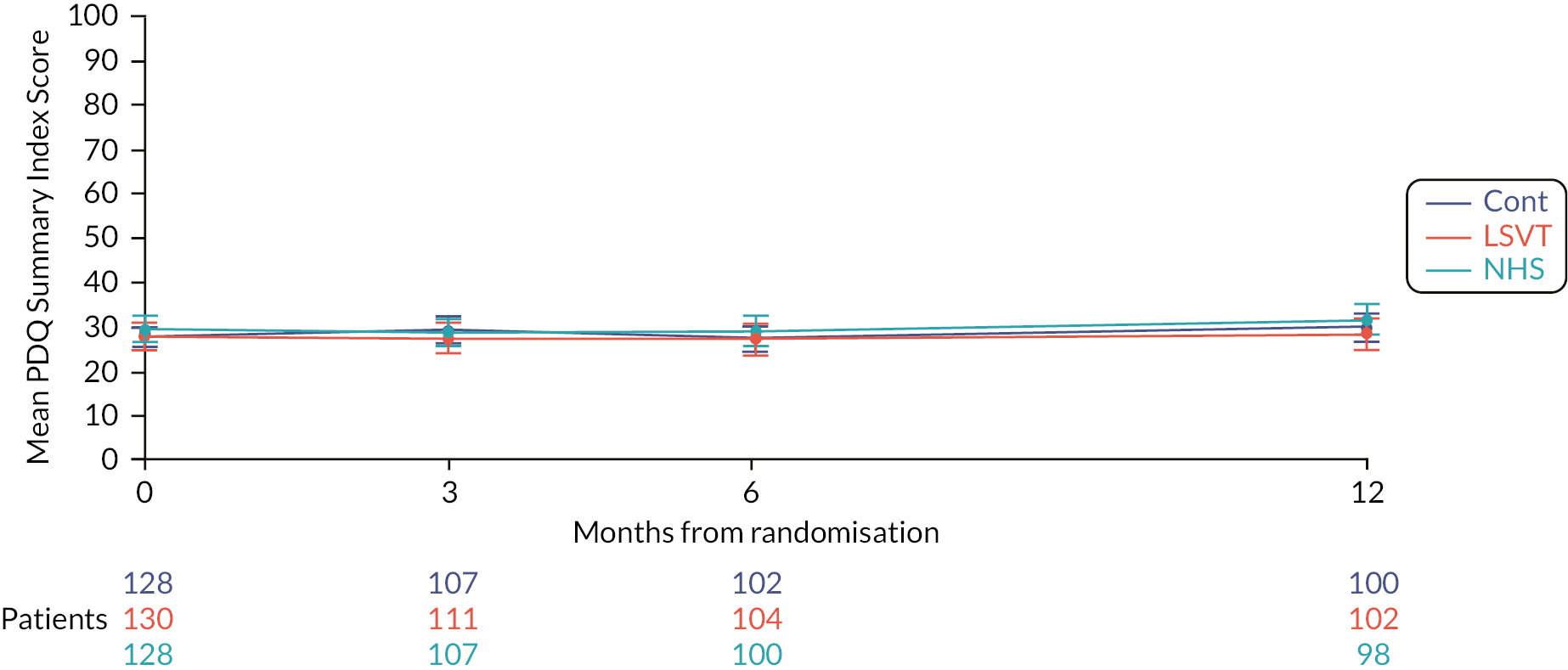

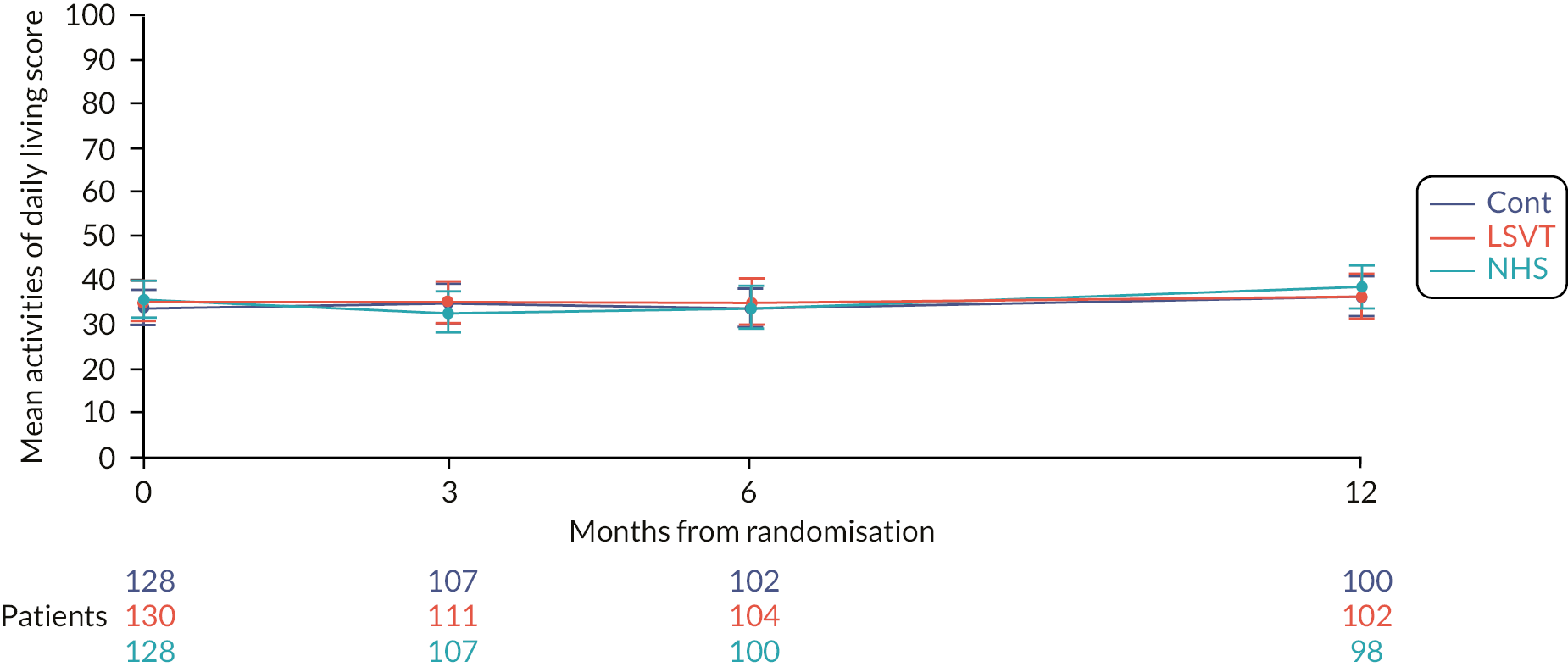

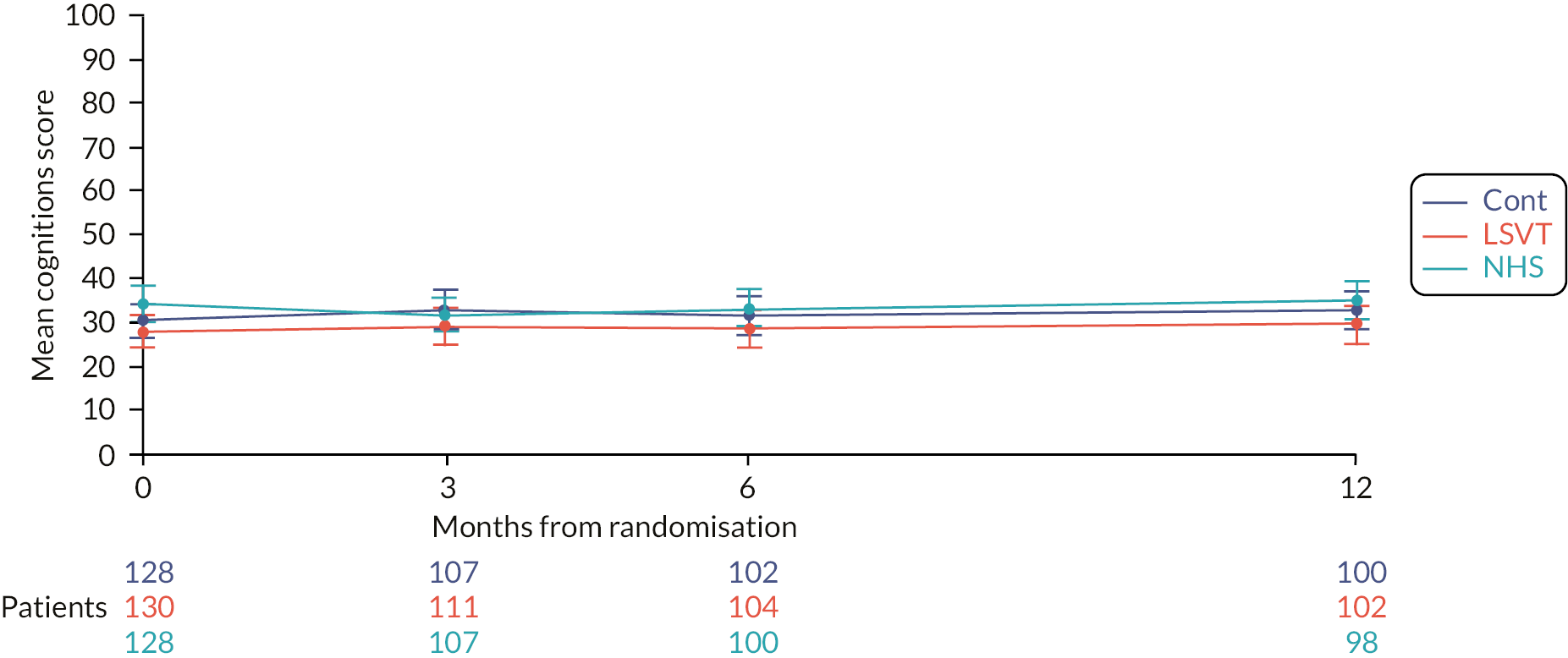

Effectiveness of speech and language therapies on the participant’s Parkinson’s disease-specific quality of life (secondary outcome)

The participant assessed the quality-of-life measure PDQ-39 assesses the impact on mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, stigma, social support, cognition, communication and bodily discomfort. The plots and results of the analyses for the different domains are provided in the Appendix (see Appendix 1, Table 30, Figures 33–39). Not surprisingly, the largest differences were observed in the communication domain for the comparison of LSVT LOUD and no SLT (control). At 3 months, the mean difference between groups was −6.2 points (99% CI −11.9 to −0.6; p = 0.004) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Mean PDQ-39 communication subscale profile plot with error bars over 12 months by intervention.

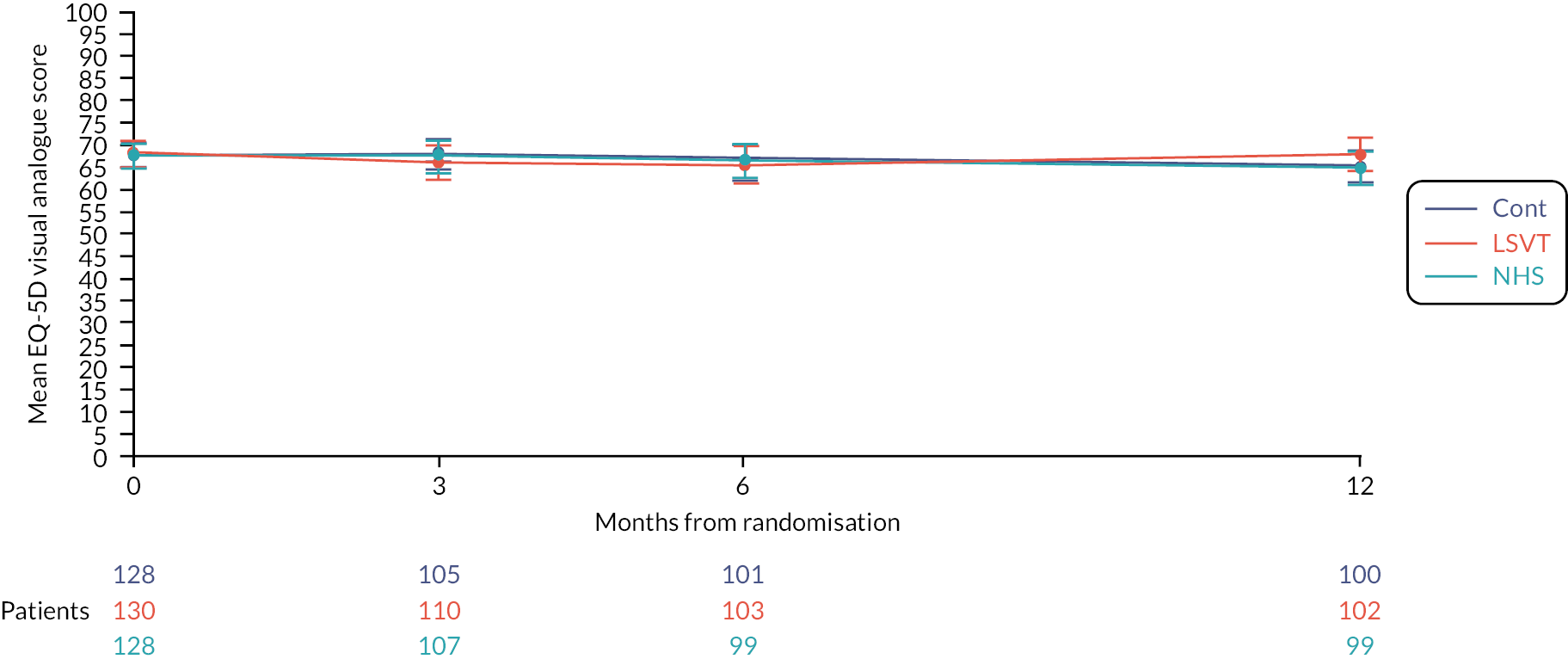

Effectiveness of speech and language therapies on the participant’s general health status (secondary outcome)

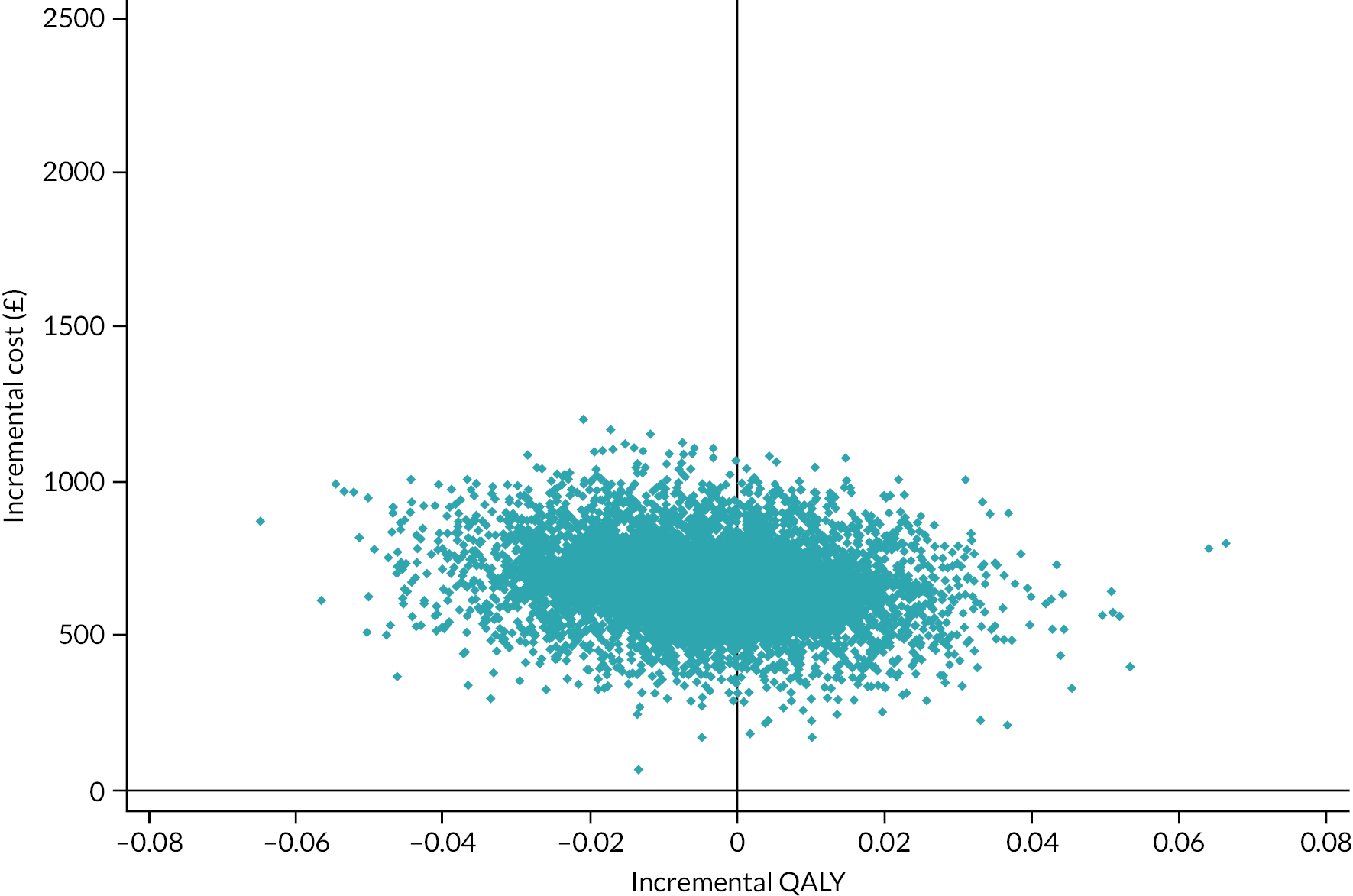

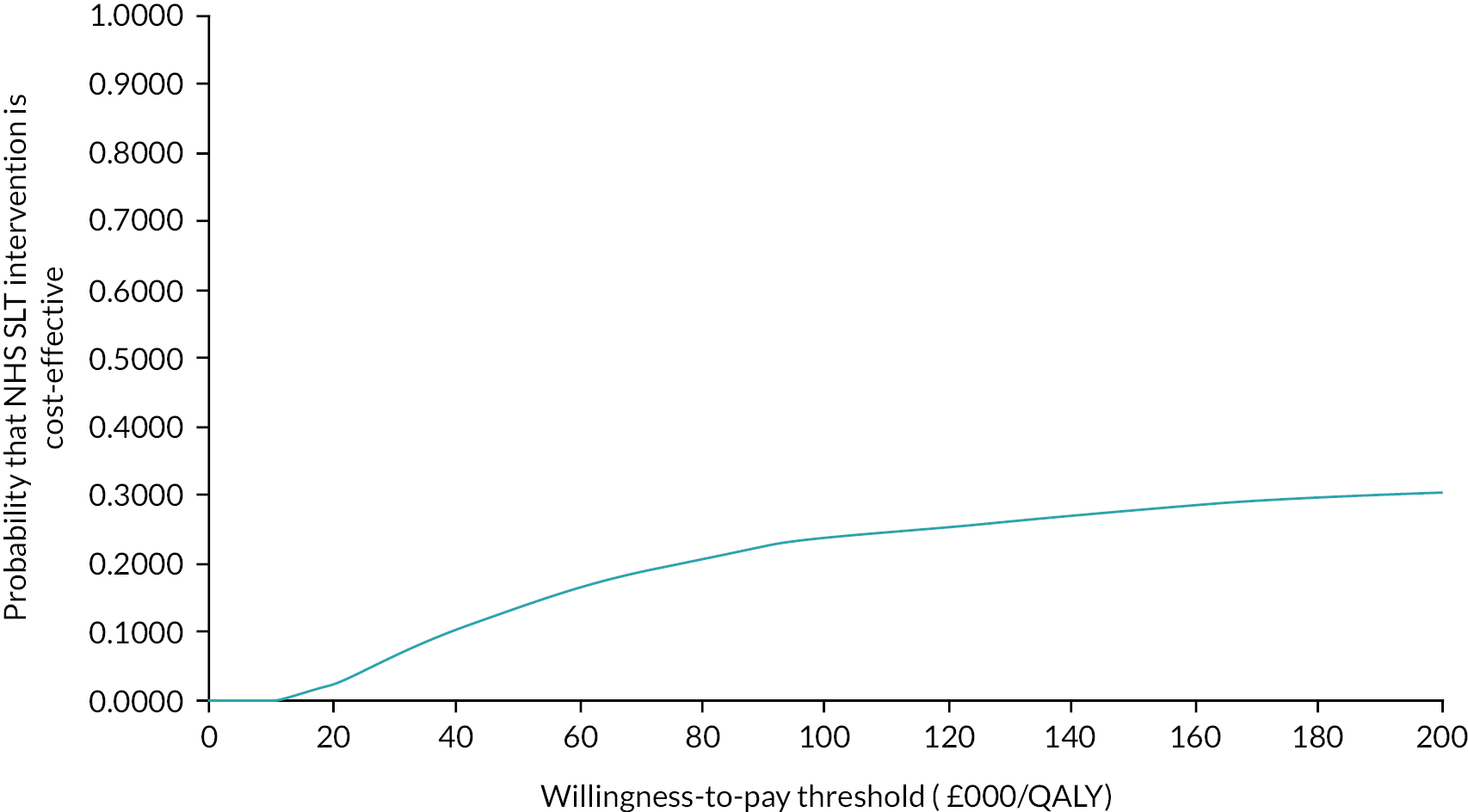

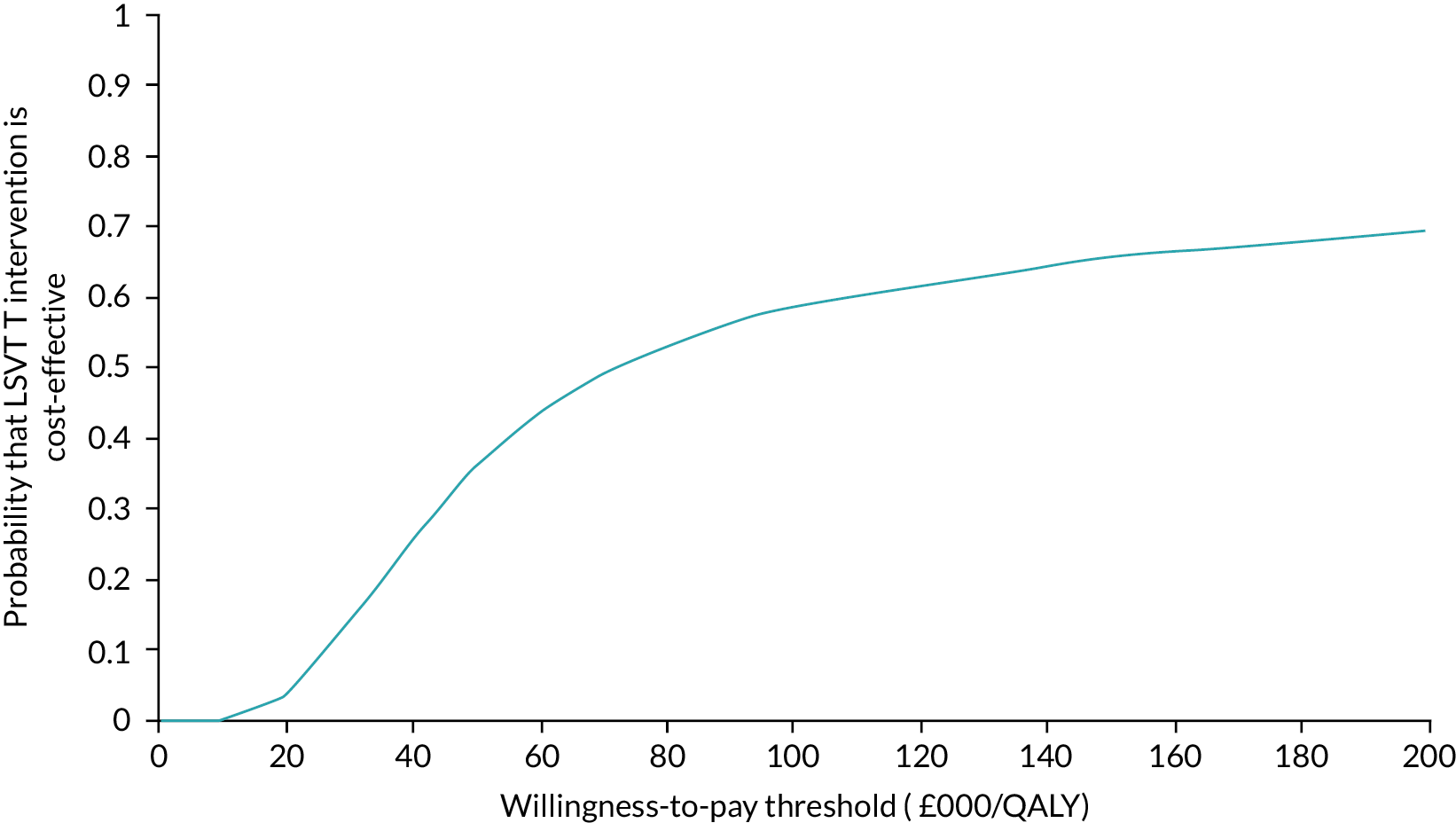

The general health-related quality of life for participants was measured using the EQ-5D-5L and there was no evidence of differences between interventions (see Figures 9 and 10 and Appendix 1, Table 31).

FIGURE 9.

Mean EQ5D index score profile plot with error bars over 12 months by intervention.

FIGURE 10.

Mean EQ5D visual analogue score profile plot with error bars over 12 months by intervention.