Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/82/04. The contractual start date was in May 2016. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Daniels et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Daniels et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Group B Streptococcus disease

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) (Streptococcus agalactiae) is a ubiquitous bacterium that forms part of the normal bacterial flora of the gut and genital tract. In adults, GBS is an occasional cause of serious systemic infections in immunocompromised people, but is more commonly seen as an opportunistic pathogen of the female urogenital tract. 2 However, if a neonate, whose immune system is immature, is exposed to GBS then it can lead to sepsis and death. Most systemic GBS infections usually present within 24 hours of delivery as rapidly progressing septicaemia. However, early-onset GBS disease of the newborn is defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as occurring within the first 72 hours of life,3 and by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) as occurring before the first 7 days of age. 4,5 Exposure to GBS present in the genital tract of the mother during birth is thought to be the most common route for early-onset colonisation in the neonate. The incidence of early-onset GBS sepsis can be decreased if women colonised with GBS or who have risk factors associated with early-onset GBS infection are given intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) during labour. Any infection with GBS in babies between 7 days and 3 months of age is deemed late onset and is more often associated with localised infections (especially meningitis and pneumonia). Colonisation from environmental sources is thought to be the most common cause of late-onset GBS infection and is beyond the remit of the Group B Streptococcus 2 (GBS2) trial.

Early-onset group B Streptococcus infection

Maternal colonisation

The gastrointestinal tract is the natural reservoir of GBS in humans and is the likely source of vaginal colonisation. Asymptomatic maternal colonisation with GBS has been reported at a global level of 15%,6 although this figure can vary with race, region and the method of laboratory culture used for its detection. 6,7 A previous review of UK studies indicated an overall colonisation rate of 18% from vaginal/rectal swabs [95% confidence interval (CI) 16% to 21%], higher than from vaginal swabs alone. 8

Transmission

Neonates with early-onset GBS infection show initial colonisation mainly in the mucous membranes of their respiratory tract, and the major route of vertical transmission at the time of birth is thought to be through aspiration of vaginal, rectal and amniotic aerosols during birth. Vertical transmission in utero is thought to occur as a consequence of prolonged rupture of membranes (although GBS can cross intact membranes9) and is regarded as one of the causes of stillbirth. 10 Colonisation of the mother is less predictive for late-onset GBS infection, with prematurity being the major risk factor. 11

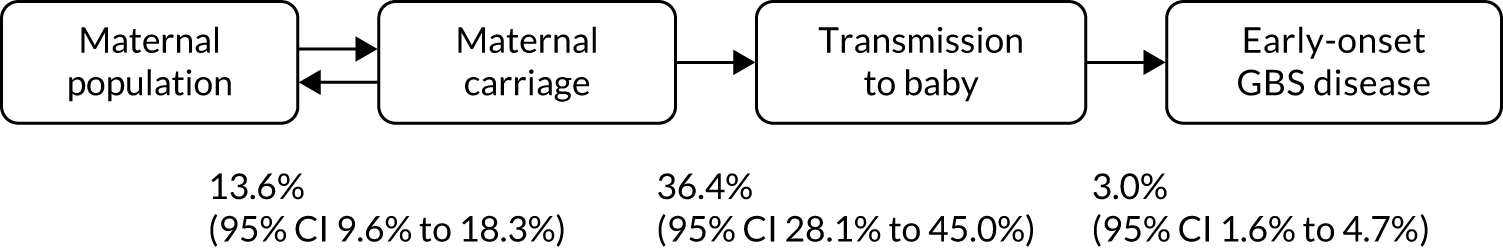

The association between the rates of maternal colonisation, transmission and infection has been established (Figure 1). A meta-analysis of six studies of the maternal and baby colonisation rates in an untreated general population showed a transmission rate between the colonised mother and her baby of 36.4% (95% CI 28.1% to 45.0%). A further analysis in the same report gave an average incidence of 3.0% (95% CI 1.6% to 4.7%) of babies born to colonised mothers who went on to develop early-onset GBS disease. 8 There is some evidence that maternal colonisation with GBS is associated with preterm birth, particularly ascending infection due to GBS bacteriuria. 12

FIGURE 1.

Model of colonisation, transmission and early-onset GBS disease.

Burden of early-onset group B Streptococcus infection

Group B Streptococcus remains one of the most important causes of severe early-onset infection in newborn infants. A systematic review estimated that the global incidence of early-onset GBS infection was 0.41 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.47) per 1000 live births, with the highest burden found in the Caribbean and South Africa. 13 Enhanced surveillance in the UK and Ireland from 2014 to 2015 showed an incidence of culture-proven GBS infection in babies aged < 90 days of 0.94 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.00) per 1000 live births. 14 In this study, 60% of cases were early-onset infection, a rate of 0.57 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.62) per 1000 live births, an increase from 0.48 per 1000 live births in 2000. In the USA, the incidence of early-onset GBS infection fell from 1.7 per 1000 live births in the early 1990s to 0.22 per 1000 live births in 2014, without any concurrent rise in Gram-negative sepsis. 15

The global case–fatality ratio is estimated at 8.4%, with a fourfold variation between Africa and high-income countries,13 whereas in the UK it was 6.2% in 2014, an improvement from 9.6% in 2001, possibly because of the improvements in neonatal care. Mortality is much higher in preterm babies. Oddie and Embleton16 found that preterm infants accounted for 38% of all cases and 83% of the deaths from early-onset GBS infection. Information on morbidity among survivors is less clear, but significant long-term morbidity, including impaired psychomotor development, has been reported in up to 30% of survivors. 17

It is highly likely that some cases of serious early-onset sepsis caused by GBS are unrecognised because cultures of blood and cerebrospinal fluid are negative. By taking into account superficial swab culture results from all neonates who underwent a septic screen in the first 72 hours of life, Luck et al. 18 concluded that the true incidence of early-onset GBS disease in the UK may be as high as 3.6 per 1000 live births (i.e. over seven times higher than previously estimated). Epidemiological studies have suggested that various factors present at the time of birth are associated with the neonate having an increased risk of developing GBS disease, presenting as either an early- or late-onset infection. UK surveillance data suggest that only 35% of infants with early-onset GBS infection were born to mothers with one or more risk factors,14 as defined by the RCOG guidelines implemented at that time. 19

Maternal risk factor for neonatal disease

Maternal risk factors for vertical GBS transmission to the newborn disease have been suggested to include the following.

Prematurity

Colonised premature babies are at a high risk of developing early-onset GBS infection, as their immune system is immature and they are less likely to have received passive immunity transplacentally. The pooled odds of maternal colonisation in preterm births, compared with births at > 37 weeks’ gestation, was 1.53 (95% CI 1.14 to 2.05). Birth weight is highly correlated with prematurity and inversely related to developing early-onset GBS infection. The UK surveillance study indicated an incidence of 2.24 (95% CI 1.31 to 3.59) early-onset GBS infection cases per 1000 live births in babies weighing < 1500 g at birth, compared with 0.43 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.49) per 1000 live births in those weighing ≥ 2500 g at birth. 14

Prelabour rupture of membranes

Prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM) with a delay in progress to established labour would be expected to lead to an increased likelihood of ascending infection and baby colonisation in utero, although there is debate as to what, if any, role the presence of GBS plays in the induction of PROM. Rupture of the membranes > 18 hours before birth is significantly associated with early-onset GBS infection (odds ratio 25.8, 95% CI 10.2 to 64.8) compared with non-infected infants. 17 Therefore, babies born to mothers who experience preterm labour with PROM of any duration, or preterm labour if there is suspected or confirmed intrapartum rupture of membranes lasting > 18 hours, are especially thought to be at risk of developing early-onset GBS infection. UK NICE guidelines recommend that induction of labour at term is offered at 24 hours after PROM. 3

Maternal fever

Intrapartum fever is also highly associated with the development of early-onset GBS infection (odds ratio 10.0, 95% CI 2.4 to 40.8). 16 In a UK surveillance study, 19% of babies with early-onset GBS infection were born to mothers with intrapartum pyrexia and 31% to mothers with suspected chorioamnionitis. 14

Previous baby with group B Streptococcus disease

The proportion of women giving birth at term who have had a previous baby with early-onset GBS infection was estimated at 0.08%. These women are considered to be at higher risk of another infected baby, than multiparous women whose previous babies were not affected, although the data are insufficient to describe the size of this increased risk. 20

Group B Streptococcus detected in current pregnancy

Group B Streptococcus bacteriuria is associated with higher risk of chorioamnionitis and neonatal disease, although the data are insufficient to quantify the increased risk. 21,22 In the 2014 UK surveillance study, 9% of mothers of GBS-infected babies were known to be colonised with GBS, although a figure of 5% was used in a model of the effectiveness of screening. 23

Testing for risk of group B Streptococcus disease

The aim of maternal GBS testing is to prevent early-onset GBS infection. However, no tests discriminate between colonised mothers who will or will not transmit GBS to their babies, or between babies who will or will not develop early-onset GBS infection. Instead, there are several methods for identifying GBS maternal colonisation in late pregnancy or during labour.

Tests for maternal group B Streptococcus colonisation

Bacteriological culture

The sensitivity of testing methods based on the culture identification of maternal colonisation of GBS depends on the timing of specimen collection, the source of the specimen and the culture technique used by the microbiology laboratory. A systematic review of prospective studies showed that a single vaginal/rectal swab has a positive predictive value (i.e. the proportion positive at 35–37 weeks’ gestation who remain positive at term labour) of 70.2% and a negative predictive value of 95.2%, but there were variations in testing methods. 24 Overall, using retrospective and prospective studies and different types of swabs and culture methods, sensitivities of the antenatal tests ranged from 51% to 71% and specificities were consistently around 85%. 24

Molecular tests for group B Streptococcus colonisation

Development of molecular methods that allow rapid bedside detection of microorganisms, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods, offers the potential to target use of antibiotics more specifically than was previously possible. Previous experience shows that implementation of complex point-of-care (POC) tests for GBS colonisation are technically feasible. 25 However, the practical value of any POC test depends on accurate results being reliably available within the clinically required time frame. To this end, careful consideration is required of a number of factors, including the expected frequency of testing, achievable results turnaround times, the amount of hands-on test time, strategies to deal with test failure and assurance of the ongoing availability of sufficient trained staff able to undertake testing when required.

The majority of the commercially available test systems required multiple preparation and incubation steps. What is required, is a system that can use swabs directly and be operated by midwives on a maternity unit. In the light of these limitations, the technology used in the GBS2 trial was the Cepheid GeneXpert® system (Cepheid, Maurens-Scopont France), which is feasible as a POC test. The Xpert® GBS test (Cepheid) for this platform allows detection of GBS within 35 minutes of placing a swab into a cartridge and loading one machine, with a hands-on preparation time of < 2 minutes.

Accuracy of GeneXpert rapid test to detect group B Streptococcus colonisation

The Cepheid GeneXpert GBS system has been available since 2008 and several groups have assessed its accuracy in studies, although with different swabbing strategies and reference standard comparators. The manufacturer cites a sensitivity (1 – false-positive rate) of 91.9% (95% CI 84.7% to 96.5%) and a specificity of 95.6% (95% CI 95.0% to 98.9%) for intrapartum vaginal/rectal samples, compared with selective enrichment culture of a second intrapartum swab. 26 A meta-analysis, undertaken in 2014, of nine studies, which used an enrichment culture method for the reference standard, obtained estimates of the average accuracy of the test of sensitivity 96.4% (95% CI 90.8% to 98.6%) and specificity 98.9% (95% CI 97.5% to 99.5%) (Jane Daniels, University of Nottingham, 2014, personal communication). Overall, the quality of the studies was rated as being adequate, but the potential for biases remained, from the lack of blinding, the use of only vaginal swabs and the inappropriate use of non-enrichment culture as the reference standard, which could underestimate colonisation rates. A subsequent meta-analysis of 15 studies using various test PCR platforms produced a pooled sensitivity of 93.7% (95% CI 92.1% to 95.3%) and specificity of 97.6% (95% CI 97.0 % to 98.1%). 27 These accuracy parameters, together with the turnaround time, suggest that the GeneXpert system meets the proposed criteria set by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for a clinically useful GBS test, namely that it should consist of a simple bedside kit that can be used by delivery suite staff, have a turnaround time of < 30 minutes, and have a sensitivity and specificity of ≥ 90%. 26

Current policy for prevention of early-onset group B Streptococcus infection

The strategy recommended by the UK’s RCOG is to consider and offer IAP to women who have risk factors identified during the pregnancy or in labour for having a baby with early-onset GBS infection. 4 Reviews by the UK National Screening Committee (NSC)24,28 and NICE3 have endorsed this approach.

The risk factors to consider in this approach, and the management options available in the original,29 the 201219 and the 20174 revised guidance are summarised below.

Women with a previous baby with group B Streptococcus disease

-

2003, 2012, 2017 guidelines: offer IAP.

Women with group B Streptococcus bacteriuria in the current pregnancy

-

2003 guidelines: consider IAP.

-

2012 and 2017 guidelines: offer IAP.

Women with an incidental finding of vaginal or rectal group B Streptococcus colonisation, or from an intentional test, in the current pregnancy

-

2003 guidelines: consider IAP.

-

2012 and 2017 guidelines: offer IAP.

Prematurity of < 37 weeks’ gestation without known group B Streptococcus colonisation

-

2003 guidelines: discuss IAP.

-

2012 guidelines: do not offer IAP in women presenting in established preterm labour with intact membranes and with no other risk factors for GBS, unless they are known to be colonised with GBS.

-

2017 guidelines: recommend IAP to all women in confirmed preterm labour.

Prolonged rupture of membranes > 18 hours

-

2003 guidelines: consider IAP.

-

2012 guidelines: states that the evidence for IAP is unclear for women at term with PROM.

-

2017 guidelines: if a woman is known to be colonised then she should be offered IAP and the induction of labour. If colonisation status is negative or unknown, offer the induction of labour immediately or by 24 hours.

Fever in labour > 38 °C

-

2003 guidelines: discuss IAP.

-

2012 and 2017 guidelines: offer IAP.

The 2017 revision recommends that (1) antenatal antibiotics (before labour starts or membranes rupture) are not offered to women, even if proven to be colonised with GBS by a vaginal or rectal swab, and (2) women undergoing planned caesarean in absence of labour and with intact membranes, whether at term or preterm, do not require GBS-specific antibiotics. A further recommendation is that women who were diagnosed as GBS carriers in a previous pregnancy, the opportunity for culture-based testing in the late third trimester or IAP without testing should be offered in subsequent pregnancies.

NICE issued guidance in 2012 on antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of early-onset neonatal infection. 3 The guidance recommends that IAP should be offered to women who have had:

-

a previous baby with an invasive GBS infection

-

GBS colonisation, bacteriuria or infection in the current pregnancy.

The guidance suggests that IAP is considered for women in preterm labour if there is:

-

PROM of any duration

-

suspected or confirmed intrapartum rupture of membranes lasting > 18 hours.

For women with PROM at term, including prolonged (> 24 hours) rupture, the use of prophylactic antibiotics is not recommended. 30

Evidence for group B Streptococcus testing strategies

Introducing universal testing for maternal GBS colonisation into the UK health-care system has been considered alongside other testing and vaccination strategies from the perspectives of both cost-effectiveness and overtreatment. The UK NSC reviewed the evidence for universal and risk factor-based screening in 2012 and again in 2017, and at both times concluded that there was insufficient evidence against its standardised criteria to justify a change from the current risk factor-based screening approach to guide administration of IAP. 24,28 The NSC estimated that the number of women needing to receive IAP on the basis of culture-based testing at 35–37 weeks to prevent one case of early-onset GBS infection missed by the risk factor approach was 1000–1500 in the 2012 analysis and 1675–1854 in the 2017 analysis. In the 2019 hypothetical cohort, an additional 96,260 women would receive IAP under a testing policy; however, with the test having a positive predictive power of 0.2%, the overwhelming majority of infants born to women receiving IAP would never have been at risk. 23 However, the model’s input parameters have been called into question, as the risk factor strategy emerged with an early-onset GBS infection rate of 0.49 per 1000 live births, which is significantly lower than UK surveillance data suggest. 14,23

A French study31 assessed whether or not rapid intrapartum testing for GBS reduced the proportion of women inappropriately given IAP, compared with a hypothetical situation in which the national screening programme standard of antenatal testing prevailed. The French investigators assessed the diagnostic performance of both the GeneXpert test and microbiological screening at 34–38 weeks’ gestation compared with a reference standard of microbiological culture of intrapartum swabs. IAP was directed during the study by the rapid test, and the adequacy of this strategy compared with what hypothetically would have been followed by use of the 35–37 weeks’ gestation culture result. The authors31 concluded that the universal rapid intrapartum test would correspond to an absolute risk reduction of 0.925%, equivalent to 108 more women needing to be tested in labour and provided IAP to prevent a single case of early-onset GBS infection that would be missed by the culture-based testing. 31

Acceptability and implementation of testing for maternal group B Streptococcus colonisation

Even if the trial shows the superiority of one test over the other, the likelihood of successful implementation will depend on the acceptability of the test for childbearing women and for maternity care professionals. The previous UK GBS rapid testing study24 did examine the acceptability of the swabbing process and the information provided, but in a hypothetical situation in which the results were not being used to direct care. Although study participation was less than half of those approached, among the women who did agree to participate, there was a high level of satisfaction with the process, with 80.5% of women satisfied or very satisfied with the information provided, 94.3% of women happy or very happy with the way the swabs were taken and 94.1% of women confident in its use in routine care. The NSC consider evidence that the criterion, namely that any test should be acceptable to the target population, has been met as uncertain. 24

Cost-effectiveness of group B Streptococcus testing for maternal group B Streptococcus colonisation

At the time of the initiation of the GBS2 trial, the most relevant cost-effectiveness evidence was a 2010 decision model, which suggested that a policy of routine culture testing at 35–37 weeks was considered the most cost-effective once routine untargeted IAP was eliminated as a potential strategy. 32 Intrapartum testing using first-generation PCR tests was not cost-effective unless the average cost of testing was reduced from £29.95 to £7.00. The 2017 NSC review did not identify any new cost-effectiveness estimates relevant to testing in a UK setting. 4 Economic models do not yet have the data to incorporate aspects such as the effect of widespread use of antibiotics on the development of antibiotic resistance and the impact this will have, the impact of maternal and neonatal microbiomes, and the effect of very rare but potentially catastrophic anaphylaxis in labour.

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is considered an imminent threat to human health and the impact of antibiotic resistance spans all ages, including infants. 33–35 Children may be colonised with antibiotic-resistant bacteria early in life. 36 Antibiotic (treatment)-resistant bacteria have been increasingly shown to cause early- and late-onset neonatal sepsis and neonatal intensive care unit sepsis outbreaks. 37,38 Studies of transmission of bacteria from mothers to their infants have predominantly focused on the causative agents of early neonatal sepsis: Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) and Escherichia coli. 39,40 Risk factors for neonatal colonisation with multiantibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli, for example extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing strains, have been described, but the relative contribution of maternal carriage at the time of birth is uncertain. 41 As part of an Olympics surveillance project and in collaboration with Public Health England in 2014, ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from 20% of women of childbearing age (i.e. 15–45 years) who submitted a faecal sample for laboratory examinations in the north-east of London. 42 At the same time, colonisation with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae has been demonstrated in 7% of neonatal intensive care unit infants of < 31 weeks’ gestational age recruited into a multicentre double-blind placebo-controlled randomised probiotic feeding study in the south-east of England. 43

Strategies for control of antibiotic resistance have focused on antibiotic stewardship programmes designed to reduce the selection pressure for resistance and early detection of carriers. Carriers of antibiotic-resistant microbes can be identified by screening and actions can be taken to prevent the spread from carriers to others, including the implementation of contact precautions and decontamination of colonised individuals, when this is feasible. By contrast with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), there is currently no reliable method of decontamination of individuals colonised with antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, including those with ESβLs. ESβLs have recently emerged in community-acquired E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, and their identification as causal agents of infections in neonatal units and the lack of effective therapeutic options is a worrying development. 36

Prevalence of antibiotic resistant group B Streptococcus

Penicillin remains the first choice of antibiotic for GBS prophylaxis and treatment. 44–47 However, since 2008, strains with reduced susceptibility have emerged. Studies in Japan have detected alarming rates of resistance, with 14.7% of GBS isolates testing resistant to penicillin, a marked increase from 2.3% in 2005–6, albeit from a range of samples and populations and not vaginal/rectal swabs from pregnant women. 48 Although resistance to penicillin appears to be low outside Japan, resistance to the secondary antibiotics of choice, clindamycin and erythromycin, is high, and so it is possible that these will not forever be available as an alternative for penicillin-allergic women. Clindamycin was removed as a recommended alternative to benzylpenicillin in the 2017 RCOG guidelines, as the resistance rate in the UK is reported as 16%. 14 Other research highlights substantial risks of adverse consequences arising from exposure of the fetus and newborn infant to unnecessary antibiotics, including necrotising enterocolitis, inflammatory bowel disease, fungal infection49 and cerebral palsy. 50

Chapter 2 Aims of the GBS2 trial and design

The aim of the GBS2 trial was to establish whether or not, a strategy of targeted IAP based on the results of a rapid intrapartum test for maternal GBS colonisation can reduce unnecessary maternal and neonatal antibiotic exposure in women with risk factors for their babies developing early-onset GBS disease, and if the rapid test can accurately diagnose GBS colonisation in clinical practice.

Primary objectives

-

To determine if the use of the rapid intrapartum test for maternal GBS colonisation reduces maternal and neonatal antibiotic exposure, compared with usual care in which IAP is based on maternal risk factors, in a cluster randomised trial.

-

To determine the real-time accuracy of the rapid intrapartum test for GBS colonisation among women in labour with risk factors for GBS transmission, compared with the reference standard of selective enrichment culture, in a cross-sectional study nested within the randomised cohort.

Secondary objectives

-

To evaluate if the rapid intrapartum test reduces IAP in the mother for any indication compared with usual care.

-

To evaluate the effect of the rapid test, compared with the usual-care strategy, on neonatal exposure to antibiotics, neonatal morbidity and neonatal mortality.

-

To evaluate if timely IAP administration can be achieved with a rapid intrapartum test to ensure adequate antibiotic exposure by establishing a standard operating procedure for use of the test.

-

To evaluate the cost and cost-effectiveness of using the rapid intrapartum test compared with usual care.

-

To evaluate the antibiotic resistance profile of GBS and the colonisation by other antibiotic-resistant bacteria of the mother from the intrapartum vaginal/rectal swab, and the risk of such colonisation in the baby at 6 weeks of age.

-

To evaluate the colonisation rate of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, particularly E. coli, MRSA and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), in vaginal/rectal samples from women.

-

To evaluate the extent to which colonisation of specific resistant bacteria or resistance elements of the mother at the time of birth increase the risk of carriage of those specific bacteria or elements to the infant at 6 weeks of postnatal age.

-

To gather some information on peripartum risk factors for transmission (e.g. mode of birth, gestational age and antibiotic exposure).

Rationale for trial design

A randomised comparison provides the most reliable data to compare test strategies for IAP to prevent early-onset GBS infection. It was decided that individual randomisation would not be feasible for the GBS2 trial because of two factors. First, if a GeneXpert system is available on a maternity ward, given its presumed high accuracy, it would be difficult and potentially unethical not to offer this test to all women in labour. Second, women would have to provide consent at the point of diagnosis of labour. The first GBS study51 showed that obtaining consent for research delays the start of the testing process and inevitably means that many women are not approached by midwives for participation. This undermines the principle that it is the strategy of targeted testing being compared and, hence, is not generalisable at the population level.

The cluster trial randomised different maternity units to follow either the rapid testing or the usual-care strategy of offering IAP to all women with risk factors, and required that all women with risk factors followed the same strategy within each unit. In cluster trials, it is important that either all eligible participants are identified prior to the unit being randomised, which is possible with a prevalent population, or outcome data from all eligible participants are included in the analysis. As intrapartum risk factors can be identified only at the time when the screening strategy needs to be applied, it was necessary to include all women with risk factors in the analysis. If consent was sought, there would be selection by midwife (overtly or unintentionally, because of time pressures) and resulting in women declining to provide swabs or data for research. The selection bias caused by the need to approach and individually consent participants within a cluster leads to unreliable estimates of screening effectiveness. 52 However, if the testing strategy is adopted as standard practice by the maternity unit and anonymous routinely collected data are retrieved, consent for research is unnecessary (although clinical consent for vaginal/rectal and neonatal swabs would prevail).

For the test to be proven useful, it will need to detect a higher proportion of GBS maternal carriage than other tests, but not at the cost of low specificity and overuse of IAP. The appropriate evaluation of the test’s performance was to follow a classic test accuracy design. The rapid test performed on intrapartum rectovaginal swabs was the index test, which was compared with microbiological culture of duplicate swabs serving as the reference standard. The a priori sample size was computed to determine the sensitivity of the rapid test within a 10% margin, but with the ability to assess specificity with greater precision.

If a rapid POC test improves the detection of maternal GBS colonisation in the intrapartum period, then it is likely that important cost implications will be seen for the health-care sector. For example, IAP will be avoided for many women who test negative and appropriate treatment for those who test positive should lead to a reduction in admission to neonatal intensive care. The accuracy of the test must be carefully examined and established for its impact on both false-positive and false-negative results, and the costs and outcomes that follow based on decisions made as a result of the test must be evaluated. For example, the rapid test may detect additional cases of maternal GBS colonisation compared with the usual-care risk factor-based strategy, which will increase the use of antibiotics prescribed in the intrapartum period; however, it could ultimately reduce the risk of early-onset GBS infection and avoid costly neonatal admissions. Alternatively, replacement of the risk factor-based strategy with the rapid test may lead to an increased number of false positives, resulting in the administration of unnecessary IAP, or it could lead to an increased number of false-negative test results and consequential adverse outcomes.

This trial provided an opportunity to correlate maternal carriage of resistant bacteria with early colonisation of the corresponding infant. Maternal vaginal/rectal samples collected for the trial and used for the enrichment culture reference standard, and neonatal swabs and routinely collected specimens, were reprocessed to determine the presence of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, focusing particularly on ESBL-producing strains using selective media. Strains isolated from mothers and their infants were typed to determine the degree of relatedness. The outcomes from this part of the trial include the carriage rates of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negatives in the trial population of pregnant women, the risk of colonisation in their infant(s) and the peripartum risk factors for transmission (e.g. mode of birth, maternal comorbidities and colonising species).

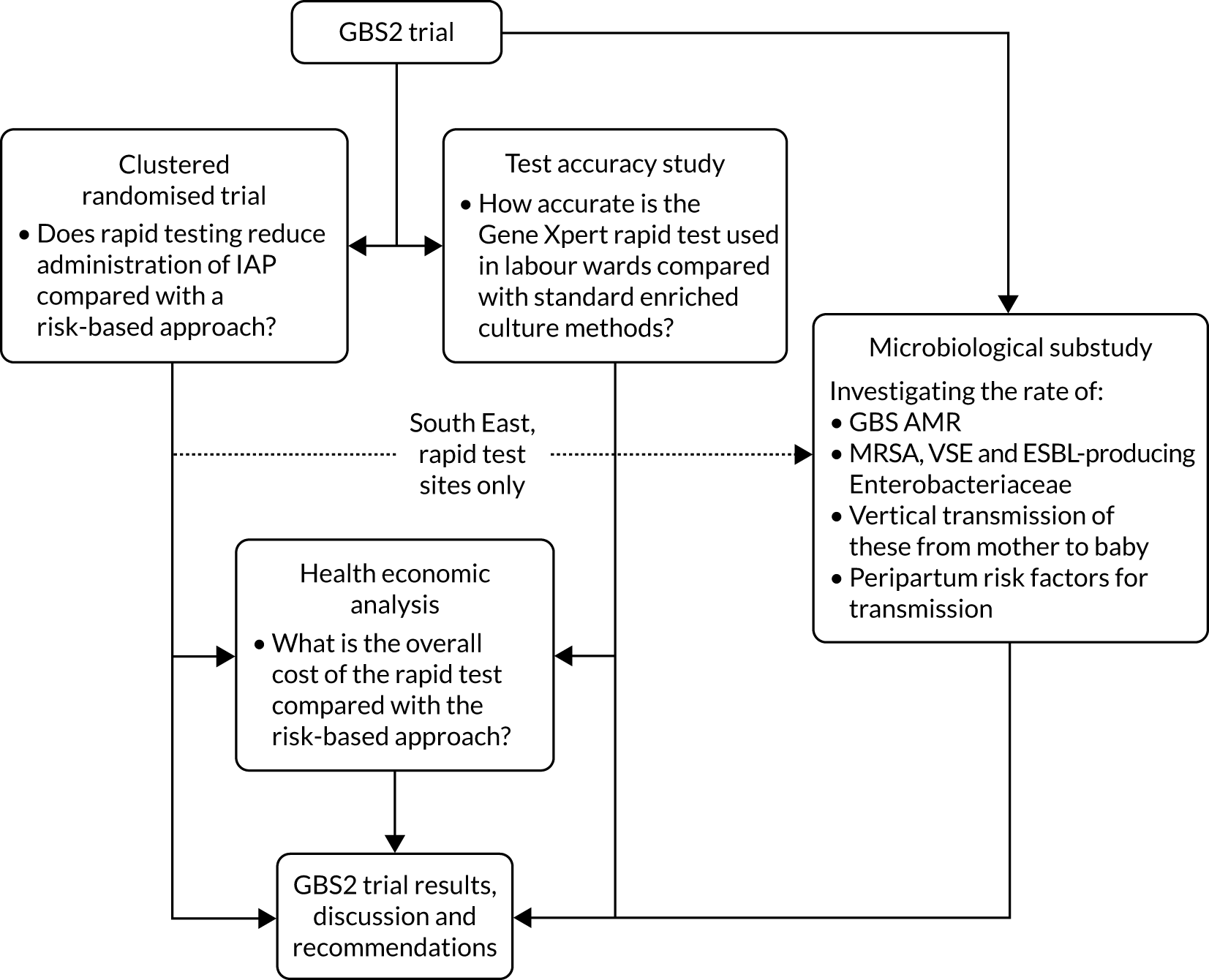

An overall trial schema for the GBS2 trial is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Overall trial schema for the GBS2 trial. AMR, antimicrobial resistance.

Chapter 3 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Daniels et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

The GBS2 trial was a multicentre, prospective, unblinded, parallel-cluster, randomised controlled trial (RCT), with a nested test accuracy study and a nested microbiological substudy, with economic evaluation.

The GBS2 trial had a favourable ethics opinion from the West Midlands – Edgbaston Research Ethics Committee (reference number 16/WM/0036), including waiver of individual research consent.

There were three substantial amendments to the protocol. The first amendment was approved on 18 April 2017, before the first unit started identifying women, and aligned eligibility criteria to those anticipated to be in the revised 2017 RCOG guidelines,4 which redefined the maternal risk factors for early-onset GBS infection. The second amendment was approved on 7 March 2018 and updated the recommended antibiotics, following the publication of the RCOG’s guidelines. The third amendment was approved on 3 December 2018 and formally capped each unit’s recruitment target at 86 women.

Cluster randomised controlled trial

The GBS2 trial was designed as a cluster RCT that was randomised at the level of the maternity unit. Sites were randomised to the rapid test strategy (i.e. IAP administration based on the rapid test results) or to usual care (i.e. the standard risk-based screening strategy and IAP offered to all women with risk factors).

Nested test accuracy study

To establish the real-time accuracy of the Cepheid GeneXpert system rapid POC test for GBS colonisation in women presenting to a labour ward with risk factors for early-onset GBS infection, the results of the rapid test were compared with the reference standard of selective enrichment culture in a prospective cohort study. The results of the rapid test preceded those of the culture test and interpretation of the reference standard was performed blind to the rapid test.

Process evaluation in rapid test sites

In the units that were allocated to rapid testing in the cluster randomised trial, we undertook an observational study to determine in real time the timings between rapid test results and commencement of IAP, and to identify if there were any failures in producing results once the tests were initiated on the machine.

Economic evaluation

The economic analysis is based on primary clinical data collected in the cluster RCT, adopting the UK NHS perspective. Full methods of the health economics analysis are described in Chapter 7.

Microbiological substudy

A substudy embedded in the GBS2 trial estimated the relatedness of certain bacterial species that are of public health concern that may colonise the mother during the birth of her baby and her child when they reach 6 weeks of age. The substudy also aimed to detect the antibiotic susceptibility of these strains. This substudy took place in participating units in London and the south-east of England (LSE) that were randomised to receive a rapid test system. The methods are described in Chapter 8.

Centres and participants

Eligibility of centres

Maternity units were eligible to participate in the GBS2 trial if they were prepared to accept a policy of rapid test-directed IAP administration to all women with risk factors for the duration of the trial period when allocated to the rapid test strategy. Maternity units also had to be prepared to include all preterm labours considered as high risk, irrespective of the implementation date of the RCOG’s guidelines and its current local policy. The trusts hosting the maternity units were also required to have access to microbiology facilities that were able to perform a selective enrichment bacteriological culture to detect GBS.

Randomisation

Randomisation of clusters was performed at the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit using a minimisation algorithm programed in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) incorporating the following factors:

-

region [the Midlands (MID) or LSE]

-

pre-trial IAP rate (above or below the median)

-

the number of vaginal or emergency caesarean births (above or below the median).

The pre-trial IAP rates and the birth rates over a period of 12 months were determined from all potential recruiting units prior to randomisation. This estimate provided the trial with the size of the population eligible to be tested, and served as a minimisation variable and as the denominator for the IAP use calculation. Antibiotic data were derived from interrogation of hospital records and pharmacy prescribing databases at the level of the maternity unit, not at the individual level. Using the standard dosing regimen of antibiotics, the size of the eligible population and the assumptions regarding the average duration of antibiotic administration, we estimated the number of women who received IAP prior to the trial. The median value of the eligible population sizes and pre-trial IAP rates were calculated for the first 20 maternity units that were intending to participate in the GBS2 trial, and these were used as thresholds for dichotomising the minimisation variable data.

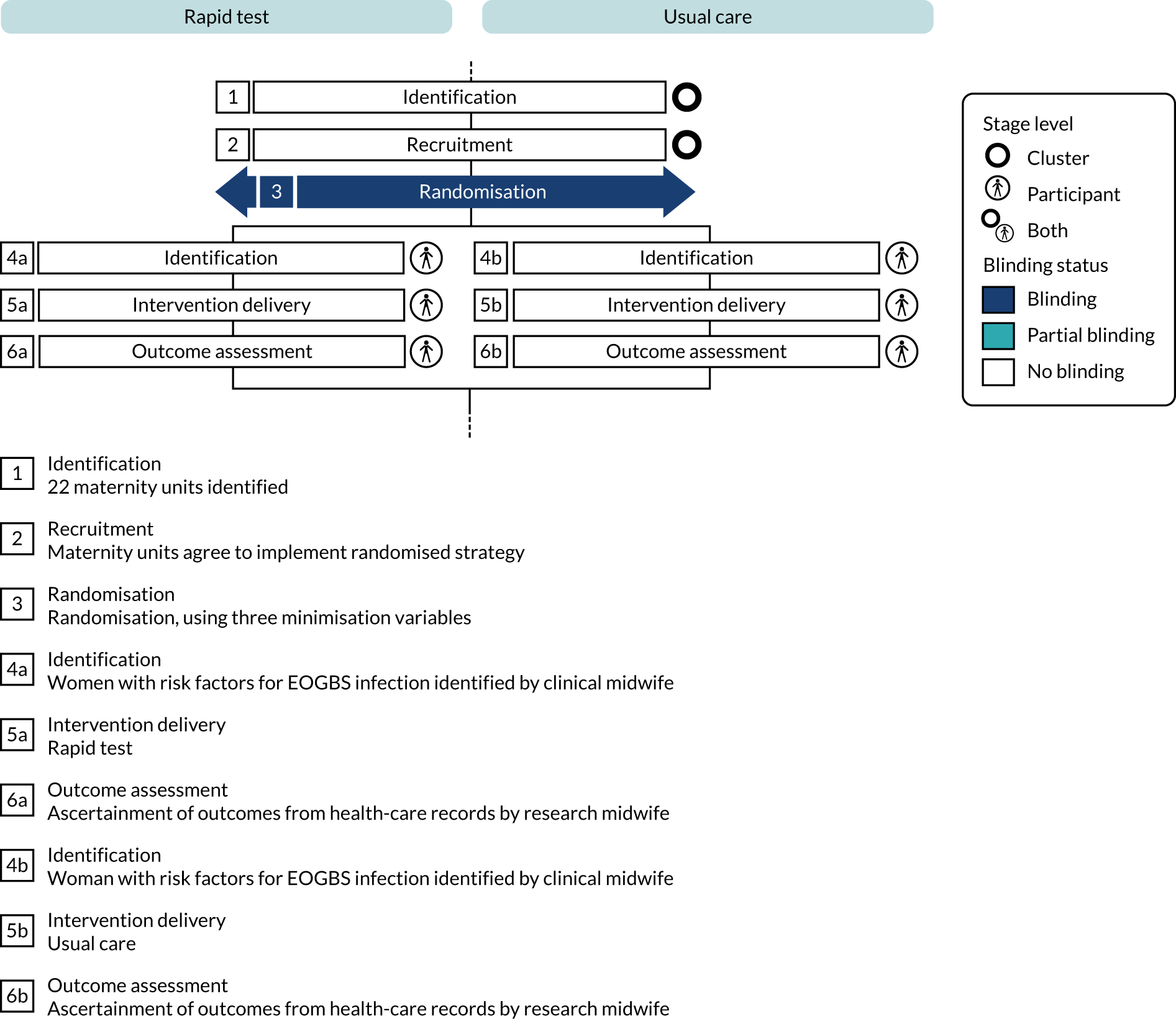

Blinding

Owing to the different study procedures under the two testing strategies, it was not possible to blind maternity unit staff to their allocation. A summary of the blinding status along the trial pathway is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Cluster randomised trial blinding timeline for the GBS2 trial. EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus (disease/infection). This figure was produced using the Timeline Cluster Tool. 53

Setting

The cluster was defined as the maternity unit. Women were identified and screened for eligibility by clinical midwives and doctors in various locations, including the delivery suite, the maternity triage unit and the induction ward. No research-specific consent was obtained, although women in the rapid test units provided verbal clinical assent to have the vaginal/rectal swab.

Participant eligibility criteria

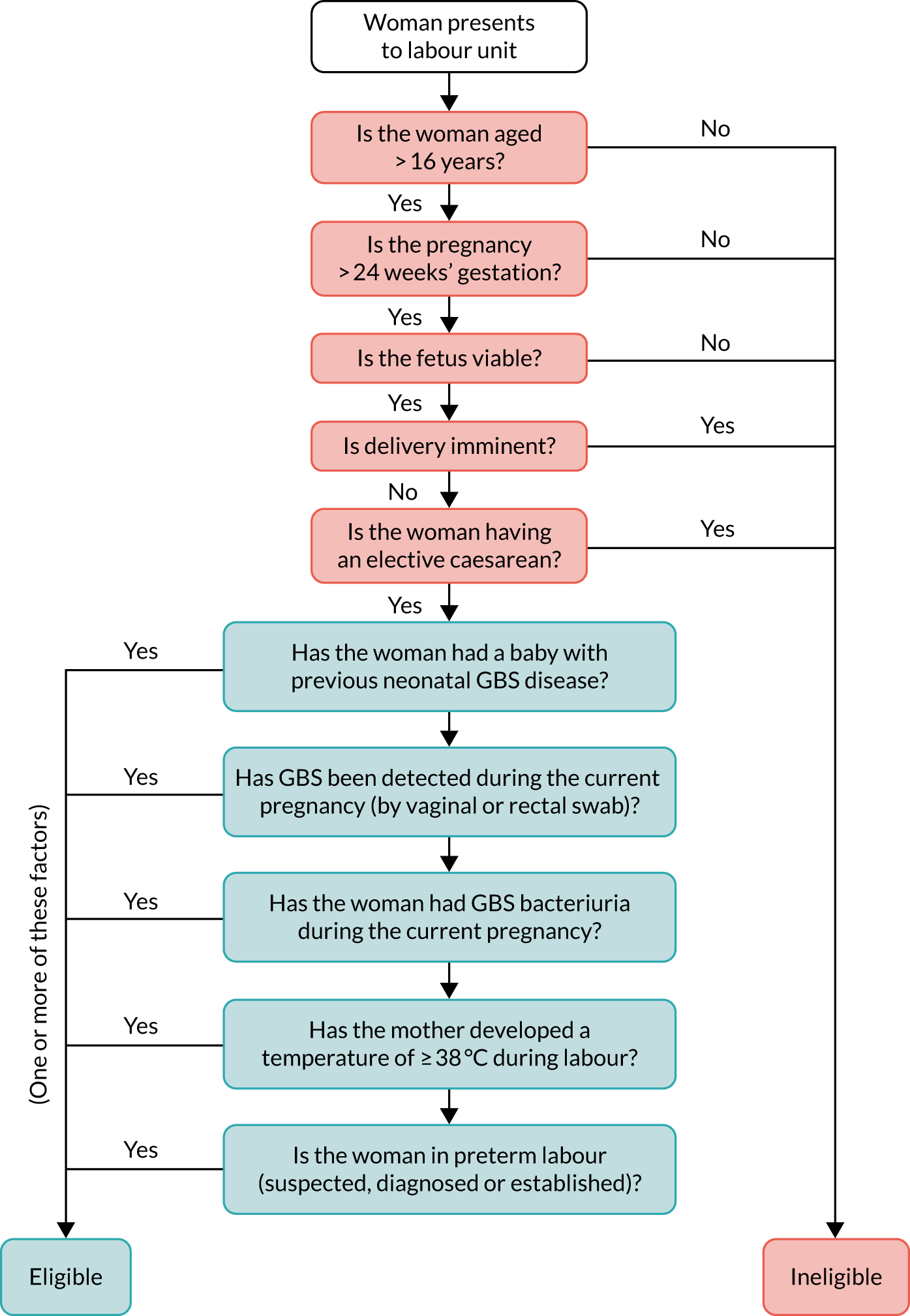

The eligibility pathway for the GBS2 trial is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The GBS2 trial eligibility criteria flow chart.

Women were eligible for inclusion in the GBS2 trial if they met one or more of the following criteria:

-

a previous baby with early- or late-onset neonatal GBS disease, as reported by the mother and documented in the maternal notes

-

GBS bacteriuria during the current pregnancy, as documented in the maternal notes, irrespective of whether or not the GBS bacteriuria was treated at the time of diagnosis with antibiotics

-

GBS colonisation of the vagina and/or rectum (determined from a vaginal/rectal swab) in current pregnancy, as documented in the maternal notes

-

preterm labour (< 37 weeks’ gestation) whether suspected, diagnosed or established, regardless of whether membranes were intact or there was PROM of any duration

-

maternal pyrexia (≥ 38 °C) observed at any point in labour, including clinically suspected/confirmed chorioamnionitis.

Women were screened for eligibility to participate in the GBS2 trial if they presented to the maternity unit in preterm labour (suspected, diagnosed or established), regardless of rupture of membranes, in term labour (latent or established) or if they were about to be induced.

Participant exclusion criteria

Women were ineligible for inclusion in the GBS2 trial if they were aged < 16 years; their pregnancy was at < 24 weeks’ gestation; they were in the second stage of labour at admission or considered likely to give birth to their baby imminently; they had planned an elective caesarean birth; or their baby was known to have died in utero or had a congenital anomaly incompatible with survival at birth.

Study procedures

The study procedures at each site varied according to the testing strategy randomly allocated to the participating maternity unit. The recommended antibiotic regimen for preventing early-onset GBS infection in both maternity unit groups of the trial were identical: intravenous administration of 3 g of benzylpenicillin as soon as possible after the onset of labour, and half of that dose at 4-hourly intervals until birth. If the woman was known to be allergic to penicillin she was offered a cephalosporin, and if she had a history of serious reactions to beta-lactams, vancomycin was indicated.

The protocol stipulated that all women in the usual-care group should have received IAP, whereas only those who tested positive or for whom a test result was not available should be offered IAP in the rapid test group (unless there was a clinical reason for prescribing IAP or the women had already had a previous baby with GBS infection and requested IAP).

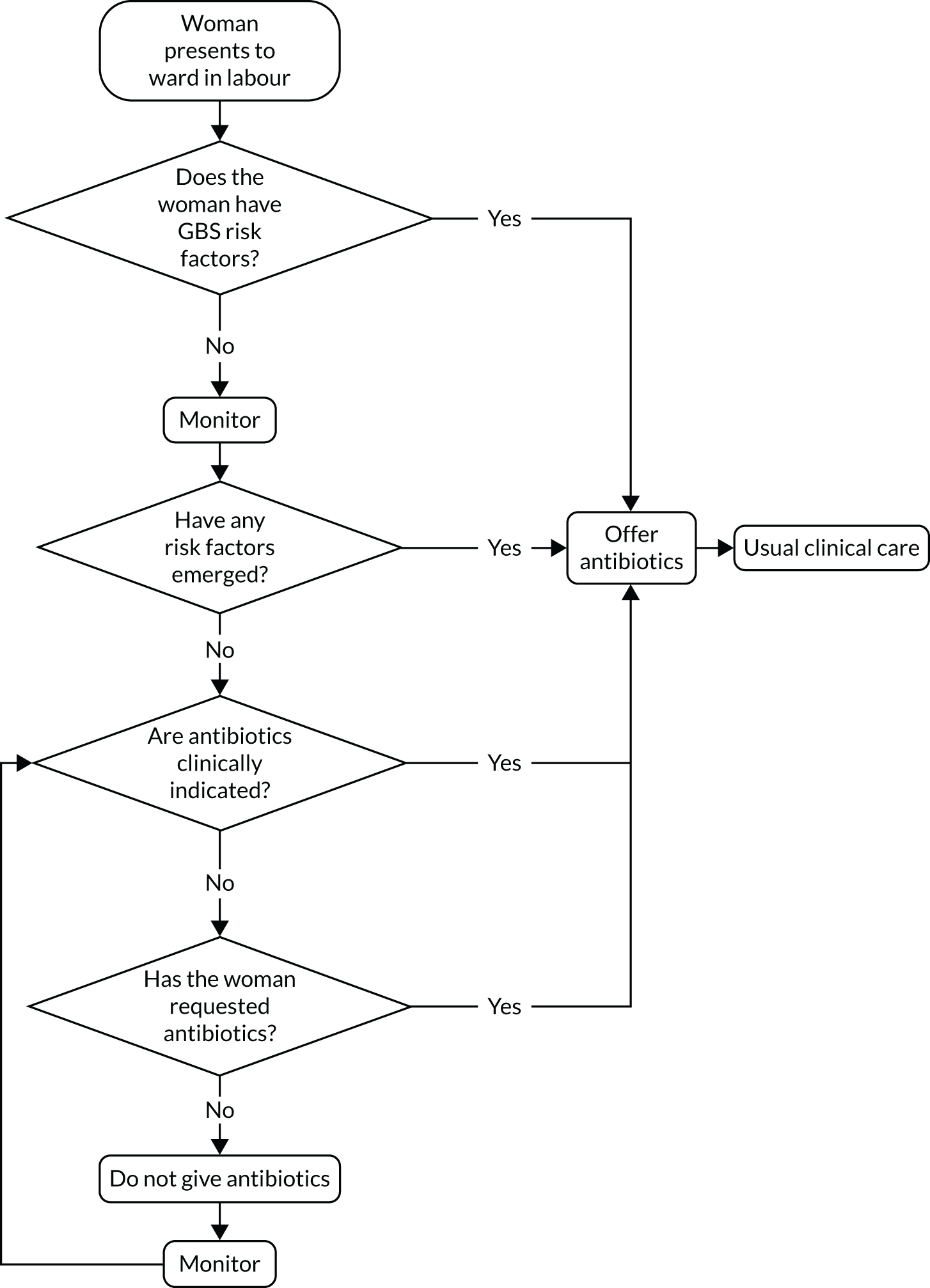

Usual-care units (risk factor-based provision of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis)

The study procedure for usual-care sites, in which IAP is offered to women with clinical risk factors, is outlined in Figure 5. All women with risk factors for early-onset GBS infection, whether initially apparent or emerging, were considered eligible for the study.

FIGURE 5.

Study procedures for usual practice maternity units.

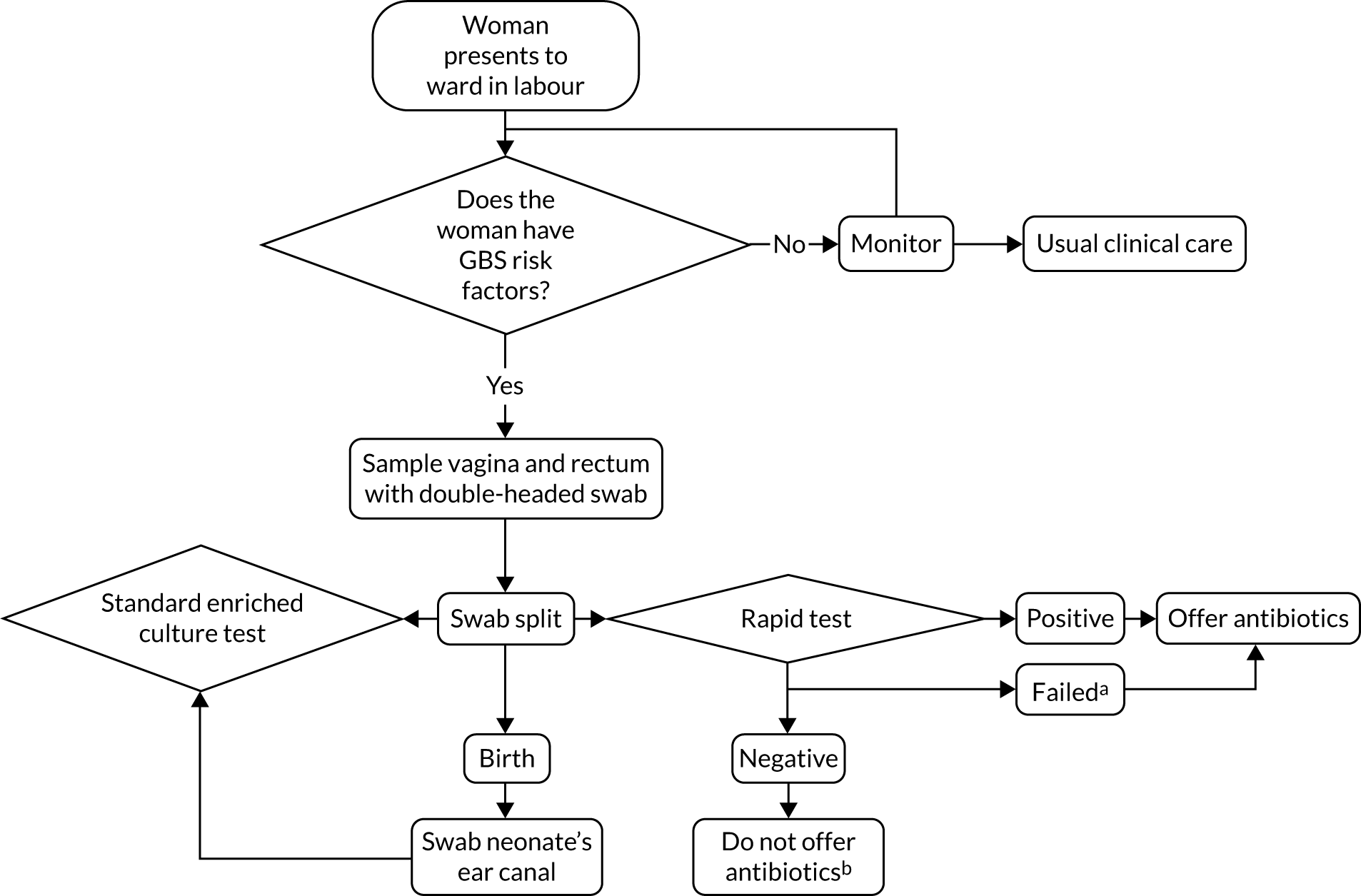

Rapid test strategy

The units that were randomised to the rapid test received a GeneXpert® Dx IV GBS rapid testing system (Cepheid), which was installed and commissioned by a field specialist from the manufacturers. Each unit allocated to the rapid test screening policy was required to house the GeneXpert machine and computer centrally in the unit and have it operational at all times. Units were provided with a sufficient supply of Xpert GBS test cartridges (Cepheid) and double-headed swabs in transport tubes containing Stuart transport medium. In units participating in the substudy, additional single-headed swabs were also supplied. The use of the rapid test for screening was restricted to women who presented to the labour ward and who were eligible according to the participant eligibility criteria. A summary of the pathway for rapid test units is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Study procedures for rapid test maternity units. a, Failed tests include, but are not limited to, machine failure and failure to process swab in required time frame; and b, unless otherwise clinically indicated. This was at the discretion of local clinical care.

Obtaining a vaginal/rectal swab

Swabs were taken using a double-headed swab. Depending on the stage of labour, the swabs were obtained by either the woman herself or a suitably trained member of the woman’s care team. This could be on admission to the labour or induction ward before a vaginal examination was performed, or after a risk factor was detected (e.g. when maternal fever was observed). Swabs were first taken by gently rotating the swabs across the mucosa of the lower vagina. The same swab was then used to take a sample from the rectum, inserting the swab through the anal sphincter then gently rotating. The shafts of the double-headed swabs were then separated carefully. One was returned to the transport tube and sent to the local microbiology laboratory for selective enrichment culture to detect GBS (see Enrichment culture method) and the other was immediately used for the rapid test. For sites taking part in the microbiological substudy, and for participants who had consented to take part, an additional single-headed swab was taken and sent to the substudy laboratory (see Chapter 8).

In practice, a number of substances containing antimicrobial compounds administered vaginally may interfere with the results of the rapid test. The use of lubricant that contains antimicrobial substances, such as K-Y Jelly (Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK), for vaginal examination or for taking swabs was discouraged. It was suggested that sterile non-bacteriostatic fluid (e.g. sterile water or saline) was used when lubrication was necessary. Other procedures that may have involved antimicrobial substances include placing a pessary to induce labour, or chlorhexidine to cleanse the perineum or as a vaginal douche (although this is not currently indicated in NICE guidelines). 54 Nevertheless, as the GBS2 trial aimed to establish the use of a rapid test in a real-world setting and, indeed, vaginal examinations are usually undertaken to establish labour, women for whom antimicrobial substances were used were not excluded from the trial. Instead, the use of any antimicrobial substances after admission to the maternity and prior to the swab being taken was recorded.

Delayed labour

If more than 48 hours had elapsed since the test result became available and the woman had yet to give birth, the test result was regarded as invalid. In this situation, it was advised that the woman should be re-swabbed and the presence of GBS tested for again using both the rapid test and the microbiological techniques.

Conducting the rapid intrapartum test

After sampling, one swab was used to inoculate a test cartridge. Should the inoculated cartridge not have been loaded into the rapid test system and the test commenced within 15 minutes of the swab being introduced into the cartridge, the test was be deemed to have failed. The NHS or hospital number was entered into the GeneXpert software alongside the woman’s unique trial number. This trial number was identical on each item of study material associated with one woman and her child (or children). The test was conducted as per the operator manual. 55 It takes, on average, 35 minutes to get a result if GBS is present, 55 minutes to confirm if there is no GBS present and an error message is presented if the test has failed. Used test cartridges and swabs were disposed of in accordance with local policies for clinical waste. Instructions provided to sites for conducting the rapid test are available on request from the manufacturer.

Enrichment culture method

The second vaginal/rectal swab was sent to the local microbiology department where it was used to inoculate a selective enrichment medium prior to plating to detect the presence of any GBS, as per the current Public Health England recommendations. 56 Results from the microbiological cultures were returned to the care team using the usual reporting pathways and were recorded in the woman’s notes. Swabs, sent to the microbiology laboratory for the determination of the GBS colonisation status, were inoculated into Todd–Hewitt broth for overnight enrichment at 37 °C. This enriched broth was subcultured on chromogenic GBS agar and incubated aerobically overnight at 37 °C. GBS was identified by the presence of pink/red colonies. Microbiological data were transcribed to the GBS2 trial database by either a member of the microbiology department or a local research nurse. When manual data entry was required, the data entry screen did not allow review of the rapid test results by those outside the study office, therefore reducing the risk of review bias.

Neonatal ear canal swab

For eligible women in rapid test units, a single swab was taken from the baby’s ear canal as soon as convenient after birth. This swab was put into a transport tube, labelled with a numbered sticker and sent to microbiology for culture using the hospital’s usual request system to detect the presence of GBS, as per the mother’s swab (see Enrichment culture method). The neonatal swab was not used in the rapid test machine.

Outcome measures

Owing to the difference in the strategies for testing women and for directing IAP, it was not possible to blind women or their care team to the randomised allocation. Data were extracted from maternity and neonatal notes by research midwives within each unit who were involved in the implementation of the study, and therefore it was not possible to blind them to the randomised allocation.

Research midwives regularly collected data from consecutive eligible women regarding the use of antibiotics from the women’s health-care records, including information on whether or not any antibiotic was given, along with the date and time of IAP initiation.

Primary outcomes

-

The proportion of women who received only IAP for GBS prophylaxis, of all women identified with one or more risk factors for neonatal GBS infection.

-

Measures of test accuracy (i.e. the sensitivity and specificity of the GeneXpert GBS rapid test).

The indication for any intrapartum antibiotic administration was ascertained by making available the following options: GBS prophylaxis (in usual-care units only), a positive rapid test and a failed rapid test (both in rapid test units), pyrexia during labour, a caesarean birth, maternal request and other reason (to be specified). Multiple reasons could be recorded.

Secondary outcomes

Cluster randomised trial

Maternal

Intrapartum maternal antibiotic use for any indication

-

The proportion of women receiving any intrapartum antibiotic that has been indicated as being for GBS prophylaxis for a maternal clinical indication, such as pyrexia, on maternal request, prior to a caesarean or for any other reason, as a proportion of those women identified as having one or more risk factors for early-onset GBS infection.

Intrapartum maternal antibiotic use for any indication other than for a caesarean

-

The proportion of women receiving any intrapartum antibiotic that has been indicated as being for GBS prophylaxis for a maternal clinical indication, such as pyrexia, on maternal request or for any other reason other than for a caesarean, as a proportion of those women identified as having one or more risk factors for early-onset GBS infection.

Postpartum maternal antibiotic use for any indication

-

This was defined as those women receiving any postpartum antibiotic that had been indicated as being a maternal clinical indication, such as pyrexia, on maternal request or for any other reason, as a proportion of those women identified by the delivery suite midwives as having one or more risk factors for early-onset GBS infection. The period in which these data were collected was from birth until the mother’s discharge from either the hospital she gave birth or any hospital to which she was immediately transferred. Data on antibiotic use following any readmittance or prescribed by her general practitioner were not collected.

Time of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis exposure

-

This was defined as the duration between the start time of the first dose of IAP and the birth of the baby. Sufficient exposure was considered as an interval of either > 2 hours or > 4 hours before birth.

Neonatal

Neonatal antibiotic use for prophylaxis or treatment

-

The proportion of babies receiving antibiotic prophylaxis because of maternal GBS status or antibiotic treatment for suspected or confirmed neonatal infection, as a proportion of babies born to women identified as having risk factors for early-onset GBS infection.

Suspected neonatal infection

-

The number of babies prescribed antibiotics for presumed neonatal infection, as a proportion of all live born babies.

Neonatal group B Streptococcus colonisation rates

-

The rate of GBS-positive selective enrichment cultures from the neonatal ear swabs, as a proportion of all neonatal ear swabs cultured.

Neonatal mortality

-

Includes stillbirth rate and early neonatal death (before 7 days), and these are combined as the perinatal mortality rate.

Test accuracy secondary outcomes

Maternal and neonatal colonisation rates, and the mother-to-baby transmission rate.

Process outcomes

A number of process outcomes were also evaluated, for the rapid test units only, including the:

-

duration between a positive test becoming available on the GeneXpert machine and the time the result is collected by a midwife, and the duration between that point and the start of IAP

-

proportion of the cartridges on which the tests were not commenced within 15 minutes of inoculation, which is defined as an invalid test

-

proportion of tests initiated on the Cepheid GeneXpert machine that failed to produce a result within 55 minutes, which is defined as a failed test, or were reported as failed by the system.

Serious adverse event outcomes

Serious adverse events are expected to be extremely rare. There may be significant consequences of the failure to offer IAP to a woman with GBS risk factors and to women identified by rapid test as being colonised with GBS in terms of the increased risk of their baby developing early-onset GBS infection. Conversely, there is a risk of overtreatment if IAP is administered to women without risk factors or with a negative rapid test. However, these instances were considered outcomes of interest within the study, and not adverse events. The risk-based approach involves the noting of historical risk factors and the monitoring of women for emerging risk factors, such as chorioamnionitis. This presents no risk to the women other than a failure to identify and act on these risk factors. The rapid test requires a vaginal/rectal swab to be collected during labour, which is benign and presents no foreseeable risk of harm. As with almost any diagnostic test, there was a risk that testers may suffer an inoculation injury (most likely mucous membrane exposure) with clinical material. A proportion of women will receive antibiotics, particularly benzylpenicillin for IAP, which carry a very small risk of anaphylaxis. 58

The outcomes of economic evaluation and for microbiological substudy are provided in Chapters 7 and 8.

Statistical methods

For baseline characteristics, categorical data are summarised by frequencies and percentages. Continuous data are summarised by the number of responses, mean and standard deviation (SD) if deemed to be normally distributed, and number of responses, median and interquartile range (IQR) if data appear skewed. Tests of statistical significance were not undertaken. In accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline, both absolute and relative measures of treatment effects are reported, and so for the primary and secondary outcomes in the cluster randomised trial component both risk differences (RDs) and relative risks (RDs) are presented where possible. Estimates of differences between groups are presented with 95% two-sided CIs. p-values are reported from two-sided tests at the 5% significance level and no corrections are made for multiple testing.

In the primary analysis for the cluster randomised trial, a mixed-effects binomial regression with a log-link was used to estimate the RR, and a binomial model with identity link was used to estimate the RD. In the case of non-convergence of the binomial model with a log-link, a Poisson model with robust standard errors was fitted. If the binomial model with the identity link did not converge, then only a RR was reported. Both models allowed for clustering by maternity unit as a random effect. To correct the potential inflation of the type I error rate due to small number of clusters, the Kenward and Roger method59 was used.

Comparative estimates of differences between groups were adjusted for the hospital and the minimisation variables of region (i.e. LSE or MID), baseline IAP rate (i.e. equal to or greater than the median or less than the median) and the number of vaginal or emergency caesarean births (i.e. equal to or greater than the median or less than the median). These effects were all be assumed to be fixed in the regression models used. A secondary analysis for the primary outcome additionally adjusted for maternal temperature of ≥ 38 °C observed while in labour, any previous baby with GBS disease, GBS bacterium detected in current pregnancy, and woman in suspected/diagnosed/established preterm labour. When covariate adjustment was not practical, unadjusted estimates were produced and it was made clear in the output why this occurred (e.g. not possible because of low event rate, lack of model convergence or poor recording accuracy of covariates). Multiple imputation analysis, accounting for clustering, was planned if the proportion of observations with missing complete information on these covariates was > 5%.

Prespecified subgroup analyses were limited to the primary outcome. The following subgroup effects were investigated:

-

maternal temperature of ≥ 38 °C observed while in labour

-

previous baby with GBS disease

-

GBS bacterium detected in current pregnancy

-

preterm labour (< 37 weeks’ gestation) with intact membranes or rupture of membranes of any duration, whether suspected, diagnosed or established.

Treatment effects were summarised within each subgroup separately, and an interaction test was performed between each subgroup variable and the received allocation.

The diagnostic accuracy of the rapid test was estimated through the standard calculations of sensitivity and specificity. Estimates are presented with 95% CIs calculated using binomial exact methods. 60 We also undertook a binomial proportions test to compare the observed sensitivity with the hypothesised minimal performance value of 90%.

Sample size for the cluster randomised trial

The focus of sample size calculation was on the effectiveness of the rapid test. We aimed to recruit a minimum of eight clusters per randomisation group (i.e. a total of 16 maternity units). This was a realistic recruitment goal and was deemed sufficient to allow estimation of model parameters. We estimated that the sample size per cluster would be approximately 83 (this is informed by routinely collected data on number of eligible women giving birth). This equated to a total sample size of approximately 664 per strategy group to allow recruitment of the required number of individuals for the test accuracy study. As there were two strategy groups (i.e. usual care and rapid test), each with at least 664 participants, it was expected to provide a sample size of 1328 women. This was rounded up to a target sample size of 1340 women. To allow for dropouts at the level of the cluster, anticipating implementation issues in maternity units, the number of clusters was increased from 16 to 20.

The proportion of women receiving antibiotics to prevent vertical GBS transmission (i.e. the primary outcome in the cluster RCT) was expected to be in the region of 50–75% (based on the previous study51 and assuming better compliance with RCOG guidelines since that study). This primary outcome was a process outcome and so the within-cluster correlation of this outcome [the intracluster coefficient (ICC)] was expected to be higher than it would be for a clinical outcome. We therefore considered sensitivity of our calculations to a range of proportions in the usual-care units and a range of ICC values, which we believe to be quite conservative. All of our calculations allowed for 90% power and 5% significance. We did not acknowledge varying cluster sizes in our calculations, as we considered the coefficient of variation of unit birth sizes to be small (approximately 0.21 based on annual birth rates for 2013) and could be altered by varying the study duration at maternity units. However, given our conservative assumptions, and that the impact of the testing strategies on the primary outcome was expected to be large (i.e. a priori we expect the effect size to be large), we expected the impact of any varying cluster sizes to be minimal. For a range of values for the important parameters, as described above, we worked out the detectable differences and equivalent relative RR (Table 1).

| IAP rate in risk factor strategy | ICC, % (RR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.01 | |

| 75 | 38 (0.51) | 48 (0.64) | 55 (0.73) | 63 (0.84) |

| 60 | 22 (0.37) | 32 (0.53) | 39 (0.65) | 47 (0.78) |

This means that this trial would have around 90% power to detect a reduction in proportion of women prescribed antibiotics to prevent GBS transmission from 75% to 63% (i.e. a RR of about 20%) for a low value of the ICC to a reduction from 75% to 38% for a very conservative value of the ICC (0.2), equating to a RR reduction of 50%.

Sample size for the test accuracy study

The sample size of the test accuracy study was dependent on the sensitivity of the rapid test. For the test to be proven useful, we needed to show that it would detect a higher proportion of GBS colonisation than other tests, but not at the cost of low specificity and/or unnecessary administration of IAP. Results from the Group B Streptococcus 1 (GBS1) study51 suggested that the most cost-effective test (if untargeted universal IAP was excluded) was antenatal culture for GBS at 35–37 weeks’ gestation. In the GBS1 study51 the sensitivity of this test was 75.8% (95% CI 47.2% to 91.5%). Therefore, if we could prove that the sensitivity of rapid test was > 90% then the results of the GBS2 study51 would be convincing. This was a stringent test and a lower threshold might also be adequate. We did not compare the rapid test with antenatal GBS culture testing within the study, but compared with this result from external literature. Therefore, we undertook a ‘one sample, sample size’ computation comparing against a fixed value.

We had data from a systematic review on the performance of the GeneXpert GBS test (J Daniels, personal communication). From the meta-analysis of nine studies, the pooled accuracy of the test was estimated, giving a sensitivity of 96.4% (95% CI 90.8% to 98.6%) and specificity of 98.9% (95% CI 97.5% to 99.5%). Sample size calculations are therefore based on showing that a test with sensitivity of 96.4% is greater than a fixed value of 90%. With a power of 90% to demonstrate this sensitivity, 167 cases of maternal GBS colonisation are required (or 136 at 80% power).

A sample size of 676 women would provide 90% chance of us accruing enough GBS-colonised women to have 90% power to show the sensitivity of the rapid intrapartum test to be statistically significantly (with p < 0.05) > 90% should the meta-analytical estimate of its performance (96.4%) be correct, while allowing for 10% loss from failed tests, based on the GBS prevalence observed in the GBS1 study,51 which was 29.8% (89/299, 95% CI 24.6% to 35.2%). Of the 606 participants with data, we would expect 167 to be GBS carriers and 439 to be negative for GBS colonisation. If the prevalence of GBS colonisation was actually at the lower end of the 95% CI from GBS1 study,51 namely 24.6%, then a total of 673 women would give a 90% chance of observing 136 cases of GBS colonisation, including 10% lost tests. The 95% CIs we would observe on sensitivities and specificities of 85%, 90%, 95% and 98% with a sample size of 676 women (606 women with data) are shown in Table 2, and these have adequate precision (sensitivity within 10% and specificity within 6%) for modelling.

| Point estimate | 95% CI for sensitivity (n = 167) | 95% CI for specificity (n = 439) |

|---|---|---|

| 85 | 78.7 to 90.1 | 81.3 to 88.2 |

| 90 | 84.2 to 94.0 | 86.8 to 92.7 |

| 95 | 90.9 to 97.9 | 92.5 to 96.8 |

| 98 | 94.8 to 99.6 | 96.2 to 99.1 |

Chapter 4 Characteristics of sites and participants

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Daniels et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

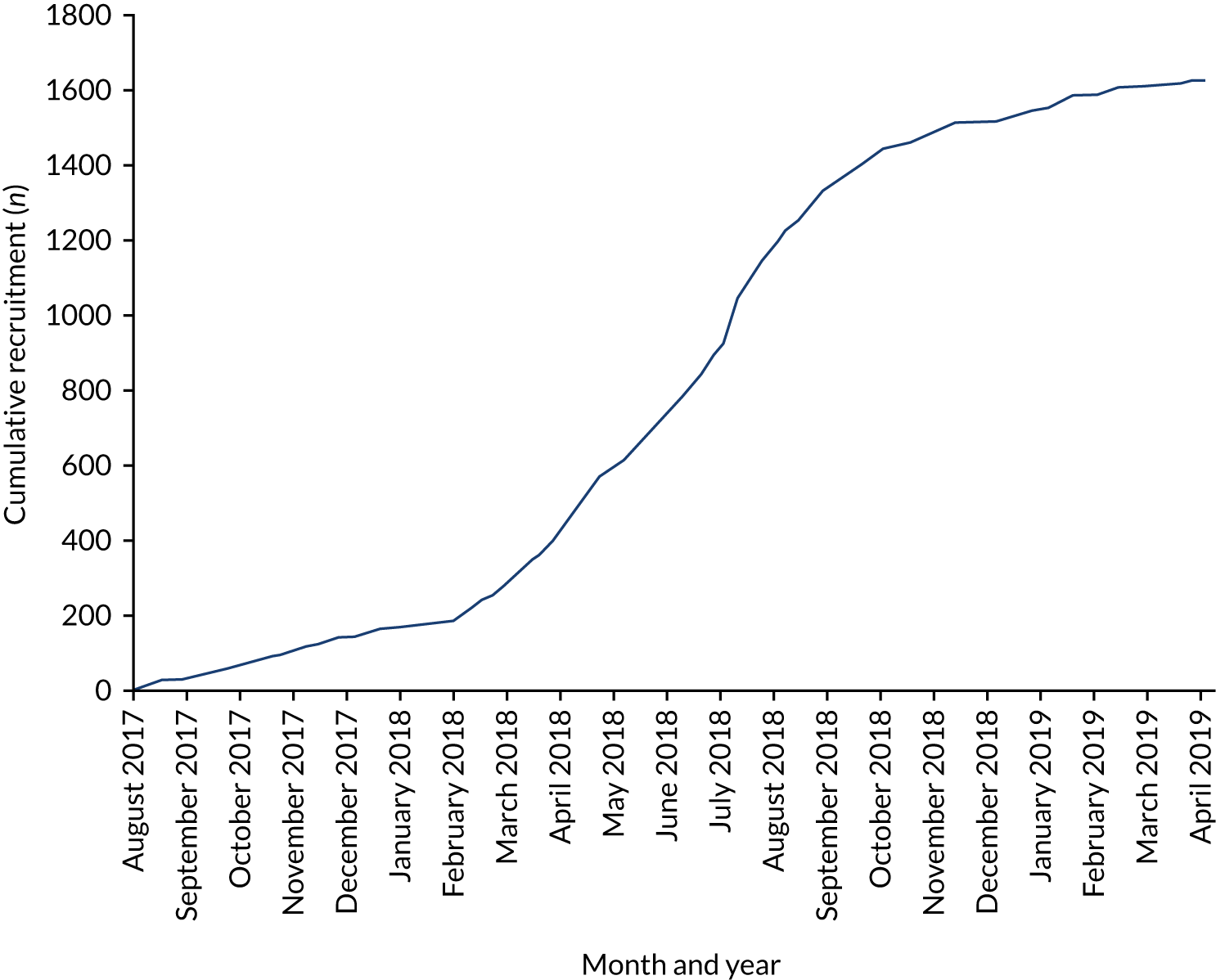

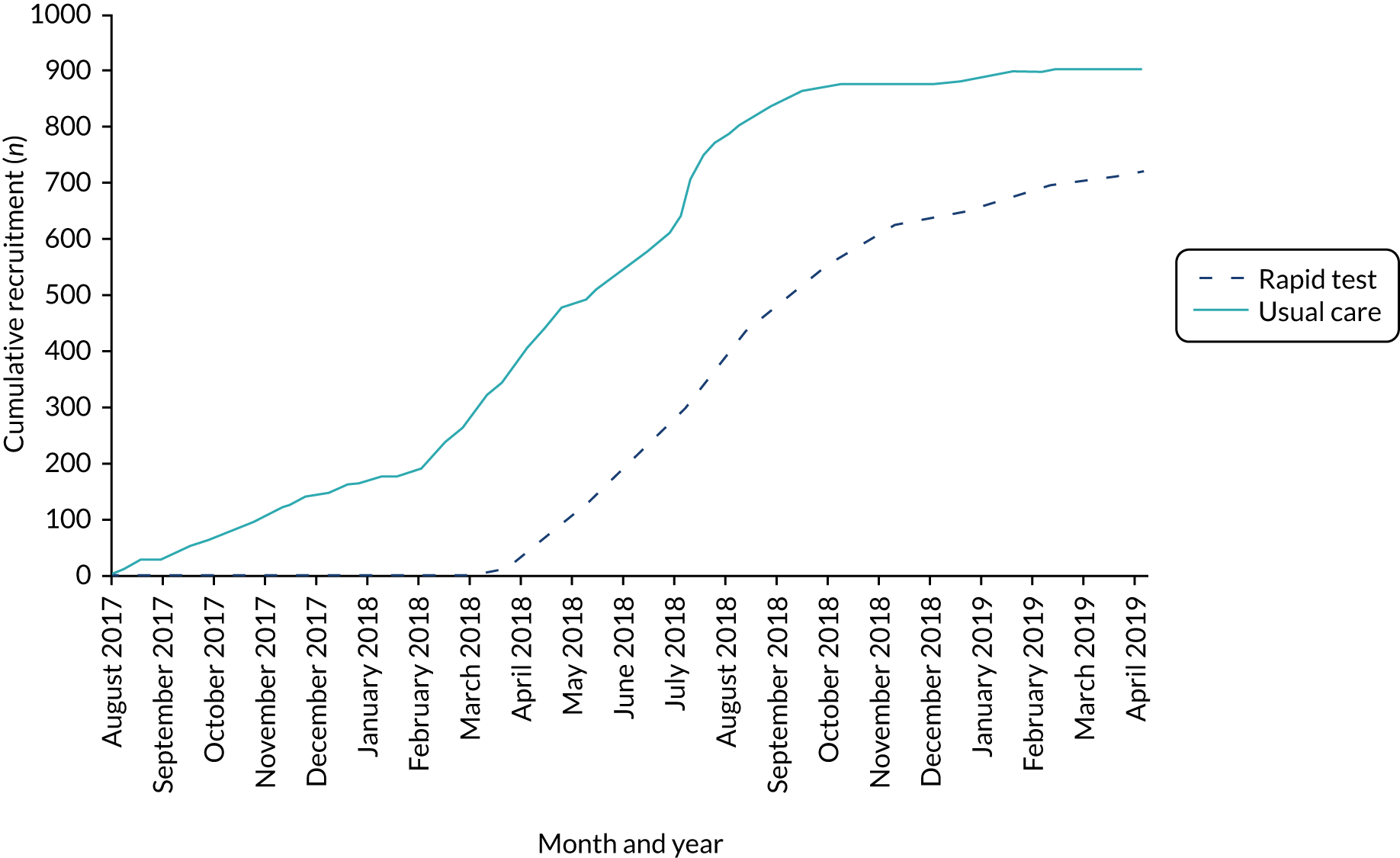

Accrual period

The first site opened to recruitment on 26 July 2017, and the trial closed to recruitment on 30 April 2019. Ten usual-care sites and eight rapid test sites met or exceeded their recruitment target of 86 women. As the sample size requirements were met (i.e. at least eight sites in each arm recruited 86 women per site), the Trial Steering Committee requested that recruitment ended.

Site-level randomisation

Overall, 22 maternity units agreed to participate and were randomised to usual-care or rapid test pathways. Initially, we randomised 20 sites (see Appendix 1). The allocations were revealed to the units at the same time, after all units had commited to participation. Following randomisation, two sites, one allocated to each strategy, requested withdrawal from the study. One usual-care site withdrew as it lost a key staff member and one rapid test site was not able to implement the rapid test using the no-consent model. We replaced these with two other sites that were randomised to usual-care and rapid test strategies, respectively. The anonymised maternity unit characteristics that were used within the minimisation algorithm are shown in Table 3. The units had around 2000–6000 births per year that were not planned elective caesareans. There was variation in the reported rates of IAP to prevent early-onset GBS infection.

| Site | Region | Annual number of vaginal or emergency caesarean deliveries | Estimated IAP rate (proportion of all deliveries receiving IAP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid test | |||

| R1 | MID | 4144 | 44.48 |

| R2 | LSE | 2385 | 24.12 |

| R3 | LSE | 2138 | 14.78 |

| R4 | LSE | 6021 | 22.77 |

| R5 | MID | 5583 | 32.64 |

| R6 | MID | 3952 | 24.71 |

| R7 | MID | 5627 | 7.24 |

| R8 | LSE | 4934 | 29.89 |

| R9 | LSE | 5105 | 25.84 |

| R10 | MID | 2148 | 10.01 |

| R11 | MID | 3567 | 62.7 |

| Usual care | |||

| U1 | MID | 2930 | 9.13 |

| U2 | LSE | 3701 | 29.22 |

| U3 | LSE | 2403 | 11.24 |

| U4 | LSE | 5050 | 31.73 |

| U5 | LSE | 4803 | 8.81 |

| U6 | MID | 5373 | 26.98 |

| U7 | MID | 1929 | 9.90 |

| U8 | MID | 2679 | 73.64 |

| U9 | LSE | 5231 | 87.28 |

| U10 | MID | 4291 | 12.06 |

| U11 | LSE | 2954 | 27.93 |

Individual-level accrual

The cumulative rate of accrual of women into the GBS2 trial, by screening pathway, is shown in Appendix 2. The date on which the woman was identified as having GBS risk factors was used as the date of study entry. The weekly total number of intended vaginal deliveries was requested from each unit to enable monitoring of the accrual rate. In the early phase of the trial, usual-care units were allowed to exceed their target of 86 women and continue to 100 women per unit. This was curtailed after the second unit reached a total of 100 women. At the end of the recruitment period, when sample size requirements were met, recruitment at two rapid test units was stopped: in one when 83 women had been recruited and in one after three women had been recruited. An estimate of the proportion of women recruited into the study of the total from the population giving birth vaginally or by emergency caesarean (using data from Table 3, pro rata for the duration of participation) is shown in Table 4.

| Site | Estimated number of vaginal or emergency caesarean deliveries during accrual period | Proportion of women accrued (% of all vaginal or emergency caesarean deliveries) |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid test | ||

| R1 | 1856 | 4.7 |

| R2 | 1684 | 5.1 |

| R3 | 1474 | 5.9 |

| R4 | 3209 | 1.0 |

| R5 | 1273 | 6.8 |

| R6 | 1791 | 4.8 |

| R7 | 1175 | 7.3 |

| R8 | 2562 | 3.1 |

| R9 | 1809 | 5.0 |

| R11 | 774 | 0.3 |

| Usual care | ||

| U1 | 1240 | 7.3 |

| U2 | 641 | 13.4 |

| U4 | 1013 | 8.5 |

| U5 | 739 | 13.5 |

| U6 | 2687 | 3.2 |

| U7 | 890 | 11.2 |

| U8 | 228 | 37.7 |

| U9 | 805 | 12.4 |

| U10 | 613 | 13.9 |

| U11 | 771 | 11.2 |

Characteristics of the included sites and participants

Maternity sites

Following randomisation, the maternity units were balanced according to the minimisation characteristics (Table 5).

| Minimisation factor | Rapid test (N = 10) | Usual care (N = 10) | Overall (N = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of vaginal deliveries or emergency caesareans | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4539 (3567–5583) | 3996 (2930–5050) | 4218 (2942–5168) |

| Below median, n (%) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 10 (50) |

| Above median, n (%) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 10 (50) |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| LSE | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 10 (50) |

| MID | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 10 (50) |

| Estimated IAP rate as a proportion of all vaginal deliveries | |||

| Median (IQR) | 25.3 (22.8–32.6) | 27.5 (9.9–31.7) | 26.4 (13.4–32.2) |

| Below median, n (%) | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 10 (50) |

| Above median, n (%) | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 10 (50) |

Participants

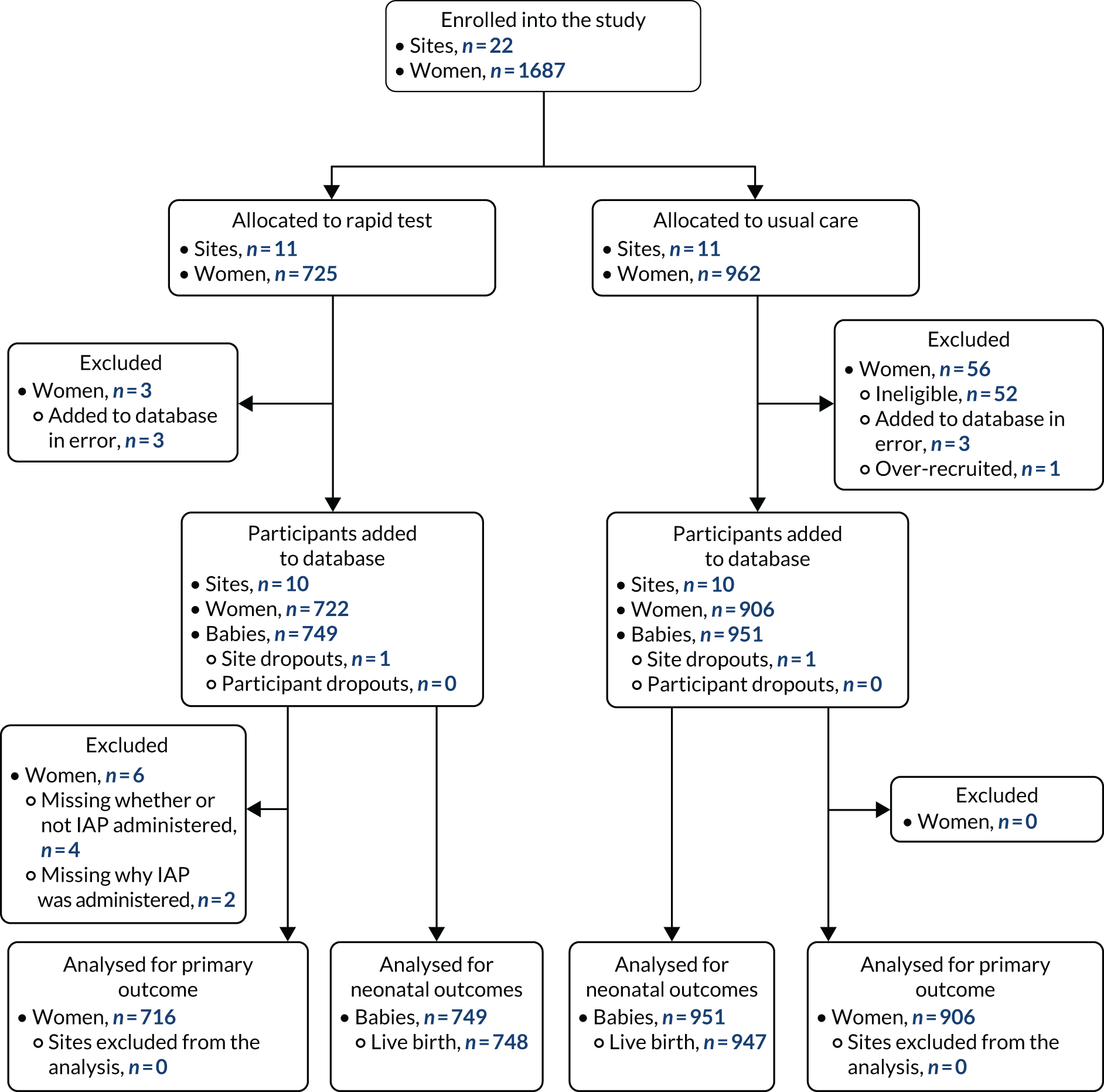

Overall, 1687 women were identified and added to the trial database during the recruitment window for the 20 randomised sites. There were 52 women from two usual-care maternity units who were added to the database but who were ineligible for the study, as the database eligibility criteria initially did not reflect the protocol. A further three women in each group who, on closer examination, were added to the database in error, as they were not eligible and one woman’s record was duplicated. These women’s data were excluded from the analysis, leaving 1628 women in the data set.

The overall numbers of women recruited were 722 in rapid test sites and 906 in usual-care sites. There were 67 pairs of twins and three trios of triplets and, therefore, the number of babies available for assessment was 749 in the rapid test group and 951 in the usual-care units (Figure 7). Similar proportions of women in the two study groups were recruited from the two regions, and the women were similar in their parity and type of birth. A higher proportion of women in the rapid test sites entered labour after being induced than in the usual-care units (Table 6).

FIGURE 7.

The CONSORT flow diagram of sites and participants in the GBS2 study.

| Maternal characteristic | Rapid test (N = 722) | Usual care (N = 906) | Overall (N = 1628) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.3 (5.8) | 30.1 (5.8) | 29.7 (5.8) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| LSE | 375 (52) | 458 (51) | 833 (51) |

| MID | 347 (48) | 448 (49) | 795 (49) |

| Onset of labour, n (%) | |||

| Spontaneous | 343 (48) | 527 (58) | 870 (53) |

| Induced | 354 (49) | 364 (40) | 718 (44) |

| Missing | 8 (1) | 0 (0) | 8 (< 1) |

| Type of delivery, n (%) | |||

| Spontaneous vaginal | 439 (61) | 542 (60) | 981 (60) |

| Instrumental | 102 (14) | 131 (14) | 233 (14) |

| Emergency caesarean | 173 (24) | 233 (26) | 406 (25) |

| Missing | 8 (1) | 0 (0) | 8 (< 1) |

| Multiparity, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 465 (64) | 585 (65) | 1050 (65) |

| No | 255 (35) | 321 (35) | 576 (35) |

| Missing | 2 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 2 (< 1) |

| If yes, number of previous pregnancies | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| If yes, number of previous vaginal deliveries | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In 93% of women there was one risk factor for neonatal GBS disease, and two risk factors in 6–7% of women. The most common risk factor was preterm labour. The distribution of risk factors among the study population is shown in Tables 7 and 8.

| Risk factor | Rapid test (N = 722), n (%) | Usual care (N = 906), n (%) | Overall (N = 1628), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal temperature ≥ 38 °C | 66 (9) | 156 (17) | 222 (14) |

| Previous baby with GBS | 51 (7) | 53 (6) | 104 (6) |

| GBS detected in this pregnancy | 330 (46) | 332 (37) | 662 (41) |

| Preterm labour | 324 (45) | 432 (48) | 756 (47) |

| Number of risk factors | Combinations of risk factors | Rapid test (N = 722), n (%) | Usual care (N = 906), n (%) | Overall (N = 1628), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Maternal temperature ≥ 38 °C | 55 (8) | 139 (15) | 194 (12) |

| Previous baby with GBS | 35 (5) | 40 (4) | 75 (5) | |

| GBS detected in this pregnancy | 293 (41) | 278 (31) | 571 (35) | |

| Preterm labour | 291 (40) | 384 (42) | 675 (41) | |

| Total | 674 (93) | 841 (93) | 1515 (93) | |

| Two | Maternal temperature ≥ 38 °C + GBS detected in this pregnancy | 5 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) |

| Maternal temperature ≥ 38 °C + preterm labour | 5 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 12 (< 1) | |

| Previous baby with GBS + GBS detected in this pregnancy | 8 (1) | 8 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | |

| Previous baby with GBS + preterm labour | 6 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 10 (< 1) | |

| GBS detected in this pregnancy + preterm labour | 22 (3) | 36 (4) | 58 (6) | |

| Total | 46 (6) | 63 (7) | 109 (7) | |

| Three | Maternal temperature ≥ 38 °C + previous baby with GBS + GBS detected in this pregnancy | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) |

| Maternal temperature ≥ 38 °C + GBS detected in this pregnancy + preterm labour | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | |

| Previous baby with GBS + GBS detected in this pregnancy + preterm labour | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | |

| Total | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) |

Among those women with only one risk factor, more women in rapid test units had GBS detected in the current pregnancy (41%, 293/722) than those in the usual-care units (31%, 278/906). In addition, 15% (139/906) of women in usual-care units had a raised maternal temperature compared with 8% (55/722) of women in rapid test units. GBS was detected in the vaginal or rectal swab commonly in both groups, followed by diagnosis in the midstream sample (Table 9).

| GBS sampling method for culture | Rapid test (N = 722), n (%) | Usual care (N = 906), n (%) | Overall (N = 1628), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-stream urine sample | 57 (17) | 81 (25) | 138 (21) |

| Vaginal or rectal swab | 251 (76) | 206 (64) | 457 (70) |

| Both | 7 (2) | 26 (8) | 33 (5) |

| Not stated | 15 (5) | 10 (3) | 25 (4) |

| Total | 330 | 323a | 653a |

Compliance to group allocation and test strategy

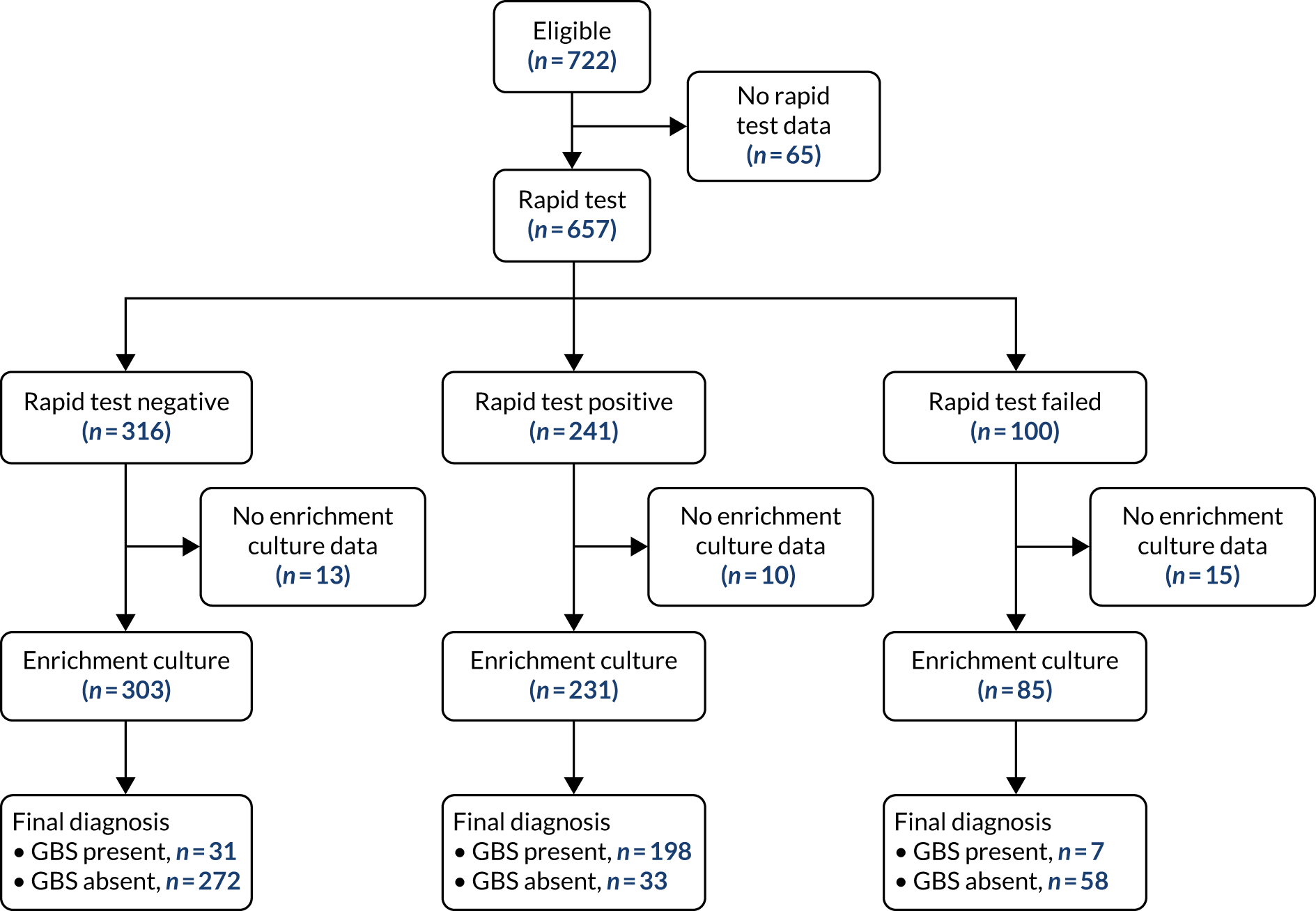

At a site level, complete compliance was achieved because the rapid test machines were supplied only to those sites allocated to the rapid test. In 53 women (7.35%), a swab was taken but the test failed to yield a result because of equipment problems; half of these problems arose in two maternity units where the GeneXpert machine developed an intermittent fault during the recruitment period. A further 23 tests were considered invalid, as > 15 minutes had passed between swabbing and initiating the test, with other reasons or no documented reason for the test failing in 24 attempts. There were 56 women who should have had a second test because their labours failed to progress within 48 hours, but who were missed. Among individual participants, for three women in the rapid test strategy group it is unknown whether or not a swab was taken and no test results are available. We were unable to calculate the duration between the test becoming available, the midwife collecting the result and the IAP being administered.

Of the 241 women in rapid test units who tested positive, 79% (190/241) received IAP to prevent GBS vertical transmission and a further 8% received antibiotics for other reasons. Of the 316 women who tested negative for GBS, 17% received IAP to prevent GBS and a further 39% did so for other indications. Table 10 shows the adherence to the test result.

| Rapid test result | Administration of antibiotics, n (%) | Missing IAP data | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAP for GBS (± other reasons) | Antibiotic for other reasons | No antibiotics | |||

| Positive | 190 (79) | 20 (8) | 31 (13)c | 0 (0) | 241 (33) |

| Negative | 52 (16)c | 124 (39) | 138 (44) | 2 (1) | 316 (44) |

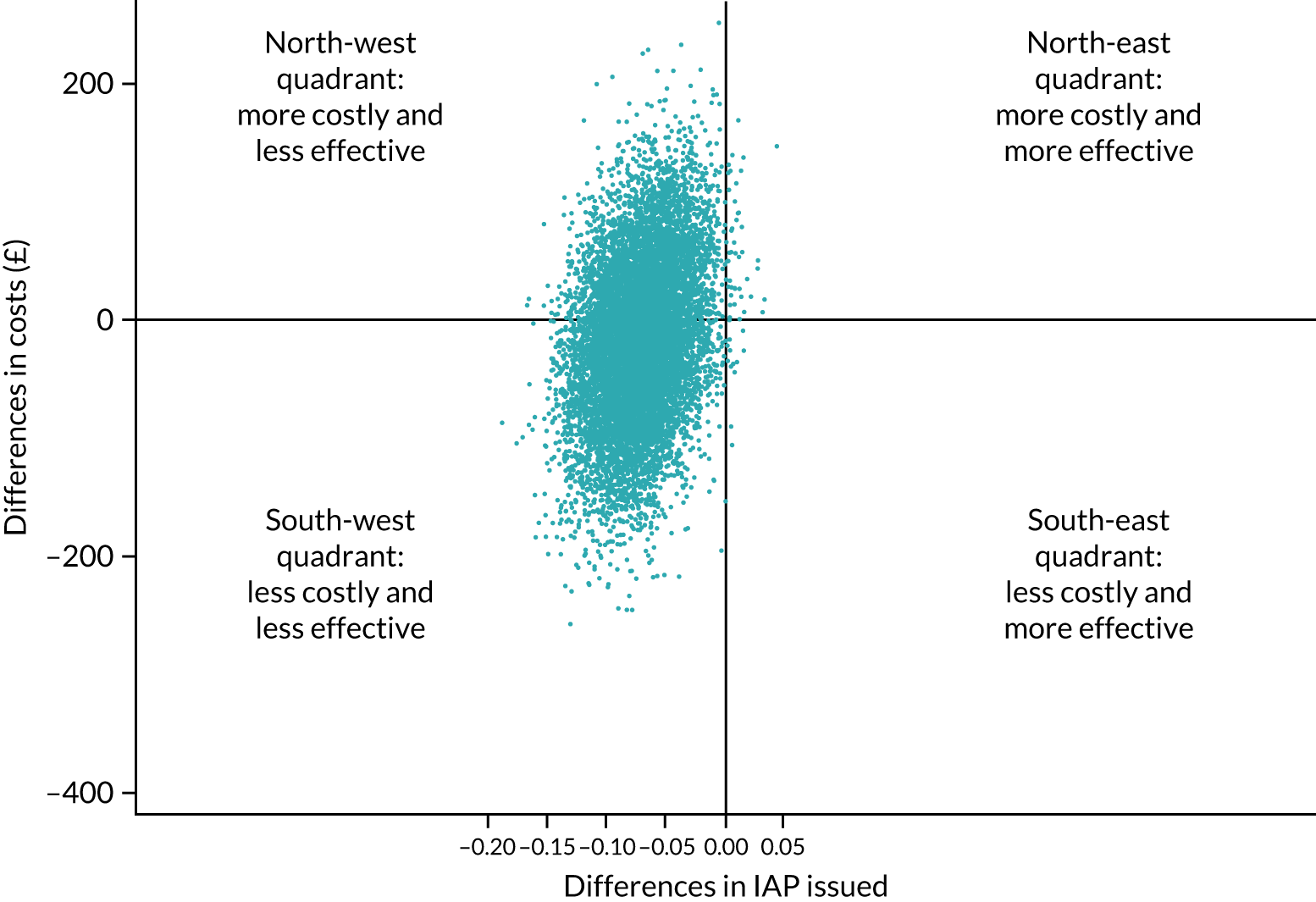

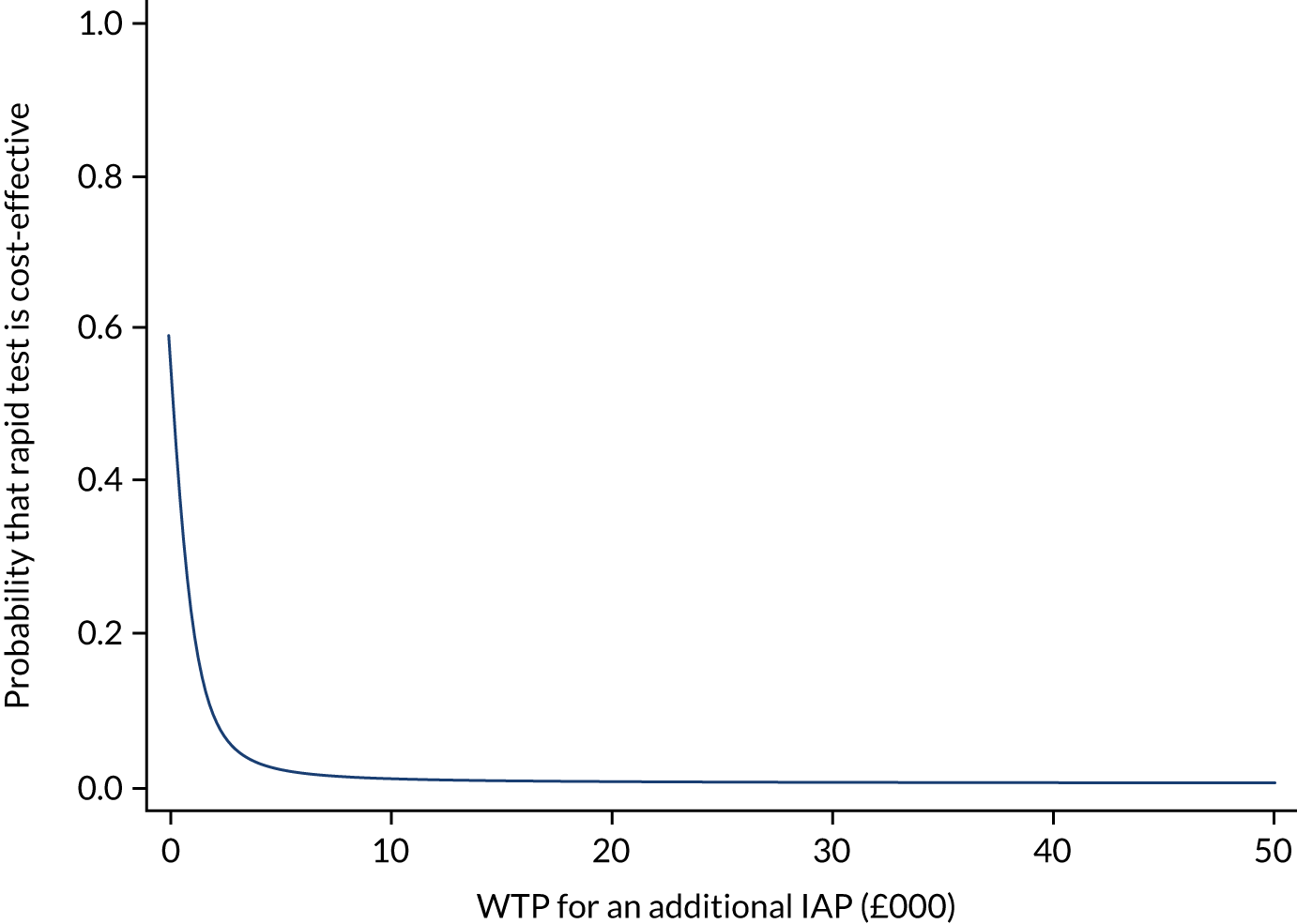

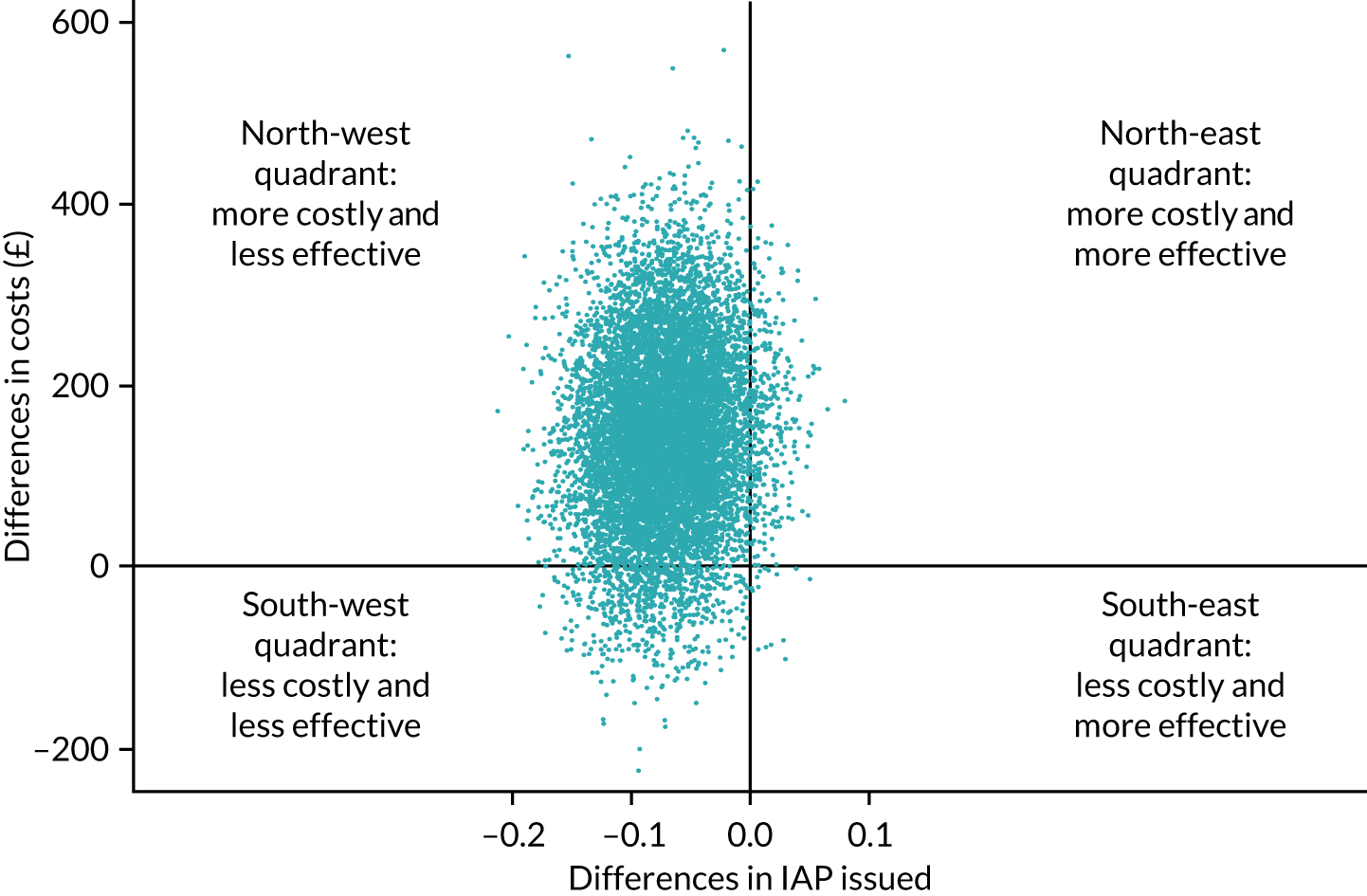

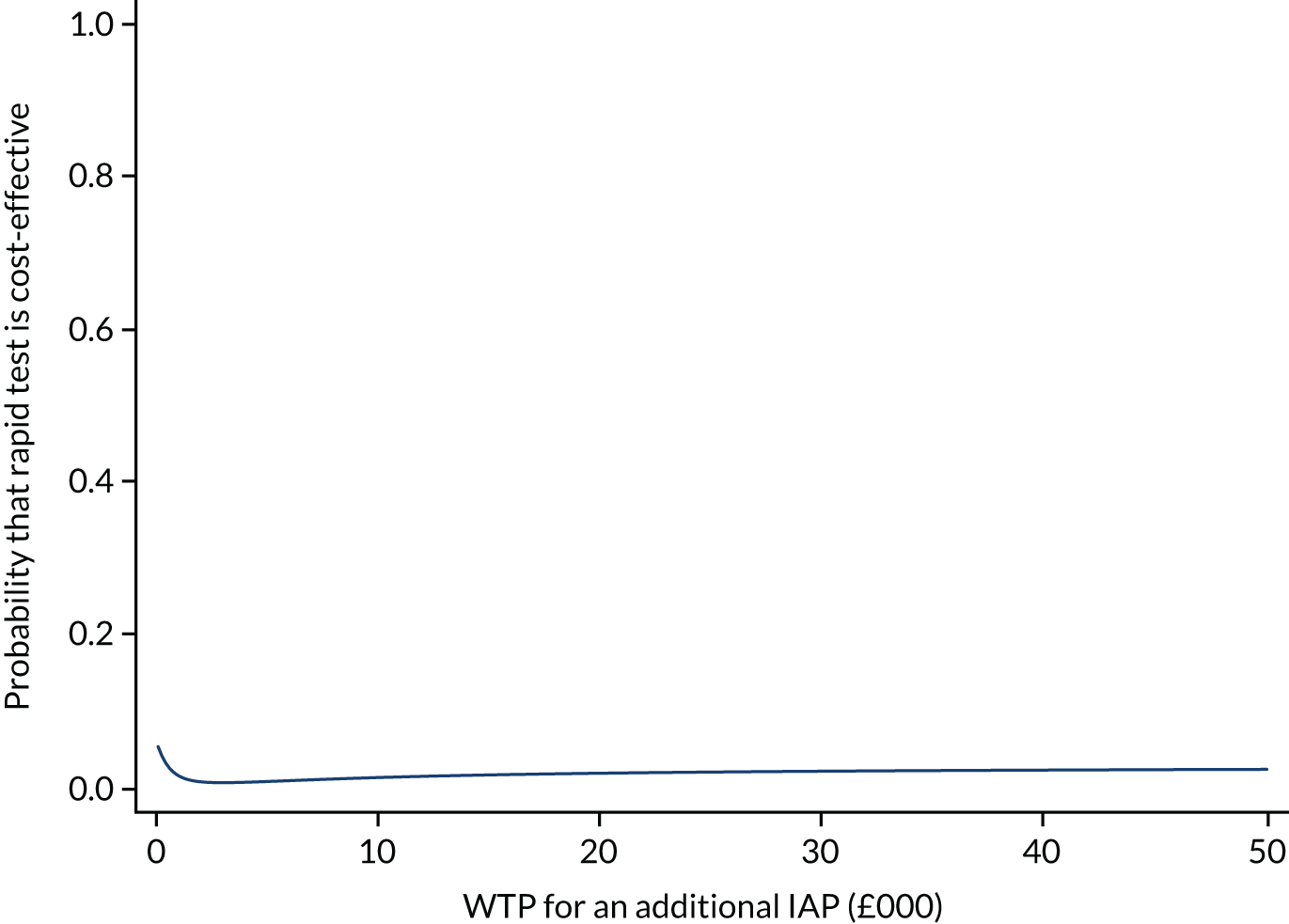

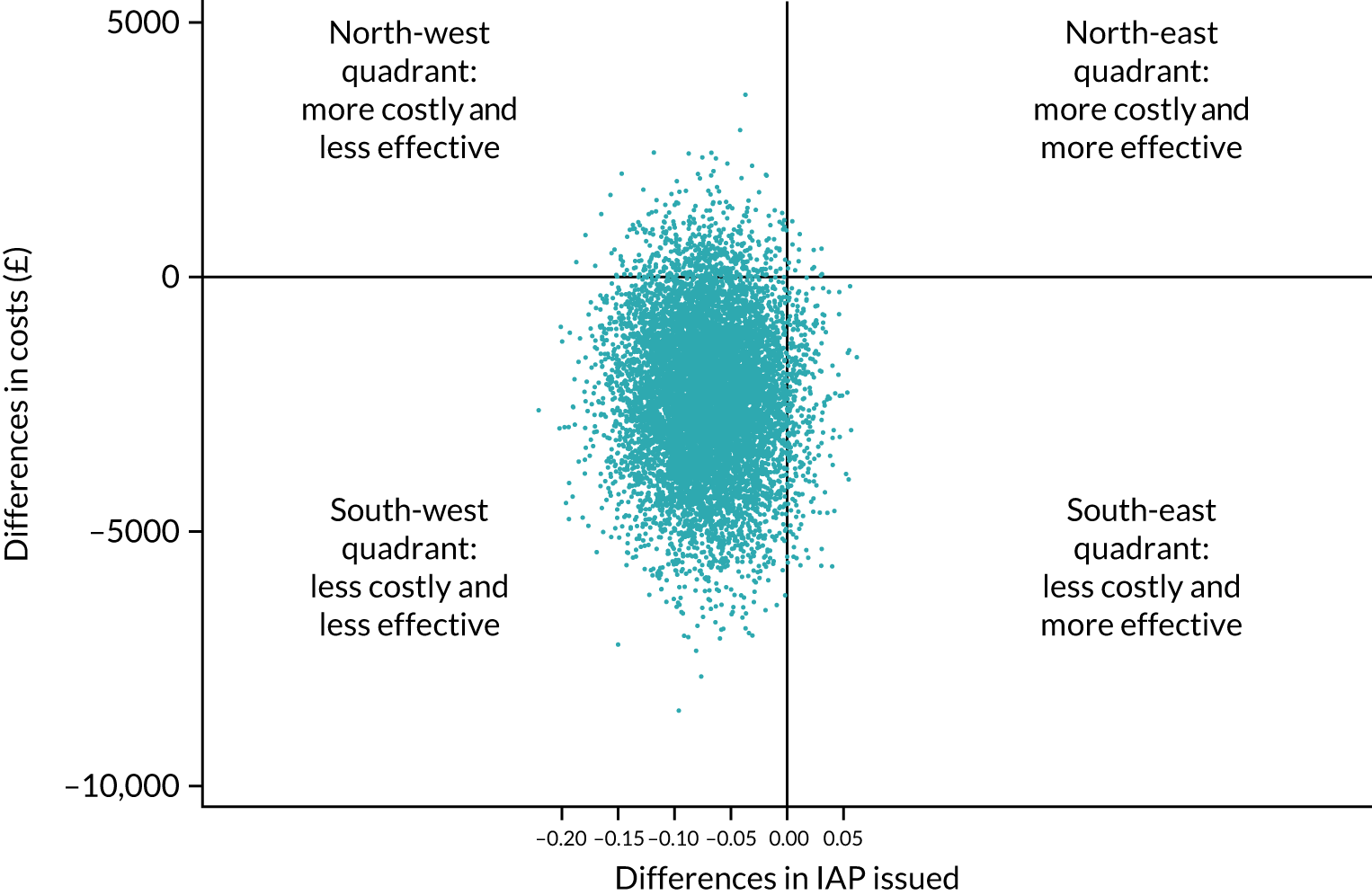

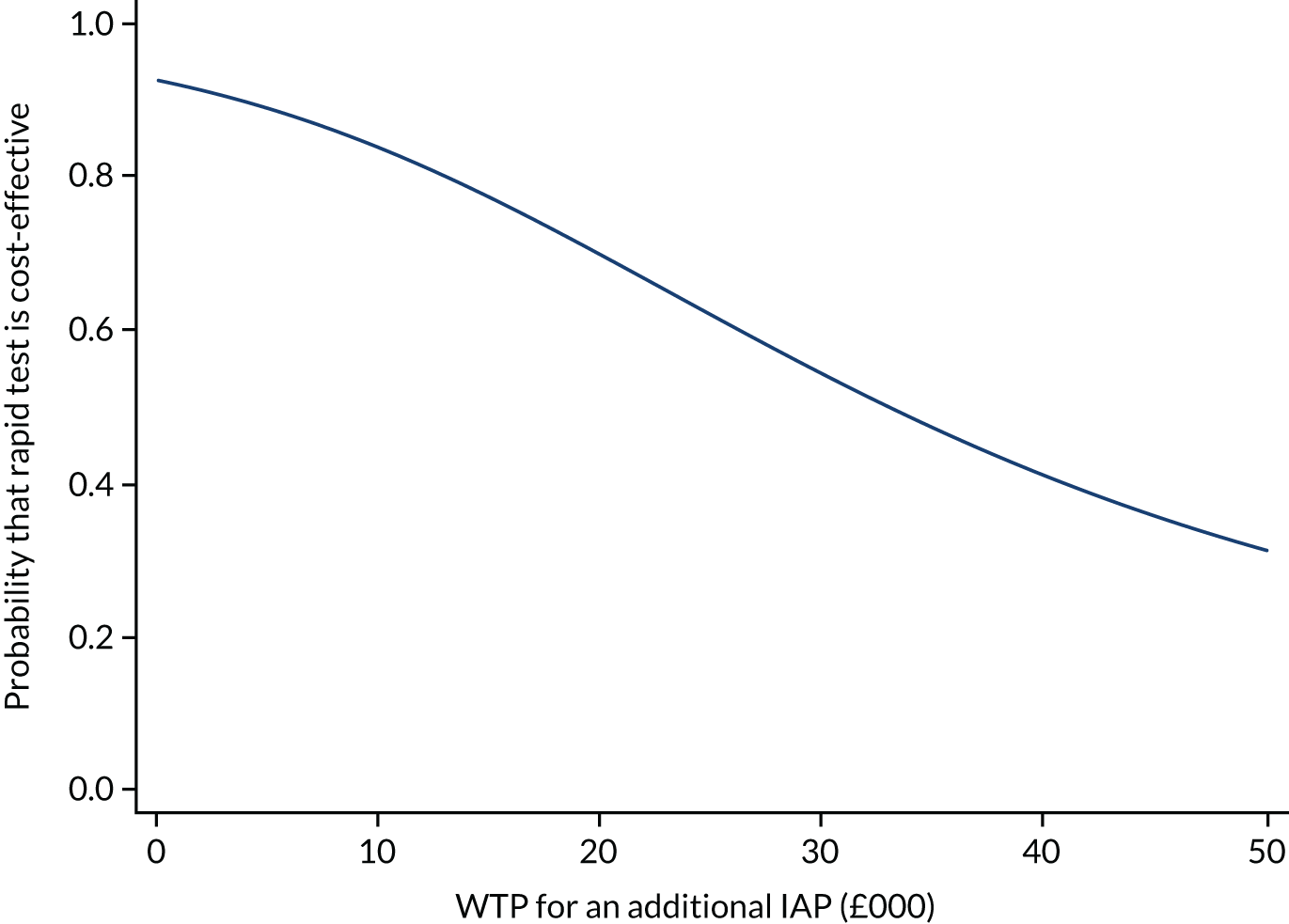

| Faileda | 47 (47) | 26 (26) | 27 (27) | 0 (0) | 100 (14) |