Notes

Article history

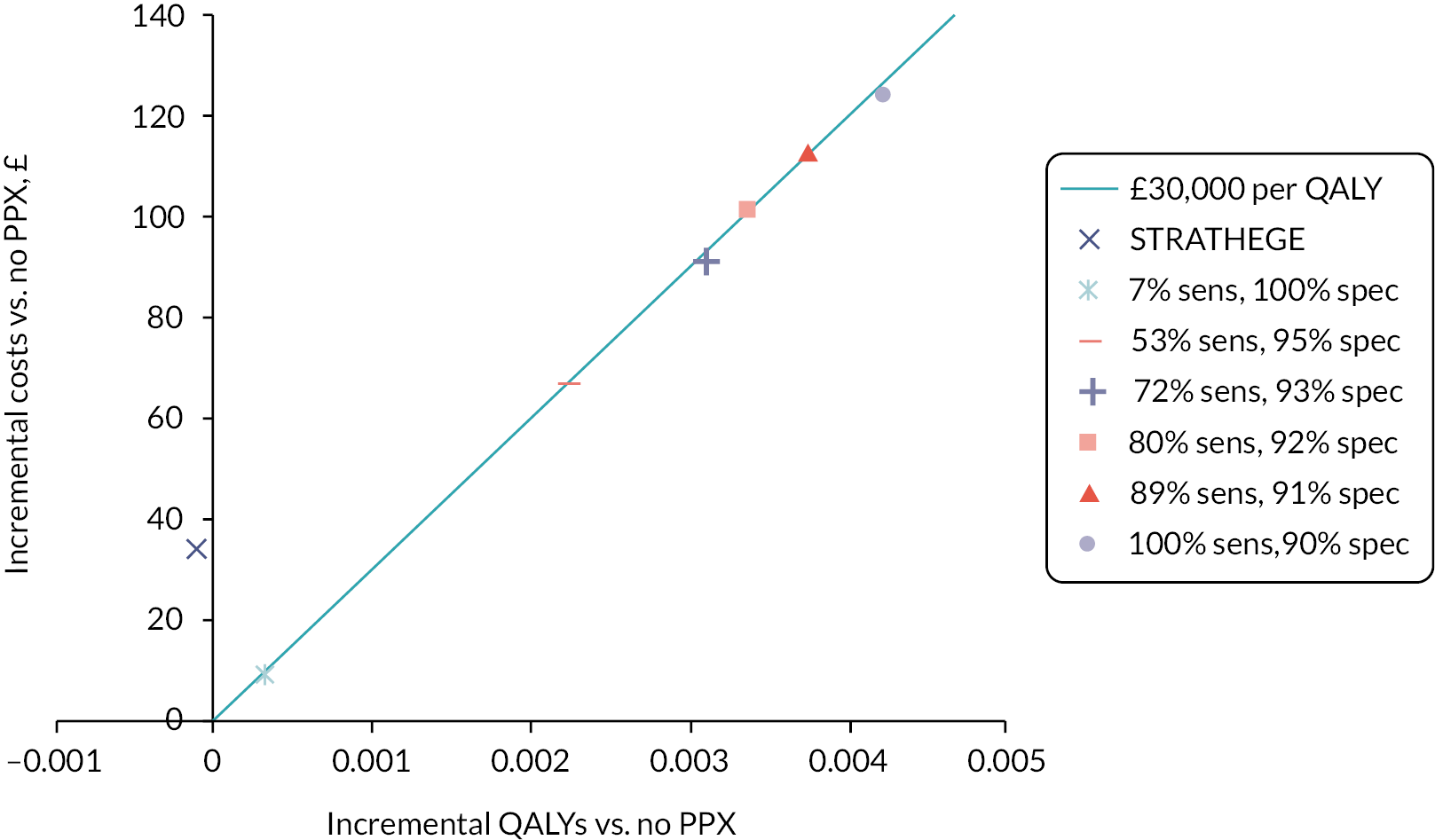

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR131021. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The draft report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Davis et al. This work was produced by Davis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Davis et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The clinical need and current uncertainties

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains the leading cause of direct maternal death in the UK, with the most recent Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK (MBRRACE-UK) report highlighting its importance. 1 While uncommon, VTE can occur at a rate of 1–2 per 1000 deliveries and can develop at any time during pregnancy and the puerperium (up to 6 weeks after delivery). 2–4 Deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) has an incidence of 1.1 per 1000 pregnancies, whereas pulmonary embolism (PE) has an incidence of 0.3% per 1000 pregnancies. 5 The maternal mortality rate for thrombosis and thromboembolism is 1 per 100,000 maternities. 1 Thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is known to reduce VTE risk in medical and surgical patients, but it is also associated with an increased risk of bleeding in these groups. 6 In the UK, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Guideline recommends LMWH for prophylaxis to prevent VTE in women at higher risk, assessed using a variety or risk factors, during pregnancy and the puerperium. 7 However, the evidence about the benefits and potential harms of offering LMWH to prevent VTE in women who are pregnant or in the puerperium is very uncertain due to a lack of high-quality trials of sufficient size. 8 This evidence gap has resulted in inconsistent recommendations for prophylaxis across international guidelines, with many recommendations based on observational research or findings extrapolated from other populations. 9

Risk assessment models (RAMs) have been developed to help stratify the risk of VTE during pregnancy and the early postnatal period. These models use clinical information from the patient’s history and patient characteristics [such as parity and body mass index (BMI)] to identify those with an increased risk of developing VTE who are most likely to benefit from pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. The use of appropriate RAMs to select high-risk patients for prophylaxis is clearly important as the balance of risks and harms varies according to whether the woman is at high or low risk of a VTE. 10 In addition, guidelines used in different countries, using different RAMs, have been shown to result in significantly different numbers of patients being eligible for LMWH,11,12 which will result in significantly different costs for preventing VTE.

The current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline on the prevention of VTE in hospitalised women who are pregnant or who are in the puerperium recommends that clinicians use a RAM published by a national UK body, professional network or peer-reviewed journal. 6 The NICE Guideline states that the most commonly used RAM is the RCOG guideline. In Wales, the All-Wales maternity risk assessment tool has also been used as an alternative to the RCOG guideline. 6,7,13

A cross-sectional survey to estimate the impact of implementing the 2009 RCOG recommendations for thromboprophylaxis found that 41% of postnatal women and 7% of antenatal women would have qualified for thromboprophylaxis. 14 A more recent estimate, obtained by applying the 2015 RCOG guidance retrospectively to a large, longitudinal primary care database, suggests that 35% of postpartum women (without prior VTE) would have qualified for at least 10 days of postpartum thromboprophylaxis. 11 A retrospective analysis comparing the All-Wales maternity risk assessment to the RCOG guidelines suggests that there may be scope for reducing the numbers receiving thromboprophylaxis without increasing preventable VTE events, although the authors recommend that a prospective study should be conducted. 13 Various other international guidelines on preventing pregnancy-associated VTE have been shown to result in differing proportions of women being offered postpartum prophylaxis ranging from 7% to 37%. 15 We do not currently know whether using an alternative RAM with a higher or lower threshold for offering prophylaxis than RCOG would offer greater benefits on balance when taking into account risks, benefits and costs.

Chapter 2 Rationale and objectives

Rationale

Decision-analytic modelling is particularly useful in this situation, as it allows us to explore the optimal cut-off for thromboprophylaxis intervention in terms of the balance of risks, benefits and costs. For example, a higher threshold for providing thromboprophylaxis may result in more pregnancy-associated VTE, with an associated increase in long-term morbidity and mortality, but this must be balanced against the benefits of exposing fewer women to the risk of major bleeding during thromboprophylaxis which can itself have significant ongoing morbidity. In addition, fewer women receiving thromboprophylaxis will result in lower thromboprophylaxis costs and lower costs for managing thromboprophylaxis related major bleeding. These may somewhat offset the additional costs of short- and long-term VTE management from any increase in pregnancy-related VTE. Decision-analytic modelling could therefore be used to assess whether the current approach to thromboprophylaxis based on the RCOG guidelines is effective and cost-effective compared to the use of alternative RAMs, all of which will have a different balance of benefits, harms and costs. This assessment is dependent on data assessing the performance of the various RAMs which can be identified, and the quality assessed using systematic review methods.

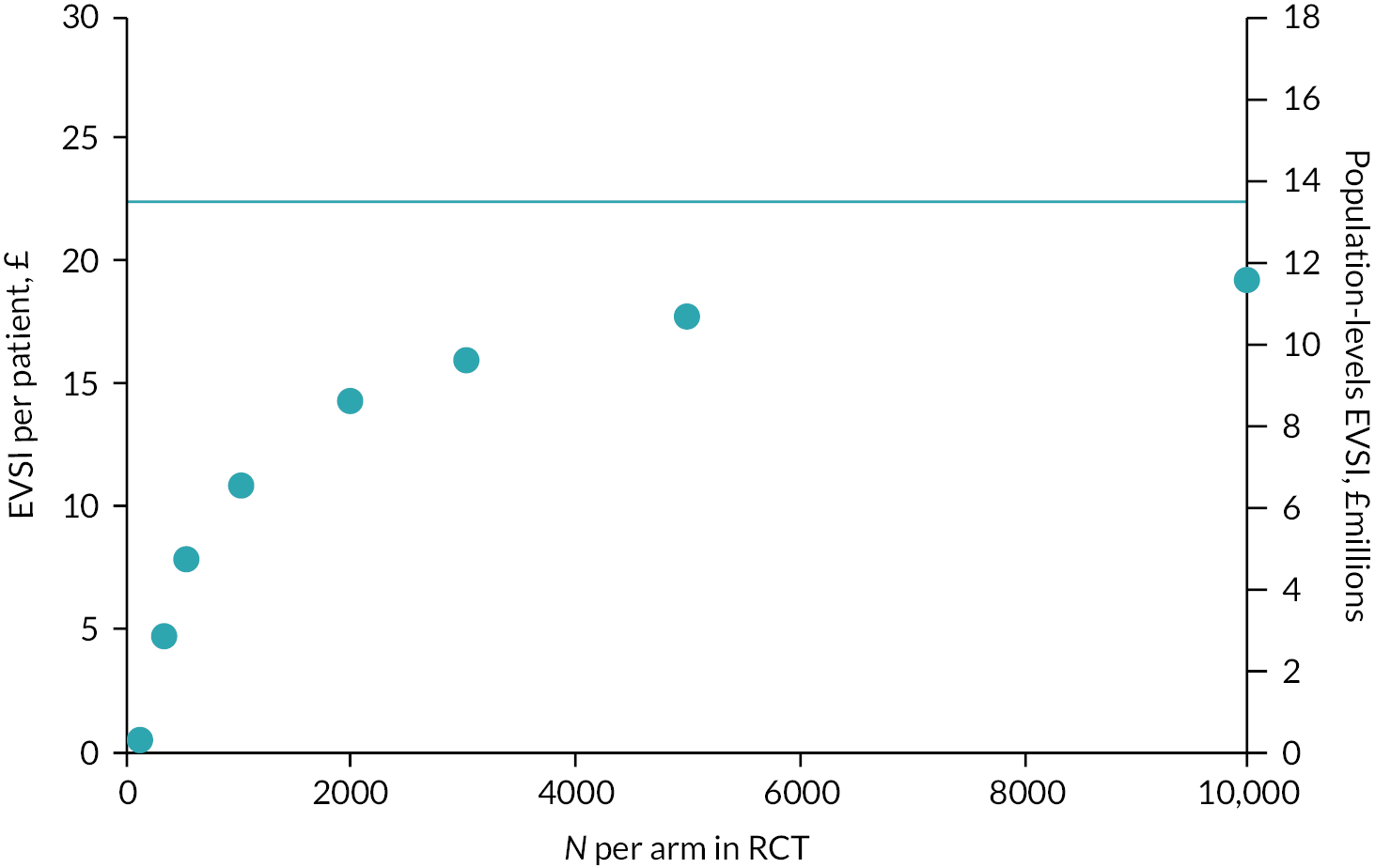

Expected value of perfect information (EVPI) analysis is a form of decision analysis that provides a framework for synthesising the best available evidence at the current time to assess not only the optimal strategy given the current evidence, but also the areas of uncertainty where further research would be worthwhile. 16 Expected value of sample information (EVSI) analysis allows researchers to determine the value of conducting different research studies in the future, by simulating the potential outcomes of those studies. 17 It this context, decision-analytic modelling can be used to determine which factors contribute the most to uncertainty regarding the optimal prophylaxis strategy in women at risk of VTE during pregnancy or the puerperium and what future research would be most worthwhile.

The balance of risk, benefits and costs of alternative VTE prophylaxis strategies will be dependent on the effectiveness of prophylaxis in this population, among other factors. A 2021 Cochrane systematic review concluded that, ‘further high-quality very large-scale randomised trials are needed to determine effects of currently used treatments in women with different VTE risk factors’. 8 However, several pilot studies have been unable to recruit sufficient high-risk patients to such a trial. 18,19 This highlights the need for researchers planning future studies to ensure that they are both feasible to conduct and acceptable to patients, the public and clinicians. This can be achieved by engaging with patients and clinicians through qualitative research to ask whether future research studies assessed as being worthwhile through decision-analytic modelling would actually be acceptable and feasible in practice.

Objectives

Our aim was to determine whether further primary research would be worthwhile to inform NHS practice on the use of RAMs for the prediction of VTE and appropriate provision of thromboprophylaxis for women in pregnancy and in the puerperium. Our specific objectives were as follows:

-

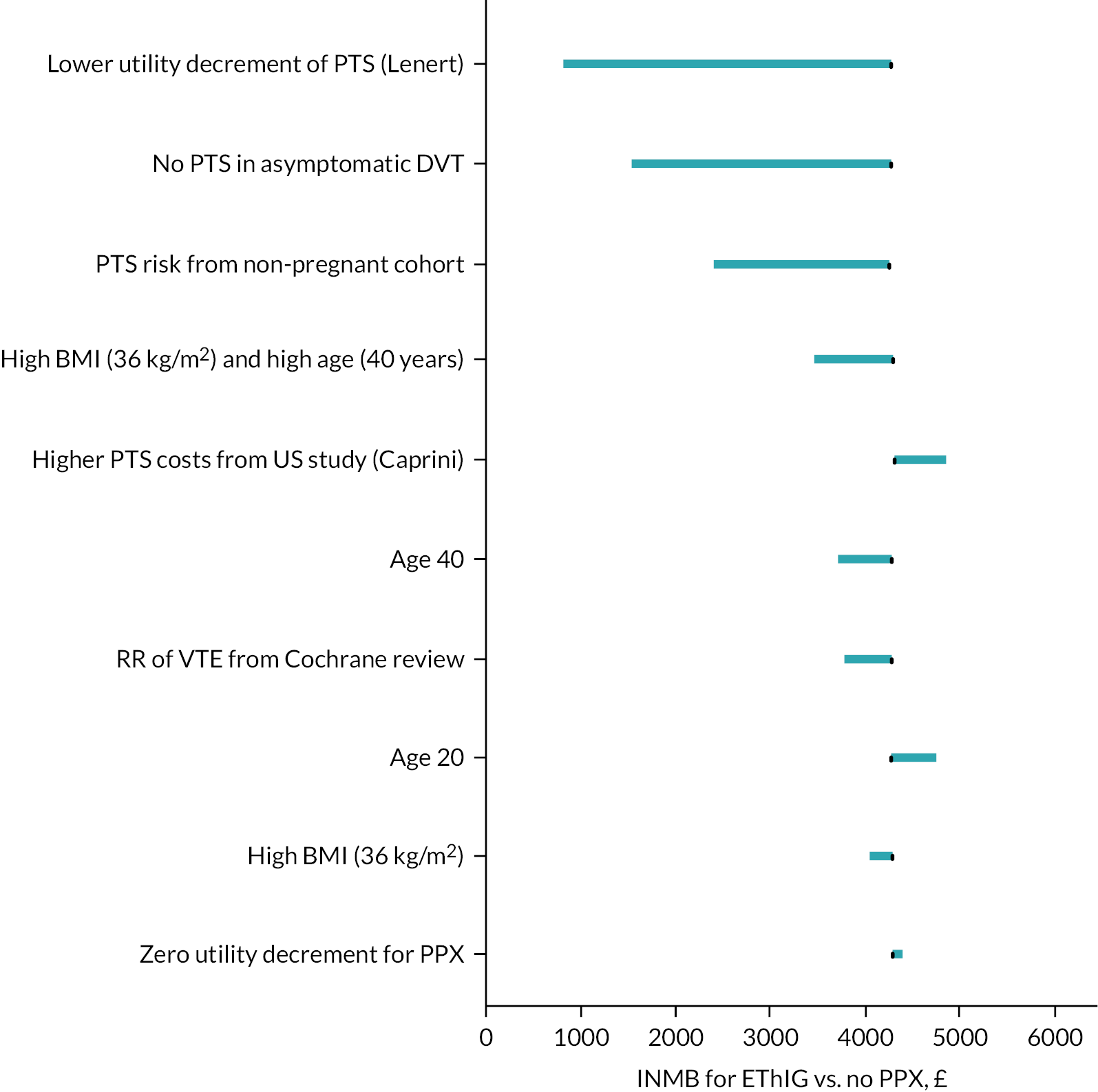

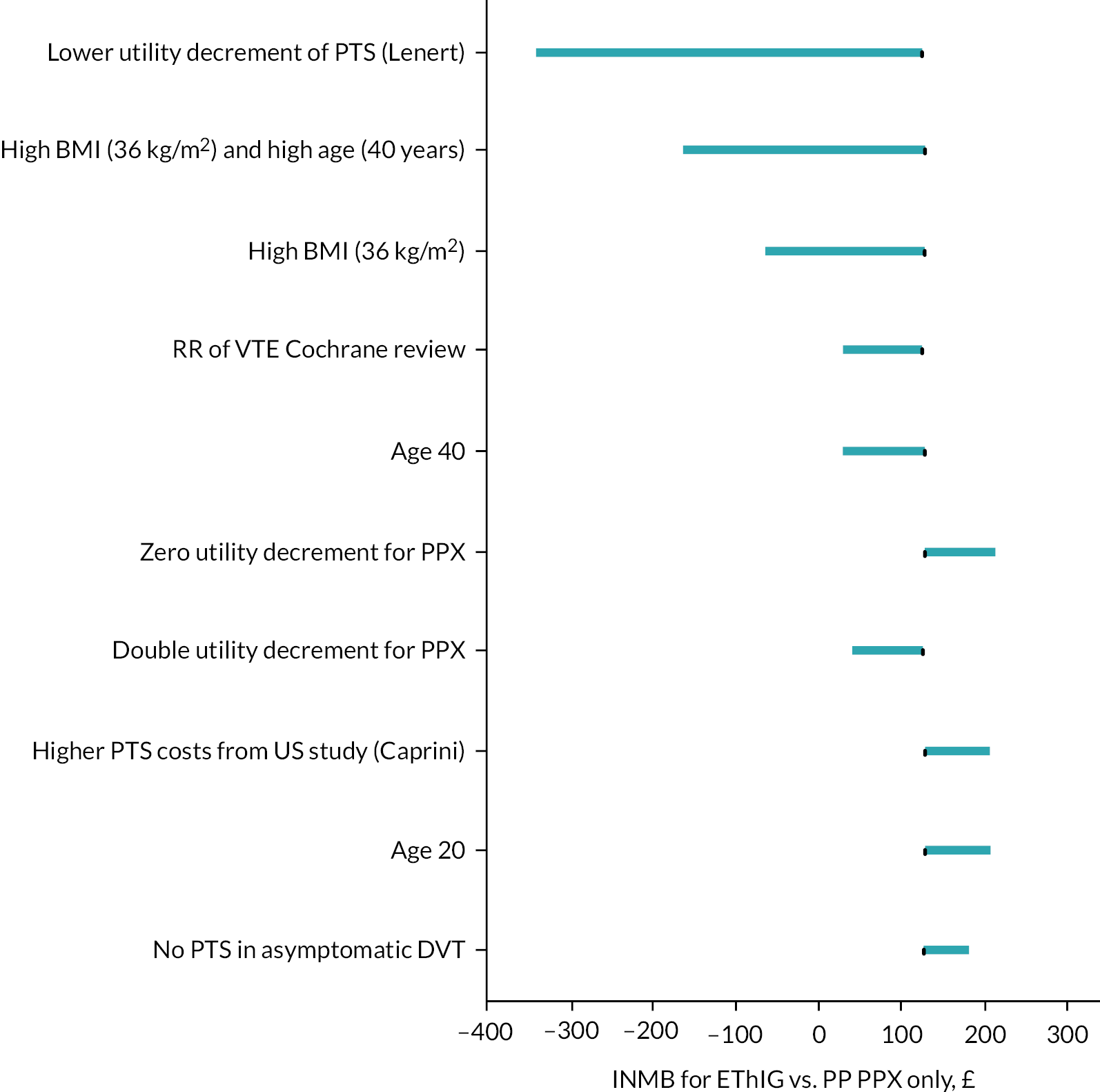

to estimate the expected costs, health benefits [quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)] and incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) for providing thromboprophylaxis using current and alternative RAMs and to quantify the uncertainty around those estimates, given current evidence

-

to determine which factors are the most important drivers of uncertainty when trying to determine the optimal RAM and thromboprophylaxis treatment strategy in this population

-

to identify one or more potential future studies to gather additional evidence that would reduce the current decision uncertainty, while being acceptable to patients and clinicians

-

to evaluate the value of the potential future research studies in terms of the net health benefits to patients and the cost of the research.

Objectives 1 and 2 are addressed by the cost-effectiveness and EVPI analysis (see Chapter 4), which is informed by the systematic review of RAMs (see Chapter 3). Objective 3 is informed by the findings of the EVPI analysis (see Chapter 4) and further addressed by the qualitative research (see Chapter 5). Objective 4 is addressed by the EVSI analysis (see Chapter 6).

Chapter 3 Systematic review of risk assessment models

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to determine the comparative accuracy of individual RAMs that identify pregnant and postpartum women at increased risk of developing VTE who could be selected for thromboprophylaxis.

This review was undertaken in accordance with the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement20 and was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (CRD42020221094). The systematic review of RAMs was conducted in accordance with the review protocol registered with PROSPERO and the methods outlined in the project protocol (version 1.0) which can be accessed on https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR131021 (accessed February 2023).

Methods

Eligibility criteria

All studies evaluating the accuracy (e.g. sensitivity, specificity, c-statistic) of a multivariable RAM (or scoring system) for predicting the risk of developing VTE were eligible for inclusion. We primarily sought and selected studies that included validation of the model in a group of patients that were not involved in the development of the prediction model. Although the included studies could have reported derivation of the model (for internal validation), we only used the external validation data to estimate accuracy, where appropriate. The study population of interest in our review consisted of pregnant and postpartum (within 6 weeks post delivery) women who are at increased risk of developing a VTE and receiving care in hospital, community and primary care settings. Studies that focused on non-pregnant women were excluded as these patient groups have VTE risk profiles that differ markedly from the obstetric population.

Data sources and searches

Potentially relevant studies were identified by searching the following electronic databases and research registers:

-

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily, MEDLINE and Versions(R) (OvidSP) 1946 to February 2021

-

EMBASE (OvidSP) 1974 to February 2021

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (www.cochranelibrary.com/) Inception to February 2021

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (www.cochranelibrary.com/) Inception to February 2021

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (US National Institutes of Health) 2000 to February 2021

-

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (World Health Organisation) 1990 to February 2021.

The search strategy used free-text and thesaurus terms and combined synonyms relating to the condition (e.g. VTE in pregnant and postpartum women) with risk prediction modelling terms. 21 No language or date restrictions were used. Searches were supplemented by hand-searching the reference lists of all relevant studies (including existing systematic reviews); forward citation searching of included studies (using the Web of Science Citation Index Expanded and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science) to identify articles that cite the relevant articles; contacting key experts in the field; and undertaking targeted searches of the World Wide Web using the Google search engine. Further details on the search strategy are provided (see Appendix 1).

Study selection process

The inclusion of potentially relevant articles was undertaken using a two-step process. First, all titles were examined for inclusion by one reviewer (GR) and any citations that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. non-human, unrelated to VTE in pregnancy and the puerperium) were excluded (for quality assurance a random subset of 20% was checked by a second reviewer). All abstracts and full-text articles were then examined independently by two reviewers (GR and AP). Any disagreements in the selection process were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, arbitration by a third reviewer (JD) or the wider group (BH, CNP, SG) and included by consensus.

Data abstraction and quality-assessment strategy

For eligible studies, data relating to study design, methodological quality and outcomes were extracted by one reviewer (GR) into a standardised data extraction form and independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (AP). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, or if this was unsuccessful, a third reviewer’s opinion was sought (JD). Where multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as a single study.

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed using Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool (PROBAST). 22,23 This instrument includes four key domains: participants (e.g. study design and patient selection), predictors (e.g. differences in definition and measurement of the predictors), outcome (e.g. differences related to the definition and outcome assessment) and statistical analysis (e.g. sample size, choice of analysis method and handling of missing data). Each domain is assessed in terms of risk of bias and the concern regarding applicability to the review (first three domains only). To guide the overall domain-level judgement about whether a study is at high, low or an unclear (in the event of insufficient data in the publication to answer the corresponding question) risk of bias, subdomains within each domain include several signalling questions to help judge bias and applicability concerns. An overall risk of bias for each individual study was defined as low risk when all domains were judged as low and high risk of bias when one or more domains were considered as high. Studies were assigned an unclear risk of bias if one or more domains were unclear, and all other domains were low.

The methodological quality of each included study was independently evaluated by two reviewers (GR and AP). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, with involvement of a third reviewer (JD). Blinding of the quality assessor to author, institution or journal was not considered necessary.

Data synthesis and analysis

We were unable to perform meta-analysis due to significant levels of heterogeneity between studies (study design, participants, inclusion criteria) and variable reporting of items. As a result, a pre-specified narrative synthesis approach24,25 was undertaken, with data being summarised in tables with accompanying narrative summaries that included a description of the included variables, statistical methods and performance measures [e.g. sensitivity, specificity and c-statistic (a value between 0.7 and 0.8 and > 0.8 indicated good and excellent discrimination, respectively; and values < 0.7 were considered weak)],26 where applicable. All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or conduct of this systematic review.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

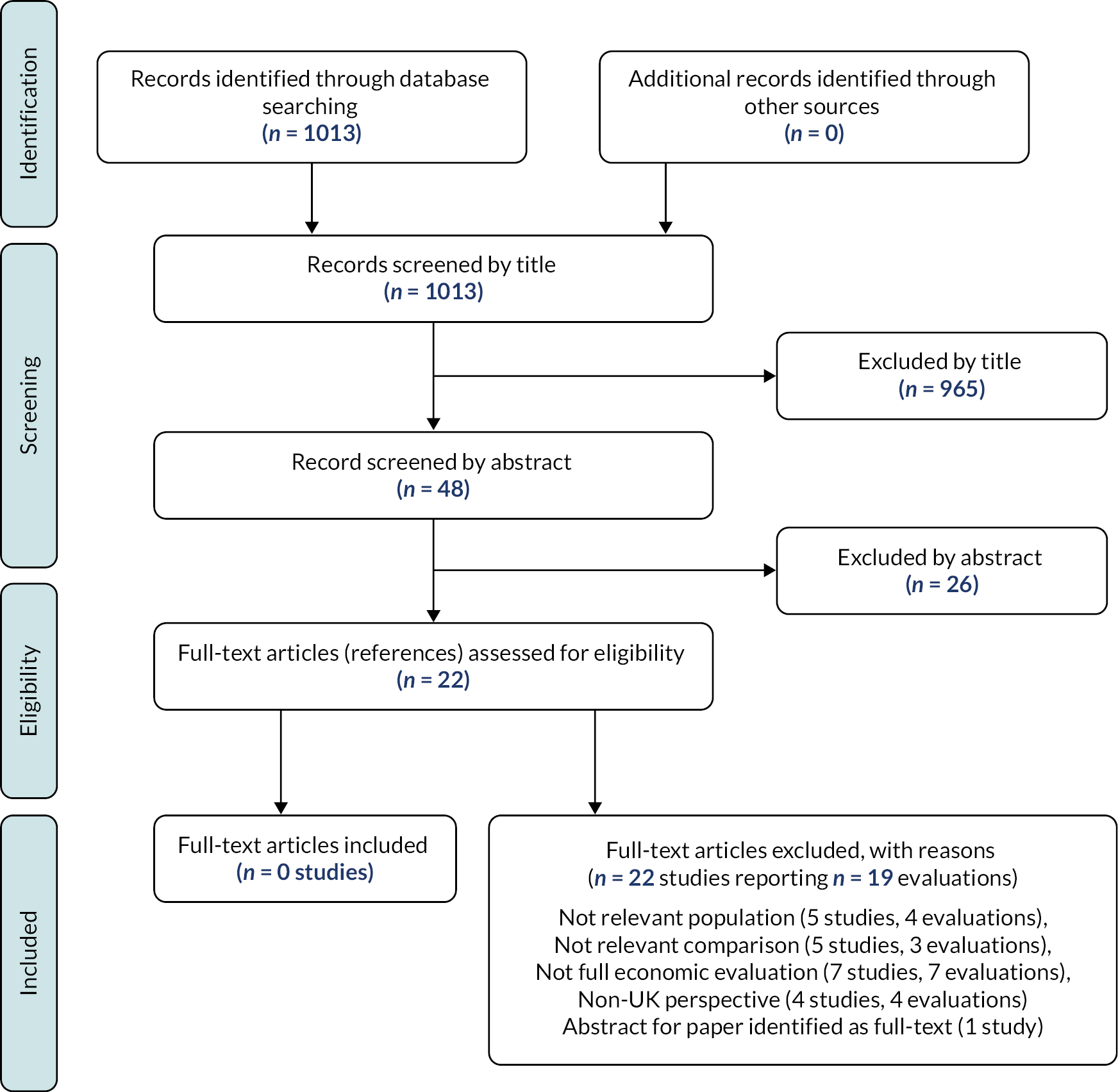

The literature searches identified 2268 citations. Of these, 16 studies11,13,27–40 investigating 19 unique externally validated RAMs met the inclusion criteria. Only one of these studies11 presented data on model development and external validation [this study used UK Clinical Practice Research Data (CPRD) linked to Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) to develop a risk prediction model and externally validated it using Swedish medical birth registry data]. The remaining studies focused on external validation with no description of the initial derivation methodology. 13,27–40 Due to the lack of model derivation studies with external validation, we also identified and included one internal validation study for completeness (i.e. prediction model development without external validation). 41 This study used a bootstrap validation approach to capture optimism in model performance42,43 when applied to similar future patients. Most of the full-text articles (n = 97) were excluded primarily based on not using a RAM for predicting the risk of developing VTE during pregnancy or the puerperium, having no useable or relevant outcome data or an inappropriate study design (e.g. reviews, commentaries or study protocols). A full list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion is provided on https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR131021 (accessed February 2023). Figure 1 summarises the study identification process.

Description of included studies (design and patient characteristics)

The design and participant characteristics of the 17 included studies that provided data on the comparative accuracy of RAMs for predicting the risk of developing VTE in women during pregnancy and the puerperium periods are summarised in Table 1. All studies were published between 2000 and 2020 and were undertaken in North America (n = 4),28,39–41 Southeast Asia (n = 1),37 Europe (n = 10),13,27,29–34,36,38 South America (n = 1)35 and one study was multicountry. 11 Sample sizes ranged from 5235 to 662,38711 patients in 14 observational cohort studies [6 prospective29,31,32,35,37,38 (all single-centre) and 8 retrospective11,13,28,30,33,34,39,41 (2 of which were multicentre) in design]. Sample sizes in 2 single-centre case–control studies36,40 ranged from 7640 to 242136 patients and 1 study used a non-randomised multicentre study design. 27 The mean age ranged from 27.841 to 34 years29,33 (not reported in 7 studies). 13,28,31,36,38–40

| Author, year | Country | Design | Single/multicentre | Sample size | Population | Period | Mean age (years) | VTE prophylaxis (%) | RAMs evaluated | Target condition, definition (risk period) | Incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antepartum and postpartum following vaginal and caesarean delivery | |||||||||||

| Bauersachs et al., 200727 | Germany | P, NRS | Multi | 810 | Women at increased risk of VTE (due to thromboembolic status and prior VTE) | March 1999–December 2002 | 30.8 | 100 | EThIG | Antepartum and postpartum VTE, symptomatic (NR) | 0.62% (antepartum: 0.25%; postpartum: 0.37%) |

| Chauleur et al., 200831 | France | P, CS | Single | 2685 | All women who delivered | July 2002–June 2003 | NR (median, 29) |

NR | STRATHEGE | Antepartum and postpartum VTE (NR) | 0.34% (antepartum: 0.19%; postpartum: 0.15%) |

| Dargaud et al., 201732 | France | P, CS | Single | 445 | Women at increased risk of VTE (due to thromboembolic status and prior VTE) | January 2005–January 2015 | 33 | 100 | Lyon | Antepartum and postpartum VTE, not defined (pregnancy and 3 months postpartum) | 1.35% |

| Dargaud et al., 200533 | France | R, CS | Single | 116 | Women at increased risk of VTE (due to thromboembolic status and prior VTE) | 2001–3 | 34 | 53 | Lyon | Antepartum and postpartum VTE, not defined (NR) | 0.86% (antepartum only) |

| Hase et al., 201835 | Brazil | P, CS | Single | 52 | Hospitalised pregnant women with cancer | 1 December 2014–31 July 2016 | 31 | 57.7 | RCOG (modified) | Antepartum and postpartum VTE, not defined (pregnancy and 3 months postpartum) | Unable to estimate – no VTE |

| Shacaluga et al., 201913 (correspondence) | Wales | R, CS | Single | 42,000 | All managed pregnancies | 2009–15 | NR | NR | All Wales RCOG |

Antepartum and postpartum VTE, not defined, (NR) | 0.08% (ante partum: 0.04%; postpartum: 0.04%) |

| Testa et al., 201538 | Italy | P, CS | Single | 1719 | All pregnant women enrolled in Pregnancy Healthcare Program | January 2008–December 2010 | NR (median 33) | 4.6 | Novel (Testa) | Antepartum and postpartum VTE (NR) | Unable to estimate – no VTE |

| Weiss et al., 200040 | USA | CC | Single | 19 cases: 57 controla | Women with (confirmed cases) and without (unmatched control) VTE | 1987–98 | NR | NR | Novel (Weiss) | Antepartum and postpartum VTE, not defined (pregnancy and 6 weeks postpartum) | - |

| Postpartum only following vaginal and caesarean delivery | |||||||||||

| Chau et al., 201930 | France | R, CS | Single | 1069 (time period 2012: 557; 2015: 512) |

All women who delivered | February–April 2012 and February–April 2015 | 2012: 29 2015: 29 |

NR | Novel (Chau) | Postpartum VTE, not defined (8 weeks) | 2012: 0.18% 2015: 0.20% |

| Ellis-Kahana et al., 202041,b | USA | R, CS | Multi | 83,500 | All obese women (BMI > 30 kg/m2) who delivered | 2002–8 | 27.8 | NR | Novel (Ellis-Kahana) | Postpartum VTE (NR) | 0.13% |

| Gassmann et al., 202034 | Switzerland | R, CSc | Single | 344 | All women who delivered | 1–31 January 2019 | 32.2 | 24 | RCOG ACOG ACCP ASH |

Postpartum VTE, not defined (3 months) | Unable to estimate – no VTE |

| Lindqvist et al., 200836 | Sweden | CC | Single | 37 cases: 2384 control | All women with (confirmed cases) and without (unselected population-based control) VTE | 1990–2005 | NR | NR | SFOG (Swedish guidelines) | Postpartum VTE (NR) | – |

| Sultan et al., 201611 | England (derivation)d and, Sweden (validation) | R, CS | Multi | 662,387 (validation cohort)d | All women (with no history of VTE) who delivered | 1 July 2005–31 December 2011 | 30.32 | 3 | Novel (Sultan) RCOGd SFOG (Swedish Guidelines) |

Postpartum VTE (6 weeks) |

0.08% (validation cohort) |

| Tran et al., 201939 | USA | R, CS | Single | 6094 | All women who delivered after 14 weeks | 01 January 2015–31 December 2016 | NR | NR | RCOG Padua Caprini |

Postpartum VTE (6 months) | 0.05% |

| Postpartum following caesarean delivery | |||||||||||

| Binstock and Larkin, 2019 (abstract)28 | USA | R, CS | Single | 2875 | Postpartum women following caesarean section | 2011 | NR | NR | Novel (Binstock) RCOG |

Postpartum VTE, not defined (NR) | 0.38% |

| Cavazza et al., 201229 | Italy | P, CS | Single | 501 | Postpartum women following caesarean section | 2007–9 | 34 | 53.5 | Novel (Cavazza) | Postpartum VTE, symptomatic, not defined (90 days) | 0.20% |

| Lok et al., 201937 | Hong Kong | P, CS | Single | 859 | Postpartum women following caesarean section | May 2017–April 2018 | 32.9 | 3.3 | Novel (Lok) R COG ACOG |

Postpartum VTE, symptomatic, not defined (NR) | Unable to estimate – no VTE |

The majority of studies were conducted across antenatal and postnatal periods,13,27,31–33,35,38,40 or postpartum period only11,28–30,34,36,37,39,41 and generally included women at increased risk of VTE. 27–29,32,33,35–37,40,41 One study excluded women with a history of VTE11 and six studies13,30,31,34,38,39 included all pregnant women who delivered. Thromboprophylaxis was employed in about half (n = 9)11,27,29,32–35,37,38 of the studies, with the proportion receiving thromboprophylaxis ranging from 3%11 to 100%. 27,32 The remaining studies did not report data on thromboprophylaxis use.

Only a few studies27,31,36,38 defined the VTE end point (DVT and or PE) as being confirmed by objective testing. Of the remainder, 3 studies11,39,41 had no objective confirmation of VTE and 10 studies13,28–30,32–35,37,40 did not report the methods for diagnosis confirmation. Although nine studies13,27,28,31,33,36–38,41 did not report the VTE risk period, the majority of the remaining studies utilised the RAMs to predict the occurrence of VTE up to 3 months after delivery. 29,32,34,35 Despite differences in study design, study participants, definitions, different criteria for the use of thromboprophylaxis and differences between doses of LMWH, the reported overall incidence of VTE in pregnancy and the puerperium was < 1.3%.

The studies included in this review evaluated 19 externally validated RAMs11,13,27–40 and one internally validated risk model. 41 While most RAMs focused solely on the estimate of thromboembolic risk, RAMs varied in design, structure, threshold, dosage and duration for pharmacological prophylaxis. In addition, the individual predictors and their weighting varied markedly between RAMs. The most commonly used tools were the RCOG guidelines (six studies),11,13,28,34,37,39 American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) guidelines (two studies),34,37 Swedish Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (SFOG) guidelines (two studies)11,36 and the Lyon score (two studies). 32,33 A simplified summary of their associated characteristics and composite clinical variables are provided (see Appendix 2).

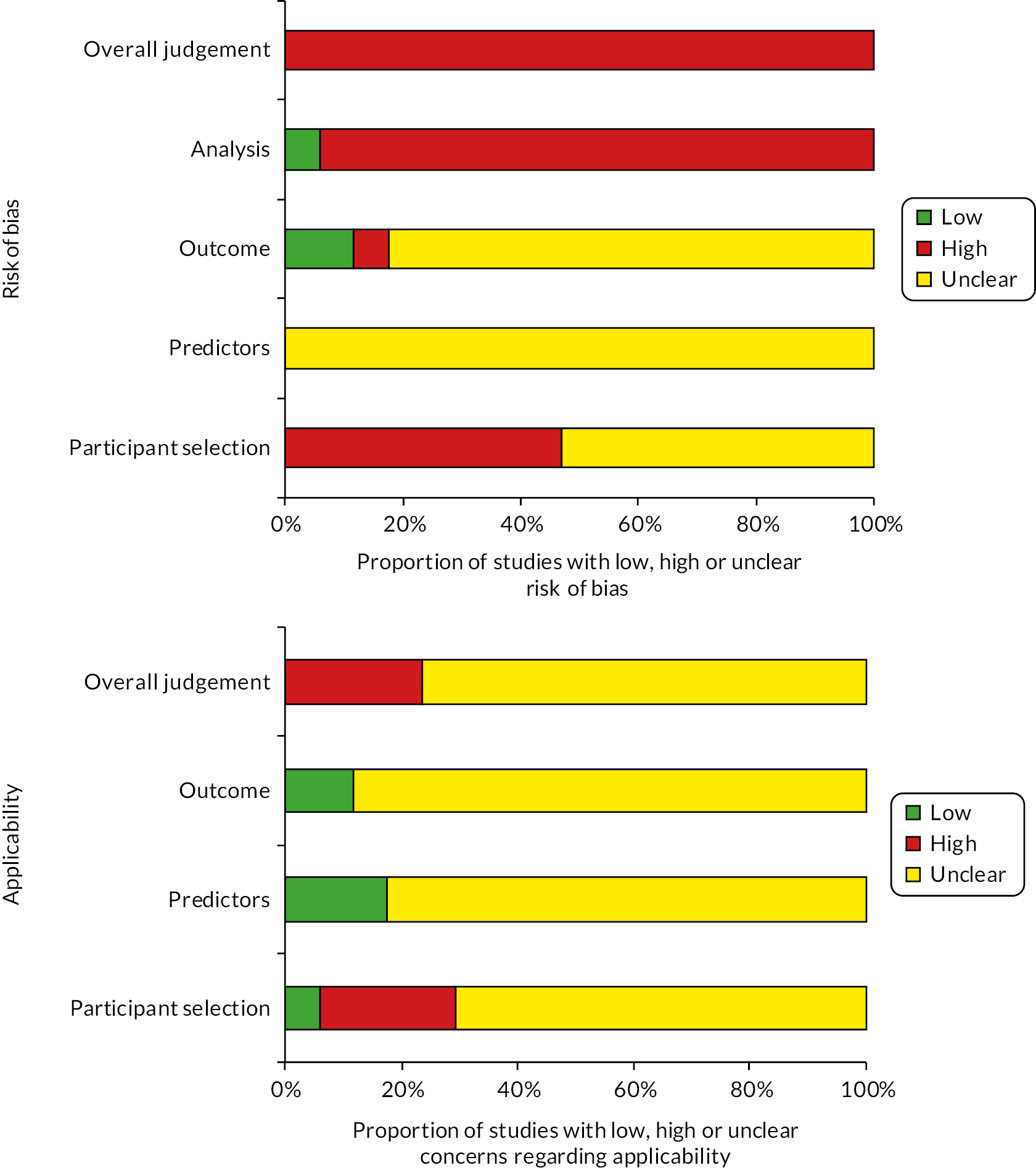

Risk of bias and applicability assessments of included studies

The overall methodological quality of the 17 included studies is summarised in Table 2 and Figure 2. The methodological quality of the included studies was variable, with most studies having high or unclear risk of bias in at least one item of the PROBAST tool. The main risk of bias limitations was related to patient selection factors (arising from retrospective data collection,13,28,30,33,34,36,39–41 unclear exclusions/incomplete patient enrolment13,28,30,31,35–38,40,41 or unclear criteria for patients receiving VTE prophylaxis);11,27,34 predictor and outcome bias (due to a general lack of details on the definition13,28–30,32–35,37,40 and methods of outcome determination13,28,30,32–35,37,39–41 and whether all predictors were available at the models intended time of use13,27,28,33,35,36,38–41 or influenced by the outcome measurement)11,13,27–32,34–41 and analysis factors (low event rates,11,13,27–35,37–39,41 unclear handling of missing data13,27–33,35–41 and failure in reporting relevant performance measures such as calibration and discrimination). 13,27–40

| Author, year | Risk of bias | Concern regarding applicability | Overall | Overall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Participant selection | 2. Predictors | 3. Outcome | 4. Analysis | 1. Participant selection | 2. Predictors | 3. Outcomes | Risk of bias | Applicability | |

| Bauersachs et al., 200727 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear |

| Chauleur et al., 200831 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Dargaud et al., 201732 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Dargaud et al., 200533 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Hase et al., 201835 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | High |

| Shacaluga et al., 201913 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Testa et al., 201538 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Weiss and Bernstein, 200040 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Chau et al., 201930 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Ellis-Kahana et al., 202041 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Gassmann et al., 202034 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Lindqvist et al., 200836 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Sultan et al., 201611 | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear |

| Tran et al., 201939 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Binstock and Larkin, 201928 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | High |

| Cavazza et al., 201229 | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Low | Unclear | High | High |

| Lok et al., 201937 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | High | High |

FIGURE 2.

PROBAST assessment summary graph – review authors’ judgements.

Assessment of applicability to the review question led to the majority of studies being classed either as unclear (n = 13)11,13,27,30–34,36,38–41 or high (n = 4)28,29,35,37 risk of inapplicability. These assessments were generally related to patient selection (highly selected study populations, for example, selected women at increased risk of VTE, caesarean delivery only, single disease pathologies, single-site settings), predictors (inconsistency in definition, assessment or timing of predictors) and outcome determination.

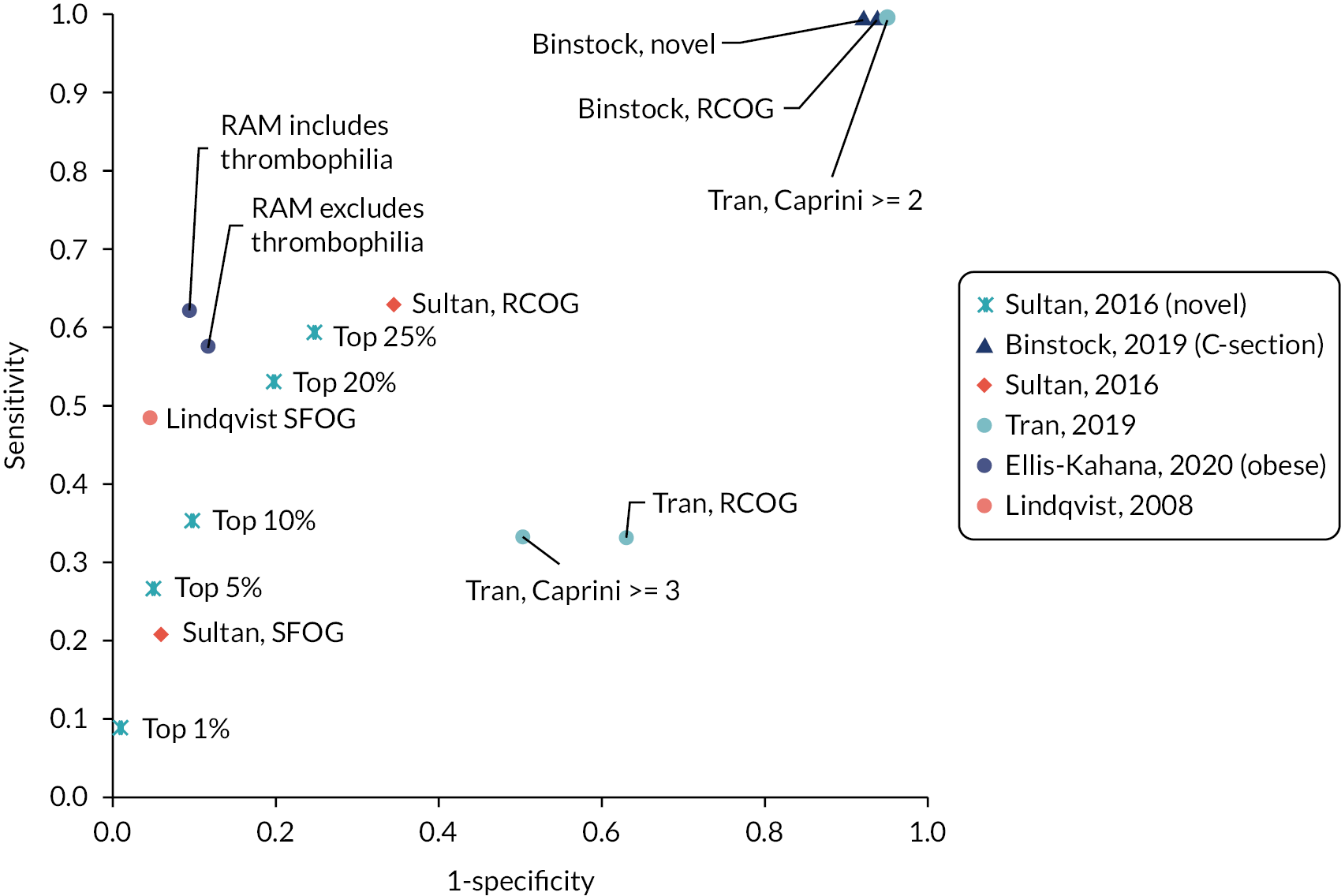

Quantitative data synthesis (summary of results)

A summary of the sensitivity and specificity of RAMs that were applied to antepartum women to predict antepartum or postpartum VTE or applied postpartum (PP) to predict postpartum VTE, respectively, is presented in Tables 3 and 4, with the results grouped by RAM. However, any meaningful comparisons between these alone is difficult, without considering the models’ corresponding discrimination and calibration metrics, which were not universally reported. Only one external validation study considered model discrimination and calibration. In this study by Sultan et al.,11 their recalibrated novel risk prediction model (also known as the Maternity Clot Risk) provided good discrimination and was able to discriminate postpartum women with and without VTE in the external Swedish cohort with a c-statistic of 0.73 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 0.75], and calibration, of observed and predicted VTE risk, close to ideal [calibration slope of 1.11 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.20)]. In the remaining studies, interpretation was further limited by marked heterogeneity, which was exacerbated when different thresholds were reported by different studies evaluating the same model. In general, model accuracy was generally poor, with high sensitivity usually reflecting a threshold effect, as indicated by corresponding low specificity values (and vice versa).

| RAMs | Threshold or cut-off | End point | Data source | Performance measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | ||||

| Predicting either antepartum or postpartum VTE | |||||||||

| All Wales (1 study) | NR | VTE | Shacaluga et al., 201913 | 25 | NR | 9 | NR | 0.74 (0.57 to 0.85) | NR |

| EThIG (1 study) | High/very high risk | VTE | Bauersachs et al., 200727 | 5 | 580 | 0 | 225 | 1.00 (0.57 to 1) | 0.28 (0.25 to 0.31) |

| Lyon (2 studies) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Dargaud et al., 201732 | 5 | 282 | 1 | 157 | 0.83 (0.44 to 0.97) | 0.36 (0.31 to 0.4) |

| Lyon | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Dargaud et al., 200533 | 1 | 56 | 0 | 59 | 1.00 (0.21 to 1) | 0.51 (0.42 to 0.6) |

| RCOG (modified) (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Hase et al., 201835 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 18 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.35 (0.23 to 0.48) |

| STRATHEGE (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Chauleur et al., 200831 | 0 | 54 | 9 | 2622 | 0.00 (0 to 0.3) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) |

| Testa 2015 (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 2.5 | VTE | Testa et al., 201538 | 0 | 85 | 0 | 1634 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) |

| Predicting antepartum VTE | |||||||||

| EThIG (1 study) | High/very high risk | VTE | Bauersachs et al., 200727 | 2 | 583 | 0 | 225 | 1.00 (0.34 to 1) | 0.28 (0.25 to 0.31) |

| Lyon (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Dargaud et al., 201732 | 1 | 286 | 1 | 157 | 0.50 (0.09 to 0.91) | 0.35 (0.31 to 0.4) |

| STRATHEGE (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 1 | VTE | Chauleur et al., 200831 | 0 | 54 | 4 | 2627 | 0.00 (0 to 0.49) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) |

| Weiss 2000 (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 2 | VTE | Weiss et al., 200040 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 54 | 0.21 (0.09 to 0.43) | 0.95 (0.86 to 0.98) |

| Predicting postpartum VTE | |||||||||

| EThIG (1 study) | High/very high risk | VTE | Bauersachs et al., 200727 | 3 | 582 | 0 | 225 | 1.00 (0.44 to 1) | 0.28 (0.25 to 0.31) |

| Lyon (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Dargaud et al., 201732 | 4 | 283 | 0 | 158 | 1.00 (0.51 to 1) | 0.36 (0.31 to 0.4) |

| STRATHEGE (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 1 | VTE | Chauleur et al., 200831 | 0 | 54 | 5 | 2626 | 0.00 (0 to 0.43) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) |

| RAMs | Threshold or cut-off | End point | Data source | Performance measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | ||||

| Predicting postpartum VTE following vaginal and caesarean delivery | |||||||||

| ACCP (1 study) | NR | VTE | Gassmann et al., 202034 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 310 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.93) |

| ACOG (1 study) | NR | VTE | Gassmann et al., 202034 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 314 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) |

| ASH (1 study) | NR | VTE | Gassmann et al., 202034 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 344 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 1.00 (0.99 to 1) |

| Caprini (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 2 | VTE | Tran et al., 201939 | 3 | 5780 | 0 | 311 | 1.00 (0.44 to 1) | 0.05 (0.05 to 0.06) |

| Caprini | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Tran et al., 201939 | 1 | 3066 | 2 | 3025 | 0.33 (0.06 to 0.79) | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.51) |

| Caprini | Risk score ≥ 4 | VTE | Tran et al., 201939 | 0 | 1257 | 3 | 4834 | 0.00 (0 to 0.56) | 0.79 (0.78 to 0.80) |

| Padua (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 4 | VTE | Tran et al., 201939 | 0 | 50 | 3 | 6041 | 0.00 (0 to 0.56) | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) |

| RCOG (3 studies) | NR | VTE | Gassmann et al., 202034 | 0 | 138 | 0 | 206 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.65) |

| RCOG | Risk score ≥ 2 | VTE | Tran et al., 201939 | 1 | 3837 | 2 | 2254 | 0.33 (0.06 to 0.79) | 0.37 (0.36 to 0.38) |

| RCOG | ≥ 2 low risk factors or 1 high risk factor | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 197 | 149,205 | 115 | 283,836 | 0.63 (0.58 to 0.68) | 0.66 (0.65 to 0.66) |

| SFOG (2 studies) | Risk score ≥ 2 | VTE | Lindqvist et al., 200836 | 18 | 111 | 19 | 2273 | 0.49 (0.33 to 0.64) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) |

| SFOG | ≥ 2 risk factors | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 109 | 41,145 | 412 | 620,721 | 0.21 (0.18 to 0.25) | 0.94 (0.94 to 0.94) |

| Chau, 2019 (1 studya) | Risk score ≥ 3 (2012 data set) | VTE | Chau et al., 201930 | 0 | 101 | 1 | 456 | 0.00 (0 to 0.79) | 0.82 (0.78 to 0.85) |

| Chau, 2019 | Risk score ≥ 3 (2015 data set) | VTE | Chau et al., 201930 | 0 | 113 | 1 | 393 | 0.00 (0 to 0.79) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.81) |

| Ellis-Kahana, 2020 (full model) (1 studyb) | Risk score > 3 (high risk) | VTE | Ellis-Kahana et al., 202041 | 68 | 7942 | 41 | 75,449 | 0.62 (0.53 to 0.71) | 0.90 (0.90 to 0.91) |

| Ellis-Kahana, 2020 (without antepartum thromboembolic disorder) | Risk score > 3 (high risk) | VTE | Ellis-Kahana et al., 202041 | 63 | 9926 | 46 | 73,465 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.67) | 0.88 (0.88 to 0.88) |

| Sultan, 2016 (1 studyc) | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 35% (threshold: 7.2 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 355 | 231,480 | 166 | 430,386 | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.72) | 0.65 (0.65 to 0.65) |

| Sultan, 2016 | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 25% (threshold: 8.7 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 310 | 164,976 | 211 | 496,890 | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.64) | 0.75 (0.75 to 0.75) |

| Sultan, 2016 | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 20% (threshold: 9.8 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 278 | 131,921 | 243 | 529,945 | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.58) | 0.80 (0.80 to 0.80) |

| Sultan, 2016 | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 10% (threshold: 14 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 185 | 66,053 | 336 | 595,813 | 0.36 (0.32 to 0.40) | 0.90 (0.90 to 0.90) |

| Sultan, 2016 | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 6% (threshold: 18 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 158 | 41,096 | 363 | 620,770 | 0.30 (0.27 to 0.34) | 0.94 (0.94 to 0.94) |

| Sultan, 2016 | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 5% (threshold: 19.7 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 139 | 32,980 | 382 | 628,886 | 0.27 (0.23 to 0.31) | 0.95 (0.95 to 0.95) |

| Sultan, 2016 | ≥ 2 risk factors: top 1% (threshold: 41.2 per 10,000 deliveries) | VTE | Sultan et al., 201611 | 47 | 6576 | 474 | 655,290 | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.12) | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) |

| Predicting postpartum VTE following caesarean delivery only | |||||||||

| ACOG (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Lok et al., 201937 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 859 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 1.00 (1 to 1) |

| RCOG (2 studies) | NR | VTE | Binstock and Larkin, 2019 (abstract)28 | 11 | 2692 | 0 | 172 | 1.00 (0.74 to 1) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) |

| RCOG | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Lok et al., 201937 | 0 | 649 | 0 | 210 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.24 (0.22 to 0.27) |

| Binstock, 2019 (1 study) | NR | VTE | Binstock and Larkin, 2019 (abstract)28 | 11 | 2635 | 0 | 229 | 1.00 (0.74 to 1) | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.09) |

| Cavazza, 2012 (1 study) | Moderate/high/very high | VTE | Cavazza et al., 201229 | 0 | 268 | 1 | 232 | 0.00 (0 to 0.79) | 0.46 (0.42 to 0.51) |

| Lok, 2019 (1 study) | Risk score ≥ 3 | VTE | Lok et al., 201937 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 831 | Unable to estimate – no VTE | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.98) |

Summary of key findings

-

Several RAMs for VTE in pregnancy and the puerperium have been developed using a variety of methods and based on a variety of predictor variables.

-

This systematic review provides a comprehensive review of RAMs for predicting the risk of developing VTE in women who are pregnant or in the puerperium (within 6 weeks post delivery).

-

In general, external validation studies have poor designs and limited generalisability.

-

Available data suggest that external validation studies have weak designs and limited generalisability, and so estimates of prognostic accuracy are very uncertain.

Chapter 4 Decision-analytic modelling

Decision problem

Aim

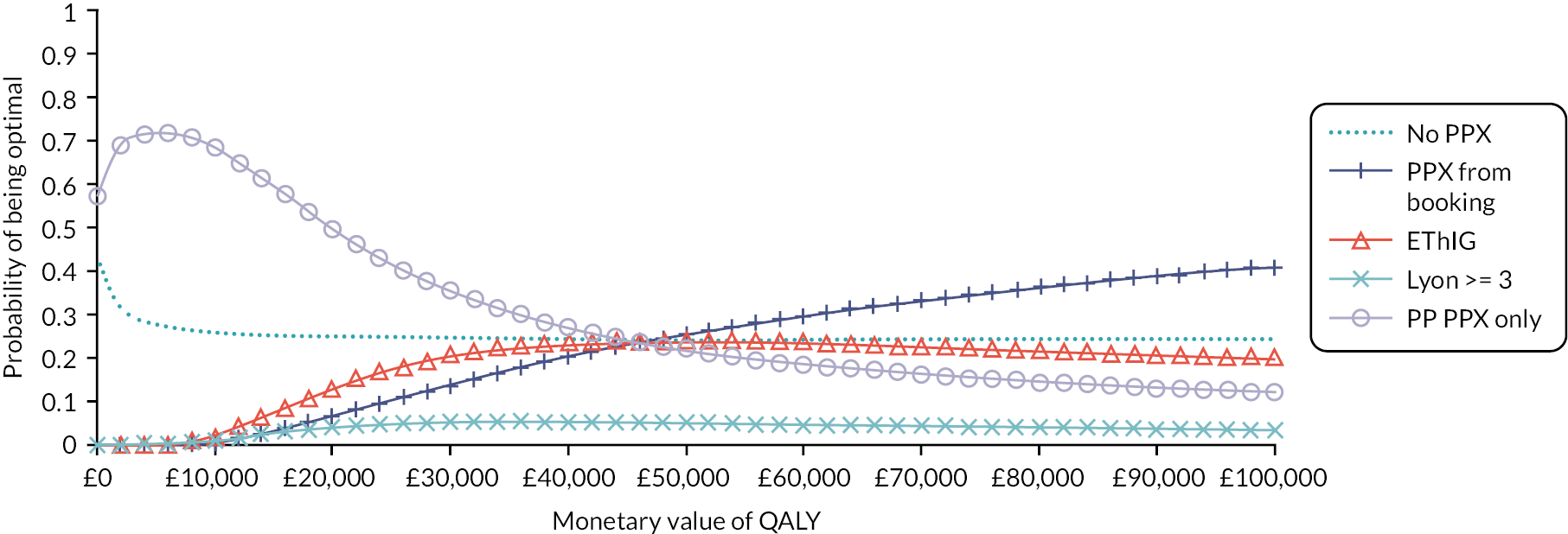

The cost-effectiveness analysis aims to estimate the expected costs, health benefits (QALYs) and INMB of providing thromboprophylaxis, to women who are pregnant or who are in the puerperium, using current and alternative risk stratification tools. The EVPI analysis aims to quantify the uncertainty around those estimates, given current evidence, and to determine which factors are the most important drivers of uncertainty when trying to determine the optimal risk-based thromboprophylaxis strategy in this population. The outcomes of the EVPI analysis are then used alongside the qualitative research (see Chapter 5) to identify potential future studies to gather additional evidence that would reduce the current decision uncertainty, while being feasible and acceptable to patients and clinicians. The EVSI aims to evaluate the value of the potential future research studies in terms of the net health benefits to patients and the cost of the research (see Chapter 6).

Population

The target population for the decision-analytic modelling is women who are pregnant or in the puerperium (within 6 weeks post delivery) receiving care in both hospital and primary care settings. The antenatal and postnatal populations are considered separately. In addition, the systematic review (see Chapter 3) identified RAMs that are specifically targeted at antenatal women at high risk of VTE due to either prior VTE and/or known thrombophilia, and RAMs that are specifically targeted at obese postpartum women and postpartum women following caesarean section. One RAM was identified for use in an unselected antepartum population, but the performance data for this RAM were poor. Therefore, the analysis in the unselected antepartum population was limited to exploratory analysis to determine the range of sensitivity and specificity values that would be required for a RAM in this population. As women who have a prior VTE or known thrombophilia are likely to have received antepartum risk assessment, the postpartum modelling excludes these groups. Therefore, the following subgroups are considered in the decision-analytic model:

-

antepartum women identified as being at high risk (prior VTE or known thrombophilia)

-

unselected postpartum women (excluding those with prior VTE or known thrombophilia)

-

postpartum women identified due to specific risk factors (caesarean section, obesity)

-

unselected antepartum women (exploratory analysis only).

Strategies for prophylaxis

Strategies for prophylaxis in women having antepartum risk assessment

The current NICE Guideline on the prevention of VTE in hospitalised women who are pregnant or who are in the puerperium recommends that clinicians use a tool published by a national UK body, professional network or peer-reviewed journal. 6 The NICE Guideline states that the most commonly used tool is the RCOG guideline;6,7 this is considered to represent current practice in the decision analysis. No data were identified to assess the sensitivity and specificity of RCOG in predicting VTE in women having antepartum risk assessment. (The only study assessing the use of RCOG in antepartum women was not suitable for inclusion in the modelling because it was in a small cohort of hospitalised pregnant women with cancer and no sensitivity data were available.) However, two RAMs for antepartum VTE risk assessment [Lyon32,33 and Efficacy of Thromboprophylaxis as an Intervention during Gravidity (EThIG)27] in women at high risk of VTE (prior VTE and/or thrombophilia) were identified in the systematic review (see Chapter 3). Therefore, in the high-risk antepartum population, the Lyon and EThIG RAMs are compared against each other and against strategies of prophylaxis for all and prophylaxis for none. Table 5 summarises current RCOG guidance on antepartum thromboprophylaxis for high-risk women (prior VTE and/or thrombophilia),7 and compares these with the two RAMs for high-risk patients. 27,32

| Risk factors | RCOG7 | Lyon32 | EThIG27 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior pregnancy-related VTE | LMWH from booking | LMWH from booking | LMWH from booking |

| Prior VTE which was unprovoked | LMWH from booking | LMWH from 28 weeks gestation | LMWH from booking |

| Prior VTE associated with major surgery | LMWH from 28 weeks gestation | Postnatal LMWH only | Postnatal LMWH only |

| Thrombophilia without prior VTE | Consider antenatal LMWH (depends on type of thrombophilia) | LMWH from 28 weeks gestation or postnatal only depending on type of thrombophilia | From booking or postnatal only depending on type of thrombophilia |

As the RAMs vary in their recommendations regarding the timing of prophylaxis for some groups, the base-case analysis assumes that risk assessment occurs at the time of the antenatal booking appointment and LMWH is offered from booking to women identified as being high risk using the RAM. Scenario analysis is then used to explore whether the conclusions are sensitive to prophylaxis being deferred to 28 weeks. In scenarios where antepartum prophylaxis is offered, it is assumed that prophylaxis is also continued for 6 weeks after delivery.

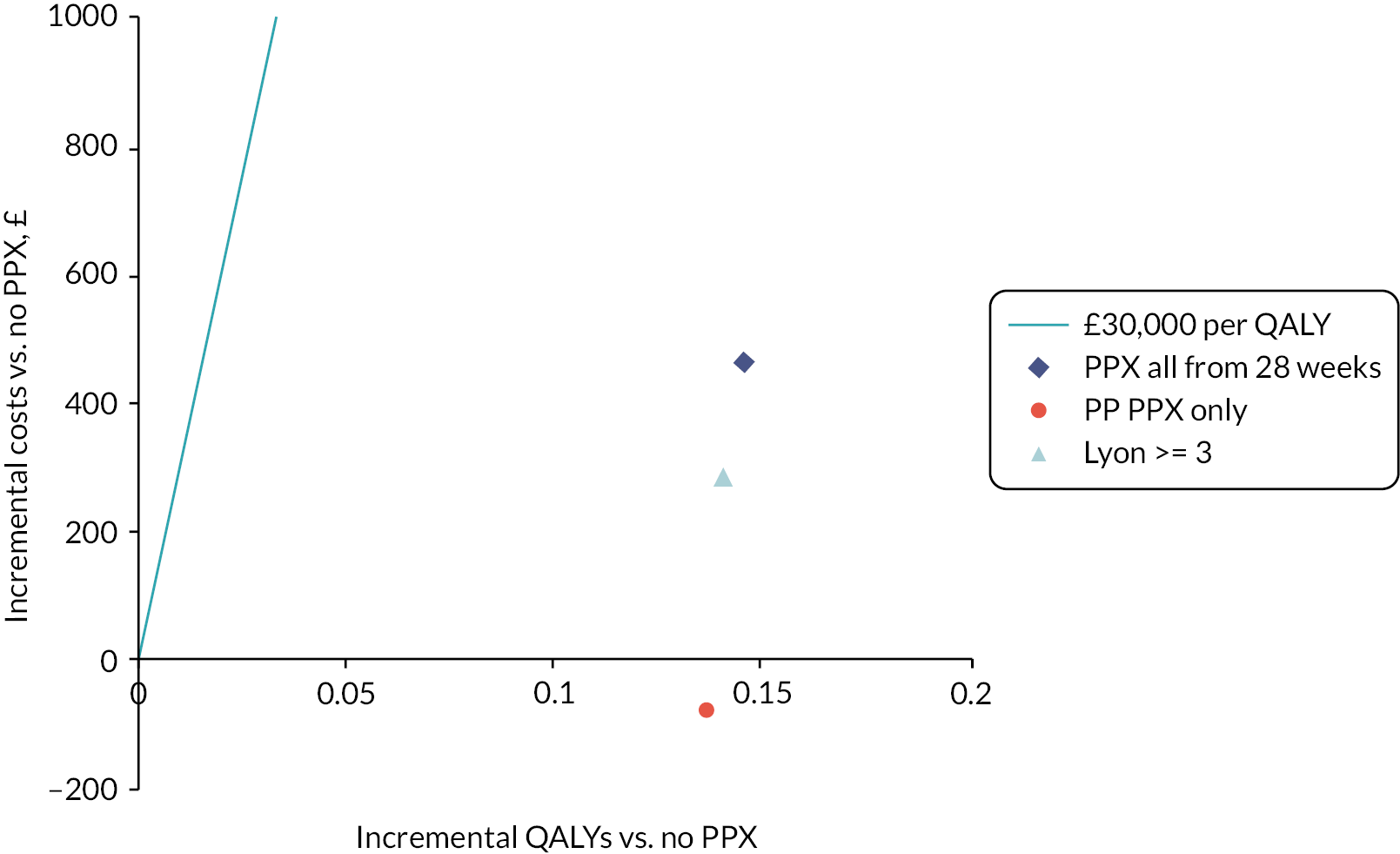

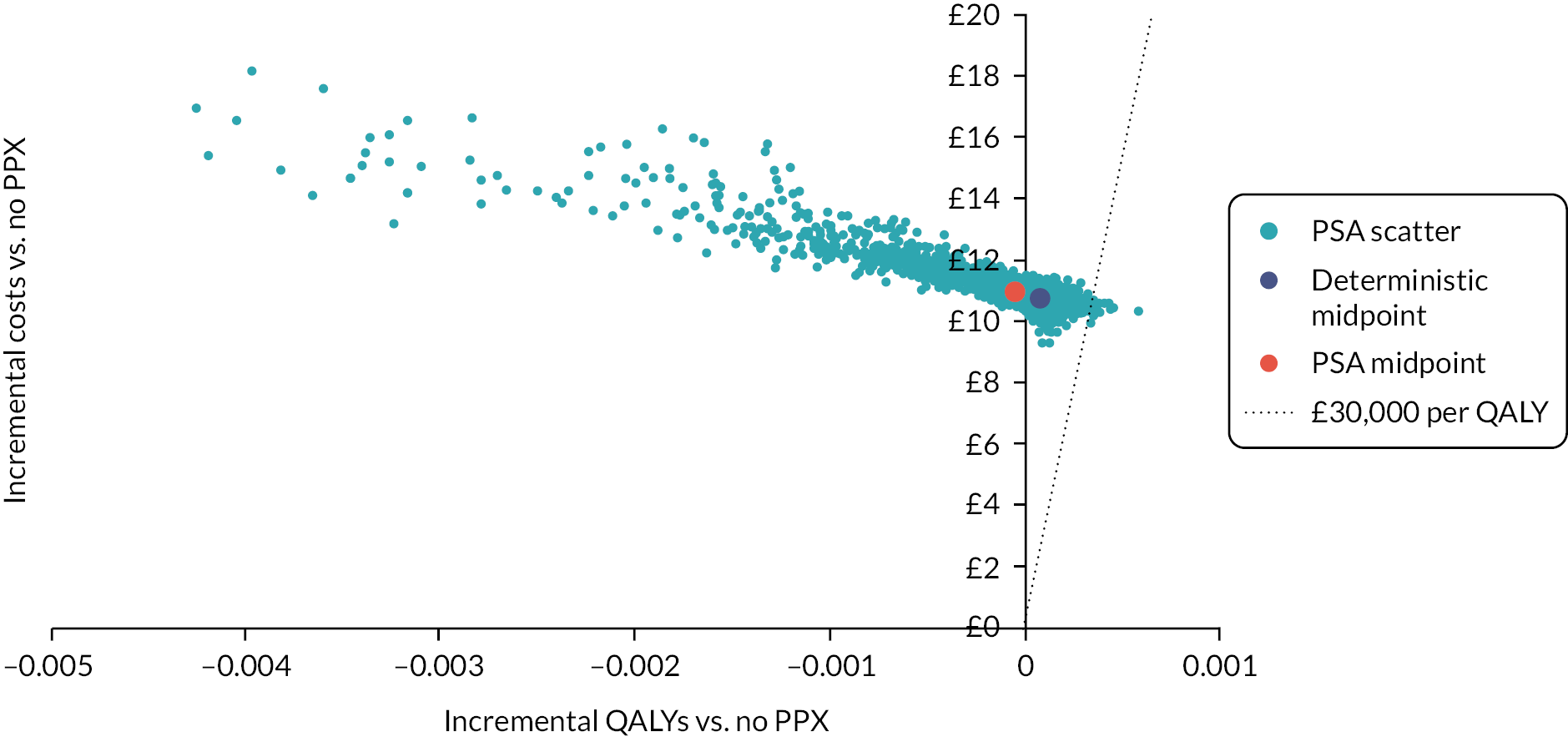

In the high-risk antepartum scenario, the model estimates outcomes for prophylaxis for the following strategies:

-

antepartum prophylaxis followed by postpartum prophylaxis for all [prophylaxis (PPX) from booking]

-

antepartum prophylaxis based on a RAM (Lyon/EThIG)27,32 followed by postpartum prophylaxis for all

-

postpartum prophylaxis for all but no antepartum prophylaxis [postpartum (PP) PPX only]

-

no prophylaxis, either antepartum or postpartum (no PPX).

The exploratory analysis for unselected antepartum women makes similar assumptions regarding the timing of risk assessment (antenatal booking appointment) and the duration of prophylaxis offered to those identified as high risk (from booking until 6 weeks postpartum); however, the comparator strategy of postpartum prophylaxis for all (PP PPX only) is not included as unselected women not receiving antepartum prophylaxis are likely to receive a further risk assessment after delivery.

Strategies for prophylaxis in women having postpartum risk assessment

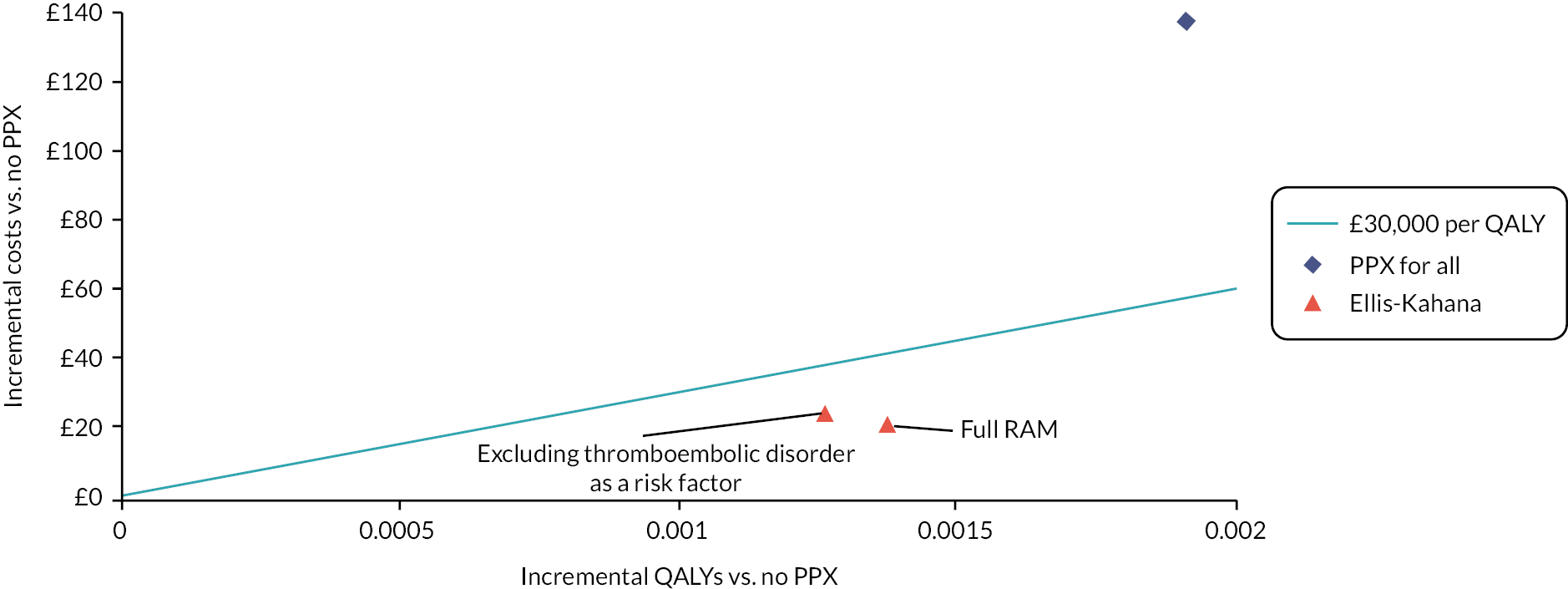

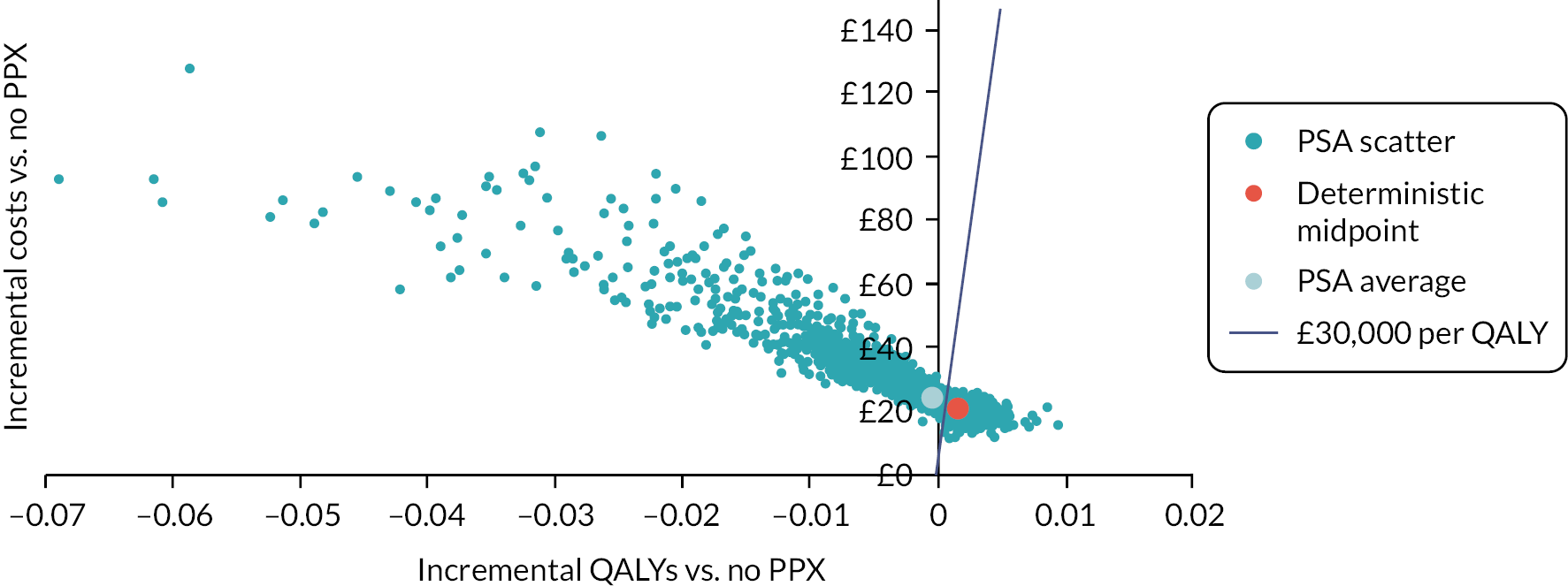

In the postpartum population model, the strategies compared are:

-

postpartum prophylaxis for all (PP PPX for all)

-

postpartum prophylaxis based on a RAM

-

no postpartum prophylaxis (no PPX).

In each case, postpartum prophylaxis is assumed to be offered for 10 days. This is because for the majority of women receiving postpartum thromboprophylaxis, they would fit the criteria for short-term VTE prevention strategies based on their transient risk factors in line with the RCOG guidance. Extended postnatal prophylaxis lasting 6 weeks is mainly offered to those having antepartum prophylaxis, who are excluded from this analysis, and some women with multiple or persistent risk factors. For the unselected postpartum population, the RAMs compared are RCOG,11,39 SFOG,11,36 Caprini39 and the novel RAM reported by Sultan et al. 11 In the postpartum subgroups selected based on specific risk factors, the RAMs compared are RCOG and the novel RAM reported by Binstock et al. 28 in the post-caesarean section population and the novel RAM reported by Ellis-Kahana et al. 41 in the obese population.

Modelling methods

Context

The model estimates lifetime costs and QALYs for the different thromboprophylaxis strategies and the comparator of no thromboprophylaxis under an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. Future costs and benefits are both discounted to their net present value at a rate of 3.5% per annum in accordance with the 2013 NICE guide to the methods of technology appraisal. 44 Costs are reported in Great British pounds based on 2020 prices. To achieve this, historical prices used as model inputs were uplifted using the hospital and community health services pay and prices index up to 2016 and the NHS Cost Inflation Index thereafter. 45

Conceptual model for antepartum women

The conceptual model has been developed in collaboration with the project management group (which included both clinical and patient experts). The group provided guidance on the selection of model outcomes based on clinical importance and assessed the appropriateness of data sources and model assumptions. An existing published model that has been used to evaluate RAM-based thromboprophylaxis strategies in other populations was used as a starting point for discussion. 46,47 Other models that were excluded from the systematic review of published economic evaluations, which addressed similar but not identical decision problems (see Appendix 3), were also used to inform discussions regarding relevant clinical outcomes for inclusion.

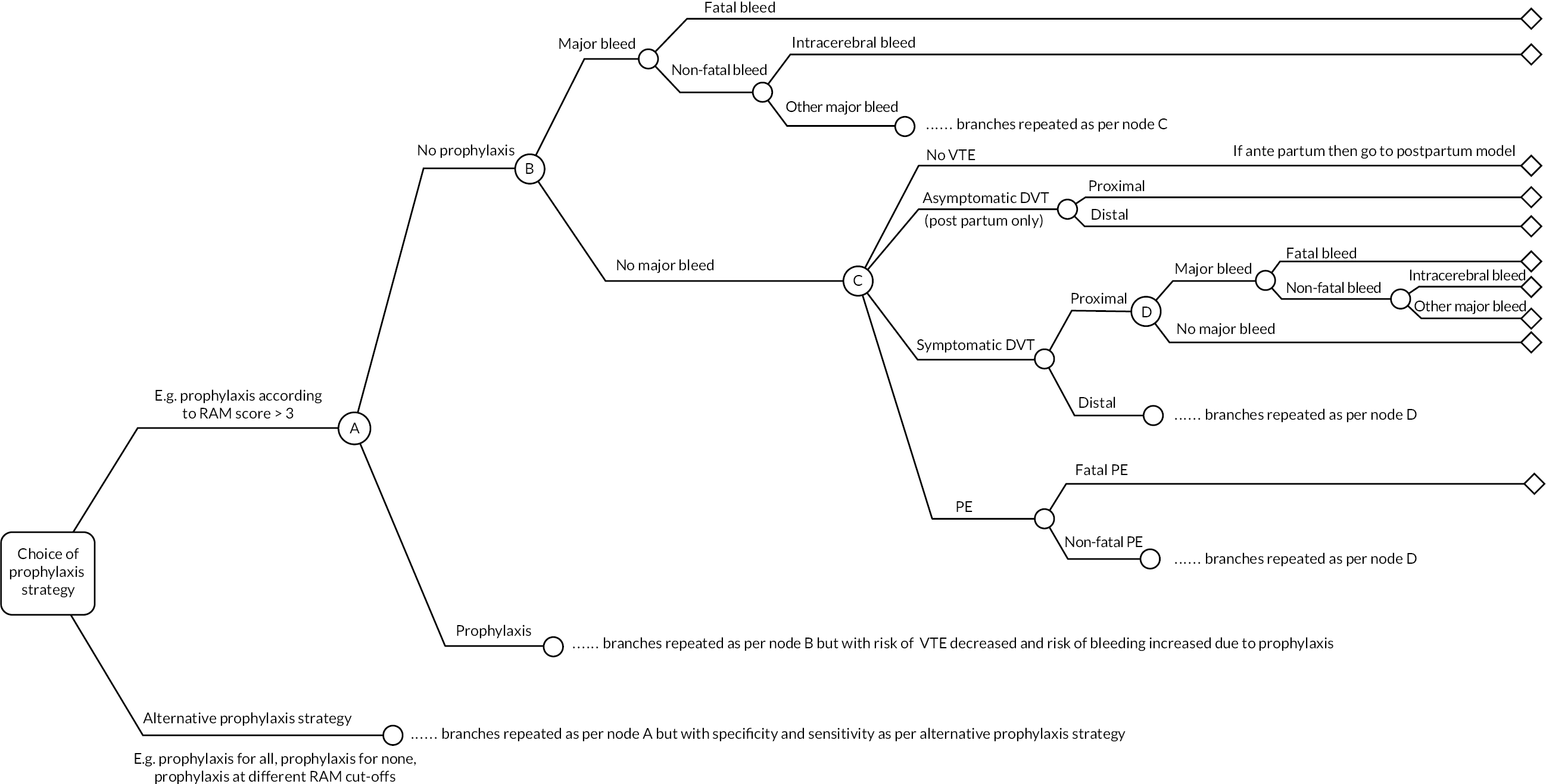

The model consists of a decision-tree phase, summarised in Figure 3, to capture short-term outcomes followed by a lifetime state-transition (Markov) model, summarised in Figure 4, to capture the impactof outcomes that result in death or ongoing morbidity. For women being assessed for antepartum prophylaxis, the decision-tree phase of the model is repeated to capture the antepartum and postpartum periods separately. Those patients who are well at the end of the antepartum decision tree remain at riskof postpartum VTE and enter into a postpartum decision tree with the same structure. Those patients who have experienced a symptomatic VTE or a non-fatal intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) in the antepartum model are assumed to have ongoing costs and utility decrements [reductions in health-related quality of life (HRQoL)] driven mainly by these events, so they remain in the same health state in the postpartum phase.

FIGURE 3.

Short-term decision-tree model structure (repeated for antepartum and postpartum phases).

FIGURE 4.

Long-term state-transition model. CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

The decision tree is used to estimate for each strategy: the number of patients receiving thromboprophylaxis; the impact of thromboprophylaxis on VTE outcomes (PEs and DVTs); and the incidence of major bleeds during either thromboprophylaxis or VTE treatment with anticoagulants. PEs were divided into fatal and non-fatal events. DVTs were divided first into symptomatic and asymptomatic DVTs and then into proximal and distal DVTs. Symptomatic DVTs and non-fatal PEs are assumed to result in 3 months of anticoagulant treatment, which should be continued until at least 6 weeks post delivery.

In our previous analysis of thromboprophylaxis strategies in patients having lower limb immobilisation following injury, we found that the prevention of post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) following asymptomatic DVT was an important driver of both cost effectiveness and decision uncertainty due to asymptomatic DVTs being more common than symptomatic DVTs but their long-term consequences being more uncertain. 46 So while asymptomatic DVTs are assumed to remain undetected and untreated, it is important to capture these DVTs in the decision-tree phase of the model in order to capture any ongoing morbidity due to PTS in the long-term state-transition model. However, asymptomatic DVTs are only included in the postpartum model as this ensures that women without symptomatic VTE at delivery progress to the postpartum model where they remain at risk of symptomatic DVT. The risk of asymptomatic DVT is therefore only applied to those not experiencing symptomatic VTE in either the antepartum or postpartum periods. The total period covered by the decision-tree model is 1 year, with the first 30 weeks (from booking appointment at 10 weeks to delivery) covered by the antepartum model, and the remainder (155 days) covered by the postpartum model. This is considered sufficient to capture both the periods at risk of VTE (pregnancy and the 6 weeks after delivery) in addition to the period of VTE treatment if this occurs at the end of the period of risk. Diagnosis of PTS and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is assumed not to occur until the end of the decision-tree phase of the model, as it is difficult to distinguish these chronic complications from acute symptoms during the first 3 months after VTE. Major bleeding can occur both with and without prophylaxis. Major bleeds were considered to be those meeting the criteria proposed by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) subcommittee on the control of anticoagulation (Tardy et al. 2019). 48 Major bleeds were divided into fatal bleeds, non-fatal ICHs and other major bleeds (referred to as non-fatal non-ICH major bleeds). These other major bleeds were assumed to have no impact on costs or quality-of-life implications after 1 month, whereas ICHs are assumed to have long-term morbidity which is captured in the state-transition model. Wound haematomas can result in delayed discharge from hospital or women consulting at general practice (GP) surgeries or emergency departments (EDs) and they can also impact on HRQoL. These are included in the model as a form of clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNMB). Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) was not included in the model because in a systematic review of 2777 pregnancies, there were no cases of HIT. 49 Heparin-related osteoporosis was not included as an adverse event in the model because use of LMWH in pregnancy has not been found to be associated with reduced bone mineral density. 50

The model estimates outcomes for a cohort of identical patients with average characteristics. In reality, the application of RAMs may lead to treated and untreated patients having different characteristics. This could lead to the cost effectiveness being over- or underestimated if the consequences of VTE are different for those selected for prophylaxis according to the RAMs. For example, if those being selected for prophylaxis by the RAMs are older, then any deaths prevented by prophylaxis will result in fewer life-years gained than for the model estimates based on women with an average age. Similarly, if the women offered prophylaxis have higher BMI than those not being offered prophylaxis, then the costs of prophylaxis will be higher than estimated based on average BMI. While the impact of these factors was expected to be small, this was checked by varying the starting age and BMI in scenario analysis to determine if the optimal prophylaxis strategy was sensitive to these characteristics. Age was found to have a bigger impact than BMI, but overall the cohort approach using average characteristics was considered a reasonable approximation for determining the optimal prophylaxis strategy.

The key model assumptions for the decision-tree phase are as follows:

-

Patients who are well at the end of the antepartum decision-tree progress to the postpartum decision tree, while those experiencing an antepartum VTE event or ICH remain in their current state until entering the long-term state-transition model.

-

No patient experiences an asymptomatic DVT in the antepartum decision tree as this ensures that they continue to be at risk of a symptomatic DVT in the postpartum model.

-

Bleeding events are possible in both those having thromboprophylaxis and those having no thromboprophylaxis.

-

VTE associated with pregnancy is assumed to occur within 6 weeks of delivery.

-

Patients who stop or have a pause in prophylaxis due to major bleeding are assumed to have the same reduction in VTE risk as those who completed treatment.

-

All patients with symptomatic DVT receive accurate diagnosis and initiate treatment with anticoagulants (LMWH until 6 weeks after delivery or a minimum or 3 months).

-

Asymptomatic DVTs are not detected and are not treated.

-

All PEs are symptomatic and lead to detection and treatment (LMWH until 6 weeks after delivery or a minimum or 3 months).

-

Patients treated for symptomatic DVT and PE have a bleed risk associated with treatment, which is assumed to occur during the 3 months treatment period.

-

Chronic complications of VTE (CTEPH following PE and PTS following DVT) are assumed to be diagnosed at least 3 months after VTE and therefore occur after any bleeds associated with VTE treatment.

-

Patients having fatal PE are not at risk of other adverse outcomes prior to death (e.g. bleeding due to anticoagulant treatment).

-

Risk of bleeding during treatment for VTE is independent of whether the patient bled during prophylaxis.

-

Risk of VTE, risk of bleeding and risk of PTS/CTEPH are based on average patient characteristics (e.g. age and BMI) for the cohort being risk assessed.

A state-transition model (see Figure 4) was then used to extrapolate lifetime outcomes, including overall survival and ongoing morbidity related to either bleeds or VTE. The health states included within the state-transition model capture the risk of PTS following VTE and the risk of CTEPH following PE. The risk of PTS is modelled separately according to whether the DVT is asymptomatic or symptomatic and also whether the DVT is proximal or distal. All patients with PTS are combined in a single health state as costs, utilities (a measure of HRQoL on a scale of 0 to 1) and survival are not expected to be affected by whether PTS occurred following proximal or distal DVT. The PTS health state is not split into different severity levels as the utility estimates are based on the average utility across severity levels and the costs are not expected to differ by severity. The CTEPH health state is divided according to whether patients receive medical or surgical management to allow for differential costs and survival between these groups. There is also a post-ICH state to capture ongoing morbidity following ICHs. Further adverse outcomes (PTS, CTEPH) are not modelled following ICH, as lifetime costs and QALYs are assumed to be predominantly determined by morbidity related to ICH. The state-transition model has annual cycles. All-cause mortality during the first year is applied before patients enter the state-transition model. Health state occupancy is half-cycle corrected such that all transitions between states, including mortality, is assumed to occur mid-cycle. The key model assumptions during the state-transition phase are as follows:

-

All symptomatic DVTs are associated with a risk of PTS, but the rate is allowed to differ depending on whether the DVT is distal or proximal and whether it is symptomatic or asymptomatic.

-

There is no risk of PTS following PE, and CTEPH is possible only after PE.

-

Further outcomes (i.e. VTE, CTEPH and PTS) are not modelled for those who experience ICH as lifetime cost and QALYs will be determined predominantly by disability related to the ICH.

-

All-cause mortality is applied to all transition states except CTEPH and post ICH which have state-specific mortality rates.

-

Recurrent VTE (that is a second VTE occurring after the first VTE during the index pregnancy) is not modelled.

Conceptual model for postpartum women

The conceptual model for postpartum women is identical except that it starts at the point that women deliver and therefore no events occur during the antepartum phase of the model described above. Therefore, women spend 155 days in the postpartum model before progressing to the long-term state-transition model.

Data sources

The input parameters used in a previous analysis of thromboprophylaxis during hospitalisation were examined to identify any that were less relevant to women at risk of VTE during pregnancy and the puerperium. 47 The following data were updated to use data specific to our target population: data related to population characteristics (age, BMI and life expectancy); incidence of VTE; incidence of bleeding; incidence of PTS; costs of prophylaxis and cost of VTE treatment. Other data were generally based on the same sources used in the previous analysis with costs updated to reflect changes in prices. These included incidence of CTEPH following VTE; costs following PTS, CTEPH and ICH; the utility values for patients experiencing adverse outcomes and mortality risks following CTEPH and ICH.

A systematic review of published economic evaluations was conducted, which failed to identify any full economic evaluations that directly addressed the research question (see Appendix 3). However, several full-text articles that addressed similar research questions were examined to identify relevant data sources. These were supplemented with ad hoc searches for relevant literature, focusing where possible on systematic reviews.

When identifying data sources to populate the antepartum model for women at high risk of VTE, we focused on sources related to women with a prior VTE. Two-way scenario analysis was then used to explore whether the conclusions would differ if the target group had a higher or lower risk of VTE or major bleeding. When identifying data sources to populate the postpartum model, we focused first on sources related to women who have had a caesarean section as this is one of the most common risk factors that results in women requiring postpartum prophylaxis. O’Shaughnessy et al. estimated that the RCOG guideline would result in 85% of women having caesarean delivery receiving prophylaxis compared with only 15% of women having vaginal delivery. 15 Therefore, the consequences of postpartum prophylaxis are likely to be best represented by outcomes estimated in women having caesarean delivery even when modelling an unselected postpartum population. However, VTE risks have been estimated specifically for each of the postpartum populations and drug dosages, which are dependent on weight, have been adjusted for the obese postpartum population. In addition, two-way scenario analyses have been conducted to explore whether the conclusions would differ if the target group had a higher or lower risk of VTE or major bleeding than assumed in the base case.

Clinical input parameters are described below with a summary of the key parameters for each of the different populations provided in Table 6 (for reference all parameters are provided in Appendix 4, Tables 22–28).

| Parameter | High-risk antepartum women (e.g. prior VTE) |

Postpartum women (unselected, C-section or obese) |

Report section |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 | 30 | Population characteristics |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 | 27 36 (obese subgroup) |

Population characteristics |

| Duration of prophylaxis | From booking until 6 weeks PP | 10 days | Strategies for prophylaxis in women having antepartum risk assessment and Strategies for prophylaxis in women having postpartum risk assessment |

| Absolute risk of PE without prophylaxis | 1.40% AP and 1.65% PP | 0.017% (unselected) 0.029% (C-section) 0.037% (obese) |

Risk of venous thromboembolism in antepartum women with a prior venous thromboembolism, Risk of venous thromboembolism in postpartum women and Proportion of venous thromboembolism that is deep-vein thrombosis without pulmonary embolism |

| Absolute risk of symptomatic DVT without prophylaxis | 4.41% AP and 5.20% PP | 0.055% (unselected) 0.092% (C-section) 0.116% (obese) |

Risk of venous thromboembolism in antepartum women with a prior venous thromboembolism, Risk of venous thromboembolism in postpartum women and Proportion of venous thromboembolism that is deep-vein thrombosis without pulmonary embolism |

| Absolute risk of asymptomatic DVT without prophylaxis | 0% APa 20.80% PP |

0.229% (unselected) 0.370% (C-section) 0.460% (obese) |

Ratio of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis to symptomatic deep-vein thrombosis in postpartum women |

| RR of VTE for prophylaxis (LMWH) vs. no prophylaxis | 0.33 | 0.53b |

Relative risk of venous thromboembolism in women having antepartum prophylaxis and Relative risk of venous thromboembolism in women having postpartum prophylaxis |

| Absolute risk of major bleeding with prophylaxis (LMWH) | 0.24% AP and 5.49% PP | 4.58% | Risk of major bleeding in women having antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis and Risk of major bleeding in women having postpartum prophylaxis |

| RR of bleeding for prophylaxis (LMWH) vs. no prophylaxis | 1.53 | 1.53 | Relative risk of major bleeding in women having antepartum prophylaxis compared to no antepartum prophylaxis and Relative risk of major bleeding for postpartum prophylaxis compared to no postpartum prophylaxis |

| Absolute risk of fatal major bleeding (without LMWH) | 0.5 in 100,000 AP 0.6 in 100,000 PP |

0.6 in 100,000 | Risk of fatal bleeding and non-fatal intracerebral haemorrhage |

| Absolute risk of non-fatal ICH (without LMWH) | 0.9 in 100,000 AP 1.1 in 100,000 PP |

1.1 in 100,000 | Risk of fatal bleeding and non-fatal intracerebral haemorrhage |

| Increased risk of wound haematoma for LMWH | 2.1% | 0.6% | Risk of wound haematoma in women having antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis and Risk of wound haematoma in women having postpartum prophylaxis |

Population characteristics

The average age in the cohort (30 years) is based on the mean age reported by Sultan et al. (2016) from a large UK longitudinal primary care database (CPRD). 11 The cohort included 433,353 women, without a history of VTE, whose pregnancy ended in a live birth or still birth between 1997 and 2014 and who had at least 6 weeks of postpartum follow-up. The average weight, which is required for estimating LMWH dosing, is based on the average BMI of 27.4 kg/m2 for 25- to 44-year-olds reported in the 2019 Health Survey for England. 51 For the obese subgroup, we have assumed a BMI of 35.8 kg/m2, based on the average BMI in the RAM study in an obese cohort reported by Ellis-Kahana et al. 41

Risk of venous thromboembolism in antepartum women with a prior venous thromboembolism

De Stefano et al. report 19 VTE events in 155 pregnancies where the women had a history of VTE prior to pregnancy but did not receive prophylaxis during pregnancy. 52 This gives an overall probability of 12.3% of having a VTE associated with the current pregnancy. The antepartum VTE risk was 5.8%, and the risk of postpartum VTE was of 6.9% (conditional on not having an antepartum VTE). Pabinger et al. reported similar VTE risks of 4% during pregnancy and 5% postpartum. 53 Brill-Edwards et al. reported a lower risk of VTE during pregnancy (2%), but their cohort excluded women with known thrombophilia and women could be recruited up to 20 weeks gestation, meaning that those having VTE early in pregnancy may have been excluded. 54 The risks from De Stefano et al. have been applied in the model. Higher and lower VTE risks have been explored in scenario analyses.

Risk of venous thromboembolism in unselected antepartum women

The risk of VTE in unselected antepartum women is based on the risk reported by Chauleur et al. in the cohort risk assessed using the STRATHEGE RAM. 31 There were nine VTE events in 2685 women (0.34%), of which four were antepartum and five were postpartum, giving absolute risks of 0.15% and 0.19% for antepartum and postpartum VTE, respectively. These data were only used in the exploratory analysis for unselected antepartum women.

Risk of venous thromboembolism in postpartum women

The risk of VTE in women following caesarean section has been estimated from an earlier analysis of the CPRD database (data from 1997 to 2010) reported by Sultan et al. (2014) in which women with prior VTE were excluded from the analysis. 55 For comparison, the risk of VTE within 6 weeks was 0.071% in this earlier cohort (158 in 222,334 deliveries) compared with 0.072% in the later cohort used to derive the Sultan RAM. 11,55 In this earlier study, the incidence of VTE within 6 weeks of any caesarean delivery was estimated to be 0.137% (74 VTEs occurring within 6 weeks across 31,843 emergency and 22,341 elective caesarean sections). 55 The risk of postpartum VTE within 6 weeks of delivery in women with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was 0.153% (37 VTEs in 24,141 women). The risk of VTE over 6 weeks in unselected postpartum women was taken to be 0.072% based on the later study by Sultan et al. 11

Ratio of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis to symptomatic deep-vein thrombosis in postpartum women

A review by Blondon et al. 56 examining the incidence of VTE following caesarean section or vaginal delivery identified six studies which screened women postnatally to identify asymptomatic DVT. Over the 6 studies, we identified 1 symptomatic and 4 asymptomatic cases in a combined cohort of 717 patients. 57–62 Therefore, a ratio of 4:1 is applied in the base case. All of the asymptomatic cases of DVT identified were distal calf DVTs. A zero rate of asymptomatic DVT is explored in scenario analyses as the clinical significance of asymptomatic distal calf DVTs is unclear.

Proportion of venous thromboembolism that is deep-vein thrombosis without pulmonary embolism

The proportion of symptomatic VTE that is PE compared with DVT without PE has been estimated from studies included in the systematic review by Meng et al., which reported the incidence of PE and DVT without PE (24% of VTE is PE based on ratio of 17,035 DVT without PE to 5401 PE). 5 The review included both antepartum and postpartum VTE and the same ratio is applied to both the antepartum and postpartum incidences of VTE.

Proportion of deep-vein thrombosis that is distal

Data from the Computerized Registry of Patients with VTE (RIETE) were used to determine the proportion of symptomatic DVTs that are distal versus proximal. RIETE is an ongoing prospective registry of patients with objectively confirmed VTE and Elgendy et al. describe clinical characteristics for the subset of women who were pregnant or postpartum (within 2 months of delivery) at the time of VTE presentation. 63 Elgendy et al. report that 71% of postpartum DVTs (215 of 301) were proximal, whereas 78% of antepartum DVTs (342 of 438) were proximal. 63

We assumed that all asymptomatic DVTs are distal as none of the asymptomatic DVTs identified through systematic screening of postnatal women in the six studies described in section Ratio of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis to symptomatic deep-vein thrombosis in postpartum women were proximal.

Relative risk of venous thromboembolism in women having antepartum prophylaxis

The relative risk (RR) of symptomatic VTE for antenatal LMWH (with or without postnatal prophylaxis) compared with no prophylaxis is reported as being 0.39 (95% CI 0.08 to 1.98) based on four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) included in the updated Cochrane review by Middleton et al. 8 However, three of the RCTs included in this meta-analysis were considered by our clinical experts to be less applicable to the modelled population of high-risk women with a prior VTE. Two of the papers related to the LMWH (FRagmin®) in pregnant women with a history of Uteroplacental Insufficiency and Thrombophilia (FRUIT) trial, which aimed to investigate LMWH combined with aspirin to prevent recurrent early-onset pre-eclampsia. This trial specifically excluded women at high risk of VTE due to prior history of VTE. 64,65 The third study was the Thrombophilia in Pregnancy Prophylaxis Study (TIPPS), in which LMWH was not given specifically for the indication of reducing VTE risk and less than half of the cohort had risk factors for VTE. 66 The dose of LMWH used in the TIPPS study was also higher than recommended for prophylaxis by RCOG. 7,66 The remaining RCT by Gates et al. was the only study included in the previous Cochrane review, and this had a RR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.02 to 7.14). 67 It should be noted that this was in fact a pilot study and the numbers recruited were small (n = 8 in each arm), and only one VTE event was observed, hence the wide CIs. The RR from this single pilot RCT was used in the base-case analysis due to the indirectness of the populations recruited in the FRUIT and TIPPS RCTs and also because of concerns regarding the dose used in the TIPPS study and the use of aspirin in the FRUIT study. However, scenario analysis was conducted using the meta-analysed estimate from all four papers reported by Middleton et al. 8

Relative risk of venous thromboembolism in women having postpartum prophylaxis

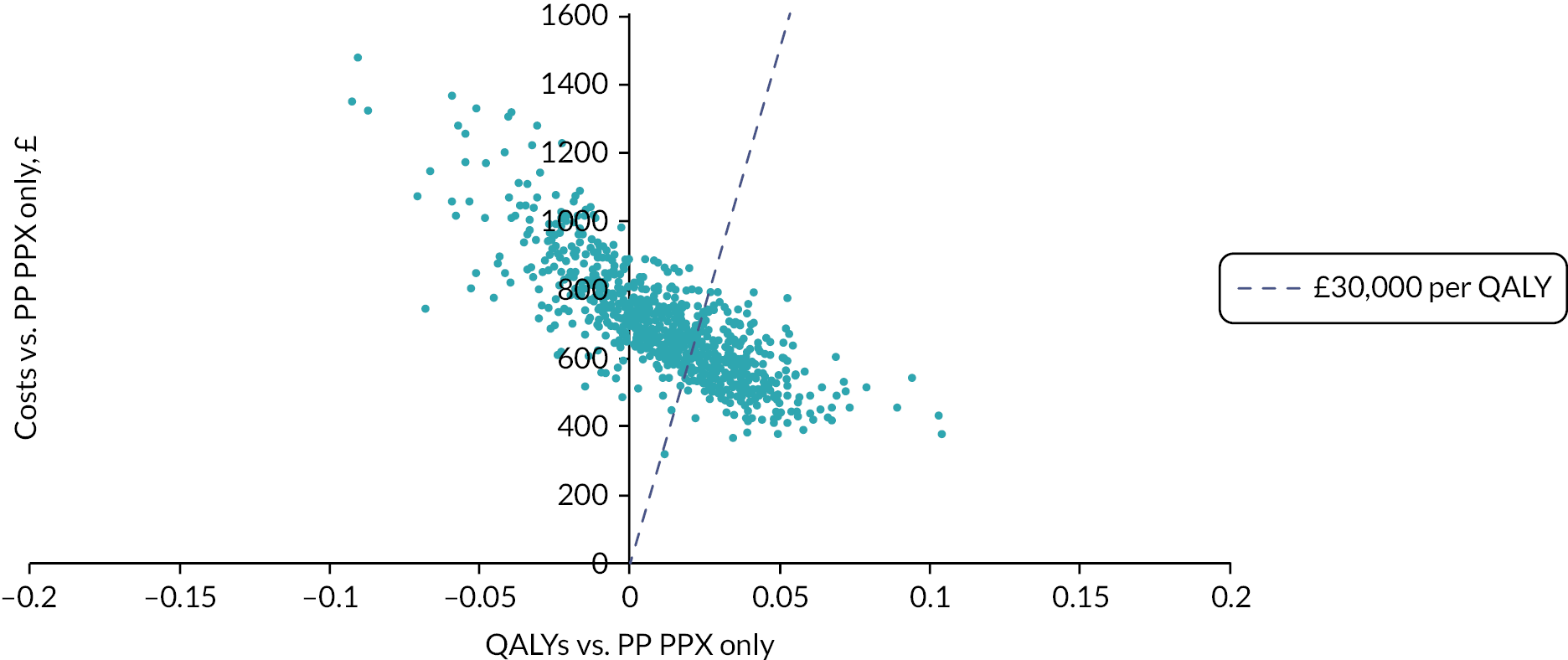

The updated Cochrane review reports a RR for VTE of 2.97 (95% CI 0.31 to 28.03) for LMWH versus no prophylaxis following caesarean section based on two studies. 67,68 Both of these were pilot studies. The dose used in one was lower than recommended in the RCOG guideline [2500 IU of dalteparin (Fragmin, Roche) daily for 4–5 days]. 68 For symptomatic DVT, an estimate of 1.40 (95% CI 0.17 to 11.55) is reported by Middleton et al. 8 based on two RCTs. 68,69 Two feasibility studies on postnatal prophylaxis in higher-risk postpartum women (low-risk thrombophilia, immobilisation or two or more risk factors) were also included in the updated Cochrane review (Rodger et al. 2015, 2016),18,19 but neither of these reported any VTE outcomes and both struggled to recruit. There is therefore a paucity of data on the efficacy of LMWH when used as postpartum prophylaxis and those studies that do exist estimate a higher risk of VTE compared with no LMWH, which is the opposite of what is expected based on studies in medical (RR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.67) and surgical cohorts [odds ratio (OR) = 0.26, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.87]. 47 To conduct EVPI analysis to estimate the value of future research, it is necessary to have some prior estimate of treatment efficacy even if that is based on indirect sources or expert consensus. In order to capture both our experience from other populations that LMWH is expected to reduce VTE, and the high degree of uncertainty in the efficacy of LMWH when used as postpartum prophylaxis, we decided to use the RR applied for antepartum prophylaxis (0.33, 95% CI 0.02 to 7.14).

It is unclear whether giving 10 days of LMWH provides protection from VTE for 10 days or for a longer period. Studies in general medical and surgical patients usually involve patients being offered LMWH during admission, or for a defined period such as 7 or 10 days and then they report the RR for VTE over a longer period such as 90 days post admission. Therefore, in these studies, the RR attributed to a short period of LMWH has been estimated over a longer time. Therefore, in previous models of thromboprophylaxis in medical and surgical in patients, the RR estimated from the meta-analyses of RCTs has been applied to the whole period at risk. 47 However, in this case, the RR has been taken from a study of antenatal prophylaxis in which LMWH was continued over the whole period at risk. It is therefore unclear whether the RR estimated in this setting should be applied to the whole 6 weeks over which patients are at risk of VTE, or just to the 10 days during which they received treatment. It was considered that giving 10 days of postpartum thromboprophylaxis would provide a risk reduction of VTE for longer than 10 days. This is because the development of clots occurs in the early postpartum period but may present symptomatically after 10 days, but not beyond 6 weeks postpartum. Given this uncertainty, we have assumed in the base-case scenario that risk falling in the first 3 weeks has the full treatment effect and risk falling beyond this has no treatment effect. This gives an average RR of 0.53 across the 6 weeks when applying a RR of 0.33 to risk falling in the first 3 weeks and a RR of 1 to risk falling from then up to 6 weeks. We have also conducted scenarios exploring the two extreme scenarios of having the RR apply to all 6 weeks and only the first 10 days. The proportion of the 6-week VTE risk falling within each time frame was estimated from the data provided by Sultan et al. 55 The RRs applied when assuming that the efficacy applies for 3 weeks (base case), 10 days (pessimistic scenario) and 6 weeks (optimistic scenario) are 0.53, 0.69 and 0.33, respectively.

Risk of major bleeding in women having antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis

A paper by Nelson-Piercy et al. reports the incidence of serious antepartum bleeds within their reporting of adverse events in a cohort of women having antenatal tinzaparin (Innohep®, LEO Pharma). 70 Serious was defined as ‘clinical events that: resulted in death; were life-threatening; required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation; resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity; were congenital anomalies/birth defects; were other medically important conditions’. The incidence was 3 in 1267 (0.24%), but this included 1013 women having LMWH as prophylaxis and 254 having LMWH as treatment for VTE. 70 Therefore, this may overestimate the risk of major antepartum bleeding for prophylaxis doses of LMWH as some women were having higher doses of LMWH for VTE treatment. All three of the serious bleeds were recorded as possibly, but not probably, related to LMWH. In a UK cohort, reported by Schoenbeck et al., one of the 91 women who received both antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis experienced major obstetric haemorrhage (placental abruption requiring caesarean section at full term) giving a major antepartum bleeding risk of 1%. 71 In contrast, Cox et al. reported four severe antepartum bleeds requiring urgent delivery in 98 pregnancies (4.08%) exposed to LMWH in a New Zealand cohort. 72 Therefore, the risks of antepartum major bleeding appear to vary greatly (0.24–4.08%). Some of this variation is likely to be due to inconsistent definitions of what constitutes major bleeding and some due to differences in the cohorts of women described.

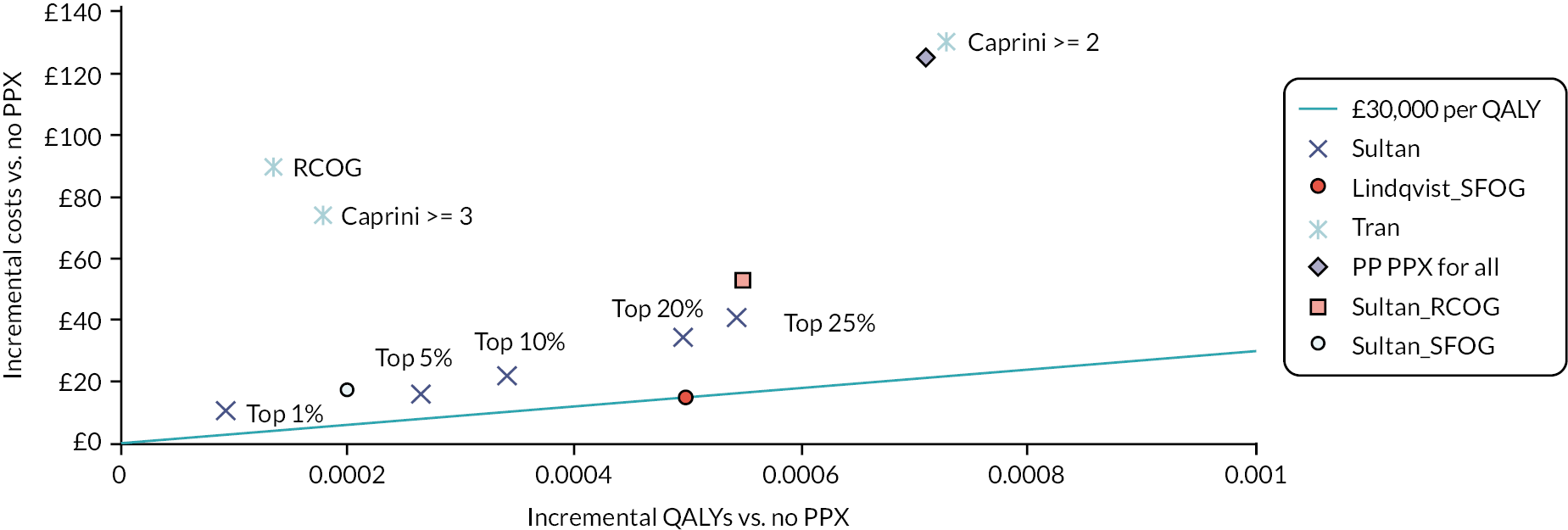

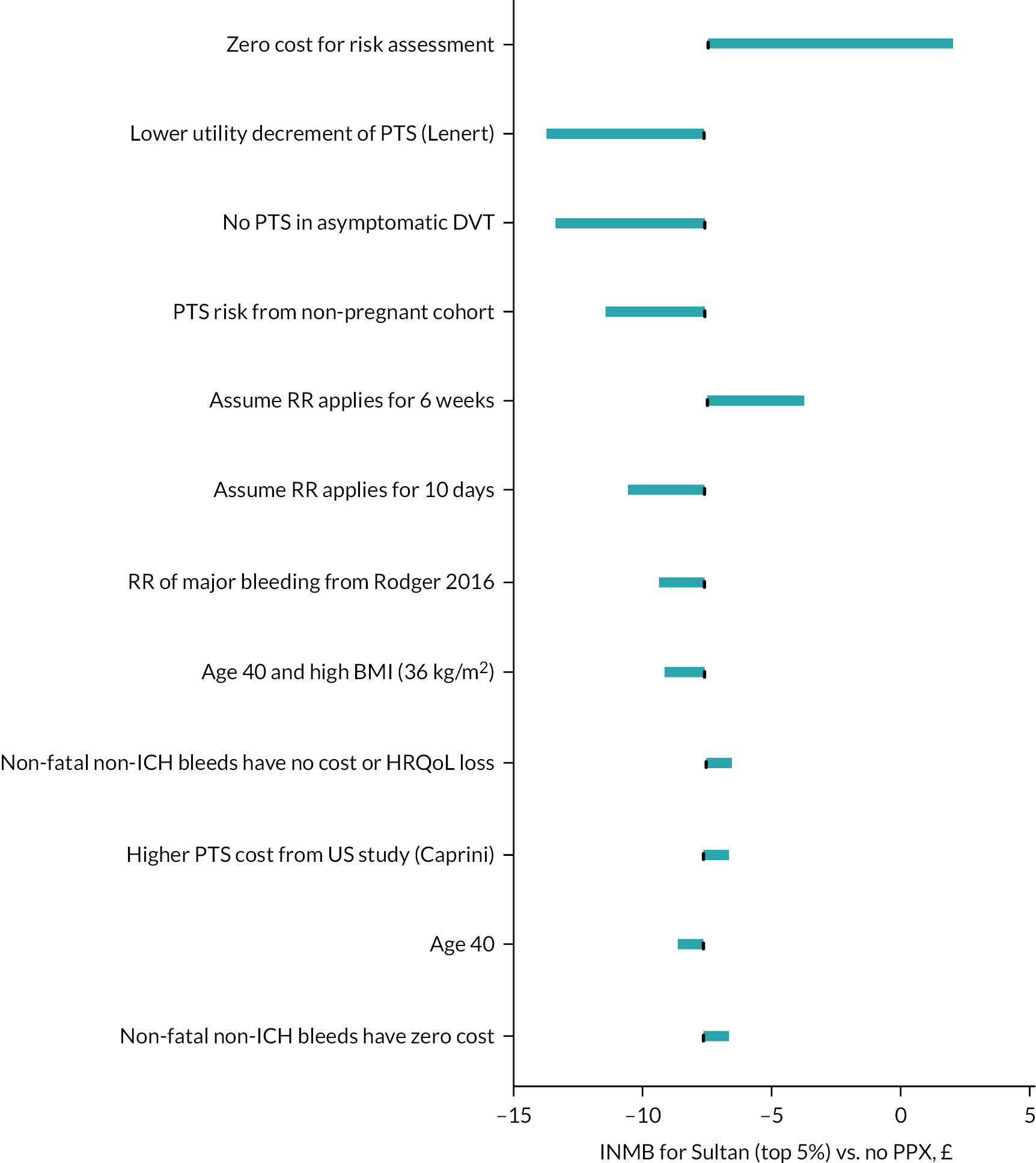

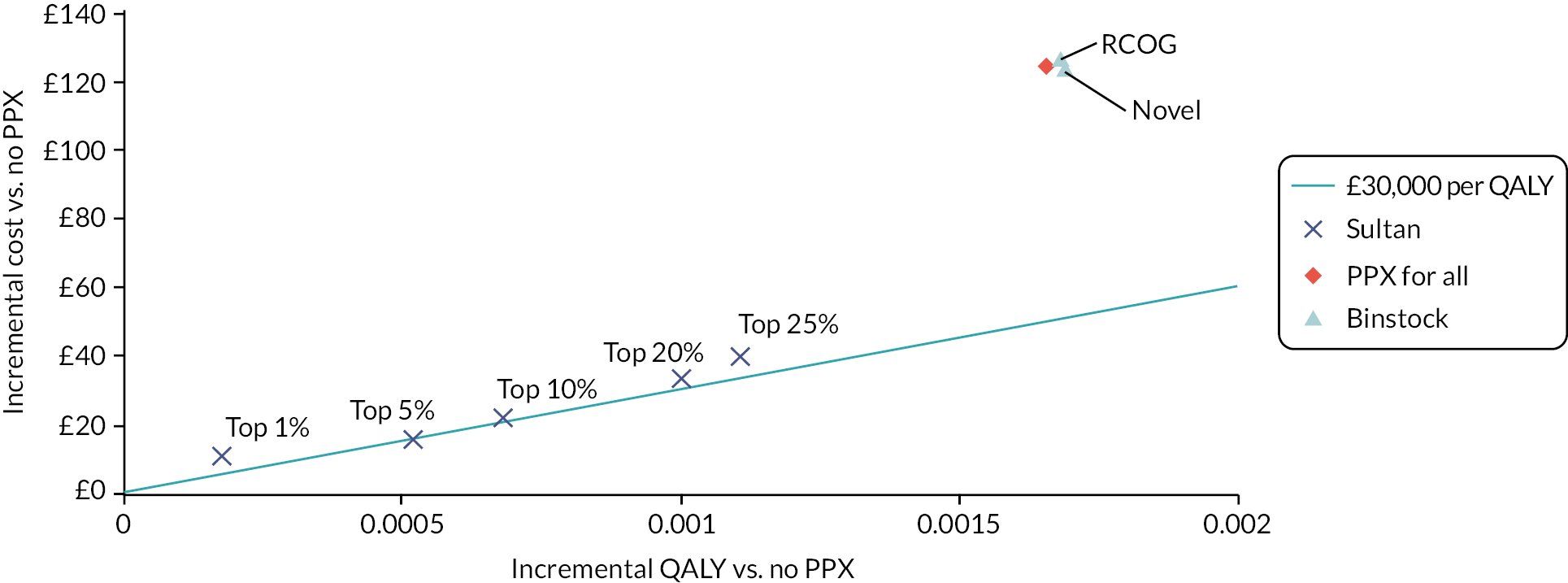

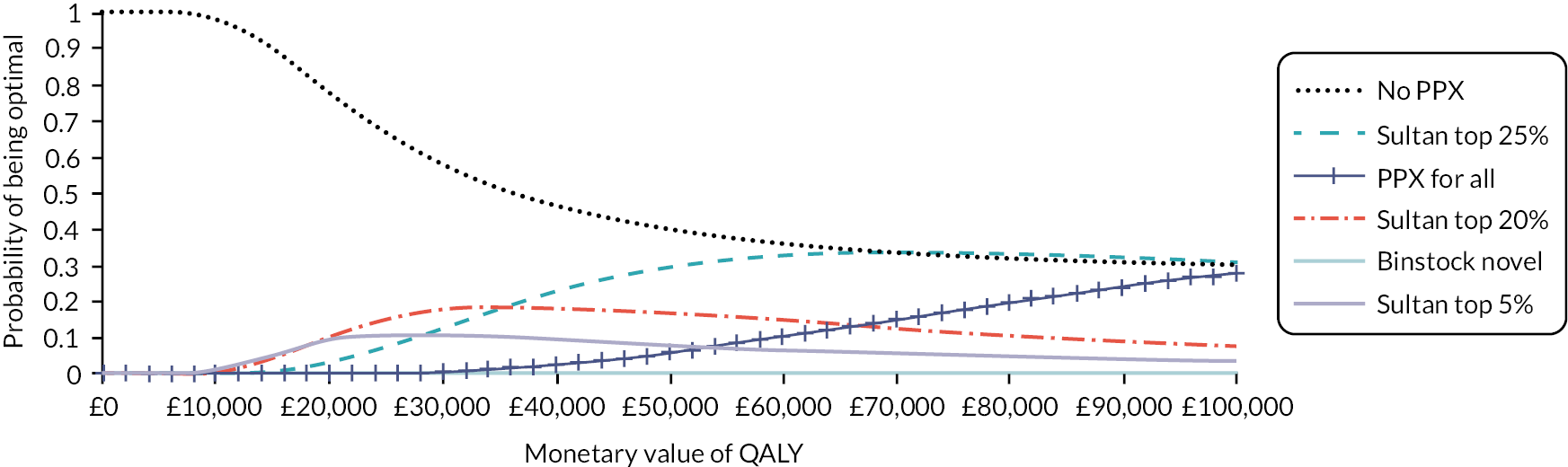

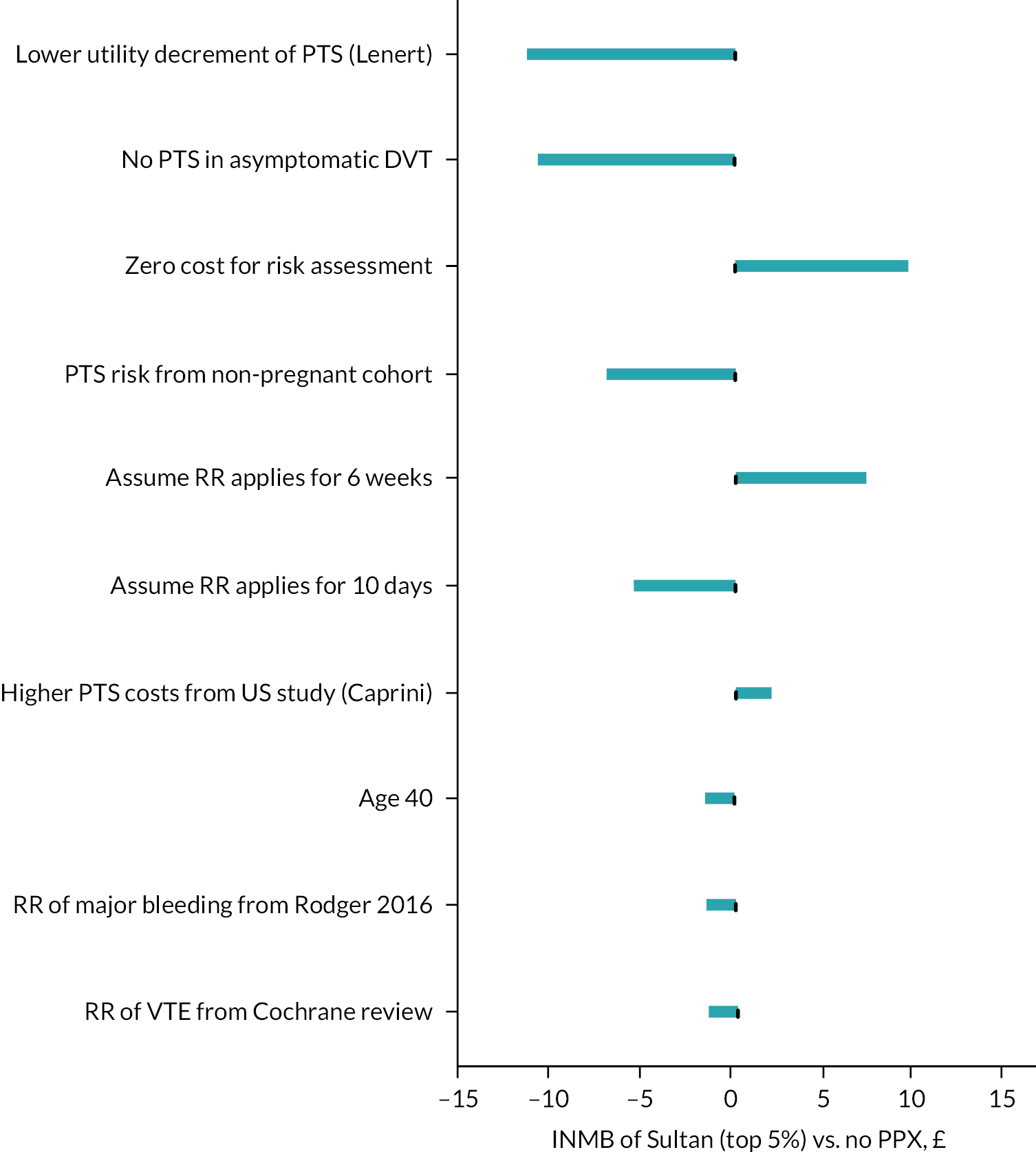

Tardy et al. conducted a review of RCTs of pregnant women having heparin to identify how RCTs have reported bleeding complications from heparin in the past. 48 Tardy et al. conclude, ‘at present it is impossible to estimate the rates and severities of either antepartum bleeding or primary PPH occurring during prophylactic treatment with heparin’. 48 They propose a definition for major bleeding in antepartum women that includes both the standard definition for major bleeding applied in medical inpatients and risks specific to pregnancy. 48,73 Although the definition proposed by the ISTH includes outcomes such as placenta previa requiring delivery and placenta abruption, it is unclear if these are likely to be causally related to the use of LMWH. Tardy et al. also state that antepartum bleeding due to placenta previa and placenta abruption is observed in 2–5% of all pregnancies in the absence of thromboprophylaxis. 48 We have applied the risk of serious antepartum bleeding from Nelson-Piercy et al. in the base case (0.24%), because it has been estimated in a large cohort of women receiving antenatal LMWH (N = 1267) and the definition of serious antepartum bleeding is specified. 70 However, given the uncertainty associated with this parameter, a range of major antepartum bleeding risk up to 4.08% is explored in sensitivity analysis to determine the significance of this parameter for decision-making.