Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/101/02. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The draft report began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Price et al. This work was produced by Price et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Price et al.

Chapter 1 Literature review

Literature reviews underpinning EDITION’s intervention development had the following objectives:

-

Investigate the effectiveness and acceptability of de-escalation training interventions.

-

Understand barriers and facilitators to adult acute and adult forensic mental health inpatient staff’s engagement in de-escalation of conflict.

Consequently, the following chapter is divided into two sections, the first meeting objective (1) and the second objective (2).

Review A: the effectiveness and acceptability of de-escalation training programmes for healthcare staff working in adult acute and forensic mental health inpatient settings

Rationale

The authors’ original systematic review of de-escalation training effectiveness and acceptability identified 38 eligible studies. 1 A lack of high-quality evidence limited conclusions as to the effectiveness of de-escalation training on clinical safety outcomes. This was an update of our previous review1 and was not registered with Prospero, but the review protocol can be accessed here: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/101/02.

Objective

To provide a rigorous and up-to-date synthesis of the evidence for the acceptability and effectiveness of de-escalation training for mental health staff.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included that met the following criteria:

Population: healthcare staff (qualified and unqualified) working with adult populations (18–65 years) with mental health difficulties.

Intervention: training with a de-escalation techniques component.

Comparison: all controlled studies meeting eligibility criteria, irrespective of their control condition. Comparisons of two or more active interventions or of an active treatment with a ‘no treatment’ comparator will be included.

Outcomes (effectiveness): changes in rates of conflict (e.g. violence, verbal and physical aggression) and use of restrictive interventions (e.g. seclusion and physical restraint) post training. Secondary outcomes were cognitive (e.g. knowledge), affective (e.g. confidence) and skills-based (e.g. de-escalation performance) changes in trainee performance.

Outcomes (acceptability): Defined, for the purpose of the review, as intervention uptake, adherence and participant satisfaction and views.

Design: randomised controlled trials (RCTs), nRCTs, controlled before-and-after (CBA) and interrupted time series (ITS) designs. All studies that (1) asked trainees or trainers for their views of interventions using qualitative or quantitative methods, and/or (2) studies that quantitatively assessed non-participation, withdrawal, or adherence rates.

Information sources

Searches were undertaken on the following electronic databases: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Social Services Abstracts, British Nursing Index (and archive), Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), PsycINFO, Cochrane Library (all sources), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) + SCIEXPANDED, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials. Grey literature including user-led projects, service evaluations, policy documents and third sector reports was sought from government and charity websites, the British National Bibliography for Report Literature and Google Scholar. All databases were searched from 1 month prior to the date of the searches conducted in the original review (August 2014) to the date of the new search date (12–16 October 2017).

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed using search terms relevant to the review objectives using the key concepts of mental health, staff attitudes, de-escalation, training and violence (full strategy available upon request). Searches were limited to English-language publications only. No other search restrictions were applied.

Selection process

All potentially eligible records were imported into Endnote version 9, where duplicate references were identified and deleted. The records were then uploaded to ‘Covidence’ (Melbourne, VIC, Australia), which is a systematic review-management software programme. Using Covidence, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full texts were retrieved when both reviewers agreed on inclusion or where there was a disagreement, the full-text article. Two reviewers independently assessed the full texts against the eligibility criteria and disagreements were resolved through discussion with the wider project team.

Data-collection process and data items

Data extraction from eligible studies by one reviewer then independently verified by another reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers with reference to the relevant paper and, where necessary, discussion with the wider project team. Data extraction was informed by a pre-specified data-extraction sheet detailing:

-

study information (author, date, country, study design, single/multisite)

-

recruitment (setting, method, inclusion/exclusion criteria)

-

intervention (intervention components and development, duration, frequency, facilitators, delivery methods, control/comparator)

-

participant characteristics (service users: age, gender, ethnicity; staff: professional status, experience, age, gender)

-

primary outcome (changes in the rate of conflict and restrictive interventions)

-

secondary outcomes (cognitive, affective and skill-based outcomes)

-

acceptability outcomes [quantitative: % drop-out, number of staff approached, number consented, response rate, adherence (number of sessions attended); qualitative: participant satisfaction, views of intervention, any other qualitative comments].

Risk of bias assessment

Evidence of clinical effectiveness was quality assessed by two independent researchers using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. 2 Qualitative acceptability evidence was assessed by two independent researchers using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) criteria for qualitative research. 3

Effect measures and synthesis methods

Because of the heterogeneity of study designs and outcome measures in the included studies, and because of the small number of studies providing data for the primary and secondary outcomes, meaningful pooling of quantitative data was not possible. Narrative syntheses of clinical effectiveness and acceptability were, therefore, conducted in parallel. Quantitative effectiveness data were tabulated by review outcome (changes in rates of conflict, changes in rates of containment, cognitive, affective and skills-based) and Cohen’s d Standardised Effect Sizes were calculated for all studies except those not reporting means and standard deviations (SDs) or those that omitted the outcome of a statistical test. Quantitative and qualitative acceptability were analysed separately. Quantitative acceptability data were tabulated and synthesised within the following theoretically important outcomes: percentage drop-out, number of staff approached, number consented, response rate, adherence (number of sessions attended). Due to the sparsity of qualitative acceptability data available, no formal qualitative analysis was possible. As such the limited qualitative comments on participant views on training were organised into related themes and synthesised into brief narratives for each theme.

Results

Search results

All eligible results (n = 3309) were imported into Endnote version 9 where duplicate references were identified and removed, resulting in 2774 papers to be screened for eligibility. Twenty-nine results were eligible for retrieval of full texts. Of these, 21 were excluded (8 wrong intervention, 5 wrong population, 4 wrong study design, 2 wrong setting, 2 wrong language) leaving 8 new papers eligible for inclusion in the updated review. These eight papers were combined with the 38 studies from our original and 46 studies were included in the synthesis.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 46 included studies are presented in Table 1. Of the included studies, 12 used non-randomised controlled studies, two used retrospective cohort study designs, 27 used uncontrolled pre and post designs and 10 reported qualitative findings (five of which reported only qualitative findings). No RCTs were identified in the search.

| Author (date) | Country | Study design | Single vs. multisite | Setting | Sample size | Outcome measures | Statistical analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azuela and Robertson (2016)4 | New Zealand | Uncontrolled pre and post (repeated measures) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = not reported) | 23 mental health professionals Baseline: n = 23 Follow-up: n = 23 |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of knowledge, skills and attitudes |

Multivariate analysis of variance |

| Beech and Leather (2003)5; Beech (2008)6 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | University setting | 243 undergraduate nursing students (numbers at baseline and follow-up points not reported) | Primary outcome Study-specific measure of attitudes, beliefs and confidence |

Paired sample t-tests |

| Beech (2001)7 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | University setting | 53 undergraduate nursing students (numbers at baseline and follow-up points not reported) |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of attitudes |

Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank |

| Biondo (2017)8 | USA | Mixed methods (qualitative study and post training survey) | Single | University setting | 73 postgraduate mental health nursing students | Primary outcome Study-specific measure of empathy, skills and self-efficacy |

Descriptive statistics |

| Bjorkdahl et al. (2013)9 | Sweden | Uncontrolled pre and post (time series) | Multi | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = 41) | Baseline: 854 ward staff Follow-up: 260 ward staff |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of emotion regulation |

Mann–Whitney U-test |

| Bowers et al. (2006)10 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post | Multi | Acute admission psychiatric wards (n = 2) | Baseline: 254 shift reports Follow-up: 1315 shift reports Baseline: (n = 28 staff) Follow-up: (n = 30 staff) Baseline: (n = 31 staff) Follow-up: (n = 26 staff) Baseline: (n = 39 staff) Follow-up: (n = 32 staff) |

Primary outcome PCC-SR11 Secondary outcomes APPQ12 MBI13 WAS14 |

One-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests Independent samples t-tests |

| Bowers et al. (2008)15 | UK | Non-RCT | Multi | 8 acute psychiatric wards (3 experimental, 5 control wards) | 2074 shift reports (experimental wards) 3242 shift reports (control wards) |

Primary outcome PCC-SR11 |

Ordinal logistic regression |

| Calabro et al. (2002)16 | USA | Uncontrolled pre and post (repeated measures) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = 12) | 118 ward staff Baseline: n = 118 ward staff Follow-up: n = 118 |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy and behavioural intention |

Paired t-tests |

| Carmel and Hunter (1990)17 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = 27) | 9 trained wards 18 untrained wards |

Primary outcome Staff injuries |

Not reported |

| Chigbundu (2015)18 | USA | Qualitative study | Single | Acute mental health inpatient setting | 16 mental health nurses | N/A | N/A |

| Collins et al. (1994)19 | Scotland | Uncontrolled pre and post (repeated measures) | Single | University setting | Mixed sample of 26 undergraduate student nurses and ward staff. Baseline n = 26 Follow-up: n = 23 |

Primary outcome Attitude to aggressive behaviour questionnaire19 |

Descriptive statistics |

| Collins (2014)20 | USA | Qualitative study | Single | Non-specified psychiatric hospital | 7 ward staff | N/A | N/A |

| Cowin et al. (2003)21 | Australia | Uncontrolled pre and post (time series) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric unit | 40 mental health nurses Baseline: 21 mental health nurses Follow-up: 19 mental health nurses |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of knowledge and attitudes |

Analysis of variance |

| Davies et al. (2016)22 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post (time series) | Single | Medium secure psychiatric forensic unit | Baseline: 79 ward staff Follow-up: 67 ward staff |

Primary outcome Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument23 |

Paired t-tests |

| Geoffrion et al. (2017)24 | Canada | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Psychiatric intensive care and psychiatric emergency | 2 units (routinely collected data in both units) | Primary outcome Seclusion and restraint incidence |

Regression (no further information provided) |

| Gertz (1980)25 | UK | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric setting | 1 unit (routinely collected data) | Primary outcome Assaults |

Descriptive statistics |

| Goodykoontz and Herrick (1990)26 | USA | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric setting | Not reported | Primary outcome Burnout Scale27 |

Descriptive statistics |

| Grenyer et al. (2003)28 | Australia | Uncontrolled pre and post (repeated measures) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric setting | 34 ward staff Baseline: 34 Follow-up: 34 |

Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument23 Attitude to aggressive behaviour questionnaire19 (No primary outcome specified) |

Paired t-tests |

| Hahn et al. (2006)29 | Switzerland | Non-RCT | Multi | Acute psychiatric wards (n = 6) | Experimental group: 29 mental health nurses Control group: 34 mental health nurses |

Primary outcome Management of Aggression and Violence Attitude Scale30 |

Wilcoxon signed rank test for matched pairs |

| Ilkiw-Lavalle et al. (2002)31 | Australia | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Multi | Acute psychiatric units (n = 3) | 103 mental health staff (mixed sample of professionals and ward staff) Baseline: n = 103 Follow-up: n = 103 |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of knowledge |

Paired t-tests |

| Infantino and Musingo (1985)32 | USA | Non-RCT | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient setting | Experimental group: 31 ward staff Control group: 65 ward staff |

Primary outcome Injuries and assault frequency (No primary outcome specified) |

Not reported |

| Jonikas et al. (2004)33 | USA | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient units (n = 3) | Routinely collected incidence data from 3 units 6 months pre and post training | Primary outcome Physical restraint |

Two-way analysis of variance |

| Laker et al. (2010)34 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Psychiatric intensive unit (n = 1) | Routinely collected incidence data from one unit 12 months pre and post training | Primary outcome Incidents requiring de-escalation or restraints |

Poisson regression |

| Lee et al. (2012)35 | UK | Retrospective cohort study | Multi | PICU (n = 5) | n = 3 ‘SCIP’ trained units n = 2 control and restraint trained wards |

Primary outcome Incidence of ‘disturbed behaviour’ |

Poisson regression |

| Martin (1995)36 | USA | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient setting | Routinely collected incidence data in one psychiatric unit 12 months pre and post training | Aggression frequency Aggression severity (No primary outcome specified) |

Descriptive statistics |

| Martinez (2017)37 | USA | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Single | University setting | 15 undergraduate mental health nursing students | Study-specific measure of knowledge Mental health nurse clinician confidence scale38 (No primary outcome specified) |

Paired t-tests |

| McIntosh et al. (2003)39 | USA | Non-RCT | Multi | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient setting (n = 2) | Experimental group: 56 mental health professionals Control group: 34 mental health professionals |

Primary outcome Self-efficacy scale40 |

One-tailed t-test |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010)41 | UK | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Single | Acute psychiatric wards (n = 1) | 18 ward staff | Primary outcome Verbal aggression measure41 |

Descriptive statistics |

| Moore (2010)42 | USA | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient setting (n = 2) | Incident data collected 12 months pre and post training | Primary outcome Moore Safety Code Team Analysis Tool42 |

Descriptive statistics |

| Nau et al. (2009)43 | Germany | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Single | School of nursing | 68 students (unclear proportion retained at follow-up) | Primary outcome Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument23 |

Wilcoxon |

| Nau et al. (2010)44 | Germany | Non-RCT | Single | University setting | Experimental group: 52 undergraduate nursing students Control group: 52 undergraduate nursing students |

Primary outcome DABS45 |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test (differences within groups) and Mann–Whitney test (differences between groups) |

| Nau et al. (2011)46 | Germany | Non-RCT | Single | University setting | Experimental group: 52 undergraduate nursing students Control group: 52 undergraduate nursing students |

Primary outcome Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument23 |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test (differences within groups) and Mann–Whitney test (differences between groups) |

| Needham et al. (2004)47 | Switzerland | Uncontrolled pre and post | Multi | Acute psychiatric wards (n = 2) | 273 aggressive incidents | The Staff Observation Aggression Scale–Revised (SOAS-R)48 | Chi-squared tests were employed to compare incidence rates of events, using hospitalisation days as the unit of analysis. The severity of aggression was compared across periods by the Student’s t-test |

| Needham et al. (2005)49 | Switzerland | Non-RCT | Multi | University setting | Experimental group: 57 Control group: 60 |

Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument23 The SOAS-R48 (No primary outcome specified) |

Univariate analysis of variance across three time points |

| Nijman et al. (1997)50 | Netherlands | Non-RCT | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = 3) | Experimental group: n = 2 wards Control group: n = 1 ward |

Primary outcome SOAS-R48 |

Not reported |

| Paterson et al. (1992)51 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Not reported | 25 mental health nurses (how many completed pre and post measures was not clearly reported) | Study-specific measure of knowledge Study-specific measures of de-escalation performance and job satisfaction. General Health Questionnaire52 (No primary outcome specified) |

t-test Wilcoxon test Wilcoxon test |

| Rice et al. (1985)53 | Canada | Non-RCT | Single | One maximum security forensic psychiatric hospital | Experimental group: 62 ward staff Control group: 37 ward staff |

Primary outcome Study-specific measures of knowledge, confidence and performance Secondary outcomes Assault frequency Use of PRN (extra) medicines |

Simplified time series analysis designed for studies with relatively few observations 2 × 2 repeated measures analyses of variance in which the factors were Group (experimental and control), and Time (pre and post course) |

| Robinson et al. (2011)54 | Australia | Mixed methods (qualitative study and uncontrolled pre and post) | Single | One mental health service | Baseline: 24 participants Follow-up: 24 participants |

Perceived self-efficacy scale55 (No primary outcome specified) |

Paired t-tests |

| Sjostrom et al. (2001)56 | Sweden | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient setting | 386 aggressive incidents | Social Dysfunction Aggression Scale57 SOAS-R48 (No primary outcome specified) |

Cox proportional hazards models |

| Smoot and Gonzales (1995)58 | USA | Non-RCT | Multi | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = 2) | Routinely collected incidence data 6 months pre and post training | Primary outcome Assault frequency |

Descriptive statistics |

| Taylor and Sambrook (2012)59 | UK | Uncontrolled pre and post (time series) | Single | Non-specified psychiatric inpatient wards (n = 1) | Routinely collected incidence data 8 months pre and post training. MBI sample size not reported |

Frequency of ‘challenging behaviour’ MBI13 (No primary outcome specified) |

Two-tailed Fisher’s exact p = 0.011 MBI scores descriptive only |

| Thackrey et al. (1987)23 | USA | Non-RCT | Multi | Mixed settings: general psychiatric hospitals (n = 2) and one forensic hospital (n = 1) | Experimental group: 68 health professionals and paraprofessionals Control group: 57 health professionals and paraprofessionals |

Primary outcome Confidence in Coping with Patient Aggression Instrument23 |

Not reported |

| Whittington and Wykes (1996)60 | UK | Non-RCT | Multi | General psychiatric hospitals (n = 2) | Experimental group: 47 members of nursing staff (89% registered nurses) Control group: 108 members of nursing staff (71% registered nurses) |

Primary outcome Assaults directly reported to researchers via daily telephone contacts with ward staff |

Comparisons between groups were evaluated using chi-squared tests of association and changes within groups using the McNemar change test |

| Wondrak and Dolan (1992)61 | UK | Non-RCT | Single | University setting | Experimental group: 14 undergraduate nursing students Control group: 15 undergraduate nursing students |

Primary outcome Study-specific measure of de-escalation performance |

Repeated measures t-tests |

| Yang et al. (2014)62 | USA | Uncontrolled pre and post | Single | Acute psychiatric inpatient unit | Routinely collected incidence data 6 months pre and post training | Primary outcome Seclusion and restraint frequency |

Hierarchical logistic regression |

Risk of bias assessment

According to (ROBINS-I), 18 studies were assessed to be at moderate risk of bias and 21 presented a serious risk (Table 2). The 10 qualitative studies met between 6 and 24 COREQ items (Table 3).

| Study | Selection bias | Intervention classification | Adherence | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selective reporting | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azuela et al. (2016)4 | Moderate | Moderate | Not reported | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Beech et al. (2003; 2008)5,6 | Serious | Low | Serious | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Beech (2001)7 | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Bjorkdahl et al. (2013)9 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bowers et al. (2006)10 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Bowers et al. (2008)15 | Serious | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Calabro et al. (2002)16 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Carmel et al. (1990)17 | Low | Low | Low | Not reported | Not reported | Low | Low |

| Collins et al. (1994)19 | Low | Serious | Low | Moderate | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Cowin et al. (2003)21 | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Davies et al. (2016)22 | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious | Low | Serious |

| Geoffrion et al. (2017)24 | Serious | Moderate | Not reported | Not reported | Moderate | Serious | Serious |

| Gertz (1980)25 | Critical | Critical | Critical | Critical | Critical | Critical | Critical |

| Goodykoontz et al. (1990)26 | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Grenyer et al. (2003)28 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Not reported | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Hahn et al. (2006)29 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Ilkiw-Lavalle et al. (2002)31 | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Infantino et al. (1985)32 | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Serious |

| Jonikas et al. (2004)33 | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Laker et al. (2010)34 | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Lee et al. (2012)35 | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Martin (1995)36 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Martinez (2017)37 | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| McIntosh et al. (2003)39 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010)41 | Moderate | Low | Not reported | Not reported | Moderate | Serious | Serious |

| Moore (2010)42 | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Low | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Nau et al. (2009)43 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Nau et al. (2010)44 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Nau et al. (2011)46 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate |

| Needham et al. (2004)47 | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious | Low | Serious |

| Needham et al. (2005)49 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Not reported | Serious | Moderate | Moderate |

| Nijman et al. (1997)50 | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Paterson et al. (1992)51 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Not reported | Not reported | Serious | Moderate |

| Rice et al. (1985)53 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Moderate |

| Robinson et al. (2011)54 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Sjostrom et al. (2001)56 | Serious | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Smoot et al. (1995)58 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Taylor et al. (2012)59 | Serious | Serious | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Thackrey et al. (1987)23 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Whittington et al. (1996)60 | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Wondrak et al. (1992)61 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Yang et al. (2014)62 | Moderate | Serious | Not reported | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Study | Research team and reflexivity | Study design | Analysis and findings | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biondo (2017)8 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 13 |

| Chigbundu (2015)18 | 4 | 13 | 7 | 24 |

| Collins (2014)20 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 21 |

| Gertz (1980)25 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Goodykoontz and Herrick (1990)26 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Ilkiw-Lavalle et al. (2002)31 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Martinez (2017)37 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 13 |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010)41 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Nau et al. (2009)43 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 13 |

| Robinson et al. (2011)54 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

Intervention intensity and content

The included studies considered interventions that varied widely in terms of content and the setting in which they were delivered. Of the 45 studies, seven studies did not provide enough detail to accurately categorise the content of training (see Report Supplementary Material 1, SM1.1). Training duration ranged from 1.5 hours to 6 weeks.

Primary outcome

Rates of conflict

In total six studies of moderate quality provided outcome data related to rates of conflict. One study measured impact of training on conflict broadly (including aggression, self-harm, absconding, rule-breaking, medication refusal, drug and alcohol use) and found a significant effect (effect size (ES) 0.13) in reducing conflict. 10 This finding represented a 44% decrease in verbal aggression, a 53% decrease in physical aggression, a 72% decrease in self-harm and a 43% reduction in absconding attempts. 10 However, when this study was repeated using a controlled design, no effects on conflict outcomes were detected. 15

Another study reported reductions in patient assaults post training but did not test significance. 58 Two studies measured patient assault-related injuries. One found a reduction but did not test significance16 and the other found a statistically significant reduction in rate of injuries, although the effect size was not calculable. 17 Two studies found negative effects of training in relation to assaults on staff. One study measured impact of training on what they referred to as ‘disturbed behaviour’ (defined as any untoward incident involving patient behaviour that met the threshold for incident reporting) and found a non-significant negative effect of training between intervention and control wards. 35 The hazard ratio for staff assaults in the de-escalation training arm of the study was 48% higher than for staff in the usual care arm (control and restraint training). 35 One study found a significant, medium-sized effect (0.64) increasing rates of assaults post training, attributed to increased patient acuity in the follow-up period. 53

In total, 12 weak-quality studies provided outcome data related to rates of conflict. One study, again, measured conflict broadly and found no statistically significant difference in rates between trained and untrained wards. 15 One study found a significant overall reduction in conflict59 but the omission of SD prevented calculation of effect size. One study only referred to the measurement of ‘incidents’ but did not define what this meant or test the significance of a reported reduction in frequency post training. 26 Two studies found statistically significant reductions in assaults compared with control conditions, one study measuring rates at ward level47 and one following up individual trainees. 32 Neither study reported the required statistics to calculate effect sizes. Two studies found reductions in patient assaults compared with control conditions but neither reached statistical significance. 34,60 One study found a reduction in assaults comparing 12 months pre and post training but did not test significance. 25

Two studies measured aggression, incorporating verbal and physical aggression and, again, both found reductions compared with control conditions that did not reach statistical significance. 50,56 One study measured actual and threatened physical aggression separately and found a negligible reduction in actual aggression and an increase in threatened aggression although the statistical significance of neither finding was reported. 36 One study measured verbal aggression alone and reported a reduction without evaluating statistical significance. 41

Rates of containment

In total, four studies of moderate quality provided outcome data on rates of containment. One uncontrolled pre and post study measured impact of training on rates of ‘restraint’ (definition limited to ‘physical restraint’ interpreted as ‘manual restraint’ excluding seclusion or mechanical or chemical restraint). They found a significant reduction in frequency of restraint usage at 3 months (representing an 85% decrease) and 6 months (99% decrease) follow-up which was maintained at 9 and 12 months. 33 Two studies found no effect on containment use. One study measured containment broadly including manual restraint, seclusion, rapid tranquilisation, time out, PRN (extra psychotropic medicines), transfer to psychiatric intensive care, special observations (intermittent or continuous) and show-of-force and found no reduction associated with training. 10 The other moderate-quality study reporting no effect measured impact on PRN only. 53

In total, five studies of weak methodological quality provided outcome data on rates of containment. One uncontrolled pre and post study in two wards measured impact of training on frequency and duration of ‘restraint’ (definition included manual and mechanical restraint) and ‘seclusion’ (defined as confinement of a patient in a ward area from which they cannot freely leave). Both the number and duration of restraint and seclusion episodes in the training period (10 months) and in the post-training period (21 months) were significantly reduced compared with the pre-training period (21 months). 24 Because of the omission of SDs in their reporting, calculations of effect sizes were not possible. One study, which again used the broad definition of ‘containment’, measured rates pre and post training using a controlled design (three training wards and five control (no intervention) wards). 15 On the intervention wards there was a significant, medium-sized (0.33) pre and post reduction in containment. There was no overall difference in containment detected between intervention and control wards but there were two significant effects detected at individual containment item level (‘PRN’ and ‘Transfer to PICU’). No SDs were reported for the comparisons with control wards for these two items, so we were unable to calculate effect sizes.

An uncontrolled pre and post study in two wards measured the effect of training on ‘coercive measures’ but did not provide further definition. 47 They found a significant reduction in rates of coercive measures between the pre-training period (3 months) and the post-training period (3 months). However, because of the lack of reported means and SDs, no effect size calculation was possible. An additional, uncontrolled pre and post study measured rates of manual restraint and rapid tranquilisation associated with training. 34 They found a significant reduction in both manual restraint (0.4) and rapid tranquilisation (0.52) after training, once differences in patient demographics between pre and post periods (6 months pre, 6 months post training) were adjusted for. However, the confidence intervals (CIs) for these effects were wide (manual restraint CI 0.17 to 0.94; rapid tranquilisation CI 0.23 to 1.21). The final study, rated as methodologically weak, was an uncontrolled pre and post study in a single ward, which measured rates of ‘restraint’ and ‘seclusion’ (no more specific definition provided for either) associated with training. 62 They found a small (self-reported, the necessary statistics for calculation were omitted) non-significant effect of training in reduced rates of both seclusion and restraint.

Secondary outcomes

Cognitive outcomes

Knowledge outcomes: In total, five studies of moderate methodological quality provided outcome data on changes in trainee knowledge following training. Four of these studies found significant improvements post training. 16,31,51,53 Two of these studies provided sufficient statistical information to calculate effect sizes: one reported a medium-sized effect (0.73)16 and one reported large effects (effect sizes ranged from 1.13 to 2.2 between different staff subgroups). 31 One study did not assess the significance of reported improvements in trainee knowledge. 28 Although these studies rated as moderate methodological strength according to the ROBINS-I, there were some specific problems with measurement that should be considered in the interpretation of training impact on this outcome. All five studies developed study-specific scales to measure knowledge outcomes and only one study provided any robust evidence of internal consistency and reliability [Ilkiw-Lavelle31 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.86)].

In total, six studies of weak methodological quality provided outcome data on changes in trainee knowledge. 5,19,21,36,37,41 Only two studies measured the significance of changes: one found a significant effect of training, but effect size calculation was not possible owing to the omission of a SD. 5 The other found a non-significant improvement in knowledge. 21 No weak study tested the internal consistency of their measure of de-escalation knowledge.

Affective outcomes: In total, 15 studies of moderate methodological quality and 11 studies of weak methodological quality reported on changes associated with trainee affective outcomes associated with training. These studies measured a range of relevant outcomes relating to emotion regulation, confidence and self-efficacy, fear and anxiety, attitudes, stress and burnout and empathy.

Emotion regulation: One moderate-quality study measured ‘emotion regulation’ which they defined as ‘awareness and control of feelings, especially fear and anger’ (p. 398)9 and found a significant, large effect (2.24) of training in enhancing this outcome (follow-up measurements were conducted between 3 and 6 months post training). Two weak studies measured emotion regulation outcomes. One weak study61 used a non-randomised controlled design and measured emotion regulation immediately pre and post training in role-play scenarios. They used an observer rated scale [including the following subscales: ‘calm’, ‘upset’, ‘angry’, ‘relaxed’, ‘defensive’ (p. 111)] and a self-report scale [including the following subscales: ‘anger’, ‘upset’, ‘anxiety’, ‘in control’ (p. 109)]. They found significant and large (0.76–5.24) pre-and-post effects of training on observer-rated items including ‘relaxed’, ‘defensive’, ‘upset’ and ‘calm’ but no significant change on ‘angry’. However, there were significant, medium to large (0.69–2.81) effects observed in the control group on ‘relaxed’ and ‘upset’, indicating a significant impact of practice effects on emotion regulation. No between-group analysis was conducted. In terms of self-report outcomes, they found significant, large effects in the trained group (0.79–1.5) on ‘anger’ and ‘in control’. There were no significant self-rated changes in the control group.

The other weak study measuring emotion regulation7 used an uncontrolled pre and post design and measured the following item related to emotion regulation (of a 20-item questionnaire measuring attitudes to aggression in student nurses): ‘When a patient gets aggressive, I get so nervous I can hardly think straight’ (p. 208). They found no effect of training on this item. Of the three studies measuring emotion regulation outcomes, only Bjorkdahl et al. 9 provided any evidence of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83).

Confidence and self-efficacy: Nine moderate-quality studies measured either trainee confidence16,23,28,43,46,49,51,53 or self-efficacy. 39 Five of these were non-randomised controlled studies23,39,46,49,53 and four uncontrolled pre and post studies. 16,28,43,51 Five studies measured these outcomes only immediately pre and post training. 16,28,46,51,53 Four studies included an additional longer-term follow-up, one at 2 weeks post training,43 one at 8 months,49 one at 6 months post training39 and one at 18 months. 23 All nine studies reported improvements in these outcomes associated with training at follow-up, eight found statistically significant improvements and one study53 failed to assess the significance of the improvement. Four studies provided the necessary statistical information to calculate effect sizes and, of these, three produced small effects (range 0.19–0.34)16,28,39 and one a large effect (0.87). 46 Improvements in confidence were retained in all studies that included a longer-term follow-up. 23,39,43,49

Nine studies of weak methodological quality provided outcome data related to confidence or self-efficacy. Eight measured confidence6,7,19,22,26,36,37,41 and one measured self-efficacy. 54 All nine studies used uncontrolled pre and post designs. Six studies measured these outcomes immediately pre and post training7,22,26,37,41,54 and three studies included longer-term follow-up time points. One study had an additional follow-up at 6 months,19 one study had four time points across 8 months (two pre, two post training, no more specific detail provided)6 and the final study measured confidence 12 months pre and post training. 36 All nine weak studies found improvements in confidence or self-efficacy but only five assessed significance6,7,22,37,54 and the statistical reporting in these five studies did not allow for effect size calculation. All three weak studies including longer-term post-training follow-ups found that improved confidence had been retained. 6,19,36 Of the 18 studies measuring confidence or self-efficacy outcomes, nine used validated measures,16,22,28,37,39,43,49,53,54 with Cronbach’s alphas ranging between 0.7153 and 0.97. 39

Fear and anxiety: Two moderate-quality studies measured outcomes related to staff fear or anxiety. 39,44 Both were non-randomised, controlled studies. One study measured these outcomes immediately pre and post training44 and the other measured pre and post and included an additional 6-month follow-up time point. 39 McIntosh39 measured ‘anxiety arousal’, which was defined as the level of concern about patient-perpetrated violence experienced by staff at work, and found no effect of training on this outcome post training or at 6 months follow-up. Nau et al. measured ‘fear’ (no further description provided) as a subscale of the observer-rated DABS. 44 They found significantly reduced fear from pre and post within trained subjects as well as between trained and untrained groups. The statistical reporting did not permit calculations of the sizes of these effects.

One weak-quality study measured outcomes related to staff fear. This study adopted a non-randomised uncontrolled design36 and measured ‘Fear when managing aggressive or potentially aggressive patients’ (p. 212) 12 months pre and post training. They found reduced fear at 12 months but failed to assess the significance of this reported effect. Two out of three studies measuring fear or anxiety outcomes provided evidence of the internal consistency of scales used. Nau et al. 44 reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 for the DABS scale and McIntosh (2003) reported a Cronbach’s alpha or between 0.88 and 0.97 for the Self-efficacy scale. 39

Attitudes: Six moderate-quality studies measured outcomes related to trainee attitudes. 4,10,16,28,29,49 Two of these were non-RCTs29,49 and four adopted uncontrolled pre and post designs. 4,10,16,28 Five studies measured attitudes immediately pre and post training, with only one study including an additional 3-month follow-up. 49 Three studies measured trainee attitudes to patient aggression,28,29,49 two studies measured attitudes to using de-escalation4,16 and one study measured trainee attitudes to personality disorder. 10

Two moderate-quality studies reported significant effects of training in improving trainee attitudes to aggression. 28,49 Grenyer et al. 28 found significant effects of training on four of eight subscales of the ‘Attitudes to Aggressive Behaviour Questionnaire’, with effect sizes ranging between 0.33 and 0.97. Needham et al. 49 found a significant effect (sample size calculation was not possible due to statistical reporting) of training on a visual analogue scale which measured positive and negative attitudes towards patient aggression, but no effect of training on the ‘Perception of Aggression Scale’. One study found no effect of training on trainee attitudes. 29 Both studies measuring attitudes to using de-escalation found significant effects of training;4,16 a medium effect size of 0.39 was calculable for one of these studies. 16 The only study measuring attitudes to personality disorder found no effect of training. 10

Three weak-quality studies measured outcomes related to trainee attitudes. 19,41,47 All three studies used uncontrolled pre and post designs and all measured attitudes to patient aggression immediately pre and post training, except Collins,19 who included an additional 6-month follow-up time point. Only Needham et al. 47 found a significant effect of training on ‘Subjective perceptions of the severity of aggressive incidents’ (effect size calculation was not possible). Only three of nine studies measuring trainee attitudes provided a rigorous test of internal consistency. 16,29,49

Cronbach’s alphas for the Management of Aggression and Violence Scale (MAVAS) ranged from 0.25 (situational factors), 0.41 (external factors), 0.54 (internal factors) to 0.71 (management approach) on its four subscales. 29 Needham et al. 49 reported Cronbach’s alphas of 0.69 (factor 1) and 0.67 (factor 2) for the two subscales of the Perception of Aggression Scale (POAS). The final study, Calabro et al.,16 reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.68 of their study-specific measure of attitudes, knowledge, self-efficacy and behavioural intention in respect of training.

Stress and burnout: Two studies rated as moderate methodological quality measured stress and burnout as training outcomes. 10,51 Both studies used uncontrolled pre and post designs and both measured stress and burnout at a single time point immediately pre and post training. Bowers et al. 10 used the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)13 (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86) and Paterson et al. 51 used the General Health Questionnaire52 to measure stress and burnout (Cronbach’s alpha 0.82–0.86). Paterson et al. 51 found significantly reduced stress and burnout associated with training (effect size not calculable due to statistical reporting) and Bowers et al. 10 found no significant effect of training on burnout.

Two studies rated as weak in methodological quality measured burnout as a training outcome. 26,59 Both studies used uncontrolled pre and post designs and measured stress and burnout at a single time point immediately pre and post training. Goodykoontz and Herrick 26 used The Burnout Scale27 and Taylor and Sambrook59 used the MBI. 13 Both studies reported reduced burnout in trainees in the post-training period, but both failed to test the significance of these changes.

Skills-based outcomes: Seven moderate-quality studies provided outcome data related to trainee de-escalation skills. Two used a non-randomised controlled design29,44 and five used an uncontrolled pre and post design. 4,10,16,51,53 Six measured skills outcomes at a single time point immediately pre and post training4,10,16,29,44,51 and one study included an additional 15-month follow-up time point. 53 Six of the seven studies providing data on this outcome found a significant effect of training. 4,10,16,44,51,53 Effect sizes were calculable for two of these studies. In one study, medium effect sizes were reported for two skills outcomes relevant to de-escalation, measured with the support (staff supportiveness of patients) (0.6) and autonomy (degree of autonomy and independence granted to patients) (0.68) subscales of the Ward Atmosphere Scale (WAS). 10 The remaining study reported a small effect (0.16) of training on ‘behavioural intention’ (intention to use de-escalation). 16 Only three of seven moderate-quality studies measured skills outcomes using validated scales. These reported Cronbach’s alphas ranging between 0.69 and 0.79 (subscales of the WAS),10 0.87 (DABS)44 and between 0.25 and 0.71 (subscales of the MAVAS). 29

One weak study provided outcome data related to trainee de-escalation skills. They used a non-randomised controlled design61 and measured skills at a single time point immediately pre and post training. The authors found significant improvements associated with training on the following subscales of their observer-rated measure to assess skills changes: ‘ability to defuse the situation’, ‘ability to deal with the situation’, ‘ability to control the situation’, ‘ability to be supportive’, ‘ability to deal with criticism’ and ‘effective use of confrontation’ (p. 111). They found no significant effect of training on ‘eye contact’, ‘posture’ or ‘empathy’ (p. 111). Effect sizes for the subscales with significant effects ranged between 0.8 and 2.0. No Cronbach’s alphas were reported for these scales.

Intervention acceptability

Participant drop-out rate was reported in 23 studies and ranged from 0% to 58.0% (M = 17.0%). 5–7,10,15–17,19,21,23,26,28,31,37,39,41,43,44,54,56,59,60 Explanations for dropouts or data removal were offered in eight of these studies and included missing data points,17,39,44 possible conflicts,10,15 insufficient completion of content23,39,59 and removal after data collection due to invalid responses. 16,44,59 Response rates were reported in 15 studies and ranged from 14% to 100% with a mean average of 74%. 5,7,10,15,16,23,28,31,32,37,41,44,58–60

Participant satisfaction

A total of 12 studies provided some qualitative evaluation of participant’s views on and experiences of the interventions. In one study, many participants perceived the training to have no positive impacts but no further information on these views was discussed. 43 One study reported a mix of positive and negative perceptions of the training intervention. 19 The remaining 10 studies reported positive views of the training from the majority of, if not all, participants. Suggested improvements to the training by participants are described in the following four themes.

Duration, frequency and availability: Participants discussed the importance of offering regular refresher courses to increase the frequency of training and maintain learning. 26,31,41,58 Conflicting views on duration were reported; some felt training was too long and others requested that increased content and time to process learning be included. 26 Participants reported a need for more opportunities to complete de-escalation, and related, training courses in general. 20

Delivery methods: Participants felt training should be tailored to the clinical context in which they were employed31 and more specific clinical examples provided from these contexts. They felt it was important to include role plays and opportunities to practise real de-escalation interventions using a diverse array of case examples. 8,20,26,31 Live demonstrations were reported as preferable to video-recorded examples26 and there were requests for trainer observation and feedback on real staff–patient interactions. 31,58 Some participants requested smaller training groups,8 while others felt training ward teams together was preferable to support whole-team approaches. 25,41 It was felt that all members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) should be trained in de-escalation techniques. 25,41 Access to a de-escalation manual on wards was also suggested. 58

Intervention content: In multiple studies participants felt it was important to include a more in-depth coverage of the components of de-escalation. 8,20 There was a perceived need for focus on early detection of aggression20 and consideration of ‘illness and non-illness related aggression’. 31 Participants felt it was important to cover theoretical models of de-escalation8 and also that training should be tailored to individuals and cultures. 20

Facilitator attributes: Participants felt trainers with current ward experience to be more credible facilitators and emphasised the importance of trainers linking training content with personal experiences working on the wards. 31

Review B: a Theoretical Domains Framework-informed, qualitative evidence synthesis of barriers and facilitators to the de-escalation of conflict in adult acute and adult forensic mental health inpatient settings

Rationale

There has been no prior review which has adopted implementation science and behaviour change theory to identify factors that influence de-escalation behaviours in adult acute and adult forensic mental health inpatient settings.

Objective

To identify barriers and enablers to effective staff engagement in the de-escalation of conflict behaviours in adult acute and adult forensic inpatient mental health settings.

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO: CRD42018089753.

Eligibility criteria

Qualitative studies and qualitative components of mixed-methods studies that considered the engagement of healthcare staff in the de-escalation of conflict behaviours in adult acute and forensic mental health inpatient settings. English-language papers. No date restrictions were imposed. Studies conducted in learning disability, child/adolescent or geriatric settings were excluded, as were papers concerned with only the prevention of conflict, rather than de-escalation.

Search strategy

Electronic database searches were conducted in January 2018, using AMED, British Nursing Index (and archive), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and CINAHL. Free-text searches relating to key concepts such as ‘de-escalation’, ‘mental health’ and ‘conflict’ were combined with relevant medical subject heading (MeSH) terms/subject headings.

Eligibility screening

Search returns were uploaded to Covidence, a review-management programme. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. Data extraction was conducted by PM and another member of the co-applicant team verified 10% of extractions. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, where necessary, third-party arbitration.

Data extraction and synthesis

Article characteristics, such as country of origin and language and setting, study characteristics, including aims, methods, participants, data collection and data analysis procedures, and key findings were recorded using a bespoke extraction form.

Data were synthesised in three stages.

Stage 1: All included studies were uploaded to NVivo10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Six frameworks (one per conflict behaviour) were developed using the Framework function of NVivo10, with columns representing the 14 Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) domains and rows representing each included study. Line-by-line analysis of the results sections of each included study was then conducted. Barriers and enablers were summarised, labelled and assigned to the relevant cell. A permanent link between the summaries and the original data was created using the Create Summary Link function of NVivo10.

Stage 2: Labelled summaries within each framework column were grouped by similarity, integrated and relabelled as themes, allowing a visual overview of the common and divergent issues emerging across included studies within each framework.

Stage 3: Findings across frameworks were analysed and integrated into a single framework describing barriers to and enablers of staff engagement in de-escalation of conflict. The integration of findings across frameworks was conducted by two researchers (PM and OP) and the process was reviewed by the wider research team in a series of meetings, to resolve any disagreements and ensure rigour.

Quality/risk of bias assessment

All eligible studies were assessed using the COREQ criteria for qualitative research. All eligible qualitative studies were assessed for quality, but no study was excluded on the grounds of quality.

Results

The frequency of extracted data varied according to domains (see Report Supplementary Material 1, SM1.2). To present an applicable and theoretically rich synthesis, we only report findings related to domains with high rates of extracted data. The domains Reinforcement, Goals, Behavioural Regulation and Social Influences were underrepresented, with each identified in fewer than six papers (see Report Supplementary Material 1, SM1.2); as such, data relating to these domains are not reported here, due to limited relevance. A summary of all findings, however, is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, SM1.3. The following provides analysis of barriers and facilitators in the 10 most prominent theoretical domains. These were: Knowledge; Skills; Memory, attention and decision processes; Environmental context and resources; Social/professional role and identity; Beliefs about capabilities; Optimism; Beliefs about consequences; Intention; Emotion.

Knowledge

To effectively apply de-escalation strategies, staff must possess specific Knowledge. Articles highlighted the importance of formal, procedural and patient-related knowledge.

Formal knowledge

Unsurprisingly, knowledge of de-escalation, and alternatives to control and restraint, is important. 63,64 When combined with knowledge of the patient, being aware of a range of de-escalation strategies allows staff to select and adapt specific interventions, tailored to the individual, to avoid use of containment. 63,65–72 Conversely, a lack of knowledge can lead to staff ‘defaulting’ to an authoritarian approach. This may be particularly relevant to staff responses to absconding behaviour, where staff feel that there are few alternatives to disciplining approaches (warnings, deterrents) available. 73

Knowledge regarding psychopathology also appears to be important. An awareness of symptoms and psychiatric/behavioural indicators can assist staff in predicting the occurrence of an incident, its trajectory and the level of risk present. 64,65,74 Psychiatric knowledge may improve attitudes, beliefs and attributions regarding ‘problematic’ behaviour, all of which directly affect de-escalation behaviour. 68,71,75–79 Unfortunately, inaccurate beliefs and attributions are common; for example, aggression or agitation as ‘acting out’,71 staff ‘attention’ reinforces self-harm,80 engaging with suicidal patients is ‘inappropriate’,81 punitive techniques, such as denying access to therapy, lead to improvements in behavioural and emotional self-regulation. 79 Such beliefs can lead to authoritarian and emotional staff responses to conflict behaviours. 82

Knowledge of the patient

Patient knowledge allows staff to predict incidents,66,73,83,84 identify early warning signs of potential conflict behaviours,67 select and apply individually tailored de-escalation interventions63,68,70,72,83,85,86 and improves therapeutic relationships. 86,87 Diffusion of relevant information, to all stakeholders, to enhance this knowledge is important to de-escalation. 75 Data suggest that an awareness of patients’ typical presentation can be helpful in prediction of conflict. 66,67,73,83–86,88 Changes in presentation can serve as an ‘early warning’ for escalating behaviour, thus allowing staff to intervene early. 65,67,84 Staff should also be aware of individuals’ history, significant life events, and relationships with other patients, triggers and typical trajectory of distress. This knowledge facilitates the selection of appropriate de-escalation interventions. 67,69–71,86 Knowledge of the patient can also promote empathy among staff and provide a sense of predictability and safety during incidents. 71 Some evidence suggests that patients respond better to staff who know them. 88

Understanding the meaning of behaviour is also important. For example, conflict behaviour often has a communicative value;89 improved understanding of patient motivation improves staff attitudes towards patients,90 increases a desire to help and assists staff in moving from coercive to alliance-based responses to conflict behaviour. 77,82 Limited knowledge regarding the meaning or function of behaviour leads to a blanket response to escalation, without personalisation. 76

Skills

Psychological skills are a major factor influencing the effective use of de-escalation. The importance of empathic communication and interpersonal skills, the development of the therapeutic relationship, and the role of psychological skills in optimising assessments and formal interventions are emphasised.

Empathic communication and interpersonal skills

Authentic engagement and empathic communication are perceived as sufficient, in and of themselves, to defuse unsafe situations without containment. Non-medicalised, authentic91,92 engagement with patients can create a sense of safety. 67,72 Rapport,73 active listening, and direct acknowledgement and validation of patient behaviour,85,90,93–96 experiences97 and concerns71,82,97 can be helpful to de-escalate a potentially dangerous incident. Calm, non-provocative language should be used,67,72,88 and any directions should be accompanied by an explanation and communicated with respect and care. 88 Limit-setting is generally acceptable to patients if delivered with empathy and an explanation. 88 Compassion and support should be maintained, even in the wake of a serious incident. 98

Data suggest that, while essential in managing all conflict behaviour, communication and interpersonal skills may be most important in the de-escalation of self-harming or suicidal behaviour. Engagement is described as ‘the difference between life and death’ (p. 309). 81 Both staff and patients identify the following qualities as useful when engaging in de-escalation of self-harm/suicide: empathy, respect, a willingness to help, respecting space, expertise and autonomy, negotiation, communicating hope and avoiding overreaction and judgement. 76–79,81,83,85,89,90,93–96,99–103

Therapeutic relationship

A strong, pre-established therapeutic relationship can optimise and enhance de-escalation,81 promote help-seeking before de-escalation is required,76,101,102 facilitate compliance82,97,98,104,105 and motivate patients to avoid dangerous behaviours. 73,75,90,94 The data indicate that developing the relationships for de-escalation can be difficult with involuntarily detained patients. 77 Patients may perceive trusting relationships with staff to be ‘risky’, citing concerns about reliability and consistency. 98 Staff must also be aware of the tension between casual, informal interactions, which serve to develop strong therapeutic relationships, and the need to maintain ‘professionalism’, something that is also valued by patients. 72 Use of containment interventions further damages patient trust in staff and results in a cycle of conflict followed by containment. 86

Assessment and flexible intervention

Assessments to inform individualised de-escalation approaches should be made at admission, including clinical history, current presentation, symptoms, suicidality and mental state. 73 Assessment, however, is considered an ongoing process, whereby staff are attentive to the full range of environmental, patient, milieu and relational factors66,67,72,106,107 that may precipitate conflict behaviours. Staff should be aware of person-specific triggers that may cause an escalation, and behavioural cues that indicate the likely onset of unsafe behaviour. 67,69,83,85,108 When conflict is active, staff must determine how and when to intervene,66,67 considering the success of past methods of intervention. 68 Even when containment is being used, stuff must repeatedly assess whether there is a necessity to continue. 104

Any assessment of conflict behaviour will inevitably incorporate, either implicitly or explicitly, an attribution of the cause of the behaviour. Data indicate that attribution directly impacts the nature of de-escalation intervention;71 for example, staff are less likely to use control and restraint if the behaviour is attributed to illness, rather than the person. 67

Intervention approaches are clearly articulated for aggression and self-harm/suicide; limited data are provided for the other conflict behaviours. Basic approaches, including emotional support, reassurance, comforting, focusing on the future, grounding, and distraction techniques,83,85,87,93,101 problem-solving, negotiation, collaboratively identifying solutions67,82,97,104,105 and limit-setting,86 can be used to effectively deescalate conflict situations. Passive intervention should be considered; giving an individual time and space, disengaging, or delaying intervention can allow patients to self-regulate. 63,66,67,69 Whatever intervention approach is taken, patient autonomy must be prioritised; punitive, or corrective, interventions generally lead to increased patient distress. 101

Data emphasise the need for individualised intervention, based on patient need. 76,89,91,95,107 Staff must be flexible in the selection and application of intervention, considering both the individual and the context. 68,71 The personalised adjustments are dependent on knowledge of the individual, highlighting earlier emphases on strong therapeutic relationships and assessment. Indeed, early discussions regarding personal triggers, behavioural indicators and preferences about how and when staff should engage can guide the selection and application of intervention strategies. 83,108

Memory, attention and decision processes

Data relevant to this domain included awareness of antecedents to conflict, and how and when to intervene.

Awareness of antecedents

Good practice, in relation to de-escalation, appears to be contingent upon staff awareness of patient behaviours, interactions and milieu ‘flow’. 64–67,74 By maintaining an awareness of subtle changes in the environment, staff can identify the antecedents of conflict, informing decisions about intervention. As indicated previously, staff must have a good knowledge of the patients they are supporting to identify likely triggers, early warning signs, changes in emotional states and person-specific cues of aggression. 67,73,99 Similarly, characteristics of the milieu, such as noise levels, movement, pacing and agitation, can offer an early indication of the likelihood of conflict. Combined, this form of fluid assessment allows staff to effectively predict and neutralise conflict episodes without containment. However, some early warning signs are difficult to identify73 or are ignored by staff. 109 This may contribute to the advent or escalation of conflict behaviours or, importantly, avoid unnecessary intervention.

How and when to intervene

Staff must be able to, firstly, identify situations that are becoming unsafe, and, secondly, predict the likely outcome; the outcome of each of these decision processes will dictate if, how and when they intervene. 66 Ultimately, staff must differentiate between behaviours that can be tolerated (benign), and those that require control. 67 If the decision is made to intervene, the nature of the intervention is often informed by ethical principles of respect, dignity, self-determination and safety, and an assessment of the patient’s historical responses to intervention. 72

Environmental context and resources

The inpatient environment directly influences use of de-escalation. Relevant impacts across three sub-themes were derived from the analysis: Organisational culture, Resources and Ward Environment.

Organisational culture

Ethos: The underlying beliefs, assumptions and values of an organisation directly influence the use of de-escalation procedures. The ethos of an organisation will manifest itself in the behaviours of its staff; principles such as respect for individuals and safety as a human right, and the expectation that staff will prioritise therapeutic engagement, remain calm when dealing with conflict, and focus on helping, rather than correcting, are linked to the use of de-escalation. 67,81,91 Unfortunately, coercive practices are often justified at the organisational level. For example, forced medication is typically justified by existing legal frameworks and the view that treatment is ‘necessary’. 104

Procedures: Formal clinical systems can prevent conflict behaviours and facilitate the use of de-escalation. Emergency systems and procedures must be reliable and effective if staff are to engage in de-escalation safely and confidently. 110 Additionally, risk assessment protocols and procedures for updating risk assessments should be clear, consistent and communicated among staff teams, to optimise intervention. 84 Co-produced care plans and ‘Positive Behaviour Support’ (PBS) plans also appear to enhance de-escalation; these documents are typically developed by psychologists and are designed to reinforce positive behaviours by enhancing staff and patient awareness of behavioural sequences. As such, they typically identify triggers, behaviour functions, early warning signs and patient preferences for reactive and proactive means of calming distress. 72,108

Staff support: Formal methods of staff support, such as debriefing and clinical supervision, have been found to promote active learning69 and can enhance de-escalation. 64,72,106 Staff express general dissatisfaction with a lack of post-incident debriefing and support. 73 Staff also value less-formal support processes to enhance de-escalation practices, such as emotional sharing and mutual support between colleagues. 80

Resources

Staff: Low staffing can be a barrier to the implementation of planned de-escalation strategies, such as PBS plans. 108 Low staff numbers also are implicated in de-escalation in medication refusal; when limited staff are available, or if there is a high load of acutely unwell patients, negotiation only occurs with patients who are deemed to be dangerous, or a positive outcome is predicted. 104 Some findings suggest, however, that staff mix is more important than absolute staff numbers. 71 Balanced staffing, ensuring a mix of skill and experience, can facilitate de-escalation, while a poor staff mix contributes to ineffective teamwork and poor communication. 69,71,72,106,109 Experienced staff are perceived better at deciding when to intervene, and are more likely to use de-escalation, in response to aggressive behaviour. 69

The type of staff also influences patient behaviour and the use of de-escalation. The presence of ‘authority figures’, such doctors and male nurses, can defuse conflictual situations, and having male nurses present makes staff more comfortable and confident engaging in de-escalation. 72 Well-trained nurses are seen to be most effective in managing self-harm, without containment. 80 Conversely, bank/agency staff may lack the skills and experience to identify escalating behaviours and can miss early opportunities to intervene. 99 Bank/agency staff are also often experienced by patients as aggressive in response to escalations. 109 Poorly or inadequately trained staff, and those who are unfamiliar with the ward and patients, find it difficult to predict escalating conflict behaviour. 71

Time: Often related to overall staffing levels, time, or lack thereof, represents a significant factor in the use of de-escalation on inpatient psychiatric units. The effectiveness of de-escalation is widely reported as being dependent on a strong, pre-existing therapeutic relationship; these relationships can only be developed over time. 97 Data indicate that a lack of resources, including time, has a direct impact on the quality of relationships, interventions such as sensory rooms,111 negotiation,104 observation93 and listening to patient concerns. 89

Activities: A lack of ward activities prevents these being used as de-escalation strategy. 72,112

Ward environment

Physical environment, social environment and rule application: Though difficult to manipulate, the physical environment of inpatient wards can contribute to the incidence of conflict and influence staff responses. The availability of a sensory room offers another de-escalation approach, and an alternative to containment. 113 Staff indicate that the availability of a sensory room allows agitated or aggressive patients a space to engage in self-soothing behaviours in private, thus regaining a sense of control. 111 If available, the use of sensory rooms should be incorporated into care plans. 113 When a ward has a high load of acutely unwell patients, staff may use de-escalation techniques, such as negotiation, less. 82 Patients value flexibility in the application of normal rules, where it can be facilitated safely, as a de-escalation strategy. 92,114,115

Social/professional role and identity

Aspects of professionals’ role perception was a consistent impact on de-escalation behaviour in the evidence reviewed. How staff perceive that their professional role influences the nature of their response to conflict. The conceptualisation of nursing as a supportive, ‘helping profession’,75 and the pursuit of professionalism, characterised by calmness, emotional control64 and the prioritisation of staff and patient safety,96 facilitate effective responses. 86 How staff view their role can also lead to negative outcomes; for example, when the nursing role is viewed as that of a gatekeeper or educator, this can lead to corrective approaches that escalate conflict. 86 Demanding respect (from patients), strictness and a need for authority and control appear to be most problematic aspects of typical responses. 116,117

Staff peer support

Having a strong staff team, where staff feel they can rely on each other, enhances de-escalation. 70 Good communication and a sense of ‘community’ among staff allows for transfer of de-escalation knowledge. 63 When seeking support after an incident, staff prefer to receive this from peers who have shared similar experiences; this assists in processing emotions and may help staff to maintain therapeutic relationships with patients in advance of future de-escalation events. 75

Beliefs about capabilities

Confidence is perceived as having an important impact on de-escalation and is influenced by team factors, patient factors and training. The perception of colleagues being supportive increases staff confidence, while the perception of peer support, length of time working together and clinical supervision increases the use of de-escalation. 67,72 Knowledge of patients increases staff confidence when responding to conflict. 67 Training is perceived as improving confidence to de-escalate conflict. Conversely, a lack of or inadequate training is perceived as contributing to anxious and avoidant behaviour100 that prevents the development of relationships that would facilitate de-escalation when conflict occurs. 109

Optimism

Much of the extracted Optimism data highlighted a pervasive perception among staff that de-escalation is ineffective and is of limited value in many circumstances. 64,69,73,96,97,101,113 Staff indicate that some conflict situations cannot be resolved through de-escalation64,97,101,104,113 and, in particular circumstances, containment is inevitable:69 for example, when de-escalation has previously been unsuccessful,66 there are high levels of risk73,77 and when patients are seen as being unable to make ‘reasonable decisions’. 97

Beliefs about consequences

Staff beliefs around de-escalation and outcome expectancies influence the nature of intervention. When attempting to manage patient aggression, staff are guided by an ‘on-the-spot’ risk assessment. The intensity of the situation, how the incident has progressed and the potential impact on others (milieu) dictate the nature of the intervention,66 and, when perceived as necessary, containment is used to prevent harm. 69,72 Similarly, when addressing rule-breaking, staff will assess the level of ‘disruptiveness’, use limit-setting when necessary to maintain control and the safety of the ward,88 and progress to containment if the desired response is not attained. 86 In some scenarios, non-intervention is preferred. Staff acknowledge that not all behaviour needs to be controlled; non-intervention can protect the milieu, does not disrupt the ward atmosphere and, in some cases, can lead to better outcomes than intervention. 67,89

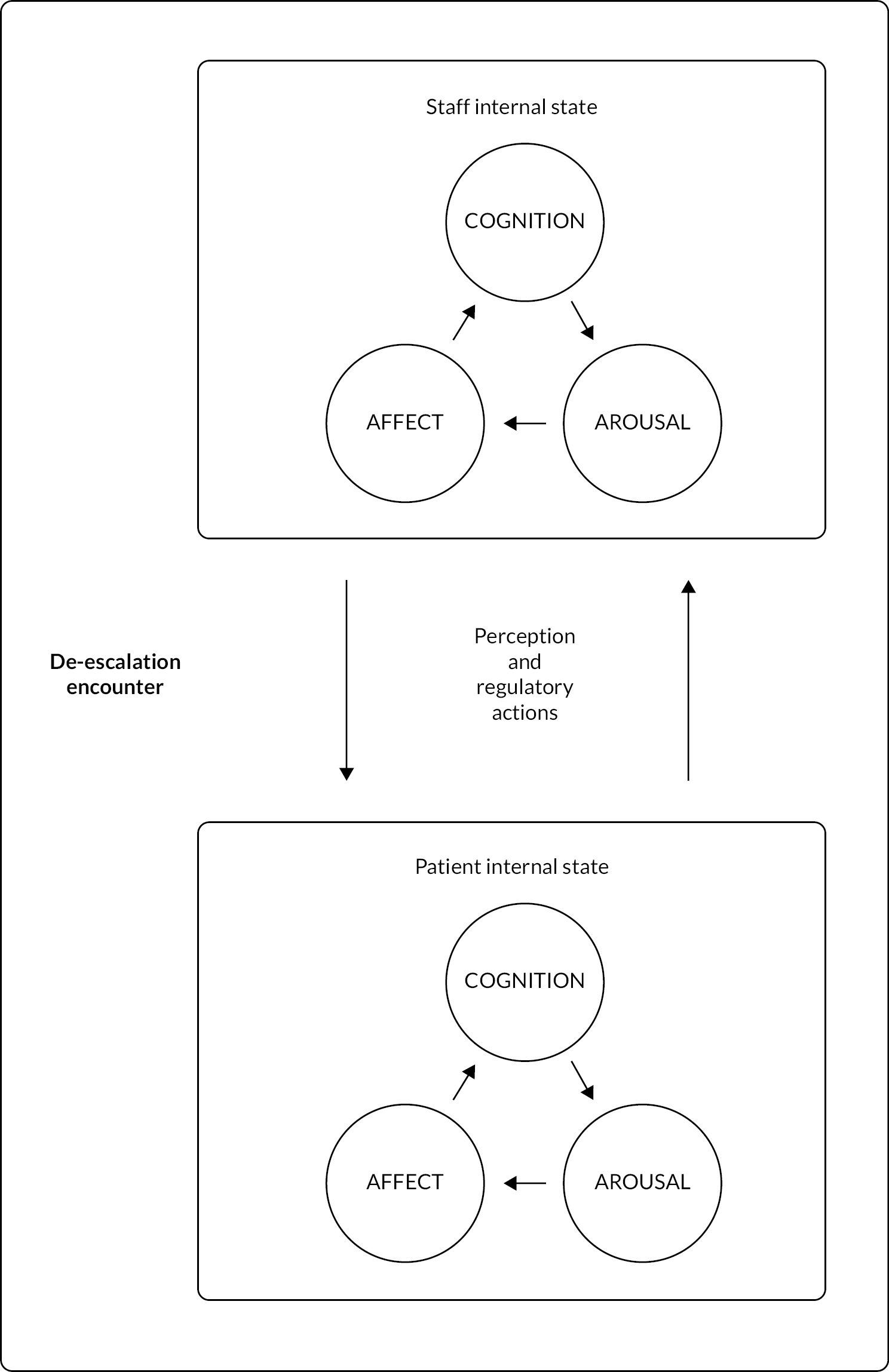

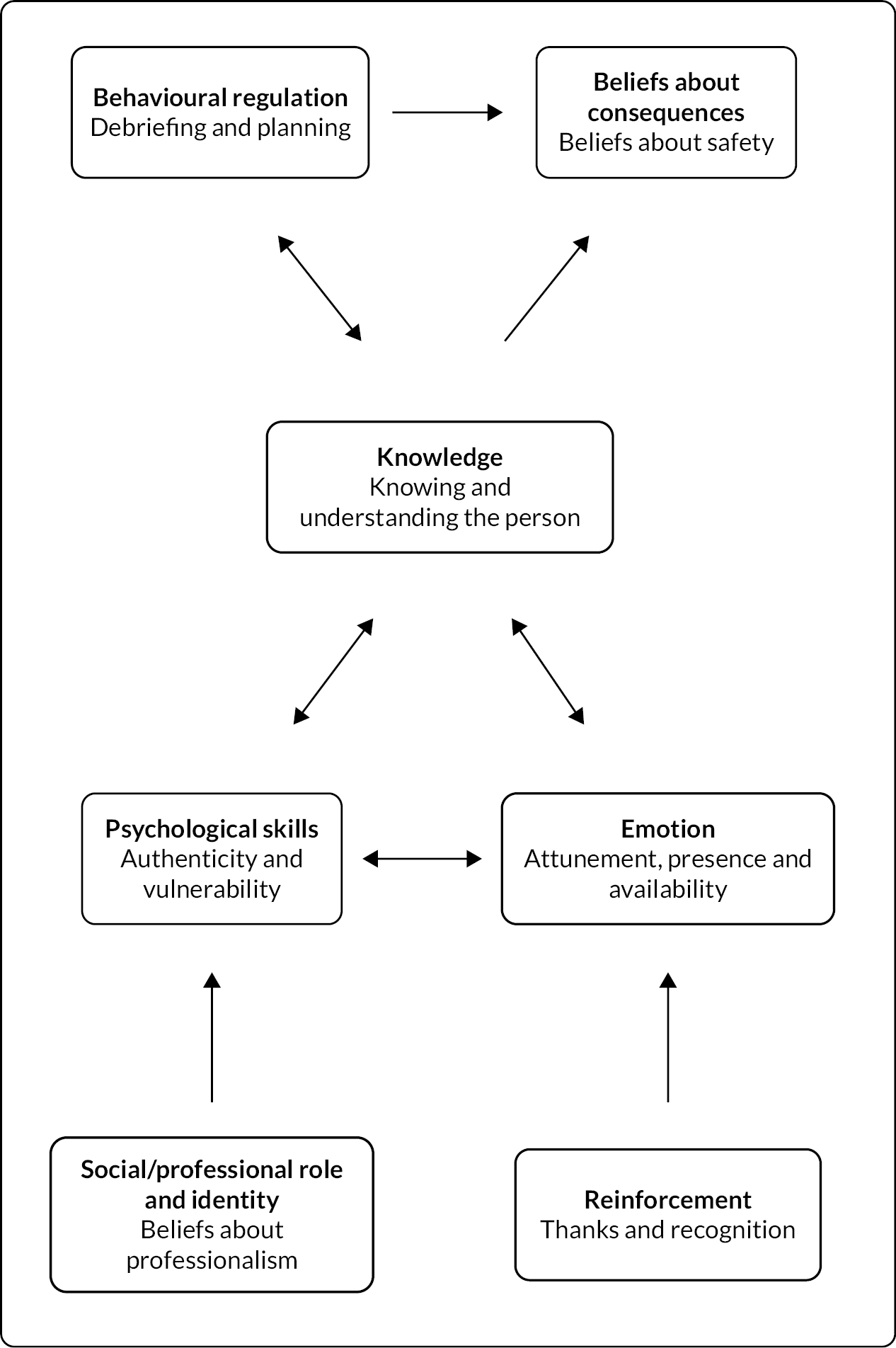

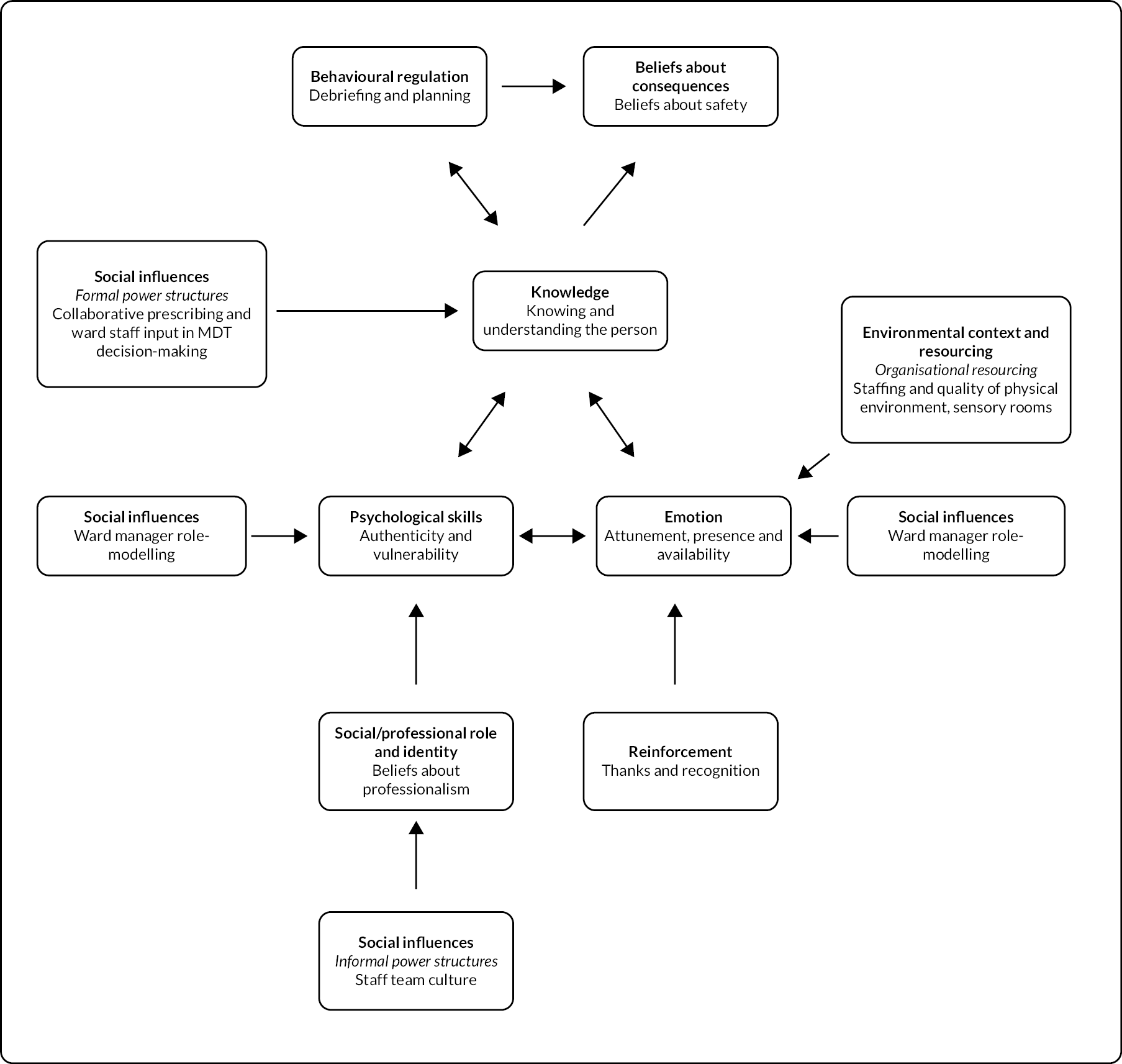

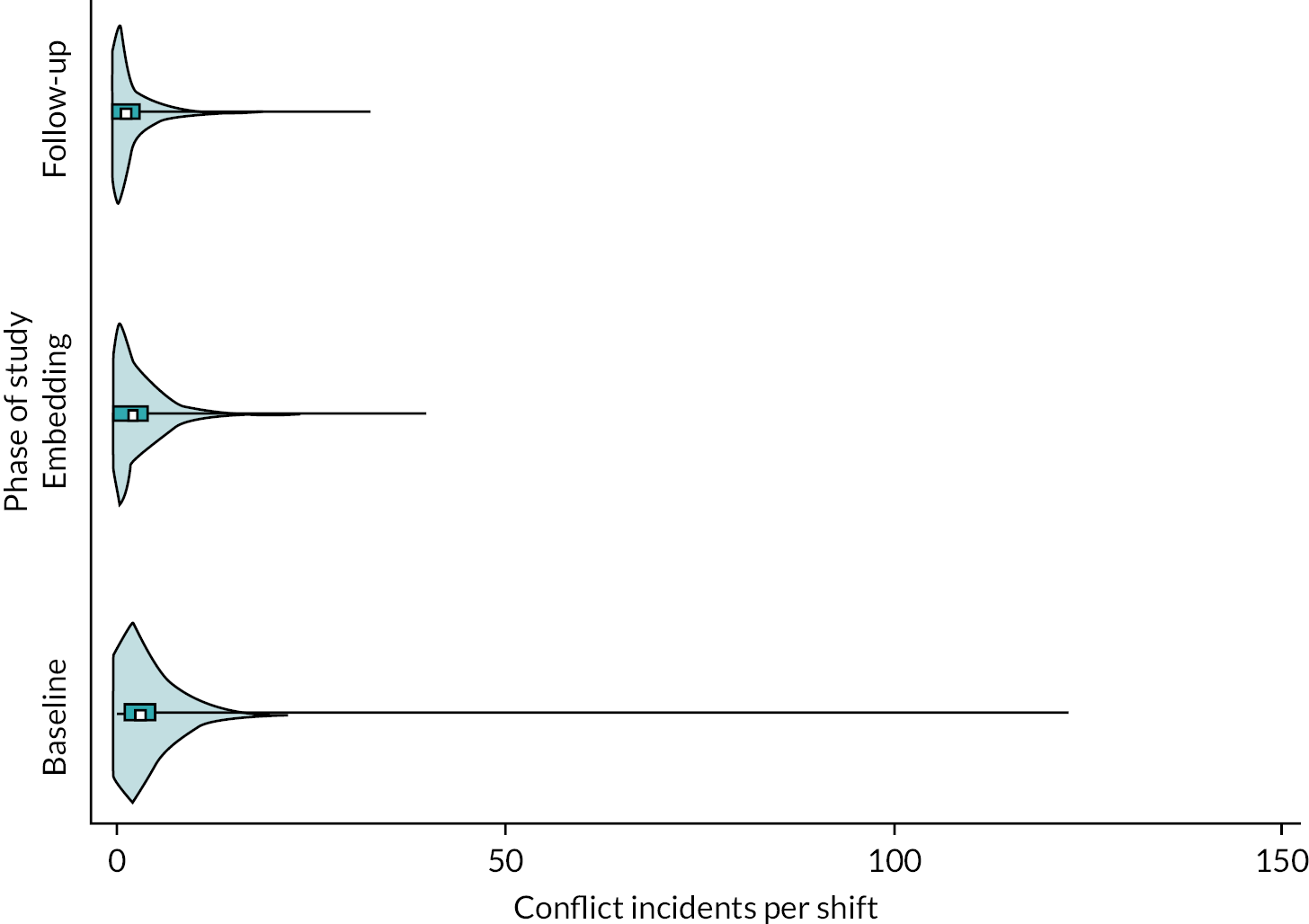

When managing medication refusal, staff justifications for coercive measures are nuanced, incorporating both risk and ethical considerations. Untreated psychosis is seen as requiring ‘care’ and may be dangerous to both the individual and others, and therefore must be addressed through medication, using force if necessary. 82,104,117,118 Despite an awareness of the tension between impaired capacity and patient autonomy and acknowledging that forced medication may be humiliating for the individual, staff often perceive an ethical responsibility to the person to forcibly administer medication. 82,117 Primarily, medication is seen as being ‘in the best interest’ of the patient; untreated psychosis is viewed as degrading, and medication refusal as a function of pathology, therefore forced treatment is conceptualised as ‘humane’. 104 Staff believe that patients will later reflect, acknowledge they were unwell and unable to make rational decisions, and therefore accept that forced medication was necessary and be ‘grateful’. 97