Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR129248. The contractual start date was in January 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Stewart et al. This work was produced by Stewart et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Stewart et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Response to commissioned call

This report presents the findings from a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded study that was conducted between January 2021 and December 2022. The study was developed in response to a cross-programme call on ‘Digital Technologies to Improve Health and Care’ in November 2018 and funded through the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The team was commissioned to explore the acceptability and feasibility of home monitoring for glaucoma and make recommendations about the need for and design of a future definitive evaluative study.

Glaucoma: a brief background

Glaucoma is a chronic disease of the optic nerve and is currently the leading cause of irreversible severe visual loss worldwide and the second most common cause of severe visual loss in the UK. 1,2 Within the UK, there are over 1 million glaucoma-related NHS appointments annually. 3 Glaucoma commonly affects older adults, requires lifelong monitoring and is increasing in prevalence due to the growing ageing population. 4 By 2040, it has been predicted that 111 million people aged 40–80 years will be diagnosed with glaucoma globally. 5

Glaucoma is typically associated with raised intraocular pressure (IOP), leading to characteristic damage of the optic nerve head and visual field (VF) loss. Early glaucoma is asymptomatic but as the pathology progresses, central visual acuity may also be lost, leading to irreversible severe visual loss. 3 Patients impacted by glaucoma-related visual loss have been found to have decreased quality of life (QoL), due to factors including vision-induced limitations, loss of ability to drive, loss of ability to participate in meaningful activities such as hobbies, and an increased risk of falls. 6

Treatment for glaucoma effectively halts or slows disease progression and is achieved by reduction of IOP with medical, laser or surgical therapies. Patients require regular, lifelong monitoring, typically by hospital eye services (HES), where they have their IOP measured and the VF tested. Imaging by scanning the retinal nerve fibre layer of the eye can also be used to monitor glaucoma. Ideally the frequency of monitoring should be individualised to patient needs. Patients need these check-ups for the rest of their lives.

Hospital eye services are very busy, accounting for the highest number of NHS outpatient appointments of any specialty and comprising nearly 10% of all NHS outpatient visits. Glaucoma services are overwhelmed and struggling to accommodate current demands. 7 Providing regular surveillance and treatment is already a major challenge for the NHS. As the prevalence of glaucoma increases with age, the demand for glaucoma care is increasing (and will continue to do so) and more efficient models of care are urgently needed. 7,8

Diagnosis and monitoring of glaucoma

Glaucoma assessment for diagnosis and monitoring is made through combining patient history with objective measures which include assessments of the optic nerve head, retinal nerve fibre layers, VFs, and tonometry. 8 When the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment with pressure-lowering eye drops or laser therapy is commenced. Treatment is escalated (e.g. eye drops added, laser or surgery) if there is evidence of disease progression, defined by worsening of the VF or appearance of the optic nerve over time; or if IOP is above the individualised target level and the risk of progressive loss of vision is high. When treatment is altered, follow-up is arranged to determine response, with success of treatment measured by IOP control and demonstration of lack of change in VF over time. IOP is the only modifiable risk factor for reducing progressive loss of vision due to glaucoma. 9 All patients require lifelong regular assessment to determine disease stability and IOP control and to decide whether further treatment escalation is necessary.

Surveillance of patients with confirmed glaucoma is typically undertaken at HES. 10 Regular monitoring is important as glaucoma is often asymptomatic, and patients are usually unaware that they have worsening VF until the advanced stages;11 however, monitoring is time-consuming, inconvenient for patients and expensive for the NHS. Currently, the NHS is overwhelmed with the demand for glaucoma services and spends over £500M annually on related care. 7,12 Evidence suggests that current lack of capacity will worsen, increasing the risk of appointment delays and inappropriately long monitoring intervals. 7 Delays in follow-up appointments are already recognised as a problem, in some cases leading to irreversible visual loss which could have been prevented with adequate monitoring resources and funding. 7 Reducing demand on hospital-based services will improve the ability to see and treat patients at the highest risk of vision loss. Digital technologies that provide opportunities for home monitoring of glaucoma have the potential to contribute to solve these challenges and, potentially, improve outcomes.

Digital technology for home monitoring chronic conditions

Traditional monitoring methods of many chronic conditions are clinician-led and performed within the hospital. However, recent technological advances allow exploration of patient-led home monitoring or telemonitoring. Interventions for telemonitoring common health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and stroke have been frequently reported in the literature. 13–18 Some of these conditions are already routinely monitored at home using methods such as blood glucose finger-prick, or sensor technology, or ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitors.

Research suggests several benefits of home monitoring. Quantitative evaluations indicate greater patient compliance to treatment, shorter hospital stays, reduced frequency of inpatient visits, and faster diagnosis and identification of acute changes. 13–18 It should be noted that systematic reviews of telemonitoring also report that outcomes are variable between studies, particularly in relation to impact upon health resource use outcomes such as the number of healthcare contacts. 13,18 Qualitative evidence synthesis of remote monitoring across a range of chronic diseases (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension and end-stage kidney disease) highlighted that remote monitoring increased patients’ disease-specific knowledge, enabled early identification of exacerbations and improved self-management and shared decision-making. 19

The 10-year NHS plan has identified chronic condition home monitoring as a priority. 20 This could allow reduced frequency of hospital appointments for stable patients, increase healthcare capacity, potentially lower costs and improve patient convenience and compliance. 20 Implementation of these technologies requires an understanding of the challenges facing the NHS workforce and patients. While the evidence for home monitoring supports opportunities for embedding technologies within routine care, this implementation should ideally be supported by evidence from rigorous evaluation. 21

Current technologies for monitoring glaucoma

Recent advances in technology mean it is now possible for glaucoma patients to monitor IOP and several aspects of visual function, including VFs, in their own home. Utilising digital technologies for glaucoma home monitoring has the potential to contribute to solving a key challenge in glaucoma care: accommodating the increasing glaucoma population with more frequent monitoring assessments against the backdrop of increased wait times, reduced clinic availability and delays in routine monitoring appointments. It is also possible that more frequent monitoring, undertaken at home, may improve health outcomes if used to supplement or replace standard infrequent visits to HES. A novel patient pathway could potentially be used in which home monitoring data would be transferred to the hospital for interpretation by a healthcare professional or artificial intelligence (AI); alternatively, patients could request a hospital appointment if the home tests show their glaucoma has worsened or IOP has increased. Home monitoring could mean patients require fewer hospital visits, while increasing convenience and potentially reducing costs and increasing capacity for healthcare providers.

Home tonometry technologies

It is now possible to collect IOP data for glaucoma patients outside the clinical environment. Prior to 2020, two CE-marked options were available: SENSIMED Triggerfish® (SensiMed, ND, Switzerland) contact lens sensor and the iCare HOME® (iCare Oy, Vantaa, Finland) rebound tonometer.

The SENSIMED Triggerfish (SensiMed, ND, Switzerland) involves wearing disposable contact lenses which transmit data in relation to changes in ocular dimensions to a wearable antenna (worn as a patch). 22 It does not measure IOP directly, but using the ocular dimensions data it can give indications of increases or decreases in IOP. 22 The lens is designed to be inserted and removed by a trained professional, and worn by the patient for a 24-hour period. 22 In the device summary evidence published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), it appears across 13 trials that the device was well tolerated by patients with few (n = 2) serious adverse events. 22 It obtained CE approval in 2010; however, its use is largely restricted to research purposes due to ongoing concerns regarding how well ocular dimensions relate to IOP, limiting its use in clinical care. 22

The iCare HOME is a handheld device which can record and store IOP measures in the same units (i.e. mmHg) as the gold standard in-clinic Goldmann applanation tonometer (GAT) assessment. 23 Rebound tonometry, developed by iCare, has been in use since 2003, but in 2014 a version, iCare HOME, was released which was specifically designed for patients to use themselves outwith the clinic setting. 23 The device takes six individual readings during each measurement, then disregards the highest and lowest reading and then calculates an average of the remaining four readings, to give a final result. 23 Several studies have compared the IOP readings from the iCare HOME tonometer to GAT. The reported mean differences between the iCare HOME and GAT measurements range from −2.7 to 0.7 mmHg. 24–28 However, variations of 0–5 mmHg are considered acceptable for home monitoring. 24–26,28 Patients are taught to operate this device themselves. Evidence suggests most study participants were able to use the iCare HOME device correctly following training. 25,28–30

Home perimetry technologies

Portable perimeters designed for testing peripheral VF at home are a potentially useful tool for remote home monitoring of glaucoma. They have a theoretical advantage of providing frequent VF data which may help to confirm disease in glaucoma suspects and possibly assess disease progression. 31 Pre-2020, when this study was commissioned, there were two reliable app-based technologies available for the remote monitoring of VFs: the Melbourne Rapid Field (MRF, GLANCE Optical Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) and Moorfields motion displacement test (MMDT). 31

The MRF is an app designed to be used on an iPad® (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) and involves the user placing the iPad on a stand and positioning themselves so that they are sitting approximately 33 cm from the screen. 31 The test is conducted in two parts, first asking users to focus on the centre of the screen (central field test) and then asking users to focus on each corner of the screen (peripheral field test). 31 Users are asked to push the space bar on a Bluetooth® (Bluetooth Special Interest Group, Kirkland, WA, USA) keyboard in response to stimuli. 31 Results of the MRF have been found to be consistent with gold standard in-clinic VF testing using the Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer. 32,33 At the point of commissioning, the MRF was yet to be tested out of clinic. 31

The MMDT is designed to be used on a laptop and involves the user resting their head and chin onto a support stand approximately 30 cm from the screen. 31 Users are then asked to focus on a central spot on the screen and click the mouse or press the space bar every time they see a moving line on screen, for a duration of around 5 minutes. 31 Although limited, evidence suggests good diagnostic performance34 and patient engagement35 with this test. Similar to the MRF, out-of-clinic use of the MMDT has not yet been reported. 31

Study rationale

Technological advances have made glaucoma home monitoring possible through the development of innovative portable tonometers and perimeters that use tablet or personal computers, or head-mounted displays. Such devices may be used for assessing IOP, VF loss and other visual parameters, without clinic visits. However, their effectiveness, their ability to detect and quantify the severity of VF damage, and patients’ ability to use them at home are yet to be tested.

At the time of commissioning In-home Tracking of glaucoma: Reliability, Acceptability, and Cost (I-TRAC) there was a lack of detailed exploration with important stakeholders such as patients and clinicians. Collecting these insights is crucial for developing an in-depth understanding of clinicians’ views on home monitoring, particularly regarding which patients would most likely benefit from this approach, and to determine obstacles preventing implementation of these technologies to improve healthcare delivery in glaucoma. From the patients’ perspective, it is important for us to understand how acceptable home monitoring technologies are; will patients engage with the devices and the remote monitoring approach? As part of this, it is important to understand design issues that are important to patients, to ensure the technologies can be used by those they are designed to help. As noted by the NIHR, economic evaluation of these glaucoma home monitoring technologies has not been undertaken. 22,36 A well-designed randomised controlled trial (RCT) is required to answer these questions. However, prior to full trial, we first need to determine the acceptability and feasibility of this approach.

Since commissioning, a small number of studies exploring the acceptability and/or feasibility of these home monitoring interventions for glaucoma have been published, but not within the context of feasibility of a future large-scale evaluative study. 37–39 These will be discussed in detail with relevance to I-TRAC findings in the Discussion (see Chapter 7).

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of digital technologies to monitor glaucoma at home and inform the possible need for and design of a definitive evaluative study.

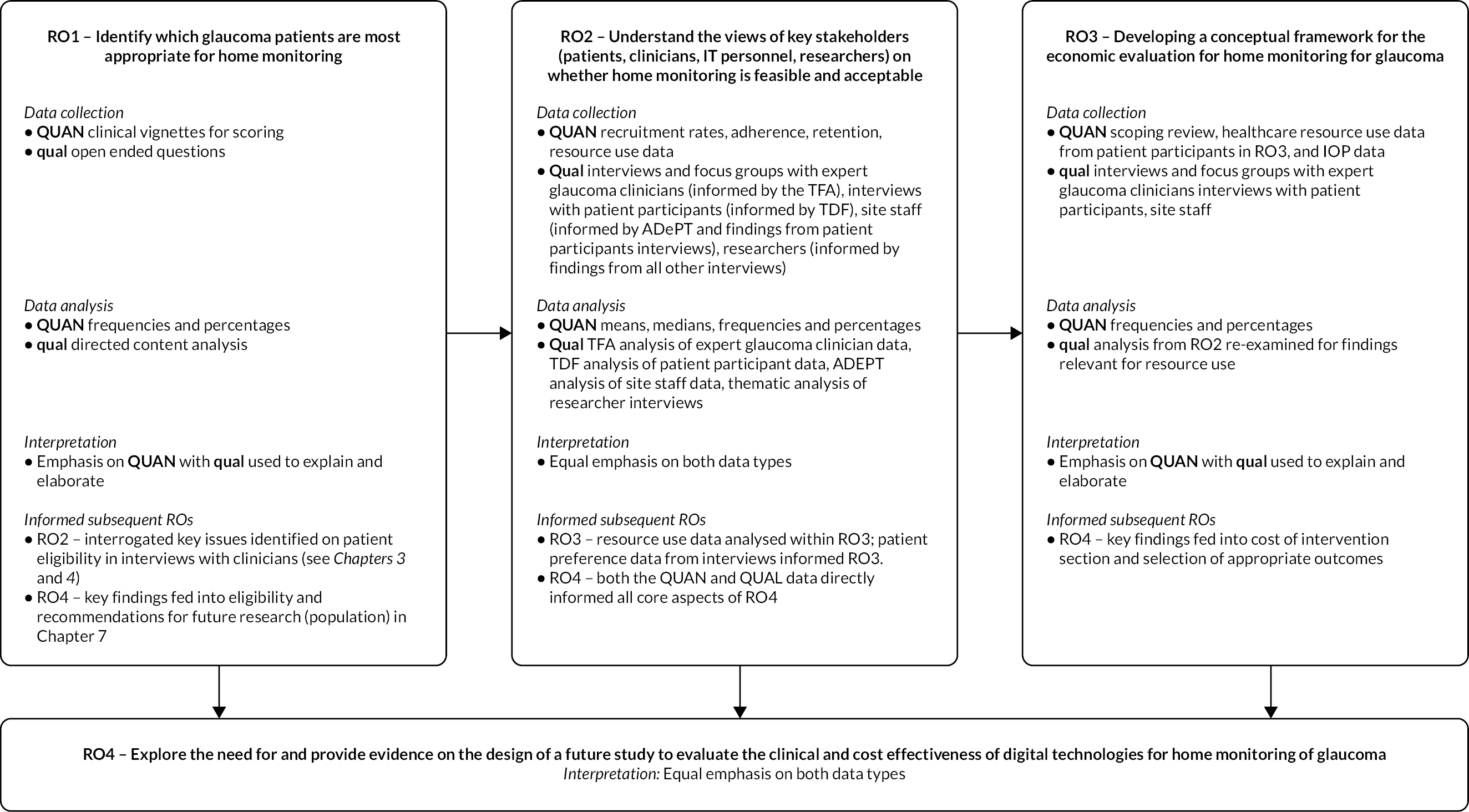

The four specific research objectives were to:

-

identify which glaucoma patients are most appropriate for home monitoring (e.g. all patients, or those with stable disease, or those with severe glaucoma?)

-

understand the views of key stakeholders [patients, clinicians, information technology (IT) personnel, researchers] on whether home monitoring is feasible and acceptable

-

develop a conceptual framework for the economic evaluation of home monitoring for glaucoma

-

explore the need for and provide evidence on the design of a future study to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of digital technologies for home monitoring of glaucoma.

Study design and overview

The I-TRAC study was a multiphase mixed-methods feasibility study with key components informed by theoretical [i.e. the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)] and conceptual [A process for Decision-making after Pilot and feasibility Trials (ADePT)] frameworks (see Appendix 1 for a diagrammatic overview of study design). Successful evaluation and future implementation of any new intervention require in-depth understanding of the potential process modifiers. It was recognised that the introduction of home monitoring using digital technology for glaucoma will involve multiple stakeholders (patients, healthcare professionals and researchers with experience of delivering evaluative studies of digital technology used for home monitoring) and various care contexts (home and secondary care) – all of which were important to capture through the study design.

We planned to use two technologies for glaucoma home monitoring, the first being the iCare HOME, a handheld tonometer for measuring IOP. The second, the MRF app, played on an iPad to measure VFs. However, due to the MRF not being CE marked, we had to replace the MRF with the OKKO Visual Health app (OKKO Health, Bristol, UK). A description of the problem and decisions relating to choice of replacement app are reported in Chapter 4. Participants were asked to use both monitoring devices once per week for 12 weeks.

Several methods were utilised to address each of the research objectives mentioned, specifically:

-

A survey regarding glaucoma home monitoring feasibility was designed and distributed among key clinical stakeholders within glaucoma care in the NHS (addresses research objective 1).

-

Glaucoma patients were trained to use the home monitoring technologies and used the technology for a period of 3 months. A sample of patients and the site staff involved in recruitment were interviewed following this to gain insight into each experience (addresses research objective 2).

-

Interviews were conducted with relevant external research teams and ophthalmology consultants (addresses research objective 2).

-

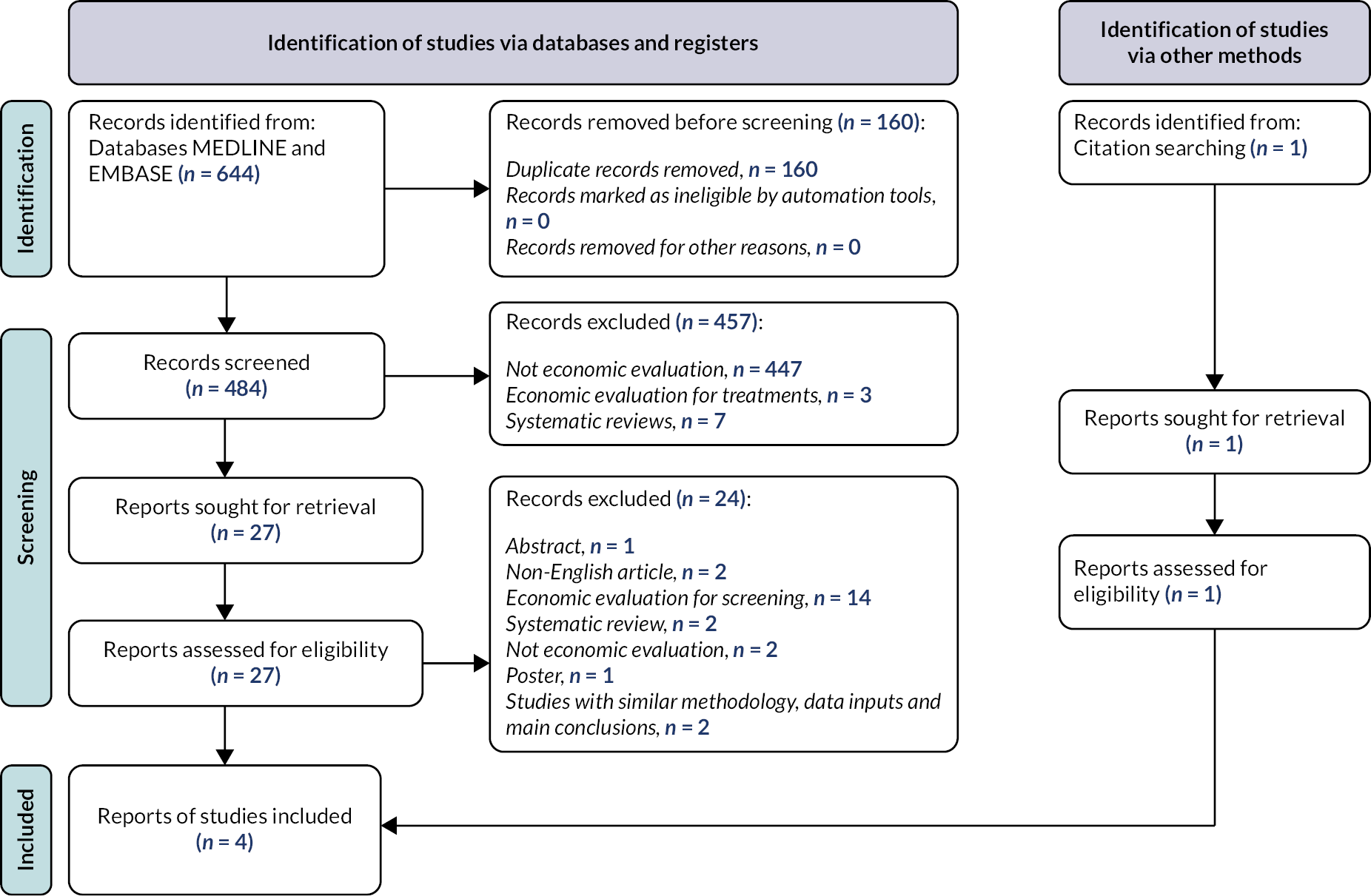

A systematic review to investigate appropriate health economic models for home monitoring of glaucoma was conducted and supplemented with quantitative and qualitative data from clinicians and patients relating to resource use and preferences (addresses research objective 3).

-

A statement was produced regarding the overall feasibility and acceptability of an evaluative study comparing current NHS glaucoma care with home monitoring (addresses research objective 4).

Chapter 2 Identification of which glaucoma patients are most appropriate for home monitoring

There is limited guidance in the literature as to which glaucoma patients would be the ideal candidates for home monitoring using digital technology. Identifying key uncertainties regarding candidate suitability, such as who are the appropriate patients to target for evaluating an intervention, is a critical first step towards evaluating its use. This chapter reports the findings from an online survey with expert glaucoma clinicians to determine which glaucoma patients are most appropriate for home monitoring and to investigate clinical decision-making in relation to patient suitability.

Methods

Study design

Online survey involving expert glaucoma clinicians, who have not been involved in the glaucoma home monitoring intervention component of the study.

Sampling and recruitment

The target population were expert glaucoma clinicians (i.e. ophthalmologists and optometrists). To take part in our study, participants needed to work within the UK NHS, presently deliver care to persons with glaucoma, and agree to take part in the study. Based upon the estimated number of glaucoma clinicians registered with the UK and Eire Glaucoma Society (UKEGS), a non-profit professional society for clinicians with a specialist interest in glaucoma (range n = 69–7240,41) we are accepting our denominator for calculating response rate as n = 72. UKEGS does not currently record the designation of its members, so the exact number of glaucoma consultants surveyed is unknown.

In order to target clinicians with directly relevant experience, the survey was disseminated via UKEGS. A link to the questionnaire with an invitation to participate was e-mailed to members of UKEGS by the UKEGS Communications Manager. In addition to the invitation e-mail, the clinical co-investigators raised awareness of the questionnaire among existing clinical networks. The survey was active from 14 May to 30 October 2021.

Data collection

An online survey including both closed and open-ended questions, informed by the literature and expert opinion within the research [including three clinical Principal Investigators (PIs): AAB, AK and AT], was created through SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA). 42 A participant information leaflet (containing general information about the I-TRAC study and the home monitoring devices) was included at the start of the survey to support informed consent but also to ensure participants were given contextual insights to promote informed responses. For example, a summary of the NICE guidelines for ocular hypertension (OHT) and primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) was included alongside an introduction to the technologies being discussed (iCare HOME tonometer and tablet-based apps for measuring visual function).

Participants were asked to decide if they would use the iCare HOME tonometer and/or an app for visual function, for four clinical scenarios. The patient scenarios were developed to reflect fictional patients (but based on real examples) and included hypothetical details on glaucoma severity (mild, moderate, severe), current treatment, risk of visual loss, disease control (apparently well controlled, uncertain, poorly controlled), and management options, as well as demographic details (Table 1). These cases were designed to reflect the NICE guidelines for OHT and POAG. When a clinician did not recommend a patient’s suitability for home monitoring, they were asked to justify this decision. Scenario 5 described a clinical model of care in which a doctor integrates the home monitoring devices within their routine glaucoma care due to reduced clinic capacity. Clinicians were asked to determine whether this model of care was acceptable to them, why it was/was not acceptable, and to tell us about perceived advantages and disadvantages to this model of care.

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Mr Smith | Ms Adams | Mr Patel | Ms McEwen |

| Age | 63 | 70 | 78 | 55 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| Brief history | 2-year history of severe bilateral glaucoma No evidence of current progression |

1-year history of bilateral OHT | 3-year history of poorly controlled pseudo exfoliation in R eye and moderate glaucoma in L eye | 5-year history of mild, bilateral normal tension glaucoma No progression noted |

| Intended level of risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk |

Survey participants were asked to provide demographic data including age, gender, ethnicity, profession, the number of years’ experience in treating glaucoma, and current or past use of technologies for measuring IOP and/or visual function in patients at home.

The data collected through SurveyMonkey were downloaded and stored in an Excel® worksheet [Microsoft® Excel for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2205 Build 16.0.15225.20394); Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA]. Participant responses were anonymous and assigned a unique identifier number.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from closed-ended questions were analysed using descriptive statistics (e.g. frequencies, percentages). Agreement with clinical scenarios was defined by the study team as being ≥ 60% in either supporting or not supporting the hypothetical patient to be home monitored using the digital technology. Agreement across clinical scenarios was also investigated in a post hoc analysis and reported using frequencies. Free-text responses, such as those asking for clinical reasoning for the monitoring decision, and the frequency and duration of monitoring, were analysed using directed content analysis. 43 Within this, a hybrid approach, combining both inductive (data-driven) and deductive (based on preconceived ideas) methods was followed. Frequency and duration responses were free text and were reviewed across all clinical scenarios (scenarios 1–4) to create categories that could be applied across scenarios for ease of comparison. Reasons behind the perceived unsuitability of each clinical scenario for home monitoring were analysed and reported within each scenario. Similarly, explorations of the acceptability of this model of care were analysed within scenario 5 where several questions regarding perceived barriers and facilitators were presented. Within this project, a barrier was defined as ‘a circumstance or obstacle that keeps people or things apart or prevents communication or progress’. 44 A facilitator was defined as ‘the factors that enable the implementation of evidence-based interventions’. 45

The Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was transferred to NVivo software (version 12 qualitative analysis programme; QSR International, Warrington, UK). 46 Data were reviewed and emerging themes noted. Following several reviews of the data by two reviewers (UA and CS), a coding dictionary describing the themes and categories found within participant responses was developed. Within NVivo, a tree chart was constructed to explore the weighting of each of the themes, subthemes and codes created from the survey responses. This allowed identification of the major themes based on the volume of responses addressing this topic, number of participant comments and relevance as deemed by the researcher.

Results

Sample demographics

A total of 64 clinicians accessed the survey, a response rate of 89% (n = 64/72, 72 being the upper limit in the range of eligible clinicians registered with UKEGS who had a special interest in glaucoma). Four participants were excluded based on lack of experience treating glaucoma (n = 3), as per the exclusion criteria, and one participant did not respond to any of the questions. A further 11 were excluded from the final analysis as they did not respond to the clinical scenario questions and only provided demographic data. Therefore, 49 clinicians who replied to at least one of the questions in relation to the clinical scenarios were included in the final analysis (77%, n = 49/64). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the respondents. The majority of participants were white (59%, n = 29), male (69%, n = 34), consultants (92%, n = 45), aged between 50 and 59 years (45%, n = 22), who have treated glaucoma patients for > 10 years (71%, n = 35). The demographics of those removed from final analysis (n = 11, not presented) showed a similar pattern in that they were mostly of white ethnicity (82%, n = 9), consultants (82%, n = 9) with extensive experience (64%, n = 7, over 10 years’ experience). However, they were younger (64%, n = 7, < 50 years of age) and the gender split was more equal between male and female (male, 36%, n = 4; female, 36%, n = 4, with 3 preferring not to report their gender).

| Variables | Responses, n (%) (N = 49) |

|---|---|

| Duration of experience with treating glaucoma | |

| < 5 years | 3 (6) |

| 5–10 years | 11 (23) |

| > 10 years | 35 (71) |

| Profession | |

| Optometrist | 4 (8) |

| Consultant ophthalmologist | 45 (92) |

| Participant age (years) | |

| < 40 | 7 (14) |

| 40–49 | 16 (33) |

| 50–59 | 22 (45) |

| > 60 | 4 (8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 34 (69) |

| Female | 13 (27) |

| Non-binary | 1 (2) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 29 (59) |

| Mixed white and Black African | 3 (6) |

| Asian/Asian British | 16 (33) |

| Black/Black British African | 1 (2) |

Clinician decisions regarding patient suitability for glaucoma home monitoring

Across the scenarios, there were varying rates of agreement regarding the suitability of each patient scenario for home monitoring (Figure 1 and Table 3). Based on the levels of agreement defined (i.e. > 60% reporting a patient as suitable), only one patient, scenario 4, was deemed suitable for home monitoring. In the scenario, 61% (n = 30) of clinicians would refer the patient to use the iCare tonometer and 65% (n = 32) the home visual function app assessment. Scenario 4 reported Ms McEwen, a low-risk patient with normal tension glaucoma (NTG) and mild disease who had not progressed in 5 years.

FIGURE 1.

Clinician agreement on home monitoring using digital technology within patient scenarios.

| Scenario 1 Mr Smith High risk, n(%) |

Scenario 2 Ms Adams Low risk n(%) |

Scenario 3 Mr Patel High risk n(%) |

Scenario 4 Ms McEwen Low risk n(%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would you consider it useful to monitor IOP at home? | ||||

| Yes | 26 (53) | 28 (57) | 26 (52) | 30 (61) |

| No | 23 (47) | 18 (36) | 18 (36) | 14 (9) |

| No response | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 6 (12) | 5 (10) |

| Recommended frequency of IOP monitoring | ||||

| Every 1–7 days | 19 (73) | 9 (32) | 13 (50) | 7 (23) |

| Monthly | 3 (12) | 3 (11) | 3 (12) | 4 (13) |

| Every 2–6 months | 3 (12) | 12 (43) | 7 (27) | 13 (43) |

| Every 7–12 months | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (13) |

| Unclear | 1 (5) | 3 (11) | 3 (12) | 2 (6) |

| No response | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Recommended duration of IOP monitoring | ||||

| Daily | 2 (8) | 1 (3) | 2 (8) | 1 (3) |

| Weekly | 4 (15) | 1 (3) | 3 (12) | 2 (6) |

| Monthly | 4 (15) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 1 (3) |

| Every 2–6 months | 8 (30) | 3 (11) | 10 (38) | 4 (13) |

| Every 7–24 months | 1 (5) | 13 (46) | 5 (19) | 17 (57) |

| Unclear | 7 (27) | 7 (25) | 2 (8) | 3 (10) |

| No response | 0 (0) | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) |

| Would you consider it useful to monitor visual function at home? | ||||

| Yes | 28 (57) | 26 (53) | 20 (41) | 32 (65) |

| No | 19 (39) | 18 (37) | 24 (49) | 12 (24) |

| No response | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) |

| Recommended frequency of visual function monitoring | ||||

| Every 1–7 days | 4 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Monthly | 11 (39) | 5 (19) | 4 (20) | 5 (16) |

| Every 2–6 months | 8 (29) | 14 (54) | 10 (50) | 20 (63) |

| Every 7–12 months | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | 1 (5) | 3 (9) |

| Unclear | 5 (18) | 3 (12) | 2 (10) | 2 (6) |

| No response | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Recommended duration of visual function monitoring | ||||

| Daily | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Monthly | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Every 2–6 months | 17 (61) | 4 (15) | 10 (50) | 4 (13) |

| Every 7–24 months | 2 (7) | 16 (62) | 3 (15) | 22 (69) |

| Unclear | 3 (11) | 2 (8) | 3 (15) | 5 (16) |

| No response | 4 (14) | 4 (15) | 3 (15) | 1 (3) |

Clinicians were asked to suggest optimal time frames for the frequency and duration of home monitoring (of both IOP and visual function) through open-ended questions in each scenario. Similar to the variation in responses to clinical scenarios, a wide spectrum of monitoring frequencies and durations for each scenario were suggested (Table 3). Despite this, greatest consensus appeared within low-risk scenarios (2 and 4) where for both IOP and visual function monitoring, participants reported opting for reduced frequency of monitoring (every 2–6 months) but over an increased duration (7–24 months). For high-risk scenarios (1 and 3), frequency and duration for visual function monitoring were consistent and similar to low-risk scenarios (2 and 4). However, in relation to IOP monitoring, participants reported increased frequency (every 1–7 days) but for a lower duration (1–6 months).

Explaining clinician glaucoma home monitoring decision-making

The justifications provided by the clinicians when reporting that Ms McEwen, scenario 4, would be suitable for home monitoring stated this was due to the nature of her stable disease and her low risk of progression. They felt that she could be safely monitored at home without high risk of missed progression, which could allow increased clinic capacity for individuals with advanced disease, ‘[f]reeing up capacity in the hospital eye service, allowing better use of resources and enabling better care of high-risk patients. Low-risk patients may prefer not having to come in the hospital’ (Consultant, 5–10 years of experience).

Among the participants who predicted that this patient would be unsuitable for home monitoring, the justification was that it may be a waste of resources due to the stable nature of her current condition. This was a contradiction with other participants who deemed her suitable due to the exact same reasoning, ‘stable for 5 years, waste of effort’ (Consultant, over 10 years of experience).

Table 4 summarises the justifications given by clinicians when deciding a patient described in the clinical scenarios would be unsuitable for home monitoring. When evaluating the rationale behind clinicians deeming the other scenarios unsuitable, the main concerns contradicted each other. However, many clinicians (n = 32) highlighted that they may be more hesitant to recommend home monitoring to high-risk individuals. They predicted that they would rather assess these patients in clinic to confidently determine their IOP and visual function. This was expressed to be important as it would avoid any discrepancies or impaired clinical judgement due to potentially ‘unreliable’ readings. They also felt that these advanced cases may require additional resources such as imaging, ‘[h]igh risk of further vision loss within lifetime – young, advanced VF defects bilaterally. Would prefer to see in clinic and discuss surgery at each visit’ [regarding scenario 1] (Optometrist, > 10 years of experience).

| Scenario | Reasons reported for ‘Unsuitable’ response | Example quote |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Mr Smith High risk |

|

|

| 2 Ms Adams Low risk |

|

|

| 3 Mr Patel High risk |

|

|

| 4 Ms McEwen Low risk |

|

|

In addition to measuring clinical agreement within each clinical scenario regarding home monitoring of glaucoma patients, we also investigated agreement across scenarios to determine whether the disagreement in scenarios is related to the digital technology or to which patients should be monitored. There was a lack of consensus relating to which patients should be monitored using the tonometer, with 23 clinicians (47%) reporting that home monitoring of patients would be useful in at least three of the four clinical scenarios. This was also true for visual function, with 22 clinicians (45%) believing it to be useful for three out of the four scenarios.

Clinicians’ acceptability of home monitoring of glaucoma within NHS Care pathways

The fifth clinical scenario in the questionnaire described a clinical care model that combined home monitoring into the current hospital-based system. Regarding acceptability, no agreement was reached on this scenario, with just over half of clinicians (52%, n = 26) reporting that this model was acceptable and around one-third (37%, n = 18) reporting that it was unsuitable; 10% (n = 5) did not respond. Thematic content analysis of free-text responses in relation to this scenario resulted in the following seven themes: Resources, Patient Characteristics, Clinician Confidence in Home Monitoring, Perception of Risk, Wider Benefits, Accessibility, and Disease Suitability of Patient. Within each theme, anticipated advantages and disadvantages in relation to glaucoma home monitoring were identified, as shown in Table 5.

| Theme | Subtheme | Code | A/D | Frequency (n) | No. of participants | Example quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources | Financial effectiveness | Cost-effective | A | 2 | 1 | ‘In the long term, it may be cheaper too’ |

| Poor value for money | D | 28 | 24 | ‘home tonometry for all patients seems a grandiose waste of resources’ | ||

| Health care/clinic capacity | Increased clinic capacity | A | 71 | 36 | ‘Utilising the limited capacity to see stable patients virtually is helpful to generate more capacity for patients who require more attention’ | |

| Decreased clinic capacity | D | 4 | 4 | ‘home monitoring would need to be well supported, to train and supervise patients, and well planned, to review data’ | ||

| No or inadequate alternatives | – | A | 13 | 11 | ‘Better to get some monitoring than just being a name on the waiting list and losing sight’ | |

| Human resource demands | Staff needed to train/support patients | D | 11 | 11 | ‘Securing the funding and staffing to train patients and to troubleshoot might be a challenge’ | |

| Staff needed to review data | D | 9 | 9 | ‘[there] would be a significant burden in virtually reviewing all these patients which would need to be accounted for in the business case’ | ||

| Patient characteristics | Patient compliance | Increased compliance | A | 4 | 4 | ‘May empower patient and improve adherence as they get direct feedback on the effects of treatment and status of disease’ |

| Decreased compliance | D | 38 | 26 | ‘The governance of non-compliancy with lack of patient involvement would be another challenge’ | ||

| Patients’ cognitive, physical and mental abilities | Cognitive impairment | D | 2 | 2 | ‘Forgetting the original treatment instruction’ | |

| Physical impairment/disability impairing use of clinic testing | A | 49 | 31 | ‘Patients with reduced mobility/health issues making clinic attendance or VF testing difficult’ | ||

| Physical impairment/disability preventing use with self-monitoring technologies | D | 7 | 6 | ‘Also, patients with physical disabilities or learning difficulties/dementia will struggle with home monitoring themselves’ | ||

| Decreased patient anxiety | D | 4 | 3 | ‘Where they are anxious about something and have phoned in to ask for early review’ | ||

| Increased patient anxiety | D | 4 | 4 | ‘They may get very anxious about small changes in results without full understanding’ | ||

| Clinician confidence in home monitoring | Beliefs that increase clinician confidence | Improved clinician trust in quality of care delivered | A | 11 | 10 | ‘In reality glaucoma patients may actually do better with more regular IOP and field testing as will pick up discrepancies sooner and we can’t [do] the tests this often in the clinic’ |

| Concerns that decrease clinician confidence | Reliability issues | D | 83 | 35 | ‘We do not have enough information about effectivity’ | |

| Standardised conditions | D | 6 | 5 | ‘There is a possibility of someone other than the patient performing the home tests and passing it as the patients’ | ||

| Hospital compatibility and consistency | D | 10 | 9 | ‘No consistency between hospital and home care tests’ | ||

| Limitations of current home monitoring technologies | D | 34 | 18 | ‘OCT not done which may be considered important by some for early disease’ | ||

| Perception of risk | Perceived patient safety of home monitoring | Increased clinical safety | A | 21 | 18 | ‘greater number of patients getting timely monitoring’ |

| Fear of patient harm | D | 51 | 29 | ‘Experience tells us that some patients will lose vision in the virtual system, despite best efforts to risk stratify and see virtually’ | ||

| IT concerns | – | D | 9 | 8 | ‘IT works well when it works well, but more than often there are barriers and incomplete data etc’ | |

| Wider benefits | Environmental benefit | – | A | 1 | 1 | ‘Good for the planet – low carbon footprint from not having to travel to the hospital’ |

| Increased patient convenience | – | A | 9 | 9 | ‘More convenient for the patient’ | |

| Assessments for patients previously unable to attend routine monitoring in clinic | – | A | 21 | 12 | ‘Bedbound patients in care homes’ | |

| Accessibility | Language | Language barrier | D | 17 | 16 | ‘Harder to reach patients would still have a low uptake of the technology. Education is more important. Even if given device might not use or not use correctly. [Patient] education empowers them to access medical help’ |

| Technology and internet access | – | D | 2 | 1 | ‘Internet availability for download of test results’ | |

| Disease suitability of patient | Stable disease | NTG | A | 42 | 25 | ‘In established NTG were progression despite good IOP in office measures’ |

| OHT | A | 10 | 7 | ‘Only OHT patients can be managed safely with virtual clinics’ | ||

| Screening | A | 7 | 7 | ‘also useful as screening test’ | ||

| Care change monitoring | A | 11 | 11 | ‘May be particularly useful immediately after diagnosis or after change in treatment to determine rate of progression’ | ||

| Phasing (24-hour monitoring) | A | 17 | 15 | ‘Patients with progressive glaucoma – with apparently “controlled” IOP’ | ||

| Low-risk suitable | A | 22 | 18 | ‘Low–medium risk patients can be monitored virtually’ | ||

| Low-risk unsuitable | D | 26 | 19 | ‘Due to the limited capacity in hospital glaucoma clinics, we should focus our resources in higher risk patients’ | ||

| Unstable disease | High-risk suitable | A | 8 | 7 | ‘concentrating on riskier cases without losing focus on the well-controlled ones’ | |

| High-risk unsuitable | D | 56 | 32 | ‘In person visits slots kept for those with uncontrolled IOP, high risk, post-op’s etc.’ |

Resources

From a resource perspective, many clinicians believe that implementing home monitoring could increase clinic capacity for review of high-risk patients and believe that this model could be better than the current alternative of no or limited monitoring. There was also a belief that access to timely care via home monitoring could prevent irreversible severe visual loss, promoting patient health and well-being. However, many doubted the cost-effectiveness of glaucoma home monitoring. Some felt that this model could reduce clinic capacity for patients by the time this service was staffed in relation to the human resource needed to train patients and review the data collected.

Patient characteristics

Clinicians had concerns about patients’ cognitive, physical and mental capacity for home monitoring. While concerns were broadly shared about physical and cognitive capacity, opinions were divided in relation to patient anxiety; while some felt home monitoring could alleviate anxiety in relation to glaucoma progression, some felt it had potential to increase this. The majority reported concerns that home monitoring could lead to reduced patient compliance with regular testing and concerns about how this would be monitored. For the few, compliance could increase as regular feedback on disease status was anticipated to be motivational for patients.

Clinician confidence in home monitoring

We found that while there was some optimism about more frequent monitoring, home monitoring was largely anticipated to cause a decrease in clinician confidence in the quality of care delivered to patients. This was related to concerns about the reliability, standardisation, and compatibility of the devices, with and against hospital equipment, and concerns about relying on a narrower range of measures, as opposed to additional measures obtained in clinic (e.g. optical coherence tomography). There was some optimism, however, that more frequent monitoring of IOP and visual function, as would be possible with home monitoring, could detect progression sooner.

Perception of risk

While several clinicians reported more timely monitoring being a positive, there was a strong concern about the risks posed by the home monitoring of glaucoma. Risks raised reflected patient harms (e.g. missing glaucoma progression, resulting in loss of vision) and data and technology risks resulting from events such as failing equipment.

Wider benefits

A couple of wider benefits to home monitoring were raised. For example, the reduced travel arising from monitoring at home offers an environmental advantage. For some, home monitoring was expected to be more convenient for patients. Some also raised the advantage of being able to monitor patients who currently are not able to be monitored in clinic, such as those who are bedbound and/or residing in care homes.

Accessibility

Several disadvantages which could be potential barriers to accessing home monitoring were reported, namely language barriers and technology/internet access. These were expected to result in low uptake of home monitoring among some population groups.

Disease suitability of patient

Similar to the variation in responses to the clinical scenarios (1–4) there was little consensus in responses made in relation to a patient’s medical suitability for home monitoring. Most agreed that those at high risk of progression were unsuitable for home monitoring. Certain disease classifications (OHT and NTG) were frequently considered good candidates. The use of these technologies for glaucoma screening and phasing purposes was often frequently suggested as having potential in addition to or instead of regular monitoring.

Chapter summary

This chapter has demonstrated that there is agreement among the expert glaucoma clinicians surveyed that there is a place for home monitoring of glaucoma patients using digital technology. However, based on the scenarios used in this study, there is limited agreement among clinicians about which glaucoma patients are most suitable for home monitoring using digital technologies to measure IOP and visual function. Agreement (> 60%) was achieved for scenario 4 (a stable, low-risk patient), with clinicians supporting monitoring of IOP and visual function at home. Clinicians reported that they were generally not supportive of the home monitoring of high-risk patients, due to the fear of missing disease progression or unreliable readings. However, they were generally supportive of home monitoring having a role within low-risk scenarios, such as NTG monitoring and 24-hour phasing. Clinicians anticipated that the integration of home monitoring into the current healthcare system could act as an adjunct to increase hospital capacity for glaucoma patients who require face-to-face assessment.

This survey has highlighted a range of issues and challenges related to the home monitoring of glaucoma patients using digital technologies. A central theme is clinicians’ lack of trust in home monitoring technologies, related to concerns about the reliability, accuracy and usefulness of these technologies. Clinicians expressed concerns about patient safety, decreased rather than increased glaucoma progression detection and concerns about how resource efficient (time and financial) this approach could be in comparison to current provision. These areas are explored in more detail in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3 Expert glaucoma clinicians’ acceptability of glaucoma home monitoring

Building on the findings from the survey data investigating expert glaucoma clinicians’ views on patient populations suitable for home monitoring using digital technology, as reported in Chapter 2, this chapter presents the findings of semistructured interviews with the same stakeholders to explore intervention acceptability in more detail. Exploring intervention acceptability among a wider group of clinicians, and in particular those not involved in I-TRAC, was important so as to understand broader community perspectives. The aim of this phase was to identify additional insights to enhance trialability of digital technology for home monitoring of glaucoma.

Methods

Study design

Online focus groups and interviews involving expert glaucoma clinicians, who have not been involved in the glaucoma home monitoring intervention component of the study, guided by the TFA.

Sampling and recruitment

Participants were recruited through the clinician survey (see Chapter 2), where respondents could indicate their willingness to be contacted for interview and provide contact details for arranging this. Participants were asked to select their preferred time and date from three available options. Those unable to accommodate focus group date/time were offered an interview as an alternative. We aimed to recruit 16 participants. We invited all clinicians who had agreed to be contacted (n = 25). Of these, 15 (60% response rate) attended a focus group or interview (seven did not respond to the invitation including a reminder e-mail, and three had booked a focus group session or interview but failed to attend). All participants provided verbal (recorded) consent prior to the focus group or interview.

Data collection

Interviews and focus groups were conducted online (MS Teams®; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by CS and facilitated by KG. Demographic data were collected via the clinician survey (see Chapter 2). Discussion was guided by a prepared semistructured topic guide. The topic guide questions were framed around the constructs of the TFA: affective attitude, intervention coherence, ethicality, perceived effectiveness, self-efficacy, anticipated costs and burden. Focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for analysis. 46 Analysis was conducted such that a deductive TFA analysis was conducted first, followed by inductive analysis to identify themes within the TFA construct findings. Transcripts were first reviewed noting underlying points, ideas or feelings being conveyed throughout each transcript. These were then considered against the TFA criteria and where applicable, organised within the TFA constructs. Data deemed relevant but not fitting TFA were retained and their relationship with TFA constructs explored. Two researchers (CS and KG) coded the first three transcripts concurrently to develop a coding strategy based upon the TFA. The coding guide developed for analyses is presented in Appendix 2. Subsequent transcripts were coded by one researcher (CS) and a random 10% sample (n = 1) was independently double coded (KG).

Results

Sample demographics

Expert glaucoma clinicians (n = 15; 13 consultant ophthalmologists and two specialist optometrists) participated across three focus groups (n = 2, n = 4, n = 4) and five individual interviews (due to clinician availability). Most (n = 12) reported that they were not currently using home monitoring devices to measure IOP, and none were using devices for home perimetry. Focus groups lasted 56–70 minutes and interviews 31–55 minutes. Most expert glaucoma clinicians who participated had over 10 years of clinical experience (n = 14). Age, gender and ethnicity data are shown in Table 6.

| n | ||

|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Consultant | 13 |

| Specialist optometrist | 2 | |

| Experience of treating glaucoma (years) | < 5 | 1 |

| 5–10 | 0 | |

| > 10 | 14 | |

| Age (years) | < 40 | 2 |

| 40–49 | 3 | |

| 50–59 | 9 | |

| 60+ | 1 | |

| Gender | Male | 6 |

| Female | 8 | |

| Non-binary | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | White (all) | 7 |

| Asian (all) | 7 | |

| Black (all) | 1 |

Findings

Data from the interviews were coded into all seven constructs of the TFA, and inductive analysis within the TFA constructs resulted in 19 themes, under a global theme of cautious optimism. Table 7 presents a summary of the interview findings.

| TFA construct | Theme |

|---|---|

| Affective attitude | Enthusiasm tempered with uncertainty |

| Concerns about negative affect for patients and staff | |

| Ethicality | Ethical ‘risks’ of remote and commercial data collection technologies |

| Intervention fit with principles of ‘good’ care | |

| Managing equity in patient selection | |

| Intervention coherence | Autonomy to determine the who, when, and where of home monitoring |

| Data relevance and integration | |

| Support for patients | |

| Anticipated costs | Beliefs about cost-effectiveness |

| Adjustments to address affordability | |

| Burden | Clinician burden |

| Patient burden | |

| Perceived effectiveness | Anticipated outcomes |

| Balancing benefits and harms | |

| Impact of perceived data and technology limitations upon intervention effectiveness | |

| Patient characteristics impacting intervention effectiveness | |

| Impact of service levels factors on effectiveness | |

| Self-efficacy | Low self-confidence and confidence in patients to use tech |

Affective attitude

Enthusiasm tempered with uncertainty

When asked how they felt about the I-TRAC home monitoring interventions for glaucoma patients, expert glaucoma clinicians were generally enthusiastic about the opportunities this intervention presented, described through terms such as ‘excited’, ‘delighted’, and ‘glad’.

I think it’s a great idea, I think we need to know this. We’ve got real problems with capacity in glaucoma and if we can have a trial that helps us better understand the patient acceptability, clinicians’ views on acceptability and the meaningfulness of the data and so on and so forth then it’s to be welcomed.

P002, Optometrist, Focus Group 1

These feelings were often reported in relation to home monitoring being a potential solution to national capacity problems across HES. However, enthusiasm was tempered with caution – as indicated by a number of conditional statements such as ‘I think it would be a great thing if it worked well and it was reliable’ (P008, Consultant, Focus Group 2) – demonstrating the connection between affective attitude and perceived effectiveness.

Concerns about negative affect for patients and staff

Expert glaucoma clinicians also reported that they felt many patients would be welcoming of this approach, highlighting how this could reduce patient stress and provide comfort, ‘some patients genuinely like writing the numbers down and they like to know what they were before and they get great comfort in knowing there are numbers written down that they have control over’ (P018, Consultant, Interview).

However, among the positive feelings, some clinicians reported feelings of anxiety and frustration as a risk of such interventions, which could be experienced by both staff and patients.

Digital data, I mean it does sound like this panacea and it’s wonderful, but actually when it doesn’t go quite so right it can be extremely difficult and frustrating, and I’m thinking about the age group of our patients, how hard it might be for them.

P004, Consultant, Focus Group 1

Ethicality

When exploring the ethical construct of acceptability, responses generated three linked categories: ethical risks of remote and commercial data collection technologies, how the intervention fits with principles of ‘good’ care and managing equity in patient selection. These are discussed in turn below.

Ethical risks of remote and commercial data collection technologies

When asked about ethical issues this intervention may pose, many clinicians discussed aspects of data security. There were concerns about how to protect these systems from external threats, and the need for secure data exchange. Many felt that NHS systems of governance for IT should be adequate to adopt this; however, one clinician raised the need to consider how commercial entities also manage data governance:

[O]ne thing we’ve not necessarily quite touched on is the link with the commercial sector. So OKKO Health are a commercial sector organisation, whoever’s come up with [home visual field intervention] presumably is as well. So who owns the data, who’s responsible for the governance of the data, all of that.

P002, Optometrist, Focus Group 1

Also related to the commercial side were concerns about what would happen to data should a private enterprise withdraw from service, posing the risk that patient data could be lost and no longer governed by NHS data governance. There were concerns that these data could then be misused. There were also some concerns about safety, with calls for regular data auditing being required to establish the safety of this service. One issue raised by a number of clinicians connected to data control is the risk that patients may allow the device to be used by others. The potential risks from this include poor treatment decisions from non-patient data, issues about consent if researchers hold data that are not from the consented patients, and the potential for detecting eye diseases in others (not the patient). However, having user logins to prevent non-patients from using the devices was suggested as an approach that could overcome this, suggesting addressing this concern was not insurmountable.

I wonder… the temptation would be to try it on your family and friends. I mean, I don’t know. But they might say, ‘Have a go. This is what I have. Look at what the hospital’s given me’ which will mess up your data.

P010, Consultant, Interview

Intervention fit with principles of good care

There were a number of references to how this intervention fits with the principles of good care. For some, home monitoring fits well within the self-management framework, where it is considered appropriate to empower patients to manage their own health care. For others, there was concern that home monitoring could lead to reducing glaucoma clinics to little more than data monitoring hubs, leading to a loss of personalised and holistic care.

. . . there’s the reduction potentially of… it could be that glaucoma clinics are seen to be reduced down to data collection on instruments. We know that many of these patients have things they want to talk to us about, we know that they have things wrong with their eyes other than glaucoma and there’s a loss of the holistic approach to patients when things are reduced down to maybe a few questions on a proforma and some data supplied intermittently versus a face-to-face interaction.

P002, Optometrist, Focus Group 1

For others, limitations in the current system are contributing to the overtreatment of glaucoma, whereby clinicians, knowing it could be some time before they review a patient again, tend to provide medical treatment, on a ‘just in case’ basis. Being able to offer home monitoring was viewed as a solution to this and could reduce unnecessary medical treatment.

I think actually virtual clinics you often overtreat and also I guess many of you have these, what we call follow up pending lists, and certainly COVID’s made them go much higher, and you think a patient may have a problem and you say, ‘Okay, we’ll see you again in six months’, but six months maybe 18 months, and, so on that basis I think you sometimes overtreat because you just don’t know when you’re going to see this patient again. So the fact you could have a facility which can help with monitoring patients that you haven’t got capacity to see within the hospital eye service may enable you to treat less patients and therefore get less morbidity from their treatments.

P005, Consultant, Focus Group 2

For one clinician, while supportive of home monitoring, they wondered if this focus upon already diagnosed patients was missing a bigger problem in glaucoma care, specifically, the low level of detection of the disease in its earlier stage.

I think it’s fine this sort of study, but there is a bigger picture that there are lots of people in the UK and particularly in the developing world who don’t get picked up in the community and there has to be solutions to that that could involve these mobile technologies or whatever.

P009, Consultant, Focus group 2

Managing equity in patient selection

Clinicians frequently reported concerns related to equity and equality, particularly in relation to making decisions as to who should obtain home monitoring equipment, and what fallout there may be from those decisions. Frequent references to factors which may make it difficult for some to participate include accessibility, language, education, and technical abilities (discussed in detail in Perceived effectiveness). However, these led to ethical consequences: how to select and prioritise patients for home monitoring (particularly where there will be resource constraints), impact upon those who are not selected for home monitoring and the risk of creating a two-tier system. The latter was in relation to an expectation that patients may have to contribute financially towards equipment, which opens the door to one system for those who can afford and one for those who cannot.

Well actually, prioritisation. If say someone’s neighbour got this and someone else didn’t get it, word goes around in the glaucoma community: ‘Why did she get it? How come I didn’t get it. Am I more less important? Are you more important?’ That’s not going to go well, I suppose. Ethically how do you choose because you have a limited resource, so that limited resource ethic problem. Even if you gave them the option to buy it, then it’s also another ethical dilemma, because the rich are getting better monitoring. But, having said that, it frees up space, frees up one iCare for another person who can’t afford it, so I mean it’s that ethical dilemma of privatisation versus, you know, but… so that same story. But if they want to buy it, I think they should be able to buy it.

P010, Consultant, Interview

However, some argued that such a two-tier system would be inevitable and necessary to accommodate those for whom home monitoring is not suitable regardless of affordability. Clinicians’ accounts report the need for clear guidance as to how to select patients for home monitoring.

I suppose the other ethical issue is, and we’ve kind of touched on it with patients that are able to use these devices and patients that aren’t able to use these devices, if this becomes the gold standard of treatment for patients and then you have a patient that is unable to do it, how can you ethically not let them have treatment, do you then pass(?) that on to go and take the measurements as regularly in-house. That’s obviously years down the line.

P015, Consultant, Focus Group 3

Intervention coherence

Autonomy to determine the who, when and where of home monitoring

When asked about the advantages and disadvantages of this intervention, several attributes became apparent. The first was that there was a desire among clinicians for autonomy to decide how best to integrate home monitoring into usual care.

So I don’t think we could decide or should decide as to who can use it. I guess if the underpinning evidence is that these are meaningful measurements, then it’s about the training and accreditation and ability to autonomously make decisions by whoever is looking after the case mix of patients where that service is being commissioned, and that could be primary care or secondary care.

P002, Optometrist, Focus Group 1

Clinicians discussed varied purposes and patient scenarios (varied clinical situations and parameters) where these technologies could be helpful, and it became apparent there was no consensus among clinicians as to the ideal clinical scenario or patient for glaucoma home monitoring. Suggested clinical scenarios included phasing, reducing overtreatment, monitoring for progression, risk-stratifying/referral strategies, promoting patient self-management, increasing localised care (reducing hospital visits) and increasing clinic testing capacity for higher-risk patients.

[T]he way I envisaged it is more as a trigger to find the patients that need intervention. So this isn’t going to be the be all [and] end all care of a patient’s pathway, it’ll be a service where you can gather whatever data you can regularly that gives you a trigger to say, ‘Well actually that patient’s doing absolutely fine, don’t need to get involved’, whereas another patient, ‘Oh, they need to come in hospital, we need to have a proper look at them’.

P015, Consultant, Focus Group 3

It could also be valuable across patient groups as some felt the increase in data collected would be relevant and beneficial for all groups.

[A]ny data points you can get will enable you to have a better picture and diagnosis of what’s going on with a patient, but I think the more points you can get, the more data you can get, the better. I think that could be taken to any patient group.

P015, Consultant, Focus Group 3

Clinicians generally agreed with the use of home monitoring technologies for patients considered at low risk of progressing to significant visual loss, but some could see value in considering these technologies for higher-risk patients in specific circumstances.

[C]hecking your pressure having changed treatment in somebody who’s relatively low risk and your next clinical decision probably isn’t going to be surgery. Then again, you’ve got your ocular hypertensive, in fact we discharge ours to community optometrists, but if you haven’t managed that service with your local optometry committee then you could argue very low risk glaucomas could be monitored quite long term with fields and IOP.

P005, Consultant, Focus Group 2

I think the patient… the people who we see in the hospital services are high risk that need to be seen, because I think the addition of… additional pathology, the very nature of the discussions we have to have with the patients that a home monitoring system isn’t ideal. However, for… even with our high-risk patients, I think again it comes down to how accurate the data is. This might help with anxiety for some patients who are always worried about what their pressures are doing and obviously you can’t see patients frequently, but if you get a baseline with this then patients being able to measure their own pressure at home a couple of… two or three times a week, it might ease that.

P004, Consultant, Focus Group 1

There were several statements suggesting that defining an ideal patient was perhaps not the right approach and that there should be flexibility afforded to individual services as to for whom and how home monitoring is used.

So I suppose each local… well it will have to be very individual to each place and how they work isn’t it as to who looks at the data and which group of patients, that kind of thing as well.

P016, Consultant, Focus Group 3

Some mentioned that age may be a deciding factor. Partly this was in relation to ability to use the devices, partly this was in relation to those considered at risk of the greatest QoL losses from losing visual function at younger age, and partly this was in relation to a subgroup of glaucoma patients who may still be working, and therefore for whom attending clinics for testing is perceived as being more burdensome.

I’m thinking of young normal tension glaucoma patients, so I mean 50. They’re the ones I worry about because they’ve got a lot of life to live and so they’ve got higher likelihood of going blind. And the normal tension glaucomas have trans-central scotomas, so they’re very sensitive. As soon as they lose one decibel that’s it, the whole vision is really bad, so those might be the ones.

P010, Consultant, Interview

Some clinicians felt that home monitoring may not be able to replace usual care for complex cases (e.g. multimorbidities) where information gathered from face-to-face observations is really important.

[T]he people who we see in the hospital services are high risk that need to be seen, because I think the addition of… additional pathology, the very nature of the discussions we have to have with the patients that a home monitoring system isn’t ideal.

P004, Consultant, Focus Group 1

Data relevance and integration

Distinct but complementary to concerns about data ‘ethicality’ was the intervention coherence concerns about the reliability and relevance of the data collected, and how these data will be integrated with electronic medical records. Those claiming to be less familiar with the evidence appeared sceptical that these technologies would produce reliable data to make meaningful decisions about patients’ care. There was disagreement about what aspects of visual health need to be measured; some agreed with both IOP and VF, others felt only IOP is required, others VF only and others worried about the lack of data in relation to other visual health domains, such as disc imaging and acuity, often measured in clinic. While it was agreed that data must be meaningful to clinicians (i.e. the measures being assessed are useful to make clinical judgements), there was little agreement regarding exactly what measures are relevant to make home monitoring meaningful, ‘[u]nless you can make the disc images cheaper and the pressures cheaper, then you can’t just rule out fields. I mean, fields itself are known as not very useful, if you catch my drift’ (P010, Consultant, Interview).

Some were so enthused by the evidence for glaucoma home monitoring that they were keen to see what future technology developments could achieve and made suggestions as to what else this home monitoring intervention could look to incorporate and overcome limitations from just assessing IOP and VF (data-related opportunities to improve for the future). For example, several clinicians discussed a contact lens device which can measure IOP or technologies permitting home disc imaging.

I was just wondering if when we’re talking about disc photographs, there are a few devices now that you can attach to smartphones to give you a disc photograph, I’m not sure would it be worth expanding to that you know, and you get your disc photograph.

P019, Consultant, Interview

Some participants reported being worried about how these data would integrate with existing medical records and any associated time required to input the data into existing systems. This links with perceived burden, discussed below. A solution put forward by many was to make the intervention software compatible with electronic patient records so that results can be immediately integrated without additional effort. A further solution proposed by some participants is the future use of AI for helping review the data as it comes in, making it quicker for clinicians to interpret the data collected remotely.

I’m pretty sure with artificial intelligence, we may be able to even define that what has changed has really change[d] or not, and then we can fast-track that… the results can be interpreted with the AI, I think I can see in five, ten years’ time, this is the way we do.

P001, Consultant, Interview

Support for patients

There was also significant importance placed upon the need to ensure the intervention is supportive for patients to address potential concerns. Participants felt many patients would require professional reassurance in understanding this intervention, particularly in terms of educating patients to understand that readings can fluctuate day to day and that it is the overall trend that the clinicians are concerned with rather than daily readings. Clinicians felt this would be important to prevent unnecessary worry.

You know, as long as they know that someone’s going to tell them I want a report of it or something, then all that hard work’s not for nothing, then I think that’s fine… then you could tell them that everyone’s pressure varies with… there’s a variation every day etc, and warn them not to worry about it, and the whole point is that we gather data over time so that we can make a judgement at the end of the day, so don’t worry about that. If you give them a clause, that will be fine….

P010, Consultant, Interview

Limiting access to results or reconsidering how results are presented to patients was one area of patient-related opportunities to improve in the future suggested by several participants. For example, more generic feedback, such as informing the patient that they had completed the tests correctly, was suggested to be a compromise to maintain engagement and prevent worry from results that may not be fully understood by the patient, causing unnecessary worry.

[W]e should just say in the app, ‘You have correctly answered 75% and you are among the top grade who have done the test very nicely’, or ‘You’ve done test reasonably, but it could be improved if you pay attention to these things’, or, ‘Your test needs to be repeated’. That is the only feedback going to the patient, and then we say, ‘Okay, now, you’ve done the test, it will be reviewed by the doctor… medical team, and we will come back to you.’ So that when we inform them that the situation is getting worse or the visual function is getting worse, we give them the solution there and then that, ‘Okay, we reviewed your results, your results shows deterioration, we have looked at your management plan, and we suggest you should be changing this, and after this you will be reviewed again by somebody.’

P001, Consultant, Interview

Another solution proposed is to offer a simpler intervention in the community for those struggling with the technology, for example facilities at shopping centres, etc.

This could even be done by a trained station in a supermarket, and we can just tell that person to go… you can’t do the technology for somebody, maybe there to help you guys, they don’t need to come to the hospital. They could go for their weekly shopping, and they go to a booth where there is one trained person who could have these appointments for these eighty, eight five… and those people who cannot cope with technology. And it is then outside the hospital, so we basically take it to the community in real sense.

P001, Consultant, Interview

In addition to clinician-provided support, participants felt this intervention would likely require utilisation of social support, making use of family and friends. For example, reminding patients to perform their assessments or physical support to use the devices.

[I]n the same way that we’re quite content to have, a lot of our elderly patients have their partner put their eye drops in, well it can be a team effort. Sometimes elderly people cope rather better when, ‘Oh, yes, my husband always remembers to do this’, who locks the door, there’s a certain way, people survive together don’t they and I just wonder whether there’s something in that for some of our patients. It goes beyond this technology really, but yes, you’d probably need to involve the younger generation.

P002, Optometrist, Focus Group 1

Anticipated costs

Beliefs about cost-effectiveness

Two clinicians reported that they believed the proposed intervention would be good value for money.

Well, it could potentially reduce the cost. If you’re not having to bring patients in, you don’t require transports, you won’t need technicians to gather the data of the patients as they can gather the data themselves. It would be an actual virtual data collection, and fewer staff costs.

P018, Consultant, Interview

Several clinicians specifically stated that this approach is not good value for money, and many were concerned about the cost of the equipment, particularly the home tonometer. Additional costs raised were maintenance of this equipment, having spares in case of damages, and the staffing to train patients and review data.

[W]e could be looking at wasting our resources looking after too much data points from patients who are well and were not really at risk of going blind with their glaucoma and are we diverting our resources be it instrumentation, time looking at the data and collecting the data which could be used more effectively for other patients.

P017, Consultant, Focus Group 3

I think I prefer something which would be a bit even easier than Home iCare tonometer at the moment, and perhaps less expensive as well, because we give it to such a big population and if you can just give it to one person they will take it for a week, so just calculate for one person the population how many Home Care eye tonometer you need, and then if you extrapolate that cost and the overall benefit you are going to get from that, I’m not convinced that it is for everyone.

P001, Consultant, Interview

Some felt this would make it difficult to obtain management or clinical commissioners’ support for such a service.

I think the distribution and the (inaudible) the devices and persuading the health and social care service that we want to spend thousands of pounds on purchasing these things, I think that could potentially be an issue.

P019, Consultant, Interview

Adjustments to address affordability

However, several clinicians perceived that it could be made more affordable, firstly by looking at app services and dropping the iCare tonometer or asking patients to purchase their own equipment. One clinician felt that the costs would reduce as the technology improved and became more mainstream.

Yeah, that’s where your visual field app may be more cost effective in terms of economics and access to the piece of equipment that the patient has to take home, perhaps an app or something that they can download on to a tablet with a licence, it may be much more generalisable than to take home an iCare HOME.

P009, Consultant, Focus Group 2

Burden

Burden was discussed in relation to the clinicians themselves, the services they operate within and upon patients.