Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/162/01. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in July 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Wright-Hughes et al. This work was produced by Wright-Hughes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Wright-Hughes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, chronic, disorder of gut–brain interaction, characterised by abdominal pain in association with a change in stool form or frequency. 1 Prevalence is 5% in the community,2 and IBS accounts for > 3% of all consultations in primary care. 3 The total cost to the health service in the UK has been estimated to be > £1 billion/year. 4 Quality of life of people with IBS is impaired substantially, to a level comparable with that seen in some organic bowel disorders, such as Crohn’s disease. 5 Current first-line treatment of IBS in primary care includes dietary and lifestyle advice, fibre supplements, laxatives, antispasmodic drugs, or loperamide, but if these are ineffective, general practitioners (GPs) are often left with few treatment options, meaning people are frequently referred to see a specialist in secondary care. 6

Medical management of IBS is unsatisfactory, with no therapy proven to alter the long-term natural history and, at best, modest symptom reduction. Previous meta-analyses have suggested tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may be an efficacious treatment. 7–9 The most recent of these identified 12 trials, which included 787 patients. 9 Beneficial effects on IBS symptoms may arise from their well-known pain-modifying properties,10–13 as well as their influence on gut motility,14 rather than any antidepressive effects, as the doses used in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in IBS are considerably less than the dose required to have any effect on mood. However, duration of follow-up was limited to 12 weeks, all trials were conducted in secondary or tertiary care, where patients have more severe symptoms, and most studies were small. These limitations are important. The clinical relevance of demonstrating the effectiveness of a drug over a 12-week RCT in a condition that is chronic, and often lifelong,15 is debatable. In addition, although there is evidence from pooling data from secondary and tertiary care-based trials in a meta-analysis, it is not clear whether this effect would translate into a benefit in primary care, and whether this will reduce resource use and referrals to secondary care or improve quality of life and social functioning.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for the management of IBS in primary care states only that GPs should ‘consider’ TCAs as second-line treatment for IBS for their analgesic effect,16 for example ‘amitriptyline at a dose of 10 mg to 30 mg’, if dietary changes, fibre supplements, laxatives, antispasmodics or loperamide have not helped. However, this guideline also acknowledges that there is limited evidence to support this statement and proposes that a large RCT be conducted comparing a TCA with placebo in adults with IBS in primary care, with outcomes assessed at 3, 6 and 12 months, and including global improvement in IBS symptoms, effect on health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

At present, therefore, there is uncertainty as to whether TCAs are effective for the treatment of IBS in primary care, and this may mean GPs are reluctant to consider using them. In a prior survey < 10% of GPs used them often, and only 50% believed they were effective. 17 Given that 95% of GPs use these drugs for the treatment of insomnia in primary care,18 it is presumably uncertainty over their efficacy in IBS, rather than concerns about side effects, which explains this reluctance. If a drug that is potentially efficacious for IBS is being under-utilised, this will have a negative effect on both the health service and society, in terms of worse control of IBS symptoms, which will lead to lower quality of life for people with IBS, increased sickness absences from work, and higher costs of managing IBS in secondary care, due to greater numbers of referrals and increased rates of investigation.

Given the recommendations of the NICE guideline,16 together with the fact that two of the trials in the meta-analyses used amitriptyline,19,20 both of which were small, but positive, and its proven pain-modifying properties,11,12 as well as its effects on gut motility14 and visceral hypersensitivity,21 we chose to assess amitriptyline. This study was funded successfully as part of a commissioned call by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (NIHR award ref: 16/162/01), which identified the need to address the short- and long-term benefits of low-dose antidepressants for IBS in primary care, to help guide treatment decisions. Our work with patients and the public prior to obtaining funding confirmed a perceived need for the study but identified potential concerns about the use of a drug identified as an antidepressant for a condition like IBS. This provided a rationale for both the trial and a nested qualitative study to explore potential barriers to implementation, should low-dose amitriptyline prove to be effective.

Objectives

The objective of the AmitripTyline at Low-dose ANd Titrated for IBS as Second-line treatment (ATLANTIS) trial was to determine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of low-dose amitriptyline for IBS in primary care compared with placebo. A nested, qualitative study explored participant and GP experiences of treatments and trial participation, and implications for wider use of amitriptyline for IBS in primary care. We aimed to deliver a definitive assessment of the benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of low-dose amitriptyline as second-line treatment for IBS in primary care, within the NHS, to guide future adoption and implementation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

ATLANTIS was a pragmatic, randomised, multicentre, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, superiority trial of low-dose amitriptyline as a second-line treatment for adults with IBS in primary care. The majority of participants recruited consented to 12-month study participation, consisting of an initial 6 months of trial medication with the option to continue this voluntarily for a further 6 months. Treatment duration and follow-up was curtailed to 6 months for later recruits, due to protocol changes made during the coronavirus disease discovered in 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Additionally, although the data to inform a cost-effectiveness analysis were collected, the analysis was unable to be completed and is planned as future work, if further funding becomes available. A nested, qualitative study explored participants’ and GPs’ experiences of treatments and participating in the trial, including acceptability, adherence, unanticipated effects, and implications for the wider use of amitriptyline for IBS.

Patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives were involved at all stages and provided valuable contributions to trial design, documentation and outputs. The final protocol and subsequent amendments were approved by Yorkshire and the Humber (Sheffield) Research Ethics Committee (19/YH/0150) and published in full. 22 The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki and registered with the ISRCTN (ISRCTN48075063).

Trial objectives and outcome measures

Primary

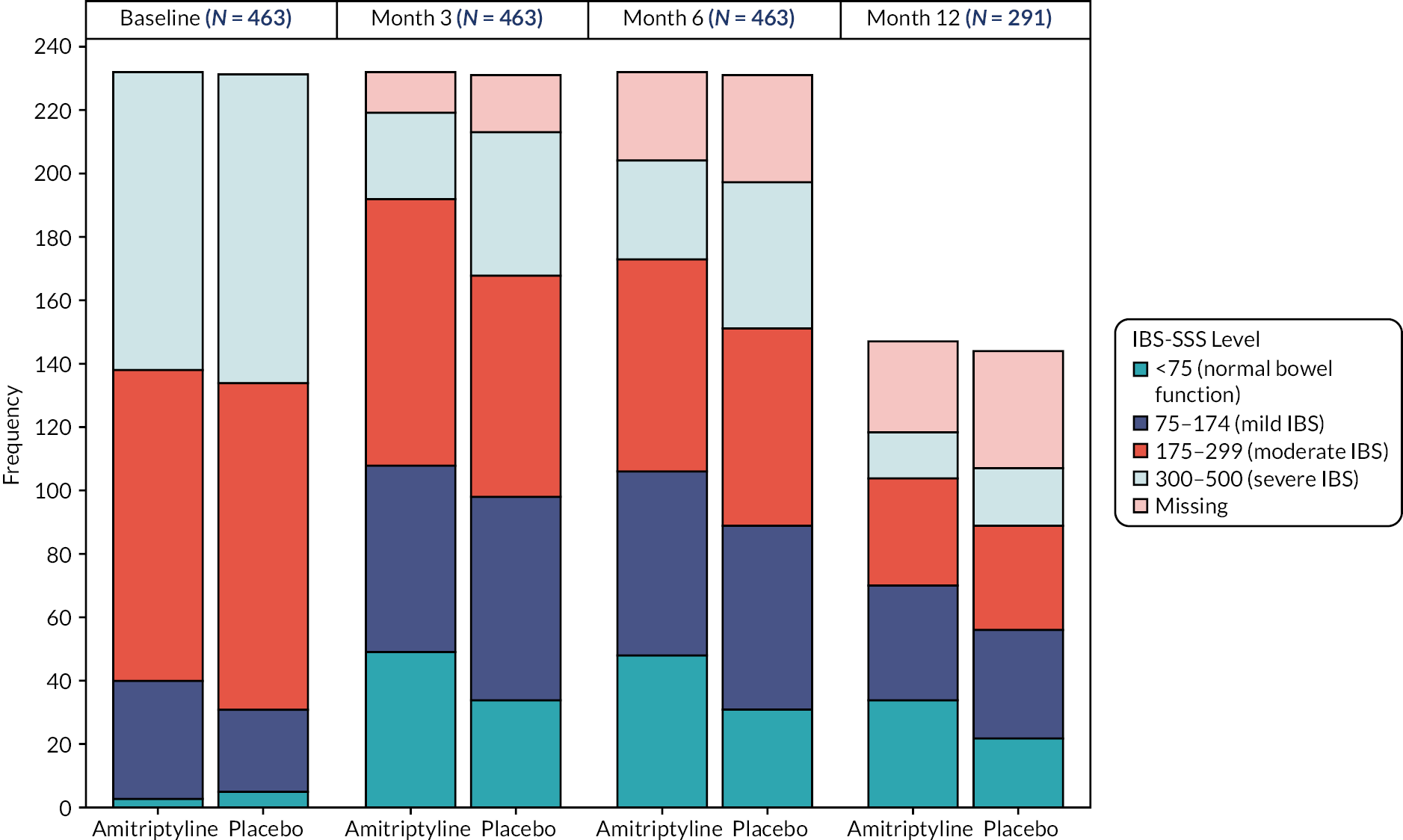

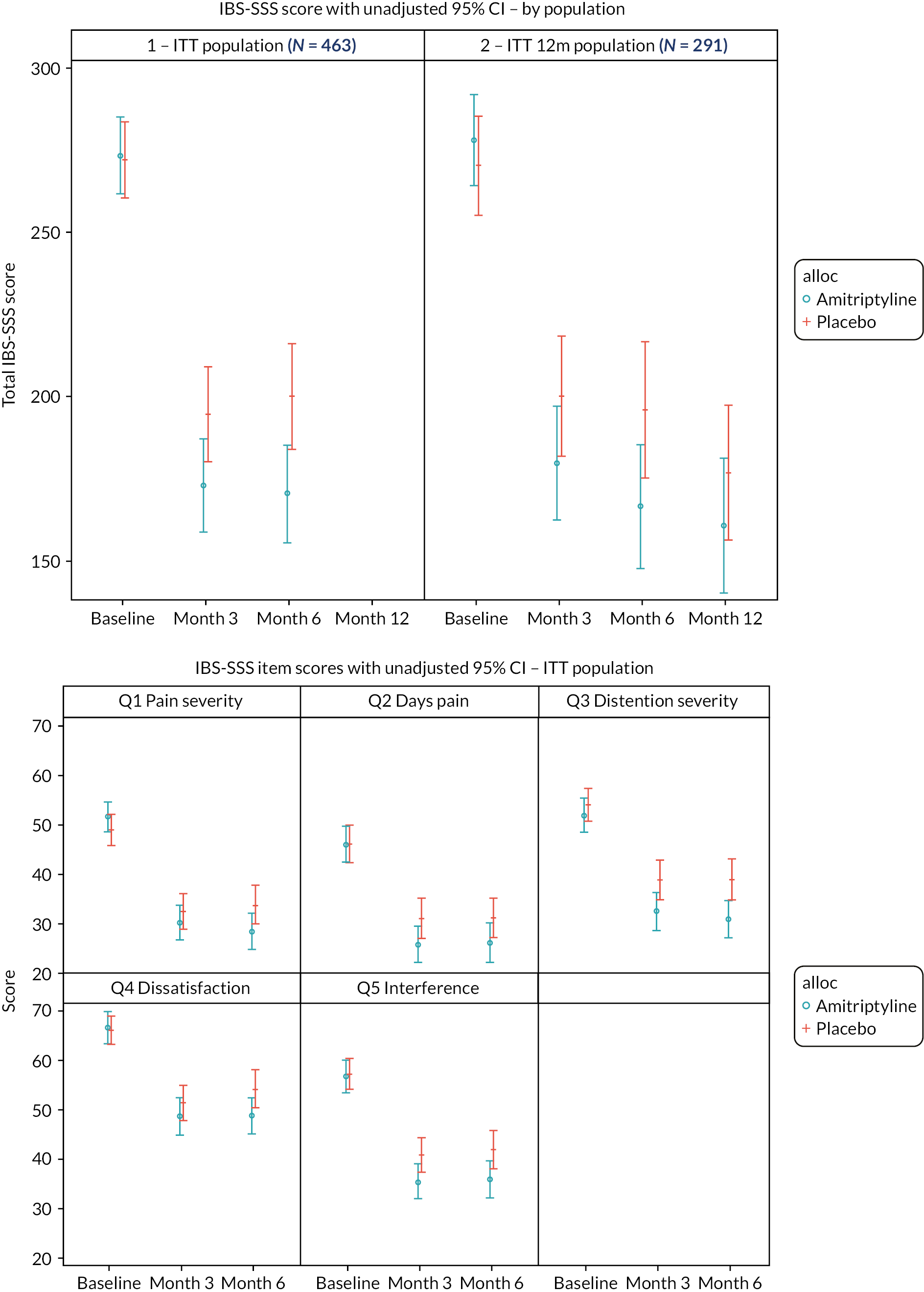

The primary objective was to determine the effect of amitriptyline on global symptoms of IBS, as measured by the IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS), 6 months after randomisation. The IBS-SSS is a validated, participant-reported, five-item questionnaire used widely in IBS trials. 23 It measures presence, severity and frequency of abdominal pain, presence and severity of abdominal distension or tightness, satisfaction with bowel habit and degree to which IBS symptoms are affecting, or interfering with, the person’s life in general. The maximum score is 500 points: a score of < 75 points indicates symptoms that are felt to be in remission, with normal bowel function; 75–174 points indicates mild IBS symptoms, 175–299 points moderate IBS and 300–500 points severe IBS.

Key secondary

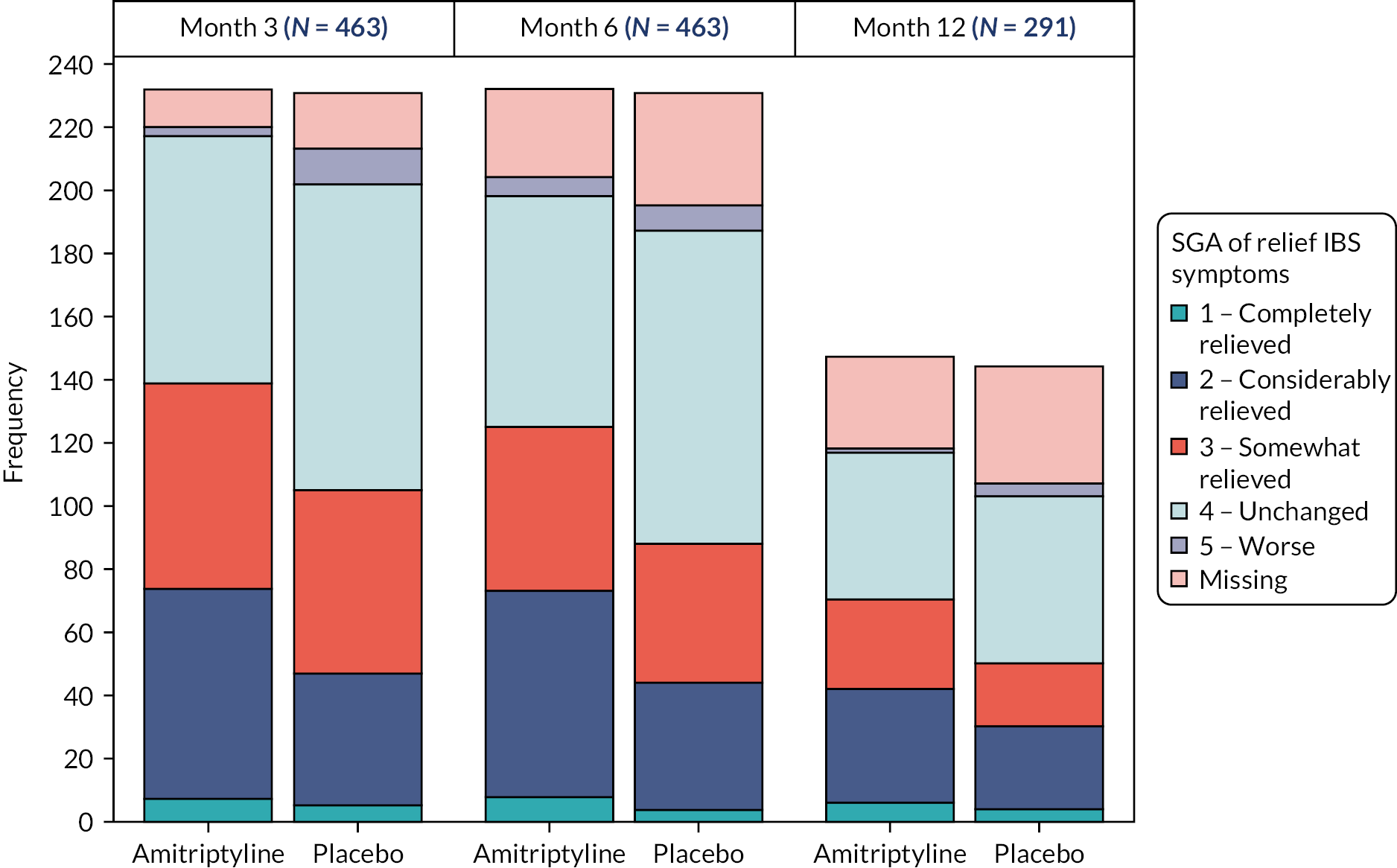

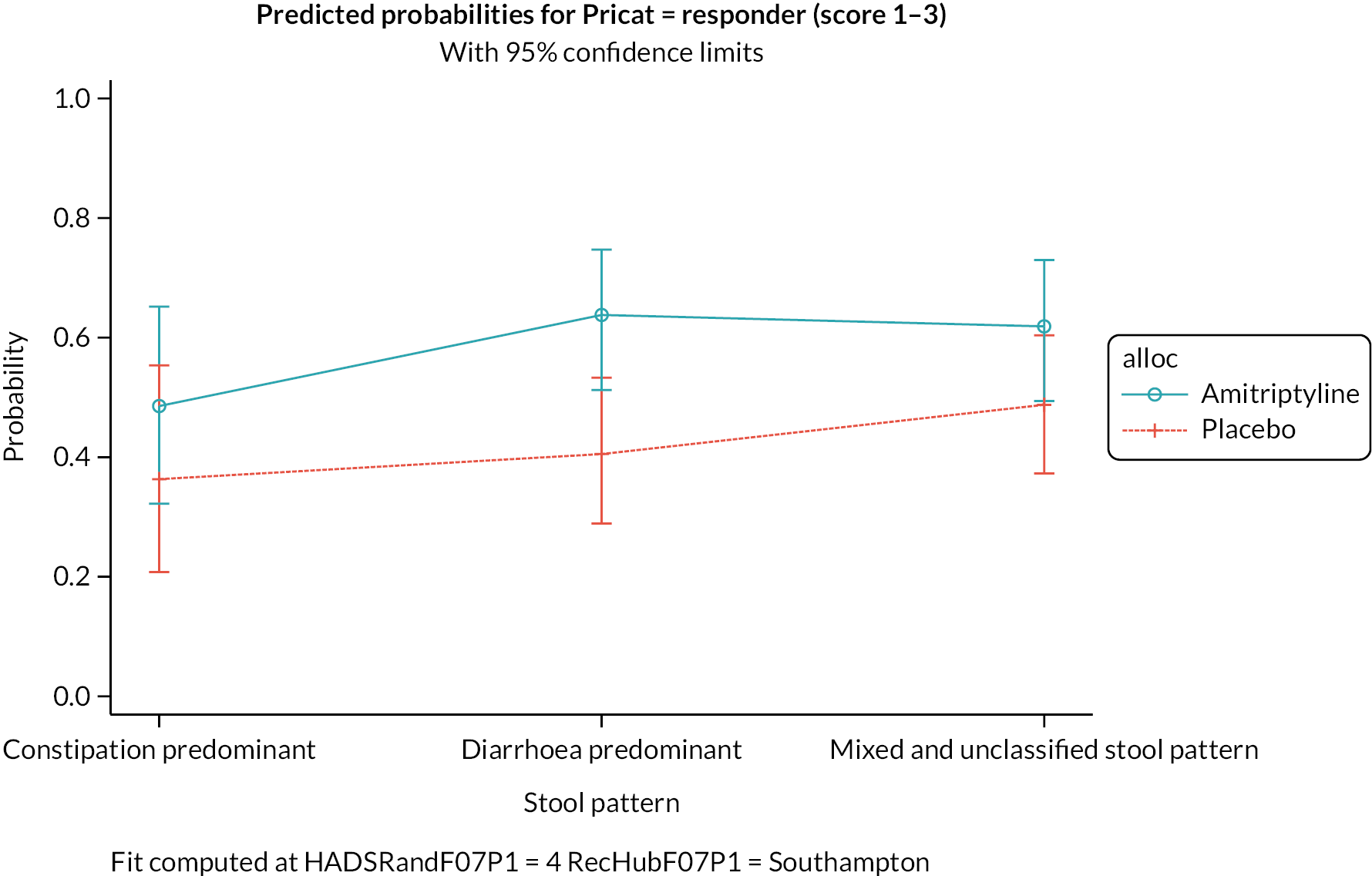

The key secondary objective was to determine the effect of amitriptyline on global symptoms of IBS, according to the proportion of participants with subjective global assessment (SGA) of relief of IBS symptoms. 24 Participants rate their relief from IBS symptoms on a scale of 1 to 5 ranging from ‘completely relieved’ to ‘worse’. Scores are dichotomised so that those scoring from 1 to 3 are considered responders and those 4 or 5 non-responders. At 6 months after randomisation, response was, therefore, defined as reporting somewhat, considerable, or complete relief of IBS symptoms.

Secondary

Secondary objectives were to assess the effect of amitriptyline on:

-

Global symptoms of IBS, as measured by the IBS-SSS at 3 and 12 months.

-

Global symptoms of IBS, as measured by the proportion of participants with SGA of relief of IBS symptoms,24 at 3 and 12 months, with response defined as above.

-

Adequate relief of IBS symptoms via a weekly response to the question ‘Have you had adequate relief of your IBS symptoms?’

-

IBS-associated somatic symptoms, as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-12 (PHQ-12),25,26 at 6 months.

-

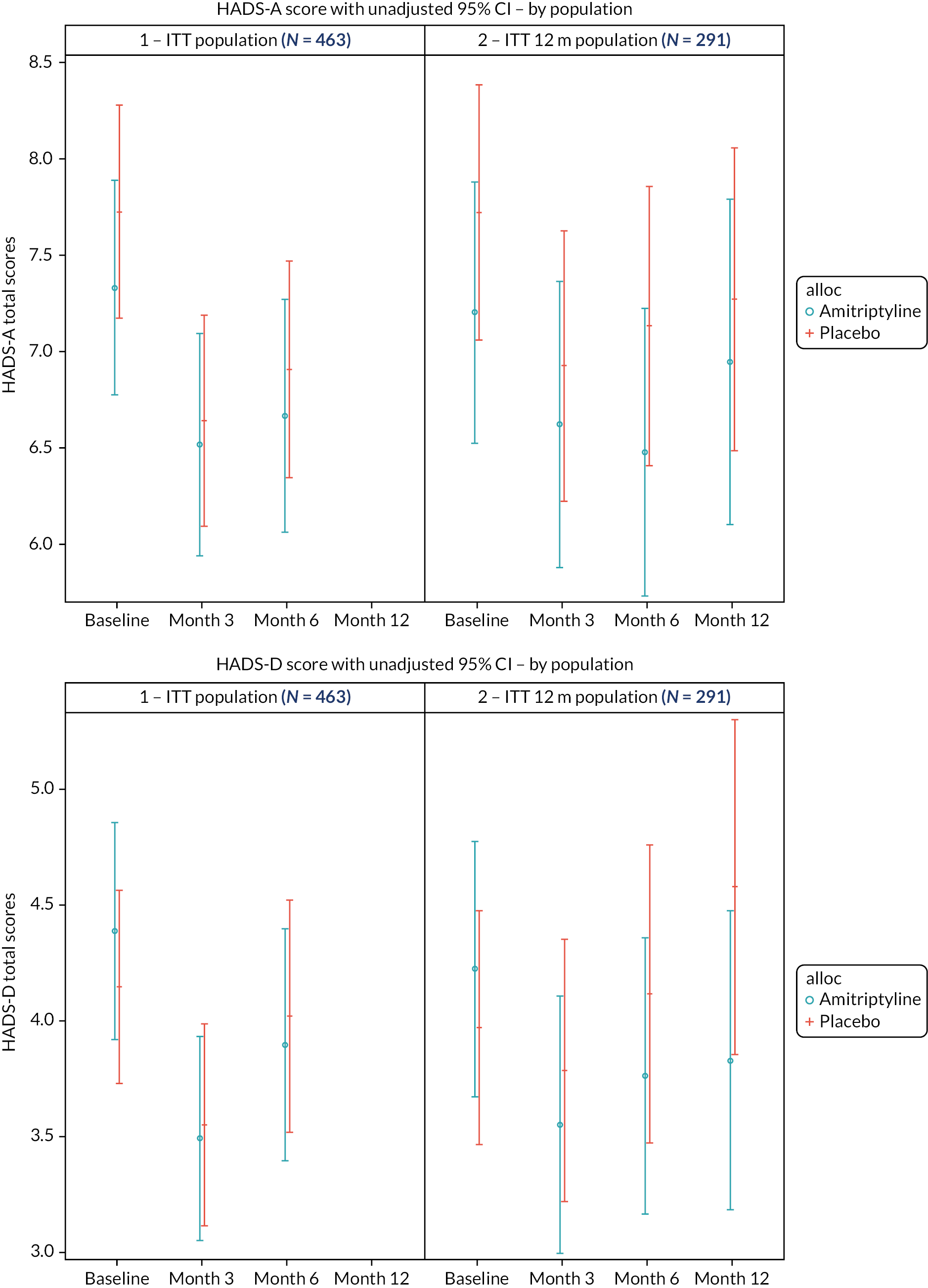

Anxiety and depression scores, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),27 at 3, 6 and 12 months.

-

Ability to work and participate in other activities, as measured by the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS),28–30 at 3, 6 and 12 months.

-

Acceptability of treatment, as measured by a response of ‘Yes’ to the participant-reported question at 6 months: ‘On balance do you find this medication acceptable to take and would you want to keep taking it?’. Non-acceptability defined for any participants reporting ‘No’, having discontinued treatment before 6 months, not starting trial treatment, or lost to follow-up.

-

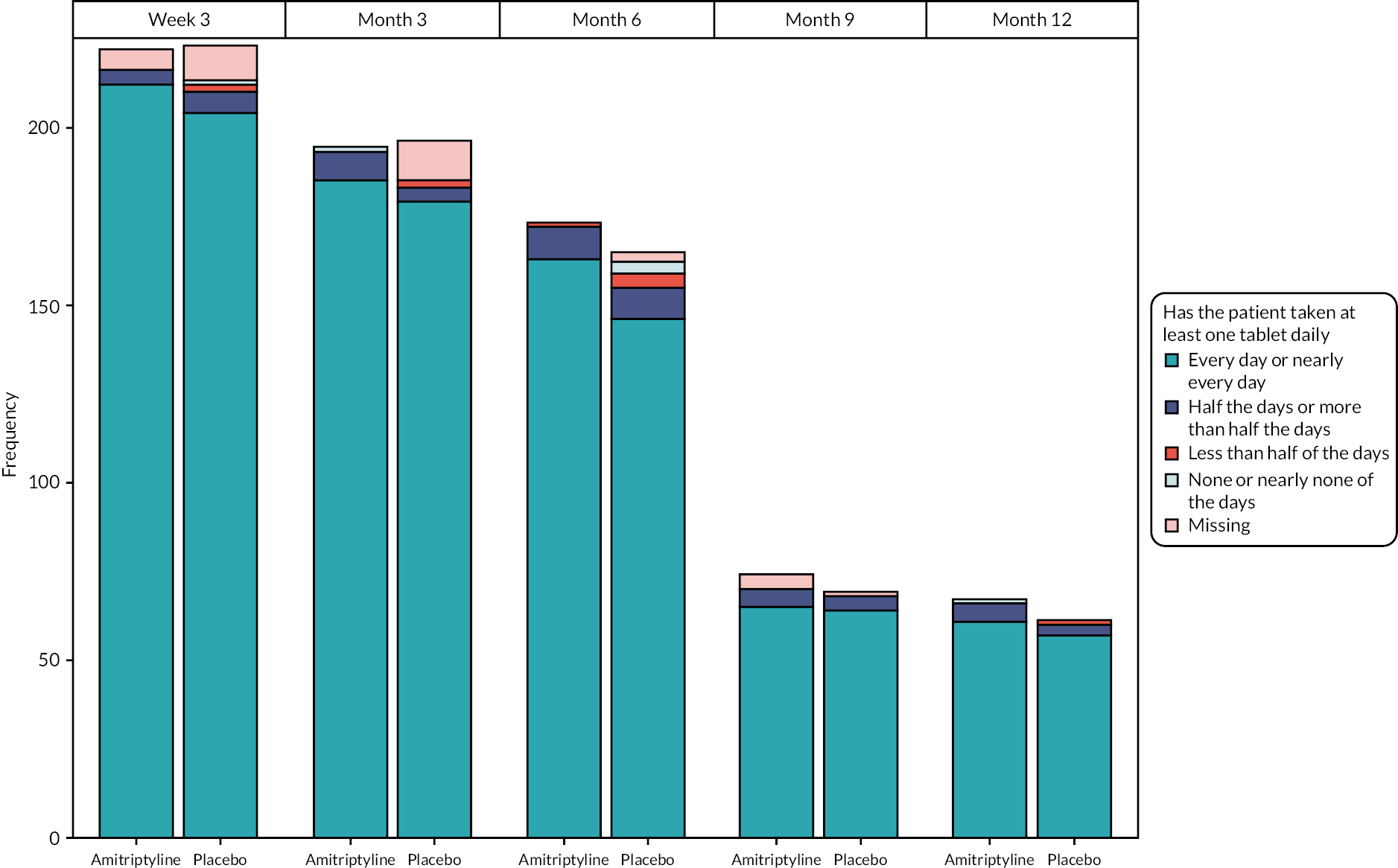

Self-reported adherence to treatment, based on participant-report, via the question: ‘Since you were last asked, which of the options best describes how often you have taken at least one tablet of the trial medication daily?’: ‘Every day or nearly every day’, ‘Half of the days or more than half the days’, ‘Less than half of the days’, ‘None or nearly none of the days’, with an additional response for participants having discontinued or not started trial treatment or lost to follow-up, at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months.

-

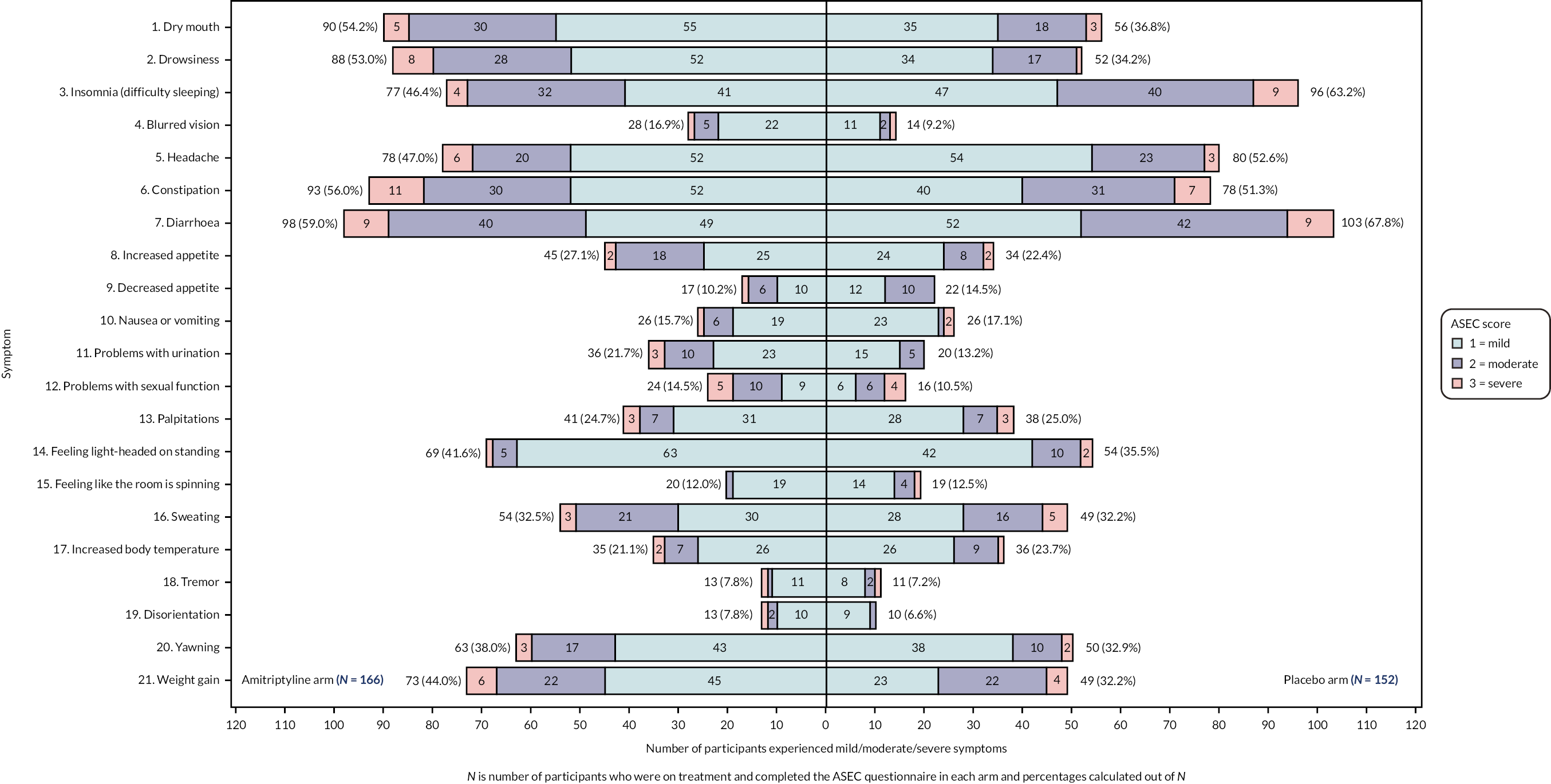

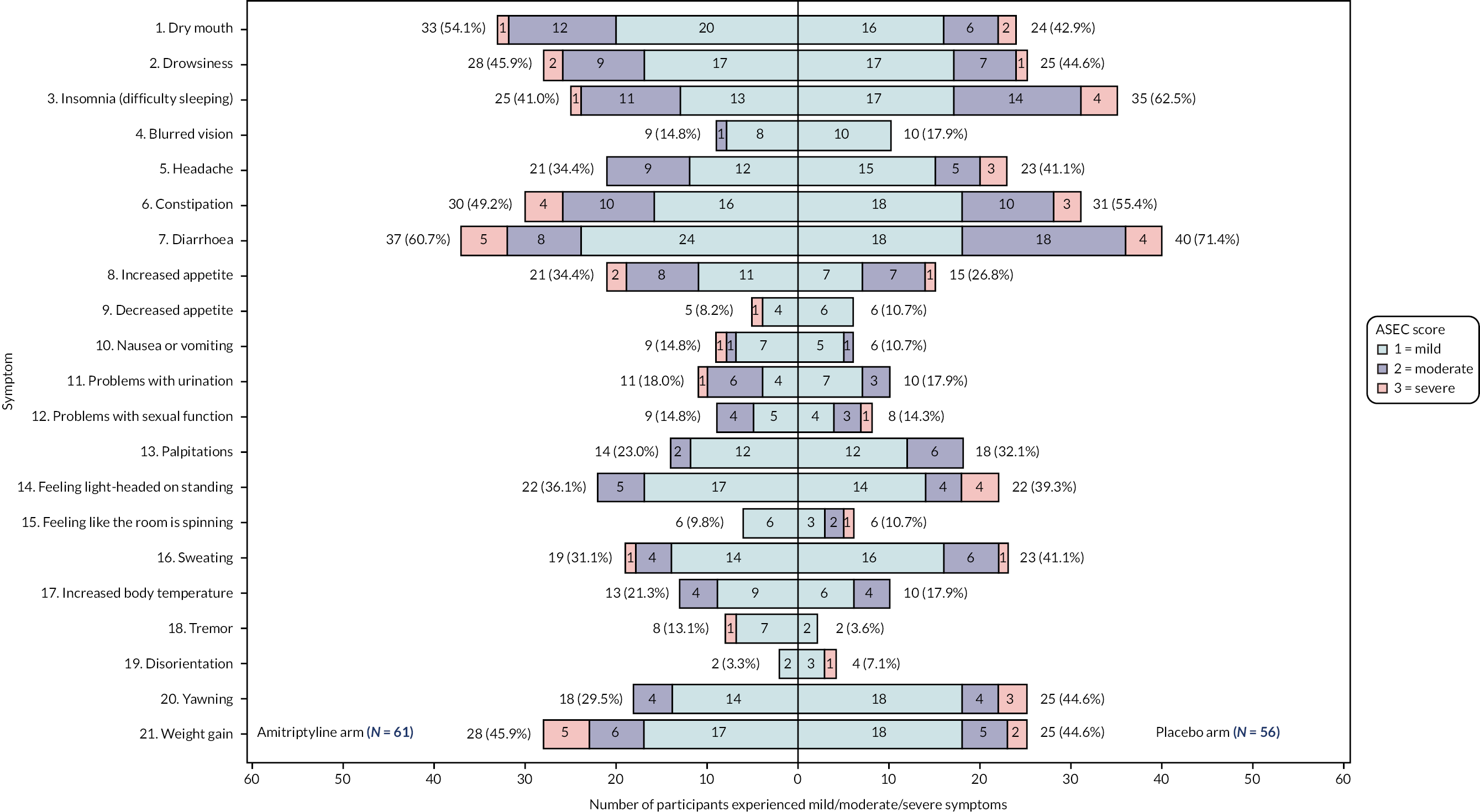

Tolerability of treatment, as measured by the Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist (ASEC),31 and mean ASEC total score [providing an approximate index of all reported adverse events (AEs) between arms], at 3, 6 and 12 months.

Cost-effectiveness objectives

Cost-effectiveness objectives were to assess the effect of amitriptyline on:

-

self-reported healthcare use, as measured by a health resource use questionnaire, at 3, 6 and 12 months

-

health-related quality of life, as measured by the EQ-5D-3L,32,33 at 3, 6 and 12 months

-

cost-effectiveness, as measured via the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, and expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) at 6 and 12 months.

Data were collected but analysis is on hold, awaiting further funding.

Nested qualitative study objectives

These are provided in Aims.

Participants

Adult patients with IBS in primary care, who were still symptomatic despite first-line therapies, as defined by NICE, were potentially eligible to take part in the trial. Eligible patients met all the listed inclusion criteria, and none of the exclusion criteria. Eligibility waivers to inclusion and exclusion criteria were not permitted.

Inclusion criteria

-

A diagnosis of IBS [of any subtype [IBS with constipation (IBS-C), diarrhoea (IBS-D), mixed bowel habits (IBS-M), or unclassified (IBS-U)]} in the patient’s primary care record, and fulfilling the Rome IV criteria34 (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

Ongoing symptoms, defined as an IBS-SSS score of ≥ 75 at screening,23 despite having tried dietary changes and first-line therapies as defined by NICE [fibre supplements (e.g. ispaghula husk), laxatives (e.g. bisacodyl), antispasmodics (e.g. mebeverine) or anti-diarrhoeals (e.g. loperamide)],16 which was assessed at screening via patient self-report.

-

A normal haemoglobin, total white cell count (WCC), and platelets within the last 6 months prior to screening.

-

A normal C-reactive protein (CRP) within the last 6 months prior to screening.

-

Exclusion of coeliac disease, via anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibodies, as per NICE guidance. 16

-

No evidence of active suicidal ideation, as determined by three clinical screening questions below, and no recent history of self-harm (an episode of self-harm within the last 12 months prior to screening). Any positive response on any of the three questions triggered urgent review by the patient’s GP. These clinical questions were used in preference to a formal suicidal risk rating scale, as such scales perform poorly in clinical practice:

-

whether the patient had experienced any thoughts of harming themselves, or ending their life, in the last 7–10 days

-

whether the patient currently had any thoughts of harming themselves or ending their life

-

whether the patient had any active plans or ideas about harming themselves, or taking their life, in the near future.

-

-

If female:

-

post menopausal (no menses for 12 months without an alternative medical cause), or

-

surgically sterile (hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy or bilateral oophorectomy), or

-

using highly effective contraception (and had to agree to continue for 7 days after the last dose of the investigational medicinal product).

-

-

Able to complete questionnaires and trial assessments.

-

Able to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Age > 60 years with no GP review in the 12 months prior to screening (to assess for organic gastrointestinal disease as a cause of gastrointestinal symptoms, as this becomes more likely with increasing age).

-

Meeting locally adapted NICE 2-week referral criteria for suspected lower gastrointestinal cancer. 35

-

A known documented diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease or coeliac disease.

-

A previous diagnosis of colorectal cancer.

-

Currently participating in, or within the 3 months prior to screening having been involved in, another clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product.

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Planning to become pregnant within the next 18 months.

-

Currently using a TCA or using a TCA for another indication within the last 2 weeks prior to randomisation.

-

Allergy to TCAs.

-

Other known contraindications to the use of TCAs, including patients with any of the following:

-

taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or receiving them within the last 2 weeks

-

already prescribed a TCA for the treatment of depression

-

previous myocardial infarction

-

recorded arrhythmias, particularly heart block of any degree, prolonged Q-T interval on ECG

-

mania

-

severe liver disease

-

porphyria

-

congestive heart failure

-

coronary artery insufficiency

-

receiving concomitant drugs that prolong the QT interval (e.g. amiodarone, terfenadine or sotalol)

-

Study settings

Participants were recruited from 55 general practices [including two participant identification centres (PICs)] within urban and rural settings, with a range of sociodemographic and diversity characteristics. A further three general practices (two in West Yorkshire and one in Wessex) were opened to recruitment but did not mail-out before the recruitment period had ended. Each practice was classed as a research site with a GP as the principal investigator (PI). Practices were required to have obtained management approval and to have undertaken a site initiation meeting prior to the start of recruitment into the trial.

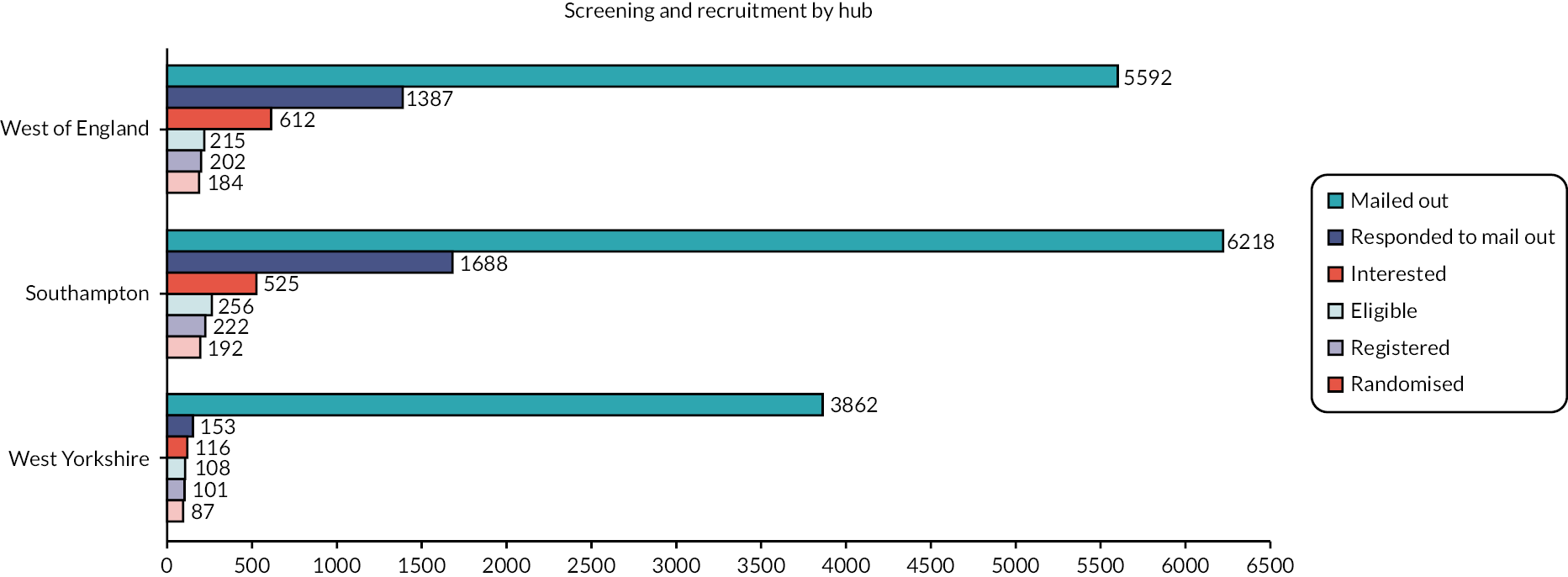

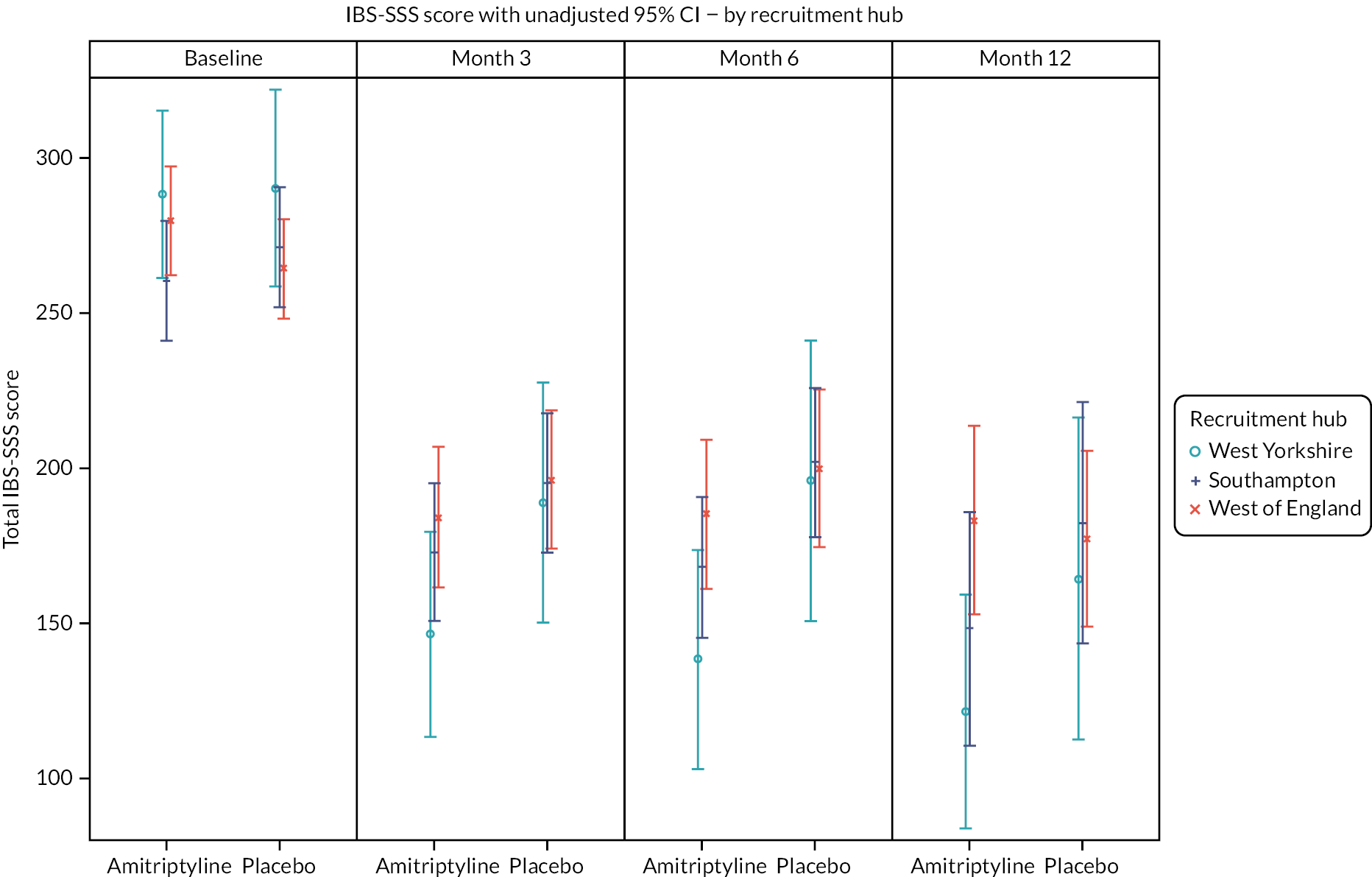

The 55 involved general practices were in three geographical regions, 22 in West of England (including one PIC), 13 in West Yorkshire (including one PIC) and 20 in Wessex. These three geographical regions were referred to as ‘hubs’. Each hub research team included a hub lead clinician and research nurse(s) or clinical study officer and was responsible for co-ordinating patient activity.

Screening, recruitment and registration

General practices willing to participate in the study were recruited with the assistance of the regional clinical research networks (CRNs). They searched their patient registers for potentially eligible patients aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of IBS, using a SnoMed clinical terms search, which was developed previously in the NIHR-funded ACTIB trial,36,37 and updated with the support of the Wessex CRN. A GP at the practice checked the list of patients to be contacted prior to the invitation letters being sent out, to ensure that it was appropriate to contact them. Potentially eligible individuals were then contacted by letter, sent by the general practice via DocMail, informing them about the trial and inviting them to take part.

The postal invitation included a participant information sheet and informed consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Potential participants interested in taking part returned a reply slip in a pre-paid envelope or contacted the study team directly via e-mail or telephone. The reply slip included a section for the potential participant to agree to be contacted about the study and, following this, for information to be requested from their GP to confirm their suitability to take part in the trial. This agreement was obtained by e-mail or telephone if the initial contact was not via returning a reply slip. The reply slip also included a ‘reason to decline’ section so that we could gather information on why people chose not to participate in the trial. Recruiting general practices were asked to provide an anonymised list of the age and sex of those invited so that the characteristics of those invited could be compared with those entering the trial.

General practitioners could also provide information about the trial to potential eligible patients opportunistically during their surgeries. Posters and leaflets were displayed in waiting rooms and the trial was advertised on general practice websites, where possible. Thus, if a patient with IBS attended a consultation, they were able to ask the GP about the study and to be given contact details for the study team, if appropriate.

Patients with IBS could also be identified by general practices working as PICs. PICs were responsible for the identification of potential patients for the trial and mailing out the invitation letter, participant information sheet, and informed consent form. Patients were then directed to respond to the invitation to the main hub research team. Patients identified from PICs were seen at the main general practice.

In an attempt to recruit an ethnically diverse sample, we reached out to minority ethnic organisations for advice as to how to make the trial more attractive to people from minority ethnic backgrounds and to publicise and raise the profile of the trial among these particular groups of potential participants.

The hub research nurse or clinical study officer contacted potential participants who replied to the study invitation to arrange a screening call. At this call, they provided further information about the trial and obtained verbal consent to telephone-screen the potential participants, using a screening form consisting of the Rome IV criteria,34 the IBS-SSS,23 and questions about the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All potential participants were assigned a unique screening identification number.

To allow generalisation of the trial results, and in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, each recruitment hub, on behalf of each general practice, maintained and provided to the Leeds Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) an anonymised screening log of the age and sex of all patients who were screened for entry into the study, including all those who confirmed interest. Documented reasons for ineligibility or declining participation were recorded and were closely monitored by the CTRU as part of a regular review of recruitment progress.

Patients who were potentially eligible, after telephone screening, were asked to attend a face-to-face appointment at their general practice to complete full eligibility screening, provide written informed consent, and obtain blood tests, if required. Patients were allowed sufficient time, and at least 24 hours, unless they wished to participate sooner, to consider participation and were given the opportunity to discuss the study with their family and healthcare professionals before they were asked whether they would be willing to take part. The research nurses and clinical study officer were trained in both the informed consent process and the ATLANTIS study and provided the patient with full and adequate oral and written information about the study, including the background, purpose, and risks and benefits of participation, as well as ensuring that the opportunity to ask questions concerning study participation was given. A GP was available to answer any questions or concerns, if required. The research nurses or clinical study officer also confirmed that the participant was free to withdraw from the study at any time without it affecting their future care. The original copy of the signed, dated, informed consent form was stored in the investigator site file. One copy was also filed in the medical records, one given to the participant, and one returned to the CTRU.

Informed consent from participants also included a request to take part in qualitative interviews at 6 and 12 months (for participants who had consented to 12-month follow-up), or 6 months only (for later participants who had only consented to 6-month follow-up), with information concerning the likely duration of these interviews provided. Finally, permission was also sought to collect longer-term routine data from electronic health records concerning amitriptyline and other IBS medication prescriptions, GP consultations for IBS, and secondary care referrals, outside the time frame of the trial itself, should further funding become available.

Following confirmation of written informed consent, participants were registered into the trial as soon as possible by an authorised member of the hub research staff. Informed consent for entry into the trial had to be obtained prior to registration. Registration was performed centrally using the CTRU automated web-based registration and randomisation system. All participants were allocated a unique trial identification number after they had been registered.

Blood test results were made available to the hub lead clinician (or delegate), the research nurse or clinical study officer, and the participant’s GP. In accordance with the trial inclusion criteria, if the blood tests showed an abnormal result (i.e. anaemia, raised or lowered total WCC, raised or lowered platelet count, a CRP over the normal laboratory range, or a positive anti-tTG antibody), the individual was not randomised into the trial, but was referred back to their GP for further assessment. However, if there were marginal, and potentially clinically insignificant, abnormalities of haemoglobin, WCC, or platelets, these were reviewed by the responsible GP and the hub lead clinician for consideration for inclusion into the study. In the case of an abnormal blood result for haemoglobin, WCC, platelets, or CRP that may have been a temporary abnormality (e.g. secondary to a recent infection), or a marginal or minor abnormality, the blood test could be repeated 2 to 4 weeks later, if the participant wished to undertake further screening for the study. If on repeat testing total haemoglobin, WCC, platelet count, and CRP were acceptable clinically, the participant could continue with screening.

If blood results were within acceptable limits, the GP from the research site was asked to confirm eligibility and sign the study-specific trial medication prescription form. Participants were then provided with web-based or postal questionnaires, depending on preference, to complete at baseline. These had to be completed no more than 7 days prior to randomisation if online, and within 14 days prior if postal. Participants were not randomised until the baseline questionnaires were completed. If randomisation had not taken place within 4 weeks of the baseline questionnaires being completed, these were repeated.

Prior to randomisation, women of childbearing potential were asked to confirm verbally that they were not pregnant and were on reliable contraception due to the potential risks of amitriptyline in pregnancy. If they were unable to do so, they were asked to perform a urine pregnancy test within the 7 days prior to randomisation. They were provided with a pregnancy test to use at home, to facilitate a result as close as possible to randomisation, and hence treatment commencing. Because this formed part of the eligibility criteria, the lead clinician at each hub reviewed and signed the final eligibility for these participants. If the test was positive or unclear the individual was not randomised into the trial but was directed to their GP.

If the participant was ineligible, or no longer wished to take part in the trial, the local research team withdrew the participant. They did not undergo any other study assessments and they were referred to their GP. Reasons for non-randomisation were documented, where available.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to receive amitriptyline or placebo. Allocation, via a web randomisation system at the University of Leeds CTRU, was performed using minimisation with a random element, to ensure balance with respect to the presence of raised HADS-depression scores (score ≥ 8), IBS subtype (IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M or IBS-U) and recruitment hub between treatment arms.

Blinding

As the trial was double-blind, neither the participant nor those responsible for their care and evaluation (treating team and research team) knew the treatment allocation or coding of the treatment allocation. Central pharmacy was also blinded to treatment allocation. This was achieved by identical tablets, packaging, and labelling of both the amitriptyline and placebo. The process for dose titration was the same for amitriptyline and placebo. Each bottle of amitriptyline or placebo was identified by a unique kit code, generated randomly. Lists of the kit codes and their corresponding treatments were generated by the CTRU and sent to Modepharma Limited, who supplied the kits and the code break envelopes. Management of kit codes on the kit logistics application, which was linked to the 24-hour randomisation system, were conducted by the unblinded CTRU safety statistician, in addition to maintaining the back-up kit code list.

Access to the code break envelopes at CTRU was restricted to the safety statistician and designated safety team. Interim emergency unblinding before 6- or 12-month assessments was strongly discouraged and the blind was only to be broken if information about the participant’s trial treatment was clearly necessary and would alter the appropriate medical management of the participant. Interim unblinding could be requested on the grounds of safety by the chief investigator, local PI, an authorised delegate, or a treating physician. It was anticipated that these requests would most likely originate at the time of an AE or planned change in non-trial related drug therapy. In the event of a serious adverse event (SAE), all participants were to be treated as though they were receiving the active medication (i.e. amitriptyline). Any unblinded interim reports supplied to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) were provided by the CTRU safety statistician and were password-protected securely.

At study entry, all participants were asked to provide their consent to be contacted by the CTRU to send them their treatment allocation after they had reached the 12-month assessment point in the trial, for participants who had consented to 12-month follow-up, or after they had reached the 6-month assessment point in the trial, for later participants who had consented to only 6-month follow-up. If they agreed, they and their GP were informed of their treatment allocation shortly after their final follow-up at 6 or 12 months. This was done to facilitate post-trial treatment decisions. The information was provided via e-mail, supported by an evidence-based unblinding leaflet (see Report Supplementary Material 1) to deal with any potential questions that may arise, which was developed with input from PPI representatives. Information concerning treatment allocation was provided only when CTRU had confirmation that all study assessments and contacts were complete, and all required data had been received. This information was only provided to the participant and their GP to protect and maintain the overall blind for the research team. Where participants needed further support following provision of treatment allocation and the evidence-based leaflet, they were directed to the ATLANTIS qualitative researcher, who was independent of the day-to-day running of the trial, recruitment, data collection, and treatment decisions.

Intervention

Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to receive titrated low-dose amitriptyline (Teva, the Netherlands) or identical-appearing placebo for 6 months. All participants also received the British Dietetic Association NICE-approved dietary advice sheet for IBS,38 and were provided with usual care for IBS from their GP during the trial, with the exception that amitriptyline or other TCAs could not be commenced during the trial. In addition, drugs contraindicated with TCAs, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors or drugs prolonging the QT interval, were prohibited during the trial. Following randomisation, participants were offered an optional GP appointment at 1 month, in case of any questions, in addition to research nurse and clinical study officer support.

All participants were provided with standardised written information about dose adjustment (see Report Supplementary Material 1), developed with input from PPI representatives, to guide participant-led dose titration. This advised participants to commence at a dose of amitriptyline or placebo of 10 mg (one tablet) once-daily at night, with dose titration occurring over 3 weeks, up to a maximum of 30 mg (three tablets) once-daily at night or down to a minimum of 10 mg on alternate days, depending on side effects and response to treatment. Participants were supported throughout the titration phase, with telephone calls from the research nurse or clinical study officer at weeks 1 and 3 to assess tolerability. After an initial 3-week titration, it was expected the majority of participants would remain on a steady dose, but they could modify their dose throughout the study in response to their symptoms and any side effects, reflecting how amitriptyline would be used in usual care.

For safety purposes, due to the potential risks from amitriptyline in overdose, participants were provided with an initial 1-month supply of trial medication following randomisation. Further trial medication was dispensed at months 1 (2-month re-supply), 3 (3-month re-supply), 6 (3-month re-supply) and 9 (3-month re-supply), as appropriate, with the hub research nurse or clinical study officer contacting participants by telephone prior to re-supply at weeks 1 and 3 and months 3, 6, 9 and 12 to assess both for new evidence of suicidal ideation, adherence to trial medication, tolerability of trial medication via the ASEC, and reasons for discontinuation of trial medication (if appropriate), as well as recording concomitant medications and providing support as needed.

Participants were planned to be followed up for up to 12 months. Our PPI input prior to the grant submission revealed that 6 months of blinded treatment was felt to be the maximum reasonable initial commitment. Therefore, participants randomised in the first stage of recruitment (before 7 October 2021) received 6 months of trial medication initially and then were able to either continue blinded trial medication for a further 6 months or stop trial medication; participants randomised in the later stages of recruitment (on or after 7 October 2021) received 6 months of trial medication only. Following trial and outcome measure completion participants had the option to be unblinded and discuss amitriptyline prescription for IBS under the care of their GP if they wished.

Trial medication was supplied by Modepharma Limited and dispensed by post to the participant’s home by a central pharmacy at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. A copy of the study-specific trial medication prescription form was sent to the central pharmacy to facilitate prompt dispensing when the participant was randomised, although a wet ink copy was required before the study trial medication was dispensed and shipped to the participant. The participant confirmed medication receipt with the hub research team.

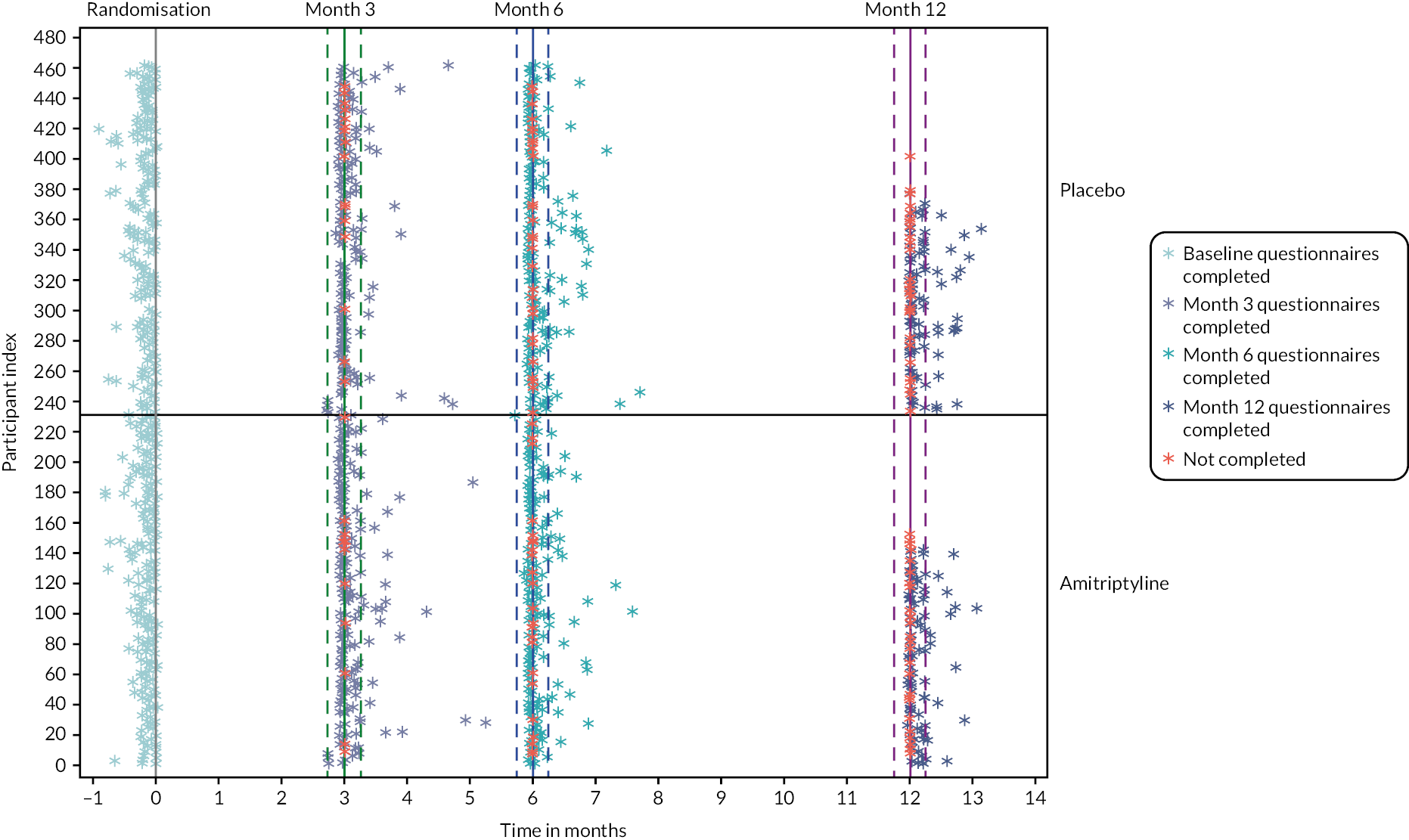

Assessments and data collection

Trial assessments are summarised in Table 1 with further details of assessment instruments provided below. Participants were contacted by the researcher via telephone at 1 and 3 weeks and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (as appropriate) to support titration and ongoing treatment, including assessments of suicidal ideation, toxicity, adherence to, and acceptability of trial medication. Participants completed electronic or postal questionnaires at baseline, and 3 and 6 months, and answered a weekly question ‘Have you had adequate relief of your IBS symptoms?’ for the initial 6-month study duration. Participants recruited to 12-month follow-up, before 7 October 2021, also completed electronic or postal questionnaires at 12 months. Text message and e-mail reminders were sent at 1 week to prompt completion of questionnaires. Non-responders were telephoned with a final reminder.

| Time point | Study period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening, recruitment, registration | Randomisation | Follow-up | |||||||

| −4 weeks − 0 | 0 | Week 1 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 9a | Month 12a | |

| Enrolment | |||||||||

| Verbal consent and eligibility screen | X | ||||||||

| Eligibility confirmation (including Rome IV criteria, blood and pregnancy tests) | X | ||||||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||||

| Sociodemographic details: medical history; duration of IBS symptoms; previous depression or anxiety; Bristol Stool Form Scale | X | ||||||||

| Allocation | X | ||||||||

| Interventions | |||||||||

| Amitriptyline |

|

||||||||

| Placebo | |||||||||

| Study medication provision | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Optional GP review | X | ||||||||

| Assessments (research nurse/clinical study officer collected, while on treatment) | |||||||||

| Suicidal ideation | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Current dose | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Concomitant Medications Review | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Treatment adherence | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Treatment acceptability | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ASEC | X | X | X | ||||||

| Exit survey | X | ||||||||

| Assessments (self-completed questionnaire) | |||||||||

| ASEC | X | X | X | ||||||

| IBS-SSS | X | X | X | X | |||||

| HADS | X | X | X | X | |||||

| EQ-5D-3L | X | X | X | X | |||||

| WSAS | X | X | X | X | |||||

| PHQ-12 | X | X | |||||||

| SGA of relief of IBS symptoms | X | X | X | ||||||

| Health resource use | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Relief of IBS symptoms | Weekly diary with SMS text reminder | ||||||||

| Optional participant interview (nested qualitative study) | X | X | |||||||

Suicidal ideation was assessed by the researcher during all planned telephone calls via three brief questions. If yes to any, the participant was not issued with any further trial medication and their GP was contacted immediately.

-

Has the participant experienced any thoughts of harming themselves, or ending their life, in the last 7–10 days?

-

Does the participant currently have thoughts of harming themselves or ending their life?

-

Does the participant have any active plans or ideas about harming themselves, or taking their life, in the near future?

Adherence to treatment was measured by the researcher during the planned telephone calls. Participants were asked ‘Since you were last asked, which of the options best describes how often you have taken at least one tablet of the trial medication daily?’ with response options: ‘Every day or nearly every day’, ‘More than half of the days’, ‘Less than half of the days’ or ‘None or nearly none of the days’.

Acceptability of treatment was measured by participant self-report during the researcher telephone calls, as well as the decision to continue trial medication beyond 6 months. Participants were asked ‘On balance do you find this medication acceptable to take and would you want to keep taking it?’.

Adverse events were collected via a validated self-completed questionnaire, the ASEC,31 which consists of 21 potential AEs rated on a scale of 0 (absent) to 3 (severe), and also asks the individual whether they deem the AE to be treatment-related. This has been shown to demonstrate good agreement with a psychiatrist’s rating of the occurrence of treatment-related AEs with antidepressants. The ASEC was completed as part of toxicity and tolerability assessments conducted by the researcher at weeks 1 and 3, and month 9 telephone calls, and via participant-completed questionnaires at months 3, 6 and 12.

An exit survey was completed with the participant by the researcher during the 6-month telephone call to record any changes participants had made to diet, exercise levels, or IBS treatments, their experience of the ATLANTIS trial medication, and which treatment they thought they were allocated to and why.

The IBS-SSS is used widely in trials of medical therapies in IBS. It is a five-item self-administered questionnaire, as described above. 23

The HADS is a well-validated, commonly used, self-report instrument for detecting symptoms of anxiety and depression in people with medical illnesses. 27 It consists of a total of 7 items measuring anxiety, and 7 measuring depression, scored from 0 to 3, with a total score of 21 for each. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms of anxiety or depression.

The EQ-5D-3L is the most frequently used measure for generating QALYs. 32,33 It has been demonstrated to be appropriate in patients with IBS.

The WSAS measures the effect of chronic diseases on peoples’ ability to work and manage at home and participate in social or private leisure activities and relationships. 28–30 The WSAS has been shown to be sensitive to change in IBS trials. It has five aspects scored from 0 (not affected) to 8 (severely affected), with a total possible score of 40.

The PHQ-12 comprises 12 somatic symptoms from the full Patient Health Questionnaire-15. Each symptom is scored from 0 (‘not bothered at all’) to 2 (‘bothered a lot’). Higher scores indicate the presence of somatoform-type behaviour, which is a measure of psychological health.

The SGA of relief of IBS symptoms is frequently used in treatment trials in IBS to identify responders to therapy as described above. 24

Health resource use, including healthcare use, use of other medications for IBS, and need for referral to secondary care, was self-reported by the participant via a resource use questionnaire, using a 3-month recall period. If the participant consented to 12-month follow-up, then the recall period was extended to 6 months. This collected data concerning all resource use and medications in the community, in primary and secondary care, social care, hospitalisation, outpatient specialist visits, and diagnostic investigations. Because of the societal perspective, the questionnaire also included questions on out-of-pocket expenses, employment status, and days lost due to illness.

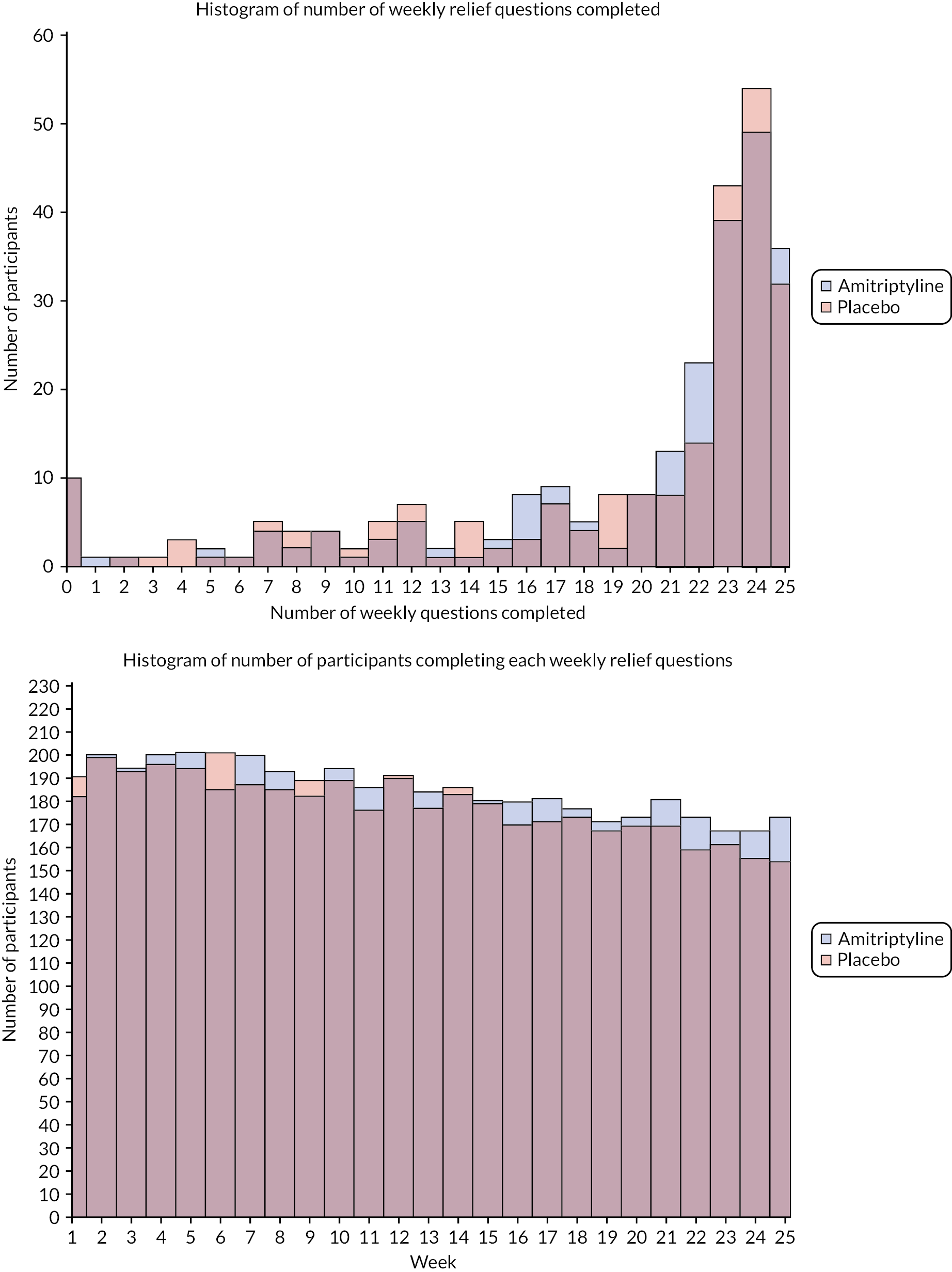

Relief of IBS symptoms was measured by the yes/no response to ‘Have you had adequate relief of your IBS symptoms?’ asked electronically, or via a paper-based diary. Participants were sent a weekly text reminder from CTRU to complete the assessment.

Summary of changes to the protocol

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the trial pausing recruitment in March 2020 for 4 months, with a series of national lockdowns, and led to subsequent reduced rates of new practice and participant recruitment. Internal pilot objectives were, therefore, difficult to evaluate in the original time frame and a costed trial extension was required to complete recruitment and follow-up of the trial. Several substantial amendments were made to the trial protocol, including an approved amendment due to the impact of COVID-19, to reduce the duration of trial medication and follow-up from 12 months to 6 months and to remove the cost-effectiveness analysis, which is now dependent on further additional funding. This was done to minimise additional funding required to complete the trial and to prioritise funds for participant recruitment. Site and hub PIs, hub researchers, and participants were informed of all protocol amendments following ethical and regulatory approvals. A summary of all protocol changes can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Sample size

We estimated that an evaluable sample size of 414 participants would provide 90% power to detect the minimum clinically important difference of 35 points between amitriptyline and placebo at 6 months on the IBS-SSS,23 assuming a maximum standard deviation (SD) of 110 points on the IBS-SSS,39,40 and 5% two-sided significance level, equating to a small to moderate effect size of 0.32. The 35-point between-group difference on the IBS-SSS was agreed as a minimum clinically important difference in the ACTIB trial, which was another treatment trial in IBS in UK primary care. 36,37 The evaluable sample size gave at least 85% power to detect a 15% absolute difference in SGA of relief of IBS symptoms,24 our key secondary outcome. We planned to recruit 518 participants to allow for 20% loss to follow-up. 22

Statistical methods

A detailed statistical analysis plan was written and signed off by the Trial Management Group (TMG) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) before analysis was undertaken.

Analyses of data up to 6 months post randomisation were conducted on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as all participants randomised, regardless of adherence to the intervention, unless otherwise indicated. Analyses of treatment-related data beyond 6 months, and secondary outcomes at 12 months, were conducted on the 12-month ITT population, defined as all participants who were randomised and who consented to 12-month follow-up, regardless of adherence to the intervention. Analysis of data beyond 6 months is presented separately in the report as results are applicable only to a subset of participants and are no longer a fully randomised comparison as participants could choose to continue treatment or not at 6 months.

An overall two-sided 5% significance level was used for all outcome comparisons. Outcome data were analysed once only after data lock, at final analysis, and no interim analyses were planned. Analyses were completed in SAS® (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) version 9.4. Statistical monitoring of safety data was conducted throughout the trial and reported at agreed 6-monthly intervals to the DMEC.

Descriptive analysis

Summary statistics, by treatment group (where applicable) and overall, are used to provide a descriptive analysis of the study conduct, including screening, accrual, protocol violations, withdrawals, treatment receipt, participant follow-up, and analysis populations informing the study CONSORT diagram.

A flow diagram further summarises the course of participants through the screening and recruitment process, including total number of patients approached by GP mail-out, as well as the number who expressed interest, and were screened, eligible, consented, registered, and randomised, along with reasons for drop-out at each stage. Age and sex of all patients were also summarised at each stage of the screening and recruitment process and compared with those randomised.

Baseline characteristics and questionnaire scores of recruited participants were summarised overall, by treatment group, and by availability of 6-month primary outcome data (to inform our missing data approach).

Treatment delivery and receipt were summarised overall and by treatment group, including details of treatment received and discontinuation; dosage, titration, and modifications; adherence; kit replenishment and replacement; ongoing monitoring of suicidal ideation and concomitant medications; uptake of optional GP review; and participant-reported changes in diet, exercise, other treatments, IBS symptoms, and any potential contributing factors.

The success and process of blinding are summarised overall and by arm, including details of an exit survey of participants, that is which treatment the participant thought they received and why, and end-of-trial participation unblinding.

Primary outcome analysis

A linear regression model, adjusted for true values of minimisation variables (recruitment hub, stool type, baseline HADS-depression score) and IBS-SSS score at baseline, was used to test for differences between the treatment groups on the IBS-SSS at 6 months. Missing data were imputed by treatment arm via multiple imputation by chained equations with 25 imputations, including recruitment hub, IBS subtype, sex, age, baseline questionnaire scores (IBS-SSS, PHQ-12, HADS and WSAS), 3-month IBS-SSS score and 6-month treatment status in the model. The 3-month IBS-SSS score was imputed within the same model in a preliminary step, incorporating 3-month (rather than 6-month) treatment status. Sensitivity analyses on a per-protocol population (using multiple imputation), and on participants with complete data (ITT to data availability), were performed to test robustness of results. Results were expressed as point estimates of the mean difference, together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values.

Secondary outcome analysis

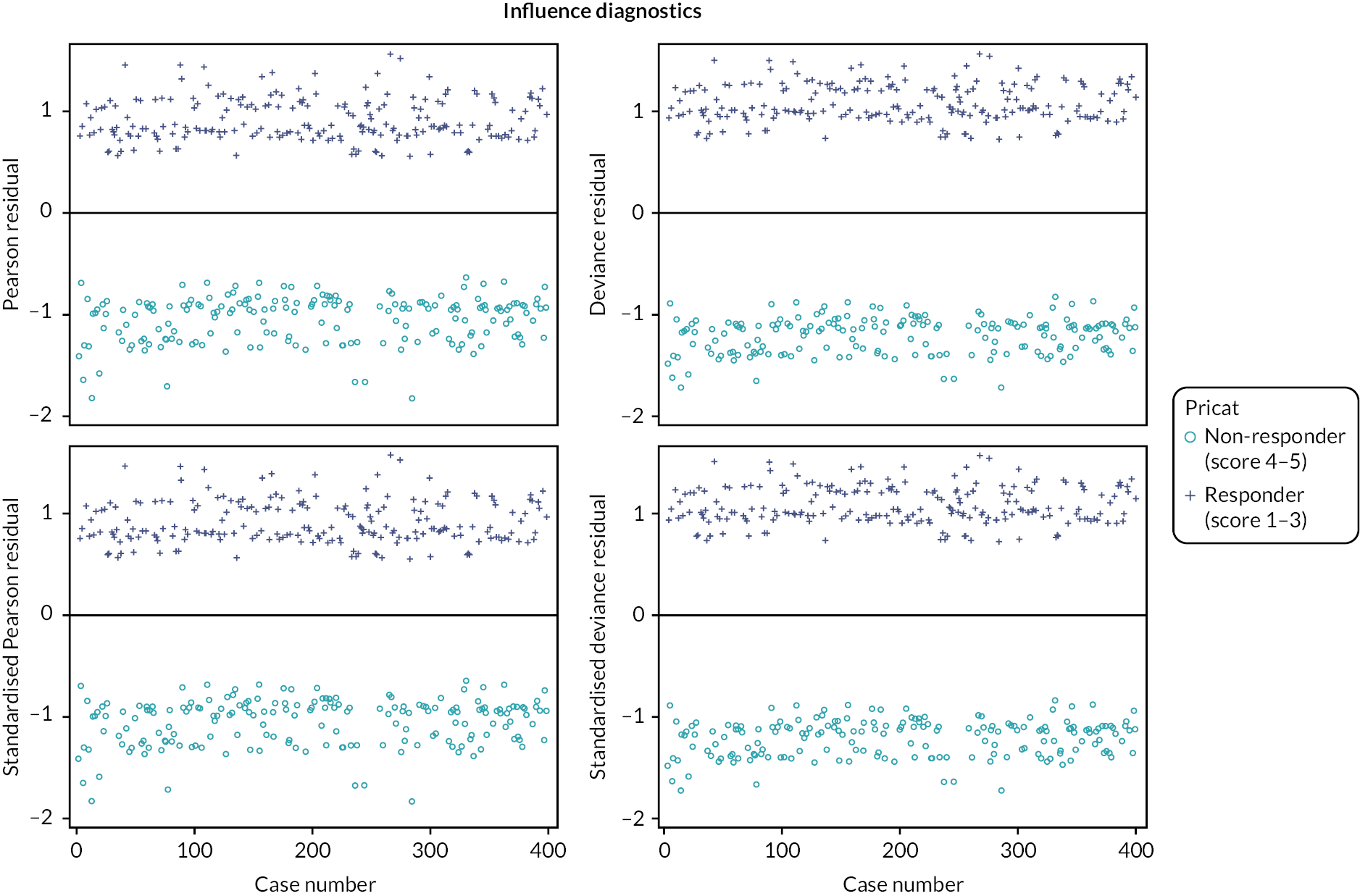

Continuous outcomes (where applicable at 3, 6 and 12 months), including IBS-SSS, HADS, WSAS and PHQ-12 scores, were analysed in the same manner as the primary outcome adjusted for the respective baseline score. Analysis of the PHQ-12 was adjusted additionally for sex due to differences in the maximum available total score for male and females. Secondary binary outcomes, including SGA of relief of IBS symptoms at 3, 6 and 12 months, and acceptability of treatment at 6 months were analysed similarly in logistic regression models with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Missing IBS-SSS, HADS, WSAS, PHQ-12, SGA and acceptability data were imputed in the same manner as the primary outcome, as appropriate to outcome type and incorporating both 3- and 6-month outcomes where applicable.

We planned to analyse adherence (at week 3, months 3, 6, 9 and 12) using ordinal regression. However, due to violation of the proportional odds assumption, only descriptive analyses are presented.

Adequate relief of IBS symptoms, measured weekly to 6 months, was analysed using a repeated-measures model based on available data (all participants in the ITT population with at least one weekly observation included). A likelihood-based generalised linear mixed model with population-averaged (marginal) inference and unstructured covariance matrix was used to compare response between treatment groups at each week and overall, across weeks. The treatment group, true values of minimisation variables, time (in weeks) and the treatment time interactions were fitted as fixed effects. Results were expressed as ORs, together with 95% CIs and p-values. Descriptive analysis of aggregated weekly data included responder status based on the number and proportion of participants reporting adequate relief in ≥ 50% of weeks (i.e. ≥ 13 of 25 weeks).

Tolerability of trial treatment, based on the participant’s self-reported symptoms on the ASEC at 3, 6 and 12 months, was analysed according to the safety population (see Safety analysis) and using available data for participants on trial treatment at each time point. A linear regression model, adjusted for true values of minimisation variables, was used to test for differences between the treatment groups on the total ASEC score at each time point.

Sensitivity analyses of secondary outcomes were performed to test robustness of results. These included:

-

analysis of complete data (ITT to data availability) where the primary analysis was based on multiple imputation (for IBS-SSS, HADS, WSAS, PHQ-12, SGA of relief of IBS symptoms, and acceptability)

-

analysis of SGA of relief of IBS symptoms:

-

using an alternative definition of response, with response defined as reporting only considerable or complete relief of IBS symptoms

-

as an ordinal outcome using ordinal logistic regression

-

-

analysis of acceptability, with additional multiple imputation for participants who did not start trial treatment or were lost to follow-up on or before the 6-month call (derived as not acceptable in primary analysis)

Safety analysis

All participants receiving at least one dose of trial medication were included in the safety population and analysis; participants who received at least one dose of amitriptyline were included in the amitriptyline group, regardless of the arm they were allocated to. The number of participants reporting a SAE, including serious adverse reactions (SARs) and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs), and details of all SAEs were reported for each treatment group. The number and details of emergency unblinding events, pregnancies and deaths were also reported for each treatment group.

Exploratory analysis

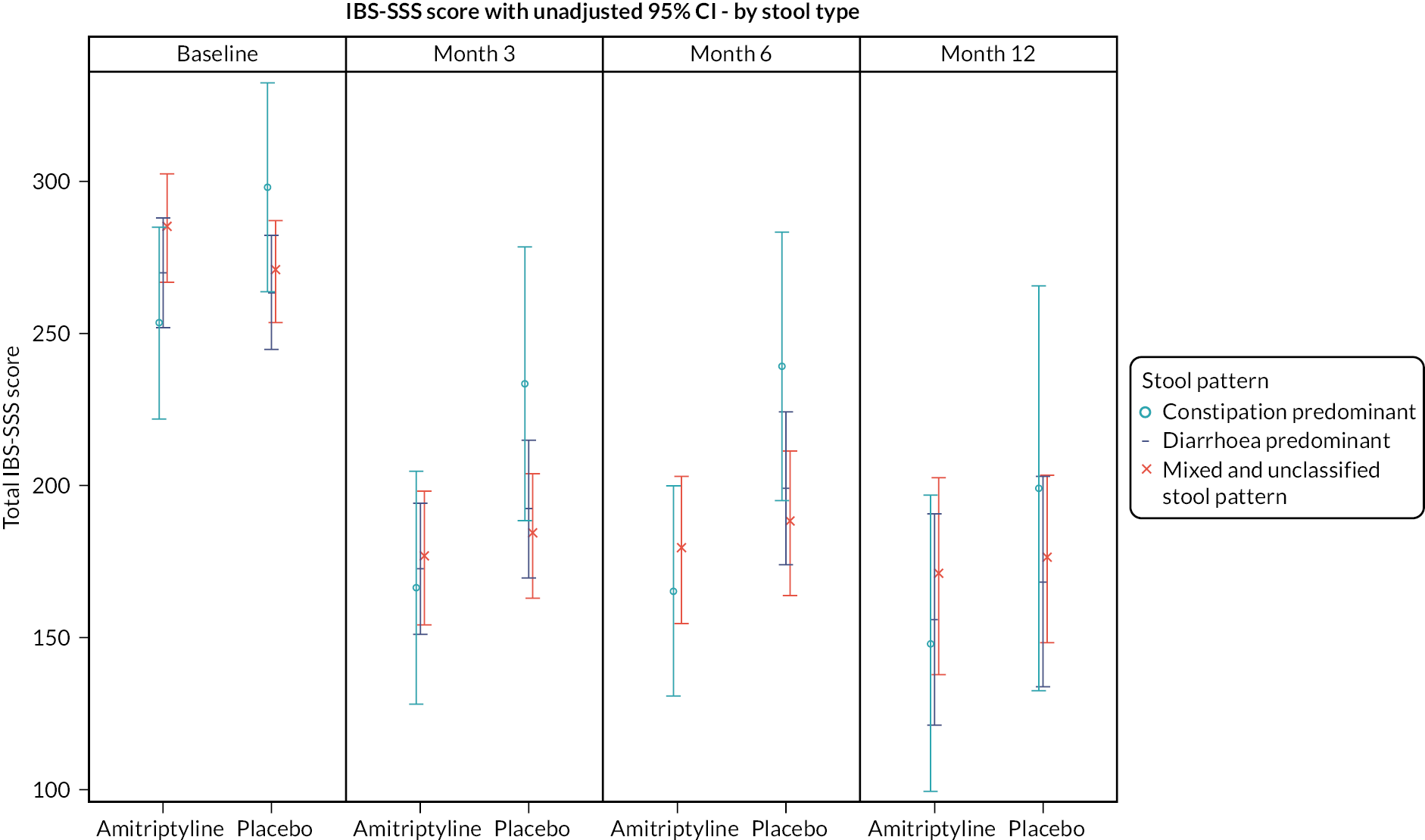

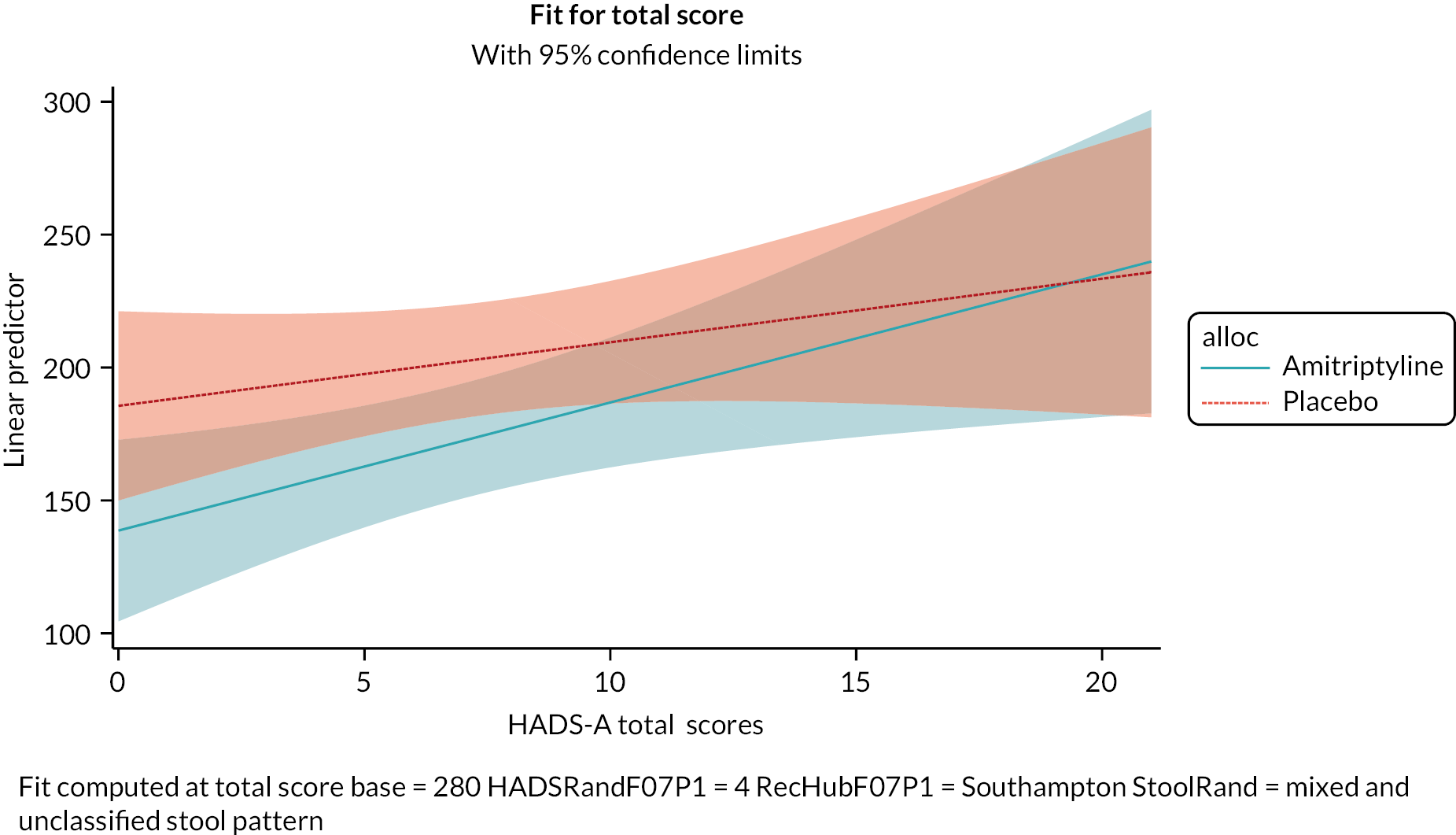

Exploratory moderator analyses were conducted to investigate if the 6-month treatment effect on the IBS-SSS varied by baseline IBS-SSS score, recruitment hub, IBS subtype or mood (baseline HADS-depression or HADS-anxiety scores), by including an interaction between the treatment arm and each potential moderator in the primary analysis model. Moderator analyses were also conducted to investigate if the 6-month treatment effect on the key secondary outcome, SGA response, varied by IBS subtype.

Further exploratory analyses of the IBS-SSS at 3 and 6 months were conducted using logistic regression, adjusted for true values of minimisation variables, to test for differences between the treatment groups on response rates according to:

-

a ≥ 50-point decrease in the total IBS-SSS score

-

a ≥ 30% decrease in abdominal pain severity on the IBS-SSS item response score at 3 and 6 months

-

a ≥ 30% decrease in abdominal distension severity on the IBS-SSS item response score at 3 and 6 months.

Missing response data, according to the definitions above, were imputed in the same manner as the primary and secondary outcomes.

Health economics methods

We planned to perform a within-study cost-effectiveness analysis, which adopted the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services and a societal perspective. We planned to use a time horizon of 6 months; hence costs and outcomes were not to be discounted. Our primary outcome was intended to be cost per QALY, with uncertainty assessed using a within-trial probabilistic sensitivity analysis. This would be performed using Monte Carlo simulation, with the results presented as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. We planned to assume a willingness to pay (lambda) of £20,000 per QALY. Sensitivity analyses were planned, which would include a 12-month time horizon, as well as a scenario similar to real NHS practice, with treatment prescribed by a GP with repeated prescriptions, tests, and necessary appointments. As stated previously, health economic analyses were removed after a discussion and meeting with the HTA to minimise additional funding required to complete the trial and to prioritise funds for participant recruitment and are now on hold subject to further funding.

Qualitative study

The nested qualitative study is reported in Nested qualitative study.

Chapter 3 Clinical trial results

Study summary

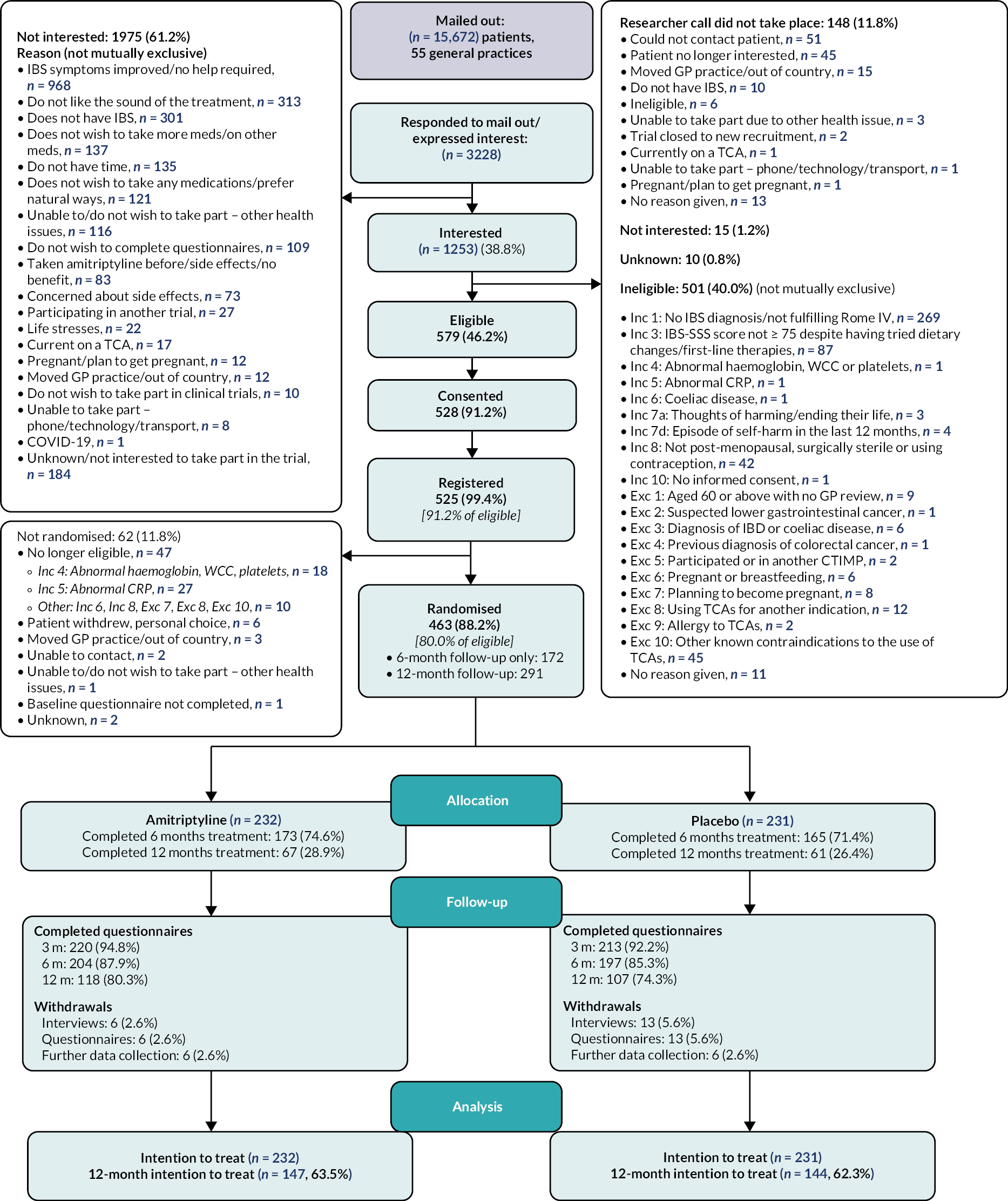

The numbers of patients identified via GP mail-out, responding and screened for entry into ATLANTIS, eligible, randomised, followed up at 3, 6 and 12 months, withdrawn and analysed are presented in the CONSORT diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting trial flow diagram.

Screening and recruitment

Screening

A total of 15,672 potentially eligible patients were identified via SnoMed clinical terms searches by 55 general practices and contacted by letter to provide information and invite them to take part in the trial. Screening subsequently took place for 3228 patients who either responded via reply slip to the general practice mail-out (n = 3144, 97.4%) or were identified opportunistically following a GP visit, publicity, or other means and contacted a research nurse directly.

Of the 3228 who responded, 1253 (38.8%) expressed an interest in joining the trial, of whom 1105 (88.2%) had a screening call with a research nurse. Of these, 579 (52.4%) were eligible, of whom 528 (91.2%) consented, 525 (90.7%) were registered and 463 (80.0%) were randomised. Figure 2 and Appendix 1, Table 42 present screening and recruitment by hub.

FIGURE 2.

Screening and recruitment by hub.

The most common reasons why the other 1975 (61.2%) patients were not interested in taking part were that their IBS symptoms had improved and no further help was required [n = 968 (49.0%) of those not interested], they did not like the sound of the treatment [n = 313 (15.8%)], they did not have IBS [n = 301 (15.2%)], they did not wish to take more medications [n = 137 (6.9%)], they did not have time [n = 135 (6.8%)], they did not wish to take any medications [n = 121 (6.1%)], their other health issues meant they felt unable to or did not wish to take part [n = 116 (5.9%)], they did not wish to complete questionnaires [n = 109 (5.5%)], they had taken amitriptyline before and experienced side effects or no benefit [n = 83 (4.2%)], or they were concerned about side effects [n = 73 (3.7%)].

The most common reasons for ineligibility of 501 (45.3% of those with a screening researcher call) patients were not having a diagnosis of IBS in the primary care record and fulfilling Rome IV criteria [n = 269 (53.7%) of those ineligible], not having ongoing symptoms, as defined by an IBS-SSS score ≥ 75 despite having tried dietary changes and first-line therapies [n = 87 (17.4%)], known contraindication to the use of TCAs [n = 45 (9.0%)], and potential for pregnancy [not post menopausal, surgically sterile or using effective contraception, n = 42 (8.4%)].

Reasons why 62 (11.8%) registered patients did not go on to be randomised included subsequently not meeting eligibility criteria [n = 47 (75.8%)], in the majority of cases due to abnormal blood test results, patient choice [n = 6 (9.7%)] or other reasons [n = 9 (14.5%)].

Recruitment

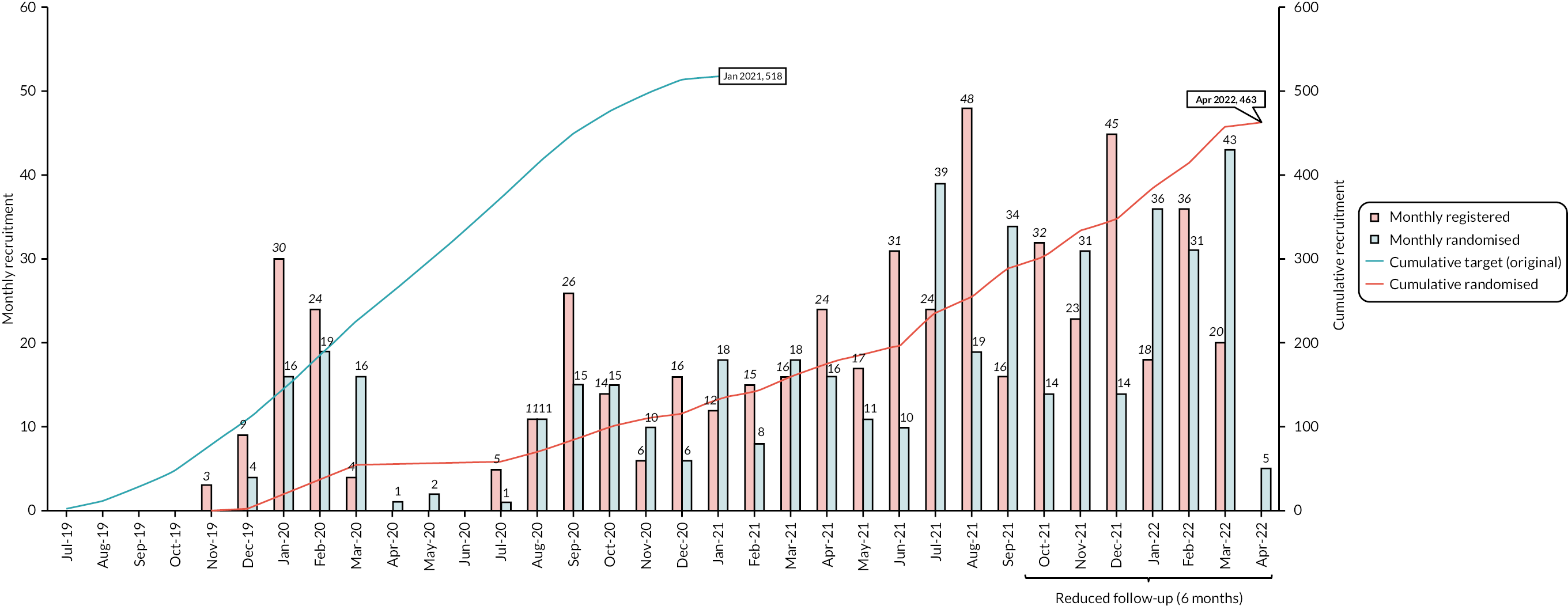

The first mail-out took place on 18 October 2019 and the first participant was randomised on 5 December 2019 and the last on 11 April 2022, with 232 participants randomised to receive low-dose amitriptyline and 231 participants randomised to receive placebo, across 55 general practices. Figure 3 shows overall, monthly and cumulative recruitment of participants into the trial. Appendix 1, Figure 8 depicts the timing between practice mail-out and subsequent randomisations.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment graph.

Recruitment was originally expected to be completed within 18 months. Owing to a delay in trial opening, a pause in recruitment between March and July 2020, in line with national guidance related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequent slower than anticipated recruitment rates, again due to the COVID-19 pandemic, recruitment was extended and took place over 29 months. A number of changes were made to the trial protocol and study processes to enable recruitment to continue, including a reduction in follow-up from 12 to 6 months for the final cohort of recruited participants (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The first 291 (62.9%) recruited participants were therefore consented to 12-month follow-up, whereas the final 172 (37.1%) could only provide consent to 6 months of follow-up.

Characteristics of the screened, eligible and randomised participants

The age and sex of the mailed out, screened, interested, eligible and randomised patient populations were broadly similar (Table 2). Patients who responded to the mail-out or expressed interest were slightly older (mean age 57.0 vs. 48.4 years) and more likely to be female (75.5% vs. 71.3%). However, the mean age of those subsequently interested, eligible and randomised was similar to the overall mailed-out population, and the proportion of males increased through later stages of the screening process.

| Mailed-out (n = 15,672) | Responded (n = 3228) | Interested (n = 1253) | Eligible (n = 579) | Registered (n = 525) | Randomised (n = 463) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.4 (16.8) | 57.0 (16.9) | 51.0 (17.0) | 48.4 (16.5) | 48.4 (16.3) | 48.4 (16.1) |

| Median (range) | 48.0 (18–100) | 59.0 (19–98) | 51.0 (19–92) | 49.0 (19–92) | 49.0 (18–92) | 49.0 (18–87) |

| Missing | 333 | 74 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4419 (28.8%) | 797 (25.5%) | 357 (29.3%) | 162 (28.7%) | 158 (30.1%) | 148 (32.0%) |

| Female | 10,918 (71.2%) | 2332 (75.5%) | 862 (70.7%) | 402 (71.3%) | 367 (69.9%) | 315 (68.0%) |

| Missing | 335 | 99 | 34 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

Protocol violations, withdrawals and follow-up

Protocol violations

Protocol violations were identified for six (1.3%) participants, three in each arm, four of which were classed as major protocol violations (see Appendix 1, Table 43). One participant was found to be ineligible 6 days after randomisation following receipt of an abnormal blood test result (positive anti-tTG antibody; major violation). Four participants experienced unplanned treatment errors, including: two participants (one in each arm) who reported having taken four tablets daily (40 mg), more than the maximum 30 mg daily allowance, at 3-month follow-up (minor violations). One participant allocated to placebo was sent the incorrect bottle of medication at randomisation due to a kit number identification error at pharmacy and received a bottle of amitriptyline; this was identified 14 days post randomisation after which the participant was asked to return the incorrect bottle and they subsequently discontinued trial medication (major violation). A further participant allocated to placebo disclosed at 6-month follow-up that they had taken 30 mg of their friend’s amitriptyline on a single day (major violation). A further protocol violation was reported for one participant allocated to amitriptyline who was asked to stop and return trial medication after reporting suicidal ideation at 3 months follow-up. However, they continued to take trial medication for a further week (major violation).

Research withdrawals

Participants could withdraw from optional interviews, weekly or monthly (3-, 6- or 12-month) questionnaires, or further data collection. A total of 23 (5.0%) participants withdrew from at least one study process: 6 (2.6%) in the amitriptyline arm and 17 (7.4%) in the placebo arm (Table 3). Participants most frequently withdrew from optional interviews and monthly questionnaires: 6 (2.6%) in the amitriptyline arm and 13 (5.6%) in the placebo arm, all but one of whom also withdrew from the weekly questionnaire, and 6 participants in each arm withdrew from further data collection. The mean time of withdrawal was 3.5 months post randomisation. The main reasons for withdrawal included treatment side effects or lack of benefit, with study withdrawal accompanying treatment discontinuation, personal choice, difficult personal circumstances, or lack of time.

| Amitriptyline (n = 232) | Placebo (n = 231) | Total (n = 463) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants with a withdrawal | 6 (2.6%) | 17 (7.4%) | 23 (5.0%) |

| Withdrawn from | |||

| Optional interviews (of participants consented to interview) | 6 (2.9%) | 13 (6.3%) | 19 (4.6%) |

| Consented to optional interview (of randomised) | 204 (87.9%) | 206 (89.2%) | 410 (88.6%) |

| Completing questionnaires | 6 (2.6%) | 13 (5.6%) | 19 (4.1%) |

| Withdrawn from monthly questionnaires only | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Withdrawn from weekly and monthly questionnaires | 6 (2.6%) | 12 (5.2 %) | 18 (3.9%) |

| Further data collection | 6 (2.6%) | 6 (2.6%) | 12 (2.6%) |

| Time from randomisation to withdrawal (months) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (4.6) | 3.5 (3.8) | 3.5 (3.9) |

| Median (range) | 2.1 (0.6, 12.7) | 1.6 (0.4, 12.3) | 1.8 (0.4, 12.7) |

| IQR | 1.0–3.0 | 0.8–5.8 | 0.8–5.8 |

| n | 6 | 17 | 23 |

| Reason for withdrawal | |||

| Side effects | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (17.6%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Difficult personal circumstances | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (17.6%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Lack of benefit | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Do not have time | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Personal choice | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Due to COVID-19 | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| SAE/SUSAR | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.8%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Unknown | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Total | 6 (100%) | 17 (100%) | 23 (100%) |

Questionnaire follow-up

Monthly follow-up questionnaires were completed and returned by 433 (93.5%) of 463 participants at 3 months, 401 (86.6%) of 463 at 6 months and 225 (77.3%) of 291 participants at 12 months (Table 4). Response rates were slightly higher in the amitriptyline arm compared with the placebo arm, particularly at 12 months (80.3% vs. 74.3%). Individual questionnaire completion rates (arranged in the order they appear within each questionnaire pack in Table 4) showed a slight reduction in completion rates for questionnaires appearing later within the questionnaire packs. All baseline questionnaires were completed within 1 month prior to randomisation and follow-up questionnaires were largely completed within a 7-day window either side of the point of follow-up (see Table 4 and Appendix 1, Figure 9). The majority of the participants completed questionnaires online via REDCap, with online completion for 93.3% at baseline, and 95.2%, 96.0% and 96.9% of responders at 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively and the remainder completing paper-based questionnaires by post. Participants provided a median of 23 responses to the weekly question ‘Have you had adequate relief of your IBS symptoms?’ up to 6 months (25 weeks in total) (see Appendix 1, Figure 10). At least one response was provided by all except 10 participants in each arm, and responses were provided for at least 75% of weeks (≥ 19 weeks) for 337 (72.8%) participants, with similar rates between treatment arms.

| Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 12a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline (n = 232) | Placebo (n = 231) | Total (n = 463) | Amitriptyline (n = 232) | Placebo (n = 231) | Total (n = 463) | Amitriptyline (n = 147) | Placebo (n = 144) | Total (n = 291) | |

| Questionnaire completed? | |||||||||

| Completedb | 220 (94.8%) | 213 (92.2%) | 433 (93.5%) | 204 (87.9%) | 197 (85.3%) | 401 (86.6%) | 118 (80.3%) | 107 (74.3%) | 225 (77.3%) |

| Did not complete | 12 (5.2%) | 18 (7.8%) | 30 (6.5%) | 28 (12.1%) | 34 (14.7%) | 62 (13.4%) | 29 (19.7%) | 37 (25.7%) | 66 (22.7%) |

| Reason not completed | |||||||||

| Withdrawn questionnaires | 5 (41.7%) | 7 (38.9%) | 12 (40.0%) | 5 (17.9%) | 10 (29.4%) | 15 (24.2%) | 6 (20.7%) | 10 (27.0%) | 16 (24.2%) |

| No response | 7 (58.3%) | 11 (61.1%) | 18 (60.0%) | 23 (82.1%) | 24 (70.6%) | 47 (75.8%) | 23 (79.3%) | 27 (73.0%) | 50 (75.8%) |

| Total | 12 (100%) | 18 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 28 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 62 (100%) | 29 (100%) | 37 (100%) | 66 (100%) |

| Individual questionnairesc | |||||||||

| IBS-SSS | 219 (94.4%) | 213 (92.2%) | 432 (93.3%) | 204 (87.9%) | 197 (85.3%) | 401 (86.6%) | 118 (80.3%) | 107 (74.3%) | 225 (77.3%) |

| SGA | 220 (94.8%) | 213 (92.2%) | 433 (93.5%) | 204 (87.9%) | 195 (84.4%) | 399 (86.2%) | 118 (80.3%) | 107 (74.3%) | 225 (77.3%) |

| HADS | 220 (94.8%) | 212 (91.8%) | 432 (93.3%) | 203 (87.5%) | 193 (83.5%) | 396 (85.5%) | 117 (79.6%) | 107 (74.3%) | 224 (77.0%) |

| PHQ-12 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 202 (87.1%) | 192 (83.1%) | 394 (85.1%) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| WSAS | 219 (94.4%) | 212 (91.8%) | 431 (93.1%) | 202 (87.1%) | 193 (83.5%) | 395 (85.3%) | 117 (79.6%) | 107 (74.3%) | 224 (77.0%) |

| ASEC | 219 (94.4%) | 212 (91.8%) | 431 (93.1%) | 201 (86.6%) | 192 (83.1%) | 393 (84.9%) | 117 (79.6%) | 107 (74.3%) | 224 (77.0%) |

| EQ-5D | 218 (94.0%) | 210 (90.9%) | 428 (92.4%) | 200 (86.2%) | 192 (83.1%) | 392 (84.7%) | 117 (79.6%) | 107 (74.3%) | 224 (77.0%) |

| Health resource use | 217 (93.5%) | 210 (90.9%) | 427 (92.2%) | 200 (86.2%) | 192 (83.1%) | 392 (84.7%) | 117 (79.6%) | 107 (74.3%) | 224 (77.0%) |

| Time to completion (days) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.2) | 6.1 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.2) | 12.1 (0.2) | 12.2 (0.3) | 12.1 (0.2) |

| Median (range) | 3.0 (2.7, 5.3) | 3.0 (2.7, 4.7) | 3.0 (2.7, 5.3) | 6.0 (5.7, 7.6) | 6.0 (5.9, 7.7) | 6.0 (5.7, 7.7) | 12.0 (12.0, 13.1) | 12.1 (12.0, 13.2) | 12.0 (12.0, 13.2) |

| n | 220 | 213 | 433 | 203d | 197 | 400 | 118 | 107 | 225 |

| Timing of completion | |||||||||

| ≤ ± 7 days | 185 (84.1%) | 181 (85.0%) | 366 (84.5%) | 182 (89.2%) | 167 (84.8%) | 349 (87.0%) | 103 (87.3%) | 85 (79.4%) | 188 (83.6%) |

| ≤ ± 30 days | 31 (14.1%) | 29 (13.6%) | 60 (13.9%) | 19 (9.3%) | 27 (13.7%) | 46 (11.5%) | 14 (11.9%) | 21 (19.6%) | 35 (15.6%) |

| > ± 30 days | 4 (1.8%) | 3 (1.4%) | 7 (1.6%) | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (1.5%) | 5 (1.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (0.9%) |

| Total completed | 220 (100%) | 213 (100%) | 433 (100%) | 203 (100%) | 197 (100%) | 401 (100%) | 118 (100%) | 107 (100%) | 225 (100%) |

Comparison of baseline characteristics between participants with and without monthly follow-up questionnaires (Table 5) indicated that those not completing the primary 6-month follow-up questionnaire were more likely to have discontinued trial medication before 6 months, to be younger, to be in the West Yorkshire hub, and to have had more severe scores on the baseline IBS-SSS and WSAS.

| Completed (n = 401) | Not completed (n = 62) | Total (n = 463) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment allocation and receipt | ||||

| Treatment allocation | ||||

| Amitriptyline | 204 (50.9%) | 28 (45.2%) | 232 (50.1%) | |

| Placebo | 197 (49.1%) | 34 (54.8%) | 231 (49.9%) | 0.1883 |

| Did not start or discontinued trial medication before 6 months | ||||

| Yes | 80 (20.0%) | 45 (72.6%) | 125 (27.0%) | |

| No | 321 (80.0%) | 17 (27.4%) | 338 (73.0%) | < 0.0001 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Recruitment hub | ||||

| West Yorkshire | 67 (16.7%) | 20 (32.3%) | 87 (18.8%) | |

| Wessex | 171 (42.6%) | 21 (33.9%) | 192 (41.5%) | |

| West of England | 163 (40.6%) | 21 (33.9%) | 184 (39.7%) | 0.0068 |

| IBS subtype | ||||

| IBS-C | 67 (16.7%) | 10 (16.1%) | 77 (16.6%) | |

| IBS-D | 158 (39.4%) | 23 (37.1%) | 181 (39.1%) | |

| IBS-M | 163 (40.6%) | 28 (45.2%) | 191 (41.3%) | |

| IBS-U | 13 (3.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | 14 (3.0%) | 0.8896 |

| Age at randomisation | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.9 (15.8) | 45.7 (17.8) | 48.5 (16.1) | |

| Median (range) | 50.0 (19.0, 86.0) | 44.5 (20.0, 87.0) | 49.0 (19.0, 87.0) | 0.0489 |

| Participant sex | ||||

| Male | 132 (32.9%) | 16 (25.8%) | 148 (32.0%) | |

| Female | 269 (67.1%) | 46 (74.2%) | 315 (68.0%) | 0.4370 |

| Baseline questionnaires | ||||

| Baseline IBS-SSS score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 269.3 (88.2) | 295.3 (100.7) | 272.8 (90.3) | |

| Median (range) | 270.0 (10.0, 480.0) | 310.0 (60.0, 480.0) | 280.0 (10.0, 480.0) | 0.0140 |

| IBS-SSS severity | ||||

| Normal (< 75) | 6 (1.5%) | 2 (3.2%) | 8 (1.7%) | |

| Mild (75–174) | 55 (13.7%) | 8 (12.9%) | 63 (13.6%) | |

| Moderate (175–299) | 184 (45.9%) | 17 (27.4%) | 201 (43.4%) | |

| Severe (300–500) | 156 (38.9%) | 35 (56.5%) | 191 (41.3%) | |

| Baseline HADS-anxiety score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.5 (4.2) | 7.7 (4.6) | 7.5 (4.3) | |

| Median (range) | 7.0 (0.0, 21.0) | 7.0 (0.0, 21.0) | 7.0 (0.0, 21.0) | 0.8471 |

| Baseline HADS-depression score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.2 (3.4) | 4.4 (3.4) | 4.3 (3.4) | |

| Median (range) | 4.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 4.0 (0.0, 14.0) | 4.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 0.8202 |

| Baseline PHQ-12 score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.2 (3.4) | 6.8 (4.4) | 6.3 (3.5) | |

| Median (range) | 6.0 (0.0, 16.4) | 5.5 (0.0, 18.0) | 6.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 0.2396 |

| Missing | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| Baseline WSAS score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.9 (7.5) | 14.3 (9.6) | 11.4 (7.9) | |

| Median (range) | 10.0 (0.0, 36.0) | 13.5 (0.0, 40.0) | 10.0 (0.0, 40.0) | 0.0024 |

| Missing | 18 | 2 | 20 | |

Analysis populations

Intention to treat

All 463 randomised participants were included in the ITT population, including 232 allocated to amitriptyline and 232 to placebo. Prior to the protocol amendment reducing follow-up to 6 months, the first 291 randomised participants [147 (63.4%) in the amitriptyline arm; 144 (62.3%) in the placebo arm] were consented to 12-month follow-up and are included in the 12-month ITT population (Figure 1).

Per protocol

The per-protocol population included 376 (81.2%) participants at 3 months and 323 (69.8%) participants at 6 months, with slightly greater numbers of participants in the amitriptyline arm (Table 6). The majority of participants excluded from the per-protocol population were excluded because they discontinued trial medication before either 3 or 6 months. Of those excluded at 3 and 6 months, 69.0% and 72.9% had discontinued trial medication before 3 and 6 months, respectively, 12.6% and 2.1% had not responded to the treatment adherence question at the 3- and 6-month researcher follow-up calls, respectively, and 8.0% and 12.1% were lost to follow-up by 3 and 6 months, respectively. A smaller proportion of participants had not started treatment, reported inadequate levels of adherence to treatment, breached eligibility criteria, or had a major protocol violation.

| Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 12a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline (n = 232) | Placebo (n = 231) | Total (n = 463) | Amitriptyline (n = 232) | Placebo (n = 231) | Total (n = 463) | Amitriptyline (n = 147) | Placebo (n = 144) | Total (n = 291) | |

| In per-protocol population | |||||||||

| Yes | 193 (83.2%) | 183 (79.2%) | 376 (81.2%) | 172 (74.1%) | 151 (65.4%) | 323 (69.8%) | |||

| No | 39 (16.8%) | 48 (20.8%) | 87 (18.8%) | 60 (25.9%) | 80 (34.6%) | 140 (30.2%) | |||

| Total | 232 (100%) | 231 (100%) | 463 (100%) | 232 (100%) | 231 (100%) | 463 (100%) | |||

| Reasons for exclusionb | |||||||||

| Discontinued trial medication | 30 (76.9%) | 30 (62.5%) | 60 (69.0%) | 44 (73.3%) | 58 (72.5%) | 102 (72.9%) | |||

| Breach eligibility and discontinued trial medication | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | |||

| Major violation and discontinued trial medication | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (2.1%) | 2 (2.3%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.3%) | 2 (1.4%) | |||

| Not started treatment | 2 (5.1%) | 1 (2.1%) | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | 3 (2.1%) | |||

| Lost to follow-up | 4 (10.3%) | 3 (6.3%) | 7 (8.0%) | 11 (18.3%) | 6 (7.5%) | 17 (12.1%) | |||

| Major violation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | |||

| Not adhered to trial medication | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (4.2%) | 3 (3.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | 6 (7.5%) | 7 (5.0%) | |||

| No response to treatment adherence question | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (22.9%) | 11 (12.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.8%) | 3 (2.1%) | |||

| Other non-adherence | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (5.0%) | 4 (2.9%) | |||

| Total excluded | 39 (100%) | 48 (100%) | 87 (100%) | 60 (100%) | 80 (100%) | 140 (100%) | |||

| Safety population | |||||||||

| Amitriptyline | 230 (100.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 231 (50.2%) | 230 (100.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 232 (50.4%) | 145 (100.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 146 (50.7%) |

| Placebo | 0 (0.0%) | 229 (99.6%) | 229 (49.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 228 (99.1%) | 228 (49.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 142 (99.3%) | 142 (49.3%) |

| Excluded | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

Safety population

The safety population mirrored the ITT and 12-month ITT populations with the exception of three participants who were excluded as they did not start trial medication, and two participants for whom treatment cross-over was observed. One participant allocated to placebo received a bottle of amitriptyline by error within the first 2 weeks of randomisation and is included in the amitriptyline arm in the 3-, 6- and 12-month safety populations. A further participant allocated to placebo (and consenting to 6-month follow-up) reported having taken their friend’s amitriptyline on a single day at their 6-month follow-up call and is included in the amitriptyline arm for the 6-month safety population (see Table 6).

Baseline characteristics

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Participants allocated to amitriptyline and placebo were well balanced with respect to randomisation stratification factors (Table 7), demographic characteristics (Table 8), and clinical characteristics (Table 9). Wessex randomised 41.5% of participants, West of England 39.7%, and West Yorkshire 18.8% (Table 7). A small proportion of participants had IBS-U (3.0%), 41.3% had IBS-M, 39.1% IBS-D and 16.6% IBS-C. The majority of participants (84.2%) had a HADS-D score ˂ 8, indicating the absence of symptoms of depression.

| Amitriptyline (n = 232) (%) | Placebo (n = 231) (%) | Total (n = 463) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment hub | |||

| West Yorkshire | 43 (18.5) | 44 (19.0) | 87 (18.8) |

| Wessex | 97 (41.8) | 95 (41.1) | 192 (41.5) |

| West of England | 92 (39.7) | 92 (39.8) | 184 (39.7) |

| IBS subtype | |||

| IBS-C | 40 (17.2) | 37 (16.0) | 77 (16.6) |

| IBS-D | 92 (39.7) | 89 (38.5) | 181 (39.1) |

| IBS-M | 93 (40.1) | 98 (42.4) | 191 (41.3) |

| IBS-U | 7 (3.0) | 7 (3.0) | 14 (3.0) |

| Baseline HADS-D score | |||

| 0–7 (normal range) | 195 (84.1) | 195 (84.4) | 390 (84.2) |

| 8–21 (mild, moderate, severe depression) | 37 (15.9) | 36 (15.6) | 73 (15.8) |

| Amitriptyline (n = 232) | Placebo (n = 231) | Total (n = 463) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 49.2 (16.2) | 47.8 (15.9) | 48.5 (16.1) |

| Median (range) | 50 (19, 86) | 49 (19, 87) | 49 (19, 87) |

| Participant sex | |||

| Female | 156 (67.2%) | 159 (68.8%) | 315 (68.0%) |

| Male | 76 (32.8%) | 72 (31.2%) | 148 (32.0%) |

| Ethnic origin | |||

| White | 226 (97.4%) | 225 (97.8%) | 451 (97.6%) |

| Black | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Asian | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| Other ethnic group | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| Mixed | 3 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 37 (15.9%) | 55 (23.8%) | 92 (19.9%) |

| Married | 123 (53.0%) | 110 (47.6%) | 233 (50.3%) |

| Living with partner | 43 (18.5%) | 36 (15.6%) | 79 (17.1%) |

| Separated | 2 (0.9%) | 4 (1.7%) | 6 (1.3%) |

| Divorced | 20 (8.6%) | 19 (8.2%) | 39 (8.4%) |

| Widowed | 7 (3.0%) | 7 (3.0%) | 14 (3.0%) |

| Highest education level achieved | |||

| No formal | 13 (5.6%) | 18 (7.8%) | 31 (6.7%) |

| GCSE/O level or equivalent | 61 (26.4%) | 61 (26.5%) | 122 (26.5%) |

| A level or equivalent | 54 (23.4%) | 54 (23.5%) | 108 (23.4%) |

| Degree | 52 (22.5%) | 58 (25.2%) | 110 (23.9%) |