Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/90/03. The contractual start date was in November 2017. The draft report began editorial review in August 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Worthington et al. This work was produced by Worthington et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Worthington et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Frost et al. 1 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background and review of current literature

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men substantially affect quality of life, work and other activities; such problematic LUTS are described as ‘bothersome’ according to the impact on the patient. 2 LUTS can relate to storage (increased urinary frequency, nocturia, urgency, incontinence), voiding (slow stream, hesitancy, straining) or post-voiding (post-voiding dribble, sensation of incomplete emptying) symptoms.

Men usually present with a range of LUTS. Particularly high-impact LUTS for men are urgency/urgency incontinence, post-micturition dribble, nocturia and increased urinary frequency. 3–5 In population-based studies, measures of disease-specific, health-related quality of life are substantially worse among men with higher symptom severity and bother ratings than among men with low symptom severity and bother ratings. 6 LUTS can be caused by prostate enlargement, leading to obstruction and/or bladder dysfunction, but are also influenced by men’s lifestyle and habits, such as overall fluid and caffeine intake.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline 97 recommends that, on initial presentation with LUTS, men should undergo key assessments to exclude serious medical conditions [malignancy and urinary tract infection (UTI)] and should be asked to complete a bladder diary, to assess the impact of their LUTS and to aid diagnosis. 7 Conservative treatment measures (fluid advice, bladder training, urethral compression and release, and pelvic floor muscle exercises) are then recommended as initial interventions. 7 On the basis of a systematic review of assessment and therapy of male LUTS, the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on male LUTS for secondary care state that categorising precise symptoms (storage/voiding/post voiding) is an expectation of urological practice, and EAU also recommends conservative treatment measures. 8

Proper symptom assessment and explanation of conservative measures are more time-consuming and complex than they may at first appear, owing to differences in individual symptoms and potential causative factors, and the need for conservative care to be tailored. As the average general practitioner (GP) consultation lasts 12 minutes and covers 2.5 problems,9 and given a lack of resources to support the guidelines and conservative approach, the proportion of men receiving the recommended standard of care in primary care is potentially small.

In terms of symptom assessment, a 2016 Royal College of Physicians audit of continence care in primary care showed that < 50% of patients had completed a bladder diary and < 30% had a validated symptom score. 10 Thus, men may undergo limited assessment mainly to exclude serious underlying conditions, potentially resulting in treatment for LUTS being sidelined.

The frequency of delivery of conservative treatment measures was also low, with the Royal College of Physicians’ audit demonstrating that < 65% of men had used lifestyle modification, < 50% used behavioural modification and < 35% used bladder training (worse among men aged > 65 years). 10 Ineffective delivery of conservative measures in primary care can mean that men simply receive a prescription of medication to treat the prostate, are inappropriately referred to secondary care or endure persistent symptoms.

The evidence to support conservative interventions is also limited. The Cochrane review on lifestyle interventions for the treatment of urinary incontinence in adults11 suggested that there is insufficient evidence to justify fluid advice for treatment of urgency incontinence. However, an NHS evidence update indicated that self-management may have a role in the treatment of LUTS,12 citing a post hoc analysis13 of a single-centre randomised controlled trial (RCT)14 of 140 men with LUTS assigned to standard care plus a self-management programme or standard care alone. Men assigned to the self-management programme reported better voided volumes, and reduced daytime frequency and nocturia. The trial had a relatively small patient population and was conducted in a single tertiary treatment centre. According to NICE Clinical Guideline 97, a multicentre RCT is needed to determine if such results could be replicated in everyday clinical practice. 15

Rationale for the trial

The risk of LUTS increases with age, with a prevalence of up to 30% in men aged > 65 years;7 therefore, the number of patients affected is likely to increase as the population ages. As most men with LUTS are managed within primary care, the burden on primary care is likely to grow, and, consequently, so will the need for effective provision of LUTS care.

As only a small proportion of men with LUTS receive the recommended assessments, or recommended standard of conservative care as initial treatment within primary care, there is a clear need for an effective, evidence-based intervention that can be feasibly implemented in routine primary care to support delivery of NICE guidelines. The TRIUMPH (TReatIng Urinary symptoms in Men in Primary Health care using non-pharmacological and non-surgical interventions) trial aimed to address this need within primary care. In addition, with evidence lacking on the effectiveness of self-management programmes for LUTS, the trial aimed to provide the evidence needed to justify this approach and the current guidelines.

The TRIUMPH trial intervention sought to provide detailed conservative care advice for male LUTS. The trial was primarily designed to establish whether or not this approach improved symptomatic outcomes compared with usual care, and whether or not the result was sustained over a longer duration beyond the last follow-up contact with the healthcare professional (HCP). If the TRIUMPH approach proved to be effective, it would provide the necessary resource for general practices to effectively deliver conservative treatment through a pathway led by a practice nurse/healthcare assistant (HCA), reducing GP reconsultation for symptoms, prescribing and unnecessary secondary care referrals.

Trial aims and objectives

The key aim of the TRIUMPH trial was to determine whether or not a standardised and manualised care intervention achieves superior symptomatic outcome, compared with usual care, for male LUTS, with a primary outcome of overall International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) measured 12 months after consent, in a primary care setting.

The secondary objectives were to compare the two trial arms with regard to:

-

disease-specific quality of life

-

symptomatic outcomes

-

cost effectiveness

-

relative harms

-

use of NHS resources

-

overall quality of life and general health

-

acceptability of assessment and provision of care

-

patients’ perception of their LUTS condition.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Frost et al. 1 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are also reproduced from the published statistical analysis plan by MacNeill and Drake. 16 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

The TRIUMPH trial was a multicentre, pragmatic, two-arm cluster RCT of a care pathway based on a standardised and manualised care intervention (TRIUMPH intervention arm) and usual care (comparator arm) for men with LUTS. The trial was conducted in 30 general practice sites within nine Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) across the West of England and Wessex Clinical Research Network (CRN) regions in the UK, recruiting patients from June 2018 to August 2019. Sites were randomised to the intervention or comparator arm, with men with bothersome LUTS consented from these sites. The main aim of the trial was to determine whether or not the TRIUMPH intervention arm achieves superior symptomatic outcome, compared with the usual-care arm, for male LUTS, with a primary outcome of overall IPSS measured 12 months after consent.

The trial design included an internal pilot recruitment phase of 4 months’ duration, primarily to verify that recruitment was possible before progression to the main phase of the trial. Targets for progression to the main phase of the trial were as follows:

-

The number of practices agreeing to take part was at least 18 (75%) by the end of month 6.

-

The number of patients recruited was at least 120 by the end of month 4 of the recruitment phase.

Ethics approval and research governance

Approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West – Preston (reference number 18/NW/0135) was received on 11 April 2018 and applied to all NHS sites that took part in the trial.

The trial is registered at the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry with the reference ISRCTN11669964.

All participants provided their written, informed consent to participation before entering the trial. Participants consented by post, following GP screening of their medical notes and a screening call by CRN nurses/clinical practitioners.

All serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded; the sponsor and Research Ethics Committee were notified within 15 days of any SAEs categorised as unexpected and related. General practices were responsible for reporting SAEs for their trial participants during the course of the trial; however, participants were also asked to self-report any inpatient stays in their follow-up questionnaires, which prompted GP review. All other adverse events not deemed serious were collected from participant electronic medical records (EMRs) at the end of participants’ 12-month involvement in the trial, as part of the secondary outcomes.

A number of protocol changes were made during the course of the trial, as listed below:

-

The Self-Assessment Goal Achievement questionnaire that was originally planned was replaced with the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ). The B-IPQ was more relevant to the trial, as the Self-Assessment Goal Achievement questionnaire mentions goals set with the healthcare providers, which was not applicable to the TRIUMPH intervention.

-

Qualitative interviews with a small number of men who decided not to take part in the TRIUMPH trial (decliner interviews) were added.

-

As well as practice nurses, HCAs were specified as able to deliver the intervention.

-

Hypercalcaemia was removed from the exclusion criteria.

-

A criterion about a competing primary care LUTS study was added to general practice eligibility requirements.

-

‘Date of LUTS diagnosis’ was removed from the baseline data to be collected, as this date is arbitrary and depends on when the patient chose to seek help regarding his symptoms, and therefore was not considered relevant.

-

Specification of an exact figure for the number of eligible patients required by general practices to take part in the trial was removed, as determined by a pre-randomisation practice database search.

The protocol was also updated during the trial to make minor clarifications to trial procedures.

Participants remained in the trial unless they chose to withdraw, or if they were unable to continue. Participants could withdraw fully from the trial or from specific elements without giving a reason. Any data collected up until the point of withdrawal were retained. Participants were informed of this in the patient information leaflet prior to consent.

General practice recruitment and selection

The trial recruited from two centres: West of England and Wessex CRNs. The CRNs invited general practices to express an interest in taking part in the trial. The general practice inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

inclusion criterion – adequate number of eligible patients, determined by pre-randomisation practice database search (to achieve site target recruitment of 35 patients)

-

exclusion criterion – unable to provide adequate treatment room space and availability for trial or practice nurse/HCA to complete HCP training and baseline visits.

However, to achieve a balanced range of practices, the following factors were also considered in practice selection:

-

number of potentially eligible patients, on conduct of a preliminary database search

-

patient list size

-

deprivation score (calculated using the general practice postcode)

-

preference for intervention delivery (practice staff or trial research nurses).

The sites selected to take part in the trial underwent site initiation training. An internal pilot phase was conducted with eight initial sites over a period of 4 months before the main phase of the trial, for which a further 22 sites were recruited. In total, 32 general practices were recruited within nine CCGs across the West of England and Wessex CRN regions in the UK. These constituted 30 sites, owing to a collaboration of three practices operating a hub-and-spoke model, sharing nurse resource, and therefore randomised as a single site for the trial.

Participants

Participant population

The TRIUMPH trial was a pragmatic trial, comprising adult men who considered themselves to have bothersome LUTS and who presented to primary care within the preceding 5 years with at least one symptom. Only men already known to have LUTS (prevalent cases) were screened for inclusion in the trial. Screening was undertaken once by each site before randomisation, so men newly presenting with LUTS (incident cases) after site randomisation were not included. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table 1.

| Inclusion criterion |

| Adult men above the age of 18 years old who have bothersome LUTS |

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Patient screening and invitation

The process of patient invitation and screening is detailed below:

-

General practices conducted a single database search to identify potentially eligible patients. The database search was developed specifically for the trial, based on the trial inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Appendix 1, Table 38), for both EMIS Web (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK) and SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership, Leeds, UK) patient administration systems used in primary care sites in both CRN regions.

-

The patient list identified by the search was manually screened by GPs at the site against patients’ EMRs using the eligibility criteria listed (see Appendix 1, Table 38), including criteria that could not be fully included in the search, such as lack of capacity to consent, and referral to or review by secondary care.

-

A de-identified screening log populated with eligibility codes for all patients identified from the search was sent to the central trial team.

-

Invitation letters, with patient information leaflets and expression of interest (EOI) forms, were mailed out to eligible patients by practices using an approved third party [Docmail® (Docmail Ltd, Radstock, UK), a secure service that automates sending invitation letters to potential participants]. A single mail-out was conducted by each site, before notification of their randomisation, to avoid any bias in patient selection.

-

Interested patients completed their EOI forms online or returned paper copies by post. Participants could also decline to take part on their returned EOI form, and indicate whether or not they would be willing to take part in a decliner interview for the qualitative element of the trial.

-

Clinical Research Network nurses or clinical practitioners trained by the trial team telephoned interested patients. These calls were conducted while masked to the allocation of the practice, and therefore the patient, to avoid any bias. Calls were conducted to confirm eligibility, particularly the subjective criterion of whether or not the patient’s LUTS were bothersome to him; to ensure patient understanding of the trial; to answer any questions; and to confirm willingness to participate.

Following a review of the pilot phase figures, the key changes that were made to the conduct of the trial for the main phase were an increase in the maximum number of patients invited by a single site from 150 to 220, and confirmation that 30 sites would be required to maintain the trial power calculation in the light of variation in the number of patients recruited per site. The decision was also taken to conduct only a single invitation mail-out from each site, rather than inviting additional patients in a second mail-out to achieve site targets as necessary, to avoid introducing any bias post randomisation. Although screening of all patients for both mail-outs would have been conducted before randomisation, rescreening would have been required to check patient status before a later second mail-out, when sites would have been aware of their allocation. Details of the processes for the two phases were as follows:

-

Pilot phase. During the pilot phase of the trial, sites manually screened up to 325 potentially eligible patients identified from their database search, in order of NHS number. The maximum number of patients for an individual site to include in its invitation mail-out was 150; however, the screening allowed for the potential of a second mail-out. For sites with > 150 eligible patients, the central trial team randomly identified 150 patients for invitation.

-

Main phase. During the main phase of the trial, sites with > 220 eligible patients screened up to this number, in order of NHS number. The maximum number of patients invited to participate in the trial from a single site was 220.

Patient consent

Patients deemed willing and eligible to participate in the trial following their telephone call with the CRN nurse or practitioner were posted a consent form and a questionnaire containing baseline measures specific to trial arm for completion (Table 2). All patients received the same consent forms and questionnaires, but those in the intervention arm also received a bladder diary to be completed before their face-to-face visit.

| Schedule | Screening (pre consent) | Trial period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient enrolment | Post enrolment | |||||||

| Baseline | Visit 1 | 1 week | 4 weeks | 12 weeks | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| Practice eligibility screen | ✗ | |||||||

| Practice allocation | ✗ | |||||||

| CRN eligibility screen | ✗ | |||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | |||||||

| Interventions | ||||||||

| Usual care | •—————————————————————————————————————• | |||||||

| HCP-delivered booklet | ✗a | |||||||

| Follow-up nurse contacts | ✗a | ✗a | ✗a | |||||

| Assessments | ||||||||

| Case report form | ✗a | ✗a | ✗a | ✗a | ✗ | |||

| ICIQ bladder diary | ✗a | |||||||

| IPSS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| ICIQ-UI-SF | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| B-IPQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Interviews | •—————————————————————————————————————• | |||||||

| Resource use via GP EMRs | ✗ | |||||||

For patients in both arms, the return of the completed consent form by post demonstrated explicit consent to participate in the trial. Alongside providing explicit consent to take part in the trial, the men were also asked on the consent form if they were willing to consent to (1) being contacted by a qualitative researcher to undertake an interview and (2) being contacted about other research. Declining to consent to these did not disqualify a man from participating in the main trial.

All men who entered the trial were logged with the central trial office at the University of Bristol and given a unique study number. Each patient’s GP was informed by the central trial team by letter about the patient’s participation in the trial. Sites were encouraged to update their GP EMRs to record participation.

Interventions

The TRIUMPH trial intervention arm

Principle of the TRIUMPH trial intervention

Presentations of LUTS are typically a composite of different symptom combinations. The TRIUMPH trial intervention targeted component symptoms with specific educational information and active management. This was provided in a standardised way in the form of a booklet that patients could read in their own time to encourage take-up of the information. However, the intervention also provided manualised care, with a HCP using basic assessments and discussion with the patient to direct them to the most applicable information in the booklet. The discussion considered their personal circumstances, symptom needs, bothersomeness of these symptoms and impact on quality of life. The TRIUMPH trial intervention arm therefore offered standardised and manualised care according to the symptomatic presentation of the individual participants.

The TRIUMPH trial intervention aimed to address key limitations in the current provision of care to men with LUTS in primary care through the use of symptom scores and bladder diaries to effectively diagnose specific LUTS, the provision of effective written materials, the training of nurses/HCAs in the interpretation of symptom scores and the use of the theory of planned behaviour to support self-management. 17

The TRIUMPH trial intervention booklet

The TRIUMPH trial intervention booklet was developed for the trial from the British Association of Urological Surgeons’ patient information sheets, and underwent sequential development in multiple iterations and consultations involving patients, HCPs and health psychologists. The booklet comprises written information and illustrations, and is titled Helping You to Take Control of Your Waterworks [the booklet is available on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169003/#/ (accessed March 2022)]. The sections included are as follows:

-

advice on drinks and liquid intake

-

advice on controlling an urgent need to urinate

-

exercising the muscles between the legs (pelvic floor) to help stop bladder leakage

-

advice on emptying the bladder as completely as possible

-

advice on getting rid of the last drops

-

reducing sleep disturbance caused by needing to urinate.

The booklet is water-resistant and able to lie flat when open, which is useful when potentially used in the bathroom. Pictorial representations were used for clarity and avoid the use of potentially embarrassing images. Sections are tabbed and colour-coded for specific symptoms and advice.

The TRIUMPH trial intervention procedure

The details of the TRIUMPH trial intervention procedure are as follows:

-

The intervention was delivered by a trained HCP, either a general practice clinical nurse, a research nurse or a HCA, or a dedicated trial research nurse, depending on site preference.

-

The HCP reviewed the patient’s baseline urinary symptoms using their completed IPSS, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence-Short Form (ICIQ-UI-SF) and International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) bladder diary. Any missing elements of questionnaires/bladder diaries were discussed with the patient to obtain approximate measures for the symptom assessment. Updated responses were used only for these purposes and baseline data remained as originally completed.

-

The participant attended for a single intervention visit, during which the HCP discussed their individual symptoms and level of bother. The HCPs were provided with decision tools (see Report Supplementary Material 1) to assist them in tailoring the treatment for each participant at their intervention visit, based on their symptoms.

-

The HCP provided the participant with the TRIUMPH trial booklet.

-

The delivery of the booklet was individualised by the HCP, who directed the participant to the relevant sections of the booklet, and therefore steps to take personally. A maximum of three sections were recommended to each participant and tabbed with discreet stickers. If more than three sections were identified as relevant to a participant, the three most bothersome symptoms were chosen. The choice of a maximum of three sections was guided by patient and public involvement (PPI) consultation on what they considered to be a manageable level of advice to follow.

-

To encourage and gauge adherence to the intervention, regular participant contact was provided following the initial face-to-face appointment. Follow-up contacts were conducted by telephone at 1 week, and then by telephone, e-mail or text at 4 and 12 weeks, according to participant preference. Participants retained the intervention booklet at the end of this period.

Participants in the intervention arm continued to receive usual care from their GP for their LUTS when necessary; details of this were collected at 12 months.

The TRIUMPH trial intervention training

The chief investigator developed the training and delivered this to the TRIUMPH trial research nurses. Materials were developed to support the training, as well as the intervention visits. The TRIUMPH trial nurses attended general practices randomised to the intervention arm to deliver training to practice nurses or HCAs for those sites opting to use their own staff. Training included examples of bladder diaries and how primary care staff should interpret them for the purpose of the trial. Nurses were trained on the responses to the questionnaires and which sections of the booklet they should direct the participant to. This was supported by a checklist developed specifically for the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Ongoing support was available for practice nurses/HCAs in the form of regular teleconferences held by the trial team and trial research nurses.

Usual-care arm

Usual care (the comparator arm for the TRIUMPH trial) in this trial requested that sites continue to follow their standard local practice for trial participants. Usual care was chosen as the comparator for the trial to reflect the actual care provided by control arm general practices, rather than the NICE guidance, which may be variably implemented. The qualitative aspect of this trial explored what usual care looked like for a sample of comparator and intervention practices (see Chapter 5).

Post-trial care

Following the end of the trial, participants in the intervention arm retained the booklet provided, and participants in the control arm were provided with the booklet, alongside a summary of the results of the trial. Their LUTS care was the responsibility of their GP throughout the trial and after they had completed the TRIUMPH trial at 12 months.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was the participant-reported IPSS at 12 months after consent. The IPSS is validated, extensively tested in LUTS research and widely employed in urology services. 18 It produces a score from 0 to 35, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The end point of 12 months was chosen to measure whether or not any effect of the TRIUMPH trial intervention on LUTS was sustained after the initial 12-week intervention delivery period.

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary outcomes were collected by questionnaire at 6 and/or 12 months.

-

International Prostate Symptom Score-Quality of Life Index (IPSS-QoL) – LUTS quality-of-life score measured at 6 and 12 months.

-

IPSS – overall urinary symptom score at 6 months.

-

ICIQ-UI-SF19 – measured at 6 and 12 months. This questionnaire supplements the IPSS with the measurement of incontinence.

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)20 – measure of health status.

-

B-IPQ21 – patient perception of their LUTS. It was modified slightly, with permission, to ask participants about ‘urinary symptoms’ rather than ‘illness’.

The number of adverse events (specified as UTIs, catheterisations, urinary retention, prostatitis or death) and the number of referrals to secondary care (urology) were extracted from primary care EMRs at 12 months.

Sample size

This trial was powered to detect a mean between-group difference of 2 points on the primary outcome of IPSS at 12 months post consent. This target difference was chosen because, although the recognised minimum important difference in IPSS is 3.0 points,22 men may be bothered by just one symptom (e.g. nocturia). A change of 2 points might mean a small improvement in two symptoms or a bigger improvement in one symptom.

To inform the sample size calculation, a scoping search was conducted with local general practices within the NHS Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire CCG to gain a sense of the likely number of patients available on their lists based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. This search suggested that an average-sized general practice might identify 100 patients. We originally assumed that 50% of these patients would be eligible and, of these, 70% would consent, so each practice would consent ≈35 eligible patients. Our estimates of eligibility rates, consent and loss to follow-up were conservative and based on our experience running pragmatic trials in primary care settings.

Based on this, we estimated that 840 patients were needed from at least 24 practices to detect a difference in IPSS of 2 [common standard deviation (SD) of 5: in line with the assumptions made in UPSTREAM (Urodynamics for Prostate Surgery Trial; Randomised Evaluation of Assessment Methods3)] with 90% power and a significance level of 5%. Our estimate incorporated a design effect to account for clustering of effects in practices, which assumed that practices would be able to recruit 35 patients each (i.e. mean cluster size of 35) and that the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) between practices would be 0.05, an estimate in line with results from other primary care studies. 23 We allowed for up to 30% of men being lost to follow-up.

During the early stages of recruitment, however, it became apparent that practices were not consistently consenting 35 patients and that the variability in recruitment would necessitate more practices being recruited to achieve our objective of 90% power to detect a mean difference in IPSS of 2 points. Using information from the numbers and proportions of patients consenting from practices recruited early in the trial, and projections regarding practices soon to start recruiting patients, we revised our assumptions and assumed that the mean number of patients consented at each practice would be 26 and that the coefficient of variation for the mean cluster size between practices would be 0.26. Based on these revised assumptions, this increased the number of practices required for the study by six; the Trial Management Group agreed to recruit additional practices. This amendment was agreed with both the Trial Steering Committee and the funder.

Randomisation and implementation

General practices were the unit of allocation to the two trial arms. Practices were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to either receive the intervention or continue care as usual [control group (CG)] by a statistician from the Bristol Trials Centre, who was outside the trial team and was masked to the identity of practices. This was done after the practice list searches had been conducted, lists were screened by GPs and the mail-out was uploaded (see Patient screening and invitation). As there were a relatively small number of general practices in the trial, minimisation was used to allocate practices to treatment arms to ensure balance. Allocation was minimised by centre (West of England and Wessex), practice size (numeric variable) and area-level deprivation [Index of multiple deprivation (IMD), a numeric variable] of the practice. A random element was incorporated in the minimisation procedure such that there was a 40% probability that allocation was random. When allocation was random, there was a 50 : 50 chance of practices being allocated to either arm.

Although it is common to use lower-layer super output area (LSOA) deprivation scores to estimate deprivation for individuals (using home postcodes to identify the LSOA), it has been shown that middle-layer super output area (MSOA) data better reflect the area-level deprivation of general practices. 24 Therefore, general practice postcodes were mapped onto LSOAs first and then onto MSOAs. Population-averaged IMD scores (from 2015) were then calculated based on the scores of LSOAs within each MSOA.

Masking

Two statisticians and two health economists supported this trial. The senior statistician and senior health economist were masked throughout the trial. A junior statistician performed all disaggregated analyses according to the statistical analysis plan16 and the junior health economist conducted the economic analyses according to the health economics analysis plan. The junior statistician attended closed meetings of the independent Data Monitoring Committee as required. The CRN support team was masked to minimise selection and recruitment bias. The remaining members of the trial team were masked to aggregate data only. General practice staff, research nurses involved in delivering the intervention and participants were not masked.

The protocol was written before recruitment end and published in Trials. 1 The statistical analysis plan16 was written and agreed by the trial team in July 2020, prior to completion of participant follow-up. The health economics analysis plan was written and agreed by the trial team in February 2021, prior to database lock.

Data collection

Participant-reported outcomes

The components and timing of follow-up measures are shown in Table 2. All participants were asked to complete self-reported outcome measures in the form of questionnaires (IPSS, ICIQ-UI-SF, EQ-5D-5L and B-IPQ) at baseline (postal), and 6 and 12 months (postal, online or telephone) post enrolment. Participants were sent one reminder to return their baseline materials, and up to three reminders to return their 6- and 12-month questionnaires.

All participants were provided with trial progress updates at 3 and 9 months via a newsletter to maintain engagement with the trial and encourage responses to follow-up questionnaires. The newsletter did not provide any detail on the TRIUMPH trial intervention.

Intervention delivery

Trial-designed case report forms were completed for the intervention arm only, at the intervention visit and during the 12-week treatment phase, to collect details of the booklet sections advised to the participant and feedback on the booklet.

Electronic medical record data extraction

Data extraction from GP EMRs was conducted by sites a minimum of 1 month after their final participant had completed follow-up. Database searches were developed specifically for the trial, for both EMIS Web and SystmOne patient administration systems used in primary care sites in both CRN regions. The EMR data extracted comprised baseline measures, clinical outcome measures and health economic outcome measures. The baseline and clinical data extracted are detailed in the following list; the health economic data are described in Chapter 4.

-

Baseline comorbidities: any comorbidity coded on a participant’s record according to the Quality and Outcomes Framework.

-

Baseline urinalysis: the most recent urinalysis results (normal/abnormal) in the 6 months pre consent.

-

Baseline renal function: the most recent estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the 6 months pre consent.

-

Baseline medication: relevant prescriptions issued to patients in the 3 months pre consent.

-

Baseline GP consultations: the number of consultations in the 12 months pre consent.

-

Baseline referrals: referrals to urology in the 12 months pre consent.

-

Adverse events: UTI, catheterisation, urinary retention, prostatitis, deaths in the 12 months post consent.

-

Secondary care referrals: urology referrals in the 12 months post consent.

Patient and public involvement

We involved PPI representatives at all stages of the project. We had a patient representative on our Trial Management Group (also a co-applicant involved at the grant application stage) and a patient representative on our Trial Steering Committee. Both contributed to the management of the trial, providing an invaluable patient perspective to all aspects of trial conduct. In addition, we have held wider patient advisory group meetings throughout the trial; our two PPI representatives had a substantial role in planning, as well as chairing, these meetings.

One of the key roles of the PPI input was in the development of the TRIUMPH trial intervention booklet, which resulted in key changes to aid clarity and usability. We also undertook PPI review of the patient-facing trial materials, including the patient questionnaires, newsletters and website. Further PPI has included discussion of some of the initial qualitative findings relating to men’s experiences of the patient pathways for LUTS within the NHS, as well as routes for implementation and dissemination. Overall, PPI has played an invaluable part in the trial from conception to dissemination.

Statistical methods

Baseline data analyses

The baseline characteristics of patients and practice characteristics were compared between the two arms by reporting relevant summary statistics to determine whether or not any potentially influential imbalance occurred by chance. Baseline characteristics were summarised using means, SDs, medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)] or number (%) depending on the nature of the data and their respective distributions.

Primary analysis

Analysis and reporting were in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines,25,26 with the primary analyses being conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. The primary outcome was the IPSS collected at 12 months post consent. It was described in each treatment group using means and SDs. Comparisons between treatment arms were made using a mixed-effect multilevel linear model [individual patients (level 1) nested within general practices (level 2)] and adjusting for patient-level baseline IPSS and practice-level variables used in the randomisation. Results for a model adjusting only for baseline scores have also been presented. The results have been presented as the mean between-group difference with 95% confidence interval (CI), p-value and model ICC with corresponding 95% CI.

Secondary outcomes

The approach for the analysis of the secondary outcomes was on an ITT basis, defined as analysing all participants according to the group to which their practice was randomised. IPSS at 6 months were analysed in the same manner as the primary outcome using a linear mixed model [individual patients (level 1) nested within general practices (level 2)], adjusting for baseline scores and minimisation variables. A separate repeated measures analysis using a linear mixed model [6-monthly observations of IPSS (level 1), nested within participants (level 2) and nested within general practices (level 3)] was also conducted to incorporate all time points. The ICIQ-UI-SF, IPSS-QoL and B-IPQ at 6 and 12 months were studied in the same manner.

Whether or not a patient had a referral to secondary care was studied using a logistic mixed model with individual patients nested within general practices. The model adjusted for minimisation variables and whether or not the patient had a referral to urology pre baseline.

Sensitivity analyses

Predefined sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the sensitivity of the primary analysis to various assumptions, and are described in this section. As these are exploratory in nature, 95% CIs and p-values are presented, but are interpreted with due caution.

-

Imbalance of baseline characteristics. We planned to explore the sensitivity of the primary analysis to imbalance of baseline characteristics by running models adjusting for these variables. Imbalance is defined as a difference of 10%, or half a SD, between treatment groups.

-

Clustering by HCA/nurse. To allow for clustering of outcomes within nurses/HCAs delivering the intervention, a model was run grouping the patient-level data into clusters based on the combination of the practice where the patient is registered and the nurse/HCA delivering the intervention (first visit). The primary analysis of the IPSS at 12 months was repeated using a single random effect for this level of clustering and the results were compared with those of the primary analysis.

-

Per-protocol analyses. Five per-protocol analyses were conducted using different definitions of protocol compliance:

-

excluding those in the intervention arm who received no intervention booklet by the time of the primary outcome measure at 12 months and had none of the follow-up contacts at 1, 4 and 12 weeks

-

excluding those in the intervention arm who received the intervention booklet by the time of the primary outcome measure at 12 months, but had only two of the three follow-up contact visits (regardless of whether these were early or late)

-

excluding those in the intervention arm who received the intervention booklet by the time of the primary outcome measure at 12 months and had only one follow-up contact (regardless of whether this was early or late)

-

excluding those in the intervention arm who received the intervention booklet by the time of the primary outcome measure at 12 months but had no follow-up contact

-

excluding those in the intervention arm who did not receive the follow-up contact in the protocolised format (i.e. by telephone, post or e-mail).

-

-

Complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis. Recognising the inherent bias in estimates derived from per-protocol analyses, we planned a CACE analysis of the primary outcome. Compliers were defined as those who received the intervention booklet by the time of the primary outcome follow-up. Non-compliers were defined as those who had not received the booklet at all or received it after the primary outcome time point. The CACE estimates were to be obtained using instrumental variable regression including the same variables used in the primary analysis, with randomised group as the instrumental variable and the indicator variable for compliance.

-

Impact of COVID-19. By the time the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March 2020, the trial had already reached its target recruitment and was no longer recruiting. Recognising that trial participation and symptom reporting may have been affected by the outbreak and subsequent lockdown, we used descriptive statistics to explore whether or not there were differences in the proportions of missing data for the primary outcome (IPSS at 12 months) before and after 11 March 2020. We also assessed whether or not IPSS at 12 months differed depending on whether data were collected before or during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scores before and after 11 March 2020 were described using descriptive statistics and the primary analysis model was refitted including a binary term to indicate whether the outcome was measured before 11 March 2020 (0) or from 11 March 2020 onwards (1).

-

Excluding patients later found to be ineligible. A small number of patients participated in the trial who, after consenting and providing data, were found to be ineligible, but were included in the primary ITT analysis. A sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome excluding these individuals was conducted.

Subgroup analyses

Four prespecified subgroup analyses were performed to explore whether or not baseline characteristics modified the effectiveness of the intervention:

-

Nature of LUTS at baseline. The ratio of the IPSS voiding subscore to the storage subscore has been used to describe the relative dominance of voiding to storage LUTS. This measure was used to explore whether or not the treatment effect differed by the nature of LUTS at baseline, as quantified using this ratio.

-

Intervention delivery. We explored whether or not the effect of the intervention differed according to whether a practice nurse/HCA or TRIUMPH trial nurse delivered the intervention to the participant.

-

Method of contact. Participants in the intervention arm specified how they preferred to be contacted by the research team for their intervention follow-up contacts. This might be by telephone or text, for example. The frequency of each preferred mode of contact, the model of contact used and how often this differed were reported. We explored whether or not the effect of the intervention differed by model of contact by including a ‘preferred method of contact’ and treatment group interaction term in the model.

-

Intervention ‘dose’. To explore the possibility that the number of nurse/HCA contacts modified the effect of the intervention, we created a ‘dose’ variable equal to the number of nurse/HCA contacts that participants at the intervention practices received (0–3). The primary analysis was repeated using the ‘dose’ variable as the treatment variable.

In all cases, effect modification was assessed including an interaction term in the regression model, and formal tests of interaction were performed to test whether or not the treatment effect differed between these groups. As with all other analyses, a significance level of 5% was used and, as these analyses were not statistically powered, they are interpreted with due caution as exploratory. A post hoc subgroup analysis was also performed according to whether or not the primary outcome was collected before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Multiple imputation

For our analysis of the primary outcome, we investigated the influence of missing data using sensitivity analyses that made different assumptions regarding missingness: ‘best’- and ‘worst’-case scenarios and multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) to impute missing data.

Chapter 3 Results

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Frost et al. 1 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Recruitment

Recruitment of general practices

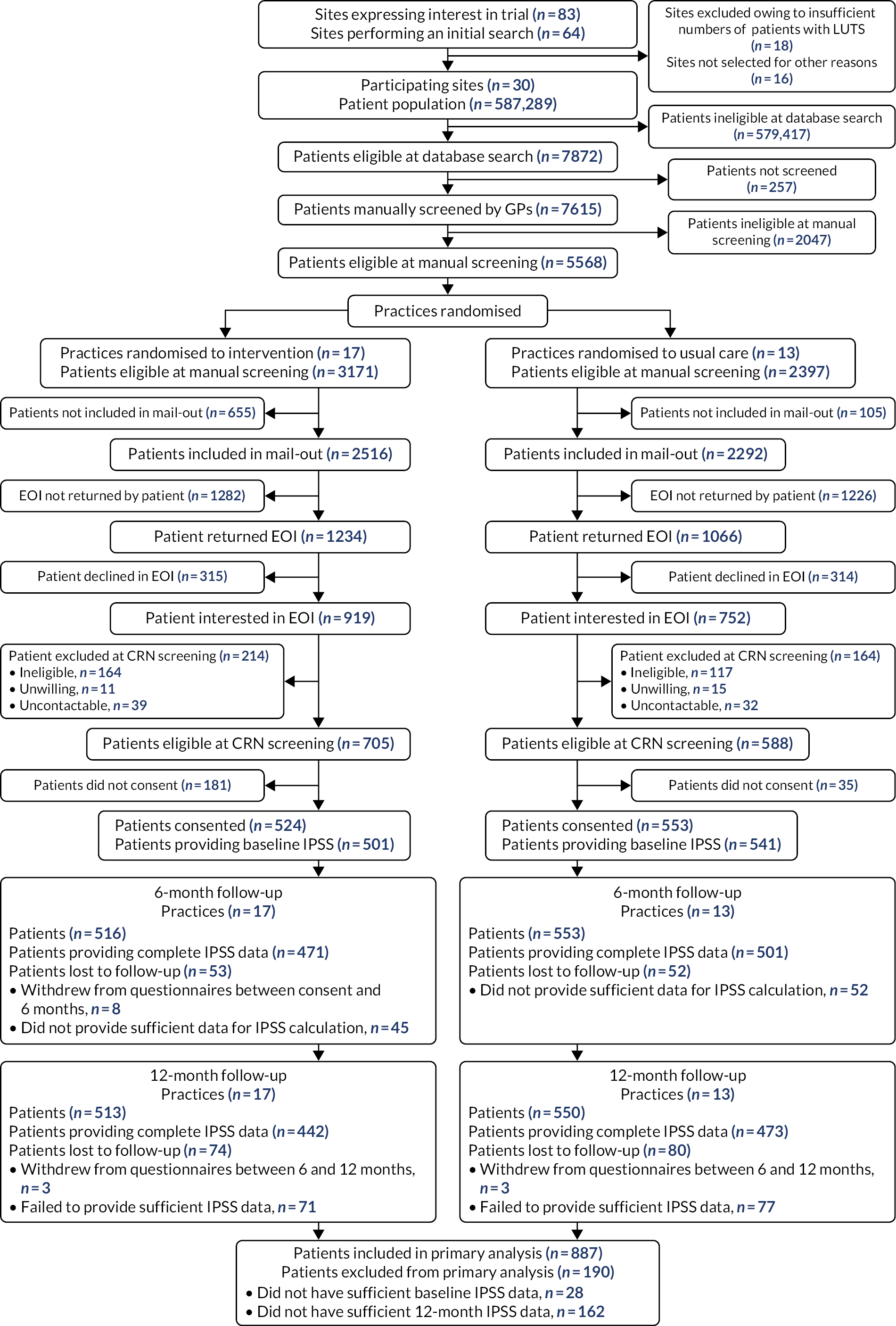

As outlined in General practice recruitment and selection, the West of England and Wessex CRNs invited general practices to express an interest in taking part in the trial. A total of 83 practices expressed an interest, of which 64 performed an initial search (Figure 1). On performing the search, 18 practices were excluded because they did not have sufficient numbers of patients and 16 other practices did not progress further. Practices were recruited between July 2018 and May 2019 (Figure 2). After having conducted contractual agreements and consent processes with practices, we randomised 30 general practice sites. These comprised 32 general practices, owing to one collaboration of three practices operating a hub-and-spoke model and sharing nurse resource, and therefore randomised as a single site for the trial.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative number of practices randomised over time.

Characteristics of participating general practices

At the time of recruitment, practices provided estimated list sizes; these ranged from 7600 to 48,623 patients (mean 19,576) (see Appendix 1, Table 39). Although routinely available data on general practices in this region do not allow us to identify and merge smaller practices operating as a hub-and-spoke model as participating practices have, participating practices reflect some of the larger practices in the region [regional median practice size in June 2019: 9440 patients (IQR 6429 to 13,239)]. Intervention practices, on average, recruited 31 patients each and control practices recruited 43 patients each, on average.

Patient-level socioeconomic data were not available for all registered practice patients. General practices were therefore characterised using area-level deprivation, which was estimated for the hypothesised catchment area for the practice (estimated as the MSOA). Deprivation scores ranged from 4.22 to 33.62, and scores were slightly higher in the usual-care arm [mean 16 (SD 8.39)] than in the intervention arm [mean 11 (SD 5.00)], indicating higher levels of socioeconomic deprivation.

Patient screening and randomisation of sites

When participating practices conducted a detailed database search, as outlined in Patient screening and invitation, they identified 7872 potentially eligible patients. A random selection of 160 patients from two practices were not screened as their practices were very large and they had already committed to screening a set number of patients, and 97 patients were not screened owing to practice capacity. Manual screening by GPs of the remaining 7615 patients used the eligibility criteria outlined (see Appendix 1, Table 38). Reasons for ineligibility are outlined in Table 3.

| Reason for exclusion | n (%) |

|---|---|

| GP screening/mail-out | |

| Patients not manually screened by GP (unable to confirm eligibility) | 257 (4) |

| Patients ineligible at GP manual screening | 2047 (30) |

| Reasons for ineligibility (inclusion/exclusion criteria) | |

| Currently being treated for prostate or bladder cancer | 50 |

| Lack of capacity | 85 |

| Does not have LUTS | 871 |

| Is aged < 18 years | 4 |

| Has poorly controlled diabetes mellitus | 18 |

| Previous prostate surgery | 71 |

| Recently referred for, or currently under, urological review | 441 |

| Relevant neurological disease or referral | 56 |

| Unable to complete assessments in English | 9 |

| Unable to pass urine without a catheter | 6 |

| Undergoing neurological testing for LUTS | 38 |

| Visible haematuria | 42 |

| Othera | 299 |

| Patients not included in mail-out | 760 (11) |

| Patient EOI | |

| EOI not returned by patient | 2508 (37) |

| Patients declined in EOI | 629 (9) |

| CRN telephone screening | |

| Patients excluded at CRN screening | 378 (6) |

| Ineligible | 281 (4) |

| Unwilling | 26 (0) |

| Uncontactable | 71 (1) |

| Consent | |

| Patients did not consent | 216 (3) |

Once general practices completed their manual screening of patient lists, sites were randomised. The randomisation process, which was minimised by centre, practice size and area-level deprivation of the practice, resulted in 17 sites being randomised to deliver the intervention (3171 eligible patients) and 13 sites being randomised to deliver usual care (2397 eligible patients). Practices themselves, however, were not informed of their allocation until patient screening had been completed and the invitation letter mail-out uploaded (see Patient screening and invitation).

Patient recruitment

Letters of invitation were sent to 4808 of the 5568 eligible patients (intervention practices, 2516; usual-care practices, 2292). Randomly selected eligible patients were not included in this mail-out (intervention practices, n = 655; usual-care practices, n = 105), as a maximum number was specified for mail-out from individual sites to avoid disproportionate recruitment at larger practices (see Patient screening and invitation). Expressions of interest were returned by 2300 patients [intervention practices, n = 1234 (49%); usual-care practices, n = 1066 (47%)], of whom 1671 [intervention practices, n = 919 (74%); usual-care practices, n = 752 (71%)] confirmed their interest in participating. Using available age data on those who were sent letters of invitation (Table 4), we observed that those who expressed an interest in participating in the trial were similar in age to those who said that they were not interested (mean age 68.7 and 71.0 years, respectively). Those who did not get in touch to confirm their interest were much younger (mean age 62.7 years).

| EOI status | N | n a | Mean age (years) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Returned EOI and interested | 1671 | 1671 | 68.68 | 10.13 |

| Returned EOI and not interested | 629 | 629 | 70.99 | 11.05 |

| Did not return EOI | 2508 | 2508 | 62.72 | 14.10 |

| All groups combined | 4808 | 4808 | 65.87 | 12.91 |

Those who expressed an interest in participating were approached for screening by the CRN team. A total of 71 patients were not contactable at this stage; of those whom the CRN teams were able to reach, 281 were deemed ineligible, 26 were unwilling to proceed further and 1293 were found to be eligible. Men who were eligible at CRN screening and were willing to participate in the trial tended to be slightly younger than those eligible but unwilling to participate, although comparable to those ineligible at screening (mean age 68.3 years vs. 74.1 years vs. 70.7 years) (Table 5).

| Eligibility and willingness to participate | N | n a | Mean age (years) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible at CRN screening and willing to participate in the trial | 1293 | 1293 | 68.32 | 9.72 |

| Eligible at CRN screening and not willing to participate in the trial | 26 | 26 | 74.12 | 8.05 |

| Ineligible at CRN screening | 281 | 281 | 70.68 | 10.62 |

| Not contactable by the CRN | 71 | 71 | 66.45 | 13.70 |

| All groups combined | 1671 | 1671 | 68.68 | 10.13 |

Patients who were found to be eligible at the CRN screening stage were invited to participate in the trial and 1077 consented [intervention practices: n = 524 (74%); usual-care practices: n = 553 (94%)]. The men who were eligible and consented to participate tended to be slightly older than those who were eligible and did not consent (68.7 years vs. 66.5 years, respectively) (Table 6).

| Eligible men | All practices | Intervention practices | Usual-care practices | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n a | Mean | SD | Minimum, maximum | N | n a | Mean | SD | Minimum, maximum | N | n a | Mean | SD | Minimum, maximum | |

| Eligible men who consented to participate | 1077 | 1077 | 68.68 | 9.26 | 30, 95 | 524 | 524 | 68.95 | 9.27 | 32, 94 | 553 | 553 | 68.44 | 9.25 | 30, 95 |

| Eligible men who did not consent to participate | 216 | 216 | 66.51 | 11.61 | 26, 90 | 181 | 181 | 66.22 | 11.89 | 26, 90 | 35 | 35 | 68.03 | 10.10 | 38, 89 |

| Both groups combined | 1293 | 1293 | 68.32 | 9.72 | 26, 95 | 705 | 705 | 68.25 | 10.07 | 26, 94 | 588 | 588 | 68.41 | 9.29 | 30, 95 |

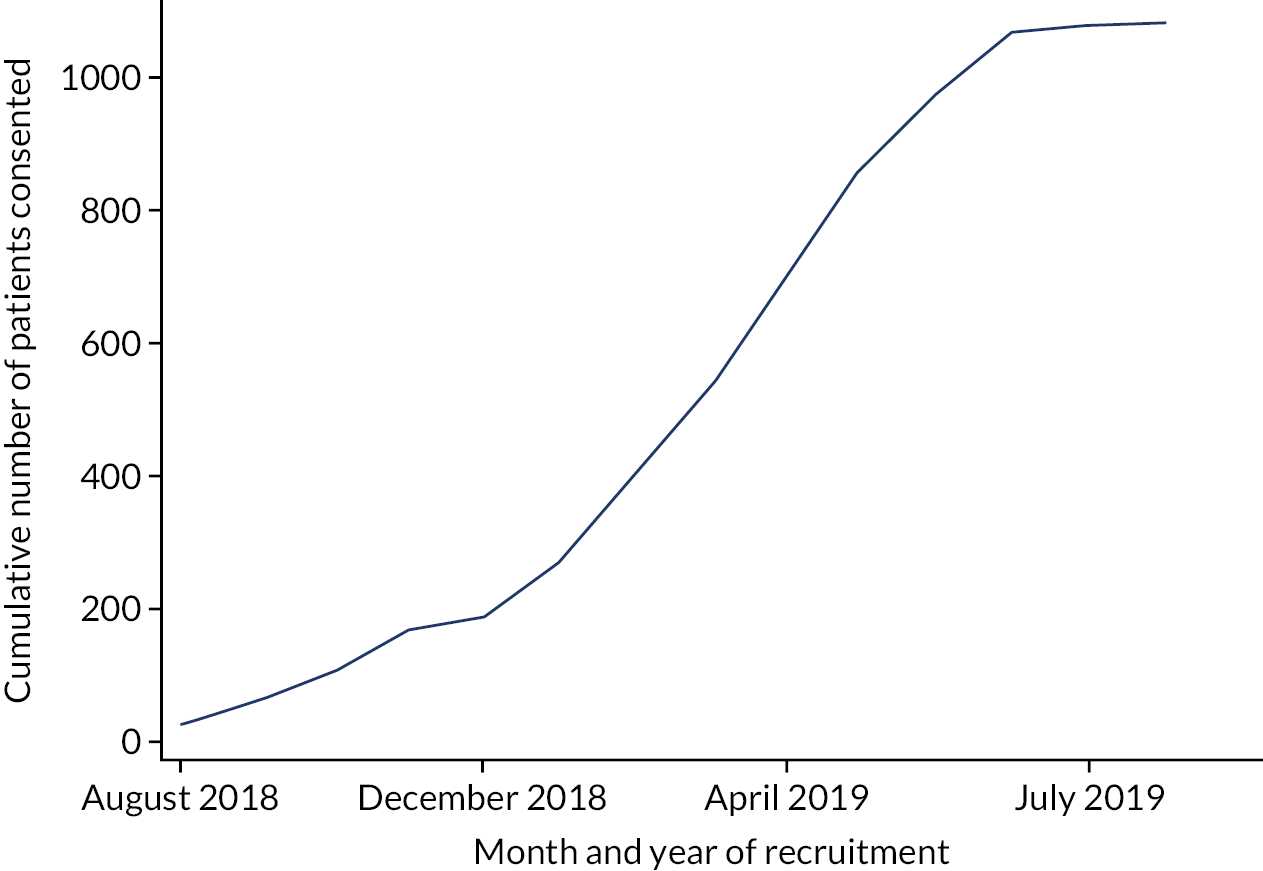

Patient recruitment over time is illustrated in Figure 3 and recruitment by practice is presented in Appendix 1, Table 40.

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative patient recruitment over time.

The CONSORT flow diagram (see Figure 1) describes how and when participants were lost to follow-up between consent and 12 months. Ultimately, 154 participants were lost to follow-up and 915 of the recruited 1077 participants (85.0%) provided primary outcome data at 12 months.

Pilot phase

The 4-month internal pilot phase of the trial was successfully completed in November 2018. A total of 142 participants were recruited, exceeding the target of 120 participants. Sixteen practices had formally agreed to take part in the trial during the pilot phase, which, although slightly short of the target of 18, was sufficient for progression to the main phase of the trial. The key changes that were made to the conduct of the trial between the pilot phase and the main phase of the trial were an increase in the maximum number of patients invited by a single site from 150 to 220, and confirmation that 30 sites would be required to maintain the trial power calculation in the light of variation in the number of patients recruited per site. The decision was also taken to conduct only a single invitation mail-out from each site, rather than inviting additional patients in a second mail-out to achieve site targets as necessary, to avoid introducing any bias post randomisation. Although screening of all patients for both mail-outs would have been conducted before randomisation, rescreening would have been required to check patient status before a later, second, mail-out, when sites would have been aware of their allocation.

Baseline data

The baseline characteristics of the participants of the TRIUMPH trial are presented in Table 7. The mean age was 69 years in the intervention arm and 68 years in the usual-care arm, although the trial included some younger men who were in their thirties. In both arms, participants were overwhelmingly white, with only 13 participants overall describing themselves as being from another ethnic group. In both arms, most men were married or in civil partnerships. Socioeconomic status was determined using area-level IMD based on the home postcode; participants were from all five quintiles of deprivation, although the proportion from the least deprived quintile was in both arms higher than the 20% we would expect if participants were equally distributed by quintile (intervention arm, 49.0%; usual-care arm, 42.9%). Participants self-reported height and weight; mean values of both were comparable between treatment arms.

| Characteristics | Intervention | Usual care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Value | n a | Value | |

| Total number of participants (N) | 524 | 553 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 524 | 68.95 (9.27) [32, 94] | 553 | 68.44 (9.25) [30, 95] |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 522 | 550 | ||

| White | 513 (98.28) | 542 (98.55) | ||

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 1 (0.19) | 1 (0.18) | ||

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 2 (0.38) | 2 (0.36) | ||

| Asian/Asian British | 3 (0.57) | 2 (0.36) | ||

| Other ethnic group | 2 (0.38) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Disclosure declined | 1 (0.19) | 3 (0.55) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | 517 | 543 | ||

| Single | 21 (4.06) | 25 (4.60) | ||

| Married | 429 (82.98) | 440 (81.03) | ||

| Civil partnered | 7 (1.35) | 15 (2.76) | ||

| Divorced | 31 (6.00) | 32 (5.89) | ||

| Widowed | 27 (5.22) | 28 (5.16) | ||

| Disclosure declined | 2 (0.39) | 3 (0.55) | ||

| IMD score, median (IQR) [minimum, maximum] | 506 | 8.80 (5.75–13.71) [1.18, 60.30] | 525 | 9.89 (6.21–15.45) [1.64, 55.13] |

| IMD quintile, n (%) | 506 | 525 | ||

| 1 (most deprived) | 17 (3.36) | 21 (4.00) | ||

| 2 | 33 (6.52) | 37 (7.05) | ||

| 3 | 67 (13.24) | 106 (20.19) | ||

| 4 | 141 (27.87) | 136 (25.90) | ||

| 5 (least deprived) | 248 (49.01) | 225 (42.86) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Height (cm), mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 518 | 176.72 (6.77) [152.40, 198.12] | 550 | 176.93 (7.41) [157.48, 208.28] |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 510 | 83.35 (14.45) [55.02, 152.41] | 549 | 83.89 (14.29) [53.98, 136.98] |

| EMRs search data | ||||

| Number of comorbidities, n (%) | 478 | 544 | ||

| 0 | 151 (31.59) | 171 (31.43) | ||

| 1 | 160 (33.47) | 197 (36.21) | ||

| > 1 | 167 (34.94) | 176 (32.35) | ||

| Most recent urine analysis results in the 6 months pre baseline: abnormal, n (%) | 79 | 1 (1.27) | 52 | 2 (3.85) |

| Kidney function: most recent eGFR (ml/minute/1.73m2) measure in the 6 months pre baseline | 170 | 215 | ||

| Number of patients with an eGFR measure | 170 | 215 | ||

| eGFR: mean (SD) | 73.46 (15.72) | 74.56 (13.17) | ||

| eGFR: median (IQR) | 76.5 (65–87) | 75 (66–87) | ||

| eGFR: minimum, maximum | 28, 98 | 36, 100 | ||

| CKD stages based on most recent eGFR in the 6 months pre baseline, n (%) | 170 | 215 | ||

| ≥ 90 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (normal) | 28 (16.47) | 33 (15.35) | ||

| 60–90 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (CKD stages G1 and G2) | 114 (67.06) | 154 (71.63) | ||

| 30–59 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (CKD stage G3) | 27 (15.88) | 28 (13.02) | ||

| < 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2 (CKD stages G4 and G5) | 1 (0.59) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Number of GP consultations in the 12 months before baseline | 478 | 544 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.4 (3.7) | 4.8 (5.0) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | ||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 23 | 0, 58 | ||

| Referrals to urology in the 12 months pre baseline, n (%) | 478 | 544 | ||

| None | 464 (97.07) | 525 (96.51) | ||

| One | 14 (2.93) | 19 (3.49) | ||

| More than one | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life | ||||

| IPSS symptoms, mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | ||||

| Incomplete emptying | 512 | 1.66 (1.46) [0, 5] | 549 | 1.85 (1.49) [0, 5] |

| Frequency | 514 | 2.68 (1.33) [0, 5] | 551 | 2.92 (1.37) [0, 5] |

| Intermittency | 514 | 1.87 (1.64) [0, 5] | 549 | 1.96 (1.69) [0, 5] |

| Urgency | 513 | 2.14 (1.61) [0, 5] | 549 | 2.35 (1.66) [0, 5] |

| Weak stream | 510 | 1.93 (1.53) [0, 5] | 549 | 2.02 (1.66) [0, 5] |

| Straining | 513 | 0.85 (1.19) [0, 5] | 548 | 0.99 (1.31) [0, 5] |

| Nocturia | 516 | 2.59 (1.36) [0, 5] | 551 | 2.43 (1.25) [0, 5] |

| Total IPSS score, mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 501 | 13.62 (5.83) [1, 33] | 541 | 14.59 (6.58) [2, 34] |

| IPSS-QoL score, mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 516 | 3.47 (1.19) [0, 6] | 551 | 3.55 (1.13) [0, 6] |

| ICIQ-UI-SF total score, mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 513 | 3.57 (3.57) [0, 14] | 542 | 3.93 (3.66) [0, 15] |

| ICIQ-UI-SF: when does urine leak?, n (%) | 523 | 553 | ||

| Never | 185 (35.37) | 162 (29.29) | ||

| Leaks before you can get to the toilet | 205 (39.20) | 237 (42.86) | ||

| Leaks when you cough/sneeze | 24 (4.59) | 24 (4.34) | ||

| Leaks when you are asleep | 12 (2.29) | 15 (2.71) | ||

| Leaks when you are physically active | 23 (4.40) | 27 (4.88) | ||

| Leaks when you have finished urinating/are dressed | 175 (33.46) | 205 (37.07) | ||

| Leaks for no obvious reason | 36 (6.88) | 42 (7.59) | ||

| Leaks all of the time | 1 (0.19) | 1 (0.18) | ||

| EQ-5D-5L utility score, median (IQR) [minimum, maximum]b | 522 | 0.84 (0.77–1) [–0.118, 1] | 547 | 0.84 (0.75–1) [–0.06, 1] |

| EQ VAS score, median (IQR) [minimum, maximum] | 522 | 80 (70–90) [15, 100] | 551 | 80 (70–90) [15, 100] |

| B-IPQ total score, mean (SD) [minimum, maximum] | 440 | 38.74 (11.02) [1, 75] | 478 | 39.40 (10.36) [6, 72] |

| Bladder diary, n (%) | ||||

| Incontinence | 502 | 100 (19.92) | N/A | N/A |

| Urgency | 507 | 364 (71.79) | ||

| Nocturiac | 261 | 222 (85.06) | ||

Electronic medical records were used to gather further information on the clinical characteristics at baseline. As not all practices were able to provide such data, more data were missing in the intervention arm. Approximately one-third of participants had no record of comorbidities, one-third had one comorbidity and one-third had more than one comorbidity. The distribution was comparable between treatment arms. The median number of GP consultations in the 12 months before baseline was the same in both arms (4 consultations), but the proportion with a referral to urological services in that period was slightly lower in the intervention arm than in the usual-care arm (intervention arm, 2.93%; usual-care arm, 3.49%).

We also used primary care EMRs to assess recent urine and kidney function tests. Few men in either arm reported having undergone urine analyses in the 6 months before baseline (intervention arm, n = 79; usual-care arm, n = 52), and few of these had abnormal test results (intervention arm, 1.27%; usual-care arm, 3.85%). Kidney function testing was more common (intervention arm, n = 170; usual-care arm, n = 215), and the most recent eGFR measure was similar in both arms. The majority of men in both arms who had such testing had chronic kidney disease stage 1 or 2 (intervention arm, 67.1%; usual-care arm, 71.63%).

International Prostate Symptom Score, the primary outcome measure, was measured at baseline; the total score was slightly lower in the intervention arm (mean total score 13.62 points) than in the usual-care arm (mean total score 14.59 points). When examining individual symptoms, the symptoms with the highest mean scores were frequency, nocturia and urgency. The IPSS-QoL scores were very similar in both arms (intervention: 3.47 points; usual care: 3.55 points).

The ICIQ-UI-SF total symptom scores were similar in both groups (intervention arm, mean of 3.6, usual care arm, mean of 3.9). When asked when men leaked urine, the most common responses were before getting to the toilet (intervention, 39.2%; usual care, 42.86%), and when finished urinating and dressed (intervention arm, 33.46%; usual-care arm, 37.07%). Approximately one-third of men in each arm said they never leaked (intervention arm, 35.37%; usual-care arm, 29.29%). Men in the intervention arm completed a bladder diary at baseline to help inform intervention delivery; they most frequently reported nocturia (85.06%) and urgency (71.79%). The EQ-5D-5L data were comparable in both arms, as were the B-IPQ data.

To explore whether or not the disease-specific IPSS-QoL score yields information different from the EQ-5D-5L, we plotted the baseline values of one versus the other (Figure 4). The correlation coefficient of –0.22 suggests a weak to no linear association between the two measures, that the IPSS-QoL score yields information different from that of the EQ-5D-5L and that the use of both is not redundant.

FIGURE 4.

Relationship between the EQ-5D-5L and IPSS-QoL scores at baseline.

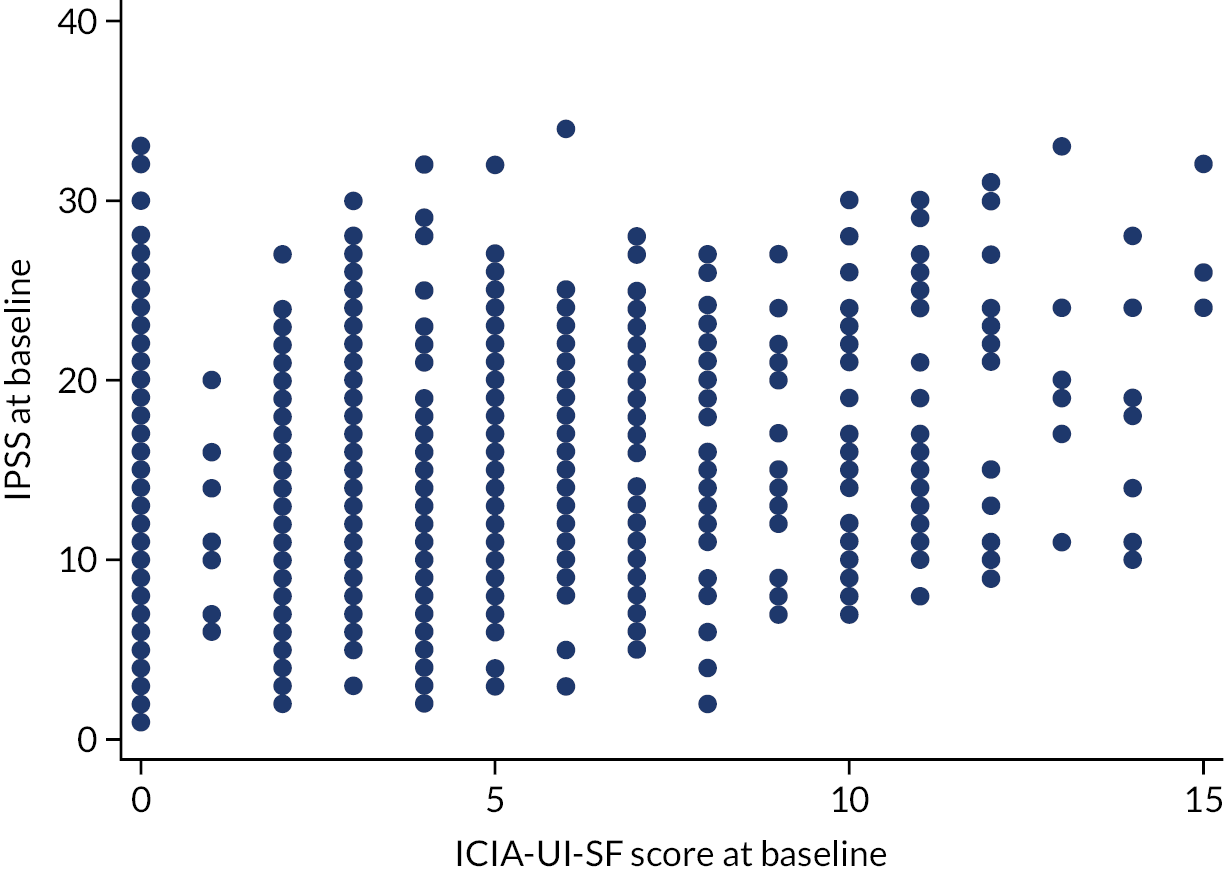

The IPSS does not capture all urinary symptoms; leakage is captured only in the ICIQ-UI-SF. Therefore, we explored how IPSS at baseline correlated with ICIQ-UI-SF scores at baseline. A scatterplot of the two variables is presented in Figure 5. There was little evidence that the two measures were strongly correlated (p = 0.28), suggesting that those with a higher IPSS do not necessarily have higher ICIQ-UI-SF scores, and vice versa, thus confirming the value of both measures.

FIGURE 5.

Baseline IPSS and baseline ICIQ-UI-SF scores.

As well as using EMRs to identify GP consultations and clinical test results, we also explored the prescriptions that patients were issued in the 3 months pre baseline with a potential indication for treating LUTS (Table 8). Relevant medications for LUTS are alpha-adrenergic antagonists (alfuzosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin) and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (tadalafil) to treat bladder outlet obstruction, and antimuscarinics (oxybutynin, solifenacin, tolterodine, trospium) and beta-3 agonist (mirabegron) to treat overactive bladder syndrome. Approximately 40% of men had at least one prescription of this type in this period. The most common prescription by far was tamsulosin, prescribed to 30.5% of men in the intervention arm and 34.01% of men in the usual-care arm. Oxybutynin and doxazosin were the next most commonly prescribled treatments; both were more common in the usual-care arm.

| EMR search | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Usual care | |

| Total number of patients | 524 | 553 |

| Number of patients for whom EMR data were available | 478 | 544 |

| Patients having at least one relevant prescription, n (%) | 188 (39.33) | 227 (41.72) |

| List of medications as observed, n (%) | ||

| Tamsulosin | 146 (30.54) | 185 (34.01) |

| Oxybutynin | 8 (1.67) | 24 (4.41) |

| Doxazosin | 2 (0.42) | 19 (3.49) |

| Solifenacin | 17 (3.56) | 14 (2.57) |

| Tolterodine | 9 (1.88) | 12 (2.21) |

| Mirabegron | 11 (2.30) | 9 (1.65) |

| Alfuzosin | 6 (1.26) | 3 (0.55) |

| Tadalafil | 1 (0.21) | 2 (0.37) |

| Trospium | 0 (0) | 1 (0.18) |

| Solifenacin/tamsulosin fixed-dose combination | 4 (0.84) | 0 (0) |

Intervention delivery

Seven out of 16 West of England sites and 10 out of 14 Wessex sites were randomised to the intervention arm. The intervention was delivered by the TRIUMPH trial research nurses at nine sites (three West of England, six Wessex), by practice nurses/HCAs at six sites (three West of England, three Wessex) and by both at two sites (one West of England, one Wessex) (Table 9). Overall, compliance with the intervention visit and follow-up contacts was very high (see Table 9), as was adherence to patient preferences in the format of their follow-up visits (Table 10).

| Site ID | Centre | Delivered by practice nurse/HCA or TRIUMPH nurse | Number of patients consented | Intervention visit, n (%) | 1-week follow-up, n (%) | 4-week follow-up, n (%) | 12-week follow-up, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients receiving this stage of the intervention | Loss to follow-up | Patients receiving this stage of the intervention | Loss to follow-up | Patients receiving this stage of the intervention | Loss to follow-up | Patients receiving this stage of the intervention | Loss to follow-up | ||||

| B10 | WoE | TRIUMPH | 32 | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | 32 (100) | 0 (0) |

| B11 | WoE | TRIUMPH | 35 | 34 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) | 34 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) | 34 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) | 34 (97.1) | 1 (2.9) |

| B12 | WoE | Practice nurse/HCA | 40 | 38 (95.0) | 2 (5.0) | 38 (95.0) | 2 (5.0) | 38 (95.0) | 2 (5.0) | 36 (90.0) | 4 (10.0) |

| B13 | WoE | Practice nurse/HCA | 20 | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) |

| B22 | WoE | Practice nurse/HCA | 40 | 38 (95.0) | 2 (5.0) | 37 (92.5) | 3 (7.5) | 35 (87.5) | 5 (12.5) | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) |

| B32–B34 | WoE | Mixed | 63 | 63 (100) | 0 (0) | 59 (93.7) | 4 (6.3) | 63 (100) | 0 (0) | 62 (98.4) | 1 (1.6) |

| B36 | WoE | TRIUMPH | 32 | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | 31 (96.9) | 1 (3.1) | 32 (100) | 0 (0) | 32 (100) | 0 (0) |

| S15 | Wessex | Practice nurse/HCA | 24 | 22 (91.7) | 2 (8.3) | 20 (83.3) | 4 (16.7) | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) |

| S18 | Wessex | Practice nurse/HCA | 25 | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (100) | 0 (0) |

| S19 | Wessex | TRIUMPH | 13 | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) |

| S21 | Wessex | TRIUMPH | 29 | 28 (96.6) | 1 (3.4) | 26 (89.7) | 3 (10.3) | 27 (93.1) | 2 (6.9) | 28 (96.6) | 1 (3.4) |

| S26 | Wessex | TRIUMPH | 41 | 41 (100) | 0 (0) | 39 (95.1) | 2 (4.9) | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) |

| S27 | Wessex | TRIUMPH | 36 | 36 (100) | 0 (0) | 35 (97.2) | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) | 1 (2.8) |

| S28 | Wessex | Practice nurse/HCA | 15 | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3) | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3) |

| S30 | Wessex | Mixed | 29 | 28 (96.6) | 1 (3.4) | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | 27 (93.1) | 2 (6.9) | 28 (96.6) | 1 (3.4) |

| S40 | Wessex | TRIUMPH | 33 | 33 (100) | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | 0 (0) |

| S41 | Wessex | TRIUMPH | 17 | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 17 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Across WoE practices | 262 | 257 (98.1) | 5 (1.9) | 251 (95.8) | 11 (4.2) | 253 (96.6) | 9 (3.4) | 247 (94.3) | 15 (5.7) | ||

| Across Wessex practices | 262 | 258 (98.5) | 4 (1.5) | 238 (90.8) | 24 (9.2) | 251 (95.8) | 11 (4.2) | 252 (96.2) | 10 (3.8) | ||

| Formats and preferences | N or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of participants in the intervention arm | 524 |

| Participants who received the booklet | 516 (98) |

| Participants who had their telephone call at week 1 | 489 (93) |

| Participants who had all three contacts | 470 (90) |

| Week 4 | |

| Preference | |

| N | 508 |

| Phone | 364 |

| Text | 18 |

| 126 | |

| Method of contact | |

| N | 501 |

| Phone | 356 |

| Text | 24 |

| 121 | |

| Week 12 | |

| Preference | |

| N | 508 |

| Phone | 348 |

| Text | 17 |

| 143 | |

| Method of contact | |

| N | 498 |

| Phone | 323 |

| Text | 26 |

| 149 | |

| Participants who had their contact in the preferred method at week 4 | 477 (91) |

| Participants who had their contact in the preferred method at week 12 | 475 (91) |

| Participants who had the week 1 contact by telephone and both the 4- and 12-week visits in their preferred method | 414 (79) |

Participants were directed to different sections of the intervention booklet based on their baseline data, including the bladder diary. We recorded the sections of the booklet that each participant was referred to in the trial case report forms, and compared the baseline IPSS and ICIQ-UI-SF scores between groups (see Appendix 1, Table 41). The most commonly referred booklet sections related to ‘drinks and water intake’, ‘controlling an urgent need to pass urine’ and ‘reducing sleep disturbance caused by needing to pass urine’.

Protocol deviations

No serious protocol deviations were experienced during the trial. Protocol deviations are summarised in Table 11 and detailed in Appendix 1, Table 42.

| Protocol deviation category | Trial group (n) | Overall (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||

| Consent | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Intervention visit/booklet delivery | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Intervention follow-up contacts | 88 | 0 | 88 |

| Follow-up | 16 | 1 | 17 |

| COVID-19 | 74 | 93 | 167 |

| Total | 185 | 94 | 279 |

Follow-up rates and International Prostate Symptom Score data completeness

Follow-up rates were monitored by the practice over the trial period and are described in Table 12. All had at least 80% follow-up for the 12-month visit. Completeness of the primary outcome (IPSS at 12 months) ranged from 75.8% to a high of 95.5%. Overall completeness of the primary outcome was > 80% in both arms.

| Centre | Arm | Practice ID | Total number of patients consented | Follow-up,a n (%) | Complete IPSS, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||||

| WoE | Intervention | B10 | 32 | 30 (93.8) | 29 (90.6) | 28 (87.5) | 29 (90.6) |

| WoE | Intervention | B11 | 35 | 32 (91.4) | 30 (85.7) | 32 (91.4) | 30 (85.7) |

| WoE | Intervention | B12 | 40 | 37 (92.5) | 38 (95.0) | 36 (90.0) | 37 (92.5) |

| WoE | Intervention | B13 | 20 | 17 (85.0) | 16 (80.0) | 17 (85.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| WoE | Intervention | B22 | 40 | 36 (90.0) | 34 (85.0) | 33 (82.5) | 32 (80.0) |

| WoE | Intervention | B32-B34 | 63 | 57 (90.5) | 55 (87.3) | 55 (87.3) | 52 (82.5) |

| WoE | Intervention | B36 | 32 | 30 (93.8) | 26 (81.3) | 28 (87.5) | 25 (78.1) |

| Wessex | Intervention | S15 | 24 | 22 (91.7) | 22 (91.7) | 22 (91.7) | 21 (87.5) |

| Wessex | Intervention | S18 | 25 | 25 (100) | 24 (96.0) | 24 (96.0) | 23 (92.0) |

| Wessex | Intervention | S19 | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 11 (84.6) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (76.9) |

| Wessex | Intervention | S21 | 29 | 27 (93.1) | 27 (93.1) | 24 (82.8) | 25 (86.2) |

| Wessex | Intervention | S26 | 41 | 38 (92.7) | 38 (92.7) | 36 (87.8) | 36 (87.8) |

| Wessex | Intervention | S27 | 36 | 35 (97.2) | 33 (91.7) | 35 (97.2) | 32 (88.9) |