Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 02/37/03. The contractual start date was in May 2005. The draft report began editorial review in December 2009 and was accepted for publication in July 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Venous leg ulcers

Leg ulceration is a chronic, recurring condition, affecting 15–18/1000 adults in industrialised countries,1 with venous leg ulcers representing up to 84% of all leg ulcer cases in developed countries. 2 Venous insufficiency occurs when the foot or calf muscle pumps are unable to empty the veins effectively, causing the pressure within the veins and capillaries to rise above normal limits. 3 This raised pressure leads to numerous changes in the capillaries and surrounding tissues, manifested by signs and symptoms such as venous flare, oedema, and hardening and staining of the dermal tissue (lipodermatosclerosis), the progressive stages of which can eventually lead to ulceration. 4 These ulcers have a significant personal impact on health and quality of life (QoL). 2,5

Treating venous leg ulcers

The only therapy so far shown to be clearly effective in the treatment of venous leg ulcers is the application of compression therapy, as either bandaging or hosiery, with high compression (around 40 mmHg pressure at the ankle) being more effective than lower levels of compression [relative risk of healing 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2 to 2.0]. 6 We know from both trials of compression therapy and other prognostic studies that small ulcers [< 5 cm2 in area] and new ulcers (< 6 months in duration) treated with high compression heal quickly. For example, in a large trial of compression bandaging the median time to healing of ulcers with pre-trial duration of < 6 months was 77 days. 7 New ulcers treated with high compression, therefore, can be described as generally healing without the need for adjuvant therapies. One high-quality prognostic study has found that 95% of venous ulcers that are both small (< 5 cm2 in area ) and new (< 6 months in duration), if treated with high compression, can be expected to heal within 6 months (95% CI 75% to 99%). 8 Audits of healing times using four-layer high compression (widely used in the UK) confirm the importance of ulcer area and duration in predicting healing at 6 months. 9,10 One of the remaining clinical challenges is how to increase healing in those ulcers that are not ‘easy to heal’ (i.e. the big/old ulcers rather than the small/new ulcers). The goal is both to increase the proportion of ulcers healed (20% remained unhealed in a large bandaging trial at 12 months)7 and to decrease the time to healing among people with longstanding ulceration or large ulcers.

Cost of venous leg ulceration

Leg ulceration is a condition associated with large financial costs to health-care providers. The cost of leg ulcer management in the UK in 1989 was estimated to be between £150M and £600M per annum, with > 60% of this cost attributed to community-based nursing services. 11 Recent studies have estimated the annual cost of treating a venous leg ulcer patient as being approximately £700–900, which increases the longer it takes for the ulcer to heal or the larger it becomes. 12,13 The 2004 Healthcare Commission estimated that NHS leg ulcer treatments cost £300–600M per annum and wound dressings accounted for 5 million community prescriptions in England during 2006 at a cost of £122M. 14 With the majority of leg ulcer patients in the UK treated within the community,15 such patients often constitute a large proportion of community nurses’ caseloads. 16

Therapeutic ultrasound

Ultrasound therapy is a well-recognised treatment option for soft tissue injuries in the physiotherapy clinic, but has been more recently used in some specialist centres for the management of chronic wounds. 3

Mechanical vibrations transmitted at a frequency > 20,000 Hz are above the level of human hearing and are known as ultrasonic. 17 Ultrasound may be divided into two classes: those using ‘high’ intensities (> 3 W/cm2), used for ultrasonic scalpels, and those using ‘low’ intensities (up to 3 W/cm2), used to stimulate normal physiological responses to injury to aid repair. 18 The type of ultrasound used is dependent on the target tissues (structure and depth) and the intended effect (i.e. heating the tissues or not). Tissues with a higher protein content (e.g. ligament and tendon) are able to absorb ultrasound to a greater extent than those with a low protein content (e.g. blood and fat). 19 Therapeutic ultrasound has a frequency of 0.75–3.00 MHz, and most machines used to deliver it are set at a frequency of either 1 or 3 MHz. 20 The absorption coefficient of ultrasound in soft tissue increases linearly with frequency, so using higher frequencies (say 3 rather than 1 MHz) reduces the penetration depth by about one-third (from 37 to 12 mm in skin). 21

Presumed mechanisms of action

There are two types of mechanisms commonly thought to explain the effects produced by therapeutic ultrasound, and these are classed as thermal and non-thermal effects,18 although ter Haar18 and Baker et al. 21 argue that both effects may be present to varying degrees. They agree that it is difficult to identify the mechanisms involved, let alone separate the thermal and non-thermal effects. Investigators have described the effects of ultrasound on tissues in vitro and in vivo, but it is not clear whether these are responsible for reported clinical effects, or merely incidental.

Many physiological responses to the biophysical effects of therapeutic ultrasound have been described, and the research has been reviewed by Baker et al. 21 and others. 18,20

When ultrasound travels through tissue, a percentage of it is absorbed, which leads to the generation of heat within the tissue. 19 The beneficial effects thought to arise from this heating include an increase in blood flow, reduction in muscle spasm, increased extensibility of collagen fibres and a proinflammatory response. 20 Any problem of excess heat is reduced by using pulsed ultrasound (which has an on/off cycle), as the effective intensity is lower, with the heat being dissipated between the pulses. 22 While ultrasound has historically been used primarily for its professed thermal effects, it is suggested that ‘non-thermal’ mechanisms play a role in producing therapeutic effects. 19 Watson19 concludes that although the therapeutic benefits of tissue heating are well known, the ability of ultrasound to generate sufficient thermal change in tissues to achieve these effects is doubtful.

Purported non-thermal mechanisms are predominantly attributed to ‘cavitation’ – the production and vibration of micron-sized bubbles within the tissue fluids which, as the bubbles move and oscillate within the fluids, can cause changes in the cellular activities of the targeted tissues. 17 An additional outcome of ultrasound is ‘acoustic streaming’, which is described as the ‘localised liquid flow in the fluid around the vibrating bubble’. 22 Baker et al. ,21 however, argue that there is no evidence from in vivo studies in humans that cavitation occurs at the ultrasound doses used for tissue repair. Given the absence of cavitation, except in gas-filled cavities (such as the lungs), it is further argued that acoustic streaming does not occur in vivo. The way in which cavitation or acoustic streaming might contribute to tissue repair is not obvious, but it is postulated that they might lead to a reversible increase in cell membrane permeability and increased protein synthesis. 17

Ultrasound application

Ultrasound is reflected at the skin, as the air–skin interface presents a barrier to the transmission of ultrasound; thus, it is necessary to provide a coupling medium to allow the ultrasound to be transmitted into the tissues. 19 Suitable coupling mediums include gel with a high water content, a film dressing, water or saline. 17

The dose at which ultrasound is delivered at is related to its frequency (Hz), power (W/cm2), duty cycle (pulsed or continuous) and the duration of treatment, which produce a large number of possible combinations. 19

Ultrasound is contraindicated in people with ankle prostheses/metal anywhere in the foot (e.g. pin and plate, shrapnel), because both metal and the bone cement used in the replacement of joints have a high absorption capacity. The application of ultrasound to the ankle area may lead to heat damage of the local area and any prosthetic joints. 23 Ultrasound is also contraindicated for people with suspected thrombophlebitis (the mechanical vibrations may cause an embolism), people with active cellulitis (potential risk of accelerated growth and dissemination of bacteria throughout the body), in cases of suspected or confirmed local cancer/metastatic disease and in cases of obvious ulcer infection. 23

Existing evidence for the effect of ultrasound on healing

A number of studies have investigated the impact of ultrasound on skin cells (in vitro) and chronic wounds (in vivo). In general, there have been few good-quality studies demonstrating that any of the ‘in vitro’ effects have any clinical importance. 21

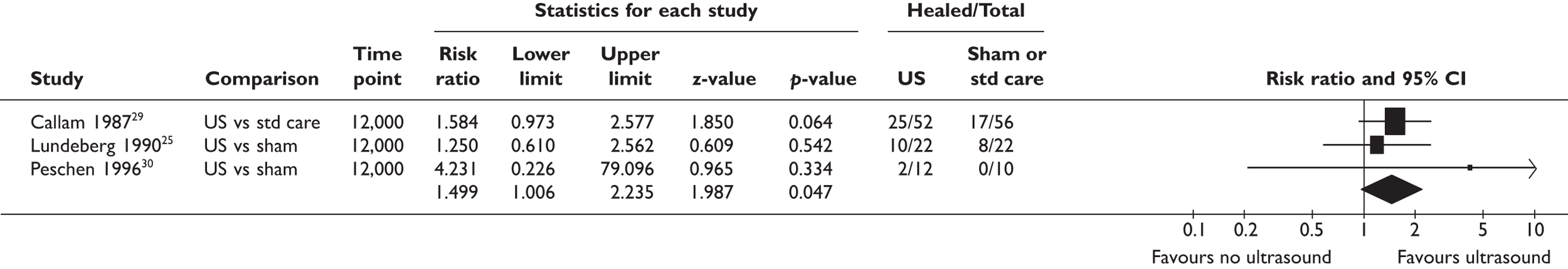

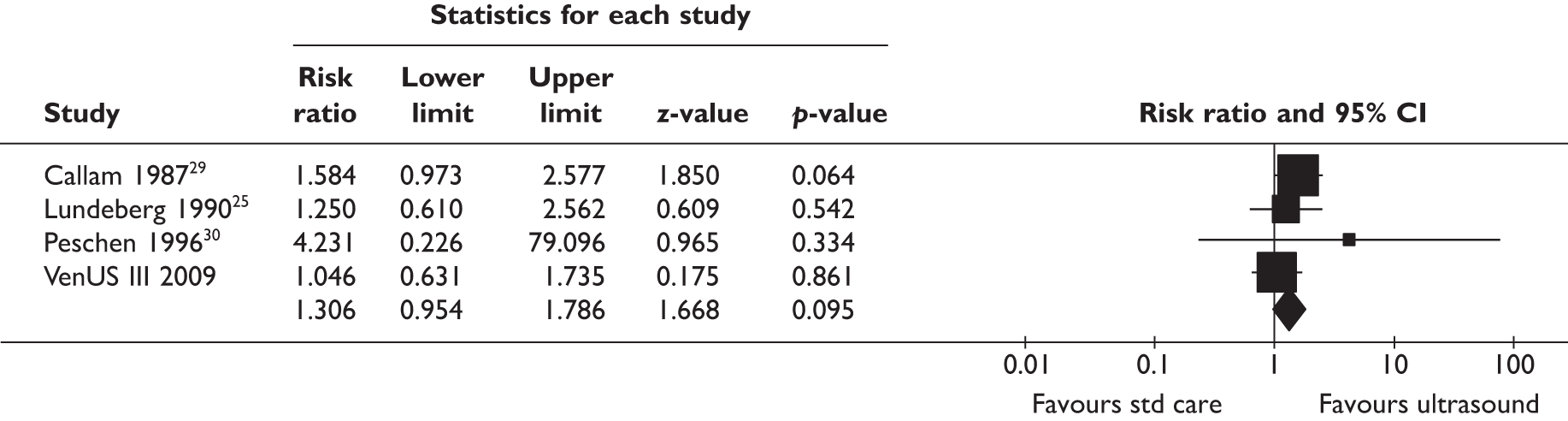

Before designing this trial we were aware of seven trials24–30 of ultrasound for treating venous leg ulcers, and one31 became available during this period (Table 1). These were summarised in a systematic review. 32 The sample sizes in these trials ranged from 12 to 108 patients, and four trials25,26,28,29 used true randomisation with allocation concealment. The trials made various comparisons of ultrasound versus sham (four trials24–27) or ultrasound as an adjunct to standard care versus standard care alone. Various types of ultrasound at different dose were used. Frequency of ultrasound ranged between 0.03 and 3 MHz: 0.03 MHz was used in two trials28,30 (applied via a water bath), 1 MHz was used in four trials24,25,29,31 and 3 MHz was used in another two trials26,27 (1 MHz has greater depth penetration than 3 MHz). Ultrasound doses ranged between 0.1 and 1.0 W/cm2. In two trials28,30 in which a water bath ultrasound device was used, 0.1 W/cm2 was used. Doses of 0.5 W/cm2 were used in three trials25,29,31 and 1.0 W/cm2 in four trials24,26,27,31 (one trial31 compared both 0.5 and 1 W/cm2 against standard care). In the seven trials available during the study design phase the following therapeutic regimens were used:

-

One24 reported an evaluation of ultrasound at 1 MHz and 1.0 W/cm2 (38 people).

-

Two28,30 reported evaluations of ultrasound with a water bath at 30 kHz and 0.1 W/cm2 (61 people).

-

Two26,27 reported evaluations of ultrasound at 3 MHz and 1.0 W/cm2 (53 people).

-

Two25,29 reported evaluations of ultrasound at 1 MHz and 0.5 cm2 (152 people).

| First author of trial (number in trial) | Comparison (sham/standard care) | Ultrasound regimen (frequency/dose) | Times per week | Duration of each treatment (minutes) | Period of ultrasound therapy (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eriksson24 (n = 38) | Sham | 1 MHz/1.0 W/cm2 | Two | 10 | 8 |

| Lundeberg25 (n = 44) | Sham | 1 MHz/0.5 W/cm2 | Three, two, one | 10 | 12 |

| Roche26 (n = 26) | Sham | 3 MHz/1.0W/cm2 | Three | ? | 4 |

| Dyson27 (n = 25) | Sham | 3 MHz/1.0W/cm2 | Three | 10 | 4 |

| Weichenthal28 (n = 37) | Standard care | 0.3 MHz/0.1W/cm2 | Three | 10 | 8 |

| Callam29 (n = 108) | Standard care | 1 MHz/0.5 W/cm2 | One | 5–10 | 12 |

| Peschen30 (n = 12) | Standard care | 0.3 MHz/0.1 W/cm2 | Three | 3 | 12 |

Given that the most evidence was available for the combination of ultrasound at 1 MHz and 0.5 cm2, and this included the study with only moderate risk of bias, we decided to use this regimen for the trial. No trials reported that they confirmed ultrasound equipment output.

The largest trial29 (108 people) evaluated ultrasound administered weekly, but the other trials administered ultrasound two or three times a week, with one25 having a reducing frequency from three to one time(s) a week. Four trials25,29–31 used ultrasound for 12 weeks, two24,28 for 8 weeks and two26,27 for 4 weeks. The five trials that described duration of ultrasound regimen used 10 minutes (three trials24,28,30) or 5–10 minutes, depending on ulcer area (two trials26,27).

The heterogeneity of these trials with respect to the delivery mode, dose, duration, treatment length and frequency used means that meta-analysis of all these trials may not be reliable. Another problem with synthesising these studies is the likely difference in the ultrasound actually delivered, even when treatment regimens appear similar, owing to the differences in output between machines and over time (drift). Not all these trials restricted their recruitment to people with ‘hard-to-heal ulcers’ and some were performed without high-compression therapy as the standard care system; hence, their applicability to current care challenges faced by clinicians is unclear. Given that standard care of venous ulcers, using high compression and simple dressings, heals around 80% of all ulcers within 12 months, ultrasound as an adjuvant therapy is likely to be reserved for those resistant to standard therapy, or whose ulcers are identified at the outset as ‘hard-to-heal’.

The Cochrane review32 concluded that there was tentative evidence that ultrasound increased the healing of venous ulcers, but that the trials identified had moderate to high risk of bias. The reviewers, therefore, called for a large, methodologically robust trial of ultrasound to be undertaken; hence, we set out to determine whether adding ultrasound to best practice for venous ulcers (appropriate compression therapy) increased the chance and rate of healing.

Summary of main points

The majority of venous leg ulcers heal in 6–12 months, but those with a duration of > 6 months, or which are larger than average, are harder to heal. With the best available standard care – simple dressings and high-compression bandages – these ‘harder to heal’ ulcers usually take > 6 months to heal. With the burden, in terms of both patients’ finances and QoL, attributed to leg ulcers being significant, increasing the numbers of ulcers healing and decreasing the time taken for ulcers to heal is important.

Ultrasound has been used for many years to help tissue repair and it is commonly given by physiotherapists to help joint and muscle repair, using ultrasound treatment regimens of treatment three to seven times a week. It is not feasible to administer ultrasound with this frequency when treating venous ulcers in the community as delivering ultrasound to an ulcer can be done only when bandages are removed, for example during regular dressing changes. Compression bandages stay in place for up to a week and current thinking about wound healing suggests that wounds should be disturbed as little as possible to avoid damaging delicate tissues at each dressing change. The costs of having daily appointments with the nurse for dressing changes for the purpose of administering ultrasound is likely to be prohibitive (even if nurse workload allowed daily dressings for this purpose, which is unlikely).

There is some evidence that delivering ultrasound to the wound can help heal leg ulcers, although the previous studies were methodologically weak, small in size and varied widely in application regimens, and not all used high-compression therapy as standard care. In addition, the previous trials included people with small, new ulcers, which heal relatively quickly using compression bandaging, and therefore the results of these studies may not be applicable to ‘hard-to-heal’ ulcers.

Research objectives

To compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-dose ultrasound (0.5 W/cm2 spatial average and temporal peak) delivered at 1 MHz in conjunction with standard care against standard care alone in the treatment of hard-to-heal venous ulcers.

Primary objective

-

To compare the effects of low-dose ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone on the time to healing of the reference (largest) ulcer.

Secondary objectives

-

To compare the cost-effectiveness of ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone.

-

To compare the effects of ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone on the proportion of patients with ulcers healed at 12 months.

-

To compare the effects of ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone on percentage and absolute change in ulcer size.

-

To compare the effects of ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

-

To compare the effects of ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone on reported adverse events, withdrawals and loss to follow-up.

-

To compare the effects of ultrasound plus standard care with standard care alone on the proportion of time patients are ulcer free.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The Venus Ulcer Study (VenUS) III trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, two-armed, randomised controlled, open trial with equal randomisation. Participants with ‘hard-to-heal’ ulcers (> 6 months’ duration and/or larger than 5 cm2) were randomised (1 : 1) to receive either:

-

low-dose (0.5 W/cm2) ultrasound, 1 MHz, and a pulsed pattern of 1 : 4 weekly for up to 12 weeks, plus standard care, or

-

standard care alone.

The study protocol can be seen in Appendix 1.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on median time to healing. Lambourne et al. 9 and Vowden et al. 10 found that 60% of large ulcers (> 10 cm2) and 60% of ulcers of > 6 months’ duration (treated with four-layer compression) healed in 24 weeks. This represents a median time to heal of 15–22 weeks (estimated from published survival curve). Our sample was to include some smaller ulcers, but importantly it would also include people with both high ulcer duration and large area (of whom between 13% and 37% heal at 24 weeks with high compression),8 and therefore, overall we estimated that 50% of ulcers in the standard care group would heal within 22 weeks (compared with 11 weeks for small, new ulcers as determined in VenUS I). 7

Estimating that clinicians and patients would value a reduction in healing time of 7 weeks (i.e. from 22 weeks to 15 weeks), we based our sample size calculation on this premise. This moderately sized effect was deemed as being required before clinicians would introduce a new therapy, with the consequent requirements to undergo training, arrange for purchase and servicing of machines, etc. To give us 90% power to detect this 7-week difference in median healing time we required a sample size of 306 patients, or 336 patients allowing for 10% attrition. This sample size also gave us 80% power to detect an 8-week reduction in median time to healing from 24 weeks and 90% power to detect an 8-week reduction from 26 weeks.

Approvals obtained

The York Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) approved the study on 4 February 2005. The details of the MREC, Local Research Ethics Committees (LREC) and Research and Development Department approvals are provided in Appendix 2. The trial was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) of ISRCTN21175670; EudraCT number 2004-004911-51 and National Research Register number N0484162339.

Trial sites

The study was conducted in 11 UK sites and one Irish site (Dublin). These sites were recruited throughout the duration of the study and represented a range of urban and rural settings plus a number of different types of leg ulcer service. Details of the study sites are provided in Appendix 3.

Participant eligibility

Only people with ‘hard-to-heal’ venous leg ulcers were to be recruited into this study. For the purpose of this study a hard-to-heal venous leg ulcer was considered to be any break in the skin on the leg (below the knee), which either (a) had been present for > 6 weeks or (b) occurred in a person with a history of venous leg ulceration. A participant was considered to have a venous leg ulcer where there was no other evident causative aetiology, the ulcer appeared clinically venous (moist, shallow, irregular shape, venous eczema, ankle oedema, and/or lipodermatosclerosis, not confined to the foot), and the study participant had an Ankle–Brachial Pressure Index (ABPI) of ≥ 0.8. An ABPI of < 0.8 indicates that there is a high probability that arterial insufficiency is present and that the ulcer should not be regarded as venous. 33

Prognostic studies have found that patients with ulcers larger than 5 cm2 and with duration of > 6 months are less likely to heal within 24 weeks. 34

Inclusion criteria

All people with venous leg ulcers were potentially eligible for inclusion in the proposed trial if they met the following criteria:

-

They were receiving care from community/leg ulcer/outpatients nurses in trial centres.

-

They were able to give written informed consent to participate in the study. Information sheets and consent forms were to be provided in languages other than English if required.

-

The primary cause of their ulcer was chronic venous insufficiency. This diagnosis was made using the same diagnostic criteria currently employed by caregivers in the community, namely the clinical appearance of the ulcer, patient history and an ABPI to rule out arterial insufficiency. 33

-

They had ‘hard-to-heal ulcers’ as defined by the presence of at least one of these criteria:

-

a venous ulcer of > 6 months’ duration

-

a venous ulcer > 5 cm2.

-

-

They had Doppler-determined ABPI of ≥ 0.8 measured within last 3 months.

-

Those with an ulcer infection (based on a clinical signs and symptoms checklist) at baseline were eligible to participate once the infection had been resolved. 35

-

Those who were unable to self-complete the English language QoL tools were still eligible to participate, but we did not collect QoL data from them [the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) is validated in English, Spanish, Italian, French and German and we anticipated that the number of non-English speakers who use these languages would be very small, based on previous trial experience].

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if they met the following criteria:

-

Their leg ulcer was due to causes other than venous insufficiency (e.g. arterial insufficiency, malignancy, pyoderma gangrenosum, etc.).

-

They had poorly controlled diabetes, as evidenced by a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of > 10%.

-

They had ankle prostheses/metal anywhere in the foot (e.g. pin and plate): because bone cement used in the replacement of joints has a high absorption capacity, the application of ultrasound to the ankle area may lead to heat damage of the prosthetic joint. 23

-

They had suspected thrombophlebitis: because the mechanical vibrations may cause an embolism. 23

-

They had active cellulitis: because of the potential risk of accelerated growth and dissemination of bacteria throughout the body. 23

-

They had suspected or confirmed local cancer/metastatic disease. 23

Patients previously enrolled into the study who had become ulcer free were not eligible for rerandomisation into the trial if their ulcer(s) recurred.

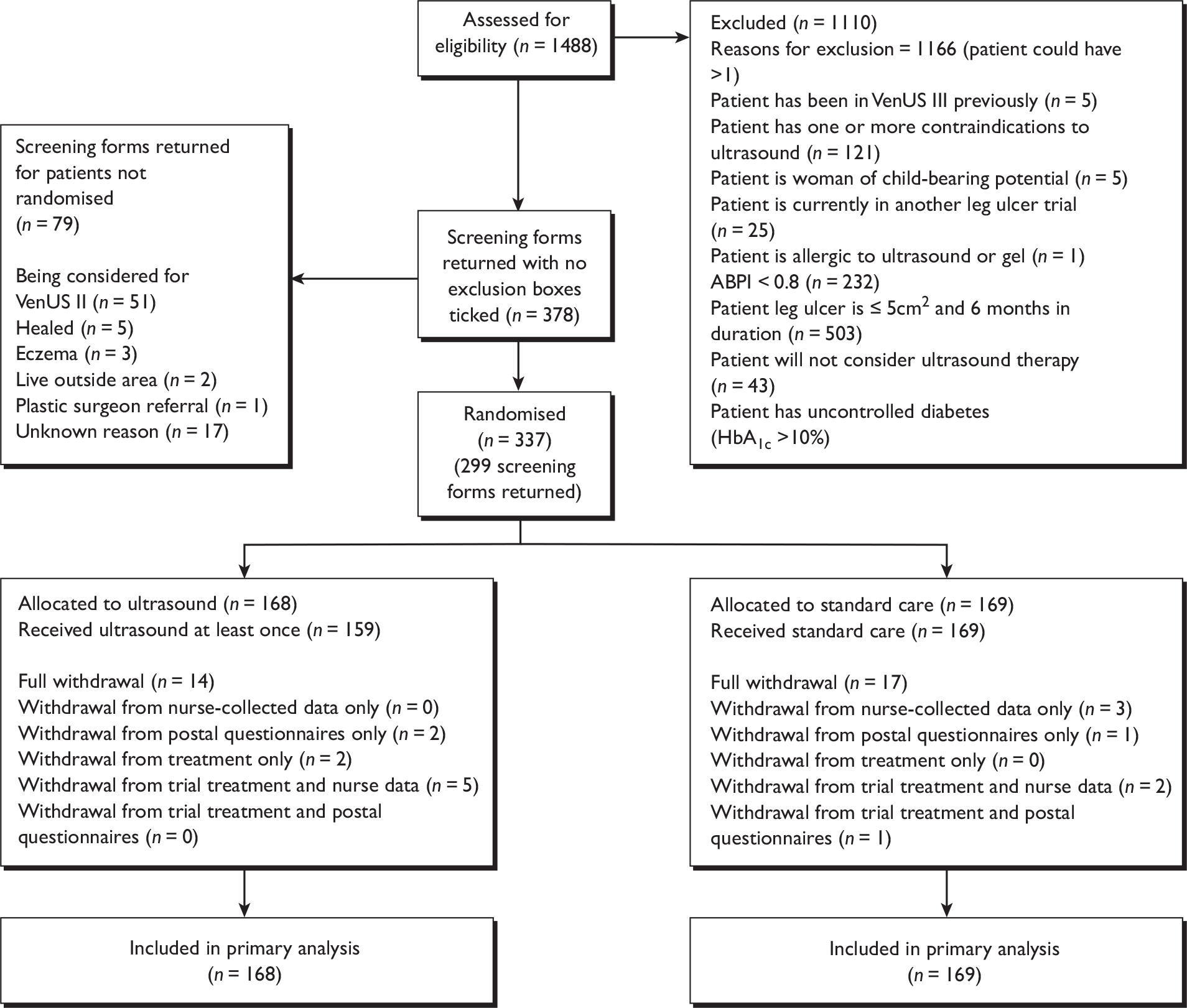

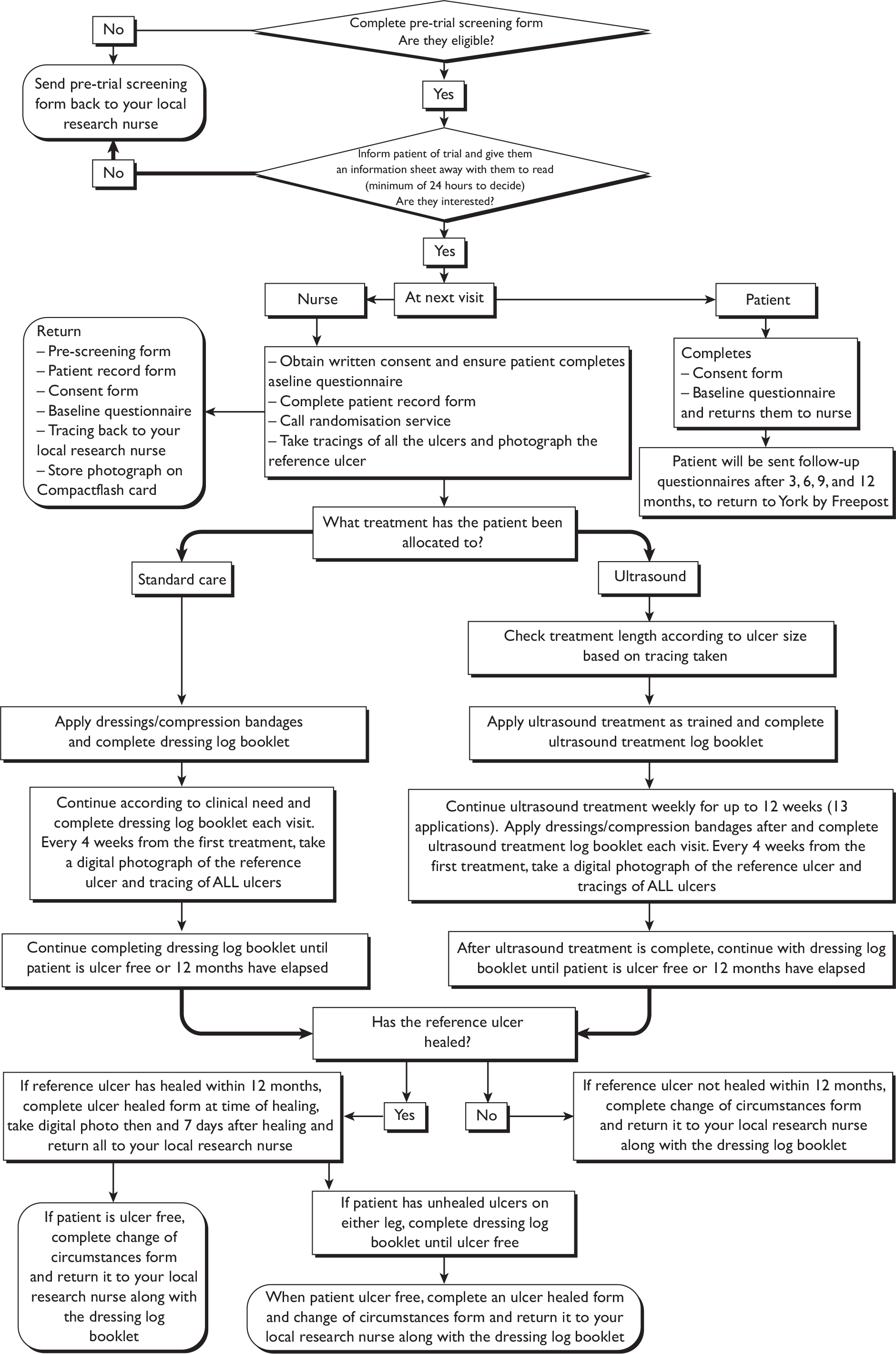

Recruitment into the trial

Local nursing staff, community nurses, leg ulcer nurses and trial nurses identified potential participants and supplied them with an information sheet about the trial (see Appendix 4). Patients were given a minimum of 24 hours to read the information sheet and consider participation. All potential venous leg ulcer patients were screened using a pre-trial screening form (see Appendix 5) which listed the main eligibility criteria. Patients potentially eligible and interested in participating were seen by their local trial nurse, who would discuss the study if more detail was requested, obtain written informed consent, record baseline data and administer the first allocated treatment. Participants’ general practitioners (GPs) were notified of their involvement in VenUS III after recruitment. Information provided on the pre-trial screening forms was collected centrally at York Trials Unit to allow reasons for non-eligibility to be collated.

Baseline assessment

After written informed consent had been obtained, baseline data were collected on the patient using a Patient Record Form (see Appendix 5). The following data were collected.

Ulcer history and initial assessment

If the patient had more than one ulcer, nurses were asked to define which ulcer was the ‘reference ulcer’ (and therefore the reference leg), which was classed as the largest eligible ulcer. The outline of the reference ulcer was traced onto an acetate film grid marked with 1 cm2 squares and an assessment was then made by the recruiting nurse of whether the reference ulcer area was ≤ 5 cm2 or > 5 cm2. The actual area was calculated at the York Trials Unit at a later date using the mouseyes computer program, Version 3.1 (Dr Robert John Taylor, Salford). 36 The reference ulcer was labelled according to leg (R for right; L for left) and the number 1 given to it (e.g. reference ulcer present on right leg = R1). Nurses completed tracings of all ulcers a patient had and labelled them in descending order of area (R2, R3, etc.) to allow follow-up of all ulcers on the limb.

Measurement of ankle–brachial pressure index

The result of a Doppler-determined ABPI measurement for the reference leg was noted along with the date it was measured. For inclusion in the study, this reading must have been obtained in the last 3 months as readings change over time. 37

Number of ulcer episodes on leg with reference ulcer

Data from VenUS I7 suggested that a greater number of ulcer episodes are prognostic of a longer healing time; we therefore recorded the number of ulcer episodes on the leg of the reference ulcer since the first episode.

Duration of reference ulcer and duration of oldest ulcer

Duration of reference ulcer was recorded based on participant report along with the duration of the oldest ulcer on the reference leg.

Patient mobility

Reduction in mobility can potentially contribute to ulceration by means of reduced venous return, secondary to calf muscle wastage. 38 It was recorded whether the patient was able to move freely, with difficulty or was immobile.

Ankle mobility, patient’s height and weight

The VenUS I7 reported that, as well as ulcer area, duration and number of episodes, ankle mobility (full, reduced range or fixed), and body weight were also prognostic for healing. These data were all collected at baseline.

Ulcer position and image

For monitoring purposes a record of the position of all ulcers on the trial leg including the reference ulcer was made. A dated digital photograph was also taken of the reference ulcer.

Pain

Patients were asked to indicate how intense the pain had been in their reference ulcer during the past 24 hours using a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from ‘no pain’ to ‘worst pain imaginable’. The minimum value on the scale was 0 mm and the maximum was 150 mm.

Date of birth

Date of birth was recorded at recruitment, allowing age at recruitment to be calculated. Increased age was associated with slower healing rates in one study. 38

Gender

The gender of participants was recorded, allowing a comparison with the existing information on the population of people with venous ulcers, in which women outnumber men. 39

Compression level

Whether the participant was currently being treated with two-, three- or four-layer high-compression bandaging was recorded.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised equally between the two trial arms: ultrasound plus standard care and standard care alone. Randomisation was carried out using varying block sizes of four and six participants. To maintain allocation concealment the generation of the randomisation sequence and subsequent treatment allocation were performed by an independent, secure, remote, telephone randomisation service (York Trials Unit). The computerised randomisation system was checked periodically during the trial following standard operating procedures. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to conceal the treatment allocation from either the patient or the nurse.

Trial interventions

Participants were randomised to receive either:

-

Low-dose (0.5 W/cm2) ultrasound, 1 MHz, with a pulsed pattern of 1 : 4 as per trials by Callam et al. 29 and Lundeberg et al. 25 The ultrasound was to be applied to periulcer skin, weekly for up to 12 weeks, at regular dressing changes, plus standard care (see below for the definition of standard care). After the 12 weeks of ultrasound, patients returned to standard care alone.

or:

-

Standard care: this was defined as a simple low-adherent dressing and high-compression, four-layer bandaging, reduced compression or no compression, according to the clinical assessment of the level of pressure tolerated by the patient. This is based upon UK Clinical Practice Guidelines. 33

Preparation for ultrasound treatment

Prior to the application of the ultrasound the leg would be washed and any loose skin from around the ulcer and remnants of emollients removed. The ultrasound was applied directly to the skin surrounding the ulcer, using a water-based contact gel to ensure passage of the waveform from the transducer to the tissues.

Target ulcer

The ultrasound treatment was applied for 5–10 minutes to the previously defined reference ulcer (see Appendix 6).

Calculating ultrasound treatment time

Previous studies had applied ultrasound for varying amounts of time. We sought to balance the need for larger ulcers to have more treatment time, the need for treatment time to be feasible as an addition to standard practice, and the need for a simple system to help nurses titrate ultrasound to the various patients she or he would see.

Ulcers of area < 5 cm2 received 5 minutes’ ultrasound; those of 10 cm2 or larger received 10 minutes’ ultrasound. For ulcer areas between 5 and 10 cm2, the treatment time in minutes was calculated as the ulcer area in square centimetres (for example: an ulcer calculated as 6 cm2 received 6 minutes of ultrasound). Ulcer area was recalculated every 4 weeks using acetate film grids with pre-printed 1 cm2 areas.

Concurrent therapy

All dressings and bandages were to be replaced at each visit, as per standard practice. Concurrent therapy for all patients was low-adherent dressings and four-layer high-compression bandaging, reduced compression or no compression, according to the clinical assessment of the level of pressure tolerated by the patient. Should a change from the low-adherent dressing or the prescribed level of compression be required, in the opinion of the clinician, then this was recorded. The patient did not withdraw from the trial should the concurrent therapy change.

Nurse training

Prior to the trial starting, participating nurses attended a training programme on the rationale for the trial, patient eligibility, recruitment procedures (including consent and randomisation), ultrasound treatment application, data collection (completion of trial documentation and tracing ulcer outlines), handling participant withdrawal and adverse event reporting (see Appendix 7). Competency in ultrasound administration was assessed at the end of the training. The trained trial nurses were also permitted to cascade training in delivering ultrasound for the purposes of the trial to other local nurses so that treatments could be maintained during holiday periods or staff absences.

Checks were made by the local trial nurses regarding the use of ultrasound within the trial, to ensure that the ultrasound was being delivered as per protocol.

Ultrasound machines

The ultrasound machines were supplied, at discounted price, by EMS Physio Ltd, the largest UK manufacturer of ultrasound machines. The machine chosen was the EMS Therasonic 355 Physiotherapy system (EMS Physio Ltd, Wantage) which delivers only 1 MHz ultrasound: effective radiation area 4 cm2, with a large transducer head, collimated beam, and beam non-uniformity ratio (BNR) < 5. We used a pulsed mode; each pulse lasted 2 milliseconds and the pulse ratio was 1 : 4. Prior to acceptance, all machines were tested at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) to confirm that they were delivering ultrasound at the necessary frequency and intensity.

Auditing ultrasound machine performance

The ultrasound machines were assessed after 3 months’ recruitment and 3-monthly thereafter to check the intensity of ultrasound delivered. Checks were undertaken by the ultrasound machine suppliers. These originally took place at each clinical site by the ultrasound machine suppliers except where there were no available engineers (Northern Ireland and Scotland). Previous studies have indicated that there are differences between the ‘nominal’ dose and that actually delivered by the machines. 42 Some of this is apparent at machine delivery, and some is due to drift or step changes in output. 43 Each ultrasound machine was numbered so that patients who received treatment from individual machines could be identified. This check took place when a site had been recruiting for 3 months and 3-monthly thereafter.

Ultrasound therapy arm

During the 12 weeks of ultrasound therapy, the date of every nurse visit was recorded in an Ultrasound Treatment Log Booklet by the treating nurse, along with location and whether or not ultrasound had been applied and, if so, for how long, machine number and signature of the nurse applying it for (see Appendix 5). Information relating to dressings and bandaging applied was also recorded. Reasons for any changes in these from the previous visit were requested. If for any reason the patient was not given his or her weekly ultrasound treatment (infection, illness, non-attendance, etc.), that week was not carried over. Thus, the maximum number of ultrasound treatments a patient could receive was 13 (one at baseline plus one per week for a total of 12 weeks).

After the patient’s ultrasound treatment period had finished, treatment reverted to standard care alone with the visit dates, locations, dressings and bandage changes recorded in a separate booklet – Dressing Log Booklet (see Appendix 5). Follow-up then continued as per the protocol.

Standard care arm

Visits to patients allocated to standard care alone with the visit dates, locations, dressings and bandage changes were recorded in the Dressing Log Booklet (see Appendix 5). Follow-up continued throughout their treatment period as per the protocol.

For all patients, acetate film tracings of all ulcers and digital photographs of the reference ulcer were taken every 4 weeks until 12 months after randomisation (or between 6 and 12 months in some cases depending on when they were recruited in the trial recruitment period) or the patient became ulcer free, whichever happened first.

Participant follow-up

Appendix 8 shows a summary of VenUS III.

Trial completion

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when:

-

The participant became ulcer free.

-

The participant had been in the trial for 12 months (or between 6 and 12 months in some cases depending on when they were recruited in the trial recruitment period).

-

The participant wished to exit the trial fully.

-

The participant’s doctor or nurse withdrew him or her from the trial.

-

The participant was lost to follow-up.

-

The participant died.

Participants whose reference ulcer had healed but who still had a venous ulcer (because the reference ulcer was not their only ulcer) continued to have routine clinical data collected about them until they became ulcer free or they had been in the trial for > 12 months (or between 6 and 12 months for cases recruited during the last months).

Instead of withdrawing fully from the trial, participants had the option of:

-

withdrawing only from nurse data collection by the nurse

-

withdrawing only from receiving the trial treatment

-

withdrawing only from postal questionnaires; or

-

any combination of the above.

Patients who elected to withdraw from all three (data collection, trial treatment and postal questionnaires) were deemed to be full withdrawals (trial exit). Nurses were able to indicate any change in the patient’s level of participation by completing a Change of Circumstances Form (see Appendix 5). This ensured appropriate follow-up from the Trials Unit.

Measurement and verification of primary measure

The primary end point was time to healing of the reference ulcer.

Secondary outcomes were cost-effectiveness of ultrasound, proportion of patients with ulcers healed at 3, 6 and 12 months, percentage and absolute change in ulcer size, HRQoL and adverse events.

Determination of reference ulcer healing

Healing was defined as ‘full epithelial cover without a scab, where a scab is a thick crust over the wound’. This meant that an ulcer in which there was full epithelialisation overlaid by a thin layer of dry skin could be classified as healed. Clinically, this type of wound would not require a primary contact layer.

When the treating nurse deemed the reference ulcer to be healed, she or he completed an Ulcer Healed Form (see Appendix 5) and took a digital photograph of the healed ulcer (see Appendix 9). In addition, nurses were asked to take another digital photograph 7 days after they had considered the reference ulcer healed.

Two blinded assessors independently assessed all photographs for each participant to determine a date for healing. This assessment followed the same successful process as that used in VenUS II. 44 The assessors discussed any discrepancies with referral to a third assessor for a final decision if required. The primary outcome was calculated using the date of healing as decided by the blind assessors. However, if no photographs were available for a participant, then the date of healing decided by the treating nurse was taken as the healed date.

Measurement and verification of secondary outcomes

Collection of resource use data

During their treatment period within the study, data were recorded (see Appendix 5) about treatment received, location of the visit and the level of compression bandaging applied.

At recruitment and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after randomisation, patients were asked to complete a questionnaire on health and social care resource use during the previous month (see Appendix 5). The questionnaire was designed for participant completion and was returned to the trial office using a reply-paid envelope. Participants indicated how many times in the previous month they had used health services (e.g. seen a GP or nurse or received hospital care) and whether any health service use was ulcer related. The collection of self-reported resource use data was continued until the patient had been in the study for 12 months (or between 6 and 12 months for cases recruited during the last months).

Proportion of ulcers healed at 3, 6 and 12 months

The proportion of reference ulcers healed at 3 and 6 months post randomisation was reported to summarise the effects of the two regimens. Proportions healed are commonly used in wound care trials and hence this allowed us to compare our results directly with other trials which have rarely used time to event data.

Proportions of time patients are ulcer free

Reduction in recurrence would help reduce the prevalence of this condition and thus costs. Crude recurrence rates are potentially biased by any difference in healing rates associated with the two groups (ultrasound or standard care). As the treatment group which experiences faster healing is, by definition, exposed to more risk of recurrence if one group has more rapid healing, then people in that group are at risk of earlier recurrence. To account for this we used the proportion of time that patients were ulcer free. Patients with healed ulcers were contacted by telephone at 6, 9 and 12 months (up to June 2009) after healing in order to obtain recurrence data.

Percentage and absolute change in ulcer size

Data collected at 1, 3 and 12 months post randomisation allowed us to determine the reduction in ulcer area in patients who did not achieve complete ulcer healing. If the ultrasound and standard care groups achieved similar times to complete healing but one resulted in larger changes in ulcer area, then this may be clinically important as smaller ulcers may exude less and therefore require less frequent dressing changes. Furthermore, the recording of ulcer area at these time points allowed further study of the trajectory of healing for venous leg ulcers and the relationship between the reduction in ulcer area and eventual healing.

One study found that increased ulcer area at 1 month after initiation of treatment is a useful predictor for non-healing. 45 Identifying patients who are likely to fail to heal early in treatment allows these patients to have prompt referral to specialist centres for further assessment and treatment. Measurement of ulcer size involved taking tracing using acetate wound grids and a fine-nibbed, indelible pen, taking the outer edge of the ulcer rim as the outer edge of the tracing line (i.e. ulcer area = area enclosed by tracing and area of line). Ulcer area, as determined by acetate tracing, is an accurate and reliable measure. 46

Health-related quality of life

Participants were asked to answer questions relating to their HRQoL throughout the study, when they were asked to complete two generic instruments (EQ-5D and SF-12). Generic instruments were used to measure participants’ perceptions of health outcome in this trial, which have previously been shown to be sensitive to changes venous ulcer healing status. 47 In addition, these instruments are also particularly useful for comparing groups of participants, while also having a broad capacity for use in economic evaluation. Their generic nature also makes them potentially responsive to side effects or unforeseen effects of treatment.

Each participant’s perception of his or her general health was assessed using the acute version of the SF-1248 and the EQ-5D (EuroQol). 41 The SF-12 is a reliable and well-validated questionnaire,49 and has been used in UK populations including older people and leg ulcer patients. 50,51 We used a layout of the SF-12 shown in previous work to yield improved response rates and quality. 52 The EQ-5D is a generic measure of health status, in which health is characterised on five dimensions (mobility, self-care, ability to undertake usual activities, pain, anxiety/depression). 41 Participants were asked to describe their level of health on each dimension using one of three levels: no problems, moderate problems and severe problems. Each response locates a person into one of 243 mutually exclusive health states, each of which has previously been valued on the 0 (equivalent to dead) to 1 (equivalent to perfect health) ‘utility’ scale based on interviews with a sample of 3395 members of the UK public. 53 The EQ-5D has been validated in the UK and questionnaires containing both instruments were administered to patients by postal survey at baseline and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months.

Optimising questionnaire response rates is of vital importance, and a recent systematic review has investigated strategies to increase questionnaire response rates. 54 The review reported that response rates to postal questionnaires doubled (odds ratio = 2.02, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.27) when a financial reward was included with the questionnaire compared with rates obtained with no incentive. The response rate increased further when the incentive was not conditional on response versus upon return of questionnaire (odds ratio = 1.71, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.26). Based on these data, we enclosed an unconditional payment to participants along with their final (usually the 12th month) questionnaire. They received notification in advance that would receive £5 in recognition of their commitment to our study and the time they spent completing questionnaires.

Adverse events

An adverse event is defined as ‘any undesirable clinical occurrence in a subject, whether it is considered to be device related or not’. 55 Both treatment-related and -unrelated adverse events were reported to the trial office (see Appendix 5). The reporting nurse indicated whether, in his or her opinion, the event was related to trial treatment or not. Events were also classed as serious or non-serious. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined as death, life-threatening risk, hospitalisation, persistent or significant disability/incapacity and patient being newly diagnosed as diabetic. For other events the treating nurse made a clinical decision about the seriousness. A list of possible treatment-related adverse events was established a priori, based on reports in the literature and VenUS I and VenUS II. These were pressure damage, infection, skin damage surrounding ulcer, new ulcer, ulcer deterioration and also adverse reaction to the ultrasound treatment or gel.

All nurses were asked to report any SAEs within 24 hours of the event occurring, or within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event. Sites were also provided with review forms in order to follow up all events so that information on eventual outcomes was recorded.

Clinical analysis

The objective of the clinical analyses was to compare the clinical effectiveness of low-dose ultrasound (0.5 W/cm2 spatial average and temporal peak) delivered at 1 MHz plus standard care with standard care alone in the treatment of hard-to-heal venous ulcers (i.e. those with duration of > 6 months and/or surface area > 5 cm2). Our aim was to assess whether the addition of 5–10 minutes of ultrasound (depending on ulcer area) to a package of best available standard care had any affect on:

-

time to ulcer healing

-

complete ulcer healing (the patient is completely healed of all ulcers)

-

HRQoL

-

adverse events.

Outcomes

Primary

-

Time to complete healing of the reference ulcer.

The reference ulcer was the largest ulcer on either leg (as assessed at the time of trial entry). The date of healing was recorded by the research nurses on the Ulcer Healed Form and the photographs of the reference ulcer as assessed independently by two people blind to treatment group. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or referral to a third blinded assessor. The primary outcome was calculated using the date of healing as decided by the blind assessors. If the blinded assessors did not agree on a healing date, then the date as recorded on the Ulcer Healed Form was used. Time to healing was derived as the number of days between randomisation and the first date that healing was confirmed. Patients who withdrew unhealed from the trial or died prior to healing were treated as censored in the analysis. Their time to censoring was derived using the date of trial exit, the date of their last ulcer assessment or the date of trial closure. Patients who completed the full 12-month follow-up without their reference ulcer healing were also treated as censored and their time to censoring was calculated as 12 months (365 days).

Secondary

-

Reduction in ulcer area.

-

HRQoL (SF-12) (baseline and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months).

-

Complete healing of all ulcers during the trial period (up to 12 months).

-

Adverse events.

-

Ulcer recurrence.

Analyses

Primary statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis using a two-sided, 5% significance level.

Primary outcome

The primary analysis compared the time to complete healing of the reference ulcer between the two randomised groups using a Cox regression model. 56 The analysis adjusted for centre as a random effect, ulcer area (from baseline tracing), ulcer duration and whether or not the patient was treated with high-compression bandaging. If centres recruited a small number of patients (five or fewer) then the analysis was repeated with no adjustment for centre, as a sensitivity analysis. Hazard ratios and corresponding 95% CIs were presented. The assumption of proportional hazards was checked using log–log plots, inclusion of interaction terms in the model (for each term with time) and by looking at plots of Schoenfeld residuals. The linearity assumption of continuous terms in the model (ulcer area and duration) was assessed using plots of the Martingale residuals and, if necessary, a suitable transformation used.

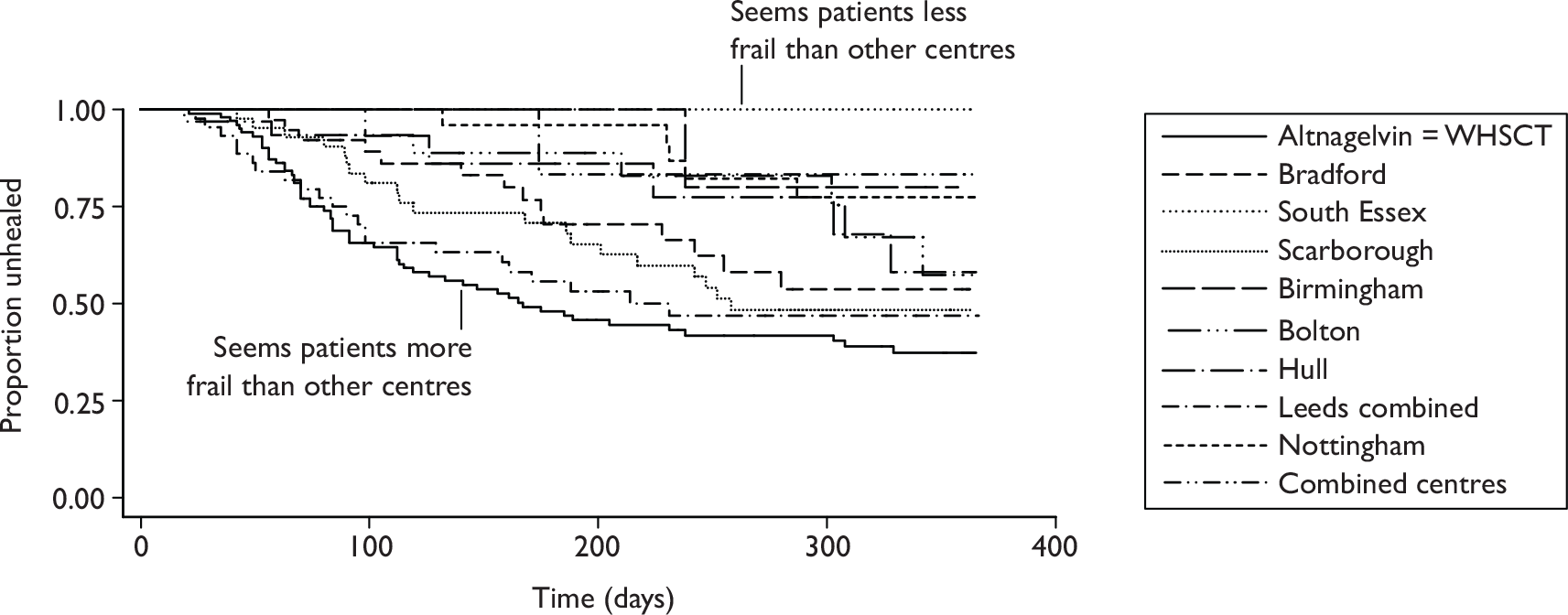

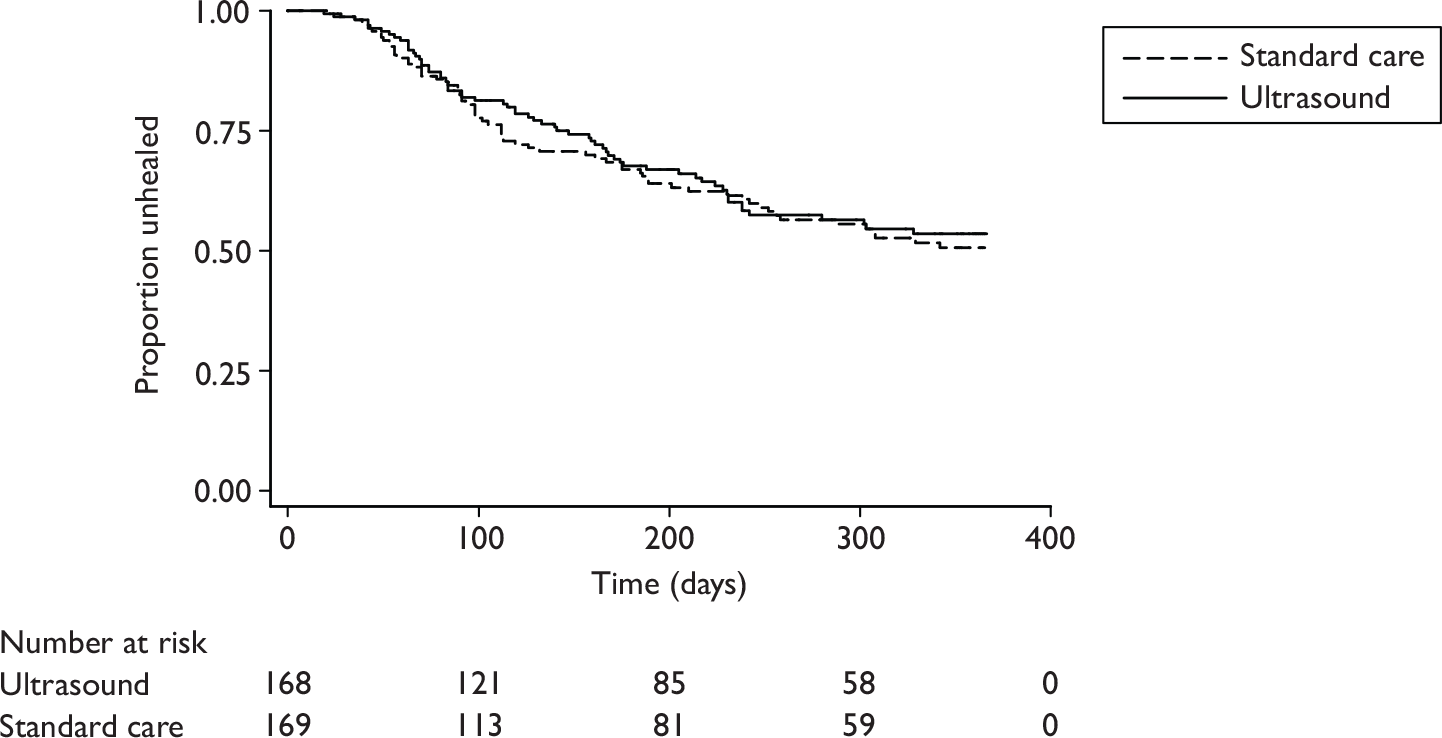

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were produced for the two groups and the median time to healing with 95% CI, as well as the Kaplan–Meier estimates of the proportions of ulcers healed at 12 and 24 weeks (for comparison with the results of other venous leg ulcer trials) presented.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to repeat the primary analysis using only the data of healing as recorded by the research nurses, and not using the data from the photographs.

Agreement on date of healing

The Cohen’s kappa measure of inter-rater agreement was used to assess agreement between the two assessors of the photographs for time to healing. This was repeated to look at agreement between the final decision from the photograph assessment and the nurses’ recorded date of healing.

Secondary outcomes

Ulcer area

Ulcer area tracing data were measured using a specialist computer package (mouseyes). 36 The areas at baseline and each assessment were summarised using descriptive statistics [mean, standard deviation (SD), median, range]. Previous research has shown that the initial reduction in ulcer area (percentage reduction after 4 weeks of good wound care) is predictive of eventual healing. 45 Therefore, we compared the initial healing rates between the ultrasound and standard care groups. The ulcer area at week 4 was compared between treatment groups using analysis of covariance to adjust for baseline ulcer area, centre, ulcer duration and use of compression.

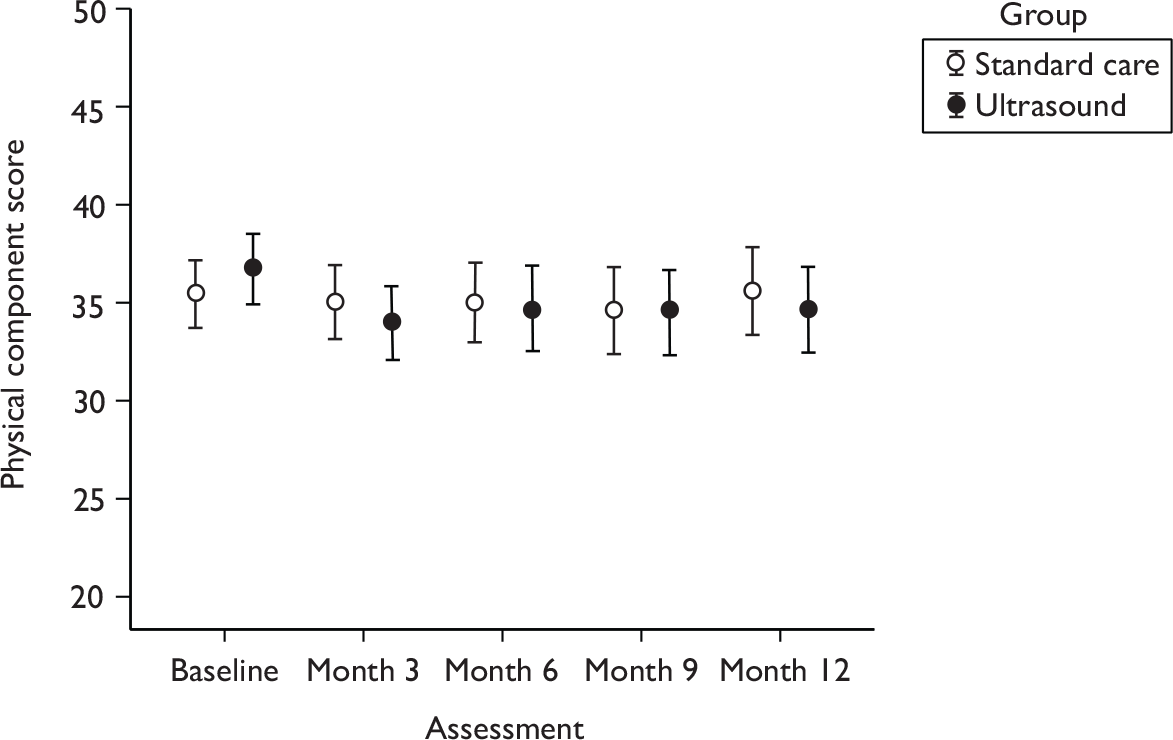

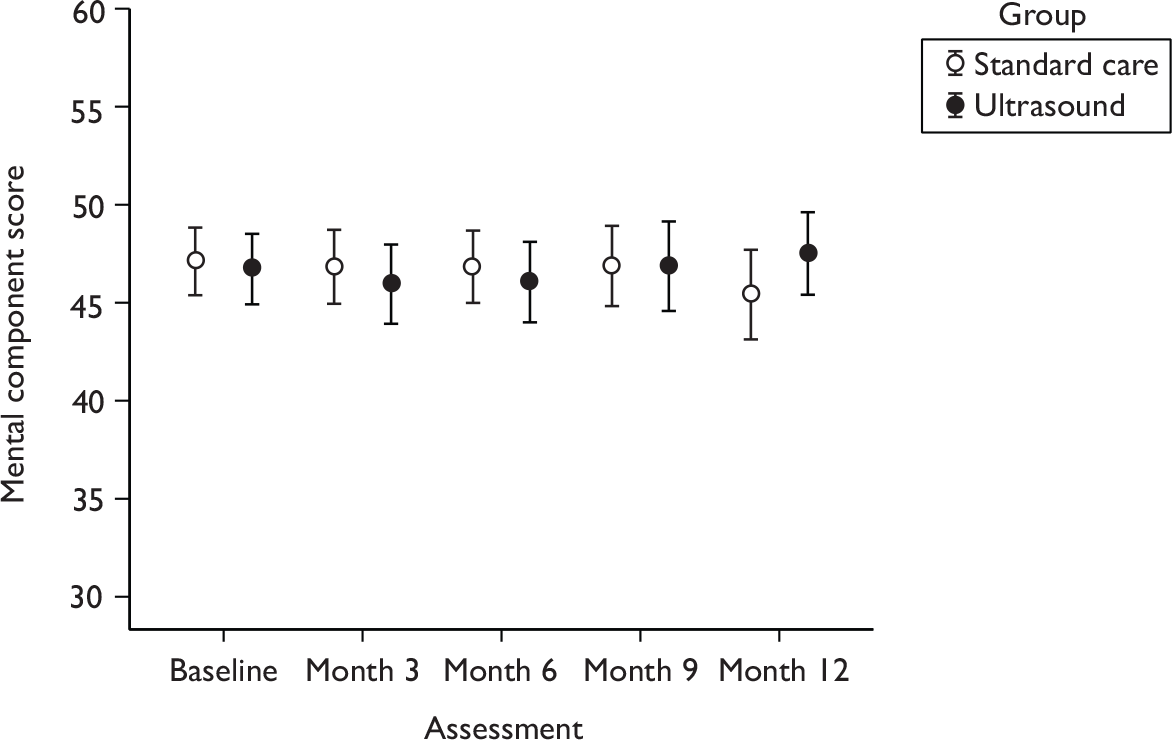

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using the SF-12 questionnaire [measured at baseline (0), and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months]. The scores for the physical and mental health components were analysed using a multilevel regression model approach. The outcomes at each time point were used in a single model, with time points nested within patients to account for within-patient correlation in scores. The model was used to estimate the difference between treatments over the whole 12-month follow-up period. The outcome modelled was the score at each follow-up assessment and the covariates included in the model were centre, baseline health component score, baseline ulcer area, ulcer duration, use of compression and time (indicators for 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months). Whether the pattern in QoL scores over time is different between the two treatments was assessed by including an interaction term between treatment and time in the model.

The assumption of normally distributed data was assessed and, if necessary, log transformations or other analysis methods used.

The numbers of patients with missing data at each time point were summarised together with reasons for missing data (if available). We summarised the proportions of missing questionnaires at each time point by healing status and used joint modelling of repeated QoL data and time to ulcer healing. 57

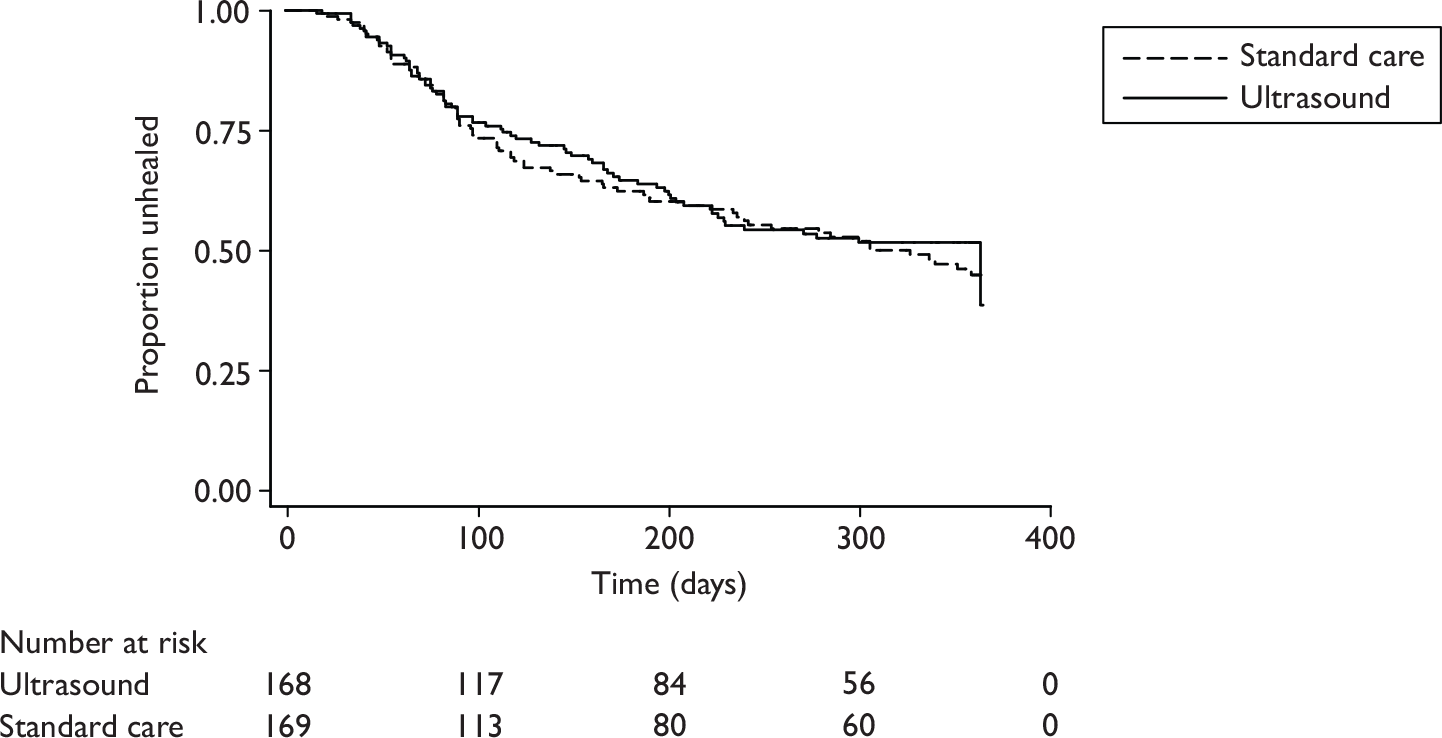

Complete healing of all ulcers at 12 months

The proportions of patients completely healed of all ulcers on both legs by the end of trial follow-up (12 months or earlier) were summarised by treatment group. A Kaplan–Meier plot of the time to complete healing and estimates of the median time to complete healing and 95% CI for each group was presented. Any patient not completely healed by the end of the trial was treated as censored.

Ulcer recurrence

The proportions of patients whose reference ulcer healed and then recurred was summarised by treatment group.

Adverse events

The number of adverse events experienced by each patient was compared between treatment groups using a negative binomial model adjusting for the same covariates as the primary analyses (centre, ulcer size, ulcer duration, use of compression). This analysis summarised all adverse events and then SAEs and non-serious adverse events (NSAEs) separately. The number of patients with one or more adverse events and the numbers of adverse events, their severity and whether they were considered treatment related or not, were summarised descriptively by treatment group.

Economic analysis

Economic evaluation of health interventions is a tool used to assist decision makers in prioritising and allocating resources in the health-care sector, by assessing the value for money (cost-effectiveness) of alternative interventions. 58

The aim of the economic evaluation was to assess cost-effectiveness of low-dose ultrasound in conjunction with standard care compared with standard care alone in the treatment of hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers. Using individual-level data, cost-effectiveness analysis and cost–utility analysis were performed. These analyses are expected to provide evidence, taking into account both comparative cost and effectiveness simultaneously, to assist the decision on whether or not to adopt ultrasound in conjunction with standard care for the treatment of hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers.

The analysis was conducted on an ‘intention-to-treat’ basis, comparing incremental costs with incremental ulcer-free days (cost-effectiveness analysis) and incremental quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) (cost–utility analysis). The perspective of NHS and Personal Social Services was adopted in the current analysis considering that the findings will be used to inform the decision maker in the NHS. Discounting for the future cost and health outcome was not necessary as the time frame of the trial was 12 months after randomisation. The year of pricing was 2007. The analyses were conducted using stata 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). 59

Data

Cost and health benefits data used in the economic analysis were extracted from the current trial. There were two sources of cost data: nurse-completed and patient-completed questionnaires. Nurse-completed questionnaires provide detailed information on each treatment the patients received, such as the choice of compression therapy, the duration of ultrasound treatment (if applied) and the treatment setting, whereas patient-completed data, derived from patient self-reported questionnaires at 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up, provided information on frequency of health-care consultations, including doctor, nurse and hospital outpatient visits. Two different measures of health benefit were used: the time to healing and QALY. Time to healing was recorded by nurses and assessed by blinded investigators, whereas QALYs, representing years living in full health, were calculated based on information obtained from patient self-reported questionnaires every 3 months. Details of each constituent component of the economic analysis are discussed in the following sections.

Owing to the restricted follow-up period (1 year) as well as death and loss to follow-up, censoring occurred in both cost and health benefits data. To adjust for this censoring issue, in order to obtain more accurate estimation, the inverse probability weight (IPW) approach60 was applied. This method applies a set of different weights to account for the censoring. The same approach was used in VenUS II. 61 Taking the time to healing as an example, in this IPW approach only participants with observed time to healing data contribute with non-zero terms, but their contributions are inversely weighted by the probability of being observed. 61 Consequently, individuals who are less likely to be observed are weighted most heavily. The censoring distribution was estimated through the Kaplan–Meier estimator. Similarly, an IPW approach was adopted in the estimation of mean costs and QALYs to adjust for the censoring issues in the cost and QALY data, respectively.

Outcomes of the economic analysis

The economic analysis used incremental costs and incremental health benefits, estimated from the trial data, to evaluate the value for money of the ultrasound with standard care treatment. Time to healing of the reference ulcer and QALYs were the units of health benefit in the cost-effectiveness analysis and cost–utility analysis, respectively.

Health benefits

Time to healing estimation

The mean time to healing was estimated from the IPW regression using the same covariates as in the clinical analysis to adjust for the nature of the censoring, possible baseline imbalances and randomisation stratification, namely baseline ulcer duration (logarithmic), ulcer area (logarithmic), use or not of compression therapy and centres (aggregating centres with fewer than five cases). The centre effect was treated as fixed effect in all subsequent analyses. In order to facilitate the interpretation of the cost-effectiveness analysis, the effectiveness outcome was reported as ‘gain in ulcer-free days’. The gain in ulcer-free days is the same as the difference in mean time to healing between two trial arms (same absolute value), but with the opposite sign (–/+).

Utility scores and quality-adjusted life-year estimation

Utilities of patients were measured by the EQ-5D62 questionnaire at baseline and at each follow-up of 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, independent of healing status. EQ-5D is one of the most widely used HRQoL measures and provides summary index (utility) scores of health states for the purpose of economic evaluation. The EQ-5D description system contains five dimensions – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression; each dimension has three levels – no, some and severe problems. The utility, also known as EQ-5D index score, of each patient at each observed time point was derived from patient’s responses to the EQ-5D description system at that time point and a predefined weight was assigned accordingly. The predefined weight represents the social preference of the general population in England and Wales towards EQ-5D health states. 63 These utility scores, 1 representing full health and 0 indicating death, were then used in QALY calculation.

According to the data collection, the study time horizon was partitioned in homogeneous subintervals (quarterly intervals). Quarterly QALYs were calculated by multiplying an individual’s utility score with survival time using the area under the curve approach, which was defined by linearly interpolating the utility scores measured over time. 64 However, not all participants were followed up for a full trial period because of censoring. To account for the impact of censoring, thus avoiding biased estimates, mean quarterly QALYs were estimated using the IPW method. To ensure comparability with the clinical analysis, linear regression was used to adjust QALYs by the same clinical covariates and also baseline utility. In the presence of imbalance, failure to include baseline utility results in biased results and a misrepresentation of uncertainty. 65 QALYs were weighted by the inverse of the probability of an individual not being censored. In the case of participants who died, utility values were recoded as zero. Mean total QALYs, over the 12-month follow-up period were then estimated as the sum of the estimated mean QALYs per period for each trial arm given the mean value of the rest of the covariates observed in the whole sample.

Resource use and unit costs

A cost for each trial participant was calculated as the product of resources used and their relevant costs. The analysis was costed at 2007 prices (mid-point of the trial). Three components were considered in the estimation of leg ulcer treatment cost: cost of ultrasound machine, cost of compression therapy and cost of health-care consultations (focusing on cost of health-care provider’s time). Other treatments, such as primary and secondary dressing or skin preparations, were assumed to be used equally across treatment arms; these resources were not included in the economic analyses. Incorporating costs categorised as irrelevant in distinguishing treatments into the analysis will increase the variance (and the standard error) of total costs for each arm and, thus, misrepresent uncertainty in the incremental costs. 66

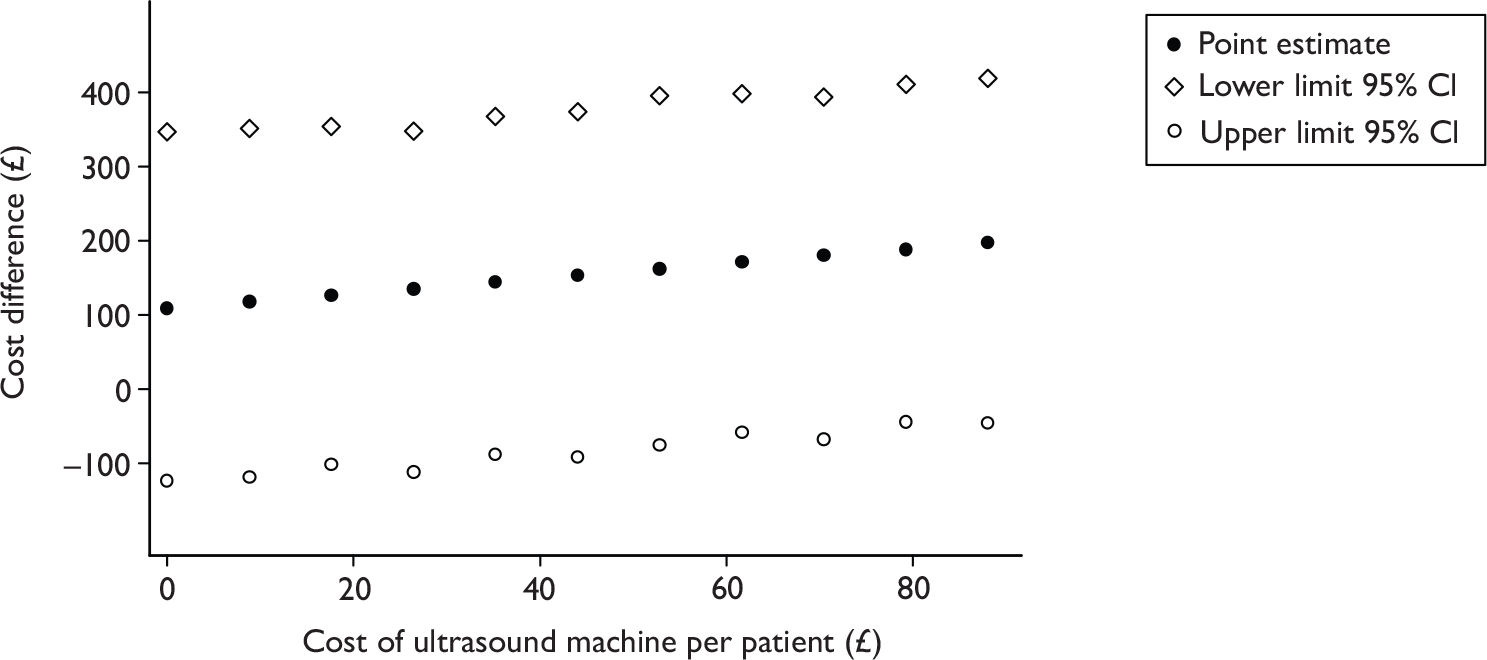

Cost of ultrasound machine

We purchased 40 ultrasound machines at a cost of £26,267.87 including the purchasing and testing fees as listed in Table 2. These fees are regarded as one-off equipment costs. Following the suggested method58 for dealing with one-off equipment costs in economic evaluation, the study calculated the equivalent annual equipment cost, taking into account depreciation of the ultrasound machine and its opportunity cost. By assuming that the average lifespan of an ultrasound machine is 7 years and considering linear depreciation with the interest rate for opportunity cost at 3.5%, the equivalent annual equipment cost over the period of 7 years is £4659.15. The information on lifespan and cost of ultrasound machines was provided by the machine supplier (EMS Physio Ltd). The interest rate chosen here was based on the discounting rate suggested in the reference case for technology appraisal recommend by National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 67 Note that discounting was not applied in the current analysis.

| Item | Total cost (£) | Note | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine purchasing fee | 19,180.00 | Forty machines | EMS Physio Ltd |

| Testing fee | 7087.87 | One-off at machine set-up | NPL |

| Equivalent annual equipment cost | 4659.15 | Assuming 7-year lifespan and an interest rate of 3.5% | |

| Servicing fee | 10,133.71 | Once every 3 months | EMS Physio Ltd |

| Cost of ultrasound machine per patient | 88.05 | Dividing the sum of the servicing fee and equivalent annual equipment cost by the number of participants in the ultrasound arm |

The cost of ultrasound machines per patient in the treatment arm was estimated to be £88.05. This was calculated by summing the equivalent annual equipment cost of ultrasound machines with their servicing fee through a year (occurring every 3 months), then dividing by the number of participants in the treatment arm. This cost was added to each participant in the treatment arm to calculate their total costs of leg ulcer treatment.

As detailed, the costs associated with the ultrasound machine were based on the cost of the current trial, and might not reflect the ‘real’ cost in other, more generalised, settings. For instance, if the ultrasound machines are also used for other purposes (therefore more patients use them), the cost of ultrasound machine per patient could be lower (as a result of a larger denominator). The impact of this estimation was explored in the sensitivity analysis.

Cost of compression therapy

Table 3 shows the unit cost of each compression bandaging system. The composition of the compression bandaging system was obtained from VenUS II and updated based on the supply and prices as listed in the British National Formulary (BNF). 68 The choice of the class of compression therapies was recorded by a nurse at each treatment (high compression: four-layer, three-layer, two-layer and short-stretch high compression; low compression: three-layer reduced compression; light compression). As no information on the size or brand of the system was available, an arithmetic average cost for commercially available systems was used to cost the class recorded. The cost of compression therapy per patient/per visit was then calculated accordingly.

| Bandaging system | Example | Cost (£) (from BNF) |

|---|---|---|

| High-compression bandaging: 4LB | K-Four® | 6.25 |

| Profore® | 8.35 | |

| System 4® | 7.77 | |

| Ultra Four® | 5.67 | |

| Mean cost | 7.01 | |

| High-compression bandaging: SSB | Actiban® | 3.18 |

| Actico® | 3.21 | |

| Comprilan® | 3.12 | |

| Rosidal K® | 3.36 | |

| Silkolan® | 3.39 | |

| Mean cost | 3.25 | |

| High compression: two-layer kits | ProGuide® | 8.49 |

| Coban® | 8.08 | |

| Mean cost | 8.29 | |

| Layer 1 | Advasoft® | 0.39 |

| Cellona Undercast padding® | 0.42 | |

| Flexi-Ban® | 0.44 | |

| K-Soft® | 0.4 | |

| Ortho-Band Plus® | 0.37 | |

| Softexe® | 0.58 | |

| Ultra Soft® | 0.42 | |

| Velband® | 0.66 | |

| Surerpress® | 0.53 | |

| Profore #1® | 0.62 | |

| Mean cost | 0.48 | |

| Class 2 | Neosport® | 0.99 |

| Soffcrepe® | 1.14 | |

| Setocrepe® | 1.18 | |

| Profore #2® | 1.16 | |

| K-Lite® | 0.89 | |

| Mean cost | 1.07 | |

| Class 3A | Elset® | 3.06 |

| Elset S® | 5.13 | |

| K-Plus® | 2.17 | |

| Profore #3® | 3.46 | |

| Mean cost | 3.46 | |

| Cohesive | Coban® | 3.61 |

| Profore #4® | 2.86 | |

| Hospifour # 4® | 1.93 | |

| Mean cost | 2.80 | |

| Class 3C | Setopress® | 3.46 |

| Tensopress® | 3.47 | |

| Profore Plus® | 3.24 | |

| Mean cost | 3.39 | |

| Compression systems (using mean costs presented) | Three-layer high compression: 1, 3C, cohesive | 6.67 |

| Three-layer reduced compression: 1, 2, cohesive | 4.36 | |

| Light compression: 1, cohesive | 3.28 |

Cost of health-care consultation

Both nurse- and patient-reported data regarding visits to or from health-care providers were available. Unless patients refused, nurse-reported data were intended to record every single nurse-administered ulcer treatment a participant received until healed, death or end of follow-up. Therefore, nurse-reported data comprised ulcer-related resource use only. Health-care consultations in patient self-reported data were extracted from the follow-up questionnaires (every 3 months). Participants were asked how many times they had seen a doctor or nurse and had been to hospital as an outpatient in the past 4 weeks and how many consultations were related to their ulcer. There were a large number of missing data regarding health-care consultations (for instance, the missing rates for patient-reported nurse visits are 28%, 32%, 37% and 38% in the 3, 6, 9 and 12-month follow-up questionnaires, respectively) so we used the nurse-reported data for the base case, while the use of patient-reported data were explored in a sensitivity analysis.

The cost per nurse visit was calculated by multiplying the duration of each visit by the cost per minute of nurse consultations, which varied depending on the location of treatment (Table 4). There was, however, no direct information available in the current trial for the duration of each nurse visit. We followed the approach used in VenUS I,7 in which the duration of a home visit was assigned as 40 minutes and a clinic visit as 22 minutes. The number was taken from the national estimates and was in agreement with a survey conducted within VenUS I to investigate the duration of time nurses spent on treating ulcer patients. Therefore, in the current study it is assumed that the duration of a nurse home visit was 40 minutes and all other visits were 22 minutes. When the visits included ultrasound treatment, the amount of time to apply ultrasound, as recorded by nurses, was added to the duration of visits.

| Item | Mean unit value (£ or minutes) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse consultation (per minute) | ||

| Community | 1.00 | PSSRU |

| Home visit | 1.07 | PSSRU |

| Travel cost for home visit | 1.40 | PSSRU |

| GP surgery | 0.48 | PSSRU |

| Hospital | 0.63 | PSSRU |

| Duration of nurse consultation | ||

| Home visit | 40 | VenUS I |

| Other visit | 22 | VenUS I |

All cost units/values regarding nurse consultation are listed in Table 4. The sources of costing include the VenUS I trial and the costs of health and social care published by the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU), University of Kent. 69

In the current trial, adverse events were recorded by the nurse. However, there was too little information available to allow for an accurate estimation of costs associated with these episodes. Therefore, the cost of adverse events was ignored in the base-case analysis. In sensitivity analysis, however, further resources used, e.g. hospital visits, were self-reported by patients. Thus, in this alternative analysis possible resource consumptions due to adverse event might be captured.

Total cost estimation

Resource use data are also subject to censoring, and estimating the mean total cost based on complete case analysis will underestimate the true expected costs. An IPW regression (as described above) was used to account for censoring, possible baseline imbalances and randomisation stratification variables. Mean cost estimation was made by partitioning the study period into quarterly periods and the IPW regression estimates obtained for each period were then summed to obtain the total expected costs.

Cost-effectiveness

To assess cost-effectiveness, the mean difference in costs between trial arms was compared with the mean difference in health benefits. For instance, if ultrasound plus standard care is more expensive and is associated with fewer health benefits than standard care alone, then ultrasound with standard care is dominated by standard care alone and the decision whether or not to adopt ultrasound is straightforward (not adopt). The decision arising from the converse situation (in which ultrasound plus standard care is dominant, i.e. less costly and more beneficial than standard care alone) is similarly straightforward (adopt). However, if ultrasound is more costly and more beneficial or less costly and less beneficial than standard care, we need to assess whether the increased cost of the ultrasound is worth the increased benefit, or whether the reduced benefit conferred by the ultrasound is justified by the reduced cost.

To ascertain the cost-effectiveness of a health-care intervention relative to another in the absence of dominance, an incremental analysis of cost-effectiveness is conducted. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is the most commonly used cost-effectiveness measure and combines costs and health benefit in a single measure to which a decision rule for cost-effectiveness can be applied. It combines costs and benefits in a ratio of the mean difference in cost between the alternative treatments being compared with the mean difference in health benefits:

where C1 and B1 are, respectively, the mean costs and mean health benefits associated with the technology under evaluation (ultrasound with standard care in the current analysis), while C0 and B0 are the mean costs and mean health benefits associated with the comparator technology (standard care alone).

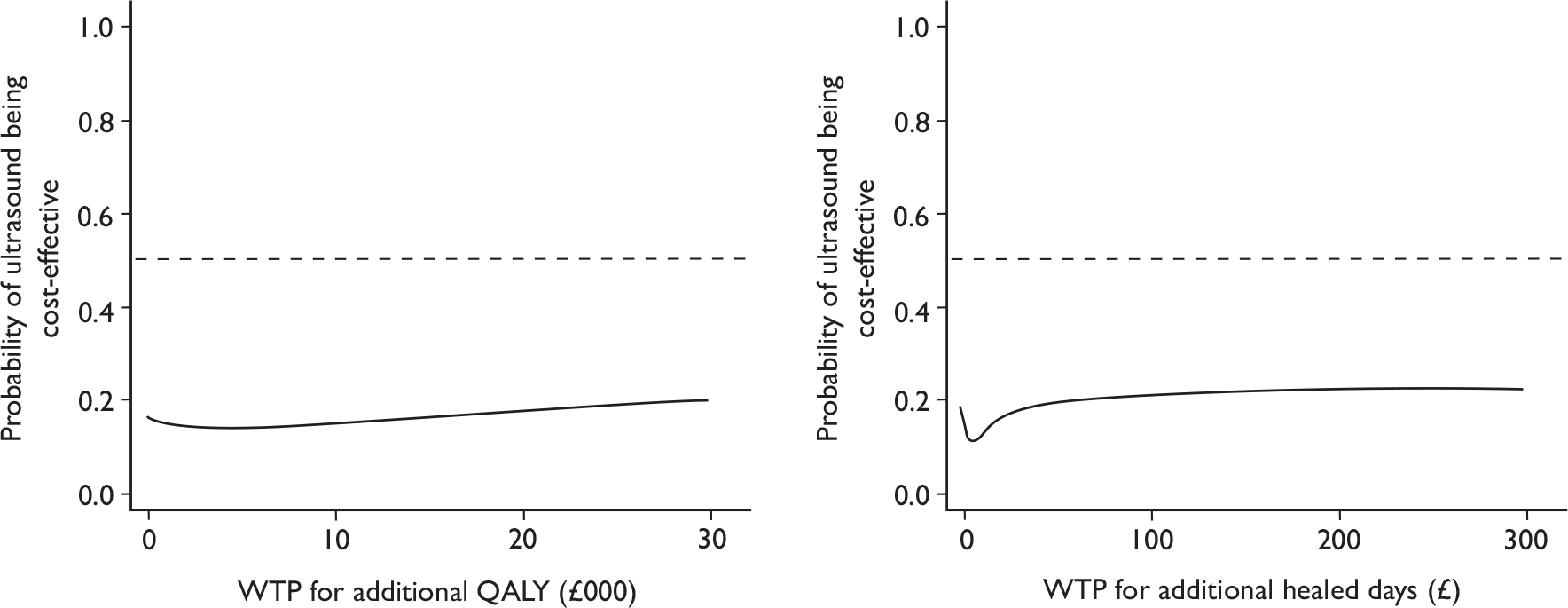

The decision rule for cost-effectiveness on the basis of the ICER indicates that a treatment strategy can be considered cost-effective only if the decision maker’s willingness to pay for an additional unit of health benefit (QALYs and ulcer-free days) is greater (or equal) to the ICER. According to NICE, the willingness to pay for an additional QALY ranges between £20,000 and £30,000. 67 Therefore, if the results of a cost–utility analysis (the estimated cost per QALY) is below this threshold, the intervention will be considered cost-effective.

Cost-effectiveness analysis in which the outcome is expressed in a natural unit, for example cost per ulcer-free day, may be more intuitive for clinicians. Despite this, and for the purpose of informing adoption decisions, the results of cost-effectiveness analysis are harder to interpret because there is no information on the willingness to pay for an additional ulcer-free day. Without this information we cannot determine whether or not the new intervention is cost-effective. To inform a decision based on this measure of health benefit, a threshold has to be established, and the decision maker is responsible for establishing this. Another reason to include this type of analysis is to facilitate the comparisons between relevant studies.

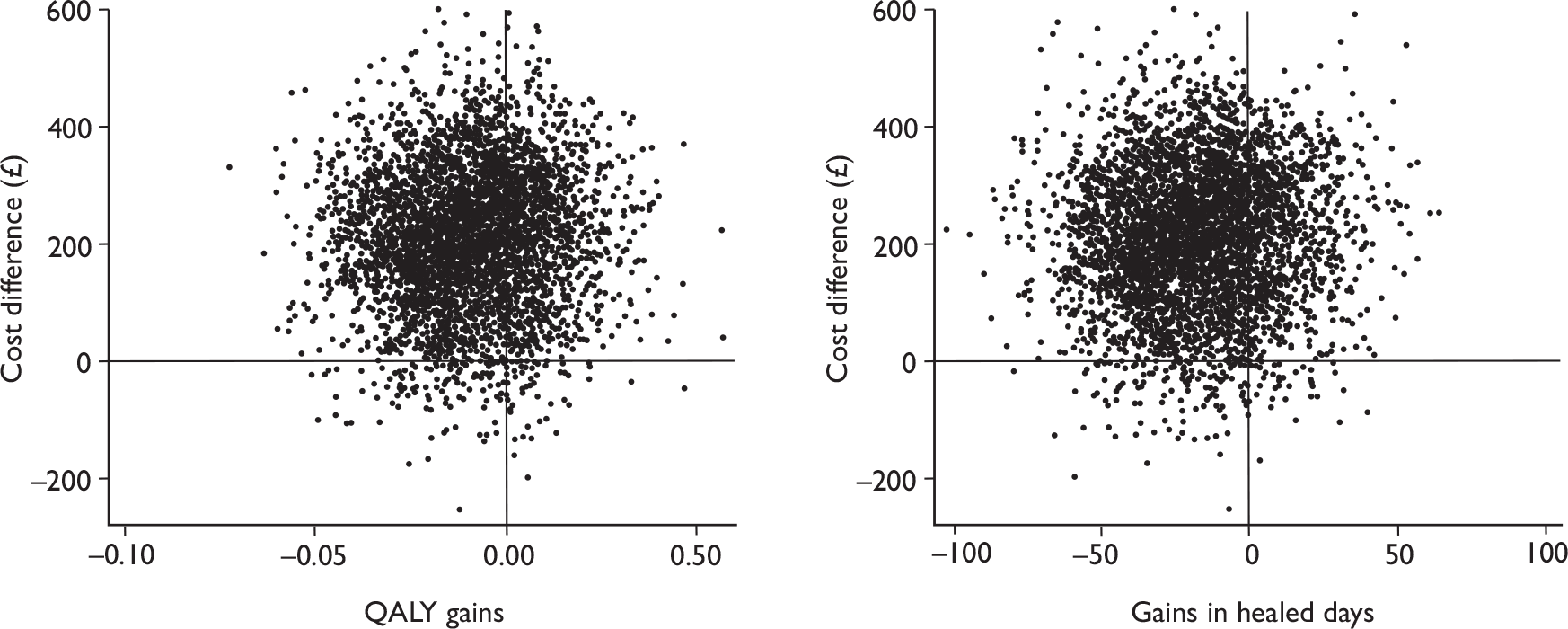

Uncertainty assessment

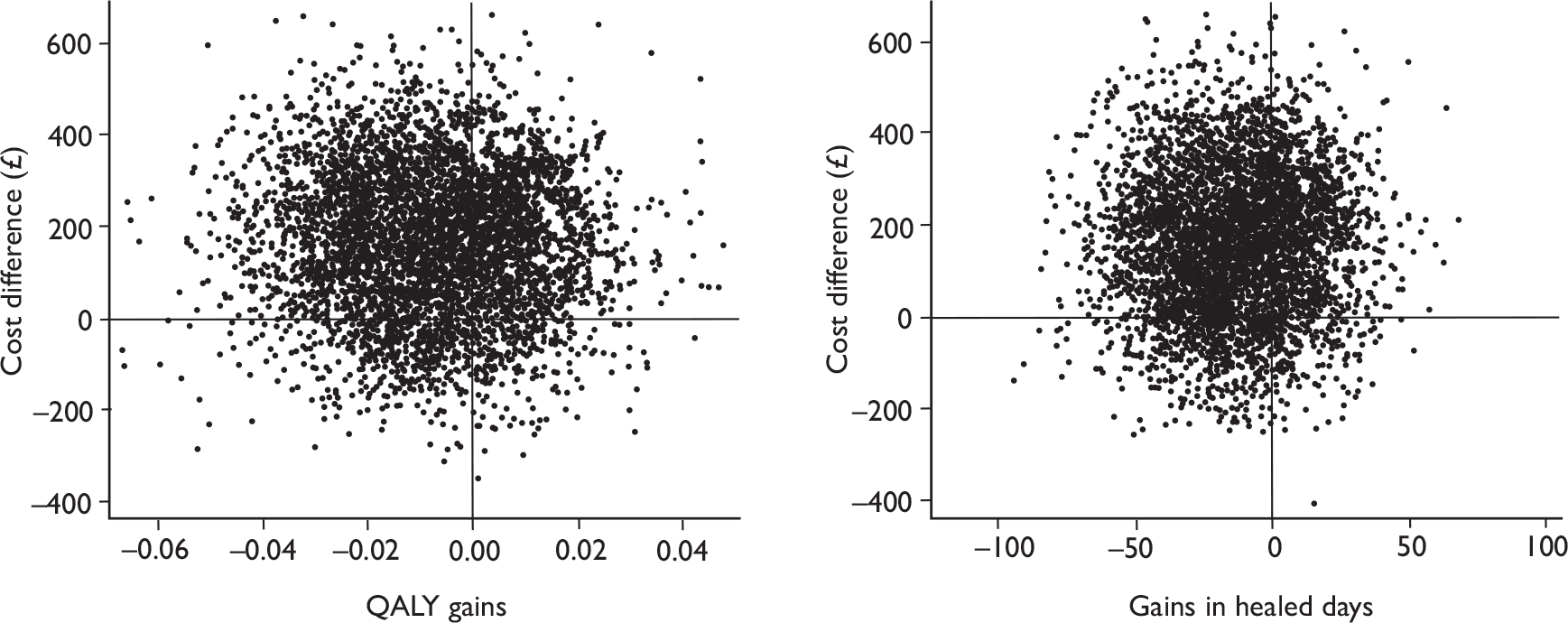

There is uncertainty in the incremental cost-effectiveness between two interventions, and this can be summarised graphically in a cost-effectiveness plane. By plotting the non-parametric bootstrapping results – 4000 replicates of difference in costs and health benefits (QALYs and ulcer-free days), the position of the estimates can indicate the degree of certainty that one of the interventions is dominant (north-west or south-east quadrants).

The ICER is associated with uncertainty because its numerator (expected costs) and its denominator (effectiveness) are estimated with sampling uncertainty. Therefore, a decision on whether or not to adopt a treatment based on the ICER estimate is also associated with uncertainty. In other words, if the trial were repeated, we might observe a different mean incremental cost and effectiveness, resulting in a different ICER estimate. The analysis of the consequences of this uncertainty and the extent to which it impacts on the adoption decision should be investigated to inform whether further research is needed. 70 Thus, the uncertainty around incremental costs and effects estimates and its impact on the adoption decision were investigated here.

Confidence intervals

Uncertainty around the decision to adopt the treatment under evaluation was assessed through a non-parametric bootstrap resampling technique. 71 This is a common methodology used to construct CIs around the incremental costs and health benefits from sampled cost and effectiveness random variables. Firstly, the bootstrap technique was used to sample (with replacement) from the observed cost and effectiveness pairs, maintaining the correlation structure. For each bootstrap resample, an IPW estimate of expected total costs, expected QALYs and expected time to healing was calculated, which allowed computation of cost-effectiveness and cost–utility outcome replicates. The 95% CIs for the differential costs and QALYs were then calculated using bias-corrected non-parametric bootstrapping.

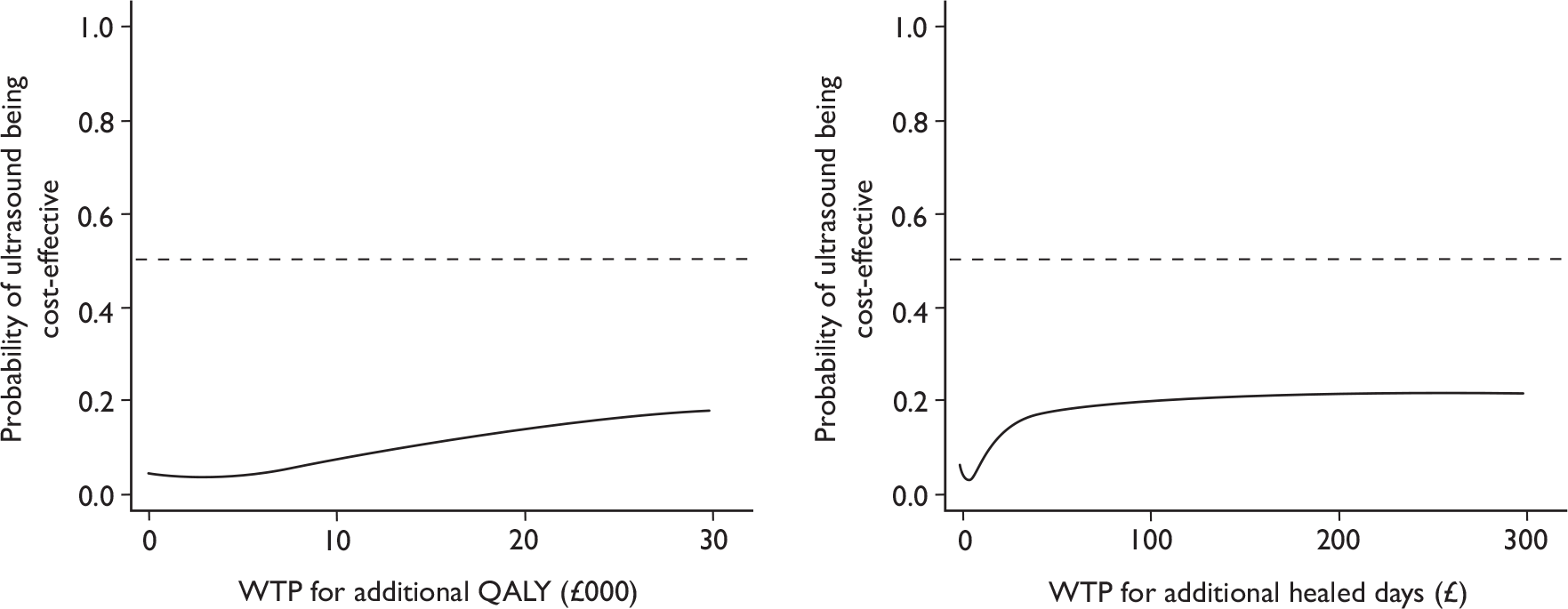

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves

To explore the decision uncertainty regarding the cost-effectiveness of ultrasound treatment, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were plotted. The CEAC expresses the probability that an intervention is cost-effective in relation to the comparator intervention, as a function of the threshold willingness to pay. 72 Thus, the CEAC summarises, for every value of willingness to pay, the evidence in favour of the intervention being cost-effective. In this case, given the trial data, the CEAC for ultrasound with standard care represents the probability of this treatment being cost-effective compared with standard care alone for a range of willingness-to-pay values for an additional ulcer-free day/QALY.

Sensitivity analysis

Scenario 1

To explore the impact of the source of health-care consultation on cost-effectiveness/cost–utility analysis, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. In this analysis, patient-reported, instead of nurse-reported, data were used to calculate leg ulcer-related costs. Costs unrelated to leg ulcers were assumed to be equal between arms and were thus not considered in this analysis. 66 In contrast to the base-case analysis, in which only nurse consultations were costed, in this scenario we also considered ulcer-related hospital visits and doctor consultations. The cost per visit was calculated assuming different duration of home and clinic visits, as stated in Table 4. The self-reported data collected information about the visit setting (home or clinic). However, this information was recorded for all doctor/nurse/outpatient visits rather than for ulcer-related visits only. Consequently, we assumed that the setting of ulcer-related visits from self-reported data would follow the same pattern as that reported for all visits, for which data were available.

As shown in Table 5, the additional unit cost applied in this sensitivity analysis included doctor visit at GP surgery and at home, £31 and £50 per visit, respectively. Furthermore, the cost per hospital outpatient was charged as a non-consultant-led follow-up attendance fee, £71.

| Item | Mean unit value (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Doctor visit | ||

| GP surgery | 31 | PSSRU |

| Home visit | 50 | PSSRU |

| Hospital outpatient | 71 | PSSRU |

Scenario 2