Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/130/07. The contractual start date was in May 2017. The draft report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Ridd et al. This work was produced by Ridd et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Ridd et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Eczema

Around 20% of children in the UK have eczema (also known as atopic eczema/atopic dermatitis). 1 It is most commonly diagnosed in the first 2 years of life. 2 The majority of children have a mild or moderate disease and are diagnosed and managed exclusively in primary care. 3

The main symptoms of eczema are dry and inflamed, itchy skin. The condition can have a significant impact on the quality of a child’s life and on their family. 4 It can adversely influence the affected child’s emotional and social development5 and may lead to psychological difficulties. 6 Parents report loss of sleep and stress, and families can become socially isolated. 7 Impairment in health-related quality of life is comparable to that of many other long-term childhood conditions, including diabetes and asthma. 8

In 1995–6, the total annual UK cost of eczema in children aged ≤ 5 years was estimated to be £47M (or £79.59 per child), of which 64% was NHS costs. 9

Emollients for eczema

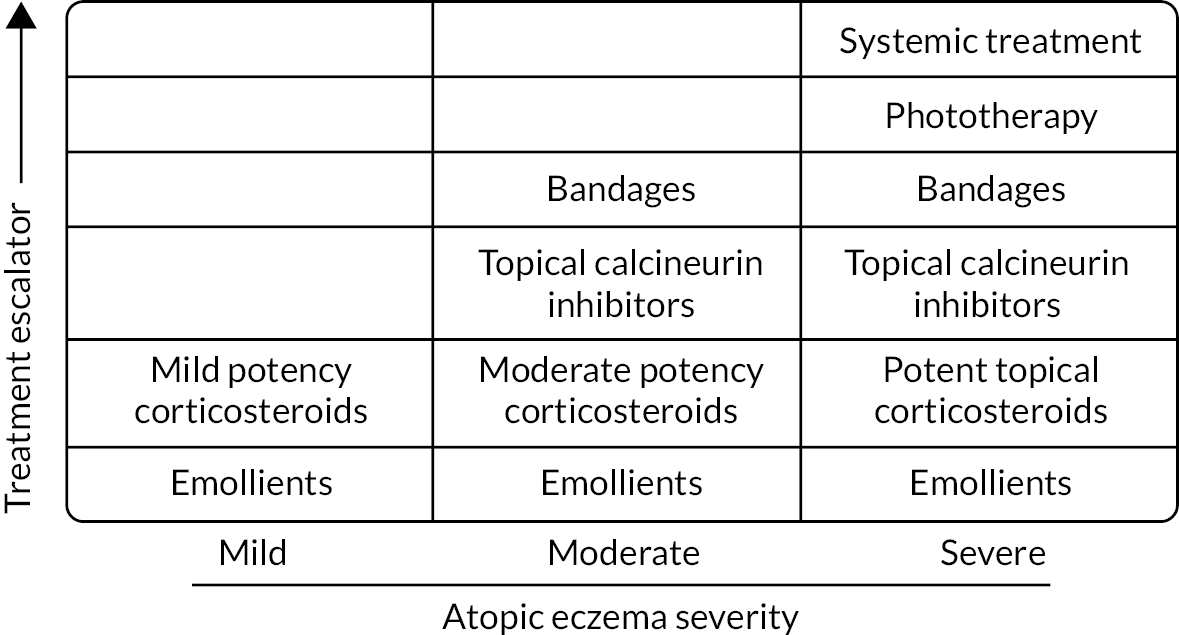

Treatments are usually tailored to disease severity (see Figure 1). Emollients as a ‘leave-on’ treatment are recommended for all disease severities, with topical corticosteroids (or sometimes topical calcineurin inhibitors) used alongside to treat or prevent ‘flares’. Emollients may be also used as a soap substitutes, but bath additive products do not confer any additional benefit. 10

FIGURE 1.

Stepped approach for managing atopic eczema in children (adapted from the NICE guidelines). 12 Reproduced from ‘Exacerbation of atopic eczema in children’, Ridd M and Purdy S, 339, b2997, 2009, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. [License no 5444140896947].

Applied directly to the skin, emollients treat symptoms by directly adding water to the dry outer layers of the skin and reducing water loss by occlusion. 11 They can also act as a barrier to irritants, especially for the hands and around the mouth, and have mild anti-inflammatory properties, thereby reducing reliance on topical corticosteroids.

Multiple emollients are available, but there is limited evidence that any one emollient is better than another. The main types are lotions, creams, gels and ointments. The differences in their consistency (from ‘light’ to ‘heavy’) mainly reflect differences in oil (lipid) to water ratios. Some products contain humectants, which may help retain moisture. Emollients that contain urea or antimicrobial compounds are usually sanctioned for more severe disease only.

There are many emollient formularies, developed by medicine management teams across England and Wales,13 which vary widely in their recommendations. A simplistic approach, prescribing emollients on a cheapest ‘per gram or millilitre’ basis,14 is wrong for two reasons. First, it assumes that all products are equally acceptable and effective. Second, it ignores wider health-care costs associated with repeated consultations for alternative products.

Parents and carers often end up trying many different emollients, seeking one that works for them. 15–17 This ‘trial and error’ approach takes time, causes frustration18 and can cause some families to ‘give up’ using emollients altogether, resulting in suboptimal eczema care.

Development of research priority

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2007) and a James Lind Alliance research priority-setting partnership for eczema (2013) have both recommended research comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and safety, of emollients in eczema. 19 van Zuuren et al. ,20 in a Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials of emollients and moisturisers for eczema, identified 77 studies, 70 of which were at an unclear or a high risk of bias. Reporting of adverse events was limited and only 13 studies assessed participant satisfaction with treatment. The authors were unable to conclude whether some emollients, or their ingredients, were better than others.

Aims and objectives

Pragmatic randomised trial

The aim of the trial was to compare the effectiveness and acceptability of four commonly used types of emollients for the treatment of childhood eczema.

The objectives of the trial were to compare the four types of emollients at both 16 weeks (medium term) and 52 weeks (long term) in respect of:

-

parent-reported eczema symptoms

-

objective assessment of eczema signs

-

quality of life for the child

-

impact of eczema on the family

-

adverse effects

-

parent satisfaction with study emollient

-

frequency and quantity of study emollient and other emollient use

-

use of topical corticosteroids

-

number of well-controlled weeks.

Nested qualitative study

The aim of the nested qualitative study was to complement, explain and aid understanding of the quantitative findings regarding the delivery/receipt of the intervention, its acceptability and perceived or experienced benefits or harms.

The objectives of the nested qualitative study were to:

-

explore facilitators of or barriers to use and follow up with participants who stopped treatment early

-

explore carers’ and children’s experiences of study emollient use and their views about perceived effectiveness and/or acceptability of study emollients

-

contextualise the trial findings, as an aid to interpreting the results and their potential impact on clinical practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The Best Emollients for Eczema (BEE) study was a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel-group superiority trial of four types of emollient in children with eczema, with a nested qualitative study. 21,22

It was a type A clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product because some of the study emollients were classed as medicines (others were classed as medical devices or cosmetic products). It was classed as low risk because the use of the medicinal product was not higher than the risk of standard medical care.

Changes to trial protocol

The final study protocol (version 7.0, 19 November 2019) is available via the study website (www.bristol.ac.uk/bee-study; accessed 10 September 2022). Amendments are listed in Appendix 1.

The trial design was based on the feasibility trial Choice of Moisturiser in Eczema Treatment (COMET). 16 Like this study, in the original approved BEE protocol (version 1.0, 21 March 2017) participants were to be randomised to four specific named emollients [Aveeno® (Johnson & Johnson, Brunswick, NJ, USA) lotion, Diprobase® (Bayer, Reading, UK) cream, Doublebase™ (Dermal Laboratories Limited, Hitchin, UK) gel or Epaderm® (Mölnlycke Health Care Limited, Oldham, UK) ointment]. However, when participant recruitment was due to start, we submitted a substantial amendment (version 4.0, 3 November 2017) that changed the intervention to four types of emollient, with a list of approved emollients for each category. This was because between applying for funding and trial authorisation, several integrated care boards (ICBs) in the recruiting areas implemented significant changes to their local formularies that did not include the original proposed specific emollients; because the trial intervention was prescribed by participants’ general practitioners (GPs), there was the risk that participants would not receive their allocated emollient.

Protocol amendments to change the duration of the recruitment period of the study were made twice: first to extend the participant recruitment period by 6 months to 26 months (version 6.0, 10 June 2019), and second (after an increase in recruitment rate) to reduce the participant recruitment period back to 22 months total (version 7.0, 19 November 2019).

Other changes to the protocol during the study have been minor, involving clarifications or minor corrections.

Terminology and definitions

Unless otherwise stated, we use the following terms in the ways described.

For the sake of brevity, we use the term parent to include the child’s main carer/legal guardian. In the trial, participants are the children, whereas in the qualitative study, this term could refer to both parents and children. We refer to trial groups (rather than arms), to avoid potential for confusion between trial arms and participants’ upper limbs. Centres are the regional hubs (Bristol, Nottingham – including Lincolnshire and Southampton) through which GP surgeries and participants were recruited, with GP surgeries being the participant identification centres. We prefer the term masking to blinding, although this term is used for the Bang blinding index.

The terms emollient and moisturiser are commonly used interchangeably, but, as explained in Chapter 3, we consistently used moisturiser for patient-facing materials. In lay speak, as captured in the qualitative findings, ‘cream’ is commonly used in a generic sense to describe all the different types of emollients, but in the report we use ‘type’ to refer to lotions, creams, gels and ointments, or their actual group label, as appropriate.

Regarding the use of allocated and non-allocated study emollients, in our protocol and statistical analysis plan we refer to adherence and contamination. We have retained the same definitions, as below, but for clarity refer throughout this report to allocated and non-allocated study emollient use:

-

Allocated emollient use (or ‘adherence’) was defined as the number of days of a non-missing week of emollient use data in which the emollient used was the allocated emollient type.

-

Non-allocated emollient use (or ‘contamination’) was defined as the number of days of a non-missing week of emollient use data in which an emollient other than the allocated emollient type was used.

Participant recruitment and follow-up

Participants were recruited between 19 January 2018 and 31 October 2019.

Identification of potentially eligible children

Participant recruitment was via GP surgeries in the three clinical research network (CRN) areas of West of England (Bristol), Wessex (Southampton) and East Midlands (Nottingham and Lincoln).

General practitioner surgeries

General practitioner surgeries were recruited via CRNs, direct approaches from the study team and promotion at meetings/events. Practices that submitted an expression of interest form had a study set-up meeting, where the study was explained in full and practices were to sign a contract if they were happy to proceed. Research leads at participating surgeries were required to have good clinical practice (GCP) certification.

Participant screening

Practices were sent a specific electronic search that identified all children registered at the practice aged between 6 months and 12 years, who had an eczema diagnosis and had been prescribed an eczema treatment in the past 12 months. They then screened the list, removing any participants who did not fit the inclusion/criteria or should not be approached for social or medical reasons. An anonymised copy (with reasons for exclusion) was submitted to the research team, and invitation letters were sent out to potentially eligible children via DocMail, a NHS-approved mail-out service.

Participant eligibility criteria

To be eligible, children and the responsible adult had to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

Child

-

aged between 6 months and 12 years

-

have eczema diagnosed by an appropriately qualified health-care professional (registered doctor, nurse or health visitor)

-

mild eczema or worse (POEM score of > 2 points within previous 28 days). At the point of randomisation, at least two POEM scores were available for all participants – one recorded at the time of expression of interest and one recorded at baseline. The expression of interest POEM score was used to determine eligibility and for randomisation; a further POEM score was recorded if the baseline visit was > 28 days later.

-

-

The person giving consent must

-

have parental responsibility for the participant

-

be willing to use the randomly allocated emollient type as the only leave-on emollient for 16 weeks.

-

Exclusion criteria for the child and the responsible adult were as follows:

-

Child

-

known sensitivity to study emollients or their constituents

-

participating in another research study currently or in the last 4 months

-

any other known adverse medical or social circumstance that would make invitation to the study inappropriate (as determined by GP practice staff).

-

-

The person giving consent

-

was unable to give informed consent

-

had insufficient written English to complete outcome measures.

-

Participant recruitment

Mail-out invitation

Invitation packs included (see Report Supplementary Materials 1 and 2):

-

a covering letter

-

a two-page summary, which gave an overview of the study and outlined how to find more information

-

a ‘reply to invitation form’, asking those not interested to give a reason why, and, for interested families, their contact details and POEM questionnaire.

Parents could either complete and return the response form using the enclosed pre-paid envelope or complete an identical online version.

Self-referral

Participating GP surgeries were asked to display posters and put promotional flyers in their waiting rooms, and the study was promoted at various events. If the child was registered at a participating GP surgery, parents could contact the team directly to register their interest via the online form.

Screening telephone call

Interested parents of potentially eligible children were sent participant information sheets (adult and child versions; see Report Supplementary Materials 3 and 4) by e-mail or post and were telephoned by the researcher. During the telephone call, the researcher outlined what taking part would involve and answered any initial questions. If the parent was happy to proceed, a baseline study visit was arranged.

If the visit was > 28 days after the expression of interest, POEM was repeated over the telephone in advance of the visit, either during the main screening telephone call or by means of a further telephone call prior to the visit.

Baseline study visit

Baseline visits took place in the participant’s home, or in a suitable room at the GP practice. Visits lasted approximately 1 hour.

A sample of baseline visits were recorded to help with training and to inform recruitment strategy. With multiple emollients of each type and no control group, this was a complex trial to recruit to. Equipoise was important to establish to minimise the contamination (use of non-allocated emollients) and to maximise participant retention. At these visits, parent were asked to give verbal permission for audio-recording, followed up by written consent at the end of the encounter. We sought at least one recording for each recruiting researcher. The recordings were listened to by the qualitative Senior Research Associate. Any issues identified in the recruitment process were fed back to researchers to improve communication between researchers and participants.

At the baseline visit, the researcher summarised the study and shared a sheet listing which study-approved emollients were available of each type in their local area. They explained what taking part would involve, and demonstrated how the weekly/monthly questionnaires should be completed. They checked that the parent had read and understood the participant information leaflet (and, when relevant, the child their equivalent), and questions were invited and answered. Parents and children were reminded that study researchers were masked and, in any future contact with them, they must not disclose which emollient they were using.

If the parent was happy to continue, written informed consent was taken, with the option for older child to complete an assent form (see Report Supplementary Materials 5 and 6).

Participant follow-up

Parents were telephoned by an unmasked member of the research team with their allocation after randomisation, and told to collect their corresponding prescription from their GP surgery. This was followed up with another telephone call 7 days later to confirm that they had received the study emollient and started using it.

Thereafter, with the exception of the week 16 visit, follow-up was remote, by means of parent-completed questionnaires (see Chapter 2, Data collection, Follow-up questionnaires).

The final week 16 follow-up visit was on 17 February 2020. The trial finished after the last participant’s week 52 follow-up questionnaire was returned.

Participant withdrawals

Participants were free to withdraw at any time, without any consequences for their usual care or follow-up. We analysed any data already collected and obtained their electronic medical record (EMR) data, unless the participant expressly withdrew their consent prior to the database being locked. Participants who actively withdrew were asked to give reason(s).

Participant engagement

Parents were thanked for their time in the study with a £10 voucher at the baseline visit and a £10 voucher on completion of the week 16 visit, and a final £10 voucher was sent on completion of the week 52 survey.

At the baseline visit, children were offered a small thank you of a bee soft toy or a bouncy ball. In addition, children were given an A4 bee colouring template to colour in/decorate while the researcher talked to their parent. Once complete, families were encouraged to share pictures with the BEE research team. Submitted colourings were shared via the study website and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com), and used in dissemination of the study findings, for example in presentations. At the week 16 visit, children were given a certificate to congratulate them on their participation in the study.

Newsletters were sent out to families via e-mail approximately three times per year and e-cards were sent at Christmas. Newsletters contained information on recruitment, reminders on how to complete the questionnaires, seasonal information relating to eczema, and profiles of research team members.

Parents were encouraged to follow the study Twitter account, which charted progress and shared children’s coloured-in bees. Finally, a study website was maintained, containing study information and links to relevant documents.

Intervention

Participants were randomised to receive a study-approved emollient of one of the following types: lotion, cream, gel or ointment. Which study-approved emollients were available for GPs to prescribe varied by ICB, but all the options are listed in Table 1. Study-approved emollients were all paraffin based and member types shared the characteristics as detailed in the table. Although emollients were allowed to ‘join or leave’ the study as eligible emollients were introduced or removed from local formularies, the list presented remained stable over the life of the trial.

| Treatment | Emollient type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lotion | Cream | Gel | Ointment | |

| Study emollients | Cetraben® (Thornton & Ross Ltd, Linthwaite, UK) | AproDerm® (Fontus Health Ltd, Walsall, UK) | AproDerm (Fontus Health Ltd, Walsall, UK) | Diprobase (Bayer UK Ltd, Reading, UK) |

| Diprobase (Bayer UK Ltd, Reading, UK) | Aquamax® (Intrapharm Laboratories, Maidenhead, UK) | Doublebase (Diomed Developments, Hitchin, UK) | Emulsifying ointment BP | |

| QV™ (QC Skincare, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) | Diprobase (Bayer UK Ltd, Reading, UK) | Epimax Isomol gel (Aspire Pharma, Petersfield, UK) | Paraffin White soft | |

| Epimax (Aspire Pharma, Petersfield, UK) | MyriBase™ (Penlan Healthcare, Weybridge, UK) | Paraffin Yellow soft | ||

| Zerobase® (Zeroderma®, Thornton & Ross Ltd, Linthwaite, UK) | Zerodouble® (Zeroderma®; Thornton & Ross Ltd, Linthwaite, UK) | White soft/Liquid paraffin 50/50 | ||

General practitioners were instructed to issue the prescription with the directions to apply twice per day and as required, and parents were asked to agree to use the study emollient as their child’s only leave-on emollient for 16 weeks.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the Patient Orientated Eczema Measure (POEM) score, measured weekly for 16 weeks. POEM scores were calculated by summing the seven questions, with a possible range of 0–28 points.

The POEM is a patient-reported outcome measure that can be completed by proxy (carer report) and captures symptoms of importance to parents and patients over the previous week. 23 It demonstrates good validity, repeatability and responsiveness to change,24,25 and was favoured as the main outcome by patient contributors.

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary outcomes (time period) were collected and/or calculated:

-

Eczema symptoms (POEM), once every 4 weeks for 52 weeks.

-

Eczema signs [Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI)] at 16 weeks. The total EASI score is a weighted sum of the four EASI scores for each body area (head and neck, upper limbs, trunk and lower limbs). The weights allocated to each body area differ according to the age of the child (≤ 7 or ≥ 8 years). The final EASI scores range between 0 and 72.

-

Masking of researcher at the week 16 visit, using the Bang blinding index. 26

-

Use of study emollient/topical corticosteroids.

-

Participant quality of life [disease-specific Atopic Dermatitis Quality of Life (ADQoL)27 and generic Child Health Utility 9-Dimension (CHU-9D)28,29 scores], coded according to the developer’s instructions. The CHU-9D is validated for children aged ≥ 7 years. The pilot versions for younger children were used with additional guidance notes.

-

Impact of the participant’s eczema on the family [Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI) questionnaire]. 30 The DFI was obtained by summing responses to the 10 items to give a score of 0–30 points.

-

Satisfaction with study emollient.

-

Adverse events – localised skin reactions, slips and falls, and unplanned hospital admissions.

-

Number and quantity of study emollients and other emollients used.

-

Proportion of well-controlled weeks between weeks 1 and 16.

All the above were collected by parent-completed questionnaires, except b, which was assessed by a masked researcher; c, which was obtained by researcher-completed questionnaire at the week 16 visit; i, which was obtained from participants’ EMRs; and j, which was derived from POEM scores, in which each week was classified as well-controlled (POEM score ≤ 2) or not (POEM score > 2), with the proportion of weeks with well-controlled symptoms calculated as the number of well-controlled weeks divided by the number of weeks with non-missing POEM scores.

The format of questions for d was changed in month 12 of recruitment from a numbered (day 1, day 2, etc.) to a named day (Monday, Tuesday, etc.), to improve ease of completion (see Chapter 3, Parent and public involvement during the study).

Items in the final questionnaire asked about trial participation, specifically about following directions on study emollient use.

With a view to carrying out economic analyses in the future, we also asked questions about personal costs related to eczema and health-care consultations (4-weekly).

Data collection

Table 2 sets out what data were collected and when. Parents were given the option to complete questionnaires after the baseline visit online (default) or on paper when this was preferred.

| Data collection | S | V0 | Participant questionnaires | V1 | Participant questionnaires | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 40 | 44 | 48 | 52 | EMR | |

| Eligibility checks | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demographics (and consent) | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UK diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opinion about study emollients | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| POEM | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Use of treatments for eczema | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Adverse events | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Consultations (non-EMR) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal costs | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||

| DFI | • | • | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ADQoL | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CHU-9D | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Satisfaction with study emollient | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EASI | • | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EMR review | • | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Baseline visit

Once consent was received, the following baseline data were collected:

-

participant contact details and demographics

-

eczema history and treatment, POEM score, DFI score, parent opinions about different types of emollients, quality of life (ADQoL and CHU-9D scores)

-

skin assessment by researcher (EASI score and UK diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis).

Parents choosing to complete online were offered a laminated aide memoire to enable them to keep a note of their child’s daily emollient use in-between completing the surveys.

Follow-up questionnaires

Participants completed follow-up questionnaires weekly for 16 weeks, then 4-weekly until 52 weeks. Weekly questionnaires comprised POEM and questions about the use of eczema treatments (study emollient, other leave-on emollients and topical corticosteroids) and adverse events. Parents were asked to report eczema treatment use over the previous week, with the first week commencing the Monday after randomisation.

In addition to the above, the 4-weekly questionnaires asked about consultations with health-care professionals (health visitor, pharmacist, dermatologist, and dermatology nurse) and costs (out-of-pocket expenses for eczema-related purchases, private/alternative treatments, travel costs to appointments).

Quality-of-life measures (ADQoL, CHU-9D) were administered at 6, 16 and 52 weeks, and the impact of the condition on the family (DFI) was determined at 16 and 52 weeks. Participants were asked about their satisfaction with their study emollient at 16 weeks.

Parents received e-mail and/or text reminders to complete the questionnaires, with telephone calls if needed.

Follow-up visit

The follow-up visit was scheduled for 16 weeks (± 10 days) after the baseline visit. Participants’ skin was assessed, usually in their own home, by a masked researcher. To maximise data collection, from month 10 of recruitment, researchers were asked to collect POEM scores at 16 weeks as well as EASI scores. When both parent-completed and researcher-collected week 16 POEM scores were available, the scores were compared and sensitivity analysis undertaken (see Statistical methods, Primary outcome, Sensitivity analyses including imputation of missing data).

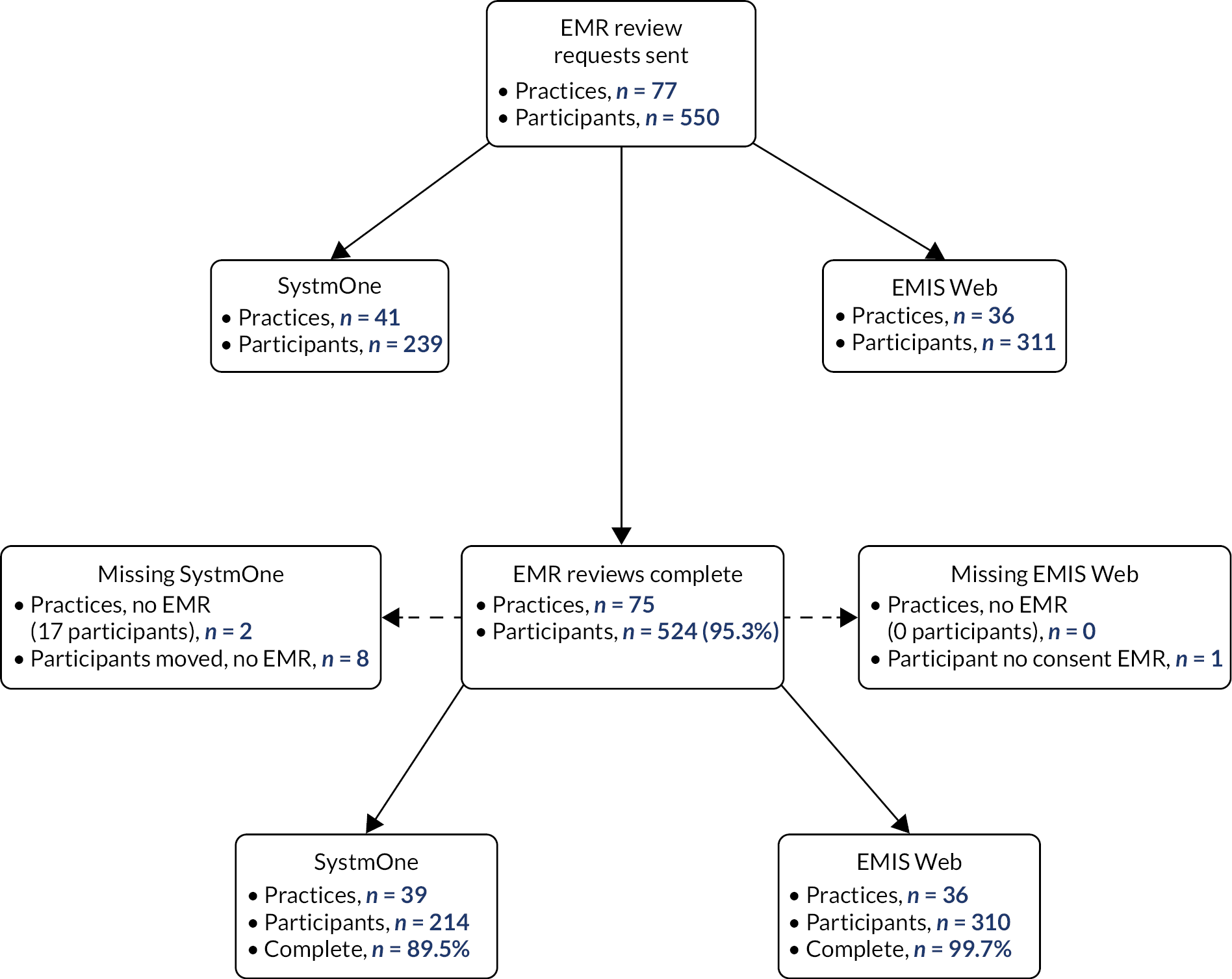

Electronic medical record review

Consultation and prescription data (from 4 weeks prior to and 52 weeks after randomisation for each participant) were extracted from participants’ EMR remotely, using reports written for SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership, Leeds, UK) and EMIS Web (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK). After the last participant from each GP surgery had completed their week 52 follow-up questionnaire, their practice was sent the appropriate electronic search strategy, instructions and list of patients recruited into the study. It was not possible to obtain data on quantity (in grams or millilitres) for items prescribed in SystmOne practices.

Data management and validation

Each participant was assigned a trial participant identification number, which was used on questionnaires and the electronic database. All data relating to participants were stored securely in locked cabinets and/or password-protected file stores. Patient identifiers were separate from clinical data. The trial database was locked on 11 December 2020.

Data for a random sample of 10% of participant questionnaires were checked for quality purposes.

Sample size

We sought to recruit 520 participants. This was based on detecting a minimum clinically important difference in POEM scores of 3.0 points between any two treatment groups with 90% power and a significance level of 0.05 (after adjustment for multiple pairwise comparisons). We based our sample size on a standard deviation (SD) of 5.5 and allowed for 20% loss to follow-up.

Participant randomisation, notification and receipt of allocation

Participants were randomised using a validated web-based randomisation system supplied by the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration. Using computerised randomly generated numbers, participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to one of the four groups, stratified by centre and minimised by expression of interest POEM score [3–7 points (mild) vs. 17–28 points (severe to very severe)] and participant age (aged < 2 years vs. > 2 years).

Unmasked members of the Bristol-based research team undertook randomisation, notified the parent and asked the GP surgery to prescribe accordingly. Consequently, there was a delay between the baseline visit, randomisation, and the participant starting their study emollient. The study-approved emollient(s) of each type varied among different ICBs, and emollients were issued by participants’ local pharmacist.

Masking

Participants, their parents and clinicians involved in their care were not masked to allocation. They were asked not to disclose their allocation to masked members of the research team.

The trial management group (TMG) were masked to allocation. The trial manager/co-ordinator and administrator were unmasked to undertake randomisation process above, and the qualitative research team (ES, JB and Alison Heawood) were unmasked for the purposes of interview data collection and analysis. The trial statistician was masked until the first version of the statistical analysis plan was approved. They were unmasked after this point, to allow for reporting of contamination so they could discuss unmasked data with the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) as needed.

Researchers undertaking the objective skin assessments were masked. Masking at the 16-week EASI assessment was assessed by means of a self-complete question, which asked ‘[w]hich moisturiser type do you think the child is using?’ (lotion, cream, gel, ointment or ‘don’t know’). The Bang blinding index26 was estimated for each treatment group comparing correct treatment responses with incorrect or ‘don’t know’ responses. Indices can range from –1 (opposite guesses potentially caused by unmasking) to 1 (complete lack of masking). An index of 0 indicates perfect blinding.

Statistical methods

The analysis and presentation of trial data were in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines. 31,32 Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) version 16 was used for all statistical analyses. A full statistical analysis plan was developed and approved by the independent statistician from the study’s Trial Steering Committee (TSC) ahead of analysis of post-randomisation data and is available via the study website.

Characteristics of non-study patients

We compared the age and sex of study participants with non-study patients using means and SDs (age) and frequencies and proportions (sex). The purpose of this was to investigate whether or not the study participants differed from those who were excluded at earlier stages of the recruitment and screening process.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants were described by treatment group. Any imbalances informed additional adjustment of the primary analyses as appropriate. Continuous variables were summarised using the mean and SD [or median and interquartile range (IQR) if the distribution was skewed] and categorical data were summarised as frequencies and proportions.

Primary outcome

Primary statistical analyses between the randomised groups were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, defined as analysing participants as randomised, regardless of the adherence to their allocated group and without imputation for missing data. For the primary outcome, linear mixed models (weekly observations, level 1; nested within participants, level 2) were used to explore whether or not there were differences in mean POEM scores between treatment groups after adjusting for baseline scores and all stratification and minimisation variables used in the randomisation.

This approach allowed incomplete cases (i.e. participants who did not complete all of their weekly scores) to contribute to the analysis. Therefore, all participants who contributed at least two POEM scores (one baseline and another between weeks 1 and 16) were included in the primary outcome analysis.

Pairwise comparisons were conducted to identify which intervention groups differed and were presented as mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. To account for multiple testing, we used a modified alpha of 0.0083 (0.05/6 pairwise comparisons equivalent) as a threshold when interpreting p-values.

Sensitivity analyses including imputation of missing data

To assess the robustness of the primary analysis to model selection and data collection, the following sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome were carried out:

-

adjustments for sex imbalance at baseline, because the sex of participants differed by more than 10% between two groups (cream and gel), as per our statistical analysis plan

-

16-week POEM researcher-collected rather than by parent self-report

-

imputation for missing data, using ‘best’ and ‘worst’ case scenarios, and multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE).

For the ‘best’ case scenario, missing POEM scores were replaced by the mean –1 SD for that treatment group. For the ‘worst’ case scenario, missing scores were replaced by the mean +1 SD for that treatment group.

Subgroup analyses

Four prespecified subgroup analyses investigated whether or not treatment effectiveness (POEM) was modified by the below factors measured at randomisation. These were carried out by introducing appropriate interaction terms in the regression models, and likelihood ratio tests were used to compare the model with the interaction term with the model without the interaction term:

-

Parent expectation – parents were asked to score on a scale of 1 (‘very poor’) to 5 (‘very good’) or ‘don’t know’ their thoughts on how effective they thought different moisturisers were for treating the dry skin of eczema. For the purpose of subgroup analysis, the variable was classified as ‘poor’ (score of 1 or 2), ‘average or unsure’ (score of 3 or ‘don’t know’) or ‘good’ (score of 4 or 5). Analysis was based on an individual’s pre-randomisation expectations of effectiveness of the emollient to which they were later allocated.

-

Age – younger (< 2 years) versus older patients (≥ 2 years).

-

Disease severity – mild eczema (POEM score of 3–7 points) versus moderate/severe eczema (POEM score of ≥ 8 points).

-

Diagnosis of eczema – children who did and did not fulfil the UK diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis.

Per-protocol analysis

In the statistical analysis plan, we wrote that in the event of ‘substantial contamination’ (undefined), we would undertake a per-protocol analysis (also not specified). Contamination (or use of non-allocated emollient) during the primary outcome period was low, but on the basis of variable allocated emollient use (adherence), we repeated the primary analysis, restricted to participants who had reported using their allocated emollient at least 1 week in every 4 (i.e. in weeks 1–4, 5–8, 9–12 and 13–16) and for at least 60% of days in a reported week.

Secondary outcomes

Analyses of secondary outcomes were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, according to the data type and frequency of recording. Continuous outcomes measured at multiple time points (POEM, ADQoL, DFI and CHU-9D scores) were analysed similarly to that described in Primary outcome above.

The EASI scores measured at baseline and 16 weeks were analysed using a linear regression model, adjusting for baseline values when available. A sensitivity analysis for the collection of EASI scores at baseline and 16 weeks by the same and different researchers was also undertaken.

The EASI and DFI scores at follow-up were found to be highly skewed and contained values of 0; therefore, scores were transformed by taking the natural log of the score plus 1. The results of these analyses are presented as the ratio of the geometric means of the two groups being compared.

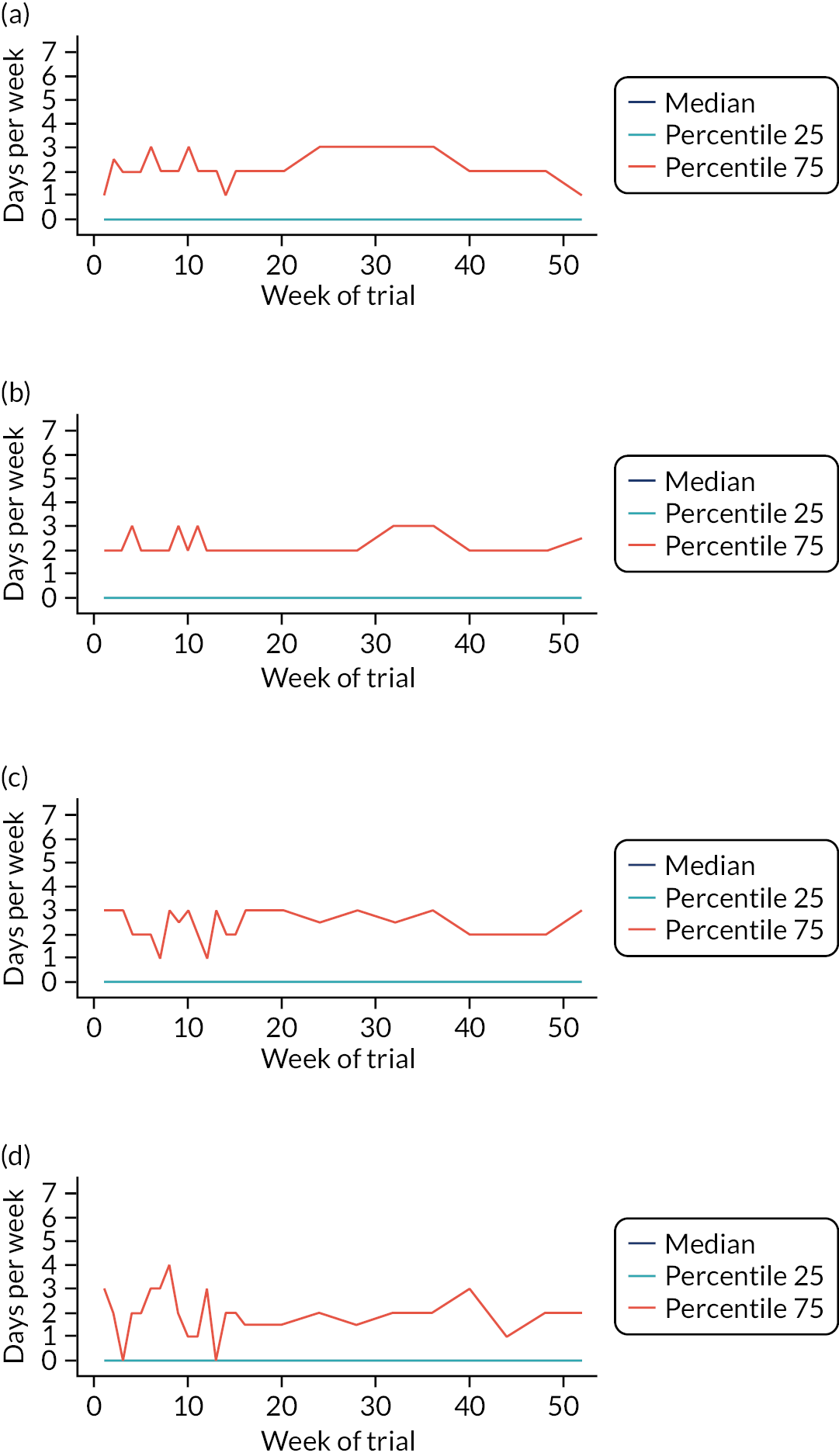

Patterns of the use eczema treatments over the primary outcome period (weeks 1–16) are summarised using descriptive statistics. The number of days in a week that participants used their allocated emollient was analysed using a mixed-effects Poisson regression model adjusting for all stratification and minimisation variables. A mixed-effects negative binomial model was used for the number of days in a week that participants used a non-study emollient.

Parental satisfaction with the study emollient at 16 weeks was analysed using an ordered logistic regression model adjusting for all stratification and minimisation variables.

The proportion of weeks with well controlled symptoms was analysed using a linear regression model adjusting for stratification and minimisation variables.

Impact of COVID-19

On 11 March 2020, the UK Government issued public health guidance recommending that residents wash hands with soap and water, or use hand sanitiser to protect against COVID-19 transmission. 33 A concern was raised by the TMG that increased hand washing and use of sanitiser gels might worsen eczema symptoms and reduce the effectiveness of the intervention.

To explore the possible impact this guidance had on symptoms, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on the repeated-measures POEM scores, before and after the handwashing advice was issued. A binary variable classifying the follow-up period as pre- or post-COVID-19 handwashing advice was generated. A linear mixed model [weekly observations (level 1) nested within participants (level 2)] including a COVID group interaction term was used to explore whether or not the differences in mean POEM scores between treatment groups differed between the periods before and after handwashing advice. The model also adjusted for baseline POEM scores and variables used in the randomisation.

Analysis of safety

Descriptive analysis of safety end points are presented by allocation. The number of events and the number of participants having at least one are tabulated.

Nested qualitative study

Design

We conducted semistructured interviews with parents of participants from each trial group at 2–4 weeks (hereafter termed week 4 interviews) and 16 weeks after randomisation. The week 4 interviews aimed to capture initial experiences with, and opinions of, the study emollient, along with any early deviations from allocation and the reasons for change. The week 16 interviews aimed to capture the longer-term experiences of using the allocated emollients or reasons for stopping or changing, along with parents’ future intentions around emollient use.

Recruitment and consent of parents/assent of children for interviews

All parents received brief information about the qualitative interview study at the time of recruitment into the trial and were asked for consent to be contacted for interview. Following the sampling framework, potential interviewees were invited to take part by means of an e-mailed invitation letter with accompanying qualitative study information sheet (see Report Supplementary Materials 7 and 8).

Informed written consent was received from the parent (see Report Supplementary Material 9). At the discretion of the parent and the preference of their child, children (usually aged ≥ 7 years) using the emollient were invited to participate in the interview and, if they agreed, written assent (see Report Supplementary Material 6) was obtained from the child.

Recruitment stopped when there was agreement that inductive thematic saturation had been reached for the main themes. 34,35

Sampling

Our original design was cross-sectional, in that we anticipated sampling different participants at the week 4 and week 16 time points. However, we revisited a small number of participants from week 4 at week 16. Their data were analysed, as with all the data, cross-sectionally. We sampled from the characteristics of the participants but primarily interviewed parents. At the preference and with the assent of parents/carers and their children, children also sometimes participated in the interviews.

At week 4, we sampled parents across the four trial groups, with variation according to recruiting centre (Bristol, Southampton and Nottingham), age of child, eczema severity (mild, moderate or severe, determined by categorised baseline POEM score)36 and length of use of study emollient, to include some who had stopped using their allocated treatment (determined from patient contact and information from Clinical Studies Officer/Research Nurses). As secondary sampling criteria we included parents/carers whose children represented a range of different ethnicities to capture the experiences of using emollients for different skin types.

The week 16 interviews were conducted from each group of the trial as soon as possible after participants’ primary outcome had been collected or their week 16 visit conducted by the Clinical Studies Officer, whichever was later. Sampling criteria were the same as the week 4 interviews, with the addition of participant intentions regarding future use of the allocated emollient (e.g. intending to continue, stop or switch to another type of emollient, or already stopped).

Qualitative data collection

Data were collected by an experienced qualitative researcher based in Bristol (ESu) using semi-structured face-to-face or telephone interviews. For the week 4 interviews, participants in the Bristol area were interviewed face to face in their home on all but one occasion. Interviews with participants from the other research sites and the repeat interviews were conducted via telephone.

The interview process followed an agreed study protocol using NHS Research Ethics Committee approved topic guides. The topic guides (see Appendix 3, Topic guide) were informed by the qualitative study aims, the feasibility study16 and the wider literature. They were used flexibly to allow unanticipated issues to emerge and to incorporate new topics that were developing from ongoing analysis. For example, following discussion between the qualitative research team and the chief investigator at analysis meetings, and also as a result of input from the study patient and public involvement (PPI) group, some additional prompts were added during the week 4 interviews. We used a range of prompts building on the topics covered with parents/carers, to enable the child to contribute their views and experience.

The week 4 interviews focused on the initial acceptability of the assigned emollient to families; their prior experiences and beliefs about emollient use; their experiences of early use of the assigned emollient; whether, and how, their use of emollient was consistent with, or differed from, recommended use and anticipated adherence to the emollient during the trial. We elicited barriers to and facilitators of use, particularly examining these with participants who stopped using the emollient early or switched to another type of emollient.

At the week 16 interviews, participants reflected on their emollient use over the full trial period to that date. The topics covered were similar to the week 4 interviews, with additional prompts relating to their overall experience, acceptability and effectiveness of the assigned emollient, and planned future use of emollients. These interviews were also informed by themes emerging from the week 4 interviews.

When parents and children were interviewed together, telephone interviews were conducted via speakerphone. A subtopic guide was created (see Appendix 3, Topic guide), adapting questions to enable children to participate.

All interviews were audio-recorded using an encrypted digital recorder. The qualitative researcher (ESu) met the senior qualitative co-applicants (ARGS, JB) on a fortnightly basis to share progress and discuss issues arising in interviews regarding process and content.

Qualitative data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by a University of Bristol (Bristol, UK) member of staff and fully anonymised by Eileen Sutton. Coding and data management were aided by NVivo12 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Analysis took place alongside data collection in an iterative process, to allow insights from earlier interviews to shape future interviews. 37 Analysis was led by the qualitative researcher (ESu) with detailed input from the senior qualitative researchers (ARGS, JB), who read and independently conducted preliminary coding on a subset of transcripts from both time points (week 4 and week 16). The chief investigator (MJR) also contributed, but only had sight of redacted transcripts and data excerpts to preserve masking.

Using a thematic approach drawing on Braun and Clarke,34 analysis incorporated a combination of deductive (based on the qualitative study aim) and inductive (data-driven) coding strategies, from which a preliminary coding framework was developed (see Appendix 3, Coding framework). The coding framework was repeatedly refined through discussion within the qualitative team and incorporated feedback from the PPI panel, the TMG and the TSC. The codes used for the week 4 and week 16 interviews were broadly the same, with the addition of some codes for the week 16 data. Eileen Sutton flexibly applied the coding framework to the whole data set, with Alison R G Shaw, Jonathan Banks and Matthew J Ridd checking a subset of the coding for coherence and completeness. Alison R G Shaw, Jonathan Banks and Matthew J Ridd read and independently coded a subset of interview transcripts.

Following coding of the whole data set, the coded data were examined and compared both across and within trial groups. Themes and subthemes were identified and refined through continual comparison of data elements with each other in an iterative manner. A narrative summary of the findings from the interviews was produced (by ESu, JB and ARGS), attending to areas of divergence and convergence in the data sets and the different perspectives represented.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

This chapter reports on how the involvement of patients and the public shaped the design, delivery and interpretation of the study. Its format observes the GRIPP2 recommendations for reporting. 38

Public involvement in this study can be traced back to 2012 when ‘which emollients are the most effective and safe in treating eczema?’ emerged as one of the top four uncertainties in the patient-led James Lind Alliance eczema research priority-setting exercise. 19 We adopted the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) definition of PPI in our trial, as being ‘research being carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them’39 (© NIHR 2022, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0).

Aim and objectives

The overall aim was to involve parents of children with eczema throughout the study to help us deliver a study in a topic that is not easy to research and generate answers that were meaningful to patients. Specifically, the objectives were to:

-

ensure that all aspects of trial design were relevant and suitable for recruitment and retention of the target population of children with eczema and their parents

-

ensure that the patient perspective was included in the management and oversight of the trial

-

plan effectively for the dissemination of results such that key messages would make sense to parents in the light of the daily challenges of managing childhood eczema

-

provide GPs and commissioners with data that were most relevant and useful in guiding treatment decisions that would be in the best interests of patients.

Although the clinicians on the research team had extensive experience and expertise in the treatment of children with eczema, we were keen to avoid professional ‘blind spots’ or unintended consequences.

Method

To achieve our aim and objectives, we worked to create and maintain mutual understanding and trust between the researchers and the lay contributors, and to ensure that there were opportunities for parent involvement throughout the research process.

Parent and public involvement before the study

The design of the study to answer the James Lind Alliance question was informed by face-to-face discussions and a ‘tweet chat’ with parents of children with eczema who supported the COMET study, the feasibility trial that preceded this study. We also undertook an online survey of 176 parents/carers of children with eczema, which we have previously reported. 17

Parent and public involvement during the study

Co-applicant Amanda Roberts, a mother of children with eczema and who also has the condition herself, fully participated in study development, delivery and dissemination planning. She brought her experience from involvement in this capacity on previous primary care eczema trials (CREAM,40 BATHE41) by attending TMG, lay advisory group and other ad hoc meetings as appropriate.

We convened a group of parents of children with eczema who met six times over the course of the trial (in person, except for the final meeting owing to COVID-19 restrictions). We also involved members of the UK Dermatology Controlled Trials Network patient panel, mainly by e-mail but also through two online meetings towards the end of the project. Members had lived experience of different skin diseases, but were not necessarily parents of children with eczema.

The TSC included lay contributors, initially Abbi Gutierrez (2017–8) and then Sariqa Wagley (2019–21). They commented on trial progress and findings and provided oversight from a parent perspective.

The remit of different parent and public contributors was agreed at the beginning of the study, aligned with the aim and objectives above. Their collective focus was (but not restricted to) assisting with protocol development and design of all patient-facing study materials, identifying potential problems and helping to troubleshoot unanticipated difficulties, and helping with dissemination and planning pathways to meaningful impact.

Study materials

All public contributors were invited to review and comment on study materials, including the study logo design, study flyer and invitation letter, patient information sheets and consent/assent forms for parents and children, and questionnaires. They also tested draft versions of the online questionnaires.

During the internal pilot, it became evident that there were some issues with participants’ interpretation of the section of the weekly/4-weekly questionnaires that asked about the use of eczema treatments. In the first version (see Report Supplementary Material 10, completed between January 2018 and February 2019), days of the week were numbered 1–7 and parents were asked to complete it with day 1 as the day their child was randomised (‘the day you were told which treatment you had been given’). We received feedback that some parents were confusing the day of the week on which emollients were used with the number of days of emollient use, and were unsure which questions to answer if the child had changed from their allocated emollient.

Two potential versions of the adapted BEE questionnaire were shown to four volunteers from the advisory group. They were invited to work through the questions, reading and ‘thinking aloud’ as they completed the questionnaires, with prompts from the accompanying researcher (a cognitive interviewing technique known as verbal probing).

Nested qualitative study

During three of the meetings with the public advisory group over the course of the study, the qualitative researcher (ES) presented a summary of qualitative work and invited the group to comment on the qualitative study topic guide and suggest additional questions (2017); an update of work to date, including early findings on effectiveness and acceptability, and invited comments on a draft qualitative coding framework (2018); and progress on analysis of findings and invited comments on these (2019).

Pathways to impact

Prior to the results being available, we discussed various potential trial findings with the public advisory group, and how these may be interpreted by different stakeholders. This helped us to think through how some of these findings could be communicated.

Support for parent and public involvement

All parent and public activity was supported by a dedicated co-ordinator, Julie Clayton. She liaised with public contributors, facilitated meetings, and dealt with queries and administration of payments. Dr Clayton developed role descriptions and terms of reference for the public advisory group, and provided support and training opportunities (e.g. FutureLearn Research Ethics and Clinical Research in Health Care online courses).

All public contributors were sent copies of the newsletter, which was sent to study participants on an approximately 4-monthly basis.

Other public engagement activity

The lead trial team undertook three public engagement events, led by Shoba Dawson and Anna Gilbertson, supported by two public engagement grants from the NIHR Schools for Primary Care Research. These took place in different venues close to communities that were under-represented in health research and involved two University of Bristol (Bristol, UK) medical students (Jonathan Chan and Alisha Bhanot) in planning and delivering the events.

The first event was in October 2019, at Barton Hill Settlement in East Bristol, as part of ‘Fun Palaces’, a national initiative designed to support people to co-create cultural and community events across the UK and worldwide, with local communities co-developing and hosting events. It involved art and other activities designed to engage with parents and children about eczema. Co-applicant Amanda Roberts attended and shared her experiences of living with eczema, being a mother of children with eczema and being involved in research as a public contributor.

The second event was in January 2020, at St. Werburgh’s Community Centre, East/Central Bristol, in partnership with a South Asian community group. It was more structured, with short presentations and plenty of opportunities for attendees to ask questions. Community group organisers acted as interpreters throughout the event when needed.

The third event was in September 2020 during National Eczema Awareness Week, ‘hosted’ by East Bristol Children’s Centre (a group of four children’s centres); owing to COVID-19 restrictions, this event was online and so was advertised more widely.

In addition to regular tweets via the study Twitter account (@bee_study), we published a series of blogs by different team members on the study website.

Results

Parent and public involvement before the study

Discussions with parents face to face in groups and online confirmed that the question ‘Which emollients are the most effective and safe in treating eczema?’ remained highly relevant. They also supported comparing the four main types of emollient (lotion, cream, gel or ointment) for treating eczema but that a ‘no emollient’ group would not be acceptable. Parents thought that the evaluation should be driven by patient-reported outcomes. They also advocated for qualitative research to understand the trade-offs described between effectiveness and acceptability.

We discussed issues of masking with public contributors, including the influence of brand and packaging on use and the perceived effectiveness of different products. In common with participants in the feasibility trial and respondents to our public pre-grant application survey,17 public advisory group members and their children had used many different emollients. Although some disliked the ‘medicalised’ nature of the emollients and may have initially valued products that look more attractive and ‘cosmetic’, they also told us that the proof was in their use – that is, whether it helped with eczema symptoms and did not cause any harm. Attempts to mask users to the intervention would have required repackaging or overpackaging of products, and public contributors were concerned about the potential effects of on the usability and portability of the emollients. For these, and the other reasons listed in Chapter 10, Strengths and limitations, Pragmatic randomised trial, Internal validity, we decided not to try to mask participants to the emollients.

Parent and public involvement during the study

Co-applicant Amanda Roberts attended most TMG meetings and acted as a ‘critical friend’, giving sufficient challenge and support as needed over time. She also liaised with patient stakeholder groups, such as the National Eczema Society (London, UK) and the Nottingham Support Group for Carers of

Children with Eczema (Nottingham, UK). Online, she helped to promote the study through her @eczemasupport Twitter feed (with over 6500 followers).

We initially established a group local to the lead centre of four parents of children with eczema, who were variously involved in the feasibility study and in developing the BEE study application and had expressed interest in continuing involvement. We expanded membership of the group to nine, and recruited new members at later stages, as some parents were unable to continue for the full duration of the study owing to work and other commitments. For example, new contributors joined following public engagement work in 2019/2020.

General principles

Early on, we agreed with parents that we should be consistent in all patient-facing materials and refer to the study treatments as either emollients or moisturisers. Public contributors favoured the latter, as it was less medical and it explained the action of the treatment.

We were encouraged by parents’ support for the research, because ‘choice can be overwhelming’. They welcomed evidence that informed a ‘start here’ approach (especially for newly diagnosed eczema). However, from the beginning there were shared concerns that the findings should inform (not restrict) choice, and families should not be forced to ‘change to this’ if they were happy with their current emollient.

The public-facing name for the study was originally ‘Best Emollient for Eczema’, but we amended this to ‘Best Emollients for Eczema’ on contributor feedback, in recognition of the fact that no one type of emollient is likely to suit everyone. Although the BEE study acronym and logo was child-friendly and easy to remember, it was also a source of confusion for some people, who assumed that the emollients under investigation were products of bees. Consequently, we agreed that all dissemination material should refer to the Best Emollients for Eczema, without the bee logo.

Study materials

Of the two alternative versions of the treatment use questionnaire, one (see Report Supplementary Material 11) was thought by all the public contributors consulted to be superior to the other, with instructions to complete it from the first Monday following randomisation. However, there were still some potential points that could be misinterpreted in this version, such as:

-

how to complete if you were allocated an emollient already being used

-

completing the questionnaire before starting the study emollient

-

how to distinguish problems related to different emollients (if using more than one).

The public contributors felt that a clear explanation by the consenting researcher, and using a laminated aide memoire, could help to overcome these problems. An amendment was submitted to approve these changes to the questionnaire, and these were subsequently approved.

Nested qualitative study

Early feedback from public contributors on the qualitative study highlighted the need to explore issues of emollient acceptability with both parents and children whenever possible, the ways that topical corticosteroids were used in conjunction with emollients; and any variations according to ethnic or other backgrounds. Subsequent meetings prompted exploration of the time given by families to test the efficacy of emollients, the impact of study participation on emollient use and prior sources of information on emollient use.

Pathways to impact

We met consecutively with the UK Dermatology Controlled Trials Network patient panel and the local Bristol PPI group in October 2020 to consider four different hypothetical scenarios around different findings with respect to effectiveness and acceptability:

-

One type of emollient is found more effective/acceptable than others.

-

One or more type of emollient is more effective/others are more acceptable.

-

None of the emollient types differ in effectiveness/acceptability.

-

One type of emollient is less effective/acceptable than all the others.

The groups made many helpful suggestions, although it was mainly those with eczema who contributed from the patient panel. From this we generated the following list of potential messages:

-

Having information around the use of emollients is important, such as what the choices are and how long to persevere with a new emollient.

-

Findings offering choice (e.g. comparable effectiveness and acceptability between two or more types) could be empowering to families.

-

The key message of the study should be ‘where to start’ as opposed to ‘change to this’; people who are happy with their treatments do not want to be forced to change.

-

There may be trade-offs between effectiveness and acceptability according to age, severity, body site and local climate. A ‘stronger’ emollient may be better if it means less frequent application.

-

As the results may be specific to the study moisturisers and not to other lotions, creams, gels or ointments, care needs to be taken to ensure that the results are not applied to non-study moisturisers.

The findings of the trial were revealed to our public advisory group in a confidential online meeting in March 2021. Contributors welcomed the findings, because ‘as a parent you can sometimes feel very helpless when you are trying to support your child’. They felt that the study provided ‘a real opportunity to offer reassurances to parents that there was no need to be worried that what you are prescribed is the “best”’ and to communicate to parents that it is fine to continue what they have been using or ‘find something that works for you’.

Public contributors said that the qualitative findings also concurred with their own experiences. They suggested that most suitable messages to parents might be as follows:

-

‘You have a choice’ – choice is good and finding what works for you is important.

-

None of the emollients is perfect and problems are common.

-

‘Give it time’ to find out if the emollient prescribed works for you.

-

Keeping a diary of emollient use and symptoms during the first weeks of trying a new emollient may be helpful.

However, the group also raised concerns that if all emollients are as effective as each other then choice could be restricted to the cheapest. They recommended that summaries for GPs and prescribers needed to be clear, so that they can help parents to understand the implications, and also cautioned that extra attention needs to be paid to how children describe symptoms; for example, children may not be able to communicate their symptoms (e.g. ‘stinging’). The group suggested an animation and an infographic to effectively share the key findings.

Other public engagement activity

Only 10, predominantly white, families attended the first public engagement ‘Fun Palaces’ event. Discussions with attendees revealed a low awareness of the different types of emollients available or how to use them safely and effectively. After the event, we shared our experiences and lessons learned with the public advisory group and their suggestions (reducing the number of activities and adopting a more structured approach) shaped the second event. This was attended by approximately 20 people, primarily of South Asian origin, and led to new members joining the public advisory group. More detail on both the events can be found in a subsequently published paper. 42

The third, 1-hour Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA), event was attended by 16 people, including student nurses, mothers and grandmothers of children with eczema, and a health visitor. Eight attendees returned online evaluation forms, with an overall score of 4 out of 5, and statements that the event was either ‘useful’ or ‘very useful’. One responded that the event was ‘[v]ery well planned and executed. Was left in awe of [those] who are doing so much for children suffering eczema. The practical tips were invaluable.’

By June 2021, we had published four blogs on the study website: ‘Including the views and experiences of parents and children in a clinical trial’ [Eileen Sutton, May 2019, URL: https://capcbristol.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2019/05/20/including-the-views-and-experiences-of-parents-and-children-in-a-clinical-trial-the-best-emollient-for-eczema-bee-study/ (accessed 10 September 2022)], ‘Finding the best moisturiser for eczema’ [Zoe Wilkins, May 2020, URL: https://capcbristol.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2020/05/20/finding-the-best-moisturiser-for-eczema-the-impact-research-can-have-on-everyday-lives/ (accessed 10 September 2022)], ‘Why does the type of moisturiser matter to a child with eczema?’ [Sue Davis-Jones, July 2020, URL: https://capcbristol.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2020/07/29/why-does-the-type-of-moisturiser-matter-to-a-child-with-eczema-a-research-nurses-perspective/ (accessed 10 September 2022)], and ‘A for planning, BEE for impact’ [Amanda Roberts, November 2020, URL: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/primaryhealthcare/researchthemes/bee-study/blogs/ (accessed 10 September 2022)]. Further blogs to accompany the publication of the trial results are planned.

Discussion and conclusions

We were successful in recruiting public contributors and facilitating their input throughout the study. Lay colleagues inspired and encouraged us in our interactions with them, reminding us of the confusion and frustration they had experienced in not knowing which emollient(s) to use for their children. Parent and public involvement influenced the study at all stages but was particularly important in:

-

supporting participant recruitment and data collection, by road-testing written and verbal participant information about a study with complex elements, and helping us improve the eczema treatment use questions

-

interpretation and dissemination of the results, by highlighting from the start concerns about the findings being misinterpreted or misused, to restrict rather inform emollient choice.

Reflections/critical perspective

Retaining members in the public advisory group over > 4 years was challenging, with three parents declining to continue after the first year because they had taken on new work roles or schedules, which meant that they were no longer able to attend meetings. Similarly, the study was supported by two PPI co-ordinators, prior to Dr Clayton taking on the role. Ongoing engagement work provided opportunities to invite new parent members to join, which was a positive development in helping to maintain enthusiasm for the study and broaden the experiences shared by advisory group members. The drawback, however, was that new members did not have full knowledge of the trial history, or first-hand experience of influencing the trial design or materials. We took care at all meetings to ensure that there was time to revise the purpose and aims of the trial and to make new contributors feel welcome.

Another challenge was the transition to an online meeting format during COVID-19 lockdown. This meant needing to have shorter meetings of 1–1.5 hours rather than 2-hour face-to-face meetings, to avoid ‘Zoom fatigue’. Because of the limitations of online meetings, discussions may have been less rich or dynamic than in person. However, there were definite advantages to the research and to public contributors, as we were able to easily involve people beyond the Bristol locality for no extra monetary, time or carbon cost. For example, a joint meeting with the UK Dermatology Controlled Trials Network patient advisory group based in Nottingham took place with public contributors in London and Exeter.

Consequently, future PPI is likely to take a blended approach, with some meetings face to face but also offering videoconference as an option, to enable researchers and members of the public to join who might not otherwise be able to because of time or travel constraints.

Chapter 4 Trial results

Participant recruitment

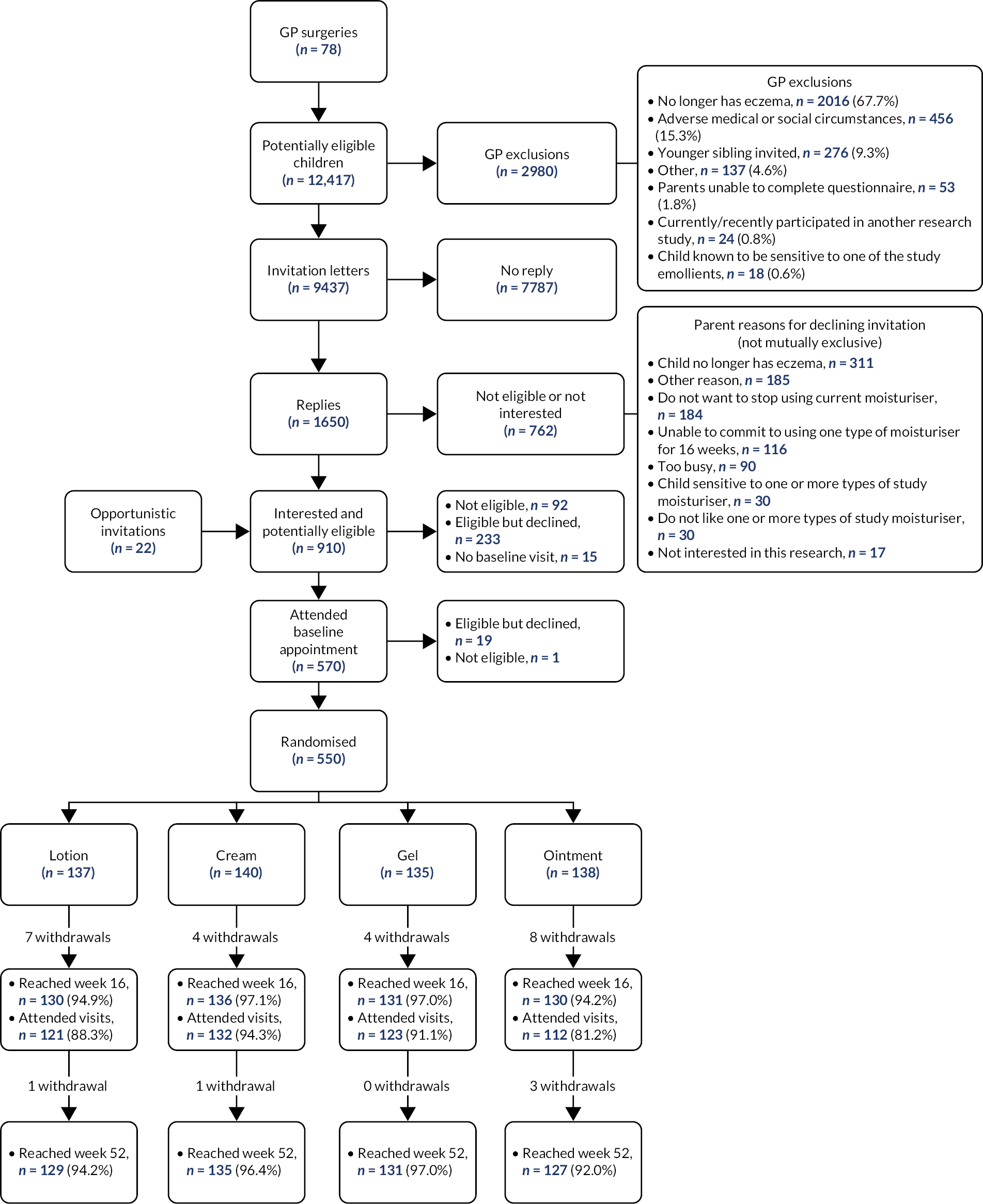

Searches of EMRs identified 12,417 potentially eligible children, of whom GPs excluded 2980 (see Figure 2). Reasons for GP exclusion are presented in Figure 2. The age and sex of potentially eligible children of those excluded by their GP were similar (see Appendix 2, Table 22).

FIGURE 2.

Participant recruitment and follow-up.

Invitation letters were sent to 9437 families from 78 GP surgeries, with 1650 replies. Of these, 762 declined to take part and 7787 did not reply. Reasons for parent non-participation are listed in Figure 2. Of those potentially eligible children identified by searches of EMRs, those who were screened by the research study were slightly younger than those who did not respond or declined (see Appendix 2, Table 23).

In total, 888 expressions of interest were received from the mail-out, with a further 22 families expressing an interest in participating via opportunistic recruitment (n = 910 in total). Of those who expressed an interest in participating, 92 were found not to be eligible, 233 were eligible yet declined to participate, 15 were eligible yet had no baseline visit booked and 570 attended a baseline visit. A further 20 either declined or were not eligible. Therefore, 550 children were randomised from 77 GP surgeries (no participants were recruited from one practice that sent invitation letters).

The 340 children excluded before the baseline visit were similar in respect of sex to those attending the baseline visit, although they tended to be slightly older (see Appendix 2, Table 24). The age and sex of children who did not attend a baseline visit or give consent were similar to those who did, but mean POEM scores were lower among those who attended but did not give consent (see Appendix 2, Table 25).

Participant characteristics

The variables on which participants were stratified (centre) and minimised (categorised age and POEM scores) were balanced at baseline (see Appendix 2, Table 26).

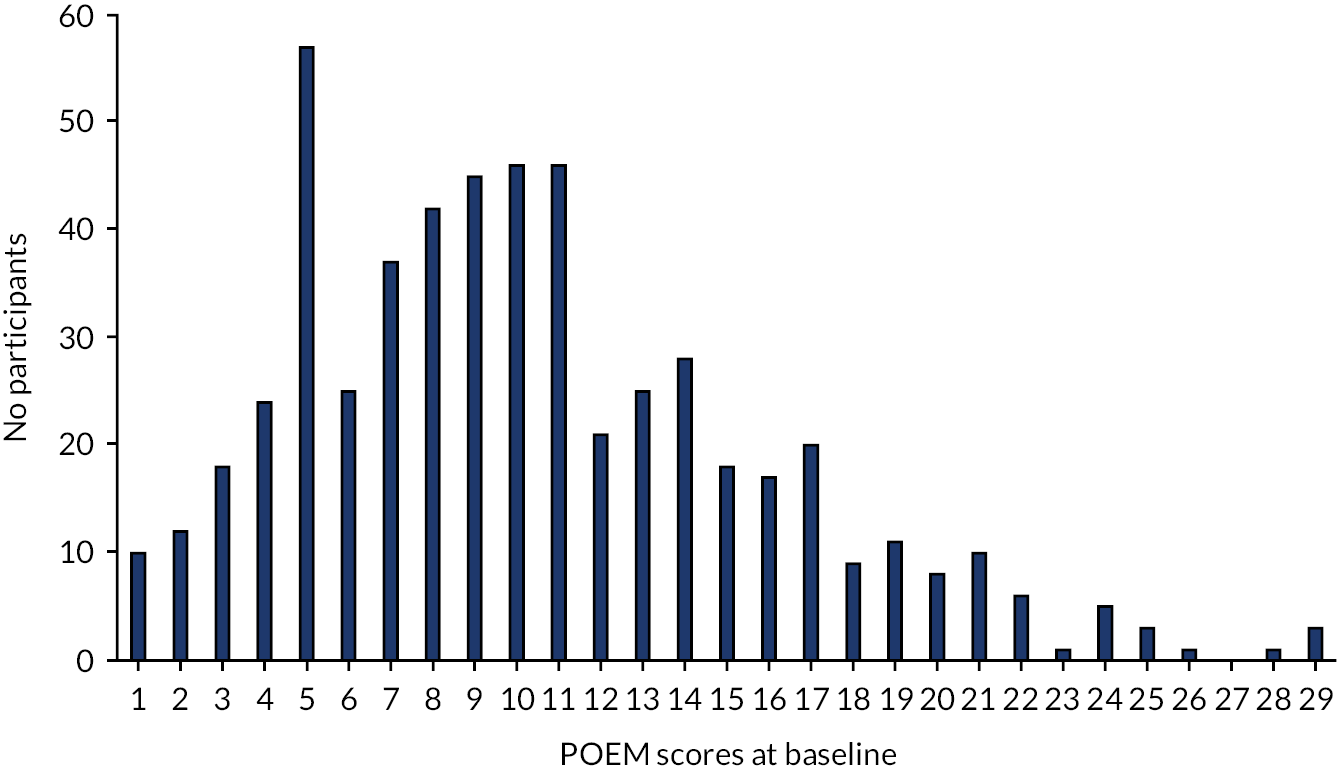

The characteristics of participants at baseline were balanced at baseline (see Table 3) apart from sex, as there were more girls in the cream group than in the gel group (55% vs. 40%, respectively). The median age of participants was 4 years (IQR 2–8 years), with the majority being white (86.0%). Most (81.3%) of the children met the UK diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis, with moderate severity eczema (mean POEM scores of 9.32 points, SD 5.46 points; see Appendix 2, Figure 8 and Table 27). Appendix 2, Table 28 presents the socioeconomic characteristics of the main carer. Almost 50% of parents were self-employed and reported ‘other’ qualifications.

| Characteristics | Treatment group | Total (N = 550) | Overall, N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lotion (N = 137) | Cream (N = 140) | Gel (N = 135) | Ointment (N = 138) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 5 (2–8) | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–8) | 550 |

| Number female, n (%) | 64 (46.72) | 77 (55.00) | 54 (40.00) | 60 (43.48) | 255 (46.36) | 550 |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 119 (86.86) | 126 (90.00) | 112 (82.96) | 116 (84.06) | 473 (86.00) | |

| African/Caribbean/Black British | 1 (0.73) | 4 (2.86) | 4 (2.96) | 9 (6.52) | 18 (3.27) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 3 (2.19) | 4 (2.86) | 7 (5.19) | 2 (1.45) | 16 (2.91) | |

| Mixed | 14 (10.22) | 6 (4.29) | 12 (8.89) | 11 (7.97) | 43 (7.82) | |

| IMD score, median (IQR) | 13.75 (7.58–20.24) | 11.74 (5.84–21.09) | 13.20 (6.39–20.63) | 11.80 (5.89–20.84) | 12.50 (6.30–20.63) | 503 |

| History of atopy, n (%) | ||||||

| Self-reported food allergy | ||||||

| No | 103 (76.30) | 109 (77.86) | 111 (82.84) | 112 (82.35) | 435 (79.82) | |

| Yes | 26 (19.26) | 20 (14.29) | 15 (11.19) | 17 (12.50) | 78 (14.3) | |

| Unsure/not diagnosed | 6 (4.44) | 11 (7.86) | 8 (5.97) | 7 (5.15) | 32 (5.87) | |

| Meet UK diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis | 113 (82.48) | 108 (77.14) | 109 (80.74) | 117 (84.78) | 447 (81.27) | 550 |

| Eczema severity | ||||||

| POEM score, mean (SD) | 8.67 (5.15) | 9.34 (5.25) | 9.80 (5.42) | 9.50 (5.97) | 9.32 (5.46) | 549 |

| EASI score, median (IQR) | 3.3 (2–7.2) | 3.15 (2–6.3) | 4 (2.35–8) | 3.3 (1.58–6.5) | 3.45 (1.9–6.9) | 543 |

| Quality of life, median (IQR) | ||||||

| DFI sore | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–8) | 2 (0–6) | 3 (1–6) | 543 |

| ADQoL | 0.36 (0.36–0.50) | 0.36 (0.36–0.50) | 0.36 (0.36–0.56) | 0.36 (0.36–0.50) | 0.356 (0.356–0.5) | 540 |

| CHU-9D score | 0.90 (0.80–0.97) | 0.91 (0.78–0.97) | 0.90 (0.78–0.97) | 0.89 (0.78–0.97) | 0.90 (0.78–0.97) | 533 |

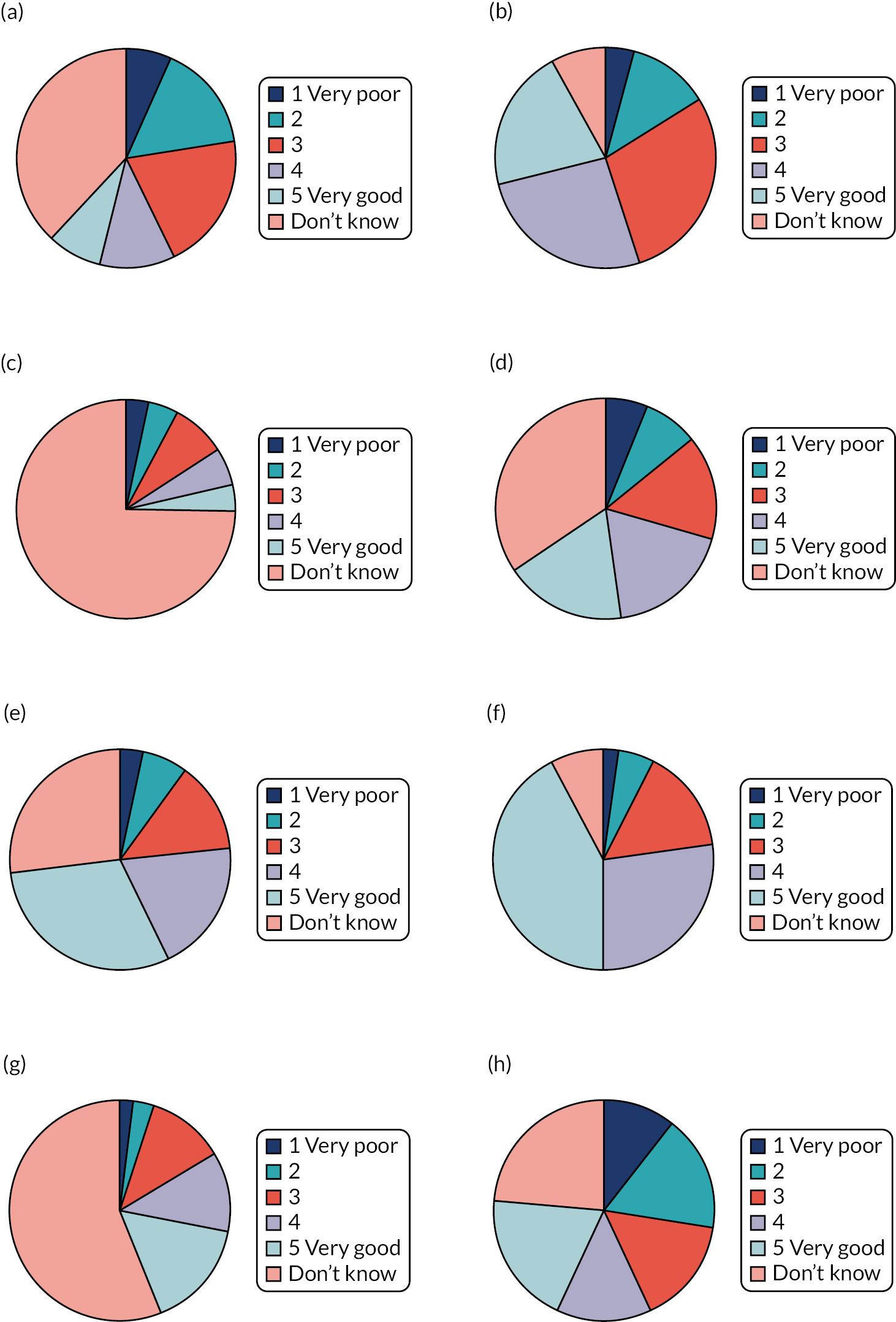

Parent-reported use of the topical corticosteroids, bath additives and the four emollient types of lotion, cream, gel and ointment was balanced across the groups at baseline (see Appendix 2, Table 29). The most used (current or past) type of emollient was cream (94.5%), followed by ointment (66.0%), lotion (63.0%) and gel (25.0%). The lower levels of prior ‘exposure’ to gels are reflected in parent perception of the effectiveness and acceptability of different emollient types (see Figure 3), with half to three-quarters of parents reporting ‘Don’t know’ for gels.

FIGURE 3.

Parent-reported opinion of effectiveness and acceptability of different emollient types at baseline. (a) Lotion effectiveness (n = 548); (b) cream effectiveness (n = 549); (c) gel effectiveness (n = 545); (d) ointment effectiveness (n = 548); (e) lotion acceptability (n = 549); (f) cream acceptability (n = 549); (g) gel acceptability (n = 548); and (h) ointment acceptability (n = 548).

Allocation and receipt of intervention

The 550 participants were randomly allocated to the lotion (n = 137), cream (n = 140), gel (n = 135) and ointment (n = 138) groups. The median number of days between baseline visit and randomisation was 0 (IQR 0–1; minimum 0, maximum 5 days). The median number of days between randomisation and self-reported first use of emollient was 4 (IQR 3–7; minimum 0, maximum 45), with 80% reporting first use within 7 days of randomisation. Breakdown by recruiting centre is shown in Appendix 2, Table 31.

A review of available prescribing data from EMRs (n = 522 participants) confirmed that 97.5% (509/522) were issued with a study-approved emollient of the correct type in the first 10 days after randomisation. The name of the specific emollients and number of participants prescribed these at baseline are presented in Table 4.

| Type (prescription data available/number randomised) | Specific emollient | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lotion (132/137) | QV lotion | 77 (59.1) |

| Cetraben lotion | 37 (28.0) | |

| Diprobase lotion | 15 (11.4) | |

| Non-lotiona | 2 (1.5) | |

| Cream (132/140) | Epimax cream | 72 (54.5) |

| Zerobase cream | 40 (31.1) | |

| Diprobase cream | 10 (6.8) | |

| Aquamax cream | 8 (6.0) | |

| AproDerm cream | 0 (0.0) | |