Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/19/02. The contractual start date was in October 2017. The draft report began editorial review in July 2022 and was accepted for publication in December 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Hollis et al. This work was produced by Hollis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Hollis et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some sections of this chapter have been reproduced from the online remote behavioural intervention for tics (ORBIT) trial protocol, which has been published. 1

Scientific background

Tourette syndrome (TS) and chronic tic disorders (CTDs) are common, disabling, childhood-onset conditions characterised by motor and vocal tics (i.e. involuntary, repetitive movements or vocalisations) that have been present for at least 1 year. 2 Affecting approximately 1% of young people (an estimated 70,000 people aged 7–17 years in England), they are associated with significant distress, psychosocial impairment and reduced quality of life (QoL). 3 In many cases, symptoms decline in severity during late adolescence and into early adulthood,4 leading to lower rates in adult populations. 5

Tourette syndrome and CTDs rarely occur alone, and it is estimated that around 85% of people with TS or a CTD experience one or more co-occurring psychiatric conditions. 6 The most common comorbidities are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), both affecting approximately 50% of the TS population across the lifetime. 6 Symptoms associated with anxiety disorders, disruptive behaviour and ‘episodic rage’, depression, self-injurious behaviour and autism spectrum disorders are also frequently experienced in this patient group. 7,8 The extent of overlap with other diagnostic categories and symptoms has led many to argue that TS belongs to a broader spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders with shared risk factors and overlapping behavioural, cognitive and social-emotional features. 9 Furthermore, additional comorbidities are often associated with greater functional impairment and distress than tics themselves10 and may contribute to difficulties managing tics in daily life. Therefore, tic treatment can be complex, and it is important to take the impact of comorbid conditions on the child and their tics into account.

Current treatment options

To date, in the UK there are still no National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the management of tics in children and young people (CYP), though evidence-based pharmacological and behavioural therapy (BT) treatments exist,3,11–13 together with consensus and evidence-based treatment guidelines. 11,14 For many years, pharmacological treatments were considered the first-line treatments, with randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of both antipsychotics and noradrenergic agents demonstrating effectiveness with small effect sizes (see Hollis et al. 3 for a review). However, such drugs are often associated with significant adverse effects such as weight gain and sedation,3 and there has been accumulating evidence for the efficacy of BTs as a viable alternative. Recognising this, recent European guidelines,11 North American guidelines15 and a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Evidence Synthesis3 all recommend that BT should be offered as the first-line treatment for tics in children and adolescents in a stepped-care approach. These guidelines universally highlight two key BT approaches for their notable evidence base: habit reversal training (HRT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP). 11,12 The comprehensive behavioural intervention for tics (CBIT) package, which is based on HRT with additional components, shows similar efficacy to medication. 12 However, it is noteworthy that the evidence base for ERP is weaker than that for HRT/CBIT.

Behavioural therapy for tics

Clinical data and background

The effectiveness of BT for reducing tics is now well established,3 with systematic reviews demonstrating a similar magnitude of effect for HRT/CBIT as for pharmaceutical interventions. 3,11,12 With numerous larger-scale RCTs having been conducted to date, CBIT in particular is supported by a strong evidence base regarding its efficacy and safety. 11 ERP is also endorsed, though ‘to a lesser degree of certainty’11 than HRT/CBIT, owing to its more limited evidence base to date. Systematic reviews of the literature also highlight that psychoeducation, whilst shown to be inferior to BT for tics as a standalone treatment in numerous RCTs, should always be offered as an initial component in BT, regardless of subsequent therapeutic approach. 11

Whilst BT models differ in their therapeutic processes, they share similar rationales, theoretical underpinnings and goals. There are various theories highlighting different mechanisms that may be involved in BT for tics. For instance, one theory suggests that HRT/CBIT and ERP work on an underlying principle that motor and vocal tics are linked to a ‘premonitory urge’ (a somatosensory discomfort that occurs before a tic). Tics are then reinforced over time through their association with the premonitory urge, creating an urge–tic cycle. A core aim of BTs for tics is to disrupt the urge–tic reinforcement cycle. This theory also posits that other internal stressors (e.g. emotional distress) and external or situational factors (e.g. environmental stressors, such as noise or social context) may maintain or worsen tics, and so the therapist will also work with patients to address these factors. However, the exact mechanisms involved in BT for tics remain unclear.

Detailed session-by-session guidance on the delivery of HRT/CBIT and ERP can be found in published treatment manuals, but we provide a brief overview of these approaches below. To date there has been no specific research into which BT is preferable for whom or when either HRT/CBIT or ERP in particular may be indicated. From clinical experience alone, Verdellen et al. 16 posit that patients with a large number of tics may obtain greater benefit from ERP, as the model addresses multiple (all) tics simultaneously. There is also some clinical or theoretical rationale to applying ERP where there is comorbid OCD, as ERP is the primary evidence-based therapy for OCD symptoms. However, more studies are needed to clarify which BT works best for whom and when. In clinical practice, clinicians often report combining approaches.

Habit reversal training

In HRT, the core aim of therapy is to break the urge–tic–relief cycle by developing alternative or ‘competing’ responses to the premonitory urge. The process of HRT comprises two main components: (1) awareness training, which involves strategies and techniques to increase awareness of both premonitory urges and tics themselves and (2) competing response training, where physically incompatible actions are identified and performed to disrupt/block tic expression. Competing response training only commences for each tic once the individual has developed good awareness of the tic occurring and the ‘tic signal’ preceding it. This process is followed for each tic individually, such that tics are treated one by one in a hierarchy, usually starting with the most bothersome. Working sequentially through each tic in the hierarchy, treatment involves competing response practice and mastery in-session, followed by continued practice at home.

Comprehensive behavioural intervention for tics

Comprehensive behavioural intervention for tics, which is supported by the largest trials to date,17 is simply an extended package of HRT with additional therapeutic components. These include relaxation training, contingency management and functional analyses to identify and address contextual factors that may exacerbate tics, as well as working with families/schools to promote social support. Though there is some uncertainty as to the ‘active’ components of CBIT, several RCTs have consistently demonstrated the superiority of CBIT to psychoeducation-based treatment in young people and adults, with reductions in tic severity maintained at up to 6 months. 3,11 An 11-year naturalistic follow-up of the original CBIT trial17 showed reduced tic severity was maintained in those who had received CBIT. 18 A recent pilot trial also provided preliminary evidence for the efficacy of a modified form of CBIT with play-based adaptations and significant parent involvement for young children with tics. 19

Exposure and response prevention

Exposure and response prevention also aims to break the urge–tic–relief cycle of reinforcement, but instead of developing a competing response to individual tics, the patient learns to tolerate premonitory urges and suppress tic expression altogether. As such, all tics are addressed simultaneously. During therapy sessions, the patient is supported in practicing suppressing tics for prolonged periods (i.e. ‘response prevention’), and strategies are then used to increase ‘exposure’ to the premonitory urge and tic-inducing environmental factors. This typically includes practice focusing on the urge and gradually increasing exposure to situations and activities that typically elicit tics, whilst at all times resisting the urge to tic.

Randomised controlled trial evidence for ERP is more limited, though the available studies suggest that it may be as effective as HRT in reducing tics. One study directly compared HRT with ERP for children with tics and found no statistically significant difference in the reduction of symptoms in terms of tic frequency and a slightly favourable response to ERP on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS). 20 Another study involving both children and adults (n = 43; 7–55 years of age) randomised to either ERP or HRT also demonstrated comparable effects maintained up to the 3-month follow-up. 16 Other naturalistic studies have provided supplementary evidence that ERP can be implemented in clinical settings, with comparable effect sizes to those seen in trials to date. 11 Though larger-scale trials of ERP-based interventions are needed, these findings highlight the potential for BTs as effective and safe first-line treatments for tics.

Access to BTs for tics

Despite an increasingly clear evidence base and guidelines consistently recommending BT as a first-line treatment approach, access to BTs remains limited. Estimates suggest that only around one in five young people with TS are currently able to access BT for tics in the UK,21 contrasting with approximately 50% receiving medication, despite their more significant risks of adverse effects. 12,13 Furthermore, those young people who manage to access BT typically receive four or fewer face-to-face therapy sessions, which is under half the recommended number. 21

Research also suggests that families prefer and request better access to BT for tics and are often unsatisfied with current treatment options. Qualitative analysis collated from interviews with 42 young people with TS and a survey of 295 parents of children with TS identified that many families felt health-care professionals were not knowledgeable about TS. 21 Specifically, respondents noted the struggle to access limited BT resources, with 76% of parents saying they would like BT to be available for their child, highlighting the need for improved access to behavioural interventions for TS.

Though various factors are likely at play, the ongoing lack of expert therapists trained to deliver behavioural interventions for tics is a considerable barrier to provision. At present, Tourettes Action (https://www.tourettes-action.org.uk) lists fewer than 10 endorsed NHS behavioural therapists for young people with TS throughout the UK. In England, this equates to approximately one therapist to every 10,000 CYP with TS. This lack of provision is compounded by an uneven geographical distribution of therapists, with the majority located in London and surrounding areas. As a result, many families face long-distance travel to national specialist centres for support, which is expensive, disruptive and time-consuming, creating further inequity of access. There is therefore a desperate need for solutions to improve access to specialist treatment for tics, including scaling up provision of BTs.

Digital therapy and internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy

Over the last decade, internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy (iCBT) has been developed, which can enable effective and often less therapist-intensive interventions to be delivered over long distances and at reduced cost. 22 The potential for internet-delivered treatments to widen access and meet treatment needs more flexibly has been further highlighted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, with many services increasing their remote and online therapy options through necessity. However, research with service users and staff during this period has also highlighted the importance of appropriate therapist training and technology for online delivery and the need to minimise digital exclusion of the most vulnerable groups. 23

The first substantial evidence for iCBT as an effective delivery approach was in the treatment of adults with depression and anxiety disorders, and there is now a large literature indicating that iCBT, in various forms, can be effective and have lasting impact. 24–26 Across diagnostic conditions, studies have now shown the efficacy of iCBT compared to no-treatment control conditions and results comparable to face-to-face treatment in terms of symptom reduction,26,27 which could also result in as much as 50% cost savings. 26

There is also now a growing literature on digital therapies for mental health difficulties in CYP. Reflecting findings with adult iCBT, effect sizes for short- to medium-term outcomes appear broadly equivalent to those seen in face-to-face treatment. 3 Recognising this evidence, NICE now recommend digitally delivered CBT in the treatment of mild to moderate depression in CYP,28 and there has been growing interest in the potential utility of online platforms for a wide range of patient groups and therapeutic approaches; these include iCBT-based programmes for post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), OCD and eating disorders, parenting programmes for behavioural support and interventions designed for use with specific physical health or neurodevelopmental problems. 22

Therapist-guided iCBT

Research has demonstrated that an important factor in the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of iCBT, mediated by engagement/adherence with therapy, is the provision of therapist guidance. Though self-guided programmes may seem superficially attractive due to their very low implementation costs, data indicate that low adherence is a major drawback. 29 Overall, research has shown that therapist-supported platforms perform better in terms of engagement and adherence; moreover, they deliver higher effect sizes and are more cost-effective than pure self-help. 25,30 Supporting a low-intensity model of practitioner involvement, even a ‘minimal’ amount of therapist support can be of significant benefit. 31 Importantly, service users themselves also report a preference for online interventions that integrate some traditional face-to-face or telephone support. 23

One multi-diagnostic, therapist-supported platform of note is the ‘BIP’ [Barninternetprojektet (Child Internet Project; Swedish digital platform)] iCBT programme developed by researchers at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden. Delivered via a secure, password-protected internet platform that enables the presentation of different treatment content to different paediatric populations, the BIP research platform has been used to deliver iCBT for a range of conditions, including phobias,32 anxiety33 and OCD. 34 Similar to models adopted by improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) in the UK, where graduate mental health workers support adults through manualised, evidence-based iCBT treatment for mild to moderate depression, anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms, the BIP-iCBT treatment content is presented in chapters, like a self-help book, but with interactive materials and videos.

There are some clinical data to support the use of the BIP system for therapist-guided iCBT. A RCT using the BIP system compared participants who received BIP OCD therapy with a waiting-list control and found a significant reduction in OCD symptoms at 3 months post-treatment. 34 Additionally, there were no adverse events (AEs) reported, and participants were generally satisfied with the delivery of treatment, with only 4% stating they would have preferred face-to-face therapy. Qualitative interviews with participants in this trial also demonstrated support for the online delivery of the therapy. Specifically, they noted that iCBT allowed them to control the pace and intensity of the therapy and facilitated self-disclosure, whilst still allowing them to feel supported by a clinician. 35 Symptom reduction was also noted in a RCT using the BIP system for anxiety,36 social anxiety disorder37 and OCD,38 and in a pilot study using BIP for specific phobia,32 demonstrating the potential diversity of this platform. Whilst the evidence base for the BIP system has primarily derived from Swedish studies, recent research has demonstrated its generalisability to youth populations in the UK and Australia. 39

Remote delivery of BT for tics

Despite the growing literature on iCBT using BIP and other systems, there is little research evidence with regards to the effectiveness of the online treatment of TS. In a recent review of digital health interventions (DHIs), Hollis et al. 40 found that the majority of online interventions have been designed to help CYP at risk of developing or with a diagnosis of an anxiety and/or depression, with neurodevelopmental disorders such as TS/CTDs being largely overlooked to date.

Innovations in remote BT for tics to date have primarily focused on video conference delivery, using software such as Skype, with two pilot RCTs providing some support for this approach in CYP. 41,42 Himle et al. 41 compared video conference-delivered CBIT to traditional face-to-face treatment (8–17 years of age; N =20) and found equivalent reductions in tic severity in both groups, which were sustained at the 4-month follow-up. Ricketts et al. 42 compared CBIT delivered over Skype to a wait list control group (N= 20) and reported greater reductions in tic severity in the video conference group. Though both studies were small, ratings from patients indicated high levels of satisfaction with the treatment and a strong therapeutic alliance. Despite some technical challenges (e.g. video/audio disruption, difficulties viewing homework), video conference delivery was generally rated as highly acceptable by the participants. 41 Another related pilot RCT also evaluated DVD-supported HRT, where young people (7–13 years of age, N = 44) were guided through a HRT programme with the support of a parent. The results showed the equivalence of DVD-supported HRT and face-to-face treatment, though large drop-out rates make these findings difficult to interpret.

Similarly, there have been two preliminary studies of internet-delivered BT for tics to date, using interactive self-help programmes with therapist support (text/phone). In one pilot study using the BIP system in Sweden, children (8–16 years of age, N =23) were randomised to either an ERP-based or a HRT-based intervention delivered online via the BIP system. 43 Participants in both intervention groups showed improvement 3 months after treatment completion in terms of tic-related impairment and parent-rated tic severity; however, only those in the ERP arm showed significant reductions in clinician-rated tic severity as measured with the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-total tic severity score (YGTSS-TTSS). Furthermore, therapeutic gains were maintained at the 12-month follow-up, and no severe adverse events (SAEs) were reported. Although this was not a study powered to compare efficacy, the findings show that ERP treatment delivered online via a therapist-supported platform such as BIP may be effective in reducing tics and provide some support for an ERP-based format over HRT when delivering BT for tics online. Engagement with and acceptability of the treatment were good, with no dropouts or data loss at any of the assessment points, and 83% of users rated the treatment as good or very good. The researchers in Sweden also noted that the online treatment format demanded less therapist time (approximately 25 minutes/week per participant) than face-to-face BT using primarily text-based support.

Most recently, an Israeli RCT randomised young people (7–18 years of age; N = 45) to either internet-delivered CBIT or a wait list control. 44 The results showed a significant reduction in total tic severity (YGTSS-TTSS) in the CBIT group relative to the control condition, with therapeutic benefits maintained at the 6-month follow-up. Again, this study highlighted the potential for considerable time- and cost-saving benefits relative to traditional face-to-face treatment, with therapists spending on average just 7 minutes per participant per week providing telephone support.

Summary and study rationale

There is now reasonable RCT evidence to support the clinical effectiveness of BT for treating tics in CYP. Overall, findings demonstrate the equal effectiveness of BT compared to pharmacological alternatives, with considerably reduced risks of side effects. Whilst most trial data relate to HRT/CBIT, which has the broadest evidence base at present, there are promising clinical and pilot trial data on the acceptability and benefits of ERP and its suitability for adaptation to online delivery. Reflecting the current evidence base, BTs are now recommended as first-line treatment approaches in the treatment of tics in CYP, though there is a need for more research focusing on longer-term outcomes and larger-scale RCT evaluations of ERP. 11

Despite growing support for BT in terms of both its evidence base and acceptability amongst service users, access to BT for tics remains very limited, with geographical barriers and a lack of trained therapists noted as key ongoing issues. Qualitative research underlines patient dissatisfaction with the lack of behavioural treatment availability for tics and the need for improved access to treatment. This has led to an increased focus on training, dissemination and adapted treatment delivery in recent years. Particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and the necessity to deliver patient care remotely where possible to maintain existing service provisions, harnessing digital technologies and service innovations is becoming an increasingly important part of NHS policy for the UK. 45

There is now a sizeable evidence base supporting internet-delivered treatments or iCBT more broadly, with research showing treatment effects comparable to face-to-face interventions for a growing range of conditions and groups. 40 Significant cost-saving potential is indicated, particularly for therapist-guided platforms that bolster better engagement, adherence and efficacy. However, research to date has largely focused on common mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, with less attention given to online BT for tics or other more ‘specialist’ interventions. Most studies to date have also evaluated treatments outside of the UK, with many being conducted in Sweden using the BIP platform. Whilst a limited number of small RCTs have recently provided preliminary support for internet-delivered BT for tics, larger-scale (adequately powered) RCTs and clarifications on the generalisabilty of internet-delivered BT to the UK population are needed. There is evidence that uptake and use of DHIs (such as BIP TIC) are highly context dependent,46,47 and it would therefore be unwise to assume that a delivery package that works in Sweden will work equally well in the UK.

Study aims and design

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a therapist-guided, parent-assisted ERP BT intervention for tics in young people with TS/CTDs. The interventions were delivered remotely via the BIP technical platform. Building on previous evidence from a Swedish pilot trial,43 the study compared an online ERP-based behavioural intervention and online tic-related psychoeducation. Our primary hypothesis was that remotely delivered, therapist-supported ERP-based BT would be superior to an active comparator intervention of online tic-related psychoeducation in reducing tic severity.

The study design was a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled superiority trial, with an internal pilot and strict ‘stop–go’ progression criteria. The primary clinical outcome (tic severity) was measured via blind-assessed, clinician-rated YGTSS-TTSS. 4 A range of secondary clinician-, parent- and child-completed outcome measures were also implemented, addressing tic-related impairment, behavioural and emotional difficulties and global improvement. Measures of QoL, service use and treatment credibility and satisfaction were also obtained. Details of all primary and secondary measures, including their psychometric properties, can be found in the ‘Trial methods’ section.

The overarching aim of this study was to address the BT treatment gap for young people with tic disorders in a cost-effective manner that can be feasibly scaled up to provide widespread and equitable access to evidence-based treatment for tics across the NHS. In particular, the study aimed to add to the currently limited evidence base relating to online BT for tics by implementing an adequately powered RCT of an ERP-based, therapist-supported online intervention compared with an appropriate (psychoeducation-based) active control intervention. As the therapist role in guided iCBT is to encourage uptake and adherence to the programme, not to deliver highly specialised therapy, the skill set required is easily acquired, as demonstrated by the successful low-intensity IAPT programme, which uses graduate mental health workers to facilitate use of self-help materials by patients. Hence, if the acceptability and efficacy of the proposed therapist-guided behavioural intervention for tics is demonstrated in this trial, it should be feasible to roll it out and adopt it at scale in the NHS, IAPT BT for CYP with tics.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Some sections of this chapter have been reproduced from the ORBIT trial protocol, which has been published. 1

The interventions were hosted on BIP, a Swedish web-based research platform that has been specifically designed for use by CYP and their parents, with an age-appropriate appearance, animations and interactive scripts (http://www.bup.se/BIP/). Both the ERP and psychoeducation interventions consisted of 10 chapters, to be completed over 10–12 weeks.

Both the interventions had a ‘child’ and ‘supporter’ component – the child and supporter had separate logins to access their respective interventions. The content that the supporter accessed reflected/aligned with the content in their child’s intervention. Both the child and supporter received remote access from a therapist via the BIP platform. Please note that the term ‘supporter’ was used in both interventions to reflect the child’s caregiver involved in the trial. This typically meant their parent but could also mean another caregiver.

Exposure with response prevention intervention

The ERP intervention was based on ERP techniques with functional analyses and social support. The first case study of ERP was reported in an adult by Bullen and Hemsley. 48 Since then, ERP for tic management has been shown to be effective in children and adults. 16,43,49 ERP as a component of BT for tics has also been advocated within the recently published European guidelines for psychological interventions for tics. 11

Most children can relate to a pattern of feeling a premonitory urge (a sensation that lets them know a tic is coming), which causes a tic and then results in relief. Over time, this pattern results in a negative reinforcement cycle that helps to maintain the tics. The ERP model serves to disrupt this cycle. During the initial phase of treatment, participants are instructed to practice suppressing their tics: this is known as ‘response prevention’. Then, with the help of another person, typically a therapist or carer/parent, the participant is instructed to provoke premonitory urges and control the need to express the tic: this is known as ‘exposure with response prevention’. The child feels the urge and does not respond, and so the cycle between urge, tic and relief is broken. There are various hypotheses on why ERP breaks the pattern and results in reduced tics. Previously, it was thought that habituation to the premonitory urge occurs and therefore the urge reduces,50 as do the tics. More recent research has suggested that for many individuals the urge remains despite not expressing the tics. 51,52 It may be that, similar to changes in cognitions in anxiety during treatment following extinction learning,53 the tic is evaluated differently, and previous cognitions such as ‘I dislike or fear the urge/I cannot control my tics’ are disproven, and, with practice, the child becomes more effective at controlling their tics and tolerating the urge. The basic ERP technique described in the ORBIT treatment is drawn from a published manual for face-to-face treatment for children. 54 However, the intervention has been successfully adapted for delivery in different formats including group-based treatment55,56 and therapist-supported online self-help. 43

The Swedish team did an in-house translation of all the ERP intervention content (text from chapters, scripts for videos) from Swedish to English and shared this with us as MS Word documents. This content was reviewed and edited by E. Bethan Davies and Tara Murphy for clarity and to keep relevant terminology consistent and understandable within an English context. The chapter content is described in Table 1.

| Chapter | Child intervention | Parent/supporter intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Learn about tics Introduction to ERP, learn about different types of tics and child asked to think about tics they have |

Introduction Introduction to ERP, learn about their role as supporter in intervention and how to use a credit and reward system for child’s practice |

| 2 | More about tics Child learns about tic signals (premonitory urge), creates a list of their own tics and ranks how personally bothersome the tics are for them |

Thoughts and behaviours of supporters Supporter learns about tic signals (premonitory urge), learns about importance of not commenting on tics, common thoughts and feelings parents/caregivers have about their child’s tics and how emotions are linked to behaviours |

| 3 | Practising stopping your tics Child learns about how to gain some control of tics via tic signal and ERP practice, how their supporter will help them do this and how to use tic stopwatch within the programme to practice ERP |

Praise Supporter learns how to support their child with ERP practice, the importance of providing praise with practice and how to prompt their child to engage with ERP practice |

| 4 | Making the practice more challenging Child learns how to increase tic signals (premonitory urge), how to practise in different situations/places and to use tic stopwatch to practice in different situations/places |

Prompts Parent/supporter learns effective ways to prompt and encourage their child with ERP practice and to plan specific times to do ERP practice |

| 5 | Continued practice Child to continue doing ERP practice and to heighten their premonitory urge for practice |

Situations and reactions Supporter learns about changing situations that impact frequency of tics, about changing their reactions that may trigger tics and about influence of external factors in maintaining tics |

| 6 | School Child learns about how tics may interfere with school and strategies they could use in school to help with tics. Child is asked if they can talk to their teacher about their tics and learns about bullying, if they are affected by it and to talk to an adult if so |

Troubleshooting Supporter learns to solve potential problems they may face in ERP, which areas to focus on if child’s ERP practice is not going as well as intended and to contact child’s school about tics (if appropriate) |

| 7 | Talk about your tics Child learns to talk to other people about their tics; they will write an explanation about tics that they can use to tell other people; optional task to tell their class at school about tics |

Continued practice Supporter reviews all strategies learnt so far and to evaluate how they feel their child’s ERP practice is progressing |

| 8 | Continued practice Child to continue doing ERP practice in different situations/places |

Continued practice Supporter to assist child in doing ERP practice as much as possible |

| 9 | The final sprint Child to learn/plan how to manage tics once ERP finishes and to decide what is most important for them to focus on in future practice |

Continued practice Supporter to continue assisting child in doing ERP practice and to highlight key areas to focus on in remaining treatment |

| 10 | Plan for the future Child to make plan on how to continue working on tics in future, asked for feedback on what they liked and did not like about ERP and asked for feedback on what aspects of ERP they found helpful |

Plan for the future Supporter to make plan on how to work with child to continue working on tics in future, asked to review information learnt in ERP and asked for positive and negative feedback about ERP |

Psychoeducation intervention

Psychoeducation about tics has been shown to be useful for improving the knowledge and attitudes of children with tic disorders and other people around them. 57 Research suggests helping carers develop positive attitudes and expert knowledge on tics can help them support the individual with the condition to better manage their tics and associated symptoms. Psychoeducation has been used as a comparator in several RCTs in tic interventions to date. 17,58–60

The psychoeducation content was created in-house by Tara Murphy and E. Bethan Davies. This consisted of psychoeducational information about TS and co-occurring conditions (chapter contents are described in Table 2). Information and activities ranged from reviewing the definition of tics, natural history, common presentations and co-occurring conditions, prevalence, aetiology, risk and protective factors and strategies for describing tics to other people. Development of expertise and a positive perspective on tic disorders were emphasised. The psychoeducation chapters included strategies for promoting positive behaviours that are rewarded by a carer or parent as a parallel element to the tic control practice in ERP. There was no information on tic control within the psychoeducational intervention. The material for psychoeducation was modified and adapted from the supportive psychotherapy intervention for children, used within the RCT to evaluate CBIT17 and relevant self-help psychoeducation for parents. 61

| Chapter | Child intervention | Parent/supporter intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Learn about tics Introduction to psychoeducation, learn about different types of tics and child asked to think about tics they have |

Introduction Introduction to psychoeducation, learn about their role as supporter in intervention and how to use a credit and reward system for child’s engagement with psychoeducation |

| 2 | Tics and tic list Child learns about tic signals (premonitory urge), creates a list of their own tics and ranks how personally bothersome the tics are for them |

Praise Supporter learns how to support their child with psychoeducation and how to prompt their child to engage with psychoeducation |

| 3 | Learning about tics Child learns more information about tics and how their supporter will help them during the next phase of psychoeducation |

Prompts Parent/supporter learns effective ways to prompt and encourage their child to use the new knowledge they have learnt in psychoeducation |

| 4 | More than tics Child learns about common comorbid conditions and other challenges that occur with tics and to practice their research skills through finding out information about a chosen comorbid condition |

More than tics Supporter learns about common comorbid conditions and other challenges that occur with tics and to think about whether any of these conditions affect their child |

| 5 | Healthy habits Child to learn about healthy habits, including habits they already do, and whether they can put any more into practice |

Healthy habits for your child Supporter learns about healthy habits to ensure their child is as strong as possible to cope with their tics and to think of daily routine changes for their child to help with tic management |

| 6 | School Child learns about how tics may interfere with school and strategies they could use in school to help with tics. Child is asked if they can talk to their teacher about their tics and learns about bullying, if they are affected by it and to talk to an adult if so |

School Supporter learns to solve potential problems they may face in psychoeducation, which areas to focus on if child’s engagement with psychoeducation is not going as well as intended and to contact child’s school about tics (if appropriate) |

| 7 | Talking about tics with your class Child learns to talk to other people about their tics; optional task to tell their class at school about tics |

Thoughts and behaviours of supporters Supporter learns about tic signals (premonitory urge), about importance of not commenting on tics and common thoughts and feelings parents/caregivers have about their child’s tics |

| 8 | Risk and protective factors Child learns about risk and protective factors in relation to tics and about resiliency in relation to tics |

Risk and protective factors Supporter learns about risk and protective factors for tics and to identify factors that may help their child cope better with their tics |

| 9 | Tics and the future Child learns about some recent research about tics and about what happens to tics and coexisting conditions as people get older |

Looking after yourself Supporter reviews all strategies so far and learns about ways to look after themselves so they are able to support child as best they can |

| 10 | Plan for the future Child to make plan on how to continue working on tics in future, asked for feedback on what they liked and did not like about psychoeducation and asked for feedback on what aspects of psychoeducation they found helpful |

Plan for the future Supporter to make plan on how to work with child to continue being educated on tics in future, asked to review information learnt in psychoeducation and asked for positive and negative feedback about psychoeducation |

The role of the therapist

Patients had regular contact with a therapist during the 10-week period via messages that could be sent inside the treatment platform (resembling an email). The therapist could directly comment on exercises that the patient had been working on and give specific feedback to motivate the patient. The patient typically had contact with the therapist at least once a week. The therapist role was to support the participant in completing the intervention; they did not deliver any therapeutic content and were not trained in how to deliver BT. Key tasks included troubleshooting, technical support and promoting engagement with the intervention.

If necessary, it was possible to allow the therapist-guided treatment to be given over a 12-week period if the therapist only offered support for a maximum of 10 weeks during the 12-week period. This may have been needed if the participant was unable to engage with the ORBIT treatment for reasons such as holidays, exam periods, illness or bereavement. Access to the BIP system was granted for 1 year.

If any circumstance occurred meaning that the child was unable to log in and access the ORBIT treatment for 5 days or more, therapist support and access to the intervention were paused for that week, until the child was able to fully engage in the treatment again. Treatment and therapist support could be paused for a maximum of 2 weeks. Therapists consulted with the trial manager and their clinical supervisor in these cases.

During the screening/baseline assessment (prior to starting the therapy), participants were introduced to the therapy platform and, where possible, met their therapist. During the treatment, the participants received remote contact with this therapist via an in-built text message function in the system (similar to an email); at the same time, an SMS reminder was delivered to their phone through the BIP system each time they received a new message from their therapist inside the BIP platform. Phone calls to the family were made when the participants/therapists felt it was necessary. Therapists logged in to the system to provide the participants with feedback, answer questions or remind them to complete the next chapter/module if required. The amount of contact the therapist had with the family was determined on an individual basis as the therapist deemed necessary. Any phone calls made outside the BIP system were not logged in the BIP system but recorded manually in a data file. All therapist activity was logged in the system. Additionally, therapists kept their own log of contacts in an Excel file. This file allowed them to keep track of when a chapter/module was opened to check progress and provide a brief log of messages/contacts with the family. The therapists were able to log in at least every 48 hours of a working week but were advised to log in daily to check for messages/inactivity.

Chapter 3 Trial methods

Some sections of this chapter have been reproduced from the ORBIT trial protocol, which has been published1 under the CC-BY-4.0 licence.

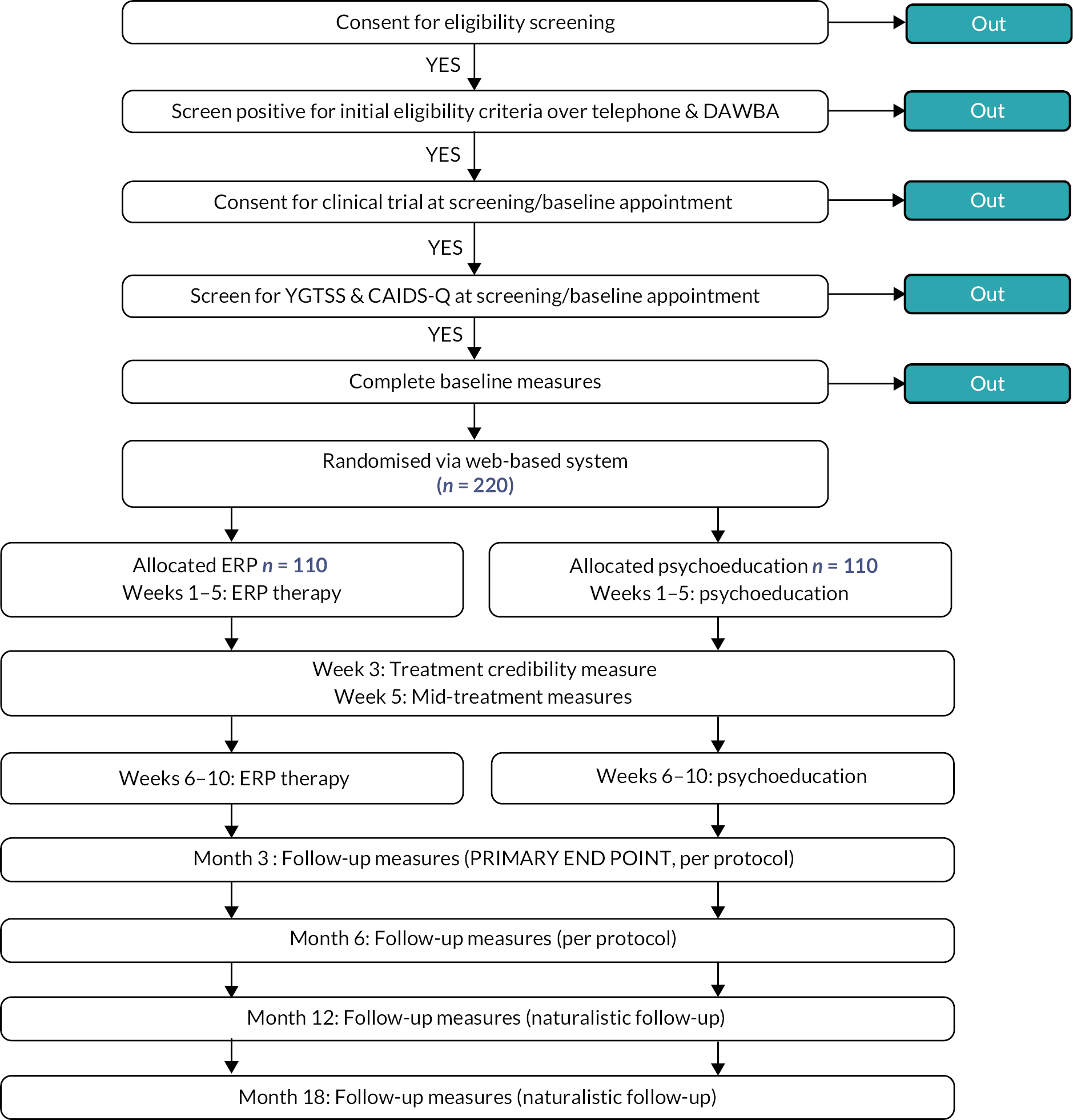

Trial design

ORBIT was a parallel-group, single-blind, non-commercial, randomised controlled superiority trial with an internal pilot for CYP with tics. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive 10 weeks of treatment of either online, remotely delivered, therapist-supported BT for tics or online, remotely delivered, therapist-supported psychoeducation on tics. Participants were followed-up at mid-treatment and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months post-randomisation. Months 3 and 6 were per-protocol follow-ups in which participants were encouraged not to change medication or start alternative therapies for tics. Months 12 and 18 were naturalistic follow-ups where participants might be using alternative treatments in accordance with standard practice recommended by their usual treating clinician. A sub-sample of participants and parents were purposively selected to participate in process evaluation interviews after the 3-month follow-up time point. A flow chart of the study design is shown in Figure 1.

Internal pilot

The objective of the internal pilot was to determine whether recruitment, engagement with the intervention and retention to the trial were sufficient to allow the trial to progress and provide a definitive answer on the effectiveness of the intervention. The internal pilot ran for the first 9 months of recruitment. Allowing for a staggered start to recruitment, the stop–go rules for the internal pilot were as follows:

-

The study needed to have recruited 66 patients by the end of the ninth month of recruitment.

-

At least 60% of participants needed to have completed the intervention (with completion defined as completing at least the first four child chapters).

-

80% of participants who had reached the relevant time window needed to have completed the primary outcome measure (YGTSS) at the primary end point (3 months) within the specified time frame for measure completion.

The success of the internal pilot was judged by the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC).

Ethical approval and research governance

The trial was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1996), the principles of good clinical practice (GCP) and in accordance with all applicable regulatory requirements including but not limited to the Research Governance Framework and the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Ethical and Health Research Authority (HRA) approval was received from Northwest Greater Manchester Research Ethics Committee on 23 March 2018 (protocol v2.0; ref.: 18/NW/0079). The published trial protocol1 was approved by an independent TSC and DMC. Two substantial amendments were made and approved; these are described below. The trial was prospectively registered with the ISRCTN (ISRCTN70758207) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03483493).

Substantial amendments

One subsequent amendment was made to the protocol (v.3.0, 16 April 2018) after initial Research Ethics Committee (REC)/HRA approval. This amendment was to allow the 10-week intervention to be delivered over a 12-week period to account for periods of therapist absence during bank holidays or unforeseen circumstances. The amendment was approved by the committee on 15 May 2018. There was one further subsequent substantial amendment; however, this was not to trial protocol. An amendment was submitted on 28 June 2018 to give REC/HRA approval for the interview schedules as part of the process evaluation; this was approved on 2 July 2018 for interview schedules. The limited number of amendments from the original protocol is testament to the fidelity to the original proposal and indicates that the study procedures and interventions could be successfully delivered within the ORBIT trial.

Study oversight

The study was overseen by three groups.

Trial Management Group

The full Trial Management Group (TMG) consisted of all the co-investigators listed on the protocol and a representative from the patient and public involvement (PPI) group when possible. The TMG met at least every 6 months to discuss study progress and overall conduct of the trial.

Trial Steering Committee

The role of the TSC was to provide overall supervision of the trial on behalf of the Trial Sponsor and Trial Funder and to ensure that the trial was conducted to the rigorous standards set out in the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) Guidelines for GCP. The TSC met every year, with an additional meeting to review the internal pilot.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC assessed whether there were any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. The DMC met annually and reviewed the internal pilot.

Participants

The study sought to recruit CYP with tic disorders.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 9–17 years: patient confirmed through screening.

-

Suspected or confirmed TS/chronic tic disorder:

-

- Including moderate/severe tics: score > 15 on the YGTSS-TTSS; TTSS score > 10 if motor or vocal tics only: researcher confirms at screening appointment.

-

-

Competent to provide written informed consent (parental consent for child aged < 16 years): researcher confirms at screening appointment.

-

Broadband internet access and regular PC/laptop/Mac user, with mobile phone SMS: patient confirmed through screening.

Exclusion criteria

-

Previous structured behavioural intervention for tics (e.g. HRT/CBIT or ERP) within last 12 months: patient confirmed through screening.

-

Change to medication for tics (start or stop of tic medication) within the previous 2 months: patient confirmed through screening, and subsequent medication/interventions commenced throughout the trial recorded at each time point for analysis.

-

Diagnoses of alcohol/substance dependence, psychosis, suicidality or anorexia nervosa: confirmed through parent development and well-being assessment (DAWBA).

-

Moderate/severe intellectual disability: confirmed through qualitative judgement of the assessor at the telephone screen [and confirmed at baseline through child and adolescent intellectual disability screening questionnaire (CAIDS-Q)] through questions relating to type of school the child attends and previous diagnoses.

-

Immediate risk to self or others: confirmed through screening questions and DAWBA.

-

Parent or child not able to speak or read/write English: patient confirmed through screening by the assessor.

Recruitment procedures

Participant identification

There were three streams to participant identification. Patients could be identified via previous or current referrals at (1) one of the two study sites or (2) the patient identification centres (PICs). For both instances, a member of the usual care team identified potential participants from the patient records or current referrals held at the two study sites. Patients were provided with a brief information sheet and ‘consent to contact’ (C2C) form, which was passed to the research team once completed.

The third stream was through public recruitment campaigns. Specifically, the study advertised for participant recruitment via the Tourettes Action website (a national charity for people with tics) and a study website. A brief information sheet and a C2C form were hosted online.

Screening and baseline appointment

Once C2C had been established, patients were contacted by a member of the research team to go through the telephone screening questionnaire. The screening questionnaire was developed by the research team to understand the patient’s eligibility for the trial and took approximately 20–30 minutes to complete.

Patients who met the eligibility requirements were invited to attend a screening/baseline appointment. The appointment was held at one of the two study sites. All patients were reimbursed for their travel costs to attend this appointment. Before participants attended the screening/baseline appointment parents were asked to complete an online DAWBA. 62 Further details on the DAWBA are described under the Measures section.

At the screening/baseline appointment the researcher took informed consent and went through the eligibility criteria. As part of the eligibility check, the YGTSS assessment and the CAIDS-Q63 were conducted. Further details on measures are described under the Measures section.

After completion of baseline measures, patients were randomised into the study by the researcher via the web-based system hosted on a secure server by Sealed Envelope. At this appointment participants were introduced to the ORBIT therapy platform and provided with login details. Participants set their own start date for therapy but were encouraged to make it with 24–48 hours of their baseline appointment.

Consent

All participants provided written informed consent before completion of screening measures. For young people under 16 years old legal consent was sought from parents/carers and verbal or written assent from the young person. At 16 years of age or over written consent was sought from both the young person and their parent/carer. The original signed and dated consent forms were held securely as part of the trial site file, with copies sent to the participant, their general practitioner (GP) and the referring site (if applicable) for their records.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Randomisation was conducted using the Sealed Envelope online randomisation system and managed by Priment Clinical Trials Unit. Participants were randomised online by an outcome assessor. Randomisations were on ratio 1 : 1 and stratified by study site using block randomisation with varying block sizes.

The outcome assessor, statisticians, health economists, trial manager and chief investigator were blind to the treatment allocation, and the therapist was notified by the randomisation system of the treatment allocation. Although participants were not directly informed of their treatment allocation, it was likely that they would have been able to guess their allocation once the intervention had started.

Interventions

The two interventions have been described in detail in Chapter 2. The experimental arm consisted of 10 weeks of online, therapist-supported ERP therapy and the control arm consisted of 10 weeks of online, therapist-supported psychoeducation for tics.

Follow-up

Follow-up measures were completed at the mid-treatment point (5 weeks) and at 3 and 6 months (this formed phase 1, per-protocol design). For phase 2 (a naturalist design), follow-up measures were obtained at 12 and 18 months. Follow-up measures were completed remotely (via videoconferencing or telephone) and via an online database.

Measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the severity of tics as measured by the TTSS (0–50) on the YGTSS. 4 The primary end point was 3 months post-randomisation. The primary outcome (YGTSS-TTSS) was measured at baseline (pre-intervention; face-to-face), at 3 months (primary end point) and at 6, 12 and 18 months post-randomisation (online via videoconferencing or telephone where this was not possible).

The YGTSS was administered by a blinded assessor as an investigator-based semistructured interview focusing on motor and vocal tic frequency, severity and tic-related impairment over the previous week.

In this study, four index YGTSS scores were obtained: Total Motor Tic Score, Total Phonic Tic Score, TTSS (primary outcome) and Overall Impairment Rating (secondary outcome). The Total Motor Tic Score is derived by adding the five items pertaining to motor tics (range 0–25); the Total Phonic Tic Score is derived by adding the five items pertaining to phonic tics (range 0–25); the TTSS (range 0–50) is derived by adding the Total Motor Tic Score and the Total Phonic Tic Score.

The YGTSS takes between 15 and 35 minutes to administer.

All outcome assessors underwent training alongside 6-month rater-agreement checks in the YGTSS (see Appendix 1, Table 31).

Secondary outcome measures

Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: impairment scale4

The impairment scale forms one of the four index YGTSS scores described above. The impairment rating is on a 50-point scale ranging from 0 (no impairment) to 50 (severe impairment). The rating focuses on distress and impairment experienced in interpersonal, academic and occupational realms.

Parent tic questionnaire64

The parent tic questionnaire (PTQ) assesses the number, frequency and intensity of motor and vocal tics. Frequency ratings are made on a 1–4 scale (constantly, hourly, daily and weekly) and intensity ratings are made on a 1–4 scale. A separate score for each tic is calculated by adding the frequency and intensity ratings, giving a score ranging from 0 to 8. Motor and vocal tic severity scores are computed by summing the scores for all motor and vocal tics respectively and a severity score computed by summing the two sub-scores. The PTQ was completed by parents/carers at all measurement time points (baseline, mid-treatment, 3-, 6-, 12- and 18-month follow-up) via the online web-based data platform.

Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale65

The Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I) provides an overall clinician-determined summary measure that takes into account all available information to determine improvement since initiation of the intervention. The CGI-I consists of one item scored on a seven-point scale from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). The measure was completed online via the online data platform at each follow-up time point after treatment (3, 6, 12, 18 months) by the outcome assessor who completed the YGTSS.

Children’s Global Assessment Scale66

The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) is a 0–100 scale that integrates psychological, social and academic functioning in children as a measure of psychiatric disturbance. Scores above 70 indicate functioning in a normal range. The CGAS was completed by the researcher who completes the YGTSS via the online data platform at baseline and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up.

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire (parent completed)67

The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief measure of behavioural and emotional difficulties. The SDQ consists of 25 items that are rated on a three-point Likert scale (not true, somewhat true and certainly true). The items are designed to be divided between five sub-scales, each consisting of five items, which can be used to create scores for emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity–inattention, peer problems and pro-social behaviour. The items for all but pro-social behaviours can be summed to generate a ‘total difficulties score’. 68 The standard SDQ can be supplemented with a brief impact supplement that assesses the impact of the child’s difficulties in terms of distress, social impairment, burden and chronicity. 67 The SDQ was completed by parents/carers as part of the DAWBA at baseline and via the online data platform at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up.

The mood and feelings questionnaire (child-completed version)69

The moods and feelings questionnaire (MFQ) is a 33-item questionnaire designed to report depressive symptoms. The items are rated on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes, 2 = true). The MFQ is scored by summing together the values for each item. The MFQ was completed by the child/young person at each time point (baseline, mid-treatment, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up) via the online data platform. The measure was used to check for side effects as well as outcomes in this trial.

Spence Child Anxiety Scale (self-report)70

The Spence Child Anxiety Scale (SCAS) is a child self-report measure designed to evaluate symptoms relating to anxiety. The SCAS consists of 44 items. Children are asked to rate on a four-point scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, 3 = always) the frequency with which they experience each symptom. The ratings are summed from the 38 anxiety items to provide a total score (maximum = 114), with high scores reflecting greater anxiety. The SCAS was completed by the child/young person at baseline and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up via the online data platform.

Child health utility 9D (parent- and child-completed versions)71

The CHU9D is a paediatric QoL measure for use in health-care resource-allocation decision-making. The questionnaire consists of nine items, each with a five-level response category. There are two versions of the questionnaire: a self-report measure and a proxy measure, which can be completed by the parent/carer of the child. The CHU9D was completed at baseline and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up via the Swedish BASS data platform (online) by the parent/carer and the child/young person.

The Child and Adolescent Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome Quality of Life Scale72

The Child and Adolescent Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome Quality of Life Scale (CandA-GTS-QoL) is a disease-specific measure of health-related QoL (HRQoL) designed for children and adolescents with TS. There are two versions of the measure: one for children aged 6–12 years and one for young people aged 13–18 years. The questionnaire consists of 27 items, each with a five-level response category. The CandA-GTS-QoL was completed at baseline and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up via the online data platform by the child/young person.

Client service receipt inventory73

The client service receipt inventory (CSRI) is a flexible research instrument developed to collect information on service receipt, service-related issues and income. The questions of the CSRI are largely structured in a multiple-choice format, but, to contend with the complexity of community care arrangements, a few open-ended questions are also asked. The measure also asks about school attendance since the last measure completion time point (3/6 months). A modified version of the CSRI was to be completed at baseline and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up via the BASS platform (online). This modified version also combines elements of the child and adolescent service use schedule (CA-SUS). 74 The questionnaire takes < 15 minutes to complete.

Adverse events/side effects

Adverse events/side effects were recorded on a modified version of the side effects scale developed by Hill and Taylor. 75 The scale consists of 17 short items relating to common side effects (such as headaches, anxiety, sleep and low mood). The participant is asked to respond on a five-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘all the time’ to describe the presence of each item. The scale was completed at baseline (to ascertain the presence of these symptoms prior to treatment), mid-treatment and at 3 and 6 months of follow-up via the BASS platform (online) by the parent/carer, with input from the child/young person.

Treatment credibility

To assess treatment credibility, we administered a short questionnaire created by the research team. The questionnaire consisted of two items that are scored on a five-point scale. The questionnaire asks how well the internet treatment suits children for managing tics and how much improvement they expect from the treatment. The questionnaire was completed 3 weeks into the treatment by parents/carers and CYP via the online data platform.

Treatment satisfaction and need for further treatment

To assess treatment satisfaction, the research team created a brief questionnaire consisting of seven items. Six of the seven items are scored on a five-point scale and ask how helpful the treatment was and whether the participant would recommend it to others. The seventh item is a three-choice option asking whether the families would prefer face-to-face treatment, had no preference or would prefer internet treatment. The need for further treatment questionnaire consists of one item that asks the CYP and parents/carers and to rate whether they feel they/their child needs more treatment for their tics. This is rated on a five-point scale ranging from ‘I/my child doesn’t need any more treatment’ to ‘I/my child needs a lot more treatment’. Both the satisfaction and need for further treatment questionnaires were completed online at the 3-month follow-up point by parents/carers and CYP.

Concomitant interventions

Parents completed a short questionnaire that asked about other treatments/interventions/medications in progress. This was completed at baseline and then again at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up with the researcher via online videoconferencing/telephone.

Screening measures

Two measures were used as screening measures.

Development and well-being assessment

The DAWBA is a package of interviews and questionnaires completed by parents and teachers and designed to generate International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)/Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) psychiatric diagnoses for CYP. The DAWBA computer algorithm estimates the probability of having a psychiatric disorder in bands of < 0.1%, 0.5%, 3%, 15%, 50% and > 70% based on large community-based population studies. 62 DAWBA was used to exclude people who are rated as being likely (50–70%) to experience self-harm, psychosis and anorexia nervosa or suicidality. If the DAWBA indicated a high likelihood of suicidality, the participant’s GP or usual treating clinician would be informed.

Child and adolescent intellectual disability screening questionnaire76

The CAIDS-Q determines the presence of intellectual disability and was used at baseline only. The questionnaire contains seven items answered in a yes/no format by someone who knows the person well. A total score is calculated and a cut-off (by age group) indicates whether the child is likely to have an intellectual disability or not. The score can also be used as a proxy for IQ in situations where only an approximate indication of intellectual ability is needed, and it was used to exclude participants who were likely to have an intellectual disability.

Sample size

To detect a clinically important average difference of 0.5 of a standard deviation (SD) between intervention and comparator with 90% power at p < 0.05 (two-sided), after making an allowance of 20% for dropout, requires a total sample size of 220 participants. Our systematic review77 found the average estimate for the SD of the YGTSS-TTSS from 19 trials of behavioural intervention for tics was 6.6. Thus, the trial was powered to detect an average change of 3.3 on the YGTSS, which was sufficient to ensure the risk of missing a clinically significant effect in the trial was low.

Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata® (version 16; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) in line with a predefined statistical analysis plan (SAP) approved by the TSC. The SAP stated that confidence intervals (CIs) rather than p-values were to be reported. Analysis was performed on a modified intention-to-treat basis, in which participants were analysed according to their allocated group for cases where data were available. Baseline demographic characteristics of participants, as well as their clinical and mental health outcomes at baseline and at 3 and 6 months of follow-up, were summarised by randomised group using mean (SD) or count (percentage), respectively, for continuous and categorical data.

Phase 1 analysis

This analysis has been described and published; sections have been reproduced from the Hollis et al. 78 publication under the CC-BY 4.0 Licence.

The primary outcome was estimated using a linear regression model with YGTSS-TTSS at 3 months as the outcome and study group as the main explanatory variable, adjusting for YGTSS-TTSS at baseline and site (Nottingham/London).

Linear regression models were also fitted to estimate the effect of the intervention on secondary outcomes at mid-treatment and at 3 and 6 months of follow-up (post-randomisation). The statistical model for the CGI-I did not adjust for baseline as this is a measure of change. Using CGI-I to indicate response to treatment, the scale was dichotomised to define response as ‘improved’ or ‘much improved’ versus non-response as ‘minimally improved’, ‘stayed the same’, ‘worse’ or ‘very much worse’. Two unplanned subgroup analyses explored whether the effect of the intervention on the primary outcome was modified by either anxiety diagnosis or ADHD diagnosis. The statistical models were the same as for the main analysis of the primary outcome, with the addition of a fixed effect of the comorbidity (anxiety or ADHD) and an interaction between the comorbidity and the study arm. All statistical analyses were conducted on complete cases. This analysis has been described in Hollis et al. 78

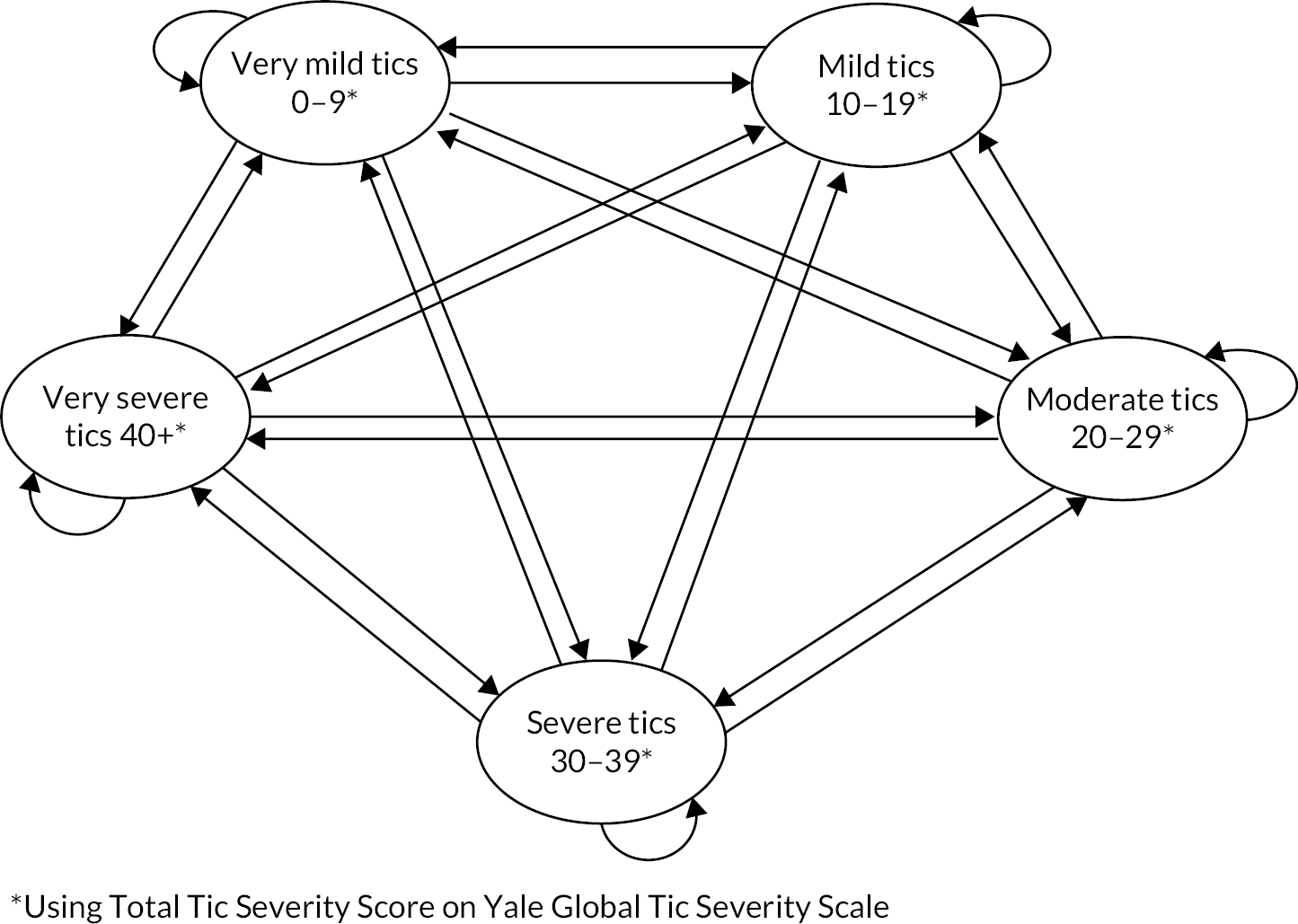

Phase 2 analysis

For the phase 2 follow-up, a sample power calculation was not specified. Outcomes at 12 and 18 months were summarised by randomised group, for continuous data using mean (SD) or for categorical data using count (percentage). A single linear mixed model was fitted for each outcome, with measures from all available time points (at mid-treatment and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months of follow-up) as the repeated-measures outcome and a random effect of participant to account for correlations between the repeated measures on each individual at different time points. The main explanatory variables were treatment, time and the treatment by time interaction, adjusting for site and the baseline measure of the outcome. Since correlations are commonly smaller over longer time periods, we adjusted for baseline through an interaction with time, which allowed correlations with baseline to differ between follow-up times. The effect of the intervention at 12 and 18 months was estimated from this model.

As with the phase 1 analysis, the statistical model for CGI-I did not adjust for baseline as this is a measure of change. Response to treatment was compared between study arms using separate logistic regression models at 12 and 18 months, adjusting for site. Estimated effects are reported with 95% CIs.

We summarised changes in other (non-trial) tic treatments (medication or therapy) between 6 and 12 months and between 6 and 18 months by study arm and for the sample overall using counts (N) and percentages (%). The phase 2 analysis is currently under peer review with the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 79

Chapter 4 Trial results

Participant flow

In total, 445 individuals registered their interest in taking part in the trial between 8 May 2018 and 30 September 2019. Figure 2 presents the recruitment and screening flow diagram for the trial, summarising information for exclusion at both the initial telephone screen and the baseline appointment through to randomisation. Phase 1 of the trial was considered complete on 30 April 2020 when the last participant completed the 6-month follow-up. Phase 2 and the trial overall were considered complete on 12 April 2021 when the last participant completed the 18-month follow-up. Retention to follow-up data during phase 1 (3-month primary end point and 6-month follow-up) and phase 2 (12- and 18-month follow-ups) are shown in the CONSORT flow diagram in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment and screening flow.

Internal pilot

The TSC met on 28 January 2019 to judge the success of the internal pilot against the three targets. The TSC judged that all three targets had been met; a summary is provided in Table 3. As a result, the trial was recommended to continue.

| Criteria | Target | Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | 66 by month 6 | 67 by month 6 |

| Intervention completion | 66% | 96% |

| Primary outcome completion | 80% | 88% |

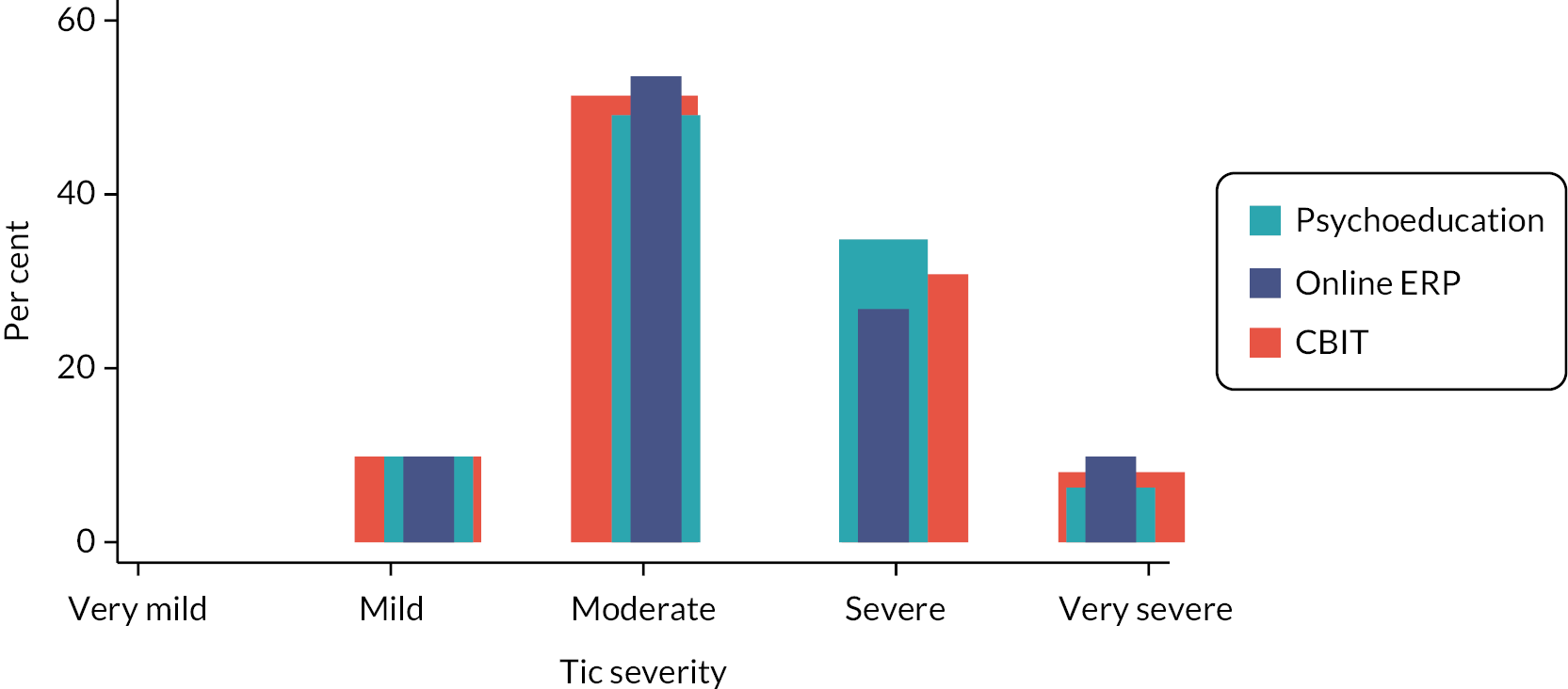

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 4 and show that characteristics and scores on the primary outcome and secondary outcomes were similar between the two arms. Participants had a mean age of 12 years, were predominately male (177/224; 79%) and defined their ethnicity as white (195/224; 87%). It is interesting to note that very few participants (30/224; 13%) were receiving medication for tics at baseline. Given that the phase 1 and phase 2 results were analysed at separate time points, the findings are reported separately for each phase.

| Psychoeducation (N = 112) n (%) |

ERP (N = 112) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age at randomisation (years) – mean (SD) | 12.4 (2.1) | 12.2 (2.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 87 (78%) | 90 (80%) |

| Female | 25 (22%) | 22 (20%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 99 (88%) | 96 (86%) |

| Asian | 3 (3%) | 7 (6%) |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Mixed | 7 (6%) | 3 (3%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not given | 2 (2%) | 5 (4%) |

| Main caregiver in trial | ||

| Mother | 101 (90%) | 93 (83%) |

| Father | 10 (9%) | 16 (14%) |

| Grandmother | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) |

| Mother’s highest educational level | ||

| No qualifications | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) |

| Mandatory secondary education (e.g. GCSEs) | 17 (15%) | 16 (14%) |

| Further education (e.g. A levels, BTEC, NVQ) | 32 (29%) | 33 (29%) |

| Higher education (e.g. BA, BSc) | 46 (41%) | 46 (41%) |

| Postgraduate education (e.g. MA, MSc, PhD) | 16 (14%) | 14 (13%) |

| Father’s highest educational level | ||

| No qualifications | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Mandatory secondary education (e.g. GCSEs) | 29 (26%) | 29 (26%) |

| Further education (e.g. A levels, BTEC, NVQ) | 33 (29%) | 35 (31%) |

| Higher education (e.g. BA, BSc) | 34 (30%) | 32 (29%) |

| Postgraduate education (e.g. MA, MSc, PhD) | 11 (9%) | 14 (13%) |

| Mother’s occupational status | ||

| Not in work/unemployed | 22 (20%) | 19 (20%) |

| Lower occupational statusa | 26 (23%) | 24 (21%) |

| Higher occupational statusb | 57 (51%) | 65 (58%) |

| Other | 7 (6%) | 4 (4%) |

| Father’s occupational status | ||

| Not in work/unemployed | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Lower occupational statusa | 30 (27%) | 33 (29%) |

| Higher occupational statusb | 67 (60%) | 65 (58%) |

| Other | 10 (9%) | 12 (11%) |

| Tic typology | ||

| Both motor and vocal tics | 106 (95%) | 103 (92%) |

| Motor tics only | 6 (5%) | 9 (8%) |

| Vocal tics only | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 27 (24%) | 34 (30%) |

| ADHD | 25 (22%) | 26 (23%) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 23/111 (21%) | 26/110 (24%) |

| Autism spectrum disorders | 4/112 (4%) | 9/111 (8%) |

| OCD | 3 (3%) | 8 (7%) |

| Major depression | 6 (5%) | 2 (2%) |

| Conduct disorder | 2/111 (2%) | 3/110 (3%) |

| Taking any tic medicationc | 16 (13%) | 14 (13%) |

| Centre | ||

| Nottingham | 57 (51%) | 57 (51%) |

| London | 55 (49%) | 55 (49%) |

Instances of unblinding

Four occasions of unblinding occurred throughout the entire trial. Each instance was reported to the trial manager and reviewed by the independent TSC and DMC for monitoring. For all occasions, the young person disclosed information about their treatment to the outcome assessor at the end of the follow-up assessment. When this occurred, all remaining follow-ups were conducted by an alternative, blinded assessor.

Phase 1 results

The phase 1 results were published in Hollis et al. 78

Losses to follow-up

The sample size calculation allowed for 20% missing data; however, data from the primary outcome measure (YGTSS-TTSS) at the primary end point (3 months) were collected from 99/112 participants (88.4%) in the intervention group and 105/112 participants (93.7%) in the psychoeducation group. Thus, retention to follow-up was better than anticipated. Data from the primary measure at 6 months were obtained from 93/112 participants (84.5%) for each group. The only predictor of missingness was site, which was included as a covariate in the statistical models.

Primary outcome

The mean scores for the primary outcome – the YGTSS-TTSS at 3 months – were lower in the ERP group (23.9, SD 8.2) than in the psychoeducation group (26.8, SD 7.3). When comparing to baseline scores, the mean total decrease in the YGTSS-TTSS was greater in the ERP group (4.5; 16%) than the psychoeducation group (1.6; 6%). Table 5 shows the results of the adjusted (for baseline and site) difference in mean scores when comparing the ERP group with the psychoeducation group. The results showed that the ERP intervention reduced the YGTSS-TTSS by −2.29 points (95% CI −3.86 to −0.71) in comparison to psychoeducation, with an effect size of −0.31 (95% CI −0.52 to −0.10).

At 6 months, this adjusted effect on tics (YGTSS-TTSS) was slightly increased (estimated difference −2.64, 95% CI −4.56 to −0.73), with an effect size of −0.36 (95% CI −0.62 to −0.10).

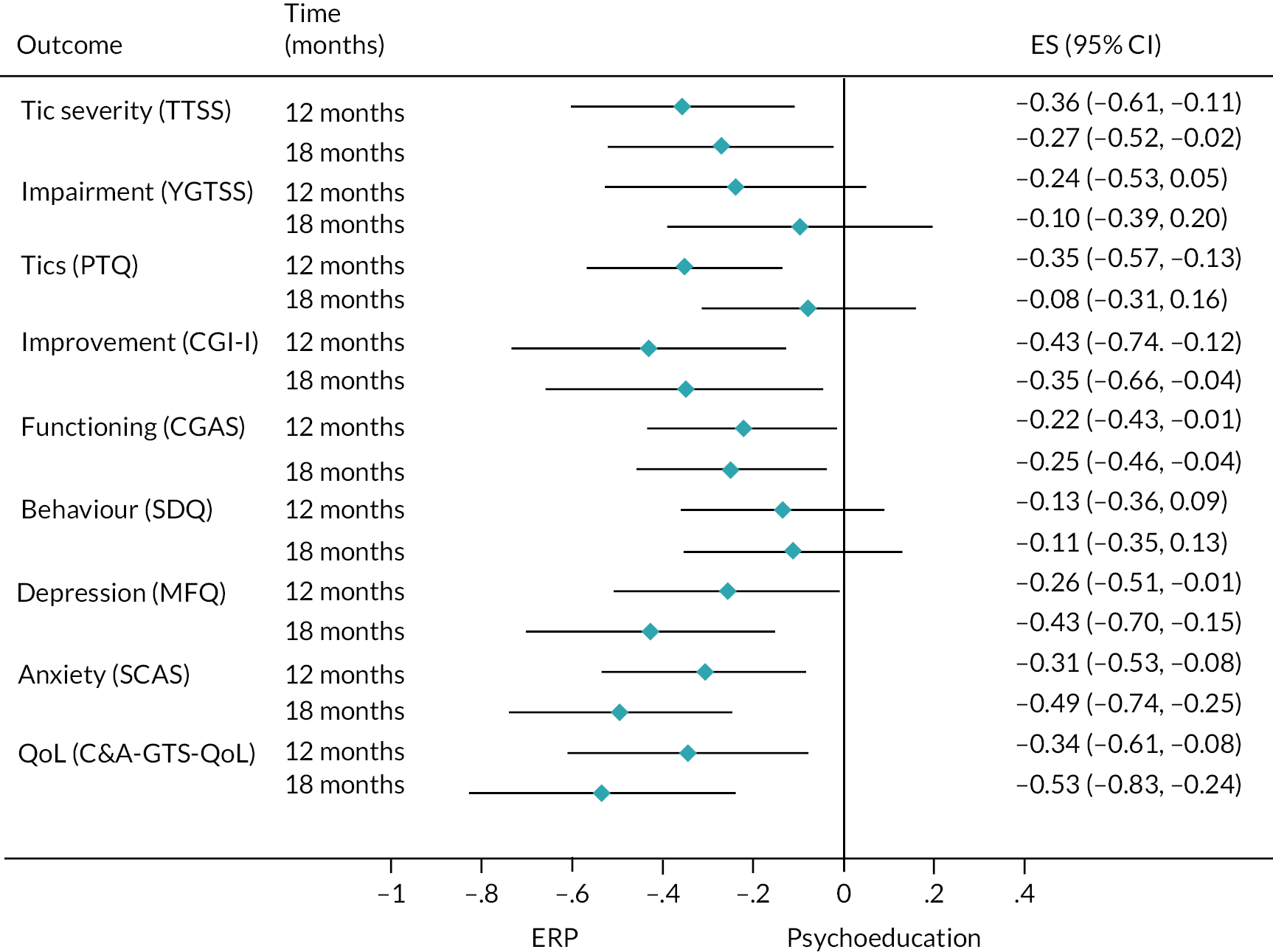

Effect sizes for the primary and secondary outcomes are presented in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Effect sizes for primary and secondary outcomes up to the 6-month follow-up. Note: Figure published in Hollis et al. 78

Secondary outcomes

Figure 4 shows the forest plot of effect sizes for secondary outcomes.

Secondary tic measures

An additional measure of tic symptoms was recorded through the PTQ. The findings supported that of the primary outcome: that is, participants in the ERP group showed greater tic reduction than those in the psychoeducation group at 3 months (−9.44, 95% CI −15.37 to −3.51) and 6 months (−8.60, 95% CI −14.43 to −2.77). However, the findings from the YGTSS impairment scale did not show any statistically significant difference in tic-related impairment at either time point (see Table 5).

| Psychoeducation mean (SD) |

ERP mean (SD) |

Estimated difference (95% CI) |

Standardised effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ( N = 112) | ( N = 112) | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| TTSS on the YGTSS | 28.4 (7.1) | 28.4 (7.7) | ||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Impairment score on the YGTSS | 22.9 (9.9) | 23.8 (10.3) | ||

| PTQ | 53.1 (26.1) | 54.7 (29.9) | ||

| CGAS | 72.1 (11.8) | 70.7 (13.7) | ||

| SDQ | 16.3 (6.2) | 18.0 (6.5) | ||

| MFQ | 15.9 (11.5) | 16.3 (11.3) | ||

| SCAS | 30.5 (17.9) | 32.9 (20.2) | ||

| CandA-GTS-QoL | 35.0 (17.2) | 36.6 (16.4) | ||

| 3 months | ||||

| Patients analysed for primary outcome | ( N = 100) | ( N = 101) | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| TTSS on the YGTSS | 26.8 (7.3) | 23.9 (8.2) | −2.29 (−3.86 to −0.71) | −0.31 (−0.52 to −0.10) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Impairment score on the YGTSS | 19.1 (10.9) | 16.7 (10.4) | −2.24 (−4.82 to 0.33) | |

| PTQ | 45.7 (25.5) | 34.7 (26.4) | −9.44 (−15.37 to −3.51) | |

| CGI-I | 3.37 (1.11) | 2.96 (1.1) | −0.41 (−0.71 to −0.11) | |

| CGAS | 75.2 (12.6) | 75.9 (12.6) | 0.96 (−1.48 to 3.41) | |

| SDQ | 14.2 (6.3) | 14.7 (6.1) | −0.38 (−1.62 to 0.85) | |

| MFQ | 12.6 (11.1) | 10.7 (11.1) | −1.36 (−3.75 to 1.02) | |

| SCAS | 28.2 (18.3) | 27.2 (19.0) | −2.80 (−6.52 to 0.93) | |

| CandA-GTS-QoL | 31.8 (17.7) | 25.7 (18.0) | −4.81 (−8.79 to −0.83) | |

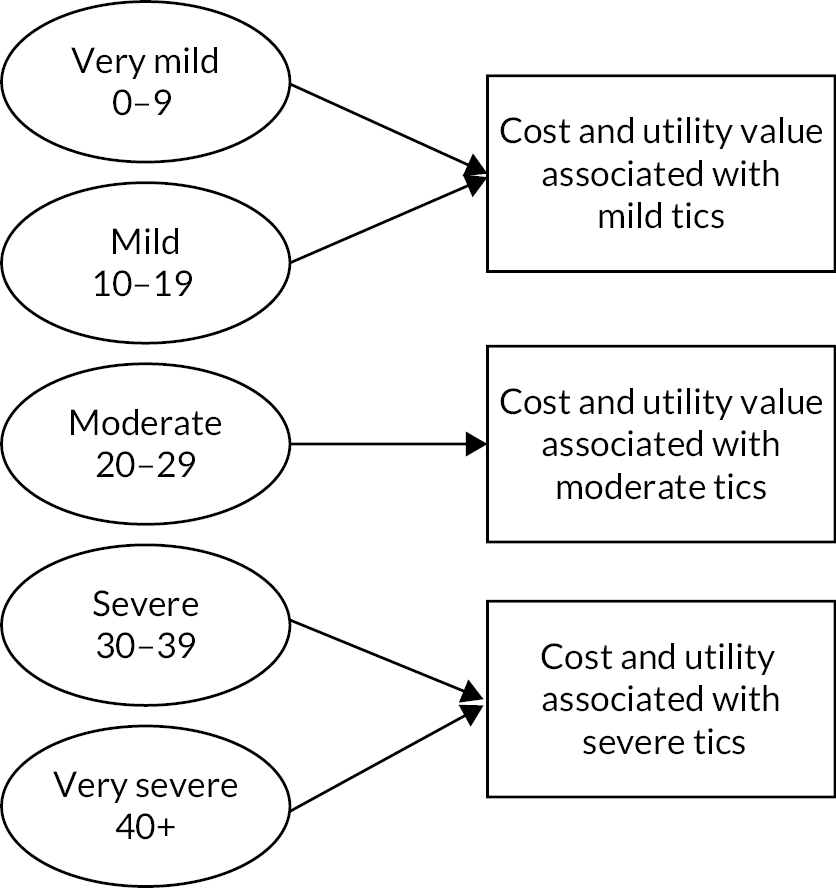

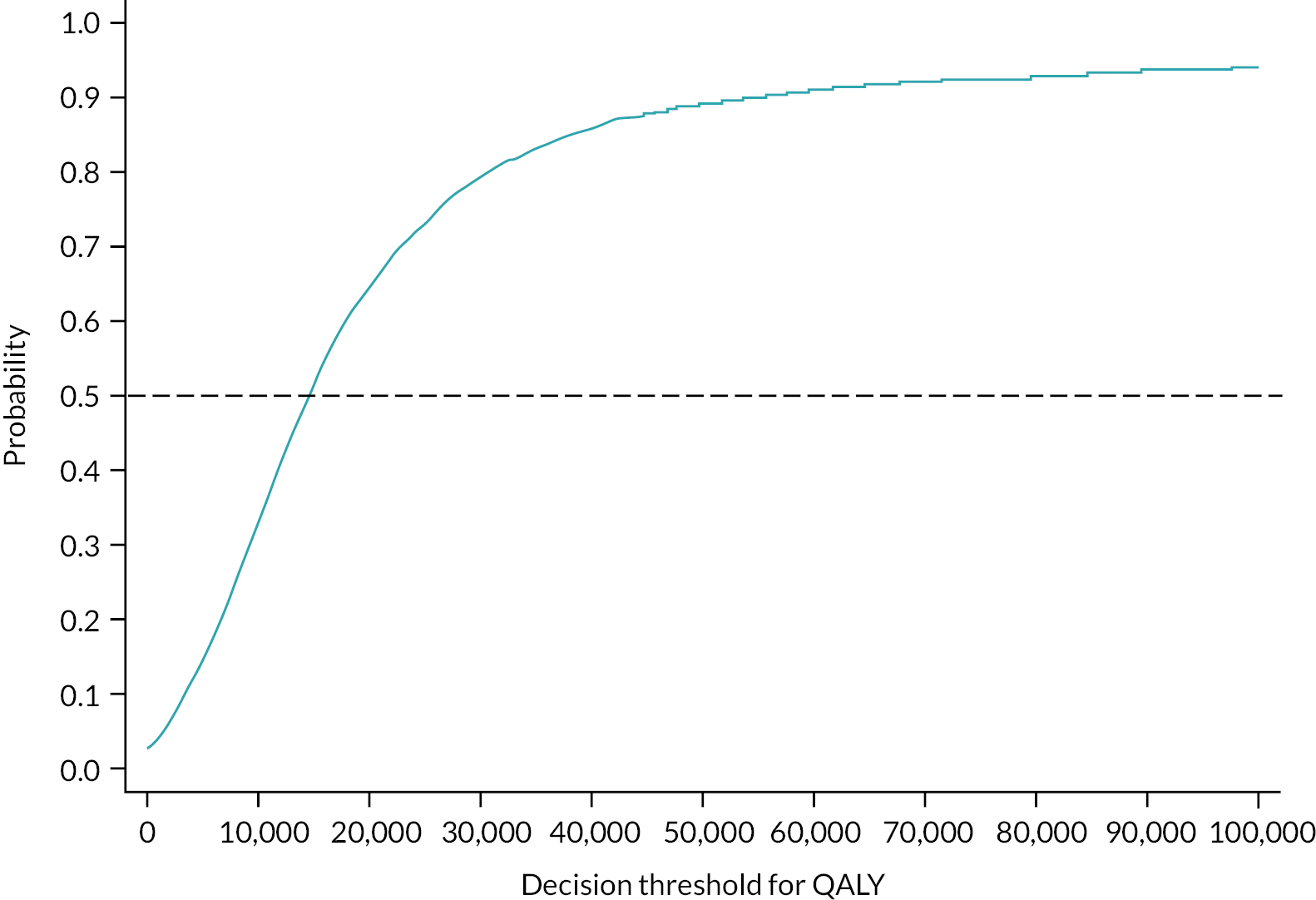

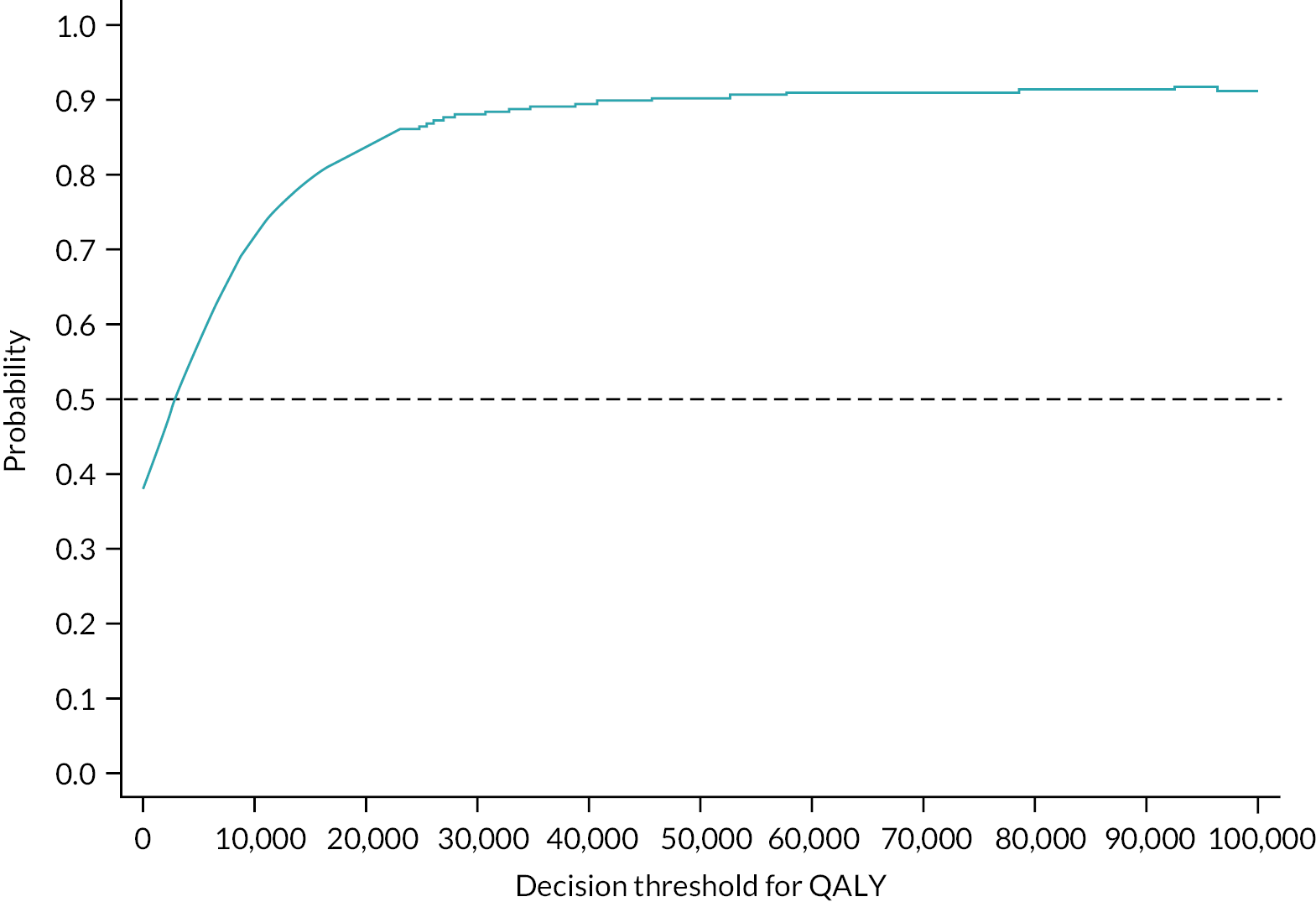

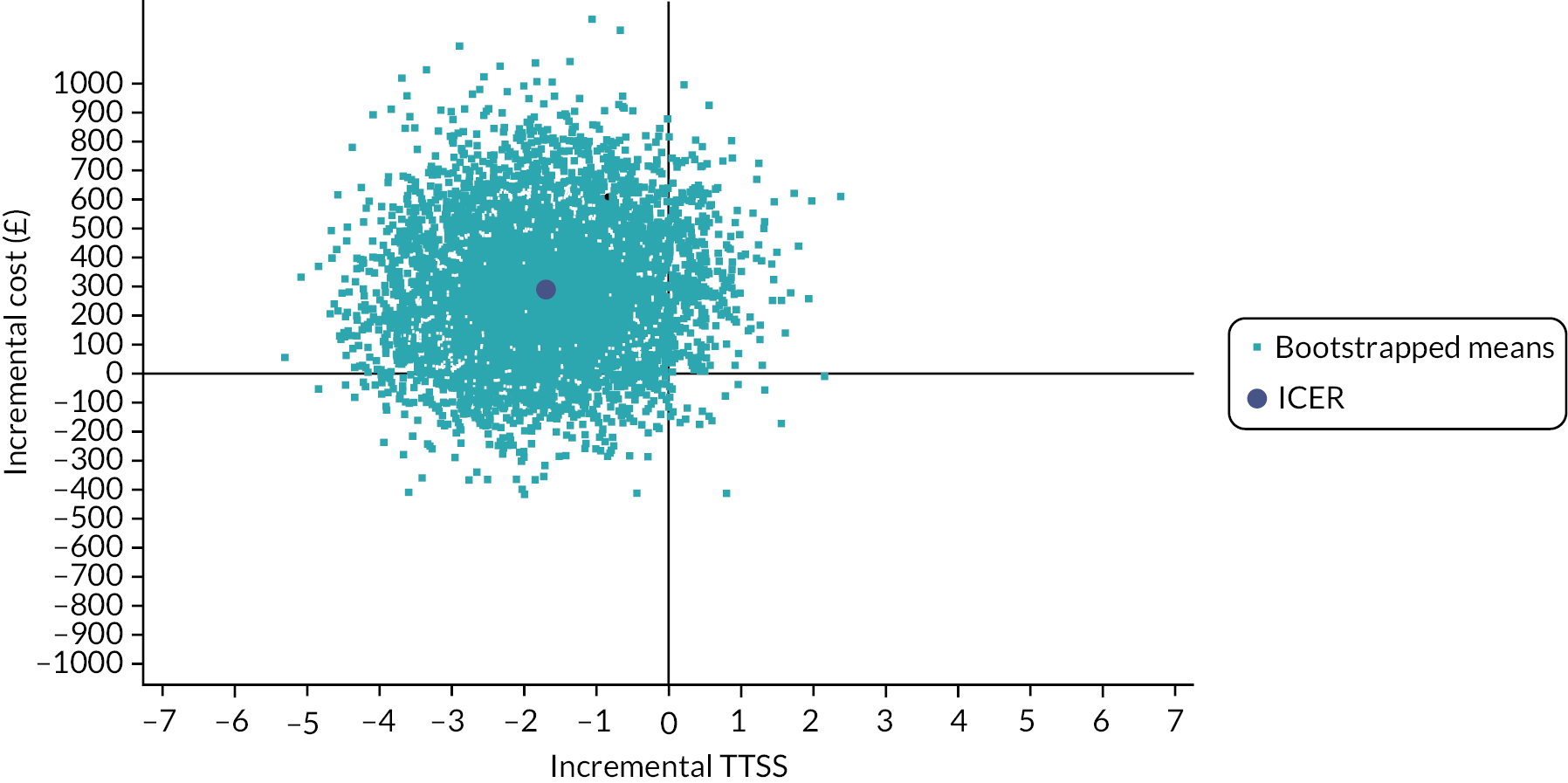

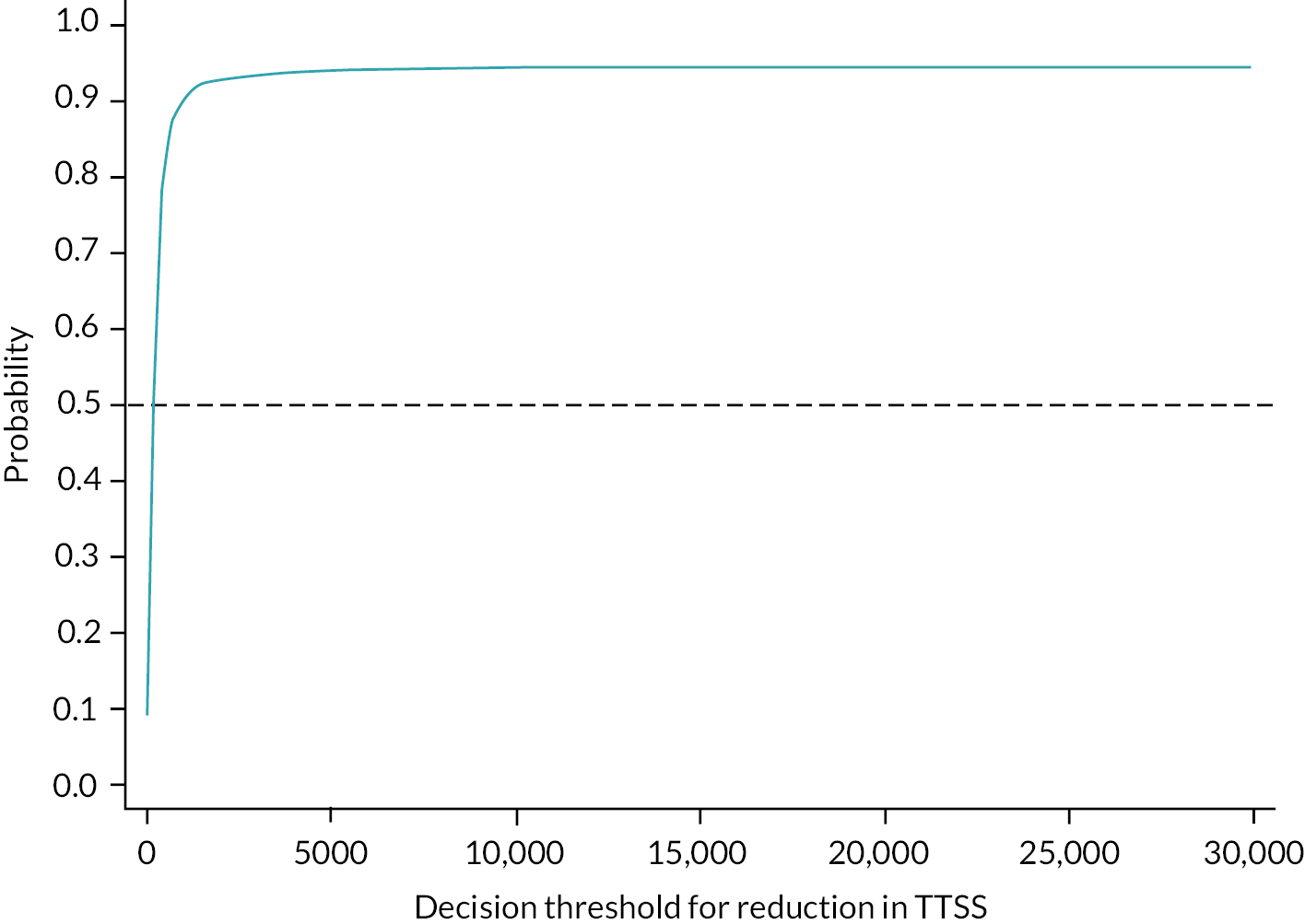

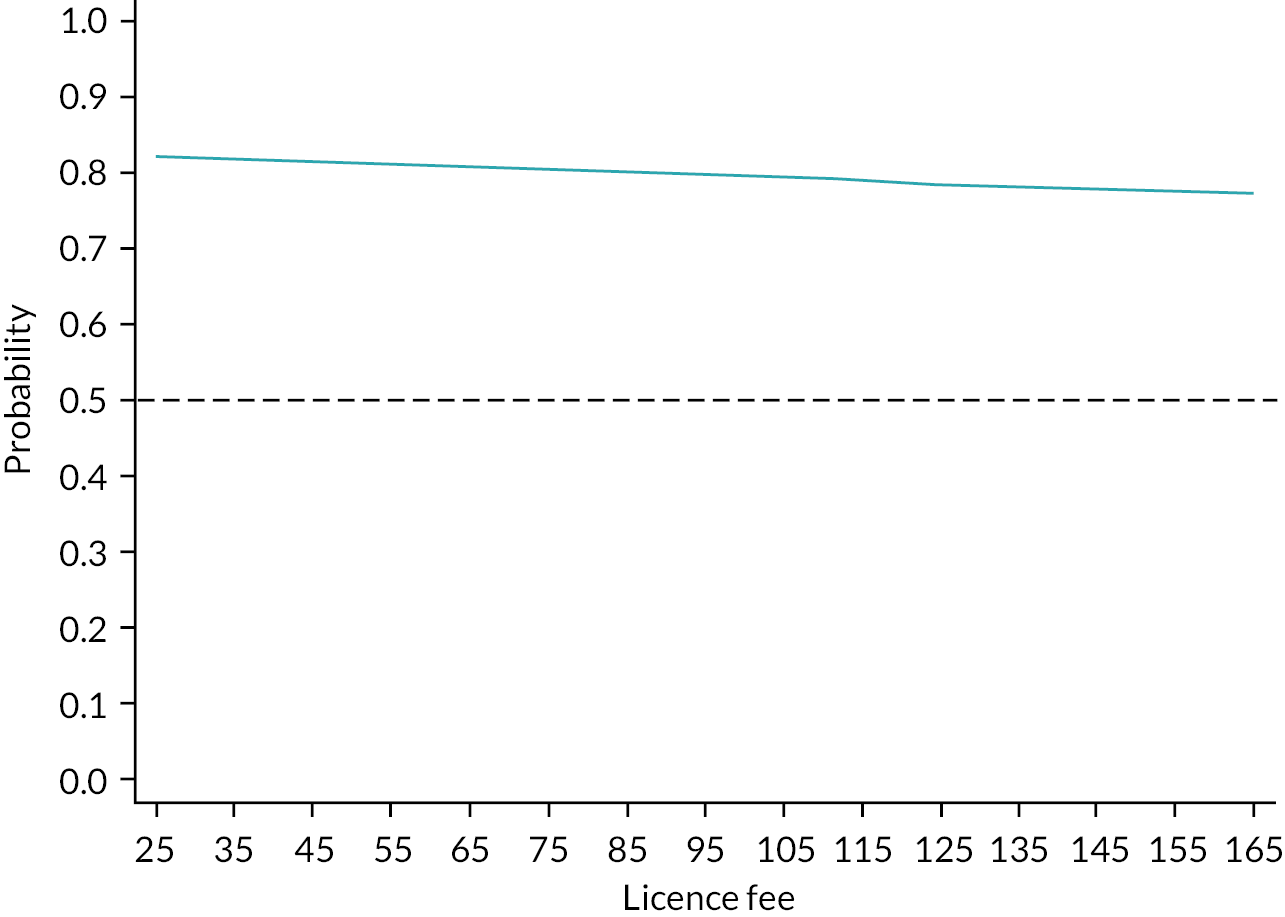

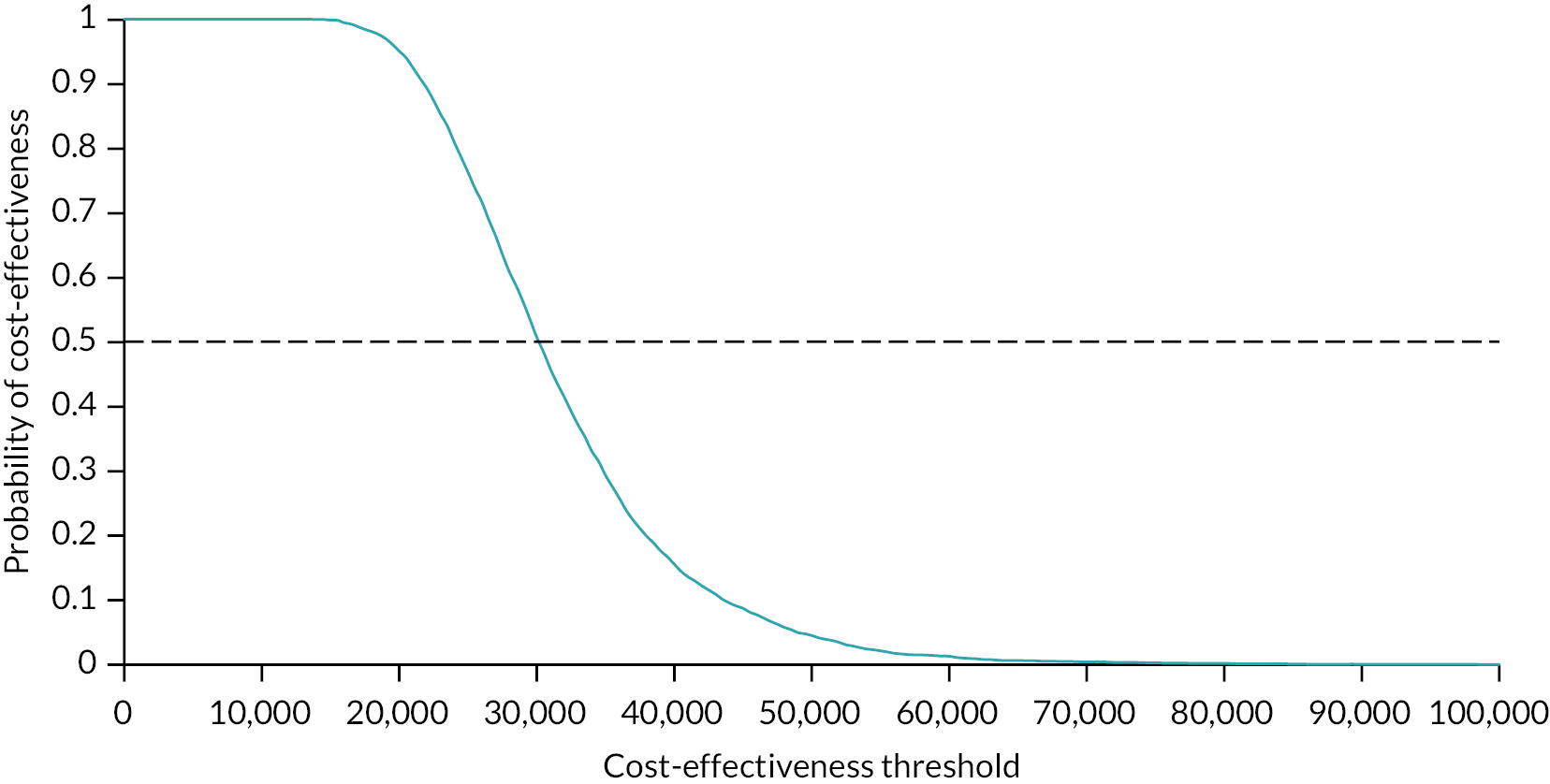

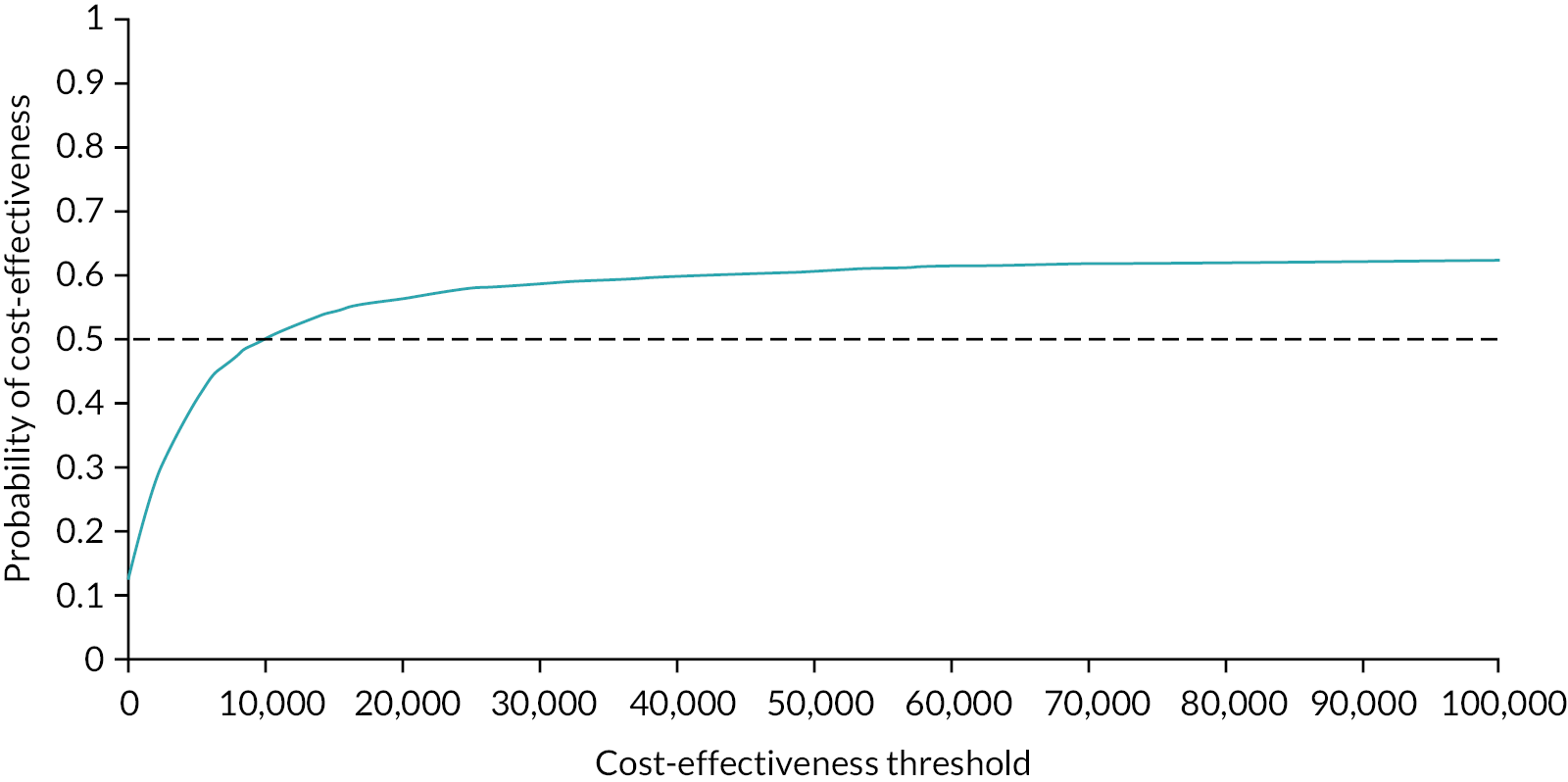

| 6 months | ||||