Notes

Article history

This themed issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a collection of research commissioned by the NIHR as part of the Department of Health’s (DH) response to the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. The NIHR through the NIHR Evaluation Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) commissioned a number of research projects looking into the treatment and management of H1N1 influenza. NETSCC managed the pandemic flu research over a very short timescale in two ways. Firstly, it responded to urgent national research priority areas identified by the Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE). Secondly, a call for research proposals to inform policy and patient care in the current influenza pandemic was issued in June 2009. All research proposals went through a process of academic peer review by clinicians and methodologists as well as being reviewed by a specially convened NIHR Flu Commissioning Board.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 General introduction

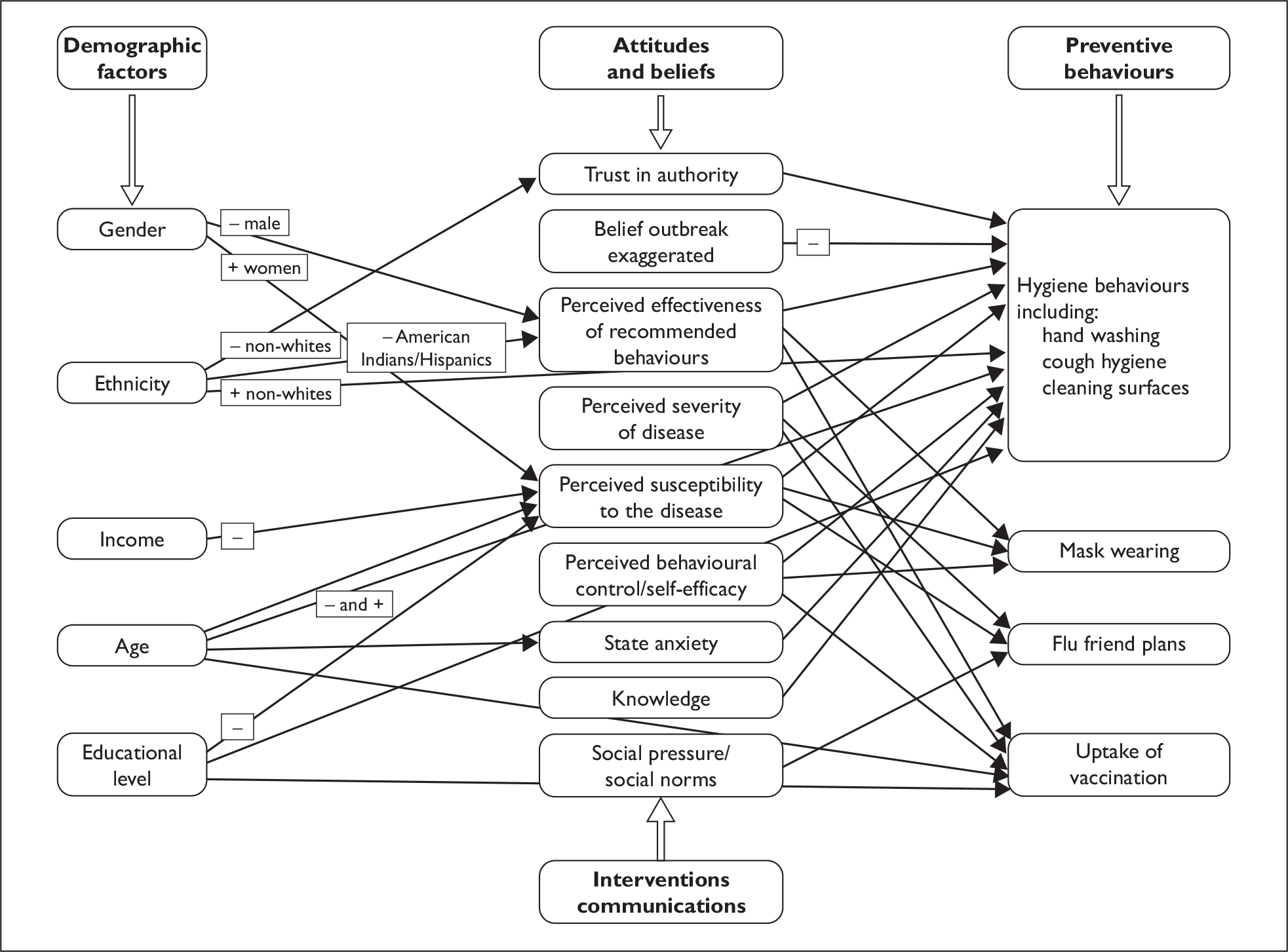

How members of the public react when informed about the outbreak of a novel infectious disease can play a large role in determining the outbreak’s health,1 social2 and economic3 impact. Depending on the disease and the cultural context, governments often recommend that members of the public adopt protective behaviours, such as wearing masks,1 avoiding social events,4 washing their hands more frequently,1 taking prophylactic medication5 or receiving a vaccination. 6 Other actions that members of the public sometimes take, such as avoiding economically important activities that are perceived to be risky,3 shunning particular social groups2 or unnecessarily seeking medical care,7 are often discouraged by governments as causing more harm than good.

Levels of compliance with these official recommendations are rarely perfect. 5,8,9 As well as information received from public health campaigns, information from social contacts or the media and previous experiences with similar incidents can influence how people react during an outbreak, or if they will react at all. One important task that public health bodies can perform during any major incident is to assess how the public responds to the novel threat and what factors are important in influencing those responses. 10,11 Armed with this information, communication campaigns can be designed or fine-tuned to target those factors, with the aim of improving uptake of recommended behaviours and reducing the rates of other, less helpful, actions. Measuring and analysing public responses using theoretical frameworks of behaviour change strengthens this process; it provides greater understanding of the psychological mechanisms through which communication campaigns translate into behaviour and it informs us about the behaviour change techniques that are likely to be effective. 12

The influenza A H1N1v pandemic of 2009–10, commonly referred to in the UK as the ‘swine flu’ outbreak, saw the UK government make several behaviour recommendations to the public using an extensive multimedia campaign. After the first cases of swine flu were confirmed in the UK on 27 April 2009, the government’s messages focused on the importance of hygiene behaviours, such as hand-washing and tissue use, as ways to reduce the spread of the virus, and the appropriate use of NHS health services by people who were concerned that they might have caught swine flu. Later in the outbreak, the government also recommended that those who were believed to be at heightened risk from swine flu should receive the newly available vaccination against it. Consideration was also given to offering this vaccine to the UK population more generally. However, although this policy was widely discussed, it was never put into practice.

In order to assess the impact of the government’s communications campaigns, the Department of Health, England commissioned a series of 40 telephone surveys in which randomly selected members of the public were asked about the information they had heard regarding swine flu and about a range of cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses to the outbreak. As well as providing data that were of immediate relevance in informing policy, the surveys also provided an opportunity to gather data to improve communication strategies in future influenza pandemics or in outbreaks of other forms of infectious disease.

In this report, we present three studies that used unweighted data drawn from the first 36 of these surveys, which took place between 1 May 2009 and 10 January 2010. Data for the final four surveys were still being checked and finalised at the time of our analyses. In the first study we assessed how public perceptions relating to the swine flu outbreak changed over time, with a particular focus on levels of self-reported worry about the possibility of catching swine flu. Because media reporting is an area that official agencies may be able to influence during an outbreak, we also assessed the association between changes in the volume of media attention devoted to swine flu and changes in public perceptions.

In the second study, we used data from 20 of the surveys that were conducted before, during and after the UK’s summer wave of swine flu in order to assess how many people would have accepted the swine flu vaccine, had it been offered to them. Using cross-sectional analyses of the survey data, we also assessed whether the amount of information people had heard about the outbreak or their level of satisfaction with that information was associated with likely acceptance of the vaccine, and whether other factors that could be targeted by future communications campaigns were associated with likely acceptance, such as worry about the possibility of catching swine flu.

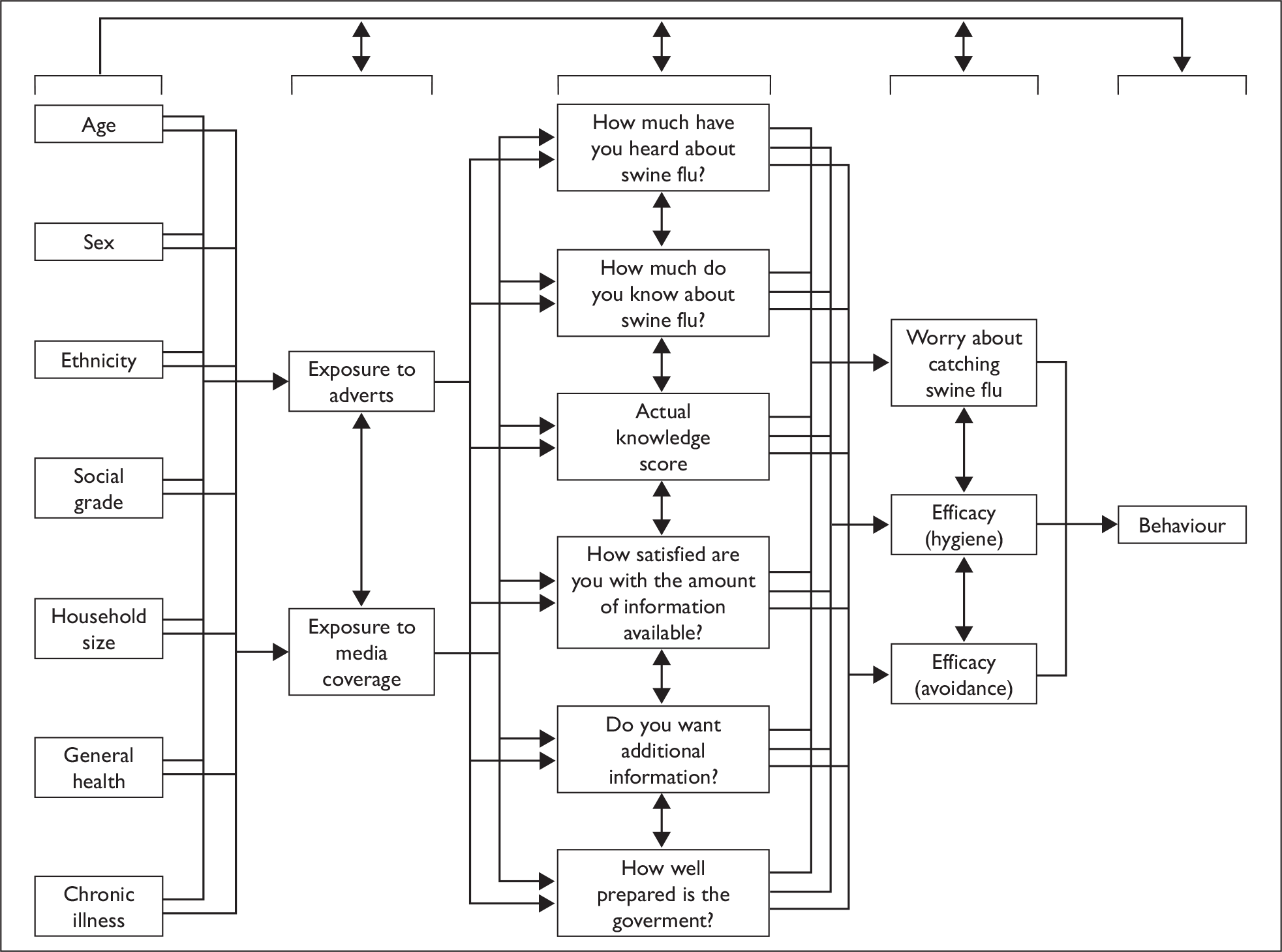

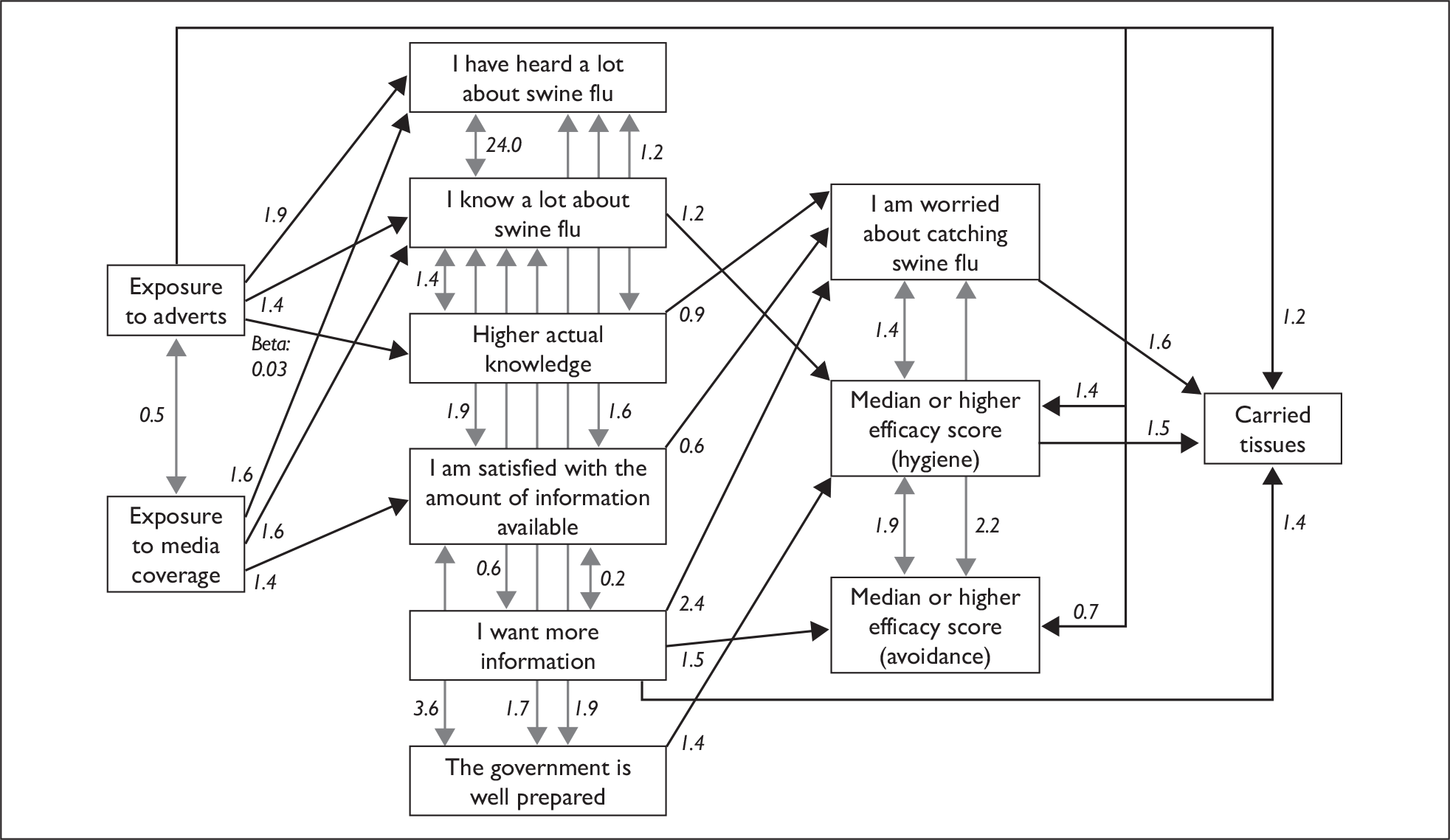

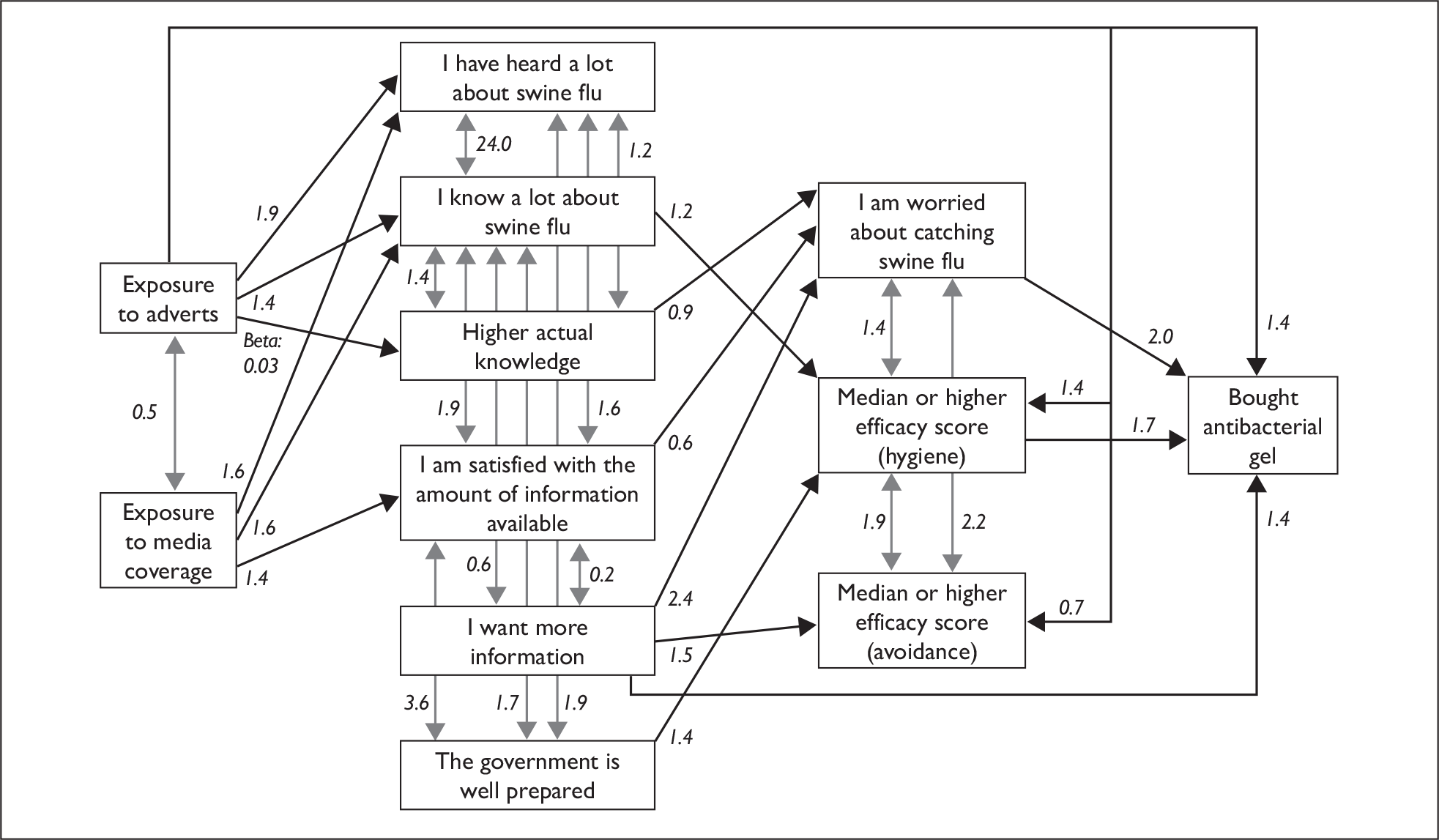

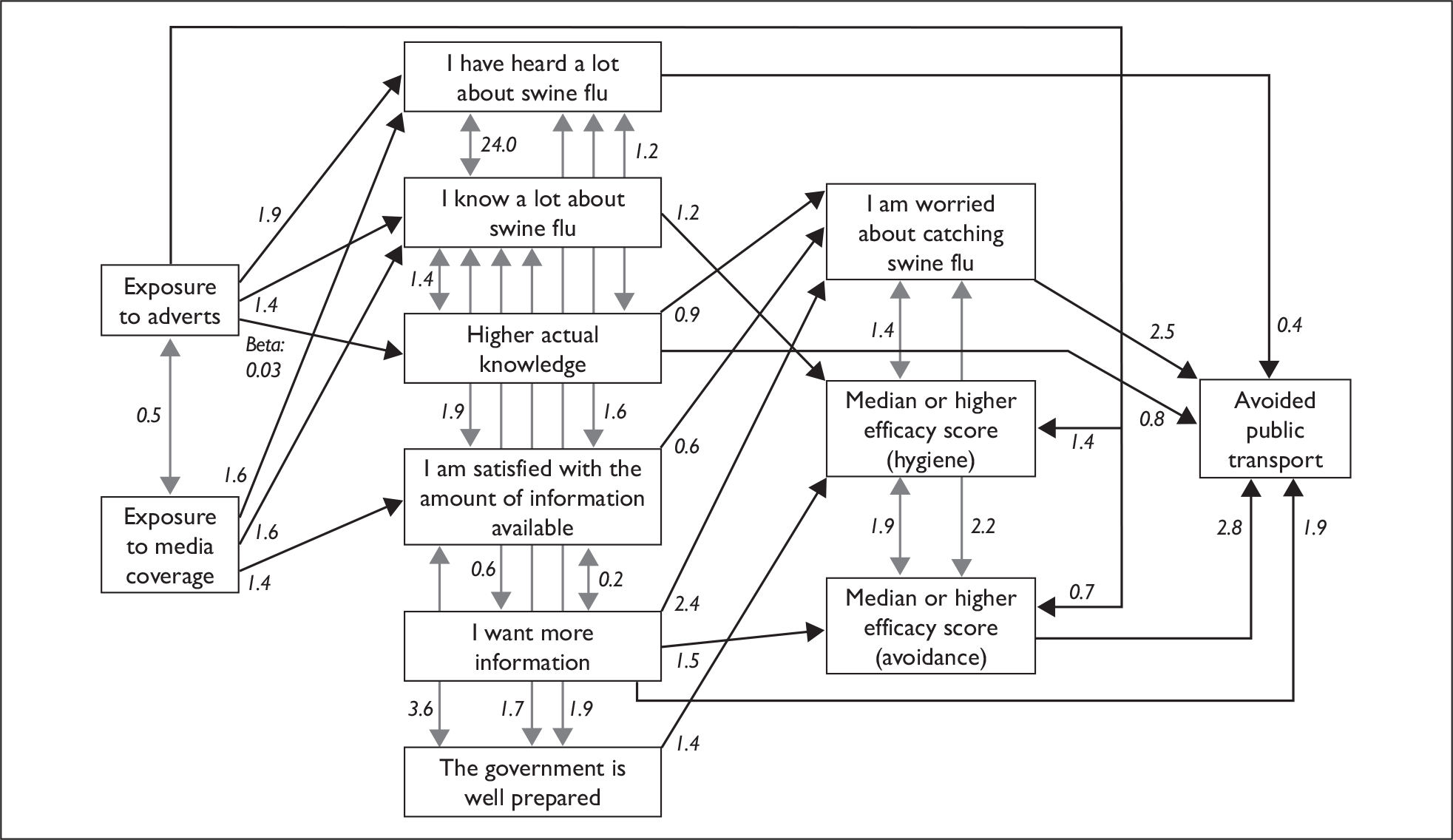

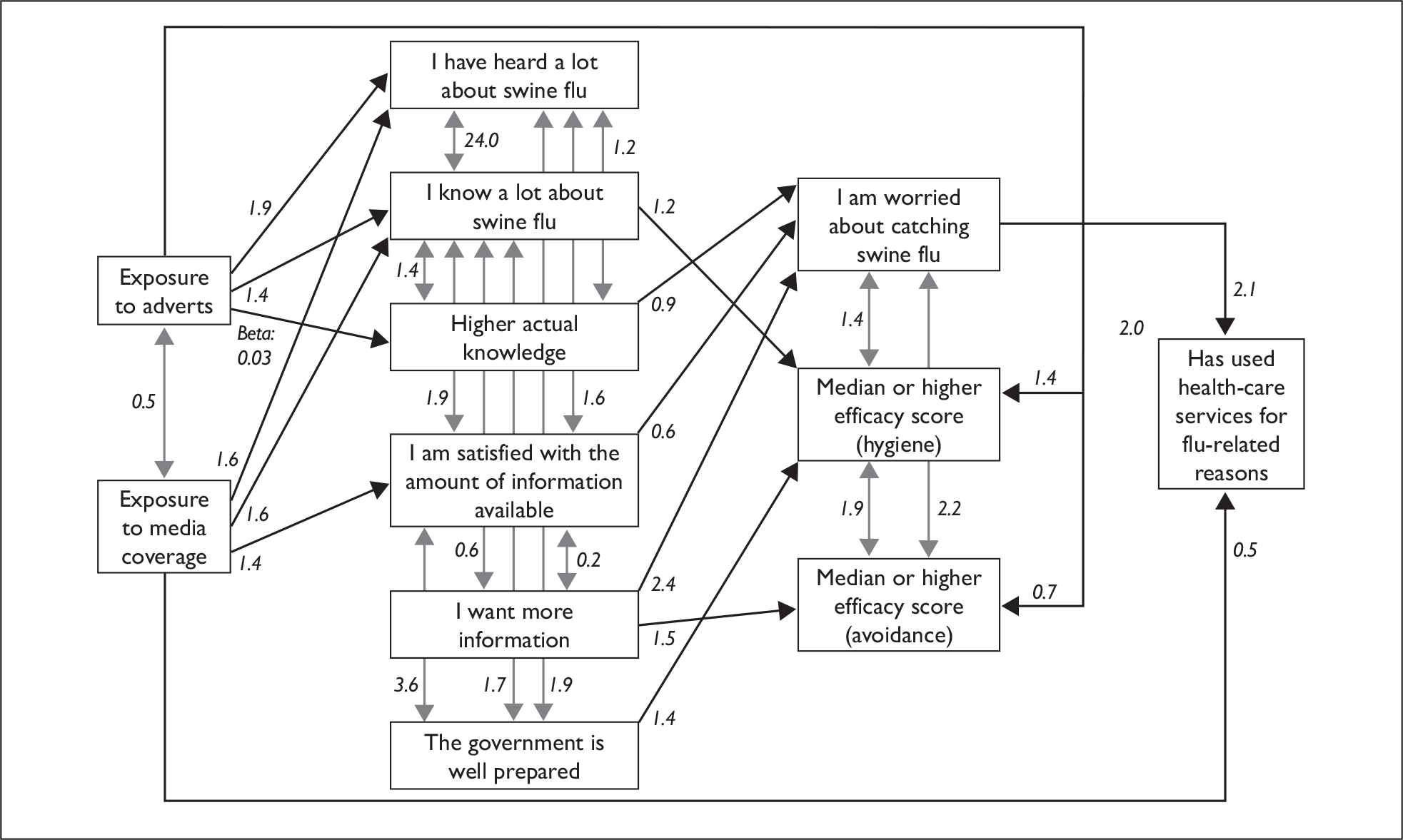

In the third study, we analysed data from the first five surveys that were conducted during May 2009, prior to any large-scale community spread of swine flu occurring in the UK. We assessed the percentage of people who had complied with official recommendations to carry tissues, had bought sanitising gel in order to clean their hands, avoided public transport (a behaviour that was not recommended by the UK government) and unnecessarily used NHS resources for a flu-related reason. We also assessed whether exposure to advertising or media coverage about swine flu influenced whether or not people had engaged in these behaviours, and whether this influence was because exposure altered the amount of knowledge they had regarding swine flu, their perceptions about the information available to them about swine flu, their perceptions about the efficacy of different protective actions or their level of worry about the possibility of catching swine flu.

These studies therefore assessed changes in the survey data over time (study 1) and the cross-sectional associations within the survey data at specific points during the outbreak (studies 2 and 3). Our approach to these analyses was informed by existing psychological models suggesting that worry about a health risk and perceptions about the efficacy of protective behaviours are important factors determining whether an individual will perform a given behaviour in response to a health threat. 13

Our research arose from collaborative work between the Department of Health’s Communications Directorate and the Behaviour and Communications subgroup of the UK’s Scientific Pandemic Influenza Committee, which reported to the Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies during the outbreak (see Appendix 1 for our initial protocol). Analyses were led by the research team of psychologists and a statistician, with regular consultations with colleagues in the Department of Health’s Communications Directorate.

Chapter 2 Study 1: The influence of the media on levels of worry in the community

Key points

-

Members of the public get much of their information about health risks from the mass media. How the media report a given health risk therefore has the potential to affect how the public perceive it.

-

Using aggregate data from 36 UK national telephone surveys, this study demonstrated a correlation between the volume of media reporting about swine flu at any given time point and the number of people worried about the possibility of catching it. However, this association was only observable during the first wave of the outbreak during the summer of 2009. No such associations existed before swine flu had become established in the UK or during the second (winter) wave of the outbreak.

-

In future outbreaks involving a prolonged risk to the public’s health, attempting to keep the media’s attention focused on the outbreak is unlikely to maintain public concern about the risk over the medium to long term and hence their motivation to adhere to recommended protective behaviours. Other strategies may need to be used to maintain the public’s motivation.

Introduction

Members of the public are regularly exposed to health-related information from multiple sources, including friends and family, the internet, commercial advertising and health-care professionals. Most of the health-related information that people receive, however, is obtained from television, radio and the print media. 14,15 Reporting by these news sources has long been recognised as a key factor that can affect people’s health-related behaviours and have both positive and negative consequences for the public’s health. 16–22

One way in which the media exert these effects is by ‘setting the agenda’. The theory of agenda setting suggests that the more coverage an issue receives, regardless of the nature of that coverage, the more important it becomes to members of the public. 23,24 Where the issue is a health risk, an extension to the theory suggests that the more coverage the risk receives then the more concerned about it the public will become, regardless of the nature of the coverage. 25 Numerous studies have demonstrated a link between greater exposure to media reports about a health issue and concern, worry or anxiety about it: examples include anxiety about breast cancer,26 disquiet about genetically modified foods,27 fear of avian influenza28 or worry about a cryptosporidiosis outbreak. 29 Whether such effects persist during a sustained period of reporting is less certain. Two previous studies have assessed the impact of media coverage about severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or the 2001 US anthrax attacks on distress or behaviour change. 9,30 In both studies, while media coverage in the early stages of the incident strongly predicted emotional or behavioural responses, media coverage in the later stages had little impact.

The content of media reporting about a risk may also affect how the public reacts to it. The theories of ‘second-level agenda setting’ and the closely related concept of ‘framing’31 suggest that those attributes of an issue that are made particularly salient by the media, or which are used to place an issue in context, can affect how people perceive it. 24 For health risks, there is a tendency for the media to make salient those attributes that are known to cause greater concern among the public or to reduce the perceived credibility or competence of the government. Examples of such attributes are a hazard’s adverse effects on children, its fatal consequences, and disagreement or uncertainty among scientific experts about the nature of the risk. 32–34 Conversely, portrayal of a risk as having been deliberately exaggerated by politicians, scientists or the media may increase scepticism among the public as to the true importance of the issue and result in decreased levels of concern. 35,36

The 2009 outbreak of swine flu was accompanied by extensive reporting by the UK news media. 36,37 In this study, we assessed whether the quantity of media reporting over the period of the outbreak was associated with changes in the number of people who reported being worried about the possibility of catching swine flu. We also sought to assess whether the amount of media reporting that specifically related to children, deaths, scientific uncertainty or disagreement, or which portrayed swine flu as an overexaggerated risk, was associated with levels of worry. Because swine flu was portrayed as a particular risk to children, we also conducted subgroup analyses to examine the relationship between media reporting and worry for survey respondents who had children in their households. As secondary outcomes, we assessed whether media reporting was associated with being satisfied with the amount of information available about swine flu, having heard a lot recently about swine flu, believing that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu or believing that the government was well prepared for a swine flu pandemic.

Methods

The telephone surveys

Thirty-six telephone surveys were conducted between 1 May 2009 and 10 January 2010 by the Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute on behalf of the Department of Health, England. Each collected data over a 3-day period. The first five surveys were run with less than 2 days between them. Subsequent surveys were run weekly and then fortnightly. Random digit dialling and proportional quota sampling were used to ensure that each sample was demographically representative of the UK population, as determined by the most recent census data, with quotas based on age, gender, geographical region and social grade. 38 To be eligible for a survey, respondents had to be 16 years or over and speak English. Each survey was introduced to respondents as being ‘a national survey covering a variety of subjects’. Any other subjects were covered after the flu-related questions had been asked. The questions included in the surveys changed as the pandemic progressed, with time for completion ranging from 8 to 15 minutes.

The first survey (1–3 May 2009) had a sample size of 1173. All others had sample sizes of between 1047 and 1070. These sample sizes provided a sampling error of about plus or minus 3% for each survey. The total sample size for all 36 surveys was 38,182. Response rates for each survey, calculated as the number of completed interviews divided by the total number of people spoken to regardless of eligibility, were in the region of 8–11%. This is typical for surveys of this nature. 35,39,40

Survey questions

Participants in all surveys were told that ‘Swine flu is a form of influenza that originated in pigs but can be caught by, and spread among, people’ and were then asked ‘How worried, if at all, would you say you are now about the possibility of personally catching swine flu?’ Possible answers were ‘very worried’, ‘fairly worried’, ‘not very worried’ and ‘not at all worried’.

Participants were also asked ‘How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the amount of information available to you about swine flu, from any source?’ Responses of ‘very satisfied’, ‘fairly satisfied’, ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, ‘fairly dissatisfied’ or ‘very dissatisfied’ were recorded.

Participants were asked ‘Please tell me whether you agree or disagree with the following statement: too much fuss is being made about the risk of swine flu.’ Responses of ‘strongly agree’, ‘tend to agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘tend to disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ were allowed.

Perceptions of governmental preparedness were assessed by asking ‘How well prepared do you think the government is for a swine flu pandemic?’ Possible responses were ‘very well prepared’, ‘fairly well prepared’, ‘not very well prepared’ and ‘not at all well prepared’.

In five surveys conducted between 1 May and 17 May 2009, participants were asked ‘How much have you heard about swine flu?’, with possible responses being ‘a lot’, ‘a moderate amount’, ‘a little’ or ‘nothing at all’. A similar question was then introduced in 22 surveys between 24 July 2009 and 10 January 2010, in which participants were asked ‘How much have you heard about swine flu in the past week?’, with responses of ‘a great deal’, ‘a fair amount’, ‘not very much’ or ‘nothing at all’ being allowed. For these later surveys, participants who reported having heard anything about swine flu in the past week were asked where they had heard this information. Responses were coded as relating to advertising (in newspapers or on television), news coverage (in local or national newspapers, on television or on radio), via a general practitioner (through a GP’s surgery or a letter from the GP), on the internet, from friends/family or at work.

In addition to a range of other personal and demographic questions, all participants were asked to state how many, if any, children under the age of 16 years were in their household.

All questions allowed participants to give a response of ‘don’t know’. ‘Don’t know’ responses accounted for no more than 1% of responses to the ‘worry’ and ‘how much have you heard’ items in any given survey, and no more than 3% for the ‘too much fuss’ and ‘satisfaction with the amount of information available’ items. The item relating to government preparedness was the hardest for participants to answer, with between 4% and 13% of respondents replying ‘don’t know’ in each survey. We excluded ‘don’t know’ responses from all analyses.

Media coverage

We assessed media coverage using software supplied by Meltwater News (http://meltwaternews.com). All searches were restricted to the internet sites of 11,132 UK-based news sources. These sources included a mix of national and regional newspapers, magazines, trade journals, television and radio stations and internet news providers. Searches were performed for the start dates of the 36 surveys.

As an indicator of the total amount of coverage devoted to swine flu we searched for any stories that contained the words swine flu, ‘pandemic’ or ‘H1N1’ in their opening paragraph. To assess the number of stories in which children were specifically linked to swine flu, we added a requirement that stories must include a word such as ‘child’, ‘baby’, ‘pupil’ or ‘school’ in the title. Similarly, to identify stories that discussed deaths relating to swine flu we added a requirement that the story must include a word such as ‘death’, ‘dies’ or ‘dead’ in its title. Stories relating to uncertainty or disagreement were identified as those which included the following terms, or common variations, in their title: ‘contradiction’, ‘muddle’, ‘disagree’, ‘uncertain’, ‘controversy’, ‘debate’, ‘doubt’, ‘argument’, ‘confusion’, ‘inconsistent’ or ‘critic’. Stories relating to the exaggeration of swine flu were identified as those that included variations on the following terms in the title: ‘alarmist’, ‘hype’, ‘hysteria’, ‘exaggerated’, ‘overplayed’, ‘overreacting’, ‘over the top’, ‘overstated’, ‘overblown’, ‘embellished’, ‘inflated’ or ‘sensationalised’. The exact searches used are given in Appendix 2.

In order to describe the type of reporting occurring on the start date for each survey, we also conducted a separate search using the Nexis database (www.lexisnexis.com/uk/nexis) to identify all UK-based national or regional newspaper stories with the terms swine flu, ‘H1N1’ or ‘pandemic’ in their title. A random sample of 30 stories was selected for each day to generate a short synopsis of the main aspects of media reporting.

Potential confounders

Because any association between public concern about swine flu and media reporting of it might simply reflect the changing severity of the outbreak, we obtained data on hospitalisations from swine flu in England as an objective marker of outbreak severity. These data were obtained from the Health Protection Agency41 and reflected the number of new patients admitted to hospital with suspected swine flu over a 7-day period.

Analyses

All media variables had a large positive skew, because of a small number of dates on which there was an unusually high level of media reporting. For our analyses, we transformed these data by adding 1 and taking the natural log. For the survey data we grouped together participant responses of ‘very worried’ and ‘fairly worried’ about the possibility of catching swine flu, ‘strongly agree’ and ‘tend to agree’ about too much fuss having been made, answers that the government was ‘very well prepared’ or ‘fairly well prepared’, and answers that the participant was ‘very satisfied’ or ‘fairly satisfied’ with the amount of information available about swine flu. For worry, although responses of ‘very worried’ might have reflected qualitatively different underlying mechanisms than responses of ‘fairy worried’, in practice the data for these two responses showed similar changes over time.

A consistent time interval between the data was required for our analyses. We therefore excluded results from the second and fourth surveys, and from the last three surveys to ensure that those surveys that were included had a gap of roughly 1 week between them. Most analyses were therefore based on data from 31 surveys. We excluded all of the May results for the question relating to the amount heard about swine flu, because excluding the second and fourth surveys left only three results for May followed by a lengthy gap until the question was reintroduced in July. This variable was therefore analysed for 19 surveys. Results from all surveys were plotted on the figures given below.

For the associations between survey data and hospitalisation or media data, we used regression models with autoregressive moving average disturbances. Here the dependent variable is regressed on the independent variable(s) as in a normal regression model but an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model is fitted to the residuals to take into account the time series nature of the data. Although some of the variables are non-stationary, the residuals broadly meet the required assumptions, allowing this approach. For each dependent variable, diagnostic plots were examined and suggested low-order autoregressive modes with either one or two terms. The final model was selected based on the lowest Akaike’s information criterion: a first order autoregressive [AR(1)] model was the best fitting for all of the variables. Associations between the survey variables were then assessed using a likelihood ratio test comparing an AR(1) model with no independent variable and an AR(1) model with a survey variable as the independent variable. Associations between the media variables were tested using Kendall’s non-parametric correlation.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for worry data obtained from people who had children aged under 16 years of age in the household (between 21.7% and 27.9% of respondents in each survey).

Results

Changes in outcome measures over the course of the outbreak

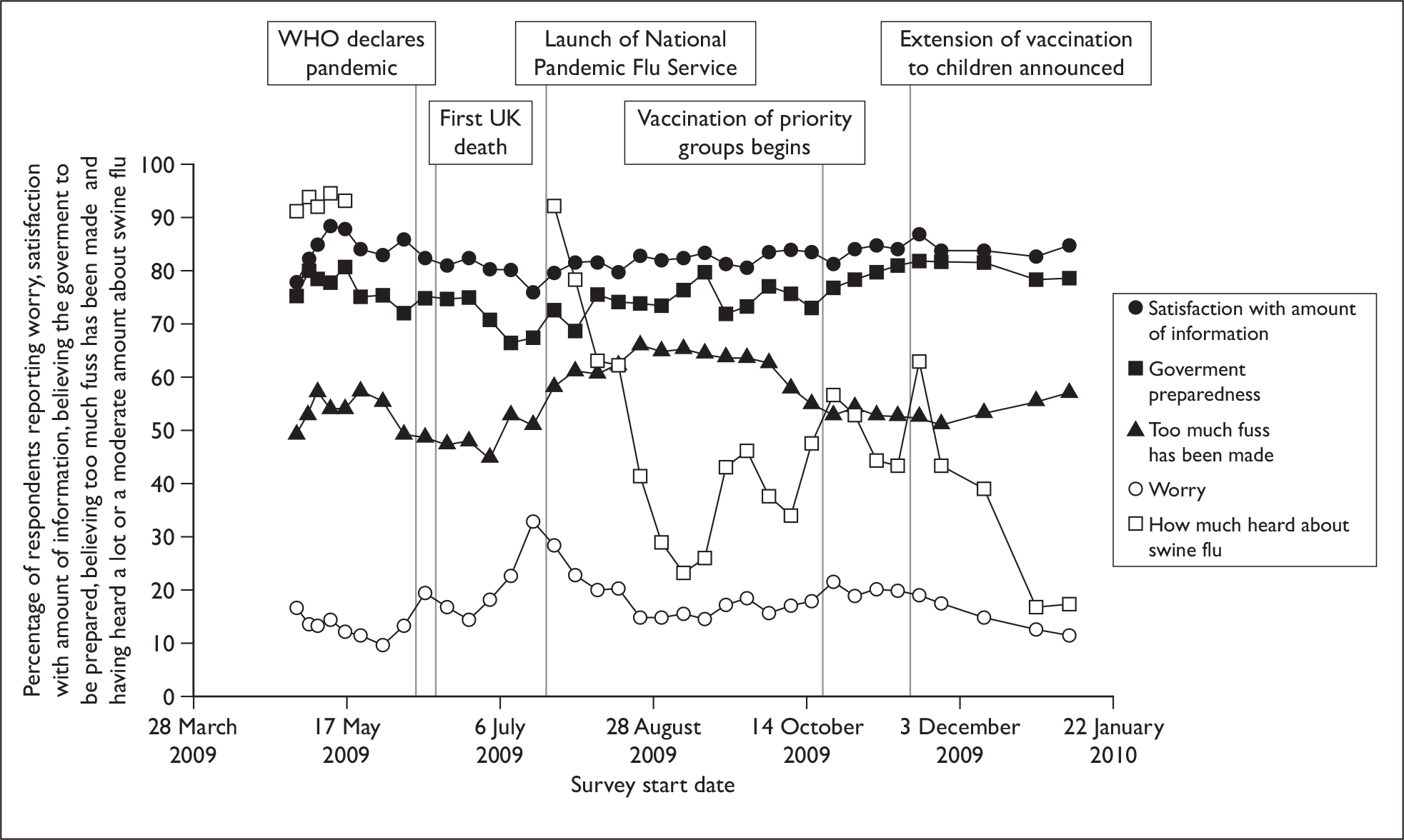

Figure 1 shows the percentages of people within each survey who reported being worried about the possibility of catching swine flu, agreed that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu, felt that the government was well prepared for a pandemic, were satisfied with the amount of information available about swine flu and reported having heard a lot or a moderate amount about swine flu.

FIGURE 1.

Changes over time in survey data. WHO, World Health Organization.

The percentage of people who were satisfied with the amount of information available or who felt that the government was well prepared for a pandemic ranged from 77.6% to 88.4% and from 66.4% to 81.7% respectively. Levels of worry showed larger fluctuations in the first half of the data collection period, rising from initially low levels (9.6–16.6% during May) to a peak of 19.3% in mid-June immediately following the declaration of a full pandemic by the World Health Organization, and a second peak of 32.9% in mid-July at the height of the summer wave of the outbreak. Following the summer wave, levels of worry then remained more stable from the end of August onwards, although smaller increases coinciding with the start of the winter wave of the outbreak and the start of the vaccination campaign were observed. Reports of the amount heard about swine flu showed the most dramatic changes, from initially high levels with over 90% of respondents reporting that they had heard ‘a lot’ or a ‘a moderate amount’ dropping to 11.4% having heard ‘a great deal’ or ‘a fair amount’ by early January 2010. Three noticeable peaks in ‘how much heard’ were observed in late September, late October and late November. These appeared to coincide with the winter wave of swine flu, the start of the swine flu vaccination campaign and the extension of the vaccination campaign to young children, respectively.

Table 1 shows the associations between the aggregate survey data. Overall, a higher level of worry about the possibility of catching swine flu tended to occur at the same time as lower satisfaction with the amount of information available about swine flu and having heard more about swine flu. Higher levels of belief that the government was very or fairly well prepared for a pandemic were associated with greater satisfaction with the amount of information available.

| Predictor variable | Dependent variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very or fairly worried about the possibility of catching swine flu | Strongly agree or agree that too much fuss has been made about swine flu | Believe that the government is very well prepared or fairly well prepared for a pandemic | Very satisfied or fairly satisfied with the amount of information available about swine flu | |

| Too much fuss | χ2(1) = 3.2, p = 0.074, coeff. = –0.3 | |||

| Government preparedness | χ2(1) = 2.0, p = 0.2, coeff. = –0.3 | χ2(1) = 0.1, p = 0.8, coeff. = 0.1 | ||

| Satisfaction with amount of information available | χ2(1) = 12.1, p < 0.001, coeff. = –0.8 | χ2(1) = 3.6, p = 0.058, coeff. = 0.4 | χ2(1) = 5.1, p = 0.024, coeff. = 0.6 | |

| Heard a lot about swine flu | χ2(1) = 22.5, p < 0.001, coeff. = 0.2 | χ2(1) = 1.1, p = 0.3, coeff. = 0.0 | χ2(1) = 2.1, p = 0.1, coeff. = –0.1 | χ2(1) = 1.9, p = 0.2, coeff. = 0.0 |

Participants who had heard something about swine flu had mostly received their information from the mainstream news media (n = 13,581, 74.7%), followed by friends, family or work (n = 3579, 19.7%), advertisements (n = 1959, 10.8%), the internet (n = 1426, 7.8%) and GPs (n = 846, 4.7%).

Changes in media reporting and hospitalisations

The general themes in media reporting on the start dates of each survey are summarised in Appendix 3. Overall, the media were consistent in characterising swine flu as a mild illness for most people. More specific themes changed over time. Throughout most of May, media reports about UK cases of swine flu typically described their connection to Mexico or the USA, either as a result of travel or through contact with a returned traveller. This trend was no longer apparent by early June, as the number of tertiary cases or cases with no known history of travel or contact with a traveller increased. Initial reports focused on ‘firsts’, such as the first cases occurring in local areas or the first instance of person-to-person transmission in the UK. As cases increased during the summer wave of the outbreak, media reporting started to focus on issues relating to government strategy, the capacity of the NHS, the suitability of the newly set up National Pandemic Flu Service, and the safety and efficacy of antiviral medications. From the start of August, the issue of swine flu vaccination became more prominent, with concerns raised about the vaccine’s safety, efficacy and availability, the information given about the order in which it would be provided to different sections of the population, and the apparently low uptake of the vaccine.

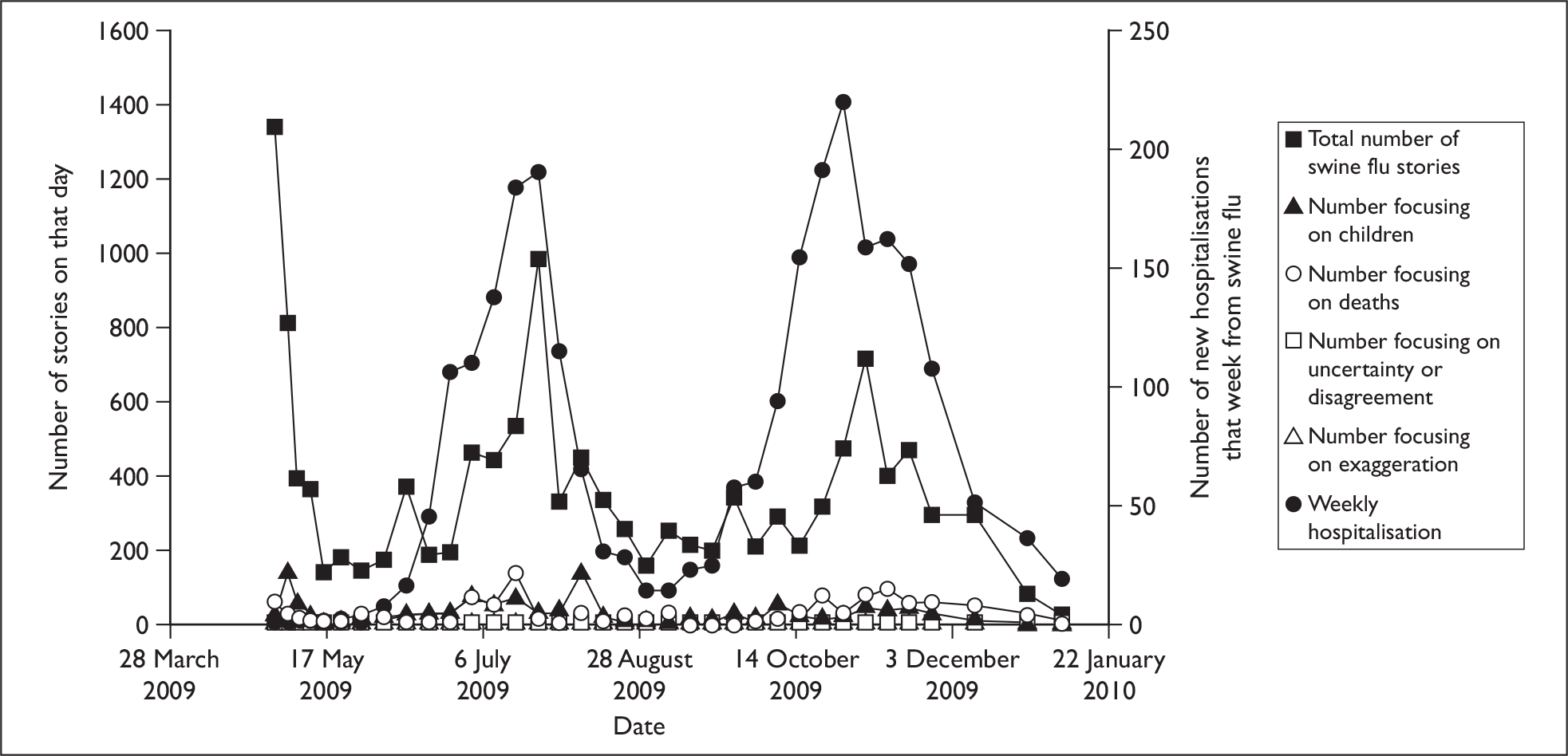

Figure 2 shows the changes in media reporting over time in terms of the total number of stories relating to swine flu and the number relating to children, death, uncertainty or exaggeration. Figure 2 also shows the changes in the number of new hospitalisations from swine flu reported to the Health Protection Agency. The total volume of media reporting started at a high level on 1 May, but decreased rapidly. After a small spike in reporting, which related to the World Health Organization’s declaration of a full pandemic on 11 June, two main peaks in reporting were observed, which largely coincided with the increased prevalence of swine flu during the summer and winter months. There was relatively little reporting that specifically focused on children or deaths. Those reports mentioning death showed a similar pattern to the total volume of coverage, with increases coinciding with the peaks of the outbreak. Articles mentioning children showed two main peaks: on 5 May 2009 following the reporting of the closure of two schools in London and on 7 August 2009 during discussions on whether or not to vaccinate school children. Levels of reporting relating to uncertainty or exaggeration were too low to be analysed and were dropped from all further analyses.

FIGURE 2.

Media reporting and number of new hospitalisations from swine flu.

The association between survey outcomes and media reporting

Table 2 shows the associations between the survey and hospitalisation data, and between the survey and media data adjusting for hospitalisations. Across the whole epidemic, the percentage of people reporting worry about the possibility of catching swine flu correlated with the number of hospitalisations recorded that week [χ2(1) = 8.2, p = 0.004, coefficient = 0.04], the total volume of reporting relating to swine flu after adjusting for hospitalisations [χ2(1) = 6.6, p = 0.010, coefficient = 2.6] and the total number of stories relating to death after adjusting for hospitalisations [χ2(1) = 4.3, p = 0.038, coefficient = 1.0]. Restricting the worry data to that obtained from participants with children in the house did not affect the pattern of results. There was no effect of the volume of reporting relating to children adjusting for hospitalisations [χ2(1) = 0.9, p = 0.3, coefficient = 0.8].

| No. of new hospitalisations that week from swine flu | Total no. of storiesa | No. of stories relating to childrena | No. of stories relating to deatha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worry about the possibility of catching swine flu | χ2(1) = 8.2, p = 0.004, coeff. = 0.04 | χ2(1) = 6.6, p = 0.010, coeff. = 2.6 | χ2(1) = 0.6, p = 0.4, coeff. = 0.0 | χ2(1) = 4.3, p = 0.038, coeff. = 1.0 |

| Too much fuss is being made about the risk of swine flu | χ2(1) = 0.3, p = 0.6, coeff. = –0.01 | χ2(1) = 0.8, p = 0.4, coeff. = –1.1 | χ2(1) < 0.1, p = 0.8, coeff. = 0.1 | χ2(1) = 4.7, p = 0.030, coeff. = –1.0 |

| Perceptions of government preparedness | χ2(1) < 0.1, p = 0.9, coeff. = 0.00 | χ2(1) = 0.1, p = 0.8, coeff. = 0.3 | 2(1) < 0.1, p = 0.9, coeff. = 0.1 | χ2(1) < 0.1, p = 0.9, coeff. = 0.0 |

| Satisfaction with amount of information available | χ2(1) = 0.2, p = 0.6, coeff. = 0.00 | χ2(1) = 6.0, p = 0.014, coeff. = –2.0 | χ2(1) = 1.4, p = 0.2, coeff. = –0.7 | χ2(1) = 1.0, p = 0.3, coeff. = –0.4 |

| How much have you heard about swine flu in the past week? | χ2(1) = 7.7, p = 0.006, coeff. = 0.19 | χ2(1) = 0.7, p = 0.4, coeff. = 4.9 | χ2(1) = 0.2, p = 0.7, coeff. = –1.1 | χ2(1) = 3.0, p = 0.083, coeff. = –4.5 |

Adjusting for hospitalisations, lower volume of reporting about swine flu was associated with greater satisfaction with the amount of information available [χ2(1) = 6.0, p = 0.014, coefficient = –2.0], and fewer stories relating to death was associated with more frequent perceptions that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu [χ2(1) = 4.7, p = 0.030, coefficient = –1.0]. How much someone had heard about swine flu in the past week was associated with the number of hospitalisations for swine flu [χ2(1) = 7.7, p = 0.006, coefficient = 0.19].

The significant associations we identified between the survey data and reporting relating to children or death might have reflected the fact that both reporting relating to children (τb = 0.53, p < 0.001) and to death (τb = 0.51, p < 0.001) were correlated with the total volume of reporting. We investigated this by calculating additional models to test whether adjusting for the total volume of reporting affected the relevant associations shown in Table 2. With worry about the possibility of catching swine flu as the dependent variable, adding the number of stories relating to death to a model that already included the total number of stories did not significantly add to the effect [χ2(1) = 1.6, p = 0.2]. Similarly, with perceptions of too much fuss as the dependent variable, adding the number of stories relating to death to a model that already included the total volume of reporting as an independent variable did not significantly improve the model [χ2(1) = 3.8, p = 0.053].

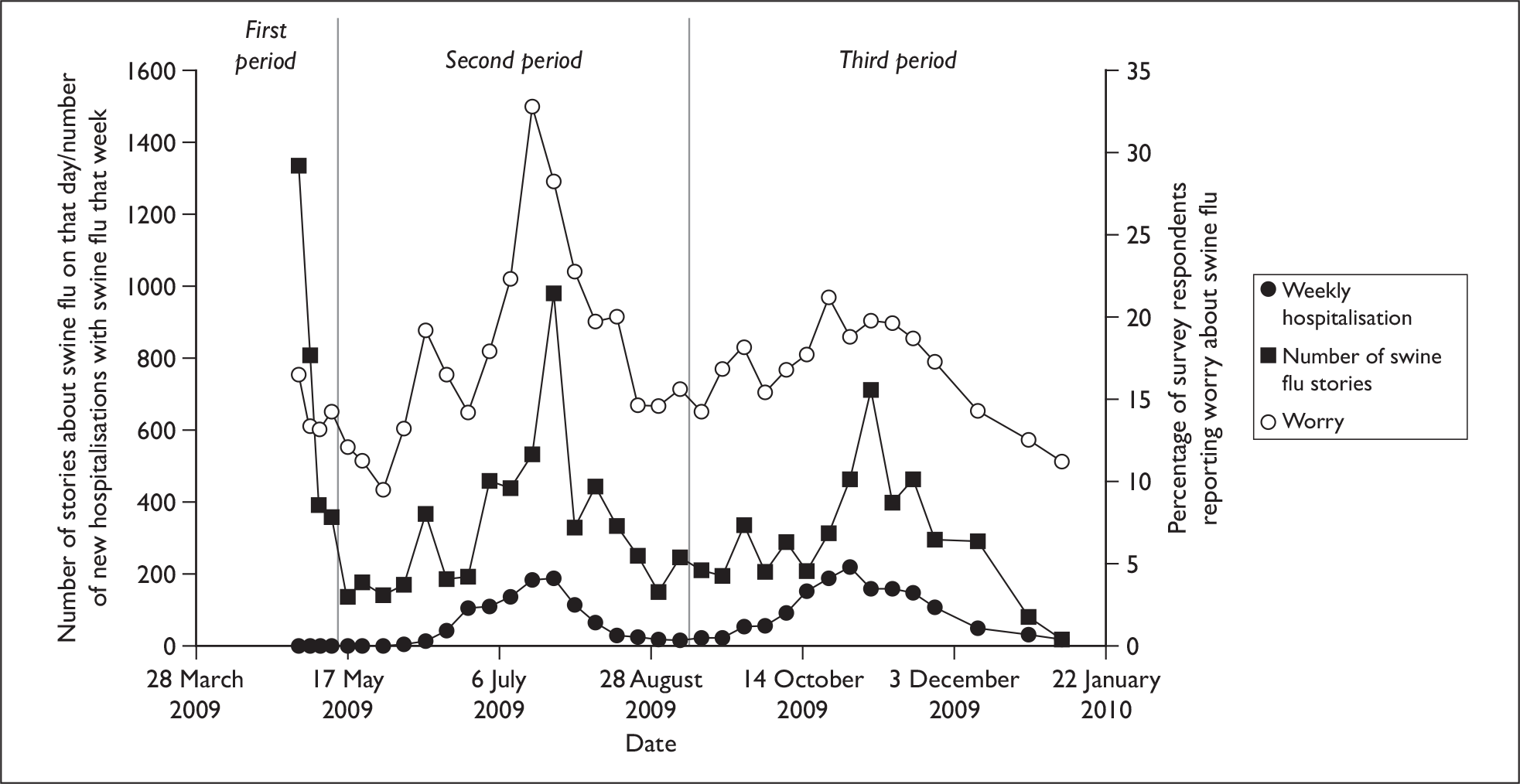

Figure 3 shows changes over time in worry about the possibility of catching swine flu, hospitalisation and the total amount of reporting. On the basis of visual inspection, we split the data into three periods: a first period in which a large volume of media reporting existed but without any substantial spread of swine flu in the community and two further periods reflecting the two peaks of the outbreak (see Figure 3). Although there were insufficient data to assess the relevant associations in the first period, the total volume of media reporting was positively associated with worry about the possibility of catching swine flu in the second and third periods (Table 3). After adjusting for the number of hospitalisations, however, this association remained only in the second period [χ2(1) = 6.8, p = 0.009, coefficient = 6.9].

FIGURE 3.

Changes over time for hospitalisations, media reporting and worry.

| Total no. of stories | Total no. of storiesa | |

|---|---|---|

| Worry about the possibility of catching swine flu (period 2) | χ2(1) = 13.1, p < 0.001, coefficient = 11.0 | χ2(1) = 6.8, p = 0.009, coefficient = 6.9 |

| Worry about the possibility of catching swine flu (period 3) | χ2(1) = 5.2, p = 0.023, coefficient = 3.2 | χ2(1) = 1.4, p = 0.2, coefficient = 1.1 |

Discussion

Our results show that public worry about the possibility of catching swine flu remained at relatively low levels throughout the outbreak. These levels showed some fluctuation, however, and were generally associated with the amount of media reporting about swine flu even after controlling for the potentially confounding influence of the changing nature of the outbreak.

The influence of total volume of reporting

The data relating to the outbreak’s summer wave were largely consistent with a theory suggesting that the total volume of reporting plays an important role in predicting levels of public concern. 25 Indeed, across the outbreak as a whole, quantitative changes in more specific aspects of media reporting, such as coverage relating to children or to deaths, were not associated with changes in worry about the possibility of catching swine flu after we adjusted for the severity of the outbreak and for the total volume of reporting. Although previous research has suggested that the personal relevance of a news story is a key factor in determining whether someone will pay attention to it,42 this lack of effect for specific aspects of reporting held true even for the effects of child-related reporting on participants who had children in their household.

This support for the quantity of coverage theory did not hold for every stage of the outbreak, however. In particular, it was notable that the earliest stage of the outbreak had the highest levels of media reporting yet relatively low levels of worry about the possibility of catching swine flu. One possible explanation for the apparent lack of association during this period is that at the time media reporting did not contain many examples of people in the UK being affected by swine flu unless they had some form of contact with the outbreak in Mexico. 43 This may have led many members of the public to conclude that swine flu was unlikely to be a risk to them. Previous research has suggested that a degree of geographical proximity may be required before people feel that a risk applies to them. 44 This may be particularly true for media coverage relating to infectious disease outbreaks, as the UK press has a history of reporting emerging infectious diseases, such as avian influenza, SARS and Ebola fever, which subsequently failed to become a risk to most people in the UK.

Levels of worry about the possibility of catching swine flu during the winter wave of the swine flu outbreak also failed to show any robust association with the total volume of media reporting. In part, this may reflect the fact that by the time the winter wave had arrived, members of the public had already built up a coherent understanding of the illness and of the outbreak, something that additional reporting did little to change. The decreased level of worry during the second wave suggests that the public had become habituated to flu-related messages and/or that their experience had demonstrated that worst-case scenarios had not occurred. It may also be that changes in the nature of the media reporting were responsible for this lack of an association, with a large proportion of the swine flu-related coverage during the winter period discussing the risks, benefits and roll-out of the swine flu vaccination rather than the impact of the disease itself.

The influence of key events

Although the total volume of media reporting did not show any clear association with worry about the possibility of catching swine flu during the winter period, examination of where changes in survey data occurred suggested that specific developments in the pandemic, such as the start of the winter wave of infections, the start of the vaccination campaign and discussions about the vaccination of children, did appear to be associated with an increase in the proportions of people who had recently heard information about swine flu and who were worried about the possibility of catching it. Even several months into the pandemic, key events were still able to generate increased concern.

One event that did not seem to trigger an increase in worry about the possibility of catching swine flu was the first death in the UK. This is inconsistent with reports from other countries. 45 It is possible than any genuine effect of this event was masked by a greater effect produced by the World Health Organization’s statement that a full pandemic had begun 4 days previously. Alternatively, any effect of the first death may have subsided over the 4-day interval which occurred before data collection began for the next survey wave. Other notable events that might be expected to trigger increased worry, such as the UK’s first case of swine flu, the move by the World Health Organization to phase 5 of its pandemic alert system, and the first case of swine flu in the UK resulting from transmission within the community, occurred either before or on the start date of the first survey, preventing us from examining their effects.

Changes in non-worry variables

Aside from worry about the possibility of catching swine flu and the amount of information heard about swine flu, the other survey data were notable for their relative stability. Satisfaction with the amount of information available about swine flu and belief that the government was well prepared for a pandemic showed little fluctuation and remained at relatively high levels throughout. It may be that this stability reflected the general lack of worry about the outbreak, which restricted any fluctuation in these variables to the minority of people who were worried. With little motivation to actively seek out information, it makes sense that most people were satisfied with the amount of information available to them. It is also understandable that most people were not overtly critical of governmental preparedness for a swine flu pandemic, given that they themselves did not believe swine flu to be particularly concerning. Perceptions that too much fuss had been made were also relatively stable, although some reductions that coincided with the summer and winter waves of the outbreak were observed. The relative stability of this variable suggests that this perception was determined by factors that were not readily amenable to change, for example an already established scepticism regarding the credibility of health warnings issued by the media or the government. 46

Methodological limitations

Several methodological limitations should be borne in mind when considering these results:

-

First, and most importantly, because they were based on aggregate data, our analyses ran the risk of falling prey to the ecological fallacy. 47 While our results indicate that periods of high reporting tended to coincide with high levels of worry about the possibility of catching swine flu among the community, this does not necessarily imply that the same correlations existed on an individual level.

-

Second, our measures of the quantity of media reporting were not ideal. It is likely that we missed some coverage, particularly for news stories that were broadcast on television or radio. Many of these stories will not have been catalogued by the database we used for our searches. Given that television and radio are widely used, this will have reduced the accuracy of our media measures. We were also unable to produce a metric to represent the amount that each story had been viewed, listened to or read. This would have resulted in a more accurate estimate of the effect of media coverage than simply calculating the total number of stories present on any given day. A more detailed content analysis of reporting by specific UK newspapers, coupled with individual-level data on the newspaper-reading habits of the survey participants, will allow a more fine-grained analysis to be conducted at a later date.

-

Third, our use of hospitalisation data as an objective marker of outbreak severity was limited. As well as being influenced by the number of people with swine flu, this measure may also have been affected by changes in doctor and patient behaviour as a result of changing information, perceptions or concerns about the illness. 48 However, alternative measures, such as the volume of calls to a telephone helpline or the number of GP consultations relating to influenza-like illness, were even more likely to be affected by levels of worry in the community,7,45 whereas the number of deaths from swine flu were too low to be a useful marker.

-

Fourth, the power of our analyses was restricted by the number of surveys that we were able to include. In particular, this may have had implications for those analyses that were restricted to data collected during the winter period of the outbreak. These analyses were based on only 12 surveys.

-

Fifth, the generalisability of our findings to other countries or other, more severe, outbreaks cannot be assumed. It is conceivable, for example, that at higher levels of threat and worry, the association between media coverage and worry might disappear, or even reverse. Similarly, in situations where media reporting diverges more dramatically from the official government position, it is possible that media reporting will have a larger impact on levels of uncertainty or worry among the public. Cross-cultural difference in terms of patterns of media use or perceptions of the trustworthiness of the media may also limit the generalisability of our findings.

Conclusions

Despite these methodological caveats, our results suggest that once a new risk has arrived in a country, the volume of media reporting about it will help to determine changes in the level of concern among members of the public. Once the risk has become more familiar, however, this association may be weakened. Given that worry about a risk is an important factor that motivates people to take protective actions13 and that the use of recommended protective actions can fade over time during an infectious disease outbreak,49 maintaining a degree of public concern about a new risk might be an important medium-term strategy for public health bodies that wish to promote the use of particular protective behaviours. Our results imply that attempting to influence the volume of media reporting about a new risk may become a less productive way of achieving this as public familiarity with the risk grows. Nonetheless, the occurrence of key events may continue to trigger increased levels of worry and, potentially, uptake of protective behaviours, even several months after a new risk has emerged.

In terms of the aspects of media reporting that might be the most important to engage with or monitor in any future infectious disease outbreak, our results suggest that the traditional news media remain the source most used by the public in obtaining information about public health incidents. About 75% of survey respondents who had heard anything about swine flu reported having heard this information via local or national newspapers, television or radio. In comparison, despite a growing interest in the use of the internet to convey information to the public,50 only 8% of the public reported having seen information on the internet. While 70% of UK households have internet access,51 there is clearly some way to go before this can become the main route of information transmission between the government and the public during a public health emergency.

Chapter 3 Study 2: Factors predicting likely acceptance of vaccination against swine or seasonal flu

Key points

-

Within the UK, vaccination against swine flu was restricted to specific priority groups. Although wider vaccination of the general public was discussed, it was never implemented.

-

Analysis of survey data collected prior to the start of the swine flu vaccination campaign suggested that only 56.1% of the general population were likely to have accepted the vaccine if offered it. Strong predictors for being likely to accept it were being worried about the possibility of personally catching swine flu, or being worried about the possibility of one’s children catching it, and disagreeing that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu. Predictors for being more likely to accept the seasonal flu vaccine as a result of swine flu were similar, but also included the misperception that the seasonal flu vaccine would protect against swine flu.

-

If a vaccine needs to be given to the general public during a future infectious disease outbreak, messages that highlight people’s concerns or worries about the outbreak may be effective in improving uptake. Communications that emphasise the effectiveness of the vaccine in protecting against the disease are also likely to be effective.

Introduction

Within the UK, vaccination against swine flu began to be provided to priority groups from 21 October 2009. These groups consisted of frontline health and social care staff, people in clinical at-risk groups for seasonal influenza, pregnant women and household contacts of people with compromised immune systems. Other members of the public were also considered for vaccination at a later date,52 although this policy was never put into practice. At the time, efforts to increase the uptake of the seasonal flu vaccine were also renewed. 53

Maximising the uptake of either vaccine would have reduced the health and economic impact of influenza during the pandemic,54 but it is unclear what uptake rates would have been possible. In the UK, uptake of the seasonal flu vaccine for people aged 65 or over was 74.1% in 2008, close to World Health Organization targets;55 whether the focus on swine flu during 2009 increased this rate is currently uncertain. Given that swine flu was a relatively mild illness for most people, it is possible that had the swine flu vaccine been offered to the general public, its uptake would have been relatively low. 56,57 Furthermore, while confidence in the government’s handling of the outbreak appears to have been high35 and might be expected to have improved compliance with official recommendations concerning vaccination,58 the perception by some members of the public that journalists, scientists and other commentators had overexaggerated the risks of swine flu may have partly counteracted this effect. 35,59

Specific perceptions concerning the nature of the swine flu outbreak may also have affected desire for vaccination. For example, research conducted during the SARS outbreak of 2003 suggested that changes in media reporting relating to the incidence, prevalence and location of cases had an effect on levels of anxiety and other health-related behaviours. 9,19,60 Although the impact of mass media campaigns on vaccine uptake has previously been documented,20,61 few studies have assessed whether the way in which an infectious disease outbreak is reported or perceived affects desire for vaccination. 21

In this study, we analysed data from the telephone surveys commissioned by the Department of Health, England to identify variables associated with the 2009 swine flu outbreak that might encourage people to receive vaccination. We assessed the extent to which worry about the possibility of catching swine flu, perceptions of government preparedness for swine flu and perceiving that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu predicted self-reported likelihood of accepting an offer of vaccination against swine flu. We also assessed whether the amount and type of information heard about swine flu, and satisfaction with the amount of information available predicted likely uptake. Because we were also interested in whether the 2009 outbreak might encourage people to receive the seasonal flu vaccine, we assessed whether any of these variables were associated with a self-reported increase in the likelihood of accepting the offer of vaccination against seasonal flu as a result of swine flu.

Methods

The surveys

Twenty of the telephone surveys contained relevant data for these analyses. These surveys were conducted between 8 May 2009 and 13 September 2009. Their sample sizes varied between 1047 and 1070.

Likely vaccine uptake

Likely uptake of the swine flu vaccine was measured in five surveys conducted between 14 August and 13 September 2009. Participants were asked: ‘The government announced recently that a swine flu vaccination programme will be rolled out across the UK starting this autumn. How likely, if at all, are you to take up a swine flu vaccination if offered it?’ Possible answers were ‘very likely’, ‘fairly likely’, ‘not very likely’ and ‘not at all likely’. These were divided into ‘likely’ and ‘not likely’ for our analyses.

Likely uptake of the seasonal flu vaccine was measured in all 20 surveys from 8 May to 13 September. Participants were asked whether they agreed or disagreed that ‘as a result of swine flu, I am now more likely to get the regular winter flu jab’. Possible answers were ‘strongly agree’, ‘tend to agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘tend to disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’. For our analyses, responses were dichotomised into ‘agree’ versus ‘disagree’. Because the question would have been hypothetical for some respondents, particularly those who would not usually expect to be offered the seasonal flu vaccine, we felt that responses of ‘neither agree nor disagree’ might have indicated either a participant’s uncertainty about being vaccinated or the fact that they did not feel the question was applicable to them. Rather than conflate these two groups, we chose to exclude responses of ‘neither agree nor disagree’.

Worry and perceptions

All participants were asked ‘How worried, if at all, would you say you are now about the possibility of personally catching swine flu?’ Possible answers were ‘very worried’, ‘fairly worried’, ‘not very worried’ or ‘not at all worried’. In four surveys (conducted from 21 August to 13 September), parents of children aged under 16 years were also asked how worried they were about the possibility of their child or children catching swine flu. Participants in all surveys were asked ‘How well prepared do you think the government is for a swine flu pandemic? Would you say very well, fairly well, not very well, or not at all well prepared?’ They were also asked whether they agreed or disagreed that ‘Too much fuss is being made about the risk of swine flu.’ Finally, in six surveys (7 August to 13 September), participants were asked whether they, or anyone they knew, had caught swine flu.

Information heard about swine flu

Participants in eight surveys (24 July–13 September) were asked ‘How much have you heard about swine flu in the past week?’, with possible responses being ‘a great deal’, ‘a fair amount’, ‘not very much’ and ‘nothing at all’. Those who had heard anything were asked to describe what they had heard. We categorised responses to this open-ended item as relating to: increased number of deaths; increased number of new cases; decreased number of new cases; information about vaccines or priority groups for vaccination; information about antiviral drugs or hygiene measures; and suggestions that the number of cases would rise later in the year. Three true or false items were included relating to vaccines or immunity: ‘Currently, there is no vaccine to protect against swine flu’ (true: 14 surveys, 8 May–2 August), ‘If swine flu breaks out, most people will have some natural immunity to it’ (false: three surveys, 8–17 May) and ‘The ordinary flu vaccine will protect me from swine flu’ (false: 14 surveys, 8 May–2 August). All participants were asked about their satisfaction with the amount of information available to them about swine flu (‘very satisfied’, ‘fairly satisfied’, ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, ‘fairly dissatisfied’, ‘very dissatisfied’).

Personal and health-related variables

Personal data collected included: gender, age, social grade,38 working status, ethnicity, parental status and household size (the number of adults or children living at home, including self). For ethnicity, although 16 categories were included, the sample sizes for many of our analyses prevented us from comparing between these categories. We therefore separated the 16 categories into ‘white’ and ‘ethnic minority’ groups. All participants were asked whether their health in general was very good or good, fair, or poor or very poor, and whether they had any ‘long-standing illness, disability or infirmity’. Participants were also asked in which region of the UK they lived.

Analyses

We used binary logistic regressions to calculate the univariate associations between personal and health-related variables and likely uptake of vaccination. We calculated a second set of regressions for each personal or health-related variable, which adjusted for the effects of all other personal or health-related variables. In order to assess whether coming from a region that had been heavily affected by the outbreak affected these associations, we recalculated these regressions using data from participants who lived only in England and adjusting for whether a participant lived in one of the two regions of England with the highest prevalence rates of swine flu (London and the West Midlands). 41 This did not noticeably alter any of the aORs and is not discussed further.

We used two sets of binary logistic regressions to assess the univariate associations between other variables and likely uptake of vaccination, and to assess the multivariate associations adjusting for those personal or health-related variables that were found to have significant univariate associations with the outcome measure.

Finally, in order to assess the potential role of worry in mediating any of the effects that we identified, we calculated another set of logistic regressions for any variable that showed a significant multivariate association with vaccination uptake, including worry about the possibility of personally catching swine flu as one of the variables for which we adjusted.

We maximised the statistical power for these analyses by combining data from all surveys that included the relevant questions. As different questions were used in different weeks, the sample sizes for each analysis differed. While the frequencies for individual variables obtained for these surveys changed over time, we assumed that the associations between variables would remain constant. In order to check this, we identified three periods during the data collection period that, we judged, might be qualitatively different in terms of public perceptions relating to swine flu. Two periods (May to July and August to mid-September) reflected relatively low levels of activity in media reporting, internet searches in the UK for the phrase swine flu62 and GP consultations for influenza like-illnesses. 41 The other period (July to August) reflected higher activity in all three parameters. For any univariate analysis that drew on data from two or more of these periods, we calculated the equivalent odds ratios (ORs) for that analysis using only the individual surveys closest to the midpoints of the respective periods. Wald tests were used to compare the regression coefficients obtained for these individual surveys. Six associations were found to differ significantly over time (data not shown). In all cases but one, these differences reflected relatively small changes in the strength of the association. An association between ethnicity and being more likely to accept the seasonal flu vaccine as a result of swine flu appeared to display larger changes over time. Plotting the relevant OR from each individual survey over time showed no readily interpretable pattern.

In all analyses, we counted responses of ‘don’t know’, ‘unsure’ or ‘neither agree nor disagree’ as missing data: such responses typically had low frequencies for the predictor variables. For six surveys in which the relevant question was asked (7 August 2009 to 13 September 2009), we excluded participants who reported that they had already had swine flu (2–3% of participants in each survey).

Results

Likely vaccine uptake

Out of 5175 eligible respondents questioned between 14 August 2009 and 13 September 2009, 1642 (31.7%) reported being very likely to accept the swine flu vaccine if offered it, 1263 (24.4%) were fairly likely, 1005 (19.4%) were not very likely and 1074 (20.8%) were very unlikely; 191 (3.7%) said they did not know. Out of 20,999 eligible participants interviewed between 8 May and 13 September, 3506 (16.7%) strongly agreed that as a result of swine flu they were now more likely to get the seasonal flu vaccine, 2700 (12.9%) tended to agree, 3219 (15.3%) neither agreed nor disagreed, 5865 (27.9%) tended to disagree and 5475 (26.1%) strongly disagreed; 234 respondents (1.1%) did not know.

Association with personal and health-related variables

Tables 4 and 5 show the association between personal or health-related variables and vaccine-related outcomes. After adjusting for all other personal or health-related variables, the following groups reported being most likely to accept the swine flu vaccine if offered it: participants aged 16–24 (aOR versus those aged 65 or more: 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.4); people from ethnic minority groups (aOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.5); people from households of six individuals or more (aOR versus those who lived alone: 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.6); people who rated their health as fair (aOR versus those with good or very good health: 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7); and people with long-standing illnesses or disabilities (aOR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.7). The same groups also reported being more likely to accept the seasonal flu vaccine as a result of swine flu. In addition, participants aged 65 or more, people from social groups C2DE (that is, manual or unskilled workers, or those dependent on state welfare),38 and participants who rated their health as poor or very poor were also more likely to accept the seasonal flu vaccine (see Table 5 for ORs).

| Variable levels | n (%) | n (%) likely to accept vaccine | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 2957 (59.3) | 1747 (59.1) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) |

| Male | 2027 (40.7) | 1158 (57.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Age – years | ||||

| 16–24 | 435 (8.7) | 308 (70.8) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) |

| 25–34 | 578 (11.6) | 360 (62.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.6) |

| 35–54 | 11,677 (33.6) | 884 (52.7) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) |

| 55–64 | 927 (18.6) | 511 (55.1) | 0.8 (0.6 to 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| ≥ 65 | 1367 (27.4) | 842 (61.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Social grade | ||||

| C2DE | 2225 (44.6) | 1334 (60.0) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| ABC1 | 2759 (55.4) | 1571 (56.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Working status | ||||

| Housewife | 241 (4.8) | 143 (59.3) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Unemployed | 173 (3.5) | 106 (61.3) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| Retired | 1633 (32.8) | 985 (60.3) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Student | 242 (4.9) | 162 (66.9) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Other (including disabled) | 167 (3.4) | 102 (61.1) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| Working full or part-time | 2528 (50.7) | 1407 (55.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Other ethnicity | 357 (7.2) | 260 (72.8) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.6) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) |

| White | 4627 (92.8) | 2645 (57.2) | Reference | Reference |

| Parental status | ||||

| Has child 16 years or under | 947 (23.9) | 529 (55.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| Has older child or no children | 3022 (76.1) | 1730 (57.2) | Reference | Reference |

| Household size | ||||

| Six people or more | 97 (2.0) | 73 (75.3) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.4) | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.6) |

| Three to five people | 1660 (33.5) | 978 (58.9) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) |

| Two people | 1802 (36.4) | 1017 (56.4) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) |

| One person | 1395 (28.2) | 823 (59.0) | Reference | Reference |

| General health status | ||||

| Poor or very poor | 350 (7.0) | 231 (66.0) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Fair | 766 (15.4) | 507 (66.2) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Very good or good | 3855 (77.5) | 2159 (56.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Does participant have any long-standing infirmity or illness? | ||||

| Yes | 1477 (29.7) | 960 (65.0) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) |

| No | 3496 (70.3) | 1938 (55.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Variable levels | n (%) | n (%) more likely to accept vaccine | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 10,283 (58.6) | 3720 (36.2) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Male | 7263 (41.4) | 2486 (34.2) | Reference | Reference |

| Age – years | ||||

| 16–24 | 1584 (9.0) | 649 (41.0) | 0.5 (0.5 to 0.6) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.1) |

| 25–34 | 2082 (11.9) | 517 (24.8) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) |

| 35–54 | 5982 (34.1) | 1269 (21.2) | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.2) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) |

| 55–64 | 3219 (18.3) | 1109 (34.5) | 0.4 (0.4 to 0.4) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) |

| ≥ 65 | 4679 (26.7) | 2662 (56.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Social grade | ||||

| C2DE | 7773 (44.3) | 3497 (45.0) | 2.1 (2.0 to 2.3) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) |

| ABC1 | 9773 (55.7) | 2709 (27.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Working status | ||||

| Housewife | 773 (4.4) | 269 (34.8) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) |

| Unemployed | 701 (4.0) | 247 (35.2) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.2) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) |

| Retired | 5547 (31.6) | 2989 (53.9) | 4.0 (3.7 to 4.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Student | 837 (4.8) | 359 (42.9) | 2.5 (2.2 to 2.9) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Other (including disabled) | 636 (3.6) | 277 (43.6) | 2.6 (2.2 to 3.1) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Working full or part-time | 9052 (516) | 2065 (22.8) | Reference | Reference |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Other ethnicity | 1277 (7.3) | 585 (45.8) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.4) |

| White | 16,269 (92.7) | 5621 (34.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Parental status | ||||

| Has child 16 years or under | 832 (24.7) | 216 (26.0) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Has older child or no children | 2542 (75.3) | 959 (37.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Household size | ||||

| Six people or more | 378 (2.2) | 169 (44.7) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.4) |

| Three to five people | 5801 (33.3) | 1565 (27.0) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.5) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Two people | 6295 (36.1) | 2266 (36.0) | 0.7 (0.7 to 0.8) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| One person | 4944 (28.4) | 2160 (43.7) | Reference | Reference |

| General health status | ||||

| Poor or very poor | 1338 (7.7) | 719 (53.7) | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.9) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

| Fair | 2733 (15.6) | 1316 (48.2) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.3) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

| Very good or good | 13,422 (76.7) | 4145 (30.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Presence of any long-standing infirmity or illness | ||||

| Yes | 5264 (30.1) | 2428 (46.1) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.5) |

| No | 12,224 (69.9) | 3756 (30.7) | Reference | Reference |

Association with worry and perceptions

Controlling for personal and health-related factors, the following variables were associated with being more likely to accept the swine flu vaccine if offered it (Table 6): having higher levels of worry about the possibility of your child catching swine flu (aOR 8.0, 95% CI 4.6 to 13.9); having higher levels of worry about the possibility of personally catching swine flu (aOR 4.7, 95% CI 3.2 to 7.0); disagreeing that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu (aOR 2.2, 95% CI 1.9 to 2.7); perceiving the government to be well prepared for swine flu (aOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.8); and knowing someone who had had swine flu (aOR 1.2, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.3). All of these variables except for perceptions about government preparedness and knowing someone who had had swine flu were associated with being more likely to accept the seasonal flu vaccine as a result of swine flu (Table 7).

| Variable levels | n (%)a | n (%) likely to accept vaccine | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worry about self catching swine flu | ||||

| Very worried | 177 (3.6) | 143 (80.8) | 5.1 (3.5 to 7.5) | 4.7 (3.2 to 7.0) |

| Fairly worried | 624 (12.6) | 498 (79.8) | 4.8 (3.9 to 5.9) | 4.9 (4.0 to 6.2) |

| Not very worried | 1916 (38.6) | 1233 (64.4) | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.5) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.6) |

| Not at all worried | 2246 (45.3) | 1014 (45.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Worry about child catching swine flu | ||||

| Very worried | 180 (19.1) | 148 (82.2) | 9.7 (5.7 to 16.4) | 8.0 (4.6 to 13.9) |

| Fairly worried | 301 (32.0) | 187 (62.1) | 3.4 (2.2 to 5.3) | 3.3 (2.1 to 5.3) |

| Not very worried | 328 (34.8) | 149 (45.4) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.7) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.7) |

| Not at all worried | 133 (14.1) | 43 (32.3) | Reference | Reference |

| Too much fuss is being made about the risk of swine flu | ||||

| Disagree | 1351 (29.8) | 952 (70.5) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.4) | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.5) |

| Agree | 3178 (70.2) | 1679 (52.8) | Reference | Reference |

| How well prepared is the government for swine flu? | ||||

| Well prepared | 3423 (75.4) | 2100 (61.3) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.8) |

| Not well prepared | 1118 (24.6) | 590 (52.8) | Reference | Reference |

| Has anyone you know been ill with swine flu? | ||||

| Yes | 1600 (32.1) | 976 (61.0) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) |

| No | 3384 (67.9) | 1929 (57.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Variable levels | n (%)a | n (%) more likely to accept vaccine | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worry about self catching swine flu | ||||

| Very worried | 714 (4.1) | 441 (61.8) | 4.0 (3.4 to 4.7) | 4.5 (3.0 to 6.9) |

| Fairly worried | 2372 (13.6) | 1203 (50.7) | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.8) | 3.2 (2.5 to 4.1) |

| Not very worried | 6835 (39.1) | 2359 (34.5) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) |

| Not at all worried | 7544 (43.2) | 2154 (28.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Worry about child catching swine flu | ||||

| Very worried | 164 (19.8) | 79 (48.2) | 5.3 (2.9 to 9.5) | 3.4 (1.8 to 6.4) |

| Fairly worried | 257 (31.0) | 67 (26.1) | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.5) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.1) |

| Not very worried | 289 (34.8) | 51 (17.6) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) |

| Not at all worried | 120 (14.5) | 18 (15.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Too much fuss is being made about the risk of swine flu | ||||

| Disagree | 6398 (39.6) | 2479 (38.7) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) |

| Agree | 9776 (60.4) | 3255 (33.3) | Reference | Reference |

| How well prepared is the government for swine flu? | ||||

| Well prepared | 12,221 (73.9) | 4309 (35.3) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) |

| Not well prepared | 4308 (26.1) | 1554 (36.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Has anyone you know been ill with swine flu? | ||||

| Yes | 1583 (31.6) | 518 (32.7) | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) |

| No | 3425 (68.4) | 1327 (38.7) | Reference | Reference |

Association with information heard about swine flu

Tables 8 and 9 show the associations between information heard about the outbreak and likely vaccine uptake. Adjusting for personal and health-related variables, only two variables were associated with being more likely to accept the swine flu vaccine if offered it: being satisfied with the amount of information available about swine flu (aOR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.9) and having recently heard that the number of deaths from swine flu had increased (aOR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.6). Once personal variables and health were controlled for, only satisfaction with the amount of information available about swine flu (aOR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.0) and believing that the seasonal flu vaccine would protect against swine flu (aOR 2.4, 95% CI 2.1 to 2.7) were associated with being more likely to get the seasonal flu vaccine as a result of swine flu.

| Variable levels | n (%)a | n (%) likely to accept vaccine | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much have you heard about swine flu this week? | ||||

| A great deal | 684 (13.7) | 388 (56.7) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| A fair amount | 1139 (22.9) | 695 (61.0) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) |

| Not very much | 1939 (39.0) | 1131 (58.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) |

| Nothing at all | 1215 (24.4) | 687 (56.5) | Reference | Reference |

| How satisfied are you with the amount of information available? | ||||

| Satisfied | 4024 (90.9) | 2437 (55.0) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

| Not satisfied | 403 (9.1) | 212 (52.6) | Reference | Reference |

| What have you heard? | ||||

| Number of cases increased | ||||

| Heard | 454 (12.3) | 290 (63.9) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) |

| Not heard | 3243 (87.7) | 1882 (50.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of cases decreased | ||||

| Heard | 740 (20.0) | 1767 (59.8) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) |

| Not heard | 2957 (80.0) | 405 (54.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of deaths increased | ||||

| Heard | 370 (10.0) | 238 (64.3) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) |

| Not heard | 3327 (90.0) | 1934 (58.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Anything about vaccination | ||||

| Heard | 375 (10.1) | 228 (60.8) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) |

| Not heard | 3322 (89.9) | 1944 (58.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Anything about antiviral agents or hygiene | ||||

| Heard | 433 (11.7) | 258 (59.6) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Not heard | 3264 (88.3) | 1914 (58.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of cases will rise later in year | ||||

| Heard | 153 (4.1) | 84 (54.9) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Not heard | 3544 (95.9) | 2088 (58.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Variable levels | n (%)a | n (%) more likely to accept vaccine | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much have you heard about swine flu this week? | ||||

| A great deal | 1665 (24.7) | 603 (36.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| A fair amount | 1862 (27.6) | 791 (42.5) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| Not very much | 2080 (30.8) | 743 (35.7) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Nothing at all | 1145 (17) | 410 (35.8) | Reference | Reference |

| How satisfied are you with the amount of information available? | ||||

| Satisfied | 14,337 (89.6) | 5154 (35.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) |

| Not satisfied | 1656 (10.4) | 644 (38.9) | Reference | Reference |

| There is no vaccine for swine flu | ||||

| True | 5873 (50.4) | 1963 (33.4) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) |

| False | 5774 (49.6) | 2013 (34.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Most people have some natural immunity to swine flu | ||||

| True | 1501 (62.8) | 451 (30.0) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) |

| False | 889 (37.2) | 231 (26.0) | Reference | Reference |

| The ordinary flu vaccine will protect me from swine flu | ||||

| True | 1787 (15.6) | 966 (54.1) | 2.7 (2.5 to 3.0) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.7) |

| False | 9636 (84.4) | 2903 (30.1) | Reference | Reference |

| What have you heard? | ||||

| Number of cases increased | ||||

| Heard | 1215 (22.0) | 470 (38.7) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Not heard | 4297 (78.0) | 1631 (38.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of cases decreased | ||||

| Heard | 809 (14.7) | 282 (34.9) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Not heard | 4703 (85.3) | 1819 (38.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of deaths increased | ||||

| Heard | 765 (13.9) | 303 (39.6) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.6) |

| Not heard | 4747 (86.1) | 1798 (37.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Anything about vaccination | ||||

| Heard | 459 (8.3) | 164 (35.7) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Not heard | 5053 (91.7) | 1937 (35.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Anything about antiviral agents or hygiene | ||||

| Heard | 680 (12.3) | 244 (35.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) |

| Not heard | 4832 (87.7) | 1857 (33.7) | Reference | Reference |

| Number of cases will rise later | ||||

| Heard | 169 (3.1) | 49 (29.0) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) |

| Not heard | 5343 (96.9) | 2052 (38.4) | Reference | Reference |

Adjusting for worry about the possibility of catching swine flu

Controlling for worry about the possibility of personally catching swine flu did not substantially alter the strength of association for any of the significant non-worry-related predictor variables (results not shown), other than reducing to insignificance for the predictor ‘having heard that the number of deaths from swine flu had increased’ (aOR 1.0, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.6).

Discussion

The usefulness of vaccination as a means of reducing the overall impact of influenza depends on the willingness of members of the public to be vaccinated. 54 At the time of our data collection (14 August to 13 September 2009), only 56.1% of respondents reported being likely to accept the swine flu vaccination if offered it. While this figure may have altered following the start of the Department of Health’s vaccine-related communications campaign, this pre-campaign baseline suggests that ample scope existed for interventions to improve uptake. Our identification of demographic and psychological predictors for increased likelihood of accepting both swine and seasonal flu vaccines suggests possible ways of developing effective communication campaigns in future, and suggests that the same messages delivered as part of a single vaccine-related communications campaign may be effective in improving the uptake of both types of vaccine.

By far the strongest predictors were worry about the possibility of personally catching swine flu and, for parents, worry about a child catching swine flu. Similar associations between emotional and behavioural responses to an infectious disease outbreak have been observed before. 35,60,63 Focusing on the more worrying aspects of catching flu, be they financial, social or health, may be one way of increasing vaccination rates. However, it should be noted that this will depend on the baseline level of worry in any population and that there are individual differences, so that increasing worry may have negative consequences for some members of the population. At the levels of worry present during this pandemic outbreak, messages intended to reassure people about the risks from swine flu are unlikely to have a positive impact on vaccine uptake.

Conversely, perceiving that too much fuss had been made about the risk of swine flu was associated with decreased likelihood of accepting either form of vaccine. This corresponds well with earlier work showing that people who felt that the risks from swine flu were being exaggerated were less likely to adopt recommended behaviours such as increased hand-washing. 35 From a policy perspective, no easy short-term answer exists to this. Providing an appropriate level of warning and advice to members of the public while not being perceived as ‘making too much fuss’ is inevitably difficult. 64 At a minimum, giving sufficient assurances to the public that the necessary plans and resources are in place to deal with the situation does appear to be helpful, with respondents who expressed confidence in government preparedness being more likely to accept vaccination.