Notes

Article history

This themed issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a collection of research commissioned by the NIHR as part of the Department of Health’s (DH) response to the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. The NIHR through the NIHR Evaluation Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) commissioned a number of research projects looking into the treatment and management of H1N1 influenza. NETSCC managed the pandemic flu research over a very short timescale in two ways. Firstly, it responded to urgent national research priority areas identified by the Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE). Secondly, a call for research proposals to inform policy and patient care in the current influenza pandemic was issued in June 2009. All research proposals went through a process of academic peer review by clinicians and methodologists as well as being reviewed by a specially convened NIHR Flu Commissioning Board.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

2009 AH1N1v influenza

April 2009 saw the emergence of a novel influenza A virus of swine origin, subsequently subtyped (and referred to in this report) as AH1N1v. Over the subsequent months, this AH1N1v or swine flu virus spread rapidly among humans, achieving pandemic status on 11 June 2009, as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO). The detection of avian influenza H5N1 in humans less than a year previously had stimulated preparation for a possible influenza pandemic. A document produced in anticipation of such an event by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA1 identified pregnant women as being at high risk of severe influenza-related complications. Concerns about the effect of AH1N1v infection in pregnancy were further highlighted following the death of a previously healthy pregnant woman in the USA as the second documented death associated with the 2009 outbreak. In the UK, the Department of Health identified pregnant women as a high-risk group requiring early assessment and treatment of flu-like symptoms at the beginning of the pandemic, and, subsequently, as a priority group for vaccination against AH1N1v.

Influenza in pregnancy

Maternal risks

Reports from previous influenza epidemics, such as the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–19, and research on seasonal influenza, have been cited as evidence that pregnant women are at risk of increased maternal mortality and morbidity from influenza infection compared with non-pregnant women. 2

There are inconsistent data, however, regarding the risk of complications in pregnancy after influenza infection. A hospital database-matched cohort study by Cox et al. in the USA3 identified pregnant women with underlying respiratory conditions as having longer hospital admissions and increased delivery complications during the influenza season than hospitalised pregnant women without comorbid respiratory conditions. An earlier study in the USA by Hartert et al. ,4 using a similar design but in which influenza and non-influenza cases were matched for comorbid conditions and trimester of pregnancy, failed to identify a significant difference in mode of delivery, duration of delivery admission, episodes of preterm labour and adverse perinatal outcomes between the two groups. The authors did identify, however, that miscarriages, early neonatal deaths and maternal deaths were not studied, potentially resulting in an underestimate of maternal and perinatal mortality.

Pregnant women, particularly in the third trimester of pregnancy, have been reported as being at a higher risk of developing influenza-associated pneumonia and cardiorespiratory complications. 5,6

Fetal risks

In addition to the maternal risks, there are concerns about the direct and indirect effects of maternal influenza infection on the fetus. An increased risk of spontaneous abortion7 and stillbirth8 have been reported in pregnant women with influenza, and there are inconsistent data to suggest that maternal influenza may be associated with an increased risk of certain congenital malformations, including oesophageal atresia9 and anophthalmos/microphthalmos. 10 An increased risk of anencephaly was also reported following epidemics of Asian influenza. 11–13

The Hungarian Case–Control Surveillance of Congenital Abnormalities reported an association between maternal influenza during the second and third month of pregnancy and congenital malformations in the offspring, including cleft lip or palate, neural tube defects (NTDs) and cardiovascular abnormalities. 14 In this study the use of antipyretic drugs reduced the risk of congenital malformations, suggesting that these might be due to fever. Use of folic acid supplements reduced or eliminated the apparent risk associated with influenza during pregnancy.

A further case–control study, involving 363 infants with NTDs and 523 normal newborns, indicated an increased risk of NTDs associated with maternal influenza. However, in this study, risk was enhanced when antipyretic drugs were used, in contrast with the findings of the Hungarian study described above. 15

Antiviral therapy during pregnancy

Oseltamivir (Tamiflu®, Roche Products) and zanamivir (Relenza®, GlaxoSmithKline) are neuraminidase inhibitors that are effective in the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza types A and B in adults. AH1N1v has been shown to be susceptible to these agents. These drugs prevent viral release from infected cells and subsequent infection of adjacent cells. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has concluded that both of these agents are clinically effective treatments for influenza in the general population,16 with no clear distinctions between the two agents on the basis of clinical efficacy, and that both are effective for seasonal or postexposure prophylaxis. 17 Oseltamivir is readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract following oral administration, and has significant systemic activity. 18 Zanamivir is administered through inhalation and has lower systemic bioavailability. 19 It may therefore be less suitable for severe systemic illness, but low transplacental bioavailability may reduce risks of adverse fetal effects.

Limited information was available on the safety of neuraminidase inhibitor use during pregnancy prior to the AH1N1v pandemic. A review article cited a total of 61 cases of oseltamivir exposure in pregnancy, collected during postmarketing surveillance. 20 Although complete details of these cases were not provided, the majority of pregnancies were reported to result in a normal baby. Ten abortions (of which six were therapeutic – no further details provided) were reported. There were also single cases of trisomy 21 and anencephaly; in both cases causality was considered as not related to treatment with oseltamivir.

There were no epidemiological studies regarding exposure to zanamivir during human pregnancy. Three pregnancies were reported during preclinical marketing studies carried out by the manufacturer; of these pregnancies, one resulted in the birth of a normal healthy baby, one pregnancy was terminated electively and one resulted in a spontaneous abortion. No other details were available. 21

Influenza vaccination during pregnancy

Published outcome data on the use of seasonal influenza vaccines during pregnancy have not indicated an association with an increased incidence of congenital malformations. 22–30 However, the majority of reports focused on use during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, after organogenesis has taken place.

In a prospective cohort study comparing 189 women who were vaccinated with the influenza A vaccine during pregnancy (41 of whom were vaccinated in the first trimester) with a control group of 517 non-vaccinated women, the rate of congenital malformations was within the expected range in both groups. 24 In addition, no increase in perinatal or infant complications was observed following maternal vaccination. A prospective longitudinal, population-based study by the Collaborative Perinatal Project published findings from 650 pregnant women who were given seasonal influenza vaccinations in the first 4 months of pregnancy. 23 After follow-up from birth to 7 years of age, there was no observed increase in risk of stillbirth, congenital malformation, childhood cancer or neurocognitive disability in the offspring.

Other prospectively and retrospectively gathered data have not indicated an increased incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes in over 4000 pregnant women who received the influenza vaccine during the second or third trimesters of pregnancy. 23–29

A recent randomised controlled trial found that immunisation of pregnant women against influenza in the third trimester (n = 172) reduced the rate of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the mothers and children by 29% and reduced laboratory-proven influenza infections in 0- to 6-month-olds by 63% (95% CI 5% to 85%). 27 The authors did not report any congenital malformations or adverse fetal effects that were attributable to vaccination in the influenza vaccine-exposed infants. The rates of maternal, neonatal and infant mortality were all within the expected ranges.

Review of published and unpublished data from the first AH1N1v influenza wave up to September 2009

Prior to commencing recruitment for this study, a systematic search for information about AH1N1v influenza and its treatment in pregnancy was performed by the research team and has been reported separately. 31 In addition to reviewing data published in the scientific literature, this also considered evidence provided by antiviral manufacturers, teratology information services and drug regulatory bodies. Interpretation of data identified in this systematic review was difficult because important information was often missing or incomplete, and there was overlap of data collected from different sources, the extent of which was uncertain. Pooling of published data from different sources identified reports involving 135 pregnant women with AH1N1v infection.

Mortality

Mortality in this group of 135 women was high, with death occurring in at least 26 of the women involved. However, these reports addressed the characteristics of patients with AH1N1v influenza who were admitted to hospital and/or who died. It is thus likely that this published literature is heavily biased towards reporting of severe or fatal cases. Estimation of mortality from these data is likely to be very misleading.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity was also common amongst these published cases. At least 26 (19.4%) of the 135 pregnant women with swine flu were reported to have coexisting medical conditions. These included asthma, tuberculosis, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and hyperthyroidism, obesity and Factor V Leiden deficiency. It should be noted that three (50%) out of the six women reported by Jamieson et al. 2 to have died had underlying health conditions, as did 8 out of the 16 fatal cases reported by Vaillant et al. 32 Although comorbidity is reported in other case series, it is not clear from the data presented whether this correlates with a higher risk of hospital admission or of death. Asthma was the most frequently reported associated chronic illness in these women, in keeping with experience from the study of Hartert et al. 4 on seasonal influenza, in which pregnant women with asthma accounted for one-half of all respiratory admissions during influenza seasons.

Trimester of illness

It has been widely quoted that women in the third trimester of pregnancy are at increased risk of hospitalisation due to respiratory illness during the influenza season. 6 With respect to the published literature on the 2009 AH1N1v pandemic, most papers do not report on pregnancy trimester for the women admitted to hospital or who die. Although the numbers are too small to identify a statistically significant difference between hospitalisation rate and case fatality rate by trimester of pregnancy for the cases reported by Jain et al. 33 and Jamieson et al. ,2 respectively, the absolute number and percentage of women affected in the third trimester is greater than the percentage of women in the first and second trimesters. This may reflect a trend of increased risk to women in the third trimester of pregnancy. It should be emphasised, however, that none of the 16 deaths from AH1N1v infection in pregnancy reported by Vaillant et al. 32 was categorised by trimester.

Timing of antiviral treatment

Only two articles provided details of the interval between onset of symptoms and initiation of antiviral treatment. 2,34 Of the 34 women described in the study of Jamieson et al. ,2 17 received treatment with oseltamivir and eight were treated within 2 days of symptom onset. The six women who died received antiviral drugs, a median of 9 days (range 6–15) after symptom onset. No details of antiviral treatment were provided in any of the other studies.

Fetal risks

From the data available thus far, no clear pattern of congenital abnormalities suggestive of teratogenicity due to oseltamivir or zanamivir exposure has emerged. Information on fetal outcome is not available for the majority of AH1N1v infection in pregnancy cases referred to in the published literature, as many of these women were still pregnant at the time of publication. This is in keeping with the lack of outcome data available from the UK and other teratology information services. Interestingly, live born infants were delivered by caesarean section to five of the six fatal cases described by Jamieson et al. 2 and were doing well with no evidence of influenza infection. The sixth case was associated with a miscarriage at 11 weeks’ gestation at the time of maternal death. At the time of writing, it was too early in the pandemic to expect sufficient information regarding congenital malformation rates in babies born to mothers infected with AH1N1v in the first trimester.

Preparation for the AH1N1v (2009) influenza ‘second wave’

As the initial peak of the 2009 AH1N1v pandemic subsided in the summer, predictions were made about a second, potentially more virulent, wave of AH1N1v influenza emerging in the autumn of 2009. In anticipation of a second peak, expedited AH1N1v research was identified as a government priority, and the need for evidence-based guidance of the management of AH1N1v (2009) influenza in pregnancy during the second wave was evident. In particular, there was a need to better characterise the adverse maternal and fetal effects of influenza infection involving this new pandemic strain, and to obtain more data on the safety of antiviral therapy during pregnancy. Subsequently, following the licensing of vaccines for AH1N1v, there was a need to collect information on the safety of these vaccines when used in pregnancy.

This study, one of several commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), aimed to collect information on pregnant women during the second wave of the pandemic, with a view to providing interim analyses of the data to inform guidance on the management of AH1N1v infection in pregnancy.

Study objectives

The objectives of this research were to:

-

estimate the incidence of AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy during the second wave

-

determine the effect of AH1N1v influenza infection and/or treatment with neuraminidase antiviral drugs in pregnant women and/or AH1N1v vaccination (timing of use, dose and agent) on pregnancy outcome, including specific adverse or beneficial effects of antiviral treatment or AH1N1v vaccination on eventual maternal and fetal outcome

-

ascertain the influence of demographic or pregnancy characteristics and additional aspects of pregnancy management on outcomes for mother and infant

-

produce guidance on the management of AH1N1v infection in pregnancy: initially following systematic review, updated subsequently by monthly review of emerging data from this study such that outcomes for women and infants could be optimised during the current pandemic.

This report describes study results for the period September 2009 to January 2010, concentrating on clinical outcomes of episodes of influenza in pregnant women. Data collection is continuing and further information on pregnancy and fetal outcomes will be published when this is available.

Chapter 2 Methods

The research described in this report comprises two separate prospective observational cohort studies. In one, information was collected with consent from pregnant women who were recruited in the primary care setting and met the study inclusion criteria. This research was lead by the UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS). The second study, performed in a secondary care setting, used anonymised data collected by the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) on pregnant women with confirmed influenza who were admitted to hospital. These two studies were intended to provide data on the full spectrum of AH1N1v infection and its management during pregnancy. Information on participants was collected directly from heath professionals caring for these women in secondary care settings, and from health professionals, as well as the women themselves, for women recruited in primary care.

Health professionals were made aware of the study via information on the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) online database TOXBASE® and websites of the UKTIS, UKOSS, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and via advice provided on AH1N1v influenza by the Health Protection Agency (HPA). Recruitment in primary care was encouraged across the UK and was supported by the Primary Care Research Networks (PCRNs).

Women with suspected AH1N1v infection or antiviral exposure managed in primary care

Case definition

Initially, pregnant women in the UK with confirmed or suspected AH1N1v influenza, or, who were offered antiviral medication for treatment or prophylaxis, were eligible for inclusion in the study. The study protocol was subsequently amended in November 2009 (see details for assessing the full study protocol at the end of the paragraph), following licensing of AH1N1v vaccines, to allow in addition the recruitment of pregnant women offered immunisation against AH1N1v influenza (full study protocol available at www.uktis.org).

Influenza cases were defined as pregnant women with suspected or confirmed AH1N1v influenza. Antiviral exposure cases included women exposed to antiviral medication in pregnancy, either for treatment of suspected swine flu or as prophylaxis. AH1N1v vaccination cases were defined as pregnant women vaccinated with the AH1N1v vaccine. Data were also sought from pregnant women who were offered, but were not subsequently undergoing, vaccination. Data provided in this report include women who had suspected AH1N1v infection or antiviral treatment or were offered immunisation between 7 September 2009 and 29 January 2010.

Data collection

Women presenting in primary care with suspected AH1N1v infection were notified to UKTIS by health professionals when clinical advice was sought from the service, by means of a dedicated UKTIS swine flu reporting line or by reporting form available for download from the UKTIS website. In addition, the MHRA and HPA Regional Microbiology Laboratory Network alerted clinicians to the study when they reported adverse events or sent specimens. Clinicians were then asked to seek consent from patients for their details to be provided to UKTIS. Women were also invited to self-report to UKTIS via the dedicated swine flu reporting telephone line referred to above.

Brief clinical details of women identified by their health professionals or identifying themselves to the research team were collected. Health professionals sought verbal consent from eligible women for the provision of this personally identifiable information to UKTIS, to allow an approach for written consent to participate from the research team.

Potential participants were then sent a participant information sheet and consent documentation, together with an initial data collection sheet that they were asked to complete if they wished to take part. Only women providing written consent were asked to provide further health information.

The reporting health professional was asked to alert the research team should the status of the patient change after initial notification, to avoid the small risk of contacting individuals who might have died or experienced a distressing or adverse pregnancy outcome. In these cases, information was collected from the health professional only when consent to do so had been granted. For cases where women were notified with suspected swine flu, further information on the illness was sought from the participant and health professional 4 weeks after initial contact. Patients who remained unwell from influenza continued to be followed up at 4-weekly intervals until recovery. If the patient had recovered, the next follow-up was planned for approximately 2 weeks after the expected date of delivery, in order to obtain maternal and pregnancy outcome information, again collected from the woman and her health professional. If a completed data collection form was not received back by UKTIS after 3 weeks, a further reminder was sent. Anonymised details of patients declining participation were also notified to UKTIS.

Participants and health professionals were offered the opportunity to report any additional information of relevance to the study (e.g. illnesses, exposures or pregnancy complications) at any point during the study in addition to the planned follow-up intervals.

Virological testing of women with suspected AH1N1v infection

Virological confirmation of infection was not a requirement for participation in the primary care element of the study, but details of those who had not been tested for AH1N1v in a diagnostic setting were forwarded to the HPA North East virology laboratory, with their consent. A self-administered swabbing kit was provided to the participant by post from the UKTIS research team, enclosed with the initial participant information sheet, and consent forms as detailed below. The kit comprised two viral swabs, an instruction leaflet and a prepaid envelope with the necessary transport tubes for return of the sample to the virology laboratory. Given the known difficulties of obtaining informative throat swabs by self-testing, a nasal swab from each nostril was requested. This is thought to achieve an equivalent diagnostic yield. Swabs returned through research testing were processed immediately by the HPA North East virology laboratory to extract and store total nucleic acids and tested for AH1N1v. Testing including extraction, amplification and detection was performed in accordance with the national standard operating procedures for detection of AH1N1v. Samples needing additional testing to clarify status were referred to the HPA Centre for Infections, Colindale, London.

Assessment of incidence in primary care

The incidence of presentation in primary care with ILI and of use of antiviral therapy and vaccination was estimated by collecting all cases from selected general practives agreeing to act as ‘sentinel’ sites. These practices were asked to submit weekly anonymised data, with null reporting, of all pregnant women consulting with suspected swine flu, prescribed antiviral drugs, offered AH1N1v vaccination and receiving the AH1N1v vaccine over the period of study. Details were also provided of practice list sizes and the numbers of women aged 15–45 years, as well as the numbers of women in the practices who were recorded as being pregnant on 1 December 2009.

Comparison groups

The characteristics of pregnant women with suspected or confirmed AH1N1v influenza were compared with those of pregnant women who did not report influenza-like symptoms and who were not treated with antiviral drugs, but who qualified for inclusion in the study because they were offered vaccination and consented to provide their details to the research team. Information from women receiving AH1N1v vaccination in pregnancy was compared with that collected from participants who were offered vaccination but not vaccinated.

Sample size

The available sample size was dependent on rates of infection, antiviral use or vaccination among pregnant women, the list sizes of participating general practices, the proportion of potential participants who provided consent for data handling and subsequent follow-up, and the UK maternity rate (around 760,000 maternities per year at the outset of the study). With the limited available data from the first wave of AH1N1v influenza and assuming similar rates of presentation, we anticipated identifying 500–1000 affected pregnancies, using the combined UKTIS and UKOSS approach, over the 6-month initial study period.

Statistical analyses

Index of multiple deprivation (IMD) scores were obtained by linking patients’ postcodes to small geographical areas referred to as Super Output Areas (SOAs). IMD scores35 are publicly available continuous measures of compound social and material deprivation, and are calculated using a variety of data including current income, employment, health, education and housing. As the IMD score increases, the level of deprivation increases.

Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for women displaying swine flu symptoms compared with women not displaying symptoms nor taking antiviral drugs were estimated for potential risk factors, using unconditional logistic regression and adjusted for putative confounding factors. A full regression model was developed by including both potential explanatory and confounding factors in a core model if there was a pre-existing hypothesis or evidence to suggest that they were causally related to AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy, for example asthma. Potential interactions were tested by the addition of interaction terms between all variables in the model and subsequent likelihood ratio testing on removal. Data for case and comparison women were compared using the chi-squared test – p < 0.05 was considered evidence for a significant interaction.

Secondary care hospital admission with confirmed AH1N1v infection in pregnancy

Case definition

Cases were defined as any pregnant women admitted to hospital in the UK with confirmed AH1N1v infection between 1 September 2009 and 31 January 2010. Women with AH1N1v infection in pregnancy who were not admitted to hospital and women with AH1N1v infection diagnosed post partum were excluded from this arm of the study.

Data collection

Cases were identified through the UKOSS network of collaborating clinicians. 36 In view of the need for rapid and ongoing data analysis, clinicians were asked to report, using a web-based rapid reporting system, all pregnant women with confirmed AH1N1v infection who were admitted to their unit, as soon as possible after the woman’s admission. In response to a report of a case, clinicians were able to download a data collection form with a unique UKOSS identification number, asking for further detailed information about diagnosis, management and outcomes. If a completed data collection form was not received back by the central team after 3 weeks, a reminder letter was sent. A further reminder was sent 6 weeks after the initial case report, and, if the completed form had not been received after 9 weeks, a further prompt was sent with a new copy of the form to complete.

In addition, every 2 weeks nominated UKOSS reporting clinicians were sent a summary detailing the cases that had been reported from their unit and were asked to confirm that there were no additional cases to report. Clinicians were also asked to return a ‘nil report’ indicating that there had been no women admitted so that participation could be monitored and the denominator population for the study could be confirmed. The cases included in this report include all data returned up to, and including, 23 February 2010.

All data were double-entered into a customised database. Cases were checked to confirm that they met the case definition and to exclude duplicate reports. Where data were missing or the response invalid, the reporting clinician was contacted by e-mail and asked for the correct information. If the woman was undelivered at the time of discharge following her AH1N1v infection, a further copy of the data collection form was sent to the reporting clinician 2 weeks after the expected date of delivery in order to obtain details of the outcome of pregnancy.

All information collected was anonymous.

Additional case ascertainment

At the end of the data collection period, the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE) was contacted and provided with information on cases of maternal death in association with AH1N1v infection in pregnancy reported through UKOSS, identifying the hospital and date of death. They were asked to compare the cases they had identified with the cases reported to UKOSS.

Comparison group

Information about comparison women delivering in UK hospitals was obtained from previously collected UKOSS data. The comparison women were identified by UKOSS reporters as the two women delivering in the same hospital immediately before other UKOSS cases. 37 This cohort was chosen for pragmatic reasons to facilitate rapid comparisons during the epidemic, and, as a historical cohort, to ensure that none of the women could have been infected with AH1N1v.

Statistical analyses

The incidence of hospitalisation with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy was estimated with 95% CIs using the most recently available birth data (2007) as a proxy for September 2009 to January 2010. 38

Data for case and comparison women were compared using the chi-squared test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Figures presented show the percentages of those with data. Unadjusted ORs with 95% CIs were estimated for potential risk and confounding factors using unconditional logistic regression. A full regression model was developed by including both potential explanatory and confounding factors in a core model if there was a pre-existing hypothesis or evidence to suggest that they were causally related to admission with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy, for example asthma. Continuous variables were tested for departure from linearity, and potential interactions were tested by the addition of interaction terms between all variables in the model and subsequent likelihood ratio testing on removal – p < 0.05 was considered evidence for a significant interaction or departure from linearity.

The risk factors for admission to an intensive care unit were examined in a regression model including only women admitted to hospital with confirmed AH1N1v infection. This analysis had 80% power at the 5% level of statistical significance to detect an OR for obesity [body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater] in pregnancy of 3.0 or greater.

Interim reporting

During the pandemic, clinical guidance was produced by the Department of Health and RCOG. Rather than issuing potentially confusing additional guidance, the team informed the development of management guidelines through a series of reports to the organisations developing guidance. The data were analysed on an approximately monthly basis from November 2009. Interim reports were produced and made available to the Department of Health, the Influenza Clinical Information Network and the RCOG pandemic influenza working group, as well as to collaborating clinicians, in order to inform development of ongoing clinical guidance during the course of the pandemic. Interim reports were also publicly available on the UKOSS website. 39–41

Research approvals

This study, and the subsequent protocol amendment allowing the inclusion of pregnant women undergoing vaccination, was approved by the County Durham & Tees Valley 1 Research Ethics Committee (study reference 09/H0905/66). The UKOSS general methodology has previously been approved by the London Research Ethics Committee (study reference 04/MRE02/45).

For the primary care element, research management and governance (RM&G) approval was required from all UK NHS organisations acting as participant identification sites for the original study and, subsequently, for the protocol amendment. This entailed applications to 319 NHS organisations for the original study and 192 organisations for the amendment.

Chapter 3 Results

Women identified in primary care

Incidence of AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy in primary care

Twenty-four general practices, including some linked to the PCRNs in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as well as some non-PCRN practices, provided complete weekly figures to UKTIS, with null reporting, of numbers of pregnant women consulting with suspected swine flu during the study period from 7 September 2009 to 29 January 2010 by the cut-off date of 8 March 2010. These sentinel practices had a combined list size of 216,193 women, including 45,647 who were aged 15–45 and 2431 (1.1%) who were recorded as pregnant as of 1 December 2009. These practices reported 26 consultations involving ILI in pregnant women over the 21 study weeks, giving a mean weekly consultation rate of 51/100,000 amongst pregnant women. As a proportion of all pregnant women, 1.1% (95% CI 0.7% to 1.6%) were reported to have presented with suspected influenza at some point during the study period.

Twenty-three of the practices (combined list size 189,245, with 2061 pregnant women and 40,555 women aged 15–45 years) also provided weekly data on prescribing of antiviral drugs and use of AH1N1v vaccination in pregnant women over the 21-week study period. Antiviral drugs were offered to 100 pregnant women (4.85%, 95% CI 3.98% to 5.89%) and vaccination to 1378 (64.8%, 95% CI 64.7% to 68.9%). Of the pregnant women who were offered vaccination, 520 were reported to have been vaccinated, representing 25.2% (95% CI 23.4% to 27.7%) of all pregnant women and 37.7% (95% CI 35.2% to 40.4%) of those reported to have been offered vaccination.

Recruitment of participants

In total, 159 general practices across the UK forwarded details of at least one pregnant woman who met UKTIS study inclusion criteria and who gave verbal consent for her/their details to be forwarded to the research team. The number of women notified per practice ranged from 1 to 69.

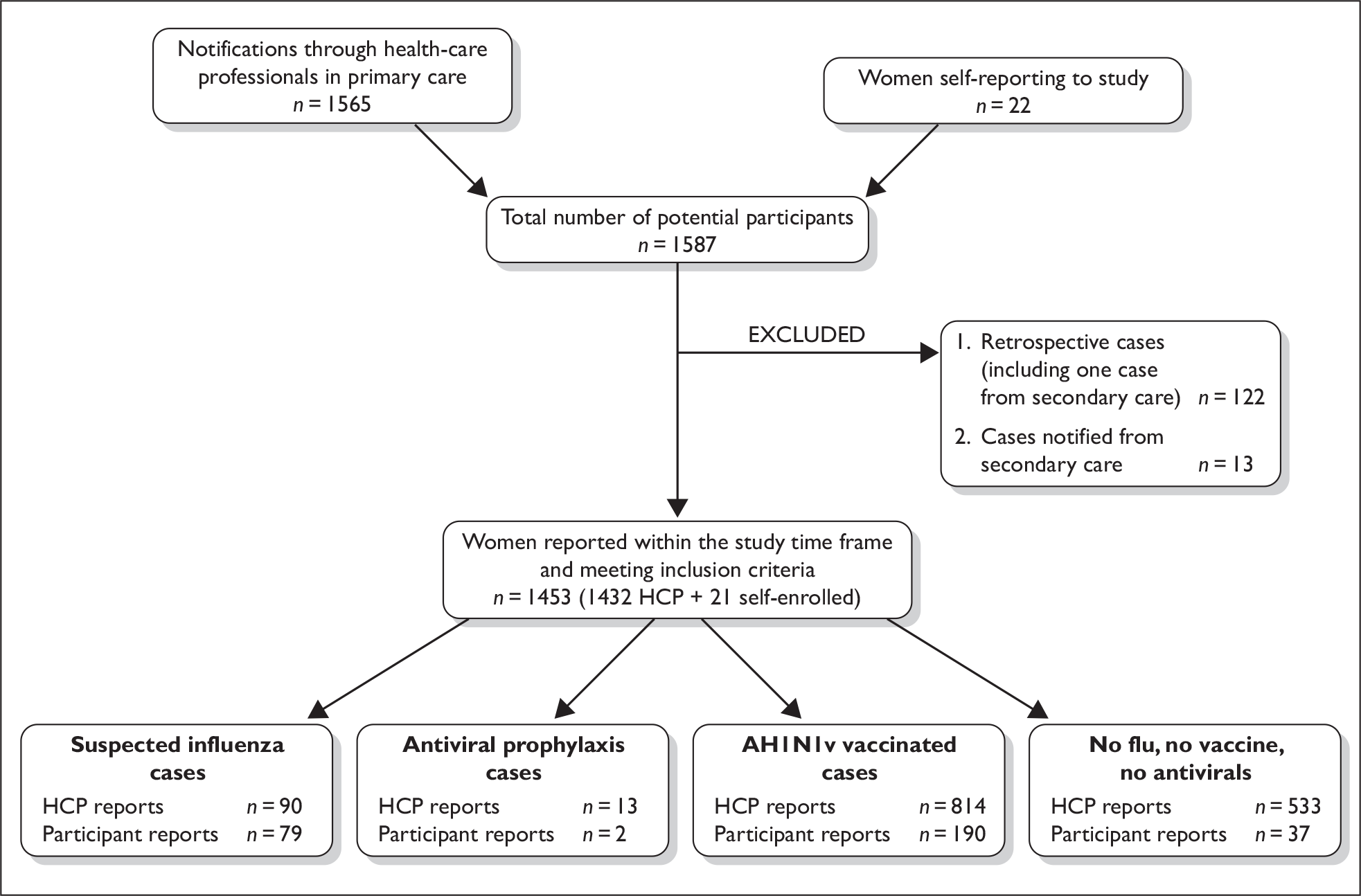

A total of 1587 women were notified to the research team for the period of study. Of these, 1565 were notified with their verbal consent by health professionals and 22 self-reported to the study team. Thirteen notifications from secondary care and 122 retrospective reports (121 health professionals and one self-report) were excluded because pregnancy outcome or an abnormal antenatal result was already known at the time of reporting. There were 1432 health-care reports that met the study inclusion criteria and were included in the current analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment in primary care. HCP, health-care professional.

The health professional reports comprised 90 patients with ILI, 55 of whom were treated with antiviral drugs; 13 patients without symptoms who received antiviral drugs; and 1329 women who were not reported to have influenza symptoms or to have received antiviral therapy but who met the study inclusion criteria because they were pregnant and were offered vaccination.

Of the 13 women reported via secondary care, nine were also included in the UKOSS data set described below, while three cases did not meet the UKOSS inclusion criteria for this study. One case had not been reported to UKOSS, but the information available for this woman was insufficient to determine whether or not she would have met the UKOSS case definition for inclusion in the hospital cohort. None of these women was included in the primary care analysis.

Of the 1565 women consenting verbally to their details being passed to the study team, 234 had provided written consent by the end of the data collection period to allow the study team to collect further information on their pregnancy outcome and infant’s health at 6 months. In total, 263 women meeting the study inclusion criteria had completed the initial participant questionnaire; 26 women withdrew from the study during the period of this analysis.

Of the 90 women reported with influenza symptoms, 23 had been tested for AH1N1v at the time of reporting by a health professional. Of these, two swabs were AH1N1v positive, six were AH1N1v negative and results were pending for 16 (one women whose initial swab was negative was swabbed again). The study team posted virology swabs to 25 women with suspected AH1N1v influenza or influenza symptoms who had not been tested as part of their routine health care. Of the 25 swabs sent, eight swabs were returned to the virology laboratory: two of these were positive and six were negative for AH1Nv and 17 swabs were not returned. Swabs were not sent to the remaining 42 participants as notification occurred outside the period of illness.

Characteristics of women with ILI

Characteristics of the 90 women reported from primary care with suspected or confirmed AH1N1v infection and those of the comparison cohort are detailed in Table 1. Of these, 14 (15.6%) were in their first trimester, 25 (27.8%) in their second trimester and 43 (47.8%) in their third trimester. The trimester was not specified on eight (8.9%) reports.

| Cases | All | (%) | Trimester | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | Unknown | |||

| 14 | 25 | 43 | 8 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Unknown | 9 | (10) | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| < 20 | 2 | (2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–34 | 71 | (79) | 13 | 16 | 36 | 6 |

| ≥ 35 | 8 | (9) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| British or white background | 48 | (53) | 6 | 11 | 30 | 1 |

| Black or other ethnic minority | 11 | (12) | 4 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Unknown | 31 | (34) | ||||

| Smoking behaviour | ||||||

| Never smoked | 34 | (38) | 8 | 7 | 16 | 3 |

| Gave up | 15 | (17) | 2 | 3 | 10 | 0 |

| Current smoker | 12 | (13) | 0 | 2 | 9 | 1 |

| Unknown | 29 | (32) | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Asthma | 14 | (16) | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Psychiatric illness | 3 | (3) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 2 | (2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Obesity | 4 | (4) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Factors associated with increased risk of presenting with ILI were assessed by comparing suspected influenza cases with a comparison group of 1329 women without reported symptoms or antiviral treatment offered vaccination. The characteristics of this control group of women are shown in Table 2.

| Controls | All | (%) | Trimester | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | Unknown | |||

| 131 | 507 | 576 | 115 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Unknown | 114 | (9) | 16 | 40 | 42 | 16 |

| < 20 | 47 | (4) | 3 | 21 | 20 | 3 |

| 20–34 | 932 | (70) | 95 | 340 | 418 | 79 |

| ≥ 35 | 236 | (18) | 17 | 106 | 96 | 17 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| British or white background | 743 | (56) | 78 | 290 | 334 | 41 |

| Black or other ethnic minority | 105 | (8) | 10 | 43 | 49 | 3 |

| Unknown | 481 | (36) | ||||

| Smoking behaviour | ||||||

| Never smoked | 533 | (40) | 45 | 209 | 241 | 38 |

| Gave up | 243 | (18) | 25 | 89 | 119 | 10 |

| Current | 106 | (8) | 14 | 39 | 48 | 5 |

| Unknown | 447 | (34) | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Asthma | 95 | (7) | 5 | 36 | 48 | 6 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 | (0) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1 | (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 | (0) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic heart disease | 1 | (0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic neurological disease | 9 | (1) | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Obesity | 68 | (5) | 5 | 30 | 33 | 0 |

| Psychiatric illness | 3 | (0) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Epilepsy | 3 | (0) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Immunosuppression | 1 | (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 5 | (0) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 4 | (0) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

The low number of cases limits the power of this analysis to compare the characteristics of pregnant women, described in Tables 1 and 2, with an ILI and those who were not ill. Nevertheless, we found a significant association between presentation with an ILI and asthma [adjusted OR (aOR) 2.0, 95% CI 1.0 to 3.9]; there were no statistically significant associations with other comorbid conditions or age (including as a continuous variable), racial group, BMI, IMD score or smoking status (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Case frequency (%a), n = 90 | Comparison group frequency (%), n = 1329 | Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | aOR [95% CI] | p-value | |||

| Age | ||||||

| < 20 | 2 (2) | 47 (4) | 0.6 [0.1 to1.9] | 0.05 | 0.6 [0.1 to 2.1] | 0.08b |

| 20–34 | 71 (88) | 932 (77) | 1c | 1c | ||

| ≥ 35 | 8 (10) | 236 (19) | 0.4 [0.2 to 0.8] | 0.5 [0.2 to 1.0] | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| Normal | 15 (54) | 225 (56) | 1c | 0.84 | –d | |

| Overweight | 9 (32) | 109 (27) | 1.2 [0.5 to 2.9] | |||

| Obese | 4 (14) | 67 (17) | 1.9 [0.2 to 2.6] | |||

| IMD score | ||||||

| IMD < 20 | 50 (61) | 844 (67) | 1c | 0.56 | 1c | 0.73b |

| IMD 20–40 | 23 (29) | 311 (25) | 1.2 [0.7 to 2.0] | 1.2 [0.5 to 2.5] | ||

| IMD > 40 | 8 (10) | 97 (8) | 1.4 [0.6 to 2.9] | 1.2 [0.7 to 2.1] | ||

| Black or other minority ethnic group | ||||||

| Yes | 11 (19) | 105 (12) | 1.6 [0.8 to3.1] | 0.16 | –d | |

| No | 48 (81) | 743 (88) | 1c | |||

| Current smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (13) | 106 (12) | 1.8 [0.9 to 3.2] | 0.08 | 1.3 [0.6 to 2.7] | 0.33 |

| No | 78 (87) | 1223 (88) | 1c | |||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (16) | 95 (7) | 2.4 [1.3 to 4.3] | 0.005 | 2.0 [1.0 to 3.9] | 0.04 |

| No | 76 (84) | 1234 (93) | 1c | |||

| Trimester | ||||||

| 1 | 14 (17) | 131 (11) | 2.2 [1.1 to 4.2] | 0.07 | –d | |

| II | 25 (31) | 507 (42) | 1c | |||

| III | 43 (52) | 576 (47) | 1.5 [0.9 to 2.5] | |||

Presenting symptoms of pregnant women with an ILI, as reported by their general practitioner (GP) or midwife, are shown in Table 4; fever (n = 64, 71%), cough (n = 61, 68%) and sore throat (n = 54, 60%) were the most frequent.

| Symptom | All | (%) | Trimester | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | Unknown | |||

| 14 | 25 | 43 | 8 | |||

| Aching muscles | 22 | (24) | 4 | 11 | 3 | 4 |

| Breathlessness | 24 | (27) | 3 | 8 | 12 | 1 |

| Chills | 31 | (34) | 6 | 7 | 16 | 2 |

| Cough | 61 | (68) | 12 | 16 | 27 | 6 |

| Diarrhoea | 13 | (14) | 0 | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| Fever (> 38°C) | 64 | (71) | 10 | 16 | 31 | 7 |

| Headache | 47 | (52) | 6 | 16 | 23 | 2 |

| Limb or joint pain | 30 | (33) | 6 | 8 | 16 | 0 |

| Loss of appetite | 26 | (29) | 5 | 6 | 14 | 1 |

| Rhinorrhoea | 32 | (36) | 1 | 13 | 14 | 4 |

| Sneezing | 12 | (13) | 0 | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| Sore throat | 54 | (60) | 3 | 14 | 31 | 6 |

| Tiredness | 41 | (46) | 8 | 10 | 20 | 3 |

| Vomiting | 23 | (26) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

| Other | 17 | (19) | 3 | 5 | 9 | 0 |

The information provided by health professionals indicated that 55 (61%) of women with influenza symptoms were prescribed zanamivir or oseltamivir. In 42 cases (76%) these were prescribed within 2 days of symptom onset (Table 5).

| All | % | Antiviral agents administered for | Trimester | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Not reported | Unknown | I | II | III | |||

| Antiviral agents prescribed | ||||||||

| Zanamivir | 50 | (56) | 30 | 20 | 2 | 10 | 14 | 24 |

| Oseltamivir | 5 | (6) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| None | 35 | (39) | ||||||

| Intervals between first symptoms and prescription | ||||||||

| 0–2 days | 42 | (76) | 26 | 16 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| 3–5 days | 8 | (15) | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| > 5 | 1 | (2) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 4 | (7) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Thirty-five (39%) of the symptomatic women did not receive antiviral treatment. In 28 cases reasons were not provided; in the remaining cases reasons were: the antiviral drugs were offered but refused, the GP wanted to see the participant before prescribing treatment, the participant was worried about the effects of the antiviral drugs, symptoms were mild, the symptoms had resolved by the time the participant presented themselves at the surgery, and in two cases participants were prescribed antibiotics instead of antiviral drugs.

The only reported adverse effects attributed to antiviral use were vomiting in one woman taking zanamivir, and nausea and vomiting in one woman who was prescribed oseltamivir.

AH1N1v vaccination in pregnancy

Of the 1432 pregnant women reported to us for this study, 194 (13.5%) were not offered vaccination, often because the report predated availability of the vaccines. A further 406 declined vaccination and 814 women (56.8%) were reported as vaccinated. Other than injection site reactions, health professionals reported adverse effects infrequently (Table 6).

| Study patients | All | % | Trimester | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III | I | II | Unknown | |||

| Immunised (n = 1432) | ||||||

| Yes | 814 | (57) | 369 | 70 | 308 | 67 |

| No | 470 | (33) | 205 | 63 | 164 | 38 |

| Not offered | 194 | (14) | 86 | 14 | 77 | 17 |

| Refused | 406 | (28) | 172 | 58 | 142 | 34 |

| Not known/reported | 98 | (10) | 5 | 14 | 66 | 13 |

| Reported adverse effects (n = 814) | ||||||

| Headache | 15 | (2) | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Arthralgia | 6 | (1) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 26 | (3) | 10 | 1 | 12 | 3 |

| Reaction at injection site | 127 | (16) | 66 | 8 | 48 | 5 |

| Fever | 22 | (3) | 5 | 3 | 9 | 5 |

Data reported by participants

Data were received directly from 263 participants, 79 of whom had symptoms of ILI. Of these, eight had been tested for AH1N1v, with one positive and one negative result available and the remainder pending or unreported. The most common reported symptoms were rhinorrhoea (n = 57, 72%), sore throat (n = 56, 71%), and cough and tiredness (each n = 57, 66%). Eighteen women (23%) had been prescribed antiviral drugs, in 16 cases (89%) zanamivir and in two cases (11%) oseltamivir. In five cases (28%) antiviral drugs were prescribed within 2 days of symptom onset. Two women reported adverse effects with zanamivir (nausea, headaches and dizziness, worsening of asthma) and one reported adverse effects with oseltamivir (nausea and nightmares).

Comparison of the characteristics of the 79 women with symptoms with 182 women without symptoms did not identify significant associations with age, BMI, IMD score, black or ethnic minority group, asthma or trimester of pregnancy, although the conclusions that can be drawn are limited by the very small sample size involved.

Of the asymptomatic participants, two had received antiviral drugs and 212 had been offered vaccination. Of the latter group, 190 (89.6%) had been vaccinated. Adverse effects reported by participants being vaccinated included injection site reactions (n = 97, 51%), myalgia (n = 54, 28%), fever (n = 25, 13%), headache (n = 19, 10%) and arthralgia (n = 8, 4.2%).

Maternal and fetal outcomes

No maternal deaths of pregnant women with suspected swine flu or cases requiring hospitalisation have been reported in the primary care cohort for this study period. However, the amount of follow-up information available from consenting women is currently very limited.

Further follow-up of women included in the study will take place until 6 months after the latest expected dates of delivery and these data, including maternal and fetal outcomes, will be reported when available.

Women admitted to secondary care with confirmed AH1N1v infection in pregnancy

Cases reported

Reports were received from 221 of the 223 hospitals with consultant-led maternity units in the UK (99%). Using the most recently available birth data from the Office for National Statistics (2007), there were an estimated 314,135 maternities (women delivering) during the study period. Thirty-five per cent of hospitals returned negative reports, i.e. hospitals indicated that there had not been any pregnant women admitted with confirmed AH1N1v influenza during the study period. Hospitals reporting cases recorded between 1 and 18 cases, with a median of two cases reported per hospital.

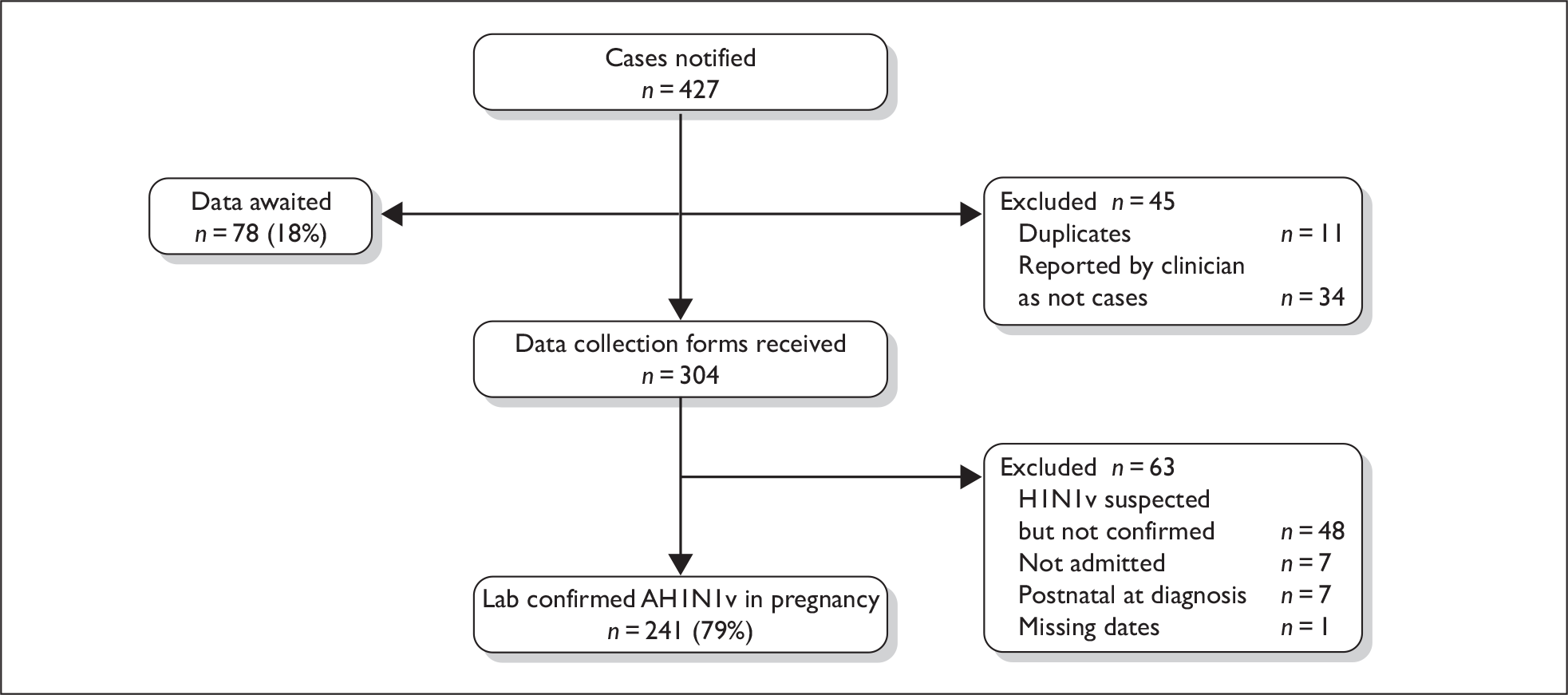

A total of 427 cases were reported, with complete data received for 349 cases (82%) (Figure 2). Thirty-four cases were subsequently reported by clinicians as not cases and there were 11 duplicate reports. Data collection forms were received for 304 women. A further 63 women were excluded because on further examination they did not meet the case definition: 48 women were not confirmed to have had AH1N1v influenza on testing, seven were never admitted to hospital, seven contracted AH1N1v, or were admitted to hospital, after delivery; for one woman, dates of symptoms and admission were missing and thus we were unable to confirm that she met the case definition. There was thus a total of 241 women admitted to hospital in the UK with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in an estimated 314,135 maternities, representing an estimated incidence of 7.7 hospitalised cases per 10,000 maternities (95% CI 6.7 to 8.7 per 10,000 maternities).

FIGURE 2.

Case reporting and completeness of data collection for women hospitalised with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy.

The women who were not confirmed to have AH1N1v infection had a range of final diagnoses: 14 had an unspecified viral respiratory infection, four had a bacterial chest infection, three had a urinary tract infection and seven had a variety of other diagnoses. The final diagnosis was unknown for 20 women.

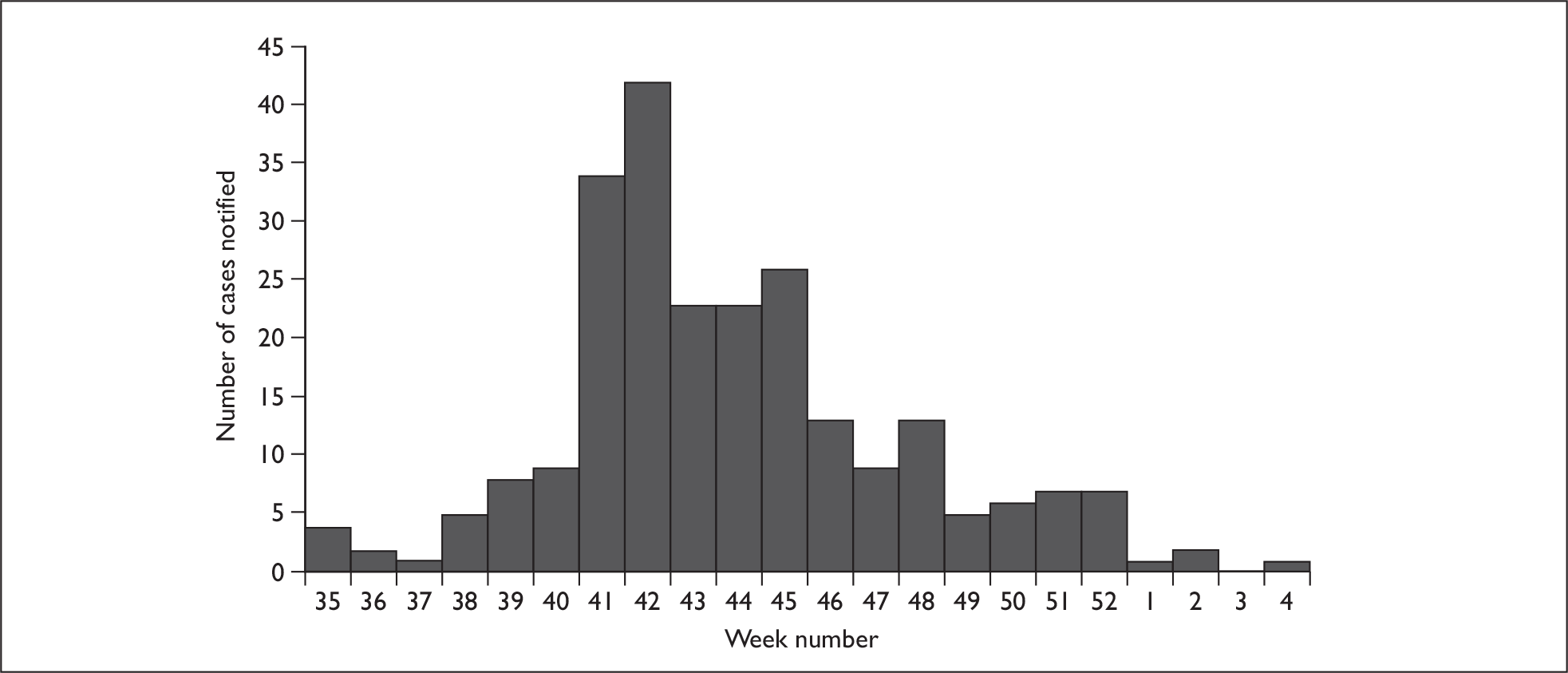

Figure 3 shows the distribution of cases by week of hospital admission or start of symptoms if the date of admission was unknown. The peak number of admissions occurred in week 42, the week commencing 12 October 2009. The epidemic was largely over by the end of 2009, with only four reported admissions during January 2010.

FIGURE 3.

Hospital admissions of pregnant women with AH1N1v by week of hospital admission or start of symptoms (2009–10).

Characteristics of cases and risk factors

Of the 241 women admitted with confirmed AH1N1v, 15 (6%) were in their first trimester, 32 (13%) were in their second trimester and 193 (80%) were in their third trimester. For one woman, the trimester of admission was unknown. Table 7 shows the characteristics of women who were admitted with AH1N1v and the comparison cohort. A one unit increase in BMI was associated with a 5% increase in the odds of admission with AH1N1v in pregnancy (95% CI 2% to 8%) after adjusting for potential confounders, thus women admitted with AH1N1v influenza were significantly more likely to be overweight (aOR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.4) or obese (aOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.0) than the comparison cohort. They were also more likely to have asthma requiring inhaled or oral steroids (aOR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4 to 3.9), to be multiparous (aOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.2), to have a multiple pregnancy (aOR 5.2, 95% CI 1.9 to 13.8) and to be from a black or other minority ethnic group (aOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.3), although this last association was of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.03).

| Characteristic case frequency (%), n = 241 | Comparison group frequency (%), n = 1223 | Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | |||

| Age | ||||||

| < 20 | 25 (10) | 62 (5) | 1.9 [1.2 to 3.1] | < 0.001a | –c | |

| 20–34 | 188 (78) | 897 (73) | 1b | |||

| ≥ 35 | 28 (12) | 264 (22) | 0.5 [0.3 to 0.8] | |||

| BMI | ||||||

| Normal | 84 (40) | 563 (53) | 1b | 0.001a | 1b | 0.0014a |

| Overweight | 70 (33) | 306 (29) | 1.5 [1.1 to 2.2] | 1.7 [1.2 to 2.4] | ||

| Obese | 58 (27) | 202 (19) | 1.9 [1.3 to 2.8] | 2.0 [1.3 to 3.0] | ||

| Managerial or professional occupation | ||||||

| Yes | 44 (28) | 766 (70) | 0.9 [0.6 to 1.3] | 0.58 | –d | |

| No | 112 (72) | 334 (30) | 1b | |||

| Black or other minority ethnic group | ||||||

| Yes | 54 (23) | 220 (18) | 1.3 [0.9 to 1.8] | 0.13 | 1.6 [1.1 to 2.3] | 0.03 |

| No | 184 (77) | 974 (82) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Current smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 55 (23) | 258 (22) | 1.1 [0.8 to 1.6] | 0.53 | c | |

| No | 180 (77) | 940 (78) | 1b | |||

| Multiparous | ||||||

| Yes | 148 (62) | 696 (57) | 1.3 [0.9 to 1.7] | 0.12 | 1.6 [1.1 to 2.2] | 0.01 |

| No | 89 (38) | 525 (43) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Yes | 32 (13) | 66 (5) | 2.7 [1.7 to 4.2] | < 0.001 | 2.3 [1.4 to 3.9] | 0.001 |

| No | 206 (87) | 1154 (95) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Multiple pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (3) | 13 (1) | 3.3 [1.3 to 8.0] | 0.006 | 5.2 [1.9 to 13.8] | 0.001 |

| No | 228 (97) | 8 (3) | 1b | 1b | ||

Women hospitalised with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy were younger than comparison women (unadjusted OR for age less than 20 years = 1.9, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.1; OR associated with a 1-year increase in age OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.92 to 0.96). After testing for all possible two-way interactions in the adjusted model, there was a statistically significant interaction found between age and smoking (p = 0.01, Table 8). Amongst non-smokers, a 1-year increase in age was associated with a 6% decrease in the odds of admission with AH1N1v in pregnancy (95% CI 3% to 9%), among smokers, a 1-year increase in age was associated with a 15% decrease in the odds of admission with AH1N1v in pregnancy (95% CI 8% to 20%). Thus, younger smokers had the highest odds of admission with confirmed AH1N1v influenza (aOR 4.2, 95% CI 2.0 to 8.9) when compared with older non-smokers (Table 8).

| Exposure | n cases (%) | n comparison group (%) | Adjusted OR [95% CI]a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age under 20, smoking | 13 (6) | 25 (2) | 4.2 [2.0 to 8.9] |

| Age under 20, non-smoking | 11 (5) | 35 (3) | 1.8 [0.8 to 4.1] |

| Age 20 or over, smoking | 42 (18) | 233 (19) | 1.0 [0.7 to 1.5] |

| Age 20 or over, non-smoking | 169 (72) | 905 (76) | 1b |

Women hospitalised with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy also had a number of other medical problems, although owing to differences in data collection we were unable to compare these formally with the frequency in comparison women in the multivariate model. Forty-two women had other medical problems, but these disorders were very heterogeneous: 10 women had a metabolic disease, 10 women a haematological disorder, five women had chronic lung disease (excluding asthma), four women had cardiac disease, four women had neurological disease, four women had gastrointestinal disease, three women had endocrine disorders, two women had essential hypertension, and nine women had other problems. Seven women had two or more additional medical problems.

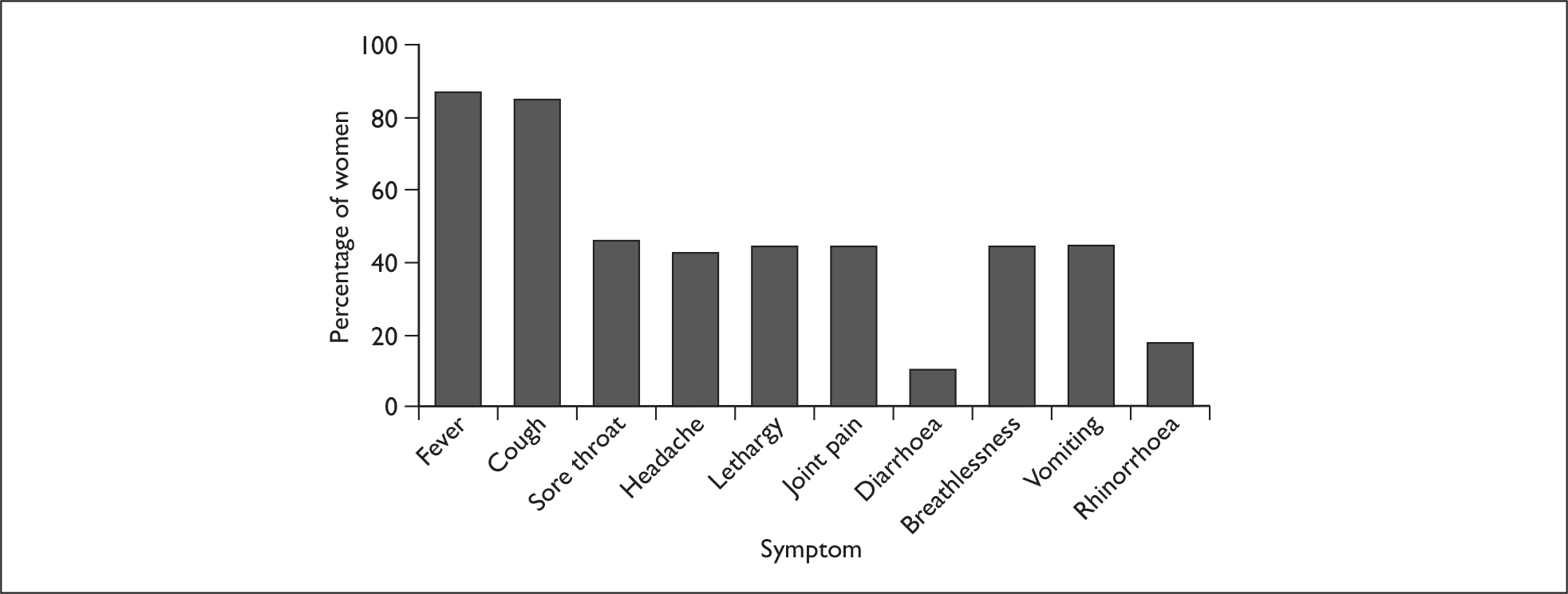

Presenting symptoms and prior immunisation

The most frequent presenting symptoms of AH1N1v infection in pregnancy were fever (206 women, 88%) and cough (201 women, 86%) (Figure 4). Almost one-half of all women also reported a sore throat, vomiting, headache, lethargy and joint pain. The median number of symptoms experienced was five (interquartile range 3–6). Four women had fever as their sole symptom.

FIGURE 4.

Presenting symptoms of AH1N1v influenza in hospitalised pregnant women.

Six women (2%) had been vaccinated before their admission for AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy. These women had been vaccinated a median of 3 days before the onset of symptoms (range 0–9 days) and a median of 7.5 days before the diagnosis of AH1N1v infection was confirmed (range 3–16 days).

Inpatient management

Eighty-three per cent of women hospitalised with AH1N1v were treated with antiviral agents (197 of 237 with known treatment status). The most common first-line antiviral treatment was zanamivir (139 of 196 women where the agent was known, 71%). The route of administration was known for 129 women treated with zanamivir, with 99% (128 women) inhaled (two women, 2% by nebuliser) and 1% (1 woman) intravenous. The remaining 28% of women were given oseltamivir as first line treatment (57 of 196 women), all receiving it orally or by nasogastric tube. Eighteen women who were initially given zanamivir were subsequently switched to oseltamivir. One woman treated initially with oseltamivir was subsequently switched to intravenous zanamivir. Overall, 60% of women received an antiviral agent within the recommended 2 days from symptom onset (134 of 224), but only 6% (14 of 224) received antiviral treatment before admission to hospital (a median of 2 days before admission, range 1–5).

In addition, 34 women (14%) were managed with corticosteroids to enhance fetal lung maturation.

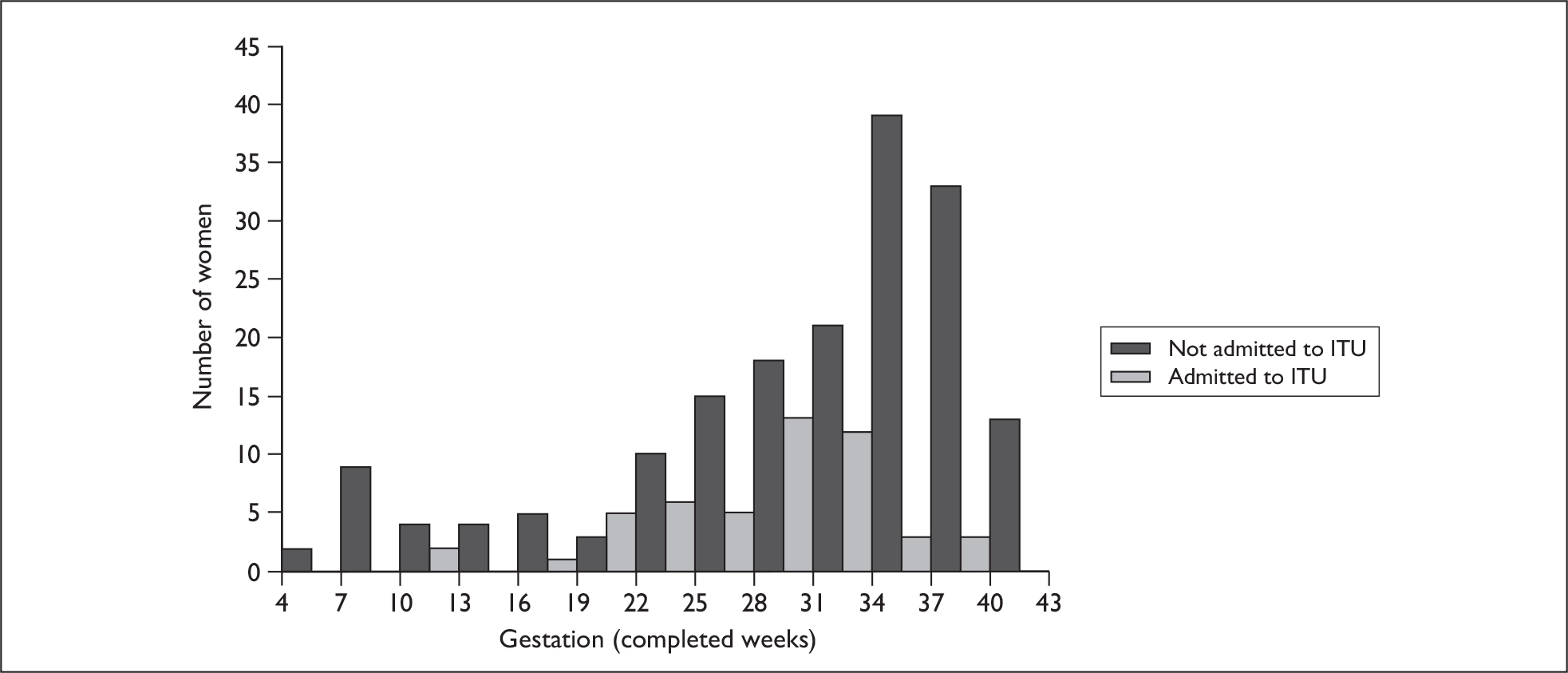

Women were admitted for a median of 3 days with 50% of cases in the range 2–6 days. The longest length of stay was 76 days. Twenty-two per cent of women were admitted to an intensive therapy unit (ITU) (51 of 234 women) and eight women (3%) were reported to have received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. This represents an estimated incidence of 1.6 pregnant women admitted to ITU with confirmed AH1N1v infection per 10,000 maternities (95% CI 1.2 to 2.1 per 10,000 maternities). Forty-four of the women admitted to ITU (86%) were in their third trimester of pregnancy (Figure 5). Women admitted to ITU were more likely to report breathlessness as a symptom of AH1N1v infection than those not admitted to ITU (n = 31, 62% versus n = 74, 41%; p = 0.01), but were less likely to report sore throat (n = 17, 34% versus n = 91, 51%; p = 0.04) or joint pain (n = 14, 28% versus n = 89, 50%; p = 0.006). Table 9 shows the characteristics of women admitted to ITU and those who were admitted to hospital but not to an ITU. Treatment within 2 days of symptom onset was associated with an 84% reduction in the odds of admission to ITU (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.34); 26% of women (12 of 46) admitted to ITU were treated within 2 days of symptom onset compared with 68% of women who were not admitted to ITU (119 of 174). After adjustment, the only other factor statistically significantly associated with ITU admission was BMI; women admitted to ITU were more likely to be obese (aOR 3.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 9.2) than women not admitted to an ITU; a one-unit increase in BMI was associated with a 9% increase in odds of ITU admission (95% CI 2% to 17%) (Table 9).

FIGURE 5.

Gestation at admission for pregnant women with confirmed AH1N1v influenza admitted to an ITU and those admitted to hospital but not to an ITU.

| Characteristic | ITU frequency (%), n = 51 | Non-ITU frequency (%), n = 183 | Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | |||

| Age | 0.44a | 0.81a | ||||

| < 20 | 2 (4) | 22 (12) | 0.3 [0.1 to 1.3] | 0.3 [0.1 to 2.1] | ||

| 20–34 | 44 (86) | 139 (76) | 1b | 1b | ||

| ≥ 35 | 5 (10) | 22 (12) | 0.7 [0.3 to 2.0] | 0.4 [0.1 to 2.0] | ||

| BMI | 0.01a | 0.008a | ||||

| Normal | 11 (25) | 71 (44) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Overweight | 14 (32) | 56 (34) | 1.6 [0.7 to 3.8] | 1.3 [0.5 to 3.5] | ||

| Obese | 19 (43) | 36 (22) | 3.4 [1.5 to 7.9] | 3.4 [1.2 to 9.2] | ||

| Managerial or professional occupation | ||||||

| Yes | 9 (29) | 35 (28) | 1.0 [0.4 to 2.5] | 0.95 | –c | |

| No | 22 (71) | 88 (72) | 1b | |||

| Black or other minority ethnic group | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (14) | 47 (26) | 0.5 [0.2 to 1.1] | 0.08 | 0.6 [0.2 to 1.8] | 0.37 |

| No | 43 (86) | 134 (74) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Current smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 15 (30) | 39 (22) | 1.5 [0.8 to 3.1] | 0.23 | 2.1 [0.8 to 5.5] | 0.14 |

| No | 35 (70) | 140 (78) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Multiparous | ||||||

| Yes | 35 (70) | 110 (61) | 1.5 [0.8 to 2.9] | 0.25 | 0.8 [0.3 to 1.8] | 0.55 |

| No | 15 (30) | 70 (39) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (8) | 28 (15) | 0.5 [0.2 to 1.4] | 0.18 | 2.2 [0.6 to 9.0] | 0.26 |

| No | 46 (92) | 154 (85) | 1b | 1b | ||

| Multiple pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 8 (4) | –d | –d | ||

| No | 51 (100) | 172 (96) | ||||

| Treated within 2 days | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (26) | 119 (68) | 0.2 [0.1 to 0.3] | <0.001 | 0.1 [0.1 to 0.3] | < 0.001 |

| No | 34 (74) | 55 (32) | 1 | 1 | ||

Maternal outcomes

Four women reported to UKOSS, who met the case definition, died, representing a case fatality of 1.7% of women admitted to hospital with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy (95% CI 0.5% to 4.2%). Note that an additional two women who died were reported to UKOSS but did not meet the case definition; one woman did not have virological confirmation of AH1N1v infection and the second had symptom onset after delivery. Maternal deaths were cross-checked with those reported to the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE); four cases meeting the case criteria had been reported to CMACE. Three of these cases had also been reported to UKOSS; one case was identified uniquely through UKOSS and one uniquely through CMACE, representing a total of five deaths in women hospitalised with confirmed AH1N1v infection in pregnancy in an estimated 314,135 maternities, an estimated 1.6 deaths per 100,000 maternities (95% CI 0.5 to 3.7). Note that this figure does not include deaths in women with a symptom onset in the postpartum period.

Pregnancy outcomes

One hundred and fifty-three women (63%) had completed their pregnancy at the time of reporting; the remainder currently have ongoing pregnancies. Among those who have delivered, three pregnancies were miscarried or terminated. There were six stillbirths and 147 live births, representing a perinatal mortality of 39 per 1000 total births (95% CI 15 to 83 per 1000 total births). Forty-five women of the 152 with a known gestation at delivery (30%) delivered preterm at less than 37 weeks’ completed gestation, taking into account three women who were admitted after 37 weeks’ gestation but for whom we do not have other outcome information. Comparison with the uninfected cohort shows that women admitted to hospital with AH1N1v infection were more likely to deliver preterm (OR 5.5, 95% CI 3.7 to 8.3). Note that, owing due to the large number of ongoing pregnancies, these outcome figures are likely to represent a significant overestimate of the proportion of pregnancies with poor outcomes. If we assume, in order to obtain an estimate not biased by lack of outcome data, that all women who are not yet delivered go on to deliver at term, there is still a significant increase in the odds of preterm delivery associated with admission with AH1N1v infection in pregnancy (OR 3.1, 95% CI 2.1 to 4.5).

These figures are very similar when we consider preterm delivery at less than 32 weeks’ completed gestation; 12 women of the 164 with a known gestation at delivery (7%) delivered preterm at less than 32 weeks’ completed gestation, taking into account 11 women who were admitted while still pregnant after 32 weeks’ gestation, who can be assumed to have delivered after 32 weeks’ gestation. Comparison with the uninfected cohort shows that women admitted to hospital with AH1N1v infection are also more likely to deliver very preterm at less than 32 weeks (OR 4.3, 95% CI 2.1 to 8.9). If we assume, in order to obtain an estimate not biased by lack of outcome data, that all women who are not yet delivered go on to deliver at greater than 32 weeks’ gestation, there is still a significant increase in the odds of very preterm delivery associated with admission with AH1N1v infection in pregnancy (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.4 to 6.0).

Chapter 4 Discussion

Management of AH1N1v (2009) influenza in primary care

ILI in primary care

Population data from primary care on the effects of influenza, and, more specifically, AH1N1v (2009) influenza, in pregnancy are lacking. Reports published thus far have focused on cases managed in secondary care and are thus likely to be biased towards the severe end of the spectrum. The primary care element of this study aimed to capture information on the incidence and characteristics of pregnant women with suspected AH1N1v influenza presenting in the community, with a view to identifying factors contributing to adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

The UKTIS is a service commissioned by the HPA to provide advice on drug and chemical exposures during pregnancy. Details of women on whom we provide advice are held to enable follow-up of pregnancy outcome. During the first wave of the 2009 AH1N1v pandemic we collected details of 259 women with suspected AH1N1v influenza or who had been prescribed antiviral medication during pregnancy as part of our routine surveillance activities. Given these figures, the predicted incidence of AH1N1v infection in the second wave, the adoption of our study as NIHR portfolio research and the support of PCRNs across the UK, we had anticipated that we would recruit around 500 pregnant women with suspected AH1N1v influenza presenting in primary care during this 6-month study period. However, recruitment to the study was significantly less than expected for several reasons. First, the incidence of AH1N1v infection circulating in the community during the study period was not as high as anticipated. Second, fewer GP practices than expected were willing to act as participant identification centres for the study. Concern about high influenza consultation rates and staffing during the pandemic was the most frequently expressed reason for non-participation. Compounding this, data that were provided were often incomplete. Third, while ethical approval was provided within a few days of application, there were delays in obtaining the RM&G approvals required before this expedited research could start locally, especially in some parts of the UK. For individual NHS organisations, intervals to approval ranged from 0 to 141 days, with 55% and 19% providing approval for the original application and amendment, respectively, within 2 days. Fourth, although participants had provided verbal permission for their details to be passed to the research team, the numbers of women eventually providing written consent for active follow-up was lower than anticipated.

The move from laboratory-based AH1N1v diagnosis to the treatment phase of the pandemic on 2 July 2009 meant that virological confirmation of AH1N1v in pregnant women presenting in primary care with ILI was no longer performed as a matter of routine. Although AH1N1v rapidly became the dominant circulating strain in certain regions, this was not true in all regions of the UK. In order to characterise accurately the features of AH1N1v infection in pregnancy in primary care and to compare these with those of seasonal influenza, virological confirmation of influenza cases was sought by the study team. The significant delay in launching this study, as described above, resulted in many cases being reported to the study team several weeks after their acute illness. The situation was further exacerbated by the low return rate of consent for follow-up and of self-swabbing kits by consenting participants (8 out of 25).

Interpretation of the AH1N1v influenza infection data collected in primary care is thus limited by the relatively small sample size (n = 90) and low rates of virological confirmation. Nevertheless, the study provides some valuable information about the epidemiology of ILI, although not necessarily AH1N1v influenza, during pregnancy in primary care during the second wave of AH1N1v infection. To put this in context, surveillance data during the same period (weeks 37–53 of 2009) identified that between 15% and 50% of GP consultations for respiratory viral infection in England, and 10% and 34.1% in Scotland, were due to AH1N1v. 42,43

Data collected from the sentinel sites suggests a mean weekly consultation rate for ILI of 51/100,000 pregnant women over the study period. Although it is not possible to undertake a direct comparison with the non-pregnant female population, these figures are within the range reported by the RCGP Research & Surveillance Centre44 for the non-pregnant population over the study period. It should be noted that the National Pandemic Flu Service was in operation throughout the study period. This service, consisting of a website and a network of call centres, was able to assess symptoms and provide antiviral drugs for collection without the need for a GP consultation. Policy, however, was for this service to direct pregnant women to their GP for provision of antiviral therapy, so this was not expected to have a major effect on GP consultation rates for pregnant women.

Comparison of data provided about women presenting with suspected AH1N1v infection with that of pregnant women without features of infection who were being offered vaccination allows assessment of factors that may be associated with infection. The limited numbers of women with suspected infection restrict the power of this comparison. The only factor showing a statistically significant association with an increased risk of AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy in this analysis was maternal asthma. This finding is consistent with reports following the first AH1N1v influenza wave and with data collected in the secondary care arm of this study (see below). Although not statistically significant, our data suggest a similarity in characteristics between women with influenza managed in primary care and the more serious cases requiring hospital admission, with a trend towards women who smoke or who have an IMD score of greater than 20 being at increased risk of influenza when compared with pregnant women who did not report influenza symptoms during the second AH1N1v influenza wave.

Use of antiviral drugs

The proportion of pregnant women with ILI who were prescribed antiviral drugs was 61%, with 76% of these treated within 2 days of symptom onset, when reported by health professionals. In contrast, when reported by participants, 23% were treated with antiviral drugs and only 20% received these within 2 days of symptom onset. The differences may be due to women not taking prescribed antiviral drugs, symptoms being of longer duration than recorded by health professionals or women not seeking antiviral therapy when they develop symptoms. The impact of antiviral therapy on outcomes of influenza during a pandemic would be enhanced by encouraging pregnant women to seek medical advice as soon as possible during their illness and to have facilities for this group to be provided with antiviral drugs at an early stage.

Use of AH1N1v vaccines

The majority of pregnant women were offered vaccination during the study period, with the precise proportion depending on the method of data collection. In the sentinel practices, the data indicate that only 65% of pregnant women were offered vaccination; however, it should be recognised that the vaccines were not available for the initial part of data collection. Much higher proportions were reported by health professionals (86.5%) and by participants (88.5%), although these figures may be inflated by under-reporting of women offered but declining vaccination. Uptake of vaccination was lower, with 37% (sentinel practices), 57% (health professional reports) and 79% (participant reports) of those offered vaccination receiving it. Considering that the vaccines became available only during the study period, the levels of vaccination reported in these cohorts are a considerable achievement by the practices involved. It should be recognised, however, that the UK Chief Medical Officer has reported that as of 3 March 2010 148,000 pregnant women had been vaccinated, which is less than one-quarter of the total. 45 It is important to ensure that all pregnant women without contraindications are offered vaccination and that these women have adequate information available about safety and efficacy of vaccines in pregnancy to make an informed choice.

Pregnancy outcomes

Consenting women will undergo follow-up until 6 months after their expected dates of delivery. Because of the very limited number of women with ILI who have provided consent, it is unlikely that this cohort will provide robust information on adverse maternal effects of influenza in pregnancy or the adverse effects of the use of antiviral drugs. In contrast, the number of women available for follow-up following vaccination is substantially larger, and useful information on the safety of vaccine use in pregnancy will become available in due course. Recruitment into the study is continuing and this will increase the amount of follow-up information eventually available.

Hospitalised women with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy

This study has shown that the UKOSS can be used effectively in response to a public health emergency to rapidly collect data on disease incidence, management and outcomes in pregnant women. The UKOSS network of collaborating clinicians is based in all UK hospital consultant-led maternity units, allowing comprehensive surveillance of women admitted to hospital with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy. This approach, effectively collecting information on the severe end of the disease spectrum, has been recommended as an appropriate method in the pandemic situation, when surveillance of all cases becomes impractical. 46 The availability of the established UKOSS infrastructure allowed for commencement of surveillance within 4 weeks of the study receiving funding and highlights the importance of maintaining such unique national collaborations, especially in the perinatal field where pregnancy exposures, both infective and pharmaceutical, may have major and long-lasting impacts.

We estimate from this study that eight women were hospitalised with AH1N1v influenza for every 10,000 women delivering in the UK. Other national figures for admission with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy have been estimated but use both different numerator and denominator figures. The risk of admission to an ITU with AH1N1v influenza in Australia and New Zealand has been estimated as 1 in 14,600 in women with a gestation of less than 20 weeks and 1 in 2700 for women of 20 weeks’ or greater gestation. 47 The authors do not report figures for women hospitalised with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy. They record 59 women who were pregnant at the time of symptoms of influenza who were subsequently admitted to an ITU during the 3 months of 1 June to 31 August 2009, which we calculate to represent an estimated 6.6 women admitted to ITUs in Australia and New Zealand per 10,000 maternities, based on 2008 birth figures48,49 (95% CI 5.1 to 8.6). This clearly represents a significantly higher rate of admission to an ITU with confirmed AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy than the 1.6 women per 10,000 maternities we estimate in the UK. These differences may reflect an underascertainment of cases admitted to ITUs in the UK, which we hope to investigate further through collaboration with the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, or it may represent a difference in hospital practice or health-care systems between the three countries, for example in access to health care and hence delay in treatment resulting in greater disease severity. It may also reflect a difference in population characteristics between the countries; for example, indigenous ethnicity was an important factor associated with critical illness due to AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy in Australia and New Zealand, clearly not a factor that would impact on illness in the UK. In addition, the Australian and New Zealand data were collected during the peak 3 months of the first wave of the epidemic, whereas our data were collected over 5 months during the second wave; averaging of admissions over a longer period of time may also lead to an apparently lower admission rate, and also there is a possibility that the properties of the circulating virus may have changed over time.

Comprehensive data have recently been reported from the US state of California,50 documenting 94 pregnant women who were admitted to hospital with confirmed AH1N1v between 3 April and 5 August 2009, a period with an estimated 188,383 live births. This represents an estimated 5.0 admissions per 10,000 live births (95% CI 4.0 to 6.1). The UK data expressed with the same denominator represent an estimated 7.5 admissions per 10,000 live births (95% CI 6.6 to 8.5). 38 This observed difference is likely to be explained entirely by differential case ascertainment in areas with different epidemic characteristics. Disease incidence is known to vary widely across regions;51 the US study obtained case reports for pregnant cases from jurisdictions representing only 79% of the population, whereas this UK study covered 98.6% of the population of women giving birth.

The date of the peak of admissions with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy corresponds directly with the peak of infections reported in the UK by the HPA. 52 Only six women hospitalised with AH1N1v influenza in pregnancy had received specific immunisation against the infection; all of these women were infected well within the 3 weeks following vaccination, which it is suggested is required to achieve 98% seroconversion. 53 Note that the main vaccination programme in the UK was rolled out after the peak of hospital admission in this series and these secondary care data are not therefore useful to assess the efficacy of the vaccine.