Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 15/97/02. The contractual start date was in October 2017. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in December 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Hogg et al. This work was produced by Hogg et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Hogg et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from our study protocol, Ward E, Wickens RA, O’Connell A, Culliford LA, Rogers CA, Gidman EA, et al. Monitoring for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) reactivation at home: the MONARCH study. Eye (Lond) 2021;35(2):592-600. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0910-4, published under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Background and rationale

Despite significant therapeutic advances, neovascular or wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) remains the leading cause of blindness in older adults. 1 While the early stages of AMD have subtle visual symptoms, the advanced stages [neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) and geographic atrophy (GA)] result in substantial retinal damage with accompanying loss of central vision and reduced quality of life. 2

A range of intravitreal drugs that inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; anti-VEGF antibodies) for nAMD are currently available, with treatment generally starting with a loading phase of three injections over 3 consecutive months. A proportion of eyes become fluid free in the subsequent maintenance phase, but relapse is common and most patients require retreatment in affected eyes at some stage, with the disease typically becoming inactive for a period and then becoming active again. 3 Patients in the maintenance phase with inactive disease still need to be monitored in hospital by measurement of best corrected visual acuity and optical coherence tomography (OCT). When disease reactivation is detected, treatment is restarted.

A large study has shown that, while many patients have many months of treatment-free periods, a significant burden falls on hospitals (as well as patients) with respect to the need for regular and repeated review. 3 Thus, methods that might allow the patient to self-monitor at home would reduce the burden on hospitals.

When diagnosis of active nAMD is confirmed, treatment with anti-VEGF therapy is almost always initiated. In most cases, patients receive three injections every 4–6 weeks initially (loading phase) and then patients are reassessed at each subsequent visit in the treatment cycle to determine lesion activity and decide whether retreatment is necessary (maintenance phase). Monitoring visits use a combination of visual acuity, clinical biomicroscopic examination and OCT to determine if the neovascular lesion is active (wet) or inactive (dry). It is these monitoring appointments which are causing a significant strain on NHS outpatient clinics in eye hospitals.

Pre-coronavirus disease (COVID), during the maintenance phase, patients were monitored for relapse at regular monitoring outpatients’ visits at eye hospitals. The frequency of monitoring depended on the drug being used (ranibizumab or aflibercept) and the preferred treatment regimen [treat (active disease)-as-necessary or treat-and-extend]. Ranibizumab is licensed for monthly treatment as required, and aflibercept every 2 months, during the maintenance phase. For treat-as-necessary regimens, a lesion found to be active is treated and a further monitoring visit is arranged; treatment is withheld if the nAMD lesion is inactive, and a further monitoring visit is arranged. For treat-and-extend regimens, ‘prophylactic’ treatment is administered to an eye with an inactive lesion, extending the interval between monitoring visits providing the disease remains inactive; if the nAMD lesion is found to be active, the interval between monitoring visits returns to the standard interval (1 month for ranibizumab or 2 months for aflibercept until the lesion becomes inactive, and the interval is then extended again). A disadvantage of the treat-and-extend treatment regimen is that it can lead to unnecessary overtreatment.

The seminal clinical trials of anti-VEGF therapy for nAMD used change in best corrected distance visual acuity as their primary end point. 4–6 This was measured using strict protocols to standardise refraction methods, visual acuity recording, distance measurements and illumination between trial sites. Visual function was used as a surrogate biomarker for the therapeutic response to treatment and other functional tests together with retinal imaging parameters were used as secondary outcomes. The clinical trials mainly reported results at 2 years, though most continued to follow patients to provide longer-term data and information of time to reactivation was obtained from the IVAN study (personal communication). A database observational study of treat-and-extend patients in Australia reported that the risk of reactivation rose from 2.2% for a 6-week interval to 15.6% for 20 weeks. 3

In this diagnostic test accuracy study, monitoring of patients continued as usual in eye hospitals. Ophthalmologists in the six centres continued their preferred drug and treatment regimen to monitor and treat nAMD in their patients. The study added weekly home monitoring, using three different tests (time 20–40 minutes), to the usual care pathway. Where possible, data from both eyes were collected.

The reference standard was the usual care clinical decision about the activity of nAMD in the study eye at the hospital outpatient appointment. Each participant remained in the study throughout the follow-up period. Therefore, there will be some monitoring visits when the study eye is judged by the participant’s ophthalmologist to have active disease and some visits when the study eye is judged to have inactive disease. The primary quantitative analysis compared the results of the home-monitoring tests during the interval preceding the monitoring visit with the reference standard assessed at the monitoring visit.

Because of (1) the clinic workload in treating and monitoring nAMD patients and (2) the high cost of establishing a robust reference standard for people at high risk of nAMD but not currently being monitored by the NHS, we decided that the most urgent priority was to identify a home-monitoring test that could detect reactivation in the patients currently being managed in the NHS. We envisaged that, ideally, after diagnosis, patients would have their initial loading-dose injections in a hospital clinic and would then be discharged with the home-monitoring test; if the test subsequently indicated a deterioration in their vision, they would arrange an urgent appointment. The focus of NHS hospital nAMD clinics would then shift to providing urgent appointments to administer treatment, rather than regular monitoring.

Since the start of the study, several other studies have evaluated home monitoring in AMD; this has also been facilitated by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic which necessitated a focus on home monitoring and forced an increase in digital literacy in the older age groups. A recent study which recruited patients with diabetic macular disease prior to the lockdown in October 2019 and after the lockdown in February 2020 provided patients with the Alleye (Oculocare, Switzerland) app on their own smartphone or provided them with it preloaded on an apple iPod TouchTM (6th generation, Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA) reported that the smartphone home tests were able to indicate worsening pathology and the need for treatment. 7

Test accuracy of tests for self-monitoring neovascular age-related macular degeneration activity

The advent of tablet computers and mobile/wireless technology has led to the development of devices for self-monitoring of visual function in nAMD. 8 The disadvantages of the standard Amsler chart have long been recognised; its sensitivity to detect the onset of nAMD has been estimated to be only 50–70%. 9 Perceptual completion10 and the inability of patients to understand the test or reliably report the results are thought to contribute to poor performance.

Reactivation of nAMD is more difficult to detect because some patients have distortion due to scarring and photoreceptor disorganisation in the absence of disease activity; therefore, a test has to enable patients to perceive an increase in distortion rather than solely its presence. Newer technologies such as visual- and memory-stimulating grids (VMS grid),11 preferential hyperacuity perimetry home devices,12,13 and shape discrimination tests14–16 have been reported to quantify distortion more accurately than either the Amsler grid or visual acuity in clinical settings. 17

During the application and commissioning stage of this study, the literature was searched and all tests with longitudinal data (including usability data) in patients with nAMD were considered for inclusion. This study investigated the test accuracy of home-monitoring ‘index’ tests to detect reactivation. The tests chosen spanned a range of complexity and cost, one used paper and pencil and two used modern information technology, implemented as software applications (apps) on an iPod Touch device.

These were:

-

KeepSight Journal (KSJ) originally developed by Mark Rosner and collaborators at KeepSight adapted for UK use for this study (a paper-based booklet of near vision tests).

-

MyVisionTrack® (mVT®) electronic vision test, owned by Genentech Inc., a member of the Roche Group.

-

MultiBit (MBT) electronic vision test, developed by Visumetrics, licensed by Novartis.

The KeepSight Journal

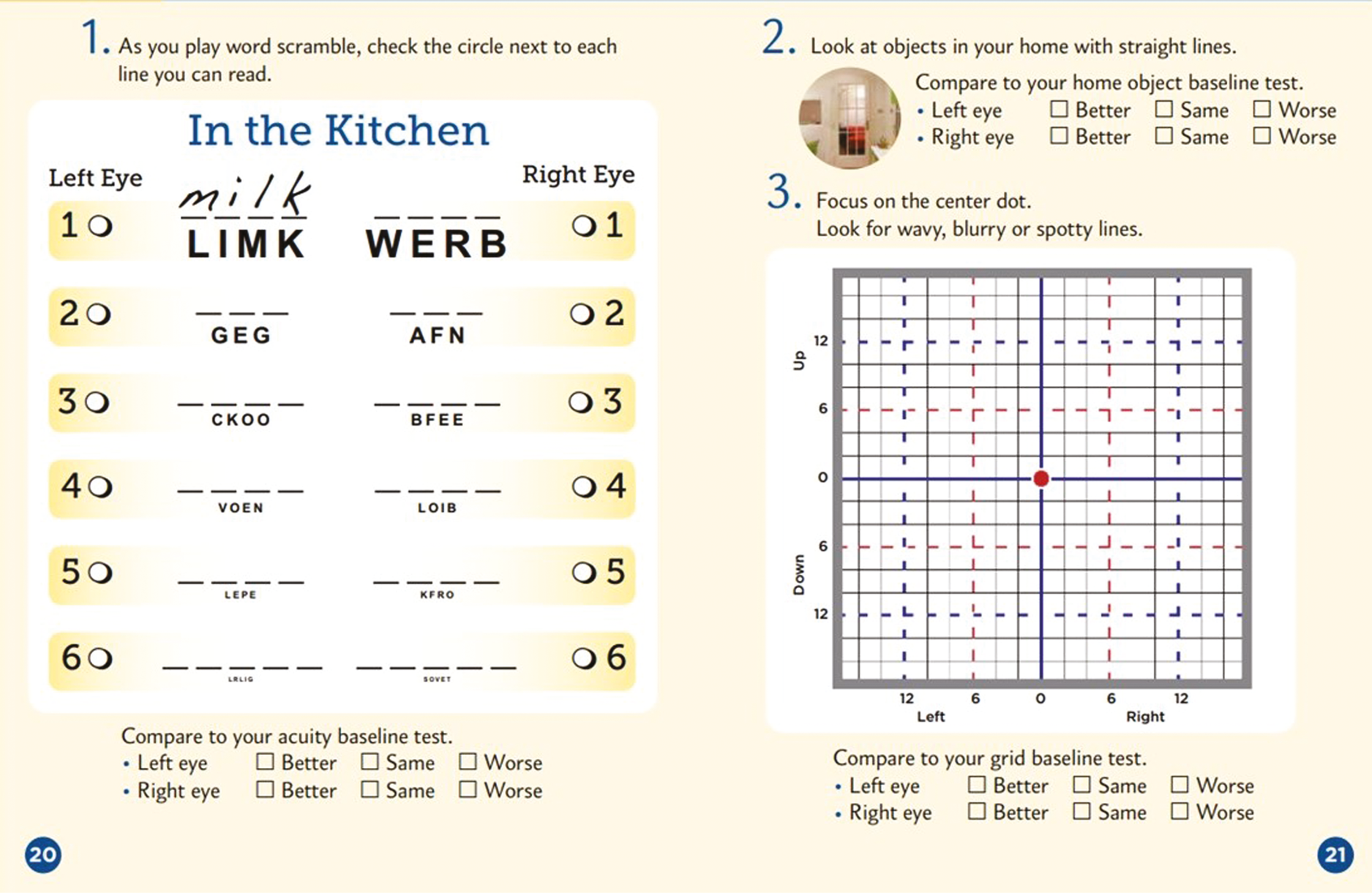

The KSJ encouraged weekly monitoring using a paper journal. It included three different monitoring strategies, viewed one eye at a time. Firstly, near-visual acuity was assessed using a puzzle (crossword or word search) employing a variety of font sizes (an example is shown in Figure 1). Secondly, patients were encouraged to view objects with straight lines in the home to check for distortion (wall panelling, floor tiles, venetian blinds, etc.). Finally, they used a modified Amsler chart (VMS grid) to record areas of distortion or scotoma in their vision. The KSJ has been used before; 198 patients with intermediate AMD (at high risk of progression to late stage) were randomised to use the KSJ to self-monitor or usual care, with follow-up at 6 and 12 months to assess adherence. 11 The results showed significantly better adherence in the journal group with the findings supporting the efficacy of the journal for increasing vision self-monitoring adherence and confidence while promoting persistence in weekly monitoring.

FIGURE 1.

Example week in the KSJ.

MyVisionTrack

MyVisionTrack is a software application (app) on an iPod Touch device. It is a shape discrimination test which measures hyperacuity, by displaying four circles, one of which is radially deformed (‘bumpy’ rather than perfectly circular). Viewing the display monocularly, the patient has to identify the odd one out (Figure 2). Studies have shown that the task implemented on an iPod Touch can distinguish between intermediate and advanced nAMD and a survey reported that 98% of patients found the test easy to use. 18 Studies at the Liverpool site led by Paul Knox (co-investigator) successfully used the test in macular clinics and patients have found the test straightforward to complete. 19,20

FIGURE 2.

Diagram illustrating the steps when self-monitoring with the mVT app.

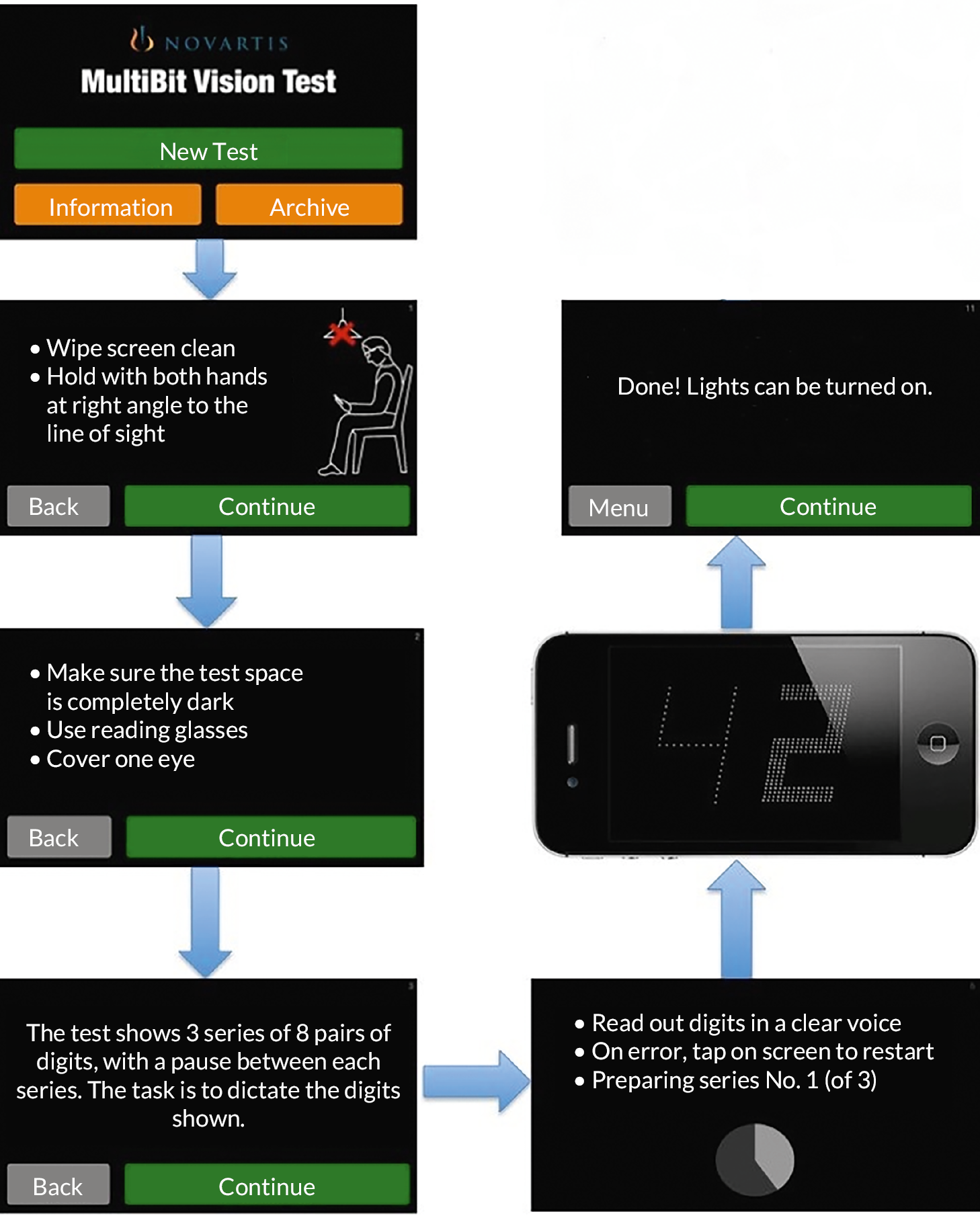

MultiBit test

MultiBit test (MBT) is also an app on an iPod Touch. It is a near-acuity threshold test of neuroretinal damage. Traditional tests fail to detect such damage because they are suprathreshold. The MBT displays receptive field-sized dots or ‘rarebits’, which provide a miniscule amount of information to the visual system compared to conventional targets (Figure 3). Patients are presented with pairs of numbers; they state the numbers that they see out loud and the numbers are then represented at high contrast together with a recording of the patient’s responses. MBT is the only test with published data describing its performance to alongside changes in nAMD activation. 21 It was used to track 29 patients during treatment and monitoring in NHS outpatient clinics (average 39 weeks follow-up), with patients monitoring themselves at home with an iPod Touch. 21 MBT performance improved gradually after treatment, stabilised during periods of disease inactivity and deteriorated gradually preceding reactivation. MBT performance also agreed well with retinal imaging clinical assessments but not with visual acuity (known to be an insensitive test of reactivation).

FIGURE 3.

Diagram illustrating steps when self-monitoring with the MBT app.

Reference standard

The reference standard (sometimes called the ‘gold standard’) is a test that classifies an observation in a way that is considered ‘definitive’. In the case of monitoring for neovascular age-related macular degeneration reactivation at home (MONARCH), this was the nAMD status of a study eye being monitored at a clinical visit. The reference standard is sometimes imperfect but represents how diagnostic decisions are currently being made.

The reference standard test for the study was defined as the reviewing ophthalmologist’s decision at a monitoring visit about the activity status of a study eye. This decision was made on the basis of clinical examination and the results of hospital-based retinal imaging investigations such as colour fundus (CF) photographs and OCT images. We recognise that it is possible that the reviewing ophthalmologist sometimes misjudges the status of a study eye at a monitoring visit, the judgements required are complex and can be difficult; even experts can disagree when judging the activity status of a nAMD lesion,22 but the decisions made by ophthalmologists currently represent the best reference standard.

Potential inequalities in uptake

The study also aimed to address the question: How do demographic, socioeconomic and visual function factors influence the uptake of home-monitoring tests for detecting active nAMD?

A survey by Age UK in 2013 found that internet use among people aged 65 years or over varied across the UK, with a ‘north–south’ divide; more than 50% in the south (Surrey, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Suffolk and Oxfordshire) used the internet, but less than a third in the north (Cumbria, Yorkshire, Hull, Tyne and Wear). 23 With respect to smartphone use, only 20% of 65- to 74-year-olds used such a device to access the internet in 2013;24 perhaps more importantly, this percentage had increased from only 12% in 2012, suggesting that the situation is changing rapidly over time. The potential importance of failure to access the internet has been highlighted by a study of men and women in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing from 2004 to 2011 internet use was found to be significantly ‘protective against health literacy decline’. 25

During the study design phase, the small percentage of regular internet and smartphone users was considered a potential threat to the study; we were especially concerned that potential participants might feel alienated by the technology and would not be prepared to try out the solutions we proposed. Therefore, we sought to determine the extent to which the technology was a barrier to consent and participation in order to project wider adoption of home monitoring in the future if it is found to have satisfactory performance. Moreover, among participants, it is possible that some tests will be easier to do for participants with limited experience of smart devices and the internet. This was an important factor to weigh against test performance if differences in test performance were found to be small.

We designed the study to include the following features to try to minimise the extent to which technology could be a barrier to home monitoring:

-

We included a simple paper-based home-monitoring test, which we hoped would feel familiar to participants. This test involves a series of puzzles which require participants to use their near-vision correction.

-

We also provided a mobile broadband device so that participation was not limited by the lack of home Wi-Fi. The device had a simple on/off switch; the only things that a participant needed to remember to do were to keep the device charged (a main micro-USB charger was provided) and to switch on the device before performing the home-monitoring tests that use the iPod. The iPod interacted with the mobile broadband device automatically to transmit data.

We explained the use of the devices during an initial training and information session with each potential participant and also provided a help line for participants to call in the event of the experiencing difficulty.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the MONARCH study is to quantify the performance of three non-invasive test strategies for use by patients at home to detect active nAMD compared to diagnosis of active nAMD during usual monitoring of patients in the Hospital Eye Service (HES).

The study had five objectives:

-

Estimate the test accuracy of three tests to self-monitor reactivation of nAMD compared to the reference standard of detection of reactivation during hospital follow-up with OCT imaging, clinical examination and Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (EDTRS) visual acuity.

-

Determine the acceptability of the tests to patients and carers and their adherence to home-monitoring testing regimens.

-

Explore whether inequalities (by age, sex, socioeconomic status and visual acuity) exist in recruitment to the study and impact the ability of participants to do the tests during follow-up and the adherence of participants to weekly testing.

-

Provide pilot data for the use of home monitoring to detect conversion to nAMD in the fellow eyes of patients with unilateral disease, compared to the reference standard of detection of conversion during hospital follow-up with EDTRS visual acuity and OCT imaging.

-

Describe the challenges of implementing and evaluating home-monitoring technologies (see Changes to trial design after commencement of the trial).

The study population recruited for Objective B (the integrated qualitative study) differed from that required for Objectives A, C and D. Only selected sites, Belfast, Moorfields and James Paget, participated in procedures and data collection for the patient and carer aspects of Objective B. All participating NHS centres took part in the healthcare professional (HCP) aspect of Objective B.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Ward et al. 26

Study design

The MONARCH study was a multicentre diagnostic test accuracy cohort study to estimate the sensitivity and specificity of home-monitoring tests to detect active nAMD in patients previously diagnosed with nAMD and quiescent after treatment.

MONARCH was designed to compare the results of the home-monitoring tests being evaluated (‘index tests’, see Index tests) with the results of a reference standard (see Clarification of reference outcome). These comparisons allowed the accuracy of the index tests to be quantified with respect to the reference standard.

Participants were followed for at least 6 months, accruing on average six clinic attendances at which home monitoring and reference test results were compared.

The nature of active nAMD may change over time since diagnosis, if the disease progresses despite monitoring and treatment. Therefore, the study population was stratified by time since first treatment of nAMD in the first-treated study eye (see Stratification of study population). This design was to avoid the prolonged duration of follow-up which would be required if, instead, we were to follow participants from diagnosis to an equivalent time in the natural history of their condition. These design features are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Study schema: Objectives A, C and D.

All study data collections were planned before the first participant was recruited, although additions were made to the case report forms (CRFs) in the first month to clarify some data items, for example, eye classification. Case report forms are available at: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/97/02.

Changes to trial design after commencement of the trial

Visual acuity eligibility

When recruitment began, the exclusion criteria have been amended to specify that study eyes with vision equal to or worse than Snellen score 6/24, LogMar0.64 or 53 letters are ineligible for the study due to concern that participants with poorer visual acuity would ‘perform’ less well than other participants. This change was agreed with the funder and Study Steering Committee (SSC) with the proviso that the Study Management Group carefully monitor performance of the patients at the lower end of the visual acuity cut-off threshold and extend recruitment criteria accordingly if these patients do appear to cope with the home eye tests, in order to recruit as broad a patient population as possible. In February 2019, data reviewed by the SSC of the first 59 participants showed that participants with lower visual acuity performed no less well than participants with higher visual acuity. The SSC agreed with the recommendation to lower the visual acuity eligibility threshold to 6/60. This change was approved on 11 May 2019.

New objective

Due to the technical difficulties faced during this study, the SSC supported the addition of a new Objective E when producing the final report, namely, to describe the challenges of implementing and evaluating home-monitoring technologies. This additional objective has not been added to the protocol. The objective used data that were available from processes instituted during the study, for example, a telephone helpline, and accrued other data during the conduct of the study. This objective describes both anticipated and unanticipated challenges of implementing and using the digital apps and the methods used to capture these challenges, mindful that they may be applicable in a variety of contexts in which home monitoring is being attempted beyond ophthalmology.

Clarification of reference outcome

As stated in the grant application, the reference standard is classification of eyes being monitored by the HES as active/inactive nAMD at a management visit. However, consideration of how home monitoring might be implemented (e.g. patient with an inactive lesion discharged with test equipment, with an appointment subsequently triggered by test data indicating reactivation) led us to define a secondary outcome, change from inactive to active lesion status between adjacent management visits. Analyses for this outcome had low power, mainly due to lesions in study eyes being classified as active in a much higher proportion of management visits than expected.

Recruitment and follow-up periods

Following discussions with the SSC in June and September of 2019 regarding the slower-than-anticipated rate of recruitment, it was agreed that the recruitment period would be extended by 6 months (to March 2020), while retaining the original end of follow-up date (September 2020), effectively shortening the minimum follow-up period to 6 months. The purpose of this was to maximise recruitment and the number of monitoring visits without a funded extension. Two hundred and ninety-seven patients of the target 400 were recruited.

Frequency of active lesion status

Monitoring during the study found that the percentage of study eyes classified as active at clinics was much higher than anticipated (75% of study eyes at baseline and 60% of subsequent management visits, compared to the expected 30%). 26 This prompted concern about whether ophthalmologists’ classification decisions at monitoring visits reflected usual care or were being modified due to the study. As a result, some of the underspend from research costs for sites due to lower than expected required was allocated to Central Administrative Research Facility (CARF) to grade OCTs with respect to activity status. The difference between observed and expected percentages was suspected to be due to clinicians treating eyes in such a way that a small amount of fluid in the retina was maintained because this is believed to protect against the development of macular atrophy; such eyes might be classified as having an active lesion. Grading of activity by CARF permitted sensitivity analyses for Objectives A and D.

Stratum recruitment

The protocol stated that study would aim to recruit equally to the three strata (6–17, 18–29 and 30–41 months since first treatment). This approach was relaxed once it became clear that after the pool of existing patients had been approached for the study, only new patients were being recruited as they became eligible. This led to a larger proportion of patients in the 6–17-month strata as recruitment to the 30–41- and 18–29-month strata became more difficult.

Participant eligibility

The study population for the quantitative part of the study were patients with at least one study eye being monitored by HES for nAMD, stratified by time since starting treatment in the first-treated study eye (6–17 months; 18–29 months; 30–41 months) to ensure test performance was estimated across this range of duration of nAMD.

Classification of eyes and eligibility of patients with bilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration

A patient must have had at least one study eye to enter MONARCH.

A study eye was an eye with a nAMD diagnosis meeting the study eye eligibility criteria (below). Participants with bilateral nAMD may have had two study eyes if both eyes met the criteria for eligibility.

A fellow eye was an eye without a nAMD diagnosis, but which met all other eligibility criteria.

An excluded eye is an eye which is not eligible to be a study eye or a fellow eye.

It was possible at the time of consent for a participant to have had one study eye and one excluded eye and for the excluded eye to become eligible later during follow-up. An excluded eye of a participant could become eligible if either: (1) the time since last treatment was < 6 months at screening but enough time had passed while the participant was in the study so that the time since last treatment became ≥ 6 months and/or (2) the participant had surgery in the excluded eye in the 6 months prior to screening but enough time had passed while the participant was in the study that time since surgery became ≥ 6 months. In such instances, the excluded eye of a study participant was rescreened and became a study eye if all eligibility criteria were met.

If a participant had two study eyes, stratification by time since first treatment was based on the date of first treatment in the eye first treated for nAMD (see Stratification of study population).

Participants were asked to complete the home-monitoring tests for study and fellow eyes.

Inclusion criteria

Participants could enter the study if they were ≥ 50 years old and had at least one study eye, that is, meeting the inclusion criteria.

All of the following had to apply for an eye to be considered for inclusion:

-

first treated for active nAMD ≥ 6 months ago

-

first treated for active nAMD not more than 42 months ago

-

currently being monitored for nAMD disease by the NHS.

Exclusion criteria

A patient could not enter the study if the patient did not have a study eye.

A potential study eye was excluded if ANY of the following applied:

-

vision in the potential study eye was worse than Snellen score 6/60, LogMar 1.04 or 33 letters – comment here on the change in visual acuity (VA) eligibility over time

-

vision in the potential study eye was limited by a condition other than nAMD

-

surgery in the potential study eye in the previous 6 months

-

refractive error in the potential study eye > −6D

-

retinal or choroidal neovascularisation in the potential study eye not due to nAMD

-

in addition, a participant will be excluded if ANY of the following apply

-

inability to do one or more of the proposed tests as assessed during ‘further information and training’ session (see Training and equipment)

-

unable to understand English

-

home or personal circumstances are unsuitable for home testing.

Stratification of study population

Home monitoring to detect active nAMD is relevant at any stage of the condition after diagnosis, apart from an initial phase of treatment (usually 3 months). To recruit a study population that evaluates home monitoring across the time spectrum of monitoring, recruitment was stratified into three strata according to time since first treatment for nAMD in the study eye (time since the first-treated study eye for participants with two study eyes): (1) 6–17 months; (2) 18–29 months; (3) 30–41 months.

Settings

The study was run in the homes of patients being monitored by HES for nAMD at participating NHS hospitals and in the participating NHS hospitals.

Participants were recruited in secondary care (HES clinics). During the study, the reference standard for an eye being monitored was determined at HES clinic visits. During intervals between clinical visits, participants used home-monitoring tests to test their vision themselves. Participants were asked to complete the home-monitoring tests themselves weekly at home.

Index tests

There were three home-monitoring (‘index’) tests spanning low to moderate cost and complexity. These were:

-

KSJ test: a paper-based booklet of near-vision tests presented as word puzzles developed in the USA by KeepSight and adapted by the study team for use in the study (UK wording and defining test scores for estimating diagnostic test accuracy).

-

mVT: electronic vision test, owned by Genentech Inc., a member of the Roche Group, intended to be viewed on a tablet device.

-

MultiBit test (MBT): electronic vision test, developed by Visumetrics, licensed by Novartis, intended to be viewed on a tablet device.

Each electronic test took approximately 5 minutes (2–3 minutes per eye) to complete, though some participants took longer. The KSJ took between 10 and 20 minutes (5–10 minutes per eye) depending on the difficulty of the puzzle. Therefore, weekly monitoring was expected to take 20–40 minutes (10–20 minutes per eye). Participants were asked to try to complete all three of the index tests for both eyes but could opt to stop up to two of the three tests and continue with the study.

Each KSJ booklet lasted approximately 6–7 months. Every 6 months, participants were sent a new booklet and instructed to return the used booklet in a pre-paid envelope to the study management team at Clinical Trials and Evaluation Unit (CTEU) Bristol.

Data were collected automatically from the electronic tests.

The KeepSight Journal

The KSJ encourages weekly monitoring using a paper booklet covering 6 months. It includes three different monitoring strategies, viewed one eye at a time. Firstly, near-visual acuity is assessed formally or in a puzzle (crossword, anagrams or word search) employing a variety of font sizes. Secondly, patients are encouraged to view objects with straight lines in the home to check for distortion (wall panelling, floor tiles, venetian blinds, etc.). Finally, they use a modified Amsler chart (VMS grid) to record areas of distortion or scotoma in their vision (see Figure 1). Different booklets were prepared for each 6-month follow-up period (available on request). New booklets were posted to participants towards the end of a period, with a reply-paid envelope to return the completed one.

MyVisionTrack

MyVisionTrack is a software application (app) viewed on Apple devices. It is a shape discrimination test which measures hyperacuity, by displaying four circles, one of which is radially deformed (‘bumpy’ rather than perfectly circular). Viewing the display monocularly, the patient has to identify the odd one out (see Figure 2).

MultiBit

The MBT is also an app viewed on an iPod Touch. It is a near-acuity threshold test of neuroretinal damage. Traditional tests fail to detect such damage because they are suprathreshold. The MBT displays receptive field-sized dots or ‘rarebits’, which provide a miniscule amount of information to the visual system compared to conventional targets (see Figure 3). Patients are presented with pairs of numbers; they state the numbers that they see out loud and the numbers are then represented at high contrast together with a recording of the patient’s responses. The patient’s stated responses are recorded by the app and, after testing, must be played back and scored by the patient, that is, a patient scores their own performance.

Reference standard

The reference standard represents the classification that the index tests are intended to ‘diagnose’. The reference standard is sometimes imperfect but represents how diagnostic decisions are currently being made. The rationale of home-monitoring tests is that a test can ‘diagnose’ the status classification that will be made at the next usual care monitoring clinic review. Therefore, in MONARCH, this reference standard was the reviewing ophthalmologist’s decision at a monitoring visit about the activity status of a study eye; response options were inactive, active or uncertain. These decisions were made on the basis of clinical examination and the results of hospital-based retinal imaging investigations such as CF photographs and OCT images. It is possible that the reviewing ophthalmologist sometimes misjudged the status of a study eye at a monitoring visit [the judgements required are complex and can be difficult; even experts can disagree when judging the activity status of a nAMD lesion (20)], but the decisions made by ophthalmologists currently represent the best reference standard. The reference standard grouped uncertain judgements with inactive ones for all analyses.

Sample size

Objective A and C

In MONARCH, each monitoring visit (and the immediately preceding period of home monitoring) represented the unit of observation. We wanted to recruit enough participants to accrue sufficient visits to allow the study to have 90% (80%) power to detect a difference of 0.06 (0.05) in the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves for two tests if the AUROC is 0.75. 27

We had to make several assumptions to estimate the sample size required:

-

The reference standard would be ‘active’ for 30% of monitoring visits.

-

Correlations between the index test and reference standard classifications (unknown) would be 0.6 for both active and inactive lesions. 27

-

Participants would on average have index test and reference standard data for six monitoring visits, based on durations of follow-up between 12 and 30 months and information about treatment regimens at participating sites.

-

Each monitoring visit (and the immediately preceding period of home monitoring) represents the unit of observation; due to nesting of monitoring visits within participants and the consequent lack of independence of observation, we assumed that the effective average number of visits per participant with data would be 4 rather than 6.

-

The measurement errors of index tests were unknown, and we simply inflated the calculated sample size by 30% to make some allowance for dilution of the power to discriminate differences in performance between tests.

-

The ratio of the standard deviation (SD) of the negative group to the positive group for a home-monitoring test would be 1.

-

Attrition of participants during follow-up (e.g. due to mortality, changes in participants’ circumstances or participants’ unwillingness to continue participating) ≤ 5%.

To achieve the desired power (above), we estimated that we should recruit ≥ 400 participants. With, on average, 6 visits per participant (about 2400 visits with data for at least one index test and the reference standard, allowing for 5% attrition), we estimated that these parameters would yield an effective sample size of about 1200 visits after allowing for (4) and (5) above.

Objective D

Estimates of the rate of conversion to nAMD among fellow eyes vary, ranging from 4% to 16%. 9,28,29 Assuming the risk in unselected patients is 5–6% per year, up to 50 of the 400 target patients were expected to have nAMD in both eyes at the time of recruitment. Among the remaining 350 patients, it was expected to identify conversion of fellow eyes to nAMD in about 25–30 patients. We recognised that test accuracy estimates based on such a small number of true positives would inevitably be imprecise but nevertheless useful as pilot data for future research.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was classification of a study eye at a monitoring visit as having active or inactive disease, that is, the reviewing ophthalmologist’s decision at a monitoring visit about the activity status of the study eye (active, inactive, uncertain). Index tests generated a scaled or categorical score on each occasion when they were used for testing, often many times between monitoring visits. Summary scores were derived for each test for each interval preceding a monitoring visit (see Objective A: analytic approach and methods).

Secondary outcomes

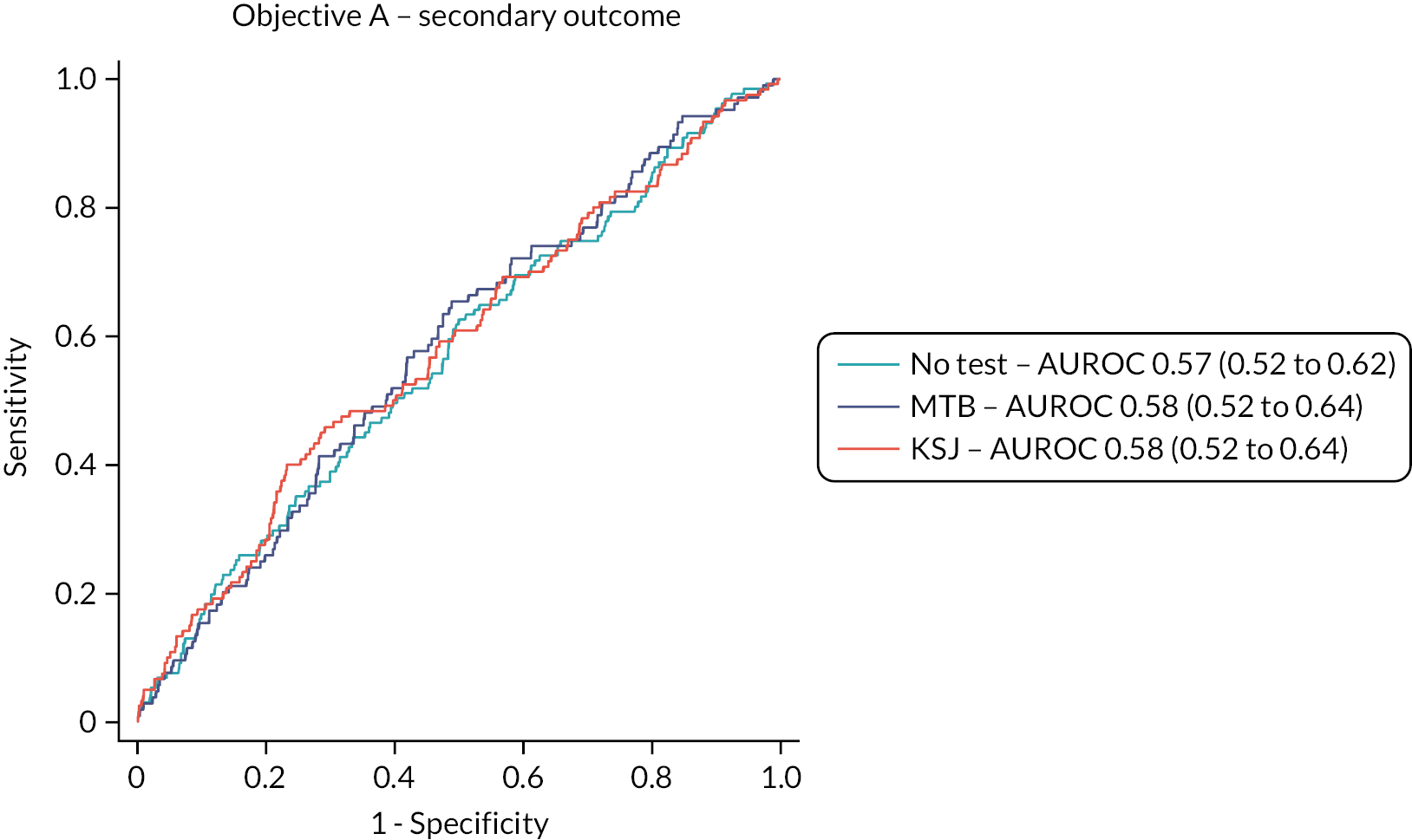

A secondary outcome for Objective A was defined, namely change in classification of lesion activity from inactive at the previous management visit to active as assessed at a management visit.

For Objective C, the following outcomes were investigated as measures of uptake of home-monitoring tests:

-

impacts of inequalities on willingness in principle to participate;

-

impact of inequalities on ability and adherence to weekly testing.

For Objective D, the test accuracy of the three tests to self-monitor conversion of fellow eyes to nAMD compared to reference standard was investigated.

For Objective E, the following outcomes were described as measures of the technical and logistical challenges identified during the study:

-

frequency and reason for incoming calls made to the helpline and outgoing calls made to participants;

-

frequency and duration of events leading to the digital tests being unavailable for testing;

-

other technical and logistical challenges.

Data collection

Patient identification

Potential study participants were identified by local teams from established clinical databases of patients and by reviewing lists for outpatient clinics. Potential participants were screened for eligibility by the healthcare team through review of their medical notes and any existing imaging.

Potential participants were sent by post or given an invitation letter and patient information leaflet (PIL) describing the study. An appropriately trained and qualified member of the local research team (e.g. study clinician/research nurse/optometrist) discussed the study with them by telephone or in person. The potential participant will have had time to read the PIL and to discuss their participation with others outside the research team (e.g. relatives or friends). All potential participants who were provided a PIL were given a unique study number against which details, including reason(s) for non-participation (e.g. reason for being ineligible or patient refusal) along with equality monitoring data [age, sex, ethnicity, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), most recent visual acuities for both eyes] were collected.

Training and equipment

Verbal consent to attend the further information and training session was taken by a member of the local research team and recorded in the patient’s hospital record. The information and training session was led by an appropriately qualified member of the local research team with an experience of working with patients. At the information and training session, the potential participant was shown the equipment and how it should be used for the study. The local research team member answered any further questions, checked and confirmed the participant’s eligibility and took written informed consent if the potential participant was eligible and agreed to participate.

Participants were also asked for consent to their address and telephone number being held at the study coordination centre for receipt of new KSJs and pre-paid envelopes and participant newsletters, to receive optional SMS text reminders during the study, and an optional copy of the final study results at the end of the study. Following consent, the participant was provided with the following to take home: an iPod Touch, a lens cloth, an eye patch, stylus pen, the KSJ and a mobile broadband router. Eye classification (study eye, fellow eye, excluded eye) was confirmed, visual acuities were updated if necessary and information about the participant’s use, ‘at least weekly’, of widespread technologies (e.g. electronic devices, e-mail, internet at home) was collected. The local study team sent a letter to the participant’s general practitioner (GP) to inform them of study participation.

Follow-up

Patients were followed up for at least 6 months. There was no specific follow-up schedule required for the study. Participants continued to have usual care (i.e. review of disease activity and treatment if required) in NHS monitoring clinics. Retinal imaging was also be carried out as required to inform usual care management decisions. Local site teams collected data for study and fellow eyes at each usual care follow-up visit.

Imaging, review and treatment may have all be completed on the same day or depending on the usual care arrangements at a site, may have been carried out over a number of days. Retinal imaging could be reviewed (i.e. a management decision made) in the absence of a patient, with the patient being advised that they only needed to return if the nAMD was active and treatment was required. A management decision was a decision about the status of a nAMD lesion and/or the treatment plan.

Participants were contacted before the management decision for each follow-up visit was made. Participants were telephoned before (maximum of 5 working days before retinal imaging) or seen in clinic before having an appointment. A member of the local research team asked the participant questions on how they felt their vision has been since their last visit, whether the participant had been carrying out home monitoring, whether the participant had experienced any problem with home monitoring, to confirm the participant’s willingness to continue and whether there was need for retraining.

Technical support

The study management team operated a technical support phone line during standard office hours Monday to Friday (except holidays) to resolve issues with use of the applications, iPod touches, mobile broadband devices, automatic data upload or other technical queries. Calls received to the support line are documented and reasons reviewed. The study management team also made periodic calls to patients for whom data had not been received in > 21 days (or > 14 since consent). Reasons for the absence of test data are documented.

Retinal images

Patients were asked to provide consent to retinal image collection (optional). For participants who agreed to retinal image collection, all retinal images (e.g. CF, OCT) taken during follow-up were submitted to CARF to be stored for use in future ethically approved research.

Given the higher-than-expected proportion of active lesions, we decided that the stored retinal images should be assessed for presence of activity by senior staff from the NetwORC UK reading centre (www.networcuk.com/) according to a standardised protocol. All available images were used to make the assessment. Presence of the following features was assessed in both eyes:

-

Presence of subretinal fluid.

-

If present, was it more or less than previous visit?

-

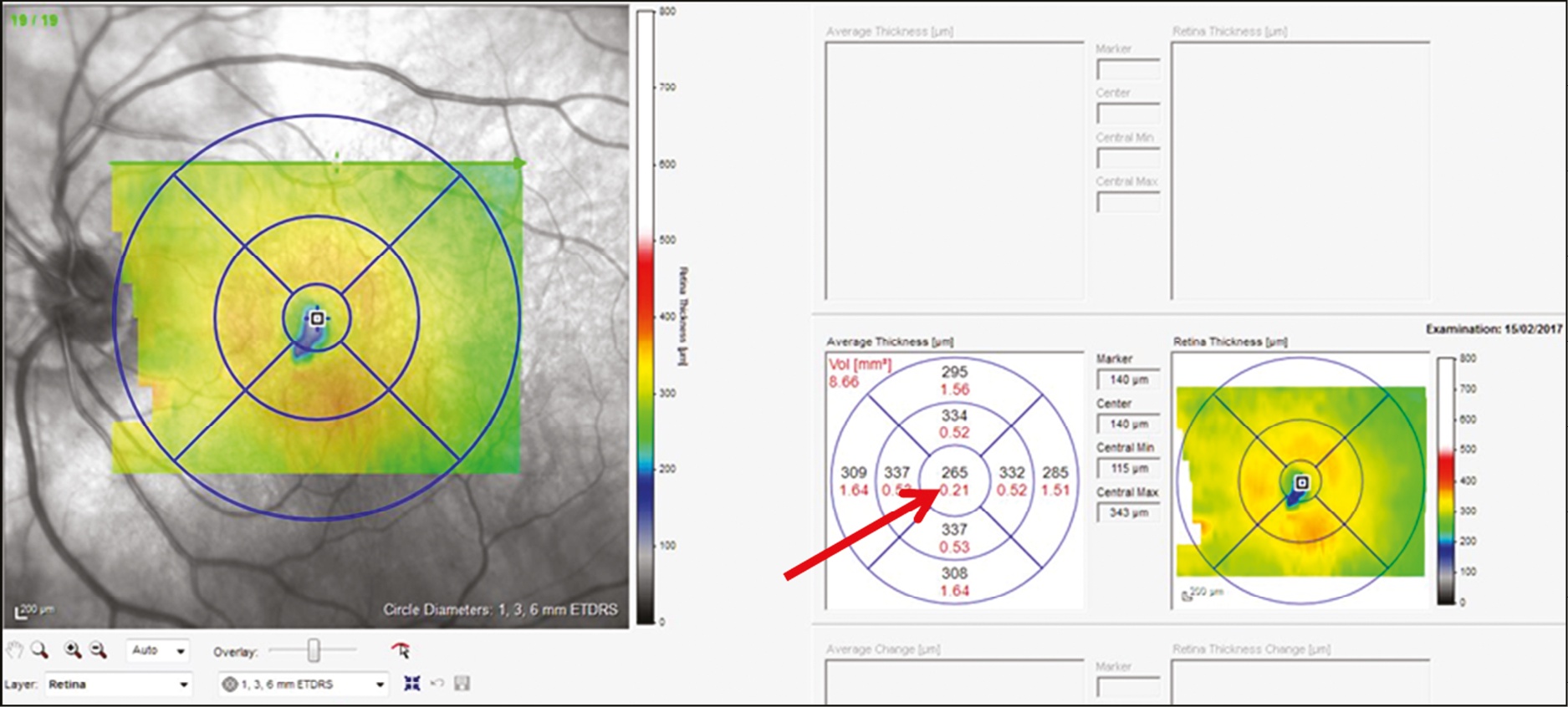

Central subfield thickness (Figure 5) is recorded from the OCT machine automatic algorithm.

FIGURE 5.

Red arrow shows central subfield thickness from OCT scan.

Features to minimise bias

Risk of bias was considered with respect to bias domains described in an appraisal tool for diagnostic accuracy studies. 30 Information here should be read in conjunction with information about the proposed methods of analyses (see Methods for Objective E).

Blinding

All personnel carrying out usual care NHS monitoring were masked to data from index tests. However, participants may have gained an impression that their vision had changed from home-monitoring tests and may have communicated their impressions to their ophthalmologists.

Bias due to selection of participants

Bias in this domain was avoided by using a cohort study design and recruiting a representative sample of eligible patients. We cannot guarantee that consecutive eligible patients were recruited but factors such as absence of research staff (e.g. annual leave) or other logistical issues were very unlikely to be associated with the characteristics of patients. Therefore, we anticipated that, when staff were available, research teams would invite consecutive eligible patients to take part and hence recruit a representative sample of patients. The exclusion criteria were appropriate, that is, they would prevent a person self-monitoring using one or more of the tests even if the test(s) were implemented as part of usual care (if shown to detect nAMD reactivation accurately).

Bias in the assessment of the index tests

Bias in this domain was avoided by ensuring that the index tests were to be ‘scored’ without knowledge of the results of the reference standard. (Index tests were performed before monitoring visits; so, they could not have been influenced by the reference standard classification.) We chose methods to summarise test scores before carrying out any analyses and estimated the AUROCs based on these, across the range of summary test scores. We did not pre-specify threshold scores for classifying test summary results as active/inactive and report sensitivity and specificity based on Youden’s index, acknowledging the latter takes no account of the relative clinical and other implications of false-positive and false-negative misclassifications. We could not specify test thresholds at the outset because there were no available data to inform these definitions.

Bias in the assessment of the reference standard

Bias in this domain was avoided by ensuring that the reference standard was assessed without knowledge of the results of the index tests. The reference standard represents a usual care decision about the reactivation of nAMD and, although these decisions will not always have been accurate,22 we assumed that these decisions could reasonably be considered likely to classify participants correctly with respect to reactivation of nAMD.

Bias due to exclusion of participants or inappropriate intervals between the times of index testing and the reference standard

Bias in this domain was avoided by ensuring the analysis included all follow-up visits for which the reference standard was assessed and by carefully describing the time intervals between index tests and the reference standard. We also accounted for all patients recruited into the study, for example, using a flow diagram and tables as appropriate. We acknowledge potential differences between participating centres and present information that may characterise this, for example, variation in methods used to obtain the reference standard and the centre-specific rate of reactivation of nAMD.

Qualitative methods (Objective B)

Semistructured interviews were conducted face to face and via telephone. The interview schedule (see Appendix 1, Table 29) was based on the experience of the research team and was informed by models and theories of technology acceptance. The members of the team that collected and analysed the data have extensive experience in the application of qualitative methods in healthcare research. The study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) criteria. 31

Participant recruitment and data collection

Recruitment to the qualitative component began 3 months after the MONARCH study began recruiting. During the consent process for participation in the diagnostic accuracy study, individuals who consented to further contact to discuss participation in this qualitative study were approached via a telephone call from a qualitative researcher. Researchers confirmed if participants were happy to take part and arranged an interview date. Informed consent was obtained prior to interviews and following an explanation of study procedures. Maximum variation sampling was used to ensure that a range of perspectives were captured in relation to age category (young-old 50–69 years and older-old 70+ years), gender, laterality of nAMD (unilateral and bilateral) and time since first treatment (6–17, 18–29 and 30–41 months). In addition, test usage data were used to sample participants with different levels of adherence to home monitoring. Usage data from the two digital index tests were examined by the qualitative researchers to categorise participants into two groups: (1) ‘Regular’ testers who completed weekly home monitoring without two or more gaps in testing of greater than 3 weeks, and (2) ‘Irregular’ testers who stopped and started testing on more than two occasions or stopped testing completely. Patients who declined to participate in MONARCH but provided consent to be contacted about the qualitative study were also approached. We approached informal ‘carers’, supporters or significant others in the lives of patients, and HCPs who interacted with participants at study sites visits in order to gather their perspectives about the acceptability of home monitoring.

Data management and analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. A directed content analysis approach based on deductive and inductive coding was used. 32 An initial coding scheme was developed based on a synthesis of relevant theories, including the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT),33 the technology acceptance model (TAM)34 and the theoretical framework of acceptability (TFA). 35 The coding framework underwent iterative development as individual transcripts were reviewed and rereviewed during data familiarisation. Following line-by-line coding of each transcript, findings were summarised based on the coding scheme and these summaries were used to revise initial codes if necessary and develop new codes based on emerging data (see Appendix 1, Table 30 for final coding scheme). A third researcher coded a random sample of 10% of the transcripts and subsequently discussed and compared coding with CT (Charlene Treanor) and SOC (Sean O’Connor) in order to ensure adequate rigour and reflexivity. Related codes were then clustered and grouped into initial themes. Narrative summaries were written for each theme, then reviewed and discussed to refine main themes and subthemes to ensure coherence. NVivo version 12 was used to manage data and facilitate the analysis process, which, in summary, included the following stages: (1) independent transcription, (2) data familiarisation, (3) independent coding, (4) development of an analytical framework, (5) indexing, (6) charting and (7) interpreting data.

Methods for Objective E

Due to the age range of the patient population, the study team anticipated that participants with little or no experience in using electronic devices may have difficulty operating and interacting with the study equipment [iPod and Mobile Wireless-Fidelity (MiFi) router]. As described, participants’ exposure to various types of electronic technology was recorded at consent. Reasons for not consenting were also recorded when participants did not want to engage with the technologies required for the study.

Throughout the study, at or before each follow-up appointment, the local research staff asked participants if they were experiencing any issues with the equipment and additional training sessions were offered. This information was captured in the CRFs and was used as a means of troubleshooting participants technical issues and maintaining participant testing.

Participants were encouraged to contact the study team on the technical support to resolve technical issues (incoming calls). Details of all calls received were logged, including call length, issues discussed, actions taken and resolution status. The helpline acted not only to capture the details and frequency of various technical issues, but also to resolve them and maintain participant testing.

The study team realised early on during the study that data were not being received from some participants, often immediately following consent. To try to identify and resolve any technical issues that participants may be facing, periodic calls were made from the helpline to participants for whom data had not been received in more than 3 weeks or more than 2 weeks since consent (outgoing calls, only to participants who had consented to being contacted by telephone). Logging these calls documented the challenges participants were experiencing, and also meant that members of the research team could try to resolve any technical issues, or prompt participants to test. The same details were recorded as for incoming calls.

In addition to periodic calls to participants, a SMS text message notified a participant if test data had not been received in more than 3 weeks since last test or more than 2 weeks since consent, or to thank them if their data were being regularly received (when consent to send these messages had been given). These messages were intended to act as a prompt to participants to test or to contact the study team if they were experiencing technical issues. All notifications sent to participants were logged.

The study team experienced a range of different logistical and technical issues relating directly to the study equipment and applications used. All issues with the study equipment and the apps were logged with as much detail as possible and are described in the results, including time frames, impact on participants and resolutions, where possible.

Statistical methods

A pre-specified analysis plan was written before analyses were carried out.

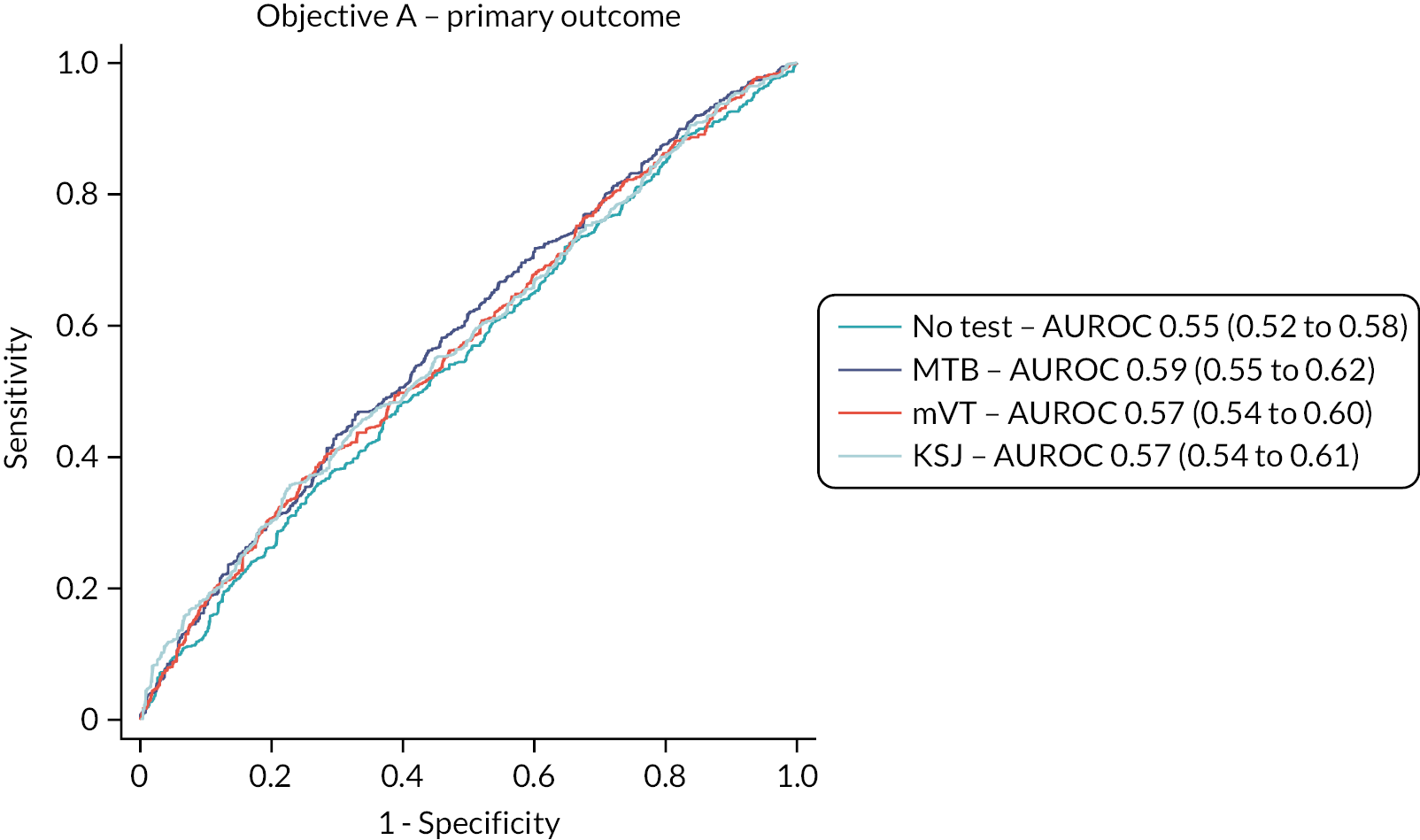

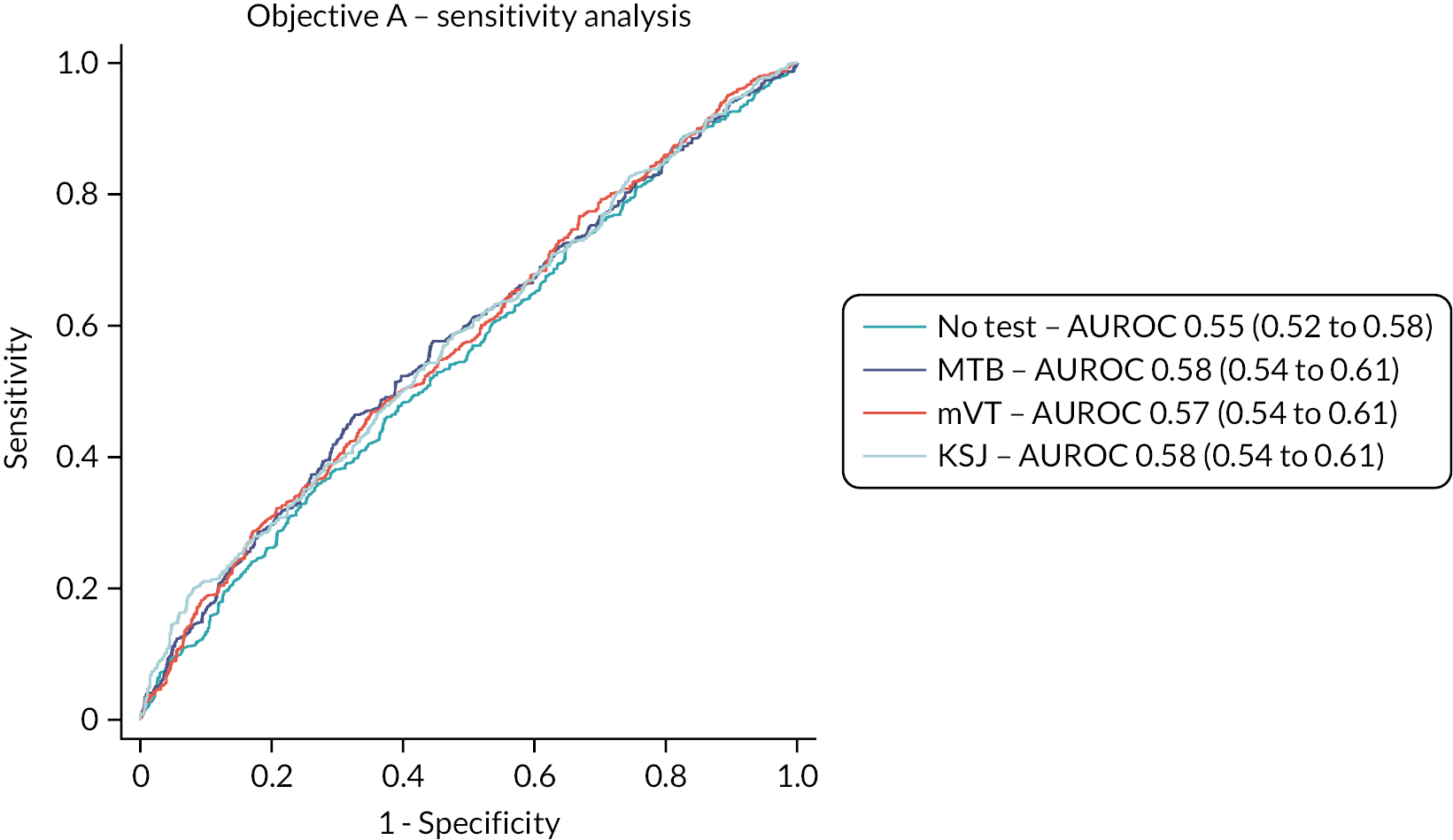

Objective A: analytic approach and methods

The test accuracy of all three home-monitoring tests was examined using three outcomes:

-

Primary analysis: the reference standard of the classification of a study eye at a complete management visit as having either active or inactive disease, using all available test data.

-

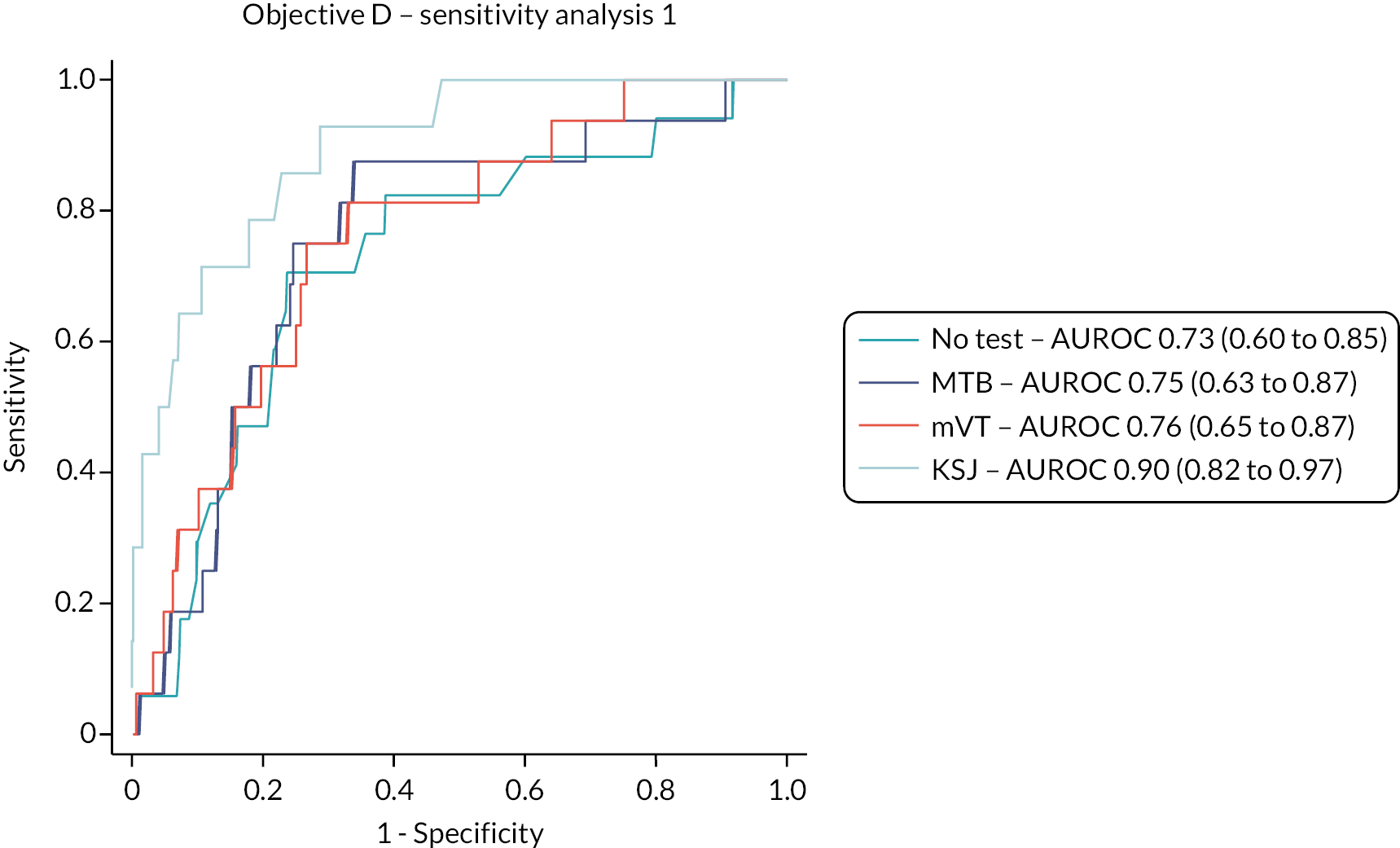

Sensitivity analysis 1: the reference standard of the classification of a study eye at a complete management visit as having either active or inactive disease, using test data for the 4 weeks preceding the management visit.

-

Sensitivity analysis 2: the alternative reference standard of the classification of a study eye as having either active or inactive disease based on the OCT image taken during a complete management visit, using all available test data.

-

Secondary outcome: the reference standard of a change in classification of a study eye from inactive at the previous complete management visit (including baseline assessment) to active at the subsequent complete management visit, using all available test data.

Two test summary scores (predictors) for each test were calculated per management visit per patient. The first was an average (mean, proportion or median) of the test raw scores across the entire preceding intervisit follow-up period. The second was calculated in the same way, but only using raw scores during the 4-week period immediately preceding the management decision, since the periods between visits were not of fixed length (affecting the precision of the summary score and containing older test information that might be out of date).

Models used all available data. The reference standard was always available for a complete management visit, but summary tests scores were not because participants did not always do all index tests.

Means of MBT and mVT test scores were fitted in all models. The KSJ generated four test raw scores: ordinal near VA (on a scale of 1–6; added before carrying out analyses to make use of the scaled nature of these data); VA worse than baseline; Amsler grid worse than baseline; household object appearance worse than baseline. The latter three binary scores were created by combining ‘same’ or ‘better’ responses (score = 0). KSJ summary test scores for a complete visit were created as a median for near VA and percentages of the three other scores that were worse across the respective preceding interval. All four scores were fitted in the KSJ model and a single AUROC was estimated. Correlations between the four KSJ summary tests scores were estimated.

Separate models were fitted for each test/summary test score for the primary outcome, the two sensitivity analyses and the secondary outcomes. All models included the fixed effects of sex, stratum for time since first treatment for nAMD at baseline, age, visual acuity stratum at baseline and days since baseline management visit. Each model was fitted, where possible, with a random intercept and random slope on calendar quarter since baseline visit at the participant level, and a random intercept at the eye level.

Higher MBT scores represent better performance (requiring less information to identify numbers correctly). Higher mVT scores (on the logMAR scale) represent poorer performance (more pronounced deviations required to identify the bumpy circle correctly). Test scores from the mVT application were multiplied by a factor of 100 before fitting the models, so that odds ratio (OR) estimates for this test correspond to changes in ORs for every 0.01 change in mVT score. For the KSJ, a higher median represented better near VA; higher percentages of worse raw scores for the other outcomes represented poorer performance. Unless otherwise stated, the fixed effect of days since baseline was estimated after applying a natural log transformation due to non-linearity and improvements in model specification. No interactions were tested.

Model performance in all cases was examined by inspecting the OR for the index test summary score(s) and the estimate of the AUROC and their respective confidence intervals (CIs). AUROCs were based on predicted probabilities calculated using only the fixed effects in the models. Finally, home-monitoring score thresholds associated with predicting active lesion status were calculated by identifying the point on the AUROC curve that maximised sensitivity and specificity based on Youden’s index. The predicted probability associated with the cut-off point was then applied to the data to estimate average test scores above and below the threshold.

The overall performance of the tests was quantified by the AUROC. We intended to compare AUROCs for the tests to determine if one or more tests is superior to one or more of the others but did not do this due to the emerging results. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of each test were also reported with 95% CIs. Analyses took account of the structure within the data, that is, the nesting of visits (and eyes) within patients.

Objective B

Qualitative research methods were used to explore individual responses, views and experiences around Hand Movements (HM) acceptability, as well as to examine variations in personal contexts. 32 Semistructured interviews were conducted face to face and via telephone. Participants were not known to the researchers who conducted the interviews. The interview schedule (see Appendix 1, Table 29) was based on the experience of the research team and was informed by models and theories of technology acceptance. Several theories have been developed to improve understanding about technology acceptance, including the original and extended versions of the UTAUT,33 the TAM,34 the TFA35 and the senior technology acceptance model (STAM). 36 The study followed the COREQ criteria. 31

Recruitment to the qualitative component began 3 months after the MONARCH study. During the consent process for participation in the diagnostic accuracy study, individuals who consented to further contact to discuss participation in this qualitative study were approached via a telephone call from a qualitative researcher. Researchers confirmed whether participants were happy to take part and arranged an interview date. Informed consent was obtained prior to interviews and following an explanation of study procedures. Maximum variation sampling was used to ensure that a range of perspectives were captured in relation to age category (young-old 50–69 years and older-old 70+ years), gender, laterality of nAMD (unilateral and bilateral) and time since first treatment (6–17, 18–29 and 30–41 months). In addition, test usage data were used to sample participants with different levels of adherence to HM. Usage data from the two digital index tests were examined by the qualitative researchers to categorise participants into two groups: (1) ‘Regular’ testers who completed weekly HM without two or more gaps in testing of greater than 3 weeks, and (2) ‘Irregular’ testers who stopped and started testing on more than two occasions or stopped testing completely. Patients who declined to participate in MONARCH but provided consent to be contacted about the qualitative study were also approached. We approached informal ‘carers’, supporters or significant others in the lives of patients, and HCPs who interacted with participants at study sites visits in order to gather their perspectives about the acceptability of HM.

Objective C

Three outcomes were considered for this objective: (1) willingness in principle to participate in principle among approached patients, (2) consent to participate when eligible and willing in principle and (3) ability to perform tests and adherence to weekly testing. Ability to perform an index test was defined as the proportion of qualifying management visits for which some valid index test data are available. Adherence was defined as the proportion of weeks between qualifying management visits for which some valid data for an index test were available. The ability and adherence models were performed for each test separately at the level of the patient.

Regression models explored the influences of age, sex, IMD, stratum of time since first diagnosis and baseline visual acuity at diagnosis on the outcomes of: willingness to participate in screening (when first approached), consent to take part (among all patients approached); ability of a participant to complete a test, analysed separately for each index test (among all participants); and adherence to the study protocol (among all participants). The influence of these factors is reported as ORs with 95% CIs. Analyses of adherence and ability took account of nesting of visits within participants.

The IMD was used as an indicator of participant socioeconomic status. However, IMD ranks cannot be directly compared between UK countries. To allow comparison of Belfast Northern Ireland with English IMD ranks, adjusted IMD ranks were used, by normalising 2010 Northern Ireland IMD data to the 2015 English IMD. The approach required back-converting available (English) IMD ranks on the MONARCH database to Lower Layer Super Output Areas geographies, allowing linkage to an adjusted IMD data source (https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/1ef3q32gybk001v77c1ifmty7x). During this process, seven patients were identified as having erroneous IMD ranks: four due to residing in the Isle of Man and three due to having out of range IMD ranks. These patients were excluded from analyses using IMD.

The exposure to technology indicator was based on whether the participant stated that they used at least weekly any of smartphone, tablet, laptop/home computer, internet, e-mail or social media. As these questions were only asked after consent, the indicator could not be examined in the analysis of inequalities on willingness in principle to participate.

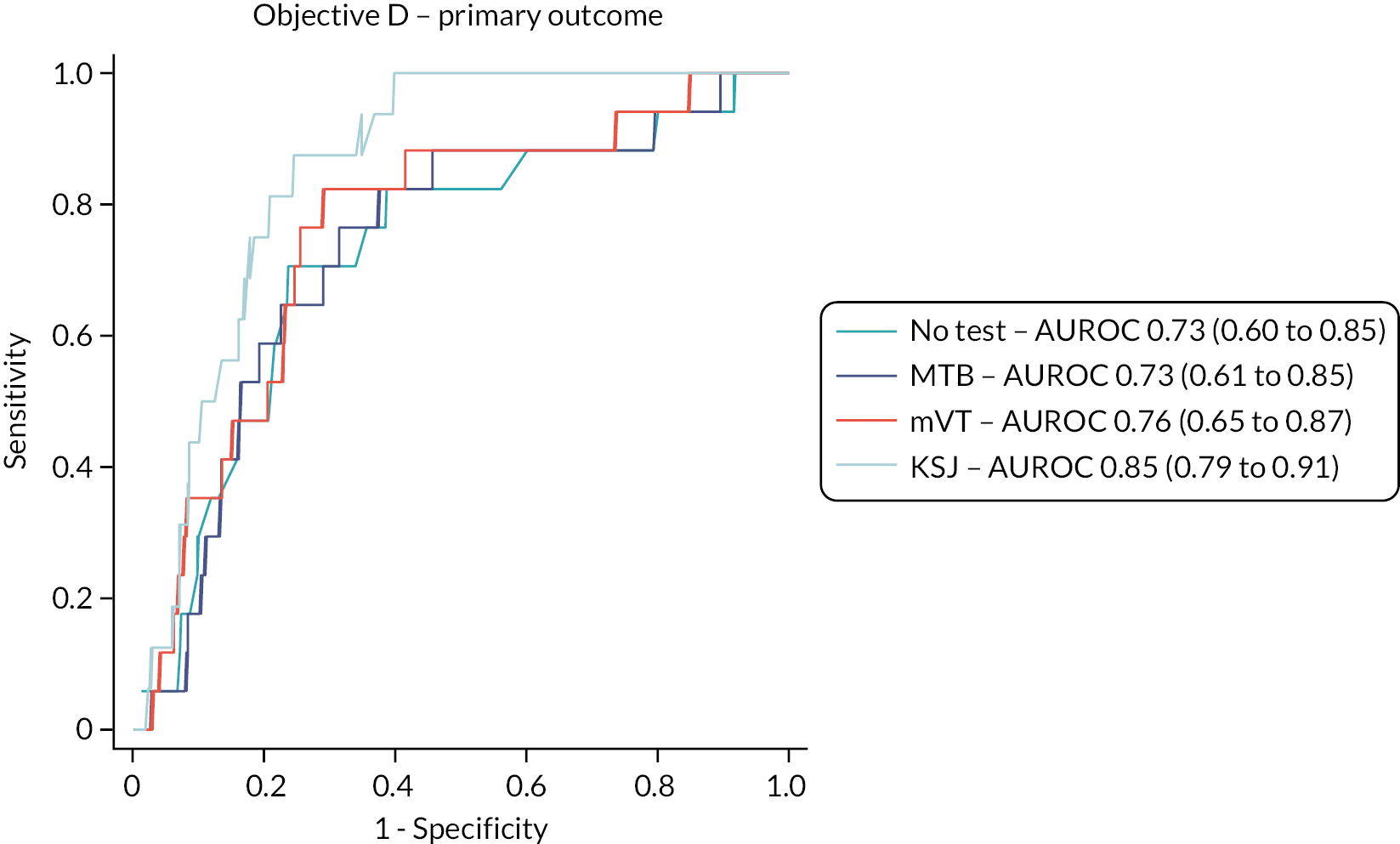

Objective D

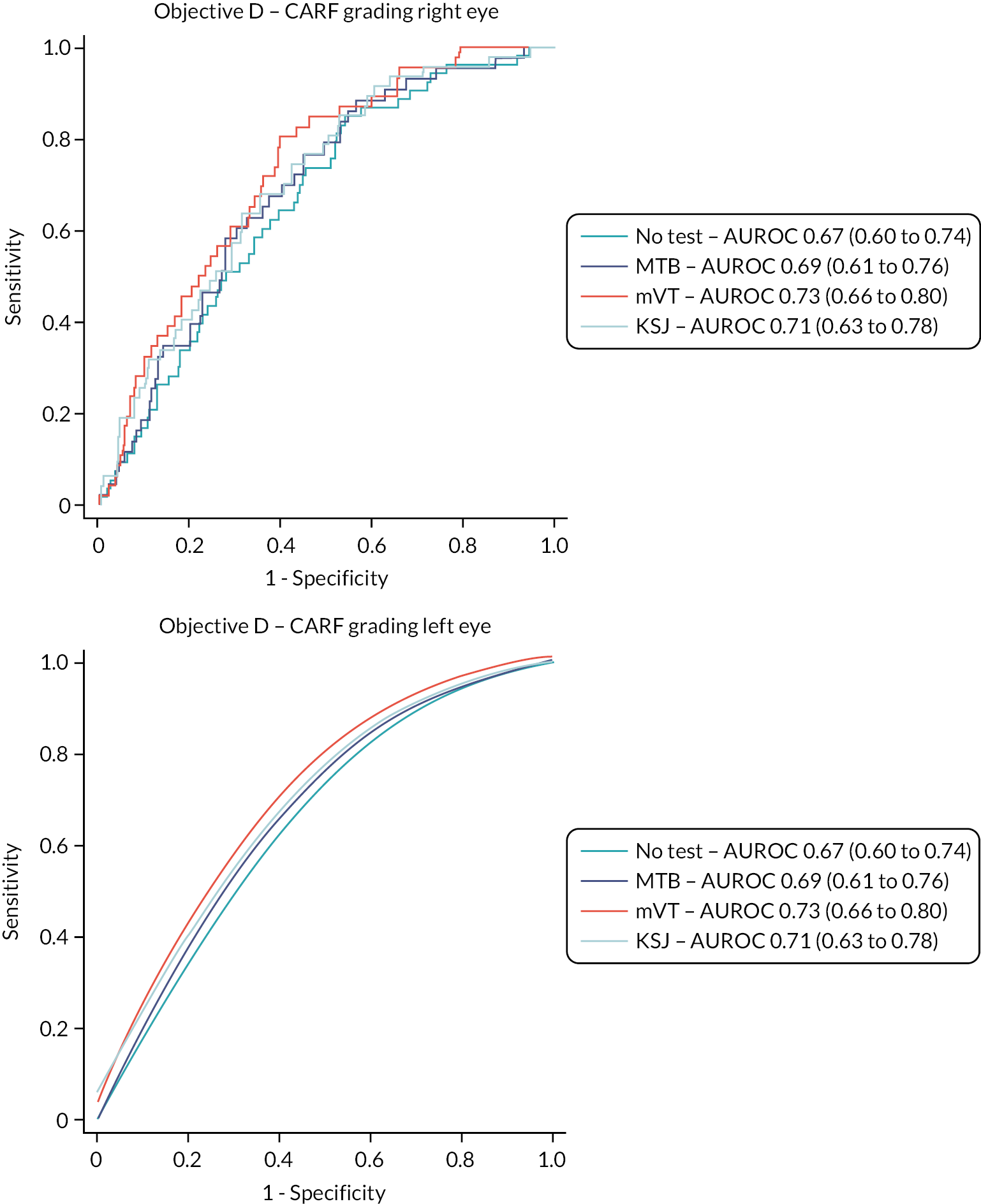

The test accuracy of the index tests was examined for the reference standard of an ophthalmologist’s classification of a fellow eye having active disease at a management visit, that is, conversion to active nAMD. Two sensitivity analyses were carried out:

-

Sensitivity analysis 1: the same reference standard outcome but using test data for the 4 weeks preceding the management visit only.

-

Sensitivity analysis 2: the alternative reference standard of classification of a fellow eye having active disease at a management visit based on grading by CARF of OCT images taken during the management visits.

In other respects, the analyses used the same methods as for Objective A.

Objective D

This objective used descriptive summary descriptive statistics only.

Patient and public involvement

From the beginning we recognised that effective patient and public involvement (PPI) was central to the delivery of high-quality research. Discussions with patients, clinical and academic colleagues informed the initial proposal and, in particular, the frustration articulated by patients about the burden of monthly monitoring hospital visits, both for them and their carers. This was the stimulus for our focus on home monitoring for patients already being treated for nAMD. During the design phase, both the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) and the Macular Society were contacted about the proposal and provided helpful feedback. One of the tests was also demonstrated to, and discussed with, a group of current AMD patients. They welcomed the development of technologies for home monitoring and said that they would be interested in using the test at home to monitor their vision. Feedback from a larger group of patients who had used the test as part of a formal study was also sought, and they confirmed that the test was easy to use, even for older patients with little or no experience of using ‘smart’ devices like the iPod Touch. Throughout the study, we sought to use the INVOLVE principles and resources to guide our active involvement with patients and the public. A representative from both the RNIB and the Macular Society agreed to sit on the SSC as these are both key stakeholders for patients with AMD and severe sight loss.

A group consisting of both four patients and two carers was also established [managed by Dr Hogg and a post doctoral research associate (PDRA) based in Belfast] provided crucial feedback on appropriateness of the study materials, with particular focus on the design of the training materials for using the apps and the study equipment. They also provided feedback on content of visits and frequency of procedures. Input from the PPI group was very helpful for the content of the KSJ, firstly in adapting the original one for a UK audience and then for the development of the subsequent versions.

Specific feedback that proved very useful included:

-

Removal of the motivational quotes from the KSJ as the PPI group member did not like them and felt they were not appropriate for a UK audience.

-

Requested removal of italicised text in the equipment instruction sheet.

-

Members did not like the term ‘carer’ as they felt very few patients would describe their spouse or friend/family member who helps them as a carer and requested the patient information be changed accordingly.

-

They felt there was too much reading in the PIL and so it was explained that a lot of it was necessary for legal purposes.

-

They requested removal of coloured text from the study newsletter and replaced by either black on white or black on yellow text.

-

They expressed no strong preference as to how they were contacted throughout the study but felt that updates via a study website would not be effective, so it was decided to not produce a dedicated study website.

Chapter 3 Results: study cohort

Recruitment

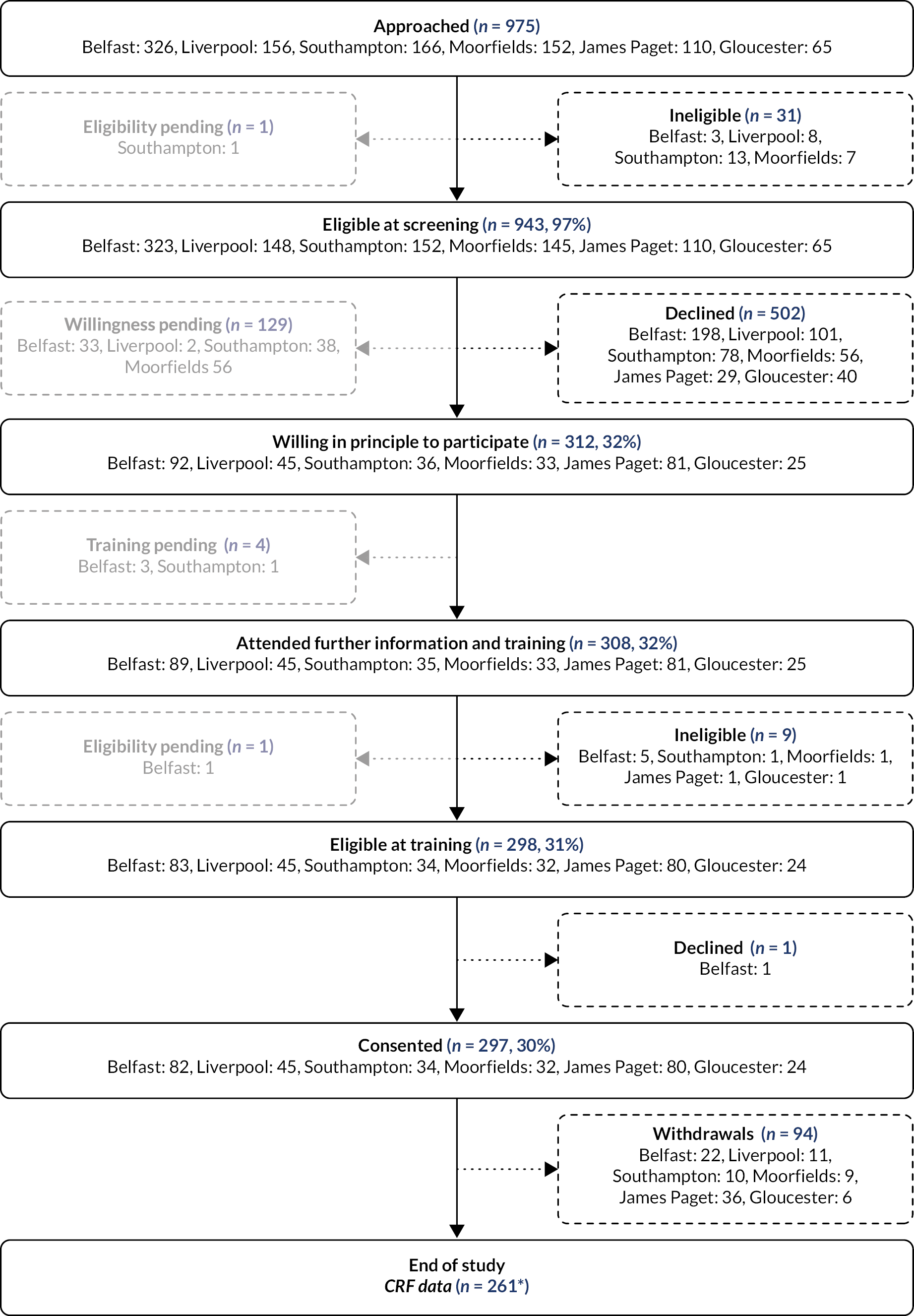

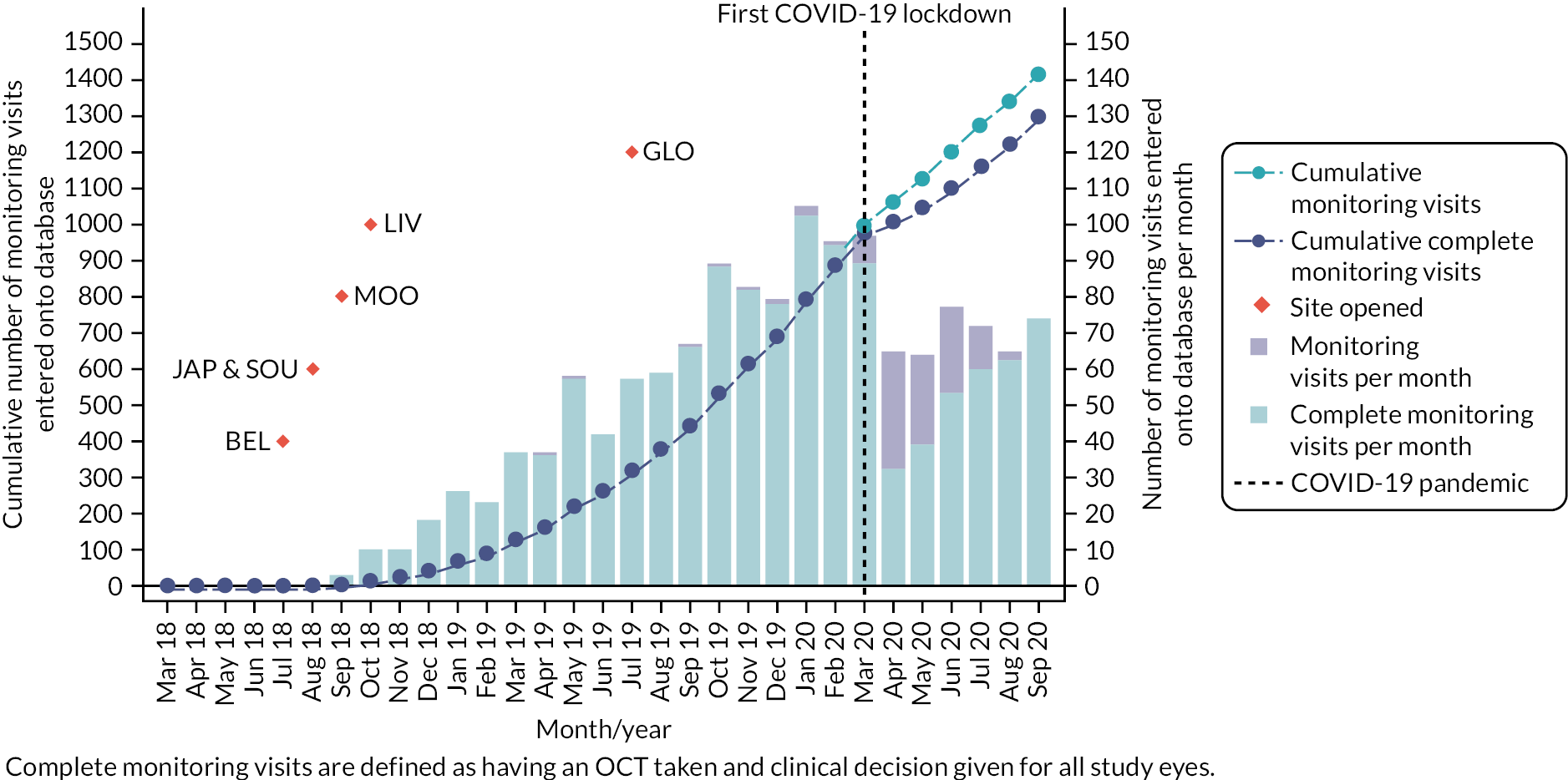

Details of patients approached and screened are described in Appendix 1 (see Table 31). The flow of patients approached and screened, and the numbers of patients who were willing in principle, trained to use the index tests, eligible and who consented to take part are shown in Figure 6 and summarised in Table 1. Recruitment over the lifetime of the study (21 August 2018 to 31 March 2020) is shown in Figure 7. The last patients were recruited in March 2020, before the first UK lockdown due to COVID-19 (see Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the study). A total of 297 patients (participants) consented to take part.

FIGURE 6.

Patient flow chart. (1) Figure counts all participants with at least one management decision visit, irrespective of whether the management visit was complete (includes imaging and lesion status information) or whether they withdrew before the end of the study. (2) Percentages above are all calculated with respect to the number approached.

| Stage in recruitment pathway | Belfast n (%) |

Liverpool n (%) |

Southampton n (%) |

Moorfields n (%) |

James Paget n (%) |

Gloucester n (%) |

Overall n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approached | 326 | 156 | 166 | 152 | 110 | 65 | 975 |

| Eligibility pending at screening | 0/326 (0) | 0/156 (0) | 1/166 (1) | 0/152 (0) | 0/110 (0) | 0/65 (0) | 1/975 (0) |

| Ineligible at screeninga | 3/326 (1) | 8/156 (5) | 13/165 (8) | 7/152 (5) | 0/110 (0) | 0/65 (0) | 31/974 (3) |

| Eligible at screening a | 323/326 (99) | 148/156 (95) | 152/165 (92) | 145/152 (95) | 110/110 (100) | 65/65 (100) | 943/974 (97) |

| Willingness pending | 33/323 (10) | 2/148 (1) | 38/152 (25) | 56/145 (39) | 0/110 (0) | 0/65 (0) | 129/943 (14) |

| Declined (at screening)b | 198/290 (68) | 101/146 (69) | 78/114 (68) | 56/89 (63) | 29/110 (26) | 40/65 (62) | 502/814 (62) |

| Willing in principle to participate b | 92/290 (32) | 45/146 (31) | 36/114 (32) | 33/89 (37) | 81/110 (74) | 25/65 (38) | 312/814 (38) |

| Attended further information and training | 89/92 (97) | 45/45 (100) | 35/36 (97) | 33/33 (100) | 81/81 (100) | 25/25 (100) | 308/312 (99) |

| Eligibility pending after training | 1/89 (1) | 0/45 (0) | 0/35 (0) | 0/33 (0) | 0/81 (0) | 0/25 (0) | 1/308 (0) |

| Ineligible after trainingc | 5/88 (6) | 0/45 (0) | 1/35 (3) | 1/33 (3) | 1/81 (1) | 1/25 (4) | 9/307 (3) |

| Eligible c | 83/88 (94) | 45/45 (100) | 34/35 (97) | 32/33 (97) | 80/81 (99) | 24/25 (96) | 298/307 (97) |

| Consent pending | 0/83 (0) | 0/45 (0) | 0/34 (0) | 0/32 (0) | 0/80 (0) | 0/24 (0) | 0/298 (0) |

| Declined consentd | 1/83 (1) | 0/45 (0) | 0/34 (0) | 0/32 (0) | 0/80 (0) | 0/24 (0) | 1/298 (0) |

| Consented d | 82/83 (99) | 45/45 (100) | 34/34 (100) | 32/32 (100) | 80/80 (100) | 24/24 (100) | 297/298 (100) |

FIGURE 7.

Cumulative number of participants recruited for Objectives A, C and D.

Overall, eligibility was high at screening (943/974, 97%), about two-fifths of screened patients were willing in principle to participate (312/814, 38%), and of those willing, the majority attended training and consented (297/312, 95%).

Reasons for ineligibility at screening and training are shown in Appendix 1 (see Table 32). The most common reasons for ineligibility at screening were due to patients not being previously treated or monitored for active nAMD (20/31, 65%) or to vision being limited by another condition (18/31, 58%). The most common reason for ineligibility at training was due to patients being unable to perform the MultiBit (MBT) electronic test (8/9, 89%).

Reasons for being unwilling in principle to participate are shown in Table 2. Being ‘put off by technology’ was the most common reason (19%, 95/502); other commonly cited reasons included ‘personal reasons’ (17%, 86/502), not interested (17%, 83/502) and ‘other’ (17%, 87/502).

| Reason for not willing | Belfast n (%) |

Liverpool n (%) |

Southampton n (%) |

Moorfields n (%) |

James Paget n (%) |

Gloucester n (%) |

Overall n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ineligible | – (–) | 3 (3) | 5 (6) | – (–) | 2 (7) | – (–) | 10 (2) |

| No reason given | 32 (16) | 18 (18) | 12 (15) | – (–) | 4 (14) | 10 (25) | 76 (15) |

| Not interested | 18 (9) | 11 (11) | 16 (21) | 19 (34) | 6 (21) | 13 (33) | 83 (17) |

| Put off by technology | 44 (22) | 11 (11) | 8 (10) | 20 (36) | 10 (34) | 2 (5) | 95 (19) |

| No benefit in taking part | 6 (3) | – (–) | 2 (3) | – (–) | 1 (3) | – (–) | 9 (2) |

| Personal reasons | 21 (11) | 8 (8) | 32 (41) | 10 (18) | 6 (21) | 9 (23) | 86 (17) |

| Not enough time to consider | – (–) | 1 (1) | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | 1 (0) |

| Insurance invalidated | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) |

| Unable to agree to consent questions | – (–) | – (–) | – (–) | 1 (2) | – (–) | – (–) | 1 (0) |

| Too much of a commitment | 37 (19) | 11 (11) | 1 (1) | 5 (9) | – (–) | – (–) | 54 (11) |

| Othera | 40 (20) | 38 (38) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | – (–) | 6 (15) | 87 (17) |

| Overall (within site) | 198 (100) | 101 (100) | 78 (100) | 56 (100) | 29 (100) | 40 (100) | 502 (100) |

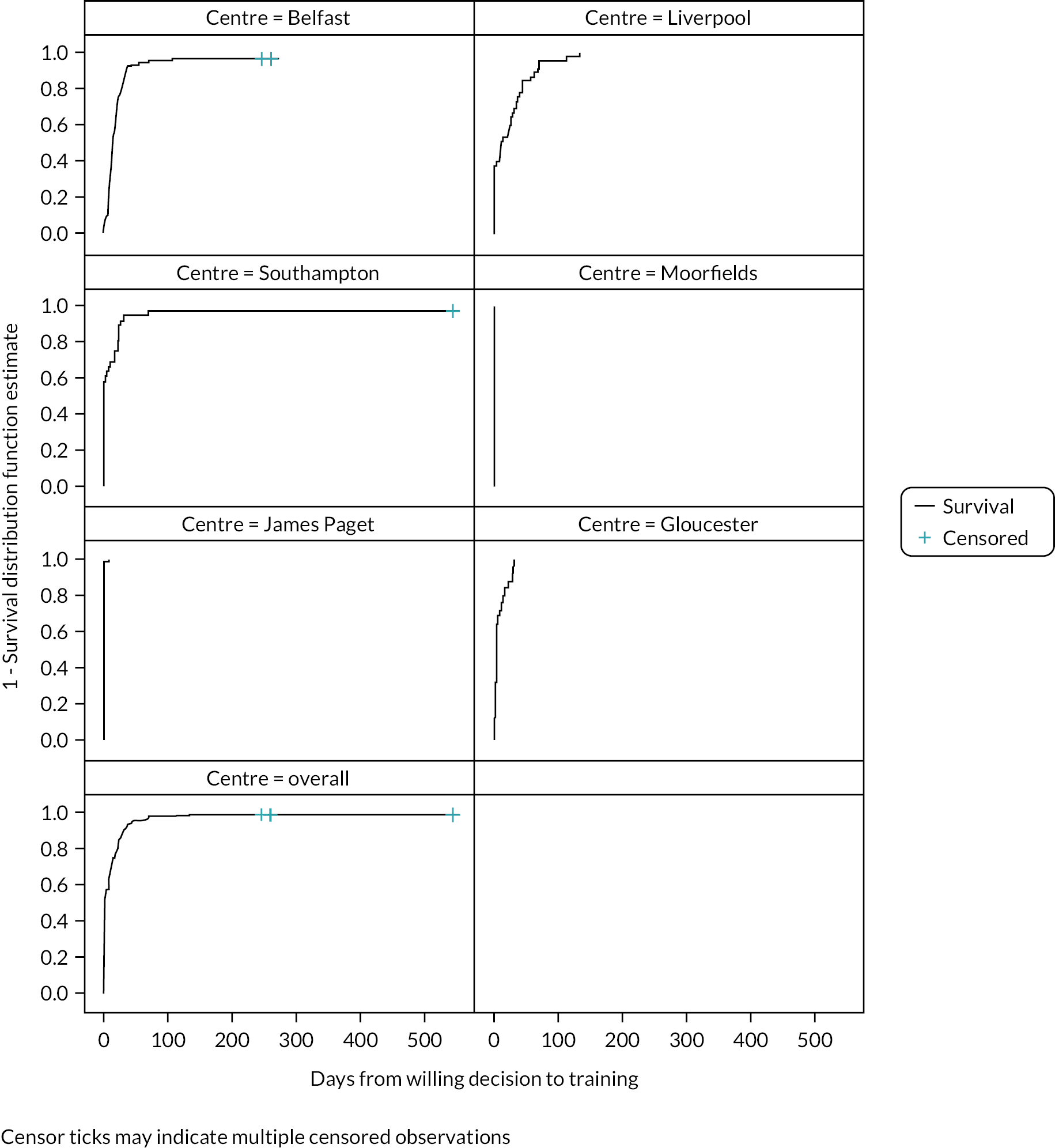

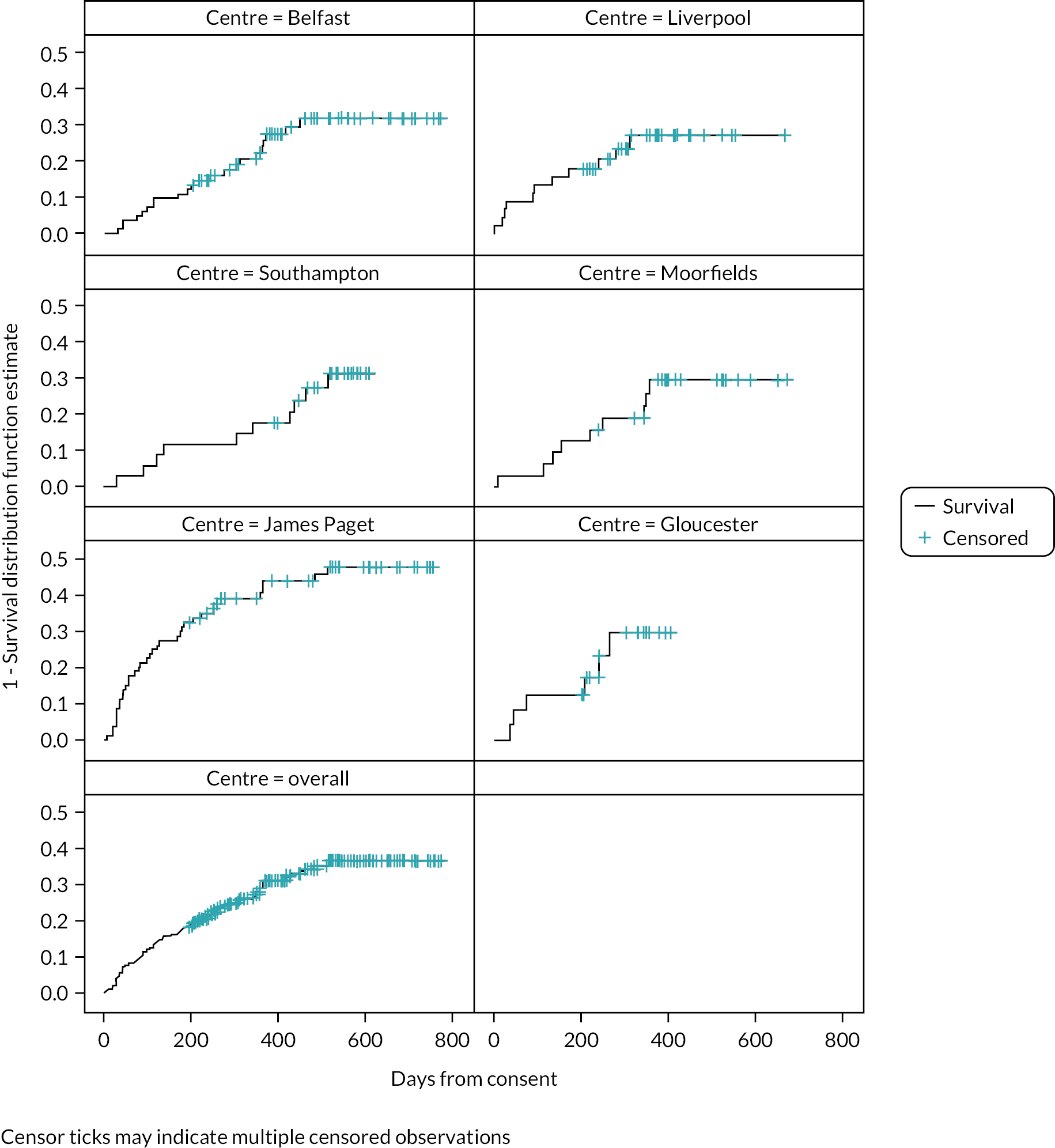

The time taken from screening to a receipt of a willingness decision, and from expressing willingness to training, are shown as a survival analysis by site and overall in Appendix 1 (see Figures 21 and 22). Most centres received a decision from around 80% of their patients within 200 days. Exceptions were James Paget, with received decisions from 80% of patients after < 100 days, and Moorfields with a maximum of 60% of decisions received in total. About 90% patients had received their training within 50 days of notifying their willingness; patients from Moorfields and James Paget received their training on the day when they expressed willingness.

Recruitment by stratum of time since first treatment is shown in Table 3. Half of recruited participants were first treated for nAMD 6–17 months before consenting, 28% 18–29 months prior to consent and 22% 30–41 months prior to consent. Eighteen of 297 participants (6%) were retrained (see Appendix 1, Table 33), most of whom were being managed at James Paget (11/18, 61%).

| Site | Months in study | Expected overall recruitment | Total recruitment n (%)a | Stratum of time since first treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–17 months n (%)b | 18–29 months n (%)b | 30–41 months n (%)b | ||||

| BEL | 27 | 80.0 | 82 (103) | 40 (49) | 21 (26) | 21 (26) |

| LIV | 24 | 80.0 | 45 (56) | 23 (51) | 10 (22) | 12 (27) |

| SOU | 26 | 80.0 | 34 (43) | 14 (41) | 15 (44) | 5 (15) |

| MOO | 25 | 80.0 | 32 (40) | 17 (53) | 11 (34) | 4 (13) |

| JAP | 26 | 50.0 | 80 (160) | 42 (53) | 20 (25) | 18 (23) |

| GLO | 15 | 30.0 | 24 (80) | 13 (54) | 7 (29) | 4 (17) |

| Overall | 143 | 400.0 | 297 (74) | 149 (50) | 84 (28) | 64 (22) |

Monitoring visits

At the end of the study, data for at least one monitoring visit after starting to use the index monitoring tests were available for 357 study eyes in 297 patients. Data were available for at least one complete monitoring visit after starting to use the index monitoring tests for 317 study eyes in 261 patients. The cumulative numbers of monitoring visits, and complete visits (including an OCT), over time are shown in Figure 8. The number of complete visits decreased after the first UK COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020 because many appointments after this date were virtual consultations or treatment was administered without formal review. This situation slowly improved in the following months. Despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, 91% of the recorded monitoring visits were classified as complete for study eyes. Further reporting of the results focuses on the complete visits, except where indicated. Further information about total visits is described in Appendix 1 (see Table 34).

FIGURE 8.

Number of monitoring visits recorded on database.