Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 99/33/51. The contractual start date was in April 2003. The draft report began editorial review in August 2006 and was accepted for publication in October 2008. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

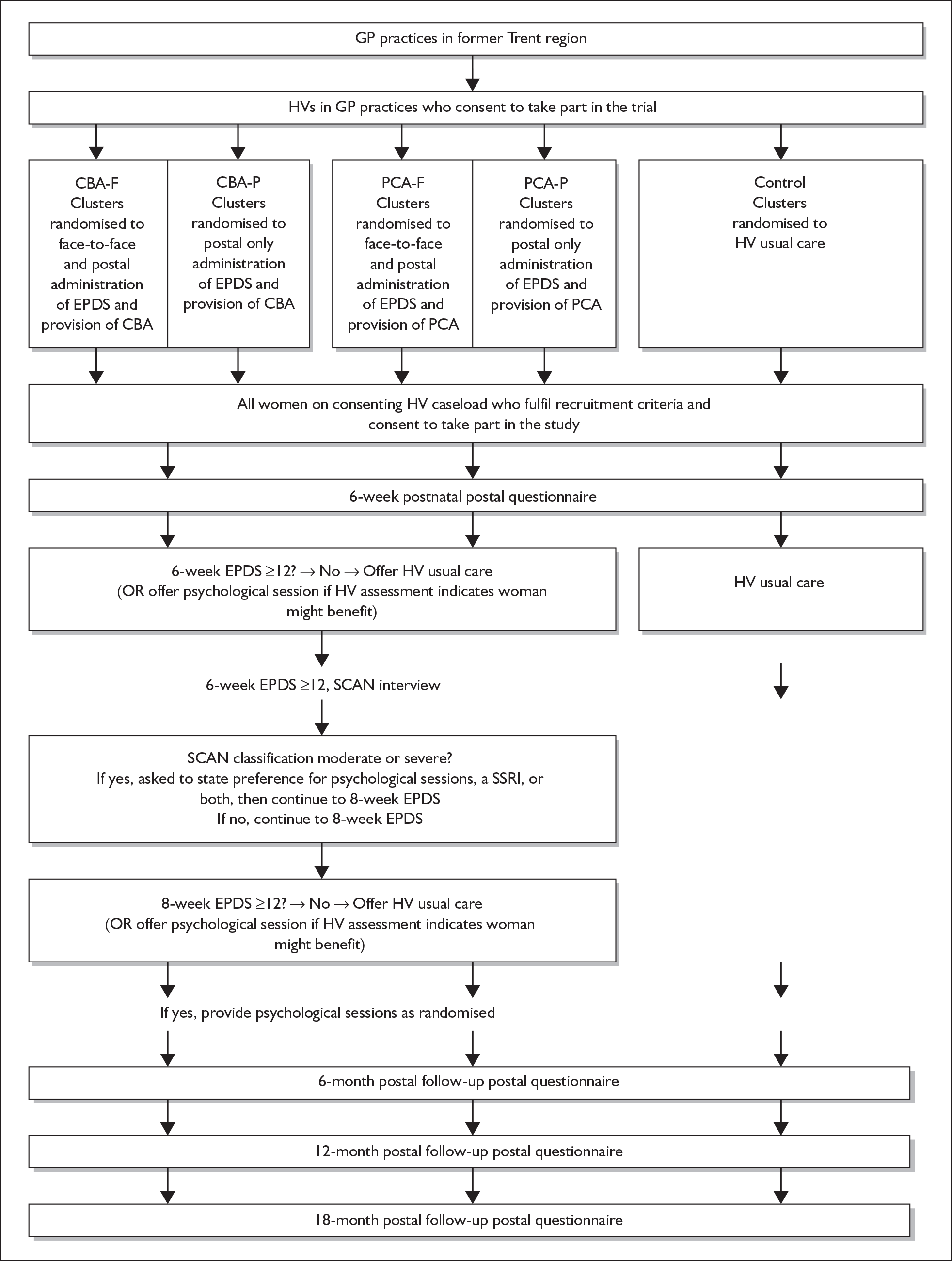

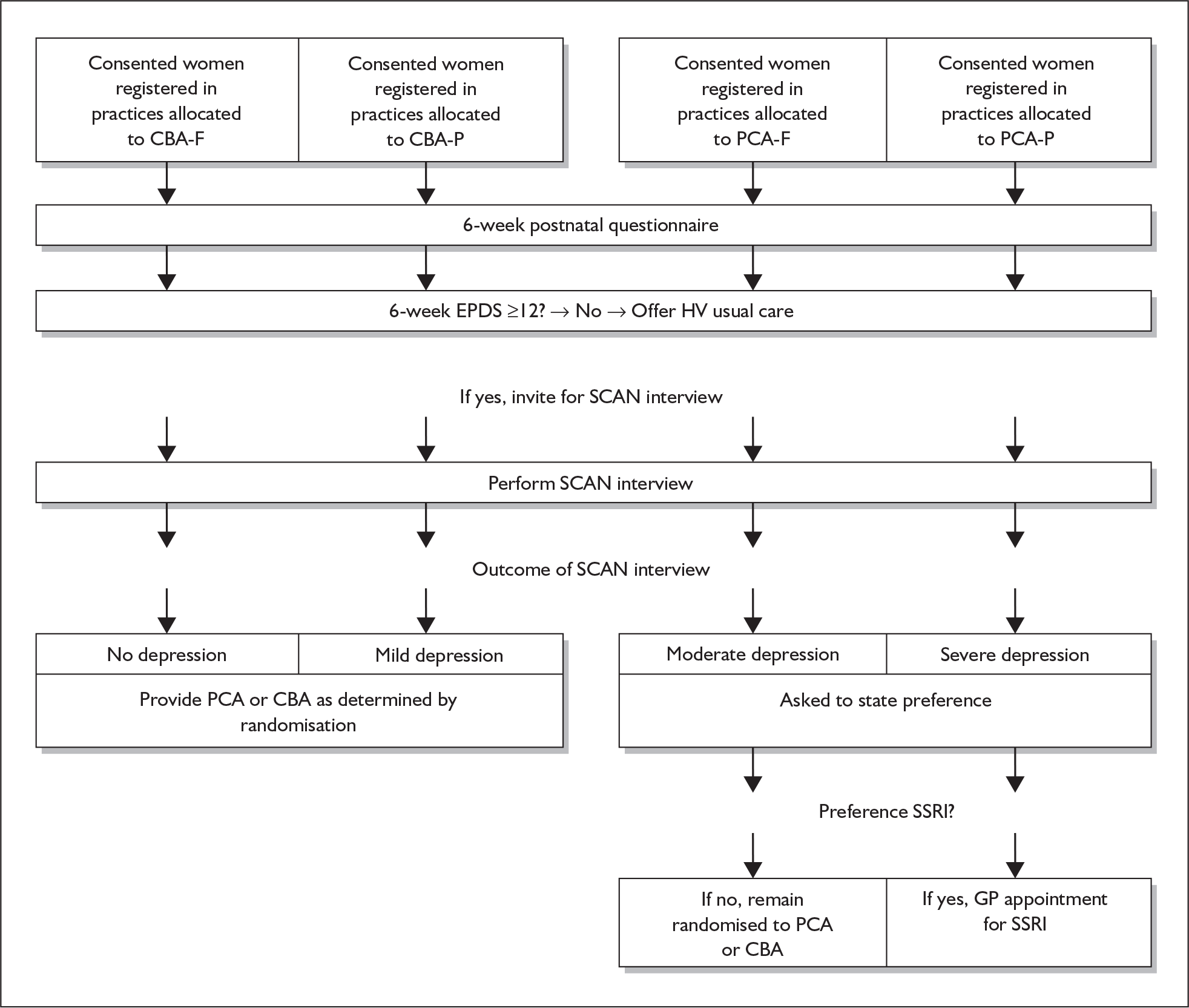

This report describes a cluster randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of two different psychological interventions delivered by health visitors (HVs) in their usual care setting, for women with depression soon after they had given birth. The aim of the trial was to reliably estimate any differences in outcomes for mother, child or family from training HVs in systematically detecting depressive symptoms and in delivering a psychological intervention based on either cognitive behavioural principles or person-centred principles in primary care at an individual level for women at risk of postnatal depression (PND). The secondary aim was to establish the relative cost-effectiveness of both psychological interventions from an NHS perspective relative to health visitor usual care.

The original NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme call for proposals in 1999 proceeded from a widening recognition of the gravity of the condition and an increasing awareness of the potential impact of depression on a new mother’s infant and wider family.

The two experimental interventions built upon promising work on the potential for psychological interventions to help women recover from PND,1,2 as an alternative to pharmaceutical interventions. 3 There was also further indication of the potential role for HVs in this context. 4–7 The trial therefore aimed to build upon existing evidence and to address the limitations of previous research in the area of PND and to examine, in particular, the role of HVs in this context.

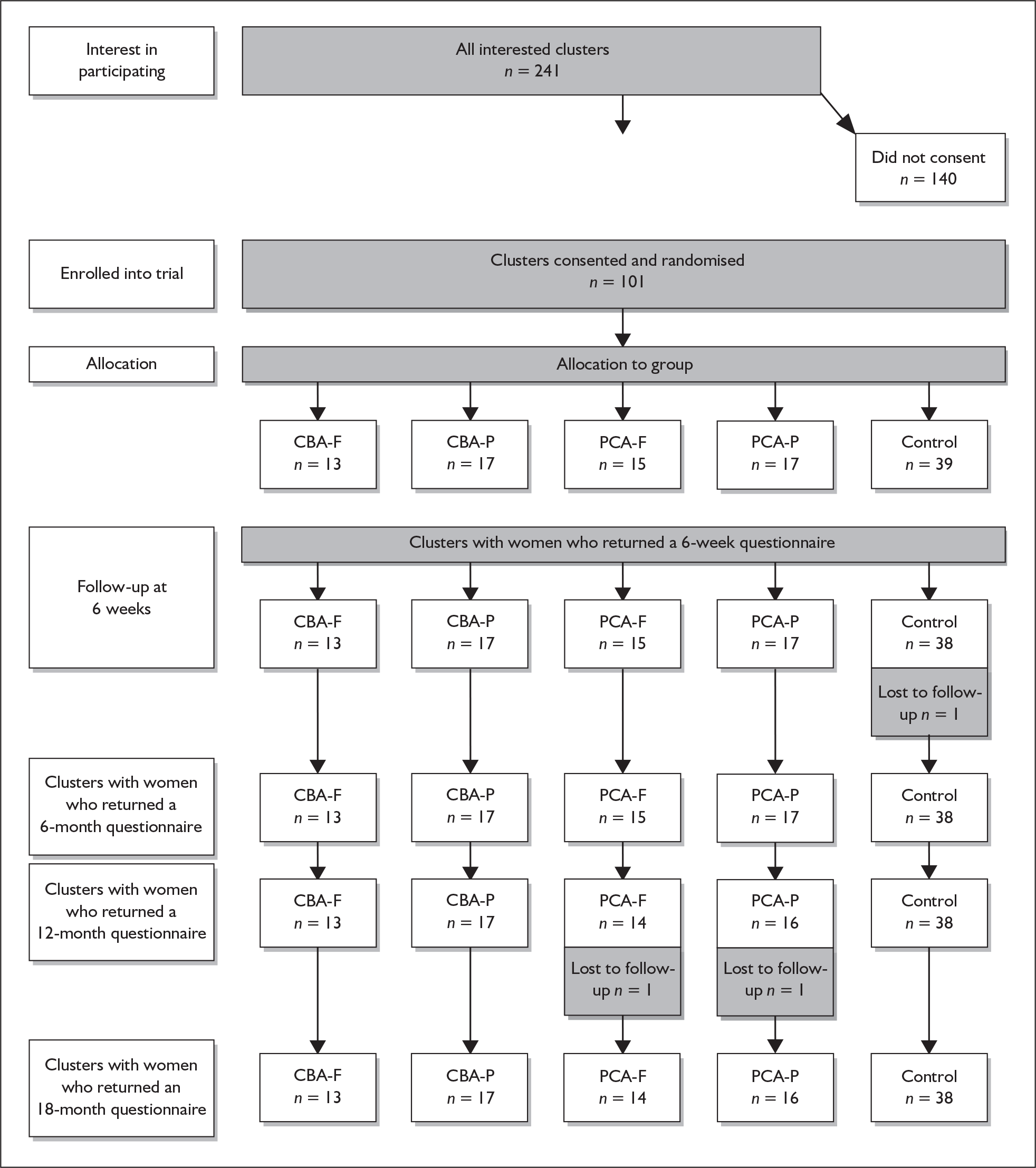

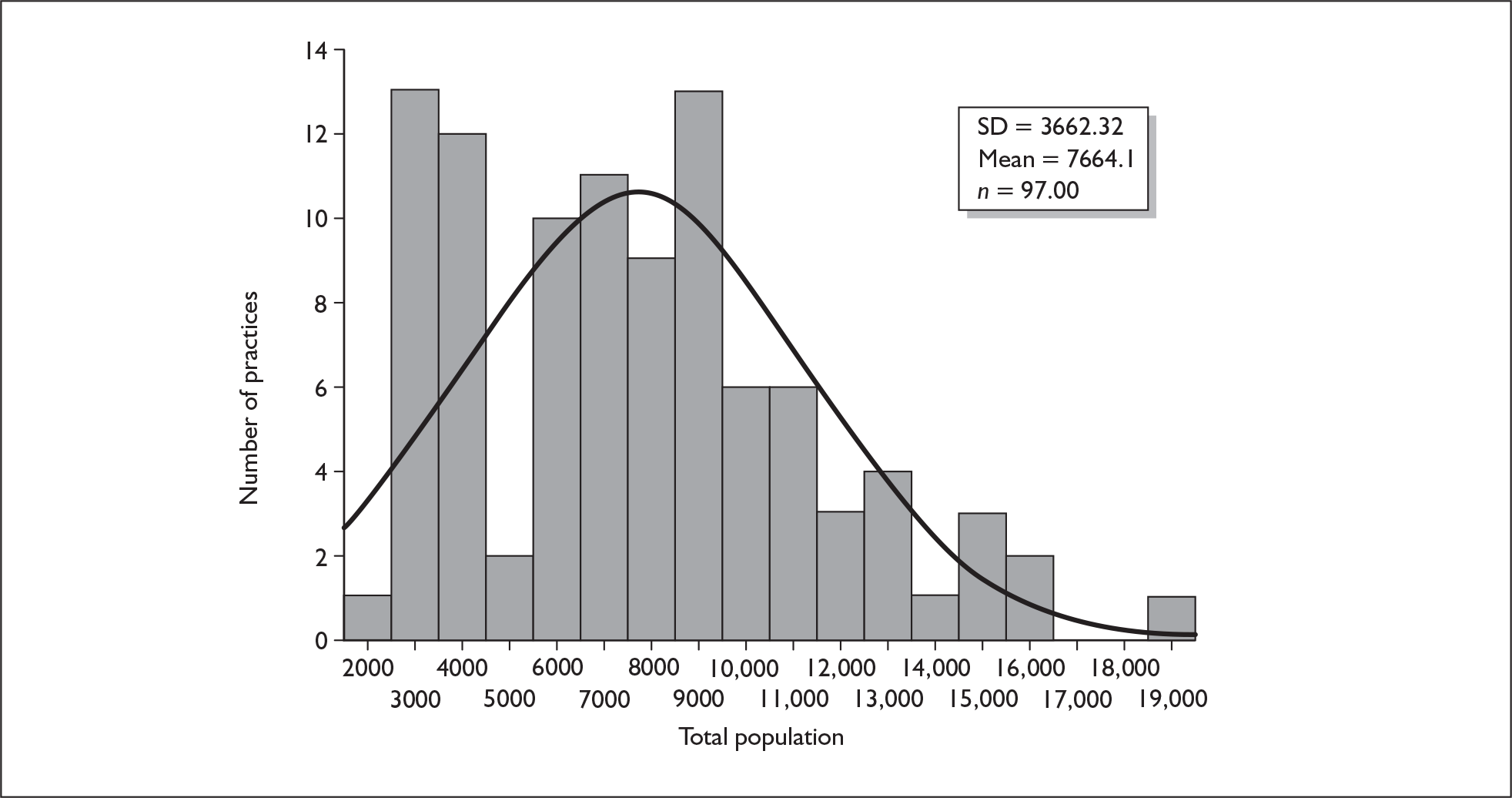

Health visitors in 103 clusters in 29 primary care trusts (PCTs), mainly from the former Trent region, and 4084 women consented to take part in the 3-year study, which began formally on 1 April 2003. There was a long pre-trial preparatory phase to surmount the research governance requirements; to enlist the support of interested HVs and GPs; and to arrange a comprehensive and detailed preparation of the HV intervention, which included an 8-day equivalent group training session.

The study also examined the use of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),8 which has been widely used in the UK to help detect women who are depressed after having their baby. It was designed to help indicate the top decile of women4 most likely to be suffering from depression and able to benefit from an intervention. As such, the outcome of greatest pragmatic interest for health visiting services was the proportion of women who had moved below the threshold for concern score. Also, because of the inefficiency of administering the EPDS to all postnatal women face-to-face at home,4 and the precedent of administering the self-reported assessment by post,9 the trial investigated the potential clinical and economic consequences of a postal 6-week EPDS administration.

Background

Depression

Mental health is considered to be ‘a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’. 10

Conversely, mental ill health covers mental health problems, strain, impaired functioning associated with distress, symptoms and diagnosable mental disorders such as schizophrenia and depression. 11 Each year, more than a quarter of European adults will experience mental ill health of one form or another,12 most commonly depression.

Postnatal mental health

Most women feel exhausted after the birth of their baby and will be tearful and feel low because of the exhaustion. There continues to be some debate about the classification of postnatal mental health conditions and whether PND exists as a unique diagnosis or whether depression occurring postnatally is just coincidental. 13 However, both of the internationally used classification systems no longer provide a separate category of PND. In effect, the presence of depression is determined by the same set of criteria, regardless of timing or context. When mood states were measured in a sample of pregnant women and a group of matched non-childbearing women,14 there were no differences between the two groups in rates of major or minor depression after the babies were born, but the postnatal women had more symptoms of depression. 14 Women do experience postnatal distress and less satisfaction in their relationships at this time, especially with their partners. 14,15 It has been proposed that the depressive symptoms or distress that some women experience are an appropriate response following childbirth and so should not be confused with clinical depression. 16 Any emphasis on depression might draw attention away from the social and cultural context of parenting and the changes and losses that accompany the birth of a baby and consequently the sharing of the responsibility for the distress that the women experience. 16

There is some evidence that women are more vulnerable to depression within the first 6 postnatal months, not just the first few postnatal weeks. 17 Because of issues of context and in particular the welfare of the infant, and other family members, health professionals need to be aware of the postnatal onset of depression, puerperal psychosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder and relapse of other illnesses such as schizophrenia. 18

Within the first days after the birth of a baby, 39–85% of women feel more emotional than usual, weepy, irritable and anxious and have insomnia and a low mood because of what is called postnatal ‘blues’ or baby ‘blues’. 14 Women can be given information about symptoms and reassurance that postnatal blues resolve quickly within a few days, without treatment, and can be advised about self-help. However, there is no evidence for the effectiveness of these measures. 18

At the other extreme, puerperal psychosis is a severe mental illness affecting one or two per thousand women soon after delivery. 19 Women with a history of a postnatal mood disorder carry a very high risk of recurrence. The dramatic symptoms are severe depression with a risk of suicide or even infanticide. 20 Mania, hallucinations or delusions require urgent psychiatric treatment, often as an inpatient. This very small but important risk of suicide and infanticide in some severely depressed mothers manifests itself in violent methods, more often than in the population generally, sometimes before and sometimes after 6 weeks postnatally. 21 Although exceptionally serious, statistically suicide is rare and most HVs will never encounter maternal suicide.

In 1992 the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)22 first included an optional supplementary code for diseases that occur during and complicate pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium (the O99 code can be applied to any form of mental disorder).

The American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)23 makes provision for a postpartum-onset specifier code that can be added to a diagnosis of manic depression, bipolar disorder or major depression among others, provided onset is within 4 weeks of childbirth. No reason for the 4-week timing is provided and the ICD does not suggest a time period for onset. The diagnosis of depression (irrespective of the gender of the sufferer or the timing of the episode) relies on the presence of at least five of the following symptoms for at least 2 continuous weeks:23

-

depressed mood

-

loss of interest or pleasure

-

significant increase or decrease in appetite

-

insomnia or hypersomnia

-

psychomotor agitation or retardation

-

fatigue or loss of energy

-

feelings of worthlessness or guilt

-

diminished concentration

-

recurrent thoughts of suicide.

Depression is far more common than psychosis at any time as well as in the context of pregnancy and childbirth. Depression can last for up to 1 year after delivery in about 4% of all mothers20 or a quarter of mothers who become depressed, and may last even longer. 24 But the relevance of this is not clear as not many studies have followed up women for long enough to determine the depression duration and no study has described in a standardised way the course of depression (in women) with respect to whether or not the episode occurred within the context of childbirth.

The proportion of postnatal women who might be depressed varies between 11%20 and 22%25,26 depending on the sample of women, the criteria used and the time of assessment postnatally. 14 Based on a meta-analysis of estimates from 59 studies internationally, the average prevalence of depression postnatally is 13%. 27 A later meta-analysis estimated that 14.5% of women may have a new episode of major or minor depression during the first 3 postnatal months, with 6.5% having a new episode of major depression. 28 The same review estimated a prevalence of 6.5–12.9% for major and minor depression at any time during the first postnatal year, and a 1–5.9% prevalence of major depression. 28

Consequences of depression

Depression is a public health problem with financial costs to the gross domestic product associated with sickness absence,29 mainly through lost productivity. There is a high risk of relapse. 30 The UK spends 12% of its total health expenditure on mental health,11 and the cost for antidepressant prescriptions is around £401 million. 31 The costs of the stigma and discrimination associated with mental ill health remain intangible.

Depression can lead to more deaths from suicide each year than there are deaths from road accidents. Suicide rates and mental health states vary across European countries, reflecting their diverse traditions, cultures, situations and religious variations in reporting suicide. 11 The number of deaths from psychiatric illness is underestimated as suicidal deaths may not be classified as such, to spare family feelings. 32 The sixth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the UK, Why Mothers Die,21 reported suicide as the most common cause of maternal death for women in the first year after childbirth.

The natural history of PND varies among women, but around one-third develop a chronic problem with long-term adverse consequences. Although there is little evidence to date, there is a belief that women’s depression may affect their partners,33 who become depressed,34–36 thereby reducing their ability to cope with supporting the mother or caring for the new infant or other children.

There has been growing concern from the literature on the evidence of the effects that depression might have on the cognitive37 and emotional development of children38 and the attachment of infants to their mothers, particularly for boys, possibly well beyond infancy. 39 Boys whose mothers are depressed in the first year may have particular problems with reading. 40 Infants are highly sensitive to the quality of their interpersonal contacts, which are most often provided by the mother in the first few months of life. 39 This could be because the baby has a rapidly developing brain in the first 6 months of life and is heavily dependent on external stimulation and therefore particularly vulnerable during this sensitive period. 39,40 It is also possible that the association between PND and the development of infants represents a complex two-way interaction. 41 Also, mothers with depression are more likely to report parenting stress, negative perceptions of their infant’s behaviour and hostile feelings towards their infant. 42

Aware of the link, the European Union’s project on building mental health in infants, children and adolescents recognised the need to address PND. 11 Similarly, guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) on treating depression in children and young people also referred to the need for parents’ own depression to be treated in parallel. 43

Causes of depression

The factors that can contribute to depression include an individual’s personal experiences, biological or inherited tendencies, social support factors, and economic and environmental factors. 11 For example, people with mental health problems are more likely than the general population to live in rented housing and to say they are dissatisfied with their accommodation. 44 Because of the growing concern over mental health, policy initiatives have been developed, recognising that health-care interventions alone are not the only solution.

There is no consensus about the cause of PND, but there is an association with risk in women who have a number of psychosocial risk factors. A meta-analysis of 59 studies27 used regression analyses to evaluate the relative contributions of several postnatal variables to the development of PND (Table 1). The strongest predictors are related to antenatal anxiety or depression, lack of social support and stressful life events. Weaker predictors are neuroticism, negative cognitive attributional style and obstetric variables. The suggestion that women having a traumatic delivery, by emergency Caesarean section, might be more likely to become depressed45 may be true only for women who have a previous history of a depressive disorder. 46 For the general population of women, complications such as forceps or emergency Caesarean section are not associated with depression. 46 A link between Caesarean section and PND was not established in a meta-analysis of suitable studies. 47

| Cohen’s da | |

|---|---|

| Depression antenatally | 0.75 |

| Anxiety antenatally | 0.68 |

| Social support | –0.63 |

| Stressful life events | 0.60 |

| Mother’s history of psychopathology | 0.57 |

| Self-esteem | |

| Childcare stress | |

| Neuroticism | 0.39 |

| Marital relationship | –0.13 |

| Infant temperament | |

| Maternity blues | |

| Obstetric variables | 0.26 |

| Marital status | |

| Negative cognitive attributional style | 0.24 |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Unplanned/unwanted pregnancy |

Recognising that it is a simplification, O’Hara and Swain synthesised all of the risk factors that emerged from the meta-analysis27 to present a prototype of a pregnant women at risk of PND, as most likely to:

-

occupy a lower social stratum

-

have experienced stressors during pregnancy

-

have had a more difficult than normal pregnancy or delivery

-

be experiencing marital difficulties

-

experience her partner as providing little social support

-

perceive others in her social network as not supportive

-

have a history of psychopathology

-

show evidence of being at least mildly depressed, anxious and worried.

A prospective study48 of women recruited antenatally found that those who were depressed postnatally felt that the practical and emotional support provided by their partners was inadequate. The depressed women felt that they could not talk freely with their partners, they were not there for them when they needed them and they were not able to rely on them for childcare help as much as they would have liked. In general, they felt that their partners made their lives less easy. 48

Management of postnatal depression

Assessment and detection

There is a general problem with the detection of depression in primary care. 49 For many women with PND their problem will not have been fully recognised in routine clinical practice. 24,26,50 Because the onset of PND may be gradual, it is not easy to distinguish it from the fatigue and emotional liability that most mothers feel when adjusting to the demands of a new baby and recovering from childbirth. 50 It is also not easy to detect depression, partly because some women are not willing to disclose their true feelings. 51 Some women feel that they become depressed as a result of feeling exhausted, unwell, unsupported or isolated as mothers, with no time for themselves. 52 These women may not try to access professional or other support, either because they feel that their problem is not so bad or they ought to deal with it on their own or because they do not have anyone to ask for support. 52 Some women may feel that there is a stigma attached to being depressed and they may feel embarrassed or ashamed to seek help for what they might regard as a sign of personal inadequacy or an admission of failure on their part. 53 They may not regard professional intervention as relevant or may not want to be labelled as an unfit mother. 53

The EPDS is one of the mood assessment instruments most widely used in clinical practice. 54 It was not developed as a diagnostic test. 55 The EPDS is not adequate to confirm PND without a clinical interview to assess a mother’s mood, depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts, and explore her relationship with the baby. 56

The National Screening Committee commissioned a review57 to evaluate the evidence of the validity of the EPDS as a screening tool; the most effective intervention for PND; and the size of the beneficial or adverse effects for interventions. The report stated that:

At present, it is not recommended to the National Screening Committee that screening for postnatal depression be introduced . . . the introduction of isolated screening programmes which are not part of a research project will not add to the evidence base which is agreed to be insufficient to justify the introduction of screening.

Until more research is conducted into its potential for routine use in screening for PND the NSC recommends that the EPDS should not be used as a screening tool.

It may, however, serve as a checklist as part of a mood assessment for postnatal mothers, when it should be used alongside professional judgement and a clinical interview. The professional administering it should have training in its appropriate use and should not use it as a pass/fail screening tool.

The difficulties of the EPDS have been openly discussed;58–61 many HVs do find the instrument valuable whereas others highlight the limitations. Some PCTs endorsed the systematic use of the EPDS by HVs and established a system of cascade HV training in its use. 62 Other PCTs were mindful of the criticism of the EPDS following the review commissioned by the National Screening Committee. This prompted some PCTs to restrict the use of the EPDS by HVs.

The guidance from the National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care18 on the postnatal care of women and their babies proposes that it is good practice to ask women who have had a baby how they are feeling emotionally, but cautions that the use of the EPDS is not acceptable to some women.

Pharmacological treatment for depression in primary care

There is not enough evidence from well-controlled and reported trials about the costs and benefits of different interventions for depression. Within the UK, depression in primary care is usually treated with either tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or, more recently, the newer non-tricyclic drugs or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). 29 The SSRIs are believed to be as effective as TCAs but less toxic in overdose. 29 Many people are uncertain about taking drugs for depression, believing that they are addictive or that drug treatment is not appropriate for what is seen as a reasonable reaction to adverse events. 29 There are certainly concerns about the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes following exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy. 63

Antidepressants are effective for postpartum depression. 64 However, it is not known which specific class of antidepressants or which individual antidepressant is most helpful; which is the best prevention for high-risk women; or what impact antenatal treatment or excretion of antidepressants via breast milk might have on the cognitive and emotional development of exposed infants. 64 Because there is insufficient information on the overall effectiveness of antidepressant drugs in PND, there are very little data upon which to base decisions about the safety of breastfeeding while taking these medications. 65 Women with PND prefer not to take antidepressants66 and so compliance is not good. Physicians either prescribe a reduced, potentially non-therapeutic dose, advise women not to breastfeed or delay offering treatment until the woman has finished breastfeeding. 67

An American expert panel68 reached a majority consensus on the appropriateness of including antidepressants (specifically SSRIs) and non-pharmacological treatments for women with severe depressive symptoms. For milder symptoms the panel gave equal endorsement to other treatment modalities or preferred psychotherapy over antidepressant medication. 68

Psychological interventions for mental health problems in primary care

Partly in response to concerns about antidepressants,29 over the past 25 years there has been a move towards increasing the availability of psychological interventions. 69

Psychological interventions include counselling and psychotherapy, and it can be difficult to distinguish between the two. Both cover a range of modalities, the most common being cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychoanalytic, psychodynamic, interpersonal and client-centred, non-directive approaches.

The British Association of Counselling (BAC)70 presents an ethical framework for good practice in counselling and psychotherapy, including values, principles and personal moral qualities. The BAC refers to counselling as:71

. . . the skilled and principled use of relationships which develop self-knowledge, emotional acceptance and growth, and personal resources.

. . . concerned with addressing and resolving specific problems, making decisions, coping with crises, working through feelings and inner conflict, or improving relationships with others.

Some patients with depression actively choose counselling over antidepressants. 72 The availability of counselling will depend upon the number of effectively trained practitioners.

In primary care a range of professionals can offer psychological interventions, including counsellors, community psychiatric nurses (CPNs), clinical psychologists, HVs and social workers. 69,73

In primary care, generic brief counselling74 or psychological interventions using non-directive psychotherapy are as effective as routine GP care, or perhaps more effective. 75–77 Generic counselling is as effective as antidepressants, although those taking antidepressants may recover more quickly. 72 In the short term psychological symptoms of patients who receive counselling may improve more than symptoms in those who have usual GP care. 69 Primary care patients may prefer brief psychotherapy to usual GP care75–77 and, given the choice, patients who choose counselling over antidepressants may improve more than those who have no strong preference. 72 Interventions using CBT also appear to be cost-effective in primary care78 and possibly helpful in preventing relapse. 30

Health visitors’ detection and treatment of postnatal depression

There is some evidence of the effectiveness of HVs in using psychological approaches to support women with PND. In a pioneering small randomised trial in Edinburgh and Livingston,1 HVs were asked to administer the EPDS to all women at around 6 weeks postnatally. Those who had a raised EPDS score were interviewed by psychiatric interview at 13 weeks postnatally, and those identified as depressed were allocated to an intervention group (IG) (n = 26) or a control group (CG) (n = 24). The IG were offered a postnatal one-to-one non-directive type counselling intervention of eight 1-hour weekly sessions by 17 HVs, whilst the CG received routine care. Outcomes included the Goldberg Standardised Psychiatric Interview and EPDS after 13 weeks. Although the HVs providing the intervention continued to visit the CG women, the statistically significant result was that 69% of the IG women (n = 18) recovered compared with 38% of the CG women (n = 9). In the absence of stronger evidence, the findings of this trial have been widely implemented throughout the UK.

The Lewisham primary prevention programme was one of the more important, small studies, which was not a randomised controlled trial. 6,79 The study compared outcomes for women screened antenatally as ‘vulnerable’ (using the Leverton questionnaire) in ‘Preparing for Parenthood’ (for first-time mothers) or ‘Surviving Parenthood’ (for second-time mothers) against routine primary care. The allocation to group was not random but by the baby’s date of birth and it was flawed because of the lack of concealment. HVs were asked to make contact with the women as soon as possible, in mid-pregnancy. There were five antenatal group sessions, beginning at 24 weeks, and six postnatal sessions, led by a clinical psychologist and a HV. At 3 months the women were interviewed, in part using the Present State Examination (PSE). Among the more vulnerable women, for those who had been offered the service, 19% (n = 48) were depressed compared with 40% of those who had not been offered the service. There was a significant reduction in EPDS for first-time mothers (n = 21) at 3 months compared with control subjects (n = 24), but no difference at 3 months for second-time mothers and no difference at 1 year for invited women. The authors concluded that some depression following childbirth can be prevented by brief psychological interventions, which can be incorporated within existing systems of antenatal classes and postnatal support groups, and pointed out that first-time mothers may be more likely to accept an invitation and attend meetings. 6

Following the Edinburgh trial1 Holden and Elliott wanted to give HVs the chance to take part in a training programme to adopt strategies for detecting PND and for early interventions. 4 To test whether the Edinburgh intervention, which appeared successful within a small trial, could be effective in routine HV practice they set up a three-centre study in Edinburgh, North Staffordshire and Lewisham, south-east London.

Health visitors were invited to a minimum of seven 2-hour training sessions and were asked to administer the EPDS to women, normally at the child health clinic, with a home visit for non-attenders. The preventive strategies included antenatal visits and education about PND, the realities of parenting and the potential benefit of support groups. 4 The study used an EPDS cut-off score of 12 so that each HV would counsel about three women on their caseload over the study period, using non-directive counselling (NDC). The HVs did not wish to be regarded as counsellors and preferred the term ‘listening visits’ to the term ‘non-directive counselling’. 4 In the North Staffordshire arm, the median EPDS score changed from 7 at baseline to 5 post training. 4 There were reported improvements in counselling skills and an increase in HVs’ mental health assessments, recording of symptoms and referrals to mental health services. Elliott et al. 7 suggested that the training and intervention should be evaluated using a rigorous research design. The study was not a randomised trial and the limited reporting suggests that it was probably subject to selection bias. It showed the potential role for HVs in using a structured approach for delivering an intervention following a brief training in psychological counselling for PND.

Another study with postnatal women, which was not a randomised controlled trial, explored the effect of care from HVs who were trained to detect PND using the EPDS and to manage PND using counselling and cognitive behavioural techniques, such as problem-solving. In total, there were 30 women who received routine primary care before the training and who became historical control subjects and 70 women who were seen after the HV training. 5 The study, which was not rigorously controlled, or reported, found a significant reduction in EPDS scores after the training. 5

Support for the role of health visitors in perinatal mental health

Health visitors have been working in multidisciplinary teams for some time in the area of prevention and the early identification of maternal depression and support for affected women. 80–88 A series of proposals and guidance has offered backing for the role of HVs in perinatal mental health. 79

NICE asked the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) to develop a clinical guideline on the treatment and management of mental health problems in the antenatal and postnatal period. 89 Before this, the National Service Framework (NSF) for Mental Health90 set priorities for the way that services were to be provided, four of which were relevant to the role of HVs. Standard one related to mental health promotion and emphasised the need to build capacity and capability in primary care by supporting staff through continuing professional development. Standards two and three referred to primary care and access to services. The NSF proposed protocols to be implemented for the management of PND, anxiety disorders and those needing referral to psychological therapies. The NSF recognised the role of HVs with training who could use routine contact with new mothers to identify PND and treat its milder forms. The NSF seventh standard90 related to actions to reduce suicides, by ensuring that staff would be competent to assess the risk of suicide among individuals at greatest risk. This standard was relevant to HVs, as maternal suicide was cited as the largest cause of maternal death in the first postnatal year. 21 The later review of the NSF prioritised investing more in mental health promotion. 91

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) evidence-based guideline on PND and puerperal psychosis emphasised the role for HVs in the detection and management of PND. 92

The Department of Health published guidance in September 2003, Into the Mainstream, Implementation Plan: Mainstreaming Gender and Women’s Mental Health, for developing services for perinatal depression, which supported the role of HVs. 93

In the UK, the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, the Local Government Association, the NHS Confederation and the Association of Directors of Social Services produced a joint policy paper. 94 The report presented a vision for 2015, which minimised public fear, stigma and discrimination for people with mental health problems, shifted resources to primary care, invested in the mental health workforce and extended the availability of psychological therapies to people with a range of mental health problems.

Given the absence of a national policy on PND, HVs in many PCTs developed their own local policies,95 with differing strategies and integrated care pathways (ICPs) for the detection and management of the depression. 83 Some PCTs developed protocols for GPs for the management of PND, with information on treatment options and criteria for referral to the community mental health team. It is appropriate for HVs to refer some women to mental health services rather than offer support themselves. These circumstances include women who have obsessive compulsive disorder, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and panic disorder, as well those who have psychosis or suicidal plans, and other situations in which a HV feels very concerned. 7 This approach has been supported by Department of Health policy. 90,93

Health visitors’ professional support

Support for the role of HVs in perinatal mental health came from the HVs’ professional body. In 2000 the Community Practitioners’ and Health Visitors’ Association (CPHVA) established a Postnatal Depression and Maternal Mental Health (PDMMH) network for HVs to enhance perinatal services for women and their families. The PDMMH network facilitated the exchange of information on the development of ICPs, conferences, resources, publications and multicultural work. The CPHVA ran workshops about the use of the EPDS as part of a full mood assessment and advertised courses in identifying and managing perinatal depression.

An audit of the CPHVA membership was published in the network newsletter in June 2003. 96 The results suggested that 85% of PCTs had formal mechanisms for managing PND; 55% had a lead professional for perinatal mental health (72% of these being HVs); and 85% of PCTs were using the EPDS to some degree, but only 70% of these (sic) had received training in its proper use.

The generic role of health visitors

Health visiting relies on a sound interpersonal process and establishing a relationship with a client. The use of interpersonal skills and communication skills lie at the core of health visiting. 97 Whether regarded from a medical or psychosocial perspective, PND is acknowledged as an important health problem, and a key area of HVs’ work given their established role and unique personal contact with postnatal women. The following explains the historical, generic role of HVs and presents the context and rationale for their role in postnatal maternal health.

Health visiting has its origins in Salford, Manchester, where the Ladies’ Sanitary Reform Association first began home visiting to offer a universal service, with some focus on maternal and child welfare. 98,99 Since 1962 HVs have been qualified nurses, with special experience in child health, health promotion and health education, employed as part of the NHS community health service. They work with GPs and other primary health-care team workers (practice nurse, district nurse, midwife) and other community-based health and social care professionals, based within the GP surgery or practice premises or local health centre.

The Council for the Education and Training of Health Visitors100 identified the four main principles of health visiting as the philosophy underpinning practice:

-

the search for health needs

-

stimulation of the awareness of health needs

-

influencing policies that affect health

-

facilitating health-enhancing activities.

As policies within the NHS and in child health surveillance services have changed over time,101 so has the role of HVs. 99 In the 1990s HVs were encouraged to change the way that they worked, to offer a more targeted, needs-based service, rather than a universal service. The work of contemporary HVs is mainly around primary preventive activities on a broad range of health issues. However, recently there has been a strong drive for HVs to focus increasingly at the level of secondary prevention, targeting vulnerable children102 and using more community-based public health approaches. 103

The review of the British literature on health visiting104 indicated that HVs’ work can fall into the following categories:

-

individuals and groups with special needs

-

children with special needs

-

elderly

-

homeless families

-

mothers with PND

-

prevention of sudden infant death syndrome

-

traveller families, vulnerable families and families in poverty

-

child protection, domestic violence, childhood injury

-

child health services, child health surveillance.

Health visitors are concerned with all aspects of a woman’s health and the health and welfare of her child and family. HVs maintain a ‘caseload’ of individual clients and part of a HV’s role is to visit families with new babies, in their homes, as part of routine child health surveillance. Therefore, every family with a child under 5 years has a named HV who can advise parents on everyday infant and childcare difficulties and immunisation programmes, as well as signposting families to other sources of health support, for example housing, financial benefits or specialist services. Some HVs also work in corporate teams with HVs sharing the caseload and so families have access to different HVs.

The standard HV contact times for women with a baby are around 4 weeks antenatally, at a new birth visit and in well-baby clinics. Routine contacts for assessment of infants’ developmental progress are being phased out.

The effectiveness of health visiting

There has been wide discussion over the evidence of the effectiveness of the work of HVs. 97,104,105 One of the first systematic overviews of home visiting106 indicated that there were positive outcomes in children’s mental development, mental health and physical growth; reductions in mother’s anxiety, depression and tobacco use; and improvements in maternal employment and nutrition, among others. There are very few reports of UK-based research in health visiting. 107 The review of articles on the effectiveness of home visiting in relation to child and maternal outcomes107 found evidence to suggest that home visiting programmes for parents of young children can have an effect on improvements in:

-

various dimensions of parenting108

-

some child behaviour problems

-

cognitive development, especially for some groups of children

-

childhood accidental injury rates109

-

the detection and management of PND. 1

There was no evidence that home visiting increased the uptake of immunisations or hospital admissions. 107 As is often the case, the review indicated a need to address methodological limitations of trials in this area to provide, in particular,104 a clear theoretical framework; clear descriptions of the intervention content, intensity, timing and duration; process measures; long follow-up times; a client perspective and assessment of satisfaction.

The role of the health visitor in black and ethnic minority communities

There are specific mental health issues affecting Asian and other non-indigenous women bringing up children in the UK. For example, the suicide rate among women who are born in South Asia and live in England is higher than that in the general population. When they are providing supportive care, HVs need to consider cultural practices about childrearing.

English language is not an issue for some second-generation immigrant women who speak Punjabi and Urdu, and some HVs have used the EPDS with English-speaking women from Asian and other ethnic minority groups. Some women who have recently entered the UK from Pakistan are unable to speak English, and there are growing numbers of Arabic-speaking women as well as Kosovans, Kurdish people and asylum seekers from other mid-European countries and elsewhere. For Pakistani women, link workers are employed who speak Punjabi and can read Urdu. There are also interpreters and link workers who speak other relevant languages. Aside from any language difficulty, literacy for women from Pakistan is more likely to be an issue.

There are no effective, validated, culturally sensitive tools for many women who have English as a second language. As well as literacy and language difficulties, immigrant women may also be isolated, and so women who are vulnerable to PND may be missed. Some work is beginning to develop and validate linguistically and culturally competent tools for use in primary care, using link workers and health professionals to identify psychological distress and assist the early detection of women from South Asian communities who speak Bengali, Gujarati, Punjabi and Urdu, as well as those from other ethnic minority communities. This may be useful in instances in which it is not possible to detect PND in other ways.

A Punjabi Postnatal Depression Screening Questionnaire (PPDSQ) was developed by a consultant psychologist in Bradford City PCT and the University of Bradford. 110 Also, the CPHVA has supported the development of a pictorial method for women who have English as a second language, to detect those who may be depressed. This work is undergoing a pilot validation study.

Chapter 2 Literature review of the prevention and treatment of postnatal depression

Although the role of HVs has been promoted in perinatal mental health there is still not enough evidence upon which to base practice to prevent or treat PND. A literature search was performed in July 2005 to identify and synthesise published literature on trials of interventions to prevent or treat postnatal morbidity and the costs associated with these. This was not a systematic review.

The main method used to identify relevant articles was a search of electronic bibliographic databases from the first date that the databases would allow. The electronic databases searched to provide the best coverage of trials were:

-

health databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE – 1966 to July 2005

-

evidence-based databases: the Cochrane Library, covering the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCTR)

-

PsycINFO – to date.

The search strategy used the key text words depression, postpartum, postnatal, review, trial, random, blind and systematic as follows:

exp Depression, Postpartum

(postnatal or post-natal or post natal or perinatal or peri-natal or peri natal).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

depress$.mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

exp psychological techniques/or exp psychotherapy

(post partum or postpartum or post-partum).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

limit to “therapy (sensitivity)”

limit to (humans and English language and “therapy (sensitivity)”)

social.mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

(review$or trial$or random$or blind$or systematic$).mp. [mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word)

The articles were considered relevant if they included a population of antenatal or postnatal women; psychosocial or other interventions to offer additional support; maternal reports of health status, morbidity or PND measured using validated tools; reports of use of services; and a planned comparison group using a rigorous research design.

Of the 241 published articles identified through the search, 185 potentially relevant abstracts were scrutinised and assessed for eligibility criteria and methodological quality. In total, 64 papers were selected for review and 43 were regarded as suitable for inclusion in the review. Studies were included if they were randomised controlled trials in a population of antenatal or postnatal women and they examined any association between support or interventions, to prevent or treat PND. The articles were relevant if they included maternal reports of health status.

Studies that were not written in the English language were not included. In a systematic review, two reviewers independently assign a quality rating to each trial being reviewed. Criteria that contribute to the assessment of the methodological quality of a trial are a clear and accurate description of:

-

participant selection, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and recruitment response rates

-

statistical power and sample size determination

-

random allocation, concealment, blinding, control for potential bias

-

experimental and control interventions

-

length and completeness of follow-up, compliance and attrition

-

outcome measures and statistical analysis.

Poorly controlled trials are also likely to be poorly reported, but if a well-controlled trial is not well reported it will be assessed as poor quality and the results will not be incorporated into a systematic review.

In this particular review it was difficult to grade and rank the quality of each trial as many of the quality criteria were not reported in the articles. Few authors described a pre-trial sample size calculation and the number of participants required to achieve statistical power. In reporting results many authors reported only absolute numbers, without confidence intervals, or a mean value without a standard deviation.

The quality of each study was not graded but was judged according to whether the study included a clear and accurate description of the experimental design, a sample size determination, participants’ baseline characteristics and comparison of groups, randomisation, blinding, setting, intervention, control intervention, compliance and attrition.

Cochrane and other reviews111,112 were also examined for additional relevant trials. The following reviews from the CDSR (Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group and Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group) were relevant:

-

Dennis CL, Creedy D. Psychosocial and psychological intervention for preventing postpartum depression. 113

-

Hodnett ED. Caregiver support for women during childbirth. 114

-

Barlow J, Coren E. Parent training programmes for improving maternal psychosocial health. 115

-

Ray KL, Hodnett ED. Caregiver support for postpartum depression. 116

All together there were 43 relevant trials identified from the literature search and the Cochrane and other reviews. These trials are summarised under the following six headings:

-

antenatal prevention of PND (9 trials)

-

perinatal support or treatment to prevent PND (10 trials)

-

postnatal support interventions (3 trials)

-

postnatal prevention of PND (5 trials)

-

postnatal treatment of PND (16 trials).

Trials of antenatal prevention of postnatal depression

Because the strongest predictors of PND are antenatal anxiety or depression, lack of social support and stressful life events, theoretically, addressing some of these features could prevent PND. The Cochrane review113 of psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression included antenatal trials, and a qualitative review111 specifically examined antenatal group interventions to reduce PND. The antenatal trials that aimed to prevent PND are summarised in alphabetical order in Table 2.

| Authors, location | Method | Subjects | Intervention | Sample | Outcomes | Results and conclusions | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chabrol et al., 2002,118 Toulouse, Narbonne, France | Controlled randomised study | ‘At-risk women’ with EPDS scores > 8 on French version of EPDS | One antenatal session including an educational component, a supportive component and a CB component during hospitalisation | n = 22 IG; n = 38 CG | EPDS | Significant reductions in frequency of probable depression in IG: IG – 30.2%, mean EPDS = 5.0; CG – 48.2%, mean EPDS = 13.7 (p = 0.0067) | Poor quality. Many limitations. Not ITT. ‘This programme for prevention and treatment of postpartum depression is reasonably well accepted and efficacious’ |

| Gorman, 2002,119 Iowa and St Louis, USA | RCT | Pregnant women at risk of postpartum depression | Five individual antenatal sessions based on IPT by a mental health specialist, in late pregnancy, ending around 4 weeks postnatally | n = 24 IG; n = 21 CG | EPDS, SCID – at 4 and 24 weeks | Mean EPDS scores were 7.9 in the IG (n = 15) and 8.0 in the CG (n = 15) (NS) | Very small sample |

| Hayes et al., 2001,120 Queensland, Australia | RCT | Primiparous women | One-to-one education intervention by specially trained midwives conducted at 28–36 weeks in an interview room or in their own home, about mood changes and symptoms and help-seeking vs CG | n = 95 IG; n = 93 CG | POMS, NSSQ – at 8–12 weeks and 16–24 weeks |

There was a steady reduction in POMS scale scores over all subscales in both groups, with no difference between groups at any follow-up time Women in both groups were more depressed antenatally than postnatally |

Duration of IG and CG not described. Did not use a measure of PND |

| Logsden et al., 2005,121 Louisville, USA | Random assignment | Adolescent girls 32–36 weeks’ gestation | (1) Pamphlet, (2) video and (3) pamphlet and video vs (4) CG | n = 128 | CES-D – at 6 weeks | There were no significant differences in CES-D scores between groups at any follow-up time | The education intervention had no effect on women |

| Marks et al., 2003,122 London, UK | RCT with random permuted blocks of 8 and 16, stratified by 6 offices | Antenatal women with history of major depressive disorder | Continuous midwifery care vs standard maternity care | n = 51 IG; n = 47 CG | DIS DSM-III-R case of major or minor depression | No differences in rates of PND between treatment conditions | ‘Continuous midwifery care had no impact on psychiatric outcomes’ |

| Matthey et al., 2004,123 London, UK | RCT | Antenatal women and men | Preparation for parenthood programmes: (1) ‘Empathy’ (experimental, focusing on psychosocial issues related to becoming first-time parents) and (2) ‘Baby play’ (control) vs usual service ‘control’ | n = 51 IG; n = 47 CG | DIS DSM-III-R case of major or minor depression | Reduction in postpartum distress in some first-time mothers at 6 weeks postpartum. Women with low self-esteem who had received the intervention were significantly better adjusted on measures of mood and sense of competence | ‘This brief psychosocial intervention can be readily applied to antenatal classes and is suitable for those who attend preparation for parenthood classes’ |

| Stamp et al., 1995,124 Adelaide, Australia | RCT, women stratified by parity | English-speaking women with a single pregnancy identified as being more vulnerable to PND | Antenatal groups: two special classes – simple primary PND preventive intervention, focusing on access to information, practical and emotional preparation and support, and one postnatal group run by midwives vs CG | n = 64 IG; n = 65 CG | EPDS – at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months | 13%, 11% and 15% of the IG women scored over 12 on the EPDS at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months, respectively, compared with 17%, 15% and 10% of the CG women, respectively | Privately insured women not able to participate. Attendance 31% overall. Return rate 92%, 92% and 87% at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months, respectively |

| Zlotnick et al., 2001,125 Providence, USA | Pilot RCT | Pregnant women receiving public assistance with at least one risk factor for PND | Four antenatal group sessions ‘Survival skills for new moms’ – four sessions (1 hour) IPT-oriented intervention vs treatment as usual | n = 17 IG; n = 18 CG | BDI, SCID – at 3 months | Significant difference in BDI score changes between IG and CG (p = 0.001). Women in the IG were significantly less likely to develop postnatal major depression compared with CG women (p = 0.02) | ‘A 4-session IPT-oriented group intervention was successful in preventing major depression in the first 3 postpartum months.’ In total, 50% of eligible women declined; 77% of women were single; 88% attended three sessions. Very small sample |

The trials mainly included women variously assigned as vulnerable or high risk using a modified screening tool, or women having their first baby, or both. Among all trials several outcome measures were used, mainly at 3 months.

The trials of groups had poor attendance and were not successful in reducing PND. 117,124 In the two very small trials,118,125 one French and one American, with limited quality, there appeared to be some effect. It is unclear whether the comparatively good attendance rate and the outcomes would be reflected in a larger trial.

There was not enough evidence from antenatal-targeted interventions provided for ‘at-risk women’. 111 Overall, the women in the IG were just as likely to become depressed as those in the CG. These antenatal studies do not provide sufficient evidence upon which to base care.

Trials of perinatal support or treatment to prevent postnatal depression

The perinatal studies that aimed to prevent PND113,114 can be summarised as midwifery, ‘debriefing’ or counselling studies, massage, doulas (experienced lay women providing support to women in labour) or companionship in prevention of PND, and these are summarised in alphabetical order below (Table 3).

| Authors, location | Method | Subjects | Intervention | Sample | Outcomes | Results and conclusions | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field et al., 1997,126 Miami, USA | Random assignment | Middle socioeconomic status women recruited from prenatal class | Massage by partner every hour for a total of 4 hours and partner coaching in breathing during labour vs coaching from partners | n = 28 | CES-D, POMS |

There was less depressed mood on the POMS scale in the IG: IG 6.9; CG 14.9 Also on the CES-D: 15.4 vs 19.8 |

‘Data suggest that the massaged mothers had shorter labours, shorter hospital stay and less postpartum depression’ |

| Gamble et al., 2005,127 Brisbane, Australia | RCT | Postnatal women assessed in the immediate postpartum for risk of developing psychological trauma | One midwifery-led ‘debriefing’ within 72 hours of birth, then another 4–6 weeks postpartum by phone vs CG standard care | n = 50 IG; n = 53 CG | EPDS – at 12 weeks | 4/50 IG women EPDS score > 12 vs 15/53 of the CG women. Women in the IG reported decreased trauma and low relative risk of depression and stress | ‘A brief intervention for a distressing birth experience effective in reducing trauma symptoms, depression, stress and feelings of self-blame’ |

| Gordon et al., 1999,128 San Fransisco Bay, USA | Randomised study | Primiparous women aged ≥ 18 years, uncomplicated deliveries | Trained doulas in hospital-based labours and deliveries vs usual care | n = 149 IG; n = 165 CG | MHI from SF-36 – at 4–6 weeks postnatally | No difference in postpartum depression or self-esteem measures | ‘In general, women who had doulas were very enthusiastic about them’ |

| Hagan et al., 2004,129 Perth, Western Australia | Single blind randomised controlled study | English-speaking mothers of very preterm infants (< 33 weeks) | Six CBT sessions in programme by a research midwife, postnatal weeks 2–6, vs standard care | n = 101 IG; n = 98 CG | EPDS, BDI, GHQ, SADS – at 2 weeks, 2 months, 6 months and 12 months | 29% of IG diagnosed with major or minor depression vs 26% CG | ‘Intervention programme did not alter the prevention of depression’ |

| Lavender and Walkinshaw, 1998,130 Merseyside, UK | RCT | Postnatal primigravidous women with a single birth by normal delivery | Midwife ‘debriefing’, 30- to 120-minute sessions, on postnatal wards, vs CG | n = 56 IG; n = 58 CG | HAD scale – at 3 weeks | Women in the IG were less likely than women in the CG to have HAD scale anxiety and depression scores of more than 10 (p < 0.0001) | Sample size based on HAD scores > 7; reporting by HAD scores of 10. Follow-up time of 3 weeks is too early to evaluate morbidity after childbirth |

| Priest et al., 2003,131 Perth, Australia | RCT | Mothers under psychological care at the time of delivery | One midwife ‘debriefing’ after childbirth for 15 minutes to 1 hour | n = 875 IG; n = 870 CG | EPDS – at 8 weeks, 24 weeks, 52 weeks | 37/696 IG women scored > 12 on the EPDS compared with 42/705 CG women | 19% attrition at 1 year |

| Selkirk et al., 2006,132 Victoria, Australia | Random assignment | Women recruited in third trimester | Midwife ‘debriefing’ vs CG | n = 149 | DAS, STAI, EPDS, POMS, PSI | EPDS at 3 months postpartum: IG, 6.69 low intervention and 6.13 high intervention vs CG, 5.25 low intervention and 5.57 high intervention | ‘Debriefed women were no less likely to develop symptoms of postnatal depression (using EPDS) than women who did not receive debriefing’ |

| Small et al., 2000,133 Melbourne, Australia | RCT | Women who had given birth by Caesarean section, forceps or vacuum extraction | Midwife ‘debriefing’, at least 24 hours after the birth, up to 1 hour, in hospital vs standard care | n = 464 IG; n = 447 CG | EPDS, SF-36 subscales – at 6 months | 17% of women in debriefing scored ≥ 13 on EPDS vs 14% CG. Also poorer health on seven out of eight SF-36 subscales | CG women received a brief visit and a leaflet. Nearly all women found the debriefing helpful |

| Tam et al., 2003,134 China | RCT | Chinese women who had suffered suboptimal outcomes in pregnancy and labour | One to four ‘educational counselling’ sessions for high-risk women by a research nurse before discharge from hospital | n = 280 IG; n = 280 CG | HADS > 4 – at 6 weeks postpartum | 26/261 IG women depressed compared with 35/255 CG women. Mean depression scores 3.30 IG vs 3.50 CG | Short follow-up |

| Wolman et al., 1993,135 USA | RCT | 189 nulliparous labouring women | Additional companionship from community volunteer vs usual care | n = 92 IG; n = 97 CG | IG women attained higher self-esteem scores and lower postpartum depression and anxiety ratings at 6 weeks | ‘Companionship modifies factors that contribute to the development of postnatal depression’ |

The massage trial126 was not described sufficiently well and the sample size was too small, but the reported significant difference in the mean time in labour suggests that the intervention could be worthy of further investigation and longer follow-up.

Of the five midwifery debriefing studies, the two smaller studies, one in the UK130 and one in Australia,127 reported a short-term effect. The two larger trials,131,133 however, and the most recent132 did not report a positive outcome.

The trial of companionship135 suggested that self-esteem might be improved. The authors of the ‘doula’ trial128 indicated that participating women were very enthusiastic about the doulas and appreciated their knowledge, support and reassurance. Unlike other trials there were no differences demonstrated in perinatal outcomes.

The Cochrane review of caregiver support for women during childbirth concluded that there were a number of benefits for mothers and their babies, and there did not appear to be any harmful effects. 116

The trial of CBT for women with very preterm infants129 did not reduce the prevalence of major or minor depression at follow-up.

In the Chinese education sessions trial follow-up was only 6 weeks. 134

Trials of postnatal support

Three trials of postnatal interventions to support socially disadvantaged mothers examined maternal outcomes of feeling tired, feeling miserable and negative feelings. The studies included mothers in an eastern US city,136 262 mothers in Dublin137 and mothers in the eastern USA. 138 Mothers who received support were less likely to report being tired, unhappy, not wanting to go out and other negative feelings at 1 year postnatally. 137 In all three trials childhood immunisation was more likely to be complete in the IG. 138 Without valid and reliable methods of obtaining mothers’ evaluations, these trials were not large or rigorous enough to examine the impact of social support on maternal and child health outcomes.

The Hackney Daycare Study139 was a randomised controlled trial of 120 mothers with a child age from 6 months to 3½ years, allocated to receive a place at the Mapledene Early Years Centre, or not. Although not the main outcome, maternal psychological well-being was measured using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Mothers in both groups had a mean GHQ-12 score of 10.8, indicating no apparent benefit as measured by the GHQ-12.

A Cochrane systematic review of parent-training programmes115 for improving maternal psychosocial health among population women or clinical groups of women included data from 20 studies. The meta-analysis showed that the intervention was associated with positive outcomes for depression, anxiety or stress, self-esteem and relationship with spouse or marital adjustment. The results suggested that parenting programmes could help promote positive mental health in the short term, but there was insufficient evidence regarding the long-term effectiveness of the programmes. 115

More recently there was a trial of two forms of postnatal social support offered to mothers living in disadvantaged inner-city areas of London. 140 Among the 367 IG women there was no evidence of an impact of either a programme of visits from HVs trained in supportive listening or the services of local community support organisations on maternal depression, child injury or maternal smoking, compared with the 364 women in the CG.

Postnatal trials to prevent postnatal depression

Because lack of social support and stressful life events have been correlated with the development of PND, many studies have aimed to ameliorate the potential impact of these by providing additional support or helping women develop coping techniques before depression develops. A Cochrane review of psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression113 identified postnatal support trials that aimed to prevent PND by offering an intervention postnatally. These trials are summarised in alphabetical order in Table 4.

| Authors, location | Method | Subjects | Intervention | Sample | Outcomes | Results and conclusions | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong et al., 1999,141 Armstrong et al., 2000,142 Fraser et al., 2000,143 Queensland, Australia | RCT double-blind | Women in the immediate postpartum with self-reported vulnerability factors (Brisbane Evaluation of Needs Questionnaire) | Nurse weekly home visiting structured programme of 20–60 minutes, minimum 18 per family (weekly for 6 weeks, fortnightly to 3 months, monthly to 12 months), supported by a social worker and paediatrician, vs standard community child health services | n = 90 IG; n = 91 CG | PSI, EPDS – at 6 weeks and 12 months |

Mean 6-week EPDS scores: IG 5.8 vs CG 20.7 (p = 0.003). Improved experience of the maternal role. No difference in breastfeeding or use of health services. Intervention was welcomed; 90 women were willing to accept the programme (one refused) No difference in mean EPDS scores at 4 months: IG 5.75 vs CG 6.64; 6.2% IG and 13.6% CG scored > 12 |

Targeted families in which child was at risk. Significant differences after randomisation. Focused on adjustment to parenting role 76% response to follow-up. Baseline EPDS, physical child abuse potential, PST all predicted level of PND at 12-month follow-up |

| Gunn et al., 1998,144 Melbourne, Australia | RCT with block randomisation stratified by recruiting centre | Postnatal women who gave birth at a rural and a metropolitan hospital, recruited on second or third day postnatally | GP appointment 1 week after discharge vs GP appointment 6 weeks after discharge | n = 232 IG; n = 243 CG | EPDS, SF-36 – at 3 months and 6 months |

3-month mean EPDS scores: IG 7.38 vs CG 7.48 (p = 0.85); 6-month mean EPDS scores: IG 5.87 vs CG 6.08 (p = 0.67) 3-month EPDS > 12: IG 16.6 vs CG 13.6 (p = 0.37); 6-month EPDS > 12: IG 11.6 vs CG 12.8 (p = 0.69) No difference in any SF-36 scores on any domain at 3 or 6 months 46.3% IG vs 51.4% CG breastfeeding at 6 months (p = 0.28) |

IG women were less likely to attend their appointment (p = 0.001). Many commented that the 1-week appointment was too early |

| MacArthur et al., 2002,145 West Midlands, UK | Cluster RCT | Postnatal women registered with 17 intervention practices and 19 control care practices. Recruitment time unclear | 42 midwives offering midwifery-led care, using symptom checklists, EPDS, no routine GP contact, last visits at 28 days, discharged at 10–12 weeks, vs 38 midwives trained in postnatal care and health and trial design offering control care | n = 101 IG; n = 98 CG | SF-36 physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) score, EPDS at 4 months |

Mean EPDS scores: IG 6.40 vs CG 8.06 (p < 0.0001). EPDS > 12: IG 14.39 vs CG 21.25 (p = 0.01) Mean PCS: IG 47.54 vs CG 50.50 (p = 0.002). Mean MCS: IG 46.68 vs CG 47.84 (p = 0.089). |

IG significantly more likely than CG to rate care as better than expected. Economic evaluation reported separately |

| Morrell et al., 2000,146 Sheffield, UK | RCT | Postnatal women who gave birth at an urban teaching hospital | Support workers offering up to 10 home visits of up to 3 hours in the first postnatal month vs usual postnatal care | n = 311 IG; n = 312 CG | SF-36, EPDS, DUFSS, breastfeeding – at 6 months | Mean EPDS: IG 7.4 vs CG 6.7 (p = 0.05) | ‘No evidence of any health benefit at the 6-week or 6-month follow-up.’ Cost per woman was £160 |

| Reid et al., 2002,147 Ayrshire and Grampian, Scotland | Pragmatic RCT | Primiparous women | 4 cells: (1) support pack, (2) support group, (3) support group and pack, (4) CG | (1) n = 250; (2) n = 250; (3) n = 253; (4) n = 251 | EPDS, SF-36, SSQ-6 – at 3 months and 6 months |

Mean EPDS scores: (1) 5.6, (2) 6.1, (3) 6.1, (4) 5.9 at 3 months Percentage scoring 12 or more on EPDS: (1) 12.0, (2) 16.8, (3) 15.2, (4) 11.7 at 3 months |

Low uptake of support groups (around six attenders, with 89 groups having no attenders). Cost per group was £21.31 per attendance, packs cost £1.75 |

There was some short-term benefit of the nurse home visiting programme in lower EPDS scores at 6 weeks,141 but there was no difference in maternal mood at 4 months. 142 The only other intervention that had an impact on mean EPDS scores at 4 months was the redesigned midwifery care trial. 145 There were some implementation problems with the early GP appointment trial144 and there were no significant differences in EPDS scores at 3 months.

In the support worker trial146 there were no differences in any of the instruments used, even though the women said that they felt that they had benefited from the intervention. The mean cost for the support worker service was £160 per woman.

The trial comparing social support groups and packs147 found that few women attended the groups, but more reported that they had read the pack at least once. The reasons given by those who did not attend were that the groups were too inconvenient or that they were too shy to attend alone. There was no difference in the mean EPDS scores between any of the groups or the percentage of women scoring 12 or more on the EPDS. The total cost for providing the packs was £439 and for running the postnatal support groups was £14,000. 147 The main outcomes indicated that intensive postpartum support showed promising results, and that identifying ‘at-risk’ mothers was helpful. 113 There was insufficient evidence that the diverse interventions reduced the number of postnatally depressed women.

Trials of postnatal treatment of postnatal depression

An early Cochrane review (withdrawn) to assess the effect of professional or social support interventions on postpartum depression was based on the theoretical premise that supportive relationships during the perinatal period could enhance a mother’s feeling of well-being. Two trials were included in the review,1,3 which concluded that professional and/or social support may help in the treatment of postpartum depression but that it was too early to draw conclusions for practice based on so little evidence. One of these trials3 was also included in a Cochrane review of antidepressant treatment for PND. 67 Since this early Cochrane review, further postnatal treatment studies of psychotherapy or psychological support have been published and reviewed13,112,148 and these are summarised below in alphabetical order (Table 5). The extensive range of approaches developed to treat PND reflects its broad aetiology. Among these trials are some in which the ‘therapist is not professionally prepared’. 149

| Authors, location | Method | Subjects | Intervention | Sample | Outcomes | Results and conclusions | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appleby et al., 1997,3 Manchester, UK | RCT, double-blind | Community postnatal women satisfying criteria for major depression at 6–8 weeks | (1) Fluoxetine 20 mg and one session CBC, (2) fluoxetine and six sessions CBC, (3) placebo and one session CBC, (4) placebo and six sessions CBC | n = 87 | EPDS, HRSD – at 1, 4 and 12 weeks | Fluoxetine more effective than placebo; six sessions of CBC more effective than one session of CBC; fluoxetine and CBC equally effective | 101/188 (54%) eligible women refused to participate (reluctance to take drug). Excluded breastfeeding. 61/87 completed (30% dropout) |

| Armstrong and Edwards, 2004,150 Queensland, Australia | RCT | Women with an EPDS score > 11 and infant 6 weeks–18 months, and medical certificate about physical activity | 12 pram-walking exercise sessions vs weekly social support meeting | n = 12 IG; n = 12 CG | EPDS and social support interview | There was a significant difference in mean (SD) EPDS scores between exercise group, 6.33 (3.67), and social support group, 13.33 (7.66) (p < 0.05) | Small sample. Exercise group had reduced feelings of depression and improved physical fitness; no change in perceived social support. Not ITT. Not generalisable |

| Chen et al., 2000,151 Kaohsiung, Taiwan | RCT | Postnatal women recruited on ward 2–3 days postnatally and scoring 9 or above on BDI at 3 weeks | Postnatal groups – four weekly meetings of 1.5–2 hours on transition to motherhood, postnatal stress, communication skills and life planning, vs CG. | n = 30 IG; n = 30 CG | BDI, PSS, ISEL, CSEI – at the end of the 4-week programme | 33% IG women depressed using BDI vs 60% CG women (p < 0.05). Attenders had significant positive changes in BDI, PSS and ISEL scores (p < 0.01) but no significant changes in any measure in the CG | Poor quality. 115 met the inclusion criteria; 60 enrolled; 44% returned screening questionnaire. The postnatal time of outcome measurement is not clear. 92% average attendance. |

| Cooper and Murray, 1997,152 Cooper et al., 2003,2 Cambridge, UK | RCT – the Cambridge treatment trial | Primiparous women screened to identify those who met DSM-III-R criteria for major depression | Home therapy 8–18 weeks. (1) NDC, (2) CBT, (3) dynamic psychotherapy (DPT) vs (4) routine care | (1) n = 49; (2) n = 42; (3) n = 48; (4) n = 52 | EPDS, SCID – at 18 weeks, 9 months and 18 months |

25–35% reduction in EPDS in three IGs vs 4% in the CG % women not depressed: (1) NDC 52%, (2) CBT 59%, (3) DPT 75%, (4) routine care 40% |

By 9 and 18 months’ follow-up differences between all four groups were not significant. Dropouts: (1) 14%, (2) 2%, (3) 17% |

| Dennis, 2003,153 British Columbia, Canada | RCT pilot study | Women with EPDS score > 9 at 8 weeks postpartum, defined as high risk for postpartum depression | Peer telephone support mother-to-mother using trained volunteers with a personal history of PND vs standard care | n = 34 IG; n = 27 CG | EPDS – at 4 months | Significant differences in EPDS scores >12 at 4 months: 15% IG vs 52% CG. Acceptance rate 67% | ‘Telephone-based peer support may effectively decrease depressive symptomatology among new mothers’ |

| Field et al., 1996,154 San Diego, US | Random assignment | Depressed adolescent mothers, identified using BDI | 10 massage therapy sessions for 30 minutes over 5 weeks vs 10 relaxation sessions for 30 minutes over 5 weeks | n = 32 | POMS 14-item depression scale, urinary cortisol | Massage therapy had a significant immediate effect on behavioural and stress hormone changes, including decreased anxious behaviour, pulse and salivary cortisol levels and urinary cortisol | Poor quality: small sample size, no true CG, randomisation unclear |

| Heh and Fu, 2003,155 Taipei, Taiwan | Random allocation | Women scoring over 10 on the EPDS (considered to be ‘at risk’ of PND) | Informational support about PND during the sixth week postpartum vs routine care | n = 35 IG; n = 35 CG | EPDS – at 3 months | 60% IG women scored below 10 on EPDS vs 31% CG women | ‘Informational support given postnatally may contribute to psychological well-being.’ No power calculation. Small sample |

| Holden et al., 1989,1 Edinburgh and Livingston, Scotland, UK | Controlled random order trial | Depressed women (psychiatric interview at 13 weeks postnatally) | One-to one ‘listening visits’ (eight 1-hour weekly sessions) by 17 HVs vs routine care | n = 26 IG; n = 24 CG | Goldberg, EPDS – after 13 weeks | 69% of IG women recovered vs 38% of CG women | The HVs providing the intervention continued to visit the CG women |

| Honey et al., 2002,156 Cardiff, UK | Block random allocation procedures | Women < 12 months postpartum scoring > 12 on EPDS | Eight HV 2-hour psychological–educational group (CBT and relaxation) vs routine primary care | n = 23 IG; n = 22 CG | EPDS, DUFSS, DAS |

Mean EPDS: 12.55 IG vs 15.63 CG 65% IG women scored below the cut-off for major probable PND (< 13) vs 36% CG women |

‘A brief psychological–educational group is an effective form of treatment for women with low postpartum mood’ |

| Milgrom et al., 2005,157 Melbourne, Australia | Cycled random allocation, by slips drawn from a bag. RCT | Community women with a diagnosis of depression confirmed by CIDI | 12 weeks × 90 minutes: (1) CBT, (2) group counselling, (3) one-to-one counselling vs (4) routine care | (1) n = 46; (2) n = 47; (3) n = 66; (4) n = 33 | BDI, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Social Provisions Scale | Proportions of post-intervention BDI scores below threshold for clinical depression were (1) 55%, (2) 64%, (3) 59% and (4) 29% | Psychological intervention per se was superior to routine care in reducing depression and anxiety |

| Misri et al., 2000, Vancouver, Canada. 158 | RCT | Women with major postpartum-onset depression | Six psychoeducational visits weekly, four with partners, vs six psychoeducational visits | n = 16 IG; n = 13 CG | EPDS, KSQ, DAS, PBI, MINI | Mean EPDS: 8.6 IG vs 14.7 CG (p = 0.013). Mean KSQ: IG 2.1 vs 6.6 CG (p = 0.021). Lower morbidity in partners who attended vs others (p = 0.01) | Poor quality: randomisation not described, small sample size, group differences in baseline characteristics |

| Misri et al., 2004,159 Vancouver, Canada | RCT | Women referred to tertiary care with DSM-IV criteria for major depression | Paroxetine plus 12 sessions of CBT vs paroxetine monotherapy | n = 16 IG; n = 19 CG | HRSD, EPDS – at 12 weeks | Both groups having antidepressant therapy and CBT showed improvement (p < 0.01) in mood and anxiety | No treatment as usual or CG |

| O’Hara et al., 2000,149 Iowa, USA | RCT | 120 postpartum women meeting DSM-IV criteria for major depression with modified SCID | 12 × 1-hour sessions of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) by 10 experienced psychotherapists vs waiting list control. Women with history of major depression separately randomised | n = 48 IG; n = 51 CG | IDD, amended HRSD, BDI, SAS, DAS, PPAQ, modified SCID – at 4, 8 and 12 weeks |

12-week HRSD scores: 8.3 IG vs 16.8 CG (p < 0.001). 12-week BDI scores: 10.6 IG vs 19.2 CG (p < 0.001). PPAQ and SAS scores improved in the IPT group No difference in DAS |

Most women were white and well educated 132 declined participation; 20% withdrew from IPT Women in the CG were phoned every 2 weeks Non-blinded raters |

| Onozawa et al., 2001,160 UK | RCT | Primiparous women 4 weeks postpartum, identified using EPDS | 12 × weekly 1-hour infant massage classes and 30-minute informal support group | n = 34 | EPDS | Significant differences between groups | Poor quality: small sample size, randomisation unclear, high drop-out rate from IG, analysis not ITT |

| Prendergast and Austin, 2001,161 Australia | RCT | Postnatal women with DSM-IV major or minor depression | Six modified CBC nurse-delivered home-based weekly 1-hour sessions vs standard care | n = 17 IG; n = 20 CG | EPDS, MADRS |

No significant difference post treatment; 70–80% recovered (EPDS < 10) in both groups 6-month postal follow-up |

‘Early childhood nurses could deliver modified CBT for PND.’ Perceived support from nurse appeared to be as effective as modified CBT |

| Wickberg and Hwang, 1996,162 Goteborg, Sweden | Controlled study | Women with EPDS ≥ 12 and major depression (MADRS) at 2 months and 3 months | Six × 1-hour counselling sessions by child health nurse vs routine care | n = 20 IG; n = 21 CG | MADRS – at about 19 weeks | 12/15 (80%) IG women showed no major depression after six sessions vs 4/16 (25%) CG women (p < 0.01) | Small sample, seriously ill excluded, randomisation not described. Nurses received 4 half-days of training |

Antidepressants to treat postnatal depression

The Cochrane review of antidepressant drug treatment for PND aimed to compare the effectiveness and safety of different antidepressants with other forms of treatment. 67 The Cochrane review included only one trial of fluoxetine,3 which was rated for methodological quality as category A. This was a community-based, randomised, double-blind controlled trial of 87 depressed postnatal women in Manchester that had four treatment groups:

-

fluoxetine 20 mg with one session of cognitive behavioural counselling (CBC) by a psychologist

-

fluoxetine with six sessions of CBC

-

placebo with one session of CBC

-

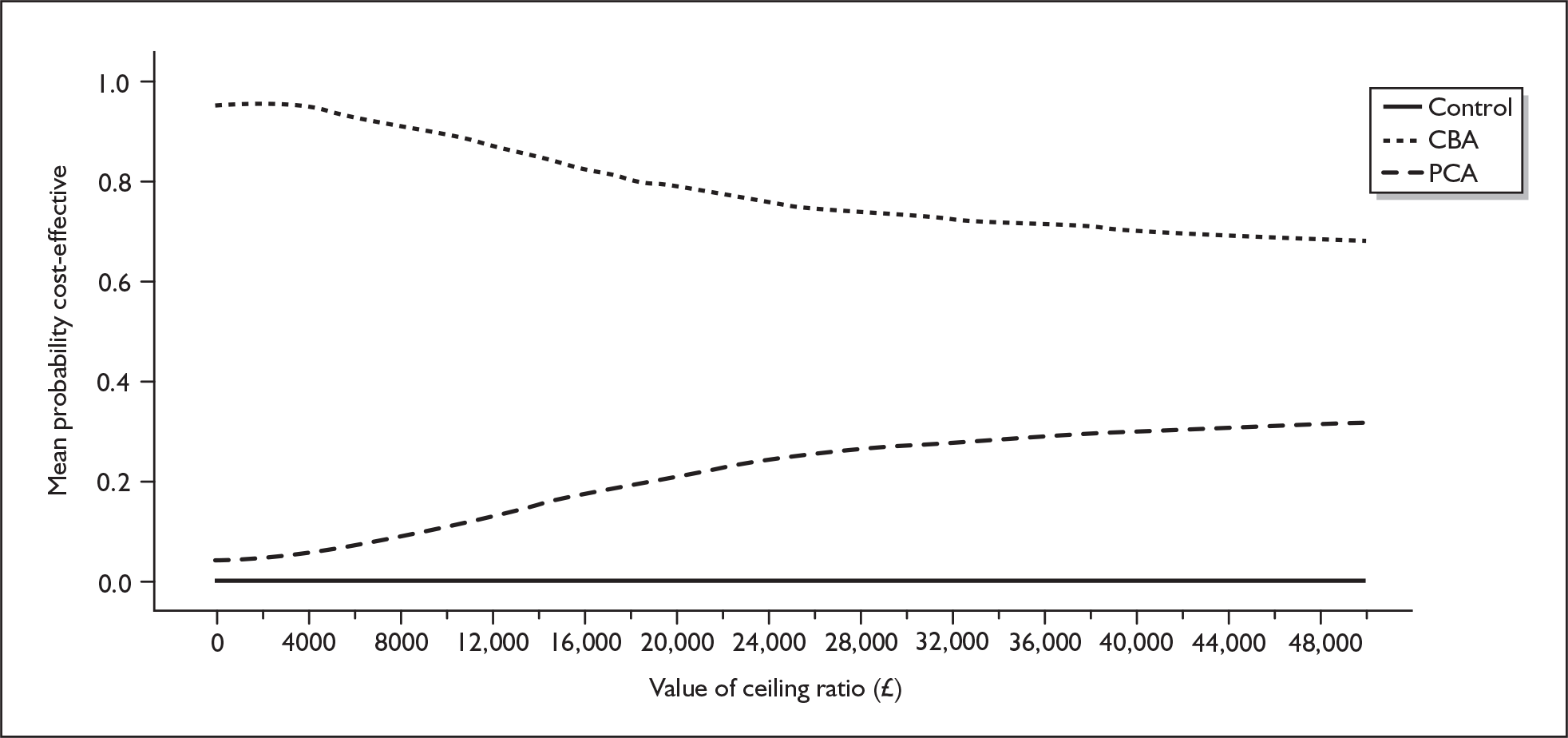

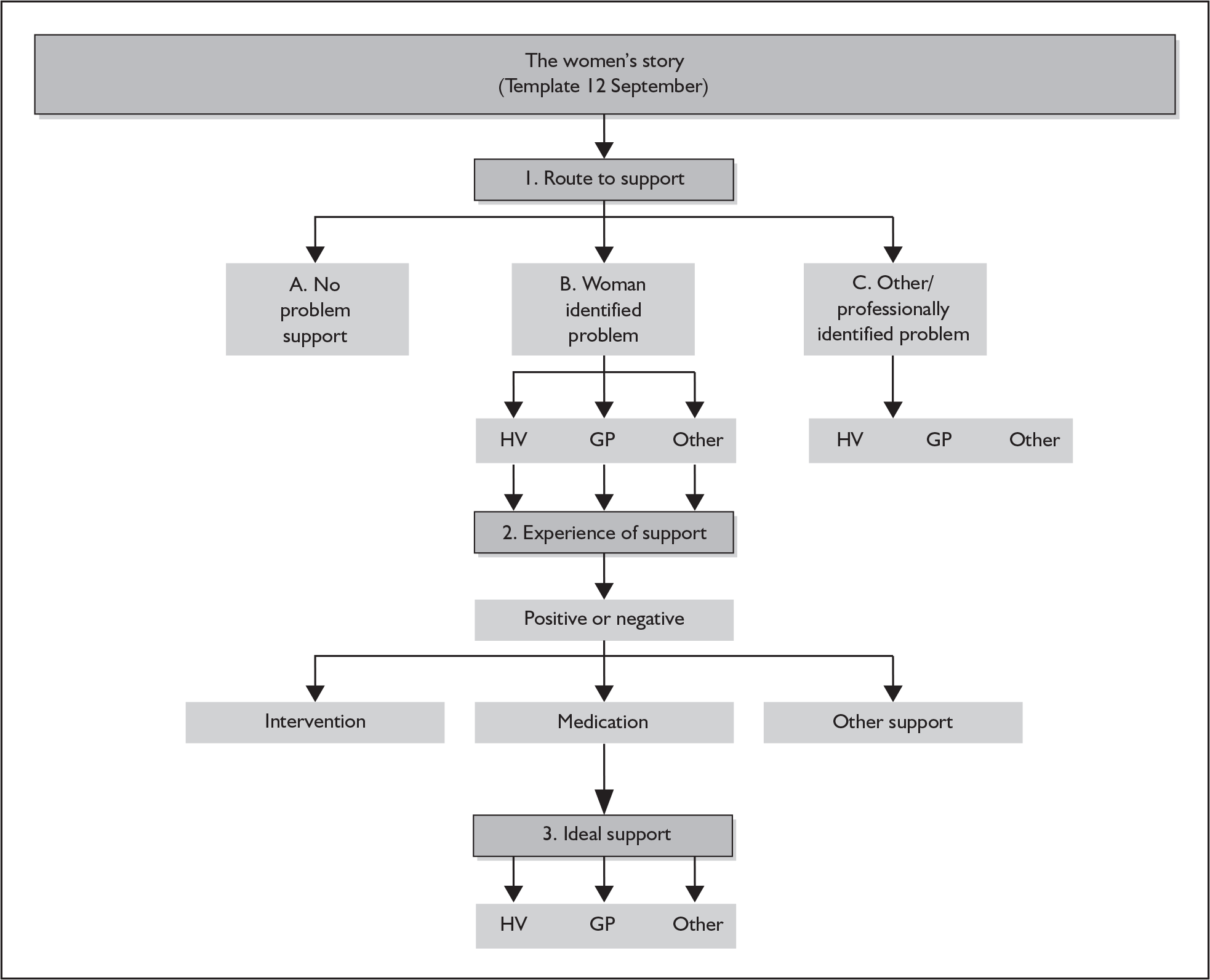

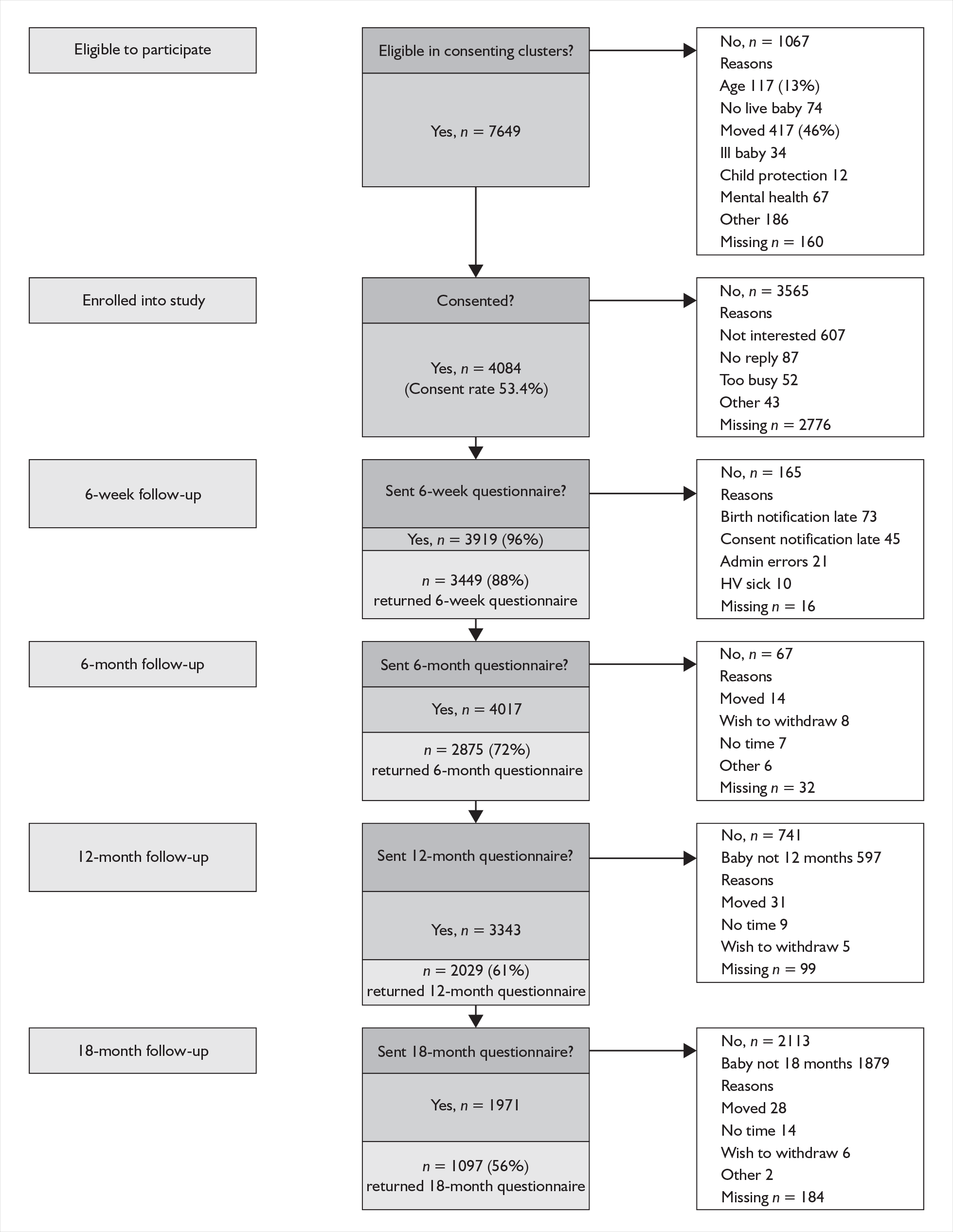

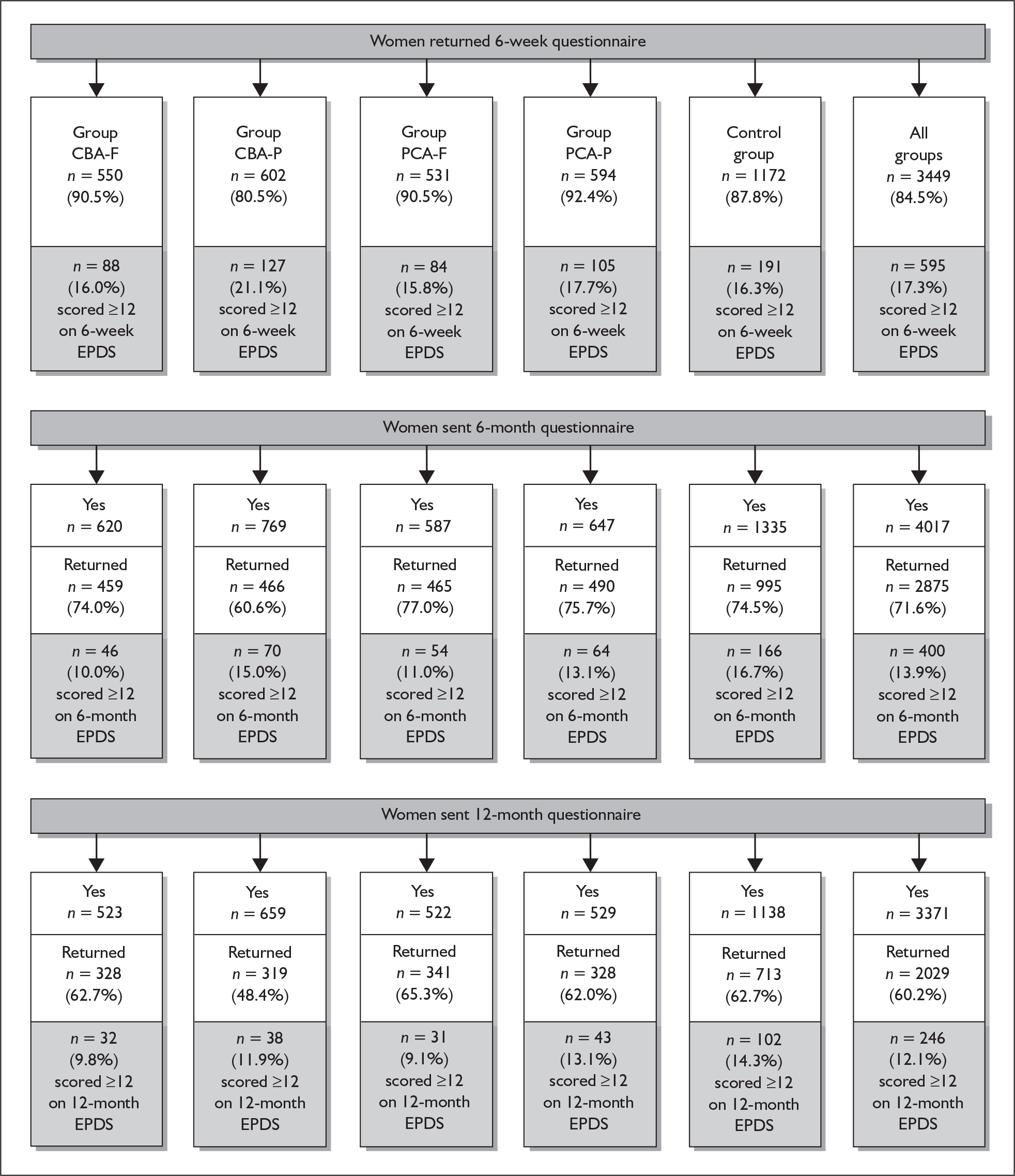

placebo with six sessions of CBC.