Notes

Article history

The research reported in this article of the journal supplement was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 07/71/01. The assessment report began editorial review in February 2008 and was accepted for publication in April 2009. See the HTA programme web site for further project information (www.hta.ac.uk). This summary of the ERG report was compiled after the Appraisal Committee’s review. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the HTA programme or the Department of Health.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

This paper presents a summary of the evidence review group (ERG) report into the clinical and cost-effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis based upon a review of the manufacturer’s submission to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) as part of the single technology appraisal (STA) process. The submission’s clinical evidence came from three randomised controlled trials comparing adalimumab with placebo, two extension studies and one ongoing open-label extension study. The studies were of reasonable quality and measured a range of clinically relevant outcomes. A higher proportion of patients on 40 mg adalimumab every other week achieved an improvement on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) of at least 75% (PASI 75) compared with placebo groups after 12 or 16 weeks of treatment, and there was a statistically significant difference in favour of adalimumab for the proportion of patients achieving a PASI 50 and a PASI 90. In a mixed treatment comparison, for each PASI outcome the probability of a response was greater for infliximab than for adalimumab, but the probability of response with adalimumab was greater than that with etanercept, efalizumab and non-biological systemic therapies. Adverse event rates were similar in the treatment and placebo arms and discontinuations because of adverse events were low and comparable between groups. The submission’s economic model presents treatment effectiveness for adalimumab versus other biological therapies based upon utility values obtained from two clinical trials. The model is generally internally consistent and appropriate to psoriasis in terms of structural assumptions and the methods used are appropriate. The base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for adalimumab compared with supportive care for patients with severe psoriasis was £30,538 per quality-adjusted life-year. Scenario analysis shows that the model was most sensitive to the utility values used. Weaknesses of the clinical evidence included not undertaking a systematic review of the comparator trials, providing very little in the way of a narrative synthesis of outcome data from the key trials and not performing a meta-analysis so that the overall treatment effect of adalimumab achieved across the trials is unknown. Weaknesses of the economic model included that the assumptions made to estimate the cost-effectiveness of intermittent etanercept used inconsistent methodology for costs and benefits and there were no clear data on the amount of inpatient care required under supportive care. The NICE guidance issued as a result of the STA states that adalimumab is recommended as a treatment option for adults with plaque psoriasis in whom anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment is being considered and when the disease is severe and when the psoriasis has not responded to standard systemic therapies or the person is intolerant to or has a contraindication to these treatments.

Introduction

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is an independent organisation within the NHS that is responsible for providing national guidance on the treatment and care of people using the NHS in England and Wales. One of the responsibilities of NICE is to provide guidance to the NHS on the use of selected new and established health technologies, based on an appraisal of those technologies.

NICE’s single technology appraisal (STA) process is specifically designed for the appraisal of a single product, device or other technology, with a single indication, for which most of the relevant evidence lies with one manufacturer or sponsor. 1 Typically, it is used for new pharmaceutical products close to launch. The principal evidence for an STA is derived from a submission by the manufacturer/sponsor of the technology. In addition, a report reviewing the evidence submission is submitted by the evidence review group (ERG), an external organisation independent of NICE. This paper presents a summary of the ERG report for the STA of adalimumab for the treatment of psoriasis.

Description of the underlying health problem

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin disease that can take several forms. The most common type is plaque psoriasis, characterised by exacerbations of thickened, erythematous, scaly patches of skin that can occur anywhere on the body. The severity of psoriasis can vary from mild through to moderate and severe. The disease impacts on quality of life at all levels of disease severity.

It is well recognised that obtaining estimates for psoriasis prevalence is difficult. NICE guidance on the use of etanercept and efalizumab indicates that approximately 2% of the UK population have psoriasis. 2 Defining what constitutes mild, moderate and severe psoriasis is also problematic as a number of different criteria are available and differing approaches are taken. One of the main accepted systems for classifying the severity of psoriasis is the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The limitations of this measure have been well documented,3 but despite its shortcomings it is the measure used in most clinical trials. Body surface area (BSA) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) are also commonly used as systems for classifying the severity of psoriasis. The guidance for the use of biological therapies in psoriasis issued by NICE in July 20062 defines severe psoriasis as a PASI of ≥ 10 combined with a DLQI > 10. A 2005 review4 of the PASI alone (i.e. without DLQI or BSA) as an instrument in determining the severity of chronic plaque-type psoriasis defines severe psoriasis as a PASI > 12 and moderate psoriasis as a PASI ranging from 7 to 12.

Scope of the ERG report

The ERG critically evaluated the evidence submission from Abbott Laboratories on the use of adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. At the time of the evaluation adalimumab had not yet been licensed for this indication.

Adalimumab is a recombinant human immunoglobulin monoclonal antibody that binds to the proinflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Adalimumab neutralises the biological function of TNF-α by blocking its interaction with the p55 and p75 cell-surface TNF receptors.

The anticipated licensed indication for adalimumab is the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adult patients who failed to respond to or who have a contraindication to or who are intolerant to other systemic therapy including ciclosporin, methotrexate or PUVA.

The outcomes stated in the manufacturer’s definition of the decision problem were measures of severity of psoriasis, remission rate, adverse effects of treatment and health-related quality of life.

Methods

The ERG report comprised a critical review of the evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the technology based upon the manufacturer’s/sponsor’s submission to NICE as part of the STA process.

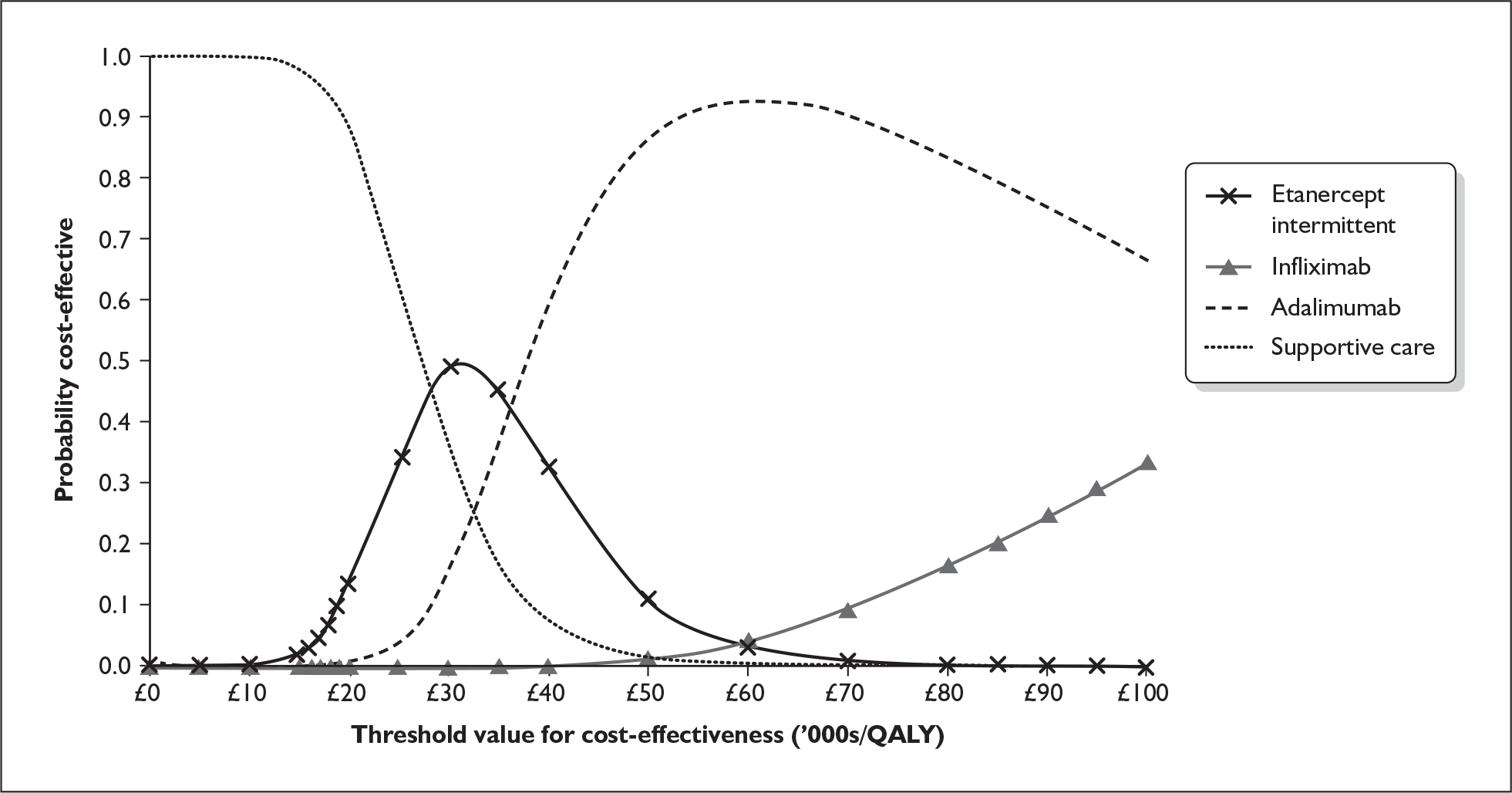

The ERG checked the literature searches and applied the NICE critical appraisal checklist to the included studies and checked the quality of the manufacturer’s submission with the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) quality assessment criteria for a systematic review. In addition, the ERG checked and provided commentary on the manufacturer’s model using standard checklists. A one-way sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis and a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (Figure 1) were undertaken by the ERG.

FIGURE 1.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for ERG probabilistic sensitivity analysis. QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Results

Summary of submitted clinical evidence

The main evidence on efficacy in the submission comes from three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing adalimumab with placebo. One of these RCTs also compares adalimumab with methotrexate. One further RCT contributes evidence on efficacy and time to relapse. Additionally two extension studies and one ongoing open-label extension study were included. Other than the one RCT mentioned above, which included a methotrexate arm, no trials of potential comparator treatments were included.

A higher proportion of patients on 40 mg adalimumab every other week achieved an improvement on the PASI of at least 75% (PASI 75) compared with placebo groups after either 12 weeks (two trials) or 16 weeks (two trials) of treatment. There was also a statistically significant difference in favour of adalimumab for the proportion of patients achieving a PASI 50 (three trials) and a PASI 90 (four trials).

The manufacturer’s submission did not present a narrative or quantitative synthesis of the data from the four trials except in the mixed treatment comparison. The mixed treatment comparison result for treatment with 40 mg adalimumab every other week was a mean probability of achieving a PASI 75 response to treatment of 67% (2.5–97.5% credible interval of 57–74%), compared with a mean probability of achieving a PASI 75 of 5% (2.5–97.5% credible interval of 4–6%) with supportive care. The mixed treatment comparison results for PASI 50 and PASI 90 were also in favour of adalimumab over supportive care. For each PASI outcome in the mixed treatment comparison the probability of a response was greater for infliximab 5 mg/kg/day than for adalimumab, but the probability of response with adalimumab was greater than the probability of response with etanercept, efalizumab and the non-biological systemic therapies.

In terms of secondary outcomes there were statistically significant differences between adalimumab and placebo in Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score, DLQI, the EuroQoL quality of life questionnaire (EQ-5D) and the short-form version 36 (SF-36) quality of life outcomes. The incidence of any adverse event was similar in the treatment and placebo arms, serious adverse events were comparable and discontinuations because of adverse events were low and comparable between groups.

Summary of submitted cost-effectiveness evidence

The cost-effectiveness analysis estimates the mean length of time that an individual would respond to treatment, and the utility gains associated with this response. The model is based closely upon the model reported in the NICE appraisal of etanercept and efalizumab for psoriasis. 2 The results are presented for adalimumab compared with other biological therapies, including intermittent etanercept, based upon utility values obtained from two clinical trials.

The model is generally internally consistent and appropriate to psoriasis in terms of structural assumptions. The cost-effectiveness analysis generally conforms to the NICE reference case, the scope and the decision problem.

Treatment effectiveness is reported in terms of the numbers of patients achieving PASI 50, 75 and 90 goals at the end of the trial period. Evidence was synthesised from a variety of trials for all therapies considered in the model using a mixed treatment comparison model. Patients who achieve improvements in PASI score were assigned an associated improvement in quality of life with higher responses associated with larger improvements in quality of life.

The base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for adalimumab compared with supportive care for patients with severe psoriasis was £30,538 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Scenario analysis reported in the manufacturer’s submission shows that the model was most sensitive to the utility values used (with DLQI ≤ 10 having much higher cost-effectiveness ratios then DLQI > 10).

Commentary on the robustness of submitted evidence

Strengths

The manufacturer conducted a systematic search for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies of adalimumab. It appears unlikely that the searches missed any additional trials that would have met the inclusion criteria. The four key adalimumab trials identified were of reasonable methodological quality and measured a range of outcomes that are as appropriate and clinically relevant as possible. Overall, the manufacturer’s submission presents an unbiased estimate of treatment efficacy for adalimumab based on the results of the placebo-controlled trials.

The economic model presented with the manufacturer’s submission used an appropriate approach for the disease area given the available data. The measure of utility gain was taken from two randomised clinical trials that directly linked changes in PASI score to changes in utility using the EQ-5D.

Weaknesses

The processes undertaken by the manufacturer for screening references, data extraction and quality assessment of included studies were not well reported in the manufacturer’s submission. However, the manufacturer was able to provide details when requested.

The manufacturer did not undertake a systematic review of the comparator trials and reported very limited information on the comparator trials that were included in the mixed treatment comparison. The manufacturer’s submission provided very little in the way of a narrative synthesis of outcome data from the key trials and did not perform a meta-analysis. A mixed treatment comparison was conducted, but few methodological details were provided on this.

The assumptions made to estimate the cost-effectiveness of intermittent etanercept used inconsistent methodology for costs and benefits. The estimation of QALYs and costs generated were based upon different estimates of the length of time that individuals would spend on etanercept, with the estimate used for costs greater than that used for QALYs.

There were no clear data on the amount of inpatient care required under supportive care.

A fourth infusion for infliximab was included in the trial period at 14 weeks. This would last for the first 8 weeks of the treatment period and hence is most appropriately included in the treatment period costs. The clinical expert consulted believed that generally in clinical practice the fourth infusion would be given only after the individual’s response category was assessed.

Conclusions

Areas of uncertainty

As a standard meta-analysis was not conducted the overall treatment effect of adalimumab achieved across the trials is unknown. A meta-analysis might also have identified whether there is heterogeneity across the trials. If heterogeneity was found to be present the appropriateness of conducting a mixed treatment comparison would need to be reconsidered.

The limited descriptions of both the comparator trials included in the mixed treatment comparison and the methodological assumptions underlying the mixed treatment comparison make it difficult for the ERG to critique the model outputs.

The extent to which the trial populations of the included adalimumab trials match the population specified in the decision problem, in terms of previous treatment with systemic therapy, is uncertain.

A regression model was used to relate changes in PASI score to EQ-5D data. However, few details were given of this model and so the ERG could not be sure of the appropriateness of the approach taken.

Uncertainty exists as to the correct way to model key alternatives to adalimumab, particularly intermittent etanercept. It is unclear how widely intermittent etanercept is used in clinical practice and the degree to which costs are avoided with intermittent therapy. It is also unclear as to how much utility is lost because of psoriasis flare-ups.

There appears to be a paucity of data regarding the need for inpatient stays in psoriasis patients. The assumption is that individuals who are not responders to treatment receive 21 days per year and those who are on treatment receive no inpatient stays. The model is sensitive to changes in the length of supportive care inpatient stay.

Key issues

The majority of the trials of adalimumab efficacy presented in the manufacturer’s submission were placebo-controlled trials. Only one head-tohead RCT was included that directly compared adalimumab with methotrexate. No studies were identified that directly compared adalimumab with the other possible comparators listed in the scope. The manufacturer carried out an indirect comparison, but because of the limited information presented on the included comparison trials and the methodological assumptions the ERG have reservations about this.

The precise definition of the severity of the psoriasis patients included in the model is unclear. A clear specification of this and a tailoring of the effectiveness, quality of life and cost data, to reflect specific severities, would improve the applicability of the model.

There is a need for better data relating to the need for inpatient stays for non-responders with various severities of disease.

The assumptions made in estimating the values for key parameters used for the comparators are important in determining the relative cost-effectiveness of adalimumab compared with other biological treatments, particularly the costing assumptions made for intermittent etanercept.

Summary of NICE guidance issued as a result of the STA

NICE issued an Appraisal Consultation Document in January 2008 which states that:

1.1 Adalimumab is recommended as a treatment option for adults with plaque psoriasis in whom anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) treatment is being considered and when the following criteria are both met.

-

– The disease is severe as defined by a total Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) of 10 or more and a Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) of more than 10.

-

– The psoriasis has not responded to standard systemic therapies including ciclosporin, methotrexate and PUVA (psoralen and long-wave ultraviolet radiation); or the person is intolerant to, or has a contraindication to, these treatments.

1.2 It is recommended that adalimumab is discontinued in people whose psoriasis has not responded adequately at 12 weeks. An adequate response is defined as either:

-

– a 75% reduction in the PASI score (PASI 75) from when treatment started, or

-

– a 50% reduction in the PASI score (PASI 50) and a five-point reduction in DLQI from start of treatment.

1.3 It is recommended that, when using the DLQI, healthcare professionals take care to ensure that a person’s disabilities (such as physical impairments) and linguistic or other communication difficulties are taken into account when reaching conclusions on the severity of plaque psoriasis. In such cases, healthcare professionals should ensure that their use of the DLQI continues to be a sufficiently accurate measure. The same approach should apply in the context of a decision about whether to continue the use of the drug in accordance with section 1.2.

Disclaimers

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health.

Key references

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Guide to the Single Technology (STA) Process 2006. www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=STAprocessguide.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Etanercept and Efalizumab for the Treatment of Adults With Psoriasis 2006.

- Woolacott N, Bravo VY, Hawkins N, Kainth A, Khadjesari Z, Misso K, et al. Etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:iii-239.

- Schmitt J, Wozel G. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index is the adequate criterion to define severity in chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Dermatology 2005;210:194-9.