Notes

Article history

The research reported in this article of the journal supplement was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 08/94/01. The assessment report began editorial review in October 2009 and was accepted for publication in November 2009. See the HTA programme website for further project information (www.hta.ac.uk). This summary of the ERG report was compiled after the Appraisal Committee’s review. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the HTA programme or the Department of Health

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

This paper presents a summary of the evidence review group (ERG) report on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rituximab with chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy only for the treatment of relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) based on the manufacturer’s submission to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) as part of the single technology appraisal (STA) process. Evidence was available in the form of one open-label, ongoing, unpublished randomised controlled trial (RCT), REACH (Rituximab in the Study of Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia), conducted by the manufacturer, which compared rituximab with a fludarabine and cyclophosphamide combination (R-FC) to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) only. REACH was scheduled to run for 8 years; however, the data provided were immature, with a median observation time at the time of data analysis of 2.1 years. REACH provided evidence of prolonged progression free survival with R-FC compared to FC (10 months, investigators’ data), but no evidence of an overall survival benefit with R-FC. Patients refractory to fludarabine and with prior rituximab exposure were excluded from REACH and no controlled studies were identified by the ERG for these patient groups. The ERG had concerns about the structure of the economic model submitted by the manufacturer, which did not allow improvement in quality of life from treatment while in a progressed state. The manufacturer’s model further assumed a divergence in cumulative deaths between the R-FC and FC treatment arms from the outset, which did not accord with observed data from REACH. When the survival advantage was removed, the manufacturer’s base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) changed from £15,593 to between £40,000 and £42,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). With no survival advantage, the ICER became sensitive to changes in utility. There was no good empirical evidence on the utility of CLL patients in different states. Allowing for the possibility of a survival advantage with rituximab (although not supported by current evidence), the ERG performed further modelling, which found that rituximab would be cost-effective at £20,000/QALY (£30,000/QALY) if a reduction in survival advantage relative to the manufacturer’s base case of 40% (80%) was assumed. The guidance issued by NICE in July 2010 as a result of the STA recommends rituximab with FC for people with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, except when the condition is refractory to fludarabine or where there has been previous treatment with rituximab.

Introduction

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is an independent organisation within the NHS that is responsible for providing national guidance on the treatment and care of people using the NHS in England and Wales. One of the responsibilities of NICE is to provide guidance to the NHS on the use of selected new and established health technologies, based on an appraisal of those technologies.

NICE’s single technology appraisal (STA) process1 is specifically designed for the appraisal of a single product, device or other technology, with a single indication, where most of the relevant evidence lies with one manufacturer or sponsor (here, Roche Products Ltd). Typically, it is used for new pharmaceutical products close to launch. The principal evidence for an STA is derived from a submission by the manufacturer/sponsor of the technology. In addition, a report reviewing the evidence submission is submitted by the evidence review group (ERG), an external organisation independent of NICE. This paper presents a summary of the ERG report for the STA entitled ‘Rituximab for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia’. 2

Description of the underlying health problem

The underlying health problem is relapsed/progressed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). CLL is defined as relapsed in a patient who has previously achieved the criteria for a complete or partial response, but after a period of 6 or more months demonstrates evidence of disease progression. Refractory disease is defined as treatment failure (stable disease or non-response) or disease progression within 6 months of the last therapy. 3 Median age at diagnosis lies between 65 and 70 years, so will be higher for relapse, and the incidence rate at diagnosis is 3/100,000. The proportion of patients that progress in a 1-year period is estimated at 30–40% (Dr Jim Murray, University Hospitals Birmingham, personal communication). Prognosis can vary depending on the presence or absence of various cytogenetic abnormalities. Loss or mutation in the p-arm of chromosome 17 (del 17) is associated with decreased survival.

Treatment of CLL is with cytotoxic drugs/drug combinations (chemotherapy) including alkylating agents (chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, bendamustine) or antimetabolites/purine analogues (fludarabine, cladripine). Drug combinations are also used, such as FC (fludarabine and cyclophosphamide), CHOP [cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine (also called oncovin), prednisolone] and CVP [cyclophosphamide, vincristine (also called oncovin), prednisolone]. Monoclonal antibodies (biological therapy, immunotherapy) such as rituximab or alemtuzumab are also used, with rituximab (+FC) recently approved for first-line treatment by NICE [technology appraisal (TA) 1744].

In UK practice, most patients receive fludarabine or FC as first-line treatment then on progression may receive F(C) again, CVP, CHOP or CVP/CHOP with (off-licence) rituximab. Chlorambucil is predominantly reserved for patients unable to tolerate fludarabine or FC. Testing for genetic markers for tailoring treatment is not routinely undertaken but is being investigated in clinical trials. The choice of first and second-line treatment, and the decision about the stage of disease at which to (re-)initiate treatment is made on a patient-by-patient basis and varies according to regional treatment policies, previous treatment(s) and fitness of the patient. The British Committee for Standards in Haematology 2004 guidelines5 are in the process of being updated to reflect findings of recent trials.

Scope of the evidence review group report

The key research question was the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rituximab plus chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy only in the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL, including patients with a del 17p mutation. Rituximab (MabThera®; Roche Products Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK) in combination with chemotherapy has been licensed for use in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. 6

The bulk of the clinical effectiveness data submitted by the manufacturer was based on one ongoing, open-label, 8-year randomised controlled trial (RCT) [REACH (Rituximab in the Study of Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia), n = 552], which compared rituximab with a fludarabine and cyclophosphamide combination (R-FC) versus FC alone. At the time of data analysis (on which this report is based) median observation time was 2.1 years. Refractory patients included in the trial were those refractory to alkylators (CHOP, CVP, chlorambucil). The trial was not representative of all UK rituximab eligible patients as it excluded those refractory to fludarabine and those with prior rituximab exposure. Outcome measures in REACH were progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), event-free survival and response rates. Quality of life (QoL) measurements were based on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General and measured for 1 year only and only up to the time of a patient experiencing an event.

Further (unpublished) evidence was submitted by the manufacturer in the form of uncontrolled studies to support evidence of effectiveness of rituximab in fludarabine refractory patients and for rituximab in combination with other chemotherapy regimens.

The manufacturer submitted an economic model to assess the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) of R-FC compared to FC. Clinical effectiveness parameters were based mainly on the REACH trial. QoL in REACH was not measured in a way that allowed conversion into utility values. Estimated (non-preference based) utility values were obtained from the literature. 7

Methods

The ERG report comprised a critical review of the evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the technology based upon the manufacturer’s/sponsor’s submission to NICE as part of the STA process.

The ERG reran the searches for RCTs using slightly modified versions of the search strategies employed by the manufacturer and independently assessed the validity of the REACH trial. The ERG also looked at commercial-in-confidence (CIC) results based on an independent (blinded) assessment of progression (as well as the investigators’ assessment); summary data (rather than individual patient data) on the independent analysis were supplied by the manufacturer in a separate document.

The main results on PFS and OS in the submission were presented in Kaplan–Meier plots. These plots were modelled using a variety of parametric distributions (exponential, lognormal, log logistic, Weibull, Gompertz and gamma) to identify the best fitting function according to Akaike’s information criteria. For economic modelling, the fits were extrapolated beyond observed data to a time horizon of 25 years. The ERG would have liked to independently obtain their own parametric fits in order to (a) test the biological plausibility of all the PFS extrapolations used in the manufacturer’s economic modelling, (b) make a comparison of the relative advantage of R-FC versus FC delivered by the various parametric models and (c) effectively compare the investigator and independent assessments of PFS. This was not possible as individual patient data were not made available, and furthermore not all the requested parameters were supplied by the manufacturer.

The model structure and internal model validity were analysed by the ERG, and model parameters were assessed for their appropriateness. A number of additional sensitivity analyses were run based on varying assumptions set out in the submission, and the effect on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was assessed.

Results

Summary of submitted clinical evidence

Progression-free survival

Investigators’ assessment The curves for the FC and R-FC arm were similar in slope for most of the time represented but separated from each other especially during a 3-month period between 15 and 18 months. There was a statistically significant difference in median time to progression of 10.2 months in favour of R-FC. At the time of this analysis, an event had occurred in 53% of patients, the remainder were censored.

Independent assessment An independent, blinded assessment of progression, which is less likely to be susceptible to bias, was performed as part of REACH. The results are CIC.

Overall survival

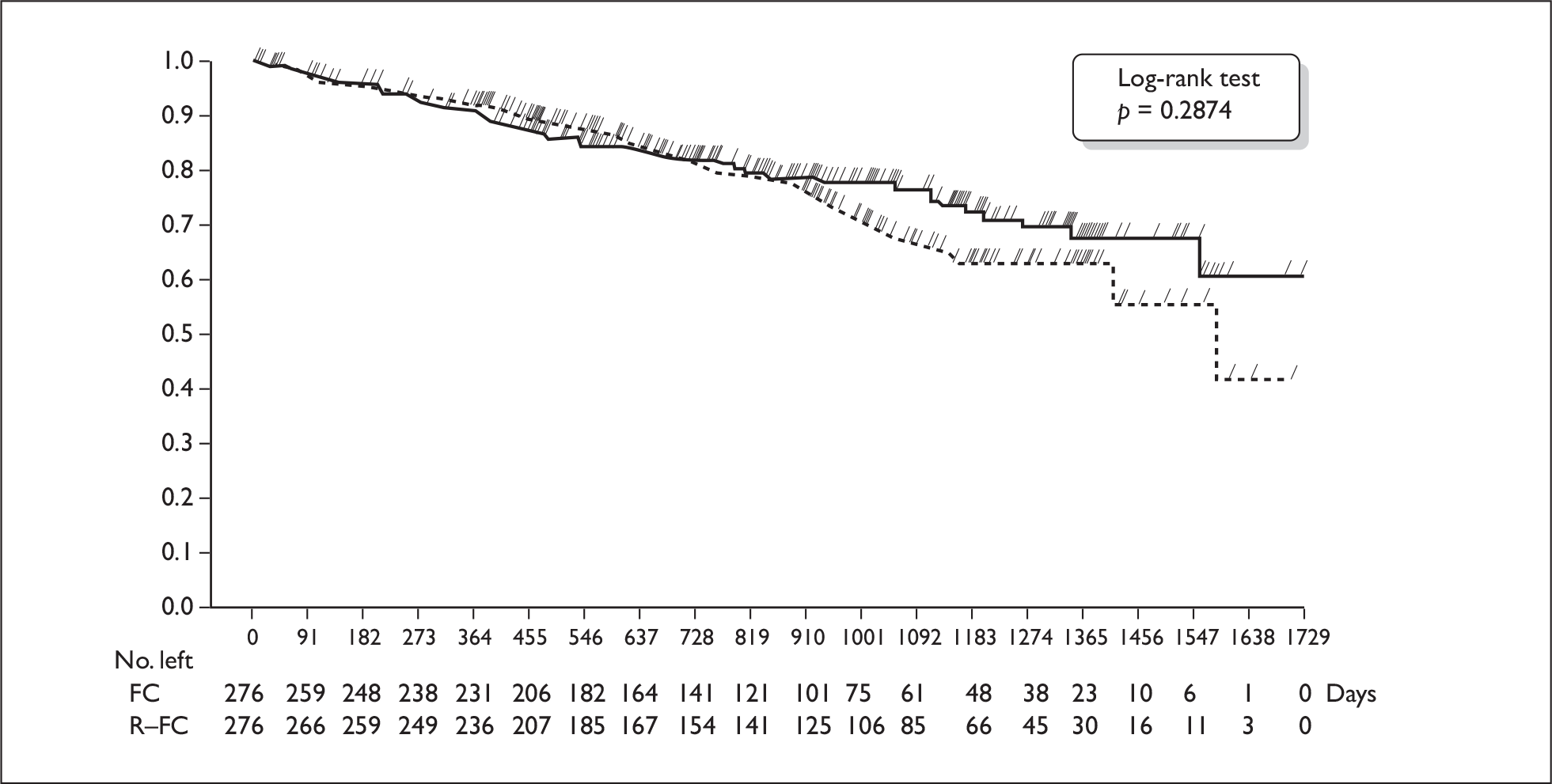

At the time of data analysis, 75% (FC arm) and 78% (R-FC arm) of patients were still alive. Median survival could not be estimated for the R-FC arm. The curves were the same for both arms up to 2.5 years, after which they separated (Figure 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the curves (hazard ratio 0.83; 95% confidence interval 0.59 to 1.17).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of overall survival (intention to treat) (from manufacturer’s submission). FC, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; R-FC, rituximab, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide.

Non-randomised studies

The manufacturer provided data from one uncontrolled study on salvage therapy with R-FC in sub-groups of patients with and without prior fludarabine exposure, and with and without prior rituximab exposure. These confidential results were provided ahead of publication, and the ERG were unable to identify data in the public domain.

Summary of submitted cost-effectiveness evidence

The cost per QALY for the base case (manufacturer’s calculation) was £15,593. This was based on utility values of 0.8 for PFS and 0.6 for progression, and on a difference in mean life-years between the R-FC arm and FC arm of 0.671, and a difference in mean QALYs of 0.585. The results for a number of one-way sensitivity analyses varied between £13,017 and £23,790. Parameters that were varied in the submission include the utility values, type of curve fit, rituximab costs, adverse event costs and supportive care costs.

A number of alternative analyses were carried out by the ERG in order to test the effect of changes to various assumptions within the manufacturer’s submission. The effects on the ICER can be found in Table 1.

| General issue | Details for this submission | Effect on ICER (£) |

|---|---|---|

| (Roche base case following clarification questions) | 15,593 | |

| Model structure | Alternative choice of curves for PFS | 13,140–17,317 |

| Correction of minor errors of logic | 15,584 | |

| Measurement of effectiveness | Removal of overall survival benefit from rituximab | 31,009–47,963 |

| Use of PFS curves based on independent assessment of progression | 16,911–17,467 | |

| Measurement of utility | Halving and doubling difference between utilities for PFS and progressed states | 13,017–17,306 |

| Adverse events | Doubling costs for rituximab arm only | 16,455 |

| Rituximab costs | One fewer or one more 100-mg vial per cycle | 13,803–17,383 |

| Retiming of rituximab costs | 15,277–20,110 | |

| Assessment of progression | Independent (blinded) assessment rather than investigators’ assessment (Weibull) | 17,507 |

| Survival | No OS benefit | 40,568–42,444 |

| Combination | Independent assessment of progression combined with no OS benefit | 44,669–48,385 |

| Combination | No OS benefit and utilities: PFS = 0.9; progressed = 0.5 | 20,284–21,222 |

| Combination | No OS benefit and utilities: PFS = 0.75; progressed = 0.65 | 81,135–84,889 |

Removing the survival effect had the most substantial impact on the ICER and results were subsequently more sensitive to changes in utilities.

Intermediate results can be obtained by taking a weighted average of the two survival curves. This makes it possible to consider any desired fraction of the modelled advantage in overall survival from rituximab. Table 2 shows the effect of such changes, using a Weibull curve for PFS. Similar patterns could be expected for other curve options.

| Case considered | ICER (£) | |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage reduction in OS advantage for rituximab | Amended 1a | Amended 2b |

| 0 (as base case) | 15,593 | 15,593 |

| 10 | 16,457 | 16,478 |

| 20 | 17,453 | 17,508 |

| 30 | 18,615 | 18,721 |

| 40 | 19,991 | 20,169 |

| 50 | 21,647 | 21,925 |

| 60 | 23,681 | 24,098 |

| 70 | 26,242 | 26,852 |

| 80 | 29,573 | 30,455 |

| 90 | 34,088 | 35,365 |

| 100 (no OS advantage) | 40,568 | 42,444 |

Commentary on the robustness of submitted evidence

The analysis relies on the results of a single open-label, unpublished, ongoing RCT with immature data (median observation time of only 2.1 years at the time of analysis).

There was evidence that treatment with R-FC compared to FC alone results in a statistically significantly longer period of progression-free survival (10 months investigators’ assessment; independent assessment results CIC) in both patients with and without the del 17 mutation. It is likely that this delay was associated with QoL gains, although there was a lack of suitable empirical evidence.

For OS, the median had not yet been reached in the R-FC arm and 75% and 78% of patients were still alive in the FC and R-FC arms respectively. There was no convincing evidence that there was a survival benefit in the R-FC arm. The Kaplan–Meier curves separate out after 2.5 years (see Figure 1), and the ERG was unsure whether there was a biologically plausible reason for why this might happen. Because of crossover from the FC to the R-FC arm over time, the curves are likely to become increasingly susceptible to bias.

The patients in REACH do not appear representative of a general relapsed CLL population, but may be representative of those eligible for treatment with FC. The median age in REACH was 63 years at relapse compared to a median age of 65–70 years at diagnosis in the general population. Ten per cent of included relapsed patients were at Binet stage A, which appears high. Younger and/or healthier patients are less likely to drop out due to side effects.

In REACH, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide were given as an infusion. These drugs are usually given orally in the UK. It is unclear whether this would have an impact on the effectiveness of the drugs.

There was no evidence on the effectiveness of R-FC compared to another treatment in fludarabine refractory patients or patients with prior rituximab exposure.

The model submitted by Roche follows the same structure as that used in the assessment of rituximab for first line treatment of CLL. There are three states in the model: PFS, progressed and death. No transition from progressed to PFS is possible. We share the concerns of the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG) about this structure. In summary, this has the effect of combining all patients post-progression into a single state. It is therefore not possible to improve QoL from treatment while in the progressed state.

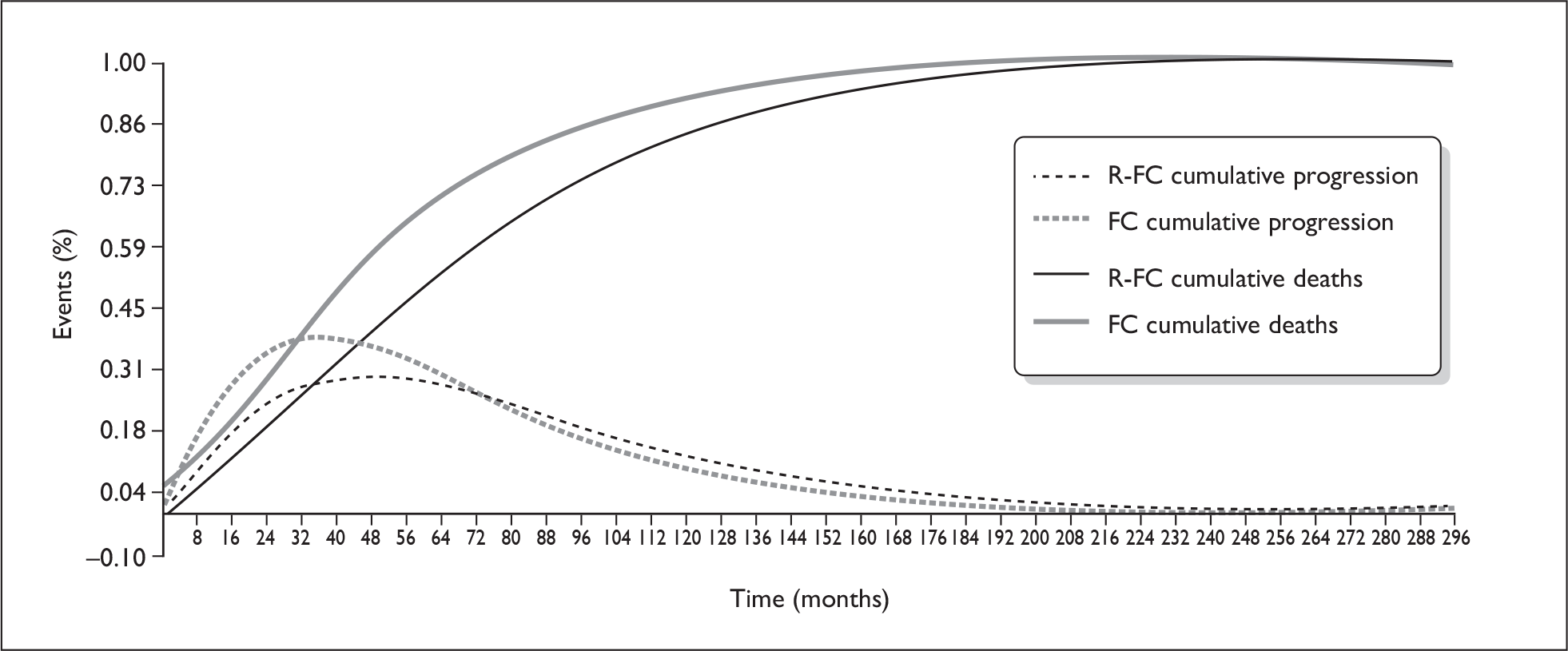

There was considerable uncertainty associated with estimates of OS in the economic model. OS has been modelled by applying death rates to the PFS and progressed states in each arm of the model separately. The cumulative deaths modelled show a divergence between the two arms of the model from the start (Figure 2): this is not in accord with the observed pattern of deaths in the trial (see Figure 1). When the survival advantage is removed, the base-case ICER changes from £15,593 to between £40,000 and £42,000/QALY.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative time to progression and death (from manufacturer’s submission). FC, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; R-FC, rituximab, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide.

With no OS advantage for the rituximab arm, the economic model output becomes sensitive to the differential in utility between the non-progressed and the progressed state. There is a lack of empirical evidence about the utility of patients in these states.

While a range of different parametric curves have been applied to the data for PFS, none of them is a particularly good fit to the data, and there are doubts about the long term extrapolation of these curves.

The model assumes that the costs of rituximab are incurred throughout a cycle, so a patient progressing after half a cycle incurs only half of that cycle’s cost. As rituximab is given as a one-off infusion at the start of each cycle, this assumption does not seem appropriate.

The model uses the investigators’ assessment of progression rather than the independent (blinded) assessments, which are likely to give less biased results. However, when parametric fits were made to the independent analysis results, only small differences in the resulting ICERs were observed and the direction of change was not consistent.

An area of uncertainty is the difference in the cost of relapse therapy with rituximab (£9128) compared to the cost of first line therapy (£11,617) as given in the recent submission on rituximab in CLL. 8

Conclusions

The ERG found evidence that R-FC delays progression by 10 months (investigators’ assessment) compared to treatment with FC alone in patients who have previously received alkylator-containing chemotherapy or fludarabine alone, are fludarabine sensitive and are considered suitable for treatment with FC. There was no evidence from current data to show that R-FC prolongs survival compared to FC. With no survival benefit assumed in the economic model, the base-case ICER changes from £15,593 to between £40,000 and £42,000/QALY and becomes sensitive to changes in utility. Further modelling around a hypothetical survival benefit found that rituximab would be cost-effective at a threshold of around £20,000/QALY (£30,000/QALY) when a 40% (80%) reduction in survival benefit relative to the manufacturer’s base case was assumed. Further evidence is needed on whether there is a survival benefit, the extent of this benefit and the associated utilities. Robust evidence is lacking on (a) the effectiveness of R-FC in patients who have previously received FC, R-FC or R-chemotherapy (other) as first-line therapy and (b) the effectiveness of R-chemotherapy (other) as treatment for relapsed CLL.

Summary of NICE guidance issued as a result of the STA

NICE guidance from July 2010 recommends rituximab in combination with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide for people with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, but not when there has been previous treatment with rituximab. Exceptions to the previous treatment with rituximab rule apply where this was in the context of a clinical trial (with any chemotherapy), or at a dose lower than the dose currently licensed for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

People who are currently receiving rituximab in combination with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide should have the option to continue treatment until they and their clinicians consider it appropriate to stop. The guidance is due to be reviewed in December 2010.

Disclaimers

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health.

Key references

- NICE . Guide to Single Technology (STA) Process n.d. www.nice.org.uk/media/42D/B3/STAguideLrFinal.pdf (accessed 24 September 2010).

- Dretzke J, Barton P, Kaambwa B, Connock M, Uthman O, Bayliss S, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Birmingham, West Midlands Health Technology Assessment Collaboration, University of Birmingham; 2009.

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Dohner H, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (IWCLL) updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group (NCI-WG) 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008;111:5446-56.

- Technology Appraisal 174 . Rituximab for First Line Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia n.d. www.nice.org.uk/TA174 (accessed October 2010).

- Oscier D, Fegan C, Hillmen P, Illidge T, Johnson S, Maguire P, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2004;125:294-317.

- European Medicines Agency . Summary of Product Characteristics 2010. www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_Product_Information/human/000165/WC500025821.pdf./.

- Hancock S, Wake B, Hyde C, Doordujin A. Fludaribine as first line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Birmingham, University of Birmingham; 2009.

- Roche Products Limited . Rituximab for the 1st Line Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia 2009. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/RituximabSubmissionFinalCICAIC.pdf.