Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 08/42/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2009. The assessment report began editorial review in November 2009 and was accepted for publication in June 2010. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

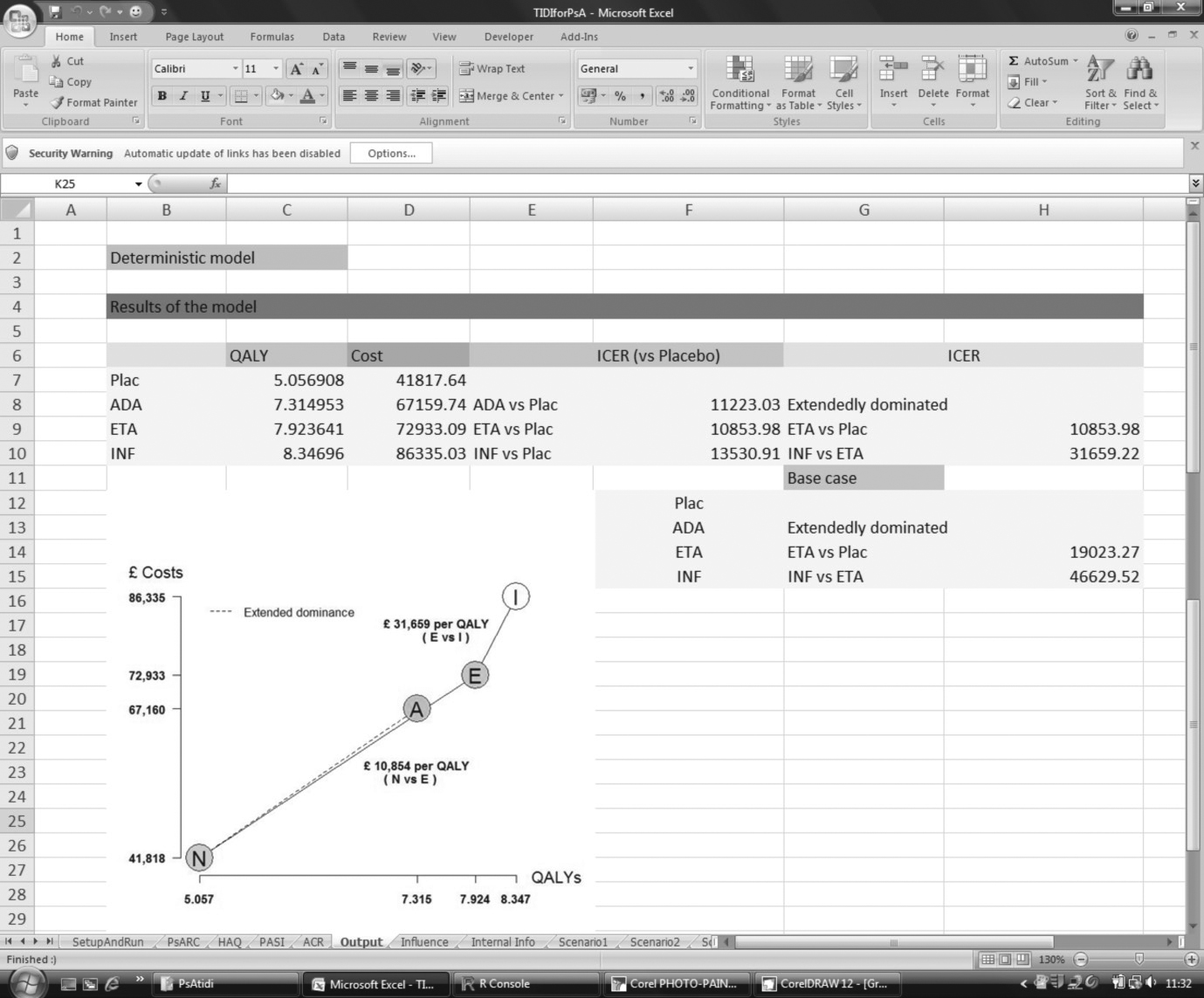

MS has a financial interest in a consulting company that has undertaken work for Abbott, Schering-Plough and Wyeth, but not relating to psoriatic arthritis, and he has not personally participated in this consultancy work. He has personally undertaken paid consultancy for some of the comparator manufacturers, again not relating to psoriatic arthritis. IB has received speaker fees and attended Advisory Board Meetings for Abbott, Schering-Plough and Wyeth.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Epidemiology

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined as a unique inflammatory arthritis affecting the joints and connective tissue, and is associated with psoriasis of the skin or nails. 1 There are difficulties in estimating its prevalence due to the lack of a precise definition and diagnostic criteria for PsA. 2 The prevalence of psoriasis in the general population has been estimated at between 2% and 3%,1 and the prevalence of inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriasis has been estimated to be up to 30%. 3 PsA affects males and females equally, with a worldwide distribution. Figures for the UK have estimated the adjusted prevalence of PsA in the primary care setting to be 0.3%, based on data from north-east England involving six general practices, covering a population of 26,348. 4 Another study reported PsA prevalence rates per 100,000 of 3.5 for males and 3.4 for females, based on data from 77 general practices in the Norwich Health Authority, with a population of 413,421. 5 Severe PsA with progressive joint lesions can be found in at least 20% of patients with psoriasis. 6

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Psoriatic arthritis is a hyperproliferative and inflammatory arthritis that is distinct from rheumatoid arthritis (RA). 7,8 The aetiology of PsA is not fully known; genetic susceptibility and exogenous influences might play roles in the cause of disease. 9 The expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens [e.g. human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27] might also predispose certain patients to develop PsA, as well as a number of environmental factors, such as trauma, repetitive motion, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and bacterial infection. 9 PsA is diagnosed when a patient with psoriasis has a distinctive pattern of peripheral and/or spinal arthropathy. 10 The rheumatic characteristics of PsA include stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness of the joints and surrounding ligaments and tendons. 11

Several clinical features distinguish PsA from RA. In PsA, the absolute number of affected joints is less and the pattern of joint lesion involvement tends to be asymmetric. 12 The joint distribution tends to occur in a ray pattern in PsA, with the common involvement of distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and nail lesions. All joints of a single digit are thus more likely to be affected in PsA, whereas in RA the same joints on both sides tend to be affected. 1 Dactylitis, spondylitis and sacroiliitis are common in PsA, whereas they are not in RA. 12 In PsA the affected joints are tighter, contain less fluid, and are less tender than those in RA, with a propensity for inflammation of the entheseal sites. PsA and RA also show differences in the inflammatory reaction that accompanies each form of arthritis. 12 Extra-articular manifestations of PsA are also different from those of RA; rheumatoid nodules are particularly absent in patients with PsA. 1 Most patients with PsA develop psoriasis first, while joint involvement appears first only in 19% of patients, and concurrently with psoriasis in 16% of cases. 10 For those who develop psoriasis first, the onset time of PsA is around 10 years after the first signs of psoriasis. 1 In addition, rheumatoid factor (RF) (an antibody produced by plasma cells) may be detected in about 13% of patients with PsA, whereas it can be detected in more than 80% of patients with RA. 1

Psoriatic arthritis is a progressive disorder, ranging from mild synovitis to severe progressive erosive arthropathy. 11,13 Research has found that patients PsA presenting with oligoarticular disease progress to polyarticular disease; a large percentage of patients develop joint lesions and deformities, which progress over time. 9 Despite clinical improvement with current disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment, radiological joint damage has been shown in up to 47% of patients with PsA at a median interval of 2 years. 14 Untreated patients with PsA may have persistent inflammation and progressive joint damage. 11 The deformities resulting from PsA can lead to shortening of digits due to severe joints or bone lysis. 1 Remission can occur in PsA, especially in patients with Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) levels of < 1 score. 15 Of those who can sustain clinical remission, only a small fraction of patients can discontinue medication with no evidence of damage. 16 Research has reported that the frequency of remission was 17.6% in patients with PsA, and the average duration of remission was 2.6 years, from data of 391 patients with peripheral arthritis. 16 Joint damage can occur early in the disease often prior to functional limitation. 9,17 This appears to be associated with the development of inflamed entheses close to peripheral joints, although the link still remains largely unclear. 13 It has been shown that there is an association between polyarthritis and functional disability, with higher mean HAQ scores than those in oligoarthritic patients. 18,19

A number of risk factors have been found to be predictive of the progression of PsA. A polyarticular onset (five or more swollen joints) of PsA is an important risk factor in predicting the progressive joint deformity. 20 Each actively inflamed joint in PsA is associated with a 4% risk of increased damage within 6 months. 1 HLA antigens have also been found to be predictive of the progression of joint damage. It has been shown that HLA-B27, HLA-B39 and HLA-DQW3 were associated with disease progression. 21 Other risk factors for a more progressive course of PsA include the presence of an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and being female. 1,22

A classification scheme for PsA on the basis of joint manifestations describes five patterns of disease:9,23

-

Distal interphalangeal arthritis This condition is considered as the classic form of PsA. It can occur as the sole presentation or in combination with other symptoms. It can be symmetrical or asymmetrical and can involve a few or many joints. Adjacent nails may demonstrate psoriatic changes and progressive joint erosions are common.

-

Arthritis mutilans It is a severe presentation of the disease with osteolysis of the phalanges, metatarsals and metacarpals.

-

Symmetric polyarthritis The clinical feature of symmetric polyarthritis is similar to RA, with inflammation of the metacarpals and the proximal interphalangeal joints being prominent. However, it is usually milder than RA and patients are often RF-negative.

-

Oligoarthritis This is the most common condition of PsA, which is characterised by asymmetric involvement of a small number of joints (fewer than four). Arthritis in a single knee might be the first symptom of oligoarthritis.

-

Spondylitis and/or sacroiliitis It resembles ankylosing spondylitis, but is generally less severe and less disabling. The axial skeleton tends to be involved in an atypical fashion, with the lumbar spine as the most common site of involvement.

Despite this classification, these patterns of PsA often overlap and evolve from one pattern to another as the disease progresses and diagnostic investigations become more thorough. 13 A common feature of PsA is dactylitis (or ‘sausage digit’) in which the whole digit appears swollen due to inflammation of the tendons and periosteum as well as the joints. 9,11 Radiographic features of PsA involve the distinctive asymmetric pattern of joint involvement, sacroiliitis and spondylitis, bone erosions, new bone formation, bony ankylosis, bony outgrowths in the axial skeleton, osteolysis and enthesopathy.

Significance in terms of ill health

The health burden of PsA can be considerable. PsA is a lifelong disorder and its impact on patients’ functional status and quality of life (QoL) fluctuates over time. 24 As it involves both skin and joints, PsA can result in significant impairment of QoL and psychosocial disability7,10 compared with a healthy population. Patients with PsA score significantly worse in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) assessment on physical mobility, pain, energy, sleep, social isolation and emotional reaction. 25 A comparison of HRQoL between patients with PsA and patients with RA found that both patient populations had lower physical health than healthy control patients. 26 Patients with PsA reported more role limitations due to emotional problems and more bodily pain after the adjustment of the difference in vitality and other covariates. These findings were also reflected in another comparison of disability and QoL between patients with RA and patients with PsA; this study reported that despite greater peripheral joint damage in patients with RA the function and QoL scores were similar for both groups. 27,28 These reveal that there might be unique psychological disabilities associated with the psoriasis dimension (i.e. skin lesion) of PsA. Due to the skin involvement, patients with PsA may also suffer from other psychological consequences, such as embarrassment, self-consciousness and even depression. Because of a significant reduction in a patient’s HRQoL, ideally PsA should be diagnosed early and treated aggressively in order to minimise joint damage and skin disease. 17

The severity of PsA is also reflected in increased mortality. Patients with PsA have a 60% higher risk of mortality relative to the general population. 24,29,30 The causes of premature death are similar to those noted in the general population, with cardiovascular causes being the most common. 1 The estimated reduction in life expectancy for patients with PsA is approximately 3 years. 31

The economic costs of PsA have not been well quantified. In the USA, the mean annual direct (health and social care) cost per patient with PsA is estimated as US$3638 according to data from Medstat MarketScan in 1999–2000. 32 In Germany, the mean annual direct cost per patient with PsA is estimated as €3162, with a mean indirect cost (time lost from work and normal activities) per patient of €11,075. 33 Studies of RA34–36 and psoriasis37 have shown that costs increase with the severity of both diseases, and productivity losses are significant,38,39 largely as a consequence of extensive work disability. 35 These findings are likely to be generalisable to PsA.

Studies of the economic impact of RA in the UK before the introduction of biologic therapies found that direct health-care costs represented about one-quarter of all costs, and these were dominated by inpatient and community day care,40 with DMARDs representing a minor proportion: 3%–4% of total costs and 13%–15% of direct costs. 41 Evidence from the USA suggests that expenditure on biologic therapies might represent 35% of direct cost,42 but similar data are not yet available for the UK. Increasing expenditure on biologic therapies might be at least partly offset by cost savings elsewhere,43 although, as yet, the evidence for this is only suggestive.

Assessment of treatment response in psoriatic arthritis

The assessment of effectiveness of treatments for PsA relies on there being outcome measures that accurately and sensitively measure disease activity. Overall response criteria have not yet been clearly defined; they are being developed by an international collaboration on outcome measures in rheumatology (OMERACT – Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials). There are a number of different parameters of disease activity in arthropathies, including: number of swollen joints, number of tender joints, pain, level of disability, patient’s global assessment, physician’s global assessment and biochemical markers in the blood. Selecting which to assess in clinical trials and which to appoint as the primary variable can be difficult. Different ways of combining the various outcome measures have been suggested including a simple ‘pooled index’. 44 In recent years the compound response criterion, the American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR 20), has gained general acceptance for the assessment of treatments for PsA, and this has been adopted for many PsA trials. Another compound measure, Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC), was developed specifically for a trial in PsA and has been adopted by the BSR. 45

American College of Rheumatology response criteria

The ACR response criteria were developed after the identification of a set of core disease activity measures. ACR 20 requires a 20% reduction in the tender joint count (TJC), a 20% reduction in the swollen joint count (SJC), and a 20% reduction in three out of five additional measures, including patient and physician global assessment, pain, disability and an acute-phase reactant. In patients with RA, ACR 20 has been confirmed as being able to discriminate between a clinically significant improvement and a clinically insignificant one. 46,47 It is unclear whether the ACR 20 has the same discriminatory validity in PsA. 48 The ACR 20 is generally accepted to be the minimal clinically important difference that indicates some response to a particular intervention. The ACR 50 reflects significant and important changes in the patient’s disease status that may be acceptable to both clinician and patient in long-term management. The ACR 70 represents a major change and approximates in most minds to a near remission. Because of the differences between PsA and RA, it is imperative that, when the ACR response criteria are used in the trials of treatment for PsA, the DIP joints are included. Rather than changes from bad to moderate synovitis in any individual joint, these criteria detect improvement from swollen to not swollen or from tender to not tender joints. Therefore, patients with oligoarthritis in a few large joints may not appear to respond as well on this outcome as patients with polyarthritis involving many smaller joints.

Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria

The Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria were developed for a trial of sulfasalazine in PsA,49 and incorporate four assessment measures (patient self-assessment, physician assessment, joint pain/tenderness score and joint swelling score). Treatment response was defined as an improvement in at least two of these four measures, one of which had to be joint pain/tenderness score or joint swelling score, with no worsening in any of these four measures. PsARC has not been validated, but responses assessed by it do parallel those identified with ACR 20. A limitation of PsARC is that although it was developed for assessment of PsA, it does not incorporate an assessment of psoriasis. The working group producing the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) guidelines for the use of biologics in PsA50 elected to use PsARC as the primary joint response to biologic treatment, although it advocates some extra data collection, such as a patient self-assessed disability (HAQ), and a biochemical marker of disease activity, such as ESR or C-reactive protein (CRP).

Radiological assessments

In all arthropathies progression of the disease can only be truly measured by assessment of the joint damage. The radiological assessments include the Steinbrocker, Sharp and Larsen methods. A modification of the Steinbrocker method, which assigns a score for each joint has been validated for PsA. The Sharp method grades all the joints of the hand separately for erosions and joint space narrowing, each erosion being assigned a score of 0–5 and each joint space narrowing a score of 0–4. A total score (maximum 149) is calculated. The Total Sharp Score (TSS), modified to include the DIP and metatarsophalangeal joints of the feet and interphalangeal joint of the first toe, has been used in the trials of etanercept and adalimumab. 51,52 None of these methods that were developed for RA score additional radiographic changes that are specific to PsA. A new score has been tested by Wassenberg et al. ,53 but this scoring method has not yet been validated in clinical trials. Whichever method is selected it is important that trials should be stratified by baseline radiographic findings.

Health Assessment Questionnaire

The HAQ score is a well-validated tool in the assessment of patients with RA. 48 It focuses on two dimensions of health status: physical disability (eight scales) and pain, generating a score of 0 (least disability) to 3 (most severe disability). A modification of the HAQ for spondylarthropathies (HAQ-S) and for psoriasis (HAQ-SK) have been developed, but when tested against HAQ their scores were almost identical,54 suggesting either can be used in PsA. 48 The HAQ is one component of the ACR 20 (50 or 70) response criteria.

The HAQ has been tested in patients with PsA, showing a moderate-to-close correlation with disease activity as measured by the actively inflamed joint count and some measures of clinical function (including the ACR functional class). 55 Although the HAQ has been used as a disability measure and is a common outcome measure in PsA trials, it may not sufficiently incorporate all aspects of disease activity (i.e. deformity or damage resulting from disease process, especially in late PsA), therefore, clinical assessment of disease activity and both clinical and radiological assessments of joint damage remain important outcome measures in PsA. 56

Overall, the advantage of the HAQ as an instrument is that it can measure the functional and psychological impact of the disease. HAQ is conventionally used as a driver of QoL scores and costs in main economic evaluations on the use of biologics and DMARDs in RA. 57–59

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

When evaluating the efficacy of interventions in the treatment of PsA, the outcome measures used must assess disease activity in both the joint and the skin. 48 In clinical trials of patients with psoriasis, assessment of the response to treatment is usually based on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The PASI is also used in trials of PsA; given the various degrees of severity of psoriasis in these patients, not all patients are evaluable for the assessment of response – at least 3% of the body surface area (BSA) has to be affected by the skin disease in order for the PASI measure to be used. 48 Although it is widely used, the PASI measure also has a number of deficiencies: its constituent parameters have never been properly defined; it is insensitive to change in mild-to-moderate psoriasis; estimation of disease extent is notoriously inaccurate; and the complexity of the formula required to calculate the final score further increases the risk of errors. It combines an extent and a severity score for each of the four body areas (head, trunk, upper extremities and lower extremities). The extent score of 0–6 is allocated according to the percentage of skin involvement (e.g. 0 and 6 represent no psoriasis and 90%–100% involvement, respectively). The severity score of 0–12 is derived by adding scores of 0–4 for each of the qualities of erythema (redness), induration and desquamation representative of the psoriasis within the affected area. It is probable, but usually not specified in trial reports, that most investigators take induration to mean plaque thickness without adherent scale and desquamation to mean thickness of scale rather than severity of scale shedding. The severity score for each area is multiplied by the extent score and the resultant body area scores, weighted according to the percentage of total BSA that the body area represents (10% for head, 30% for trunk, 20% for upper extremities and 40% for lower extremities), are added together to give the PASI score. Although PASI can theoretically reach 72, scores in the upper half of the range (> 36) are not common even in severe psoriasis. Furthermore, it fails to capture the disability that commonly arises from involvement of functionally or psychosocially important areas (hands, feet, face, scalp and genitalia), which together represent only a small proportion of total BSA.

Although the optimum assessment outcomes for PsA trials are yet to be defined, those selected as the primary measures of efficacy in this review, namely PsARC-, ACR 20/50/70-, HAQ- and PASI-based measures, all have discriminatory capability and are generally accepted for the assessment of treatment effect. HAQ has been chosen as our primary outcome variable of arthritis in the economic evaluation because it makes it technically feasible to evaluate the impact of retarding and/or halting the progression of the disease, both in an economic sense and in terms of QoL. PASI has been chosen as the primary outcome variable of psoriasis in the economic evaluation because it is recommended to assess severity and response in the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) guidelines and used in the majority of randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Current service provision

The effective treatment for PsA needs to consider both skin and joint conditions, especially if both are significantly affected. In current services it is rheumatologists who manage the majority of patients with PsA. Although dermatologists focus principally on the cutaneous expression of psoriasis, they frequently use drugs, such as methotrexate (MTX) or biological agents, which may benefit both skin and joints. Patients with severe manifestations of PsA in joints and skin will tend to be managed jointly by rheumatologists and dermatologists, whereas many patients with less severe joint disease may remain under the care of dermatologists alone.

Most treatments for PsA have been borrowed from those used for RA and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used. 10 There is a concern that NSAIDs may provoke a flare of the psoriasis component of the disease, but this may not be of clinical significance. 13 Local corticosteroid injections are also frequently used,10 although there is a significant risk of a serious flare in psoriasis when corticosteroids are withdrawn. Disease that is unresponsive to NSAIDs, and in particular polyarticular disease, should be treated with DMARDs in order to reduce the joint damage and prevent disability. 13 It is also suggested that aggressive treatment of early-stage progressive PsA should be used in order to improve prognosis. 13 Again, the treatments used are based on the experience in RA rather than knowledge of the pathophysiology of PsA or trial-based efficacy. Currently, MTX and sulfasalazine are considered the DMARDs of choice, despite the largely empirical evidence for MTX and the modest effects of sulfasalazine. 13 A review of the experience of 100 patients with PsA treated with DMARDs60 reported that of those treated with sulfasalazine, gold, MTX or hydroxychloroquine over 70% of patients had discontinued due to a lack of efficacy or adverse events (range 35% with MTX to 94% with hydroxychloroquine).

Another DMARD (leflunomide) has, in addition to being licensed for RA, also been licensed for use in PsA. This is the only non-biologic licensed in PsA. Leflunomide inhibits de novo pyrimidine synthesis and because activated lymphocytes require a large pyrimidine pool, it preferentially inhibits T-cell activation and proliferation. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy in RA61 and PsA. 62 Evidence also suggests that clinical responses in patients with RA receiving leflunomide treatment are equivalent to those receiving MTX treatment. 63 Unlike MTX, however, leflunomide has little effect on the skin. Other drugs investigated for the treatment of PsA are auranofin, etretinate, fumaric acid, intramuscular gold, azathioprine, and Efamol Marine. 54 Ciclosporin and penicillamine are also sometimes used in clinical practice. 64

Costs of current service

Based on prices from the British National Formulary (BNF),65 weekly treatment costs with the most commonly used DMARDs in PsA, sulfasalazine and MTX are approximately £2 and < £0.50, respectively. The cost of ciclosporin is approximately £40–80 per week.

Prescriptions for DMARDs for all indications have been rising rapidly in general practice in England from 300,000 per quarter year in December 2003 to over 500,000 in December 2008, with expenditure increasing from £2M per quarter year to nearly £4.5M during this period. In addition to the cost of DMARDs, the cost of NSAIDs was almost £4M per quarter year in December 2008, although the number of prescriptions and expenditure on NSAIDS has fallen sharply in recent years. 66

Variation in service

No surveys of UK service models for PsA have been conducted. Although PsA is a disease of joints and skin it is treated mainly by rheumatologists. A study of patients with confirmed PsA in the Netherlands found considerable variations among rheumatologists in the delivery of care; 29% failed to diagnose PsA, mainly due to their failure to enquire about skin lesions. 67 Of those who did correctly diagnose PsA, only 43% referred patients to a dermatologist and 66% ordered laboratory tests. The median costs for imaging and laboratory investigations were higher for those patients who were correctly diagnosed with PsA than for the remaining patients who were incorrectly diagnosed.

Description of technology under assessment

Numerous chemokines and cytokines are believed to play an important role in triggering cell proliferation and sustaining joint inflammation in PsA. Cytokines stimulate inflammatory processes, resulting in the migration and activation of T cells, which then release tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). TNF-α is one of several proinflammatory cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis and PsA. 68,69 Newer strategies for the treatment of PsA focus on modifying T cells in this disease through direct elimination of activated T cells, inhibition of T-cell activation, or inhibition of cytokine secretion or activity. 70 Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab are among a number of these new biological agents that have been developed and investigated for the treatment of various diseases, including psoriasis and PsA. Etanercept is a human dimeric fusion protein that binds specifically to TNF and blocks its interaction with cell surface receptors. 10 Infliximab is a murine/human chimeric anti-TNF monoclonal gamma immunoglobulin that inhibits the binding of TNF to its receptor. 10 Adalimumab is a fully humanised monoclonal IgG1 antibody and TNF antagonist. 71 All three biologics are licensed in the UK for the treatment of active and progressive PsA in adults when the response to previous DMARD therapy has been inadequate.

Anticipated costs of biologic interventions

Based on the recommended dose regimen (25-mg injections administered twice weekly as a subcutaneous injection), the initial 3-month acquisition cost of etanercept is £2324, and the annual cost thereafter is £9296. The acquisition costs of adalimumab are the same, based on the recommended dose regimen (40-mg subcutaneous injections administered every other week). The recommended dose for infliximab is 5 mg/kg is given as an intravenous (i.v.) infusion over a 2-hour period followed by additional 5-mg/kg infusion doses at 2 and 6 weeks after the first infusion then every 8 weeks thereafter, each dose corresponding to three, four or five vials of infliximab depending upon the patient’s body weight. The initial 3-month acquisition cost of infliximab is estimated to be £5035, assuming four vials, and the annual cost thereafter is £10,912.

Current expenditure on biologic therapies in England is considerable. For all indications, the cost of prescribing in 2008 was £152.2M for etanercept, £102.7M for adalimumab and £77.1M for infliximab, with > 95% of these prescriptions dispensed by hospitals. 72 Expenditure for biologic drugs increased during 2008 by 15% for etanercept, 55% for adalimumab and 25% for infliximab. Among the drugs appraised by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), etanercept and adalimumab are now ranked in the top five by estimated cost of prescribing in England.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 2 Definition of decision problem

Decision problem

The use of biologics in inflammatory disease is a rapidly evolving area. Etanercept and infliximab were previously evaluated together for their efficacy and safety in PsA in 200673 and adalimumab was separately evaluated more recently. 74 There is a need for an up-to-date evaluation of all three biological agents that are licensed for use in the treatment of PsA.

It is important to establish how well these three licensed biologics work in patients with PsA, in terms of both joint and skin response, as well as disease progression. In addition to determining the absolute efficacy of the biologics relative to placebo, it is important to determine their relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

To determine the clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab for the treatment of active and progressive PsA in patients who have an inadequate response to standard treatment (including DMARD therapy).

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

A systematic review of the evidence for the clinical effectiveness and safety of etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab for the treatment of active and progressive PsA in patients who have an inadequate response to standard treatment (including DMARD therapy) was conducted following the general principles recommended in the guidance of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance75 and the quality of reporting of meta-analyses (QUOROM) statement. 76

Search strategy

The following databases were searched for relevant clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness research:

-

MEDLINE

-

EMBASE

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

Science Citation Index (SCI)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S)

-

ClinicalTrials.gov

-

metaRegister of Current Controlled Trials (mRCT)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

-

Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED)

-

EconLit.

Searches of major bibliographic databases were undertaken in three tranches – for RCTs, for economic evaluations and for studies of serious adverse effects. In the RCT and economic evaluation searches, the etanercept and infliximab search was limited by date (1 April 2004 to date), updating the searches undertaken for the 2006 Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report. 73 The search for adalimumab had no date limits. The searches for studies of adverse effects of all three drugs were not date limited. Internet resources were also searched for information on adverse effects. At the time of receiving the company submission (August 2009), update searches were conducted to ensure that the review remained up to date and covered all relevant evidence at the time of submission. No language or other restrictions were applied. In addition, reference lists of all included studies and industry submissions made to NICE were hand-searched to identify further relevant studies.

The terms for search strategies were identified through discussion between an information specialist and the research team, by scanning the background literature and browsing the MEDLINE medical subject headings (MeSH). As several databases were searched, some degree of duplication resulted. To manage this issue, the titles and abstracts of bibliographic records were imported into endnote bibliographic management software to remove duplicate records.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts. Full paper manuscripts of any titles/abstracts that may be relevant were obtained where possible and the relevance of each study was assessed by two reviewers according to the criteria below. Studies were included in the review according to the inclusion criteria, described as follows. Studies that did not meet all of the criteria were excluded and their bibliographic details listed with reasons for exclusion. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or consulting a third reviewer if necessary.

Study design

Randomised controlled trials (including any open-label extensions of these RCTs) were included in the evaluation of efficacy. Information on the rate of serious adverse events was sought from regulatory sources [the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMEA)]. If these failed to report the necessary data to calculate event rates then non-randomised studies that provided these data for etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab were included in the review. If multiple non-randomised studies were identified, inclusion was limited to those studies reporting outcomes for a minimum of 500 patients receiving biologic therapy.

Interventions

Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab were the interventions of interest. Comparators were placebo, another of the three listed agents, or conventional management strategies for active and progressive PsA that have responded inadequately to previous DMARD therapy, excluding TNF inhibitors.

Participants

For the evaluation of the effectiveness of etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab, included studies were of adults with active and progressive PsA with an inadequate response to previous standard therapy (including at least one DMARD). Trials of effectiveness had to specify that the patients had PsA, with the definition and/or the inclusion criteria for PsA stated. For the assessment of adverse effects, studies of patients with other conditions were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Outcomes

The eligible outcomes of effectiveness were measures of the anti-inflammatory response (PsARC, ACR 20/50/70), response of psoriatic skin lesions (PASI), functional measures (HAQ), radiological assessments of disease progression or remission, QoL assessments [e.g. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)] and overall global assessments.

In terms of the outcomes of adverse events of biologics, we provided an initial overview of previous systematic reviews of biologic safety (see Results of review of clinical effectiveness) before conducting our systematic review of adverse events of these agents. Our systematic review specifically focused on the known serious adverse events of these agents: malignancies, severe infections (i.e. those that require i.v. antibiotic therapy and/or hospitalisation or cause death) and reactivation of latent tuberculosis (TB). If additional serious adverse events have been reported to regulatory bodies then the incidence of these were also assessed. In addition, data relating to serious adverse events in indications other than PsA were also considered in our systematic review, provided it was clinically appropriate to do so.

Data extraction strategy

Data on study and participant characteristics, efficacy outcomes, adverse effects, costs to the health service and cost-effectiveness were extracted. Baseline data were extracted where reported. Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and independently checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. The results of data extraction were presented in the structured tables (see Appendix 3, Efficacy data extraction: etanercept/infliximab/adalimumab). Disagreements were resolved through consensus, or consulting a third reviewer if necessary. Attempts were made, where possible, to contact authors for missing data. Data from studies with multiple publications were extracted and reported as a single study. In the rare case of minor discrepancies for the same data between published and unpublished data, data from published sources were used.

Quality assessment strategy

The quality of RCTs and other study designs were assessed using standard checklists. 75 Regarding the additional studies reviewed for data on serious adverse events: as all observational studies are prone to confounding and bias to some extent, non-randomised studies including < 500 patients receiving biologics were excluded from the review. The assessment was performed by one reviewer and checked independently by a second. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer if necessary.

Data analysis

Where sufficient clinically and statistically homogeneous data were available, data were pooled using standard meta-analytic methods. The levels of clinical and methodological heterogeneity were investigated, and statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Q- and I2-statistics. Given the small number of trials available, a fixed-effects model was used to pool outcomes where pooling was appropriate. Sensitivity analyses were undertaken when permitted by sufficient data (e.g. exclusion of concomitant MTX treatment). The potential short- and long-term benefits of etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab on both the psoriasis and arthritis components of PsA were investigated. The rates of serious adverse effects of these biologic agents were synthesised narratively.

As trials conducting head-to-head comparisons of etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab were not available the possibility of conducting some form of indirect comparison was investigated. Indirect comparisons are useful analytic tools when direct evidence on comparisons of interest is absent or sparse. 77 Meta-analysis using indirect comparisons enables data from several sources to be combined, while taking into account differences between the different sources, in a similar way to, but distinct from, how a random-effects model takes into account between-trial heterogeneity. As with a mixed-treatment comparison (MTC), Bayesian indirect comparisons need a ‘network of evidence’ to be established between all of the interventions of interest. The three drugs being evaluated all have a common comparator: placebo. It is this common comparator that allows the network between etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab to be established and provide information on the benefits of these agents relative to placebo and each other.

To help inform both the clinical review and the economic modelling four separate outcomes were considered. These outcomes were: PsARC response, HAQ score conditional on PsARC response, ACR 20/50/70 responses and PASI 50/75/90 responses. All outcomes were evaluated at 12 weeks. The evidence synthesis was undertaken using winbugs (version 1.4.2). winbugs is a Bayesian analysis software tool that, through the use of Markov chain Monte Carlo, calculates posterior distributions for the parameters of interest given likelihood functions derived from data and prior probabilities. Full details of the Bayesian indirect comparison methods and the winbugs codes along for the four different analyses are presented in Appendix 5.

Results of review of clinical effectiveness

Quantity and quality of research available

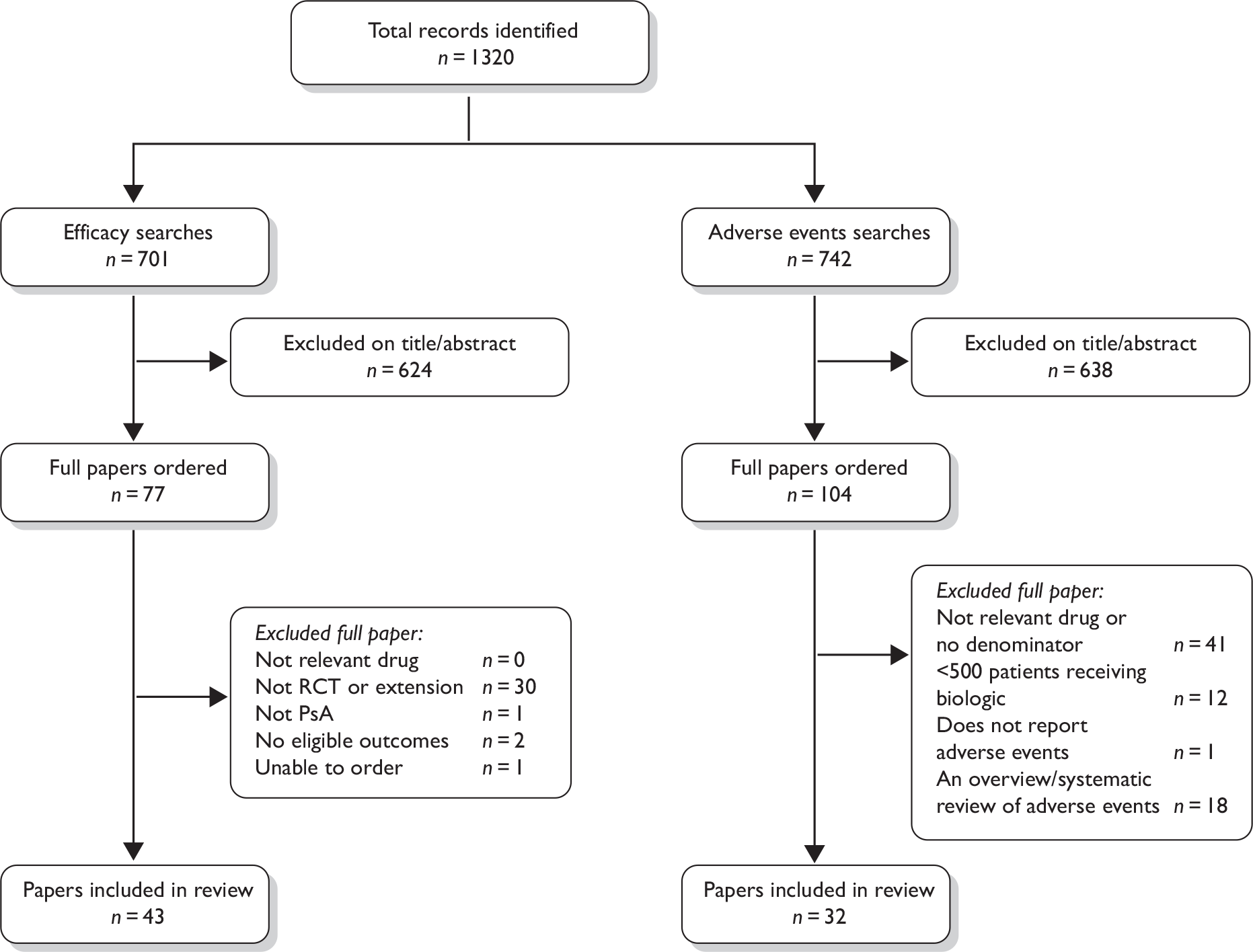

A total of 1320 records were identified from both the clinical effectiveness and adverse event searches (Figure 1). Details of studies excluded at the full publication stage are provided in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing the number of studies identified and included.

Randomised controlled trials and extensions in psoriatic arthritis

Of the 701 studies identified from the search for RCTs, a total of 43 publications, representing multiple publications of six RCTs and their extensions met the inclusion criteria for the review of efficacy. 51,52,78–118 Two placebo-controlled RCTs in patients with PsA were found for each of the three agents: etanercept,52,78,97,99,105,107,110 infliximab79–82,89–91,95,96,98,106,109,111–118 and adalimumab. 51,83,88,92,93,100–104 Baseline characteristics from all six RCTs are presented in Table 1.

| Etanercept | Infliximab | Adalimumab | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mease 200078 | Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | IMPACT 2 82,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | ADEPT51,88,92,93,100–104 | Genovese 200783 | |||||||

| Etanercept (n = 30) | Placebo (n = 30) | Etanercept (n = 101) | Placebo (n = 104) | Infliximab (n = 52) | Placebo (n = 52) | Infliximab (n = 100) | Placebo (n = 100) | Adalimumab (n = 151) | Placebo (n = 162) | Adalimumab (n = 51) | Placebo (n = 49) | |

| Age (years): mean (SD) | 46.0 (30.0–70.0)a | 43.5 (24.0–63.0)a | 47.6 (18–76)a | 47.3 (21–73)a | 45.7 (11.1) | 45.2 (9.7) | 47.1 (12.8) | 46.5 (11.3) | 48.6 (12.5) | 49.2 (11.1) | 50.4 (11.1) | 47.7 (11.3) |

| Male (%) | 53 | 60 | 57 | 45 | 58 | 58 | 71 | 51 | 56 | 55 | 57 | 51 |

| Duration of PsA (years): mean (SD) | 9.0 (1–31)a | 9.5 (1–30)a | 9.0 (–)a | 9.2 (–)a | 8.7 (8.0) | 8.5 (6.4) | 8.4 (7.2) | 7.5 (7.8) | 9.8 (8.3) | 9.2 (8.7) | 7.5 (7.0) | 7.2 (7.0) |

| Duration of psoriasis (years): mean (SD) | 19.0 (4–53)a | 17.5 (2–43)a | 18.3 (–)a | 19.7 (–)a | 16.9 (10.9) | 19.4 (11.6) | 16.2 (11.0) | 16.8 (12.0) | 17.2 (12.0) | 17.1 (12.6) | 18.0 (13.2) | 13.8 (10.7) |

| Number of prior DMARDs: mean (SD) | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.7 | – | – | – | – | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| Proportion of patients with numbers of previous DMARDsb | – | – | 27% = 0 40% = 1 20% = 2 | 21%=0 50% =1 19% =2 | 0% = 0 52% = 1 37% = 2–3 12% = 3+ | 2% = 0 38% = 1 48% = 2–3 12% = 3+ | 71% = 1–2 12% = 2+ | 67% = 1–2 9% = 2+ | – | – | – | |

| Concomitant therapies during study (%) | ||||||||||||

| Corticosteroids | 20 | 40 | 19 | 15 | 17 | 29 | 15 | 10 | – | – | – | – |

| NSAIDs | 67 | 77 | 88 | 83 | 89 | 79 | 71 | 73 | – | – | 73 | 86 |

| MTX | 47 | 47 | 45 | 49 | 46 | 65 | 47 | 45 | 51 | 50 | 47 | 47 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16 | 16 |

| Sulfasalazine | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | 14 |

| Leflunomide | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6 | 4 |

| Other DMARDs | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 6 |

| Type of PsA (%) | ||||||||||||

| DIP joints in hand and feet | – | – | 51 | 50 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Arthritis mutilans | – | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Polyarticular arthritis | – | – | 86 | 83 | 100 | 100 | – | – | 64 | 70 | 82 | 84 |

| Asymmetric peripheral arthritis | – | – | 41 | 38 | – | – | – | – | 25 | 25 | 10 | 14 |

| Ankylosing arthritis | – | – | 3 | 4 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| TJC: mean (SD) | 22.5 (11, 32)b | 19.0 (10, 39)b | 20.4 (–)b | 22.1 (–)b | 23.7 (13.7) | 20.4 (12.1) | 24.6 (14.1) | 25.1 (13.3) | 23.9 (17.3) | 25.8 (18.0) | 25.3 (18.3) | 29.3 (18.1) |

| SJC: mean (SD) | 14.0 (8, 23)b | 14.7 (7, 24)b | 15.9 (–)b | 15.3 (–)b | 14.6 (7.5) | 14.7 (8.2) | 13.9 (7.9) | 14.4 (8.9) | 14.3 (12.2) | 14.3 (11.1) | 18.2 (10.9) | 18.4 (12.1) |

| HAQ (0–3): mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.6)b | 1.2 (0.8, 1.6)b | 1.1 (–)b | 1.1 (–)b | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.7) |

| Patients evaluable for PASI at baseline: no. (%) | 19 (63%)c | 19 (63%)c | CiC | CiC | 22 (42%)d | 17 (33%)d | 83 (83%)c | 87 (87%)c | 70 (46%)c | 70 (43%)c | – | – |

| PASI (0–72) at baseline among patients evaluable for PASI: mean (SD) | 10.1 (2.3–30.0)a | 6.0 (1.5–17.7)a | CiC | CiC | 8.6 (6.6) | 8.1 (6.6) | 11.4 (12.7) | 10.2 (9.0) | 7.4 (6.0) | 8.3 (7.2) | – | – |

Additional adverse event studies

In total, 742 records were identified from the separate search for larger studies reporting adverse event rates for biologic agents in any indication. Of these records, 32 publications reported treatment with etanercept, infliximab or adalimumab in 500 or more patients, and reported either adverse event rates directly or provided sufficient information to calculate these rates (Figure 1). 89,97,99,119–148

Assessment of effectiveness

Efficacy of etanercept

Both trials evaluating etanercept for PsA were double-blind and placebo-controlled, and both were rated as ‘good’ on the quality assessment rating (Table 2). 52,78,97,99,105,107,110 Both trials were available as industry trial reports and journal publications.

| Quality assessment criteria | Study | |

|---|---|---|

| Mease 200078 | Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | |

| Eligibility criteria specified? | Y | Y |

| Power calculation? | Y | Y |

| Adequate sample size? | Y | Y |

| Number randomised stated? | Y | Y |

| True randomisation? | Y | Y |

| Double blind? | Y | Y |

| Allocation of treatment concealed? | Y | Y |

| Treatment administered blind? | Y | Y |

| Outcome assessment blind? | Y | Y |

| Patients blind? | Y | Y |

| Blinding successful? | NR | NR |

| Adequate baseline details presented? | Y | Y |

| Baseline comparability? | Y | Y |

| Similar cointerventions? | Y | Y |

| Compliance with treatment adequate? | Y | Y |

| All randomised patients accounted for? | Y | Y |

| Valid ITT analysis? | Y | Y |

| ≥ 80% patients in follow-up assessment? | Y | Y |

| Quality rating | Good | Good |

The baseline characteristics of the trial population are summarised in Table 1. Both trials were of adults (aged 18–70 years), with active PsA (defined in both trials as at least three swollen joints and at least three tender or painful joints, although only the more recent trial52,97,99,105,107,110 specified stable plaque psoriasis). Patients in both trials had demonstrated an inadequate response to NSAIDs. Over 70% of the patients in the larger trial52,97,99,105,107,110 had previously used at least one DMARD. Over 80% of patients in the Mease et al. 52,97,99,105,107,110 trial had polyarticular disease, indicating that, overall, the disease was severe. Patients were not required to have active psoriasis at baseline, but 77% of etanercept patients and 73% of placebo patients did have. The proportion of patients with spine involvement and arthritis mutilans at baseline was reported only for the larger trial, where such patients made up only a small proportion of the trial population. These details were not available for the smaller of the two trials, so the severity of disease across that population is unknown. However, given the similarity between the trials for other measures of disease activity (TJC, SJC, HAQ at baseline, plus baseline and previous medication), significant differences between the populations in terms of overall disease severity are unlikely. Patients taking stable doses of MTX or corticosteroids were permitted to continue with that dose and randomisation was stratified for MTX use at baseline. Overall, the baseline characteristics demonstrate that the trial populations are similar and are likely to be representative of a population with PsA requiring DMARD or biologic therapy. It should be noted, however, that the populations in these trials of etanercept are not representative of the patients for whom etanercept is recommended for use: these patients, according to the BSR, would have demonstrated a lack of response to at least two DMARDs. 149

In both trials, etanercept was administered by subcutaneous (s.c.) injection twice weekly at a dose of 25 mg. Treatment with active drug or placebo was administered for 12 weeks in the smaller trial78 and for 24 weeks in the larger trial. 52,97,99,105,107,110 In both trials the controlled phase was followed by a follow-up period during which etanercept was administered in an open-label fashion to all patients.

Outcome data derived under RCT conditions are available from both trials for PsARC, ACR 20/50/70 and HAQ at week 12. The primary outcome variable in the Mease 2000 trial78 was PsARC, whereas in the Mease et al. 52,97,99,105,107,110 trial it was ACR 20. Data on PASI at week 12 are available from the small78 trial only. RCT outcome data for PsARC, ACR 20/50/70, HAQ, PASI and radiographic assessment of progression at week 24 are available from the larger trial52,97,99,105,107,110 (n = 205). In addition, a subgroup analyses by concomitant MTX use provided additional PsARC, ACR 20/50/70 data at weeks 12 and 24. As subgroup analyses in already fairly small trials, the findings generated must be interpreted with some caution. They are useful, however, to explore the influence concomitant MTX has on the main treatment effect. All outcome data are summarised in Table 3, with pooled 12-week data shown in Table 4.

| Outcomes | Etanercept: n (%) | Placebo: n (%) | RR or mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mease 2000,78 12 weeks | ||||

| PsARCa | 26/30 (87) | 7/30 (23) | 3.71 (1.91 to 7.21) | |

| ACR 20 | 22/30 (73.0) | 4/30 (13) | 5.50 (2.15 to 14.04) | |

| ACR 50 | 15/30 (50.0) | 1/30 (3) | 15.00 (2.11 to 106.49) | |

| ACR 70 | 4/30 (13) | 0/30 (0) | 9.00 (0.51 to 160.17) | |

| HAQ% change from baseline: mean (SD) | n = 29 (64.2–38.7) | n = 30 (9.9–42.9) | CiC | |

| PASI 50 | 8/19 (42) | 4/19 (21) | 2.00 (0.72 to 5.53), p = 0.295 | |

| PASI 75 | 5/19 (26) | 0/19 (0) | 11.00 (0.65 to 186.02), p = 0.0154 | |

| Mease 2004,52,97,99,105,107,110 12 weeks | ||||

| PsARC | All pts | 73/101 (72) | 32/104 (31) | 2.35 (1.72 to 3.21), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 32/42 (76) | 14/43 (33) | 2.34 (1.47 to 3.72) | |

| –MTX | 41/59 (69) | 18/61 (30) | 2.35 (1.54 to 3.60) | |

| ACR 20a | All pts | 60/101 (59) | 16/104 (15) | 3.86 (2.39 to 6.23), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 26/42 (62) | 8/43 (19) | 3.33 (1.70 to 6.49) | |

| –MTX | 34/59 (58) | 8/61 (13) | 4.39 (2.22 to 8.7) | |

| ACR 50 | All pts | 38/101 (38) | 4/104 (4) | 9.78 (3.62 to 26.41), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 17/42 (40) | 1/43 (2) | 17.40 (2.42 to 124.99) | |

| –MTX | 21/59 (36) | 3/61 (5) | 7.24 (2.28 to 22.98) | |

| ACR 70 | All pts | 11/101 (11) | 0/104 (0) | 23.68 (1.41 to 396,53), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 4/42 (10) | 0/43 (0) | 9.21 (0.51 to 165.93) | |

| –MTX | 7/59 (12) | 0/61 (0) | 15.5 (0.91 to 265.46) | |

| HAQ% change from baseline: mean (SD) | (n = 96) 53.5, (43.4) | (n = 99) 6.3, (42.7) | CiC | |

| Mease 2004,52,97,99,105,107,110 24 weeks | ||||

| PsARC | All pts | 71/101 (70) | 24/104 (23) | 3.05 (2.10 to 4.42), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 31/42 (74) | 11/43 (26) | 2.89 (1.68 to 4.95) | |

| –MTX | 40/59 (68) | 13/61 (21) | 3.18 (1.90 to 5.32) | |

| ACR 20 | All pts | 50/101 (50) | 14/104 (13) | 3.68 (2.17 to 6.22), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 23/42 (55) | 8/43 (19) | 2.94 (1.49 to 5.83) | |

| –MTX | 27/59 (46) | 6/61 (10) | 4.73 (2.10 to 10.63) | |

| ACR 50 | All pts | 37/101 (37) | 4/104 (4) | 9.52 (3.52 to 25.75), p < 0.001 |

| +MTX | 16/42 (38) | 3/43 (7) | 5.46 (1.72 to 17.37) | |

| –MTX | 21/59 (36) | 1/61 (2) | 21.71 (3.02 to 156.30) | |

| ACR 70 | All pts | 9/101 (9) | 1/104 (1) | 9.27 (1.20 to 71.83), p = 0.009 |

| +MTX | 2/42 (5) | 0/43 (0) | 5.12 (0.25 to 103.50) | |

| –MTX | 7/59 (12) | 0/61 (0) | 15.50 (0.91 to 265.46) | |

| HAQ% change from baseline: mean (SD) | (n = 96) 53.6 (55.1) | (n = 99) 6.4 (49.6) | 47.20 (32.47 to 61.93), p < 0.001 | |

| PASI 50 | 31/66 (47) | 11/62 (18); | 2.65 (1.46 to 4.80), p < 0.001 | |

| PASI 75 | 15/66 (23) | 2/62 (3) | 7.05 (1.68 to 29.56), p = 0.001 | |

| PASI 90 | 4/66 (6) | 2/62 (3) | 1.88 (0.36 to 9.90), p = 0.681 | |

| TSS mean (SD) annualised rate of progression | All pts | (n = 101) –0.03 (0.73) | (n = 104) 0.53 (1.39) | –0.56 (–0.86 to –0.26), p = 0.0006 |

| +MTX | (n = 42) 0.06 (0.76) | (n = 43) 0.48 (1.00) | –0.42 (–0.80 to –0.04), p = 0.12345 | |

| –MTX | (n = 59) –0.09 (0.71) | (n = 61) 0.57 (1.62) | –0.66 (–1.11 to –0.21), p = 0.0014 | |

| Trial | Etanercept | Placebo | RR or mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PsARC | |||

| Mease 200078 | 26/30 (87%) | 7/30 (23%) | 3.71 (1.91 to 7.21) |

| Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | 73/101 (72%) | 32/104 (31%) | 2.35 (1.72 to 3.21), p < 0.001 |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value, I 2 : 2.60 (1.96 to 3.45), p < 0.00001, I 2 = 34% | |||

| ACR 20 | |||

| Mease 200078 | 22/30 (73%) | 4/30 (13%) | 5.50 (2.15 to 14.04) |

| Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | 60/101 (59%) | 16/104 (15%) | 3.86 (2.39 to 6.23), p < 0.001 |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value, I 2 : 4.19 (2.74 to 6.42), p < 0.00001, I 2 = 0% | |||

| ACR 50 | |||

| Mease 200078 | 15/30 (50%) | 1/30 (3%) | 15.00 (2.11 to 106.49) |

| Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | 38/101 (38%) | 4/104 (4%) | 9.78 (3.62 to 26.41), p < 0.001 |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value, I 2 : 10.84 (4.47 to 26.28), p < 0.00001, I 2 = 0% | |||

| ACR 70 | |||

| Mease 200078 | 4/30 (13%) | 0/30 (0%) | 9.00 (0.51 to 160.17) |

| Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | 11/101 (11%) | 0/104 (0%) | 23.68 (1.41 to 396,53), p < 0.001 |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value, I 2 : 16.28 (2.20 to 120.54), p = 0.006, I 2 = 0% | |||

| HAQ% change from baseline: mean (SD) | |||

| Mease 200078 | (n = 29) –64.2 (CiC) | (n = 30) –9.9 (CiC) | –54.3 (33.47 to 75.13) |

| Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | (n = 96) –53.5 (CiC) | (n = 99) –6.3 (CiC) | –47.20 (35.11 to 59.29) |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value, I 2 : –48.99 (38.53 to 59.44), p < 0.00001, I 2 = 0% | |||

Uncontrolled data on all outcomes are also available at 36 weeks or 12 months (uncontrolled follow-up data). These data are summarised in Table 4.

Efficacy after 12 weeks’ treatment

The individual trial results (Table 3) and pooled estimates of effect (Table 4) demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of etanercept for all joint disease and HAQ score outcomes. There was no statistical heterogeneity for any outcome.

Across the two trials at 12 weeks almost 85% of patients treated with etanercept achieved a PsARC response, which is the only joint disease outcome measure that has been specifically defined for PsA. In addition, around 65% of patients treated with etanercept achieved an ACR 20 response, demonstrating a basic degree of efficacy in terms of arthritis-related symptoms. Around 45% of patients treated with etanercept achieved an ACR 50 response, and around 12% achieved an ACR 70 response, demonstrating a good level of efficacy. The subgroup analyses conducted on the Mease et al. 52,97,99,105,107,110 data revealed that the effect of etanercept was not dependent on patients’ concomitant use, or not, of MTX. The PASI results from Mease et al. 78 indicate some beneficial effect on psoriasis at 12 weeks; however, the data were too sparse (38 patients in total) to establish statistical significance. The statistically significant reduction in HAQ score with etanercept compared with placebo indicates a beneficial effect of etanercept on functional status.

Efficacy after 24 weeks’ treatment

At 24 weeks, the treatment effect for all joint disease outcome measures was statistically significantly greater with etanercept than with placebo, although these data were available only for one trial (see Table 3). As at 12 weeks, the subgroup analyses conducted on the Mease et al. 52,97,99,105,107,110 data revealed that the effect of etanercept was not dependent upon patients’ concomitant use, or not, of MTX. The size of treatment effect did not appear greater at 24 weeks than at 12 weeks.

At 24 weeks, the TSS annualised rate of progression was statistically significantly lower in patients treated with etanercept than in patients receiving placebo. This treatment difference did not vary with or without concomitant MTX use. However, this duration of follow-up is to be considered short and barely adequate for this outcome.

At 24 weeks, the treatment effect on psoriasis favoured etanercept with relative risks (RRs) for PASI 75 of 7.05 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.68 to 29.56], PASI 50 of 2.65 (95% CI 1.46 to 4.80) and PASI 90 of 1.88 (95% CI 0.36 to 9.90). The result for PASI 75 and PASI 50 was statistically significant despite there being only 66 patients on etanercept evaluable for psoriasis. 52,97,99,105,107,110

Longer-term follow-up

The results for long-term follow-up are summarised in Table 5. The data are uncontrolled and therefore cannot be taken as reliable. In general, they do indicate that the improvements in patients’ joint and skin symptoms and HAQ score achieved during the controlled phase of the trials are maintained in the medium term. At 1 year, the mean annualised rate of progression TSS for all patients was –0.03 [standard deviation (SD 0.87)] indicating that on average no clinically significant progression of joint erosion had occurred. Limited 2-year data indicated little change in mean TSS, although data on patient numbers or variability were not reported.

| Trial | Type of data | Duration | Outcomes | Etanercept/placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mease 200078 | Uncontrolled | 36 weeks | PsARC | 26/30 (87%) | |

| ACR 20 | 26/30 (87%) | ||||

| ACR 50 | 19/30 (63%) | ||||

| ACR 70 | 10/30 (33%) | ||||

| HAQ% change from baseline: mean (median) | CiC | ||||

| PASI 75 | 7/19 (37%) | ||||

| PASI 50 | 11/19 (58%) | ||||

| Mease 200452,97,99,105,107,110 | Uncontrolled | 12 months | ACR results, etc. only as brief text | Maintained as at 24 weeks | |

| TSS mean (SD) annualised rate of progression | All pts | (n = 101) –0.03 (0.87) | |||

| +MTX | (n = 42) 0.01 (0.81) | ||||

| –MTX | (n = 59) –0.13 (0.91) | ||||

| 24 months | TSS mean change from baseline | Etanercept/etanercept –0.38 | |||

| Placebo/etanercept 0.50 | |||||

Summary of the efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis

-

There is evidence from double-blind placebo-controlled trials of a good level efficacy for etanercept in the treatment of PsA. Conclusions to be drawn from these data are limited by the small sample size and the short duration of one of the trials.

-

There is evidence from two RCTs that etanercept treatment improves patients’ functional status as assessed using the HAQ score.

-

There is limited evidence from the two RCTs that etanercept treatment has a beneficial effect on the psoriasis component of the disease.

-

Uncontrolled follow-up of patients indicate that treatment benefit is maintained for at least 50 weeks; however, these data may not be reliable.

-

There are radiographic data from controlled trials for etanercept in PsA that demonstrate a beneficial effect on progression of joint disease at 24 weeks. This is a very short time over which to identify a statistically significant effect of therapy and indicates a rapid onset of action of etanercept. Data from uncontrolled follow-up indicate that, on average, disease progression may be halted for at least 1 year; however, these data may not be reliable.

Efficacy of infliximab

The literature search identified two RCTs of infliximab for the treatment of PsA. 79–82,89–91,95,96,98,106, 109,111–118 Both were rated as ‘good’ by the quality assessment (Table 6). The trials were reported in published papers and abstracts, and the industry trial report was made available.

| Quality assessment criteria | Study | |

|---|---|---|

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | |

| Eligibility criteria specified? | Y | Y |

| Power calculation? | Y | Y |

| Adequate sample size? | Y | Y |

| Number randomised stated? | Y | Y |

| True randomisation? | Y | Y |

| Double blind? | Y | Y |

| Allocation of treatment concealed? | Y | Y |

| Treatment administered blind? | Y | Y |

| Outcome assessment blind? | Y | Y |

| Patients blind? | Y | Y |

| Blinding successful? | NR | NR |

| Adequate baseline details presented? | Y | Y |

| Baseline comparability? | Y | Y |

| Similar cointerventions? | Y | Y |

| Compliance with treatment adequate? | Y | Y |

| All randomised patients accounted for? | Y | Y |

| Valid ITT analysis? | Y | Y |

| ≥ 80% patients in follow-up assessment? | Y | Y |

| Quality rating | Good | Good |

Both were double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adult patients with active PsA, randomising a total of 304 patients. All patients had been diagnosed with PsA for at least 6 months, with a negative RF and active disease including 5+ swollen/tender joints. All patients must have had an inadequate response to at least one DMARD. 79–82,89–91,95,96,98,106,109,111–118 One trial required patients to have active plaque psoriasis with at least one qualifying target lesion (≥ 2-cm diameter). 82,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 The earlier of the two trials did not require patients to have active psoriasis at baseline, but 42% of infliximab patients and 33% of placebo patients did have (defined as PASI score of at least 2.5). 79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 The proportion of patients with spine involvement, arthritis mutilans and erosions at baseline was not reported for either trial, so the severity of disease across the populations is unknown. The baseline characteristics of the trial populations are summarised in Table 1. These demonstrate that the trial populations are broadly similar, are likely to be representative of a population with quite severe PsA requiring further DMARD or biologic therapy, and that the treatment and placebo groups were well balanced. Relative to the patients for whom infliximab treatment is recommended in practice, these trial populations may be less severely affected, with only around one-half in the Infliximab Multinational Psoriatic Arthritis Controlled Trial (IMPACT)79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 and possibly even fewer in IMPACT 2,82,90,90,95,98,106,112,116 having failed to respond to two or more DMARDs (failure to respond to DMARDs as defined by the BSR). 149

In the RCT phase of the IMPACT trial,79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 infliximab (5 mg/kg) or placebo was infused at weeks 0, 2, 6 and 14, with follow-up at week 16. Further infusions of infliximab were administered to all patients in an open-label fashion at 8-week intervals, with further follow-up at week 50. Patients in the IMPACT 2 trial82,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 were randomised to receive infusions of placebo or infliximab, 5 mg/kg, at weeks 0, 2, 6, 14 and 22, with assessments at weeks 14 and 24. Further infusions of infliximab were administered to all patients in an open-label fashion (timing dependent upon whether they were originally randomised to infliximab, or crossed over from placebo either at week 16 or 24) with further follow-up at week 54.

The primary outcome variable in these trials was ACR 20 at 14 or 16 weeks. The two trials also reported 14-week and/or 16-week outcome data for ACR 50, ACR 70, PsARC, HAQ, PASI 50, PASI 75 and PASI 90 (RCT data). IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 also maintained randomisation and reported these outcomes at week 24. Both studies reported longer-term open-label follow-up of patients after 50 and 54 weeks (IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 and IMPACT 2,82,90,91,95,98,105,112,115 respectively). All data are summarised in Table 7, with pooled data presented in Table 8.

| Trial | Duration (weeks) | Outcomes | Infliximab | Placebo | RR or mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMPACT (randomised period)79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 14 | PsARC | 40/52 (76.9%) | 7/52 (13.5%) | 5.71 (2.82 to 11.57) | |

| ACR 20 | All pts | 35/52 (67.3%) | 6/52 (11.5%) | 5.83 (2.68 to 12.68) | ||

| +MTX | NR | NR | – | |||

| –MTX | NR | NR | – | |||

| ACR 50 | 19/52 (36.5%) | 1/52 (1.9%) | 19.00 (2.64 to 136.76) | |||

| ACR 70 | 11/52 (21.2%) | 0/52 (0%) | 23.00 (1.39 to 380.39) | |||

| 16 | PsARC | 39/52 (75.0%) | 11/52 (21.2%) | 3.55 (2.05 to 6.13), p < 0.01 | ||

| ACR 20 | All pts | 34/52 (65.4%) | 5/52 (9.6%) | 6.80 (2.89 to 16.01) p < 0.01 | ||

| +MTX | 15/24 (62.5%) | 4/34 (11.8%) | 5.31 (2.01 to 14.03), p < 0.01 | |||

| –MTX | 19/28 (67.9%) | 1/18 (5.6%) | 12.21 (1.79 to 83.46), p < 0.01 | |||

| ACR 50 | 24/52 (46.2%) | 0/52 (0%) | 49.00 (3.06 to 785.06), p < 0.01 | |||

| ACR 70 | 15/52 (28.8%) | 0/52 (0%) | 31.00 (1.90 to 504.86), p < 0.01 | |||

| HAQ mean (SD)% change from baseline | (n = 48) –49.8 (56.8) | (n = 47) 1.6 (56.9) | –51.4 (–74.5 to –28.3), p < 0.01 | |||

| PASI 50a | 22/22 (100%) | 0/16 (0%) | 33.26 (2.17 to 510.71) | |||

| PASI 75a | 15/22 (68.2%) | 0/16 (0%) | 22.91 (1.47 to 356.81) | |||

| PASI 90a | 8/22 (36.4%) | 0/16 (0%) | 12.57 (0.78 to 203.03) | |||

| PASI mean (SD) change from baselineb | (n = 42) –4.1 (3.9) | (n = 38) 0.9 (3.7) | –5 (–6.8 to –3.3), p < 0.01 | |||

| IMPACT 2 (randomised)82,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | 14 | PsARC | 77/100 (77%) | 27/100 (27%) | 2.85 (2.03 to 4.01) | |

| ACR 20 | All pts | 58/100 (58%) | 11/100 (11%) | 5.27 (2.95 to 9.44) | ||

| +MTX | NR | NR | – | |||

| –MTX | NR | NR | – | |||

| ACR 50 | 36/100 (36%) | 3/100 (3)% | 12.00 (3.82 to 37.70) | |||

| ACR 70 | 15/100 (15%) | 1/100 (1%) | 15.00 (2.02 to 111.41) | |||

| HAQ mean (SD)% change from baseline | (n = 100) –48.6 (43.3) | (n = 100) 18.4 (90.5) | –67.00 (–86.66 to –47.33) | |||

| PASI 50b | CiC | CiC | CiC | |||

| PASI 75b | CiC | CiC | CiC | |||

| PASI 90b | CiC | CiC | CiC | |||

| PASI mean (SD)% change from baseline | NR | NR | – | |||

| 24 | PsARC | 70/100 (70%) | 32/100 (32%) | 2.19 (1.60 to 3.00) | ||

| ACR 20 | All pts | 54/100 (54%) | 16/100 (16%) | 3.38 (2.08 to 5.48) | ||

| +MTX | NR | NR | – | |||

| –MTX | NR | NR | – | |||

| ACR 50 | 41/100 (41%) | 4/100 (4%) | 10.25 (3.81 to 27.55) | |||

| ACR 70 | 27/100 (27%) | 2/100 (2%) | 13.5 (3.30 to 55.26) | |||

| PASI 50b | CiC | CiC | CiC | |||

| PASI 75b | CiC | CiC | CiC | |||

| PASI 90b | CiC | CiC | CiC | |||

| HAQ mean (SD)% change from baseline | (n = 100) –46.0 (42.5) | (n = 100) 19.4 (102.8) | –65.40 (–87.20 to –43.60) | |||

| PASI mean (SD)% change from baseline | NR | NR | – | |||

| Total modified van der Heijde–Sharp score: mean (SD) change from baseline | –0.70 (2.53) | 0.82 (2.62) | – | |||

| Trial | Outcomes | Infliximab | Placebo | RR or mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsARC | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 40/52 (76.9%) | 7/52 (13.5%) | 5.71 (2.82 to 11.57) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | 77/100 (77%) | 27/100 (27%) | 2.85 (2.03 to 4.01) | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI) to p-value | 3.44 (2.53 to 4.69), p < 0.0001 | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 68% | |||

| ACR 20 | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 35/52 (67.3%) | 6/52 (11.5%) | 5.83 (2.68 to 12.68) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | 58/100 (58%) | 11/100 (11%) | 5.27 (2.95 to 9.44) | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value | 5.47 (3.43 to 8.71) | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 0% | |||

| ACR 50 | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 19/52 (36.5%) | 1/52 (1.9%) | 19.00 (2.64 to 136.76) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | 36/100 (36%) | 3/100 (3%) | 12.00 (3.82 to 37.70) | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value | 13.75 (5.11 to 37.00), p < 0.0001 | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 0% | |||

| ACR 70 | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 11/52 (21.2%) | 0/52 (0%) | 23.00 (1.39 to 380.39) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | 15/100 (15%) | 1/100 (1%) | 15.00 (2.02 to 111.41) | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value | 17.67 (3.46 to 90.14), p = 0.001 | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 0% | |||

| PASI 50 | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 22/22 (100%) | 0/16 (0%) | 33.26 (2.17 to 510.71) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | CiC | CiC | CiC | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value | 10.58 (5.47 to 20.48), p < 0.0001a | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 0% | |||

| PASI 75 | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 15/22 (68.2%) | 0/16 (0%) | 22.91 (1.47 to 356.81) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | CiC | CiC | CiC | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value | 26.68 (7.79 to 91.44), p < 0.0001a | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 0% | |||

| PASI 90 | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 8/22 (36.4%) | 0/16 (0%) | 12.57 (0.78 to 203.03) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | CiC | CiC | CiC | |

| Pooled RR (95% CI), p-value | 40.01 (5.93 to 270.15), p < 0.0001a | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 0% | |||

| HAQ% change from baseline: mean (SD) | ||||

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | (n = 48) –49.8 (56.8) | (n = 47) 1.6 (56.9) | –51.4 (–74.27 to –28.54) | |

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | (n = 100) –48.6 (43.3) | (n = 100) 18.4 (90.5) | –67.00 (–86.66 to –47.33) | |

| Pooled WMD (95% CI), p-value | –60.37 (–75.28 to –45.46) | |||

| I 2 | I2 = 3% | |||

Efficacy after 14–16 weeks’ treatment

At 14 weeks, both trials reported a significant improvement in the PsA-specific PsARC measure for patients receiving infliximab, relative to those receiving placebo (pooled RR 3.44, 95% CI 2.53 to 4.69 – Table 8). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 68%) between the two study estimates, due to the different placebo response rates (13.5% vs 27%). PsARC response on infliximab was around 77% in both trials.

The pooled RR for ACR 20 at 14 weeks was 5.47 (95% CI 3.43 to 8.71), with an overall response of 61% in infliximab-treated patients, demonstrating a clear degree of efficacy of infliximab in terms of arthritis-related symptoms. As very few patients receiving placebo achieved an ACR 50 or ACR 70 response, the pooled RRs clearly favoured infliximab in terms of these outcomes, although the limited number of observations mean that there is considerable uncertainty around these pooled estimates, as reflected by their CIs (see Table 8). Despite the potentially large relative effects, it should also be noted that only the minority of infliximab-treated patients achieved an ACR 50 or ACR 70 response at 14 weeks (36% and 17%, respectively). Data from the IMPACT trial79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 indicated no significant difference in ACR 20 response at 16 weeks between patients with and without concomitant MTX, although the number of patients in each of these groups was small.

As with the ACR outcomes, few patients receiving placebo demonstrated skin improvements over 14–16 weeks in terms of a PASI response; the pooled RR for PASI 50 was 10.58 (95% CI 5.47 to 20.48), demonstrating a clear degree of efficacy of infliximab in terms of skin-related symptoms. PASI 75 and PASI 90 response measures favoured infliximab even more strongly, although it should be noted that PASI outcomes were recorded only for those patients with a score of at least 2.5 at baseline. Forty-two per cent of patients receiving infliximab achieved the highest level of skin response (PASI 90), although again there is considerable uncertainty around the estimates (see Table 7).

The statistically significant pooled percentage change from baseline in HAQ score with infliximab compared with placebo [mean difference –60.37 (–75.28 to –45.46)] indicates a beneficial effect of infliximab on functional status.

Efficacy after 24 weeks

The IMPACT 2 trial82,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 maintained randomisation for 24 weeks. The data for all measures of joint disease, psoriasis and HAQ are similar to those observed at the earlier 14-week follow-up, suggesting that the benefits of infliximab are maintained up to 24 weeks of treatment (see Table 7). Change from baseline in modified van der Heijde–Sharp score significantly differed between infliximab and placebo groups, indicating that infliximab may inhibit progression of joint damage at 24 weeks (see Table 7).

Longer-term follow-up

The data for longer-term follow-up (50 or 54 weeks) from the two IMPACT trials are summarised in Table 9. These data are uncontrolled and may therefore be unreliable. Also, the duration of treatment varied between participants, as some will have crossed over from placebo treatment. However, the data broadly indicate that the levels of efficacy achieved with infliximab in terms of joint disease, psoriasis and HAQ after 14–24 weeks’ treatment might be maintained in the medium term.

| Trial | Duration (weeks) | Outcomes | Infliximab/placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMPACT79–81,89,96,109,111,113–115,117,118 | 50 | ACR 20 | All pts | 34/49 (69.4%) |

| +MTX | 16/22 (72.7%) | |||

| –MTX | 18/27 (66.7%) | |||

| ACR 50 | 26/49 (53.1%) | |||

| ACR 70 | 19/49 (38.8%) | |||

| PsARC | 36/49 (73.5%) | |||

| HAQ: mean (SD)% change from baseline | (n = 45) –42.5 (59.0) | |||

| PASI 50a | 19/22 (86.3%) | |||

| PASI 75a | 13/22 (59%) | |||

| PASI 90a | 9/22 (40.9%) | |||

| PASI: mean (SD) change from baselinea | (n = 35) –4.8 (5.9) | |||

| Total modified van%%der%%Heijde–Sharp score: mean (SD) change from baseline | (n = 70) –1.72 (5.82) | |||

| IMPACT 282,90,91,95,98,106,112,116 | 54 | PsARC | 67/90 (74.4%) | |

| PASI 50a | 57/82 (69.5%) | |||

| PASI 75a | 40/82 (48.8%) | |||

| PASI 90a | 32/82 (39%) | |||

| Total modified van der Heijde–Sharp score: mean (SD) change from baseline |

Infliximab/infliximab –0.94 (3.4) Placebo/infliximab 0.53 (2.6) |

|||

In terms of radiographic assessment, there was no significant change from baseline in the total modified van der Heijde–Sharp score for those infliximab-treated patients followed up at 50 or 54 weeks in the two studies, suggesting infliximab may inhibit progression of joint damage. However, as with other post-24-week outcomes, there was no placebo group for comparison.

Summary of the efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of PsA

-

There is evidence from two double-blind placebo controlled trials of a good level of efficacy for infliximab in the treatment of PsA, with beneficial effects on joint disease, psoriasis and functional status as assessed by HAQ.

-

Conclusions to be drawn from these data are limited by the short duration of the controlled trials; controlled data to evaluate long-term effects are not available.

-

Uncontrolled follow-up of patients indicate that short-term benefit is maintained for at least 50 weeks; however, these data may not be reliable.

-

Radiographic data from uncontrolled follow-up of infliximab trials suggest that the drug may delay the progression of joint disease in PsA, although these data are not of high quality.

Efficacy of adalimumab

Both trials evaluating adalimumab for PsA were double blind and placebo controlled, and both were rated as ‘good’ on the quality assessment rating (Table 10). 51,83,88,92,93,100–104

| Quality assessment criteria | Study | |

|---|---|---|

| ADEPT51,88,92,93,100–104 | Genovese 200783 | |

| Eligibility criteria specified? | Y | Y |

| Power calculation? | Y | Y |

| Adequate sample size? | Y | Y |

| Number randomised stated? | Y | Y |

| True randomisation? | Y | Y |

| Double blind? | Y | Y |

| Allocation of treatment concealed? | NR | Y |

| Treatment administered blind? | Y | Y |

| Outcome assessment blind? | Y | Y |

| Patients blind? | Y | Y |

| Blinding successful? | NR | NR |

| Adequate baseline details presented? | Y | Y |

| Baseline comparability? | Y | Y |

| Similar cointerventions? | Y | Y |

| Compliance with treatment adequate? | Y | Y |

| All randomised patients accounted for? | Y | Y |

| Valid ITT analysis? | Y | Y |

| ≥ 80% patients in follow-up assessment? | Y | Y |

| Quality rating | Good | Good |

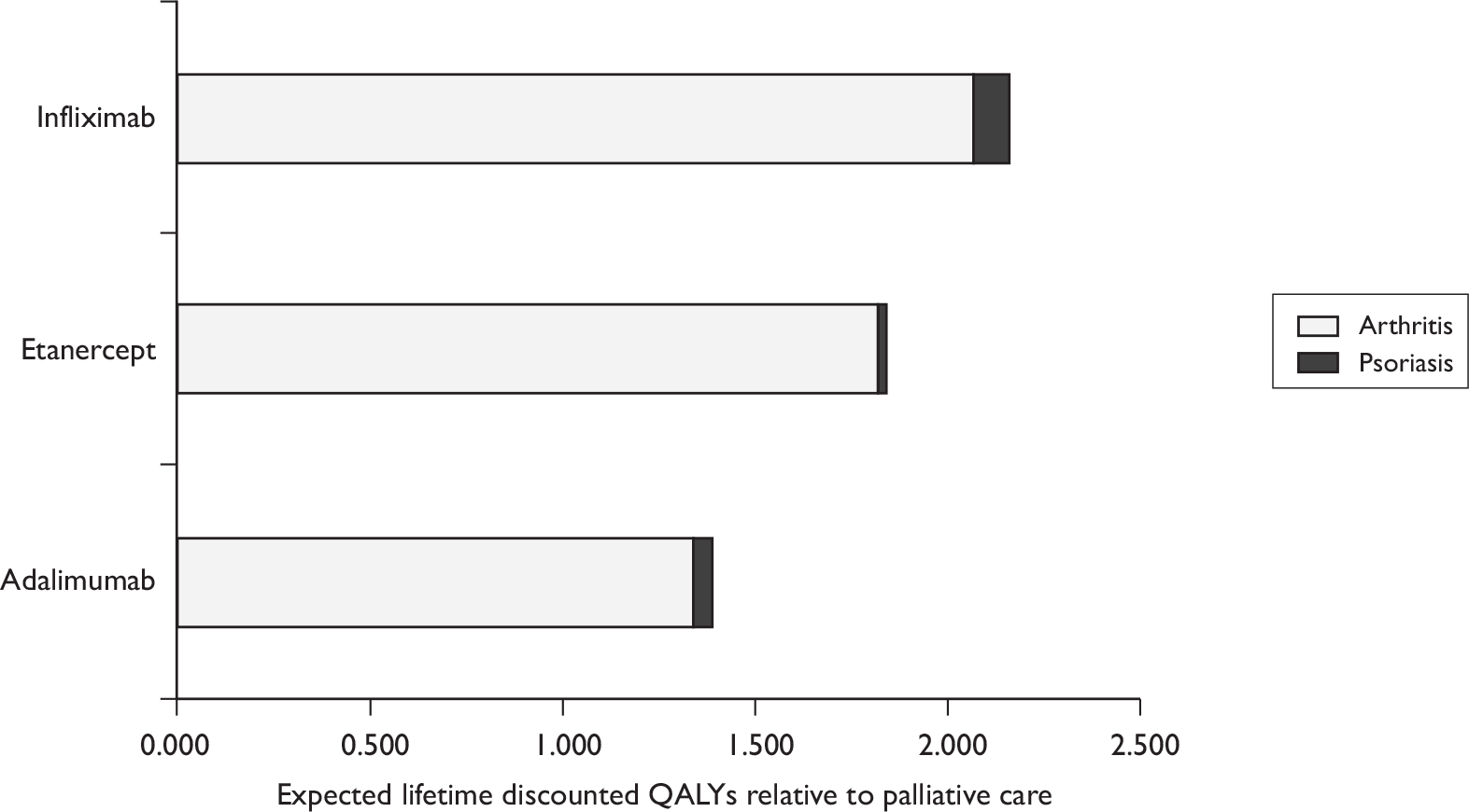

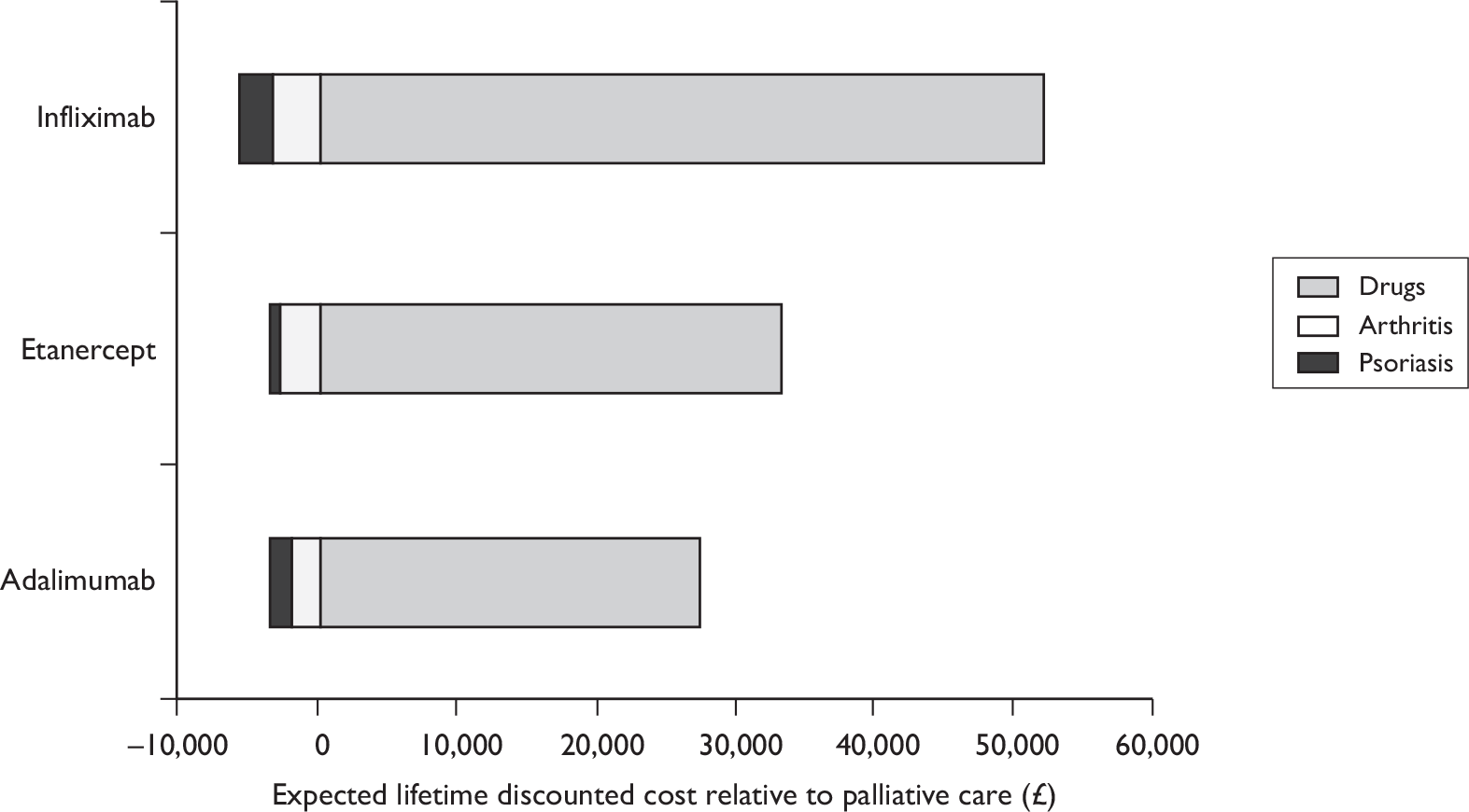

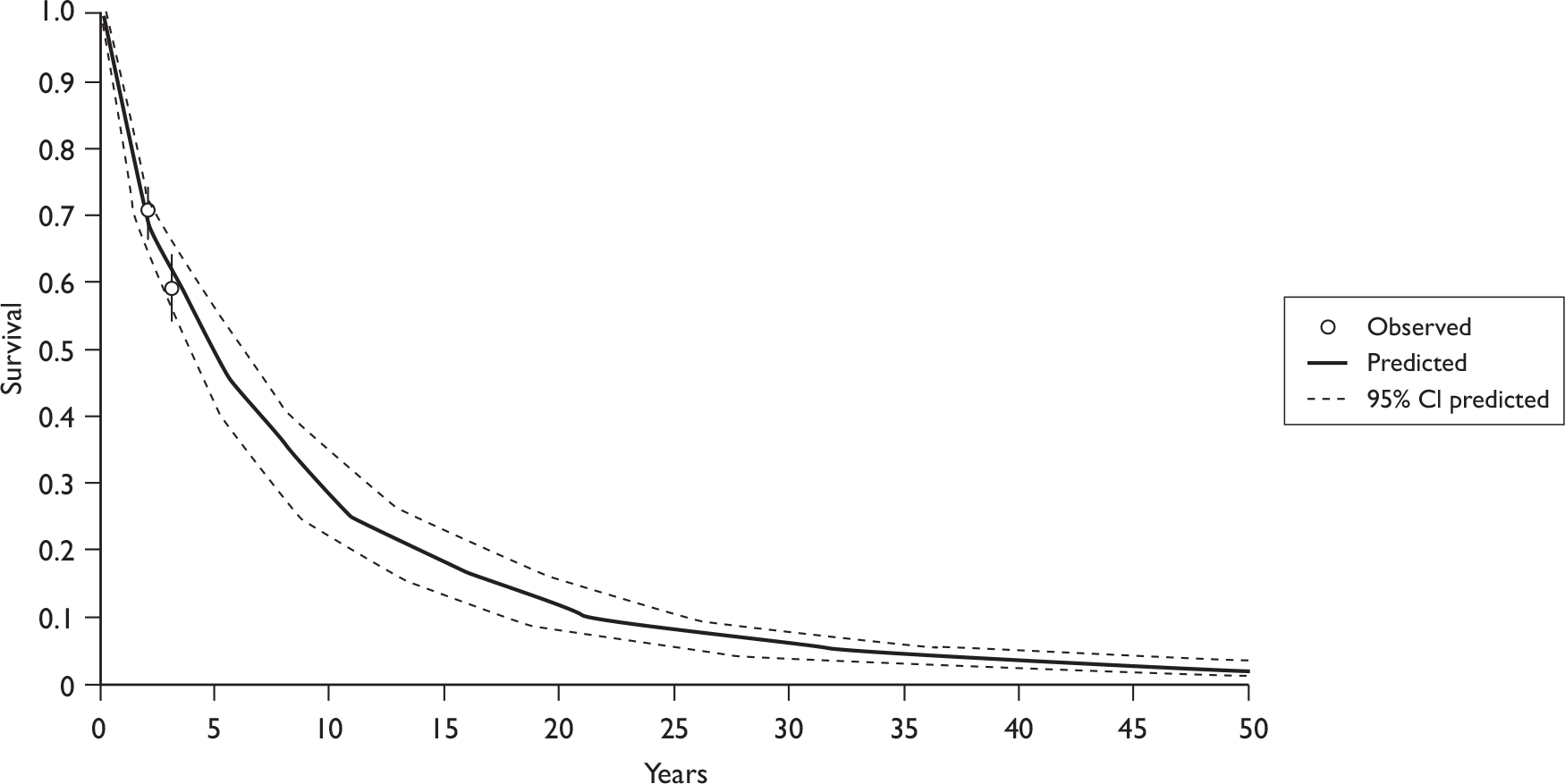

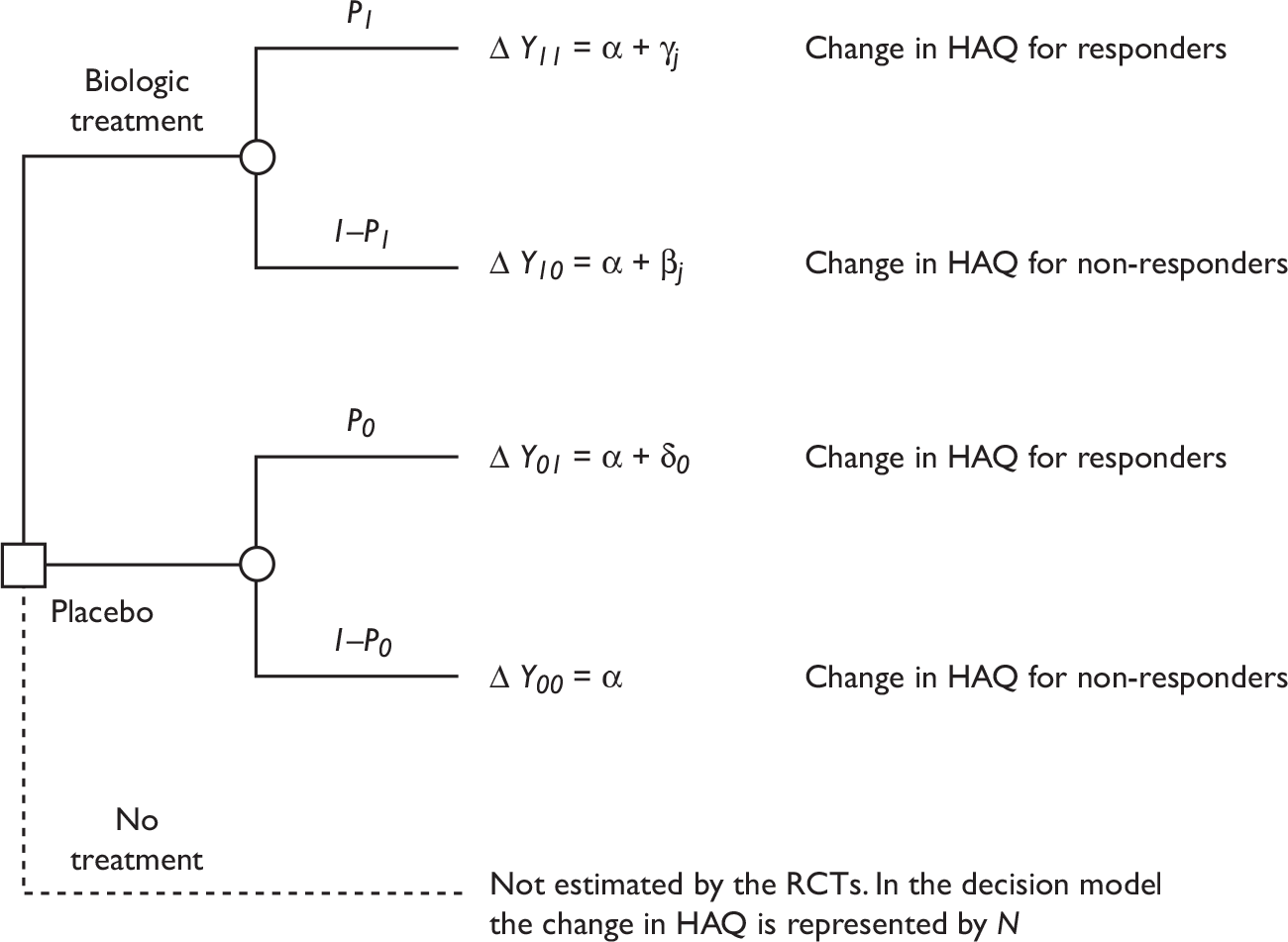

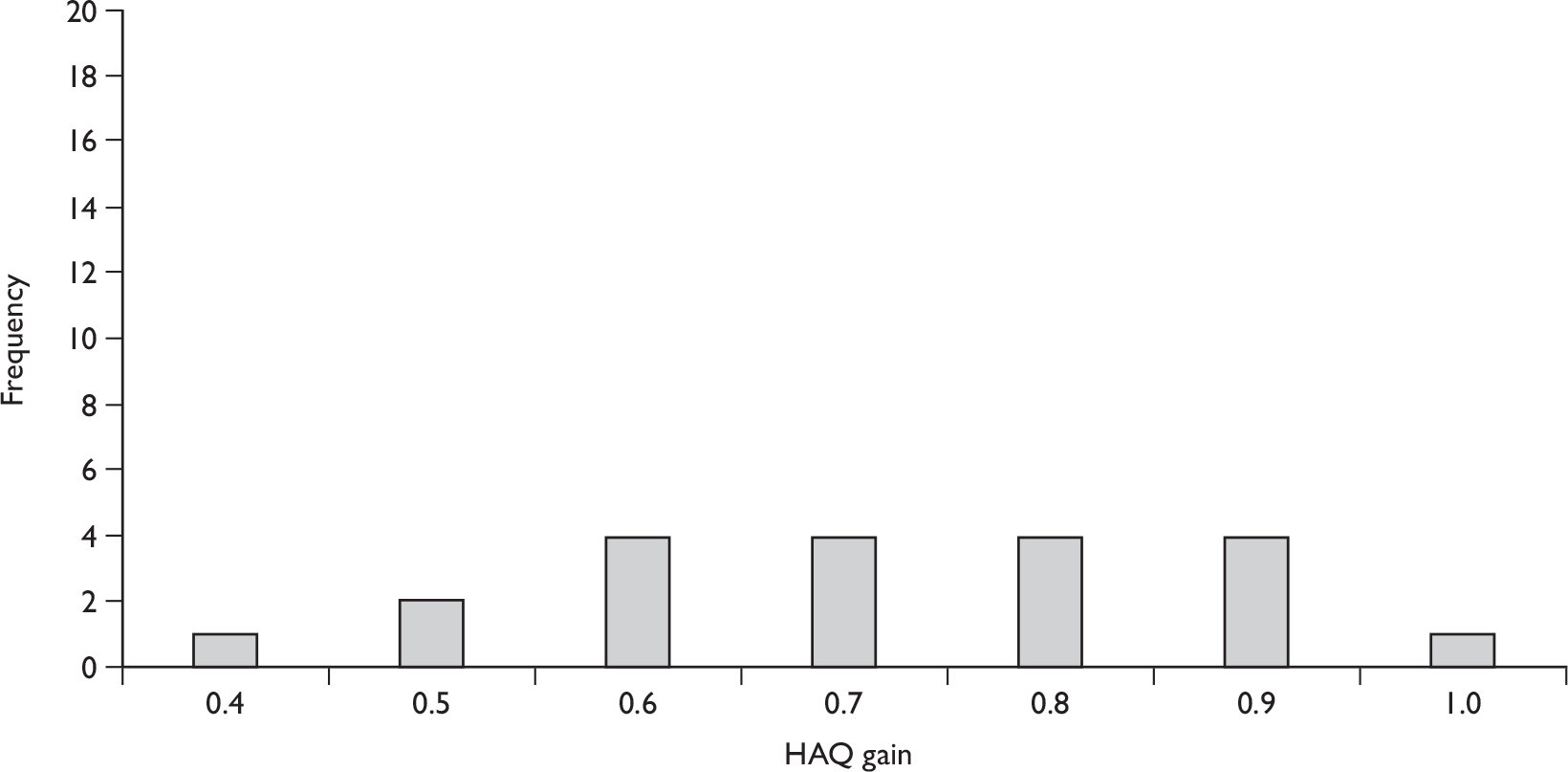

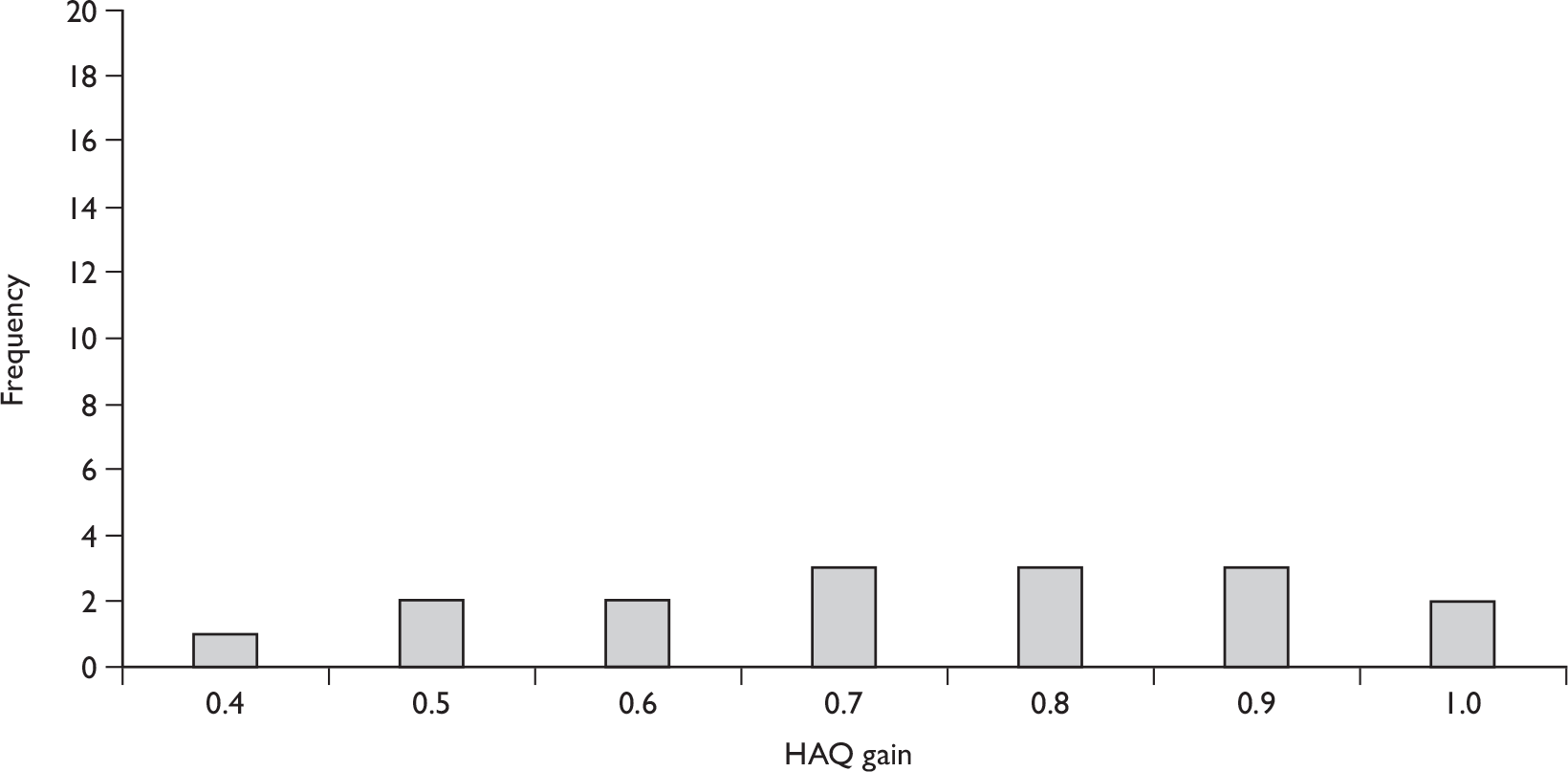

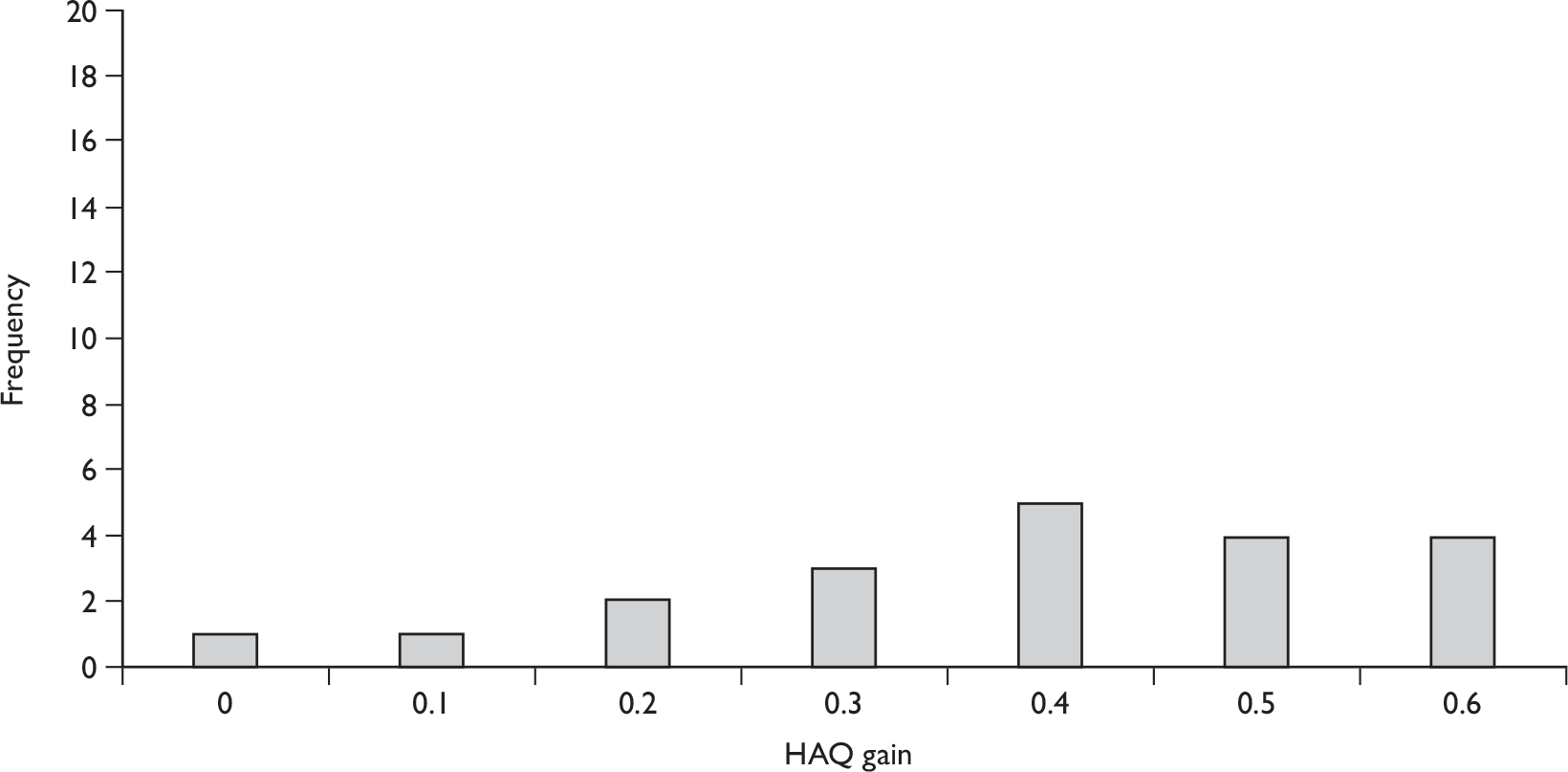

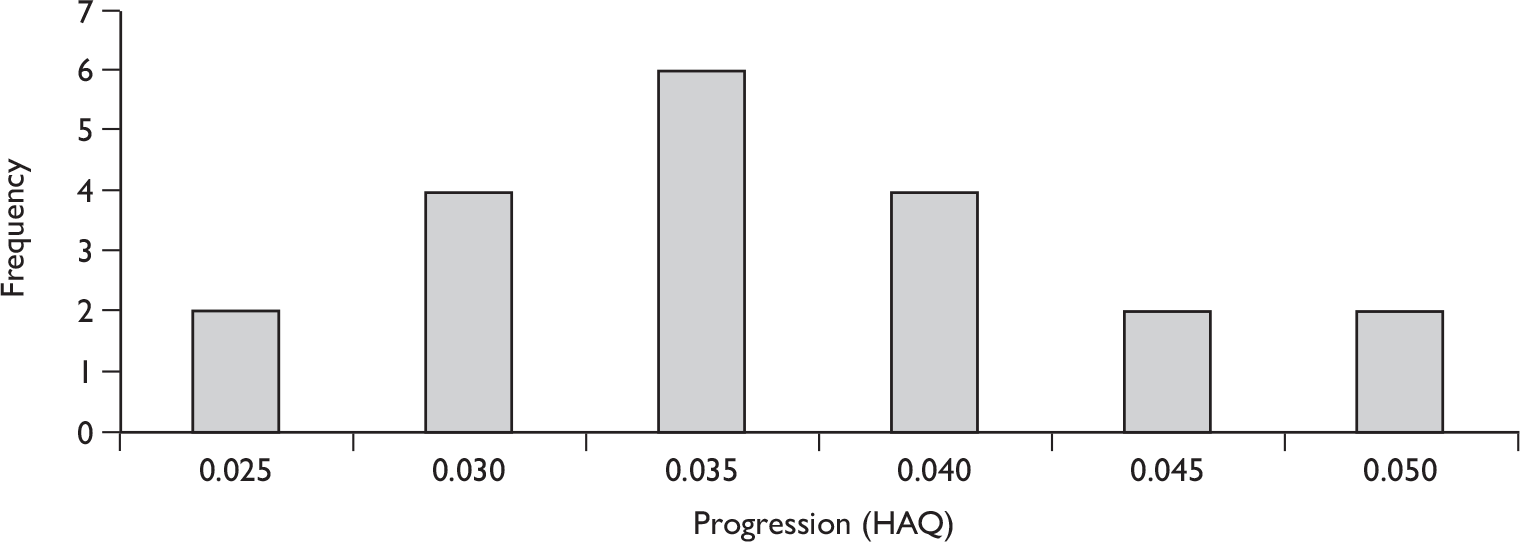

Both trials were of adults (aged 18–70 years), with active PsA (defined in both trials as three or more swollen joints and three or more tender or painful joints, with active psoriatic skin lesions or a documented history of psoriasis). Patients in the larger trial had demonstrated an inadequate response to NSAIDs and received no concomitant DMARDs other than MTX. 51,88,92,93,100–104 All patients in the smaller trial received concomitant DMARDs or had a history of DMARD therapy with inadequate response. 83